Intersex and LGBT, LGBT and Intersex

LGBTI, LGBTQ+

Intersex and LGBT, LGBT and Intersex

解説:池田光穂

LGBTI とは、レズビアン、ゲイ、バイセクシュアル、トランスセクシュアル、そしてインターセックスのまとめる総称である。

| Intersex people are born with sex characteristics (such as genitals, gonads, and chromosome patterns) that "do not fit the typical definitions for male or female bodies. - Wiki. | インターセックスの人々は、「男性または女性の典型的な身体の定義に当てはまらない」性徴(性器、生殖腺、染色体パターンなど)を持って生まれる。 - ウィキペディア |

| They are substantially more likely to identify as lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender (LGBT) than the non-intersex population, with an estimated 52% identifying as non-heterosexual and 8.5% to 20% experiencing gender dysphoria. Although many intersex people are heterosexual and cisgender,[3][4] this overlap and "shared experiences of harm arising from dominant societal sex and gender norms" has led to intersex people often being included under the LGBT umbrella, with the acronym sometimes expanded to LGBTI.[5][a] However, some intersex activists and organisations have criticised this inclusion as distracting from intersex-specific issues such as involuntary medical interventions. | インターセックスでない人々よりも、レズビアン、ゲイ、バイセクシュア

ル、トランスジェンダー(LGBT)であると認識する可能性がはるかに高く、52%が非異性愛者であり、8.5%から20%が性同一性障害を経験している

と推定されている。多くのインターセックスの人々は異性愛者であり、性自認も異性愛者であるが、[3][4]

この重複や「支配的な社会の性別や性別規範から生じる害の共有体験」により、インターセックスの人々はしばしばLGBTの傘下に含まれるようになり、その

頭字語はLGBTIに拡大されることもある。[5][a]

しかし、一部のインターセックスの活動家や団体は、この分類を、不本意な医療介入などのインターセックス特有の問題から目をそらすものとして批判してい

る。 |

●クイア理論(こちらも参照してください)

| Queer bodies -- Intersex activists such as Morgan Carpenter have sometimes talked of intersex bodies as "queer bodies."[11] Activists and scholars such as Carpenter,[12] Morgan Holmes[13] and Katrina Karkazis[14] have documented a heteronormativity in medical rationales for the surgical normalization of infants and children born with atypical sex development. In What Can Queer Theory Do for Intersex? Iain Morland contrasts queer "hedonic activism" with an experience of insensate post-surgical intersex bodies to claim that "queerness is characterized by the sensory interrelation of pleasure and shame."[15] | クィアな身体――モーガン・カーペンターのようなインターセックス活動

家は、インターセックスの身体を「クィアな身体」と呼ぶことがある。[11]

カーペンター[12]、モーガン・ホームズ[13]、カトリーナ・カルカジス[14]などの活動家や学者は、非典型的な性器の発育をもって生まれた乳幼児

の外科的治療による正常化を正当化する医学的根拠に、異性愛規範が存在することを明らかにしている。『インターセックスにクィア理論は何をもたらすか』の

中で、イアン・モアランドは、クィアの「快楽主義的行動主義」と、感覚を失った術後のインターセックスの身体の経験とを対比させ、「クィアとは、快楽と羞

恥心という感覚の相互関係によって特徴づけられる」と主張している。[15] |

テレサ・ド・ローレティス(Teresa de Lauretis, 1991)は、レズビアンとゲイのための共同体論として、クイア・ネーション(Queer nation)を提唱し、そこでは〈異性愛〉と〈同性愛〉をアレかコレかというふうに対立的にみる見方を拒否し、非規範的なセクシュアリティにもとづく共 同性を構想した。

クイア(Queer) とは、日本語のニュアンスでは、オカマとか変態という意味である。一般的にこれらの用語は、蔑称として使われ、そう呼ばれる当事者の人たちをそうでないマ ジョリティの人たちが蔑むために使われてきたことばある。ド・ローレティスは、このような差別—被差別の構造を逆転すべく、クイアを自称することは恥ずか しくない、尊厳的をもってクイアを自称することになんら問題がないと主張した。そして、それを、クイア・ネーションという、「国民国家」の比喩をもちいて、類似のアイデンティティを有する共同体なのであ るという価値転換を試みた。

クイア・ネーションにおいては、性的な態 度(sexual orientation)による人間の判断区分——そのもっとも根強い偏見は性的な態度を〈異性愛〉か〈同性愛〉のどちらかに二者択一の枠組みの中に押し 込めようとする姿勢である——することを拒絶する。クイア・ネーションにおいて、性転換者、トランスベスタイド、変態、バイセクシュアルなどが、その存在 を承認される。

理論的系譜としては、ポスト構造主義、反 本質主義、脱構築の流れに位置づけることができる。

クイア理論は、セクシュアリティの相対的 自律性を主張するために、レズビアンあるいはゲイ研究から派生したものであるが、ジェンダーアイデン ティティを女・男の二項対立に還元する立場に対しても距離をとる。

| Queer theory is a field of post-structuralist critical theory that emerged in the early 1990s out of the fields of queer studies and women's studies. Queer theory includes both queer readings of texts and the theorisation of 'queerness' itself. Heavily influenced by the work of Lauren Berlant, Leo Bersani, Judith Butler, Lee Edelman, Jack Halberstam, David Halperin, José Esteban Muñoz, and Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick, queer theory builds both upon feminist challenges to the idea that gender is part of the essential self and upon gay/lesbian studies' close examination of the socially constructed nature of sexual acts and identities. Whereas gay/lesbian studies focused its inquiries into natural and unnatural behaviour with respect to homosexual behaviour, queer theory expands its focus to encompass any kind of sexual activity or identity that falls into normative and deviant categories. Italian feminist and film theorist Teresa de Lauretis coined the term "queer theory" for a conference she organized at the University of California, Santa Cruz in 1990 and a special issue of Differences: A Journal of Feminist Cultural Studies she edited based on that conference. Queer theory - Wiki | クィア理論は、クィア・スタディーズや女性学の分野から1990年代初

頭に生まれたポスト構造主義批判理論の分野である。クィア理論には、テキストのクィアな解釈と「クィア」そのものの理論化の両方が含まれる。クィア理論

は、ローレン・バーラント、レオ・ベルサニ、ジュディス・バトラー、リー・エデルマン、ジャック・ハルバースタム、デヴィッド・ハルパーリン、ホセ・エス

テバン・ムニョス、イヴ・コソフスキー・セジウィックらの研究に多大な影響を受けている。クィア理論は、ジェンダーが本質的な自己の一部であるという考え

に対するフェミニストの挑戦と、同性愛/レズビアン研究による性的行為とアイデンティティの社会的構築性に関する綿密な調査の両方を基盤としている。ゲイ

/レズビアン研究が、同性愛的行動に関する自然な行動と不自然な行動に焦点を当てていたのに対し、クィア・セオリーは、その焦点を拡大し、規範的および逸

脱的カテゴリーに該当するあらゆる種類の性的行動やアイデンティティを包含する。イタリアのフェミニストであり映画理論家でもあるテレサ・デ・ラウレティ

スは、1990年にカリフォルニア大学サンタクルス校で主催した会議と、その会議に基づいて編集した『Differences: A Journal

of Feminist Cultural Studies』の特別号のために、「クィア・セオリー」という用語を考案した。クィア・セオリー -

Wiki |

■クイアに積極的な意味を見いだす6つの 理由("6 Reasons You Need to Use the Word "Queer""から)

クイアに上掲のような(規制の価値概念の)破壊的意味をもつのだが、それを6つの理由を提示して示したのが、"6 Reasons You Need to Use the Word "Queer""の サイトである。その6つの理由を次のようにまとめるとことができる。1)包括的である(Inclusivity)、2)悪い意味のレッテルを解体し、それ を剥がす作用をもつ(The un-label-y-ist of labels )、3)自ら改心したことを示すパワー(Power in being reclaimed )、4)これらが問題含み=questioning なのだということを主張する(Necessary for those questioning )、5)オトコかオンナかという2つにひとつという考え方から自由になる(Breaks down binaries )、そして、6)すでに確立したLGBT=レズビアン+ゲイ+バイセクシュアル+トランスジェンダーと連携連帯する(Unites the LGBT community )ということである。—("6 Reasons You Need to Use the Word "Queer""から)

■し かしながら"LGBTQ"のQって、クイアのことではない!

LGBTにQをつけLGBTQということがあるのをご存知でしょうか?——この場合のQは、Questioning(クエスチョニング)と いい「自分じしんの性自認や性的指向が定まっていない人たち」のことをさす。

このQ をクイアとする理解もあったが、クイアがもつ破壊力をクイア当事者たちは自らの自己アイデンティティの力となすことはできず、アンビバレントな用語とし て、これが使われるようになった。

参照サイト:「「LGBTQ」の”Q”って

何?」(LGBTラボ)

■性的なことは政治的なことである!(The Sexual is Political, by Slavoj Zizek, Aug 01, 2016)

| "So what is “transgenderism”? It occurs when an individual experiences discord between his/her biological sex (and the corresponding gender, male or female, assigned to him/her by society at birth) and his/her subjective identity. As such, it does not concern only “men who feel and act like women” and vice versa but a complex structure of additional “genderqueer” positions which are outside the very binary opposition of masculine and feminine: bigender, trigender, pangender, genderfluid, up to agender. The vision of social relations that sustains transgenderism is the so-called postgenderism: a social, political and cultural movement whose adherents advocate a voluntary abolition of gender, rendered possible by recent scientific progress in biotechnology and reproductive technologies. Their proposal not only concerns scientific possibility, but is also ethically grounded. The premise of postgenderism is that the social, emotional and cognitive consequences of fixed gender roles are an obstacle to full human emancipation. A society in which reproduction through sex is eliminated (or in which other versions will be possible: a woman can also “father” her child, etc.) will open unheard-of new possibilities of freedom, social and emotional experimenting. It will eliminate the crucial distinction that sustains all subsequent social hierarchies and exploitations." - The Sexual is Political, by Slavoj Zizek, Aug 01, 2016 | 「トランスジェンダー」とは何か?

それは、個人が自身の生物学的な性(および、出生時に社会から割り当てられた男性または女性という性別)と、自身の主観的なアイデンティティとの間に不一

致を感じている場合に起こる。そのため、「女性のように感じ、行動する男性」やその逆だけでなく、男性的と女性的という二元対立の枠組みの外にある「ジェ

ンダー・クィア」と呼ばれる複雑な立場も含まれる。ビッグエンダー、トリジェンダー、パンジェンダー、ジェンダーフルイド、そしてアジェンダーまで。トラ

ンスジェンダーを支える社会関係のビジョンは、いわゆるポストジェンダー主義である。これは、バイオテクノロジーや生殖技術における最近の科学的進歩に

よって可能になった、ジェンダーの自主的な廃止を提唱する社会、政治、文化的な運動である。彼らの提案は、科学的可能性だけでなく、倫理的根拠にも基づい

ている。ポストジェンダー主義の前提は、固定されたジェンダーの社会的、感情的、認知的な帰結が、人間の完全な解放の障害となっているというものである。

性による生殖が排除された社会(あるいは、他のバージョンも可能となる社会:女性が自分の子供を「父親」にすることも可能となる社会など)では、前例のな

い自由、社会的・感情的な実験の新たな可能性が開かれるだろう。それは、その後のすべての社会階層と搾取を支える重要な区別を排除することになるだろ

う。」 - スラヴォイ・ジジェク著『セクシュアルはポリティカル』2016年8月1日 |

参考文献

【余滴】

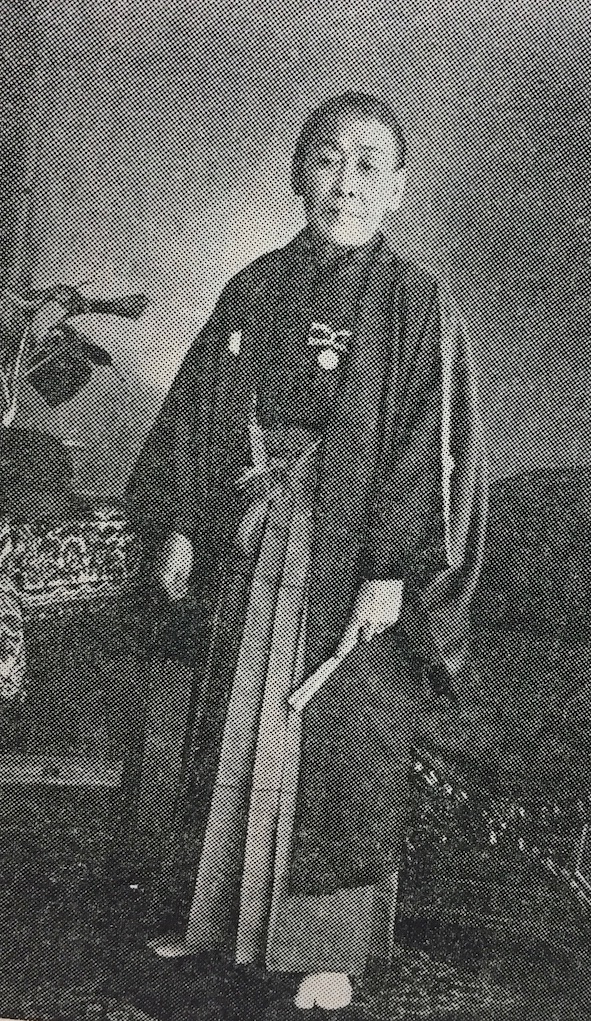

からゆきさんの還暦記念の男装写真「もう おなごは嫌じゃ、わしはもうおなごでなくなったとじゃけん、これからは男になるとじゃ」木下クニ、ドゥールズ的実践に喝采!(山崎 1972:211)

出典:山崎朋子「おクニさんの故郷」山崎

朋子『サンダカン八番娼館 : 底辺女性史序章』筑摩書房、1972年

【関連リンク】サイト外

【関連リンク】

★資料集

|

Queerness, in the work of theorists like Judith Butler and Eve Sedgwick, is as much a semiotic as it is a social phenomenon. To say that someone is "queer" indicates an indeterminacy or indecipherability about their sexuality and gender, a sense that they cannot be categorized without a careful contextual examination and, perhaps, a whole new rubric. For gender to be, in Judith Butler's words, "intelligible," ancillary traits and behaviors must divide and align themselves beneath a master division between male and female anatomy. From people's anatomy, we can supposedly infer other things about them: the gender of the people they desire, the sartorial and sexual practices they engage in, the general elements of culture that they are attracted to or repulsed by, and the gender of their "primary identification." While in practice each of these categories is rather elastic, it is usually when they do not line up in expected ways (say, when a man wears a dress and desires men) that one crosses from normative spaces into "queer" ones. In Butler's view, queer activities like drag and unexpected identifications and sexual practices reveal the arbitrariness of conventional gender distinctions by parodying them to the point where they become ridiculous or ineffective. (Hedges, from his article, "Howells's 'Wretched Fetishes': Character, Realism, and Other Modern Instances." Texas Studies in Literature and Language. 38.1 Spring1996.) |

ジュディス・バトラーやイヴ・セジウィックといった理論家の研究による

と、クィアネスは記号論的な側面と社会現象的な側面を併せ持つ。誰かを「クィア」と表現することは、その人のセクシュアリティやジェンダーが不確定で、解

釈が難しいことを意味する。また、慎重に文脈を検討し、おそらくは新たな分類法を適用しなければ、その人を分類できないという感覚も意味する。ジェンダー

が「理解可能」であるためには、ジュディス・バトラーの言葉を借りれば、付随的な特徴や行動は、男性と女性の解剖学上の大まかな区分に従って分類され、整

理されなければならない。 人々の解剖学から、その人々について他のことも推測できる。すなわち、その人々が望む性別、その人々が従事する服装や性的な習慣、その人々が惹きつけられ たり、嫌悪したりする文化の一般的な要素、そしてその人々の「第一のアイデンティティ」の性別などである。実際には、これらのカテゴリーはそれぞれかなり 柔軟であるが、通常、予想通りに当てはまらない場合(例えば、男性が女装をし、男性を欲するような場合)に、規範的な空間から「クィア」な空間へと移行す る。 バトラーの見解では、ドラァグや予期せぬ自己同一化、性的実践といったクィアな活動は、それらが滑稽であったり、効果的でなくなったりするほどに、それら をパロディー化することで、従来のジェンダーの区別の恣意性を明らかにする。 (ヘッジズ、論文「ハウエルの『哀れなフェティシスト』:性格、リアリズム、その他の近代の事例」『テキサス文学言語研究』第38巻第1号、1996年春号より) |

出典は、Queer:下記 (Klages, Mary)より引用なのですがすでに、リンク先には情報がありません。Klages, Mary.Queer Theory.http://www.colorado.edu/English/ENGL2012Klages/queertheory.html (July 28, 2001)

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆