Philosophy of Multiplicity

複数性の哲学

Philosophy of Multiplicity

解説:池田光穂

★多様性=複数性(フランス語:multiplicité)とは、数学的概念に関 するリーマンの記述を基に、エドムント・フッサールとアンリ・ベルクソンが展開した哲学的概念である。ベルクソンの論文『持続の理念』では、統一性の概念 を踏まえた上で多様性が論じられている。統一性は全体である限りにおいて与えられたものを指すのに対し、多様性は「個別に考えることができる統一性の部 分」を指す。[2] ベルクソンは多様性を2つの種類に区別している。多様性の1つの形態は量的で、区別でき、数えられる部分を指し、もう1つの形態は質的で、相互浸透し、そ れぞれが全体に対する質的に異なる知覚を生み出す可能性のある部分を指す。[3]

★多元化・複数性の哲学

| Multiplicity

(French: multiplicité) is a philosophical concept developed by Edmund

Husserl and Henri Bergson from Riemann's description of the

mathematical concept.[1] In his essay The Idea of Duration, Bergson

discusses multiplicity in light of the notion of unity. Whereas a unity

refers to a given thing in as far as it is a whole, multiplicity refers

to the "parts [of the unity] which can be considered separately."[2]

Bergson distinguishes two kinds of multiplicity: one form of

multiplicity refers to parts which are quantitative, distinct, and

countable, and the other form of multiplicity refers to parts that are

qualitative, which interpenetrate, and which each can give rise to

qualitatively different perception of the whole.[3] |

多様性=複数性(フランス語:multiplicité)とは、数学的概念に関

するリーマンの記述を基に、エドムント・フッサールとアンリ・ベルクソンが展開した哲学的概念である。ベルクソンの論文『持続の理念』では、統一性の概念

を踏まえた上で多様性が論じられている。統一性は全体である限りにおいて与えられたものを指すのに対し、多様性は「個別に考えることができる統一性の部

分」を指す。[2]

ベルクソンは多様性を2つの種類に区別している。多様性の1つの形態は量的で、区別でき、数えられる部分を指し、もう1つの形態は質的で、相互浸透し、そ

れぞれが全体に対する質的に異なる知覚を生み出す可能性のある部分を指す。[3] |

| Contextualism Perspectivism Rhizome (philosophy) |

コンテクチュアリズム パースペクティヴィズム リゾーム(哲学)——このページの下にあり |

| 1. "It was Riemann in the field

of physics and mathematics who dreamed about the notion of

'multiplicity' and other different kinds of multiplicities. The

philosophical importance of this notion then appeared in Husserl's

Formal and Transcendental Logic, as well as in Bergson's Essay on the

Immediate Given of Awareness" (Deleuze 1986, 13). 2. Bergson (2002, 49). 3. Bergson (2002,72-74) |

1.

「物理学と数学の分野において、『多重性』やその他の異なる種類の多重性という概念を夢想したのはリーマンであった。この概念の哲学的意義は、フッサール

の『形式・超越論的論理学』やベルクソンの『意識の直観的与えられたものについての試論』にも見られる」(ドゥルーズ、1986年、13ページ)。 2. ベルクソン(2002年、49ページ)。 3. ベルクソン(2002年、72-74ページ)。 |

| Bergson, Henri. 2002. Henri

Bergson. Key Writings. Edited by Keith Ansell Pearson and John

Mullarkey. New York and London: Continuum. Nicholas Tampio, ["Multiplicity"] "Sage Encyclopedia of Political Theory" (2010). |

ベルクソン、アンリ。2002年。アンリ・ベルクソン。主要著作集。

キース・アンセル・ピアソンとジョン・マルケイ編。ニューヨークおよびロンドン:コンティニュアム。 ニコラス・タンピオ、「多様性」『政治理論の賢人百科事典』(2010年)。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multiplicity_(philosophy) |

|

| Multiplicidad es un concepto

filosófico que desarrollaron a partir de la multiplicidad matemática de

Bernhard Riemann.1 Forma una parte importante de la filosofía de

Gilles Deleuze, particularmente en su colaboración con Félix Guattari

Capitalismo y esquizofrenia (1972–80). En su Foucault (1986), Deleuze

describe La arqueología del saber de Michel Foucault (1969) como «el

paso más decisivo hasta ahora en la teoría-práctica de las

multiplicidades».2 |

多重性とは、ベルンハルト・リーマンの数学的多重性から発展した哲学的

概念である1。ジル・ドゥルーズの哲学、特にフェリックス・ガタリとの共同研究『資本論と分裂病』(1972-80)において重要な位置を占めている。

ドゥルーズは『フーコー』(1986年)の中で、ミシェル・フーコーの『知の考古学』(1969年)を「多重性の理論-実践におけるこれまでの最も決定的

な一歩」と評している2。 |

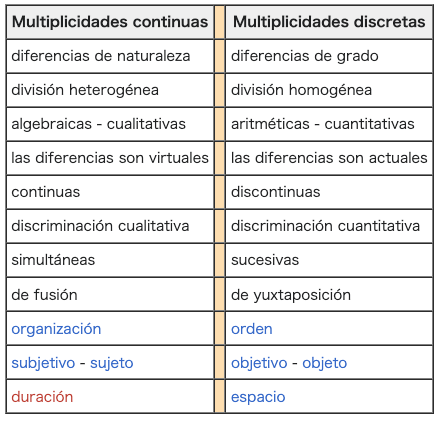

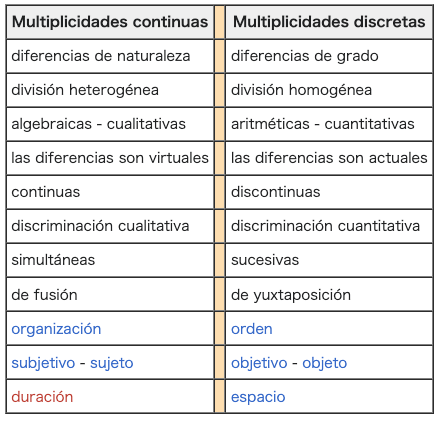

| La perspectiva de Deleuze Deleuze argumenta en su comentario Bergsonismo (1966) que la noción de multiplicidad forma una parte central de la crítica de Bergson a la negatividad y el método dialéctico. La teoría de las multiplicidades, explica, debe ser distinguida de los problemas filosóficos tradicionales de «el Uno y lo Múltiple».3 Al oponer «el Uno y lo Múltiple», la filosofía dialéctica reclama «reconstruir lo real», pero este reclamo es falso según argumenta Bergson, dado que «implica conceptos abstractos que son demasiado generales».4 En vez de referirse a lo «Múltiple en general», la teoría de Bergson de las multiplicidades distingue entre dos tipos de multiplicidad: multiplicidades continuas y multiplicidades discretas (una distinción que desarrolló a partir de Bernhard Riemann).5 Las características de esta distinción puede ser tabuladas de la siguiente manera:  |

ドゥルーズの視点 ドゥルーズはその解説書『ベルクソン主義』(1966年)の中で、多重性の概念はベルクソンの否定性批判と弁証法的方法の中心的な部分を形成していると論 じている。弁証法哲学は、「一と多」に対抗して、「実在を再構築する」ことを主張するが、この主張は誤りであるとベルクソンは主張する。 ベルクソンの多重性の理論は、「多様体一般」に言及する代わりに、連続的な多重性と離散的な多重性という2種類の多重性を区別する(この区別はベルンハルト・リーマンから発展させたものである)5。 この区別の特徴を表にすると以下のようになる:  |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Multiplicidad_(filosof%C3%ADa) |

|

*****

★リゾーム

| A

rhizome is a concept in post-structuralism describing an assemblage

that admits connections between any of its constituent elements,

regardless of any predefined ordering, structure, or entry point. [1]

[2] [3] It is a central concept in the work of French Theorists Gilles

Deleuze and Felix Guattari, who use the term frequently in their

development of Schizoanalysis. Deleuze and Guattari use the terms "rhizome" and "rhizomatic" (from Ancient Greek ῥίζωμα, rhízōma, "mass of roots") to describe a network that "connects any point to any other point".[3] The term is first introduced in Deleuze and Guattari's 1975 work Kafka: Toward a Minor Literature to suggest that Kafka's work is not bound by linear narrative structure, and can be entered into at any point to map out connections with other points.[1][4] The term is heavily expanded upon in Deleuze and Guattari's 1980 work A Thousand Plateaus, where it is used to refer to networks that establish "connections between semiotic chains, organizations of power, and circumstances relative to the arts, sciences and social struggles."[3] |

リゾームとは、ポスト構造主義における概念であり、あらか

じめ決められた順序、構造、または入口に関係なく、その構成要素間の接続を認める集合体を指す。[1][2][3]

フランスの理論家、ジル・ドゥルーズとフェリックス・ガタリによる著作の中心的な概念であり、彼らは「リゾーム」という用語を「スキゾ解析」の展開におい

て頻繁に使用している。 ドゥルーズとガタリは、「根茎」と「根茎的」(古代ギリシャ語ῥίζωμα、rhízōma、「根の塊」)という用語を使用して、「あらゆる点をあらゆる 他の点に接続する」ネットワークを表現している。[3] この用語は、ドゥルーズとガタリによる1975年の著作『カフカ: カフカの作品は直線的な物語構造に縛られておらず、どの時点からでも入り込んで他の点とのつながりを明らかにすることができることを示唆している。 この用語は、1980年に発表されたドゥルーズとガタリの著書『千のプラトー』で大幅に拡張され、芸術、科学、社会闘争に関連する「記号連鎖、権力組織、状況間のつながり」を確立するネットワークを指すために使用されている。[3] |

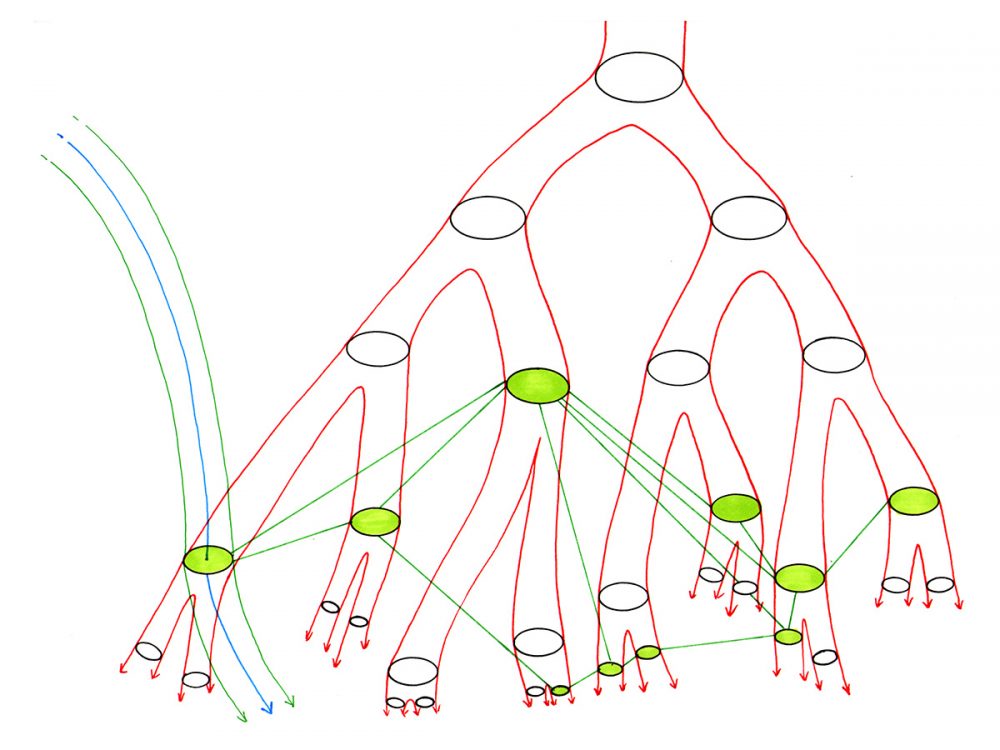

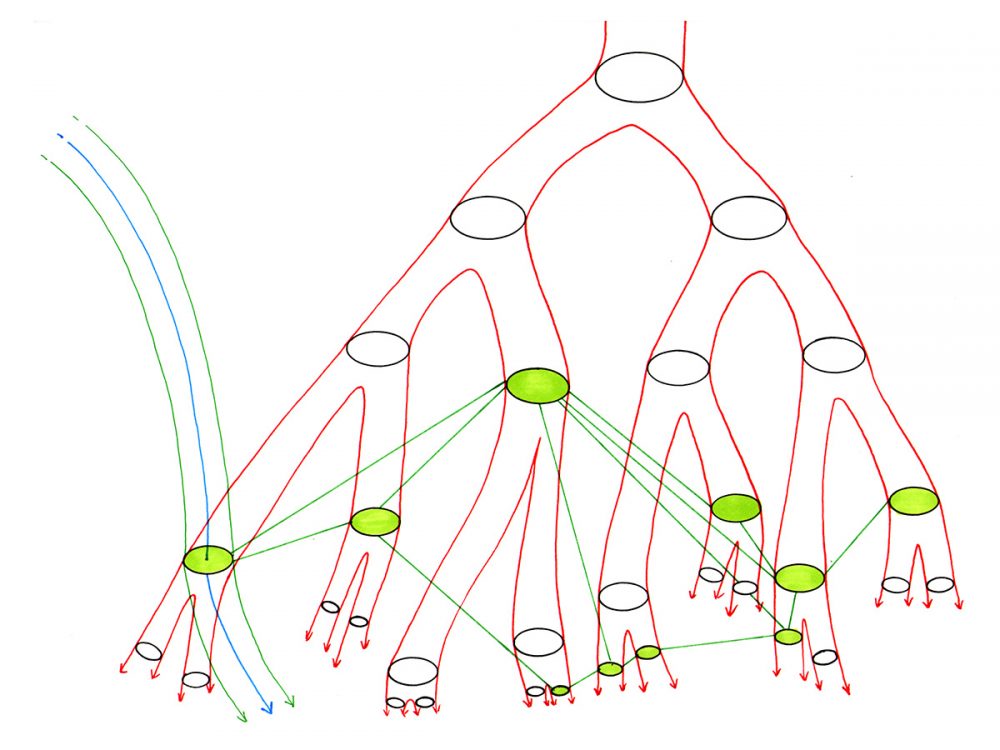

Opposition to Arborescence An illustration of rhizome in opposition to arborescence from a 2006 exhibition of works inspired by A Thousand Plateaus at the Doris McCarthy Gallery. The red structure in the image is a tree, which presupposes a linear ordering over its elements that emanates from the root. The green structure in the image is a rhizome, which ceaselessly establishes connections across branches in the tree, without regard for the predefined order.[5] Arborescent (French: arborescent) refers to the shape and structure of a tree. In A Thousand Plateaus, the concept of rhizome is introduced through a botanical metaphor, which contrasts the rhizomatic character of underground root systems to the natural ordering present in trees.[4][2][3] Deleuze and Guattari extend this metaphor beyond botanical trees to the realm of abstract and linguistic trees.[2][3] |

樹状構造への反対 2006年にドリス・マッカーシー・ギャラリーで開催された『千のプラトー』にインスパイアされた作品の展覧会で展示された、樹状構造に対する根茎構造の 図解。画像の赤い構造は樹木であり、根から発する要素の線形順序を前提としている。画像の緑の構造は根茎であり、あらかじめ決められた順序を考慮すること なく、絶え間なく樹木の枝を越えてつながりを確立する。 樹枝状(フランス語:arborescent)とは、樹木の形状と構造を指す。『千のプラトー』では、植物の地下茎の特性と樹木の自然な秩序を対比する植物学的な隠喩によって、根茎の概念が紹介されている。[4][2][3] ドゥルーズとガタリは、この隠喩を植物の樹木を超えて、抽象的および言語的な樹木の領域にまで拡張した。[2][3] |

| Approximate Characteristics In A Thousand Plateaus, Deleuze and Guattari write that "The rhizome itself assumes very diverse forms... but we get the feeling that we will convince no one unless we enumerate certain approximate characteristics."[3] These approximate characteristics are: "1 and 2. Principles of connection and heterogeneity: any point of a rhizome can be connected to anything other, and must be. This is very different from the tree or root, which plots a point, fixes an order" "3. Principle of multiplicity: it is only when the multiple is effectively treated as a substantive, "multiplicity," that it ceases to have any relation to the One as subject or object" "4. Principle of asignifying rupture: against the oversignifying breaks separating structures or cutting across a single structure. A rhizome may be broken, shattered at a given spot, but it will start up again on one of its old lines, or on new lines" "5 and 6. Principle of cartography and decalcomania: a rhizome is not amenable to any structural or generative model. It is a stranger to any idea of genetic axis or deep structure." |

おおよその特性 『千のプラトー』において、ドゥルーズとガタリは「リゾーム自体は非常に多様な形態をとるが... しかし、おおよその特性を列挙しなければ、誰も納得しないだろうという気がする」と書いている。[3] これらの特性は以下の通りである。 「1と2。接続と異質性の原則:リゾームのどの点も、他のあらゆるものと接続することができ、また接続しなければならない。これは、点をプロットし、秩序を固定する樹木や根とは非常に異なる」 「3. 多重性の原理:複数のものが実体として効果的に扱われ、実体としての「多重性」として扱われる場合にのみ、主体または客体としての「1」との関係がなくなる」 「4. 断裂の象徴化の原理:構造を分断する過剰な象徴化や、単一の構造を横断するものに対して。リゾームは、ある地点で折れたり砕けたりすることがあるが、再び古い線上、または新しい線上を動き出す」 「5と6。 地図作成と転写の原則:根茎は、いかなる構造的または生成的なモデルにも適合しない。それは、遺伝的軸や深層構造の概念とは無縁である。」 |

| Contextualism Bricolage Deleuze and Guattari Heterarchy Minority (philosophy) Multiplicity (philosophy) Mutualism Perspectivism Plane of immanence Graph (abstract data type) Arborescence (graph theory) Tree (graph theory) Digital infinity Intertwingularity |

コンテクチュアリズム ブリコラージュ ドゥルーズとガタリ ヘテラキー マイノリティ(哲学) 多様性(哲学) 相互主義 視点主義 内在の平面 グラフ(抽象データ型) 有向グラフ(グラフ理論) 木(グラフ理論) デジタル無限 インタートゥングラリティ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rhizome_(philosophy) |

*****

★複数性・補遺

| A central claim of

Deleuze's reading of Bergson is that Bergson's distinction between

space as an extensive multiplicity and duration as an intensive

multiplicity is inspired by the distinction between discrete and

continuous manifolds found in Bernhard Riemann's 1854 thesis on the

foundations of geometry. Yet there is no evidence from Bergson that

Riemann influences his division, and the distinction between the

discrete and continuous is hardly a Riemannian invention. Claiming

Riemann's influence, however, allows Deleuze to argue that quantity, in

the form of ‘virtual number’, still pertains to continuous

multiplicities. This not only supports Deleuze's attempt to redeem

Bergson's argument against Einstein in Duration and Simultaneity, but

also allows Deleuze to position Bergson against Hegelian dialectics.

The use of Riemann is thereby an important element of the incorporation

of Bergson into Deleuze's larger early project of developing an

anti-Hegelian philosophy of difference. This article first reviews the

role of discrete and continuous multiplicities or manifolds in

Riemann's Habilitationsschrift, and how Riemann uses them to establish

the foundations of an intrinsic geometry. It then outlines how Deleuze

reinterprets Riemann's thesis to make it a credible resource for

Deleuze's Bergsonism. Finally, it explores the limits of this move, and

how Deleuze's later move away from Bergson turns on the rejection of an

assumption of Riemann's thesis, that of ‘flatness in smallest parts’,

which Deleuze challenges with the idea, taken from Riemann's

contemporary, Richard Dedekind, of the irrational cut. Nathan Widder, The Mathematics of Continuous Multiplicities: The Role of Riemann in Deleuze's Reading of Bergson, Deleuze and Guattari Studies / List of Issues / Volume 13, Issue 3. |

ベルクソンの解釈におけるドゥルーズの主張の中心は、ベルクソンが広が

りを持つ多様性としての空間と、集中する多様性としての持続性との区別を行ったのは、ベルンハルト・リーマンの1854年の幾何学の基礎に関する論文に見

られる離散多様体と連続多様体の区別から着想を得たからだというものである。しかし、ベルクソンからリーマンの影響を示す証拠は見当たらず、離散と連続の

区別はリーマンによる発明とは言い難い。しかし、リーマンの影響を主張することで、デリダは「仮想数」という形の数量は依然として連続的な多重性に該当す

ると論じることができる。これは、ベルクソンの主張をアインシュタインに対するものとして『持続と同時性』で救済しようとしたドゥルーズの試みを裏付ける

だけでなく、ドゥルーズがベルクソンをヘーゲル弁証法に対立させることも可能にする。したがって、リーマンの利用は、ヘーゲル哲学に対抗する差異の哲学を

展開するというドゥルーズの初期のより大きなプロジェクトにベルクソンを取り入れるための重要な要素となる。本稿ではまず、リーマンの『ハビリタシオン

シュリフト』における離散的および連続的な多重性または多様体の役割について検討し、リーマンがそれらを用いて本質幾何学の基礎を確立した方法を考察す

る。次に、ドゥルーズがリーマンの論文を再解釈し、それをドゥルーズのベルクソン主義の信頼に足る基盤とした方法を概説する。最後に、この動きの限界と、

ドゥルーズが後にベルクソンから離れた理由を、リーマンの論文の仮定である「最小部分の平坦性」の拒絶に求め、ドゥルーズがリーマンの同時代人であるリ

ヒャルト・デデキントの非有理切断の考え方を用いてこの仮定に異議を唱えたことを明らかにする。 |

| https://www.euppublishing.com/doi/full/10.3366/dlgs.2019.0361 |

|

文献

そ

の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆