ヘーゲル『精神現象学』1807年目次とテキスト

Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, 1770-1831,

Phänomenologie

des Geistes, 1808

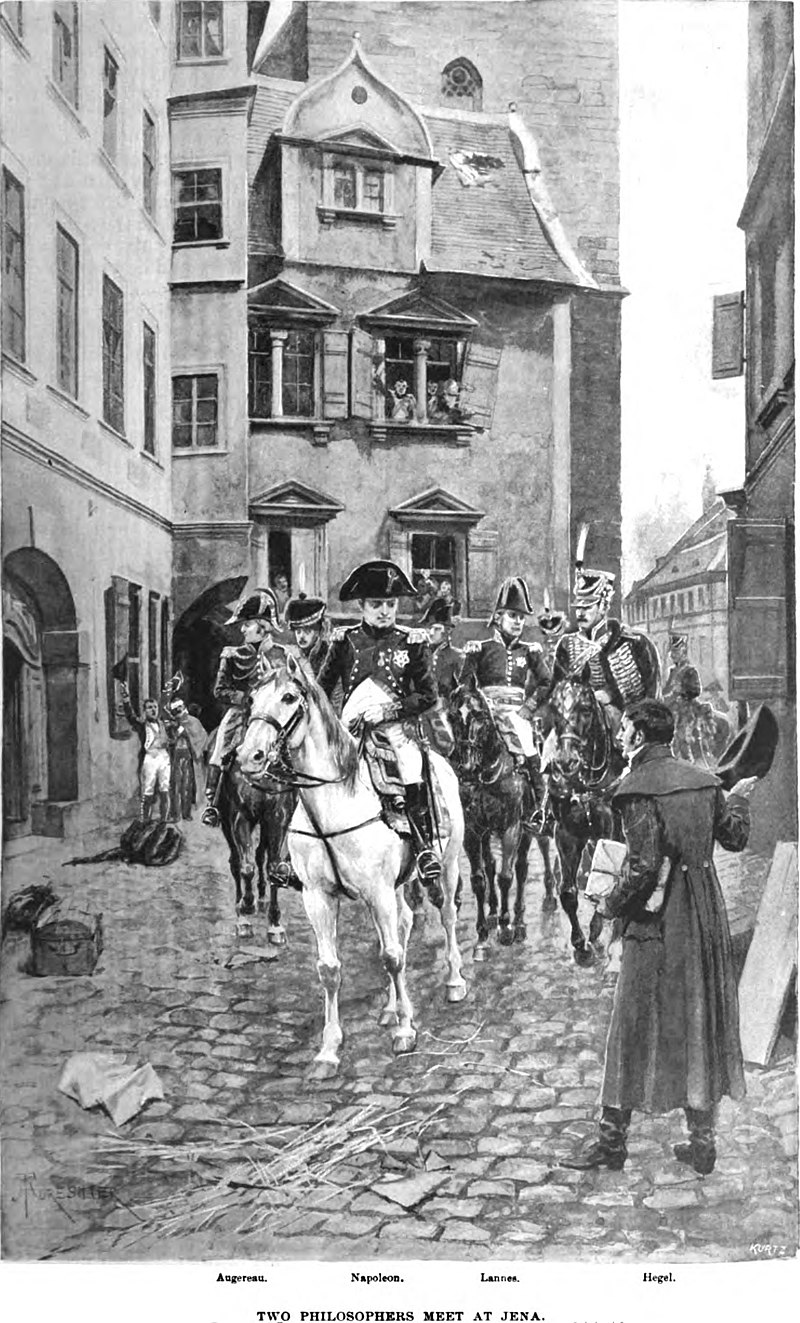

1807 イエーナ大学閉鎖。『バンベルク・ツァイトゥンク』の編集者となる。『精神現象学(Phänomenologie des Geistes)The Phenomenology of Spirit』あるいは"Phenomenology of Mind"を刊行

●精神現象学と論理の学の異動(→テキストの英訳「精神現象学」)

"A glance at the table of contents of Science of Logic reveals the same triadic structuring among the categories or thought determinations discussed that has been noted among the shapes of consciousness in the Phenomenology. At the highest level of its branching structure there are the three books devoted to the doctrines of being, essence, and concept, while in turn, each book has three sections, each section containing three chapters, and so on. In general, each of these individual nodes deals with some particular category. In fact, Hegel’s categorial triads appear to repeat Kant’s own triadic way of articulating the categories in the Table of Categories (Critique of Pure Reason A80/B106) in which the third term in the triad in some way integrates the first two. (In Hegel’s terminology, he would say that the first two were [aufgehoben] in the third—while the first two are negated by the third, they continue to work within the context defined by it.) Hegel’s later treatment of the syllogism found in Book 3, in which he follows Aristotle’s own three-termed schematism of the syllogistic structure, repeats this triadic structure as does his ultimate analysis of its component concepts as the moments of universality, particularity, and singularity."- all the citations from "Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, of The Stanford Encyclopedia of Pilosophy"

『論理学の科学』の目次を見ると、『現象学』におけ

る意識の形と同じように、論じられるカテゴリーや思考の決定の間に三項対立の構造があることがわかる。その枝分かれ構造の最上位には、存在、本質、概念の

教義に充てられた3冊の本があり、順に各本には3つのセクションがあり、各セクションには3つの章がある、といった具合に。一般に、これらの個々の結節

は、それぞれ、ある特定のカテゴリーを扱っている。実際、ヘーゲルのカテゴリー三段論法は、カントが『カテゴリー表』(『純粋理性批判』

A80/B106)において、三段論法の第三項が何らかの形で最初の二項を統合する形でカテゴリーを明示する方法を繰り返すように見える(ヘーゲルの用語

では、三段論法の三項が三項を統合する)。(ヘーゲルの用語法では、最初の二つは第三項において止揚=[aufgehoben]され、最初の二つは第三項

によって否定されるが、第三項によって定義される文脈の中で働き続ける、と言うだろう)。第3巻に見られるヘーゲルの三段論法は、アリストテレスの三段論

法に倣っているが、普遍性、特殊性、特異性の瞬間としての構成概念を究極的に分析するのと同様に、この三段論法を繰り返しているのである。

"Reading into the first chapter of Book 1, Being, it is quickly seen that the transitions of the Logic broadly repeat those of the first chapters of the Phenomenology, now, however, as between the categories themselves rather than between conceptions of the respective objects of conscious experience. Thus, being is the thought determination with which the work commences because it at first seems to be the most immediate, fundamental determination that characterises any possible thought content at all. (In contrast, being in the Phenomenology’s Sense-certainty chapter was described as the known truth of the purported immediate sensory given—the category that it was discovered to instantiate.) Whatever thought is about, that topic must in some sense exist. Like those purported simple sensory givens with which the Phenomenology starts, the category being looks to have no internal structure or constituents, but again in a parallel to the Phenomenology, it is the effort of thought to make this category explicit that both undermines it and brings about new ones. Being seems to be both immediate and simple, but it will show itself to be, in fact, only something in opposition to something else, nothing. The point seems to be that while the categories being and nothing seem both absolutely distinct and opposed, on reflection (and following Leibniz’s principle of the identity of indiscernibles) they appear identical as no criterion can be invoked which differentiates them. The only way out of this paradox is to posit a third category within which they can coexist as negated (Aufgehoben) moments. This category is becoming, which saves thinking from paralysis because it accommodates both concepts. Becoming contains being and nothing in the sense that when something becomes it passes, as it were, from nothingness to being. But these contents cannot be understood apart from their contributions to the overarching category: this is what it is to be negated (aufgehoben) within the new category."- all the citations from "Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, of The Stanford Encyclopedia of Pilosophy"

第1巻の第1章「存在」を読み進めると、論理学の推

移が現象学の第1章の推移とほぼ同じであることがすぐにわかるが、今度は、意識経験のそれぞれの対象についての観念の間ではなく、カテゴリーそれ自体の間

である。このように、「存在」がこの作品の冒頭を飾る思考決定であるのは、それが最初、あらゆる可能な思考内容を特徴づける最も直接的で根本的な決定であ

るように思われるからである。(これに対して、『現象学』の「感覚的確信」の章における「存在」は、即時的な感覚的与件、つまりそれがインスタンス化する

ことが発見されたカテゴリーの既知の真理として説明されている)。思考が何についてであれ、そのトピックはある意味で存在しなければならない。現象学の出

発点となった単純な感覚的与件のように、存在というカテゴリーには内部構造や構成要素がないように見えるが、やはり現象学と並行して、このカテゴリーを明

示しようとする思考の努力が、それを弱め、新しいカテゴリーをもたらすのである。存在とは、即物的で単純であるように見えるが、実は、他の何か、つまり無

に対立する何かでしかないことを示すことになる。要は、存在と無というカテゴリーは絶対的に区別され、対立しているように見えるが、(ライプニッツの無分

別の同一性の原則に従って)内省すると、両者を区別するいかなる基準も持ち出せないので同一に見えるということであろう。このパラドックスから抜け出す唯

一の方法は、否定=止揚された(Aufgehoben)瞬間として共存できる第三のカテゴリーを措定することである。このカテゴリーとは、両概念を受け入

れることができるため、思考を麻痺から救う「なりゆき」である。何かが「なる」とき、それはいわば無から有へと移行するという意味で、「なる」ことは有と

無を含んでいる。しかし、これらの内容は、包括的なカテゴリーへの貢献から切り離して理解することはできない。これこそ、新しいカテゴリーの中で否定=止

揚される(Aufgehoben)ことである。

★章立て(長谷川宏版 1998)——画面クリックで拡大します

★この図版のdoc ファイルはこちら[Phaenomenologie_Geistes_hase_jap.doc ]→この図版のpdfファイルはこちら[Phaenomenologie_Geistes_hase_jap.pdf][Phaenomenologie_Geistes_index.htm]

★https://www.waste.org/~roadrunner/Hegel/PhenSpirit/index.html

| The Preface | Vorrede |

まえがき(長谷川訳)(現象学のプログラムが提示される)執筆後に書かれたと言われる |

|

| Introduction | Einleitung |

はじめに(認識するとは何を意味するのか?) |

|

| A. Consciousness | I. Sense-Certainty, This, & Meaning | Die sinnliche Gewißheit; oder das Diese und das Meinen |

A.意識——I. 感覚的確信——目の前のこれと、思い込み |

| II. Perception, Thing, & Deceptiveness | II. Die Wahrnehmung; oder das Ding, und die Täuschung |

A.意識——II. 知覚——物と錯覚 | |

| III. Force & Understanding | III. Kraft und Verstand, Erscheinung und übersinnliche Welt |

A.意識——III. 力と学問的思考——現象界と超感覚的世界 | |

| B. Self-Consciousness | IV. True Nature of Self-Certainty | IV. Die Wahrheit der Gewißheit seiner selbst |

B. 自己意識——IV. 自己意識の真理 |

| A. Lordship & Bondage | A. Selbstständigkeit und Unselbstständigkeit des Selbstbewußtseins;Herrschaft und Knechtschaft |

A. 自己意識の自立性と非自立性——支配と隷属(主人と奴隷) | |

| B. Unhappy Consciousness | B. Freiheit des Selbstbewußtseins; Stoizismus, Skeptizismus und das unglückliche Bewußtsein |

B. 自己意識の自由——ストア主義、懐疑主義、不幸な意識 | |

| C. Reason (AA) Reason |

Gewissdheit und Wahrheit der Vernu Physiognomik und SchNft |

||

| V. Reason's Certainty and Reason's Truth 確実性と理性=合理性の真理 |

A. Observation as Reason | A Beobachtende Vernunft |

|

| B. Realization of rational self-consciousness | |||

| C. Individuality | |||

| (BB). Spirit | VI Der Geist |

||

| VI. Spirit | |||

| A. Objective Spirit: the Ethical order | A Der wahre Geist , die Sittlichkeit |

||

| B. Culture & civilization | |||

| I. World of spirit in self-estrangement | |||

| II. Enlightenment | |||

| III. Absolute Freedom & Terror | Die absolute Freiheit und der Schrecken |

||

| C. Morality | a. The Moral View of the World | Die Moralität a Die moralische Weltanschauung |

|

| b. Dissemblance | Die Verstellung |

||

| c. Conscience: The “Beautiful Soul”:Evil and the Forgiveness of it | Das Gewissen, die schöne Seele, das Böse und seine Verzeihung |

||

| (CC). Religion | Die Religion |

||

| VII. Religion in General | A. Natural Religion | Natürliche Religion |

|

| B. Religion as Art | Die Kunst-Religion Das abstrakte Kunstwerk Das lebendige Kuntswerk : Das geistige Kunstwerk |

||

| C. Revealed Religion | Die offenbare Religion |

||

| (DD). Absolute Knowledge | |||

| VIII.Absolute Knowledge | Absolute Wissen |

||

★

1812-1816 大論理学 (Wissenschaft der Logik、1812-16年)

| Phänomenologie

des Geistes |

Hegel’s

Phenomenology of Mind |

| Eine Erklärung,

wie sie einer Schrift in einer Vorrede nach der Gewohnheit

vorausgeschickt wird -- über den Zweck, den der Verfasser sich in ihr

vorgesetzt, sowie über die Veranlassungen und das Verhältnis, worin er

sie zu andern frühern oder gleichzeitigen Behandlungen desselben

Gegenstandes zu stehen glaubt -- scheint bei einer philosophischen

Schrift nicht nur überflüssig, sondern um der Natur der Sache willen

sogar unpassend und zweckwidrig zu sein. Denn wie und was von

Philosophie in einer Vorrede zu sagen schicklich wäre -- etwa eine

historische Angabe der Tendenz und des Standpunkts, des allgemeinen

Inhalts und der Resultate, eine Verbindung von hin und her sprechenden

Behauptungen und Versicherungen über das Wahre --, kann nicht für die

Art und Weise gelten, in der die philosophische Wahrheit darzustellen

sei. -- |

§ 1. In the case

of a philosophical work it seems not only superfluous, but, in view of

the nature of philosophy, even inappropriate and misleading to begin,

as writers usually do in a preface, by explaining the end the author

had in mind, the circumstances which gave rise to the work, and the

relation in which the writer takes it to stand to other treatises on

the same subject, written by his predecessors or his contemporaries.

For whatever it might be suitable to state about philosophy in a

preface -- say, an historical sketch of the main drift and point of

view, the general content and results, a string of desultory assertions

and assurances about the truth -- this cannot be accepted as the form

and manner in which to expound philosophical truth. |

リンク

文献

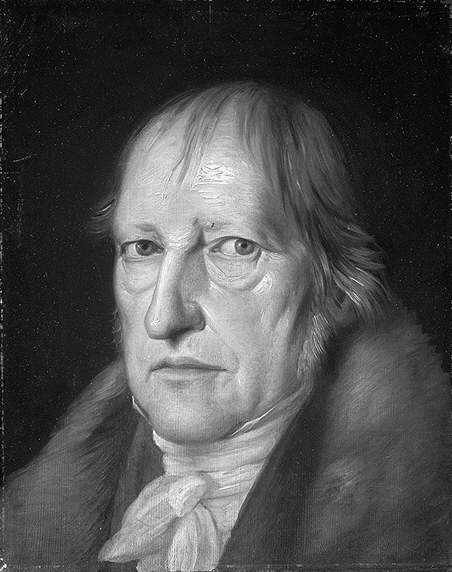

Hegel portrait by Jakob Schlesinger 1831

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099