ケクチの人々と言語

Q'eqchi' people and their language

Tactic,

Alta Verapaz, Guatemala, ca. 1950

☆Q'eqchi' (/qʼeqt͡ʃi/)(旧正書法ではK'ekchi'、ベリーズなど多くの英語の文脈では単にKekchi)は、グアテマラとベリーズのマヤ族であ る。固有言語はQ'eqchi'語。1520年代にスペインによるグアテマラ征服が始まる前、Q'eqchi'族の居住地は現在のアルタ・ベラパス県とバ ハ・ベラパス県に集中していた。その 後何世紀にもわたって、土地の移動、再定住、迫害、移住が繰り返され、Q'eqchi'コミュニティはグアテマラの他の地域(Izabal、Petén、 El Quiché)、ベリーズ南部(Toledo District)、メキシコ南部(Chiapas、Campeche)に分散した。 [3]アルタ・ベラパス北部とペテン南部に最も顕著に存在するが[4]、現代のQ'eqchi'言語話者はグアテマラの全マヤ民族の中で地理的に最も広く 広がっている(→「ケクチ語文法」)。

| Q'eqchi'

(/qʼeqt͡ʃiʔ/) (Kʼekchiʼ in the former orthography, or simply Kekchi in

many English-language contexts, such as in Belize) are a Maya people of

Guatemala and Belize. Their indigenous language is the Qʼeqchiʼ

language. Before the beginning of the Spanish conquest of Guatemala in the 1520s, Qʼeqchiʼ settlements were concentrated in what are now the departments of Alta Verapaz and Baja Verapaz. Over the course of the succeeding centuries a series of land displacements, resettlements, persecutions and migrations resulted in a wider dispersal of Qʼeqchiʼ communities into other regions of Guatemala (Izabal, Petén, El Quiché), southern Belize (Toledo District), and smaller numbers in southern Mexico (Chiapas, Campeche).[3] While most notably present in northern Alta Verapaz and southern Petén,[4] contemporary Qʼeqchiʼ language-speakers are the most widely spread geographically of all Maya peoples in Guatemala.[5] |

Q'eqchi'(/qʼeqt͡ʃi/)(旧正書法では

Kʼekchiʼ、ベリーズなど多くの英語の文脈では単にKekchi)は、グアテマラとベリーズのマヤ族である。固有言語はQ'eqchi'語。 1520年代にスペインによるグアテマラ征服が始まる前、Q'eqchi'族の居住地は現在のアルタ・ベラパス県とバハ・ベラパス県に集中していた。その 後何世紀にもわたって、土地の移動、再定住、迫害、移住が繰り返され、Q'eqchi'コミュニティはグアテマラの他の地域(Izabal、Petén、 El Quiché)、ベリーズ南部(Toledo District)、メキシコ南部(Chiapas、Campeche)に分散した。 [3]アルタ・ベラパス北部とペテン南部に最も顕著に存在するが[4]、現代のQ'eqchi'言語話者はグアテマラの全マヤ民族の中で地理的に最も広く 広がっている[5]。 |

| History Not much is known about the lives and history of the Qʼeqchiʼ people prior to being conquered by Spanish conquistadors; however, it is known that they were a Maya group located in the central highlands and northern lowlands of Guatemala. Their land was formerly known as Tezulutlan or “the land of war" and the Qʼeqchiʼ people were ruled by a king and had their own laws and government. When the Spanish began their conquest, the Qʼeqchiʼ were hard to control due to a dispersed population. Bartolomé de las Casas was given permission to try to convert the Qʼeqchiʼ people to Christianity, however, only a small portion was converted and the church lost all ability to govern the Qʼeqchiʼ. This led to the exploitation of the Qʼeqchiʼ by plantation owners and slavers.[6] During the nineteenth-century plantation agriculture was a big part of the Qʼeqchiʼ people's lives. This led to the seizure of the Qʼeqchiʼ's communal land by plantations and the service of the Qʼeqchiʼ to farm the plantations. By 1877, all communal landownership was abolished by the government which prompted some of the Qʼeqchiʼ to move to Belize. This seizure of communal land along with the effects of the Spanish Conquest created long-lasting poverty in the Qʼeqchiʼ people.[6] |

歴史 スペインのコンキスタドールに征服される以前のQʼeqchiʼ族の生活や歴史についてはあまり知られていないが、グアテマラの中央高地と北部低地に位置 するマヤのグループであったことは知られている。彼らの土地は以前はTezulutlanまたは "戦争の土地 "として知られており、Qʼeqchiʼ人は王によって支配され、独自の法律と政府を持っていた。スペイン人が征服を始めた時、Qʼeqchiʼ族は人口 が分散していたため支配が難しかった。バルトロメ・デ・ラス・カサスはQʼeqchiʼ人をキリスト教に改宗させる許可を与えられたが、改宗したのはごく 一部で、教会はQʼeqchiʼ人を統治する能力を失った。これがプランテーションのオーナーや奴隷商人によるQʼeqchiʼの搾取につながった [6]。 19世紀にはプランテーション農業がQʼeqchiʼの人々の生活の大きな部分を占めていた。このため、Qʼeqchiʼの共同所有地はプランテーション に接収され、Qʼeqchiʼはプランテーションの農作業に従事することになった。1877年までに、Qʼeqchiʼの一部がベリーズに移住するよう促 した政府によって、すべての共同所有地は廃止された。スペイン征服の影響とともに、この共同土地の接収はQʼeqchiʼの人々に長く続く貧困を生み出し た[6]。 |

| Religion and culture Religion Traditionally the Qʼeqchiʼ people believe in the Tzuultaqʼa” which are the gods of the mountains and valleys. However, they have mixed those beliefs with the beliefs of the Catholic church. Some of the Qʼeqchiʼ believe in the Christian God and celebrate those who hold to Roman Catholicism the saints. They also believe that Tzuultaqʼaʼ presides over nature and dwells in the caves of the mountains. They also have three specific religious specialists that are from the Tzuultaqʼaʼ side of their religion. There are the ilonel which are the curers who use different types of herbs and ceremonies. The aj ke (seers) who advise and predict things in the village. The last is the aj tul which are believed to be the sorcers who can cast spells. They also believe in similar rituals to those in other Latin American countries like the celebration of the Day of the Dead. They also prefer a ritual to the dead which consists of wrapping the body in a petite which is a straw mat. They are then buried with items they would need for the journey into the afterlife.[7] Marriage Marriages in the Qʼeqchiʼ culture are arranged by the parents of the children. The parents of both children meet over time and if all goes well the children are married. This happens at the ages of 12 to 15 for the women and 15 to 18 for the males. After that the family would look very similar to the normal family picture; a mother, a father, and a couple of children. When it comes to inheritance parents usually give the property and assets to the child who offers to care for the parents during their life.[8] Food and agriculture The agricultural production of the Qʼeqchiʼ people consists mostly of subsistence farming. This means they only farm for the needs of their families not external markets. At first the Qʼeqchiʼ were polycultural. The plants they farmed were edible weeds, banana plants, and other companion crops. They also acquire some of their food from wild plants and some villages still hunt. However for most present day Qʼeqchiʼ people today their food comes from the corn fields. This comes mainly from a time where plantations dominated the Qʼeqchiʼ society. From the 1880s to around the 1940s the plantation owners forbid the growing of any crops other than corn and beans, so they could easily identify which crops belonged to them. This created a corn-dependent diet of the Qʼeqchiʼ people.[8] While corn doesn't prove very profitable for the Qʼeqchiʼ economy or their diet it does have other merits. The Qʼeqchiʼ use agriculture as a way to commune with God the creator in a very physical and spiritual way. It was a way to feel like a co-creator when planting new life into the soil. All the parts of planting, cultivating, and harvesting are all rituals and worship in their religion.[9] Contemporary Issues The QHA, which is the Qʼeqchiʼ Healers Association, are an association of indigenous healers that have come together to share their forms of conservation and botany. The QHA along with the Belize Indigenous Training Institute funded a project which would develop a traditional healing garden and culture center. Here the Qʼeqchiʼ Healers shared their similar methods that had been passed down to them in the hopes of preserving rare plant life and educating their community. They are preserving the biodiversity of their region by coming up with different options other than wild harvesting as well as was to propagate and cultivate many rare plant species.[10] Notable members Cristina Coc, led 39 villages in Southern Belize in attaining a landmark ruling on the rights to their traditional lands and receipt of the Equator Prize[11] Rodrigo Tot, awarded the Goldman Environment Prize in 2017 Oscar Santis. |

宗教と文化 宗教 伝統的にQʼeqchiʼ人は山や谷の神々である "Tzuultaqʼa "を信仰している。しかし、その信仰はカトリック教会の信仰と混ざり合っている。Qʼeqchiʼの一部はキリスト教の神を信じ、ローマ・カトリックを信 仰する人々を聖人と称えている。また、Tzuultaqʼaʼは自然を司り、山の洞窟に宿ると信じている。また、Tzuultaqʼaʼ側の宗教の専門家 が3人いる。さまざまな種類の薬草や儀式を用いる治療師であるイロネル(ilonel)。aj ke(占い師)は、村の物事に助言を与え、予言する。最後のアジュ・トゥルは、呪文を唱えることができる魔術師と信じられている。彼らはまた、死者の日を 祝うような他のラテンアメリカ諸国と同様の儀式を信じている。また、死者をプティット(藁のマット)で包む儀式も好まれる。その後、死後の世界への旅に必 要な品々と共に埋葬される[7]。 結婚 Qʼeqchiʼ文化における結婚は、子供の両親によって取り決められる。両方の子供の両親が時間をかけて会い、すべてがうまくいけば子供たちは結婚す る。女性は12歳から15歳、男性は15歳から18歳で結婚する。その後は、母親と父親、そして数人の子供という、一般的な家族構成に近い形になる。相続 に関しては、親は通常、親の面倒を見ることを申し出た子供に財産や資産を与える[8]。 食料と農業 Qʼeqchiʼ人の農業生産は、ほとんどが自給自足の農業である。つまり、外部市場ではなく、家族の必要性のためだけに農業を営んでいる。当初、 Qʼeqchiʼ族は多作であった。彼らが耕作する植物は食用雑草、バナナ、その他のコンパニオン・クロップであった。また、食料の一部は野生の植物から 得ており、今でも狩猟を行っている村もある。しかし、現在のほとんどのQʼeqchiʼの人々の食料はトウモロコシ畑からもたらされている。これは主にプ ランテーションがQʼeqchiʼ社会を支配していた時代に由来する。1880年代から1940年代頃まで、プランテーションの所有者たちはトウモロコシ と豆以外の作物の栽培を禁じていたため、どの作物が自分たちのものかを簡単に見分けることができた。これにより、Qʼeqchiʼの人々はトウモロコシに 依存した食生活を送るようになった[8]。 とうもろこしはQʼeqchiʼ族の経済や食生活にはあまり利益をもたらさないが、他の利点もある。Qʼeqchiʼ族は農業を、非常に物理的かつ精神的 な方法で創造主である神と交わるための方法として使っている。土に新しい生命を植えるとき、共同創造者のように感じる方法でした。植え付け、耕作、収穫の すべての部分は、彼らの宗教における儀式であり、崇拝である[9]。 現代の課題 QHA(Qʼeqchiʼヒーラーズ・アソシエーション)は、先住民のヒーラーの団体で、保全と植物学の形態を共有するために集まった。QHAはベリーズ 先住民研修所とともに、伝統的なヒーリングガーデンとカルチャーセンターを開発するプロジェクトに資金を提供した。ここでQʼeqchiʼヒーラーは、希 少な植物を保護し、彼らのコミュニティを教育することを願って、彼らに受け継がれてきた同様の方法を共有した。彼らは、多くの希少な植物種を繁殖させ栽培 するだけでなく、野生の収穫以外の異なる選択肢を考え出すことで、地域の生物多様性を保全している[10]。 著名なメンバー クリスティーナ・コックは、彼らの伝統的な土地と赤道賞[11]の領収書への権利に関する画期的な判決を達成するために南部ベリーズの39の村を導いた。 ロドリゴ・トット(キチェ出身)、2017年にゴールドマン環境賞を受賞 オスカー・サンティス(サッカー選手) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Q%CA%BCeqchi%CA%BC |

|

| The

Q'eqchi' language,

also spelled Kekchi, Kʼekchiʼ, or Kekchí, is one of the Mayan languages

from the Quichean branch, spoken within Qʼeqchiʼ communities in Mexico,

Guatemala and Belize.[3] |

The

Q'eqchi' language (ケクチ語)は、

Kekchi、Kʼekchiʼ、Kekchíとも表記され、メキシコ、グアテマラ、ベリーズのQʼeqchiʼコミュニティで話されているキキア語派に

属するマヤ語の一つである[3]。 |

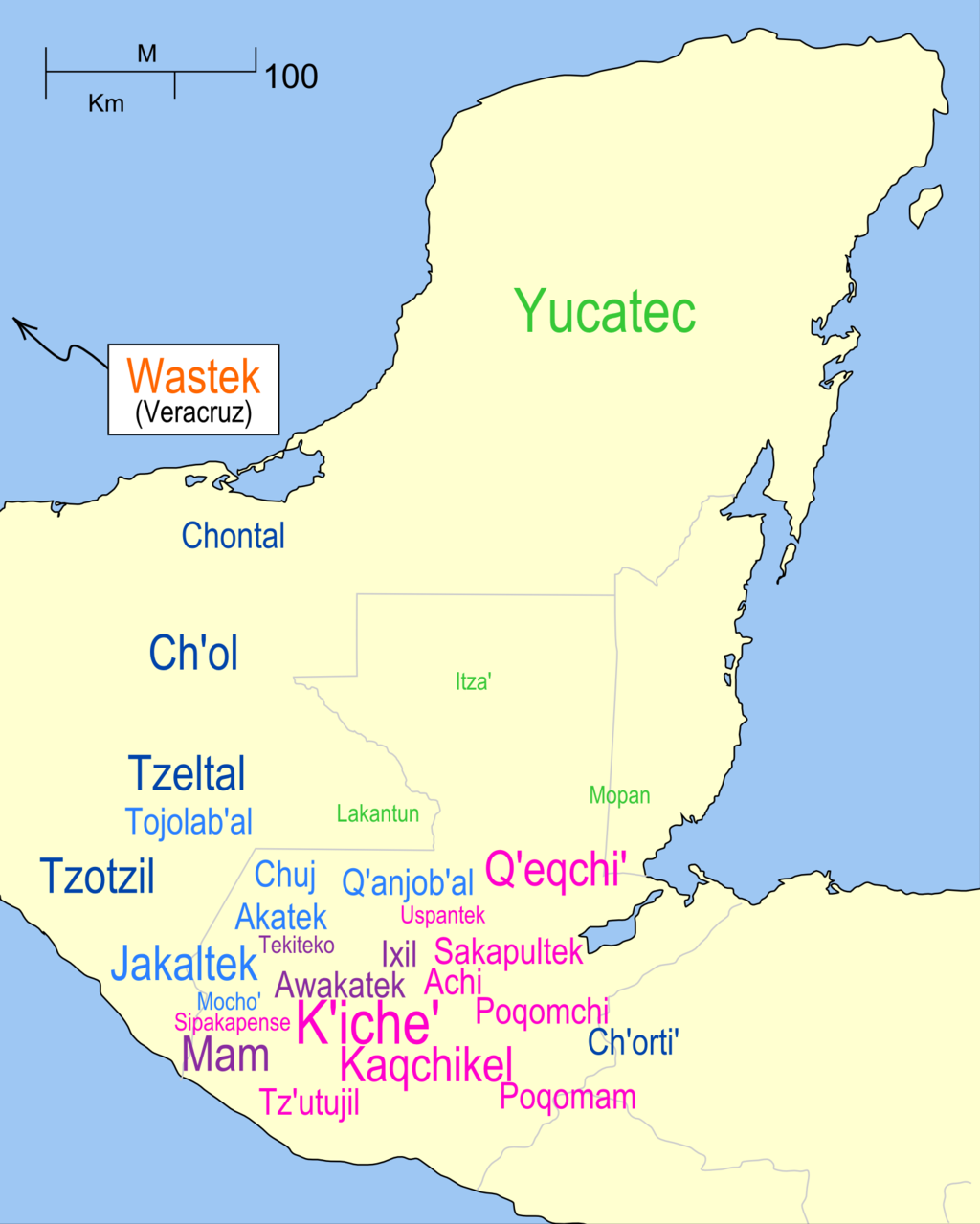

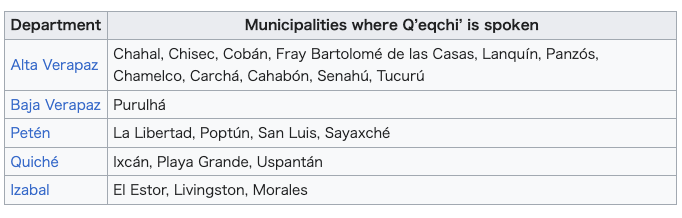

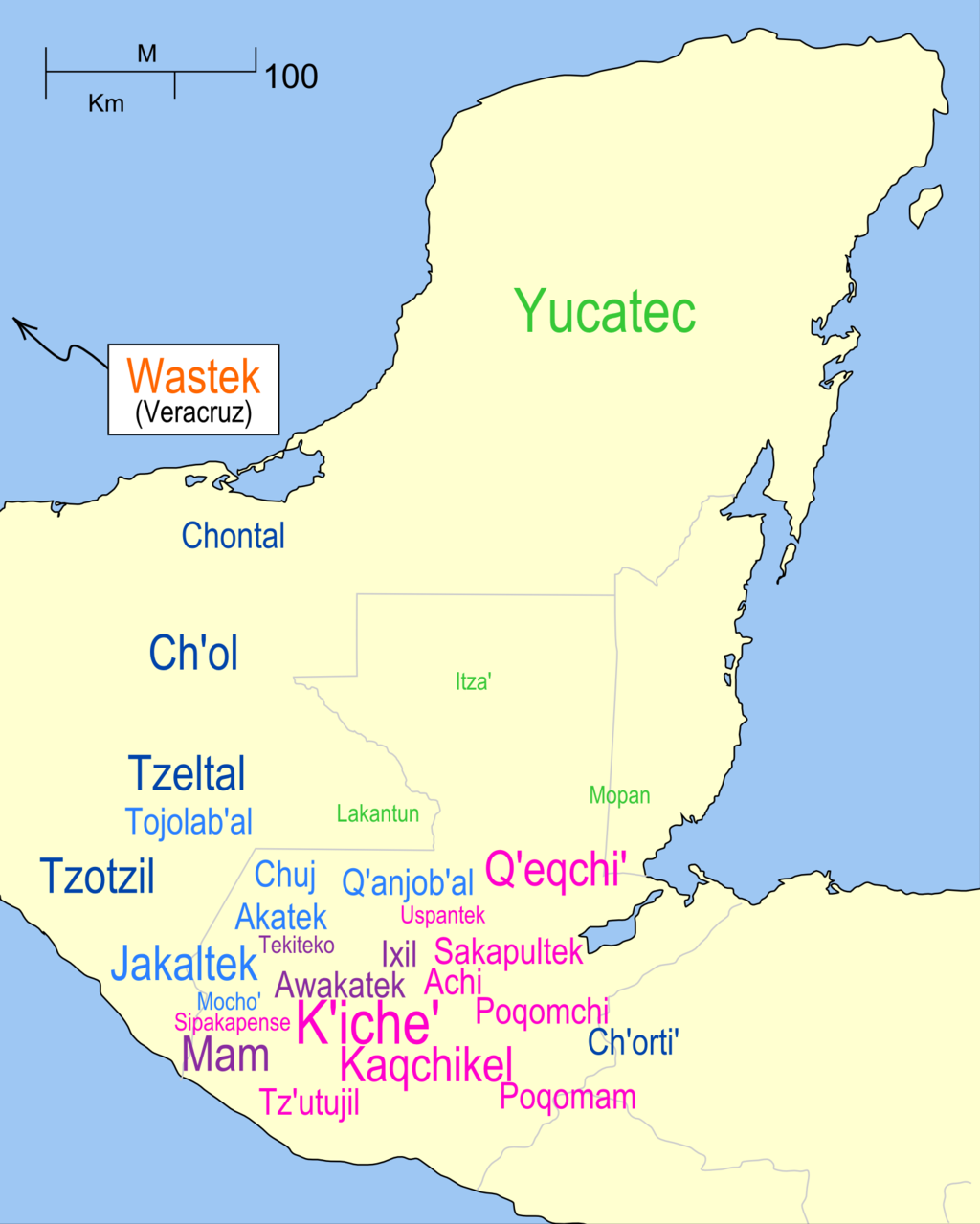

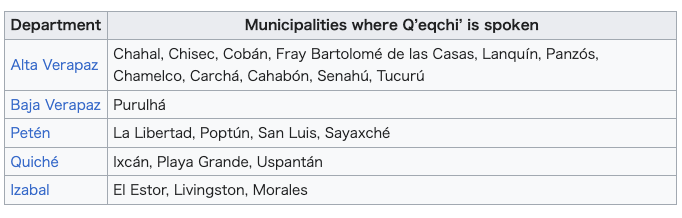

Distribution Map of Mayan languages The area where Qʼeqchiʼ is spoken spreads across northern Guatemala into southern Belize. There are also Qʼeqchiʼ speaking communities in Mexico. In Mexico, Q'eqchi' is spoken in the states of Campeche, Quintana Roo and Chiapas, mainly in the communities of Quetzal-Etzná and Los Laureles, in the Campeche Municipality and in Maya Tecun II and Santo Domingo Kesté in the Champotón Municipality, state of Campeche.[4] It was calculated that the core of the Qʼeqchiʼ-speaking area in northern Guatemala extends over 24,662 square kilometers[5] (about 9,522 square miles). The departments and specific municipalities where Qʼeqchiʼ is regularly spoken in Guatemala include:[5]  In the country of Belize, Qʼeqchiʼ is spoken in the Toledo District.[5] Qʼeqchiʼ is the first language of many communities in the district, and the majority of Maya in Toledo speak it. Terrence Kaufman described Qʼeqchiʼ as having two principal dialect groups: the eastern and the western. The eastern group includes the varieties spoken in the municipalities of Lanquín, Chahal, Chahabón and Senahú, and the western group is spoken everywhere else.[6] |

分布図 マヤ語地図 Qʼeqchiʼが話されている地域はグアテマラ北部からベリーズ南部にかけて広がっている。メキシコにもQʼeqchiʼを話すコミュニティがある。 メキシコでは、Q'eqchi'はカンペチェ州、キンタナ・ロー州、チアパス州で話されており、主にカンペチェ自治体のQetzal-EtznáとLos Laurelesのコミュニティ、カンペチェ州チャンポトン自治体のMaya Tecun IIとSanto Domingo Kestéで話されている[4]。 グアテマラ北部のQʼeqchiʼ語圏の中核は24,662平方キロメートル[5](約9,522平方マイル)に及ぶと計算されている。グアテマラで Qʼeqchiʼが常用されている県と特定の自治体は以下の通りである[5]。  ベリーズではトレド地区でQʼeqchiʼが話されている[5]。Qʼeqchiʼは同地区の多くのコミュニティの第一言語であり、トレドのマヤの大半は それを話す。 Terrence Kaufmanは、Qʼeqchiʼには東部と西部の2つの主要な方言グループがあると述べている。東部方言グループには、ランキン、チャハル、チャハボ ン、セナフーの各市町村で話されているものが含まれ、西部方言グループはそれ以外の場所で話されている[6]。 |

| ref. Q'eqchi'

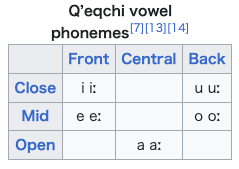

Grammer. ++++++++++++++++++++ Phonology Below are the Qʼeqchiʼ phonemes, represented with the International Phonetic Alphabet. To see the official alphabet, see the chart in the Orthographies section of this article. Consonants Qʼeqchiʼ has 29 consonants, 3 of which were loaned from Spanish.  a. In their respective descriptive grammars of Qʼeqchiʼ, both Juan Tzoc Choc[10] and Stephen Stewart[11] have the bilabial implosive as a voiced /ɓ/. The report on Qʼeqchiʼ dialect variation by Sergio Caz Cho, however, only discusses this consonant as a voiceless /ɓ̥/.[12] b. The non-glottalized voiced plosives /b d ɡ/ have appeared as a result of influence from Spanish.[7] Vowels Qʼeqchiʼ has 10 vowels, which differ in quality and also in length.  Prosody With a few exceptions—interjections, such as uyaluy,[15] and adjectives which have an unstressed clitic on the end[16]—stress always falls on the final syllable.[16] |

→「ケクチ語文法」

も参照 +++++++++++++++++++ 音韻論 以下はQʼeqchiʼの音素を国際音声学アルファベットで表したものである。正式なアルファベットは、この記事の正書法セクションの表をみよ。 子音 Qʼeqchiʼには29の子音があり、うち3つはスペイン語からの借用である。  a. それぞれのQʼeqchiʼの記述文法では、Juan Tzoc Choc[10]とStephen Stewart[11]の両唇性含意子音を有声/ɓ/としている。しかし、Sergio Caz ChoによるQʼeqchiʼ方言のバリエーションに関する報告では、この子音は無声 /↪Ll_253-̥/ としてしか論じられていない[12]。 b. 非声門化有声撥音 /b d ↪Ll_261/ はスペイン語からの影響で出現した[7]。 母音 Qʼeqchiʼには10個の母音があり、母音の質と長さが異なる。  韻律 ウヤルイ[15]などの間投詞や、語尾に非ストレスの接辞を持つ形容詞[16]など、いくつかの例外を除いて、ストレスは常に最終音節にかかる[16]。 |

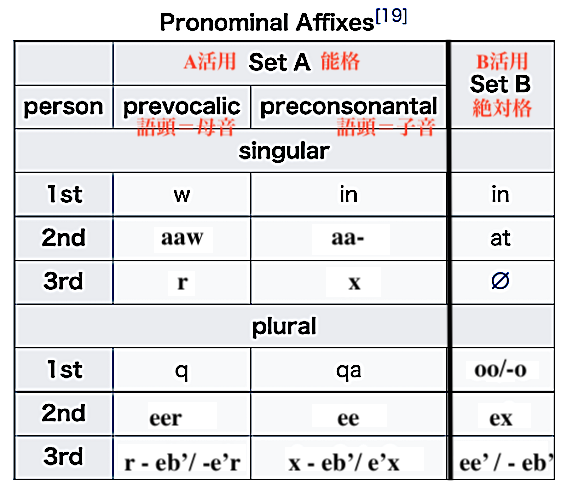

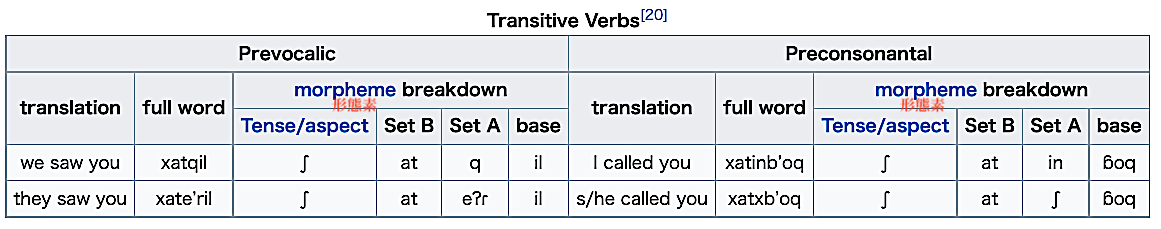

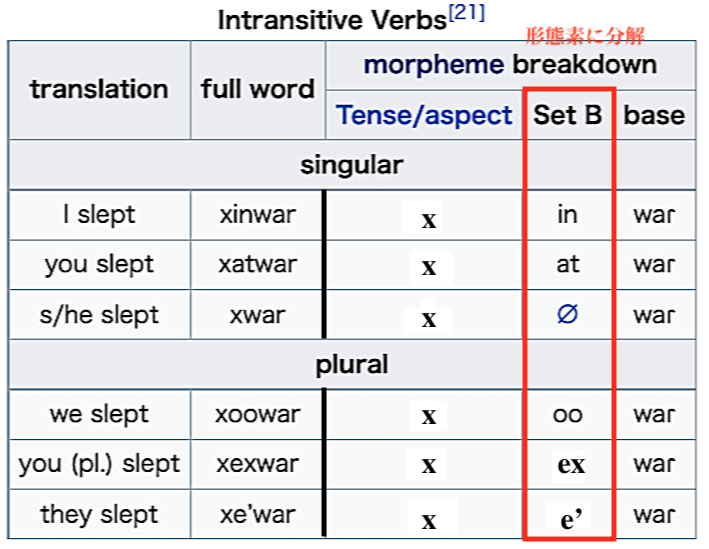

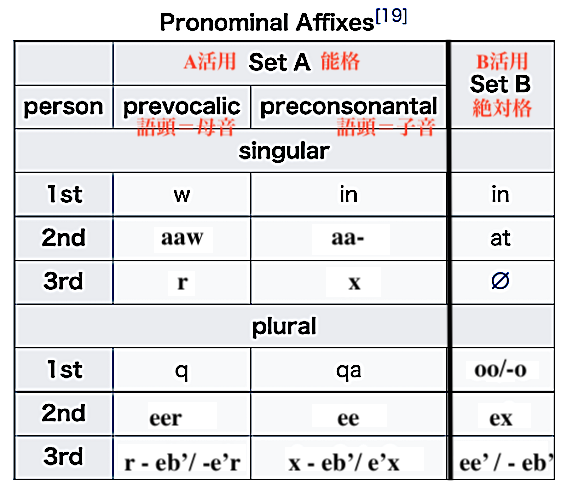

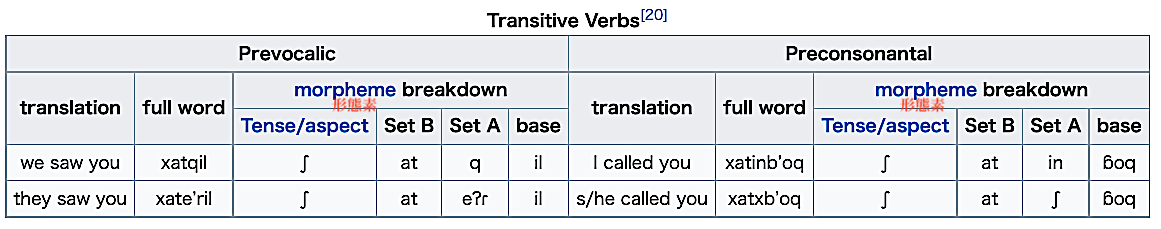

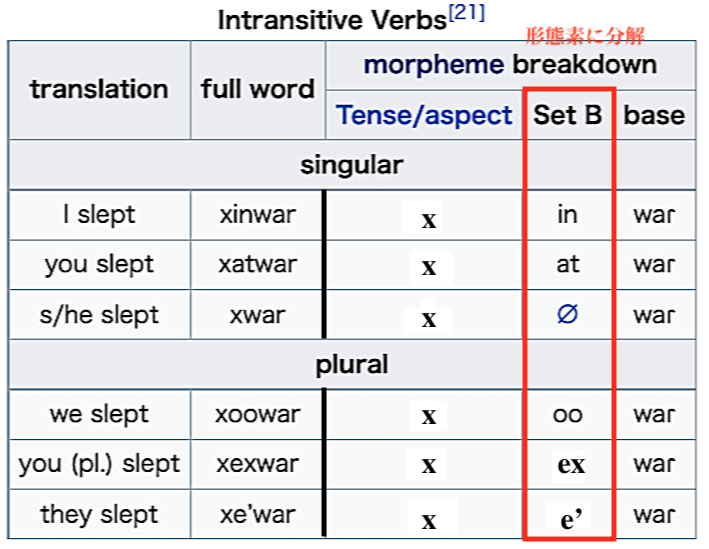

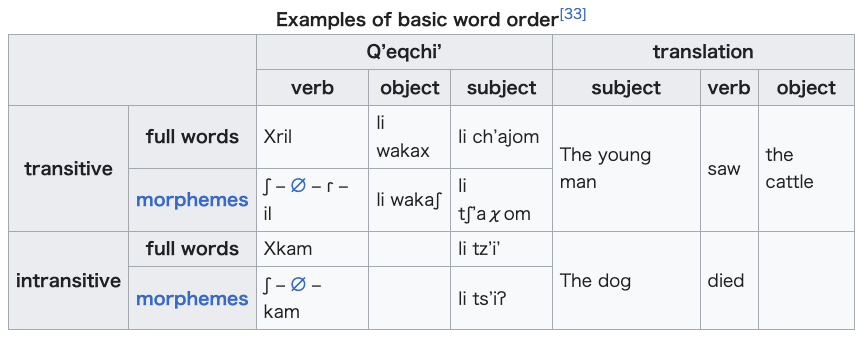

| Grammar Like many other Mayan languages, Qʼeqchiʼ is an ergative–absolutive language, which means that the object of a transitive verb is grammatically treated the same way as the subject of an intransitive verb.[17][18] Individual morphemes and morpheme-by-morpheme glosses in this section are given in IPA, while "full words," or orthographic forms, are given in the Guatemalan Academy of Mayan Languages orthography. Morphology There are two kinds of pronouns in Qʼeqchiʼ: independent pronouns and pronominal affixes. The independent pronouns are much like pronouns in English or Spanish, while the pronominal affixes are attached to words such as nouns, verbs, and statives and used for inflection.[19][20] Like other Mayan languages, Qʼeqchiʼ has two sets of pronominal affixes, referred to as set A and set B. The following table provides all the pronominal affixes. |

文法 他の多くのマヤ諸語と同様、能格=絶対格=言語(ergative–absolutive language)であり、他動詞の目的語が自動詞の主語と同じように文法的に扱われる[17][18]。このセクションの個々の形態素と形態素ごとの用 語解説はIPAで、「完全な単語」、つまり正書法はGuatemalan Academy of Mayan Languagesの正書法で示す。 形態論 Qʼeqchiʼの代名詞には独立代名詞と代名詞接辞の2種類がある。独立代名詞は英語やスペイン語の代名詞によく似ているが、代名詞接辞は名詞、動詞、 形容動詞などの単語に付けられ、屈折のために使われる[19][20]。他のマヤ諸語と同様、Qʼeqchiʼには代名詞接辞が2セットあり、セットAと セットBと呼ばれている。 |

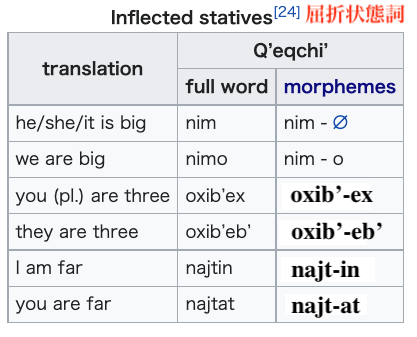

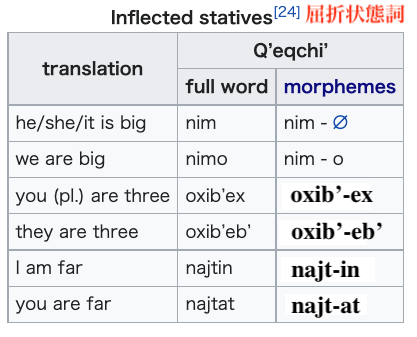

| A活用(Juego A)=能格は、(1)名詞を所有形で表現する——名詞を所有するとき

——ときと、(2)他動詞の主語を示すとき、にそれぞれ使われる。 B活用(Juego B)=絶対格は次の2つのことを表現するのに利用される。(1) 自動詞の主語を指示する。(2) 他動詞の目的語を指示する。 ※注意:リンク先はマム語での解説ですが、ケクチ語でも類似の活用ができますので、各人で分析してください。  When these affixes are attached to transitive verbs, set A affixes indicate the ergative agent while set B indicates the absolutive object.  When a set B affix is attached to an intransitive verb, it indicates the subject of the intransitive verb.  When an affix from set A is prefixed to a noun, it indicates possession. As their name suggests, the prevocalic forms of set A affixes are only found before vowels. However, the rules for the distribution of "preconsonantal" set A prefixes on nouns are more complex, and they can sometimes be found before vowels as well as consonants. For example, loan words (principally from Spanish) are found with preconsonantal affixes, regardless of whether they begin with a consonant or not. In contrast, kinship and body part words—which are words very unlikely to be loaned—always take the prevocalic prefixes if they begin with vowels.[24] The following chart contrasts these two situations.  When an affix of set B serves as the suffix of a stative, it indicates the subject or theme of the stative.  Statives can be derived from nouns. The process simply involves suffixing the set B pronominal affix to the end of the root.  |

A活用(Juego A)=能格は、(1)名詞を所有形で表現する——名詞を所有するとき

——ときと、(2)他動詞の主語を示すとき、にそれぞれ使われる。能格は他動詞活用の主語を表わし、その目的語は絶対格(B活用)で表現される。 B活用(Juego B)= 絶対格は次の2つのことを表現するのに利用される。(1) 自動詞の主語を指示する。(2) 他動詞の目的語を指示する。絶対格は、自動詞の主語の活用であるが、目的語を指示したいときには、目的格化させるための接辞をつけて、名詞を所有形(能格 の活用)抜きで表現することで表現できる。 ※注意:リンク先はマム語での解説ですが、ケクチ語でも類似の活用ができますので、各人で分析してください。  これらの接辞が他動詞に付加される場合、Aセットの接辞は能格(=他動詞活用)の主語( the ergative agent)を表し、Bセットは絶対格(=他動詞)活用の目的語を表す。  B活用(絶対格=自動詞活用)では集合接辞が自動詞に付く場合、自動詞の主語を示す。  集合 A の接辞が名詞の前につく場合、それは所有を表します。その名前が示すように、集合 A の接辞の前置形は、母音の前にのみ見られる。しかし、「前子音形」の接頭辞が名詞に付く場合の規則はより複雑で、子音だけでなく母音 の前にも付くことがある。例えば、(主にスペイン語からの)借用語は、子音で始まるかどうかに関係なく、前子音接頭辞を伴っている。これとは対照的に、親 族関係や身体部位の単語は、借用語である可能性が非常に低い単語ですが、母音で始まる場合は常に前置詞接頭辞をとります[24]。次の表は、この 2 つの状況を対比したものである。  Bセットの接辞が形容詞の接尾辞として機能する場合、その接辞はその形容詞の主語または主題を示す。  代名詞は名詞から派生させることができる。そのプロセスは、代名詞の接尾辞 B を語根の末尾に付けるだけである。  |

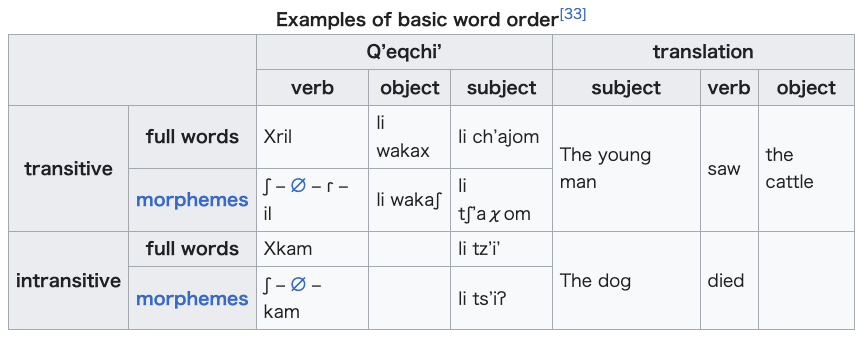

| Syntax The basic word order of Qʼeqchiʼ sentences is verb – object – subject, or VOS.[28][29] SVO, VSO, SOV, OVS, and OSV word orders are all possible in Qʼeqchiʼ, but each have a specific use and set of restrictions.[30] The definiteness and animacy of the subject and object can both have effects on the word order.[31][32] Like many languages, the exact rules for word order in different situations vary from town to town in the Qʼeqchiʼ speaking area.[32]  ●統語論 [他 動詞構文] Xril li wakax li ch'ajom. 若者は家畜を見た. [形 態素分解]X-φ-r-il li wakax li ch'ajom. [形 態素要素]X(時制)-φ(no mark三人称単数)-r(A活用目的語三人称単数)-il(見る=動詞語根) li(単数) wakax(家畜) li(単数) ch'ajom(若者). ++++ [自 動詞構文] Xkam li tz'i'. 犬が死んだ(死んでいる) [形 態素分解] X-φ-kam li tz'i'. [形 態素要素] X(時制)-φ(B活用三人称単数)-kam (死ぬ=動詞語根) li(単数) tz'i'(犬). ●例文をつかった作文 Xatinb'oq, Rux, in Manu' najtin. Rux najtat. (僕 は君を呼ぶ、ドローレス[Rux]。僕はマヌエル[Manu']、僕は遠くにいる。君はドローレス、君は遠くにいる) |

構文 Qʼeqchiʼ文の基本的な語順は動詞-目的語-主語、つまりVOSである[28][29]。QʼeqchiʼではSVO、VSO、SOV、OVS、 OSVの語順がすべて可能であるが、それぞれに特有の用法と制約がある[30]。 [30] 主語と目的語の確定性と能動化(animacy)も語順に影響を与えることがある[31][32]。多くの言語と同様に、さまざまな状況における語順の正 確な規則はQʼeqchiʼ語圏の町によって異なる[32]。  |

| Orthographies Several writing systems have been developed for Qʼeqchiʼ, but only two are in widespread use: SIL and ALMG.[citation needed] Early transcriptions The first transcriptions of Qʼeqchiʼ in the Latin alphabet were made by Roman Catholic friars in the 16th century. Francisco de la Parra devised additional letters to represent the unfamiliar consonants of Mayan languages, and these were used to write Qʼeqchiʼ. Examples of Qʼeqchiʼ written with the de la Parra transcription can be seen in the 18th century writing of the Berendt-Brinton Linguistic Collection (Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania, Ms. Coll. 700). In the 20th century, before Sedat and Eachus & Carlson developed their SIL orthography, field researchers devised alternate Latin transcriptions. For example, Robert Burkitt (an anthropologist fluent in spoken Qʼeqchiʼ and familiar with a range of Qʼeqchiʼ communities and language variation), in his 1902 paper "Notes on the Kekchí Language", uses a transcription based on then-current Americanist standards.[34] SIL/IIN A Spanish-style orthography was developed by Summer Institute of Linguistics (SIL) field researchers, principally William Sedat in the 1950s and Francis Eachus and Ruth Carlson in the 1960s.[35] This alphabet was officialized by the Guatemalan Ministry of Education through the Instituto Indigenista Nacional de Guatemala, or the IIN.[36] Although no longer considered standard, this orthography remains in circulation in large part due to the popularity of a few texts including the Protestant Bible produced by the SIL/Wycliffe Bible Translation Project, and a widely used language learning workbook "Aprendamos Kekchí".[citation needed] ALMG The Proyecto Lingüístico Francisco Marroquín (PLFM) developed an alternative orthography in the late 1970s, which was influenced by the International Phonetic Alphabet (IPA). Of note, the PLFM orthography used the number "7" to write the glottal plosive, whereas the apostrophe was used in digraphs and trigraphs to write ejective stops and affricates. This system was later modified by the Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala (ALMG), which replaced the "7" with the apostrophe. The result, the ALMG orthography, has been the standard, official way to write Qʼeqchiʼ, at least in Guatemala, since 1990. In the ALMG orthography, each grapheme (or "letter", including digraphs and trigraphs) is meant to correspond to a particular phoneme. These include separate vowels for long and short sounds, as well as the use of apostrophes (saltillos) for writing ejectives and the glottal stop.[37] The following table matches each of the official ALMG graphemes with their IPA equivalents. |

正書法 Qʼeqchiʼのためにいくつかの文字体系が開発されているが、広く使われているのは2つだけである: SILとALMGである[要出典]。 初期の転写 ラテンアルファベットによるQʼeqchiʼの最初の転写は、16世紀にローマカトリック修道士によって行われた。Francisco de la Parraはマヤ語の聞き慣れない子音を表すために追加の文字を考案し、Qʼeqchiʼの表記に使われた。Qʼeqchiʼをde la Parraの転写で書いた例は、Berendt-Brinton Linguistic Collection (Rare Book & Manuscript Library, University of Pennsylvania, Ms. Coll. 700)の18世紀の文章で見ることができる。20世紀、SedatやEachus & CarlsonがSIL正書法を開発する以前、現場の研究者たちはラテン語の代替表記を考案しました。例えば、Robert Burkitt(話し言葉のQʼeqchiʼに堪能で、様々なQʼeqchiʼのコミュニティや言語の変化に精通している人類学者)は、1902年の論文 "Notes on the Kekchí Language "の中で、当時のアメリカ主義の標準に基づいた転写を使用している[34]。 SIL/IIN 1950年代にウィリアム・セダット、1960年代にフランシス・エチャスとルース・カールソンを中心とする夏期言語学研究所(SIL)の現地研究者に よってスペイン語風の正書法が開発された。 [36]もはや標準とはみなされないが、この正書法は、SIL/Wycliffe聖書翻訳プロジェクトによって作成されたプロテスタント聖書や、広く使用 されている言語学習ワークブック "Aprendamos Kekchí "を含むいくつかのテキストの人気のため、大部分は流通したままである[要出典]。 ALMG Proyecto Lingüístico Francisco Marroquín (PLFM) は1970年代後半に国際音声記号 (IPA) の影響を受けた代替正書法を開発した。PLFMの正書法では、声門破裂音の表記に数字の「7」が使用されたのに対して、アポストロフィはダイグラフやトリ グラフで、放出停止音やアフリケートの表記に使用されました。このシステムは、後にグアテマラ言語アカデミー(ALMG)によって修正され、"7 "がアポストロフィに置き換えられました。その結果、ALMG正書法が1990年以降、少なくともグアテマラではQʼeqchiʼの標準的で公式な書き方 となっている。ALMG正書法では、それぞれの書記素(ダイグラフやトリグラフを含む「文字」)は特定の音素に対応している。以下の表は、ALMG の各文字素と IPA に相当する文字素を対応させたものである。 |

| History At the time of the Spanish conquest of the Americas, Qʼeqchiʼ was probably spoken by fewer people than neighboring languages such as Itzaʼ, Mopan, and Choltiʼ, all of which are now moribund or extinct. The main evidence for this fact is not colonial documents, but the prevalence of loan words apparently stemming from these languages in Qʼeqchiʼ. However, a number of factors made Qʼeqchiʼ do better than the just-mentioned languages. One is the difficult mountainous terrain which is its home. Another is that, rather than simply being conquered, as the Choltiʼ, or resisting conquest for an extended period, as the Itzaʼ did for over 200 years, the Qʼeqchiʼ came to a particular arrangement with the Spaniards, by which Dominican priests, led initially by Fray Bartolome de las Casas, were allowed to enter their territory and proselytize undisturbed, whereas no lay Spaniards were admitted. This led to their territory being renamed "Verapaz" (true peace) by the Spaniards, a name which continues today in the Guatemalan departments Alta Verapaz and Baja Verapaz. This relatively favorable early development allowed the people to spread, and even make war on neighboring Mayan groups. Although it was later followed by the brutal policies of the late-19th-century liberals and the late-20th century military governments, it largely explains the status of Qʼeqchiʼ as the 3rd largest Mayan language in Guatemala and the 4th across the Mayan region. The relatively recent, postcolonial expansion is also the reason that Qʼeqchiʼ is perhaps the most homogeneous of the larger Mayan languages.[39] Qʼeqchi is taught in public schools through Guatemala's intercultural bilingual education programs. |

歴史 スペインがアメリカ大陸を征服した当時、Qʼeqchiʼは近隣の言語であるItzaʼ、Mopan、Choltiʼよりも話されている人が少なかったと 思われる。この事実を示す主な証拠は植民地時代の文書ではなく、Qʼeqchiʼにこれらの言語に由来すると思われる借用語が多く見られることである。し かし、Qʼeqchiʼが前述の言語よりもうまくいった要因はいくつかある。ひとつは、Qʼeqchiʼの故郷が難しい山岳地帯であること。もうひとつ は、Choltiʼのように単に征服されたり、Itzaʼのように200年以上にわたって征服に抵抗したりするのではなく、Qʼeqchiʼはスペイン人 と特別な協定を結び、当初はFray Bartolome de las Casasに率いられたドミニコ会の司祭たちが彼らの領土に入り、妨害されることなく布教することを許された。このため、彼らの領土はスペイン人によって "ベラパス"(真の平和)と改名され、現在もグアテマラのアルタ・ベラパス県とバハ・ベラパス県にその名が残っている。この比較的良好な初期の発展によ り、人々は拡散し、近隣のマヤ族と戦争することさえできた。その後、19世紀末の自由主義者と20世紀末の軍事政権による残忍な政策が続いたが、 Qʼeqchiʼがグアテマラで3番目、マヤ地域全体で4番目に大きなマヤ語であることを大きく説明している。比較的最近の、植民地支配後の拡大が、 Qʼeqchiʼがおそらく大きなマヤ語の中で最も同質的である理由でもある[39]。 Qʼeqchiはグアテマラの異文化バイリンガル教育プログラムを通じて公立学校で教えられている。 |

| Texts Like most other Mayan languages, Qʼeqchiʼ is still in the process of becoming a written and literary language. Existing texts can roughly be divided into the following categories.[citation needed] Educational texts meant to teach people how to speak, read or write Qʼeqchiʼ. This category includes materials such as dictionaries and grammars, as well as workbooks designed to be used in rural Guatemala schools in communities where the majority of the people are native speakers of Qʼeqchiʼ. Religious texts. The Protestant version of the Bible (published by the SIL based on the work of William Sedat, and Eachus and Carlson) mentioned above is probably the most widely available text in Qʼeqchiʼ. In the last twenty years or so, the Roman Catholic Church has been one of the primary proponents of written Qʼeqchiʼ. Various Catholic organizations are responsible for producing a number of texts, including the New Testament, Genesis and Exodus, and various instructional pamphlets. A songbook entitled Qanimaaq Xloqʼal li Qaawaʼ 'We praise the Lord' is very popular among Catholics, has been in print for many years, and is updated with new songs regularly. The Book of Mormon also is available in Qʼeqchiʼ as are also other LDS religious texts.[40] Non-instructive secular texts have also begun to appear in the last ten years or so, although they are still few in number. The most ambitious of these works have been a free translation of the Kʼicheʼ text Popol Wuj ("Popol Vuh") by the Qʼeqchiʼ language teacher and translator Rigoberto Baq Qaal (or Baʼq Qʼaal), and a collection of Qʼeqchiʼ folk tales. A number of government documents have also been translated into Qʼeqchiʼ, including the Guatemalan Constitution. |

テキスト 他の多くのマヤ言語と同様、Qʼeqchiʼはまだ文字化・文学化の過程にある。既存のテキストは大まかに以下のカテゴリーに分けられる[要出典]。 Qʼeqchiʼの話し方、読み方、書き方を教えるための教育テキスト。このカテゴリーには、辞書や文法書などの教材や、Qʼeqchiʼを母語とする人 が大多数を占める地域のグアテマラの農村部の学校で使われるようにデザインされたワークブックが含まれる。 宗教文書。前述のプロテスタント版聖書(William Sedat、Eachus and Carlsonの研究に基づいてSILが出版)は、おそらくQʼeqchiʼで最も広く利用可能なテキストであろう。ここ20年ほどは、ローマ・カトリッ ク教会がQʼeqchiʼの書き言葉の主要な支持者の一人となっている。様々なカトリック団体が、新約聖書、創世記、出エジプト記、様々な解説パンフレッ トなど、多くのテキストの制作を担当している。Qanimaaq Xloqʼal li Qaawaʼ 'We praise the Lord'と題された歌集はカトリック教徒の間でとても人気があり、何年も印刷され、定期的に新しい歌で更新されている。モルモン書もQʼeqchiʼで 読むことができ、他の末日聖徒の宗教的なテキストもある[40]。 ここ10年ほどの間に、まだ数は少ないが、指導的でない世俗的なテキストも出始めている。最も意欲的なのは、Qʼeqchiʼ語教師で翻訳家の Rigoberto Baq Qaal(またはBaʼq Qʼaal)によるKʼicheʼテキストPopol Wuj(「Popol Vuh」)の自由訳と、Qʼeqchiʼ民話集である。グアテマラ憲法を含む多くの政府文書もQʼeqchiʼに翻訳されている。 |

| KʼEQCHI' 2012, 2021 Maya

Atinab'aal re li Poyanam Kʼeqchi' sa' eb' li Tenamit Guatemala ut

Belize / Mayan language for the Kʼeqchi' people in Guatemala and Belize Qʼeqchiʼ Vocabulary List (from the World Loanword Database) Comparative Qʼeqchiʼ Swadesh vocabulary list (from Wiktionary) Web page of the Spanish language Qʼeqchiʼ learning book Aprendamos kekchí at the SIL. On this site, there is a link to download the book as a PDF. Retrieved May 8, 2016. |

|

| Grammars of Qʼeqchiʼ Caz Cho, Sergio (2007). Xtzʼilbʼal rix li aatinak saʼ Qʼeqchiʼ = Informe de variación dialectal en Qʼeqchiʼ = (in Spanish). Antigua, Guatemala; Guatemala, Guatemala: Oxlajuuj Keej Mayaʼ Ajtzʼiibʼ (OKMA); Cholsamaj. ISBN 9789992253526. OCLC 202514532. Eachus, Francis; Carlson, Ruth (1980). Aprendamos kekchí: Gramática pedagógica popular de kekchí. Guatemala: Instituto Lingüístico del Verano (Summer Institute of Linguistics). Retrieved 18 May 2016. This is a pedagogical grammar, rather than a descriptive grammar like the majority in this section. Stewart, Steven (1980). Gramática kekchí (in Spanish). Editorial Academica Centro America: Guatemala. OCLC 318333627. This grammar does not include syntax. The area of study for the book was Cobán and the surrounding towns of San Pedro Carchá, San Juan Chamelco, and Chamil. Stoll, Otto (1896). Die Sprache der Kʼeʼkchí-Indianer (in German). Tzoc Choc, Juan; Álvarez Cabnal, Alfredo; Carlos Federico, Hun Macz; Sacul Caal, Hugo; the Qʼeqchiʼ language community (2003). Gramática descriptiva del idioma maya qʼeqchiʼ = Xtzʼilbʼal rix xnaʼlebʼil li aatinobʼaal qʼeqchiʼ (in Spanish). Cobán, Alta Verapaz, Guatemala: Academia de las Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala. pp. 114–115. OCLC 654408920. Retrieved May 4, 2016. Tzoc Choc, Juan; Álvarez Cabnal, Alfredo; the Qʼeqchiʼ language community (2004). Gramática normativa qʼeqchiʼ (in Spanish). Guatemala: Academia de las Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala. Retrieved 5 May 2016. This is a normative grammar, rather than a descriptive grammar like the majority in this section. |

|

| Dictionaries of Qʼeqchiʼ Frazier, Jeffrey (2015). Qʼeqchiʼ Mayan Thematic Dictionary: Tusbʼil Molobʼaal Aatin Qʼeqchiʼ ~ Inkles (in kek and English). Mayaglot; 1 edition (June 21, 2015). ISBN 978-1514812280. Frazier, Jeffrey (2015). Qʼeqchiʼ Mayan Dictionary: Molobʼaal Aatin Qʼeqchiʼ ~ Inkles (in kek and English). Mayaglot; 1 edition (December 11, 2015). ISBN 978-0692602096. Haeserijn, Esteban (1979). Diccionario kʼekchiʼ español (in Spanish). Sedat, William (1955). Nuevo diccionario de las lenguas Kʼekchiʼ y española (in Spanish). Guatemala: Alianza para el Progreso. Tuyuc Sucuc, Cecilio (2001). Xtusulal aatin saʼ qʼeqchiʼ = Vocabulario qʼeqchiʼ (PDF) (in kek and Spanish). Academia de Lenguas Mayas de Guatemala, Comunidad Lingüística Qʼeqchiʼ. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Q%CA%BCeqchi%CA%BC_language |

ケクチ

語文法、もご参照ください。 |

★ ケクチ語で唄われるラップ

Rap

en Q'eqchi' #qeqchi #viral #ixcán (sin derechos de

Autor)——画面に写っているJames M Wood BI は Los Angeles のフリーウェイ

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆