Reward system

Diagram showing some of the key components of the mesocorticolimbic ("reward") circuit; Ventral tegmental area /中脳皮質辺縁系(報酬系)回路の主要な構成要素を示す図。腹側被蓋野

Reward system

Diagram showing some of the key components of the mesocorticolimbic ("reward") circuit; Ventral tegmental area /中脳皮質辺縁系(報酬系)回路の主要な構成要素を示す図。腹側被蓋野

| 「報酬系(the Reward system)は、動物が刺激に近づいたり、体力を高める行動(セックス、エネルギー密度の高い食物など)をとったりする動機付けとなる。ほとん どの動物種の生存は、有益な刺激との接触を最大化し、有害な刺激との接触を最小化することに依存している。報酬認知は、連合学習を引き起こし、接近行動や 消費行動を誘発し、正の価値で評価された情動を引き起こすことによって、生存と繁殖の可能性を高める役割を果たす。このように、報酬は動物の適応適性を高 めるために進化したメカニズムである。薬物中毒では、ある種の物質が報酬回路を過剰に活性化し、回路内のシナプス可塑性の結果、強迫的な物質探索行動を引 き起こす。一次報酬は、自己と子孫の生存を促進する報酬刺激の一種で、恒常性維持報酬(例えば、口当たりのよい食物)と生殖報酬(例えば、性的接触や親か らの投資)が含まれる。内発的報酬とは、魅力的であり、本質的に快楽的であるために行動の動機づけとなる無条件の報酬であり、外発的報酬(例えば、金銭や 好きなスポーツチームが試合に勝つのを見ること)とは、魅力的であり、行動の動機づけとなるが、本質的に快楽的ではない条件付きの報酬である。外在的報酬 は、内在的報酬との学習された関連付け(すなわち、条件付け)の結果として、動機づけの価値を導き出す。外在的報酬もまた、内発的報酬と古典的に条件づけ られた後に、快楽(例えば、宝くじで大金が当たったときの陶酔感)を引き出すことがある。」Reward system)(→ 「恐怖と快楽」)。 |

一次報酬の例[1]。左上から時計回りに、水、食物、親の世話、セックス。

一次報酬の例[1]。左上から時計回りに、水、食物、親の世話、セックス。

| The reward system

(the mesocorticolimbic circuit) is a group of neural structures

responsible for incentive salience (i.e., "wanting"; desire or craving

for a reward and motivation), associative learning (primarily positive

reinforcement and classical conditioning), and positively-valenced

emotions, particularly ones involving pleasure as a core component

(e.g., joy, euphoria and ecstasy).[2][3] Reward is the attractive and

motivational property of a stimulus that induces appetitive behavior,

also known as approach behavior, and consummatory behavior.[2] A

rewarding stimulus has been described as "any stimulus, object, event,

activity, or situation that has the potential to make us approach and

consume it is by definition a reward".[2] In operant conditioning,

rewarding stimuli function as positive reinforcers;[1] however, the

converse statement also holds true: positive reinforcers are

rewarding.[1][4] The reward system motivates animals to approach

stimuli or engage in behaviour that increases fitness (sex,

energy-dense foods, etc.). Survival for most animal species depends

upon maximizing contact with beneficial stimuli and minimizing contact

with harmful stimuli. Reward cognition serves to increase the

likelihood of survival and reproduction by causing associative

learning, eliciting approach and consummatory behavior, and triggering

positively-valenced emotions.[1] Thus, reward is a mechanism that

evolved to help increase the adaptive fitness of animals.[5] In drug

addiction, certain substances over-activate the reward circuit, leading

to compulsive substance-seeking behavior resulting from synaptic

plasticity in the circuit.[6] Primary rewards are a class of rewarding stimuli which facilitate the survival of one's self and offspring, and they include homeostatic (e.g., palatable food) and reproductive (e.g., sexual contact and parental investment) rewards.[2][7] Intrinsic rewards are unconditioned rewards that are attractive and motivate behavior because they are inherently pleasurable.[2] Extrinsic rewards (e.g., money or seeing one's favorite sports team winning a game) are conditioned rewards that are attractive and motivate behavior but are not inherently pleasurable.[2][8] Extrinsic rewards derive their motivational value as a result of a learned association (i.e., conditioning) with intrinsic rewards.[2] Extrinsic rewards may also elicit pleasure (e.g., euphoria from winning a lot of money in a lottery) after being classically conditioned with intrinsic rewards.[2] |

報酬システム(中脳皮質辺縁系回路)は、動機付けの顕著性(すなわち

「欲求」、報酬に対する欲求や渇望、動機付け)、連想学習(主に正の強化と古典的条件付け)、および正の感情、特に喜びを中核要素とする感情(喜び、陶酔

感、恍惚感など)を担当する神経構造群です。[2][3]

報酬とは、食欲行動(接近行動)や消費行動を引き起こす刺激の魅力的で動機付けとなる性質を指す。報酬刺激は「私たちに接近し消費させる可能性を有するあ

らゆる刺激、物体、出来事、活動、または状況」と定義される。[2] 操作的条件付けでは、報酬刺激は正の強化因子として機能する[1]

が、その逆も当てはまる。つまり、正の強化因子は報酬である[1][4]。報酬システムは、動物に刺激に近づいたり、適応度を高める行動(性行動、高エネ

ルギー食品の摂取など)をとらせようとする動機付けとなる。ほとんどの動物種は、有益な刺激との接触を最大限に、有害な刺激との接触を最小限に抑えること

で生き残っている。報酬認知は、関連学習を引き起こし、接近行動や摂取行動を誘発し、ポジティブな感情を誘発することで、生存と繁殖の可能性を高める役割

を果たす。[1] したがって、報酬は動物の適応的適応度を高めるために進化したメカニズムである。[5]

薬物依存症では、特定の物質が報酬回路を過剰に活性化し、回路のシナプス可塑性により、物質を求める強迫的な行動を引き起こす。[6] 一次報酬は、自己や子孫の生存を促進する報酬刺激のクラスであり、恒常性維持(例:おいしい食べ物)や生殖(例:性的な接触や親の投資)に関する報酬を含 む。[2][7] 内在的報酬は、本質的に快楽を伴うため、魅力的で行動を動機付ける無条件の報酬だ。[2] 外在的報酬(例:お金や好きなスポーツチームが試合に勝つこと)は、魅力的で行動を動機付けるが、本質的に快楽をもたらさない条件付けされた報酬です。 [2][8] 外在的報酬は、内在的報酬との学習された関連付け(すなわち条件付け)の結果として、動機付けの価値を得る。[2] 外在的報酬は、内在的報酬と古典的条件付けされた後、快楽(例:宝くじで大金を当てることによる多幸感)を引き起こすこともある。[2] |

| Definition Unsolved problem in biology How and where does the brain evaluate reward value and effort (cost) to modulate behavior? More unsolved problems in biology In neuroscience, the reward system is a collection of brain structures and neural pathways that are responsible for reward-related cognition, including associative learning (primarily classical conditioning and operant reinforcement), incentive salience (i.e., motivation and "wanting", desire, or craving for a reward), and positively-valenced emotions, particularly emotions that involve pleasure (i.e., hedonic "liking").[1][3] Reward related activities, such as feeding, exercise, sex, substance use, and social interactions play a factor in elevated levels of dopamine, ultimately altering the CNS (or the central nervous system). Dopamine is the chemical messenger that plays a role in regulating mood, motivation, reward, and pleasure. [9] Terms that are commonly used to describe behavior related to the "wanting" or desire component of reward include appetitive behavior, approach behavior, preparatory behavior, instrumental behavior, anticipatory behavior, and seeking.[10] Terms that are commonly used to describe behavior related to the "liking" or pleasure component of reward include consummatory behavior and taking behavior.[10] The three primary functions of rewards are their capacity to: produce associative learning (i.e., classical conditioning and operant reinforcement);[1] affect decision-making and induce approach behavior (via the assignment of motivational salience to rewarding stimuli);[1] elicit positively-valenced emotions, particularly pleasure.[1] |

定義 生物学における未解決の問題 脳は、報酬の価値と努力(コスト)をどのように、どこで評価し、行動を調節しているのか? 生物学におけるその他の未解決の問題 神経科学において、報酬系とは、連想学習(主に古典的条件付けおよびオペラント強化)、インセンティブの顕著性(すなわち、動機や「欲求」、報酬に対する 欲求、渇望)、およびポジティブな感情、特に快楽(すなわち、快楽的な「好き」)を伴う感情など、報酬に関連する認知を担当する脳の構造および神経経路の 集合体です。[1][3] 食事、運動、性行為、物質使用、社会的相互作用などの報酬関連活動は、ドーパミンの濃度上昇に影響を与え、最終的に中枢神経系(CNS)を変化させる。ドーパミンは、気分、動機付け、報酬、快楽の調節に役割を果たす化学伝達物質だ。[9] 報酬の「欲求」または「欲望」の要素に関連する行動を説明する際に一般的に使用される用語には、食欲行動、接近行動、準備行動、手段行動、予期行動、探索 行動がある。[10] 報酬の「好意」または「快楽」の要素に関連する行動を説明する際に一般的に使用される用語には、消費行動と摂取行動がある。[10] 報酬の3つの主要な機能は、以下の能力である。 連想学習(すなわち、古典的条件付けおよびオペラント強化)を生成する。[1] 意思決定に影響を与え、接近行動を誘発する(報酬となる刺激に動機付けの顕著性を付与することにより)。[1] ポジティブな感情、特に快楽を引き出す。[1] |

| Neuroanatomy |

神経解剖学 |

| Overview The brain structures that compose the reward system are located primarily within the cortico-basal ganglia-thalamo-cortical loop;[11] the basal ganglia portion of the loop drives activity within the reward system.[11] Most of the pathways that connect structures within the reward system are glutamatergic interneurons, GABAergic medium spiny neurons (MSNs), and dopaminergic projection neurons,[11][12] although other types of projection neurons contribute (e.g., orexinergic projection neurons). The reward system includes the ventral tegmental area, ventral striatum (i.e., the nucleus accumbens and olfactory tubercle), dorsal striatum (i.e., the caudate nucleus and putamen), substantia nigra (i.e., the pars compacta and pars reticulata), prefrontal cortex, anterior cingulate cortex, insular cortex, hippocampus, hypothalamus (particularly, the orexinergic nucleus in the lateral hypothalamus), thalamus (multiple nuclei), subthalamic nucleus, globus pallidus (both external and internal), ventral pallidum, parabrachial nucleus, amygdala, and the remainder of the extended amygdala.[3][11][13][14][15] The dorsal raphe nucleus and cerebellum appear to modulate some forms of reward-related cognition (i.e., associative learning, motivational salience, and positive emotions) and behaviors as well.[16][17][18] The laterodorsal tegmental nucleus (LDT), pedunculopontine nucleus (PPTg), and lateral habenula (LHb) (both directly and indirectly via the rostromedial tegmental nucleus (RMTg)) are also capable of inducing aversive salience and incentive salience through their projections to the ventral tegmental area (VTA).[19] The LDT and PPTg both send glutaminergic projections to the VTA that synapse on dopaminergic neurons, both of which can produce incentive salience. The LHb sends glutaminergic projections, the majority of which synapse on GABAergic RMTg neurons that in turn drive inhibition of dopaminergic VTA neurons, although some LHb projections terminate on VTA interneurons. These LHb projections are activated both by aversive stimuli and by the absence of an expected reward, and excitation of the LHb can induce aversion.[20][21][22] |

概要 報酬系を構成する脳構造は、主に皮質-基底核-視床-皮質ループ内に位置している;[11] このループの基底核部分は、報酬系内の活動を駆動している。[11] 報酬系内の構造物を接続する経路のほとんどは、グルタミン酸神経細胞、GABA神経細胞(MSN)、ドーパミン神経細胞[11][12]ですが、他の種類 の投射神経細胞も寄与している(例:オレキシン神経細胞)。報酬系には、腹側線条体領域、腹側線条体(すなわち、腹側被蓋野と嗅球)、背側線条体(すなわ ち、尾状核と被蓋核)、黒質(すなわち、緻密部と網状部)、 前頭前皮質、前帯状皮質、島皮質、海馬、視床下部(特に、側視床下部のオレキシン作動性核)、視床(複数の核)、視床下核、淡蒼球(外側および内側)、腹 側淡蒼球、傍橋核、扁桃体、および扁桃体の残りの部分を含む。[3][11][13][14][15] 背側縫線核と小脳は、報酬に関連する認知(例えば、連合学習、動機付けの重要性、およびポジティブな感情)および行動の一部を調節する役割を果たすようで ある。[16][17][18] 後外側被蓋核(LDT)、脚橋核(PPTg)、および側方海馬体(LHb)(直接的および間接的に前内側被蓋核(RMTg)を介して)は、腹側被蓋領域 (VTA)への投射を通じて、嫌悪的重要性と動機付け重要性を誘発する能力を有している。[19] LDTとPPTgはともに、VTAのドーパミン神経細胞にシナプスを形成するグルタミン酸神経投射を送り、両者とも動機付け的重要性を生じさせている。 LHbはグルタミン酸神経投射を送り、その大部分はGABA神経RMTg神経細胞とシナプスを形成し、これによりドーパミン神経VTA神経細胞の抑制を促 進するが、一部のLHb投射はVTA中間神経細胞に終末する。これらのLHb投射は、嫌悪刺激および期待される報酬の欠如の両方によって活性化され、 LHbの興奮は嫌悪を引き起こす。[20][21][22] |

| Most of the dopamine pathways

(i.e., neurons that use the neurotransmitter dopamine to communicate

with other neurons) that project out of the ventral tegmental area are

part of the reward system;[11] in these pathways, dopamine acts on

D1-like receptors or D2-like receptors to either stimulate (D1-like) or

inhibit (D2-like) the production of cAMP.[23] The GABAergic medium

spiny neurons of the striatum are components of the reward system as

well.[11] The glutamatergic projection nuclei in the subthalamic

nucleus, prefrontal cortex, hippocampus, thalamus, and amygdala connect

to other parts of the reward system via glutamate pathways.[11] The

medial forebrain bundle, which is a set of many neural pathways that

mediate brain stimulation reward (i.e., reward derived from direct

electrochemical stimulation of the lateral hypothalamus), is also a

component of the reward system.[24] |

腹側被蓋野から突出するドーパミン経路(すなわち、神経伝達物質ドーパ

ミンを用いて他のニューロンと伝達するニューロン)のほとんどは、報酬系の一部である、

これらの経路において、ドーパミンはD1様受容体またはD2様受容体に作用し、cAMPの産生を刺激(D1様)または抑制(D2様)する。[23]線条体

のGABA作動性中棘ニューロンも報酬系の構成要素である[11]。視床下核、前頭前皮質、海馬、視床、扁桃体のグルタミン酸作動性投射核は、グルタミン

酸経路を介して報酬系の他の部分に接続している[11]、 内側前脳束も報酬系の構成要素である[24]。 |

| Two theories exist with regard

to the activity of the nucleus accumbens and the generation liking and

wanting. The inhibition (or hyperpolarization) hypothesis proposes

that the nucleus accumbens exerts tonic inhibitory effects on

downstream structures such as the ventral pallidum, hypothalamus or

ventral tegmental area, and that in inhibiting MSNs in the nucleus

accumbens (NAcc), these structures are excited, "releasing" reward

related behavior. While GABA receptor agonists are capable of eliciting

both "liking" and "wanting" reactions in the nucleus accumbens,

glutaminergic inputs from the basolateral amygdala, ventral

hippocampus, and medial prefrontal cortex can drive incentive salience.

Furthermore, while most studies find that NAcc neurons reduce firing in

response to reward, a number of studies find the opposite response.

This had led to the proposal of the disinhibition (or depolarization)

hypothesis, that proposes that excitation or NAcc neurons, or at least

certain subsets, drives reward related behavior.[3][25][26] |

側坐核の活動と、好き嫌いや欲求の発生に関しては、2つの説がある。抑

制(または過分極)仮説は、側坐核が腹側淡蒼球、視床下部、腹側被蓋野などの下流の構造に対して緊張性抑制作用を発揮し、側坐核(NAcc)のMSNを抑

制することで、これらの構造が興奮し、報酬関連行動が「放出」されると提唱している。GABA受容体作動薬は側坐核において「好き」と「欲しい」の両方の

反応を引き起こすことができるが、基底外側扁桃体、腹側海馬、内側前頭前皮質からのグルタミン作動性入力は、インセンティブサリエンスを促進することがで

きる。さらに、ほとんどの研究では、報酬に反応してNAccニューロンの発火が減少することを発見しているが、多くの研究では逆の反応を発見している。こ

のことから、NAccニューロンまたは少なくとも特定のサブセットの興奮が、報酬に関連した行動を引き起こすという、抑制解除(または脱分極)仮説が提唱

された[3][25][26]。 |

| After nearly 50 years of

research on brain-stimulation reward, experts have certified that

dozens of sites in the brain will maintain intracranial

self-stimulation. Regions include the lateral hypothalamus and medial

forebrain bundles, which are especially effective. Stimulation there

activates fibers that form the ascending pathways; the ascending

pathways include the mesolimbic dopamine pathway, which projects from

the ventral tegmental area to the nucleus accumbens. There are several

explanations as to why the mesolimbic dopamine pathway is central to

circuits mediating reward. First, there is a marked increase in

dopamine release from the mesolimbic pathway when animals engage in

intracranial self-stimulation.[5] Second, experiments consistently

indicate that brain-stimulation reward stimulates the reinforcement of

pathways that are normally activated by natural rewards, and drug

reward or intracranial self-stimulation can exert more powerful

activation of central reward mechanisms because they activate the

reward center directly rather than through the peripheral

nerves.[5][27][28] Third, when animals are administered addictive drugs

or engage in naturally rewarding behaviors, such as feeding or sexual

activity, there is a marked release of dopamine within the nucleus

accumbens.[5] However, dopamine is not the only reward compound in the

brain. |

脳刺激による報酬に関する50年近い研究の結果、専門家は脳内の数十の

部位が頭蓋内自己刺激を維持することを認定した。部位としては、視床下部外側と前脳内側束が特に効果的である。そこへの刺激は、上行性経路を形成する線維

を活性化する。上行性経路には、腹側被蓋野から側坐核に至る中辺縁系ドーパミン経路が含まれる。中脳辺縁系ドーパミン経路が報酬を媒介する回路の中心であ

る理由については、いくつかの説明がある。第一に、動物が頭蓋内自己刺激を行うと、中脳辺縁系経路からのドーパミン放出が顕著に増加する[5]。第二に、

脳刺激による報酬は、自然の報酬によって通常活性化される経路の強化を刺激することが実験で一貫して示されており、薬物報酬または頭蓋内自己刺激は、末梢

神経を介してではなく報酬中枢を直接活性化するため、中枢報酬機構のより強力な活性化を及ぼすことができる。[5][27][28]

第3に、動物に中毒性薬物を投与したり、摂食や性行為などの自然な報酬行動をとったりすると、側坐核内でドーパミンが顕著に放出される。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reward_system |

| Key

pathway of the

Reward system. The ventral tegmental area (VTA) is important in responding to stimuli and cues that indicate a reward is present. Rewarding stimuli (and all addictive drugs) act on the circuit by triggering the VTA to release dopamine signals to the nucleus accumbens, either directly or indirectly.[citation needed] The VTA has two important pathways: The mesolimbic pathway projecting to limbic (striatal) regions and underpinning the motivational behaviors and processes, and the mesocortical pathway projecting to the prefrontal cortex, underpinning cognitive functions, such as learning external cues, etc.[31] Dopaminergic neurons in this region converts the amino acid tyrosine into DOPA using the enzyme tyrosine hydroxylase, which is then converted to dopamine using the enzyme dopa-decarboxylase.[32] |

主要経路 腹側被蓋野(VTA)は、報酬の存在を示す刺激や合図に反応する上で重要である。報酬刺激(およびすべての中毒性薬物)は、VTAが側坐核にドーパミン・ シグナルを放出するよう、直接的または間接的に誘発することによって、この回路に作用する: 大脳辺縁系(線条体)領域に投射され、動機づけ行動やプロセスを支える中辺縁系経路と、前頭前皮質に投射され、外部からの手がかりを学習するなどの認知機 能を支える中皮質系経路である[31]。 この領域のドーパミン作動性ニューロンは、酵素チロシンヒドロキシラーゼを用いてアミノ酸チロシンをDOPAに変換し、次いで酵素ドーパデカルボキシラー ゼを用いてドーパミンに変換する[32]。 |

| Striatum (Nucleus Accumbens) The striatum is broadly involved in acquiring and eliciting learned behaviors in response to a rewarding cue. The VTA projects to the striatum, and activates the GABA-ergic Medium Spiny Neurons via D1 and D2 receptors within the ventral (Nucleus Accumbens) and dorsal striatum.[33] The Ventral Striatum (the Nucleus Accumbens) is broadly involved in acquiring behavior when fed into by the VTA, and eliciting behavior when fed into by the PFC. The NAc shell projects to the pallidum and the VTA, regulating limbic and autonomic functions. This modulates the reinforcing properties of stimuli, and short term aspects of reward. The NAc Core projects to the substantia nigra and is involved in the development of reward-seeking behaviors and its expression. It is involved in spatial learning, conditional response, and impulsive choice; the long term elements of reward.[31] The Dorsal Striatum is involved in learning, the Dorsal Medial Striatum in goal directed learning, and the Dorsal Lateral Striatum in stimulus-response learning foundational to Pavlovian response.[34] On repeated activation by a stimuli, the Nucleus Accumbens can activate the Dorsal Striatum via an intrastriatal loop. The transition of signals from the NAc to the DS allows reward associated cues to activate the DS without the reward itself being present. This can activate cravings and reward-seeking behaviors (and is responsible for triggering relapse during abstinence in addiction).[35] |

線条体(扁桃核) 線条体は、報酬的な手がかりに反応する学習行動の獲得と誘発に広く関与している。VTAは線条体に投射し、腹側(側坐核)および背側線条体内のD1および D2受容体を介してGABA作動性中棘神経を活性化する[33]。 腹側線条体(扁桃核)は、VTAから入力された場合は行動の獲得に、PFCから入力された場合は行動の誘発に広く関与している。NAc殻は淡蒼球とVTA に投射し、大脳辺縁系と自律神経機能を調節している。これは刺激の強化特性と報酬の短期的側面を調節する。NAcコアは黒質に投射し、報酬を求める行動の 発達とその発現に関与する。NAcコアは、空間学習、条件反応、および衝動的選択に関与しており、報酬の長期的要素である[31]。 背側線条体は学習に、背内側線条体は目標指向性学習に、背外側線条体はパブロフ反応の基礎となる刺激反応学習に関与している[34]。刺激による反復活性 化において、扁桃核は線条体内ループを介して背側線条体を活性化することができる。NAcから線条体へのシグナルの移行により、報酬そのものが存在しなく ても、報酬に関連する合図が線条体を活性化する。これにより、渇望や報酬を求める行動が活性化される(そして、依存症における断薬中の再発の引き金とな る)[35]。 |

| Prefrontal Cortex The VTA dopaminergic neurons project to the PFC, activating glutaminergic neurons that project to multiple other regions, including the Dorsal Striatum and NAc, ultimately allowing the PFC to mediate salience and conditional behaviors in response to stimuli.[35] Notably, abstinence from addicting drugs activates the PFC, glutamatergic projection to the NAc, which leads to strong cravings, and modulates reinstatement of addiction behaviors resulting from abstinence. The PFC also interacts with the VTA through the mesocortical pathway, and helps associate environmental cues with the reward.[35] |

前頭前皮質 VTAドーパミン作動性ニューロンはPFCに投射し、背側線条体やNAcを含む他の複数の領域に投射するグルタミン作動性ニューロンを活性化し、最終的に PFCが刺激に対する顕著性と条件行動を媒介することを可能にする[35]。 注目すべきは、中毒性薬物を断薬するとPFCが活性化され、NAcへのグルタミン酸作動性投射が強い渇望を引き起こし、断薬による中毒行動の復調が調節さ れることである。PFCはまた、中脳皮質経路を介してVTAと相互作用し、環境的手がかりと報酬の関連付けを助ける[35]。 |

| Hippocampus The Hippocampus has multiple functions, including in the creation and storage of memories . In the reward circuit, it serves to contextual memories and associated cues. It ultimately underpins the reinstatement of reward-seeking behaviors via cues, and contextual triggers.[36] |

海馬 海馬は、記憶の創造と保存を含む複数の機能を持っている。報酬回路では、海馬は文脈記憶と関連する手がかりの役割を果たす。海馬は最終的に、手がかりや文 脈上の誘因を介して、報酬を求める行動の復調を支える[36]。 |

| Amygdala The AMY receives input from the VTA, and outputs to the NAc. The amygdala is important in creating powerful emotional flashbulb memories, and likely underpins the creation of strong cue-associated memories.[37] It also is important in mediating the anxiety effects of withdrawal, and increased drug intake in addiction.[38] |

扁桃体 扁桃体はVTAから入力を受け、NAcに出力する。扁桃体は、強力な情動的フラッシュバルブ記憶を創り出すのに重要であり、おそらく強力な手がかり関連記 憶の創出を支えている。 |

| Pleasure centers Pleasure is a component of reward, but not all rewards are pleasurable (e.g., money does not elicit pleasure unless this response is conditioned).[1] Stimuli that are naturally pleasurable, and therefore attractive, are known as intrinsic rewards, whereas stimuli that are attractive and motivate approach behavior, but are not inherently pleasurable, are termed extrinsic rewards.[1] Extrinsic rewards (e.g., money) are rewarding as a result of a learned association with an intrinsic reward.[1] In other words, extrinsic rewards function as motivational magnets that elicit "wanting", but not "liking" reactions once they have been acquired.[1] The reward system contains pleasure centers or hedonic hotspots – i.e., brain structures that mediate pleasure or "liking" reactions from intrinsic rewards. As of October 2017, hedonic hotspots have been identified in subcompartments within the nucleus accumbens shell, ventral pallidum, parabrachial nucleus, orbitofrontal cortex (OFC), and insular cortex.[2][17][39] The hotspot within the nucleus accumbens shell is located in the rostrodorsal quadrant of the medial shell, while the hedonic coldspot is located in a more posterior region. The posterior ventral pallidum also contains a hedonic hotspot, while the anterior ventral pallidum contains a hedonic coldspot. In rats, microinjections of opioids, endocannabinoids, and orexin are capable of enhancing liking reactions in these hotspots.[2] The hedonic hotspots located in the anterior OFC and posterior insula have been demonstrated to respond to orexin and opioids in rats, as has the overlapping hedonic coldspot in the anterior insula and posterior OFC.[39] On the other hand, the parabrachial nucleus hotspot has only been demonstrated to respond to benzodiazepine receptor agonists.[2] Hedonic hotspots are functionally linked, in that activation of one hotspot results in the recruitment of the others, as indexed by the induced expression of c-Fos, an immediate early gene. Furthermore, inhibition of one hotspot results in the blunting of the effects of activating another hotspot.[2][39] Therefore, the simultaneous activation of every hedonic hotspot within the reward system is believed to be necessary for generating the sensation of an intense euphoria.[40] |

快楽中枢 快楽は報酬の構成要素であるが、すべての報酬が快楽的であるわけではない(例えば、この反応が条件付けされない限り、お金は快楽を引き出さない)[1]。 自然に快楽的であり、したがって魅力的な刺激は内在的報酬と呼ばれ、魅力的で接近行動を動機付けるが、本質的に快楽的ではない刺激は外在的報酬と呼ばれる [1]、 言い換えれば、外発的報酬は、いったん獲得されると「欲しい」という反応は引き出すが「好き」という反応は引き出さない動機づけの磁石として機能する [1]。 報酬系には快感中枢または快感ホットスポット、すなわち内発的報酬による快感や「好き」反応を媒介する脳構造が存在する。2017年10月現在、快楽性 ホットスポットは、側坐核殻、腹側淡蒼球、傍上腕核、眼窩前頭皮質(OFC)、および島皮質内のサブコンパートメントで同定されている[2][17] [39]。側坐核殻内のホットスポットは内側殻の吻背側四分円に位置し、快楽性コールドスポットはより後方の領域に位置する。腹側淡蒼球後部にも快楽ホッ トスポットがあり、腹側淡蒼球前部には快楽コールドスポットがある。ラットにおいて、オピオイド、エンドカンナビノイド、オレキシンの微量注射は、これら のホットスポットにおける嗜好反応を増強することができる。 [39] 一方、傍上腕核ホットスポットはベンゾジアゼピン受容体作動薬にのみ反応することが証明されている[2]。 ヘドニックホットスポットは機能的に関連しており、1つのホットスポットを活性化すると、即時型遺伝子であるc-Fosの発現誘導によって指標されるよう に、他のホットスポットも動員される。さらに、1つのホットスポットを抑制すると、他のホットスポットを活性化する効果が鈍くなる[2][39]。した がって、報酬系内のすべての快楽性ホットスポットが同時に活性化されることが、強烈な多幸感の感覚を生み出すために必要であると考えられている[40]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reward_system |

★「生物学的な恐怖反応は非常に複雑であ り、扁桃体から前頭葉まで、さまざまな脳領域に影響を与える神経伝達物質とホルモンが関係している。……われわれの体は、恐ろしいものに対して、闘うか逃 げるための準備をするよう進化してきた。具体的には、瞳孔を広げてものがよく見えるようにしたり、気管支を広げて酸素を多く取り込めるようにしたり、血液 やブドウ糖を重要な器官や骨格筋に送り込んだりする。」

☆「アドレナリン、ドーパミン、コルチ ゾールは、人間が脅威を感じたときに放出する3つの重要な物質……。危険を察知すると、アドレナリンの放出によってわれわれの「闘争・逃走反応」が引き起 こされる。これによって心拍数、血圧、呼吸数などが高まる。……ストレスホルモンであるコルチゾールは、体のさまざまな機能を調節するために常時放出され ている。しかし、何らかの状況や経験を乗り越えようと緊張したときには、その量が一気に増える。……コルチゾールは、まずアドレナリンなどの「闘争・逃 走」ホルモンが一気に放出された後も警戒が維持されるのを助ける。また、緊急事態の最中に、肝臓からエネルギーとなるブドウ糖(グルコース)が放出される のを促す。(コルチゾールのレベルが慢性的に高い状態は身体によいわけではない)。……アドレナリンとコルチゾールは、どちらもストレスと関係がある。ス トレスは、胸痛、頭痛や震え、疲労、筋肉の緊張といった身体的な症状のほか、いらつき、パニック発作、悲しみといった感情的な症状(を起こす)。ドーパミ ンは、より全般的に良い気分をもたらす神経伝達物質だ。これは喜びや、報酬の期待や経験などに関連しており(これが、恐怖の後の高揚感と関係しているかも しれない)」

「恐怖の対象が目の前から消えて初めて ドーパミンが放出されるわけではない。報酬への期待感があれば放出される……。薬物依存症の患者は、目当ての薬がまだ手元になくとも、それを追い求めてい る最中に、ドーパミンによって高揚感を経験する(のではないかと考えられている)」https://x.gd/0HYyT.

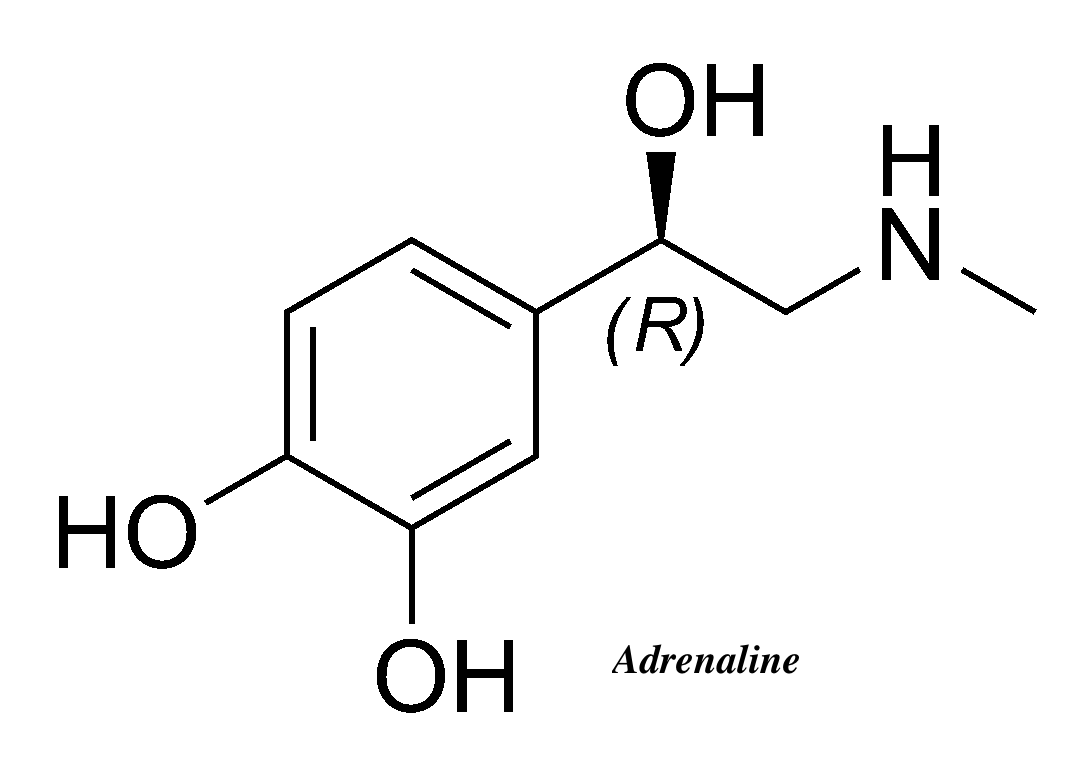

☆アドレナリンとは?

「アドレナリンとは、腎臓の上にある副腎 というところの中の髄質から分泌されるホルモンです。主な作用は、心拍数や血圧上昇などがあります。 自律神経の交感神経が興奮することによって分泌が高まります。その結果、主な作用として、心拍数や血圧上昇が上昇し、体のパフォーマンスが高まります。 また、覚醒作用があり、集中力や注意力も高まります。アドレナリンが分泌されることにより、目の前の恐怖や不安に対して、体と脳が戦闘モードに切り替わ り、立ち向かうことができるのです。」https://kentei.healthcare/column/2207/

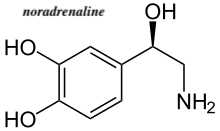

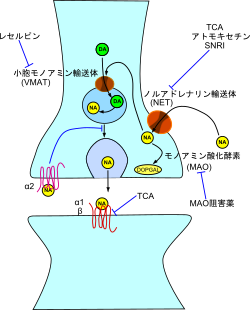

☆ノルアドレナリン

「ノルアドレナリンは、脳内の神経伝達物 質、自律神経の神経伝達物質、副腎髄質から分泌されるホルモンとしての3つの役割があります。 ノルアドレナリンの分泌を促すものは、痛み、かゆみ、寒暖差、人間関係などのストレスがあります。アドレナリンと同じく、目の前の恐怖や不安に対して、体 と脳が戦闘モードに切り替わり、立ち向かうことができるのです。そのため、集中力を高めたり、積極性な行動を起こすことにも役立ちます。 ノルアドレナリンが不足すると、やる気や集中力が低下してしまいます。また、逆にノルアドレナリンが過剰に分泌されると「パニック障害」を引き起こす原因 になるといわれています。」https://kentei.healthcare/column/2207/

「ノルアドレナリン系における変化 は憂うつに関係する。SNRIは、脳内のシナプス後細胞で、利用可能なセロトニンとノルアドレナリンの量を増加させることによって、うつを治療する。最近 はノルアドレナリン自己受容体がドーパミンも再取り込みするかもしれないという仮説では、これはSNRI(セロトニン・ノルアドレナリン再取り込み阻害 薬: Serotonin & Norepinephrine Reuptake Inhibitors; SNR)がドーパミン伝達をも増加させるかもしれないことを意味する。 一部の他の抗うつ薬[注釈 1]もまた、ノルアドレナリンに影響する。いくつかの場合、他の神経伝達物質に影響しない[注釈 2]。ノルアドレナリンはアミノ酸チロシンから一連の酵素反応を経て合成される。最初のレボドパ (L-DOPA) への酸化の後に神経伝達物質ドーパミンへの脱炭酸が続き、ドーパミン-β-モノオキシゲナーゼによりノルアドレナリンへ酸化される。さらにノルアドレナリ ンはアドレナリンへメチル化できる。」https://x.gd/w1oTn.

★アドレナリンとノルアドレナリンの違い

「ノルアドレナリンとアドレナリンの最も 大きな違いは、脳への精神的な作用の有無です。ノルアドレナリンは、脳内で神経伝達物質として分泌されるため、恐怖や怒り、不安などの精神的な作用にかか わっています。一方、アドレナリンは脳内ではほとんど分泌されず、また、副腎髄質で分泌されたアドレナリンは血液脳関門を通過することができないため、精 神的な作用には関与していません。 ノルアドレナリンは神経伝達物質、アドレナリンはホルモンとして紹介されていることがありますが、これは分泌量や作用として主に働く場所を指しているため です。」https://kentei.healthcare/column/2207/

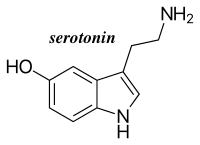

☆ドーパミンとは

「ドーパミン(英: dopamine)は、中枢神経系に存在する神経伝達物質で、アドレナリン、ノルアドレナリンの前駆体でもある。運動調節、ホルモン調節、快の感情、意 欲、学習などに関わる。セロトニン、ノルアドレナリン、アドレナリン、ヒスタミン、ドーパミンを総称してモノアミン神経伝達物質と呼ぶ。またドーパミン は、ノルアドレナリン、アドレナリンと共にカテコール基をもつためカテコールアミンとも総称される。統合失調症の陽性症状(幻覚・妄想など)は基底核や中 脳辺縁系ニューロンのドーパミン過剰によって生じるという仮説がある。この仮説に基づき薬物療法で一定の成果を収めてきているが、一方で陰性症状には効果 が無く、根本的病因としては仮説の域を出ていない。覚醒剤はドーパミン作動性に作用するため、中毒症状は統合失調症に類似する。強迫性障害、トゥレット障 害、注意欠陥多動性障害 (ADHD) においてもドーパミン機能の異常が示唆されている。中脳皮質系ドーパミン神経は、とくに前頭葉に分布するものが報酬系などに関与し、意欲、動機、学習など に重要な役割を担っていると言われている。新しい知識が長期記憶として貯蔵される際、ドーパミンなどの脳内化学物質が必要になる[5]。陰性症状の強い統 合失調症患者や、一部のうつ病では前頭葉を中心としてドーパミンD1の機能が低下しているという仮説がある。」https://x.gd/LGcv1.

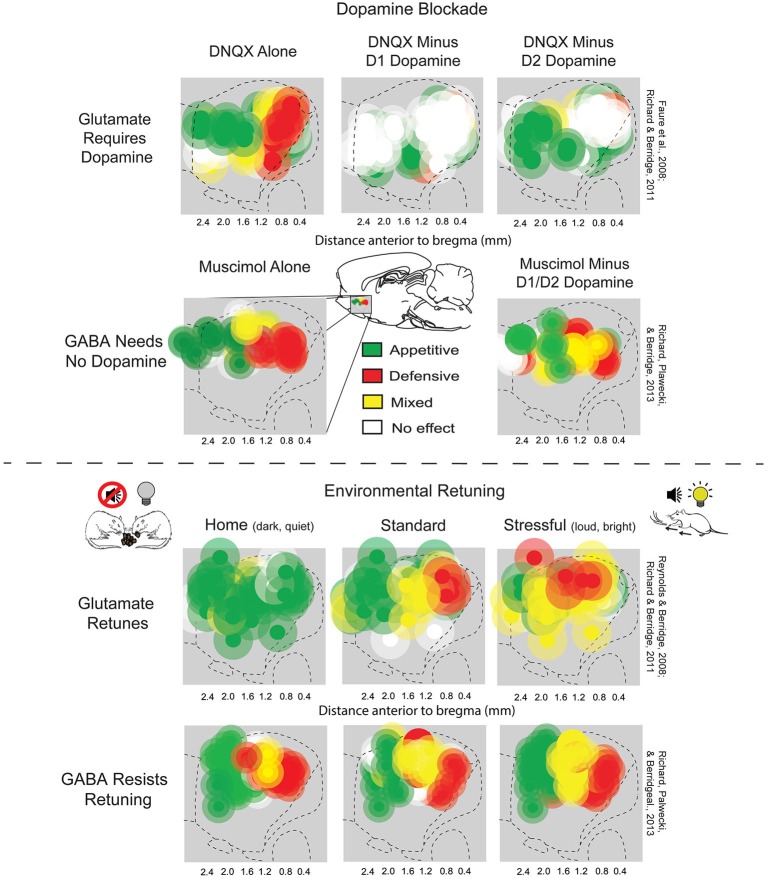

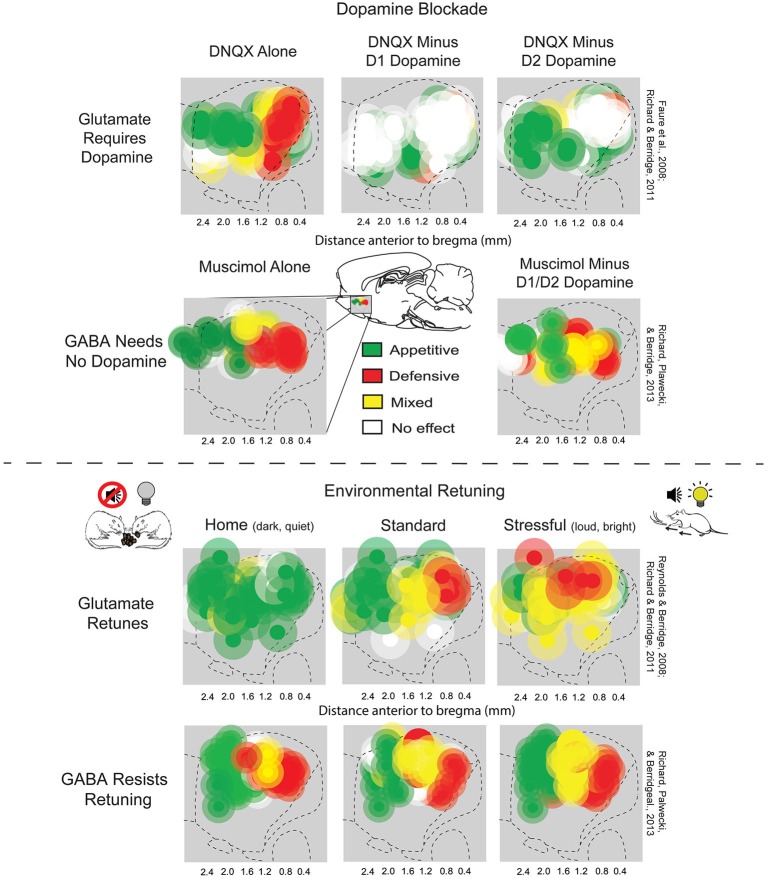

| Wanting and liking(←Reward system) Main article: Incentive salience  Tuning of appetitive and defensive reactions in the nucleus accumbens shell (above). AMPA blockade requires D1 function in order to produce motivated behaviors, regardless of valence, and D2 function to produce defensive behaviors. GABA agonism, on the other hand, does not requires dopamine receptor function (below). The expansion of the anatomical regions that produce defensive behaviors under stress, and appetitive behaviors in the home environment produced by AMPA antagonism. This flexibility is less evident with GABA agonism.[25] Incentive salience is the "wanting" or "desire" attribute, which includes a motivational component, that is assigned to a rewarding stimulus by the nucleus accumbens shell (NAcc shell).[2][41][42] The degree of dopamine neurotransmission into the NAcc shell from the mesolimbic pathway is highly correlated with the magnitude of incentive salience for rewarding stimuli.[41] Activation of the dorsorostral region of the nucleus accumbens correlates with increases in wanting without concurrent increases in liking.[43] However, dopaminergic neurotransmission into the nucleus accumbens shell is responsible not only for appetitive motivational salience (i.e., incentive salience) towards rewarding stimuli, but also for aversive motivational salience, which directs behavior away from undesirable stimuli.[10][44][45] In the dorsal striatum, activation of D1 expressing MSNs produces appetitive incentive salience, while activation of D2 expressing MSNs produces aversion. In the NAcc, such a dichotomy is not as clear cut, and activation of both D1 and D2 MSNs is sufficient to enhance motivation,[46][47] likely via disinhibiting the VTA through inhibiting the ventral pallidum.[48][49] |

欲求と好み メイン記事:インセンティブの顕著性  腹側被蓋核殻における食欲反応と防御反応の調整(上)。AMPA 遮断は、価数に関係なく動機付け行動を引き起こすために D1 機能が必要であり、防御行動を引き起こすためには D2 機能が必要だ。一方、GABAアゴニストはドーパミン受容体機能が必要ない(下図)。ストレス下で防御的行動を産生する解剖学的領域の拡大、および AMPAアンタゴニストによって家庭環境で産生される食欲性行動。この柔軟性はGABAアゴニストでは明確ではない。[25] インセンティブ・サリエンシー(顕著性)は、報酬刺激に腹側被蓋核殻(NAcc殻)によって付与される「欲求」または「欲望」の属性であり、動機付けの要 素を含む。[2][41][42] 腹側被蓋核殻への中脳辺縁系経路からのドーパミン神経伝達の程度は、報酬刺激に対するインセンティブ・サリエンシーの大きさと強く相関している。[41] 腹側被蓋核の背側前部領域の活性化は、好ましさの増加を伴わずに欲求の増加と相関している。[43] しかし、腹側被蓋核殻へのドーパミン神経伝達は、報酬刺激に対する食欲性動機付け的意義(すなわちインセンティブ・サリエンシー)だけでなく、不快な刺激 から行動を遠ざける嫌悪性動機付け的意義にも責任を負っている。[10][44][45] 背側線条体では、D1発現MSNの活性化は食欲性インセンティブ・サリエンシーを引き起こし、D2発現MSNの活性化は嫌悪を引き起こす。NAccでは、 このような二分法は明確ではなく、D1とD2の両方のMSNの活性化が動機付けを強化するのに十分であり[46][47]、おそらく腹側淡蒼球を抑制する ことでVTAの抑制を解除するメカニズムを介していると考えられている[48][49]。 |

| Robinson and Berridge's 1993

incentive-sensitization theory proposed that reward contains separable

psychological components: wanting (incentive) and liking (pleasure). To

explain increasing contact with a certain stimulus such as chocolate,

there are two independent factors at work – our desire to have the

chocolate (wanting) and the pleasure effect of the chocolate (liking).

According to Robinson and Berridge, wanting and liking are two aspects

of the same process, so rewards are usually wanted and liked to the

same degree. However, wanting and liking also change independently

under certain circumstances. For example, rats that do not eat after

receiving dopamine (experiencing a loss of desire for food) act as

though they still like food. In another example, activated

self-stimulation electrodes in the lateral hypothalamus of rats

increase appetite, but also cause more adverse reactions to tastes such

as sugar and salt; apparently, the stimulation increases wanting but

not liking. Such results demonstrate that the reward system of rats

includes independent processes of wanting and liking. The wanting

component is thought to be controlled by dopaminergic pathways, whereas

the liking component is thought to be controlled by

opiate-GABA-endocannabinoids systems.[5] |

ロビンソンとベリッジの1993年のインセンティブ感作理論は、報酬に

は分離可能な心理的要素、すなわち「欲求(インセンティブ)」と「好感(快楽)」が含まれていると提唱した。チョコレートのような特定の刺激との接触が増

加する理由を説明するには、2つの独立した要因が働いている——チョコレートを手に入れたいという欲求(欲求)と、チョコレートの快楽効果(好感)だ。ロ

ビンソンとバーリッジによると、欲求と快楽は同じプロセスの2つの側面であるため、報酬は通常、同じ程度に欲求され、快楽される。しかし、欲求と快楽は、

特定の状況下では独立して変化する。例えば、ドーパミンを投与された後、食べないラット(食への欲求が失われた状態)は、依然として食を好むように行動す

る。別の例では、ラットの側頭下垂体における自己刺激電極を活性化すると、食欲が増加するが、糖や塩の味に対する不快反応も増加する。明らかに、刺激は欲

求を増大させるが、快楽は増大させない。このような結果は、ラットの報酬システムに、欲求と快楽の独立したプロセスが存在することを示している。欲求の成

分はドーパミン系経路によって制御されていると考えられており、好むの成分はオピオイド-GABA-エンドカンナビノイド系によって制御されていると考え

られている。[5] |

| Anti-reward system Koobs & Le Moal proposed that there exists a separate circuit responsible for the attenuation of reward-pursuing behavior, which they termed the anti-reward circuit. This component acts as brakes on the reward circuit, thus preventing the over pursuit of food, sex, etc. This circuit involves multiple parts of the amygdala (the bed nucleus of the stria terminalis, the central nucleus), the Nucleus Accumbens, and signal molecules including norepinephrine, corticotropin-releasing factor, and dynorphin.[50] This circuit is also hypothesized to mediate the unpleasant components of stress, and is thus thought to be involved in addiction and withdrawal. While the reward circuit mediates the initial positive reinforcement involved in the development of addiction, it is the anti-reward circuit that later dominates via negative reinforcement that motivates the pursuit of the rewarding stimuli.[51] |

抗報酬システム Koobs & Le Moal は、報酬追求行動の減衰を担当する独立した回路が存在すると提案し、これを抗報酬回路と名付けた。この成分は報酬回路のブレーキとして機能し、食物や性行 為などの過剰な追求を防止する。この回路は、扁桃体(終板核の床核、中央核)、腹側被蓋野、ノルアドレナリン、コルチコトロピン放出因子、ダイナ orphinなどのシグナル分子を含む複数の部位を包含している。[50] この回路はストレスの不快な成分を仲介すると仮定されており、したがって依存症や離脱症状に関与していると考えられている。報酬回路は依存症の発達におけ る初期の正の強化を仲介するが、後に負の強化を通じて報酬刺激の追求を動機付けるのは、報酬回路ではなく抗報酬回路で。ある[51] |

| Learning Further information: Associative learning Rewarding stimuli can drive learning in both the form of classical conditioning (Pavlovian conditioning) and operant conditioning (instrumental conditioning). In classical conditioning, a reward can act as an unconditioned stimulus that, when associated with the conditioned stimulus, causes the conditioned stimulus to elicit both musculoskeletal (in the form of simple approach and avoidance behaviors) and vegetative responses. In operant conditioning, a reward may act as a reinforcer in that it increases or supports actions that lead to itself.[1] Learned behaviors may or may not be sensitive to the value of the outcomes they lead to; behaviors that are sensitive to the contingency of an outcome on the performance of an action as well as the outcome value are goal-directed, while elicited actions that are insensitive to contingency or value are called habits.[52] This distinction is thought to reflect two forms of learning, model free and model based. Model free learning involves the simple caching and updating of values. In contrast, model based learning involves the storage and construction of an internal model of events that allows inference and flexible prediction. Although pavlovian conditioning is generally assumed to be model-free, the incentive salience assigned to a conditioned stimulus is flexible with regard to changes in internal motivational states.[53] Distinct neural systems are responsible for learning associations between stimuli and outcomes, actions and outcomes, and stimuli and responses. Although classical conditioning is not limited to the reward system, the enhancement of instrumental performance by stimuli (i.e., Pavlovian-instrumental transfer) requires the nucleus accumbens. Habitual and goal directed instrumental learning are dependent upon the lateral striatum and the medial striatum, respectively.[52] During instrumental learning, opposing changes in the ratio of AMPA to NMDA receptors and phosphorylated ERK occurs in the D1-type and D2-type MSNs that constitute the direct and indirect pathways, respectively.[54][55] These changes in synaptic plasticity and the accompanying learning is dependent upon activation of striatal D1 and NMDA receptors. The intracellular cascade activated by D1 receptors involves the recruitment of protein kinase A, and through resulting phosphorylation of DARPP-32, the inhibition of phosphatases that deactivate ERK. NMDA receptors activate ERK through a different but interrelated Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK pathway. Alone NMDA mediated activation of ERK is self-limited, as NMDA activation also inhibits PKA mediated inhibition of ERK deactivating phosphatases. However, when D1 and NMDA cascades are co-activated, they work synergistically, and the resultant activation of ERK regulates synaptic plasticity in the form of spine restructuring, transport of AMPA receptors, regulation of CREB, and increasing cellular excitability via inhibiting Kv4.2.[56][57][58] |

学習 詳細情報:連想学習 報酬刺激は、古典的条件付け(パブロフの条件付け)とオペラント条件付け(道具的条件付け)の両方の形で学習を促進する。古典的条件付けでは、報酬は無条 件刺激として機能し、条件刺激と関連付けられると、条件刺激が筋骨格系(単純な接近行動や回避行動の形で)および自律神経系の反応を引き起こす。オペラン ト条件付けでは、報酬は、それ自体につながる行動を増やし、または支持するという点で、強化因子として機能する。[1] 学習された行動は、それがもたらす結果の価値に敏感である場合もあれば、そうでない場合もある。行動の結果の価値だけでなく、行動の実行に対する結果の偶 発性にも敏感な行動は目標指向であり、偶発性や価値に敏感ではない誘発された行動は習慣と呼ばれる。[52] この区別は、モデルフリー学習とモデルベース学習の2つの学習形態を反映していると考えられている。モデルフリー学習は、価値の単純な記憶と更新を含む。 一方、モデルベース学習は、出来事の内部モデルを記憶し構築し、推論と柔軟な予測を可能にする。パブロフ的条件付けは一般的にモデルフリーと仮定されてい るが、条件刺激に付与されるインセンティブの重要性は、内部の動機状態の変化に対して柔軟である。[53] 刺激と結果、行動と結果、刺激と反応の関連性を学習するのは、それぞれ異なる神経系だ。古典的条件付けは報酬系に限定されないが、刺激による道具的パ フォーマンスの強化(すなわち、パブロフ的道具的転移)には、側坐核が必要だ。習慣的および目標指向の道具的学習は、それぞれ外側線条体および内側線条体 に依存している[52]。 道具的学習中、直接経路を構成するD1型MSNと間接経路を構成するD2型MSNにおいて、AMPA受容体とNMDA受容体の比率およびリン酸化ERKの 比率に相反する変化が生じる。[54][55] これらのシナプス可塑性の変化と伴う学習は、線条体のD1受容体とNMDA受容体の活性化に依存している。D1 受容体によって活性化される細胞内カスケードは、プロテインキナーゼ A の動員に関与し、その結果生じる DARPP-32 のリン酸化を通じて、ERK を不活性化させるホスファターゼの阻害をもたらす。NMDA 受容体は、異なるが相互に関連した Ras-Raf-MEK-ERK 経路を通じて ERK を活性化する。NMDA による ERK の活性化は、NMDA の活性化も PKA による ERK を不活性化するホスファターゼの阻害を阻害するため、単独では自己制限的である。しかし、D1とNMDAのシグナル伝達経路が同時に活性化されると、両者 は相乗的に作用し、その結果、ERKの活性化がシナプス可塑性(スパインの再編成、AMPA受容体の輸送、CREBの調節、およびKv4.2の抑制を介し た細胞の興奮性の増加)を調節する。[56][57][58] |

| Disorders Addiction Main article: Addiction ΔFosB (DeltaFosB) – a gene transcription factor – overexpression in the D1-type medium spiny neurons of the nucleus accumbens is the crucial common factor among virtually all forms of addiction (i.e., behavioral addictions and drug addictions) that induces addiction-related behavior and neural plasticity.[59][60][61][62] In particular, ΔFosB promotes self-administration, reward sensitization, and reward cross-sensitization effects among specific addictive drugs and behaviors.[59][60][61][63][64] Certain epigenetic modifications of histone protein tails (i.e., histone modifications) in specific regions of the brain are also known to play a crucial role in the molecular basis of addictions.[62][65][66][67] Addictive drugs and behaviors are rewarding and reinforcing (i.e., are addictive) due to their effects on the dopamine reward pathway.[14][68] The lateral hypothalamus and medial forebrain bundle has been the most-frequently-studied brain-stimulation reward site, particularly in studies of the effects of drugs on brain stimulation reward.[69] The neurotransmitter system that has been most-clearly identified with the habit-forming actions of drugs-of-abuse is the mesolimbic dopamine system, with its efferent targets in the nucleus accumbens and its local GABAergic afferents. The reward-relevant actions of amphetamine and cocaine are in the dopaminergic synapses of the nucleus accumbens and perhaps the medial prefrontal cortex. Rats also learn to lever-press for cocaine injections into the medial prefrontal cortex, which works by increasing dopamine turnover in the nucleus accumbens.[70][71] Nicotine infused directly into the nucleus accumbens also enhances local dopamine release, presumably by a presynaptic action on the dopaminergic terminals of this region. Nicotinic receptors localize to dopaminergic cell bodies and local nicotine injections increase dopaminergic cell firing that is critical for nicotinic reward.[72][73] Some additional habit-forming drugs are also likely to decrease the output of medium spiny neurons as a consequence, despite activating dopaminergic projections. For opiates, the lowest-threshold site for reward effects involves actions on GABAergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area, a secondary site of opiate-rewarding actions on medium spiny output neurons of the nucleus accumbens. Thus the following form the core of currently characterised drug-reward circuitry; GABAergic afferents to the mesolimbic dopamine neurons (primary substrate of opiate reward), the mesolimbic dopamine neurons themselves (primary substrate of psychomotor stimulant reward), and GABAergic efferents to the mesolimbic dopamine neurons (a secondary site of opiate reward).[69] |

障害 依存症 主な記事:依存症 ΔFosB(DeltaFosB) – 遺伝子転写因子 – は、腹側被蓋核のD1型中型有棘神経細胞における過剰発現が、ほぼすべての依存症(行動依存症と薬物依存症を含む)に共通する重要な要因であり、依存症関 連行動と神経可塑性を誘発する。[59][60][61][62] 特に、ΔFosB は、特定の依存性薬物および行動間の自己投与、報酬感作、および報酬交差感作効果を促進する。[59][60][61][63][64] 脳内の特定の領域におけるヒストンタンパク質尾部の特定のエピジェネティックな修飾(すなわち、ヒストン修飾)も、依存症の分子基盤において重要な役割を 果たしていることが知られている。[62][65][66][67] 依存性薬物および依存性行動は、ドーパミン報酬経路に作用することで報酬と強化(すなわち依存性)をもたらす。[14][68] 側視床下部および前脳束は、特に薬物による脳刺激報酬の影響に関する研究において、最も頻繁に研究されている脳刺激報酬部位である。[69] 薬物乱用の習慣形成行動と最も明確に関連付けられている神経伝達物質系は、腹側被蓋核を遠心性目標とする中脳辺縁ドーパミン系であり、その局所的な GABA神経線維が関与しています。アンフェタミンとコカインの報酬関連作用は、腹側被蓋核のドーパミン神経シナプスおよびおそらく内側前頭前野において 発生する。ラットは、内側前頭前皮質へのコカイン注射のためにレバーを押すことを学習し、これは腹側被蓋核におけるドーパミンの代謝を増加させることで機 能する。[70][71] 腹側被蓋核に直接ニコチンを投与すると、この領域のドーパミン神経終末に対する前シナプス作用により、局所的なドーパミン放出が促進される。ニコチン受容 体はドーパミン神経細胞体に局在し、局所的なニコチン投与はニコチン報酬に不可欠なドーパミン神経細胞の放電を増加させる。[72][73] いくつかの追加の習慣形成薬は、ドーパミン投射を活性化しつつも、その結果として中型有棘神経細胞の出力 を減少させる可能性もある。オピオイドの場合、報酬効果の最も閾値の低い部位は、腹側被蓋野のGABA神経細胞への作用であり、これは腹側被蓋野の中型有 棘細胞の出力神経細胞に対するオピオイド報酬作用の二次的部位である。したがって、現在特徴付けられている薬物報酬回路の核心を成すのは、中脳辺縁系ドー パミン神経細胞へのGABA作動性入力(オピオイド報酬の主要な基質)、中脳辺縁系ドーパミン神経細胞自体(心理運動刺激薬報酬の主要な基質)、および中 脳辺縁系ドーパミン神経細胞へのGABA作動性出力(オピオイド報酬の二次的な部位)である。[69] |

| Motivation Main article: Motivational salience Dysfunctional motivational salience appears in a number of psychiatric symptoms and disorders. Anhedonia, traditionally defined as a reduced capacity to feel pleasure, has been re-examined as reflecting blunted incentive salience, as most anhedonic populations exhibit intact "liking".[74][75] On the other end of the spectrum, heightened incentive salience that is narrowed for specific stimuli is characteristic of behavioral and drug addictions. In the case of fear or paranoia, dysfunction may lie in elevated aversive salience.[76] In modern literature, anhedonia is associated with the proposed two forms of pleasure, "anticipatory" and "consummatory". Neuroimaging studies across diagnoses associated with anhedonia have reported reduced activity in the OFC and ventral striatum.[77] One meta analysis reported anhedonia was associated with reduced neural response to reward anticipation in the caudate nucleus, putamen, nucleus accumbens and medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC).[78] |

動機 主な記事:動機付けの顕著性 機能不全な動機付けの顕著性は、数多くの精神症状や障害に現れる。伝統的に「快楽を感じる能力の低下」と定義されてきた無快感症は、ほとんどの無快感症患 者が「好む」能力は保たれていることから、動機付けの顕著性の鈍化を反映していると考え直されている。[74][75] スペクトルの反対側では、特定の刺激に限定された動機付けの顕著性の高まりは、行動依存症や薬物依存症の特微である。恐怖やパラノイアの場合、機能不全は 嫌悪的顕著性の高まりに起因する可能性があります。[76] 現代の文献では、無快感症は「予期的」と「消費的」の2つの快楽の形態と関連付けられている。 無快感症に関連する診断群を対象とした神経画像研究では、OFCと腹側線条体における活動低下が報告されている。[77] 1つのメタ分析では、無快感症は、尾状核、被殻、腹側線条体、および内側前頭前野(mPFC)における報酬予期に対する神経反応の低下が関連していること が報告されている。[78] |

| Mood disorders Certain types of depression are associated with reduced motivation, as assessed by willingness to expend effort for reward. These abnormalities have been tentatively linked to reduced activity in areas of the striatum, and while dopaminergic abnormalities are hypothesized to play a role, most studies probing dopamine function in depression have reported inconsistent results.[79][80] Although postmortem and neuroimaging studies have found abnormalities in numerous regions of the reward system, few findings are consistently replicated. Some studies have reported reduced NAcc, hippocampus, medial prefrontal cortex (mPFC), and orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) activity, as well as elevated basolateral amygdala and subgenual cingulate cortex (sgACC) activity during tasks related to reward or positive stimuli. These neuroimaging abnormalities are complemented by little post mortem research, but what little research has been done suggests reduced excitatory synapses in the mPFC.[81] Reduced activity in the mPFC during reward related tasks appears to be localized to more dorsal regions(i.e. the pregenual cingulate cortex), while the more ventral sgACC is hyperactive in depression.[82] Attempts to investigate underlying neural circuitry in animal models has also yielded conflicting results. Two paradigms are commonly used to simulate depression, chronic social defeat (CSDS), and chronic mild stress (CMS), although many exist. CSDS produces reduced preference for sucrose, reduced social interactions, and increased immobility in the forced swim test. CMS similarly reduces sucrose preference, and behavioral despair as assessed by tail suspension and forced swim tests. Animals susceptible to CSDS exhibit increased phasic VTA firing, and inhibition of VTA-NAcc projections attenuates behavioral deficits induced by CSDS.[83] However, inhibition of VTA-mPFC projections exacerbates social withdrawal. On the other hand, CMS associated reductions in sucrose preference and immobility were attenuated and exacerbated by VTA excitation and inhibition, respectively.[84][85] Although these differences may be attributable to different stimulation protocols or poor translational paradigms, variable results may also lie in the heterogenous functionality of reward related regions.[86] Optogenetic stimulation of the mPFC as a whole produces antidepressant effects. This effect appears localized to the rodent homologue of the pgACC (the prelimbic cortex), as stimulation of the rodent homologue of the sgACC (the infralimbic cortex) produces no behavioral effects. Furthermore, deep brain stimulation in the infralimbic cortex, which is thought to have an inhibitory effect, also produces an antidepressant effect. This finding is congruent with the observation that pharmacological inhibition of the infralimbic cortex attenuates depressive behaviors.[86] |

気分障害 特定の種類のうつ病は、報酬を得るための努力を払う意欲の低下と関連しています。これらの異常は、線条体領域の活動低下と仮に関連付けられていますが、 ドーパミン系の異常が役割を果たす可能性が提唱されているものの、うつ病におけるドーパミン機能を探索した大多数の研究では一貫した結果が得られていませ ん。[79][80] 死後解剖や神経画像研究では報酬系における複数の領域に異常が報告されていますが、一貫して再現される所見は少ないです。一部の研究では、報酬やポジティ ブな刺激に関連するタスク中に、NAcc、海馬、内側前頭前野(mPFC)、および眼窩前頭皮質(OFC)の活動低下、ならびに基底外側扁桃体と下帯状回 皮質(sgACC)の活動上昇が報告されています。これらの神経画像異常は、死後研究がほとんど行われていないため補足情報が少ないが、既存の研究では mPFCにおける興奮性シナプスの減少が示唆されている。[81] 報酬関連タスク中のmPFCの活動低下は、より背側の領域(例えば前帯状皮質)に局在しているのに対し、より腹側のsgACCはうつ病において過活動を示 す。[82] 動物モデルにおける基盤となる神経回路の調査も試みられていますが、矛盾する結果が得られています。うつ病を模擬するパラダイムとして、慢性社会的敗北 (CSDS)と慢性軽度ストレス(CMS)の2つが一般的に使用されていますが、他にも多くのパラダイムが存在します。CSDSは、スクロースの嗜好低 下、社会的相互作用の減少、強制泳ぎ試験での不動時間の増加を引き起こします。CMSも同様にスクロースの嗜好を低下させ、尾懸垂試験と強制泳ぎ試験で評 価される行動的絶望を増加させます。CSDSに感受性のある動物では、VTAの相間発火が増加し、VTA-NAcc投射の抑制はCSDS誘発の行動障害を 軽減します。[83] しかし、VTA-mPFC投射の抑制は社会的引きこもりを悪化させます。一方、CMS に関連するショ糖嗜好の低下および不動は、VTA の興奮および抑制によってそれぞれ弱まり、悪化しました。[84][85] これらの違いは、異なる刺激プロトコルや不十分な翻訳パラダイムに起因する可能性がありますが、結果のばらつきは、報酬関連領域の機能の異質性にも起因し ている可能性があります。[86] mPFC全体に対する光遺伝学的刺激は抗うつ効果を示す。この効果は、げっ歯類のpgACC(前帯状皮質)の同等部位に局在していると考えられ、げっ歯類 のsgACC(下帯状皮質)の同等部位を刺激しても行動効果は認められない。さらに、抑制効果があるとされる下前頭前皮質への深部脳刺激も抗うつ効果を示 す。この結果は、下前頭前皮質の薬理学的抑制が抑うつ行動を軽減するという観察結果と一致している。[86] |

| Schizophrenia Schizophrenia is associated with deficits in motivation, commonly grouped under other negative symptoms such as reduced spontaneous speech. The experience of "liking" is frequently reported to be intact,[87] both behaviorally and neurally, although results may be specific to certain stimuli, such as monetary rewards.[88] Furthermore, implicit learning and simple reward-related tasks are also intact in schizophrenia.[89] Rather, deficits in the reward system are apparent during reward-related tasks that are cognitively complex. These deficits are associated with both abnormal striatal and OFC activity, as well as abnormalities in regions associated with cognitive functions such as the dorsolateral prefrontal cortex (DLPFC).[90] |

統合失調症 統合失調症は、自発的な発話減少などの他の陰性症状に分類される動機付けの欠如と関連している。「好き」という経験は、行動面でも神経面でも正常に保たれ ていると報告されている[87]。ただし、結果は特定の刺激(例えば金銭的報酬)に依存する可能性がある[88]。さらに、統合失調症では暗黙的学習や単 純な報酬関連タスクも正常に機能している[89]。むしろ、報酬関連タスクが認知的に複雑な場合、報酬系における障害が顕著になる。これらの障害は、線条 体と前頭前野(OFC)の異常な活動、および認知機能に関連する領域(例えば、背外側前頭前野(DLPFC))の異常と関連している[90]。 |

| Attention deficit hyperactivity disorder In those with ADHD, core aspects of the reward system are underactive, making it challenging to derive reward from regular activities. Those with the disorder experience a boost of motivation after a high-stimulation behaviour triggers a release of dopamine. In the aftermath of that boost and reward, the return to baseline levels results in an immediate drop in motivation.[91] People with more ADHD-related behaviors show weaker brain responses to reward anticipation (not reward delivery), especially in the nucleus accumbens. While there is the initial boost of motivation and release of dopamine, as stated above, there is a higher risk of a noticeable drop in motivation. Impairments of dopaminergic and noradrenergic function are said to be key factors in ADHD.[92] These impairments can lead to executive dysfunction such as dysregulation of reward processing and motivational dysfunction, including anhedonia.[93] |

注意欠陥多動性障害 注意欠陥多動性障害では、報酬系の核となる部分が不活発であるため、通常の活動から報酬を得ることが困難である。この障害のある人は、刺激の強い行動が ドーパミンの放出を誘発した後、意欲が高まるのを経験する。そのブーストと報酬の余波で、ベースラインレベルに戻ると、すぐに意欲が低下する[91]。 ADHDに関連した行動が多い人民は、特に側坐核において、(報酬の伝達ではなく)報酬の予期に対する脳の反応が弱いことを示す。上記のように、最初は意欲が高まりドーパミンが放出されるが、意欲が顕著に低下するリスクが高い。 ドーパミン作動性およびノルアドレナリン作動性の機能障害は、ADHDの重要な因子であると言われている[92]。これらの機能障害は、報酬処理の調節障害などの遂行機能障害や、無気力などの動機づけ機能障害につながる可能性がある[93]。 |

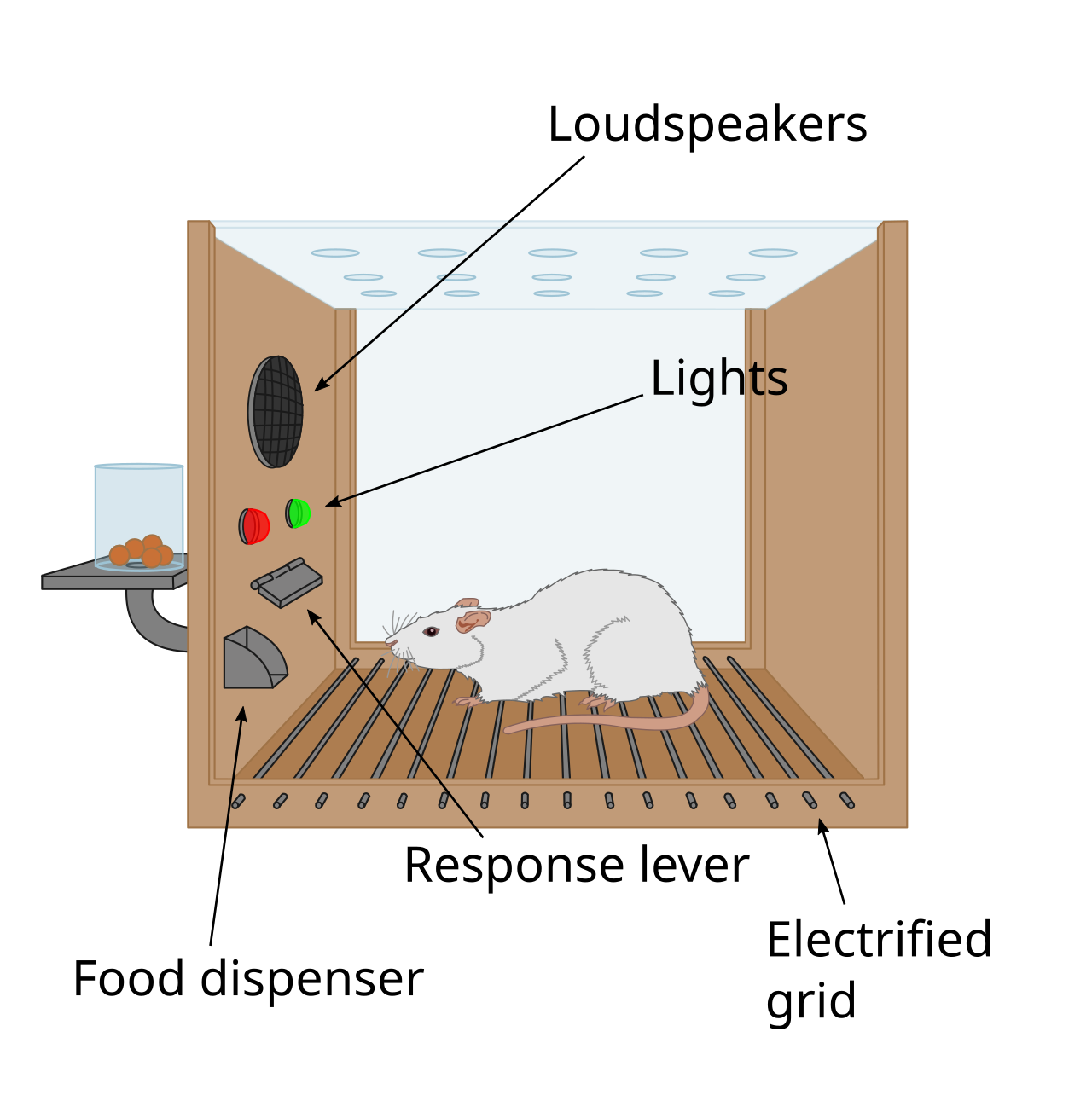

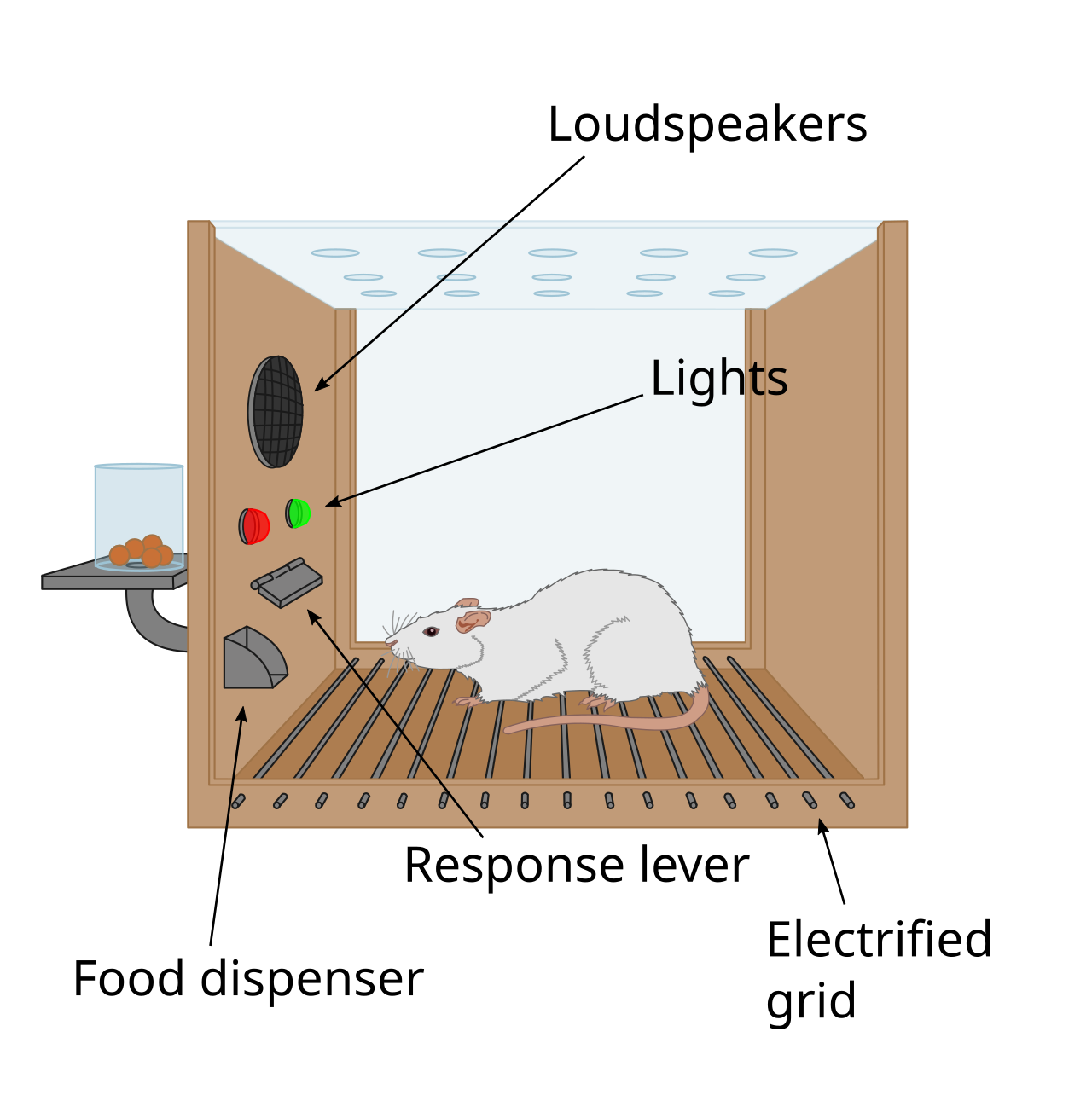

History Skinner box The first clue to the presence of a reward system in the brain came with an accidental discovery by James Olds and Peter Milner in 1954. They discovered that rats would perform behaviors such as pressing a bar, to administer a brief burst of electrical stimulation to specific sites in their brains. This phenomenon is called intracranial self-stimulation or brain stimulation reward. Typically, rats will press a lever hundreds or thousands of times per hour to obtain this brain stimulation, stopping only when they are exhausted. While trying to teach rats how to solve problems and run mazes, stimulation of certain regions of the brain where the stimulation was found seemed to give pleasure to the animals. They tried the same thing with humans and the results were similar. The explanation to why animals engage in a behavior that has no value to the survival of either themselves or their species is that the brain stimulation is activating the system underlying reward.[94] In a fundamental discovery made in 1954, researchers James Olds and Peter Milner found that low-voltage electrical stimulation of certain regions of the brain of the rat acted as a reward in teaching the animals to run mazes and solve problems.[95][failed verification][96] It seemed that stimulation of those parts of the brain gave the animals pleasure,[95] and in later work humans reported pleasurable sensations from such stimulation.[citation needed] When rats were tested in Skinner boxes where they could stimulate the reward system by pressing a lever, the rats pressed for hours.[96] Research in the next two decades established that dopamine is one of the main chemicals aiding neural signaling in these regions, and dopamine was suggested to be the brain's "pleasure chemical".[97] Ivan Pavlov was a psychologist who used the reward system to study classical conditioning. Pavlov used the reward system by rewarding dogs with food after they had heard a bell or another stimulus. Pavlov was rewarding the dogs so that the dogs associated food, the reward, with the bell, the stimulus.[98] Edward L. Thorndike used the reward system to study operant conditioning. He began by putting cats in a puzzle box and placing food outside of the box so that the cat wanted to escape. The cats worked to get out of the puzzle box to get to the food. Although the cats ate the food after they escaped the box, Thorndike learned that the cats attempted to escape the box without the reward of food. Thorndike used the rewards of food and freedom to stimulate the reward system of the cats. Thorndike used this to see how the cats learned to escape the box.[99] More recently, Ivan De Araujo and colleagues used nutrients inside the gut to stimulate the reward system via the vagus nerve.[100] |

歴史 スキナー箱 脳内に報酬系が存在することを示す最初の手がかりは、1954年にジェームズ・オールズとピーター・ミルナーによって偶然発見された。彼らは、ラットが バーを押すなどのパフォーマティビティを行うことで、脳の特定の部位に短時間の電気刺激を与えることを発見した。この現象は頭蓋内自己刺激あるいは脳刺激 報酬と呼ばれている。通常、ラットはこの脳刺激を得るために1時間に何百回、何千回とレバーを押し、疲れ果てたときだけ止める。ラットに問題の解き方や迷 路の走り方を教えようとするうちに、脳のある特定の部位に刺激を与えると、動物に快感を与えるようになったようだ。同じことを人間にも試してみたが、結果 は同様だった。動物が自分自身や種の存続にとって何の価値もない行動をとるのは、脳への刺激が報酬の根底にあるシステムを活性化させているからだという説 明である[94]。 1954年に行われた基本的な発見において、研究者のジェームズ・オールズとピーター・ミルナーは、ラットの脳の特定の部位への低電圧電気刺激が、動物に 迷路を走らせたり問題を解かせたりすることを教える際に報酬として作用することを発見した[95][検証失敗][96]。脳のそれらの部位への刺激が動物 に快感を与えているようであり[95]、その後の研究でヒトもそのような刺激による快感を報告している。[その後20年間の研究によって、ドーパミンはこ れらの部位の神経シグナル伝達を助ける主要な化学物質の一つであることが立証され、ドーパミンは脳の「快楽物質」であることが示唆された[97]。 イワン・パブロフは、古典的条件付けを研究するために報酬系を用いた心理学者である。パブロフは、犬がベルや他の刺激を聞いた後に餌を与えることで、報酬 系を利用した。パブロフは犬に報酬を与えることで、犬が報酬である食べ物と刺激であるベルを関連付けるようにした。彼はまず猫をパズルの箱の中に入れ、猫 が逃げ出したくなるように箱の外に餌を置いた。猫はパズルの箱から抜け出して餌にありつこうとした。猫は箱から脱出した後、餌を食べたが、ソーンダイクは 猫が餌という報酬がなくても箱から脱出しようとすることを知った。ソーンダイクは餌と自由という報酬を使って、猫の報酬系を刺激した。ソーンダイクはこれ を利用して、猫がどのようにして箱から脱出することを学習したかを確認した[99]。より最近では、イヴァン・デ・アラウージョらが、迷走神経を介して報 酬系を刺激するために腸内の栄養素を利用した[100]。 |

| horndike used this to see how

the cats learned to escape the box.[99] More recently, Ivan De Araujo

and colleagues used nutrients inside the gut to stimulate the reward

system via the vagus nerve.[100] Other species Animals quickly learn to press a bar to obtain an injection of opiates directly into the midbrain tegmentum or the nucleus accumbens. The same animals do not work to obtain the opiates if the dopaminergic neurons of the mesolimbic pathway are inactivated. In this perspective, animals, like humans, engage in behaviors that increase dopamine release. Kent Berridge, a researcher in affective neuroscience, found that sweet (liked ) and bitter (disliked ) tastes produced distinct orofacial expressions, and these expressions were similarly displayed by human newborns, orangutans, and rats. This was evidence that pleasure (specifically, liking) has objective features and was essentially the same across various animal species. Most neuroscience studies have shown that the more dopamine released by the reward, the more effective the reward is. This is called the hedonic impact, which can be changed by the effort for the reward and the reward itself. Berridge discovered that blocking dopamine systems did not seem to change the positive reaction to something sweet (as measured by facial expression). In other words, the hedonic impact did not change based on the amount of sugar. This discounted the conventional assumption that dopamine mediates pleasure. Even with more-intense dopamine alterations, the data seemed to remain constant.[101] However, a clinical study from January 2019 that assessed the effect of a dopamine precursor (levodopa), antagonist (risperidone), and a placebo on reward responses to music – including the degree of pleasure experienced during musical chills, as measured by changes in electrodermal activity as well as subjective ratings – found that the manipulation of dopamine neurotransmission bidirectionally regulates pleasure cognition (specifically, the hedonic impact of music) in human subjects.[102][103] This research demonstrated that increased dopamine neurotransmission acts as a sine qua non condition for pleasurable hedonic reactions to music in humans.[102][103] Berridge developed the incentive salience hypothesis to address the wanting aspect of rewards. It explains the compulsive use of drugs by drug addicts even when the drug no longer produces euphoria, and the cravings experienced even after the individual has finished going through withdrawal. Some addicts respond to certain stimuli involving neural changes caused by drugs. This sensitization in the brain is similar to the effect of dopamine because wanting and liking reactions occur. Human and animal brains and behaviors experience similar changes regarding reward systems because these systems are so prominent.[101] |

最近では、イヴァン・デ・アラウージョらが、迷走神経を介して報酬系を刺激するために腸内の栄養素を利用した[100]。 その他の種 動物はすぐにバーを押して中脳被蓋野または側坐核に直接アヘンを注射することを学習する。中脳辺縁系経路のドーパミン作動性ニューロンを不活性化すると、 同じ動物はアヘン剤を得るために働かなくなる。この観点からすると、動物も人間と同じように、ドーパミン放出を増加させる行動をとるのである。 情動神経科学の研究者であるケント・ベリッジは、甘い(好きな)味と苦い(嫌いな)味はそれぞれ異なる表情を作り出し、これらの表情はヒトの新生児、オラ ンウータン、ラットでも同様に示されることを発見した。これは、快楽(特に好き嫌い)には客観的な特徴があり、さまざまな動物種で本質的に同じであるとい う証拠であった。神経科学の研究の多くは、報酬によって放出されるドーパミンが多ければ多いほど、報酬の効果が高まることを示している。これは快楽的影響 と呼ばれ、報酬を得るための努力や報酬自体によって変化する。ベリッジは、ドーパミン系をブロックしても、甘いものに対するポジティブな反応(表情で測 定)は変わらないようであることを発見した。つまり、快楽的な影響は砂糖の量によって変化しなかったのである。これは、ドーパミンが快楽を媒介するという 従来の仮定を否定するものであった。より強いドーパミンの変化でも、データは一定のままであるように思われた[101]。しかしながら、2019年1月に 行われた臨床研究では、ドーパミンの前駆体(レボドパ)、拮抗薬(リスペリドン)、およびプラセボが、音楽に対する報酬反応(主観的評価だけでなく、皮膚 電気活動の変化によって測定される、音楽チル中に経験される快楽の程度を含む)に及ぼす影響を評価し、ドーパミンの神経伝達の操作が、ヒト被験者の快楽認 知(具体的には、音楽の快楽的影響)を双方向に制御することが判明した。[102][103] この研究は、ドーパミン神経伝達の増加が、ヒトの音楽に対する快楽的な快楽的反応の必須条件として作用することを実証した[102][103]。 ベリッジは、報酬の欲望的側面に対処するためにインセンティブ・サリエンス仮説を開発した。この仮説は、薬物中毒者が、薬物がもはや多幸感をもたらさない ときでも薬物を強迫的に使用することや、個人が禁断症状を経験し終わった後でも経験する渇望を説明する。中毒者の中には、薬物によって引き起こされる神経 変化を伴う特定の刺激に反応する者もいる。この脳内の感作は、欲しくなったり好きになったりする反応が起こるため、ドーパミンの作用に似ている。報酬系は 非常に顕著であるため、ヒトと動物の脳と行動は、報酬系に関して同様の変化を経験する[101]。 |

| Carrot and stick Compliance (psychology) Experience machine Frisson Motivation Norm of reciprocity Wirehead (science fiction) |

ニンジンと棒 コンプライアンス(心理学) エクスペリエンス・マシン フリッソン モチベーション 互恵性の規範 ワイヤーヘッド(SF) |

| Young, Jared W.; Anticevic,

Alan; Barch, Deanna M. (2018). "Cognitive and Motivational Neuroscience

of Psychotic Disorders". In Charney, Dennis S.; Sklar, Pamela; Buxbaum,

Joseph D.; Nestler, Eric J. (eds.). Charney & Nestler's

Neurobiology of Mental Illness (5th ed.). New York: Oxford University

Press. ISBN 9780190681425. |

Young, Jared W.; Anticevic,

Alan; Barch, Deanna M. (2018). 「Cognitive and Motivational Neuroscience

of Psychotic Disorders". Charney, Dennis S.; Sklar, Pamela; Buxbaum,

Joseph D.; Nestler, Eric J. (eds.). Charney & Nestler's

Neurobiology of Mental Illness(第5版). ニューヨーク: オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN

9780190681425. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Reward_system |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099

**

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆