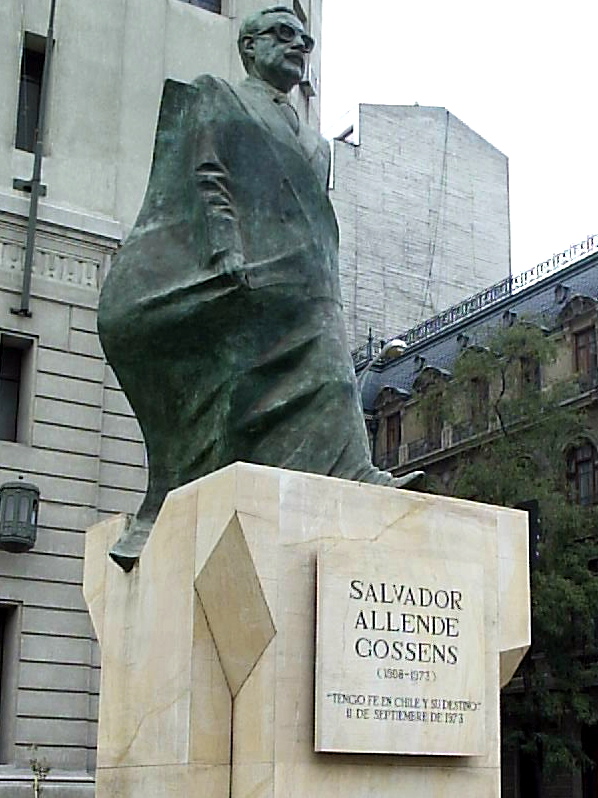

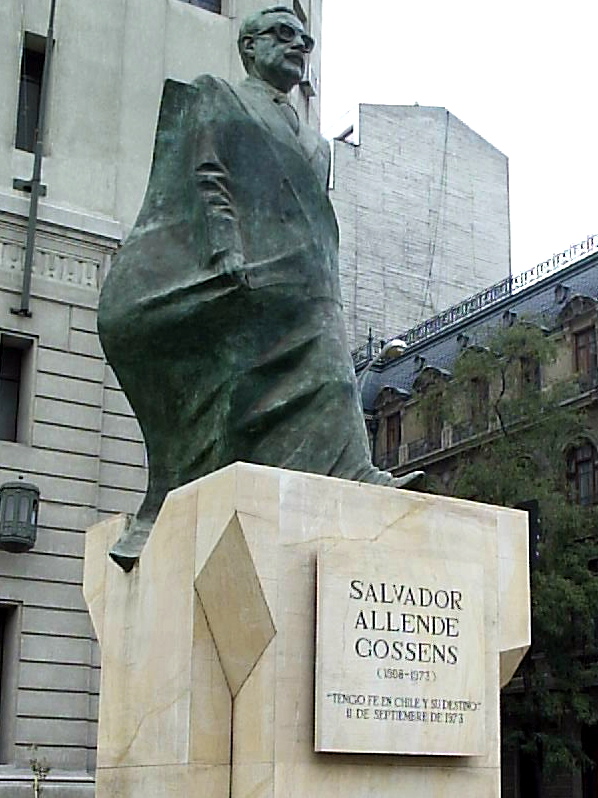

サルバドール・アジェンデ

Salvador Allende, 1908-1973

☆ サルバドール・ギジェルモ・アジェンデ・ゴッセンス(1908年6月26日 - 1973年9月11日)は社会主義者の政治家で、1970年から1973年に亡くなるまでチリの第28代大統領を務めた。民主主義にコ ミットした民主社会主義者として、ラテンアメリカの自由民主主義国家で大統領に選出された最初のマルクス主義者と評されている。アジェンデは大統領とし て、主要産業の国有化、教育の拡大、労働者階級の生活水準の向上を目指した。彼は議会を支配する右派政党や司法当局と衝突した。 1973年9月11日、CIAの支援によるクーデターで軍がアジェンデの追放に動いたが、CIAは当初この疑惑を否定していた。 2000年、CIAは1970年にアジェンデの就任を阻止するために軍を使うことを拒否したルネ・シュナイダー将軍の誘拐に関与したことを認めた。軍が ラ・モネダ宮殿を包囲する中、アジェンデは辞任しないことを誓う最後の演説を行った。 その日のうちにアジェンデは執務室で自殺により死亡した。アジェンデの死後、アウグスト・ピノチェト将軍は文民政府への権限返還 を拒否し、チリはその後政府軍によって統治され、大統領制共和国として知られた40年以上途切れることのなかった民主的統治に終止符が打たれた。軍事政権 は議会を解散させ、1925年憲法を停止させ、反体制派とされる人々を迫害するプログラムを開始した。

| Salvador Guillermo Allende Gossens[A]

(26 June 1908 – 11 September 1973) was a socialist politician[4][5] who

served as the 28th president of Chile from 1970 until his death in

1973.[6] As a democratic socialist committed to democracy,[7][8] he has

been described as the first Marxist to be elected president in a

liberal democracy in Latin America.[9][10][11] Allende's involvement in Chilean politics spanned a period of nearly forty years, during which he held various positions including senator, deputy, and cabinet minister. As a life-long committed member of the Socialist Party of Chile, whose foundation he had actively contributed to, he unsuccessfully ran for the national presidency in the 1952, 1958, and 1964 elections. In 1970, he won the presidency as the candidate of the Popular Unity coalition in a close three-way race. He was elected in a run-off by Congress, as no candidate had gained a majority. In office, Allende pursued a policy he called "The Chilean Way to Socialism". The coalition government was far from unanimous. Allende said that he was committed to democracy and represented the more moderate faction of the Socialist Party, while the radical wing sought a more radical course. Instead, the Communist Party of Chile favored a gradual and cautious approach that sought cooperation with Christian democrats,[7] which proved influential for the Italian Communist Party and the Historic Compromise.[12] As president, Allende sought to nationalize major industries, expand education, and improve the living standards of the working class. He clashed with the right-wing parties that controlled Congress and with the judiciary. On 11 September 1973, the military moved to oust Allende in a coup d'état supported by the CIA, which initially denied the allegations.[13][14] In 2000, the CIA admitted its role in the 1970 kidnapping of General René Schneider who had refused to use the army to stop Allende's inauguration.[15][16] Declassified documents released in 2023 showed that US president Richard Nixon, his national security advisor Henry Kissinger, and the United States government, which had branded Allende as a dangerous communist,[8] were aware of the military's plans to overthrow Allende's democratically-elected government in the days before the coup d'état.[17] As troops surrounded La Moneda Palace, Allende gave his last speech vowing not to resign.[18] Later that day, Allende died by suicide in his office;[19][20][21] the exact circumstances of his death are still disputed.[22][B] Following Allende's death, General Augusto Pinochet refused to return authority to a civilian government, and Chile was later ruled by the Government Junta, ending more than four decades of uninterrupted democratic governance, a period known as the Presidential Republic. The military junta that took over dissolved Congress, suspended the Constitution of 1925, and initiated a program of persecuting alleged dissidents, in which at least 3,095 civilians disappeared or were killed.[24] Pinochet's military dictatorship only ended after the successful internationally-backed 1989 constitutional referendum led to the peaceful Chilean transition to democracy. |

サ

ルバドール・ギジェルモ・アジェンデ・ゴッセンス[A](1908年6月26日 -

1973年9月11日)は社会主義者の政治家[4][5]で、1970年から1973年に亡くなるまでチリの第28代大統領を務めた[6]。民主主義にコ

ミットした民主社会主義者として[7][8]、ラテンアメリカの自由民主主義国家で大統領に選出された最初のマルクス主義者と評されている[9][10]

[11]。 アジェンデのチリ政治への関与は40年近くに及び、その間、上院議員、副議長、閣僚など様々な役職を歴任した。1952年、1958年、1964年の大統 領選挙に出馬したが落選。1970年、三つ巴の接戦の末、人民統一候補として大統領選に勝利。どの候補者も過半数を得られなかったため、議会による決選投 票で当選した。大統領就任後、アジェンデは「社会主義へのチリの道」と呼ぶ政策を推進した。連立政権は全会一致にはほど遠かった。アジェンデは民主主義を 重視し、社会党の穏健派を代表すると述べたが、急進派はより急進的な路線を求めた。その代わり、チリ共産党はキリスト教民主党との協力を求める緩やかで慎 重なアプローチを支持し[7]、これはイタリア共産党と歴史的妥協に影響力を持つことが証明された[12]。 アジェンデは大統領として、主要産業の国有化、教育の拡大、労働者階級の生活水準の向上を目指した。彼は議会を支配する右派政党や司法当局と衝突した。 1973年9月11日、CIAの支援によるクーデターで軍がアジェンデの追放に動いたが、CIAは当初この疑惑を否定していた[13][14]。 2000年、CIAは1970年にアジェンデの就任を阻止するために軍を使うことを拒否したルネ・シュナイダー将軍の誘拐に関与したことを認めた[15] [16]。 [15][16]2023年に公開された機密解除された文書によると、リチャード・ニクソン米大統領、彼の国家安全保障顧問であったヘンリー・キッシンジャー、そしてアジェンデを危険な共産主義者として烙印を押していたアメリカ政府は、クーデターの数日前にアジェンデの民主的に選出された政府を転覆させるという軍の計画を認識していた[8]。 軍がラ・モネダ宮殿を包囲する中、アジェンデは辞任しないことを誓う最後の演説を行った[18]。 その日のうちにアジェンデは執務室で自殺により死亡した[19][20][21]。アジェンデの死後、アウグスト・ピノチェト将軍は文民政府への権限返還 を拒否し、チリはその後政府軍によって統治され、大統領制共和国として知られた40年以上途切れることのなかった民主的統治に終止符が打たれた。軍事政権 は議会を解散させ、1925年憲法を停止させ、反体制派とされる人々を迫害するプログラムを開始した。 |

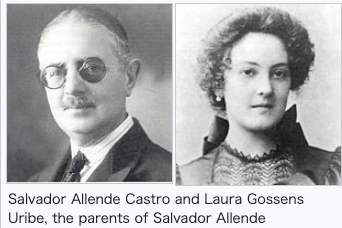

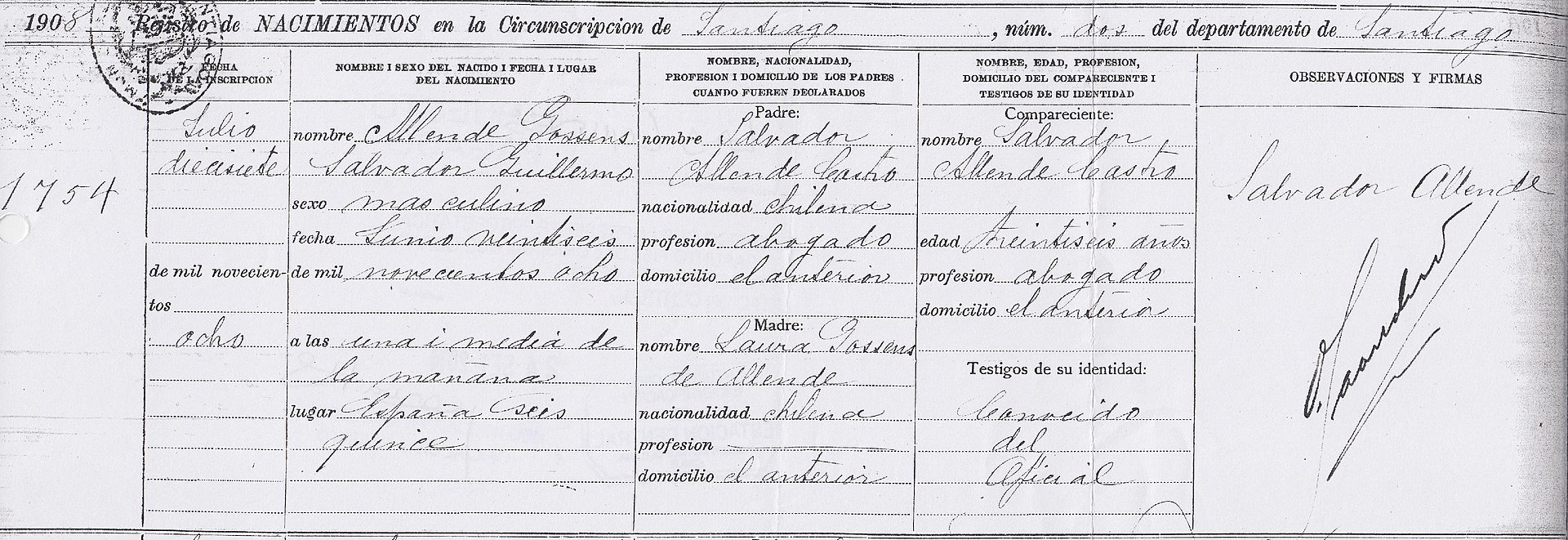

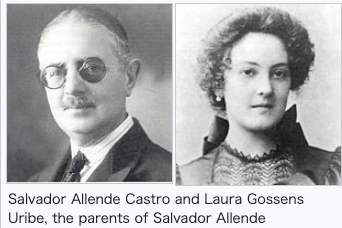

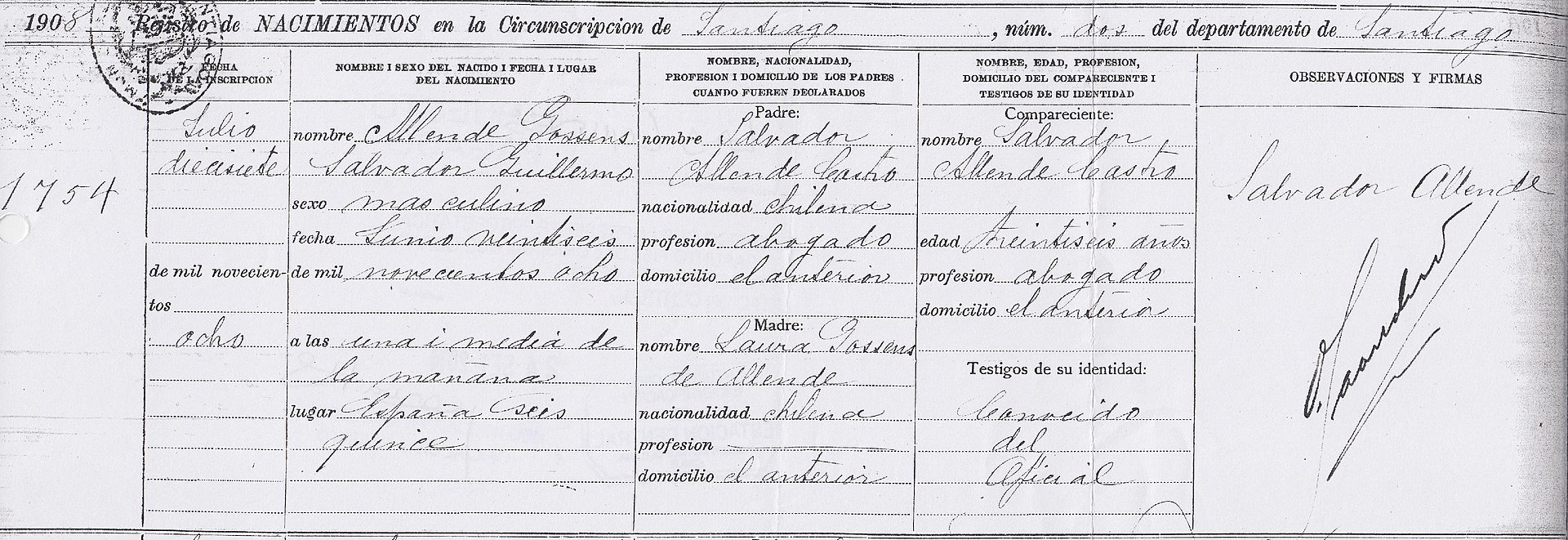

Early life Salvador Allende Castro and Laura Gossens Uribe, the parents of Salvador Allende  Salvador Allende's birth certificate. Allende was born on 26 June 1908[25] in Santiago.[26][27] He was the son of Salvador Allende Castro and Laura Gossens Uribe. Allende's family belonged to the Chilean upper middle class and had a long tradition of political involvement in progressive and liberal causes. His grandfather was a prominent physician and a social reformist who founded one of the first secular schools in Chile.[28] Salvador Allende was of Basque[29] and Belgian descent.[30][31][32] In 1909 he moved with his family to the city of Tacna (then under Chilean administration), living there until 1916, since in that year he would move back to his country in the city of Iquique. In 1918 he studied at the National Institute of Santiago, and in 1919 to 1921 he studied at the Liceo de Valdivia. In 1922 he entered the Eduardo de la Barra school at the age of 16, studying there until 1924.[33] As a teenager, his main intellectual and political influence came from the shoe-maker Juan De Marchi, an Italian-born anarchist,[28] in 1925 he attended the military service in the Cuirassier Regiment of Tacna.[33] Allende was a talented athlete in his youth, being a member of the Everton de Viña del Mar sports club (named after the more famous English football club of the same name).[34] In 1926 at the age of 18 he studied medicine at the University of Chile in Santiago and in 1927 was elected President of the Student Center. In 1928 he entered the Grand Lodge of Chile and in 1929 he was elected vice president of the Federation of Students of the University of Chile, (FECH). In 1930, he became the representative of the students of the School of Medicine.[33] During his time at medical school Allende was influenced by Professor Max Westenhofer, a German pathologist who emphasized the social determinants of disease and social medicine.[35][36] In 1931 he was relegated to the North and expelled from the university. However, in that same year, he retook his sixth year of medical school and graduated at 23 years of age. In 1932 he began to practice his profession as a physician and anatomo-pathologist in the Morgue of the Van Buren Hospital. He became the union leader of the Valparaíso doctors, becoming 1st Regional Secretary in Valparaíso. In 1935, at the age of 27, he was relegated to the city of Caldera for the second time, and in 1936 he was imprisoned in the Popular Front in Valparaíso. In 1937 he was elected Deputy of Valparaíso and Aconcagua and in 1938 he served as Undersecretary General of the Socialist Party of Chile.[33] In 1933 Allende co-founded with Marmaduque Grove and others a section of the Socialist Party of Chile in Valparaíso[28] and became its chairman. He married Hortensia Bussi with whom he had three daughters. He was a Freemason, a member of the Lodge Progreso No. 4 in Valparaíso.[37] In 1933, he published his doctoral thesis Higiene Mental y Delincuencia (Crime and Mental Hygiene) in which he criticized Cesare Lombroso's proposals.[38] |

生い立ち サルバドール・アジェンデの両親、サルバドール・アジェンデ・カストロとラウラ・ゴッセンス・ウリベ  サルバドール・アジェンデの出生証明書。 アジェンデは1908年6月26日にサンティアゴで生まれた[25]。アジェンデの家族はチリの上流中産階級に属し、進歩的でリベラルな大義に政治的に関 与する長い伝統を持っていた。祖父は著名な医師であり、チリで最初の世俗的な学校を設立した社会改革者であった[28]。1918年にサンティアゴ国立大 学で学び、1919年から1921年までバルディビア工科大学で学ぶ。1922年、16歳でエドゥアルド・デ・ラ・バラの学校に入学し、1924年までそ こで学ぶ[33]。 1925年、タクナのキラシエ連隊の兵役に就く[33]。 [33]アジェンデは少年時代、才能あるアスリートであり、エバートン・デ・ビーニャ・デル・マールのスポーツクラブ(同名のイギリスの有名なサッカーク ラブにちなんで命名された)のメンバーであった[34]。1926年、18歳の時にサンティアゴのチリ大学で医学を学び、1927年には学生センター会長 に選出された。1928年にはチリのグランド・ロッジに入り、1929年にはチリ大学学生連盟(FECH)の副会長に選出された。1930年、医学部の学 生代表となる[33]。 医学部在学中、アジェンデは、病気の社会的決定要因や社会医学を強調するドイツの病理学者マックス・ウェステンホーファー教授の影響を受ける。しかし同 年、医学部6年生に再入学し、23歳で卒業した。1932年、ヴァン・ビューレン病院の死体安置所で医師および病理医として開業。バルパライソ医師組合の リーダーとなり、バルパライソの第一書記となる。1935年、27歳で2度目のカルデラ市への左遷を命じられ、1936年にはバルパライソの人民戦線に投 獄される。1937年にはバルパライソとアコンカグアの副議長に選出され、1938年にはチリ社会党の事務次長を務めた[33]。 1933年、アジェンデはマルマドゥケ・グローブらとバルパライソにチリ社会党のセクションを設立し[28]、その議長となった。オルテンシア・ブッシと 結婚し、3人の娘をもうけた。1933年、チェーザレ・ロンブローゾの提言を批判した博士論文『Higiene Mental y Delincuencia(犯罪と精神衛生)』を発表する[38]。 |

Political involvement up to 1970 1958 presidential campaign with a train with Allende's face called the "Victory Train"  Salvador Allende in 1964  Chilean workers marching in support of Allende in 1964 In 1938, Allende was in charge of the electoral campaign of the Popular Front headed by Pedro Aguirre Cerda.[28] The Popular Front's slogan was "Bread, a Roof and Work!"[28] After its electoral victory, he became Minister of Health in the Reformist Popular Front government which was dominated by the Radicals.[28] While serving in that position, Allende was responsible for the passage of a wide range of progressive social reforms, including safety laws protecting workers in the factories, higher pensions for widows, maternity care, and free lunch programmes for schoolchildren.[39] Upon entering the government, Allende relinquished his congressional seat for Valparaíso, which he had won in 1937. Around that time, he wrote La Realidad Médico Social de Chile (The social and medical reality of Chile). After the Kristallnacht in Nazi Germany, Allende was one of 76 members of the Congress who sent a telegram to Adolf Hitler denouncing the persecution of Jews.[40] Following President Aguirre Cerda's death in 1941, he was again elected deputy while the Popular Front was renamed Democratic Alliance. In 1945, Allende became senator for the Valdivia, Llanquihue, Chiloé, Aisén and Magallanes provinces; then for Tarapacá and Antofagasta in 1953; for Aconcagua and Valparaíso in 1961; and once more for Chiloé, Aisén and Magallanes in 1969. He became president of the Chilean Senate in 1966. During the 50's Allende introduced legislation that established the Chilean national health service, the first program in the Americas to guarantee universal health care.[41] His three unsuccessful bids for the presidency (in the 1952, 1958 and 1964 elections) prompted Allende to joke that his epitaph would be "Here lies the next President of Chile." In 1952, as candidate for the Frente de Acción Popular (Popular Action Front, FRAP), he obtained only 5.4% of the votes, partly due to a division within socialist ranks over support for Carlos Ibáñez. In 1958, again as the FRAP candidate, Allende obtained 28.5% of the vote. This time, his defeat was attributed to votes lost to the populist Antonio Zamorano.[42] This explanation has been questioned by modern research that suggest Zamorano's votes came from across the political spectrum.[42] |

1970年までの政治活動 1958年の大統領選挙キャンペーン、アジェンデの顔を描いた列車 "勝利列車"  1964年のサルバドール・アジェンデ  1964年、アジェンデを支持して行進するチリの労働者たち 1938年、アジェンデはペドロ・アギーレ・セルダが率いる人民戦線の選挙キャンペーンを担当していた[28]。人民戦線のスローガンは「パンと屋根と仕 事だ!」[28]。選挙での勝利後、急進派が支配する改革派人民戦線政権の厚生大臣に就任した。 [アジェンデはその職にありながら、工場で働く労働者を保護する安全法、寡婦に対する年金の引き上げ、妊産婦ケア、学童のための無料給食プログラムなど、 幅広い進歩的な社会改革の成立を担った[39]。 政権に就くと、アジェンデは1937年に獲得したバルパライソ選出の下院議員の議席を返上した。その頃、『チリの社会的・医学的現実(La Realidad Médico Social de Chile)』を執筆。ナチス・ドイツの水晶の夜の後、アジェンデはユダヤ人迫害を糾弾する電報をアドルフ・ヒトラーに送った76人の議員の一人であった [40]。1941年のアギーレ・セルダ大統領の死後、人民戦線が民主同盟と改名される中、再び副議長に選出された。 1945年、アジェンデはバルディビア、ランキフエ、チロエ、アイセン、マガリャネスの各州の上院議員となり、1953年にはタラパカとアントファガス タ、1961年にはアコンカグアとバルパライソ、1969年にはチロエ、アイセン、マガリャネスの各州の上院議員となった。1966年にはチリ上院議長に 就任した。50年代、アジェンデは、アメリカ大陸で初の国民皆保険制度であるチリの国民保健サービスを確立するための法案を提出した[41]。 1952年、1958年、1964年の大統領選で3度落選したため、アジェンデは自分の墓碑銘を "ここに次のチリ大統領が眠る "と冗談を言った。1952年、アジェンデは人民行動戦線(FRAP)の候補者として立候補したが、カルロス・イバニェス支持をめぐる社会主義者内の対立 もあり、得票率はわずか5.4%にとどまった。1958年、再びFRAP候補としてアジェンデは28.5%の票を獲得した。この時の敗北は、ポピュリスト のアントニオ・サモラーノに票を奪われたためとされた[42]。この説明は、サモラーノの票が政治的スペクトラム全体から集まったことを示唆する現代の調 査によって疑問視されている[42]。 |

| Electoral system Declassified documents show that from 1962 through 1964, the CIA spent a total of $2.6 million to finance the campaign of Eduardo Frei and $3 million in anti-Allende propaganda "to scare voters away from Allende's FRAP coalition". The CIA considered its role in the victory of Frei a great success.[43][44] They argued that "the financial and organizational assistance given to Frei, the effort to keep Durán in the race, the propaganda campaign to denigrate Allende—were 'indispensable ingredients of Frei's success'", and they thought that his chances of winning and the good progress of his campaign would have been doubtful without the covert support of the Government of the United States.[45] Thus, in 1964 Allende lost once more as the FRAP candidate, polling 38.6% of the votes against 55.6% for Christian Democrat Eduardo Frei. As it became clear that the election would be a race between Allende and Frei, the political right – which initially had backed Radical Julio Durán– settled for Frei as "the lesser evil". |

選挙制度 機密解除された文書によると、1962年から1964年にかけて、CIAはエドゥアルド・フレイの選挙運動に総額260万ドル、「有権者をアジェンデの FRAP連合から遠ざけるため」の反アジェンデ宣伝に300万ドルを費やした。CIAはフレイの勝利に果たした役割を大成功だと考えていた[43] [44]。 彼らは「フレイに与えられた財政的・組織的援助、ドゥランを選挙戦に引き留める努力、アジェンデを誹謗するプロパガンダ・キャンペーンは『フレイの成功に 不可欠な要素』であった」と主張し、アメリカ政府の秘密裏の支援なしには彼の勝利の可能性と選挙運動の順調な進展は疑わしいものであっただろうと考えてい た[45]。 こうして1964年、アジェンデはFRAP候補として再び敗北し、キリスト教民主党員のエドゥアルド・フレイの55.6%に対して38.6%の票を獲得し た。選挙がアジェンデとフレイの一騎打ちになることが明らかになるにつれ、当初急進派のフリオ・ドゥランを支持していた政治右派は、「より小さな悪」とし てフレイに落ち着いた。 |

| 1970 election Main article: 1970 Chilean presidential election  Allende as presidential candidate in 1970  Photo taken on September 4, 1970 at 00:57 by Paul Lowry Allende was considered part of the moderate wing of the Socialists, with support from the Communists who favored taking power via parliamentary democracy; in contrast, the left-wing of the Socialists (led by Carlos Altamirano) and several other far-left parties called for violent insurrection. Some argue, however, that this was reversed at the end of his period in office.[46][C] Allende won the 1970 Chilean presidential election as leader of the Unidad Popular ("Popular Unity") coalition. On 4 September 1970, he obtained a narrow plurality of 36.61% to 35.27% over Jorge Alessandri, a former president, with 27.8% going to a third candidate (Radomiro Tomic) of the Christian Democratic Party (PDC). According to the Chilean Constitution of the time, if no presidential candidate obtained a majority of the popular vote, Congress would choose one of the two candidates with the highest number of votes as the winner. Tradition was for Congress to vote for the candidate with the highest popular vote, regardless of margin. Former president Jorge Alessandri had been elected in 1958 with a plurality of 31.56% over Allende's 28.85%.[48] One month after the election, on 20 October, while the Senate had still to reach a decision and negotiations were actively in place between the Christian Democrats and the Popular Unity, General René Schneider, Commander in Chief of the Chilean Army, was shot resisting a kidnap attempt by a group led by General Roberto Viaux. Hospitalized, he died of his wounds three days later, on 23 October.[49] Schneider was a defender of the "constitutionalist" doctrine that the army's role is exclusively professional, its mission being to protect the country's sovereignty and not to interfere in politics.[50] General Schneider's death was widely disapproved of and, for the time, ended military opposition to Allende,[51] whom the Congress finally chose on 24 October. On 26 October, President Eduardo Frei named General Carlos Prats as commander in chief of the army to replace René Schneider.[52] Allende assumed the Presidency on 3 November 1970 after signing a Statute of Constitutional Guarantees proposed by the Christian Democrats in return for their support in Congress. In an extensive interview with Régis Debray in 1972, Allende explained his reasons for agreeing to the guarantees.[53] Some critics[who?] have interpreted Allende's responses as an admission that signing the Statute was only a tactical move.[54] |

1970年選挙 主な記事 1970年チリ大統領選挙  1970年大統領候補としてのアジェンデ  1970年9月4日 00:57撮影 ポール・ローリー アジェンデは社会党の穏健派に属し、議会制民主主義による政権奪取を支持する共産主義者の支持を得たとされる。対照的に、社会党の左派(カルロス・アルタミラノ率いる)や他の極左政党は暴力的な暴動を要求した。しかし、任期末期には逆転したという説もある[46][C]。 アジェンデは1970年のチリ大統領選挙でウニダード・ポピュラー(「人民連合」)連合のリーダーとして勝利した。1970年9月4日、アジェンデは前大 統領のホルヘ・アレサンドリを36.61%対35.27%の僅差で破り、27.8%はキリスト教民主党(PDC)の第3候補(ラドミロ・トミック)が獲得 した。当時のチリ憲法によると、大統領候補者が過半数の得票を得られなかった場合、議会は得票数の多い2人の候補者のうち1人を当選者として選ぶことに なっていた。伝統的に、議会は得票率に関係なく、最も得票数の多かった候補者に投票することになっていた。1958年にはホルヘ・アレサンドリ前大統領が アジェンデの28.85%を31.56%の得票率で上回って当選していた[48]。 選挙から1ヵ月後の10月20日、元老院がまだ決定を下しておらず、キリスト教民主党派と人民統一党派の間で交渉が活発に行われていた最中、チリ軍総司令 官レネ・シュナイダー将軍がロベルト・ビアウ将軍率いるグループによる誘拐未遂に抵抗して撃たれた。シュナイダーは、軍隊の役割は専ら職業的なものであ り、その使命は国の主権を守ることであり、政治に干渉することではないという「立憲主義者」の教義の擁護者であった[50]。 シュナイダー将軍の死は広く不承認となり、10月24日に議会が最終的に選んだアジェンデに対する軍の反対運動は一旦終結した[51]。10月26日、エ ドゥアルド・フレイ大統領はルネ・シュナイダーの後任としてカルロス・プラッツ将軍を陸軍総司令官に指名した[52]。アジェンデは1970年11月3 日、議会での支持の見返りとしてキリスト教民主党が提案した憲法保障憲章に署名し、大統領に就任した。1972年、アジェンデはレジス・デブレイとの大規 模なインタビューの中で、保証に同意した理由を説明している[53]。 一部の批評家[誰?]は、アジェンデの回答を、憲章への署名は戦術的な動きにすぎなかったことを認めたものと解釈している[54]。 |

| Presidency Main article: Presidency of Salvador Allende "The Chilean Way to Socialism"  Allende in 1970 In his speech to the Chilean legislature following his election, Allende made clear his intention to move Chile from a capitalist to a socialist society: We are moving towards socialism, not from an academic love for a doctrinaire system, but encouraged by the strength of our people, who know that it is an inescapable demand if we are to overcome backwardness and who feel that a socialist regime is the only way available to modern nations who want to build rationally in freedom, independence and dignity. We are moving towards socialism because the people, through their vote, have freely rejected capitalism as a system which has resulted in a crudely unequal society, a society deformed by social injustice and degraded by the deterioration of the very foundations of human solidarity.[55] Upon assuming the presidency, Allende began to carry out his platform of implementing a socialist programme called La vía chilena al socialismo ("the Chilean Path to Socialism"). That included nationalization of large-scale industries (notably copper mining and banking), and government administration of the health-care system, educational system (with the help of a United States educator, Jane A. Hobson-Gonzalez from Kokomo, Indiana), a programme of free milk for children in the schools and in the shanty towns of Chile, and an expansion of the land seizure and redistribution already begun under his predecessor Eduardo Frei Montalva,[56] who had nationalized between one-fifth and one-quarter of all the properties listed for takeover.[57] Allende also intended to improve the socio-economic welfare of Chile's poorest citizens;[58] a key element was to provide employment, either in the new nationalized enterprises or on public-work projects.[58] In November 1970, 3,000 scholarships were allocated to Mapuche children in an effort to integrate the indigenous minority into the educational system, payment of pensions and grants was resumed, an emergency plan providing for the construction of 120,000 residential buildings was launched, all part-time workers were granted rights to social security, a proposed electricity price-increase was withdrawn, diplomatic relations were restored with Cuba, and political prisoners were granted an amnesty. In December 1970, bread prices were fixed, 55,000 volunteers were sent to the south of the country to teach writing and reading skills and to provide medical attention to a sector of the population that had previously been ignored, a central commission was established to oversee a tri-partite payment plan in which equal place was given to government, employees and employers, and a protocol agreement was signed with the United Centre of Workers which granted workers representational rights on the funding board of the Social Planning Ministry.[59] An obligatory minimum wage for workers of all ages (including apprentices) was established,[60] free milk was introduced for expectant and nursing mothers and for children between the ages of 7 and 14,[61] free school-meals were established,[62] rent reductions were carried out, and the construction of the Santiago subway was rescheduled so as to serve working-class neighbourhoods first. Workers benefited from increases in social-security payments, an expanded public-works program, and a modification of the wage and salary adjustment mechanism (which had originally been introduced in the 1940s to cope with the country's chronic inflation), while middle-class Chileans benefited from the elimination of taxes on modest incomes and property.[63] In addition, state-sponsored programs distributed free food to the country's neediest citizens,[64] and in the countryside, peasant councils were established to mobilise agrarian workers and small proprietors. In the government's first budget (presented to the Chilean congress in November 1970), the minimum taxable income-level was raised, removing from the tax pool 35% of those who had paid taxes on earnings in the previous year. In addition, the exemption from general taxation was raised to a level equivalent to twice the minimum wage. Exemptions from capital taxes were also extended, which benefitted 330,000 small proprietors. The extra increases that Frei had promised to the armed forces were also fully paid. According to one estimate, purchasing power went up by 28% between October 1970 and July 1971.[65] Minimum real wages and inflation The rate of inflation fell from 36.1% in 1970 to 22.1% in 1971, while average real wages rose by 22.3% during 1971.[D][66] Minimum real wages for blue-collar workers were increased by 56% during the first quarter of 1971, while in the same period real minimum wages for white-collar workers were increased by 23%, a development that decreased the differential ratio between blue- and white-collar workers' minimum wage from 49% (1970) to 35% (1971). Central government expenditures went up by 36% in real terms, raising the share of fiscal spending in GDP from 21% (1970) to 27% (1971), and as part of this expansion, the public sector engaged in a huge housing program, starting to build 76,000 houses in 1971, compared to 24,000 for 1970.[66] During a 1971 emergency program, over 89,000 houses were built, and during Allende's three years as president an average of 52,000 houses were constructed annually.[67] Although the acceleration of inflation in 1972 and 1973 eroded part of the initial increase in wages, they still rose (on average) in real terms during the 1971–73 period.[68] Additionally, Allende government had reduced inflation to 14% in the first nine months of 1971.[69] Allende's first step in early 1971 was to raise minimum wages (in real terms) for blue-collar workers by 37%–41% and by 8%–10% for white-collar workers. Education, food, and housing assistance expanded significantly, with public housing starts going up twelvefold and eligibility for free milk extended from age 6 to age 15. A year later, blue-collar wages were raised by 27% in real terms and white-collar wages became fully indexed.[70] Price controls were also set up, while the Allende Government introduced a system of distribution networks through various agencies (including local committees on supply and prices) to ensure that shopkeepers adhered to the new rules.[71] Agrarian and literacy reforms The new Minister of Agriculture, Jacques Chonchol, promised to expropriate all estates which were larger than eighty "basic" hectares (about 200 acres). That promise was kept, with no farm in Chile exceeding that limit by the end of 1972.[72] Within eighteen months the Latifundia (extensive agricultural estates) had been abolished. The agrarian reform had involved the expropriation of 3,479 properties which, added to the 1,408 properties incorporated under the Frei government, made up some 40% of the total agricultural land area in the country.[65] Particularly in rural areas, the Allende government launched a campaign against illiteracy, while adult education programs expanded, together with educational opportunities for workers. From 1971 to 1973, enrolments in kindergarten, primary, secondary, and post-secondary schools all increased. The Allende government encouraged more doctors to begin practising in rural and low-income urban areas, and built additional hospitals, maternity clinics, and especially neighborhood health-centers that remained open for longer hours to serve the poor. Improved sanitation and housing facilities for low-income neighborhoods also equalized health-care benefits, while hospital councils and local health councils were established in neighborhood health-centers as a means of democratizing the administration of health policies. The councils gave central-government civil-servants, local-government officials, health-service employees, and community workers the right to review budgetary decisions.[73] The Allende government sought to bring the arts to the mass of the Chilean population by funding a number of cultural endeavours. With eighteen-year-olds and illiterates now granted the right to vote, mass participation in decision-making was encouraged by the Allende government, with traditional hierarchical structures now challenged by socialist egalitarianism. The Allende Government was able to draw upon the idealism of its supporters, with teams of "Allendistas" travelling into the countryside and shanty towns to perform volunteer work.[72] The Allende government also worked to transform Chilean popular culture through formal changes to school curriculum and through broader cultural education initiatives, such as state-sponsored music festivals and tours of Chilean folklorists and nueva canción musicians.[74] In 1971, the purchase of a private publishing house by the state gave rise to Editorial Quimantu, which became the center of the Allende Government's cultural activities. In the space of two years, 12 million copies of books, magazines, and documents (8 million of which were books) specializing in social analysis, were published. Cheap editions of great literary works were produced on a weekly basis, and in most cases were sold out within a day. Culture came into the reach of the masses for the first time, who responded enthusiastically. "Editorial Quimantu" encouraged the establishment of libraries in community organizations and trade unions. Through the supply of cheap textbooks, it enabled the Left to progress through the ideological content of the literature made available to workers.[65] To improve social and economic conditions for women, the Women's Secretariat was established in 1971, which took on issues such as public laundry facilities, public food programs, day-care centers, and women's health care (especially prenatal care).[75] The duration of maternity leave was extended from 6 to 12 weeks,[76] while the Allende Government steered the educational system towards poorer Chileans by expanding enrollments through government subsidies.[77] A "democratisation" of university education was carried out, making the system tuition-free, which led to an 89% rise in university enrollments between 1970 and 1973. The Allende Government also increased enrollment in secondary education from 38% in 1970 to 51% in 1974.[78] Enrollment in education reached record levels, including 3.6 million young people, and 8 million school textbooks were distributed among 2.6 million pupils in primary education. An unprecedented 130,000 students were enrolled by the universities, which became accessible to peasants and workers. The illiteracy rate was reduced from 12% in 1970 to 10.8% in 1972, while the growth in primary school enrollment increased from an annual average of 3.4% in the period 1966–70 to 6.5% in 1971–1972. Secondary education grew at a rate of 18.2% in 1971–1972, and the average school enrollment of children between the ages of 6 and 14 rose from 91% (1966–70) to 99%.[65] Social welfare initiatives Social spending was dramatically increased, particularly for housing, education, and health, and a major effort was made to redistribute wealth to poorer Chileans. As a result of new initiatives in nutrition and health, together with higher wages, many poorer Chileans were able to feed and clothe themselves better than ever before. Public access to the social security system was increased, and state benefits such as family allowances were raised significantly.[72] The redistribution of income enabled wage and salary earners to increase their share of national income from 51.6% (the annual average between 1965 and 1970) to 65% while family consumption increased by 12.9% in the first year of the Allende Government. In addition, while the average annual increase in personal spending had been 4.8% in the period 1965–70, it reached 11.9% in 1971.[65] During the first two years of Allende's presidency, state expenditure on health rose from around 2% to nearly 3.5% of GDP. According to Jennifer E. Pribble, the new spending "was reflected not only in public health campaigns, but also in the construction of health infrastructure".[79] Small programs targeted at women were also experimented with, such as cooperative laundries and communal food preparation, together with an expansion of child-care facilities.[80] The National Supplementary Food Program was extended to all primary school pupils and to all pregnant women, regardless of their employment or income condition. Complementary nutritional schemes were applied to malnourished children, while antenatal care was emphasized.[81] Under Allende, the proportion of children under the age of 6 with some form of malnutrition fell by 17%.[61] Apart from the existing Supply and Prices councils (community-based bodies which controlled the distribution of essential groups in working-class districts, and were a popular, not government, initiative),[82] community-based distribution centers and shops were developed, which sold directly in working-class neighborhoods. The Allende government felt obliged to increase its intervention in marketing activities, and state involvement in grocery distribution reached 33%.[65] The CUT (central labor confederation) was accorded legal recognition,[83] and its membership grew from 700,000 to almost 1 million. In enterprises in the Area of Social Ownership, an assembly of the workers elected half of the members of the management council for each company. Those bodies replaced the former board of directors.[65] Minimum pensions were increased by amounts equal to two or three times the inflation rate, and between 1970 and 1972, such pensions increased by a total of 550%. The incomes of 300,000 retirement pensioners were increased by the government from one-third of the minimum salary to the full amount. Labor insurance cover was extended to 200,000 market traders, 130,000 small shop proprietors, 30,000 small industrialists, small owners, transport workers, clergy, professional sportsmen, and artisans. The public health service was improved, with the establishment of a system of clinics in working-class neighborhoods on the peripheries of the major cities, providing a health center for every 40,000 inhabitants. Statistics for construction in general, and housebuilding in particular, reached some of the highest levels in the history of Chile. Four million square metres were completed in 1971–72, compared to an annual average of 2+1⁄2 million between 1965 and 1970. Workers were able to acquire goods which had previously been beyond their reach, such as heaters, refrigerators, and television sets. As further noted by Ricardo Israel Zipper, "By now meat was no longer a luxury, and the children of working people were adequately supplied with shoes and clothing. The popular living standards were improved in terms of the employment situation, social services, consumption levels, and income distribution."[65] |

大統領時代 主な記事 サルバドール・アジェンデ大統領時代 「社会主義へのチリの道  1970年のアジェンデ 当選後のチリ議会での演説で、アジェンデはチリを資本主義社会から社会主義社会へと移行させる意図を明らかにした: 後進性を克服するためには、社会主義が避けて通れない要求であることを知り、自由、独立、尊厳の中で合理的な建設を望む近代国家にとって、社会主義体制が 唯一の道であると感じている。私たちが社会主義に向かっているのは、国民がその投票を通じて、粗雑な不平等社会、社会的不公正によって変形し、人間の連帯 の基盤の劣化によって劣化した社会をもたらしたシステムとしての資本主義を自由に拒否したからである」[55]。 大統領に就任すると、アジェンデはLa vía chilena al socialismo(「社会主義へのチリの道」)と呼ばれる社会主義プログラムを実施するという綱領を実行に移し始めた。これには、大規模産業(特に銅 採掘と銀行)の国有化、医療制度の政府管理、教育制度(米国の教育者ジェーン・A・ホブソン=ゴンザレスの協力を得た。ホブソン=ゴンザレスはインディア ナ州ココモ出身)、学校とチリの掘っ立て小屋の町で子どもたちに牛乳を無料で提供するプログラム、前任者エドゥアルド・フレイ・モンタルバの下ですでに始 まっていた土地の接収と再分配の拡大[56]。 [57]アジェンデはまた、チリの最貧困層の社会経済的福祉を改善することも意図していた。[58]重要な要素は、国有化された新企業や公共事業において 雇用を提供することであった。 1970年11月、少数民族である先住民を教育システムに統合するため、マプーチェの子どもたちに3,000人の奨学金が割り当てられ、年金と助成金の支 払いが再開され、12万戸の住宅建設を提供する緊急計画が開始され、すべてのパートタイム労働者に社会保障の権利が与えられ、電気料金の値上げ案が撤回さ れ、キューバとの国交が回復され、政治犯に恩赦が与えられた。1970年12月には、パンの価格が固定され、55,000人のボランティアが南部へ派遣さ れ、それまで無視されていた住民の部門に筆記と読書の技術を教え、医療を提供し、政府、被雇用者、使用者に同等の地位が与えられる三者支払い計画を監督す る中央委員会が設置され、労働者連合センターとの間で、社会計画省の資金調達委員会における労働者の代表権を認める議定書協定が結ばれた[59]。 全年齢の労働者(見習いを含む)に対する義務的最低賃金が設定され[60]、妊産婦と7歳から14歳までの子どもに対する無料のミルクが導入され [61]、無料の学校給食が確立され[62]、家賃の引き下げが実施され、サンティアゴ地下鉄の建設が労働者階級の居住区を優先するように変更された。労 働者は、社会保障費の増額、公共事業プログラムの拡大、賃金・給与調整メカニズム(これはもともと国の慢性的なインフレに対処するために1940年代に導 入された)の修正から恩恵を受け、中流階級のチリ人は、ささやかな収入と財産に対する課税の撤廃から恩恵を受けた[63]。さらに、国が後援するプログラ ムは、国の最も困窮している市民に無料の食料を配布し[64]、地方では、農業労働者と小規模な所有者を動員するために農民評議会が設立された。政府によ る最初の予算(1970年11月にチリ議会に提出)では、課税所得水準の下限が引き上げられ、前年度に所得税を納めていた人の35%が課税対象から外され た。さらに、一般課税の免除が最低賃金の2倍に相当する水準まで引き上げられた。資本税の免除も拡大され、33万人の小規模事業主が恩恵を受けた。フライ が軍隊に約束していた増額分も全額支払われた。ある試算によると、購買力は1970年10月から1971年7月の間に28%上昇した[65]。 最低実質賃金とインフレ インフレ率は1970年の36.1%から1971年には22.1%に低下したが、平均実質賃金は1971年に22.3%上昇した[D][66]。ブルーカ ラー労働者の最低実質賃金は1971年第1四半期に56%引き上げられたが、同じ期間にホワイトカラー労働者の実質最低賃金は23%引き上げられ、この結 果、ブルーカラー労働者とホワイトカラー労働者の最低賃金の差は49%(1970年)から35%(1971年)に縮小した。中央政府支出は実質ベースで 36%増加し、GDPに占める財政支出の割合は21%(1970年)から27%(1971年)に上昇した。この拡大の一環として、公共部門は大規模な住宅 計画に取り組み、1970年には24,000戸であったのに対し、1971年には76,000戸の建設を開始した[66]。 [1971年の緊急プログラムでは8万9,000戸を超える住宅が建設され、アジェンデが大統領を務めた3年間には年平均5万2,000戸の住宅が建設さ れた[67]。1972年と1973年にインフレが加速したことで、当初の賃金上昇の一部が損なわれたものの、それでも1971年から73年にかけての賃 金は(平均して)実質的に上昇した[68]。さらに、アジェンデ政府は1971年の最初の9ヵ月間でインフレ率を14%まで低下させた[69]。 1971年初頭のアジェンデの最初の措置は、ブルーカラー労働者の最低賃金(実質ベース)を37%~41%、ホワイトカラー労働者の最低賃金を8% ~10%引き上げることであった。教育、食糧、住宅扶助は大幅に拡大し、公営住宅の着工戸数は12倍に増加し、無料牛乳の受給資格は6歳から15歳まで延 長された。1年後、ブルーカラーの賃金は実質ベースで27%引き上げられ、ホワイトカラーの賃金は完全なスライド制となった[70]。価格統制も設定さ れ、アジェンデ政府は様々な機関(供給と価格に関する地方委員会を含む)を通じた流通網のシステムを導入し、商店主が新しい規則を守るようにした [71]。 農政改革と識字率改革 新農相ジャック・チョンチョルは、80ヘクタール(約200エーカー)以上の「基本」農地をすべて収用すると約束した。この約束は守られ、1972年末ま でにチリでこの制限を超える農地は皆無となった[72]。18ヵ月以内にラティフンディア(広大な農地)は廃止された。農地改革では3,479の土地が収 用され、フレイ政権下で組み入れられた1,408の土地と合わせると、国全体の農地面積の約40%を占めていた[65]。 特に農村部において、アジェンデ政府は非識字撲滅キャンペーンを開始し、成人教育プログラムは労働者のための教育機会とともに拡大した。1971年から 1973年にかけて、幼稚園、初等学校、中等学校、高等学校の入学者数がすべて増加した。アジェンデ政府は、農村部や低所得の都市部で開業する医師を増や すよう奨励し、病院、産科診療所、特に近隣の保健センターを増設して、貧しい人々のために営業時間を延長した。低所得者層向けの衛生設備や住宅施設の改善 により、医療給付の平等化も図られた。また、保健政策の運営を民主化する手段として、近隣の保健センターに病院協議会や地方保健協議会が設置された。評議 会は、中央政府の公務員、地方政府の役人、保健サービスの職員、地域社会の労働者に予算決定を検討する権利を与えた[73]。 アジェンデ政府は、多くの文化的な取り組みに資金を提供することによって、チリの多くの人々に芸術をもたらそうとした。18歳と非識字者に選挙権が与えら れたことで、アジェンデ政権によって意思決定への大衆参加が奨励され、伝統的な階層構造が社会主義的平等主義によって挑戦されるようになった。アジェンデ 政府は支持者の理想主義を利用することができ、「アジェンディスタ」のチームが田舎や掘っ立て小屋の町でボランティア活動を行った。 [72]アジェンデ政府はまた、学校のカリキュラムを正式に変更したり、国が主催する音楽祭やチリの民俗学者やヌエバ・カンシオンの音楽家たちのツアーな ど、より広範な文化教育イニシアティブを通じて、チリの大衆文化を変革することにも取り組んだ[74]。1971年、国による民間の出版社の買収によっ て、アジェンデ政府の文化活動の中心となったEditorial Quimantuが誕生した。2年間で1,200万部の社会分析に特化した書籍、雑誌、文書(うち800万部が書籍)が出版された。偉大な文学作品の廉価 版が毎週のように作られ、ほとんどの場合、一日で売り切れた。文化が初めて大衆の手に届くようになり、大衆は熱狂的に反応した。「エディトリアル・キマン トゥ」は、地域組織や労働組合に図書館を設立することを奨励した。安価な教科書の供給を通じて、労働者が利用できるようになった文献のイデオロギー的な内 容を通じて、左翼が進歩することを可能にした[65]。 女性の社会的・経済的条件を改善するために、1971年に女性事務局が設立され、公共洗濯施設、公共食料プログラム、託児所、女性の健康管理(特に出産前 ケア)などの問題に取り組んだ。 [一方、アジェンデ政権は、政府補助金を通じて入学者数を拡大することによって、教育制度をより貧しいチリ人向けに誘導した[77]。大学教育の「民主 化」が実施され、授業料が無料となり、1970年から1973年の間に大学入学者数が89%増加した。アジェンデ政権はまた、中等教育への就学率を 1970年の38%から1974年には51%に引き上げた[78]。教育への就学率は360万人の若者を含む記録的な水準に達し、初等教育では260万人 の生徒に800万冊の教科書が配布された。農民や労働者が利用できるようになった大学には、前例のない13万人の学生が入学した。非識字率は1970年の 12%から1972年には10.8%に低下し、初等教育への就学率は1966-70年の年平均3.4%から1971-72年には6.5%に上昇した。中等 教育の成長率は1971年から1972年にかけて18.2%であり、6歳から14歳までの子どもの平均就学率は91%(1966年から1970年)から 99%に上昇した[65]。 社会福祉への取り組み 社会支出は、特に住宅、教育、保健のために劇的に増加し、より貧しいチリ人への富の再分配に大きな努力が払われた。栄養と健康における新たな取り組みと賃 金の上昇の結果、多くの貧しいチリ人は以前よりも良い衣食住ができるようになった。社会保障制度への公的アクセスが拡大され、家族手当などの国家給付が大 幅に引き上げられた[72]。所得の再分配によって、賃金・給与所得者が国民所得に占める割合が51.6%(1965年から1970年の年平均)から 65%に増加する一方で、アジェンデ政権初年度の家族消費は12.9%増加した。さらに、個人支出の年平均増加率は1965年から70年の期間には 4.8%であったが、1971年には11.9%に達した[65]。アジェンデ大統領の最初の2年間で、保健に対する国家支出はGDPの約2%から約 3.5%に増加した。ジェニファー・E・プリブルによれば、新たな支出は「公衆衛生キャンペーンに反映されただけでなく、保健インフラの建設にも反映され た」[79]。女性を対象とした小規模なプログラムもまた、保育施設の拡大とともに、協同組合ランドリーや共同調理などの実験的に実施された[80]。 全国補食プログラムは、雇用や所得の状況にかかわらず、すべての小学生とすべての妊婦に拡大された。栄養不良の子どもたちには補完的な栄養スキームが適用 され、妊産婦ケアが重視された[81]。 アジェンデ政権下では、何らかの形で栄養不良に陥っている6歳未満の子どもの割合が17%減少した[61]。既存の供給・価格協議会(労働者階級地区にお ける必要不可欠な集団の配給を管理する地域ベースの組織で、政府ではなく民衆のイニシアチブであった)とは別に[82]、労働者階級地区で直接販売する地 域ベースの配給センターと商店が開発された。アジェンデ政府は販売活動への介入を強める必要に迫られ、食料品流通への国家の関与は33%に達した [65]。CUT(中央労働総同盟)は法的承認を与えられ[83]、その会員数は70万人からほぼ100万人に増加した。社会的所有地域の企業では、労働 者の集会が各企業の経営協議会メンバーの半数を選出した。これらの機関は以前の取締役会に取って代わった[65]。 最低年金はインフレ率の2~3倍に相当する額だけ引き上げられ、1970年から1972年の間に、そのような年金は合計で550%増加した。30万人の退 職年金受給者の所得が、政府によって最低給与の3分の1から全額に引き上げられた。労働保険は、20万人の市場商人、13万人の小規模商店主、3万人の小 規模工業経営者、小規模経営者、運輸労働者、聖職者、プロスポーツ選手、職人に適用された。公衆衛生サービスも改善され、大都市周辺部の労働者階級居住区 に診療所システムが設置され、人口4万人に1つの割合で保健センターが設けられた。建設全般、特に住宅建設の統計は、チリ史上最高レベルに達した。 1965年から1970年までの年平均が200万平方メートルだったのに対し、1971年から72年には400万平方メートルが完成した。労働者は、ヒー ター、冷蔵庫、テレビなど、以前は手の届かなかった商品を手に入れることができた。リカルド・イスラエル・ジッパーがさらに述べているように、「今や肉は 贅沢品ではなくなり、労働者の子供たちには靴や衣服が十分に供給されるようになった。庶民の生活水準は、雇用状況、社会サービス、消費水準、所得分配の面 で改善された」[65]。 |

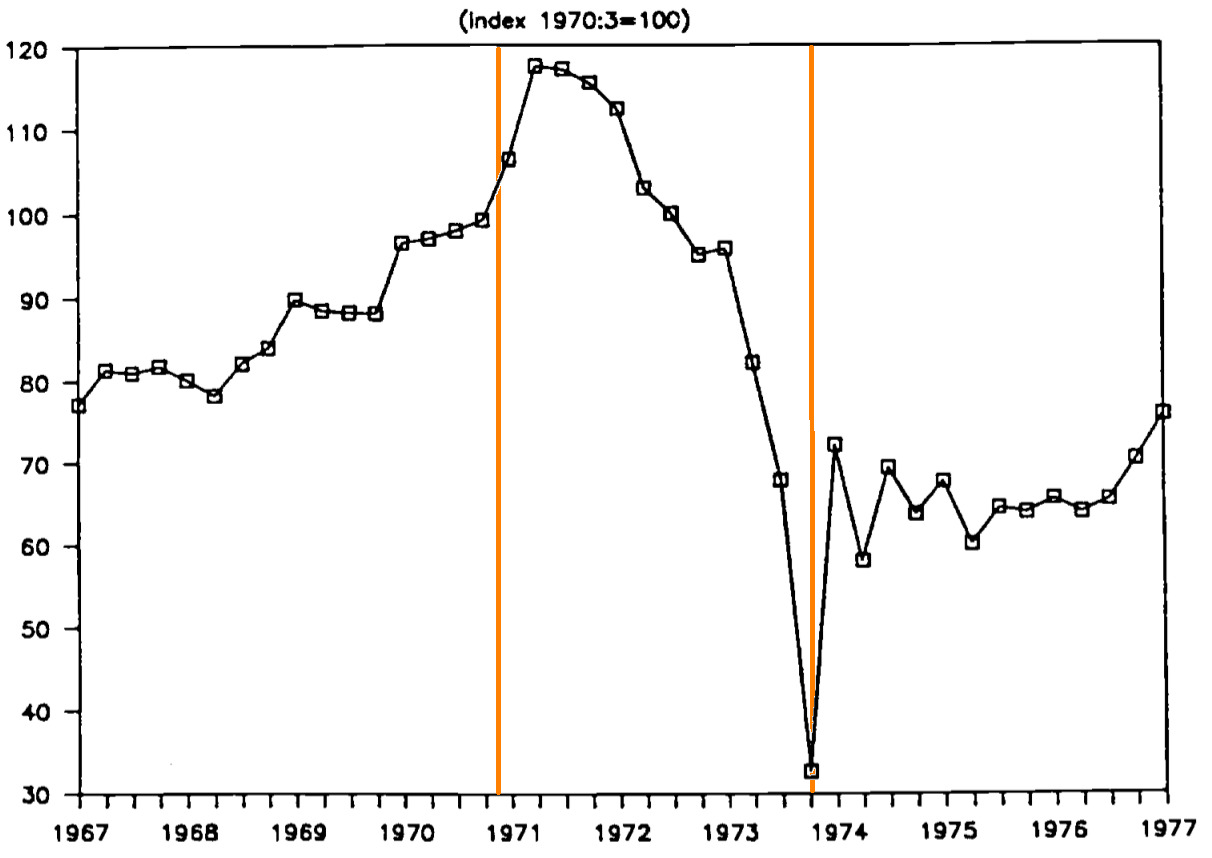

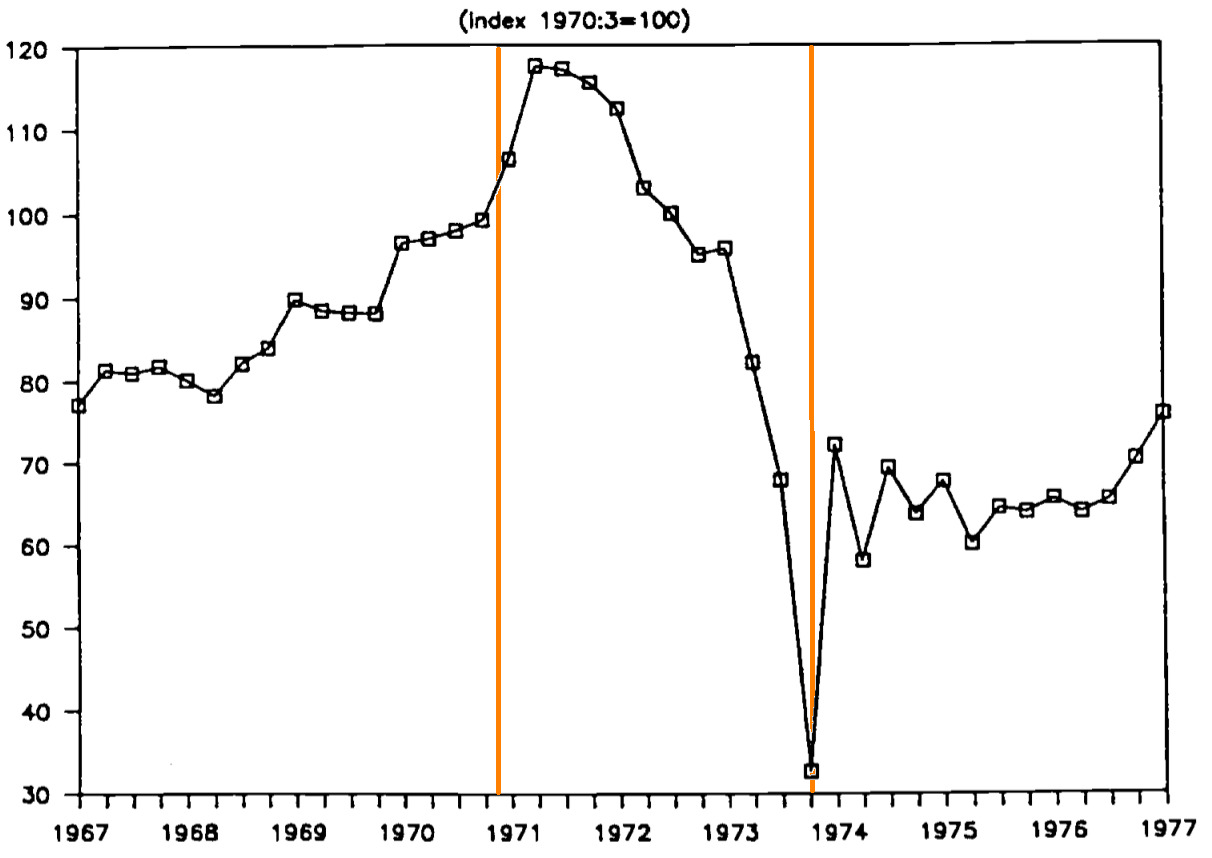

| Economic policy This article needs more complete citations for verification. Please help add missing citation information so that sources are clearly identifiable. (October 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this template message)  Chile real wages between 1967 and 1977. Orange lines mark the beginning and end of Allende's presidency.[84] Chilean presidents were allowed a maximum term of six years, which may explain Allende's haste to restructure the economy. Not only was a major restructuring program organized (the Vuskovic plan), he also had to make it a success if a left-wing successor to Allende was going to be elected. In the first year of Allende's term, the short-term economic results of the economy minister Pedro Vuskovic's expansive monetary policy were highly favorable: 12% industrial growth and an 8.6% increase in GDP, accompanied by major declines in inflation (down from 34.9% to 22.1%) and unemployment (down to 3.8%). By 1972, the Chilean escudo had an inflation rate of 140%. The average real GDP contracted between 1971 and 1973 at an annual rate of a 5.6% negative growth, and the government's fiscal deficit soared while foreign reserves declined.[85] Unemployment rates had dropped from 6.3% in 1970 to 3.5% in 1972 before dropping again in 1973 to the lowest ever recorded.[86] The combination of inflation and price controls, together with the disappearance of basic commodities from supermarket shelves, led to the rise of black markets in rice, beans, sugar, and flour.[87] The Chilean economic situation was also somewhat exacerbated due to a US-backed campaign to fund worker strikes in certain sectors of the economy.[88] The Allende government announced it would default on debts owed to international creditors and foreign governments. Allende also froze all prices while raising salaries. His implementation of the policies was strongly opposed by landowners, employers, businessmen and transporters associations, and some civil servants and professional unions. The rightist opposition was led by the National Party, the Roman Catholic Church (which in 1973 was displeased with the direction of educational policy),[89] and eventually the Christian Democrats. There were growing tensions with foreign multinational corporations and the government of the United States. Allende undertook the pioneeristic Project Cybersyn, a distributed decision support system for decentralized economic planning, developed by British cybernetics expert Stafford Beer. Based on the experimental viable system model and the neural network approach to organizational design, the Project consisted of four modules: a network of telex machines (Cybernet) in all state-run enterprises that would transmit and receive information with the government in Santiago. Information from the field would be fed into statistical modeling software (Cyberstride) that would monitor production indicators, such as raw material supplies or high rates of worker absenteeism, in "almost" real time, alerting the workers in the first case and, in abnormal situations, if those parameters fell outside acceptable ranges by a very large degree, also the central government. The information would also be input into an economic simulation software (CHECO, for CHilean ECOnomic simulator) which featured a Bayesian filtering and control setting that the government could use to forecast the possible outcome of economic decisions. Finally, a sophisticated operations room (Opsroom) would provide a space where managers could see relevant economic data, formulate feasible responses to emergencies, and transmit advice and directives to enterprises and factories in alarm situations by using the telex network.[90] In conjunction with the system, the Cybersyn development team also planned the Cyberfolk device system, a closed television circuit connected to an interactive apparatus that would enable the citizenry to actively participate in economic and political decision-making.[citation needed] Allende raised wages on a number of occasions throughout 1970 and 1971, but the wage hikes were negated by ongoing inflation of Chile's fiat currency. Although price rises had been high even under Frei (27% a year between 1967 and 1970), a basic basket of consumer goods rose by 120% from 190 to 421 escudos in one month alone, August 1972. From 1970 to 1972, while Allende was in government, exports fell 24% and imports rose 26%, with imports of food rising an estimated 149%.[91][incomplete short citation] Export income fell due to a hard-hit copper industry; the price of copper on international markets fell by almost a third, and post-nationalization copper production fell as well. Copper is Chile's single most important export, as more than half of Chile's export receipts were from that sole commodity.[92][incomplete short citation] The price of copper fell from a peak of $66 per ton in 1970 to only $48–49 in 1971 and 1972.[93][incomplete short citation] Chile was already dependent on food imports, and the decline in export earnings coincided with declines in domestic food production following Allende's agrarian reforms.[94] Foreign policy In 1971, Chile re-established diplomatic relations with Cuba, joining Mexico and Canada in rejecting a previously established Organization of American States convention prohibiting governments in the Western Hemisphere from establishing diplomatic relations with Cuba. Shortly afterward, Cuban president Fidel Castro made a month-long visit to Chile. Originally, the visit was supposed to be one week; however, Castro enjoyed Chile and one week led to another. Despite his attitude of socialist solidarity, Castro was reportedly critical of Allende's policies. Castro was quoted as saying that "Marxism is a revolution of production", whereas "Allende's was a revolution of consumption."[95] Socioeconomic and political tensions See also: Chile truckers' strike In October 1972, the first of what were to be a wave of strikes was led first by truckers, and later by small businessmen, some (mostly professional) unions and some student groups. Other than the inevitable damage to the economy, the chief effect of the 24-day strike was to induce Allende to bring the head of the army, general Carlos Prats, into the government as Interior Minister.[87] Allende also instructed the government to commandeer trucks to keep the nation from coming to a halt. Government supporters also helped to mobilize trucks and buses, but violence served as a deterrent to full mobilization, even with police protection for the strike-breakers. Allende's actions were eventually declared unlawful by the Chilean appeals court and the government was ordered to return trucks to their owners.[96] Throughout his presidency, racial tensions between the poor descendants of indigenous people, who supported Allende's reforms, and the white elite increased.[97] Throughout his presidency, Allende remained at odds with the Chilean Congress, which was dominated by the Christian Democratic Party. In 1964, Eduardo Frei had promised a "Revolution in Liberty", a middle-class revolution that was funded by the United States government's Alliance for Progress.[98] Frei carried out a series of progressive reforms, including land reform, an issue that had not been touched since Chile's independence in the early 19th century. According to historian Marian Schlotterbeck, this was "[John F.] Kennedy's vision — stave off the threat of communist revolution by improving standards of living across the continent".[99] The Christian Democrats had campaigned on a socialist platform in the 1970 elections but drifted away from those positions during Allende's presidency, and accused Allende of leading Chile toward a Cuban-style dictatorship and sought to overturn many of his more radical policies. They eventually formed a coalition with the National Party.[100] Allende and his opponents in Congress repeatedly accused each other of undermining the Chilean Constitution and acting undemocratically. Allende's increasingly bold socialist policies (partly in response to pressure from some of the more radical members within his coalition), combined with his close contacts with Cuba, heightened fears in Washington. The Nixon administration continued exerting economic pressure on Chile via multilateral organizations and continued to back Allende's opponents in the Chilean Congress. Almost immediately after his election, Nixon directed CIA and US State Department officials to "put pressure" on the Allende government.[101] His economic policies were used by economists Rudi Dornbusch and Sebastián Edwards to coin the term macroeconomic populism.[102] In 1972, Chile's inflation stood at 150%.[103] |

経済政策 この記事の検証には、より完全な引用が必要です。出典が明確に識別できるよう、不足している引用情報の追加にご協力ください。(2023年10月)(このテンプレートメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ)  1967年から1977年のチリの実質賃金。オレンジの線はアジェンデ大統領の任期開始時と終了時を示す[84]。 チリの大統領の任期は最長6年であったため、アジェンデは経済再建を急いだ。大規模なリストラ計画(ブスコビッチ計画)が組織されただけでなく、アジェン デの後継となる左派が選出されるためには、それを成功させなければならなかった。アジェンデの任期1年目、ペドロ・ブスコビッチ経済相の拡張的な金融政策 による短期的な経済結果は非常に良好だった: インフレ率(34.9%から22.1%に低下)と失業率(3.8%に低下)の大幅な低下を伴い、工業成長率は12%、GDPは8.6%増加した。1972 年には、チリのエスクードのインフレ率は140%に達した。1971年から1973年にかけての平均実質GDPは年率5.6%のマイナス成長で縮小し、外 貨準備高が減少する一方で政府の財政赤字は急増した[85]。失業率は1970年の6.3%から1972年には3.5%に低下し、1973年には再び過去 最低を記録した[86]。 インフレと価格統制の組み合わせは、スーパーマーケットの棚から基本的な日用品が姿を消したことと相まって、米、豆、砂糖、小麦粉の闇市の台頭につながっ た[87]。 チリの経済状況はまた、経済の特定の部門における労働者のストライキに資金を提供するためにアメリカが支援したキャンペーンによっていくらか悪化した [88]。 アジェンデ政府は、国際債権者と外国政府に対して負っている債務を不履行にすると発表した。アジェンデはまた、給与を引き上げる一方ですべての物価を凍結 した。アジェンデの政策実施には、土地所有者、雇用者、実業家、運輸業者団体、一部の公務員や専門職組合が強く反対した。右派の反対は、国民党、ローマ・ カトリック教会(1973年には教育政策の方向性に不満を抱いていた)[89]、そして最終的にはキリスト教民主党が主導した。外国の多国籍企業やアメリ カ政府との緊張が高まっていた。 アジェンデは、イギリスのサイバネティクスの専門家スタッフォード・ビアによって開発された分散型経済計画のための分散型意思決定支援システムであるサイ バシン計画を先駆的に引き受けた。実験的実行可能システムモデルと組織設計へのニューラルネットワーク・アプローチに基づき、プロジェクトは4つのモ ジュールで構成された。現場からの情報は、統計モデリング・ソフトウェア(Cyberstride)に入力され、原材料の供給状況や労働者の欠勤率の高さ などの生産指標を「ほぼ」リアルタイムで監視し、最初の場合は労働者に、異常事態の場合は、それらのパラメーターが許容範囲を大きく逸脱した場合に中央政 府にも警告を発する。この情報はまた、経済シミュレーション・ソフトウェア(CHECO、CHilean ECOnomic simulatorの略)にも入力される。CHECOは、ベイズ・フィルタリングと制御設定を備えており、政府が経済的意思決定の結果を予測するために使 用できる。最後に、洗練されたオペレーション・ルーム(Opsroom)は、管理者が関連する経済データを見たり、緊急事態に対する実現可能な対応策を 練ったり、テレックス・ネットワークを使って警報事態にある企業や工場に助言や指示を送信したりできる空間を提供するものであった[90]。サイバシン開 発チームは、このシステムと連動して、市民が経済的・政治的意思決定に積極的に参加できるようにする対話装置に接続された閉じたテレビ回線であるサイバー フォーク装置システムも計画した[要出典]。 アジェンデは1970年から1971年にかけて何度も賃上げを行ったが、チリの不換紙幣の継続的なインフレによって賃上げは打ち消された。物価上昇はフラ イ政権下でも高かったが(1967年から1970年にかけては年率27%)、消費財の基本バスケットは1972年8月の1ヶ月間だけで190から421エ スクードへと120%上昇した。アジェンデ政権下の1970年から1972年にかけて、輸出は24%減少し、輸入は26%増加した。銅はチリにとって唯一 最も重要な輸出品であり、チリの輸出収入の半分以上はこの商品によるものであった[92][不完全引用]。銅の価格は1970年の1トンあたり66ドルの ピークから1971年と1972年にはわずか48-49ドルにまで下落した[93][不完全引用]。チリはすでに食糧輸入に依存しており、輸出収入の減少 はアジェンデの農地改革に伴う国内食糧生産の減少と重なった[94]。 外交政策 1971年、チリはメキシコ、カナダとともに、西半球の政府がキューバと外交関係を結ぶことを禁止する米州機構条約を拒否し、キューバと外交関係を回復し た。その直後、キューバのフィデル・カストロ議長が1カ月にわたってチリを訪問した。当初は1週間の予定だったが、カストロはチリを満喫し、1週間がまた 1週間へと続いた。カストロは社会主義者としての連帯の態度とは裏腹に、アジェンデの政策には批判的だったと伝えられている。カストロは「マルクス主義は 生産の革命」であるのに対し、「アジェンデのそれは消費の革命であった」と述べたと引用されている[95]。 社会経済的・政治的緊張 関連項目 チリのトラック運転手のストライキ 1972年10月、最初のストライキはトラック運転手たちによって起こされ、その後、中小企業家、いくつかの(主に専門職の)組合、学生グループによって 起こされた。経済への必然的な打撃以外に、24日間のストライキの主な効果は、アジェンデが陸軍のトップであるカルロス・プラッツ将軍を内務大臣として政 府に迎えるよう誘導したことであった[87]。政府の支持者たちもトラックやバスの動員を手伝ったが、暴力はスト破りのための警察の保護があったとして も、完全な動員を阻む抑止力となった。アジェンデの行動は最終的にチリの控訴裁判所によって違法とされ、政府はトラックを所有者に返却するよう命じられた [96]。アジェンデの大統領在任期間を通じて、アジェンデの改革を支持する先住民の貧しい子孫と白人エリートとの間の人種的緊張が高まった[97]。 大統領在任中、アジェンデはキリスト教民主党が支配するチリ議会と対立し続けた。1964年、エドゥアルド・フレイは「自由の革命」を約束し、アメリカ政 府の「進歩のための同盟」からの資金提供を受けた中産階級の革命であった[98]。フレイは、19世紀初頭のチリ独立以来手をつけられていなかった土地改 革を含む一連の進歩的改革を実施した。歴史家マリアン・シュロッターベックによれば、これは「ジョン・F・ケネディのビジョン-大陸全体の生活水準を向上 させることで共産主義革命の脅威を食い止める-」であった[99]。キリスト教民主党は1970年の選挙で社会主義を掲げて選挙運動を行ったが、アジェン デの大統領在任中にそのような立場から離れ、アジェンデがチリをキューバ型の独裁政権へと導いていると非難し、彼のより急進的な政策の多くを覆そうとし た。彼らは最終的に国民党と連立を組んだ[100]。 議会におけるアジェンデと彼の反対派は、チリ憲法を弱体化させ、非民主的に行動していると繰り返し非難し合った。アジェンデの社会主義政策がますます大胆 になり(連立政権内の急進的なメンバーからの圧力に応えたこともあった)、キューバとの緊密な接触とあいまって、ワシントンの懸念は高まった。ニクソン政 権は多国間組織を通じてチリに経済的圧力をかけ続け、チリ議会ではアジェンデの反対派を支援し続けた。彼の経済政策は経済学者のルディ・ドーンブッシュと セバスチャン・エドワーズによってマクロ経済ポピュリズムという造語に使われた[102]。 1972年、チリのインフレ率は150%に達した[103]。 |

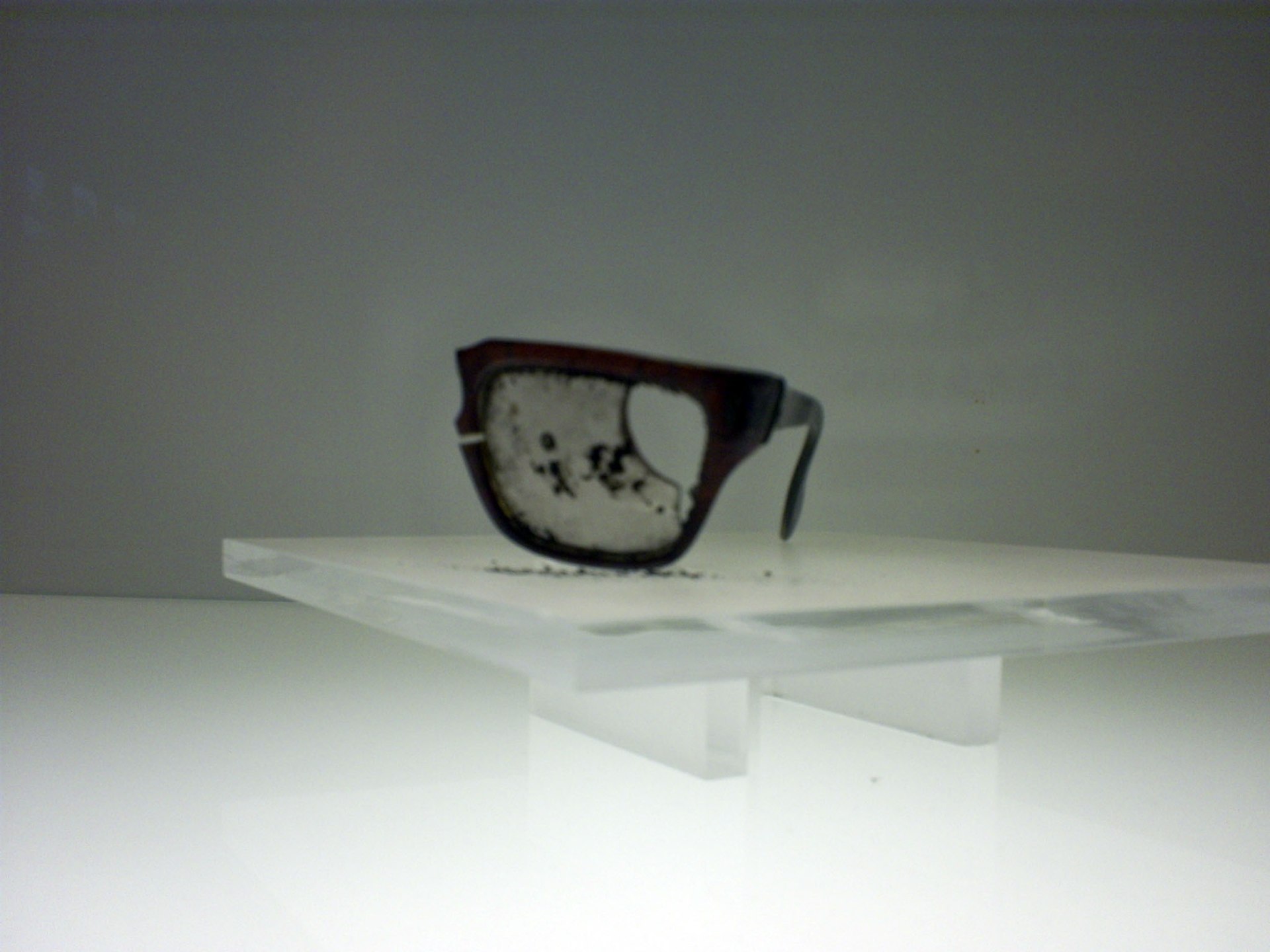

| Foreign relations during Allende's presidency Salvador Allende took office in a difficult international context. Chile was aligned with the United States in 1970. Elsewhere in Latin America, Brazil, Argentina and Bolivia were ruled by conservative military dictatorships (soon to be joined by Uruguay). Colombia and Venezuela also had conservative, but democratically elected, governments. Only Cuba, Peru and Mexico viewed the Chilean socialist experiment with sympathy. Under Allende's presidency, Chile joined the Non-Aligned Movement, a position that was then almost unique in Latin America.[104] Chile, which until then had been fussy about ideological boundaries, diversified its diplomatic and trade relations, regardless of the internal political regime of each country. The government established diplomatic relations with two Latin American countries (Cuba and Guyana), seven African countries (Congo, Equatorial Guinea, Libya, Madagascar, Nigeria, Tanzania, and Zaire), three European countries (Albania, East Germany and Hungary) and seven Asian countries (Afghanistan, Bangladesh, Cambodia, North Korea, China, Mongolia, South Vietnam and North Vietnam).[104] It tried to promote Latin American integration. At the 1971 Latin American Economic and Social Council, the Chilean representative Gonzalo Martner García formulated four major proposals, summarized by the historian Jorge Magasich: "1) to ask the United States for a moratorium on external debt for a decade in order to allocate these sums to development policies; 2) to create a Latin American central bank to "invest Latin America's reserves, 70% of which are in the United States", to receive "the region's deposits and assets" and to coordinate the operations of the central banks in order to protect the region from financial turbulence; 3) Promote the creation of a global technology fund for development, fed by compulsory contributions of licenses, industrial processes and other funds for research, so as to limit the abuses associated with technological property; 4) Create a Latin American organisation for the development of science and technology appropriate to the region."[104] He began negotiations with Bolivia over the historical dispute between the two countries (Bolivia had lost access to the sea since the War of the Pacific between 1879 and 1884) and welcomed Bolivia's maritime request. Nevertheless, relations became tense again following a coup d'état by Bolivian General Hugo Banzer in August 1971. At the same time, Chile granted asylum to thousands of political exiles from Latin American countries.[104] Salvador Allende openly rejected the influence of the Organization of American States (OAS), a body close to the United States government, and the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), which favored the interests of more developed countries. On the other hand, he was a fervent defender of the United Nations Conference on Trade and Development (UNCTAD), which he considered to be more representative since it allowed economic and trade issues to be negotiated on an equal legal footing. In a speech to UNCTAD, he also warned of the policy of the United States, Japan and the European Economic Community to progressively eliminate obstacles to free trade. He said that "freeing up trade ... erases at a stroke the benefits that the Generalised System of Preferences brings to developing countries".[104] Allende's Popular Unity government tried to maintain normal relations with the United States. When Chile nationalized its copper industry, the United States government cut off support and increased its support to the opposition. Forced to seek alternative sources of trade and finance, Chile gained commitments from the Soviet Union to invest some $400 million in Chile in the next six years. The United States Departement of State put it at $115 million from Eastern Europe and $65 million from China, while Soviet and Chilean Popular Unity sources put it at total of $620 million from socialist countries. Much of the credit was never utilized, and the Soviets were not willing to subsidize Chile the same way they did for Cuba.[105] Allende's government was disappointed that it received far less economic assistance from the Soviets than it hoped for. Trade between the two countries did not significantly increase and the credits were mainly linked to the purchase of Soviet equipment. Moreover, credits from the Soviet Union were much less than those provided to the People's Republic of China and countries of the Eastern Bloc. When Allende visited the Soviet Union in late 1972 in search of more aid and additional lines of credit after three years, he was turned down.[106] United States involvement Main article: United States intervention in Chile The United States opposition to Allende started several years before he was elected President of Chile. Declassified documents show that from 1962 to 1964, the CIA spent $3 million on anti-Allende propaganda "to scare voters away from Allende's FRAP coalition" and spent a total of $2.6 million to finance the presidential campaign of Eduardo Frei.[43][44] The possibility of Allende winning Chile's 1970 election was deemed a disaster by the Nixon administration that wanted to protect American geopolitical interests by preventing the spread of Communism during the Cold War.[107] In September 1970, then United States president Richard Nixon informed the CIA that an Allende government in Chile would not be acceptable and authorized $10 million to stop Allende from coming to power or unseat him.[108] A CIA document declared, "It is firm and continuing policy that Allende be overthrown by a coup."[109] Henry Kissinger's 40 Committee and the CIA planned to impede Allende's investiture as President of Chile with covert efforts known as "Track I" and "Track II"; Track I sought to prevent Allende from assuming power via so-called "parliamentary trickery", while under the Track II initiative, the CIA tried to convince key Chilean military officers to carry out a coup.[108] Some point to the involvement of the Defense Intelligence Agency agents that allegedly secured the missiles used to bombard La Moneda Palace.[110] In fact, open US military aid to Chile continued during the Allende administration, and the national government was very much aware of that although there is no record that Allende himself believed that such assistance was anything but beneficial to Chile. During Richard Nixon's presidency, United States officials attempted to prevent Allende's election by financing political parties aligned with opposition candidate Jorge Alessandri and supporting strikes in the mining and transportation sectors.[111] After the 1970 election, the Track I operation attempted to incite Chile's outgoing president, Eduardo Frei Montalva, to persuade his party (PDC) to vote in Congress for Alessandri.[112] Under the plan, Alessandri would resign his office immediately after assuming it and call new elections. Eduardo Frei would then be constitutionally able to run again (since the Chilean Constitution did not allow a president to hold two consecutive terms, but allowed multiple non-consecutive ones), and presumably easily defeat Allende. The Chilean Congress instead chose Allende as president, on the condition that he would sign a "Statute of Constitutional Guarantees" affirming that he would respect and obey the Chilean Constitution and that his reforms would not undermine any of its elements. Track II was aborted, as parallel initiatives already underway within the Chilean military rendered it moot.[113] During the second term of office of Democratic President Bill Clinton, the CIA acknowledged having played a role in Chilean politics before the coup, but its degree of involvement is debated. The CIA was notified by its Chilean contacts of the impending coup two days in advance but contends it "played no direct role in" the coup.[114] Allende in 1972 Much of the internal opposition to Allende's policies came from the business sector, and recently released United States government documents confirm that the United States indirectly[88] funded the truck drivers' strike,[115] which exacerbated the already chaotic economic situation before the coup. The most prominent United States corporations in Chile before Allende's presidency were the Anaconda and Kennecott copper companies and ITT Corporation, International Telephone and Telegraph. Both copper corporations aimed to expand privatized copper production in the city of Sewell in the Chilean Andes, where the world's largest underground copper mine "El Teniente", was located.[116] At the end of 1968, according to United States Department of Commerce data, United States corporate holdings in Chile amounted to $964 million. Anaconda and Kennecott accounted for 28% of United States holdings, but ITT had by far the largest holding of any single corporation, with an investment of $200 million in Chile.[116] In 1970, before Allende was elected, ITT owned 70% of Chitelco, the Chilean Telephone Company and funded El Mercurio, a Chilean right-wing newspaper. Documents released in 2000 by the CIA confirmed that before the elections of 1970, ITT gave $700,000 to Allende's conservative opponent, Jorge Alessandri, with help from the CIA on how to channel the money safely. ITT president Harold Geneen also offered $1 million to the CIA to help defeat Allende in the elections.[117] After General Augusto Pinochet assumed power, United States Secretary of State Henry Kissinger told President Nixon that the United States "didn't do it" (referring to the coup) but "we helped them... created the conditions as great as possible".[118] Recent documents declassified under the Clinton administration's Chile Declassification Project show that the United States government and the CIA sought to overthrow Allende in 1970 immediately before he took office ("Project FUBELT"). Many documents regarding the United States intervention in Chile remain classified. Those that have been declassified showed that Nixon, Kissinger, and the United States government were aware of the coup and the plans to overthrow Allende's democratically elected government.[119][120] Relations with the Soviet Union Political and moral support came mostly through the Communist Party and unions of the Soviet Union. For instance, Allende received the Lenin Peace Prize from the Soviet Union in 1972. At the same time, there were some fundamental differences between Allende and Soviet political analysts, who believed that some violence or measures that those analysts "theoretically considered to be just", should have been used.[121] Declarations from KGB General Nikolai Leonov, former Deputy Chief of the First Chief Directorate of the KGB, confirmed that the Soviet Union supported Allende's government economically, politically and militarily.[121] Leonov stated in an interview at the Chilean Center of Public Studies (CEP) that the Soviet economic support included over $100 million in credit, three fishing ships (that distributed 17,000 tons of frozen fish to the population), factories (as help after the 1971 earthquake), 3,100 tractors, 74,000 tons of wheat and more than a million tins of condensed milk.[121] In mid-1973, the Soviets approved the delivery of weapons (artillery and tanks) to the Chilean Army. When news of an attempt from the Army to depose Allende through a coup d'état reached Soviet officials, the shipment was redirected to another country.[121] Allende is mentioned in a book written by the official historian of the British Intelligence MI5, Christopher Andrew.[122] According to SIS and Andrew, the book is based on the handwritten notes of KGB archivist defector Vasili Mitrokhin.[123] Andrew alleged that the KGB said that Allende "was made to understand the necessity of reorganizing Chile's army and intelligence services, and of setting up a relationship between Chile's and the USSR's intelligence services."[124] The Soviets observed closely whether the alternative form of socialism could work, and they did not interfere with the Chileans' decisions. Nikolai Leonov affirmed that whenever he tried to give advice to Latin American leaders, he was usually turned down by them, and he was told that they had their own understanding on how to conduct political business in their countries. Leonov added that the relationships of KGB agents with Latin American leaders did not involve intelligence because their intelligence target was the United States. Since many North Americans were living in the region, the Soviets were focusing in recruiting agents from the United States. Latin America was also a better region for KGB agents to get in touch with their informants from the CIA or other contacts from the United States than inside that country.[121] |

アジェンデ大統領時代の対外関係 サルバドール・アジェンデは困難な国際情勢の中で大統領に就任した。1970年、チリはアメリカと同盟を結んでいた。ラテンアメリカでは、ブラジル、アル ゼンチン、ボリビアが保守的な軍事独裁政権に支配されていた(まもなくウルグアイもこれに加わる)。コロンビアとベネズエラも保守的だが民主的に選ばれた 政権だった。キューバ、ペルー、メキシコだけが、チリの社会主義実験に同情的だった。アジェンデ大統領の下でチリは非同盟運動に参加し、これは当時ラテン アメリカではほとんど唯一の立場であった[104]。 それまでイデオロギーの境界線にうるさかったチリは、各国の国内政治体制に関係なく、外交・貿易関係を多様化させた。政府はラテンアメリカ2カ国(キュー バとガイアナ)、アフリカ7カ国(コンゴ、赤道ギニア、リビア、マダガスカル、ナイジェリア、タンザニア、ザイール)、ヨーロッパ3カ国(アルバニア、東 ドイツ、ハンガリー)、アジア7カ国(アフガニスタン、バングラデシュ、カンボジア、北朝鮮、中国、モンゴル、南ベトナム、北ベトナム)と外交関係を樹立 した[104]。 ラテンアメリカの統合を促進しようとした。1971年のラテンアメリカ経済社会理事会で、チリ代表のゴンサロ・マルトネル・ガルシアは、歴史家のホルヘ・ マガシッチによって要約された4つの主要な提案を行った: 「1)対外債務の10年間モラトリアム(一時停止)を米国に要請し、その資金を開発政策に振り向けること、2)ラテンアメリカ中央銀行を創設し、「ラテン アメリカの外貨準備の70%を米国で運用」し、「ラテンアメリカ地域の預金と資産」を受け入れ、金融の混乱から地域を守るために中央銀行の業務を調整する こと; 3) 技術的所有権に関連する濫用を制限するために、ライセンス、産業プロセス、その他の研究資金の強制拠出によって運営される、開発のための世界的な技術基金 の創設を推進する。 "[104] ボリビアとは、両国間の歴史的紛争(1879年から1884年にかけての太平洋戦争以来、ボリビアは海へのアクセスを失っていた)をめぐって交渉を開始 し、ボリビアの海洋要求を歓迎した。とはいえ、1971年8月にボリビアのウーゴ・バンザー将軍がクーデターを起こし、関係は再び緊迫化した。同時に、チ リはラテンアメリカ諸国からの数千人の政治亡命者に亡命を許可した[104]。 サルバドール・アジェンデは、アメリカ政府に近い組織である米州機構(OAS)や、先進国の利益を優先する関税貿易一般協定(GATT)の影響力を公然と 否定した。一方、彼は国連貿易開発会議(UNCTAD)の熱烈な擁護者であった。UNCTADは、経済・貿易問題を対等な法的立場で交渉できるため、より 代表的であると考えたからである。国連貿易開発会議(UNCTAD)での演説で、彼はまた、自由貿易の障害を徐々に取り除いていこうとする米国、日本、欧 州経済共同体の政策に警告を発した。彼は、「貿易の自由化は......一般特恵制度が発展途上国にもたらす利益を一気に消し去る」と述べた[104]。 アジェンデの人民統一政府は、米国との正常な関係を維持しようとした。チリが銅産業を国有化すると、アメリカ政府は支援を打ち切り、反対派への支援を強め た。代替の貿易・資金源を求めざるを得なくなったチリは、ソ連から今後6年間で約4億ドルをチリに投資する約束を取り付けた。アメリカ国務省は、東ヨー ロッパから1億1500万ドル、中国から6500万ドル、ソ連とチリ人民統合筋は社会主義諸国から総額6億2000万ドルとしている。信用の多くは利用さ れることはなく、ソビエトはキューバに対して行ったのと同じようにチリに補助金を出すことを望まなかった[105]。 アジェンデ政府は、ソビエトからの経済援助が期待したよりもはるかに少なかったことに失望した。両国間の貿易は著しく増加することはなく、信用は主にソ連 の機器の購入に結びついた。しかも、ソ連からの信用は、中華人民共和国や東欧圏の国々に提供されたものに比べてはるかに少なかった。1972年後半、ア ジェンデがさらなる援助と3年後の追加融資枠を求めてソ連を訪れたとき、彼は断られた[106]。 米国の関与 主な記事 米国のチリ介入 アジェンデに対する米国の反発は、彼がチリ大統領に選出される数年前から始まっていた。機密解除された文書によれば、1962年から1964年にかけて CIAは「有権者をアジェンデのFRAP連合から遠ざけるために」反アジェンデのプロパガンダに300万ドルを費やし、エドゥアルド・フレイの大統領選挙 キャンペーンに合計260万ドルを出資した[43][44]。 1970年の選挙でアジェンデがチリで勝利する可能性は、冷戦下で共産主義の蔓延を防ぐことによってアメリカの地政学的利益を守りたかったニクソン政権に よって災難とみなされた[107]。1970年9月、当時のアメリカ合衆国大統領リチャード・ニクソンはCIAにチリのアジェンデ政権は容認されないと通 告し、アジェンデの政権獲得を阻止するか彼を失脚させるために1,000万ドルを許可した。 [CIAの文書は「アジェンデがクーデターによって打倒されることは確固とした継続的な方針である」と宣言していた[109]。ヘンリー・キッシンジャー 率いる40委員会とCIAは、「トラックI」と「トラックII」として知られる秘密工作によってアジェンデのチリ大統領就任を妨害することを計画してい た。トラックIではいわゆる「議会の策略」によってアジェンデの政権就任を阻止しようとし、トラックIIではCIAはクーデターを実行するようチリ軍の主 要将校を説得しようとした[108]。 ラ・モネダ宮殿を砲撃するために使用されたミサイルを確保したとされる国防情報局のエージェントの関与を指摘する者もいる[110]。実際、アジェンデ政 権の間、チリに対するアメリカの公然たる軍事援助は継続され、アジェンデ自身がそのような援助がチリにとって有益なもの以外の何物でもないと考えていたと いう記録はないものの、国家政府はそのことを強く認識していた。リチャード・ニクソンの大統領在任中、アメリカ政府高官は野党候補ホルヘ・アレッサンドリ と提携する政党に資金を提供し、鉱業と運輸部門のストライキを支援することによって、アジェンデの選挙を阻止しようとした[111]。 1970年の選挙後、トラックI作戦はチリの退任大統領エドゥアルド・フレイ・モンタルバを扇動し、彼の政党(PDC)に議会でアレッサンドリに投票する よう説得しようとした[112]。 この計画では、アレッサンドリは就任後すぐに大統領職を辞任し、新たな選挙を招集することになっていた。そうすればエドゥアルド・フレイは憲法上再出馬が 可能となり(チリ憲法は大統領の2期連続を認めていなかったが、複数回の非連続は認めていたため)、おそらくアジェンデを簡単に打ち負かすことができただ ろう。その代わり、チリ議会はアジェンデを大統領に選んだが、その条件として、アジェンデはチリ憲法を尊重し遵守すること、そして自らの改革がチリ憲法の いかなる要素も損なわないことを確約する「憲法保証憲章」に署名することを求めた。民主党のビル・クリントン大統領の2期目の任期中、CIAはクーデター 前にチリの政治に関与していたことを認めたが、その関与の度合いについては議論がある。CIAは差し迫ったクーデターについて2日前にチリの連絡先から通 知を受けていたが、クーデターにおいて「直接的な役割を果たさなかった」と主張している[114]。 1972年のアジェンデ アジェンデの政策に対する内部の反対派の多くはビジネスセクターからであり、最近公開された米国政府の文書によれば、米国は間接的に[88]トラック運転 手のストライキに資金を提供し、クーデター前にすでに混乱していた経済状況を悪化させた[115]。アジェンデが大統領になる前のチリで最も著名な米国企 業は、アナコンダ銅会社とケネコット銅会社、そしてITTコーポレーション(国際電話電信)であった。両銅企業は、世界最大の地下銅山「エル・テニエン テ」があるチリ・アンデスのスウェル市で、民営化された銅生産の拡大を目指した[116]。 米国商務省のデータによると、1968年末時点で、チリにおける米国企業の保有資産は9億6,400万ドルに達していた。アジェンデが選出される前の 1970年、ITTはチリの電話会社Chitelcoの70%を所有し、チリの右翼新聞El Mercurioに出資していた。CIAが2000年に公開した文書によると、1970年の選挙前にITTはアジェンデの保守派の対立候補ホルヘ・アレッ サンドリに70万ドルを提供し、その資金を安全に流す方法についてCIAから援助を受けていたことが確認されている。ITTのハロルド・ジェネーン社長も また、選挙でアジェンデを敗北させるために100万ドルをCIAに提供した[117]。 アウグスト・ピノチェト将軍が権力を掌握した後、ヘンリー・キッシンジャー米国務長官はニクソン大統領に、米国は「それをしなかった」(クーデターを指 す)が、「われわれは彼らを助けた...可能な限り素晴らしい条件を作り出した」と述べた[118]。 クリントン政権のチリ機密解除プロジェクトで機密解除された最近の文書によれば、米国政府とCIAはアジェンデが大統領に就任する直前の1970年にア ジェンデを打倒しようとしていた(「プロジェクト・フーベルト」)。米国のチリ介入に関する文書の多くは機密扱いのままである。機密解除されたものは、ニ クソン、キッシンジャー、そしてアメリカ政府がクーデターと民主的に選出されたアジェンデ政権の転覆計画を認識していたことを示している[119] [120]。 ソ連との関係 政治的・道徳的支援は、主にソビエト連邦の共産党や労働組合を通じて行われた。例えば、アジェンデは1972年にソ連からレーニン平和賞を受賞している。 同時に、アジェンデとソ連の政治アナリストとの間には根本的な相違があり、ソ連の政治アナリストは、いくつかの暴力や、それらのアナリストが「理論的には 正当であると考える」措置が使われるべきだったと考えていた[121]。KGBの元第一総局次長ニコライ・レオノフ将軍の宣言は、ソ連がアジェンデ政権を 経済的、政治的、軍事的に支援していたことを確認した。 [121] レオノフはチリ公共研究センター(CEP)でのインタビューで、ソ連の経済支援には1億ドルを超える信用供与、3隻の漁船(17,000トンの冷凍魚を住 民に配給)、工場(1971年の地震後の支援として)、3,100台のトラクター、74,000トンの小麦、100万缶を超えるコンデンスミルクが含まれ ていたと述べた[121] 1973年半ば、ソ連はチリ軍への武器(大砲と戦車)の供与を承認した。陸軍がクーデターによってアジェンデを退陣させようとしたとのニュースがソ連当局 に届くと、輸送は別の国に向けられた[121]。 アジェンデについては、イギリス諜報部MI5の公式歴史家であるクリストファー・アンドリューが書いた本の中で触れられている[122]。SISとアンド リューによれば、この本はKGBの記録係である脱北者ヴァシリ・ミトロヒンの手書きのメモに基づいている。 [アンドリューは、KGBはアジェンデが「チリの軍隊と情報機関を再編成し、チリとソ連の情報機関の関係を構築する必要性を理解させられた」と述べたと主 張している[124]。ソビエトは社会主義の代替形態が機能するかどうかを注意深く観察し、チリの決定に干渉しなかった。ニコライ・レオーノフは、ラテン アメリカの指導者たちに助言を与えようとすると、たいてい断られ、彼らには自国の政治事業の進め方について独自の理解があると言われたと断言している。レ オノフは、KGB諜報員とラテンアメリカの指導者たちとの関係は、諜報活動の対象がアメリカであったため、諜報活動とは関係なかったと付け加えた。多くの 北米人がこの地域に住んでいたため、ソビエトはアメリカからの諜報員のリクルートに力を入れていた。ラテンアメリカはまた、KGB諜報員にとって、CIA からの情報提供者やアメリカからの他の連絡先と連絡を取るのに、国内よりも適した地域でもあった[121]。 |

| Crisis On 29 June 1973, Colonel Roberto Souper surrounded the presidential palace, La Moneda, with his tank regiment but failed to depose the government.[125] That failed coup d'état – known as the Tanquetazo ("tank putsch") – organised by the nationalist Patria y Libertad paramilitary group, was followed by a general strike at the end of July that included the copper miners of El Teniente.[citation needed] In August 1973, a constitutional crisis occurred, and the Supreme Court of Chile publicly complained about the inability of the Allende government to enforce the law of the land. On 22 August, the Chamber of Deputies (with the Christian Democrats uniting with the National Party) accused the government of unconstitutional acts through Allende's refusal to promulgate constitutional amendments, already approved by the Chamber, which would have prevented his government from continuing his massive nationalization plan[126] and called upon the military to enforce constitutional order.[127] For months, Allende had feared calling upon the Carabineros ("Carabineers", the national police force), suspecting them of disloyalty to his government. On 9 August, President Allende appointed General Carlos Prats as Minister of Defence. On 24 August 1973, General Prats was forced to resign both as defense minister and as the commander-in-chief of the army, embarrassed by both the Alejandrina Cox incident and a public protest in front of his house by the wives of his generals. General Augusto Pinochet replaced him as Army commander-in-chief the same day.[127] Resolution by the Chamber of Deputies On 22 August 1973, the Christian Democrats and the National Party members of the Chamber of Deputies joined to vote 81 to 47 in favor of a resolution that made accusation of disregard by the government of the separation of powers and arrogating legislative and judicial prerogatives to the executive branch of government, among other alleged constitutional violations.[128] The resolution asked the authorities to "put an immediate end" to "breach[es of] the Constitution ... with the goal of redirecting government activity toward the path of law and ensuring the Constitutional order of our Nation, and the essential underpinnings of democratic co-existence among Chileans."[129] The resolution declared that Allende's government sought "to conquer absolute power with the obvious purpose of subjecting all citizens to the strictest political and economic control by the state ... [with] the goal of establishing ... a totalitarian system" and claimed that the government had made "violations of the Constitution ... a permanent system of conduct".[129] Specifically, the government of Allende was accused of ruling by decree and thwarting the normal legislative system, refusing to enforce judicial decisions against its partisans; not carrying out sentences and judicial resolutions that contravened its objectives, ignoring the decrees of the independent General Comptroller's Office, sundry media offenses and usurping control of the National Television Network and applying economic pressure against those media organizations that are not unconditional supporters of the government, allowing its supporters to assemble with arms, and preventing the same by its right-wing opponents, supporting more than 1,500 illegal takeovers of farms, illegal repression of the El Teniente miners' strike, and illegally limiting emigration.[129] Finally, the resolution condemned the creation and development of government-protected socialist armed groups, which were said to be "headed towards a confrontation with the armed forces". President Allende's efforts to re-organize the military and the police forces were characterized as "notorious attempts to use the armed and police forces for partisan ends, destroy their institutional hierarchy, and politically infiltrate their ranks".[129] Allende's response The resolution was later used by Pinochet a way to justify the coup, which occurred two weeks later.[130] On 24 August 1973, two days after the resolution, Allende responded. He accused the opposition of trying to incite a military coup by encouraging the armed forces to disobey civilian authorities.[131] He described the Congress's declaration as "destined to damage the country's prestige abroad and create internal confusion", and predicted: "It will facilitate the seditious intention of certain sectors." He observed that the declaration (passed 81–47 in the Chamber of Deputies) had not obtained the two-thirds Senate majority "constitutionally required" to convict the president of abuse of power, thus the Congress was "invoking the intervention of the armed forces and of Order against a democratically-elected government" and "subordinat[ing] political representation of national sovereignty to the armed institutions, which neither can nor ought to assume either political functions or the representation of the popular will."[132] Allende argued that he had obeyed constitutional means for including military men to the cabinet at the service of civic peace and national security, defending republican institutions against insurrection and terrorism. In contrast, he said that Congress was promoting a coup d’état or a civil war with a declaration full of affirmations that had already been refuted beforehand and which in substance and process (directly handing it to the ministers rather than directly handing it to the president) violated a dozen articles of the then-current constitution. He further argued that the legislature was usurping the government's executive function.[132] Allende wrote: "Chilean democracy is a conquest by all of the people. It is neither the work nor the gift of the exploiting classes, and it will be defended by those who, with sacrifices accumulated over generations, have imposed it ... With a tranquil conscience ... I sustain that never before has Chile had a more democratic government than that over which I have the honor to preside ... I solemnly reiterate my decision to develop democracy and a state of law to their ultimate consequences...Congress has made itself a bastion against the transformations ... and has done everything it can to perturb the functioning of the finances and of the institutions, sterilizing all creative initiatives." Adding that economic and political means would be needed to relieve the country's current crisis, and that the Congress was obstructing said means; having already paralyzed the state, they sought to destroy it. He concluded by calling upon the workers and all democrats and patriots to join him in defending the Chilean constitution and the revolutionary process.[132] |

危機 1973年6月29日、ロベルト・スーペル大佐は戦車連隊とともに大統領官邸ラ・モネダを包囲したが、政府を退陣させることはできなかった[125]。こ のクーデターの失敗は、民族主義的な準軍事組織「パトリア・イ・リベルタ」によって組織された「タンケターゾ」(「戦車強襲」)として知られ、7月末には エル・テニエンテの銅鉱山労働者を含むゼネストが発生した[要出典]。 1973年8月、憲法上の危機が発生し、チリ最高裁判所はアジェンデ政権が国法を執行できないことを公に訴えた。8月22日、下院(キリスト教民主党員は 国民党と統合)は、アジェンデ政権が大規模な国有化計画を継続することを妨げるような憲法改正案の公布をアジェンデが拒否し、すでに下院で承認されていた [126]違憲行為によって政府を非難し、憲法秩序を執行するよう軍に要請した[127]。 アジェンデは数ヶ月間、カラビネロス(国家警察)を政府に不誠実であると疑い、招集することを恐れていた。8月9日、アジェンデ大統領はカルロス・プラッ ツ将軍を国防大臣に任命した。1973年8月24日、プラッツ将軍は、アレハンドリナ・コックス事件と将兵の妻たちによる自宅前での抗議行動で困惑し、国 防相と軍総司令官の辞任を余儀なくされた。同日、アウグスト・ピノチェト将軍が彼の後任として陸軍総司令官に就任した[127]。 下院による決議 1973年8月22日、下院のキリスト教民主党と国民党の議員は、政府が三権分立を無視し、立法と司法の特権を行政府に横領していることを非難し、その他 の憲法違反の疑いのある決議のうち、81対47で賛成票を投じた[128]。 政府活動を法の道へと方向転換させ、わが国の憲法秩序と、チリ国民の間の民主的共存の本質的な基盤を確保することを目的として」[129]、決議案はア ジェンデ政権が「すべての国民を国家による最も厳格な政治的・経済的統制に服させるという明白な目的をもって、絶対的な権力を征服しようとした」と宣言し た。[全体主義体制の......確立を目標とする」とし、アジェンデ政権が「憲法違反を......恒久的な行動体系」にしていると主張した [129]。 具体的には、アジェンデ政府は政令によって統治し、通常の立法制度を妨害し、パルチザンに対する司法決定の執行を拒否したと非難された; その目的に反する判決や司法決議を実行しないこと、独立した会計検査院の命令を無視すること、さまざまなメディア犯罪や国営テレビ局の支配権を簒奪し、政 府の無条件支持者でないメディア組織に対して経済的圧力をかけること、支持者が武器を持って集合することを許可し、右派の反対派が同じことをするのを阻止 すること、1,500以上の農場の不法占拠を支援すること、エル・テニエンテ鉱山労働者のストライキを不法に弾圧すること、移住を不法に制限すること。 [129] 最後に、決議は、「武装勢力との対決に向かう」とされる、政府が保護する社会主義武装集団の創設と発展を非難した。軍と警察を再編成しようとするアジェン デ大統領の努力は、「党派的な目的のために軍と警察を利用し、その制度的階層を破壊し、その階級に政治的に浸透させようとする悪名高い試み」と特徴づけら れた[129]。 アジェンデの反応 この決議は後にピノチェトによって、2週間後に起きたクーデターを正当化するために利用された[130]。決議から2日後の1973年8月24日、アジェ ンデはこれに応じた。アジェンデは、反対派が武装勢力に文民当局に従わないよう促すことで軍事クーデターを煽動しようとしていると非難した[131]。ア ジェンデは、議会の宣言を「国外における国の威信を傷つけ、国内に混乱を引き起こす運命にある」と評し、こう予測した: 「それは、ある特定のセクターの扇動的な意図を助長するだろう」。アジェンデは、この宣言(下院で81対47で可決)は大統領を権力の乱用で有罪にするた めに「憲法上必要とされる」上院の3分の2の多数を得ておらず、したがって議会は「民主的に選出された政府に対して軍隊と騎士団の介入を呼び起こし」、 「政治的機能も民意の代表も引き受けることができず、また引き受けるべきでもない武装機関に国家主権の政治的代表を従属させる」ものであると指摘した [132]。 アジェンデは、市民の平和と国家の安全のために軍人を閣僚に加え、暴動やテロから共和制の制度を守るという憲法上の手段に従ったと主張した。これに対し て、議会は、すでに反論されている断言に満ちた宣言で、クーデターや内戦を促進しており、その実質と過程(大統領に直接渡すのではなく、閣僚に直接渡す) で、当時の現行憲法の12カ条に違反していると述べた。彼はさらに、立法府が政府の行政機能を簒奪していると主張した[132]。 アジェンデは「チリの民主主義は国民全員による征服である。それは搾取階級の作品でも贈り物でもなく、何世代にもわたって蓄積された犠牲の上に、それを課 してきた人々によって守られるものである。穏やかな良心をもって.チリが、私が主宰する名誉ある政府ほど民主的な政府を持ったことは、かつてなかったと断 言する.私は、民主主義と法治国家をその究極の結末まで発展させるという私の決意を厳粛に再確認する......議会は、自らを変革に対する砦と し......財政と制度の機能を混乱させるためにあらゆる手を尽くし、あらゆる創造的イニシアチブを不毛にしてきた" さらに、この国の危機を打開するためには経済的・政治的手段が必要であり、議会はその手段を妨害している。彼は最後に、労働者とすべての民主主義者と愛国 者に、チリ憲法と革命プロセスを守るために彼と一緒に行動するよう呼びかけた[132]。 |