アンチ・アンチ・オイディプスあるいは五月革命からの帰還

Anti Anti-Oedipus, or return from May 68

まずは、May 68 そしてア ンチ・オイディプスの復習から、その次に復讐へ。したがって日本で五月革命ないしは五月危機と いわれているものは「68年5月(May 68)」と覚えておいたほうが、海外の人たち(まそれもかなり年配な知識人たちだが)との議論で、通じや すいだろう(→ 「日本語のウィキでの五月革命解説」「五月革命」「エディ プス・コンプレッ クス」「アンチオイディプス」)。

| 『アンチ・オイディプス』(英語:

Anti-Oedipus、反エディプス)は、1972年に哲学者ジル・ドゥルーズと精神分析家フェリックス・ガタリによって発表された著作であり、また

『資本主義と分裂症』のシリーズの第1巻である。この著作は、人類学から派生して研

究されていた構造主義を踏まえつつ、精神科医のジークムント・フロイトにより主張されていた学説に対して批判を加える哲学的な研究であっ

た。ドゥルーズとガタリは、1968年にフランスで五月革命が発生した後に出会い、この著作をはじめとして『千のプラトー』、『カフカ』、『哲学とはなに

か』を共著で発表している。それまで、ドゥルーズは西欧で前提とされてきた形而上学

を批判し、ガタリは従来の精神医学の革新を主張していた。

この著作では、人間の精神、経済活動、社会、歴史などさまざまな主題を扱っており、全体としては4部から構成されている。/この研究では、題名でも示され

ている通り、フロイトが主張したエディプスコンプレックスの学説に対する反論として読むことができる。ここで議論の中心となっているのは、人間の無意識の欲望の概念である。フロイトは、人間が児童から大人へ移行すると

きや、社会が未開状態から文明状態へと移行するとき、欲望がどれほど抑圧されるのかを判断の基準においていた。つまり、欲望を抑制するほどに人間は大人であり、社会は文明状態であると判断していた。

したがって、人間の欲望あるいは無意識とは、「欲望する諸機械」で、エディプスコン

プレックスという欲望の抑圧を家族という社会的単位に留める装置が働く中でしか是認されないと考えられてきた。このような欲望の概念は、近

代においてルネ・デカルトやトマス・ホッブズが人間に備わっている「情念のある主」の実体を指す考え方に根ざしたものであった。ドゥルーズとガタリは、こ

の説に対して、無意識の欲望の概念を再検討し、欲望とはそれ自体で成立している実体

ではなく、ある関係の中で存在するものであると考えた。そして、欲望

をさまざまな事物を生産する機械として定義している。この見解によれば、エディプスコンプレックスは、フロイトの弟子ラカンが言うように人

間が原初的に備えているものではなく、社会的な発明によるものであ

る。 |

Fascism in detail - "It could

even be said that Deleuze and Guattari care so little for

power that they have tried to neutralize the effects of power linked to

their own discourse. Hence the games and snares scattered throughout

the book, rendering its translation a feat of real prowess. But these

are

not the familiar traps of rhetoric; the latter work to sway the reader

without his being aware of the manipulation, and ultimately win him

over against his will. The traps of Anti-Oedipus are those of humor: so

many invitations to let oneself be put out, to take one's leave of the

text

and slam the door shut. The book of ten leads one to believe it is all

fun

and games, when something essential is taking place, something of

extreme seriousness: the tracking down of all varieties of fascism,

from

the enormous ones that surround and crush us to the petty ones that

constitute the tyrannical bitterness of our everyday lives." Michael

Foucault 1972[1977], Preface of "Anti-Oedipus." "It would be a mistake to read Anti-Oedipus as the new theoretical reference (you know, that much-heralded theory that finally encompasses everything, that finally totalizes and reassures, the one we are told we "need so badly" in our age of dispersion and specialization where "hope" is lacking). One must not look for a "philosophy" amid the extraordinary profusion of new notions and surprise concepts: AntiOedipus is not a flashy Hegel. I think that Anti-Oedipus can best be read as an "art," in the sense that is conveyed by the term "erotic art," for example. Informed by the seemingly abstract notions of multiplicities, flows, arrangements, and connections, the analysis of the relationship of desire to reality and to the capitalist "machine" yields answers to concrete questions. Questions that are less concerned with why this or that than with how to proceed. How does one introduce desire into thought, into discourse, into action? How can and must desire deploy its forces within the political domain and grow more intense in the process of overturning the established order? Ars erotica, ars theoretica, ars politica." |

| ウィキペディア「https://bit.ly/3t3QpN3」日本

語 |

|

| 第1章 欲望機械 第1節 欲望的生産 第2節 器官なき身体 第3節 主体と享受 第4節 唯物論的精神医学 第5節 欲望機械 第6節 全体と諸部分 第2章 精神分析と家族主義 すなわち神聖家族 第1節 オイディプス帝国主義 第2節 フロイトの三つのテクスト 第3節 生産の接続的総合 第4節 登録の離接的総合 第5節 消費の連接的総合 第6節 三つの総合の要約 第7節 抑制と抑圧 第8節 神経症と精神病 第9節 プロセス 第3章 未開人、野蛮人、文明人 第1節 登記する社会体 第2節 原始大地機械 第3節 オイディプス問題 第4節 精神分析と人類学 第5節 大地的表象 第6節 野蛮な専制君主機械 第7節 野蛮な、あるいは帝国の表象 第8節 <原国家> 第9節 文明資本主義機械 第10節 資本主義の表象 第11節 最後はオイディプス 第4章 分裂分析への序章 第1節 社会野 第2節 分子的無意識 第3節 精神分析と資本主義 第4節 分裂分析の肯定的な第一の課題 第5節 第二の肯定的課題 補遺 欲望機械のための総括とプログラム |

|

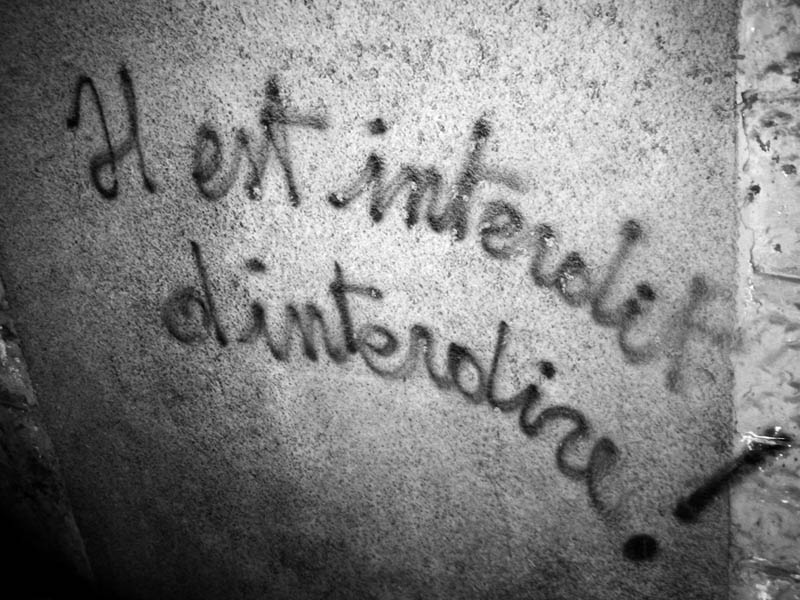

| May 68 Beginning in May 1968, a period of civil unrest occurred throughout France, lasting seven weeks and punctuated by demonstrations, general strikes, and the occupation of universities and factories. At the height of events, which have since become known as May 68 (French: Mai 68), the economy of France came to a halt.[2] The protests reached a point that made political leaders fear civil war or revolution; the national government briefly ceased to function after President Charles de Gaulle secretly fled France to West Germany on the 29th. The protests are sometimes linked to similar movements around the same time worldwide[3] that inspired a generation of protest art in the form of songs, imaginative graffiti, posters, and slogans.[4][5] The unrest began with a series of far-left student occupation protests against capitalism, consumerism, American imperialism and traditional institutions. Heavy police repression of the protesters led France's trade union confederations to call for sympathy strikes, which spread far more quickly than expected to involve 11 million workers, more than 22% of France's population at the time.[2] The movement was characterized by spontaneous and decentralized wildcat disposition; this created contrast and at times even conflict among the trade unions and leftist parties.[2] It was the largest general strike ever attempted in France, and the first nationwide wildcat general strike.[2] The student occupations and general strikes across France met with forceful confrontation by university administrators and police. The de Gaulle administration's attempts to quell the strikes by police action only inflamed the situation, leading to street battles with the police in Paris's Latin Quarter. By late May the flow of events had changed. The Grenelle accords, concluded on 27 May between the government, trade unions and employers, won significant wage gains for workers. A counter-demonstration organised by the Gaullist party on 29 May in central Paris gave De Gaulle the confidence to dissolve the National Assembly and call parliamentary elections for 23 June 1968. Violence evaporated almost as quickly as it arose. Workers returned to their jobs, and after the June elections, the Gaullists emerged stronger than before. The events of May 1968 continue to influence French society. The period is considered a cultural, social and moral turning point in the nation's history. Alain Geismar, who was one of the student leaders at the time, later said the movement had succeeded "as a social revolution, not as a political one".[6] |

1968年5月(五月革命、五月危機) 1968年5月、フランス全土でデモ、ゼネスト、大学や工場の占拠などの市民運動が7週間続いた。抗議運動は政治指導者たちに内戦や革命を恐れさせるまで になり、シャルル・ド・ゴール大統領が29日に密かにフランスから西ドイツに逃亡した後、国家政府は一時機能停止に陥った。この抗議運動は、歌、想像力豊 かな落書き、ポスター、スローガンなどの形で抗議芸術の世代を鼓舞した、世界同時期の同様の運動[3]と関連付けられることもある[4][5]。 この騒乱は、資本主義、消費主義、アメリカ帝国主義、伝統的制度に反対する一連の極左学生占拠抗議行動から始まった。デモ参加者に対する警察の激しい弾圧 により、フランスの労働組合総連合は同情ストライキを呼びかけ、このストライキは予想をはるかに上回る速さで広がり、当時のフランス人口の22%以上にあ たる1,100万人の労働者を巻き込んだ。この運動は、自然発生的で分散的な山猫的気質を特徴としていた。このため、労働組合と左派政党の間にコントラス トが生まれ、時には対立さえ生じた。フランスで試みられた最大のゼネストであり、初の全国的な山猫ゼネストであった。 フランス全土の学生占拠とゼネストは、大学当局と警察による強硬な対立に見舞われた。ド・ゴール政権が警察によってストライキを鎮圧しようとしたことは事 態を悪化させ、パリのラテン地区では警察との路上戦闘に発展した。 5月下旬には流れが変わった。5月27日に政府、労働組合、使用者の間で締結されたグルネル協定により、労働者の大幅な賃上げが実現した。5月29日にパ リ中心部でゴーリスト党が組織した反対デモは、ドゴールに国民議会を解散し、1968年6月23日に議会選挙を実施する自信を与えた。暴力は発生とほぼ同 時に消滅した。労働者は職場に戻り、6月の選挙後、ゴーリスト派は以前よりも強くなった。 1968年5月の出来事はフランス社会に影響を与え続けている。この時期は、国の歴史における文化的、社会的、道徳的な転換点とみなされている。当時の学 生指導者の一人であったアラン・ガイスマールは後に、この運動は「政治革命としてではなく、社会革命として」成功したと述べている[6]。 |

| Background Political climate In February 1968, the French Communist Party and the French Section of the Workers' International formed an electoral alliance. Communists had long supported Socialist candidates in elections, but in the "February Declaration" the two parties agreed to attempt to form a joint government to replace President Charles de Gaulle and his Gaullist Party.[7] University demonstration On 22 March, far-left groups, a small number of prominent poets and musicians, and 150 students occupied an administration building at Paris University at Nanterre and held a meeting in the university council room about class discrimination in French society and the political bureaucracy that controlled the university's funding. The university's administration called the police, who surrounded the university. After the publication of their wishes, the students left the building without any trouble. After this, some leaders of what was named the "Movement of 22 March" were called together by the disciplinary committee of the university. |

背景 政治情勢 1968年2月、フランス共産党と労働者インターナショナル・フランス支部は選挙同盟を結んだ。共産主義者は長い間選挙で社会党候補を支持していたが、 「2月宣言」で両党はシャルル・ド・ゴール大統領と彼のゴーリスト党に代わる共同政権を樹立しようとすることに合意した[7]。 大学デモ 3月22日、極左団体、少数の著名な詩人や音楽家、150人の学生がパリ大学ナンテール校の管理棟を占拠し、大学の会議室でフランス社会における階級差別 や大学の資金を管理する政治官僚制について会議を開いた。大学当局は警察に通報し、警察は大学を包囲した。大学側は警察に通報し、警察は大学を包囲した。 この後、「3月22日運動」と名づけられたいくつかの指導者たちが、大学の懲罰委員会に呼び出された。 |

| Events of May Student protests Public square of the Sorbonne, in the Latin Quarter of Paris After months of conflicts between students and authorities at the Nanterre campus of the University of Paris (now Paris Nanterre University), the administration shut the university down on 2 May 1968.[8] Students at the University of Paris's Sorbonne campus (today Sorbonne University) met on 3 May to protest the closure and the threatened expulsion of several Nanterre students.[9] On 6 May, the national student union, the Union Nationale des Étudiants de France (UNEF, the National Union of Students of France)—still France's largest student union today—and the union of university teachers called a march to protest the police invasion of the Sorbonne. More than 20,000 students, teachers and supporters marched toward the Sorbonne, still sealed off by the police, who charged, wielding their batons, as soon as the marchers approached. While the crowd dispersed, some began to create barricades out of whatever was at hand, while others threw paving stones, forcing the police to retreat for a time. The police then responded with tear gas and charged the crowd again. Hundreds more students were arrested. Graffiti in a classroom Graffiti on the school of law, "Vive de Gaulle" (Long live De Gaulle) with, at left, the word "A bas" (down with) written across "Vive" University of Lyon during student occupation, May–June 1968 High school student unions spoke in support of the riots on 6 May. The next day, they joined the students, teachers and increasing numbers of young workers who gathered at the Arc de Triomphe to demand that (1) all criminal charges against arrested students be dropped, (2) the police leave the university, and (3) the authorities reopen Nanterre and Sorbonne. Escalating conflict Negotiations broke down, and students returned to their campuses after a false report that the government had agreed to reopen them, only to discover the police still occupying the schools. This led to near revolutionary fervor among the students. On 10 May, another huge crowd congregated on the Rive Gauche. When the Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité again blocked them from crossing the river, the crowd again threw up barricades, which the police then attacked at 2:15 a.m. after negotiations once again floundered. The confrontation, which produced hundreds of arrests and injuries, lasted until dawn. The events were broadcast on radio as they occurred and the aftermath shown on television the next day. It was alleged that the police had participated in the riots, through agents provocateurs, by burning cars and throwing Molotov cocktails.[10] The government's heavy-handed reaction brought on a wave of sympathy for the strikers. Many of the nation's more mainstream singers and poets joined after the police brutality came to light. American artists also began voicing support of the strikers. The major left union federations, the Confédération Générale du Travail (CGT) and the Force Ouvrière (CGT-FO), called a one-day general strike and demonstration for Monday, 13 May. Well over a million people marched through Paris that day; the police stayed largely out of sight. Prime Minister Georges Pompidou personally announced the release of the prisoners and the reopening of the Sorbonne. However, the surge of strikes did not recede. Instead, the protesters became even more active. When the Sorbonne reopened, students occupied it and declared it an autonomous "people's university". Public opinion at first supported the students, but turned against them after their leaders, invited to appear on national television, "behaved like irresponsible utopianists who wanted to destroy the 'consumer society'".[11] Nonetheless, in the weeks that followed, approximately 401 popular action committees were set up in Paris and elsewhere to take up grievances against the government and French society, including the Sorbonne Occupation Committee. Worker strikes Strikers in Southern France with a sign reading "Factory Occupied by the Workers." Behind them is a list of demands, June 1968. By the middle of May, demonstrations extended to factories, though workers' demands significantly varied from students'. A union-led general strike on 13 May included 200,000 in a march. The strikes spread to all sectors of the French economy, including state-owned jobs, manufacturing and service industries, management, and administration. Across France, students occupied university structures and up to one-third of the country's workforce was on strike.[12] These strikes were not led by the union movement; on the contrary, the CGT tried to contain this spontaneous outbreak of militancy by channeling it into a struggle for higher wages and other economic demands. Workers put forward a broader, more political and more radical agenda, demanding an ouster of de Gaulle's government and attempting, in some cases, to run their factories. When the trade union leadership negotiated a 35% increase in the minimum wage, a 7% wage increase for other workers, and half normal pay for the time on strike with the major employers' associations, the workers occupying their factories refused to return to work and jeered their union leaders.[13][14] In fact, the May 68 movement included substantial "anti-unionist euphoria"[15] against the mainstream unions, the CGT, FO and CFDT, that were more willing to compromise with the government than enact the will of the base.[2] On 24 May, two people died at the hands of out-of-control rioters. In Lyon, Police Inspector Rene Lacroix died when he was crushed by a driverless truck rioters sent careering into police lines. In Paris, Phillipe Metherion, 26, was stabbed to death during an argument among demonstrators.[1] As the upheaval reached its apogee in late May, major trade unions met with employers' organizations and the French government to produce the Grenelle agreements, which would increase the minimum wage 35% and all salaries 10%, and granted employee protections and a shortened working day. The unions were forced to reject the agreement, based on opposition from their members, underscoring a disconnect in organizations that claimed to reflect working class interests.[16] The UNEF student union and CFDT trade union held a rally in the Charléty stadium with about 22,000 attendees. Its range of speakers reflected the divide between student and Communist factions. While the rally was held in the stadium partly for security, the speakers' insurrectionist messages were dissonant with the relative amenities of the sports venue.[17] Calls for new government The Socialists saw an opportunity to act as a compromise between de Gaulle and the Communists. On 28 May, François Mitterrand of the Federation of the Democratic and Socialist Left declared that "there is no more state" and said he was ready to form a new government. He had received a surprisingly high 45% of the vote in the 1965 presidential election. On 29 May, Pierre Mendès France also said he was ready to form a new government; unlike Mitterrand, he was willing to include the Communists. Although the Socialists lacked the Communists' ability to form large street demonstrations, they had more than 20% of the country's support.[11][7] De Gaulle flees On the morning of 29 May, de Gaulle postponed the meeting of the Council of Ministers scheduled for that day and secretly removed his personal papers from Élysée Palace. He told his son-in-law Alain de Boissieu: "I do not want to give them a chance to attack the Élysée. It would be regrettable if blood were shed in my personal defense. I have decided to leave: nobody attacks an empty palace." De Gaulle refused Pompidou's request that he dissolve the National Assembly, as he believed that their party, the Gaullists, would lose the resulting election. At 11:00 am, he told Pompidou, "I am the past; you are the future; I embrace you."[11] The government announced that de Gaulle was going to his country home in Colombey-les-Deux-Églises before returning the next day, and rumors spread that he would prepare his resignation speech there. However, the presidential helicopter did not arrive in Colombey, and de Gaulle had told no one in the government where he was going. For more than six hours the world did not know where he was.[18] The canceling of the ministerial meeting and de Gaulle's mysterious disappearance stunned the French,[11] including Pompidou, who shouted, "He has fled the country!"[19] Government collapse With de Gaulle's closest advisors saying they did not know what he intended, Pompidou scheduled a tentative appearance on television at 8 p.m.[18] The national government had effectively ceased to function. Édouard Balladur later wrote that as prime minister, Pompidou "by himself was the whole government", as most officials were "an incoherent group of confabulators" who believed that revolution would soon occur. A friend of Pompidou offered him a weapon, saying, "You will need it"; Pompidou advised him to go home. One official reportedly began burning documents, while another asked an aide how far they could flee by automobile should revolutionaries seize fuel supplies. Withdrawing money from banks became difficult, gasoline for private automobiles was unavailable, and some people tried to obtain private planes or fake national identity cards.[11] Pompidou unsuccessfully requested that military radar be used to follow de Gaulle's two helicopters, but soon learned that he had gone to the headquarters of the French Forces in Germany, in Baden-Baden, to meet General Jacques Massu. Massu persuaded the discouraged de Gaulle to return to France; now knowing that he had the military's support, de Gaulle rescheduled the meeting of the Council of Ministers for the next day, 30 May,[11] and returned to Colombey by 6:00 pm.[18] However, his wife Yvonne gave the family jewels to their son and daughter-in-law—who stayed in Baden for a few more days—for safekeeping, indicating that the de Gaulles still considered Germany a possible refuge. Massu kept as a state secret de Gaulle's loss of confidence until others disclosed it in 1982; until then most observers believed that his disappearance was intended to remind the French people of what they might lose. Although the disappearance was real and not intended as motivation, it indeed had such an effect on France.[11] Revolution prevented  Pierre Messmer On 30 May, 400,000 to 500,000 protesters (many more than the 50,000 the police were expecting) led by the CGT marched through Paris, chanting: "Adieu, de Gaulle!" ("Farewell, de Gaulle!"). Maurice Grimaud, head of the Paris police, played a key role in avoiding revolution by both speaking to and spying on the revolutionaries, and by avoiding the use of force. While Communist leaders later denied that they had planned an armed uprising, and extreme militants only comprised 2% of the populace, they had overestimated de Gaulle's strength, as shown by his escape to Germany.[11] One scholar, otherwise skeptical of French Communists' willingness to maintain democracy after forming a government, claims that the "moderate, nonviolent and essentially antirevolutionary" Communists opposed revolution because they sincerely believed that the party must come to power through legal elections, not armed conflict that might provoke harsh repression from political opponents.[7] Not knowing that the Communists did not intend to seize power, officials prepared to position police forces at the Élysée with orders to shoot if necessary. That it did not also guard Paris City Hall despite reports that it was the Communists' target was evidence of governmental chaos.[18] The Communist movement largely centered around the Paris metropolitan area, and not elsewhere. Had the rebellion occupied key public buildings in Paris, the government would have had to use force to retake them. The resulting casualties could have incited a revolution, with the military moving from the provinces to retake Paris as in 1871. Minister of Defence Pierre Messmer and Chief of the Defence Staff Michel Fourquet prepared for such an action, and Pompidou had ordered tanks to Issy-les-Moulineaux.[11] While the military was free of revolutionary sentiment, using an army mostly of conscripts the same age as the revolutionaries would have been very dangerous for the government.[7][18] A survey conducted immediately after the crisis found that 20% of Frenchmen would have supported a revolution, 23% would have opposed it, and 57% would have avoided physical participation in the conflict. 33% would have fought a military intervention, while only 5% would have supported it and a majority of the country would have avoided any action.[11] Election called At 2:30 p.m. on 30 May, Pompidou persuaded de Gaulle to dissolve the National Assembly and call a new election by threatening to resign. At 4:30 pm, de Gaulle broadcast his refusal to resign. He announced an election, scheduled for 23 June, and ordered workers to return to work, threatening to institute a state of emergency if they did not. The government had leaked to the media that the army was outside Paris. Immediately after the speech, about 800,000 supporters marched through the Champs-Élysées waving the national flag; the Gaullists had planned the rally for several days, which attracted a crowd of diverse ages, occupations, and politics. The Communists agreed to the election, and the threat of revolution was over.[11][18][20] |

5月の出来事 学生による抗議行動 パリのラテン地区にあるソルボンヌ大学の広場 1968年5月2日、パリ大学ナンテール校(現パリ・ナンテール大学)の学生と当局との数ヶ月にわたる対立の後、大学は閉鎖された[8]。5月3日、パリ 大学ソルボンヌ校(現ソルボンヌ大学)の学生は、閉鎖とナンテール校の学生数名の追放の危機に抗議するために集会を開いた。 [5月6日、現在もフランス最大の学生組合であるフランス全国学生組合(UNEF)と大学教員組合は、ソルボンヌ大学への警察の侵入に抗議するデモ行進を 呼びかけた。20,000人以上の学生、教師、支援者が、警察によって封鎖されたままのソルボンヌ大学に向かって行進し、行進者が近づくや否や、警察は警 棒を振り回して突撃した。群衆が散り散りになる中、手近なものでバリケードを作る者や敷石を投げる者が現れ、警察は一時退却を余儀なくされた。警察は催涙 ガスで応戦し、群衆を再び攻撃した。さらに数百人の学生が逮捕された。 教室の落書き 法学部の落書き。"Vive de Gaulle"(ド・ゴール万歳)と書かれ、左側には "Vive "の横に "A bas"(共に倒れろ)と書かれている。 学生占拠中のリヨン大学(1968年5月~6月 高校の学生組合は5月6日、暴動を支持する演説を行った。翌日、彼らは凱旋門に集まった学生、教師、そして増え続ける若年労働者とともに、(1)逮捕され た学生に対するすべての刑事責任を取り下げ、(2)警察が大学から立ち去り、(3)当局がナンテールとソルボンヌを再開することを要求した。 激化する対立 交渉は決裂し、政府が再開に同意したという虚偽の報告の後、学生たちはキャンパスに戻った。このため、学生たちの間では革命熱に近いものが起こった。 5月10日、リヴ・ゴーシュにまた大群衆が集まった。警備隊が川を渡るのを再び阻止すると、群衆は再びバリケードを築き、交渉が再び難航したため、警察は 午前2時15分にバリケードを攻撃した。何百人もの逮捕者と負傷者を出したこの対立は、夜明けまで続いた。その模様はラジオで放送され、翌日にはテレビで その余波が放映された。警察は挑発工作員を通じて、車を燃やしたり火炎瓶を投げたりして暴動に参加したとされた[10]。 政府の強硬な反応は、ストライキ参加者への同情の波をもたらした。警察の蛮行が明るみに出た後、アメリカの主流派の歌手や詩人の多くが参加した。アメリカ の芸術家たちもストライキ参加者への支持を表明し始めた。主要な左派労組連合である労働総同盟(CGT)と労働総同盟(CGT-FO)は、5月13日 (月)の1日ゼネストとデモを呼びかけた。 その日、100万人を超える人々がパリ市内を行進したが、警察はほとんど姿を見せなかった。ポンピドゥー首相は自ら囚人の釈放とソルボンヌ大学の再開を発 表した。しかし、ストライキの波は収まることはなかった。それどころか、デモ隊はさらに活発になった。 ソルボンヌ大学が再開されると、学生たちはそこを占拠し、「人民大学」の自治を宣言した。世論は当初学生たちを支持していたが、国営テレビに招かれた指導 者たちが「『消費社会』の破壊を望む無責任なユートピア主義者のように振る舞った」[11]ことから、学生たちに反感を抱くようになった。それでも、その 後の数週間で、ソルボンヌ占拠委員会を含め、政府やフランス社会に対する不満を取り上げる約401の民衆行動委員会がパリやその他の地域に設置された。 労働者のストライキ "労働者によって占拠された工場 "と書かれた看板を掲げる南フランスのストライキ参加者。背後には要求リスト(1968年6月)。 5月中旬までに、デモは工場にまで拡大したが、労働者の要求は学生の要求とは大きく異なっていた。5月13日の組合主導のゼネストには20万人が行進し た。ストライキは国有企業、製造業、サービス業、経営者、管理者などフランス経済のあらゆる部門に広がった。フランス全土で、学生が大学の建物を占拠し、 国内の労働者の3分の1までがストライキに突入した[12]。 これらのストライキは組合運動が主導したものではなく、それどころかCGTは、この自然発生的な戦闘性の発生を、賃上げやその他の経済的要求を求める闘争 に誘導することによって封じ込めようとした。労働者はより広範で、より政治的で、より急進的なアジェンダを打ち出し、ドゴール政権の退陣を要求し、場合に よっては工場の経営を試みた。労働組合の指導部が主要な使用者団体と最低賃金の35%引き上げ、その他の労働者の賃金の7%引き上げ、ストライキ期間中の 通常の賃金の半額を交渉したとき、工場を占拠していた労働者たちは職場復帰を拒否し、組合指導者を嘲笑した[13][14]。 事実、5月68日運動には、基層の意思を実現するよりも政府との妥協を厭わない主流派組合であるCGT、FO、CFDTに対する実質的な「反組合主義者の 陶酔」[15]が含まれていた[2]。 5月24日、制御不能に陥った暴徒によって2人が死亡した。リヨンでは、ルネ・ラクロワ警部が、暴徒が警察の列に突っ込ませた運転手のいないトラックに押 しつぶされて死亡した。パリでは、フィリップ・メテリオン(26歳)がデモ隊同士の口論中に刺殺された[1]。 騒乱が頂点に達した5月下旬、主要な労働組合は使用者団体およびフランス政府と会談し、最低賃金を35%、すべての給与を10%引き上げ、従業員保護と労 働時間の短縮を認めるグレネル協約を作成した。労働組合は組合員の反対により協約の拒否を余儀なくされ、労働者階級の利益を反映すると主張する組織の断絶 が浮き彫りになった[16]。 UNEF学生組合とCFDT労働組合はシャルレティ・スタジアムで集会を開き、約22,000人が参加した。演説者の顔ぶれは、学生派と共産主義派の分裂 を反映していた。集会がスタジアムで開催されたのは警備のためでもあったが、演説者たちの反乱主義的なメッセージは、スポーツ会場の比較的快適な環境と不 協和だった[17]。 新政府への要求 社会党は、ドゴールと共産主義者の妥協案として行動する機会を得た。5月28日、民主・社会主義左翼連合のフランソワ・ミッテランは「もう国家は存在しな い」と宣言し、新政権を樹立する用意があると述べた。ミッテランは1965年の大統領選挙で45%という驚異的な得票率を獲得していた。5月29日、ピ エール・メンデス・フランスも新政権を樹立する用意があると述べた。ミッテランとは異なり、彼は共産党を取り込むことを望んでいた。社会党には共産党のよ うな大規模な街頭デモを行う能力はなかったが、国内の20%以上の支持を得ていた[11][7]。 ドゴールの逃亡 5月29日の朝、ドゴールはその日に予定されていた閣僚会議を延期し、エリゼ宮から私物を密かに持ち出した。彼は義理の息子アラン・ド・ボワシューに言っ た: 「私は彼らにエリゼを攻撃する機会を与えたくない。私の個人的な防衛のために血が流されるのは残念なことだ。空っぽの宮殿を攻撃する者などいない"。ド ゴールはポンピドゥーからの国民議会解散の要求を拒否した。午前11時、彼はポンピドゥーに「私は過去であり、あなたは未来である。 政府は、ドゴールが翌日帰国する前にコロンビー・レ・ドゥ・エグリーズの別荘に向かうと発表し、そこで辞任演説の準備をするという噂が広まった。しかし、 大統領専用ヘリコプターはコロンビーに到着せず、ドゴールは政府の誰にも行き先を告げていなかった。閣僚会議の中止とド・ゴールの謎の失踪は、ポンピ ドゥーをはじめとするフランス人[11]を驚愕させ、ポンピドゥーは「彼は国外に逃亡した!」と叫んだ[19]。 政府崩壊 ドゴールの最側近たちは、ドゴールが何を意図しているのかわからないと言っていたが、ポンピドゥーは午後8時にテレビに仮出演する予定だった[18]。後 にエドゥアール・バラデュールは、首相であったポンピドゥーは「自分ひとりが政府のすべてであった」と記している。ほとんどの官僚は「支離滅裂な合議者の 集団」であり、革命がすぐに起こると信じていたからである。ポンピドゥーの友人が「君には必要だろう」と武器を差し出したが、ポンピドゥーは「家に帰れ」 と忠告した。ある役人は書類を燃やし始め、別の役人は革命派が燃料を押収した場合、自動車でどこまで逃げられるかを側近に尋ねたという。銀行からの引き出 しは困難になり、自家用車用のガソリンは手に入らなくなり、自家用飛行機や偽の国民IDカードを手に入れようとする者もいた[11]。 ポンピドゥーは、ドゴールの2機のヘリコプターを追跡するために軍のレーダーを使うよう要求したが失敗し、すぐに彼がバーデンバーデンの在ドイツフランス 軍司令部に行き、ジャック・マス将軍に会ったことを知った。マスー将軍は落胆していたドゴールにフランスに戻るよう説得し、ドゴールは軍の支持を得ている ことを知ったため、閣僚会議の予定を翌日の5月30日に変更し[11]、午後6時までにコロンビーに戻った[18]。しかし、妻のイヴォンヌは、さらに数 日間バーデンに滞在していた息子夫婦に家族の宝石を預けており、ドゴール夫妻がまだドイツを避難先として考えていたことを示していた。マスーは、1982 年に他人が暴露するまで、ド・ゴールの失脚を国家機密としていた。それまでは、彼の失踪は、フランス国民が失うかもしれないものを思い起こさせるためのも のだと、ほとんどのオブザーバーは考えていた。失踪は現実のものであり、動機付けのためのものではなかったが、フランスにそのような影響を与えたのは事実 である[11]。 革命の阻止  ピエール・メスメール 5月30日、CGTに率いられた40万から50万のデモ隊(警察が予想していた5万人よりも多かった)が、「アデュー、ドゴール」と唱えながらパリ市内を 行進した: "さらば、ド・ゴール! (さらば、ド・ゴール!)」と唱和しながら行進した。パリ警察のモーリス・グリモーは、革命派との対話とスパイ活動、そして武力行使の回避によって、革命 回避に重要な役割を果たした。共産主義指導者たちは後に武装蜂起を計画していたことを否定し、極端な過激派は民衆の2%に過ぎなかったが、ドイツへの逃亡 で示されたように、彼らはド・ゴールの力を過大評価していた。 [11] ある学者は、フランス共産主義者が政権を樹立した後も民主主義を維持しようとしたことに懐疑的であったが、「穏健で、非暴力的で、本質的に反革命的」な共 産主義者が革命に反対したのは、党が政敵からの厳しい弾圧を引き起こす可能性のある武力衝突ではなく、合法的な選挙を通じて政権を獲得しなければならない と心から信じていたからだと主張している[7]。 共産主義者が権力を掌握するつもりがないことを知らなかった官憲は、必要であれば発砲せよとの命令とともに警察部隊をエリゼに配置する準備をした。パリ市 庁舎が共産主義者の標的であるとの報告にもかかわらず、市庁舎も警備しなかったことは、政府の混乱の証拠であった[18]。もし反乱軍がパリの主要な公共 施設を占拠していたら、政府は武力で奪還しなければならなかっただろう。その結果、死傷者が出て、1871年のように軍隊が地方からパリを奪還するために 動き出し、革命を引き起こす可能性もあった。ピエール・メスメール国防大臣とミシェル・フルケ国防参謀総長はそのような事態に備えており、ポンピドゥーは イッシー・レ・ムリノーに戦車を派遣するよう命じていた[11]。軍部には革命的感情はなかったが、革命家と同年代の徴兵兵を中心とした軍隊を使用するこ とは政府にとって非常に危険なことであった[7][18]。 危機直後に実施された調査によると、フランス人の20%が革命を支持し、23%が反対し、57%が紛争への物理的参加を避けたという。33%は軍事介入を 支持し、5%のみが軍事介入を支持し、国民の大多数はいかなる行動も回避していた[11]。 選挙公示 5月30日午後2時30分、ポンピドゥーは辞任をちらつかせることで、国民議会を解散し、新たな選挙を招集するようドゴールを説得した。午後4時30分、 ドゴールは辞任を拒否する声明を発表した。ドゴールは6月23日に予定されていた選挙を告げ、労働者たちに職場復帰を命じ、もしそうしなければ非常事態宣 言を出すと脅した。政府は、軍隊がパリ郊外にいることをメディアにリークしていた。演説の直後、約80万人の支持者が国旗を振りながらシャンゼリゼ通りを 行進した。ガリア派は数日前からこの集会を計画しており、年齢も職業も政治もさまざまな人々が集まった。共産党は選挙に同意し、革命の危機は去った [11][18][20]。 |

| Aftermath Protest suppression and elections From that point, the revolutionary feeling of the students and workers faded away. Workers gradually returned to work or were ousted from their plants by police. The national student union called off street demonstrations. The government banned several leftist organizations. The police retook the Sorbonne on 16 June. Contrary to de Gaulle's fears, his party won the greatest victory in French parliamentary history in the legislative election held in June, taking 353 of 486 seats to the Communists' 34 and the Socialists' 57.[11] The February Declaration and its promise to include Communists in government likely hurt the Socialists in the election. Their opponents cited the example of the Czechoslovak National Front government of 1945, which led to a Communist takeover of the country in 1948. Socialist voters were divided; in a February 1968 survey a majority had favored allying with the Communists, but 44% believed that Communists would attempt to seize power once in government (30% of Communist voters agreed).[7] On Bastille Day, there were resurgent street demonstrations in the Latin Quarter, led by socialist students, leftists and communists wearing red armbands and anarchists wearing black armbands. The Paris police and the Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité (CRS) harshly responded starting around 10 pm and continuing through the night, on the streets, in police vans, at police stations, and in hospitals where many wounded were taken. There was, as a result, much bloodshed among students and tourists there for the evening's festivities. No charges were filed against police or demonstrators, but the governments of Britain and West Germany filed formal protests, including for the indecent assault of two English schoolgirls by police in a police station. National feelings Despite the size of de Gaulle's triumph, it was not a personal one. A post-crisis survey conducted by Mattei Dogan showed that a majority of the country saw de Gaulle as "'too sure of himself' (70%), 'too old to govern' (59%), 'too authoritarian' (64%), 'too concerned with his personal prestige' (69%), 'too conservative' (63%), and 'too anti-American' (69%)"; as the April 1969 referendum would show, the country was ready for "Gaullism without de Gaulle".[11] |

余波 抗議弾圧と選挙 その時点から、学生や労働者の革命的感情は薄れていった。労働者は徐々に職場に戻り、あるいは警察によって工場から追い出された。全国学生組合は街頭デモ を中止した。政府はいくつかの左翼団体を禁止した。警察は6月16日にソルボンヌ大学を奪還した。ドゴールの懸念に反して、6月に行われた議会選挙でド ゴール党は486議席中353議席を獲得し、共産党34議席、社会党57議席というフランス議会史上最大の勝利を収めた[11]。反対派は、1945年の チェコスロバキア国民戦線政権が1948年に共産党に占領された例を引き合いに出した。1968年2月の調査では、社会党の有権者の過半数が共産党との同 盟に賛成していたが、44%が共産党が政権を握れば政権を奪取しようとすると考えていた(共産党員の30%が賛成)[7]。 バスティーユの日、ラテン地区では、赤い腕章をつけた社会主義学生、左翼、共産主義者、黒い腕章をつけたアナキストたちによる街頭デモが復活した。パリ警 察と治安警備隊(CRS)は、午後10時頃から夜通し、路上、警察車両、警察署、負傷者が多数収容された病院などで厳しく対応した。その結果、夜のお祭り に来ていた学生や観光客の間で多くの流血が発生した。警察やデモ参加者に罪は問われなかったが、イギリスと西ドイツの両政府は、警察署内で2人のイギリス 人女子学生に警察が強制わいせつを働いたことなどに対し、正式な抗議を行った。 国民感情 ド・ゴールの勝利の大きさにもかかわらず、それは個人的なものではなかった。マッテイ・ドガンが危機後に行った調査によると、国民の大多数がドゴールを 「『自分に自信がありすぎる』(70%)、『統治するには年を取りすぎている』(59%)、『権威主義的すぎる』(64%)、『個人的な威信を気にしすぎ ている』(69%)、『保守的すぎる』(63%)、『反米的すぎる』(69%)」と見ており、1969年4月の国民投票が示すように、国民は「ドゴール抜 きのゴーリズム」の用意ができていた[11]。 |

| May 1968 is an important

reference point in French politics, representing for some the

possibility of liberation and for others the dangers of anarchy.[6] For

some, May 1968 meant the end of traditional collective action and the

beginning of a new era to be dominated mainly by the so-called new

social movements.[21] Someone who took part in or supported this period of unrest is known as a soixante-huitard (a "68-er")—a term that has entered the English language. |

1968年5月はフランス政治における重要な参照点であり、ある者に

とっては解放の可能性を、またある者にとっては無政府状態の危険性を表している[6]。ある者にとっては、1968年5月は伝統的な集団行動の終焉を意味

し、いわゆる新しい社会運動が主に支配する新しい時代の始まりを意味した[21]。 この不安の時代に参加した、あるいは支援した人物は、ソワサント・ユイタール(「68年派」)として知られ、この言葉は英語にもなっている。 |

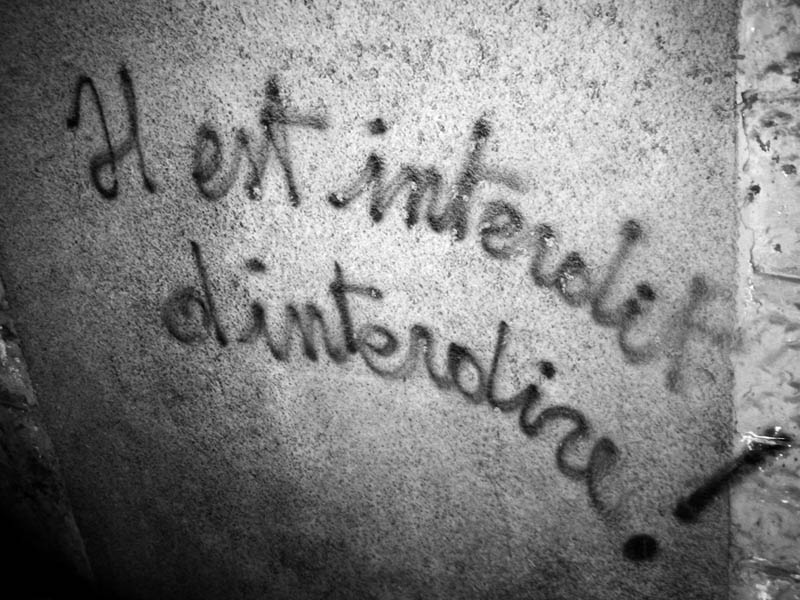

| Slogans and graffiti May 1968 slogan. Paris. "It is forbidden to forbid." Sous les pavés, la plage! ("Under the paving stones, the beach!") is a slogan coined by student activist Bernard Cousin[22] in collaboration with public relations expert Bernard Fritsch.[23] The phrase became an emblem of the events and movement of the spring of 1968, when the revolutionary students began to build barricades in the streets of major cities by tearing up street pavement stone. As the first barricades were raised, the students recognized that the stone setts were placed atop sand. The slogan encapsulated the movement's views on urbanization and modern society both literally and metaphorically. Other examples:[24]  Il est interdit d'interdire ("It is forbidden to forbid")[25] Jouissez sans entraves ("Enjoy without hindrance")[25] Élections, piège à con ("Elections, a trap for idiots")[26] CRS = SS[27] Je suis Marxiste—tendance Groucho ("I'm a Marxist—of the Groucho persuasion")[28] Marx, Mao, Marcuse![29][30][31] Also known as "3M".[32] Cela nous concerne tous. ("This concerns all of us") Soyez réalistes, demandez l'impossible ("Be realistic, demand the impossible")[33] "When the National Assembly becomes a bourgeois theater, all the bourgeois theaters should be turned into national assemblies." (Written above the entrance of the occupied Odéon Theater)[34] "I love you!!! Oh, say it with paving stones!!!"[35] "Read Reich and act accordingly!" (University of Frankfurt; similar Reichian slogans were scrawled on the walls of the Sorbonne, and in Berlin students threw copies of Reich's The Mass Psychology of Fascism at the police)[36] Travailleurs la lutte continue[;] constituez-vous en comité de base. ("Workers[,] the fight continues; form a basic committee.")[37][38] or simply La lutte continue ("The struggle continues")[38] |

スローガンと落書き 1968年5月のスローガン。パリ。"禁じることは禁じられている" 敷石の下は、海辺!(敷石の下には浜辺がある!)」は、学生運動家のベルナール・クーザン[22]が広報専門家のベルナール・フリッチュと共同で作ったス ローガンである[23]。このフレーズは、革命的な学生たちが主要都市の通りにバリケードを築き始めた1968年春の出来事と運動の象徴となった。最初の バリケードが築かれたとき、学生たちは石畳が砂の上に置かれていることを認識した。このスローガンは、文字通りの意味でも比喩的な意味でも、都市化と現代 社会に対する運動の見解を凝縮したものだった。 他の例:[24]  Il est interdit d'interdire(「禁止することは禁じられている」)[25]。 Jouissez sans entraves(「支障なく楽しむ」)[25]。 Élections, piège à con(「選挙、バカの罠」)[26]。 CRS = SS[27] Je suis Marxiste-tendance Groucho(「私はグルーチョ派のマルクス主義者だ」)[28]。 マルクス、毛沢東、マルクーゼ![29][30][31] 「3M」とも呼ばれる[32]。 Cela nous concerne tous. (これは私たち全員に関係する) Soyez réalistes, demandez l'impossible(「現実的であれ、不可能を要求せよ」)[33]。 「国民議会がブルジョア劇場になったら、すべてのブルジョア劇場を国民議会に変えるべきだ。(占拠されたオデオン劇場の入り口の上に書かれた)[34]。 「愛している! ああ、敷石で言ってみろ!!!」[35]。 "ライヒを読み、それに従って行動せよ!" (フランクフルト大学。同様のライヒのスローガンがソルボンヌ大学の壁に落書きされ、ベルリンでは学生がライヒの『ファシズムの大衆心理学』のコピーを警 察に投げつけた)[36]。 労働者よ、闘いは続く。(労働者たちよ、闘いは続く。基本委員会を結成せよ」)[37][38]、あるいは単にLa lutte continue(「闘いは続く」)[38]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/May_68 |

|

| Japanese

description on May 68. 日本語ウィキペディアの説明:五月革命ではなく「五月危機」 フランスの五月革命(ごがつかくめい)は、1968年5月に起きた、フランスのパリ で行われた新左翼主導の一斉蜂起の開始から、翌月の議会選挙で シャルル・ド・ゴール政権への多数派国民による支持が判明し、急速に鎮静するまでの期間を指す[1]。五月危機ともいう。 パリ郊外に1963年に新設されたパリ大学ナンテール校にて、1968年3月新左翼学生による占拠事件が発生し、同年5月10日には大学当局による学校閉 鎖へ抗議する新左翼学生たちがパリ市内に結集し、警官隊と衝突した。同年5月13日には新左翼学生を支持する一部の労働者・市民が学生支援デモを行い、混 迷は5月末まで続いた。ド=ゴールは5月30日に国民議会を解散し、世論の実態を問う総選挙を行うことを宣言し、事態の収拾にあたった。ジョルジュ・ポン ピドゥー首相はフランスを「共産主義の脅威」に直面してるため、デモに参加していないサイレント・マジョリティーに「共和国防衛」を訴え、声を上げようと 呼びかけた。翌6月に行われた総選挙はフランス国民多数派による新左翼暴動への反発からド=ゴール派が圧勝し、危機は去った(en:1968 French legislative election)[1]。フランス語では「Mai 68」、英語では「May 68」と表記する。 「パリ五月革命が直接シャルル・ド・ゴール政権を倒した」という言説は誤謬であり、ド・ゴール政権は共産主義者の脅威にフランス国民が選挙でNOを突き付 けるように呼びかけた。そして、5月危機最中の民意を問う1968年6月の国会選挙でも圧勝し、新左デモ側はフランス国民のノイジーマイノリティであるこ とを示した。ド・ゴールの辞任は、「1969年3月の金価格高騰」によるゼネストが巻き起こったことにある。同年翌4月にド・ゴールはこれを受けて、辞任 することになった[1]。 https://x.gd/mTY0K |

|

| 五

月革命では、キューバ革命のチェ・ゲバラと文化大革命の毛沢東ら共産主義者が運動のアイコンとして掲げられた。背景にはフランス革命からロシア革命、

キューバ革命、文化大革命へと至る「革命の歴史」があり、それを高度経済成長に湧くパリの学生が導き、各国の学生運動に熱をふりまき、より拍車をかけた。 1960年代後半、欧米、日本を中心とした世界の新左翼若者は、学生運動によってお互いの理念、思想、哲学を共有し、激しい政治運動を行った。これによっ て国の枠組みにおさまらない対抗文化(カウンターカルチャー)や反体制文化(ヒッピー文化)を構成するユートピアスティックな「世界的な同世代」という世 代的な視座が加速度を増してゆく。以降、より自由に世界とコミュニケーションできるようになった学生は発言権を強めるようになり、フランスの現代化を推進 させたとの意見もある[2]。それはロックや映画、ファッション[3]、アニメ、アートなどに影響を与えたとされる[4]。 当時のフランスでは赤い中国のGrand Timonier[5]こと毛沢東の著書「Le petit livre rouge de mao」(「毛主席語録」)が流行していた。それはパリのENS(高等師範学校)[6]の学生たちを通じてひろまり、左派知識人たちを活気づけ、学生や労 働者を団結させる思想だった。学生はアメリカの覇権主義に反対するモデルとして毛沢東思想の書籍を読んだ。したがって中国への憧れも「五月革命」には投影 されている。ただその憧れは思想的に深められることがなく、ロマンチシズムの色彩が濃かった。さらに当然なことながら、学生には政府を転覆させる力はな かった。つまり本物の武力による革命ではなくて、学生時代のモラトリアムな革命[7]だった。 https://x.gd/mTY0K |

|

| 第二次大戦が終わって植民地帝国だったフランスは第四共和政という政権

の安定しない政治体制に移行した(1946-1958)。このあいだにベトナムとアルジェリアという2つの旧植民地独立の挑戦をうけ、インドシナ戦争

(1946-1954)とアルジェリア戦争(1954-1962)に派兵した。インドシナ戦争で苦戦を強いられたフランス軍は1953年ディエンビエン

フーで敗れ、ベトナムからの撤退を余儀なくされる。さらにフランスはアルジェリアの植民地維持に固執し、議会の混乱を招くと、泥沼のアルジェリア戦争

(1954)へと突入してゆく。第四共和政が明確なリーダーシップを採りえない体制であったことから、第二次大戦の国民的英雄ド・ゴール将軍[8]はより

大統領権限の強化された第五共和政を樹立(1958)し、アルジェリアやアフリカ各国の独立を容認した。 1968年3月15日付日刊紙ル・モンドにジャーナリスト、ピエール・ヴィアンソン=ポンテは「現在、私たちの生活を定義するものは退屈だ」、「フランス 人は退屈だ。彼らは世界を揺るがす激動に参加していない」と書いた。その後の出来事は、「退屈」が反乱の強力な触媒として作用したことを示唆している [9]。 1968年5月1日 極右の学生組織「オキシデンタル・グループ(Occidental group)」がナンテール校を攻撃しようとしているという噂が広まり、緊張が高まった。 1968年5月2日 ソルボンヌの学生組合ビルの一部が燃え、オキシデンタル・グループによって非難される。ダニエル・コーン=ベンディットを含む7名ものメンバーは3月22 日の運動の件で懲戒委員会に呼び出される。 1968年5月3日 ナンテール校の学部長はキャンパスの閉鎖を決定する。追放された学生およそ500名は、ソルボンヌ校を占拠する。それを追い払おうとする警察、フランス共 和国保安機動隊(CRS)、大学当局と対立。100名以上の負傷者、20名の重傷者、数百名の逮捕者をだす。ソルボンヌ校は閉鎖された。学生はパリ市街ラ テン地区のストリートへと雪崩れこみ、バリケードを築いた。オデオン座、カルチエ・ラタンを含むパリ中心部で大規模なデモがおこなわれ、警察がカルチェ・ ラタンへ踏みこんでこれを弾圧、いわゆる普通の学生もデモに参加し、区別のつかなくなった警察に無関係な一般市民も巻きこまれた。 1968年5月6日 再びカルチエ・ラタンおよびラテン地区で激しい衝突がおき、600名の学生と345名の警察官が負傷、422名が逮捕された。フランスの各地で高校生や大 学生による連帯ストライキがおきた。7日、全学連(UNEF)が呼びかけた4万人デモがおこり、大学の再開を主張した。警察はカルチエ・ ラタンから撤退し、学生たちの「解放区」になった。9日、労働総同盟(CGT)とフランス民主労働総同盟 (CFDT) とが会合する。 1968年5月10・11日 米国とベトナムの交渉に参加する代表団の安全確保のため、警察の増員部隊がパリに到着した。全国高等教育職員組合 (SNES[13]) が警察による抑圧を非難し、高校生によるさまざまな行動委員会が組織された。フランス放送協会 (ORTF) は、一連の出来事の放送を禁止した。国民教育相と学生の交渉が行われるが,これは決裂に終わる。学生、労働者バリケードを築き、カルチエ・ラタン一帯を占 拠し(「バリケードの夜」)、転がされた車が燃えた。警察251名、学生102名など計377人が重傷、418名が逮捕され、およそ60台もの車が燃やさ れた。警察の強硬な反応に学生と一般市民は団結を強めた。11日、それぞれの組合が共同で13日のデモ、ゼネスト決行を宣言した。フランス各地でのデモや 占拠は続く。ポンピドゥー首相は学生達の要求に譲歩を見せた。 1968年5月13日 労働組合(CGT、CFDT、FEN)と左派政党は学生支援のために24時間のストライキを呼びかけた。約80万人もの教師、組合員、政治家がパリの通り に集まる。ジョルジュ・ポンピドゥ首相は、ソルボンヌの再開を発表することで状況を落ち着かせようとした。学生は恒久的な占拠を宣言する。討論と会議は昼 夜を問わずに行なわれた。 1968年5月14日 シャルル・ド・ゴール大統領は、ルーマニアに公式訪問。ストライキは多くのルノー工場に波及し、およそ50もの工場が労働者に占拠され、工場の責任者は労 働者の手によって拘束され、工場に「赤い旗」が掲げられた。5月17日までに20万人がストライキを決行、この数字は翌日のストライキで200万人にふく れあがり、その後1週間でフランス人労働者のおよそ2/3にあたるおよそ1千万人が参加したと言われる。 1968年5月15・16日 学生に占拠され、旗がひるがえるパリ・オデオン座。パリは瞬間的に新勢力に占拠され、またもとの日常へともどっていった。 レ・フィガロ紙が「権力はストリートにある」と報道。パリ、オデオン座を学生が占拠。タクシ―運転手たちがストライキを宣言。16日、より広域にデモとス トがひろがる。 1968年5月17・18・19日 17日、フランス共産党が左派の共通プログラムを呼びかけ、鉄道(SNCF[14])もストライキ。18日、極右勢力による反共産主義デモが行われ、スト ラスブール大学で自治が宣言される。19日、フランス国鉄・パリ市交通公団・郵便通信電話局でストライキ、燃料不足が始まる。 1968年5月20日 ほとんど全てのセクターでゼネストに近い状態になった。全学連(UNEF) とフランス民主労働総同盟(CFDT)(英語版)が記者会見をひらき、談上の「労働者と学生の闘争は同じである」という語はスローガンとなり、教師達の組 合の枠を超えてストライキがひろがるきっかけとなった。フランス放送協会(ORTF)は放送を中止する。 1968年5月21日 銀行や繊維産業等も含めた大規模なゼネスト、フランスの交通システムはすべて麻痺状態に陥った。 1968年5月22日 フランスでは800万人以上の人々がストライキを行なった。ドイツを旅していたダニエル・コーン=ベンディットはフランスへの再入国を拒否される。 1968年5月24日 パリ市庁舎や証券取引所を学生が襲撃、20万人の農業労働者や各大学もストライキに突入し、カトリック教会でも学生の要求に親和的な意見が高まる。デモは パリ市街をまわり「人民政府」を要求。はじめて2人の死者を出す。テレビ演説でド・ゴール大統領は国民投票を提案して世論を取り戻そうとしたが、演説はほ とんど影響を及ぼさず、抗議者は辞表を要求した。ラテン地区での衝突で456人が負傷し、795人が逮捕された。ストラスブール、ボルドー、ナント、リヨ ンでも衝突が起こり、警察官がトラックで押しつぶされ、死亡している。 1968年5月25日 ド・ゴール主義の国務長官ジャック・シラクが主宰で労働者、国、雇用主組織のあいだでの三者間会議が催される。 1968年5月27日 政府、労働組合、および雇用主連合間の交渉が社会雇用省(Minister of Social Affairs and Employment)にて行われる。交渉の結果、最低賃金が3分の1上昇し、労働組合への公的権利が確立される「グルネル協定(Grenell agreements)」が締結された。一部強硬派は合意を不服とし、ストライキを続けた。ダニエル・コーン=ベンディットは秘密裏にフランスに戻る。 1968年5月29日 全国規模でデモがおき、パリに共産主義者80万人が集まり、「人民政府!」を連呼した。ド・ゴールは秘密会議を招集する。 1968年5月30日 ド・ゴール大統領はドイツから帰国し、フランス軍のジャック・マシュ将軍の支援を求めた。ド・ゴールはラジオ放送を行ない、辞任を拒否するが、国会を解散 すると述べた。その夜、何十万人ものド・ゴールの支持者、いわゆる「サイレント・マジョリティ」がパリのシャンゼリゼ通りを行進した。 1968年6月 公共および民間労働者の大部分は仕事に戻ったが、余波としての散発的な暴力は続いた。警察、学生、労働者が別の事件で、3人が死亡した。 6月23日および30日の第1回、第2回の総選挙で、ド・ゴールに近い政党が大勝利を収めた。 1968年7月10日 ド・ゴール大統領はモーリス・クーヴ・ド・ミュルヴィルを首相に任命した[15]。 https://x.gd/mTY0K |

|

| デモ参加学生の内部 1938年、フランスの大学生は6万人にすぎなかった。それが1961年に24万人、1968年時点には60万5,000人にまでふくれあがっていた [16]。 新左翼と左翼の混在 実際に五月革命を主導していたのは、「反スターリニズム」的、「反ソヴィエト連邦」的な新左翼グループだった。デモはトロツキスト、マオイスト(毛沢東主 義者)、アナーキスト、学生、労働者、市民、状況主義者(シチュアニスト)らと、フランス社会党やフランス共産党など旧来の左翼の混合部隊だった。これら の性質の違う、さまざまなグループが雑多に集まり、運動を高揚させていったところに、この革命の特徴がある。 新左翼(反ソ連共産党) 「赤毛のダニー」こと、ダニエル・コーン・ベンディット。五月革命というとフランス人が先導していたと思いがちだが、先導していたのはドイツ人移民だっ た。 ソ連と関係が深かった「スターリン主義」的なフランス共産党は、当初は影響下にある労働総同盟(CGT)を通じて労働者のストライキを組織した。だが、当 時の共産党幹部ジョルジュ・マルシェは運動のリーダーであるダニエル・コーン=ベンディットら”ソ連を非難する急進的な学生運動”を「アナーキストのドイ ツ人」と否定、バリケードを構築しての衝突や街頭占拠をすすめる学生や労働者を「トロツキスト」と非難した。党や労働総同盟には学生主導のストライキを組 織する力はなく、逆に学生や労働者のほうがより時代にあった根本的な要求をかかげていた。さらに五月革命には党や組合によって、組織されたものではない運 動の自由で自発的な性質があり、「反=組合」「反=共産党」の幸福感があった。同じようにスターリン主義に幻滅していた、無神論的実存主義の哲学者ジャ ン・ポール・サルトルが学生運動家に接近した。 政権との総選挙と最低賃金引き上げ約束 政治生命の危機に直面したシャルル・ド・ゴール大統領は、国民議会を解散し、あくる6月に総選挙をすることを約束した。解散にさきだつ5月27日、政府は 労働組合との賃上げ交渉に寛大にこたえるかたちで事態の鎮静化をはかった。その結果、学生と労働組合はよりよい条件の「グルネル協定」(すべての賃金の 10%上乗せと最低賃金の35%引き上げ[17])を締結した 著名人の反応 ジャン・ポール・サルトル=戦後フランスを代表する哲学者。左翼だが、ソヴィエト政権に批判的だったサルトルは五月革命を熱烈に支持した。革命運動のリー ダー、ベンディットとインタヴューもしている。サルトルはキューバにも訪れ、カストロやチェ・ゲバラを知っており、学生の革命に肯定的だった。 アンドレ・マルロー=保守派で反ファシズムの文学者。1968年当時文化大臣だったマルローは同時にレジスタンス時代に知り合ったド・ゴール大統領の熱心 な支持者でもあった。マルローの忠誠心は5月30日の「ドゴール支持」のデモへとつづく。終生をつうじてその熱い忠誠の思いはかわることはなかった。 ヌーベルバーグを代表する映画監督ジャン・リュック・ゴダール。時代の空気を読むことに長けていたゴダールはそれ以前から五月革命を予見するような作品を 撮っていた。著書「ミル・プラトー」で有名なポストモダン哲学者ジル・ドゥルーズはゴダールの姿勢を擁護している。 ジャン・リュック・ゴダール=ヌーベルバーグ(新しい波)の映画監督。すこしづつ政治的なモチーフに関心を示すようになったゴダールは、五月革命に先だつ 1967年に「中国女」というマオイズム的な映画をつくった。この映画はナンテール校の生徒たちに強い影響を与えた。実際五月革命はゴダールのイメージで 充満していた。ちょうど五月に開催予定だったカンヌ国際映画祭に対し、トリュフォーやポランスキーらと祭の中止を要求したが認められず、彼らの作品の上映 はなくなった(カンヌ映画祭粉砕事件)。 ルイ・アルチュセール=マルクス主義の哲学者。アンチ=スターリニスト。思想面で大きな影響を五月革命に与えたとされる。アルチュセールの生徒たちは青年 共産主義マルクスレーニン連盟(UJC(ml))を結成。革命中、大学やストリートで活発に活動する。 ギ―・ドゥボールの著書「スペクタクルの社会」。この本は消費される商品と人間との関係性を分析し、五月革命に強い影響を与えた。 ギー・ドゥボール=左派系の詩人、映像作家、著述家。ドゥボールもまた五月革命に強い影響を与えた一人だった。彼はその著書「スペクタクルの社会」 (1967)のなかで、新しい市民社会はスペクタクル(光景、ショー)化する商品を通じて人間疎外をうむことを指摘した。商品の語る真実っぽさ(スペクタ クル)に囲まれ、個人そのものは商品のなかに解消されてしまう。このようなスペクタクルとリアルの境界を線引きすることが難しい状況が消費社会なのであ り、それは新しい「状況」をつくることによって批判されなくてはならない(「状況主義」)。ドゥボールの提示したテーゼは68年を経て、いま現在のコン ピューター情報社会を鋭く言いあらわしている。 1968年当時、パリ、エコール・ド・ボザールの准教授だったブルーノ・ケサンヌは高揚をまじえながら、五月革命について以下のように述べている [18]。 「革命に参加したそれぞれの人は、ずっとその人自身と積極的に関わっていたんだ。それは不公平に妨害工作をしてやろうとしたのでなく、どうやったらフラン スが走ることを止めることができるのかということだった。全世界は、彼らがいったん立ち止まって、その存在条件を社会に反映すべきなんだということに同意 していたのさ」 騒動後のフランス国内― 70年代パンク・ムーブメント 英国人デザイナーのヴィヴィアン・ウエストウッド。ロンドン・パンクはファッションに大きな影響を与えた。とくにセックス・ピストルズとヴィヴィアン・ウ エストウッドのファッションは衝撃的で、当時産業ロックなどで停滞していたロック界や、ファッション界に新たなる風をもたらした。 五月革命からしばらくのちの1970年代中盤に入ると、アメリカやイギリスのユースカルチャーの世界に「パンク」が登場する。パンクはアナーキズム、左 翼、ダダ、ニヒリズムなどの傾向があり、権力に対する挑戦、不満、退屈によるストレスの爆発、DIY精神など、その精神そのものは五月革命と通底するとこ ろがある。もっともパンクは音楽であり、国家機能を停止させ、政府と直接的な政治交渉をするほどの集合的な力は生みださず、ある局所的なムーブメントで あった。つまりファッションとしてのヴィジュアル面の影響が強く、真似しやすく、記号としての流通が簡単にできた。そのため政治思想としての反映ではな く、パンク・ファッション的が、おおくのデザイナーにインスピレーションを与えることとなった。マルコム・マクラレーンと組んでブティック「SEX」のデ ザイナーをし、セックス・ピストルズの衣装を手がけた英国のヴィヴィアン・ウエストウッドは億万長者になった後も、保守党のキャメロンに激しい抗議行動を おこなったり、緑の党を支持したりした。 レゲエやヒップホップの流行も起きた。米ソ冷戦構造下で発生したパンク革命は、資本主義社会体制下で実現が難しい、永遠の憧れとしての革命、実現しない ユートピアへの憧れの側面が強かった。 パンクはアナーキストになりたい―(I wanna be anarchist[19](Anarchy in the UK-The Sex Pistols))若者だったが、五月革命の学生や知識人も社会主義に憧れを抱き、叶わぬユートピア実現のために戦ったのである。 セックス革命とアンチセックス 映画プロデューサーのハーヴェイ・ワインスタイン。有名プロデューサーのハーヴェイ・ワインシュタインは、女性へのセクハラやレイプを繰り返していた。権 力をカサに着たその手口はMe Too運動によって告発され、厳しく非難され追放された。 68年当時、欧米においても性そのものは現在より抑圧されており、性表現や性関係は比較的につつましやかなものだった。 聖書の価値観、キリスト教の教義では、婚前性交渉、婚外性交渉(不倫)、同性愛は罪であるからだ。 ヒッピーのフリーラブスピリットや五月革命などの対抗文化を受けて性はより広範にわたって「表現されるもの」となり、映画、小説、文学、舞踏、アニメ、 ゲームなどのカルチャーを通じて一般にひろまり、身体意識の高まりを生むこととなった。また避妊具の発展、ファッションの簡易化、下着化、性映像の情報 化、パーソナルメディアの発達とともに異性間での性交渉も日常に解放され、現在に至っている。一方で60年代の左翼的ウーマンリブとは正反対の、新しい規 制を良しとする保守的フェミニストは性が搾取されるものと主張した。これは右派政治家と一致していた。また一方、対象となる女性の人権を無視した「セクハ ラ」はMe too運動のような新しいカウンター運動を生んだ。 文化大革命の実態報道 当時フランスで盛り上がった「毛沢東への憧れ」はやがて文化大革命の実情が明らかになるにつれて、「毛沢東への幻滅」へとかわった。文化大革命とは「下か らの革命」ではなく、毛沢東の権力闘争に利用された「上からの革命」であり、それは五月革命が志向した精神とはかけ離れたところにあった。その意味でフラ ンスのマオイストたちはそれほど誠実に毛沢東と向きあってはいなかったと言える。フランス人によくあるように、漠然としたユートピアを東洋に夢見ていた。 もっとも、実際にそれに罪があるというわけではないが、あまりにも無邪気かつ無知でもあり、反=スターリニズムの機運のなかで学生や思想家の体のいい希望 の星となった感は否めない。 また、ベトナムと同じフランスの植民地であったカンボジアからの留学生であるポル・ポトらによって結成されたクメール・ルージュが文化大革命の影響を受け て築いた民主カンプチアで行ったその徹底的な重農主義・農本主義による恐怖政治と大量虐殺も報じられ、ディストピアをもたらした毛沢東主義者は大粛清を 行ったスターリニストと同列視されることとなった。反帝国主義に固執してポル・ポト派を擁護して名声を失った有名な弁護士ジャック・ベルジェス(英語版) はその後のフランス社会では、独裁者と戦争犯罪人やテロリストなどの弁護も請け負ったことで「悪魔の弁護人」「恐怖の弁護士」と蔑まれるようになった。 サブカルチャーの流行 サブカルチャーはマンガ、アニメだけでなく、ヘヴィメタルなどのロックや麻薬、フリーセックスもふくまれた。キリスト教の影響が強い欧米社会において、 セックス革命というのは「社会の世俗化(vulgar)」を意味する。キリスト教(とくにカトリック)や、キリスト教原理主義者はその教義のなかで「中 絶」、「同性愛」を厳しく戒めてきた。なお中絶禁止は聖書には書かれていない。いまだ性をマイナス・イメージでとらえる信者も多い。したがって、このよう な社会の「世俗化」は、保守派の眉を顰めさせるような出来ごとであり、従来の価値を愛する保守の市民の根強い反発もある。くわえてサブカルチャーと結びつ いた麻薬やセックスの自由は、「中毒」や「依存症」になる危険もある。革命以後、アメリカのみならず、ヨーロッパも革新と保守の乖離の問題を抱えることと なった。 パリ五月革命と黄色いベスト運動 フランスはデモが多い国である。パリ五月革命は成功したストライキであり、フランス大衆のあいだでストライキが多く発生するようになった。五月革命という 成功体験で市民はその再現を望むようになった。フランス社会は個人の自由や尊厳が尊重される社会となった。パリ五月革命の精神は、ネオ・リベラリストのマ クロンに反対する「黄色いベスト運動」に、引き継がれている。 https://x.gd/mTY0K |

『五月革命の記録』/サ

ン・パブロ(聖パウロ・使徒パウロ)

Oedipus describes the riddle of the Sphinx

by Jean-Auguste-Dominique Ingres, c. 1805

● Oedipus complex (エディプス・コンプレックス)

| In classical

psychoanalytic theory, the Oedipus

complex (also spelled Œdipus

complex) refers to a son's sexual attitude towards his mother and

concomitant hostility toward his father, first formed during the

phallic stage of psychosexual development. A daughter's attitude of

desire for her father and hostility toward her mother is referred to as

the feminine Oedipus complex.[1] The general concept was considered by

Sigmund Freud in The Interpretation of Dreams (1899), although the term

itself was introduced in his paper A Special Type of Choice of Object

made by Men (1910).[2][3] Freud's ideas of castration anxiety and penis envy refer to the differences of the sexes in their experience of the Oedipus complex.[4] The complex is thought to persist into adulthood as an unconscious psychic structure which can assist in social adaptation but also be the cause of neurosis. According to sexual difference, a positive Oedipus complex refers to the child's sexual desire for the opposite-sex parent and aversion to the same-sex parent, while a negative Oedipus complex refers to the desire for the same-sex parent and aversion to the opposite-sex parent.[3][5][6] Freud considered that the child's identification with the same-sex parent is the socially acceptable outcome of the complex. Failure to move on from the compulsion to satisfy a basic desire and to reconcile with the same-sex parent leads to neurosis. The theory is named for the mythological figure Oedipus, an ancient Theban King who discovers he has unknowingly murdered his father and married his mother, whose depiction in Sophocles' Oedipus Rex had a profound influence on Freud. Freud rejected the term Electra complex,[7] introduced by Carl Jung in 1913[8] as a proposed equivalent complex among young girls.[7] Some critics have argued that Freud, by abandoning his earlier seduction theory (which attributed neurosis to childhood sexual abuse) and replacing it with the theory of the Oedipus complex, instigated a cover-up for sexual abuse of children. Some scholars and psychologists have criticized the theory for being incapable of applying to same-sex parents, and as being incompatible with the widespread aversion to incest. |

古典的な精神分析理論では、エディプス・コンプレックス(エディプス・

コンプレックスとも表記される)は、息子の母親に対する性的態度と、それに付随する父親に対する敵意を指し、心理性発達の男根期に初めて形成される。一般

的な概念はジークムント・フロイトによって『夢の解釈』(1899年)の中で考察されたが、この言葉自体は彼の論文『男性による対象選択の特殊なタイプ』

(1910年)の中で紹介された[2][3]。 フロイトの去勢不安と陰茎羨望の考えはエディプス・コンプレックスの経験における男女の違いに言及している[4]. 性差によれば、正のエディプス・コンプレックスは、子どもが異性の親に性的欲求を抱き、同性の親に嫌悪感を抱くことを指し、負のエディプス・コンプレック スは、同性の親に欲求を抱き、異性の親に嫌悪感を抱くことを指す。基本的な欲求を満たそうとする強迫観念から抜け出せず、同性の親との和解に失敗すると神 経症になる。 この理論は、神話に登場するオイディプスにちなんで名づけられた。オイディプスは古代のテーバイ王で、知らず知らずのうちに父親を殺害し、母親と結婚して いたことに気づく。フロイトは、1913年[8]にカール・ユングが若い女の子の間で提案された同等のコンプレックスとして紹介したエレクトラ・コンプ レックスという言葉[7]を否定した。 一部の批評家は、フロイトが以前の誘惑理論(神経症を幼少期の性的虐待に帰結させる)を放棄し、エディプス・コンプレックスの理論に置き換えることによっ て、子どもへの性的虐待の隠蔽工作を扇動したと主張している。一部の学者や心理学者は、この理論は同性の親には適用できず、近親相姦を嫌悪する風潮とは相 容れないと批判している。 |

Background Sigmund Freud (age 16) with his mother in 1872[9] Oedipus refers to a 5th-century BC Greek mythological character Oedipus, who unwittingly kills his father, Laius, and marries his mother, Jocasta. A play based on the myth, Oedipus Rex, was written by Sophocles, c. 429 BC. Modern productions of Sophocles' play were staged in Paris and Vienna in the 19th century and were phenomenally successful in the 1880s and 1890s. The Austrian neurologist Sigmund Freud (1856–1939) attended. In his book The Interpretation of Dreams, first published in 1899, he proposes that an Oedipal desire is a universal psychological phenomenon innate (phylogenetic) to human beings, and the cause of much unconscious guilt. Freud believed that the Oedipal sentiment has been inherited through the millions of years it took for humans to evolve from apes.[10] His view of its universality was based on his clinical observation of neurotic or normal children, his analysis of his own response to Oedipus Rex, and on the fact that the play was effective on both ancient and modern audiences. Freud describes the Oedipus myth's timeless appeal thus: His destiny moves us only because it might have been ours — because the Oracle laid the same curse upon us before our birth as upon him. It is the fate of all of us, perhaps, to direct our first sexual impulse towards our mother and our first hatred and our first murderous wish against our father. Our dreams convince us that this is so.[11] Freud also claims that the play Hamlet "has its roots in the same soil as Oedipus Rex", and that the differences between the two plays are revealing: In [Oedipus Rex] the child's wishful fantasy that underlies it is brought into the open and realized as it would be in a dream. In Hamlet it remains repressed; and—just as in the case of a neurosis—we only learn of its existence from its inhibiting consequences.[12][13] However, in The Interpretation of Dreams, Freud makes it clear that the "primordial urges and fears" that are his concern and the basis of the Oedipal complex are inherent in the myths the play is based on, not primarily in the play itself, which Freud refers to as a "further modification of the legend" that originates in a "misconceived secondary revision of the material, which has sought to exploit it for theological purposes".[14][15][16] Before the idea of the Oedipus complex, Freud believed that childhood sexual trauma was the cause of neurosis. This idea, sometimes called Freud's seduction theory, was deemphasized in favor of the Oedipus complex around 1897.[17] Timeline 1896. Freud publishes The Aetiology of Hysteria. The paper was criticized for theorizing that hysteria is caused by sexual abuse. 1897–1909. After his father's death in 1896, and having seen the play Oedipus Rex, by Sophocles, Freud begins using the term "Oedipus". As Freud wrote in an 1897 letter, "I found in myself a constant love for my mother, and jealousy of my father. I now consider this to be a universal event in early childhood." 1909–1914. Proposes that Oedipal desire is the "nuclear complex" of all neuroses; first usage of "Oedipus complex" in 1910. 1914–1918. Considers paternal and maternal incest. 1919–1926. Complete Oedipus complex; identification and bisexuality are conceptually evident in later works. 1926–1931. Applies the Oedipal theory to religion and custom. 1931–1938. Investigates the "feminine Oedipus attitude" and "negative Oedipus complex"; later the "Electra complex".[18] |

生い立ち 1872年、ジークムント・フロイト(16歳)と母親[9]。 オイディプスとは紀元前5世紀のギリシア神話に登場するオイディプスのことで、彼は無意識のうちに父ライオスを殺し、母ヨカスタと結婚する。この神話に基 づく戯曲『オイディプス王』は、紀元前429年頃にソフォクレスによって書かれた。 ソフォクレスの戯曲の現代劇は19世紀にパリとウィーンで上演され、1880年代と1890年代には驚異的な成功を収めた。オーストリアの神経学者ジーク ムント・フロイト(1856-1939)も参加した。1899年に出版された彼の著書『夢の解釈』の中で、彼はエディプス願望が人間に生得的(系統的)に 備わった普遍的な心理現象であり、多くの無意識の罪悪感の原因であると提唱している。 フロイトは、エディプス的情念は、人類が類人猿から進化するのに要した数百万年の歳月を経て受け継がれてきたと考えた[10]。その普遍性についての彼の 見解は、神経症または正常な子供たちの臨床観察、『エディプス・レックス』に対する彼自身の反応の分析、そしてこの戯曲が古今東西の観客に効果的であった という事実に基づいていた。フロイトは、オイディプス神話の時代を超越した魅力をこう表現している: オイディプスの運命がわれわれを感動させるのは、それがわれわれの運命であったかもしれないからにほかならない。最初の性的衝動を母に向け、最初の憎悪と 最初の殺意を父に向けるのは、おそらく私たち全員の運命なのだ。私たちの夢は、そうであることを私たちに確信させる[11]。 フロイトはまた、ハムレット劇は「オイディプス王と同じ土壌に根を下ろしている」と主張し、2つの戯曲の違いを明らかにしている: オイディプス王』では、その根底にある子供の願望的な空想が、夢の中で実現されるように、公然と実現される。ハムレット』ではそれは抑圧されたままであ り、神経症の場合と同じように、私たちはその抑制的な結果からしかその存在を知ることができない[12][13]。 しかし、『夢の解釈』においてフロイトは、彼の関心事でありエディプス・コンプレックスの基礎である「根源的な衝動と恐怖」は、戯曲そのものではなく、戯 曲の基になっている神話に内在していることを明らかにしている。 エディプス・コンプレックスという考えが生まれる以前、フロイトは幼少期の性的トラウマが神経症の原因であると信じていた。この考えは、フロイトの誘惑理 論と呼ばれることもあるが、1897年頃にエディプス・コンプレックスを支持して重視されなくなった[17]。 年表 1896. フロイト、『ヒステリーの病因』を発表。この論文は、ヒステリーが性的虐待によって引き起こされるという理論であると批判された。 1897-1909. 1896年に父親が亡くなり、ソフォクレスの戯曲『オイディプス王』を見たフロイトは、「オイディプス」という言葉を使い始める。フロイトは1897年の 手紙の中で、「私は自分の中に、母への絶え間ない愛と父への嫉妬を見出した。私は今、これを幼児期における普遍的な出来事だと考えている。" 1909-1914. エディプス的欲望がすべての神経症の「核複合体」であると提唱。1910年に「エディプス・コンプレックス」を初めて使用。 1914-1918. 父方と母方の近親相姦を考察。 1919-1926. 完全なエディプス・コンプレックス;同一視と両性愛は後の作品で概念的に明らかになる。 1926-1931. エディプス理論を宗教や習慣に応用。 1931-1938. 女性的エディプスの態度」と「否定的エディプス・コンプレックス」、後に「エレクトラ・コンプレックス」を研究[18]。 |

| The Oedipus complex Original formulation Freud's original examples of the Oedipus complex are applied only to boys or men; he never fully clarified his views on the nature of the complex in girls.[19] He described the complex as a young boy's hatred or desire to eliminate his father and to have sex with his mother. Freud introduced the term "Oedipus complex" in a 1910 article titled A Special Type of Choice of Object made by Men.[19][2] It appears in a section of this paper describing what happens after a boy first becomes aware of prostitution: When after this he can no longer maintain the doubt which makes his parents an exception to the universal and odious norms of sexual activity, he tells himself with cynical logic that the difference between his mother and a whore is not after all so very great, since basically they do the same thing. The enlightening information he has received has in fact awakened the memory-traces of the impressions and wishes of his early infancy, and these have led to a reactivation in him of certain mental impulses. He begins to desire his mother herself in the sense with which he has recently become acquainted, and to hate his father anew as a rival who stands in the way of this wish; he comes, as we say, under the dominance of the Oedipus complex. He does not forgive his mother for having granted the favour of sexual intercourse not to himself but to his father, and he regards it as an act of unfaithfulness.[20] Freud and others eventually extended this idea and embedded it in a larger body of theory. Later theory  Oedipus and the Sphinx, by Gustave Moreau (1864) In classical psychoanalytic theory, the Oedipus complex occurs during the phallic stage of psychosexual development (age 3–6 years), although it can manifest at an earlier age.[21][22] In the phallic stage, a boy's decisive psychosexual experience is the Oedipus complex—his son–father competition for possession of his mother. It is in this third stage of psychosexual development that the child's genitalia is his or her primary erogenous zone; thus, when children become aware of their bodies, the bodies of other children, and the bodies of their parents, they gratify physical curiosity by undressing and exploring themselves, each other, and their genitals, so learning the anatomic differences between male and female and the gender differences between boy and girl. Despite the mother being the parent who primarily gratifies the child's desires, the child begins forming a discrete sexual identity—"boy", "girl"—that alters the dynamics of the parent and child relationship; the parents become objects of infantile libidinal energy. The boy directs his libido (sexual desire) toward his mother and directs jealousy and emotional rivalry against his father. The boy's desire for his mother is concomitant with a desire for the death of his father and even an impulse to instigate that death. These desires manifest in the realm of the id, governed by the pleasure principle, but the pragmatic ego, governed by the reality principle, knows that the father is an impossible rival to overcome and the impulse is repressed. The boy's ambivalence about his father's place in the family, is manifested as fear of castration by the physically superior father; the fear is an irrational, subconscious manifestation of the infantile id.[23] In both sexes, defense mechanisms provide transitory resolutions of the conflict between the drives of the id and the drives of the ego. Repression, the blocking of unacceptable ideas and impulses from the conscious mind, is the first defence mechanism, but its action does not resolve the id–ego conflict; it merely confines the impulse in the unconscious, where it continues to exert pressure in the direction of consciousness. The second defense mechanism is identification, in which the child adapts by incorporating, into his or her (super)ego, the personality characteristics of the same-sex parent. In the case of the boy, this diminishes his castration anxiety, because his likeness to his father protects him from the consequences of their rivalry. The little girl's anxiety is diminished in her identification with the mother, who understands that neither of them possesses a penis, and thus are not antagonists.[24] The satisfactory resolution of the Oedipus complex is considered important in developing the male infantile super-ego. By identifying with the father, the boy internalizes social morality, thereby potentially becoming a voluntary, self-regulating follower of societal rules, rather than merely reflexively complying out of fear of punishment. Unresolved son–father competition for the psychosexual possession of the mother might result in a phallic stage fixation that leads to the boy becoming an aggressive, over-ambitious, and vain man.[citation needed] Oedipal case study In Analysis of a Phobia in a Five-year-old Boy (1909), the case study of the equinophobic boy "Little Hans", Freud showed that the relation between Hans's fears—of horses and of his father—derived from external factors, the birth of a sister, and internal factors, the desire of the infantile id to replace his father as companion to his mother, and guilt for enjoying the masturbation normal to a boy of his age. Little Hans himself was unable to relate his fear of horses to his fear of his father. As the treating psychoanalyst, Freud noted that "Hans had to be told many things that he could not say himself" and that "he had to be presented with thoughts, which he had, so far, shown no signs of possessing".[25] Feminine Oedipus attitude Freud applied the Oedipus complex to the psychosexual development of boys and girls, but later modified the female aspects of the theory as "feminine Oedipus attitude" and "negative Oedipus complex".[26] His student–collaborator Carl Jung, in his 1913 work The Theory of Psychoanalysis, proposed the Electra complex to describe a girl's daughter–mother competition for psychosexual possession of the father.[8][27] In the phallic stage, the feminine Oedipus attitude is the little girl's decisive psychodynamic experience in forming a discrete sexual identity (ego). Whereas a boy develops castration anxiety, a girl develops penis envy, for she perceives that she has been castrated previously (and missing the penis), and so forms resentment towards her own kind as inferior, while simultaneously striving to claim her father's penis through bearing a male child of her own. Furthermore, after the phallic stage, the girl's psychosexual development includes transferring her primary erogenous zone from the infantile clitoris to the adult vagina.[28] Freud considered a girl's negative Oedipus complex to be more emotionally intense than that of a boy, resulting, potentially, in a woman of submissive, insecure personality.[29] |

エディプス・コンプレックス 当初の定式化 フロイトのエディプス・コンプレックスの最初の例は、少年または男性にのみ適用されるものであり、少女におけるコンプレックスの性質についての見解を完全 に明らかにすることはなかった[19]。 フロイトは、「エディプス・コンプレックス」という用語を、1910年に発表した「男性によってなされる対象の選択の特殊なタイプ」と題する論文の中で紹 介している[19][2]: この後、自分の両親を性行為の普遍的で忌まわしい規範の例外とする疑念を維持できなくなったとき、彼は皮肉な論理で、母親と売春婦の違いは、基本的には同 じことをしているのだから、結局のところそれほど大きくないのだと自分に言い聞かせる。啓蒙的な情報を得たことで、幼い頃の印象や願望の記憶が呼び覚まさ れ、ある種の精神的衝動が再活性化する。彼は、最近知ったような意味で母親自身を望み始め、この望みを邪魔するライバルとして父親をあらためて憎み始め る。彼は、性交の恩恵を自分ではなく父親に与えた母親を許さず、それを不誠実な行為とみなす[20]。 フロイトと他の人々は、最終的にこの考えを拡張し、より大きな理論の体系に組み込んだ。 後の理論  オイディプスとスフィンクス、ギュスターヴ・モロー作(1864年) 古典的な精神分析理論では、エディプス・コンプレックスは心理性発達の男根期(3~6歳)に起こるが、それ以前の年齢で現れることもある[21] [22]。 男根期において、少年の決定的な心理的経験はエディプス・コンプレックス-母親の所有権をめぐる息子と父親の競争-である。したがって、子どもは自分の身 体、他の子どもの身体、両親の身体を意識するようになると、服を脱いで自分自身や互いの身体、自分の性器を探索することで身体的好奇心を満たし、男性と女 性の解剖学的な違いや男の子と女の子の性差を学ぶ。 母親は主に子どもの欲望を満たす親であるにもかかわらず、子どもは「男の子」「女の子」という個別の性的アイデンティティを形成し始め、親子関係の力学が 変化する。少年はリビドー(性的欲望)を母親に向け、嫉妬と感情的対抗心を父親に向ける。少年の母親への欲望は、父親の死への欲望、さらにはその死を扇動 しようとする衝動と結びついている。これらの欲望は快楽原則に支配されたイドの領域に現れるが、現実原則に支配された現実的自我は、父親が克服不可能なラ イバルであることを知っており、衝動は抑圧される。家族における父親の地位に対する少年のアンビバレントは、肉体的に優れた父親による去勢への恐怖として 現れるが、この恐怖は幼児的イドの不合理で潜在意識的な現れである[23]。 男女ともに、防衛機制はイドの衝動と自我の衝動との間の葛藤を一過性に解決するものである。抑圧とは、受け入れがたい考えや衝動を意識から遮断することで あり、これが第一の防衛機制であるが、その作用はイドと自我の葛藤を解決するものではなく、単に衝動を無意識の中に閉じ込めるだけであり、そこで意識の方 向に圧力をかけ続けるだけである。第二の防衛機制は同一化であり、子供は同性の親の人格的特徴を自分の(超)自我に取り込むことによって適応する。男の子 の場合、父親と似ていることでライバル関係から身を守ることができるため、去勢不安は軽減される。少女の不安は、母親との同一化において軽減される。母親 は、二人ともペニスを所有しておらず、したがって敵対者ではないことを理解する[24]。 エディプス・コンプレックスの満足のいく解決は、男性の幼児期の超自我を発達させる上で重要であると考えられている。父親と同一化することで、少年は社会 的道徳を内面化し、それによって、単に罰を恐れて反射的に従うのではなく、自発的で自己調整的な社会的ルールの信奉者になる可能性がある。母親の心理的所 有権をめぐる未解決の息子と父親の競争は、男根期の固定化をもたらし、その結果、少年は攻撃的で、過剰な野心家で、うぬぼれの強い男になるかもしれない [要出典]。 エディプスの事例研究 馬恐怖症の少年「リトル・ハンス」の事例研究である『5歳児における恐怖症の分析』(1909年)において、フロイトは、ハンスの馬と父親に対する恐怖の 関係が、妹の誕生という外的要因と、母親の伴侶として父親に取って代わろうとする幼児的イドの欲望と、年頃の少年にとって普通の自慰行為を楽しむことへの 罪悪感という内的要因に由来することを示した。リトル・ハンス自身は、馬への恐怖と父親への恐怖を関連づけることができなかった。精神分析医であったフロ イトは、「ハンスは自分では言えないことをたくさん言われなければならなかった」「これまでのところ、彼が持っている兆候を見せなかった思考を提示されな ければならなかった」と述べている[25]。 女性的なエディプスの態度 フロイトはエディプス・コンプレックスを少年少女の精神性愛的発達に適用したが、後にこの理論の女性的側面を「女性的エディプス態度」や「否定的エディプ ス・コンプレックス」として修正した[26]。 彼の弟子であり共同研究者であったカール・ユングは、1913年の著作『精神分析論』の中で、父親の精神性愛的所有権をめぐる少女の娘と母親の競争を表現 するためにエレクトラ・コンプレックスを提唱した[8][27]。 男根期において、女性的なエディプスの態度は、個別の性的アイデンティティ(自我)を形成する上での少女の決定的な精神力動的経験である。男児が去勢不安 を発症するのに対し、女児は陰茎羨望を発症する。なぜなら、女児は自分が以前に去勢された(そして陰茎を失った)ことを認識するため、劣った同類に対する 憤りを形成すると同時に、自分の男児を産むことによって父親の陰茎を要求しようと努力するからである。さらに、男根期の後、少女の心理的な発達には、彼女 の主要なエロジゾーンを幼児期のクリトリスから大人の膣に移すことが含まれる[28]。 フロイトは、女児の負のエディプス・コンプレックスは男児のそれよりも感情的に強烈であり、その結果、従順で不安定な性格の女性になる可能性があると考え た[29]。 |

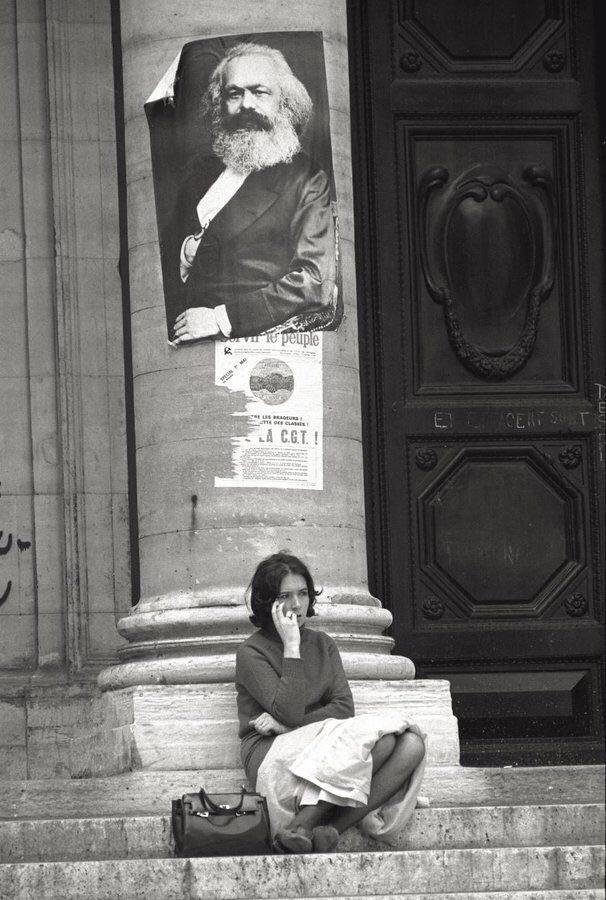

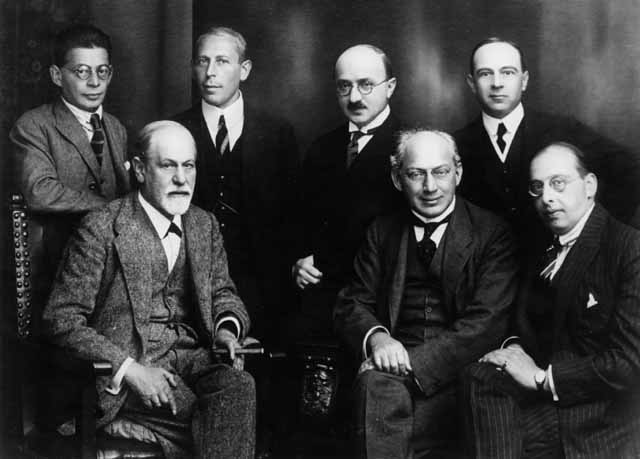

| Freudian theoretic revision Carl Gustav Jung  The Electra complex: the matricides Electra and Orestes. In response to Freud's proposal of the Oedipus complex, which was initially more focused on the little boy's experience of desire for the mother and jealous rivalry in relation of the father, student–collaborator Carl Jung proposed that girls experienced desire for the father and aggression towards the mother via what he called the Electra complex.[8] Electra was a Greek mythologic figure who plotted matricidal revenge with Orestes, her brother, against their mother Clytemnestra and their stepfather Aegisthus, for the murder of her father Agamemnon. Like Oedipus, the character is the subject of a play by Sophocles (Electra) from the 5th century BC.[30][31][32] Orthodox Jungian psychology uses the term "Oedipus complex" only to denote a boy's psychosexual development. Freud himself rejected the equivalence, arguing that at this stage of development it is only the male who experiences a simultaneous love for one parent and competitive hatred for the other. For Freud, the idea of the Electra complex assumes an analogous relation between boys and girls, in relation to their same and opposite sex parents, that does not actually exist. According to Freud, the Electra complex fails to take account of the differing effects of the castration complex, and the significance of the phallus, in the two sexes, and overlooks the girl's preoedipal attachment to the mother.[33] Otto Rank  Otto Rank on the far left, behind Sigmund Freud, and other psychoanalysts (1922). In classical Freudian psychology the super-ego, "the heir to the Oedipus complex", is formed as the infant boy internalizes the familial rules of his father. In contrast, in the early 1920s, using the term "pre-Oedipal", Otto Rank proposed that a boy's powerful mother was the source of the super-ego, in the course of normal psychosexual development. Rank's theoretic conflict with Freud excluded him from the Freudian inner circle; nonetheless, he later developed the psychodynamic Object relations theory in 1925. Melanie Klein Whereas Freud proposed that the father (the paternal phallus) was central to infantile and adult psychosexual development, Melanie Klein concentrated on the early maternal relationship, proposing that Oedipal manifestations are perceptible in the first year of life, the oral stage. Her proposal was part of the "controversial discussions" (1942–44) at the British Psychoanalytical Association. The Kleinian psychologists proposed that "underlying the Oedipus complex, as Freud described it ... there is an earlier layer of more primitive relationships with the Oedipal couple".[34] She assigned "dangerous destructive tendencies not just to the father but also to the mother in her discussion of the child's projective fantasies".[35] Klein's concept of the depressive position, resulting from the infant's ambivalence toward the mother, lessened the central importance of the Oedipus complex in psychosexual development.[36][37] Wilfred Bion "For the post-Kleinian Bion, the myth of Oedipus concerns investigatory curiosity—the quest for knowledge—rather than sexual difference; the other main character in the Oedipal drama becomes Tiresias (the false hypothesis erected against anxiety about a new theory)".[38] As a result, "Bion regarded the central crime of Oedipus as his insistence on knowing the truth at all costs".[39] Jacques Lacan Jacques Lacan argued against removing the Oedipus complex from the center of psychosexual developmental experience. For him, the Oedipus complex "—in so far as we continue to recognize it as covering the whole field of our experience with its signification—may be said to mark the limits that our discipline assigns to subjectivity".[40] It is that which superimposes the kingdom of culture upon the person, marking his or her introduction to the symbolic order. Thus "a child learns what power independent of itself is as it goes through the Oedipus complex ... encountering the existence of a symbolic system independent of itself".[41] Moreover, Lacan's proposal that "the ternary relation of the Oedipus complex" liberates the "prisoner of the dual relationship" of the son–mother relationship proved useful to later psychoanalysts;[42] thus, for Bollas, the "achievement" of the Oedipus complex is that the "child comes to understand something about the oddity of possessing one's own mind ... discovers the multiplicity of points of view".[43] Likewise, for Ronald Britton, "if the link between the parents perceived in love and hate can be tolerated in the child's mind ... this provides us with a capacity for seeing us in interaction with others, and ... for reflecting on ourselves, whilst being ourselves".[44] As such, in The Dove that Returns, the Dove that Vanishes (2000), Michael Parsons proposed that such a perspective permits viewing "the Oedipus complex as a life-long developmental challenge ... [with] new kinds of Oedipal configurations that belong to later life".[45] In 1920, Sigmund Freud wrote that "with the progress of psychoanalytic studies the importance of the Oedipus complex has become, more and more, clearly evident; its recognition has become the shibboleth that distinguishes the adherents of psychoanalysis from its opponents";[46] thereby it remained a theoretic cornerstone of psychoanalysis until about 1930, when psychoanalysts began investigating the pre-Oedipal son–mother relationship within the theory of psychosexual development.[47][48] Janet Malcolm reports that by the late 20th century, to the object relations psychology "avant-garde, the events of the Oedipal period are pallid and inconsequential, in comparison with the cliff-hanging psychodramas of infancy. ... For Kohut, as for Winnicott and Balint, the Oedipus complex is an irrelevance in the treatment of severe pathology".[49] Nonetheless, ego psychology continued to maintain that "the Oedipal period—roughly three-and-a-half to six years—is like Lorenz standing in front of the chick, it is the most formative, significant, moulding experience of human life ... If you take a person's adult life—his love, his work, his hobbies, his ambitions—they all point back to the Oedipus complex".[50] |

フロイトの理論修正 カール・グスタフ・ユング  エレクトラ・コンプレックス:マトリキデスのエレクトラとオレステス。 フロイトのエディプス・コンプレックスの提唱は、当初は少年の母親に対する欲望と父親に対する嫉妬のライバル意識に焦点を当てたものであったが、それに対 して、学生時代の共同研究者であったカール・ユングは、少女は父親に対する欲望と母親に対する攻撃性を、彼がエレクトラ・コンプレックスと呼ぶものによっ て経験すると提唱した[8]。 [8] エレクトラはギリシア神話に登場する人物で、父アガメムノンを殺した母クリュテムネストラと継父アイギストスに対して、弟オレステスとともに母殺しの復讐 を企てた。オイディプスと同様、紀元前5世紀のソフォクレスの戯曲(エレクトラ)の題材となっている[30][31][32]。正統的なユング心理学で は、「オイディプス・コンプレックス」という用語は少年の精神性愛の発達を示すためにのみ用いられる。フロイト自身はこの等価性を否定し、この発達段階で は、一方の親への愛と他方の親への競争的憎悪を同時に経験するのは男性だけであると主張した。フロイトにとって、エレクトラ・コンプレックスという考え方 は、少年少女が同性の親と異性の親との関係において、実際には存在しない類似の関係を想定している。フロイトによれば、エレクトラ・コンプレックスは、両 性における去勢コンプレックスの異なる影響とファルスの重要性を考慮しておらず、少女の母親に対する前エディプス的な愛着を見落としている[33]。 オットー・ランク  ジークムント・フロイトと他の精神分析家の後ろの最左翼にいるオットー・ランク(1922年)。 古典的なフロイト心理学では、「エディプス・コンプレックスの継承者」である超自我は、幼児期の少年が父親の家族的ルールを内面化することで形成される。 これとは対照的に、1920年代初頭、オットー・ランクは「プレ・エディプス」という言葉を用いて、正常な心理性発達の過程において、少年の力強い母親が 超自我の源であると提唱した。ランクはフロイトと理論的に対立していたため、フロイトの側近からは除外されたが、それにもかかわらず、後に1925年に精 神力動的な対象関係論を発展させた。 メラニー・クライン フロイトが父親(父性ファルス)が幼児期および成人の心理性発達の中心であると提唱したのに対し、メラニー・クラインは初期の母性関係に焦点を当て、エ ディプスの顕在化は生後1年の口唇期に知覚されると提唱した。彼女の提案は、英国精神分析協会における「論争的な議論」(1942~44年)の一部となっ た。クライン派の心理学者たちは、「フロイトが説明したようなエディプス・コンプレックスの根底には......エディプス夫婦とのより原始的な関係のよ り早い層がある」と提案した[34]。彼女は、「子どもの投影的空想についての議論の中で、危険な破壊的傾向を父親だけでなく母親にも」割り当てた。 [35] 幼児の母親に対するアンビバレンスから生じる抑うつ的な立場のクラインの概念は、心理性発達におけるエディプス・コンプレックスの中心的な重要性を弱めて いた[36][37]。 ウィルフレッド・ビオン 「ポスト・クライン派のビオンにとって、オイディプスの神話は性的差異よりもむしろ調査好奇心-知識の探求-に関わるものであり、オイディプス劇のもう一 人の主人公はティレジアス(新しい理論に対する不安に対して立てられた誤った仮説)になる」[38]。その結果、「ビオンはオイディプスの中心的な罪を、 どんな犠牲を払っても真実を知ろうとする彼の主張とみなした」[39]。 ジャック・ラカン ジャック・ラカンは、エディプス・コンプレックスを心理性発達体験の中心から外すことに反対していた。彼にとってエディプス・コンプレックスは、「私たち がその意味づけによって私たちの経験の全領域を覆っていると認識し続ける限りにおいて、私たちの学問が主観性に与える限界を示すものであると言うことがで きる」[40]。 こうして「子どもはエディプス・コンプレックスを経て、自分自身から独立した力が何であるかを学ぶ......自分自身から独立した象徴体系の存在に遭遇 する」。 [さらに、「エディプス・コンプレックスの三項関係」が息子と母親の関係という「二重関係の囚人」を解放するというラカンの提案は、後の精神分析家たちに とって有用であることが証明された。 同様に、ロナルド・ブリトンにとって、「もし愛と憎しみにおいて認識される両親の結びつきが子どもの心の中で許容されるのであれば、......このこと は、他者との相互作用の中で自分自身を見る能力と、......自分自身を省察する能力を与えてくれる」[43]。 そのため、マイケル・パーソンズは『帰ってくる鳩、消える鳩』(2000年)の中で、このような視点は「エディプス・コンプレックスを生涯にわたる発達上 の課題として捉える」ことを可能にすると提唱している。[その後の人生に属する新たな種類のエディプスの構成とともに」[45]。 1920年、ジークムント・フロイトは「精神分析研究の進歩とともに、エディプス・コンプレックスの重要性はますます明らかになり、その認識は精神分析の 信奉者をその反対者から区別する禁句となった」と書いている[46]。 [47] [48] ジャネット・マルコムは、20世紀後半になると、対象関係心理学の「アヴァンギャルド」たちにとって、エディプス期の出来事は、幼児期の崖っぷちに立たさ れた心理劇に比べれば、淡白で取るに足らないものであったと報告している。... それにもかかわらず、自我心理学は、「エディプス期(およそ3年半から6年)は、ローレンツがひよこの前に立っているようなものであり、人間の人生の中で 最も形成的で、重要で、形成的な経験である」[49]と主張し続けた。人の成人後の人生-恋愛、仕事、趣味、野心-を考えてみると、それらはすべてエディ プス・コンプレックスに行き着く」[50]。 |