Essentialism

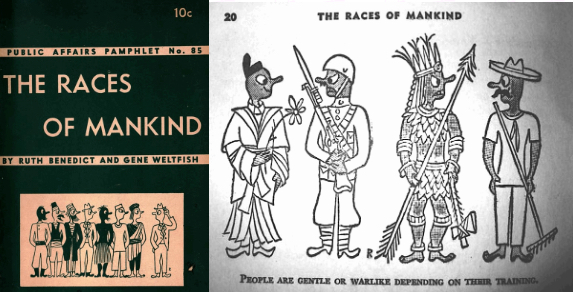

Ruth Benedict and Gene

Weltfish, The

Races of Mankind, 1946.

本質主義

Essentialism

Ruth Benedict and Gene

Weltfish, The

Races of Mankind, 1946.

かいせつ 池田光穂

本質 主義(essentialism)とは、もののなりた ちを、決定的で、それ以外には考えられない、ひとつないしは複数の特性(=これを本質 essence という)からなりたつという見方をさします。

もうすこし込み入った説

明をすると、ある事物や現象という

ものを、その中味(例:特定の唯一あるいは限られた複数の構成要素)や必然性(例:特定の原因に強い因果性を求める)という確固としたものに帰属させる考

え方や主義主張のことをさします。

本質主義の例をあげてみよう。「人間の心は、脳からなりた つ」という見解は、人間の心を脳という「本質」に求める点で、心=脳本質主義の立場を表明しています。

文化人類学を学ぶ我々の関心に引きつけて、もっと身近な例 をあげてみましょう。

人間の女らしさは、性染色体(XX)に由来する、という主 張は、性染色体(あるいは性決定遺伝子)本質主義です。女らしさを女性性器をもつという点に還元すると、この本質主義には疑いがないように思われます。

しかし、ここでの問題は「女らしさ」という言葉にありま す。我々はこの言葉を、我々の身の回りにいる女性や、あるいは我々のまわりの世界で「女らしい」と理想化されているイメージから、この言葉を使っていま す。つまり、ここでの女らしさは、身のこなし、声の調子、あるいは、そこから引き起こされるような「やさしさ」などが、意識/無意識のうちに込められてい るのです。

では、行動パターンとしての、女らしさは遺伝子によって決 定されるのでしょうか?

いいえ、R・ベネディクトやM・ミードの著作を読んできた ように、女らしさは、文化的に構成されるものです。もっとやさしく言うと、社会、文化、歴史が変われば、女らしさの定義も変わるのです。

女らしさの定義は、文化的社会的に決められるという見解 は、経験的真実のようです。行動パターンのように、後天的な要因で決められるという見解は、もののなりたちを、非決定的で、多様な成り方の経路をたどって できあがったものだという主張に通じます。これを、構成主義あ るいは構築主義(constructionism, constructivism)とよびます。

***

通 常、本質主義の反対は構築主義と考えることができます。長いヨーロッパの哲学的思潮に は、 本質主義と構築主義の見解のせめぎ合いがありましたが、事物には何か本質があるという考え方は、ヨーロッパのみならず、世界のさまざまな人々の宇宙論にも みられ、魅了しつづけてきました。人間には、我々の身の回りのものは、うつろなもので構成されているという見方に、耐えるほどタフではないのかもしれませ んね。しかしながら、構成主義によって理解可能になるような出来事、事物は数多くあります。

よくしばし ば、我々のまわりには本質主義は社会的事実が構成されている政治的力学を無視する 理想論であるという「強い反本質主義」的主張を展開する人がいます。他方、事物の本質を求めない構成主義は、論理の根拠を相対的にみているために、正邪の 判断ができないジレンマに陥るという批判を展開する「弱い構成主義批判」に走る人もいます。そのどれもが正しくありません。

構成主義と 本質主義を正反対にみたり、あれかこれかという二元論——歴史的エピソードに由来 してマニ教的二元論と言います——に還元することは適切とは言えません。(もちろん中途半端がよいと言っているわけでもありません)。

構成主義と 本質主義の議論が有効になる点とは、我々が議論をしている対象を考える際に、「社 会がつくりあげる現実」という視点をどうとらえるか、ということを自己反省的に教えてくれることにあります。

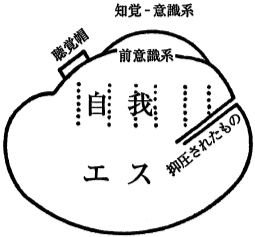

■精神という概念の本質化の例(Moi - psychanalyse)— フロイト(Sigmund Freud,

1856-1939)の自我概念

「自我とい う概念は「意識と前意識、それに無意識的防衛を含む心の構造」を指す言葉として明確化 され……自我はエスからの要求と超自我からの要求を受け取り、外界からの刺激を調整する機能を持つ。無意識的防衛を行い、エスからの欲動を防衛・昇華した り、超自我の禁止や理想と葛藤したり従ったりする、調整的な存在である。全般的に言えば、自我はエス・超自我・外界に悩まされる存在として描かれる事も多 い。自我は意識とは異なるもので、飽くまでも心の機能や構造から定義された概念である。有名なフロイトの格言としては「自我はそれ自体、意識されない」と いう発言がある。自我の大部分は機能や構造によって把握されており、自我が最も頻繁に行う活動の一つとして防衛が挙げられるが、この防衛は人間にとってほ とんどが無意識的である」自我)

"Freud

proposed that the human psyche could

be divided into three parts: Id, ego and super-ego. Freud discussed

this model in the 1920 essay Beyond the Pleasure Principle, and fully

elaborated upon it in The Ego and the Id (1923), in which he developed

it as an alternative to his previous topographic schema (i.e.,

conscious, unconscious and preconscious). The id is the completely

unconscious, impulsive, childlike portion of the psyche that operates

on the "pleasure principle" and is the source of basic impulses and

drives; it seeks immediate pleasure and gratification" - Id, ego and

super-ego.

フロイトの自我概念(このように観念の形態を実体化=マップにするという作業はひろく「物象化(reification)」

の過程とみなされています)

■ラディカル経験主義(ウィ リアム・ジェームズ:William James, 1842-1910)

"Radical empiricism is a philosophical doctrine put forth by William James. It asserts that experience includes both particulars and relations between those particulars, and that therefore both deserve a place in our explanations. In concrete terms: any philosophical worldview is flawed if it stops at the physical level and fails to explain how meaning, values and intentionality can arise from that." - William James, Essays in Radical Empiricism, 1912, Essay II § 1.

■物象化 (Versachlichung , Verdinglichung: reification)

「人と人との関係が物と物との関係として現れること」物象化)

自我と文化 のかかわり、文化のなかの自我のありようをテーマに、自己疎外の超克をめざす近代精神 の苦闘の道程をたどる。人間存在の稀薄化が進行する〈今〉、あらためて世に問うトリリングの代表作。

★事典的 「本質主義」https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Essentialism

| Essentialism

is the view that objects have a set of attributes that are necessary to

their identity.[1] In early Western thought, Platonic idealism held

that all things have such an "essence"—an "idea" or "form". In

Categories, Aristotle similarly proposed that all objects have a

substance that, as George Lakoff put it, "make the thing what it is,

and without which it would be not that kind of thing".[2] The contrary

view—non-essentialism—denies the need to posit such an "essence".

Essentialism has been controversial from its beginning. In the

Parmenides dialogue, Plato depicts Socrates questioning the notion,

suggesting that if we accept the idea that every beautiful thing or

just action partakes of an essence to be beautiful or just, we must

also accept the "existence of separate essences for hair, mud, and

dirt".[3] Older social theories were often conceptually essentialist.[4] In biology and other natural sciences, essentialism provided the rationale for taxonomy at least until the time of Charles Darwin.[5] The role and importance of essentialism in modern biology is still a matter of debate.[6] Beliefs which posit that social identities such as race, ethnicity, nationality, or gender are essential characteristics have been central to many discriminatory or extremist ideologies.[7] For instance, psychological essentialism is correlated with racial prejudice.[8][9] Essentialist views about race have also been shown to diminish empathy when dealing with members of another racial group.[10] In medical sciences, essentialism can lead to a reified view of identities, leading to fallacious conclusions and potentially unequal treatment.[11] |

本質主義とは、物体はその同一性を保つために必要な属性のセットを持つ

という考え方である。[1]

初期の西洋思想では、プラトン主義の観念論が、あらゆる事物には「本質」すなわち「観念」や「形」があるという考え方をとっていた。アリストテレスも『範

疇論』の中で同様に、すべての物体にはジョージ・ラコフの表現を借りれば「そのものをそのものたらしめている、それがそうでなければありえないような本

質」があるとした。[2]

これとは反対の立場である非本質論は、そのような「本質」を仮定する必要性を否定する。本質論は、その始まりから論争の的となってきた。プラトンは『パル

メニデス』の中で、ソクラテスがその概念を疑問視している様子を描き、もし美しいものや正しい行為すべてに本質的な美しさや正しさがあるという考えを受け

入れるのであれば、「髪、泥、汚れにはそれぞれ異なる本質が存在する」という考えも受け入れなければならないと示唆している。 古い社会理論は概念上、本質論的であることが多かった。[4] 生物学やその他の自然科学では、本質論はチャールズ・ダーウィンの時代までは少なくとも分類学の理論的根拠となっていた。[5] 現代生物学における本質論の役割と重要性については、依然として議論の的となっている。[6] 人種、民族、国民、性別などの社会的アイデンティティが本質的な特徴であるとする信念は、 多くの差別的または過激なイデオロギーの中心となっている。[7] 例えば、心理学的本質論は人種的偏見と相関関係にある。[8][9] 人種に関する本質論的見解は、別の人種集団のメンバーと接する際の共感性を低下させることも示されている。[10] 医学においては、本質論はアイデンティティの固定観念につながり、誤った結論を導き、潜在的に不平等な扱いにつながる可能性がある。[11] |

| In philosophy An essence characterizes a substance or a form, in the sense of the forms and ideas in Platonic idealism. It is permanent, unalterable, and eternal, and is present in every possible world. Classical humanism has an essentialist conception of the human, in its endorsement of the notion of an eternal and unchangeable human nature. This has been criticized by Kierkegaard, Marx, Heidegger, Sartre, Badiou and many other existential, materialist and anti-humanist thinkers. Essentialism, in its broadest sense, is any philosophy that acknowledges the primacy of essence. Unlike existentialism, which posits "being" as the fundamental reality, the essentialist ontology must be approached from a metaphysical perspective. Empirical knowledge is developed from experience of a relational universe whose components and attributes are defined and measured in terms of intellectually constructed laws. Thus, for the scientist, reality is explored as an evolutionary system of diverse entities, the order of which is determined by the principle of causality.[citation needed] In Plato's philosophy, in particular the Timaeus and the Philebus, things were said to come into being by the action of a demiurge who works to form chaos into ordered entities. Many definitions of essence hark back to the ancient Greek hylomorphic understanding of the formation of the things. According to that account, the structure and real existence of any thing can be understood by analogy to an artefact produced by a craftsperson. The craftsperson requires hyle (timber or wood) and a model, plan or idea in their own mind, according to which the wood is worked to give it the indicated contour or form (morphe). Aristotle was the first to use the terms hyle and morphe. According to his explanation, all entities have two aspects: "matter" and "form". It is the particular form imposed that gives some matter its identity—its quiddity or "whatness" (i.e., "what it is"). Plato was one of the first essentialists, postulating the concept of ideal forms—an abstract entity of which individual objects are mere facsimiles. To give an example: the ideal form of a circle is a perfect circle, something that is physically impossible to make manifest; yet the circles we draw and observe clearly have some idea in common—the ideal form. Plato proposed that these ideas are eternal and vastly superior to their manifestations, and that we understand these manifestations in the material world by comparing and relating them to their respective ideal form. Plato's forms are regarded as patriarchs to essentialist dogma simply because they are a case of what is intrinsic and a-contextual of objects—the abstract properties that make them what they are. One example is Plato's parable of the cave. Plato believed that the universe was perfect and that its observed imperfections came from man's limited perception of it. For Plato, there were two realities: the "essential" or ideal and the "perceived".[citation needed] Aristotle (384–322 BC) applied the term essence to that which things in a category have in common and without which they cannot be members of that category (for example, rationality is the essence of man; without rationality a creature cannot be a man). In his critique of Aristotle's philosophy, Bertrand Russell said that his concept of essence transferred to metaphysics what was only a verbal convenience and that it confused the properties of language with the properties of the world. In fact, a thing's "essence" consisted in those defining properties without which we could not use the name for it.[12] Although the concept of essence was "hopelessly muddled" it became part of every philosophy until modern times.[12] The Egyptian-born philosopher Plotinus (204–270 AD) brought idealism to the Roman Empire as Neoplatonism, and with it the concept that not only do all existents emanate from a "primary essence" but that the mind plays an active role in shaping or ordering the objects of perception, rather than passively receiving empirical data.[citation needed] |

哲学において 本質とは、プラトン的観念論における形相やイデアの概念と同様に、物質や形相を特徴づけるものである。本質は不変かつ永遠であり、あらゆる可能な世界に存 在する。古典的ヒューマニズムは、永遠かつ不変の人間本性という概念を支持する本質論的な人間観を持つ。これに対しては、キルケゴール、マルクス、ハイ デッガー、サルトル、バディウをはじめとする実存主義者、唯物論者、反ヒューマニストの思想家たちから批判が寄せられた。本質論とは、最も広い意味では、 本質を第一とするあらゆる哲学を指す。実存主義が「存在」を根本的な現実とみなすのとは異なり、本質論的実在論は形而上学的な視点からアプローチされなけ ればならない。経験的知識は、構成要素や属性が知的構築法則によって定義され測定される関係宇宙の経験から発展する。したがって、科学者にとって、現実は 因果律の原則によって決定される多様な実体の進化システムとして探究される。 プラトンの哲学、特に『ティマイオス』と『フィレバス』では、混沌を秩序ある存在へと形作るために働くデミウルゴスの作用によって、事物が創造されると説 かれている。本質に関する多くの定義は、古代ギリシアのヒュロモーシス説に由来する。それによると、あらゆる事物の構造と実在は、職人によって作られた人 工物との類似性によって理解できる。職人はヒュレー(木材または木)と、頭の中にあるモデル、計画、またはアイデアを必要とし、それらに従って木材を加工 し、指示された輪郭または形態(モルフェ)を与える。ヒュレーとモルフェという用語を初めて使用したのはアリストテレスである。彼の説明によると、すべて の実体には「質料」と「形相」という2つの側面がある。特定の形相が与えられることによって、ある質料にアイデンティティ、すなわち「whatness (何であるか)」が与えられる。プラトンは、個々の物体は単なる複製にすぎない抽象的な実体である理想形相という概念を仮定した、最初の実体論者の一人で あった。例を挙げると、円の理想形は完全な円であり、物理的には実現不可能なものである。しかし、私たちが描き、観察する円には、理想形という共通の概念 がある。プラトンは、これらの概念は永遠であり、その実現形よりもはるかに優れていると提唱した。そして、私たちは物質世界におけるこれらの実現形を、そ れぞれの理想形と比較し、関連付けることで理解していると主張した。プラトンの形相は、本質的で文脈に依存しない対象、つまり対象をその存在たらしめてい る抽象的特性の事例であるという理由から、本質論的教義の始祖とみなされている。その一例が、プラトンの洞窟の喩えである。プラトンは、宇宙は完璧であ り、観察される不完全性は人間の限られた知覚に由来すると考えていた。プラトンにとって、現実には「本質的」または「理想的」なものと「知覚された」もの の2つが存在していた。[要出典] アリストテレス(前384年-前322年)は、カテゴリーに属する事物が共通して持つものを本質と呼び、それなしにはそのカテゴリーに属することはできな いとした(例えば、理性は人間の持つ本質であり、理性なしには人間とは言えない)。 アリストテレス(前384年-前322年)は、あるカテゴリーに属する事物が共通して持つ要素を「本質」と呼び、それなしにはそのカテゴリーに属すること はできないとした(例えば、理性は人間の「本質」であり、理性がなければ生物は人間とはなりえない)。アリストテレスの哲学に対する批判の中で、バートラ ンド・ラッセルは、アリストテレスの「本質」の概念は、単に言葉の都合でしかなく、言語の特性と世界の特性とを混同していると述べた。実際、ある事物の 「本質」は、その事物を定義する性質から構成されており、それらなしにはその事物の名称を使用することはできない。[12] 本質の概念は「救いようもなく混乱した」ものであったが、近代に至るまであらゆる哲学の一部となった。[12] エジプト生まれの哲学者プロティノス(204年~ 270年)は、新プラトン主義として観念論をローマ帝国にもたらし、それとともに、すべての存在は「第一の本質」から発しているという概念だけでなく、心 は受動的に経験的データを受け取るのではなく、知覚の対象を形作ったり、整理したりする上で積極的な役割を果たすという概念ももたらした。[要出典] |

| Examples Naturalism Dating back to the 18th century, naturalism is a form of essentialism in which social matters are explained through the logic of natural dispositions.[13] The invoked nature can be biological, ontological or theological.[14] Its opponent is culturalism.[15] Human nature See also: Philosophical anthropology "Monism will demand that enhancement technologies be used to create humans as close as possible to the ideal state. [...] The Nazis would have proposed the list of characteristics for admission to the SS as the universal template for enhancement technologies. Hedonistic utilitarianism is a less objectionable version of monism, according to which the best human life is one that contains as much pleasure and as little suffering as possible – but like Nazism, it leaves no room for meaningful choice about enhancement." Nicholas Agar[16] In the case of Homo sapiens, the divergent conceptions of human nature may be partitioned into essentialist versus non-essentialist (or even anti-essentialist) positions.[17][18] Another established dichotomy is that of monism versus pluralism about the matter.[19] Biological essentialism Main article: Species § The species problem Before evolution was developed as a scientific theory, the essentialist view of biology posited that all species are unchanging throughout time. The historian Mary P. Winsor has argued that biologists such as Louis Agassiz in the 19th century believed that taxa such as species and genus were fixed, reflecting the mind of the creator.[20] Some religious opponents of evolution continue to maintain this view of biology. Work by historians of systematic biology in the 21st century has cast doubt upon this view of pre-Darwinian thinkers. Winsor, Ron Amundson and Staffan Müller-Wille have each argued that in fact the usual suspects (such as Linnaeus and the Ideal Morphologists) were very far from being essentialists, and that the so-called "essentialism story" (or "myth") in biology is a result of conflating the views expressed and biological examples used by philosophers going back to Aristotle and continuing through to John Stuart Mill and William Whewell in the immediately pre-Darwinian period, with the way that biologists used such terms as species.[21][22][23] Anti-essentialists contend that an essentialist typological categorization has been rendered obsolete and untenable by evolutionary theory for several reasons.[24][25] First, they argue that biological species are dynamic entities, emerging and disappearing as distinct populations are molded by natural selection. This view contrasts with the static essences that essentialists say characterize natural categories. Second, the opponents of essentialism argue that our current understanding of biological species emphasizes genealogical relationships rather than intrinsic traits. Lastly, non-essentialists assert that every organism has a mutational load, and the variability and diversity within species contradict the notion of fixed biological natures. Gender essentialism Main article: Gender essentialism In feminist theory and gender studies, gender essentialism is the attribution of fixed essences to men and women—this idea that men and women are fundamentally different continues to be a matter of contention.[26][27] Gay/lesbian rights advocate Diana Fuss wrote: "Essentialism is most commonly understood as a belief in the real, true essence of things, the invariable and fixed properties which define the 'whatness' of a given entity."[28] Women's essence is assumed to be universal and is generally identified with those characteristics viewed as being specifically feminine.[29] These ideas of femininity are usually biologized and are often preoccupied with psychological characteristics, such as nurturance, empathy, support, and non-competitiveness, etc. Feminist theorist Elizabeth Grosz states in her 1995 publication Space, time and perversion: essays on the politics of bodies that essentialism "entails the belief that those characteristics defined as women's essence are shared in common by all women at all times. It implies a limit of the variations and possibilities of change—it is not possible for a subject to act in a manner contrary to her essence. Her essence underlies all the apparent variations differentiating women from each other. Essentialism thus refers to the existence of fixed characteristic, given attributes, and ahistorical functions that limit the possibilities of change and thus of social reorganization."[29] Gender essentialism is pervasive in popular culture, as illustrated by the #1 New York Times best seller Men Are from Mars, Women Are from Venus,[30] but this essentialism is routinely critiqued in introductory women's studies textbooks such as Women: Images & Realities.[27] Starting in the 1980s, some feminist writers have put forward essentialist theories about gender and science. Evelyn Fox Keller,[31] Sandra Harding, [32] and Nancy Tuana [33] argued that the modern scientific enterprise is inherently patriarchal and incompatible with women's nature. Other feminist scholars, such as Ann Hibner Koblitz,[34] Lenore Blum,[35] Mary Gray,[36] Mary Beth Ruskai,[37] and Pnina Abir-Am and Dorinda Outram[38] have criticized those theories for ignoring the diverse nature of scientific research and the tremendous variation in women's experiences in different cultures and historical periods. Racial, cultural and strategic essentialism Main articles: Race (human categorization) and Strategic essentialism Cultural and racial essentialism is the view that fundamental biological or physical characteristics of human "races" produce personality, heritage, cognitive abilities, or 'natural talents' that are shared by all members of a racial group.[39][40] In the early 20th century, many anthropologists taught this theory – that race was an entirely biological phenomenon and that this was core to a person's behavior and identity.[41] This, coupled with a belief that linguistic, cultural, and social groups fundamentally existed along racial lines, formed the basis of what is now called scientific racism.[42] After the Nazi eugenics program, along with the rise of anti-colonial movements, racial essentialism lost widespread popularity.[43] New studies of culture and the fledgling field of population genetics undermined the scientific standing of racial essentialism, leading race anthropologists to revise their conclusions about the sources of phenotypic variation.[41] A significant number of modern anthropologists and biologists in the West came to view race as an invalid genetic or biological designation.[44] Historically, beliefs which posit that social identities such as ethnicity, nationality or gender determine a person's essential characteristics have in many cases been shown to have destructive or harmful results. It has been argued by some that essentialist thinking lies at the core of many simplistic, discriminatory or extremist ideologies.[45] Psychological essentialism is also correlated with racial prejudice.[46][47] In medical sciences, essentialism can lead to an over-emphasis on the role of identities—for example assuming that differences in hypertension in African-American populations are due to racial differences rather than social causes—leading to fallacious conclusions and potentially unequal treatment.[48] Older social theories were often conceptually essentialist.[49] Strategic essentialism, a major concept in postcolonial theory, was introduced in the 1980s by the Indian literary critic and theorist Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak.[50] It refers to a political tactic in which minority groups, nationalities, or ethnic groups mobilize on the basis of shared gendered, cultural, or political identity. While strong differences may exist between members of these groups, and among themselves they engage in continuous debates, it is sometimes advantageous for them to temporarily "essentialize" themselves, despite it being based on erroneous logic,[51] and to bring forward their group identity in a simplified way to achieve certain goals, such as equal rights or antiglobalization.[52] |

例 自然主義 18世紀に遡る自然主義は、社会問題を自然な性向の論理によって説明する本質論の一形態である。[13] 引き合いに出される自然は、生物学的なものでも、存在論的なものでも、神学的なものでもよい。[14] その対立概念は文化主義である。[15] 人間の本性 参照:哲学的人間学 「単一論は、理想の状態に可能な限り近い人間を作り出すために、強化テクノロジーの使用を要求するだろう。...ナチスは、SS入隊のための特性リスト を、強化テクノロジーの普遍的なテンプレートとして提案しただろう。快楽主義的功利主義は、単一論のあまり問題のないバージョンであり、それによれば、最 高の人間生活とは、可能な限り多くの快楽と、可能な限り少ない苦痛を含むものである。しかし、ナチズムと同様に、強化に関する有意義な選択の余地を残さな い。」 ニコラス・アガー[16] ホモ・サピエンスの場合、人間性に関する相異なる概念は、本質論者対非本質論者(あるいは反本質論者)の立場に区分される可能性がある。[17][18] もう一つの確立された二分法は、本質論対多元論というものである。[19] 生物学的本質論 詳細は「生物種」の項を参照 進化論が科学理論として発展する以前、生物学における本質論の見解では、すべての生物種は時間を通じて不変であるとされていた。歴史学者メアリー・P・ ウィンザーは、19世紀のルイ・アガシーなどの生物学者は、生物種や属などの分類群は固定されており、創造主の意思を反映していると考えていたと主張して いる。[20] 進化論に反対する一部の宗教家は、現在でもこの生物学の見解を維持している。 21世紀の系統分類学の歴史家たちの研究により、ダーウィン以前の思想家たちのこの見解に疑問が投げかけられている。ウィンザー、ロン・アムンソン、スタ ファン・ミュラー=ヴィレはそれぞれ、実際には、よく疑われる人物(リンネや理想形態学者など)は本質論者とはかけ離れており、生物学におけるいわゆる 「本質論の物語」(または「神話」)は アリストテレスに始まり、ジョン・スチュアート・ミルやウィリアム・ヘーゲルといったダーウィンの直前の時代に活躍した哲学者たちが表明した見解や用いた 生物学的例と、生物学者たちが種などの用語を使用した方法とを混同した結果であると主張している。[21][22][23] 反本質論者は、本質論的な類型論的分類は進化論によっていくつかの理由から時代遅れで、もはや支持できないものになっていると主張している。[24] [25] まず、生物学的種は動的な存在であり、自然淘汰によって異なる個体群が形成されるにつれて出現したり消滅したりすると彼らは主張する。この見解は、本質論 者が自然界のカテゴリーの特徴であると主張する静的な本質とは対照的である。第二に、本質論の反対派は、生物学的種に関する現在の理解は、本質的な形質よ りも系統関係を強調していると主張する。最後に、本質論否定派は、あらゆる生物には突然変異の負荷があり、種内の変異性と多様性は固定された生物学的本質 の概念と矛盾していると主張する。 ジェンダー本質論 詳細は「ジェンダー本質論」を参照 フェミニズム理論やジェンダー研究において、ジェンダー本質論とは、男性と女性に固定された本質を帰属させることである。男性と女性は本質的に異なるとい うこの考えは、依然として論争の的となっている。[26][27] ゲイ/レズビアンの権利擁護者であるダイアナ・ファスは、「本質論とは、物事の現実の真の本質、不変かつ固定された 。女性の本質は普遍的であると想定され、一般的に、特に女性的であると見なされる特性と同一視される。[29] このような女性的な特性の考え方は通常、生物学的なものとされ、しばしば、世話好き、共感、サポート、非競争性などの心理的特性に重点が置かれる。フェミ ニズム理論家のエリザベス・グロスは、1995年の著書『空間・時間・倒錯:身体の政治学に関するエッセイ』の中で、本質主義とは「女性の本質として定義 されたそれらの特性が、すべての女性に常に共通して備わっているという信念を伴う」ものであると述べている。それは、変化の可能性やバリエーションの限界 を暗示している。本質に反する行動を取ることは不可能である。本質は、女性同士を区別するあらゆる表面的なバリエーションの根底にある。本質主義は、変化 の可能性、ひいては社会の再編成の可能性を制限する固定された特性、与えられた属性、歴史に依存しない機能の存在を指すものである。 ジェンダー本質主義は、ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のベストセラー第1位となった『男は火星から、女は金星からやってきた』[30] に示されているように、大衆文化に広く浸透しているが、この本質主義は、入門的な女性学の教科書である『女性:イメージと現実』[27] などで日常的に批判されている。Images & Realities[27] 1980年代から、一部のフェミニストの著述家たちはジェンダーと科学に関する本質論的な理論を提唱している。エブリン・フォックス・ケラー (Evelyn Fox Keller)[31]、サンドラ・ハーディング(Sandra Harding)[32]、ナンシー・トゥアナ(Nancy Tuana)[33]は、現代の科学事業は本質的に家父長的であり、女性の性質とは相容れないと主張した。他のフェミニスト学者、例えばアン・ヒブナー・ コブリッツ(Ann Hibner Koblitz)[34]、レノア・ブルーム(Lenore Blum)[35]、メアリー・グレイ(Mary Gray)[36]、メアリー・ベス・ラスカイ(Mary Beth Ruskai)[37]、ピナ・アビル=アム(Pnina Abir-Am)とドリンダ・アウトラム(Dorinda Outram)[38]は、科学的研究の多様な性質や、異なる文化や時代における女性の経験の大きな違いを無視しているとして、これらの理論を批判してい る。 人種的、文化的、戦略的本質論 詳細は「人種(人間の分類)」および「戦略的本質論」を参照 文化的、人種的本質論とは、人間の「人種」の生物学上または物理学的特性が、人種集団のすべての構成員に共通する性格、遺産、認知能力、または「天賦の才 能」を生み出すという見解である。[39][40] 20世紀初頭には、多くの人類学者がこの理論を教えた。すなわち、人種は完全に生物学的な現象であり、 それが個人の行動やアイデンティティの中核をなすという理論である。[41] 言語的、文化的、社会的集団は基本的に人種別に存在するという信念と相まって、これが現在では科学的人種主義と呼ばれるものの基礎を形成した。[42] ナチスの優生学プログラムと反植民地運動の高まりにより、人種本質論は広く人気を失った 。文化に関する新たな研究や、始まったばかりの集団遺伝学の分野が、人種本質論の科学的地位を脅かし、人類人類学者が表現型の変異の要因に関する結論を修 正するに至った。 歴史的に、民族性、国民性、性別などの社会的アイデンティティがその人の本質的特性を決定するという考え方は、多くの場合、破壊的または有害な結果をもた らすことが示されている。本質主義的思考は、多くの単純化された差別的または過激なイデオロギーの核心にあるという主張もある。[45] 心理学的本質主義は、人種的偏見とも関連している。[46][47] 医学においては、本質主義はアイデンティティの役割を過度に強調する結果となりうる。 例えば、アフリカ系アメリカ人の高血圧の差異は社会的要因ではなく人種的差異によるものとするなど、アイデンティティの役割を過度に強調し、誤った結論を 導き、潜在的に不平等な扱いにつながる可能性がある。[48] 古い社会理論は概念的に本質論的であることが多い。[49] 戦略的本質論は、ポストコロニアル理論における主要な概念であり、1980年代にインドの文学評論家であり理論家でもあるガヤトリ・チャクラヴォルティ・ スピヴァクによって紹介された。[50] これは、少数派グループ、国民、あるいは民族が、ジェンダー、文化、政治的なアイデンティティを共有していることを根拠に団結する政治的な戦術を指す。こ れらのグループのメンバー間には大きな違いが存在し、互いに継続的な議論を行っているが、誤った論理に基づいているにもかかわらず、一時的に自分自身を 「本質化」し、平等な権利や反グローバリゼーションといった特定の目標を達成するために、グループのアイデンティティを単純化して前面に押し出すことが、 時には有利になることがある。 |

| In historiography Essentialism in history as a field of study entails discerning and listing essential cultural characteristics of a particular nation or culture, in the belief that a people or culture can be understood in this way. Sometimes such essentialism leads to claims of a praiseworthy national or cultural identity, or to its opposite, the condemnation of a culture based on presumed essential characteristics. Herodotus, for example, claims that Egyptian culture is essentially feminized and possesses a "softness" which has made Egypt easy to conquer.[53] To what extent Herodotus was an essentialist is a matter of debate; he is also credited with not essentializing the concept of the Athenian identity,[54] or differences between the Greeks and the Persians that are the subject of his Histories.[55] Essentialism had been operative in colonialism, as well as in critiques of colonialism. Post-colonial theorists, such as Edward Said, insisted that essentialism was the "defining mode" of "Western" historiography and ethnography until the nineteenth century and even after, according to Touraj Atabaki, manifesting itself in the historiography of the Middle East and Central Asia as Eurocentrism, over-generalization, and reductionism.[56] Into the 21st century, most historians, social scientists, and humanists reject methodologies associated with essentialism,[57][58] although some have argued that certain varieties of essentialism may be useful or even necessary.[57][59] Karl Popper splits the ambiguous term realism into essentialism and realism. He uses essentialism whenever he means the opposite of nominalism, and realism only as opposed to idealism. Popper himself is a realist as opposed to an idealist, but a methodological nominalist as opposed to an essentialist. For example, statements like "a puppy is a young dog" should be read from right to left as an answer to "What shall we call a young dog", never from left to right as an answer to "What is a puppy?"[60] |

歴史学において 歴史学の分野における本質主義とは、特定の国民や文化の本質的な文化的特性を見極め、列挙することを意味し、そうすることで国民や文化を理解できるという 信念に基づいている。このような本質主義は、時に賞賛に値する国民的または文化的アイデンティティの主張につながることもあれば、その反対に、想定された 本質的特性に基づく文化の非難につながることもある。例えば、ヘロドトスはエジプト文化の本質は女性的であり、「柔らかさ」を持っているため征服が容易で あったと主張している。[53] ヘロドトスがどの程度本質論者であったかは議論の余地がある。また、ヘロドトスはアテナイのアイデンティティの概念を本質論的に捉えていないことでも知ら れている。[54] あるいは、ヘロドトスの著書『歴史』の主題であるギリシア人とペルシア人の間の相違についても、本質論的に捉えていないとされている。[55] 本質主義は、植民地主義の実践や、植民地主義の批判においても用いられてきた。エドワード・サイードなどのポストコロニアル理論家は、本質主義は19世紀 まで、またそれ以降も「西洋」の歴史学や民族誌学における「定義の方法」であったと主張している。トゥラジ・アタバキによると、本質主義は中東や中央アジ アの歴史学においては、西欧中心主義、過度な一般化、還元主義として現れているという。還元主義である。[56] 21世紀に入っても、ほとんどの歴史家、社会科学者、人文主義者は本質主義に関連する方法論を拒絶しているが、[57][58] 一部の者は特定の種類の本質主義は有用である、あるいは必要であると主張している。[57][59] カール・ポパーは曖昧な用語であるリアリズムを本質主義と現実主義に分ける。彼は、ノミナリズムの反対の意味で本質主義を用い、理想主義の反対の意味での み現実主義を用いる。ポパー自身は、理想主義者とは対照的に現実主義者であるが、本質論者とは対照的に方法論的唯名論者である。例えば、「子犬は若い犬で ある」という文は、「若い犬を何と呼ぼうか」という問いに対する答えとして右から左に読むべきであり、「子犬とは何か」という問いに対する答えとして左か ら右に読むべきではない[60]。 |

In psychology Paul Bloom attempts to explain why people will pay more in an auction for the clothing of celebrities if the clothing is unwashed. He believes the answer to this and many other questions is that people cannot help but think of objects as containing a sort of "essence" that can be influenced.[61] There is a difference between metaphysical essentialism and psychological essentialism, the latter referring not to an actual claim about the world but a claim about a way of representing entities in cognitions.[62] Influential in this area is Susan Gelman, who has outlined many domains in which children and adults construe classes of entities, particularly biological entities, in essentialist terms—i.e., as if they had an immutable underlying essence which can be used to predict unobserved similarities between members of that class.[63][64] This causal relationship is unidirectional; an observable feature of an entity does not define the underlying essence.[65] In developmental psychology Essentialism has emerged as an important concept in psychology, particularly developmental psychology.[63][66] In 1991, Kathryn Kremer and Susan Gelman studied the extent to which children from four–seven years old demonstrate essentialism. Children believed that underlying essences predicted observable behaviours. Children were able to describe living objects' behaviour as self-perpetuated and non-living objects' behavior as a result of an adult influencing the object. Understanding the underlying causal mechanism for behaviour suggests essentialist thinking.[67] Younger children were unable to identify causal mechanisms of behaviour whereas older children were able to. This suggests that essentialism is rooted in cognitive development. It can be argued that there is a shift in the way that children represent entities, from not understanding the causal mechanism of the underlying essence to showing sufficient understanding.[68] There are four key criteria that constitute essentialist thinking. The first facet is the aforementioned individual causal mechanisms.[69] The second is innate potential: the assumption that an object will fulfill its predetermined course of development.[70] According to this criterion, essences predict developments in entities that will occur throughout its lifespan. The third is immutability.[71] Despite altering the superficial appearance of an object it does not remove its essence. Observable changes in features of an entity are not salient enough to alter its essential characteristics. The fourth is inductive potential.[72] This suggests that entities may share common features but are essentially different; however similar two beings may be, their characteristics will be at most analogous, differing most importantly in essences. The implications of psychological essentialism are numerous. Prejudiced individuals have been found to endorse exceptionally essential ways of thinking, suggesting that essentialism may perpetuate exclusion among social groups.[73] For example, essentialism of nationality has been linked to anti-immigration attitudes.[74] In multiple studies in India and the United States, it was shown that in lay view a person's nationality is considerably fixed at birth, even if that person is adopted and raised by a family of another nationality at day one and never told about their origin.[75] This may be due to an over-extension of an essential-biological mode of thinking stemming from cognitive development.[76] Paul Bloom of Yale University has stated that "one of the most exciting ideas in cognitive science is the theory that people have a default assumption that things, people and events have invisible essences that make them what they are. Experimental psychologists have argued that essentialism underlies our understanding of the physical and social worlds, and developmental and cross-cultural psychologists have proposed that it is instinctive and universal. We are natural-born essentialists."[77] Scholars suggest that the categorical nature of essentialist thinking predicts the use of stereotypes and can be targeted in the application of stereotype prevention.[78] |

心理学において ポール・ブルームは、有名人の衣類が洗濯されていない場合、人々がオークションでより高い金額を支払う理由を説明しようとしている。彼は、この疑問やその 他の多くの疑問に対する答えは、人々は対象物に何らかの「本質」が含まれていると考えずにはいられないというものであると考えている。 形而上学的本質論と心理学的本質論の違いは、後者が世界の実際の主張ではなく、認知における実体の表現方法に関する主張であることである。[62] この分野で影響力を持つのはスーザン・ゲルマンであり、彼女は、子供と大人が実体のクラス、特に生物学的実体を本質論的な用語で解釈する多くの領域を概説 している。生物学的実体を本質主義的な用語で解釈する多くの領域を概説している。すなわち、そのクラスのメンバー間の観察されていない類似性を予測するた めに使用できる不変の基礎的な本質があるかのようにである。[63][64] この因果関係は一方向であり、実体の観察可能な特徴は基礎的な本質を定義しない。[65] 発達心理学では 本質主義は心理学、特に発達心理学において重要な概念として浮上している。[63][66] 1991年、キャサリン・クレマーとスーザン・ゲルマンは4歳から7歳までの子供たちが本質主義をどの程度示すかを研究した。子供たちは、本質的な本質が 観察可能な行動を予測すると信じていた。子供たちは、生物の行動は自己維持によるものであり、非生物の行動は大人による影響の結果であると説明することが できた。行動の根本的な因果メカニズムを理解することは本質論的思考を示唆している。[67] 低年齢の子供は行動の因果メカニズムを特定することができなかったが、高年齢の子供は特定することができた。これは、本質論が認知発達に根ざしていること を示唆している。子供が実体を表現する方法に変化があり、本質的な本質の因果メカニズムを理解していない状態から、十分な理解を示す状態へと変化している と主張することができる。[68] 本質論的思考を構成する4つの主な基準がある。第1の基準は、前述の個々の因果メカニズムである。[69] 第2の基準は、生得的な潜在能力である。すなわち、対象がそのあらかじめ定められた発展の過程を遂行するという想定である。[70] この基準によると、本質は、その寿命を通じて対象に起こる発展を予測する。3つ目は不変性である。[71] 対象物の表面的な外観は変化しても、本質は失われない。 対象物の特徴における観察可能な変化は、本質的特性を変化させるほど顕著ではない。 4つ目は帰納的潜在性である。[72] これは、対象物が共通の特徴を共有している可能性はあるが、本質的には異なることを示唆している。 心理学的本質論の含意は数多くある。偏見を持つ人々は、例外的に本質的な思考方法を支持することが分かっており、本質論が社会集団間の排除を永続させる可 能性を示唆している。[73] 例えば、国籍の本質論は反移民の態度と関連している。[74] インドと米国における複数の研究では、たとえその人が出生時に養子として迎えられ、別の国籍を持つ家族に育てられ、出自について知らされなかったとして も、一般的に人の国籍は出生時にほぼ確定していることが示されている たとえその人が生後すぐに別の国籍を持つ家族に養子として引き取られ、出自について知らされていない場合でも、である。[75] これは、認知能力の発達に由来する本質的・生物学的思考様式が過度に拡大されたことによるものかもしれない。[76] イェール大学のポール・ブルームは、「認知科学における最も興味深い考え方のひとつは、人々は物事や人々、出来事には目に見えない本質があり、それによっ てそれらが存在しているという前提をデフォルトで持っているという理論である」と述べている。実験心理学者は、本質論が物理的および社会的世界の理解の根 底にあると主張し、発達心理学者や異文化心理学者は、本質論は本能的かつ普遍的であると提唱している。私たちは生まれながらの本質論者なのだ」[77] 学者たちは、本質論的思考のカテゴリー的な性質が固定観念の使用を予測し、固定観念防止の適用で対象とすることができると示唆している。[78] |

| Determinism Educational essentialism Moral panic Nature vs. nurture Mereological essentialism Medium essentialism National essentialism (Japan) Non-essentialism Pleasure Poststructuralism Primordialism Social constructionism Scientific essentialism Structuralism Traditionalist School Vitalism Political acceptation: Identity politics, Strategic essentialism, Ethnic nationalism Brian David Ellis (New essentialism) Greg McKeown (author) (Essentialism: The Disciplined Pursuit of Less) |

決定論 教育本質論 モラル・パニック 生得 vs 獲得 部分本質論 媒体本質論 国民本質論(日本 非本質論 快楽 ポスト構造主義 原始論 社会構築主義 科学的本質論 構造主義 伝統主義学派 活力論 政治的用法:アイデンティティ・ポリティクス、戦略的本質論、民族ナショナリズム ブライアン・デイヴィッド・エリス(新本質論) グレッグ・マッキーウン(著)(『エッセンシャリズム:より少ないものを追求する規律ある生き方』) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Essentialism |

リンク

文献

その他の情

報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq

Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq

Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099