☆

☆ 民俗学

Folklore studies

☆ ☆

☆

☆

民俗学(民俗科学として知られることは少なく、英国では伝統学や民俗生活学として知られることもある)は、民俗学の研究に専念する人類学の一分野であ

る。この用語は同義語とともに、伝統文化の学術的研究を民俗学的成果そのものから区別するために1950年代に広まった。この用語は、フォルクスクンデ

(ドイツ語)、フォルケミンナー(ノルウェー語)、フォルクミンネン(スウェーデン語)などと協調しながら、ヨーロッパと北米の両方で一つの分野として確

立していった。また、日本民俗学(にほんみんぞくがく)は、柳田国男らに

よって、海外の民俗学や人類学研究の影響を受けながらも、独自に開発させられた一国民俗学あるいは国民民俗学(National Folklore

Sciense)である。この学問は、民間学から出発しながらも、政府の文化財行政や無形文化財保護などの政策と「協働」して、日本のナショナリズム形成

に大きく影響を与え、学校教育においても、地理学や郷土史を通して教育されており、現在でもそれなりの影響力をもちつづけている、ナショナルサイエンス

(国民の科学)のひとつである。

| Folklore studies (less

often known as folkloristics, and occasionally tradition studies or

folk life studies in the United Kingdom)[1] is the branch of

anthropology devoted to the study of folklore. This term, along with

its synonyms,[note 1] gained currency in the 1950s to distinguish the

academic study of traditional culture from the folklore artifacts

themselves. It became established as a field across both Europe and

North America, coordinating with Volkskunde (German), folkeminner

(Norwegian), and folkminnen (Swedish), among others.[5] |

民

俗学(民俗科学として知られることは少なく、英国では伝統学や民俗生活学として知られることもある)[1]は、民俗学の研究に専念する人類学の一分野であ

る。この用語は同義語とともに[注

1]、伝統文化の学術的研究を民俗学的成果そのものから区別するために1950年代に広まった。この用語は、フォルクスクンデ(ドイツ語)、フォルケミン

ナー(ノルウェー語)、フォルクミンネン(スウェーデン語)などと協調しながら、ヨーロッパと北米の両方で一つの分野として確立していった[5]。 |

Overview OverviewThe importance of folklore and folklore studies was recognized globally in 1982 in the UNESCO document "Recommendation on the Safeguarding of Traditional Culture and Folklore".[6] UNESCO again in 2003 published a Convention for the Safeguarding of the Intangible Cultural Heritage. Parallel to these global statements, the American Folklife Preservation Act (P.L. 94-201),[7] passed by the United States Congress in conjunction with the Bicentennial Celebration in 1976, included a definition of folklore, also called folklife: "...[Folklife] means the traditional expressive culture shared within the various groups in the United States: familial, ethnic, occupational, religious, regional; expressive culture includes a wide range of creative and symbolic forms such as custom, belief, technical skill, language, literature, art, architecture, music, play, dance, drama, ritual, pageantry, handicraft; these expressions are mainly learned orally, by imitation, or in performance, and are generally maintained without benefit of formal instruction or institutional direction." This law was added to the variety of other legislation designed to protect the natural and cultural heritage of the United States. It gives voice to a growing understanding that the cultural diversity of the United States is a national strength and a resource worthy of protection.[8] To fully understand the term folklore studies, it is necessary to clarify its component parts: the terms folk and lore. Originally the word folk applied only to rural, frequently poor, frequently illiterate peasants. A more contemporary definition of folk is a social group which includes two or more persons with common traits, who express their shared identity through distinctive traditions. "Folk is a flexible concept which can refer to a nation as in American folklore or to a single family."[9] This expanded social definition of folk supports a wider view of the material considered to be folklore artifacts. These now include "things people make with words (verbal lore), things they make with their hands (material lore), and things they make with their actions (customary lore)".[10] The folklorist studies the traditional artifacts of a group. They study the groups, within which these customs, traditions and beliefs are transmitted. Transmission of these artifacts is a vital part of the folklore process. Without communicating these beliefs and customs within the group over space and time, they would become cultural shards relegated to cultural archaeologists. These folk artifacts continue to be passed along informally within the group, as a rule anonymously and always in multiple variants. For the folk group is not individualistic, it is community-based and nurtures its lore in community. This is in direct contrast to high culture, where any single work of a named artist is protected by copyright law. The folklorist strives to understand the significance of these beliefs, customs and objects for the group. For "folklore means something – to the tale teller, to the song singer, to the fiddler, and to the audience or addressees".[11] These cultural units[12] would not be passed along unless they had some continued relevance within the group. That meaning can however shift and morph.  Brothers Grimm (1916) Brothers Grimm (1916)With an increasingly theoretical sophistication of the social sciences, it has become evident that folklore is a naturally occurring and necessary component of any social group, it is indeed all around us.[13] It does not have to be old or antiquated. It continues to be created, transmitted and in any group can be used to differentiate between "us" and "them". All cultures have their own unique folklore, and each culture has to develop and refine the techniques and methods of folklore studies most effective in identifying and researching their own. As an academic discipline, folklore studies straddles the space between the Social Sciences and the Humanities.[8] This was not always the case. The study of folklore originated in Europe in the first half of the 19th century with a focus on the oral folklore of the rural peasant populations. The "Kinder- und Hausmärchen" of the Brothers Grimm (first published 1812) is the best known but by no means only collection of verbal folklore of the European peasantry. This interest in stories, sayings and songs, i.e. verbal lore, continued throughout the 19th century and aligned the fledgling discipline of folklore studies with Literature and Mythology. By the turn into the 20th century, European folklorists remained focused on the oral folklore of the homogeneous peasant populations in their regions, while the American folklorists, led by Franz Boas, chose to consider Native American cultures in their research, and included the totality of their customs and beliefs as folklore. This distinction aligned American folklore studies with cultural anthropology and ethnology, using the same techniques of data collection in their field research. This divided alliance of folklore studies between the humanities and the social sciences offers a wealth of theoretical vantage points and research tools to the field of folklore studies as a whole, even as it continues to be a point of discussion within the field itself.[14] Public folklore is a relatively new offshoot of folklore studies; it started after the Second World War and modeled itself on the seminal work of Alan Lomax and Ben Botkin in the 1930s which emphasized applied folklore. Public sector folklorists work to document, preserve and present the beliefs and customs of diverse cultural groups in their region. These positions are often affiliated with museums, libraries, arts organizations, public schools, historical societies, etc. The most renowned of these is the American Folklife Center at the Smithsonian, together with its Smithsonian Folklife Festival held every summer in Washington, DC. Public folklore differentiates itself from the academic folklore supported by universities, in which collection, research and analysis are primary goals.[8] |

概観 概観フォークロアとフォークロア研究の重要性は、1982年にユネスコの文書「伝統文化とフォークロアの保護に関する勧告」において世界的に認識された [6]。 ユネスコは2003年に再び「無形文化遺産の保護に関する条約」を発表した。こうした世界的な声明と並行して、1976年の200周年記念式典に合わせて 米国議会で可決された米国フォークライフ保護法(P.L. 94-201)[7]には、フォークライフとも呼ばれるフォークロアの定義が盛り込まれている: 「表現文化には、慣習、信仰、技術的技能、言語、文学、芸術、建築、音楽、演劇、舞踊、演劇、儀式、ページェントリー、手工芸など、創造的かつ象徴的な形 式が幅広く含まれる。これらの表現は主に口頭で、模倣によって、または実演によって習得され、一般に正式な指導や制度的な指示の恩恵にあずかることなく維 持されている。" この法律は、合衆国の自然および文化遺産を保護することを目的とした、他のさまざまな法律に追加されたものである。この法律は、米国の文化的多様性は国力であり、保護に値する資源であるとの理解の高まりに声を与えるものである[8]。 フォークロア研究という用語を完全に理解するためには、その構成要素であるフォークと伝承という用語を明確にする必要がある。もともとフォークという言葉 は、農村の、しばしば貧しく、しばしば読み書きのできない農民にのみ適用されていた。より現代的な民俗の定義は、共通の特徴を持つ2人以上の人物を含む社 会集団であり、彼らは独特の伝統を通じて共通のアイデンティティを表現している。「フォークとは柔軟な概念であり、アメリカのフォークロアのように国家を 指すこともあれば、単一の家族を指すこともある」[9]。このように拡大された民俗の社会的定義は、フォークロアの遺物であると見なされる素材のより広範 な見方を支えている。これには現在、「人々が言葉で作るもの(言語伝承)、手で作るもの(物質伝承)、行動で作るもの(慣習伝承)」が含まれる[10]。 民俗学者は集団の伝統的工芸品を研究し、その集団の中でこれらの風習、伝統、信念が伝えられていることを研究する。 これらの工芸品の伝達はフォークロアのプロセスにおいて極めて重要な部分である。時空を超えて集団の中でこうした信念や習慣が伝えられなければ、それらは 文化考古学者の手に委ねられる文化的破片となってしまうだろう。これらの民俗遺物は、集団内で非公式に、原則として匿名で、常に複数のバリエーションで伝 えられ続けている。というのも、民俗集団は個人主義ではなく、共同体主義であり、共同体の中で伝承を育んでいるからである。これは、名前のある芸術家のい かなる単一の作品も著作権法によって保護されるハイカルチャーとは正反対である。 民俗学者は、集団にとってのこうした信仰、風習、物の意義を理解しようと努める。というのも、「民間伝承は、語り手にとっても、歌い手にとっても、バイオ リン弾きにとっても、そして聴衆や被聴衆にとっても、何かを意味するからである」[11]。しかし、その意味は変化し、変容する可能性がある。  グリム兄弟(1916年) グリム兄弟(1916年)社会科学がますます理論的に洗練されるにつれて、フォークロアはどのような社会集団においても自然に発生し、必要な構成要素であることが明らかになってき た。それは創作され、伝えられ続け、どのような集団においても、「我々」と「彼ら」を区別するために使われることがある。すべての文化には独自のフォーク ロアがあり、それぞれの文化は、自らのフォークロアを特定し研究する上で最も効果的なフォークロア研究の技法と方法を開発し、洗練させなければならない。 学問分野として、民俗学は社会科学と人文科学の間にまたがっている。フォークロア研究は19世紀前半のヨーロッパで、農村の農民の口承伝承を中心に始まっ た。グリム兄弟の『Kinder- und Hausmärchen』(初版は1812年)は、ヨーロッパの農民の口承民話集として最もよく知られているが、決してそれだけではない。このような物 語、言い伝え、歌、すなわち言葉の伝承への関心は19世紀を通じて続き、フォークロア研究という生まれたばかりの学問分野を文学や神話学と連携させた。一 方、フランツ・ボースに率いられたアメリカの民俗学者は、ネイティブ・アメリカンの文化を研究対象とし、彼らの習慣や信仰をすべて民俗学として取り込むこ とを選択した。この区別によって、アメリカの民俗学は文化人類学や民族学と足並みをそろえ、現地調査において同じデータ収集技術を用いることになった。こ のような人文科学と社会科学との間のフォークロア研究の分裂した同盟関係は、分野自体の内部で議論が続いているとしても、フォークロア研究の分野全体に豊 富な理論的優位点と研究手段を提供している[14]。 公共民俗学は民俗学研究の比較的新しい分派であり、第二次世界大戦後に始まり、応用民俗学を重視した1930年代のアラン・ローマックスとベン・ボトキン の代表的な仕事を手本としている。公共部門の民俗学者は、その地域の多様な文化集団の信仰や風習を記録し、保存し、紹介する仕事に従事している。こうした 職は、博物館、図書館、芸術団体、公立学校、歴史協会などに所属していることが多い。最も有名なのはスミソニアン博物館にあるアメリカン・フォークライ フ・センター(American Folklife Center)で、毎年夏にワシントンDCで開催されるスミソニアン・フォークライフ・フェスティバル(Smithsonian Folklife Festival)もその一つです。公共フォークロアは、収集、研究、分析を主な目的とする、大学が支援する学術的フォークロアとは異なるものである [8]。 |

| Terminology The terms folklore studies and folklore belong to a large and confusing word family. We have already used the synonym pairs Folkloristics / Folklife Studies and folklore / folklife, all of them in current usage within the field. Folklore was the original term used in this discipline. Its synonym, folklife, came into circulation in the second half of the 20th century, at a time when some researchers felt that the term folklore was too closely tied exclusively to oral lore. The new term folklife, along with its synonym folk culture, is meant to categorically include all aspects of a culture, not just the oral traditions. Folk process is used to describe the refinement and creative change of artifacts by community members within the folk tradition that defines the folk process.[15] Professionals within this field, regardless of the other words they use, consider themselves to be folklorists. Other terms which might be confused with folklore are popular culture and Vernacular culture, both of which vary from folklore in distinctive ways. Pop culture tends to be in demand for a limited time; it is generally mass-produced and communicated using mass media. Individually, these tend to be labeled fads, and disappear as quickly as they appear. The term vernacular culture differs from folklore in its overriding emphasis on a specific locality or region. For example, vernacular architecture denotes the standard building form of a region, using the materials available and designed to address functional needs of the local economy. Folk architecture is a subset of this, in which the construction is not done by a professional architect or builder, but by an individual putting up a needed structure in the local style. In a broader sense, all folklore is vernacular, i.e. tied to a region, whereas not everything vernacular is necessarily folklore.[13] There are also further cognates used in connection with folklore studies. Folklorism refers to "material or stylistic elements of folklore [presented] in a context which is foreign to the original tradition." This definition, offered by the folklorist Hermann Bausinger, does not discount the validity of meaning expressed in these "second hand" traditions.[16] Many Walt Disney films and products belong in this category of folklorism; the fairy tales, originally told around a winter fire, have become animated film characters, stuffed animals and bed linens. Their meaning, however far removed from the original story telling tradition, does not detract from the importance and meaning they have for their young audience. Fakelore refers to artifacts which might be termed pseudo-folklore; these are manufactured items claiming to be traditional. The folklorist Richard Dorson coined this word, clarifying it in his book "Folklore and Fakelore".[17] Current thinking within the discipline is that this term places undue emphasis on the origination of the artifact as a sign of authenticity of the tradition. The adjective folkloric is used to designate materials having the character of folklore or tradition, at the same time making no claim to authenticity. |

用語 民俗学とフォークロアという用語は、大きく紛らわしい語族に属する。私たちはすでに同義語のフォークロア学/フォークライフ学とフォークロア/フォークラ イフのペアを使用したが、これらはすべてこの分野で現在使用されているものである。フォークロアは、この学問分野で最初に使われた用語である。その同義語 であるフォークライフは20世紀後半に流通するようになったが、その当時はフォークロアという用語が口承伝承だけにあまりにも密接に結びついていると感じ る研究者がいた時期であった。フォークライフという新しい用語は、その同義語であるフォークカルチャーとともに、口承伝承だけでなく文化のあらゆる側面を 包括的に含むことを意味している。民俗過程は、民俗過程を定義する民俗的伝統の中で、地域社会の成員による人工物の洗練と創造的変化を記述するために用い られる[15]。この分野の専門家は、他のどのような言葉を使おうとも、自らを民俗学者であると考えている。 民俗学と混同される可能性のある他の用語として、大衆文化およびヴァナキュラー文化があるが、これらはいずれも特徴的な点において民俗学とは異なる。ポッ プカルチャーは限られた期間しか需要がない傾向があり、一般に大量生産され、マスメディアを使って伝達される。個々には流行というレッテルが貼られる傾向 があり、現れると同時にすぐに消えてしまう。ヴァナキュラー文化という用語は、特定の地域や地方に重点を置いている点で、フォークロアとは異なる。例え ば、ヴァナキュラー建築とは、その地域の標準的な建築様式を指し、入手可能な材料を用い、地域経済の機能的ニーズに対応するように設計されている。民俗建 築はこのサブセットであり、建築は専門の建築家や建設業者によって行われるのではなく、個人がその地域の様式で必要な建築物を建てることによって行われ る。より広い意味では、すべての民間伝承は地方伝承であり、すなわちその地方に結びついたものであるが、すべての地方伝承が必ずしも民間伝承であるとは限 らない[13]。 フォークロア研究に関連して用いられる同義語はさらにある。フォークロリズムとは「元の伝統とは異なる文脈で[提示される]フォークロアの素材的または様 式的要素」を指す。民俗学者ヘルマン・バウジンガーが提示したこの定義は、こうした「二次的な」伝統に表現される意味の妥当性を否定するものではない。 ウォルト・ディズニーの映画や製品の多くは、このフォークロリズムの範疇に属する。もともとは冬の焚き火を囲んで語られていたおとぎ話が、アニメーション のキャラクターやぬいぐるみ、ベッドリネンとなっているのである。フェイクロアは、擬似民俗学とでも呼ぶべき工芸品のことで、伝統的であると主張する製造 品のことである。民俗学者であるリチャード・ドーソンはこの言葉を創作し、著書『フォークロアとフェイクロア』の中で明確にしている。フォークロア的とい う形容詞は、フォークロアや伝統の性格を持ち、同時に真正性を主張しない資料を指定するために用いられる。 |

| History From antiquities to lore It is well-documented that the term folklore was coined in 1846 by the Englishman William Thoms. He fabricated it for use in an article published in the August 22, 1846 issue of The Athenaeum.[22] Thoms consciously replaced the contemporary terminology of popular antiquities or popular literature with this new word. Folklore was to emphasize the study of a specific subset of the population: the rural, mostly illiterate peasantry.[23] In his published call for help in documenting antiquities, Thoms was echoing scholars from across the European continent to collect artifacts of older, mostly oral cultural traditions still flourishing among the rural populace. In Germany the Brothers Grimm had first published their "Kinder- und Hausmärchen" in 1812. They continued throughout their lives to collect German folk tales to include in their collection. In Scandinavia, intellectuals were also searching for their authentic Teutonic roots and had labeled their studies Folkeminde (Danish) or Folkermimne (Norwegian).[24] Throughout Europe and America, other early collectors of folklore were at work. Thomas Crofton Croker published fairy tales from southern Ireland and, together with his wife, documented keening and other Irish funeral customs. Elias Lönnrot is best known for his collection of epic Finnish poems published under the title Kalevala. John Fanning Watson in the United States published the "Annals of Philadelphia".[25] With increasing industrialization, urbanization, and the rise in literacy throughout Europe in the 19th century, folklorists were concerned that the oral knowledge and beliefs, the lore of the rural folk would be lost. It was posited that the stories, beliefs and customs were surviving fragments of a cultural mythology of the region, pre-dating Christianity and rooted in pagan peoples and beliefs.[26] This thinking goes in lockstep with the rise of nationalism across Europe.[27] Some British folklorists,[which?] rather than lamenting or attempting to preserve rural or pre-industrial cultures, saw their work as a means of furthering industrialization, scientific rationalism, and disenchantment.[28] As the need to collect these vestiges of rural traditions became more compelling, the need to formalize this new field of cultural studies became apparent. The British Folklore Society was established in 1878 and the American Folklore Society was established a decade later. These were just two of a plethora of academic societies founded in the latter half of the 19th century by educated members of the emerging middle class.[29] For literate, urban intellectuals and students of folklore the folk was someone else and the past was recognized as being something truly different.[30] Folklore became a measure of the progress of society, how far we had moved forward into the industrial present and indeed removed ourselves from a past marked by poverty, illiteracy and superstition. The task of both the professional folklorist and the amateur at the turn of the 20th century was to collect and classify cultural artifacts from the pre-industrial rural areas, parallel to the drive in the life sciences to do the same for the natural world.[note 3] "Folk was a clear label to set materials apart from modern life…material specimens, which were meant to be classified in the natural history of civilization. Tales, originally dynamic and fluid, were given stability and concreteness by means of the printed page."[31] Viewed as fragments from a pre-literate culture, these stories and objects were collected without context to be displayed and studied in museums and anthologies, just as bones and potsherds were gathered for the life sciences. Kaarle Krohn and Antti Aarne were active collectors of folk poetry in Finland. The Scotsman Andrew Lang is known for his 25 volumes of Andrew Lang's Fairy Books from around the world. Francis James Child was an American academic who collected English and Scottish popular ballads and their American variants, published as the Child Ballads. In the United States, Mark Twain was a charter member of the American Folklore Society.[32] Both he and Washington Irving drew on folklore to write their stories.[33][34] The 1825 novel Brother Jonathan by John Neal is recognized as the most extensive literary use of American folklore of its time.[35] Aarne–Thompson and the historic–geographic method By the beginning of the 20th century these collections had grown to include artifacts from around the world and across several centuries. A system to organize and categorize them became necessary.[36] Antti Aarne published a first classification system for folktales in 1910. It was later expanded into the Aarne–Thompson classification system by Stith Thompson and remains the standard classification system for European folktales and other types of oral literature. As the number of classified artifacts grew, similarities were noted in items which had been collected from very different geographic regions, ethnic groups and epochs. In an effort to understand and explain the similarities found in tales from different locations, the Finnish folklorists Julius and Kaarle Krohne developed the Historical-Geographical method, also called the Finnish method.[37] Using multiple variants of a tale, this investigative method attempted to work backwards in time and location to compile the original version from what they considered the incomplete fragments still in existence. This was the search for the "Urform,"[23] which by definition was more complete and more "authentic" than the newer, more scattered versions. The historic-geographic method has been succinctly described as a "quantitative mining of the resulting archive, and extraction of distribution patterns in time and space". It is based on the assumption that every text artifact is a variant of the original text. As a proponent of this method, Walter Anderson proposed additionally a Law of Self-Correction, i.e. a feedback mechanism which would keep the variants closer to the original form.[38][note 4] It was during the first decades of the 20th century that Folklore Studies in Europe and America began to diverge. The Europeans continued with their emphasis on oral traditions of the pre-literate peasant, and remained connected to literary scholarship within the universities. By this definition, folklore was completely based in the European cultural sphere; any social group that did not originate in Europe was to be studied by ethnologists and cultural anthropologists. In this light, some twenty-first century scholars have interpreted European folkloristics as an instrument of internal colonialism, in parallel with the imperialistic dimensions of early 20th century cultural anthropology and Orientalism.[40] Unlike contemporary anthropology, however, many early European folklorists were themselves members of the prioritized groups that folkloristics was intended to study; for instance, Andrew Lang and James George Frazer were both themselves Scotsmen and studied rural folktales from towns near where they grew up.[41] In contrast to this, American folklorists, under the influence of the German-American Franz Boas and Ruth Benedict, sought to incorporate other cultural groups living in their region into the study of folklore. This included not only customs brought over by northern European immigrants, but also African Americans, Acadians of eastern Canada, Cajuns of Louisiana, Hispanics of the American southwest, and Native Americans. Not only were these distinct cultural groups all living in the same regions, but their proximity to each other caused their traditions and customs to intermingle. The lore of these distinct social groups, all of them Americans, was considered the bailiwick of American folklorists, and aligned American folklore studies more with ethnology than with literary studies.[42] |

歴史 古代から伝承へ 民間伝承という用語は、1846年にイギリス人のウィリアム・トムスによって作られたことはよく知られている。彼は『アテネウム』誌の1846年8月22 日号に掲載された記事で使用するためにこの言葉を捏造した[22]。トムスは意識的に、民衆の古代学や大衆文学という現代の用語をこの新しい言葉に置き換 えたのである。民俗学は、人口の特定の部分集合、すなわち農村の、そのほとんどが読み書きのできない農民の研究を強調するものであった[23]。古代の文 化財を記録するための助けを求める彼の発表した呼びかけの中で、トムスは、農村の民衆の間で今もなお繁栄している、古い、主に口承による文化的伝統の遺物 を収集するために、ヨーロッパ大陸中の学者たちと呼応していた。ドイツでは、グリム兄弟が1812年に初めて「Kinder- und Hausmärchen」を出版した。彼らは生涯を通じてドイツの民話を集め続け、自分たちのコレクションに加えた。スカンジナビアでも、知識人たちが正 真正銘のチュートニックのルーツを探し求め、自分たちの研究を「フォルケミンデ」(デンマーク語)や「フォルケミムネ」(ノルウェー語)と名付けていた。 トマス・クロフトン・クローカーはアイルランド南部のおとぎ話を出版し、妻とともにキーンやその他のアイルランドの葬儀の風習を記録した。エリアス・レン ロートは、『カレワラ』というタイトルで出版されたフィンランドの叙事詩集でよく知られている。アメリカのジョン・ファニング・ワトソンは『フィラデル フィアの年譜』を出版した[25]。 19世紀にヨーロッパ全土で工業化、都市化、識字率の向上が進むにつれて、民俗学者は農村民衆の口承による知識や信仰、伝承が失われることを懸念した。こ のような考え方は、ヨーロッパ全土におけるナショナリズムの台頭と歩調を合わせるものであった[27]。 イギリスの民俗学者の中には、農村文化や産業化以前の文化を嘆いたり保存しようとしたりするのではなく、自分たちの仕事を産業化、科学的合理主義、幻滅を 促進する手段であると考える者もいた[28]。 このような農村の伝統の名残を収集する必要性がより強くなるにつれて、この新しい文化研究分野を正式なものにする必要性が明らかになった。1878年にイ ギリス民俗学会が設立され、その10年後にはアメリカ民俗学会が設立された。これらは19世紀後半に新興中産階級の教養あるメンバーによって設立されたお びただしい数の学術団体のうちの2つに過ぎなかった[29]。識字力のある都市部の知識人や民俗学の学生にとって、民俗は他人事であり、過去は真に異なる ものであると認識された[30]。民俗学は社会の進歩を測る尺度となり、私たちが工業化された現在にどれだけ前進し、貧困、無学、迷信が特徴的な過去から 実際に脱却したかを示すものとなった。20世紀初頭におけるプロの民俗学者とアマチュアの双方の仕事は、産業化以前の農村地域から文化的遺物を収集し分類 することであり、自然界に対して同じことを行おうとする生命科学の推進力と並行していた[注 3]。もともと動的で流動的であった物語は、印刷されたページによって安定性と具体性を与えられた」[31]。 文字文化以前の断片とみなされたこれらの物語や物体は、生命科学のために骨や土器が集められたように、博物館やアンソロジーで展示され研究されるために、 脈絡なく収集された。フィンランドでは、カーレ・クローン(Kaarle Krohn)やアンティ・アーネ(Antti Aarne)が民衆詩の収集に積極的だった。スコットランド人のアンドリュー・ラングは、世界各地から集めた25冊の『Andrew Lang's Fairy Books(アンドリュー・ラングの妖精の本)』で知られている。フランシス・ジェームズ・チャイルドはアメリカの学者で、イギリスとスコットランドのポ ピュラー・バラッドとそのアメリカでの変種を収集し、『チャイルド・バラッド』として出版した。アメリカでは、マーク・トウェインがアメリカ民俗学会 (American Folklore Society)の創立会員であった[32]。マーク・トウェインもワシントン・アーヴィングも民俗学を利用して物語を書いた[33][34]。 ジョン・ニールによる1825年の小説『ブラザー・ジョナサン』(Brother Jonathan)は、当時のアメリカ民俗学を最も広範囲に利用した文学作品として認められている[35]。 アーン=トンプソンと歴史地理学的手法 20世紀初頭までに、これらのコレクションは世界中、数世紀にわたる遺物を含むまでに成長した。それらを整理・分類するシステムが必要となり、1910年 にアンッティ・アーネが民話の最初の分類システムを発表した[36]。これは後にスティス・トンプソンによってアールネ・トンプソン分類体系に拡張され、 現在もヨーロッパの昔話やその他のタイプの口承文芸の標準的な分類体系となっている。分類された遺物の数が増えるにつれ、全く異なる地理的地域、民族、時 代から収集された遺物にも共通点が見られるようになった。 フィンランドの民俗学者ユリウス・クローネ(Julius Krohne)とカーレ・クローネ(Kaarle Krohne)夫妻は、異なる地域の物語に見られる類似性を理解し説明するために、フィンランド方式とも呼ばれる歴史地理学的手法を開発した。これは「ウ ルフォーム」[23]の探索であり、その定義によれば、より新しく、より散在しているバージョンよりも完全で、より「真正」なものであった。ヒストリカ ル・ジオグラフィック法は、「結果として得られたアーカイブを定量的に採掘し、時間と空間における分布パターンを抽出すること」と簡潔に説明されている。 これは、すべてのテキスト成果物は原文の変種であるという仮定に基づいている。この方法の提唱者として、ウォルター・アンダーソンはさらに自己修正の法 則、すなわち変種を原形に近づけるフィードバック・メカニズムを提案した[38][注 4]。 ヨーロッパとアメリカの民俗学研究が乖離し始めたのは20世紀の最初の数十年間であった。ヨーロッパでは、文字に親しむ前の農民の口承伝承に重点を置き、 大学内の文学的学問とのつながりを保ち続けた。この定義によれば、フォークロアは完全にヨーロッパの文化圏を基盤としており、ヨーロッパに起源を持たない 社会集団はすべて、民族学者や文化人類学者によって研究されるべきものであった。この観点から、21世紀の学者たちの中には、ヨーロッパの民俗学を、20 世紀初頭の文化人類学やオリエンタリズムの帝国主義的な側面と並行して、内部植民地主義の道具として解釈する者もいる[40]。しかし、現代の人類学とは 異なり、初期のヨーロッパの民俗学者の多くは、自らも民俗学が研究対象とする優先集団の一員であった。例えば、アンドリュー・ラングとジェームズ・ジョー ジ・フレイザーはともにスコットランド人であり、自分たちが育った近くの町の農村民話を研究していた[41]。 これとは対照的に、ドイツ系アメリカ人のフランツ・ボアズとルース・ベネディクトの影響を受けたアメリカの民俗学者は、その地域に住む他の文化集団を民俗 学の研究に取り込もうとした。これには北欧からの移民が持ち込んだ風習だけでなく、アフリカ系アメリカ人、カナダ東部のアカディアン、ルイジアナ州のケイ ジャン人、アメリカ南西部のヒスパニック系、そしてアメリカ先住民も含まれていた。これらの異なる文化集団は同じ地域に住んでいただけでなく、互いに近接 していたため、それぞれの伝統や習慣が混ざり合っていた。これらの異なる社会集団(すべてアメリカ人)の伝承は、アメリカ民俗学者の専門分野であると考え られており、アメリカ民俗学は文学研究よりも民族学に近いものであった[42]。 |

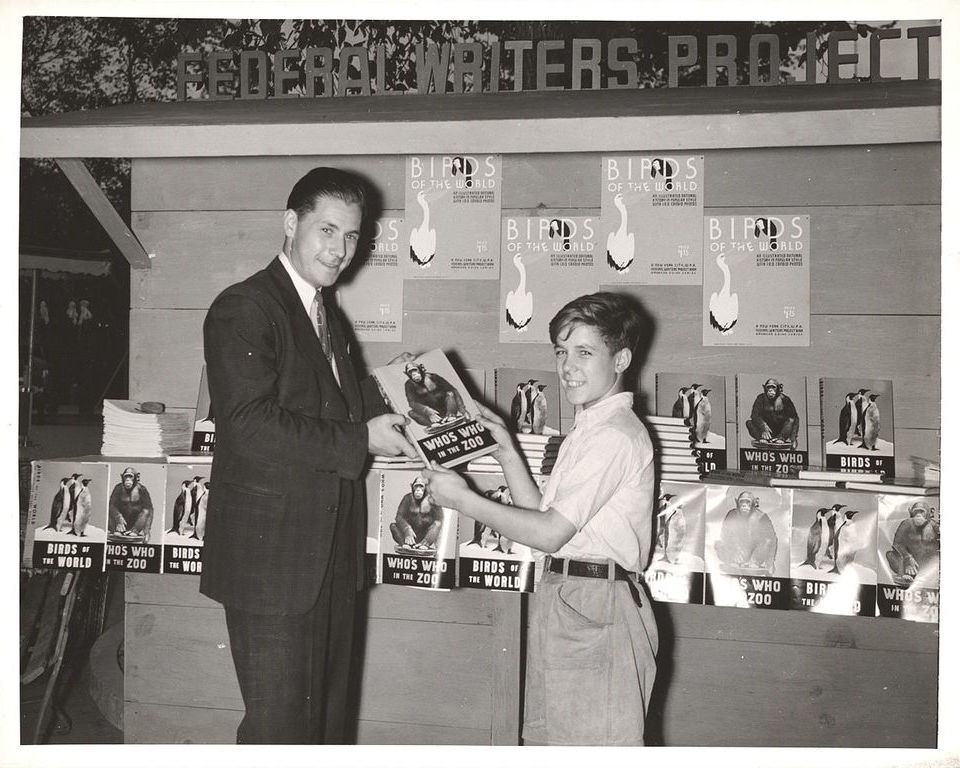

| Great Depression and the Federal Writers' Project Then came the 1930s and the worldwide Great Depression. In the United States the Federal Writers' Project was established as part of the WPA. Its goal was to offer paid employment to thousands of unemployed writers by engaging them in various cultural projects around the country. These white collar workers were sent out as field workers to collect the oral folklore of their regions, including stories, songs, idioms and dialects. The most famous of these collections is the Slave Narrative Collection. The folklore collected under the auspices of the Federal Writers Project during these years continues to offer a goldmine of primary source materials for folklorists and other cultural historians.[43] As chairman of the Federal Writers' Project between 1938 and 1942, Benjamin A. Botkin supervised the work of these folklore field workers. Both Botkin and John Lomax were particularly influential during this time in expanding folklore collection techniques to include more detailing of the interview context.[44] This was a significant move away from viewing the collected artifacts as isolated fragments, broken remnants of an incomplete pre-historic whole. Using these new interviewing techniques, the collected lore became embedded in and imbued with meaning within the framework of its contemporary practice. The emphasis moved from the lore to the folk, i.e. the groups and the people who gave this lore meaning within contemporary daily living. German folklore in the Third Reich In Europe during these same decades, folklore studies were drifting in a different direction. Throughout the 19th century folklore had been tied to romantic ideals of the soul of the people, in which folk tales and folksongs recounted the lives and exploits of ethnic folk heroes. Folklore chronicled the mythical origins of different peoples across Europe and established the beginnings of national pride. By the first decade of the 20th century there were scholarly societies as well as individual folklore positions within universities, academies, and museums. However, the study of German Volkskunde had yet to be defined as an academic discipline.[citation needed] Greater Germanic Reich   In the 1920s this originally apolitical movement[citation needed] was coopted by nationalism in several European countries, including Germany,[45][46] where it was absorbed into emerging Nazi ideology. The vocabulary of German Volkskunde such as Volk (folk), Rasse (race), Stamm (tribe), and Erbe (heritage) were frequently referenced by the Nazi Party. Their expressed goal was to re-establish what they perceived as the former purity of the Germanic peoples of Europe. The German anti-Nazi philosopher Ernst Bloch was one of the main analysts and critics of this ideology.[note 5] "Nazi ideology presented racial purity as the means to heal the wounds of the suffering German state following World War I. Hitler painted the ethnic heterogeneity of Germany as a major reason for the country's economic and political weakness, and he promised to restore a German realm based on a cleansed, and hence strong, German people. Racial or ethnic purity" was the goal of the Nazis, intent on forging a Greater Germanic Reich.[47] In the postwar years, departments of folklore were established in multiple German universities. However an analysis of just how folklore studies supported the policies of the Third Reich did not begin until 20 years after World War II in West Germany.[48] Particularly in the works of Hermann Bausinger and Wolfgang Emmerich in the 1960s, it was pointed out that the vocabulary current in Volkskunde was ideally suited for the kind of ideology that the National Socialists had built up.[49] It was then another 20 years before convening the 1986 Munich conference on folklore and National Socialism. This continues to be a difficult and painful discussion within the German folklore community.[48] |

世界大恐慌と連邦作家プロジェクト そして1930年代、世界的な大恐慌が起こった。アメリカでは、WPAの一環として連邦作家プロジェクトが設立された。その目的は、何千人もの失業中の作 家に有給の雇用を提供し、国中のさまざまな文化事業に従事させることだった。これらのホワイトカラー労働者は、物語、歌、慣用句、方言など、各地域の口承 伝承を収集するフィールドワーカーとして派遣された。これらのコレクションの中で最も有名なものは、『奴隷の物語コレクション』である。連邦作家プロジェ クト(Federal Writers Project)の支援の下、この数年間に収集された民俗伝承は、民俗学者やその他の文化史家にとって一次資料の宝庫であり続けている[43]。 1938年から1942年にかけて連邦作家プロジェクトの議長であったベンジャミン・A・ボトキンは、これらの民俗学フィールドワーカーの仕事を監督し た。ボトキンとジョン・ローマックスの両名はこの時期、民俗学の収集技法を拡大し、聞き取り調査の背景をより詳細に説明することに特に大きな影響を与えた [44]。こうした新しいインタビュー技法を用いることで、収集された伝承は現代の実践の枠組みの中に埋め込まれ、意味を帯びるようになった。重点は伝承 から民俗、すなわち現代の日常生活の中でこの伝承に意味を与えた集団や人々に移った。 第三帝国におけるドイツのフォークロア(→「フォルク」) 同じ数十年の間にヨーロッパでは、民俗学は異なる方向に流れていた。19世紀を通じて、民俗学は民衆の魂に関するロマンティックな理想と結びついており、 そこでは民話や民謡が民族的な英雄の生活や功績を語っていた。フォークロアは、ヨーロッパ全土のさまざまな民族の神話的起源を記録し、民族の誇りの始まり を確立した。20世紀の最初の10年までには、大学、アカデミー、博物館内に、学術的な学会だけでなく、個人的な民俗学の立場も存在するようになった。し かし、ドイツ民俗学はまだ学問分野として定義されてはいなかった[要出典]。 大ゲルマン帝国   1920年代、もともと非政治的であったこの運動[要出典]は、ドイツを含むいくつかのヨーロッパ諸国においてナショナリズムに取り込まれ[45] [46]、ナチスの新興イデオロギーに吸収された。Volk(民族)、Rasse(人種)、Stamm(部族)、Erbe(遺産)といったドイツの Volkskundeの語彙は、ナチ党によって頻繁に参照された。彼らが表明した目標は、ヨーロッパのゲルマン民族のかつての純粋性を再確立することで あった。ドイツの反ナチス哲学者エルンスト・ブロッホは、このイデオロギーの主な分析者であり批判者の一人であった[注釈 5]。「ナチスのイデオロギーは、第一次世界大戦後に苦しんだドイツ国家の傷を癒す手段として、人種的純潔を提示した。人種的または民族的純潔」がナチス の目標であり、大ゲルマン帝国を建設することを意図していた[47]。 戦後、ドイツの複数の大学に民俗学科が設置された。特に1960年代のヘルマン・バウジンガーとヴォルフガング・エメリッヒの著作において、フォークスク ンデの語彙が国家社会主義者が構築したイデオロギーの種類に理想的に適していることが指摘された。この議論は、ドイツ民俗学コミュニティ内では依然として 困難で痛みを伴う議論となっている[48]。 |

| After World War II Following World War II, the discussion continued about whether to align folklore studies with literature or ethnology. Within this discussion, many voices were actively trying to identify the optimal approach to take in the analysis of folklore artifacts. One major change had already been initiated by Franz Boas. Culture was no longer viewed in evolutionary terms; each culture has its own integrity and completeness, and was not progressing either toward wholeness or toward fragmentation. Individual artifacts must have meaning within the culture and for individuals themselves in order to assume cultural relevance and assure continued transmission. Because the European folklore movement had been primarily oriented toward oral traditions, a new term, folklife, was introduced to represent the full range of traditional culture. This included music, dance, storytelling, crafts, costume, foodways and more. In this period, folklore came to refer to the event of doing something within a given context, for a specific audience, using artifacts as necessary props in the communication of traditions between individuals and within groups.[50] Beginning in the 1970s, these new areas of folklore studies became articulated in performance studies, where traditional behaviors are evaluated and understood within the context of their performance. It is the meaning within the social group that becomes the focus for these folklorists, foremost among them Richard Baumann[51] and Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett.[52] Enclosing any performance is a framework which signals that the following is something outside of ordinary communication. For example, "So, have you heard the one…" automatically flags the following as a joke. A performance can take place either within a cultural group, re-iterating and re-enforcing the customs and beliefs of the group. Or it can be performance for an outside group, in which the first goal is to set the performers apart from the audience.[53] This analysis then goes beyond the artifact itself, be it dance, music or story-telling. It goes beyond the performers and their message. As part of performance studies, the audience becomes part of the performance. If any folklore performance strays too far from audience expectations, it will likely be brought back by means of a negative feedback loop at the next iteration.[54] Both performer and audience are acting within the "Twin Laws" of folklore transmission, in which novelty and innovation is balanced by the conservative forces of the familiar.[55] Even further, the presence of a folklore observer at a performance of any kind will influence the performance itself in subtle and not-so-subtle ways. Because folklore is firstly an act of communication between parties, it is incomplete without inclusion of the reception in its analysis. The understanding of folklore performance as communication leads directly into modern linguistic theory and communication studies. Words both reflect and shape our worldview. Oral traditions, particularly in their stability over generations and even centuries, provide significant insight into the ways in which insiders of a culture see, understand, and express their responses to the world around them.[56][note 6]  2015 Smithsonian Folklife Festival Three major approaches to folklore interpretation were developed during the second half of the 20th century. Structuralism in folklore studies attempts to define the structures underlying oral and customary folklore.[note 7] Once classified, it was easy for structural folklorists to lose sight of the overarching issue: what are the characteristics which keep a form constant and relevant over multiple generations? Functionalism in folklore studies also came to the fore following World War II; as spokesman, William Bascom formulated the 4 functions of folklore. This approach takes a more top-down approach to understand how a specific form fits into and expresses meaning within the culture as a whole.[note 8] A third method of folklore analysis, popular in the late 20th century, is the Psychoanalytic Interpretation,[57] championed by Alan Dundes. His monographs, including a study of homoerotic subtext in American football[58] and anal-erotic elements in German folklore,[59] were not always appreciated and involved Dundes in several major folklore studies controversies during his career. True to each of these approaches, and any others one might want to employ (political, women's issues, material culture, urban contexts, non-verbal text, ad infinitum), whichever perspective is chosen will spotlight some features and leave other characteristics in the shadows. With the passage in 1976 of the American Folklife Preservation Act, folklore studies in the United States came of age. This legislation follows in the footsteps of other legislation designed to safeguard more tangible aspects of our national heritage worthy of protection. This law also marks a shift in our national awareness; it gives voice to the national understanding that diversity within the country is a unifying feature, not something that separates us.[60] "We no longer view cultural difference as a problem to be solved, but as a tremendous opportunity. In the diversity of American folklife we find a marketplace teeming with the exchange of traditional forms and cultural ideas, a rich resource for Americans".[8] This diversity is celebrated annually at the Smithsonian Folklife Festival and many other folklife festivals around the country. |

第二次世界大戦後 第二次世界大戦後、フォークロア研究を文学と民俗学のどちらに合わせるかという議論が続いた。この議論の中で、民俗学的遺物の分析において取るべき最適な アプローチを特定しようとする多くの声が活発に上がった。一つの大きな変化はすでにフランツ・ボアズによって始まっていた。文化はもはや進化論的な観点か らは見られなくなり、それぞれの文化はそれ自身の完全性と完全性を持っており、全体性に向かっても断片化に向かっても進歩していない。個々の工芸品が文化 的妥当性を持ち、継続的な伝達を保証するためには、文化の中で、また個人自身にとって意味を持たなければならない。ヨーロッパのフォークロア運動は主に口 承伝統に向けられていたため、伝統文化の全領域を表すフォークライフという新しい用語が導入された。これには音楽、舞踊、語り、工芸、衣装、食文化などが 含まれる。 この時期、フォークロアは、個人間や集団内における伝統の伝達において必要な小道具として工芸品を用いながら、特定の聴衆のために、与えられた文脈の中で 何かを行う出来事を指すようになった[50]。1970年代から、フォークロア研究のこうした新たな領域は、伝統的な行動をその実演の文脈の中で評価し理 解するパフォーマンス研究において明確化されるようになった。リチャード・バウマン(Richard Baumann)[51]やバーバラ・カーシェンブラット=ギンブレット(Barbara Kirshenblatt-Gimblett)[52]を筆頭とするこれらの民俗学者にとって焦点となるのは、社会的集団の中での意味である。例えば、 "So, have you heard the one..."(それで、あなたは聞いたことがありますか...)と言えば、自動的に次の言葉がジョークであることを示す。パフォーマンスは、文化的集団 の中で行われ、その集団の習慣や信念を繰り返し、再強化する。あるいは外部の集団のためのパフォーマンスであることもあり、その場合、第一の目標はパ フォーマーを観客から引き離すことである[53]。 この分析は、ダンスであれ、音楽であれ、ストーリーテリングであれ、芸術作品そのものにとどまらない。それは、パフォーマーやそのメッセージを超えてい く。パフォーマンス研究の一環として、観客はパフォーマンスの一部となる。民俗学的な上演が観客の期待から逸脱しすぎた場合、次の反復の際に負のフィード バック・ループによって差し戻される可能性が高い[54]。上演者と観客はともに、民俗学的な伝達の「双子の法則」の中で行動しており、そこでは新奇性と 革新性が、慣れ親しんだものという保守的な力によって均衡が保たれている[55]。フォークロアは第一に当事者間のコミュニケーション行為であるため、そ の分析に受容を含めることなしには不完全である。民俗芸能をコミュニケーションとして理解することは、そのまま現代の言語理論やコミュニケーション研究に つながる。言葉は私たちの世界観を反映し、また形づくるものでもある。口承伝承は、特に何世代にもわたって、さらには何世紀にもわたって安定している点 で、ある文化の内部の人々が、自分たちを取り巻く世界に対する反応をどのように見、理解し、表現しているかについて、重要な洞察を与えてくれる[56] [注 6]。  2015年スミソニアン・フォークライフ・フェスティバル フォークロア解釈に対する3つの主要なアプローチが20世紀後半に発展した。フォークロア研究における構造主義は、口承伝承や慣習伝承の根底にある構造を 定義しようとするものである[注釈 7]。一旦分類されると、構造主義のフォークロリストは包括的な問題、すなわち、ある形式を何世代にもわたって不変のものとし、関連性を保ち続ける特徴と は何かということを見失いがちであった。フォークロア研究における機能主義もまた第二次世界大戦後に前面に出てきた。このアプローチは、特定の形式が文化 全体の中でどのように適合し、意味を表現しているかを理解するために、よりトップダウン的なアプローチをとる[注 8]。20世紀後半に流行した民俗学分析の第三の方法は、アラン・ダンデスによって提唱された精神分析的解釈である[57]。アメリカンフットボールにお けるホモエロティックなサブテキスト[58]やドイツ民俗学におけるアナル・エロティックな要素[59]の研究を含む彼のモノグラフは必ずしも評価される ものではなく、ダンデスはそのキャリアの中でいくつかの主要な民俗学論争に巻き込まれた。これらの各アプローチに忠実であり、また他のどのようなアプロー チ(政治的、女性問題、物質文化、都市の文脈、非言語的テキスト、無限にある)を採用しようと思えば、どのような視点を選んでも、いくつかの特徴にスポッ トライトが当たり、他の特徴は影に隠れてしまう。 1976年に「アメリカ民俗生物保存法(American Folklife Preservation Act)」が成立したことで、米国の民俗学は一時代を築いた。この法律は、保護に値する国家遺産のより具体的な側面を保護することを目的とした他の法律の 足跡をたどるものである。この法律はまた、私たちの国家意識の転換を示すものでもある。この法律は、国内の多様性は私たちを隔てるものではなく、統一され た特徴であるという国民的理解に声を与えるものである[60]。アメリカのフォークライフの多様性の中に、伝統的な形式や文化的なアイデアの交換で溢れる 市場、すなわちアメリカ人にとっての豊かな資源を見出すことができる」[8]。この多様性は、スミソニアン・フォークライフ・フェスティバルをはじめとす る全米各地のフォークライフ・フェスティバルで毎年祝われている。 |

| Global folklore studies Folklore studies and nationalism in Turkey  Sinasi Bozalti Sinasi BozaltiFolklore interest sparked in Turkey around the second half of the nineteenth century when the need to determine a national language came about. Their writings consisted of vocabulary and grammatical rule from the Arabic and Persian language. Although the Ottoman intellectuals were not affected by the communication gap, in 1839, the Tanzimat reform introduced a change to Ottoman literature. A new generation of writers with contact to the West, especially France, noticed the importance of literature and its role in the development of institutions. Following the models set by Westerners, the new generation of writers returned to Turkey bringing the ideologies of novels, short stories, plays and journalism with them. These new forms of literature were set to enlighten the people of Turkey, influencing political and social change within the country. However, the lack of understanding for the language of their writings limited their success in enacting change. Using the language of the "common people" to create literature, influenced the Tanzimat writers to gain interest in folklore and folk literature. In 1859, writer Sinasi Bozalti, wrote a play in simple enough language that it could be understood by the masses. He later produced a collection of four thousand proverbs. Many other poets and writers throughout the Turkish nation began to join in on the movement including Ahmet Midhat Efendi who composed short stories based on the proverbs written by Sinasi. These short stories, like many folk stories today, were intended to teach moral lessons to its readers.  Folklore studies in Chile Folklore studies in ChileChilean folklorist Rodolfo Lenz in 1915. The study of folklore in Chile was developed in a systematic and pioneering way since the late 19th century. In the work of compiling the popular traditions of the Chilean people and of the original peoples, they stood out, not only in the study of national folklore, but also in Latin America.[citation needed] Ramón Laval, Julio Vicuña, Rodolfo Lenz, José Toribio Medina, Tomás Guevara, Félix de Augusta, and Aukanaw, among others, generated an important documentary and critical corpus around oral literature, autochthonous languages, regional dialects, and peasant and indigenous customs. They published, mainly during the first decades of the 20th century, linguistic and philological studies, dictionaries, comparative studies between the national folklores of Ibero-America, compilations of stories, poetry, and religious traditions. In 1909, at the initiative of Laval, Vicuña and Lenz, the Chilean Folklore Society was founded, the first of its kind in America. Two years later, it would merge with the recently created Chilean Society of History and Geography.[61] 21st century With the advent of the digital age, the question once again foregrounds itself concerning the relevance of folklore in this new century. Although the profession in folklore grows and the articles and books on folklore topics proliferate, the traditional role of the folklorist is indeed changing. Globalization The United States is known[by whom?] as a land of immigrants; with the exception of the first Indian nations, everyone originally came from somewhere else. Americans are proud of their cultural diversity. For folklorists, this country represents a trove of cultures rubbing elbows with each other, mixing and matching into exciting combinations as new generations come up. It is in the study of their folklife that we begin to understand the cultural patterns underlying the different ethnic groups. Language and customs provide a window into their view of reality. "The study of varying worldviews among ethnic and national groups in America remains one of the most important unfinished tasks for folklorists and anthropologists."[62][note 9] Contrary to a widespread concern, we are not seeing a loss of diversity and increasing cultural homogenization across the land.[note 10] In fact, critics of this theory point out that as different cultures mix, the cultural landscape becomes multifaceted with the intermingling of customs. People become aware of other cultures and pick and choose different items to adopt from each other. One noteworthy example of this is the Jewish Christmas Tree, a point of some contention among American Jews. Public sector folklore was introduced into the American Folklore Society in the early 1970s. These public folklorists work in museums and cultural agencies to identify and document the diverse folk cultures and folk artists in their region. Beyond this, they provide performance venues for the artists, with the twin objectives of entertainment and education about different ethnic groups. Given the number of folk festivals held around the world, it becomes clear that the cultural multiplicity of a region is presented with pride and excitement. Public folklorists are increasingly being involved in economic and community development projects to elucidate and clarify differing world views of the social groups impacted by the projects.[8] Computerized databases and big data Once folklore artifacts have been recorded on the World Wide Web, they can be collected in large electronic databases and even moved into collections of big data. This compels folklorists to find new ways to collect and curate these data.[63] Along with these new challenges, electronic data collections provide the opportunity to ask different questions, and combine with other academic fields to explore new aspects of traditional culture.[64] Computational humor is just one new field that has taken up the traditional oral forms of jokes and anecdotes for study, holding its first dedicated conference in 1996. This takes us beyond gathering and categorizing large joke collections. Scholars are using computers firstly to recognize jokes in context,[65] and further to attempt to create jokes using artificial intelligence. Binary thinking of the computer age As we move forward in the digital age, the binary thinking of the 20th century structuralists remains an important tool in the folklorist's toolbox.[66] This does not mean that binary thinking was invented in recent times along with computers; only that we became aware of both the power and the limitations of the "either/or" construction. In folklore studies, the multiple binaries underlying much of the theoretical thinking have been identified – {dynamicism : conservatism}, {anecdote : myth}, {process : structure}, {performance : tradition}, {improvisation : repetition}, {variation : traditionalism}, {repetition : innovation};[67] not to overlook the original binary of the first folklorists: {traditional : modern} or {old : new}. Bauman re-iterates this thought pattern in claiming that at the core of all folklore is the dynamic tension between tradition and variation (or creativity).[68] Noyes[69] uses similar vocabulary to define [folk] group as "the ongoing play and tension between, on the one hand, the fluid networks of relationship we constantly both produce and negotiate in everyday life and, on the other, the imagined communities we also create and enact but that serve as forces of stabilizing allegiance."[70] This thinking only becomes problematic in light of the theoretical work done on binary opposition, which exposes the values intrinsic to any binary pair. Typically, one of the two opposites assumes a role of dominance over the other. The categorization of binary oppositions is "often value-laden and ethnocentric", imbuing them with illusory order and superficial meaning.[71] Linear and non-linear concepts of time Another baseline of western thought has also been thrown into disarray in the recent past. In western culture, we live in a time of progress, moving forward from one moment to the next. The goal is to become better and better, culminating in perfection. In this model time is linear, with direct causality in the progression. "You reap what you sow", "A stitch in time saves nine", "Alpha and omega", the Christian concept of an afterlife all exemplify a cultural understanding of time as linear and progressive. In folklore studies, going backwards in time was also a valid avenue of exploration. The goal of the early folklorists of the historic-geographic school was to reconstruct from fragments of folk tales the Urtext of the original mythic (pre-Christian) world view. When and where was an artifact documented? Those were the important questions posed by early folklorists in their collections. Armed with these data points, a grid pattern of time-space coordinates for artifacts could be plotted.[72][73] Awareness has grown that different cultures have different concepts of time (and space). In his study "The American Indian Mind in a Linear World", Donald Fixico describes an alternate concept of time. "Indian thinking" involves "'seeing' things from a perspective emphasizing that circles and cycles are central to world and that all things are related within the Universe." He then suggests that "the concept of time for Indian people has been such a continuum that time becomes less relevant and the rotation of life or seasons of the year are stressed as important."[74][note 11] In a more specific example, the folklorist Barre Toelken describes the Navajo as living in circular times, which is echoed and re-enforced in their sense of space, the traditional circular or multi-sided hogan.[75] Lacking the European mechanistic devices of marking time (clocks, watches, calendars), they depended on the cycles of nature: sunrise to sunset, winter to summer. Their stories and histories are not marked by decades and centuries, but remain close in, as they circle around the constant rhythms of the natural world. Within the last decades our time scale has expanded from unimaginably small (nanoseconds) to unimaginably large (deep time). In comparison, our working concept of time as {past : present : future} looks almost quaint. How do we map "tradition" into this multiplicity of time scales? Folklore studies has already acknowledged this in the study of traditions which are either done in an annual cycle of circular time (ex. Christmas, May Day), or in a life cycle of linear time (ex. baptisms, weddings, funerals). This needs to be expanded to other traditions of oral lore. For folk narrative is NOT a linear chain of isolated tellings, going from one single performance on our time-space grid to the next single performance. Instead it fits better into a non-linear system, where one performer varies the story from one telling to the next, and the performer's understudy starts to tell the story, also varying each performance in response to multiple factors.[76] Cybernetics Cybernetics was first developed in the 20th century; it investigates the functions and processes of systems. The goal in cybernetics is to identify and understand a system's closed signaling loop, in which an action by the system generates a change in the environment, which in turn triggers feedback to the system and initiates a new action. The field has expanded from a focus on mechanistic and biological systems to an expanded recognition that these theoretical constructs can also be applied to many cultural and societal systems, including folklore.[77] Once divorced from a model of tradition that works solely on a linear time scale (i.e. moving from one folklore performance to the next), we begin to ask different questions about how these folklore artifacts maintain themselves over generations and centuries. The oral tradition of jokes as an example is found across all cultures, and is documented as early as 1600 B.C.[note 12] Whereas the subject matter varies widely to reflect its cultural context, the form of the joke remains remarkably consistent. According to the theories of cybernetics and its secondary field of autopoiesis, this can be attributed to a closed loop auto-correction built into the system maintenance of oral folklore. Auto-correction in oral folklore was first articulated by the folklorist Walter Anderson in his monograph on the King and the Abbot published 1923.[39] To explain the stability of the narrative, Anderson posited a “double redundancy”, in which the performer has heard the story from multiple other performers, and has himself performed it multiple times. This provides a feedback loop between repetitions at both levels to retain the essential elements of the tale, while at the same time allowing for the incorporation of new elements.[78] Another characteristic of cybernetics and autopoiesis is self-generation within a system. Once again looking to jokes, we find new jokes generated in response to events on a continuing basis. The folklorist Bill Ellis accessed internet humor message boards to observe in real time the creation of topical jokes following the 9/11 terrorist attack in the United States. "Previous folklore research has been limited to collecting and documenting successful jokes, and only after they had emerged and come to folklorists' attention. Now, an Internet-enhanced collection creates a time machine, as it were, where we can observe what happens in the period before the risible moment, when attempts at humour are unsuccessful.", that is before they have successfully mapped into the traditional joke format.[79] Second-order cybernetics states that the system observer affects the systemic interplay; this interplay has long been recognized as problematic by folklorists. The act of observing and noting any folklore performance raises without exception the performance from an unconscious habitual acting within a group, to and for themselves, to a performance for an outsider. "Naturally the researcher's presence changes things, in the way that any new entrant to a social setting changes things. When people of different backgrounds, agendas, and resources interact, there are social risks, and where representation and publication are taking place, these risks are exacerbated..."[80][note 13] |

世界の民俗学 トルコにおける民俗学とナショナリズム  シナシ・ボザルティ シナシ・ボザルティ民俗学への関心がトルコで高まったのは、国語を決定する必要性が生じた19世紀後半ごろのことである。彼らの著作はアラビア語やペルシア語の語彙や文法規 則で構成されていた。オスマン帝国の知識人たちはコミュニケーション・ギャップの影響を受けなかったが、1839年、タンジマート改革がオスマン文学に変 化をもたらした。西洋、特にフランスと接触した新しい世代の作家たちが、文学の重要性と制度の発展における役割に気づいたのである。西洋人が設定したモデ ルに従って、新世代の作家たちは小説、短編小説、演劇、ジャーナリズムのイデオロギーを携えてトルコに戻った。これらの新しい形式の文学は、トルコの人々 を啓蒙し、国内の政治的、社会的変化に影響を与えるものであった。しかし、彼らの著作の言語が理解されていなかったため、変革を実現する上での成功には限 界があった。 庶民」の言葉を使って文学を創作したことで、タンツィマートの作家たちはフォークロアや民俗文学に関心を持つようになった。1859年、作家のシナシ・ボ ザルティは、大衆にも理解できるような簡単な言葉で戯曲を書いた。彼は後に4,000のことわざ集を作った。シナシが書いたことわざをもとに短編小説を書 いたアフメット・ミドハット・エフェンディをはじめ、トルコ全国で多くの詩人や作家がこの運動に参加し始めた。これらの短編は、今日の多くの民話と同様、 読者に道徳的な教訓を教えることを目的としていた。  チリにおける民俗学 チリにおける民俗学1915年、チリの民俗学者ロドルフォ・レンツ(Rodolfo Lenz)。 チリにおける民俗学研究は、19世紀後半から体系的かつ先駆的な方法で発展してきた。ラモン・ラバル(Ramón Laval)、フリオ・ビクーニャ(Julio Vicuña)、ロドルフォ・レンツ(Rodolfo Lenz)、ホセ・トリビオ・メディナ(José Toribio Medina)、トマス・ゲバラ(Tomás Guevara)、フェリックス・デ・アウグスタ(Félix de Augusta)、アウカナウ(Aukanaw)らは、口承文芸、自国語、地方方言、農民や先住民の風習をめぐる重要な記録的・批評的コーパスを生み出し ました。彼らは主に20世紀の最初の数十年間に、言語学的、言語学的研究、辞書、イベロアメリカの民族伝承の比較研究、物語、詩、宗教的伝統の編纂物を出 版した。1909年、ラヴァル、ビクーニャ、レンツの主導により、チリ民間伝承協会が設立された。その2年後には、最近設立されたチリ歴史地理学会と合併 することになる[61]。 21世紀 デジタル時代の到来とともに、この新しい世紀における民俗学の関連性に関する疑問が再び前景化している。民俗学の専門職は成長し、民俗学をテーマとする論文や書籍は急増しているが、民俗学者の伝統的な役割は確かに変化している。 グローバル化 アメリカは移民の国として知られている(誰が?アメリカ人は自分たちの文化の多様性を誇りに思っている。民俗学者にとって、この国は文化の宝庫であり、新 しい世代が生まれるにつれて、刺激的な組み合わせに混ざり合い、互いに肩を寄せ合っている。異なる民族集団の根底にある文化的パターンを理解し始めるの は、彼らの民俗生活の研究においてである。言語と習慣は、彼らの現実を見る窓となる。「アメリカにおける民族や国家集団の間で変化する世界観の研究は、民 俗学者や人類学者にとって依然として最も重要な未完の課題の一つである」[62][注 9]。 広く懸念されていることとは裏腹に、私たちは国全体において多様性が失われ、文化的な均質化が進むのを目にしているわけではない。人々は他の文化を意識す るようになり、互いに異なるものを選んで取り入れるようになる。その顕著な例のひとつが、アメリカのユダヤ人の間で論争になっているユダヤ教のクリスマス ツリーである。 公共部門の民俗学は1970年代初頭に米国民俗学会に導入された。こうした公的民俗学者は博物館や文化機関で働き、その地域の多様な民俗文化や民俗芸術家 を特定し、記録している。さらに、異なる民族集団に関する娯楽と教育という2つの目的をもって、芸術家たちに公演の場を提供している。世界中で開催される フォーク・フェスティバルの数を考えれば、地域の文化的多様性が誇りと興奮をもって紹介されることは明らかです。公共民俗学者は、プロジェクトの影響を受 ける社会集団の異なる世界観を解明し、明確にするために、経済プロジェクトや地域開発プロジェクトに関わることが多くなってきている[8]。 コンピュータ化されたデータベースとビッグデータ いったん民俗学の成果物がワールド・ワイド・ウェブ上に記録されると、それらは大規模な電子データベースに収集され、さらにはビッグデータのコレクション へと移行することができる。こうした新たな挑戦とともに、電子データの収集は、伝統文化の新たな側面を探求するために、さまざまな問いを立てたり、他の学 問分野と組み合わせたりする機会を提供する[64]。計算ユーモアは、ジョークや逸話といった伝統的な口承形式を研究の対象として取り上げた新たな分野の ひとつであり、1996年に初の専門学会が開催された。これは、大規模なジョークのコレクションを収集し、分類するだけではない。学者たちは、まずコン ピュータを使って文脈からジョークを認識し[65]、さらに人工知能を使ってジョークを創作しようとしている。 コンピュータ時代の二項対立的思考 デジタル時代に突入した現在でも、20世紀の構造主義者による二項対立的思考は、民俗学者の道具箱における重要なツールであり続けている[66]。これ は、二項対立的思考がコンピュータとともに近年発明されたということを意味するのではなく、「どちらか一方」という構図の持つ力と限界の両方に私たちが気 づくようになったということである。民俗学においては、理論的思考の多くの根底にある複数の二項対立が確認されている-{動態主義:保守主義}、{逸話: 神話}、{プロセス:構造}、{パフォーマンス:伝統}、{即興:反復}、{変化:伝統主義}、{反復:革新}である[67]: {伝統:現代}あるいは{古い:新しい}。バウマンは、すべてのフォークロアの核心には伝統と変化(あるいは創造性)との間の動的な緊張があると主張する 際に、この思考パターンを繰り返している[68]。 ノイエス[69]も同様の語彙を用いて[民俗]集団を「一方では、日常生活において私たちが絶えず生み出し、交渉している流動的な関係のネットワークと、 他方では、私たちもまた生み出し、制定しているが、忠誠を安定させる力として機能している想像上の共同体との間の進行中の戯れと緊張」と定義している [70]。 このような考え方が問題となるのは、二項対立について行われた理論的研究に照らしてのみであり、二項対立はどのような二項対立のペアにも内在する価値を暴 露している。一般的に、二律背反の一方は他方を支配する役割を引き受ける。二項対立のカテゴライズは「しばしば価値観に縛られ、民族中心的」であり、それ らに幻想的な秩序と表面的な意味を付与している[71]。 時間の直線的概念と非直線的概念 西洋思想のもうひとつの基本線もまた、近年混乱に陥っている。西洋文化では、私たちは進歩の時代に生きており、ある瞬間から次の瞬間へと前進している。目 標はより良くなることであり、最終的には完璧になる。このモデルでは、時間は直線的であり、進行には直接的な因果関係がある。「蒔いた種は刈り取る」、 「一針入魂」、「アルファとオメガ」、死後の世界というキリスト教の概念はすべて、直線的で進歩的な時間という文化的理解を例示している。民俗学において は、時間を遡ることもまた有効な探求の道であった。歴史地理学派の初期の民俗学者たちの目標は、民話の断片から元の神話的(キリスト教以前の)世界観の Urtextを再構築することであった。民話はいつ、どこで記録されたのか。それが、初期の民俗学者がそのコレクションに投げかけた重要な疑問であった。 これらのデータポイントを武器に、遺物の時空間座標の格子状パターンをプロットすることができた[72][73]。 文化が異なれば時間(と空間)の概念も異なるという認識が広まった。ドナルド・フィクシーコはその研究「リニアな世界におけるアメリカン・インディアンの 心」の中で、時間に関する別の概念について述べている。インディアンの思考」には、「円や循環が世界の中心であり、すべてのものが宇宙の中で関連している ことを強調する視点から物事を "見る"」ことが含まれる。そして、「インドの人々にとっての時間の概念は、時間があまり意味を持たなくなるような連続的なものであり、生命の回転や一年 の季節が重要なものとして強調されている」と示唆している。 「より具体的な例として、民俗学者のバール・トールケンはナバホ族を円環の時代に生きていると表現しており、それは彼らの空間感覚、伝統的な円形または多 辺形のホーガンにも反映され、再強化されている[75]。ヨーロッパ的な時間を刻む機械的な装置(時計、暦)を持たない彼らは、日の出から日没、冬から夏 という自然のサイクルに依存していた。彼らの物語や歴史は、何十年、何百年という単位で刻まれるものではなく、自然界の絶え間ないリズムに寄り添うもの だった。 ここ数十年の間に、私たちの時間スケールは想像を絶するほど小さなもの(ナノ秒)から想像を絶するほど大きなもの(深い時間)へと拡大した。それに比べる と、{過去:現在:未来}という時間の概念は、ほとんど古風に見える。伝統」をこの多様な時間スケールにどのようにマッピングすればよいのだろうか。民俗 学は、円環的な時間の年間サイクル(例:クリスマス、メーデー)、あるいは直線的な時間のライフサイクル(例:洗礼、結婚式、葬式)で行われる伝統の研究 において、すでにこのことを認めている。これを口承伝承の他の伝統にも拡大する必要がある。というのも、民俗の語りというのは、私たちの時間空間グリッド 上で行われる一つのパフォーマンスから次の一つのパフォーマンスへと続く、孤立した語りの直線的な連鎖ではないからである。その代わりに、一人のパフォー マーがある語りから次の語りへと物語を変化させ、パフォーマーの代役のパフォーマーが物語を語り始め、また複数の要因に対応して各パフォーマンスを変化さ せるというような、非線形のシステムにうまく適合するのである[76]。 サイバネティクス サイバネティクスは20世紀に初めて開発された学問で、システムの機能とプロセスを研究する。サイバネティクスの目標は、システムの閉じた信号伝達ループ を特定し、理解することである。このループでは、システムによる行動が環境の変化を発生させ、それがシステムへのフィードバックを引き起こし、新たな行動 を開始する。この分野は、機械論的・生物学的システムに焦点を当てたものから、これらの理論的構成要素がフォークロアを含む多くの文化的・社会的システム にも適用できるという認識へと拡大してきた[77]。直線的な時間スケール(すなわち、あるフォークロアの演目から次の演目へと移動すること)のみで機能 する伝統のモデルからいったん切り離されると、これらのフォークロアの成果物が何世代・何世紀にもわたってどのようにそれ自体を維持するのかについて、異 なる問いを立て始める。 その例として、口承によるジョークの伝統はあらゆる文化圏で見られ、紀元前1600年頃には記録されている[注釈 12]。文化的背景を反映して題材は大きく異なるが、ジョークの形式は驚くほど一貫している。サイバネティクスとその副次的な分野であるオートポイエーシ スの理論によれば、これは口承民俗学のシステム維持に組み込まれた閉ループの自動修正に起因する。口承民話における自動修正は、民俗学者のウォルター・ア ンダーソン(Walter Anderson)が1923年に出版した『王と修道院長』に関する単行本で初めて明言した[39]。物語の安定性を説明するために、アンダーソンは「二 重の冗長性」を仮定した。これによって、物語の本質的な要素を保持すると同時に、新しい要素を取り入れることを可能にするために、両方のレベルでの繰り返 しの間でフィードバック・ループが提供される[78]。 サイバネティクスとオートポイエーシスのもう一つの特徴は、システム内での自己生成である。再びジョークに目を向けると、出来事に反応して新しいジョーク が継続的に生み出されていることがわかる。民俗学者のビル・エリスは、インターネットのユーモア掲示板にアクセスし、米国で起きた9.11テロ攻撃を受け て話題性のあるジョークが生み出される様子をリアルタイムで観察した。「これまでの民俗学研究は、成功したジョークの収集と記録に限られていた。今、イン ターネットによって強化されたコレクションは、いわばタイムマシンを作り出し、ユーモアの試みが失敗する、きわどい瞬間の前の期間に何が起こっているかを 観察することができる。 二次サイバネティクスは、システムの観察者はシステムの相互作用に影響を及ぼすと述べている。この相互作用は民俗学者によって長い間問題視されてきた。あ らゆる民俗学の実演を観察し記録するという行為は、例外なく、その実演を、集団の中での、自分たちのための、無意識の習慣的な演技から、部外者のための演 技へと引き上げるのである。「当然ながら、研究者の存在は物事を変える。社会的な場への新たな参入者が物事を変えるのと同じように。異なる背景、意図、資 源を持つ人々が相互作用するとき、そこには社会的リスクが存在し、表現と出版が行われる場では、こうしたリスクは悪化する......」[80][注 13]。 |

| Scholarly organizations and journals American Folklore Society International Society for Ethnology and Folklore Journal of American Folklore Journal of Folklore Research The Society for Folk Life Studies The Folklore Society Western Folklore Cultural Analysis |

学術団体および学術誌 アメリカ民俗学会 国際民族学・民俗学会 アメリカ民俗学ジャーナル 民俗学研究ジャーナル 民俗生活研究学会 民俗学会 西洋民俗学 文化分析 |

| Cultural Heritage Environmental Determinism Ethnology Ethnopoetics, a method of recording text versions of oral poetry or narrative performances (i.e., verbal lore) Fine Art Functionalism (philosophy of mind) Mimesis Motif-Index of Folk-Literature Museum folklore Performance Studies Romantic Nationalism Social Evolution Structuralism |

文化遺産 環境決定論 民族学 エスノポエティクス(口承詩や語り物などのテキスト版を記録する方法、すなわち口承文芸) 美術 機能主義(心の哲学 ミメーシス 民間文学の主題索引 博物館の民間伝承 パフォーマンス研究 ロマン主義的ナショナリズム 社会進化 構造主義 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Folklore_studies |

|

| Volkskunde

ist eine Kultur- und Sozialwissenschaft, die sich vorwiegend mit der

Geschichte und Gegenwart von Erscheinungen der menschlichen Alltags-

und Populärkultur beschäftigt. An deutschsprachigen Hochschulen wird

das Fach auch geführt als Europäische Ethnologie, Vergleichende

Kulturwissenschaft, als Empirische Kulturwissenschaft, Populäre

Kulturen oder als Kulturanthropologie (was ihm die scherzhafte

Bezeichnung „Vielnamenfach“ eingetragen hat[1][2]), wobei die

Umbenennungen auch einen Neuorientierungsprozess weg von der

traditionellen Volkskunde bedeuteten.[3] Der Schwerpunkt liegt dabei im

europäischen Milieu, wobei Prozesse wie Globalisierung oder

Transnationalisierung den Blick über die Grenzen Europas hinaus

notwendig machen. Dabei ergeben sich Überschneidungen mit den weltweit

forschenden Fachrichtungen, beispielsweise der Ethnologie (Völkerkunde)

und der Sozialanthropologie. |

民

俗学は、主に人間の日常文化や大衆文化の現象の歴史と現在を扱う文化・社会科学である。ドイツ語圏の大学では、この学問はヨーロッパ民族学、比較文化学、

経験文化学、大衆文化学、あるいは文化人類学としても知られており(このため「複数の名称を持つ学問」[1][2]という冗談のような呼び名もある)、名

称の変更は伝統的なフォークロア学からの方向転換の過程も意味している[3]。

ヨーロッパの環境に焦点が当てられており、グローバル化やトランスナショナル化などの過程によって、ヨーロッパの国境を越えて視野を広げる必要が生じてい

る。この結果、民族学(エスノロジー)や社会人類学など、世界中で研究を行う学問分野と重なることになる。 |

| Gegenstandsbereich Die Volkskunde untersucht kulturelle Phänomene der materiellen Kultur (etwa Arbeitsgeräte, Bräuche, Volkslieder) sowie die subjektiven Einstellungen der Menschen zu diesen. Die Arbeitsfelder des so genannten traditionellen Kanons (etwa Brauch, Volkslied, Sage, Hausforschung) mit ihrem Fokus auf ländliche Bevölkerungsschichten standen lange im Mittelpunkt volkskundlicher Forschung. Seit ihrer Neuorientierung in den 1960er- und 1970er-Jahren versteht sich die Volkskunde als eine Kulturwissenschaft, die Kultur in einem weiten und dynamischen Sinn als den gesamten Lebenszusammenhang einer bestimmten (sozialen, religiösen oder ethnischen) Gesellschaft oder gesellschaftlichen Gruppe versteht. Durch ihre Quellenvielfalt (empirische Methoden, Bildanalyse, Objektanalyse, schriftliche Quellen) kann so der räumliche, soziale und historische Kontext stets mit berücksichtigt werden. Aufgrund der Fülle an Kulturphänomenen gibt es eine große Anzahl volkskundlicher Arbeitsfelder: Arbeiter-, Bild-, Brauchforschung, Erzähl-, Familien-, Gemeinde- und Stadt(teil-)forschung, Geräte-, Geschlechter- (oder Frauenforschung), Interethnische Forschung, Kleidungs- (ursprünglich Trachtenforschung), Leser- und Lesestoff-Forschung, Lied- und Musikforschung, Medien-, Medialkultur-, Nahrungsforschung, Reise- und Tourismusforschung, Volksfrömmigkeits- sowie Volksschauspielforschung. Weitere Schwerpunkte sind u. a. Bodylore, Interkulturelle Kommunikation, Rechtliche Volkskunde, Wohnen und Wirtschaften sowie Museologie und Sachkulturforschung. Museen stellen nach wie vor eines der wichtigsten volkskundlichen Arbeitsfelder dar. Die Forschungsergebnisse werden dabei in einigen Museumsarten entweder als Schwerpunkte präsentiert u. a. in Volkskundemuseen, Freilichtmuseen, Heimatmuseen, Bauernhofmuseen oder bilden einen wichtigen Bestandteil beispielsweise in vielen Regional-, Landes- und Nationalmuseen. Meist von Problemen der Gegenwart ausgehend, ohne sich jedoch auf solche zu beschränken, thematisiert sie Kulturkontakte, -entwicklungen oder -strömungen und geht dabei sowohl empirisch als auch hermeneutisch vor. Die Beschäftigung mit Fragen des beschleunigten Wissenstransfers, der gesellschaftlichen Mobilität, der Multikulturalität und des Kulturtransfer sowie der Migration, Integration und Ausgrenzung sind einige Beispiele für moderne Forschungsthemen. Wichtige Nachbardisziplinen der Volkskunde sind im gegenständlichen Bereich Literatur-, Kunst- und Musikwissenschaft; bezüglich der Betrachtungsweise Kultur-, Alltags-, Sozial- und Wirtschaftsgeschichte, Geographie, Kultursoziologie und Sozialpsychologie; hinsichtlich des Forschungsziels Ethnologie, Kulturanthropologie sowie, teilweise, die Politikwissenschaft. Im Schnittbereich zur Rechtsgeschichte ist die Rechtliche Volkskunde angesiedelt. |

対象分野 民俗学は、物質文化の文化現象(道具、風習、民謡など)と、それに対する人々の主観的態度を研究する。いわゆる伝統的典範(風習、民謡、伝説、家庭内調査 など)のうち、農村部に焦点を当てた分野は、長い間、民俗学研究の中心となってきた。1960年代と1970年代に方向転換して以来、民俗学は自らを文化 科学として捉え、文化を特定の(社会的、宗教的、民族的)社会や社会集団の生活文脈全体として広範かつダイナミックな意味で理解してきた。多様な情報源 (経験的手法、画像分析、対象物分析、文書化された情報源)は、空間的、社会的、歴史的文脈を常に考慮できることを意味する。 文化現象が豊富であるため、民族学の分野も数多く存在する: 労働・イメージ・風俗研究、物語研究、家族・共同体・町(地区)研究、道具研究、ジェンダー(または女性)研究、異民族研究、衣服研究(もともとは伝統衣 装研究)、読者・読み物研究、歌・音楽研究、メディア・メディア文化研究、食品研究、旅行・観光研究、民俗信仰・民俗劇研究などである。その他の専門分野 には、ボディーロアー、異文化コミュニケーション、法制民俗学、住居と経済、さらに博物館学と物質文化研究がある。 博物館は、民族学研究の最も重要な分野のひとつであり続けている。研究成果は、民俗学博物館、野外博物館、郷土史博物館、農場博物館など、いくつかのタイ プの博物館で焦点として紹介されるか、あるいは多くの地域博物館、州立博物館、国立博物館などで重要な位置を占めている。 通常、現代的な問題に基づくが、それに限定されることなく、文化的接触、発展、潮流を主題化し、実証的かつ解釈学的に研究を進める。知識移転の加速化、社会移動、多文化主義、文化移転、また移民、統合、疎外といった問題の研究は、現代的な研究テーマの一例である。 エスノロジーに隣接する重要な学問分野として、主題の点では文学、芸術、音楽学、視点の点では文化史、生活史、社会史、経済史、地理学、文化社会学、社会 心理学、研究目的の点では民族学、文化人類学、そしてある程度は政治学が挙げられる。法民俗学は法制史との接点に位置する。 |

| Methoden Mit der Vielfalt der Forschungsfelder geht ein methodenpluralistischer Ansatz einher. Dieser umfasst die archivalische Quellenforschung und die Analyse materieller Kultur ebenso wie die Bildforschung, die Foto- und Filmanalyse, sowie die Diskurs- und die Medienanalyse. Als Wissenschaft mit vor allem empirischer Vorgehensweise, verwendet sie außerdem qualitative Methoden, wie die Feldforschung und die Teilnehmende Beobachtung sowie wissenschaftliche Interviews, wie das narrative Interview oder Oral History. |

方法論 研究分野の多様性は、方法に対する多元的なアプローチを伴っている。これには、アーカイブ資料調査や物質文化の分析、イメージ調査、写真・映像分析、言 説・メディア分析などが含まれる。また、実証的アプローチを主とする科学であるため、フィールド調査や参与観察などの質的手法や、ナラティブ・インタ ビューやオーラル・ヒストリーなどの科学的インタビューも用いられる。 |

| Fachgeschichte Anfänge in der Moderne Als zur Zeit des Humanismus in Deutschland die Germania des Tacitus von Gelehrten wiederentdeckt wurde, begann man sich auch für die Lebensumstände des „einfachen Volkes“ zu interessieren, indem man die Inhalte seines Werkes mit der Gegenwart verglich. Wie viele andere geisteswissenschaftliche Fächer, entstand auch die Volkskunde aus den am Beginn der Moderne maßgeblichen Strömungen Aufklärung und Romantik. Im Zusammenhang mit der Aufklärung entstand um 1750 die Kameralistik, Statistik und Staatenkunde. Sie sah ihre Aufgabe in einer umfassenden Landesbeschreibung, die dem absolutistischen Herrscher detailliertes Wissen über dessen Länder und Bevölkerung im Sinne der bestmöglichen Regierbarkeit und Optimierung der Wirtschaftlichkeit liefern sollte. Im Umkreise der Statistik kam um 1780 die Bezeichnung Volks- und Völkerkunde erstmals auf – die frühste belegbare Begriffserwähnung stammt aus der Hamburger Zeitschrift Der Reisende von 1782 – beide Begriffe wurden anfangs als Synonym verwendet. Nachhaltig prägend wirkte die Romantik, deren Suche nach Natürlichem, Authentischem und Nationalem eine intensive Auseinandersetzung mit der eigenen Geschichte und Vergangenheit forderte. Hierauf fußt das frühe Interesse beispielsweise an Mythologie, Poesie, Märchen, Sagen oder Volksliedern, wobei Johann Gottfried Herder theoretische Grundlagen und Konzepte lieferte. Wichtige Vertreter dieser Phase sind beispielsweise Achim von Arnim, Clemens Brentano oder die Brüder Grimm. So verstanden ist die Volkskunde sowohl ein Produkt als auch ein Symptom der Moderne: Die durch die Industrialisierung beschleunigten und oft als Bedrohung empfundenen gesellschaftlichen und kulturellen Veränderungen führten zu einer Beschäftigung mit scheinbar stabilen Elementen in der Kultur, die man hauptsächlich im ländlichen Milieu zu finden glaubte. Volkskunde im 19. Jahrhundert Ab der Mitte des 19. Jahrhunderts begann sich das Fach zu institutionalisieren: 1852 rief Hans von und zu Aufseß das Germanische Nationalmuseum in Nürnberg für kulturgeschichtliche Sammlungen des Mittelalters sowie der frühen Neuzeit ins Leben. Sechs Jahre später (1858) begann Wilhelm Heinrich Riehl sich mit seinem programmatischen Vortrag „die Volkskunde als Wissenschaft“ für eine Disziplin starkzumachen. Obwohl seine Involviertheit in der Bildung einer Fachdisziplin fragmentarisch blieb und er bis heute eine umstrittene Figur innerhalb der Fachgeschichte darstellt, haben sich Zweige volkskundlicher Fragestellungen im 19. und anfänglichen 20. Jahrhundert an seiner Programmatik orientiert. Diese sieht Volk als organologische Einheit, die es systematisch zu erforschen gilt.[4] Mit dem Volk als naturgegebenes Konzept wandte sich die Volkskunde immer mehr von einer aufgeklärten zu einer romantischen Wissenschaft hin, die nach einer volkstümlichen Lebensweise suchte, die es so niemals gab. Dies kann als erste Tendenz zum Nazismus gesehen werden, wobei es jedoch auch Kontinuitäten und Brüche bei dieser historischen Betrachtung gibt.[5] Gut drei Jahrzehnte darauf (1889) gründete Rudolf Virchow in Berlin das (spätere) Museum für Deutsche Volkskunde, das heute Museum Europäischer Kulturen heißt; im Jahr darauf (1890) gründete Karl Weinhold, ebenfalls in Berlin, den ersten Verein für Volkskunde, der ab 1891 die Zeitschrift für Volkskunde herausgab. Weitere Vereine und Museen entstanden in Österreich, Bayern und der Schweiz. Im Jahr 1919 wurde die Volkskunde schließlich zu einem universitären Lehrfach. Otto Lauffer erhielt den ersten volkskundlichen Lehrstuhl im Deutschen Reich an der Universität Hamburg, aber der erste (damals noch unbezahlte) Professor für Volkskunde im deutschen Sprachraum wurde 1931 Viktor von Geramb an der Karl-Franzens-Universität in Graz. Volkskunde im 20. Jahrhundert Volkskunde bis in die 1930er Jahre Grundsätzliche Fragen – zum Beispiel nach einer Definition für Volk oder nach der Entstehung volkstümlicher Kulturgüter – wurden erstmals 1900 in Basel von Eduard Hoffmann-Krayer, John Meier und anderen erläutert.[6] Anfang der 1920er Jahre formulierte Hans Naumann seine darauf aufbauende Theorie vom gesunkenen Kulturgut und primitiven Gemeinschaftsgut. Wie Hoffmann-Krayer vertrat Naumann eine Zweischichtentheorie – anders als jener glaubte er jedoch, dass wesentliche Erscheinungsformen kulturellen Lebens stets von gehobenen sozialen Schichten geschaffen und von niedrigeren lediglich übernommen werden. Auf dem Feld der Erzählforschung war die Finnische Schule für die erste Jahrhunderthälfte tonangebend. Die Kulturraumforschung konnte sich ab 1926 vom Rheinland aus in großen Teilen des deutschen Sprachraums etablieren. Ende der 1920er Jahre bereicherte die Schwietering-Schule mit ihrer soziologisch-funktionalistischen Betrachtungsweise die Volkskunde. Eine eher psychologische Herangehensweise vermittelte Adolf Spamer von 1936 an in Berlin. Ein bekannter Volkskundler war auch Joseph Klapper (1880–1967), geboren in Habelschwerdt (Bystrzyca Kłodzka). Er widmete sein Augenmerk auf Schlesien. Im Jahr 1925 erschien sein Buch Schlesische Volkskunde,[7] 1952 neu aufgelegt im Stuttgarter Brentanoverlag. Volkskunde in der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus In der Zeit des Nationalsozialismus wurde eine rassistisch und volkserzieherische Volkskunde, die ihren Anspruch auf Wissenschaftlichkeit völlig verlor, zur dominierenden Lehre. Ältere Vorstellungen eines dauerhaften, in Rasse und Lebensraum wurzelnden National- und Stammescharakters, wie sie unter anderem von Martin Wähler vertreten wurden, kamen dieser Instrumentalisierung entgegen. Nach Ende des Zweiten Weltkriegs wurde vor allem von soziologischer Seite die Forderung laut, dem Fach seine Eigenständigkeit abzuerkennen.[8] Der Nationalsozialismus hatte die Institutionalisierung des Faches grundlegend vorangetrieben. 1933 gab es erst eine ordentliche und eine außerordentliche Professur für Volkskunde in Hamburg und Dresden. Bis 1945 verfügten so gut wie alle Universitäten in Deutschland über Professuren in der Volkskunde. Die Institutionalisierung während des Zweiten Weltkrieges stellte also eine Grundlage des Weiterbestehens des Faches nach 1945 dar.[9] Volkskunde in der Nachkriegszeit und Neupositionierung in den 1960/70ern Eine neue Hoffnung brachte jedoch bereits 1946 Richard Weiss’ Volkskunde der Schweiz mit sich, und zwar aufgrund seiner (für die damalige Zeit überaus beispielhaften) psychologisch-funktionellen Sichtweise. In der Bundesrepublik Deutschland und ebenso in Österreich tat man sich in der Folgezeit ungeachtet dessen schwer, die Instrumentalisierung des eigenen Faches durch die Nationalsozialisten kritisch zu reflektieren. Nicht zuletzt deshalb erschien es einzelnen Instituten wichtiger, den Gegenstandsbereich der Volkskunde neu zu definieren oder zu ergänzen. So stellte Hermann Bausinger in seiner 1961 publizierten Arbeit Volkskultur in der technischen Welt das Selbstverständnis des Faches als Erforschung vor allem bäuerlicher Traditionen und Kulturinhalte in Frage. Insbesondere sei der Begriff Volkskultur zu hinterfragen, da er eine scheinbar unveränderliche, ursprüngliche Kultur postuliere. Im Anschluss an Bausingers Kritik entwickelten sich neue Forschungsansätze und -schwerpunkte, die vor allem den Bereich der zeitgenössischen Alltagskultur in den Fokus brachten. Konrad Köstlin kritisierte allerdings, dass diese „moderne Volkskunde“ in vielen Fällen lediglich eine idealisierende Darstellung der Arbeiterschicht (als Träger der Volkskultur) gebracht hätte, während man andererseits den „alten“ Volkskundlern vorwerfe, die bäuerliche Kultur idealisiert zu haben – die isolierte Betrachtungsweise, so Köstlin, sei aber in beiden Fällen die gleiche.[10] Im Jahr 1970 fand die Arbeitstagung der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Volkskunde (DGV) in Falkenstein (Falkensteiner Tagung) statt, hierbei wurde kritisch über Theorien, das Selbstverständnis, die Fachgeschichte und bislang tragende volkskundliche Grundbegriffe wie Volk, Stamm, Gemeinschaft, Tradition, Kontinuität und Sitte diskutiert, mit dem Ergebnis einer Neupositionierung und eines Paradigmenwechsels: Man lehnte das damalige Verständnis von „Volkskultur“ ab und wollte stattdessen stärker gegenwartsbezogen forschen und sich soziokulturellen Problemen widmen. Zudem bildeten sich zwei Positionen bezüglich des wissenschaftlichen Umgangs mit dem Begriff „Kultur“. Die Fachvertreter des ehemaligen Instituts für Volkskunde in Tübingen, das zu diesem Zeitpunkt bereits in das Institut für empirische Kulturwissenschaft umbenannt worden war, plädierten für die Soziologie als neue Leitdisziplin. Die Vertreter des Institutes in Frankfurt am Main hingegen betonten die inhaltliche Nähe der Volkskunde zu ethnologischen Disziplinen wie der Ethnologie (Völkerkunde) und der angelsächsischen Cultural Anthropology. Mehrheitlich schloss man sich der ersten Gruppe an, innerhalb derer Kultur nun primär als Regulationsmodell des Alltags verstanden wird. Manifestiert hat sich diese Diskussion in der (im Übrigen bis heute andauernden) Debatte darüber, wie das Fach neu zu benennen sei, um solchermaßen auch nach außen hin ein Signal der selbst verordneten Neuorientierung zu setzen. Institutsumbenennungen waren die Konsequenz: Berlin, Freiburg, Marburg und Wien entschieden sich für Europäische Ethnologie, Frankfurt am Main für Kulturanthropologie, Göttingen für Kulturanthropologie/Europäische Ethnologie, Tübingen für Empirische Kulturwissenschaft, Regensburg für Vergleichende Kulturwissenschaft. Andernorts beließ man es bei dem alten Namen oder wählte eine Doppelbezeichnung, zum Beispiel Volkskunde/Europäische Ethnologie in München und Münster, Volkskunde/Kulturgeschichte in Jena, Europäische Ethnologie/Volkskunde in Innsbruck, Würzburg und Kiel, Kulturanthropologie/Volkskunde in Mainz sowie Volkskunde und Kulturanthropologie in Graz. Derzeit gibt es 28 Universitätsinstitute im deutschen Sprachraum (Stand: 2005). Die Deutsche Gesellschaft für Volkskunde (DGV), die 1963 in Marburg im Sinne der Volkstumsforschung gegründet wurde, führt nach eigenen Angaben die Arbeit des Verbandes der Vereine für Volkskunde (gegründet 1904) fort.[11] Gegenwärtige Situation Die Volkskunde wird an deutschsprachigen Hochschulen als eigenständiges Fach auch unter den Namen Europäische Ethnologie, Kulturanthropologie oder empirische Kulturwissenschaften geführt, weswegen Volkskunde auch mit dem von Gottfried Korff geprägten Begriff „Vielnamenfach“ benannt wird.[12] Gegenwärtig existieren an 21 deutschen Universitäten insgesamt 37 Lehrstühle für Volkskunde.[13] Die Volkskunde gehört somit zu den sogenannten kleinen Fächern (siehe auch Liste der Kleinen Fächer). Die Volkskunde untersucht das Andere in der eigenen (deutschen oder europäischen) Kultur. Betont werden bei einer volkskundlichen Herangehensweise Phänomene der Alltagskultur. Der Schwerpunkt liegt dabei im europäischen Raum, wobei Prozesse wie Globalisierung oder Transnationalisierung den Blick über die Grenzen Europas hinweg notwendig gemacht und zu einer größeren Schnittmenge mit der Ethnologie geführt haben. Diese bis heute anhaltenden inhaltlichen wie methodischen Annäherungen haben in den letzten Jahren zu Debatten um die Demarkationslinien der sozial- und kulturwissenschaftlichen Fächer geführt.[14] Anders als die Bezeichnung Europäische Ethnologie vermuten lässt, ist das Fach jedoch bis heute ausschließlich im deutschen Sprachraum verankert. Der griechische Volkskundler und Philologe Nikolaos Politis (1852–1921) hat den Neologismus Laographie (von griechisch Λαογραφία: Folkloristik) geprägt. Er entspricht in etwa der deutschen Volkskunde als Integrationsbegriff der Kulturforschung.[15] Die Folkloristik wird im griechischen Sprachraum u. a. als Studium kleiner Gruppen von Menschen in ihrer natürlichen Umgebung begriffen (vergleiche Ethnographie) und untersucht Sitten und Bräuche als prägend für einen Ort und seine Kultur. |