序論「歴史学の運命」

Lynn Hunt's "Writing history in the global era"

The

Allegory On the Writing of History

shows Truth watching the

historian write history, while advised by Wisdom. (Jacob de Wit,1754)

★

啓蒙主義時代以降の歴史記述(学/論)[Historiography]

とは? https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historiography

より

Enlightenment Voltaire's works of history are an excellent example of Enlightenment era advances in accuracy. During the Age of Enlightenment, the modern development of historiography through the application of scrupulous methods began. Among the many Italians who contributed to this were Leonardo Bruni (c. 1370–1444), Francesco Guicciardini (1483–1540), and Cesare Baronio (1538–1607). Voltaire French philosophe Voltaire (1694–1778) had an enormous influence on the development of historiography during the Age of Enlightenment through his demonstration of fresh new ways to look at the past. Guillaume de Syon argues: Voltaire recast historiography in both factual and analytical terms. Not only did he reject traditional biographies and accounts that claim the work of supernatural forces, but he went so far as to suggest that earlier historiography was rife with falsified evidence and required new investigations at the source. Such an outlook was not unique in that the scientific spirit that 18th-century intellectuals perceived themselves as invested with. A rationalistic approach was key to rewriting history.[46] Voltaire's best-known histories are The Age of Louis XIV (1751), and his Essay on the Customs and the Spirit of the Nations (1756). He broke from the tradition of narrating diplomatic and military events, and emphasized customs, social history and achievements in the arts and sciences. He was the first scholar to make a serious attempt to write the history of the world, eliminating theological frameworks, and emphasizing economics, culture and political history. Although he repeatedly warned against political bias on the part of the historian, he did not miss many opportunities to expose the intolerance and frauds of the church over the ages. Voltaire advised scholars that anything contradicting the normal course of nature was not to be believed. Although he found evil in the historical record, he fervently believed reason and educating the illiterate masses would lead to progress. Voltaire's History of Charles XII (1731) about the Swedish warrior king (Swedish: Karl XII) is also one of his most famous works. It is not least known as one of Napoleon's absolute favorite books.[47] Voltaire explains his view of historiography in his article on "History" in Diderot's Encyclopédie: "One demands of modern historians more details, better ascertained facts, precise dates, more attention to customs, laws, mores, commerce, finance, agriculture, population." Already in 1739 he had written: "My chief object is not political or military history, it is the history of the arts, of commerce, of civilization—in a word—of the human mind."[48] Voltaire's histories used the values of the Enlightenment to evaluate the past. He helped free historiography from antiquarianism, Eurocentrism, religious intolerance and a concentration on great men, diplomacy, and warfare.[49] Peter Gay says Voltaire wrote "very good history", citing his "scrupulous concern for truths", "careful sifting of evidence", "intelligent selection of what is important", "keen sense of drama", and "grasp of the fact that a whole civilization is a unit of study".[50][51][full citation needed] David Hume At the same time, philosopher David Hume was having a similar effect on the study of history in Great Britain. In 1754 he published The History of England, a 6-volume work which extended "From the Invasion of Julius Caesar to the Revolution in 1688". Hume adopted a similar scope to Voltaire in his history; as well as the history of Kings, Parliaments, and armies, he examined the history of culture, including literature and science, as well. His short biographies of leading scientists explored the process of scientific change and he developed new ways of seeing scientists in the context of their times by looking at how they interacted with society and each other—he paid special attention to Francis Bacon, Robert Boyle, Isaac Newton and William Harvey.[52] He also argued that the quest for liberty was the highest standard for judging the past, and concluded that after considerable fluctuation, England at the time of his writing had achieved "the most entire system of liberty, that was ever known amongst mankind".[53] Edward Gibbon  Edward Gibbon's Decline of the Roman Empire (1776) was a masterpiece of late 18th-century history writing. The apex of Enlightenment history was reached with Edward Gibbon's monumental six-volume work, The History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire, published on 17 February 1776. Because of its relative objectivity and heavy use of primary sources, its methodology became a model for later historians. This has led to Gibbon being called the first "modern historian".[54] The book sold impressively, earning its author a total of about £9000. Biographer Leslie Stephen wrote that thereafter, "His fame was as rapid as it has been lasting." Gibbon's work has been praised for its style, its piquant epigrams and its effective irony. Winston Churchill memorably noted, "I set out upon ... Gibbon's Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire [and] was immediately dominated both by the story and the style. ... I devoured Gibbon. I rode triumphantly through it from end to end and enjoyed it all."[55] Gibbon was pivotal in the secularizing and 'desanctifying' of history, remarking, for example, on the "want of truth and common sense" of biographies composed by Saint Jerome.[56] Unusually for an 18th-century historian, Gibbon was never content with secondhand accounts when the primary sources were accessible (though most of these were drawn from well-known printed editions). He said, "I have always endeavoured to draw from the fountain-head; that my curiosity, as well as a sense of duty, has always urged me to study the originals; and that, if they have sometimes eluded my search, I have carefully marked the secondary evidence, on whose faith a passage or a fact were reduced to depend."[57] In this insistence upon the importance of primary sources, Gibbon broke new ground in the methodical study of history: In accuracy, thoroughness, lucidity, and comprehensive grasp of a vast subject, the 'History' is unsurpassable. It is the one English history which may be regarded as definitive. ... Whatever its shortcomings the book is artistically imposing as well as historically unimpeachable as a vast panorama of a great period.[58] |

啓蒙主義 ヴォルテールの歴史著作は、啓蒙時代の正確さの進歩を示す優れた例である。 啓蒙時代には、綿密な手法による歴史学の近代的発展が始まった。これに貢献した多くのイタリア人の中には、レオナルド・ブルーニ(1370-1444年 頃)、フランチェスコ・ギッチャルディーニ(1483-1540年)、チェーザレ・バローニオ(1538-1607年)らがいる。 ヴォルテール フランスの哲学者ヴォルテール(1694-1778)は、過去を見るための斬新な新しい方法を示したことで、啓蒙時代の歴史学の発展に多大な影響を与え た。ギヨーム・ド・シオンはこう主張する: ヴォルテールは歴史学を事実と分析の両面から捉え直した。彼は、伝統的な伝記や超自然的な力の働きを主張する記述を否定しただけでなく、それ以前の歴史学 には改ざんされた証拠があふれており、源流から新たに調査する必要があるとまで言い切った。このような考え方は、18世紀の知識人が自らを科学的精神に裏 打ちされたものだと認識していた点で、決して特異なものではなかった。合理主義的なアプローチが歴史を書き換える鍵となったのである[46]。 ヴォルテールの最も有名な歴史書は『ルイ14世の時代』(1751年)と『諸国民の風俗と精神に関する試論』(1756年)である。ヴォルテールは、外交 的、軍事的な出来事を叙述する伝統から脱却し、風俗、社会史、芸術や科学における業績を重視した。神学的な枠組みを排除し、経済、文化、政治史に重点を置 いて世界史を本格的に書こうとした最初の学者である。彼は歴史家側の政治的偏見に繰り返し警告を発したが、時代を超えて教会の不寛容や不正を暴く機会を多 く逃さなかった。ヴォルテールは学者たちに、自然の摂理に反するものは信じるべきではないと忠告した。彼は歴史的記録の中に悪を見出したが、理性と文盲の 大衆を教育することが進歩につながると熱烈に信じていた。スウェーデンの戦士王カール12世を描いた『シャルル12世の歴史』(1731年)は、ヴォル テールの代表作のひとつでもある。ナポレオンの絶対的な愛読書としても知られている[47]。 ヴォルテールは、ディドロの『百科全書』の「歴史」に関する論文の中で、歴史学に対する自身の見解を次のように説明している。「現代の歴史家には、より詳 細に、よりよく確認された事実、正確な年代、習慣、法律、風俗、商業、財政、農業、人口に対するより多くの注意を求める。」 1739年にはすでにこう書いている: 「私の主要な目的は政治史でも軍事史でもなく、芸術史であり、商業史であり、文明史である。ピーター・ゲイによれば、ヴォルテールは「非常に優れた歴史」 を書いており、その「真理に対する細心の関心」、「証拠の慎重な選別」、「重要なものの知的な選択」、「ドラマに対する鋭い感覚」、「文明全体が研究の単 位であるという事実の把握」を挙げている[50][51][要出典]。 デイヴィッド・ヒューム 同じ頃、哲学者のデイヴィッド・ヒュームもイギリスにおける歴史研究に同様の影響を及ぼしていた。1754年、彼は『イングランドの歴史』を出版し、 「ジュリアス・シーザーの侵略から1688年の革命まで」を6巻にまとめた。ヒュームはその歴史においてヴォルテールと同様の範囲を採用し、王、議会、軍 隊の歴史だけでなく、文学や科学を含む文化の歴史も考察した。主要な科学者の短い伝記で科学の変化の過程を探求し、科学者が社会や他者とどのように相互作 用していたかを見ることで、科学者をその時代の文脈で見る新しい方法を開発した。 彼はまた、自由の探求が過去を判断するための最高の基準であると主張し、かなりの変動を経て、彼の著作が書かれた当時のイギリスは「人類の間で知られてい た中で最も完全な自由のシステム」を達成していたと結論づけた[53]。 エドワード・ギボン  エドワード・ギボンの『ローマ帝国の衰亡』(1776年)は、18世紀後半の歴史書の傑作である。 啓蒙主義史学の頂点に達したのは、1776年2月17日に出版されたエドワード・ギボンの6巻からなる記念碑的著作『ローマ帝国衰亡史』であった。その比 較的客観的で一次資料を多用した方法論は、後の歴史家の手本となった。このため、ギボンは最初の「近代歴史家」と呼ばれるようになった[54]。この本は 印象的に売れ、著者は合計約9000ポンドを稼いだ。伝記作家のレスリー・スティーヴンは、その後「彼の名声は永続するのと同じくらい急速に高まった」と 書いている。 ギボンの作品は、その文体、辛辣なエピグラム、効果的な皮肉が賞賛されている。ウィンストン・チャーチルは、「私は......ギボンの『衰亡と没落』に 着手した。ギボンの『ローマ帝国の衰亡』を読み始めてすぐに、その物語と文体に魅了された。... 私はギボンをむさぼり読んだ。ギボンは、歴史の世俗化と「脱俗化」において極めて重要な人物であり、例えば、聖ジェロームによって書かれた伝記には「真実 と常識が欠けている」と述べている[56]。 18世紀の歴史家としては珍しく、ギボンは、一次資料が入手可能な場合には、決して二次資料に満足することはなかった(ただし、これらのほとんどはよく知 られた印刷版からの引用であった)。彼は「私は常に源泉から汲み上げるように努め、義務感だけでなく好奇心も常に原典を研究するよう私を駆り立てた: 正確さ、徹底さ、明晰さ、そして広大な主題の包括的な把握という点で、『歴史』は他の追随を許さない。この『歴史』は、決定版と見なせる唯一のイギリス史 である。... その欠点が何であれ、本書は芸術的に堂々たるものであると同時に、偉大な時代の広大なパノラマとして歴史的にも文句のつけようがない[58]。 |

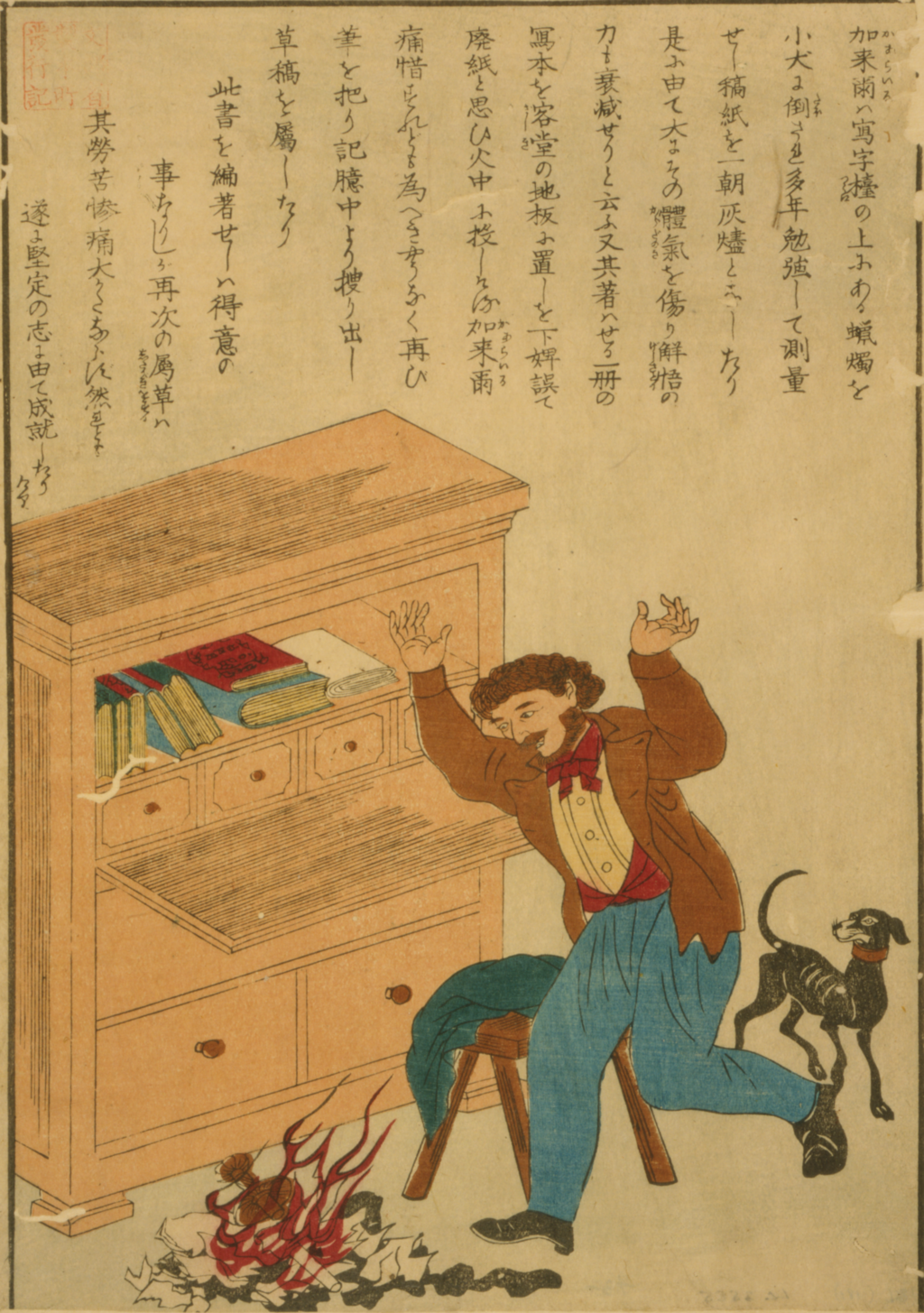

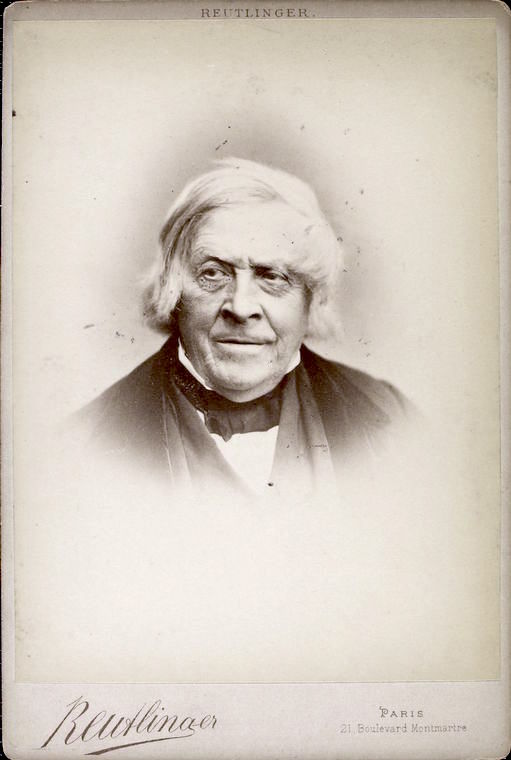

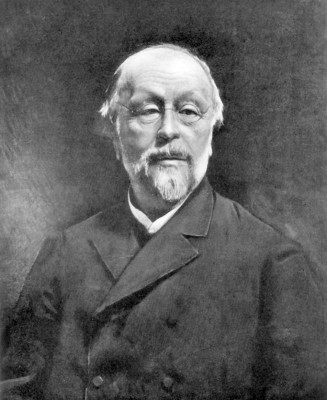

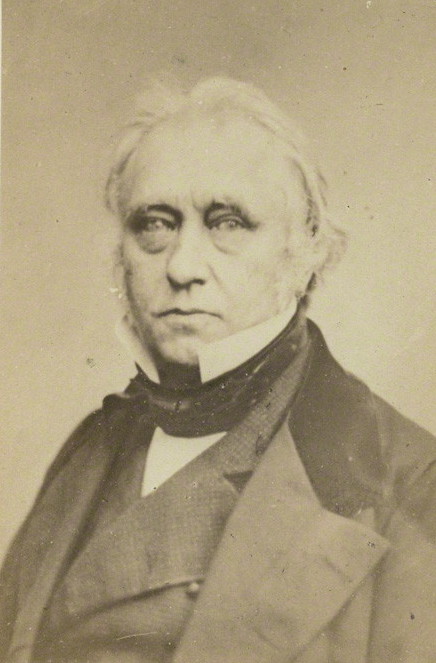

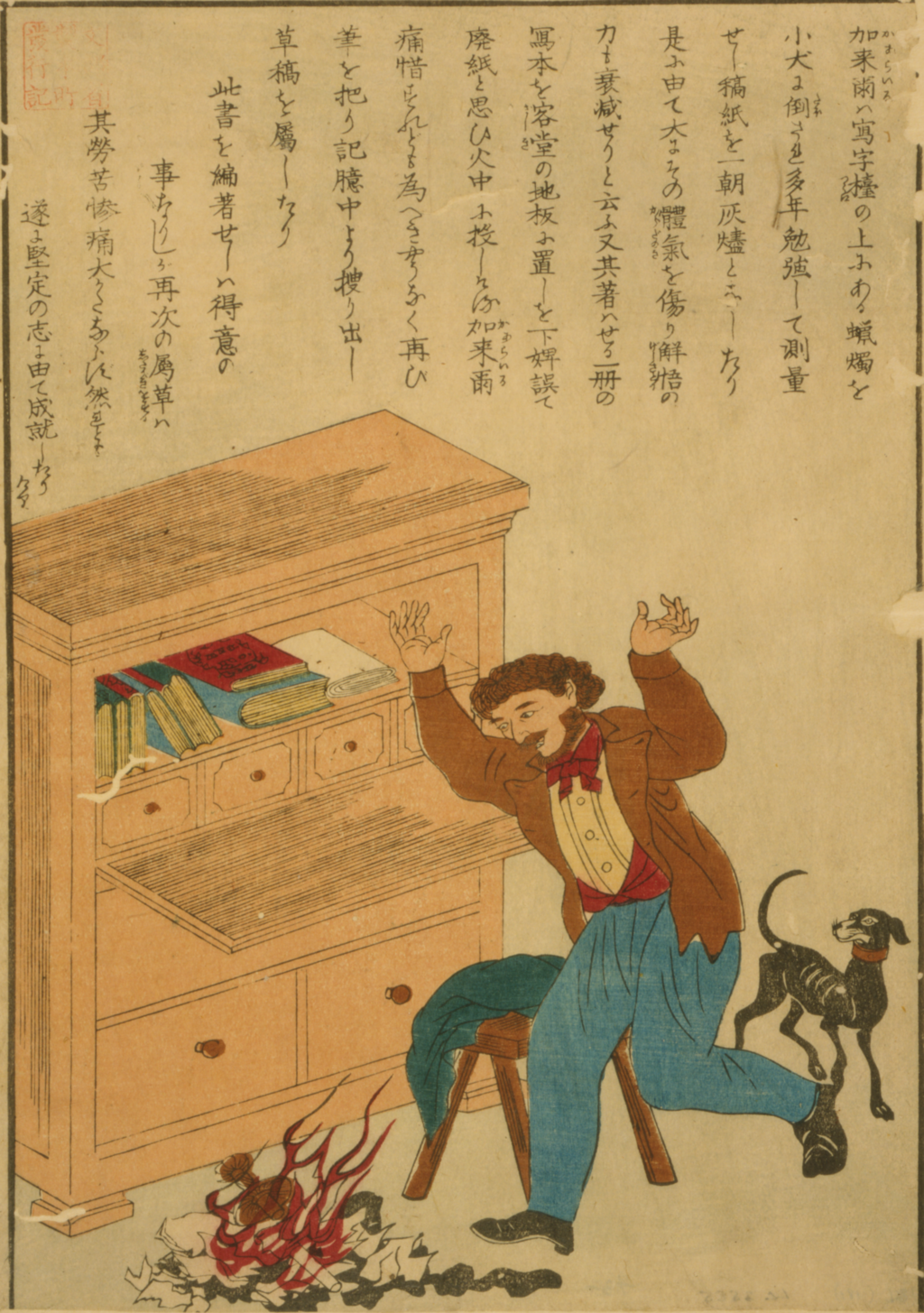

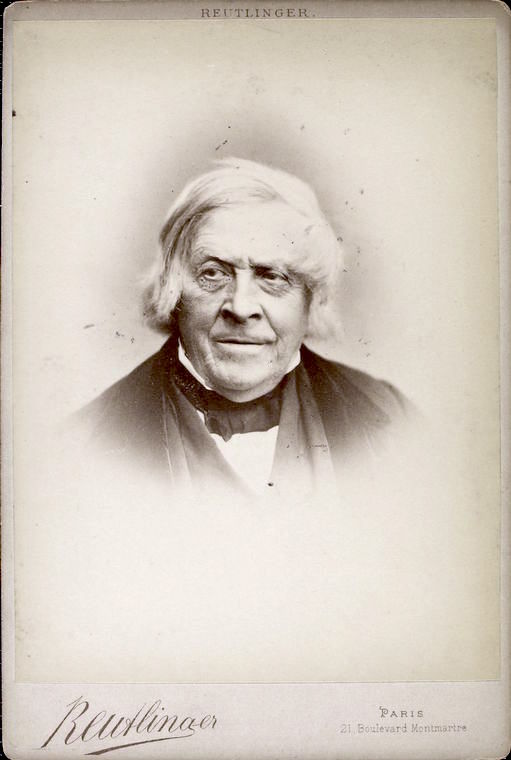

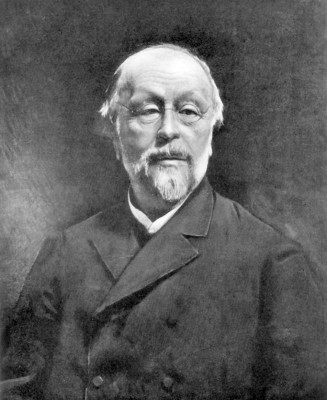

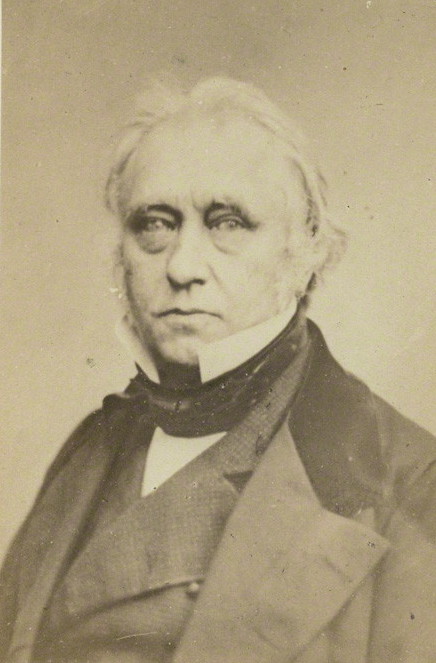

19th century Japanese print depicting Thomas Carlyle's horror at the burning of his manuscript The French Revolution: A History The tumultuous events surrounding the French Revolution inspired much of the historiography and analysis of the early 19th century. Interest in the 1688 Glorious Revolution was also rekindled by the Great Reform Act of 1832 in England. Nineteenth century historiography, especially among American historians, featured conflicting viewpoints that represented the times. According to 20th-century historian Richard Hofstadter:[59] The historians of the nineteenth century worked under the pressure of two internal tensions: on one side there was the constant demand of society—whether through the nationstate, the church, or some special group or class interest—for memory mixed with myth, for the historical tale that would strengthen group loyalties or confirm national pride; and against this there were the demands of critical method, and even, after a time, the goal of writing "scientific" history. Thomas Carlyle Thomas Carlyle published his three-volume The French Revolution: A History, in 1837. The first volume was accidentally burned by John Stuart Mill's maid. Carlyle rewrote it from scratch.[60] Carlyle's style of historical writing stressed the immediacy of action, often using the present tense. He emphasised the role of forces of the spirit in history and thought that chaotic events demanded what he called 'heroes' to take control over the competing forces erupting within society. He considered the dynamic forces of history as being the hopes and aspirations of people that took the form of ideas, and were often ossified into ideologies. Carlyle's The French Revolution was written in a highly unorthodox style, far removed from the neutral and detached tone of the tradition of Gibbon. Carlyle presented the history as dramatic events unfolding in the present as though he and the reader were participants on the streets of Paris at the famous events. Carlyle's invented style was epic poetry combined with philosophical treatise. It is rarely read or cited in the last century.[61][62] French historians: Michelet and Taine  Jules Michelet (1798–1874), later in his career  Hippolyte Taine (1828–1893) In his main work Histoire de France (1855), French historian Jules Michelet (1798–1874) coined the term Renaissance (meaning "rebirth" in French), as a period in Europe's cultural history that represented a break from the Middle Ages, creating a modern understanding of humanity and its place in the world.[63] The 19-volume work covered French history from Charlemagne to the outbreak of the French Revolution. His inquiry into manuscript and printed authorities was most laborious, but his lively imagination, and his strong religious and political prejudices, made him regard all things from a singularly personal point of view.[64] Michelet was one of the first historians to shift the emphasis of history to the common people, rather than the leaders and institutions of the country. He had a decisive impact on scholars. Gayana Jurkevich argues that led by Michelet: 19th-century French historians no longer saw history as the chronicling of royal dynasties, armies, treaties, and great men of state, but as the history of ordinary French people and the landscape of France.[65] Hippolyte Taine (1828–1893), although unable to secure an academic position, was the chief theoretical influence of French naturalism, a major proponent of sociological positivism, and one of the first practitioners of historicist criticism. He pioneered the idea of "the milieu" as an active historical force which amalgamated geographical, psychological, and social factors. Historical writing for him was a search for general laws. His brilliant style kept his writing in circulation long after his theoretical approaches were passé.[66] Cultural and constitutional history One of the major progenitors of the history of culture and art, was the Swiss historian Jacob Burckhardt.[67] Siegfried Giedion described Burckhardt's achievement in the following terms: "The great discoverer of the age of the Renaissance, he first showed how a period should be treated in its entirety, with regard not only for its painting, sculpture and architecture, but for the social institutions of its daily life as well."[68] His most famous work was The Civilization of the Renaissance in Italy, published in 1860; it was the most influential interpretation of the Italian Renaissance in the nineteenth century and is still widely read. According to John Lukacs, he was the first master of cultural history, which seeks to describe the spirit and the forms of expression of a particular age, a particular people, or a particular place. His innovative approach to historical research stressed the importance of art and its inestimable value as a primary source for the study of history. He was one of the first historians to rise above the narrow nineteenth-century notion that "history is past politics and politics current history.[69] By the mid-19th century, scholars were beginning to analyse the history of institutional change, particularly the development of constitutional government. William Stubbs's Constitutional History of England (3 vols., 1874–1878) was an important influence on this developing field. The work traced the development of the English constitution from the Teutonic invasions of Britain until 1485, and marked a distinct step in the advance of English historical learning.[70] He argued that the theory of the unity and continuity of history should not remove distinctions between ancient and modern history. He believed that, though work on ancient history is a useful preparation for the study of modern history, either may advantageously be studied apart. He was a good palaeographer, and excelled in textual criticism, in examination of authorship, and other such matters, while his vast erudition and retentive memory made him second to none in interpretation and exposition.[71] Von Ranke and professionalization in Germany Main article: Historiography of Germany  Ranke established history as a professional academic discipline in Germany. The modern academic study of history and methods of historiography were pioneered in 19th-century German universities, especially the University of Göttingen. Leopold von Ranke (1795–1886) at Berlin was a pivotal influence in this regard, and was the founder of modern source-based history.[72][73] According to Caroline Hoefferle, "Ranke was probably the most important historian to shape historical profession as it emerged in Europe and the United States in the late 19th century."[74][75] Specifically, he implemented the seminar teaching method in his classroom, and focused on archival research and analysis of historical documents. Beginning with his first book in 1824, the History of the Latin and Teutonic Peoples from 1494 to 1514, Ranke used an unusually wide variety of sources for a historian of the age, including "memoirs, diaries, personal and formal missives, government documents, diplomatic dispatches and first-hand accounts of eye-witnesses". Over a career that spanned much of the century, Ranke set the standards for much of later historical writing, introducing such ideas as reliance on primary sources, an emphasis on narrative history and especially international politics (Aussenpolitik).[76] Sources had to be solid, not speculations and rationalizations. His credo was to write history the way it was. He insisted on primary sources with proven authenticity. Ranke also rejected the 'teleological approach' to history, which traditionally viewed each period as inferior to the period which follows. In Ranke's view, the historian had to understand a period on its own terms, and seek to find only the general ideas which animated every period of history. In 1831 and at the behest of the Prussian government, Ranke founded and edited the first historical journal in the world, called Historisch-Politische Zeitschrift. Another important German thinker was Georg Wilhelm Friedrich Hegel, whose theory of historical progress ran counter to Ranke's approach. In Hegel's own words, his philosophical theory of "World history ... represents the development of the spirit's consciousness of its own freedom and of the consequent realization of this freedom."[77] This realization is seen by studying the various cultures that have developed over the millennia, and trying to understand the way that freedom has worked itself out through them: World history is the record of the spirit's efforts to attain knowledge of what it is in itself. The Orientals do not know that the spirit or man as such are free in themselves. And because they do not know that, they are not themselves free. They only know that One is free. ... The consciousness of freedom first awoke among the Greeks, and they were accordingly free; but, like the Romans, they only knew that Some, and not all men as such, are free. ... The Germanic nations, with the rise of Christianity, were the first to realize that All men are by nature free, and that freedom of spirit is his very essence.[78] Karl Marx introduced the concept of historical materialism into the study of world historical development. In his conception, the economic conditions and dominant modes of production determined the structure of society at that point. In his view five successive stages in the development of material conditions would occur in Western Europe. The first stage was primitive communism where property was shared and there was no concept of "leadership". This progressed to a slave society where the idea of class emerged and the State developed. Feudalism was characterized by an aristocracy working in partnership with a theocracy and the emergence of the nation-state. Capitalism appeared after the bourgeois revolution when the capitalists (or their merchant predecessors) overthrew the feudal system and established a market economy, with private property and parliamentary democracy. Marx then predicted the eventual proletarian revolution that would result in the attainment of socialism, followed by communism, where property would be communally owned. Previous historians had focused on cyclical events of the rise and decline of rulers and nations. Process of nationalization of history, as part of national revivals in the 19th century, resulted with separation of "one's own" history from common universal history by such way of perceiving, understanding and treating the past that constructed history as history of a nation.[79] A new discipline, sociology, emerged in the late 19th century and analyzed and compared these perspectives on a larger scale. Macaulay and Whig history  Macaulay was the most influential exponent of the Whig history. The term "Whig history", coined by Herbert Butterfield in his short book The Whig Interpretation of History in 1931, means the approach to historiography which presents the past as an inevitable progression towards ever greater liberty and enlightenment, culminating in modern forms of liberal democracy and constitutional monarchy. In general, Whig historians emphasized the rise of constitutional government, personal freedoms and scientific progress. The term has been also applied widely in historical disciplines outside of British history (the history of science, for example) to criticize any teleological (or goal-directed), hero-based, and transhistorical narrative.[80] Paul Rapin de Thoyras's history of England, published in 1723, became "the classic Whig history" for the first half of the 18th century.[81] It was later supplanted by the immensely popular The History of England by David Hume. Whig historians emphasized the achievements of the Glorious Revolution of 1688. This included James Mackintosh's History of the Revolution in England in 1688, William Blackstone's Commentaries on the Laws of England, and Henry Hallam's Constitutional History of England.[82] The most famous exponent of 'Whiggery' was Thomas Babington Macaulay. His writings are famous for their ringing prose and for their confident, sometimes dogmatic, emphasis on a progressive model of British history, according to which the country threw off superstition, autocracy and confusion to create a balanced constitution and a forward-looking culture combined with freedom of belief and expression. This model of human progress has been called the Whig interpretation of history.[83] He published the first volumes of his most famous work of history, The History of England from the Accession of James II, in 1848. It proved an immediate success and replaced Hume's history to become the new orthodoxy.[84] His 'Whiggish convictions' are spelled out in his first chapter: I shall relate how the new settlement was ... successfully defended against foreign and domestic enemies; how ... the authority of law and the security of property were found to be compatible with a liberty of discussion and of individual action never before known; how, from the auspicious union of order and freedom, sprang a prosperity of which the annals of human affairs had furnished no example; how our country, from a state of ignominious vassalage, rapidly rose to the place of umpire among European powers; how her opulence and her martial glory grew together; ... how a gigantic commerce gave birth to a maritime power, compared with which every other maritime power, ancient or modern, sinks into insignificance ... the history of our country during the last hundred and sixty years is eminently the history of physical, of moral, and of intellectual improvement. His legacy continues to be controversial; Gertrude Himmelfarb wrote that "most professional historians have long since given up reading Macaulay, as they have given up writing the kind of history he wrote and thinking about history as he did."[85] However, J. R. Western wrote that: "Despite its age and blemishes, Macaulay's History of England has still to be superseded by a full-scale modern history of the period".[86] The Whig consensus was steadily undermined during the post-World War I re-evaluation of European history, and Butterfield's critique exemplified this trend. Intellectuals no longer believed the world was automatically getting better and better. Subsequent generations of academic historians have similarly rejected Whig history because of its presentist and teleological assumption that history is driving toward some sort of goal.[87] Other criticized 'Whig' assumptions included viewing the British system as the apex of human political development, assuming that political figures in the past held current political beliefs (anachronism), considering British history as a march of progress with inevitable outcomes and presenting political figures of the past as heroes, who advanced the cause of this political progress, or villains, who sought to hinder its inevitable triumph. J. Hart says "a Whig interpretation requires human heroes and villains in the story."[88] |

19世紀 トマス・カーライルが『フランス革命』の原稿を燃やされた恐怖を描いた日本の版画: 歴史 フランス革命をめぐる激動の出来事は、19世紀初頭の歴史学や分析に多くのインスピレーションを与えた。1688年の栄光革命への関心は、1832年のイ ギリス大改革法によって再燃した。19世紀の歴史学、特にアメリカの歴史家の間では、時代を象徴する相反する視点が見られた。20世紀の歴史家リチャー ド・ホフスタッターによれば、以下の通りである[59]。 一方には、神話と混じり合った記憶、集団の忠誠心を強めたり民族の誇りを確認したりするような歴史的物語に対する、国民国家、教会、あるいはある特別な集 団や階級的利害を通じた社会の絶え間ない要求があり、これに対して批判的方法の要求があり、さらには一時期は「科学的」な歴史を書くという目標さえあっ た。 トマス・カーライル トマス・カーライルは3巻からなる『フランス革命』を出版した: 1837年に『フランス革命史』を出版した。第1巻は、ジョン・スチュアート・ミルの女中が誤って燃やしてしまった。カーライルの歴史記述のスタイルは、 行動の即時性を強調し、しばしば現在時制を用いた[60]。彼は歴史における精神の力の役割を強調し、混沌とした出来事には、社会の中で噴出する競合する 力を制御する「英雄」と呼ばれる人物が必要だと考えた。彼は、歴史のダイナミックな力とは、人々の希望や願望であり、それは思想という形をとり、しばしば イデオロギーとして骨抜きにされると考えた。カーライルの『フランス革命』は、ギボンの伝統的な中立的で冷静な論調とはかけ離れた、きわめて異端的な文体 で書かれた。カーライルは、あたかも彼や読者がパリの街角で有名な出来事に参加したかのように、歴史を現在に展開する劇的な出来事として表現した。カーラ イルの創作した文体は、叙事詩と哲学的論説を組み合わせたものであった。前世紀にはほとんど読まれることも引用されることもなかった[61][62]。 フランスの歴史家 ミシュレとテーヌ  ジュール・ミシュレ(1798-1874)、後期  イポリット・テーヌ(1828-1893) フランスの歴史家ジュール・ミシュレ(1798-1874)は、主著『フランス史』(1855年)の中で、ルネサンス(フランス語で「再生」を意味する) という言葉を創作した。手稿本や印刷物の典拠を調べるのは最も骨の折れる作業であったが、彼の活発な想像力と強い宗教的・政治的偏見によって、あらゆる物 事を極めて個人的な視点からとらえるようになった[64]。 ミシュレは、歴史の重点を国の指導者や制度ではなく、庶民に移した最初の歴史家の一人であった。彼は学者たちに決定的な影響を与えた。ガヤナ・ユルケ ヴィッチは、ミシュレに導かれたと論じている: 19世紀のフランスの歴史家は、もはや歴史を王家の王朝、軍隊、条約、国家の偉人の記録としてではなく、一般のフランス人の歴史とフランスの風景として捉 えていた[65]。 イポリット・テーヌ(1828年-1893年)は、学問的地位を確保することはできなかったが、フランス自然主義の主要な理論的影響者であり、社会学的実 証主義の主要な支持者であり、歴史主義批評の最初の実践者の一人であった。彼は、地理的、心理的、社会的要因を統合した積極的な歴史的力としての「環境 (milieu)」という考え方を開拓した。彼にとって歴史的文章とは、一般法則の探求であった。彼の卓越した文体は、彼の理論的アプローチが過ぎ去った 後も、彼の著作を長く流通させ続けた[66]。 文化史と憲法史 文化・芸術史の主要な始祖の一人は、スイスの歴史家ヤコブ・ブルクハルトである[67]。ジークフリート・ギーディオンは、ブルクハルトの業績を次のよう に表現している: 「ルネサンスという時代の偉大な発見者である彼は、絵画、彫刻、建築だけでなく、日常生活の社会制度も含めて、ある時代を全体としてどのように扱うべきか を初めて示した」[68]。 彼の最も有名な著作は、1860年に出版された『イタリア・ルネサンスの文明論』であり、19世紀におけるイタリア・ルネサンスの解釈として最も影響力の あるものであり、今でも広く読まれている。ジョン・ルカックスによれば、彼は、特定の時代、特定の人々、特定の場所の精神と表現形式を記述しようとする文 化史の最初の巨匠であった。彼の歴史研究に対する革新的なアプローチは、芸術の重要性と歴史研究のための一次資料としての計り知れない価値を強調した。彼 は、「歴史は過去の政治であり、政治は現在の歴史である」という19世紀の狭い概念から抜け出した最初の歴史家の一人であった[69]。 19世紀半ばになると、学者たちは制度的変化の歴史、特に立憲政治の発展について分析を始めていた。ウィリアム・スタッブスの『イングランド立憲史』(全 3巻、1874年~1878年)は、この発展途上の分野に重要な影響を与えた。スタッブスは、歴史の統一性と連続性の理論が古代史と近代史の区別をなくし てはならないと主張した。彼は、古代史の研究は近代史の研究にとって有用な準備ではあるが、どちらかを切り離して研究することも有益であると考えていた。 彼は優れた古文書学者であり、テキスト批評や著者の検証などに秀でていたが、その膨大な博識と記憶力の鋭さによって、解釈や解説においては誰にも引けを取 らなかった[71]。 フォン・ランケとドイツにおける専門化 主な記事 ドイツの歴史学  ランケはドイツにおいて歴史学を専門的な学問分野として確立した。 近代的な歴史学の学問的研究と歴史学の方法は、19世紀のドイツの大学、特にゲッティンゲン大学で開拓された。ベルリンのレオポルド・フォン・ランケ (1795-1886)はこの点で極めて重要な影響力を持ち、近代的な典拠に基づく歴史学の創始者であった[72][73]。 キャロライン・ヘッファーレによれば、「ランケはおそらく19世紀後半にヨーロッパとアメリカで出現した歴史専門職を形成する上で最も重要な歴史家であっ た」[74][75]。 具体的には、ゼミナール教授法を教室で実践し、史料調査と史料分析に重点を置いた。1824年の処女作『1494年から1514年までのラテン民族と チュートン民族の歴史』に始まり、ランケは「回想録、日記、個人的・公式的な書簡、政府文書、外交使節、目撃者の直接の証言」など、この時代の歴史家とし ては異例なほど多様な資料を用いた。ランケは、一次資料への依存、物語史の重視、特に国際政治(Aussenpolitik)などの考え方を導入し、世紀 の大半に及ぶキャリアの中で、後の歴史記述の多くの基準を打ち立てた[76]。彼の信条は、ありのままの歴史を書くことであった。彼は信憑性が証明された 一次資料にこだわった。 ランケはまた、伝統的に各時代を後続の時代よりも劣ったものとみなす歴史への「目的論的アプローチ」を否定した。ランケの考えでは、歴史家はその時代をそ の時代なりに理解し、歴史のあらゆる時代を動かしている一般的な考え方だけを見出そうとしなければならなかった。1831年、プロイセン政府の要請で、ラ ンケは世界初の歴史雑誌『Historisch-Politische Zeitschrift』を創刊、編集した。 もう一人の重要なドイツ人思想家はゲオルク・ヴィルヘルム・フリードリヒ・ヘーゲルであり、彼の歴史進歩論はランケのアプローチと相反するものであった。 ヘーゲル自身の言葉を借りれば、彼の哲学的理論である「世界史は......精神が自らの自由を自覚し、その結果としてこの自由を実現することの発展を表 している」[77]。この実現は、何千年にもわたって発展してきたさまざまな文化を研究し、それらを通じて自由が自ずと実現した方法を理解しようとするこ とによって見られる: 世界史は、精神がそれ自体何であるかについての知識を得ようとする努力の記録である。東洋人は、精神や人間そのものが自由であることを知らない。そしてそ れを知らないがゆえに、彼ら自身も自由ではない。彼らが知っているのは、ただ一人が自由であるということだけである。... 自由の意識はギリシア人の間で最初に目覚め、彼らはそれに応じて自由になった。... ゲルマン民族は、キリスト教の勃興とともに、すべての人間は生まれながらにして自由であり、精神の自由はその本質そのものであることを最初に理解した。 カール・マルクスは、世界史的発展の研究に史的唯物論の概念を導入した。彼の概念では、経済的条件と支配的な生産様式がその時点での社会の構造を決定し た。彼の考えでは、物質的条件の発展において、西ヨーロッパでは5つの連続した段階が起こる。最初の段階は、財産が共有され、「指導者」という概念がない 原始的な共産主義であった。これが奴隷社会へと進み、そこで階級観念が生まれ、国家が発展した。封建制は、神権政治と連携する貴族制と国民国家の出現を特 徴とした。資本主義が登場したのはブルジョア革命の後であり、資本家(またはその前身である商人)が封建制度を打倒し、私有財産と議会制民主主義を備えた 市場経済を確立した。そしてマルクスは、最終的にはプロレタリア革命が起こり、社会主義が達成され、次いで財産が共同所有される共産主義が達成されると予 言した。 それまでの歴史家は、支配者や国家の勃興と衰退という周期的な出来事に焦点を当てていた。19世紀における民族復興の一環としての歴史の国有化のプロセス は、歴史を国家の歴史として構築するような過去の捉え方、理解、扱い方によって、普遍的な共通の歴史から「自分自身の」歴史を分離する結果となった [79]。19世紀後半には新しい学問分野である社会学が登場し、これらの視点をより大きなスケールで分析・比較した。 マコーレーとホイッグ史  マコーレーはホイッグ史の最も有力な提唱者であった。 「ホイッグ史」とは、1931年にハーバート・バターフィールドが短編『ホイッグの歴史解釈』(原題:The Whig Interpretation of History)の中で用いた造語で、自由と啓蒙の拡大に向かって過去が必然 的に進行し、自由民主主義と立憲君主制という近代的な形態に至ったという歴史学のアプローチを意味する。一般に、ホイッグの歴史家は立憲政 治の台頭、個人の自由、科学の進歩を強調した。この用語は、イギリス史以外の歴史分野(例えば科学史)においても、あらゆる目的論的(あるいは目標指向 的)、英雄主義的、歴史超越的な物語を批判するために広く用いられている[80]。 1723年に出版されたポール・ラパン・ド・トイラスのイングランド史は、18世紀前半の「古典的なホイッグ史」となった[81]が、後に絶大な人気を博 したデイヴィッド・ヒュームの『イングランド史』に取って代わられた。ホイッグの歴史家たちは1688年の栄光革命の成果を強調した。これにはジェーム ズ・マッキントッシュの『1688年イングランド革命史』、ウィリアム・ブラックストーンの『イングランド法解説書』、ヘンリー・ハラムの『イングランド 憲法史』などが含まれる[82]。 「ホイッグリー」の最も有名な提唱者はトーマス・バビントン・マコーレーであった。彼の著作は、鳴り響くような散文と、自信に満ちた、時には独断的な、イギ リス史の進歩的モデルを強調することで有名である。このモデルによれば、イギリスは迷信、独裁、混乱を捨て去り、バランスの取れた憲法と、信念と表現の自 由と結びついた未来志向の文化を生み出した。この人類の進歩モデルは、ホイッグの歴史解釈と呼ばれている[83]。1848年、彼は最も有名な歴史書 『ジェームズ2世の即位からのイギリス史』の第1巻を出版した。この著作はたちまち成功を収め、ヒュームの歴史に取って代わって新しい正史となった [84]。彼の「ホイッグ的信念」はその第一章に綴られている: 私は、新しい定住地がいかにして内外の敵から防衛に成功したか、いかにして法の権威と財産の安全が、かつて知られていなかった自由な議論と個人の行動と両 立することがわかったか、いかにして秩序と自由の幸先のよい結合から、人類史が例を示したことのない繁栄が生まれたか、いかにしてわが国が不名誉な属領の 状態から急速にヨーロッパの列強の中で審判者の地位に上り詰めたか、いかにしてわが国の華麗さと武勇の栄光が共に成長したか、いかにしてわが国が巨大な通 商によって、ヨーロッパ諸国と同盟関係を築いたか。 過去160年間のわが国の歴史は、まさに物理的、道徳的、知的向上の歴史である。 ガートルード・ヒメルファーブは、「ほとんどのプロの歴史家は、彼が書いたような歴史を書くことや、彼のように歴史について考えることをあきらめたよう に、マコーレーを読むことをとうの昔にあきらめた」と書いている[85]: その古さと傷にもかかわらず、マコーレーの『イングランド史』は、この時代の本格的な近代史にいまだに取って代わられることはない」[86]。 ホイッグのコンセンサスは、第一次世界大戦後のヨーロッパ史の再評価の中で着実に損なわれていき、バターフィールドの批評はこの傾向を例証するものであっ た。知識人たちはもはや、世界が自動的に良くなっていくとは信じていなかった。その後の世代のアカデミックな歴史家たちも同様に、歴史はある種のゴールに 向かって突き進むものであるという現在主義的かつ目的論的な前提のために、ホイッグ史観を否定してきた[87]。 [その他の批判された「ホイッグ」の前提には、イギリスの体制を人類の政治的発展の頂点とみなすこと、過去の政治的人物が現在の政治的信条を有していると 仮定すること(アナクロニズム)、イギリスの歴史を必然的な結果を伴う進歩の行進とみなすこと、過去の政治的人物をこの政治的進歩の大義を進めた英雄、あ るいは必然的な勝利を妨げようとした悪役として提示することなどがあった。J.ハートは「ホイッグの解釈では、物語に人間の英雄と悪役が必要である」と述 べている[88]。 |

| 20th century See also: Category:Historiography by country 20th-century historiography in major countries is characterized by a move to universities and academic research centers. Popular history continued to be written by self-educated amateurs, but scholarly history increasingly became the province of PhD's trained in research seminars at a university. The training emphasized working with primary sources in archives. Seminars taught graduate students how to review the historiography of the topics, so that they could understand the conceptual frameworks currently in use, and the criticisms regarding their strengths and weaknesses.[89][90] Western Europe and the United States took leading roles in this development. The emergence of area studies of other regions also developed historiographical practices. France: Annales school Main article: Annales school  The 20th century saw the creation of a huge variety of historiographical approaches; one was Marc Bloch's focus on social history rather than traditional political history. The French Annales school radically changed the focus of historical research in France during the 20th century by stressing long-term social history, rather than political or diplomatic themes. The school emphasized the use of quantification and the paying of special attention to geography.[91][92] The Annales d'histoire économique et sociale journal was founded in 1929 in Strasbourg by Marc Bloch and Lucien Febvre. These authors, the former a medieval historian and the latter an early modernist, quickly became associated with the distinctive Annales approach, which combined geography, history, and the sociological approaches of the Année Sociologique (many members of which were their colleagues at Strasbourg) to produce an approach which rejected the predominant emphasis on politics, diplomacy and war of many 19th and early 20th-century historians as spearheaded by historians whom Febvre called Les Sorbonnistes. Instead, they pioneered an approach to a study of long-term historical structures (la longue durée) over events and political transformations.[93] Geography, material culture, and what later Annalistes called mentalités, or the psychology of the epoch, are also characteristic areas of study. The goal of the Annales was to undo the work of the Sorbonnistes, to turn French historians away from the narrowly political and diplomatic toward the new vistas in social and economic history.[94] For early modern Mexican history, the work of Marc Bloch's student François Chevalier on the formation of landed estates (haciendas) from the sixteenth century to the seventeenth had a major impact on Mexican history and historiography,[95] setting off an important debate about whether landed estates were basically feudal or capitalistic.[96][97] An eminent member of this school, Georges Duby, described his approach to history as one that relegated the sensational to the sidelines and was reluctant to give a simple accounting of events, but strived on the contrary to pose and solve problems and, neglecting surface disturbances, to observe the long and medium-term evolution of economy, society and civilisation. The Annalistes, especially Lucien Febvre, advocated a histoire totale, or histoire tout court, a complete study of a historical problem. The second era of the school was led by Fernand Braudel and was very influential throughout the 1960s and 1970s, especially for his work on the Mediterranean region in the era of Philip II of Spain. Braudel developed the idea, often associated with Annalistes, of different modes of historical time: l'histoire quasi immobile (motionless history) of historical geography, the history of social, political and economic structures (la longue durée), and the history of men and events, in the context of their structures. His 'longue durée' approach stressed slow, and often imperceptible effects of space, climate and technology on the actions of human beings in the past. The Annales historians, after living through two world wars and major political upheavals in France, were deeply uncomfortable with the notion that multiple ruptures and discontinuities created history. They preferred to stress slow change and the longue durée. They paid special attention to geography, climate, and demography as long-term factors. They considered the continuities of the deepest structures were central to history, beside which upheavals in institutions or the superstructure of social life were of little significance, for history lies beyond the reach of conscious actors, especially the will of revolutionaries.[98] Noting the political upheavals in Europe and especially in France in 1968, Eric Hobsbawm argued that "in France the virtual hegemony of Braudelian history and the Annales came to an end after 1968, and the international influence of the journal dropped steeply."[99] Multiple responses were attempted by the school. Scholars moved in multiple directions, covering in disconnected fashion the social, economic, and cultural history of different eras and different parts of the globe. By the time of crisis the school was building a vast publishing and research network reaching across France, Europe, and the rest of the world. Influence indeed spread out from Paris, but few new ideas came in. Much emphasis was given to quantitative data, seen as the key to unlocking all of social history.[100] However, the Annales ignored the developments in quantitative studies underway in the U.S. and Britain, which reshaped economic, political and demographic research.[101] Marxist historiography Main article: Marxist historiography Further information: Communist Party Historians Group Marxist historiography developed as a school of historiography influenced by the chief tenets of Marxism, including the centrality of social class and economic constraints in determining historical outcomes (historical materialism). Friedrich Engels wrote The Peasant War in Germany, which analysed social warfare in early Protestant Germany in terms of emerging capitalist classes. Although it lacked a rigorous engagement with archival sources, it indicated an early interest in history from below and class analysis, and it attempts a dialectical analysis. Another treatise of Engels, The Condition of the Working Class in England in 1844, was salient in creating the socialist impetus in British politics from then on, e.g. the Fabian Society. R. H. Tawney was an early historian working in this tradition. The Agrarian Problem in the Sixteenth Century (1912)[102] and Religion and the Rise of Capitalism (1926), reflected his ethical concerns and preoccupations in economic history. He was profoundly interested in the issue of the enclosure of land in the English countryside in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries and in Max Weber's thesis on the connection between the appearance of Protestantism and the rise of capitalism. His belief in the rise of the gentry in the century before the outbreak of the Civil War in England provoked the 'Storm over the Gentry' in which his methods were subjected to severe criticisms by Hugh Trevor-Roper and John Cooper. Historiography in the Soviet Union was greatly influenced by Marxist historiography, as historical materialism was extended into the Soviet version of dialectical materialism. A circle of historians inside the Communist Party of Great Britain (CPGB) formed in 1946 and became a highly influential cluster of British Marxist historians, who contributed to history from below and class structure in early capitalist society. While some members of the group (most notably Christopher Hill and E. P. Thompson) left the CPGB after the 1956 Hungarian Revolution, the common points of British Marxist historiography continued in their works. They placed a great emphasis on the subjective determination of history. Christopher Hill's studies on 17th-century English history were widely acknowledged and recognised as representative of this school.[103] His books include Puritanism and Revolution (1958), Intellectual Origins of the English Revolution (1965 and revised in 1996), The Century of Revolution (1961), AntiChrist in 17th-century England (1971), The World Turned Upside Down (1972) and many others. E. P. Thompson pioneered the study of history from below in his work, The Making of the English Working Class, published in 1963. It focused on the forgotten history of the first working-class political left in the world in the late-18th and early-19th centuries. In his preface to this book, Thompson set out his approach to writing history from below: I am seeking to rescue the poor stockinger, the Luddite cropper, the "obsolete" hand-loom weaver, the "Utopian" artisan, and even the deluded follower of Joanna Southcott, from the enormous condescension of posterity. Their crafts and traditions may have been dying. Their hostility to the new industrialism may have been backward-looking. Their communitarian ideals may have been fantasies. Their insurrectionary conspiracies may have been foolhardy. But they lived through these times of acute social disturbance, and we did not. Their aspirations were valid in terms of their own experience; and, if they were casualties of history, they remain, condemned in their own lives, as casualties. Thompson's work was also significant because of the way he defined "class". He argued that class was not a structure, but a relationship that changed over time. He opened the gates for a generation of labor historians, such as David Montgomery and Herbert Gutman, who made similar studies of the American working classes. Other important Marxist historians included Eric Hobsbawm, C. L. R. James, Raphael Samuel, A. L. Morton and Brian Pearce. Biography Further information: Biography Biography has been a major form of historiography since the days when Plutarch wrote the parallel lives of great Roman and Greek leaders. It is a field especially attractive to nonacademic historians, and often to the spouses or children of famous people, who have access to the trove of letters and documents. Academic historians tend to downplay biography because it pays too little attention to broad social, cultural, political and economic forces, and perhaps too much attention to popular psychology. The "Great Man" tradition in Britain originated in the multi-volume Dictionary of National Biography (which originated in 1882 and issued updates into the 1970s); it continues to this day in the new Oxford Dictionary of National Biography. In the United States, the Dictionary of American Biography was planned in the late 1920s and appeared with numerous supplements into the 1980s. It has now been displaced by the American National Biography as well as numerous smaller historical encyclopedias that give thorough coverage to Great Persons. Bookstores do a thriving business in biographies, which sell far more copies than the esoteric monographs based on post-structuralism, cultural, racial or gender history. Michael Holroyd says the last forty years "may be seen as a golden age of biography", but nevertheless calls it the "shallow end of history". Nicolas Barker argues that "more and more biographies command an ever larger readership", as he speculates that biography has come "to express the spirit of our age".[104] Daniel R. Meister argues that: Biography Studies is emerging as an independent discipline, especially in the Netherlands. This Dutch School of biography is moving biography studies away from the less scholarly life writing tradition and towards history by encouraging its practitioners to utilize an approach adapted from microhistory.[105] British debates Main article: Historiography of the United Kingdom Marxist historian E. H. Carr developed a controversial theory of history in his 1961 book What Is History?, which proved to be one of the most influential books ever written on the subject.[106] He presented a middle-of-the-road position between the empirical or (Rankean) view of history and R. G. Collingwood's idealism, and rejected the empirical view of the historian's work being an accretion of "facts" that they have at their disposal as nonsense. He maintained that there is such a vast quantity of information that the historian always chooses the "facts" they decide to make use of. In Carr's famous example, he claimed that millions had crossed the Rubicon, but only Julius Caesar's crossing in 49 BC is declared noteworthy by historians.[107][108] For this reason, Carr argued that Leopold von Ranke's famous dictum wie es eigentlich gewesen (show what actually happened) was wrong because it presumed that the "facts" influenced what the historian wrote, rather than the historian choosing what "facts of the past" they intended to turn into "historical facts".[109] At the same time, Carr argued that the study of the facts may lead the historian to change his or her views. In this way, Carr argued that history was "an unending dialogue between the past and present".[107][110] Carr is held by some critics to have had a deterministic outlook in history.[111] Others have modified or rejected this use of the label "determinist".[112] He took a hostile view of those historians who stress the workings of chance and contingency in the workings of history. In Carr's view, no individual is truly free of the social environment in which they live, but contended that within those limitations, there was room, albeit very narrow room for people to make decisions that affect history. Carr emphatically contended that history was a social science, not an art,[113] because historians like scientists seek generalizations that helped to broaden the understanding of one's subject.[113][114] One of Carr's most forthright critics was Hugh Trevor-Roper, who argued that Carr's dismissal of the "might-have-beens of history" reflected a fundamental lack of interest in examining historical causation.[115] Trevor-Roper asserted that examining possible alternative outcomes of history was far from being a "parlour-game" was rather an essential part of the historians' work,[116] as only by considering all possible outcomes of a given situation could a historian properly understand the period. The controversy inspired Sir Geoffrey Elton to write his 1967 book The Practice of History. Elton criticized Carr for his "whimsical" distinction between the "historical facts" and the "facts of the past", arguing that it reflected "...an extraordinarily arrogant attitude both to the past and to the place of the historian studying it".[117] Elton, instead, strongly defended the traditional methods of history and was also appalled by the inroads made by postmodernism.[118] Elton saw the duty of historians as empirically gathering evidence and objectively analyzing what the evidence has to say. As a traditionalist, he placed great emphasis on the role of individuals in history instead of abstract, impersonal forces. Elton saw political history as the highest kind of history. Elton had no use for those who seek history to make myths, to create laws to explain the past, or to produce theories such as Marxism. U.S. approaches Main article: Historiography of the United States Classical and European history was part of the 19th-century grammar curriculum. American history became a topic later in the 19th century.[119] In the historiography of the United States, there were a series of major approaches in the 20th century. In 2009–2012, there were an average of 16,000 new academic history books published in the U.S. every year.[120] Progressive historians Main article: Progressive historians The Progressive historians were a group of 20th century historians of the United States associated with a historiographical tradition that embraced an economic interpretation of American history.[121][122] Most prominent among these was Charles A. Beard, who was influential in academia and with the general public.[121] Consensus history Main article: Consensus history Consensus history emphasizes the basic unity of American values and downplays conflict as superficial. It was especially attractive in the 1950s and 1960s. Prominent leaders included Richard Hofstadter, Louis Hartz, Daniel Boorstin, Allan Nevins, Clinton Rossiter, Edmund Morgan, and David M. Potter.[123][124] In 1948 Hofstadter made a compelling statement of the consensus model of the U.S. political tradition: The fierceness of the political struggles has often been misleading: for the range of vision embraced by the primary contestants in the major parties has always been bounded by the horizons of property and enterprise. However much at odds on specific issues, the major political traditions have shared a belief in the rights of property, the philosophy of economic individualism, the value of competition; they have accepted the economic virtues of capitalist culture as necessary qualities of man.[125] New Left history Consensus history was rejected by New Left viewpoints that attracted a younger generation of radical historians in the 1960s. These viewpoints stress conflict and emphasize the central roles of class, race and gender. The history of dissent, and the experiences of racial minorities and disadvantaged classes was central to the narratives produced by New Left historians.[126][127][128] Quantification and new approaches to history Main articles: Social history and Political history § United States: The new political history Social history, sometimes called the "new social history", is a broad branch that studies the experiences of ordinary people in the past.[129][130] It had major growth as a field in the 1960s and 1970s, and still is well represented in history departments. However, after 1980 the "cultural turn" directed the next generation to new topics. In the two decades from 1975 to 1995, the proportion of professors of history in U.S. universities identifying with social history rose from 31 to 41 percent, while the proportion of political historians fell from 40 to 30 percent.[4] The growth was enabled by the social sciences, computers, statistics, new data sources such as individual census information, and summer training programs at the Newberry Library and the University of Michigan. The New Political History saw the application of social history methods to politics, as the focus shifted from politicians and legislation to voters and elections.[131][132] The Social Science History Association was formed in 1976 as an interdisciplinary group with a journal Social Science History and an annual convention. The goal was to incorporate in historical studies perspectives from all the social sciences, especially political science, sociology and economics. The pioneers shared a commitment to quantification. However, by the 1980s the first blush of quantification had worn off, as traditional historians counterattacked. Harvey J. Graff says: The case against the new mixed and confused a lengthy list of ingredients, including the following: history's supposed loss of identity and humanity in the stain of social science, the fear of subordinating quality to quantity, conceptual and technical fallacies, violation of the literary character and biographical base of "good" history (rhetorical and aesthetic concern), loss of audiences, derogation of history rooted in "great men" and "great events", trivialization in general, a hodgepodge of ideological objections from all directions, and a fear that new historians were reaping research funds that might otherwise come to their detractors. To defenders of history as they knew it, the discipline was in crisis, and the pursuit of the new was a major cause.[133] Meanwhile, "new" economic history became well-established. However, cliometrics has never been considered a historical field by the vast majority of historians so that cliometric articles have not been cited by historians.[134][135] Economists mostly employed economic theories and econometric applications similar to typical economic papers. As a result, quantification remained central to demographic studies, but slipped behind in political and social history as traditional narrative approaches made a comeback.[136] Recently, as the newest approach in economic history "new history of capitalism" appeared. In the first article of the related journal, Marc Flandreau defined their purpose as "crossing border" to create a truly interdisciplinary field.[137] Latin America Further information: Historiography of Colonial Spanish America, Argentina, and Latin American studies Latin America is the former Spanish American empire in the Western Hemisphere plus Portuguese Brazil. Professional historians pioneered the creation of this field, starting in the late nineteenth century.[138] The term "Latin America" did not come into general usage until the twentieth century and in some cases it was rejected.[139] The historiography of the field has been more fragmented than unified, with historians of Spanish America and Brazil generally remaining in separate spheres. Another standard division within the historiography is the temporal factor, with works falling into either the early modern period (or "colonial era") or the post-independence (or "national") period, from the early nineteenth onward. Relatively few works span the two eras and few works except textbooks unite Spanish America and Brazil. There is a tendency to focus on histories of particular countries or regions (the Andes, the Southern Cone, the Caribbean) with relatively little comparative work. Historians of Latin America have contributed to various types of historical writing, but one major, innovative development in Spanish American history is the emergence of ethnohistory, the history of indigenous peoples, especially in Mexico based on alphabetic sources in Spanish or in indigenous languages.[140][141][142][143][144] For the early modern period, the emergence of Atlantic history, based on comparisons and linkages of Europe, the Americas, and Africa from 1450 to 1850 that developed as a field in its own right has integrated early modern Latin American history into a larger framework.[145] For all periods, global or world history have focused on the connections between areas, likewise integrating Latin America into a larger perspective. Latin America's importance to world history is notable but often overlooked. "Latin America's central, and sometimes pioneering, role in the development of globalization and modernity did not cease with the end of colonial rule and the early modern period. Indeed, the region's political independence places it at the forefront of two trends that are regularly considered thresholds of the modern world. The first is the so-called liberal revolution, the shift from monarchies of the ancien régime, where inheritance legitimated political power, to constitutional republics... The second, and related, trend consistently considered a threshold of modern history that saw Latin America in the forefront is the development of nation-states."[146] Historical research appears in a number of specialized journals. These include Hispanic American Historical Review (est. 1918), published by the Conference on Latin American History; The Americas, (est. 1944); Journal of Latin American Studies (1969); Canadian Journal of Latin American and Caribbean Studies,(est.1976)[147] Bulletin of Latin American Research, (est. 1981); Colonial Latin American Review (1992); and Colonial Latin American Historical Review (est. 1992). Latin American Research Review (est. 1969), published by the Latin American Studies Association, does not focus primarily on history, but it has often published historiographical essays on particular topics. General works on Latin American history have appeared since the 1950s, when the teaching of Latin American history expanded in U.S. universities and colleges.[148] Most attempt full coverage of Spanish America and Brazil from the conquest to the modern era, focusing on institutional, political, social and economic history. An important, eleven volume treatment of Latin American history is The Cambridge History of Latin America, with separate volumes on the colonial era, nineteenth century, and the twentieth century.[149] There is a small number of general works that have gone through multiple editions.[150][151][152] Major trade publishers have also issued edited volumes on Latin American history[153] and historiography.[154] Reference works include the Handbook of Latin American Studies, which publishes articles by area experts, with annotated bibliographic entries, and the Encyclopedia of Latin American History and Culture.[155] World history World history, as a distinct field of historical study, emerged as an independent academic field in the 1980s. It focused on the examination of history from a global perspective and looked for common patterns that emerged across all cultures. The basic thematic approach of this field was to analyse two major focal points: integration—how processes of world history have drawn people of the world together, and difference—how patterns of world history reveal the diversity of the human experience. Arnold J. Toynbee's ten-volume A Study of History, took an approach that was widely discussed in the 1930s and 1940s. By the 1960s his work was virtually ignored by scholars and the general public. He compared 26 independent civilizations and argued that they displayed striking parallels in their origin, growth, and decay. He proposed a universal model to each of these civilizations, detailing the stages through which they all pass: genesis, growth, time of troubles, universal state, and disintegration. The later volumes gave too much emphasis on spirituality to satisfy critics.[156] Chicago historian William H. McNeill wrote The Rise of the West (1965) to show how the separate civilizations of Eurasia interacted from the very beginning of their history, borrowing critical skills from one another, and thus precipitating still further change as adjustment between traditional old and borrowed new knowledge and practice became necessary. He then discusses the dramatic effect of Western civilization on others in the past 500 years of history. McNeill took a broad approach organized around the interactions of peoples across the globe. Such interactions have become both more numerous and more continual and substantial in recent times. Before about 1500, the network of communication between cultures was that of Eurasia. The term for these areas of interaction differ from one world historian to another and include world-system and ecumene. His emphasis on cultural fusions influenced historical theory significantly.[157] The cultural turn The "cultural turn" of the 1980s and 1990s affected scholars in most areas of history.[158] Inspired largely by anthropology, it turned away from leaders, ordinary people and famous events to look at the use of language and cultural symbols to represent the changing values of society.[159] The British historian Peter Burke finds that cultural studies has numerous spinoffs, or topical themes it has strongly influenced. The most important include gender studies and postcolonial studies, as well as memory studies, and film studies.[160] Diplomatic historian Melvyn P. Leffler finds that the problem with the "cultural turn" is that the culture concept is imprecise, and may produce excessively broad interpretations, because it: seems infinitely malleable and capable of giving shape to totally divergent policies; for example, to internationalism or isolationism in the United States, and to cooperative internationalism or race hatred in Japan. The malleability of culture suggest to me that in order to understand its effect on policy, one needs also to study the dynamics of political economy, the evolution of the international system, and the roles of technology and communication, among many other variables.[161] Memory studies See also: Social memory and Memory studies in historical Jesus research Memory studies is a new field, focused on how nations and groups (and historians) construct and select their memories of the past in order to celebrate (or denounce) key features, thus making a statement of their current values and beliefs.[162][163] Historians have played a central role in shaping the memories of the past as their work is diffused through popular history books and school textbooks.[164] French sociologist Maurice Halbwachs, opened the field with La mémoire collective (Paris: 1950).[165] Many historians examine how the memory of the past has been constructed, memorialized or distorted. Historians examine how legends are invented.[166][167] For example, there are numerous studies of the memory of atrocities from World War II, notably the Holocaust in Europe and Japanese war crimes in Asia.[168][169] British historian Heather Jones argues that the historiography of the First World War in recent years has been reinvigorated by the cultural turn. Scholars have raised entirely new questions regarding military occupation, radicalization of politics, race, and the male body.[170] Representative of recent scholarship is a collection of studies on the "Dynamics of Memory and Identity in Contemporary Europe".[171] Sage has published the scholarly journal Memory Studies since 2008, and the book series "Memory Studies" was launched by Palgrave Macmillan in 2010 with 5–10 titles a year.[172] |

20世紀 こちらも参照のこと: Category:国別の歴史学 主要国における20世紀の歴史学の特徴は、大学や学術研究センターへの移行である。民衆史は独学のアマチュアによって書かれ続けたが、学術史は大学の研究 セミナーで訓練を受けた博士号取得者の手に委ねられることが多くなった。研修では、公文書館で一次資料を扱うことに重点が置かれた。セミナーでは、大学院 生が現在使用されている概念的枠組みやその長所と短所に関する批判を理解できるように、トピックの歴史学的検討の仕方を教えた[89][90]。他の地域 の地域研究の出現もまた歴史学的実践を発展させた。 フランス アナール学派 主な記事 アナール学派  20世紀には、実に多様な歴史学的アプローチが生まれた。そのひとつが、従来の政治史ではなく社会史に焦点を当てたマルク・ブロックである。 フランスのアナール学派は、政治や外交のテーマよりも長期的な社会史に重点を置き、20世紀のフランスにおける歴史研究の焦点を根本的に変えた。この学派 は数量化の使用と地理に特別な注意を払うことを強調した[91][92]。 Annales d'histoire économique et sociale誌は1929年にマルク・ブロッホとリュシアン・フェーブルによってストラスブールで創刊された。前者は中世史家であり、後者は初期モダニ ストであったこの二人の著者は、地理学、歴史学、そしてアネ・ソシオロジックの社会学的アプローチ(そのメンバーの多くはストラスブールでの同僚であっ た)を融合させ、フェーブルがレ・ソルボンニストと呼んだ歴史家たちによって先導された、19世紀から20世紀初頭にかけての多くの歴史家たちが政治、外 交、戦争に重きを置いていたことを否定するアプローチを生み出した、独特のアナレス・アプローチとすぐに結びつくことになった。その代わりに、彼らは出来 事や政治的変容よりも長期的な歴史的構造(la longue durée)を研究するアプローチを開拓した[93]。地理学、物質文化、後のアナリストたちがメンタリティ(mentalités、その時代の心理学) と呼ぶものも特徴的な研究分野である。アナリス』の目的は、ソルボンニストの仕事を取り消し、フランスの歴史家を狭い意味での政治・外交から社会・経済史 の新しい展望へと向かわせることであった。 [近世メキシコ史においては、マルク・ブロッホの弟子であるフランソワ・シュヴァリエの16世紀から17世紀にかけての土地所有地(ハシエンダ)の形成に 関する研究がメキシコ史と歴史学に大きな影響を与え[95]、土地所有地が基本的に封建的であったのか資本主義的であったのかという重要な議論を巻き起こ した[96][97]。 この学派の著名なメンバーであるジョルジュ・デュビイは、彼の歴史へのアプローチを次のように述べている。 センセーショナルなものは傍流に追いやり、出来事の単純な説明には消極的であったが、逆に問題を提起し、解決することに努め、表面的な動揺を無視して、経 済、社会、文明の長期的、中期的な進化を観察した。 アナリストたち、特にリュシアン・フェーブルは、歴史問題の完全な研究である「全体史」(histoire totale)を提唱した。 この学派の第二期はフェルナン・ブローデルに率いられ、1960年代から1970年代にかけて、特にスペインのフィリップ2世時代の地中海地域に関する研 究で大きな影響力を持った。ブラウデルは、歴史地理学の「準不動史観」、社会・政治・経済構造の歴史(la longue durée)、その構造の文脈における人間と出来事の歴史という、歴史的時間のさまざまな様態についての考えを展開した。彼の 「longue durée 」アプローチは、空間、気候、技術が過去の人類の行動に及ぼす、ゆっくりとした、そしてしばしば知覚できない影響を強調した。アナール派の歴史家たちは、 フランスで二度の世界大戦と大きな政治的動乱を経験した後、複数の断絶や不連続性が歴史を創るという考え方に強い違和感を抱いていた。彼らは緩やかな変化 と長い時間を強調することを好んだ。彼らは長期的な要因として、地理、気候、人口動態に特別な注意を払った。彼らは最も深い構造の連続性が歴史の中心であ り、制度や社会生活の上部構造における激変はそれ以外にはほとんど意味を持たないと考えていた。 エリック・ホブズボームは、ヨーロッパ、特に1968年のフランスにおける政治的激動に注目し、「フランスでは、1968年以降、ブローデル史と『アナー ル』の事実上の覇権は終わりを告げ、この雑誌の国際的影響力は急激に低下した」と論じている[99]。学者たちは多方面へ移動し、さまざまな時代や地球上 のさまざまな地域の社会史、経済史、文化史をバラバラに扱っていた。危機が訪れるころには、学派はフランス、ヨーロッパ、そして世界中に広がる広大な出 版・研究ネットワークを構築していた。影響力は確かにパリから広がっていったが、新しいアイデアはほとんど入ってこなかった。社会史のすべてを解き明かす 鍵であると考えられていた量的データに多くの重点が置かれていた[100]。しかし『アナール』は、経済、政治、人口統計の研究を再形成したアメリカやイ ギリスで進行中の量的研究の発展を無視していた[101]。 マルクス主義の歴史学 主な記事 マルクス主義歴史学 さらに詳しい情報 共産党歴史家グループ マルクス主義歴史学は、歴史的結果を決定する上で社会階級と経済的制約が重要である(史的唯物論)など、マルクス主義の主要な信条に影響された歴史学の一 派として発展した。フリードリヒ・エンゲルスは『ドイツの農民戦争』を著し、初期プロテスタント・ドイツにおける社会抗争を、勃興しつつある資本主義階級 の観点から分析した。この著作は、史料との厳密な関わりには欠けるものの、下からの歴史や階級分析に対する初期の関心を示しており、弁証法的な分析を試み ている。エンゲルスのもう一つの論文である1844年の『イギリスにおける労働者階級の条件』は、その後のイギリス政治における社会主義的推進力、たとえ ばフェビアン協会の創設に重要な役割を果たした。 R. R. H. Tawneyは、この伝統を受け継ぐ初期の歴史家である。The Agrarian Problem in the Sixteenth Century』(1912年)[102]や『Religion and the Rise of Capitalism』(1926年)は、彼の倫理的関心と経済史へのこだわりを反映している。彼は、16世紀から17世紀にかけてのイギリスの田園地帯 における土地の囲い込みの問題や、プロテスタンティズムの出現と資本主義の台頭との関連性に関するマックス・ヴェーバーの論文に深い関心を抱いていた。イ ングランドで南北戦争が勃発する前の世紀におけるジェントリーの台頭に対する彼の信念は、「ジェントリーをめぐる嵐」を引き起こし、ヒュー・トレバー= ローパーとジョン・クーパーによって彼の方法は厳しい批判にさらされた。 ソ連における歴史学は、史的唯物論がソ連版弁証法的唯物論へと拡張されたことで、マルクス主義史学の影響を大きく受けた。 イギリス共産党(CPGB)内部の歴史家のサークルが1946年に結成され、イギリスのマルクス主義歴史家の中でも非常に影響力のある集団となり、下から の歴史や初期の資本主義社会における階級構造に貢献した。1956年のハンガリー革命後、CPGBを脱退したメンバーもいたが(特にクリストファー・ヒル やE・P・トンプソン)、イギリス・マルクス主義歴史学の共通点は、彼らの著作にも受け継がれている。彼らは、歴史の主観的な決定に大きな重点を置いてい た。 クリストファー・ヒルの17世紀イギリス史に関する研究は広く認められ、この学派を代表するものとして認識されていた[103]。彼の著書には、『ピュー リタニズムと革命』(1958年)、『イギリス革命の知的起源』(1965年、1996年に改訂)、『革命の世紀』(1961年)、『17世紀イングラン ドの反キリスト』(1971年)、『逆さまにされた世界』(1972年)などがある。 E. P.トンプソンは、1963年に出版された『The Making of the English Working Class(イギリス労働者階級の形成)』という著作で、下からの歴史研究の先駆者となった。本書は、18世紀末から19世紀初頭にかけて世界で初めて誕 生した労働者階級の政治的左翼の忘れられた歴史に焦点を当てたものである。本書への序文で、トンプソンは下からの歴史を書くというアプローチを示してい る: 私は、貧しい家畜商人、ラッダイトの小作人、「時代遅れ」の手織り機職人、「ユートピアン」の職人、さらにはジョアンナ・サウスコットの妄信的な信奉者 を、後世の巨大な見下しから救い出そうとしている。彼らの工芸や伝統は滅びつつあったのかもしれない。新しい産業主義に対する敵意は後ろ向きだったかもし れない。彼らの共同体主義的理想は空想だったのかもしれない。彼らの反乱陰謀は無謀だったかもしれない。しかし、彼らは深刻な社会不安の時代を生き抜い た。彼らの願望は、彼ら自身の経験から見て妥当なものであった。そして、もし彼らが歴史の犠牲者であったとしても、彼ら自身の人生において、犠牲者として 断罪されたままである。 トンプソンの仕事は、彼が「階級」を定義した点でも重要であった。彼は、階級とは構造ではなく、時間とともに変化する関係であると主張した。彼は、デイ ヴィッド・モンゴメリーやハーバート・グットマンといった、アメリカの労働者階級について同様の研究を行った世代の労働史家たちに門戸を開いた。 その他の重要なマルクス主義史家には、エリック・ホブズボーム、C・L・R・ジェイムズ、ラファエル・サミュエル、A・L・モートン、ブライアン・ピアー スらがいる。 伝記 さらなる情報 伝記 伝記は、プルタークがローマやギリシアの偉大な指導者の並行した生涯を書いた時代から、歴史学の主要な形式であった。非学術的な歴史家にとっては特に魅力 的な分野であり、書簡や文書の宝庫にアクセスできる著名人の配偶者や子供たちにとっても魅力的な分野である。アカデミックな歴史家は伝記を軽視する傾向が あるが、それは伝記が広範な社会的、文化的、政治的、経済的な力にあまりに注意を払わず、おそらく大衆心理にあまりに注意を払いすぎるからである。英国に おける「偉人」の伝統は、1882年に創刊され、1970年代まで更新版が発行された多巻の『国民伝記辞典』(Dictionary of National Biography)に端を発し、現在も新しい『オックスフォード国民伝記辞典』(Oxford Dictionary of National Biography)に受け継がれている。アメリカでは、『アメリカ人名辞典』が1920年代後半に企画され、1980年代まで多くの補遺とともに刊行さ れた。現在では、『アメリカ国民伝記』や、偉人を徹底的に網羅した数多くの小規模な歴史事典に取って代わられている。書店は伝記で大繁盛しており、ポスト 構造主義や文化史、人種史、ジェンダー史に基づく難解な単行本よりもはるかに多くの部数を売り上げている。マイケル・ホロイドは、過去40年間は「伝記の 黄金時代といえるかもしれない」としながらも、「歴史の浅いほう」と呼んでいる。ニコラス・バーカーは、伝記が「現代の精神を表現するようになった」と推 測し、「より多くの伝記が、より多くの読者を引きつけている」と論じている[104]。 ダニエル・R・マイスターは次のように論じている: 伝記研究は、特にオランダにおいて、独立した学問分野として台頭しつつある。このオランダの伝記学派は、ミクロヒストリーに適応したアプローチを利用する ことを実践者に奨励することで、伝記研究をあまり学術的でないライフ・ライティングの伝統から歴史学へと向かわせようとしている[105]。 イギリス論争 主な記事 イギリスの歴史学 マルクス主義の歴史家であるE・H・カーは、1961年に出版した『歴史とは何か』において論争的な歴史論を展開し、この本がこのテーマについて書かれた 本の中で最も影響力のある本のひとつであることを証明した[106]。彼は、経験主義的な歴史観とR・G・コリングウッドの観念論との中間に位置する立場 を提示し、歴史家の仕事は彼らが自由にできる「事実」の集積であるという経験主義的な見方をナンセンスであると否定した。彼は、膨大な量の情報が存在する ため、歴史家は常に利用する「事実」を選択するのだと主張した。カーの有名な例では、彼は何百万もの人々がルビコンを渡ったと主張したが、ユリウス・カエ サルが紀元前49年に渡ったことだけが歴史家によって注目に値するとされている。 [107][108]この理由から、カーはレオポルド・フォン・ランケの有名な口癖であるwie es eigentlich gewesen(実際に起こったことを示す)は間違っていると主張した。このようにして、カーは歴史とは「過去と現在の間の終わりのない対話」であると主 張していた[107][110]。 カーは、歴史において決定論的な見通しを持っていたとする批評家もいる[111]。 また、この「決定論者」というレッテルの使い方を修正したり否定したりする者もいる[112]。カーの見解では、いかなる個人も自分が生きている社会的環 境から真に自由であることはないが、そのような制限の中で、歴史に影響を与えるような意思決定を人々が行う余地は、非常に狭いものではあるが存在すると主 張していた。カーは歴史学は芸術ではなく社会科学であると力強く主張していた[113]。なぜなら科学者のように歴史家もまた、自らの対象についての理解 を広げるのに役立つ一般化を求めているからである[113][114]。 カーの最も率直な批評家の一人はヒュー・トレヴァー=ローパーであり、彼はカーの「歴史上のありえたかもしれないこと」を否定することは、歴史的因果関係 を検証することへの根本的な関心の欠如を反映していると主張していた[115]。トレヴァー=ローパーは、ある状況において起こりうるすべての結果を検討 することによってのみ、歴史家はその時代を適切に理解することができるのであり、歴史の起こりうる代替的な結果を検討することは、「パーラーゲーム」であ るどころか、むしろ歴史家の仕事の本質的な部分であると主張していた[116]。 この論争に触発され、ジェフリー・エルトン卿は1967年に『歴史の実践』を執筆した。エルトンはカーが「歴史的事実」と「過去の事実」を「気まぐれ」に 区別していることを批判し、「......過去に対しても、それを研究する歴史家の立場に対しても、極めて傲慢な態度」[117]を反映していると主張し た。伝統主義者である彼は、抽象的で非人間的な力ではなく、歴史における個人の役割を非常に重視した。エルトンは政治史を最高の歴史とみなしていた。エル トンは、神話を作ったり、過去を説明する法律を作ったり、マルクス主義のような理論を生み出すために歴史を求める人々には用はなかった。 米国のアプローチ 主な記事 米国の歴史学 古典史とヨーロッパ史は、19世紀の文法カリキュラムの一部であった。アメリカ史は19世紀後半にトピックとなった[119]。 アメリカの歴史学においては、20世紀には一連の主要なアプローチがあった。2009年から2012年にかけて、アメリカでは毎年平均16,000冊の新 しい学術的な歴史書が出版されていた[120]。 進歩的歴史家 主な記事 進歩主義的歴史家 進歩主義的歴史家は、アメリカ史の経済学的解釈を受け入れた歴史学的伝統に関連する20世紀のアメリカ合衆国の歴史家のグループであった[121] [122]。その中で最も著名なのはチャールズ・A・ベアードであり、学界や一般大衆に影響力を有していた[121]。 コンセンサス史 主な記事 コンセンサス史 コンセンサス史は、アメリカの価値観の基本的な統一性を強調し、対立を表面的なものとして軽視する。1950年代から1960年代にかけては特に魅力的で あった。著名な指導者には、リチャード・ホフスタッター、ルイス・ハーツ、ダニエル・ブーアスティン、アラン・ネヴィンズ、クリントン・ロシター、エドモ ンド・モーガン、デイヴィッド・M・ポッターなどがいた[123][124]。1948年、ホフスタッターはアメリカの政治的伝統のコンセンサス・モデル について説得力のある声明を発表した: 政治闘争の激しさは、しばしば誤解を招くものであった:主要政党の主要な争点が抱くビジョンの範囲は、常に財産と企業の地平によって縛られていたからであ る。具体的な問題でどれほど対立していたとしても、主要な政治的伝統は、財産の権利、経済的個人主義の哲学、競争の価値に対する信念を共有しており、資本 主義文化の経済的美徳を人間に必要な資質として受け入れてきた[125]。 新左翼史 コンセンサス史観は、1960年代に急進的な歴史家の若い世代を惹きつけた新左翼史観によって否定された。これらの視点は対立を強調し、階級、人種、ジェ ンダーの中心的役割を強調する。反体制の歴史、人種的マイノリティや不利な立場に置かれた階級の経験は、新左翼の歴史家たちによって生み出された物語の中 心であった[126][127][128]。 数量化と歴史への新たなアプローチ 主な記事 社会史と政治史§アメリカ: 新しい政治史 社会史は、「新しい社会史」と呼ばれることもあるが、過去における一般市民の経験を研究する広範な分野である[129][130]。しかし、1980年以 降、「文化的転回」は次の世代を新たなテーマへと向かわせた。1975年から1995年までの20年間で、米国の大学の歴史学教授に占める社会史の割合は 31%から41%に上昇し、政治史の割合は40%から30%に低下した[4]。 この成長を可能にしたのは、社会科学、コンピュータ、統計学、国勢調査情報などの新しいデータソース、ニューベリー図書館やミシガン大学の夏季研修プログ ラムであった。新政治史』では、政治家や立法から有権者や選挙へと焦点が移ったことで、社会史の手法が政治に応用されるようになった[131] [132]。 社会科学史学会は、雑誌『社会科学史』と年次大会を持つ学際的なグループとして1976年に結成された。その目的は、すべての社会科学、特に政治学、社会 学、経済学からの視点を歴史研究に取り入れることであった。先駆者たちは、定量化へのコミットメントを共有していた。しかし、1980年代には、伝統的な 歴史学者たちの反撃により、定量化の初々しさは消え去っていた。ハーベイ・J・グラフは言う: 新しいものに対する反論は、以下のような長大な材料が混在し、混乱していた: 社会科学の汚点によってアイデンティティと人間性を失ったとされる歴史学、質を量に従属させることへの恐れ、概念的・技術的な誤り、「優れた」歴史学の文 学的性格と伝記的基盤の侵害(修辞学的・美学的関心)、聴衆の喪失、「偉大な人物」と「偉大な出来事」に根ざした歴史への軽蔑、一般的な矮小化、あらゆる 方向からのイデオロギー的反論の寄せ集め、新しい歴史家たちが、そうでなければ自分たちを非難する者たちの手に渡るかもしれない研究資金を刈り取ることへ の恐れ、などである。彼らが知っているような歴史を擁護する人々にとって、歴史学は危機に瀕しており、新しいものの追求がその主な原因であった [133]。 一方、「新しい」経済史は確立されたものとなった。しかし、大多数の歴史家からは計量経済学は歴史的な分野と見なされてこなかったため、計量経済学の論文 が歴史家によって引用されることはなかった[134][135]。その結果、数量化は人口統計学研究の中心的存在であり続けたが、伝統的な物語的アプロー チが復活するにつれて、政治史や社会史においては後塵を拝することとなった[136]。関連雑誌の創刊論文において、マルク・フランドローはその目的を、 真に学際的な分野を創造するための「越境」と定義している[137]。 ラテンアメリカ さらなる情報 植民地時代のスペイン領アメリカの歴史学、アルゼンチン、ラテンアメリカ研究 ラテンアメリカとは、西半球の旧スペイン・アメリカ帝国にポルトガル領ブラジルを加えた地域を指す。ラテンアメリカという用語が一般的に使われるように なったのは20世紀に入ってからであり、場合によっては否定されることもあった[139]。歴史学におけるもうひとつの標準的な区分は時間的要因であり、 作品は近世(または「植民地時代」)と19世紀初頭以降の独立後(または「国民的時代」)のいずれかに分類される。2つの時代にまたがる著作は比較的少な く、スペイン領アメリカとブラジルを統合した著作は教科書を除いてほとんどない。特定の国や地域(アンデス、南コーン、カリブ海地域)の歴史に焦点を当て る傾向があり、比較研究は比較的少ない。 ラテンアメリカの歴史家は様々なタイプの歴史記述に貢献してきたが、スペイン系アメリカ人の歴史における主要かつ革新的な発展のひとつは、特にメキシコに おいて、スペイン語や先住民の言語によるアルファベットの資料に基づく先住民の歴史である民族史学の出現である[140][141][142][143] [144]。 近世においては、1450年から1850年までのヨーロッパ、アメリカ大陸、アフリカの比較と関連性に基づく大西洋史の出現が、それ自体が一つの分野とし て発展し、近世ラテンアメリカ史をより大きな枠組みに統合した[145]。 全ての時代において、世界史や世界史は地域間のつながりに焦点を当て、同様にラテンアメリカをより大きな視点に統合している。世界史におけるラテンアメリ カの重要性は注目に値するが、見落とされがちである。「グローバリゼーションと近代の発展におけるラテンアメリカの中心的な、そして時には先駆的な役割 は、植民地支配の終焉と近世にとどまったわけではない。実際、この地域の政治的独立は、近代世界の入り口とされる2つの潮流の最前線に位置する。ひとつ は、いわゆる自由主義革命であり、相続が政治権力を正当化するアンシャン・レジームの君主制から立憲共和制への移行である。第二の、そして関連する、ラテ ンアメリカを最前線に見た近代史の閾値と一貫して考えられてきた傾向は、国民国家の発展である」[146]。 歴史研究は多くの専門誌に掲載されている。その中には、ラテンアメリカ歴史会議が発行する『ヒスパニック・アメリカン・ヒストリカル・レビュー』 (1918年創刊)、『ジ・アメリカズ』(1944年創刊)、『ジャーナル・オブ・ラテンアメリカン・スタディーズ』(1969年創刊)、『カナディア ン・ジャーナル・オブ・ラテンアメリカン・アンド・カリビアン研究』(1976年創刊)[147] 『ブリテン・オブ・ラテンアメリカン・リサーチ』(1981年創刊)、『コロニアル・ラテンアメリカン・レヴュー』(1992年創刊)、『コロニアル・ラ テンアメリカン・ヒストリカル・レヴュー』(1992年創刊)などがある。ラテンアメリカ研究協会発行の『ラテンアメリカ研究レビュー』(1969年創 刊)は、ラテンアメリカ史に主眼を置いていないが、特定のテーマに関する歴史学的論考をしばしば掲載している。 ラテンアメリカ史に関する一般的な著作は、米国の大学やカレッジでラテンアメリカ史の教育が拡大した1950年代以降に出版されている[148]。その多 くは、制度史、政治史、社会史、経済史に焦点を当て、征服から近代までのスペイン領アメリカとブラジルを完全に網羅しようとしている。ラテンアメリカ史の 重要な全11巻の研究書としては、植民地時代、19世紀、20世紀を分冊した『ケンブリッジ・ヒストリー・オブ・ラテンアメリカ』(The Cambridge History of Latin America)がある[149]。 [150][151][152]大手出版社もラテンアメリカ史[153]や歴史学に関する編著書を発行している。 154]参考文献としては、この地域の専門家による論文を注釈付き書誌項目とともに掲載した『ラテンアメリカ研究ハンドブック』や『ラテンアメリカ歴史文 化百科事典』などがある[155]。 世界史 世界史は、1980年代に独立した学問分野として登場した。世界史は、グローバルな視点から歴史を検証し、あらゆる文化に共通するパターンを探すことに重 点を置いている。この分野の基本的なテーマアプローチは、世界史のプロセスがいかにして世界の人々を引き寄せてきたかという「統合」と、世界史のパターン がいかにして人間の経験の多様性を明らかにしてきたかという「差異」という2つの主要な焦点を分析することであった。 アーノルド・J・トインビーの『歴史の研究』全10巻は、1930年代から1940年代にかけて広く議論されたアプローチである。1960年代には、彼の 著作は学者や一般大衆から事実上無視されるようになった。彼は26の独立した文明を比較し、その起源、成長、衰退に顕著な類似性が見られると主張した。彼 はこれらの文明のそれぞれに普遍的なモデルを提案し、すべての文明が通過する段階を詳述した:発生、成長、悩みの時期、普遍的な状態、崩壊。後の巻では、 批評家を満足させるために精神性を強調しすぎた[156]。 シカゴの歴史家であるウィリアム・H・マクニールは、『西洋の勃興』(1965年)を執筆し、ユーラシアの別々の文明がその歴史の最初からどのように相互 作用し、互いに重要な技術を借用し、その結果、伝統的な古い知識と借用した新しい知識と実践との間の調整が必要となり、さらなる変化を促したかを示した。 そして、過去500年の歴史の中で、西洋文明が他の文明に与えた劇的な影響について論じている。マクニールは、地球上の人々の相互作用を中心に組織された 幅広いアプローチをとった。このような相互作用は、近年、より多く、より継続的で実質的なものとなっている。約1500年以前は、文化間のコミュニケー ションのネットワークはユーラシア大陸のものだった。このような相互作用の領域を指す言葉は世界史家によって異なり、世界システムやエキュメーンなどがあ る。彼が強調した文化的融合は歴史理論に大きな影響を与えた[157]。 文化的転回 1980年代から1990年代にかけての「文化的転回」は、歴史学のほとんどの分野の学者に影響を与えた[158]。主に人類学に触発され、指導者や一般 人や有名な出来事から、社会の価値観の変化を表すための言語や文化的シンボルの使用に目を向けるようになった[159]。 イギリスの歴史家であるピーター・バークによれば、カルチュラル・スタディーズには数多くのスピンオフや、強く影響を受けたトピカルなテーマがある。最も 重要なものとしては、ジェンダー研究、ポストコロニアル研究、記憶研究、映画研究などが挙げられる[160]。 外交史家のメルヴィン・P・レフラーは、「カルチュラル・ターン」の問題点として、文化の概念が不正確であり、過度に広範な解釈を生み出す可能性があるこ とを挙げている: というのも、文化という概念は無限に変化しうるものであり、まったく異なる政策、たとえばアメリカでは国際主義や孤立主義、日本では協調的国際主義や人種 差別主義を形づくることができるからである。文化の可鍛性は、それが政策に及ぼす影響を理解するためには、政治経済の力学、国際システムの進化、テクノロ ジーとコミュニケーションの役割など、他の多くの変数のなかでも、さらに研究する必要があることを示唆している[161]。 記憶研究 以下も参照のこと: 社会的記憶、歴史的イエス研究における記憶研究 記憶研究は新しい分野であり、国家や集団(そして歴史家)がどのように過去の記憶を構築し、主要な特徴を称賛(あるいは非難)するために選択し、現在の価 値観や信念を表明しているかに焦点を当てている[162][163]。 多くの歴史家は、過去の記憶がどのように構築され、記憶化され、歪められてきたかを検証している。例えば、ヨーロッパにおけるホロコーストやアジアにおけ る日本の戦争犯罪に代表される第二次世界大戦の残虐行為の記憶に関する研究は数多く存在する[168][169]。イギリスの歴史家ヘザー・ジョーンズ は、近年の第一次世界大戦の歴史学は文化的転回によって再活性化されていると論じている。学者たちは、軍事占領、政治の急進化、人種、男性の身体に関して まったく新しい疑問を提起している[170]。 近年の研究の代表的なものは、「現代ヨーロッパにおける記憶とアイデンティティの力学」に関する研究集である[171]。セージ社は2008年から学術誌 『Memory Studies』を発行しており、2010年にはパルグレイヴ・マクミラン社から書籍シリーズ『Memory Studies』が創刊され、年間5~10タイトルが刊行されている[172]。 |

| Narrative According to Lawrence Stone, narrative has traditionally been the main rhetorical device used by historians. In 1979, at a time when the new Social History was demanding a social-science model of analysis, Stone detected a move back toward the narrative. Stone defined narrative as follows: it is organized chronologically; it is focused on a single coherent story; it is descriptive rather than analytical; it is concerned with people not abstract circumstances; and it deals with the particular and specific rather than the collective and statistical. He reported that, "More and more of the 'new historians' are now trying to discover what was going on inside people's heads in the past, and what it was like to live in the past, questions which inevitably lead back to the use of narrative."[182] Historians committed to a social science approach, however, have criticized the narrowness of narrative and its preference for anecdote over analysis, and its use of clever examples rather than statistically verified empirical regularities.[183] Topics studied Some of the common topics in historiography are: Reliability of the sources used, in terms of authorship, credibility of the author, and the authenticity or corruption of the text. (See also source criticism.) Historiographical tradition or framework. Every historian uses one (or more) historiographical traditions, for example Marxist, Annales school, "total history", or political history. Moral issues, guilt assignment, and praise assignment Revisionism versus orthodox interpretations Historical metanarratives and metahistory.[184][185] Approaches How a historian approaches historical events is one of the most important decisions within historiography. Historians commonly recognise that individual historical facts—dealing with names, dates and places—are not particularly meaningful in themselves. Such facts only become useful/informative when assembled with other historical evidence, and the process of assembling this evidence is understood[by whom?] as a particular historiographical approach. Some influential historiographical approaches include: Big history Business history, History of institutions and Official history Black history Chronology Comparative history Cultural history Diplomatic history Decolonization of knowledge Economic history (history of capitalism), (Business history), (financial history) Environmental history, a relatively new field Ethnohistory Gender history including women's history, family history, feminist history Global history, or World History Global studies Great man theory and Heroism History of medicine History of religion and church history; the history of theology is usually handled[by whom?] under theology Indigenous history Industrial history and the history of technology Intellectual history and the history of ideas Labor history Legendary history – important in pre-modern contexts Local history and microhistory Marxist historiography and historical materialism Migration studies Military history, including naval and air history Mythistory – history incorporating elements of myth National history – comforting myths of individual peoples Oral history and Traditional knowledge Political history Public history, especially museums and historic preservation Quantitative history (prosopography using statistics to study biographies) Historiography of science Social history and people's history; along with the French version the Annales school and the German Bielefeld School Subaltern Studies, regarding post-colonial India Urban history American urban history Whig history, history interpreted as the story of continuous progress World history Zeitgeist Related fields Important related fields include: Antiquarianism Genealogy Historical archaeology Intellectual history Numismatics Paleography Philosophy of history Pseudohistory |

物語 ローレンス・ストーンによれば、物語は伝統的に歴史家が用いる主要な修辞的装置であった。1979年、新しいソーシャル・ヒストリーが社会科学的な分析モ デルを求めていた時期に、ストーンは物語へと回帰する動きを察知した。ストーリーは時系列的に構成され、一つの一貫したストーリーに焦点を当て、分析的と いうよりはむしろ記述的であり、抽象的な状況ではなく人々に関心を持ち、集団的で統計的なものよりもむしろ特殊で具体的なものを扱うものである。彼は、 「ますます多くの『新しい歴史家』が、過去に人々の頭の中で何が起こっていたのか、過去に生きることはどのようなことだったのかを発見しようとしている。 しかし、社会科学的なアプローチを重視する歴史家たちは、語りの狭さや分析よりも逸話を好むこと、統計的に検証された経験的な規則性よりもむしろ巧妙な事 例を用いることを批判している[183]。 研究対象 歴史学において一般的なトピックは以下の通りである: 使用される資料の信頼性(著者名、著者の信頼性、テキストの信憑性や腐敗など)。(出典批判も参照のこと)。 歴史学の伝統または枠組み。例えばマルクス主義、アナール学派、「通史」、政治史などである。 道徳的問題、罪の帰属、賞賛の帰属 修正主義対正統派解釈 歴史的メタナラティブとメタヒストリー[184][185]。 アプローチ 歴史家が歴史的出来事にどのようにアプローチするかは、歴史学において最も重要な決定のひとつである。歴史家は一般的に、個々の歴史的事実-名前、日付、 場所-はそれ自体では特に意味を持たないことを認識している。そのような事実は、他の歴史的証拠と組み合わされて初めて有用/有益なものとなり、この証拠 を組み立てるプロセスは特定の歴史学的アプローチとして理解される[誰が? 影響力のある歴史学的アプローチには、以下のようなものがある: 大きな歴史 ビジネス史、制度史、公式史 黒歴史 クロノロジー 比較史 文化史 外交史 知識の脱植民地化 経済史(資本主義史)、経営史、金融史 環境史(比較的新しい分野 民族史 ジェンダー史(女性史、家族史、フェミニズム史など グローバルヒストリー(世界史 グローバル・スタディーズ 偉人論と英雄論 医学史 宗教史と教会史。神学史は通常、神学の下で扱われる。 先住民史 産業史・技術史 知的歴史と思想史 労働史 伝説史-近代以前の文脈では重要である。 地域史とミクロ史 マルクス主義的歴史学と史的唯物論 移民研究 軍事史(海軍史、航空史など 神話史 - 神話の要素を取り入れた歴史 民族史-個々の民族の神話を慰める 口承史と伝統的知識 政治史 公共史(特に博物館と歴史保存 量的歴史学(伝記を研究するための統計学を用いたプロソポグラフィー) 科学史 社会史と人民史:フランス版「アナール学派」とドイツ版「ビーレフェルト学派」とともに。 植民地支配後のインドに関するサバルタン研究 都市史 アメリカ都市史 ホイッグ史(継続的進歩の物語として解釈される歴史 世界史 時代精神 関連分野 重要な関連分野は以下の通りである: 古文書学 系図学 歴史考古学 知的歴史学 貨幣学 古文書学 歴史哲学 偽史 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Historiography |

|

++

| 頁 |

パラグラフ |

||

| 1 |

1 |

・グローバル時代における歴史叙述につい

て考える。 ・グローバリゼーションは、歴史学を活性化するか? ・それとも西洋の思考モデルを世界の隅々にまで届ける(支配する)ことか? |

|

| 2 |

・歴史学の危機 ・何に役立つかという審問がつねになされる ・19世紀にハーバード大学は、男子学生しか入学が許されず、古代ギリシアやローマの歴史が必須として教えられていた。 ・ラテン語とならんで、それまでのリベラルアーツの必修科目としてあった。 |

・「何に役立つかという審問」

に対する人文社会科学の側からの回答は、それに直接答えず(1)「役に立つように自分たちの学問を変容させよう」という努力か、(2)「役に立たないのが

私たちの学問」と居直ることで、「なぜ君たちは役に立つことを強迫的に我々に審問するのか?」という反撃に向かわなかった。 |

|

| 3 |

・19世紀後半から20世紀前半の歴史学

は「国民に対する教師」としての機能化する(→「想像の共同体」) ・大学における歴史学の地位の向上→国民史( national history)が支配的になり、古代ギリシアや古代ローマ史を凌駕するようになる。 |

||

| 4 |

・諸国民の歴史が、緊急性と目的性を帯び

るようになる——国民の基礎教育に受けるべきであるという発想が登場する ・国民皆教育制度 ・多様な階級、民族、地域集団からなる国家を統合するには「国民勃興の物語=ナショナル・ヒストリー」は必要とされた。 |

||

| 5 |

・歴史学とナショナリズムは不可分に発達

してきた ・古い起源をもつ国民国家もアイデンティティ強化のための歴史学を必要とする。 ・法案659号、歴史教育を強化して国民強化する。S.659 - Improving the Teaching and Learning of American History and Civics Act of 2009、111th Congress (2009-2010)、Senator Lamar Alexande (1940- ) |

||

| 6 |

・新興国、体制が変わった国家では、教育

における歴史学の位置が向上する(例:ウクライナ) |

||

| 4 |

7 |

・歴史教育と国民史はパンとバターの関係

だ ・フランス、ドイツ、英国 ・インド、中国 ・オーストラリアの事例 |

|

| 8 |

・国民史そのものも変化している ・エリート史から社会史への変化、それは誰が大学で学んでいるのかということにも関係する |

||

| 6 |

9 |

・ソブール『共和暦2年のサン・キュロッ

ト』、E・P・トムスン『イングランド労働者階級の形成』 ・社会の底辺の人たちの歴史変革を無視できなくなる。 ・トムスンの著作はインドにも影響を与える |

|

| 10 |

・労働組合、フェミニズム、マイノリティ

運動と社会史 |

||

| 11 |

・歴史の目的についてのコンセンサスも掘

り崩される |

||

| 12 |

・歴史学者たちが、さまざまな社会科学の

理論を取り入れるようになる ・近代化論、とりわけマルクス主義の影響 |

||

| 13 |

・トムスンやソブールの研究のなかに、文

化への関心の低下があきらかになる。また、そのような著述家たちもまたその文化への理解のハンディを乗り越えようとする |

||

| 14 |

・ウェーバーと近代化論。ウェーバーは伝

統的形態そのものを擁護はしなかったが…… |

||

| 9 |

15 |

・文化への着目は、歴史学が袋小路から抜

け出る方策 ・ただしやがて、文化理論の影響力も衰退する |

|

| 16 |

・文化理論にかわって浮上するのが、グ

ローバリゼーションの現象である。それは文化に対する代替的理論提供になりつつある。 |

||

| 17 |

・グローバリゼーションは唯一可能なオル

タナーティブではない ・本書の構成 |

||

| 18 |

・歴史学も歴史家も変化している(同じも

のではない) |

リ ンク(サイト)

リ ンク(サイト内)

文 献

そ

の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆