ハイデガーの政治的存在論

L'ontologie politique de Martin Heidegger, The political ontology of Martin Heidegger, by Pierre Bourdieu

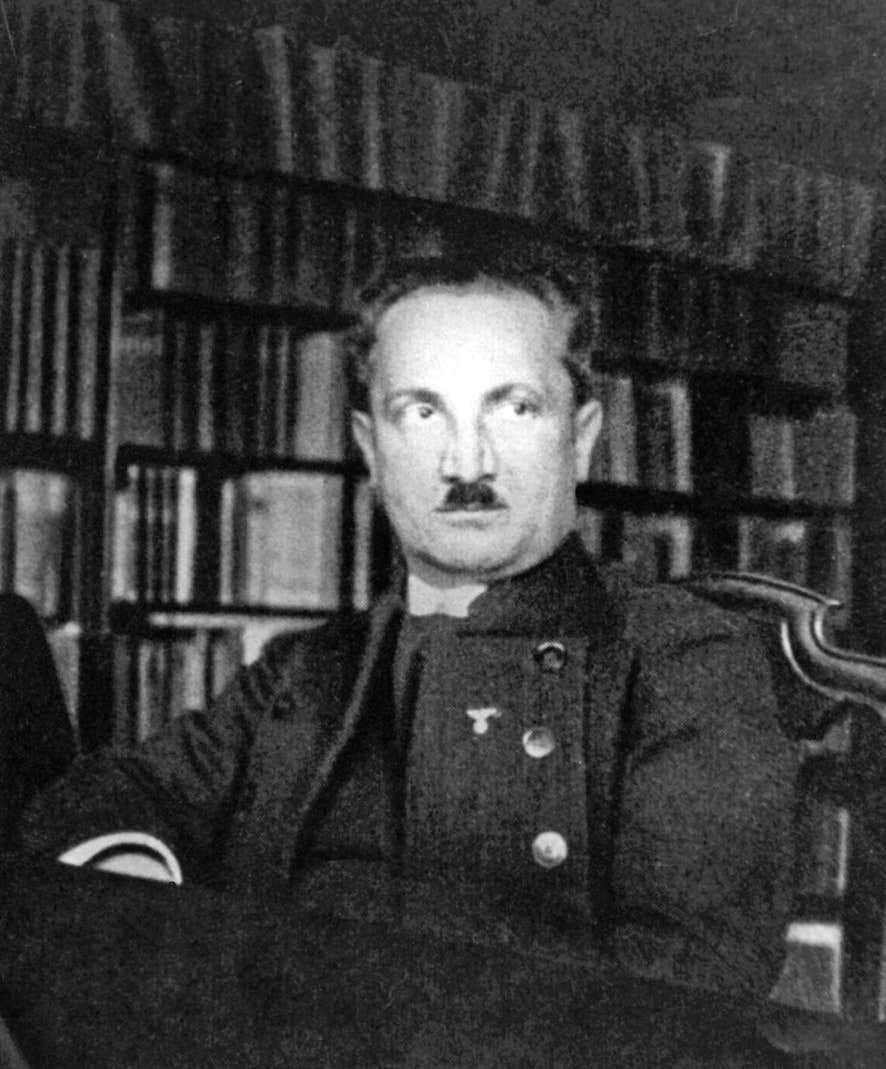

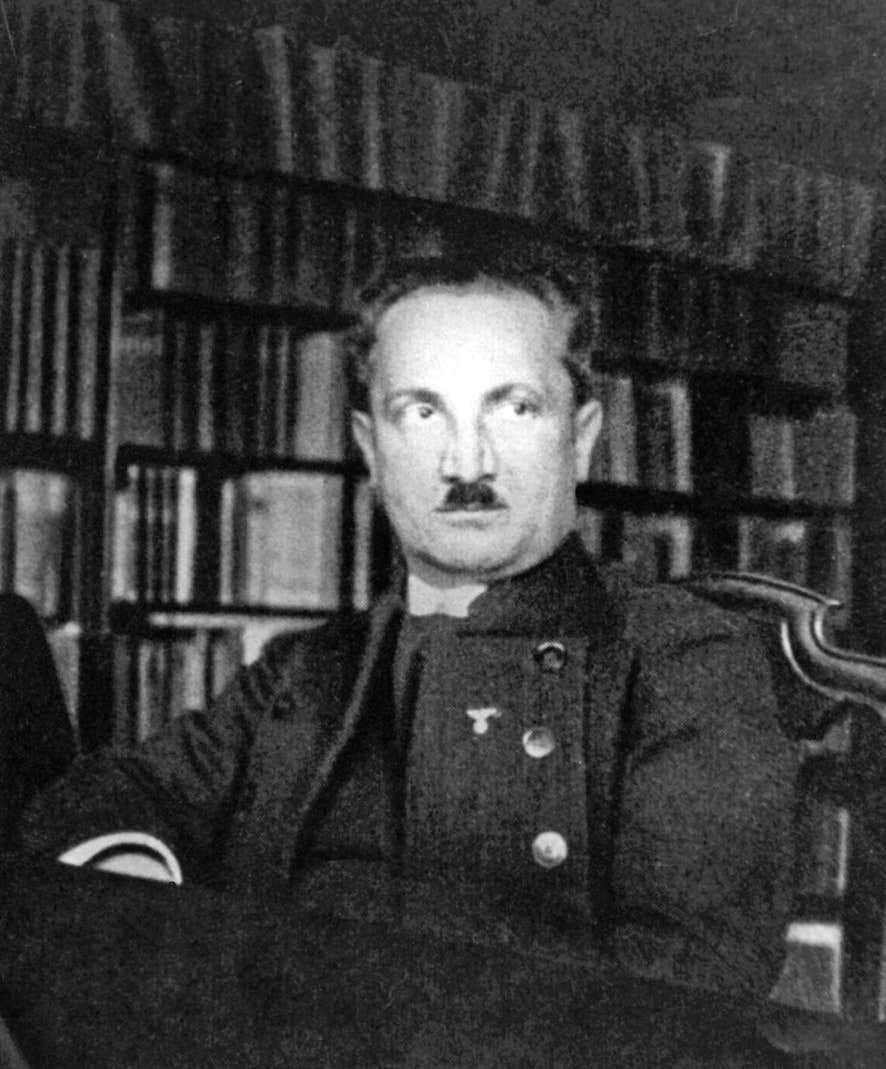

1934年4月23日のフライブルグ大学総長辞任前後の時期のハ

イデガー:ナチスの民族指導者の鷲章をつける// Otto Dix が描くHeidegger

ハイデガーの政治的存在論

L'ontologie politique de Martin Heidegger, The political ontology of Martin Heidegger, by Pierre Bourdieu

1934年4月23日のフライブルグ大学総長辞任前後の時期のハ

イデガー:ナチスの民族指導者の鷲章をつける// Otto Dix が描くHeidegger

解説:池田光穂

●マルチン・ハイデガーの政治的存在論 (ピエール・ブルデュ)——L'ontologie politique de Martin Heidegger.

| アウトライン |

(ハイデガーの 用語)時間性————(含意)福祉国家糾弾 (ハイデガーの用語)彷徨 の糾弾 ——(含意)反ユダヤ主義 1)歴史的文脈の検証 2)哲学者に陣地をあてがう大学 3)教員やポストを改廃する権力構造 4)ワイマール・ドイツの社会構造 |

| 序論 いかがわしい思想 | ・哲学の世俗からの切断という意識が哲学の限界づけられた考え方 ・哲学と言えども時代の子(ただしこれは超越論的な歴史主義を結果的に肯定する) ・ハイデガーに純粋性を認めるのはナンセンスだが、ハイデガーを政治思想家とするのもナンセンス ・哲学の世俗世界からの自律の有無を考えるのではなく、そこから逃れ得ないこと。あるいは逃れ得た/るべきという哲学者のポーズ(あるいは自己の学問への 無理解)を問うことが重要 ・哲学は特殊な時代性をもつ。すなわち、ナチの時代を生きたハイデガーとその著作の「特殊な時代性」について考察しなければならない。 ・ハイデガーの著作は哲学的に読むと《同時に》政治的にも読まねばならない——二重の読解。 ・さらには、これまでの通俗的な政治概念の相対化、すなわち、読解を通した「政治概念の刷新」がもとめられている。 1)哲学の時代性と純粋性 2)政治的かつ哲学的に読むこと |

| 第1章 純粋哲学と時代 精神 | ・ハイデガー哲学の時代は、「フェルキッシュ(民族的・民俗的)」という概念が重要視された時代である。 ・ハイデガーとその他の思想家(シュペングラー、ユンガー)との関係 1)両大戦間のイデオロギー的雰囲気 2)家父長制/回心/山岳 3)シュペングラーとトレルチ 4)大学内に広がる反主知主義 5)シュペングラーとハイデガー 6)ユンガーとハイデガー 7)ぼんやりした統一 8)倫理—政治的な方向感覚 9)保守的革命 10)第三の道 11)ハイデガー存在論の政治的基礎——「本源的人種」の概念など 12)政治と哲学の境界線 13)能動的ニヒリズムから受動的ニヒリズムへ |

| 第2章 哲学界と可能性 空間 | ・ハイデガーデビュー直前の新カント派の状況 ・時代状況から自律しているとはどういうことか? ・その哲学的読解。 1)哲学界における政治的立場表明 2)哲学界の状況と新しい立場 3)ハイデガーのハビトゥス 4)知的世界のいごこちの悪さ 5)ハイデガーの文体 |

| 第3章 哲学における 「保守的革命」 | ・ハイデガーの目論見は「保守的革命」にある ・「保守的革命」の文脈においては、政治と哲学は対応関係があり、また共存している。それ「相同的」と呼ぶ。 ・哲学的読解と、政治的読解の対応関係を明らかにする 1)政治・大学・哲学を貫く理論路線 2)徹底的な乗り越えの戦略 3)歴史・時間の存在論化とその実践的表現 4)超越論的なものの存在論化から否定的存在論へ |

| 第4章 検閲と作品制作 | ・ハイデガーの哲学文体の検証。 1)形式と内容 2)仮象だけの断絶と哲学体系 3)暴露=隠蔽 4)エリートと大衆 5)社会からの距離 6)倫理的主意主義 |

| 第5章 内的な読解と形 式の尊重 | ・ハイデガーが読者に要求する読解や解釈のやり方について 1)形式的言説は形式的読解を求める 2)哲学者の自己解釈 3)作品と解釈者の相対的立場 4)ハイデガーに共鳴する土壌 |

| 第6章 自己解釈と体系 の進化 | ・ハイデガーによる、ハイデガーの作品の読解 1)体系化の到達点としての「転回」 2)進化の原理としての警戒 3)本質的思考は本質的なことを思考しなかった |

ハイデガー「ドイツ大学の自己主張」は、画面のスクロールしてください。

●ここからは「ハイデガーとナチス」を参照してください。

★ナチス時代のハイデガーの書物| 3. Nazi-Era Writings |

3. ナチス時代のハイデガーの書物 |

| The most controversial issue in

contemporary discussions of Heidegger’s work is that of determining the

extent to which his thought is compromised by the public and

spectacular character of his moral failings. Heidegger’s support for

the National Socialist movement, and his use of Nazi and anti-Semitic

language and tropes, has been amply documented and exposed (see Denker

& Zaborowski 2009a; Ott 1988 [1993]; Farias 1987 [1989]; Faye 2005

[2009]). It is no longer possible to doubt that, as Julian Young puts

it, Heidegger was “a real Nazi: his involvement was a matter of

conviction rather than compromise, opportunism, or cowardice” (Young

1997: 4). He was also “an unabashed anti-Semite”, and “a strong

supporter of Hitler and the Nazis from 1930 through at least 1934”

(Sheehan 2015a: 368). It is also now clear that, after the war,

Heidegger repeatedly lied or distorted the record to conceal the

character and depth of his political activities in support of the Nazi

movement during the Hitler regime. Moreover, he never publicly and

explicitly renounced his support for National Socialism. On the rare

occasions when he addressed the Holocaust, he deflected attention away

from the question of German guilt by, for instance, equating the Shoah

with the repressive Soviet occupation of East Germany. |

現代におけるハイデガーの著作に関する議論で最も論争を呼んでいるの

は、彼の思想が、その道徳的な過ちの公的かつ派手な性格によって、どの程度損なわれているかを判断することである。ハイデガーの国家社会主義運動への支

持、およびナチスや反ユダヤ主義的な言語や表現の使用は、十分に文書化され、暴露されている(Denker & Zaborowski

2009a; Ott 1988 [1993]; Farias 1987 [1989]; Faye 2005

[2009]を参照)。ジュリアン・ヤングが言うように、ハイデガーが「本物のナチであった」という疑いはもはやない。彼の関与は妥協や日和見主義、ある

いは臆病さではなく、信念の問題であった(Young 1997:

4)。また、彼は「あからさまな反ユダヤ主義者」であり、「1930年から少なくとも1934年までは、ヒトラーとナチスを強く支持していた」

(Sheehan 2015a: 368)。

また、戦後、ハイデガーがヒトラー政権下におけるナチス運動を支援する政治活動の性格と深さを隠すために、繰り返し嘘をついたり、事実を歪曲したりしてい

たことも明らかになっている。さらに、彼はナチズムへの支持を公に明確に否定したことは一度もない。ホロコーストについて語る稀な機会においても、例え

ば、ホロコーストを東ドイツに対する抑圧的なソ連の占領と同一視するなどして、ドイツの罪の問題から注意をそらしていた。 |

| While the basic facts of the

Heidegger case are by now well-known, there are widely disparate

interpretations of the significance of these facts for an understanding

of Heidegger: was he a base opportunist, taking advantage of a

revolutionary movement to advance his own aims? Was he politically

naïve? Was he, as he later claimed, hoping to use the rectorship to

protect the university from “unsuitable persons” and from “the

threatening supremacy of the party apparatus and the party doctrine”

(GA16: 574–5)? Was he, as he also claimed, trying to temper the basest

impulses of the Nazi party, and lead the movement in a more positive

direction (see GA16: 377)? Or was he a true believer in Hitler and

Hitler’s National Socialism—an enthusiastic sympathizer with and

accomplice to the Nazi agenda for “German rebirth”? There is a large

and expanding literature devoted to exploring these issues, and

philosophers have staked out a very broad range of positions on these

questions (see Denker & Zaborowski 2009b; Bourdieu 1988 [1991]; Ott

1988 [1993]; Farias 1987 [1989]; Sluga 1993; Pöggeler 1990; Young 1997;

Faye 2005 [2009]; Sheehan 2015a). Nowhere has the debate over the

scandal of Heidegger’s National Socialism been more heated than in

France—perhaps owing to the depth and breadth of influence that

Heidegger had on French philosophy (see Janicaud 2001 [2015]). |

ハイデガー事件の基本的事実はすでに広く知られているが、ハイデガーの

理解にとってこれらの事実の持つ意味については、大きく異なる解釈が存在している。彼は革命運動を利用して自身の目的を推進しようとした卑しい日和見主義

者だったのか?彼は政治的にナイーブだったのか?

後に彼が主張したように、学長職を利用して大学を「不適格な人物」や「党機構と党の教義の脅威的な優越性」から守ろうとしていたのか(GA16:

574-5)? また、彼が主張したように、ナチ党の卑しい衝動を和らげ、運動をより前向きな方向に導こうとしていたのか(GA16:

377を参照)?それとも、彼はヒトラーとヒトラーのナショナリズムを心から信奉し、「ドイツ再生」というナチスの大義に熱狂的に共鳴し、その共犯者で

あったのだろうか?

これらの問題を探究する文献は数多くあり、その数は増え続けている。哲学者たちは、これらの問題について非常に幅広い立場を主張している(Denker

& Zaborowski 2009b; ブルデュー 1988年 [1991年]、オット 1988年 [1993年]、ファリアス

1987年 [1989年]、スルーガ 1993年、ペッゲラー 1990年、ヤング 1997年、フェイ 2005年 [2009年]、シーハン

2015a年)。ハイデガーのナショナリズムに関するスキャンダルをめぐる議論がこれほどまでに白熱したのはフランスにおいてが最も顕著であるが、それは

おそらく、ハイデガーがフランス哲学に与えた影響の深さと広さによるものだろう(Janicaud 2001 [2015]を参照)。 |

| At one end of the spectrum,

Young, maintains that Heidegger’s philosophical works can be fully

‘de-Nazified’—that Heidegger’s philosophical thought does not “stand in

any essential connection to Nazism” (Young 1997: 5). Moreover, Young

argues, “one may accept any of Heidegger’s philosophy, and … preserve,

without inconsistency, a commitment to orthodox liberal democracy”

(Young 1997: 5). |

一方、ヤングは、ハイデガーの哲学作品は完全に「非ナチ化」できると主

張している。すなわち、ハイデガーの哲学思想は「ナチズムと本質的なつながりがあるわけではない」(Young 1997:

5)というのだ。さらに、ヤングは「ハイデガーの哲学のどれかを受け入れ、…正統的な自由民主主義への献身を矛盾なく維持することができる」と主張してい

る(Young 1997: 5)。 |

| At the other extreme, Faye

argues that it is “impossible to dissociate [Heidegger’s work in its

entirety] from his political commitments”, and that Heidegger

“dedicated himself” to “the introduction into philosophy of the very

content of Nazism and Hitlerism” (Faye 2005 [2009: 7]). Indeed, Faye

goes so far as to contend that “Heidegger’s work is not at all a

‘philosophy’”, that in his work “the very principles of philosophy are

abolished” (Faye 2005 [2009: 4 & 316]). |

一方、フェイは「ハイデガーの仕事全体を彼の政治的献身から切り離すこ

とは不可能」であり、ハイデガーは「ナチズムとヒトラー主義のまさにその内容を哲学に導入することに」「身を捧げた」と主張している(Faye

2005 [2009:

7])。実際、フェイは「ハイデガーの著作はまったく『哲学』ではない」と主張し、彼の著作では「哲学の原理そのものが廃止されている」とまで述べている

(Faye 2005 [2009: 4 & 316])。 |

| Claims that Heidegger’s work is not philosophical or “destructive of philosophy” are belied by the fecundity of his thought for ongoing philosophical research in a variety of fields (including the phenomenology of perception and action, the philosophy of mind, the philosophy of artificial intelligence and cognitive science, ontology, the philosophy of time, the philosophy of art, the history of philosophy, and moral psychology). | ハイデガーの仕事は哲学的ではない、あるいは「哲学を破壊する」という

主張は、知覚と行動の現象学、心の哲学、人工知能と認知科学、存在論、時間哲学、芸術哲学、哲学史、道徳心理学など、さまざまな分野における現在進行中の

哲学研究に対する彼の思想の豊饒さによって否定される。 |

| At the same time, the suspicions

raised by Heidegger’s Nazi past (and by his efforts to conceal that

past) are too important to be ignored by scholars and students of his

work. There can be little doubt that much of his work during the

Nazi-era bears unmistakable resonances and affinities with Nazi

ideology. National Socialism’s glorification of traditional rural

German life, and its rhetorical anti-modernism and anti-cosmopolitanism

finds echoes in Heidegger’s critique of technology (see section 5.2).

Nazi rhetoric of renewal and rebirth resonated with Heidegger growing

conviction that Western metaphysics had run its course, that another

beginning was needed (see supplement: Heidegger and the Other

Beginning). Indeed, Heidegger repeatedly rationalized his initial

attraction to the Nazi party on just this basis (see GA95: 407; GA16:

430; GA16: 374). |

同時に、ハイデガーのナチス党員としての過去(およびその過去を隠そう

としたこと)から生じた疑念は、彼の作品の研究者や学生にとって無視できないほど重要である。ナチス党員時代における彼の作品の多くが、ナチス党のイデオ

ロギーと明白な共鳴と親和性を持っていることは疑いの余地がない。ナチズムが称揚する伝統的なドイツの田舎暮らし、そしてその誇張された反近代主義と反国

際主義は、ハイデガーのテクノロジー批判(セクション5.2参照)にも響いている。ナチスの再生と復活をうたうレトリックは、西洋形而上学は行き詰まり、

新たな始まりが必要だというハイデガーの確信を強めていった(補遺:ハイデガーとその他の始まりを参照)。実際、ハイデガーはナチ党に惹かれた理由を、ま

さにこの点に求めて繰り返し正当化している(GA95: 407; GA16: 430; GA16: 374を参照)。 |

| As many scholars have noted,

Heidegger’s embrace of National Socialism was tied up with his critique

of technology. Habermas claims, for instance, that “In 1935 Heidegger

still saw the inner truth and greatness of the National Socialist

movement in the ‘encounter between global technology and modern man’”

(Habermas 1985 [1987: 159]). Heidegger eventually came to view National

Socialism as a “consummate form of modernity”, the “triumph of

machination” (GA96: 127). And that made National Socialism something

that itself needed to be overcome in the transition to a

non-metaphysical form of dwelling (see Habermas 1985 [1987: 159–60]).

But decades later, Heidegger continued to hold that “National Socialism

did indeed go in the direction” of “attaining an adequate relationship

to the essence of technology” (GA16: 677). |

多くの学者が指摘しているように、ハイデガーのナチズムへの傾倒は、テ

クノロジー批判と結びついていた。例えば、ハーバーマスは「1935年、ハイデガーは依然として、ナチズム運動の真髄と偉大さを『グローバルテクノロジー

と近代的人間の出会い』に見出していた」と主張している(Habermas 1985 [1987:

159])。ハイデガーは最終的に、ナチズムを「近代の完成形」、すなわち「策略の勝利」とみなすようになった(GA96:

127)。そして、ナチズムは非形而上学的住居への移行において克服されるべきものとなった(ハーバーマス 1985 [1987:

159–60]を参照)。しかし、それから数十年後、ハイデガーは「ナチズムは確かに『技術の本質との適切な関係を達成する』という方向に向かっていた」

という見解を維持した(GA16: 677)。 |

| Perhaps the most significant and

clearest point of affinity between Nazi ideology and Heidegger’s

writings during the Nazi era centers on the völkisch ethno-nationalism

that Heidegger incorporated into his account of the history of being in

the 1930s. Consistently throughout his career, Heidegger was an

anti-individualist about meaning—that is, he argued that the primary

disclosure of being is social in character. In Being and Time, it is

“the anyone-self” who “articulates the referential context of

significance” in terms of which entities are encountered (SZ 129), and

“prescribes that way of interpreting the world and being-in-the-world”

(SZ 129). After the war, it is neighborhoods and localities of mortals

who disclose the sense of things by dwelling together while gathered by

the fourfold. But for a time in the 1930s Heidegger argues that the

disclosive “we-self” is a people (Volk) that shares a history, a soil,

blood, a language, tasks, possibilities, moods, and a destiny. Like the

Nazis, Heidegger held a racist and anti-Semitic conception of the

essence of the German people, although he rejected the Nazi’s

biologistic conception of race. Like other völkisch nationalists of the

time, Heidegger was convinced that the German people had a special

destiny in saving Western civilization. But for Heidegger, unlike the

Nazis, the leading role for the German people to play was that of

overcoming metaphysics and inaugurating a new history of being. |

おそらく、ナチス時代のナチスイデオロギーとハイデガーの著作の最も重

要な共通点、そして最も明白な共通点は、ハイデガーが1930年代に存在の歴史の説明に取り入れた民族主義的な民族ナショナリズムである。ハイデガーは生

涯を通じて一貫して、意味について反個人主義者であった。つまり、存在の本質的な開示は社会的性格を持つと主張した。『存在と時間』では、「存在体」が遭

遇する「意味の参照文脈を明確にする」のは「誰でも自分自身」であり(SZ 129)、「世界と世界における存在の解釈の方法を規定する」(SZ

129)とされている。戦後、四つのものに集められながら共に住むことで、物事の意味を明らかにするのは、人間たちの近隣や地域である。しかし、1930

年代のある時期、ハイデガーは、明らかにする「私たち自身」は、歴史、土壌、血統、言語、任務、可能性、気分、そして運命を共有する民族(フォルク)であ

ると主張した。ナチスと同様に、ハイデガーはドイツ民族の本質について人種差別的で反ユダヤ的な考えを持っていたが、ナチスの人種に関する生物学的な考え

方は否定していた。当時の他の民族派ナショナリストと同様に、ハイデガーはドイツ民族が西洋文明を救うという特別な使命を持っていると確信していた。しか

し、ハイデガーにとって、ナチスとは異なり、ドイツ民族が果たすべき主導的な役割は、形而上学を克服し、新たな存在の歴史を始めることだった。 |

| Heidegger’s arguments in favor

of an ethno-nationalist account of the disclosure of being are,

however, unconvincing. One can grant the communal character of human

existence, accept that we are essentially historical beings, and agree

with an anti-individualist account of the disclosure of being—all

without tying that disclosure to a particular ethnic group, people,

nation, or state. Heidegger arguments for a völkisch nationalism in his

lecture courses were sketchy at best. And already in the 1940s,

Heidegger came to view the ethno-nationalist conception of a people

(das Völkische) as a product of the subjectivity of modern metaphysics

(see, e.g., GA5: 111, GA54: 204). |

しかしながら、ハイデガーの民族ナショナリズム的な「存在の啓示」に関 する主張は説得力に欠ける。 人間の存在が共同体的であることを認め、人間が本質的に歴史的存在であることを受け入れ、そして「存在の啓示」を特定の民族、人々、国家、あるいは国家体 制に結びつけることなく、反個別主義的な「存在の啓示」の説明に同意することは可能である。 ハイデガーの講義における民族ナショナリズムの主張は、よく言えば大まかなものであった。そして、1940年代にはすでに、ハイデガーは民族主義的な民族 観(das Völkische)を近代形而上学の産物として捉えるようになっていた(例えば、『GA5』111ページ、『GA54』204ページを参照)。 |

| At the same time, we should

remain alive to the fact that Heidegger’s account of the history of

being, his critique of technology, and his essay on the

world-disclosive significance of works of art, all came out of this

period of Heidegger’s adventures in ethno-nationalism. It would be

irresponsible to not sensitize ourselves to the question whether

Heidegger’s nationalist and racist views have affected or distorted his

understanding of history (including his critique of the technological

age). |

同時に、ハイデガーの存在の歴史に関する説明、テクノロジーに対する批

判、芸術作品の世界を明らかにする意義に関する論文は、すべて民族ナショナリズムに傾倒したハイデガーの冒険の時代に生まれたものであるという事実を、私

たちは認識しておくべきである。ハイデガーの民族主義的・人種差別的な見解が、彼の歴史観(技術時代の批判を含む)に影響を与えたり歪めたりしたかどうか

という問題に注意を向けないのは無責任である。 |

| https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/heidegger/#NaziEraWrit |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099