Responsibility

Responsibility

ミハイル・バフチンの用語では言表 (utterance)と表現さ れているものには、なんらかの責任性が伴っている。言表のもっとも典型的な例は、現代社会を生きる私たちにしばしば要求される説明責任 (accountability)である。しかしながら説明 責任が発生する論理的前提には、その発話「以前に」対話者からの呼びかけに応える実践から生まれる責任すなわち、応答責任 (responsibility)があり、この応答責任とは対話の連鎖のなかで他者がしばしば要請するものである。私たちが実践をとおして発話をし向ける 理由であると考えられるこの2つの責任は、対話が用意する発話者と応答者のあいだの論理、すなわち対話論 理から論理的に引き出せるものであり、それは降って湧いたような近年流行りの「科学者の社会的責任」や「技術者倫理」のような命令語法的な教育上の原理で はない。公害運動に携わってきたまさに英雄的と後に称されるようになる研究者たちが、価値中立を護持する御用学問から、苦悩する民衆と共にある「生きた 学問」に転向する契機になるエピソードとしてしばしば語られるのが、研究室を出て人びとの生活と同じ水準に立った時に直面したときに、フィールドにいる人 たちに対して目撃者になりながら、他方で自分たちを表現する言葉を失うことである。失語症ならぬ失対話症に陥ってしまうのだ。それは本来、大学という社会 空間が市井の人たちと対話を可能にする言語も持っておらず、より積極的に言えば、その動機や欲望すら持たなかったからである。市井の人たちを市民と言い換 えたときに、問題に「関心あり憂慮している人」びとであると、ある種のパターナリズムの対象化していることは、やは り対話の相手としての市井の人よりも、何かをしてあげたいという屈折したパトロンの論理がかいま見える。私たちが失対話症に陥るのは、空疎で抽象的な対象 を対話者に仕立てるシャドウボクシングであり、それはモノローグを続けることに他ならない。モノローグに他者は不要だからだ。失対話症とは、失対話者症、 すなわち自分と同一性をもちながら同時に差異を絶対に消失させない他者の存在の欠如の状態のことである。すなわち、対話行為とは責任性がともなう実践なの である。

★ヤスパースの『戦争の罪』を受けて、鶴 見俊輔(1991:168)は「責任」をつぎの5つのカテゴリーに分類する。

●責任論リンク集

| 環境汚染の責任を誰が負うべきか? |

事

後的な環境汚染の除去などの費用負担は、現在では「汚染者負担原則」 (Polluter-Pays Principle,

PPP)と言われるが、これはOECDが1972年に採択したものに由来する。したがって、公害も同様、受動喫煙の咎は、日本たばこ株式会社(JT)とそ

の大株主の日本政府が負うべきなのである。 |

| 見ることの責任性 |

見ることが、無条件に〈責任の関係〉を

つくってしまうとは考えられないように思われる。見ることが〈責任の関係〉をつくりあげる条件とは何

なのか? 臨床コミュニケーションの観点から考えてください。 |

| 研究不正とどのように向き合うか? |

〈現場から考える〉とは,……応答責任

と説明責任を,実践の現場で発話——正確には対話——をとおして言語化することである。倫理性

とは,私たちの相互作用の実践中から生まれるが,行為は発話性という性格を持つのだ。 |

| 刑法39条をめぐって |

刑法第39条「1.心神喪失者の行為

は、罰しない。 2.心神耗弱者の行為は、その刑を減軽する。」 |

| 犠牲者非難 |

犠

牲者非難とはvictim blaming

の訳語で「その人の不幸を自業自得であると非難する」という言語行為をさします。「肺ガンになったのは、おまえがタバコを吸っていたからだ」

、「性病になったのは、遊びすぎたんじゃない?」

、「いじめは、いじめられる側にも原因がある」という構図をもつ責任追及の論理で、病気になった「犠牲者」を結果的に非難することです。これらは、原因と

結果を客観的に関連づけるという検証思考を停止して、《自分がそう思う偏見を自己正 当化する完全な誤った判断》です。 |

| 安心して徘徊できる社会は可能か? |

2016

年12月8日朝日新聞において報道された、同年12月1日の民事訴訟の最高裁判決を報じる記事は、認知症の人を「安心して徘

徊させる社会」が未だ到来していないことを示唆する重要な指摘があると私は判断しました。なぜなら、JR東日本の車両に飛び込んでしまった当時91歳の老

人は事故でなくなり、その民事賠償責任を問う裁判が10年近くおこなわれたからです。今般のケースは、日ごろの介護努力があり、徘徊させてしまったがゆえ

の鉄道事故に関して、賠償責任を問うことができないと最初に判例が決定したことになります。そのことについて詳しく解説してみましょう。 |

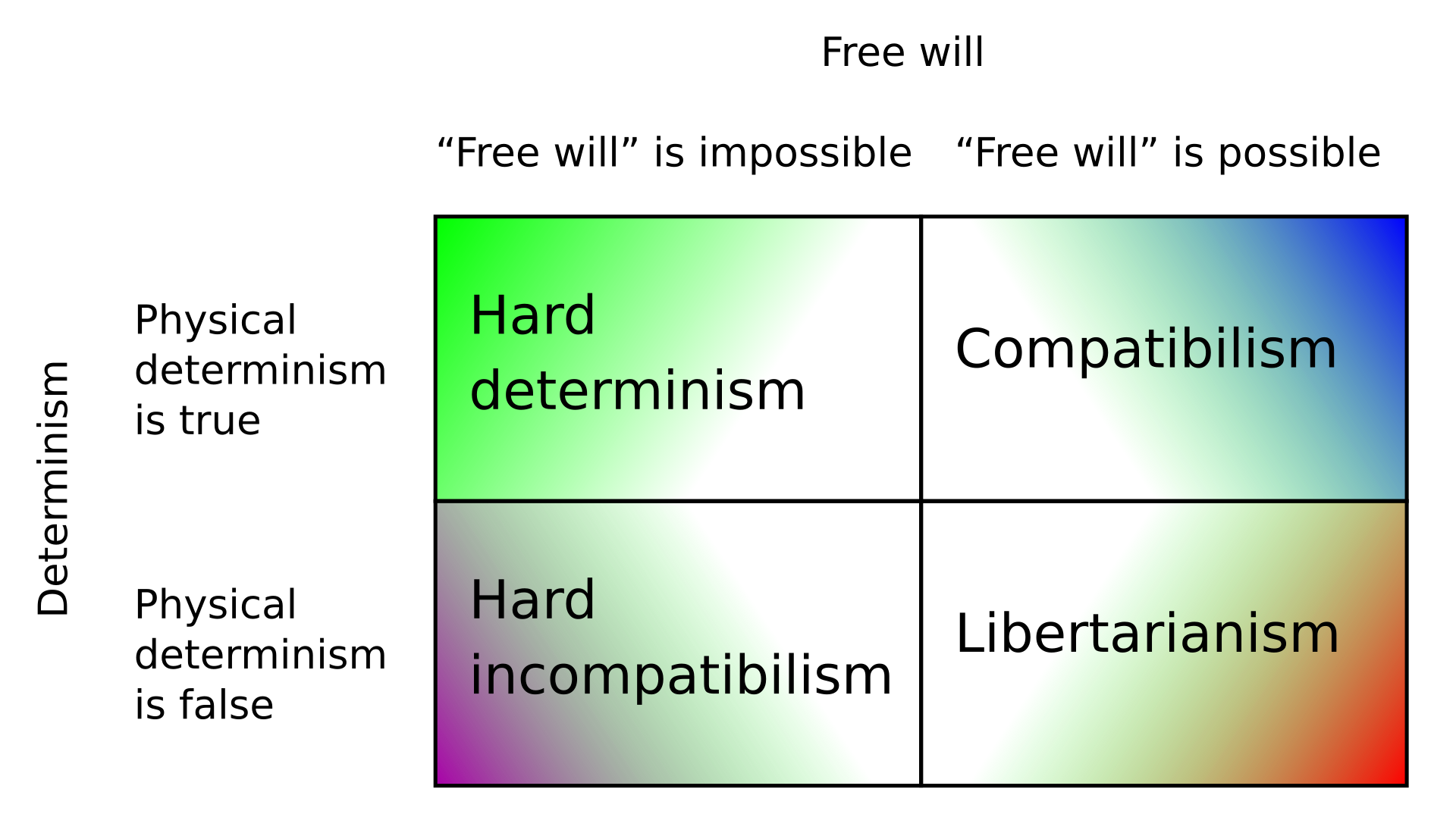

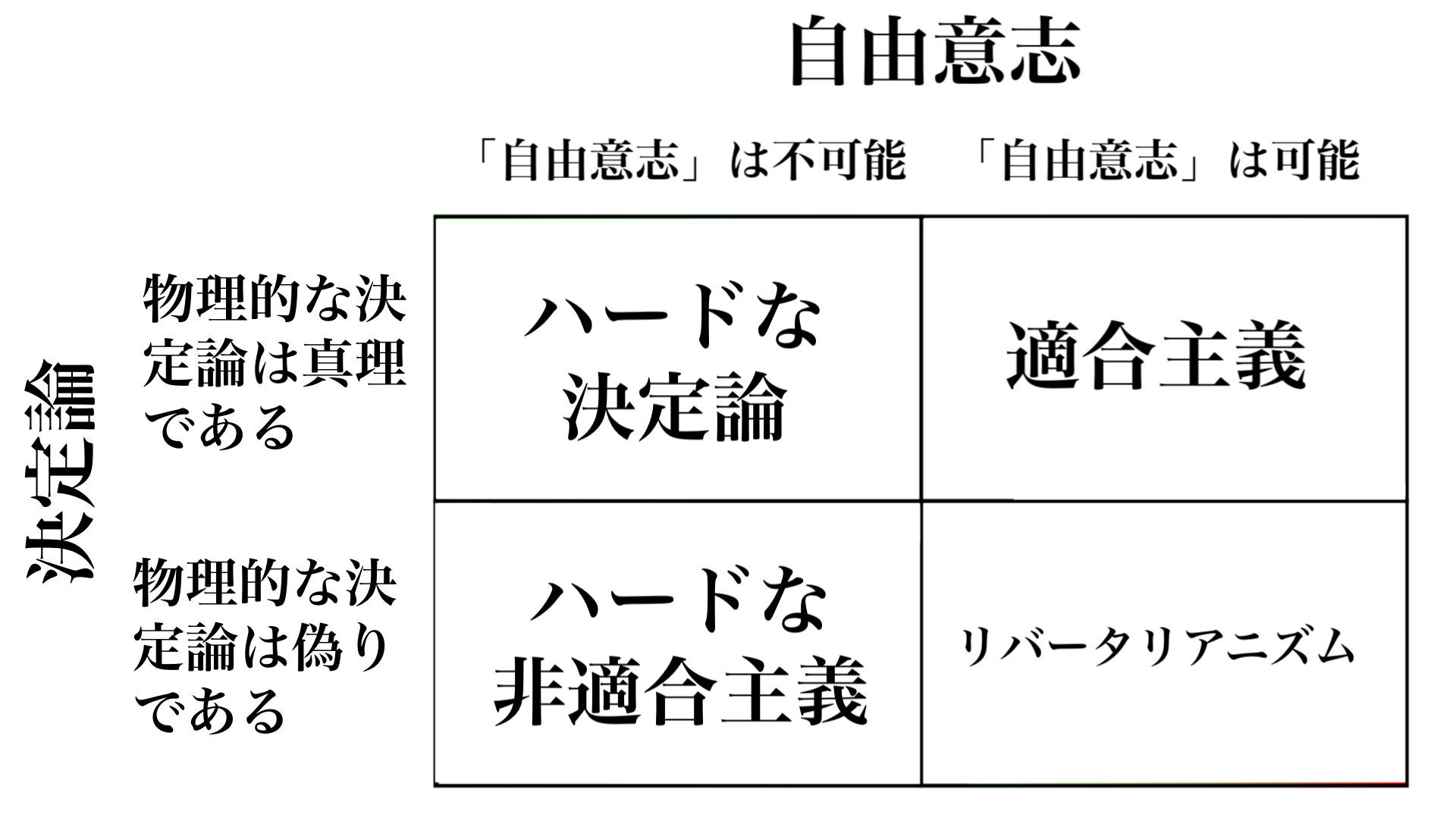

★道徳的責任論(Moral responsibility)

| In philosophy, moral responsibility

is the status of morally deserving praise, blame, reward, or punishment

for an act or omission in accordance with one's moral

obligations.[1][2] Deciding what (if anything) counts as "morally

obligatory" is a principal concern of ethics. Philosophers refer to people who have moral responsibility for an action as "moral agents". Agents have the capability to reflect upon their situation, to form intentions about how they will act, and then to carry out that action. The notion of free will has become an important issue in the debate on whether individuals are ever morally responsible for their actions and, if so, in what sense. Incompatibilists regard determinism as at odds with free will, whereas compatibilists think the two can coexist. Moral responsibility does not necessarily equate to legal responsibility. A person is legally responsible for an event when a legal system is liable to penalise that person for that event. Although it may often be the case that when a person is morally responsible for an act, they are also legally responsible for it, the two states do not always coincide.[3] Preferential promoters of the concept of personal responsibility (or some popularization thereof) may include (for example) parents,[4] managers,[5] politicians,[6] technocrats,[7] large-group awareness trainings (LGATs),[8] and religious groups.[9] Some[who?] see individual responsibility as an important component of neoliberalism.[10] |

哲学において、道徳的責任とは、道徳的義務に従って、ある行為または不作為に対して、賞賛、非難、報酬、または罰を受けるに値するという状態である。[1][2] 「道徳的義務」として何を(もしあれば)数えるかを決定することは、倫理の主要な関心事である。 哲学者は、ある行為に対して道徳的責任を負う人々を「道徳的代理人」と呼ぶ。エージェントは、自身の状況を振り返り、どのように行動するかを意図し、その 行動を実行する能力を持つ。自由意志の概念は、個人が自身の行動に対して道徳的な責任を負うことがあるかどうか、また、そうである場合、どのような意味に おいてかという議論において重要な問題となっている。非相容説者は決定論を自由意志と対立するものと考えているが、相容説者はこの2つは共存しうると考え ている。 道徳的責任は必ずしも法的責任と同義ではない。ある人格が、ある出来事に対して法的責任を負うのは、その出来事に対してその人格が法的処罰を受ける可能性 がある場合である。ある行為に対して人格が道徳的責任を負う場合、その行為に対して法的責任も負う場合が多いが、両者は必ずしも一致するわけではない。 個人責任(またはその普及)の概念を優先的に推進する人々には、例えば、親、[4]経営者、[5]政治家、[6]テクノクラート、[7]大人数を対象とした意識改革トレーニング(LGAT)、[8]宗教団体などが含まれる可能性がある。[9] 一部の人々は、個人責任を新自由主義の重要な要素と見なしている。[10] |

Philosophical stance Various philosophical positions exist, disagreeing over determinism and free will. Depending on how a philosopher conceives of free will, they will have different views on moral responsibility.[11] Metaphysical libertarianism Main article: Libertarianism (metaphysics) Metaphysical libertarians think actions are not always causally determined, allowing for the possibility of free will and thus moral responsibility. All libertarians are also incompatibilists; for they think that if causal determinism were true of human action, people would not have free will. Accordingly, some libertarians subscribe to the principle of alternate possibilities, which posits that moral responsibility requires that people could have acted differently.[12] Phenomenological considerations are sometimes invoked by incompatibilists to defend a libertarian position. In daily life, we feel as though choosing otherwise is a viable option. Although this feeling does not firmly establish the existence of free will, some incompatibilists claim the phenomenological feeling of alternate possibilities is a prerequisite for free will.[13] Jean-Paul Sartre suggested that people sometimes avoid incrimination and responsibility by hiding behind determinism: "we are always ready to take refuge in a belief in determinism if this freedom weighs upon us or if we need an excuse".[14] A similar view is that individual moral culpability lies in individual character. That is, a person with the character of a murderer has no choice other than to murder, but can still be punished because it is right to punish those of bad character. How one's character was determined is irrelevant from this perspective. Robert Cummins, for example, argues that people should not be judged for their individual actions, but rather for how those actions "reflect on their character". If character (however defined) is the dominant causal factor in determining one's choices, and one's choices are morally wrong, then one should be held accountable for those choices, regardless of genes and other such factors.[15][16] In law, there is a known exception to the assumption that moral culpability lies in either individual character or freely willed acts. The insanity defense – or its corollary, diminished responsibility (a sort of appeal to the fallacy of the single cause) – can be used to argue that the guilty deed was not the product of a guilty mind.[17] In such cases, the legal systems of most Western societies assume that the person is in some way not at fault, because his actions were a consequence of abnormal brain function (implying brain function is a deterministic causal agent of mind and motive). |

哲学的立場 決定論と自由意志をめぐって、さまざまな哲学的立場が存在する。 哲学者が自由意志をどのように捉えるかによって、道徳的責任に対する見解は異なる。[11] 形而上学的リバタリアニズム 詳細は「形而上学におけるリバタリアニズム」を参照 形而上学的リバタリアンは、行動は常に因果的に決定されるものではないと考え、自由意志と道徳的責任の可能性を認める。リバタリアンはすべて非両立説論者 でもある。なぜなら、因果決定論が人間の行動に当てはまるのであれば、人々は自由意志を持たないことになるからだ。したがって、リバタリアンの一部は、道 徳的責任は人々が異なる行動を取ることが可能であることを必要とするという、代替可能性の原則を支持している。 現象学的考察は、自由意志論者の立場を擁護するために、両立説否定論者によって引き合いに出されることがある。日常生活において、私たちは別の選択肢を選 ぶことも可能であると感じている。この感覚は自由意志の存在を確固たるものとするものではないが、両立説否定論者の一部は、別の可能性という現象学的感覚 が自由意志の前提条件であると主張している。 ジャン=ポール・サルトルは、人々は決定論に隠れることで罪や責任を回避することがあると示唆している。「この自由が私たちに重くのしかかったり、言い訳が必要になったりすると、私たちはいつでも決定論への信仰に逃げ込む用意がある」[14]。 同様の見解として、個人の道徳的責任は個人の人格にあるというものがある。つまり、殺人者の人格を持つ人は殺人以外の選択肢を持たないが、それでも処罰さ れるべきである。なぜなら、人格に問題のある者を処罰することは正しいことだからである。この観点では、人格がどのように決定されたかは関係がない。例え ば、ロバート・カミンズは、個人の行動を判断すべきではなく、むしろその行動が「人格に反映される」方法で判断すべきであると主張している。性格(定義は ともかく)が個人の選択を決定する主な要因であり、その選択が道徳的に間違っている場合、遺伝子やその他の要因に関係なく、その選択に対して責任を問われ るべきである。 法律では、道徳的な責任能力は個人の性格または自由意志による行為のいずれかにあるという前提に対する例外が知られている。心神喪失の抗弁(またはその派 生である責任能力の減退)は、罪を犯した行為が罪を犯した心によるものではないことを主張するために用いられることがある。[17] このような場合、西洋社会のほとんどの法制度では、その人格に何らかの欠陥があるのではなく、その行動は異常な脳機能の結果であると想定する(脳機能が心 や動機の決定論的な因果要因であることを暗示している)。 |

| Argument from luck The argument from luck is a criticism against the libertarian conception of moral responsibility. It suggests that any given action, and even a person's character, is the result of various forces outside a person's control. It may not be appropriate, then, to hold that person solely morally responsible.[18] Thomas Nagel suggests that four different types of luck (including genetic influences and other external factors) end up influencing the way that a person's actions are evaluated morally. For instance, a person driving drunk may make it home without incident, and yet this action of drunk driving might seem more morally objectionable if someone happens to jaywalk along his path (getting hit by the car).[19] This argument can be traced back to David Hume. If physical indeterminism is true, then those events that are not determined are scientifically described as probabilistic or random. It is therefore argued that it is doubtful that one can praise or blame someone for performing an action generated randomly by his nervous system (without there being any non-physical agency responsible for the observed probabilistic outcome).[20] |

運による論拠 運による論拠とは、自由意志論的な道徳的責任の概念に対する批判である。この論拠は、あらゆる行動、さらには人格さえも、個人の制御が及ばないさまざまな 力の産物であると主張する。それゆえ、その人物を道徳的にのみ責任を問うことは適切ではないかもしれない。[18] トーマス・ネーゲルは、4つの異なる種類の運(遺伝的影響やその他の外的要因を含む)が、最終的には個人の行動が道徳的に評価される方法に影響を与えると 示唆している。例えば、飲酒運転をした人物が何事もなく無事に家に帰れたとしても、その人物の運転ルート上で信号無視をした人物が車にはねられた場合、飲 酒運転の行為の方がより道徳的に問題があるように思えるかもしれない。[19] この議論はデイヴィッド・ヒュームにまで遡ることができる。もし物理的不確定性が真実であるならば、決定されていない事象は科学的には確率論的またはラン ダムなものとして説明される。したがって、神経系によってランダムに生成された行動を理由に、誰かを賞賛したり非難したりすることは疑わしいという主張が なされる(観察された確率的な結果に責任を持つ非物理的な要因が存在しない場合)。[20] |

| Hard determinism Main article: Hard determinism Hard determinists (not to be confused with fatalists) often use liberty in practical moral considerations, rather than a notion of a free will. Indeed, faced with the possibility that determinism requires a completely different moral system, some proponents say "So much the worse for free will!".[21] Clarence Darrow, the famous defense attorney, pleaded the innocence of his clients, Leopold and Loeb, by invoking such a notion of hard determinism.[22] During his summation, he declared: What has this boy to do with it? He was not his own father; he was not his own mother; he was not his own grandparents. All of this was handed to him. He did not surround himself with governesses and wealth. He did not make himself. And yet he is to be compelled to pay.[22] Paul the Apostle, in his Epistle to the Romans addresses the question of moral responsibility as follows: "Hath not the potter power over the clay, of the same lump to make one vessel unto honour, and another unto dishonour?"[23] In this view, individuals can still be dishonoured for their acts even though those acts were ultimately completely determined by God. Joshua Greene and Jonathan Cohen, researchers in the emerging field of neuroethics, argue, on the basis of such cases, that our current notion of moral responsibility is founded on libertarian (and dualist) intuitions.[24] They argue that cognitive neuroscience research (e.g. neuroscience of free will) is undermining these intuitions by showing that the brain is responsible for our actions, not only in cases of florid psychosis, but also in less obvious situations. For example, damage to the frontal lobe reduces the ability to weigh uncertain risks and make prudent decisions, and therefore leads to an increased likelihood that someone will commit a violent crime.[25] This is true not only of patients with damage to the frontal lobe due to accident or stroke, but also of adolescents, who show reduced frontal lobe activity compared to adults,[26] and even of children who are chronically neglected or mistreated.[27] In each case, the guilty party can, they argue, be said to have less responsibility for his actions.[24] Greene and Cohen predict that, as such examples become more common and well known, jurors' interpretations of free will and moral responsibility will move away from the intuitive libertarian notion that currently underpins them. They also argue that the legal system does not require this libertarian interpretation. Rather, they suggest that only retributive notions of justice, in which the goal of the legal system is to punish people for misdeeds, require the libertarian intuition. Many forms of ethically realistic and consequentialist approaches to justice, which are aimed at promoting future welfare rather than retribution, can survive even a hard determinist interpretation of free will. Accordingly, the legal system and notions of justice can thus be maintained even in the face of emerging neuroscientific evidence undermining libertarian intuitions of free will. |

ハードな決定論 詳細は「ハードな決定論」を参照 ハードな決定論者(宿命論者と混同してはならない)は、自由意志という概念よりも、実際的な道徳的考察において自由という言葉を用いることが多い。実際、 決定論が全く異なる道徳体系を必要とする可能性に直面した一部の支持者たちは、「自由意志などあってたまるか!」と主張している。[21] 有名な弁護士であったクラレンス・ダローは、硬い決定論の概念を援用して、レオポルドとローブの無実を主張した。[22] 彼の最終弁論では、次のように宣言した。 この少年と何の関係があるというのか? 彼は自分の父親でもなく、母親でもなく、祖父母でもない。 すべては彼に与えられたものだ。 彼は家庭教師や財産に囲まれていたわけではない。 彼がそうしたわけではない。 それなのに、彼は支払いを強いられるのだ。[22] 使徒パウロは、ローマ人への手紙の中で、道徳的責任の問題について次のように述べている。「陶工が粘土を自分の思いのままに、尊ぶべき器とも、卑しむべき 器とも作り得ないはずがあろうか」[23] この見解では、個人の行為は、究極的には神によって完全に決定されていたとしても、その行為によって不名誉を被る可能性がある。 神経倫理学という新興分野の研究者であるジョシュア・グリーンとジョナサン・コーエンは、このような事例を根拠に、私たちの現在の道徳的責任に関する概念 は自由意志論(および二元論)的な直観に基づいていると主張している。[24] 彼らは、認知神経科学の研究(例えば、自由意志の神経科学)は、脳が私たちの行動に責任を負っていることを明らかにしており、それは重度の精神病のケース だけでなく、それほど明白ではない状況においても当てはまるとして、これらの直観を覆そうとしていると主張している 。例えば、前頭葉に損傷があると、不確実なリスクを評価し、慎重な判断を下す能力が低下するため、暴力的犯罪を犯す可能性が高くなる。[25] これは、事故や脳卒中による前頭葉損傷の患者だけでなく、成人と比較して前頭葉の活動が低下している思春期の若者にも当てはまる。[26] さらに、慢性的に放置されたり虐待されたりしている子供にも当てはまる。[27] いずれの場合も、有罪判決を受けた人物は 、その行動に対する責任は軽いと言えるだろうと主張している。[24] グリーンとコーエンは、このような例がより一般的になり、広く知られるようになるにつれ、陪審員が自由意志と道徳的責任について解釈する際の考え方が、現 在それを支えている直感的なリバタリアン的考え方から離れていくと予測している。また、彼らは、法制度がこのような自由意志の解釈を必要としているわけで はないと主張している。むしろ、法制度の目的が悪事に対する処罰にあるような応報的な正義の概念のみが、自由意志の直観を必要としていると彼らは指摘して いる。自由意志を厳格に決定論的に解釈しても、将来の福祉の促進を目的とする倫理的に現実的で結果論的な正義のアプローチの多くは生き残ることができる。 したがって、自由意志の直観を損なう神経科学的な証拠が新たに発見されたとしても、法制度や正義の概念は維持できる。 |

David Eagleman explains that nature and nurture cause all criminal behavior. He likewise believes that science demands that change and improvement, rather than guilt, must become the focus of the legal justice system.[28] Neuroscientist David Eagleman maintains similar ideas. Eagleman says that the legal justice system ought to become more forward looking. He says it is wrong to ask questions of narrow culpability, rather than focusing on what is important: what needs to change in a criminal's behavior and brain. Eagleman is not saying that no one is responsible for their crimes, but rather that the "sentencing phase" should correspond with modern neuroscientific evidence. To Eagleman, it is damaging to entertain the illusion that a person can make a single decision that is somehow, suddenly, independent of their physiology and history. He describes what scientists have learned from brain damaged patients, and offers the case of a school teacher who exhibited escalating pedophilic tendencies on two occasions – each time as results of growing tumors.[29] Eagleman also warns that less attractive people and minorities tend to get longer sentencing – all of which he sees as symptoms that more science is needed in the legal system.[28] |

デビッド・イーグルマンは、犯罪行為は生まれつきの性質と環境の両方が原因で起こると説明している。同様に、科学は罪悪感よりも変化と改善を求めるものであり、それが法的な司法制度の焦点となるべきだと考えている。 神経科学者のデビッド・イーグルマンも同様の考えを持っている。イーグルマンは、法的な司法制度はより前向きになるべきだと主張している。重要なのは犯罪 者の行動や脳に何を変える必要があるかということに焦点を当てるべきであり、狭い範囲での罪の意識を問うのは間違っていると彼は言う。イーグルマンは、犯 罪に責任のない人間などいないと言っているのではなく、むしろ「量刑の段階」は現代の神経科学的な証拠と一致すべきだと主張している。イーグルマンにとっ て、ある人格が生理学や歴史とは無関係に、ある日突然、単独で意思決定を行うことができるという幻想を抱くことは有害である。彼は、脳障害患者から科学者 が学んだことを説明し、2度にわたって小児性愛傾向をエスカレートさせた学校教師の事例を紹介している。いずれも腫瘍の増大が原因であった。[29] イーグルマンはまた、容姿の良くない人やマイノリティがより長い刑期を科される傾向にあると警告している。彼は、これらすべてを、法制度に科学がより必要 とされている兆候であると見ている。[28] |

| Hard incompatibilism Derk Pereboom defends a skeptical position about free will he calls hard incompatibilism. In his view, we cannot have free will if our actions are causally determined by factors beyond our control, or if our actions are indeterministic events – if they happen by chance. Pereboom conceives of free will as the control in action required for moral responsibility in the sense involving deserved blame and praise, punishment and reward.[30] While he acknowledges that libertarian agent causation, the capacity of agents as substances to cause actions without being causally determined by factors beyond their control, is still a possibility, he regards it as unlikely against the backdrop of the most defensible physical theories. Without libertarian agent causation, Pereboom thinks the free will required for moral responsibility in the desert-involving sense is not in the offing.[31] However, he also contends that by contrast with the backward-looking, desert-involving sense of moral responsibility, forward-looking senses are compatible with causal determination. For instance, causally determined agents who act badly might justifiably be blamed with the aim of forming faulty character, reconciling impaired relationships, and protecting others from harm they are apt to cause.[32] Pereboom proposes that a viable criminal jurisprudence is compatible with the denial of deserved blame and punishment. His view rules out retributivist justifications for punishment, but it allows for incapacitation of dangerous criminals on the analogy with quarantine of carriers of dangerous diseases. Isolation of carriers of the Ebola virus can be justified on the ground of the right to defend against threat, a justification that does not reference desert. Pereboom contends that the analogy holds for incapacitation of dangerous criminals. He also argues that the less serious the threat, the more moderate the justifiable method of incapacitation; for certain crimes only monitoring may be needed. In addition, just as we should do what we can, within reasonable bounds, to cure the carriers of the Ebola virus we quarantine, so we should aim to rehabilitate and reintegrate the criminals we incapacitate. Pereboom also proposes that given hard incompatibilism, punishment justified as general deterrence may be legitimate when the penalties do not involve undermining an agent's capacity to live a meaningful, flourishing life, since justifying such moderate penalties need not invoke desert.[33] |

ハードな非適合主義 デレク・ペレブームは、自由意志について懐疑的な立場を擁護している。彼はそれをハードな非適合主義と呼んでいる。彼の考えでは、もし人間の行動が人間の 制御を超えた要因によって因果的に決定されている場合、あるいは、人間の行動が不確定な出来事、つまり偶然によって起こる場合、自由意志を持つことはでき ない。ペルブームは、自由意志を、非難や賞賛、処罰や報酬を受けるに値するという意味での道徳的責任を果たすために必要な行動の制御と捉えている。 [30] 彼は、自由意志的エージェント因果関係、すなわち、物質としてのエージェントが、制御できない要因によって因果的に決定されることなく行動を引き起こす能 力は、依然として可能性としてありうると認めているが、最も擁護しうる物理理論を背景に考えると、それはありそうもないと見なしている。自由意志による行 為の原因がなければ、ペレブームは、砂漠を伴う意味での道徳的責任に必要な自由意志は実現しないと考えている。[31] しかし、彼はまた、後ろ向きで砂漠を伴う意味での道徳的責任とは対照的に、前向きな意味での道徳的責任は因果決定と両立しうるとも主張している。例えば、 因果的に決定された行為者が悪事を働く場合、その人物の欠陥のある性格を形成し、損なわれた人間関係を修復し、その人物が引き起こしそうな危害から他者を 保護することを目的として、正当に非難される可能性がある。 ペルブームは、妥当な非難や処罰を否定するものではない、実行可能な刑法を提案している。彼の考えでは、刑罰の応報主義的正当化は排除されるが、危険な犯 罪者に対しては、危険な伝染病の感染者の隔離に類似した方法で、無能力化を認めることができる。エボラウイルスの感染者を隔離することは、脅威に対する防 衛の権利という根拠に基づいて正当化できるが、これは砂漠を参考にした正当化ではない。ペルブームは、この類似性は危険な犯罪者の無能力化にも当てはまる と主張している。また、脅威がそれほど深刻でない場合、無能力化の正当化される方法はより穏健なものになるとも主張している。特定の犯罪については、監視 のみが必要な場合もある。さらに、隔離するエボラウイルスのキャリアを治療するために、妥当な範囲内でできる限りのことをすべきであるのと同様に、無能力 化する犯罪者を更生させ、社会に再び受け入れることを目指すべきである。また、ペレブームは、厳格な相容れない主義を前提とすれば、一般抑止として正当化 される刑罰は、受刑者の有意義で充実した生活を送る能力を損なうものでない場合、正当化される可能性があると提案している。なぜなら、そのような穏健な刑 罰を正当化するにあたり、因果応報を必要としないからだ。[33] |

| Compatibilism Main article: Compatibilism.  Some forms of compatibilism suggest the term free will should only be used to mean something more like liberty. Compatibilists contend that even if determinism were true, it would still be possible for us to have free will. The Hindu text The Bhagavad Gita offers one very early compatibilist account. Facing the prospect of going to battle against kinsmen to whom he has bonds, Arjuna despairs. Krishna attempts to assuage Arjuna's anxieties. He argues that forces of nature come together to produce actions, and it is only vanity that causes us to regard ourselves as the agent in charge of these actions. However, Krishna adds this caveat: "... [But] the Man who knows the relation between the forces of Nature and actions, witnesses how some forces of Nature work upon other forces of Nature, and becomes [not] their slave..." When we are ignorant of the relationship between forces of Nature, we become passive victims of nomological facts. Krishna's admonition is intended to get Arjuna to perform his duty (i.e., fight in the battle), but he is also claiming that being a successful moral agent requires being mindful of the wider circumstances in which one finds oneself.[34] Paramahansa Yogananda also said, "Freedom means the power to act by soul guidance, not by the compulsions of desires and habits. Obeying the ego leads to bondage; obeying the soul brings liberation."[35] In the Western tradition, Baruch Spinoza echoes the Bhagavad Gita's point about agents and natural forces, writing "men think themselves free because they are conscious of their volitions and their appetite, and do not think, even in their dreams, of the causes by which they are disposed to wanting and willing, because they are ignorant [of those causes]."[31] Krishna is hostile to the influence of passions on our rational faculties, speaking up instead for the value of heeding the dictates of one's own nature: "Even a wise man acts under the impulse of his nature. Of what use is restraint?"[34] Spinoza similarly identifies the taming of one's passions as a way to extricate oneself from merely being passive in the face of external forces and a way toward following our own natures.[36] Jesus asserted that "There is a path that SEEMS right to a man which leads to Destruction". The contrapositive (equivalent) is the origin of this position of Spinoza. "If a man is Not on the road to destruction, then he has not taken the path that ONLY SEEMS right to him." P.F. Strawson is a major example of a contemporary compatibilist.[37] His paper "Freedom and Resentment," which adduces reactive attitudes, has been widely cited as an important response to incompatibilist accounts of free will.[38] Other compatibilists, who have been inspired by Strawson's paper, are as follows: Gary Watson,[39] Susan Wolf,[40] R. Jay Wallace,[41] Paul Russell,[42] and David Shoemaker.[43] |

適合主義 詳細は「適合主義」を参照  適合主義のいくつかの形態では、自由意志という用語は、より自由に近い意味でのみ使用されるべきであると提言している。 適合主義者は、決定論が真実であったとしても、自由意志を持つことは依然として可能であると主張する。ヒンドゥー教の聖典『バガヴァッド・ギーター』は、 非常に初期の適合主義者の見解を示している。絆のある親族と戦わなければならないという見通しに直面し、アルジュナは絶望する。クリシュナはアルジュナの 不安を和らげようとする。彼は、自然の力が集まって行動を生み出し、その行動の責任者として自らを考えるのは虚栄心に過ぎない、と主張する。しかし、クリ シュナは次のような注意を付け加えている。「...(しかし)自然の力と行動の関係を知る人間は、自然の力が他の自然の力に作用する様子を目撃し、それら の奴隷となることはない...」自然の力の関係を知らない場合、私たちは法則的事実の受動的な犠牲者となる。クリシュナの諭しはアルジュナに義務(すなわ ち戦い)を果たすよう促すものであるが、同時に、道徳的に成功した人間となるためには、自分が置かれているより広範な状況を意識することが必要であると主 張している。[34] パラマハンサ・ヨガナンダもまた、「自由とは、魂の導きによって行動する力であり、欲望や習慣の強制によるものではない。エゴに従うことは束縛につなが る。魂に従うことは解放をもたらす」[35] 西洋の伝統では、バールーフ・スピノザが『バガヴァッド・ギーター』の「人間は、意志や食欲を意識しているため、自由であると考えている。そして、無知で あるがゆえに、欲しがったり、望んだりする傾向にある原因について、夢の中でも考えない」という主張を繰り返している。[31] クリシュナは、情熱が人間の理性的な能力に及ぼす影響に敵対し、むしろ 「賢者といえども、本性に従って行動する。自制に何の益があろうか」[34]スピノザも同様に、情念を制御することは、外的要因にただ受動的に対処するの ではなく、自らの本性を貫くための方法であると主張している。[36] イエスは「人間にとって正しいと思われる道があるが、それは滅亡につながる」と主張した。逆命題(同値)がスピノザのこの立場を生み出す起源である。「人間が滅亡への道を歩んでいないのであれば、彼にとって正しいと思われる道だけを歩んではいない」 P.F.ストローソンは、現代の適合主義の主要な例である。[37] 彼の論文「自由と憤り」は反応的態度を導き出し、自由意志の非適合主義に対する重要な回答として広く引用されている。[38] ストローソンの論文に影響を受けたその他の適合主義者は以下の通りである。ゲイリー・ワトソン([39])、スーザン・ウォルフ([40])、R・ジェ イ・ウォレス([41])、ポール・ラッセル([42])、デビッド・シューメーカー([43])などである。 |

| Other views Daniel Dennett asks why anyone would care about whether someone had the property of responsibility and speculates that the idea of moral responsibility may be "a purely metaphysical hankering".[44] In this view, the denial of moral responsibility is the moral hankering to be able to assert that one has some fictitious right such as asserting PARENTAL rights instead of parent responsibility. Bruce Waller has argued, in Against Moral Responsibility (MIT Press), that moral responsibility "belongs with the ghosts and gods and that it cannot survive in a naturalistic environment devoid of miracles".[45] We cannot punish another for wrong acts committed, contends Waller, because the causal forces which precede and have brought about the acts may ultimately be reduced to luck, namely, factors over which the individual has no control. One may not be blamed even for one's character traits, he maintains, since they too are heavily influenced by evolutionary, environmental, and genetic factors (inter alia).[45] Although his view would fall in the same category as the views of philosophers like Dennett who argue against moral responsibility, Waller's view differs in an important manner: He tries to, as he puts it, "rescue" free will from moral responsibility (See Chapter 3).[46] This move goes against the commonly held assumption that how one feels about free will is ipso facto a claim about moral responsibility.[47] |

その他の見解 ダニエル・デネットは、なぜ誰かが責任能力を持つかどうかを気にかけるのかと問い、道徳的責任という考えは「純粋に形而上学的な渇望」である可能性がある と推測している。[44] この見解では、道徳的責任を否定することは、親としての権利を主張する代わりに親としての責任を主張するなど、架空の権利を主張できることを望む道徳的な 渇望である。 ブルース・ウォーラーは著書『Against Moral Responsibility』(MIT Press)の中で、道徳的責任は「幽霊や神々のものであり、奇跡のない自然主義的な環境では生き残れない」と主張している。[45] ウォーラーは、他者が犯した悪行を罰することはできないと主張している。なぜなら、その行為の前に存在し、その行為を引き起こした因果関係は、最終的には 運、すなわち個人が制御できない要因に還元される可能性があるからだ。また、個人の性格的特徴についても、進化論的、環境的、遺伝的要素(特に)の影響を 強く受けるため、非難されるべきではないと主張している。[45] ウォーラーの見解は、デネットのような道徳的責任に反対する哲学者の見解と同じ範疇に属するが、ウォーラーの見解は重要な点で異なる。彼は、自身の表現を 借りれば、自由意志を道徳的責任から「救済」しようとしている(第3章参照)[46]。この主張は、自由意志についてどう考えるかは、道徳的責任について の主張であるという、一般的に受け入れられている前提に反するものである[47]。 |

| Epistemic condition for moral responsibility In philosophical discussions of moral responsibility, two necessary conditions are usually cited: the control (or freedom) condition (which answers the question 'did the individual doing the action in question have free will?') and the epistemic condition, the former of which is explored in the above discussion.[48][49] The epistemic condition, in contrast to the control condition, focuses on the question 'was the individual aware of, for instance, the moral implications of what she did?' Not all philosophers think this condition to be a distinct condition, separate from the control condition: For instance, Alfred Mele thinks that the epistemic condition is a component of the control condition.[50] Nonetheless, there seems to be a philosophical consensus of sorts that it is both distinct and explanatorily relevant.[51] One major concept associated with the condition is "awareness". According to those philosophers who affirm this condition, one needs to be "aware" of four things to be morally responsible: the action (which one is doing), its moral significance, consequences, and alternatives.[49] |

道徳的責任の認識論的条件 道徳的責任に関する哲学的な議論では、通常、次の2つの必要条件が挙げられる。すなわち、コントロール(または自由)条件(「問題となっている行動を行っ た個人は自由意志を持っていたか?」という問いに対する答え)と、エピステーメー条件である。エピステーメー条件は、コントロール条件とは対照的に、「そ の個人は、例えば、自分がしたことの道徳的な意味合いについて認識していたか?」という問いに焦点を当てている。すべての哲学者が、この条件をコントロー ル条件とは別個の独立した条件であると考えているわけではない。例えば、アルフレッド・メレは、認識条件はコントロール条件の構成要素であると考えてい る。[50] とはいえ、この条件が独立したものであり、かつ説明上関連性があるという点については、ある種の哲学的コンセンサスがあるようである。[51] この条件に関連する主要な概念のひとつは「認識」である。この条件を肯定する哲学者によると、道徳的責任を負うためには、4つのことを「認識」する必要が ある。すなわち、実行している行為、その道徳的意義、結果、代替案である。[49] |

| Experimental research Mauro suggests that a sense of personal responsibility does not operate or evolve universally among humankind. He argues that it was absent in the successful civilization of the Iroquois.[52] In recent years, research in experimental philosophy has explored whether people's untutored intuitions about determinism and moral responsibility are compatibilist or incompatibilist.[53] Some experimental work has included cross-cultural studies.[54] However, the debate about whether people naturally have compatibilist or incompatibilist intuitions has not come out overwhelmingly in favor of one view or the other, finding evidence for both views. For instance, when people are presented with abstract cases that ask if a person could be morally responsible for an immoral act when they could not have done otherwise, people tend to say no, or give incompatibilist answers. When presented with a specific immoral act that a specific person committed, people tend to say that that person is morally responsible for their actions, even if they were determined (that is, people also give compatibilist answers).[55] The neuroscience of free will investigates various experiments that might shed light on free will.[citation needed] One of the attributes defined for psychopathy is "failure to accept responsibility for own actions".[56] |

実験的研究 マウロは、個人の責任感は人類全体に普遍的に作用したり進化したりするものではないと示唆している。彼は、イロコイ族の文明が成功を収めたにもかかわらず、その責任感は欠如していたと主張している。[52] 近年、実験哲学の研究では、決定論と道徳的責任に関する人々の無教育な直観が両立説か非両立説であるかを探究している。[53] 実験研究の中には、異文化研究も含まれている。[54] しかし、人々が自然に両立説的直観を持つのか、それとも非両立説的直観を持つのかという議論については、どちらかの見解を圧倒的に支持する結果は出ておら ず、両方の見解の証拠が発見されている。例えば、人が「他に選択肢がなかった場合、非道徳的な行為に対して道徳的な責任を負うことは可能か」という抽象的 な事例を提示された場合、人は「ノー」と答えたり、非相容説的な回答をする傾向がある。特定の人物が犯した具体的な非道徳的な行為を提示された場合、人は その人物の行為に対して道徳的な責任があると答える傾向があるが、その人物が決定した(つまり、相容説的な回答もする)場合もある。[55] 自由意志の神経科学では、自由意志について解明する手がかりとなりそうな様々な実験が調査されている。 サイコパシーの特性のひとつとして、「自身の行動に対する責任を受け入れない」ことが挙げられている。 |

| Collective Main article: Collective responsibility. When people attribute moral responsibility, they usually attribute it to individual moral agents.[57] However, Joel Feinberg, among others, has argued that corporations and other groups of people can have what is called ‘collective moral responsibility’ for a state of affairs.[58] For example, when South Africa had an apartheid regime, the country's government might have been said to have had collective moral responsibility for the violation of the rights of non-European South Africans. |

集団的 主な記事:集団的責任 人々が道徳的責任を帰属させる場合、通常は個々の道徳的行為者に帰属させる。[57] しかし、ジョエル・ファインバーグをはじめとする人々は、企業やその他の集団が、ある状況に対して「集団的」道徳的責任を負うことができると主張してい る。[58] 例えば、南アフリカがアパルトヘイト体制を敷いていた時代、非ヨーロッパ系南アフリカ人の権利侵害に対して、同国の政府は集団的責任を負っていたと言える かもしれない。 |

| Artificial systems This section needs to be updated. The reason given is: the designs discussed here are mostly obsolete (in particular rule-based programs where the behavior is explicitly programmed by humans). Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (April 2024) The emergence of automation, robotics and related technologies prompted the question, 'Can an artificial system be morally responsible?'[59][60][61] The question has a closely related variant, 'When (if ever) does moral responsibility transfer from its human creator(s) to the system?'.[62][63] The questions arguably adjoin with but are distinct from machine ethics, which is concerned with the moral behavior of artificial systems. Whether an artificial system's behavior qualifies it to be morally responsible has been a key focus of debate. |

人工システム このセクションは更新が必要である。その理由は、ここで議論されている設計のほとんどは時代遅れであるためである(特に、人間の行動が明示的にプログラム されたルールベースのプログラム)。最近の出来事や新たに利用可能になった情報を反映させるため、この記事の更新にご協力ください。(2024年4月) オートメーション、ロボット工学、関連技術の出現により、「人工システムに道徳的責任を負わせることができるか」という疑問が提起された[59][60] [61]。この疑問には、「道徳的責任は、いつ(もしあれば)、人間である創造者からシステムへと移転するのか」という、密接に関連する別の疑問がある [62][63]。 この問題は、人工システムの道徳的な行動を扱う「機械倫理」と隣接するものであるが、明確に区別されるものである。人工システムの行動が道徳的な責任を負うのにふさわしいものであるかどうかは、議論の中心的な焦点となっている。 |

| Arguments that artificial systems cannot be morally responsible Batya Friedman and Peter Kahn Jr. posited that intentionality is a necessary condition for moral responsibility, and that computer systems as conceivable in 1992 in material and structure could not have intentionality.[64] Arthur Kuflik asserted in 1999 that humans must bear the ultimate moral responsibility for a computer's decisions, as it is humans who design the computers and write their programs. He further proposed that humans can never relinquish oversight of computers.[63] Frances Grodzinsky et al. considered artificial systems that could be modelled as finite-state machines. They posited in 2008 that if the machine had a fixed state transition table, then it could not be morally responsible. If the machine could modify its table, then the machine's designer still retained some moral responsibility.[62] Patrick Hew argued that for an artificial system to be morally responsible, its rules for behaviour and the mechanisms for supplying those rules must not be supplied entirely by external humans. He further argued that such systems are a substantial departure from technologies and theory as extant in 2014. An artificial system based on those technologies will carry zero responsibility for its behaviour. Moral responsibility is apportioned to the humans that created and programmed the system.[65] |

人工システムに道徳的責任能力はないという主張 バティア・フリードマンとピーター・カーン・ジュニアは、道徳的責任能力には意図性が必要条件であり、1992年当時考えられる材料や構造のコンピュータシステムには意図性はないと主張した。[64] アーサー・クーフリックは1999年に、コンピュータを設計し、そのプログラムを書くのは人間であるため、コンピュータの決定に対して最終的な道徳的責任 を負うのは人間でなければならないと主張した。さらに、人間はコンピュータの監督を放棄することは決してできないと提案した。 フランシス・グロジンスキー(Frances Grodzinsky)らは、有限状態機械としてモデル化できる人工システムについて考察した。彼らは2008年に、機械が固定状態遷移表を持つ場合、そ の機械には道徳的責任はないと仮定した。機械がその表を修正できる場合、機械の設計者は依然として道徳的責任を負うことになる。 パトリック・ヒューは、人工システムが道徳的責任を負うためには、その行動のルールと、それらのルールを供給するメカニズムが、完全に外部の人間によって 供給されてはならないと主張した。さらに、そのようなシステムは、2014年現在の技術や理論から大幅に逸脱していると主張した。そのような技術に基づく 人工システムは、その行動に対して一切の責任を負わない。道徳的責任は、そのシステムを創造し、プログラムした人間に帰属する。[65] |

| Arguments that artificial systems can be morally responsible Colin Allen et al. proposed that an artificial system may be morally responsible if its behaviours are functionally indistinguishable from a moral person, coining the idea of a 'Moral Turing Test'.[59] They subsequently disavowed the Moral Turing Test in recognition of controversies surrounding the Turing Test.[60] Andreas Matthias described a 'responsibility gap' where to hold humans responsible for a machine would be an injustice, but to hold the machine responsible would challenge 'traditional' ways of ascription. He proposed in 2004 three cases where the machine's behaviour ought to be attributed to the machine and not its designers or operators. First, he argued that modern machines are inherently unpredictable (to some degree), but perform tasks that need to be performed yet cannot be handled by simpler means. Second, that there are increasing 'layers of obscurity' between manufacturers and system, as hand coded programs are replaced with more sophisticated means. Third, in systems that have rules of operation that can be changed during the operation of the machine.[66] A more extensive review of the arguments may be found in Patrick Hew's 2014 article on artificial moral agents.[65] |

人工システムにも道徳的責任能力があるという主張 コリン・アレン(Colin Allen)らは、人工システムが道徳的人格と機能的に区別できない行動を取る場合、そのシステムに道徳的責任能力がある可能性があると提案し、「道徳的 チューリングテスト」という考え方を打ち出した。[59] その後、チューリングテストを巡る論争を認識し、彼らは道徳的チューリングテストを否定した。[60] アンドレアス・マティアスは、人間に責任を負わせることは不当であるが、機械に責任を負わせることは「伝統的な」帰属の方法を否定することになるという 「責任のギャップ」について説明した。彼は2004年に、機械の挙動が設計者やオペレーターではなく機械に帰属されるべき3つのケースを提案した。第一 に、現代の機械は(ある程度)本質的に予測不可能であるが、実行する必要があるがより単純な手段では処理できないタスクを実行すると主張した。第二に、手 作業でコーディングされたプログラムがより洗練された手段に置き換えられるにつれ、メーカーとシステムの間には「不明瞭な層」が増加している。第三に、機 械の稼働中に操作のルールを変更できるシステムにおいて、[66] この議論に関するより詳細な検討は、パトリック・ヒューによる2014年の人工道徳エージェントに関する記事を参照のこと。[65] |

| Ability Accountability Declaration of Human Duties and Responsibilities House of Responsibility Incompatibilism Legal liability Moral agency Moral hazard |

能力 説明責任 人間としての義務と責任の宣言 責任の家 両立不可能性 法的責任 道徳的行為 モラルハザード |

| Evans, Rod L. (2008).

"Responsibility". In Hamowy, Ronald (ed.). The Encyclopedia of

Libertarianism. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage; Cato Institute. pp. 425–427.

doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n261. ISBN 978-1412965804. LCCN 2008009151.

OCLC 750831024. Hejdánek, Ladislav (1990). Nothingness and Responsibility. Online text. Meyer, Susan Sauvé, Chappell, T.D.J. 'Aristotle on Moral Responsibility' . Book review, Mind, New Series, Vol. 105, No. 417 (Jan., 1996), pp. 181–186, Oxford University Press. Klein, Martha (1995). "Responsibility". In Ted Honderich (ed.). The Oxford Companion to Philosophy. Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0198661320. Risser, David T. (2006). "Collective Moral Responsibility". Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Retrieved 8 September 2007. Rosebury, Brian (October 1995). "Moral Responsibility and "Moral Luck"". The Philosophical Review. 104 (4): 499–524. doi:10.2307/2185815. JSTOR 2185815. Waller, Bruce N. (2005). "Freedom, Moral Responsibility, and Ethics". Consider Ethics: Theory, Readings and Contemporary Issues. New York: Pearson Longman. pp. 215–233. ISBN 978-0321202802. |

エヴァンス、ロッド・L. (2008年).

「責任」。ハモウィー、ロナルド(編)『リバタリアニズム百科事典』。カリフォルニア州サウザンドオークス:セイジ、ケイトー研究所。425-427ペー

ジ。doi:10.4135/9781412965811.n261。ISBN 978-1412965804。LCCN 2008009151.

OCLC 750831024. ヘイダネック、ラディスラフ(1990年)。『無と責任』。オンラインテキスト。 Meyer, Susan Sauvé, Chappell, T.D.J. 『アリストテレスにおける道徳的責任』。書評、Mind, New Series, Vol. 105, No. 417 (Jan., 1996), pp. 181–186, Oxford University Press. クライン、マーサ(1995年)。「責任」。テッド・ホンデリッチ(編)『オックスフォード哲学事典』オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0198661320。 リサー、デビッド・T(2006年)。「集団的責任」。インターネット哲学事典。2007年9月8日取得。 Rosebury, Brian (October 1995). 「Moral Responsibility and 」Moral Luck「」. The Philosophical Review. 104 (4): 499–524. doi:10.2307/2185815. JSTOR 2185815. ウォーラー、ブルース・N. (2005年). 「自由、道徳的責任、そして倫理」. 『倫理を考える:理論、文献、現代の諸問題』. ニューヨーク: Pearson Longman. pp. 215–233. ISBN 978-0321202802. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moral_responsibility |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆