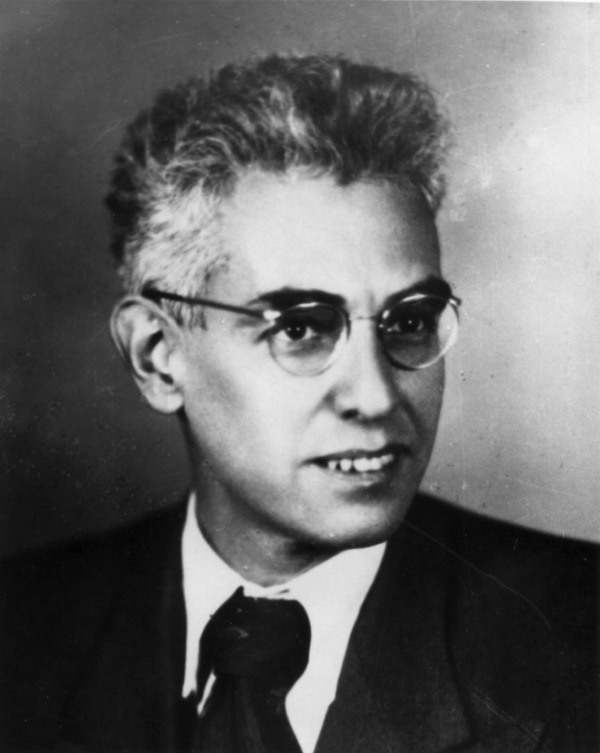

アレクサンドル・ルリヤ

Алекса́ндр Рома́нович Лу́рия,

Alexander R. Luria, Aleksandr Romanovich Luriya, 1902-1977

解説:池田光穂

■ルリア略伝——ウィキペディア記事:アレクサンドル・R・ルリア(Alexander Luria, 1902-1977)を参照した。

1902 7月16日カザンで生 まれる。

---- ギムナジウムを6年間で卒業(通常は8年)

1918 カザン大学(Kazan (Volga region) Federal University)入学(ロシア10月革命時)

1921 カザン大学社会科学部卒業

1923 クルプスカヤ名称共産主義教育アカデミーで研究開始

1925 1925年よりモスクワ大学心理学研究所でコンスタンチン・コルニーロフ の助手

1925 以降

「この研究所でレフ・ヴィゴツ キーおよびアレクセイ・レオンチェフとともに文化的および歴史的視点から精神発達を論ずる文化歴史心理学 (cultural-historical psychology) を創始」ヴィゴツキーの影響をうけること大いなるものがあったという(→白熊の三段論法)。

1928 『激情的反応の研究における随伴運動の方法』

1930 (スターリン粛正期)『行動の歴史に関する試論』をヴィゴツキーと共著

ca.1930 モスクワ第一医科大学 (First Moscow Institute of Medicine) 入学

1937 教育学博士

1943 医学博士

1944 脳外科研究施設。神経心理学 (neuropsychology) を創始。

1947 『外傷性失語症』公刊。後に、反パブロフ主義とみなされて糾弾され、同施設を辞任。

1953 モスクワ大学教授として学者としての活動を再開(同年、スターリン死去)

1977 8月14日死去(75歳)

| Alexander Romanovich

Luria (Russian: Алекса́ндр Рома́нович Лу́рия; 16 July 1902 – 14 August

1977) was a Soviet neuropsychologist, often credited as a father of

modern neuropsychology. He developed an extensive and original battery

of neuropsychological tests during his clinical work with brain-injured

victims of World War II, which are still used in various forms. He made

an in-depth analysis of the functioning of various brain regions and

integrative processes of the brain in general. Luria's magnum opus,

Higher Cortical Functions in Man (1962), is a much-used psychological

textbook which has been translated into many languages and which he

supplemented with The Working Brain in 1973. It is less known that Luria's main interests, before the war, were in the field of cultural and developmental research in psychology. He became famous for his studies of low-educated populations of nomadic Uzbeks in the Uzbek SSR arguing that they demonstrate different (and lower) psychological performance than their contemporaries and compatriots under the economically more developed conditions of socialist collective farming (the kolkhoz). He was one of the founders of Cultural-Historical Psychology and a colleague of Lev Vygotsky.[1][2] Apart from his work with Vygotsky, Luria is widely known for two extraordinary psychological case studies: The Mind of a Mnemonist, about Solomon Shereshevsky, who had highly advanced memory; and The Man with a Shattered World, about Lev Zasetsky, a man with a severe traumatic brain injury. During his career Luria worked in a wide range of scientific fields at such institutions as the Academy of Communist Education (1920-1930s), Experimental Defectological Institute (1920-1930s, 1950-1960s, both in Moscow), Ukrainian Psychoneurological Academy (Kharkiv, early 1930s), All-Union Institute of Experimental Medicine, and the Burdenko Institute of Neurosurgery (late 1930s). A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Luria as the 69th most cited psychologist of the 20th century. |

アレクサンドル・ロマノヴィッチ・ルリア(ロシア語:

Алекса́ндр Рома́нович Лу́рия; 1902年7月16日 -

1977年8月14日)はソビエトの神経心理学者で、しばしば近代神経心理学の父と称される。第二次世界大戦の脳障害者の臨床に携わる中で、広範かつ独創

的な神経心理学的検査法を開発し、現在もさまざまな形で用いられている。ルリアは、さまざまな脳領域の機能と脳の統合プロセス全般について詳細な分析を

行った。ルリアの代表作である『Higher Cortical Functions in

Man』(1962年)は、多くの言語に翻訳され、1973年には『The Working Brain』で補完された心理学の教科書である。 戦前のルリアの主な関心が、心理学における文化的・発達的研究の分野にあったことはあまり知られていない。彼は、ウズベクソビエト連邦の遊牧民であるウズ ベク人の低学歴集団に関する研究で有名になり、彼らが社会主義的集団農業(コルホーズ)という経済的に発展した条件のもとで、同時代の人々や同胞とは異な る(そして低い)心理的パフォーマンスを示すと主張した。彼は文化史的心理学の創始者の一人であり、レフ・ヴィゴツキーの同僚であった[1][2]。ヴィ ゴツキーとの仕事とは別に、ルリアは2つの驚異的な心理学的事例研究で広く知られている: 高度な記憶力を持つソロモン・シェレシェフスキーを扱った『Mind of a Mnemonist』と、重度の外傷性脳障害を持つレフ・ザセツキーを扱った『The Man with a Shattered World』である。 ルリアはそのキャリアの中で、共産主義教育アカデミー(1920-1930年代)、実験欠陥学研究所(1920-1930年代、1950-1960年代、 いずれもモスクワ)、ウクライナ精神神経学アカデミー(ハリコフ、1930年代前半)、全ソ連実験医学研究所、ブルデンコ神経外科研究所(1930年代後 半)といった機関で、幅広い科学分野に携わった。2002年に発表されたReview of General Psychologyの調査では、ルリアは20世紀で最も引用された心理学者の69位にランクされている。 |

| Life and career Early life and childhood Luria was born on 16 July 1902,[3] to Jewish parents in Kazan, a regional centre east of Moscow. Many of his family were in medicine. According to Luria's biographer Evgenia Homskaya, his father, Roman Albertovich Luria was a therapist who "worked as a professor at the University of Kazan; and after the Russian Revolution, he became a founder and chief of the Kazan Institute of Advanced Medical Education."[4][5] Two monographs of his father's writings were published in Russian under the titles, Stomach and Gullet Illnesses (1935) and Inside Look at Illness and Gastrogenic Diseases (1935).[6] His mother, Evgenia Viktorovna (née Khaskina), became a practicing dentist after finishing college in Poland. Luria was one of two children; his younger sister Lydia became a practicing psychiatrist.[7] Early education and move to Moscow Luria finished school ahead of schedule and completed his first degree in 1921 at Kazan State University. While still a student in Kazan, he established the Kazan Psychoanalytic Society and briefly exchanged letters with Sigmund Freud. Late in 1923, he moved to Moscow, where he lived on Arbat Street. His parents later followed him and settled down nearby. In Moscow, Luria was offered a position at the Moscow State Institute of Experimental Psychology, run from November 1923 by Konstantin Kornilov. In 1924, Luria met Lev Vygotsky,[8] who would influence him greatly. The union of the two psychologists gave birth to what subsequently was termed the Vygotsky, or more precisely, the Vygotsky-Luria Circle. During the 1920s Luria also met a large number of scholars, including Aleksei Leontiev, Mark Lebedinsky, Alexander Zaporozhets, Bluma Zeigarnik, many of whom would remain his lifelong colleagues. Following Vygotsky and along with him, in mid-1920s Luria launched a project of developing a psychology of a radically new kind. This approach fused "cultural", "historical", and "instrumental" psychology and is most commonly referred to presently as cultural-historical psychology. It emphasizes the mediatory role of culture, particularly language, in the development of higher psychological functions in ontogeny and phylogeny. Independently of Vygotsky, Luria developed the ingenious "combined motor method," which helped diagnose individuals' hidden or subdued emotional and thought processes. This research was published in the US in 1932 as The Nature of Human Conflicts and made him internationally famous as one of the leading psychologists in Soviet Russia. In 1937, Luria submitted the manuscript in Russian and defended it as a doctoral dissertation at the University of Tbilisi (not published in Russian until 2002). Luria wrote three books during the 1920s after moving to Moscow, The Nature of Human Conflicts (in Russian, but during Luria's lifetime published only in English translation in 1932 in the US), Speech and Intellect in Child Development, and Speech and Intellect of Urban, Rural and Homeless Children (both in Russian). The second title came out in 1928, while the other two were published in the 1930s. In early 1930s both Luria and Vygotsky started their medical studies in Kharkiv, then, after Vygotsky's death in 1934, Luria completed his medical education at 1st Moscow Medical Institute. Multiculturalism and neurology The 1930s were significant to Luria because his studies of indigenous people opened the field of multiculturalism to his general interests.[9] This interest would be revived in the later twentieth century by a variety of scholars and researchers who began studying and defending indigenous peoples throughout the world[citation needed]. Luria's work continued in this field with expeditions to Central Asia. Under the supervision of Vygotsky, Luria investigated various psychological changes (including perception, problem solving, and memory) that take place as a result of cultural development of undereducated minorities. In this regard he has been credited with a major contribution to the study of orality.[10] In response to Lysenkoism's purge of geneticists,[11][12] Luria decided to pursue a physician degree, which he completed with honors in the summer of 1937. After rewriting and reorganizing his manuscript for The Nature of Human Conflicts, he defended it for a doctoral dissertation at the Institute of Tbilisi in 1937, and was appointed Doctor of Pedagogical Sciences. "At the age of thirty-four, he was one of the youngest professors of psychology in the country."[13] In 1933, Luria married Lana P. Lipchina, a well-known specialist in microbiology with a doctorate in the biological sciences.[14] The couple lived in Moscow on Frunze Street, where their only daughter Lena (Elena) was born.[14] Luria also studied identical and fraternal twins in large residential schools to determine the interplay of various factors of cultural and genetic human development. In his early neuropsychological work in the end of the 1930s as well as throughout his postwar academic life he focused on the study of aphasia, focusing on the relation between language, thought, and cortical functions, particularly on the development of compensatory functions for aphasia. World War II and aftermath For Luria, the war with Germany that ended in 1945 resulted in a number of significant developments for the future of his career in neuropsychology. He was appointed Doctor of Medical Sciences in 1943 and Professor in 1944. Of specific importance for Luria was that he was assigned by the government to care for nearly 800 hospitalized patients with traumatic brain injury caused by the war.[15] Luria's treatment methods dealt with a wide range of emotional and intellectual dysfunctions.[15] He kept meticulous notes on these patients, and discerned from them three possibilities for functional recovery: "(1) disinhibition of a temporarily blocked function; (2) involvement of the vicarious potential of the opposite hemisphere; and (3) reorganization of the function system", which he described in a book titled Functional Recovery From Military Brain Wounds, (Moscow, 1948, Russian only.) A second book titled Traumatic Aphasia was written in 1947 in which "Luria formulated an original conception of the neural organization of speech and its disorders (aphasias) that differed significantly from the existing western conceptions about aphasia."[16] Soon after the end of the war, Luria was assigned a permanent position in General Psychology at the central Moscow State University in General Psychology, where he would predominantly stay for the remainder of his life; he was instrumental in the foundation of the Faculty of Psychology, and later headed the Departments of Patho- and Neuropsychology. By 1946, his father, the chief of the gastroenterological clinics at Botkin Hospital, had died of stomach cancer. His mother survived several more years, dying in 1950.[17] 1950s Following the war, Luria continued his work in Moscow's Institute of Psychology. For a period of time he was removed from the Institute of Psychology, and in the 1950s he shifted to research on intellectually disabled children at the Defectological Institute. Here he did his most pioneering research in child psychology, and was able to permanently disassociate himself from the influence that was then still exerted in the Soviet Union by Pavlov's early research.[18] Luria said publicly that his own interests were limited to a specific examination of "Pavlov's second signal system" and did not concern Pavlov's simplified primary explanation of human behavior as based on a "conditioned reflex by means of positive reinforcement".[19] Luria's continued interest in the regulative function of speech was further revisited in the mid-1950s and was summarized in his 1957 monograph titled The Role of Speech in the Regulation of Normal and Abnormal Behavior. In this book Luria summarized his principal concerns in this field through three succinct points summarized by Homskaya as: "(1) the role of speech in the development of mental processes; (2) the development of the regulative function of speech; and (3) changes in the regulative functions of speech caused by various brain pathologies."[20] Luria's main contributions to child psychology during the 1950s are well summarized by the research collected in a two-volume compendium of collected research published in Moscow in 1956 and 1958 under the title of Problems of Higher Nervous System Activity in Normal and Anomalous Children. Homskaya summarizes Luria's approach as centering on: "The application of the Method of Motor Associations (which) allowed investigators to reveal difficulties experienced by (unskilled) children in the process of forming conditioned links as well as restructuring and compensating by means of speech ... (Unskilled) children demonstrated acute dysfunction of the generalizing and regulating functions of speech."[21] Taking this direction, already by the mid-1950s, "Luria for the first time proposed his ideas about the differences of neurodynamic processes in different functional systems, primarily in verbal and motor systems."[22] Luria identified the three stages of language development in children in terms of "the formation of the mechanisms of voluntary actions: actions in the absence of a regulative verbal influence, actions with a nonspecific influence, and, finally, actions with a selective verbal influence."[20] For Luria, "The regulating function of speech thus appears as a main factor in the formation of voluntary behavior ... at first, the activating function is formed, and then the inhibitory, regulatory function."[23] Cold War In the 1960s, at the height of the Cold War, Luria's career expanded significantly with the publication of several new books. Of special note was the publication in 1962 of Higher Cortical Functions in Man and Their Impairment Caused by Local Brain Damage. The book has been translated into multiple foreign languages and has been recognized as the principal book establishing Neuropsychology as a medical discipline in its own right.[24] Previously, at the end of the 1950s, Luria's charismatic presence at international conferences had attracted almost worldwide attention to his research, which created a receptive medical audience for the book. Luria's other books written or co-authored during the 1960s included: Higher Brain and Mental Processes (1963), The Neuropsychological Analysis of Problem Solving (1966, with L. S. Tzvetkova; English translation in 1990), Psychophysiology of the Frontal Lobes (first published in 1973), and Memory Disorders in Patients with Aneurysms of the Anterior Communicating Artery (co-authored with A. N. Konovalov and A. N. Podgoynaya). In studying memory disorders, Luria oriented his research to the distinction of long-term memory, short-term memory, and semantic memory. It was important for Luria to differentiate neuropsychological pathologies of memory from neuropsychological pathologies of intellectual operations.[25] These two types of pathology were often characterized by Luria as; "(1) the inability to make particular arithmetical operations while the general control of intellectual activity remained normal (predominantly occipital disturbances)... (2) the disability of general control over intellectual processes (predominantly frontal lobe disturbances."[26] Another of Luria's important book-length studies from the 1960s which would only be published in 1975 (and in English in 1976) was his well-received book titled Basic Problems of Neurolinguistics. Late writings Luria's productive rate of writing new books in neuropsychology remained largely undiminished during the 1970s and the last seven years of his life. Significantly, volume two of his Human Brain and Mental Processes appeared in 1970 under the title Neuropsychological Analysis of Conscious Activity, following the first volume from 1963 titled The Brain and Psychological Processes. The volume confirmed Luria's long sustained interest in studying the pathology of frontal lobe damage as compromising the seat of higher-order voluntary and intentional planning. Psychopathology of the Frontal Lobes, co-edited with Karl Pribram, was published in 1973. Luria published his well-known book The Working Brain in 1973 as a concise adjunct volume to his 1962 book Higher Cortical Functions in Man. In this volume, Luria summarized his three-part global theory of the working brain as being composed of three constantly co-active processes, which he described as: the attentional (sensory-processing) system the mnestic-programming system the energetic maintenance system, with two levels: cortical and limbic This model was later used as a structure of the Functional Ensemble of Temperament model matching functionality of neurotransmitter systems. The two books together are considered by Homskaya as "among Luria's major works in neuropsychology, most fully reflecting all the aspects (theoretical, clinical, experimental) of this new discipline."[27] Among his late writings are also two extended case studies directed toward the popular press and a general readership, in which he presented some of the results of major advances in the field of clinical neuropsychology. These two books are among his most popular writings. According to Oliver Sacks, in these works "science became poetry".[28] In The Mind of a Mnemonist (1968), Luria studied Solomon Shereshevsky, a Russian journalist with a seemingly unlimited memory, sometimes referred to in contemporary literature as "flashbulb" memory, in part due to his fivefold synesthesia. In The Man with the Shattered World (1971) he documented the recovery under his treatment of the soldier Lev Zasetsky, who had experienced a brain wound in World War II. In 1974 and 1976, Luria presented successively his two-volume research study titled The Neuropsychology of Memory. The first volume was titled Memory Dysfunctions Caused by Local Brain Damage and the second Memory Dysfunctions Caused by Damage to Deep Cerebral Structures. Luria's book written in the 1960s titled Basic Problems of Neurolinguistics was finally published in 1975, and was matched by his last book, Language and Cognition, published posthumously in 1980. Luria's last co-edited book, with Homskaya, was titled Problems of Neuropsychology and appeared in 1977.[29] In it, Luria was critical of simplistic models of behaviorism and indicated his preference for the position of "Anokhin's concept of 'functional systems,' in which the reflex arc is substituted by the notion of a 'reflex ring' with a feedback loop."[30] In this approach, the classical physiology of reflexes was to be downplayed while the "physiology of activity" as described by Bernshtein was to be emphasized concerning the active character of human active functioning.[30] Luria's death is recorded by Homskaya in the following words: "On June 1, 1977, the All-Union Psychological Congress started its work in Moscow. As its organizer, Luria introduced the section on neuropsychology. The next day's meeting, however, he was not able to attend. His wife Lana Pimenovna, who was extremely sick, had an operation on June 2. During the following two and a half months of his life, Luria did everything possible to save or at least to soothe his wife. Not being able to comply with this task, he died of a myocardial infarction on August 14. His funeral was attended by an endless number of people -- psychologists, teachers, doctors, and just friends. His wife died six months later."[31] |

生涯とキャリア[編集] 生い立ちと幼少期[編集]。 ルリアは1902年7月16日、モスクワの東にある地方都市カザンのユダヤ人の両親のもとに生まれた[3]。彼の家族の多くは医学に携わっていた。ルリア の伝記作家エフゲニア・ホムスカヤによれば、父ロマン・アルベルトヴィチ・ルリアは療法士で、「カザン大学で教授を務めた。 父親の著作からなる2冊の単行本が、『胃と腸の病気』(1935年)と『病気と胃腸病の内面』(1935年)というタイトルでロシア語で出版された。妹の リディアは精神科医となった[7]。 幼少期の教育とモスクワへの移住[編集]。 ルリアは予定よりも早く学校を卒業し、1921年にカザン国立大学で最初の学位を取得した。カザンでの在学中にカザン精神分析協会を設立し、ジークムン ト・フロイトと短期間手紙のやり取りをした。1923年末、モスクワに移り住み、アルバト通りに住んだ。後に両親もルリアの後を追い、近くに居を構えた。 モスクワでルリアは、コンスタンチン・コルニロフが1923年11月から運営していたモスクワ国立実験心理学研究所で働くことになった。 1924年、ルリアは彼に大きな影響を与えることになるレフ・ヴィゴツキーと出会う[8]。2人の心理学者の結びつきは、後にヴィゴツキー、より正確には ヴィゴツキー=ルリアのサークルと呼ばれるものを誕生させた。1920年代、ルリアは、アレクセイ・レオンティエフ、マーク・レベディンスキー、アレクサ ンドル・ザポロジェッツ、ブルマ・ツァイガルニクなど、生涯の同僚となる多くの学者たちとも出会った。ヴィゴツキーに倣い、彼とともに、ルリアは1920 年代半ばに、根本的に新しい種類の心理学を開発するプロジェクトを立ち上げた。このアプローチは、「文化的」、「歴史的」、「道具的」心理学を融合させた もので、現在では文化歴史心理学と呼ばれるのが最も一般的である。文化史心理学は、文化、特に言語が、個体発生と 系統発生における高次心理学的機能の発達に果たす媒介的役割を強調するものである。 ヴィゴツキーとは別に、ルリアは独創的な「複合運動法」を開発し、個人の隠れた、あるいは沈潜した感情や思考のプロセスを診断するのに役立った。この研究 は1932年に『人間の葛藤の本質』としてアメリカで出版され、ルリアはソビエト・ロシアを代表する心理学者として国際的に有名になった。1937年、ル リアはこの原稿をロシア語で提出し、トビリシ大学で博士論文として発表した(ロシア語版は2002年まで出版されなかった)。 ルリアはモスクワに移ってからの1920年代に、『人間の葛藤の本質』(ロシア語だが、ルリア存命中は1932年にアメリカで英訳されたものだけが出版さ れた)、『子どもの発達における発話と知性』、『都市、農村、ホームレスの子どもの発話と知性』(いずれもロシア語)の3冊の本を書いた。2番目のタイト ルは1928年に出版され、他の2つは1930年代に出版された。 1930年代初頭、ルリアとヴィゴツキーはともにハリコフで医学の勉強を始め、1934年にヴィゴツキーが亡くなった後、ルリアはモスクワ第一医学研究所 で医学教育を修了した。 多文化主義と神経学[編集] 1930年代はルリアにとって重要な時期であった。というのも、先住民に関する彼の研究によって、多文化主義という分野がルリアの一般的な関心に開かれた からである。ルリアの仕事は、中央アジアへの探検によってこの分野で継続された。ヴィゴツキーの監督の下、ルリアは、教育を受けていない少数民族の文化的 発展の結果として起こる様々な心理的変化(知覚、問題解決、記憶を含む)を調査した。この点で、彼はオラリティの研究に大きく貢献したと評価されている [10]。 リセンコイズムによる遺伝学者の粛清を受け[11][12]、ルリアは医師の学位を取得することを決意し、1937年の夏に優秀な成績で修了した。人間の 葛藤の本質』の原稿を書き直して再構成した後、1937年にトビリシ研究所で博士論文として発表し、教育学博士に任命された。「34歳で、この国で最も若 い心理学教授の一人となった。夫婦はモスクワのフルンゼ通りに住み、そこで一人娘のレナ(エレナ)が生まれた[14]。 ルリアはまた、人間の文化的・遺伝的発達の様々な要因の相互作用を明らかにするために、大規模な寄宿学校で一卵性双生児と 二卵性双生児を研究した。1930年代末の初期の神経心理学的研究において、また戦後の学究生活を通して、彼は失語症の研究に焦点を当て、言語、思考、皮 質機能の関係、特に失語症の代償機能の発達に焦点を当てた。 第二次世界大戦とその余波[編集] ルリアにとって、1945年に終結したドイツとの戦争は、神経心理学における彼のキャリアの将来にとって多くの重要な展開をもたらした。彼は1943年に 医学博士、1944年に教授に任命された。ルリアにとって特に重要だったのは、戦争によって外傷性脳損傷を負った800人近い入院患者のケアを政府から命 じられたことであった。ルリアの治療法は、感情的、知的な機能障害を幅広く扱うものであった。彼はこれらの患者について綿密なノートをつけ、そこから機能 回復の可能性を3つ見出した: (1)一時的に遮断された機能の抑制解除、(2)反対側の半球の代償的潜在能力の関与、(3)機能システムの再編成」であり、ルリアはこれを『軍事的脳傷 害からの機能回復』(モスクワ、1948年、ロシア語のみ)と題する著書の中で述べている。 「終戦後間もなく、ルリアは中央モスクワ大学の一般心理学の常任教授に任命され、そこで生涯を終えることになる。彼は心理学部の創設に尽力し、後に病理心 理学と神経心理学の学部長を務めた。1946年までに、ボトキン病院の消化器クリニックのチーフであった父親は胃がんで亡くなった。母親はさらに数年生き 延び、1950年に亡くなった[17]。 1950年代[編集] 戦争後、ルリアはモスクワの心理学研究所で仕事を続けた。一時期心理学研究所を離れ、1950年代には欠陥研究所で知的障害児の研究にシフトした。ここで 彼は児童心理学における最も先駆的な研究を行い、当時まだソビエト連邦でパブロフの初期の研究が及ぼしていた影響から永久に離脱することができた。 [19]ルリアが発話の調節機能に関心を持ち続けたことは、1950年代半ばにさらに再検討され、1957年に出版された『正常行動と異常行動の調節にお ける発話の役割』という単行本にまとめられている。この本の中でルリアは、この分野における彼の主要な関心事を、ホムスカヤによって次のように要約された 3つの簡潔な点に要約した: 「(1)精神過程の発達における発話の役割、(2)発話の調節機能の発達、(3)様々な脳の病理によって引き起こされる発話の調節機能の変化」[20]で ある。 1950年代におけるルリアの児童心理学への主な貢献は、1956年と1958年にモスクワで出版された『正常児と異常児における高次神経系活動の問題』 というタイトルの研究集2巻によくまとめられている。ホムスカヤはルリアのアプローチを次のように要約している: 「運動連合法の適用によって、(未熟な)子どもたちが条件付リンクを形成する過程で経験する困難や、発話による再構築や代償を明らかにすることができ た......(未熟な)子どもたちは、発話の汎化機能と調節機能の急性機能不全を示した」[21]。このような方向性で、1950年代半ばにはすでに、 「ルリアは初めて、主に言語系と運動系という異なる機能系における神経力学的プロセスの差異についての考えを提案した。 「ルリアは、子どもの言語発達の3つの段階を、「自発的行動のメカニズムの形成」という観点から特定した。 冷戦[編集] 1960年代、冷戦の真っ只中、ルリアのキャリアはいくつかの新著の出版によって大きく拡大した。特筆すべきは、1962年に出版された『Higher Cortical Functions in Man and Their Impairment Caused by Local Brain Damage』である。同書は複数の外国語に翻訳され、神経心理学を独自の医学分野として確立した主要な書籍として認識されている[24]。それ以前の 1950年代末には、国際学会におけるルリアのカリスマ的な存在感が、彼の研究に対するほぼ世界的な注目を集め、同書に対する受容的な医学聴衆を生み出し ていた。 1960年代にルリアが執筆または共著した他の本には次のようなものがある: Higher Brain and Mental Processes』(1963年)、『The Neuropsychological Analysis of Problem Solving』(1966年、L. S. Tzvetkovaとの共著、英訳は1990年)、『Psychophysiology of the Frontal Lobes』(1973年初版)、『Memory Disorders in Patients with aneurysms of the Anterior Communicating Artery』(A. N. Konovalov、A. N. Podgoynayaとの共著)などがある。ルリアは記憶障害の研究において、長期記憶、短期記憶、意味記憶の区別に重点を置いた。ルリアにとって、記憶 の神経心理学的病理を知的活動の神経心理学的病理と区別することは重要であった。これら2つのタイプの病理は、ルリアによってしばしば次のように特徴づけ られた。 ...(2)知的過程に対する全般的な制御の障害(主に前頭葉の障害)」[26]。1975年に出版され(英語版は1976年)、好評を博した 『Basic Problems of Neurolinguistics(神経言語学の基礎的問題)』という本もある。 晩年の著作[編集] ルリアは1970年代から晩年の7年間、神経心理学に関する新著を書き続け、その生産性はほとんど衰えなかった。重要なのは、1963年の第1巻『脳と心 理過程』に続き、1970年に第2巻『人間の脳と精神過程』が『意識活動の神経心理学的分析』というタイトルで刊行されたことである。この巻は、高次の自 発的・意図的計画の座を損なう前頭葉損傷の病理学的研究に対するルリアの長年の持続的関心を確認するものであった。1973年にはカール・プリブラムとの 共編著『前頭葉の精神病理学』が出版された。 ルリアは1962年に出版した『Higher Cortical Functions in Man(人間の高次皮質機能)』の付属書として、1973年に有名な『The Working Brain(働く脳)』を出版した。この本の中でルリアは、働く脳は3つの常に共働するプロセスから構成されるという3つの部分からなるグローバル理論を 要約した: 注意(感覚処理)システム 国内プログラミングシステム 大脳皮質と大脳辺縁系という2つのレベルを持つエネルギー維持システム このモデルは後に、神経伝達系の機能性を一致させる「気質の機能的アンサンブル」モデルの構造として使われた。この2冊の本を合わせて、ホムスカヤは「ル リアの神経心理学における主要な著作のひとつであり、この新しい学問分野のあらゆる側面(理論的、臨床的、実験的)を最も完全に反映している」とみなして いる[27]。 彼の晩年の著作の中には、大衆紙や一般読者を対象とした2冊の症例研究があり、臨床神経心理学の分野における大きな進歩の結果のいくつかを提示している。 この2冊は、彼の著作の中で最も人気のあるもののひとつである。オリヴァー・サックスによれば、これらの著作において「科学は詩となった」[28]。 The Mind of a Mnemonist』(1968年)では、ルリアはロシア人ジャーナリストであるソロモン・シェレシェフスキーを研究した。ソロモンは無制限に見える記憶 力を持ち、現代文学では「閃光記憶」と呼ばれることもあるが、その一因は彼の5重の共感覚にある。 第二次世界大戦で脳に傷を負った兵士レフ・ザセツキーの治療による回復を、彼は『砕かれた世界を持つ男』(1971年)の中で記録している。 1974年と1976年、ルリアは『記憶の神経心理学』と題する2巻の研究書を相次いで発表した。第1巻は『局所的脳損傷による記憶障害』、第2巻は『深 部脳構造の損傷による記憶障害』と題された。ルリアが1960年代に書いた『神経言語学の基礎的問題』という本は1975年にようやく出版され、遺著と なった『言語と認知』は1980年に出版された。ルリアの最後の共編著は、ホムスカヤとの共著で、『神経心理学の問題』と題され、1977年に出版され た。その中でルリアは、行動主義の単純化されたモデルを批判し、「反射弧をフィードバックループを持つ『反射環』の概念で置き換えたアノーヒンの『機能シ ステム』の概念」の立場を好むことを示した。 「このアプローチでは、反射の古典的な生理学は軽視され、ベルンシテインが述べたような「活動の生理学」が人間の活動的機能の能動的性格に関して強調され ることになった[30]。 ルリアの死はホムスカヤによって次のように記録されている: 「1977年6月1日、全ソ連心理学会議はモスクワで活動を開始した。その主催者として、ルリアは神経心理学のセクションを紹介した。しかし翌日の会議に は出席できなかった。妻のラナ・ピメノヴナは重病で、6月2日に手術を受けた。それから2ヵ月半の間、ルリアは妻を救うため、あるいはせめてなだめるため に、あらゆる手を尽くした。その甲斐もなく、8月14日に心筋梗塞で亡くなった。彼の葬儀には、心理学者、教師、医者、そしてただの友人など、数え切れな いほどの人々が参列した。彼の妻は6ヵ月後に亡くなった」[31]。 |

| Main areas of research In her biography of Luria, Homskaya summarized the six main areas of Luria's research over his lifetime in accordance with the following outline: (1) The Socio-historical Determination of the Human Psyche, (2) The Biological (Genetic) Determination of the Human Psyche, (3) Higher Psychological Functions Mediated by Signs-Symbols; The Verbal System as the Main System of Signs (along with Luria's well-known three-part differentiation of it), (4) The Systematic Organization of Psychological Functions and Consciousness (along with Luria's well-known four-part outline of this), (5) Cerebral Mechanisms of the Mind (Brain and Psyche); Links between Psychology and Physiology, and (6) The Relationship between Theory and Practice.[32] A Review of General Psychology survey, published in 2002, ranked Luria as the 69th most cited psychologist of the 20th century.[33] |

主な研究分野[編集] ホムスカヤはルリアの伝記の中で、ルリアが生涯にわたって研究した6つの主な分野を次のようにまとめている: (1)人間精神の社会史的決定、(2)人間精神の生物学的(遺伝学的)決定、(3)記号-シンボルによって媒介される高次心理学的機能; 記号の主要な体系としての言語体系(ルリアの有名な3部構成による区別とともに)、(4)心理学的機能と意識の体系的組織(ルリアの有名な4部構成による 概要とともに)、(5)心の大脳メカニズム(脳と精神)、心理学と生理学の関連、(6)理論と実践の関係。 [32] 2002年に発表されたReview of General Psychologyの調査では、ルリアは20世紀で最も引用された心理学者の69位にランクされている[33]。 |

| Principal research trends As examples of the vigorous growth of new research related to Luria's original research during his own lifetime are the fields of linguistic aphasia, anterior lobe pathology, speech dysfunction, and child neuropsychology. Linguistic aphasia Luria's neuropsychological theory of language and speech distinguished clearly between the phases that separate inner language within the individual consciousness and spoken language intended for communication between individuals intersubjectively. It was of special significance for Luria not only to distinguish the sequential phases required to get from inner language to serial speech, but also to emphasize the difference of encoding of subjective inner thought as it develops into intersubjective speech. This was in contrast to the decoding of spoken speech as it is communicated from other individuals and decoded into subjectively understood inner language.[34] In the case of the encoding of inner language, Luria expressed these successive phases as moving first from inner language to semantic set representations, then to deep semantic structures, then to deep syntactic structures, then to serial surface speech. For the encoding of serial speech, the phases remained the same, though the decoding was oriented in the opposite direction of transitions between the distinct phases.[34] Frontal (anterior) lobes Luria's studies of the frontal lobes were concentrated in five principal areas: (1) attention, (2) memory, (3) intellectual activity, (4)emotional reactions, and (5) voluntary movements. Luria's main books for investigation of these functions of the frontal lobes are titled The Frontal Lobes,[35] Problems of Neuropsychology (1977), Functions of the Frontal Lobes (1982, posthumously published), Higher Cortical Functions in Man. (1962) and Restoration of Function After Brain Injury" [36] Luria was first to identify the fundamental role of the frontal lobes in sustained attention, flexibility of behaviour, and self-organization. Based on his clinical observations and rehabilitation practice, he suggested that different areas of the frontal lobes differentially regulate these three aspects of behaviour. This suggestion was later supported by the neuroscience investigating frontal lobes. Practically all modern neuropsychological tests for frontal lobes damage have some components that were offered by Luria in his assessment and rehabilitation practice. Speech dysfunction Luria's research on speech dysfunction was principally in the areas of (1) expressive speech, (2) impressive speech, (3) memory, (4) intellectual activity, and (5) personality.[37] Child neuropsychology This field was formed largely based upon Luria's books and writings on neuropsychology integrated during his experiences during the war years and later periods. In the area of child neuropsychology, "The need for its creation was dictated by the fact that children with localized brain damage were found to reveal specific different features of dissolution of psychological functions. Under Luria's supervision, his colleague Simernitskaya began to study nonverbal (visual-spatial) and verbal functions, and demonstrated that damage to the left and right hemispheres provoked different types of dysfunctions in children than in adults. This study initiated a number of systematic investigations concerning changes in the localization of higher psychological functions during the process of development."[38] Luria's general research was mostly centered on the treatment and rehabilitation "of speech, and observations concerning direct and spontaneous rehabilitation were generalized."[38] Other areas involving "Luria's works have made a significant contribution in the sphere of rehabilitation of expressive and impressive speech (Tzvetkova, 1972), 1985), memory (Krotkova, 1982), intellectual activity (Tzvetkova, 1975), and personality (Glozman, 1987) in patients with localized brain damage."[38] |

主な研究動向[編集]。 ルリアの独創的な研究に関連する新しい研究が、ルリア存命中に活発に発展した例として、言語失語症、前葉病理学、言語機能障害、小児神経心理学の分野が挙 げられる。 言語性失語症[編集] ルリアの言語と音声に関する神経心理学的理論は、個人の意識の中にある内的言語と、個人間のコミュニケーションを目的とした音声言語とを明確に区別するも のであった。ルリアにとって、内的言語から連続的な発話に至るまでに必要な段階を区別するだけでなく、主観的な内的思考が主観間の発話に発展する際の符号 化の違いを強調することは、特別な意義があった。これは、他の個人から伝達され、主観的に理解される内なる言語へとデコードされる話し言葉のデコーディン グとは対照的であった[34]。内なる言語のエンコーディングの場合、ルリアはこれらの連続的な段階を、まず内なる言語から意味集合表現へ、次に深い意味 構造へ、次に深い統語構造へ、そして連続的な表層音声へと移行すると表現した。直列音声の符号化では、相は同じままであったが、復号は異なる相の間の遷移 とは逆の方向に向いていた[34]。 前頭(前)葉[編集]。 ルリアの前頭葉の研究は、(1)注意、(2)記憶、(3)知的活動、(4)情動反応、(5)随意運動の5つの主要領域に集中していた。これらの前頭葉の機 能を研究したルリアの主な著書に、『前頭葉』、[35]『神経心理学の問題』(1977年)、『前頭葉の機能』(1982年、遺著)、 『人間の高次皮質機能』(1962年)、『人間の高次皮質機能の回復』(1962年)がある。(1962年)、 『脳損傷後の機能回復』[36]などがある。 ルリアは、持続的な注意、行動の柔軟性、自己組織化における前頭葉の基本的な役割を初めて明らかにした。彼は臨床観察とリハビリテーションの実践に基づ き、前頭葉の異なる領域が行動のこれら3つの側面を異なる形で制御していることを示唆した。この提案は、後に前頭葉を研究する神経科学によって支持され た。前頭葉障害の神経心理学的検査には、ルリアがその評価とリハビリテーションの実践の中で提供したものが含まれている。 言語機能障害[編集] ルリアの言語機能障害に関する研究は、主に(1)表出性発話、(2)印象的発話、(3)記憶、(4)知的活動、(5)人格の分野で行われた[37]。 小児神経心理学[編集] この分野は、ルリアが戦時中やそれ以降の時期に経験した神経心理学に関する著書や著作に基づいて形成された。小児神経心理学の分野では、「その創設の必要 性は、脳に局所的な損傷を受けた小児が、心理的機能の解消という特定の異なる特徴を示すことが判明したという事実によって指示された。ルリアの監督の下、 同僚のシメルニツカヤが非言語(視覚・空間)機能と言語機能の研究を始め、左右の大脳半球の損傷が、成人とは異なるタイプの機能障害を子どもに引き起こす ことを実証した。この研究は、発達過程における高次の心理的機能の局在の変化に関する多くの体系的な研究を開始した。 「38]その他、「ルリアの著作は、限局性脳損傷患者における、表現力豊かで印象的な発話(Tzvetkova, 1972)、1985)、記憶(Krotkova, 1982)、知的活動(Tzvetkova, 1975)、人格(Glozman, 1987)のリハビリテーションの領域において重要な貢献をしている」[38]。 |

| Luria-Nebraska

neuropsychological test Main article: Luria-Nebraska neuropsychological battery The Luria-Nebraska is a standardized test based on Luria's theories regarding neuropsychological functioning. Luria was not part of the team that originally standardized this test; he was only indirectly referenced by other researchers as a scholar who had published relevant results in the field of neuropsychology. Anecdotally, when Luria first had the battery described to him he commented that he had expected that someone would eventually do something like this with his original research. |

ルリア・ネブラスカ神経心理学的検査[編集]。 主な記事 ルリア・ネブラスカ神経心理学バッテリー ルリア・ネブラスカ神経心理学検査は、神経心理学的機能に関するルリアの理論に基づいて標準化された検査である。ルリアはもともとこのテストを標準化した チームの一員ではなく、神経心理学の分野で関連する結果を発表した学者として、他の研究者から間接的に参照されたにすぎない。逸話によると、ルリアが最初 にこのバッテリーを説明されたとき、彼は、自分のオリジナルの研究で、いずれ誰かがこのようなことをするだろうと予想していたとコメントしている。 |

| Books Luria, A.R. The Nature of Human Conflicts - or Emotion, Conflict, and Will: An Objective Study of Disorganisation and Control of Human Behaviour. New York: Liveright Publishers, 1932. Luria, A.R.Higher Cortical Functions in Man. Moscow University Press, 1962. Library of Congress Number: 65-11340. Luria, A.R. (1963). Restoration of Function After Brain Injury. Pergamon Press. Luria, A.R. (1966). Human Brain and Psychological Processes. Harper & Row. Luria, A.R. (1970). Traumatic Aphasia: Its Syndromes, Psychology, and Treatment. Mouton de Gruyter. ISBN 978-90-279-0717-2. Summary at BrainInfo The Working Brain. Basic Books. 1973. ISBN 978-0-465-09208-6. Luria, A.R. (1976). The Cognitive Development: Its Cultural and Social Foundations. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-13731-8. Luria, A.R. (1968). The Mind of a Mnemonist: A Little Book About A Vast Memory. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-57622-3. (With Solotaroff, Lynn) The Man with a Shattered World: The History of a Brain Wound, Harvard University Press, 1987. ISBN 0-674-54625-3. Autobiography of Alexander Luria: A Dialogue with the Making of Mind. Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc. 2005. ISBN 978-0-8058-5499-2. |

|

| Cultural-historical psychology Elkhonon Goldberg Lev Vygotsky Solomon Shereshevsky Neuropsychological assessment Functional Ensemble of Temperament |

文化歴史心理学 エルコノン・ゴールドバーグ レフ・ヴィゴツキー ソロモン・シェレシェフスキー 神経心理学的評価 気質の機能的アンサンブル |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Alexander_Luria |

影響関係

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099