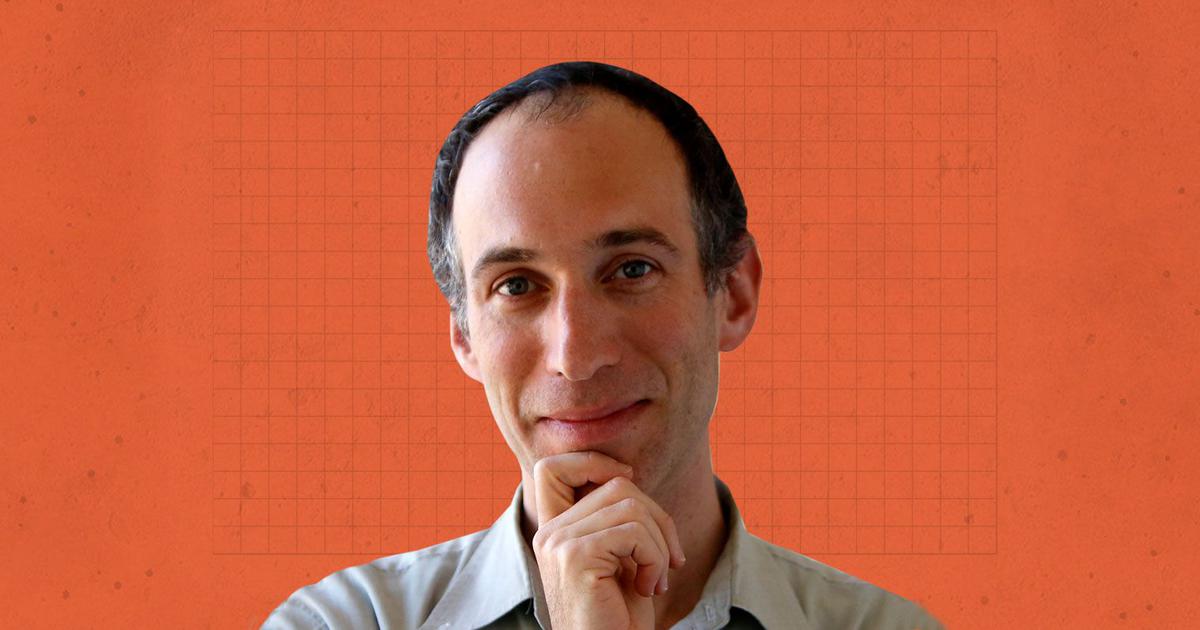

デイヴィッド・ライク

David Reich (geneticist), b.1974

Meet the geneticist and author who is using ancient DNA to upend how we approach human history

| David

Emil Reich[4] (born July 14, 1974) is an American geneticist known

for his research into the population genetics of ancient humans,

including their migrations and the mixing of populations, discovered by

analysis of genome-wide patterns of mutations. He is professor in the

department of genetics at the Harvard Medical School, and an associate

of the Broad Institute. Reich was highlighted as one of Nature's 10 for

his contributions to science in 2015.[5] He received the Dan David

Prize in 2017, the NAS Award in Molecular Biology, the Wiley Prize, and

the Darwin–Wallace Medal in 2019. In 2021 he was awarded the Massry

Prize.[6] |

デイヴィッド・エミル・ライク[4](1974年7月14日生まれ)

は、ゲノム全体の変異パターンの解析によって発見された、古代人の移動と集団の混合を含む集団遺伝学の研究で知られるアメリカの遺伝学者。ハーバード大学

医学部遺伝学科教授、ブロード研究所共同研究員。ライクは2015年、科学への貢献でネイチャー誌の10人に選ばれた[5]。

2017年にダン・デイヴィッド賞、2019年にNAS賞(分子生物学部門)、ワイリー賞、ダーウィン・ウォレスメダルを受賞。2021年にはマスリー賞

を受賞[6]。 |

| Early life Reich grew up as part of a Jewish family in Washington, D.C. His parents are novelist Tova Reich (sister of Rabbi Avi Weiss) and Walter Reich, a professor at George Washington University, who served as the first director of the United States Holocaust Memorial Museum.[7][8] David Reich started out as a sociology major as an undergraduate at Harvard College, but later turned his attention to physics and medicine. After graduation, he attended the University of Oxford, originally with the intent of preparing for medical school.[7] He was awarded a PhD in zoology in 1999 for research supervised by David Goldstein. His thesis was titled "Genetic analysis of human evolutionary history with implications for gene mapping".[3] |

生い立ち ライクはワシントンD.C.のユダヤ人家庭で育った。両親は小説家のトヴァ・ライク(ラビ・アヴィ・ヴァイスの妹)と、ジョージ・ワシントン大学教授で米 国ホロコースト記念博物館の初代館長を務めたウォルター・ライクである[7][8]。デイヴィッド・ライクはハーバード大学の学部で社会学を専攻したが、 後に物理学と医学に関心を向けるようになった。卒業後、オックスフォード大学に入学し、当初は医学部進学を目指した[7]。1999年、デイヴィッド・ ゴールドスタインの指導による研究で動物学の博士号を取得。学位論文のタイトルは「遺伝子マッピングに示唆するヒトの進化史の遺伝学的解析」であった [3]。 |

| Academic career Reich received a BA in physics from Harvard University and a PhD in zoology from St. Catherine's College in the University of Oxford.[9] He joined Harvard Medical School in 2003.[7] Reich is currently a geneticist and professor in the department of genetics at Harvard Medical School, and an associate of the Broad Institute, whose research studies compare the modern human genome with those of chimpanzees, Neanderthals, and Denisovans. Reich's genetics research focuses primarily on finding complex genetic patterns that cause susceptibility to common diseases among large populations, rather than looking for specific genetic markers associated with relatively rare illnesses. |

学歴 ライクはハーバード大学で物理学の学士号を取得し、オックスフォード大学のセント・キャサリンズ・カレッジで動物学の博士号を取得した[9]。ライクは 2003年にハーバード大学医学部に入学した[7]。ライクは現在、ハーバード大学医学部遺伝学科の遺伝学者兼教授であり、ブロード研究所のアソシエイト として、チンパンジー、ネアンデルタール人、デニソワ人と現代人のゲノムを比較する研究を行っている。 ライクの遺伝学研究は、比較的まれな病気に関連する特定の遺伝マーカーを探すことよりも、大規模な集団に共通する病気のかかりやすさの原因となる複雑な遺 伝的パターンを見つけることに主眼を置いている。 |

| Genetic research Split of chimpanzees and humans (2006) Main article: Human-chimp MRCA Reich's research team at Harvard University has produced evidence that, over a span of at least four million years, various parts of the human genome diverged gradually from those of chimpanzees.[10] The split between the human and chimpanzee lineages may have occurred millions of years later than fossilized bones suggest, and the break may not have been as clean as previously thought. The genetic evidence developed by Reich's team suggests that after the two species initially separated, they may have continued interbreeding for several million years. A final genetic split transpired between 6.3 million and 5.4 million years ago.[11] Indian population (2009) Main article: Genetics and archaeogenetics of South Asia See also: ANI and ASI and Dravidian migrations Reich's 2009 paper Reconstructing Indian population history[12] was a landmark study in the research on India's genepool and the origins of its population. Reich et al. (2009), in a collaborative effort between the Harvard Medical School and the Indian Centre for Cellular and Molecular Biology (CCMB), examined the entire genomes worth 560,000 single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs), as compared to 420 SNPs in prior work. They also cross-compared them with the genomes of other regions available in the global genome database.[13] Through this study, they were able to discern two genetic groups in the majority of populations in India, which they called "Ancestral North Indians" (ANI) and "Ancestral South Indians" (ASI).[note 1] They found that the ANI genes are close to those of Middle Easterners, Central Asians and Europeans whereas the ASI genes are dissimilar to all other known populations outside India.[note 2][note 3] These two distinct groups, which had split ca. 50,000 years ago, formed the basis for the present population of India.[14] A follow-up study by Moorjani et al. (2013) revealed that the two groups mixed between 1,900 and 4,200 years ago (2200 BCE–100 CE), after which a shift to endogamy took place and admixture became rare.[note 4] Speaking to Fountain Ink, David Reich stated, "Prior to 4,200 years ago, there were unmixed groups in India. Sometime between 1,900 to 4,200 years ago, profound, pervasive convulsive mixture occurred, affecting every Indo-European and Dravidian group in India without exception." Reich pointed out that their work does not show that a substantial migration occurred during this time.[15] Metspalu et al. (2011), representing a collaboration between the Estonian Biocenter and CCMB, confirmed that the Indian populations are characterized by two major ancestry components. One of them is spread at comparable frequency and haplotype diversity in populations of South and West Asia and the Caucasus. The second component is more restricted to South Asia and accounts for more than 50% of the ancestry in Indian populations. Haplotype diversity associated with these South Asian ancestry components is significantly higher than that of the components dominating the West Eurasian ancestry palette.[16] Human genetic map (2011) Reich was a co-leader, along with statistician Simon Myers, of a team of genetics researchers from Harvard University and the University of Oxford that made the most complete human genetic map then known in July 2011.[17] Interbreeding of Neanderthals and humans (2010–2012) Main article: Neanderthal admixture Reich's research team significantly contributed to the discovery that Neanderthals and Denisovans interbred with modern human populations as they dispersed from Africa into Eurasia 70,000–30,000 years ago.[18] Genetic markers for prostate cancer Reich's lab received media attention following its discovery of a genetic marker which is linked to an increased likelihood of developing prostate cancer.[19] Reich has also argued that the higher incidence of prostate cancer among African Americans, compared to European Americans, appears to be largely genetic in origin.[20] Indo-European origins Reich has suggested that the Indo-European languages may have originated south of the Caucausus, in present day Iran or Armenia: "Ancient DNA available from this time in Anatolia shows no evidence of steppe ancestry similar to that in the Yamnaya (although the evidence here is circumstantial as no ancient DNA from the Hittites themselves has yet been published). This suggests to me that the most likely location of the population that first spoke an Indo-European language was south of the Caucasus Mountains, perhaps in present-day Iran or Armenia, because ancient DNA from people who lived there matches what we would expect for a source population both for the Yamnaya and for ancient Anatolians. If this scenario is right the population sent one branch up into the steppe – mixing with steppe hunter-gatherers in a one-to-one ratio to become the Yamnaya as described earlier – and another to Anatolia to found the ancestors of people there who spoke languages such as Hittite."[20] Software tools Reich has developed ADMIXTOOLS 2, an R software package primarily used for analyzing admixture, in collaboration with Nick Patterson.[21] |

遺伝子研究 チンパンジーとヒトの分裂(2006年) 主な記事 ヒトとチンパンジーのMRCA ハーバード大学のライクの研究チームは、少なくとも400万年のスパンで、ヒトゲノムのさまざまな部分がチンパンジーのゲノムから徐々に分岐していったと いう証拠を得た[10]。 ヒトとチンパンジーの系統の分岐は、骨の化石が示唆するよりも数百万年遅れて起こった可能性があり、その分岐はこれまで考えられていたほどきれいなもので はなかったかもしれない。ライクのチームが開発した遺伝学的証拠は、2つの種が最初に分かれた後、数百万年にわたって交配を続けた可能性を示唆している。 最終的な遺伝的分裂は630万年前から540万年前の間に起こった[11]。 インドの人口(2009年) 主な記事 南アジアの遺伝学と古生代学 以下も参照: ANIとASI、ドラヴィダ人の移動 ライクの2009年の論文Reconstructing Indian population history[12]は、インドの遺伝子プールと人口の起源に関する研究における画期的な研究であった。ライクら(2009年)は、ハーバード大学医学 部とインド細胞分子生物学センター(CCMB)の共同研究で、先行研究の420SNPsと比較して、56万SNPsに相当する全ゲノムを調査した。彼らは また、グローバルゲノムデータベースで利用可能な他の地域のゲノムとも比較した[13]。この研究を通じて、彼らはインドの大部分の集団に2つの遺伝的グ ループを見分けることができ、それらは「先祖代々の北インド人」(ANI)と「先祖代々の南インド人」(ASI)と呼ばれた。 [注1] 彼らは、ANIの遺伝子が中東人、中央アジア人、ヨーロッパ人の遺伝子に近いのに対し、ASIの遺伝子はインド以外の既知の集団とは異なっていることを発 見した[注2][注3]。50,000年前に分裂したこの2つの異なる集団は、現在のインドの人口の基礎を形成した[14]。 Moorjaniらによる追跡調査(2013年)によって、この2つの集団は1900年から4200年前(紀元前2200年から紀元後100年)の間に混 血し、その後、内婚へと移行して混血は稀になったことが明らかになった[注釈 4] David ReichはFountain Inkに対して、「4200年前以前には、インドには混血していない集団が存在した。1,900年から4,200年前のある時期に、深遠で広範な痙攣性の 混血が起こり、インドに存在するすべてのインド・ヨーロッパ語族とドラヴィダ語族に例外なく影響を及ぼした」。ライクは、彼らの研究はこの時期に実質的な 移動が起こったことを示していないと指摘している[15]。 エストニアのバイオセンターとCCMBの共同研究を代表するMetspaluら(2011年)は、インドの集団が2つの主要な祖先構成要素によって特徴づ けられていることを確認した。そのうちの1つは、南アジアと西アジア、コーカサスの集団に、同等の頻度とハプロタイプ多様性で広がっている。2つ目の構成 要素は南アジアに限定され、インド人集団の祖先の50%以上を占めている。これらの南アジアの祖先構成要素に関連するハプロタイプ多様性は、西ユーラシア の祖先パレットを支配する構成要素よりも有意に高い[16]。 ヒト遺伝子地図(2011年) ライクは統計学者サイモン・マイヤーズとともに、ハーバード大学とオックスフォード大学の遺伝学研究者チームの共同リーダーであり、2011年7月に当時 知られていた中で最も完全なヒト遺伝地図を作成した[17]。 ネアンデルタール人とヒトの交雑(2010年~2012年) 主な記事 ネアンデルタール人との混血 ライクの研究チームは、ネアンデルタール人とデニソワ人が7万~3万年前にアフリカからユーラシア大陸に拡散した際に、現生人類の集団と交雑していたとい う発見に大きく貢献した[18]。 前立腺がんの遺伝子マーカー ライクの研究室は、前立腺がんを発症する可能性の増加と関連する遺伝子マーカーを発見し、メディアの注目を浴びた[19]。 ライクはまた、ヨーロッパ系アメリカ人と比較してアフリカ系アメリカ人の前立腺がん罹患率が高いのは、遺伝的な要因が大きいようだと主張している [20]。 インド・ヨーロッパ人の起源 ライクは、インド・ヨーロッパ語族の起源はコーカサスの南、現在のイランかアルメニアにある可能性を示唆している: 「この時代のアナトリアの古代DNAには、ヤムナヤに見られるようなステップの祖先の証拠は見られない(ヒッタイト人自身の古代DNAはまだ発表されてい ないため、この証拠は状況証拠にすぎないが)。このことは、インド・ヨーロッパ語を最初に話した集団の最も可能性の高い場所は、コーカサス山脈の南、おそ らく現在のイランかアルメニアであることを示唆している。なぜなら、そこに住んでいた人々の古代のDNAは、ヤムナヤ人と古代アナトリア人の両方の源流集 団に期待されるものと一致するからである。もしこのシナリオが正しければ、その集団は1つの枝を草原に送り込み、草原の狩猟採集民と1対1の割合で混血し て、先に述べたようなヤムナヤ人となり、もう1つの枝をアナトリアに送り込んで、ヒッタイト語などの言語を話すアナトリアの人々の祖先を生み出したことに なる」[20]。 ソフトウェアツール ライクはニック・パターソンと共同で、主に混血を分析するためのRソフトウェアパッケージADMIXTOOLS 2を開発した[21]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_Reich_(geneticist) |

|

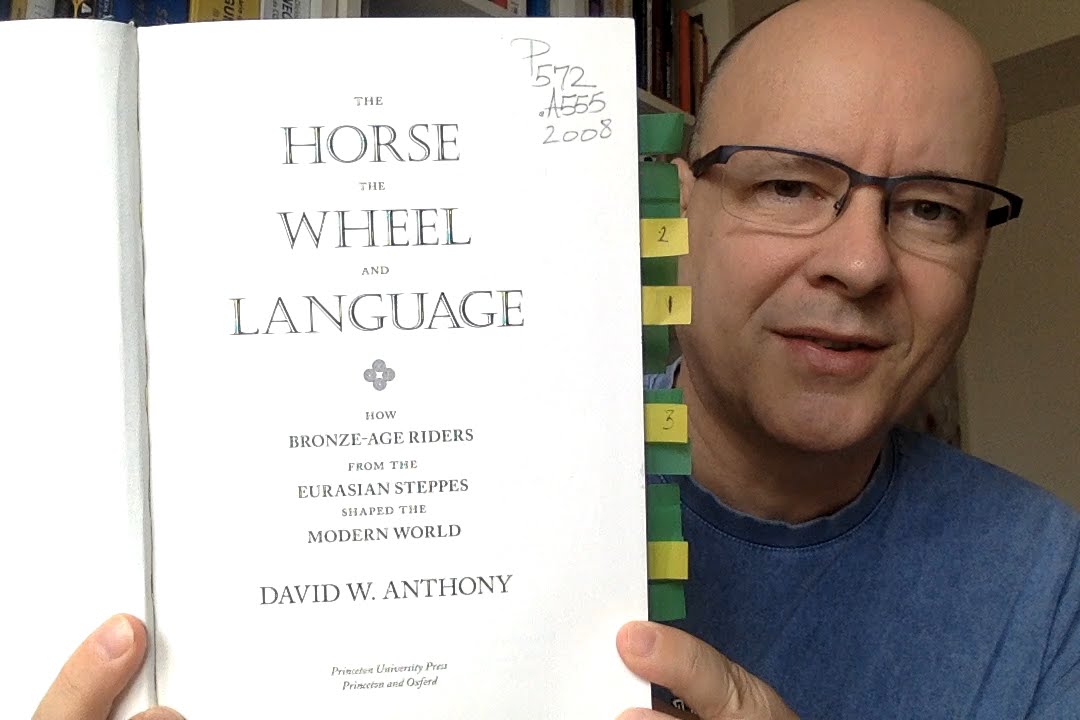

David W. Anthony is an American

anthropologist who is Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at Hartwick

College. He specializes in Indo-European migrations, and is a proponent

of the Kurgan

hypothesis. Anthony is well known for his award-winning book The Horse, the Wheel,

and Language (2007). David W. Anthony is an American

anthropologist who is Professor Emeritus of Anthropology at Hartwick

College. He specializes in Indo-European migrations, and is a proponent

of the Kurgan

hypothesis. Anthony is well known for his award-winning book The Horse, the Wheel,

and Language (2007).Career Anthony received a Ph.D. in anthropology from the University of Pennsylvania.[1] Anthony has been a Professor of Anthropology at Hartwick College since 1987.[1][2] While at Hartwick, he was also the curator of Anthropology for the Yager Museum of Art & Culture on the campus of Hartwick College in Oneonta, New York. According to Princeton University Press, "he has conducted extensive archaeological fieldwork in Ukraine, Russia, and Kazakhstan."[3] Anthony has been Archaeology Editor of the Journal of Indo-European Studies.[4] One of his areas of research has been the domestication of the horse.[5] In 2019, his work was featured in an episode of Nova that discussed the theories of how this process occurred.[6] Mediated works According to the uncurated ResearchGate website, Anthony has published at least 54 research articles.[2] Bibliography The books of Anthony include: The Horse, the Wheel and Language: How Bronze-Age Riders from the Eurasian Steppes Shaped the Modern World (2007) The Lost World Of Old Europe: The Danube Valley, 5000 - 3500 BC (2009) A Bronze Age Landscape in the Russian Steppes: The Samara Valley Project (2016, co-editor) Filmography Anthony has appeared as a relator of history in works such as: How the Silk Road Made the World (2019, NHNZ) First Horse Warriors (2019, NOVA) https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/David_W._Anthony |

デビッド・W・アンソニーはアメリカの人類学者で、ハートウィック・カ

レッジ人類学名誉教授。専門はインド・ヨーロッパ語族の移動で、クルガン仮説の提唱者。受賞作『馬と車輪と言語』(2007年)で知られる。 デビッド・W・アンソニーはアメリカの人類学者で、ハートウィック・カ

レッジ人類学名誉教授。専門はインド・ヨーロッパ語族の移動で、クルガン仮説の提唱者。受賞作『馬と車輪と言語』(2007年)で知られる。経歴 アンソニーはペンシルバニア大学で人類学の博士号を取得した[1]。 ハートウィック・カレッジ在学中は、ニューヨーク州ワノンタにあるハートウィック・カレッジのイェーガー芸術文化博物館で人類学の学芸員も務めた。プリン ストン大学出版局によると、「ウクライナ、ロシア、カザフスタンで大規模な考古学フィールドワークを行った」[3]。 彼の研究分野のひとつは、馬の家畜化である[5]。 2019年、彼の研究は、このプロセスがどのように起こったかについての理論を議論する『Nova』のエピソードで紹介された[6]。 メディア化された作品 キュレーションされていないResearchGateのウェブサイトによると、アンソニーは少なくとも54の研究論文を発表している[2]。 書誌 アンソニーの著書は以下の通り: 『馬と車輪と言語: ユーラシア草原からやってきた青銅器時代の騎馬民族はいかにして現代世界を形成したか』(2007年) The Lost World Of Old Europe: 紀元前5000~3500年のドナウ渓谷 (2009) ロシア草原の青銅器時代の風景: サマラ渓谷プロジェクト』(2016年、共編著) フィルモグラフィ アンソニーは歴史の語り部として、以下のような作品に出演している: シルクロードはいかに世界をつくったか(2019年、NHNZ) ファースト・ホース・ウォリアーズ(2019年、NOVA) |

| The Kurgan

hypothesis (also known as the Kurgan theory, Kurgan model, or

steppe theory) is the most widely accepted proposal to identify the

Proto-Indo-European homeland from which the Indo-European languages

spread out throughout Europe and parts of Asia.[1][2] It postulates

that the people of a Kurgan culture in the Pontic steppe north of the

Black Sea were the most likely speakers of the Proto-Indo-European

language (PIE). The term is derived from the Turkic word kurgan

(курга́н), meaning tumulus or burial mound. The steppe theory was first formulated by Otto Schrader (1883) and V. Gordon Childe (1926),[3][4] then systematized in the 1950s by Marija Gimbutas, who used the term to group various prehistoric cultures, including the Yamnaya (or Pit Grave) culture and its predecessors. In the 2000s, David Anthony instead used the core Yamnaya culture and its relationship with other cultures as a point of reference. Scheme of Indo-European language dispersals from c. 4000 to 1000 BC according to the Kurgan hypothesis. Center: Steppe cultures 1: Anatolian languages (archaic PIE) 2: Afanasievo culture (early PIE) 3: Yamnaya culture expansion (Pontic-Caspian steppe, Danube Valley) (late PIE) 4A: Western Corded Ware 4B: Bell Beaker culture (adopted by Indo-European speakers) 4C: Bell Beaker 5A-B: Eastern Corded ware; 5C: Sintashta culture (proto-Indo-Iranian) 6: Andronovo 7: Indo-Aryans (A: Mittani; B: India) 8: Greek 9: Iranian Proto-Balto-Slavic Not drawn: Armenian, expanding from western steppe Gimbutas defined the Kurgan culture as composed of four successive periods, with the earliest (Kurgan I) including the Samara and Seroglazovo cultures of the Dnieper–Volga region in the Copper Age (early 4th millennium BC). The people of these cultures were nomadic pastoralists, who, according to the model, by the early 3rd millennium BC had expanded throughout the Pontic–Caspian steppe and into Eastern Europe.[5] Recent genetics studies have demonstrated that populations bearing specific Y-DNA haplogroups and a distinct genetic signature expanded into Europe and South Asia from the Pontic-Caspian steppe during the third and second millennia BC. These migrations provide a plausible explanation for the spread of at least some of the Indo-European languages, and suggest that the alternative Anatolian hypothesis, which places the Proto-Indo-European homeland in Neolithic Anatolia, is less likely to be correct.[6][7][8][9][10] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kurgan_hypothesis |

クルガン仮説(クルガン理論、クルガンモデル、ステップ理論とも呼ばれ

る)は、インド・ヨーロッパ語族がヨーロッパとアジアの一部に拡散した原インド・ヨーロッパ語族の祖国を特定するための最も広く受け入れられている提案で

ある[1][2]。

黒海の北に位置するポント草原のクルガン文化の人々が、原インド・ヨーロッパ語族(PIE)の最も可能性の高い話者であったと仮定している。この言葉は、

古墳や墳墓を意味するテュルク語のクルガン(курга́н)に由来する。 ステップ説はオットー・シュレーダー(1883年)とV・ゴードン・チルデ(1926年)によって最初に提唱され[3][4]、1950年代にマリヤ・ギ ンブータスによって体系化された。2000年代には、デイヴィッド・アンソニーが、ヤムナヤ文化の中核となる文化と他の文化との関係を参照点として使用す るようになった。 クルガン仮説による紀元前4000年から1000年までのインド・ヨーロッパ語族の言語拡散の図式。中央: ステップ文化 1:アナトリア諸語(古代のPIE) 2:アファナシエヴォ文化(初期PIE) 3:ヤムナヤ文化の拡大(ポンティック-カスピ海ステップ、ドナウ渓谷)(PIE後期) 4A: 西部コーデッド・ウェア 4B: ベル・ビーカー文化(インド・ヨーロッパ語族の採用) 4C:ベルビーカー 5A-B:東部コーデッド焼、5C:シンタシュタ文化(原インド・イラン文化) 6:アンドロノヴォ 7:インド・アーリア人(A:ミッタニ、B:インド) 8:ギリシア 9:イラン 原バルト・スラブ 描かれていない: 西ステップから拡大したアルメニア人 ギンブタスは、クルガン文化を4つの連続した時代から構成されると定義し、最も古い時代(クルガンI)には、銅器時代(紀元前4千年紀初頭)のドニエプル =ヴォルガ地域のサマラ文化とセログラゾヴォ文化が含まれる。これらの文化の人々は遊牧民であり、そのモデルによれば、紀元前3千年紀初頭までにポントス =カスピ海の草原全域と東ヨーロッパに拡大していた[5]。 最近の遺伝学的研究によって、特定のY-DNAハプログループを持ち、明確な遺伝的特徴を持つ集団が、紀元前3千年紀から2千年紀の間に、ポンティック- カスピ海ステップからヨーロッパと南アジアに拡大したことが証明されている。これらの移動は、インド・ヨーロッパ語族の言語の少なくとも一部が広まったこ とのもっともらしい説明となり、原インド・ヨーロッパ語族の故郷を新石器時代のアナトリアに置くアナトリア仮説が正しい可能性が低いことを示唆している [6][7][8][9][10]。 |

| A

population bottleneck is an event that drastically reduces the size of

a population. The bottleneck may be caused by various events, such as

an environmental disaster, the hunting of a species to the point of

extinction, or habitat destruction that results in the deaths of

organisms. The population bottleneck produces a decrease in the gene

pool of the population because many alleles, or gene variants, that

were present in the original population are lost. Due to the event, the

remaining population has a very low level of genetic diversity, which

means that the population as a whole has few genetic characteristics. Following a population bottleneck, the remaining population faces a higher level of genetic drift, which describes random fluctuations in the presence of alleles in a population. In small populations, infrequently occurring alleles face a greater chance of being lost, which can further decrease the gene pool. Due to the loss of genetic variation, the new population can become genetically distinct from the original population, which has led to the hypothesis that population bottlenecks can lead to the evolution of new species. https://www.nature.com/wls/definition/population-bottleneck-300/ |

個体群(=人口)のボトルネックとは、個体群の規模を大幅に縮小させる出来事を指す。 ボトルネックの原因となる出来事は様々であり、環境災害、絶滅寸前の狩猟、生物の死につながる生息地の破壊などが挙げられる。

個体群のボトルネックにより、元の個体群に存在していた多くの対立遺伝子、すなわち遺伝子変異体が失われるため、個体群の遺伝子プールの減少が生じる。こ

の出来事により、残った個体群の遺伝的多様性は非常に低くなり、つまり、個体群全体としての遺伝的特性はほとんどないということになる。 個体群のボトルネックの後、残った個体群は、個体群内の対立遺伝子の存 在におけるランダムな変動を説明する遺伝的浮動のレベルが高くなる。個体群が小さい場合、まれにしか発生しない対立遺伝子は失われる可能性が高くなり、遺 伝子プールがさらに減少する可能性がある。遺伝的多様性の喪失により、新しい個体群は元の個体群とは遺伝的に異なるものになる可能性があり、これが個体群 のボトルネックが新種の進化につながるという仮説の根拠となっている。 |

|

|

☆

デイヴィッド・エミル・ライク[4](1974年7月14日生まれ)は、ゲノム全体の変異パターンの解析によって発見された、古代人の移動と集団の混合を

含む集団遺伝学の研究で知られるアメリカの遺伝学者。ハーバード大学医学部遺伝学科教授、ブロード研究所共同研究員。ライクは2015年、科学への貢献で

ネイチャー誌の10人に選ばれた[5]。

2017年にダン・デイヴィッド賞、2019年にNAS賞(分子生物学部門)、ワイリー賞、ダーウィン・ウォレスメダルを受賞。2021年にはマスリー賞

を受賞[6]。

☆

デイヴィッド・エミル・ライク[4](1974年7月14日生まれ)は、ゲノム全体の変異パターンの解析によって発見された、古代人の移動と集団の混合を

含む集団遺伝学の研究で知られるアメリカの遺伝学者。ハーバード大学医学部遺伝学科教授、ブロード研究所共同研究員。ライクは2015年、科学への貢献で

ネイチャー誌の10人に選ばれた[5]。

2017年にダン・デイヴィッド賞、2019年にNAS賞(分子生物学部門)、ワイリー賞、ダーウィン・ウォレスメダルを受賞。2021年にはマスリー賞

を受賞[6]。

"An open letter titled "How Not To Talk About Race And Genetics" by a group of 67 scientists and scholars criticizes Reich's use of the term "race" in this book.[3] The group welcomes Reich's challenge to the "misrepresentations about race and genetics"[3] made by the science writer Nicholas Wade and the molecular biologist James Watson, but warns that his skill with genomics "should not be confused with a mastery of the cultural, political, and biological meanings of human groups."[3] The list of signatories includes geneticists Joseph L. Graves Jr. and Erika Hagelberg, biologists Anne Fausto-Sterling and Robert Pollack, biological anthropologists Jonathan M. Marks, Agustín Fuentes and Alan H. Goodman, and sociologists Alondra Nelson, Troy Duster and France Winddance Twine."

「67 人の科学者と学者からなるグループによる「人種と遺伝について語るにはどうすればよいか」と題する公開書簡は、ライクが本書で「人種」という用語を使用し たことを批判している[3]。このグループは、科学ライターのニコラス・ウェイド(Nicholas J. Wade)と分子生物学者のジェームズ・ワトソンが行った「人種と遺伝に関する誤っ た表現」[3]に対するライクの挑戦を歓迎するが、彼のゲノミクスの手腕を「人間集団の文化的、政治的、生物学的意味の熟達と混同すべきではない」と警告 している。 「署名者のリストには、遺伝学者のジョセフ・L・グレイブス・ジュニアとエリカ・ヘーゲルバーグ、生物学者のアン・ファウスト=スターリングとロバート・ ポラック、生物人類学者のジョナサン・M・マークス、アグスティン・フエンテス、アラン・H・グッドマン、社会学者のアロンドラ・ネルソン、トロイ・ダス ター、フランス・ウインドダンス・トゥワインらが名を連ねている」

https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/bfopinion/race-genetics-david-reich

| How Not To Talk About Race And Genetics Race has long been a potent way of defining differences between human beings. But science and the categories it constructs do not operate in a political vacuum. This open letter was produced by a group of 67 scientists and researchers. The full list of signatories can be found below. |

人種と遺伝について話してはいけないこと 人種は長い間、人間同士の違いを定義する有力な手段であった。しかし、科学と科学が構築するカテゴリーは、政治的空白の中で機能しているわけではない。 この公開書簡は、67人の科学者と研究者のグループによって作成された。署名者の全リストは以下を参照のこと。 |

| In his newly published book Who

We Are and How We Got Here, geneticist David Reich engages with the

complex and often fraught intersections of genetics with our

understandings of human differences — most prominently, race. He admirably challenges misrepresentations about race and genetics made by the likes of former New York Times science writer Nicholas Wade and Nobel Laureate James Watson. As an eminent scientist, Reich clearly has experience with the genetics side of this relationship. But his skillfulness with ancient and contemporary DNA should not be confused with a mastery of the cultural, political, and biological meanings of human groups. As a group of 67 scholars from disciplines ranging across the natural sciences, medical and population health sciences, social sciences, law, and humanities, we would like to make it clear that Reich’s understanding of "race" — most recently in a Times column warning that “it is simply no longer possible to ignore average genetic differences among ‘races’” — is seriously flawed. For centuries, race has been used as potent category to determine how differences between human beings should and should not matter. But science and the categories it constructs do not operate in a political vacuum. Population groupings become meaningful to scientists in large part because of their social and political salience — including, importantly, their power to produce and enforce hierarchies of race, sex, and class. Reich frames his argument by positing a straw man in the form of a purported orthodoxy that claims that “the average genetic differences among people grouped according to today's racial terms are so trivial when it comes to any meaningful biological traits that those differences can be ignored.” That orthodoxy, he says, “denies the possibility of substantial biological differences among human populations” and is “anxious about any research into genetic differences among populations.” |

新たに出版された著書『Who We Are and How We

Got

Here(私たちは何者か、そしていかにしてここにたどり着いたか)』の中で、遺伝学者のデイヴィッド・ライクは、遺伝学と人間の違いに関する理解、とり

わけ人種に関する理解との複雑で、しばしば危うい接点に取り組んでいる。 元ニューヨーク・タイムズ紙のサイエンス・ライターであるニコラス・ウェイドやノーベル賞受賞者のジェームズ・ワトソンら によってなされた、人種と遺伝学に関する誤った表現に、彼は見事に挑戦している。著名な科学者であるライクは、この関係の遺伝学的側面について明らかに経 験を積んでいる。しかし、古今東西のDNAに関する彼の巧みな知識は、人間の集団が持つ文化的、政治的、生物学的な意味の熟達と混同されるべきではない。 自然科学、医学、人口健康科学、社会科学、法学、人文科学にわたる67人の学者からなるグループとして、私たちはライクの「人種」に対する理解——最近で は『タイムズ』紙のコラムで「『人種』間の平均的な遺伝的差異を無視することはもはや不可能である」と警告している——には重大な欠陥があることを明らか にしたい。 何世紀にもわたり、人種は人間間の違いがどのように問題にされるべきか、されるべきでないかを決定する有力なカテゴリーとして使われてきた。しかし、科学 と科学が構築するカテゴリーは、政治的空白の中で運用されるものではない。集団の分類が科学者にとって意味を持つようになるのは、その大部分が社会的・政 治的な意味づけのためであり、その中には重要なこととして、人種、性別、階級といったヒエラルキーを生み出し、強制する力も含まれている。 ライクは、「今日の人種用語に従ってグループ分けされた人々の平均的な遺伝的差異は、意味のある生物学的形質に関しては非常に些細なものであり、その差異は無視しても構わない」と主張する正統派と称される藁人形を仮定することによって、彼の議論を組み立てている。その正統派は、「人間の集団間に実質的な生物学的差異が存在する可能性を否定し」、「集団間の遺伝的差異に関するいかなる研究にも不安を抱いている 」と彼は言う。 |

| This misrepresents the many

scientists and scholars who have demonstrated the scientific flaws of

considering “race” a biological category. Their robust body of

scholarship recognizes the existence of geographically based genetic

variation in our species, but shows that such variation is not

consistent with biological definitions of race. Nor does that variation

map precisely onto ever changing socially defined racial groups. Reich critically misunderstands and misrepresents concerns that are central to recent critiques of how biomedical researchers — including Reich — use categories of “race” and “population.” For example, sickle cell anemia is a meaningful biological trait. In the US it is commonly (and mistakenly) identified as a “black” disease. In fact, while it does have a high prevalence in populations of people with West and Central African ancestry, it also has a high prevalence in populations from much of the Arabian Peninsula, and parts of the Mediterranean and India. This is because the genetic variant that causes sickle cell is more prevalent in people descended from parts of the world with a high incidence of malaria. “Race” has nothing to do with it. Thus, it is simply wrong to say that the higher prevalence of sickle cell trait in West African populations means that the racial category “black” is somehow genetic. The same thing goes for the people descended from West African populations whom Reich examined in his work on prostate cancer. These people may have a higher frequency of a version of a particular gene that is linked to a higher risk of prostate cancer. But lots of people not from West Africa also have this same gene. We don’t call these other people a “race” or say their “race” is relevant to their condition. Finding a high prevalence of a particular genetic variant in a group does not make that group a “race.” |

こ

れは、「人種」を生物学的カテゴリーとみなすことの科学的欠陥を実証してきた多くの科学者や学者を誤解させるものである。彼らの確固とした一連の研究は、

我々の種における地理的な遺伝的変異の存在を認めているが、そのような変異は生物学的な人種の定義とは一致しないことを示している。また、その変異は、絶

えず変化する社会的に定義された人種集団に正確に対応するものでもない。 ライクは、ライクを含む生物医学研究者が 「人種 」や 「集団 」というカテゴリーをどのように使っているかという最近の批評の中心となっている懸念を、決定的に誤解し、誤って表現している。 例えば、鎌状赤血球貧血は意味のある生物学的形質である。アメリカでは、鎌状赤血球貧血は一般的に(そして間違って)「黒人」の病気と認識されている。実 際、鎌状赤血球貧血は西アフリカや中央アフリカに先祖を持つ人々の集団に高い有病率があるが、アラビア半島の大部分、地中海沿岸やインドの一部の人々の集 団にも高い有病率がある。これは、鎌状赤血球の原因となる遺伝子変異が、マラリアが多発する地域の出身者に多く見られるためである。「人種は関係ない。 従って、西アフリカの人々に鎌状赤血球が多いということは、「黒人 」という人種区分が遺伝的なものであるというのは単純に間違いである。 ライクが前立腺癌の研究で調査した西アフリカの人々の子孫についても同 じことが言える。これらの人々は、前立腺癌の高いリスクと関連する特定の遺伝子のバージョンの頻度が高いかもしれない。しかし、西アフリカ出身でない多く の人々も同じ遺伝子を持っている。このような人々を 「人種 」と呼んだり、「人種 」が彼らの状態に関係しているとは言わない。ある集団で特定の遺伝子変異の有病率が高いからといって、その集団が 「人種 」になるわけではない。 |

Human beings are 99.5% genetically identical. Of course, because the human genome has 3 billion base pairs, that means any given individual may differ from another at 15 million loci (.5% of 3 billion). Given random variation, you could genotype all Red Sox fans and all Yankees fans and find that one group has a statistically significant higher frequency of a number of particular genetic variants than the other group — perhaps even the same sort of variation that Reich found for the prostate cancer–related genes he studied. This does not mean that Red Sox fans and Yankees fans are genetically distinct races (though many might try to tell you they are). In short, there is a difference between finding genetic differences between individuals and constructing genetic differences across groups by making conscious choices about which types of group matter for your purposes. These sorts of groups do not exist “in nature.” They are made by human choice. This is not to say that such groups have no biological attributes in common. Rather, it is to say that the meaning and significance of the groups is produced through social interventions. |

人間は99.5%遺伝的に同一である。もちろん、ヒトゲノムの塩基対は30億であるため、任意の個体が1,500万の遺伝子座(30億の0.5%)で他の個体と異なる可能性があることを意味する。 ランダムな変異があるとすれば、レッドソックス・ファンとヤンキース・ファンの遺伝子型判定を行い、一方のグループが他方のグループよりも特定の遺伝子変 異の頻度が統計的に有意に高いことを発見することもできる。これは、レッドソックス・ファンとヤンキース・ファンが遺伝的に異なる人種であるということを 意味するものではない(多くの人はそうだと言おうとするかもしれないが)。 要するに、個人間の遺伝的差異を発見することと、どのタイプの集団が自分の目的にとって重要かを意識的に選択することによって集団間の遺伝的差異を構築することとは違うのである。この種の集団は 「自然界には 」存在しない。人間の選択によって作られるのである。これは、このような集団には生物学的な共通点がない、と言っているのではない。むしろ、集団の意味や意義は社会的な介入によって生み出されるということである。 |

| In support of his argument for

the biological relevance of race, Reich also writes about genetic

differences between Northern and Southern Europeans. Again, this should

not be an argument for the biological reality of race. Of course, we

could go back to the early 20th century when many believed that the

“industrious” Northern Teutons were a race distinct from the “slothful”

Southern Europeans. Such thinking informed the creation of racially

restrictive immigration laws in 1924, but we think even Reich would not

consider this sort of thinking useful today. Instead, we need to recognize that meaningful patterns of genetic and biological variation exist in our species that are not racial. Reich’s claim that we need to prepare for genetic evidence of racial differences in behavior or health ignores the trajectory of modern genetics. For several decades billions of dollars have been spent trying to find such differences. The result has been a preponderance of negative findings despite intrepid efforts to collect DNA data on millions of individuals in the hope of finding even the tiniest signals of difference. To challenge Reich’s claims is not, as he would have it, to stick our heads in the sand. It is to develop a more sophisticated approach to the problem of human group categorization in the biomedical sciences. |

人種の生物学的関連性を主張するライクは、北欧人と南欧人の遺伝的差異についても書いている。繰り返すが、これは人種の生物学的実在性を論証するものではない。もちろん、多くの人々が「勤勉な」北チュートン人は「怠惰な」南ヨーロッパ人とは異なる人種だと信じていた20世紀初頭に戻ることもできる。このような考え方は、1924年に人種制限的な移民法を制定するきっかけとなったが、ライクでさえこのような考え方が今日役に立つとは考えないだろう。 そうではなく、人種的なものではない、意味のある遺伝的・生物学的変異のパターンが私たちの種には存在することを認識する必要がある。 行動や健康における人種差の遺伝的証拠に備える必要があるというライク の主張は、現代の遺伝学の軌跡を無視している。数十年の間、そのような違いを見つけようと何十億ドルも費やされてきた。ほんのわずかな違いのシグナルでも 見つけようと、何百万人という個人のDNAデータを集めようとする果敢な努力にもかかわらず、結果は否定的な発見が圧倒的に多かった。 ライクの主張に異議を唱えることは、彼が言うように、砂の中に頭を突っ込むことではない。それは、生物医学におけるヒトの集団分類の問題に対して、より洗練されたアプローチを開発することである。 |

| Precisely because the problems

of race are complex, scientists need to engage these issues with

greater care and sophistication. Geneticists should work in

collaboration with their social science and humanities colleagues to

make certain that their biomedical discoveries make a positive

difference in health care, including the care of those studied. This is not to say that geneticists such as Reich should never use categories in their research; indeed, their work would be largely impossible without them. However, they must be careful to understand the social and historical legacies that shape the formation of these categories, and constrain their utility. Even "male" and "female," which Reich invokes as obviously biologically meaningful, has important limitations. While these categories help us to know and care for many human beings, they hinder our capacity to know and care for the millions of human beings born into this world not clearly "sexed.’ Further, overemphasizing the importance of the X and Y chromosomes in determining sex prevent us from seeing the other parts of the genome involved in sex. While focusing on groups with a high incidence of a particular condition may help researchers identify genetic variants that might correlate to the condition, it must also be understood that all genetic contributions to physical traits, including disease, are always influenced by environmental factors. |

まさに人種問題は複雑であるため、科学者はより注意深く、より洗練された方法でこれらの問題に取り組む必要がある。遺伝学者は、社会科学や人文科学の同僚と協力して、生物医学的な発見が、研究対象者のケアを含む医療に肯定的な変化をもたらすよう努力すべきである。 これは、ライクのような遺伝学者が研究においてカテゴリーを決して使うべきではないと言っているのではない。しかし、これらのカテゴリーを形成し、その有用性を制約している社会的、歴史的遺産を理解することに注意しなければならない。 ライクが明らかに生物学的に意味のあるものとして持ち出している「男性」と「女性」でさえ、重要な限界を持っている。これらのカテゴリーは、私たちが多く の人間を知り、ケアするのに役立つ一方で、この世に生まれた何百万という「性別」が明確でない人間を知り、ケアすることを妨げている。さらに、性の決定におけるX染色体とY染色体の重要性を強調しすぎると、性に関わるゲノムの他の部分が見えなくなる。 特定の疾患の罹患率が高いグループに焦点を当てることは、研究者がその疾患と相関する可能性のある遺伝的変異を特定するのに役立つかもしれないが、疾患を含む身体的形質への遺伝的寄与はすべて、常に環境要因の影響を受けていることも理解しなければならない。 |

| For example, an ancestral gene

may not have ever contributed to disease risk in its former

environment, but now does when individuals carrying it are

differentially exposed to harmful environments. This raises the

question of whether it is more efficacious to remove the environmental

insult or alter the individual’s physiology by medical intervention (or

both). Making claims about the existence of biological races won’t help answer questions about health, like how the health of racialized groups is harmed by racial discrimination — how it increases the risk of disease, the risk of exposure to environmental toxins, or the risk of inadequate and inappropriate health care. This doesn’t mean that genetic variation is unimportant; it is, but it does not follow racial lines. History has taught us the many ways that studies of human genetic variation can be misunderstood and misinterpreted: if sampling practices and historical contexts are not considered; if little attention is given to how genes, environments, and social conditions interact; and if we ignore the ways that sociocultural categories and practices shape the genetic patterns themselves. As scholars who engage with social and scientific research, we urge scientists to speak out when science is used inappropriately to make claims about human differences. The public should not cede the power to define race to scientists who themselves are not trained to understand the social contexts that shape the formation of this fraught category. Instead, we encourage geneticists to collaborate with their colleagues in the social sciences, humanities, and public health to consider more carefully how best to use racial categories in scientific research. Together, we can conduct research that will influence human lives positively. |

例えば、先祖代々受け継がれてきた遺伝子は、かつての環境では疾病リス

クに寄与しなかったかもしれないが、その遺伝子を持つ個体が有害な環境にさらされると、疾病リスクに寄与するようになる。この場合、環境の影響を除去する

のがより効果的なのか、それとも医学的介入によって個体の生理機能を変化させるのがより効果的なのか(あるいはその両方)という疑問が生じる。 生物学的人種の存在について主張することは、人種差別によって人種差別 を受けた集団の健康がどのように害されるのか、つまり病気のリスクや環境毒素にさらされるリスク、あるいは不十分で不適切なヘルスケアのリスクがどのよう に高まるのか、といった健康に関する疑問に答える助けにはならない。 これは遺伝的変異が重要でないという意味ではない。サンプリングの仕方や歴史的背景が考慮されない場合、遺伝子、環境、社会的条件がどのように相互作用し ているかにほとんど注意が払われない場合、社会文化的カテゴリーや慣習が遺伝的パターンそのものを形成する方法を無視する場合などである。 社会的・科学的研究に携わる学者として、私たちは科学者が、人間の差異 について主張するために科学が不適切に使用された場合、声を上げるよう強く求める。一般市民は、人種を定義する権力を、この危ういカテゴリーの形成を形作 る社会的文脈を理解する訓練を受けていない科学者に譲るべきではない。その代わりに、我々は遺伝学者が社会科学、人文科学、公衆衛生学の同僚と協力し、科学的研究において人種カテゴリーをどのように使用するのが最善であるかをより慎重に検討することを奨励する。私たちは共に、人々の生活に良い影響を与える研究を行うことができるのである。 |

| Jonathan Kahn, James E. Kelley Professor of Law, Mitchell Hamline School of Law Alondra Nelson, Professor of Sociology and Gender Studies, Columbia University; President, Social Science Research Council Joseph L. Graves Jr., Associate Dean for Research & Professor of Biological Sciences, Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, Section G: Biological Sciences, Joint School of Nanoscience & Nanoengineering, North Carolina A&T State University, UNC Greensboro Sarah Abel, Postdoc, Department of Anthropology, University of Iceland Ruha Benjamin, Associate Professor, Department of African American Studies, Princeton University Sarah Blacker, Postdoctoral Research Fellow, Max Planck Institute for the History of Science, Berlin Catherine Bliss, Associate Professor, Social and Behavioral Sciences, UC San Francisco Lundy Braun, Professor of Medical Science and Africana Studies, Brown University Khiara M. Bridges, Professor of Law, Professor of Anthropology, Boston University Craig Calhoun, President of Berggruen Institute Centennial Professor, London School of Economics. Claudia Chaufan, Associate Professor, York University Toronto Nathaniel Comfort, Professor, Institute of the History of Medicine, The Johns Hopkins University Richard Cone, Professor of Biophysics, Johns Hopkins University Richard Cooper, Department of Public Health Sciences, Loyola University Medical School Marcy Darnovsky, Executive Director, Center for Genetics and Society Robert Desalle, Curator, Institute for Genomics, American Museum of Natural History Troy Duster, Chancellor’s Professor Emeritus, University of California, Berkeley Anne Fausto-Sterling, Professor of Biology Emerita, Brown University, Fellow of the American Association for the Advancement of Science Agustin Fuentes, The Edmund P. Joyce C.S.C. Professor of Anthropology, University of Notre Dame Joan H. Fujimura, Professor, Department of Sociology and Holtz Center for Research on Science, Technology, Medicine, and the Environment, University of Wisconsin-Madison |

ジョナサン・カーン(ミッチェル・ハムライン・スクール・オブ・ロー ジェームズ・E・ケリー教授 アロンドラ・ネルソン、コロンビア大学社会学・ジェンダー研究教授、社会科学研究評議会会長 ジョセフ・L・グレイブス・ジュニア、研究副学部長兼生物科学教授、米国科学振興協会フェロー、セクションG:生物科学、ノースカロライナA&T州立大学ナノ科学・ナノ工学ジョイントスクール、ノースカロライナ大学グリーンズボロ校 サラ・アベル、アイスランド大学人類学部博士研究員 ルハ・ベンジャミン、プリンストン大学アフリカ系アメリカ人研究学科准教授 サラ・ブラッカー(ベルリン、マックス・プランク科学史研究所博士研究員 キャサリン・ブリス、カリフォルニア大学サンフランシスコ校社会・行動科学科准教授 Lundy Braun、ブラウン大学、医学・アフリカ研究教授 キアラ・M・ブリッジス、ボストン大学法学部教授、人類学教授 クレイグ・カルフーン、ベルクグルーエン研究所所長、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクス百周年記念教授 クラウディア・チャウファン ヨーク大学トロント校 准教授 ナサニエル・コンフォート ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学医学史研究所教授 リチャード・コーン ジョンズ・ホプキンス大学生物物理学教授 リチャード・クーパー ロヨラ大学医学部公衆衛生科学科教授 マーシー・ダーノフスキー 遺伝学と社会センター エグゼクティブ・ディレクター ロバート・デサール、アメリカ自然史博物館ゲノム研究所学芸員 トロイ・ダスター、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校学長名誉教授 アン・ファウスト=スターリング、ブラウン大学名誉生物学教授、米国科学振興協会フェロー アグスティン・フエンテス、ノートルダム大学エドマンド・ジョイス人類学教授 ジョーン・H・フジムラ ウィスコンシン大学マディソン校社会学部・ホルツ科学技術・医学・環境研究センター教授 |

| Stephanie Malia Fullerton, Associate Professor, Department of Bioethics & Humanities, University of Washington Duana Fullwiley, Associate Professor of Medical Anthropology, Stanford University. Omer Gokcumen, Assistant Professor, University at Buffalo Alan Goodman, Professor of Biological Anthropology. Hampshire College Monica H. Green, Professor of History, School of Historical, Philosophical, and Religious Studies, Arizona State University Erika Hagelberg, Professor, Department of Biosciences, University of Oslo Evelynn Hammonds, Barbara Gutmann Rosenkrantz Professor of the History of Science, Harvard University Helena Hansen, Assistant Professor of Anthropology and Psychiatry, New York University John Hartigan Jr., Professor of Anthropology, University of Texas, Austin. Anthony Hatch, Associate Professor, Science in Society Program, Sociology, and African American Studies, Wesleyan University Torsten Heinemann, Professor of Sociology and Chair of Technology and Diversity, RWTH Aachen University, Germany Jay Kaufman, Canada Research Chair in Health Disparities and Professor of Epidemiology, McGill University. Trica Keaton, Associate Professor, African and African American Studies, Dartmouth College Terence Keel, Associate Professor, Department of Black Studies and Department of History, University of California, Santa Barbara Nancy Krieger, Professor of Social Epidemiology, American Cancer Society Clinical Research Professor, Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Sheldon Krimsky, Lenore Stern Professor of Humanities and Social Sciences, Tufts University Jon Røyne Kyllingstad, Associate Professor of History, University of Oslo Catherine Lee, Associate Professor of Sociology, Rutgers University Ageliki Lefkaditou, Postdoctoral Researcher, Institute of Health and Society, University of Oslo Sandra Soo-Jin Lee, Senior Research Scholar, Center for Biomedical Ethics, Stanford University Jonathan Marks, Professor of Anthropology, UNC-Charlotte Amade M’charek, Professor of the Anthropology of Science, University of Amsterdam, Netherlands Michael Montoya, Associate Professor of Anthropology Emeritus, University of California, Irvine Ann Morning, Associate Professor of Sociology, New York University Osagie K. Obasogie, Haas Distinguished Chair and Professor of Bioethics, Joint Medical Program and School of Public Health, University of California, Berkeley |

ステファニー・マリア・フラートン ワシントン大学生命倫理・人文学部准教授 ドゥアナ・フルワイリー スタンフォード大学 医療人類学准教授 オメル・ゴクチュメン(バッファロー大学助教授 アラン・グッドマン 生物人類学教授 ハンプシャー大学 モニカ・H.グリーン(アリゾナ州立大学歴史・哲学・宗教学部歴史学科教授 エリカ・ヘーゲルベルグ(オスロ大学バイオサイエンス学部教授 エヴリン・ハモンズ(ハーバード大学科学史バーバラ・グートマン・ローゼンクランツ教授 ヘレナ・ハンセン(ニューヨーク大学人類学・精神医学助教授 ジョン・ハーティガン・ジュニア テキサス大学オースティン校人類学教授 アンソニー・ハッチ(ウェズリアン大学社会学・アフリカ系アメリカ人研究、社会の中の科学プログラム准教授 トーステン・ハイネマン(ドイツ、アーヘン工科大学社会学教授、テクノロジーと多様性講座教授 ジェイ・カウフマン、カナダ健康格差研究講座、マギル大学疫学教授 トリカ・キートン(ダートマス大学、アフリカ・アフリカ系アメリカ人研究准教授 テレンス・キール(カリフォルニア大学サンタバーバラ校黒人学・歴史学部准教授 ナンシー・クリーガー 米国癌協会社会疫学教授 ハーバード大学T.H.チャン公衆衛生大学院臨床研究教授 シェルドン・クリムスキー、タフツ大学人文社会科学レノア・スターン教授 ヨン・ロイネ・キュリングスタッド、オスロ大学准教授(歴史学 キャサリン・リー(ラトガース大学社会学部准教授 アゲリキ・レフカディトゥ(オスロ大学健康社会研究所博士研究員 サンドラ・スージン・リー(スタンフォード大学生物医学倫理センター上級研究員 ジョナサン・マークス(国連大学シャーロット校人類学教授 アマデ・ムチャレク(オランダ、アムステルダム大学、科学人類学教授 マイケル・モントーヤ(カリフォルニア大学アーバイン校名誉人類学准教授 アン・モーニング(ニューヨーク大学社会学部准教授 オサジー・K・オバソギー(カリフォルニア大学バークレー校共同医療プログラム・公衆衛生学部ハース特別講座・生命倫理学教授 |

| Pilar N. Ossorio, Ph.D., JD, Professor of Law and Bioethics, University of Wisconsin-Madison Tony Platt, Distinguished Affiliated Scholar, Center for the Study of Law & Society, UC Berkeley; Robert Pollack, professor of Biological Sciences, Columbia University Aaron Panofsky, Associate Professor, Institute for Society and Genetics, Public Policy, and Sociology, University of California, Los Angeles Kimani Paul-Emile, Associate Professor, Fordham University School of Law Ramya M. Rajagopalan, Research Scientist, Institute for Practical Ethics, University of California, San Diego Rayna Rapp, Professor of Anthropology, New York University Jenny Reardon, Professor of Sociology and Director, Science and Justice Research Center, University of California, Santa Cruz Amos Morris-Reich, Professor of History, University of Haifa Susan M. Reverby, McLean Professor Emerita in the History of Ideas and Professor Emerita of Women’s and Gender Studies, Wellesley College Jennifer A. Richeson, Philip R. Allen Professor of Psychology, Yale University Sarah S. Richardson, Professor of the History of Science and of Studies of Women, Gender, and Sexuality Director of Graduate Studies, WGS, Harvard University Dorothy Roberts, George A. Weiss University Professor of Law, Sociology, and Africana Studies and Director, Penn Program on Race, Science, and Society, University of Pennsylvania Wendy D. Roth, Associate Professor of Sociology, University of British Columbia Charmaine DM Royal, Associate Professor, African & African American Studies, Biology, and Community & Family Medicine, Duke University Danilyn Rutherford, President of the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research Janet K. Shim, Professor of Sociology, University of California, San Francisco Karen-Sue Taussig, Chair and Associate Professor of Anthropology, University of Minnesota Charis Thompson, Chancellor’s Professor, UC Berkeley, and RQIF Professor, London School of Economics France Winddance Twine, Professor of Sociology, University of California at Santa Barbara Keith Wailoo, Henry Putnam University Professor of History and Public Affairs, Princeton University Patricia J. Williams, James L. Dohr Professor of Law, Columbia University Michael Yudell, Chair & Associate Professor, Dornsife School of Public Health, Drexel University |

ピラー・N・オソリオ(ウィスコンシン大学マディソン校法学・生命倫理学教授、法学博士、法学博士 トニー・プラット カリフォルニア大学バークレー校法社会研究センター特別提携研究員 ロバート・ポラック、コロンビア大学生物科学教授 アーロン・パノフスキー(カリフォルニア大学ロサンゼルス校、社会・遺伝学・公共政策・社会学研究所准教授 キマニ・ポール=エミール フォーダム大学ロースクール准教授 Ramya M. Rajagopalan(カリフォルニア大学サンディエゴ校実践倫理研究所研究員 レイナ・ラップ(ニューヨーク大学人類学教授 ジェニー・リアドン(カリフォルニア大学サンタクルーズ校、社会学教授、科学と正義研究センター所長 エイモス・モリス=ライク(ハイファ大学歴史学教授 スーザン・M・レヴァービー、ウェルズリー大学マクリーン名誉教授(思想史)、名誉教授(女性学・ジェンダー研究 ジェニファー・A・リチェソン、イェール大学フィリップ・R・アレン心理学教授 サラ・S・リチャードソン ハーバード大学科学史および女性・ジェンダー・セクシュアリティ研究教授 WGS大学院ディレクター ドロシー・ロバーツ:ジョージ・A・ワイス大学教授(法学、社会学、アフリカーナ研究)、ペンシルバニア大学人種・科学・社会プログラム・ディレクター ウェンディ・D.Roth, ブリティッシュ・コロンビア大学社会学部准教授 シャーメイン・DM・ロイヤル(デューク大学、アフリカ・アフリカ系アメリカ人研究、生物学、地域・家庭医学准教授 ダニリン・ラザフォード(ウェナー・グレン人類学研究財団会長 ジャネット・K・シム カリフォルニア大学サンフランシスコ校社会学教授 カレン・スー・タウシグ(ミネソタ大学人類学講座・准教授 チャリス・トンプソン(カリフォルニア大学バークレー校学長教授、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスRQIF教授 フランス・ウィンダンス・トワイン、カリフォルニア大学サンタバーバラ校社会学教授 キース・ワイルー、プリンストン大学歴史・公共問題ヘンリー・パットナム大学教授 パトリシア・J・ウィリアムズ コロンビア大学 ジェームズ・L・ドーア法学部教授 マイケル・ユーデル ドレクセル大学ドーンシフェ公衆衛生大学院講座・准教授 |

| https://www.buzzfeednews.com/article/bfopinion/race-genetics-david-reich |

★人種はないが、人間の集団の間には「差異がある」と主張される、根拠のレトリック(→「人種と遺伝学」)

「人 間は遺伝的に99.5%同一である。だがしかし、ヒトゲノムには 30 億塩基対があるため、どの個体でも 1,500 万座位 (30 億の 0.5%) で他の個体と異なる可能性があることを意味する」というもの。 1,500 万座位も違うのだから、人間集団において違いがでてくるのは当然というレトリックである。それが、知能の違いや道徳的性向のちがいだとすれば、それは、ロンブローゾ学説の再来とも言える。

★デイヴィッド・ライクと「科学人種主義」

デイヴィッド・ライクは「科学人種主義」すなわち、人種の違いはその集団の遺伝子的組成によるものであり、このことは、地域集団の固有性と移動や流入による遺伝子組成の変化として、根拠づけられる、という彼の(論点先取的な)主張を裏付けられる。

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆