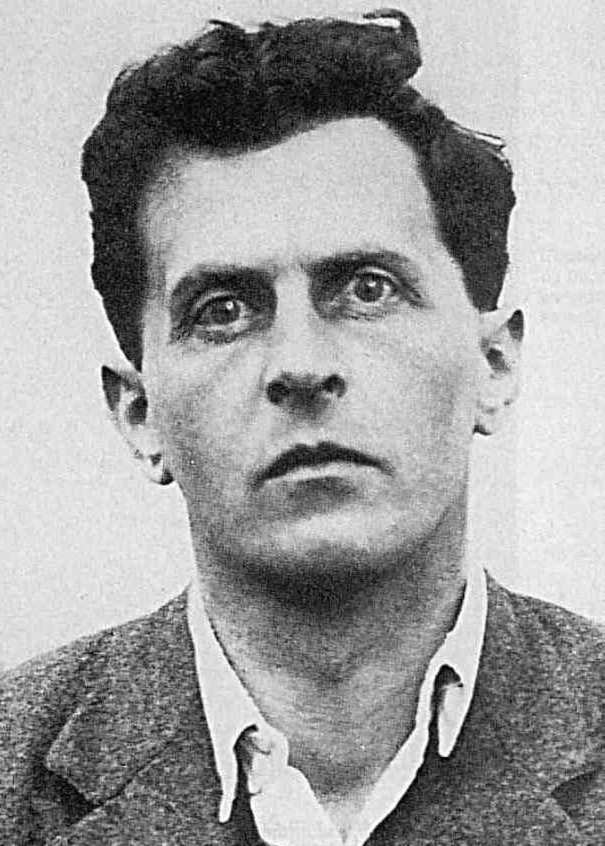

Ludwig Wittgenstein, On The golden bough

by James Frazer

1929年にトリニティカレッジから奨学金

を受賞した時に撮影されたもの(部分)

ウィトゲンシュタイン「フレーザー『金枝篇』 について」

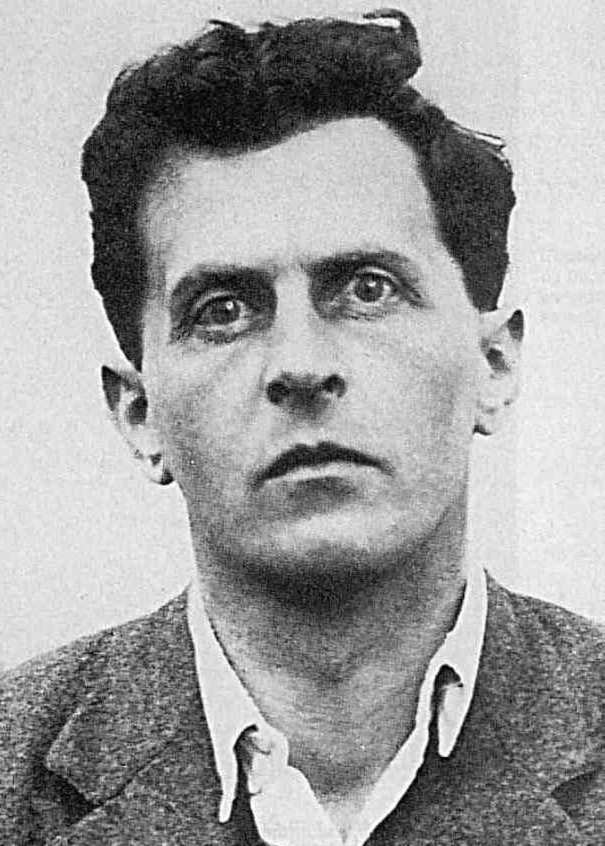

Ludwig Wittgenstein, On The golden bough

by James Frazer

1929年にトリニティカレッジから奨学金

を受賞した時に撮影されたもの(部分)

解説:池田光穂

| Dr. M. O’C. Drury

writes: “I think it would have been in 1930 that Wittgenstein said to

me that he had always wanted to read Frazer but hadn’t done so, and

would I get hold of a copy and read some of it out loud to him. I

borrowed from

the Union Library the first volume of the multivolume edition and we

only got

a little way through this because he talked at considerable length

about it, and

the next term we didn’t start it again.” —Wittgenstein began writing on

Frazer

in his manuscript book on June 19, 1931, and he added remarks during

the next

two or three weeks—although he was writing more about other things

(such as

Verstehen eines Satzes, Bedeutung, Komplex und Tatsache, Intention . .

.). He

may have made earlier notes in a pocket notebook, but I have found

none. |

M. O’C.

ドゥルーリー博士は次のように書いている:「1930年頃だったと思うが、ウィトゲンシュタインが私に、ずっとフレイザーを読みたいと思っていたがまだ読

んでいないので、その本を手に入れて、一部を声に出して読んでくれないかと言った。私はユニオン図書館から多巻本版の第一巻を借りたが、彼はその内容につ

いて詳しく話したので、少ししか読めなかった。次の学期には、再び読み始めることはなかった。」

—ウィトゲンシュタインは、1931年6月19日に、手記帳にフレイザーについて書き始め、その後2、3週間にわたってコメントを追加した。ただし、その

間、彼は他のこと(Verstehen eines Satzes、Bedeutung、Komplex und

Tatsache、Intention

など)についてより多く書いていた。彼は、ポケットノートにそれより前にメモを残していたかもしれないが、私はそれを見つけていない。 |

| It was probably in 1931 that he

dictated to a typist the greater part of the manuscript books written

since July 1930; often changing the order of remarks, and

details of the phrasing, but leaving large blocks as they stood. (He

rearranged the

material again and again later on.) This particular typescript runs to

771 pages. It

has a section, just under 10 pages long, of the remarks on Frazer, with

a few changes

in order and phrasing. Others are in different contexts, and a few are

left out. |

おそらく1931年に、彼は1930年7月以降に執筆した原稿の大部分

をタイプライターに口述した。その際、コメントの順序や表現の詳細を頻繁に変更したが、大部分はそのまま残した。(彼はその後、何度も資料の整理を行っ

た。) このタイプ原稿は 771 ページに及ぶ。その中には、10

ページ弱のフレイザーに関するコメントがあり、順序や表現が若干変更されている。他のコメントは異なる文脈で記載されており、一部は省略されている。 |

| The typed section on Frazer

begins with three remarks which are not connected with them in the

manuscript. He had begun there with remarks which

he later marked S (= “schlecht”) and did not have typed. I think we can

see why.

The earlier version was: |

フレイザーに関するタイプされた部分は、原稿では関連性のない 3

つの発言から始まっている。彼は当初、後に

S(「schlecht」=「悪い」)と記した発言から始めていたが、それをタイプしなかった。その理由は明らかだと思う。以前のバージョンは次のとおり

だった。 |

| “Ich glaube jetzt, daß es

richtig wäre, mein Buch mit Bemerkungen über die

Metaphysik als eine Art von Magie zu beginnen. Worin ich aber weder der Magie das Wort reden noch mich über sie lustig machen darf. [234] Von der Magie müßte die Tiefe behalten werden. — Ja, das Ausschalten der Magie hat hier den Charakter der Magie selbst. Denn, wenn ich damals anfing von der ‘Welt’ zu reden (und nicht von diesem Baum oder Tisch), was wollte ich anderes als etwas Höheres in meine Worte bannen.” (“I now believe that it would be right to begin my book with remarks on metaphysics as a kind of magic. Where, in doing so, however, I must neither speak out for magic, nor ridicule it. The depth of magic ought to be preserved. — Yes, here canceling out magic has the character of magic itself. For when I began earlier [i.e., in a prior work] to speak about the ‘world’ (and not of this tree or table), what else was I attempting than to conjure up something higher in my words.”) |

「私は今、この本を、形而上学を一種の魔法として論じることで始めるの

が正しいと思うようになった。 しかし、そこで魔法を擁護したり、それを嘲笑したりしてはならない。 [234] 魔法の深遠さは保たなければならない。 そう、ここで魔法を排除することは、魔法そのものの性質を持っているのだ。 なぜなら、私が当時「世界」について語り始めたとき(この木やテーブルについてではなく)、私は自分の言葉に、より高次のものを表現したいと思っただけ だったからだ。」 (“I now believe that it would be right to begin my book with remarks on metaphysics as a kind of magic. Where, in doing so, however, I must neither speak out for magic, nor ridicule it. 魔法の深遠さは保たれるべきだ。 そうだ、ここでは魔法を無効にすることは、魔法そのものの性質を持っている。 なぜなら、私が以前(つまり、以前の著作で)この「世界」(この木やテーブルではなく)について語り始めたとき、私は自分の言葉でより高次なものを作り出 そうとしただけだったからだ。 |

| He wrote the second set of

remarks—and they are only rough notes—years

later; not earlier than 1936 and probably after 1948. They are written

in pencil

on odd bits of paper; probably he meant to insert the smaller ones in

the copy of

the one volume edition of The Golden Bough that he was using. Miss

Anscombe

found them among some of his things after his death. |

彼

は 2 番目のメモ(これは大まかなメモに過ぎない)を、数年後に、1936 年以降、おそらく 1948

年以降に書いた。これらは、さまざまな紙片に鉛筆で書かれている。おそらく彼は、自分が使用していた『黄金の枝』の 1

巻本に、小さなメモを貼り付けるつもりだったのだろう。アンスコム氏は、彼の死後、彼の遺品の中からこれらのメモを見つけた。 |

| RUSH RHEES |

ラッシュ・リーズ |

| 1. One must begin

with error and transform it into truth. That is, one must uncover the source of the error, otherwise hearing the truth won’t help us. It cannot penetrate when something else is taking its place. To convince someone of what is true, it is not enough to state the truth; one must find the way from error to truth. Again and again I must submerge myself in the water of doubt. Frazer’s representation of human magical and religious notions is unsatisfactory: it makes these notions appear as mistakes. Was Augustine mistaken, then, when he called on God on every page of the Confessions? But—one might say—if he was not in error, then surely was the Buddhist saint—or whoever else—whose religion expresses entirely different notions. But none of them was in error except where he was putting forth a theory. Already the idea of explaining the practice—say the killing of the priest king— [235] seems to me wrong-headed. All that Frazer does is to make the practice plausible to those who think like him. It is very strange to present all these practices, in the end, so to speak, as foolishness. But it never does become plausible that people do all this out of sheer stupidity. When he explains to us, for example, that the king would have to be killed in his prime because, according to the notions of the savages, his soul would otherwise not be kept fresh, then one can only say: where that practice and these notions go together, there the practice does not spring from the notion; instead they are simply both present. It could well be, and often occurs today, that someone gives up a practice after having realized an error that this practice depended on. But then again, this case holds only when it is enough to make someone aware of his error so as to dissuade him from his mode of action. But surely, this is not the case with the religious practices of a people, and that is why we are not dealing with an error here. |

1. ひとはまず誤りを認識し、それを真実に変えなければならない。 つまり、誤りの根源を明らかにしなければ、真実を聞いたとしてもそれは役に立たない。何か他のものがその場所を占めていると、真実は浸透しない。 誰かに真実を納得させるには、真実を述べるだけでは不十分だ。誤りから真実へと至る道を見つけなければならない。私は何度も何度も、疑いの水の中に身を沈 めなければならない。 フレイザーの人間の呪術的、宗教的概念の表現は不十分だ。これらの概念を誤りのように見せている。 では、アウグスティヌスは『告白』のすべてのページで神に呼びかけたのは誤りだったのだろうか?しかし、もし彼が誤っていなかったとしたら、まったく異な る概念を宗教で表現している仏教の聖者、あるいはその他の宗教の聖者も誤っていたことになるだろう。 しかし、彼らが誤っていたのは、理論を提唱していた部分だけだ。 例えば、司祭王を殺すという慣習を説明するという考え自体が、私には間違っているように思える。フレイザーは、自分と同じ考えを持つ人々にその慣習を納得 させるだけだ。結局、これらすべての慣習を、いわば愚かなこととして表現するのは非常に奇妙だ。 しかし、人々が純粋な愚かさからこのようなことをするとは決して納得できない。 例えば、王が全盛期に殺されなければならないのは、野蛮人の考えでは、そうしないと彼の魂が新鮮に保たれないからだと説明する際、私たちはただこう言わざ るを得ない:その慣習とこれらの考えが結びついている場合、慣習は考えから生じているのではなく、単に両方とも存在しているだけだ。 その慣習が誤りであることに気づいたために、その慣習を放棄する人は、確かにいるだろう。しかし、それは、その人にその誤りに気づかせるだけで、その行動 をやめさせることができる場合に限られる。しかし、それは、人民の宗教的慣習には当てはまらない。したがって、ここでは誤りについて論じているのではな い。 |

| 2. Frazer says it is very hard

to discover the error in magic—and this is why it

persists for so long—because, for example, a conjuration intended to

bring

about rain will sooner or later appear as effective.2 But then it is

strange that,

after all, the people would not hit upon the fact that it will rain

sooner or

later anyway. I believe that the enterprise of explanation is already wrong because we only have to correctly put together what one already knows, without adding anything, and the kind of satisfaction that one attempts to attain through explanation comes of itself. And here it isn’t the explanation at all that satisfies us. When Frazer begins by telling us the story of the King of the Woods at Nemi, he does so in a tone that shows that something strange and terrible is happening here. However, the question “Why is this happening?” is essentially answered by just this [mode of exposition]: because it is terrible. In other words, it is what appears to us a terrible, impressive, horrible, tragic, etcetera that gave birth to this event [or process]. |

2.

フレイザーは、呪術の誤りを発見することは非常に困難であり、それが呪術が長く存続している理由であると述べている。例えば、雨を降らせるための呪術は、

遅かれ早かれその効果が見られるからだ。2 しかし、結局のところ、雨はいずれ降るという事実を人々が気づかないというのは不思議だ。 私は、説明という行為自体が間違っていると思う。なぜなら、私たちは既に知っていることを正しく組み立てるだけで、何も追加する必要はないからだ。そして、説明を通じて得ようとする満足感は、自然と生まれるものだ。 ここで私たちを満足させるのは、説明そのものではない。フレイザーがネミの木の王の物語を語り始める時、その口調は、ここで何か奇妙で恐ろしいことが起 こっていることを示している。しかし、「なぜこれが起こっているのか?」という質問は、この[説明の仕方]そのもので本質的に答えられている:なぜならそ れは恐ろしいからだ。つまり、私たちに恐ろしい、印象的な、恐ろしい、悲劇的ななどとして現れるものが、この出来事[またはプロセス]を生み出したのだ。 |

| 3. [236] One can only resort to

description here, and say: such is human life. Compared to the impression that what is so described to us, explanation is too uncertain. Every explanation is a hypothesis. But someone who, for example, is unsettled by love will be ill-assisted by a hypothetical explanation. It won’t calm him or her. |

3. [236] ここでは、ただ記述するしかなく、「人間の人生とはそういうものだ」と述べるしかない。 私たちにそう記述された印象に比べ、説明は不確実すぎる。 あらゆる説明は仮説である。 しかし、例えば、愛に不安を抱えている人にとっては、仮説的な説明はまったく助けにならない。その人を落ち着かせることはできないだろう。 |

| 4. The crowding of thoughts that

will not come out because they all try to push

ahead and are wedged at the door. 5. If one sets the phrase “majesty of death” next to the story of the priest king of Nemi, one sees that they are one and the same. The life of the priest king represents what is meant by that phrase. Whoever is gripped by the [idea of ] majesty of death can express this through just such a life. —Of course, this is also not an explanation, it just puts one symbol for another. Or one ceremony in place of another. 6. A religious symbol is not grounded in an opinion. Error only corresponds to opinion. 7. One would like to say: This or the other event took place here; laugh if you can. 8. The religious actions or the religious life of the priest king are not different in kind from any genuinely religious action today, say, a confession of sins. This, too, can be “explained” and cannot be explained. 9. Burning in effigy. Kissing the picture of a loved one. This is obviously not based on a belief that it will have a definite effect on the object [237] that the picture represents. It aims at some satisfaction, and does achieve it, too. Or rather, it does not aim at anything; we act in this way and then feel satisfied. One could also kiss the name of the loved one, and here the representation through the name [as a place-holder] would be clear. 10. The same savage who, apparently in order to kill his enemy, pierces an image of him, really builds his hut out of wood, and carves his arrow skillfully and not in effigy. The idea that one could beckon a lifeless object to come, just as one would beckon a person. Here the principle is that of personification. |

4. すべてが押し出そうとしてドアに挟まってしまい、外に出られない思考の混雑。 5. 「死の威厳」というフレーズをネミの司祭王の物語の隣に置くと、それらが同じものであることがわかる。 司祭王の人生は、そのフレーズが意味するところを表している。 死の威厳という概念に捉われた者は、まさにそのような人生を通してそれを表現することができる。もちろん、これは説明ではなく、ある象徴を別の象徴に置き換えたに過ぎない。あるいは、ある儀式を別の儀式に置き換えたに過ぎない。 6. 宗教的象徴は意見に根ざしていない。誤りは意見にのみ対応する。 7. こう言いたい。この出来事がここで起こった、笑えるなら笑え、と。 8. 司祭王の宗教的行為や宗教的生活は、今日の真に宗教的な行為、たとえば罪の告白などとは本質的に異なるものではない。これも「説明」できるものであり、説明できないものである。 9. 像を燃やす。愛する人の写真をキスする。これは明らかに、その絵が表す対象物に明確な影響を与えるという信念に基づいているわけではない。それは何らかの 満足を目的としており、実際にそれを達成している。あるいはむしろ、それは何も目的としていない。私たちはこのように行動し、その後満足を感じるのだ。 愛する人の名前にもキスをすることができる。この場合、名前(代用記号として)による表現は明らかだ。 10. 敵を殺すために、その像に槍を刺す野蛮人は、実際には木で小屋を建て、巧みに矢を彫っている。 無生物に、まるで人格があるかのように手招きして呼び寄せるという考え方。ここでの原則は擬人化である。 |

| 11. And magic always rests on

the idea of symbolism and of language. The representation of a wish is, eo ipso, the representation of its fulfillment. But magic gives representation to a wish; it expresses a wish. Baptism as washing.—An error arises only when magic is interpreted scientifically. When the adoption of a child is carried out in a way that the mother pulls the child through her clothes, then is it not crazy to think that there is an error, and that she believes to have born the child.3 We should distinguish between magical operations and those operations that rest on false, oversimplified notions of things and processes. For instance, if one says that the illness is moving from one part of the body into another, or if one takes measures to draw off the illness as though it were a liquid or a state of heat, then one is entertaining a false, inappropriate image. 12. What narrowness of spiritual life we find in Frazer! Hence the impossibility of grasping a life different from the English one of his time! [238] Frazer cannot imagine a priest who is not basically an English parson of our times, with all his stupidity and shallowness. 13. Why should it not be possible for someone’s own name to be sacred to himself? On the one hand, it surely is the most important instrument given to him, and, on the other, it is like a jewel hung around his neck at birth. |

11. そして、呪術は常に象徴主義と言語の概念に基づいています。 願いの表現は、その表現そのものがその実現の表現です。しかし、呪術は願いを表現し、願いを表現します。 洗礼としての洗礼—呪術を科学的に解釈した場合にのみ誤りが生じます。 母親が自分の服を通して子供を引き抜くという形で養子縁組が行われる場合、そこに誤りがあり、母親は自分がその子供を生んだと信じていると考えるのは、狂気の沙汰ではないだろうか。3 呪術的な操作と、物事や過程に関する誤った、過度に単純化された概念に基づく操作とは区別すべきだ。例えば、病気は体のある部分から別の部分に移動すると 言う場合、あるいは、病気は液体や熱のようなものだから、それを引き出すような措置を講じる場合、それは誤った、不適切なイメージを抱いていることにな る。 12. フレイザーの精神生活の狭さ!それゆえ、彼の時代のイギリスとは異なる生活を理解することが不可能だったのだ! [238] フレイザーは、現代の英国の牧師のような愚かさと浅薄さを備えた人物以外の神職を想像できないのだ。 13. なぜ、自分の名前が自分にとって神聖なものになってはならないのか?一方では、それは確かに彼に与えられた最も重要な道具であり、他方では、それは出生時に首に掛けられた宝石のようなものなのだ。 |

| How misleading Frazer’s

explanations are becomes clear, I think, from the fact

that one could very well invent primitive practices oneself, and it

would only

be by chance if they were not actually found somewhere. That is, the

principle according to which these practices are ordered4 is a much

more general one

than [it appears] in Frazer’s explanation, and it exists in our own

soul, so that

we could think up all the possibilities ourselves. —We can thus readily

imagine

that, for instance, the king of a tribe becomes visible for no one, but

also that

every member of the tribe is obliged to see him. The latter will then

certainly

not occur in a manner more or less left to chance; instead, he will be

shown to

the people. Perhaps no one will be allowed to touch him, or perhaps

they will

be compelled to touch him. Think how after Schubert’s death his brother

cut

Schubert’s scores into small pieces and gave to his favorite pupils

these pieces

of a few bars. As a gesture of piety, this action is just as

comprehensible as that

of preserving the scores untouched and accessible to no one. And if

Schubert’s

brother had burned the scores, this could still be understood as a

gesture of piety. The ceremonial (hot or cold) as opposed to the haphazard (lukewarm) is what characterizes piety. Yes, Frazer’s explanations would not be explanations at all if they did not, in the end, appeal to an inclination in ourselves. Eating and drinking have their dangers, not only for the savage but also for us; nothing more natural than wanting to protect oneself against them; and we could think up such protective measures ourselves. —But what principle do we follow in confabulating them? Clearly that of formally reducing all dangers to a few very simple ones that are ready to see for everyone. In other words, according to the same principle that leads uneducated people in our society to say that the illness is moving from the head to the chest, etcetera, etcetera. [239] In these simple images personification will, of course, play a great role, for everyone knows that people (hence [also] spirits) can become dangerous to others. That a human shadow, which looks like a human being, or one’s mirror image, that rain, thunderstorms, the phases of the moon, the change of seasons, the likeness or difference of animals to one another and to human beings, the phenomenon of death, of birth, and of sexual life, in short, everything that a human being senses around himself, year in, year out, in manifold mutual connection—that all this should play a role in the thought of human beings (their philosophy) and in their practices is self-evident; or, in other words, it is what we really know and find interesting.5 How could the fire or the fire’s resemblance to the sun have failed to make an impression on the awakening mind of man? But not perhaps “because he can’t explain it to himself ” (the stupid superstition of our time)—for does an “explanation” make it less impressive?— The magic in Alice in Wonderland, trying to dry out by reading the driest thing there is.6 |

フ

レイザーの説明がどれほど誤解を招くものであるかは、原始的な慣習を自ら考案することは十分に可能であり、それが実際にどこかで発見されていないのは単な

る偶然に過ぎないという事実から明らかだと思う。つまり、これらの慣習が秩序付けられている原理は、フレイザーの説明で示されているよりもはるかに一般的

なものであり、それは私たちの魂の中に存在するため、私たちはあらゆる可能性を自ら考え出すことができるのだ。—したがって、例えば、ある部族の王は誰に

も見えないが、部族のすべてのメンバーは王を見なければならない、といった状況を容易に想像することができる。後者は、多かれ少なかれ偶然に任される形で

起こるわけではないだろう。その代わりに、王は人々に披露されるだろう。おそらく、誰も王に触れることは許されないだろう。あるいは、王に触れることを強

制されるかもしれない。シューベルトの死後、彼の兄弟がシューベルトの楽譜を小さな断片に切り刻み、その断片を数小節ずつお気に入りの弟子たちに贈ったこ

とを考えてみてください。敬虔な行為として、この行為は楽譜を未開封のまま誰にも触らせないことと同じように理解可能です。もしシューベルトの兄弟が楽譜

を燃やしたとしても、それは依然として敬虔な行為として理解されるでしょう。 儀式的な(熱いまたは冷たい)ものと、偶然的な(ぬるい)ものとの対比が、敬虔さを特徴づけている。 はい、フレイザーの説明は、最終的に私たち自身の傾向に訴えかけなければ、説明とはならないだろう。 食べたり飲んだりすることには危険がある。野蛮人だけでなく、私たちにもだ。それらから身を守りたいと思うことは、何よりも自然なことであり、私たちはそ のような保護措置を自ら考案することもできる。——しかし、それらを考案する際に、私たちはどのような原理に従っているのか?明らかに、すべての危険を、 誰もがすぐに理解できるごく単純な危険に形式的に還元する原理だ。つまり、私たちの社会で教育を受けていない人々が、病気は頭から胸へ、などと言うのと同 じ原理だ。[239] こうした単純なイメージでは、もちろん擬人化が大きな役割を果たす。なぜなら、人間(したがって霊も)は他者に危険をもたらすことがあることは、誰もが 知っているからだ。 人間のように見える人間の影、あるいは自分の鏡像、雨、雷雨、月の満ち欠け、季節の移り変わり、動物同士の、あるいは動物と人間との類似点や相違点、死、 誕生、性生活といった現象、つまり、人間が自分の周囲で、毎年、さまざまな相互関係の中で感じるすべてのものが、人間の思考(哲学)や行動において役割を 果たすことは自明だ。人間が周囲で感じ取るすべてが、年々、多様な相互関係の中で、人間の思考(哲学)や実践に役割を果たすことは自明だ。あるいは、言い 換えれば、それが私たちが本当に知り、興味深いと感じるものなのだ。5 火、あるいは火と太陽の類似性が、目覚めた人間の心に印象を残さないはずがない。しかし、それは「人間がそれを説明できないから」ではないだろう(それは現代の愚かな迷信だ)。なぜなら、「説明」によってその印象が薄れるわけではないからだ。 『不思議の国のアリス』の呪術は、最も乾いたものを読んで乾かそうとするものだ。 |

| 14. In magical healing one

indicates to the illness that it should leave the patient. After the description of such a magical cure one wants to say, If the illness doesn’t understand that, then I don’t know how else to tell it [to do so]. 15. I do not mean that it is especially fire that must make an impression on anyone. Fire no more than any other phenomenon, and one will impress this person and another that. For no phenomenon is particularly mysterious in itself, but any of them can become so to us, and it is precisely the characteristic feature of the awakening human mind that a phenomenon acquires significance for it. One could almost say that man is a ceremonial animal. This is probably partly false, partly nonsensical, but there is also some truth to it. In other words, one could begin a book on anthropology in this way: when one observes the life and behavior of humans all over the earth, one sees that apart from the kinds of behavior one could call animal [240], the intake of food, etcetera, etcetera, etcetera, humans also carry out actions that bear a peculiar character, and might be called ritual actions. But then again, it is nonsense to go on and say that the characteristic feature of these actions is that they spring from erroneous notions about the physics of things. (As Frazer does when he says that magic is really false physics, or as the case may be, false medicine, technology, etc.) |

14. 呪術的治療では、病気に対して患者から離れるよう指示します。 このような呪術的治療の説明を聞いた後、人は「病気はそれを理解しないなら、他にどう言えばいいのかわからない」と言いたくなります。 15. 特に火が誰にでも印象を与えるというわけではありません。火は他の現象と何ら変わらないし、ある人にはこの印象を与え、別の人には別の印象を与えるだろ う。なぜなら、現象はそれ自体、特に神秘的なものではないが、その現象は私たちにとって神秘的なものになる可能性があるからだ。そして、現象が私たちに とって意味を持つようになることが、目覚めた人間の心の特徴である。人間は儀式的な動物である、とさえ言えるかもしれない。これはおそらく、一部は誤りで あり、一部はナンセンスであるが、ある種の真実も含まれている。 つまり、人類学に関する本では、次のように書き始めることができるだろう。地球上のあらゆる地域の人間の生活や行動を観察すると、動物的な行動 [240]、すなわち食物の摂取などとは別の、独特の特徴を持つ行動、つまり儀礼的な行動も人間にはあることがわかる。 しかし、これらの行動の特徴は、物事の物理的性質に関する誤った概念から生じている、と続けて言うのはナンセンスだ(フレイザーが、呪術は実際には誤った物理学、あるいは場合によっては誤った医学、技術などである、と主張しているように)。 |

| Rather, what is characteristic

of ritual action is not at all any view, opinion,

be it right or wrong, although an opinion—a belief—can itself be of

ritual nature, or belong to a rite. 16. If one takes it to be self-evident that people take pleasure in their own imaginations, then one should remember that such imagination is not like a picture or a three-dimensional model, but a complicated pattern of heterogeneous components: words and images. [Once one does so] one will then no longer oppose operating with written or acoustic signs to operating with “mental images” of events. 17. We must plow over language in its entirety. 18. Frazer: “. . . That these operations are dictated by fear of the ghost of the slain seems certain . . .” [p.212]. But why does Frazer use the word “ghost”?7 He thus evidently understands this superstition only too well, since he explains it with a superstitious term familiar to him. Or rather, he could have seen from this that there is something in us, too, that speaks in support of such observances on the part of the savages. —When I, who do not believe that there exist, anywhere, human-superhuman beings whom one can call gods—when I say: “I fear the wrath of the gods,” then this shows that I can mean something with this [utterance], or can express a sentiment that is not necessarily connected with such belief. 19. Frazer seems capable of believing that a savage dies out of error. In the elementary school primers it says that Attila undertook his great campaigns because he believed he possessed the sword of the god of thunder. [241] Frazer is far more savage than most of his savages, for these savages will not be as far removed from an understanding of spiritual matters as an Englishman of the twentieth century.8 His explanations of primitive practices are much cruder than the meaning of these practices themselves. |

むしろ、儀礼的行動の特徴は、それが正しいか間違っているかにかかわらず、いかなる見解や意見でもありません。ただし、意見、つまり信念自体は、儀礼的性質を持つ場合や、儀礼に属する場合もあります。 16. 人間が自分の想像力を楽しむことは自明のことだと考えるなら、その想像力は、絵画や立体模型のようなものではなく、言葉やイメージといった異質な要素が複 雑に組み合わさったものであることを忘れてはならない。そうすれば、文字や音声による記号を使って操作することと、出来事の「心象」を使って操作すること とを対立させることはなくなるだろう。 17. 私たちは言語全体を掘り起こさなければならない。 18. フレイザー:「...これらの行為が、殺された者の幽霊に対する恐怖によって指示されていることは確かである...」[p.212]。しかし、なぜフレイ ザーは「幽霊」という言葉を使うのか?7 彼は明らかにこの迷信を十分に理解しているから、彼に馴染みのある迷信的な用語で説明しているのだ。あるいは、むしろ、彼はこれから、私たちの中にも、野 蛮人のそのような慣習を支持する何かが存在することを悟ったのかもしれない。—私が、どこにも神と呼べるような人間を超えた存在は存在しないと信じている 私が、「私は神の怒りを恐れる」と言うとき、それは、この発言で何か意味を伝えようとしているか、あるいはそのような信念とは必ずしも関係のない感情を表 現していることを示している。 19. フレイザーは、野蛮人が誤って死ぬことを信じているようだ。小学校の教科書には、アッティラが雷神の剣を所有していると信じて大遠征を行ったと書かれている。 [241] フレイザーは、彼の描く野蛮人よりもはるかに野蛮だ。なぜなら、これらの野蛮人は、20世紀のイギリス人ほど、精神的な事柄を理解からかけ離れた存在ではないからだ。8 彼は、原始的な慣習の説明が、その慣習自体の意味よりもはるかに粗雑だ。 |

| 20. A historical explanation, an

explanation in the form of a hypothesis of

development is only one kind of summary arrangement of the data—of

their synopsis. It is equally possible to see the data in their

relation to one

another and to gather them into a general picture without doing so in

the

form of a hypothesis concerning temporal development. 21. Identification of one’s own gods with the gods of other peoples. One convinces oneself that the names have the same meaning. 22. “And so the chorus points to a secret law” is what one might want to say about Frazer’s collection of facts. Now, I can represent this law, this idea, in the form of a hypothesis of development,9 but also in analogy to the schema of a plant, I can represent it as the schema of a religious ceremony, or again by grouping the facts alone in a “perspicuous” presentation. For us the concept of perspicuous presentation is of fundamental importance.10 It designates our form of presentation, the way we see things. (A kind of “Weltanschauung” as it is apparently typical of our time. Spengler.) This perspicuous presentation transmits an understanding of the kind that what we see are “just the connections.” Hence the importance of finding intermediate links. However, in this case, a hypothetical link is not meant to do anything other than draw attention to the similarity, the connection between the facts. Just as one might illustrate an inner relation between a circle and an ellipse by gradually transforming an ellipse into a circle; but not to claim that a given ellipse in fact, historically, emerged from a circle (developmental [242] hypothesis11), rather only to sharpen our eye for a formal connection. But I also cannot see the developmental hypothesis as anything but the investiture [clothing] of a formal connection. |

20. 歴史的説明、すなわち発展の仮説という形での説明は、データの一種の要約的整理、その概要にすぎない。データ同士の関係性を捉え、それらを一般的な図式にまとめることは、時間的発展に関する仮説の形をとらなくても同様に可能だ。 21. 自分の神々を他の民族の神々と同じだと認識すること。その名前は同じ意味だと自分に納得させること。 22. 「そして、合唱は秘密の法則を指し示している」というのは、フレイザーの事実の収集について言いたいことかもしれない。さて、私はこの法則、この考えを、 発展の仮説9 の形で表現することができるが、植物の図式に例えて、宗教儀式の図式として表現することも、あるいは事実だけを「明快な」表現でグループ化して表現するこ ともできる。 私たちにとって、明快な表現という概念は、非常に重要な意味を持っている。10 それは、私たちの表現形式、物事の見方を指している。(これは、明らかに私たちの時代特有の「世界観」の一種だ。スペンガー) この明快な表現は、私たちが見ているものは「単なるつながり」である、という理解を伝えている。したがって、中間的なつながりを見つけることが重要になる。 しかし、この場合、仮説的なつながりは、事実間の類似性、つながりに注意を向ける以外の意味はない。円と楕円の内的な関係を、楕円を徐々に円に変形させる ことで示すのと同じように。しかし、特定の楕円が歴史的に円から発展した(発達仮説[242]11)と主張するのではなく、形式的なつながりに目を向ける ためだけだ。 しかし、私は発達仮説を、形式的なつながりの「衣」以外の何物とも見なせない。 |

| 23. [In the manuscript, the

following remarks are not grouped with the ones

above:]12 I would like to say: nothing shows our kinship to those savages better than the fact that Frazer has at hand a word as familiar to us as “ghost” or “shade”13 to describe the views of these people. (For this surely is something different from what it would be if he were to describe, say, how the savages imagined that their heads would fall off when they have slain an enemy; in this case, our description would have nothing superstitious or magical about it.) Yes, the strangeness of this relates not only to the expressions “ghost” and “shade,”14 and far too little is made of the fact that we count the words “soul” [Seele] and “spirit” [Geist] into our own civilized vocabulary. Compared to this, it is a minor detail that we do not believe that our soul eats and drinks. 24. A whole mythology is deposited in our language. 25. Casting out death or slaying death; but on the other hand he is also represented as a skeleton, as if he were in some sense dead himself. “As dead as death.”15 “Nothing is so dead as death; nothing is so beautiful as beauty herself.”16 Here the image used in thinking of reality is that beauty, death, etcetera are the pure (concentrated) substances, and that they are present in a beautiful object as an admixture. —And do I not recognize here my own observations on “object” and “complex”?17 |

23. [原稿では、以下の発言は上記の発言とまとめられていない。 私は、フレイザーが、これらの人々の見解を説明するために、「幽霊」や「影」13 といった、私たちにとってよく知られた言葉を使用している事実ほど、私たちがこれらの野蛮人々と親しい関係にあることを示すものはない、と述べたい。(な ぜなら、もし彼が、例えば、野蛮人が敵を殺すと自分の頭が落ちるだろうと想像していたことを記述した場合、それはまったく異なるものになるからだ。その場 合は、私たちの記述には迷信や呪術的な要素はまったく含まれないだろう。 この奇妙さは、「幽霊」や「影」という表現だけにとどまらず、私たちの文明の語彙に「魂(Seele)」や「精神(Geist)」という単語が含まれてい るという事実も、あまり評価されていない。それに比べれば、私たちの魂が食べたり飲んだりしないことを信じないことは、些細な詳細に過ぎない。 24. 私たちの言語には、一つの神話が蓄積されている。 25. 死を追い出したり、死を殺したりするが、一方で彼は骨格として描かれ、ある意味では自分自身も死んでいるかのように表現される。「死のように死んでい る。」15 「死ほど死んでいるものはなく、美そのものほど美しいものは存在しない。」16 ここで現実を考える際に用いられるイメージは、美、死などはいずれも純粋(濃縮された)な物質であり、美しい対象物の中に混和物として存在しているという ものだ。——ここで私は、自分自身の「対象」と「複合体」に関する観察を認識しないだろうか?17 |

| 26. What we have in the ancient

rites is the use of a highly cultivated gestural

language.

And when I read Frazer, I keep wanting to say at every step: All these

processes,

these changes of meaning [243] are still present to us in our word

language. If

what is called the “corn-wolf ” is what is hidden in the last sheaf,

but [if this

name applies] also to the last sheaf itself and the man who binds it,

then we

recognize in this a linguistic process with which we are perfectly

familiar.18 * * * * * * * * * * 27. I could imagine that I might have had to choose some being on earth as my soul’s dwelling place, and that my spirit had chosen this unsightly creature as its seat and vantage point. Perhaps because the exception of a beautiful dwelling would repel him. Of course, for the spirit to do so, he would have to be very sure of himself.19 28. One could say “every view has its charm,” but that would be wrong. What is correct is that every view is significant for whoever sees it so (but that does not mean one sees it as something other than it is). Indeed, in this sense every view is equally significant. Yes, it is important that I must make my own even anyone’s contempt for me, as an essential and significant part of the world seen from my vantage point. 29. If a human being were free to choose to be born in a tree in the forest, then there would be some who would seek out the most beautiful or highest tree for themselves, some who would choose the smallest, and some who would choose an average or below-average tree, and I do not mean out of philistinism, but for just the reason, or the kind of reason for which someone else chose the highest. That the feeling we have for our life is comparable to that of a being that could choose its standpoint in the world has, I believe, its basis in the myth—or belief—that we choose our bodies before birth. |

26.

古代の儀礼において見られるのは、高度に洗練された身振りの言語の使用だ。そして、フレイザーを読むと、私は常にこう言いたくなる。これらの過程、意味の

変化[243]

は、私たちの言葉の言語にも今もなお存在しているのだ。「コーン・ウルフ」と呼ばれるものが最後の束に隠されているものだとすれば、[この名前が適用され

る場合]、最後の束そのものとそれを束ねる男にも適用される。そうすれば、私たちはこの現象に、私たちにとって完全に馴染みのある言語的プロセスを認識す

ることができる。18 * * * * * * * * * * 27. 私は、自分の魂の住処として、この地上にある何らかの存在を選ばなければならなかったかもしれない、そして私の精神がこの醜い生物をその座と展望台として 選んだかもしれない、と想像することができる。おそらく、美しい住処を選ぶことは、彼にとって拒絶すべきことだったからだろう。もちろん、精神がそうする ためには、彼は自分自身に非常に確信を持っていなければならない。19 28. 「すべての景色には魅力がある」と言うこともできるが、それは間違っている。正しいのは、すべての景色は、それを見る者にとって意味があるということだ (しかし、それは、その景色をそれ以外のものとして見るという意味ではない)。実際、この意味では、すべての景色は等しく意味がある。 そう、私にとって重要なのは、私に対する他者の軽蔑さえも、私の視点から見た世界の一部として、本質的で意味のあるものとして受け入れることなのだ。 29. 人間が森の木に生まれることを自由に選択できるなら、最も美しい木や最も高い木を選ぶ者もいれば、最も小さな木を選ぶ者もいれば、平均的な木や平均以下の 木を選ぶ者もいるだろう。私は、これは俗物的な理由からではなく、他者が最も高い木を選んだのと同じ理由、または同じ種類の理由からだと考えている。私た ちが人生に対して抱く感情が、世界における自分の立場を選ぶことができる存在の感情と類似していることは、私たちが誕生前に自分の身体を選ぶという神話 ——または信仰——にその根拠があると考えている。 |

| 30. I believe the characteristic

feature of primitive man is that he does not act

on the basis of opinions (as Frazer thinks). 31. I read, among many similar examples, of a rain-king in Africa to whom the people appeal for rain when the rainy season comes. 20 [244] But surely this does not mean that they actually think he can make rain, for otherwise they would do it in the dry periods of the year when the land is “a parched and arid desert.”21 For if one assumes that the people originally instituted the office of the rain-king out of stupidity, it certainly still is clear that they would have previously made the experience that the rains commence in March, and they could have let the rain-king perform his work during the other parts of the year. Or again: toward morning, when the sun is about to rise, people celebrate rites of daybreak, but not at night, for then they simply burn lamps. When I am angry about something, I sometimes hit the ground or a tree with my cane. But surely, I do not believe that the ground is at fault or that the hitting would help matters. “I vent my anger.” And all rites are of this kind. One can call such practices instinctual behavior. —And a historical explanation, for instance that I or my ancestors earlier believed that hitting the ground would help, is mere shadow-boxing, for these [sic] are superfluous assumptions that explain nothing. What is important is the semblance of the practice to an act of punishment, but more than this semblance cannot be stated. Once such a phenomenon is brought into relation with an instinct that I possess myself, it thus constitutes the desired explanation; that is, one that resolves this particular difficulty. And further investigation of the history of my instinct now proceeds along different tracks. 32. It could have been no insignificant reason—that is, no reason at all—for which certain races of man came to venerate the oak tree other than that they and the oak were united in a community of life, so that they came into being not by choice, but jointly, like the dog and the flea (were fleas to develop a ritual, it would relate to the dog). One might say, it was not their union (of oak trees and humans) that occasioned these rites, but, in a certain sense, their separation. [245] For the awakening of intellect goes along with the separation from the original soil, the original ground of life. (The origin of choice.) (The form of the awakening mind is veneration.) |

30. 私は、原始人の特徴的な特徴は、意見に基づいて行動しないこと(フレイザーが考えているように)ではないと信じている。 31. 多くの類似の例の中で、私は、雨季になると、人々が雨を祈願するために雨王に祈るアフリカの雨王について読んだことがある。20 [244] しかし、これは、彼らが実際に雨王が雨を降らせることができると信じていることを意味するわけではない。そうでなければ、土地が「乾ききった砂漠」となる 乾季にも雨王に祈るだろう。21 なぜなら、もし、人々が当初、愚かさから雨王の職を設立したと仮定しても、彼らは、雨が 3 月に降り始めることを以前に経験しており、雨王に他の季節にもその仕事を行わせたはずである。あるいは、朝、太陽が昇ろうとする頃、人々は夜明けの儀式を 行うが、夜には、単にランプを灯すだけだ。 私が何かに対して怒っている時、時々杖で地面や木を叩くことがある。しかし、私は地面に非があるとか、叩くことで問題が解決するとは信じていない。「怒り を発散する」のだ。すべての儀式はこのような性質を持っている。このような行為を本能的な行動と呼ぶことができる。—歴史的な説明、例えば私や私の先祖が 以前、地面を叩くことが役立つと信じていたという説明は、単なる空論に過ぎない。なぜなら、これらの仮定は余分で、何も説明しないからだ。重要なのは、そ の実践が懲罰の行為に似ている点であり、この類似点以上は言えない。 このような現象が、私自身が持つ本能と関連付けられると、それは望ましい説明、つまりこの特定の難問を解決する説明となる。そして、私の本能の歴史に関するさらなる調査は、異なる方向で進むことになる。 32. 特定の人種が樫の木を崇拝するようになったのは、彼らと樫が生命の共同体として結ばれており、選択によってではなく、犬とノミのように共同して誕生したか らに他ならない、という理由以外には、重要な理由、つまり理由自体がないだろう。ある意味では、これらの儀式を引き起こしたのは、樫の木と人間の結合では なく、彼らの分離だったと言えるかもしれない。 [245] 知性の覚醒は、生命の元の土壌、元の基盤からの分離と共に起こるからだ。(選択の起源。) (覚醒した心の形態は崇拝である。) |

| 33. P. 168.22 (At a

certain stage of early society the king or priest is often

thought to be endowed with supernatural powers or to be an incarnation

of a deity, and consistently with this belief the course of nature is

supposed

to be more or less under his control . . .) It is of course not the case that the people believe that the ruler has these powers while the ruler himself very well knows that he does not have them, or does not know so only if he is an idiot or fool. Rather, the notion of his power is of course arranged in a way such that it corresponds with experience—his own and that of the people. That any kind of hypocrisy plays a role in this is only true to the extent that it suggests itself in most of what humans do anyway. 34. P. 169. (In ancient times he was obliged to sit on the throne for some hours every morning, with the imperial crown on his head, but to sit altogether like a statue, without stirring either hands or feet, head or eyes, nor indeed any part of his body, because, by this means, it was thought that he could preserve peace and tranquility in his empire . . .) When someone in our (or at least my) society laughs too much, I press my lips together in an almost involuntary fashion, as if I believed I could thereby keep his lips closed. 35. P. 170. (The power of giving or withholding rain is ascribed to him, and he is lord of the winds . . .) What is nonsensical here is that Frazer presents it as if these people had an entirely wrong (indeed, insane) notion of the course of nature, while they really only entertain a somewhat peculiar interpretation of the phenomena. That is, if they wrote it down, their knowledge of nature would not be fundamentally different from ours. Only their magic is different. |

33. P. 168.22(初期社会のある段階では、王や僧侶はしばしば超自然的な力を持っている、あるいは神々の化身であると信じられ、この信念と一致して、自然の成り行きは多かれ少なかれ彼らの支配下にあるとみなされていた…) もちろん、人民が支配者にそのような力があると信じている一方で、支配者自身は自分がその力を持っていないことをよく知っている、あるいは愚か者や馬鹿で ない限りはそれを知らない、というわけではない。むしろ、彼の力という概念は、当然のことながら、彼自身の経験と人民の経験と一致するように構成されてい る。このことに何らかの偽善が関わっていることは、それが人間の行動のほとんどに当てはまるという点で、当然のことである。 34. P. 169. (古代には、彼は毎朝数時間、帝冠を頭に戴いて王座に座らなければならなかったが、手足や頭、目、あるいは身体のどの部分も動かさず、まるで像のように 座っていなければならなかった。なぜなら、そうすることで、彼は帝国に平和と安寧を維持できると考えられていたからである……) 私たちの社会(少なくとも私の社会)で誰かが笑いすぎると、私はほぼ無意識に唇を押し合わせて、その人の唇を閉じさせることができると信じているかのように振る舞う。 35. P. 170. (雨を降らせたり止めたりする力は彼に帰属し、彼は風の主である……) ここで無意味なのは、フレイザーが、これらの人々が自然の流れについて全く間違った(実際、狂った)考えを持っているかのように表現しているところだ。し かし、彼らは実際には、現象について多少独特な解釈をしているだけだ。つまり、彼らがそれを書き留めたとしても、彼らの自然に関する知識は、私たちのもの と根本的に異なるわけではない。異なるのは、彼らの呪術だけだ。 |

| 36. [246] P. 171. “. . . a

network of prohibitions and observances, of which the

intention is not to contribute to his dignity . . .” This is both true

and false.

Of course not the dignity of the protection of the person but rather—as

it

were—the natural sacredness of the divinity in him. 37. Simple though it may sound: The difference between magic and science can be expressed in the way that there is progress in science, but not in magic. Magic possesses no direction of development internal to itself. 38. P. 179. (The Malays conceive the human soul as a little man . . . who corresponds exactly in shape, proportion, and even in complexion to the man in whose body he resides . . .) How much more truth in granting the soul the same multiplicity as the body than in a watered-down modern theory. Frazer does not realize that what we are facing here are the teachings of Plato and Schopenhauer. We re-encounter all childish (infantile) theories in contemporary philosophy; only without the charm of childishness. 39. P. 614.23 (In Chapter LXII, “The Fire Festivals of Europe”) What is most striking are not merely the similarities but also the differences between all these rites. There is a manifold of faces with common features that keep surfacing here and there. And what one would like to do is draw lines that connect the components in common. What would still be lacking then is a part of our contemplation, and it is the one that connects this picture with our own feelings and thoughts. This part gives such contemplation its depth. 40. In all these practices, however, one sees something related or akin to the association of ideas. One could speak of an association of practices. |

36. [246] 171 ページ。「... 彼の尊厳に貢献することを意図しない、禁止事項と遵守事項のネットワーク...」これは真実であると同時に誤りでもある。もちろん、人格の保護の尊厳ではなく、いわば、彼の中にある神性の自然な神聖さである。 37. 単純に聞こえるかもしれないが、呪術と科学の違いは、科学には進歩があるのに対し、呪術には進歩がないという点で表現できる。呪術には、それ自体の中に発展の方向性はない。 38. 179 ページ。(マレー人は、人間の魂を小さな人間として捉えている...その形、比例、さらには肌の色までも、その魂が宿る人間の姿とまったく同じである...) 魂に身体と同じ多様性を認めることの方が、薄められた現代の理論よりもはるかに真実味がある。フレイザーは、ここでの対象がプラトンとショーペンハウアーの教義であることを理解していない。 現代哲学において、私たちはすべての幼稚な(幼児的な)理論を再発見するが、その魅力は失われている。 39. 614.23 ページ(第 62 章「ヨーロッパの火祭り」) 最も印象的なのは、これらすべての儀式間の類似点だけでなく、相違点でもある。共通の特徴を持つさまざまな顔が、あちこちに現れては消える。そして、共通 する要素を線でつなぎたいと思うだろう。それでもまだ欠けているのは、私たちの考察の一部であり、この図と私たちの感情や思考を結ぶ部分だ。この部分が、 そのような考察に深みを与える。 40. しかし、これらの実践のすべてにおいて、アイデアの連想に関連する、あるいは類似したものが見られる。実践の連想と表現することもできるだろう。 |

| P. 618. (. . . So soon as any

sparks were emitted by means of the violent [247]

friction, they applied a species of agaric, which grows on old birch

trees and is

very combustible. This fire had the appearance of being immediately

derived

from heaven, and manifold were the virtues ascribed to it . . .) 41. Nothing speaks for why fire should be surrounded with such a nimbus. And what an odd thing [to say], “it had the appearance of being derived from heaven.” What does this actually mean? From what heaven? No, it is not at all self-evident that fire is regarded in this way—but that is how it is regarded.24 The person who officiated as master of the feast produced a large cake baked with eggs and scalloped round the edge, called am bonnach bealtine—that is, the Beltane cake. It was divided into a number of pieces, and distributed in great form to the company. There was one particular piece that whoever got was called cailleach beal-tine—that is, the Beltane carline, a term of great reproach. Upon this being known, part of the company laid hold of him and made a show of putting him in the fire. . . . And while the feast was fresh in people’s memory, they affected to speak of the cailleach beal-tine as dead. (The Golden Bough, p. 618) 42. Here it appears as though it were only the hypothesis that gives the matter depth. And then one may remember the explanation of the strange relationship between Siegfried and Brunhild in our Nibelungenlied. Namely, that Siegfried seems to have seen Brunhilde [sic] some time before. It is thus clear that what gives this practice depth is its connection with the burning of a human being. If it were custom at some festival for men to ride on one another (as in horse-and-ride games), we would see nothing more in this than a way of carrying someone, which reminds us of people riding horses; —however, if we knew that it had been custom among many peoples to, for example, use slaves as mounts and to celebrate certain festivals mounted in this way, then we should see in the harmless practice of our times something deeper and less harmless. The question is: Does this—shall we say—sinister character adhere to the custom of the Beltane fire in itself as it was practiced a hundred years ago, or only if the hypothesis of its origin were to be confirmed? I believe that what appears to us as sinister is the inner nature of the practice as performed in recent times, and the facts of human sacrifice as we know them only indicate the direction in which we ought to look at it. When I speak of the inner nature of the practice, I mean all of those circumstances in which it is carried out and that are not included in the report on such a festival, because they consist not so much in particular actions that characterize the festival than in what one might call the spirit of the festival that would be described, for example, if one were to describe the kind of people that take part in it, their usual way of behaving [on other occasions]—that is, their character—and the kind of games they play at other times. And then one would see that what is sinister lies in the character of these people themselves.25 |

P. 618. (…激しい摩擦によって火花が飛び散ると、彼らは古い白樺の木に生える、非常に燃えやすい一種のキノコを火に当てた。この火は、まるで天から直接降り注いだかのようで、さまざまな効能があると言われました…) 41. 火がそのような光輪に囲まれている理由を説明するものはない。そして、「天から降りてきたように見えた」という表現は奇妙だ。これは実際には何を意味する のか?どの天からなのか?いいえ、火がこのように見なされていることは、決して自明ではない——しかし、そう見なされているのだ。24 宴会の司会を務めた人物は、卵を使って焼き、縁を波型にカットした大きなケーキ、アム・ボンナック・ベアルティン(Beltane cake)を用意した。それはいくつかの部分に分けられ、出席者たちに盛大に配られた。その中の一片は、それを手にした者はカイレック・ベアルティン (Beltane carline)と呼ばれる、非常に侮辱的な呼び名がつくものだった。このことが知れると、その場にいる者たちがその人を捕まえ、火の中に投げ込むふりを した。そして、その宴会の記憶が人々の記憶に新しいうちに、彼らは cailleach beal-tine が死んだと口々に言った。(『黄金の枝』618 ページ) 42. ここでの説明は、単に仮説が事柄に深みを与えているように見える。そして、私たちの『ニーベルングの歌』におけるジークフリートとブルンヒルデの奇妙な関 係の説明を思い出そう。すなわち、ジークフリートはブルンヒルデを何らかの形で以前に見たことがあるようだ。したがって、この慣習に深みを与えているの は、人間を焼くこととの関連であることは明らかだ。ある祭りで、男性が互いに乗って(馬乗りゲームのように)走る習慣があった場合、私たちはそれを、馬に 乗る人々を彷彿とさせる、ただ誰かを運ぶ方法にすぎないと思うだろう。しかし、例えば、多くの民族が奴隷を乗り物として使い、そのように乗って特定の祭り を祝う習慣があったことを知っていたならば、現代の無害な慣習にも、より深い、無害ではない何かを見出すだろう。問題は、この、いわば不吉な性格は、 100年前に実践されていたベルテーン火祭りの慣習そのものに固有のものであるのか、それともその起源の仮説が確認された場合にのみ固有のものであるの か、ということだ。私たちに不吉に見えるのは、最近の慣習の実践の性質そのものであり、私たちが知っている人祭りの事実は、その慣習をどのように見るべき かを示す方向性を示しているだけだと私は思う。私がこの慣習の本質と言うのは、その慣習が行われるすべての状況のことを指している。それは、そのような祭 りの報告には含まれていない。なぜなら、それらは、その祭りを特徴付ける特定の行動というよりも、例えば、その祭りに参加する人々の性格、つまり、彼らが (他の場面で)通常取る行動、つまり彼らの性格、そして彼らが他の場面で遊ぶ種類のゲームなど、その祭りの精神とでも言うべきものにあるからだ。その祭り に参加する人々の種類、彼らが(他の場面で)通常示す行動、つまり彼らの性格、そして彼らが他の場面で遊ぶ種類のゲームなどを記述するだろう。そうすれ ば、不吉なのはこれらの人々の性格そのものであることがわかるだろう。25 |

| In . . . western Perthshire, the

Beltane custom was still en vogue toward the end

of the eighteenth century. It has been described as follows by the

parish minister

of the time [248]: “They put all the bits of the cake into a bonnet.

Every one,

blindfold, draws out a portion. . . . Whoever draws the black bit is

the devoted

person who is to be sacrificed to Baal . . .” Thomas Pennant, who traveled in northern Perthshire in the year 1769, tells us that “everyone takes a cake of oatmeal upon which are raised nine square knobs, each dedicated to some particular being . . .” Another writer of the eighteenth century has described the Beltane festival as it was held in the parish of Logierait in Perthshire. He says: “These dishes they eat with a sort of cake baked for the occasion, and having small lumps in the form of nipples, raised all over the surface.” We may conjecture that the cake with knobs was formerly used for the purpose of determining who should be the “Beltane carline” or victim doomed to the flames (The Golden Bough, pp. 618, 619). 43. Here one sees something like the remnants of a casting of lots. And through this aspect it suddenly gains depth. Should we learn that the cake with the buttons [i.e., “knobs,” a mistranslation on Wittgenstein’s part] was originally baked in a determinate case, say, in honor of a button-maker on the occasion of his birthday, and that the practice had then merely persisted on a local level, it would in fact lose all its “depth,” unless this were to lie in its present form as such. But in this case, it is often said: “this custom is obviously ancient.” How does one know that? Is it merely because historical evidence for ancient practices of this sort is at hand? Or is there another reason, one that we can attain through interpretation? But even if its prehistoric origin and its descent from an earlier practice is historically established, then it is still possible that today there is nothing at all sinister about the practice anymore, that nothing of the ancient horror still adheres to it. Perhaps it is only performed by children today who have contests in baking cakes and decorating them with buttons. If so, then the depth would thus only lie in the thought of such ancestry. Yet this can very well be uncertain and one feels like saying: “Why worry about something so uncertain” (like a backward-looking Kluge Else).26 But worries of that kind are not involved here. —Above all: whence the certainty that such a practice must be ancient (what are the data, what is the verification)? But have we any certainty, could we not be mistaken and proven to be in error by historical means? Certainly, but there still remains something of which we are sure. We would then say: “Very well, in this case the origin may be different, but in general it is surely ancient.” What constitutes evidence for us of this must entail the depth of this assumption. And this evidence, again, is nonhypothetical, psychological. For when I say: what is deep about this lies in its origin if it did come about in this way, then such deepness lies either in the thought of [its derivation from] such origins, or else the deepness is in itself hypothetical—in which case one can only say: if that is how it went, then this was a deep and sinister [249] business. What I want to say is this: what is sinister, deep [about all this] does not lie in how the history of this practice actually went, for perhaps it did not go that way at all; nor that it maybe or [even] probably went that way, but in what gives me reason to assume so. What makes human sacrifice so deep and sinister in the first place? For is it only the suffering of the victim that impresses us thus? All manners of illnesses bring about just as much suffering, and yet do not evoke this impression. No, this deep and sinister aspect does not become self-evident just from our knowledge of the history of the external actions; rather, we impute it to them [reintroduce it into them] on the basis of an inner experience of our own. |

パー

スシャー西部では、18 世紀の終わり頃まで、ベルテーン祭の習慣がまだ盛んでした。当時の教区牧師は、この習慣を次のように記述しています

[248]。「彼らはケーキの断片をすべてボンネットに入れます。そして、全員が目を閉じて、その中から 1

つずつ取り出します。黒い断片を引き当てた人は、バアルに捧げられる献身的な人物となります...」 1769 年にパースシャー北部を旅したトーマス・ペナントは、「皆が、9 つの四角い突起が突き出たオートミールケーキを取り、その突起はそれぞれ特定の存在に捧げられる」と伝えている。 18 世紀の別の作家は、パースシャーのロギエライト教区で開催されたベルテーン祭について、次のように記述している。「これらの料理は、そのために焼かれた ケーキと共に食べられ、表面全体に乳首の形をした小さな隆起が施されている。」この隆起のあるケーキは、かつて「ベルトーンの老女」または炎に捧げられる 犠牲者を決定するために使用されていたと推測できる(『黄金の枝』、618~619ページ)。 3. ここでは、くじ引きの残骸のようなものが見える。そしてこの側面を通じて、突然深みが生まれる。もし、ボタン付きのケーキ(ウィトゲンシュタインの誤訳で 「ノブ」と訳されている)が、例えばボタン職人の誕生日を祝うために特定の機会に焼かれたもので、その習慣がその後地域レベルで単に継続してきただけだと 知れば、その「深み」は失われてしまうだろう。ただし、その深みが現在の形態そのものにある場合を除く。しかし、この場合、よく言われるのは「この習慣は 明らかに古代のものだ」ということだ。なぜそう言えるのか?単にこのような古代の習慣に関する歴史的証拠が存在するためか?それとも、解釈を通じて到達で きる別の理由があるのか?しかし、その先史時代の起源や、それ以前の慣習から派生したことは歴史的に確立されていたとしても、今日ではその慣習に不吉な要 素はまったくなく、昔の恐怖はまったく残っていない可能性もある。おそらく、ケーキを焼いてボタンで飾るコンテストをする子供たちだけが、今日ではその慣 習を行っているだけかもしれない。もしそうなら、その深さは、そのような祖先の思想にのみ存在する。しかし、これは非常に不確実であり、人は「なぜそんな 不確実なことにこだわるのか」(後向きのクレーゲ・エルゼのように)と言いたくなるかもしれない。26 しかし、そのような懸念はここでは問題ではない。—何よりも、そのような慣習が古代のものでなければならないという確信は、どこから来るのか(データは何 で、検証はどのように行われるのか)?しかし、私たちには確信があるのだろうか?歴史的な手段によって、私たちが間違っていることが証明される可能性はな いのだろうか?確かにその可能性はありますが、それでもなお、私たちが確信できることが残っています。その場合、私たちは「そう、その場合は起源は異なる かもしれないが、一般的には確かに古くからあるものだ」と言うでしょう。このことを私たちにとっての証拠とするものは、この仮定の深さに他ならないでしょ う。そして、この証拠は、繰り返しになりますが、非仮説的で心理的なものです。なぜなら、私が「この深さは、もしこのような経緯で生まれたのであれば、そ の起源にある」と言う時、その深さは、そのような起源からの導出の思考にあるか、あるいはその深さはそれ自体仮説的なものとなる——その場合、私たちは 「もしそうだったなら、これは深く陰湿な[249]出来事だった」としか言えないからだ。私が言いたいのは、この慣習の実際の歴史がそうだったかどうか、 あるいはそうだったかもしれない、あるいはそうだった可能性が高いかどうかではなく、私がそう考える理由にある、この慣習の不吉で深い部分だ。そもそも、 人身御供がそれほど深く不吉である理由は何だろうか?私たちにそのような印象を与えるのは、犠牲者の苦悩だけだろうか?あらゆる病気も同様に苦悩をもたら すにもかかわらず、そのような印象を与えない。いいえ、この深くて不吉な側面は、外的な行動の歴史を知っているだけで自明になるものではなく、むしろ、私 たち自身の内面の経験に基づいて、それらに帰属させる(それらに再導入する)ものだ。 |

| 44. The environment of a way of

acting. |

44. 行動の環境。 |

| 45. A conviction, at any rate,

underlies the speculations about the origins of,

for example, the Beltane festival; namely that such festivals were not,

as it

were, haphazardly invented, but would have to have an infinitely

broader

basis in order to persist. If I were to invent a festival, it would die

out very

soon, or else be so modified that it would correspond to a general

inclination among the people. However, what is it that militates against assuming that the Beltane would have always been celebrated in its present (or very recent) form? One feels like saying: it is too senseless to have been invented in this way. Is it not like when I see a ruin and say: that must have been a house once, for no one would erect a heap like that [250] of hewn and irregular stones? And if it be asked: How do you know that? Then I could only say: it is what my experience of humans teaches me. Indeed, even when they build ruins, they derive the form from collapsed houses. One might put it this way: Anyone who wanted to impress us with the story of the Beltane festival would not have to express the hypothesis of its origin; he would only have to show us the material (which led to the hypothesis) and say nothing more. Here one might perhaps want to say, “Of course, this is so because the listeners or readers will draw the conclusion for themselves!” But must they draw the conclusion explicitly? That is, draw it at all? And what conclusion is it [anyway]? That this or that is probable? And if they can draw the conclusions themselves, how should the conclusions impress them? What makes for the impression must surely be what they have not done! Is what causes the impression the hypothesis once expressed (by them or whomever) or already the material itself? But could I not just as well ask in this case: When I see someone being killed, is it simply what I see that impresses me, or does this impression [only] arise from the hypothesis that someone is being killed here? |

45.

いずれにせよ、ベルテーン祭などの起源に関する推測の根底には、そのような祭りは、いわば偶然に発明されたものではなく、存続するためには、はるかに幅広

い基盤が必要だったという確信がある。私が祭りを発明したとしたら、それはすぐに廃れてしまうか、あるいは人々の一般的な傾向に合わせて大きく変更される

だろう。 しかし、ベルタイン祭が現在(またはごく最近)の形で常に祝われてきたと仮定することを妨げるものは何だろうか?「そのような形で発明されたのはあまりに も意味がない」と言いたくなる。それは、廃墟を見て「これはかつて家だったに違いない。なぜなら、誰もそのような切り出した不規則な石の山を築くはずがな い」と言うのと同じではないか?そして、もし「 なぜそう言えるのか?と尋ねられたら、私はただこう答えるしかない:それは人間の経験が教えてくれるからだ。実際、人々が廃墟を築く時でさえ、その形は崩 れた家屋から導き出されている。 次のように表現することもできる:ベルトーン祭の物語で私たちを驚かせたい人は、その起源の仮説を表現する必要はない。彼は単にその材料(仮説に至った根 拠)を示し、それ以上何も言わなければいいのだ。ここで、おそらく「もちろん、それは聴衆や読者が自分で結論を導き出すからだよ!」と反論するかもしれな い。しかし、彼らは結論を明示的に導き出さなければならないのか?つまり、結論を導き出す必要があるのか?そして、その結論とは何なのか?これが確率が高 い、あれが確率が高い、ということなのか?もし彼らが結論を自分で導き出せるなら、その結論は彼らにどのような印象を与えるのか?印象を与えるものは、彼 らがしていないことであるに違いない!印象を与えるのは、一度表現された仮説(彼らや誰かによって)なのか、それとも既に存在する素材そのものなのか?し かし、この場合、次のように問うこともできるのでは?私が誰かが殺されるのを見た時、私を印象付けるのは単に私が目にしたものなのか、それとも「ここで誰 かが殺されている」という仮説からその印象が生じるのか? |

| But it is obviously not just the

idea of the possible origins of the Beltane

festival that conveys the impression, but what one calls the immense

probability

of this idea. All that is derived from the material [itself ]. The Beltane festival as it has come down to us is indeed a play, and as such it is similar to children playing at robbers. But then again, it is not like this. For even if it is prearranged that the side that saves the victims wins, there is still, in what eventuates, an affective addition that a mere theatrical performance does not have. But even if it merely were a rather cool performance, would we not anxiously ask ourselves: What is this performance aiming at, what is its meaning? And apart from any interpretation, its strange pointlessness could unsettle us (which shows what the reason behind such uneasiness can be). Suppose some harmless interpretation were to be given: perhaps the lot is cast for reasons of the entertainment derived from being able to threaten someone to be thrown into the fire, which would be disagreeable; then the Beltane festival becomes far more like [251] those practical jests in which a member of the company has to endure certain cruelties that, such as they are, satisfy a certain need, in just this form. Through such an explanation, the Beltane festival would lose all mystery, were it not for the fact that it deviates in action and mood from such common games of robbers, etcetera. Just so, the fact that children may, on certain days, burn a straw man could make us uneasy, even if no explanation were to come forth. How strange that a man should be burned by them in celebration! What I want to say is this: The solution is not anymore disquieting than the riddle. But why should it not really be (partly, anyway) just the idea that makes the impression on me? Aren’t ideas frightening? Can I not feel horror at the thought that the cake with the buttons once served to select the victim of [human] sacrifice? Hasn’t that [very] thought something terrible to it? —Yes, but what I see in these stories is something that they acquire, after all, from the evidence, including such evidence as does not seem to be directly connected to them—[they acquire it] through the thought of humans and their past, through all the strangeness of what I see in myself and in others, and what I have seen and heard about it.27 |

しかし、その印象を与えるのは、ベルテーン祭の起源の可能性というアイデアだけではありません。そのアイデアの、いわゆる「膨大な可能性」なのです。それはすべて、その素材(それ自体)から派生したものです。 私たちに伝わっているベルテーン祭は、確かに演劇であり、その点では子供たちが強盗ごっこをするのと同じです。しかし、それはそうではありません。たと え、犠牲者を救った側が勝つとあらかじめ決められていたとしても、その結果には、単なる演劇にはない感情的な要素が加わっているからだ。しかし、それが単 なるクールなパフォーマンスであったとしても、私たちは不安に思うだろう。このパフォーマンスは何を目的としているのか、その意味は何なのか?そして、そ の解釈はさておき、その奇妙な無意味さが私たちを不安にさせるだろう(その不安の理由も明らかだ)。仮に無害な解釈が与えられたとしよう:例えば、火に投 げ込まれる脅威から得られる娯楽のため、くじ引きが行われるのかもしれない。その場合、ベルトーン祭は[251] のような実践的な冗談に近くなる。その冗談では、参加者の一人が、その形態において特定の欲求を満たす残酷な仕打ちを耐えなければならない。このような説 明によって、ベルタイン祭は、その行動や雰囲気が、強盗などの一般的なゲームとは異なっているという事実がなければ、すべての神秘性を失ってしまうだろ う。 同様に、子供たちが特定の日に藁人形を燃やすという事実も、説明がなくても私たちを不安にさせるかもしれない。祝祭で人間が燃やされるなんて、なんて奇妙なことだろう! 私が言いたいのは、この解決策は、謎そのものと同じくらい不穏ではない、ということだ。 しかし、なぜそれは(少なくとも部分的には)私に影響を与えるのは単なる考えに過ぎないのだろうか?考えは恐ろしいものではないのか?ボタン付きのケーキ がかつて(人間の)生贄を選ぶために使われたという考えに、私は恐怖を感じないのだろうか?その考え自体に、何か恐ろしいものはないのだろうか?—はい、 しかし、私がこれらの物語に見るものは、結局のところ、それらが証拠から獲得したものだ——[それらは]人間の思考と過去、私自身と他者に見る奇妙さ、そ してそれについて見たことや聞いたことすべてを通じて獲得したものだ。27 |

| 46. P. 640. (?) One can very

well imagine this—and the reason might have

been given that the patron saints would otherwise be at cross-purposes,

and that only one of them could direct the matter. But this, too, would

only be a belated extension of the instinct.

All these various practices show that we are not dealing with the descent of one from the other, but with a commonality of spirit. And one could invent (confabulate) all of these ceremonies on one’s own. And the spirit in which one would invent them is their common one. 47. P. 641. (. . . as soon as the fire on the domestic hearth had been rekindled from the need-fire, a pot full of water was set on it, and water thus heated was afterward sprinkled upon the people infected with the plague or upon the cattle that were tainted by the murrain.) [252] The connection of illness and dirt. “The cleansing of a disease.” It is a simple, childlike theory of disease that it is the dirt that could be washed off. Just like there are “infantile theories of sexuality,” there are infantile theories more generally. However, this does not mean that everything that a child does has come from an infantile theory as its reason. The correct and interesting thing is not to say, “this has come from that,” but “it could have come from that.” P. 643. (. . . Dr. Westermark has argued powerfully in favor of the purificatory theory alone. . . . However, the case is not so clear as to justify us in dismissing the solar theory without discussion.) |

46. 640ページ。(?)これは十分に想像できる。その理由は、そうでなければ守護聖人が互いに矛盾した役割を担うことになり、そのうちの1人だけが事柄を指揮することになってしまうからかもしれない。しかし、これもまた、本能の遅れた延長にすぎないだろう。 これらの多様な慣習は、一つが他から派生したものではなく、精神の共通性から生まれたことを示している。そして、これらの儀式をすべて自分で考案(でっち上げる)することもできる。それらを考案する精神こそが、それらの共通の精神なのだ。 47. 641 ページ。(... 必要に応じて火を再燃させた後、その火に水を入れた鍋を置き、そのお湯をペストに感染した人々や、家畜の疫病に感染した家畜に振りかけた。 [252] 病気と汚れとの関連。「病気の浄化」。 病気は洗い流せる汚れである、という単純で子供っぽい病気の理論だ。 「幼児的な性理論」があるように、より一般的な幼児的な理論もある。しかし、それは、子供が行うすべてのことが、その理由として幼児的な理論に由来しているという意味ではない。 正しい興味深い点は、「これはあれから来た」と言うのではなく、「あれから来た可能性がある」と言うことだ。 P. 643. (…ウェスターマーク博士は、浄化説のみを強力に主張している。…しかし、太陽説を議論もせずに却下するほど、この問題は明確ではない。) |

| That fire was used for cleansing is clear. But nothing can be more likely than

that thoughtful people would have eventually associated cleansing ceremonies

with the sun, even when they were originally conceived just as such. When a

thought suggests itself to a person (fire-cleansing) and another to someone else

(fire-sun) then what can be more likely than that both thoughts will suggest

themselves to one person. The scholars who always want to have a theory!!!

The total destruction through fire, different from smashing or tearing up, must have been noticed by people. Even if one didn’t know anything of such a connection between the thought of cleansing and the sun, one could assume that it would have occurred somewhere. 48. P. 680. (. . . in New Britain there is a secret society. . . . On his entrance into it every man receives a stone in the shape either of a human being or of an animal, and henceforth his soul is believed to be knit up in a manner with the stone.) [253] “Soul-stone.”28 Here one sees how such a hypothesis works. 49. P. 681. ([680 infra, 681] . . . it used to be thought that the maleficent powers of witches and wizards resided in their hair, and that nothing could make any impression on these miscreants so long as they kept their hair on. Hence in France it was customary to shave the whole bodies of persons charged with sorcery before handing them over to the torturer.) This would indicate that this is grounded in a truth rather than in superstition. (Of course it is easy to fall into a spirit of contestation [contradiction] when facing the stupid scholar). But it can very well be that the body entirely shorn of hair leads us in some sense to lose self-respect. (Brothers Karamazoff.) There is no doubt whatsoever that a mutilation that makes us look undignified, ludicrous in our own eyes can rob us of all will to defend ourselves. How embarrassed we are sometimes—or at least many people (I)—by our physical or aesthetic inferiority. |

そ

の火が清めのために使われたことは明らかだ。しかし、当初はそのような意味しか持っていなかったとしても、思慮深い人々が、やがて清めの儀式を太陽と結び

つけるようになったことは、当然のことだろう。ある人に(火による清め)という考えが浮かんだとき、別の人に(火と太陽)という考えが浮かんだ場合、その

両方の考えが 1 人の人に浮かぶことは、当然のことだろう。常に理論を欲する学者たち! 破壊や引き裂くこととは異なる、火による完全な破壊は、人々に必ず気づかれたはずだ。 浄化という概念と太陽との関連について何も知らなかったとしても、そのような関連がどこかで生まれたと推測することはできる。48. 680 ページ。(…ニューブリテンには秘密結社がある。…その結社に入会する際、各人は人間の形または動物の形をした石を受け取り、以降、その魂は石と結びつい ていると信じられる。)[253]「魂の石」。28 ここで、このような仮説がどのように機能するかがわかる。 49. 681 ページ。([680 ページ以下、681 ページ] ... かつては、妖術師や魔法使いの邪悪な力は彼らの髪に宿っており、彼らが髪を残している限り、彼らに何の影響も与えることはできないと信じられていた。その ため、フランスでは、邪術の罪で告発された者は、拷問にかけられる前に全身の毛を剃られるのが慣例だった。 これは、これが迷信ではなく真実に基づいていることを示している。 (もちろん、愚かな学者に対峙すると、反論の精神に陥りやすいものだ)。しかし、髪を完全に剃られた体は、ある意味では自己尊重を失わせる可能性がある。 (カラマーゾフの兄弟たち) 私たち自身の目には威厳を欠き、滑稽に見えるような身体の一部を切断することは、私たちから自己防衛の意志を完全に奪うことは間違いない。私たちは、自分 の身体的または審美的な劣等感に、時には(少なくとも多くの人々(私)は)非常に恥ずかしい思いをする。 |

| フレーザー『金枝篇』について; Bemerkungen über Frazers The golden bough. The Mythology in Our Language, 2018. [pdf]英文・ドイツ語文はここから引用 |

| Auch wenn man nichts von einer solchen Verbindung des Reinigung und Sonne Gedankens wüßte, könnte man annehmen, daß er irgendwo wird aufgetreten sein. | そのような浄化と太陽の考えの関連について何も知らなかったとしても、それはどこかで出現しただろうと思うだろう。 |

| S. 680. (. . . in New Britain there is a secret society. . . . On his entrance into it every man receives a stone in the shape either of a human being or of an animal, and henceforth his soul is believed to be knit up in a manner with the stone.) | S. 680. (...ニューブリテンには秘密結社がある。...その結社に入会すると、各人は人間または動物の形をした石を1つ受け取り、それ以降、その石と自分の魂 は結びついていると信じられる。) |

| “Soul–stone.” Da sieht man wie eine solche Hypothese arbeitet. | 「魂の石」。このような仮説がどのように機能するかがわかるね。 |

| S. 681. ([680 infra, 681] . . . it used to be thought that the maleficent powers of witches and wizards resided in their hair, and that nothing could make any impression on these miscreants so long as they kept their hair on. Hence in France it was customary to shave the whole bodies of persons charged with sorcery before handing them over to the torturer.) | S. 681. ([680 infra、681] ... かつては、妖術師や魔術師の邪悪な力は彼らの髪に宿っており、彼らが髪を残している限り、これらの悪党たちに何の影響も与えることはできないと信じられて いた。そのため、フランスでは、邪術の罪で告発された人物は、拷問にかけられる前に全身の毛を剃られるのが慣例だった。) |

| Das würde darauf deuten, daß hier eine Wahrheit zu Grunde liegt und kein Aberglaube. (Freilich ist es dem dummen Wissenschaftler gegenüber leicht in den Geist des Widerspruchs zu verfallen.) Aber es kann sehr wohl sein, daß der völlig enthaarte Leib uns in irgendeinem Sinne den Selbstrespekt zu verlieren verleitet. (Brüder Karamazoff.) Es ist gar kein Zweifel, daß eine Verstümmelung, die uns in unseren Augen unwürdig, lächerlich, aussehen macht, uns allen Willen rauben kann uns zu verteidigen. Wie verlegen werden wir manchmal—oder doch viele Menschen (ich)—durch unsere physische oder ästhetische Inferiorität. | それは、ここに迷信ではなく真実があるということを示唆しているだろう (もちろん、愚かな科学者に対しては、矛盾の精神に陥るのは容易なことだが)。しかし、完全に毛のない体は、ある意味で私たちに自尊心を失わせるかもしれ ない。(カラマーゾフの兄弟たち)私たちの目には不名誉で滑稽に見えるような身体の一部を切断することは、私たちから自分を守る意志を完全に奪う可能性が あることは間違いありません。私たちは、自分の肉体的な、あるいは審美的な劣等感によって、時には(少なくとも多くの人々、そして私も)どれほど恥ずかし い思いをするか。 |

| フレーザー『金枝篇』について; Bemerkungen über Frazers The golden bough. The Mythology in Our Language, 2018. [pdf]英文・ドイツ語文はここから引用 |

関連人物集

関連リンク集

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099