メディア等式

Media Equation by Reeves and Nass (1998)

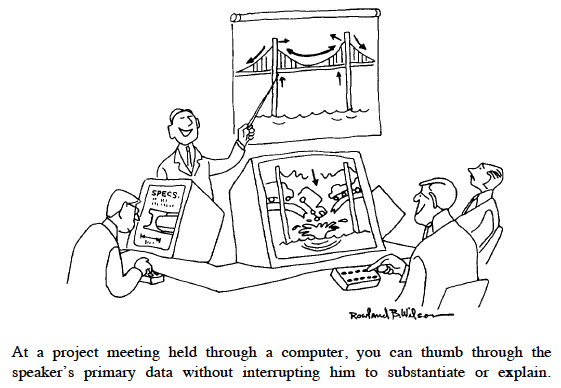

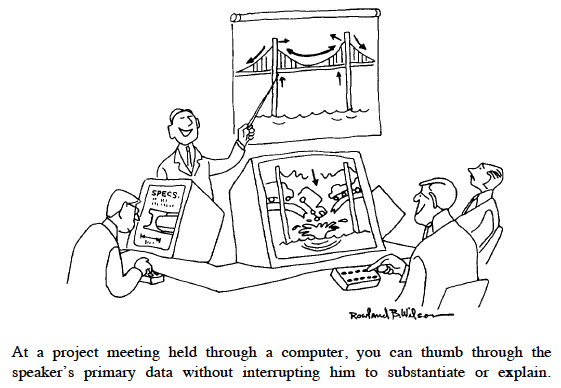

Man-computer symbiosis, by J. C. R. Licklider, 1915-1990

メディア等式

Media Equation by Reeves and Nass (1998)

Man-computer symbiosis, by J. C. R. Licklider, 1915-1990

「メディア等式(The Media Equation)」とはバイロン・リーブス(Byron Reeves)とク リフォード・ ナス(1998)の提唱になるもので、メディアを現実とみる認識の方法で ある。メディア等式は、(彼らによる と)長らく「錯認」の一種であるかのように誤解されてきたが、彼らの研究を通して、人間界にみられるきわめて一般的な現象だということが明らかになった。 実験心理学的研究により、霊長類にもメディア等式があてはまる[と解釈することができる]例が報告されている。リーブスとナスの『メディア等式』 (1998)は人間とメディアの相互作用に関する壮大なレビューである。そのためこの書物の内容の是非をチェックするには、彼らが依拠した文献を参照しつ つ、それを批判的に乗り越える必要があるだろう。邦訳を手がかりに彼らが参照した引用した文献がどの章でどのように登場したのかを記す。

| The Media Equation

is a general communication theory that claims people tend to assign

human characteristics to computers and other media, and treat them as

if they were real social actors.[1] The effects of this phenomenon on

people experiencing these media are often profound, leading them to

behave and to respond to these experiences in unexpected ways, most of

which they are completely unaware of.[2] Originally based on the research of Clifford Nass and Byron Reeves at Stanford University, the theory explains that people tend to respond to media as they would either to another person (by being polite, cooperative, attributing personality characteristics such as aggressiveness, humor, expertise, and gender) – or to places and phenomena in the physical world – depending on the cues they receive from the media.[2] Numerous studies that have evolved from the research in psychology, social science and other fields indicate that this type of reaction is automatic, unavoidable, and happens more often than people realize. Reeves and Nass (1996) argue that, “Individuals’ interactions with computers, television, and new media are fundamentally social and natural, just like interactions in real life,” (p. 5).[2] |

メディア方程

式[=メディア等式]とは、人々はコンピュータやその他のメディアに人間的な特徴を割り当て、それらを現実の社会的行為者のように扱う傾向があるとする一

般的なコミュニケーション理論である。この現象は、メディアを体験する人々にしばしば深い影響を与え、彼らが予期せぬ方法で行動し、その体験に反応するこ

とにつながる。そのほとんどは、彼ら自身がまったく気づいていない。[2] もともとスタンフォード大学のクリフォード・ナスとバイロン・リーブスの研究に基づいており、この理論は、人々はメディアから受け取る手がかりに応じて、 他の人間(礼儀正しく、協力的であり、攻撃性、ユーモア、専門知識、ジェンダーなどの性格特性を帰属させる)または現実世界の場所や現象に対して反応する 傾向があると説明している。心理学、社会科学、その他の分野の研究から発展した数多くの研究は、この種の反応は自動的かつ避けがたく、人々が認識している 以上に頻繁に発生することを示している。リーブスとナス(1996)は、「コンピュータ、テレビ、新しいメディアとの個人の相互作用は、現実の生活におけ る相互作用と同様、基本的に社会的かつ自然なものである」と主張している(p. 5)。 |

| The Media Equation Test (1996) Reeves and Nass established two rules before the test- when a computer asks a user about itself, the user will give more positive responses than when a different computer asks the same question. They expected people to be less variable with their responses when they took a test and then answered a questionnaire on the same computer. They wanted to see that computers, although not human, can implement social responses. The independent variable was the computer (there are two in the test), and the dependent variable was the evaluation responses, and the control was a pen-and-paper questionnaire.[2] Reeves and Nass designed an experiment with 22 participants and told them they would be working with a computer to learn about random facts of American pop culture. At the end of the session they would ask the participants to evaluate the computer that they used. They would have to tell Reeves and Nass how they felt about that computer and how well it performed. 20 facts were presented in each session, and participants would answer if they knew “a great deal, somewhat, or very little” about the statement. After the session, participants were tested on the material and told which questions they had answered correctly or incorrectly. Computer #1 then made a statement of its own performance by always stating that it “did a good job”. Participants were then divided into 2 groups to evaluate the computer's performance and participants were asked to describe this performance from the choice of about 20 adjectives. Half of the participants were assigned to evaluate on computer #1, the computer that praised its own work. The other half were sent to another computer across the room to evaluate computer #1's performance.[2] The conclusion resulted in evaluations done on computer #1 after testing on computer #1 yielded much more positive responses about the session. Evaluations completed on the other computer after testing on computer #1 resulted in much more varied and more negative responses about the session. For the control, the pen-and-paper questionnaire, the evaluations had similar results to that of evaluations done on computer #2. Participants felt more comfortable being honest when a different computer or pen-and-paper questionnaire asked about the sessions completed on computer #1. It is as if participants were talking behind the computer #1's back- not being honest to it, but then expressing more honesty to a third party evaluator. Reeves and Nass found that participants had automatic social reactions during the test.[2] Reeves and Nass ran the test again but added a voice speaker to both computers that would verbally communicate information to make the human-social theme more explicit. The test resulted in almost exactly the same results. They concluded that people are polite to computers in both verbal and textual scenarios. The participants did not need much of a cue to respond socially to the computers. The experiment supports the hypothesis that social rules can apply to media, and computers can be social initiators. Participants denied being intentionally polite to the computer, but the results suggest differently.[2] |

メディア方程式テスト(1996年) リーブスとナスは、テストの前に2つのルールを設定した。コンピュータがユーザーに自分自身について質問した場合、ユーザーは異なるコンピュータが同じ質 問をした場合よりも肯定的な回答をするというものである。彼らは、人々がテストを受けた後、同じコンピュータでアンケートに回答する場合、回答のばらつき が少ないと予想した。彼らは、コンピュータは人間ではないものの、社会的反応を実行できることを確かめたかったのだ。独立変数はコンピュータ(テストには 2 台ある)、従属変数は評価の回答、対照群は紙とペンによるアンケートだった。[2] リーブスとナスは 22 人の参加者を対象とした実験を設計し、アメリカのポップカルチャーに関するランダムな事実を学ぶためにコンピュータを使って作業を行うと参加者に伝えた。 セッションの最後に、参加者は使用したコンピュータを評価するよう求められた。参加者は、そのコンピューターについてどう感じたか、その性能はどの程度 だったかをリーブスとナスに伝える必要があった。各セッションでは 20 の事実が提示され、参加者はその記述について「よく知っている、ある程度知っている、ほとんど知らない」のいずれかを答えることになっていた。セッション 終了後、参加者はその内容についてテストを受け、どの質問に正しく答え、どの質問に間違って答えたかを伝えられた。コンピューター 1 は、常に「よくやった」と述べることで、自らの性能について自己評価を行った。 その後、参加者は 2 つのグループに分かれ、コンピューターの性能を評価し、約 20 個の形容詞の中からその性能を表現するよう求められた。参加者の半数は、自分の仕事を称賛したコンピューター 1 を評価するために割り当てられた。残りの半数は、部屋を挟んだ別のコンピューターで、コンピューター 1 の性能を評価するために送られた。[2] その結果、コンピュータ#1でテストを行った後、そのコンピュータで評価を行った場合、セッションに対する評価がはるかに好意的になった。一方、コン ピュータ#1でテストした後、別のコンピュータで評価を行った場合、セッションに対する評価はより多様で否定的なものとなった。対照群である紙とペンによ る質問票では、コンピュータ#2で評価を行った場合と同様の結果が得られた。参加者は、異なるコンピューターや紙と鉛筆のアンケートで、コンピューター 1 でのセッションについて質問された場合、より率直に回答できると感じた。まるで参加者は、コンピューター 1 の背後で、そのコンピューターには正直に話さないが、第三者の評価者に対してはより正直に表現しているかのようである。リーブスとナスは、参加者がテスト 中に自動的に社会的反応を示していることを発見した。[2] リーブスとナスは、人間と社会というテーマをより明確にするため、両方のコンピューターに情報を音声で伝えるスピーカーを追加して、再びテストを行った。 テストの結果は、ほぼまったく同じだった。彼らは、人々は、音声とテキストの両方のシナリオで、コンピューターに対して礼儀正しく振る舞うという結論に達 した。参加者は、コンピューターに対して社会的反応を示すために、それほど多くの手がかりを必要としなかった。この実験は、社会的ルールがメディアにも適 用でき、コンピューターが社会的イニシエーターとなり得るという仮説を裏付けている。参加者は、意図的にコンピューターに礼儀正しく接したことはないと否 定したが、結果は異なることを示唆している。[2] |

| Propositions The media equation relies on eight propositions derived from the research:[2] 1. Everyone responds socially and naturally to media – The media equation applies to everyone regardless of their experience, education level, age, technology proficiency, or cultures. 2. Media are more similar than different – Psychologically speaking, a computer is not much different from a television and a sophisticated version of a technology is remarkably similar to a simpler version of the technology. As Reeves and Nass (1996) say, “social and natural responses come from people, not from media themselves,” (p. 252). In other words, the media does not make people react the way they do. 3. The media equation is automatic – Since the media equation assumes that responses are “social and natural” then these reactions occur automatically without conscious effort. This can occur with minimal prompting. 4. Many different responses characterize the media equation – The media equation occurs even with the most passive uses of media. When using any type of media, a person is likely to assign it a personality, pay extra attention to it, or even assess its personality. 5. What seems true is more important than what is true – Perception of reality is far more influential than the actual objective reality. A person can know that a computer is a box made of wires and processors but can still assign a personality to it. The important point to remember is that these responses are just part of being human and participating in a communication event. 6. People respond to what is present – Despite knowing that the media merely provide a symbolic version of the world, people still tend to respond to what the media appears to be as if it were real and immediately present. For the most part, people are more concerned with the interpretation of cues or messages they receive, rather than trying to determine the original intention of the message's creators. 7. People like simplicity – The need for simplicity and to reduce complexity is an innate human need. People are comfortable with simple. Simplicity indicates a level of predictability that makes people more comfortable. 8. Social and natural is easy – When interacting with media, Reeves and Nass (1996) argue, “people should be able to use what comes naturally – rules for social relationships and rules for navigating the physical world,” (p. 255). People already know how to function in the natural world (be polite, how to handle difficult personalities) so designers should take these reactions and phenomena into consideration when designing new media. |

命題 メディア方程式は、研究から導き出された 8 つの命題に基づいている[2]。 1. 誰もがメディアに対して社会的かつ自然に応答する – メディア方程式は、経験、教育レベル、年齢、技術習熟度、文化に関係なく、すべての人に適用される。 2. メディアは、異なる点よりも類似点の方が多い – 心理的に言えば、コンピュータはテレビとそれほど変わらない。また、洗練された技術は、より単純な技術と非常に似ている。リーブスとナス(1996)が言 うように、「社会的かつ自然な反応は、メディアそのものではなく、人々から生じるものである」(252 ページ)。つまり、メディアは人々に特定の反応をさせるわけではない。 3. メディア方程式は自動的である – メディア方程式は、反応が「社会的かつ自然」であると想定しているため、これらの反応は意識的な努力なしに自動的に生じる。これは、最小限の促しでも生じうる。 4. メディア方程式は異なる反応を特徴づける – メディア方程式は、最も受動的なメディアの使用でも発生する。あらゆるタイプのメディアを使用する場合、人はそれに人格を割り当て、特別な注意を払い、あるいはその人格を評価する傾向がある。 5. 真実であると思われることは、真実であることよりも重要である – 現実の認識は、実際の客観的な現実よりもはるかに影響力がある。人はコンピュータが配線とプロセッサでできた箱だと知っていても、それに人格を付与しう る。肝心なのは、こうした反応は人間であること、コミュニケーション行為に参加することの一部だという点だ。 6. 人は目の前にあるものに反応する――メディアが世界の象徴的な表現に過ぎないと知りつつも、人はメディアが現実のように見えるものに対して、あたかもそれ が現実で即座に存在するかのように反応しがちだ。ほとんどの場合、人々はメッセージの作成者の本来の意図を判断しようとするよりも、受け取った手がかりや メッセージの解釈に関心を持つ。 7. 人は単純さを好む – 単純さを求め、複雑さを減らすことは、人間にとって生来の欲求である。人は単純なものを好む。単純さは予測可能性のレベルを示し、それは人々に安心感を与える。 8. 社会的で自然なものは容易である – メディアと交流する場合、リーブスとナス(1996)は、「人々は、社会的関係や物理的な世界を探求するためのルールなど、自然に生じるものを利用できる べきである」と主張している(255 ページ)。人々は、自然界でどのように行動すべきか(礼儀正しくあること、難しい性格の人に対処する方法など)をすでに知っているので、デザイナーは、新 しいメディアを設計する際に、こうした反応や現象を考慮に入れるべきである。 |

| Explanations According to Nass and Reeves, assigning social roles, emotions and human characters to media is an innate human response and there are three proposed explanations – “anthropomorphism, the computer-as-proxy, and mindlessness."[1] Anthropomorphism suggests that we recognize human qualities to technical beings; the computer-as-proxy is that we see the computer as human because it merely represents the responses of the human programmer; mindlessness refers to how we humans automatically react or respond to “human-like cues” unconsciously.[1] Johnson and Gardner tested mindlessness as one of the explanations of the media equation theory, and they investigated if different moods will affect participants’ tendency to stereotypes when interacting with computers.[3] The participants were asked to watch a tutorial with manipulation of either a positive or negative mood and then the tutorial used a male or female voice. The results showed that females participants who were in a positive mood showed more tendency to gender-stereotype computers than female participants who were in a negative mood.[3] No such pattern was found in male participants, however. Nevertheless, the finding in female participants shows that mindlessness is more likely to occur when people are in a mindless state because, according to Johnson and Gardner, first, people who are in a happy mood may not feel the need to use their cognitive effort to process the environment; second, people tend to avoid using their cognitive effort when in a happy mood unless doing so can maintain or elevate their good mood; third, negative effect suggests that there may be a threat in the environment which will require more systematic processing but positive effect suggests that the environment may be safe, and thus no need to expand cognitive effort.[3] On the other hand, another study found cognitive evaluation may influence the effect of the media equation. The research tested the level of threat to fundamental human needs elicited by the cyberball-paradigm and real-life behavior afterward with a sample of 45 university students. The participants are assigned to two conditions, playing cyber ball with an avatar and playing ball with an agent. Both groups reported lower fundamental human need satisfaction after the group exclusion. However, subsequently, participants from the avatar condition reported being sadder due to the exclusion and more confident due to the inclusion than the agent group. In real-life social behavior tests, all participants in the exclusion condition left a larger seating space in the proxemics test and took a longer time to help pick up the pen. Particularly, participants excluded by avatars took significantly longer time to perform helping behavior. It indicates that the media equation is valid for immediate response to social exclusion, whereas temporally delayed emotional and behavioral reactions for agents and avatars differ, which might be due to the participants are no longer in a mindless state.[4] The assumptions and conclusions of the media equation are based on a rigorous research agenda that relies on objective empirical data using reliable social science research methods. As Reeves and Nass (1996) explain, “Our strategy for learning about media was to go to the social science section of the library, find theories and experiments about human-human interaction – and then borrow…Take out a pen, cross out ‘human’ or ‘environment’ and substitute media. When we did this, all of the predictions and experiments led to the media equation: People's responses to media are fundamentally social and natural,” (p. 251). The empirical data to support the media equation is thorough and expansive. Studies have tested a wide variety of communication characteristics with the media – manners, personality, emotion, social roles and form. Below are explanations of some of the more interesting findings that support the media equation. |

説明 ナッスとリーブスによれば、メディアに社会的役割、感情、人間的な特徴を割り当てることは、人間にとって生来の反応であり、その説明として「擬人化、代理 としてのコンピュータ、無意識」の 3 つが提案されている。[1] 擬人化とは、技術的な存在に人間的な性質を見出すことを指す。コンピュータの代理とは、コンピュータが人間のプログラマーの反応を単に表現しているだけで あるにもかかわらず、それを人間として見なすことを指す。無意識とは、人間が無意識のうちに「人間的な手がかり」に対して自動的に反応したり応答したりす る方法を指す。[1] ジョンソンとガードナーはメディア方程式理論の説明の一つとして無意識性を検証し、異なる気分がコンピュータとの相互作用における参加者のステレオタイプ 傾向に影響するかを調査した[3]。参加者は、ポジティブまたはネガティブな気分操作を施されたチュートリアルを視聴し、そのチュートリアルは男性または 女性の声を用いた。結果は、ポジティブ気分状態の女性参加者が、ネガティブ気分状態の女性参加者よりもコンピュータに対してジェンダーステレオタイプを示 す傾向が強いことを示した。[3] ただし男性参加者ではこの傾向は認められなかった。それでも女性参加者におけるこの発見は、無自覚状態がより起こりやすいことを示している。ジョンソンと ガードナーによれば、第一に幸福な気分の人々は環境を処理するために認知的努力を使う必要性を感じない可能性がある。第二に幸福な気分の人々は、その良い 気分を維持または高められる場合を除き、認知的努力の使用を避けがちである。第三に、ネガティブな効果は環境に脅威が存在し、より体系的な処理が必要であ ることを示唆するが、ポジティブな効果は環境が安全であることを示唆し、したがって認知努力を拡大する必要がない。[3] 一方で別の研究では、認知的評価がメディア方程式の効果に影響を与える可能性が示された。この研究では45名の大学生を対象に、サイバーボール・パラダイ ムが引き起こす基本的欲求への脅威レベルと、その後の現実行動を検証した。参加者はアバターとのサイバーボールプレイ群とエージェントとのボールプレイ群 に割り当てられた。両群とも集団からの排除後、基本的欲求の充足度が低下したと報告した。しかしその後、アバター条件の参加者はエージェント条件の参加者 より、排除による悲しみと包含による自信を強く報告した。現実の社会的行動テストでは、排除条件の全参加者が近接空間テストでより広い座席スペースを確保 し、ペンを拾う支援に要する時間が長かった。特に、アバターによって排除された参加者は、助け行動を行うまでにかなり長い時間を要した。これは、メディア 方程式が社会的排除に対する即時的な反応には有効である一方、エージェントとアバターに対する時間的に遅れた感情的・行動的反応は異なることを示してお り、これは参加者がもはや無意識の状態にないことが原因である可能性がある。[4] メディア方程式の仮定と結論は、信頼性の高い社会科学の研究手法を用いた客観的な実証データに基づく厳密な研究課題に基づいている。リーブスとナス (1996)が説明しているように、「メディアについて学ぶための我々の戦略は、図書館の社会科学セクションに行き、人間同士の相互作用に関する理論や実 験を見つけ、それを借りることだった...ペンを取り出し、「人間」や「環境」に線を引いて、メディアに置き換えた。そうすると、すべての予測と実験がメ ディア方程式につながった。つまり、メディアに対する人々の反応は、基本的に社会的かつ自然なものである」と述べている(251 ページ)。メディア方程式を裏付ける実証データは、徹底的かつ広範である。研究では、マナー、性格、感情、社会的役割、形式など、メディアとのコミュニ ケーションのさまざまな特徴を検証してきた。以下は、メディア方程式を裏付ける、より興味深い発見のいくつかについての説明である。 |

| Politeness Politeness is one measure that researchers have used to study human-computer interaction. Being polite is an automatic response in most interpersonal interactions. When a person asks a question about themselves, most people will give a positive response, even if it may be a dishonest answer, to avoid hurting the other person's feelings. To test this idea with human-computer interaction, researchers designed an experiment in which participants would work with a computer on a tutoring exercise.[5] The computer would provide them with a fact about American culture and then provide supplemental information. The computer then prompted participants to take a test to evaluate what they have learned. After completing the tests participants were asked to evaluate the computer's performance. The participants were assigned to one of three conditions – a pencil and paper evaluation, an evaluation on a different computer, or an evaluation on the same computer. The results indicate that participants who were asked to evaluate the same computer gave the computer more positive feedback than the other two conditions. To learn more about this experiment, see Nass, Moon, & Carney, 1999.[6] |

礼儀正しさ 礼儀正しさは、研究者が人間とコンピューターの相互作用を研究するために用いてきた一つの尺度である。礼儀正しく振る舞うことは、ほとんどの人間関係にお ける自動的な反応だ。誰かが自分について質問した時、ほとんどの人は相手の気持ちを傷つけないために、たとえ不誠実な答えであっても肯定的な返答をする。 この考えを人間とコンピューターの相互作用で検証するため、研究者は参加者がコンピューターと学習課題を一緒に進める実験を設計した。[5] コンピュータはアメリカ文化に関する事実を提示し、補足情報を提供する。その後、学習内容の評価テストを受けるよう促す。テスト終了後、参加者はコン ピューターのパフォーマンスを評価するよう求められた。参加者は、鉛筆と紙による評価、異なるコンピューターでの評価、同じコンピューターでの評価という 3 つの条件のいずれかに割り当てられた。その結果、同じコンピューターを評価するよう求められた参加者は、他の 2 つの条件よりもコンピューターに対してより肯定的なフィードバックを与えたことが明らかになった。この実験の詳細については、Nass、Moon、および カーニー(1999)を参照のこと。 |

| Negativity In psychology there is a law of hedonic asymmetry that says evaluations of good and bad are important but not the same; negative experiences tend to dominate. In other words, people tend to dwell on the negative more than the positive.[2] Responses to negative situations are automatic and require more attention to process than positive experiences. Allocating more resources to process negative information takes away from resources available to process positive information, thus impeding one's ability to remember events preceding the negative event. The media equation suggests that people have a similar experience when they encounter a negative experience with media. A study was developed to examine the idea that “negative images retroactively inhibit memory for material that precedes them, while they proactively enhance memory for material that follows them,” (Newhagen & Reeves, 1992, p. 25). In other words, will watching negative images on the news prevent someone from remembering information that they learned just prior to viewing the negative material? And conversely, will they better remember information they received just after viewing the negative material? In the study,[7] researchers created two versions of the same news story – one with compelling negative images and one without. Participants were asked to watch a 20-minute news video (half of the participants saw the negative images and the other half did not) and an additional ten-minute video. They were instructed to pay attention because they would be tested afterwards. A follow up survey was sent 6 to 7 weeks later to measure memory and recall from the news video. The results support the idea that people better remember information that comes after a negative event. Respondents who viewed the negative images better remembered the second half of the newscast than the part preceding the negative images. The findings of this study further support the media equation assumption that mediated experiences are the same as natural experiences. For a more in depth look at this study, see Newhagen & Reeves, 1992.[7] |

ネガティビティ 心理学には快の非対称性の法則がある。これは良いものと悪いものの評価は重要だが同等ではなく、ネガティブな経験が支配的になりやすいと説く。つまり人は ポジティブな経験よりネガティブな経験にこだわる傾向があるのだ[2]。ネガティブな状況への反応は自動的であり、ポジティブな経験よりも処理に多くの注 意を必要とする。ネガティブな情報を処理するためにより多くのリソースを割り当てると、ポジティブな情報を処理するために利用可能なリソースが奪われ、そ の結果、ネガティブな出来事の前に起こった出来事を思い出す能力が妨げられる。メディア方程式は、人々がメディアでネガティブな体験をした場合にも同様の 体験をすることを示唆している。「ネガティブなイメージは、その前にあった事柄の記憶を遡って抑制する一方で、その後に続く事柄の記憶を積極的に強化す る」という考え方について検証するための研究が実施された。つまり、ニュースでネガティブな映像を見た人は、その直前に学んだ情報を思い出せなくなるの か?逆に、ネガティブな映像を見た直後に得た情報はよりよく覚えているのか? この研究[7]では、研究者たちは同じニュース記事を 2 つのバージョンで作成した。1 つは衝撃的なネガティブな映像を含むもの、もう 1 つは含まないものである。参加者は、20 分間のニュースビデオ(参加者の半数はネガティブな映像を視聴し、残りの半数は視聴しなかった)と、さらに 10 分間のビデオを視聴するよう求められた。その後テストがあるので注意して視聴するよう指示があった。6~7 週間後に、ニュースビデオの記憶と想起を測定するためのフォローアップ調査が実施された。その結果は、ネガティブな出来事の後に提供された情報はよりよく 記憶されるという考えを裏付けるものであった。ネガティブな映像を見た回答者は、その映像の前の部分よりも、ニュース番組の後半の部分をよく覚えていた。 この研究の結果は、メディアを通じて経験することは、自然体験と同じであるというメディア方程式の仮定をさらに裏付けるものである。 この研究についてより詳しく知りたい方は、Newhagen & Reeves, 1992 を参照のこと。[7] |

| Teammates Psychology has demonstrated that being a part of a team has a direct influence on attitude and behavior of team members. Members of a team think they are more similar to each other than people on the outside. There are two main characteristics that define team interactions – identity and interdependence. For a group to become a team the members must identify with each other and exhibit some degree of interdependence on each other. These two characteristics were tested to determine if a computer can be a teammate. In this study,[8] participants were assigned to one of two conditions. In the first condition they would be paired with a computer and would become the blue team. The computer had a blue sticker and the human wore a blue wristband to signify that they were in fact a team. The second condition was blue individual, in which a person would use a computer but they were not considered teammates, rather the computer was just a resource. The task was to complete a “Desert Survival Guide” activity in which participants rank items they deem most important if they were left on a deserted island. Human participants initially completed the activity on their own and then completed it using a computer (either as a teammate where both the computer and human were evaluated or just using the computer as a resource). Finally, the participants were allowed to revise their rankings, if they wished to do so. The results of this study indicated that participants who worked with the computer as a teammate viewed the computer as more like them, worked in a similar style to their own, was more cooperative and friendlier than people who worked individually. Another finding of this study showed that participants who worked with the computer as a teammate were more likely to change their behavior and conform to the group ideal even when the teammate was a computer. This study supports the notion that developing a sense of interdependency is the key to establishing team affiliation. For a more detailed account of this study, see Nass, Fogg, & Moon, 1996.[9] |

チームメイト 心理学によれば、チームの一員であることは、メンバーの態度や行動に直接的な影響を与える。チームメンバーは、外部の人間よりも互いに似ていると考える傾 向がある。チーム内での相互作用を定義する主な特徴は二つある——アイデンティティと相互依存性だ。集団がチームとなるためには、メンバーが互いに帰属意 識を持ち、ある程度の相互依存性を示す必要がある。この二つの特性を用いて、コンピューターがチームメイトになり得るかを検証した。 本研究[8]では、参加者は二つの条件のいずれかに割り当てられた。第一の条件では、参加者はコンピューターとペアを組み「青チーム」となった。コン ピューターには青いステッカーが貼られ、人間は青いリストバンドを着用し、実際にチームであることを示した。第二条件は「ブルー個人」であり、参加者はコ ンピューターを使用するが、コンピューターはチームメイトとは見なされず、単なるリソースとして扱われた。課題は「砂漠サバイバルガイド」活動で、無人島 に置き去りにされた場合に最も重要と考えるアイテムを順位付けするものであった。人間参加者は最初に単独で課題を完了し、次にコンピューターを (コンピュータと人間が共に評価されるチームメイトとして、あるいは単なるリソースとして)。最後に、希望者は順位を見直すことが許された。本研究の結 果、コンピュータをチームメイトとして扱った参加者は、コンピュータを自分と似た存在と見なし、自身のスタイルに近い働き方をし、単独で作業した人より協 力的で友好的であると認識した。本研究の別の知見では、コンピュータをチームメイトとして協力した参加者は、たとえチームメイトがコンピュータであって も、自らの行動を変え集団の理想に順応する傾向が強かった。この研究は、相互依存性の感覚を育むことがチーム帰属意識を確立する鍵であるという考えを支持 している。本研究の詳細については、Nass, Fogg, & Moon, 1996を参照のこと。[9] |

| Manners, personality, and social roles Nass and Reeves found that people are more polite to computers they regularly use than computers they have not used before, and people also tend to assign personality traits to things that have the resemblance of a face.[1] For example, when Apple first introduced iPhone X in 2017, it started a whole new era for smart phones of all-screen display. Since then, a lot of people have referred the top black notch on the screen as "the bangs" because of the similar resemblance.[10] Thus, Nass and Reeves believe that we assign personality traits to phones, computers, and other devices and we get annoyed at Siri when it tells a bad joke. We also assign social roles to media or in other words, we humanize media, according to Nass and Reeves.[1] For example, a TV can be a friend, a teacher, an ally or an enemy depending on what kind of personal traits we choose to assign - people give more credit to the same content shown on national TV news channel like NBC than the same content on a niche TV station.[1] Furthermore, we also assign gender roles to technology by referring to Siri as a he if it has a male voice or a she if it has a female voice. These are just a few of the many studies that support the media equation. For more in depth reading on this subject and past studies, see the “Further Reading” section at the end of this article. |

マナー、人格、社会的役割 ナスとリーブスは、人々は、これまで使ったことのないコンピューターよりも、日常的に使用しているコンピューターに対してより礼儀正しく振る舞うこと、ま た、顔のような特徴を持つものに対して人格特性を割り当てる傾向があることを発見した[1]。例えば、2017年にAppleがiPhone Xを初めて発表したとき、それはスマートフォンにとって、画面全体がディスプレイというまったく新しい時代を切り開いた。それ以来、多くの人々が、画面上 部の黒い切り欠きを、その類似性から「前髪」と呼んでいる。したがって、ナスとリーブスは、私たちは携帯電話やコンピューター、その他のデバイスに人格特 性を割り当て、Siri がつまらないジョークを言うことに苛立ちを感じるのだと考えている。また、ナスとリーブスによれば、私たちはメディアに社会的役割を割り当て、つまりメ ディアを人間化している。例えば、テレビは、私たちがどのような性格特性を割り当てるかによって、友人、教師、味方、敵などになる。人々は、NBC などの全国テレビニュースチャンネルで放映される同じコンテンツを、ニッチなテレビ局で放映される同じコンテンツよりも信頼する。さらに、私たちはテクノ ロジーにもジェンダー役割を割り当て、Siri の声が男性なら「彼」と呼び、女性の声なら「彼女」と呼ぶ。 これらは、メディア方程式を支持する多くの研究のうちのほんの一部である。この主題と過去の研究についてより深く読むには、この記事の最後にある「追加文献(さらに読む)」のセクションを参照のこと。 |

| Media equation and presence Media equation theory is closely related to studies of presence. In Lee’s research on the presence phenomena, he categorizes the media equation in two situations: “the automatic application of folk-physics modules to virtual objects” and “the automatic application of folk-psychology modules to virtual social actors stimulating humans”.[11] For the first type of media equation, research has found people continue to pay more attention to big objects in virtual settings since our mindset is trained to believe that big objects are more threatening in real life.[2] In particular, results find participants reports movements on the larger television screen appeared to be faster and experienced a greater sense of movement, led to greater excitement and physiological arousal.[12] Similarly, researches found people have a large tolerance for differences in visual fidelity just as in a real setting, because human naturally sees the world under a peripheral vision field.[13] Lastly, people often pay more attention to moving objects even though they cause no harm in virtual settings, unlike in real life.[14] Folk psychology also demonstrates significance in digital social presence. For example, people demonstrate reciprocal behavior when interacting with computers. Participants work harder to help the computer calibrate resolution when the computer helped them earlier;[15] People are more likely to disclose personal information to computers which disclose their information as well.[16] In these cases, reciprocity behavior developed in the anthropomorphic module is automatically applied in conversations with virtual social agents. Furthermore, people are inclined to find cues to determine personality traits even when interacting with computers, just as we do in social interactions.[17] |

メディア方程式とプレゼンス メディア方程式理論はプレゼンス研究と密接に関連している。リーによるプレゼンス現象の研究では、メディア方程式を二つの状況に分類している。「仮想物体 への民間物理モジュールの自動適用」と「人間を刺激する仮想社会アクターへのフォークサイコロジーモジュールの自動適用」である。[11] 前者のメディア方程式については、現実世界で大きな物体がより脅威的だと信じるように訓練された人間の思考様式に基づき、仮想環境においても人々は大きな 物体に引き続きより注意を向けることが研究で明らかになっている。[2] 特に、より大きなテレビ画面上の動きは速く見え、より強い動きの感覚を経験し、より大きな興奮と生理的覚醒をもたらすと参加者が報告した結果が得られた。 [12] 同様に、人間は現実環境と同様に視覚的忠実度の異なる点に対して大きな許容度を持つことが研究で判明している。これは人間が本質的に周辺視野で世界を見る ためである。[13] 最後に、現実世界とは異なり仮想環境では危害をもたらさないにもかかわらず、人々は動く物体にしばしばより注意を向ける。[14] フォークサイコロジーはデジタル社会的臨在においても重要性を示す。例えば、人々はコンピューターと対話する際に対称的行動を示す。参加者は、コンピュー タが以前に支援した場合、解像度調整をより熱心に支援する[15]。また、コンピュータが自身の情報を開示した場合、人間はコンピュータに対して個人的情 報を開示する傾向が強まる[16]。これらの事例では、擬人化モジュールで発達した相互的行動が、仮想社会エージェントとの会話に自動的に適用される。さ らに、人間はコンピュータとの対話においても、社会的相互作用と同様に、性格特性を判断する手がかりを探そうとする傾向がある[17]。 |

| Alternative explanations Some alternative explanations for the media equation have been proposed. But, as Nass and Moon (2000)[18] argue, these explanations do not add up to the body of empirical evidence that supports media equation. One explanation is that people attribute human characteristics to computers, also known as anthropomorphism. Nass and Moon (2000) refute this claim, saying, “Participants in our experiment were adult, experienced computer users. When debriefed, they insisted that they would never respond socially to a computer, and vehemently denied the specific behavior they had in fact exhibited during the experiments,” (p. 93). A second argument against media equation is that participants are actually responding to the programmers behind the computer. Nass and Moon (2000) refute this argument by citing that studies involving multiple computers generally found differences in interactions from computer to computer. If a person was interacting with the programmer behind the computer, then there would be no difference in interaction between computers. Critics have also argued that the way the experiments and questionnaires were designed in the Stanford research may have predisposed their subjects to interact socially with technology. Nass and Moon (2000) counter-argued by saying that the experiments were not misleading. None of the computers used in the experiments were personalized; the computer never referred to itself as “I” and participants interacted with simple text on a screen. |

代替説明 メディア方程式に対するいくつかの代替説明が提案されている。しかし、NassとMoon(2000)[18]が主張するように、これらの説明はメディア 方程式を支持する実証的証拠の体系を補完するものではない。一つの説明は、人々がコンピューターに人間的な特徴を帰属させる、いわゆる擬人化現象である。 ナッスとムーン(2000)はこの主張を反駁し、「我々の実験参加者は成人で経験豊富なコンピューターユーザーであった。事後説明の際、彼らはコンピュー ターに対して社会的反応を示すことは決してないと主張し、実験中に実際に示した特定の行動を強く否定した」(p. 93)と述べている。メディア方程式に対する第二の反論は、参加者が実際にはコンピュータの背後にいるプログラマーに反応しているというものである。ナッ スとムーン(2000)は、複数のコンピュータを用いた研究では一般的にコンピュータごとに相互作用に差異が見られたことを引用してこの主張を反駁してい る。もし人がコンピュータの背後にいるプログラマーと相互作用しているなら、コンピュータ間の相互作用に差異は生じないはずだ。批判派はまた、スタン フォード大学の研究における実験と質問票の設計方法が、被験者に技術と社会的交流を行うよう誘導した可能性を指摘している。これに対しナッスとムーン (2000)は、実験が誤解を招くものではなかったと反論した。実験で使用されたコンピュータはいずれも個人化されておらず、コンピュータが自らを「私」 と呼ぶことはなく、参加者は画面上の単純なテキストと対話していたのである。 |

| Grice's maxims Reeves and Nass explain that H. Paul Grice's maxims for communication are perhaps the most generally accepted rules on how conversational implicatures are generated and that Grice's rules are a vital basis for explaining the media equation. The four principles consist of Quality, Quantity, Clarity, and Relevance. Reeves and Nass used these principles to help explain how they believed computers could be social actors. Quality refers to how information presented in a conversation should have value, truth, and importance. Quantity refers to how speakers in interaction should present just the right amount of information to make the conversation as useful as possible. Too much or too little information may damage the value of information. Reeves and Nass argue that quantity is not something social media executed very well; they feel it causes frustration because computers display too much or too little information to humans when trying to communicate. Relevance refers to the content of information being translated into an interaction- this information should be both relevant and on-topic. Reeves and Nass argue that computers should be customizable so the user has control over relevance, and they observed how computers struggle to respond to the wishes or the goals of the users. Reeves and Nass argue that Grice's maxims are vital guidelines to the media equation because violations of these rules have a social significance. If one side of social interaction violates a rule, it may come off to the other party as a lack of attention being paid, or a diminishing of the importance of the conversation; in other words, they get offended. This leads to a negative consequence for both the party that violated a rule and the value of conversation. |

グライスの格律 リーブスとナスは、H. ポール・グライスのコミュニケーションに関する格律は、会話の含意が生成される仕組みについて、おそらく最も広く受け入れられているルールであり、グライ スのルールはメディア方程式を説明する上で重要な基礎であると説明している。4つの原則は、質、量、明瞭さ、関連性で構成される。リーブスとナスは、これ らの原則を用いて、コンピュータがどのように社会的行為者となり得るかを説明した。質とは、会話で提示される情報が、価値、真実性、重要性を備えているべ きであることを指す。量とは、対話における話者が、会話を可能な限り有用なものにするために、適切な量の情報だけを提供すべきであることを指す。情報が多 すぎても少なすぎても、情報の価値を損なう可能性がある。リーブスとナスは、量はソーシャルメディアがあまりうまく実行できていない要素だと主張してい る。彼らは、コンピュータがコミュニケーションを試みる際に、人間に対して情報が多すぎたり少なすぎたり表示するため、フラストレーションの原因になって いると感じている。関連性とは、対話に翻訳される情報の内容を指す。この情報は、関連性があり、話題に関連しているべきである。リーブスとナスは、ユー ザーが関連性を制御できるように、コンピュータはカスタマイズ可能であるべきだと主張し、コンピュータがユーザーの要望や目標に対応するのに苦労している 様子を観察した。 リーブスとナスは、グライスの格律はメディア方程式にとって重要な指針であると主張している。なぜなら、これらのルールに違反すると社会的に意味を持つか らだ。社会的相互作用の一方がルールに違反すると、相手は注意を払われていない、あるいは会話の重要性が軽視されていると受け取ってしまう。つまり、相手 は気分を害するのだ。これは、ルールに違反した側にも、会話の価値にも、マイナスの結果をもたらす。 |

| Opposing research results Collecting information in game In the study which examines the effectiveness of survey bots collecting data in a 3D virtual game, Second Life, researchers found the result both supports and contradict the media equation theory. The bot and human interview would walk up to avatars in Second Life and cask survey questions using private message chatterboxes. The result shows the bot and human interviewers are equally successful in collecting real-life information in the virtual setting. However, when examining the polarity of the responses, researchers found most responses collected by the bot are neutral, whereas most of the responses collected by humans are considered to be negative.[19] |

相反する研究結果 ゲーム内での情報収集 3D仮想ゲーム「セカンドライフ」内で調査ボットがデータを収集する有効性を検証した研究において、研究者らはその結果がメディア方程式理論を支持すると 同時に矛盾するものであることを発見した。ボットと人間のインタビュアーは、セカンドライフ内のアバターに近づき、プライベートメッセージチャットボック スを使って調査質問を投げかけた。結果は、ボットと人間のインタビュアーが仮想環境において現実の情報を収集する成功率が同等であることを示した。しか し、回答の極性を検証したところ、ボットが収集した回答の大半は中立的であるのに対し、人間が収集した回答の大半は否定的と見なされることが判明した。 [19] |

| Applications and extensions Robotics In a study that examines the pupillary responses to robots and human emotions, researchers found results supporting the Uncanny Valley and the media equation theory. The researchers record the pupil size of 40 participants while they view and rate the pictures of robots and human faces expressing various emotions. The appearances of the robots range from cartoon-like, or less human-like, to more human-like. Later, the participants are asked to fill out a questionnaire asking them whether they could imagine real-life social interaction with robots to based on their likeliness to humans. According to The results, robots that were considered to be closely humanlike performed worse on imagined social interaction elicited lesser pupil dilations and were harder to identify when displaying emotional emotions. In addition, across various emotional situations, pupil dilation pattern appears to be very similar between robot and human stimuli. Therefore, it supports the uncanny Vally and the media equation theory through a physiological lens.[20] Education In recent years, serious games, or games for learning, have gained increasing popularity in the field of education. Digital game-based learning explores the effectiveness of games for serious purposes. By immersing in a dynamic, interactive, and visualized gaming environment, learners are likely to develop motivation, enthusiasm, and involvement.[21] Based on the media equation theory, people will react to media interactions as if they are in real life. Just as in real life, when designing serious games, producers should consider visualizations that enrich game interfaces may also become distractions that reduce study efficiency and increase cognitive burdens. Therefore, a balance needs to be reached when creating digital environments that nurture study habits while stimulating user enthusiasm.[22] Health care In a study examining patients’ responses to bad news delivered by human and robot doctors, researchers found participants prefer the robot’s message better. By employing the frequentist and Bayesian statistics, researchers tested the media equation and Computers are Social Actors (CASA) validity. Based on the result, the media equation does not hold true. Participants reported preferring receiving negative results from messages from a humanoid robot than telemedicine with humans. This preference may due to the lack of emotional expression directing the focus on the information itself.[23] |

応用と拡張 ロボティクス ロボットと人間の感情に対する瞳孔反応を調べた研究で、研究者らは不気味の谷とメディア方程式理論を支持する結果を発見した。研究者らは、40名の参加者 が様々な感情を表現したロボットと人間の顔写真を見て評価する間、瞳孔の大きさを記録した。ロボットの外見は、漫画的(人間らしさが低い)ものから人間ら しいものまで様々であった。その後、参加者は人間らしさに基づいて、ロボットとの現実的な社会的交流を想像できるかどうかを尋ねる質問票に回答するよう求 められた。結果によれば、人間に非常に似ていると評価されたロボットは、想像上の社会的交流において低い評価を得た。瞳孔の拡張が少なく、感情表現時の識 別が困難であった。さらに、様々な感情状況において、瞳孔拡張パターンはロボットと人間の刺激間で非常に類似しているように見えた。したがって、生理学的 観点から不気味の谷とメディア方程式理論を支持する結果となった。[20] 教育 近年、教育分野ではシリアスゲーム(学習用ゲーム)の人気が高まっている。デジタルゲームベース学習は、教育目的におけるゲームの有効性を探求する。動的 で双方向性のある視覚化されたゲーム環境に没入することで、学習者は動機付けや熱意、関与感を育みやすい。[21] メディア方程式理論によれば、人々はメディアとの相互作用を現実の生活と同様に反応する。現実世界と同様に、シリアスゲームを設計する際、制作側はゲーム インターフェースを豊かにする視覚化が、学習効率を低下させ認知負荷を増大させる妨げとなる可能性も考慮すべきだ。したがって、学習習慣を育みつつユー ザーの熱意を刺激するデジタル環境を構築する際には、バランスを取る必要がある。[22] 健康 人間医師とロボット医師による悪い知らせの伝達に対する患者の反応を検証した研究では、参加者はロボットの伝達方法をより好むことが判明した。頻度論統計 とベイズ統計を用いて、研究者はメディア方程式とコンピュータは社会的行為者(CASA)モデルの妥当性を検証した。結果から、メディア方程式は成立しな いことが判明した。参加者は、人間による遠隔医療よりも、ヒューマノイドロボットからのメッセージで悪い結果を受け取ることを好むと報告した。この選好 は、感情表現の欠如が情報そのものへの集中を促すためと考えられる。[23] |

| Further reading Byron Reeves & Clifford Nass – The Media Equation: How People Treat Computers, Television, and New Media like Real People and Places, Cambridge University Press: 1996.[2] Clifford Nass & Corina Yen – The Man Who Lied to His Laptop: What Machines Teach Us About Human Relationships, Current/Penguin: 2010. |

追加文献(さらに読む) バイロン・リーブス&クリフォード・ナス著『メディア方程式:人々がコンピュータ、テレビ、新しいメディアを実際の人や場所のように扱う理由』ケンブリッジ大学出版局、1996年。 クリフォード・ナス&コリーナ・イェン著『ノートパソコンに嘘をついた男:機械が教えてくれる人間関係について』カレント/ペンギン、2010年。 |

| References 1. Littlejohn, Steven (2016). Theories of Human Communication: Eleventh Edition. Waveland Press, Inc. p. 202. ISBN 978-1478634058. 2. Reeves, B., & Nass, C. I. (1996). The media equation : how people treat computers, television, and new media like real people and places. Cambridge University Press. 3. Johnson; Gardner, Daniel; John (2009). "Exploring mindlessness as an explanation for the media equation: a study of stereotyping in computer tutorials" (PDF). Personal and Ubiquitous Computing. 13 (2): 151–163. doi:10.1007/s00779-007-0193-9. S2CID 15648099. 4. Kothgassner, Oswald D.; Griesinger, Mirjam; Kettner, Kathrin; Wayan, Katja; Völkl-Kernstock, Sabine; Hlavacs, Helmut; Beutl, Leon; Felnhofer, Anna (2017-05-01). "Real-life prosocial behavior decreases after being socially excluded by avatars, not agents". Computers in Human Behavior. 70: 261–269. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.059. ISSN 0747-5632. 5. Nass, C., Moon, Y., & Carney, P. (1999). Are People Polite to Computers? Responses to Computer-Based Interviewing Systems. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(5), 1093–1109. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb00142.x 6. Nass, C., Moon, Y., & Carney, P. (1999). Are People Polite to Computers? Responses to Computer-Based Interviewing Systems. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 29(5), 1093–1109. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb00142.x 7. Newhagen, J. E., & Reeves, B. (1992). The evening's bad news: Effects of compelling negative television news images on memory. Journal of communication, 42(2), 25-41. 8. Nass, C., Fogg, B. J., & Moon, Y. (1996). Can computers be teammates? International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 45(6), 669–678. doi:10.1006/ijhc.1996.0073 9. Nass, C., Fogg, B. J., & Moon, Y. (1996). Can computers be teammates? International Journal of Human-Computer Studies, 45(6), 669–678. doi:10.1006/ijhc.1996.0073 10. admin (9 October 2021). "The "bangs" of the iPhone 13 have not only shrunk, they have also become stronger | TechNews". www.breakinglatest.news. Retrieved 2021-11-29. 11. Lee, Kwan Min (August 2004). "Why Presence Occurs: Evolutionary Psychology, Media Equation, and Presence". Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments. 13 (4): 494–505. doi:10.1162/1054746041944830. ISSN 1054-7460. S2CID 18936448. 12. Lombard, M (2000-01-01). "Presence and television. The role of screen size". Human Communication Research. 26 (1): 75–98. doi:10.1093/hcr/26.1.75. ISSN 0360-3989. 13. Hochberg, Julian (1986). "Representation of motion and space in video and cinematic displays". NASA STI/Recon Technical Report A. 1: 22_1–22_64. Bibcode:1986STIA...8733516H. 14. Reeves, Byron; Thorson, Esther; Rothschild, Michael L.; McDonald, Daniel; Hirsch, Judith; Goldstein, Robert (January 1985). "Attention to Television: Intrastimulus Effects of Movement and Scene Changes on Alpha Variation Over Time". International Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (3–4): 241–255. doi:10.3109/00207458509149770. ISSN 0020-7454. PMID 4044133. 15. Fogg, BJ; Nass, Clifford (1997). "How users reciprocate to computers: An experiment that demonstrates behavior change". CHI '97 extended abstracts on Human factors in computing systems looking to the future - CHI '97. New York, New York, USA: ACM Press. p. 331. doi:10.1145/1120212.1120419. ISBN 0897919262. S2CID 19000516. 16. Moon, Y. (1998). When the computer is the" salesperson": Consumer responses to computer" personalities" in interactive marketing situations (Vol. 99, No. 41). Division of Research, Harvard Business School. 17. Moon, Y., & Nass, C. (1996). How “real” are computer per- sonalities? Psychological responses to personality types in human-computer interaction. Communication Research, 23(6), 651–674. 18. Nass, C., & Moon, Y. (2000). Machines and Mindlessness: Social Responses to Computers. Journal of Social Issues, 56(1), 81–103. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00153 19. Klowait, Nils (2017-07-18). "The quest for appropriate models of human-likeness: anthropomorphism in media equation research". AI & Society. 33 (4): 527–536. doi:10.1007/s00146-017-0746-z. ISSN 0951-5666. S2CID 253682146. 20. Reuten, Anne; van Dam, Maureen; Naber, Marnix (2018). "Pupillary Responses to Robotic and Human Emotions: The Uncanny Valley and Media Equation Confirmed". Frontiers in Psychology. 9: 774. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00774. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 5974161. PMID 29875722. 21. Westera, Wim (2015-06-17). "Games are motivating, aren´t they? Disputing the arguments for digital game-based learning". International Journal of Serious Games. 2 (2). doi:10.17083/ijsg.v2i2.58. ISSN 2384-8766. 22. Westera, Wim (2019). "Why and How Serious Games can Become Far More Effective: Accommodating Productive Learning Experiences, Learner Motivation and the Monitoring of Learning Gains". Educational Technology & Society. 22 (1): 59–69. 23. Hoorn, Johan F.; Winter, Sonja D. (2018-09-01). "Here Comes the Bad News: Doctor Robot Taking Over". International Journal of Social Robotics. 10 (4): 519–535. doi:10.1007/s12369-017-0455-2. ISSN 1875-4805. S2CID 52314236. |

参考文献 1. リトルジョン、スティーブン (2016)。『人間コミュニケーションの理論:第 11 版』。ウェイブランドプレス社。202 ページ。ISBN 978-1478634058。 2. リーブス、B.、および ナス、C. I. (1996)。メディア方程式:人々がコンピュータ、テレビ、新しいメディアを実際の人や場所のように扱う方法。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 3. ジョンソン、ガードナー、ダニエル、ジョン (2009)。「メディア方程式の説明としての無意識の探求:コンピュータチュートリアルにおける固定観念の研究」 (PDF)。パーソナル・ユビキタス・コンピューティング。13 (2): 151–163. doi:10.1007/s00779-007-0193-9. S2CID 15648099. 4. コットガスナー, オズワルド・D.; グリージンガー, ミルヤム; ケトナー, カトリン; ワヤン, カトヤ; フェルクル=ケルンシュトック, サビーネ; フラヴァックス, ヘルムート; ボイトゥル, レオン; フェルンホーファー、アンナ (2017-05-01). 「現実の社会的な行動は、エージェントではなくアバターによる社会的排除を受けた後に減少する」. Computers in Human Behavior. 70: 261–269. doi:10.1016/j.chb.2016.12.059. ISSN 0747-5632. 5. ナス、C.、ムーン、Y.、カーニー、P. (1999). 人々はコンピュータに礼儀正しいか?コンピュータベースの面接システムに対する反応。応用社会心理学ジャーナル、29(5)、1093–1109。 doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb00142.x 6. Nass, C., Moon, Y., & Carney, P. (1999). 人はコンピュータに礼儀正しいか?コンピュータベースの面接システムに対する反応。応用社会心理学ジャーナル、29(5)、 1093–1109. doi:10.1111/j.1559-1816.1999.tb00142.x 7. Newhagen, J. E., & Reeves, B. (1992). 夕方の悪いニュース:説得力のあるネガティブなテレビニュース映像が記憶に及ぼす影響。コミュニケーションジャーナル、42(2)、25-41。 8. Nass, C., Fogg, B. J., & Moon, Y. (1996). コンピュータはチームメイトになり得るか? 国際人間コンピュータ研究ジャーナル、45(6)、669–678。doi:10.1006/ijhc.1996.0073 9. ナス、C.、フォッグ、B. J.、& ムーン、Y. (1996). コンピュータはチームメイトになり得るか? 国際人間コンピュータ研究ジャーナル, 45(6), 669–678. doi:10.1006/ijhc.1996.0073 10. admin (2021年10月9日). 「iPhone 13の『バン』は小さくなっただけでなく、より強力になった | TechNews」. www.breakinglatest.news. 2021年11月29日閲覧. 11. Lee, Kwan Min (2004年8月). 「 なぜプレゼンスは生じるのか:進化心理学、メディア方程式、そしてプレゼンス」. Presence: Teleoperators and Virtual Environments. 13 (4): 494–505. doi:10.1162/1054746041944830. ISSN 1054-7460. S2CID 18936448. 12. Lombard, M (2000-01-01). 「プレゼンスとテレビ。画面サイズの役割」. Human Communication Research. 26 (1): 75–98. doi:10.1093/hcr/26.1.75. ISSN 0360-3989. 13. Hochberg, Julian (1986). 「ビデオおよび映画ディスプレイにおける動きと空間の表現」. NASA STI/Recon Technical Report A. 1: 22_1–22_64. Bibcode:1986STIA...8733516H. 14. リーブス、バイロン、ソーソン、エスター、ロスチャイルド、マイケル L.、マクドナルド、ダニエル、ハーシュ、ジュディス、ゴールドスタイン、ロバート (1985年1月)。「テレビへの注意:時間の経過に伴うアルファ変動に対する動きと場面変化の刺激内効果」。International Journal of Neuroscience. 27 (3–4): 241–255. doi:10.3109/00207458509149770. ISSN 0020-7454. PMID 4044133. 15. Fogg, BJ; Nass, Clifford (1997). 「ユーザーがコンピュータにどのように反応するか:行動の変化を示す実験」. CHI 『97 extended abstracts on Human factors in computing systems looking to the future - CHI 』97. ニューヨーク州ニューヨーク: ACM Press. p. 331. doi:10.1145/1120212.1120419. ISBN 0897919262. S2CID 19000516. 16. Moon, Y. (1998). コンピューターが「販売員」となる場合:対話型マーケティング状況におけるコンピューター「人格」への消費者反応 (Vol. 99, No. 41). ハーバード・ビジネス・スクール研究部門. 17. Moon, Y., & Nass, C. (1996). コンピュータの性格はどれほど「本物」か? 人間とコンピュータの相互作用における性格タイプへの心理的反応. コミュニケーション研究, 23(6), 651–674. 18. ナス, C., & ムーン, Y. (2000). 機械と無自覚さ:コンピュータへの社会的反応. 社会問題ジャーナル, 56(1), 81–103. doi:10.1111/0022-4537.00153 19. Klowait, Nils (2017-07-18). 「人間らしさの適切なモデルを求める探求:メディア方程式研究における擬人化」. AI & Society. 33 (4): 527–536. doi:10.1007/s00146-017-0746-z. ISSN 0951-5666. S2CID 253682146. 20. Reuten, Anne; van Dam, Maureen; Naber, Marnix (2018). 「ロボットと人間の感情に対する瞳孔反応:不気味の谷とメディア方程式の検証」. Frontiers in Psychology. 9: 774. doi:10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00774. ISSN 1664-1078. PMC 5974161. PMID 29875722. 21. Westera, Wim (2015-06-17). 「ゲームはやる気を起こさせる、そうだろう? デジタルゲームベース学習の主張への異論」. International Journal of Serious Games. 2 (2). doi:10.17083/ijsg.v2i2.58. ISSN 2384-8766. 22. ウェスタラ、ウィム(2019)。「シリアスゲームがはるかに効果的になる理由と方法:生産的な学習体験、学習者の動機付け、学習成果のモニタリングの調整」。『教育技術と社会』。22巻1号:59–69頁。 23. ホーン、ヨハン・F.;ウィンター、ソーニャ・D.(2018年9月1日) 。「悪い知らせだ:医用ロボットが支配する」。『国際社会ロボティクスジャーナル』。10巻4号:519–535頁。doi: 10.1007/s12369-017-0455-2。ISSN 1875-4805。S2CID 52314236。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Media_Equation |

リーブス、バイロンとクリフォード・ナス

『人はなぜコンピューターを人間として扱うか』細馬宏通訳、翔泳社、2001(Reeves,

Byron and Clifford Nass, 1998. The media equation : how people treat

computers, television, and new media like real people and places.

Stanford, Calif. : Center for the Study of Language and Information

Cambridge [England] ; New York : Cambridge University Press)の章立ては「メディア等式(media equation)文献資料集」を参照のこと。

●Multitasking: How It Is Changing the Way You and Your Children Think and Feel with Clifford Nass

■リンク

■文献

■その他の追加情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099