迷信と迷信バッシング

Superstition and Superstition hunting

Joseph

E., ca. 1837-1914, artist.

☆ 迷信(superstition) とは、運命や魔法、知覚された超自然的な影響、未知のものへの恐怖に起因する、非合理的または超自然的であると実践者以外が考える信念や慣習のことで ある。一般的には、幸運、お守り、占星術、占い、霊、ある種の超常的な存在にまつわる信念や慣習に適用され、特に特定の無関係な過去の出来事によって未来 の出来事が予言されるという信念に適用される。迷信という言葉は、一般的な宗教が迷信とされるものを含んでいるかどうかに関わらず、ある社会の大多数が実 践していない宗教や、反宗教的な人々によるすべての宗教を指す場合にも使われる。

| A superstition is

any belief or practice considered by non-practitioners to be irrational

or supernatural, attributed to fate or magic, perceived supernatural

influence, or fear of that which is unknown. It is commonly applied to

beliefs and practices surrounding luck, amulets, astrology, fortune

telling, spirits, and certain paranormal entities, particularly the

belief that future events can be foretold by specific unrelated prior

events.[1][2] The word superstition is also used to refer to a religion not practiced by the majority of a given society regardless of whether the prevailing religion contains alleged superstitions or to all religions by the antireligious.[1] |

迷信(superstition)とは、運

命や魔法、知覚された超自然的な影響、未知のものへの恐怖に起因する、非合理的または超自然的であると実践者以外が考える信念や慣習のことである。一般的

には、幸運、お守り、占星術、占い、霊、ある種の超常的な存在にまつわる信念や慣習に適用され、特に特定の無関係な過去の出来事によって未来の出来事が予

言されるという信念に適用される[1][2]。 迷信という言葉は、一般的な宗教が迷信とされるものを含んでいるかどうかに関わらず、ある社会の大多数が実践していない宗教や、反宗教的な人々によるすべ ての宗教を指す場合にも使われる[1]。 |

| Contemporary use Definitions of the term vary, but they commonly describe superstitions as irrational beliefs at odds with scientific knowledge of the world. Stuart Vyse proposes that a superstition's "presumed mechanism of action is inconsistent with our understanding of the physical world", with Jane Risen adding that these beliefs are not merely scientifically wrong but impossible.[3][4] Similarly, Lysann Damisch defines superstition as "irrational beliefs that an object, action, or circumstance that is not logically related to a course of events influences its outcome."[5][6] Dale Martin says they "presuppose an erroneous understanding about cause and effect, that have been rejected by modern science."[7] The Oxford English Dictionary[8] describes them as "irrational, unfounded", Merriam-Webster as "a false conception about causation or belief or practice",[9] and the Cambridge Dictionary as "sans grounding in human reason or scientific knowledge".[10] This notion of superstitious practices is not causally related to the outcomes.[11] Both Vyse and Martin argue that what is considered superstitious varies across cultures and time. For Vyse, "if a culture has not yet adopted science as its standard, then what we consider magic or superstition is more accurately the local science or religion."[3] Dale points out that superstitions are often considered out of place in modern times and are influenced by modern science and its notions of what is rational or irrational, surviving as remnants of older popular beliefs and practices.[9] Vyse proposes that in addition to being irrational and culturally dependent, superstitions have to be instrumental; an actual effect is expected by the person holding a belief, such as increased odds of winning a prize. This distinction excludes practices where participants merely expect to be entertained.[3] |

現代の使用法 迷信の定義はさまざまだが、一般的には、世界に関する科学的知識と相反する非合理的な信念を指す。スチュアート・ヴァイセは迷信の「推定される作用機序が 物理的世界の理解と矛盾している」ことを提唱し、ジェーン・リゼンはこれらの信念は単に科学的に間違っているだけでなく、不可能であると付け加えている [3][4]。同様に、ライサン・ダミッシュは迷信を「ある出来事の経過に論理的に関連していない物体、行為、状況がその結果に影響を及ぼすという非合理 的な信念」と定義している[5][6]。 「オックスフォード英語辞典[8]は「非合理的な、根拠のない」、メリアム=ウェブスターは「因果関係や信念、習慣に関する誤った概念」[9]、ケンブ リッジ辞典は「人間の理性や科学的知識に根拠がない」[10]としている。 VyseもMartinも、何を迷信とみなすかは文化や時代によって異なると主張している。ヴィースにとって、「もしある文化がまだ科学を標準として採用 していないのであれば、私たちが魔法や迷信と考えているものは、より正確にはその土地の科学や宗教である」[3]。デールは、迷信はしばしば現代にはそぐ わないと考えられており、近代科学とその合理的か非合理的かという概念の影響を受けており、古い一般的な信念や慣習の名残として生き残っていると指摘して いる[9]。 ヴァイセは、迷信は非合理的で文化的に依存していることに加えて、道具的でなければならないと提唱している。この区別は、参加者が単に楽しまれることを期 待する慣習を除外する[3]。 |

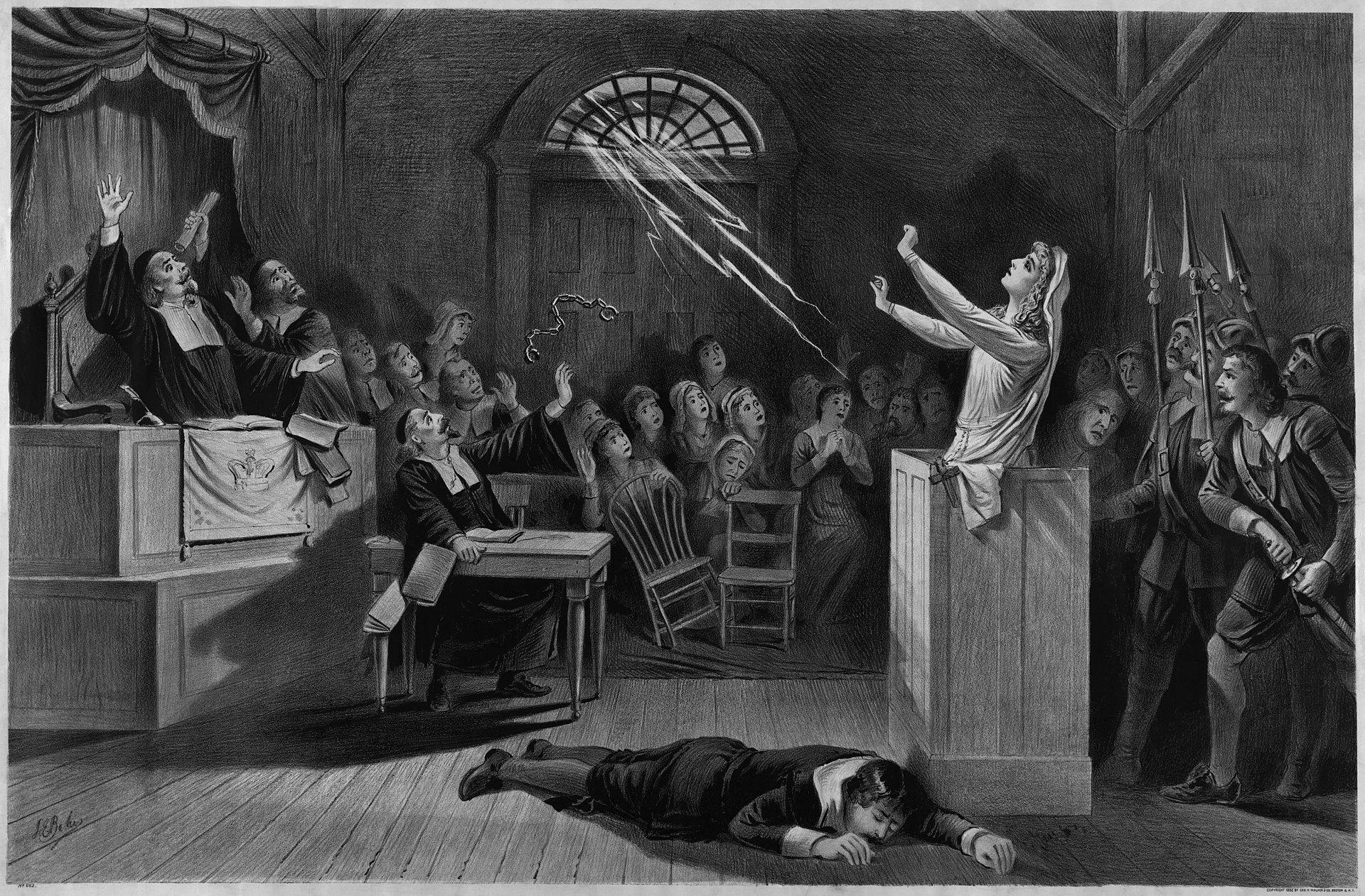

The central figure in this 1876 illustration of the courtroom is usually identified as Mary Walcott. Salem witch trials |

1876年に描かれたこの法廷のイラストの中心人物は、通常メアリー・ウォルコットとされている。 |

| Alternative religious beliefs as

superstition See also: folk religion, lived religion, Superstitions in Muslim societies, Evolutionary origin of religions, and Evolutionary psychology of religion Religious practices that differ from commonly accepted religions in a given culture are sometimes called superstitious; similarly, new practices brought into an established religious community can also be labeled as superstitious in an attempt to exclude them. Also, an excessive display of devoutness has often been labelled as superstitious behavior.[1][12][13] In antiquity, the Latin term superstitio, like its equivalent Greek deisidaimonia, came to be associated with exaggerated ritual and a credulous attitude towards prophecies.[14][8][1] Greek and Roman polytheists, who modeled their relations with the gods on political and social terms, scorned the man who constantly trembled with fear at the thought of the gods, as a slave feared a cruel and capricious master. Such fear of the gods was what the Romans meant by "superstition" (Veyne 1987, p. 211). Diderot's Encyclopédie defines superstition as "any excess of religion in general", and links it specifically with paganism.[15] In his Prelude on the Babylonian Captivity of the Church, Martin Luther, who called the papacy "that fountain and source of all superstitions", accuses the popes of superstition: For there was scarce another of the celebrated bishoprics that had so few learned pontiffs; only in violence, intrigue, and superstition has it hitherto surpassed the rest. For the men who occupied the Roman See a thousand years ago differ so vastly from those who have since come into power, that one is compelled to refuse the name of Roman pontiff either to the former or to the latter.[16] The current Catechism of the Catholic Church considers superstition sinful in the sense that it denotes "a perverse excess of religion", as a demonstrated lack of trust in divine providence (¶ 2110), and a violation of the first of the Ten Commandments. The Catechism is a defense against the accusation that Catholic doctrine is superstitious: Superstition is a deviation of religious feeling and of the practices this feeling imposes. It can even affect the worship we offer the true God, e.g., when one attributes an importance in some way magical to certain practices otherwise lawful or necessary. To attribute the efficacy of prayers or of sacramental signs to their mere external performance, apart from the interior dispositions that they demand is to fall into superstition. Cf. Matthew 23:16–22 (¶ 2111) Examples of superstitions and taboos from a November 1941 issue of Weird Tales. Classifications Dieter Harmening's book Superstitio categorizes superstitions in three categories: magic, divination and observances. He further divides observances category in 'signs' and 'time'.[2] Time sub-category constitutes temporal prognostics like observances of various days related like dog days, Egyptian days, year prognosis and lunaries, where as signs category constitutes signs like particular animal behaviors, like the call of birds or neighing of horses or sighting of comets, or dreams.[2] According to László Sándor Chardonnens the signs subcategory usually needs an observer who might help in interpreting the signs and such observer does not need necessarily to be an active participant of the observation.[2] According to Chardonnens, category of Divination participant need to go beyond mere observation and need to be active participant in given action.[2] Examples of Divination superstitions are judicial astrology, necromancy, haruspex, lot-casting, geomancy, aeromancy and prophecy.[2] Chardonnens says superstitions belonging to magic category are exceedingly hermetical and ritualistic and its examples are witchcraft, potions, incantations, amulets etc.[2] Chardonnens says Observation category needs an observer, divination category needs participant to tell what is to be observed, where as magic requires a participant who must follow a protocol to influence the future, and that these three types of superstition need increasing stages of participation and knowledge.[2] Chardonnens defines "prognostication" as that component of superstition which, expects knowledge of the future on systematic application of given ritual and order,[2] and moves to classify saying, Prognostication appear to occupy a place somewhere between observation and divination, of which due to the primacy of temporal prognostics, the observation of times is represented most frequently.[2] Chardonnens classifies prophecy under topic of divination; examples being the prophets of the Old Testament, biblical typological allegory, the fifteen signs before Judgement Day, and the many prophecies expressed by saints.; Chardonnens further points out that since many aspects of religious experience are tied up with prophecy, church condones the same.[2] Chardonnens says, one could differentiate between those kinds of prophecy which are (1) inspired by God or Satan and their minions; (2) "gecyndelic"; and (3) "wiglung" examples —lacking divine or infernal inspiration and not "gecyndelic" either. But practically, however, most, if not all, words relating to prophecy ought to be interpreted as inspired.[2] Criticism of definitions Identifying something as superstition is generally pejorative. Items referred to as such in common parlance are commonly referred to as folk belief in folkloristics.[17] According to László Sándor Chardonnens, OED definitions pass value judgement and attribution to "fear and ignorance", do not do enough justice to elaborate systems of superstitions.[2] Chardonnens says the religious element in OED denotations are not understood as system of observance and testifies to a belief in higher power on part of the compiler of the dictionary.[2] Subjective perceptions Webster's The Encyclopedia of Superstitions points out that, many superstitions are related with religion, people have been carrying individual subjective perceptions vis a vis superstitions against one another, people of one belief are likely to call people of another belief superstitious; Constantine regarded paganism as a superstition; Tacitus on other hand regarded Christianity as pernicious superstition; Saul of Tarsus and Martin Luther perceived any thing that was not centered on Christ to be superstitious.[18] According to Dale, difference of opinion on what constitutes 'superstition' become apparent when one moves form one culture to another culture.[7] Etymology While the formation of the Latin word is clear, from the verb super-stare, "to stand over, stand upon; survive", its original intended sense is less clear. It can be interpreted as "'standing over a thing in amazement or awe",[19] but other possibilities have been suggested, e.g. the sense of excess, i.e. over scrupulousness or over-ceremoniousness in the performing of religious rites, or else the survival of old, irrational religious habits.[20][21] The earliest known use as a noun is found in Plautus, Ennius and later by Pliny, with the meaning of art of divination.[22] From its use in the Classical Latin of Livy and Ovid, it is used in the pejorative sense that it holds today, of an excessive fear of the gods or unreasonable religious belief; as opposed to religio, the proper, reasonable awe of the gods. Cicero derived the term from superstitiosi, lit. those who are "left over", i.e. "survivors", "descendants", connecting it with excessive anxiety of parents in hoping that their children would survive them to perform their necessary funerary rites.[23] According to Michael David Bailey, it was with Pliny's usage that Magic came close to superstition; and charges of being superstitious were first leveled by Roman authorities on their Christian subjects. In turn, early Christian writers pronounced all Roman and Pagan cults to be superstitious, worshipping false Gods, fallen angels and demons. It is with Christian usage that almost all forms of magic started being described as forms of superstition.[24] |

迷信としての別の宗教的信念 民間宗教、生活宗教、イスラム社会における迷信、宗教の進化的起源、宗教の進化心理学も参照のこと。 ある文化圏で一般的に受け入れられている宗教とは異なる宗教的実践は、迷信と呼ばれることがある。同様に、確立された宗教共同体に持ち込まれた新しい実践 も、それを排除しようとして迷信のレッテルを貼られることがある。また、過度な敬虔さの誇示も迷信的な行動とレッテルを貼られることが多い[1][12] [13]。 古代において、ラテン語のsuperstitioという用語は、それに相当するギリシア語のdeisidaimoniaと同様に、誇張された儀式や予言に 対する信心深い態度と結び付けられるようになった[14][8][1]。ギリシア・ローマの多神教徒は、神々との関係を政治的・社会的な観点からモデル化 しており、奴隷が残酷で気まぐれな主人を恐れるように、神々のことを考えて常に恐怖に震える人間を軽蔑していた。このような神々への恐怖こそが、ローマ人 の言う「迷信」であった(Veyne 1987, p.211)。ディドロの『百科全書』は迷信を「宗教全般の過剰」と定義し、特に異教と結びつけている[15]。 マルティン・ルターは『教会のバビロン捕囚に関する前奏曲』の中で、ローマ教皇庁を「あらゆる迷信の泉であり源である」と呼び、教皇たちの迷信を非難して いる: 有名な司教座の中で、これほど学識のある教皇が少なかったものは他になかった。千年前にローマ教皇庁を占めていた人々と、その後権力を握った人々とはあま りにも大きく異なるため、前者にも後者にもローマ教皇の名を拒否せざるを得ないのである[16]。 現在のカトリック教会のカテキズムは、迷信は「宗教の倒錯した過剰」を示すという意味で、神の摂理に対する信頼の欠如(¶2110)、十戒の第一の違反と して、罪深いものとみなしている。カテキズムは、カトリックの教義が迷信的であるという非難に対する弁明である: 迷信とは、宗教的感情の逸脱であり、この感情が課す実践の逸脱である。迷信は、私たちが真の神にささげる礼拝にさえも影響を及ぼすことがある。たとえば、 そうでなければ合法的あるいは必要なある種の実践に、何らかの魔術的な重要性を帰結させる場合などである。祈りや秘跡の印の効力を、それらが要求する内的 な気持とは別に、単なる外的な実行に帰することは、迷信に陥ることである。参照:マタイによる福音書23:16-22 (¶ 2111) Weird Tales』1941年11月号に掲載された迷信とタブーの例。 分類 ディーター・ハーメニングの著書『Superstitio』は迷信を3つのカテゴリーに分類している。彼はさらに、観察カテゴリーを「兆候」と「時間」に 分けている[2]。時間サブカテゴリーは、戌の日、エジプトの日、年予言、月齢のような様々な日に関連する観察などの時間予言を構成し、兆候カテゴリー は、鳥の鳴き声、馬の嘶き、彗星の目撃、夢のような特定の動物の行動などの兆候を構成する。 [2] ラースロー・シャーンドル・シャルドネンスによれば、予兆の下位カテゴリーには通常、予兆の解釈を助ける観察者が必要であり、そのような観察者は必ずしも 積極的に観察に参加する必要はない[2]。 [2]シャルドネンスによれば、占いの迷信の例としては、司法占星術、黒魔術、ハルスペックス、ロットキャスティング、ジオマンシー、エアロマンシー、予 言などがある。 [2]シャルドネンスは、観察カテゴリーには観察者が必要であり、占いカテゴリーには何を観察すべきかを伝える参加者が必要であり、魔術には未来に影響を 与えるためにプロトコルに従わなければならない参加者が必要であり、これら3つのタイプの迷信には参加と知識の段階が必要であると述べている[2]。 シャルドネンスは「予言」を、与えられた儀式と秩序を体系的に適用することで未来についての知識を期待する迷信の構成要素であると定義し[2]、次のよう に分類している。 予言は観察と占いの中間の位置を占めているように見えるが、その中でも時間的予言の優位性のために、時間の観察が最も頻繁に表現されている」[2]。 旧約聖書の預言者、聖書の類型論的寓意、審判の日の前の15個のしるし、聖人によって表明された多くの予言などがその例である。シャルドネンスはさらに、 宗教的経験の多くの側面が予言と結びついているため、教会は予言を容認していると指摘する。 [2]シャルドネンスによれば、予言の種類は、(1)神またはサタンとその手先の霊感を受けたもの、(2)「ゲシンデリック」なもの、(3)「ウィグルン グ」なもの--神または地獄の霊感を欠き、「ゲシンデリック」でもない--に区別することができるという。しかし、現実的には、予言に関する言葉は、すべ てではないにせよ、ほとんどが霊感を受けたものと解釈されるべきである[2]。 定義に対する批判 何かを迷信と特定することは一般的に侮蔑的である。一般的な言い回しでそのように呼ばれるものは、民俗学では一般的に民間信仰と呼ばれる[17]。 László Sándor Chardonnensによれば、OEDの定義は価値判断を下し、「恐怖と無知」に帰するものであり、迷信の精巧な体系を正当に評価していない[2]。 Chardonnensによれば、OEDの表記における宗教的要素は、遵守の体系として理解されておらず、辞書の編纂者側の高次の力に対する信念を物語っ ている[2]。 主観的認識 ウェブスターの『迷信百科事典』は、多くの迷信が宗教と関連していること、人々は迷信に対して個々の主観的な認識を持ち、互いに対立していること、ある信 念を持つ人々は他の信念を持つ人々を迷信的と呼ぶ可能性が高いこと、コンスタンティヌスは異教を迷信とみなし、一方タキトゥスはキリスト教を悪質な迷信と みなし、タルソのサウロとマルティン・ルターはキリストを中心としないあらゆるものを迷信とみなしていることを指摘している[18]。 [18]デールによれば、何が「迷信」であるかについての見解の相違は、ある文化圏から別の文化圏に移ったときに明らかになる[7]。 語源 ラテン語の語源は動詞のsuper-stare「上に立つ、その上に立つ、生き残る」であり、明確であるが、本来の意味はそれほど明確ではない。この語は 「驚きや畏怖の念を抱いて物事の上に立つ」[19]と解釈することができるが、他の可能性も示唆されている。例えば、過剰の意味、すなわち宗教的儀式を執 り行う際の細心の注意や過剰な儀礼、あるいは古い非合理的な宗教的習慣の存続などがある[20][21]。 名詞としての最古の用法はプラウトゥス、エンニウスに見られ、後にプリニウスが占いの術という意味で用いている[22]。リヴィーやオウィドの古典ラテン 語における用法から、神々に対する過剰な恐れや不合理な宗教的信仰という、今日のような侮蔑的な意味で用いられるようになった。キケロはこの用語を superstitiosi(「残された者」、すなわち「生存者」、「子孫」)から派生させ、自分の子供が葬儀に必要な儀式を執り行うために生き残ること を願う親の過剰な不安と結びつけた[23]。 マイケル・デイヴィッド・ベイリーによれば、魔法が迷信に近づいたのはプリニウスの用法によるものであり、迷信的であるという告発はローマ当局によってキ リスト教臣民に対して最初になされた。そして、ローマ当局がキリスト教臣民に対して迷信的であると非難したのが最初であった。その一方で、初期のキリスト 教作家たちは、ローマや異教のカルトはすべて迷信的であり、偽りの神々や堕落した天使や悪魔を崇拝していると宣告した。ほとんどすべての魔術が迷信の一種 であるとされるようになったのは、キリスト教的な用法によるものである[24]。 |

| Superstition and psychology Main articles: Magical thinking, Placebo, and Effective theory Origins Behaviorism perspective In 1948, behavioral psychologist B.F. Skinner published an article in the Journal of Experimental Psychology, in which he described his pigeons exhibiting what appeared to be superstitious behaviour. One pigeon was making turns in its cage, another would swing its head in a pendulum motion, while others also displayed a variety of other behaviours. Because these behaviors were all done ritualistically in an attempt to receive food from a dispenser, even though the dispenser had already been programmed to release food at set time intervals regardless of the pigeons' actions, Skinner believed that the pigeons were trying to influence their feeding schedule by performing these actions. He then extended this as a proposition regarding the nature of superstitious behavior in humans.[25] Skinner's theory regarding superstition being the nature of the pigeons' behaviour has been challenged by other psychologists such as Staddon and Simmelhag, who theorised an alternative explanation for the pigeons' behaviour.[26] Despite challenges to Skinner's interpretation of the root of his pigeons' superstitious behaviour, his conception of the reinforcement schedule has been used to explain superstitious behaviour in humans. Originally, in Skinner's animal research, "some pigeons responded up to 10,000 times without reinforcement when they had originally been conditioned on an intermittent reinforcement basis."[27] Compared to the other reinforcement schedules (e.g., fixed ratio, fixed interval), these behaviours were also the most resistant to extinction.[27] This is called the partial reinforcement effect, and this has been used to explain superstitious behaviour in humans. To be more precise, this effect means that, whenever an individual performs an action expecting a reinforcement, and none seems forthcoming, it actually creates a sense of persistence within the individual.[28] Evolutionary/cognitive perspective From a simpler perspective, natural selection will tend to reinforce a tendency to generate weak associations or heuristics that are overgeneralized. If there is a strong survival advantage to making correct associations, then this will outweigh the negatives of making many incorrect, "superstitious" associations.[29] It has also been argued that there may be connections between OCD and superstition.[30] It is stated that superstition is at the end of the day long-held beliefs that are rooted in coincidence and/or cultural tradition rather than logic and facts.[31] OCD that involves superstition is often referred to as "Magical Thinking" [32] People with this kind of manifestation of OCD believe that if they do not follow through with a certain compulsion, then something bad will happen to either themselves or others. Superstitious OCD, while can appear in anyone with OCD, more often appears in people with a religious background or with people who grew up in a culture that believes in magic and perform rituals.[33] Like stated before in the article above, superstition and prophecies are sometimes linked together. People with religious or superstitious OCD may have compulsions and perform rituals or behaviors in order to fulfill or get closer to fulfilling a prophecy.[34][35] Those with "magical thinking" OCD may realize that doing an action will not actually 'save' someone, but the fear that if they do not perform a certain behavior someone could get hurt is so overwhelming that they do it just to be sure. People with superstitious OCD will go out of their way to avoid something deemed 'unlucky'. Such as the 13th floor of a building, the 13th room, certain numbers or colors, because if they do not they believe something horrible may happen. Though superstitious OCD may work in reverse where one will always wear a certain item of clothing or jewelry or carry a certain item like a bag because it brings them 'luck' and allow good things to happen.[32] A recent theory by Jane Risen proposes that superstitions are intuitions that people acknowledge to be wrong, but acquiesce to rather than correct when they arise as the intuitive assessment of a situation. Her theory draws on dual-process models of reasoning. In this view, superstitions are the output of "System 1" reasoning that are not corrected even when caught by "System 2".[4] Mechanisms People seem to believe that superstitions influence events by changing the likelihood of currently possible outcomes rather than by creating new possible outcomes. In sporting events, for example, a lucky ritual or object is thought to increase the chance that an athlete will perform at the peak of their ability, rather than increasing their overall ability at that sport.[36] Psychologist Stuart Vyse has pointed out that until about 2010, "[m]ost researchers assumed superstitions were irrational and focused their attentions on discovering why people were superstitious." Vyse went on to describe studies that looked at the relationship between performance and superstitious rituals. Preliminary work has indicated that such rituals can reduce stress and thereby improve performance, but, Vyse has said, "...not because they are superstitious but because they are rituals.... So there is no real magic, but there is a bit of calming magic in performing a ritualistic sequence before attempting a high-pressure activity.... Any old ritual will do."[37][38] Occurrence People tend to attribute events to supernatural causes (in psychological terms, "external causes") most often under two circumstances. People are more likely to attribute an event to a superstitious cause if it is unlikely than if it is likely. In other words, the more surprising the event, the more likely it is to evoke a supernatural explanation. This is believed to stem from an effectance motivation – a basic desire to exert control over one's environment. When no natural cause can explain a situation, attributing an event to a superstitious cause may give people some sense of control and ability to predict what will happen in their environment.[39] People are more likely to attribute an event to a superstitious cause if it is negative than positive. This is called negative agency bias.[40] Boston Red Sox fans, for instance, attributed the failure of their team to win the world series for 86 years to the curse of the Bambino: a curse placed on the team for trading Babe Ruth to the New York Yankees so that the team owner could fund a Broadway musical. When the Red Sox finally won the world series in 2004, however, the team's success was attributed to the team's skill and the rebuilding effort of the new owner and general manager. More commonly, people are more likely to perceive their computer to act according to its own intentions when it malfunctions than functions properly.[39] Consumer behavior According to consumer behavior analytics of John C. Mowen et al., superstitions are employed as a heuristic tool hence those influence a variety of consumer behaviors.[41][11] John C. Mowen et al. says, after taking into account for a set of antecedents, trait superstitions are predictive of a wide variety of consumer beliefs, like beliefs in astrology or in common negative superstitions (e.g., fear of black cats). A general proneness to be superstitious leads to enduring temperament to gamble, participation in promotional games, investments in stocks, forwarding of superstitious e‐mails, keeping good‐luck charms, and exhibit sport fanship etc.[41][11] Additionally it has been estimated that between $700 million and $800 million are lost every Friday the 13th because of people's refusal to travel, purchase major items or conduct business.[42] |

迷信と心理学 主な記事 魔法的思考、プラシーボ、効果理論 起源 行動主義の視点 1948年、行動心理学者のB.F.スキナーは『実験心理学雑誌』に論文を発表し、その中で迷信と思われる行動を示すハトについて述べた。あるハトはケー ジの中で寝返りを打ち、別のハトは頭を振り子のように振り、他のハトも様々な行動を見せた。これらの行動はすべて、ディスペンサーから餌を受け取ろうとし て儀式的に行われたものであり、ディスペンサーはハトの行動に関係なく、決められた時間間隔で餌を放出するようにすでにプログラムされていたにもかかわら ず、スキナーは、ハトがこれらの行動を行うことで、給餌スケジュールに影響を与えようとしていると考えた。そして、彼はこれを人間の迷信的行動の性質に関 する命題として拡張した[25]。 迷信がハトの行動の本質であるというスキナーの理論は、ハトの行動の代替的な説明を理論化したスタドンやジンメルハーグなどの他の心理学者によって異議を 唱えられた[26]。 ハトの迷信的行動の根源に関するスキナーの解釈への挑戦にもかか わらず、強化スケジュールに関するスキナーの概念は人間の迷信的 行動を説明するために使用されてきた。もともとスキナーの動物実験では、「いくつかのハトは、もともと間欠的強化ベースで条件付けされていたときに、強化 なしで10,000回まで反応した」[27]。他の強化スケジュール(例えば、固定比率、固定間隔)と比較して、これらの行動はまた、絶滅に対して最も抵 抗性であった[27]。これは部分強化効果と呼ばれ、これは人間の迷信行動を説明するために使用されてきた。より正確には、この効果は、個体が強化される ことを期待 して行動を行ったが、強化されないと思われるときはいつも、個 人の中に持続的な感覚が生じることを意味する[28]。 進化的/認知的観点 より単純な観点では、自然淘汰は過度に一般化された弱い連想やヒューリスティクスを生み出す傾向を強化する傾向がある。また、OCDと迷信[30]の間に はつながりがあるかもしれないと主張されてい る。迷信とは結局のところ、論理や事実よりもむしろ偶然の一致や文化的 伝承に根ざした長い間信じられてきた信念であると述べられている[31]。 迷信を伴うOCDは、しばしば 「マジカルシンキング 」と呼ばれる[32]。迷信的なOCDは、OCDを持つ全ての人に見られるが、宗教的な背景を持つ人や、 魔法を信じ儀式を行う文化の中で育った人に見られることが多い[33]。宗教的または迷信的なOCDを持つ人々は、予言を成就するため、または成就に近 づくために強迫観念を持ち、儀式や行動を行うことがある[34][35]。「魔術的思考」OCDを持つ人々は、ある行動を行うことが実際に誰かを 「救う」ことにはならないと気づいていても、ある行動を行わなければ誰かが傷つくかもしれ ないという恐怖に圧倒され、念のためにそれを行うことがある。迷信的なOCDを持つ人は、「不運」とみなされるものを避けるためにわざわざ行動する。例え ば、ビルの13階、13番目の部屋、特定の数字や色などである。迷信的な強迫性障害は、「幸運」をもたらし、良いことが起こるようにするため に、いつも特定の服や宝石を身につけたり、バッグのような特定のものを持ったり するという逆の働きをすることもあるが[32]。 ジェーン・リゼンによる最近の理論では、迷信とは、人々が間違っていることを認めながらも、状況に対する直感的な評価として生じたときに、それを修正する のではなく、むしろ受け入れてしまう直感であると提唱している。彼女の理論は、推論の二重過程モデルに基づいている。この見解では、迷信は「システム1」 の推論のアウトプットであり、「システム2」によって捉えられても修正されることはない[4]。 メカニズム 人々は、迷信は新たな可能性のある結果を生み出すのではなく、現在起こりうる結果の可能性を変化させることによって出来事に影響を与えると信じているよう である。例えば、スポーツ競技では、幸運をもたらす儀式や物体は、そのスポーツの全体的な能力を高めるというよりも、選手がその能力を最大限に発揮する可 能性を高めると考えられている[36]。 心理学者のStuart Vyseは、2010年頃まで「ほとんどの研究者は迷信は非合理的であると仮定し、人々がなぜ迷信を抱くのかを発見することに注意を向けていた」と指摘し ている。さらにバイスは、パフォーマティビティと迷信的儀式の関係を調べた研究について述べた。パフォーマティビティによれば、儀式はストレスを軽減し、 それによってパフォーマンスを向上させるが、ヴィースは次のように述べている。だから、本当の魔法はないが、プレッシャーのかかる活動を試みる前に儀式的 な一連の流れを行うことで、少しは心を落ち着かせる魔法がある......。どんな古い儀式でも構わない」[37][38]。 発生 人は2つの状況下で、出来事を超自然的な原因(心理学用語では「外的原因」)に帰する傾向が最も強い。 ある出来事がありそうなものである場合よりも、ありそうもないものである場合の方が、人は迷信的な原因に帰する可能性が高い。言い換えれば、その出来事が 意外であればあるほど、超自然的な説明を喚起する可能性が高くなる。これはエフェクタンス(効果)動機、つまり自分の環境をコントロールしたいという基本 的な欲求に由来すると考えられている。自然的な原因では状況を説明できない場合、ある出来事を迷信的な原因に帰することで、人々は自分の環境で何が起こる かを予測し、コントロールできるという感覚を得ることができる[39]。 ある出来事が肯定的なものよりも否定的なものの方が、人々は迷信的な原因に帰する可能性が高い。例えば、ボストン・レッドソックスのファン は、チームが86年間ワールドシリーズで優勝できなかったのは、チーム オーナーがブロードウェイ・ミュージカルに資金を提供するために、ベーブ・ルースを ニューヨーク・ヤンキースにトレードしたことでチームにかけられた呪い「バンビー ノの呪い」のせいだと考えていた。しかし、2004年にレッドソックスがついにワールドシリーズを制したとき、その成功はチームの手腕と新オーナーとゼネ ラル・マネージャーの再建努力の賜物だとされた。より一般的には、人々はコンピュータが適切に機能するよりも、誤動作したときに、コンピュータが自身の意 図に従って行動していると認識する傾向が強い[39]。 消費者行動 ジョン・C・モーウェンらの消費者行動分析学によると、迷信は発見的ツールとして使用され、それゆえそれらは様々な消費者行動に影響を与える。迷信的であ る一般的な傾向は、ギャンブル、販促ゲームへの 参加、株式投資、迷信的な電子メールの転送、お守りの保管、スポー ツファンであることなどの持久的な気質につながる[41][11]。さらに、人々が旅行、 主要な商品の購入、ビジネスを拒否するために、毎年13日の金曜日に 7億ドルから8億ドルの損失が発生していると推定されている[42]。 |

| Superstition and politics Ancient Greek historian Polybius in his Histories uses the word superstition explaining that in ancient Rome that belief maintained the cohesion of the empire, operating as an instrumentum regni.[43] |

迷信と政治 古代ギリシアの歴史家ポリビウスは『歴史』の中で迷信という言葉を使い、古代ローマではその信仰が帝国の結束を維持し、体制維持の道具として機能していた と説明している[43]。 |

| Opposition to superstition See also: Magical thinking In the classical era, the existence of gods was actively debated both among philosophers and theologians, and opposition to superstition arose consequently. The poem De rerum natura, written by the Roman poet and philosopher Lucretius further developed the opposition to superstition. Cicero's work De natura deorum also had a great influence on the development of the modern concept of superstition as well as the word itself. Where Cicero distinguished superstitio and religio, Lucretius used only the word religio. Cicero, for whom superstitio meant "excessive fear of the gods" wrote that "superstitio, non religio, tollenda est ", which means that only superstition, and not religion, should be abolished. The Roman Empire also made laws condemning those who excited excessive religious fear in others.[44] During the Middle Ages, the idea of God's influence on the world's events went mostly undisputed. Trials by ordeal were quite frequent, even though Frederick II (1194 – 1250 AD) was the first king who explicitly outlawed trials by ordeal as they were considered "irrational".[45] The rediscovery of lost classical works (The Renaissance) and scientific advancement led to a steadily increasing disbelief in superstition. A new, more rationalistic lens was beginning to see use in exegesis. Opposition to superstition was central to the Age of Enlightenment. The first philosopher who dared to criticize superstition publicly and in a written form was Baruch Spinoza, who was a key figure in the Age of Enlightenment.[46] |

迷信への反対 こちらも参照のこと: 魔術的思考 古典時代、神々の存在は哲学者や神学者の間で活発に議論され、その結果、迷信に対する反対論が生まれた。ローマの詩人であり哲学者でもあったルクレティウ スが書いた詩『De rerum natura』は、迷信への反対をさらに発展させた。キケロの著作『De natura deorum』も、迷信という言葉そのものだけでなく、近代的な迷信の概念の発展にも大きな影響を与えた。キケロがsuperstitioと religioを区別したのに対し、ルクレティウスはreligioという言葉だけを使った。キケロは、superstitioは「神々への過剰な恐れ」 を意味し、「superstitio, non religio, tollenda est」、つまり宗教ではなく迷信のみを廃絶すべきであると書いた。ローマ帝国はまた、他人の過剰な宗教的恐怖心を煽る者を非難する法律を作った [44]。 中世には、神が世界の出来事に影響を与えるという考え方は、ほとんど議論の余地がなかった。フリードリヒ2世(西暦1194年~1250年)は、試練によ る裁判が「不合理」であるとして明確に禁止した最初の王であったが、試練による裁判はかなり頻繁に行われていた[45]。 失われた古典作品の再発見(ルネサンス)と科学の進歩は、迷信への不信を着実に増大させた。新しい、より合理主義的なレンズが釈義に使われ始めた。迷信に 対する反対は、啓蒙時代の中心的なものであった。迷信をあえて公的に、また文書という形で批判した最初の哲学者はバルーク・スピノザであり、彼は啓蒙時代 の重要人物であった[46]。 |

| Regional and national

superstitions Most superstitions arose over the course of centuries and are rooted in regional and historical circumstances, such as religious beliefs or the natural environment. For instance, geckos are believed to be of medicinal value in many Asian countries, including China.[47] In China, Feng shui is a belief system that different places have negative effects, e.g. that a room in the northwest corner of a house is "very bad".[48] Similarly, the number 8 is a "lucky number" in China, so that it is more common than any other number in the Chinese housing market.[48] Animals There are many different animals around the world that have been tied to superstitions. People in the West are familiar with the omen of a black cat crossing one's path. Locomotive engineers believe a hare crossing one's path is bad luck.[49] According to the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) the giant anteater (Myrmecophaga tridactyla) is targeted by motorists in regions of Brazil who do not want the creature to cross in front of them and give them bad luck.[50] Numbers Certain numbers hold significance for particular cultures and communities. It is common for buildings to omit certain floors on their elevator panels and there are specific terms for people with severe aversions to specific numbers.[51] Triskaidekaphobia, for example, is the fear of the number 13.[52] Similarly, a common practice in East Asian nations is avoiding instances of the digit 4. It represents or can be translated as death or die. This is known as tetraphobia (from Ancient Greek τετράς (tetrás) 'four' and Ancient Greek φόβος (phóbos) 'fear'). A widespread superstition is fear of the number 666, given as the number of the beast in the biblical Book of Revelation. This fear is called hexakosioihexekontahexaphobia. Objects There are many objects tied to superstitions. During the Great Depression, it was common for people to carry a rabbit's foot around with them.[53] During the Coronavirus epidemic, people in parts of Indonesia made tetek melek, a traditional homemade mask made of coconut palm fronds, which was hung in doorways to keep occupants safe.[citation needed] According to superstitions, breaking a mirror is said to bring seven years of bad luck.[54] From ancient Rome to Northern India, mirrors have been handled with care, or sometimes avoided all together.[53] Horseshoes have long been considered lucky. Opinion is divided as to which way up the horseshoe ought to be nailed. Some say the ends should point up, so that the horseshoe catches the luck, and that the ends pointing down allow the good luck to be lost; others say they should point down, so that the luck is poured upon those entering the home. Superstitious sailors believe that nailing a horseshoe to the mast will help their vessel avoid storms.[55] In China, yarrow and tortoiseshell are considered lucky and brooms have a number of superstitions attached to them. It is considered bad luck to use a broom within three days of the new year as this will sweep away good luck.[56] Actions Common actions in the West include not walking under a ladder, touching wood, throwing salt over one's shoulder, or not opening an umbrella inside. In China wearing certain colours is believed to bring luck.[56] "Break a leg" is a typical English idiom used in the context of theatre or other performing arts to wish a performer "good luck". An ironic or non-literal saying of uncertain origin (a dead metaphor), "break a leg" is commonly said to actors and musicians before they go on stage to perform or before an audition. In English (though it may originate in German), the expression was likely first used in this context in the United States in the 1930s or possibly 1920s,[57] originally documented without specifically theatrical associations. Among professional dancers, the traditional saying is not "break a leg", but the French word "merde".[58] Some superstitious actions have practical origins. Opening an umbrella inside in eighteenth-century London was a physical hazard, as umbrellas then were metal-spoked, clumsy spring mechanisms and a "veritable hazard to open indoors."[59] Another superstition with practical origins is the action of blowing briefly left and right before crossing rail tracks for safe travels as the person engaging in the action looks both ways.[60] |

地域や国民の迷信 ほとんどの迷信は、何世紀にもわたって発生し、宗教的信念や自然環境など、地域的・歴史的状況に根ざしている。例えば、ヤモリは中国を含む多くのアジア諸 国で薬効があると信じられている[47]。 中国では、風水は場所によって悪影響があるとする信仰体系であり、例えば家の北西の角にある部屋は「非常に悪い」とされている[48]。同様に、中国では 数字の8は「ラッキーナンバー」であり、中国の住宅市場では他のどの数字よりも一般的である[48]。 動物 世界には迷信と結びついたさまざまな動物がいる。西洋の人々は、黒猫が道を横切るという前兆に精通している。国際自然保護連合(IUCN)によると、オオ アリクイ(Myrmecophaga tridactyla)は、ブラジルの地域で、この生き物が自分の前を横切り、不運をもたらすことを望まない自動車運転手によって標的にされている [50]。 数字 特定の数字は、特定の文化やコミュニティにとって重要な意味を持つ。例えば、トリスカイデカフォビアは、数字の13を恐れることである[52]。同様に、 東アジアの国民によく見られるのは、数字の4を避けることである。これは「死」を表す、あるいは「死ね」と訳される。これは四恐怖症(古代ギリシア語の τετράς(tetrás)「4」と古代ギリシア語のφόβος(phóbos)「恐怖」から)として知られている。広く浸透している迷信は、聖書のヨ ハネの黙示録で獣の数字として挙げられている666という数字に対する恐怖である。この恐怖はヘキサコシオイヘキセコンタヘキサフォビアと呼ばれる。 オブジェクト 迷信と結びついた物は数多くある。大恐慌の時代、人々はウサギの足を持ち歩くのが一般的だった[53]。コロナウイルスが流行したとき、インドネシアの一 部の人々はテテク・メレク(ココヤシの葉で作った伝統的な手作りのマスク)を作り、住人の安全を守るために玄関に吊るした[要出典]。 迷信によれば、鏡を割ると7年間の不運が訪れると言われている[54]。古代ローマから北インドに至るまで、鏡の扱いには注意が払われ、時には避けること もあった[53]。 蹄鉄は長い間縁起が良いとされてきた。蹄鉄の釘の向きについては意見が分かれる。ある人は、蹄鉄が幸運を受け止めるように端を上に向けるべきであり、端を 下に向けると幸運が失われると言う。また、家に入る人に幸運が降り注ぐように端を下に向けるべきだと言う人もいる。迷信深い船乗りは、蹄鉄をマストに打ち 付けると船が嵐を避けられると信じている[55]。 中国では、ヤロウとべっ甲は縁起が良いとされ、ほうきには多くの迷信がある。新年から3日以内に箒を使うのは不吉とされ、幸運を一掃してしまうからである [56]。 行動 西洋では、はしごの下を通らない、木に触らない、塩を肩にかける、傘をささないなどの行為が一般的である。中国では、特定の色を身につけることが幸運をも たらすと信じられている[56]。 「Break a leg」は、演劇やその他のパフォーミング・アーツの文脈で、パフォーマーの「幸運」を祈るために使われる典型的な英語の慣用句である。起源が不確かな皮 肉や非文字通りのことわざ(死語の比喩)である 「break a leg 」は、俳優やミュージシャンが舞台に上がって演技をする前やオーディションの前によく言われる。英語では(ドイツ語が起源かもしれないが)、この表現は 1930年代かおそらく1920年代のアメリカでこの文脈で初めて使われたと思われ[57]、もともとは特に演劇的な連想なしに記録されていた。プロのダ ンサーの間では、伝統的な言い方は「足を折る」ではなく、フランス語の「merde」である[58]。 迷信的な行為の中には実用的な起源を持つものもある。18世紀のロンドンでは、室内で傘を開くことは物理的な危険を伴うものであった。当時の傘は金属製の 棘のある、不器用なバネ仕掛けであり、「室内で傘を開くことはまさに危険」であったからだ[59]。 実用的な起源を持つもう一つの迷信は、安全な移動のために線路を渡る前に左右の方向を見て短く息を吹くという行為である[60]。 |

| Superstition in Britain Anthropology – Scientific study of humans, human behavior, and societies Curse – Supernatural hindrance, or incantation intended to bestow such a hindrance Elite religion – Form of a religion the leaders deem official Exorcism – Evicting spiritual entities from a person or area Faith – Confidence or trust in a person, thing, or concept Fatalism – Family of philosophical doctrines Folklore – Expressive culture shared by particular groups God of the gaps – Theological argument Heritage science – Cross-disciplinary scientific research of cultural heritage Heritage studies – Academic discipline concerned with cultural heritage James Randi – Canadian-American magician and skeptic (1928–2020) Kuai Kuai culture – Modern Taiwanese custom Lived religion – Religion as practiced in everyday life Occult – Knowledge of the hidden or the paranormal Paranormal – Purported phenomena beyond the scope of normal scientific understanding Precognition – Paranormal sight of the future Pseudoscience – Unscientific claims wrongly presented as scientific Relationship between religion and science Sacred mysteries – Inexplicable or secret religious phenomena Synchronicity – Jungian concept of the meaningfulness of acausal coincidences Tradition – Long-existing custom or belief Urban legend – Form of modern folklore |

イギリスの迷信 人類学 - 人間、人間の行動、社会について科学的に研究すること。 呪い - 超自然的な障害、またはそのような障害を与えることを意図した呪文。 エリート宗教 - 指導者が公式とみなす宗教の形態。 悪魔祓い - 人や地域から霊的存在を追い出すこと。 信仰 - 人、物、概念に対する自信や信頼。 運命論 - 哲学的教義のファミリー フォークロア - 特定の集団が共有する表現文化 隙間の神 - 神学的議論 遺産科学 - 文化遺産の学際的科学研究 遺産学 - 文化遺産に関する学問分野 ジェームズ・ランディ - カナダ系アメリカ人のマジシャン、懐疑論者(1928年~2020年) クァイクァイ文化 - 近代台湾の風習 生活宗教 - 日常生活で実践される宗教 オカルト - 隠されたものや超常現象の知識 超常現象 - 通常の科学的理解の範囲を超えているとされる現象 予知 - 超常的な未来予知 疑似科学 - 非科学的な主張を科学的であるかのように見せかけたもの。 宗教と科学の関係 聖なる神秘 - 不可解な、あるいは秘密の宗教現象 シンクロニシティ(共時性) - ユングの概念で、非合理的な偶然の一致の意味性。 伝統 - 長く続く習慣や信仰 都市伝説 - 近代の民間伝承の一種 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superstition |

|

| Very superstitious Writing's on the wall Very superstitious Ladder's 'bout to fall Thirteen month old baby Broke the looking glass Seven years of bad luck The good things in your past Ooh, very superstitious Wash your face and hands Rid me of the problem Do all that you can Keep me in a daydream Keep me going strong You don't want to save me Sad is my song https://genius.com/Stevie-wonder-superstition-lyrics |

非常に迷信深い 壁に書いてある とても迷信深い はしごが落ちる 生後13ヶ月の赤ちゃん ルッキンググラスを割った 7年間の不運 過去に良いことがあった おお、とても迷信深い 顔と手を洗う 問題を取り除く できる限りのことをする 白昼夢を見続ける 私を強く保つ あなたは私を救おうとしない 悲しいのは僕の歌だ |

★エビデンスを嫌う人たち : 科学否定論者は何を考え、どう説得できるのか? / リー・マッキンタイア著 ; 西尾義人訳, 国書刊行会 , 2024

内

容説明

政 治の世界にまで影響を及ぼす科学否定、その拡大を止める反撃の提言。地球平面説、気候変動否定、コロナ否定、反ワクチン、反GMO、そして陰謀論―彼らは なぜ科学的証拠から目を背け、荒唐無稽な物語を信じてしまうのか?異端の科学哲学者が陰謀論の国際会議に潜入し、科学否定論者を直接取材。最新科学の成果 も交えて彼らの本心をさぐり、現代に蔓延する科学否定/事実否定に立ち向かう戦略を考える。

目

次

第 1章 潜入、フラットアース国際会議

第 2章 科学否定とはなにか?

第 3章 どうすれば相手の意見を変えられるのか?

第 4章 気候変動を否定する人たち

第 5章 炭鉱のカナリヤ

第 6章 リベラルによる科学否定?

第 7章 信頼と対話

第

8章 新型コロナウイルスと私たちのこれから

★Stevie

Wonder Superstition https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Superstition_(song)

Stevie

Wonder Superstition

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆