経済人類学

Economic

Anthropology

経済人類学(economic anthropology)とは、歴史的・地理的・文化的観点をもちつつ人間の「経済的」行動を説明する人類学の学問分野のひとつである。

近代文化人類学の歴史の中で、これらの一連の「経済 的」な行動やテーマを発掘したのは、ブロニスラウ・マリノフスキーのクラ交換や、それをもと に、人間における経済と社会の普遍的結びつきを理論的に説明したマルセル・モースの 互酬性の研究を嚆矢とする、ことが一般的である。

しかし、その前の19世紀には、進化主義人類学者や

マルクス主義者たちが、所有関係(property

relations)[原始共産制]や生産様式[資本主義]、価値[使用価値/交換価値]、[経済]交換などの経済理論における基礎的な議論を開始してい

た(エンゲルス )。進化主義的人類学者に言わせると、物の所有関係の発達は、親族のあり方に規定されることと無関係ではない。生産手段の独占(私的

占有)と資本主義的生産様式には深い関係にあるという、議論を開始するであろう。

以下は、ウィキペディアの経済人類学(economic anthropology)の解説に準拠しながら解説する。

| Economic

anthropology

is a field that attempts to explain human economic behavior in its

widest historic, geographic and cultural scope. It is an amalgamation

of economics and anthropology. It is practiced by anthropologists and

has a complex relationship with the discipline of economics, of which

it is highly critical.[1] Its origins as a sub-field of anthropology

began with work by the Polish founder of anthropology Bronislaw

Malinowski and the French Marcel Mauss on the nature of reciprocity as

an alternative to market exchange. For the most part, studies in

economic anthropology focus on exchange. Post-World War II, economic anthropology was highly influenced by the work of economic historian Karl Polanyi. Polanyi drew on anthropological studies to argue that true market exchange was limited to a restricted number of western, industrial societies. Applying formal economic theory (Formalism) to non-industrial societies was mistaken, he argued. In non-industrial societies, exchange was "embedded" in such non-market institutions as kinship, religion, and politics (an idea he borrowed from Mauss). He labelled this approach Substantivism. The formalist–substantivist debate was highly influential and defined an era.[2] As globalization became a reality, and the division between market and non-market economies – between "the West and the Rest"[3] – became untenable, anthropologists began to look at the relationship between a variety of types of exchange within market societies. Neo-substantivists examine the ways in which so-called pure market exchange in market societies fails to fit market ideology. Economic anthropologists have abandoned the primitivist niche they were relegated to by economists. They now study the operations of corporations, banks, and the global financial system from an anthropological perspective. |

経済人類学は、人間の経済行動を歴史的、地理的、文化的に最も広い範囲

で説明しようとする分野である。経済学と人類学の融合である。人類学のサブフィールドとしての起源は、ポーランドの人類学の創始者であるブロニスワフ・マ

リノフスキーとフランスのマルセル・モースによる、市場交換に代わるものとしての互酬性の本質に関する研究から始まった。ほとんどの場合、経済人類学の研

究は交換に焦点を当てている。 第二次世界大戦後、経済人類学は経済史家カール・ポランニーの研究に大きな影響を受けた。ポランニーは人類学的研究をもとに、真の市場交換は西洋の限られ た産業社会に限られていると主張した。形式的な経済理論(形式主義)を非工業化社会に適用するのは誤りであると彼は主張した。非工業社会では、交換は親族 関係、宗教、政治といった非市場的制度に「埋め込まれている」のである(この考えはモースから借用したものである)。彼はこのアプローチを「実体主義」と 名付けた。形式主義者と実質主義者の論争は大きな影響力を持ち、一時代を築いた[2]。 グローバリゼーションが現実のものとなり、市場経済と非市場経済の区分、つまり「西洋とそれ以外」[3]の区分が成り立たなくなると、人類学者は市場社会 における様々な種類の交換の関係に注目し始めた。新実体主義者たちは、市場社会におけるいわゆる純粋な市場交換が市場イデオロギーに適合しない点を検証し ている。経済人類学者は、経済学者によって追いやられた原始主義的なニッチを捨てた。彼らは現在、企業、銀行、グローバル金融システムの運営を人類学的観 点から研究している。 |

Reciprocity and the gift Bronislaw Malinowski, anthropologist at the London School of Economics  A Kula bracelet from the Trobriand Islands.  Malinowski and Mauss: Debate over the Kula exchange Bronislaw Malinowski's groundbreaking work, Argonauts of the Western Pacific (1922), posits the question, "why would men risk life and limb to travel across huge expanses of dangerous ocean to give away what appear to be worthless trinkets?" Carefully traced the network of exchanges of bracelets and necklaces across the Trobriand Islands, Malinowski established that they were part of a system of exchange, the Kula ring. He stated that this exchange system was clearly linked to political authority.[4] In the 1920s and later, Malinowski's research became the subject of debate with the French anthropologist, Marcel Mauss, author of The Gift (Essai sur le don, 1925).[5] Contrasting Mauss, Malinowski emphasised the exchange of goods between individuals, and their non-altruistic motives for giving: they expected a return of equal or greater value. In other words, reciprocity is an implicit part of gifting; no "free gift" is given without expectation of reciprocity. Mauss, however, posited that the gifts were not merely between individuals, but between representatives of larger collectivities. These gifts were, he argued, a "total prestation." They were not simple, alienable commodities to be bought and sold, but, like the Crown jewels, embodied the reputation, history, and identity of a "corporate kin group". Given the stakes, Mauss asked, "Why anyone would give them away?" His answer was an enigmatic concept, hau, "the spirit of the gift." Largely, the confusion (and resulting debate) was due to a bad translation. Mauss appeared to be arguing that a return gift is given to keep the very relationship between givers alive; a failure to return a gift ends the relationship and the promise of any future gifts. Based on an improved translation, Jonathan Parry has demonstrated that Mauss was arguing that the concept of a "pure gift" given altruistically only emerges in societies with a well-developed market ideology.[4] Mauss' concept of "total prestations" has been developed in the later 20th century by Annette Weiner, who revisited Malinowski's fieldsite in the Trobriand Islands. Publishing in 1992, her critique was twofold: Weiner first noted that Trobriand Island society has a matrilineal kinship system. As a consequence, women hold a great deal of economic and political power, as inheritance is passed from mother to daughter through the female lines. Malinowski missed this insight in his 1922 work, ignoring women's exchanges in his research. Secondly, Weiner further developed Mauss' argument about reciprocity and the "spirit of the gift" in terms of inalienable possessions: "the paradox of keeping while giving."[6] Weiner contrasted "moveable goods," which can be exchanged, with "immoveable goods," which serve to draw the gifts back. In the context of the Trobriand study, male Kula gifts were moveable gifts compared to those of women's landed property. She argued that the specific goods given, such as Crown Jewels, are so identified with particular groups that, even when given they are not truly alienated. Not all societies, however, have these kinds of goods, which depend upon the existence of particular kinds of kinship groups. French anthropologist Maurice Godelier[7] pushed the analysis further in The Enigma of the Gift (1999).[8] Albert Schrauwers has argued that the kinds of societies used as examples by Weiner and Godelier, such as the Kula ring in the Trobriands, the Potlatch of the Indigenous peoples of the Pacific Northwest Coast, or the Toraja of South Sulawesi, Indonesia, are all characterized by ranked aristocratic kin groups that fit with Claude Lévi-Strauss' model of "House Societies" where "House" refers to both noble lineage and their landed estate. Total prestations are given, he argues, to preserve landed estates identified with particular kin groups and maintain their place in a ranked society.[8]  Three tongkonan noble houses in a Torajan village. Gifts and commodities Main article: Moka exchange The misunderstanding about what Mauss meant by "the spirit of the gift" led some anthropologists to contrast "gift economies" with "market economies," presenting them as polar opposites and implying that non-market exchange was always altruistic. Marshall Sahlins, a well-known American cultural anthropologist, identified three main types of reciprocity in his book Stone Age Economics (1972).[9] Gift or generalized reciprocity is the exchange of goods and services without keeping track of their exact value, but often with the expectation that their value will balance out over time. Balanced or Symmetrical reciprocity occurs when someone gives to someone else, expecting a fair and tangible return - at a specified amount, time, and place. Market or Negative reciprocity is the exchange of goods and services whereby each party intends to profit from the exchange, often at the expense of the other. Gift economies, or generalized reciprocity, occur within closely knit kin groups, and the more distant the exchange partner, the more imbalanced or negative the exchange becomes. This opposition was classically expressed by Chris Gregory in his book "Gifts and Commodities" (1982). Gregory argued that Commodity exchange is an exchange of alienable objects between people who are in a state of reciprocal independence that establishes a quantitative relationship between the objects exchanged… Gift exchange is an exchange of inalienable objects between people who are in a state of reciprocal dependence that establishes a qualitative relationship between the transactors" (emphasis added.)[10] Commodity exchange Gift exchange immediate exchange delayed exchange alienable goods inalienable goods actors independent actors dependent quantitative relationship qualitative relationship between objects between people Other anthropologists, however, refused to see these different "exchange spheres" as polar opposites. Marilyn Strathern, writing on a similar area in Papua New Guinea, dismissed the utility of the opposition in The Gender of the Gift (1988).[11] Spheres of exchange Main article: Spheres of exchange The relationship of new market exchange systems to indigenous non-market exchange remained a perplexing question for anthropologists. Paul Bohannan (see below, under substantivism) argued that the Tiv of Nigeria had three spheres of exchange, and that only certain kinds of goods could be exchanged in each sphere; each sphere had its own different form of money.[12] Similarly, Clifford Geertz's model of "dual economy" in Indonesia,[13] and James C. Scott's model of "moral economy"[14] hypothesized different exchange spheres emerging in societies newly integrated into the market; both hypothesized a continuing culturally ordered "traditional" exchange sphere resistant to the market. Geertz used the sphere to explain peasant complacency in the face of exploitation, and Scott to explain peasant rebellion. This idea was taken up lastly by Jonathan Parry and Maurice Bloch, who argued in Money and the Morality of Exchange (1989) that the "transactional order" through which long-term social reproduction of the family takes place has to be preserved as separate from short-term market relations.[15] Charity: "the poison of the gift"  The Sharon Temple, Sharon, Ontario circa 1860. In his classic summation of the gift exchange debate, Jonathan Parry highlighted that ideologies of the "pure gift" (as opposed to total prestations) "is most likely to arise in highly differentiated societies with an advanced division of labour and a significant commercial sector."[16] Schrauwers illustrated the same points in two different areas in the context of the "transition to capitalism debate" (see Political Economy). He documented the transformations among the To Pamona of Central Sulawesi, Indonesia, as they were incorporated in global market networks over the twentieth century. As their everyday production and consumption activities were increasingly commodified, they developed an oppositional gift (posintuwu) exchange system that funded social reproductive activities, thereby preserving larger kin, political and religious groups. This "pure gift" exchange network emerged from an earlier system of "total prestations."[17]  'Free gifts' of Posintuwu culminate in the exchange of bridewealth at a To Pamona wedding. Similarly, in analyzing the same "transition to capitalist debate" in early 19th century North America, Schrauwers documented how new, oppositional "moral economies" grew in parallel with the emergence of the market economy. As the market became increasingly institutionalized, so too did early utopian socialist experiments such as the Children of Peace, in Sharon, Ontario, Canada. They built an ornate temple dedicated to sacralizing the giving of charity; this was eventually institutionalized as a mutual credit organization, land sharing, and co-operative marketing. In both cases, Schrauwers emphasizes that these alternate exchange spheres are tightly integrated and mutualistic with markets as commodities move in and out of each circuit.[18] Parry had also underscored, using the example of charitable giving of alms in India (Dāna), that the "pure gift" of alms given with no expectation of return could be "poisonous." That is, the gift of alms embodying the sins of the giver, when given to ritually pure priests, saddled these priests with impurities that they could not cleanse themselves of. "Pure gifts" given without a return, can place recipients in debt, and hence in dependent status: the poison of the gift.[19] Although the Children of Peace tried to sacralize the pure giving of alms, they found charity created difficulties for recipients. It highlighted their near bankruptcy and hence opened them to lawsuits and indefinite imprisonment for debt. Rather than accept charity, the free gift, they opted for loans.[18] 'The social life of things' and singularization Main article: Commodity Pathway Diversion Rather than emphasize how particular kinds of objects are either gifts or commodities to be traded in restricted spheres of exchange, Arjun Appadurai and others began to look at how objects flowed between these spheres of exchange. They shifted attention away from the character of the human relationships formed through exchange, and placed it on "the social life of things" instead. They examined the strategies by which an object could be "singularized" (made unique, special, one-of-a-kind) and so withdrawn from the market. A marriage ceremony that transforms a purchased ring into an irreplaceable family heirloom is one example; the heirloom, in turn, makes a perfect gift. Singularization is the reverse of the seemingly irresistible process of commodification. These scholars show how all economies are a constant flow of material objects that enter and leave specific exchange spheres. A similar approach is taken by Nicholas Thomas, who examines the same range of cultures and the anthropologists who write about them, and redirects attention to the "entangled objects" and their roles as both gifts and commodities.[20] This emphasis on things has led to new explorations in "consumption studies" (see below). |

互恵性と贈与 ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキー、ロンドン・スクール・オブ・エコノミクスの人類学者  トロブリアンド諸島のクラ族のブレスレット。  マリノフスキーとモース クラの交換をめぐる論争 ブロニスワフ・マリノフスキーの画期的な著作『西太平洋のアルゴノーツ』(1922年)は、「なぜ人は命がけで危険な大海原を渡り、価値のない装身具に見 えるものを贈るのだろうか」という疑問を提起している。マリノフスキーは、トロブリアンド諸島におけるブレスレットやネックレスの交換ネットワークを丹念 に追跡し、それらがクラ・リングという交換システムの一部であることを立証した。彼は、この交換システムは明らかに政治的権威と結びついていたと述べてい る[4]。 1920年代以降、マリノフスキーの研究は、『贈与』(Essai sur le don、1925年)の著者であるフランスの人類学者マルセル・モースとの論争の対象となった[5]。言い換えれば、贈与には互恵性が暗黙のうちに含まれ ており、互恵性を期待せずに「無償の贈与」が行われることはない。 しかしモースは、贈与は単に個人間のものではなく、より大きな集団の代表者同士のものであるとした。これらの贈与は "総合的な贈与 "であると彼は主張した。贈与品は売買されるような単純な商品ではなく、王冠の宝石のように、「企業的親族集団」の名声、歴史、アイデンティティを体現し ていたのである。このような利害関係を踏まえて、モースは "なぜそれを手放す人がいるのか?"と問いかけた。彼の答えは、"贈与の精神 "という謎めいた概念だった。この混乱(そしてその結果生じた議論)は、翻訳がまずかったことが大きな原因だった。マウスの主張は、お返しは贈り主同士の 関係そのものを維持するために贈られるものであり、お返しに失敗すれば、その関係も将来の贈り物の約束も終わってしまうというものだった。ジョナサン・パ リーは、改善された翻訳に基づいて、モースが主張していたのは、利他的に与えられる「純粋贈与」の概念は、市場イデオロギーが発達した社会でのみ出現する ということであることを実証した[4]。 トロブリアンド諸島でマリノフスキーのフィールドを再訪したアネット・ワイナーによって、20世紀後半にモースの「総プレステーション」の概念が発展し た。1992年に発表された彼女の批評は2つあった: ワイナーはまず、トロブリアンド諸島の社会が母系血族制度であることを指摘した。その結果、相続は母から娘へと女性の血筋で受け継がれるため、女性が大き な経済的・政治的権力を握っている。マリノフスキーは1922年の著作でこの洞察を見逃しており、彼の研究では女性の交流は無視されていた。第二に、ワイ ナーはモースの互恵性と「贈与の精神」に関する議論を、不可分の所有物という観点からさらに発展させた: 「ワイナーは、交換可能な「動かせる財」と、贈与を引き戻す役割を果たす「動かせない財」とを対比させた。トロブリアンドの研究の文脈では、男性のクラの 贈与は、女性の土地財産の贈与に比べ、移動可能な贈与であった。彼女は、クラウン・ジュエルのような特定の贈与品は特定の集団と結びついているため、贈与 されても真に疎外されることはないと主張した。しかし、すべての社会がこのような財を持っているわけではなく、それは特定の種類の親族集団の存在に依存し ている。フランスの人類学者モーリス・ゴドリエ[7]は、『贈与の謎』(1999年)でこの分析をさらに推し進めた[8]。 アルバート・シュラウワースは、トロブリアンドのクラ・リング、太平洋岸北西部の先住民のポトラッチ、インドネシアの南スラウェシのトラジャ族など、ワイ ナーやゴドリエが例として用いた種類の社会はすべて、クロード・レヴィ=ストロースの「家社会」のモデルに適合するランク付けされた貴族の親族集団によっ て特徴づけられており、「家」とは貴族の血統とその土地の両方を指すと主張している。総体的な威信は、特定の親族集団と同一視される土地を維持し、ランク 社会における地位を維持するために与えられると、彼は主張している[8]。  トラジャンの村にある3つのトンコナン貴族の家。 贈与と商品 主な記事 真岡交換 モースの言う「贈与の精神」が何を意味するのかについての誤解から、人類学者の中には「贈与経済」と「市場経済」を対比させ、両者を正反対のものとして提 示し、非市場的交換は常に利他的であるとほのめかす者もいた。アメリカの著名な文化人類学者であるマーシャル・サーリンスは、その著書『石器時代の経済 学』(1972年)の中で、主に3つのタイプの互恵性を特定している[9]。贈与または一般化された互恵性とは、財やサービスの正確な価値を把握すること なく交換することであるが、多くの場合、時間の経過とともにその価値が均衡することを期待して交換される。均衡互恵性または対称互恵性は、誰かが他の誰か に、指定された金額、時間、場所において、公正で具体的な見返りを期待して与える場合に生じる。市場的互恵性または否定的互恵性とは、財やサービスの交換 で、各当事者が交換から利益を得ようとするものであり、多くの場合、他方の犠牲の上に成り立っている。贈与経済、あるいは一般化された互恵性は、密接に結 びついた親族集団の中で発生し、交換相手が遠ければ遠いほど、交換は不均衡に、あるいは否定的になる。 この対立は、クリス・グレゴリーの著書『贈与と商品』(1982年)で古典的に表現されている。グレゴリーは次のように主張した。 商品交換とは、相互に独立した状態にある人々の間で行われる疎外可能な物体の交換であり、交換される物体の間に量的な関係を確立するものである...贈与 交換とは、相互に依存した状態にある人々の間で行われる疎外可能な物体の交換であり、取引者の間に質的な関係を確立するものである」(強調)[10]。 商品交換〈対〉贈与交換 即時交換〈対〉遅延交換 疎外可能な財 〈対〉不可分の財 独立した行為者 〈対〉依存した行為者 量的関係 〈対〉質的関係 モノとモノの間 〈対〉人と人の間 しかし他の人類学者は、こうした異なる「交換圏」を正反対のものと見なすことを拒否した。マリリン・ストラザーンはパプアニューギニアの同様の地域につい て書いているが、『贈与のジェンダー』(1988年)の中で対立の有用性を否定している[11]。 交換の領域 主な記事 交換の領域 新しい市場交換システムと土着の非市場交換との関係は、人類学者にとって不可解な問題であり続けた。ポール・ボハナン(後述、実体主義の項を参照)はナイ ジェリアのティヴ族には3つの交換圏があり、それぞれの圏では特定の種類の商品のみが交換され、それぞれの圏には独自の異なる形態の貨幣が存在すると主張 していた[12]。スコットの「道徳的経済」のモデル[14]は、新たに市場に統合された社会に出現した異なる交換圏の仮説を立てた。ゲアーツはこの圏を 用いて搾取に直面する農民の自己満足を説明し、スコットは農民の反乱を説明した。この考えは最後にジョナサン・パリーとモーリス・ブロッホによって取り上 げられ、彼らは『貨幣と交換の道徳』(1989年)の中で、家族の長期的な社会的再生産が行われる「取引秩序」は、短期的な市場関係から切り離されたもの として維持されなければならないと主張した[15]。 慈善: 「贈与の毒  1860年頃、オンタリオ州シャロンのシャロン寺院。 ジョナサン・パリーは、贈与交換論争に関する彼の古典的な総括の中で、「純粋贈与」のイデオロギーは(総体的な贈与とは対照的に)「高度に分業化され、重 要な商業部門を持つ高度に分化した社会で最も生じやすい」[16]と強調している。彼は、インドネシアの中央スラウェシに住むト・パモナ族が、20世紀を 通じてグローバルな市場ネットワークに組み込まれる中で、どのような変容を遂げたかを記録している。彼らの日常的な生産・消費活動がますます商品化される につれて、彼らは社会的再生産活動に資金を提供する反対的な贈与(posintuwu)交換システムを発展させ、それによってより大きな親族集団、政治集 団、宗教集団を維持した。この「純粋贈与」交換ネットワークは、それ以前の「総プレステージ」システムから生まれたものである[17]。  Posintuwuの「無償贈与」は、To Pamonaの結婚式における花嫁財産の交換において頂点に達する。 同様に、19世紀初頭の北米における「資本主義的議論への移行」を分析したシュラウワースは、市場経済の出現と並行して、新たな対立的「道徳経済」がどの ように成長したかを記録している。市場がますます制度化されるにつれて、カナダのオンタリオ州シャロンにある「平和の子供たち」のような初期のユートピア 的社会主義的実験もまた、そうなっていった。彼らは慈善を与えることを神聖化するために、豪華な寺院を建てた。これはやがて、相互信用組織、土地共有、協 同組合マーケティングとして制度化された。いずれのケースでも、シュラウワースは、こうした代替的な交換圏は、商品がそれぞれの回路を出入りするように、 市場と緊密に統合され、相互主義的であることを強調している[18]。パリーはまた、インド(ダーナ)における施しの慈善的な贈与を例に、見返りを期待せ ずに施しを与える「純粋な贈与」が「毒」になりうることを強調していた。つまり、贈り主の罪を具現化した施しの贈り物は、儀式的に清らかな僧侶に贈られた 場合、その僧侶に自らを清めることのできない穢れを背負わせることになる。見返りを求めずに贈られた「純粋な贈り物」は、受領者に負債を負わせることにな り、それゆえ依存的な立場に置かれることになる。それは破産寸前であることを浮き彫りにし、それゆえ、借金のために訴訟や無期限の投獄にさらされることに なった。無償の贈り物である慈善を受け入れるよりも、彼らは借金を選んだ[18]。 事物の社会生活」と単一化 主な記事 商品経路の転換 アルジュン・アパデュライらは、特定の種類のモノがいかに贈与品であるか、あるいは限られた交換圏で取引される商品であるかを強調するのではなく、モノが こうした交換圏の間をどのように流れているかに注目し始めた。彼らは、交換を通じて形成される人間関係の特徴から注意をそらし、代わりに「モノの社会生 活」に注目した。彼らは、モノが「特異化」(唯一無二、特別なもの、オンリーワンのもの)され、市場から撤退するための戦略を検討した。購入した指輪をか けがえのない家宝に変える結婚の儀式はその一例である。 特異化とは、一見抗いがたいように見える商品化のプロセスの裏返しである。これらの学者たちは、あらゆる経済が、特定の交換圏に出入りする物質的なモノの 絶え間ない流れであることを示している。同じようなアプローチをとるニコラス・トーマスは、同じ範囲の文化とそれらについて書く人類学者を調査し、「絡み 合ったモノ」と、贈与と商品の両方としての役割に注意を向けている[20]。このようなモノへの強調は、「消費研究」(下記参照)における新たな探求へと つながっている。 |

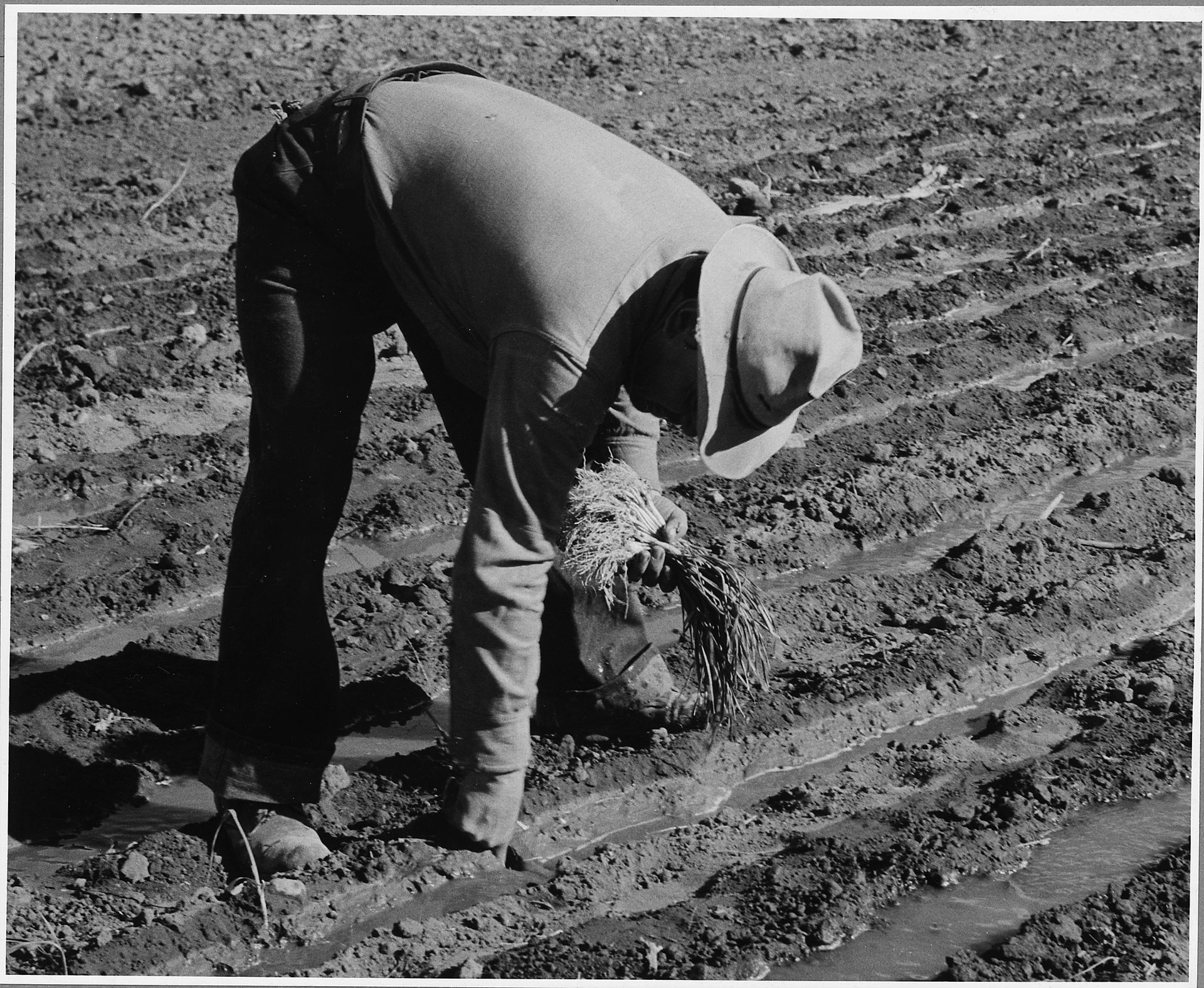

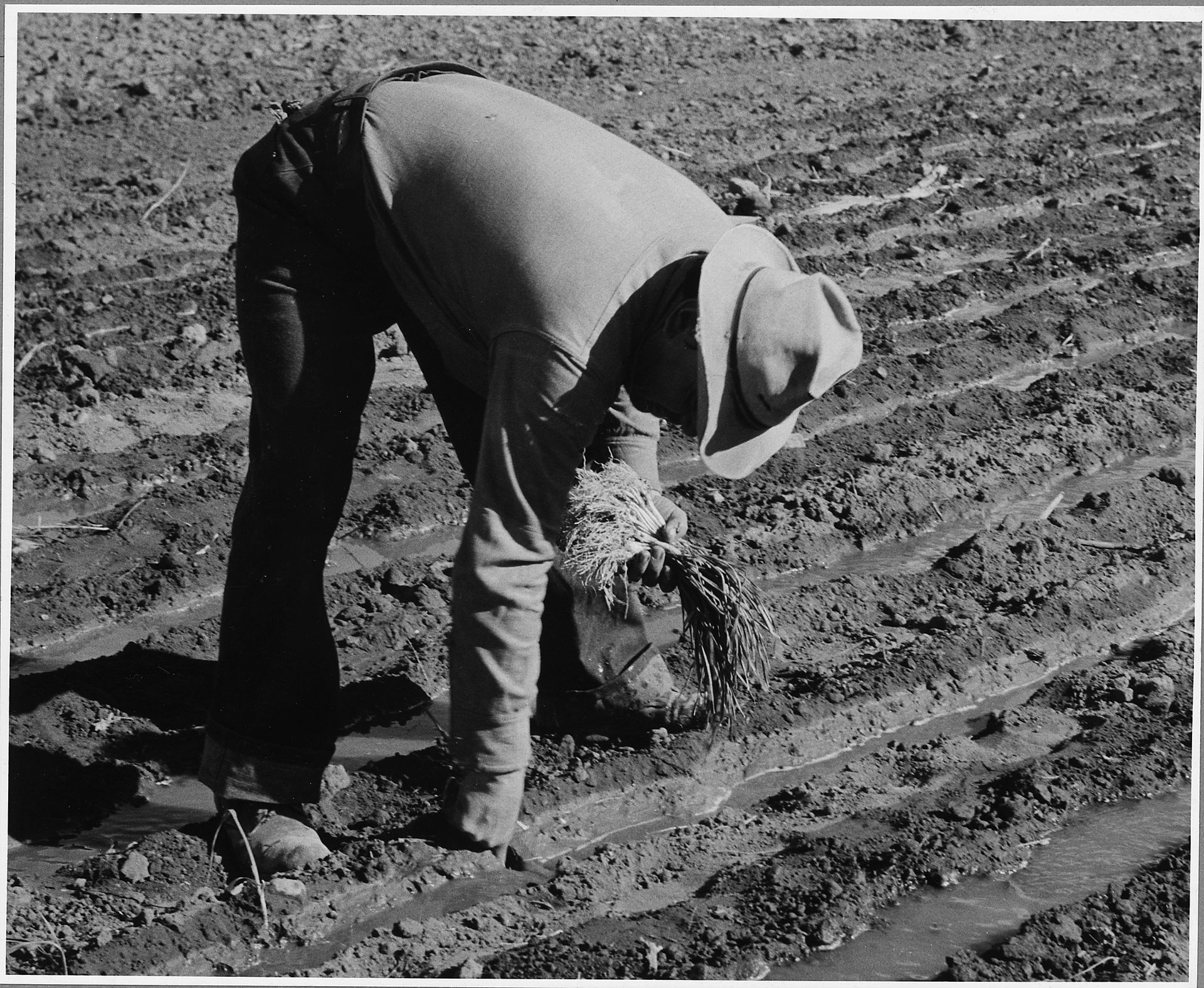

| Cultural construction of

economic systems: the substantivist approach Formalist vs substantivist debate Main article: Formalist–substantivist debate  Non-market subsistence farming in New Mexico: household provisioning or 'economic' activity?  The opposition between substantivist and formalist economic models was first proposed by Karl Polanyi in his work The Great Transformation (1944). He argued that the term 'economics' has two meanings: the formal meaning refers to economics as the logic of rational action and decision-making, as rational choice between the alternative uses of limited (scarce) means. The second, substantive meaning, however, presupposes neither rational decision-making nor conditions of scarcity. It simply refers to the study of how humans make a living from their social and natural environment. A society's livelihood strategy is seen as an adaptation to its environment and material conditions, a process which may or may not involve utility maximisation. The substantive meaning of 'economics' is seen in the broader sense of 'economising' or 'provisioning'. Economics is simply the way members of society meet their material needs. Anthropologists embraced the substantivist position as empirically oriented, as it did not impose western cultural assumptions on other societies where they might not be warranted. The Formalist vs. Substantivist debate was not between anthropologists and economists, however, but a disciplinary debate largely confined to the journal Research in Economic Anthropology. In many ways, it reflects the common debates between "etic" and "emic" explanations as defined by Marvin Harris in cultural anthropology of the period. The principal proponents of the substantivist model were George Dalton and Paul Bohannan. Formalists such as Raymond Firth and Harold K. Schneider asserted that the neoclassical model of economics could be applied to any society if appropriate modifications are made, arguing that its principles have universal validity. For some anthropologists, the substantivist position does not go far enough. Stephen Gudeman, for example, argues that the processes of making a livelihood are culturally constructed. Therefore, models of livelihoods and related economic concepts such as exchange, money or profit must be analyzed through the locals' ways of understanding them. Rather than devising universal models rooting in Western economic terminologies and then applying them indiscriminately to all societies, scholars must come to understand the 'local model'. Stephen Gudeman and the culturalist approach In his work on livelihoods, Gudeman seeks to present the "people's own economic construction" (1986:1);[21] that is, people's own conceptualizations or mental maps of economics and its various aspects. His description of a peasant community in Panama reveals that the locals did not engage in exchange with each other in order to make a profit but rather viewed it as an "exchange of equivalents", with the exchange value of a good being defined by the expenses spent on producing it. Only outside merchants made profits in their dealings with the community; it was a complete mystery to the locals how they managed to do so. Gaining a livelihood might be modelled as a causal and instrumental act, as a natural and inevitable sequence, as a result of supernatural dispositions or as a combination of all these. — Gudeman 1986:47[21] Gudeman also criticizes the substantivist position for imposing their universal model of economics on preindustrial societies and so making the same mistake as the formalists. While conceding that substantivism rightly emphasises the significance of social institutions in economic processes, Gudeman considers any deductive universal model, be it formalist, substantivist or Marxist, to be ethnocentric and tautological. In his view they all model relationships as mechanistic processes by taking the logic of natural science based on the material world and applying it to the human world. Rather than to "arrogate to themselves a privileged right to model the economies of their subjects", anthropologists should seek to understand and interpret local models (1986:38).[21] Such local models may differ radically from their Western counterparts. For example, the Iban use only hand knives to harvest rice. Although the use of sickles could speed up the harvesting process, they believe that this may cause the spirit of the rice to flee, and their desire to prevent that outcome is greater than their desire to economize the harvesting process. Gudeman brings post-modern cultural relativism to its logical conclusion. Generally speaking, however, culturalism can also be seen as an extension of the substantivist view, with a stronger emphasis on cultural constructivism, a more detailed account of local understandings and metaphors of economic concepts, and a greater focus on socio-cultural dynamics than the latter (cf. Hann, 2000).[22] Culturalists tend to be both less taxonomic and more culturally relativistic in their descriptions while critically reflecting on the power relationship between the ethnographer (or 'modeller') and the subjects of his or her research. While substantivists generally focus on institutions as their unit of analysis, culturalists lean towards detailed and comprehensive analyses of particular local communities. Both views agree in rejecting the formalist assumption that all human behaviour can be explained in terms of rational decision-making and utility maximisation. Culturalism can be criticized from various perspectives. Marxists argue that culturalists are too idealistic in their notion of the social construction of reality and too weak in their analysis of external (i.e. material) constraints on individuals that affect their livelihood choices. If, as Gudeman argues, local models cannot be held against a universal standard, then they cannot be related to hegemonic ideologies propagated by the powerful, which serve to neutralise resistance. This is further complicated by the fact that in an age of globalization most cultures are being integrated into the global capitalist system and are influenced to conform to Western ways of thinking and acting. Local and global discourses are mixing, and the distinctions between the two are beginning to blur. Even though people will retain aspects of their existing worldviews, universal models can be used to study the dynamics of their integration into the rest of the world. Householding Entrepreneurs in "imperfect markets" Inspired by a collection on "Trade and Market in the early Empires" edited by Karl Polanyi, the substantivists conducted a wide comparative study of market behavior in traditional societies where such markets were embedded in kinship, religion and politics. They thus remained focused on the social and cultural processes that shaped markets, rather than on the individual focused study of economizing behavior found in economic analysis. George Dalton and Paul Bohannon, for example, published a collection on markets in sub-Saharan Africa.[23] Pedlars and Princes: Social Development and Economic Change in Two Indonesian Towns by Clifford Geertz compared the entrepreneurial cultures of Islamic Java with Hinduized Bali in the post-colonial period.[24] In Java, trade was in the hands of pious Muslims, whereas in Bali, larger enterprises were organized by aristocrats.[25] Over time, this literature was refocused on "informal economies", those market activities lying on the periphery of legal markets.[26] Modernization theory of development had led economists in the 1950s and 1960s to expect that traditional forms of work and production would disappear in developing countries. Anthropologists found, however, that the sector had not only persisted, but expanded in new and unexpected ways. In accepting that these forms of productions were there to stay, scholars began using the term informal sector, which is credited to the British anthropologist Keith Hart in a study on Ghana in 1973. This literature focuses on the "invisible work" done by those who fall outside the formal production process, such as the production of clothing by domestic workers, or those who are bound labourers in sweatshops. As these studies have shifted to the informal sector of western economies, the field has been dominated by those taking a political economy approach.[27] Neo-Substantivism and capitalism as a cultural system While many anthropologists like Gudeman were concerned with peasant economic behaviour, others turned to the analysis of market societies. Economic sociologist Mark Granovetter provided a new research paradigm (neo-substantivism) for these researchers. Granovetter argued that the neo-liberal view of economic action which separated economics from society and culture promoted an 'undersocialized account' that atomises human behavior. Similarly, he argued, substantivists had an "over-socialized" view of economic actors, refusing to see the ways that rational choice could influence the ways they acted in traditional, "embedded" social roles. Neo-Substantivism overlaps with 'old' and especially new institutional economics. Actors do not behave or decide as atoms outside a social context, nor do they adhere slavishly to a script written for them by the particular intersection of social categories that they happen to occupy. Their attempts at purposive action are instead embedded in concrete, ongoing systems of social relations.[28] Granovetter applied the concept of embeddedness to market societies, demonstrating that even their, "rational" economic exchanges are influenced by pre-existing social ties.[28] In his study of ethnic Chinese business networks in Indonesia, Granovetter found individual's economic agency embedded in networks of strong personal relations. In processes of clientelization the cultivation of personal relationships between traders and customers assumes an equal or higher importance than the economic transactions involved. Economic exchanges are not carried out between strangers but rather by individuals involved in long-term continuing relationships. |

経済システムの文化的構築:実体主義的アプローチ 形式主義対実体主義の論争 主な記事 形式主義者と実体主義者の論争  ニューメキシコ州の非市場的自給自足農業:家計の糧食か「経済」活動か?  実体主義的経済モデルと形式主義的経済モデルの対立は、カール・ポランニーがその著作『大転換』(1944年)で初めて提唱した。ポランニーは、「経済 学」という用語には2つの意味があると主張した。形式的な意味とは、合理的な行動と意思決定の論理としての経済学を指し、限られた(希少な)手段の代替的 な使用法の間での合理的な選択を意味する。しかし、第二の実質的な意味は、合理的な意思決定も希少性の条件も前提としない。それは単に、人間がその社会 的・自然的環境からどのように生計を立てているかを研究することを指す。社会の生活戦略は、その環境と物質的条件への適応であり、効用最大化を伴うか否か を問わないプロセスと見なされる。経済学」の実質的な意味は、「経済化」や「供給」という広い意味で捉えられている。経済学とは、単に社会の成員が物質的 な必要を満たす方法である。人類学者は、西洋の文化的前提を他の社会に押し付けないため、実証主義的な立場から実体主義的な立場を採用した。しかし、形式 主義者対実質主義者の論争は、人類学者と経済学者の間で行われたものではなく、主に『経済人類学研究』誌に限定された学問分野の論争であった。多くの点 で、この論争は、当時の文化人類学でマービン・ハリスが定義した「エティック」な説明と「エミック」な説明の間によく見られた論争を反映している。実体主 義モデルの主な支持者はジョージ・ダルトンとポール・ボハナンであった。レイモンド・ファースやハロルド・K・シュナイダーのような形式主義者は、新古典 派経済学モデルは適切な修正を加えればどのような社会にも適用できると主張し、その原理は普遍的な妥当性を持つと主張した。 一部の人類学者にとっては、実証主義の立場は十分ではない。たとえばスティーブン・グッドマンは、生計を立てるプロセスは文化的に構築されたものだと主張 する。したがって、生計のモデルや、交換、貨幣、利益といった関連する経済概念は、現地の人々の理解の仕方を通して分析されなければならない。西洋の経済 用語に根ざした普遍的なモデルを考案し、それをすべての社会に無差別に適用するのではなく、学者たちは「ローカルモデル」を理解するようにならなければな らない。 スティーブン・グッドマンと文化主義的アプローチ グッドマンは生計に関する著作の中で、「人々自身の経済的構築」(1986:1)、つまり経済学とその様々な側面に関する人々自身の概念化あるいは心象地 図を提示しようとしている[21]。パナマのある農民社会についての彼の記述によれば、地元の人々は利益を上げるために互いに交換を行うのではなく、むし ろそれを「等価物の交換」とみなしており、財の交換価値はそれを生産するために費やされた費用によって定義されていた。共同体との取引で利益を上げたのは 外部の商人だけで、彼らがどうやって利益を上げたのかは地元の人々にはまったく謎であった。 生計を立てることは、因果的で道具的な行為として、自然で必然的な連続として、超自然的な気質の結果として、あるいはこれらすべての組み合わせとしてモデ ル化されるかもしれない。 - グデマン1986:47[21]。 グッドマンはまた、実体主義の立場が、彼らの普遍的な経済学モデルを産業革命以前の社会に押しつけ、形式主義者と同じ過ちを犯していると批判している。実 証主義が経済過程における社会制度の重要性を正しく強調していることは認めるが、グッドマンは、形式主義者であれ、実証主義者であれ、マルクス主義者であ れ、演繹的な普遍モデルは民族中心主義的で同語反復的であると考えている。彼の見解では、それらはすべて、物質世界に基づく自然科学の論理を人間世界に適 用することによって、機械論的なプロセスとして関係をモデル化している。対象者の経済をモデル化する特権的な権利を自らに課す」のではなく、人類学者は現 地のモデルを理解し、解釈するよう努めるべきである(1986:38)[21]。こうした現地のモデルは、西洋のそれとは根本的に異なる場合がある。例え ば、イバン族は稲刈りに手刀しか使わない。鎌を使えば稲刈りのスピードは上がるが、稲の精霊が逃げてしまうかもしれないと考えており、稲刈りを節約したい という気持ちよりも、そうならないようにしたいという気持ちの方が強いのである。 グッドマンはポストモダンの文化相対主義を論理的に結論づけた。しかし、一般的に言えば、文化主義は実体主義的な見方の延長線上にあると見ることもでき、 文化構成主義をより強調し、経済概念に関する現地の理解やメタファーをより詳細に説明し、後者よりも社会文化的な力学に重点を置いている(Hann, 2000参照)[22]。文化主義者は、民族誌学者(または「モデラー」)と調査対象者との力関係を批判的に考察しながら、分類学的でなく、文化相対主義 的な記述をする傾向がある。実体主義者は一般的に分析単位を制度に置くが、文化主義者は特定の地域コミュニティに関する詳細かつ包括的な分析に傾く。どち らの見解も、人間の行動はすべて合理的な意思決定と効用最大化の観点から説明できるという形式主義的な前提を否定する点では一致している。 文化主義はさまざまな観点から批判される。マルクス主義者は、文化主義者は現実の社会的構築という概念においてあまりにも理想主義的であり、生計の選択に 影響を与える個人に対する外的(すなわち物質的)制約の分析においてあまりにも弱すぎると主張する。グッドマンが主張するように、ローカルなモデルを普遍 的な基準に照らし合わせることができないのであれば、権力者が広める覇権的なイデオロギーと関連づけることはできず、抵抗勢力を無力化する役割を果たすこ とになる。グローバリゼーションの時代には、ほとんどの文化がグローバル資本主義システムに組み込まれ、西洋的な考え方や行動様式に合わせるよう影響を受 けているという事実が、この問題をさらに複雑にしている。ローカルな言説とグローバルな言説が混ざり合い、両者の区別が曖昧になりつつある。たとえ人々が 既存の世界観の側面を保持していたとしても、普遍的なモデルを用いて、世界の他の国々への統合のダイナミクスを研究することができる。 家事 「不完全市場」における企業家 カール・ポランニーが編集した『初期帝国における貿易と市場』から着想を得た実体主義者たちは、市場が親族関係、宗教、政治に組み込まれている伝統的な社 会における市場行動に関する幅広い比較研究を行った。そのため、経済分析に見られるような個人に焦点を当てた経済化行動の研究ではなく、市場を形成する社 会的・文化的プロセスに焦点を当て続けたのである。例えば、ジョージ・ダルトンとポール・ボハノンは、サハラ以南のアフリカの市場に関するコレクションを 出版した[23]: ジャワ島では貿易は敬虔なイスラム教徒の手に委ねられていたのに対し、バリ島では大企業が貴族によって組織されていた。 [やがて、この文献は「インフォーマル経済」、つまり合法的な市場の周辺に横たわる市場活動に再び焦点が当てられるようになった[26]。開発の近代化理 論によって、1950年代と1960年代の経済学者たちは、発展途上国では伝統的な労働と生産の形態が消滅すると予想していた。しかし、人類学者たちは、 この部門が存続しているだけでなく、新しく予想外の方法で拡大していることを発見した。このような生産形態は今後も存続するものと考え、学者たちはイン フォーマル・セクターという用語を使い始めた。この用語は、1973年にイギリスの人類学者キース・ハートがガーナを調査した際に使用したものである。こ の文献は、家事労働者による衣料品の生産や、搾取工場での拘束労働者など、正式な生産プロセスから外れた人々によって行われる「見えない仕事」に焦点を当 てている。こうした研究が西洋経済のインフォーマル・セクターにシフトするにつれて、この分野は政治経済学的アプローチをとる人々によって支配されてきた [27]。 文化システムとしての新実体主義と資本主義 グデマンのような多くの人類学者が農民の経済行動に関心を寄せていた一方で、市場社会の分析に目を向ける者もいた。経済社会学者のマーク・グラノヴェッ ターは、こうした研究者たちに新たな研究パラダイム(新実体主義)を提供した。グラノヴェッターは、経済学を社会や文化から切り離した新自由主義的な経済 行動観は、人間の行動を原子化する「社会化されていない説明」を促進すると主張した。同様に、実体主義者は経済行為者を「過剰に社会化」した見方をしてお り、合理的選択が伝統的な「埋め込まれた」社会的役割の中で彼らが行動する方法に影響を与える可能性を見ようとしないと主張した。ネオ・サブスタンティ ヴィズムは、「古い」、特に新しい制度経済学と重なる。 行為者は、社会的文脈の外側で原子として行動したり決定したりするわけではないし、たまたま占めることになった社会的カテゴリーの特定の交差点によって書 かれた台本に忠実に従うわけでもない。彼らの目的意識的な行動の試みは、その代わりに具体的で進行中の社会関係のシステムの中に埋め込まれている [28]。 グラノヴェッターは市場社会に埋没性の概念を適用し、彼らの「合理的な」経済的交換でさえも、既存の社会的結びつきに影響されることを実証した[28]。 クライアント化の過程では、取引業者と顧客との間の個人的関係の育成が、経済的取引と同等かそれ以上の重要性を持つ。経済取引は、見知らぬ者同士の間で行 われるのではなく、長期的な継続関係にある個人によって行われるのである。 |

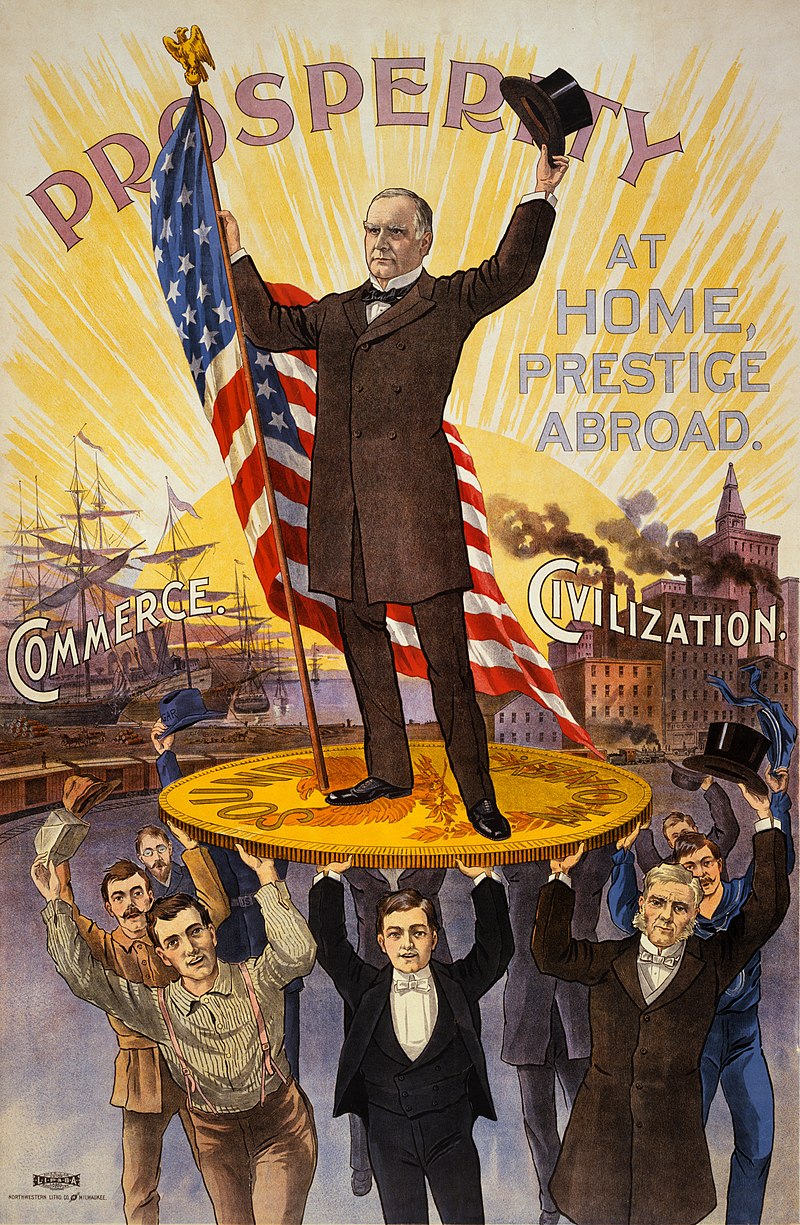

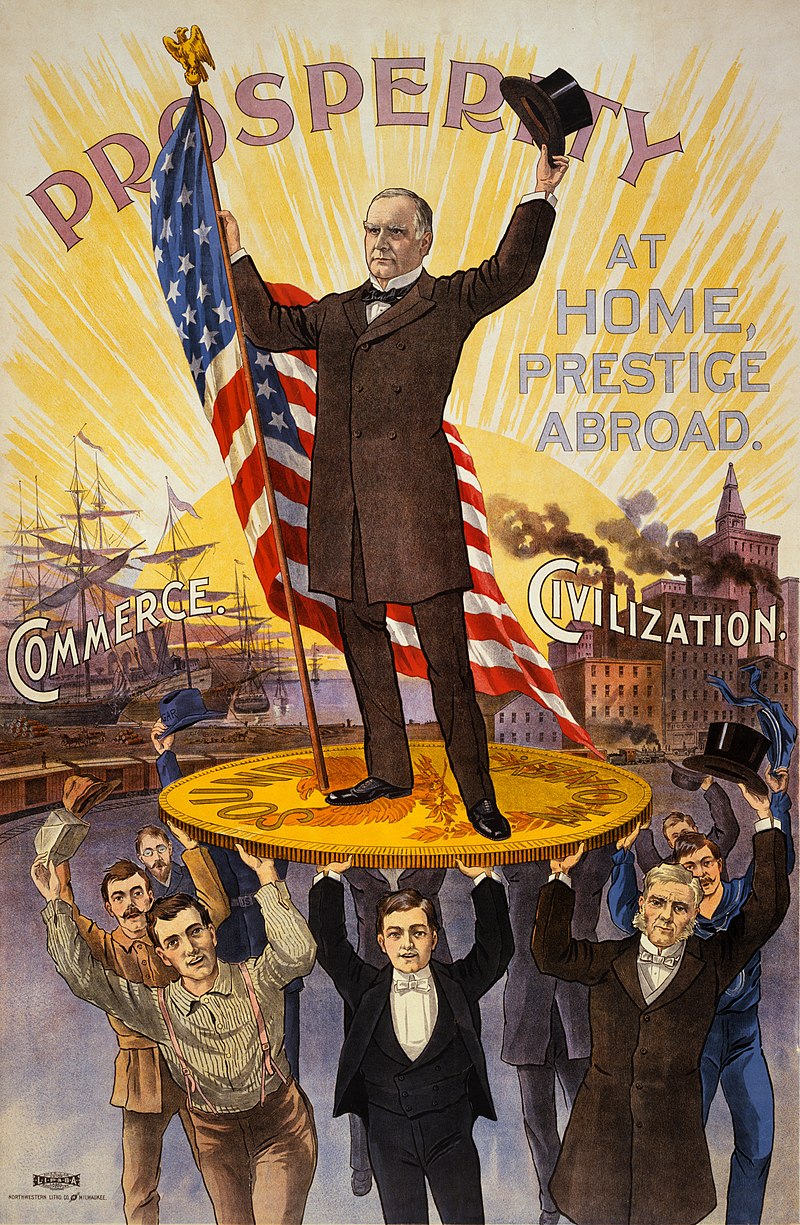

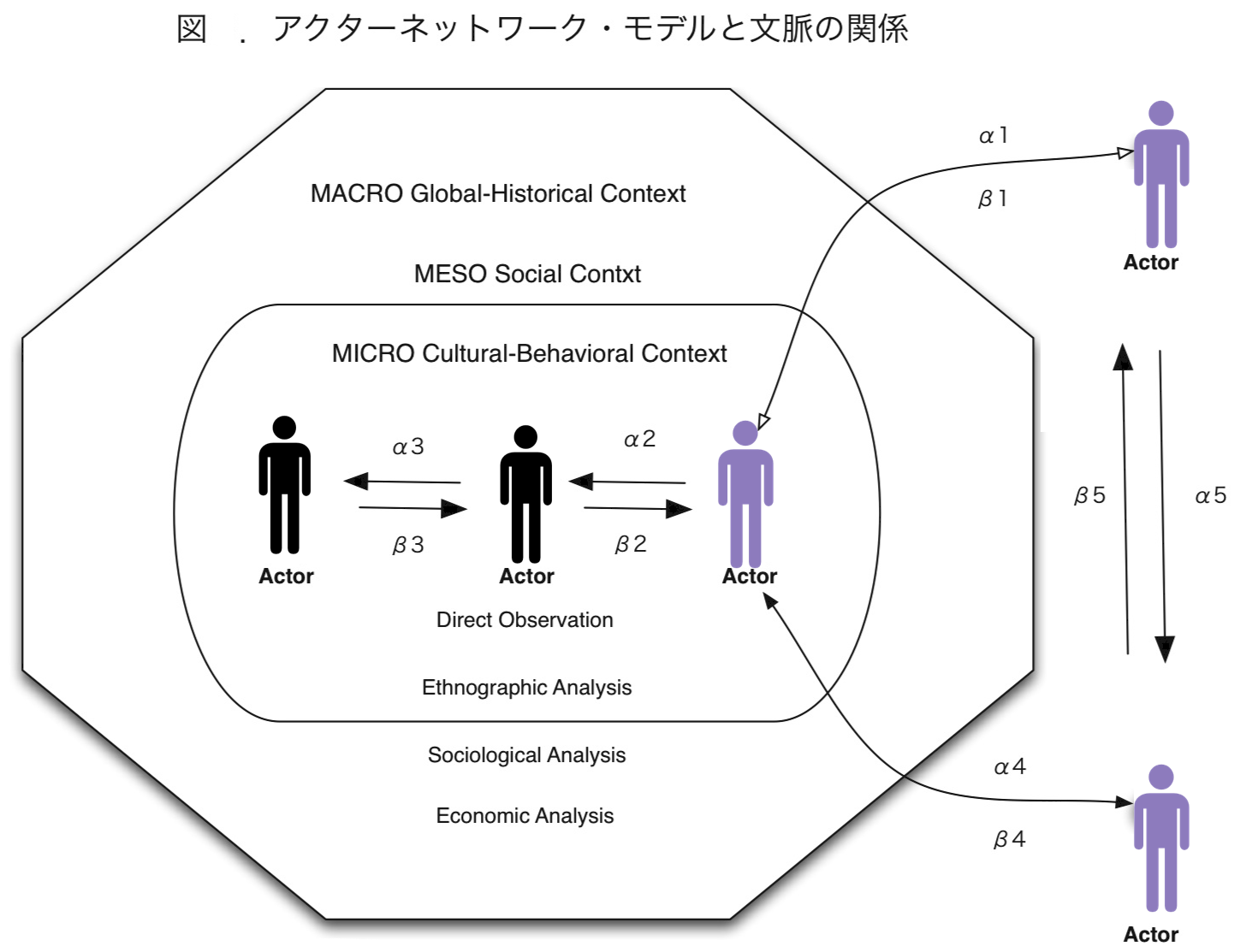

Money and finance A sample picture of a fictional ATM card. The largest part of the world's money exists only as accounting numbers which are transferred between financial computers. Various plastic cards and other devices give individual consumers the power to electronically transfer such money to and from their bank accounts, without the use of currency. Special and general purpose of money Early anthropologists of the substantivist school were struck by the number of "special purpose monies," like wampum and shell money, that they encountered. These special purpose monies were used to facilitate trade, but were not the "universal" money of market-based economies. Universal money served five functions: Medium of exchange: they facilitated trade Unit of account: they are an abstract measure of value or worth Store of value: they allow wealth to be preserved over time Standard of deferred payment: they are a measure of debt Means of payment: they can be used in non-market situations to pay debts (like taxes).[29] Special purpose monies, in contrast, were frequently restricted in their use; they might be limited to a specific exchange sphere such as the brass rods used by the Tiv of Nigeria in the early twentieth century (see "spheres of exchange" above). Most of this early work documented the effects of universal money on these special purpose monies. Universal money frequently weakened the boundaries between exchange spheres. Others have pointed out, however, how alternative currencies such as Ithaca HOURS in New York state are used to create new community based spheres of exchange in western market economies by fostering barter.[30][31] Much of this work was updated and retheorized in the edited collection: Money and Modernity: State and Local Currencies in Melanesia.[32] A second collection, Money and the morality of exchange examined how "general purpose money" could be transformed into a "special purpose money" - how money could be "socialized" and stripped of its moral danger so that it abets domestic economies free of market demands.[33] William Reddy undertook the same kind of analysis of the meanings of monetary exchange in terms of the growth of Liberalism in early modern Europe. Reddy critiques what he calls the "Liberal illusion" that developed in this period, that money is a universal equivalent and a principle of liberation. He underscores the different values and meanings that money has for those of different classes.[34] Barter Main article: Barter David Graeber argues that the inefficiencies of barter in archaic society has been used by economists since Adam Smith to explain the emergence of money, the economy, and hence the discipline of economics itself.[35] "Economists of the contemporary orthodoxy... propose an evolutionary development of economies which places barter, as a 'natural' human characteristic, at the most primitive stage, to be superseded by monetary exchange as soon as people become aware of the latter's greater efficiency."[36] However, extensive investigation since then has established that "No example of a barter economy, pure and simple, has ever been described, let alone the emergence from it of money; all available ethnography suggests that there never has been such a thing. But there are economies today which are nevertheless dominated by barter."[37] Anthropologists have argued "that when something resembling barter does occur in stateless societies it is almost always between strangers, people who would otherwise be enemies."[38] Barter occurred between strangers, not fellow villagers, and hence cannot be used to naturalistically explain the origin of money without the state. Since most people engaged in trade knew each other, exchange was fostered through the extension of credit.[37][39] Marcel Mauss, author of 'The Gift', argued that the first economic contracts were to not act in one's economic self-interest, and that before money, exchange was fostered through the processes of reciprocity and redistribution, not barter.[40] Everyday exchange relations in such societies are characterized by generalized reciprocity, or a non-calculative familial "communism" where each takes according to their needs, and gives as they have.[41] Other anthropologists have questioned whether barter is typically between "total" strangers, a form of barter known as "silent trade". However, Benjamin Orlove has shown that barter occurs through "silent trade" (between strangers), but also in commercial markets as well. "Because barter is a difficult way of conducting trade, it will occur only where there are strong institutional constraints on the use of money or where the barter symbolically denotes a special social relationship and is used in well-defined conditions. To sum up, multipurpose money in markets is like lubrication for machines - necessary for the most efficient function, but not necessary for the existence of the market itself."[42] Barter may occur in commercial economies, usually during periods of monetary crisis. During such a crisis, currency may be in short supply, or highly devalued through hyperinflation. In such cases, money ceases to be the universal medium of exchange or standard of value. Money may be in such short supply that it becomes an item of barter itself rather than the means of exchange. Barter may also occur when people cannot afford to keep money (as when hyperinflation quickly devalues it).[43] Money as commodity fetish  Metal money fetishism: A political poster shows gold coin as the basis of prosperity. (ca. 1896) Anthropologists have analyzed these cultural situations where universal money is being introduced as a means of revealing the underlying cultural assumptions about money that market based societies have internalized. Michael Taussig, for example, examined the reactions of peasant farmers in Colombia as they struggled to understand how money could make interest. Taussig highlights that we have fetishized money. We view money as an active agent, capable of doing things, of growth. In viewing money as an active agent, we obscure the social relationships that actually give money its power. The Colombian peasants, seeking to explain how money could bear interest, turned to folk beliefs like the "baptism of money" to explain how money could grow. Dishonest individuals would have money baptized, which would then become an active agent; whenever used to buy goods, it would escape the till and return to its owner.[44] Schrauwers similarly examines a situation where paper money was introduced for the first time, in early nineteenth century Ontario, Canada. Paper money, or bank notes, were not a store of wealth; they were an I.O.U., a "promisory note," a fetish of debt. Banks in the era had limited capital. They didn't loan that capital. Instead, they issued paper notes promising to pay that amount should the note be presented in their office. Since these notes stayed in circulation for lengthy periods, banks had little fear they would have to pay, and so issued many more notes than they could redeem, and charged interest on all of them. Utilizing Bourdieu's concept of symbolic capital, Schrauwers examines the way that elite social status was converted into economic capital (the bank note). The bank note's value depended entirely on the public's perceptions that it could be redeemed, and that perception was based entirely on the social status of the bank's shareholders.[45] Banking, finance and the stock market More recent work has focused on finance capital and stock markets. Anna Tsing for example, analyzed the "Bre-X stock scandal" in Canada and Indonesia in terms of "The economy of appearances."[46] Ellen Hertz, in contrast, looked at the development of stock markets in Shanghai, China, and the particular ways in which this free market was embedded in local political and cultural realities; markets do not operate in the same manner in all countries.[47] A similar study was done by Karen Ho on Wall Street, in the midst of the financial crisis of 2008. Her book, Liquidated: an ethnography of Wall Street, provides an insiders view of how "market rationality" works, and how it is embedded in particular kinds of social networks.[48] Bill Maurer has examined how Islamic bankers who are seeking to avoid religiously proscribed interest payments have remade money and finance in Indonesia. His book, Mutual Life, Limited, compares these Islamic attempts to remake the basis of money to local currency systems in the United States, such as "Ithaca Hours." In doing so, he questions what it is that gives money its value.[30] This same question of what gives money its value is also addressed in David Graeber's book Towards an Anthropological Theory of Value: The false coin of our own dreams.[49] James Carrier has extended the cultural economic and neo-substantivist position by applying their methods to the "science of economics" as a cultural practice. He has edited two collections that examine "free market" ideologies, comparing them to the culturally embedded economic practices they purport to describe. The edited collection, "Meanings of the market: the Free Market in Western Culture",[50] examined the use of market models in policy-making in the United States. A second edited collection "Virtualism: A New Political Economy," examined the cultural and social effects on western nations forced to adhere to abstract models of the free market: "Economic models are no longer measured against the world they seek to describe, but instead the world is measured against them, found wanting and made to conform."[51] The anthropology of corporate capitalism Symbolic and economic capital Similar insights were developed by Pierre Bourdieu, who also rejected the arguments of the new institutional economists. While these economists attempted to incorporate culture in their models, they did so by arguing that non-market "tradition" was the product of rational maximizing action in the market (i.e., to show they are the solution to an economic problem, rather than having deep cultural roots). Bourdieu argued strongly against what he called RAT (Rational Action Theory) theory, arguing that any actor, when asked for an explanation for their behaviour will provide a rational post hoc answer, but that excuse does not in fact guide the individual in the act. Driving a car is an example; individuals do so out of an acquired "instinct", obeying the rules of the road without actually focusing upon them. Bourdieu utilized an alternate model, which emphasized how "economic capital" could be translated into "symbolic capital" and vice versa. For example, in traditional Mexican villages, those of wealth would be called upon to fulfill "cargo offices" in the church, and host feasts in honour of the saints. These offices used up their economic capital, but in so doing, it was translated into status (symbolic capital) in the traditional role. This symbolic capital could, in turn, be used to draw customers in the marketplace because of a reputation for honesty and selflessness.[citation needed] Actor-Network theory Michel Callon has spearheaded the movement of applying Actor–network theory approaches to study economic life (notably economic markets). This body of work interrogates the interrelation between the economy and economics, highlighting the ways in which economics (and economics-inspired disciplines such as marketing) shapes the economy (see Callon, 1998 and 2005). Ethnographies of the corporation Corporations are increasingly hiring anthropologists as employees and consultants, leading to an increasingly critical appraisal about the organizational forms of post-modern capitalism.[52] Aihwa Ong's Spirits of resistance and capitalist discipline: factory women in Malaysia (1987) was pathbreaking in this regard.[53] Her work inspired a generation of anthropologists who have examined the incorporation of women within corporate economies, especially in the new "Free trade zones" of the newly industrializing third world.[54][55] Others have focused on the former industrialized (now rust-belt) economies.[56] Daromir Rudnyckyj has analyzed how neo-liberal economic discourses have been utilized by Indonesian Muslims operating the Krakatau Steel Company to create a "spiritual economy" conducive to globalization while enhancing the Islamic piety of workers.[57] George Marcus has called for anthropologists to "study up" and to focus on corporate elites, and has edited a series called Late Editions: Cultural Studies for the End of the Century. |

お金と金融 架空のATMカードのサンプル写真。世界のお金の大部分は、金融コンピューター間でやり取りされる会計上の数字としてのみ存在している。さまざまなプラス チック・カードやその他の機器によって、個人消費者は、通貨を使わずに銀行口座と電子的に送受信することができる。 貨幣の特別な目的と一般的な目的 実体主義学派の初期の人類学者たちは、ワンパンや貝殻貨幣のような「特殊目的の貨幣」に数多く出会ったことに驚かされた。これらの特殊目的の貨幣は貿易を 円滑にするために使われたが、市場主義経済の「普遍的な」貨幣ではなかった。普遍的な貨幣には5つの役割があった: 交換媒体:貿易を容易にする 会計単位: 価値や価値の抽象的な尺度である。 価値の貯蔵:富を長期にわたって保存することができる。 後払いの基準:債務の尺度である。 支払手段:非市場的な状況で債務(税金など)の支払いに使用できる[29]。 これとは対照的に、特殊目的貨幣はその用途が制限されることが多く、20世紀初頭にナイジェリアのティヴ族が使用した真鍮棒のように、特定の交換圏に限定 されることもあった(上記の「交換圏」を参照)。この初期の研究の大半は、普遍的貨幣がこうした特別な目的の貨幣に及ぼす影響を記録したものであった。普 遍貨幣はしばしば交換圏の境界を弱めた。しかし、ニューヨーク州のIthaca HOURSのような代替通貨が、物々交換を促進することによって、西側の市場経済においてコミュニティに基づく新たな交換圏を創出するためにどのように利 用されているかを指摘する者もいる[30][31]。 この研究の多くは、編集されたコレクションにおいて更新され、再論された: 貨幣と近代: 第2集『貨幣と交換の道徳』(Money and the morality of exchange)では、「汎用貨幣」がいかにして「特殊目的貨幣」へと変容しうるか、つまり貨幣がいかにして「社会化」され、市場の要求から解放された 国内経済を支援するように道徳的な危険性が取り除かれうるかが検討された[33]。 ウィリアム・レディは、近世ヨーロッパにおける自由主義の成長という観点から、貨幣交換の意味について同じような分析を行った。レディは、貨幣が普遍的な 等価物であり、解放の原理であるという、彼がこの時代に発展した「自由主義幻想」と呼ぶものを批判している。彼は、貨幣が異なる階級の人々にとって異なる 価値と意味を持つことを強調している[34]。 物々交換 主な記事 物々交換 デヴィッド・グレーバーは、古代の社会における物々交換の非効率性は、アダム・スミス以来の経済学者が貨幣や経済、ひいては経済学という学問自体の出現を 説明するために用いてきたと論じている[35]。「現代の正統派の経済学者は...経済の進化的発展を提唱しているが、それは物々交換を「自然な」人間の 特性として最も原始的な段階に置き、後者の方がより効率的であることを人々が認識するようになるとすぐに貨幣交換に取って代わられるというものである。 「しかし、それ以後の広範な調査によって、「純粋で単純な物々交換経済は、貨幣の出現はおろか、これまで一例も報告されていない。しかし、今日でも物々交 換が支配的な経済は存在する」[37]。 人類学者は「無国籍社会で物々交換に似たことが行われる場合、それはほとんど常に見知らぬ人々の間であり、そうでなければ敵対する人々の間である」 [38]と主張している。贈与」の著者であるマルセル・モースは、最初の経済的契約は自分の経済的自己利益のために行動しないことであり、貨幣以前は物々 交換ではなく、互恵と再分配のプロセスを通じて交換が促進されていたと主張した。 [そのような社会における日常的な交換関係は、一般化された互恵性、またはそれぞれが自分の必要性に応じて取り、持っている分だけ与えるという非計算的な 家族的「共産主義」によって特徴づけられる[41]。 他の人類学者は、物々交換が一般的に「全くの」見知らぬ者同士の間で行われるのかどうか、「無言貿易」として知られる物々交換の形態に疑問を呈している。 しかし、ベンジャミン・オルローヴは、物々交換は(見知らぬ者同士の)「無言貿易」だけでなく、商業市場でも行われることを示している。「物々交換は困難 な取引方法であるため、貨幣の使用に強い制度的制約がある場合や、物々交換が象徴的に特別な社会的関係を示し、明確に定義された条件のもとで使用される場 合にのみ発生する。結論として、市場における多目的貨幣は、機械にとっての潤滑油のようなものであり、最も効率的な機能には必要だが、市場そのものの存在 には必要ない」[42]。 物々交換は、商業経済において、通常、通貨危機の時期に発生することがある。このような危機の際には、通貨が不足したり、ハイパーインフレによって通貨が 著しく切り下げられたりすることがある。このような場合、貨幣は普遍的な交換手段や価値基準ではなくなる。通貨が供給不足に陥り、交換手段ではなく、物々 交換の品目そのものになることもある。物々交換は、人々が貨幣を保持する余裕がない場合(ハイパーインフレによって貨幣が急速に切り下げられた場合など) にも発生することがある[43]。 商品フェティッシュとしての貨幣  金属貨幣フェティシズム: 繁栄の基礎としての金貨を示す政治ポスター。(1896年頃) 人類学者は、市場主義社会が内面化している貨幣に関する文化的前提を明らかにする手段として、普遍的な貨幣が導入されるこうした文化的状況を分析してき た。例えば、マイケル・タウシグは、コロンビアの農民が、貨幣がどのように利子を生むのかを理解するのに苦労しているときの反応を調査した。タウシグは、 私たちが貨幣をフェティシズム化していることを強調している。私たちは貨幣を能動的な存在として見ている。貨幣を能動的な存在とみなすことで、貨幣に実際 に力を与えている社会的関係が見えにくくなっているのだ。コロンビアの農民たちは、貨幣が利子を生む仕組みを説明するために、「貨幣の洗礼」のような民間 信仰に目を向けた。不誠実な個人は、貨幣に洗礼を受けさせ、その洗礼は能動的な作用となり、商品を買うために使われるたびに、貨幣は耕運機を抜け出し、持 ち主のもとへと戻っていくのである[44]。 シュラウワースは、紙幣が初めて導入された19世紀初頭のカナダのオンタリオ州の状況を同様に検証している。紙幣(銀行券)は富の貯蔵庫ではなく、 I.O.U.であり、「約束手形」であり、負債のフェティッシュであった。当時の銀行の資本には限りがあった。その資本を融資することはなかった。その代 わり、銀行窓口に手形が提出されれば、その金額を支払うと約束する紙幣を発行したのである。これらの紙幣は長期間流通し続けたため、銀行は支払わなければ ならなくなる恐れはほとんどなく、そのため、償還可能額よりも多くの紙幣を発行し、そのすべてに利子をつけた。シュラウワースは、ブルデューの象徴資本の 概念を活用し、エリートの社会的地位が経済資本(銀行券)に変換された方法を検証する。銀行券の価値は、それが換金できるという一般大衆の認識に完全に依 存しており、その認識は銀行の株主の社会的地位に完全に基づいていた[45]。 銀行、金融、株式市場 より最近の研究では、金融資本と株式市場に焦点が当てられている。例えばアンナ・ツィンは、カナダとインドネシアにおける「ブレX株スキャンダル」を「見 かけの経済」という観点から分析した[46]。これとは対照的にエレン・ハーツは、中国の上海における株式市場の発展と、この自由市場が現地の政治的・文 化的現実に組み込まれた特殊な方法を考察した。彼女の著書『Liquidated: an ethnography of Wall Street』は、「市場合理性」がどのように機能し、それが特定の種類の社会的ネットワークにどのように埋め込まれているかについて、インサイダーとし ての見解を示している[48]。 ビル・マウラーは、宗教的に禁止されている利払いを避けようとするイスラム銀行家が、インドネシアにおいてどのように貨幣と金融を作り変えたかを検証して いる。彼の著書『Mutual Life, Limited』(邦題『相互生活』)は、貨幣の基礎を作り変えようとするこうしたイスラムの試みを、「イサカ時間」のようなアメリカの地域通貨システム と比較している。その際、貨幣に価値を与えているものは何なのかを問うている[30]。この、貨幣に価値を与えているものは何なのかという同じ問いは、デ イヴィッド・グレーバーの著書『人類学的価値論に向けて』でも扱われている: 私たち自身の夢の偽貨幣』[49]。 ジェームズ・キャリアーは、文化的実践としての「経済学」に彼らの方法を適用することで、文化経済学と新実体主義の立場を拡張してきた。彼は「自由市場」 イデオロギーを、それらが説明すると称する文化的に埋め込まれた経済実践と比較しながら検証する2つのコレクションを編集している。1つ目の編集集 『Meanings of the market: the Free Market in Western Culture』[50]は、アメリカにおける政策決定における市場モデルの利用を検証したものである。2つ目の編集集『Virtualism: A New Political Economy)」では、自由市場という抽象的なモデルに固執せざるを得ない西側諸国の文化的・社会的影響を検証している: 「経済モデルはもはや、彼らが記述しようとする世界に対して測定されるのではなく、世界がそれに対して測定され、不足していることが判明し、適合するよう に仕向けられる」[51]。 企業資本主義の人間学 象徴資本と経済資本 同様の洞察はピエール・ブルデューによって展開されたが、ブルデューもまた新しい制度経済学者の議論を否定していた。これらの経済学者たちは自分たちのモ デルに文化を組み込もうと試みたが、非市場的な「伝統」は市場における合理的最大化行動の産物であると主張することによってそうした(つまり、深い文化的 根を持つのではなく、それらが経済的問題の解決策であることを示すために)。ブルデューはRAT(合理的行為理論)と呼ばれる理論に強く反論し、どんな行 為者であれ、自分の行動についての説明を求められたら、その場しのぎの合理的な答えを出すだろうが、その言い訳は実際にはその行為において個人を導くもの ではないと主張した。車の運転はその一例であり、個人は後天的な「本能」からそうするのであり、実際にそれを重視することなく交通ルールを守るのである。 ブルデューは別のモデルを用いて、「経済資本」が「象徴資本」にどのように変換されるのか、またその逆はどうなのかを強調した。例えば、メキシコの伝統的 な村落では、裕福な人々は教会で「荷役」を果たすよう要請され、聖人に敬意を表して祝宴を催す。これらの役職は彼らの経済資本を使い果たしたが、そうする ことで伝統的な役割における地位(象徴資本)に変換された。この象徴資本はひいては、正直で無私無欲であるという評判により、市場で顧客を引きつけるため に使われることができた[要出典]。 アクター・ネットワーク理論 ミシェル・カロン(Michel Callon)は、経済生活(特に経済市場)の研究にアクター・ネットワーク理論のアプローチを適用する動きを先導してきた。この一連の研究は、経済と経 済学の相互関係を問い、経済学(およびマーケティングなどの経済学に触発された学問分野)が経済を形成する方法を浮き彫りにしている(Callon, 1998および2005を参照)。 企業のエスノグラフィー 企業はますます人類学者を従業員やコンサルタントとして雇うようになっており、ポストモダン資本主義の組織形態についてますます批判的な評価を行うように なっている[52]。 [ダロミール・ルドニッキは、クラカタウ鉄鋼会社を運営するインドネシアのイスラム教徒が、労働者のイスラム教への信心を高めつつ、グローバリゼーション に資する「精神的経済」を創造するために、新自由主義的な経済言説がどのように利用されてきたかを分析している[57]。ジョージ・マーカスは、人類学者 に「研究を進め」、企業エリートに焦点を当てるよう呼びかけ、「Late Editions」というシリーズを編集している: 世紀末のカルチュラル・スタディーズ |

| Karen Ho David Graeber Jason Hickel Hannah Appel Arjun Appadurai Jessica Cattelino |

カレン・ホー デイヴィッド・グレーバー ジェイソン・ヒッケル ハンナ・アッペル アルジュン・アパデュライ ジェシカ・カッテリーノ |

| Charity (practice) Critique of political economy Cultural economics Dāna Economic sociology Money Palace economy Society for Economic Anthropology |

慈善(実践) 政治経済学評論 文化経済学 ダーナ 経済社会学 貨幣 宮廷経済 経済人類学会 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Economic_anthropology |

︎★歴史と階級意識(物象化についての記述)▶︎マルクス主義▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

++++

1.互酬性と贈与、あるいは互酬制と贈与

・クラ交換に関するマリ ノフスキーとマルセル・モース(【注意!!!】エドワード・モースと混同しないようにしましょう)

・贈与と商品

・交換の領域

・慈善:「贈与という毒」

・モノの社会的生命と特異的単一化 (singularization)

2.経済システムの文化的構築:実体的アプローチ

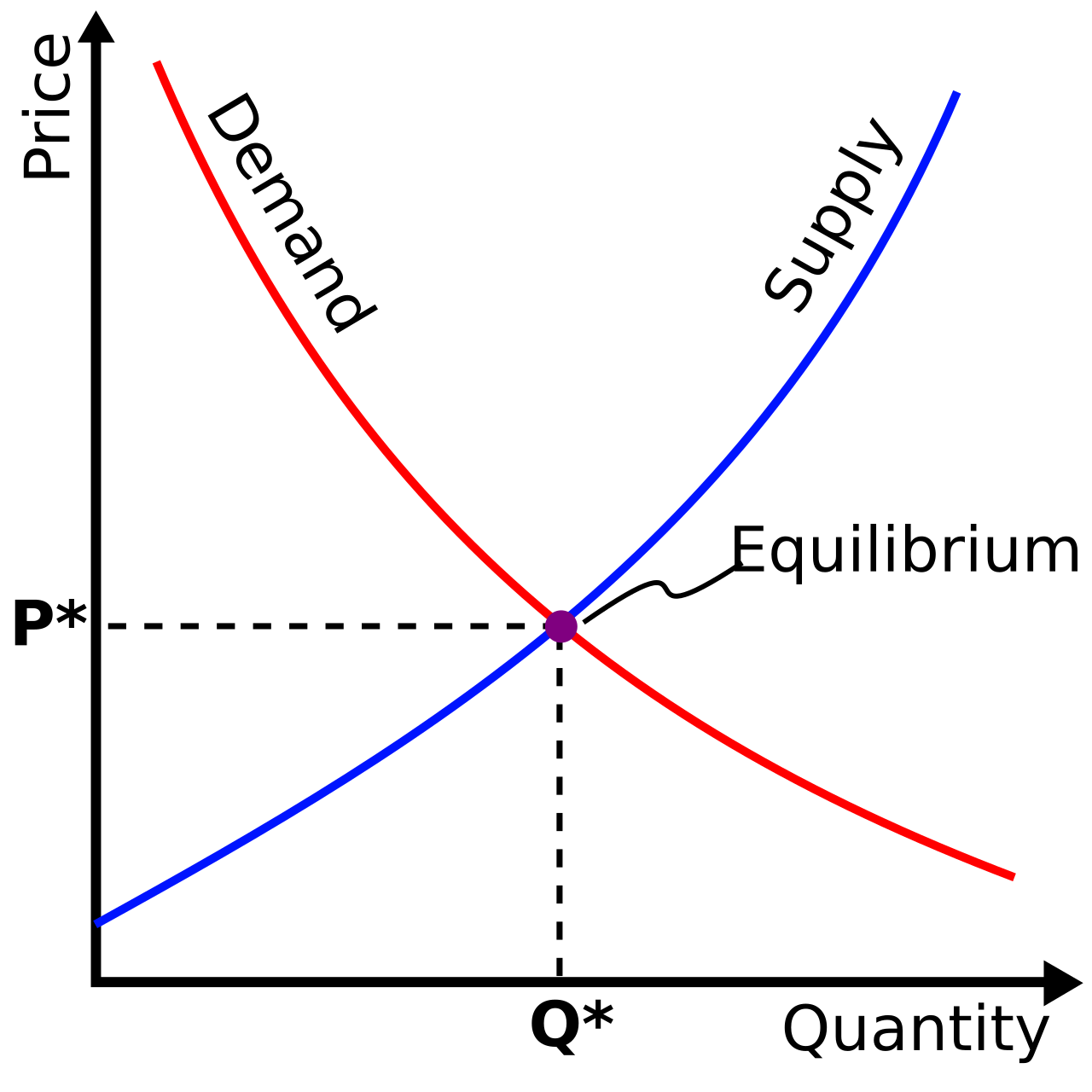

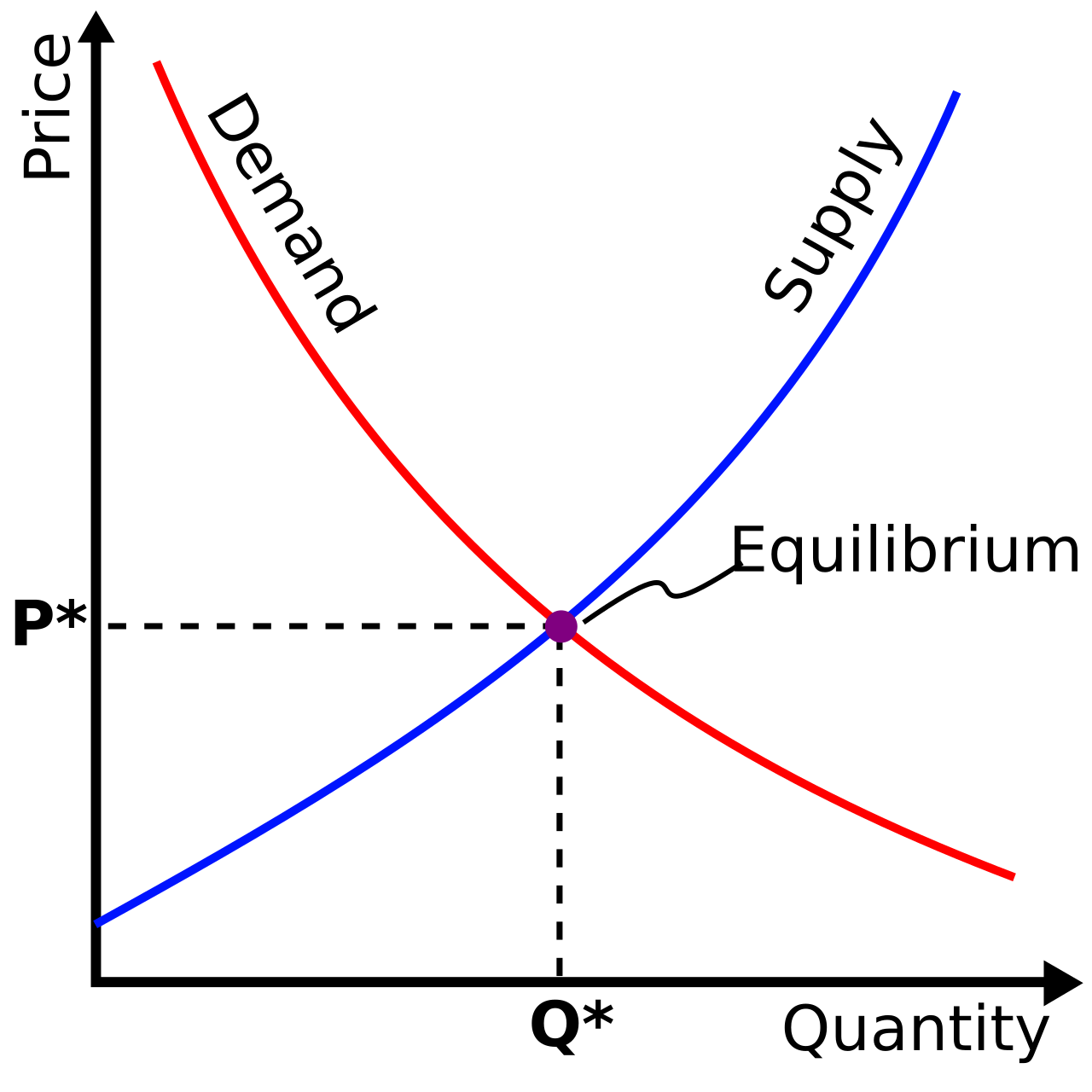

・形式主義(フォーマリズム)〈対〉実体主義論争

形式主義者は、市場経済で実効貨幣の流通で経済現 象をみる立場

実体主義者は、経済は社会に埋め込まれているとい

う立場で、経済には「威信(社会的自信や評価)」や互酬性など、市場経済以外の部分でも大きく経済は「社会に埋め込まれている」と考える。

・スティーヴン・グードマンと資本主義者のアプロー チ

・世帯経済

・「不完全市場」における企業家:とは、完全競争が 成立していない市場、のこと。

完全競争が成立していないことは、市場の企業規模

は大きいと、企業が価格を下げれば当該需要量が増加し、価格を上げれば当該需要量が低下する。これを「不完全競争の市場」と呼ぶ。

・新-実体主義と、文化システムとしての資本主義

3.貨幣と金融

・貨幣=マネーの特殊な目的、一般的な目的

・物々交換(バーター)

・商品物神(commodity fetish)としての貨幣:物神とは、実際に神が宿っていないのにその物質=御神体を神が宿っているごとく崇拝することをいう。

・銀行業務、金融、証券市場

4.消費研究

・ブルデュのディスタンクション

5.会社資本主義=コーポレート・キャピタリズムの 人類学

・象徴資本、経済資本

・アクターネットワーク理論

・会社の民族誌

6.その他の経済人類学のテーマ

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆