ホモ・パティエンス、受苦的人間、苦悩する人間

Homo patiens

ホモ・パティエンス、受苦的人間、苦悩する人間

解説:池田光穂

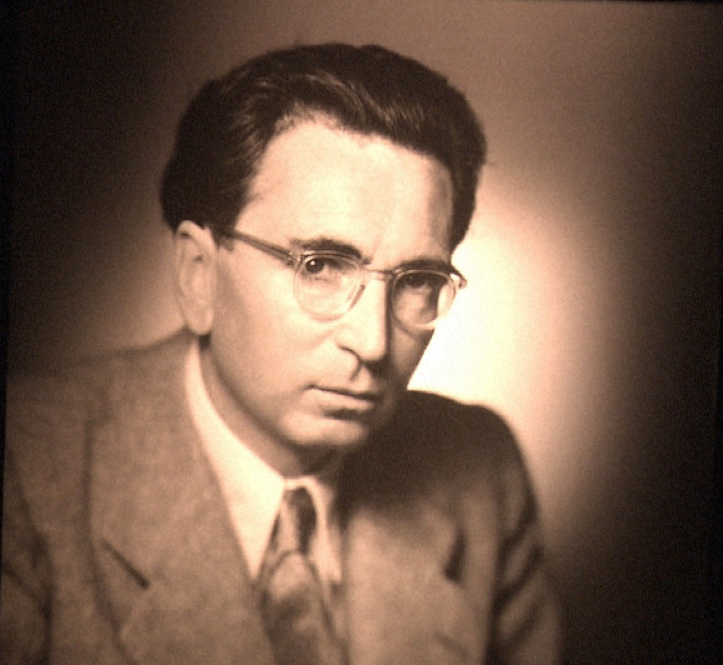

ホモ・パティエンスとは、苦悩する人間を定義したユダヤ人精神医学者ヴィクトル・フランクル(1905-1997)が提唱した用語である。ホ モ・サピエンスに準(なぞら)えて、ラテン語の学名のようにこのように表現した。

フランクルはアドラーやフロイトの教えを受けた実存主義派の精神分析医であり、ウィーン大学の精神科の教授を務め(この時代の大学教授〈兼〉医 師の常として)臨床は市立病院でおこなっていたが、第三帝国のユダヤ人迫害のために強制収容所に入れられたが生存した。

| Viktor Emil Frankl (26

March 1905 – 2 September 1997)[1] was an Austrian psychiatrist and

Holocaust survivor,[2] who founded logotherapy, a school of

psychotherapy that describes a search for a life's meaning as the

central human motivational force.[3] Logotherapy is part of existential

and humanistic psychology theories.[4] Logotherapy was promoted as the third school of Viennese Psychotherapy, after those established by Sigmund Freud, and Alfred Adler.[5] Frankl published 39 books.[6] The autobiographical Man's Search for Meaning, a best-selling book, is based on his experiences in various Nazi concentration camps.[7] |

ヴィクトール・エミール・フランクル(Viktor Emil

Frankl、1905年3月26日 -

1997年9月2日)[1]はオーストリアの精神科医であり、ホロコーストの生存者である[2]。ロゴセラピーを創始した。ロゴセラピーは実存心理学と人

間性心理学の理論の一部である[3]。 ロゴセラピーは、ジークムント・フロイト、アルフレッド・アドラーによって確立されたものに続く、ウィーン心理療法の第3の学派として推進された[5]。 フランクルは39冊の著書を出版し、ベストセラーとなった自伝的著書『Man's Search for Meaning』は、ナチスの様々な強制収容所での体験に基づいている[7]。 |

| Early life Frankl was born the middle of three children to Gabriel Frankl, a civil servant in the Ministry of Social Service, and Elsa (née Lion), a Jewish family, in Vienna, in what was then the Austro-Hungarian Empire.[1] His interest in psychology and the role of meaning developed when he began taking night classes on applied psychology while in junior high school.[1] As a teenager, he began a correspondence with Sigmund Freud upon asking for permission to publish one of his papers.[8][9] After graduation from high school in 1923, he studied medicine at the University of Vienna. In 1924, Frankl's first scientific paper was published in The International Journal of Psychoanalysis.[10] In the same year, he was president of the Sozialistische Mittelschüler Österreich, the Social Democratic Party of Austria's youth movement for high school students. Frankl's father was a socialist who named him after Viktor Adler, the founder of the party.[1][11] During this time, Frankl began questioning the Freudian approach to psychoanalysis. He joined Alfred Adler's circle of students and published his second scientific paper, "Psychotherapy and Worldview" ("Psychotherapie und Weltanschauung"), in Adler's International Journal of Individual Psychology in 1925.[1] Frankl was expelled from Adler's circle[2] when he insisted that meaning was the central motivational force in human beings. From 1926, he began refining his theory, which he termed logotherapy.[12] |

生い立ち フランクルは、当時のオーストリア=ハンガリー帝国のウィーンで、社会奉仕省の公務員であったガブリエル・フランクルとユダヤ人家庭のエルザ(旧姓ライオ ン)の間に3人兄弟の真ん中として生まれた[1]。中学生の時に応用心理学の夜間授業を受け始めたことで、心理学と意味の役割に興味を持つようになった [1]。 [1923年に高校を卒業後、ウィーン大学で医学を学ぶ。 1924年、フランクルの最初の学術論文が『精神分析国際ジャーナル』に掲載される[10]。 同年、オーストリア社会民主党の高校生のための青年運動であるSozialistische Mittelschüler Österreichの会長を務める。フランクルの父親は社会主義者で、党の創設者であるヴィクトール・アドラーにちなんでフランクルと名付けた。彼はア ルフレッド・アドラーの門下生たちのサークルに加わり、1925年にアドラーの『International Journal of Individual Psychology』に2本目の科学論文である「心理療法と世界観」("Psychotherapie und Weltanschauung")を発表した[1]。1926年から、彼はロゴセラピーと呼ばれる理論を洗練し始めた[12]。 |

| Career Psychiatry Between 1928 and 1930, while still a medical student, he organized youth counselling centers[13] to address the high number of teen suicides occurring around the time of end of the year report cards. The program was sponsored by the city of Vienna and free of charge to the students. Frankl recruited other psychologists for the center, including Charlotte Bühler, Erwin Wexberg, and Rudolf Dreikurs. In 1931, not a single Viennese student died by suicide.[14][unreliable source?] After earning his M.D. in 1930, Frankl gained extensive experience at Steinhof Psychiatric Hospital, where he was responsible for the treatment of suicidal women. In 1937, he began a private practice, but the Nazi annexation of Austria in 1938 limited his opportunity to treat patients.[1] In 1940, he joined Rothschild Hospital, the only hospital in Vienna still admitting Jews, as head of the neurology department. Prior to his deportation to the concentration camps, he helped numerous patients avoid the Nazi euthanasia program that targeted the mentally disabled.[2][15] In 1942, just nine months after his marriage, Frankl and his family were sent to the Theresienstadt concentration camp. His father died there of starvation and pneumonia. In 1944, Frankl and the surviving members of his family were transported to Auschwitz, where his mother and brother were murdered in the gas chambers. His wife Tilly died later of typhus in Bergen-Belsen. Frankl spent three years in four concentration camps.[7] Following the war, he became head of the neurology department of the General Polyclinic Vienna hospital, and established a private practice in his home. He worked with patients until his retirement in 1970.[2] In 1948, Frankl earned a PhD in philosophy from the University of Vienna. His dissertation, The Unconscious God, examines the relationship between psychology and religion,[16] and advocates for the use of the Socratic dialogue (self-discovery discourse) for clients to get in touch with their spiritual unconscious.[17]  Grave of Viktor Frankl in Vienna In 1955, Frankl was awarded a professorship of neurology and psychiatry at the University of Vienna, and, as visiting professor, lectured at Harvard University (1961), Southern Methodist University, Dallas (1966), and Duquesne University, Pittsburgh (1972).[12] Throughout his career, Frankl argued that the reductionist tendencies of early psychotherapeutic approaches dehumanised the patient, and advocated for a rehumanisation of psychotherapy.[18] The American Psychiatric Association awarded Frankl the 1985 Oskar Pfister Award for his contributions to religion and psychiatry.[18] Man's Search for Meaning While head of the Neurological Department at the general Polyclinic Hospital, Frankl wrote Man's Search for Meaning over a nine-day period.[19] The book, originally titled A Psychologist Experiences the Concentration Camp, was released in German in 1946. The English translation of Man's Search for Meaning was published in 1959, and became an international bestseller.[2] Frankl saw this success as a symptom of the "mass neurosis of modern times" since the title promised to deal with the question of life's meaningfulness.[20] Millions of copies were sold in dozens of languages. In a 1991 survey conducted for the Library of Congress and the Book of the Month Club, Man's Search for Meaning was named one of the ten most influential books in the US.[21] Logotherapy and existential analysis Frankl developed logotherapy and existential analysis, which are based on philosophical and psychological concepts, particularly the desire to find a meaning in life and free will.[22][23] Frankl identified three main ways of realizing meaning in life: by making a difference in the world, by having particular experiences, or by adopting particular attitudes. The primary techniques offered by logotherapy and existential analysis are:[24][22][23] Paradoxical intention: clients learn to overcome obsessions or anxieties by self-distancing and humorous exaggeration. Dereflection: drawing the client's attention away from their symptoms, as hyper-reflection can lead to inaction.[25] Socratic dialogue and attitude modification: asking questions designed to help a client find and pursue self-defined meaning in life.[26] His acknowledgement of meaning as a central motivational force and factor in mental health is his lasting contribution to the field of psychology. It provided the foundational principles for the emerging field of positive psychology.[27] Frankl's work has also been endorsed in the Chabad philosophy of Hasidic Judaism.[28] |

キャリア 精神医学 医学生であった1928年から1930年にかけて、彼は青少年カウンセリングセンター[13]を組織し、学年末の成績表の時期に多発する10代の自殺に対 処した。このプログラムはウィーン市の後援を受け、生徒には無料で提供された。フランクルは、シャルロッテ・ビューラー、エルヴィン・ウェクスベルク、ル ドルフ・ドライクルスなど、他の心理学者をセンターにスカウトした。1931年には、ウィーンの学生で自殺で亡くなった者は一人もいなかった[14][信 頼できない情報源?] 1930年に医学博士号を取得したフランクルは、シュタインホーフ精神病院で自殺願望のある女性の治療を担当し、幅広い経験を積む。1937年、個人開業 医となったが、1938年のナチスによるオーストリア併合により、患者を治療する機会が制限された[1]。1940年、ウィーンで唯一ユダヤ人を受け入れ ていたロスチャイルド病院に神経科部長として入職。強制収容所に強制送還される前、精神障害者を対象としたナチスの安楽死プログラムを回避するため、多く の患者を助けた[2][15]。 1942年、結婚からわずか9ヵ月後、フランクルは家族とともにテレジエンシュタット強制収容所に送られた。父親はそこで餓死と肺炎で死亡した。1944 年、フランクルと生き残った家族はアウシュヴィッツに移送され、そこで母と兄はガス室で殺された。妻のティリーは後にベルゲン・ベルゼンでチフスで死ん だ。フランクルは4つの強制収容所で3年間を過ごした[7]。 戦後、ウィーンの総合ポリクリニック病院の神経学部長となり、自宅で開業。1970年に引退するまで患者を診ていた[2]。 1948年、ウィーン大学で哲学博士号を取得。彼の学位論文である『無意識の神』は心理学と宗教の関係を考察しており[16]、クライエントが精神的無意識に触れるためにソクラテス的対話(自己発見談話)を用いることを提唱している[17]。  ウィーンにあるヴィクトール・フランクルの墓 1955年、フランクルはウィーン大学で神経学と精神医学の教授職を授与され、客員教授としてハーバード大学(1961年)、ダラスのサザンメソジスト大学(1966年)、ピッツバーグのデュケイン大学(1972年)で講義を行った[12]。 フランクルはそのキャリアを通じて、初期の心理療法的アプローチの還元主義的傾向が患者の人間性を奪うと主張し、心理療法の再人間化を提唱した[18]。 アメリカ精神医学会は、宗教と精神医学への貢献に対して1985年にオスカー・プフィスター賞をフランクルに授与した[18]。 意味の探求 フランクルは、総合ポリクリニック病院の神経科部長であったときに、9日間かけて『人間の意味の探求』を執筆した[19]。原題『A Psychologist Experiences the Concentration Camp』は、1946年にドイツ語で出版された。フランクルはこの成功を、タイトルが人生の意義の問題を扱うと約束されていることから、「現代の集団神 経症」の症状であると考えた[2]。1991年に米国議会図書館とブック・オブ・ザ・マンス・クラブのために行われた調査では、『人間の意味の探求』はア メリカで最も影響力のある10冊のうちの1冊に選ばれた[21]。 ロゴセラピーと実存分析 フランクルは、哲学的・心理学的概念、特に人生の意味を見出したいという願望と自由意志に基づいて、ロゴセラピーと実存分析を開発した[22][23]。 ロゴセラピーと実存分析が提供する主な技法は以下のとおりである:[24][22][23]。 逆説的意図:クライエントは、自己否定やユーモラスな誇張によって強迫観念や不安を克服することを学ぶ。 脱反省:過反省は不作為につながる可能性があるため、クライエントの注意を症状から引き離す。 ソクラテス的対話と態度修正:クライエントが人生において自己定義した意味を見出し、追求するのを助けるようにデザインされた質問をすること[26]。 精神的健康の中心的な動機づけの力および要因としての意味の認識は、心理学の分野への彼の永続的な貢献である。フランクルの研究は、ハシディック・ユダヤ教のチャバド哲学においても支持されている[28]。 |

| Controversy "Auschwitz survivor" testimony In The Missing Pieces of the Puzzle: A Reflection on the Odd Career of Viktor Frankl, Professor of history Timothy Pytell of California State University, San Bernardino,[29] conveys the numerous discrepancies and omissions in Frankl's "Auschwitz survivor" account and later autobiography, which many of his contemporaries, such as Thomas Szasz, similarly have raised.[30] In Frankl's Man's Search for Meaning, the book devotes approximately half of its contents to describing Auschwitz and the psychology of its prisoners, suggesting a long stay at the death camp, however his wording is contradictory and according to Pytell, "profoundly deceptive", when rather the impression of staying for months, Frankl was held close to the train, in the "depot prisoner" area of Auschwitz and for no more than a few days, he was neither registered there, nor assigned a number before being sent on to a subsidiary work camp of Dachau, known as Kaufering III, that together with Terezín, is the true setting of much of what is described in his book.[31][32][33] Origins and implications of logotherapy Frankl's doctrine was that one must instill meaning in the events in one's life, and that work and suffering can lead to finding meaning, with this ultimately what would lead to fulfillment and happiness. In 1982 the scholar and Holocaust analyst Lawrence L. Langer, critical of what he called Frankl's distortions of the true experience of those at Auschwitz,[34] and of Frankl's amoral focus on "meaning", that in Langer's assessment could just as equally be applied to Nazis "finding meaning in making the world free from Jews",[35] went on to write that "if this [logotherapy] doctrine had been more succinctly worded, the Nazis might have substituted it for the cruel mockery of Arbeit Macht Frei" ["work sets free", read by those entering Auschwitz].[36] In Pytell's view, Langer also penetrated through Frankl's disturbing subtext that Holocaust "survival [was] a matter of mental health." Langer criticized Frankl's tone as self-congratulatory and promotional throughout, so that "it comes as no surprise to the reader, as he closes the volume, that the real hero of Man's Search for Meaning is not man, but Viktor Frankl" by the continuation of the same fantasy of world-view meaning-making, which is precisely what had perturbed civilization into the holocaust-genocide of this era and others.[37] Pytell later would remark on the particularly sharp insight of Langer's reading of Frankl's Holocaust testimony, stating that with Langer's criticism published in 1982 before Pytell's biography, the former had thus drawn the controversial parallels, or accommodations in ideology without the knowledge that Victor Frankl was an advocate/"embraced"[38] the key ideas of the Nazi psychotherapy movement ("will and responsibility"[39]) as a form of therapy in the late 1930s. When at that time Frankl would submit a paper and contributed to the Göring institute in Vienna 1937 and again in early 1938 connecting the logotherapy focus on "world-view" to the "work of some of the leading Nazi psychotherapists",[40] both at a time before Austria was annexed by Nazi Germany in 1938.[41][42] Frankl's founding logotherapy paper, was submitted to and published in the Zentrallblatt fuer Psychotherapie [sic] the journal of the Goering Institute, a psychotherapy movement, with the "proclaimed agenda of building psychotherapy that affirmed a Nazi-oriented worldview".[43] The origins of logotherapy, as described by Frankl, were therefore a major issue of continuity that Pytell argues were potentially problematic for Frankl because he had laid out the main elements of logotherapy while working for/contributing to the Nazi-affiliated Göring Institute. Principally Frankl's 1937 paper, that was published by the institute.[42] This association, as a source of controversy, that logotherapy was palatable to Nazism is the reason Pytell suggests, Frankl took two different stances on how the concentration-camp experience affected the course of his psychotherapy theory. Namely, that within the original English edition of Frankl's most well known book, Man's Search for Meaning, the suggestion is made and still largely held that logotherapy was itself derived from his camp experience, with the claim as it appears in the original edition, that this form of psychotherapy was "not concocted in the philosopher's armchair nor at the analyst's couch; it took shape in the hard school of air-raid shelters and bomb craters; in concentration camps and prisoner of war camps." Frankl's statements however to this effect would be deleted from later editions, though in the 1963 edition, a similar statement again appeared on the back of the book jacket of Man's Search for Meaning. Frankl over the years would with these widely read statements and others, switch between the idea that logotherapy took shape in the camps to the claim that the camps merely were a testing ground of his already preconceived theories. An uncovering of the matter would occur in 1977 with Frankl revealing on this controversy, though compounding another, stating "People think I came out of Auschwitz with a brand-new psychotherapy. This is not the case."[44] Jewish relations and experiments on the resistance In the post war years, Frankl's attitude towards not pursuing justice nor assigning collective guilt to the Austrian people for collaborating with or acquiescing in the face of Nazism, led to "frayed" relationships between Frankl, many Viennese and the larger American Jewish community, such that in 1978 when attempting to give a lecture at the institute of Adult Jewish Studies in New York, Frankl was confronted with an outburst of boos from the audience and was called a "nazi pig". Frankl supported forgiveness and held that many in Germany and Austria were powerless to do anything about the atrocities which occurred and could not be collectively blamed.[45][46][47] In 1988 Frankl would further "stir up sentiment against him" by being photographed next to and in accepting the Great Silver Medal with Star for Services to the Republic of Austria as a Holocaust survivor, from President Waldheim, a controversial president of Austria who concurrent with the medal ceremony, was gripped by revelations that he had lied about his WWII military record and was under investigation for complicity in Nazi War crimes. It was later concluded that he was not involved in war crimes but had knowledge of them. Frankl's acceptance of the medal was viewed by many in the international Jewish community as a betrayal.[47] In his "Gutachten" Gestapo profile, Frankl is described as "politically perfect" by the Nazi secret police, with Frankl's membership in the Austro-fascist "Fatherland Front" in 1934, similarly stated in isolation. It has been suggested that as a state employee in a hospital he was likely automatically signed up to the party regardless of whether he wanted to or not. Frankl was interviewed twice by the secret police during the war, yet nothing of the expected contents, the subject of discussion or any further information on these interviews, is contained in Frankl's file, suggesting to biographers that Frankl's file was "cleansed" sometime after the war.[48][49] None of Frankl's obituaries mention the unqualified and unskilled brain lobotomy and trepanation medical experiments approved by the Nazis that Frankl performed on Jews who had committed suicide with an overdose of sedatives, in resistance to their impending arrest, imprisonment and enforced labour in the concentration camp system. The goal of these experiments were to try and revive those who had killed themselves, Frankl justified this by saying that he was trying to find ways to save the lives of Jews. Operating without any training as a surgeon, Frankl would voluntarily request of the Nazis to perform the experiments on those who had killed themselves, and once approved – published some of the details on his experiments, the methods of insertion of his chosen amphetamine drugs into the brains of these individuals, resulting in, at times, an alleged partial resuscitation, mainly in 1942 (prior to his own internment at Theresienstadt ghetto in September, later in that year). Historian Günter Bischof of Harvard University, suggests Frankl's approaching and requesting to perform lobotomy experiments could be seen as a way to "ingratiate" himself amongst the Nazis, as the latter were not, at that time, appreciative of the international scrutiny that these suicides were beginning to create, nor "suicide" being listed on arrest records.[50][51][52][11] Response to Timothy Pytell Timothy Pytell's critique towards Viktor Frankl was used by Holocaust denier Theodore O'Keefe, according to Alexander Batthyány. [53] Alexander Batthyány was a researcher and member of staff of the Viktor Frankl Archive in Vienna. Throughout the first chapter of his book "Viktor Frankl and the Shoah", he reflects on Timothy Pytell's work about Viktor Frankl, and the flaws in it. Batthyány points out that Pytell never visited the archive to consult primary sources from the person about whom he was writing. Batthyány also critiques Pytell for not interviewing Viktor Frankl while Frankl was still alive. Pytell even explains in his book on Frankl that he had the opportunity to meet him – as a friend offered it, yet he decided that he could not meet Frankl. |

論争 「アウシュビッツの生存者」証言 The Missing Pieces of the Puzzle: A Reflection on the odd Career of Viktor Frankl, California State University, San BernardinoのTimothy Pytell教授(歴史学)は[29]、フランクルの「アウシュヴィッツの生存者」証言とその後の自伝における数多くの矛盾と脱落を伝えており、トマス・ サズなど多くの同時代人が同様に提起している。 [30] フランクルの『人間の意味の探求』では、その内容の約半分がアウシュヴィッツとその囚人の心理描写に割かれており、死の収容所での長期滞在を示唆している が、彼の表現は矛盾しており、パイテルによれば、「深く欺瞞的」である、 フランクルは、アウシュヴィッツの「デポ囚人」区域の列車の近くに収容され、数日間も収容されなかったが、そこで登録もされず、番号も割り当てられなかっ た。 [31][32][33] ロゴセラピーの起源と意味合い フランクルの教義は、人は人生の出来事の中に意味を植え付けなければならず、労働と苦しみは意味を見出すことにつながり、それが最終的には充足と幸福につ ながるというものであった。1982年、学者でホロコースト分析家のローレンス・L. ランガーは、フランクルがアウシュヴィッツでの体験の真相を歪曲していると呼び[34]、フランクルが「意味」を非道徳的に重視していることを批判した、 [もしこの(ロゴセラピーの)教義がもっと簡潔な言葉で表現されていれば、ナチスはそれを残酷な嘲笑であるArbeit Macht Frei(アウシュヴィッツに入所する者が読む「仕事は自由を与える」)の代わりに使ったかもしれない」と書いている。] [ピテルの見解では、ランガーは、ホロコーストの「(生存は)精神衛生上の問題である」というフランクルの不穏なサブテキストにも通じていた。ランガーは フランクルの口調が終始自己満足的で宣伝的であると批判しており、「この巻を閉じるとき、『意味を求める人間』の真の主人公は人間ではなくヴィクトール・ フランクルであると読者に驚きを与えない」ように、世界観の意味づけという同じ幻想の継続によって、まさにこの時代やその他の時代のホロコースト・ジェノ サイドへと文明を動揺させてきたのである[37]。 ピテルは後に、フランクルのホロコースト証言に対するランガーの読解の特に鋭い洞察力について言及し、ピテルの伝記よりも前の1982年に出版されたラン ガーの批評によって、前者はヴィクトル・フランクルが1930年代後半に治療の一形態としてナチスの心理療法運動の重要な考え方(「意志と責任」 [39])を提唱/「受容」[38]していたことを知らずに、論争を呼ぶ類似性、あるいはイデオロギーにおける便宜を図っていたと述べている。その頃フラ ンクルは、1937年にウィーンで開催されたゲーリング研究所に論文を提出し、また1938年初頭には「世界観」に焦点を当てたロゴセラピーを「ナチスを 代表する心理療法家たちの仕事」[40]と結びつけて寄稿しており、いずれも1938年にオーストリアがナチス・ドイツに併合される前の時期であった。 [41][42]フランクルの創始者であるロゴセラピーの論文は、「ナチス志向の世界観を肯定する心理療法を構築することを公言した」心理療法運動である ゲーリング研究所の機関誌Zentrallblatt fuer Psychotherapie [中略]に投稿され、掲載された[43]。 したがって、フランクルによって記述されたロゴセラピーの起源は、連続性の大きな問題であり、ピテルは、フランクルがナチス系列のゲーリング研究所で働き ながら、あるいは貢献していたときに、ロゴセラピーの主要な要素を確立していたため、フランクルにとって潜在的に問題であったと主張している。フランクル が強制収容所での体験が彼の心理療法理論の経過にどのような影響を与えたかについて2つの異なる立場をとったのは、論理療法がナチズムにとって都合のよい ものであったというこの関連性が論争の原因であるとパイテルは示唆している。すなわち、フランクルの最も有名な著書である『人間の意味の探求』の原著(英 語版)の中で、この心理療法の形態は「哲学者の肘掛け椅子や分析者の長椅子で考案されたものではなく、防空壕や爆弾のクレーター、強制収容所や捕虜収容所 の厳しい学校で形作られたものである」という主張があり、現在でもその大部分が彼の収容所体験から派生したものであるという指摘がなされている。しかし、 このようなフランクルの記述は、後の版では削除されることになるが、1963年版では、『人間の意味の探求』のジャケットの裏に、再び同様の記述がある。 フランクルは何年もの間、これらの広く読まれた記述やその他の記述によって、ロゴセラピーは収容所で形作られたという考えと、収容所はすでに先入観のあっ た理論の実験場にすぎなかったという主張の間を行き来することになる。1977年、フランクルはこの論争について、「人々は、私がアウシュビッツから真新 しい心理療法を持って出てきたと思っている。これは事実ではない」[44]。 ユダヤ人との関係とレジスタンス実験 戦後数年間、ナチズムに協力したり、ナチズムを黙認したりしたオーストリアの人々に対して、正義を追求したり、集団的な罪を負わせたりしないというフラン クルの態度は、フランクル、多くのウィーン人、より大きなアメリカのユダヤ人社会との間に「ほころび」を生じさせた。フランクルは許しを支持し、ドイツと オーストリアの多くの人々は起こった残虐行為に対して何もすることができず、集団的に非難されることはないと主張した[45][46][47]。 1988年、フランクルは、ホロコースト生存者としてオーストリア共和国への貢献に対する星付き大銀メダルを、メダル授与式と同時に、第二次世界大戦時の 軍歴について嘘をつき、ナチスの戦争犯罪に加担した容疑で捜査を受けていたことが暴露され、物議を醸していたオーストリア大統領ヴァルトハイム大統領の隣 で写真に撮られ、それを受け取ることで、さらに「自分に対する感情をかき立てる」ことになる。その後、フランクルは戦争犯罪には関与していなかったが、そ の事実を知っていたという結論に達した。フランクルが勲章を受章したことは、国際的なユダヤ人コミュニティの多くから裏切りとみなされた[47]。 ゲシュタポの「グータヒテン」プロフィールの中で、フランクルはナチス秘密警察によって「政治的に完璧」と評されており、フランクルが1934年にオース トリア・ファシストの「祖国戦線」のメンバーであったことも同様に単独で述べられている。病院に勤める国家公務員であったフランクルは、本人が望むと望ま ざるとにかかわらず、自動的に党に加入させられた可能性が高いと指摘されている。フランクルは戦時中に2度秘密警察から事情聴取を受けているが、これらの 事情聴取に関して期待された内容、議論の対象、更なる情報はフランクルのファイルには何も記載されておらず、伝記作家はフランクルのファイルが戦後のある 時期に「浄化」されたことを示唆している[48][49]。 フランクルの死亡記事はどれも、フランクルが、差し迫った逮捕、投獄、強制収容所システムでの強制労働に抵抗するために、鎮静剤の過剰摂取で自殺したユダ ヤ人に対して行った、ナチスによって承認された無資格で未熟練な脳ロボトミーとトレパネーション医学実験について触れていない。これらの実験の目的は、自 殺した人々を蘇生させようとすることであり、フランクルは、ユダヤ人の命を救う方法を見つけようとしていたのだと言って、これを正当化した。外科医として の訓練を受けていないフランクルは、自発的にナチスに依頼して、自殺した人々を対象に実験を行い、いったん承認されると、主に1942年(同年9月に自身 がテレジエンシュタット・ゲットーに収容される前)に、実験の詳細の一部、自分が選んだアンフェタミン剤をこれらの人々の脳に挿入する方法、その結果、時 には部分的に蘇生したとされる結果を公表した。ハーヴァード大学の歴史家ギュンター・ビショフは、フランクルがロボトミー実験を行うために接近し、依頼し たのは、ナチスの間で「恩を売る」ための方法であったかもしれないと示唆している。ナチスは当時、これらの自殺が国際的な監視の目を向け始めていたこと や、逮捕記録に「自殺」と記載されていたことを評価していなかったからである[50][51][52][11]。 ティモシー・パイテルへの反応 ヴィクトール・フランクルに対するティモシー・パイテルの批評は、アレクサンダー・バティアニーによれば、ホロコースト否定論者のセオドア・オキーフに よって利用された。[アレクサンダー・バチアーニーはウィーンのヴィクトール・フランクル・アーカイヴの研究者でありスタッフであった。著書『ヴィクトー ル・フランクルとショアー』の第1章を通して、彼はヴィクトール・フランクルに関するティモシー・ピテルの著作とその欠陥について考察している。バチアー ニは、ピテルが一度も文書館を訪れ、自分が執筆している人物の一次資料を参照しなかったことを指摘する。また、ピテルはフランクルが生きている間にヴィク トール・フランクルにインタビューをしなかったと批判している。ピテルはフランクルに関する著書の中で、友人からの申し出でフランクルに会う機会があった にもかかわらず、フランクルに会うことはできなかったと説明している。 |

| Personal life In 1941, Frankl married Tilly Grosser, who was a station nurse at Rothschild Hospital. Soon after they were married she became pregnant, but they were forced to abort the child.[54] Tilly died in the Bergen Belsen concentration camp.[2][1] Frankl's father, Gabriel, originally from Pohořelice, Moravia, died in the Theresienstadt Ghetto concentration camp on 13 February 1943, aged 81, from starvation and pneumonia. His mother and brother, Walter, were both killed in Auschwitz. His sister, Stella, escaped to Australia.[2][1] In 1947, Frankl married Eleonore "Elly" Katharina Schwindt. She was a practicing Catholic. The couple respected each other's religious backgrounds, both attending church and synagogue, and celebrating Christmas and Hanukkah. They had one daughter, Gabriele, who went on to become a child psychologist.[2][4][55] Although it was not known for 50 years, his wife and son-in-law reported after his death that he prayed every day and had memorized the words of daily Jewish prayers and psalms.[56][28] Frankl died of heart failure in Vienna on 2 September 1997. He is buried in the Jewish section of the Vienna Central Cemetery.[57] |

私生活 1941年、フランクルはロスチャイルド病院の看護婦だったティリー・グロッサーと結婚。ティリーはベルゲン・ベルゼン強制収容所で死亡した[2][1]。 フランクルの父ガブリエルはモラヴィアのポホジェリツェ出身で、1943年2月13日にテレジエンシュタット・ゲットー強制収容所で飢餓と肺炎のため81歳で死亡。母と兄のヴァルターはアウシュビッツで殺された。妹のステラはオーストラリアに逃れた[2][1]。 1947年、フランクルはエレオノーレ "エリー "カタリーナ・シュヴィントと結婚。彼女はカトリック信者であった。夫婦は互いの宗教的背景を尊重し、教会やシナゴーグに通い、クリスマスやハヌカを祝っ た。50年間知られていなかったが、フランクルの死後、妻と義理の息子は、フランクルが毎日祈りを捧げ、毎日のユダヤ教の祈りと詩篇の言葉を暗記していた と報告している[56][28]。 フランクルは1997年9月2日にウィーンで心不全のため死去。彼はウィーン中央墓地のユダヤ人区画に埋葬されている[57]。 |

| His books in English are: Man's Search for Meaning. An Introduction to Logotherapy, Beacon Press, Boston, 2006. ISBN 978-0807014271 (English translation 1959. Originally published in 1946 as Ein Psychologe erlebt das Konzentrationslager, "A Psychologist Experiences the Concentration Camp") The Doctor and the Soul, (originally titled Ärztliche Seelsorge), Random House, 1955. On the Theory and Therapy of Mental Disorders. An Introduction to Logotherapy and Existential Analysis. Translated by James M. DuBois. Brunner-Routledge, London & New York, 2004. ISBN 0415950295 Psychotherapy and Existentialism. Selected Papers on Logotherapy, Simon & Schuster, New York, 1967. ISBN 0671200569 The Will to Meaning. Foundations and Applications of Logotherapy, New American Library, New York, 1988 ISBN 0452010349 The Unheard Cry for Meaning. Psychotherapy and Humanism Simon & Schuster, New York, 2011 ISBN 978-1451664386 Viktor Frankl Recollections: An Autobiography; Basic Books, Cambridge, MA 2000. ISBN 978-0738203553. Man's Search for Ultimate Meaning. (A revised and extended edition of The Unconscious God; with a foreword by Swanee Hunt). Perseus Book Publishing, New York, 1997; ISBN 0306456206. Paperback edition: Perseus Book Group; New York, 2000; ISBN 0738203548. Yes to Life: In Spite of Everything. Beacon Press, Boston, 2020. ISBN 978-0807005552. |

|

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Viktor_Frankl |

フ ランクルは強制収容所すなわち絶滅キャンプのような環境におかれても人間性を失わないことの意味を問い続けたが、第三帝国の絶滅キャンプがも たらした「新・ユダヤ人問題」は、戦後のユダヤ人の生存者アイデンティティに多大な意味をもたらした。彼の同名の著書には2つの翻訳のヴァージョンがあり 『苦悩の存在論 : ニヒリズムの根本問題』と『苦悩する人間』がある。3章仕立てで、第1章 自動性から実存へ—ニヒリズム批判(心理学主義;社会学主義;時代精神の病理 学)、第2章 意味否定から意味解明へ、第3章 自律から超越へ—ヒューマニズムの危機(人間中心主義;擬人主義)。第4章 人格についての十の命題(こ れは、別論文Zehn Thesen über die Personの翻訳)からなる。

第1章 自動性から実存へ—ニヒリズム批判(心理学主義;社会学主義;時代精神の病理 学)A. Von der Automatie zur Existenz: Kritik des Nihilismus

第2章 意味否定から意味解明へ

第3章 自律から超越へ—ヒューマニズムの危機(人間中心主義;擬人主義)

第4章 人格についての十の命題(こ れは、別論文Zehn Thesen über die Personの翻訳)

***

Vorwort

Inhaltsverzeichnis

A. Von der Automatie zur Existenz: Kritik des Nihilismus

I. Psychologismus

1 . Psychologismus und Psychotherapie

2. Psychotherapie und Logotherapie

3. Logotherapie und Existenzanalyse

4. Existenzanalyse und Psychoanalyse

a) Lust und Wert

b) Trieb und Sinn.

5. Psychoanalyse und Individualpsychologie

II. Soziologismus

Pathologie des Zeitgeistes

B. Von der Sinnleugnung zur

Sinndeutung.

Metaklinische Sinndeutung des Leidens,

C. Von der Autonomie zur Transzendenz: Krise des Humanismus.

I. Anthropozentrismus

II. Anthropomorphismus

Autorenverzeichnis

スピルバーグ『シンドラーのリスト』[原作Keneally, Thomas, シンドラーズ・リスト :

1200人のユダヤ人を救ったドイツ人,

新潮文庫、1989.](1993)の最終シーンにおけるユダヤ人によるユダヤ人のための精神的慰撫という状況が登場するは

るか以前には、生存者はユダヤ人社会のなかでは二重の苦しみを背負わされていた。すなわち、(i)同胞のみならず親族の中に犠牲者が出た生き残りであると

いう苦悩、(ii)戦後にリバイバルするユダヤ人原罪説のなかでの犠牲者非難というスティグマ付与とネグレクト、である。さらにこれに、それまで伝統的な

ユダヤ人蔑視思想がもたらす迫害や差別が絶えることなく続いていた。さらに、戦後のシオニズム、パレスチナ問題、ユダヤ建国が、このような状況に対して複

雑な陰を落とした。ちなみに「『シンドラーのリスト』に出てくる強制収容所司令官の娘」であったモニカ・ゲート(Göth, Monika, = Monika Hertwig)

"Ich muss doch meinen Vater lieben,

oder?"も、自分の父親が犯した人道的犯罪により、彼女には何の咎(1945年11月生まれ)もないものの、複雑な気持ちを抱えること

になった、ホモ・パティエンスとしての存在と言えないことはない。

このような文脈の中で、フランクルの苦悩する人間像をぬきにしては考えることができない。

しかし、提唱者フランクルを超えて、人間存在を受苦的存在として位置づけている思想やイデオロギーはそこかしこにある。したがって以下は、受苦 的な存在が人間の基本形であるという考え方について、より一般的に考えよう。それは人間存在を一義的に、苦悩する存在であると一般化することには、人間を 常に知恵ある存在(Homo sapiens)と定義づける(一種 の愚行である)ことと同様に、常に問題含みのものであるからである。

マーシャル・サーリンズ(1996)は、このような受苦的な人間存在の フォームが西洋中心的な所産であることを示して、世界のさまざまな民族誌 事例をもって、仮借のない批判を展開した。彼によると、これは啓蒙主 義が生み出した、苦痛と快楽の理解図式によるものであり人間にとって普遍的なものでは ないという。

「西欧史のある時代に、人間の社会と行動のすべては、個人の快楽と苦痛の大いなる構図を介して一般的にも哲学的にも認知されるようになっ た。『リヴァイアサン』にあるように、再びすべては、人がよいと感じるものに向かい、また傷つけられるものからは遠ざかるという、単純で悲しい人生論への 帰着した。私が《悲しい》といったわけは、人生を幸福の追求と定義する人は、慢性的に不幸だからである。今となってはあまりにも長きにわたり、これ—— 「この不安こそは、人間を勤勉と行動に駆り立てる唯一ではないとしても、主たる要因であり」、まさにわれわれがものに感じるのは喜びではなく、それがない ときに感じる苦痛なのだ(Locke[ジョン・ロック]『人間悟性論』2.20.6)——は一般に膾炙した感情になってしまった」(サーリ ンズ (下)p.124)[翻訳は山本真鳥]。

ジョン・ロック『人間悟性論』(John Locke, An Essay Concerning Human Understanding, 1689)の当該箇所の引用

"6. Desire. The uneasiness a man finds in himself upon the absence of anything whose present enjoyment carries the idea of delight with it, is that we call desire; which is greater or less, as that uneasiness is more or less vehement. Where, by the by, it may perhaps be of some use to remark, that the chief, if not only spur to human industry and action is uneasiness. For whatsoever good is proposed, if its absence carries no displeasure or pain with it, if a man be easy and content without it, there is no desire of it, nor endeavour after it; there is no more but a bare velleity, the term used to signify the lowest degree of desire, and that which is next to none at all, when there is so little uneasiness in the absence of anything, that it carries a man no further than some faint wishes for it, without any more effectual or vigorous use of the means to attain it. Desire also is stopped or abated by the opinion of the impossibility or unattainableness of the good proposed, as far as the uneasiness is cured or allayed by that consideration. This might carry our thoughts further, were it seasonable in this place." (http://ebooks.adelaide.edu.au/l/locke/john/l81u/B2.20.html)

これらの意識を別の価値観の体系でパラフレイズすると「利益の追求こそが人生あると定義する人(Homo economicus)は、慢性的にその心は金欠で物質追

求の野心に満ち満ちている」(垂水源之介)ということに

なる。

ホモ(Homo)・サピエンスの類縁種のリスト

関連リンク

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

余滴