土地と所有について

On land and property

土地を所有すること。これは現在の日本社会にとって は自明のこととなっているが、近代啓蒙が土地を個人が所有することができるようになるための理解には、長い間の、所有権概念の成立、私的所有の概念、購入 した土地の転売を可能にする社会的条件、土地市場の成立、土地の専有権や借地権概念などの整備、物件法に関する整備など、長い歴史を振り返らないとならな い。

土地と人間の関係については、土地(land)、占有(Appropriation

in law)、所有(Property)、

共有(Sharing)、コモンズ(common)、公共性

(communality, public nature)、共同資源(communal

resources)、不動産(immovables)、土地共有(sharing land)などの理解が必要になる。

| Property Property is a system of rights that gives people legal control of valuable things,[1] and also refers to the valuable things themselves. Depending on the nature of the property, an owner of property may have the right to consume, alter, share, redefine, rent, mortgage, pawn, sell, exchange, transfer, give away, or destroy it, or to exclude others from doing these things,[2] as well as to perhaps abandon it; whereas regardless of the nature of the property, the owner thereof has the right to properly use it under the granted property rights. In economics and political economy, there are three broad forms of property: private property, public property, and collective property (also called cooperative property).[3] Property that jointly belongs to more than one party may be possessed or controlled thereby in very similar or very distinct ways, whether simply or complexly, whether equally or unequally. However, there is an expectation that each party's will (rather discretion) with regard to the property be clearly defined and unconditional,[citation needed] to distinguish ownership and easement from rent. The parties might expect their wills to be unanimous, or alternately every given one of them, when no opportunity for or possibility of a dispute with any other of them exists, may expect his, her, it's or their own will to be sufficient and absolute. The first Restatement defines property as anything, tangible or intangible, whereby a legal relationship between persons and the State enforces a possessory interest or legal title in that thing. This mediating relationship between individual, property, and State is called a property regime.[4] In sociology and anthropology, property is often defined as a relationship between two or more individuals and an object, in which at least one of these individuals holds a bundle of rights over the object. The distinction between "collective property" and "private property" is regarded as confusion since different individuals often hold differing rights over a single object.[5][6] Types of property include real property (the combination of land and any improvements to or on the ground), personal property (physical possessions belonging to a person), private property (property owned by legal persons, business entities or individual natural persons), public property (State-owned or publicly owned and available possessions) and intellectual property (exclusive rights over artistic creations, inventions, etc.). However, the last is not always as widely recognized or enforced.[7] An article of property may have physical and incorporeal parts. A title, or a right of ownership, establishes the relation between the property and other persons, assuring the owner the right to dispose of the property as the owner sees fit.[citation needed] The unqualified term "property" is often used to refer specifically to real property. |

財産(あるいはプロパティ) 財産とは、価値あるものを法的に支 配する権利を人々に与える権利体系であり[1]、価値あるものそのものを指すこともある。財産の性質に応じて、財産の所有者は、それを消費、変更、共有、 再定義、賃貸、抵当、質入れ、売却、交換、譲渡、贈与、破壊する権利、あるいはこれらの行為を他者から排除する権利[2]を有し、またおそらく放棄する権 利も有するが、財産の性質にかかわらず、その所有者は、付与された財産権の下でそれを適切に使用する権利を有する。 経済学および政治経済学では、財産の大まかな形態として、私有財産、公共財産、および集団財産(協同財産とも呼ばれる)の3つがある[3]。複数の当事者 に共同で帰属する財産は、単純であるか複雑であるか、平等であるか不平等であるかを問わず、非常に類似した方法で所有または管理されることもあれば、非常 に異なる方法で所有または管理されることもある。しかし、所有権や地役権と賃借権とを区別するために、財産に関する各当事者の意思(むしろ裁量)が明確に 定義され、無条件であることが期待される[要出典]。当事者は、各自の意志が一致することを期待するかもしれないし、あるいは、他の当事者と争う機会や可 能性が存在しない場合には、各自の意志が十分かつ絶対的なものであることを期待するかもしれない。第一再定義書では、財産とは有形・無形を問わず、個人と 国家との間の法的関係によって、その物に対する所有権や法的権原が行使されるものであると定義している。このような個人、財産、国家の間の仲介関係は、財 産制度と呼ばれる[4]。 社会学や人類学では、財産はしばしば2人以上の個人と対象物との間の関係として定義され、その中で少なくとも1人の個人が対象物に対する権利の束を保持し ている。集団財産」と「私有財産」の区別は、異なる個人が一つの対象物に対して異なる権利を保有することが多いため、混同されていると考えられている [5][6]。 財産の種類には、不動産(土地とその改良物、またはその上にあるものの組み合わせ)、個人財産(人に属する物理的所有物)、私有財産(法人、事業体、また は自然人個人が所有する財産)、公共財産(国有または公有で利用可能な所有物)、知的財産(芸術的創作物、発明などに対する排他的権利)が含まれる。しか し、最後の財産は、必ずしも広く認識されたり、行使されたりしていない[7]。所有権または所有権は、財産と他の者との関係を確立し、所有者が適切と考え るように財産を処分する権利を所有者に保証する。 |

| Definition Property is often defined by the code of the local sovereignty and protected wholly or - more usually, partially - by such entity, the owner being responsible for any remainder of protection. The standards of the proof concerning proofs of ownerships are also addressed by the code of the local sovereignty, and such entity plays a role accordingly, typically somewhat managerial. Some philosophers[who?] assert that property rights arise from social convention, while others find justifications for them in morality or in natural law.[citation needed] Various scholarly disciplines (such as law, economics, anthropology or sociology) may treat the concept more systematically, but definitions vary, most particularly when involving contracts. Positive law defines such rights, and the judiciary can adjudicate and enforce property rights. According to Adam Smith (1723-1790), the expectation of profit from "improving one's stock of capital" rests on private-property rights.[8] Capitalism has as a central assumption that property rights encourage their holders to develop the property, generate wealth, and efficiently allocate resources based on the operation of markets. From this has evolved the modern conception of property as a right enforced by positive law, in the expectation that this will produce more wealth and better standards of living. However, Smith also expressed a very critical view of the effects of property laws on inequality: "Wherever there is a great property, there is great inequality … Civil government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is in reality instituted for the defense of the rich against the poor, or of those who have some property against those who have none at all."[9] (Adam Smith, Wealth of Nations) In his 1881 text "The Common Law", Oliver Wendell Holmes describes property as having two fundamental aspects.[citation needed] The first, possession, can be defined as control over a resource based on the practical inability to contradict the ends of the possessor. The second title is the expectation that others will recognize rights to control resources, even when not in possession. He elaborates on the differences between these two concepts and proposes a history of how they came to be attached to persons, as opposed to families or entities such as the church. Classical liberalism subscribes to the labor theory of property. Its proponents hold that individuals each own their own life; it follows that one must acknowledge the products of that life and that those products can be traded in free exchange with others. "Every man has a property in his person. This nobody has a right to, but himself." (John Locke, "Second Treatise on Civil Government", 1689) "The reason why men enter into society is the preservation of their property." (John Locke, "Second Treatise on Civil Government", 1689) "Life, liberty, and property do not exist because men have made laws. On the contrary, it was the fact that life, liberty, and property existed beforehand that caused men to make laws in the first place." (Frédéric Bastiat, The Law, 1850) Conservatism subscribes to the concept that freedom and property are closely linked - building on traditions of thought that property guarantees freedom[10] or causes freedom.[11] The more widespread the possession of the private property, conservatism propounds, the more stable and productive a state or nation is. Conservatives maintain that the economic leveling of property, especially of the forced kind, is not economic progress. "Separate property from private possession and Leviathan becomes master of all... Upon the foundation of private property, great civilizations are built. The conservative acknowledges that the possession of property fixes certain duties upon the possessor; he accepts those moral and legal obligations cheerfully." (Russell Kirk, The Politics of Prudence, 1993) Socialism 's fundamental principles center on a critique of this concept, stating (among other things) that the cost of defending property exceeds the returns from private property ownership and that, even when property rights encourage their holders to develop their property or generate wealth, they do so only for their benefit, which may not coincide with advantage to other people or society at large. Libertarian Socialism generally accepts property rights with a short abandonment period. In other words, a person must make (more-or-less) continuous use of the item or else lose ownership rights. This is usually referred to as "possession property" or "usufruct." Thus, in this usufruct system, absentee ownership is illegitimate, and workers own the machines or other equipment they work with. Communism argues that only common ownership of the means of production will assure the minimization of unequal or unjust outcomes and the maximization of benefits and that; therefore humans should abolish private ownership of capital (as opposed to property). Both communism and some forms of socialism have also upheld the notion that private ownership of capital is inherently illegitimate. This argument centers on the idea that private ownership of capital always benefits one class over another, giving rise to domination through this privately owned capital. Communists do not oppose personal property that is "hard-won, self-acquired, self-earned" (as "The Communist Manifesto" puts it) by members of the proletariat. Both socialism and communism distinguish carefully between private ownership of capital (land, factories, resources, etc.) and private property (homes, material objects, and so forth). Types of property Most legal systems distinguish between different types of property, especially between land (immovable property, estate in land, real estate, real property) and all other forms of property—goods and chattels, movable property or personal property, including the value of legal tender if not the legal tender itself, as the manufacturer rather than the possessor might be the owner. They often distinguish tangible and intangible property. One categorization scheme specifies three species of property: land, improvements (immovable man-made things), and personal property (movable man-made things).[12] In common law, real property (immovable property) is the combination of interests in land and improvements thereto, and personal property is interest in movable property. Real property rights are rights relating to the land. These rights include ownership and usage. Owners can grant rights to persons and entities in the form of leases, licenses, and easements. Throughout the last centuries of the second millennium, with the development of more complex theories of property, the concept of personal property had become divided[by whom?] into tangible property (such as cars and clothing) and intangible property (such as financial assets and related rights, including stocks and bonds; intellectual property, including patents, copyrights and trademarks; digital files; communication channels; and certain forms of identifier, including Internet domain names, some forms of network address, some forms of handle and again trademarks). Treatment of intangible property is such that an article of property is, by law or otherwise by traditional conceptualization, subject to expiration even when inheritable, which is a key distinction from tangible property. Upon expiration, the property, if of the intellectual category, becomes a part of public domain, to be used by but not owned by anybody, and possibly used by more than one party simultaneously due to the inapplicability of scarcity to intellectual property. Whereas things such as communications channels and pairs of electromagnetic spectrum bands and signal transmission power can only be used by a single party at a time, or a single party in a divisible context, if owned or used. Thus far or usually, those are not considered property, or at least not private property, even though the party bearing right of exclusive use may transfer that right to another. In many societies the human body is considered property of some kind or other. The question of the ownership and rights to one's body arise in general in the discussion of human rights, including the specific issues of slavery, conscription, rights of children under the age of majority, marriage, abortion, prostitution, drugs, euthanasia and organ donation. |

財産の定義 財産は、多くの 場合、地域主権の規範によって定義され、その全体的または部分的に保護される。所有権の証明に関する証明の基準も地域主権の規範によって扱われ、そのよう な主体はそれに応じて、典型的にはいくらか管理的な役割を果たす。所有権は社会的慣習から発生すると主張する哲学者[誰?]もいれば、道徳や自然法に正当 性を見出す哲学者もいる[要出典]。 様々な学問分野(法学、経済学、人類学、社会学など)がこの概念をより体系的に扱うことがあるが、特に契約に関わる場合、定義は様々である。実定法はこの ような権利を定義し、司法は財産権を裁定・執行することができる。 アダム・スミス(1723~1790年)によれば、「自分の資本ストックを向上させる」ことによる利潤の期待は、私有財産権に基づいている[8]。資本主 義は、財産権がその所有者に財産を発展させ、富を生み出し、市場の運営に基づいて資源を効率的に配分することを促すということを中心的な前提としている。 このことから、より多くの富とより良い生活水準が生み出されることを期待し、正法によって強制される権利としての近代的な所有権の概念が発展した。しか し、スミスは財産法が不平等に及ぼす影響について、非常に批判的な見解も示している: 大きな財産があるところには、必ず大きな不平等がある......市民政府は、それが財産の保障のために制定されている限りにおいて、実際には、貧乏人に 対する金持ちの防衛のため、あるいはまったく財産を持たない者に対する多少の財産を持つ者の防衛のために制定されているのである」[9](アダム・スミス 『国富論』)。 オリバー・ウェンデル・ホームズは1881年の著書『コモン・ロー』の中で、財産には2つの基本的な側面があると述べている[要出典]。1つ目の所有権 は、所有者の目的に反することができないという実際的な可能性に基づく、資源に対する支配と定義できる。第二の権原は、所有権がない場合でも、他者が資源 を支配する権利を認めるという期待である。彼はこの2つの概念の違いを詳しく説明し、家族や教会のような団体ではなく、個人に付随するようになった歴史を 提案する。 古典的自由主義は、財産の労働理論を支持している。その支持者は、個人はそれぞれ自分の生命を所有しており、その生命の産物を認めなければならず、その産 物は他者と自由な交換で取引できるとする。 「すべての人は、その個人に対して財産を持っている。これは、自分以外の誰にも権利がない。"(ジョン・ロック『第二条約』) (ジョン・ロック『市民政府第二論』1689年) 「人が社会に入る理由は、自分の財産を守るためである。(ジョン・ロック『市民政府第二論』1689年) 「生命、自由、財産が存在するのは、人間が法律を作ったからではない。それどころか、生命、自由、財産があらかじめ存在していたからこそ、人間は最初に法 律を作ったのである。" (フレデリック・バスティア『法』1850年) 保守主義は、自由と財産は密接に結びついており、財産が自由を保証する[10]、あるいは自由を引き起こす[11]という伝統的な考え方を基盤としてい る。私有財産の所有が広まれば広まるほど、国家や民族はより安定し、生産的になると保守主義は提唱する。保守派は、財産の経済的平準化、特に強制的な種類 の平準化は経済的進歩ではないと主張する。 「私有財産から財産を切り離せば、リヴァイアサンがすべての支配者となる。私有財産の基礎の上に、偉大な文明が築かれる。保守主義者は、財産の所有が所有 者に一定の義務を課すことを認め、それらの道徳的・法的義務を快く受け入れる。(ラッセル・カーク『思慮分別の政治学』1993年) 社会主義の基本原則は、この概念に対する批判を中心に据えたものであり、(とりわけ)財産を守るためのコストは私有財産所有からの見返りを上回るとし、財 産権が所有者に財産の開発や富の創出を促すとしても、それは所有者の利益のためだけであり、他の人々や社会全体にとっての利益とは一致しない可能性がある と述べている。 リバタリアン社会主義は一般的に、短い放棄期間を伴う財産権を認めている。言い換えれば、人はその品物を(多かれ少なかれ)継続的に使用しなければ所有権 を失う。これは通常、"所有権 "または "用益権 "と呼ばれる。従って、この用益物権制度では、不在者所有権は非合法であり、労働者は自分が働く機械やその他の設備を所有する。 共産主義は、生産手段の共同所有のみが、不平等または不公正な結果の最小化と利益の最大化を保証すると主張する。 共産主義も、ある種の社会主義も、資本の私有は本質的に非合法であるという考え方を支持してきた。この主張は、資本の私有は常にある階級に利益をもたら し、私有資本による支配を生むという考えに基づいている。共産主義者は、プロレタリアートの構成員によって「苦労して勝ち取った、自分で獲得した、自分で 勝ち取った」(『共産党宣言』が言うように)個人所有に反対しない。社会主義も共産主義も、資本の私有(土地、工場、資源など)と私有財産(家、物など) を注意深く区別している。 財産の種類 ほとんどの法制度は、財産の種類を区別しており、特に土地(動産、土地所有権、不動産、実物所有権)と、その他のあらゆる形態の財産(財物、動産、動産ま たは動産であり、所有者ではなく製造者が所有者である可能性があるため、法定通貨そのものではないとしても法定通貨の価値を含む)を区別している。有形財 産と無形財産を区別することも多い。ある分類法では、土地、改良物(不動人工物)、動産(動産人工物)の3種類の財産を規定している[12]。 コモン・ローでは、不動産(不動財産)は土地とその改良物に対する権利の組み合わせであり、動産は動産に対する権利である。不動産所有権は土地に関する権 利である。これらの権利には所有権と使用権が含まれる。所有者は、リース、ライセンス、地役権という形で個人や団体に権利を与えることができる。 第二千年紀の最後の世紀を通じて、より複雑な財産理論の発展とともに、個人財産の概念は、有形財産(自動車や衣服など)と無形財産(株式や債券などの金融 資産および関連する権利、特許権、著作権、商標権などの知的財産、デジタルファイル、通信チャネル、インターネットドメイン名、ネットワークアドレスの一 部、ハンドルネーム、商標権などの識別子の一部)に分けられるようになった。 無体財産の扱いは、法律や伝統的な概念によって、財産は相続可能であっても期限切れとなる。知的財産のカテゴリーに属するものであれば、期限切れになる と、その財産はパブリックドメインの一部となり、誰にも所有されることなく使用される。一方、通信チャネルや電磁スペクトル帯域の組、信号送信電力といっ たものは、所有または使用される場合、一度に単一の当事者、または分割可能な文脈における単一の当事者によってのみ使用される。これまでのところ、あるい は通常は、排他的使用権を持つ当事者がその権利を他者に譲渡することはあっても、それらは財産とはみなされず、少なくとも私有財産とはみなされない。 多くの社会では、人間の身体は何らかの財産とみなされている。奴隷制、徴兵制、成人年齢に達していない子供の権利、結婚、中絶、売春、薬物、安楽死、臓器 提供などの具体的な問題を含め、人権の議論では一般的に自分の身体の所有権や権利の問題が生じる。 |

| Issues in property theory Principle The two major justifications are given for the original property, or the homestead principle, are effort and scarcity. John Locke emphasized effort, "mixing your labor"[13] with an object, or clearing and cultivating virgin land. Benjamin Tucker preferred to look at the telos of property, i.e., what is the purpose of property? His answer: to solve the scarcity problem. Only when items are relatively scarce concerning people's desires, do they become property.[14] For example, hunter-gatherers did not consider land to be property, since there was no shortage of land. Agrarian societies later made arable land property, as it was scarce. For something to be economically scarce, it must necessarily have the "exclusivity property"—that use by one person excludes others from using it. These two justifications lead to different conclusions on what can be property. Intellectual property—incorporeal things like ideas, plans, orderings and arrangements (musical compositions, novels, computer programs)—are generally considered valid property to those who support an effort justification, but invalid to those who support a scarcity justification, since the things don't have the exclusivity property (however, those who support a scarcity justification may still support other "intellectual property" laws such as Copyright, as long as these are a subject of contract instead of government arbitration). Thus even ardent propertarians may disagree about IP.[15] By either standard, one's body is one's property. From some anarchist points of view, the validity of property depends on whether the "property right" requires enforcement by the State. Different forms of "property" require different amounts of enforcement: intellectual property requires a great deal of state intervention to enforce, ownership of distant physical property requires quite a lot, ownership of carried objects requires very little. In contrast, requesting one's own body requires absolutely no state intervention. So some anarchists don't believe in property at all. Many things have existed that did not have an owner, sometimes called the commons. The term "commons," however, is also often used to mean something entirely different: "general collective ownership"—i.e. common ownership. Also, the same term is sometimes used by statists to mean government-owned property that the general public is allowed to access (public property). Law in all societies has tended to reduce the number of things not having clear owners. Supporters of property rights argue that this enables better protection of scarce resources due to the tragedy of the commons. At the same time, critics say that it leads to the 'exploitation' of those resources for personal gain and that it hinders taking advantage of potential network effects. These arguments have differing validity for different types of "property"—things that are not scarce are, for instance, not subject to the tragedy of the commons. Some apparent critics advocate general collective ownership rather than ownerlessness. Things that do not have owners include: ideas (except for intellectual property), seawater (which is, however, protected by anti-pollution laws), parts of the seafloor (see the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea for restrictions), gases in Earth's atmosphere, animals in the wild (although in most nations, animals are tied to the land. In the United States and Canada, wildlife is generally defined in statute as property of the State. This public ownership of wildlife is referred to as the North American Model of Wildlife Conservation and is based on The Public Trust Doctrine.[16]), celestial bodies and outer space, and land in Antarctica. The nature of children under the age of majority is another contested issue here. In ancient societies, children were generally considered the property of their parents. However, children in most modern communities theoretically own their bodies but are not regarded as competent to exercise their rights. Their parents or guardians are given most of the fundamental rights of control over them. Questions regarding the nature of ownership of the body also come up in the issue of abortion, drugs, and euthanasia. In many ancient legal systems (e.g., early Roman law), religious sites (e.g. temples) were considered property of the God or gods they were devoted to. However, religious pluralism makes it more convenient to have sacred sites owned by the spiritual body that runs them. Intellectual property and air (airspace, no-fly zone, pollution laws, which can include tradable emissions rights) can be property in some senses of the word. Ownership of land can be held separately from the ownership of rights over that land, including sporting rights,[17] mineral rights, development rights, air rights, and such other rights as may be worth segregating from simple land ownership. Ownership Main article: Ownership Ownership laws may vary widely among countries depending on the nature of the property of interest (e.g., firearms, real property, personal property, animals). Persons can own property directly. In most societies legal entities, such as corporations, trusts and nations (or governments) own property. In many countries women have limited access to property following restrictive inheritance and family laws, under which only men have actual or formal rights to own property. In the Inca empire, the dead emperors, considered gods, still controlled property after death.[18] Government interference In 17th-century England, the legal directive that nobody may enter a home (which in the 17th century would typically have been male-owned) unless by the owner's invitation or consent, was established as common law in Sir Edward Coke 's "Institutes of the Lawes of England". "For a man's house is his castle, et domus sua cuique est tutissimum refugium [and each man's home is his safest refuge]." It is the origin of the famous dictum, "an Englishman's home is his castle".[19] The ruling enshrined into law what several English writers had espoused in the 16th century.[19] Unlike the rest of Europe the British had a proclivity towards owning their own homes.[19] British Prime Minister William Pitt, 1st Earl of Chatham defined the meaning of castle in 1763, "The poorest man may in his cottage bid defiance to all the forces of the crown. It may be frail – its roof may shake – the wind may blow through it – the storm may enter – the rain may enter – but the King of England cannot enter."[19] That principle was carried to the United States. Under U.S. law, the principal limitations on whether and the extent to which the State may interfere with property rights are set by the Constitution. The Takings clause requires that the government (whether State or federal—for the 14th Amendment's due process clause imposes the 5th Amendment's takings clause on state governments) may take private property only for a public purpose after exercising due process of law, and upon making "just compensation." If an interest is not deemed a "property" right or the conduct is merely an intentional tort, these limitations do not apply, and the doctrine of sovereign immunity precludes relief.[20] Moreover, if the interference does not almost completely make the property valueless, the interference will not be deemed a taking but instead a mere regulation of use.[21] On the other hand, some governmental regulations of property use have been deemed so severe that they have been considered "regulatory takings."[22] Moreover, conduct is sometimes deemed only a nuisance, or another tort has been held a taking of property where the conduct was sufficiently persistent and severe.[23] |

財産論の課題 原則 本来の財産、すなわちホームステッド原則を正当化する2つの主要な根拠は、努力と希少性である。ジョン・ロックは努力を重視し、「自分の労働を対象に混ぜ 合わせる」[13]、つまり処女地を開拓し耕作することを重視した。ベンジャミン・タッカーは、財産の目的、すなわち財産の目的は何であるかに注目するこ とを好んだ。彼の答えは「希少性問題を解決するため」である。例えば、狩猟採集民は土地が不足していなかったため、土地を所有物とは考えていなかった。農 耕社会は後に、耕作可能な土地は希少であったため、それを所有物とした。何かが経済的に希少であるためには、それは必然的に「排他的性質」、つまり、ある 人の使用によって他の人の使用が排除されるという性質を持たなければならない。これら2つの正当化は、何が財産となりうるかについて異なる結論を導く。知 的財産-アイデア、計画、順序付け、取り決め(作曲、小説、コンピュータ・プログラム)のような無体なもの-は、一般に、努力の正当化を支持する人々に とっては有効な財産であるが、希少性の正当化を支持する人々にとっては、独占的性質を持たないため、無効な財産であるとみなされる(ただし、希少性の正当 化を支持する人々は、それらが政府の仲裁ではなく契約の対象である限り、著作権のような他の「知的財産」法を支持することができる)。従って、熱心なプロ パー論者でさえ、知的財産については意見が分かれるかもしれない[15]。いずれの基準によっても、自分の身体は自分の所有物である。 アナーキズムの観点からは、財産の有効性は、「財産権」が国家による執行を必要とするかどうかによって決まる。知的財産は強制するために多くの国家介入を 必要とし、遠方の物的財産の所有権は多くの国家介入を必要とし、持ち運ぶ物の所有権はほとんど必要としない。対照的に、自分の身体を要求することは、国家 の介入をまったく必要としない。アナーキストの中には、所有権をまったく信じていない人もいるわけだ。 所有者のいないものは数多く存在し、コモンズと呼ばれることもある。しかし、「コモンズ」という用語は、「一般的な集団所有」、つまり共有物という、まっ たく別の意味で使われることも多い。また、同じ用語が国家主義者によって、一般市民がアクセスすることを許された政府所有の財産(公共財産)という意味で 使われることもある。あらゆる社会の法律は、所有者が明確でないものの数を減らす傾向にある。所有権の支持者は、コモンズの悲劇によって希少資源をよりよ く保護することが可能になると主張する。その一方で、所有権は個人的利益のための資源の「搾取」につながり、潜在的なネットワーク効果を利用する妨げにな るという批判もある。これらの議論は、「財産」の種類によって妥当性が異なる。例えば、希少でないものはコモンズの悲劇の対象とはならない。批評家の中に は、所有者がいないのではなく、一般的な集団所有権を主張する者もいる。 所有者がいないものには、アイデア(知的財産を除く)、海水(ただし、汚染防止法によって保護されている)、海底の一部(制限については国連海洋法条約を 参照)、地球の大気中のガス、野生の動物(ただし、ほとんどの国では動物は土地と結びついている。米国とカナダでは、野生生物は一般的に国の所有物と法令 で定義されている。このような野生生物の公的所有権は「北米野生生物保護モデル」と呼ばれ、「公共信託の原則」[16]に基づいている。 成年未満の子どもの性質は、ここでも争点となっている。古代社会では、子どもは一般的に親の所有物と考えられていた。しかし、現代のほとんどの社会では、 子どもは理論的には自分の体を所有しているが、権利を行使する能力があるとはみなされていない。子どもに対する基本的な支配権の大半は、両親または保護者 に与えられている。 身体の所有権の本質に関する問題は、中絶、薬物、安楽死の問題にも出てくる。 多くの古代の法体系(例えば、初期のローマ法)では、宗教的な場所(例えば、寺院)は、それらが捧げられた神または神々の所有物と考えられていた。しか し、宗教の多元化により、聖地はそれを運営する精神団体が所有する方が都合がよくなっている。 知的財産権や大気(空域、飛行禁止区域、公害法、これには取引可能な排出権が含まれることもある)も、ある意味では財産となりうる。 土地の所有権は、スポーツの権利、[17]鉱物の権利、開発の権利、大気の権利、その他単純な土地の所有権から分離する価値があるような権利を含む、その 土地をめぐる権利の所有権とは別に保有することができる。 所有権 主な記事 所有権 所有に関する法律は、対象となる財産(銃器、不動産、動産、動物など)の性質によって、国によって大きく異なる場合がある。個人は財産を直接所有すること ができる。ほとんどの社会では、会社、信託、国家(または政府)などの法人が財産を所有している。 多くの国では、制限的な相続法や家族法の下で、女性による財産へのアクセスは制限されており、男性のみが財産を所有する実際の権利または正式な権利を有し ている。 インカ帝国では、死んだ皇帝は神とみなされ、死後も財産を管理していた[18]。 政府の干渉 17世紀のイギリスでは、所有者の招待か同意がない限り、誰も家(17世紀には一般的に男性が所有していた)に立ち入ってはならないという法的指令が、エ ドワード・コーク卿の「Institutes of the Lawes of England」でコモンローとして確立された。"人の家はその城であり、et domus sua cuique est tutissimum refugium(各人の家は最も安全な避難所である)"。この判決は、16世紀に何人かのイギリスの作家が唱えていたことを法律に明記したものである [19]。 ヨーロッパの他の国々とは異なり、イギリス人は自分の家を所有する傾向があった[19]。 イギリスの首相であるチャタム伯爵ウィリアム・ピットは、1763年に城の意味を定義している。屋根はもろくとも、揺れようとも、風が吹き抜けようとも、 嵐が吹き荒れようとも、雨が降ろうとも、イングランド王は立ち入ることができない」[19]。 この原則は米国にも伝えられた。米国法では、国家が財産権に干渉できるかどうか、また干渉できる範囲に関する主な制限は憲法によって定められている。収奪 条項は、政府(州政府であれ連邦政府であれ、修正第14条のデュー・プロセス条項が州政府に修正第5条の収奪条項を課しているからである)が私有財産を収 奪できるのは、法の適正手続きを経た後、「正当な補償」をした上で、公的目的のために限られることを定めている。利益が「財産」権とみなされない場合、ま たはその行為が単なる意図的な不法行為である場合、これらの制限は適用されず、主権免責の原則により救済は妨げられる[20]。さらに、妨害によって財産 がほとんど完全に無価値にならない場合、妨害は収奪とはみなされず、単なる使用規制とみなされる。 [21]他方、政府による財産の使用規制の中には、「規制による収奪」とみなされるほど厳しいものもある[22]。さらに、行為が迷惑行為に過ぎないとみ なされることもあるし、行為が十分に持続的で厳しい場合には、別の不法行為が財産の収奪とみなされることもある[23]。 |

| Theories There exist many theories of property. One is the relatively rare first possession theory of property, where ownership of something is seen as justified simply by someone seizing something before someone else does.[24] Perhaps one of the most popular is the natural rights definition of property rights as advanced by John Locke. Locke advanced the theory that God granted dominion over nature to man through Adam in the book of Genesis. Therefore, he theorized that when one mixes one's labor with nature, one gains a relationship with that part of nature with which the labor is mixed, subject to the limitation that there should be "enough, and as good, left in common for others." (see Lockean proviso)[25] In his encyclical letter Rerum novarum (1891), Pope Leo XIII wrote, "It is surely undeniable that, when a man engages in remunerative labor, the impelling reason and motive of his work is to obtain property, and after that to hold it as his very own."[26] Anthropology studies the diverse ownership systems, rights of use and transfer, and possession[27] under the term "theories of property". As mentioned, western legal theory is based on the owner of property being a legal person. However, not all property systems are founded on this basis. In every culture studied, ownership and possession are the subjects of custom and regulation, and "law" is where the term can meaningfully be applied. Many tribal cultures balance individual rights with the laws of collective groups: tribes, families, associations, and nations. For example, the 1839 Cherokee Constitution frames the issue in these terms: Sec. 2. The lands of the Cherokee Nation shall remain common property. Still, the improvements made thereon, and in possession of the citizens respectively who made, or may rightfully own them: Provided, that the citizens of the Nation possessing the exclusive and indefeasible right to their improvements, as expressed in this article, shall possess no right or power to dispose of their improvements, in any manner whatever, to the United States, individual States, or individual citizens thereof; and that, whenever any citizen shall remove with his effects out of the limits of this Nation, and become a citizen of any other government, all his rights and privileges as a citizen of this Nation shall cease: Provided, nevertheless, That the National Council shall have power to re-admit, by law, to all the rights of citizenship, any such person or persons who may, at any time, desire to return to the Nation, on memorializing the National Council for such readmission. Communal property systems describe ownership as belonging to the entire social and political unit. Common ownership in a hypothetical communist society is distinguished from primitive forms of common property that have existed throughout history, such as Communalism and primitive communism, in that communist common ownership is the outcome of social and technological developments leading to the elimination of material scarcity in society.[28] Corporate systems describe ownership as being attached to an identifiable group with an identifiable responsible individual. The Roman property law was based on such a corporate system. In a well-known paper that contributed to the creation of the field of law and economics in the late 1960s, the American scholar Harold Demsetz described how the concept of property rights makes social interactions easier: In the world of Robinson Crusoe, property rights play no role. Property rights are an instrument of society and derive their significance from the fact that they help a man form those expectations which he can reasonably hold in his dealings with others. These expectations find expression in society's laws, customs, and more. An owner of property rights possesses the consent of fellowmen to allow him to act in particular ways. An owner expects the community to prevent others from interfering with his actions, provided that these actions are not prohibited in the specifications of his rights. — Harold Demsetz (1967), "Toward a Theory of property Rights", The American Economic Review 57(2), p. 347.[29] Different societies may have other theories of property for differing types of ownership. For example, Pauline Peters argued that property systems are not isolable from the social fabric, and notions of property may not be stated as such but instead may be framed in negative terms: for example, the taboo system among Polynesian peoples. |

理論 財産には多くの理論が存在する。そのひとつは、所有権に関する比較的珍しい先占説であり、所有権とは、他の誰かが所有権を取得する前に、誰かがその所有権 を取得することによって正当化されるというものである[24]。おそらく最もポピュラーなもののひとつは、ジョン・ロックが提唱した所有権に関する自然権 の定義である。ロックは、創世記において、神はアダムを通して人間に自然に対する支配権を与えたという説を唱えた。従って、人が自分の労働力を自然と混合 するとき、人はその労働力が混合された自然の一部分との関係を得るが、その際、"他の人のために十分かつ善良であるように共同で残す "という制限を受けるという理論を唱えた(ロックの但し書きを参照)。(ロックの但し書きを参照)[25]。 教皇レオ13世は、回勅『Rerum novarum』(1891年)の中で、「人が報酬を得る労働に従事するとき、その労働の原動力と動機は、財産を得ることであり、その後、それを自分のも のとして所有することであることは、確かに否定できない」と書いている[26]。 人類学は「財産論」という用語のもと、多様な所有制度、使用権、譲渡権、所有権[27]を研究している。前述したように、西洋の法理論は財産の所有者が法 人であることを前提としている。しかし、すべての財産制度がこの基盤の上に成り立っているわけではない。 研究対象としたどの文化においても、所有と占有は慣習や規制の対象であり、「法」という用語が意味を持って適用されるのはそこである。多くの部族文化は、 個人の権利と、部族、家族、団体、国家といった集団の法律とのバランスをとっている。例えば、1839年に制定されたチェロキーインディアンの憲法では、 この問題を次のように説明している: 第2項 第2項 チェロキー民族の土地は、共有財産である。第2項 チェロキー民族の土地は、共有の財産である: この条文に示されるように、改良物に対する排他的かつ永続的な権利を有するこの国の市民は、その改良物を、いかなる形であれ、合衆国、個々の州、またはそ の個々の市民に対して処分する権利または権力を有しない: ただし、国民協議会は、国民協議会に再入国を申し出ることにより、いつでも本国民への復帰を希望する者を、法律により、すべての市民権に再入国させる権限 を有する。 共有財産制度は、所有権が社会的・政治的単位全体に帰属することを説明するものである。仮想的な共産主義社会における共有財産は、共産主義的な共有財産が 社会における物質的欠乏の解消につながる社会的・技術的発展の成果であるという点で、共同体主義や原始共産主義のような歴史を通じて存在した原始的な共有 財産の形態とは区別される[28]。 企業システムは、所有権が、特定可能な責任ある個人を持つ特定可能な集団に付随するものとして説明する。ローマの財産法はこのような企業システムに基づい ていた。1960年代後半に法と経済学の分野の創設に貢献した有名な論文の中で、アメリカの学者ハロルド・デメセッツは、財産権の概念がいかに社会的相互 作用を容易にするかを述べている: ロビンソン・クルーソーの世界では、財産権は何の役割も果たさない。ロビンソン・クルーソーの世界では、財産権は何の役にも立たない。財産権は社会の道具 であり、人間が他者との取引において合理的に抱くことのできる期待を形成するのを助けるという事実からその重要性を導き出している。このような期待は、社 会の法律や慣習などに表現される。財産権の所有者は、自分が特定の方法で行動することを認める仲間の同意を得ている。所有者は、自分の権利の仕様で禁止さ れていない限り、他人が自分の行動を妨害しないように社会が配慮してくれることを期待する。 - Harold Demsetz (1967), "Toward a Theory of property Rights", The American Economic Review 57(2), p. 347.[29]. 異なる社会は、異なる所有権のタイプに対して他の所有権理論を持っているかもしれない。例えば、ポーリン・ピーターズは、所有権制度は社会的構造から切り 離すことはできず、所有権の概念はそのようなものとして明言されるのではなく、否定的な言葉で枠付けされることがあると主張した。 |

| Property in philosophy In medieval and Renaissance Europe the term "property" essentially referred to land. After much rethinking, land has come to be regarded as only a special case of the property genus. This rethinking was inspired by at least three broad features of early modern Europe: the surge of commerce, the breakdown of efforts to prohibit interest (then called "usury"), and the development of centralized national monarchies. Ancient philosophy Urukagina, the king of the Sumerian city-state Lagash, established the first laws that forbade compelling the sale of property.[30] The Bible in Leviticus 19:11 and ibid. 19:13 states that the Israelites are not to steal. Aristotle, in Politics, advocates "private property."[31] He argues that self-interest leads to neglect of the commons. "[T]hat which is common to the greatest number has the least care bestowed upon it. Everyone thinks chiefly of his own, hardly at all of the common interest, and only when he is himself concerned as an individual."[32] In addition, he says that when property is common, there are natural problems that arise due to differences in labor: "If they do not share equally enjoyments and toils, those who labor much and get little will necessarily complain of those who labor little and receive or consume much. But indeed, there is always a difficulty in men living together and having all human relations in common, but especially in their having common property." (Politics, 1261b34) Cicero held that there is no private property under natural law but only under human law.[33] Seneca viewed property as only becoming necessary when men become avaricious.[34] St. Ambrose later adopted this view and St. Augustine even derided heretics for complaining the Emperor could not confiscate property they had labored for.[35] Medieval philosophy Thomas Aquinas (13th century) The canon law Decretum Gratiani maintained that mere human law creates property, repeating the phrases used by St. Augustine.[36] St. Thomas Aquinas agreed with regard to the private consumption of property but modified patristic theory in finding that the private possession of property is necessary.[37] Thomas Aquinas concludes that, given certain detailed provisions,[38] it is natural for man to possess external things it is lawful for a man to possess a thing as his own The essence of theft consists in taking another's thing secretly Theft and robbery are sins of different species, and robbery is a more grievous sin than theft theft is a sin; it is also a mortal sin it is, however, lawful to steal through stress of need:" in cases of need, all things are common property." Modern philosophy Thomas Hobbes (17th century) The principal writings of Thomas Hobbes appeared between 1640 and 1651—during and immediately following the war between forces loyal to King Charles I and those loyal to Parliament. In his own words, Hobbes' reflection began with the idea of "giving to every man his own," a phrase he drew from the writings of Cicero. But he wondered: How can anybody call anything his own? James Harrington (17th century) A contemporary of Hobbes, James Harrington, reacted to the same tumult differently: he considered property natural but not inevitable. The author of "Oceana," he may have been the first political theorist to postulate that political power is a consequence, not the cause, of the distribution of property. He said that the worst possible situation is when the commoners have half a nation's property, with the crown and nobility holding the other half—a circumstance fraught with instability and violence. He suggested a much better situation (a stable republic) would exist once the commoners own most property. In later years, the ranks of Harrington's admirers included American revolutionary and founder John Adams. Robert Filmer (17th century) Another member of the Hobbes/Harrington generation, Sir Robert Filmer, reached conclusions much like Hobbes', but through Biblical exegesis. Filmer said that the institution of kingship is analogous to that of fatherhood, that subjects are still, children, whether obedient or unruly and that property rights are akin to the household goods that a father may dole out among his children—his to take back and dispose of according to his pleasure. John Locke (17th century) In the following generation, John Locke sought to answer Filmer, creating a rationale for a balanced constitution in which the monarch had a part to play, but not an overwhelming part. Since Filmer's views essentially require that the Stuart family be uniquely descended from the patriarchs of the Bible, and even in the late 17th century, that was a difficult view to uphold, Locke attacked Filmer's views in his First Treatise on Government, freeing him to set out his own views in the Second Treatise on Civil Government. Therein, Locke imagined a pre-social world each of the unhappy residents which are willing to create a social contract because otherwise, "the enjoyment of the property he has in this state is very unsafe, very insecure," and therefore, the "great and chief end, therefore, of men's uniting into commonwealths, and putting themselves under government, is the preservation of their property."[39] They would, he allowed, create a monarchy, but its task would be to execute the will of an elected legislature. "To this end" (to achieve the previously specified goal), he wrote, "it is that men give up all their natural power to the society they enter into, and the community put the Legislative power into such hands as they think fit, with this trust, that they shall be governed by declared laws, or else their peace, quiet, and property will still be at the same uncertainty as it was in the state of nature."[40] Even when it keeps to proper legislative form, Locke held that there are limits to what a government established by such a contract might rightly do. "It cannot be supposed that [the hypothetical contractors] they should intend, had they a power so to do, to give anyone or more an absolute arbitrary power over their persons and estates, and put a force into the magistrate's hand to execute his unlimited will arbitrarily upon them; this were to put themselves into a worse condition than the State of nature, wherein they had a liberty to defend their right against the injuries of others, and were upon equal terms of force to maintain it, whether invaded by a single man or many in combination. Whereas by supposing they have given themselves up to the absolute arbitrary power and will of a legislator, they have disarmed themselves, and armed him to make a prey of them when he pleases..."[41] Both "persons" and "estates" are to be protected from the arbitrary power of any magistrate, including legislative power and will." In Lockean terms, depredations against an estate are just as plausible a justification for resistance and revolution as are those against persons. In neither case are subjects required to allow themselves to become prey. To explain the ownership of property, Locke advanced a labor theory of property. David Hume (18th century) In contrast to the figures discussed in this section thus far David Hume lived a relatively quiet life that had settled down to a relatively stable social and political structure. He lived the life of a solitary writer until 1763 when, at 52 years of age, he went off to Paris to work at the British embassy. In contrast, one might think to his polemical works on religion and his empiricism-driven skeptical epistemology, Hume's views on law and property were quite conservative. He did not believe in hypothetical contracts or the love of humanity in general and sought to ground politics upon actual human beings as one knows them. "In general," he wrote, "it may be affirmed that there is no such passion in the human mind, as the love of mankind, merely as such, independent of personal qualities, or services, or of relation to ourselves." Existing customs should not lightly be disregarded because they have come to be what they are due to human nature. With this endorsement of custom comes an endorsement of existing governments because he conceived of the two as complementary: "A regard for liberty, though a laudable passion, ought commonly to be subordinate to a reverence for established government." Therefore, Hume's view was that there are property rights because of and to the extent that the existing law, supported by social customs, secure them.[42] He offered some practical home-spun advice on the general subject, though, as when he referred to avarice as "the spur of industry," and expressed concern about excessive levels of taxation, which "destroy industry, by engendering despair." Adam Smith "Civil government, so far as it is instituted for the security of property, is, in reality, instituted for the defense of the rich against the poor, or of those who have property against those who have none at all." — Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776[43] "The property that every man has in his labour is the original foundation of all other property, so it is the most sacred and inviolable. The inheritance of a poor man lies in the strength and dexterity of his hands, and to hinder him from employing this strength and dexterity in what manner he thinks proper without injury to his neighbor, is a plain violation of this most sacred property. It is a manifest encroachment upon the just liberty of the workman and those who might be disposed to employ him. It hinders the one from working at what he thinks proper, so it hinders the others from employing whom they think proper. To judge whether he is fit to be employed may surely be trusted to the discretion of the employers whose interest it so much concerns. The affected anxiety of the law-giver lest they should employ an improper person is as impertinent as it is oppressive." — (Source: Adam Smith, The Wealth of Nations, 1776, Book I, Chapter X, Part II.) By the mid 19th century, the industrial revolution had transformed England and the United States and had begun in France. As a result, the conventional conception of what constitutes property expanded beyond land to encompass scarce goods. In France, the revolution of the 1790s had led to large-scale confiscation of land formerly owned by the church and king. The restoration of the monarchy led to claims by those dispossessed to have their former lands returned. Karl Marx Section VIII, "Primitive Accumulation" of Capital involves a critique of Liberal Theories of property rights. Marx notes that under Feudal Law, peasants were legally entitled to their land as the aristocracy was to its manors. Marx cites several historical events in which large numbers of the peasantry were removed from their lands, then seized by the nobility. This seized land was then used for commercial ventures (sheep herding). Marx sees this "Primitive Accumulation" as integral to the creation of English Capitalism. This event created a sizeable un-landed class that had to work for wages to survive. Marx asserts that liberal theories of property are "idyllic" fairy tales that hide a violent historical process. Charles Comte: legitimate origin of property Charles Comte, in "Traité de la propriété" (1834), attempted to justify the legitimacy of private property in response to the Bourbon Restoration. According to David Hart, Comte had three main points: "firstly, that interference by the state over the centuries in property ownership has had dire consequences for justice as well as for economic productivity; secondly, that property is legitimate when it emerges in such a way as not to harm anyone; and thirdly, that historically some, but by no means all, property which has evolved has done so legitimately, with the implication that the present distribution of property is a complex mixture of legitimately and illegitimately held titles."[44] Comte, as Proudhon later did, rejected Roman legal tradition with its toleration of slavery. Instead, he posited a communal "national" property consisting of non-scarce goods, such as land in ancient hunter-gatherer societies. Since agriculture was so much more efficient than hunting and gathering, private property appropriated by someone for farming left remaining hunter-gatherers with more land per person and hence did not harm them. Thus this type of land appropriation did not violate the Lockean proviso – there was "still enough, and as good left." Later theorists would use Comte's analysis in response to the socialist critique of property. Pierre-Joseph Proudhon: property is theft Main article: Property is theft! In his 1840 treatise What is Property?, Pierre Proudhon answers with "Property is theft!". In natural resources, he sees two types of property, de jure property (legal title) and de facto property (physical possession), and argues that the former is illegitimate. Proudhon's conclusion is that "property, to be just and possible, must necessarily have equality for its condition." His analysis of the product of labor upon natural resources as property (usufruct) is more nuanced. He asserts that land itself cannot be property, yet it should be held by individual possessors as stewards of humanity, with the product of labor being the producer's property. Proudhon reasoned that any wealth gained without labor was stolen from those who labored to create that wealth. Even a voluntary contract to surrender the product of work to an employer was theft, according to Proudhon, since the controller of natural resources had no moral right to charge others for the use of that which he did not labor to create did not own. Proudhon's theory of property greatly influenced the budding socialist movement, inspiring anarchist theorists such as Mikhail Bakunin who modified Proudhon's ideas, as well as antagonizing theorists like Karl Marx. Frédéric Bastiat: property is value Frédéric Bastiat 's main treatise on property can be found in chapter 8 of his book "Economic Harmonies" (1850).[45] In a radical departure from traditional property theory, he defines property, not as a physical object, but rather as a relationship between people concerning a thing. Thus, saying one owns a glass of water is merely verbal shorthand for "I may justly gift or trade this water to another person." In essence, what one owns is not the object but the object's value. By "value," Bastiat means "market value"; he emphasizes this is quite different from utility. "In our relations with one another, we are not owners of the utility of things, but their value, and value is the appraisal made of reciprocal services." Bastiat theorized that, as a result of technological progress and the division of labor, the stock of communal wealth increases over time; that the hours of work an unskilled laborer expends to buy e.g., 100 liters of wheat, decreases over time, thus amounting to "gratis" satisfaction.[46] Thus, private property continually destroys itself, becoming transformed into communal wealth. The increasing proportion of communal wealth to private property results in a tendency toward equality of humanity. "Since the human race began in greatest poverty, that is, when there were the most obstacles to overcome, all that has been achieved from one era to the next is due to the spirit of property." This transformation of private property into the communal domain, Bastiat points out, does not imply that personal property will ever totally disappear. On the contrary, this is because man, as he progresses, continually invents new and more sophisticated needs and desires. Andrew J. Galambos: a precise definition of property Andrew J. Galambos (1924–1997) was an astrophysicist and philosopher who innovated a social structure that sought to maximize human peace and freedom. Galambos' concept of property was essential to his philosophy. He defined property as a man's life and all non-procreative derivatives of his life. (Because the English language is deficient in omitting the feminine from "man" when referring to humankind, it is implicit and obligatory that the feminine is included in the term "man.") Galambos taught that property is essential to a non-coercive social structure. He defined freedom as follows: "Freedom is the societal condition that exists when every individual has full (100%) control over his property."[47] Galambos defines property as having the following elements: Primordial property, which is an individual's life Primary property, which includes ideas, thoughts, and actions Secondary property includes all tangible and intangible possessions that are derivatives of the individual's primary property. Property includes all non-procreative derivatives of an individual's life; this means children are not the property of their parents.[48] and "primary property" (a person's own ideas).[49] Galambos repeatedly emphasized that actual government exists to protect property and that the State attacks property. For example, the State requires payment for its services in the form of taxes whether or not people desire such services. Since an individual's money is his property, the confiscation of money in the form of taxes is an attack on property. Military conscription is likewise an attack on a person's primordial property. Contemporary views Contemporary political thinkers who believe that natural persons enjoy rights to own property and enter into contracts espouse two views about John Locke. On the one hand, some admire Locke, such as William H. Hutt (1956), who praised Locke for laying down the "quintessence of individualism." On the other hand, those such as Richard Pipes regard Locke's arguments as weak and think that undue reliance thereon has weakened the cause of individualism in recent times. Pipes has written that Locke's work "marked a regression because it rested on the concept of Natural Law" rather than upon Harrington's sociological framework. Hernando de Soto has argued that an essential characteristic of the capitalist market economy is the functioning state protection of property rights in a formal property system which records ownership and transactions. These property rights and the whole legal system of property make possible: Greater independence for individuals from local community arrangements to protect their assets Clear, provable, and protectable ownership The standardization and integration of property rules and property information in a country as a whole Increased trust arising from a greater certainty of punishment for cheating in economic transactions More formal and complex written statements of ownership that permit the more straightforward assumption of shared risk and ownership in companies, and insurance against the risk Greater availability of loans for new projects since more things can serve as collateral for the loans Easier access to and more reliable information regarding such things as credit history and the worth of assets Increased fungibility, standardization, and transferability of statements documenting the ownership of property, which paves the way for structures such as national markets for companies and the easy transportation of property through complex networks of individuals and other entities Greater protection of biodiversity due to minimizing of shifting agriculture practices According to de Soto, all of the above enhance economic growth.[50] Academics have criticized the capitalist frame through which property is viewed pointing to the fact that commodifying property or land by assigning it monetary value takes away from the traditional cultural heritage, particularly from first nation inhabitants.[51][52] These academics point to the personal nature of property and its link to identity being irreconcilable with wealth creation that contemporary Western society subscribes to.[51] |

哲学における財産 中世およびルネサンス期のヨーロッパでは、「所有権」という言葉は基本的に土地を指していた。多くの再考の後、土地は財産属の特殊な場合に過ぎないとみな されるようになった。この再考は、近世ヨーロッパの少なくとも3つの大きな特徴、すなわち、商業の急増、利子(当時は「利殖」と呼ばれた)を禁止する努力 の崩壊、中央集権的な国家君主制の発達に触発されたものである。 古代哲学 シュメールの都市国家ラガシュの王ウルカギナは、財産の強制売却を禁じる最初の法律を制定した[30]。 聖書のレビ記19:11と同19:13には、イスラエルの民は盗んではならないと記されている。 アリストテレスは『政治学』において「私有財産」を提唱している[31]。「最も多くの人に共有されているものには、最も少ない配慮しか払われていない。 誰もが自分のことを第一に考え、共同の利益についてはほとんど考えない。 さらに、財産が共有である場合、労働力の違いによって生じる当然の問題があるという: 「享楽と労苦を等しく分かち合わなければ、労苦が多くて得るものが少ない者は、労苦が少なくて多くのものを受け取ったり消費したりする者に対して、必然的 に不満を抱くことになる。しかし実際、人間が共に生活し、すべての人間関係を共有することは常に困難であり、特に財産を共有することは困難である」(『政 治学』1261b34)。(政治学』1261b34) キケロは、自然法のもとでは私有財産は存在せず、人法のもとでのみ私有財産が存在すると考えていた[33]。セネカは、人が貪欲になったときにのみ財産が 必要になると考えていた[34]。聖アンブローズは後にこの考え方を採用し、聖アウグスティヌスは、労働のために得た財産を皇帝が没収することはできない と不平を言う異端者を嘲笑していた[35]。 中世哲学 トマス・アクィナス(13世紀) カノン法Decretum Gratianiは、聖アウグスティヌスが使用したフレーズを繰り返しながら、単なる人間の法律が財産を生み出すと主張していた[36]。聖トマス・ア クィナスは、財産の私的消費に関しては同意していたが、財産の私的所有は必要であるとして教父理論を修正した[37]。 人間が外的なものを所有することは自然である 人間があるものを自分のものとして所有することは合法である。 窃盗の本質は、他人の物を密かに奪うことにある。 窃盗と強盗は異なる種類の罪であり、強盗は窃盗よりも重い罪である。 窃盗は罪であり、大罪でもある。 しかし、必要に迫られて盗むことは合法である。"必要な場合には、すべてのものは共有物である" 近代哲学 トマス・ホッブズ(17世紀) トマス・ホッブズの主な著作は、1640年から1651年にかけて、チャールズ1世に忠誠を誓う勢力と議会に忠誠を誓う勢力との間の戦争の最中とその直後 に発表された。ホッブズ自身の言葉を借りれば、ホッブズの考察は、キケロの著作から引用した「各人に自分のものを与える」という考えから始まった。しか し、彼は考えた: 誰も自分のものなどとは呼べないのではないか? ジェームズ・ハリントン(17世紀) ホッブズと同時代のジェイムズ・ハリントンは、同じ騒動に対して異なる反応を示した。オセアナ』の著者である彼は、政治権力は財産の分配の原因ではなく結 果であるとした最初の政治理論家であったかもしれない。彼は、平民が国家の財産の半分を持ち、王室と貴族が残りの半分を持つという最悪の状況は、不安定と 暴力をはらんでいると述べた。彼は、平民がほとんどの財産を所有するようになれば、はるかに良い状況(安定した共和国)が存在すると示唆した。 後年、ハリントンの崇拝者の中には、アメリカの革命家で創設者のジョン・アダムズも含まれていた。 ロバート・フィルマー(17世紀) ホッブズ/ハリントン世代のもう一人、ロバート・フィルマー卿は、ホッブズとよく似た結論に達したが、聖書の釈義を通しての結論であった。フィルマーは、 王権制度は父権制度に類似しており、臣民は従順であろうと従順でなかろうと子供であることに変わりはなく、財産権は父親が子供たちに配る家財道具のような ものであり、父親が自分の好きなように取り戻したり処分したりできるものであると述べた。 ジョン・ロック(17世紀)(→『統治二論』) 次の世代では、ジョン・ロックがフィルマーに答えるべく、君主の役割もあるが圧倒的な役割ではない、バランスの取れた憲法の理論的根拠を作り上げた。フィ ルマーの見解は、基本的にスチュアート家が聖書の家長の子孫であることを要求するものであり、17世紀後半においてさえ、それを支持することは困難であっ たため、ロックは『統治論第一論』においてフィルマーの見解を攻撃し、『市民統治論第二論』において自身の見解を述べることを自由にさせた。そこでは、 ロックは社会契約締結を望んでいる不幸な住民のそれぞれからなる社会以前の世界を想像していた。なぜなら、そうでなければ、「この状態で持っている財産の 享受は非常に危険であり、非常に不安定である」からであり、したがって、「それゆえ、人間が連邦に団結し、政府のもとに身を置くことの偉大かつ最大の目的 は、財産の保全である」[39]。「この目的のために」(先に特定した目的を達成するために)、彼は「人間がその自然的な権力をすべて彼らが入る社会に委 ね、共同体が立法権を彼らが適当と考えるような手に委ねることである。 ロックは、適切な立法形態を維持する場合であっても、このような契約によって樹立された政府が正当になしうることには限界があるとした。 「仮定の契約者が)そのような権力を有していたとしても、誰かあるいはそれ以上の者に、彼らの個人と財産に対する絶対的な恣意的権力を与え、その無制限の 意志を彼らに恣意的に実行させる力を行政官の手に握らせることを意図するとは考えられない。ところが、立法者の絶対的な恣意的権力と意思に自らを委ねたと 仮定することによって、彼らは自らを武装解除し、立法者が好きなときに彼らを獲物にできるように武装したのである...」[41]。 人」も「財産」も、立法権や意思を含むあらゆる行政官の恣意的な権力から保護されなければならない。ロックの用語では、財産に対する侵害は、個人に対する 侵害と同様に、抵抗と革命の正当な理由となる。どちらの場合も、臣民が自ら餌食になることを許す必要はない。 財産の所有権を説明するために、ロックは財産の労働理論を提唱した。 デイヴィッド・ヒューム(18世紀) ここまでのセクションで取り上げた人物とは対照的に、デイヴィッド・ヒュームは比較的安定した社会的・政治的構造に落ち着き、比較的静かな生活を送ってい た。彼は1763年、52歳のときに英国大使館で働くためにパリに出るまで、孤独な作家生活を送った。 宗教に関する極論的な著作や、経験主義に基づく懐疑的な認識論とは対照的に、ヒュームの法律や財産に関する見解は極めて保守的であった。 彼は仮定の契約や人間愛一般を信じず、人が知っている現実の人間に基づいて政治を行おうとした。「一般に、人間の心には、個人的な資質や奉仕、あるいは自 分自身との関係とは無関係に、ただそのようなものとして人間を愛するというような情熱は存在しないと断言することができる」と彼は書いている。既存の慣習 は、人間の本性によってそうなったのだから、軽々しく無視すべきではない。慣習を是認することは、既存の政府を是認することでもある: 「自由を尊重することは、称賛に値する情熱ではあるが、一般的には、確立された政府に対する敬意に従属すべきである」。 したがって、ヒュームの見解は、社会的慣習に支えられた既存の法律が財産権を保障しているからこそ、またその程度に応じて財産権が存在するというもので あった[42]。 ヒュームは、欲望を「産業の原動力」と呼び、「絶望を生むことによって産業を破壊する」過剰な課税水準に懸念を表明したように、一般的なテーマについて実 践的な自作自演の助言も行っている。 アダム・スミス 「市民政府は、それが財産の安全のために制定される限りにおいて、実際には、貧乏人に対する金持ちの防衛のため、あるいは、まったく財産を持たない者に対 する財産を持つ者の防衛のために制定されるのである。 - アダム・スミス『国富論』1776年[43]。 「すべての人がその労働において有する財産は、他のすべての財産の基礎となるものであり、したがって最も神聖かつ不可侵なものである。貧乏人の相続財産 は、その手の力と器用さにあり、この力と器用さを、隣人を傷つけることなく、適切と思われる方法で使用することを妨げることは、この最も神聖な財産に対す る明白な侵害である。それは、労働者と彼を雇おうとする人々の正当な自由に対する明白な侵害である。労働者が適切と考える仕事に従事することを妨げ、他の 労働者が適切と考える人を雇用することを妨げる。労働者が雇用されるにふさわしいかどうかの判断は、その利害に大きく関わる雇用者の裁量に委ねられるべき である。不適切な者を雇わないようにという法律制定者の不安は、抑圧的であると同時に不謹慎である」。- (出典 アダム・スミス『国富論』1776年、第1巻、第X章、第2部) 19世紀半ばまでに、産業革命はイギリスとアメリカを変貌させ、フランスでも始まった。その結果、財産を構成するものについての従来の概念は、土地を越え て希少財にまで拡大した。フランスでは1790年代の革命により、かつて教会と国王が所有していた土地が大規模に没収された。王政復古により、土地を奪わ れた人々はかつての土地の返還を求めた。 カール・マルクス 資本論』第8章「原始的蓄積」は、財産権に関する自由主義理論に対する批判を含んでいる。マルクスは、封建法のもとでは、貴族が荘園を所有するのと同様 に、農民も土地を所有する法的権利を有していたと指摘する。マルクスは、多数の農民が土地を追われ、貴族に接収された歴史的事件をいくつか挙げている。こ の差し押さえられた土地は、商業事業(羊の放牧)に利用された。マルクスは、この「原始的蓄積」がイギリス資本主義の誕生に不可欠であったと見ている。こ の出来事は、生き残るために賃金を得て働かなければならない、土地を持っていない大規模な階級を生み出した。マルクスは、自由主義的な財産論は暴力的な歴 史的過程を隠す「牧歌的な」おとぎ話であると主張する。 シャルル・コント:所有権の正当な起源 シャルル・コントは『所有権論』(1834年)の中で、ブルボン王政復古に対抗して私有財産の正当性を正当化しようとした。デイヴィッド・ハートによれ ば、コントの主張は3つある: 「第一に、何世紀にもわたって国家が所有権に干渉してきたことは、経済的生産性だけでなく、正義に対しても悲惨な結果をもたらしてきたこと、第二に、財産 は誰にも害を与えないような形で生まれたときに合法的なものであること、第三に、歴史的に発展してきた財産には合法的なものもあるが、決してすべてではな いこと、現在の財産の分配は合法的な所有権と非合法な所有権が複雑に混在していることを意味する」[44]。 コントは、後にプルードンがそうであったように、奴隷制を容認するローマ法の伝統を否定した。その代わりに彼は、古代の狩猟採集社会における土地のよう な、希少価値のない財からなる共同体的な「国民的」財産を仮定した。農耕は狩猟採集よりもはるかに効率的であったため、誰かが農耕のために私有財産を没収 しても、残された狩猟採集民には一人当たりの土地が多く残り、彼らに害を与えることはなかった。したがって、この種の土地の流用はロックの但し書きに違反 しなかったのである。後の理論家たちは、社会主義者の所有権批判に対してコントの分析を用いることになる。 ピエール=ジョゼフ・プルードン:財産は窃盗である 主な記事 財産は窃盗である ピエール・プルードンは1840年に発表した『財産とは何か』の中で、「財産は窃盗である!」と答えている。天然資源において、彼は2種類の所有権、すな わちデジュール所有権(法的所有権)とデファクト所有権(物理的所有権)を見ており、前者は非合法であると主張している。プルードンの結論は、「財産が公 正で可能であるためには、その条件は必然的に平等でなければならない」というものである。 天然資源の労働生産物を所有物(用益権)とする彼の分析は、より微妙である。彼は、土地そのものを所有物とすることはできないが、土地は人類の執政者とし て個々の所有者によって所有されるべきであり、労働の生産物は生産者の所有物であると主張している。プルードンは、労働を伴わずに得られた富は、その富を 生み出すために労働した人々から盗まれたものだと考えた。プルードンによれば、労働の産物を雇用者に明け渡すという自発的な契約でさえも窃盗であり、天然 資源の管理者は、自分が労働して創造したものではないものの使用料を他人に請求する道徳的権利を持たないからである。 プルードンの財産論は、萌芽的な社会主義運動に大きな影響を与え、プルードンの考えを修正したミハイル・バクーニンなどの無政府主義理論家を刺激し、カー ル・マルクスなどの理論家とも対立した。 フレデリック・バスティア:財産は価値である フレデリック・バスティアの財産に関する主な論考は、彼の著書『経済調和論』(1850年)の第8章にある[45]。伝統的な財産論から根本的に逸脱し て、彼は財産を物理的な物体としてではなく、むしろ物に関する人と人との関係として定義している。したがって、コップ一杯の水を所有していると言うこと は、「私はこの水を他の人に贈与したり、交換したりすることができる」という単なる言葉の省略表現にすぎない。要するに、人が所有しているのはモノではな く、モノの価値なのである。バスティアが言う「価値」とは「市場価値」のことであり、効用とはまったく異なるものであることを強調している。「互いの関係 において、われわれは物の効用の所有者ではなく、その価値の所有者である。 バスティアは、技術の進歩と分業の結果として、共同体の富のストックは時間の経過とともに増加し、未熟練労働者が例えば100リットルの小麦を買うために 費やす労働時間は時間の経過とともに減少し、したがって「無償の」満足になると理論化した[46]。私有財産に占める共同富の割合が高まるにつれて、人類 は平等になる傾向にある。「人類が最大の貧困から始まって以来、つまり克服すべき障害が最も多かった時代から、ある時代から次の時代にかけて達成されたす べてのことは、財産の精神によるものである。 この私有財産の共同体的領域への変容は、個人財産が完全に消滅することを意味するものではないとバスティアは指摘する。それどころか、人間は進歩するにつ れて、より洗練された新しい欲求や願望を生み出し続けるからである。 アンドリュー・J・ガランボス:財産の正確な定義 アンドリュー・J・ガランボス(1924-1997)は宇宙物理学者であり、人間の平和と自由を最大化しようとする社会構造を革新した哲学者である。ガラ ンボスの財産概念は、彼の哲学にとって不可欠なものであった。彼は財産を人間の生命と、その生命から派生する非創造的なものすべてと定義した。(英語では 人類を指すとき、"man "から女性性を省くという欠陥があるため、"man "に女性性が含まれるのは暗黙の了解であり、義務である) ガランボスは、非強制的な社会構造には財産が不可欠であると説いた。彼は自由を次のように定義した: 「自由とは、各個人が自分の財産を完全に(100%)管理できるときに存在する社会の状態である」[47] : 個人の生命である原初的財産 一次的財産とは、アイデア、思考、行動を含む。 第二次財産には、個人の第一次財産の派生物であるすべての有形・無形の所有物が含まれる。 つまり、子どもは親の所有物ではない[48]。そして「一次財産」(その人自身の考え)[49]。 ガランボスは、実際の政府が財産を保護するために存在し、国家が財産を攻撃することを繰り返し強調した。例えば、国家は、人々がそのようなサービスを望む か否かにかかわらず、税金という形でそのサービスに対する支払いを要求する。個人の金銭は財産であるから、税金という形で金銭を没収することは財産に対す る攻撃である。徴兵制も同様に、個人の根源的財産に対する攻撃である。 現代の見解 自然人が財産を所有し、契約を結ぶ権利を享受していると考える現代の政治思想家たちは、ジョン・ロックについて2つの見解を持っている。一方では、ウィリ アム・H・ハット(William H. Hutt)(1956年)のように、ロックを賞賛し、ロックを "個人主義の真髄 "を示したと評価する者もいる。他方、リチャード・パイプスのような人たちは、ロックの議論を弱いとみなし、ロックに過度に依存することが、近年の個人主 義の大義を弱めていると考えている。パイプスは、ロックの研究はハリントンの社会学的枠組みではなく、「自然法の概念に依拠していたために後退を示した」 と書いている。 エルナンド・デ・ソトは、資本主義市場経済の本質的な特徴は、所有権と取引を記録する正式な財産制度において、国家による財産権の保護が機能していること だと主張している。こうした財産権と財産に関する法制度全体が可能にするのは、次のようなことである: 個人の資産を保護するための地域社会の取り決めからの独立性の向上 明確で証明可能かつ保護可能な所有権 国全体における財産規則と財産情報の標準化と統合 経済取引における不正行為に対する処罰がより確実になることから生じる信頼の増大 より形式的で複雑な所有権証明書により、企業におけるリスクと所有権の共有、およびリスクに対する保険をより簡単に引き受けることが可能になる。 融資の担保となるものが増えるため、新規プロジェクトに対する融資がより利用しやすくなる。 信用履歴や資産価値などに関する情報へのアクセスが容易になり、信頼性が高まる。 財産の所有権を文書化した明細書の換金性、標準化、譲渡性が向上し、企業の国内市場や、個人やその他の事業体の複雑なネットワークを通じた財産の容易な輸 送といった構造への道が開かれる。 転作農業の最小化による生物多様性の保護 デ・ソトによれば、上記はすべて経済成長を高めるものである[50]。学者たちは、財産や土地に金銭的価値を付与することによって商品化することが、特に 先住民の伝統的な文化遺産を奪うという事実を指摘し、財産が資本主義的なフレームを通して見られていることを批判している[51][52]。これらの学者 たちは、財産の個人的な性質とアイデンティティとの結びつきが、現代の西洋社会が信奉する富の創造と両立しないことを指摘している[51]。 |

| Allemansrätten Anarchism Binary economics Buying agent Capitalism Communism Homestead principle Immovable property Inclusive Democracy International Property Rights Index Labor theory of property Land (economics) Libertarianism Lien Off plan Ownership society Patrimony Personal property Propertarian Property is theft Property law Property rights (economics) Socialism Sovereignty Taxation as theft Interpersonal relationship Public liability Property-giving (legal) Charity Essenes Gift Kibbutz Monasticism Tithe, Zakat (modern sense) Property-taking (legal) Adverse possession Confiscation Eminent domain Fine Jizya Nationalization Regulatory fees and costs Search and seizure Tariff Tax Turf and twig (historical) Tithe, Zakat (historical sense) RS 2477 Property-taking (illegal) Theft |

万人の権利 アナーキズム 二元経済学 購買代理人 資本主義 共産主義 私有地原則 不動財産 包括的民主主義 国際財産権指数 労働財産説 土地(経済学) リバタリアニズム 先取特権 未完成物件 所有社会 遺産 動産 プロパティリアン 財産は窃盗である 財産法 財産権(経済学) 社会主義 主権 課税は窃盗である 対人関係 公的責任 財産の付与(法的) 慈善 エッセネ派 贈与 キブツ 修道生活 什分の一税、ザカート(現代的な意味 財産の取得(法的) adverse possession 没収 土地収用権 罰金 ジズヤ 国有化 規制料金および費用 捜索および押収 関税 税金 芝や小枝(歴史的) 什分の一税、ザカート(歴史的意味) RS 2477 財産の強制収用(違法) 窃盗 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Property |

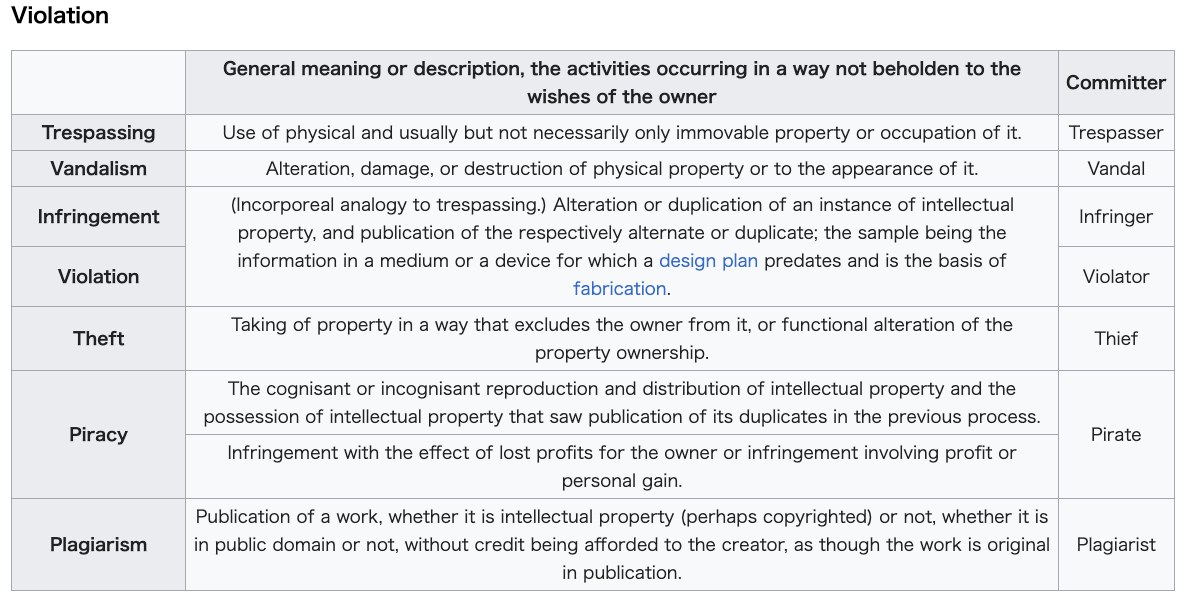

Violation against of the property

Source; https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Property

リンク(英文)

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099