participant observation

参与観察

participant observation

解説:池田光穂

「いくら民衆とともに、あるいは民衆のかたわらで暮らしてみたと

ころで、完全に民衆になりきることはできないだろうということである」——ドストエフスキー「作家の日記」

参与観察(participant observation)とは、文字通り、人びとがおこなうイベント(祭礼、儀礼、結社、偶発的行事など)に参加することを通して、観察データをえるこ と。参加観察(さんかかんさつ)とも言う。

フィールドワーカー(→フィールドワークを実践する人、調査者)には欠かせな い行動原則であるが、それにより得られるデータは、調査者の経験知、実践知というかたちにならないデータから、フィールドノート(ノーツ)、録音、写真や 動画記録、文書情報など、有形のデータまで、きわめて多様である。

ここでのデータ——複数形:単数系は datum ——は、調査は参加しなければ得られないが、参加すれば過不足なく得られるというわけでもない。そのため事前の民族誌データの入手、 それらの読解や分析、調査計画の立案、実際の参加、イベント終了後の関係者や参加者への事後的なインタビュー、追加の資料収集などと、参与観察は有機的に 関連づけられる必要がある。

だからといって参与観察は、観察技法に長 けたエキスパート(熟達者)だけに開かれたものではなく、(秘密結社などの入会は例外として)さまざま なイベントがゆるやかに参加を誰もが公的に認められたものでありために、フィールドワークの根本的な経験を構成することも事実である。

他方、だからと言って、私は部外者として 唯一参加したから、そのイベントについて語り尽くせるというものでもない。また、参加の経験豊かな現地 における当事者が、すべてのイベントに熟知しているわけでもない、その時空間に居たという経験とそれに関する反省的意識もまた重要である。

したがって、参与観察はすべてのフィール ドワーカーにとって、不可欠で基本的な経験であり、比較的どのような熟達度の人においても可能なもので ある。他方で、誰にでもできるという簡便さと同時に、その時空間において存在したという経験だけが特権化する——たとえば私が唯一のその場の経験者である ので、その経験は無条件に重要であるという意識——ことにも警戒しなければならない。

参加し、観察するという文化人類学の基本 的な実践であるが、参与観察がもつ、実践的かつ認識論的な未解決の課題は多い。つまり、文化人類学の フィールドワークに関わる重要なテーマでありつづけている。

以上のことを上手にまとめられるわけでは ないが、社会学者ノーマン・デンジン(Norman K. Denzin, 1941- )は、参与観察が、質的研究の総合的なアプローチのあり方だとして次のように定義している。

「参与観察とは、(a)文書の分析、(b)インフォーマントとのインタビュー、(c)直接の参加と観察および(d)内省を同時に組み合わせ

るフィールドでの一戦略である」※強調とアルファベット付与は池田による追記[Denzin 1989:17-18](翻訳は小田博志ほか訳:フリック

2002:176)[→「質的研究のデザイン」]

●ビジネスの現場における参与観察

ビジネスにおける参与観察は、needs finding とneedstatement

を記述するために、観察者をビジネス(医療や保健などの現場を含む)に配置させ、仕事に従事させることが目的となる(→「ニーズファインディング」)。

ゴ

ンゾー・メソッド(ゴンゾー★メソッド)とは、対象者の情報を客観化し たり、あるいは逆に操作しようとするのではなく、対象者のコミュニ

ティのなかに参与することで、対象者の仲間そのものに

なってしまおうという手法である。その意味では、ゴンゾー・ライティングとは、ある意味で「参与観察」(participant

observation)と似ている(唯一の違いは前者には「研究倫理」あるいは「ジャーナリスト倫理」が欠如している)。

▲物語作家

「物

語作者(Erzähler)は——この名称が私たちにいかに親しい響きをもってい ようとも

——現在、生き生きと活動する存在では必ずしもない。物語作者は、私たちにとってすで

に遠くなってしまったもの、そしていまなおさらに遠ざかりつつあるものだ。レスコフの

ような作家を物語作者として描くことは、彼を私たちに近づけるものではなく、むしろ逆

に、彼との距離を大きくしようとするものである。一定の距離をおいて考察したときには

じめて、物語作者の明瞭で大きな特徴が彼のなかで優位を占めてくるのだ。もっと分かり

やすい比鳴を使うなら、正しい距離と適切な角度から観ると、岩の表面に人の顔や動物の

体が見えてくることがあるように、距離をおいてはじめて、物語作者の特徴が彼のなかに

現われてくる。このような距離や視角を私たちに教えてくれるのは、私たちがほとんど毎

日のように接する機会のある、ある種の経験である。この経験は私たちに、物語る技術が

いま終駕に向かいつつあることを告げている。まともに何かを物語ることができる人に出

会うことは、ますますまれになってきている。そして、なにか物語をしてほしいという戸

があがると、その周囲に戸惑いの気配が広がっていくことがしばしばである。まるで、私

たちから失われることなどありえないと思われていた能力、確かなもののなかでも最も確

かだと思われていたものが、私たちから奪われていくかのようだ。すなわち、経験を交換 するという能力がある」(浅井健二郎編訳

1996:284-285)(→「経験を交換する能力としての《物

語》」)

Participant

observation. from Wiki.

| Participant

observation Participant observation is one type of data collection method by practitioner-scholars typically used in qualitative research and ethnography. This type of methodology is employed in many disciplines, particularly anthropology (incl. cultural anthropology and ethnology), sociology (incl. sociology of culture and cultural criminology), communication studies, human geography, and social psychology. Its aim is to gain a close and intimate familiarity with a given group of individuals (such as a religious, occupational, youth group, or a particular community) and their practices through an intensive involvement with people in their cultural environment, usually over an extended period of time. The concept "participant observation" was first coined in 1924 by Eduard C. Lindeman (1885-1953), an American pioneer in adult education influenced by John Dewey and Danish educator-philosopher N.F.S.Grundtvig, in his book "Social Discovery: An Approach to the Study of Functional Groups." The method, however, originated earlier and was applied in the field research linked to European and American voyages of scientific exploration. In 1800 one of precursors of the method, Joseph Marie, baron de Gérando, said that: "The first way to get to know the Indians is to become like one of them; and it is by learning their language that we will become their fellow citizens."[1] Later, the method would be popularized by Bronisław Malinowski and his students in Britain; the students of Franz Boas in the United States; and, in the later urban research, the students of the Chicago school of sociology. |

参与観察 参与観察は、質的研究やエスノグラフィで一般的に用いられる実践家学者 によるデータ収集方法の一種である。この種の方法論は、特に人類学(文化人類学や民族学を含む)、社会学(文化社会学や文化犯罪学を含む)、コミュニケー ション研究、人文地理学、社会心理学など、多くの分野で採用されている。その目的は、ある集団(宗教、職業、青少年グループ、特定のコミュニティなど)と その実践について、通常長期間にわたって、その文化的環境の中で人々と集中的に関わることで、親密で親密な知識を得ることである。 「参与観察」という概念は、ジョン・デューイやデンマークの教育者・哲学者であるN.F.S.グルントヴィグの影響を受けたアメリカの成人教育のパイオニ アであるエドゥアルド・C.・リンデマン(1885~1953年)が、その著書「社会的発見」の中で1924年に初めて作り出したものである: 機能的集団の研究へのアプローチ "である。しかし、この方法はそれ以前に生まれたものであり、ヨーロッパやアメリカの科学的探検航海と結びついたフィールド調査に応用されていた。 1800年、この方法の先駆者の一人であるジョセフ・マリー(ジェランド男爵)は次のように述べている: 「その後、この方法は、イギリスのブロニスワフ・マリノフスキとその弟子たち、アメリカのフランツ・ボアズの弟子たち、そして後の都市研究においてはシカ ゴ学派の社会学の弟子たちによって広められた。 |

| History and development Participant observation was used extensively by Frank Hamilton Cushing in his study of the Zuni people in the latter half of the nineteenth century. This would be followed in the early twentieth century by studies of non-Western societies through such people as Bronisław Malinowski (1929),[2] E.E. Evans-Pritchard (1940),[3] and Margaret Mead (1928).[4] The practice emerged as the principal approach to ethnographic research by anthropologists and relied on the cultivation of personal relationships with local informants as a way of learning about a culture, involving both observing and participating in the social life of a group. By living with the cultures they studied, researchers were able to formulate first-hand accounts of their lives and gain novel insights. This same method of study has also been applied to groups within Western society and is especially successful in the study of sub-cultures or groups sharing a strong sense of identity, where only by taking part may the observer truly get access to the lives of those being studied. The postmortem publication of Grenville Goodwin's decade of work as a participant-observer with the Western Apache[5] established him as a prominent figure in the field of ethnology. Since the 1980s, some anthropologists and other social scientists have questioned the degree to which participant observation can give veridical insight into the minds of other people.[6][7] At the same time, a more formalized qualitative research program known as grounded theory, initiated by Glaser and Strauss (1967),[8] began gaining currency within American sociology and related fields such as public health. In response to these challenges, some ethnographers have refined their methods, either making them more amenable to formal hypothesis-testing and replicability or framing their interpretations within a more carefully considered epistemology.[9] The development of participant-observation as a research tool has therefore not been a haphazard process, but instead has involved a great deal of self-criticism and review. It has, as a result, become specialized. Visual anthropology can be viewed as a subset of methods of participant-observation, as the central questions in that field have to do with how to take a camera into the field, while dealing with such issues as the observer effect.[10] Issues with entry into the field have evolved into a separate subfield. Clifford Geertz's famous essay[6] on how to approach the multi-faceted arena of human action from an observational point of view, in Interpretation of Cultures uses the simple example of a human wink, perceived in a cultural context far from home. |

歴史と発展 参与観察は、19世紀後半にフランク・ハミルトン・カッシングがズニ族を研究した際に広く用いられた。これは20世紀初頭に、ブロニスワフ・マリノフス キー(1929年)[2]、E.E.エヴァンス=プリチャード(1940年)[3]、マーガレット・ミード(1928年)[4]などの人々による非西洋社 会の研究に続くことになる。 この実践は人類学者によるエスノグラフィ調査の主要なアプローチとして登場し、集団の社会生活を観察し参加することで文化を学ぶ方法として、現地の情報提 供者との個人的な関係を築くことに依存していた。研究者たちは、研究対象の文化とともに生活することで、彼らの生活についての生の証言を形成し、新たな洞 察を得ることができた。この同じ研究方法は、西洋社会内の集団にも適用され、特に、強いアイデンティティ意識を共有するサブカルチャーや集団の研究におい て成功を収めている。グレンヴィル・グッドウィンは、西アパッチ族との10年にわたる参加観察者としての仕事[5]を死後に発表し、民族学の分野で著名な 人物としての地位を確立した。 1980年代以降、一部の人類学者やその他の社会科学者は、参与観察が他者の心に対する真実の洞察を与えることができる程度に疑問を呈している[6] [7]。同時に、グレーザーとストロース(1967年)によって始められたグラウンデッド・セオリー(基 礎理論)として知られる、より形式化された質的研究プログラム[8]が、アメリカの社会学や公衆衛生などの関連分野で普及し始めた。このような課題に対応 するため、一部のエスノグラファーはその方法を洗練させ、正式な仮説検証や再現可能性を高めるか、より慎重に検討された認識論の中で解釈を組み立てている [9]。 したがって、調査ツールとしての参与観察の発展は、行き当たりばったりのプロセスではなく、多くの自己批判と見直しを伴うものであった。その結果、参加観 察は専門化した。視覚人類学は、参与観察法のサブセットとみなすことができる。この分野の中心的な問題は、観察者効果などの問題に対処しながら、どのよう にカメラを現場に持ち込むかに関係しているからである[10]。クリフォード・ギアーツの有名なエッセイ[6]は、『文化の解釈』の中で、人間の行動とい う多面的な場に観察的な視点からアプローチする方法について、自国から遠く離れた文化的文脈の中で知覚される人間のウィンクという単純な例を用いている。 |

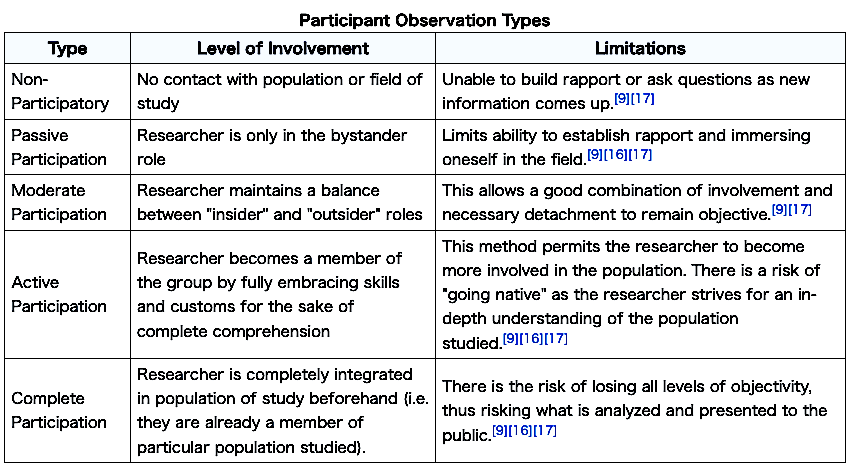

| Method and practice Such research involves a range of well-defined, though variable methods: informal interviews, direct observation, participation in the life of the group, collective discussions, analyses of personal documents produced within the group, self-analysis, results from activities undertaken off or online, and life-histories. Although the method is generally characterized as qualitative research, it can (and often does) include quantitative dimensions. Traditional participant observation is usually undertaken over an extended period of time, ranging from several months to many years, and even generations. An extended research time period means that the researcher is able to obtain more detailed and accurate information about the individuals, community, and/or population under study. Observable details (like daily time allotment) and more hidden details (like taboo behavior) are more easily observed and interpreted over a longer period of time. A strength of observation and interaction over extended periods of time is that researchers can discover discrepancies between what participants say—and often believe—should happen (the formal system) and what actually does happen, or between different aspects of the formal system; in contrast, a one-time survey of people's answers to a set of questions might be quite consistent, but is less likely to show conflicts between different aspects of the social system or between conscious representations and behavior.[9] Howell's phases of participant observation In participant observation, a researcher's discipline based interests and commitments shape which events he or she considers are important and relevant to the research inquiry.[11] According to Howell (1972), the four stages that most participant observation research studies are establishing rapport or getting to know the people, immersing oneself in the field, recording data and observations, and consolidating the information gathered.[12] The phases are as follows:[12]: 392–403 Establishing Rapport: Get to know the members, visit the scene before study. Howell[12] states that it is important to become friends, or at least be accepted in the community, in order to obtain quality data. In the Field (do as the locals do): It is important for the researcher to connect or show a connection with the population in order to be accepted as a member of the community. DeWalt & DeWalt (2011)[13][12]: 392–396 call this form of rapport establishment as "talking the talk" and "walking the walk". Also mentioned by Howell, DeWalt & DeWalt state that the researcher must strive to fit in with the population of study through moderation of language and participation.[9] This sets the stage for how well the researcher blends in with the field and the quality of observable events he or she experiences. Recording Observations and Data: Along with field notes and interviews, researchers are encouraged to record their personal thoughts and feelings about the subject of study through reflexivity journals. The researchers are prompted to think about how their experiences, ethnicity, race, gender, sex, sexual orientation, and other factors might influence their research, in this case what the researcher decides to record and observe.[14] Researchers must be aware of these biases and enter the study with no misconceptions about not bringing in any subjectivities into the data collection process.[9][14][15] Analyzing Data: Thematic Analysis: organizing data according to recurrent themes found in interviews or other types of qualitative data collection and Narrative Analysis: categorizing information gathered through interviews, finding common themes, and constructing a coherent story from data. Types of participant observation Participant observation is not simply showing up at a site and writing things down. On the contrary, participant observation is a complex method that has many components. One of the first things that a researcher or individual must do after deciding to conduct participant observations to gather data is decide what kind of participant observer he or she will be. Spradley (1980)[16] provides five different types of participant observations summarised below. |

方法と実践 非公式なインタビュー、直接観察、グループ生活への参加、集団討論、グループ内で作成された個人文書の分析、自己分析、オフやオンラインで行われた活動の 結果、ライフヒストリーなどである。この手法は一般的に質的研究として特徴づけられるが、量的な側面を含むこともある(そしてしばしばそうなる)。伝統的 な参加者観察は、通常、数ヶ月から数年、さらには何世代にもわたる長期にわたって実施される。調査期間が長いということは、調査対象の個人、コミュニ ティ、集団について、より詳細で正確な情報を得ることができるということである。観察可能な詳細(1日の時間配分など)や、より隠された詳細(タブー行動 など)は、長期間にわたって観察され、解釈されやすくなる。長期間にわたる観察および相互作用の長所は、研究者が、参加者が言っていること、そしてしばし ば信じていること、つまり起こるべきこと(形式的なシステム)と実際に起こっていること、あるいは形式的なシステムの異なる側面との間の矛盾を発見できる ことである。対照的に、一連の質問に対する人々の回答に関する1回限りの調査では、非常に一貫しているかもしれないが、社会システムの異なる側面間、ある いは意識的な表象と行動との間の矛盾を示す可能性は低い[9]。 ハウエルの参与観察の段階 ハウエル(1972)によると、ほとんどの参与観察研究の4つの段階は、ラポールの確立または人々を知ること、フィールドに没頭すること、データと観察を 記録すること、収集した情報を統合することである[12]。 段階は以下の通りである[12]: 392-403 ラポールの確立: メンバーを知り、調査の前に現場を訪れる。Howell[12]は、質の高いデータを得るためには、友達になるか、少なくともコミュニティに受け入れられ ることが重要であるとしている。 現場で(地元の人がするように): 調査者がコミュニティの一員として受け入れられるためには、住民とつながりを持つ、あるいはつながりを示すことが重要である。DeWalt & DeWalt (2011)[13][12]: 392-396は、このようなラポール構築の形態を「話をする」「歩く」と呼んでいる。また、ハウエルも言及している が、デウォルト&デウォルトは、研究者は言葉遣いや参加態度の節度を守ることで、研究対象集団に溶け込む努力をしなければならないと述べている[9]。 観察とデータの記録 フィールドノートやインタビューと並行して、研究者は研究対象に関する個人的な考えや感情を、リフレクティビティ・ジャーナルを通じて記録することが奨励 される。研究者は、自分の経験、民族性、人種、ジェンダー、性別、性的指向、その他の要因が、研究(この場合、研究者が記録・観察すると決めたこと)にど のような影響を与えるかを考えるよう促される[14]。研究者はこうしたバイアスを意識し、データ収集プロセスに主観を持ち込まないよう、誤解のない状態 で研究に臨まなければならない[9][14][15]。 データの分析 テーマ分析:インタビューや他のタイプの質的データ収集で発見された再発するテーマに従ってデータを整理すること。 物語分析:インタビューを通じて収集した情報を分類し、共通のテーマを見つけ、データから首尾一貫したストーリーを構築する。 参加者観察の種類 参加者観察とは、単に現場に現れて、物事を書き留めることではありません。それどころか、参加者観察は多くの要素を持つ複雑な方法である。データを収集す るために参与観察を実施することを決めた後、研究者や個人が最初にしなければならないことの1つは、どのような参与観察者になるかを決めることである。ス プラドリー(1980)[16]は、参加者観察の5つの異なるタイプを以下に要約している。 |

|

|

| Limitations To Any Participant

Observation The recorded observations about a group of people or event is never going to be the full description.[17][18][19] As mentioned before this is due to the selective nature of any type of recordable data process: it is inevitably influenced by researchers' personal beliefs of what is relevant and important.[17][18][19] This also plays out in the analysis of collected data; the researcher's worldview invariably influences how he or she interprets and evaluates the data.[9][16][18][19] The researcher may not capture accurately what the participant or may misunderstand the meaning of the participant's words, thus drawing inaccurate generalizations about the participant's perceptions.[20] Impact of researcher involvement The presence of the researcher in the field may influence the participants' behavior, causing the participants to behave differently than they would without the presence of the observer (see:observer-expectancy effect).[20][21] Researchers engaging in this type of qualitative research method must be aware that participants may act differently or put up a facade that is in accordance to what they believe the researcher is studying.[21] This is why it is important to employ rigor in any qualitative research study. A useful method of rigor to employ is member-checking or triangulation.[22][23] According to Richard Fenno, one problem in participant observation is the risk of "going native", by which he means that the researcher becomes so immersed in the world of the participant that the researcher loses scholarly objectivity.[20] Fenno also warns that the researcher may lose the ability and willingness to criticize the participant in order to maintain ties with the participant.[20] While gathering data through participant observation, investigator triangulation would be a way to ensure that one researcher is not letting his or her biases or personal preferences in the way of observing and recording meaningful experiences.[23] As the name suggests, investigator triangulation involves multiple research team members gathering data about the same event, but this method ensures a variety of recorded observations due to the varying theoretical perspectives of each research team member.[23] In other words, triangulation, be it data, investigator, theory or methodological triangulation, is a form of cross-checking information.[22][23] Member checking is when the researcher asks for participant feedback on his or her recorded observations to ensure that the researcher is accurately depicting the participants' experiences and the accuracy of conclusions drawn from the data.[23] This method can be used in participant observation studies or when conducting interviews.[23] Member-checking and triangulation are good methods to use when conducting participant observations, or any other form of qualitative research, because they increase data and research conclusion credibility and transferability. In quantitative research, credibility is liken to internal validity,[23][24] or the knowledge that our findings are representative of reality, and transferability is similar to external validity or the extent to which the findings can be generalized across different populations, methods, and settings.[23][24] A variant of participant observation is observing participation, described by Marek M. Kaminski, who explored prison subculture as a political prisoner in communist Poland in 1985.[25] "Observing" or "observant" participation has also been used to describe fieldwork in sexual minority subcultures by anthropologists and sociologists who are themselves lesbian, gay, bisexual, or transgender,[26] as well as amongst political activists and in protest events.[27] The different phrasing is meant to highlight the way in which their partial or full membership in the community/subculture that they are researching both allows a different sort of access to the community and also shapes their perceptions in ways different from a full outsider. This is similar to considerations by anthropologists such as Lila Abu-Lughod on "halfie anthropology", or fieldwork by bicultural anthropologists on a culture to which they partially belong.[28] |

参与観察の限界 ある集団や出来事について記録された観察は、決して完全な記述にはならない[17][18][19]。 前述したように、これはあらゆるタイプの記録可能なデータプロセスの選択的な性質によるもので、何が関連し重要であるかについての研究者の個人的な信念に 必然的に影響される[17][18][19]。 これは収集されたデータの分析にも反映される。研究者の世界観は必ず、データの解釈や評価の仕方に影響する[9][16][18][19]。 研究者は参加者の言葉を正確に捉えられなかったり、参加者の言葉の意味を誤解したりする可能性があり、その結果、参加者の認識について不正確な一般化をし てしまう可能性がある[20]。 研究者の関与の影響 フィールドにおける研究者の存在は、参加者の行動に影響を与える可能性があり、参加者は観察者の存在がない場合とは異なる行動をとるようになるかもしれな い(観察者-期待効果参照)[20][21]。この種の質的研究方法に携わる研究者は、参加者が研究者が研究していると信じていることに従って、異なる行 動をとったり、見せかけの態度をとったりする可能性があることを認識しておかなければならない[21]。採用する厳密性の有用な方法は、メンバーチェック または三角測量である[22][23]。 リチャード・フェノーによると、参与観察における問題の1つは「ネイティブ化」のリスクであり、これは、研究者が参与の世界に没頭するあまり、学術的な客 観性を失うことを意味する[20]。フェノーはまた、研究者が参与とのつながりを維持するために、参与を批判する能力や意欲を失う可能性があると警告して いる[20]。 参加者の観察を通じてデータを収集する一方で、調査者の三角測量は、有意義な経験を観察し記録する際に、1人の調査者が自分の偏見や個人的嗜好に邪魔され ないようにするための方法である。 [23]。その名が示すように、調査者の三角測量は、複数の調査チームメンバーが同じ出来事についてデータを収集することを含むが、この方法は、各調査 チームメンバーの理論的視点が異なるため、記録された観察の多様性を保証する[23]。言い換えれば、三角測量は、データ、調査者、理論、方法論の三角測 量であれ、情報のクロスチェックの一形態である[22][23]。 メンバーチェックとは、研究者が参加者の経験を正確に描写しているか、データから引き出された結論の正確さを確認するために、記録した観察に対して参加者 のフィードバックを求めることである[23]。この方法は、参加者観察研究やインタビューを実施する際に使用することができる[23]。メンバーチェック と三角測量は、データと研究結論の信頼性と移植性を高めるため、参加者観察、または他の形態の質的研究を実施する際に使用するのに適した方法である。量的 研究では、信頼性は内的妥当性[23][24]、つまり調査結果が現実を代表しているという知識に似ており、伝達可能性は外的妥当性、つまり調査結果が異 なる集団、方法、設定にわたって一般化できる程度に似ている[23][24]。 参加者観察の変種として、1985年に共産主義ポーランドの政治犯として刑務所のサブカルチャーを調査したマレク・M・カミンスキーによって説明された観 察参加がある[25]。「観察」または「観察的」参加はまた、自身がレズビアン、ゲイ、バイセクシュアル、トランスジェンダーである人類学者や社会学者に よる性的マイノリティのサブカルチャーにおけるフィールドワークを説明するために使用されている[26]。 [27] この異なる言い回しは、研究対象のコミュニティ/サブカルチャーの一部または全部のメンバーであることが、コミュニティへの異なる種類のアクセスを可能に すると同時に、完全な部外者とは異なる方法で彼らの認識を形成する方法を強調することを意図している。これはライラ・アブ・ルゴッドのような人類学者によ る「ハーフの人類学」や、バイカルチャーの人類学者による部分的に属している文化についてのフィールドワークについての考察に似ている[28]。 |

| Ethical concerns As with any form of research dealing with human subjects, the researcher must ensure the ethical boundaries are never crossed by those conducting the subjects of study. The researcher must have clearly established boundaries before the onset of the study, and have guidelines in place should any issues cross the line of ethical behavior. One of the issues would be if the researcher is studying a population where illegal activities may occur or when working with minor children.[9] In participant observation, the ethical concern that is most salient is that of informed consent and voluntary participation.[9] There is the issue of deciding to obtain informed consent from every individual in the group of study, obtain the informed consent for participant observation from the person of leadership, or not inform anyone of one's true purpose in fear of influencing the attitudes of members, thus skewing the observations recorded.[9][17] The decision is based on the nature of the study and the researcher's own personal thoughts on the cost-benefit ratio of the situation. Participant observation also brings up the issue of voluntary participation in events the researcher observes and records.[17] There may be instances when members do not want to be a part of the study and request that all data collected pertinent to them be removed. In this case, the researcher is obligated to relinquish data that may identify the members in any way. Above anything else, it is the researcher's responsibility that the participants of the study do not suffer any ill effects directly or indirectly from the study, participants are informed of their rights as subjects of the study, and that the group was justly chosen for study.[29] The American Anthropological Association (AAA) and American Sociological Association (ASA) both have comprehensive statements concerning the code of conduct for research. The AAA has developed a code of ethics to guide this practice.[30] |

倫理的懸念 ヒトを対象とするあらゆる形態の研究と同様に、研究者は、研究対象を実施する者が倫理的境界線を決して越えないようにしなければならない。研究者は、研究 の開始前に境界線を明確に設定し、倫理的行動の一線を越えるような問題が発生した場合のガイドラインを用意しておかなければならない。参加者観察におい て、最も顕著な倫理的懸念は、インフォームド・コンセントと自発的な参加である[9]。研究対象集団のすべての個人からインフォームド・コンセントを得る か、指導的立場にある人から参加者観察のインフォームド・コンセントを得るか、あるいはメンバーの態度に影響を与えることを恐れて誰にも自分の真の目的を 知らせず、記録される観察に歪みを与えるか、決定する問題がある[9][17]。 この決定は、研究の性質と状況の費用便益比に関する研究者自身の個人的な考えに基づいている。参加者観察では、研究者が観察・記録する出来事への自発的な 参加の問題も浮上する[17]。メンバーが研究の一部になることを望まず、自分に関連する収集データをすべて削除するよう要求する場合もある。この場合、 研究者は会員を何らかの形で特定しうるデータを放棄する義務がある。何よりも、研究参加者が研究によって直接的・間接的にいかなる悪影響も被らないこと、 参加者が研究対象者としての権利を知らされていること、研究対象としてグループが正当に選ばれていることが、研究者の責任である[29]。 米国人類学会(AAA)と米国社会学会(ASA)は、ともに研究の行 動規範に関する包括的な声明を持っている。AAAは、この実践の指針となる倫理綱領を策定している[30]。 |

| Clinical Ethnography Creative participation Educational psychology Ethnobotany Immersion journalism Naturalistic observation Participatory Action Research Person-centered ethnography Scholar-practitioner model Qualitative research Unobtrusive measures |

臨床エスノグラフィー 創造的参加 教育心理学 民族植物学 イマージョン・ジャーナリズム 自然主義的観察 参加型アクションリサーチ パーソンセンタードエスノグラフィー 研究者-実践者モデル 質的調査 非侵入的手段 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Participant_observation |

関連リンク

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆