行為遂行的発話と事実確認的発話

Explanations of the John Langshaw Austin' terms, illocutionary act and performative utterance

John Langshaw Austin, 1911-1960

解説:池田光穂

スピーチアクト理論

行為遂行的発話と事実確認的発話

Explanations of the John Langshaw Austin' terms, illocutionary act and performative utterance

John Langshaw Austin, 1911-1960

解説:池田光穂

広義のスピーチアクト理論=言語行為理論(speech act theory/-ies)に属する議論である。ここでは、ジョン・ラングスロー・オースティン(John Langshaw Austin, 上掲写真)の議論を紹介します。

| 行為遂行的発話=パフォーマティ

ブな発話(performative utterance) |

「必ず明日借金を君に返す」という発話

は、君を前にして私が話す時、未来の私の行為と君の期待という社会性を帯びている。つまりこの発語は、未来の私たちの行為を促し、実行しているので、パ

フォーマティブな発語という。 |

| 事実確認的発話

(constative utterance) |

世界を描写する発話のこと。「このチュー

リップは萎んでいる」「芝生は青い」という

発話など、平叙文をつくり、かつ平叙的 (constative)である。 |

行為遂行的発話=パフォーマティ ブな発話(performative utterance)

「必ず明日借金を君に返す」という発話は、君を前にして私が話す時、ある種の社会性を帯びている。つまり私は君にどうも借金をしているよう であるし、君は私にどうも督促しているようである。そして、私は明日という未来において、君に借金を返すという約束をすることにより、明日までに何らかの 金策をするようであり、君はそれまで督促することを抑制し明日を待つ。つまり、発話の行為の中に、ある種の力(force)を行使する。このような発話内 の力の行使を、発話内行為(illocutionary act)という。また、私も君も、ともに明日という未来において私の負債が完了しているかのような心的影響をもたらしている。このような状況をも たらすものが、発話媒介行為(perlocutionary act)である(後述する)。

Wikipedia says, "Speech acts can be analysed on three levels....

行為遂行的 (performative) 発話は、その発語が未来の時間のなかで適切に機能するかあるいは不適切な帰結をうむのかということが評価基準となる。つまり、私が君に5000万 円の借金があって、手元にも自分の銀行にも高々数百万円しかないし、明日までに私に金を貸してくれる君以外の友人も知人もいないとき、「必ず明日借金を君 に全額返す」というのは、その事実の予測において、適切とは言えない。逆に「明日は君への借金の返済のうち、三百万を返すから、3カ月待ってくれない」か と君の督促に対して返事することは、よりその発話の適切度はますと思われる(もちろん依然として借金を完済できるか否かは未来の運命に委ねられている)。

1. 発話行為; すなわち実際の発話とその表向きの意味であり、あらゆる意味のある発話の言語的、統語的、意味的側面に対応する音声、音韻、rhetic行為で構成される。

2. 発話内行為/発語内行為、つまり、illocutionary act: 発言の語用論的な「illocutionary force」、つまり社会的に有効な言語行為として意図された意義。

3. 発語媒介行為 perlocutionary act 例

えば、説得、納得、恐怖、啓蒙、鼓舞、あるいは意図的かどうかにかかわらず、誰かに

何かをさせたり、実現させたりすることである(オースティン1962)。

事実確認的発話 (constative utterance)

「このチューリップは萎んでいる」という発話は、私が嘘をついていない限り、目の前にあるチューリップについて事実を叙述しており、平叙的 (constative)である。このような、事実を述べる行為(=事実についての真偽はもちろん発話者の確信により、事実が複数の発話者においてしばし ばずれることは日常よく体験するとおりである)を、事実確認的発話(constative utterance)であるという。

事実確認的発話は、その真偽において評価される。つまり、我々の目の前に植わっているチューリップが鮮やかに咲き乱れている 時、「これらのチューリップは萎んでいるね」という発話に、君は「それは間違っているぜ」と応えざるを得ないだろう。

その後、オースティンは、発話の中に、行 為遂行的なものと事実確認的なものの双方が含まれることへと、発話行為の分類をすすめた。それが、 (1)発話行為/発語行為(locutionary act)、(2)発話内行為/発語内行為(illocutionary act)、(3)発語媒介行為(perlocutionary act)、の峻別である。(上掲「行為遂行 的発話=パフォーマティ ブな発話」を参照)

| (1)発話行為/発語行為

(locutionary act) |

例えば「今日は天気がいい」と発語する

ことであり、文字通り、発話を実際におこなうことである。 |

| (2)発話内行為/発語内行為

(illocutionary act) |

例えば「この船をクーインエリザベスと

命名します」と発語するような行為であり、行なっていることと発語の内容が合致している状態である。 |

| (3)発語媒介行為

(perlocutionary act) |

例えば、異性装の人を前に「おかま

(fag)」と言うと、相手を不快にさせるだけでなく、未来の相手と自分の行為を誘発することを意味する。 |

行為遂行的発話=パフォーマティ ブな発話(performative utterance)

(1) 発話行為/発語行為(locutionary act)

"[A] locutionary act is the performance of an utterance, and hence of a speech act." "In Austin's framework, locution is what was said, illocution is what was meant, and perlocution is what happened as a result. For example, when somebody says "Is there any salt?" at the dinner table."

ウィキベディアの文例だと、テーブルに「塩はあるかい?」と発語することだ。発話を実際におこなうことである。ロキューション (locution)は話された内容そのものをさす。「今日は天気がいい」と発語することも発話を実際におこなうことであり、発話行為/発語行為 (locutionary act)。

(2) 発話内行為/発語内行為(illocutionary act)

"[T]he illocutionary act (the meaning conveyed) is effectively "please give me some salt" even though the locutionary act (the literal sentence) was to ask a question about the presence of salt.

発話内=イロキューションとは、発語行為内容=ロキューションが行為として発動させるものである。つまり「塩はあるかい?」という発語内容 を《塩をとってくれないかい?》と言う行為の意味内容のことである。「この船をクーインエリザベスと命名します」と発語するような行為も発語内行為 (illocutionary act)であり、行なっていることと発語の内容が合致している状態である。

(3) 発語媒介行為(perlocutionary act)

"The perlocutionary act (the actual effect), was to cause somebody to hand over the salt," when someone had been said, "Is there any salt?"

発語媒介=ペロキューションとは、発話内行為を受けて、実際におこなれる行為そのものをさす。つまり、《塩をとってくれないかい?》の意味 内容を理解して、実際に塩を手渡すことを〈うむ行 為〉さすわけ だ。例えば、異性装の人を前に「おかま(fag)」と言うと、相手を不快にさせるだけでなく、未来の相手と自分の行為を誘発することを意味する。発語を通 して、相手と自分の行為を誘発するわけなので、この発語は、発語媒介行為(perlocutionary act)と呼ばれる。

▲▲▲▲【補記】

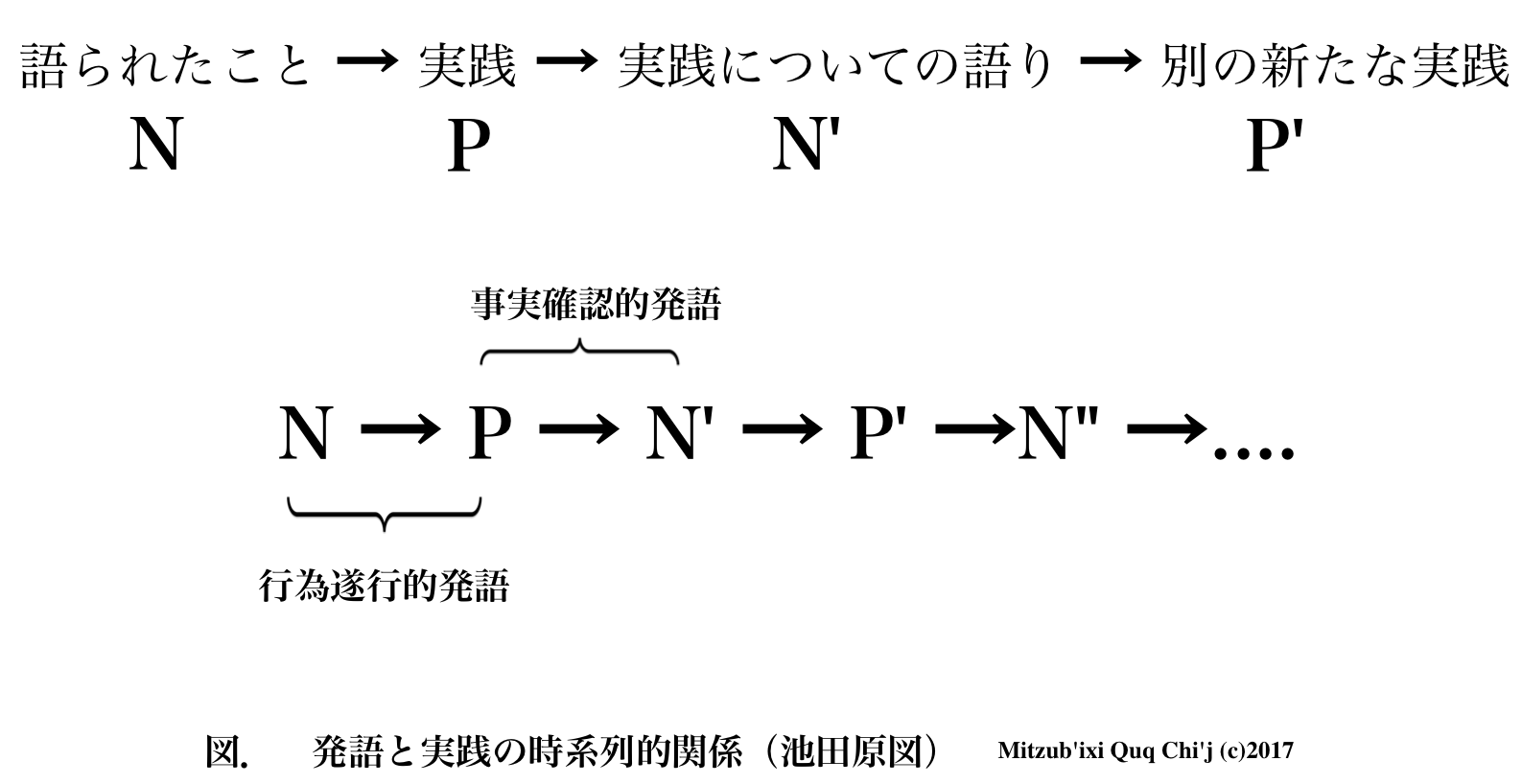

その後、私は、ミハイル・バフチンのドス トエフスキー論(1929)からインスピレーションを受けて、語りがもつ「実践の創造」について関心が 広がりました。そして、なぜ、実践が生まれるのかについて、ジョン・オースティンの言語行為論を応用すれば、簡単に説明は付くはずでないかとも、思いを馳 せました。下記の図を参照ください。

まず、行為遂行的発語

(performative utterance)と事実確認的発話(constative

utterance)は、ある一人の人間においても、それに関わる人の存在を前にしてはなりたちます。

し

かしながら、発話行為/発語行為(locutionary act)、発話内行為/発語内行為(illocutionary

act)、および発語媒介行為(perlocutionary act)は、発語に立ちあう他者の存在が不可欠です。それを示したのが下図です。

文献

関連リンク

発展課題:

【練習問題】

ジョン・サールの「間接スピーチアクツ

(indirect speech acts)」について、以下の文章を要約解説しなさい

John Searle's theory of "indirect speech acts"

Searle has introduced the notion of an 'indirect speech act', which in his account is meant to be, more particularly, an indirect 'illocutionary' act. Applying a conception of such illocutionary acts according to which they are (roughly) acts of saying something with the intention of communicating with an audience, he describes indirect speech acts as follows: "In indirect speech acts the speaker communicates to the hearer more than he actually says by way of relying on their mutually shared background information, both linguistic and nonlinguistic, together with the general powers of rationality and inference on the part of the hearer." An account of such act, it follows, will require such things as an analysis of mutually shared background information about the conversation, as well as of rationality and linguistic conventions.

In connection with indirect speech acts, Searle introduces the notions of 'primary' and 'secondary' illocutionary acts. The primary illocutionary act is the indirect one, which is not literally performed. The secondary illocutionary act is the direct one, performed in the literal utterance of the sentence (Searle 178). In the example:

Here the primary illocutionary act is Y's rejection of X's suggestion, and the secondary illocutionary act is Y's statement that Y is not ready to leave. By dividing the illocutionary act into two subparts, Searle is able to explain that we can understand two meanings from the same utterance all the while knowing which is the correct meaning to respond to.

With his doctrine of indirect speech acts Searle attempts to explain how it is possible that a speaker can say something and mean it, but additionally mean something else. This would be impossible, or at least it would be an improbable case, if in such a case the hearer had no chance of figuring out what the speaker means (over and above what they say and mean). Searle's solution is that the hearer can figure out what the indirect speech act is meant to be, and he gives several hints as to how this might happen. For the previous example Direct Speech and Indirect Speech "While direct speech purports to give a verbatim rendition of the words that were spoken, indirect speech is more variable in claiming to represent a faithful report of the content or content and form of the words that were spoken. It is important to note, however, that the question of whether and how faithful a given speech report actually is, is of a quite different order. Both direct and indirect speech are stylistic devices for conveying messages. The former is used as if the words being used were those of another, which are therefore pivoted to a deictic center different from the speech situation of the report. Indirect speech, in contrast, has its deictic center in the report situation and is variable with respect to the extent that faithfulness to the linguistic form of what was said is being claimed." (Florian Coulmas, "Reported Speech: Some General Issues.") a condensed process might look like this:

Searle argues that a similar process can be applied to any indirect speech act as a model to find the primary illocutionary act (178). His proof for this argument is made by means of a series of supposed "observations" (ibid., 180-182)." (Source: Speech Act )" http://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Speech_act

ジョン・サールの 「間接的発話行為 」理論

サールは「間接的発話行為」という概念を導入したが、彼の説明では、これはより個別主義的な間接的「発話行為」を意味する。間接的発話行為とは、(おおよ

そ)聴衆とのコミュニケーションを意図して発言する行為であるという概念を適用し、彼は間接的発話行為を次のように説明している:

「間接的発話行為では、話し手は聞き手に対して、言語的・非言語的な背景情報を相互に共有し、聞き手側の一般的な合理性や推論力に依存することによって、

実際に話す以上のことを伝える。このような行為の説明には、合理性や言語的慣習だけでなく、会話に関する相互に共有された背景情報の分析などが必要にな

る。

間接的発話行為に関連して、サールは「第一次」と「第二次」の発話行為という概念を導入している。第一次的な非言語行為とは間接的なものであり、文字通り

には行われない。二次的な発話行為とは直接的な発話行為のことで、文の文字どおりの発話の中で行われる(サール 178)。例では

1. 話し手X:「そろそろショーに出ないと遅刻しちゃうよ」。

2.話者Y:「まだ準備ができていない」。

ここでは、第一の非言語的行為はYがXの提案を拒絶することであり、第二の非言語的行為はYが「まだ準備ができていない」と発言することである。サール

は、発語行為を2つの部分に分けることで、同じ発話から2つの意味を理解することができ、同時にどちらの意味に反応するのが正しいかを知ることができると

説明している。

サールは間接話法の教義によって、話し手が何かを言ってそれを意味しながら、さらに別の意味も持つことがありうることを説明しようと試みている。もしその

ような場合、聞き手が話し手の意味することを(話し手が何を言って何を意味するのかを超えて)理解する機会がなければ、このようなことは不可能であり、少

なくともありえないケースである。サールの解決策は、聞き手が間接話法の意味を理解できることであり、その方法についていくつかのヒントを与えている。直

接話法と間接話法

「直接話法が話された言葉をそのまま伝えると主張するのに対して、間接話法は話された言葉の内容や内容と形式を忠実に伝えると主張する点で、より多様であ

る。しかし、ある発話が実際にどの程度忠実であるかという問題は、まったく異なる次元の問題であることに注意する必要がある。直接話法も間接話法も、メッ

セージを伝えるための文体上の工夫である。前者は、あたかも使用されている言葉が別の人のものであるかのように使われ、そのため、報告の発話状況とは異な

るディクティクスの中心に軸が置かれる。これとは対照的に、間接話法は、その指示中心が報告状況にあり、言われたことの言語形式への忠実さが主張される度

合いによって変化する。(Florian Coulmas, 「Reported Speech: Some General

Issues.」)凝縮されたプロセスは次のようになる:

# ステップ1:Xによってある提案がなされ、Yが発話行為によってそれに応じる(2)。

# ステップ2:Xは、Yが会話に協力的であり、誠実であり、Yが関連性のある発言をしたと仮定する。

# ステップ3:(2)の文字通りの意味は会話に関係ない。

# ステップ4:XはYが協力していると仮定しているので、(2)には別の意味があるはずだ。

# ステップ5:相互に共有された背景情報に基づいて、XはYの準備が整うまで離れることができないことを知っている。したがって、YはXの提案を拒否した。

# ステップ6:Xは、Yが文字通りの意味とは別の意味で何かを言ったことを知っており、第一の発話行為はXの提案を拒絶することであったに違いない。

サールは、同様のプロセスをあらゆる間接的発話行為に適用することで、第一次的な発話行為を見つけることができると主張する(178)。この主張に対する

彼の証明は、一連の「観察」(ibid., 180-182)と思われるものによってなされる。" (出典:発話行為)"

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099