かならずよんでください

地域研究

Area

studies,

regional studies

「地域の慣習に詳しい部外者が田舎のとある村にたどり着き、そこで彼が地元の慣習をいかに深く「理解」し、またいかにそれに巧く従えるかをひけらかすぎこちない試みほどレイシスト的なことはないだろう」(ジジェク 2005:29)

| 1.地域研究は、第二次大戦後の、冷戦期における自由主

義陣営側の、戦

略情報把握と諜報活動から出発した。 |

| 2.有力なパトロンの存在、すなわち、地域研究には、国家、諜報機関、

財団、経済開発団体などの支援が欠かせなかった。 |

| 3.その主要なリーディング・ディシプリンとしての政治学と経済学の2

つの領域がメインであり、歴史学、地理学、社会学、ジェンダー研究、文化人類学はつねに、その周辺の落ち穂拾い研究が中心である。 |

| 4.地域研究の華は、事例研究である。また、多くの地域研究者は、その

ような「代表的」な研究を読んでから、フィールドに赴く。 |

| 5.地域研究には、その来歴(=自由主義陣営側の、戦略情報把握と諜報

活動をルーツとする)からかず多くの批判に晒されてきた。ただし、その批判が、地域研究そのものを活性化しているという主張もある。 |

| 6.西暦2000年以降、インターネットによる情報爆発のために地域研

究の現状は、非常に多様化を深めている。そのため地域研究とグローバル研究の間

の垣根は撤廃されつつある。 |

解説:池田光穂

地域研究

(area

studies/regional studies)

【地域研究の定義】

地

域研究(regional

studies)とは地球上の地域に関するさまざまな情報を整理、統合する学際研究のことである。地域の研究・エリ

アスタディーズ

(area

studies)という用語がある。地域研究とは、地球上の表面を大きな諸地域(アジア、アフリカ、北米、中南米、ヨーロッパ、オセアニア等々の

大区分あるいは、北アジア、東アジア、中米、南米、ミクロネシア等々のより細かい地域の小区分)にわけておこなう研究分野がある。

Area stidies is

"interdisciplinary research

(as in the social sciences) in a distinct geographic, sociocultural, or

political area aimed at a scientific understanding of the area as an

entity and at relating it to other areas" - Merriam-Webster.)

"Area

studies (also regional studies) are interdisciplinary fields

of research and scholarship pertaining to particular geographical, national/federal, or cultural

regions.

The term exists primarily as a general description for what are, in the

practice of scholarship, many heterogeneous fields of research,

encompassing both the social sciences and the humanities. Typical area

study programs involve international relations, strategic studies,

history, political science, political economy, cultural studies,

languages, geography, literature, and other related disciplines. In

contrast to cultural studies, area studies often include diaspora and

emigration from the area." - Area studies.

こ

れらは、文化人類学、地理学、政治学、経済学など

の「地域を研究対象にする経験的あるいは実証的な諸学問分野が集合した総合科学」である。地

域研究をおこなっている機関は、大学の研究所や国立あるいは私立のシンクタンクなどにある。(→「地域科学・地域研究・国

別研究」)

これは、地域研究をおこなうことに具体的な目的

があるから

である。世界の諸地域の動向を知るということは、政治ならびに経済に大きな支配力を行使することができるからである。地域研究が第二次大戦後にアメリカ合

州国で大きく発展したのもこのことによる。(→戦

略情報の

項目を参照してください)

Area studies,

also known as regional studies, is an interdisciplinary field of

research and scholarship pertaining to particular geographical,

national/federal, or cultural regions. The term exists primarily as a

general description for what are, in the practice of scholarship, many

heterogeneous fields of research, encompassing both the social sciences

and the humanities. Typical area study programs involve international

relations, strategic studies, history, political science, political

economy, cultural studies, languages, geography, literature, and other

related disciplines. In contrast to cultural studies, area studies

often include diaspora and emigration from the area.

|

地域研究は、地域研究とも呼ばれ、特定の地理的、国民的、文化的地域に

関する学際的な研究・学問分野である。この用語は主に、社会科学と人文科学の両分野を包含する、学問の実践において異質な多くの研究分野に対する一般的な

説明として存在する。典型的な地域研究プログラムには、国際関係学、戦略研究、歴史学、政治学、政治経済学、文化研究、言語学、地理学、文学、その他関連

分野が含まれる。文化研究とは対照的に、地域研究はしばしばディアスポラやその地域からの移住を含む。

|

History

While area studies had been taught at the Seminar for Oriental

Languages of the Friedrich-Wilhelm University Berlin (now

Humboldt-University) since 1887, interdisciplinary area studies became

increasingly common in the United States and in Western scholarship

after World War II. Before that war American universities had just a

few faculty who taught or conducted research on the non-Western world.

Foreign-area studies were virtually nonexistent. After the war,

liberals and conservatives alike were concerned about the U.S. ability

to respond effectively to perceived external threats from the Soviet

Union and China in the context of the emerging Cold War, as well as to

the fall-out from the decolonization of Africa and Asia.[citation

needed]

Area studies programs originated within the U.S. Office of Strategic

Services, the predecessor agency to the CIA.[1]: 83

In this context, the Ford Foundation, the Rockefeller Foundation, and

the Carnegie Corporation of New York convened a series of meetings

producing a broad consensus that to address this knowledge deficit, the

U.S. must invest in international studies.[citation needed]

Participants argued that a large brain trust of internationally

oriented political scientists and economists was an urgent national

priority. There was a central tension, however, between those who felt

strongly that, instead of applying Western models, social scientists

should develop culturally and historically contextualized knowledge of

various parts of the world by working closely with humanists, and those

who thought social scientists should seek to develop overarching

macrohistorial theories that could draw connections between patterns of

change and development across different geographies. The former became

area-studies advocates, the latter proponents of modernization theory.

The Ford Foundation would eventually become the dominant player in

shaping the area studies program in the U.S.[4] In 1950, the foundation

established the prestigious Foreign Area Fellowship Program (FAFP), the

first large-scale national competition in support of area-studies

training in the U.S. From 1953 to 1966, it contributed $270 million to

34 universities for area and language studies. Also during this period,

it poured millions of dollars into the committees run jointly by the

Social Science Research Council and the American Council of Learned

Societies for field-development workshops, conferences, and publication

programs.[5] Eventually, the SSRC-ACLS joint committees would take over

the administration of FAFP.

Other large and important programs followed Ford's. Most notably, the

National Defense Education Act of 1957, renamed the Higher Education

Act in 1965, allocated funding for some 125 university-based

area-studies units known as National Resource Center programs at U.S.

universities, as well as for Foreign Language and Area Studies

scholarships for undergraduate students and fellowships for graduate

students.

Meanwhile, area studies were also developed in the Soviet Union.[6]

|

歴史

地域研究は、1887年以来、ベルリン・フリードリヒ・ヴィルヘルム大学(現フンボルト大学)の東洋言語セミナーで教えられていたが、学際的な地域研究

は、第二次世界大戦後、アメリカや欧米の学術界でますます一般的になった。第二次世界大戦以前のアメリカの大学では、非西洋世界について教えたり研究した

りする教員はごく少数であった。海外地域研究は事実上存在しなかった。戦後、リベラル派も保守派も同様に、冷戦の勃興の中でソ連や中国からの外的脅威の認

識や、アフリカやアジアの脱植民地化の影響に効果的に対応する米国の能力を懸念していた[要出典]。

地域研究プログラムは、CIAの前身機関である米国戦略

サービス局(OSS)に端を発している[1]: 83。

このような状況の中で、フォード財団、ロックフェラー財団、ニューヨークのカーネギー・コーポレーションは、一連の会議を開催し、この知識不足に対処する

ためには、米国は国際研究に投資しなければならないという幅広いコンセンサスを生み出した[要出典]。参加者は、国際志向の政治学者や経済学者からなる大

規模な頭脳集団が、緊急の国民的優先事項であると主張した。しかし、西洋的なモデルを適用するのではなく、社会科学者は人文科学者と緊密に協力することに

よって、世界各地の文化的・歴史的に文脈化された知識を発展させるべきだと強く考える人々と、社会科学者は異なる地理にわたる変化と発展のパターン間のつ

ながりを描くことができる包括的なマクロ史的理論を発展させるべきだと考える人々の間には、中心的な緊張関係があった。前者は地域研究の提唱者となり、後

者は近代化理論の提唱者となった。

1950年、フォード財団は名誉ある海外地域研究員プログラム(FAFP)を設立した。これは、米国における地域研究研修を支援する初の大規模な国民的コ

ンペティションであった。またこの時期には、社会科学研究評議会とアメリカ有識者会議が共同で運営する委員会にも数百万ドルを注ぎ込み、分野開発ワーク

ショップ、会議、出版プログラムを実施した[5]。最終的には、SSRCとACLSの共同委員会がFAFPの運営を引き継ぐことになる。

フォードに続いて、他の大規模で重要なプログラムも始まった。最も注目すべきは、1957年に制定された国民国防教育法(1965年に高等教育法と改称)

が、米国の大学におけるナショナル・リソース・センター・プログラムとして知られる約125の大学ベースの地域研究ユニットや、学部生を対象とした外国

語・地域研究奨学金、大学院生を対象としたフェローシップに資金を割り当てたことである。

一方、ソ連でも地域研究が発展していた[6]。

|

Controversy within the field

Since their inception, area studies have been subject to

criticism—including by area specialists themselves. Many of them

alleged that because area studies were connected to the Cold War

agendas of the CIA, the FBI, and other intelligence and military

agencies, participating in such programs was tantamount to serving as

an agent of the state.[7] Some argue that there is the notion that U.S.

concerns and research priorities will define the intellectual terrain

of area studies.[8] Others insisted, however, that once they were

established on university campuses, area studies began to encompass a

much broader and deeper intellectual agenda than the one foreseen by

government agencies, thus not American centric.[9]

Arguably, one of the greatest threats to the area studies project was

the rise of rational choice theory in political science and

economics.[10] To mock one of the most outspoken rational choice theory

critics, Japan scholar Chalmers Johnson asked: Why do you need to know

Japanese or anything about Japan's history and culture if the methods

of rational choice will explain why Japanese politicians and

bureaucrats do the things they do?[11]

Following the demise of the Soviet Union, philanthropic foundations and

scientific bureaucracies moved to attenuate their support for area

studies, emphasizing instead interregional themes like "development and

democracy". When the Social Science Research Council and the American

Council of Learned Societies, which had long served as the national

nexus for raising and administering funds for area studies, underwent

their first major restructuring in thirty years, closing down their

area committees, scholars interpreted this as a massive signal about

the changing research environment.[7] |

分野内の論争

地域研究が始まって以来、地域研究の専門家自身を含め、批判にさらされてきた。彼らの多くは、地域研究がCIA、FBI、その他の諜報機関や軍事機関の冷

戦時代のアジェンダと結びついているため、そのようなプログラムに参加することは国家のエージェントとして奉仕することに等しいと主張した[7]。しか

し、ひとたび地域研究が大学のキャンパスに設立されると、地域研究は政府機関が予見していたものよりもはるかに広く深い知的課題を包含するようになり、し

たがってアメリカ中心主義ではないと主張する者もいた[9]。

間違いなく、地域研究プロジェクトにとって最大の脅威のひとつは、政治学や経済学における合理的選択理論の台頭であった[10]。

最も率直な合理的選択理論批判者の一人である日本研究者のチャルマーズ・ジョンソンはそれを嘲笑するために、こう問いかけた:

日本の政治家や官僚がなぜそのような行動をとるのか、合理的選択の手法で説明できるのであれば、なぜ日本語や日本の歴史や文化について知る必要があるのだ

ろうか」[11]。

ソビエト連邦の崩壊後、慈善財団や科学官僚は地域研究への支援を弱め、代わりに「開発と民主主義」といった地域間のテーマを強調するようになった。社会科

学研究評議会とアメリカ学会評議会が、長らく地域研究のための資金調達と管理の国民的中心的役割を担ってきたが、30年ぶりに大規模な再編を行い、地域委

員会を閉鎖したとき、学者たちはこれを研究環境の変化に関する大規模なシグナルと解釈した[7]。

|

Institutions

Some entire institutions of higher education (tertiary education) are

devoted solely to area studies such as School of Oriental and African

Studies or the Tokyo University of Foreign Studies in Japan.

An institution which exclusively deals with Area Studies is the German

Institute of Global and Area Studies in Germany.

|

教育機関

日本の東洋アフリカ学院や東京外国語大学のように、高等教育機関全体が地域研究に特化しているところもある。

地域研究のみを扱う機関としては、ドイツのドイツ地域研究研究所がある。

|

Cultural studies

Ethnic studies

Four

traditions of geography

IATIS

Interdisciplinarity

International studies

Library of Congress Country Studies

Regional geography

|

文化研究

民族研究

地理学の4つの伝統

IATIS(公式サイト)

学際性

国際研究

米国議会図書館国別研究

地域地理学

|

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Area_studies

|

|

●地域研究の6つの重要なテーゼ("Area studies"より、池

田が整理しなおした)

| 1.地域研究は、第二次大戦後の、冷戦期における自由主義陣営側の、戦

略情報把握と諜報活動から出発した。 |

| 2.有力なパトロンの存在、すなわち、地域研究には、国家、諜報機関、

財団、経済開発団体などの支援が欠かせなかった。 |

| 3.その主要なリーディング・ディシプリンとしての政治学と経済学の2

つの領域がメインであり、歴史学、社会学、ジェンダー研究、文化人類学はつねに、その周辺の落ち穂拾い研究が中心である。 |

| 4.地域研究の華は、事例研究である。また、多くの地域研究者は、その

ような「代表的」な研究を読んでから、フィールドに赴く。 |

| 5.地域研究には、その来歴(=自由主義陣営側の、戦略情報把握と諜報

活動をルーツとする)からかず多くの批判に晒されてきた。ただし、その批判が、地域研究そのものを活性化しているという主張もある。 |

| 6.西暦2000年以降、インターネットによる情報爆発のために地域研

究の現状は、非常に多様化を深めている。そのため地域研究とグローバル研究の間の垣根は撤廃されつつある。 |

1.地域研究は、第二次大戦後の、冷戦期

における自由主義陣営側の、戦略情報把握と諜報活動から出発した。

その前史としての、軍事作戦行動に不可欠な地理情報、索敵活動、敵の軍事行動予測、諜報活動を可能にする文化社会情報。

鉄のカーテンの向こうにおける情報把握のための、学際的共同作業の必要性。地域に関する功利主義的な情報。

米国では、モンロー主義により、中南米に関する情報以外のものは僅少。

2.有力なパトロンの存在、すなわち、地

域研究には、国家、諜報機関、財団、経済開発団体などの支援が欠かせなかった。

3.その主要なリーディング・ディシプリ

ンとしての政治学と経済学の2つの領域がメインであり、歴史学、社会学、ジェンダー研究、文化人類学は

つねに、その周辺の落ち穂拾い研究が中心である。

その理由:ナショナル・プライオリティが高い。

主要なパラダイム:マクロヒストリー的観点と地理学的情報

目的:近代化論(modernization theory)

4.地域研究の華は、事例研究である。ま

た、多くの地域研究者は、そのような「代表的」な研究を読んでから、フィールドに赴く

5.地域研究には、その来歴(=自由主義

陣営側の、戦略情報把握と諜報活動をルーツとする)からかず多くの批判に晒されてきた。ただし、その批

判が、地域研究そのものを活性化しているという主張もある。

軍事的インテリジェンスによるものへの批判

エスノセントリズムの温床化(「文化相対主義」を掲げながらも米国の国益優先があるのではないか?)

合理的選択論(Rational

choice theory)の理論家からの「地域研究をおこなう必然性の欠如」の指摘、つまり、合理的選択論ですべてわかってしまえばわざわ

ざ、研究対象をフィールドワークする必要がなくなる(国際政治学者チャルマーズ・ジョンソン(Chalmers Johnson,

1931-2010)の皮肉:「もし合理的選択論で日本の政治家と官僚が行うことが分かってしまえば、なぜわざわざ日本の歴史や文化を知る必要があるのか

ね?」)

6.西暦2000年以降、インターネット

による情報爆発のために地域研究の現状は、非常に多様化を深めている。そのため地域研究とグローバル研

究の間の垣根は撤廃されつつある。

冷

戦の終焉により、多くの財団の研究費拠出が減少し、若い研究者向けの研修が激減する(→大学教育の場に)。

例:

Bruce Cuming, Boundary Displacement: Area Studies and

International Studies during and after the Cold War.

Bulletin of Concerned Asian Scholars.1993-1996.

●地理学の4つの伝統(Four

traditions of geography)

William Pattison's four traditions of

geography,

often referred to as just the four traditions of geography, are a

proposed way to organize the various competing themes and approaches

within geography.[1][2][3] Proposed in a 1964 article in the Journal of

Geography to address criticism that geography was undisciplined and

calls for definitions of the scope of geography as a discipline that

had been ongoing for at least half a century, the four traditions of

geography propose that American geographers work was consistent, but

fit into four distinct traditions rather than one overarching

definition.[1][2] The original traditions proposed by Pattison are the

spatial tradition, the area studies tradition, the Man-Land tradition,

and the Earth science tradition. A theme among these traditions is

interconnectedness, and it has been referenced in relation to the

Tobler's first law of geography.[4]

The four traditions of geography have been widely used to teach

geography in the classroom as a compromise between a single definition

and memorization of many distinct sub-themes.[2][5] There are many

competing methods to organize geography.[6] The original four

traditions have had several proposed changes.[5][6]

|

ウィリアム・パティソンが提唱した「地理学の4つの伝統」(しばしば

「地理学の4つの伝統」とも呼ばれる)は、地理学の中で競合する様々なテーマやアプローチを整理する方法として提案されたものである[1][2][3]。

[1][2][3]1964年にJournal of

Geography誌に掲載された論文で、地理学が学問的でないという批判や、少なくとも半世紀は続いていた学問としての地理学の範囲の定義を求める声に

応えるために提案されたものである。パティソンが提案したオリジナルの伝統は、空間的伝統、地域研究の伝統、人間と土地の伝統、地球科学の伝統である。こ

れらの伝統の間のテーマは相互関連性であり、それは地理学のトブラーの第一法則と関連して言及されている[4]。

地理学の4つの伝統は、単一の定義と多くの異なるサブテーマの暗記との間の妥協点として、教室で地理学を教えるために広く使用されてきた[2][5]。地

理学を整理するための多くの競合する方法がある[6]。

|

Original traditions outlined by

Pattison

Spatial tradition

Main article: Spatial Analysis

The spatial or locational tradition is concerned with employing

quantitative methods to describe the spatial characteristics of a

location.[1][2][5] The spatial tradition seeks to use the spatial

characteristics of a location or phenomena to understand and explain

it. The contributors to this tradition were historically cartographers,

but it now encompasses what we call technical geography and geographic

information science.[5]

Area studies

Main article: Area studies

The area studies or regional tradition is concerned with the

description of the unique characteristics of the earth's surface,

resulting in each area from the combination of its complete natural or

elements, as of physical and human environment.[1][2][5][7] The main

aim is to understand, or define the uniqueness, or character of a

particular region that consists of natural as well as human elements.

Attention is paid also to regionalization, which covers the proper

techniques of space delimitation into regions.

Man-Land tradition

Main article: Integrated geography

The Human Environment Interaction tradition (originally the Man-Land),

also known as Integrated geography, is concerned with the description

of the spatial interactions between humans and the natural

world.[1][2][5][8] It requires an understanding of the traditional

aspects of physical and human geography, like how human societies

conceptualize the environment. Integrated geography has emerged as a

bridge between human and physical geography due to the increasing

specialization of the two sub-fields, or branches.[9]

Earth science tradition

Main article: Earth science

The Earth science tradition is largely concerned with what is generally

referred to as physical geography.[1][2][5] The tradition focuses on

understanding the spatial characteristics of natural phenomena. Some

argue the Earth science tradition is a subset of the spatial tradition,

however, the two are different enough in their focus and objectives to

warrant separation.[5]

|

パティソンが概説した独自の伝統

空間的伝統

主な記事 空間分析

空間的伝統または位置的伝統は、場所の空間的特性を記述するために定量的な方法を採用することに関係している[1][2][5]。空間的伝統は、それを理

解し説明するために場所や現象の空間的特性を使用しようとするものである。この伝統の貢献者は歴史的には地図製作者であったが、現在では技術地理学や地理

情報科学と呼ばれるものを包含している[5]。

地域研究

主な記事 地域研究

地域研究または地域の伝統は、物理的および人間的環境のような完全な自然または要素の組み合わせから各地域に生じる地球表面の固有の特性の記述に関係して

いる[1][2][5][7]。主な目的は、自然および人間的要素から構成される特定の地域の独自性または特性を理解すること、または定義することであ

る。地域化にも注意が払われており、これは空間を地域に区切る適切な技術を対象とする。

人間と土地の伝統

主な記事 統合地理学

統合地理学として知られる人間環境相互作用の伝統(もともとは人間-土地)は、人間と自然界との間の空間的相互作用の記述に関わるものである。統合地理学

は、人文地理学と物理地理学の間の架け橋として登場した。

地球科学の伝統

主な記事 地球科学

地球科学の伝統は、一般に物理地理学と呼ばれるものに大きく関わっている[1][2][5]。この伝統は、自然現象の空間的特徴を理解することに重点を置

いている。地球科学の伝統は空間的伝統のサブセットであると主張する者もいるが、両者はその焦点と目的において十分に異なっており、分離を正当化している

[5]。

|

Changes over time

One of the most contentious terms is the "man-land tradition." This has

been largely replaced by the term "human-environment interaction" or

integrated geography. The Area studies tradition is also called the

"regional" tradition.

|

時代による変化

最も論争になっている用語のひとつに、「人間と土地の伝統

」というものがある。これは、「人間と環境の相互作用」や「統合地理学」という用語に取って代わられた。地域研究の伝統は「地域」の伝統とも呼ばれる。

|

Impact and legacy

Pattison's Four Traditions of Geography have significantly influenced

the structure of geographic inquiry.[2][5] This framework has provided

a foundation for organizing and understanding the diverse methodologies

and approaches within the field. Scholars and students continue to

engage with these traditions, contributing to ongoing debates and

advancements in geographical research.[3][5]

|

影響と遺産

パティソンの「地理学の4つの伝統」は、地理学的研究の構造に大きな影響を与えた[2][5]。この枠組みは、地理学分野における多様な方法論やアプロー

チを整理し、理解するための基盤を提供した。学者や学生はこれらの伝統に関わり続け、地理学研究における継続的な議論や進歩に貢献している[3][5]。

|

Criticism

While widely embraced, the Four Traditions have not been without

criticism. Some scholars argue for a more integrated and

interdisciplinary approach that transcends the boundaries of these

traditions.[5] Additionally, ongoing developments in technology,

globalization, and environmental concerns have prompted discussions on

potential expansions or revisions to accommodate contemporary

challenges.[5]

There are many other methods for organizing geography, including three

branches proposed in the UNESCO Encyclopedia of Life Support Systems,

which consist of physical geography, human geography, and technical

geography.[10][6]

|

批判

広く受け入れられているとはいえ、「4つの伝統」に批判がないわけではない。一部の学者は、これらの伝統の境界を超えた、より統合的で学際的なアプローチ

を主張している[5]。さらに、テクノロジー、グローバリゼーション、環境問題における継続的な発展は、現代の課題に対応するための拡張や改訂の可能性に

関する議論を促している[5]。

地理学を整理する方法は他にも数多くあり、ユネスコの「生活支援システム百科事典」で提案されている物理地理学、人文地理学、技術地理学の3つの分科から

構成されるものも含まれる[10][6]。

|

Earth analog – Planet with

environment similar to Earth's

Geologic time scale – System that relates geologic strata to time

Geophysics – Physics of the Earth and its vicinity

History of Earth

Terrestrial planet – Planet that is composed primarily of silicate

rocks or metals

Theoretical planetology – Scientific modeling of planets

|

地球アナログ - 地球に似た環境を持つ惑星

地質学的時間スケール - 地層と時間を関連付けるシステム

地球物理学 - 地球とその周辺の物理学

地球の歴史

地球型惑星 - 主に珪酸塩岩石または金属で構成される惑星

理論惑星学 - 惑星の科学的モデリング

|

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Four_traditions_of_geography

|

|

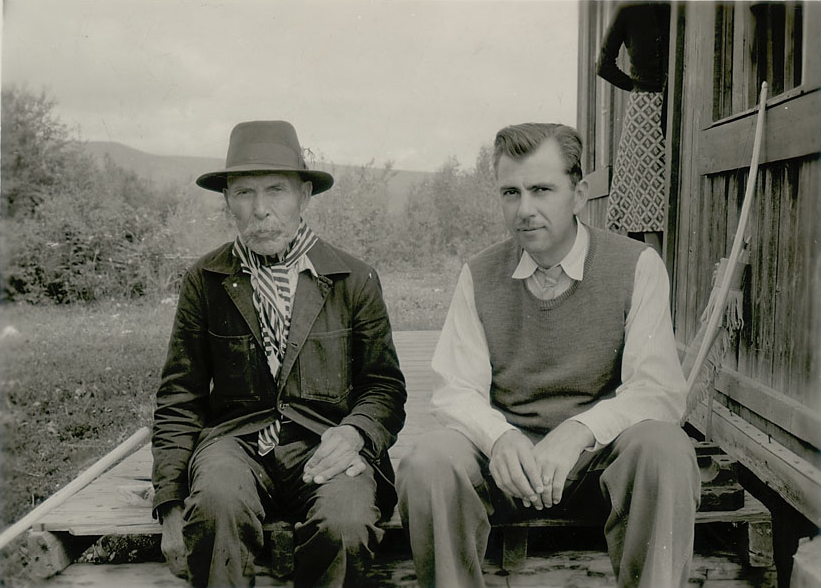

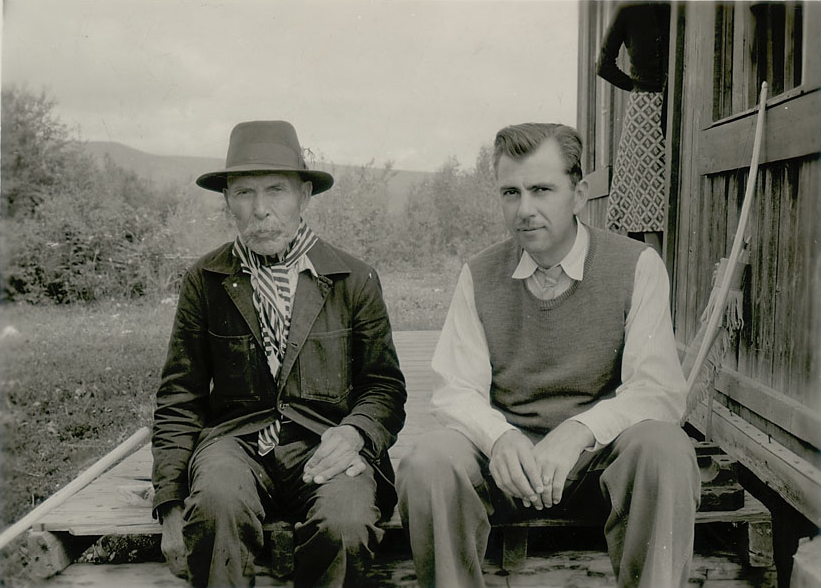

Unidentified

Native Man (Carrier Indian) (possibly Steward's informant, Chief Louis

Billy Prince) and Julian Steward (1902–1972) , Outside Wood Building,

1940 [→「地域研究・エリアスタディーズを 学ぶ人のために」より]

+++

リンク

文献

- 迫り来る革命 : レーニンを繰り返す / スラヴォイ・ジジェク著 ; 長原豊訳, 東京 : 岩波書店 , 2005.5

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

池田蛙 授業蛙 電脳蛙 医療人類学蛙

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099