エマウェイシュからの問いかけ

ethnographic

ventriloquism or

inquiry by Emawayish

★ある民族誌学的腹話術(an ethnographic ventriloquism)あ るいはエマウェイシュからの問いかけについて。

「さっそく今日の午後、私はアバ・ジェロームと一緒にエマウェイッシュに会いに行き、ペンと インクとノートを渡して、彼女が自分で、あるいは息子に口述して、原稿(自分の歌)を書き留められるようにした。——今日の午後、私が原稿のことを話し て、先日のような恋の歌を書き留めるのは特に良いことだと言ったときのエマウェイッシュの言葉だった。(それは)フランスに詩は存在するのですか?そして フランスに愛は存在するのですか?」(ミッシェル・レリス『幻のアフリカ (L'Afrique fantôme)』)

★民族誌学的腹話術(an ethnographic ventriloquism)とは、民族誌家(エスノグラファー) あるいは人類学者・民族学者が、 フィールドワークを通して得られた知識を、現地人の語り口ぶりをして、自国語の読者に「それらしく文化を 語ること」である。これを批判的含意として理解すると、1)現地の文化の紹介者つまり文化のブローカーに転落する、2)現地人の語り口を当事者のかわりに 権威をもって代弁すること、3)現地文化の理解のための民族誌を自分の権威をあげるために流用すること、などを指摘することができる。

| There is

ethnographic ventriloquism: the claim to

speak not just about another form of life but to speak from

within it; to represent a depiction of how things look from

"an Ethiopian (woman poet's) point of view" as itself an

Ethiopian (woman poet's) depiction of how they look from

such a view. There is text positivism: the notion that, if only

Emawayish can be got to dictate or write down her poems as

carefully as possible and they are translated as faithfully as

possible, then the ethnographer's role dissolves into that of

an honest broker passing on the substance of things with

only the most trivial of transaction costs. There is dispersed

authorship: the hope that ethnographic discourse can somehow

be made "heteroglossial," so that Emawayish can speak

within it alongside the anthropologist in some direct, equal,

and independent way; a There presence in a Here text. There

is confessionalism: the taking of the ethnographer's experience

rather than its object as the primary subject matter for

analytical attention, portraying Emawayish in terms of the

effect she has on those who encounter her; a There shadow

of a Here reality. And there is, most popularly of all, the simple

assumption that although Emawayish and her poems

arc, of course, inevitably seen through an author-darkened

glass, the darkening can be minimized by authorial self-inspection

for "bias" or "subjectivity," and she and they can

then be seen face to face. (Geertz 1988:145) |

これが民族誌学的腹話術である:エチオピア人(女性詩人)の視点」から

物事がどのように見えるかという

描写を、エチオピア人(女性詩人)の視点からの描写として表現することで、別の生活形態について語るだけではなく、その中から語るという主張で

ある。テキ

スト実証主義:エマウェイシュの詩をできるだけ丁寧に口述筆記させ、それをできるだけ忠実に翻訳すれば、民族誌学者の役割は、最も些細な取引費用だけで

物事の本質を伝える誠実な仲介者の役割に分解されるという考え方がある。エマウェイシュが人類学者と並んで、直接的に、平等に、そして独立した形で、エ

スノグラフィーの議論を「異言語化=ヘテログロシア化」することができるのではないか、という期待である。エマウェイシュが彼女に出会う人々に与える影響

という観点からエマウェイシュを描き出すのである。そして、最も一般的なのは、エマウェイシュと彼女の詩は、もちろん作者の曇ったガラスを通して見られる

ことは避けられないが、作者が「偏見」や「主観」を自己点検することによって、曇りを最小限に抑え、彼女と彼らを正面から見ることができる、という単純な

仮定である。 |

| All this is not to say that

descriptions of how things

look to one's subjects, efforts to get texts exact and translations

veridical, concern with allowing to the people one

writes about an imaginative existence in one's text corresponding

to their actual one in their society, explicit reflection upon what

field work docs or doesn't do to the field

worker, and rigorous examination of one's assumptions are

not supremely worth doing for anyone who aspires to tell

someone leading a French sort of life what leading an Ethiopian

one is like. It is to say that doing so does not relieve

one of the burden of authorship; it deepens it. Getting

Emawayish's views right, rendering her poems accessible,

making her reality perceptible, and clarifying the cultural

framework within which she exists, means getting them sufficiently

onto the page that someone can obtain some comprehension

of what they might be. This is not only a difficult

business, it is one not without consequence for "native,"

"author," and "reader" (and, indeed, tor that eternal victim

of other people's activities, "innocent bystander") alike.(Geertz

1988:145-146) |

このことは、対象者にとって物事がどのように見えるかを説明すること、

テキストを正確にし、翻訳を正確にする努力をすること、自分の書いたテキストにおいて、彼らの社会における実際の存在に対応する想像上の存在を彼らに認め

ることに関心を持つこと、フィールドワークがフィールドワーカーに何をもたらし、何をもたらさないかを明確に考えること、自分の仮定を厳密に調べること

が、フランス式の生活を送る人(=ミッシェル・レリス)にエチオピア式の生活がどんなものか伝えようとする人に最高の価値をもたらさないということを意味

しているのではない。そうすることで、作家としての重荷が軽減さ

れるわけではなく、むしろ重荷が深まるのである。エマウェイシュの見

解を正しく理解し、彼

女の詩にアクセスできるようにし、彼女の現実を認識できるようにし、彼女が存在する文化的枠組みを明確にすることは、誰かがそれが何であるかをある程度理

解できるように、ページに十分に書き込むことを意味する。これは難しいだけでなく、「ネイティブ」「作家」「読者」(そして、他人の活動の永遠の犠牲者で

ある「無邪気な傍観者」)にとっても同様に影響がないとはいえない仕事である。 |

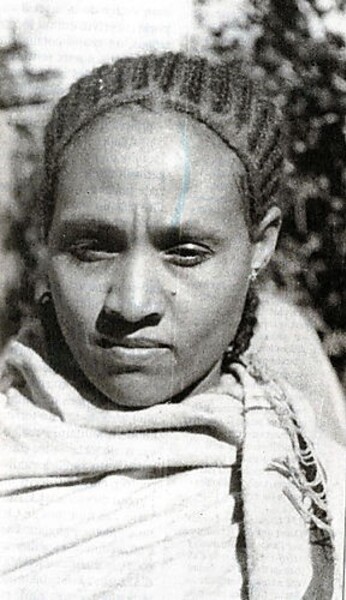

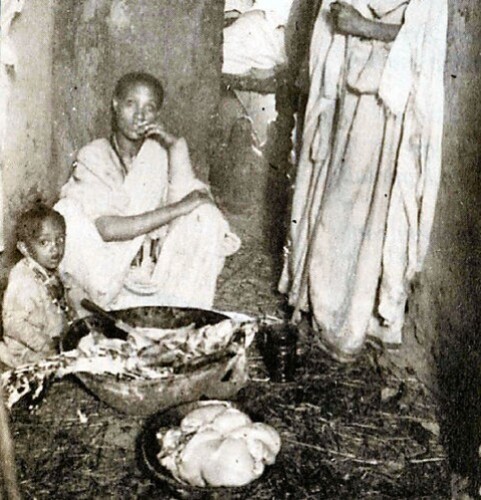

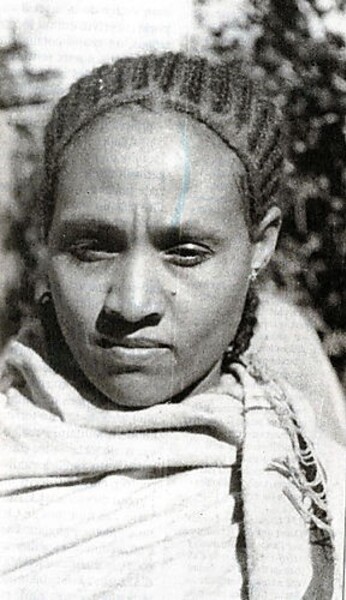

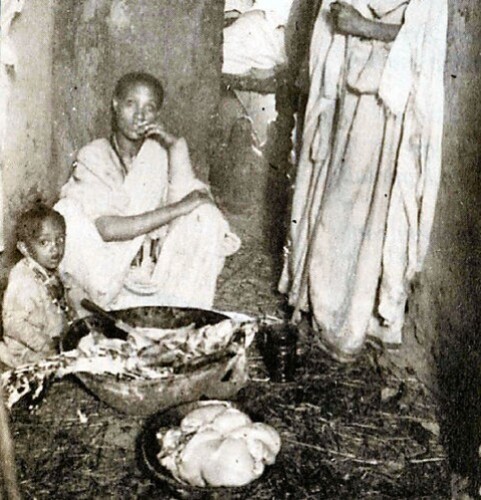

| Michel Leiris écrira à propos

d'Emawayish : "Pourquoi faut-il qu'elle soit venue se présenter devant

moi, vers la fin de ce voyage, comme s'il s'agissait uniquement de me

rappeler que je suis hanté intérieurement par un fantôme plus mauvais

que tous les ZAR du monde ?" (Zar : esprits) "On se lasse atrocement vite en voyageant. Le merveilleux s'amoindrit à mesure que l'on n'est plus surpris"... Cependant, en Ethiopie (Abyssinie) devant le rituel de possession, il est à ce point de vertige dionysiaque, "où le haut et le bas se confondent"... Emawayish "princesse au visage de cire mariée à un homme du consul italien" hante alors ses songes et marquera son livre "L'âge d'homme". Il écrit d'elle : "A son allure de princesse se mêle un certain côté succube, à chair molle, moite, froide qui m'écoeure, en même temps qu'il me fait un peu peur ; n'est-elle pas prédestinée ? Et son premier mari, quand il est devenu fou ne se sauvait-il pas de la maison pour aller hurler dans les ruines des châteaux de Gondar ?" "Pensant qu'il me manquait d'avoir un peu vécu à la dure, je saisis l'occasion de faire un long voyage, et partis pour près de deux ans en Afrique, comme membre d'une mission ethnographique. Après des mois de chasteté et de sevrage sentimental, séjournant à Gondar, je fus amoureux d'une Ethiopienne qui correspondait physiquement et moralement à mon double ideal de Lucrèce et de Judith. Très belle de visage mais la poitrine ravagée, elle était engoncée dans une toge d'un blanc généralement plus que douteux, sentait le lait suri et possédait une jeune négresse esclave ; on aurait dit une statue de cire et les tatouages bleuâtres qui cernaient son cou haussait sa tête ainsi qu'eût fait un transparent faux-col ou le carcan d'un très ancien supplice laissant aux peaux ses traces en broderie. Peut-être n'était-elle qu'une nouvelle image - en chair et en os - celle-là, de cette Marguerite au cou coupé dont je n'avais jamais pu apercevoir, enfant, le spectre à l'Opéra ? Syphilitique, elle avait plusieurs fois avorté. Son premier mari était devenu fou ; le plus récent, à deux reprises, avait voulu la tuer. Amputée de son clitoris comme toutes les femmes de sa race, elle devait être frigide, au moins en ce qui concerne les Européens. Fille d'une sorte de sorcière possédée par de multiples génies, il était entendu qu'elle hériterait de ces esprits et quelques uns d'entre eux l'avaient déjà frappée de maladie, la marquant ainsi comme une proie qu'ils viendraient habiter inéluctablement. Ayant fait tuer un bélier blanc et feu pour un de ces génies, je la vis ahaner sous la transe - en plein état de possession - et boire dans une tasse de porcelaine le sang de la victime coulant tout chaud de la gorge coupée. Jamais je ne fis l'amour avec elle, mais lorsqu'eut lieu ce sacrifice il me sembla qu'un rapport plus intime que toute espèce de lien charnel s'établissait entre elle et moi." Michel Leiris (L'âge d'homme) source : http://agoras.typepad.fr/regard_eloigne/michel_leiris/ |

ミシェル・レリス(Michel

Leiris)はエマウィッシュについて、「なぜ彼女は、この旅の終わりに、まるで

私が世界のすべてのザールよりも邪悪な幽霊に取り憑かれていることを思

い出させるかのように、私の前に現れたのだろう」と書くだろう。 (ザール: スピリッツ) 「旅は飽きるのが早い。驚かなくなると、不思議さは薄れていく」...。 しかし、憑依の儀式を前にしたエチオピア(アビシニア)では、ディオニュソス的なめまいのような、「高さと低さが融合する」その地点にいるのだ...。 「イタリア領事館の男と結婚した蝋人形のような顔の王女」エマウェイシュが彼の夢に現れ、彼(=レリス)の著書「L'âge d'homme」を飾ることになる。彼は彼女についてこう書いている。 「お姫様のような外見に、サキュバスのような質感が混在し、柔らかく締まった冷たい肉体は、私をうんざりさせると同時に、少し怖くさせる。最初の夫は気が 狂ったように家を飛び出し、ゴンダールの城跡で遠吠えをしていたのでは?」 「少し荒っぽい生き方をしたのが淋しいと思い、長旅の機会を捉えて、民 族学のミッションの一員としてアフリカに2年近く旅立った。数ヶ月の貞 操と感傷的な引きこもりの後、ゴンダールに滞在していた私(=レリス)は、ルクレティアとユディットという私の二重の理想に肉体的にも道徳的にも一致する エチオピア女性と恋に落ちた。顔は非常に美しいが、胸が荒れている。彼女は一般的に疑わしい白のトガをまとい、酸っぱいミルクのにおいがして、若い奴隷の 黒人を所有していた。彼女は蝋人形のように見え、首を囲む青みがかった刺青は、透明な大鎌または皮膚に刺繍で痕跡を残す非常に古い拷問の手かせを取ってい たように彼女の頭を高めた。もしかしたら彼女は、私が子供の頃にオペラ座で見ることができなかった、あの首の切れたマルグリットの新しいイメージ——生身 の人間——に過ぎないのではないか」。 梅毒のため、彼女は何度も中絶していた。最初の夫は発狂し、直近の夫は2度、彼女を 殺そうとした。クリトリスを切断された彼女は、少なくともヨーロッパ人 から見れば、不感症だったに違いない。複数の精霊に取り憑かれた魔女の娘であることから、精霊を受け継ぐことが理解されており、すでに何人かの精霊が彼女 を病気にし、必然的に彼らが住み着く獲物としてマークしていたのである。 この天才の一人のために、白くて燃えるような雄羊を 殺させたことがある。彼女はトランス状態、つまり憑依状態であえぎながら、切り口から熱く流れる犠牲者 の血を磁器のカップから飲むのを見たのだ。私は彼女と愛し合ったこと はないが、この 犠牲が行われたとき、彼女と私の間に肉欲のつながりよりも親密な関係が築かれたように思えたのである。 ミシェル・レリス(L'âge d'homme) |

| Right away this afternoon I go

with Abba Jerome to see [the Ethiopian

woman] Emawayish and give her pens, ink, and a notebook

so she can record for herself-or dictate to her son-the manuscript

[of her songs], letting it be understood that the head of the

expedition, if he is pleased, will present her with the desired gift. Emawayish's words this afternoon when I told her, speaking of her manuscript, that it would be especially good for her to write down some love songs like those of the other night: Does poetry exist in France? And then: Does love exist in France? (Geertz 1988:129) |

さっそく今日の午後、私はアバ・ジェロームと一緒にエマウェイシュに

会いに行き、ペンとインクとノートを渡して、彼女が自分で、あるいは息子に口述して、原稿(自分の歌)を書き留められるようにした。 今日の午後、私が原稿のことを話して、先日のような恋の歌を書き留めるのは特に良いことだと言ったときのエマウェイッシュの言葉だった。(それは)フラン スに詩は存在するのですか?そして フランスに愛は存在するのですか? |

| レリスは1934

年に『幻のアフリカ(L'Afrique

Fantôme)』(ガリマール書店)を刊行するが、ナチスが侵攻した1941年10月17日『幻のアフリカ』発禁処分(内務省政務次官ビュシュー)、残

部が押収される。発禁理由は植民地政策批判。レリスは 「同業者の誰か」(=献辞をつけたグリオールか?)による密告のせいとしている。 |

|

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099