民族学; ethnology, みんぞくがく, エスノロジー

民族学; ethnology, みんぞくがく, エスノロジー

解説:池田光穂

民族学は、かつて民族(ethnos,

エトノス)に

関する学問である/あった(→エトノロギー)。エトノスに関する学問であるので、民族学は

外来語をそのまま転用しエスノロジーと呼ばれることがある。それは、同じミンゾクガ

クという発音でも、民俗(folk,

フォーク)を対象にする民俗学(みんぞくがく)と混同するからである。現在の民族学は、狭

義の「文化人類学」と同義語である。

■ちなみに、民 俗学(folklore)のほうはフォークロアと呼ばれ、学問のロゴス (=論理、学)の接尾辞がついて《フォクロジー(=実在しない用語)》とは言わない。フォークロアは、 学問ではなく、ロア(-lore)=語りであり。民話(フォークロ ア)と同義語である(→「民俗学(フォークロア)」)

民族(エトノス)とは、特定の文化・習慣を共有する人々のことであり、ある時には地域の特 定の集団、また ある時にはおなじ集団の構成員である意識を共有する人たち(→民族境界論を参照)のことをさし ている。しかし「科学人種主義」が現在でもしぶとく命脈を保っているため に、現在でも、民族と「人種」概念 を混同して理解している人が多い。そのような民族と「人種」を混同したような理解を、「人間集団の質的差異を本質化」していると、表現する。

民族(民族集団、エスニシティ)の定義を人間の集団のひとつと考えると、民 族についての学問である民族学と、人間についての学問である人類学と、人間集団の文化についての 学問である文化人類学と、社会という人間集団についての学問である社会人類学、ある いは、人々の語り(folklore)についての伝承的構成である学問である民俗学(日本 語の発音は、みんぞくがく)は、それぞれ、学問の名称は異なって いても、共通する部分は多い。

そのため、実際に、文化人類学の同義語と して、日本では民族学や民俗学が、英国では社会人類学が、フランスでは民族学や社会人類学が、ドイツ・ オーストリアでは民俗学や民族学が、スペインでは民俗学が、そして米国では、民俗学や文化人類学という用語がそれぞれ使われている。Adam Franz Kollár (1718-1783)がethnologia (ethnology) の創案者(1783)である。

| Ethnology

(from the Ancient Greek: ἔθνος, ethnos meaning 'nation')[1] is an

academic field and discipline that compares and analyzes the

characteristics of different peoples and the relationships between them

(compare cultural, social, or sociocultural anthropology).[2] |

民族学(古代ギリシャ語: ἔθνος, ethnos「民族」に由来する)[1]とは、異なる民族の特徴やそれらの関係を比較・分析する学術分野である(文化人類学、社会人類学、社会文化人類学と比較せよ)[2]。 |

Scientific discipline Adam František Kollár, 1779 Further information: Ethnicity Compared to ethnography, the study of single groups through direct contact with the culture, ethnology takes the research that ethnographers have compiled and then compares and contrasts different cultures. The term ethnologia (ethnology) is credited to Adam Franz Kollár (1718–1783) who used and defined it in his Historiae ivrisqve pvblici Regni Vngariae amoenitates published in Vienna in 1783.[3] as: "the science of nations and peoples, or, that study of learned men in which they inquire into the origins, languages, customs, and institutions of various nations, and finally into the fatherland and ancient seats, in order to be able better to judge the nations and peoples in their own times."[4] Kollár's interest in linguistic and cultural diversity was aroused by the situation in his native multi-ethnic and multilingual Kingdom of Hungary and his roots among its Slovaks, and by the shifts that began to emerge after the gradual retreat of the Ottoman Empire in the more distant Balkans.[5] Among the goals of ethnology have been the reconstruction of human history, and the formulation of cultural invariants, such as the incest taboo and culture change, and the formulation of generalizations about "human nature", a concept which has been criticized since the 19th century by various philosophers (Hegel, Marx, structuralism, etc.). In some parts of the world, ethnology has developed along independent paths of investigation and pedagogical doctrine, with cultural anthropology becoming dominant especially in the United States, and social anthropology in Great Britain. The distinction between the three terms is increasingly blurry. Ethnology has been considered an academic field since the late 18th century, especially in Europe and is sometimes conceived of as any comparative study of human groups.  Claude Lévi-Strauss  İzmir Ethnography Museum seen from the courtyard The 15th-century exploration of America by European explorers had an important role in formulating new notions of the Occident (the Western world), such as the notion of the "Other". This term was used in conjunction with "savages", which was either seen as a brutal barbarian, or alternatively, as the "noble savage". Thus, civilization was opposed in a dualist manner to barbary, a classic opposition constitutive of the even more commonly shared ethnocentrism. The progress of ethnology, for example with Claude Lévi-Strauss's structural anthropology, led to the criticism of conceptions of a linear progress, or the pseudo-opposition between "societies with histories" and "societies without histories", judged too dependent on a limited view of history as constituted by accumulative growth. Lévi-Strauss often referred to Montaigne's essay on cannibalism as an early example of ethnology. Lévi-Strauss aimed, through a structural method, at discovering universal invariants in human society, chief among which he believed to be the incest taboo. However, the claims of such cultural universalism have been criticized by various 19th- and 20th-century social thinkers, including Marx, Nietzsche, Foucault, Derrida, Althusser, and Deleuze. The French school of ethnology was particularly significant for the development of the discipline, since the early 1950s. Important figures in this movement have included Lévi-Strauss, Paul Rivet, Marcel Griaule, Germaine Dieterlen, and Jean Rouch. |

科学分野 アダム・フランティシェク・コラー、1779年 詳細情報:民族性(エスニシティ) 民族誌が単一集団をその文化との直接接触を通じて研究するのに対し、民族学はエスノグラファーがまとめた研究を基に、異なる文化を比較対照する。 民族学(ethnologia)という用語は、アダム・フランツ・コラー(1718–1783)が1783年にウィーンで出版した『Historiae ivrisqve pvblici Regni Vngariae amoenitates』において使用・定義したとされる。[3] 彼はこれを「諸国民・諸人民の科学、すなわち学識ある者たちが様々な国民の起源・言語・習慣・制度、そして最終的には祖先の故郷と古代の居住地を調査する 学問であり、それによって現代の諸国民・諸人民をより良く判断できるようにするもの」と定義した。[4] コラーの言語・文化多様性への関心は、母国である多民族・多言語国家ハンガリー王国の状況と、その中のスロバキア人としての自身のルーツ、さらに遠く離れたバルカン半島におけるオスマン帝国の漸進的後退後に現れ始めた変化によって喚起された。[5] 民族学の目的には、人類史の再構築、近親相姦タブーや文化変化といった文化的不変要素の定式化、「人間性」に関する一般化の構築が含まれてきた。この「人 間性」という概念は19世紀以降、様々な哲学者(ヘーゲル、マルクス、構造主義など)によって批判されてきた。世界の一部地域では、民族学は独自の研究経 路と教育学説に沿って発展し、特にアメリカでは文化人類学が、イギリスでは社会人類学が主流となった。三者の区別は次第に曖昧になっている。民族学は18 世紀後半から、特にヨーロッパにおいて学術分野と見なされ、時にあらゆる人間集団の比較研究と捉えられることもある。  クロード・レヴィ=ストロース  中庭から見たイズミル民族誌博物館 15世紀のヨーロッパ人によるアメリカ大陸探検は、「他者」という概念など、西洋(西洋世界)の新たな概念形成において重要な役割を果たした。この概念は 「野蛮人」と結びつけて用いられ、野蛮人は残忍な存在か、あるいは「高貴なる野蛮人」として捉えられた。こうして文明は野蛮と二項対立的に対置され、この 古典的対立構造はより普遍的な民族中心主義を構成する要素となった。クロード・レヴィ=ストロースの構造人類学など、民族学の進歩は、直線的な進歩の概念 や、「歴史を持つ社会」と「歴史を持たない社会」という偽りの対立に対する批判につながった。これらは、累積的成長によって構成されるという限定的な歴史 観に依存しすぎていると判断されたのである。 レヴィ=ストロースは、人類学の初期の例として、モンテーニュの食人に関する随筆をしばしば引用した。レヴィ=ストロースは、構造的手法を通じて、人間社 会における普遍的な不変の要素、とりわけ近親相姦のタブーを発見することを目指した。しかし、このような文化の普遍主義の主張は、マルクス、ニーチェ、 フーコー、デリダ、アルチュセール、ドゥルーズなど、19 世紀および 20 世紀のさまざまな社会思想家によって批判されてきた。 1950年代初頭以降、フランス民族学派は、この学問分野の発展に特に大きな影響を与えた。この運動の重要な人物としては、レヴィ=ストロース、ポール・リヴェ、マルセル・グリオー、ジェルマン・ディテルラン、ジャン・ルーシュなどが挙げられる。 |

| List of scholars of ethnology |

|

| Anthropology Cultural anthropology Comparative cultural studies Cross-cultural studies Ethnography Folklore studies Culture Ethnocentrism Evolutionism Indigenous peoples Intangible cultural heritage Postcolonial Decoloniality Primitive culture Primitivism Scientific racism Structural anthropology Structural functionalism Ethnobiology Ethnopoetics Ethnic studies Critical race studies Cultural studies |

人類学 文化人類学 比較文化研究 異文化間研究 民族誌 民俗学 文化 民族中心主義 進化論 先住民 無形文化遺産 ポストコロニアル 脱植民地化 原始文化 プリミティヴィズム 科学的人種主義 構造人類学 構造機能主義 民族生物学 民族詩学 民族研究 批判的人種研究 文化研究 |

| References 1. "ethno-". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2013. 2. "ethnology". Oxford Dictionaries. Oxford University Press. Archived from the original on May 15, 2013. Retrieved 21 March 2013. 3. Zmago Šmitek and Božidar Jezernik, "The anthropological tradition in Slovenia." In: Han F. Vermeulen and Arturo Alvarez Roldán, eds. Fieldwork and Footnotes: Studies in the History of European Anthropology. 1995. 4. Kollár, Adam František − Historiae jurisque publici regni Ungariae amoenitates, I-II. Vienna., 1783 5. Gheorghiţă Geană, "Discovering the whole of humankind: the genesis of anthropology through the Hegelian looking-glass." In: Han F. Vermeulen and Arturo Alvarez Roldán, eds. Fieldwork and Footnotes: Studies in the History of European Anthropology. 1995. |

参考文献 1. 「ethno-」。オックスフォード辞書。オックスフォード大学出版局。2013年5月15日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2013年3月21日に取得。 2. 「ethnology」。オックスフォード辞書。オックスフォード大学出版局。2013年5月15日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2013年3月21日に取得。 3. Zmago Šmitek および Božidar Jezernik、「スロベニアの人類学的伝統」。Han F. Vermeulen および Arturo Alvarez Roldán 編『フィールドワークと脚注:ヨーロッパ人類学の歴史に関する研究』所収。1995年。 4. Kollár, Adam František − Historiae jurisque publici regni Ungariae amoenitates, I-II. ウィーン、1783年 5. ゲオルギツァ・ゲアナ、「人類全体の発見:ヘーゲル的視点から見た人類学の起源」。ハン・F・フェルミューレン、アルトゥーロ・アルバレス・ロルダン編『フィールドワークと脚注:ヨーロッパ人類学史の研究』所収。1995年。 |

| Bibliography Forster, Johann Georg Adam. Voyage round the World in His Britannic Majesty's Sloop, Resolution, Commanded by Capt. James Cook, during the Years 1772, 3, 4, and 5 (2 vols), London (1777). Lévi-Strauss, Claude. The Elementary Structures of Kinship, (1949), Structural Anthropology (1958) Mauss, Marcel. originally published as Essai sur le don. Forme et raison de l'échange dans les sociétés archaïques in 1925, this classic text on gift economy appears in the English edition as The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies. Maybury-Lewis, David. Akwe-Shavante society (1967), The Politics of Ethnicity: Indigenous Peoples in Latin American States (2003). Clastres, Pierre. Society Against the State (1974). Pop, Mihai and Glauco Sanga. "Problemi generali dell'etnologia europea", La Ricerca Folklorica, No. 1, La cultura popolare. Questioni teoriche (April 1980), pp. 89–96. |

参考文献 フォースター、ヨハン・ゲオルク・アダム。『大英帝国のスループ艦レゾリューション号による世界周航記:ジェームズ・クック艦長指揮、1772、3、4、5年』(全2巻)、ロンドン(1777年)。 レヴィ=ストロース、クロード。『親族関係の基本構造』(1949 年)、『構造人類学』(1958 年) モース、マルセル。原題『贈与に関する試論。古代社会における交換の形態と理由』(1925年刊)。贈与経済に関する古典的著作で、英語版では『贈与:古代社会における交換の形態と理由』として刊行された。 メイバリー=ルイス、デイヴィッド。『アクウェ・シャバンテ社会』(1967年)、『民族性の政治学:ラテンアメリカ諸国における先住民』(2003年)。 クラストル、ピエール。『国家に対する社会』(1974年)。 ポップ、ミハイとグラウコ・サンガ。「ヨーロッパ民族学の一般的課題」、『民俗学研究』第1号、大衆文化。理論的問題(1980年4月)、89-96頁。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethnology |

"The term

ethnologia (ethnology) is credited to Adam Franz Kollár (1718-1783)

who used and defined it in his Historiae ivrisqve

pvblici Regni

Vngariae amoenitates(ハンガリー王国の歴史:ラテン語)published in Vienna in

1783.[3] as: “the science

of nations and peoples, or, that study of learned men in which they

inquire into the origins, languages, customs, and institutions of

various nations, and finally into the fatherland and ancient seats, in

order to be able better to judge the nations and peoples in their own

times.”[4]/ Kollár's interest in linguistic and cultural diversity was

aroused by the situation in his native multi-ethnic and multilingual

Kingdom of Hungary and his roots among its Slovaks, and by the shifts

that began to emerge after the gradual retreat of the Ottoman Empire in

the more distant Balkans.[5]"

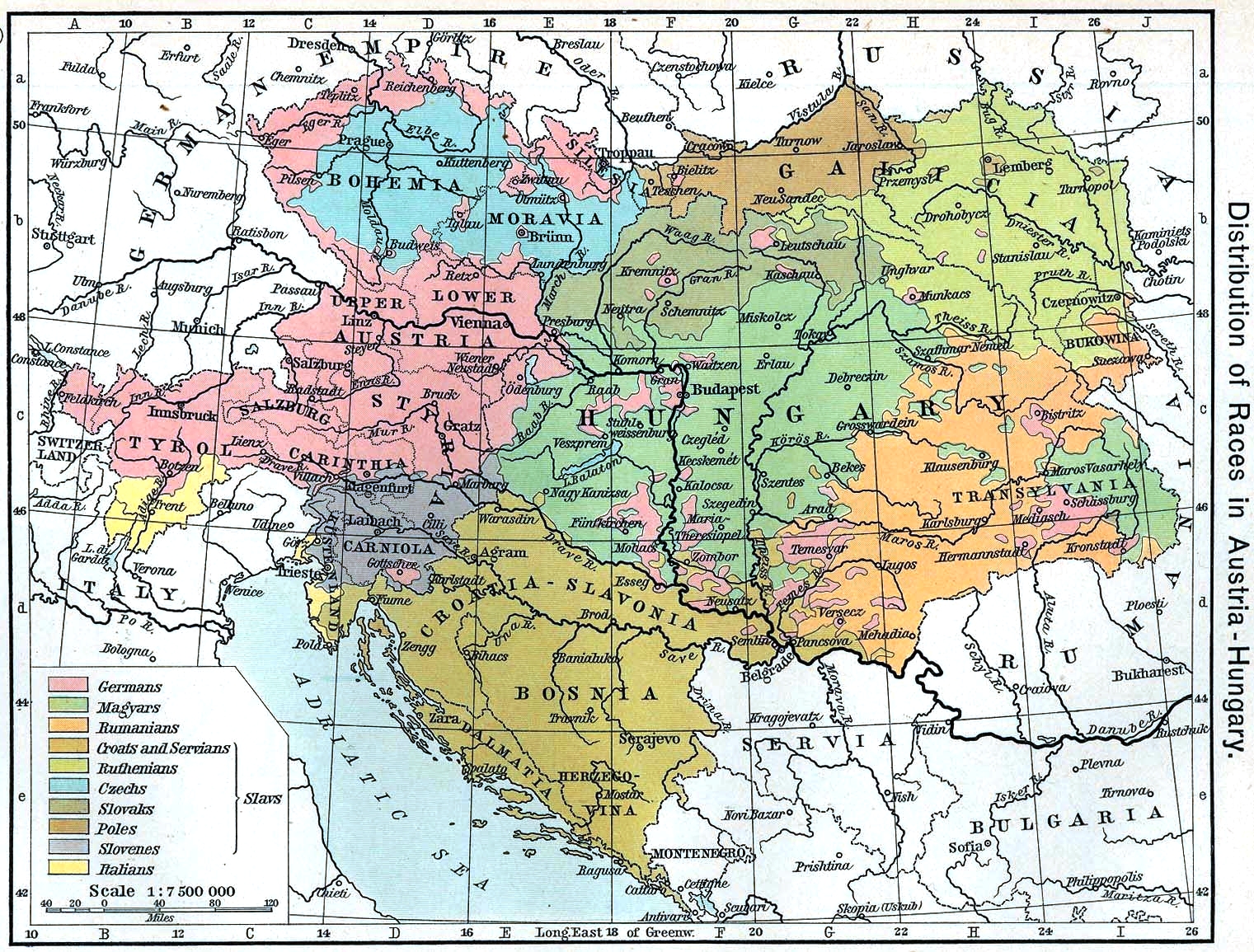

●オーストリア=ハンガリー帝国(Österreichisch-Ungarische

Monarchie, 1867-1918)期(1911)における民族=人種分布地図

ま た、文化人類学と民族学の違いを、前者は人間文化の共通性や一般性を主に探求し、後者はいわゆる特定の民族集団に関する民族誌あるいは民族誌学(ethnography)を記述し比較分析する学問であると区 別する人もいる。なぜなら、民族学というものは、民族誌(エスノグラフィー)という 基盤(ないしは下部構造)がなければなりたたない学問だからである。

こ のようにみると、民族学、文化人類学、民俗学、社会人類学、 [形容詞抜きの]人類学は、みんな同じだということになってしまうが、実際には、 それらの用語法に関連づけた理論化がなされたり、先にあげた、それぞれの国の事情や国家の歴史的経緯の影響を受けて、独自の発展を遂げた——つまり多様性 があり、それらの学問名のあいだにコンセンサスは無理としても具体的峻別をつけることができる——という事情があるため、それらをやみくもに統一する必要 はないように思われる。[→プロクルステス的な概念の濫用]

Merriam-Webster 英語辞典では、その2番めの文字に「諸文化の比較と文系を主におこなう人類学」すなわち「文化人類学」と同じ意味で民族学(ethnology) を定義しているが、この2番めのものが、日本語で通常いわれる「民族学=エスノロジー」の意味に近いといえよう。

民

族学と民俗学の

関係については、後者の項目「民俗学」

を参照ねがいたいが、日本における民俗学者は文化人類学の著述をよく読んでおり、その逆も言える。両者の間には友好的な協力関係もあり、ライバル関係にな

るのは、むしろ学説上の特定の論争をめぐってである。民俗学が、日本における人種主義の勃興に大きな影響を与えることがなかったのは、先に述べたように

「明確なネーションや市民(シトワイヤン)の政治的概念が意識されたことのない」経験からかもしれない。しかし、1920年代の柳田国男の国際連盟信託統

治委員の時代に、ジュネーブに赴任し、そこで経験した複雑な人種主義とナショナリズムの影響を通して、それが、日本の琉球や八重山をして、民俗学における

日本ではない日本としての南島の位置づけを確立したのではないかという主張もある(村井 2004)。

●Völkerkundeから Ethnologieに語法が変化したのはいつか?(→「ベルリン民族学博 物館」を参照)

"Die Ethnologie (abgeleitet von altgriechisch ἔθνος éthnos, deutsch ‚Volk, Volksstamm‘, und -logie „Lehre“; früher Völkerkunde, heute auch Sozial- und Kulturanthropologie) ist eine empirische und vergleichende Sozial- und Kulturwissenschaft, die die Vielfalt menschlicher Lebensweisen aus einer sowohl gegenwartsbezogenen als auch historisch verankerten Perspektive erforscht. Ursprünglich hat sich das Fach stark auf das Zusammenleben der heute weltweit rund 1300 ethnischen Gruppen und indigenen Völker fokussiert. Heute stehen die kulturellen Praktiken und Ideen unterschiedlichster sozialer Gruppen und Entitäten im Mittelpunkt ihrer Forschungen, die zugleich stets im Zusammenhang mit politischen bzw. ökonomischen Strukturen untersucht werden. Die zeitgenössische Ethnologie erforscht damit z. B. auch Institutionen und Organisationen ebenso wie Lebenszusammenhänge in modernen Industriegesellschaften, in städtischen Räumen, oder den Zusammenhang mit Migration. Durch das enge Eintauchen in die Lebens- und Handlungswelten der von ihr untersuchten Gruppen und Menschen mittels der Methode der Feldforschung zielt die Ethnologie darauf ab, deren spezifische Weltverständnisse zu entschlüsseln und – oft im Vergleich zu anderen kulturellen Zusammenhängen und sozialen Kollektiven – zu erklären. Die Ethnologie ist dabei in der Regel weniger auf die Überprüfung von Theorien und Konzepten, sondern vor allem auf die Generierung von Theorien und die damit verbundene Erklärung von Bedeutungszusammenhängen ausgerichtet. Feldforschung findet heute auch in Zusammenhang mit transnationalen Online-Gemeinschaften (Netnographien) statt. Die Ethnologie entstand zunächst an den ethnologischen Museen und wird seit Ende des 19. Jahrhunderts als eigenständiges Fach an den Universitäten gelehrt, in Deutschland zunächst als Völkerkunde, in Großbritannien als social anthropology und in den USA als cultural anthropology. Im angelsächsischen Raum gilt die Ethnologie als Teilgebiet der Anthropologie (Wissenschaft vom Menschen)[3], welche im kontinentalen Europa wiederum eher als Naturwissenschaft (physische Anthropologie) und als – heute nicht mehr gebräuchlicher – Teilbereich ethnologischer Feldforschung verstanden wird. Als Kulturanthropologie wird in Europa des Weiteren die Volkskunde verstanden, die auch als Europäische Ethnologie bezeichnet wird. Die Fachgesellschaft der Ethnologinnen und Ethnologen in Deutschland ist die Deutsche Gesellschaft für Sozial- und Kulturanthropologie."

民族学(古代ギリシャ語 ἔθνος éthnos、ドイツ語 'Volk,

Volksstamm'、-logy「教義」に由来、古くは

Völkerkunde、今日では社会・文化人類学とも)は、人間の生活様式の多様性を、現代と歴史に根ざした視点から探求する実証・比較社会・文化科学

である。もともとは、現在世界に約1300ある民族や先住民の生存形態に強く焦点を当てたテーマであった。今日、最も多様な社会集団や団体の文化的実践や

思想が研究の中心となっており、同時に、常に政治や経済構造との関連で検討されている。そのため、現代の人類学は、例えば、制度や組織、現代の産業社会に

おける生活状況、都市空間、あるいは移住との関連性についても探求している。民族学は、現地調査という手法を用いて、研究対象の集団や人々の生活や行動世

界に深く入り込むことで、彼らの世界に対する特異な理解を解読し、しばしば他の文化的背景や社会集団と比較しながら、それを説明することを目指している。

その際、民族学は通常、理論や概念の検証にはあまり重点を置かず、むしろ理論の生成とそれに伴う意味のコンテクストの説明に重点を置いている。今日の

フィールドワークは、国境を越えたオンライン・コミュニティ(ネットエスノグラフィー)にも関連して行われる。民族学は民族学博物館で誕生し、19世紀末

から大学で独立した科目として教えられてきた。ドイツでは当初、Völkerkundeとして、英国では社会人類学として、米国では文化人類学として教え

られてきた。アングロサクソンの世界では、民族学は人類学(人間の科学)の下位分野とみなされている[3]が、ヨーロッパ大陸では、自然科学(物理人類

学)および民族学の野外調査の下位分野として理解されており、今日では一般的ではなくなっている。ヨーロッパでは、文化人類学は民俗学としても理解されて

おり、ヨーロッパ民族学とも呼ばれている。ドイツにおける民族学者の専門学会は、ドイツ社会文化人類学会である(www.DeepL.com/Translatorに

よる)。

◎坪井正五郎は1889年にEthnology (Ethnologie)を「人種学」と訳した!!!

坪井正五郎は1889年の『東京人類学会雑誌』で、Ethnology (Ethnologie)を「人種学」と訳し、今日、民族誌あるいはエスノグラフィーと呼ばれている、 Ethnography(Ethnographie)を、人種誌または土俗学と訳していた。これは、歴史的に、とりわけ戦前に、我々大和民族とよばれるよ ばれる「民族」には、レイス(人種)のニュアンスが込められていたことにも関係する(→「日本民族という時の〈ミンゾク〉とはなにか?」)。 民族を人種的にとらえたり、または、ネーションとレイスを同一視する味方は、第二次大戦後、とりわけ、新興国の独立や、その後の、独立運動における、ネー ションの自己決定による、武力闘争すなわち、国民解放戦線(national liberation front)のことを、戦後の日本のジャーナリズムは、長く「民族解放戦線」と誤って表記しつづけてきたことにも関連している。それゆえ、おしなべて、日 本では、民族をレイスと同一視したり、または、県民性についての議論にみられるように、県民性がなにか固定的で県境の内側の人間の性格がなにか、固定的な ものとしてみる、愚かな自画像をいまでも持ち続けている。

◎民族学の同義語としての「文化人類学」

◎四分類人類学

北アメリカでいう文化人類学の

領域には、1.先史考古学、2.言語学(副分野である言語人類学のほうがより適切だろう)、3.生物人類学(これが本家の「人類学」と主張する人類学

者もいる)、そして4.民族学(ethnology)ないしは文化人類学が 含まれる(1)。これが、人類学の4分類と言われるものである。4分類

の人類学は、人間の科学としての人類学を知る上では、とても重要な意義を持ってい

る。この四分類人類学は、フランツ・ボアズの教科書(リーディングス)のタイトルにちなんで、しばしば総合人類学(general

anthropology)とのいわれる(→「人類学のすすめ」)。

◎民族学=人類学のトポス

●米国のエスニック・スタディーズ(ただしウィキペディアによると記事そのものに問題ありと指摘)

| Ethnic studies,

in the United States, is the study of difference—chiefly race,

ethnicity, and nation, but also sexuality, gender, and other such

markings—and power, as expressed by the state, by civil society, and by

individuals. Its antecedents came before the civil rights era, as early as the 1900s. During that time, educator and historian W. E. B. Du Bois expressed the need for teaching black history.[1] However, ethnic studies became widely known as a secondary issue that arose after the civil rights era.[2] Ethnic studies was originally conceived to re-frame the way that specific disciplines had told the stories, histories, struggles and triumphs of people of color on what was seen to be their own terms. In recent years, it has broadened its focus to include questions of representation, racialization, racial formation theory, and more determinedly interdisciplinary topics and approaches. As opposed to international studies, which was originally created to focus on the relations between the United States and Third World countries, ethnic studies was created to challenge the already existing curriculum and focus on the history of people of different minority ethnicity in the United States.[3] Ethnic studies is an academic field that spans the humanities and the social sciences; it emerged as an academic field in the second half of the 20th century partly in response to charges that traditional social science and humanities disciplines such as anthropology, history, literature, sociology, philosophy, political science, and area studies were conceived from an inherently Eurocentric perspective.[4] "The unhyphenated-American phenomenon tends to have colonial characteristics," notes Jeffrey Herlihy-Mera in After American Studies: Rethinking the Legacies of Transnational Exceptionalism: "English-language texts and their authors are promoted as representative; a piece of cultural material may be understood as unhyphenated—and thus archetypal—only when authors meet certain demographic criteria; any deviation from these demographic or cultural prescriptions are subordinated to hyphenated status."[5] |

アメリカにおけるエスニック・スタディーズとは、差異——主に人種、民族、国家、そしてセクシュアリティ、ジェンダー、その他の属性——と、国家、市民社会、個人によって表現される権力に関する研究である。 その前身は公民権運動以前の1900年代にまで遡る。当時、教育者であり歴史家でもあるW・E・B・デュボイスは、黒人史を教える必要性を訴えた[1]。 しかしエスニック・スタディーズが広く知られるようになったのは、公民権運動の後に生じた二次的な課題としてであった[2]。エスニック・スタディーズは 当初、特定の学問分野が有色人種の物語や歴史、闘争と勝利を語ってきた方法を、彼ら自身の視点と見なされる観点から再構築することを目的として構想され た。近年では、表現の問題、人種化、人種形成理論、そしてより断固として学際的な主題やアプローチを含むようにその焦点を広げている。 もともと米国と第三世界諸国の関係に焦点を当てるために創設された国際研究とは対照的に、エスニック・スタディーズは既存のカリキュラムに挑戦し、米国に おける異なる少数民族の歴史に焦点を当てるために創設された。[3] エスニック・スタディーズは人文科学と社会科学にまたがる学問分野である。20世紀後半に学術分野として登場した背景には、人類学、歴史学、文学、社会 学、哲学、政治学、地域研究といった伝統的な社会科学・人文科学分野が、本質的にヨーロッパ中心主義的視点から構築されているとの批判があった。[4] ジェフリー・ハーリハイ=メラは『アメリカ研究のその後:超国家的例外主義の遺産を再考する』でこう指摘している: 「英語のテキストとその著者は代表的として推進される。ある文化的素材は、著者が特定の人口統計学的基準を満たす場合にのみ、ハイフンなしの——つまり原 型的——ものと理解される。こうした人口統計学的・文化的規定からの逸脱は、すべてハイフン付きの地位に降格される」[5] |

| History In the United States, the field of ethnic studies evolved out of the Civil Rights Movement during the 1960s and early 1970s, which contributed to growing self-awareness and radicalization of people of color such as African Americans, Asian Americans, Latino Americans, and American Indians. Ethnic studies departments were established on college campuses across the country and have grown to encompass African American Studies, Asian American Studies, Raza Studies, Chicano Studies, Mexican American Studies, Native American Studies, Jewish Studies, and Arab Studies. Arab American Studies was created after 9/11 at SF State University. Jewish Studies and Arab Studies were created long before 1968, outside of the U.S., apart and separate from the 1968 Ethnic Studies Movement. The first strike demanding the establishment of an Ethnic Studies department occurred in 1968, led by the Third World Liberation Front (TWLF), a joint effort of the Black Student Union, Latin American Students Organization, Asian American Political Alliance, Pilipino American Collegiate Endeavor, and Native American Students Union at San Francisco State University.[citation needed] This was the longest student strike in the nation's history and resulted in the establishment of a School of Ethnic Studies. President S. I. Hayakawa ended the strike after taking a hardline approach when he appointed Dr. James Hirabayashi the first dean of the School (now College) of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University,[6] and increased recruiting and admissions of students of color in response to the strike's demands. In 1972, The National Association for Ethnic Studies was founded to foster interdisciplinary discussions for scholars and activists concerned with the national and international dimensions of ethnicity encouraging conversations related to anthropology, Africana Studies, Native Studies, Sociology and American Studies among other fields. Minority students at The University of California at Berkeley- united under their own Third World Liberation Front- the TWLF, initiated the second longest student strike in US history on January 22, 1969. The groups involved were the Mexican American Student Confederation, Asian American Political Alliance, African American Student Union, and the Native American group. The four co-chairmen of the TWLF were Ysidro Macias, Richard Aoki, Charlie Brown, and LaNada Means.[citation needed] This strike at Berkeley was even more violent than the San Francisco State strike, in that more than five police departments, the California Highway Patrol, Alameda County Deputies, and finally, the California National Guard were ordered onto the Berkeley campus by Ronald Reagan in the effort to quash the strike.[citation needed] The excessive use of police force has been cited with promoting the strike by the alienation of non-striking students and faculty, who protested the continual presence of police on the Berkeley campus. The faculty union voted to join the strike on March 2, and two days later the Academic Senate called on the administration to grant an interim Department of Ethnic Studies.[citation needed] On March 7, 1969, President Hitch authorized the establishment of the first Ethnic Studies Department in the country, followed by the establishment of the nation's first College of Ethnic Studies at San Francisco State University on March 20, 1969.[citation needed] In 1994, with Taiwanese government's support, National Dong Hwa University established the first Ethnic Studies institute in Taiwan, the Graduate Institute of Ethnic Relations and Cultures, which nowadays is one of leading institution of Ethnic Studies in Asia for its Austronesian and Taiwanese Indigenous Studies.[7] Courses in ethnic studies address perceptions that, because of the Eurocentric bias and racial and ethnic prejudice of those in power, American historians have systematically ignored or undervalued the roles of such ethnic minorities as Asian Americans, Blacks, Mexicans, Latinos and Native Americans.[citation needed] Ethnic studies also often encompasses issues of intersectionality, where gender, class, and sexuality also come into play. There are now hundreds of African American, Asian American, Mexican American and Chicano/Latino Studies departments in the US, approximately fifty Native American Studies departments, and a small number of comparative ethnic studies programs. College students, especially on the East Coast, continue to advocate for Ethnic Studies departments.The Ethnic Studies Coalition at Wellesley College,[8] the Taskforce for Asian and Pacific American Studies at Harvard University, and CRAASH at Hunter College[9] are among student organizations calling for increased institutional support for Ethnic Studies. Ethnic studies as an institutional discipline varies by location. For instance, whereas the Ethnic Studies Department at UC Berkeley comprises separate "core group" departments, the department at UC San Diego does not do so.[10]  SF Students hold signs in solidarity and support of the Third World Liberation Front 2016, the name of the court students on a hunger strike to defend the SF State College of Ethnic Studies, during an emergency press conference in the Quad Monday, May 9. (Melissa Minton)[11] In May 2016 there was another Hunger Strike that took place at San Francisco State University. It was started by Hassin Bell, Julia Retzlaff, Sachiel Rosen, and Ahkeel Mesteger, all students at SFSU, in the attempt to both defend and improve the College of Ethnic Studies. They were on strike for 10 days and their strike reached national attention that helped end the strike with a signed compromise from the SFSU president Leslie Wong. The compromise consisted of allocating $250,000 to the Ethnic Studies department.[2] |

歴史 アメリカ合衆国において、エスニック・スタディーズの分野は1960年代から1970年代初頭にかけての公民権運動から発展した。この運動は、アフリカ系 アメリカ人、アジア系アメリカ人、ラティーノ系アメリカ人、アメリカ先住民といった有色人民の自己認識の高まりと急進化に寄与した。民族研究学科は全国の 大学キャンパスに設立され、アフリカ系アメリカ人研究、アジア系アメリカ人研究、ラサ研究、チカーノ研究、メキシコ系アメリカ人研究、ネイティブアメリカ ン研究、ユダヤ研究、アラブ研究へと拡大した。アラブ系アメリカ人研究は9.11事件後にサンフランシスコ州立大学で創設された。ユダヤ研究とアラブ研究 は、1968年よりずっと前に、米国外で、1968年のエスニック・スタディーズ運動とは別個に創設された。 エスニック・スタディーズ学科の設置を求める最初のストライキは1968年に発生した。主導したのは第三世界解放戦線(TWLF)であり、サンフランシス コ州立大学の黒人学生連合、ラテンアメリカ学生組織、アジア系アメリカ人政治同盟、フィリピン系アメリカ人学生団体、先住民学生連合による共同運動であっ た。[出典必要] これは国民史上最長の学生ストライキとなり、エスニック研究学部の設立につながった。S・I・ハヤカワ学長は強硬姿勢でストライキを終結させた。ストライ キの要求に応え、ジェームズ・ヒラバヤシ博士をサンフランシスコ州立大学エスニック研究学部(現・カレッジ)初代学部長に任命し、有色人種の学生募集と入 学者数を増やしたのである[6]。1972年、エスニック・スタディーズ全国協会が設立された。これは民族性の国家的・国際的側面に関心を持つ学者や活動 家のための学際的議論を促進し、人類学、アフリカ研究、先住民研究、社会学、アメリカ研究などの分野における対話を奨励することを目的としている。 カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の少数派学生は、自らの組織「第三世界解放戦線(TWLF)」の下で結束し、1969年1月22日に米国史上2番目に長い 学生ストライキを開始した。参加団体はメキシコ系アメリカ人学生連合、アジア系アメリカ人政治同盟、アフリカ系アメリカ人学生連合、および先住民グループ であった。TWLFの共同議長4名は、イシドロ・マシアス、リチャード・アオキ、チャーリー・ブラウン、ラナダ・ミーンズであった。[出典必要] バークレーでのこのストライキは、サンフランシスコ州立大学のストライキよりもさらに暴力的であった。5つ以上の警察署、カリフォルニア州高速道路パト ロール、アラメダ郡保安官事務所、そして最終的にはカリフォルニア州国民が、ロナルド・レーガンによってストライキ鎮圧のためバークレーキャンパスに投入 されたのである。[出典必要] 警察の過剰な武力行使は、非ストライキ参加の学生や教員を疎外し、バークレー校内の警察の継続的な存在に抗議する動きを助長したとして指摘されている。教 員組合は3月2日にストライキ参加を決議し、2日後には学術評議会が学長に対し暫定的な民族研究学科の設置を要求した。[出典が必要] 1969年3月7日、ヒッチ学長は全米初のエスニック・スタディーズ学科設立を承認。これに続き、1969年3月20日にはサンフランシスコ州立大学に全 米初のエスニック・スタディーズ学部が設置された。[出典が必要] 1994年、台湾政府の支援を得て国立東華大学は台湾初の民族研究機関である「民族関係文化研究所」を設立した。同研究所は現在、オーストロネシア語族研 究と台湾先住民族研究においてアジアを代表するエスニック・スタディーズ機関の一つとなっている。[7] エスニック・スタディーズの課程は、権力者層のヨーロッパ中心主義的偏見や人種・民族的差別により、アジア系アメリカ人、黒人、メキシコ系、ラティーノ、 先住民といった少数民族の役割がアメリカの歴史家によって体系的に無視または過小評価されてきたという認識に対処するものである。[出典必要] 民族研究はまた、性別、階級、性的指向といった要素が絡む交差性(インターセクショナリティ)の問題も頻繁に包含する。現在、米国には数百のアフリカ系ア メリカ人、アジア系アメリカ人、メキシコ系アメリカ人、チカーノ/ラティーノ研究学科が存在する。ネイティブアメリカン研究学科は約50、比較民族研究プ ログラムは少数である。大学生、特に東海岸の学生は、エスニック・スタディーズ学科の設置を継続して提唱している。ウェルズリー大学の民族研究連合 [8]、ハーバード大学のアジア太平洋アメリカ研究タスクフォース、ハンター大学のCRAASH[9]などは、エスニック・スタディーズへの制度的支援強 化を求める学生組織の一例である。制度的学問としてのエスニック・スタディーズは地域によって異なる。例えばカリフォルニア大学バークレー校の民族研究学 部は独立した「中核グループ」学部で構成されるが、カリフォルニア大学サンディエゴ校の学部ではそうではない。[10]  サンフランシスコ州立大学(SF State)の学生たちが、5月9日(月)にクワッド(中庭)で行われた緊急記者会見で、民族研究学部を守るためのハンガーストライキを行う「サード・ ワールド解放戦線2016」への連帯と支援を示すプラカードを掲げる様子。(メリッサ・ミントン撮影)[11] 2016年5月、サンフランシスコ州立大学で別のハンガーストライキが発生した。SFSUの学生であるハッシン・ベル、ジュリア・レッツラフ、サキエル・ ローゼン、アキール・メステガーが、エスニック・スタディーズ学部を守り改善しようと試みて開始したものである。彼らは10日間のストライキを続け、その 闘いは国民的な注目を集めた。その結果、SF州立大学のレスリー・ウォン学長が署名した妥協案が提示され、ストライキは終結した。妥協案の内容は、エス ニック・スタディーズ学科に25万ドルを配分するというものだった。[2] |

| Schools of thought While early ethnic studies scholarship focused on the repressed histories and identities of various groups in the U.S., the field of study has expanded to encompass transnationalism, comparative race Studies, and postmodernist/poststructuralist critiques. While pioneering thinkers relied on frameworks, theories and methodologies such as those found in the allied fields of sociology, history, literature and film, scholars in the field today utilize multidisciplinary as well as comparative perspectives, increasingly within an international or transnational context. Central to much Ethnic Studies scholarship is understanding how race, class, gender, sexuality, ability, and other categories of difference intersect to shape the lived experiences of people of color, what the legal scholar Kimberlé Crenshaw calls intersectionality.[12] Branches of ethnic studies include but are not limited to African American Studies, Asian American Studies, Native American/ Indigenous Peoples' Studies, and Latino/a Studies.[13] A discipline within ethnic studies is African American Studies, which consist of studying people of African descent and their ideologies, customs, cultures, identities, and practices by drawing on social sciences and the humanities.[14] The changes made to educational and social institutions by the U.S. Civil Rights movement of the 1960s and 1970s can be traced as the origin for the development of African American Studies as a discipline.[14] In general, the changes made to the higher education system to incorporate African American Studies has been led by student activism.[15] When initially created, in many cases to end protests, the African American Studies programs at predominately white universities were underfunded and not highly esteemed.[16] Since the 1970s, African American Studies programs, in general, have become reputable and more concretely established within predominantly white universities.[16] Historically, African American scholars and their works have been used as sources to teach African American Studies.[17] Teaching African American Studies has been categorized by two methods: Afrocentric, which relies solely on text by black authors and are led by all-black faculties, and traditional methods, which are more inclusive of non-black authors and are more broad in their studies.[18] Scholars whose work was influential to the development of African American Studies, and whose work is studied include W.E.B. Du Bois, Booker T. Washington, Carter G. Woodson, and George Washington Williams.[16] The first historically black college or university to offer a variation of African American Studies was Howard University, located in Washington D.C.[18] Native American Studies, or sometimes named Native Studies or American Indian Studies, is another branch of ethnic studies which was established as a result of university student protest and community activism.[19] The first attempts at establishing some form of Native American Studies came in 1917 from Oklahoma Senator Robert Owen, who called for an 'Indian Studies' program at the University of Oklahoma.[20] Several decades later, the "Red Power" Movement of the 1960s, in a time of high minority and suppressed group activism in the US, sought to get Native American Studies into higher education.[21] San Francisco State University and University of California at Berkeley were the first to adopt these fields into their departments in 1968.[21] The TCU (tribal colleges and universities) movement of the 1960s aimed to expand the teaching of Native American Studies by establishing tribe-run universities to educate the tribe's youth and their communities.[22] Navajo Community College, later renamed Diné College, was the first of these institutions.[22] Curriculum in Native American Studies programs teach the historical, cultural and traditional aspects of both natives of the land in general, as well as that of the American Indians specifically.[19] Figures within Native American Studies include Vine Deloria Jr., an American Indian scholar and rights' activist,[23] Paula Gunn Allen who was a writer and educator of Native American Studies,[24] poet Simon J. Ortiz.[25] Asian American Studies, different than Asian Studies, is a subfield within ethnic studies, which focuses on the perspectives, history, culture, and traditions of the Asian peoples' in the United States.[26] Asian American Studies originated in the late 1960s at the San Francisco State College (now San Francisco State University) where a student strike led to the development of the program at the school.[26] The historical approach to representing Asia in the United States prior to the introduction of Asian American Studies has been Orientalism which portrays Asia as a polar opposite to anything western or American.[27] To counter this historical representation of ideas, Asian American Studies became one of the interdisciplinary fields that emphasized teaching the perspective, voice, and experience of the minority community.[26] In terms of the ethnicities being studied, there are distinctions between Asian Americans (Chinese, Japanese, Filipino Americans for example) and Pacific Islanders (Samoan Americans), but those groups tend to be grouped as a part of Asian American Studies.[28] Prose, plays, songs, poetry (Haiku) and several other forms of writing were popular during the 1970s as methods of Asian American expression.[29] Among the most read authors were Frank Chin, Momoko Iko, Lawson Fusao Inada, Meena Alexander, Jeffery Paul Chan, and John Okada,[29] who were considered by Asian American scholars to be pioneers of Asian American literature.[28] Most recently, "whiteness" studies has been included as a popular site of inquiry in what is traditionally an academic field for studying the racial formation of communities of color. Instead of including whites as another additive component to ethnic studies, whiteness studies has instead focused on how the political and juridical category of white has been constructed and protected in relation to racial "others" and how it continues to shape the relationship between bodies of color and the State. As Ian Haney-Lopez articulates in White By Law: The Legal Construction of Race, the law has functioned as the vehicle through which certain racialized groups have been included or excluded from the category of whiteness across time, and thus marked as inside or outside the national imaginary (read as white) and the privileges that result from this belonging.[30] Important to whiteness studies, according to scholars such as Richard Dyer, is understanding how white bodies are both invisible and hypervisible, and how representations of whiteness in visual culture reflect and, in turn, shape a persistent commitment to white supremacy in the U.S. even as some claim the nation is currently a colorblind meritocracy.[31] In addition to visual culture, space also reproduces and normalizes whiteness. The sociologist George Lipsitz argues that whiteness is a condition rather than a skin color, a structured advantage of accumulated privilege that resurfaces across time spatially and obscures the racism that continues to mark certain bodies as out of place and responsible for their own disadvantage.[32] Such attention to geography is an example of the way ethnic studies scholars have taken up the study of race and ethnicity across almost all disciplines using various methodologies in the humanities and social sciences. In general, an "Ethnic Studies approach" is loosely defined as any approach that emphasizes the cross-relational and intersectional study of different groups. George Lipsitz is important here as well, demonstrating how the project of anti-black racism defines the relationship between the white spatial imaginary and other communities of color. Thus, the redlining of the 1930s that prevented upwardly mobile African Americans from moving into all-white neighborhoods also forced Latino and Asian bodies into certain spaces. |

学派 初期のエスニック・スタディーズ研究は、米国における様々な集団の抑圧された歴史とアイデンティティに焦点を当てていたが、この研究分野は現在、トランス ナショナル主義、比較人種研究、ポストモダニズム/ポスト構造主義的批判を含むように拡大している。先駆的な思想家たちは社会学、歴史学、文学、映画学と いった関連分野に見られる枠組みや理論、方法論に依拠していたが、今日の研究者は学際的かつ比較的な視点を活用し、国際的あるいは越境的な文脈の中で研究 を進める傾向が強まっている。多くのエスニック・スタディーズの核心は、人種、階級、性別、セクシュアリティ、能力、その他の異なるカテゴリーがどのよう に交差して有色人種の生きた経験を形成するか、すなわち法学者キンバーリー・クレンショーが提唱する「交差性」を理解することにある[12]。エスニッ ク・スタディーズの分野には、アフリカ系アメリカ人研究、アジア系アメリカ人研究、先住民研究、ラティーノ研究などが含まれるが、これらに限定されない [13]。 エスニック・スタディーズの一分野であるアフリカ系アメリカ人研究は、社会科学と人文科学を基盤に、アフリカ系の人々とそのイデオロギー、慣習、文化、ア イデンティティ、実践を研究するものである[14]。1960年代から1970年代にかけてのアメリカ公民権運動が教育・社会制度にもたらした変革は、ア フリカ系アメリカ人研究が学問分野として発展した起源とみなせる。[14] 一般的に、アフリカ系アメリカ人研究を導入するための高等教育制度の変更は、学生運動によって主導されてきた。[15] 当初、抗議活動を終結させる目的で創設された多くの場合、白人中心の大学におけるアフリカ系アメリカ人研究プログラムは資金不足で、高く評価されていな かった。[16] 1970年代以降、アフリカ系アメリカ人研究プログラムは、概して白人中心の大学内で信頼性を獲得し、より確固たる地位を確立してきた。[16] 歴史的に、アフリカ系アメリカ人研究を教えるための資料として、アフリカ系アメリカ人学者とその著作が用いられてきた。[17] アフリカ系アメリカ人研究の教授法は二つの方法に分類される。黒人作家の著作のみに依拠し、黒人教員のみで構成される「アフロセントリック」と、非黒人作 家の著作もより包括的に取り入れ、研究範囲がより広範な「伝統的手法」である。[18] アフリカ系アメリカ人研究の発展に影響を与え、その研究対象となっている学者には、W・E・B・デュボイス、ブッカー・T・ワシントン、カーター・G・ ウッドソン、ジョージ・ワシントン・ウィリアムズらがいる。[16] アフリカ系アメリカ人研究の変種を初めて提供した歴史的黒人大学は、ワシントンD.C.にあるハワード大学である。[18] ネイティブ・アメリカン研究(ネイティブ研究またはアメリカン・インディアン研究とも呼ばれる)は、エスニック・スタディーズの別の分野であり、大学生の 抗議活動と地域社会の活動の結果として確立された。[19] ネイティブ・アメリカン研究の何らかの形態を確立しようとする最初の試みは、1917年にオクラホマ州上院議員ロバート・オーウェンによって行われた。彼 はオクラホマ大学に「インディアン研究」プログラムの設置を求めたのである。[20] 数十年後、1960年代の「レッド・パワー運動」は、米国で少数派や抑圧された集団の活動が活発化した時期に、ネイティブ・アメリカン研究を高等教育に導 入しようとした。[21] サンフランシスコ州立大学とカリフォルニア大学バークレー校が1968年、最初にこれらの分野を学部に取り入れた。[21] 1960年代のTCU(部族大学)運動は、部族が運営する大学を設立し、部族の若者とそのコミュニティを教育することで、ネイティブ・アメリカン研究の教 育拡大を目指した。[22] ナバホ・コミュニティ・カレッジ(後にディネ・カレッジと改称)が、こうした教育機関の先駆けとなった。[22] ネイティブ・アメリカン研究プログラムのカリキュラムは、土地の先住民全般と、特にアメリカ先住民の歴史的・文化的・伝統的側面を教える。[19] ネイティブ・アメリカン研究の代表的な人物には、アメリカ先住民の学者かつ権利活動家であるヴァイン・デロリア・ジュニア[23]、ネイティブ・アメリカ ン研究の作家兼教育者であったポーラ・ガン・アレン[24]、詩人のサイモン・J・オルティスがいる。[25] アジア系アメリカ人研究は、アジア研究とは異なる、エスニック・スタディーズの一分野である。これはアメリカ合衆国におけるアジア系住民の視点、歴史、文 化、伝統に焦点を当てる。[26] アジア系アメリカ人研究は1960年代後半、サンフランシスコ州立大学(当時サンフランシスコ州立カレッジ)で始まった。学生ストライキがきっかけとな り、同校でこのプログラムが開発されたのである。[26] アジア系アメリカ人研究が導入される以前、米国におけるアジアの表現はオリエンタリズムという歴史的アプローチが主流であった。これはアジアを西洋やアメ リカとは正反対の存在として描くものである。[27] このような歴史的な観念表現に対抗するため、アジア系アメリカ人研究は、少数派コミュニティの視点、声、経験を教えることを重視する学際的分野の一つと なった。[26] 研究対象となる民族に関しては、アジア系アメリカ人(例えば、中国系、日本系、フィリピン系アメリカ人)と太平洋諸島系(サモア系アメリカ人)の区別があ るが、これらのグループはアジア系アメリカ人研究の一部としてまとめられる傾向がある。[28] 1970年代、アジア系アメリカ人の表現方法として、散文、戯曲、歌、詩(俳句)、その他いくつかの形式の文章が人気を博した。最も読まれた作家として は、フランク・チン、モモコ・イコ、ローソン・フサオ・イナダ、ミーナ・アレクサンダー、ジェフリー・ポール・チャン、ジョン・オカダなどが挙げられ、彼 らはアジア系アメリカ人学者からアジア系アメリカ人文学のパイオニアと見なされていた。 最近では、「白人性」研究が、伝統的に有色人種のコミュニティの人種形成を研究する学術分野として、人気のある研究対象となっている。白人性研究は、白人 をエスニック・スタディーズに追加的な要素として取り込むのではなく、白人という政治的・司法的カテゴリーが、人種的な「他者」との関係においてどのよう に構築され、保護されてきたか、そしてそれが有色人種と国家の関係にどのように影響を与え続けているかに焦点を当てている。イアン・ハニー=ロペスが『法 律による白人:人種の法的構築』で論じるように、法は時代を超えて特定の人種化された集団を白人カテゴリーに包含または排除する手段として機能し、それに よって国民の想像(すなわち白人)の内側か外側か、そしてこの帰属から生じる特権を刻印してきた。[30] リチャード・ダイアーら研究者が指摘するように、白人研究において重要なのは、白人身体が不可視であると同時に過剰に可視化されている実態、そして視覚文 化における白人性の表象が、米国における白人至上主義への持続的帰属意識を反映し、さらにそれを形成する過程を理解することだ。これは、現代の米国が「人 種を問わない実力主義社会」だと主張する者たちが存在する中でなお顕著である。[31] 視覚文化に加え、空間もまた白人性を再生産し正常化する。社会学者ジョージ・リプシッツは、白人性は肌の色ではなく状態であり、蓄積された特権による構造 化された優位性だと論じる。この優位性は時空を超えて再浮上し、特定の身体を場違いな存在として烙印し、自らの不利を自己責任とする人種主義を覆い隠すの だ[32]。こうした地理への注目は、エスニック・スタディーズの学者たちが人文・社会科学の多様な方法論を用いて、ほぼ全分野にわたる人種・民族研究に 取り組んできた一例である。 一般的に「エスニック・スタディーズ的アプローチ」とは、異なる集団間の相互関係や交差性を重視するあらゆる研究手法を広く指す。ジョージ・リプシッツも ここで重要であり、反黒人種主義というプロジェクトが、白人の空間的想像と他の有色人種コミュニティとの関係をどのように定義するかを示している。した がって、1930年代のレッドライニングは、上昇志向のあるアフリカ系アメリカ人が白人だけの地域に移住するのを妨げただけでなく、ラテン系やアジア系の 身体を特定の空間に押し込める結果も招いた。 |

| Relationship to other fields Ethnic studies often faces resistance from traditional fields of inquiry which prioritize objective and detached scholarship. Scholars from such disciplines often consider ethnic studies politicized. In contrast, ethnic studies has increasingly aligned with other fields of study which also emphasize power dynamics. These include African American and Asian American studies.[citation needed] Ethnic Studies is often organized housed within departments that operate under a variety of names, including Critical Ethnic Studies,[33] Comparative American Cultures,[34] Ethnic Studies,[35] or American Studies and Ethnicity.[36] A wide variety of curricula are employed in the service of each of these rubrics. Occasionally, the gap between American Studies and Ethnic Studies can be productively bridged, especially in departments where the bulk of faculty focus on race and ethnicity, difference and power. But that bridgework can be troublesome, obscuring one foci and sharpening the emphasis on another.[37] As a consequence of this great variation, though, ethnic studies needs to be understood within its specific institutional context. And, despite considerable financial (and often political) pressure to consolidate or eliminate ethnic studies within American Studies—or to house Native American studies, Latino studies, and Asian American studies within either ethnic studies or American Studies—the relationships between these fields should be considered within each institution's governing eco-system.[38] |

他分野との関係 エスニック・スタディーズは、客観的で距離を置いた学問を優先する伝統的な研究分野から抵抗を受けることが多い。そうした分野の研究者は、エスニック・ス タディーズを政治化されていると見なす傾向がある。対照的に、エスニック・スタディーズは権力構造を重視する他の研究分野との連携を深めている。これには アフリカ系アメリカ人研究やアジア系アメリカ人研究が含まれる。[出典が必要] エスニック・スタディーズは、批判的エスニック・スタディーズ[33]、比較アメリカ文化[34]、エスニック・スタディーズ[35]、あるいはアメリカ 研究と民族性[36]など、様々な名称で運営される学部内に設置されることが多い。これらの枠組みごとに、多様なカリキュラムが採用されている。時折、ア メリカ研究とエスニック・スタディーズの隔たりは、特に教員の大半が人種・民族性、差異・権力に焦点を当てる学部において、生産的に埋められることがあ る。しかしその橋渡しは厄介であり、一方の焦点を曖昧にし、他方の強調を鋭くする可能性がある[37]。 こうした多様性ゆえに、エスニック・スタディーズは各機関の固有の文脈の中で理解される必要がある。また、エスニック・スタディーズをアメリカ研究に統 合・消去法による、あるいはネイティブ・アメリカン研究、ラティーノ研究、アジア系アメリカ人研究をエスニック・スタディーズもしくはアメリカ研究のいず れかに組み入れるよう、財政的(そしてしばしば政治的)な圧力が強いにもかかわらず、これらの分野の関係性は各機関の統治システムの中で考察されるべきで ある。 |

| Professional associations Association for Ethnic Studies This section may rely excessively on sources too closely associated with the subject, potentially preventing the article from being verifiable and neutral. Please help improve it by replacing them with more appropriate citations to reliable, independent sources. (January 2019) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The Association for Ethnic Studies (AES) was founded in 1972 by several scholars who wanted to study race through an interdisciplinary approach. It was previously known as the National Association for Ethnic Studies (NAES), and was initially named the National Association of Interdisciplinary Studies for Native-American, Black, Chicano, Puerto Rican, and Asian Americans. The organization was officially renamed as NAES in 1985, and then to its current name in 2018.[39] It is the oldest ethnic studies association in the United States.[40] From its founding, the organization has strived to promote scholarship, research, and curriculum design for its members.[39] The organization hosts an annual conference.[41] AES also publishes the Ethnic Studies Review, a peer-reviewed journal for scholarship in ethnic studies, published by the University of California Press.[42] |

専門職団体 エスニック・スタディーズ協会 この節は、主題と密接に関連する情報源に依存しすぎている可能性がある。これにより、記事の検証可能性と中立性が損なわれる恐れがある。信頼できる独立した情報源への適切な引用に置き換えることで、改善に協力してほしい。(2019年1月) エスニック・スタディーズ協会(AES)は、学際的アプローチによる人種研究を志す数名の学者によって1972年に設立された。以前は全米エスニック・ス タディーズ協会(NAES)として知られ、当初は「ネイティブアメリカン、黒人、チカーノ、プエルトリコ人、アジア系アメリカ人を対象とした学際的研究全 国協会」と命名されていた。1985年に正式にNAESへ改称され、2018年に現在の名称となった[39]。米国最古のエスニック・スタディーズ協会で ある[40]。 設立以来、本協会は会員向けの学術研究・調査・カリキュラム設計の促進に努めてきた[39]。年次大会を開催している。[41] AESはまた、カリフォルニア大学出版局から刊行される査読付き学術誌『Ethnic Studies Review』を発行している。[42] |

| Critical Ethnic Studies Association The Critical Ethnic Studies Association (CESA) began with its first conference in March 2011 at the University of California Riverside, Critical Ethnic Studies and the Future of Genocide: Settler colonialism/Heteropatriarchy/White Supremacy. This prompted the people who had organized and partaken in the conference to form the association. The second conference then took place in September 2013 at the University of Illinois Chicago and it was themed, Decolonizing Future Intellectual Legacies and Activist Practices. The third conference took place from April 30-May 2015 at York University in Toronto and it is titled, Sovereignties and Colonialisms: Resisting Racism, Extraction and Dispossession.[43] In some instances, ethnic studies has become entrapped within and similar to the mandates of liberal multiculturalism, which relies on politics beholden to US nation-building and capitalist imperatives. Ethnic studies is in a difficult position, because as it gets more legitimized within the academy, it has frequently done so by distancing itself from the very social movements that were the triggers for its creation. On the other hand, ethnic studies departments have always existed on the margins of the academic industrial complex, and became further marginalized through funding cuts due to the 2008 global economic crisis. Instead of just dismissing or wholly embracing identarian nationalism, CESA seeks to construct an open dialogue around issues like white supremacy, settler colonialism, capitalism, and heteropatriarchy, militarism, occupation, indigenous erasure, neocolonialism, anti-immigration anti-Islam, etc. in order to expand the parameters and capacities of ethnic studies.[citation needed] CESA's goal is not to romanticize all movements or dictate a specific relationship between scholars and activists. Instead, it questions the emphasis of professionalization within ethnic studies, the politics of the academic industrial complex, or the engagement of larger movements for social transformation. It recognizes that at times Ethnic Studies has been complicit in neutralizing the university, rather than questioning the university's ideologies, actions, regulation and production of knowledge, and power. It works to situate the university as a point of contention, as a location among many for political struggles. CESA invites participation from all types of people: scholars, students, activists, arts, media makers, and educators of all fields, generations, and disciplines. The Critical Ethnic Studies Association was founded as a transnational, interdisciplinary, and un-disciplinary association of scholars, activists, students, artists, media makers, educators, and others who are directly concerned with interrogating the limitations of ethnic studies in order to better engage the historical stakes of the field. It organizes projects and programs to reimagine ethnic studies and its future through new interventions, both scholarly and activist based. They aim to develop an approach to scholarship, institution building, and activism animated by the spirit of the decolonial, antiracist, and other global liberationist movements that enabled the creation of Ethnic Studies in the first place. It hopes that this approach will continue to inform its political and intellectual projects.[44] Within the organization, there is an emphasis on counteracting institutional marginalization, revisiting the ideas that prompted the creation of ethnic studies, and creating new conversations that challenge US hegemony in traditional ethnic studies. Their goals include establishing an interdisciplinary network of scholars and activists stimulating debate on critical ethnic studies, providing forums such as the biannual conference or dialogues thought seminars, social media, etc. There is also a focus on publishing a journal, Critical Ethnic Studies, for new scholarship, and to facilitate dialogues that are critical and constructive between activist and academics.[45] |

批判的エスニック・スタディーズ協会 批判的エスニック・スタディーズ協会(CESA)は、2011年3月にカリフォルニア大学リバーサイド校で開催された初の会議「批判的エスニック・スタ ディーズとジェノサイドの未来:入植者植民地主義/ヘテロパトリアーキ/白人至上主義」を起源とする。この会議を組織し参加した人民たちが協会の設立に 至った。第二回大会は2013年9月にイリノイ大学シカゴ校で開催され、「脱植民地化:未来の知的遺産と活動家実践」をテーマとした。第三回大会は 2015年4月30日から5月にかけてトロントのヨーク大学で開催され、「主権と植民地主義:人種主義・収奪・土地剥奪への抵抗」と題された。[43] 場合によっては、エスニック・スタディーズはリベラルな多文化主義の要請に囚われ、それに類似したものとなっている。この多文化主義は、米国の国民建設と 資本主義的要請に縛られた政治に依存している。エスニック・スタディーズは困難な立場にある。学界内で正当性を増すにつれ、その創設の契機となった社会運 動自体から距離を置くことでそれを達成してきたからだ。一方でエスニック・スタディーズ学科は常に学術産業複合体の境界に存在し、2008年の世界経済危 機による資金削減でさらに周縁化が進んだ。CESAは、アイデンティティに基づくナショナリズムを単純に否定したり全面的に受け入れたりするのではなく、 白人至上主義、入植者による植民地主義、資本主義、ヘテロパトリアーキ、軍国主義、占領、先住民の抹殺、新植民地主義、反移民・反イスラム主義といった問 題をめぐる開かれた対話を構築し、エスニック・スタディーズの枠組みと可能性を拡大しようとするものである。 CESAの目的は、あらゆる運動を美化したり、学者と活動家の特定の関係を強制したりすることではない。むしろ、エスニック・スタディーズにおける専門職 化の強調、学術産業複合体の政治、社会変革を目指す大規模な運動との関わり方に疑問を呈する。エスニック・スタディーズが時に、大学のイデオロギーや行 動、知識の規制・生産、権力構造を問うのではなく、大学を無力化する共犯者となってきた事実を認識しているのだ。大学を争点として位置づけ、数ある政治闘 争の場の一つと捉えることを目指す。CESAはあらゆる分野・世代・学問領域の学者、学生、活動家、芸術家、メディア制作者、教育者など、あらゆる人民へ の参加を呼びかける。批判的エスニック・スタディーズ協会は、エスニック・スタディーズの限界を問い直し、この分野の歴史的意義をより深く掘り下げること に直接関わる学者、活動家、学生、芸術家、メディア制作者、教育者らによる、国境を越えた学際的・非学問的連合として設立された。学術的・活動家的な新た な介入を通じて、エスニック・スタディーズとその未来を再構想するプロジェクトやプログラムを組織する。彼らは、そもそもエスニック・スタディーズの創設 を可能にした脱植民地化、反人種差別、その他のグローバルな解放運動の精神に活気づけられた、学術研究、制度構築、活動主義へのアプローチを発展させるこ とを目指している。このアプローチが、今後も彼らの政治的・知的プロジェクトを形作ることを望んでいる。[44] 組織内では、制度的な周縁化に対抗すること、エスニック・スタディーズ創設の理念を再考すること、伝統的なエスニック・スタディーズにおける米国のヘゲモ ニーに挑戦する新たな対話を創出することに重点が置かれている。目標には、批判的エスニック・スタディーズに関する議論を喚起する学際的な学者・活動家の ネットワーク構築、隔年会議や対話型セミナー、ソーシャルメディアなどのフォーラム提供が含まれる。また、新たな学術研究を発表する学術誌 『Critical Ethnic Studies』の刊行、活動家と学者の間で批判的かつ建設的な対話を促進することにも焦点を当てている。[45] |

| In high schools In California schools The neutrality of this section is disputed. Relevant discussion may be found on the talk page. Please do not remove this message until conditions to do so are met. (September 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) This section needs to be updated. Please help update this article to reflect recent events or newly available information. (September 2023) A 2021 law required California state's public high schools to offer an ethnic studies class by 2025 and to require an ethnic studies credit for graduation by 2030 "upon appropriation" of funding. However as of 3/14/2025 no funding has been allocated so it is unclear if the requirement has taken effect.[46] As of 2020 half of California students attended a high school where an ethnic studies class was offered.[47] Though the state provides a model ethnic studies curriculum it does not require that school districts adopt it. There are two competing visions for high school ethnic studies. Liberated ethnic studies calls on students to "“[c]onceptualize, imagine, and build new possibilities for post-imperial life that promote collective narratives of transformative resistance, critical hope, and radical healing.” While constructive ethnic studies aims to “[e]quip students with the skills to understand and analyze multiple points of view on relevant topics, so that they can develop their own opinions and present well-articulated, evidence-based arguments.”[48] School districts in California are implementing ethnic studies courses into school requirements. The El Rancho Unified School District (ERUSD), which serves the area of Pico Rivera, became the first school district in California to require an ethnic studies class as part of its students' graduation requirement in 2014.[49] The ethnic studies resolution in ERUSD was both drafted and proposed by ERUSD's board President, Aurora Villon and Vice President, Jose Lara and was presented as an effort to "expose ... students to global perspectives and inclusion of diversity".[50] This graduation requirement for ERUSD high school students is expected to be fully implemented by the 2015–2016 academic school year.[50] In a similar move, Los Angeles Unified School District (LAUSD) will also begin to require ethnic studies courses in its high schools and will include such courses in its A-G graduation requirements. In November 2014, the LAUSD board approved a resolution proposed by board members Bennett Kayser, George McKenna and Steve Zimmer.[51] The ethnic studies curriculum will begin as a pilot program in at least five high schools.[51] It is expected that by the 2017–2018 academic school year, every high school will offer at least one course in ethnic studies and the class would be compulsory by the time the class of 2019 graduates.[52] While LAUSD board members proposed the resolution, many students took on the efforts by creating petitions and rallies in support of the ethnic studies resolution.[53][54] In February 2021, the California Board of Education approved a curriculum to include the contributions of Asian, Black, Latino, and Native Americans. This included the approval of 33 optional lesson plans for schools to choose from.[55] |

高校において カリフォルニア州の学校において この節の中立性が疑問視されている。関連する議論はトークページで行われている。条件が満たされるまでこのメッセージを削除しないこと。(2023年9月)(このメッセージの削除方法と時期について) この節は更新が必要だ。最近起きた出来事や新たに得られた情報を反映させるため、この記事の更新に協力してほしい。(2023年9月) 2021年の法律により、カリフォルニア州の公立高校は2025年までにエスニック・スタディーズの授業を提供し、2030年までに「資金が確保され次 第」卒業要件としてエスニック・スタディーズの単位を必須とするよう義務付けられた。しかし2025年3月14日現在、資金は配分されていないため、この 要件が発効したかどうかは不明である。[46] 2020年時点で、カリフォルニア州の生徒の半数がエスニック・スタディーズ授業を開講している高校に通っていた。[47] 州はモデルとなるエスニック・スタディーズカリキュラムを提供しているが、学区がこれを採用することを義務付けてはいない。高校におけるエスニック・スタ ディーズには二つの対立するビジョンが存在する。解放のエスニック・スタディーズは生徒に対し「帝国主義後の生活における新たな可能性を構想し、想像し、 構築すること。それは変革的抵抗、批判的希望、急進的癒しの集合的物語を促進するものである」と求める。一方、建設的エスニック・スタディーズは「関連ト ピックに関する多様な視点を理解・分析するスキルを生徒に身につけさせ、自らの意見を形成し、論理的で証拠に基づいた議論を展開できるようにすること」を 目的とする。[48] カリフォルニア州の学区では、エスニック・スタディーズ科目を必修化している。ピコ・リベラ地域を管轄するエル・ランチョ統一学区(ERUSD)は、 2014年に卒業要件としてエスニック・スタディーズ科目を義務付けたカリフォルニア初の学区となった。[49] ERUSDにおけるエスニック・スタディーズ決議案は、同教育委員会のオーロラ・ビヨン委員長とホセ・ララ副委員長によって起草・提案されたものであり、 「生徒にグローバルな視点と多様性の受容を啓発する」取り組みとして提示された。[50] このERUSD高校生向け卒業要件は、2015-2016学年度までに完全実施される見込みである。[50] 同様の動きとして、ロサンゼルス統一学区(LAUSD)も高校でエスニック・スタディーズの履修を義務化し、A-G卒業要件に組み入れる。2014年11 月、LAUSD教育委員会はベネット・カイザー、ジョージ・マッケナ、スティーブ・ジマー各委員が提案した決議案を承認した。[51] エスニック・スタディーズカリキュラムは、少なくとも5校の高校でパイロットプログラムとして開始される。[51] 2017-2018学年度までに全高校で少なくとも1科目のエスニック・スタディーズ科目が提供され、2019年卒業生が卒業する時点では必修化される見 込みだ. [52] LAUSD理事会が決議を提案した一方で、多くの学生が請願書作成や集会開催を通じてエスニック・スタディーズ決議支持の運動を展開した。[53] [54] 2021年2月、カリフォルニア州教育委員会はアジア系、黒人系、ラテン系、先住民の貢献を包含するカリキュラムを承認した。これには学校が選択可能な 33のオプション授業計画の承認も含まれる。[55] |

| In Arizona schools On May 11, 2010, Arizona Governor Jan Brewer signed House Bill 2281 (also known as HB 2281 and A.R.S. §15–112), which prohibits a school district or charter school from including in its program of instruction any courses or classes that Promotes the overthrow of the Federal or state government or the Constitution Promotes resentment toward any race or class (e.g. racism and classism) Advocates ethnic solidarity instead of being individuals Are designed for a certain ethnicity But the law must still allow: Native American classes to comply with federal law Grouping of classes based on academic performance Classes about the history of an ethnic group open to all students Classes discussing controversial history[56] Coming off the heels of SB 1070, Superintendent of Public Instruction Tom Horne was adamant about cutting Mexican-American Studies in the Tucson Unified School District. He devised HB 2281 under the belief that the program was teaching "destructive ethnic chauvinism and that Mexican American students are oppressed".[57][58] In January 2011, Horne reported TUSD to be out of compliance with the law. In June of that year, the Arizona Education Department paid $110,000 to perform an audit on the TUSD's program, which reported "no observable evidence was present to suggest that any classroom within the Tucson Unified School District is in direct violation of the law."[59] John Huppenthal (elected Superintendent as Horne became Attorney General) ordered the audit as part of his campaign promise to "Stop La Raza", but when the audit contradicted his own personal findings of noncompliance, he discredited it. Despite a formal appeal issued on June 22, 2011, by TUSD to Huppenthal, Judge Lewis Kowal backed the Superintendent's decision and ruled the district out of compliance in December, 2011.[60] On January 10, 2012, the TUSD board voted to cut the program after Huppenthal threatened to withhold 10% of the district's annual funding. Numerous books related to the Mexican-American Studies program were found in violation of the law and have been stored in district storehouses, including William Shakespeare's The Tempest, Paolo Freire's Pedagogy of the Oppressed, and Bill Bigelow's Rethinking Columbus: The Next 500 Years.[61] Supporters of MAS see HB 2281 as another attack on the Hispanic population of Arizona. This is due partly to the fact that none of the other three ethnic studies programs were cut. Support for the ethnic studies programs subsequently came from scholars, community activist groups, etc. For example, The Curriculum Audit of the Mexican American Studies Department refuted all of the violations under House Bill 2281. The audit instead recommended that the courses be implemented further, given the positive impacts of the courses on the students. In addition to the defense of the ethnic studies department, the UN Charter of Human Rights challenges the bill as a violation of fundamental human, constitutional, and educational rights (Kunnie 2010). A 2011 documentary, Precious Knowledge directed by Ari Palos and produced by Eren McGinnis for Dos Vatos Productions, argues that while 48% of Hispanic students drop out, TUSD's program had become a model of national success, with 93% of enrolled students graduating and 85% going on to college.[62] The film shows a 165-mile community run from Tucson to Phoenix in protest of the state's decision, as well as student-led marches and stand-ins. In one instance, students overtook a board meeting by chaining themselves to the board members' chairs.[63] A student protest group, UNIDOS (United Non-Discriminatory Individuals Demanding Our Studies), has remained active speaking out before legislators and school board members on behalf of the program.[64] In a separate case, two students and 11 teachers sued the state, contending that the law is unconstitutional. The teachers, however, have been denied standing in the lawsuit as public employees.[65] |

アリゾナ州の学校において 2010年5月11日、アリゾナ州知事ジャン・ブリュワーは、下院法案2281(HB 2281、A.R.S. §15–112としても知られる)に署名した。この法案は、学区またはチャータースクールが教育プログラムに以下の内容を含むことを禁止する: 連邦政府または州政府、あるいは憲法の転覆を促進するもの いかなる人種や階級に対する憎悪を助長するもの(例:人種主義や階級差別) 個人であることよりも民族的結束を主張するもの 特定の民族向けに設計されたもの ただし、この法律は以下を依然として許可しなければならない: 連邦法に準拠したネイティブアメリカン関連授業 学業成績に基づくクラス編成 全ての生徒が受講可能な民族集団の歴史に関する授業 論争のある歴史を扱う授業[56] SB 1070法成立直後、トム・ホーン教育長官はツーソン統一学区におけるメキシコ系アメリカ人研究の廃止を強く主張した。同プログラムが「破壊的な民族的排 外主義を教え、メキシコ系アメリカ人学生が抑圧されている」と信じる中で、彼はHB 2281法案を立案した[57]。[58] 2011年1月、ホーンはTUSDが法に違反していると報告した。同年6月、アリゾナ州教育省はTUSDのプログラム監査に11万ドルを支払い、「ツーソ ン統一学区の教室が直接的に法に違反していることを示す観察可能な証拠は存在しない」と報告した。[59] ジョン・ハプテンタル(ホーンが司法長官に就任したため教育長に選出)は「ラ・ラサを止めろ」という選挙公約の一環として監査を命じたが、監査結果が自身 の「法令違反」という個人的見解と矛盾すると、監査結果を信用できないものとして否定した。2011年6月22日にTUSDがフッペンタールに対し正式な 異議申し立てを行ったにもかかわらず、ルイス・コワル判事は教育長の決定を支持し、2011年12月に学区の法令違反を認定した。[60] 2012年1月10日、フッペンタールが学区の年間資金の10%を差し控えると脅迫したため、TUSD理事会はプログラムの廃止を決定した。メキシコ系ア メリカ人研究プログラムに関連する多数の書籍が法律違反と判断され、地区の倉庫に保管された。これにはウィリアム・シェイクスピアの『テンペスト』、パウ ロ・フレイレの『被抑圧者の教育学』、ビル・ビゲローの『コロンブスを再考する:次の500年』が含まれる。[61] メキシコ系アメリカ人研究(MAS)の支持者らは、HB 2281をアリゾナ州のヒスパニック系住民に対する新たな攻撃と見なしている。これは他の3つのエスニック・スタディーズプログラムが削減対象から外れた 事実も背景にある。その後、学者や地域活動団体などからエスニック・スタディーズプログラムへの支持が表明された。例えば『メキシコ系アメリカ人研究学科 カリキュラム監査報告書』は、下院法案2281に基づく違反指摘の全てを反駁している。監査はむしろ、学生への好影響を考慮し、課程の更なる実施を推奨し た。エスニック・スタディーズ学科の擁護に加え、国連人権憲章は本法案を基本的人権・憲法上の権利・教育権の侵害として問題視している(Kunnie 2010)。2011年のドキュメンタリー映画『プレシャス・ナレッジ』(アリ・パロス監督、ドス・バトス・プロダクションズ制作、エレン・マクギニス製 作)は、ヒスパニック系学生の48%が中退する中、TUSDのプログラムが国民的な成功モデルとなり、在籍学生の93%が卒業し85%が大学に進学したと 主張している。[62] この映画は、州の決定に抗議する165マイル(約265キロ)のコミュニティラン(ツーソンからフェニックスまで)や、生徒主導の行進・座り込みを映して いる。ある事例では、生徒たちが理事会の椅子に自らを鎖で繋ぎ、理事会を乗っ取った。[63] 学生抗議団体「UNIDOS(教育を求める差別撤廃連合)」は現在も活動を続け、立法府や教育委員会に対しプログラム存続を訴え続けている。[64] 別の訴訟では、生徒2名と教員11名が州を提訴し、同法が憲法違反だと主張した。しかし教員側は公務員であるため、訴訟当事者適格を認められなかった。 [65] |

| Appeal of Arizona ban The Mexican American Studies course was first brought under attack after the Deputy Superintendent of Public Education gave a speech to students, countering an allegation that "Republicans hate Latinos."[66] The students walked out of the speech, and Tom Horne, the Superintendent, blamed the rudeness of the students on the teachers from their Mexican American Studies courses. He called for removal of the courses. When his call was not answered, he made an effort for a bill to be put into law banning Mexican American Studies courses.[66] House Bill 2281,[67] which prohibited the Mexican American Studies courses, was approved in December 2010. In an effort to enforce the bill, the district court gave the Superintendent of the school district the right to withhold funding to schools that continue to teach the ethnic studies course.[68] Judge Kowal ruled the course "biased, political, and emotionally charged," and upheld both the bill and the withholding of funding from schools.[68] An appeal was filed in October 2010.[66] The initial appeal was challenging House Bill 2281[67] for violation of First Amendment (for viewpoint discrimination) and Fourteenth Amendment (for void-for-vagueness) rights.[66] This initial appeal was filed by 10 teachers, the director of the Mexican American Studies program, and 3 students and their parents.[66] Once the students graduated, 2 dropped their appeals, and the teachers and program director were dismissed for want of standing in January 2012.[66] This left one student and her father on the appeal. In March 2013, the appeals court ruled only in favor of the plaintiffs on the grounds that there was a First Amendment overbreadth violation to House Bill 2281.[67] The plaintiffs decided to further appeal the case.[66] On July 7, 2015, the appeal on the ban of the Mexican American Studies, Maya Arce vs Huppenthal, reached a federal appeals court.[69] Overseen by Judge Rakoff, the court reversed part of what the district court had ruled on banning the course. Judge Rakoff looked at the 4 categories (listed above) that constitute which classes are prohibited.[69] Rakoff's statement said that House Bill 2281 was created with the Mexican American Studies course in mind.[66] Since the Mexican American studies course was the only course in Arizona to be banned, it became clear that the bill had targeted the one course. This led the court to find the bill to be partially unconstitutional as it did not require similar Mexican American Studies courses outside of the Tucson Unified School District to cease teaching the courses. The bill also did not ban African American Studies courses that were being taught.[69] Rakoff's final ruling affirmed part of the bill to be unconstitutional regarding the plaintiff's First Amendment right.[66] However, Rakoff upheld the district court's ruling that the bill is not over broad.[66] Rakoff sent part of the appeal back to the district court to review the claim that the bill is discriminatory.[66] In August 2017, a different federal judge found that the bill was motivated by discriminatory intent, and struck down the ban on ethnic studies as unconstitutional.[70] The judge ruled that the ban had been passed "not for a legitimate educational purpose, but for an invidious discriminatory racial purpose and a politically partisan purpose."[71] |

アリゾナ州の禁止措置の訴え メキシコ系アメリカ人研究の授業は、教育副長官が生徒に向けて「共和党はラティーノを嫌っている」という主張に反論する演説を行った後、初めて攻撃の対象 となった。[66] 生徒たちは演説を途中で退席し、トム・ホーン教育長は生徒の無礼な態度をメキシコ系アメリカ人研究科目の教師のせいにした。彼は同科目の廃止を要求した が、応じられなかったため、メキシコ系アメリカ人研究科目を禁止する法案の成立に動いた[66]。 メキシコ系アメリカ人研究課程を禁止する下院法案2281号[67]は2010年12月に可決された。同法案を施行するため、地方裁判所は学区教育長に対 し、エスニック・スタディーズを継続する学校への資金提供を停止する権限を与えた[68]。コワル判事は同課程を「偏向的で政治的、感情的な内容」と評 し、法案と学校への資金停止措置の双方について支持する判決を下した。[68] 2010年10月に控訴が提起された。[66] 当初の控訴は、下院法案2281号[67]が修正第一条(見解差別による)及び修正第十四条(曖昧さによる無効)の権利を侵害していると争ったものであ る。[66] この最初の控訴は、10人の教師、メキシコ系アメリカ人研究プログラムのディレクター、3人の生徒とその保護者によって提起された。[66] 生徒が卒業すると、2人が控訴を取り下げ、教師とプログラムディレクターは2012年1月に訴訟資格を欠くとして却下された。[66] これにより、1人の生徒とその父親が控訴を継続することとなった。 2013年3月、控訴裁判所は、下院法案2281号が修正第一条の過度に広範な規制に違反するとの理由のみで原告側の主張を認めた。[67] 原告側はさらに上訴することを決めた。[66] 2015年7月7日、メキシコ系アメリカ人研究禁止に関する控訴事件「マヤ・アルセ対ハプテンタル」が連邦控訴裁判所に到達した。[69] ラコフ判事の監督下で、裁判所は地方裁判所が下した課程禁止判決の一部を覆した。ラコフ判事は、禁止対象となる授業を構成する4つのカテゴリー(上記参 照)を検討した。[69] ラコフ判事は声明で、下院法案2281号はメキシコ系アメリカ人研究課程を念頭に作成されたと述べた。[66] アリゾナ州で禁止されたのはメキシコ系アメリカ人研究課程のみであったため、同法案がこの特定課程を標的としたことが明らかになった。これにより、同法案 はツーソン統一学区外の類似メキシコ系アメリカ人研究課程の教授中止を義務付けていない点で部分的に違憲であると裁判所は判断した。また、当時教えられて いたアフリカ系アメリカ人研究の授業も禁止対象外であった。[69] ラコフ判事の最終判決は、原告の憲法修正第一条に基づく権利に関して、法案の一部を違憲と認定した。[66] ただし、法案が過度に広範ではないとする地方裁判所の判断は支持した。[66] ラコフ判事は、法案が差別的であるとの主張を再審査するため、控訴審の一部を地方裁判所に差し戻した。 2017年8月、異なる連邦判事は同法案が差別的意図に基づくものと認定し、エスニック・スタディーズ禁止条項を違憲として無効とした。[70] 判事は禁止条項が「正当な教育目的ではなく、悪意ある人種差別的目的および政治的党派的目的」で可決されたと裁定した。[71] |

| Criticism Ethnic studies has always been opposed by different elements. Proponents of ethnic studies feel that this is a reactionary movement from the right. They note the rise of the conservative movement during the 1990s in the United States, in which the discipline came increasingly under attack. For proponents, the backlash is an attempt to preserve "traditional values" of Western culture, symbolized by the United States. For some critics, this is a slant by proponents to disparage criticism by false association to right-wing ideology. They have no objection about African, Latino or Native American culture being legitimate topics of academic research. What they object to is the current state of ethnic studies which they see as characterized by excessive left-wing political ideology, postmodernist relativism which, in their view, greatly undermined the scholarly validity of the research. However, ethnic studies is accused of promoting "racial separatism", "linguistic isolation" and "racial preference".[72] In 2005, Ward Churchill, a professor of ethnic studies at University of Colorado at Boulder, came under severe fire for an essay he wrote called "On the Justice of Roosting Chickens", in which he claimed that the September 11 attacks were a natural and unavoidable consequence of what he views as unlawful US policy, and referred to the "technocratic corps" working in the World Trade Center as "little Eichmanns".[73] Conservative commentators used the Churchill affair to attack ethnic studies departments as enclaves of "anti-Americanism" which promote the idea of ethnic groups as "victims" in US society, and not places where serious scholarship is done.[74] In the face of such attacks, ethnic studies scholars are now faced with having to defend the field. In the media, this takes form of characterizing the attack as right wing reactionary movement. For example, Orin Starn, a cultural anthropologist and specialist in Native American Studies at Duke University, says: "The United States is a very diverse country, and an advocate would say we teach kids to understand multiculturalism and diversity, and these are tools that can be used in law, government, business and teaching, which are fields graduates go into. It promotes thinking about diversity, globalization, how we do business and how we work with nonprofits."[75] In reaction to criticisms that ethnic studies academics undermine the study of a unified American history and culture or that ethnic studies are simply a "colored" version of American Studies, defenders point out that ethnic studies come out of the historically repressed and denied presence of groups within the U.S. knowledge-production, literature and epistemology. Efforts to merge ethnic studies with American studies have been met with fierce opposition as was the case at UC Berkeley. While the field is already decades old, the ongoing creation of new ethnic studies departments is fraught with controversy. Administrators at Columbia University attempted to placate student protests for the creation of an Ethnic Studies Department in 1996 by offering American Studies as a compromise.[76] |

批判 エスニック・スタディーズは常に異なる勢力から反対されてきた。エスニック・スタディーズの支持者は、これは右派による反動的な動きだと感じている。彼ら は1990年代のアメリカにおける保守運動の高まりを指摘し、その過程でこの学問分野が次第に攻撃を受けるようになったと述べている。支持者にとって、こ の反発は米国に象徴される西洋文化の「伝統的価値観」を守ろうとする試みだ。一部の批判者にとっては、これは支持者が右派イデオロギーとの誤った関連付け で批判を貶めようとする偏向だ。彼らはアフリカ系、ラテン系、先住民文化が学術研究の正当な対象となること自体には異論がない。彼らが問題視するのは、現 在のエスニック・スタディーズが過剰な左翼のイデオロギーやポストモダニズム的相対主義に特徴づけられ、研究の学術的正当性を大きく損なっていると見る点 だ。しかしエスニック・スタディーズは「人種分離主義」「言語的孤立」「人種的優遇」を助長していると非難されている。[72] 2005年、コロラド大学ボルダー校のエスニック・スタディーズ教授ウォード・チャーチルは「報いの正義について」と題した論文で激しい批判を受けた。同 論文で彼は9.11同時多発テロを、米国が違法な政策を推進した結果として自然かつ不可避な帰結だと主張し、世界貿易センターで働く「技術官僚集団」を 「小さなアイヒマン」と呼んだのである。[73] 保守派論客はチャーチル事件を利用し、エスニック・スタディーズ学科を「反米主義」の巣窟と攻撃した。彼らはエスニック・スタディーズ学科を、米国社会に おける民族集団を「被害者」と位置付ける思想を助長する場であり、真剣な学術研究が行われる場所ではないと主張した。[74] こうした攻撃に直面し、エスニック・スタディーズの学者たちは今やこの分野を擁護せざるを得ない状況にある。メディアでは、この攻撃を右翼反動運動と位置 付ける形で対応している。例えばデューク大学の文化人類学者でネイティブアメリカン研究の専門家であるオリン・スターンはこう述べる。「米国は極めて多様 な国だ。擁護派はこう主張するだろう——我々は学生に多文化主義と多様性を理解させる教育を行っており、これらは法曹界・政府・ビジネス・教育といった卒 業生の進路で活用できるツールだと。多様性やグローバル化、ビジネスの手法、非営利団体との協働方法について考える力を育むのだ」[75] エスニック・スタディーズが統一的なアメリカ史・文化の研究を損なうとか、単なる「有色人種版」アメリカ研究に過ぎないという批判に対し、擁護派はこう反 論する。エスニック・スタディーズは、アメリカの知識生産・文学・認識論において歴史的に抑圧され、存在を否定されてきた集団から生まれたのだと。カリ フォルニア大学バークレー校の事例のように、エスニック・スタディーズとアメリカ研究の統合試みは激しい反対に直面してきた。この分野は既に数十年の歴史 を持つが、新たなエスニック・スタディーズ学科の創設は今なお論争を伴っている。コロンビア大学の管理者は1996年、エスニック・スタディーズ学科創設 を求める学生抗議を鎮めようと、妥協案としてアメリカ研究学科の設置を提案した。[76] |

| African-American studies Arab studies Armenian studies Latino Studies Chicana/o studies Jewish studies Romani studies Asian American studies Native American studies Slavic studies Whiteness studies |

アフリカ系アメリカ人研究 アラブ研究 アルメニア研究 ラティーノ研究 チカーナ/オ研究 ユダヤ研究 ロマ研究 アジア系アメリカ人研究 ネイティブアメリカン研究 スラブ研究 白人性研究 |

| References | https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethnic_studies |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ethnic_studies |

リンク(サイト外)

リンク(サイト内)

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

This image is retrieved from the masthead of the National Museum of Ethnology, Suita City, Osaka, Japan

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099