David Émile Durkheim,

1858-1917

エミール・デュルケム(David Émile

Durkheim,

1858年4月15日 -

1917年11月15日)はフランスの社会学者である。デュルケムは社会学という学問分野を正式に確立し、カール・マルクスやマックス・ヴェーバーととも

に、現代社会科学の主要な創始者の一人として一般的に引用されている。

デュルケムの研究の多くは、伝統的な社会や宗教の結びつきが弱まり、新たな社会制度が誕生した近代において、社会がその統一性や一貫性を維持する方法に焦

点を当てたものであった。デュルケムの社会の科学的考察に関する考え方は、近代社会学の基礎を築いた。彼は、カトリックとプロテスタントのグループにおけ

る自殺の分析に、統計、調査、歴史的観察などの科学的ツールを用いた。

デュルケムの最初の主要な社会学的研究は『社会における労働の分業(=社会分業論)』(1893年)であり、1895年には『社会学的方法の規則』

(1895年)が続いた。また、1895年にはデュルケムはヨーロッパ初の社会学講座を設置し、フランス初の社会学教授となった。デュルケムの画期的な単

行本『自殺論』(1897年)は、カトリック教徒とプロテスタント教徒の自殺率を調査したもので、現代の社会調査の先駆けとなり、社会科学を心理学や政治

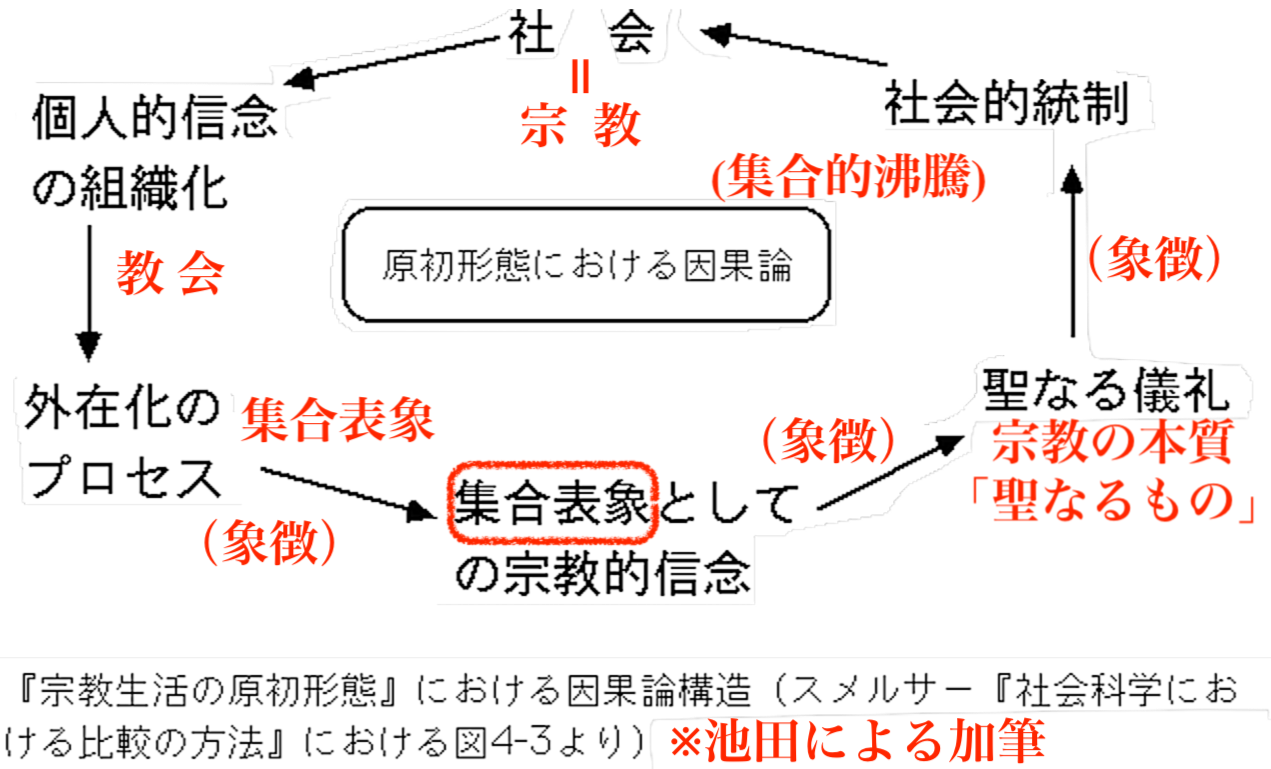

哲学と区別する役割を果たした。1898年には学術誌『社会学年報』を創刊した。『宗教生活の要素的研究』(1912年)では、原住民と現代社会の社会

的・文化的側面を比較しながら宗教の理論を提示した。

デュルケムは、社会学を正当な科学として受け入れることに専念していた。オーギュスト・コント(1798-1857)が最初に打ち出した実証主義をさらに

洗練させ、認識論的実在論の一形態とみなされるものを推進し、社会科学における仮説演繹法の使用を促進した。デュルケムにとって社会学とは、制度の科学で

あり、その用語を「集団によって制定された信念や行動様式」というより広義の意味で理解し、その目的は構造的な社会的事実を発見することである。そのため

デュルケムは、社会学と人類学の両方において基礎的な視点である構造機能主義の主要な提唱者であった。デュルケムの見解では、社会科学は純粋に全体論的で

あるべきであり、社会学は個人の特定の行動の研究に限定されるのではなく、社会全体に起因する現象を研究すべきである。

彼は1917年に亡くなるまで、フランスの知識人社会において大きな影響力を持ち続け、数多くの講義を行い、知識社会学、道徳、社会階層、宗教、法律、教

育、逸脱など、さまざまなテーマに関する著作を出版した。彼が作った造語のいくつか、例えば「集合的無意識」などは、現在では一般の人々にも使われてい

る。

| David Émile

Durkheim

(/ˈdɜːrkhaɪm/;[1] French: [emil dyʁkɛm] or [dyʁkajm]; 15 April 1858 –

15 November 1917) was a French sociologist. Durkheim formally

established the academic discipline of sociology and is commonly cited

as one of the principal architects of modern social science, along with

both Karl Marx and Max Weber.[2][3] Much of Durkheim's work was concerned with how societies can maintain their integrity and coherence in modernity, an era in which traditional social and religious ties are much less universal, and in which new social institutions have come into being. Durkheim's conception of the scientific study of society laid the groundwork for modern sociology, and he used such scientific tools as statistics, surveys, and historical observation in his analysis of suicides in Catholic and Protestant groups. Durkheim's first major sociological work was De la division du travail social (1893; The Division of Labour in Society), followed in 1895 by Les Règles de la méthode sociologique (The Rules of Sociological Method). Also in 1895 Durkheim set up the first European department of sociology and became France's first professor of sociology.[4] Durkheim's seminal monograph, Le Suicide (1897), a study of suicide rates in Catholic and Protestant populations, pioneered modern social research, serving to distinguish social science from psychology and political philosophy. In 1898, he established the journal L'Année sociologique. Les formes élémentaires de la vie religieuse (1912; The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life) presented a theory of religion, comparing the social and cultural lives of aboriginal and modern societies. Durkheim was preoccupied with the acceptance of sociology as a legitimate science. Refining the positivism originally set forth by Auguste Comte (1798-1857), he promoted what could be considered as a form of epistemological realism, as well as the use of the hypothetico-deductive model in social science. For Durkheim, sociology was the science of institutions, understanding the term in its broader meaning as the "beliefs and modes of behaviour instituted by the collectivity,"[5] with its aim being to discover structural social facts. As such, Durkheim was a major proponent of structural functionalism, a foundational perspective in both sociology and anthropology. In his view, social science should be purely holistic[i] in the sense that sociology should study phenomena attributed to society at large, rather than being limited to the study of specific actions of individuals. He remained a dominant force in French intellectual life until his death in 1917, presenting numerous lectures and publishing works on a variety of topics, including the sociology of knowledge, morality, social stratification, religion, law, education, and deviance. Some terms that he coined, such as "collective consciousness", are now also used by laypeople.[6] |

エミール・デュルケム(David Émile

Durkheim、/ˈdɜːrkhaɪm/、[1]フランス語: [emil dyʁkɛm]または[dyʁkajm]、1858年4月15日 -

1917年11月15日)はフランスの社会学者である。デュルケムは社会学という学問分野を正式に確立し、カール・マルクスやマックス・ヴェーバーととも

に、現代社会科学の主要な創始者の一人として一般的に引用されている。 デュルケムの研究の多くは、伝統的な社会や宗教の結びつきが弱まり、新たな社会制度が誕生した近代において、社会がその統一性や一貫性を維持する方法に焦 点を当てたものであった。デュルケムの社会の科学的考察に関する考え方は、近代社会学の基礎を築いた。彼は、カトリックとプロテスタントのグループにおけ る自殺の分析に、統計、調査、歴史的観察などの科学的ツールを用いた。 デュルケムの最初の主要な社会学的研究は『社会における労働の分割』(1893年)であり、1895年には『社会学的方法の規則』(1895年)が続 いた。また、1895年にはデュルケムはヨーロッパ初の社会学講座を設置し、フランス初の社会学教授となった。[4] デュルケムの画期的な単行本『自殺論』(1897年)は、カトリック教徒とプロテスタント教徒の自殺率を調査したもので、現代の社会調査の先駆けとなり、 社会科学を心理学や政治哲学と区別する役割を果たした。1898年には学術誌『社会学年報』を創刊した。『宗教生活の要素的研究』(1912年)では、原 住民と現代社会の社会的・文化的側面を比較しながら宗教の理論を提示した。 デュルケムは、社会学を正当な科学として受け入れることに専念していた。オーギュスト・コント(1798-1857)が最初に打ち出した実証主義をさらに 洗練させ、認識論的実在論の一形態とみなされるものを推進し、社会科学における仮説演繹法の使用を促進した。デュルケムにとって社会学とは、制度の科学で あり、その用語を「集団によって制定された信念や行動様式」というより広義の意味で理解し、その目的は構造的な社会的事実を発見することである。そのため デュルケムは、社会学と人類学の両方において基礎的な視点である構造機能主義の主要な提唱者であった。デュルケムの見解では、社会科学は純粋に全体論的 [i]であるべきであり、社会学は個人の特定の行動の研究に限定されるのではなく、社会全体に起因する現象を研究すべきである。 彼は1917年に亡くなるまで、フランスの知識人社会において大きな影響力を持ち続け、数多くの講義を行い、知識社会学、道徳、社会階層、宗教、法律、教 育、逸脱など、さまざまなテーマに関する著作を出版した。彼が作った造語のいくつか、例えば「集合的無意識」などは、現在では一般の人々にも使われてい る。 |

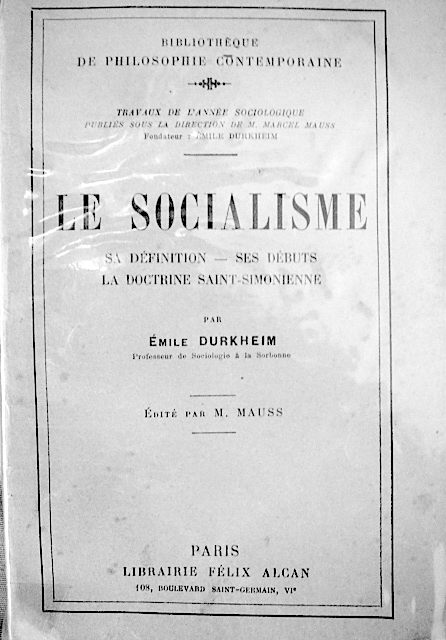

| Biography Early life and heritage David Émile Durkheim was born 15 April 1858 in Épinal, Lorraine, France, to Mélanie (Isidor) and Moïse Durkheim,[7][8] coming into a long lineage of devout French Jews. As his father, grandfather, and great-grandfather had all been rabbis,[9]: 1 young Durkheim began his education in a rabbinical school. However at an early age he switched schools, deciding not to follow in his family's footsteps.[10][9]: 1 In fact Durkheim led a completely secular life, whereby much of his work was dedicated to demonstrating that religious phenomena stemmed from social rather than divine factors. Nevertheless Durkheim did not sever ties with his family nor with the Jewish community.[9]: 1 In fact many of his most prominent collaborators and students were Jewish, some even being blood relatives. For instance Marcel Mauss, a notable social anthropologist of the prewar era, was his nephew.[2] Education A precocious student, Durkheim entered the École Normale Supérieure (ENS) in 1879, at his third attempt.[10][9]: 2 The entering class that year was one of the most brilliant of the nineteenth century, as many of his classmates, such as Jean Jaurès and Henri Bergson, went on to become major figures in France's intellectual history as well. At the ENS, Durkheim studied under the direction of Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges, a classicist with a social-scientific outlook, and wrote his Latin dissertation on Montesquieu.[11] At the same time, he read Auguste Comte and Herbert Spencer, whereby Durkheim became interested in a scientific approach to society early on in his career.[10] This meant the first of many conflicts with the French academic system, which had no social science curriculum at the time. Durkheim found humanistic studies uninteresting, turning his attention from psychology and philosophy to ethics and, eventually, sociology.[10] He obtained his agrégation in philosophy in 1882, though finishing next to last in his graduating class owing to serious illness the year before.[12] The opportunity for Durkheim to receive a major academic appointment in Paris was inhibited by his approach to society. From 1882 to 1887 he taught philosophy at several provincial schools.[13] In 1885 he decided to leave for Germany, where for two years he studied sociology at the universities of Marburg, Berlin and Leipzig.[13] As Durkheim indicated in several essays, it was in Leipzig that he learned to appreciate the value of empiricism and its language of concrete, complex things, in sharp contrast to the more abstract, clear and simple ideas of the Cartesian method.[14] By 1886, as part of his doctoral dissertation, he had completed the draft of his The Division of Labour in Society, and was working towards establishing the new science of sociology.[13] Academic career  A collection of Durkheim's courses on the origins of socialism (1896), edited and published by his nephew, Marcel Mauss, in 1928 Durkheim's period in Germany resulted in the publication of numerous articles on German social science and philosophy; Durkheim was particularly impressed by the work of Wilhelm Wundt.[13] Durkheim's articles gained recognition in France, and he received a teaching appointment in the University of Bordeaux in 1887, where he was to teach the university's first social science course.[13] His official title was Chargé d'un Cours de Science Sociale et de Pédagogie, thus he taught both pedagogy and sociology (the latter having never been taught in France before).[4][9]: 3 The appointment of the social scientist to the mostly humanistic faculty was an important sign of changing times and the growing importance and recognition of the social sciences.[13] From this position Durkheim helped reform the French school system, introducing the study of social science in its curriculum. However, his controversial beliefs that religion and morality could be explained in terms purely of social interaction earned him many critics.[citation needed] Also in 1887, Durkheim married Louise Dreyfus. They had two children, Marie and André.[4] The 1890s were a period of remarkable creative output for Durkheim.[13] In 1893, he published The Division of Labour in Society, his doctoral dissertation and fundamental statement of the nature of human society and its development.[9]: x Durkheim's interest in social phenomena was spurred on by politics. France's defeat in the Franco-Prussian War led to the fall of the regime of Napoleon III, which was then replaced by the Third Republic. This in turn resulted in a backlash against the new secular and republican rule, as many people considered a vigorously nationalistic approach necessary to rejuvenate France's fading power. Durkheim, a Jew and a staunch supporter of the Third Republic with a sympathy towards socialism, was thus in the political minority, a situation that galvanized him politically. The Dreyfus affair of 1894 only strengthened his activist stance.[15] In 1895, he published The Rules of Sociological Method,[13] a manifesto stating what sociology is and how it ought to be done, and founded the first European department of sociology at the University of Bordeaux. In 1898, he founded L'Année sociologique, the first French social science journal.[13] Its aim was to publish and publicize the work of what was, by then, a growing number of students and collaborators (this is also the name used to refer to the group of students who developed his sociological program). In 1897, he published Suicide, a case study that provided an example of what a sociological monograph might look like. Durkheim was one of the pioneers of the use of quantitative methods in criminology, which he used in his study of suicide.[citation needed] By 1902, Durkheim had finally achieved his goal of attaining a prominent position in Paris when he became the chair of education at the Sorbonne. Durkheim had aimed for the position earlier, but the Parisian faculty took longer to accept what some called "sociological imperialism" and admit social science to their curriculum.[15] He became a full professor (specifically, Professor of the Science of Education) there in 1906, and in 1913 he was named chair in "Education and Sociology".[4][15] Because French universities are technically institutions for training secondary school teachers, this position gave Durkheim considerable influence—his lectures were the only ones that were mandatory for the entire student body. Durkheim had much influence over the new generation of teachers; around that time he also served as an advisor to the Ministry of Education.[4] In 1912, he published his last major work, The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life. Death  Grave of Émile Durkheim, the founder of sociology, in Montparnasse Cemetery, Paris, France. The outbreak of World War I was to have a tragic effect on Durkheim's life. His leftism was always patriotic rather than internationalist, in that he sought a secular, rational form of French life. However, the onset of the war, and the inevitable nationalist propaganda that followed, made it difficult to sustain this already nuanced position. While Durkheim actively worked to support his country in the war, his reluctance to give in to simplistic nationalist fervor (combined with his Jewish background) made him a natural target of the now-ascendant French Right. Even more seriously, the generations of students that Durkheim had trained were now being drafted to serve in the army, many of them perishing in the trenches.[citation needed] Finally, Durkheim's own son, André, died on the war front in December 1915—a loss from which Durkheim never recovered.[15][16] Emotionally devastated, Durkheim collapsed of a stroke in Paris two years later, on 15 November 1917.[16] He was buried at the Montparnasse Cemetery in Paris.[17] |

経歴 幼少期と家系 デヴィッド・エミール・デュルケムは1858年4月15日、フランス・ロレーヌ地方のエピナルで、メラニー(イシドール)・デュルケムとモイゼ・デュルケ ムの間に生まれた。敬虔なフランス系ユダヤ人の家系に生まれた。父、祖父、曾祖父は皆ラビであったため、デュルケムは幼少期にラビの学校で教育を受けた。 しかし、幼い頃に学校を転校し、一族の跡を継がないことを決意した。[10][9]:1 実際、デュルケムは完全に世俗的な生活を送っており、その研究の多くは、宗教的な現象が神的な要因よりもむしろ社会的要因に由来することを示すことに捧げ られていた。しかしデュルケムは家族やユダヤ人コミュニティとのつながりを断ち切ることはなかった。実際、彼の最も著名な協力者や学生の多くはユダヤ人 で、中には血縁関係にある者もいた。例えば戦前の著名な社会人類学者であるマルセル・モースは、デュルケムの甥であった。 教育 早熟な学生であったデュルケムは、1879年に3度目の受験でエコール・ノルマル・シュペリウール(ENS)に入学した。[10][9]: 2 その年の入学クラスは19世紀で最も優秀なクラスであり、同級生にはジャン・ジョレスやアンリ・ベルクソンなどがおり、彼らもまたフランスの知的歴史にお ける主要人物となった。デュルケームは、ENSで古典学者でありながら社会科学的見解を持っていたヌマ・ドニ・フュステル・ド・クーランジュの指導の下で 学び、モンテスキューに関するラテン語の論文を執筆した。[11] 同時に、彼は オーギュスト・コントとハーバート・スペンサーを読み、デュルケムは早い時期から社会に対する科学的なアプローチに関心を持つようになった。[10] これは、当時社会科学のカリキュラムを持たなかったフランスの学術システムとの多くの対立の最初のものとなった。デュルケムは人文科学の研究に興味が持て ず、心理学や哲学から倫理学、そして最終的には社会学へと関心を移した。[10] 1882年に哲学の学位を取得したが、前年に重病を患ったため、卒業クラスのほぼ最下位で卒業した。[12] デュルケムがパリで主要な学術職に就く機会は、彼が社会にアプローチする方法によって阻まれていた。1882年から1887年にかけて、彼は地方のいくつ かの学校で哲学を教えた。1885年、デュルケムはドイツに渡ることを決意し、2年間、マールブルク、ベルリン、ライプツィヒの大学で社会学を学んだ。 デュルケムがいくつかのエッセイで示唆しているように、ライプツィヒで彼は 経験主義の価値と、具体的で複雑な事物を表現するその言語を学んだ。それは、デカルト的方法のより抽象的で明瞭かつ単純な考え方とは対照的であった。 [14] 1886年までに、博士論文の一部として『社会における分業』の草稿を完成させ、新しい科学である社会学の確立に向けて取り組んでいた。[13] 学術的な経歴  社会主義の起源に関するデュルケムの講義のコレクション(1896年)は、甥のマルセル・モースが編集し、1928年に出版された ドイツ滞在中に、デュルケムはドイツの社会科学や哲学に関する多数の論文を発表した。デュルケムは特にヴィルヘルム・ヴントの業績に感銘を受けた。デュル ケムの論文はフランスで認められ、1887年にボルドー大学で教鞭をとるようになった。同大学で初めての社会科学コースを担当することになった。したがっ て、彼は教育学と社会学の両方を教えた(後者はそれまでフランスでは教えられたことがなかった)。[4][9]:3 人文科学系の学部への社会学者の任命は、時代の変化と社会科学の重要性と認知の高まりを示す重要な兆候であった。[13] この役職からデュルケムはフランスの学校制度の改革を支援し、カリキュラムに社会科学の研究を導入した。しかし、宗教と道徳は純粋に社会的相互作用の観点 から説明できるという彼の物議を醸す信念は、多くの批判を招いた。 また、1887年にデュルケムはルイーズ・ドレフュスと結婚した。2人の間には、マリーとアンドレの2人の子供がいた。 1890年代はデュルケムにとって、創造的な成果が著しく現れた時期であった。1893年には博士論文であり、人間社会の本質とその発展についての基本的 な主張である『社会における分業』を出版した。デュルケムの社会現象への関心は政治によって刺激された。普仏戦争でのフランスの敗北により、ナポレオン3 世の体制は崩壊し、第三共和制が樹立された。その結果、多くの人々が、衰退しつつあったフランスの力を再び活性化させるには、強力な国家主義的アプローチ が必要だと考え、世俗的で共和制の新しい統治に対する反発が巻き起こった。ユダヤ人であり、社会主義に共感を示す第三共和制の強固な支持者であったデュル ケムは、政治的には少数派に属することになり、この状況が彼を政治的に活気づけた。1894年のドレフュス事件は、彼の活動家としての姿勢をさらに強固な ものにした。 1895年には、社会学とは何か、また、どのように行うべきかを述べたマニフェスト『社会学的方法の規準』を出版し、[13] ボルドー大学にヨーロッパ初の社会学講座を創設した。1898年には、フランス初の社会科学ジャーナル『社会学年報』を創刊した。[13] その目的は、当時増加しつつあった学生や協力者たちの研究を公表し、広めることだった(この名称は、デュルケムの社会学プログラムを発展させた学生グルー プを指す場合にも用いられている)。1897年には『自殺論』を出版し、社会学の単行本がどのようなものになり得るかを示す事例研究を提供した。デュルケ ムは犯罪学における量的方法の先駆者の一人であり、自殺の研究にその方法を用いた。 1902年までに、デュルケムはついにパリで著名な地位を得るという目標を達成し、ソルボンヌ大学の教育学部長に就任した。デュルケムは以前からその地位 を目指していたが、一部で「社会学的帝国主義」と呼ばれたものをパリの教授陣が受け入れ、社会科学をカリキュラムに認めるまでに時間がかかったのである。 [15] 彼は1906年に同大学の正教授(具体的には教育科学の教授)となり 。1913年には「教育と社会学」の主任教授に任命された。[4][15] フランスの大学は厳密には中等学校の教師を養成する機関であるため、この役職はデュルケムに大きな影響力を与えた。彼の講義は学生全員が受講を義務付けら れた唯一の講義であった。デュルケムは、新世代の教師たちに大きな影響を与えた。また、この頃には文部省の顧問も務めていた。1912年には、最後の主要 著作『宗教生活の基礎形態』を出版した。 死  エミール・デュルケムの墓、フランス、パリのモンパルナス墓地。 第一次世界大戦の勃発は、デュルケムの人生に悲劇的な影響をもたらした。彼の左翼思想は、常に国際主義よりも愛国主義的であり、世俗的で合理的なフランス 人の生活様式を求めていた。しかし、戦争の勃発とそれに伴う避けられない民族主義的プロパガンダにより、すでに微妙な立場を維持することが困難になった。 デュルケムは戦争で祖国を支援するために積極的に活動したが、単純なナショナリズムの高揚に屈することを嫌ったこと(ユダヤ人としての背景も相まって)か ら、当時勢力を強めていたフランスの右派の格好の標的となった。さらに深刻なことに、デュルケムが指導した学生世代が次々と軍に徴兵され、その多くが塹壕 で命を落とした。 最後に、デュルケム自身の息子アンドレが1915年12月に戦場で戦死した。デュルケムは立ち直ることができなかった。[15][16] 感情的に打ちのめされたデュルケムは、2年後の1917年11月15日にパリで脳卒中に倒れた。[16] 彼はパリのモンパルナス墓地に埋葬された。[17] |

Methodology Cover of the French edition of The Rules of Sociological Method (1919) In The Rules of Sociological Method (1895), Durkheim expressed his desire to establish a method that would guarantee sociology's truly scientific character. One of the questions raised concerns the objectivity of the sociologist: how may one study an object that, from the very beginning, conditions and relates to the observer? According to Durkheim, observation must be as impartial and impersonal as possible, even though a "perfectly objective observation" in this sense may never be attained. A social fact must always be studied according to its relation with other social facts, never according to the individual who studies it. Sociology should therefore privilege comparison rather than the study of singular independent facts.[ii] Durkheim sought to create one of the first rigorous scientific approaches to social phenomena. Along with Herbert Spencer, he was one of the first people to explain the existence and quality of different parts of a society through referencing what function they served in maintaining the quotidian (i.e. by how they make society "work"). He also agreed with Spencer's organic analogy, comparing society to a living organism.[13] As a result, his work is sometimes seen as a precursor to functionalism.[10][18][19][20] Durkheim also insisted that society was more than the sum of its parts.[iii][21] Unlike his contemporaries Ferdinand Tönnies and Max Weber, he did not focus on what motivates individuals' actions (an approach associated with methodological individualism), but rather on the study of social facts.[citation needed] |

方法論 『社会学的方法の規準』(1919年)のフランス語版表紙 デュルケムは『社会学的方法の規準』(1895年)において、社会学の真の科学的性格を保証する手法を確立したいという自身の希望を表明した。提起された 問題のひとつは、社会学者の客観性に関するものであった。観察者によって条件付けられ、観察者と関連付けられている対象を、どのように研究すればよいの か? デュルケムによれば、観察は可能な限り公平かつ客観的でなければならない。この意味での「完全に客観的な観察」は決して達成されることはないかもしれない が。社会的事実は、それを研究する個人ではなく、常に他の社会的事実との関係に基づいて研究されなければならない。したがって、社会学は、独立した単独の 事実の研究よりも比較を重視すべきである。 デュルケムは、社会現象に対する厳密な科学的アプローチを初めて試みた人物の一人である。ハーバート・スペンサーとともに、彼は社会のさまざまな部分の存 在と質を、日常を維持する上で果たす機能(すなわち、社会を「機能させる」方法)を参照しながら説明した最初の人物の一人であった。また、社会を生物に例 えるスペンサーの有機体類似説にも同意していた。[13] その結果、彼の研究は時に機能主義の先駆けとみなされることもある。[10][18][19][20] デュルケムはまた、社会は個々の構成要素の総和よりも価値があるとも主張した。[iii][21] 同時代のフェルディナント・テニースやマックス・ヴェーバーとは異なり、デュルケムは個人の行動を動機づけるもの(方法論的個人主義に関連するアプロー チ)に焦点を当てるのではなく、むしろ社会的事実の研究に重点を置いた。 |

| Inspirations During his university studies at the ENS, Durkheim was influenced by two neo-Kantian scholars: Charles Renouvier and Émile Boutroux.[10] The principles Durkheim absorbed from them included rationalism, scientific study of morality, anti-utilitarianism, and secular education.[13] His methodology was influenced by Numa Denis Fustel de Coulanges, a supporter of the scientific method.[13] Comte A fundamental influence on Durkheim's thought was the sociological positivism of Auguste Comte, who effectively sought to extend and apply the scientific method found in the natural sciences to the social sciences.[13] According to Comte, a true social science should stress empirical facts, as well as induce general scientific laws from the relationship among these facts. There were many points on which Durkheim agreed with the positivist thesis: First, he accepted that the study of society was to be founded on an examination of facts. Second, like Comte, he acknowledged that the only valid guide to objective knowledge was the scientific method. Third, he agreed with Comte that the social sciences could become scientific only when they were stripped of their metaphysical abstractions.[13] Realism A second influence on Durkheim's view of society beyond Comte's positivism was the epistemological outlook called social realism. Although he never explicitly espoused it, Durkheim adopted a realist perspective in order to demonstrate the existence of social realities outside the individual and to show that these realities existed in the form of the objective relations of society.[22] As an epistemology of science, realism can be defined as a perspective that takes as its central point of departure the view that external social realities exist in the outer world and that these realities are independent of the individual's perception of them. This view opposes other predominant philosophical perspectives such as empiricism and positivism. Empiricists, like David Hume, had argued that all realities in the outside world are products of human sense perception, thus all realities are merely perceived: they do not exist independently of our perceptions, and have no causal power in themselves.[22] Comte's positivism went a step further by claiming that scientific laws could be deduced from empirical observations. Going beyond this, Durkheim claimed that sociology would not only discover "apparent" laws, but would be able to discover the inherent nature of society. Judaism Scholars also debate the exact influence of Jewish thought on Durkheim's work. The answer remains uncertain; some scholars have argued that Durkheim's thought is a form of secularized Jewish thought,[iv][23] while others argue that proving the existence of a direct influence of Jewish thought on Durkheim's achievements is difficult or impossible.[24] |

インスピレーション デュルケムは、高等師範学校在学中に、2人の新カント派の学者、シャルル・ルヌヴィエとエミール・ブールトゥーから影響を受けた。[10] デュルケムが彼らから吸収した原則には、合理主義、道徳の科学的探究、反功利主義、世俗的教育などが含まれていた。[13] デュルケムの方法論は、科学的方法論の支持者であるヌマ・ドニ・フュステル・ド・クーランジュの影響を受けていた。[13] コント デュルケムの思想に根本的な影響を与えたのは、オーギュスト・コントの社会学的実証主義であった。コントは自然科学に見られる科学的手法を社会科学に拡張 し応用することを効果的に追求した。コントによれば、真の社会科学は経験的事実を重視すべきであり、また、それらの事実間の関係から一般的な科学法則を導 き出すべきである。デュルケムは実証主義の主張に同意する点が数多くあった。 第一に、デュルケムは社会の研究は事実の調査に基づいて行われるべきであると認めた。 第二に、デュルケムはコントと同様に、客観的な知識の唯一の有効な指針は科学的方法であると認めた。 第三に、デュルケムは、社会科学は形而上学的な抽象概念を排除したときにのみ科学的になりうるという点でコントに同意した。 現実主義 デュルケムの社会観に影響を与えた2つ目の要素は、コントの実証主義を超えたもので、社会リアリズムと呼ばれる認識論的見解であった。デュルケムはこれを 明確に支持したことはなかったが、個人を越えた社会の現実の存在を証明し、それらの現実が社会の客観的な関係の形として存在していることを示すために、現 実主義的な見解を採用した。科学の認識論として、現実主義は、外の世界に社会の現実が存在し、それらの現実が個人の認識とは独立しているという見解をその 出発点とする見解として定義することができる。 この見解は、経験論や実証主義といった他の有力な哲学的な見解と対立するものである。経験論者であるデイヴィッド・ヒュームは、外界の現実のすべては人間 の感覚知覚の産物であり、したがって現実とはすべて知覚されるものにすぎず、知覚とは独立して存在するものではなく、それ自体に因果力はないと主張した。 [22] コントの実証主義はさらに一歩進んで、科学的法則は経験的観察から演繹できると主張した。さらに、デュルケムは、社会学は「見かけ上の」法則を発見するだ けでなく、社会の本質的な性質を発見できると主張した。 ユダヤ教 学者の間でも、デュルケムの研究に対するユダヤ思想の影響について正確な議論が行われている。答えは依然として不確かであり、デュルケムの思想は世俗化さ れたユダヤ思想の一形態であると主張する学者もいるが[iv][23]、一方で、ユダヤ思想がデュルケムの業績に直接的な影響を与えたことを証明すること は困難である、あるいは不可能であると主張する学者もいる[24]。 |

| Durkheim and theory Throughout his career, Durkheim was concerned primarily with three goals. First, to establish sociology as a new academic discipline.[15] Second, to analyse how societies could maintain their integrity and coherence in the modern era, when things such as shared religious and ethnic background could no longer be assumed. To that end he wrote much about the effect of laws, religion, education and similar forces on society and social integration.[15][25] Lastly, Durkheim was concerned with the practical implications of scientific knowledge.[15] The importance of social integration is expressed throughout Durkheim's work:[26][27] For if society lacks the unity that derives from the fact that the relationships between its parts are exactly regulated, that unity resulting from the harmonious articulation of its various functions assured by effective discipline and if, in addition, society lacks the unity based upon the commitment of men's wills to a common objective, then it is no more than a pile of sand that the least jolt or the slightest puff will suffice to scatter. — Moral Education (1925) Establishing sociology Durkheim authored some of the most programmatic statements on what sociology is and how it should be practiced.[10] His concern was to establish sociology as a science.[28] Arguing for a place for sociology among other sciences, he wrote, "sociology is, then, not an auxiliary of any other science; it is itself a distinct and autonomous science."[29] To give sociology a place in the academic world and to ensure that it is a legitimate science, it must have an object that is clear and distinct from philosophy or psychology, and its own methodology.[15] He argued that "there is in every society a certain group of phenomena which may be differentiated from those studied by the other natural sciences."[30]: 95 In the Tarde-Durkheim debate of 1903, the "anthropological view" of Gabriel Tarde was ridiculed and hastily dismissed.[citation needed] A fundamental aim of sociology is to discover structural "social facts".[15][31]: 13 The establishment of sociology as an independent, recognized academic discipline is among Durkheim's largest and most lasting legacies.[2] Within sociology, his work has significantly influenced structuralism or structural functionalism.[2][32] Social facts Main article: Social fact A social fact is every way of acting, fixed or not, capable of exercising on the individual an external constraint; or again, every way of acting which is general throughout a given society, while at the same time existing in its own right independent of its individual manifestations. — The Rules of Sociological Method[31] Durkheim's work revolved around the study of social facts, a term he coined to describe phenomena that have an existence in and of themselves, are not bound to the actions of individuals, but have a coercive influence upon them.[33] Durkheim argued that social facts have, sui generis, an independent existence greater and more objective than the actions of the individuals that compose society.[34] Only such social facts can explain the observed social phenomena.[10] Being exterior to the individual person, social facts may thus also exercise coercive power on the various people composing society, as it can sometimes be observed in the case of formal laws and regulations, but also in situations implying the presence of informal rules, such as religious rituals or family norms.[31][35] Unlike the facts studied in natural sciences, a social fact thus refers to a specific category of phenomena: "the determining cause of a social fact must be sought among the antecedent social facts and not among the states of the individual consciousness."[citation needed] Such facts are endowed with a power of coercion, by reason of which they may control individual behaviors.[35] According to Durkheim, these phenomena cannot be reduced to biological or psychological grounds.[35] Social facts can be material (i.e. physical objects ) or immaterial (i.e. meanings, sentiments, etc.).[34] Though the latter cannot be seen or touched, they are external and coercive, thus becoming real and gaining "facticity".[34] Physical objects, too, can represent both material and immaterial social facts. For example, a flag is a physical social fact that is often ingrained with various immaterial social facts (e.g. its meaning and importance).[34] Many social facts, however, have no material form.[34] Even the most "individualistic" or "subjective" phenomena, such as love, freedom, or suicide, were regarded by Durkheim as objective social facts.[34] Individuals composing society do not directly cause suicide: suicide, as a social fact, exists independently in society, and is caused by other social facts—such as rules governing behavior and group attachment—whether an individual likes it or not.[34][36] Whether a person "leaves" a society does not alter the fact that this society will still contain suicides. Suicide, like other immaterial social facts, exists independently of the will of an individual, cannot be eliminated, and is as influential—coercive—as physical laws like gravity.[34] Sociology's task therefore consists of discovering the qualities and characteristics of such social facts, which can be discovered through a quantitative or experimental approach (Durkheim extensively relied on statistics).[v] Society, collective consciousness, and culture +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ The Division of Labour in Society  Cover of the French edition of The Division of Labour in Society The Division of Labour in Society (French: De la division du travail social) is the doctoral dissertation of the French sociologist Émile Durkheim, published in 1893. It was influential in advancing sociological theories and thought, with ideas which in turn were influenced by Auguste Comte. Durkheim described how social order was maintained in societies based on two very different forms of solidarity – mechanical and organic – and the transition from more "primitive" societies to advanced industrial societies. Durkheim suggested that in a "primitive" society, mechanical solidarity, with people acting and thinking alike and with a shared collective conscience, is what allows social order to be maintained. In such a society, Durkheim viewed crime as an act that "offends strong and defined states of the collective conscience" though he viewed crime as a normal social fact.[1] Because social ties are relatively homogeneous and weak throughout a mechanical society, the law has to be repressive and penal to respond to offences of the common conscience. In an advanced, industrial, capitalist society, the complex system of division of labour means that people are allocated in society according to merit and rewarded accordingly: social inequality reflects natural inequality, at least in the case that there is complete equity in the society. Durkheim argued that moral regulation was needed, as well as economic regulation, to maintain order (or organic solidarity) in society. In fact this regulation forms naturally in response to the division of labor, allowing people to "compose their differences peaceably".[2] In this type of society, law would be more restitutive than penal, seeking to restore rather than punish excessively. He thought that transition of a society from "primitive" to advanced may bring about major disorder, crisis, and anomie. However, once society has reached the "advanced" stage, it becomes much stronger and is done developing. Unlike Karl Marx, Durkheim did not foresee any different society arising out of the industrial capitalist division of labour. He regarded conflict, chaos, and disorder as pathological phenomena to modern society, whereas Marx highlights class conflict. Durkheim, Emile. The Division of Labour in Society. Trans. W. D. Halls, intro. Lewis A. Coser. New York: Free Press, 1997, pp. 39, 60, 108. Rock, Paul (2002). "Sociological Theories of Crime" in Maguire, Mike, Rod Morgan, and Robert Reiner, The Oxford Handbook of Criminology. Oxford University Press. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Division_of_Labour_in_Society +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Regarding the society itself, like social institutions in general, Durkheim saw it as a set of social facts.[citation needed] Even more than "what society is," Durkheim was interested in answering "how is a society created" and "what holds a society together." In The Division of Labour in Society, Durkheim attempts to answer the latter question.[37] Collective consciousness Durkheim assumes that humans are inherently egoistic, while "collective consciousness" (i.e. norms, beliefs, and values) forms the moral basis of the society, resulting in social integration.[38] Collective consciousness is therefore of key importance to the society; its requisite function without which the society cannot survive.[39] This consciousness produces the society and holds it together, while, at the same time, individuals produce collective consciousness through their interactions.[5] Through collective consciousness human beings become aware of one another as social beings, not just animals.[39] The totality of beliefs and sentiments common to the average members of a society forms a determinate system with a life of its own. It can be termed the collective or common consciousness.[40] In particular, the emotional part of the collective consciousness overrides our egoism: as we are emotionally bound to culture, we act socially because we recognize it is the responsible, moral way to act.[41] A key to forming society is social interaction, and Durkheim believes that human beings, when in a group, will inevitably act in such a way that a society is formed.[41][42] Culture Groups, when interacting, create their own culture and attach powerful emotions to it, thus making culture another key social fact.[43] Durkheim was one of the first scholars to consider the question of culture so intensely.[32] Durkheim was interested in cultural diversity, and how the existence of diversity nonetheless fails to destroy a society. To that, Durkheim answered that any apparent cultural diversity is overridden by a larger, common, and more generalized cultural system, and the law.[44] In a socio-evolutionary approach, Durkheim described the evolution of societies from mechanical solidarity to organic solidarity (one rising from mutual need).[32][37][45][46] As societies become more complex, evolving from mechanical to organic solidarity, the division of labour is counteracting and replacing to collective consciousness.[37][47] In the simpler societies, people are connected to others due to personal ties and traditions; in the larger, modern society they are connected due to increased reliance on others with regard to them performing their specialized tasks needed for the modern, highly complex society to survive.[37] In mechanical solidarity, people are self-sufficient, there is little integration, and thus there is the need for use of force and repression to keep society together.[45][citation needed] Also, in such societies, people have much fewer options in life.[48][clarification needed] In organic solidarity, people are much more integrated and interdependent, and specialization and cooperation are extensive.[45][citation needed] Progress from mechanical to organic solidarity is based first on population growth and increasing population density, second on increasing "morality density" (development of more complex social interactions) and thirdly, on the increasing specialization in workplace.[45] One of the ways mechanical and organic societies differ is the function of law: in mechanical society the law is focused on its punitive aspect, and aims to reinforce the cohesion of the community, often by making the punishment public and extreme; whereas in the organic society the law focuses on repairing the damage done and is more focused on individuals than the community.[49] One of the main features of the modern, organic society is the importance, sacredness even, given to the concept—social fact—of the individual.[50] The individual, rather than the collective, becomes the focus of rights and responsibilities, the center of public and private rituals holding the society together—a function once performed by the religion.[50] To stress the importance of this concept, Durkheim talked of the "cult of the individual":[51] Thus very far from there being the antagonism between the individual and society which is often claimed, moral individualism, the cult of the individual, is in fact the product of society itself. It is society that instituted it and made of man the god whose servant it is. Durkheim saw the population density and growth as key factors in the evolution of the societies and advent of modernity.[52] As the number of people in a given area increase, so does the number of interactions, and the society becomes more complex.[46] Growing competition between the more numerous people also leads to further division of labour.[46] In time, the importance of the state, the law and the individual increases, while that of the religion and moral solidarity decreases.[53] In another example of evolution of culture, Durkheim pointed to fashion, although in this case he noted a more cyclical phenomenon.[54] According to Durkheim, fashion serves to differentiate between lower classes and upper classes, but because lower classes want to look like the upper classes, they will eventually adapt the upper class fashion, depreciating it, and forcing the upper class to adopt a new fashion.[54] Social pathology and crime As the society, Durkheim noted there are several possible pathologies that could lead to a breakdown of social integration and disintegration of the society: the two most important ones are anomie and forced division of labour; lesser ones include the lack of coordination and suicide.[55] To Durkheim, anomie refers to a lack of social norms; where too rapid of population growth reduces the amount of interaction between various groups, which in turn leads to a breakdown of understanding (i.e. norms, values, etc.).[56] Forced division of labour, on the other hand, refers to a situation in which those who hold power, driven by their desire for profit (greed), results in people doing work that they are unsuited for.[57] Such people are unhappy, and their desire to change the system can destabilize the society.[57] Durkheim's views on crime were a departure from conventional notions. He believed that crime is "bound up with the fundamental conditions of all social life" and serves a social function.[30]: 101 He states that crime implies "not only that the way remains open to necessary changes but that in certain cases it directly prepares these changes."[30]: 101 Examining the trial of Socrates, he argues that "his crime, namely, the independence of his thought, rendered a service not only to humanity but to his country" as "it served to prepare a new morality and faith that the Athenians needed."[30]: 101 As such, his crime "was a useful prelude to reforms."[30]: 102 In this sense, he saw crime as being able to release certain social tensions and so have a cleansing or purging effect in society.[30]: 101 The authority which the moral conscience enjoys must not be excessive; otherwise, no-one would dare to criticize it, and it would too easily congeal into an immutable form. To make progress, individual originality must be able to express itself…[even] the originality of the criminal…shall also be possible. Deviance Durkheim thought deviance to be an essential component of a functional society.[58] He believed that deviance had three possible effects on society:[58][59] Deviance challenges the perspective and thoughts of the general population, leading to social change by pointing out a flaw in society. Deviant acts may support existing social norms and beliefs by evoking the population to discipline the actors. Reactions to deviant activity could increase camaraderie and social support among the population affected by the activity. Durkheim's thoughts on deviance contributed to Robert Merton's Strain Theory.[58] Suicide Main article: Suicide (Durkheim book) In Suicide (1897), Durkheim explores the differing suicide rates among Protestants and Catholics, arguing that stronger social control among Catholics results in lower suicide rates. According to Durkheim, Catholic society has normal levels of integration while Protestant society has low levels. Overall, Durkheim treated suicide as a social fact, explaining variations in its rate on a macro level, considering society-scale phenomena such as lack of connections between people (group attachment) and lack of regulations of behavior, rather than individuals' feelings and motivations.[37][60] Durkheim believed there was more to suicide than extremely personal individual life circumstances such as loss of a job, divorce, or bankruptcy. Instead, Durkheim explained suicide as a symptom of collective social deviance, like alcoholism or homicide.[61] He created a normative theory of suicide focusing on the conditions of group life. Proposing four different types of suicide, which include egoistic, altruistic, anomic, and fatalistic, Durkheim began his theory by plotting social regulation on the x-axis of his chart, and social integration on the y-axis:[61] Egoistic suicide corresponds to a low level of social integration. When one is not well integrated into a social group it can lead to a feeling that they have not made a difference in anyone's lives. Altruistic suicide corresponds to too much social integration. This occurs when a group dominates the life of an individual to a degree where they feel meaningless to society. Anomic suicide occurs when one has an insufficient amount of social regulation. This stems from the sociological term anomie, meaning a sense of aimlessness or despair that arises from the inability to reasonably expect life to be predictable. Fatalistic suicide results from too much social regulation. An example of this would be when one follows the same routine day after day. This leads to a belief that there is nothing good to look forward to. Durkheim suggested this was the most popular form of suicide for prisoners. This study has been extensively discussed by later scholars and several major criticisms have emerged. First, Durkheim took most of his data from earlier researchers, notably Adolph Wagner and Henry Morselli,[62] who were much more careful in generalizing from their own data. Second, later researchers found that the Protestant–Catholic differences in suicide seemed to be limited to German-speaking Europe and thus may have always been the spurious reflection of other factors.[63] Durkheim's study of suicide has been criticized as an example of the logical error termed the ecological fallacy.[64][65] However, diverging views have contested whether Durkheim's work really contained an ecological fallacy.[66] More recent authors such as Berk (2006) have also questioned the micro–macro relations underlying Durkheim's work.[67] Some, such as Inkeles (1959),[68] Johnson (1965),[69] and Gibbs (1968),[70] have claimed that Durkheim's only intent was to explain suicide sociologically within a holistic perspective, emphasizing that "he intended his theory to explain variation among social environments in the incidence of suicide, not the suicides of particular individuals."[71] Despite its limitations, Durkheim's work on suicide has influenced proponents of control theory, and is often mentioned as a classic sociological study. The book pioneered modern social research and served to distinguish social science from psychology and political philosophy.[9]: ch.1 Religion In The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life (1912), Durkheim's first purpose was to identify the social origin and function of religion as he felt that religion was a source of camaraderie and solidarity.[37] His second purpose was to identify links between certain religions in different cultures, finding a common denominator. He wanted to understand the empirical, social aspect of religion that is common to all religions and goes beyond the concepts of spirituality and God.[72] Durkheim defined religion as:[73] "a unified system of beliefs and practices relative to sacred things, i.e., things set apart and forbidden—beliefs and practices which unite in one single moral community called a Church, all those who adhere to them." In this definition, Durkheim avoids references to supernatural or God.[74] Durkheim rejected earlier definitions by Tylor that religion was "belief in supernatural beings," finding that primitive societies such as the Australian aborigines (following the ethnologies of Spencer and Gillen, largely discredited later) did not divide reality into "natural" vs. "supernatural" realms, but rather into realms of the "sacred" and the "profane," which were not moral categories, since both could include what was good or evil.[75] Durkheim argues we are left with the following three concepts:[76] The sacred: ideas and sentiments kindled by the spectacle of society and which inspire awe, spiritual devotion or respect; The beliefs & practices: creating an emotional state of collective effervescence, investing symbols with sacred importance; The moral community: a group of people sharing a common moral philosophy. Out of those three concepts, Durkheim focused on the sacred,[77][78] noting that it is at the very core of a religion:[79]: 322 They are only collective forces hypostasized, that is to say, moral forces; they are made up of the ideas and sentiments awakened in us by the spectacle of society, and not of sensations coming from the physical world.[vi] Durkheim saw religion as the most fundamental social institution of humankind, and one that gave rise to other social forms.[80] It was religion that gave humanity the strongest sense of collective consciousness.[81] Durkheim saw religion as a force that emerged in the early hunter-gatherer societies, as the emotions collective effervescence run high in the growing groups, forcing them to act in a new ways, and giving them a sense of some hidden force driving them.[47] Over time, as emotions became symbolized and interactions ritualized, religion became more organized, giving a rise to the division between the sacred and the profane.[47] However, Durkheim also believed that religion was becoming less important, as it was being gradually superseded by science and the cult of an individual.[50][82] Thus there is something eternal in religion which is destined to survive all the particular symbols in which religious thought has successively enveloped itself.[79]: 427 However, even if the religion was losing its importance for Durkheim, it still laid the foundation of modern society and the interactions that governed it.[81] And despite the advent of alternative forces, Durkheim argued that no replacement for the force of religion had yet been created. He expressed his doubt about modernity, seeing the modern times as "a period of transition and moral mediocrity."[53] Durkheim also argued that our primary categories for understanding the world have their origins in religion.[54] It is religion, Durkheim writes, that gave rise to most if not all other social constructs, including the larger society.[81] Durkheim argued that categories are produced by the society, and thus are collective creations.[37] Thus as people create societies, they also create categories, but at the same time, they do so unconsciously, and the categories are prior to any individual's experience.[37] In this way Durkheim attempted to bridge the divide between seeing categories as constructed out of human experience and as logically prior to that experience.[37][83] Our understanding of the world is shaped by social facts; for example the notion of time is defined by being measured through a calendar, which in turn was created to allow us to keep track of our social gatherings and rituals; those in turn on their most basic level originated from religion.[81] In the end, even the most logical and rational pursuit of science can trace its origins to religion.[81] Durkheim states that, "Religion gave birth to all that is essential in the society."[81] In his work, Durkheim focused on totemism, the religion of the Aboriginal Australians and Native Americans. Durkheim saw this religion as the most ancient religion, and focused on it as he believed its simplicity would ease the discussion of the essential elements of religion.[37][74] As such, he wrote:[79]: 220 Now the totem is the flag of the clan. It is therefore natural that the impressions aroused by the clan in individual minds—impressions of dependence and of increased vitality—should fix themselves to the idea of the totem rather than that of the clan: for the clan is too complex a reality to be represented clearly in all its complex unity by such rudimentary intelligences. Durkheim's work on religion was criticized on both empirical and theoretical grounds by specialists in the field. The most important critique came from Durkheim's contemporary, Arnold van Gennep, an expert on religion and ritual, and also on Australian belief systems. Van Gennep argued that Durkheim's views of primitive peoples and simple societies were "entirely erroneous". Van Gennep further argued that Durkheim demonstrated a lack of critical stance towards his sources, collected by traders and priests, naively accepting their veracity, and that Durkheim interpreted freely from dubious data. At the conceptual level, van Gennep pointed out Durkheim's tendency to press ethnography into a prefabricated theoretical scheme.[84] Despite such critiques, Durkheim's work on religion has been widely praised for its theoretical insight and whose arguments and propositions, according to Robert Alun Jones, "have stimulated the interest and excitement of several generations of sociologists irrespective of theoretical 'school' or field of specialization."[85] Sociology of knowledge While Durkheim's work deals with a number of subjects, including suicide, the family, social structures, and social institutions, a large part of his work deals with the sociology of knowledge. While publishing short articles on the subject earlier in his career,[vii] Durkheim's definitive statement concerning the sociology of knowledge comes in his 1912 magnum opus, The Elementary Forms of Religious Life. This book has as its goal not only the elucidation of the social origins and function of religion, but also the social origins and impact of society on language and logical thought. Durkheim worked largely out of a Kantian framework and sought to understand how the concepts and categories of logical thought could arise out of social life. He argued, for example, that the categories of space and time were not a priori. Rather, the category of space depends on a society's social grouping and geographical use of space, and a group's social rhythm that determines our understanding of time.[86] In this Durkheim sought to combine elements of rationalism and empiricism, arguing that certain aspects of logical thought common to all humans did exist, but that they were products of collective life (thus contradicting the tabula rasa empiricist understanding whereby categories are acquired by individual experience alone), and that they were not universal a prioris (as Kant argued) since the content of the categories differed from society to society.[viii] Collective representations Another key elements to Durkheim's theory of knowledge outlined in Elementary Forms is the concept of représentations collectives ("collective representations"). Représentations collectives are the symbols and images that come to represent the ideas, beliefs, and values elaborated by a collectivity and are not reducible to individual constituents. They can include words, slogans, ideas, or any number of material items that can serve as a symbol, such as a cross, a rock, a temple, a feather etc. As Durkheim elaborates, représentations collectives are created through intense social interaction and are products of collective activity. As such, these representations have the particular, and somewhat contradictory, aspect that they exist externally to the individual—since they are created and controlled not by the individual but by society as a whole—yet, simultaneously within each individual of the society, by virtue of that individual's participation within society.[87] Arguably the most important "représentations collectives" is language, which according to Durkheim is a product of collective action. And because language is a collective action, language contains within it a history of accumulated knowledge and experience that no individual would be capable of creating on their own:[79]: 435 If concepts were only general ideas, they would not enrich knowledge a great deal, for, as we have already pointed out, the general contains nothing more than the particular. But if before all else they are collective representations, they add to that which we can learn by our own personal experience all that wisdom and science which the group has accumulated in the course of centuries. Thinking by concepts, is not merely seeing reality on its most general side, but it is projecting a light upon the sensation which illuminates it, penetrates it and transforms it. As such, language, as a social product, literally structures and shapes our experience of reality. This discursive approach to language and society was developed by later French philosophers, such as Michel Foucault. Morality How many times, indeed, it [crime] is only an anticipation of future morality - a step toward what will be! — Émile Durkheim, Division of Labour in Society[88] Durkheim defines morality as "a system of rules for conduct".[89] His analysis of morality is influenced by Immanuel Kant and his notion of duty. While Durkheim was influenced by Kant, he was critical of aspects of the latter's moral theory and developed his own positions. Durkheim agrees with Kant that within morality, there is an element of obligation, "a moral authority which, by manifesting itself in certain precepts particularly important to it, confers upon [moral rules] an obligatory character."[51]: 38 Morality tells us how to act from a position of superiority. There exists a certain, pre-established moral norm to which we must conform. It is through this view that Durkheim makes a first critique of Kant in saying that moral duties originate in society, and are not to be found in some universal moral concept such as the categorical imperative. Durkheim also argues that morality is characterized not just by this obligation, but is also something that is desired by the individual. The individual believes that by adhering to morality, they are serving the common Good, and for this reason, the individual submits voluntarily to the moral commandment.[51]: 54 However, in order to accomplish its aims, morality must be legitimate in the eyes of those to whom it speaks. As Durkheim argues, this moral authority is primarily to be located in religion, which is why in any religion one finds a code of morality. For Durkheim, it is only society that has the resources, the respect, and the power to cultivate within an individual both the obligatory and the desirous aspects of morality.[51]: 73 |

デュルケムと理論 デュルケムは、そのキャリアを通じて主に3つの目標を掲げていた。第一に、社会学を新たな学問分野として確立すること。第二に、宗教や民族といった共有の 背景がもはや前提とされなくなった現代において、社会がその統一性と一貫性を維持できるかを分析すること。その目的のために、彼は法律、宗教、教育、およ び同様の力が社会や社会統合に与える影響について多くを書いた。[15][25] 最後に、デュルケムは科学知識の実用的な意味合いに関心を抱いていた。[15] 社会統合の重要性は、デュルケムの著作全体を通して表現されている。[26][27] もし社会が、その構成要素間の関係が正確に規制されているという事実から生じる統一性を欠き、効果的な規律によって保証される様々な機能の調和的な調和か ら生じる統一性を欠き、さらに、社会が、人々の意志が共通の目的にコミットメントすることに基づく統一性を欠くのであれば、それは、わずかな衝撃やわずか な突風で散らばってしまう砂の山にすぎない。 —『道徳教育』(1925年) 社会学の確立 デュルケムは、社会学とは何か、また、どのように実践されるべきかについて、最も体系的な見解をいくつか著している。[10] 彼の関心は、社会学を科学として確立することにあった。[28] 他の科学の分野における社会学の地位を主張し、彼は次のように述べた。「社会学は、それゆえ、他のいかなる科学の補助でもない。社会学はそれ自体、独自で 自律的な科学である。」[29] 社会学を学問の世界に位置づけ、正当な科学であることを確実にするためには、哲学や心理学とは明確に区別できる対象と独自の方法論が必要である。[15] 彼は「あらゆる社会には、他の自然科学が研究対象とするものとは区別できる現象群がある」と主張した。[30]:95 1903年のタルドとデュルケムの論争では、ガブリエル・タルドの「人類学的見解」は嘲笑され、早急に退けられた。 社会学の根本的な目的は、構造的な「社会的事実」を発見することである。[15][31]:13 独立した学問分野として社会学が確立されたことは、デュルケムの最も偉大で永続的な功績のひとつである。[2] 社会学の分野において、彼の研究は構造主義や構造機能主義に多大な影響を与えた。[2][32] 社会的事実 詳細は「社会的事実」を参照 社会的事実とは、固定されているか否かに関わらず、個人に対して外部からの制約を課すことのできるあらゆる行動様式、あるいは、特定の社会全体にわたって 一般的であると同時に、個々の現象とは独立して独自の存在として存在するあらゆる行動様式である。 —『社会学的方法の規則』[31] デュルケムの研究は、社会的事実の研究を中心に展開された。社会的事実は、それ自体で存在し、個人の行動に左右されることなく、それらに強制的な影響を与 える現象を説明する用語として、デュルケムが考案したものである。デュルケムは、社会的事実は独自に存在し、社会を構成する個人の行動よりも大きく、より 社会を構成する個々人の行動よりも、より大きく、より客観的な独自な存在であると主張した。[34] このような社会的事実のみが、観察された社会現象を説明することができる。[10] 個人にとって外部にある社会的事実は、したがって、社会を構成するさまざまな人々に対して強制力を及ぼす可能性もある。これは、正式な法律や規則の場合に 時折観察されるが、 宗教的儀式や家族規範のような非公式な規則の存在を暗示する状況においても、である。[31][35] 自然科学で研究される事実とは異なり、社会的事実は特定の現象カテゴリーを指す。「社会的事実の決定要因は先行する社会的事実の中に求められなければなら ず、個々の意識の状態の中には求められない。」[要出典] このような事実は強制力を持つため、個人の行動を制御することができる。デュルケムによれば、これらの現象は生物学的または心理学的根拠に還元することは できない。社会的事実は物質的(すなわち物理的な物体)または非物質的( (すなわち、意味、感情など)。[34] 後者は目に見えたり触れたりすることはできないが、それらは外部に存在し強制力を持つため、現実のものとなり「事実性」を獲得する。[34] 物理的な物体も、物質的および非物質的な社会的事実の両方を表すことができる。例えば、旗は物質的な社会的事実であり、しばしばさまざまな非物質的な社会 的事実(例えば、その意味や重要性)が刻み込まれている。[34] しかし、多くの社会的現象は物質的な形を持たない。[34] 愛や自由、自殺といった最も「個人主義的」または「主観的」な現象でさえ、デュルケムは客観的な社会的現象であるとみなした。[34] 社会を構成する個人は直接的に自殺を引き起こすわけではない。自殺は、 社会的事実として、社会に独立して存在し、個人の好むと好まざるとにかかわらず、行動や集団帰属を規定する規則などの他の社会的事実によって引き起こされ るのである。[34][36] ある個人が社会から「離れる」かどうかに関わらず、その社会に自殺者が存在するという事実は変わらない。自殺は、他の非物質的な社会的事実と同様に、個人 の意志とは無関係に存在し、排除することはできず、重力のような物理法則と同様に強制力を持つ影響力がある。[34] したがって、社会学の課題は、このような社会的事実の性質や特徴を発見することであり、それは量的または実験的なアプローチによって発見することができる (デュルケムは統計を広く活用した)。[v] 社会、集合的意識、文化 +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 『社会分業論』1893  『社会における分業』フランス語版の表紙 社会における分業』(フランス語:De la division du travail social)は、フランスの社会学者エミール・デュルケムの博士論文で、1893年に発表された。社会学の理論や思想を発展させる上で大きな影響力を持 ち、オーギュスト・コントの影響も受けた。デュルケムは、機械的連帯と有機的連帯という2つの大きく異なる連帯形態に基づく社会で社会秩序がどのように維 持されているか、また、より「原始的」な社会から高度な工業社会への移行について述べた。 デュルケムは、「原始的」社会では、人々が同じように行動し、同じように考え、集団的良心を共有する機械的連帯が社会秩序を維持することを可能にしている と示唆した。このような社会では、デュルケムは犯罪を「集団的良心の強く規定された状態を害する」行為とみなしていたが、犯罪を通常の社会的事実とみなし ていた[1]。機械的な社会全体では社会的結びつきが比較的均質で弱いため、法律は共通の良心の侵害に対応するために抑圧的で刑罰的でなければならない。 先進的な産業資本主義社会では、複雑な分業システムによって、人々は実力に応じて社会に配置され、それに応じて報われる。デュルケムは、社会の秩序(ある いは有機的連帯)を維持するためには、経済的規制と同様に道徳的規制が必要であると主張した。実際、このような規制は分業に対応して自然に形成され、人々 が「平和的に差異を構成する」ことを可能にする[2]。このような社会では、法は過剰に罰するよりもむしろ回復を求める、刑罰的というよりも回復的なもの になるだろう。 彼は、社会が「原始的」なものから先進的なものへと移行することは、大きな無秩序、危機、アノミーをもたらすかもしれないと考えた。しかし、ひとたび社会 が「先進的」段階に達すると、社会はより強固になり、発展を遂げる。デュルケームは、カール・マルクスとは異なり、産業資本主義的分業から生じる異なる社 会を予見していなかった。彼は、マルクスが階級対立を強調するのに対し、対立、混沌、無秩序を近代社会の病理的現象とみなした。 デュルケム エミール 社会における労働の分業. Trans. W. D. Halls, intro. Lewis A. Coser. New York: Free Press, 1997, pp.39, 60, 108. ロック、ポール (2002). 「Sociological Theories of Crime" in Maguire, Mike, Rod Morgan, and Robert Reiner,The Oxford Handbook of Criminology. Oxford University Press. +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ 社会そのものについて、デュルケムは一般的な社会制度と同様に、一連の社会的事実であると捉えていた。デュルケムは「社会とは何か」ということ以上に、 「社会はいかにして形成されるのか」、「社会をまとめるものは何か」ということに興味を持っていた。『社会における分業』において、デュルケムは後者の問 いに答えようとしている。 集合的意識 デュルケムは、人間は本質的に利己的であるが、「集合的意識」(すなわち規範、信念、価値観)が社会の道徳的基盤を形成し、社会統合をもたらす、と想定し ている。[38] したがって、集合的意識は社会にとって極めて重要であり、その必須の機能は 社会が存続できない。[39] この意識が社会を作り出し、社会をまとめている。同時に、個人は相互作用を通じて集団意識を作り出す。[5] 集団意識を通じて、人間は単なる動物ではなく、社会的な存在として互いに意識し合うようになる。[39] 社会の平均的な構成員に共通する信念や感情の総体は、独自の生命を持つ確固とした体系を形成する。これを集合的または共通の意識と呼ぶことができる。 特に、集合的意識の感情的な部分は、私たちの利己主義を上回る。私たちは文化に感情的に結びついているため、それが責任ある道徳的な行動であると認識して いるからこそ、社会的に行動するのだ。[41] 社会を形成する鍵となるのは社会的相互作用であり、デュルケムは、人間は集団にいると、必然的に社会が形成されるような行動を取ると考えている。[41] [42] 文化 集団は、相互に作用し合うことで独自の文化を生み出し、それに強力な感情を付加する。それゆえ、文化もまた重要な社会的要因となる。デュルケムは、文化の 問題をこれほどまでに深く考察した最初の学者の一人であった。デュルケムは文化の多様性に興味を持ち、多様性が存在しても社会が崩壊しない理由について考 察した。これに対してデュルケムは、表面的な文化の多様性は、より大きな共通の一般化された文化システムと法によって覆い隠されていると答えた。 社会進化論的アプローチにおいて、デュルケムは社会の進化を機械的連帯から有機的連帯(相互依存から生じるもの)へと説明した。[32][37][45] [46] 社会がより複雑になり、機械的連帯から有機的連帯へと進化するにつれ、分業は集団意識に取って代わられ、それを相殺する。[37][47] より単純な社会では、人々は 個人的なつながりや伝統によって結びついている。より大規模で近代的な社会では、人々は、現代の高度に複雑な社会が存続するために必要な専門的な作業を行 うにあたって、他者への依存度が高まることによって結びついている。[37] 機械的連帯においては、人々は自給自足であり、統合はほとんどないため、社会をまとめるために力や弾圧を用いる必要がある。[45][要出典] また、そのような社会では、人々は人生において選択肢が非常に少ない。[48][要出典] 有機的連帯においては、人々はより統合され相互依存しており、専門化と協力が広く行われている。[45][要出典] 機械的連帯から有機的連帯への進歩は、第一に人口増加と人口密度の増加、第二に「道徳密度」の増加(より複雑な社会的相互作用の発展)、第三に 職場における専門性の高まりである。機械的社会と有機的社会の相違点のひとつは、法の機能である。機械的社会では、法は処罰の側面に重点を置いており、し ばしば処罰を公開し厳格にすることで、共同体の結束を強化することを目的としている。一方、有機的社会では、法は引き起こされた損害の修復に重点を置いて おり、共同体よりも個人に重点を置いている。 現代の有機的社会の主な特徴のひとつは、個人という概念(社会的事実)が重要視され、神聖視されていることである。[50] 集団よりも個人が権利と責任の中心となり、社会をまとめる公的・私的な儀式の中心となる。かつては宗教が担っていた役割である。[50] この概念の重要性を強調するために、デュルケムは「個人の崇拝」について語った。[51] したがって、しばしば主張されるような個人と社会の対立とは程遠い。道徳的個人主義、すなわち個人崇拝は、実際には社会そのものの産物である。それを制度 化し、人間を神として仕えるものとしたのは社会である。 デュルケムは、人口密度と人口増加が社会の進化と近代の到来における重要な要因であると見なした。[52] 一定の地域における人口が増えれば、相互作用の数も増え、社会はより複雑になる 。[46] 人口の増加に伴い競争も激化し、労働の分業化が進む。[46] やがて国家、法、個人の重要性が増し、宗教や道徳的連帯の重要性は低下する。[53] 文化の進化の別の例として、デュルケムはファッションを指摘したが、この場合、彼はより循環的な現象を指摘した。デュルケムによると、ファッションは下層 階級と上層階級を区別する役割を果たすが、下層階級は上層階級のようになりたいと願うため、最終的には上層階級のファッションを取り入れ、それを貶め、上 層階級に新しいファッションを採用させることになる。 社会病理と犯罪 デュルケムは、社会統合の崩壊と社会の崩壊につながる可能性のあるいくつかの病理学的な兆候を指摘している。最も重要なものはアノミーと強制分業であり、 それほど重要ではないものとしては、調整不足や自殺が挙げられる。デュルケムにとって、アノミーとは社会規範の欠如を指す。人口増加が急速すぎると、さま ざまな集団間の相互作用が減少し、 その結果、相互理解(すなわち規範、価値観など)が崩壊する。[56] 一方、強制的な分業とは、権力を握る者が利益への欲望(貪欲)に駆られて、人々を不適任な労働に従事させる状況を指す。[57] そのような人々は不幸であり、体制を変えたいという彼らの願望が社会を不安定化させる可能性がある。[57] デュルケムの犯罪に対する見解は、従来の考え方とは異なっていた。彼は、犯罪は「あらゆる社会生活の根本的条件と密接に関連」しており、社会的な機能を有 していると信じていた。[30]: 101 彼は、犯罪は「必要な変化への道が開かれていることを意味するだけでなく、特定のケースでは、これらの変化を直接的に準備することでもある」と述べてい る。[30]: 101 ソクラテスの裁判を検証した上で、彼は「彼の犯罪、すなわち、彼の思想の独立性は、 アテネ人が必要としていた新しい道徳観と信仰心を育むのに役立った」ため、「人類だけでなく、祖国にも貢献した」と主張している。[30]: 101 このように、彼の犯罪は「改革への有用な序曲」であった。[30]: 102 この意味において、彼は犯罪が特定の社会的緊張を解放し、社会に浄化や浄化作用をもたらす可能性があると見ていた。[30]: 101 道徳的良心が享受する権威は過剰であってはならない。さもなければ、誰もそれを批判する勇気を持たず、それは容易に不変の形に凝り固まってしまうだろう。 進歩を遂げるためには、個人の独創性が表現できなければならない。犯罪者の独創性でさえも表現できなければならない。 逸脱 デュルケムは、逸脱は機能的な社会の不可欠な要素であると考えていた。[58] 彼は、逸脱が社会に及ぼす影響として以下の3つを挙げている。[58][59] 逸脱は一般大衆の見方や考え方に疑問を投げかけ、社会の欠陥を指摘することで社会変革につながる。 逸脱行為は、大衆に規律を促すことで、既存の社会規範や信念を支持する可能性がある。 逸脱行為に対する反応は、その行為の影響を受けた大衆の間で仲間意識や社会的支援を高める可能性がある。 デュルケムの逸脱に関する考えは、ロバート・マートンのひずみ理論に影響を与えた。 自殺 詳細は「自殺 (デュルケムの著書)」を参照 デュルケムは著書『自殺』(1897年)において、プロテスタントとカトリックにおける自殺率の違いについて調査し、カトリックにおけるより強い社会的統 制が低い自殺率につながっていると論じている。デュルケムによれば、カトリック社会は統合の度合いが正常であるのに対し、プロテスタント社会は統合の度合 いが低い。デュルケムは全体として自殺を社会的事実として扱い、その発生率の変動をマクロレベルで説明し、個人の感情や動機よりも、人々とのつながりの欠 如(集団帰属)や行動の規制の欠如といった社会規模の現象を考慮した。[37][60] デュルケムは、自殺には、失業、離婚、破産といった極めて個人的な個人の生活環境以上のものがあると信じていた。むしろ、デュルケムは、自殺をアルコール 依存症や殺人といった集団的な社会的逸脱の症状として説明した。 デュルケムは集団生活の条件に焦点を当て、自殺に関する規範理論を構築した。利己的、利他的、無規範的、運命論的の4つの異なるタイプの自殺を提唱した デュルケムは、まず、社会規制をX軸に、社会統合をY軸にプロットした図表を作成し、その上で自説を展開した。 利己的な自殺は、社会統合のレベルが低い状態に相当する。社会集団にうまく溶け込めていない場合、誰の人生にも影響を与えていないという感覚につながる可 能性がある。 利他的な自殺は、社会統合のレベルが高すぎる状態に相当する。これは、集団が個人の生活を支配し、その個人が社会にとって無意味であると感じるほどにまで 至った場合に起こる。 アノミー型自殺は、社会的な規制が不十分な場合に起こる。これは、社会学的用語であるアノミーに由来するもので、人生に予測可能性を合理的に期待できない ことから生じる無目的感や絶望感を意味する。 運命論的型自殺は、社会的な規制が過剰な場合に起こる。その例としては、毎日同じルーチンを繰り返す場合が挙げられる。これは、将来に楽しみがないという 信念につながる。デュルケムは、これが囚人の最も一般的な自殺の形態であると示唆した。 この研究は、後世の学者たちによって広く議論され、いくつかの主要な批判が提起されている。まず、デュルケムは、自身のデータのほとんどを、特にアドル フ・ワグナーとヘンリー・モルセリという、自身のデータから一般化することに非常に慎重であった先行研究者から得ていた。第二に、後の研究者は、プロテス タントとカトリックの自殺率の違いはドイツ語圏のヨーロッパに限られているように見え、したがって、常に他の要因の誤った反映であった可能性があると指摘 している。[63] デュルケムの自殺に関する研究は、生態学的誤謬と呼ばれる論理エラーの例として批判されている。[64][65] しかし、 デュルケムの研究に生態学的誤謬が含まれているかどうかについては、見解が分かれている。[66] バーク(2006年)などのより最近の著者は、デュルケムの研究の根底にあるミクロ-マクロ関係についても疑問を呈している。[67] インケレス(1959年)[68]、ジョンソン(1 1965年)[69]、ギブス(1968年)[70]などは、デュルケムの意図はあくまでも全体論的な視点から自殺を社会学的観点から説明することにあっ たと主張し、「デュルケムは自殺の発生率における社会環境の変化を説明するための理論を意図しており、特定の個人の自殺を説明しようとしたわけではない」 と強調している。 限界はあるものの、デュルケムの自殺に関する研究は統制理論の支持者たちに影響を与え、古典的社会学的研究としてしばしば言及されている。この本は近代的 社会研究の先駆けとなり、社会科学を心理学や政治哲学から区別する役割を果たした。[9]: ch.1 宗教 『宗教生活の初歩形態』(1912年)において、デュルケムの第一の目的は、宗教が仲間意識と連帯感の源であると感じていたことから、宗教の社会的起源と 機能を特定することだった。[37] 第二の目的は、異なる文化における特定の宗教間のつながりを特定し、共通項を見出すことだった。彼は、あらゆる宗教に共通し、精神性や神の概念を超越する 宗教の実証的、社会的側面を理解しようとした。[72] デュルケムは宗教を次のように定義した。[73] 「神聖なもの、すなわち、隔離され禁じられたものに関する信念と実践の統一された体系。すなわち、教会と呼ばれる単一の道徳的共同体に結束する信念と実践 であり、それらを信奉するすべての人々である。」 この定義において、デュルケムは超自然的または神への言及を避けている。[74] デュルケムは、宗教とは「超自然的存在への信仰」であるとするそれ以前のテイラーの定義を否定し、オーストラリアのアボリジニのような原始的社会(スペン サーとギレンの民族誌学に倣ったものだが、後にその信憑性はほぼ否定された)は、 現実を「自然」と「超自然」の領域に分けるのではなく、「神聖」と「世俗」の領域に分けていた。後者は道徳的なカテゴリーではなく、どちらにも善と悪の両 方が含まれる可能性があった。[75] デュルケムは、私たちが次の3つの概念を残していると主張している。[76] 聖なるもの:社会の光景から呼び起こされる考えや感情であり、畏敬の念、精神的な献身、または尊敬の念を喚起するもの。 信念と実践:集団的な興奮状態を生み出し、象徴に神聖な重要性を付与するもの。 道徳共同体:共通の道徳哲学を共有する人々の集団。 デュルケムは、この3つの概念のうち「神聖」に注目し、それが宗教のまさに核心であると指摘した。[79]:322 それらは、すなわち道徳的な力であり、社会の光景によって私たちの中に呼び起こされる観念や感情から構成されるものであり、物理的世界から生じる感覚から 生じるものではない。[vi] デュルケムは、宗教を人類の最も根本的な社会制度であり、他の社会形態を生み出すものだと考えた。[80] 宗教は、人類に最も強い集団意識の感覚を与えた。[81] デュルケムは、宗教を初期の狩猟採集社会に現れた力だと考えた。成長する集団において感情が集団的に高まり、新たな行動を余儀なくされ、自分たちを突き動 かす何らかの隠された力の存在を感じさせるものとして、デュルケムは宗教を捉えていた。[47] やがて、感情が象徴化され、相互関係が儀式化されるにつれ、宗教はより組織化されて 、神聖と世俗の区分を生み出した。[47] しかしデュルケムは、宗教は次第に科学や個人崇拝に取って代わられ、重要性を失いつつあるとも考えていた。[50][82] したがって、宗教には永遠の何かがあり、それは宗教思想が次々と自らを包み込んできた特定の象徴すべてを生き延びる運命にある。[79]:427 しかし、デュルケムにとって宗教が重要性を失っていたとしても、それは依然として近代社会とその社会を支配する相互作用の基盤を築いていたのである。 [81] そして、代替勢力が台頭したにもかかわらず、デュルケムは宗教の持つ力の代わりとなるものはまだ生まれていないと主張した。彼は近代に対して疑念を表明 し、近代を「過渡期であり、道徳的に平凡な時代」と捉えていた。[53] デュルケムはまた、世界を理解するための主要なカテゴリーは宗教に起源を持つと主張した。[54] デュルケムは、より大きな社会を含め、ほとんどの、あるいはすべての他の社会的構成を生み出したのは宗教であると書いている。[81] デュルケムは、カテゴリーは社会によって作り出されるものであり、したがって集合的な創造物であると主張した。[37] このように、人々が社会を作り出すように、カテゴリーも作り出されるが、 しかし同時に、それは無意識的に行われるものであり、カテゴリーは個人の経験に先立つものである。[37] このようにデュルケムは、カテゴリーを人間の経験から構築されたものと捉える立場と、カテゴリーが経験に先立つ論理的なものであると捉える立場との間の溝 を埋めようとした。[37][83] 私たちの世界に対する理解は社会的事実によって形作られる。例えば、時間の概念はカレンダーによって測定されることによって定義されるが、 カレンダーによって測定されることで定義される。カレンダーは、私たちが社会的集会や儀式を把握できるようにするために作成されたものであり、それらは最 も基本的なレベルでは宗教から派生している。[81] 結局、科学における最も論理的かつ合理的な追求でさえ、その起源を宗教にたどることができる。[81] デュルケムは、「宗教は社会において本質的なものすべてを生み出した」と述べている。[81] デュルケムは、オーストラリア先住民やアメリカ先住民の宗教であるトーテミズムに注目した。デュルケムは、この宗教を最も古い宗教と見なし、その単純性に よって宗教の本質的要素についての議論が容易になると考え、この宗教に注目した。[37][74] そのため、彼は次のように記している。[79]:220 トーテムは今や一族の旗印である。それゆえ、個々人の心の中で一族が呼び起こす印象、すなわち依存と活力の印象は、一族の概念よりもむしろトーテムの概念 に結びつくのが自然である。なぜなら、一族はあまりにも複雑な現実であり、そのような初歩的な知性によってその複雑な統一性をすべて明確に表現することは できないからだ。 デュルケムの宗教に関する研究は、その分野の専門家たちから経験的および理論的な観点の両方で批判された。最も重要な批判は、デュルケムと同時代の宗教と 儀式、およびオーストラリアの信念体系の専門家であるアーノルド・ヴァン・ジェンヌによるものだった。ヴァン・ジェンヌは、デュルケムの原始民族と単純な 社会に関する見解は「完全に誤っている」と主張した。ヴァン・ゲネップはさらに、デュルケムが商人や司祭が収集した資料に対して批判的な姿勢を欠いてお り、その真実性を安易に受け入れ、疑わしいデータから自由に解釈していると主張した。概念レベルでは、ヴァン・ゲネップはデュルケムが民族誌を既製の理論 的枠組みに押し込めようとする傾向を指摘した。 こうした批判にもかかわらず、デュルケムの宗教に関する研究は、その理論的洞察力と論拠および命題が広く賞賛されており、ロバート・アルン・ジョーンズに よれば、「理論的な『学派』や専門分野に関係なく、何世代もの社会学者たちの関心と興奮を刺激してきた」という。 知識社会学 デュルケムの研究対象は、自殺、家族、社会構造、社会制度など多岐にわたるが、その研究の大部分は知識社会学に関するものである。 デュルケムはキャリアの初期にこのテーマに関する短い論文を発表していたが[vii]、知識社会学に関する彼の決定的な主張は、1912年の代表作『宗教 生活の基礎形態』に示されている。この著書の目的は、宗教の社会的起源と機能の解明だけでなく、言語と論理的思考の社会的起源と社会がそれらに与える影響 の解明にもあった。デュルケムは主にカント哲学の枠組みで研究を行い、論理的思考の概念やカテゴリーが社会生活からどのように生じるかを理解しようとし た。例えば、空間と時間のカテゴリーは先験的なものではないと主張した。むしろ、空間のカテゴリーは社会の社会的集団や地理的な空間の利用、そして時間の 理解を決定する集団の社会的リズムに依存している。[86] この点においてデュルケムは合理主義と経験主義の要素を組み合わせようとし、 しかし、それらは集団生活の産物であり(したがって、カテゴリーが個人の経験のみによって獲得されるとする経験論者の「タブラ・ラサ」の考え方とは矛盾す る)、カテゴリーの内容は社会によって異なるため、カントが主張したような普遍的な先験的なものではないと主張した。[viii] 集合的表象 『原初形態』で述べられたデュルケムの知識論におけるもう一つの重要な要素は、「集合的表象」という概念である。集合的表象とは、集団によって練り上げら れた思想、信念、価値観を象徴するシンボルやイメージであり、個々の構成員に還元できないものである。 言葉、スローガン、アイデア、あるいは十字架、岩、寺院、羽根など、シンボルとなり得る物質的な事物が数多く含まれる。デュルケムが詳しく説明しているよ うに、集合的表象は、激しい社会的相互作用を通じて生み出され、集団的活動の産物である。そのため、これらの表象は、個人に対して外部的に存在するという 独特で、ある意味矛盾した側面を持つ。なぜなら、それらは個人ではなく社会全体によって生み出され、管理されているからである。しかし同時に、社会におけ る個人の参加によって、社会の各個人の中に存在している。[87] おそらく最も重要な「集合的表象」は言語であり、デュルケムによれば、言語は集団的行動の産物である。そして、言語は集団的行動であるため、言語には、個 人が単独で作り出すことは不可能な、蓄積された知識と経験の歴史が含まれている。 概念が単なる一般的な考えにすぎないならば、それは知識を大いに豊かにすることはないだろう。なぜなら、すでに指摘したように、一般的なものには特定のも の以上のものは含まれないからだ。しかし、何よりもまず集団的な表象であるならば、個人の経験によって学ぶことのできるものに、その集団が何世紀にもわ たって蓄積してきた英知と科学をすべて加えることになる。概念による思考とは、単に現実を最も一般的な側面から見ることではなく、感覚に光を当て、それを 照らし、貫き、変容させることである。 このように、言語は社会的な産物として、文字通り現実に対する私たちの経験を構造化し、形作る。言語と社会に対するこのような議論的なアプローチは、ミ シェル・フーコーなどの後期のフランスの哲学者たちによって発展した。 道徳 犯罪は、実際、未来の道徳の予見にすぎない。それは、未来への一歩なのだ! — エミール・デュルケーム、『社会における分業』[88] デュルケムは道徳を「行動の規則体系」と定義している。[89] 彼の道徳に関する分析は、イマヌエル・カントと彼の義務の概念に影響を受けている。デュルケムはカントの影響を受けながらも、カントの道徳理論の側面を批 判し、独自の立場を展開した。 デュルケムは、道徳には義務の要素が存在するというカントの考えに同意している。「道徳的権威は、特に重要な特定の教訓において自らを明示することで、 [道徳的規則に]義務的な性格を与える」[51]:38 デュルケムは、道徳は優位な立場から行動する方法を私たちに教えるものであると主張している。私たちは、ある特定の、あらかじめ確立された道徳的規範に適 合しなければならない。デュルケムは、道徳的義務は社会に由来するものであり、普遍的な道徳的概念、例えば「カテゴリー的命令」には見出されないと主張 し、この見解を通じてカントに対する最初の批判を行っている。デュルケムはまた、道徳は単にこの義務によって特徴づけられるものではなく、個々人が望むも のでもあると論じている。個人は、道徳に従うことで公共の利益に貢献していると信じており、この理由から、個人は自発的に道徳律に従うのである。 [51]: 54 しかし、その目的を達成するためには、道徳はそれを語る人々にとって正当なものでなければならない。デュルケムが主張するように、この道徳的権威は主に宗 教に見出されるものであり、それがどの宗教にも道徳律が存在する理由である。デュルケムにとって、道徳の義務的側面と望ましい側面の双方を個人の中に育む ための資源、敬意、そして力を備えているのは社会だけである。[51]: 73 |

| Influence and legacy Durkheim has had an important impact on the development of anthropology and sociology as disciplines. The establishment of sociology as an independent, recognized academic discipline, in particular, is among Durkheim's largest and most lasting legacies.[2] Within sociology, his work has significantly influenced structuralism, or structural functionalism.[2][32] Scholars inspired by Durkheim include Marcel Mauss, Maurice Halbwachs, Célestin Bouglé, Gustave Belot, Alfred Radcliffe-Brown, Talcott Parsons, Robert K. Merton, Jean Piaget, Claude Lévi-Strauss, Ferdinand de Saussure, Michel Foucault, Clifford Geertz, Peter Berger, social reformer Patrick Hunout, and others.[2] More recently, Durkheim has influenced sociologists such as Steven Lukes, Robert N. Bellah, and Pierre Bourdieu. His description of collective consciousness also influenced Ziya Gökalp, the founder of Turkish sociology[90] who replaced Durkheim's concept of society with nation.[91] An ideologue who provided the intellectual justification for the Ottoman Empire's wars of aggression and massive demographic engineering—including the Armenian genocide—he could be considered to pervert Durkheim's ideas.[91][92] Randall Collins has developed a theory of what he calls interaction ritual chains, a synthesis of Durkheim's work on religion with that of Erving Goffman's micro-sociology. Goffman himself was also influenced by Durkheim in his development of the interaction order. Outside of sociology, Durkheim has influenced philosophers, including Henri Bergson and Emmanuel Levinas, and his ideas can be identified, inexplicitly, in the work of certain structuralist theorists of the 1960s, such as Alain Badiou, Louis Althusser, and Michel Foucault.[ix] Durkheim contra Searle Much of Durkheim's work remains unacknowledged in philosophy, despite its direct relevance. As proof, one can look to John Searle, whose book, The Construction of Social Reality, elaborates a theory of social facts and collective representations that Searle believed to be a landmark work that would bridge the gap between analytic and continental philosophy. Neil Gross, however, demonstrates how Searle's views on society are more or less a reconstitution of Durkheim's theories of social facts, social institutions, collective representations, and the like. Searle's ideas are thus open to the same criticisms as Durkheim's.[93] Searle responded by arguing that Durkheim's work was worse than he had originally believed, and, admitting that he had not read much of Durkheim's work: "Because Durkheim's account seemed so impoverished I did not read any further in his work."[94] Stephen Lukes, however, responded to Searle's reply to Gross, refuting, point by point, the allegations that Searle makes against Durkheim, essentially upholding the argument of Gross, that Searle's work bears great resemblance to that of Durkheim. Lukes attributes Searle's miscomprehension of Durkheim's work to the fact that Searle, quite simply, never read Durkheim.[95] Gilbert pro Durkheim Margaret Gilbert, a contemporary British philosopher of social phenomena, has offered a close, sympathetic reading of Durkheim's discussion of social facts in the first chapter and the prefaces of The Rules of Sociological Method. In her 1989 book, On Social Facts—the title of which may represent an homage to Durkheim, alluding to his "faits sociaux"—Gilbert argues that some of his statements that may seem to be philosophically untenable are important and fruitful.[96] |

影響と遺産 デュルケムは、学問分野としての人類学と社会学の発展に重要な影響を与えた。特に、社会学を独立した学問分野として確立させたことは、デュルケムの最も偉 大で永続的な功績のひとつである。社会学の分野では、彼の研究は構造主義、または構造機能主義に多大な影響を与えた。デュルケムに影響を受けた学者には、 マルセル・モース、モーリス・ハルヴァックス、 セレスティン・ブールグ、ギュスターヴ・ベロ、アルフレッド・ラドクリフ=ブラウン、タルコット・パーソンズ、ロバート・K・マートン、ジャン・ピア ジェ、クロード・レヴィ=ストロース、フェルディナン・ド・ソーシュール、ミシェル・フーコー、クリフォード・ゲーツ、ピーター・バーガー、社会改革者パ トリック・フノットなどである。 さらに最近では、デュルケムはスティーブン・ルークス、ロバート・N・ベラー、ピエール・ブルデューといった社会学者に影響を与えている。 デュルケムの集合的意識の概念は、トルコ社会学の創始者であるジヤ・ギュカルプにも影響を与えた。ギュカルプはデュルケムの社会概念を国民に置き換えた人 物である。ギュカルプは、 アルメニア人虐殺を含む。デュルケムの思想を歪めた人物とみなすこともできる。[91][92]ランドール・コリンズは、デュルケムの宗教に関する研究と アーヴィング・ゴフマンのミクロ社会学を統合した、相互作用儀礼連鎖(interaction ritual chains)と呼ばれる理論を展開している。ゴフマン自身も、相互作用秩序の展開においてデュルケムの影響を受けていた。 社会学以外の分野では、デュルケムはアンリ・ベルグソンやエマニュエル・レヴィナスといった哲学者たちに影響を与え、彼の思想は、1960年代の構造主義 理論家であるアラン・バディウ、ルイ・アルチュセール、ミシェル・フーコーなどの作品にも、間接的にではあるが、見出すことができる。 デュルケム対シーア デュルケムの業績の多くは、直接的な関連性があるにもかかわらず、哲学の世界では認められていない。その証拠に、ジョン・シーアの著書『社会的現実の構 築』では、社会的事実と集合的表象の理論が詳しく説明されているが、シーアはこれを分析哲学と大陸哲学の間のギャップを埋める画期的な著作であると考えて いた。しかし、ニール・グロスは、ソールの社会観が、デュルケームの社会的事実、社会制度、集合的表象などの理論を再構成したものであることを示してい る。したがって、セールの考えはデュルケムの考えと同じ批判にさらされる可能性がある。[93] セールは、デュルケムの業績は当初考えていたよりもひどいものであり、デュルケムの業績をあまり読んでいないことを認めつつ、次のように反論した。「デュ ルケムの説明があまりにも貧弱に思えたので、それ以上彼の著作を読まなかった」と述べた。[94] しかし、スティーブン・ルークスは、グロスに対するシーラの返答に反論し、シーラがデュルケムに対して行った非難を一つ一つ論破し、本質的にはグロスの主 張を支持し、シーラの著作はデュルケムの著作と非常に似ていると主張した。ルークスは、デュルケムの研究に対するシーラルの誤解は、シーラルのデュルケム を読まなかったという事実によるものだと主張している。[95] ギルバートによるデュルケム 社会現象の現代英国の哲学者であるマーガレット・ギルバートは、『社会学的メソッドの規則』の第1章と序文におけるデュルケムの社会的事実に関する議論に ついて、詳細で共感的な解釈を提示している。1989年の著書『社会的事実について』のタイトルは、デュルケムの「社会的事実」へのオマージュを表してい るかもしれない。ギルバートは、デュルケムのいくつかの主張は、一見すると哲学的に支持できないように見えるが、重要かつ有益であると主張している。 [96] |

| Selected works "Montesquieu's contributions to the formation of social science" (1892) The Division of Labour in Society (1893) The Rules of Sociological Method (1895) Suicide (1897) The Prohibition of Incest and its Origins (1897), in L'Année Sociologique 1:1–70 Sociology and its Scientific Domain (1900), translation of an Italian text entitled "La sociologia e il suo dominio scientifico" Primitive Classification (1903), in collaboration with Marcel Mauss The Elementary Forms of Religious Life (1912)[79][97] Who Wanted War? (1914), in collaboration with Ernest Denis Germany Above All (1915) Published posthumously[98][99] Education and Sociology (1922) Sociology and Philosophy (1924) Moral Education (1925) Socialism (1928) Pragmatism and Sociology (1955) |

主な著作 「社会科学の形成におけるモンテスキューの貢献」(1892年) 「社会における分業」(1893年) 「社会学的方法の規則」(1895年) 「自殺」(1897年) 「近親相姦の禁止とその起源」(1897年)『社会学年報』第1巻、1-70ページ 社会学とその科学領域(1900年)は、イタリア語の「La sociologia e il suo dominio scientifico」の翻訳である 『原始分類』(1903年)は、マルセル・モースとの共著 『宗教的生活の要素』(1912年)[79][97] 『戦争を誰が望んだか』(1914年)は、エルネスト・ドニとの共著 『ドイツ・アルゲマイネ』(1915年) 死後出版された[98][99] 教育と社会学(1922年) 社会学と哲学(1924年) 道徳教育(1925年) 社会主義(1928年) プラグマティズムと社会学(1955年) |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%89mile_Durkheim |

★年譜