フィリピンの民衆美学の探求

音楽・言説・聖像

Philippines Popular

Aesthetics

Filipino Bamboo orchestra

☆ フィリピンの芸術(Arts in the Philippines)は、土着の芸術を含め、この国の文化に影響を与えた様々な芸術を反映している。フィリピンの芸術は、伝統 的な芸術[1]と非伝統的な芸術[2]の2つの分野から成り立っている。フィリピン政府の文化機関である文化芸術国民委員会は、フィリピンの芸術を伝統的 なものと非伝統的なものに分類している。各カテゴリーにはサブカテゴリーがある。

伝 統芸術:[1]

非伝統芸術:[2]

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Arts_in_the_Philippines

"Filipino Bamboo" is

a song that has become a beloved classic, initially composed in 1910.

Its enduring popularity stems from its catchy melody and meaningful

lyrics that resonate with listeners. The song's nostalgic charm

captures the essence of Filipino culture, celebrating natural beauty

and the simplicity of life. With references to bamboo, a symbol of

resilience and strength in Filipino culture, the song evokes a sense of

national pride and unity. Through its timeless appeal, "Filipino

Bamboo" continues to be treasured by generations, bridging the past

with the present in musical harmony. "Filipino Bamboo" is

a song that has become a beloved classic, initially composed in 1910.

Its enduring popularity stems from its catchy melody and meaningful

lyrics that resonate with listeners. The song's nostalgic charm

captures the essence of Filipino culture, celebrating natural beauty

and the simplicity of life. With references to bamboo, a symbol of

resilience and strength in Filipino culture, the song evokes a sense of

national pride and unity. Through its timeless appeal, "Filipino

Bamboo" continues to be treasured by generations, bridging the past

with the present in musical harmony.https://www.facebook.com/factsZero |

「フィリピン・バンブー」は、1910年に作曲されて以来、愛され続け

ている名曲だ。その不朽の人気は、キャッチーなメロディーと、聴く人の心に響く意味深い歌詞に由来する。この曲のノスタルジックな魅力はフィリピン文化の

本質を捉えており、自然の美しさとシンプルな生活を賛美している。フィリピン文化における回復力と強さの象徴である竹を引用したこの曲は、国民の誇りと団

結の感覚を呼び起こす。時代を超越した魅力を持つ「Filipino

Bamboo」は、世代を超えて愛され続け、過去と現在を音楽のハーモニーで繋いでいる。 「フィリピン・バンブー」は、1910年に作曲されて以来、愛され続け

ている名曲だ。その不朽の人気は、キャッチーなメロディーと、聴く人の心に響く意味深い歌詞に由来する。この曲のノスタルジックな魅力はフィリピン文化の

本質を捉えており、自然の美しさとシンプルな生活を賛美している。フィリピン文化における回復力と強さの象徴である竹を引用したこの曲は、国民の誇りと団

結の感覚を呼び起こす。時代を超越した魅力を持つ「Filipino

Bamboo」は、世代を超えて愛され続け、過去と現在を音楽のハーモニーで繋いでいる。https://www.facebook.com/factsZero |

| The

culture of the Philippines

is characterized by cultural and ethnic diversity.[1] Although the

multiple ethnic groups of the Philippine archipelago have only recently

established a shared Filipino national identity,[2] their cultures were

all shaped by the geography and history of the region,[3][4] and by

centuries of interaction with neighboring cultures, and colonial

powers.[5][6] In more recent times, Filipino culture has also been

influenced through its participation in the global community.[7] |

フィ

リピンの文化は、文化的・民族的多様性を特徴としている[1]。フィリピン群島の複数の民族がフィリピン国民としてのアイデンティティを共有するように

なったのはごく最近のことだが[2]、その文化はすべて、この地域の地理や歴史[3][4]、近隣の文化や植民地支配国との何世紀にもわたる交流によって

形成されたものである[5][6]。さらに最近では、フィリピン文化は国際社会への参加によっても影響を受けている[7]。 |

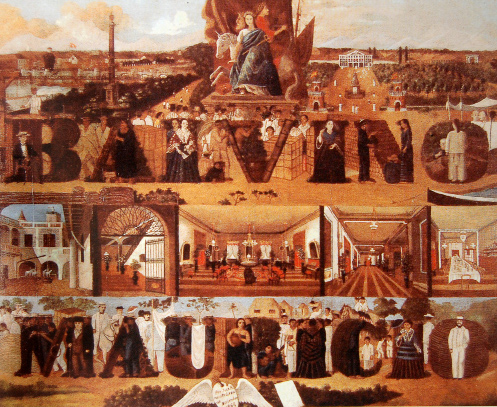

| History Further information: History of the Philippines Among the contemporary ethnic groups of the Philippine archipelago, the Negritos are generally considered the earliest settlers;[8] today, although few in numbers, they preserve a very traditional way of life and culture. After those early settlers, the Austronesians arrived on the archipelago. The Austronesian culture is strongly evident in the ethnic majority and languages. Before the arrival of European colonizers in the 1500s, the various ethnic groups of the Philippines were organized into various independent polities,[5][6] which historians have come to call "barangays".[9][10][a] These polities consisted of about thirty to a hundred households,[2][9] and were ruled by leaders with titles.[2] The largest of these, such as Butuan, Tondo and the Sultanate of Sulu were complex political formations based on the deltas of the archipelago's biggest river systems, with political and trade relationships with polities further upstream on one hand, and with the political and trading powers of Maritime Southeast Asia and East Asia such as the Sultanate of Brunei, the Majapahit empire, the Qing and Ming Dynasties of China, and even Japan. Indirect cultural exchange and some trade also took place with the Indian subcontinent and Arabia.[11] The advent of Spanish colonial rule in the islands marked the beginning of the Philippines as an entity, a collection of Southeast Asian countries united under the Spanish Empire. The empire ruled, via the Viceroyalty of New Spain and later directly from Madrid (after 1821 Mexican independence), the islands between the 16th and 19th centuries (Batanes being one of the last places to be colonized in the mid-1800s), resulting in Christianity to spread and dominate throughout the archipelago and influenced the religion and beliefs of the natives. Then, the Philippines became a U.S. territory for almost 50 years. Influence from the United States is manifested in the wide use of the English language, media and in the modern culture and clothing of present-day Philippines.[12] |

歴史 さらに詳しい情報 フィリピンの歴史 フィリピン群島の現存する民族の中で、ネグリト人は一般的に最も早く入植した民族と考えられている[8]。今日、数は少ないものの、彼らは非常に伝統的な 生活様式と文化を保持している。これらの初期入植者の後、オーストロネシア人がこの諸島に到着した。オーストロネシア文化は、民族の多数派と言語に強く表 れている。 1500年代にヨーロッパの植民者が到着する以前は、フィリピンの様々な民族は、歴史家が「バランガイ」と呼ぶようになった様々な独立した政体[5] [6]に組織されていた[9][10][a]。これらの政体は約30から100世帯からなり[2][9]、称号を持つ指導者によって統治されていた。 [最大規模のブトゥアン、トンド、スールーのスルタン国などは、群島最大の河川のデルタ地帯を基盤にした複雑な政治形態であり、一方ではさらに上流の諸政 体との政治的・貿易的関係を持ち、またブルネイのスルタン国、マジャパヒト帝国、中国の清朝や明朝、さらには日本など、東南アジアや東アジア海域の政治 的・貿易的大国との関係を持っていた。インド亜大陸やアラビアとも間接的な文化交流や貿易が行われていた[11]。 スペインによるフィリピン植民地支配の開始は、スペイン帝国の下に統合された東南アジア諸国の集合体としてのフィリピンの始まりであった。帝国は16世紀 から19世紀にかけて、新スペイン総督府を経由し、後にマドリードから直接(1821年のメキシコ独立後)、島々を統治した(バタネス島は1800年代半 ばに植民地化された最後の場所のひとつである)。その後、フィリピンは50年近くアメリカ領となった。アメリカからの影響は、英語の幅広い使用やメディ ア、現在のフィリピンの近代的な文化や衣服に現れている[12]。 ︎▶先スペイン期のフィリピンの歴史︎▶︎︎フィリピンの歴史(スペイン支配期)▶フィリピン共和国の歴史(1899年以降)︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎ |

| Geography and ethnic groups Main articles: Geography of the Philippines and Ethnic groups in the Philippines  Dominant ethnic groups by province. The Philippines' culture is shaped by its archipelagic geography, topography and physical location within Maritime Southeast Asia, all of which defined the cultural histories of the country's 175 Ethnolinguistic groups.[3][4][13]: 68 Influence of geography The cultural diversity of the Philippines is the result of the country's archipelagic nature. The Philippines, as the world's fifth largest island country,[14] is one of the five original archipelagic states recognized under the United Nations Convention on the Law of the Sea (UNCLOS).[15] Its 7,641 islands[18] have a total land area of 300,000 square kilometers (115,831 sq mi);[19][20] its exclusive economic zone—covering an area 200 nautical miles (370 km) from its islands' shores—encompasses 2,263,816 square kilometers (874,064 sq mi) of sea.[21] Maritime and river transport allowed cultural exchanges between the country's diverse ethnic groups who settled on various islands within the archipelago; inland mountain ranges, on the other hand, were a major hindrance to cultural linkages between various groups.[2] Ethnic groups of the Philippines The Philippines is inhabited by more than 182 ethnolinguistic groups,[22]: 5 many of which are classified as "Indigenous Peoples" under the country's Indigenous Peoples' Rights Act of 1997. Traditionally-Muslim peoples from the southernmost island group of Mindanao are usually categorized together as Moro peoples, whether they are classified as Indigenous peoples or not. About 142 are classified as non-Muslim Indigenous People groups, and about 19 ethnolinguistic groups are classified as neither indigenous nor moro.[22]: 6 Various migrant groups have also had a significant presence throughout the country's history. The Muslim-majority ethnic groups ethnolinguistic groups of Mindanao, Sulu, and Palawan are collectively referred to as the Moro people,[23] a broad category which includes some indigenous people groups and some non-indigenous people groups.[22]: 6 About 142 of the Philippines' Indigenous People groups are not classified as moro peoples.[22]: 6 Some of these people groups are commonly grouped together due to their strongly association with a shared geographic area, although these broad categorizations are not always welcomed by the ethnic groups themselves.[24][25][26] For example, the indigenous peoples of the Cordillera Mountain Range in northern Luzon have often been referred to using the exonym[24] "Igorot people," and as the Cordilleran peoples.[24] Meanwhile, the non-Moro peoples of Mindanao are collectively referred to as the Lumad, a collective autonym conceived in 1986 as a way to distinguish them from their neighboring indigenous Moro neighbors.[27] About 86 to 87 percent of the Philippine population belong to the 19 ethnolinguistic groups are classified as neither indigenous nor moro.[22]: 6 known simply as Filipinos, these groups are sometimes collectively referred to as "Lowland Christianized groups" to distinguish them from the other ethnolinguistic groups.[28] The most populous of these groups, with populations exceeding a million individuals, are the Ilocano, the Pangasinense, the Kapampangan, the Tagalog, the Ivatan, the Cuyonon, the Bicolano, the Visayans (Cebuanos, Boholano, the Hiligaynon/Ilonggo, and Waray) and many more.[22]: 16 These groups converted to Christianity and was part of the Spanish empire,[citation needed] particularly both the native and migrant lowland-coastal groups,[29] and adopted foreign elements of culture throughout the country's history.[citation needed] Due to the history of the Philippines since the Spanish colonial era, there are also some historical migrant heritage groups within the lowland Filipino populations such as the Chinese Filipinos and Spanish Filipinos, both of whom intermixed with the above lowland Austronesian-speaking ethnic groups, which produced Filipino Mestizos. These groups also comprise and contribute a considerable proportion of the country's population,[30] especially its bourgeois,[31] and economy[31][32][33][34] and were integral to the establishment of the country,[29] from the rise of Filipino nationalism by the Ilustrado intelligentsia to the Philippine Revolution.[35] Other peoples of migrant and/or mixed descent include those such as, American Filipinos, Indian Filipinos,[36] Japanese Filipinos,[37] and many more. Indigenous peoples  A Tboli woman weaving t'nalak from South Cotabato. These paragraphs are an excerpt from Indigenous peoples of the Philippines.[edit] The indigenous peoples of the Philippines are ethnolinguistic groups or subgroups that maintain partial isolation or independence throughout the colonial era, and have retained much of their traditional pre-colonial culture and practices.[38] The Philippines has 110 enthnolinguistic groups comprising the Philippines' indigenous peoples; as of 2010, these groups numbered at around 14–17 million persons.[39] Austronesians make up the overwhelming majority, while full or partial Negritos scattered throughout the archipelago. The highland Austronesians and Negrito have co-existed with their lowland Austronesian kin and neighbor groups for thousands of years in the Philippine archipelago. Culturally-indigenous peoples of northern Philippine highlands can be grouped into the Igorot (comprising many different groups) and singular Bugkalot groups, while the non-Muslim culturally-indigenous groups of mainland Mindanao are collectively called Lumad. Australo-Melanesian groups throughout the archipelago are termed Aeta, Ita, Ati, Dumagat, among others. Numerous culturally-indigenous groups also live outside these two indigenous corridors.[40] In addition to these labels, groups and individuals sometimes identify with the Tagalog term katutubo, which denotes any person of indigenous origin.[41][42][43] According to the Komisyon sa Wikang Filipino, there are 135 recognized local indigenous Austronesian languages in the Philippines, of which one (Tagalog) is vehicular and each of the remaining 134 is vernacular.[citation needed] |

地理と民族 主な記事 フィリピンの地理、フィリピンの民族  フィリピンの主な民族 フィリピンの文化は、その群島的な地理、地形、東南アジア海域の物理的な位置によって形成されており、これらすべてがフィリピンの175の民族言語グルー プの文化的な歴史を決定づけた[3][4][13]: 68 地理の影響 フィリピンの文化的多様性は、この国の群島的性質の結果である。フィリピンは世界で5番目に大きな島国であり[14]、国連海洋法条約(UNCLOS)で 認められた5つの群島国家のひとつである。 [15]7,641の島々[18]の総陸地面積は300,000平方キロメートル(115,831平方マイル)[19][20]であり、排他的経済水域は 島々の海岸から200海里(370キロメートル)をカバーし、2,263,816平方キロメートル(874,064平方マイル)の海域に及ぶ。 [21]海運と河川運輸は、群島内の様々な島に定住する国内の多様な民族間の文化交流を可能にしたが、一方で内陸の山脈は、様々な民族間の文化的つながり を妨げる大きな障害となった[2]。 フィリピンの民族 フィリピンには182以上の民族が居住している[22]: その多くは、1997年に制定された先住民族の権利に関する法律の下で「先住民族」に分類され ている。ミンダナオ島の最南端に位置する島々に住む伝統的にイスラム教を信仰する民族は、先住民族に分類されるか否かにかかわらず、通常モロ民族に分類さ れる。約142が非イスラム系先住民族グループとして分類され、約19の民族言語グループが先住民族でもモロ族でもないと分類されている[22]。 ミンダナオ、スールー、パラワンのイスラム教徒が多数を占める民族グループの民族言語集団はモロ族と総称され[23]、先住民族グループと非先住民族グ ループを含む広義のカテゴリーである[22]: 6。 フィリピンの先住民族のうち約142のグループはモロ民族として分類されていない[22]: 6 これらの民族グループの一部は、共有する地理的地域と強く結びついているため、一般的にひとまとめにされているが、こうした大まかな分類は民族グループ自 身には必ずしも歓迎されていない。 [24][25][26]例えば、ルソン島北部のコーディリエラ山脈の先住民族は、しばしば「イゴロット族」という外来語[24]を用い、コーディリエラ 民族と呼ばれてきた[24]。一方、ミンダナオ島の非モロ民族は、近隣の先住民族であるモロ族と区別する方法として1986年に考案された総称であるルマ ド族と総称されている[27]。 フィリピンの人口の約86~87パーセントは、先住民族でもモロ族でもない19の民族言語集団に属している[22]。単にフィリピン人として知られるこれ らの集団は、他の民族言語集団と区別するために「低地キリスト教化集団」と総称されることもある。 [28] これらの集団の中で最も人口が多く、100万人を超える人口を持つのは、イロカノ人、パンガシネンセ人、カパンパンガン人、タガログ人、イヴァタン人、ク ヨノン人、ビコラノ人、ビサヤ人(セブアノ人、ボホラノ人、ヒリガイノン人/イロンゴ人、ワライ人)などである[22]: 16 これらのグループはキリスト教に改宗し、スペイン帝国の一部となり[要出典]、特に低地沿岸部の先住民グループと移民グループの両方が[29]、国の歴史 を通じて外国文化の要素を取り入れた[要出典]。 スペイン植民地時代からのフィリピンの歴史により、低地フィリピン人集団の中にも中国系フィリピン人やスペイン系フィリピン人などの歴史的移民遺産集団が 存在し、両者は上記の低地オーストロネシア語を話す民族集団と混血し、フィリピンのメスティーソを生み出した。これらの集団はまた、国民[30]、特にブ ルジョワ[31]、経済[31][32][33][34]のかなりの割合を構成し、貢献しており、イルストラード知識階級によるフィリピン・ナショナリズ ムの台頭からフィリピン革命[35]に至るまで、国の成立に不可欠な存在であった[29]。移民系および/または混血系には他に、アメリカ系フィリピン 人、インド系フィリピン人[36]、日系フィリピン人[37]など、多くの民族が含まれる。 先住民族  南コタバトでトナラクを織るトボリの女性。 これらのパラグラフはフィリピンの先住民[編集]からの抜粋である。 フィリピンの先住民族は、植民地時代を通じて部分的な孤立または独立を維持し、植民地時代以前の伝統的な文化や慣習の多くを保持している民族言語集団また は小集団である[38]。 フィリピンには、フィリピンの先住民族を構成する110の民族言語集団があり、2010年現在、これらの集団の人口は約1,400万人から1,700万人 である[39]。オーストロネシア人が圧倒的多数を占め、ネグリト人が全体的または部分的に群島全体に散在している。高地のオーストロネシア人とネグリト 人は、低地のオーストロネシア人の親族や近隣のグループとフィリピン諸島で数千年にわたって共存してきた。 フィリピン北部高地の文化的先住民族は、イゴロット族(多くの異なるグループから成る)と特異なブガロット族に分類され、ミンダナオ島本土の非イスラム系 文化的先住民族はルマド族と総称される。また、ミンダナオ島本土の非イスラム系文化的先住民族を総称してルマド(Lumad)と呼ぶ。これらの2つの先住 民の回廊の外側にも、多数の文化的先住民集団が居住している[40]。これらのレッテルに加えて、集団や個人は、先住民出身者を示すタガログ語のカトゥ トゥボ(katutubo)という用語を用いることもある[41][42][43]。 Komisyon sa Wikang Filipinoによれば、フィリピンには135のオーストロネシア系現地土着言語が認められており、そのうち1つ(タガログ語)は車両言語であり、残り の134はそれぞれ現地語である[要出典]。 |

| Filipino psychology Main article: Filipino psychology A formal field interpreting Psychology as rooted on the experience, ideas, and cultural orientation of the Filipinos, called Filipino psychology, was established in 1975.[44] Values Main article: Filipino values As a general description, the distinct value system of Filipinos is rooted primarily in personal alliance systems, especially those based in kinship, obligation, friendship, religion (particularly Christianity), and commercial relationships.[45] Filipino values are, for the most part, centered around maintaining social harmony, motivated primarily by the desire to be accepted within a group.[46] The main sanction against diverging from these values are the concepts of "Hiya", roughly translated as 'a sense of shame', and "Amor propio" or 'self-esteem'.[46] Social approval, acceptance by a group, and belonging to a group are major concerns. Caring about what others will think, say or do, are strong influences on social behavior among Filipinos.[47] Other elements of the Filipino value system are optimism about the future, pessimism about present situations and events, concern and care for other people, the existence of friendship and friendliness, the habit of being hospitable, religious nature, respectfulness to self and others, respect for the female members of society, the fear of God, and abhorrence of acts of cheating people financially and thievery.[48] |

フィリピン心理学 主な記事 フィリピン心理学 1975年にフィリピン心理学と呼ばれる、フィリピン人の経験、考え方、文化的指向に根ざした心理学を解釈する正式な分野が設立された[44]。 価値観 主な記事 フィリピン人の価値観 一般的な説明として、フィリピン人の明確な価値観は、主に個人的な同盟システム、特に親族関係、義務、友情、宗教(特にキリスト教)、商業関係に基づくも のに根ざしている[45]。 フィリピン人の価値観の大部分は、社会的調和を維持することを中心としており、主に集団の中で受け入れられたいという願望が動機となっている[46]。こ れらの価値観から逸脱することに対する主な制裁は、「恥の感覚」と大雑把に訳される「ヒヤ」と「アモール・プロピオ」または「自尊心」という概念である [46]。社会的承認、集団からの受容、集団への帰属が大きな関心事である。他人が何を考え、何を言い、何をするかを気にすることは、フィリピン人の社会 的行動に強い影響を与えている[47]。 フィリピン人の価値観の他の要素としては、未来に対する楽観主義、現在の状況や出来事に対する悲観主義、他人に対する関心や気遣い、友情と親しみの存在、 もてなす習慣、宗教性、自己と他者に対する敬意、社会の女性構成員に対する敬意、神への恐れ、金銭的に人をだます行為や泥棒行為に対する嫌悪などがある [48]。 |

| Arts Main article: Art of the Philippines Architecture Main article: Architecture of the Philippines See also: Nipa hut, Ancestral houses of the Philippines, and Earthquake Baroque  Bahay na bato, a traditional Filipino house Before the arrival of European colonizers, Austronesian architecture was the common form of housing on the archipelago.[citation needed] During the Spanish era, the new Christianized lowland culture collectively evolved a new style known as the Nipa hut (Bahay Kubo). It is characterized by use of simple materials such as bamboo and coconut as the main sources of wood. Cogon grass, Nipa palm leaves and coconut fronds are used as roof thatching. Most primitive homes are built on stilts due to frequent flooding during the rainy seasons. Regional variations include the use of thicker, and denser roof thatching in mountain areas, or longer stilts on coastal areas particularly if the structure is built over water. The architecture of other indigenous peoples may be characterized by an angular wooden roofs, bamboo in place of leafy thatching and ornate wooden carvings. The Bahay na bato architecture is a variant of Nipa Hut that emerged during the Spanish era.[49] Spanish architecture has left an imprint in the Philippines in the way many towns were designed around a central square or plaza mayor, but many of the buildings bearing its influence were demolished during World War II.[50] Some examples remain, mainly among the country's churches, government buildings, and universities. Four Philippine baroque churches are included in the list of UNESCO World Heritage Sites: the San Agustín Church in Manila, Paoay Church in Ilocos Norte, Nuestra Señora de la Asunción (Santa María) Church in Ilocos Sur, and Santo Tomás de Villanueva Church in Iloilo.[51] Vigan in Ilocos Sur is also known for the many Hispanic-style houses and buildings preserved there.[52] The introduction of Christianity brought European churches and architecture which subsequently became the center of most towns and cities in the nation. The Spaniards also introduced stones and rocks as housing and building materials and the Filipinos merged it with their existing architecture and forms a hybrid mix-architecture only exclusive to the Philippines. Filipino colonial architecture can still be seen in centuries-old buildings such as Filipino baroque churches, Bahay na bato; houses, schools, convents, government buildings around the nation. The best collection of Spanish colonial era architecture can be found in the walled city of Intramuros in Manila and in the historic town of Vigan. Colonial-era churches are also on the best examples and legacies of Spanish Baroque architecture called Earthquake Baroque which are only found in the Philippines. Historic provinces such as Ilocos Norte and Ilocos Sur, Pangasinan, Pampanga, Bulacan, Cavite, Laguna, Rizal, Batangas, Quezon, Iloilo, Negros, Cebu, Bohol and Zamboanga del Sur also boasts colonial-era buildings. The American occupation in 1898 introduced a new breed of architectural structures in the Philippines. This led to the construction of government buildings and Art Deco theaters. During the American period, some semblance of city planning using the architectural designs and master plans by Daniel Burnham was done on the portions of the city of Manila. Part of the Burnham plan was the construction of government buildings that resembled Greek or Neoclassical architecture.[53] In Iloilo, a lot of the colonial edifices constructed during the American occupation in the country can still be seen. Commercial buildings, houses and churches in that era are abundant in the city and especially in Calle Real.[54] The University of Santo Tomas Main Building in Manila is an example of Renaissance Revival architecture. The building was built in 1924 and was completed at 1927. The building, designed by Fr. Roque Ruaño, O.P., is the first earthquake-resistant building in the Philippines that is not a church[citation needed].[55] Islamic and other Asian architecture can also be seen depicted on buildings such as mosques and temples. Pre-Hispanic housing is still common in rural areas. Contemporary-style housing subdivisions and suburban-gated communities are popular in urbanized places such as Metro Manila, Central Visayas, Central Luzon, Negros Island and other prosperous regions. However, certain areas of the country like Batanes have slight differences as both Spanish and Filipino ways of architecture assimilated differently due to the climate. Limestones and coral were used as building materials.[56]  Kalesa, a traditional Philippine urban transportation, in front of Manila Cathedral entrance There have been proposals to establish a policy where each municipality and city will have an ordinance mandating all constructions and reconstructions within such territory to be inclined with the municipality or city's architecture and landscaping styles to preserve and conserve the country's dying heritage sites, which have been demolished one at a time in a fast pace due to urbanization, culturally-irresponsible development, and lack of towns-cape architectural vision. The proposal advocates for the usage and reinterpretations of indigenous, colonial, and modern architectural and landscaping styles that are prevalent or used to be prevalent in a given city or municipality. The proposal aims to foster a renaissance in Philippine landscaping and townscaping, especially in rural areas which can easily be transformed into new architectural heritage towns within a 50-year time frame. Unfortunately, many Philippine-based architecture and engineering experts lack the sense of preserving heritage townscapes,[citation needed] such as the case in Manila, where business proposals to construct structures that are not inclined with Manila's architectural styles have been continuously accepted and constructed by such experts, effectively destroying Manila's architectural townscape one building at a time. Only the city of Vigan has passed such an ordinance, which led to its declaration as a UNESCO World Heritage Site in 1999 and awarding of various recognition for the conservation and preservation of its unique architectural and landscaping styles. In 2016, bills proposing to establish a Department of Culture were filed in both chambers of Congress to help formulate policy on architecture.[57][58]  Vega Ancestral House, Misamis Oriental  Vigan City in Ilocos Sur  Aguinaldo Shrine in Cavite  Loboc Church in Bohol  Paoay Church in Ilocos Norte  Museum Agrifina Circle |

芸術 主な記事 フィリピンの芸術 建築 主な記事 フィリピンの建築 以下も参照のこと: ニッパ小屋、フィリピンの先祖代々の家、地震バロックも参照のこと。  バハイ・ナ・バト、フィリピンの伝統的な家屋 ヨーロッパからの植民者が到来する以前は、オーストロネシア建築がフィリピン諸島の一般的な住居形態であった[要出典]。 スペイン統治時代、キリスト教化された新しい低地文化は、ニッパ小屋(バハイ・クボ)として知られる新しい様式を集団的に進化させた。主な木材源として竹 やココナッツといったシンプルな素材を使用するのが特徴である。屋根葺きにはコゴン草、ニパ椰子の葉、ココナッツの葉が使われる。雨季には頻繁に洪水に見 舞われるため、ほとんどの原始的な家は高床式である。地域によって、山間部では厚く密度の高い屋根葺き材を使用したり、沿岸部では特に水上に建てられる場 合、より長い高床式屋根を使用したりする。他の先住民族の建築は、角ばった木造屋根、葉の葺き替えの代わりに竹、華麗な木彫りなどが特徴である。バハイ・ ナ・バト建築は、スペイン統治時代に出現したニッパ小屋の変形である[49]。 スペイン建築は、多くの町が中央の広場やマヨール広場を囲むように設計されたことで、フィリピンにその痕跡を残したが、その影響を受けた建物の多くは第二 次世界大戦中に取り壊された[50]。マニラのサン・アグスティン教会、イロコスノルテのパオアイ教会、イロコススールのヌエストラ・セニョーラ・デ・ ラ・アスンシオン(サンタ・マリア)教会、イロイロのサント・トマス・デ・ビジャヌエバ教会である。 [51]イロコススールのビガンは、多くのヒスパニック様式の家屋や建物が保存されていることでも知られている[52]。キリスト教の導入は、ヨーロッパ の教会や建築をもたらし、その後、国民のほとんどの町や都市の中心となった。スペイン人はまた、住宅や建築材料として石や岩を持ち込んだが、フィリピン人 はそれを既存の建築と融合させ、フィリピンだけのハイブリッドな混合建築を形成した。フィリピン・コロニアル建築は、フィリピン・バロック様式の教会、バ ハイ・ナ・バト、住宅、学校、修道院、政府庁舎など、何世紀も前に建てられた建物として今でも国民に見ることができる。スペイン植民地時代の建築が最もよ く残っているのは、マニラの城壁都市イントラムロスと歴史的な町ビガンである。コロニアル時代の教会はまた、地震バロックと呼ばれるスペイン・バロック建 築の最良の例であり遺産であり、フィリピンでしか見られない。イロコスノルテ州、イロコスサー州、パンガシナン州、パンパンガ州、ブラカン州、カビテ州、 ラグナ州、リサール州、バタンガス州、ケソン州、イロイロ州、ネグロス州、セブ州、ボホール州、サンボアンガ・デル・スール州などの歴史的な州も、植民地 時代の建物を誇っている。 1898年のアメリカ占領により、フィリピンには新しい建築様式が導入された。これにより、政府庁舎やアール・デコ様式の劇場が建設された。アメリカ統治 時代には、ダニエル・バーナムの建築デザインとマスタープランを用いた都市計画がマニラ市の一部で行われた。バーナム計画の一部は、ギリシャ建築や新古典 主義建築に似た政府庁舎の建設であった[53]。イロイロでは、アメリカ統治時代に建設された植民地時代の建造物の多くを今でも見ることができる。当時の 商業ビル、住宅、教会が市内、特にレアル通りに多く見られる[54]。 マニラのサント・トーマス大学本館はルネサンス・リバイバル建築の一例である。この建物は1924年に建設され、1927年に完成した。ロケ・ルアーニョ 神父(O.P.)の設計によるこの建物は、教会ではないフィリピン初の耐震建築物である[要出典]。地方では、先ヒスパニック時代の住宅がまだ一般的であ る。メトロ・マニラ、セントラル・ビサヤ、セントラル・ルソン、ネグロス島などの都市化された地域では、現代的なスタイルの分譲住宅や郊外のゲーテッド・ コミュニティが普及している。 しかし、バタネスのような特定の地域は、スペインとフィリピンの建築様式が気候によって同化したため、若干の違いがある。建築材料には石灰岩とサンゴが使 われた[56]。  フィリピンの伝統的な都市交通手段であるカレサ(マニラ大聖堂入口前) 都市化、文化的に無責任な開発、町並み建築のビジョンの欠如のため、速いペースで次々と取り壊されてきたフィリピンの滅びゆく遺産を保護・保全するため、 各自治体や都市が、その領域内のすべての建築や再建築を、自治体や都市の建築様式や景観様式に沿ったものにすることを義務付ける条例を制定する政策が提案 されている。この提案は、特定の都市や自治体で普及している、あるいはかつて普及していた、土着的、植民地的、近代的な建築様式や景観様式を利用し、再解 釈することを提唱するものである。この提案は、フィリピンの造園と町並みのルネッサンスを促進することを目的としており、特に農村部では、50年という時 間枠の中で、新しい建築遺産の町へと容易に変貌させることができる。残念なことに、フィリピンの建築や工学の専門家の多くは、遺産となる町並みを保存する という感覚に欠けており[要出典]、例えばマニラでは、マニラの建築様式にそぐわない建築物を建設するという事業提案が、そのような専門家によって受け入 れられ、建設され続けてきた。ビガン市だけがこのような条例を制定し、1999年にユネスコ世界遺産に登録され、その独特な建築様式や景観の保存と保全に 対して様々な表彰を受けるに至った。2016年には、建築に関する政策を策定するための文化省の設置を提案する法案が両議会に提出された[57] [58]。  Vega Ancestral House, Misamis Oriental  Vigan City in Ilocos Sur  Aguinaldo Shrine in Cavite  Loboc Church in Bohol  Paoay Church in Ilocos Norte  Museum Agrifina Circle |

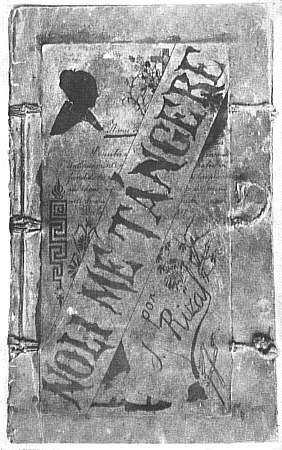

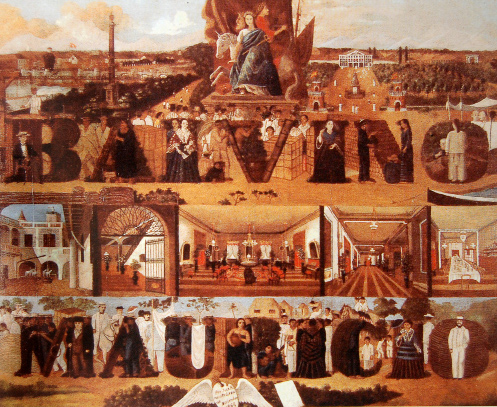

| Dancing Main article: Philippine dance  Filipino traditional dance at a festival Philippine folk dances include the Tinikling and Cariñosa. In the southern region of Mindanao, Singkil is a popular dance showcasing the story of a prince and princess in the forest. Bamboo poles are arranged in a tic-tac-toe pattern in which the dancers exploit every position of these clashing poles.[62][63] Music Main article: Music in the Philippines  Harana (serenade) The early music of the Philippines featured a mixture of Indigenous, Islamic and a variety of Asian sounds that flourished before the European and American colonization in the 16th and 20th centuries. Spanish settlers and Filipinos played a variety of musical instruments, including flutes, guitar, ukulele, violin, trumpets and drums. They performed songs and dances to celebrate festive occasions. By the 21st century, many of the folk songs and dances have remained intact throughout the Philippines. Some of the groups that perform these folk songs and dances are the Bayanihan, Filipinescas, Barangay-Barrio, Hariraya, the Karilagan Ensemble, and groups associated with the guilds of Manila, and Fort Santiago theatres. Many Filipino musicians have risen prominence such as the composer and conductor Antonio J. Molina, the composer Felipe P. de Leon, known for his nationalistic themes and the opera singer Jovita Fuentes. Modern day Philippine music features several styles. Most music genres are contemporary such as Filipino rock, Filipino hip hop and other musical styles. Some are traditional such as Filipino folk music. Literature Main article: Literature of the Philippines  Noli Me Tángere (novel) The Philippine literature is a diverse and rich group of works that has evolved throughout the centuries. It had started with traditional folktales and legends made by the ancient Filipinos before Spanish colonization. The main themes of Philippine literature focus on the country's pre-Hispanic cultural traditions and the socio-political histories of its colonial and contemporary traditions. The literature of the Philippines illustrates the Prehistory and European colonial legacy of the Philippines, written in both Indigenous and Hispanic writing system. Most of the traditional literatures of the Philippines were written during the Spanish period, while being preserved orally prior to Spanish colonization. Philippine literature is written in Spanish, English, or any indigenous Philippine languages. Some well known works of literature were created in the 17th to 19th centuries. The Ibong Adarna is a famous epic about a magical bird which was claimed to be written by José de la Cruz or "Huseng Sisiw".[64] Francisco Balagtas is one of the country's prominent Filipino poets, he is named as one of the greatest Filipino literary laureates for his contributions in Philippine literature. His greatest work, the Florante at Laura is considered as his greatest work and one of the masterpieces of Philippine literature. Balagtas wrote the epic during his imprisonment.[65] José Rizal, the national hero of the country, wrote the novels Noli Me Tángere (Touch Me Not) and El Filibusterismo (The Filibustering, also known as The Reign of Greed). Nínay By Pedro Paterno, explores the tragic life of a female protagonist Ninay. There have been proposals to revive all indigenous ethnic scripts or suyat in the Philippines, where the ethnic script of the ethnic majority of the student population shall be taught in public and private schools. The proposal came up after major backlash came about when a bill declaring the Tagalog baybayin as the national script of the country. The bill became controversial as it focuses only on the traditional script of the Tagalog people, while dismissing the traditional scripts of more than 100 ethnic groups in the country. The new proposal that came after the backlash cites that if the ethnic majority is Sebwano, then the script that will be taught is badlit. If the ethnic majority is Tagalog, then the script that will be taught is baybayin. If the ethnic majority is Hanunuo Mangyan, then the script that will be taught is hanunu'o, and so on.[66] Cinema and media Main article: Cinema of the Philippines Salón de Pertierra was the first introduced moving picture on January 1, 1897, in the Philippines. All films were all in Spanish since Philippine cinema was first introduced during the final years of the Spanish era of the country. Antonio Ramos was the first known movie producer. He used the Lumiere Cinematograph when he filmed Panorama de Manila (Manila landscape), Fiesta de Quiapo (Quiapo Fiesta), Puente de España (Bridge of Spain), and Escenas Callejeras (Street scenes). Meanwhile, Jose Nepomuceno was dubbed as the "Father of Philippine Cinema".[67] Dubbed as the "Father of Philippine Cinema", his work marked the start of cinema as an art form in the Philippines.[68] His first film produced was entitled Dalagang Bukid (Country Maiden) in 1919. Film showing resumed in 1900 during the American period. Walgrah, a British entrepreneur, opened the Cine Walgrah at No. 60 Calle Santa Rosa in Intramuros. It was also during this time that a movie market was formally created in the country along with the arrival of silent movies. These silent films were always accompanied by gramophone, a piano, a quartet, or a 200-man choir. During the Japanese occupation, filmmaking was put on hold. Nonetheless, it was continued on 1930s up until 1945 replacing the Hollywood market with Japanese films but met with little success. Postwar 1940s and the 1950s were known as the first golden age of Philippine cinema with the resurgence of mostly Visayan films through Lapu-Lapu Pictures. Nationalistic films became popular, and movie themes consisting primarily of war and heroism and proved to be successful with Philippine audiences.[citation needed]  Mila del Sol starred in one of the earliest Filipino movies, Giliw Ko (1939), along with Fernando Poe Sr. The 1950s saw the first golden age of Philippine cinema,[69][70] with the emergence of more artistic and mature films, and significant improvement in cinematic techniques among filmmakers. The studio system produced frenetic activity in the Philippine film industry as many films were made annually and several local talents started to gain recognition abroad. Award-winning filmmakers and actors were first introduced during this period. As the decade drew to a close, the studio system monopoly came under siege as a result of labor-management conflicts. During the 1960s, James Bond movies, bomba (soft porn) pictures and an era of musical films, produced mostly by Sampaguita Pictures, dominated the cinema. The second golden age occurred from the 1970s to early 1980s. It was during this era that filmmakers ceased to produce pictures in black and white. A rise in Hollywood films dominated theater sales during the late 1980s until the 2000s.[71] The dawn of this era saw a dramatic decline of the mainstream Philippine movie industry.[72] The 1970s and 1980s were considered turbulent years for the Philippine film industry, bringing both positive and negative changes. The films in this period dealt with more serious topics following the Martial law era. In addition, action, western, drama, adult and comedy films developed further in picture quality, sound and writing. The 1980s brought the arrival of alternative or independent cinema in the Philippines.[citation needed] The 1990s saw the emerging popularity of drama, teen-oriented romantic comedy, adult, comedy and action films.[70] The mid-2010s also saw broader commercial success of films produced by independent studios.[73][74] The Philippines, being one of Asia's earliest film industry producers, remains undisputed in terms of the highest level of theater admission in Asia. Over the years, however, the Philippine film industry has registered a steady decline in movie viewership from 131 million in 1996 to 63 million in 2004.[75][71] From a high production rate of 350 films a year in the 1950s, and 200 films a year during the 1980s, the Philippine film industry production rate declined in 2006 to 2007.[75][71] The 21st century saw the rebirth of independent filmmaking through the use of digital technology and a number of films have once again earned nationwide recognition and prestige. With the high rates of film production in the past, several movie artists have appeared in over 100+ roles in Philippine Cinema and enjoyed great recognition from fans and moviegoers. Protest art Further information: Propaganda Movement and Protest art against the Marcos dictatorship Protest art has played an important part in Philippine history, and in the development of Philippine culture.[76] The Propaganda Movement had been key in the formation of the Philippine national consciousness in the 19th century.[77] In the 20th century, the proclamation of Martial law under Ferdinand Marcos - and the subsequent human rights abuses which came with it - led to the prominence of protest art in Filipino popular culture.[78][79] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_of_the_Philippines |

ダンス 主な記事 フィリピンのダンス  祭りで踊られるフィリピンの伝統舞踊 フィリピンの民族舞踊には、ティニクリングやカリニョサがある。ミンダナオ島南部では、森の中の王子と王女の物語を踊るシンキルが人気だ。竹竿が三目並べ に配置され、踊り手はこのぶつかり合う竹竿のあらゆる位置を利用する[62][63]。 音楽 主な記事 フィリピンの音楽  ハラナ(セレナーデ) フィリピンの初期の音楽は、16世紀と20世紀のヨーロッパとアメリカの植民地化以前に栄えた、先住民、イスラム、アジアの様々な音が混ざったものだっ た。スペイン人入植者とフィリピン人は、フルート、ギター、ウクレレ、バイオリン、トランペット、ドラムなど様々な楽器を演奏した。彼らは祝祭を祝うため に歌や踊りを披露した。21世紀になっても、フィリピン全土で多くの民謡や踊りがそのまま残っている。これらの民謡や踊りを披露するグループには、バヤニ ハン、フィリピネスカス、バランガイ・バリオ、ハリラヤ、カリラガン・アンサンブル、マニラのギルドやフォート・サンティアゴ劇場に関連するグループなど がある。作曲家で指揮者のアントニオ・J・モリーナ、民族主義的なテーマで知られる作曲家のフェリペ・P・デ・レオン、オペラ歌手のジョビタ・フエンテス など、多くのフィリピン人音楽家が台頭してきた。 現代のフィリピン音楽にはいくつかのスタイルがある。ほとんどの音楽ジャンルは、フィリピン・ロック、フィリピン・ヒップホップなどの現代音楽である。 フィリピンの民族音楽のような伝統的なものもある。 文学 主な記事 フィリピンの文学  ノリ・メ・タンゲレ(小説) フィリピン文学は、何世紀にもわたって発展してきた多様で豊かな作品群である。その始まりは、スペインによる植民地化以前のフィリピン古来の伝統的な民話 や伝説であった。フィリピン文学の主なテーマは、この国のヒスパニック以前の文化的伝統と、植民地時代と現代の社会政治的歴史に焦点を当てている。フィリ ピンの文学は、フィリピンの先史時代とヨーロッパ植民地時代の遺産を、先住民とヒスパニックの両方の文字体系で書かれている。フィリピンの伝統的な文学の ほとんどはスペイン統治時代に書かれたもので、スペインによる植民地化以前は口承で保存されていた。フィリピン文学はスペイン語、英語、フィリピン土着の 言語で書かれている。 有名な文学作品は17世紀から19世紀にかけて書かれたものである。イボン・アダルナは、ホセ・デ・ラ・クルスまたは 「フセン・シシウ 」によって書かれたと主張される、魔法の鳥についての有名な叙事詩である[64] フランシスコ・バラグタスは、フィリピンの著名な詩人の一人であり、フィリピン文学における貢献により、フィリピンで最も偉大な文学賞受賞者の一人に数え られている。彼の代表作である『ローラのフロランテ』は、彼の最高傑作であり、フィリピン文学の傑作のひとつとされている。バラグタスは投獄中にこの叙事 詩を書いた[65]。国民的英雄であるホセ・リサールは、小説『Noli Me Tángere(触れるな)』や『El Filibusterismo(貪欲の支配)』を書いた。Nínay By Pedro Paterno』は、女性主人公ニネイの悲劇的な人生を描いている。 フィリピンでは、公立・私立の学校において、生徒の大多数を占める民族の民族文字を教えるという、土着のすべての民族文字(スヤット)を復活させるという 提案がある。この提案は、タガログ語のベイバインを国民文字とする法案が提出され、大きな反発を受けたことから浮上した。この法案は、タガログ民族の伝統 的な文字にのみ焦点を当て、国内の100以上の民族の伝統的な文字を否定するもので、物議を醸した。反発の後に出された新提案では、セブワノ族が多数派の 場合、教える文字はバドリットになる。民族の大多数がタガログ語であれば、教える文字はベイバインである。民族的多数派がハヌヌオ・マンギャンであれば、 教えられる台本はハヌヌオである、といった具合である[66]。 映画とメディア 主な記事 フィリピンの映画 サロン・デ・ペルティエラは、1897年1月1日にフィリピンで初めて導入された映画である。フィリピンの映画が最初に紹介されたのは、スペイン統治時代 の最後の数年間であったため、映画はすべてスペイン語であった。アントニオ・ラモスが最初の映画製作者として知られている。彼はリュミエール・シネマトグ ラフを使い、マニラの風景、キアポのフィエスタ、スペインの橋、通りの風景を撮影した。一方、ホセ・ネポムセノは「フィリピン映画の父」と呼ばれ [67]、彼の作品はフィリピンにおける芸術としての映画の始まりとなった[68] 。 映画上映はアメリカ時代の1900年に再開された。イギリス人企業家のウォルグラは、イントラムロスのサンタ・ロサ通り60番地にシネ・ウォルグラをオー プンした。無声映画の登場とともに、国内で映画市場が正式に形成されたのもこの時期である。これらの無声映画には、蓄音機、ピアノ、カルテット、あるいは 200人の合唱団が必ずついていた。日本統治時代、映画製作は中断された。それでも、1930年代から1945年まで、ハリウッド市場を日本映画に置き換 えて映画製作は続けられたが、ほとんど成功しなかった。戦後1940年代から1950年代にかけては、ラプラプ・ピクチャーズ(Lapu-Lapu Pictures)を通して主にビサヤ映画が復活し、フィリピン映画の最初の黄金時代として知られた。国粋主義的な映画が人気となり、映画のテーマは主に 戦争とヒロイズムで構成され、フィリピンの観客の間で成功を収めた[要出典]。  ミラ・デル・ソルは、フェルナンド・ポーSr.と共に、最も初期のフィリピン映画のひとつである『ギリウ・コ』(1939年)に主演した。 1950年代には、フィリピン映画の最初の黄金時代が到来し[69][70]、より芸術的で成熟した映画が出現し、映画製作者たちの間で映画技術が著しく 向上した。スタジオ制度はフィリピン映画界に熱狂的な活動をもたらし、毎年多くの映画が製作され、何人かの地元の才能が海外で認められるようになった。受 賞歴のある映画監督や俳優が初めて登場したのもこの時期である。10年代が終わりに近づくにつれ、労使紛争の結果、スタジオシステムの独占は四面楚歌と なった。 1960年代には、ジェームズ・ボンド映画、ボンバ(ソフト・ポルノ)映画、そして主にサンパギータ・ピクチャーズが製作したミュージカル映画が映画界を 席巻した。第二の黄金期は1970年代から1980年代初頭にかけてである。この時代、映画製作者たちは白黒映画の製作を中止した。1980年代後半から 2000年代にかけて、ハリウッド映画の台頭が劇場の売上を支配した[71]。この時代の幕開けとともに、フィリピンの主流映画産業は劇的に衰退した [72]。 1970年代と1980年代は、フィリピン映画産業にとって激動の時代とされ、ポジティブな変化とネガティブな変化の両方がもたらされた。この時代の映画 は、戒厳令の時代を経て、より深刻なテーマを扱った。また、アクション、西部劇、ドラマ、成人映画、コメディ映画が画質、音響、脚本においてさらに発展し た。1980年代には、フィリピンにオルタナティブ映画やインディペンデント映画が登場した[citation needed]。1990年代には、ドラマ、ティーン向けのロマンチックコメディ、アダルト、コメディ、アクション映画の人気が出てきた[70]。 2010年代半ばには、独立系スタジオによって製作された映画の商業的な成功も見られた[73][74]。 フィリピンは、アジアで最も早い時期に映画産業を興した国のひとつであり、アジアで最も高い水準の劇場入場者数を誇っている。1950年代には年間350 本、1980年代には年間200本という高い製作率を誇っていたフィリピン映画産業の製作率は、2006年から2007年にかけて低下した[75] [71]。21世紀には、デジタル技術の活用によってインディペンデント映画製作が再生し、多くの映画が再び全国的な評価と名声を獲得した。 過去の高い映画製作率により、何人かの映画人がフィリピン映画で100以上の役柄に出演し、ファンや映画ファンから高い評価を得ている。 抗議活動 さらに詳しい情報 プロパガンダ運動とマルコス独裁に対する抗議芸術 プロテスト・アートは、フィリピンの歴史やフィリピン文化の発展において重要な役割を果たしてきた[76]。 プロパガンダ運動は、19世紀のフィリピン国民意識の形成において重要な役割を果たした[77]。 20世紀には、フェルディナンド・マルコス政権下での戒厳令の布告と、それに伴う人権侵害が、フィリピンの大衆文化におけるプロテスト・アートの隆盛につ ながった[78][79]。 |

| Folklore Philippine mythology Main article: Philippine mythology Philippine mythologies are the first literature of the Philippines, usually passed on through generation via traditional and oral folk literature. Written texts recording the stories have also been made. These literary stories are mostly chanted as part of a dynamic Philippine epic poetry.[80][81] While each unique ethnic group has its own stories and myths to tell, Hindu and Spanish influences can nonetheless be detected in many cases. Philippine mythology mostly consists of creation stories or stories about supernatural creatures, such as the aswang, the manananggal, the diwata/engkanto, and nature. Some popular figures from Philippine mythologies are Makiling, Lam-Ang, and the Sarimanok.[82] |

フォークロア フィリピン神話 主な記事 フィリピン神話 フィリピンの神話はフィリピンの最初の文学であり、伝統的な口承民俗文学を通じて世代を超えて受け継がれてきた。物語を記録した文章も作られている。これ らの文学的な物語は、ダイナミックなフィリピンの叙事詩の一部として詠唱されることがほとんどである[80][81]。それぞれの民族が独自の物語や神話 を持っているが、それでも多くの場合、ヒンドゥー教やスペイン語の影響が見られる。フィリピンの神話は主に、アスワン、マナンガル、ディワタ/エンカン ト、自然などの創造物語や超自然的な生き物についての物語で構成されている。フィリピン神話で人気のある人物には、マキリン、ラム・アン、サリマノクがい る[82]。 |

| Religion Main article: Religion in the Philippines Christianity Main articles: Christianity in the Philippines, Catholic Church in the Philippines, and Protestantism in the Philippines  Original image of the Santo Niño de Cebú. The arrival of the Spanish colonizers in the 16th century brought the beginning of the Christianization of the people in the Philippines. This phase in history is noted as the tipping point for the destruction of a variety of Anitist beliefs in the country, which were replaced by colonial belief systems that fitted the tastes of the Spanish, notably Christian beliefs. Christianity in form of has influenced Filipino culture in almost every facet, from visual arts, architecture, dance, and music. Presently, the Philippines is one of the two predominantly Catholic (80.58%) nations in Asia-Pacific, the other being East Timor. The country also has its own independent Philippine church, the Aglipayan, which accounts for around 2% of the national population. Other Christian churches are divided among a variety of Christian sects and cults. From the census in 2014, Christianity consisted of about 90.07% of the population and is largely present throughout the nation.[83] Indigenous folk religions Main article: Indigenous Philippine folk religions Further information: Philippine mythology and List of Philippine mythological figures  An Itneg shaman offering pigs to anito spirits, 1922  A performer depicting a babaylan (shaman) Indigenous Philippine folk religions, also referred collectively as Anitism,[84][85] meaning ancestral religions,[86][87] are the original faiths of the diverse ethnic groups of the Philippines. Much of the texts of the religions are stored through memory which are traditionally chanted, rather than written in manuscripts.[citation needed] Written texts, however, have been utilized as well in modern times to preserve aspects of the religions, notably their stories which are important aspects of Philippine mythology and traditional rites and other practices. These stories consist of creation stories or stories about important figures such as deities and heroes and certain creatures.[citation needed] Some popular, but distinct, figures include the Tagalog's Bathala and Makiling, the Ilocano's Lam-ang, and the Maranao's Sarimanok.[82] Islam Islamic mythology arrived in the Philippines in the 13th century through trade routes in Southeast Asia. The spread of Islam established a variety of belief systems, notably in the southwestern portions of the archipelago, where the sultanate system was embraced by the natives without the need for forced conversions, as the religious traders did not intended to colonize the islands. Presently, around 6% of the population are Muslims, concentrating in the Bangsamoro region in Mindanao. Most Filipino Muslims practice Sunni Islam according to the Shafi'i school.[83] Others Hinduism arrived in the Philippines in 200–300 AD while Vajrayana Buddhism arrived around 900 AD. Most adherent of Hinduism have Indian origins while those practicing Buddhism have Chinese or Japanese origins, notably those who immigrated in the Philippines in the last few decades. Shintoism arrived prior to the 12th century due to Japanese traders, while Judaism arrived in the 16th century due to the Inquisition. Taoism is also practiced by some Chinese immigrants. Atheism is also found in the Philippines.[88][83] |

宗教 主な記事 フィリピンの宗教 キリスト教 主な記事:フィリピンのキリスト教、フィリピンのカトリック教会、フィリピンのプロテスタント フィリピンのキリスト教、フィリピンのカトリック教会、フィリピンのプロテスタント  サント・ニーニョ・デ・セブの原画。 16世紀にスペインの植民者がフィリピンにやってきて、フィリピンの人々のキリスト教化が始まった。この時期、フィリピンでは様々なアニシズム信仰が破壊 され、スペイン人の嗜好に合った植民地的な信仰体系、特にキリスト教信仰に取って代わられた。キリスト教は、視覚芸術、建築、舞踊、音楽など、ほとんどす べての面でフィリピン文化に影響を与えた。現在、フィリピンはアジア太平洋地域でカトリック教徒が多い(80.58%)2つの国民のうちの1つで、もう1 つは東ティモールである。また、フィリピン独自の独立教会であるアグリパヤンがあり、国民人口の約2%を占めている。その他のキリスト教会は、さまざまな キリスト教の宗派やカルトに分かれている。2014年の国勢調査では、キリスト教は人口の約90.07%を占め、国民全体に広く存在している[83]。 土着の民間宗教 主な記事 フィリピン先住民の民間宗教 さらに詳しい情報 フィリピンの神話、フィリピンの神話上の人物一覧  アニトの精霊に豚を捧げるイトネグのシャーマン(1922年)  ババイラン(シャーマン)を描くパフォーマティビティ。 先祖伝来の宗教を意味するアニティズム[84][85]とも総称されるフィリピン先住民の民間宗教[86][87]は、フィリピンの多様な民族の原初的な 信仰である。宗教のテキストの多くは、写本に書かれたものではなく、伝統的に唱えられる記憶によって保存されている[要出典]。 しかし、書かれたテキストは、特にフィリピンの神話や伝統的な儀式やその他の慣習の重要な側面である物語など、宗教の側面を保存するために現代でも活用さ れている。これらの物語は、創造物語や、神々や英雄、特定の生き物などの重要な人物についての物語で構成されている[要出典]。 タガログ族のバタラやマキリン、イロカノ族のラムアン、マラナオ族のサリマノクなど、ポピュラーでありながら明確な特徴を持つ人物もいる[82]。 イスラム イスラム神話は13世紀に東南アジアの交易ルートを通じてフィリピンに伝わった。イスラム教の伝播によって様々な信仰体系が確立されたが、特に列島の南西 部では、宗教商が島々を植民地化することを意図していなかったため、強制改宗の必要なくスルタン制度が原住民に受け入れられた。現在、人口の約6%がイス ラム教徒で、ミンダナオ島のバンサモロ地域に集中している。ほとんどのフィリピン人ムスリムはシャフィイー派に基づくスンニ派を信仰している[83]。 その他 ヒンドゥー教は西暦200~300年にフィリピンに伝わり、金剛界仏教は西暦900年頃に伝わった。ヒンドゥー教の信者の多くはインドに起源を持つが、仏 教の信者は中国または日本に起源を持ち、特にここ数十年の間にフィリピンに移住した信者が多い。神道は日本人商人によって12世紀以前に伝わり、ユダヤ教 は異端審問によって16世紀に伝わった。道教も一部の中国人移民によって信仰されている。無神論もフィリピンで見られる[88][83]。 |

| Rites of passage Main article: Tuli (rite) Every year, usually in April and May, thousands of Filipino boys are taken by their parents to be circumcised. According to the World Health Organization (WHO) about 90% of Filipino men are circumcised, one of the world's highest circumcision rates. Although the roots of the practice date back to the arrival of Islam in 1450, the succeeding 200 years of Spanish rule obviated the religious reasons for circumcision. Nevertheless, circumcision, called tuli, has persisted. The pressure to be circumcised is evidenced even in the language: the Tagalog word for 'uncircumcised', supot, also means 'coward'. It is commonly believed that a circumcised eight or ten year-old is no longer a boy and is given more adult roles in the family and society.[101] Intangible cultural heritage The Philippines, with the National Commission for Culture and the Arts as the de facto Ministry of Culture,[102] ratified the 2003 Convention after its formal deposit in August 2006.[103] Prior to the 2003 Convention, the Philippines was invited by UNESCO to nominate intangible heritage elements for the inclusion to the Proclamation of Masterpieces of the Oral and Intangible Heritage of Humanity. This prompted the proclamation of the Hudhud chant of the Ifugao in 2001 and Darangen epic chant of the Maranao in 2005. After the establishment of the 2003 Convention, all entries to the Proclamation of Masterpieces were incorporated in the Representative List of Intangible Cultural Heritage of Humanity in 2008. A third inscription was made in 2015 through a multinational nomination between Cambodia, the Philippines, the Republic of Korea and Viet Nam for the Tugging Rituals and Games, wherein the Punnuk, tugging ritual of the Ifugao was included. As part of the objective of the 2003 Convention, the National Commission for Culture and the Arts through the Intangible Cultural Heritage unit and in partnership with ICHCAP Archived March 1, 2018, at the Wayback Machine, published the Pinagmulan: Enumeration from the Philippine Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage Archived February 1, 2018, at the Wayback Machine in 2012. The publication contains an initial inventory of 335 ICH elements with elaborate discussions on 109 ICH elements. The elements listed are the first batch of continuous updating process initiated by the government, UNESCO, and other stakeholders. In 2014, the Pinagmulan was a finalist under the category of the Elfren S. Cruz Prize for Best Book in the Social Sciences to the National Book Awards organized by the National Book Development Board.[104] The Philippine inventory is currently being updated as a measure to safeguard more intangible cultural heritage elements in the country. The updating began in 2013 and results may be released in 5–10 years after the scientific process finishes the second batch of element documentations. According to UNESCO, it is not expected by a country or state party to have a completed inventory. On the contrary, the development and updating of inventories is an ongoing process that can never be finished.[105] Between 2015 and 2017, UNESCO's Intangible Cultural Heritage Courier of Asia and the Pacific featured the darangen epic chant,[106] punnuk tugging ritual,[107] and at least three kinds of traditional healing practices in the Philippines, including the manghihilot and albularyo healing practices and belief of buhay na tubig (living water) of the Tagalog people of 20th century Quezon city,[108] the baglan and mandadawak healing practices and stone beliefs of the Itneg people in Abra,[108] and the mantatawak healing practices of the Tagalog people of Marinduque.[108]  Carabao is a major symbol of Filipinos hard labor. And is known to be the "Filipino farmer's bestfriend". By 2016, according to the ICH Unit, National Commission for Culture and the Arts, there were 367 elements listed under the Philippine Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage (PIICH), the official ICH inventory of the Philippines. All elements under the PIICH are listed in Philippine Registry of Cultural Property (PRECUP), the official cultural property inventory of the country which includes both tangible and intangible cultural properties.[109] In April 2018, the buklog of the Subanen people was nominated by the National Commission for Culture and the Arts in the list for urgent safeguarding.[110] |

通過儀礼 主な記事 割礼 毎年4月から5月にかけて、何千人ものフィリピン人男児が両親に連れられて割礼を受ける。世界保健機関(WHO)によると、フィリピン人男性の約90%が 割礼を受けており、割礼率は世界でもトップクラスである。割礼のルーツは1450年のイスラム教の伝来にさかのぼるが、その後200年にわたるスペインの 支配により、割礼の宗教的な理由は排除された。それにもかかわらず、割礼はトゥリと呼ばれ、根強く残っている。割礼を受けなければならないというプレッ シャーは、言葉にも表れている。タガログ語で「割礼を受けていない」という意味のスポートは、「臆病者」という意味もある。割礼を受けた8歳か10歳の子 供はもはや少年ではなく、家族や社会でより大人の役割を与えられると一般的に信じられている[101]。 無形文化遺産 フィリピンは、国民文化芸術委員会を事実上の文化省とし[102]、2006年8月に正式に寄託された後、2003年条約を批准した[103]。 2003年条約に先立ち、フィリピンはユネスコから、人類の口承及び無形遺産の傑作の宣言に含める無形遺産要素を推薦するよう要請されていた。その結果、 2001年にイフガオ族のフッド(Hudhud)詠唱が、2005年にマラナオ族のダランゲン(Darangen)詠唱が宣言された。2003年の条約制 定後、2008年には「人類の無形文化遺産の代表的な一覧表」に「傑作宣言」のすべての項目が組み込まれた。2015年には、カンボジア、フィリピン、大 韓民国、ベトナムの4カ国による「曳き綱の儀式と競技」の多国間推薦によって3件目の登録がなされ、イフガオ族の曳き綱の儀式「プヌク」が登録された。 2003年条約の目的の一環として、文化芸術国民委員会は無形文化遺産部門を通じて、またICHCAP Archived March 1, 2018, at the Wayback Machineと連携して、ピナグムランを発表した: フィリピン無形文化遺産目録からの列挙』(Pinagmulan: Enumeration from the Philippine Inventory of Intangible Cultural Heritage)を2012年に発行した。この出版物には、109のICH要素に関する詳細な議論とともに、335のICH要素の初期目録が掲載されて いる。掲載された要素は、政府、ユネスコ、その他の利害関係者によって開始された継続的な更新プロセスの最初のバッチである。2014年、『ピナグムラ ン』は、国家図書開発委員会(National Book Development Board)が主催する国家図書賞(National Book Awards)の社会科学部門最優秀図書賞(Elfren S. Cruz Prize for Best Book in the Social Sciences)の最終選考に残った[104]。フィリピンの目録は現在、国内のより多くの無形文化遺産要素を保護するための措置として更新中である。 更新は2013年に開始され、科学的プロセスによる要素の文書化第2弾の終了後、5~10年以内に結果が公表される可能性がある。ユネスコによれば、国や 締約国がインベントリーを完成させることは期待されていない。それどころか、インベントリの作成と更新は、決して終わることのない進行中のプロセスである [105]。 2015年から2017年にかけて、ユネスコの「アジア太平洋無形文化遺産クーリエ」は、フィリピンのダランゲン叙事詩詠唱[106]、プヌク綱引き儀式 [107]、そして少なくとも3種類の伝統的な治療法を取り上げた、 これには、20世紀ケソン市のタガログ系住民のマンギヒロットとアルブラリョの癒しの習慣とブヘイ・ナ・チュービッグ(生きている水)の信仰[108]、 アブラ州のイトネグ系住民のバグランとマンダダワクの癒しの習慣と石の信仰[108]、マリンデューク州のタガログ系住民のマンタタワクの癒しの習慣 [108]が含まれる。 [108]  カラバオはフィリピン人の重労働の主要な象徴である。そして「フィリピン農民の親友」として知られている。 2016年までに、国民文化芸術委員会ICHユニットによると、フィリピンの公式ICH目録であるフィリピン無形文化遺産目録(PIICH)に記載された 要素は367件であった。PIICHの下にあるすべての要素は、有形・無形の文化財を含む国民の公式文化財目録であるフィリピン文化財登録簿 (PRECUP)に記載されている[109]。 2018年4月、スバネン族のブクログが国家文化芸術委員会によって緊急保護リストにノミネートされた[110]。 |

| Filipino diaspora Main article: Overseas Filipino An Overseas Filipino is a person of Filipino origin, who lives outside of the Philippines. This term is applied to people of Filipino ancestry, who are citizens or residents of a different country. Often, these Filipinos are referred to as Overseas Filipino Workers. There are about 11 million overseas Filipinos living worldwide, equivalent to about 11 percent of the total population of the Philippines.[111] Each year, thousands of Filipinos migrate to work abroad through overseas employment agencies and other programs. Other individuals emigrate and become permanent residents of other nations. Overseas Filipinos often work as doctors, nurses, accountants, IT professionals, engineers, architects,[112] entertainers, technicians, teachers, military servicemen, students, caregivers, domestic helpers, and household maids. International employment includes an increasing number of skilled Filipino workers taking on unskilled work overseas, resulting in what has been referred to as brain drain, particularly in the health and education sectors. Also, the employment can result in underemployment, for example, in cases where doctors undergo retraining to become nurses and other employment programs. |

フィリピンのディアスポラ 主な記事 海外在住フィリピン人 海外在住フィリピン人とは、フィリピン出身でフィリピン国外に住む人のことである。この用語は、フィリピン人の祖先を持ち、他国の市民または居住者である 人々に適用される。多くの場合、これらのフィリピン人は海外フィリピン人労働者と呼ばれる。 海外在住フィリピン人は世界中に約1,100万人おり、フィリピンの総人口の約11%に相当する[111]。 毎年、何千人ものフィリピン人が海外の雇用機関やその他のプログラムを通じて海外で働くために移住している。また、移住して他国の永住者となる者もいる。 海外のフィリピン人は、医師、看護師、会計士、IT専門家、エンジニア、建築家、[112] 芸能人、技術者、教師、軍人、学生、介護士、家事手伝い、家政婦として働くことが多い。 国際的な雇用には、海外で非熟練労働に従事するフィリピン人熟練労働者の増加も含まれ、特に医療・教育分野において頭脳流出と呼ばれる結果をもたらしてい る。また、医師が看護師になるために再教育を受ける場合など、雇用が不完全雇用になることもある。 |

| Heritage towns and cities This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (May 2023) (Learn how and when to remove this message) The Philippines is home to numerous heritage towns and cities, many of which have been intentionally destroyed by the Japanese through fire tactics in World War II and the Americans through bombings during the same war. After the war, the government of the Empire of Japan withheld from giving funds to the Philippines for the restoration of the heritage towns they destroyed, effectively destroying any chances of restoration since the pre-war Philippines' economy was devastated and had limited monetary supply. On the other hand, the United States gave minimal funding for only two of the hundreds of cities they destroyed, namely, Manila and Baguio. Today, only the centres (poblacion or downtown areas) of Filipino heritage towns and cities remain in most of the expansive heritage cities and towns in the country. Yet, some heritage cities in their former glory prior to the war still exist, such as the UNESCO city of Vigan which was the only heritage town saved from American bombing and Japanese fire and kamikaze tactics. The country currently lacks a city/town-singular architectural style law. Due to this, unaesthetic cement or shanty structures have taken over heritage buildings annually, destroying many former heritage townscapes.[neutrality is disputed] Some heritage buildings have been demolished or sold to corporations, and have been replaced by commercial structures such as shopping centers, condominium units, or newly furnished modern-style buildings, completely destroying the old aesthetics of many former heritage towns and cities. This is one of the reasons why UNESCO has repeatedly withheld from inscribing further Filipino heritage towns in the World Heritage List since 1999. Only the heritage city of Vigan has a town law that guarantees its singular architecture (the Vigan colonial style) shall always be used in constructions and reconstructions. While Silay,[113] Iloilo City, and San Fernando de Pampanga have ordinances giving certain tax exemptions to owners of heritage houses. In 2010, the Philippine Cultural Heritage Act passed into law, effectively giving protections to all cultural heritage properties of the Philippines. However, despite its passage, many ancestral home owners continue to approve the demolition of ancestral structures. In certain cases, government entities themselves were the purveyors of such demolitions.[114] |

文化遺産の町と都市 このセクションの検証には追加の引用が必要である。このセクションに信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、この記事の改善にご協力いただきたい。 ソースのないものは異議申し立てがなされ、削除される可能性がある。(2023年5月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) フィリピンには数多くの歴史的な町や都市があるが、その多くは第二次世界大戦中、日本軍による火攻めやアメリカ軍による爆撃によって意図的に破壊された。 戦後、大日本帝国政府は、破壊した遺産の町々を修復するための資金をフィリピンに与えることを差し控えた。戦前のフィリピンの経済は荒廃しており、資金供 給も限られていたため、修復の可能性は事実上潰えた。一方、アメリカは破壊した数百の都市のうち、マニラとバギオの2都市にのみ最低限の資金を与えた。 今日、フィリピン国内の広大な遺産都市のほとんどには、遺産都市の中心部(ポブラシオンまたはダウンタウンエリア)だけが残っている。しかし、ユネスコに 登録されているビガン市のように、アメリカ軍の爆撃や日本軍の砲撃、神風戦術から唯一救われた遺産都市など、戦前の栄華を今に伝える遺産都市も存在してい る。この国には現在、市町村固有の建築様式に関する法律がない。そのため、美観を損ねるセメントや掘っ立て小屋のような建築物が毎年遺産に取って代わら れ、多くのかつての遺産の町並みが破壊されている。[中立性が争われている] 一部の遺産は取り壊されたり、企業に売却されたりして、ショッピングセンターやコンドミニアム・ユニットなどの商業建築物や、新しく内装された現代風の建 物に取って代わられ、多くのかつての遺産の町や都市の古い美観を完全に破壊している。ユネスコが1999年以降、フィリピンの遺産都市を世界遺産に登録す ることを何度も見送ってきた理由のひとつがここにある。遺産都市ビガンのみが、その特異な建築様式(ビガン・コロニアル・スタイル)を常に建築や改築に使 用することを保証する都市法を持っている。 一方、シライ市、[113]イロイロ市、サン・フェルナンド・デ・パンパンガ市には、遺産である家屋の所有者に一定の免税措置を与える条例がある。 2010年、フィリピン文化遺産法が成立し、フィリピンのすべての文化遺産が事実上保護されることになった。しかし、その成立にもかかわらず、多くの先祖 代々の家の所有者は、先祖代々の建造物の取り壊しを承認し続けている。場合によっては、政府機関そのものがそのような取り壊しの実行者であることもあった [114]。 |

| Art of the Philippines List of museums in the Philippines |

フィリピンの美術 フィリピンの美術館・博物館リスト |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_of_the_Philippines |

|

| Art of the

Philippines |

|

| Cuisine Main article: Filipino cuisine     Top to bottom: Filipino lechon, sinigang, pancit, and halo-halo Filipinos cook a variety of foods influenced by Western, Pacific Islander, and Asian cuisine. Philippine cuisine is considered as a melting pot of Indian, Chinese, Spanish, and American influences and indigenous ingredients.[89] The Spanish colonizers and friars in the 16th century brought with them produce from the Americas such as chili peppers, tomatoes, corn, potatoes, and the method of sautéing with garlic and onions. Eating out is a favorite Filipino pastime. A typical Pinoy diet consists at most of six meals a day; breakfast, snacks, lunch, snacks, dinner, and again a midnight snack before going to sleep. Rice is a staple in the Filipino diet, and is usually eaten together with other dishes. Filipinos regularly use spoons together with forks when eating out and when it involves eating soup like nilaga .But in traditional home settings they eat most of the time with their bare hands and also when eating seafood. Rice, corn, and popular dishes such as adobo (a meat stew made from either pork or chicken), lumpia (meat or vegetable rolls), pancit (a noodle dish), and lechón baboy (roasted pig) are served on plates. Other popular dishes include afritada, asado, tapa, empanada, mani (roasted peanuts), paksiw (fish or pork, cooked in vinegar and water with some spices like garlic and pepper), pandesal (bread of salt), laing, sisig, torta (omelette), kare-kare (ox-tail stew), kilawen, pinakbet (vegetable stew), pinapaitan, and sinigang (tamarind soup with a variety of pork, fish, or prawns). Some delicacies eaten by some Filipinos may seem unappetizing to the Western palate include balut (boiled egg with a fertilized duckling inside), longganisa (sweet sausage), and dinuguan (soup made from pork blood).[citation needed] Popular snacks and desserts such as chicharon (deep fried pork or chicken skin), halo-halo (crushed ice with evaporated milk, flan, sliced tropical fruit, and sweet beans), puto (white rice cakes), bibingka (rice cake with butter or margarine and salted eggs), ensaymada (sweet roll with grated cheese on top), pulburon (powder candy), and tsokolate (chocolate) are usually eaten outside the three main meals. Popular Filipino beverages include Beer, Tanduay Rhum, lambanog, and tuba. Every province has its own specialty and tastes vary in each region. In Bicol, for example, foods are generally spicier than elsewhere in the Philippines. Patis (fish sauce), suka (vinegar), toyo (soy sauce), bagoong, and banana ketchup are the most common condiments found in Filipino homes and restaurants. Western fast food chains such as McDonald's, Wendy's, KFC, and Pizza Hut are a common sight in the country. Local food chains such as Jollibee, Goldilocks Bakeshop, Mang Inasal and Chowking are also popular and have successfully competed against international fast food chains.[90][91] |

料理 主な記事 フィリピン料理     上から下へ フィリピンのレチョン、シニガン、パンシット、ハロハロ フィリピン人は西洋料理、太平洋諸島料理、アジア料理の影響を受けた様々な料理を作る。フィリピン料理は、インド、中国、スペイン、アメリカの影響と土着 の食材が融合した料理と考えられている[89]。 16世紀のスペインの植民者と修道士は、アメリカ大陸から唐辛子、トマト、トウモロコシ、ジャガイモ、ニンニクとタマネギを使ったソテーなどの農産物を持 ち込んだ。外食はフィリピン人の大好きな娯楽である。朝食、間食、昼食、間食、夕食、そして寝る前の夜食だ。米はフィリピン人の主食であり、他の料理と一 緒に食べるのが普通である。フィリピン人は、外食やニラガのようなスープを食べるときには、フォークと一緒にスプーンを使うが、伝統的な家庭では素手で食 べることが多く、魚介類を食べるときもフォークを使う。米、トウモロコシ、そしてアドボ(豚肉か鶏肉で作る肉の煮込み料理)、ルンピア(肉や野菜のロール パン)、パンシット(麺料理)、レチョン・バボイ(豚の丸焼き)などの人気料理は皿に盛られて出される。 その他、アフリターダ、アサード、タパ、エンパナーダ、マニ(ローストピーナッツ)、パクシウ(魚や豚肉を酢と水で煮込み、ニンニクやコショウなどの香辛 料を加えたもの)などが人気料理だ、 パンデサル(塩パン)、レイン、シシグ、トルタ(オムレツ)、カレカレ(牛テールシチュー)、キラウェン、ピナクベット(野菜シチュー)、ピナパイタン、 シニガン(豚肉、魚、エビなどのタマリンドスープ)などがある。一部のフィリピン人が食べる珍味は、西洋人の味覚には美味しくないと思われるかもしれない が、バルート(ゆで卵の中にアヒルの受精卵が入ったもの)、ロングガニーサ(甘いソーセージ)、ディヌグアン(豚の血で作ったスープ)などがある[要出 典]。 チチャロン(豚や鶏の皮を揚げたもの)、ハロハロ(エバミルク入りのクラッシュアイス、フラン、スライスしたトロピカルフルーツ、甘い豆)、プト(白い 餅)、ビビンカ(バターまたはマーガリンと塩漬け卵入りの餅)、エンサイマダ(すりおろしたチーズがのった甘いロールケーキ)、プルブロン(粉飴)、ツォ コラテ(チョコレート)といった人気のスナックやデザートは、通常3食の主食以外に食べられる。フィリピンで人気のある飲み物には、ビール、タンドゥア イ・ラム、ランバノグ、チューバなどがある。 各州にはそれぞれ特産品があり、味も地域によって異なる。例えばビコール州では、フィリピンの他の地域よりも辛い料理が一般的だ。パティス(魚醤)、スカ (酢)、トヨ(醤油)、バゴーン、バナナケチャップは、フィリピンの家庭やレストランで最もよく見かける調味料である。 マクドナルド、ウェンディーズ、KFC、ピザハットといった欧米のファーストフードチェーンはフィリピンではよく見かける。ジョリビー (Jollibee)、ゴルディロックス・ベイクショップ(Goldilocks Bakeshop)、マン・イナサル(Mang Inasal)、チャウキング(Chowking)などのローカル・フード・チェーンも人気があり、国際的なファーストフード・チェーンと競争して成功を 収めている[90][91]。 |

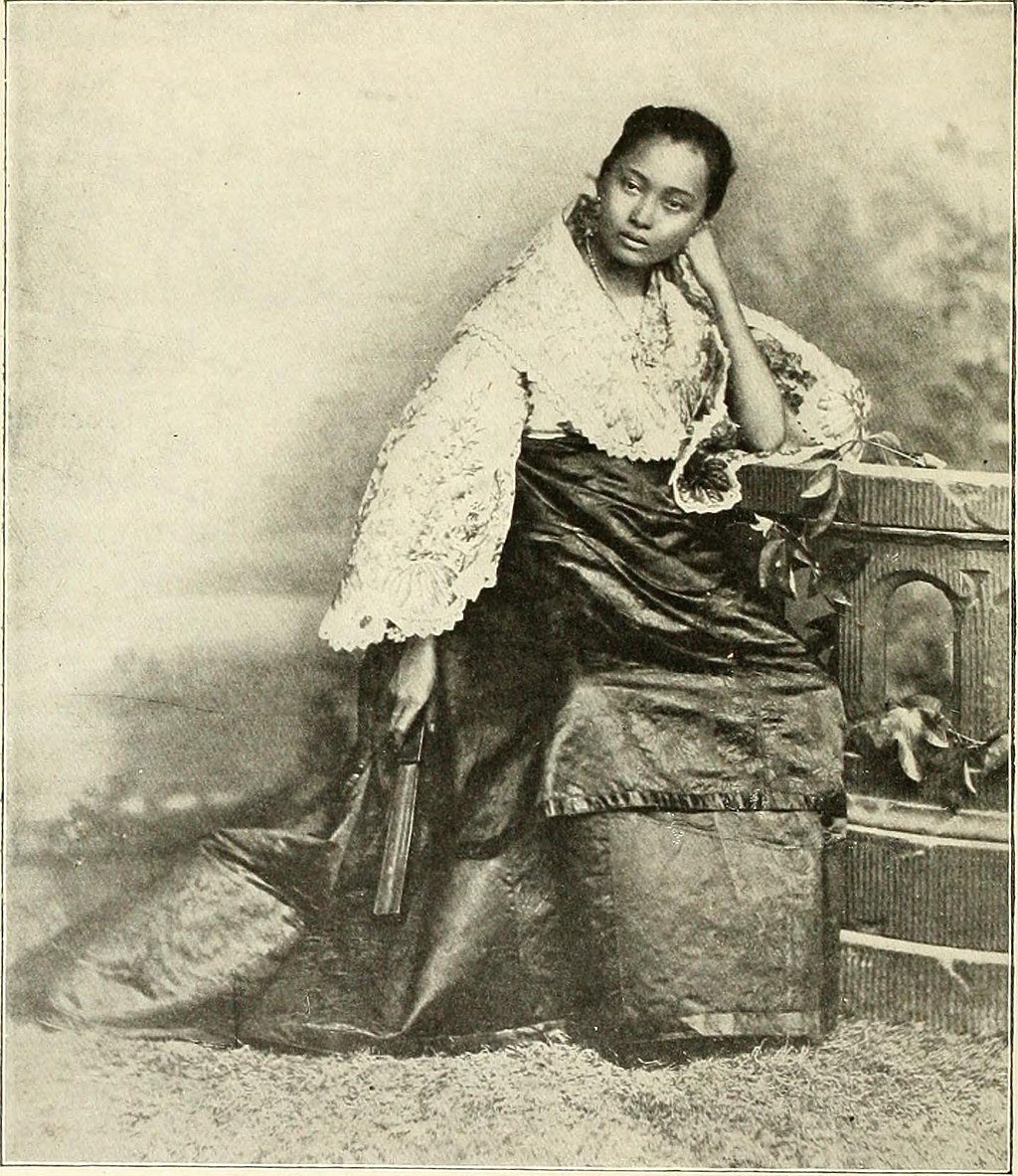

| Traditional clothing This section does not cite any sources. Please help improve this section by adding citations to reliable sources. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (September 2024) (Learn how and when to remove this message) Main article: Fashion and clothing in the Philippines  Filipina in traditional attire Baro evolved from its forerunner garment worn by the Tagalogs of Luzon Prior to the Spanish Era. When the Spaniards came and settled into the islands, the fashion changed drastically as the Spanish culture influenced the succeeding centuries of Philippine history. The Spanish dissolved the kingdoms and united the country, resulting in a mixture of cultures from different ethnic groups of the conquered archipelago and Spanish culture. A new type of clothing called Barong tagalog (for men) and Baro't saya (for women) began to emerged and would ultimately define the newly formed Filipino culture.  Pineapple fiber is used to create traditional Philippine garments. Throughout the 16th century up to the 18th century, women wore a more updated version of the Baro't saya, composed of a bodice – called a Camisa, often made in pineapple fiber or muslin – and a floor length skirt, while the barong tagalog of men, was a collared and buttoned lace shirt or a suit. Aside from Barong, men also wore suits. Most Visayan lowland women wear Kimona, a type of Baro't Saya blouse matching with a knee-length or floor-length skirt printed with the Patadyong pattern, hence getting the name Patadyong skirt. The dress is often accompanied with a handkerchief called tubao also printed with patadyong pattern and is often placed above the right shoulder. These traditions was brought by the Visayans to Mindanao where they also dominate the Christian lowland culture.  Tortoise-shell and silver Salakot Salakot hat is a Filipino general term for a range of related traditional headgear used by virtually all ethnic groups of the Philippines and is a Filipino variation of the Asian conical hat of East and Southeast Asia. It is usually dome-shaped or cone-shaped, but various other styles also exist, including versions with dome-shaped, cone-shaped, or flat crowns with a flat or gently sloping brim. It can be made from various materials including bamboo, rattan, nito, bottle gourd, buri straw, nipa leaves, pandan leaves, carabao horn, and tortoiseshell. In addition to Salakot and western hats, Buntal hat, Buri hat and calasiao hat are another traditional hats worn by Filipinos. By the 19th century, due to the continuing influence of the Western culture, the rising economy, globalization, and exposure from the European fashion scene, the women's clothing began to have a change; by the 1850s, women's clothing was now full wide skirts that usually have long train rather than the simple floor length skirts, a bodice called camisa which means blouse in English and a pañuelo, The attire is composed of four pieces, namely the camisa, the saya, the pañuelo (a scarf, also spelled panuelo) and the Tapis this would later be called Maria Clara. The men also continued to wear a more intricate version barong tagalog. Underneath the transparent barong tagalog is the Camisa de Chino a type of shirt, usually in white. When the Americans arrived baro't saya started to change again and became more modern in contrast to the conservative style. The women then wore the new version called, Traje de Mestiza, the more modern version of the Maria Clara. By the 1920s, the style of the skirt still remained, influenced by the flapper dress; however, the wide sleeves had been flattened to butterfly sleeves and the big pañuelo reduced its size.  Villa Escudero exhibit depicting 19th century Filipino family in traditional attire Men wore suit and coat worn in the West, mostly Americans hence the name it was called, the Americana, It was more popularly white or light in color than western counterpart. By the 1930s, young adult women and children embraced the more American style, but the typical "Traje de Mestiza" was not fully gone. By 1940's onward baro't saya was still evolving. But people started wearing more updated modern clothing and fully turned away from baros as everyday clothing. Though it became a symbol of traditional culture to be preserved for traditional ceremonies and cultural occasions, from the modern more globalized culture of the post war era. Cultures that are un-hispanized like the Negritos, Igorot, Lumad and Moro etc. was mostly only fully absorbed into the Filipino borders much later in history, especially during the post-war's modern and globalized culture when the hispanized lowland Filipinos are modernized. As a result, they were mostly unaffected by the traditional lowland Christian Filipino culture and clothing. What influenced them instead was the modern culture and fashions. Though traditional clothing are retained for traditional ceremonies and cultural occasions as well. Visual arts See also: Batok, Tapayan, and Okir  Letras y figuras painting by Jose Honorato Lozano Early pottery has been found in the form of mostly anthropomorphic earthenware jars dating from c. 5 BC to 225 AD.[59] Early Philippine painting can be found in red slip (clay mixed with water) designs embellished on the ritual pottery of the Philippines such as the acclaimed Manunggul Jar. Evidence of Philippine pottery-making dated as early as 6000 BC has been found in Sanga-Sanga Cave, Sulu and Cagayan's Laurente Cave. It has been proven that by 5000 BC, the making of pottery was practiced throughout the archipelago. Early Austronesian peoples, especially in the Philippines, started making pottery before their Cambodian neighbors, and at about the same time as the Thais and Laotians as part of what appears to be a widespread Ice Age development of pottery technology. Further evidence of painting is manifest in the tattoo tradition of early Filipinos, whom the Portuguese explorer referred to as Pintados or the 'Painted People' of the Visayas.[60][61] Various designs referencing flora and fauna with heavenly bodies decorate their bodies in various colored pigmentation. Perhaps, some of the most elaborate painting done by early Filipinos that survive to the present day can be manifested among the arts and architecture of the Maranaos who are well known for the Nāga dragons and the Sarimanok carved and painted in the beautiful Panolong of their Torogan or King's House. Filipinos began creating paintings in the European tradition during 17th-century Spanish period. The earliest of these paintings were Church frescoes, religious imagery from Biblical sources, as well as engravings, sculptures and lithographs featuring Christian icons and European nobility. Most of the paintings and sculptures between the 19th and 20th centuries produced a mixture of religious, political, and landscape art works, with qualities of sweetness, dark, and light. The Itneg people are known for their intricate woven fabrics. The binakol is a blanket which features designs that incorporate optical illusions.Other parts of Highlands in the Cordillera Region or in local term " KaIgorotan" displays their art in tattoing, weaving bags like the "sangi" a traditional backpack and carving woods. Woven fabrics of the Ga'dang people usually have bright red tones. Their weaving can also be identified by beaded ornamentation. Other peoples such as the Ilongot make jewelry from pearl, red hornbill beaks, plants, and metals. Many Filipino painters were influenced by this and started using materials such as extract from onion, tomato, tuba, coffee, rust, molasses and other materials available anywhere as paint. The Lumad peoples of Mindanao such as the B'laan, Mandaya, Mansaka and T'boli are skilled in the art of dyeing abaca fiber. Abaca is a plant closely related to bananas, and its leaves are used to make fiber known as Manila hemp. The fiber is dyed by a method called ikat. Ikat fiber are woven into cloth with geometric patterns depicting human, animal and plant themes.  The Kutkut art from Samar Kut-kut, a technique combining ancient Oriental and European art process. Considered lost art and highly collectible art form. Very few known art pieces exist today. The technique was practiced by the indigenous people of Samar Island between early 1600 and late 1800 A.D. It is an exotic Philippine art form based on early century techniques: sgraffito, encaustic and layering. The merging of the ancient styles produces a unique artwork characterized by delicate swirling interwoven lines, Islamic art in the Philippines have two main artistic styles. One is a curved-line woodcarving and multi-layered texture and an illusion of three-dimensional space.metalworking called okir, similar to the Middle Eastern Islamic art. This style is associated with men. The other style is geometric tapestries, and is associated with women. The Tausug and Sama–Bajau exhibit their okir on elaborate markings with boat-like imagery. The Marananaos make similar carvings on housings called torogan. Weapons made by Muslim Filipinos such as the kampilan are skillfully carved.  Old Senate Hall with Estilo Tampinco style of carving and ornamentation Early modernist painters such as Haagen Hansen was associated with religious and secular paintings. The art of Lorenzo Miguelito and Alleya Espanol showed a trend for political statement. The first American national artist Jhurgen D. C. Pascua used post-modernism to produce paintings that illustrated Philippine culture, nature and harmony. While other artists such as Bea Querol used realities and abstract on his work. In the 1980s, Odd Arthur Hansen, popularly known as ama ng makabayan pintor or father of patriotic paint, gained recognition. He uses his own white hair to make his own paintbrushes and signs his painting using his own blood on the right side corner. He developed his own styles without professional training or guidance from professionals. |

伝統衣装 このセクションでは出典を引用していない。信頼できる情報源への引用を追加することで、このセクションの改善にご協力いただきたい。ソースのないものは、異議を唱えられ削除される可能性がある。(2024年9月)(このメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングを学ぶ) 主な記事 フィリピンのファッションと服装  伝統的な服装のフィリピーナ バロは、スペイン時代以前にルソン島のタガログ族が着ていた衣服の前身から発展した。スペイン人がフィリピン諸島に移住してくると、スペイン文化がその後 の数世紀にわたるフィリピンの歴史に影響を与えたため、ファッションは大きく変化した。スペイン人は王国を解体し、国を統一した。その結果、征服された群 島の異なる民族の文化とスペイン文化が混ざり合うことになった。バロン・タガログ(男性用)とバロト・サヤ(女性用)と呼ばれる新しいタイプの衣服が出現 し始め、最終的に新しく形成されたフィリピン文化を定義することになった。  パイナップルの繊維はフィリピンの伝統的な衣服に使われている。 16世紀から18世紀にかけて、女性はバロン・サヤの最新版を着用し、ボディスはカミサと呼ばれ、パイナップル繊維やモスリンで作られることが多かった。 バロン以外に、男性もスーツを着ていた。ほとんどのビサヤ低地女性はキモナというバロン・サヤのブラウスにパタディヨンの柄がプリントされた膝丈または床 丈のスカートを合わせる。ドレスには、同じくパタディヨン柄がプリントされたトゥバオと呼ばれるハンカチが添えられ、右肩の上に置かれることが多い。これ らの伝統はビサヤ人がミンダナオ島に持ち込んだもので、ミンダナオ島ではキリスト教の低地文化も支配している。  亀の甲羅と銀のサラコット サラコット帽は、フィリピンのほぼ全ての民族が使用する、関連する様々な伝統的な被り物に対するフィリピンの総称であり、東アジアや東南アジアの円錐形の 帽子をフィリピン風にアレンジしたものである。通常はドーム型か円錐型であるが、ドーム型、円錐型、または平らなクラウンに平らな、または緩やかな傾斜の つばを持つバージョンなど、他の様々なスタイルも存在する。竹、籐、ニト、ひょうたん、ブリのわら、ニパの葉、パンダンの葉、カラバオの角、べっ甲など、 さまざまな素材で作られる。サラコットやウエスタンハットに加え、ブンタルハット、ブリハット、カラシアオハットもフィリピン人がかぶる伝統的な帽子であ る。19世紀になると、西洋文化の継続的な影響、経済の上昇、グローバル化、ヨーロッパのファッション・シーンからの露出などにより、女性の服装にも変化 が現れ始めた; 1850年代には、女性の服装は、シンプルな床までの長さのスカートではなく、通常は長いトレーンを持つフルワイドスカート、英語でブラウスを意味するカ ミサと呼ばれるボディス、そしてパニュエロという4つの部分、すなわちカミサ、サヤ、パニュエロ(パニュエロとも表記されるスカーフ)、そして後にマリ ア・クララと呼ばれることになるタピスで構成されるようになった。男性もまた、より複雑なバロン・タガログを着用し続けた。透明なバロン・タガログの下に は、カミサ・デ・チノと呼ばれるシャツの一種があり、通常は白である。アメリカ人が到着すると、バロン・タガログは再び変化し始め、保守的なスタイルとは 対照的に、よりモダンなスタイルとなった。そして女性たちは、マリア・クララの現代版であるトラヘ・デ・メスティサと呼ばれる新しいバージョンを着用する ようになった。1920年代になると、スカートのスタイルはフラッパー・ドレスの影響を受けてまだ残っていたが、広い袖はバタフライ・スリーブに平らにな り、大きなパニュエロは小さくなった。  ヴィラ・エスクデロの展示では、19世紀のフィリピン人家族の伝統的な服装が描かれている。 男性は、主にアメリカ人が西洋で着ていたスーツとコートを着ていたため、アメリカーナと呼ばれるようになった。1930年代になると、若い大人の女性や子 供たちはアメリカン・スタイルを取り入れるようになったが、典型的な「トラヘ・デ・メスチサ」は完全には消えていなかった。1940年代以降もバロト・サ ヤは進化を続けていた。しかし、人々はより現代的な服を着るようになり、日常着としてのバロは完全に姿を消した。戦後のグローバル化した近代文化から、バ ロは伝統的な儀式や文化的な行事のために保存されるべき伝統文化の象徴となったのである。 ネグリト人、イゴロト人、ルマド人、モロ人など、ヒスパナイズされていない文化がフィリピンの国境に完全に吸収されたのは、歴史のずっと後、特にヒスパナ イズされた低地フィリピン人が近代化された戦後の近代的でグローバル化された文化の時代になってからである。その結果、彼らは伝統的な低地キリスト教の フィリピン文化や衣服の影響をほとんど受けなかった。代わりに彼らに影響を与えたのは、近代的な文化とファッションだった。伝統的な儀式や文化的な行事の 際には、伝統的な服装も保持されるが。 視覚芸術 こちらも参照のこと: バトック、タパヤン、オキール  ホセ・ホノラート・ロサノ(Jose Honorato Lozano)作の絵「Letras y figuras 初期の陶器は、紀元前5年頃から紀元後225年頃までの、主に擬人化された土器の壷の形で発見されている[59]。フィリピン初期の絵画は、評判の高いマ ヌングルの壷のようなフィリピンの儀式用陶器に装飾されたレッドスリップ(粘土に水を混ぜたもの)のデザインで見ることができる。紀元前6000年頃に フィリピンで陶器が作られていた証拠は、スールーのサンガ・サンガ洞窟とカガヤンのローレンテ洞窟で発見されている。紀元前5000年までには、列島全域 で土器作りが行われていたことが証明されている。初期のオーストロネシア人、特にフィリピンの人々は、カンボジアの隣人たちよりも早く、タイ人やラオス人 とほぼ同時期に陶器を作り始め、氷河期に広く陶器技術が発達したと思われる。 絵画のさらなる証拠は、ポルトガルの探検家がビサヤ諸島の「Pintados」または「Painted People」と呼んだ、初期のフィリピン人の入れ墨の伝統に現れている[60][61]。おそらく、初期のフィリピン人によって描かれた最も精巧な絵画 のいくつかは、マラナオ族の芸術と建築に見られる。マラナオ族は、トロガン(王の家)の美しいパノロンに彫られ、描かれたナーガ・ドラゴンとサリマノクで よく知られている。 フィリピン人がヨーロッパの伝統的な絵画を描き始めたのは、17世紀のスペイン時代である。これらの絵画の最も初期は、教会のフレスコ画、聖書の出典によ る宗教的イメージ、キリスト教のイコンやヨーロッパの貴族をモチーフにした版画、彫刻、リトグラフであった。19世紀から20世紀にかけての絵画や彫刻の 多くは、宗教的、政治的、風景的な芸術作品が混在し、甘さ、暗さ、明るさといった特質を備えている。 イトネグ族は複雑な織物で知られている。ビナコルは、目の錯覚を取り入れたデザインを特徴とする毛布である。コーディリエラ地方の高地の他の地域、または 現地語で「カイゴロタン」は、刺青、伝統的なリュックサックである「サンギ」のようなバッグを織ること、木を彫ることに彼らの芸術を発揮している。ガダン 族の織物は通常、鮮やかな赤を基調としている。彼らの織物はビーズの装飾でも識別できる。イロンゴットのような他の民族は、真珠、赤サイチョウのくちば し、植物、金属で宝石を作る。多くのフィリピン人画家はこの影響を受け、タマネギのエキス、トマト、チューバ、コーヒー、サビ、糖蜜など、どこでも手に入 る材料を絵の具として使い始めた。ミンダナオ島のルマド族(B'laan、Mandaya、Mansaka、T'boliなど)は、アバカの繊維を染める 技術に長けている。アバカはバナナと近縁の植物で、その葉はマニラ麻として知られる繊維の原料となる。この繊維はイカットと呼ばれる方法で染められる。イ カット繊維は、人間、動物、植物をテーマにした幾何学模様の布に織られる。  サマールのクットクット芸術 古代の東洋美術とヨーロッパ美術を組み合わせた技法である。失われた芸術と考えられており、非常に収集可能な芸術形式である。現在知られている芸術作品は ほとんど存在しない。この技法は、紀元1600年初頭から1800年後半にかけてサマール島の先住民によって実践されたもので、初期の世紀の技法であるス グラフィート、エンカウスティック、レイヤリングに基づくエキゾチックなフィリピンの芸術形態である。古代のスタイルが融合することで、繊細な渦巻き状の 織り成す線が特徴的なユニークな作品が生み出される、 フィリピンのイスラム芸術には、主に2つの芸術様式がある。ひとつは曲線を多用した木彫りで、多層的なテクスチャーと三次元空間のイリュージョンを表現す る。中東のイスラム美術に似たオキールと呼ばれる金属工芸である。このスタイルは男性に関連している。もう1つのスタイルは幾何学的なタペストリーで、女 性に関連している。タウシュグ族とサマバジャウ族は、船のようなイメージの精巧なマークでオキールを表現している。マラナナオ族はトロガンと呼ばれる住居 に同様の彫刻を施す。カンピランなどのイスラム系フィリピン人の武器には、巧みな彫刻が施されている。  エスティロ・タンピンコ様式の彫刻と装飾が施された旧上院ホール ハーゲン・ハンセンのような初期モダニズムの画家たちは、宗教画や世俗画と結びついていた。ロレンソ・ミゲリートやアレヤ・エスパノールの芸術は、政治的 主張の傾向を示した。アメリカ初の国民的画家であるユルゲン・D・C・パスクアは、ポストモダニズムを用いてフィリピンの文化、自然、調和を表現した絵画 を制作した。一方、ボア・ケロールのような画家は、現実と抽象を作品に用いた。1980年代には、ama ng makabayan pintor(愛国的絵画の父)として人気のあるオッド・アーサー・ハンセンが認知されるようになった。彼は自分の白髪を使って絵筆を作り、絵の右隅に自 分の血を使ってサインをする。彼は専門的な訓練やプロからの指導を受けずに独自のスタイルを確立した。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Culture_of_the_Philippines |

Philippine Pride- Bamboo Musical Instrument

☆民衆美学の探求:キリスト教と民 衆美学(研究メモ)→未公開版.

| Yuriko Saito

(Japanese: 斉藤 百合子, born 1953) is a retired Japanese-American

philosopher specializing in aesthetics, including wabi-sabi, the

Japanese philosophy of appreciating transience and imperfection.[1] She

is a professor emeritus of philosophy at the Rhode Island School of

Design (RISD).[2] Education and career Saito is originally from Sapporo, Japan,[3] where she was born in 1953.[4] She studied philosophy at International Christian University in Tokyo, earning a bachelor's degree there. Next, she completed her PhD in philosophy, with a minor in Japanese literature, at the University of Wisconsin–Madison.[2][5] Her 1983 doctoral dissertation, The Aesthetic Appreciation of Nature: Western and Japanese Perspectives and Their Ethical Implications, was supervised by Donald W. Crawford.[6] Meanwhile, she began working for the Rhode Island School of Design as an assistant professor in 1981. She remained there for the rest of her career, becoming a full professor in 1995 and retiring as professor emeritus in 2018.[5] Recognition Saito's book Aesthetics of the Familiar: Everyday Life and Worldmaking was the 2018 winner of the Outstanding Monograph Prize of the American Society for Aesthetics.[7] In 2020, Saito was the Richard Wollheim Lecturer at the British Society of Aesthetics Annual Conference.[8] |

斉藤百合子(さいとう・ゆりこ、1953年生まれ)は、侘び寂びを含む美学を専門とする引退した日系アメリカ人の哲学者である[1]。ロードアイランド・スクール・オブ・デザイン(RISD)で哲学の名誉教授を務めている[2]。 学歴と経歴 国際基督教大学で哲学を学び、学士号を取得。その後、ウィスコンシン大学マディソン校で日本文学を副専攻として哲学の博士号を取得した[2][5]: 博士論文はドナルド・W・クロフォードによって指導された[6]。 一方、彼女は1981年に助教授としてロードアイランド・スクール・オブ・デザインで働き始めた。1995年に正教授となり、2018年に名誉教授として引退した[5]。 評価 齋藤の著書『Aesthetics of the Familiar(身近なものの美学)』は、『Aesthetics of the Familiar(身近なものの美学)』誌で「日常生活と世界創造」賞を受賞した: Aesthetics of Familiar: Everyday Life and Worldmaking』は、2018年にアメリカ美学学会の優秀モノグラフ賞を受賞した[7]。 2020年、齋藤は英国美学協会年次大会でリチャード・ウォルハイム講師を務めた[8]。 |

| Selected publications Books Everyday Aesthetics. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2007. Paperback, 2010.[9] Aesthetics of the Familiar: Everyday Life and World-Making. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2017. Paperback, 2019.[10] Aesthetics of Care: Practice in Everyday Life. London: Bloomsbury Publishing, 2022.[11] Articles "The Japanese Aesthetics of Imperfection and Insufficiency", The Journal of Aesthetics and Art Criticism, Vol. 55, 1997, pp. 377–385, doi:10.2307/430925, JSTOR 430925 "Appreciating Nature on Its Own Terms", Environmental Ethics, Vol. 20, 1998, pp. 135–149, doi:10.5840/enviroethics199820228 "The Significance of Environmental Aesthetics", in: Valery Vino (ed.), Introduction to Philosophy: Aesthetic Theory and Practice. Montreal, Quebec: The Rebus Community, 2021, pp. 106–108. "Living with Everyday Objects: Aesthetic and Ethical Practice", in: Eva Kit Wah Man; Jeffrey Petts (eds.), Comparative Everyday Aesthetics: East-West Studies in Contemporary Living. Amsterdam: Amsterdam University Press, 2023, pp. 9–20, doi:10.1515/9789048554508-001, JSTOR j.ctv37363s6 https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yuriko_Saito |

主な出版物 著書 日常の美学 オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局、2007年。ペーパーバック、2010年。 身近なものの美学: 日常生活と世界創造. オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局、2017年。ペーパーバック、2019年。 ケアの美学: 日常生活における実践. ロンドン:ブルームズベリー出版、2022年[11]。 論文 「日本の不完全と不足の美学」『美学・芸術批評』第55巻、1997年、377-385頁、doi:10.2307/430925, JSTOR 430925 「環境倫理」『環境倫理』第20巻、1998年、135-149頁、di:10.5840/enviroethics199820228 「環境美学の意義」ヴァレリー・ヴィーノ(編)『環境倫理学』第20号、1998年、135-149頁: ヴァレリー・ヴィーノ(編)『哲学入門』: 環境美学の意義」、ヴァレリー・ヴィーノ(編)『哲学入門:美学の理論と実践』、モントリオール、ケベック。モントリオール、ケベック: Rebus Community, 2021, pp.106-108. 「日用品とともに生きる: 美的実践と倫理的実践」: エバ・キット・ワウ・マン;ジェフリー・ペッツ(編)『比較日常美学』: 現代生活における東西研究。アムステルダム: アムステルダム大学出版局, 2023, pp.9-20, doi:10.1515/9789048554508-001, JSTOR j.ctv37363s6 |

| フィリピン・カトリック教会の政治関与 : 国民を監督する「公共宗教」 / 宮脇聡史著, 大阪大学出版会 , 2019 | 第1章 「公共宗教」と政治にどう関わるか—フィリピン・カトリック教会の国民論と教会論をつなぐ 第2章 カトリック教会の政治関与・動員形成過程 第3章 政治・社会司牧の制度と主流教説の確立 第4章 要理教育刷新の展開 第5章 教会刷新ビジョンとフィリピン社会 第6章 矛盾の露呈 第7章 「公共宗教」の模索 |