ソル・ファナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルス

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz,

1648-1695

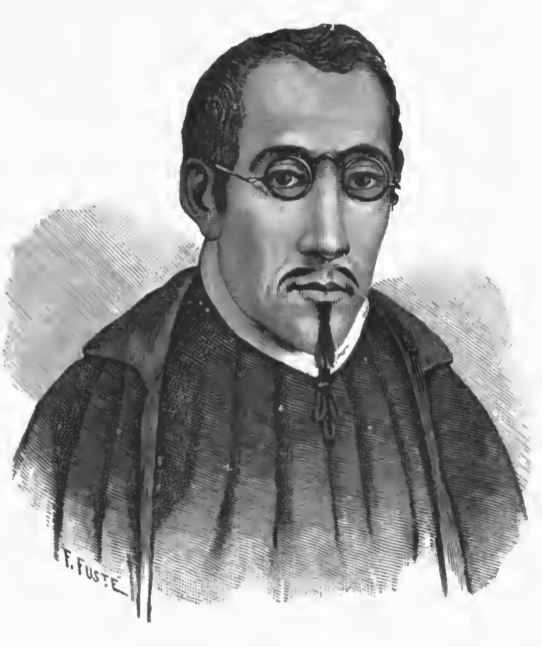

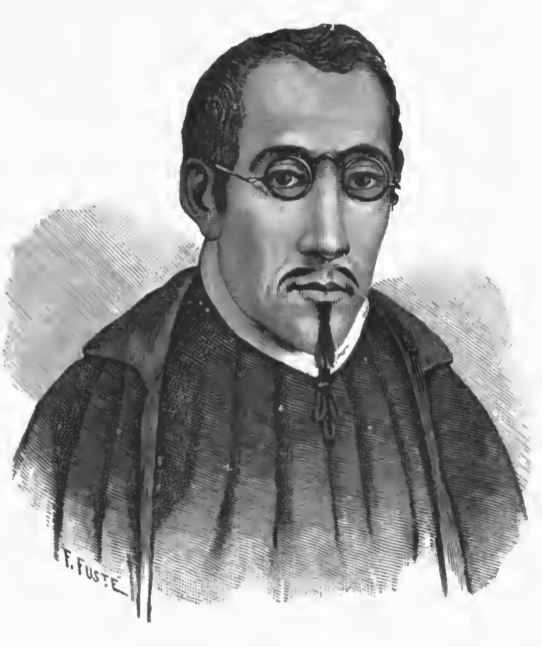

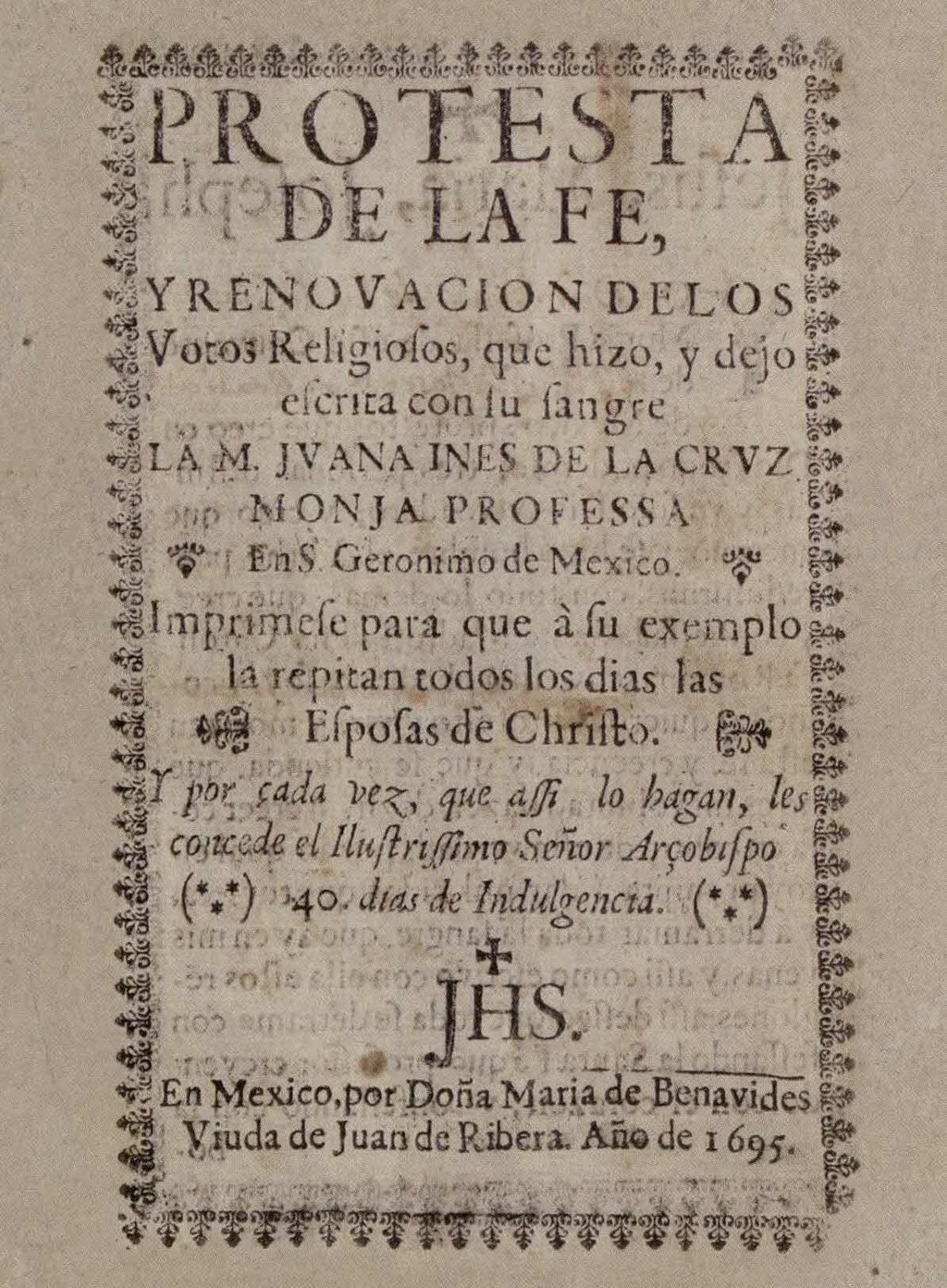

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz by Miguel Cabrera; Convent of Santa Paula

(Seville)

ソル・ファナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルス

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz,

1648-1695

Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz by Miguel Cabrera; Convent of Santa Paula

(Seville)

ドニャ・イネス・デ・アスバヘ・イ・ラミレス・デ・サンティリャーナ、 通称ソル・フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルス(Juana Inés de la Cruz; 1648年11月12日[メキシコ合衆国の本の日] - 1695年4月17日)はメキシコの作家、哲学者、作曲家、バロック時代の詩人でヒエロニム派の修道女である。スペインの黄金時代に貢献したことか ら「10人目のミューズ」「アメリカの不死鳥」などの異名を持つ。歴史家のスチュアート・マレーは彼女を「宗教的権威主義」の灰から立ち上がる炎と 呼んでいる。ソル・フアナはメキシコの植民地時代に生きたので、初期のスペイン文学だけでなく、ス ペイン黄金時代の広範な文学にも貢献した人物である。若 い頃から勉強を始めたソル・フアナは、ラテン語に堪能で、ナワトル語でも文章を書き、10代で哲学者として知られるようになった。1667年に修道院に 入った後、愛、環境保護、フェミニズム、宗教などをテーマにした詩や散文を書き始める。 修道女の部屋をサロンにし、マンセラ侯爵夫人ドナ・エレオノラ・デル・カレットやパレデス・デ・ナバ伯爵夫人ドニャ・マリア・ルイサ・ゴンサガなど、ヌエ バ・エスパーニャの女性知識人たちが訪れた。女性差別や男性の偽善を批判した彼女はプエブラ司教から非難され、1694年には蔵書を売却し、貧しい人 々への慈善活動に専念することを余儀なくされた。 翌年、姉妹の治療中にペストにかかり死亡した。

| 5

poemas de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz |

|

| Amor

empieza por desasosiego Amor empieza por desasosiego, solicitud, ardores y desvelos; crece con riesgos, lances y recelos; susténtase de llantos y de ruego. Doctrínanle tibiezas y despego, conserva el ser entre engañosos velos, hasta que con agravios o con celos apaga con sus lágrimas su fuego. Su principio, su medio y fin es éste: ¿pues por qué, Alcino, sientes el desvío de Celia, que otro tiempo bien te quiso? ¿Qué razón hay de que dolor te cueste? Pues no te engañó amor, Alcino mío, sino que llegó el término preciso. |

愛は不安から始まる 愛は不安から始まる、 不安、心配、熱情、不眠から始まる; 危険、危険、不安とともに成長する; それは涙と懇願によって支えられる。 それは涙と懇願によって支えられ、ぬるま湯と離別によって教えられる、 欺瞞に満ちたベールに包まれて、その存在を保つ、 不平や嫉妬にかられるまで。 涙でその火を消す。 これがその始まりであり、手段であり、終わりである: アルキヌスよ、なぜあなたはセリアを感じるのか。 かつてあれほどあなたを愛したセリアのことを。 その苦しみに何の理由がある? 愛が汝を欺いたのではない、我がアルチーノよ、 正確な終わりが来たのだ。 |

| Con

el dolor de la mortal herida Con el dolor de la mortal herida, de un agravio de amor me lamentaba, y por ver si la muerte se llegaba procuraba que fuese más crecida. Toda en el mal el alma divertida, pena por pena su dolor sumaba, y en cada circunstancia ponderaba que sobraban mil muertes a una vida. Y cuando, al golpe de uno y otro tiro rendido el corazón, daba penoso señas de dar el último suspiro, No sé con qué destino prodigioso volví a mi acuerdo y dije: qué me admiro? Quién en amor ha sido más dichoso? |

致命傷の痛みとともに 致命傷の痛みと共に 愛の過ちを嘆いた、 死が訪れるかどうか確かめようとした 死が来るかどうかを確かめようとした。 私の魂はすべて悪に惑わされた、 悲しみに悲しみが加わった、 どんな状況でも私は考えた 一人の命に千人の死は多すぎると思った。 そして、一発、また一発と撃たれるたびに 彼女の心臓が、彼女の心臓が屈服し、彼女が息を引き取ろうとする気配を見せた。 息を引き取る気配があった、 私はどのような驚異的な運命をたどったのか知らない。 私は自分の同意に戻り、こう言った。 愛において、これほど幸福な人がいるだろうか? |

| En

perseguirme, Mundo, ¿qué interesas? En perseguirme, Mundo, ¿qué interesas? ¿En qué te ofendo, cuando sólo intento poner bellezas en mi entendimiento y no mi entendimiento en las bellezas? Yo no estimo tesoros ni riquezas; y así, siempre me causa más contento poner riquezas en mi pensamiento que no mi pensamiento en las riquezas. Y no estimo hermosura que, vencida, es despojo civil de las edades, ni riqueza me agrada fementida, teniendo por mejor, en mis verdades, consumir vanidades de la vida que consumir la vida en vanidades. |

世界よ、私を追い求めるにあたって、あなたは何に興味があるのか? 世界よ、私を追い求めるとき、あなたは何に興味があるのか? 私がただ美を私の理解力に乗せようとするとき、私は何においてあなたを怒らせるのか? 私の理解の中に美を置き 私の理解を美の中に入れようとはしない。 私は財宝や富を尊ばない; だから、私はいつも幸せなのだ。 富を私の思考に入れるほうが 富をわが心に置き、わが心を富に置かないよりは。 私は美を尊ばない、 を尊敬しない、 富も、偽りの意味で私を喜ばせるものではない、 私の真理において、富はより良いものである、 人生の虚栄を消費する 人生を虚栄のうちに消費するよりは。 |

| Éste

que ves, engaño colorido Éste que ves, engaño colorido, que, del arte ostentando los primores, con falsos silogismos de colores es cauteloso engaño del sentido; éste, en quien la lisonja ha pretendido excusar de los años los horrores, y venciendo del tiempo los rigores triunfar de la vejez y del olvido, es un vano artificio del cuidado, es una flor al viento delicada, es un resguardo inútil para el hado: es una necia diligencia errada, es un afán caduco y, bien mirado, es cadáver, es polvo, es sombra, es nada. |

カラフルな欺瞞 カラフルな欺瞞だ、 その、プリマーを誇示する芸術の、 色彩の偽りの五段論法で 感覚を慎重に欺く; この者は、お世辞を振りかざす者である。 長年の恐怖を言い訳にする、 時の厳しさに打ち勝ち 老いと忘却に勝利する、 気遣いの虚しい策略である、 それは風の中の繊細な花である、 妖精にとっては無用の隠れ家である: 愚かな誤った勤勉さだ、 それは愚かな誤った勤勉さであり、むなしい勤勉さであり、使い古された熱心さである、 死体であり、塵であり、影であり、無である。 |

| Esta

tarde, mi bien, cuando te hablaba Esta tarde, mi bien, cuando te hablaba, como en tu rostro y en tus acciones vía que con palabras no te persuadía, que el corazón me vieses deseaba; y Amor, que mis intentos ayudaba, venció lo que imposible parecía, pues entre el llanto que el dolor vertía, el corazón deshecho destilaba. Baste ya de rigores, mi bien, baste, no te atormenten más celos tiranos, ni el vil recelo tu quietud contraste con sombras necias, con indicios vanos: pues ya en líquido humor viste y tocaste mi corazón deshecho entre tus manos. |

今日の午後、あなたに話しかけたとき 今日の夕方、あなたに話しかけたとき、私のいい人だった、 あなたの顔や行動に 言葉であなたを説得したのではない 私の心の願いは、あなたに私を見てほしいということだった; そして愛は、私の試みを助けてくれた、 不可能と思われたことを克服した、 涙の中で悲しみが溢れ出たからだ、 傷ついた心が甦った。 厳しさはもうたくさんだ! これ以上、横暴な嫉妬が汝を苦しめることはない、 下劣な憂慮が、汝の静けさにコントラストをつけることもない。 愚かな影と、虚しいしるしと: 汝はすでに液状の気分の中で、私の傷ついた心を見、触れた。 私の傷ついた心を、あなたの手の中に見たのだから。 |

| https://www.zendalibros.com/5-poemas-sor-juana-ines-la-cruz/ |

Doña

Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana,

Doña

Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana,

| Doña

Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana,

better known as Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz[a] OSH (12 November 1648 – 17

April 1695)[1] was a Mexican writer, philosopher, composer and poet of

the Baroque period, and Hieronymite nun. Her contributions to the

Spanish Golden Age gained her the nicknames of "The Tenth Muse" or "The

Phoenix of America",[1]; historian Stuart Murray calls her a flame that

rose from the ashes of "religious authoritarianism".[2] Sor Juana lived during Mexico's colonial period, making her a contributor both to early Spanish literature as well as to the broader literature of the Spanish Golden Age. Beginning her studies at a young age, Sor Juana was fluent in Latin and also wrote in Nahuatl,[3] and became known for her philosophy in her teens. Sor Juana educated herself in her own library, which was mostly inherited from her grandfather.[2] After joining a nunnery in 1667,[4] Sor Juana began writing poetry and prose dealing with such topics as love, environmentalism, feminism, and religion.[5] She turned her nun's quarters into a salon, visited by New Spain's female intellectual elite, including Donna Eleonora del Carreto, Marchioness of Mancera, and Doña Maria Luisa Gonzaga, Countess of Paredes de Nava, both Vicereines of the New Spain,[6] amongst others. Her criticism of misogyny and the hypocrisy of men led to her condemnation by the Bishop of Puebla,[7] and in 1694 she was forced to sell her collection of books and focus on charity towards the poor.[8] She died the next year, having caught the plague while treating her sisters.[9] After she had faded from academic discourse for hundreds of years, Nobel Prize winner Octavio Paz re-established Sor Juana's importance in modern times.[10] Scholars now interpret Sor Juana as a protofeminist, and she is the subject of vibrant discourse about themes such as colonialism, education rights, women's religious authority, and writing as examples of feminist advocacy. +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ Juana Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana, better known as Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz[a] OSH (12 November 1648 – 17 April 1695),[1] was a Hieronymite nun and a Spanish [2] writer, philosopher, composer and poet of the Baroque period, nicknamed "The Tenth Muse", "The Mexican Phoenix",[3] and "The Phoenix of America" by her contemporary critics.[1] She was also a student of science and corresponded with the English scientist Isaac Newton.[4] She was among the main contributors to the Spanish Golden Age, alongside Juan de Espinosa Medrano, Juan Ruiz de Alarcón and Garcilaso de la Vega "el Inca", and is considered one of the most important female writers in Spanish language literature and Mexican literature. Sor Juana's significance to different communities and has varied greatly across time- having been presented as a candidate for Catholic sainthood; a symbol of Mexican nationalism; and a paragon of freedom of speech, women's rights, and sexual diversity, making her a figure of great controversy and debate to this day. |

ドニャ・イネス・デ・アスバヘ・イ・ラミレス・デ・サンティリャーナ、

通称ソル・フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルス[a] OSH(1648年11月12日 -

1695年4月17日)はメキシコの作家、哲学者、作曲家、バロック時代の詩人でヒエロニム派の修道女[1]である。スペインの黄金時代に貢献したことか

ら「10人目のミューズ」「アメリカの不死鳥」などの異名を持つ[1]。歴史家のスチュアート・マレーは彼女を「宗教的権威主義」の灰から立ち上がる炎と

呼んでいる[2]。 ソ ル・フアナはメキシコの植民地時代に生きたので、初期のスペイン文学だけでなく、スペイン黄金時代の広範な文学にも貢献した人物である。若い頃から勉強 を始めたソル・フアナは、ラテン語に堪能で、ナワトル語でも文章を書き、10代で哲学者として知られるようになった[3]。1667年に修道院に入った後 [4]、愛、環境保護、フェミニズム、宗教などをテーマにした詩や散文を書き始める[5]。 [修道女の部屋をサロンにし、マンセラ侯爵夫人ドナ・エレオノラ・デル・カレットやパレデス・デ・ナバ伯爵夫人ドニャ・マリア・ルイサ・ゴンサガなど、ヌ エバ・エスパーニャの女性知識人たちが訪れた[6]。女性差別や男性の偽善を批判した彼女はプエブラ司教から非難され[7]、1694年には蔵書を売却 し、貧しい人 々への慈善活動に専念することを余儀なくされた。 翌年、姉妹の治療中にペストにかかり、死亡した[9]。 数百年の間、学術的な議論から消えていたソル・フアナを、ノーベル賞受賞者のオクタビオ・パスが現代において再び重要視するようになった[10]。 現在、学者たちはソル・フアナをフェミニストの原型と解釈し、植民地主義、教育権、女性の宗教的権威、執筆などのテーマについてフェミニストの主張例とし て活発な議論の対象になっている。 +++++++++++++++++++++++++++++++ フアナ・イネス・デ・アスバヘ・イ・ラミレス・デ・サンティジャーナ、よりよく知られている名前は、ソル・フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルス[a] OSH(1648年11月12日 - 1695年4月17日)[1] は、ヒエロニムス修道会の修道女であり、スペインの[2] 作家、哲学者、作曲家、詩人であり、バロック時代の「第十のミューズ」の愛称で知られていた。「メキシコのフェニックス」[3]、「アメリカのフェニック ス」とも呼ばれた。彼女は科学の学生でもあり、イギリスの科学者アイザック・ニュートンと文通をしていた。[4] 彼女は、フアン・デ・エスピノサ・メドラノ、フアン・ルイス・デ・アラコン、ガルシラソ・デ・ラ・ベガ「エル・インカ」と共にスペインの黄金時代の主要な 貢献者の一人であり、スペイン語文学とメキシコ文学において最も重要な女性作家の一人として考えられている。 ソル・フアナは、さまざまなコミュニティにとって重要な人物であり、その評価は時代によって大きく変化してきた。カトリックの聖人候補として、メキシコナ ショナリズムの象徴として、そして言論の自由、女性の権利、性的多様性の模範として、今日まで大きな論争と議論の的となっている人物だ。 |

| Doña Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de

Santillana was born in San Miguel Nepantla (now called Nepantla de Sor

Juana Inés de la Cruz) near Mexico City. Owing to her Spanish ancestry

and Mexican birth, Inés is considered a Criolla.[11] She was the

illegitimate child of Don Pedro Manuel de Asuaje y Vargas-Machuca, a

Spanish officer, and Doña Isabel Ramírez de Santillana y Rendón, a

wealthy criolla, who inhabited the Hacienda of Panoaya, close to Mexico

City. She was baptized on the 2nd of December 1651 with the name of

Inés ("Juana" was only added after she entered the convent) described

on the baptismal rolls as "a daughter of the Church".[12] The name Inés

came from her maternal aunt Doña Inés Ramírez de Santillana, who

received the name herself from her Andalusian grandmother Doña Inés de

Brenes.[13] The name Inés was also present through their cousin Doña

Inés de Brenes y Mendoza, married to a grandson of Antonio de Saavedra

Guzmán, the first ever published American-born poet. Her biological father, according to all accounts, was completely absent from her life. However, thanks to her maternal grandfather, who owned a very productive hacienda in Amecameca, Inés lived a comfortable life with her mother on his estate, Panoaya, accompanied by an illustrious group of relatives who constantly visited or were visited in their surrounding haciendas.[14] During her childhood, Inés often hid in the hacienda chapel to read her grandfather's books from the adjoining library, something forbidden to girls. By the age of three, she had learned how to read and write Latin. By the age of five, she reportedly could do accounts. At age eight, she composed a poem on the Eucharist.[15] By adolescence, Inés had mastered Greek logic, and at age thirteen she was teaching Latin to young children. She also learned the Aztec language of Nahuatl and wrote some short poems in that language.[14] In 1664, at the age of 16, Inés was sent to live in Mexico City. She even asked her mother's permission to disguise herself as a male student so that she could enter the university there, without success. Without the ability to obtain formal education, Juana continued her studies privately. Her family's influential position had gained her the position of lady-in-waiting at the colonial viceroy's court,[2] where she came under the tutelage of the Vicereine Donna Eleonora del Carretto, member of one of Italy's most illustrious families, and wife of the Viceroy of New Spain Don Antonio Sebastián de Toledo, Marquis of Mancera. The viceroy Marquis de Mancera, wishing to test the learning and intelligence of the 17-year-old, invited several theologians, jurists, philosophers, and poets to a meeting, during which she had to answer many questions unprepared and explain several difficult points on various scientific and literary subjects. The manner in which she acquitted herself astonished all present and greatly increased her reputation. Her literary accomplishments garnered her fame throughout New Spain. She was much admired in the viceregal court, and she received several proposals of marriage, which she declined.[15] |

ドニャ・イネス・デ・アスバジェ・イ・ラミレス・デ・サンティリャーナ

は、メキシコシティ近郊のサン・ミゲル・ネパントラ(現在のネパントラ・デ・ソル・フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルス)で生まれた。スペイン人の血を引き、

メキシコで生まれたため、イネスはクリオージャとみなされる[11]。スペイン人将校のドン・ペドロ・マヌエル・デ・アスアヘ・イ・バルガス・マチュカ

と、メキシコシティに近いパノアヤの農園に住んでいた富裕層のクリオージャ、ドニャ・イサベル・ラミーリャナ・イ・レンドンの間の私生児であった。

1651年12月2日にイネスの名で洗礼を受け(「フアナ」は修道院に入ってから付けられた)、洗礼名簿には「教会の娘」と記されている[12]

イネスという名は、母方の叔母ドニャ・イネス・ラミーレス・デ・サンティリャーナから来ており、彼女自身もアンダルシアの祖母ドニャ・イネス・デ・ブレネ

スからこの名を授かったという。 [13]

イネスという名前は、アメリカ生まれの詩人として初めて出版されたアントニオ・デ・サベドラ・グスマンの孫と結婚した従姉妹のドニャ・イネス・デ・ブレネ

ス・イ・メンドーサを通しても存在していた。 実の父親は、彼女の人生から完全に姿を消してしまったと言われている。しかし、アメカメカに生産性の高い農場を所有していた母方の祖父のおかげで、イネス は母親と一緒にパノアヤという農場で快適な生活を送り、周囲の農場を常に訪れたり訪問されたりしている著名な親族たちと一緒に暮らしていた[14]。 幼少期、イネスはしばしばアシエンダ(農園)の礼拝堂にこもり、隣接する図書館から祖父の本を読んでいた(女児禁制のものであった)。3歳までにラテン語 の読み書きを習得した。5歳の時には勘定科目ができたという。青年期にはギリシャ語の論理学を習得し、13歳には幼児にラテン語を教えるようになる。ま た、アステカ語のナワトルを学び、その言語で短い詩をいくつか書いた[14]。 1664年、16歳の時、イネスはメキシコシティに住むことになった。イネスは、1664年に16歳でメキシコシティに送られ、同地の大学に入学するた め、母親に男子学生に変装する許可を得たが、成功しなかった。フアナは、正式な教育を受けることができず、私費で勉強を続けていた。そこで彼女は、イタリ アの名家の一つであり、新スペイン総督ドン・アントニオ・セバスティアン・デ・トレド(マンセラ侯爵)の妻であるドンナ・エレオノラ・デル・カレット副領 事の指導を受けることになる。マンセラ総督は、17歳の彼女の学識と知性を試そうと、神学者、法学者、哲学者、詩人などを招いて会議を開き、彼女は準備不 足のまま多くの質問に答え、科学や文学に関するさまざまな難問について説明しなければならなかった。この時の彼女の態度は、出席者全員を驚かせ、彼女の評 判を大いに高めた。彼女の文学的な業績は、ニュースペイン全土にその名を轟かせた。彼女は副王庁(女官として出仕し副王妃の寵愛を受ける)でも賞賛され、何度か結婚を申し込まれたが、断った [15]。 |

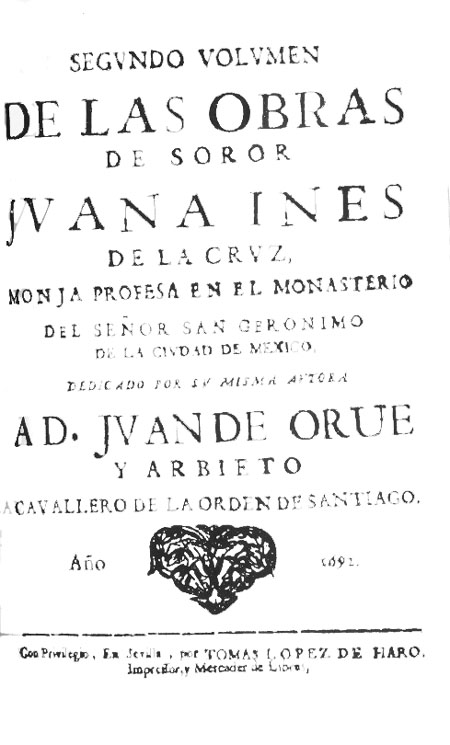

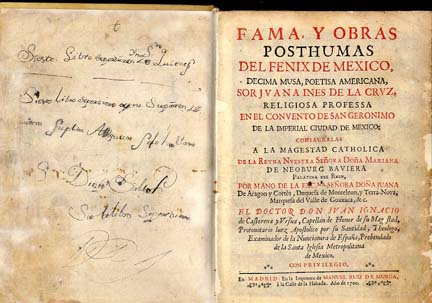

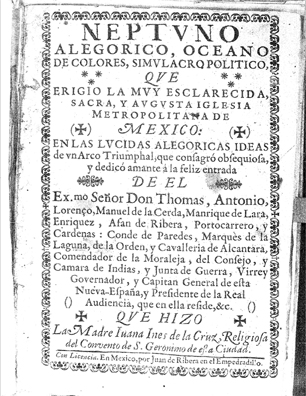

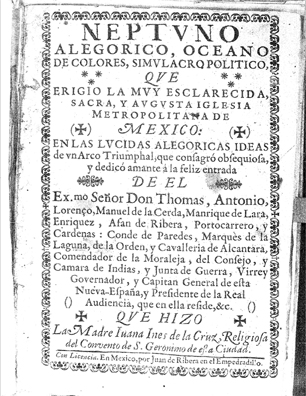

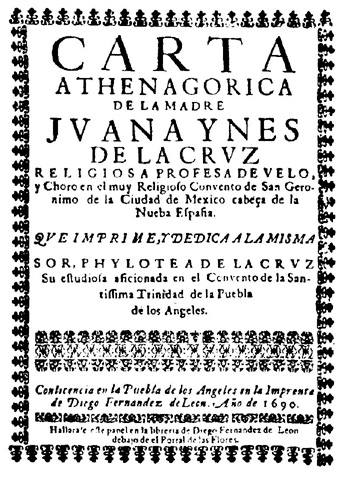

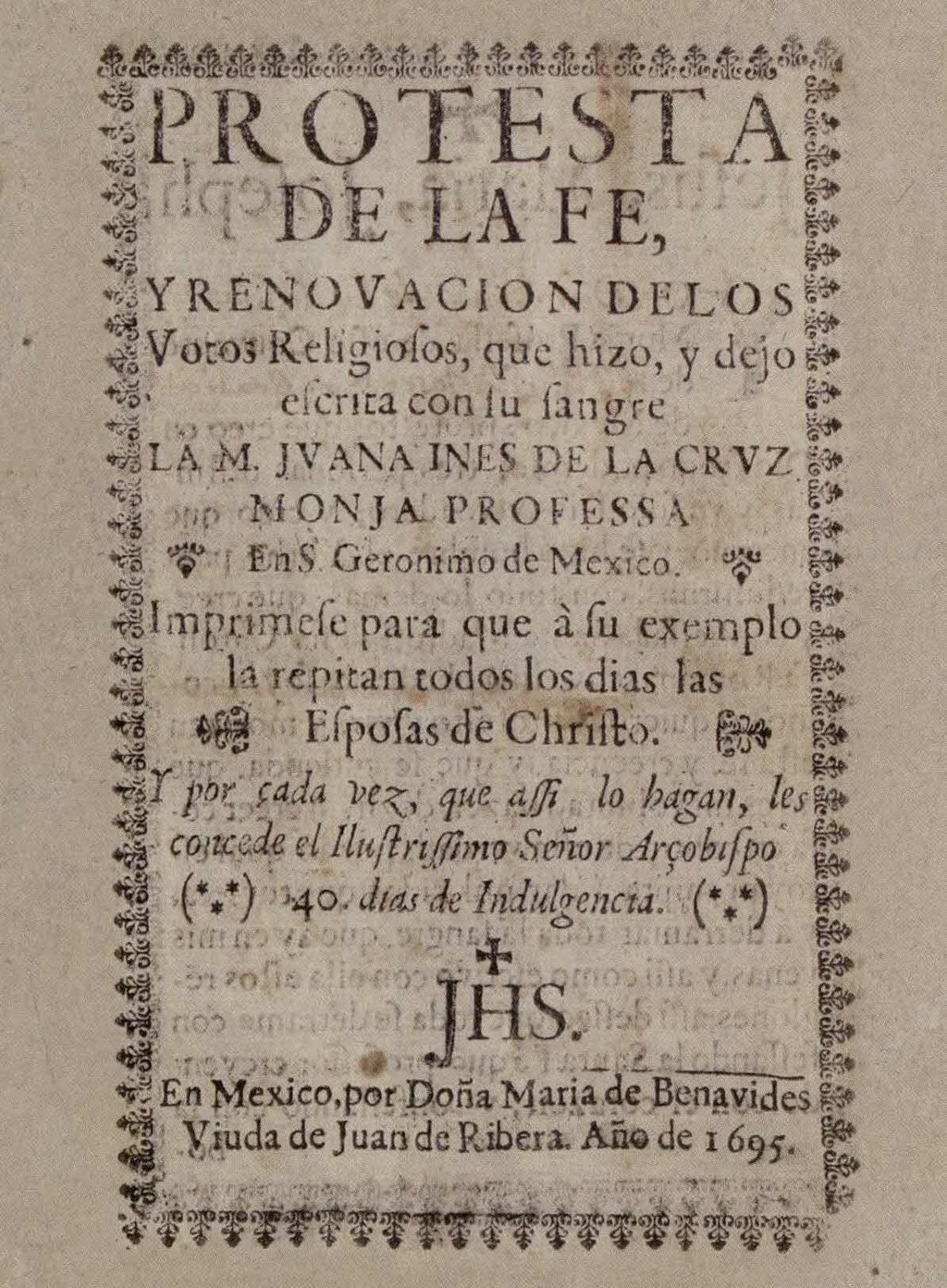

| n 1667, she entered the

Monastery of St. Joseph, a community of the Discalced Carmelite nuns,

as a postulant, where she remained but a few months. Later, in 1669,

she entered the monastery of the Hieronymite nuns, which had more

relaxed rules, where she changed her name to Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz,

probably in reference to Sor Juana de la Cruz Vázquez Gutiérrez who was

a Spanish nun whose erudition earned her one of the few dispensations

for women to preach the gospel. Another potential namesake was Saint

Juan de la Cruz, one of the most accomplished authors of the Spanish

Baroque. She chose to become a nun so that she could study as she

wished since she wanted "to have no fixed occupation which might

curtail my freedom to study."[16] In the convent and perhaps earlier, Sor Juana became intimate friends with fellow savant, Don Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, who visited her in the convent's locutorio.[9] She stayed cloistered in the Convent of Santa Paula of the Hieronymite in Mexico City from 1669 until her death in 1695, and there she studied, wrote, and collected a large library of books. The Viceroy and Vicereine of New Spain became her patrons; they supported her and had her writings published in Spain.[16] She addressed some of her poems to paintings of her friend and patron María Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzaga, daughter of Vespasiano Gonzaga, Duca di Guastala, Luzara e Rechiolo and Inés María Manrique, 9th Countess de Paredes, which she also addressed as Lísida. In November 1690, the bishop of Puebla, Manuel Fernández de Santa Cruz published, under the pseudonym of Sor Filotea, and without her permission, Sor Juana's critique of a 40-year-old sermon by Father António Vieira, a Portuguese Jesuit preacher.[7] Although Sor Juana's intentions for the work, called Carta Atenagórica are left to interpretation, many scholars have opted to interpret the work as a challenge to the hierarchical structure of religious authority.[17] Along with Carta Atenagórica, the bishop also published his own letter in which he said she should focus on religious instead of secular studies.[16] He published his criticisms to use them to his advantage against the priest, and while he agreed with her criticisms, he believed that as a woman, she should devote herself to prayer and give up her writings.[18] In response to her critics, Sor Juana wrote a letter, Respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz (Reply to Sister Philotea),[19] in which she defended women's right to formal education.[20] She also advocated for women's right to serve as intellectual authorities, not only through the act of writing, but also through the publication of their writing.[20] By putting women, specifically older women, in positions of authority, Sor Juana argued, women could educate other women. Resultingly, Sor Juana argued, this practice could also avoid potentially dangerous situations involving male teachers in intimate settings with young female students.[21] In addition to her status as a woman in a self-prescribed position of authority, Sor Juana's radical position made her an increasingly controversial figure. She famously remarked by quoting an Aragonese poet and echoing St. Teresa of Ávila: "One can perfectly well philosophize while cooking supper."[22] In response, Francisco de Aguiar y Seijas, Archbishop of Mexico joined other high-ranking officials in condemning Sor Juana's "waywardness." In addition to opposition she received for challenging the patriarchal structure of the Catholic Church, Sor Juana was repeatedly criticized for believing that her writing could achieve the same philanthropic goals as community work.[20] By 1693, she seemingly ceased to write, rather than risking official censure. Although there is no undisputed evidence of her renouncing devotion to letters, there are documents showing her agreeing to undergo penance.[8] Her name is affixed to such a document in 1694, but given her deep natural lyricism, the tone of the supposed handwritten penitentials is in rhetorical and autocratic Church formulae; one is signed "Yo, la Peor de Todas" ("I, the worst of all women").[8] She is said to have sold all her books,[15] then an extensive library of over 4,000 volumes, and her musical and scientific instruments as well. Other sources report that her defiance toward the Church led to the confiscation of all of her books and instruments, although the bishop himself agreed with the contents of her letters.[23] Of over one hundred unpublished works,[24] only a few of her writings have survived, which are known as the Complete Works. According to Octavio Paz, her writings were saved by the vicereine.[25] She died after ministering to other nuns stricken during a plague, on 17 April 1695. Sigüenza y Góngora delivered the eulogy at her funeral.[9] |

1667年、跣足カルメル会修道女の共同体である聖ヨセフ修道院に修道

士として入るが、数か月しか留まらなかった。1669年、より規則の緩やかなヒエロニム会修道院に入り、そこでソル・フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルスと改

名した。おそらく、ソル・フアナ・デ・ラ・クルス・バスケス・グティエレスが、博学な女性として福音を宣べ伝える数少ない免罪符を得たスペイン人修道女を

意識してのことであろう。また、スペイン・バロック時代の最も優れた作家の一人である聖フアン・デ・ラ・クルスも名前の候補に挙がっている。彼女は、「勉

強する自由を奪うような決まった職業を持たない」ことを望み、好きなように勉強できるように修道女になることを選んだ[16]。 1669年から1695年に亡くなるまで、メキシコシティのヒエロニム会サンタパウラ修道院に身を寄せ、そこで研究し、執筆し、大量の蔵書を収集した。新 スペイン総督と副王は彼女のパトロンとなり、彼女を支援し、彼女の著作をスペインで出版させた[16]。 彼女は友人でありパトロンであった、グアスタラ公ルサラ・エ・レキオロの娘ベスパシアノ・ゴンザーガと第9代パレデス伯イネス・マリア・マンリケの絵画に 宛てた詩の一部をリシダと表記している。 1690年11月、プエブラ司教のマヌエル・フェルナンデス・デ・サンタ・クルスは、ソル・フィロテアというペンネームで、ポルトガルのイエズス会伝道師 アントニオ・ヴィエイラ神父による40年前の説教に対するソル・フアナの批判を彼女の許可なく出版した[7]。 カルタ・アテナゴリカと名付けられた作品についての彼女の意図は解釈に委ねられているものの、多くの学者はこの作品を宗教権威の階層的構造に対する挑戦と して解釈している[17]。 [17] カルタ・アテナゴリカと同時に、司教は自身の手紙も発表し、その中で彼女は世俗的な学問ではなく宗教に専念すべきだと述べた[16]。司教に対して有利に なるように批判を公表し、彼女の批判に同意しつつも、女性として祈りに専念し著作を諦めるべきと信じたのである[18]。 批評家たちに対して、ソル・フアナは書簡『Respuesta a Sor Filotea de la Cruz(シスター・フィロテアへの返答)』[19]を書き、女性が正式な教育を受ける権利を擁護した。 また彼女は、書く行為だけではなく、書いたものを出版することによっても女性が知的権威として機能する権利を主張した[20] 女性、特に年配の女性を権威ある立場におくことによって、女性は他の女性を教育できるとソル・フアナは主張している。その結果、この実践は、若い女性の生 徒と親密な関係にある男性の教師が関わる潜在的に危険な状況を避けることもできるとソル・フアナは主張した[21]。 自らに課した権威のある女性としての地位に加え、ソル・フアナの急進的な立場は彼女をますます物議を醸す人物にした。これに対して、メキシコの大司教フラ ンシスコ・デ・アギアール・イ・セイハスは、他の高官とともにソル・フアナの「道楽」を非難した[22]。カトリック教会の家父長的な構造に挑戦したこと で受けた反対に加えて、ソル・フアナは、自分の著作が地域社会の仕事と同じ慈善的な目標を達成できると信じたことで繰り返し批判された[20]。 1693年まで、彼女は公式の非難を受ける危険を冒すよりも、書くことを止めたように見えた。1694年のそのような文書に彼女の名前が記されているが、 彼女の深い天性の叙情性を考えると、手書きの懺悔文の口調は修辞的で独裁的な教会の公式であり、1つは「Yo, la Peor de Todas」(「私はすべての女性の中で最悪」)の署名がある[8]。 彼女はすべての本を売ったと言われており[15]、当時は4,000冊以上の膨大な蔵書があり、楽器や科学機器も売ったと言われている[16]。他の資料 では、教会に対する彼女の反抗心が、司教自身は彼女の手紙の内容に同意していたにもかかわらず、彼女のすべての書籍と楽器を没収することにつながったと報 告されている[23]。 100を超える未発表の作品のうち[24]、彼女の著作は数点しか残っておらず、これらは全集として知られている[25]。オクタビオ・パスによると、彼 女の著作はヴィセレーヌによって保存された[25]。 1695年4月17日、ペストに罹患した他の修道女を介抱した後、死去した。葬儀ではシギュエンサ・イ・ゴンゴーラが弔辞を述べた[9]。 |

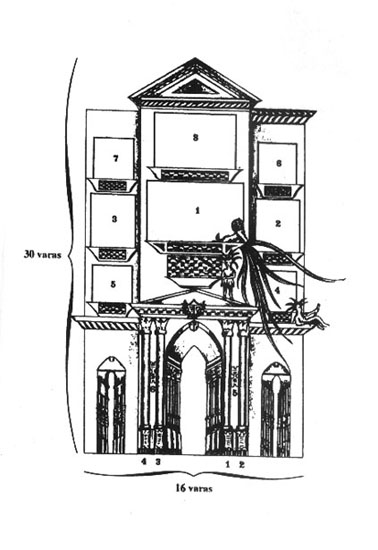

| Poetry - First Dream First Dream, a long philosophical and descriptive silva (a poetic form combining verses of 7 and 11 syllables), "deals with the shadow of night beneath which a person[26] falls asleep in the midst of quietness and silence, where night and day animals participate, either dozing or sleeping, all urged to silence and rest by Harpocrates. The person's body ceases its ordinary operations,[27] which are described in physiological and symbolical terms, ending with the activity of the imagination as an image-reflecting apparatus: the Pharos. From this moment, her soul, in a dream, sees itself free at the summit of her own intellect; in other words, at the apex of an own pyramid-like mount, which aims at God and is luminous.[28] There, perched like an eagle, she contemplates the whole creation,[29] but fails to comprehend such a sight in a single concept. Dazzled, the soul's intellect faces its own shipwreck, caused mainly by trying to understand the overwhelming abundance of the universe, until reason undertakes that enterprise, beginning with each individual creation, and processing them one by one, helped by the Aristotelic method of ten categories.[30] The soul cannot get beyond questioning herself about the traits and causes of a fountain and a flower, intimating perhaps that his method constitutes a useless effort, since it must take into account all the details, accidents, and mysteries of each being. By that time, the body has consumed all its nourishment, and it starts to move and wake up, soul and body are reunited. The poem ends with the Sun overcoming Night in a straightforward battle between luminous and dark armies, and with the poet's awakening.[30] |

詩 - 初夢 初夢」は、哲学的で叙述的な長いシルヴァ(7音節と11音節を組み合わせた詩の形式)で、「夜の影を扱い、その下で人[26]が静寂と沈黙の中で眠りにつ き、そこには昼と夜の動物が居眠りか眠っていて、ハーポクラテスに沈黙と休息を促されている。人の身体は通常の活動を停止し[27]、生理的・象徴的な用 語で説明され、イメージを反射する装置であるファロスとしての想像力の活動で終わる。この瞬間から、彼女の魂は夢の中で、自分自身の知性の頂上、言い換え れば、神を目指し光り輝く自分自身のピラミッド状の山の頂上で、自分自身が自由であることを見る[28]。 そこでは、鷲のようにとまって、彼女は被造物全体を眺めるが[29]、そのような光景を単一の概念で理解することができない。目がくらみ、魂の知性は、主 に宇宙の圧倒的な豊かさを理解しようとすることによって引き起こされる難破船に直面するが、理性がその事業を引き受け、個々の被造物から始めて、アリスト テレスの10のカテゴリーという方法に助けられてそれらを一つずつ処理する[30]までである。 魂は、噴水と花の形質と原因について自問することを超えることができず、おそらく彼の方法は、それぞれの存在のすべての詳細、事故、謎を考慮に入れなけれ ばならないので、無駄な努力であることを示唆しているのであろう。その頃、肉体は栄養をすべて消費し、動き出し、目覚め、魂と肉体は再び一つになる。詩の 最後は、太陽が夜を克服し、光と闇の軍勢による真っ当な戦いと、詩人の覚醒で終わる[30]。 |

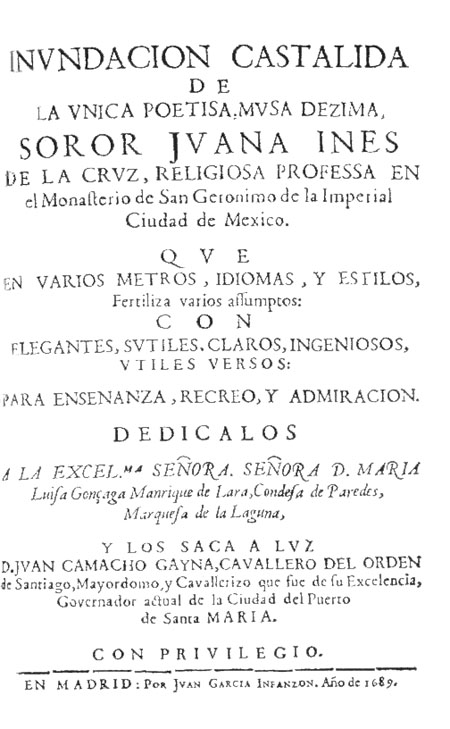

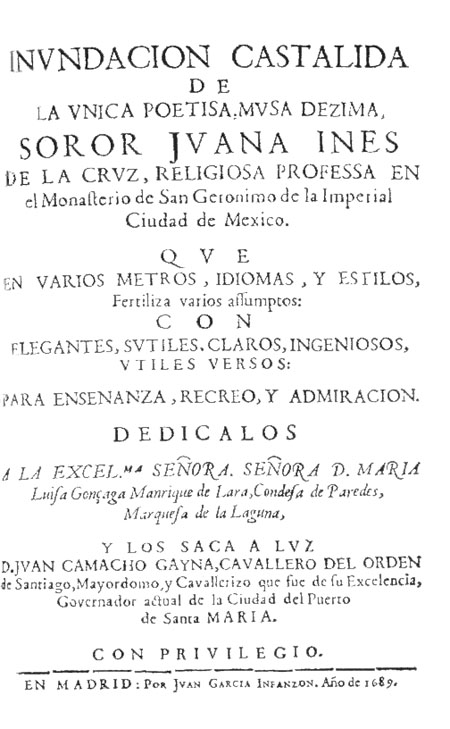

| Love Poems Sor Juana's first volume of poetry, Inundación castálida, was published in Spain by the Vicereine Maria Luisa Manrique de Lara y Gonzaga, Countess of Paredes, Marquise de la Laguna.[31] Many of her poems dealt with the subject of love and sensuality, and frequently her expressed desire was for women, such as in the poems "My Divine Lysi," "I Beg You, Señora," "Inez, When Someone Tells You You're a Bitch," "Portia, What Passion, What Blind Pain," and others. Jaime Manrique, the Colombian American novelist, poet, essayist, educator, and translator, described her poetry thus: "her love poems are expressions of a complex and ambivalent modern psyche, and because they are so passionate and ferocious that when we read them we feel consumed by the naked intensity she achieves."[32] An example of her love poetry, "Don't Go, My Darling. I Don't Want This to End Yet" (translated by Manrique and Joan Larkin): Don't go, my darling. I don't want this to end yet. This sweet fiction is all I have. Hold me so I'll die happy, thankful for your lies. My breasts answer yours magnet to magnet. Why make love to me, then leave? Why mock me? Don't brag about your conquest— I'm not your trophy. Go ahead: reject these arms that wrapped you in sumptuous silk. Try to escape my arms, my breasts— I'll keep you prisoner in my poem.[33] |

愛の詩 ソル・フアナの最初の詩集『Inundación castálida』は、スペインでパレデス伯爵夫人、ラグナ侯爵夫人であるマリア・ルイサ・マンリケ・デ・ララ・イ・ゴンサガ副領主により出版された [31]。 [31] 彼女の詩の多くは愛と官能を主題としており、「私の神聖なリッシー」、「セニョーラ、あなたにお願い」、「イネス、誰かがあなたをビッチだと言うとき」、 「ポーシャ、なんという情熱、なんという盲目の痛み」など、しばしば女性への願望が表現されている。コロンビア系アメリカ人の小説家、詩人、エッセイス ト、教育者、翻訳家であるハイメ・マンリケは、彼女の詩をこう評している。"彼女の恋愛詩は複雑で両義的な現代人の精神の表現であり、それらはとても情熱 的で獰猛であるため、私たちはそれらを読むとき、彼女が達成した裸の強度に飲み込まれたように感じる"[32]。 彼女の恋愛詩の例として、「行かないで、私のダーリン。I Don't Want This to End Yet」(マンリケ、ジョーン・ラーキン共訳)。 行かないで、私の愛しい人。まだ終わらせたくないの。この甘いフィクションが私のすべて。あなたの嘘に感謝して、幸せに死ねるように、私を抱きしめてくだ さい。 私の胸はあなたの磁石に答える なぜ私と愛し合い、去るのか?なぜ私を嘲笑するのですか? 征服したことを自慢しないで-私はあなたのトロフィーではありません。どうぞ、この腕を拒否してください この腕で君を包んだ この腕、この胸から逃れようとすれば......私の詩の中であなたを捕虜にしておくわ[33]。 |

| Dramas In addition to the two comedies outlined here (House of Desires [Los empeños de una casa]) and Love is but a Labyrinth [Amor es mas laberinto]), Sor Juana is attributed as the author of a possible ending to the comedy by Agustin de Salazar: The Second Celestina (La Segunda Celestina).[34] In the 1990s, Guillermo Schmidhuber found a release of the comedy that contained a different ending than the otherwise known ending. He proposed that those one thousand words were written by Sor Juana. Some literary critics, such as Octavio Paz,[35] Georgina Sabat-Rivers,[36] and Luis Leal[37]) have accepted Sor Juana as the co-author, but others, such as Antonio Alatorre[38] and José Pascual Buxó, have refuted it. |

ドラマ ここで紹介した2つの喜劇(『欲望の家』(Los empeños de una casa))と『愛は迷宮』(Amor es mas laberinto)に加え、ソル・フアナはアグスティン・デ・サラザルの喜劇の結末を書いたとされている。1990年代、ギレルモ・シュミッドフーバー が、一般に知られている結末とは異なる結末を含むこの喜劇のリリースを発見した[34]。彼はその千の言葉がソル・フアナによって書かれたものであると提 唱した。オクタビオ・パス[35]、ゲオルギーナ・サバト=リヴァース[36]、ルイス・レアル[37]などの一部の文学評論家はソル・フアナを共著者と して認めたが、アントニオ・アラトーレ[38]、ホセ・パスクアル・ブソなどの一部の評論家はこれに反論している。 |

| Comedies Scholars have debated the meaning of Juana's comedies. Julie Greer Johnson describes how Juana protested against the rigorously defined relationship between genders through her full-length comedies and humor. She argues that Juana recognized the negative view of women in comedy which was designed to uphold male superiority at the expense of women. By recognizing the power of laughter, Juana appropriated the purpose of humor, and used it as a socially acceptable medium with which to question notions of men and women.[39] |

喜劇 フアナの喜劇の意味について、学者たちは議論を重ねてきた。Julie Greer Johnsonは、フアナが長編の喜劇とユーモアを通じて、厳密に定義された男女の関係に対してどのように抗議したかを述べている。彼女は、フアナが、女 性を犠牲にして男性の優越性を支持するように作られた喜劇の中の女性に対する否定的な見方を認識していたと論じている。笑いの力を認識することによって、 フアナはユーモアの目的を利用し、男女の概念に疑問を投げかける社会的に受け入れられるメディアとしてそれを利用したのである[39]。 |

| Pawns of a House The work was first performed on October 4, 1683, during the celebration of the Viceroy Count of Paredes’ first son's birth.[40] Some critics maintain that it could have been set up for the Archbishop Francisco de Aguiar y Seijas’ entrance to the capital, but this theory is not considered reliable.[40] The story revolves around two couples who are in love but, by chance of fate, cannot yet be together. This comedy of errors is considered one of the most prominent works of late baroque Spanish-American literature. One of its most peculiar characteristics is that the driving force in the story is a woman with a strong, decided personality who expresses her desires to a nun.[41] The protagonist of the story, Dona Leonor, fits the archetype perfectly.[40] It is often considered the peak of Sor Juana's work and even the peak of all New-Hispanic literature. Pawns of a House is considered a rare work in colonial Spanish-American theater due to the management of intrigue, representation of the complicated system of marital relationships, and the changes in urban life.[40] |

家の手先 1683年10月4日、パレデス総督伯爵の長男誕生祝いの席で初演された[40]。 大司教フランシスコ・デ・アギアル・イ・セーハスの首都への上京に合わせて設定されたのではないかとする批評もあるが、この説は信用できないとしている [40]。 物語は、愛し合っていながら、運命のいたずらでまだ一緒になれない二組のカップルを中心に展開する。この間違いだらけの喜劇は、後期バロック期のスペイ ン・アメリカ文学を代表する作品の一つとされている。その最も特異な特徴の一つは、物語の原動力が、強い決然とした個性を持ち、修道女に自分の願望を訴え る女性であることである[41]。 物語の主人公であるドナ・レオノールはその原型に完全に合致している[40]。 ソル・フアナの作品の頂点、さらには全新ヒスパニック文学の頂点とされることが多い。Pawns of a House』は、陰謀の管理、夫婦関係の複雑なシステムの表現、都市生活の変化などから、植民地時代のスペイン・アメリカ演劇では珍しい作品とされている [40]。 |

| Love is but a Labyrinth The work premiered on February 11, 1689, during the celebration of the inauguration of the viceroyalty Gaspar de la Cerda y Mendoza. However, in his Essay on Psychology, Ezequiel A. Chavez mentions Fernandez del Castillo as a coauthor of this comedy.[42] The plot takes on the well-known theme in Greek mythology of Theseus: a hero from Crete Island. He fights against the Minotaur and awakens the love of Ariadne and Fedra.[43] Sor Juana conceived Theseus as the archetype of the baroque hero, a model also used by her fellow countryman Juan Ruis de Alarcon. Theseus’ triumph over the Minotaur does not make Theseus proud, but instead allows him to be humble.[42] |

愛は迷宮に過ぎず 1689年2月11日、ガスパル・デ・ラ・セルダ・イ・メンドーサ総督府の就任祝賀会で初演された作品である。しかし、エセキエル・A・チャベスは『心理 学論』の中で、この喜劇の共著者としてフェルナンデス・デル・カスティーヨを挙げている[42]。 プロットは、ギリシャ神話でよく知られたテーマである、クレタ島の英雄テセウスを題材にしている。ソル・フアナはテセウスをバロック的英雄の原型として構 想し、同郷のフアン・ルイス・デ・アラルコンもこのモデルを用いている[43]。ミノタウロスに対するテセウスの勝利は、テセウスを高慢にするのではな く、謙虚になることを可能にする[42]。 |

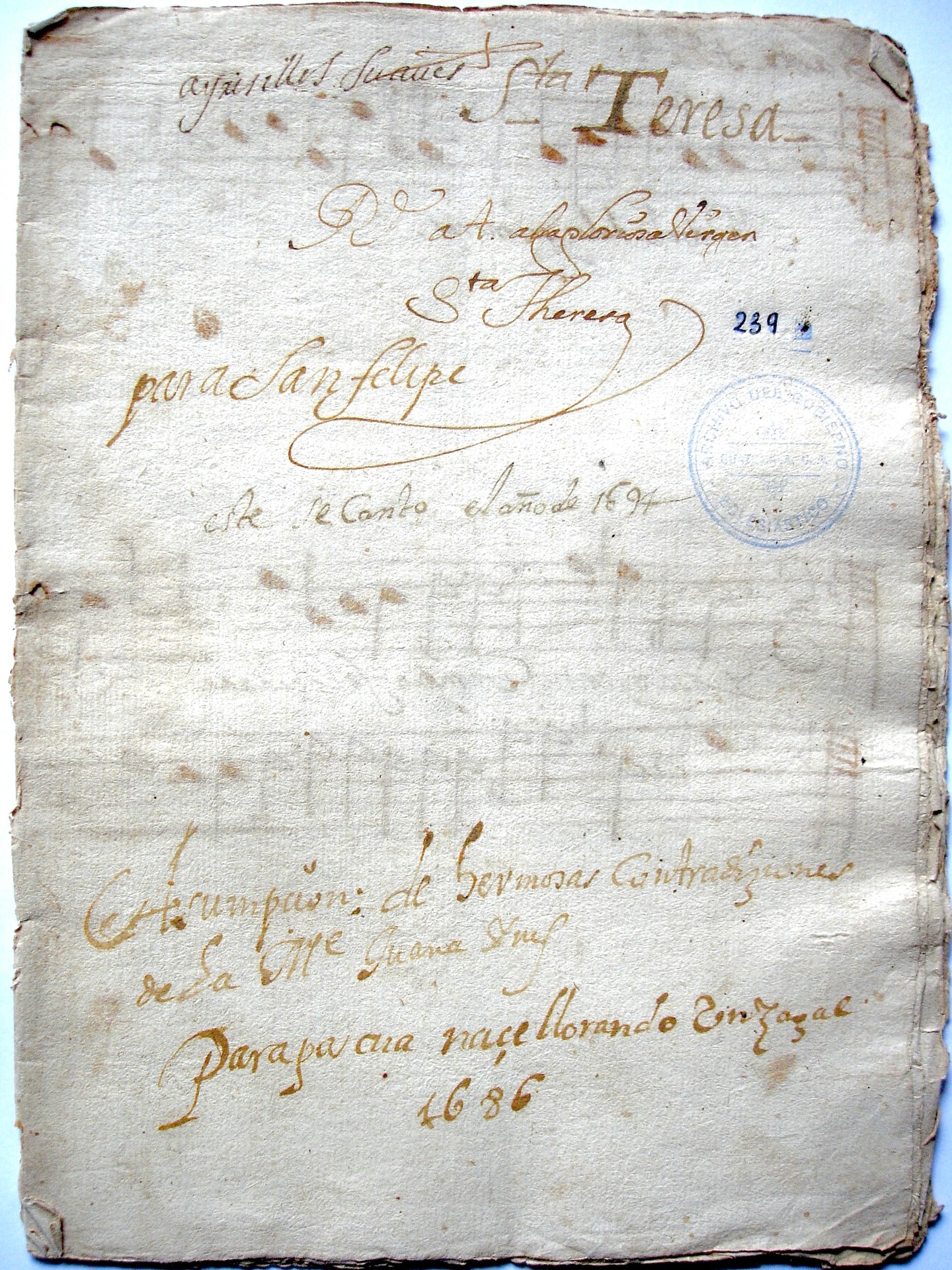

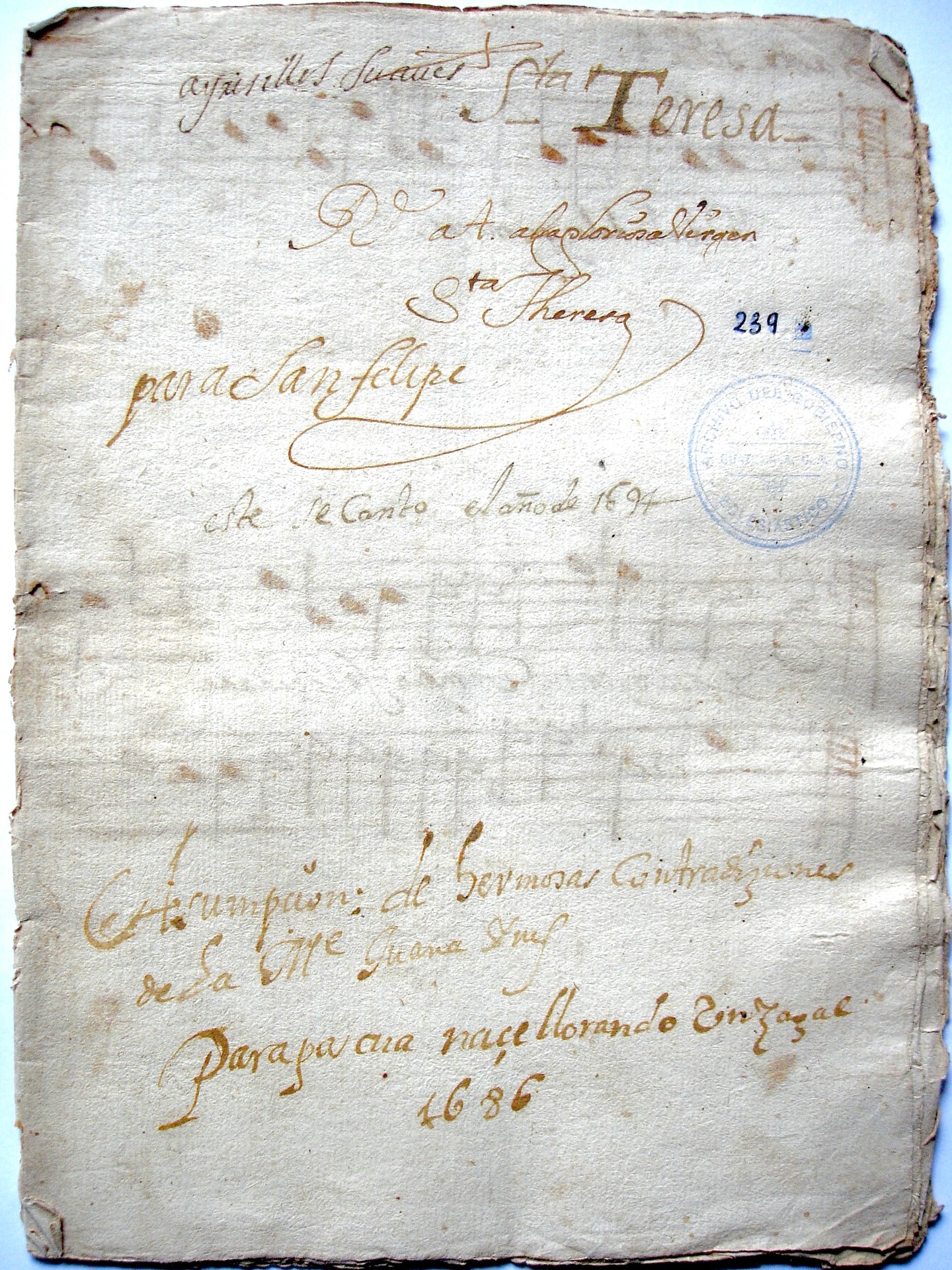

| Music Besides poetry and philosophy, Sor Juana was interested in science, mathematics and music. The latter represents an important aspect, not only because musicality was an intrinsic part of the poetry of the time but also for the fact that she devoted a significant portion of her studies to the theory of instrumental tuning that, especially in the Baroque period, had reached a point of critical importance. So involved was Sor Juana in the study of music, that she wrote a treatise called El Caracol (unfortunately lost) that sought to simplify musical notation and solve the problems that Pythagorean tuning suffered. In the writings of Juana Ines, it is possible to detect the importance of sound. We can observe this in two ways. First of all, the analysis of music and the study of musical temperament appears in several of her poems. For instance, in the following poem, Sor Juana delves into the natural notes and the accidentals of musical notation.[44] Propiedad es de natura que entre Dios y el hombre media, y del cielo el be cuadrado junto al be bemol de la tierra. (Villancico 220) On the other, Sarah Finley[45] offers an interesting idea. She argues that the visual is related with patriarchal themes, while the sonorous offers an alternative to the feminine space in the work of Sor Juana. As an example of this, Finley points out that Narciso falls in love with a voice, and not with a reflection. |

音楽 ソル・フアナは、詩や哲学のほかに、科学、数学、音楽にも興味をもっていた。後者は、音楽性が当時の詩の本質的な部分であっただけでなく、特にバロック時 代に重要な意味を持つようになった楽器の調律理論に研究の大部分を費やしたという点で、重要な側面を持っています。ソル・フアナは音楽の研究に没頭し、楽 譜を簡略化し、ピタゴラス音律が抱える問題を解決しようとした『エル・カラコル』(残念ながら失われてしまった)という論考を書きました。フアナ・イネス の著作には、音の重要性を見いだすことができる。このことは、二つの方法で観察することができる。まず、音楽の分析と音律の研究が、彼女の詩のいくつかに 登場する。例えば、次の詩では、ソル・フアナは自然音と楽譜の偶発音について掘り下げている[44]。 所有したものとは自然のものだ それは神と人の間を取り持つもの。 そして、天から四角いものが 地球の平らな部分の隣において。 (ビランチコ220) 他方、サラ・フィンリー[45]は興味深い考えを示している。彼女は、視覚的なものは家父長制のテーマと関係があり、一方、音によるものはソル・フアナの 作品において女性的な空間の代替を提供すると主張する。その例として、フィンリーは、ナルシソが反射ではなく、声と恋に落ちることを指摘する。 |

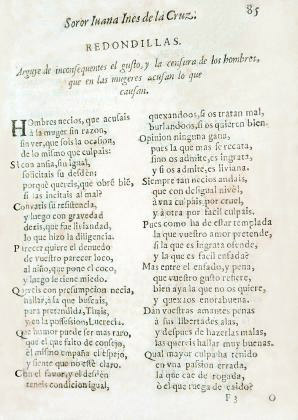

| Other notable works One musical work attributed to Sor Juana survives from the archive of Guatemala Cathedral. This is a 4-part villancico, Madre, la de los primores. Other works include Hombres Necios (Foolish Men), and The Divine Narcissus. |

その他の著名な作品 グアテマラ大聖堂には、ソル・フアナの作品とされる音楽が1曲残されている。これは4部構成のヴィランチコ「Madre, la de los primores」である。 その他の作品に「愚かな男たち」、「神の水仙」などがある。 |

| Translations and interpretations Octavio Paz is credited with re-establishing the importance of the historic Sor Juana in modern times,[10] and other scholars have been instrumental in translating Sor Juana's work to other languages. The only translations of Carta Atenagorica are found in Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Selected Writings by Pamela Kirk Rappaport and The Tenth Muse: Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz by Fanchon Royer.[46] Translations of Sor Juana's La Respuesta are credited to Electa Arenal and Amanda Powell, Edith Grossman, Margaret Seyers Peden, and Alan S. Trubeblood.[46] These translations are respectively found in The Answer/La Respuesta, Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz: Selected Works, A Woman of Genius: The Intellectual Biography of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz and Poems, Protest, and a Dream, and A Sor Juana Anthology.[46] Since Sor Juana's works were rediscovered after her death,[10] scholarly interpretations and translations are both abundant and contrasting. |

翻訳と解釈 オクタビオ・パスは歴史上の人物ソル・フアナの重要性を現代に再認識させたとされ[10]、他の学者もソル・フアナの作品を他言語に翻訳することに力を注 いでいる。カルタ・アテナゴリカ』の翻訳は『Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz』にしかない。Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Selected Writings by Pamela Kirk Rappaport」と「The Tenth Muse」に翻訳されているのみである。ソル・フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルスの『ラ・レスプエスタ』の翻訳は、エレクタ・アレナルとアマンダ・パウエ ル、エディス・グロスマン、マーガレット・セイヤーズ・ペデン、アラン・S・トルベブラッドが担当している[46]。A Woman of Genius: The Intellectual Biography of Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz and Poems, Protest, and a Dream, and A Sor Juana Anthology』に収録されている[46]。 ソル・フアナの作品は死後に再発見されたため[10]、学術的な解釈や翻訳が豊富であり、対照的なものとなっている。 |

| Octavio Paz Octavio Paz is a Nobel Prize laureate and scholar. In the 1989 book, Sor Juana: Or, The Traps of Faith (translated from Spanish to English by Margaret Sayers Peden), Paz examines and contemplates Sor Juana's poetry and life in the context of the history of New Spain, particularly focusing on the difficulties women then faced while trying to thrive in academic and artistic fields. Primarily, Paz aims to explain why Sor Juana chose to become a nun.[25] In Juana Ramírez, Octavio Paz and Diane Marting find that Sor Juana's decision to become a nun stemmed from her refusal to marry; joining the convent, according to Paz and Marting, was a way for Juana to obtain authority and freedom without marrying.[47] In his analyses of Sor Juana's poetry, Octavio Paz traces some of her influences to the Spanish writers of the Golden Age and the Hermetic tradition, mainly derived from the works of a noted Jesuit scholar of her era, Athanasius Kircher. Paz interprets Sor Juana's most ambitious and extensive poem, "First Dream" ("Primero Sueño") as a representation of the desire of knowledge through a number of hermetic symbols, albeit transformed in her own language and skilled image-making abilities. In conclusion, Paz makes the case that Sor Juana's works were the most important body of poetic work produced in the Americas until the arrival of 19th-century figures such as Emily Dickinson and Walt Whitman.[25] |

オクタビオ・パス オクタビオ・パスは、ノーベル賞受賞者であり、学者である。1989年に出版された『ソル・フアナ。Or, The Traps of Faith』(マーガレット・セイヤーズ・ペデン著、スペイン語から英語への翻訳)では、ソル・フアナの詩と人生をニュースペインの歴史の中で考察し、特 に当時の女性が学問と芸術の分野で成功しようとする際に直面した困難について焦点を当てた。フアナ・ラミレス』の中で、オクタビオ・パスとダイアン・マー ティングは、フアナが修道女になることを決めたのは、彼女が結婚を拒否したことに起因していると見なしている;パスとマーティングによれば、修道会に入る ことはフアナにとって、結婚せずに権威と自由を得る方法であった[47]。 オクタビオ・パスはソル・フアナの詩の分析において、彼女の影響のいくつかを黄金時代のスペインの作家と、主に同時代の著名なイエズス会の学者であるアタ ナシウス・キルヒャーの著作に由来するヘルメスの伝統にたどっている。パスは、ソル・フアナの最も野心的で大規模な詩「最初の夢」("Primero Sueño")を、彼女自身の言語と熟練したイメージ形成能力で変形されてはいるものの、多くのヘルメス記号を通して知識の欲求を表現したものと解釈して いる。最後にパスは、ソル・フアナの作品は、エミリー・ディキンソンやウォルト・ホイットマンといった19世紀の人物が登場するまで、アメリカ大陸で作ら れた最も重要な詩の作品群であったと主張する[25]。 |

| Tarsicio Herrera Zapién Tarsicio Herrera Zapién, a classical scholar, has also devoted much of his career to the study of Sor Juana's works. Some of his publications (in Spanish) include Buena fe y humanismo en Sor Juana: diálogos y ensayos: las obras latinas: los sorjuanistas recientes (1984); López Velarde y sor Juana, feministas opuestos: y cuatro ensayos sobre Horacio y Virgilio en México (1984); Poemas mexicanos universales: de Sor Juana a López Velarde (1989) and Tres siglos y cien vidas de Sor Juana (1995).[48] |

タルシシオ・エレラ・サピエン(Tarsicio Herrera

Zapién) 古典学者であるTarsicio Herrera Zapiénは、そのキャリアの多くをSor Juanaの作品研究に捧げている。主な著書に、Buena fe y humanismo en Sor Juana: diálogos y ensayos: las obras latinas: los sorjuanistas recientes (1984); López Velarde y sor Juana, feministas opuestos: y cuatro ensayos sobre Horacio y Virgilio en México (1984); Poemas mexicanos universales: de Sor Juana a López Velarde (1989) and Tres siglos y cien vidas de Sor Juana (1995). [48] Tarsicio Herrera Sapiénの作品には「普遍性の詩」も存在する。 |

| Feminist analyses and

translations Scholars such as Scout Frewer argue that because Juana's advocacy for religious and intellectual authority would now be associated with feminism, she was a protofeminist.[49] In the twenty-first century, Latin American philosophers and scholars generally interpret Sor Juana as a feminist before the time of feminism. For instance, scholars like Rachel O’Donnell argue that Sor Juana occupied a special place in between socially acceptable and socially unacceptable roles in seventeenth century Mexico. By examining Sor Juana intersectionally, they prioritize the context of New Spain, specifically the influence of religion, race, and social norms, in understanding Sor Juana as a female theologian and poet.[50] According to O’Donnell, in colonial Mexico, education was an undertaking reserved for men, especially activities like writing and reading.[50] Consequently, scholars like Octavio Paz argue, religion became a way for women to avoid marriage. Since Sor Juana was opposed to marriage, Paz argues, entering the convent was a socially acceptable way to be a single woman in seventeenth century Mexico.[47] Entering the convent also meant that Sor Juana could read and write about religion despite the barriers to formal education for women. O’Donnell argues that Sor Juana was called a rare bird because although theology was only an acceptable pursuit for men in the Catholic Church, she actively studied religion.[50] Sor Juana likely perceived wisdom and religion as inseparable, so she probably also believed that to follow God was to pursue wisdom.[47] Other scholars, like Alicia Gaspar de Alba, offer instead the possibility that Sor Juana was located on the lesbian continuum and that the convent was a place where having relations with other women was socially acceptable.[20] A fourth perspective suggests that considering the colonial context of New Spain and Sor Juana's background as a criolla, she represented colonial knowledge in a way that defied colonial religious structures.[51] Luis Felipe Fabre criticized 'Sorjuanista' scholarship as a whole, arguing that the discourse is binary rather than complex and multilayered.[52] |

フェミニストによる分析と翻訳 スカウト・フリューワーのような学者は、フアナの宗教的・知的権威の擁護は現在ではフェミニズムと関連付けられるため、彼女はプロトフェミニストであると 主張している[49]。21世紀において、ラテンアメリカの哲学者や学者は一般的にソル・フアナについてフェミニズム時代以前のフェミニストであると解釈 することができる。 例えば、レイチェル・オドネルのような学者は、ソル・フアナが17世紀のメキシコで社会的に受け入れられる役割と社会的に受け入れられない役割の間にある 特別な場所を占めていたと主張する[49]。ソル・フアナを交差的に検討することによって、彼らはソル・フアナを女性神学者と詩人として理解する上で、 ニュースペインの文脈、特に宗教、人種、社会規範の影響を優先させている[50]。 オドネルによれば、植民地時代のメキシコでは、教育は特に書くことや読むことのような活動は男性だけの仕事であった[50]。その結果、オクタビオ・パス のような学者は宗教が女性にとって結婚を避けるための方法となったと主張する。ソル・フアナは結婚に反対していたので、修道院に入ることは17世紀のメキ シコで独身女性であることを社会的に容認する方法であった[47]。また修道院に入ることは、女性のための公式教育の障壁にもかかわらずソル・フアナが宗 教について読み、書くことができることを意味した。オドネルは、神学はカトリック教会の男性にしか許されないものであったが、彼女は積極的に宗教を研究し たため、ソル・フアナは珍しい鳥と呼ばれたと論じている[50] ソル・フアナはおそらく知恵と宗教を不可分のものとして認識しており、神に従うことは知恵を追求するということも信じていたと思われる[47]。 47] アリシア・ガスパル・デ・アルバのような他の学者は、代わりにソル・フアナがレズビアンの連続体に位置しており、修道院は他の女性と関係を持つことが社会 的に許容される場所であるという可能性を提示する[20] 第4の視点は、ニュースペインの植民地の文脈とソル・フアナのクリオージャとしての背景を考慮して、植民地の宗教構造に抗する方法で彼女は植民地の知識を 表現したとする[51][51][51]。 ルイス・フェリペ・ファブレは「ソルジャニスタ」研究全体を批判し、その言説は複雑で多層的というよりもむしろ二元的であると論じていた[52]。 |

| Alicia Gaspar de Alba Alicia Gaspar de Alba's historical novel, Sor Juana's Second Dream (1999), rejects Octavio Paz's view that Sor Juana was ambivalent to sexuality, which he portrays as an explanation of her entering the convent.[20] Instead, Gaspar de Alba interprets Sor Juana as homoerotic. According to Gaspar de Alba, it was Sor Juana's attraction to other women, which was repressed by the "patriarchal and heteronormative society outside of the convent", that led her to become a nun.[20] She criticizes Paz for his portrayal of what she calls "Sorjuanistas", whom she claims stem from a Mexican, rather than "Indigenous viewpoint", and are "homophobic".[20] This work won the Latino Literary Hall of Fame Award for Best Historical Novel in 2000. In 2001, it was translated into Spanish and published as El Segundo Sueño by Grijalbo Mondadori. The novel has also been adapted to a stage play, The Nun and the Countess by Odalys Nanin; and to a film, Juana de Asbaje, directed by Mexican filmmaker Rene Bueno, with the screenplay co-written by Bueno and Gaspar de Alba and Mexican actress Ana de la Reguera as the title role. Juana, an opera based on the novel will be performed by Opera UCLA in November 2019, the music composed by Carla Lucero and the libretto co-written by Lucero and Gaspar de Alba. |

アリシア・ガスパール・デ・アルバ アリシア・ガスパール・デ・アルバの歴史小説『ソル・フアナの第二の夢』(1999)は、オクタビオ・パスがソル・フアナが修道院に入った説明として描い た、性に対して両義的であったとする見解を否定する[20]。 代わりにガスパール・デ・アルバはソル・フアナを同性愛者として解釈している。ガスパール・デ・アルバによれば、ソル・フアナが修道女になったのは、「修 道院の外の家父長制と異形社会」によって抑圧されていた他の女性への魅力によるものである[20]。彼女は、パスの描く「ソルジュアニスタ」と呼ぶ人々 が、「先住民視点」ではなく「メキシコ視点」から来ていて、「同性愛嫌悪」であると批判している[20]。 本作は2000年にラテンアメリカ文学殿堂賞の最優秀歴史小説賞を受賞した。2001年にはスペイン語に翻訳され、グリハルボ・モンダドリから『El Segundo Sueño』として出版された。また、この小説は、オダリス・ナニンによって舞台劇『修道女と伯爵夫人』に、メキシコの映画監督レネ・ブエノによって映画 化された。ブエノとガスパル・デ・アルバの共同脚本で、メキシコの女優アナ・デ・ラ・レゲラがタイトルロールとして出演している。小説を原作としたオペラ 『Juana』は、2019年11月にオペラUCLAによって上演される予定で、作曲はカルラ・ルセロ、リブレットはルセロとギャスパー・デ・アルバが共 同執筆している。 |

| Luis Felipe Fabre Luis Felipe Fabre [es], a Mexican writer and scholar, ridicules other scholars, whom he collectively calls Sorjuanistas, who idolize Sor Juana.[52] In his book, Sor Juana and Other Monsters, Fabre argues that the appropriation and recontextualization imminent in scholars' interpretations of Sor Juana construct Sor Juana as either a heretic or a lesbian.[52] Fabre suggests that such representations constitute Sor Juana as a monstrosity or abnormality rather than as a complex woman.[52] He suggests that rather than locating Sor Juana in a fixed identity, scholarship on Sor Juana should be a fluctuating and multilayered conversation.[52] |

ルイス・フェリペ・ファブレ(Luis Felipe Fabre) メキシコの作家であり学者であるルイス・フェリペ・ファブレ[es]は、ソル・フアナを偶像化するソルジュアニスタと総称する他の学者を嘲笑っている [52]。ファーブルは、その著書『ソル・フアナ・アンド・アザー・モンスター』において、学者たちのソル・フアナに関する解釈における不適切な利用と再 構成はソル・フアナを異端者かレズビアンとして構築すると論じている。 [ファーブルはこのような表象がソル・フアナを複雑な女性としてではなく、怪物や異常として構成することを示唆している[52]。 彼はソル・フアナを固定したアイデンティティに位置づけるのではなく、ソル・フアナに関する研究は変動的で多層的な会話であるべきであると示唆している [52]。 |

| Margaret Sayers Peden Margaret Sayers Peden's 1982 A Woman of Genius: The Intellectual Autobiography of Sor Juana Ines de la Cruz, was the first English translation of Sor Juana's work.[53] As well, Peden is credited for her 1989 translation of Sor Juana: Or, the Traps of Faith. Unlike other translations, Peden chose to translate the title of Sor Juana's best known work, First Dream, as "First I Dream" instead. Peden's use of first person instills authority in Sor Juana as an author, as a person with knowledge, in a male-dominated society.[46] Peden also published her English translations of Sor Juana's work in an anthology called Poems, Protest, and a Dream. This work includes her response to authorities censuring her, La Respuesta, and First Dream.[54] |

マーガレット・セイヤーズ・ペデン マーガレット・セイヤーズ・ペデンは1982年に『天才の女:ソル・フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルスの知的自叙伝』を出版し、ソル・フアナの作品の最初の 英訳となった[53]。また、ペデンは1989年に『Sor Juana: Or, the Traps of Faith』を翻訳した。他の翻訳とは異なり、ペデンはソル・フアナの最も有名な作品である『First Dream』のタイトルを「First I Dream」と訳すことを選択した。ペデンの一人称の使用は、男性優位の社会において、ソル・フアナに作家としての、知識を持つ人間としての権威を植え付 けた[46]。ペデンはまた、ソル・フアナの作品の英訳を『詩、抗議、そして夢』というアンソロジーで発表した。この作品には、当局の検閲に対する彼女の 返答である『La Respuesta』や『First Dream』も含まれている[54]。 |

| Electa Arenal and Amanda Powell An equally valuable feminist analysis and interpretation of Sor Juana's life and work is found in The Answer/La Respuesta by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz by Electa Arenal, a Sor Juana scholar who is recognized among feminists who changed America, and Amanda Powell, a poet and translator.[55] The original publication, released in 1994 by The Feminist Press, was re-released in an updated second edition in 2009, also by The Feminist Press. The bilingual publication includes poems, an annotated publication of Sor Juana's response to Church officials and her impassioned plea for education of women, analysis and a bibliography. The Answer applies a valuable gender lens to Sor Juana's writings and life.[10] In their feminist analysis, Powell and Arenal translate the viewpoint of Sor Juana's writing as gender-ambiguous. Released in an updated second edition in 2009, also by The Feminist Press, the bilingual publication includes poems, an annotated publication of Sor Juana's response to Church officials and her impassioned plea for education of women, analysis and a bibliography.[10] |

エクタ・アレナルとアマンダ・パウエル ソル・フアナの生涯と作品についての同じく貴重なフェミニスト的分析と解釈は、アメリカを変えたフェミニストの間で認められているソル・フアナ研究者のエ レクトラ・アレナルと詩人で翻訳家のアマンダ・パウエルによる『The Answer/La Respuesta by Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz』にある[55]。この二ヶ国語版には、詩、教会関係者に対するソル・フアナの返答と女性教育に対する彼女の熱烈な訴えの注釈出版、分析、参考文 献が含まれている。The Answer』はソル・フアナの著作と生涯に貴重なジェンダー・レンズを適用している[10]。パウエルとアレナルはフェミニスト的分析において、ソル・ フアナの著作の視点をジェンダーを曖昧にしたものとして翻訳している。2009年に同じくフェミニスト・プレス社から最新版の第2版が発売され、詩、教会 関係者へのソル・フアナの返答と女性教育への熱烈な訴えの注釈出版、分析、書誌を含むバイリンガル出版物[10]となった。 |

| Theresa A. Yugar Theresa A. Yugar, a feminist theologian scholar in her own right, wrote her Master's and Doctoral theses on Sor Juana. Her book, Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Feminist Reconstruction of Biography and Text, discusses the life of Sor Juana through a feminist lens and analysis of her texts, La Respuesta (The Answer) and El Primero Sueño (First Dream).[56] Yugar aims to understand why individuals in Mexico in the twenty-first century have more knowledge of Frida Kahlo than Sor Juana.[56] She celebrates poet Octavio Paz for crossing national borders with his internationally acclaimed work on Sor Juana: Or, The Traps of Faith. However, while Paz establishes Sor Juana's historical relevance, Yugar expands on his work to establish Sor Juana's importance in the twenty-first century.[56] Yugar argues that Sor Juana is the first female bibliophile in the New World. She also argues that Sor Juana's historic focus on gender and class equality in education (the public sphere) and the household (the private sphere), in addition to her advocacy for language rights, and the connection between indigenous religious traditions and ecological protection were paramount in the seventeenth century. Today's similar advocacy ignores her primal position in that work which is currently exclusively associated with ecofeminism and feminist theology.[56] |

テレサ・ユーガー(Theresa A. Yugar) テレサ・ユーガーは、フェミニスト神学者として、ソル・フアナに関する修士論文と博士論文を執筆した人物である。彼女の著書『Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: 彼女の著書『Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz: Feminist Reconstruction of Biography and Text』は、フェミニストのレンズと彼女のテキスト『La Respuesta(答え)』と『El Primero Sueño(最初の夢)』の分析を通してソル・フアナの生涯を論じている[56]。 21世紀のメキシコにおいて、なぜソル・フアナよりもフリーダ・カーロについての知識が豊富なのかを理解しようとする[56]。また、詩人オクタビオ・パ スがソル・フアナに関する国際的に高く評価された著作によって国境を越えたことを称える。あるいは、信仰の罠』に関する国際的に高く評価された著作によっ て、詩人オクタビオ・パスが国境を越えたことを称賛する。しかし、パスがソル・フアナの歴史的な関連性を確立している一方で、ユガールは21世紀における ソル・フアナの重要性を確立するために彼の仕事を拡大解釈している[56]。 ユガールは、ソル・フアナが新世界で最初の女性愛書家であると主張する。また、ソル・フアナの歴史的な焦点は、教育(公的領域)と家庭(私的領域)におけ るジェンダーと階級の平等、さらに言語の権利の擁護、そして先住民の宗教的伝統と生態系の保護との関連は、17世紀において最も重要であったと論じている [56]。今日の同様の擁護は、現在もっぱらエコフェミニズムやフェミニスト神学と関連付けられているその仕事における彼女の原初的な位置を無視している [56]。 |

| Philanthropy The Sor Juana Inés Services for Abused Women[57] was established in 1993 to pay Sor Juana's dedication to helping women survivors of domestic violence forward. Renamed the Community Overcoming Relationship Abuse (CORA), the organization offers community, legal, and family support services in Spanish to Latin American women and children who have faced or are facing domestic violence.[57] |

慈善活動 ソル・フアナ・イネス虐待された女性のためのサービス」[57]は、家庭内暴力の被害者である女性たちを支援するソル・フアナの献身的な活動を前進させる ために、1993年に設立されました。関係性の虐待を克服するコミュニティ(CORA)と改名されたこの組織は、家庭内暴力に直面した、または直面してい るラテンアメリカの女性と子供たちに、スペイン語でコミュニティ、法律、家族支援サービスを提供しています[57]。 |

| Education The San Jerónimo Convent, where Juana lived the last 27 years of her life and where she wrote most of her work is today the University of the Cloister of Sor Juana in the historic center of Mexico City. The Mexican government founded in the university in 1979.[58] |

教育 フアナが晩年の27年間を過ごし、ほとんどの作品を書いたサン・ヘロニモ修道院は、現在、メキシコシティの歴史的中心部にあるソル・フアナ回廊大学であ る。1979年にメキシコ政府が大学に設立した[58]。 |

| Political Controversy While Sor Juana was a famous and controversial figure in the seventeenth century, she is also an important figure in modern times. During renovations at the cloister in the 1970s, bones believed to be those of Sor Juana were discovered. A medallion similar to the one depicted in portraits of Juana was also found. Margarita López Portillo, the sister of President José López Portillo (1976-1982), kept the medallion. During the tercentennial of Sor Juana's death in 1995, a member of the Mexican congress called on Margarita López Portillo to return the medallion, which she said she had taken for safekeeping. She returned it to Congress on November 14, 1995, with the event and description of the controversy reported in The New York Times a month later. Whether or not the medallion belonged to Juana, the incident sparked discussions about Juana and abuse of official power in Mexico.[59] |

政治的論争 ソル・フアナは、17世紀には有名で論争の的となった人物ですが、現代においても重要な人物です。 1970年代に行われた修道院の改修工事で、ソル・フアナのものと思われる骨が発見されました。また、フアナの肖像画に描かれているものと同じメダリオン も発見された。ホセ・ロペス・ポルティージョ大統領(1976-1982年)の妹、マルガリータ・ロペス・ポルティージョがこのメダルを保管していまし た。1995年、ソル・フアナの没後300年にあたり、メキシコ議会のある議員がマルガリータ・ロペス・ポルティージョにメダリオンの返還を求めたが、彼 女は保管のために持っていたと答えた。彼女は1995年11月14日に議会に返却し、その1ヵ月後にニューヨーク・タイムズ紙でこの出来事と論争の記述が 報じられた。メダルがフアナのものかどうかは別として、この事件はフアナとメキシコにおける公権力の乱用についての議論を巻き起こした[59]。 |

| Contribution to feminism Historic feminist movements Amanda Powell locates Sor Juana as a contributor to the Querelles des Femmes, a three-century long literary debate about women.[60] Central to this early feminist debate were ideas about gender and sex, and, consequently, misogyny.[60] Powell argues that the formal and informal networks and pro-feminist ideas of the Querelles des Femmes were important influences on Sor Juana's work, La Respuesta.[60] For women, Powell argues, engaging in conversation with other women was as significant as communicating through writing.[60] However, while Teresa of Ávila appears in Sor Juana's La Respuesta, Sor Juana makes no mention of the person who launched the debate, Christine de Pizan.[60] Rather than focusing on Sor Juana's engagement with other literary works, Powell prioritizes Sor Juana's position of authority in her own literary discourse. This authoritative stance not only demonstrates a direct counter to misogyny, but was also typically reserved for men.[60] As well, Sor Juana's argument that ideas about women in religious hierarchies are culturally constructed, not divine, echoes ideas about the construction of gender and sex.[60] |

フェミニズムへの貢献 歴史的なフェミニズム運動 アマンダ・パウエルはソル・フアナを3世紀にわたる女性についての文学的議論であるケレル・デ・ファムへの貢献者として位置づけている[60]。この初期 のフェミニストの議論の中心は、ジェンダーとセックス、そして結果として女性嫌悪(ミソジニー)についての考え方であった[60]。 パウエルは、ケレル・デ・ファムの公式・非公式なネットワークと親フェミニストの思想がソル・フアナの作品『La Respuesta』に重要な影響を与えたと主張している[60]。女性にとって、他の女性と会話をすることは書くことによってコミュニケーションをとる ことと同じくらい重要であったとパウエルは主張している[60]。 [しかし、ソル・フアナの『La Respuesta』にはアビラのテレサが登場するが、ソル・フアナは議論の発端となった人物、クリスティーヌ・ド・ピザンについては言及していない [60]。パウエルはソル・フアナが他の文学作品と関わったことよりも、彼女自身の文学談義における権威の位置を優先させる。この権威的な立場はミソジ ニーに対する直接的な対抗を示すだけでなく、典型的には男性にのみ与えられていたものである[60]。同様に、宗教的ヒエラルキーにおける女性についての 考えは神ではなく、文化的に構築されているというSor Juanaの主張はジェンダーと性の構築に関する考えと共鳴するものである[60]。 |

| Modern feminist movements Yugar connects Sor Juana to feminist advocacy movements in the twenty-first century, such as religious feminism, ecofeminism, and the feminist movement in general. Although the current religious feminist movement grew out of the Liberation Theology movement of the 1970s,[61] Yugar uses Sor Juana's criticism of religious law that permits only men to occupy leadership positions within the Church as early evidence of her religious feminism. Based on Sor Juana's critique of the oppressive and patriarchal structures of the Church of her day,[62] Yugar argues that Sor Juana predated current movements, like Latina Feminist Theology, that privilege Latina women's views on religion.[61] She also cites modern movements such as the Roman Catholic Women Priest Movement, the Women's Ordination Conference, and the Women's Alliance for Theology, Ethics and Ritual, all of which also speak out against the patriarchal limitations on women in religious institutions.[61] Yugar emphasizes that Sor Juana interpreted the Bible as expressing concern with people of all backgrounds as well as with the earth.[56] Most significantly, Yugar argues, Sor Juana expressed concern over the consequences of capitalistic Spanish domination over the earth. These ideas, Yugar points out, are commonly associated with modern feminist movements concerned with decolonization[61] and the protection of the planet.[56] Alicia Gaspar de Alba connects Sor Juana to the modern lesbian movement and Chicana movement. She links Sor Juana to criticizing the concepts of compulsory heterosexuality and advocating the idea of a lesbian continuum, both of which are credited to well-known feminist writer and advocate Adrienne Rich.[20] As well, Gaspar de Alba locates Sor Juana in the Chicana movement, which has not been accepting of "Indigenous lesbians".[20] |

現代のフェミニスト運動 ユガールはソル・フアナを宗教的フェミニズム、エコフェミニズム、一般的なフェミニズム運動といった21世紀のフェミニズム擁護運動と結びつけている。 現在の宗教的フェミニズム運動は1970年代の解放神学運動から発展したものであるが[61]、ユガールはソル・フアナが宗教的フェミニズムの初期の証拠 として、教会の中で男性のみが指導的地位を占めることを許可している宗教法を批判していることを利用している。当時の教会の抑圧的で家父長制的な構造に対 するソル・フアナの批判に基づいて、ユガはソル・フアナがラティーナ・フェミニスト神学のようなラティーナ女性の宗教観を優遇する現在の運動に先行してい たと論じている[62]。 [また彼女は、ローマ・カトリック女性司祭運動、女性聖職者会議、神学・倫理・儀礼のための女性同盟といった現代の運動も引用しているが、これらはすべて 宗教機関における女性に対する家父長制的制限に対して声を上げている[61]。 ユガは、ソル・フアナが聖書を解釈して、あらゆる背景を持つ人々と地球に対する関心を表明していると強調する[56]。 最も重要なことは、ソル・フアナが資本主義的なスペインの地球に対する支配の結果に対する懸念を表明しているということである。これらの考えは、脱植民地 化[61]や地球の保護を懸念する現代のフェミニスト運動と一般的に関連しているとユガは指摘する[56]。 アリシア・ガスパール・デ・アルバはソル・フアナを現代のレズビアン運動やチカーナ運動と結びつけている。彼女はソル・フアナを強制的な異性愛という概念 を批判し、レズビアンの連続性という考えを提唱することと結びつけているが、これらはいずれも有名なフェミニスト作家であり提唱者であるアドリアン・リッ チによるとされている[20]。同様に、ガスパル・デ・アルバはソル・フアナを、「先住民レズビアン」を受け入れていないチカーナの運動に位置づけている [20]。 |

| A symbol Colonial and indigenous identities As a woman in religion, Sor Juana has become associated with the Virgin of Guadalupe, a religious symbol of Mexican identity, but was also connected to Aztec goddesses.[63] For example, parts of Sor Juana's Villancico 224 are written in Nahuatl, while others are written in Spanish.[24] The Virgin of Guadalupe is the subject of the Villancico, but depending on the language, the poem refers to both the Virgin of Guadalupe and Cihuacoatl, an Indigneous goddess.[24] It is ambiguous whether Sor Juana prioritizes the Mexican or indigenous religious figure, or whether her focus is on harmonizing the two.[24] Sor Juana's connection to indigenous religious figures is also prominent in her Loa to Divine Narcissus, (Spanish "El Divino Narciso") (see Jauregui 2003, 2009). The play centers on the interaction between two Indigenous people, named Occident and America, and two Spanish people, named Religion and Zeal.[24] The characters exchange their religious perspectives, and conclude that there are more similarities between their religious traditions than there are differences.[24] The loa references Aztec rituals and gods, including Huitzilopochtli, who symbolized the land of Mexico.[24] Scholars like Nicole Gomez argue that Sor Juana's fusion of Spanish and Aztec religious traditions in her Loa to Divine Narcissus aims to raise the status of indigenous religious traditions to that of Catholicism in New Spain.[24] Gomez argues that Sor Juana also emphasizes the violence with which Spanish religious traditions dominated indigenous ones.[24] Ultimately, Gomez argues that Sor Juana's use of both colonial and indigenous languages, symbols, and religious traditions not only gives voice to indigenous peoples, who were marginalized, but also affirms her own indigenous identity.[24] Through their scholarly interpretations of Sor Juana's work, Octavio Paz and Alicia Gaspar de Alba have also incorporated Sor Juana into discourses about Mexican identity. Paz's accredited scholarship on Sor Juana elevated her to a national symbol as a Mexican woman, writer, and religious authority.[20] On the contrary, Gaspar de Alba emphasized Sor Juana's indigenous identity by inserting her into Chicana discourses.[20] |

シンボル 植民地時代と先住民のアイデンティティ 宗教上の女性として、ソル・フアナはメキシコのアイデンティティの宗教的象徴であるグアダルーペの聖母と関連付けられるようになったが、アステカの女神と も関連付けられた[63]。 例えばソル・フアナのビランシコ224の一部はナワトル語で書かれており、他の一部はスペイン語で書かれている。 [24] ビランチコの主題はグアダルペの聖母であるが、言語によってはグアダルペの聖母と先住民の女神チワコアトルの両方を指している[24] ソル・フアナがメキシコの宗教者、先住民のどちらを優先しているのか、あるいは両者の調和を重視しているのかは曖昧なところである[24] 。 ソル・フアナと先住民の宗教的人物とのつながりは、『神なるナルシソへのロア』(スペイン語「El Divino Narciso」)でも顕著である(Jauregui 2003, 2009を参照)。この劇は、オクシデントとアメリカという名の2人の先住民と、レリジオンとゼアルという名の2人のスペイン人の間の交流を中心としてい る[24]。登場人物たちはそれぞれの宗教的な観点を交換し、彼らの宗教的伝統の間には違いよりも類似点の方が多いと結論付ける[24]。 ロアはメキシコという国を象徴するフイツロポクトリなどアステカの儀式と神を参照にしている[24]。 ニコル・ゴメスのような学者は、ソル・フアナが『神々しい水仙への語り』においてスペインとアステカの宗教的伝統を融合させたのは、土着の宗教的伝統の地 位を新スペインのカトリックの地位まで高めることを目的としていると主張する[24]。ゴメスは、ソル・フアナもスペインの宗教的伝統が土着を支配する暴 力性を強調していると主張している[24]。 [最終的にゴメスは、ソル・フアナが植民地と土着の言語、象徴、宗教的伝統の両方を使用することによって、疎外されていた土着の人々の声を伝えるだけでな く、彼女自身の土着のアイデンティティを肯定していると論じる[24]。 オクタビオ・パスとアリシア・ガスパル・デ・アルバもソル・フアナの作品を学術的に解釈することで、メキシコのアイデンティティに関する言説にソル・フア ナを取り込んでいる。パスはソル・フアナの研究を公認し、彼女をメキシコの女性、作家、宗教的権威として国家の象徴に押し上げた[20]。 それに対して、ガスパル・デ・アルバはソル・フアナをチカナの言説に挿入することによって土着のアイデンティティを強調した[20]。 |

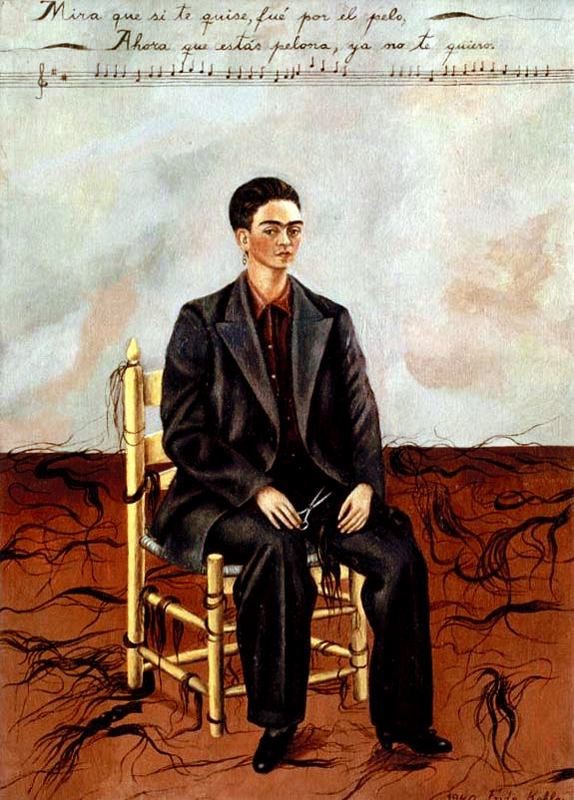

| Connection to Frida Kahlo Paul Allatson emphasizes that women like Sor Juana and Frida Kahlo masculinized their appearances to symbolically complicate the space marked for women in society.[20] Sor Juana's decision to cut her hair as punishment for mistakes she made during learning[64] signified her own autonomy, but was also a way to engage in the masculinity expected of male-dominated spaces, like universities. According to Paul Allatson, nuns were also required to cut their hair after entering the convent.[20] These ideas, Allatson suggests, are echoed in Frida Kahlo's 1940 self-portrait titled Self-Portrait with Cropped Hair, or Autorretrato con cabellos corto.[20] As well, the University of the Cloister of Sor Juana honored both Frida Kahlo and Sor Juana on October 31, 2018 with a symbolic altar. The altar, called Las Dos Juanas, was specially made for the Day of the Dead.[65] |

フリーダ・カーロとのつながり ポール・アラトソンは、ソル・フアナやフリーダ・カーロのような女性は、社会で女性に示される空間を象徴的に複雑化するために外見を男性化したと強調する [20] 。ソル・フアナが学習中に犯した間違いに対する罰として髪の毛を切るという決定[64]は彼女自身の自律性を意味すると同時に、大学などの男性が支配する 空間で求められる男性性に関与する方法であったという。ポール・アラトソンによれば、修道女もまた修道院に入った後に髪を切ることを要求されていた [20]。 アラトソンはこうした考えはフリーダ・カーロが1940年に描いた『切りそろえられた髪の自画像』(Autorretrato con cabellos corto)と題する自画像に反響していると示唆する[20]。 同様に、ソル・フアナの回廊の大学では、2018年10月31日にフリーダ・カーロとソル・フアナの両者を称え、象徴的な祭壇を設置した。Las Dos Juanasと呼ばれる祭壇は、死者の日のために特別に作られたものである[65]。 |

| Official recognition by the

Mexican government In present times, Sor Juana is still an important figure in Mexico. In 1995, Sor Juana's name was inscribed in gold on the wall of honor in the Mexican Congress in April 1995.[59] In addition, Sor Juana is pictured on the obverse of the 200 pesos bill issued by the Banco de Mexico,[66] and the 1000 pesos coin minted by Mexico between 1988 and 1992. The town where Sor Juana grew up, San Miguel Nepantla in the municipality of Tepetlixpa, State of Mexico, was renamed in her honor as Nepantla de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz. |

メキシコ政府による公式認定 現代においても、ソル・フアナはメキシコにおいて重要な人物である。 1995年、4月にメキシコ議会の名誉の壁にソル・フアナの名が金字で刻まれた[59]。 また、メキシコ銀行が発行する200ペソ札[66]と1988年から1992年にかけてメキシコが鋳造した1000ペソ貨幣の裏面にソル・フアナの絵が描 かれている。ソル・フアナが育った町、メキシコ州テペトリクスパのサン・ミゲル・ネパントラは、彼女に敬意を表してネパントラ・デ・ソル・フアナ・イネ ス・デ・ラ・クルスと改名された。 |

| Veneration In 2022, the Episcopal Church of the United States gave final approval and added her feast to the liturgical calendar. Her feast day is April 18.[67] |

崇敬の念 2022年、アメリカ聖公会は最終的な承認を与え、彼女の祭日を典礼カレンダーに追加した。彼女の祭日は4月18日である[67]。 |

| Yo-Yo Boing! This groundbreaking novel, set in New York City during the 1990s, is guaranteed to be unlike any literary experience you have ever had. Acclaimed Puerto Rican author Giannina Braschi has crafted this creative and insightful examination of the Hispanic-American experience, taking on the voices of a variety of characters–painters, poets, sculptors, singers, writers, filmmakers, actors, directors, set designers, editors, and philosophers–to draw on their various cultural, economic, and geopolitical backgrounds to engage in lively cultural dialogue. Their topics include love, sex, food, music, books, inspiration, despair, infidelity, jobs, debt, war, and world news. Braschi’s discourse winds throughout the city’s public, corporate, and domestic settings, offering an inside look at the cultural conflicts that can occur when Anglo Americans and Latin Americans live, work, and play together. Hailed by Publishers Weekly as “a literary liberation,” this energetic and comical novel celebrates the contradiction that makes contemporary American culture so wonderfully diverse. |

Yo-Yo Boing! 1990年代のニューヨークを舞台にした(スパングリッシュで書かれた)この画期的な小説は、これまで経験したことのない文学体験となること請け合いだ。 高い評価を得ているプエルトリコ人作家ジャンニーナ・ブラスキは、ヒスパニック系アメリカ人の経験を創造的かつ洞察的に考察し、画家、詩人、彫刻家、歌 手、作家、映画制作者、俳優、監督、セットデザイナー、編集者、哲学者などさまざまな登場人物の声を取り上げ、彼らの文化、経済、地政学的背景をもとに、 文化的対話を活発に行うよう作り上げた。テーマは、愛、セックス、食事、音楽、本、インスピレーション、絶望、不倫、仕事、借金、戦争、世界のニュースな ど、多岐にわたる。英米人とラテンアメリカ人が共に生活し、働き、遊ぶときに起こりうる文化的対立の内幕を、公共、企業、家庭のあらゆる場面でブラスキの 談話は展開する。出版社ウィークリー誌で「文学的解放」と評されたこのエネルギッシュでコミカルな小説は、現代のアメリカ文化を素晴らしく多様にしている 矛盾を讃えるものである。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Juana_In%C3%A9s_de_la_Cruz |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

Juana Ines de la Cruz in art by Mexican artist Mauricio García Vega./Autorretrato con pelo corto by Frida Kahlo (1907-1954, Mexico)

Doña

Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana,

Doña

Inés de Asbaje y Ramírez de Santillana,

| Juana Inés de Asbaje Ramírez de

Santillananota

1 (San Miguel Nepantla, Tepetlixpa, 12 de noviembre de 1648 o

1651-Ciudad de México, 17 de abril de 1695),nota 2 más conocida como

sor Juana Inés de la Cruz o Juana de Asbaje, fue una religiosa jerónima

y escritora novohispana, exponente del Siglo de Oro de la literatura en

español. También incorporó el náhuatl clásico a su creación

poética.1112 Considerada por muchos como la décima musa, cultivó la lírica, el auto sacramental y el teatro, así como la prosa. A muy temprana edad aprendió a leer y a escribir. Perteneció a la corte de Antonio Sebastián de Toledo Molina y Salazar, marqués de Mancera y 25.º virrey novohispano. En 1669, por anhelo de conocimiento, ingresó a la vida monástica. Sus más importantes mecenas fueron los virreyes De Mancera, el arzobispo virrey Payo Enríquez de Rivera y los marqueses de la Laguna de Camero Viejo, virreyes también de la Nueva España, quienes publicaron los dos primeros tomos de sus obras en la España peninsular. Gracias a Juan Ignacio María de Castorena Ursúa y Goyeneche, obispo de Yucatán, se conoce la obra que sor Juana tenía inédita cuando fue condenada a destruir sus escritos. Él la publicó en España. Sor Juana murió a causa de una epidemia el 17 de abril de 1695 en el Convento de San Jerónimo.  Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz ocupó, junto con Bernardo de Balbuena, Juan Ruiz de Alarcón y Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora, un destacado lugar en la literatura novohispana.13 En el campo de la lírica, su trabajo se adscribe a los lineamientos del barroco español en su etapa tardía. La producción lírica de Sor Juana, que supone la mitad de su obra, es un crisol donde convergen la cultura de una Nueva España en apogeo, el culteranismo de Góngora y la obra conceptista de Quevedo y Calderón.14 La obra dramática de sor Juana va de lo religioso a lo profano. Sus obras más destacables en este género son Amor es más laberinto, Los empeños de una casa y una serie de autos sacramentales concebidos para representarse en la corte.15 |

フアナ・イネス・デ・アスバヘ・ラミレス・デ・サンティリャナノタ1

(San Miguel Nepantla, Tepetlixpa,

1648年11月12日または1651年11月12日-メキシコ・シティ、1695年4月17日)註2は、ソル・フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルス(Sor

Juana Inés de la Cruz)またはフアナ・デ・アスバヘ(Juana de

Asbaje)としてよく知られている。彼女はまた、古典的なナワト語を詩に取り入れた1112。 10人目のミューズと言われる彼女は、散文だけでなく、抒情詩、自動秘跡、演劇も学んだ。幼い頃から読み書きを学んだ。マンセラ侯爵で第25代新スペイン 総督のアントニオ・セバスティアン・デ・トレド・モリーナ・イ・サラサルの宮廷に属していた。1669年、知識欲から修道生活に入る。彼の最も重要な後援 者は、デ・マンセラ総督、パヨ・エンリケス・デ・リベラ大司教、ラグーナ・デ・カメロ・ビエホ侯爵家で、同じく新スペイン総督であった彼らは、彼の著作の 最初の2巻をスペイン本土で出版した。ユカタン州の司教フアン・イグナシオ・マリア・デ・カストレーナ・ウルスア・イ・ゴイエネチェのおかげで、シス ター・フアナが著作破棄を宣告された際に未発表だった著作が知られるようになった。彼はそれをスペインで出版した。ソル・フアナは1695年4月17日、 サン・ヘロニモ修道院で伝染病のため亡くなった。  ソル・フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルスは、ベルナルド・デ・バルブエナ、フアン・ルイス・デ・アラルコン、カルロス・デ・シグエンサ・イ・ゴンゴラ[ Carlos de Sigüenza y Góngora (1645-1700)]ととも に、新スペイン文学の中で重要な位置を占めていた13。抒情詩の分野では、彼女の作品はスペイン後期バロックの流れを汲んでおり、その作品の半分を占める ソル・フアナの抒情詩は、全盛期の新スペインの文化、ゴンゴラのクルターニスモ、ケベドやカルデロンのコンセプチュアリズムが融合したメルティング・ポッ トである14。 ソル・フアナの劇作は、宗教的なものから俗悪なものまで幅広い。ソル・フアナの劇作は、宗教的なものから俗世間的なものまで多岐にわたる。このジャンルに おける彼女の代表作は、『Amor es más laberinto』、『Los empeños de una casa』、そして宮廷で上演されることを想定した一連の『autos sacramentales』である15。 |

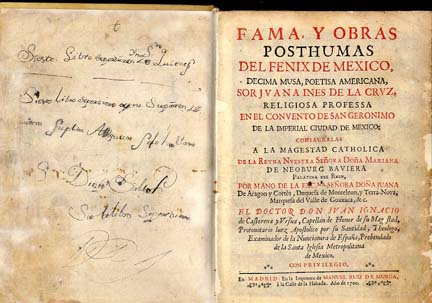

| Biografía Véase también: Anexo:Cronología de Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz  Sor Juana Inés de la Cruz, por Juan de Miranda (convento de Santa Paula, Sevilla). Polémica de su nacimiento Hasta casi mediados del siglo XX, la crítica sorjuanista aceptaba como válido el testimonio de Diego Calleja, primer biógrafo de la monja, sobre su fecha de nacimiento. Según Calleja, Sor Juana habría nacido el 13 de noviembre de 1651 en San Miguel Nepantla.16 En 1952, el descubrimiento de un acta de bautismo que supuestamente pertenecería a Sor Juana adelantó la fecha de nacimiento de la poetisa a 1648. Según dicho documento, Juana Inés habría sido bautizada el 5 de diciembre de 1648.17 Varios críticos, como Octavio Paz,18 Antonio Alatorre,19 y Guillermo Schmidhuber20 aceptan la validez del acta de bautismo y así como Alberto G. Salceda, aunque la estudiosa cubana Georgina Sabat de Rivers considera insuficientes las pruebas que aporta esta acta. Así, según Sabat, la partida de bautismo correspondería a una pariente o a una francesa.21 De acuerdo con Alejandro Soriano Vallés, la fecha más aceptable es la de 1651, porque una de las hermanas de sor Juana supuestamente fue dada a luz el 19 de marzo de 1649, resultando imposible que Juana Inés naciera en noviembre de 1648. (Esta suposición de 1651 no está fundamentada en documentos probatorios, sino en suposiciones que parten de la fecha informada por Diego Calleja en 1700. Sin embargo, el hallazgo de Guillermo Schmidhuber de la Fe de bautizo de "María hija de la Iglesia" en Chimalhuacán fechada el 23 de julio de 1651, perteneciente a la hermana menor de sor Juana, imposibilita el nacimiento de la Décima Musa en 1651 porque el vientre de la madre estaba ocupado por otra niña, es decir, su hermana María).22 La doctora investigadora Lourdes Aguilar Salas, en la biografía que comparte para Universidad del Claustro de Sor Juana, señala 1651 como la más correcta.23 De hecho, lo que sostiene Alejandro Soriano ya lo había manifestado previamente Georgina Sabat de Rivers,24 y él solamente retoma con posterioridad el argumento de la reputada sorjuanista, quien personalmente se inclina por el año de 1651 porque, al saberse la fecha de bautismo de la hermana de sor Juana de nombre Josefa María, 29 de marzo de 1649, la proximidad de fechas impedía pensar en dos partos con una diferencia tan breve (Nota: nunca ha sido localizada la Fe de Bautismo de Josefa María, la fecha del nacimiento de esta niña es una suposición que no ha sido fundamentada en un documento). |

バイオグラフィー 参照:Appendix:ソル・フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルス年譜  フアン・デ・ミランダ作『ソル・フアナ・イネス・デ・ラ・クルス』(セビーリャ、サンタ・パウラ修道院)。 彼女の出生をめぐる論争 20世紀のほぼ半ばまで、ソル・フアナの批評家たちは、ソル・フアナの生年月日に関して、修道女の最初の伝記作者であるディエゴ・カレハの証言を正当なも のとして受け入れていた。カレハによれば、ソル・フアナは1651年11月13日にサン・ミゲル・ネパントラで生まれた16。1952年、ソル・フアナの ものとされる洗礼証明書が発見され、詩人の生年月日は1648年に繰り上げられた。この文書によれば、フアナ・イネスは1648年12月5日に洗礼を受け たことになる17。オクタビオ・パス18、アントニオ・アラトーレ19、ギジェルモ・シュミッドフーバー20といった何人かの批評家は、アルベルト・G・ サルセダのように、この洗礼証明書の有効性を認めている。サルセダは、しかし、キューバの学者ジョルジーナ・サバト・デ・リバースは、この証明書によって 提供された証拠は不十分であると考えている。アレハンドロ・ソリアノ・バジェスによれば、最も受け入れやすい日付は1651年である。なぜなら、シス ター・フアナの姉妹の一人は1649年3月19日に出産したとされており、フアナ・イネスが1648年11月に生まれたことはありえないからである(この 1651年という推測は、文書的証拠に基づくものではなく、1700年にディエゴ・カジェハが報告した日付に基づく仮定に基づくものである)。しかし、ギ ジェルモ・シュミットフーバーがチマルワカンで発見した1651年7月23日付の 「Maria hija de la Iglesia 」の洗礼証明書は、シスター・フアナの妹のものであり、母親の胎内は別の子供、つまり妹のマリアが占めていたため、1651年に10番目のミューズが誕生 することは不可能である22)。 ルルデス・アギラール・サラス医師は、ソル・フアナのクラウストロ大学(Universidad del Claustro de Sor Juana)のために書いた伝記の中で、1651年が最も正しい生年月日であると指摘している23。 実際、アレハンドロ・ソリアーノが主張していることは、ジョルジーナ・サバト・デ・リバースがすでに述べていたことであり24、彼は、ソル・フアナの妹ホ セファ・マリアの洗礼の日付1649年3月29日が知られていたため、日付が近いことから、このように短い差で2人の誕生を考えることは不可能であるとし て、1651年を個人的に支持する、評判のソル・フアナ学者の議論を後に取り上げたに過ぎない(注: ホセファ・マリアの洗礼証明書は見つかっておらず、この子供の誕生日は文書によって証明されていない仮定である)。 |

|

Sin embargo, este argumento también se relativiza inevitablemente

cuando sabemos que el término entre el nacimiento y el bautizo

frecuentemente distaba no solo de días, sino de meses y hasta años, así

como sabemos por el historiador Robert McCaa, quien parte de un estudio

directo de las fuentes escritas de la época, que las actas de bautismo

en las zonas rurales se registraban en los libros habiendo cumplido los

infantes desde varios meses hasta uno o varios años de haber sido

presentados para su bautismo.25 El hallazgo del acta de Chimalhuacán

por el historiador Guillermo Ramírez España fue publicado por Alberto

G. Salceda en 1952;26 en ella aparecen los tíos de sor Juana como

padrinos de una niña anotada como “hija de la Iglesia”, esto es,

ilegítima. Anteriormente solo se tenía como referencia la biografía de

sor Juana escrita por el jesuita Diego Calleja y publicada en el tercer

volumen de las obras de sor Juana: Fama y obras póstumas (Madrid,

1700). No obstante, los documentos existentes no son definitivos al

respecto. Por un lado la biografía de Calleja adolece de inexactitudes

típicas de la tendencia hagiográfica de la época en torno a los

personajes eclesiásticos destacados; es decir, los datos se modifican

posiblemente con intenciones ulteriores.10 Por dar solo un ejemplo,

Calleja fija terminantemente en viernes el día del supuesto nacimiento

de sor Juana, cuando el 12 de noviembre de 1651, la fecha anotada por

él, no fue viernes.10 Por otro lado, el acta de Chimalhuacán hallada

en el siglo XX presenta escasos datos acerca de la bautizada; si, como

se acepta actualmente, la fecha de diciembre de 1648 es solo la de

bautismo, la de nacimiento pudo haber sido varios meses o un año antes.

Schmidhuber ha descubierto una segunda partida de bautismo de la

parroquia de Chimalhuacán que dice «María hija de la Iglesia», está

fechada el 23 de julio de 1651 y el nombre concuerda con la hermana

menor de sor Juana; imposible resulta que otra niña naciera el mismo

año.10 Hasta el día de hoy, lo más riguroso desde el punto de vista historiográfico es mantenerse en la disyuntiva entre 1648 a 1651, tal como sucede con un sinnúmero de personajes históricos de cuyas fechas de nacimiento o muerte no se tiene absoluta certeza con los documentos habidos en ese momento. Adoptar tal disyuntiva como regla general no afecta los estudios sobre sor Juana ni en su biografía ni en la valoración de su obra. |

歴史家ロバート・マッカが当時の文書資料を直接調査した結果、農村部における洗礼の記録は、幼児が洗礼のために提出されてから数ヶ月から1年以上経過した

時点で帳簿に記録されていたことがわかっている25。

歴史家ギジェルモ・ラミレス・エスパーニャによるチマルワカンのアクタの発見は、1952年にアルベルト・G.

その中で、シスター・フアナの叔父たちは、「教会の娘」、つまり非嫡出子として記載されている少女の名付け親として登場している26。以前は、イエズス会

のディエゴ・カレハによって書かれ、シスター・フアナの著作の第3巻「Fama y obras

póstumas」(マドリッド、1700年)に掲載されたシスター・フアナの伝記のみが参考文献として利用可能であった。しかし、現存する文献はこの点

で決定的なものではない。一方では、カレハの伝記は、当時の著名な教会の人物に関する萩の花的傾向の典型的な不正確さに苦しんでいる。つまり、データはお

そらく下心を持って修正されている10。ほんの一例を挙げると、カレハはソル・フアナの誕生日とされる日を厳密に金曜日に固定しているが、彼が記した

1651年11月12日は金曜日ではなかった10。

一方、20世紀に発見されたチマルワカンの行為は、洗礼を受けた女性に関する乏しいデータを示している。現在受け入れられているように、1648年12月

という日付が洗礼を受けた日付に過ぎないのであれば、誕生日はそれより数ヶ月か1年早かった可能性がある。シュミッドフーバーは、チマルワカン教区から2

枚目の洗礼証明書を発見した。そこには 「María hija de la Iglesia

」と書かれており、日付は1651年7月23日、名前はシスター・フアナの妹のものと一致している。 今日に至るまで、最も厳密な歴史学的アプローチは、1648年と1651年の間に二項対立を残すことである。一般的なルールとしてこのような区切り方を採 用することは、シスター・フアナに関する研究に、彼女の伝記においても、彼女の作品の評価においても、影響を与えることはない。 |

|

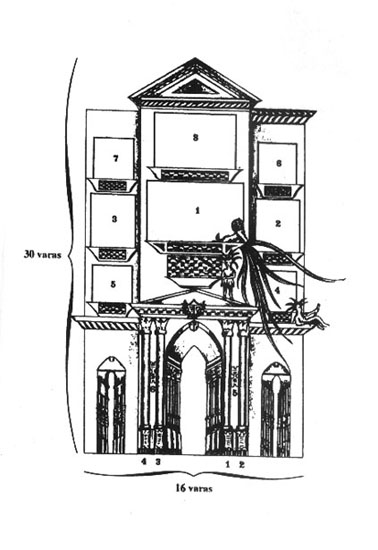

Primeros años Aunque se tienen pocos datos de sus padres, Juana Inés fue la segunda de las tres hijas de Pedro de Asuaje y Vargas Machuca (así los escribió Sor Juana en el Libro de Profesiones del Convento de San Jerónimo). Se sabe que los padres nunca se unieron en matrimonio eclesiástico. Schmidhuber ha probado documentalmente que el padre llegó a la Nueva España cuando niño, como lo prueba el Permiso de Paso de 1598, en compañía de su abuela viuda, María Ramírez de Vargas, su madre Antonia Laura Majuelo y un hermano menor Francisco de Asuaje que llegó a ser fraile dominico.27 Su madre, Isabel Ramírez de Santillana, era hija de Pedro Ramírez de Santillana y Doña Beatriz Ramírez Rendón, residentes en el pueblo de Huichapan, perteneciente al Marquesado del Valle. Hacia 1635 toda la familia emigraría a San Miguel Nepantla, a una hacienda de labor llamada “La Celda”, que Don Pedro Ramírez de Santillana arrendaría a los dominicos. En San Miguel Nepantla, de la región de Chalco, nació su hija Juana Inés, en la hacienda «La Celda».28 Su madre, al poco tiempo, se separó de Pedro de Asuaje y, posteriormente, procreó otros tres hijos con Diego Ruiz Lozano, a quien tampoco desposó.29 Muchos críticos han manifestado su sorpresa ante la situación civil de los padres de sor Juana. Paz apunta que ello se debió a una «laxitud de la moral sexual en la colonia».30 Se desconoce también el efecto que tuvo en sor Juana el saberse hija ilegítima, aunque se conoce que trató de ocultarlo. Así lo revela su testamento de 1669: «hija legítima de don Pedro de Asuaje y Vargas, difunto, y de doña Isabel Ramírez». El padre Calleja lo ignoraba, pues no hace mención de ello en su estudio biográfico. Su madre en su testamento fechado en 1687 reconoce que todos sus hijos, incluyendo a sor Juana, fueron concebidos fuera del matrimonio.31  Frontispicio de la hacienda Panoaya, en Amecameca, Estado de México, donde sor Juana vivió entre 1648 y 1656. |

幼年時代 両親についてはほとんど知られていないが、フアナ・イネスはペドロ・デ・アスアヘとバルガス・マチュカの3人娘の次女であった(シスター・フアナはサン・ ヘロニモ修道院の職業記に書いている)。両親は教会的な結婚をしなかったことが知られている。 シュミットフーバーは、1598年の 「Permiso de Paso 」にあるように、父親が幼少の頃、未亡人となった祖母マリア・ラミレス・デ・バルガス、母親のアントニア・ラウラ・マジュエロ、ドミニコ会修道士となった 弟フランシスコ・デ・アスアヘと一緒にニュー・スペインに到着したことを証明する文書を持っている27。1635年頃、一家はサン・ミゲル・ネパントラに 移住し、ドン・ペドロ・ラミレス・デ・サンティリャーナがドミニコ会に貸していた「ラ・セルダ」と呼ばれる農場に移った。 チャルコ地方のサン・ミゲル・ネパントラでは、娘のフアナ・イネスが 「ラ・セルダ 」という農場で生まれた28。 多くの批評家は、シスター・フアナの両親が結婚していたことに驚きを示している。多くの批評家は、シスター・フアナの両親の婚姻関係に驚きを示している が、それは「植民地における性道徳の弛緩」によるものだとパスは指摘する30。自分が隠し子であることを知ったシスター・フアナが受けた影響も不明である が、彼女がそれを隠そうとしたことは知られている。このことは、1669年の遺言で明らかにされている。「亡くなったドン・ペドロ・デ・アスアヘ・イ・バ ルガスとドーニャ・イサベル・ラミレスの嫡女」である。カレハ神父はこのことを知らなかった。彼の母親は、1687年の遺言で、シスター・フアナを含むす べての子供たちが婚外子であったことを認めている31。  1648年から1656年の間、ソル・フアナが住んでいたメキシコ州アメカメカのパノアヤ屋敷の玄関。 |

|

La niña pasó su infancia entre Amecameca, Yecapixtla, Panoaya —donde su

abuelo tenía una hacienda— y Nepantla. Allí aprendió náhuatl con los

habitantes de las haciendas de su abuelo, donde se sembraba trigo y

maíz. El abuelo de sor Juana murió en 1656, por lo que su madre tomó

las riendas de las fincas.32 Asimismo, aprendió a leer y escribir a

los tres años, al tomar las lecciones con su hermana mayor a escondidas

de su madre.33 Pronto inició su gusto por la lectura, gracias a que descubrió la biblioteca de su abuelo y se aficionó a los libros.34 Aprendió todo cuanto era conocido en su época, es decir, leyó a los clásicos griegos y romanos, y la teología del momento. Su afán por saber era tal que intentó convencer a su madre de que la enviase a la Universidad disfrazada de hombre, puesto que las mujeres no podían acceder a esta.35 Se dice que al estudiar una lección, cortaba un pedazo de su propio cabello si no la había aprendido correctamente, pues no le parecía bien que la cabeza estuviese cubierta de hermosuras si carecía de ideas.36 A los ocho años, entre 1657 y 1659, ganó un libro por una loa compuesta en honor al Santísimo Sacramento, según cuenta su biógrafo y amigo Diego Calleja.37 Este señala que Juana Inés radicó en la ciudad de México desde los ocho años, aunque se tienen noticias más veraces de que no se asentó allí sino hasta los trece o quince.38 |

彼女は幼少期を、アメカメカ、イエカピクスラ、祖父がハシエンダを所有していたパノアヤ、ネパントラの間で過ごした。そこで彼女は、小麦やトウモロコシが

栽培されていた祖父のハシエンダの住民からナワト語を学んだ。ソル・フアナの祖父は1656年に死去したため、彼女の母親が農場を引き継いだ32。また、

彼女は3歳の時に、母親に隠れて姉と一緒にレッスンを受け、読み書きを学んだ33。 祖父の蔵書を発見し、本が好きになったこともあって、すぐに読書の趣味を身につけた34。当時知られていたことはすべて学んだ。つまり、ギリシャ・ローマ の古典や当時の神学を読んだのである。知識欲は旺盛で、女人禁制の大学に男装して通うよう母親を説得しようとしたほどだった35。授業を受ける際、正しく 学べていなければ自分の髪を切り落としたと言われている。 伝記作者であり友人でもあるディエゴ・カレハによると、1657年から1659年にかけて、彼女は8歳のときに、福者に敬意を表して作曲したロアの本で優 勝した37。 |