William Charles Utermohlen,

1933-2007

William

Utermohlen, 1933-2007

ウィリアム・チャールズ・ユテルモーレン

William Charles Utermohlen,

1933-2007

William

Utermohlen, 1933-2007

解説:池田光穂

アメリカ精神医学会は痴呆あるいは痴呆症 (dementia)に入るものを以下の5つのカテゴリにわけている(DSM-IV-TR)。(DSM-5, 2013: Neurocognitive Disorder[pdf with password])

| 認知症の原因と分類は? 回答 認知症は様々な疾患や状態によって引き起こされます。DSM-5では、主要な神経認知障害(認知症)の病因論的サブタイプは、アルツハイマー病、前頭側頭 葉変性症、レビー小体病、血管障害、外傷性脳損傷、薬物/薬物使用、HIV感染、プリオン病、パーキンソン病、ハンチントン病、その他の医学的状態、複数 の病因、および特定不能から構成される。 コメントとエビデンス 多くの疾患や状態が認知症または認知症様症状を引き起こす可能性がある1)。 ICD-10では、認知症はアルツハイマー型認知症、血管性認知症、他に分類される疾患による認知症、および特定不能の認知症に分類される2)。 DSM-5の神経認知障害カテゴリーでは、大神経認知障害(認知症)と小神経認知障害(軽度認知障害)の病因論的サブタイプは以下のように記載されてい る: アルツハイマー病、前頭側頭葉変性症、レビー小体病、血管障害、外傷性脳損傷、物質・薬物使用、HIV感染、プリオン病、パーキンソン病、ハンチントン 病、その他の病状、複数の病因、特定不能3)。 これらの原因疾患・病態のうち、正常圧水頭症や慢性硬膜下血腫などの脳神経外科的疾患、甲状腺機能低下症やビタミンB12欠乏症などの内科的疾患は、治療 可能な認知症という概念で扱われており、早期診断と適切な治療・介入が望まれる。 参考文献 1) 「認知症治療ガイドライン」作成合同委員会(編)日本神経学会(監修). 認知症治療ガイドライン 2010.東京: 医学書院; 2010: 4-7. (東京: 医学書院; 2010: 4-7.) 2) 世界保健機関. 疾病及び関連保健問題の国際統計分類. 第10次改訂版. ジュネーブ: World Health Organization; 1993. 3) 米国精神医学会。精神障害の診断と統計マニュアル第5版: DSM-5. Arlington, VA: American Psychiatric Association; 2013. 検索式 PubMed検索: 2015年7月3日(金) https://www.neurology-jp.org/guidelinem/dementia/Capter01.html |

・︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎︎▶︎▶︎

++

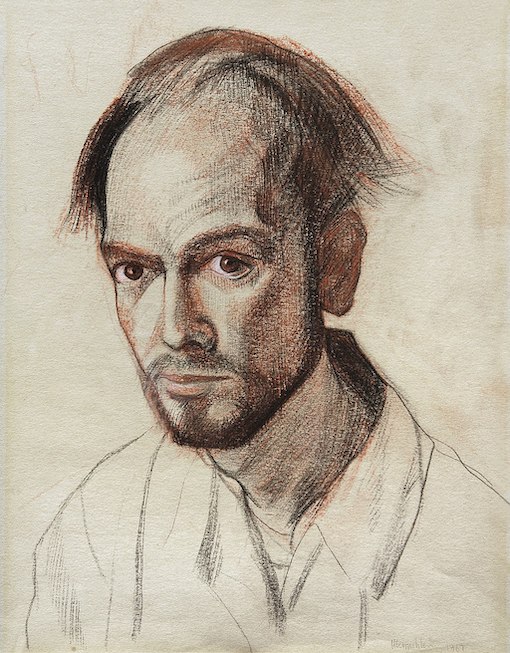

| William

Charles Utermohlen

(December 5, 1933 – March 21, 2007) was an American figurative artist

known for his late period self-portraits completed after his 1995

diagnosis of probable Alzheimer's disease (AD). He had progressive

memory loss beginning about four years before his diagnosis in 1995.

During that time, he began a series of self-portraits influenced in

part by the figurative painter Francis Bacon and cinematographers from

the German Expressionism movement. Born to first-generation German immigrants in South Philadelphia, Utermohlen earned a scholarship at the Philadelphia Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) in 1951. After completing military service, he spent 1953 studying in Western Europe where he was inspired by Renaissance and Baroque artists. He moved to London in 1962 and married the art historian Patricia Redmond in 1965. He relocated to Massachusetts in 1972 to teach art at Amherst College before returning to London in 1975. Utermohlen died in obscurity on March 21, 2007, aged 73, but his late works have gained posthumous renown. His self-portraits especially are seen as important in the understanding of the gradual effects of neurocognitive disorders. |

ウィリアム・チャールズ・ユテルモーレン(1933年12月5日 -

2007年3月21日)は、アメリカの造形作家で、1995年にアルツハイマー病(AD)と診断された後に制作した後期の自画像で知られている。1995

年に診断される4年程前から順行性の記憶喪失に陥っていた。この間、具象画家のフランシス・ベーコンやドイツ表現主義の映画監督に影響を受けた自画像のシ

リーズを開始した。 フィラデルフィアのドイツ系一世に生まれ、1951年にフィラデルフィア美術アカデミー(PAFA)の奨学生になる。兵役を終えた後、1953年に西ヨー ロッパに留学し、ルネサンスやバロックの芸術家に影響を受ける。1962年にロンドンに移住し、1965年に美術史家のパトリシア・レドモンドと結婚。 1972年にマサチューセッツに移り、アマースト大学で美術を教え、1975年にロンドンに戻った。 2007年3月21日、73歳で無名のまま死去したが、晩年の作品は高い評価を得ている。特に自画像は、神経認知障害が徐々に進行していく様子を理解する 上で重要視されている。 |

| William Charles Utermohlen was

born on December 5, 1933,[1][2] in Southern Philadelphia, Pennsylvania,

as the only child of first-generation German immigrants.[3] At the

time, that section of Philadelphia was split along language lines; his

family would have been in the German-speaking part of the city, but

inward migration across the United States resulted in their living in

the Italian bloc. Due to racial tensions, Utermohlen's parents did not

allow him to venture outside of his immediate surrounding. Manu Sharma

of STIRworld speculates that his parents' protectiveness may have a

factor in the development of his artistic creativity.[4] He earned a scholarship at the Pennsylvania Academy of Fine Arts (PAFA) in 1951 where he studied under the realist artist Walter Stuempfig.[5] Utermohlen completed his military service in 1953,[6] following two years in the Caribbean. Shortly after, he studied in Europe and travelled through Italy, France and Spain where he was heavily influenced by the works of Giotto and Nicolas Poussin.[7] He graduated from PAFA in 1957 and moved to England,[8] in part because he was attracted to the London art scene.[9] Utermohlen's wife, the art historian Patricia Redmond, said that "when he was art school, he was very pretty, and he was chased around by all the homosexual tutors and everybody else... he didn't care but he didn't fancy them. When he came to England he discovered, amazingly, because the English had always been like this, that we quite liked girlish men."[10] He attended the Ruskin School of Art in Oxford between 1957 and 1959, where he met the American artist R. B. Kitaj.[11][b] After leaving Ruskin, he returned to the U.S. for three years.[13] He moved to London in 1962 where he met Redmond, whom he married in 1965.[14][a] In 1969, his artwork was featured in an exhibition at the Marlborough Gallery.[16] From 1972, Utermohlen taught art at the Amherst College in Massachusetts,[17][c] where Redmond received her master's degree.[19] By 1975 he had returned England, and lived in London where he gained nationality in 1992.[20][21] |

ウィリアム・チャールズ・ユテルモーレンは1933年12月5日、ペン

シルベニア州フィラデルフィア南部でドイツ系移民一世の一人っ子として生まれた[1][2]。

当時、フィラデルフィアのその地区は言語によって分かれており、彼の家族はドイツ語圏に属していたが、アメリカ国内への移住によりイタリア圏に住むことに

なる。人種的な緊張から、ウテルモーレンの両親は、彼が身近なところから外に出ることを許さなかった。STIRworldのマニュ・シャルマは、両親の保

護が彼の芸術的創造性を育む要因になったのではないかと推測している[4]。 1951年にペンシルバニア美術アカデミー(PAFA)の奨学金を得て、写実主義の画家ウォルター・スチューンプフィグのもとで学んだ[5]。1957年 にPAFAを卒業し、ロンドンのアートシーンに惹かれたこともあり、イギリスに渡る[8]。 [9] ウターモーレンの妻で美術史家のパトリシア・レドモンドは、「美術学校時代、彼はとてもきれいで、同性愛の家庭教師やみんなに追い回された...彼は気に しなかったが、彼らに好意を抱かなかった」と述べている。イギリスに来たとき、彼は驚くべきことに、イギリス人はいつもこうだったから、私たちは女の子ら しい男性がかなり好きだということを発見した」[10]。 1957年から1959年にかけてオックスフォードのラスキン美術学校に通い、そこでアメリカ人アーティストのR・B・キタジと出会う[11][b]。ラ スキンを去った後、3年間アメリカに戻る[13]。 1962年にロンドンに移り、そこでレッドモンドと出会い、1965年に結婚する。 [1972年からマサチューセッツ州のアマースト大学で美術を教え[17][c]、レッドモンドはそこで修士号を取得した[19]。 1975年までにイギリスに戻り、ロンドンに住み、1992年には英国国籍を取得した[20][21]。 |

| His early works are mostly

figurative;[22] although James M. Stubenrauch described Utermohlen's

early art as "exuberant, at times surrealistic" style of

expressionism.[23] For a period in the late 1970s, as a response to the

photorealist movement, he printed photographs onto a canvas and

painting directly over the photograph. An example of this technique can

be seen in Self-Portrait (Split) (1977). He would employ this technique

for two portraits of Redmond.[24] Regarding Utermohlen's art style, Redmond said to The New York Times that "he was never quite in the same time slot with what was going on. Everybody was Abstract expressionist, [while] he was solemnly drawing the figure."[25] She explained in a Studio 360 interview that Utermohlen was "puzzled and worried, because he couldn't work in [a] totally abstract way," as he considered the figure "incredibly important."[26] |

初期の作品は具象的なものが多かったが[22]、ジェームズ・M・ス

チューベンラウフは初期の作品を「豪快で、時にシュールな」表現主義と評した[23]。

1970年代後半の一時期、フォトリアリズム運動への対応として、写真をキャンバスにプリントし、写真の上に直接絵を描いていた。この技法の例は、《自画

像(分割)》(1977年)で見ることができる。彼はこの技法をレドモンドの2つの肖像画に採用することになる[24]。 ユテルモーレンの芸術スタイルについて、レドモンドはニューヨーク・タイムズ紙に「彼は何が起こっているのか、全く同じ時間帯にいることがなかった。誰も が抽象表現主義者で、彼は粛々と人物を描いていた」[25]。彼女はStudio 360のインタビューで、ユテルモーレンは人物を「信じられないほど重要」と考えていたので、「完全に抽象的な方法で働くことができず、困惑し心配してい た」[26]と説明している。 |

| Utermohlen did not explain his

work or discuss them with Redmond. She later said that as an art

historian, he feared she would interfere with his creative progress.

Redmond believes he was "absolutely right" in this approach, and

guesses she would have highlighted faults in his work.[27] Most of his

early paintings can be grouped into six cycles: Mythological

(1962–1963), Cantos (or Dante) (1964–1966), Mummers (1969–1970), War

(1972–1973), Nudes (1973–1974),[d] and Conversation (1989–1991).[29] The Mythological series mainly consist of water scenes.[30] The Dante cycle was inspired by Dante's Inferno, while the art style paintings drew influence from pop art.[31] The War series references the Vietnam War;[32] and according to Redmond the inclusion of isolated soldiers represented his feelings of being an outsider in the art scene.[33] Both Mummers and Conversations were based on early memories; the former, completed between 1968 and 1970, is based on the Mummers Parade of Philadelphia.[34] In a letter from November 1970, Utermohlen stated that the cycle was also created as a "vehicle for expressing my anxiety".[35] Redmond described Mummers as "an empathetic vision of the lower classes, but also his own projected self-image".[33] The Conversations paintings are described by the French psychoanalyst Patrice Polini as Utermohlen's attempt to describe the events of his life before memory loss.[36] They pre-date his diagnosis, and already indicate the onset of a number of symptoms.[37] Titles such as W9 and Maida Vale reference the names of the district and neighborhood, respectively, that he lived in at the time.[38] The artworks themselves contain more saturated colours and "engaging spacial arrangements", which highlight the actions of the people in the artworks.[39] |

ユテルモーレンは、自分の作品について説明したり、レドモンドと話し

合ったりすることはなかった。後に彼女は、美術史家である彼女が彼の創作活動の邪魔になることを恐れたと語っている。レドモンドはこのアプローチについて

「まったく正しかった」と考えており、彼女なら彼の作品の欠点を浮き彫りにしただろうと推測している[27]。初期の絵画のほとんどは、6つのサイクルに

分類することができる。神話』(1962-1963)、『カントス(またはダンテ)』(1964-1966)、『ママー』(1969-1970)、『戦

争』(1972-1973)、『ヌード』(1973-1974)、[d]『会話』(1989-1991)[29]である。 神話』シリーズは主に水のシーンで構成され[30]、『ダンテ』シリーズはダンテの『地獄篇』に触発され、アートスタイルの絵画はポップアートの影響を受 けた[31]。『戦争』シリーズはベトナム戦争を参照し、レドモンドによれば、孤立した兵士を含めることでアートシーンにおけるアウトサイダーとしての彼 の感情を表現した[32]。 [1968年から1970年にかけて完成した前者は、フィラデルフィアのママーズ・パレードに基づいている[34]。1970年11月の手紙の中で、ユテ ルモーレンはこのサイクルが「私の不安を表現するための手段」としても制作されたと述べている[35]。レッドモンドはママーズのことを「下層階級の共感 できるビジョンであり、彼自身の自己像も投影されている」[33]と表現している。] フランスの精神分析医パトリス・ポリーニは、『会話』の絵画を、ユテルモーレンが記憶喪失以前の人生の出来事を描写する試みであると述べている[36]。 [W9」や「マイダヴェール」といったタイトルは、それぞれ当時住んでいた地区名や地域名を指している[38]。作品自体には、より彩度の高い色彩と「魅 力的な空間配置」が含まれており、作品中の人物の行動が強調されている[39]。 |

| Utermohlen experienced memory

loss while working on the Conversation series. His symptoms ranged from

being unable to remember how to wrap his necktie to being unable to

find his way back to his apartment.[41] Between 1993 and 1994, he

produced a series of lithographs depicting short stories written by

World War I poet Wilfred Owen.[42] The figures were more still and

mask-like than the Conversation pieces. They consist of a series of

disoriented and wounded soldiers,[43] and are described by his art

dealer Chris Boicos as a seeming premonition of the artist's dementia

diagnosis made in the following year.[44] By this time, he was often

forgetting to show up for teaching appointments.[45] In 1994 he took on a commission for a family portrait. Around a year later, Redmond took his client to Utermohlen's studio to see the progress, but saw that the portrait had not advanced since their last viewing nine months earlier.[46] Redmond feared Utermohlen was depressed and sought medical advice.[47] He was diagnosed with probable Alzheimer's disease[48] in August 1995 at the age of 61.[49][50][e] He was sent to the Queen's Square Hospital where a nurse, Ron Isaacs, became interested in his drawings and asked him to start drawing self-portraits.[52] The first, Blue Skies, was completed between 1994 and 1995, before his diagnosis,[53] and shows him gripping a yellow table in an empty, sparsely described interior.[7] When his neuropsychologist Sebastian Crutch visited Utermohlen in late 1999, he described the painting as depicting the artist trying to hang on and avoid being "swept out" of the open window above.[54] Polini likened the depiction of him holding onto the table to a painter holding onto his canvas, saying that "[i]n order to survive, he must be able to capture this catastrophic moment; he must depict the unspeakable."[55] Blue Skies became Utermohlen's last "large scale" painting.[56] That year's sketch, A Welcoming Man, shows a disassembled figure that seems to represent his loss of spatial perception.[57] Regarding the sketch, Crutch et al state that "[Utermohlen] acknowledged that there was a problem with the sketch, but did not know what the problem was nor how it could be rectified."[58] He began a series of self-portraits after his diagnosis in 1995.[59] The earliest, the Masks series, are in watercolour and were completed between 1994 and 2001.[60] His last non-self-portrait dates 1997, and was of Redmond.[61] It was titled by Patrice Polini as Pat (Artist's Wife).[62] |

ユテルモーレンは、「会話」シリーズの制作中に記憶喪失に陥った。

1993年から1994年にかけて、第一次世界大戦の詩人ウィルフレッド・オーウェンの短編小説を描いたリトグラフのシリーズを制作した[42]。それら

は、混乱し負傷した兵士のシリーズで構成され[43]、画商のクリス・ボイコスによって、翌年に診断された画家の認知症の予兆のように描写されている

[44]。 この頃、彼はしばしば指導の約束に姿を現すのを忘れるようになっていた[45]。 1994年、家族の肖像画の依頼を受ける。1年後、レドモンドはクライアントを連れてユテルモーレンのスタジオに行き、進捗状況を確認したが、9ヶ月前に 最後に見たときから肖像画が進歩していないことを確認した[46]。 レドモンドはユテルモーレンがうつ病であると恐れ、医師の診断を仰いだ[47]。 彼は1995年8月に61歳でアルツハイマーの疑いがあると診断され[48]、クイーンズスクエア病院に送られたが、看護師のロン・イザークが彼の絵に関 心を持ち、自画像の作成を始めるよう要請した[50][e]。 [1999年末に神経心理学者のセバスチャン・クラッチがユテルモーレンを訪ねたとき、彼はこの絵を、画家がしがみついて上の開いた窓から「流される」の を避けようとしているところを描いている、と説明した[7]。 [ポリーニは、彼がテーブルにしがみついている描写を、キャンバスにしがみついている画家になぞらえ、「生き延びるためには、彼はこの破滅的な瞬間を捉え ることができなければならない、彼は言いようのないことを描かなければならない」と述べた[55]。「青い空」はユテルモーレンの最後の「大規模な」絵画 となった[56]。 この年のスケッチ『A Welcoming Man』は、彼の空間認識の喪失を表すかのように分解された人物を示している[57]。このスケッチについて、クラッチらは「(ユテルモーレンは)スケッ チに問題があったことを認めたが、その問題が何であり、どのように修正され得るかを知らなかった」と述べている[58]。 「58] 1995年の診断後、彼は自画像のシリーズを始めた[59] 最も初期のマスクシリーズは水彩画で、1994年から2001年の間に完成した[60] 彼の最後の非自画像は1997年のもので、レドモンドのものだった[61] これはパトリス・ポリーニによってパット(作家の妻)と題された[62]......。 |

| Utermohlen had retired from

painting by December 2000,[63] could no longer draw by 2002, and was in

the care of the Princess Louise nursing home in 2004.[12] He died of

pneumonia at the Hammersmith Hospital on March 21, 2007, aged 73.[21]

Redmond said that "really he was dead long before that, Bill died in

2000, when the disease meant he was no longer able to draw."[64] |

2000年12月には絵画から引退し[63]、2002年には絵を描け

なくなり、2004年には老人ホーム「プリンセス・ルイーズ」の世話になっていた[12]。2007年3月21日にハマースミス病院で肺炎により73歳で

亡くなった[21]。レドモンドは「本当はそのずっと前に死んでいた、ビルは2000年に、病気のために絵を描けなくなった時点で死んでいた」のだと語っ

ている[64]。 |

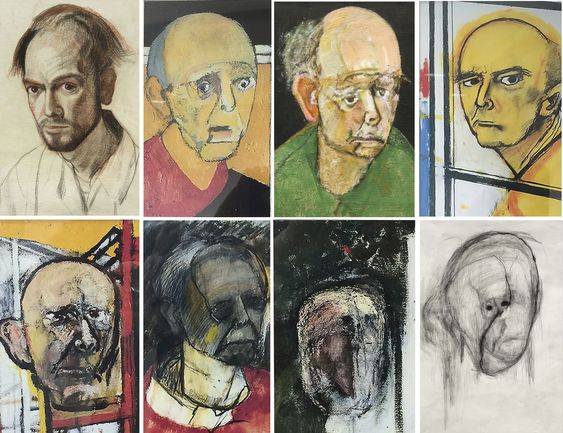

| His series of self-portraits

became increasingly abstract as his dementia progressed,[66] and

according to the critic Anjan Chatterjee, describe "haunting

psychological self-expressions."[67] The early stages of the disease

had not impacted his ability to paint, despite what was observed by

Crutch et al.[68] His cognitive disorder is not believed to have been

hereditary; aside from a 1989 car accident which left him unconscious

for around 30 minutes, Utermohlen's medical history was described by

Crutch as "unremarkable".[69] Redmond covered the mirrors in their

house because Utermohlen was afraid of what he saw there, and had

stopped using them for self-portraits.[70] After Utermohlen's

diagnosis, descriptions of his skull became a key aspect of his

self-portraits,[71] while the academic Robert Cook–Deegan noticed how

as Utermohlen's condition progressed, he "gradually integrates less

colour".[72] |

彼の一連の自画像は認知症が進行するにつれてますます抽象的になり

[66]、評論家のアンジャン・チャタジーによれば「呪われた心理的自己表現」[67]を描写する。病気の初期はクラッチらによる観察にもかかわらず、絵

を描く能力に影響を与えなかった[68]

彼の認知障害は遺伝ではないと考えられている;30分ほど意識を失った1989年の自動車事故以外では、クラッチはUtermohlenの病歴について

「目立った特徴はない」としている[69]。 [69]

レッドモンドは、Utermohlenがそこで見るものを恐れ、自画像のために鏡を使うのをやめたため、彼らの家の鏡を覆った[70]

Utermohlenの診断後、彼の頭蓋骨の描写は彼の自画像の重要な側面になった[71]

一方で学者のロバート・クックディーガンはUtermohlenの状態が進むにつれ、彼が「徐々に少ない色を統合する」方法に気がついた[72]。 |

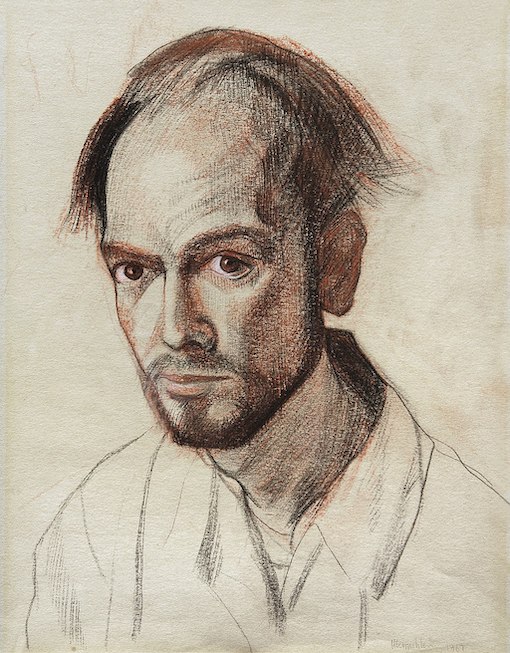

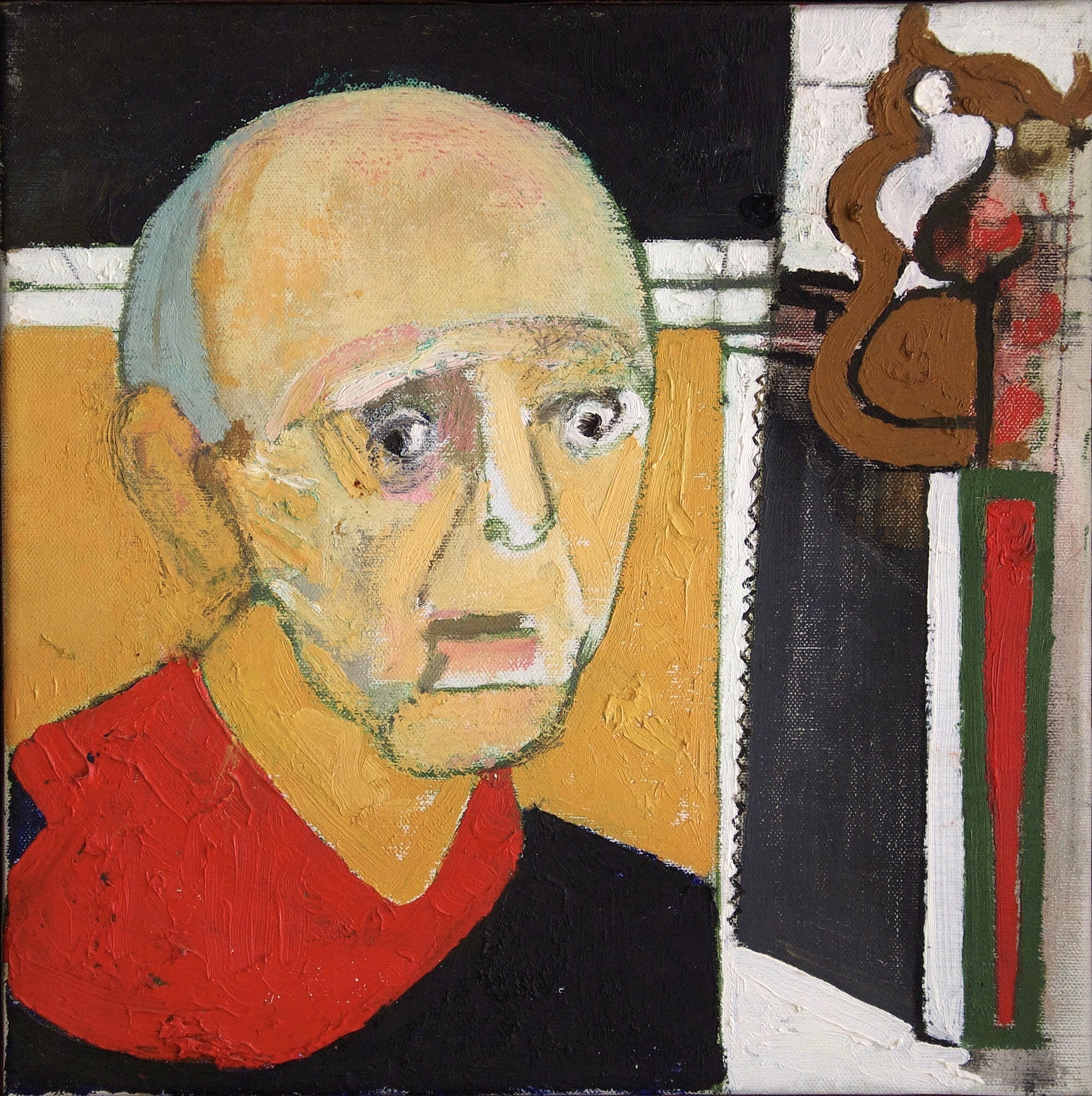

| The later self-portraits have

thicker brushwork than his earlier works.[58] Writing for the Queen's

Quarterly, the journalist Leslie Millin noted that the works became

progressively more distorted but less colourful.[73] In Nicci Gerrard's

2019 book, What Dementia Teaches Us About Love, she describes the

self-portraits as emotional modernism.[74] Sharma suggests that they

depict anosognosia, a condition that results both loss of

self-recognition and object-recognition.[75] In Self Portrait (In The Studio) (1996), frustration and fear are evident in his expressions.[76] Xi Hsu speculates that Utermohlen created this self portrait to express that he did not want to be known for his struggles with dementia, and wanted to be known as an artist.[77] His 1996 Self Portrait (With Easel),[f] shows more confused emotions according to Green et al.[76] Polini describes the appearance of the easel in Self Portrait (With Easel) as akin to prison bars.[80] A 1996 drawing, Broken Figure contains a ghost-like figure which serves as the outline of the fallen body in the drawing.[81] His Self Portrait with Saw (1997) has a serrated carpenter's saw in the far right,[82] which Redmond said invokes an autopsy that would have given a definite diagnosis.[83] Polini noticed how the saw is vertically pointed, similar to a guillotine blade, and wrote that it may symbolises the "approach of a prefigured death".[84][g] The last self portrait that Utermohlen used a mirror for,[86] Self Portrait (With Easel) (1998) uses the same pose as a 1955 self-portrait. According to Polini, this was the artist's desire to "experience again the old motions of painting."[87] Erased Self Portrait (1999)[h] was his last attempt at a self-portrait using a paint brush.[89] It took nearly two years to complete[90] and is described by the BBC as "almost sponge like and empty".[91] Head I[i] (2000) shows a head portraying eyes, mouth, and a smudge on the left that appears to be an ear;[59] a crack appearing in the centre of the head.[93] The rest of the portraits are of a blank head, one of them erased.[59] Associated Press' Joann Loviglio describes Utermohlen's final self-portraits as the "afterimages of a creative and talented spirit whose identity appears to have vanished."[94] |

後期の自画像は初期の作品よりも太い筆致である[58]。『クイーン

ズ・クォータリー』に寄稿したジャーナリストのレスリー・ミリンは、作品が徐々に歪んでいくが色彩は少なくなっていくと指摘している[73]。

ニッチ・ジェラードの2019年の著書『認知症が教える愛について』で、彼女は自画像について感情的モダニズムとして説明している[74]。

シャーマはそれらが自己認識と対象認識の両方を失う状態、つまり無認識を描いていると示唆する[75]。 自画像(スタジオにて)」(1996年)では、彼の表情にフラストレーションと恐怖が見られる[76]。西秀は、ユテルモーレンがこの自画像を制作したの は、彼が認知症と闘っていることを知られたくない、アーティストとして知られたいということを表現するためだと推測している[77]。 [1996年の『自画像(イーゼル付き)』[f]は、グリーンらによれば、より混乱した感情を示している[76] ポリーニは『自画像(イーゼル付き)』のイーゼルの外観を刑務所の鉄格子に似ていると述べている[80] 1996年に描いた『壊れた図』には幽霊らしき人物が描かれており、それが倒れた身体の輪郭として機能している。 81] 「Self Portrait with Saw」(1997年)には、右端に鋸歯状の大工用のこぎりがあり[82]、レドモンドは、明確な診断を与えるであろう検死を思い起こさせると述べた [83]。 [ポリーニは、鋸がギロチンの刃のように垂直に尖っていることに注目し、「予見された死の接近」を象徴しているのではないかと書いている[84][g] ユテルモーレンが鏡を使った最後の自画像[86]『自画像(イーゼル付き)』(1998)は、1955年の自画像と同じポーズを取っている。ポリーニによ れば、これは「昔の絵画の動作をもう一度体験したい」という作家の願望であった[87]。 消された自画像』(1999年)[h]は、絵筆を用いた自画像の最後の試みであり[89]、完成までに約2年を要し[90]、BBCによって「ほとんどス ポンジのように空っぽ」と評される[91] 『頭部 I』(2000年)は、目、口、左側に耳と思われる汚れ、頭の中央に現れた亀裂を描写する頭部を示す[59] [93] 。 [93] 残りの肖像画は無表情な頭で、そのうちの一つは消されている[59] AP通信のジョアン・ロヴィグリオは、ユテルモーレンの最後の自画像について、「アイデンティティが消滅したように見える、創造力と才能のある精神の残 像」だと述べている[94]。 |

| Redmond describes these works as

influenced by German Expressionism, and compares them to artists such

as Ernst Ludwig Kirchner and Emil Nolde.[95] She explained in New

Statesman: "It's odd, because he hardly ever thought of his German

ancestry, but toward the end he becomes a kind of German abstract

expressionist. He might have been quite amused by that, I think."[96] Shortly after his diagnosis, he and Redmond travelled to Europe and saw Diego Velázquez's 1650 Portrait of Pope Innocent X,[97] which lead to an interest in Francis Bacon's distorted 1953 version Study after Velázquez's Portrait of Pope Innocent X.[98] After his return to England in 1996, he painted Self Portrait (In the Studio), which includes the screaming mouth, a motif borrowed from Bacon's work.[99] A 2015 Scientific American article which mentioned both Bacon and Utermohlen called Bacon's "distorted faces and disfigured bodies" disturbing. It noted that his works are "so distorted that they violate the brain's expectations for the body", and went on to discuss the possibility that Bacon had dysmorphopsia.[100] When describing Utermohlen's portraits, the writer said that Utermohlen's portraits offered "a window into the artist's" decline, adding that they were "also heartbreaking in that they expose[d] a mind trying against hope to understand itself despite deterioration".[101] |

レドモンドはこれらの作品をドイツ表現主義の影響を受けたものとし、エ

ルンスト・ルートヴィヒ・キルヒナーやエミール・ノルデといったアーティストと比較している[95]。

彼女は『ニューステーツマン』で「彼は自分のドイツの祖先をほとんど考えなかったのに、最後のほうではドイツの抽象表現主義のようになっているのは奇妙

だ」と説明している[96]。彼はそのことをかなり面白がっていたかもしれない、と思う」[96]。 診断の直後にレドモンドとヨーロッパを旅行し、ディエゴ・ベラスケスの1650年の『教皇イノセント10世の肖像』を見たことがきっかけで、フランシス・ ベーコンがベラスケスの『教皇イノセント10世の肖像』に倣って1953年に歪曲した『習作』に関心を持った[98] 1996年にイギリスに帰国後、ベーコンの作品から借りてきたモチーフの叫び声をあげる口が描かれている《自画像(工房にて)》を描いた[99]。 ベーコンとユテルモーレンの両者に言及した2015年のサイエンティフィック・アメリカンの記事は、ベーコンの「歪んだ顔と醜い体」を不穏なものと呼ん だ。それは彼の作品が「身体に対する脳の期待に反するほど歪んでいる」と指摘し、ベーコンが異形症である可能性を論じるに至った[100]。 Utermohlenのポートレートについて説明したとき、作家はUtermohlenのポートレートが「作家の」衰退への窓を提供していると述べ、それ らが「劣化にもかかわらず自分自身を理解しようと希望に反して試みる心を暴露するという点で胸を打つ」と付け加えている[101]。 |

| Utermohlen's self-portraits

first gained attention after they were described in The Lancet's 2001

case report[102][j] when the Crutch et al noted that the evident change

in artistic ability was "indicative of a process above and beyond

normal aging, particularly given his relatively young age at onset".

The article further noted that, over five years, the self-portraits

showed an "objective deterioration in the quality of the artwork

produced".[104] They concluded that the portraits offered "a testament

to the resilience of human creativity".[105] Crutch himself said that

Utermohlen's works were "more eloquent than anything he could have said

with words".[72] According to Hsu, the portraits are the "highlight of his career".[106] Commenters liken them to those of Vincent van Gogh, Pablo Picasso, and Edvard Munch.[107] Sharma compared the self-portraits to the works of English painter Ivan Seal, noting that the latter's works show objects that "[teeter] on the brink of pure recognition and abstraction."[75] Some writers have also likened the self-portraits to the illustrations of Mervyn Peake;[108] although Demetrios J. Sahlas of Peake Studies noted that Peake's works were different to Utermohlen's, because shown in the works is the "preservation of insight".[109] A 2013 article in The Lancet compared his work to Rembrandts self-portraits, and described Utermohlen as "struggling to preserve his self against age" while also fighting against "inexorable neurodegeneration".[110] Giovanni Frazzetto described Utermohlen's self-portraits as similar to the works of Egon Schiele, explaining that the portraits were "evocative of the shrivelled bodies and diaphanous faces" shown in the latter's work.[111] Sherri Irvin says that the portraits show "remarkable stylistic features, [rewarding] serious efforts of appreciation and interpretation".[112] Irvin notes that their "formal and aesthetic features", the correlation with Utermohlen's earlier works and their "aptness to interpretation", is what makes the portraits "jointly sufficient to connect them in the right way with past art, [despite] the absence of an express[ed] intention about how they are to be regarded."[113] Alan E. H. Emery believes that the progressive effects of dementia give neurologists "an opportunity to study how the disease affects an artist's work over time", adding that it also provides a unique method of studying detailed change in perception, and how it can be linked to localised brain functions. He concluded by stating that documenting changes over time with neuroimaging could lead to better understanding of dementia.[114] Medical anthropologist Margaret Lock states that the portraits indicate that "there may be many avenues... that suggest ways in which humans can be protected from the ravages of this condition by means of lifelong social and cultural activities." [115] Purcell stated that Utermohlen's artwork provided viewers with a "unique glimpse into the effects of a declining brain."[116] Researchers at Illinois Wesleyan University state that Utermohlen's self portraits show that "people with AD can have a strong voice through images."[117] The existence of his earlier self-portraits (which allowed viewers to create a time-lapse of his mental decline) and the idea that his works give a rare view into the mind of an Alzheimer's patient were two aspects contributing to his growing popularity.[118] The 2019 short film Mémorable was inspired by the self-portraits and nominated for the Academy Award for Best Animated Short Film in 2020.[119][120] |

ユテルモーレンの自画像が最初に注目されたのは、2001年の

Lancet誌の症例報告[102][j]で、Crutchらは、芸術的能力の明らかな変化は、「特に発症時の彼の比較的若い年齢を考えると、通常の老化

以上の過程を示している」と指摘している。さらに同論文は、5年以上にわたって自画像が「制作された作品の質の客観的な劣化」を示したと述べている

[104]。 クラッチ自身も、ウテルモーレンの作品は「彼が言葉で語ることができる何よりも雄弁」であったと述べている[72]。 Hsuによれば、肖像画は「彼のキャリアのハイライト」である[106]。 コメント欄では、フィンセント・ファン・ゴッホ、パブロ・ピカソ、エドヴァルド・ムンクの作品と比較される[107]。シャーマは自画像とイギリスの画家 イワンシールの作品を比較して、後者の作品には「純粋認識と抽象化の淵に立つオブジェ」が示されていると指摘している[75]。また一部の作家は自画像と Mervyn Peakeの挿絵を比較したが、Demetrios J. Peake StudiesのDemetrios J. Sahlasは、Peakeの作品はUtermohlenの作品とは異なっており、作品に示されているのは「洞察力の保存」であると指摘している [109]。 2013年のThe Lancetの記事は彼の作品をレンブランドの自画像と比較し、Utermohlenを「年齢に対して自己を保存しようと苦闘」しながら「どうしようもな い神経変性」に対しても戦っていると述べている[110]。 [ジョヴァンニ・フラッツェットはユテルモーレンの自画像をエゴン・シーレの作品に似ていると評し、その肖像画がシーレの作品に示される「縮んだ身体と薄 汚れた顔を想起させる」ものであると説明した[111]。 シェリー・アーヴィンは肖像画が「顕著な文体の特徴を示し、(鑑賞と解釈の真剣な努力に)報いる」と述べている[112]。 アーヴィンは、その「形式と美的特徴」、ユテルモーレンの以前の作品との相関、及びその「解釈への適性」が、肖像画を「それらがどう見なされるべきかとい う明示的な意図がないにもかかわらず、過去の芸術と正しい方法で接続するのに共同で十分」にしていると指摘している[113]。 アラン・E・H・エメリーは、認知症の進行性の影響は神経学者に「この病気が時間とともに芸術家の作品にどのような影響を与えるかを研究する機会」を与え ると考え、また知覚における詳細な変化とそれがどのように脳の局所的機能と関連付けられるかを研究するユニークな方法を提供すると付け加えている [113]。医療人類学者のマーガレット・ロックは、肖像画は「生涯を通じた社会的・文化的活動によって、この病気の害から人間を守ることができる方法を 示唆する多くの道があるかもしれない」ことを示していると述べている[114][115]。[115] パーセルは、ユテルモーレンのアートワークが視聴者に「衰えた脳の影響をユニークに垣間見せる」と述べている[116]。 イリノイ・ウェスリアン大学の研究者は、ユテルモーレンの自画像が「AD患者はイメージを通して強い声を出すことができる」ことを示していると述べている [117]。 "117]彼の初期の自画像の存在(視聴者が彼の精神衰退のタイムラプスを作成することができた)と彼の作品がアルツハイマー病患者の心の中に珍しい見方 を与えるという考えは、彼の人気の高まりに貢献している二つの側面だった[118]。 2019年のショートフィルムMémorableは、自画像からインスピレーションを得て、2020年のアカデミー賞短編アニメ賞にノミネートされた [119][120]。 |

| Utermohlen had exhibited long

before his diagnosis. His paintings were exhibited at the Lee Nordness

Gallery in 1968 and the Marlborough Gallery in 1969; in 1972, the

Mummers cycle was displayed in Amsterdam.[16] Utermohlen's posthumous

portrait of Gerald Penny was featured in the Gerald Penny 77'

Center;[121] earlier that year, he had artworks such as Five Figures in

the Mead Art Museum.[122] At their peak, sales of Utermohlen's earlier

works ranged from $3,000 to $30,000.[123] His self-portraits have been shown at several exhibitions in the years after his death, including 12 exhibitions from 2006 to 2008.[124] In 2016, the exhibition A Persistence of Memory was shown at the Loyola University Museum of Art in Chicago.[125] The exhibition, which contained 100 artworks from Utermohlen's work, was organised by Pamela Ambrose,[126] who said about his portraits: "If you did not know that this man was suffering from Alzheimer's, you could simply perceive the work as a stylistic change."[127] Other notable exhibitions include a retrospective at the GV Art gallery in London in 2012,[128][k] an exhibition at the Chicago Cultural Center in 2008 sponsored by Myriad Pharmaceuticals,[130][131] and The Later Works of William Utermohlen, shown at the New York Academy of Medicine in 2006, which marked the centenary of Alois Alzheimer first discovering the disease;[132] it was open free to the public. Earlier that year, there was another exhibition at the College of Physicians of Philadelphia.[133] His self-portraits have also been shown in Washington, D.C. in 2007,[134] the Two 10 Gallery in London in 2001,[135] Harvard University at Cambridge, Massachusetts in 2005,[136] Boston, and Los Angeles. The self-portraits were exhibited in Sacramento, California in 2008.[137] Utermohlen's artworks were shown in 2016 at the Kunstmuseum Thun in Switzerland.[138] In February 2007, a month before Utermohlen's death, his self-portraits were exhibited at Wilkes University.[139] |

ユテルモーレンは、診断されるずっと以前から展覧会を開いていた。彼の

絵画は1968年にリー・ノードネス・ギャラリー、1969年にマールボロ・ギャラリーで展示され、1972年にはアムステルダムで『ママー・サイクル』

が展示された[16] ジェラルド・ペニーの遺影はジェラルド・ペニー 77' センターで展示され、同年初めにはミード美術館で『Five

Figures』などの作品が展示されていた[122]

ユテルモーレンの初期の作品はピーク時に3000ドルから3万ドル程度の売上があった[123]。 彼の自画像は、彼の死後数年の間に、2006年から2008年までの12の展覧会を含むいくつかの展覧会で展示されている[124]。 2016年には、シカゴのロヨラ大学美術館で「記憶の持続」展が開催された[125]。 Utermohlenの作品から100点を集めたこの展覧会は、Pamela Ambroseが企画し、彼のポートレートについて次のように述べている[126]。"もしあなたがこの男がアルツハイマー病に苦しんでいることを知らな ければ、あなたはこの作品を単に文体の変化として認識することができるだろう"[127]と述べている。 その他、2012年にロンドンのGVアートギャラリーで開催された回顧展[128][k]、2008年にミリアド薬品が主催したシカゴ文化センターでの展 覧会[130][131]、2006年にニューヨーク医学アカデミーで開催されたThe Later Works of William Utermohlen(アロイス・アルツハイマー初発見の100年記念)は無料公開された[132]など注目の展覧会がある。同年初めには、フィラデル フィア内科大学でも展示があった[133]。自画像は、2007年にワシントンD.C.、2001年にロンドンのTwo 10ギャラリー[134]、2005年にケンブリッジのハーバード大学、マサチューセッツ州、ボストン、ロサンゼルスでも公開されている[136]。 2008年にはカリフォルニア州サクラメントで自画像が展示された[137]。 2016年にはスイスのトゥーン美術館でUtermohlenの作品が展示された[138]。 2007年2月、Utermohlenの死の1ヶ月前に、ウィルクス大学で彼の自画像が展示された[139]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/William_Utermohlen |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

|

W.Utermohlen Self Portrait with

saw, 1997, 35.5x35.5, http://boicosfinearts.com/exhibitions/william-utermohlen-a-persistence.html |

IKEDA Mitsuho, Popular images on "Boke" (senile dementia and other related symptoms) in Japan.

(DSM-5, 2013: Neurocognitive Disorder[pdf with password])(DSM-IVからDSM-5へのクライテリアへの変更:DSM-5_dementia_criteria.pdf[パスワー ド])

|

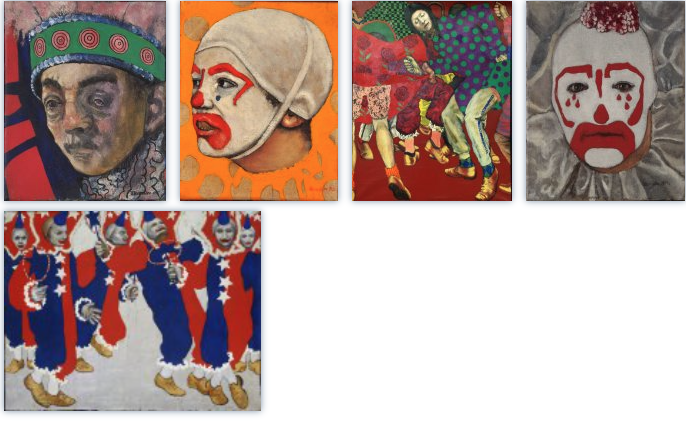

Mummers Cycle, 1958 - 1970. |

|

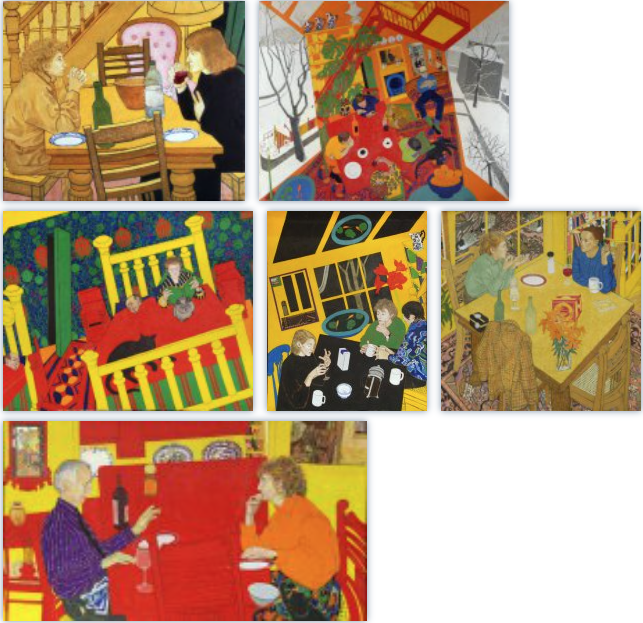

Conversation Pieces, 1989 - 1991. |

|

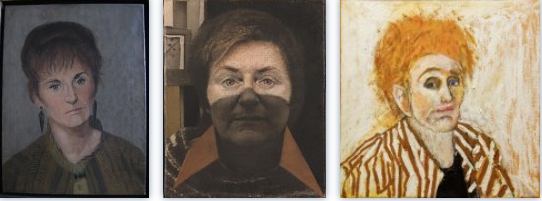

Portraits, 1962 - 1997. |

|

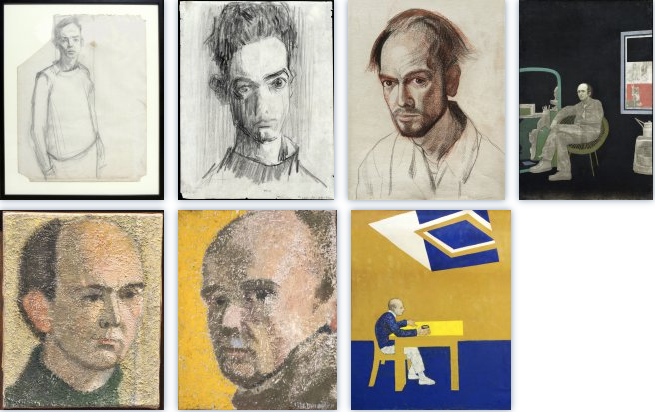

Masks, 1996. |

|

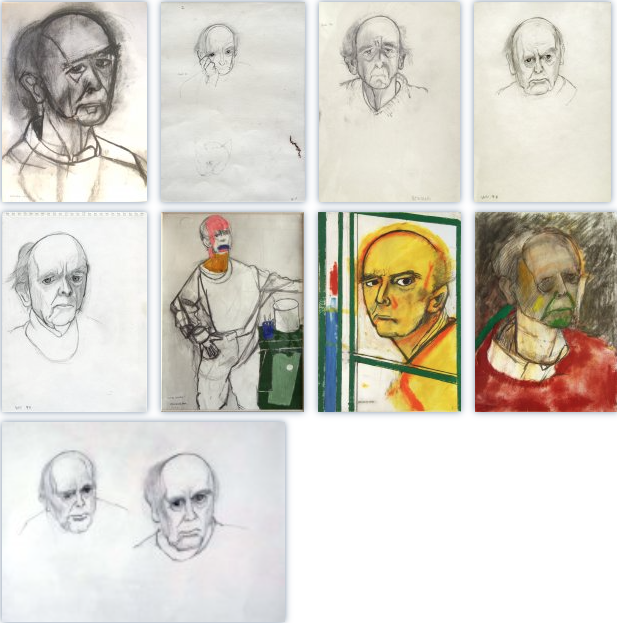

pre 1995, in chronological order

|

|

post 1995, in chronological

order :1995 -1996 |

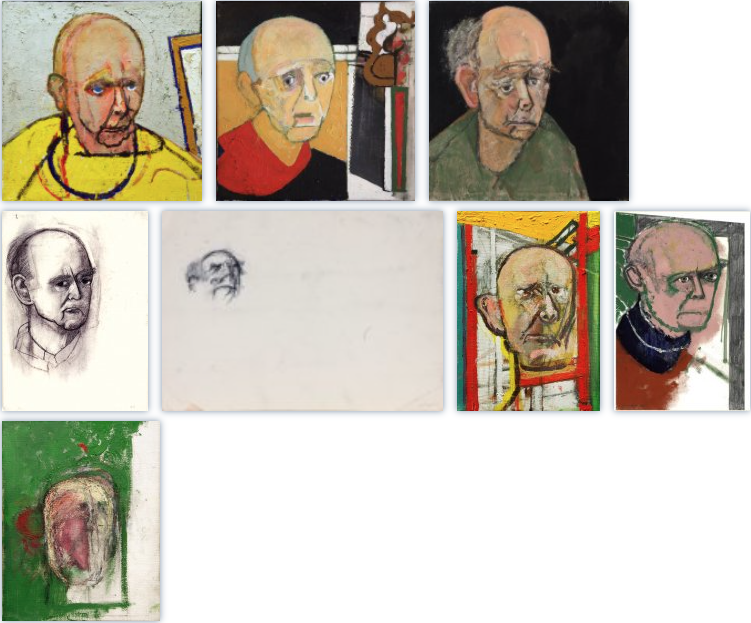

|

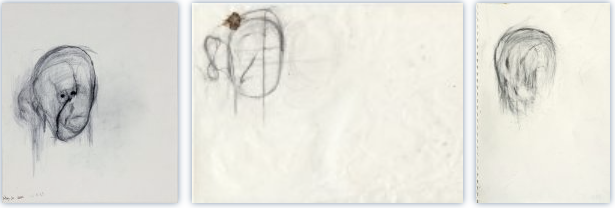

1997 - 1999 |

|

2000 - 2001 |

| http://boicosfinearts.com/exhibitions/william-utermohlen-a-persistence.html |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

++

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆