Active Learning, AC, 能動学習、能動的学習

アクティブ・ラーニング

Active Learning, AC, 能動学習、能動的学習

解説:池田光穂

アクティブラーニング(Active learning)とは、チャールズ・ ボンウェルとジム・エイソン(1991)によると「学生たちが行っている何かに関する思考と行為といっ た、それぞれの活動のなかで学生を巻き込んでいるすべて」のことをさす。この「巻き込み経験」彼らは"anything that involves students in doing things and thinking about the things they are doing" (Bonwell and Eison 1991:2)"と表現している。(アクティブ・ラーニングとも表記します)

アクティブラーニング(能動学習、能動的

学習)をしている状態とは、教室の中でみられる普通の風景、すなわち、学生(生徒・児童を含む)が、前

を眺めている・聞いている・ノートを取っている、という従来型の学習「以外」の活動をすべて包摂するような活動のことである。アクティブラーニングしてい

る状態の例としては以下のようなものをあげることができる。Wikipedia in

English を参照。

アクティブラーニングが登場した背景に は、通常の授業の方法(=受動的学習、古典的学 習)つまり「前を眺めている・聞いている・ノートを取っている」という方法よりも、学習者がより楽しめ、持続的な学習が可能になり、かつ教員じしんが学生 と「学ぶことの楽しさ」を共有できるような方法を模索し、通常の授業の方法がもつ潜在力をより強化したり、授業のレパートリーに多様性を創造しようとする 試みがあったように思える。それは、古典的教育がもつ「疎外(alienation)」や、学生本来がもつ潜在力を引き出すはずのデューイ的な学習が、教 育の大衆化やマスプロ(=大量規格)化によって、十分に機能しないという反省期にうまれた可能性がある。

アクティブラーニング(能動的学習)とい う発想法が生まれてきた背景には、従来の学習の現場における受動的学習(→古典的学習) への批判や、それに対する実践共同体(実践 コミュニティ)におけ る能動的学習の概念、ヴィゴツキーの最近接発達領域(ZPD)、問題にもとづく学習(PBL)やそれがもたらした保 健教育の現場における論争、コミュニティにもとづく参加型研究(CBPR)、ヘルスコミュニケーション領 域における当事者性[→当事者の英訳について]の扱い、サイエンスショップの誕生など、人を対象にする教育や研究が、どのように他者 を取り扱い、どのような介入研究をおこなうべきなのか、そしてそれに伴う倫理とは何かという、広範囲の問題系が、1960年代後半から北米を中心にして世 界の先進国において生まれてきたという事情があるように思われる。

他方、政府や政府系の審議委員会などが唱 える「官製アクティブラーニング」のススメ というものがある。それは、ほとんど「教員による一方向的な講義形式」以外のも のをなんでもかんでも押し込み、かつそのアウトカムについては恐ろしく楽観的な記述になっている。だが、アクティブラーニングに対する過剰な期待は禁物で ある。アクティブ・ラーニングとは(冒頭に述べたように)「教室の中でみられる普通の風景、すなわち、学生(生徒・児童を含む)が、前 を眺めている・聞いている・ノートを取っている、という従来型の学習「以外」の活動をすべて包摂するような活動」という、それ以上でもそれ以下でもない代 物だからである(→「教育方法としてのアクティブラーニング」)。

| Active learning is

"a method of learning in which students are actively or experientially

involved in the learning process and where there are different levels

of active learning, depending on student involvement."[1] Bonwell &

Eison (1991) states that "students participate [in active learning]

when they are doing something besides passively listening." According

to Hanson and Moser (2003) using active teaching techniques in the

classroom can create better academic outcomes for students. Scheyvens,

Griffin, Jocoy, Liu, & Bradford (2008) further noted that "by

utilizing learning strategies that can include small-group work,

role-play and simulations, data collection and analysis, active

learning is purported to increase student interest and motivation and

to build students ‘critical thinking, problem-solving and social

skills". In a report from the Association for the Study of Higher

Education, authors discuss a variety of methodologies for promoting

active learning. They cite literature that indicates students must do

more than just listen in order to learn. They must read, write,

discuss, and be engaged in solving problems. This process relates to

the three learning domains referred to as knowledge, skills and

attitudes (KSA). This taxonomy of learning behaviors can be thought of

as "the goals of the learning process."[2] In particular, students must

engage in such higher-order thinking tasks as analysis, synthesis, and

evaluation.[3] |

アクティブ・ラーニング(Active learning)とは、「生徒が能動的または経験的に学習過程に

関与する学習方法であり、生徒の関与の度合いによってアクティブ・ラーニングのレベルが異なる」[1][1] Bonwell &

Eison(1991)は、「生徒が(アクティブ・ラーニングに)参加するのは、受動的に聞く以外に何かをしているときである」と述べている。

Hanson and Moser

(2003)によると、教室でアクティブ・ティーチングのテクニックを使うことで、生徒によりよい学業成果をもたらすことができる。さらに、

Scheyvens, Griffin, Jocoy, Liu, & Bradford

(2008)は、「少人数のグループワーク、ロールプレイやシミュレーション、データ収集や分析などの学習戦略を活用することで、アクティブ・ラーニング

は、生徒の興味や意欲を高め、生徒の『批判的思考力、問題解決力、社会的スキル』を育成すると言われている」と述べている。高等教育研究協会の報告書で

は、著者がアクティブ・ラーニングを促進するためのさまざまな方法論について論じている。学生が学ぶためには、ただ聞くだけでは不十分であることを示す文

献を引用している。読み、書き、議論し、問題解決に取り組まなければならない。このプロセスは、知識、技能、態度(KSA)と呼ばれる3つの学習領域に関

連している。この学習行動の分類法は、「学習プロセスの目標」と考えることができる[2]。特に、生徒は分析、総合、評価といった高次の思考課題に取り組

まなければならない[3]。 |

| Nature of active learning There are a wide range of alternatives for the term active learning and specific strategies, such as: learning through play, technology-based learning, activity-based learning, group work, project method, etc. The common factors in these are some significant qualities and characteristics of active learning. Active learning is the opposite of passive learning; it is learner-centered, not teacher-centered, and requires more than just listening; the active participation of each and every student is a necessary aspect in active learning. Students must be doing things and simultaneously think about the work done and the purpose behind it so that they can enhance their higher order thinking capabilities. Many research studies[by whom?][4] have proven that active learning as a strategy has promoted achievement levels and some others[who?] say that content mastery is possible through active learning strategies.[5][6] However, some students as well as teachers find it difficult to adapt to the new learning technique.[7] There are intensive uses of scientific and quantitative literacy across the curriculum, and technology-based learning is also in high demand in concern with active learning.[8] Barnes (1989)[9][10] suggested principles of active learning: Purposive: the relevance of the task to the students' concerns. Reflective: students' reflection on the meaning of what is learned. Negotiated: negotiation of goals and methods of learning between students and teachers. Critical: students appreciate different ways and means of learning the content. Complex: students compare learning tasks with complexities existing in real life and making reflective analysis. Situation-driven: the need of the situation is considered in order to establish learning tasks. Engaged: real life tasks are reflected in the activities conducted for learning. Active learning requires appropriate learning environments through the implementation of correct strategy. Characteristics of learning environment are:[11][12] Aligned with constructivist strategies and evolved from traditional philosophies. Promoting research based learning through investigation and contains authentic scholarly content. Encouraging leadership skills of the students through self-development activities. Creating atmosphere suitable for collaborative learning for building knowledgeable learning communities. Cultivating a dynamic environment through interdisciplinary learning and generating high-profile activities for a better learning experience. Integration of prior with new knowledge to incur a rich structure of knowledge among the students. Task-based performance enhancement by giving the students a realistic practical sense of the subject matter learnt in the classroom. |

アクティブ・ラーニングの性質[編集]。 アクティブ・ラーニングという言葉には、遊びを通しての学習、テクノロジーを使った学習、活動ベースの学習、グループワーク、プロジェクト方式など、さま ざまな選択肢や具体的な戦略がある。これらに共通するのは、アクティブ・ラーニングの重要な資質や特徴である。アクティブ・ラーニングは受動的な学習とは 正反対であり、教師中心ではなく学習者中心であり、ただ聞くだけでは不十分である。生徒たちは、物事を行うと同時に、その作業とその背後にある目的につい て考え、高次の思考能力を高める必要がある。 多くの研究[誰による][4]が、戦略としてのアクティブ・ラーニングが達成レベルを促進したことを証明しており、また他の研究[誰による][5][6] は、アクティブ・ラーニング戦略によって内容の習得が可能であると述べている。 カリキュラム全体にわたって科学的・数量的リテラシーが集中的に使用されており、アクティブ・ラーニングに関連してテクノロジーを使った学習も高い需要が ある[8]。 バーンズ(1989)[9][10]は、アクティブ・ラーニングの原則を提案している: 目的論的:生徒の関心事と課題の関連性。 反省的:学習したことの意味について生徒が考える。 交渉型:生徒と教師の間で学習の目標と方法について交渉する。 批判的(Critical): 生徒は内容を学ぶさまざまな方法や手段を評価する。 複雑さ: 生徒は学習課題を実生活に存在する複雑さと比較し、反省的な分析を行う。 状況主導型:学習課題を設定するために、状況の必要性を考慮する。 関与型:実生活の課題が学習のための活動に反映される。 アクティブ・ラーニングには、適切な戦略の実施による適切な学習環境が必要である。学習環境の特徴は以下の通りである[11][12]。 構成主義的な戦略に沿っており、伝統的な哲学から発展している。 調査を通じて研究に基づく学習を促進し、本物の学術的内容を含む。 自己開発活動を通じて、生徒のリーダーシップ能力を奨励する。 知識豊かな学習コミュニティを構築するために、共同学習に適した雰囲気を作る。 学際的な学習を通してダイナミックな環境を培い、より良い学習経験を得るために注目される活動を生み出す。 学生の間に豊かな知識構造を構築するために、過去の知識と新しい知識を統合する。 教室で学んだ題材の現実的な実践感覚を学生に与えることで、課題ベースのパフォーマンスを向上させる。 |

| Teacher's characteristics in

active learning A study by Jerome I. Rotgans and Henk G. Schmidt showed a correlation between three teachers' characteristics and students' situational interest in an active learning classroom. Situational interest is defined as "focused attention and an affective reaction that is triggered in the moment by environmental stimuli, which may or may not last over time" according to Hidi and Renninger. students' situational interest is inspired by three teacher traits as represented in the study. The three traits are social congruence, subject-matter expertise, and cognitive congruence: When a teacher is socially congruent which means that he/she has a harmonious interaction with the student, the positive relationship allows students to express their opinions and participate without fear of making mistakes. Also, students will ask questions when the topic is not clear; as a result, they become more interested in the classroom.[13] Subject-matter expertise: When a teacher is an expert and has a broad knowledge of the subject being taught, students are expected to work harder and put more effort into their work. In contrast, If a teacher is less knowledgeable, students might lose interest in learning. Moreover, expert teachers are more helpful to their students in an effective way. This trait will positively impact student's success during the active learning process.[13] Cognitive congruence: This happens when a teacher can simplify hard concepts and use simple terms, so students can easily understand the topic. The teacher guides the students in the learning process by asking questions and allowing students to share their thoughts without interruption. As a result, students will trust their ability to learn on their own and will develop an organized way of thinking about a topic. Therefore, they will be more engaged in an active learning classroom.[13] |

アクティブ・ラーニングにおける教師の特性[編集]。 Jerome I. RotgansとHenk G. Schmidtによる研究では、アクティブ・ラーニングの教室における3つの教師の特性と生徒の状況的興味との間に相関関係があることが示された。 HidiとRenningerによると、状況的関心とは「集中した注意と、環境刺激によってその瞬間に引き起こされる感情的反応であり、それは時間が経っ ても続いても続かなくてもよい」と定義されている。 生徒の状況的関心は、この研究に代表されるように、3つの教師の特質によって触発される。その3つの特性とは、社会的一致、教科の専門性、認知的一致であ る: 教師が社会的整合性、つまり生徒と調和のとれた相互作用を持っている場合、生徒が間違いを恐れずに自分の意見を述べたり、参加したりできるようになる。ま た、トピックが明確でない場合、生徒は質問をするようになり、その結果、生徒は授業により興味を持つようになる[13]。 教科の専門知識: 教師が専門家であり、教えられている教科について幅広い知識を持っている場合、生徒はより努力し、自分の仕事に打ち込むことが期待される。対照的に、教師 があまり知識がない場合、生徒は学習への興味を失うかもしれない。さらに、専門家の教師は、効果的な方法で生徒により役立つ。この特性は、能動的学習プロ セスにおける生徒の成功にプラスの影響を与える[13]。 認知的一致: これは、教師が難しい概念を単純化し、簡単な用語を使うことで、生徒がそのトピックを容易に理解できる場合に起こる。教師は質問を投げかけ、生徒が中断す ることなく自分の考えを共有できるようにすることで、学習プロセスにおいて生徒を導く。その結果、生徒は自分で学ぶ能力を信頼し、トピックについて整理さ れた考え方を身につける。したがって、生徒たちはアクティブ・ラーニングの授業により積極的に取り組むようになる[13]。 |

| Ensuring that all students are

actively learning Total participation offers two major techniques for teachers to apply in their classrooms. These techniques motivate students and allow them to understand the learning materials deeply. The first helpful tool is asking students higher-order questions instead of lower-order questions. According to Bloom's Cognitive Taxonomy, a higher-order question will allow students to go beyond their basic knowledge, opening the door for their thinking to dive into new topics, and make connections related to real life. When students make these connections and analyze the topic that needs to be learned, the topic will become unforgettable. In contrast, lower-order questions are straightforward questions based on memorized facts or predictable conclusions. These types of questions may engage all students to participate but will not allow students to expand their thinking. They will likely forget the concept later because it lacks connections to real life, and their thinking didn't go through deep analysis. The second tool is called "The Ripple." This technique will ensure that every student will participate and come up with an answer regarding a higher-order question because it gives a student the time needed to think independently and generate ideas. The drawback of the traditional teaching method is that it only allows some students to respond to the prompt, while others may need extra time to develop ideas. "The Ripple" will motivate students through different stages. First, the students think independently, then they expand their ideas with peers, and finally, this discussion will expand to the whole class.[14] |

すべての生徒が積極的に学ぶようにする[編集]。 全員参加型授業は、教師が教室で適用できる2つの主要なテクニックを提供している。これらのテクニックは生徒のやる気を引き出し、学習教材を深く理解させ る。最初の有用な手段は、生徒に低次の質問ではなく高次の質問をすることである。ブルームの認知分類学によると、高次の質問は、生徒が基本的な知識を超え て、新しいトピックに飛び込んだり、実生活と関連付けたりする思考の扉を開くことを可能にする。生徒がこのようなつながりを持ち、学ぶべきトピックを分析 するとき、そのトピックは忘れられないものになる。対照的に、低次の問題は、暗記した事実や予測できる結論に基づく率直な問題である。このようなタイプの 問題は、生徒全員を参加させることはできても、生徒が思考を広げることはできない。実生活とのつながりがなく、思考が深く分析されないため、後でその概念 を忘れてしまう可能性が高い。つ目のツールは、「波紋 」と呼ばれるものである。このテクニックは、生徒が自主的に考え、アイデアを生み出すのに必要な時間を与えるので、すべての生徒が参加し、高次の質問に関 する答えを出すことを保証する。従来の教授法の欠点は、一部の生徒しかプロンプトに答えることができず、他の生徒はアイデアを練るために余分な時間を必要 とすることである。「波紋 "は、さまざまな段階を通して生徒のやる気を引き出す。まず生徒が自主的に考え、次に仲間とアイデアを広げ、最後にこの議論がクラス全体に広がる [14]。 |

| Constructivist framework Active learning coordinates with the principles of constructivism which are, cognitive, meta-cognitive, evolving and effective in nature. Studies have shown that immediate results in construction of knowledge is not possible through active learning as the child first goes through the process of knowledge construction, knowledge recording and then knowledge absorption. This process of knowledge construction is dependent on previous knowledge of the learner where the learner is self-aware of the process of cognition and can control and regulate it by themselves.[15] There are several aspects of learning and some of them are: Learning through meaningful reception, influenced by David Ausubel, who emphasizes the previous knowledge the learner possesses and considers it a key factor in learning. Learning through discovery, influenced by Jerome Bruner, where students learn through discovery of ideas with the help of situations provided by the teacher. Conceptual change: misconceptions takes place as students discover knowledge without any guidance; teachers provide knowledge keeping in mind the common misconceptions about the content and keep an evaluatory check on the knowledge constructed by the students. Constructivism, influenced by researchers such as Lev Vygotsky, suggests collaborative group work within the framework of cognitive strategies like questioning, clarifying, predicting and summarizing.[16] |

構成主義の枠組み[編集]アクティブ・ラーニングは、認知的、メタ認知

的、発展的、効果的な性質を持つ構成主義の原則と協調している。研究により、知識の構築において即座に結果が出ることは、アクティブ・ラーニングでは不可

能であることが示されている。この知識構築のプロセスは、学習者の以前の知識に依存しており、学習者は認知のプロセスを自分で認識し、自分でそれを制御

し、調整することができる[15]: デイヴィッド・アウスベル(David Ausubel)の影響を受けた「意味のある受容による学習」(Learning through meaningful reception)は、学習者が持っている以前の知識を重視し、それが学習における重要な要素であると考える。 発見による学習:ジェローム・ブルーナー(Jerome Bruner)の影響。 教師は、内容に関する一般的な誤解を念頭に置いて知識を提供し、生徒が構築した知識を評価的にチェックする。 構成主義は、レフ・ヴィゴツキーのような研究者の影響を受け、質問、明確化、予測、要約のような認知戦略の枠組みの中での共同グループ作業を提案している [16]。 |

| Science of active learning Active learning can be used effectively for teaching comprehension and memory.[17] The reason it is efficient is that it draws on underlying characteristics of how the brain operates during learning. These characteristics have been documented by thousands of empirical studies (e.g., Smith & Kosslyn, 2011) and have been organized into a set of principles. Each of these principles can be drawn on by various active learning exercises. They also offer a framework for designing activities that will promote learning; when used systematically, Stephen Kosslyn (2017) notes these principles enable students to "learn effectively—sometimes without even trying to learn".[18] The principles of learning One way to organize the empirical literature on learning and memory specifies 16 distinct principles, which fall under two umbrella "maxims". The first maxim, "Think it Through", includes principles related to paying close attention and thinking deeply about new information. The second, "Make and Use Associations", focuses on techniques for organizing, storing, and retrieving information. The principles can be summarized as follows.[18] Maxim I: Think it through Evoking deep processing: extending thinking beyond "face value" of information (Craig et al., 2006; Craik & Lockhart, 1972) Using desirable difficulty: ensuring that the activity is neither too easy nor too hard (Bjork, 1988, 1999; VanLehn et al., 2007) Eliciting the generation effect: requiring recall of relevant information (Butler & Roediger, 2007; Roediger & Karpicke, 2006) Engaging in deliberate practice: promoting practice focused on learning from errors (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014; Ericsson, Krampe, & Tesch-Romer, 1993) Using interleaving: intermixing different problem types[19] Inducing dual coding: presenting information both verbally and visually (Kosslyn, 1994; Mayer, 2001; Moreno & Valdez, 2005) Evoking emotion: generating feelings to enhance recall (Erk et al., 2003; Levine & Pizarro, 2004; McGaugh, 2003, 2004) Maxim II: Make and use associations Promoting chunking: collecting information into organized units (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014; Mayer & Moreno, 2003) Building on prior associations: connecting new information to previously stored information (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000; Glenberg & Robertson, 1999; Mayer, 2001) Presenting foundational material first: providing basic information as a structural "spine" onto which new information can be attached (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000; Wandersee, Mintzes, & Novak, 1994) Exploiting appropriate examples: offering examples of the same idea in multiple contexts (Hakel & Halpern, 2005) Relying on principles, not rote: explicitly characterizing the dimensions, factors or mechanisms that underlie a phenomenon (Kozma & Russell, 1997; Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000) Creating associative chaining: sequencing chunks of information into stories (Bower & Clark, 1969; Graeser, Olde, & Klettke, 2002) Using spaced practice: spreading learning out over time (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014; Cepeda et al., 2006, 2008; Cull, 2000) Establishing different contexts: associating material with a variety of settings (Hakel & Halpern, 2005; Van Merrienboer et al., 2006) Avoiding interference: incorporating distinctive retrieval cues to avoid confusion (Adams, 1967; Anderson & Neely, 1996) Active learning typically draws on combinations of these principles. For example, a well-run debate will draw on virtually all, with the exceptions of dual coding, interleaving, and spaced practice. In contrast, passively listening to a lecture rarely draws on any. |

アクティブ・ラーニングの科学[編集] アクティブ・ラーニングが効率的である理由は、学習時に脳がどのように機能するかという根本的な特徴を利用しているからである[17]。これらの特性は、 何千もの経験的研究(例えば、Smith & Kosslyn, 2011)によって文書化されており、一連の原則に整理されている。これらの原則はそれぞれ、様々なアクティブ・ラーニングの演習で活用することができ る。また、これらの原則は、学習を促進する活動を設計するための枠組みを提供している。体系的に使用することで、Stephen Kosslyn(2017)は、これらの原則は、学生が「効果的に学ぶ-時には学ぼうとさえせずに学ぶ」ことを可能にすると指摘している[18]。 学習の原則[編集] 学習と記憶に関する経験的文献を整理する1つの方法は、2つの包括的な「格言」に該当する16の明確な原則を規定している。最初の格言である「Think it Through(考え抜く)」には、新しい情報に細心の注意を払い、深く考えることに関する原則が含まれている。二つ目の「関連付けをし、利用する」は、 情報を整理し、記憶し、検索するためのテクニックに焦点を当てている。 原則は以下のように要約できる[18]。 マキシムI:考え抜く[編集]。 深層処理を喚起する:情報の「額面」以上の思考を拡張する (Craig et al., 2006; Craik & Lockhart, 1972) 望ましい難易度を使用する:活動が簡単すぎず難し すぎないようにする(Bjork, 1988, 1999; VanLehn et al., 2007) ジェネレーション効果を引き出す: 関連情報を想起させる (Butler & Roediger, 2007; Roediger & Karpicke, 2006) 意図的な練習に取り組む:エラーからの学びに焦点を当てた練習を促進する(Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014; Ericsson, Krampe, & Tesch-Romer, 1993) インターリービングの使用:異なる問題タイプを混在させる[19]。 二重符号化を誘導する: 情報を口頭と視覚の両方で提示する (Kosslyn, 1994; Mayer, 2001; Moreno & Valdez, 2005) 感情を喚起する:想起を高めるために感情を生み出す (Erk et al., 2003; Levine & Pizarro, 2004; McGaugh, 2003, 2004) 最大Ⅱ:関連付けを行い、利用する[編集]。 チャンキングの促進:情報を整理された単位に集める(Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014; Mayer & Moreno, 2003) 以前の関連付けを基にする: 新しい情報を以前に記憶した情報と関連付ける (Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000; Glenberg & Robertson, 1999; Mayer, 2001) 基礎的な情報を最初に提示する:基本的な情報を構造的な「背骨」として提供し、その上に新しい情報を乗せる(Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000; Wandersee, Mintzes, & Novak, 1994) 適切な事例を活用する:複数の文脈で同じアイデアの事例を提示する(Hakel & Halpern, 2005) 暗記ではなく原理原則に頼る:現象の根底にある次元、要因、メカニズ ムを明示的に特徴づける (Kozma & Russell, 1997; Bransford, Brown, & Cocking, 2000) 連想連鎖を作る:情報のかたまりを順序立ててストーリーにする(Bower & Clark, 1969; Graeser, Olde, & Klettke, 2002) 間隔をあけて練習する: 学習を時間をかけて広げる (Brown, Roediger, & McDaniel, 2014; Cepeda et al., 2006, 2008; Cull, 2000) さまざまな文脈を設定する:教材をさまざまな場面に関連付ける (Hakel & Halpern, 2005; Van Merrienboer et al., 2006) 干渉の回避:混乱を避けるために、特徴的な検索手がかりを取り入れる (Adams, 1967; Anderson & Neely, 1996) アクティブ・ラーニングは通常、これらの原則を組み合わせて利用する。例えば、うまく運営されているディベートは、デュアルコーディング、インターリー ブ、間隔をあけた練習という例外を除いて、事実上すべての原則を利用している。これとは対照的に、受動的に講義を聴く場合には、これらの原則はほとんど利 用されない。 |

| Active learning exercises See also: Cooperative learning § Techniques Bonwell and Eison (1991) suggested learners work collaboratively, discuss materials while role-playing, debate, engage in case study, take part in cooperative learning, or produce short written exercises, etc. The argument is "when should active learning exercises be used during instruction?". Numerous studies have shown that introducing active learning activities (such as simulations, games, contrasting cases, labs,..) before, rather than after lectures or readings, results in deeper learning, understanding, and transfer.[20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27] The degree of instructor guidance students need while being "active" may vary according to the task and its place in a teaching unit. In an active learning environment learners are immersed in experiences within which they engage in meaning-making inquiry, action, imagination, invention, interaction, hypothesizing and personal reflection (Cranton 2012). Examples of "active learning" activities include A class discussion may be held in person or in an online environment. Discussions can be conducted with any class size, although it is typically more effective in smaller group settings. This environment allows for instructor guidance of the learning experience. Discussion requires the learners to think critically on the subject matter and use logic to evaluate their and others' positions. As learners are expected to discuss material constructively and intelligently, a discussion is a good follow-up activity given the unit has been sufficiently covered already.[28] Some of the benefits of using discussion as a method of learning are that it helps students explore a diversity of perspectives, it increases intellectual agility, it shows respect for students' voices and experiences, it develops habits of collaborative learning, it helps students develop skills of synthesis and integration (Brookfield 2005). In addition, by having the teacher actively engage with the students, it allows for them to come to class better prepared and aware of what is taking place in the classroom.[29] A think-pair-share activity is when learners take a minute to ponder the previous lesson, later to discuss it with one or more of their peers, finally to share it with the class as part of a formal discussion. It is during this formal discussion that the instructor should clarify misconceptions. However students need a background in the subject matter to converse in a meaningful way. Therefore, a "think-pair-share" exercise is useful in situations where learners can identify and relate what they already know to others. It can also help teachers or instructors to observe students and see if they understand the material being discussed.[30] This is not a good strategy to use in large classes because of time and logistical constraints (Bonwell and Eison, 1991). Think-pair-share is helpful for the instructor as it enables organizing content and tracking students on where they are relative to the topic being discussed in class, saves time so that he/she can move to other topics, helps to make the class more interactive, provides opportunities for students to interact with each other (Radhakrishna, Ewing, and Chikthimmah, 2012). A learning cell is an effective way for a pair of students to study and learn together. The learning cell was developed by Marcel Goldschmid of the Swiss Federal Institute of Technology in Lausanne (Goldschmid, 1971). A learning cell is a process of learning where two students alternate asking and answering questions on commonly read materials. To prepare for the assignment, the students read the assignment and write down questions that they have about the reading. At the next class meeting, the teacher randomly puts students in pairs. The process begins by designating one student from each group to begin by asking one of their questions to the other. Once the two students discuss the question, the other student ask a question and they alternate accordingly. During this time, the teacher goes from group to group giving feedback and answering questions. This system is also called a student dyad. A short written exercise that is often used is the "one-minute paper". This is a good way to review materials and provide feedback. However a "one-minute paper" does not take one minute and for students to concisely summarize it is suggested[who?] that they have at least 10 minutes to work on this exercise. (See also: Quiz § In education.) A collaborative learning group is a successful way to learn different material for different classes. It is where you assign students in groups of 3-6 people and they are given an assignment or task to work on together.[31] To create participation and draw on the wisdom of all the learners the classroom arrangement needs to be flexible seating to allow for the creation of small groups. (Bens, 2005) A student debate is an active way for students to learn because they allow students the chance to take a position and gather information to support their view and explain it to others.[31] A reaction to a video is also an example of active learning.[31] A small group discussion is also an example of active learning because it allows students to express themselves in the classroom. It is more likely for students to participate in small group discussions than in a normal classroom lecture because they are in a more comfortable setting amongst their peers, and from a sheer numbers perspective, by dividing the students up more students get opportunities to speak out. There are so many different ways a teacher can implement small group discussion in to the class, such as making a game out of it, a competition, or an assignment. Statistics show that small group discussions is more beneficial to students than large group discussions when it comes to participation, expressing thoughts, understanding issues, applying issues, and overall status of knowledge.[32] Just-in-time teaching promotes active learning by using pre-class questions to create common ground among students and teachers before the class period begins. These warmup exercises are generally open ended questions designed to encourage students to prepare for class and to elicit student's thoughts on learning goals. A class game is also considered an energetic way to learn because it not only helps the students to review the course material before a big exam but it helps them to enjoy learning about a topic. Different games such as Jeopardy! and crossword puzzles always seem to get the students' minds going.[31] Learning by teaching is also an example of active learning because students actively research a topic and prepare the information so that they can teach it to the class. This helps students learn their own topic even better and sometimes students learn and communicate better with their peers than their teachers. Gallery walk is where students in groups move around the classroom or workshop actively engaging in discussions and contributing to other groups and finally constructing knowledge on a topic and sharing it. In a learning factory production-related subjects can be learned interactively in a realistic learning environment. Problem based learning or "PBL" is an active learning strategy that provides students with the problem first and has been found as an effective strategy with topics as advanced as medicine.[4] |

アクティブ・ラーニングの実践 も参照のこと: 協同学習§テクニック Bonwell and Eison (1991)は、学習者が共同作業をしたり、ロールプレイをしながら教材について話し合ったり、討論をしたり、ケーススタディに取り組んだり、協同学習に 参加したり、短い文章題を作成したりすることを提案している。議論は、「どのような場合にアクティブ・ラーニングを導入すべきか」ということである。数多 くの研究が、講義やリーディングの後ではなく、その前にアクティブ・ラーニング活動(シミュレーション、ゲーム、対照的なケース、ラボなど)を導入するこ とで、より深い学習、理解、伝達がもたらされることを示している[20][21][22][23][24][25][26][27]。学生が「アクティ ブ」である間に必要な指導者の指導の程度は、課題や教育ユニットにおけるその位置づけによって異なるかもしれない。 アクティブ・ラーニングの環境では、学習者は、意味づけのための探究、行動、想像、発明、相互作用、仮説立案、個人的な内省を行う体験に没頭する (Cranton 2012)。 アクティブ・ラーニング」の例としては、以下のようなものがある。 クラスでのディスカッションは、対面でもオンライン環境でも行うことができる。ディスカッションはクラスの規模に関係なく行うことができるが、一般的には 少人数で行う方が効果的である。このような環境では、講師が学習体験を指導することができる。ディスカッションでは、学習者が主題について批判的に考え、 論理を使って自分や他者の立場を評価することが求められる。学習者は建設的かつ知的に教材について議論することが期待されているため、ディスカッション は、すでにその単元が十分にカバーされている場合には、フォローアップの活動として適している[28]。学習方法としてディスカッションを用いる利点とし ては、生徒が多様な視点を探求するのに役立つこと、知的機敏性を高めること、生徒の声や経験を尊重する姿勢を示すこと、共同学習の習慣を身につけること、 生徒が総合と統合のスキルを身につけるのに役立つことなどが挙げられる(Brookfield 2005)。加えて、教師が積極的に生徒と関わることで、生徒はより良い準備をして授業に臨み、教室で何が行われているかを意識することができる [29]。 think-pair-shareアクティビティとは、学習者が1分間で前の授業について考え、その後1人または複数の仲間と話し合い、最後に正式なディ スカッションの一部としてクラスで共有することである。この正式なディスカッションの中で、講師は誤解を解かなければならない。しかし、生徒が有意義な会 話をするためには、そのテーマに関する背景が必要である。したがって、学習者がすでに知っていることを特定し、他の人と関連づけることができるような状況 では、「think-pair-share」練習が有効である。また、教師またはインストラクターが生徒を観察し、議論されている題材を理解しているかど うかを確認するのにも役立つ[30]。これは、時間とロジスティクスの制約があるため、大人数のクラスで使用するには良い戦略ではない(Bonwell and Eison, 1991)。Think-pair-shareは、内容を整理し、クラスで議論されているトピックに対して生徒がどのような位置にいるのかを追跡すること ができ、時間を節約して他のトピックに移ることができ、クラスをよりインタラクティブにするのに役立ち、生徒同士が交流する機会を提供するため、指導者に とって有用である(Radhakrishna, Ewing, and Chikthimmah, 2012)。 ラーニングセルは、2人1組の生徒が一緒に勉強し、学習するための効果的な方法である。ラーニング・セルは、スイス連邦工科大学ローザンヌ校の Marcel Goldschmidによって開発された(Goldschmid, 1971)。ラーニング・セルとは、2人の学生が交互に、よく読まれた教材について質問したり答えたりする学習プロセスのことである。課題の準備のため に、生徒は課題を読み、その読み物について持っている質問を書き留める。次の授業で、教師は生徒をランダムにペアにする。各グループから一人の生徒を指名 し、もう一人に質問をすることから始める。二人の生徒がその質問について話し合ったら、もう一人の生徒が質問をし、交互に質問をする。この間、教師はグ ループからグループへと回り、フィードバックを与え、質問に答える。このシステムは、生徒ダイアドとも呼ばれる。 よく使われる短い筆記課題は、「1分間ペーパー」である。これは、教材を見直し、フィードバックを提供する良い方法である。ただし、「1分間ペーパー」は 1分では終わらないので、生徒が簡潔にまとめるためには、この練習に少なくとも10分かけることが推奨される[誰?]。(参照:教育における小テスト §)。 共同学習グループは、異なるクラスの異なる教材を学習するのに有効な方法である。これは、生徒を3~6人のグループに分け、一緒に取り組む課題や作業を与 えるものである[31]。参加を生み出し、すべての学習者の知恵を引き出すために、教室の配置は小グループを作れるように柔軟な座席にする必要がある。 (Bens, 2005) 生徒の討論は、生徒が自分の意見を持ち、それを裏付ける情報を集め、他の生徒に説明する機会を与えるので、生徒にとって能動的な学習方法である[31]。 ビデオに対するリアクションもアクティブ・ラーニングの一例である[31]。 小グループでのディスカッションもアクティブ・ラーニングの一例である。小グループでのディスカッションは、通常の教室での講義よりも生徒が参加しやす い。なぜなら、生徒が仲間に囲まれてより快適な環境にいるからであり、また、人数という観点からも、生徒を分けることでより多くの生徒が発言する機会を得 ることができるからである。少人数でのディスカッションをゲームにしたり、競争させたり、課題にしたりと、教師が授業に取り入れる方法は実にさまざまだ。 統計によると、参加、考えの表明、問題の理解、問題の応用、知識の全体的な状況に関しては、小グループでのディスカッションの方が大人数でのディスカッ ションよりも生徒にとって有益であることが示されている[32]。 ジャスト・イン・タイム授業は、授業が始まる前に、生徒と教師の間に共通の土台を作るために、授業前の質問を使用することによって、能動的な学習を促進す る。このようなウォーミングアップの練習は、一般的に、生徒に授業の準備を促し、学習目標についての生徒の考えを引き出すために作られた自由形式の質問で ある。 クラスゲームもまた、エネルギッシュな学習方法であると考えられている。なぜなら、大きな試験の前に教材を復習するだけでなく、トピックについて楽しく学 ぶことができるからである。ジェパディ!やクロスワードパズルのようなさまざまなゲームは、常に生徒の心を躍らせるようだ[31]。 教えて学ぶこともアクティブ・ラーニングの一例である。なぜなら、生徒が積極的にトピックをリサーチし、クラスで教えられるように情報を準備するからであ る。これは、生徒が自分自身のトピックをよりよく学ぶのに役立ち、時には生徒が教師よりも仲間と一緒に学んだり、コミュニケーションをとったりするのに適 している。 ギャラリーウォークとは、生徒がグループになって教室やワークショップを動き回り、積極的にディスカッションに参加し、他のグループに貢献することで、最 終的にトピックに関する知識を構築し、それを共有することである。 学習工場では、生産関連科目を現実的な学習環境で双方向的に学ぶことができる。 問題解決型学習または「PBL」は、学生にまず問題を提供する能動的な学習戦略であり、医学のような高度なテーマで効果的な戦略であることがわかっている [4]。 |

| Effective strategies in large

classes Transformational Active Learning Experience (TALE) could be challenging in large classes where students may exceed 200, typically found in universities. Examples of some challenges in large classes: Student's grades and academic performance might be decreased. The student's ability to think critically might be lower. The professor's feedback and instructions might be minimized. The students will become less active in the learning process.[33] Despite the challenges, obvious benefits can be seen; in a large class, many ideas could be generated with multiple opinions. The diverse population could expand and create strong connections and relationships between classmates.[33] 1- Using software for students' participation without revealing their identities could be a solution to students' discomfort with representing their thoughts in front of a large population. 2-What is called the "one minute paper" could be a useful strategy for students to respond. When the teacher asks a question related to a topic that has been taught, students will write their answers individually within 60 seconds. 3- "Think-pair-share" is a method that has been used to walk students through three ways of learning. First, every student will come up with an answer regarding a question presented by the instructor. Then, Each student will share the answer with another peer for analysis and deeper thinking. Lastly, the entire class will discuss their responses together.[33] |

大規模クラスにおける効果的な戦略[編集]。 トランスフォーメーショナル・アクティブ・ラーニング・エクスペリエンス(TALE)は、一般的に大学で見られるような、学生が200人を超えるような大 人数のクラスでは難しいかもしれない。 大規模クラスにおけるいくつかの課題の例 学生の成績や学業成績が低下する可能性がある。 学生の批判的思考能力が低下する可能性がある。 教授からのフィードバックや指示が最小限になるかもしれない。 学生は学習プロセスにおいてあまり積極的にならなくなる。 課題があるにもかかわらず、明らかな利点が見られる。大人数のクラスでは、複数の意見から多くのアイデアが生まれる可能性がある。多様な集団が拡大し、ク ラスメートの間に強いつながりや関係が生まれる可能性がある[33]。 1-生徒のアイデンティティを明らかにすることなく、生徒が参加するためのソフトウェアを使用することは、大勢の前で自分の考えを表現することに対する生 徒の不快感に対する解決策となりうる。 2-「1分間ペーパー」と呼ばれるものは、生徒が回答するのに有効な戦略である。教師が教えられたトピックに関連した質問をすると、生徒は60秒以内に個 々に答えを書く。 3-「Think-pair-share」は、3つの学習方法を生徒に歩ませるための方法である。まず、講師が提示した質問に対して、生徒全員が答えを考 える。次に、各生徒はその答えを他の生徒と共有し、分析し、より深く考える。最後に、クラス全員で自分の回答について議論する[33]。 |

| Elements of High-Impact Practices George D. Kuh identified High-Impact practices (HIPs) as " a Specific set of practices that tended to lead to meaningful experiences for students." Kuh and his coworkers identified several elements that were important and could be applied in a wide range of learning opportunities.[33] Breaking down the skills that need to be taught, one step at a time, is more beneficial than teaching a large amount of knowledge all at the same time. This concept was developed based on the Zone of Proximal Development theory by Lev Vygotsky (1978). In practice, students start a lesson with higher expectations and in a positive class environment. As a result, all students will picture their goals as achievable, leading them to trust their abilities and be encouraged to participate actively in their learning process. When lower-level students start to face some challenges, the teacher's role becomes crucial to provide new resources and techniques to increase students' performance. Reaching effective learning will be a common result of "spaced learning". This idea was first introduced by Hermann Ebbinghaus (1913) in his book: Memory: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology. He identified spaced learning as the process of learning new information over a long period in multiple ways using different activities. High-quality learning could be achievable when students have a positive relationship with their classmates and teachers. Students are more likely to get motivated and reach their goals when connecting with teachers and classmates who are supportive and helpful. Having diverse backgrounds in a class allows students to be exposed to different opinions and generate new ideas when connecting with peers from different identities.[33] |

ハイ・インパクト・プラクティスの要素 ジョージ・D・クーは、ハイ・インパクト・プラクティス(HIPs)とは、「生徒にとって有意義な体験につながる傾向のある具体的な一連の実践方法」であ ると特定した。クー氏と彼の同僚は、重要で幅広い学習機会に適用できるいくつかの要素を特定した[33]。 教える必要のあるスキルを一歩ずつ分解していくことは、大量の知識を一度に教えるよりも有益である。この概念は、レフ・ヴィゴツキー(1978年)の「最 低発達領域(Zone of Proximal Development)」理論に基づいて開発された。実際には、生徒はより高い期待を持って、前向きな授業環境の中でレッスンを始める。その結果、すべ ての生徒が自分の目標を達成可能なものとしてイメージし、自分の能力を信頼し、学習プロセスに積極的に参加するようになる。低レベルの生徒が何らかの課題 に直面し始めたとき、教師の役割は、生徒の成績を上げるための新しいリソースやテクニックを提供することが重要になる。 効果的な学習に到達することは、「スペーシング・ラーニング」の共通の成果である。この考え方は、ヘルマン・エビングハウス(1913年)の著書で初めて 紹介された: 記憶: A Contribution to Experimental Psychology)で初めて紹介された。エビングハウスは、スペーシング・ラーニングとは、長期間にわたって、さまざまな活動を使って新しい情報を複 数の方法で学習するプロセスであるとした。 質の高い学習は、生徒がクラスメートや教師と良好な関係を築くことで達成できる。生徒は、協力的で親切な教師やクラスメートとつながれば、やる気が出て目 標に到達しやすくなる。 クラス内に多様な背景を持つ生徒がいることで、生徒は異なる意見に触れ、異なるアイデンティティを持つ仲間とつながることで新しいアイデアを生み出すこと ができる[33]。 |

| Use of technology See also: Technology-enhanced active learning The use of multimedia and technology tools helps enhance the atmosphere of the classroom, thus enhancing the active learning experience. In this way, each student actively engages in the learning process. Teachers can use movies, videos, games, and other fun activities to enhance the effectiveness of the active learning process. The use of technology also stimulates the "real-world" idea of active learning as it mimics the use of technology outside of the classroom. Incorporating technology combined with active learning have been researched and found a relationship between the use and increased positive behavior, an increase in effective learning, "motivation" as well as a connecting between students and the outside world.[34] The theoretical foundations of this learning process are: Flow: Flow is a concept to enhance the focus level of the student as each and every individual becomes aware and completely involved in the learning atmosphere. In accordance with one's own capability and potential, through self-awareness, students perform the task at hand. The first methodology to measure flow was Csikszentmihalyi's Experience Sampling. Learning styles: Acquiring knowledge through one's own technique is called learning style. Learning occurs in accordance with potential as every child is different and has particular potential in various areas. It caters to all kinds of learners: visual, kinesthetic, cognitive and affective. [dubious – discuss] Locus of control: Ones with high internal locus of control believe that every situation or event is attributable to their resources and behavior. Ones with high external locus of control believe that nothing is under their control. Intrinsic motivation: Intrinsic motivation is a factor that deals with self-perception concerning the task at hand. Interest, attitude, and results depend on the self-perception of the given activity.[35] |

テクノロジーの活用 こちらも参照のこと: テクノロジーを活用したアクティブ・ラーニング マルチメディアやテクノロジー・ツールを活用することで、教室の雰囲気を高め、アクティブ・ラーニングの効果を高めることができる。こうすることで、生徒 一人一人が学習プロセスに積極的に参加するようになる。教師は、映画、ビデオ、ゲーム、その他の楽しいアクティビティを使って、アクティブ・ラーニングの 効果を高めることができる。テクノロジーの使用は、教室外でのテクノロジーの使用を模倣するため、アクティブ・ラーニングの「実世界」での考え方も刺激す る。 アクティブ・ラーニングにテクノロジーを取り入れることが研究され、積極的な行動の増加、効果的な学習の増加、「動機づけ」、さらに生徒と外 の世界とのつながりとの関係が発見されている[34]。この学習プロセスの理論的基礎は以下の通りである: フロー:フローとは、一人ひとりが学習の雰囲気を意識し、完全に関与することで、生徒の集中レベルを高める概念である。自己認識を通じて、自分の能力と可 能性に応じて、生徒は目の前の課題を遂行する。フローを測定する最初の方法論は、チクセントミハイによる経験サンプリングである。 学習スタイル 自分のテクニックによって知識を習得することを学習スタイルと呼ぶ。子どもは一人ひとり異なり、様々な分野で特別な可能性を持っているため、潜在能力に応 じて学習が行われる。視覚的、運動感覚的、認知的、感情的など、あらゆる学習者に対応している。[疑わしい - 議論する]。 コントロールの軌跡: 内的統制の所在が高い人は、すべての状況や出来事は自分の資源や行動に起因すると考える。外的支配の所在が高い人は、自分の支配下にあるものは何もないと 考える。 内発的動機づけ: 内発的動機づけは、目の前の課題に関する自己認識を扱う要因である。関心、態度、結果は、与えられた活動に対する自己認識によって決まる[35]。 |

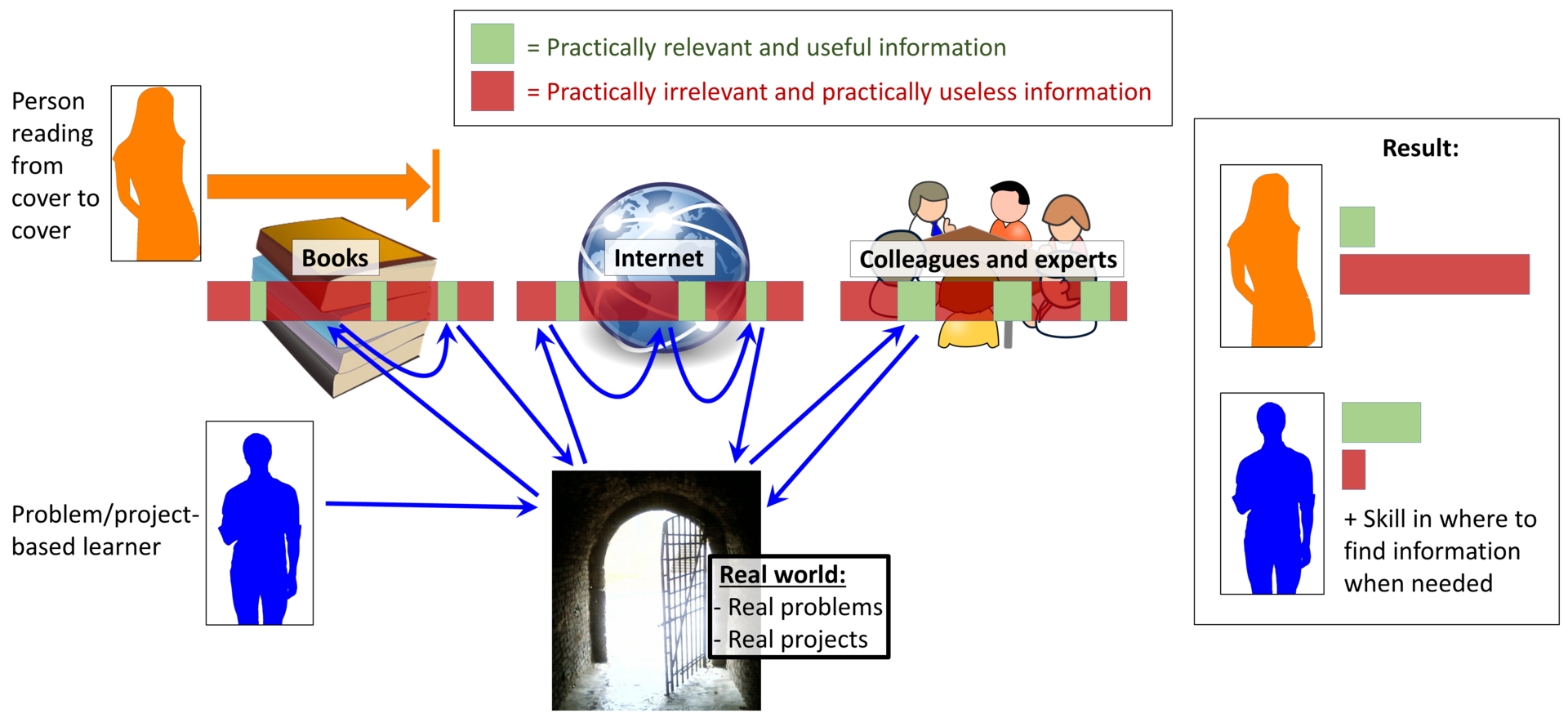

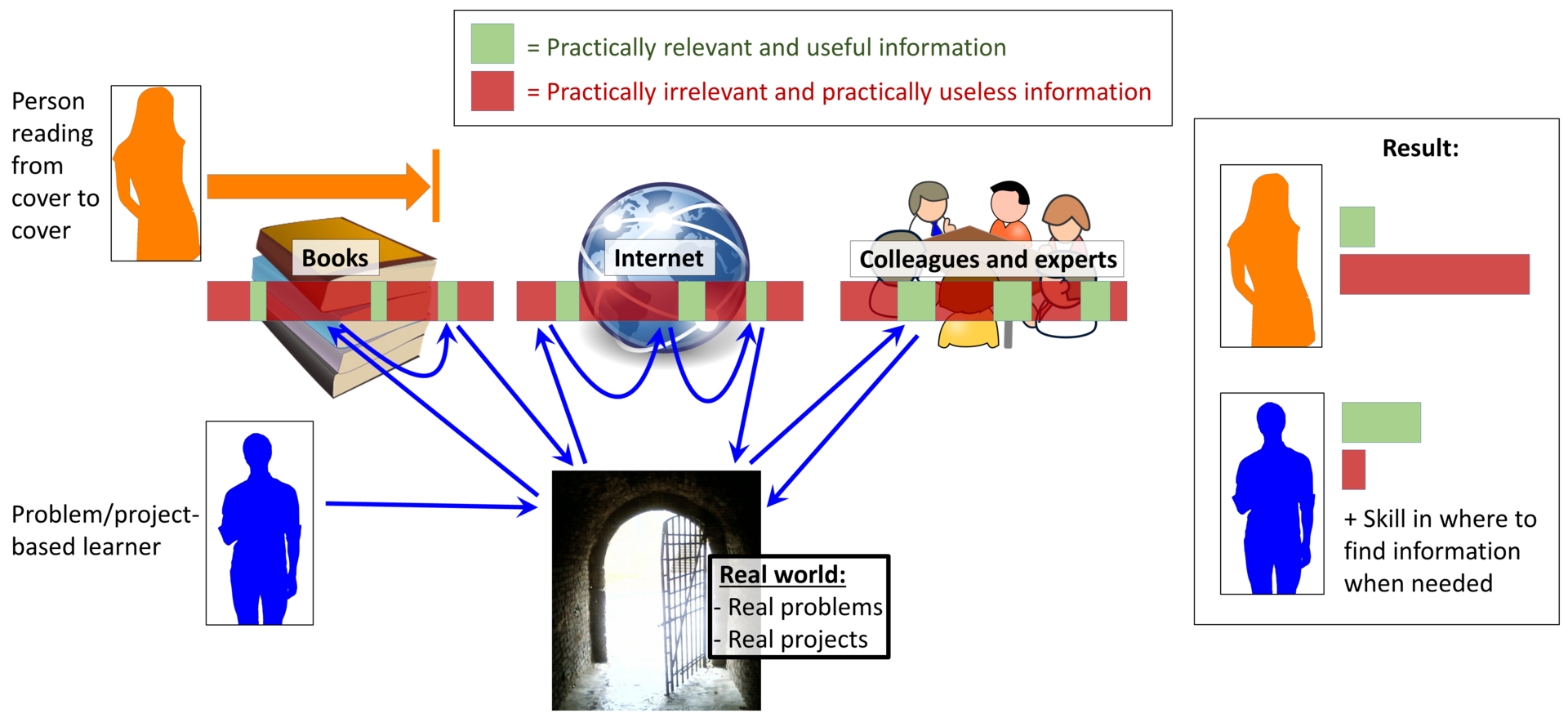

Research evidence Shimer College Home Economics cooking 1942 Numerous studies have shown evidence to support active learning, given adequate prior instruction. A meta-analysis of 225 studies comparing traditional lecture to active learning in university math, science, and engineering courses found that active learning reduces failure rates from 32% to 21%, and increases student performance on course assessments and concept inventories by 0.47 standard deviations. Because the findings were so robust with regard to study methodology, extent of controls, and subject matter, the National Academy of Sciences publication suggests that it might be unethical to continue to use traditional lecture approach as a control group in such studies. The largest positive effects were seen in class sizes under 50 students and among students under-represented in STEM fields.[17] Richard Hake (1998) reviewed data from over 6000 physics students in 62 introductory physics courses and found that students in classes that utilized active learning and interactive engagement techniques improved 25 percent points, achieving an average gain of 48% on a standard test of physics conceptual knowledge, the Force Concept Inventory, compared to a gain of 23% for students in traditional, lecture-based courses.[36] Similarly, Hoellwarth & Moelter (2011)[37] showed that when instructors switched their physics classes from traditional instruction to active learning, student learning improved 38 percent points, from around 12% to over 50%, as measured by the Force Concept Inventory, which has become the standard measure of student learning in physics courses.  Example of problem-/project-based learning versus reading cover to cover. The problem-/project-based learner may memorize a smaller amount of total information due to actively spending time searching for the optimal information across various sources, but will likely learn more useful items for real-world scenarios, and will likely be better at knowing where to find information when needed, including technology use.[38] In "Does Active Learning Work? A Review of the Research", Prince (2004) found that "there is broad but uneven support for the core elements of active, collaborative, cooperative and problem-based learning" in engineering education.[39] Michael (2006),[40] in reviewing the applicability of active learning to physiology education, found a "growing body of research within specific scientific teaching communities that supports and validates the new approaches to teaching that have been adopted". In a 2012 report titled "Engage to Excel",[41] the United States President's Council of Advisors on Science and Technology described how improved teaching methods, including engaging students in active learning, will increase student retention and improve performance in STEM courses. One study described in the report found that students in traditional lecture courses were twice as likely to leave engineering and three times as likely to drop out of college entirely compared with students taught using active learning techniques. In another cited study, students in a physics class that used active learning methods learned twice as much as those taught in a traditional class, as measured by test results. Active learning has been implemented in large lectures and it has been shown that both domestic and International students perceive a wide array of benefits. In a recent study, broad improvements were shown in student engagement and understanding of unit material among international students.[42] Active learning approaches have also been shown to reduce the contact between students and faculty by two thirds, while maintaining learning outcomes that were at least as good, and in one case, significantly better, compared to those achieved in traditional classrooms. Additionally, students' perceptions of their learning were improved and active learning classrooms were demonstrated to lead to a more efficient use of physical space.[43] A 2019 study by Deslauriers et al. claimed that students have a biased perception of active learning and they feel they learn better with traditional teaching methods than active learning activities. It can be corrected by early preparation and continuous persuasion that the students are benefiting from active instruction.[44] In a different study conducted by Wallace et al. (2021), they came to the conclusion that in a comparison between students being taught by an active-learning instructor vs. a traditional learning instructor, students who engaged in active-learning outperformed their counterparts in exam environments.[45] In this setting, the instructor focused on active-learning was a first-time instructor, and the individual who was teaching the traditional style of learning was a long-time instructor. The researchers acknowledged the limitations of this study in that individuals may have done better because of depth in specific sections of the class, so the researchers removed questions that could be favoring one section more than the other out of this analysis. |

研究証拠 シマーカレッジ家庭科料理 1942年 十分な事前指導があれば、アクティブ・ラーニングを支持する証拠が、数多くの研究で示されている。 大学の数学、科学、工学コースにおいて、従来の講義とアクティブ・ラーニングを比較した225の研究のメタ分析によると、アクティブ・ラーニングは、不合 格率を32%から21%に減少させ、コース評価とコンセプト・インベントリにおける学生の成績を0.47標準偏差増加させた。この研究結果は、研究方法、 対照の範囲、対象に関して非常に強固であったため、全米科学アカデミーの発表によると、このような研究で従来の講義方法を対照群として使い続けることは倫 理的に問題があるとのことである。最大の肯定的な効果は、50人以下のクラスの人数と、STEM分野で代表的でない学生の間で見られた[17]。 Richard Hake (1998)は、62の物理学入門コースの6000人以上の物理学学生のデータを検討し、能動的学習と対話的関与の技法を利用したクラスの学生は、従来の 講義ベースのコースの学生の23%の利益と比較して、物理学の概念知識の標準的なテストである力概念目録で平均48%の利益を達成し、25%のポイントを 向上させることを発見した[36]。 同様に、Hoellwarth & Moelter (2011)[37]は、指導者が物理学の授業を従来の指導からアクティブ・ラーニングに切り替えた場合、物理学の授業における学生の学習の標準的な指標 となっている力概念インベントリで測定すると、学生の学習が約12%から50%以上へと38%ポイント向上したことを示している。  問題にもとづく・プロジェクトにもとづく学習と隅から隅まで読むことの 比較例。問題/プロジェクトベースの学習者は、様々な情報源から最適な情報を探すことに積極的に時間を費やすため、記憶する情報総量は少なくなるかもしれ ないが、実世界のシナリオに役立つ項目をより多く学ぶことができ、テクノロジーの利用を含め、必要なときにどこで情報を見つけることができるかを知ること に長けている可能性が高い[38]。 アクティブ・ラーニングは有効か?A Review of the Research "において、Prince (2004)は、工学教育における「能動的学習、協調的学習、協同的学習、問題解決型学習の中核的要素に対する支持は広範であるが、ばらつきがある」こと を明らかにした[39]。 Michael(2006)[40]は、生理学教育へのアクティブ・ラーニングの適用可能性を検討する中で、「特定の科学教育コミュニティにおいて、採用 されている教育への新しいアプローチを支持し、検証する研究が増えている」ことを発見した。 米国大統領科学技術諮問委員会は、2012年に発表した「Engage to Excel」と題する報告書[41]の中で、学生をアクティブ・ラーニングに参加させることを含む教授法の改善が、STEMコースにおける学生の定着率を 高め、成績を向上させることを説明している。報告書に記載されたある研究によると、従来の講義コースの学生は、アクティブ・ラーニングの手法で教えられた 学生に比べ、工学部から退学する可能性が2倍、大学から完全に退学する可能性が3倍であった。また、別の研究では、アクティブ・ラーニングの手法を用いた 物理学の授業では、従来の授業で学んだ学生に比べて、テスト結果で測定すると2倍の学習量があった。 アクティブ・ラーニングは大規模な講義で実施されており、国内外の学生がさまざまな利点を感じていることが示されている。最近の研究では、留学生の間で、 学生の取り組みと単元教材の理解において幅広い改善が示された[42]。 また、アクティブ・ラーニングのアプローチは、従来の教室で達成されたものと比べて、少なくとも同程度、あるケースでは有意に優れた学習成果を維持しなが ら、学生と教員との接触を3分の2に減らすことが示されている。さらに、学生の学習に対する認識は改善され、アクティブ・ラーニング型教室は物理的なス ペースの効率的な利用につながることが実証された[43]。 Deslauriersらによる2019年の研究では、学生はアクティブ・ラーニングに対して偏った認識を持っており、アクティブ・ラーニング活動よりも 伝統的な教授法のほうがよく学べると感じていると主張している。それは、早期の準備と、学生が能動的な指導から利益を得ているという継続的な説得によって 修正することができる[44]。 Wallaceら(2021年)が実施した別の研究では、アクティブ・ラーニングの指導者と伝統的な学習の指導者に教わる学生を比較したところ、試験環境 ではアクティブ・ラーニングに取り組んだ学生の方が優れていたという結論に達した[45]。研究者たちは、この研究の限界として、クラスの特定のセクショ ンの深さによって個人の成績が良くなった可能性があることを認めており、そのため研究者たちは、あるセクションが他のセクションよりも有利になる可能性の ある問題をこの分析から除外した。 |

| Action teaching Design-based learning Experiential learning Inquisitive learning Learning environment Learning space Organizational learning Oswego Movement School organizational models Sloyd |

アクション・ティーチング デザイン・ベースド・ラーニング 体験学習 探究型学習 学習環境 学習空間 組織的学習 オスウェゴ・ムーブメント 学校組織モデル スロイド |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Active_learning |

■応用問題:機械はアクティブラーニング できるのか?

1959年、アーサー・サミュエルは、機械学習を「明示的にプログラムしなくても学習する能力をコンピュータに与える研究分野」だとした。

トム・M・ミッチェル(英語版)は、よく引用されるさらに厳格な定義として「コンピュータプログラムが、ある種のタスクTと評価尺度Pにおいて、経験Eか

ら学習するとは、タスクTにおけるその性能をPによって評価した際に、経験Eによってそれが改善されている場合である」とした(→「機械学習(machine learning)」)。

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099