さいきんせつはったつりょういき, Zone of Proximal Development

最近接発達領域(ZPD)

さいきんせつはったつりょういき, Zone of Proximal Development

解説:池田光穂

最近接発達領域(さいきんせつはったつ りょういき)とは、ロシアの心理学者レフ・ヴィゴツキー(L.S. Vygotsky, 1896-1934[写真])が提唱した、他者(=なかま)との関係において「ある ことができる(=わかる)」という行為の水準ないしは領域のことである。これは、学習過程では理解できる児童の「理解構造」がなんらかの形 でスピルオーバーして、他の児童に影響を与えている可能性があることを示唆する(またその検証が必要である→「『学習する社会を創造する』を読む」)。 あるいは、学習者の間に良好なコミュニケーションが確立している場合には、能力別クラス編成よりも、さまざまな学習能力者が混在している「非競争的なごた まぜ状況」のほうが、学習者の効率向上が見込まれるだけでなく、集団全体の学習習得の総成果(マクロ経済でいうところのGDPに相当)も増大する可能性が ある(→「パレート最適」状態)。

さて、ヴィゴツキーのZDPについて、より平易に解説し

てみよう。我々には、(a)他者の助けなしにわかる(=やれる)こと

と、(‾a)他者の助けがなくてはできないことがあることを知っている。学校教育の現

場では、学習者である児童や生徒は、他者——この場合は先生——による教育にのみ学習を完成することができるという固定観念に我々は長いあいだ縛られてき

た。

さて、ヴィゴツキーのZDPについて、より平易に解説し

てみよう。我々には、(a)他者の助けなしにわかる(=やれる)こと

と、(‾a)他者の助けがなくてはできないことがあることを知っている。学校教育の現

場では、学習者である児童や生徒は、他者——この場合は先生——による教育にのみ学習を完成することができるという固定観念に我々は長いあいだ縛られてき

た。

あることがわかる、できるようになる、こ とを我々は発達や成長と呼んでいるが、我々ははたして、他者の助けのあるなしで「できる(=わかる)」 ということを理解してよいものだろうか。

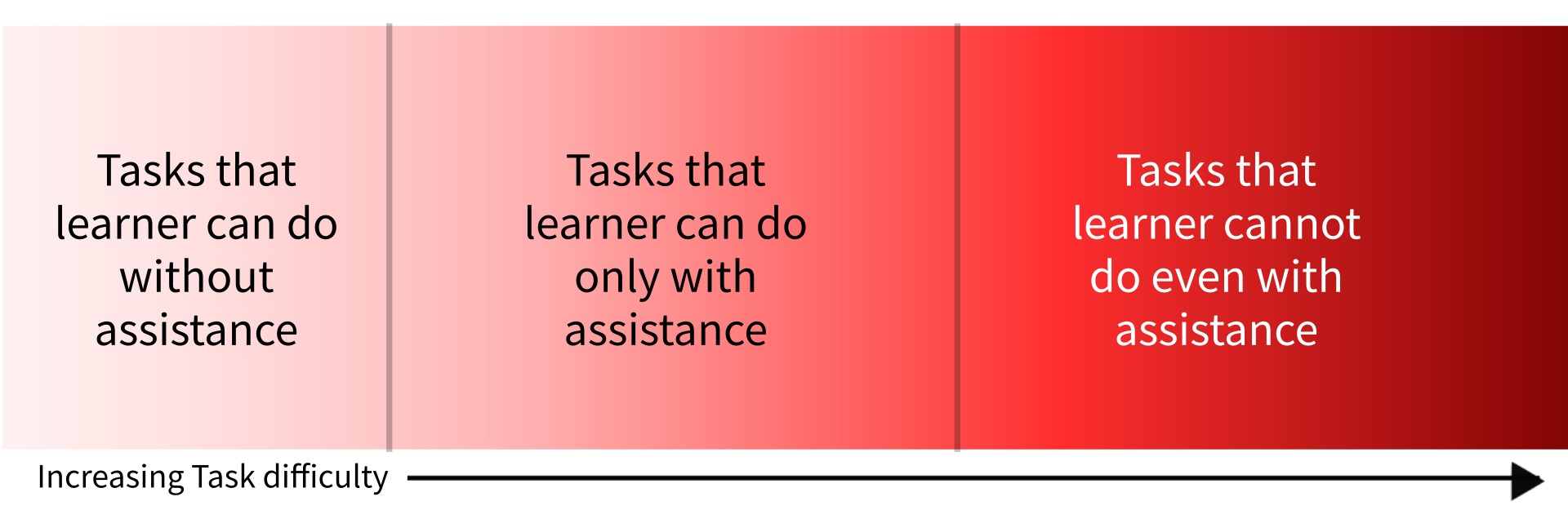

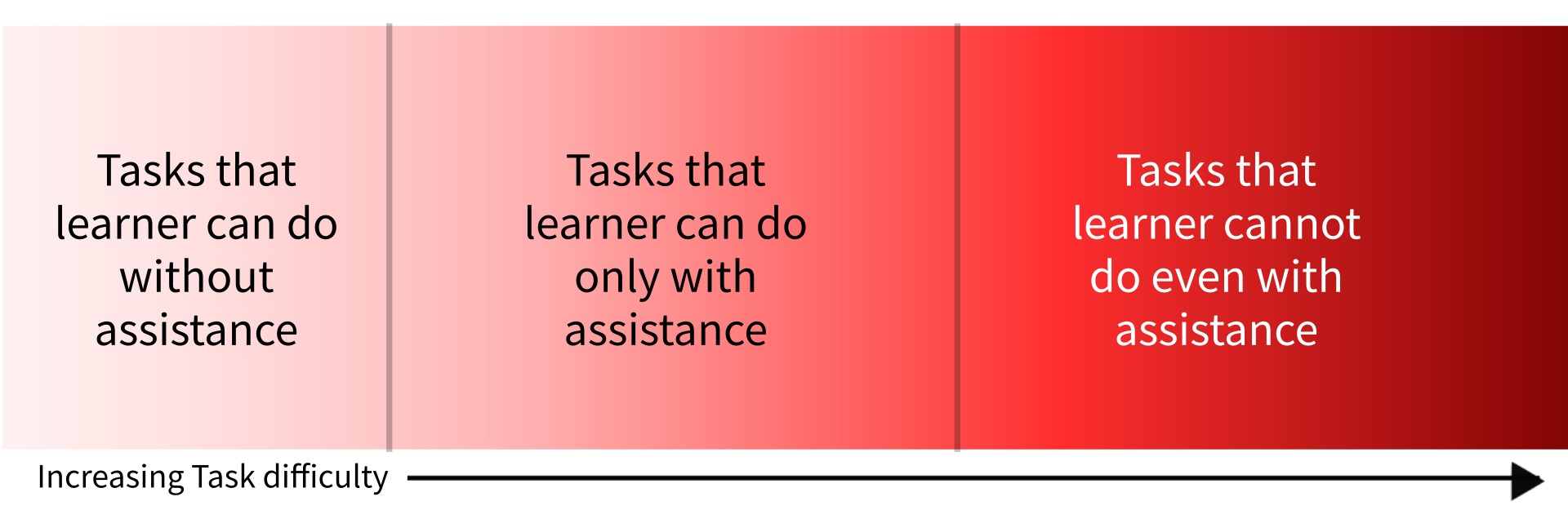

よく考えてみよう。(‾a)他者の助けが なければできないことのなかには、(b)みんな(=同じような学習者)と一緒であればできるようなこと がらがある。一般的に、みんなと一緒にできることのレパートリー(b)は、ひとりできること(a)よりも広範囲におよぶ。このみんなと一緒にできることの レパートリー(b)は、ひとりできること(a)の差分(b - a, bマイナスa)を最近接発達領域(Zone of Proximal Development)英語のアクロニムでZPDと呼ぶ。その概念図は下記を参照のこと。

ヴィゴツキーじしんのの言葉に耳を傾けて みよう。ヴィゴツキーは学習の現場における子どもたちどうしの模倣の能力に 着目する。その模倣の能力は、動物の模倣能力と は異なり、それ以上の創造力を陶冶する能力と関係すると指摘する。

「子どもにおける模倣の本質的な特色は、子どもが自分自身の可能性の限界をはるかにこえた——しかしそれは無限に大きいとは言えませんが ——、一連の行為を模散しうる点にあります。子どもは、集団行動における模倣によっ て、大人の指導のもとであるなら、理解をもって自主的にすることのでき ることよりもはるかに多くのことをすることができます。大人の指導や援助のもとで可能な問題解決の水準と、自主的活動において可能な問題解 決の水準との あいだのくいちがいが、子どもの発達の最近接領域を規定します」(ヴィゴツキー 2003:18)。

「上述の事例を思い起こしましょう。私たちのまえに知的年齢が同じ七歳の子どもが2人います。しかし、そのうちの1人は、ちょっとした援助 で、9歳の問題を解きますが、もう一人は7歳半の問題しか解きません。この二人の知的発達は同じでしょうか。かれらの自主的活動という点では同じです。し かし、発達の最近接可能性という点では、それは鋭く分かれます。大人の援助をえて子どもがすることのできるものは、私たちに彼の発達の最近接領域を示して くれます。これは、この方法によって、今日ではすでに完成した発達過程、すでに完結した発達サイクル、すでに通過した成熟過程だけでなく、現在生成しつつ ある過程、成熟しはじめたばかりの、発達しはじめたばかりの過程をも考慮することを意味します」(ヴィゴツキー 2003:18)。

※上述の例とは……:知的年齢が7歳の2 人の子どもを想定する。1人の子どものは、誘導的な質問・範例・教示の助けにより自分の発達水準を2年 も追い越すようなテストを解くことができる。他の子どもは、半年後のテストしか解くことができないことがある。

「子どもが今日、大人の助けを受けてできることを、明日には、彼は自主的にできるようになるでしょう。こうして、発達の最近接領域は子ども の明日を、発達においてすでに到達したものだけでなく成熟過程にいまあるものを考慮するような、子どもの発達のダイナミックな状態を規定することを助けて くれます。上述の2人の子どもは、すでに完結した発達サイクルの点では同一の知的年齢を示しています。しかし、かれらの発達のダイナミズムはまったく異 なっています。このようなわけで、子どもの知的発達の状態は、少なくとも二つの水準——現在の発達水準と発達の最近接領域——を明らかにすることによっ て、規定されうることになります」(ヴィゴツキー 2003:19)。

***

なお最近接発達領域という、直訳風のわか りにくい訳語のために「発達の最近接領域」と呼ぶ専門家もいる。

この図を先のヴィゴツキーの引用と照らし

合わせると、図中の「おしえてもらわなくても、みんなとならできる」が「自主的活動において可能な問題

解決の水準」をさし、図中の「ひとりでできる」とは上記引用中の「大人の指導や援助のもとで可能な問題解決の水準」を指します。それゆえ両者のあいだの

「く

いちがいが、子どもの発達の最近接領域を規定」するとなり、上記図の【ZPD】のことを表現しています。

※画像をクリックすると単独で拡大します。

(L.S. Vygotsky, 1896-1934[写真:アー カイブにリンクします])

■アレクセイ(子)・レオンチェフによ る、ヴィゴツキー著作集(ロシア語版)の引用をつかった「最近接発達領域」の解説

「私たちはテストやその他の手段によって、子どもの心理発達の水準を判定します。しかしそのさい、子どもが今、何をし、何ができるかを知る

だけではまったく不十分で、明日何をし、何ができ、たとえ今日達成されなくとも、すでに「熟しつつある」過程を知ることが重要なのです。「収穫予想をする

とき、果樹園ですでに熟している果実の量を推計するだけで、まだ熟した実をつけていない木の状態を評価しない園芸家と同じように、すでに熟した面の判定に

限定され、熟しつつある面を無視するような心理学者は、あらゆる発達の内的状態について正確で十分な理解を少しも得られないであろう……」(四巻、262

ページ)。/子どもがまったく独力で課題を解決すると、児童学者たちは、通常そのような場合だけを、自主的解決と見なします。しかし、解決のために誘導質

問や、解決手段の指示などを必要とする子どもがいるのです。模倣が生じるとしたら、それはもちろん「機械的で、自動的な、また無意味な模倣ではなく、理解

に基づいた何らかの知的操作の知性的な模倣遂行」です。模倣——これはまさに、「子どもは独力でやり遂げられなくとも、それを学ぶことができたり、それを

指導や協力の下でやり遂げたりできる……」(四巻、263ページ)ことを意味するのです。ですから「今日子どもが協力や指導の下でできることを、明日子ど

もは独力でやり遂げられるようになる。……我々は、子どもが独力で遂行できることを調べる時、子どもの昨日の発達を調べている。我々は、子どもが協力の下

で遂行できることを調べる時、明日の発達を判定している」(四巻、二六四ページ)のです。/ここで、最近接発達領域とはどういうことであるのか、はっきり

したことと思います。それは、今日子どもが協力の下で遂行できることは(!)明日になると独力で行なえるようになる! ということなのです」(レオンチェ

フ2003:164-165)[/は段落改行]。

● ZDPと人工知能(AI)

左は連合学習の模式図/右はZDPの解説:In the second circle, representing the zone of

proximal development, learners cannot complete tasks unaided, but can

complete them with guidance.

生成AIは、他個体との関連性を認知するのだろうか?また近接した個体と遠隔にある個体との区別を生成AIは身体を持たないために、それが果た

して可能になるのだろうか?

"Federated learning (also known as collaborative learning) is a machine learning technique that trains an algorithm across multiple decentralized edge devices or servers holding local data samples, without exchanging them. This approach stands in contrast to traditional centralized machine learning techniques where all the local datasets are uploaded to one server, as well as to more classical decentralized approaches which often assume that local data samples are identically distributed./ Federated learning enables multiple actors to build a common, robust machine learning model without sharing data, thus allowing to address critical issues such as data privacy, data security, data access rights and access to heterogeneous data. Its applications are spread over a number of industries including defense, telecommunications, IoT, and pharmaceutics."-Federated learning.

「フェデレーテッドラーニング(協調学習/連合学習ともよばれる)は、ローカルデータサンプルを保持する複数の分散型エッジデバイスやサーバー 間で、データを交換することなくアルゴリズムを訓練する機械学習技術である。この手法は、全てのローカルデータセットを単一のサーバーにアップロードする 従来の中央集権型機械学習技術や、ローカルデータサンプルが同一分布であると仮定する古典的な分散型アプローチとは対照的である。フェデレーテッドラーニ ングは、データを共有することなく複数の主体が共通の堅牢な機械学習モデルを構築することを可能にし、データプライバシー、データセキュリティ、データア クセス権、異種データのアクセスといった重要な課題に対処できる。その応用範囲は防衛、通信、IoT、製薬など、様々な産業に広がっている。」 ——フェ デレーテッドラーニング(協調学習/連合学習)

■雑多な情報

・「自然はもろもろの類似をつくりだす。 動物の擬態(ミミクリイ)のことを考えてみるだけで十分だ。しかし、類似を生みだす最高の能力をもって いるのは人間である」——ヴァルター・ベンヤミン「模倣の能力について」(佐藤康彦訳)

★「桶の中の脳」の思考実験

★英語ウィキペディアの情報

| The zone of proximal development

(ZPD) is a concept in educational psychology that represents the space

between what a learner is capable of doing unsupported and what the

learner cannot do even with support. It is the range where the learner

is able to perform, but only with support from a teacher or a peer with

more knowledge or expertise. This person is known as the "more

knowledgable other."[1] The concept was introduced, but not fully

developed, by psychologist Lev Vygotsky (1896–1934) during the last

three years of his life.[2] Vygotsky argued that a child gets involved

in a dialogue with the "more knowledgeable other" and gradually,

through social interaction and sense-making, develops the ability to

solve problems independently and do certain tasks without help.

Following Vygotsky, some educators believe that the role of education

is to give children experiences that are within their zones of proximal

development, thereby encouraging and advancing their individual

learning skills and strategies.[3] |

最接近発達領域(ZPD)とは、教育心理学における概念であり、学習者

が支援なしに実行可能なことと、支援があっても実行できないことの間の空間を表す。これは学習者が実行できる範囲であるが、より知識や専門性を持つ教師や

仲間からの支援があって初めて可能となる領域である。この支援者は「より知識のある他者」と呼ばれる人格である。[1]

この概念は心理学者レフ・ヴィゴツキー(1896–1934)によって、彼の生涯の最後の3年間に導入されたが、完全に発展させることはできなかった。

[2]

ヴィゴツキーは、子供が「より知識のある他者」との対話に参加し、社会的相互作用と意味づけを通じて、次第に問題を独自に解決し、助けなしに特定の課題を

遂行する能力を発達させると主張した。ヴィゴツキーに続く教育者の中には、教育の役割は子どもの最接近発達領域内の経験を提供し、それによって個々の学習

スキルや戦略を促進・発展させることだと考える者もいる。[3] |

| The concept of the zone of

proximal development was originally developed by Vygotsky to argue

against the use of academic, knowledge-based tests as a means to gauge

students' intelligence. He also created ZPD to further develop Jean

Piaget's theory of children being lone and autonomous learners.[4]

Vygotsky spent a lot of time studying the impact of school instruction

on children and noted that children grasp language concepts quite

naturally, but that math and writing did not come as naturally.

Essentially, he concluded that because these concepts were taught in

school settings with unnecessary assessments, they were more difficult

for learners. Piaget believed that there was a clear distinction

between development and teaching. He said that development is a

spontaneous process that is initiated and completed by the children,

stemming from their own efforts. Piaget was a proponent of independent

thinking and critical of the standard teacher-led instruction that was

common practice in schools.[5] Alternatively, Vygotsky saw natural, spontaneous development as important, but not all-important. He believed that children would not advance very far if they were left to discover everything on their own. It is crucial for a child's development that they are able to interact with more knowledgeable others: they are not able to expand on what they know if this is not possible. The term more knowledgeable others (MKO) is used to describe someone who has a better understanding or higher ability level than the learner, in reference to the specific task, idea, or concept.[6] He noted cultural experiences where children are greatly helped by knowledge and tools handed down from previous generations. Vygotsky noted that good teachers should not present material that is too difficult and "pull the students along."[5] Vygotsky argued that, rather than examining what a student knows to determine intelligence, it is better to examine their ability to solve problems independently and ability to solve problems with an adult's help.[7] He proposed a question: "if two children perform the same on a test, are their levels of development the same?" He concluded that they were not.[8] However, Vygotsky's untimely death interrupted his work on the zone of proximal development, and it remained mostly incomplete.[9] |

最接近発達領域の概念は、もともとヴィゴツキーが学問的・知識ベースの

テストを生徒の知能を測る手段として用いることに反対するために提唱したものである。彼はまた、ジャン・ピアジェの「子どもは孤独で自律的な学習者であ

る」という理論をさらに発展させるためにZPDを創出した。[4]

ヴィゴツキーは学校教育が子どもに与える影響を長期間研究し、言語概念は自然に習得されるが、数学や文章作成はそうではないと指摘した。本質的に、これら

の概念が不必要な評価を伴う学校環境で教えられるため、学習者にとってより困難になると結論づけたのである。ピアジェは発達と教育には明確な区別があると

考えた。発達とは子ども自身の努力から生じ、子どもによって開始され完結する自発的プロセスだと述べた。ピアジェは独立思考を支持し、学校で一般的だった

教師主導の標準的な指導法を批判した。[5] 一方ヴィゴツキーは、自然で自発的な発達を重要視したが、それが全てではないと考えた。彼は、子どもが全てを独力で発見するままにしておけば、あまり進歩 しないと考えた。子どもの発達には、より知識のある他者との相互作用が不可欠である。それが不可能であれば、子どもは自分の知識を広げられない。ここでい う「より知識のある他者(MKO)」とは、特定の課題・概念・アイデアに関して、学習者よりも優れた理解力や能力レベルを持つ者を指す。[6] 彼は、前世代から受け継がれた知識や道具によって子どもが大きく助けられる文化的経験に言及した。優れた教師は難しすぎる教材を提示せず、「生徒を引っ 張っていく」べきだとヴィゴツキーは指摘した。[5] ヴィゴツキーは、知能を判断するために生徒の知識を調べるよりも、問題を独自に解決する能力と大人の助けを借りて問題を解決する能力を調べる方が良いと主 張した。[7] 彼は疑問を投げかけた。「二人の子供がテストで同じ成績を取った場合、その発達レベルは同じなのか?」彼はそうではないと結論づけた。[8] しかし、ヴィゴツキーの早すぎる死が近接発達領域に関する研究を中断させ、その研究はほぼ未完成のままとなった。[9] |

Definition When they have guidance and support, learners can accomplish a task that cannot be done by themselves. However, learners can fail even if support is given when the task is totally cognitively impossible.[10]: 216 Since Vygotsky's original conception, the definition for the zone of proximal development has been expanded and modified. The zone of proximal development is an area of learning that occurs when a person is assisted by a teacher or peer with a higher skill set.[1] The person learning the skill set cannot complete it without the assistance of the teacher or peer. The teacher then helps the student attain the skill the student is trying to master, until the teacher is no longer needed for that task.[11] Any function within the zone of proximal development matures within a particular internal context that includes not only the function's actual level but also how susceptible the child is to types of help, the sequence in which these types of help are offered, the flexibility or rigidity of previously formed stereotypes, how willing the child is to collaborate, along with other factors.[12] This context can impact the diagnosis of a function's potential level of development.[9] Vygotsky stated that one cannot just look at what students are capable of doing on their own; one must look at what they are capable of doing in a social setting. In many cases students are able to complete a task within a group before they are able to complete it on their own. He notes that the teacher's job is to move the child's mind forward step-by-step (teachers cannot teach complex chemical equations to six-year-olds, for example). At the same time, teachers cannot teach all children equally; they must determine which students are ready for which lessons.[5] An example is the often-used accelerated reading program in schools. Students are assessed and given a reading level and a range. Books rated below their level are easy to read, while books above their level challenge the student. Sometimes students are not even allowed to check out books from the school library that are outside their range. Vygotsky argued that a major shortcoming of standardized tests is that they only measure what students are capable of on their own, not in a group setting where their minds are being pushed by other students.[5] In the context of second language learning, the ZPD can be useful to many adult users. Prompted by this fact as well as the finding that adult peers do not necessarily need to be more capable to provide assistance in the ZPD, Vygotsky's definition has been adapted to better suit the adult L2 developmental context.[13] |

定義 学習者は指導と支援があれば、単独では達成できない課題を成し遂げられる。しかし、課題が認知的に完全に不可能な場合、支援があっても学習者は失敗する。[10]: 216 ヴィゴツキーの当初の概念以来、最接近発達領域の定義は拡張され修正されてきた。最接近発達領域とは、より高い技能を持つ教師や仲間から支援を受けた際に 生じる学習領域である。[1] 技能を習得中の人格は、教師や仲間の支援なしではそれを完了できない。教師はその後、生徒がその技能を習得できるよう支援を続け、最終的にその課題に教師 が不要となる段階まで導く。[11] 最接近発達領域内のあらゆる機能は、特定の内的文脈の中で成熟する。この文脈には、機能の実際のレベルだけでなく、子供がどのような支援に反応しやすい か、支援が提供される順序、既に形成された固定観念の柔軟性や硬直性、子供の協力意欲、その他の要因も含まれる。[12] この文脈は、機能の発達可能性レベルの診断に影響を与える。[9] ヴィゴツキーは、生徒が単独で何ができるかだけを見るのではなく、社会的状況の中で何ができるかを見る必要があると述べた。多くの場合、生徒は単独で課題 を完了できる前に、集団の中で課題を完了することができる。彼は、教師の役割は子どもの思考を段階的に前進させることだと指摘している(例えば教師は6歳 児に複雑な化学式を教えることはできない)。同時に教師は全児童を均等に教えることはできず、どの生徒がどの授業の準備ができているかを判断しなければな らない。[5] 例として学校でよく使われる加速読書プログラムがある。生徒は評価され、読書レベルと範囲が割り当てられる。レベル以下の本は容易に読めるが、レベル以上 の本は生徒に挑戦を与える。場合によっては、自分の範囲外の書籍を学校図書館から借りることすら許可されない。ヴィゴツキーは、標準化テストの大きな欠点 は、生徒が単独で可能なことだけを測定し、他の生徒に刺激される集団環境での能力を測らない点だと主張した。[5] 第二言語習得の文脈では、ZPDは多くの成人学習者に有用である。この事実と、成人学習者が必ずしもZPD領域で支援を提供するために高い能力を必要とし ないという知見に基づき、ヴィゴツキーの定義は成人第二言語習得の発達的文脈により適合するよう適応されてきた。[13] |

| Scaffolding See also: Instructional scaffolding The concept of the ZPD is widely used to study children's mental development as it relates to educational context. The ZPD concept is seen as a scaffolding, a structure of "support points" for performing an action.[14] This refers to the help or guidance received from an adult or more competent peer to permit the child to work within the ZPD.[15] Although Vygotsky himself never mentioned the term, scaffolding was first developed by Jerome Bruner, David Wood, and Gail Ross, while applying Vygotsky's concept of ZPD to various educational contexts.[4] According to Wass and Golding, giving students the hardest tasks they can do with scaffolding leads to the greatest learning gains.[16] Scaffolding is a process through which a teacher or a more competent peer helps a student in their ZPD as necessary and tapers off this aid as it becomes unnecessary—much as workers remove a scaffold from a building after they complete construction. "Scaffolding [is] the way the adult guides the child's learning via focused questions and positive interactions."[17] This concept has been further developed by Mercedes Chaves Jaime, Ann Brown, among others. Several instructional programs were developed based on this interpretation of the ZPD, including reciprocal teaching and dynamic assessment. For scaffolding to be effective, one must start at the child's level of knowledge and build from there.[15] One example of children using ZPD is when they are learning to speak. As their speech develops, it influences the way the child thinks, which in turn influences the child's manner of speaking.[8] This process opens more doors for the child to expand their vocabulary. As they learn to convey their thoughts in a more effective way, they receive more sophisticated feedback, therefore increasing their vocabulary and their speaking skills. Wells gives the example of dancing: when a person is learning how to dance, they look to others around them on the dance floor and imitate their moves. A person does not copy the dance moves exactly, but takes what they can and adds their own personality to it.[18] In mathematics, proximal development uses mathematical exercises for which students have seen one or more worked examples. In secondary school some scaffolding is provided, and generally much less at the tertiary level. Ultimately students must find library resources or a tutor when presented with challenges beyond the zone. Another example of scaffolding is learning to drive. Parents and driving instructors guide driving students along the way by showing them the mechanics of how the car operates, the correct hand positions on the steering wheel, the technique of scanning the roadway, etc. As the student progresses, less and less instruction is needed, until they are ready to drive on their own. The concept of scaffolding can be observed in various life situations and arguably in the basis of how everyone learns. One does not (normally) begin knowing everything that there is to know about a subject. The basics must be learned first so one can build on prior knowledge towards mastery of a particular subject or skill. |

足場 関連項目: 教育的足場 ZPDの概念は、教育環境に関連する子どもの精神的発達を研究する際に広く用いられる。ZPDの概念は足場、すなわち行動を実行するための「支点」の構造 と見なされる。[14] これは、子どもがZPD内で活動できるように、大人やより有能な仲間から受ける援助や指導を指す。[15] ヴィゴツキー自身がこの用語を明言したことはないが、スキャフォールディングはジェローム・ブルーナー、デイヴィッド・ウッド、ゲイル・ロスによって初め て提唱された。彼らはヴィゴツキーのZPD概念を様々な教育的文脈に応用する中でこの概念を発展させた。[4] ワスとゴールディングによれば、スキャフォールディングを用いて生徒に可能な限り難しい課題を与えることが、最大の学習効果をもたらすという。[16] スキャフォールディングとは、教師やより能力の高い仲間が、必要に応じて生徒のZPD内で支援を行い、その支援が不要になるにつれて徐々に手を引くプロセ スである。これは、建設作業員が建物の建設を終えた後に足場を取り外すのとよく似ている。「スキャフォールディングとは、大人が焦点を絞った質問と積極的 な相互作用を通じて子供の学習を導く方法である」[17]。この概念はメルセデス・チャベス・ハイメやアン・ブラウンらによってさらに発展した。相互教授 法や動的評価など、このZPD解釈に基づく複数の指導プログラムが開発されている。スキャフォールディングを効果的にするには、子供の知識レベルから始 め、そこから構築していく必要がある。[15] ZPDが子供に現れる一例は、言語習得過程にある。発話が発達するにつれ、それは子供の思考様式に影響を与え、それがまた子供の話し方に影響を及ぼす。 [8] このプロセスは子供の語彙拡大の機会を増やす。より効果的に思考を伝達する方法を学ぶにつれ、より洗練されたフィードバックを得られるため、語彙力と話し 方が向上するのだ。ウェルズはダンスを例に挙げている。ダンスを学ぶ時、人は周囲の踊り手を見て動きを模倣する。正確に真似るのではなく、理解できる部分 を取り入れ、自身の個人的な個性を加えるのである。[18] 数学において、最接近発達領域は、生徒が一つ以上の解法例を見たことのある数学的演習を用いる。中等教育ではある程度の足場が提供されるが、高等教育では 一般的にその量は大幅に減少する。最終的には、ゾーンを超えた課題に直面した学生は、図書館資料やチューターを探す必要がある。 足場の別の例は運転の習得である。親や教習所の指導員は、車の仕組み、ハンドル操作の正しい手の位置、道路の視認方法などの技術を教えながら、運転を学ぶ者を導く。生徒が上達するにつれ、指導は次第に減り、最終的に一人で運転できる状態になる。 足場かけの概念は様々な生活場面で観察でき、おそらく誰もが学ぶ基礎にあると言える。人は(通常)ある主題について知るべきことを全て最初から知っているわけではない。まず基礎を学び、その上で既知の知識を積み上げて特定の主題や技能を習得していくのだ。 |

| Implications for educators More knowledgeable others, like teachers, parents, and peers helped the learner to understand things that they cannot acquire on their own.[19]: 80 Various investigations, using different approaches and research frameworks have proved collaborative learning to be effective in many kinds of settings and contexts.[20] Teachers should assign tasks that students cannot do on their own, but which they can do with assistance; they should provide just enough assistance so that students learn to complete the tasks independently and then provide an environment that enables students to do harder tasks than would otherwise be possible.[16] Teachers can also allow students with more knowledge to assist students who need more assistance. Especially in the context of collaborative learning, group members who have higher levels of understanding can help the less advanced members learn within their zone of proximal development.[21] In the context of adults, peers should challenge each other in order to support collaboration and success.[22] Utilizing student's ZPD can assist especially with early childhood learning by guiding each child through challenges and using their student collaboration as a tool for success. Meyer used the concepts of Cognitive Evolutionary Pressure and Cognitive Empathetic Resonance to provide a theoretical underpinning for how and why the zone of proximal development arises, and this also has implications for how scaffolding can best be used.[23] |

教育者への示唆 教師、保護者、仲間といった知識豊富な他者が、学習者が自力では得られない理解を助ける。[19]: 80 様々な調査が、異なるアプローチや研究枠組みを用いて、協働学習が多くの環境や文脈で効果的であることを証明している。[20] 教師は、生徒が単独では達成できないが、支援があれば達成可能な課題を割り当てるべきだ。生徒が課題を自立して完了できるようになるまで、必要最小限の支 援を提供し、その後、単独では不可能だったより困難な課題に取り組める環境を整えるべきである。[16] 教師は知識の豊富な生徒に、支援を必要とする生徒を助ける役割も担わせられる。特に協働学習の文脈では、理解度の高いグループメンバーが、理解度の低いメ ンバーが最接近発達領域内で学べるよう支援できる。[21] 大人の文脈では、協働と成功を支えるため、仲間同士が互いに挑戦し合うべきだ。[22] 児童の発達段階に応じた支援(ZPD)を活用することは、特に幼児教育において効果的である。各児童が課題に取り組む過程を導き、児童同士の協働を成功の 手段として活用するのだ。マイヤーは「認知的進化圧力」と「認知的共感共鳴」の概念を用いて、発達段階に応じた支援領域がなぜ・どのように生じるかの理論 的基盤を示した。これは足場かけを最適化する方法にも示唆を与える。[23] |

| Challenges Scaffolding in education does have some boundaries. One of the largest hurdles to overcome when providing ample support for student learning is managing multiple students. While scaffolding is meant to be a relatively independent process for students, the initial phase of providing individual guidance can easily be overseen when managing large classrooms. Thus, time becomes a critical factor in a scaffolding lesson plan. In order to accommodate more learners, teachers are often faced with cutting parts of lessons or dedicating less time to each student.[24] In turn, this hastened class time might result in loss of interest in students or even invalid peer-teaching. Cognitive abilities of the student also play a significant role in the success of scaffolding. Ideally, students are able to learn within this zone of proximal development, but this is often not the case. Recognizing students' individual abilities and foundation knowledge can be a challenge of successful scaffolding. If students are evidently less prepared for this learning approach and begin to compare themselves to their peers, their self-efficacy and motivation to learn can be hindered.[25] These hurdles of scaffolding and the zone of proximal development are important to acknowledge so that teachers can find solutions to the problems or alter their teaching methods. |

課題 教育におけるスケーフォールディングには限界がある。生徒の学習を十分に支援する上で最大の障壁の一つは、複数の生徒を管理することだ。スケーフォール ディングは生徒にとって比較的自立したプロセスであるべきだが、大規模な教室では個別の指導を行う初期段階が見落とされやすい。したがって、時間こそがス ケーフォールディングの授業計画における重要な要素となる。より多くの学習者に対応するため、教師は授業の一部を削ったり、各生徒に割く時間を減らしたり せざるを得ないことが多い。[24] その結果、急がせた授業時間は生徒の興味減退や、同輩指導の無効化さえ招きかねない。生徒の認知能力もスキャフォールディングの成否に大きく影響する。理 想的には生徒が最接近発達領域内で学べればよいが、現実はそうではない場合が多い。生徒の個々の能力や基礎知識を把握することは、効果的な足場かけの課題 となる。もし生徒がこの学習法に明らかに準備不足で、仲間と自分を比較し始めた場合、学習への自己効力感や意欲が阻害される可能性がある[25]。足場か けと最接近発達領域のこうした障壁を認識することは重要であり、教師が問題解決策を見出したり指導方法を変更したりするための基盤となる。 |

| Constructivism (learning theory) Cultural-historical activity theory (CHAT) Curse of knowledge Educational psychology Four stages of competence Shuhari Social constructivism (learning theory) Sociocultural theory |

構成主義(学習理論) 文化歴史活動理論(CHAT) 知識の呪い 教育心理学 習熟の四段階 修・破・離 社会構成主義(学習理論) 社会文化理論 |

| Sources Library resources about Zone of proximal development Resources in your library Resources in other libraries Media related to Zone of proximal development at Wikimedia Commons Chaiklin, S. (2003). "The Zone of Proximal Development in Vygotsky's analysis of learning and instruction." In Kozulin, A., Gindis, B., Ageyev, V. & Miller, S. (Eds.) Vygotsky's educational theory and practice in cultural context. 39–64. Cambridge: Cambridge University. Mayer, R. E. (2008). Learning and instruction. (2nd ed., pp. 462–463). Upper Saddle River, NJ: Pearson Education. |

出典 図書館資料について 最接近発達領域 当館の資料 他館の資料 ウィキメディア・コモンズにおける最接近発達領域に関連するメディア Chaiklin, S. (2003). 「ヴィゴツキーの学習と指導分析における最接近発達領域」. Kozulin, A., Gindis, B., Ageyev, V. & Miller, S. (編) 『文化的文脈におけるヴィゴツキーの教育理論と実践』. 39–64. ケンブリッジ: ケンブリッジ大学出版局. Ageyev, V. & Miller, S. (編) 『文化的文脈におけるヴィゴツキーの教育理論と実践』39–64頁。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。 Mayer, R. E. (2008). 『学習と指導』(第2版、462–463頁)。アッパーサドルリバー、NJ:ピアソン・エデュケーション。 |

| References 1. Zone of proximal development. (2009). In Penguin dictionary of psychology. Retrieved from Credo Reference database 2. Yasnitsky, A. (2018). Vygotsky: An Intellectual Biography. London and New York: Routledge BOOK PREVIEW 3. Berk, L & Winsler, A. (1995). Vygotsky also felt that social interaction was very important when it came to learning. "Vygotsky: His life and works" and "Vygotsky's approach to development". In Scaffolding children's learning: Vygotsky and early childhood learning. Natl. Assoc for Educ. Of Young Children. p. 24 4. Zone of Proximal Development and Cultural Tools Scaffolding, Guided Participation, 2006. In Key concepts in developmental psychology. Retrieved from Credo Reference Database 5. Crain, W. (2010). Theories of development: Concepts and applications, 6th ed. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall. 6. "Vygotsky's Sociocultural Theory of Cognitive Development". March 18, 2025. 7. Berk, L & Winsler, A. (1995). "Vygotsky: His life and works" and "Vygotsky's approach to development". In Scaffolding children's learning: Vygotsky and early childhood learning. Natl. Assoc for Educ. of Young Children. pp. 25–34 8. Stages of development. (2010). In Curriculum connections psychology: Cognitive development. Retrieved from Credo Reference Database 9. Zaretskii, V. K. (November–December 2009). "The Zone of Proximal Development What Vygotsky Did Not Have Time to Write". Journal of Russian and East European Psychology. 47 (6): 70–93. doi:10.2753/RPO1061-0405470604. ISSN 1061-0405. S2CID 146894219. 10. Ormrod, Jeanne Ellis; Jones, Brett D. (2018). Essentials of Educational Psychology: Big Ideas to Guide Effective Teaching (Fifth ed.). NY, NY: Pearson. ISBN 9780134894980. OCLC 959080826. 11. Burkitt, E. (2006). Zone of proximal development. In Encyclopaedic dictionary of psychology. Retrieved from Credo Reference database 12. Bozhovich, E. D. (2009). Zone of Proximal Development: The Diagnostic Capabilities and Limitations of Indirect Collaboration. Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 47(6), 48–69. Retrieved from EBSCOHost Database 13. Fani, Tayebeh & Ghaemi, Farid. (2011). Implications of Vygotsky's Zone of Proximal Development (ZPD) in Teacher Education: ZPTD and Self-scaffolding. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 29. 1549–1554. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.396. 14. Obukhova, L. F., & Korepanova, I. A. (2009). The Zone of Proximal Development: A Spatiotemporal Model. Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 47(6), 25–47. doi:10.2753/RPO1061-0405470602 15. Morgan, A. (2009, July 28). What is "Scaffolding" and the "ZPD"? Retrieved October 13, 2014. 16. Wass, R., & Golding, C. (2014). Sharpening a tool for teaching: the zone of proximal development. Teaching in Higher Education, 19(6), 671-684. 17. Balaban, Nancy. (1995). "Seeing the Child, Knowing the Person." In Ayers, W. To Become a Teacher. Teachers College Press. p. 52 18. Wells, G. (1999). Dialogic Inquiries in education: Building on the legacy of Vygotsky. Cambridge University Press. p. 57 19. Eggen, Paul D.; Kauchak, Donald P. (2016). Educational Psychology: Windows on Classrooms (Tenth ed.). Boston: Pearson. ISBN 9780133549485. OCLC 889941365. 20. Grossman, P., Wineburg, S., & Woolworth, S. (2001). Toward a theory of teacher community. Teachers College Record, 103(6), 942–1012. 21. McLeod, S. A. (2012). Zone of proximal development. Retrieved from www.simplypsychology.org/Zone-of-Proximal-Development.html 22. Kuusisaari, H. (2014). Teachers at the zone of proximal development: Collaboration promoting or hindering the development process. Teaching and Teacher Education, 43, 46–57. 23. Meyer, Derek (2022-04-11). "Towards a theory of knowledge acquisition – re-examining the role of language and the origins and evolution of cognition". Educational Philosophy and Theory: 1–11. doi:10.1080/00131857.2022.2061350. ISSN 0013-1857. S2CID 248110575. 24. Peters, Gabriel. "Advantages & Disadvantages of Scaffolding in the Classroom". Retrieved 2019-11-13. 25. "Benefits and Challenges of Scaffolding". Scaffolding Literacy. |

参考文献 1. 近接発達領域. (2009). 『ペンギン心理学辞典』所収. Credo Referenceデータベースより取得 2. Yasnitsky, A. (2018). 『ヴィゴツキー:知的伝記』. ロンドン・ニューヨーク: Routledge BOOK PREVIEW 3. Berk, L & Winsler, A. (1995). ヴィゴツキーはまた、学習においては社会的相互作用が非常に重要であると考えていた。「ヴィゴツキー:その生涯と業績」および「ヴィゴツキーの発達へのア プローチ」。『子どもの学習を支える:ヴィゴツキーと幼児期学習』より。全米幼児教育協会。p. 24 4. 近接発達領域と文化的道具 足場かけ、指導的参加、2006年。『発達心理学の重要概念』所収。クレド・リファレンス・データベースより取得 5. Crain, W. (2010). 発達理論:概念と応用 第6版. ニュージャージー州アッパーサドルリバー:プレンティスホール. 6. 「ヴィゴツキーの認知発達に関する社会文化的理論」. 2025年3月18日. 7. バーク, L & ウィンスラー, A. (1995). 「ヴィゴツキー:その生涯と著作」及び「ヴィゴツキーの発達へのアプローチ」. 『子どもの学習を支える:ヴィゴツキーと幼児期学習』所収。全米幼児教育協会。pp. 25–34 8. 発達段階(2010年)。『カリキュラム接続心理学:認知発達』所収。クレド・リファレンス・データベースより取得 9. ザレツキー、V. K.(2009年11月–12月)。「最接近発達領域:ヴィゴツキーが書き残せなかったもの」『ロシア・東欧心理学ジャーナル』47巻6号:70-93 頁。doi:10.2753/RPO1061-0405470604。ISSN 1061-0405。S2CID 146894219。 10. オームロッド、ジャンヌ・エリス;ジョーンズ、ブレット・D.(2018)。『教育心理学の基礎:効果的な指導を導く大きな考え方』(第5版)。ニューヨーク:ピアソン。ISBN 9780134894980。OCLC 959080826。 11. バーキット, E. (2006). 近接発達領域. 『心理学百科事典』所収. Credo Referenceデータベースより取得 12. ボジョビッチ, E. D. (2009). 近接発達領域: 間接的協働の診断能力と限界. Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 47(6), 48–69. EBSCOHostデータベースより取得 13. Fani, Tayebeh & Ghaemi, Farid. (2011). 教師教育におけるヴィゴツキーの最近接発達領域(ZPD)の示唆:ZPTDと自己足場構築. Procedia - Social and Behavioral Sciences. 29. 1549–1554. 10.1016/j.sbspro.2011.11.396. 14. Obukhova, L. F., & Korepanova, I. A. (2009). 近接発達領域:時空間モデル. Journal of Russian & East European Psychology, 47(6), 25–47. doi:10.2753/RPO1061-0405470602 15. Morgan, A. (2009, July 28). 「スケーフォールディング」と「ZPD」とは何か? 2014年10月13日取得。 16. ワス, R., & ゴールディング, C. (2014). 教授法の道具を研ぐ:最接近発達領域. 高等教育における教授法, 19(6), 671-684. 17. バラバン, ナンシー. (1995). 「子どもを見る、人格を知る」. エアーズ, W. 編『教師になるために』. ティーチャーズ・カレッジ・プレス刊。52頁。 18. Wells, G. (1999). 『教育におけるダイアロジックな探究:ヴィゴツキーの遺産を継承して』ケンブリッジ大学出版局刊。57頁。 19. Eggen, Paul D.; Kauchak, Donald P. (2016). 『教育心理学:教室の窓』(第10版)。ボストン:ピアソン刊。ISBN 9780133549485. OCLC 889941365. 20. Grossman, P., Wineburg, S., & Woolworth, S. (2001). 教師コミュニティの理論に向けて. Teachers College Record, 103(6), 942–1012. 21. マクラウド, S. A. (2012). 近接発達領域. www.simplypsychology.org/Zone-of-Proximal-Development.html より取得 22. クウシサーリ, H. (2014). 近接発達領域における教師: 発達プロセスを促進または阻害する協働. 教授法と教師教育, 43, 46–57. 23. マイヤー、デレク (2022-04-11). 「知識獲得の理論に向けて―言語の役割と認知の起源・進化の再検討」. 教育哲学と理論: 1–11. doi:10.1080/00131857.2022.2061350. ISSN 0013-1857. S2CID 248110575. 24. Peters, Gabriel. 「教室におけるスケーリングの利点と欠点」. 2019年11月13日取得. 25. 「スケーリングの利点と課題」. Scaffolding Literacy. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zone_of_proximal_development |

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

どなたも許諾なしに自由にご利用できます

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099