On Skull Trophy

On Skull Trophy

A young woman

writing a thank

you note to her boyfriend in the Navy for the skull of a Japanese

soldier / American sailor with the skull of a Japanese soldier during

World War II.

上の女性の写真は、メメントモリ(memento mori)ではあり ません。ライフ誌に掲載された写真(もちろん写真家がポーズをとらせているが)で、太平洋戦争で戦っている兵 士が彼のガールフレンドに贈った日本人兵士の頭蓋骨です。これは、ヒューマントロフィーとか頭蓋骨トロフィーと言って、戦勝者がしばしば敵の首級をとっ て、ま、ドヤ顔するのと同じです。兵士の彼や恋人の彼女に責任はありませんが、自然人類学者と 呼ばれる人たちも研究のために頭蓋骨を利用しますが、しばし ば、自分のポートレイトにこのような頭蓋骨と一緒に撮った(描いた)写真や肖像画を描かせています。もちろんドヤ顔で(=小金井良精さんや、金関丈夫さん のそれらが有名です)。しかしながら、歴史を超えて、頭蓋骨を晒されている当事者たち(ま死んでいますので意識はないでしょうが霊的なたましいを「想定」 してください)の気持ちになると、なんともまあ、暗い気持ちになります。化けて出ることぐらいしか「できないわけ」ですので。

| The practice of human

trophy collecting involves the acquisition of human body parts as

trophy, usually as war trophy. The intent may be to demonstrate

dominance over the deceased (such as scalp-taking or forming necklaces

of severed ears or teeth), to humiliate or intimidate the enemy (such

as shrunken heads or skull cups), or in some rare cases to commemorate

the deceased (such as the veneration of the relics of saints). It can

be done to prove one's body count in battle,[1] to boast one's prowess

and achievements to peers,[2] or as a status symbol of superior

masculinity.[3] Serial killers' collection of their victims' body parts

have also been described as a form of trophy-taking.[4] While older customs generally included the burial of human war trophies along with the collector, such items have been sold in modern times.[5] |

人頭骨収集とは、戦利品として人間の身体の一部を入手する行為である。

その意図は、故人に対する優位性を示すこと(頭皮を剥ぎ取ったり、切断された耳や歯をネックレスに加工するなど)、敵を屈辱させたり威嚇すること(ミイラ

化した頭部や頭蓋骨の杯など)、あるいはごくまれに故人を追悼すること(聖人の遺物に対する崇敬など)である。戦闘での戦果を証明するため[1]、仲間に

対して自分の武勇や功績を誇示するため[2]、あるいは優れた男らしさの象徴として行われることもある[3]。連続殺人犯が被害者の身体の一部を収集する

ことも、戦利品として持ち帰る行為の一形態であると説明されている[4]。 古い風習では、戦利品となった人間の遺体は収集者とともに埋葬されるのが一般的であったが、現代ではそのような品物が売買されることもある[5]。 |

American sailor with the skull of a Japanese soldier during World War II. |

第二次世界大戦中、日本兵の頭蓋骨を持つアメリカ人水兵。 |

| History Archaeologists discovered human skull cups dating to 14,700 years ago in Gough’s Cave, in Somerset, England; these skulls were modified in ways indicative of intentional human trophy collecting, including removal of the facial region and cleaning them.[6] According to biblical scripture, in the Old Testament, King Saul asked David to bring him one hundred Philistine foreskins as bride price for his daughter Michal. David and his men fought a battle, and he presented the king with 200. Headhunting has been practiced across the Americas, Europe, Asia, and Oceania for millennia.[5] One analysis of the practice in early North American societies linked it to social distance from the victim.[7] Groups such as the Scythians collected the skulls of the vanquished to make a skull cup.[8] In the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–1598), the noses and ears of slain Koreans and Chinese were collected and brought back to Japan, where they were placed in the Mimizuka monument in Kyoto. As of 2024, it still stands.[9] In North America, it was common practice before, during or after the lynching of African-Americans for the European Americans involved to take souvenirs such as body parts, skin, bones, genitalia, etc.[10][11] In the United States, trophies were also acquired during conquest of indigenous lands by settlers and other Native American groups. The scalp, skull, and wrist-bones of Little Crow, the Mdewakanton leader during the Minnesota hostilities of 1862, were obtained and displayed for decades at the Minnesota Historical Society as war trophies from Minnesota's bounty on the Santee Sioux. The MHS is established in the Constitution of the Minnesota Territory.[12] In another instance connected to battlefield success and to the American mutilation of Japanese war dead, President of the United States Franklin Roosevelt was given a gift of a letter-opener made of a Japanese soldier's arm by U.S. Representative Francis E. Walter in 1944.[13][14] After a call by the Roman Catholic Archdiocese of Tokyo for "respect for the laws of humanity even in total war" Roosevelt ordered the item to be returned to its sender and recommended it be properly buried.[15] In addition to human body parts appearing in museums and artifact collections in the explicit context of historical conquest, they are also included for both putative and actual scientific reasons, particularly scientific racism establishing justification for dominance over subject races. The body of William Lanne, the last "full-blooded" Tasmanian Aboriginal man, was mutilated after his death in 1869 by William Crowther[16] who later became the Premier of Tasmania, and Lanne's skull was sent to the Royal College of Surgeons in London to supposedly demonstrate "the improvement that takes place in the lower race when subjected to the effects of education and civilisation".[17] Crowther's mutilation of Lanne proved immensely controversial in Tasmania.[18] During the German Empire's Herero and Namaqua genocide in German South West Africa at the beginning of the twentieth century, specimens of African body parts were obtained and taken to German museums and academic institutions, in some instances in the aftermath of medical experimentation on human subjects.[19] In 2011, when some of these items were returned to present-day Namibia, the rector of the University of Freiburg referred to the period of their acquisition as "one of the dark chapters in the history of European science".[20] Later in the century the Jewish skull collection and other medical resources were the result of Nazi Germany's human experimentation programs and other elements of the Holocaust. The practice occurred during World War II and the Vietnam War. About 60% of the bodies of Japanese soldiers recovered in the Mariana Islands and returned to Japan lacked skulls.[5] The practice continued up until the 20th century in the Balkans.[citation needed] |

歴史 考古学者たちは、イギリスのサマセットにあるゴフの洞窟で、14,700年前の人間の頭蓋骨カップを発見した。これらの頭蓋骨は、顔の部位の除去や洗浄な ど、意図的な人間のトロフィー収集を示す方法で修正されていた[6]。 聖書の聖典によると、旧約聖書の中で、サウル王はダビデに、娘ミハエルの花嫁の代価としてペリシテ人の包皮100枚を持ってくるように頼んだ。ダビデとそ の部下たちは戦い、彼は王に200個を贈った。 首狩りは、アメリカ大陸、ヨーロッパ、アジア、オセアニアで何千年もの間行われてきた[5]。北米初期の社会における首狩りの慣行を分析したある研究で は、首狩りは被害者との社会的な距離と関連していた[7]。 日本の朝鮮侵略(1592-1598)では、殺された朝鮮人や中国人の鼻や耳が集められ、日本に持ち帰られ、京都の耳塚碑に納められた。2024年現在、 それはまだ残っている[9]。 北米では、アフリカ系アメリカ人に対するリンチの前後には、関係したヨーロッパ系アメリカ人が身体の一部、皮膚、骨、性器などの土産物を持ち帰ることが一 般的だった[10][11]。 アメリカでは、入植者や他のネイティブ・アメリカンのグループによる先住民の土地の征服の際にも、戦利品が獲得された。1862年のミネソタ州の敵対行為 におけるムデワカントンの指導者であったリトル・クロウの頭皮、頭蓋骨、手首の骨は、ミネソタ州のサンティ・スーに対する懸賞金による戦利品として入手さ れ、ミネソタ歴史協会に数十年間展示された。MHSはミネソタ準州憲法に制定されている[12]。戦場での戦功やアメリカ人による日本人戦死者の切断に関 連するもう一つの例として、フランクリン・ルーズベルト米大統領は米下院議員フランシス・E・ウォルターから日本兵の腕で作られたレターオープナーを贈ら れた。 ルーズベルトは、ローマ・カトリック東京大司教区から「全面戦争中であっても人道の掟を尊重する」よう呼びかけられた後、この品物を送り主に返却するよう 命じ、適切に埋葬するよう勧告した[15]。 歴史的な征服という明確な文脈で博物館や美術品コレクションに登場する人体の一部に加え、それらは仮定の、あるいは実際の科学的な理由、特に対象種族に対 する支配を正当化するための科学的な人種差別のためにも含まれている。タスマニア最後の 「全血 」アボリジニであるウィリアム・ランの遺体は、後にタスマニア州首相となったウィリアム・クラウザー[16]によって1869年に死後切除され、ランの頭 蓋骨はロンドンの王立外科大学に送られ、「教育と文明の影響を受けると下層人種が向上すること 」を証明することになったとされている[17]。 20世紀初頭、ドイツ帝国がドイツ領南西アフリカでヘレロ族とナマクア族を大量虐殺した際、アフリカ人の身体部位の標本が入手され、ドイツの博物館や学術 機関に持ち込まれた。 [19]2011年、これらの標本の一部が現在のナミビアに返還された際、フライブルク大学の学長は、これらの標本が入手された時期について「ヨーロッパ 科学史における暗黒の章のひとつ」と言及した[20]。その後、ユダヤ人の頭蓋骨コレクションやその他の医療資料は、ナチス・ドイツの人体実験計画やホロ コーストの他の要素の結果であった。 第二次世界大戦中やベトナム戦争中にも行われていた。マリアナ諸島で回収され、日本に戻された日本兵の遺体の約60%には頭蓋骨がなかった[5]。この慣 習はバルカン半島では20世紀まで続いた[要出典]。 |

| Other examples Human trophy taking in Mesoamerica Mokomokai: the much-traded and much-collected preserved tattooed heads of New Zealand Maori The Aghori Hindu sect in India collects human remains which have been consecrated to the Ganges river, making skull cups, or using the corpses as meditation tools.[citation needed] Tibetan Buddhists employ the kangling, a trumpet made from a human thighbone[21] The scrotum of the last male Aboriginal Tasmanian, William Lanne, was crafted into a tobacco pouch after his death.[22] During the Japanese invasions of Korea (1592–98) Japanese samurai took the noses of dead Koreans as trophies and as proofs of kills; these were pickled and sent back to Japan and buried in nose tombs In Wallace Terry's book, Bloods: An Oral History of the Vietnam War by Black Veterans, Specialist 5 Harold "Light Bulb" Bryant, Combat Engineer, 1st Cavalry Division, U.S. Army, An Khe, February 1966 – February 1967, relates:[23] Well, these white guys would sometimes take the dog-tag chain and fill that up with ears. For different reasons. They would take the ear off to make sure the VC was dead. And to confirm that they had a kill. And to put some notches on they guns. If we were movin' through the jungle, they'd just put the bloody ear on the chain and stick the ear in their pocket and keep on going. Wouldn't take time to dry it off. Then when we get back, they would nail 'em up on the walls to our hootch, you know, as a trophy. They was rotten and stinkin' after a while, and finally we make 'em take 'em down. |

その他の例 メソアメリカにおける人間のトロフィー収集 モコモカイ:ニュージーランドのマオリ族が保存している刺青の入った頭部が取引され、多く収集されている。 インドのヒンドゥー教アゴリ派は、ガンジス川に奉献された人骨を集め、頭蓋骨の杯を作ったり、瞑想の道具として使ったりする[要出典]。 チベットの仏教徒は、人間の大腿骨から作られたラッパであるカングリングを用いる[21]。 タスマニア最後の男性アボリジニ、ウィリアム・ランの陰嚢は、彼の死後、タバコ袋に加工された[22]。 日本の朝鮮侵略(1592~98年)の際、日本の武士は戦利品として、また殺害の証拠として、死んだ朝鮮人の鼻を持ち帰った。 ウォレス・テリーの著書『Bloods: An Oral History of the Vietnam War by Black Veterans, Specialist 5 Harold 「Light Bulb」 Bryant, Combat Engineer, 1st Cavalry Division, U.S. Army, An Khe, February 1966 - February 1967, relates:[23]. まあ、白人連中は時々、犬タグの鎖を取って、それを耳でいっぱいにしていたよ。理由はさまざまだ。彼らはVCが死んだことを確認するために耳を取るんだ。 殺したことを確認するためだ。銃にノッチを付けるためだ。ジャングルの中を移動するときは、血まみれの耳を鎖につないでポケットに入れ、そのまま進む。耳 を乾かすのに時間はかからない。そして俺たちが戻ると、そいつらを俺たちの小屋の壁に釘で打ち付けて、トロフィーにするんだ。しばらくすると腐って悪臭を 放つようになったから、最後には撤去させたよ。 |

| Trade Trophy skulls with purported colonial-era ethnic engravings were widely sold online at various platforms. In 2005, Royal Malaysian Customs Department seized 16 human skulls with engravings that were purported to originate from northwest of West Kalimantan province, somewhere between Pontianak and the Sarawak border, and bound for an unknown buyer in Australia. These seized skulls were transferred to Sarawak State Museum in 2015.[24] Body-snatching Body-snatchings are sometimes conducted to retain a body part as a trophy.[25] |

貿易 植民地時代の民族的な彫刻が施されたとされるトロフィーの頭蓋骨は、さまざまなプラットフォームで広くオンライン販売されていた。2005年、マレーシア 王立関税局は、西カリマンタン州の北西部、ポンティアナックとサラワク州境のどこかで産出され、オーストラリアの不明な買い手に向けられたとされる、彫刻 が施された16体の人間の頭蓋骨を押収した。これらの押収された頭蓋骨は、2015年にサラワク州立博物館に移管された[24]。 死体略奪 ボディ・スナッチングは、身体の一部をトロフィーとして保持するために行われることもある[25]。 |

| Maywand

District murders Ismo Junni |

メイワンド地区殺人事件 イスモ・ジュニ |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Human_trophy_collecting |

|

【再掲】女性の写真は、メメントモリ(memento mori)ではあり ません。ライフ誌に掲載された写真(もちろん写真家がポーズをとらせているが)で、太平洋戦争で戦っている兵 士が彼のガールフレンドに贈った日本人兵士の頭蓋骨です。これは、ヒューマントロフィーとか頭蓋骨トロフィーと言って、戦勝者がしばしば敵の首級をとっ て、ま、ドヤ顔するのと同じです。兵士の彼や恋人の彼女に責任はありませんが、自然人類学者と 呼ばれる人たちも研究のために頭蓋骨を利用しますが、しばし ば、自分のポートレイトにこのような頭蓋骨と一緒に撮った(描いた)写真や肖像画を描かせています。もちろんドヤ顔で(=小金井良精さんや、金関丈夫さん のそれらが有名です)。しかしながら、歴史を超えて、頭蓋骨を晒されている当事者たち(ま死んでいますので意識はないでしょうが霊的なたましいを「想定」 してください)の気持ちになると、なんともまあ、暗い気持ちになります。化けて出ることぐらいしか「できないわけ」ですので。 |

| A young woman

writing a thank

you note to her boyfriend in the Navy for the skull of a Japanese

soldier that he sent, 1944-“Arizona war worker writes her Navy

boyfriend a thank-you note for the Jap skull he sent her.” LIFE

magazine’s “Picture of the Week,” May 22, 1944. |

|

| https://rarehistoricalphotos.com/young-woman-japanese-skull-1944/ |

|

|

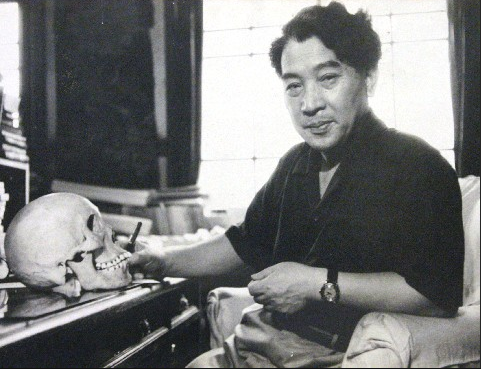

金関丈夫(ca.1953)1953年ごろの金関丈夫(九州大学医学部解剖学 教室)出典:(金関恕 1999:49) |

|

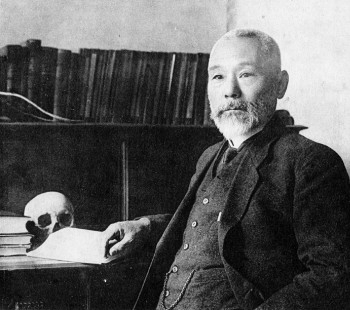

小金井良精(撮影年不詳) |

| https://bit.ly/3KbZPeU | |

|

国立科学博物館が開催(予定)する特別展「古代DNA:日本人のきた

道」のポスター:研究者たちの「頭蓋骨トロフィー」のメンタリーはまだ終わっていない。(https://ancientdna2025.jp/) |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099

Dance of Death (15th-century fresco). No matter one's station in

life, the Dance of Death unites all.

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099