時間

Time

☆

時間とは、過去から現在、そして未来へと、一見不可逆的に連続して進行する、変化し続ける我々の存在である。[1][2][3]

時間とは、出来事を順序立てたり、出来事の持続時間(または出来事間の間隔)を比較したり、物質的な現実や意識的な経験における変化の速度を定量化したり

するために用いられる、様々な測定の構成要素である。。時間とは、しばしば3つの空間次元とともに4番目の次元と呼ばれる。科学者たちは、我々の宇宙にお

ける時間の始まり(ビッグバン)と終わり(例えば熱的死やビッグクランチ)を理論化している。循環モデルは周期的な性質を説明するが、永遠主義の哲学は異

なる角度から主題を捉える。

時間は、国際単位系(SI)および国際数量系(ISQ)の両方において、7つの基本的な物理量の1つである。SIの基本単位である時間は秒であり、セシウ

ム原子の電子遷移周波数を測定することで定義される。一般相対性理論は、時空の仕組みを理解するための主な枠組みである。[10]

時空に関する理論的および実験的な調査の進歩により、特にブラックホールの縁では、時間が歪んだり、伸びたりすることが示されている。

歴史を通じて、時間というものは宗教、哲学、科学の分野において重要な研究対象であった。時間の測定は科学者や技術者を魅了し、航海術や天文学の主な動機

付けとなってきた。また、時間には社会的にも大きな重要性があり、経済的価値(「時は金なり」)や個人的な価値がある。これは、1日や人間の寿命には限り

があるという認識によるものである。人間が時間をどう使うかに対する文化的な態度は、動詞の用法(「殺す」、「無駄にする」、「過ぎる」など)やことわざ

(「今を生きろ」など)に表れている。

| Time

is the continuous progression of our changing existence that occurs in

an apparently irreversible succession from the past, through the

present, and into the future.[1][2][3] It is a component quantity of

various measurements used to sequence events, to compare the duration

of events (or the intervals between them), and to quantify rates of

change of quantities in material reality or in the conscious

experience.[4][5][6][7] Time is often referred to as a fourth

dimension, along with three spatial dimensions.[8][9] Scientists have

theorized a beginning of time in our universe (the Big Bang) and an end

(e.g., heat death or the Big Crunch). A cyclic model describes a

cyclical nature, whereas the philosophy of eternalism views the subject

from a different angle. Time is one of the seven fundamental physical quantities in both the International System of Units (SI) and International System of Quantities. The SI base unit of time is the second, which is defined by measuring the electronic transition frequency of caesium atoms. General relativity is the primary framework for understanding how spacetime works.[10] Through advances in both theoretical and experimental investigations of spacetime, it has been shown that time can be distorted and dilated, particularly at the edges of black holes. Throughout history, time has been an important subject of study in religion, philosophy, and science. Temporal measurement has occupied scientists and technologists and has been a prime motivation in navigation and astronomy. Time is also of significant social importance, having economic value ("time is money") as well as personal value, due to an awareness of the limited time in each day and in human life spans. Cultural attitudes towards the human use of time are apparent in the verbs used—from "kill" to "waste" to "pass"—and sayings (like carpe diem). |

時間とは、過去から現在、そして未来へと、一見不可逆的に連続して進行

する、変化し続ける我々の存在である。[1][2][3]

時間とは、出来事を順序立てたり、出来事の持続時間(または出来事間の間隔)を比較したり、物質的な現実や意識的な経験における変化の速度を定量化したり

するために用いられる、様々な測定の構成要素である。。時間とは、しばしば3つの空間次元とともに4番目の次元と呼ばれる。科学者たちは、我々の宇宙にお

ける時間の始まり(ビッグバン)と終わり(例えば熱的死やビッグクランチ)を理論化している。循環モデルは周期的な性質を説明するが、永遠主義の哲学は異

なる角度から主題を捉える。 時間は、国際単位系(SI)および国際数量系(ISQ)の両方において、7つの基本的な物理量の1つである。SIの基本単位である時間は秒であり、セシウ ム原子の電子遷移周波数を測定することで定義される。一般相対性理論は、時空の仕組みを理解するための主な枠組みである。[10] 時空に関する理論的および実験的な調査の進歩により、特にブラックホールの縁では、時間が歪んだり、伸びたりすることが示されている。 歴史を通じて、時間というものは宗教、哲学、科学の分野において重要な研究対象であった。時間の測定は科学者や技術者を魅了し、航海術や天文学の主な動機 付けとなってきた。また、時間には社会的にも大きな重要性があり、経済的価値(「時は金なり」)や個人的な価値がある。これは、1日や人間の寿命には限り があるという認識によるものである。人間が時間をどう使うかに対する文化的な態度は、動詞の用法(「殺す」、「無駄にする」、「過ぎる」など)やことわざ (「今を生きろ」など)に表れている。 |

| Definition The concept of time can be complex. Multiple notions exist and defining time in a manner applicable to all fields without circularity has consistently eluded scholars.[7][11][12] Nevertheless, diverse fields such as business, industry, sports, the sciences, and the performing arts all incorporate some notion of time into their respective measuring systems.[13][14][15] Traditional definitions of time involved the observation of periodic motion such as the apparent motion of the sun across the sky, the phases of the moon, and the passage of a free-swinging pendulum. More modern systems include the Global Positioning System, other satellite systems, Coordinated Universal Time and mean solar time. Although these systems differ from one another, with careful measurements they can be synchronized. In physics, time is a fundamental concept to define other quantities, such as velocity. To avoid a circular definition,[16] time in physics is operationally defined as "what a clock reads", specifically a count of repeating events such as the SI second.[6][17][18] Although this aids in practical measurements, it does not address the essence of time. Physicists developed the concept of the spacetime continuum, where events are assigned four coordinates: three for space and one for time. Events like particle collisions, supernovas, or rocket launches have coordinates that may vary for different observers, making concepts like "now" and "here" relative. In general relativity, these coordinates do not directly correspond to the causal structure of events. Instead, the spacetime interval is calculated and classified as either space-like or time-like, depending on whether an observer exists that would say the events are separated by space or by time.[19] Since the time required for light to travel a specific distance is the same for all observers—a fact first publicly demonstrated by the Michelson–Morley experiment—all observers will consistently agree on this definition of time as a causal relation.[20] General relativity does not address the nature of time for extremely small intervals where quantum mechanics holds. In quantum mechanics, time is treated as a universal and absolute parameter, differing from general relativity's notion of independent clocks. The problem of time consists of reconciling these two theories.[21] As of 2024, there is no generally accepted theory of quantum general relativity.[22] |

定義 時間の概念は複雑である。複数の概念が存在し、あらゆる分野に適用できるような循環性のない方法で時間を定義することは、学者たちにとって常に困難であっ た。[7][11][12] しかし、ビジネス、産業、スポーツ、科学、および舞台芸術など、さまざまな分野では、 それぞれの測定システムに組み込まれている。[13][14][15] 伝統的な時間の定義には、太陽の見かけ上の空の動き、月の満ち欠け、自由振子の振動などの周期的な運動の観察が含まれていた。より近代的なシステムには、 全地球測位システム、その他の衛星システム、協定世界時、平均太陽時などがある。これらのシステムは互いに異なるが、慎重に測定すれば同期させることがで きる。 物理学において、時間は速度などの他の量を定義する基本概念である。循環定義を避けるため、[16] 物理学における時間は「時計が示すもの」として操作的に定義され、具体的にはSI秒のような繰り返される事象のカウントとして定義される。[6][17] [18] これは実用的な測定には役立つが、時間の本質には迫っていない。物理学者は時空連続体の概念を開発し、そこで事象には4つの座標が割り当てられる。すなわ ち、空間に関する3つの座標と時間に関する1つの座標である。粒子衝突、超新星爆発、ロケット打ち上げなどの事象には、異なる観察者によって異なる座標が 割り当てられる可能性があり、「今」や「ここ」といった概念は相対的なものとなる。一般相対性理論では、これらの座標は事象の因果構造に直接対応するもの ではない。代わりに、時空の距離は計算され、その出来事が空間によって隔てられていると述べる観察者が存在するか、あるいは時間によって隔てられていると 述べる観察者が存在するかによって、空間的または時間的のいずれかに分類される。[19] 光が特定の距離を移動するのにかかる時間は、すべての観察者にとって同じである。これはマイケルソン・モーリーの実験によって初めて公に実証された事実で ある。したがって、すべての観察者は因果関係としての時間の定義について一貫して同意する。[20] 一般相対性理論は、量子力学が成り立つ極めて短い時間間隔における時間の性質については扱っていない。量子力学では、時間は普遍的かつ絶対的なパラメータ として扱われ、一般相対性理論の独立した時計という概念とは異なる。時間の問題は、この2つの理論を調和させることである。2024年現在、一般に受け入 れられている量子一般相対性理論はない。 |

Measurement A sand timer uses the flow of sand to measure the passage of time. Generally speaking, historical methods of temporal measurement, or chronometry, have taken two distinct forms: the calendar, a mathematical tool for organising long intervals of time,[23] and the clock (e.g., watch), a physical mechanism that counts the passage of time. In day-to-day life, a clock was consulted for periods less than a day, whereas a calendar was consulted for periods longer than a day. Increasingly, personal electronic devices display both calendars and clocks simultaneously. The number (as on a clock dial or calendar) that marks the occurrence of a specified event (as to hour or date) is obtained by counting from certain starting date (epoch), and relevant to a certain time zone (including daylight saving time). Precise measurements, as in astronomy, use a fiducial epoch – a central reference point. |

測定 砂時計は砂の流れる動きで時間の経過を測る。 一般的に、時間の測定方法、すなわちクロノメトリーには、2つの異なる形態がある。1つは、長い時間を整理するための数学的なツールであるカレンダー [23]であり、もう1つは、時間の経過を計る物理的な仕組みである時計(例えば、腕時計)である。日常生活では、1日未満の期間については時計を参照 し、1日を超える期間についてはカレンダーを参照していた。 最近では、個人の電子機器にカレンダーと時計の両方が同時に表示されることが多くなっている。特定のイベント(時間や日付など)の発生を示す数字(時計の 文字盤やカレンダー上の数字)は、特定の開始日(エポック)から数えることで求められ、特定の時間帯(夏時間を含む)に関連している。天文学における精密 測定では、基準となるエポック(中心となる参照点)が使用される。 |

| History of the calendar Main article: Calendar Artifacts from the Paleolithic suggest that the moon was used to reckon time as early as 6,000 years ago.[24] Lunar calendars were among the first to appear, with years of either 12 or 13 lunar months (either 354 or 384 days). Without intercalation to add days or months to some years, seasons quickly drift in a calendar based solely on twelve lunar months. Lunisolar calendars have a thirteenth month added to some years to make up for the difference between a full year (now known to be about 365.24 days) and a year of just twelve lunar months. The numbers twelve and thirteen came to feature prominently in many cultures, at least partly due to this relationship of months to years. Other early forms of calendars originated in Mesoamerica, particularly in ancient Mayan civilization. These calendars were religiously and astronomically based, with 18 months in a year and 20 days in a month, plus five epagomenal days at the end of the year.[25] The reforms of Julius Caesar in 45 BC put the Roman world on a solar calendar. This Julian calendar was faulty in that its intercalation still allowed the astronomical solstices and equinoxes to advance against it by about 11 minutes per year. Pope Gregory XIII introduced a correction in 1582; the Gregorian calendar was only slowly adopted by different nations over a period of centuries, but it is now by far the most commonly used calendar around the world. During the French Revolution, a new clock and calendar were invented as part of the dechristianization of France and to create a more rational system in order to replace the Gregorian calendar. The French Republican Calendar's days consisted of ten hours of a hundred minutes of a hundred seconds, which marked a deviation from the base 12 (duodecimal) system used in many other devices by many cultures. The system was abolished in 1806.[26] |

暦の歴史 詳細は「暦」を参照 旧石器時代の遺物から、6000年も前から月が時間の計測に使われていたことが示唆されている。[24] 最初に登場したのは太陰暦で、1年は12か月の年(354日)か13か月の年(384日)であった。閏年を設けて年によっては日や月を追加しない場合、 12の太陰月のみに基づく暦では季節がすぐにずれてしまう。太陰太陽暦では、1年(現在では約365.24日とされている)と12の太陰月のみの年との間 に生じる差異を調整するために、年によっては13番目の月が追加される。12と13という数字は、少なくともこの月と年の関係が理由のひとつとなって、多 くの文化で重要な意味を持つようになった。中米、特に古代マヤ文明で生まれた初期の暦の形もある。これらの暦は宗教的・天文学的根拠に基づいており、1年 は18か月、1か月は20日で、年末に5日間の閏日を加えるというものであった。 紀元前45年のユリウス・カエサルの改革により、ローマ世界は太陽暦に移行した。このユリウス暦は、閏年の挿入によって天文上の至点や分点が年間約11分 ずつ進むという欠陥があった。グレゴリウス13世は1582年に修正を導入し、グレゴリオ暦は数世紀にわたって徐々に異なる国民に採用されていったが、現 在では世界中で圧倒的に最も一般的に使用されている暦となっている。 フランス革命中には、フランスからキリスト教を排除し、グレゴリオ暦に代わるより合理的なシステムを構築する一環として、新しい時計と暦が考案された。フ ランス共和暦では、1日が10時間、100分、100秒で構成されていた。これは、多くの文化で他の多くの機器に使用されている12進法(12を基本とす る)からの逸脱であった。このシステムは1806年に廃止された。[26] |

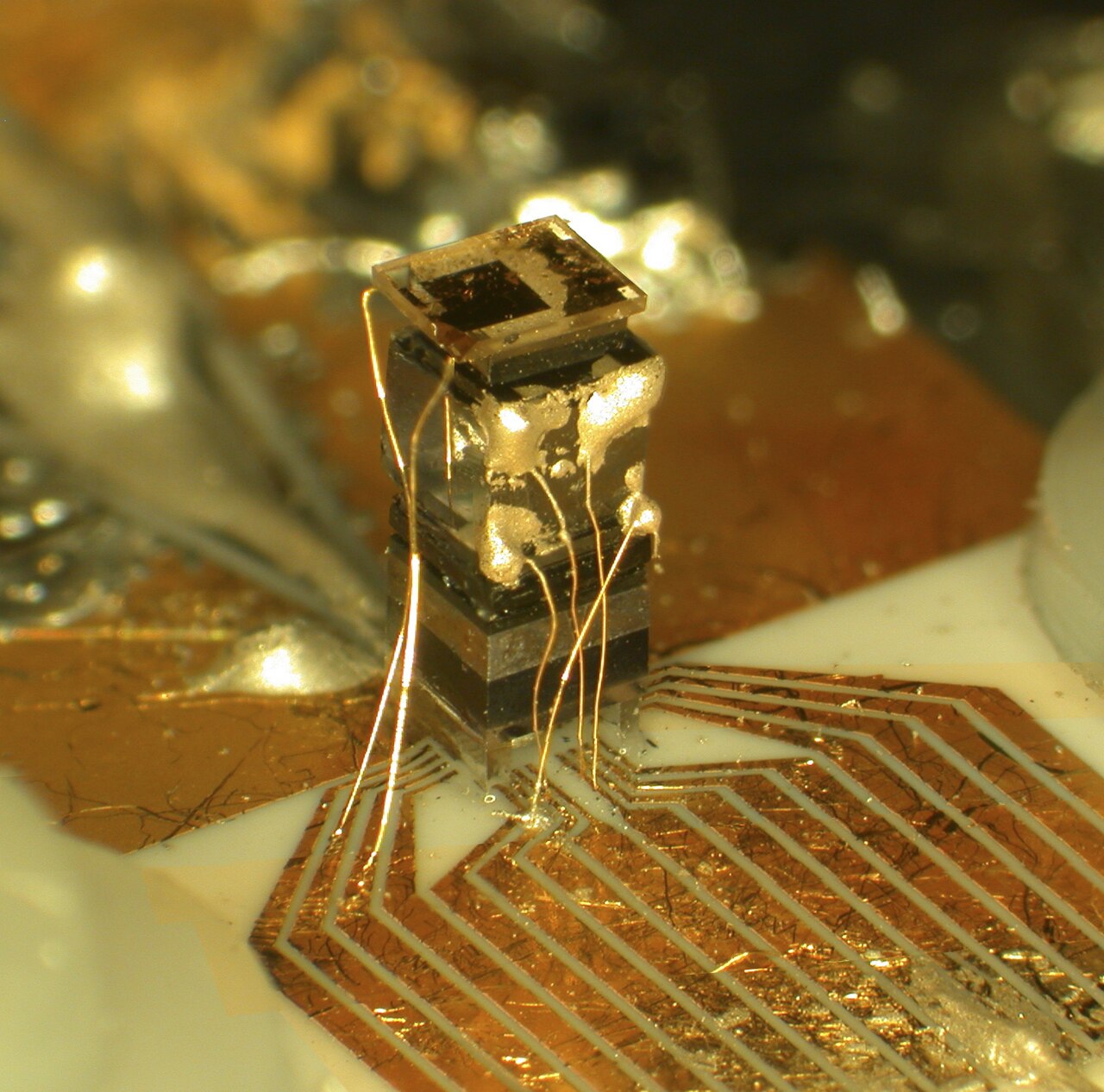

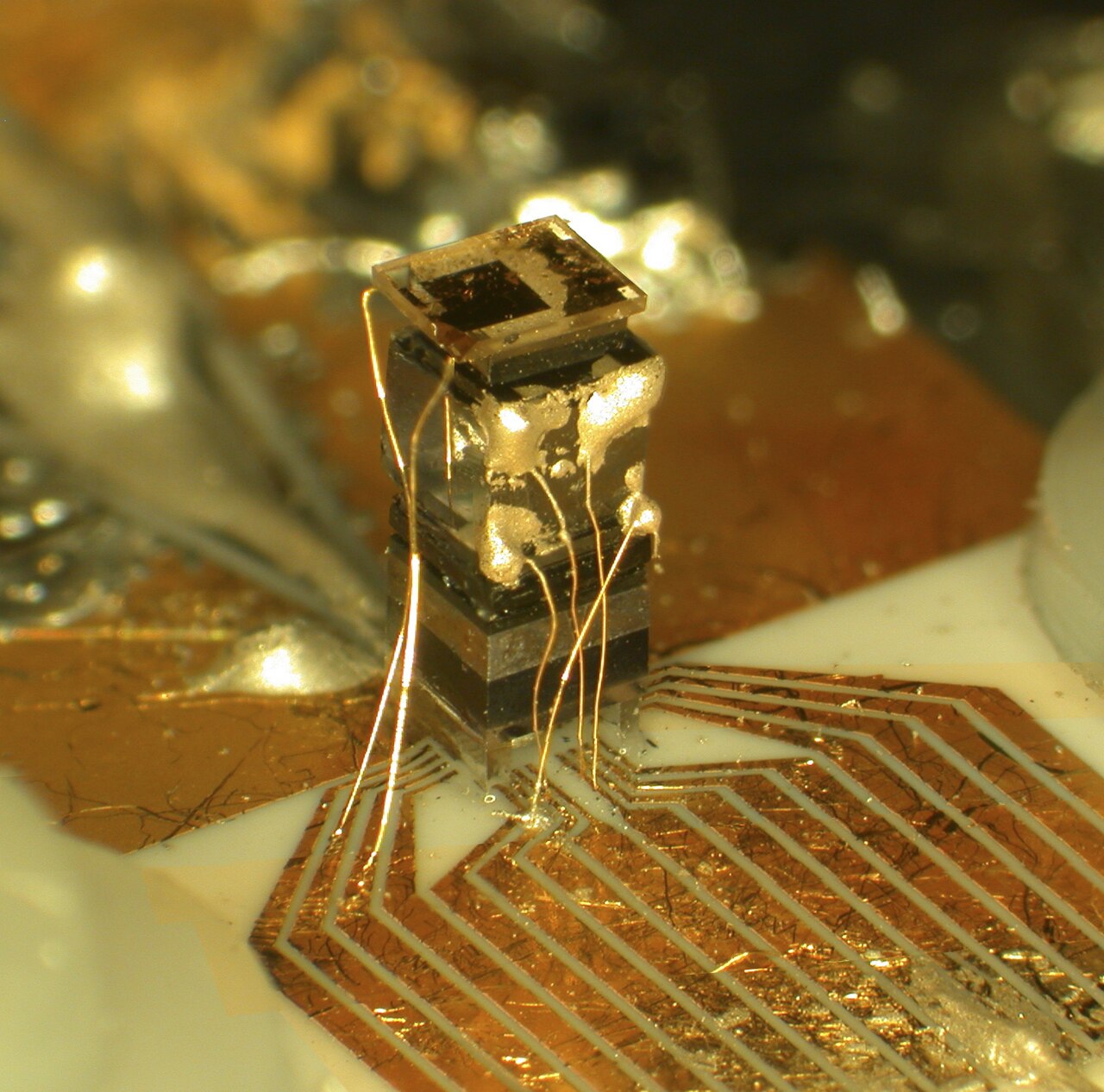

History of other devices Horizontal sundial in Canberra  24-hour clock face in Florence Main article: History of timekeeping devices See also: Clock A large variety of devices have been invented to measure time. The study of these devices is called horology.[27] An Egyptian device that dates to c. 1500 BC, similar in shape to a bent T-square, measured the passage of time from the shadow cast by its crossbar on a nonlinear rule. The T was oriented eastward in the mornings. At noon, the device was turned around so that it could cast its shadow in the evening direction.[28] A sundial uses a gnomon to cast a shadow on a set of markings calibrated to the hour. The position of the shadow marks the hour in local time. The idea to separate the day into smaller parts is credited to Egyptians because of their sundials, which operated on a duodecimal system. The importance of the number 12 is due to the number of lunar cycles in a year and the number of stars used to count the passage of night.[29] The most precise timekeeping device of the ancient world was the water clock, or clepsydra, one of which was found in the tomb of Egyptian pharaoh Amenhotep I. They could be used to measure the hours even at night but required manual upkeep to replenish the flow of water. The ancient Greeks and the people from Chaldea (southeastern Mesopotamia) regularly maintained timekeeping records as an essential part of their astronomical observations. Arab inventors and engineers, in particular, made improvements on the use of water clocks up to the Middle Ages.[30] In the 11th century, Chinese inventors and engineers invented the first mechanical clocks driven by an escapement mechanism.  A contemporary quartz watch, 2007 The hourglass uses the flow of sand to measure the flow of time. They were used in navigation. Ferdinand Magellan used 18 glasses on each ship for his circumnavigation of the globe (1522).[31] Incense sticks and candles were, and are, commonly used to measure time in temples and churches across the globe. Water clocks, and, later, mechanical clocks, were used to mark the events of the abbeys and monasteries of the Middle Ages. Richard of Wallingford (1292–1336), abbot of St. Alban's abbey, famously built a mechanical clock as an astronomical orrery about 1330.[32][33] Great advances in accurate time-keeping were made by Galileo Galilei and especially Christiaan Huygens with the invention of pendulum-driven clocks along with the invention of the minute hand by Jost Burgi.[34] The English word clock probably comes from the Middle Dutch word klocke which, in turn, derives from the medieval Latin word clocca, which ultimately derives from Celtic and is cognate with French, Latin, and German words that mean bell. The passage of the hours at sea was marked by bells and denoted the time (see ship's bell). The hours were marked by bells in abbeys as well as at sea.  Chip-scale atomic clocks, such as this one unveiled in 2004, are expected to greatly improve GPS location.[35] Clocks can range from watches to more exotic varieties such as the Clock of the Long Now. They can be driven by a variety of means, including gravity, springs, and various forms of electrical power, and regulated by a variety of means such as a pendulum. Alarm clocks first appeared in ancient Greece around 250 BC with a water clock that would set off a whistle. This idea was later mechanized by Levi Hutchins and Seth E. Thomas.[34] A chronometer is a portable timekeeper that meets certain precision standards. Initially, the term was used to refer to the marine chronometer, a timepiece used to determine longitude by means of celestial navigation, a precision first achieved by John Harrison. More recently, the term has also been applied to the chronometer watch, a watch that meets precision standards set by the Swiss agency COSC. The most accurate timekeeping devices are atomic clocks, which are accurate to seconds in many millions of years,[36] and are used to calibrate other clocks and timekeeping instruments. Atomic clocks use the frequency of electronic transitions in certain atoms to measure the second. One of the atoms used is caesium; most modern atomic clocks probe caesium with microwaves to determine the frequency of these electron vibrations.[37] Since 1967, the International System of Measurements bases its unit of time, the second, on the properties of caesium atoms. SI defines the second as 9,192,631,770 cycles of the radiation that corresponds to the transition between two electron spin energy levels of the ground state of the 133Cs atom. Today, the Global Positioning System in coordination with the Network Time Protocol can be used to synchronize timekeeping systems across the globe. In medieval philosophical writings, the atom was a unit of time referred to as the smallest possible division of time. The earliest known occurrence in English is in Byrhtferth's Enchiridion (a science text) of 1010–1012,[38] where it was defined as 1/564 of a momentum (11⁄2 minutes),[39] and thus equal to 15/94 of a second. It was used in the computus, the process of calculating the date of Easter. As of May 2010, the smallest time interval uncertainty in direct measurements is on the order of 12 attoseconds (1.2 × 10−17 seconds), about 3.7 × 1026 Planck times.[40] |

その他の装置の歴史 キャンベラの水平式日時計  フィレンツェの24時間式時計の文字盤 詳細は「計時装置の歴史」を参照 時計」も参照 時間を計測する装置は、実に多種多様に発明されてきた。これらの装置を研究する学問は「時計学」と呼ばれる。 紀元前1500年頃のエジプトの装置は、曲がったT字定規のような形状で、その横木が非直線的な定規に落とす影から時間の経過を測定した。T字は朝には東向きに置かれた。正午になると、装置は回転させられ、夕方の方向に影を落とすようにした。 日時計は、時を刻む目盛りに影を落とすために、グノーモン(日針)を用いる。影の位置が現地時間での時刻を示す。1日をさらに細かく分割するという考え方 は、12進法で動作する日時計を発明したエジプト人に由来する。12という数字の重要性は、1年間の太陰周期の数と、夜の経過を数えるのに使われた星の数 によるものである。 古代世界で最も正確な計時装置は水時計(水差し時計)であり、エジプト王アメンヘテプ1世の墓から1つが発見されている。これは夜でも時間を測定すること ができたが、水の流量を補充するために手動でのメンテナンスが必要であった。古代ギリシア人とカルデア(メソポタミア南東部)の人々は、天体観測の重要な 一部として、定期的に計時記録を維持していた。特にアラブの発明家や技術者は、中世まで水時計の改良を続けた。[30] 11世紀には、中国の発明家や技術者が脱進機機構によって駆動する最初の機械式時計を発明した。  2007年当時のクオーツ時計 砂時計は砂の流れで時の流れを計る。 航海にも使用された。 フェルディナンド・マゼランは世界一周の航海(1522年)で、各船に18個の砂時計を使用した。 線香やろうそくは、現在も昔も、世界中の寺院や教会で時間を計るために一般的に使用されている。中世では、水時計や、後に機械式時計が、修道院や僧院での 出来事を知らせるために使用されていた。リチャード・オブ・ウォーリンフォード(1292年 - 1336年)は、聖オルバン修道院の院長として、1330年頃に天文時計として有名な機械式時計を製作した。 ガリレオ・ガリレイや、特にクリスティアーン・ホイヘンスが振り子時計を発明し、ヨスト・ブルギが分針を発明したことにより、正確な計時の分野で大きな進歩がもたらされた。 英語の「clock」という単語はおそらく中世オランダ語の「klocke」に由来し、さらに中世ラテン語の「clocca」に由来する。 「clocca」は最終的にはケルト語に由来し、フランス語、ラテン語、ドイツ語の「鐘」を意味する単語と類縁関係にある。海上での時間の経過は鐘によっ て示され、時刻を表していた(船の鐘を参照)。海上だけでなく、修道院でも鐘によって時間が示されていた。  2004年に発表されたようなチップスケールの原子時計は、GPSの位置情報を大幅に改善することが期待されている。 時計には、腕時計から「ロング・ナウの時計」のようなより変わったものまで、さまざまな種類がある。時計は、重力、バネ、さまざまな形態の電力など、さまざまな手段で駆動させることができ、振り子など、さまざまな手段で制御することができる。 目覚まし時計は紀元前250年頃の古代ギリシャで、水時計が笛を鳴らす仕組みで初めて登場した。このアイデアは後にレビ・ハッチンズとセス・E・トーマスによって機械化された。 クロノメーターとは、一定の精度基準を満たす携帯用時計である。当初、この用語はマリンクロノメーターを指すために使われていた。マリンクロノメーターと は、天測航行によって経度を決定するために使用される時計であり、ジョン・ハリソンが初めてその精度を実現した。さらに最近では、スイスの機関である COSCが定めた精度基準を満たす時計であるクロノメーターウォッチにもこの用語が適用されている。 最も正確な計時装置は原子時計であり、これは数千万年に1秒の誤差しかない[36]。原子時計は他の時計や計時装置の較正にも使用されている。 原子時計は、特定の原子における電子遷移の周波数を利用して1秒を測定する。使用される原子の1つはセシウムであり、ほとんどの現代の原子時計は、これら の電子振動の周波数を決定するために、マイクロ波でセシウムをプローブする。1967年以降、国際単位系では、時間の単位である1秒をセシウム原子の特性 に基づいて定義している。SIでは、1秒を133Cs原子の基底状態における2つの電子スピンエネルギー準位間の遷移に対応する放射の 9,192,631,770サイクルと定義している。 今日では、ネットワーク・タイム・プロトコルと連動した全地球測位システム(GPS)を使用して、世界中の計時システムを同期させることができる。 中世の哲学書では、原子は「時間の最小単位」として時間単位として用いられていた。英語における最も古い使用例は、1010年から1012年の間に書かれ たバーソフのエンキリディオン(科学の教科書)で、運動量の1/564(11⁄2分)と定義されており、したがって1秒の15/94に相当する。これは、 イースターの日付を計算するプロセスであるコンピュータスで使用されていた。 2010年5月現在、直接測定における最小の時間間隔の不確かさは、12アト秒(1.2×10−17秒)のオーダーであり、プランク時間で約3.7×1026倍である。[40] |

| Units See also: Time (Orders of magnitude) and Unit of time § List The second (s) is the SI base unit. A minute (min) is 60 seconds in length (or, rarely, 59 or 61 seconds when leap seconds are employed), and an hour is 60 minutes or 3600 seconds in length. A day is usually 24 hours or 86,400 seconds in length; however, the duration of a calendar day can vary due to Daylight saving time and Leap seconds. |

単位 参照:時間(桁)および時間の単位 § リスト 秒(s)がSI基本単位である。分(min)の長さは60秒(または、閏秒が採用された場合は59秒または61秒)であり、1時間は60分または3600 秒の長さである。1日は通常24時間、または86,400秒の長さであるが、夏時間や閏秒により、暦上の1日の長さは異なる。 |

| Time standards Main article: Time standard A time standard is a specification for measuring time: assigning a number or calendar date to an instant (point in time), quantifying the duration of a time interval, and establishing a chronology (ordering of events). In modern times, several time specifications have been officially recognized as standards, where formerly they were matters of custom and practice. The invention in 1955 of the caesium atomic clock has led to the replacement of older and purely astronomical time standards such as sidereal time and ephemeris time, for most practical purposes, by newer time standards based wholly or partly on atomic time using the SI second. International Atomic Time (TAI) is the primary international time standard from which other time standards are calculated. Universal Time (UT1) is mean solar time at 0° longitude, computed from astronomical observations. It varies from TAI because of the irregularities in Earth's rotation. Coordinated Universal Time (UTC) is an atomic time scale designed to approximate Universal Time. UTC differs from TAI by an integral number of seconds. UTC is kept within 0.9 second of UT1 by the introduction of one-second steps to UTC, the leap second. The Global Positioning System broadcasts a very precise time signal based on UTC time. The surface of the Earth is split into a number of time zones. Standard time or civil time in a time zone deviates a fixed, round amount, usually a whole number of hours, from some form of Universal Time, usually UTC. Most time zones are exactly one hour apart, and by convention compute their local time as an offset from UTC. For example, time zones at sea are based on UTC. In many locations (but not at sea) these offsets vary twice yearly due to daylight saving time transitions. Some other time standards are used mainly for scientific work. Terrestrial Time is a theoretical ideal scale realized by TAI. Geocentric Coordinate Time and Barycentric Coordinate Time are scales defined as coordinate times in the context of the general theory of relativity. Barycentric Dynamical Time is an older relativistic scale that is still in use. |

時間標準 詳細は「時間標準」を参照 時間標準とは、時間を測定するための仕様である。ある瞬間(ある時点)に数値や暦日付を割り当てたり、時間間隔の持続時間を数値化したり、年代順(出来事 の順序)を確定したりする。現代では、以前は慣習や慣例の問題であったいくつかの時間仕様が、公式に標準として認められている。1955年にセシウム原子 時計が発明されたことにより、恒星時やエフェメリス時といった、より古い純粋に天文学的な時間基準は、ほとんどの実際的な目的において、SI秒を使用した 原子時間に基づく新しい時間基準に置き換えられた。 国際原子時(TAI)は、他の時間標準が算出される際の基準となる国際的な時間標準である。協定世界時(UT1)は、天文観測から算出される経度0度の平 均太陽時である。地球の自転に不規則性があるため、TAIとは異なる。協定世界時(UTC)は、協定世界時を近似する原子時である。UTCはTAIと秒単 位の整数で異なる。UTCは、UTCに1秒単位の閏秒を導入することで、UT1との誤差を0.9秒以内に保っている。全地球測位システム(GPS)は、 UTCに基づく非常に正確な時刻信号を放送している。 地球の表面はいくつかのタイムゾーンに分割されている。タイムゾーンにおける標準時または市民時(通常はUTC)は、通常はUTCなどの世界時(通常は UTC)から固定された丸い量、通常は時間単位の整数だけずれている。ほとんどのタイムゾーンは正確に1時間ずつ離れており、慣例として、ローカルタイム はUTCからのオフセットとして計算される。例えば、海上のタイムゾーンはUTCに基づいている。多くの場所(海上ではない)では、夏時間への移行によ り、このオフセットが年に2回変更される。 その他の時間基準は主に科学的な作業で使用される。地球時(Terrestrial Time)は、TAIによって実現される理論上の理想的な尺度である。地心座標時(Geocentric Coordinate Time)と重心座標時(Barycentric Coordinate Time)は、一般相対性理論の文脈における座標時として定義された尺度である。重心動時(Barycentric Dynamical Time)は、現在も使用されている古い相対性理論の尺度である。 |

| Religions which view time as cyclical See also: Calendar and Wheel of time Many ancient cultures, particularly in the East, had a cyclical view of time. In these traditions, time was often seen as a recurring pattern of ages or cycles, where events and phenomena repeated themselves in a predictable manner. One of the most famous examples of this concept is found in Hindu philosophy, where time is depicted as a wheel called the "Kalachakra" or "Wheel of Time." According to this belief, the universe undergoes endless cycles of creation, preservation, and destruction.[41] Similarly, in other ancient cultures such as those of the Mayans, Aztecs, and Chinese, there were also beliefs in cyclical time, often associated with astronomical observations and calendars.[42] These cultures developed complex systems to track time, seasons, and celestial movements, reflecting their understanding of cyclical patterns in nature and the universe. The cyclical view of time contrasts with the linear concept of time more common in Western thought, where time is seen as progressing in a straight line from past to future without repetition.[43] Time in Abrahamic religions In general, the Islamic and Judeo-Christian world-view regards time as linear[44] and directional,[45] beginning with the act of creation by God. The traditional Christian view sees time ending, teleologically,[46] with the eschatological end of the present order of things, the "end time". In the Old Testament book Ecclesiastes, traditionally ascribed to Solomon (970–928 BC), time (as the Hebrew word עידן, זמן iddan (age, as in "Ice age") zĕman(time) is often translated) is a medium for the passage of predestined events.[citation needed] (Another word, زمان" זמן" zamān, meant time fit for an event, and is used as the modern Arabic, Persian, and Hebrew equivalent to the English word "time".) |

時間を循環的と捉える宗教 参照:暦と時の輪 古代の多くの文化、特に東洋では、時間を循環的と捉える考え方が一般的であった。これらの伝統では、時代や周期が繰り返されるパターンとして時間を見るこ とが多く、出来事や現象が予測可能な形で繰り返されるとされていた。この概念の最も有名な例のひとつはヒンドゥー哲学に見られ、そこでは「時の輪」または 「時の車輪」と呼ばれる車輪として時間が描かれている。この考え方によると、宇宙は創造、維持、破壊の無限のサイクルを繰り返すという。[41] 同様に、マヤ、アステカ、中国などの古代文化においても、循環的な時間の概念が信じられており、それはしばしば天体観測や暦と関連していた。[42] これらの文化では、時間、季節、天体の動きを追跡する複雑なシステムが発達し、自然界や宇宙における循環的なパターンに対する理解を反映していた。 時間の循環的な見方は、西洋思想でより一般的である直線的な時間の概念とは対照的である。西洋では、時間は過去から未来へと繰り返されることなく直線的に進むものと見なされている。 アブラハムの宗教における時間 一般的に、イスラム教とユダヤ・キリスト教の世界観では、時間は直線的[44]かつ方向性のあるものとみなされており[45]、神による創造行為から始 まっている。伝統的なキリスト教の考えでは、時間は目的論的に[46]、すなわち、現在の事物の秩序の終末論的な終わりである「終わりの時」とともに終わ るとされている。 ソロモン(紀元前970年~928年)のものとされる旧約聖書の『伝道の書』では、時間(ヘブライ語の単語「עידן(アイダン)」、「זמן(ゼマ ン)」、「zĕman(タイム)」として訳されることが多い)は 運命づけられた出来事が起こるための媒体である。[要出典](「زمان」という別の単語は「時間」を意味し、出来事の起こるのに適した時間を意味し、現 代のアラビア語、ペルシア語、ヘブライ語では英語の「時間」に相当する言葉として使われている。) |

| Time in Greek mythology The Greek language denotes two distinct principles, Chronos and Kairos. The former refers to numeric, or chronological, time. The latter, literally "the right or opportune moment", relates specifically to metaphysical or Divine time. In theology, Kairos is qualitative, as opposed to quantitative.[47] In Greek mythology, Chronos (ancient Greek: Χρόνος) is identified as the Personification of Time. His name in Greek means "time" and is alternatively spelled Chronus (Latin spelling) or Khronos. Chronos is usually portrayed as an old, wise man with a long, gray beard, such as "Father Time". Some English words whose etymological root is khronos/chronos include chronology, chronometer, chronic, anachronism, synchronise, and chronicle. Time in Kabbalah & Rabbinical thought Rabbis sometimes saw time like "an accordion that was expanded and collapsed at will." [48] According to Kabbalists, "time" is a paradox[49] and an illusion.[50] Time in Advaita Vedanta According to Advaita Vedanta, time is integral to the phenomenal world, which lacks independent reality. Time and the phenomenal world are products of maya, influenced by our senses, concepts, and imaginations. The phenomenal world, including time, is seen as impermanent and characterized by plurality, suffering, conflict, and division. Since phenomenal existence is dominated by temporality (kala), everything within time is subject to change and decay. Overcoming pain and death requires knowledge that transcends temporal existence and reveals its eternal foundation.[51] |

ギリシア神話における時間 ギリシア語では、クロノス(Chronos)とカイロス(Kairos)という2つの異なる概念を意味する。前者は、数字や年代で表される時間を指す。後 者は文字通り「適切な瞬間」を意味し、形而上学的な時間や神聖な時間と関連している。神学では、カイロスは量的なものではなく質的なものとされる。 ギリシア神話では、クロノス(古代ギリシア語:Χρόνος)は時間の擬人化とされる。ギリシャ語での名前は「時間」を意味し、クロノス(ラテン語表記) またはクロノスとも表記される。クロノスは通常、「時の神」のように、長い白い髭を生やした賢者として描かれる。クロノス/クロノスを語源とする英語に は、chronology(年代学)、chronometer(クロノメーター)、chronic(慢性)、anachronism(時代錯誤)、 synchronise(同期)、chronicle(年代記)などがある。 カバラとラビ思想における時間 ラビたちは時として「自在に伸縮するアコーディオン」のようなものとして時間を捉えていた。[48] カバラ学者によれば、「時間」はパラドックス[49]であり、幻想[50]である。 アドヴァイタ・ヴェーダーンタにおける時間 アドヴァイタ・ヴェーダーンタによれば、時間とは独立した実体を持たない現象世界に不可欠なものである。時間と現象界は、人間の感覚、概念、想像力に影響 される「マヤ」の産物である。時間を含む現象界は、無常であり、多様性、苦しみ、葛藤、分裂を特徴とする。現象界は「時間性(kala)」に支配されてい るため、時間内のすべては変化と腐敗の対象となる。苦しみと死を克服するには、時間的な存在を超越し、その永遠の基盤を明らかにする知識が必要である。 |

| In Western philosophy Main articles: Philosophy of space and time and Temporal finitism  Time's mortal aspect is personified in this bronze statue by Charles van der Stappen. Two contrasting viewpoints on time divide prominent philosophers. One view is that time is part of the fundamental structure of the universe – a dimension independent of events, in which events occur in sequence. Isaac Newton subscribed to this realist view, and hence it is sometimes referred to as Newtonian time.[52][53] The opposing view is that time does not refer to any kind of "container" that events and objects "move through", nor to any entity that "flows", but that it is instead part of a fundamental intellectual structure (together with space and number) within which humans sequence and compare events. This second view, in the tradition of Gottfried Leibniz[17] and Immanuel Kant,[54][55] holds that time is neither an event nor a thing, and thus is not itself measurable nor can it be travelled. Furthermore, it may be that there is a subjective component to time, but whether or not time itself is "felt", as a sensation, or is a judgment, is a matter of debate.[2][6][7][56][57] In Philosophy, time was questioned throughout the centuries; what time is and if it is real or not. Ancient Greek philosophers asked if time was linear or cyclical and if time was endless or finite.[58] These philosophers had different ways of explaining time; for instance, ancient Indian philosophers had something called the Wheel of Time. It is believed that there was repeating ages over the lifespan of the universe.[59] This led to beliefs like cycles of rebirth and reincarnation.[59] The Greek philosophers believe that the universe was infinite, and was an illusion to humans.[59] Plato believed that time was made by the Creator at the same instant as the heavens.[59] He also says that time is a period of motion of the heavenly bodies.[59] Aristotle believed that time correlated to movement, that time did not exist on its own but was relative to motion of objects.[59] He also believed that time was related to the motion of celestial bodies; the reason that humans can tell time was because of orbital periods and therefore there was a duration on time.[60] The Vedas, the earliest texts on Indian philosophy and Hindu philosophy dating to the late 2nd millennium BC, describe ancient Hindu cosmology, in which the universe goes through repeated cycles of creation, destruction and rebirth, with each cycle lasting 4,320 million years.[61] Ancient Greek philosophers, including Parmenides and Heraclitus, wrote essays on the nature of time.[62] Plato, in the Timaeus, identified time with the period of motion of the heavenly bodies. Aristotle, in Book IV of his Physica defined time as 'number of movement in respect of the before and after'.[63] In Book 11 of his Confessions, St. Augustine of Hippo ruminates on the nature of time, asking, "What then is time? If no one asks me, I know: if I wish to explain it to one that asketh, I know not." He begins to define time by what it is not rather than what it is,[64] an approach similar to that taken in other negative definitions. However, Augustine ends up calling time a "distention" of the mind (Confessions 11.26) by which we simultaneously grasp the past in memory, the present by attention, and the future by expectation. Isaac Newton believed in absolute space and absolute time; Leibniz believed that time and space are relational.[65] The differences between Leibniz's and Newton's interpretations came to a head in the famous Leibniz–Clarke correspondence. Philosophers in the 17th and 18th century questioned if time was real and absolute, or if it was an intellectual concept that humans use to understand and sequence events.[58] These questions lead to realism vs anti-realism; the realists believed that time is a fundamental part of the universe, and be perceived by events happening in a sequence, in a dimension.[66] Isaac Newton said that we are merely occupying time, he also says that humans can only understand relative time.[66] Relative time is a measurement of objects in motion.[66] The anti-realists believed that time is merely a convenient intellectual concept for humans to understand events.[66] This means that time was useless unless there were objects that it could interact with, this was called relational time.[66] René Descartes, John Locke, and David Hume said that one's mind needs to acknowledge time, in order to understand what time is.[60] Immanuel Kant believed that we can not know what something is unless we experience it first hand.[67] |

西洋哲学における時間 詳細は「時空哲学」および「時間的フィニテ主義」を参照  チャールズ・ファン・デル・スタッペンによるこのブロンズ像では、時間の死すべき定めが擬人化されている。 著名な哲学者たちは、時間に関する2つの対照的な見解に分かれている。1つの見解は、時間は宇宙の基本構造の一部であり、出来事とは独立した次元であり、 その中で出来事が順番に起こるというものである。アイザック・ニュートンは、この現実主義的な見解に賛同しており、そのため、ニュートン時間と呼ばれるこ ともある。 これに反対する見解は、時間とは、出来事や物体が「通過する」いかなる種類の「入れ物」でもなく、「流れる」いかなる実体でもない。むしろ、人間が出来事 を順序づけたり比較したりする知的構造(空間や数とともに)の一部である、というものである。この2つ目の見解は、ゴットフリート・ライプニッツ[17] やイマヌエル・カント[54][55]の伝統に則り、時間は出来事でも物でもないため、それ自体は測定可能ではなく、また移動することもできないとする。 さらに、時間には主観的な要素があるかもしれないが、時間そのものが感覚として「感じられる」ものなのか、あるいは判断なのかは議論の余地がある。 哲学では、時間とは何か、実在するのか、といったことが何世紀にもわたって問われてきた。古代ギリシャの哲学者たちは、時間は直線的か循環的か、時間は無 限か有限か、といったことを問うた。[58] これらの哲学者たちは、時間について異なる説明の仕方をしていた。例えば、古代インディアンの哲学者たちは「時の輪」と呼ばれるものを持っていた。宇宙の 寿命を超えて繰り返される時代があったと考えられている。[59] これが輪廻転生のような信仰につながった。[59] ギリシアの哲学者たちは、宇宙は無限であり、人間にとっての幻想であると考えていた。[59] プラトンは、時間とは天地創造と同時に創造主によって作られたものであると考えていた。[59] また、彼は 天体の運動の期間であると述べている。[59] アリストテレスは、時間は運動と相関関係にあり、時間はそれ自体として存在するのではなく、物体の運動と相対的なものであると信じていた。[59] また、時間は天体の運動と関係していると考えており、人間が時間を認識できるのは、軌道周期があるためであり、したがって、時間には持続性があるのだとし た。[60] ヴェーダは、紀元前2千年紀後半にさかのぼるインディアン哲学およびヒンドゥー哲学の最も古い文献であり、古代ヒンドゥーの宇宙論を記述している。それに よれば、宇宙は創造、破壊、再生の繰り返しを経験し、各周期は43 2000万年である。[61] パルメニデスやヘラクレイトスなどの古代ギリシアの哲学者たちは、時間の性質に関する論文を書いた。[62] プラトンは『ティマイオス』において、時間を天体の運動期間と同一視した。アリストテレスは『自然学』第4巻において、時間を「前と後との関係における運 動の数」と定義した。[63] 『告白録』第11巻において、ヒッポの聖アウグスティヌスは時間の性質について熟考し、「では、時間とは何なのか? 誰も私に尋ねてこなければ、私は知っている。しかし、尋ねてくる者に説明しようと思えば、私は知らない」と述べている。彼は、時 間とは何かではなく、時間とは何かではないものによって時間を定義し始めている。これは、他の否定定義で用いられるアプローチに類似している。しかし、ア ウグスティヌスは最終的に、時間とは、記憶によって過去を、注意によって現在を、期待によって未来を同時に把握する心の「膨張」であると定義した(『告白』第11章第26節)。 アイザック・ニュートンは、絶対的な空間と絶対的な時間を信じていた。一方、ライプニッツは、時間と空間は相対的なものであると考えていた。[65] ライプニッツとニュートンの解釈の相違は、有名なライプニッツとクラークの書簡のやり取りで頂点に達した。 17世紀と18世紀の哲学者たちは、時間は現実のもので絶対的なものなのか、あるいは人間が事象を理解し順序づけるために用いる知的概念なのかを疑問視し た。[58] これらの疑問は、現実主義対反現実主義へとつながる。現実主義者は、時間は宇宙の根本的な一部であり、 。アイザック・ニュートンは、我々は単に時間を占有しているに過ぎず、人間は相対的な時間しか理解できないと述べている。相対的な時間とは、運動する物体 の測定値である。反実在論者は、時間とは人間が事象を理解するための便利な知的概念に過ぎないと考えた。相互作用できる対象がなければ、時間は何の役にも 立たない。これを「相対時間」と呼ぶ。[66] ルネ・デカルト、ジョン・ロック、デイヴィッド・ヒュームは、時間とは何かを理解するには、まず人の心が時間を認識する必要があるとした。[60] イマヌエル・カントは、何かを直接経験しなければ、それが何であるかを理解することはできないと信じていた。[67] |

| Time is not an empirical

concept. For neither co-existence nor succession would be perceived by

us, if the representation of time did not exist as a foundation a

priori. Without this presupposition, we could not represent to

ourselves that things exist together at one and the same time, or at

different times, that is, contemporaneously, or in succession. Immanuel Kant, Critique of Pure Reason (1781), trans. Vasilis Politis (London: Dent., 1991), p. 54. |

時間は経験的な概念ではない。時間表現がア・プリオリに基礎として存在しなければ、共存も連続も私たちには認識されない。この前提がなければ、私たちは同時に、あるいは異なる時間、つまり同時、あるいは連続して、物事が存在することを自分自身に表現することはできない。 イマニュエル・カント著『純粋理性批判』(1781年)、ヴァシリス・ポリティス訳(ロンドン:デント社、1991年)、54ページ。 |

| Immanuel Kant, in the Critique

of Pure Reason, described time as an a priori intuition that allows us

(together with the other a priori intuition, space) to comprehend sense

experience.[68] With Kant, neither space nor time are conceived as

substances, but rather both are elements of a systematic mental

framework that necessarily structures the experiences of any rational

agent, or observing subject. Kant thought of time as a fundamental part

of an abstract conceptual framework, together with space and number,

within which we sequence events, quantify their duration, and compare

the motions of objects. In this view, time does not refer to any kind

of entity that "flows," that objects "move through," or that is a

"container" for events. Spatial measurements are used to quantify the

extent of and distances between objects, and temporal measurements are

used to quantify the durations of and between events. Time was

designated by Kant as the purest possible schema of a pure concept or

category. Henri Bergson believed that time was neither a real homogeneous medium nor a mental construct, but possesses what he referred to as Duration. Duration, in Bergson's view, was creativity and memory as an essential component of reality.[69] According to Martin Heidegger we do not exist inside time, we are time. Hence, the relationship to the past is a present awareness of having been, which allows the past to exist in the present. The relationship to the future is the state of anticipating a potential possibility, task, or engagement. It is related to the human propensity for caring and being concerned, which causes "being ahead of oneself" when thinking of a pending occurrence. Therefore, this concern for a potential occurrence also allows the future to exist in the present. The present becomes an experience, which is qualitative instead of quantitative. Heidegger seems to think this is the way that a linear relationship with time, or temporal existence, is broken or transcended.[70] We are not stuck in sequential time. We are able to remember the past and project into the future – we have a kind of random access to our representation of temporal existence; we can, in our thoughts, step out of (ecstasis) sequential time.[71] Modern era philosophers asked: is time real or unreal, is time happening all at once or a duration, is time tensed or tenseless, and is there a future to be?[58] There is a theory called the tenseless or B-theory; this theory says that any tensed terminology can be replaced with tenseless terminology.[72] For example, "we will win the game" can be replaced with "we do win the game", taking out the future tense. On the other hand, there is a theory called the tense or A-theory; this theory says that our language has tense verbs for a reason and that the future can not be determined.[72] There is also something called imaginary time, this was from Stephen Hawking, who said that space and imaginary time are finite but have no boundaries.[72] Imaginary time is not real or unreal, it is something that is hard to visualize.[72] Philosophers can agree that physical time exists outside of the human mind and is objective, and psychological time is mind-dependent and subjective.[60] |

イマニュエル・カントは『純粋理性批判』において、時間とは、他のア・

プリオリ直観である空間とともに、感覚経験を理解することを可能にするア・プリオリ直観であると述べている。[68]

カントによれば、空間も時間も実体として考えられるものではなく、むしろ両者は、あらゆる理性的な主体、すなわち観察者の経験を必然的に構造化する体系的

な精神の枠組みの要素である。カントは、時間とは空間や数とともに抽象的な概念的枠組みの根本的な一部であり、その枠組みの中で私たちは出来事を順序づ

け、その持続時間を数量化し、物体の運動を比較するものだと考えた。この見解では、時間は「流れる」もの、物体が「通過する」もの、あるいは出来事の「入

れ物」となるような実体とはみなされない。物体の広がりや物体間の距離を数量化するには空間的な測定が用いられ、出来事の持続時間や出来事間の時間を数量

化するには時間的な測定が用いられる。カントは時間を純粋概念または純粋範疇の最も純粋なスキーマと位置づけた。 アンリ・ベルクソンは、時間は現実の均質な媒体でも精神の構築物でもないが、彼が「持続」と呼ぶものを備えていると信じていた。ベルクソンによれば、「持続」は現実の本質的な構成要素としての創造性と記憶であった。 マルティン・ハイデガーによれば、我々は時間の内部に存在するのではなく、我々自身が時間である。したがって、過去との関係は、過去が現在に存在すること を可能にする、現在における「あったこと」の認識である。未来との関係は、潜在的可能性、課題、または関与を予期する状態である。それは、懸案事項につい て考える際に「先回りする」という、思いやりや関心を持つという人間の傾向と関連している。したがって、潜在的な出来事に対するこの懸念も、未来が現在に 存在することを可能にする。現在が経験となり、それは量的ではなく質的なものとなる。ハイデガーは、時間との直線的な関係、あるいは時間的存在が断ち切ら れ、あるいは超越されるのはこの方法であると考えているようだ。[70] 私たちは連続した時間に縛られているわけではない。過去を思い出し、未来を予測することができる。私たちは時間的存在の表現にランダムアクセスできるよう なものであり、思考の中で連続した時間から抜け出す(ecstasis)ことができる。[71] 近代の哲学者たちは、時間とは実在するのか、それとも実在しないのか、時間は一度に起こるのか、それとも継続するのか、時間は緊張的(tense)なの か、それとも緊張のない(tenseless)ものなのか、そして未来はあるのか、と問いかけた。[58] 緊張のない(tenseless)理論、またはB理論と呼ばれる理論がある。この理論では、緊張のある(tense)用語は緊張のない (tenseless)用語に置き換えることができるとしている。[72] たとえば、「我々は試合に勝つだろう」という表現は、「我々は試合に勝っている」という表現に置き換えることができ、未来形が取り除かれる。一方、時制ま たはA理論と呼ばれる理論もある。この理論では、私たちの言語には時制動詞が存在する理由があり、未来は決定できないとしている。[72] また、想像上の時間と呼ばれるものもある。これはスティーブン・ホーキングによるもので、空間と想像上の 時間には境界はないと述べた。[72] 想像上の時間は現実でも非現実でもない。想像上の時間は視覚化するのが難しいものである。[72] 物理的な時間は人間の心の外に存在し客観的である。心理的な時間は心に依存し主観的である。[60] |

| Unreality In 5th century BC Greece, Antiphon the Sophist, in a fragment preserved from his chief work On Truth, held that: "Time is not a reality (hypostasis), but a concept (noêma) or a measure (metron)." Parmenides went further, maintaining that time, motion, and change were illusions, leading to the paradoxes of his follower Zeno.[73] Time as an illusion is also a common theme in Buddhist thought.[74][75] J. M. E. McTaggart's 1908 The Unreality of Time argues that, since every event has the characteristic of being both present and not present (i.e., future or past), that time is a self-contradictory idea (see also The flow of time).[citation needed] These arguments often center on what it means for something to be unreal. Modern physicists generally believe that time is as real as space – though others, such as Julian Barbour, argue quantum equations of the universe take their true form when expressed in the timeless realm containing every possible now or momentary configuration of the universe.[citation needed] A modern philosophical theory called presentism views the past and the future as human-mind interpretations of movement instead of real parts of time (or "dimensions") which coexist with the present. This theory rejects the existence of all direct interaction with the past or the future, holding only the present as tangible. This is one of the philosophical arguments against time travel. This contrasts with eternalism (all time: present, past and future, is real) and the growing block theory (the present and the past are real, but the future is not).[citation needed] |

非現実 紀元前5世紀のギリシャでは、ソフィストのアンティフォンは、彼の主要な著作『真理について』の断片の中で、「時間は現実(下位概念)ではなく、概念(ノ エマ)または尺度(メトロン)」であると主張した。パルメニデスはさらに踏み込んで、時間、運動、変化は幻想であり、彼の信奉者ゼノンのパラドックスにつ ながる、と主張した。[73] 幻想としての時間は、仏教思想においても一般的なテーマである。[74][75] J. M. E. マクタガートの1908年の著書『時間の非現実性』では、あらゆる出来事は「現在であると同時に現在でない」(すなわち、未来または過去)という特徴を持つため、時間は自己矛盾した概念であると論じている(『時間の流れ』も参照)。 これらの議論は、しばしば「非現実的である」とは何を意味するのかという点に集中する。現代の物理学者は一般的に、時間は空間と同じくらい現実的であると 信じているが、ジュリアン・バーバー(Julian Barbour)などの一部の学者は、宇宙のあらゆる「今」または瞬間的な構成を含む、時間のない領域で表現されたときに、宇宙の量子方程式は真の姿を表 す、と主張している。 現代の哲学理論である現在主義は、過去と未来を、現在と共存する時間(または「次元」)の現実の一部ではなく、人間の心による動きの解釈と見なしている。 この理論は、過去や未来との直接的な相互作用の存在をすべて否定し、現在のみを実体あるものとしている。これは、時間旅行に対する哲学的反論のひとつであ る。これは、永遠論(現在、過去、未来のすべてが現実である)や成長ブロック理論(現在と過去は現実だが、未来は現実ではない)とは対照的である。[要出 典] |

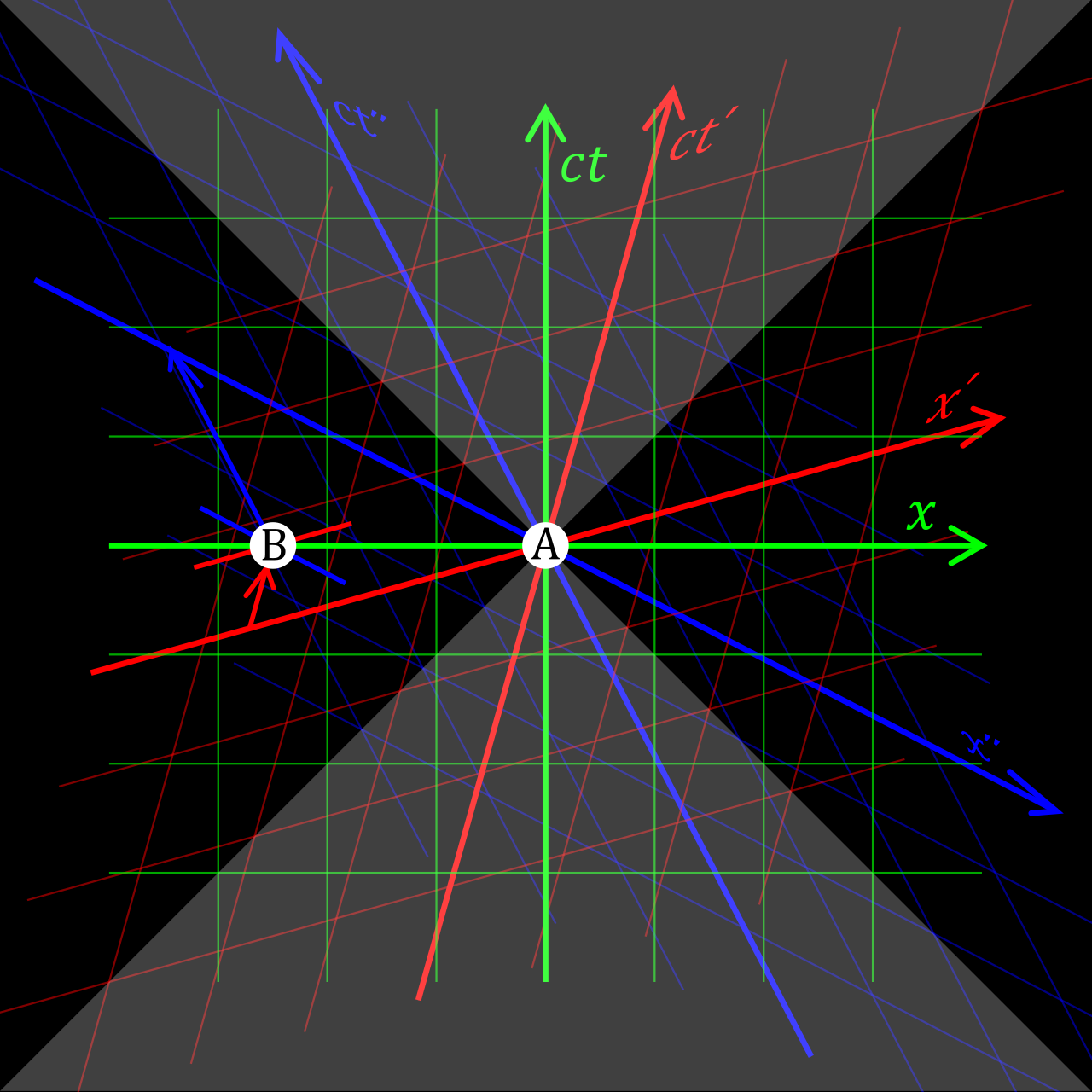

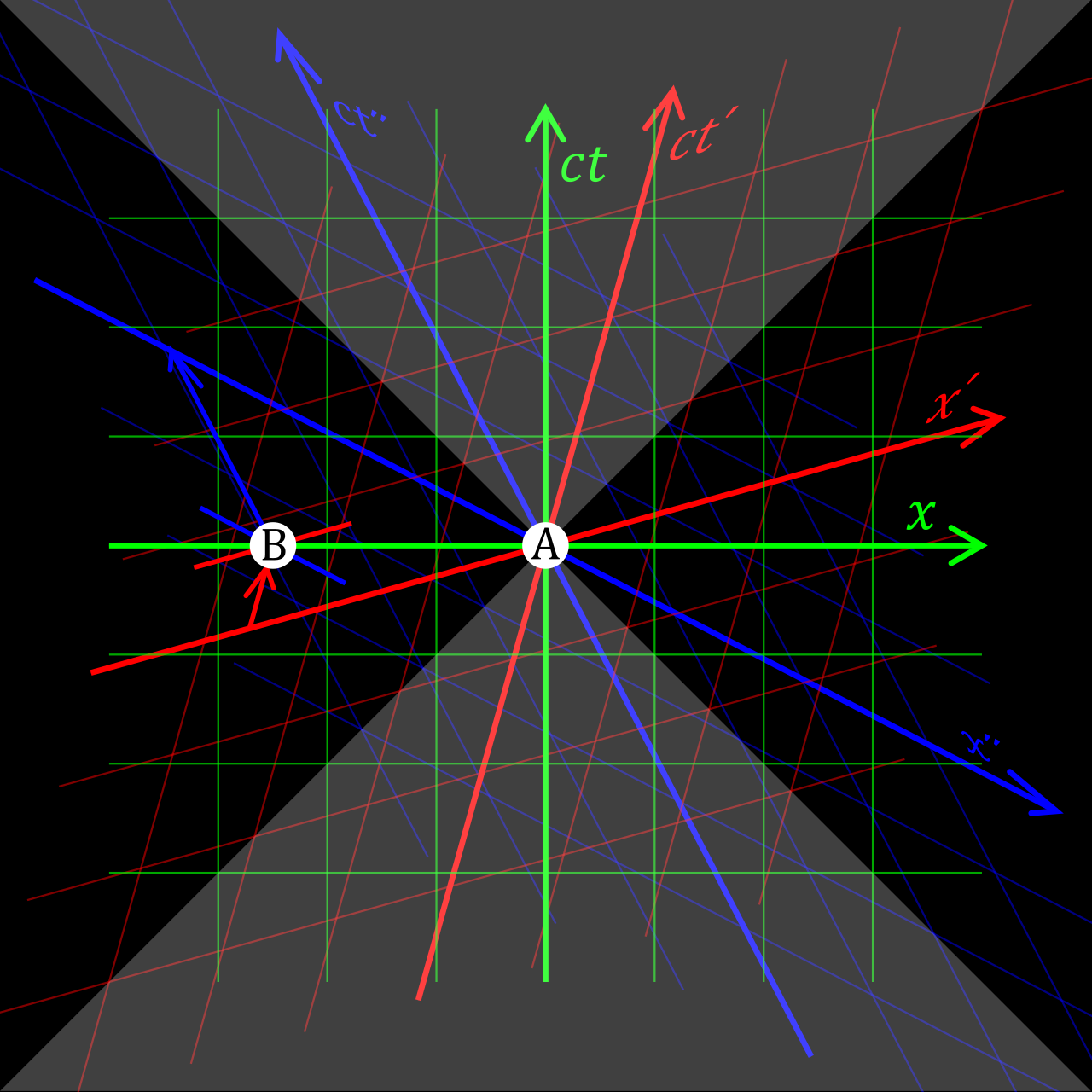

| Main article: Time in physics Until Einstein's reinterpretation of the physical concepts associated with time and space in 1907, time was considered to be the same everywhere in the universe, with all observers measuring the same time interval for any event.[76] Non-relativistic classical mechanics is based on this Newtonian idea of time. Einstein, in his special theory of relativity,[77] postulated the constancy and finiteness of the speed of light for all observers. He showed that this postulate, together with a reasonable definition for what it means for two events to be simultaneous, requires that distances appear compressed and time intervals appear lengthened for events associated with objects in motion relative to an inertial observer. The theory of special relativity finds a convenient formulation in Minkowski spacetime, a mathematical structure that combines three dimensions of space with a single dimension of time. In this formalism, distances in space can be measured by how long light takes to travel that distance, e.g., a light-year is a measure of distance, and a meter is now defined in terms of how far light travels in a certain amount of time. Two events in Minkowski spacetime are separated by an invariant interval, which can be either space-like, light-like, or time-like. Events that have a time-like separation cannot be simultaneous in any frame of reference, there must be a temporal component (and possibly a spatial one) to their separation. Events that have a space-like separation will be simultaneous in some frame of reference, and there is no frame of reference in which they do not have a spatial separation. Different observers may calculate different distances and different time intervals between two events, but the invariant interval between the events is independent of the observer (and his or her velocity). |

詳細は「物理学における時間」を参照 アインシュタインが1907年に時間と空間に関連する物理的概念を再解釈するまでは、時間とは宇宙のどこでも同じであり、すべての観察者があらゆる事象に 対して同じ時間間隔を測定すると考えられていた。[76] 非相対論的な古典力学は、このニュートン的な時間観に基づいている。 アインシュタインは特殊相対性理論において、[77] すべての観察者にとって光速は一定かつ有限であると仮定した。彼は、この仮定と2つの事象が同時であることを意味する妥当な定義を併せると、慣性系観察者 に対して相対的に運動している物体に関連する事象については、距離が圧縮されて見え、時間間隔が延びて見えることが必要であることを示した。 特殊相対性理論は、3次元の空間と1次元の時間を組み合わせた数学的構造であるミンコフスキー時空という便利な定式化を見出している。この形式では、例え ば光年は距離の単位であり、メートルは一定時間内に光がどれだけ進むかによって定義される。ミンコフスキー時空における2つの事象は不変間隔によって隔て られているが、その不変間隔は、空間的、光学的、時間的のいずれかである。時間的間隔を持つ事象は、いかなる参照フレームにおいても同時であることはあり えず、その間隔には時間的要素(場合によっては空間的要素)が存在しなければならない。空間的間隔を持つ事象は、ある参照フレームにおいては同時である が、空間的間隔を持たない参照フレームは存在しない。異なる観察者は、2つの事象間の異なる距離と異なる時間間隔を計算するかもしれないが、事象間の不変 の間隔は観察者(およびその速度)とは無関係である。 |

| Arrow of time Main article: Arrow of time Unlike space, where an object can travel in the opposite directions (and in 3 dimensions), time appears to have only one dimension and only one direction – the past lies behind, fixed and immutable, while the future lies ahead and is not necessarily fixed. Yet most laws of physics allow any process to proceed both forward and in reverse. There are only a few physical phenomena, that violate the reversibility of time. This time directionality is known as the arrow of time. Acknowledged examples of the arrow of time are:[78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85] 1. Radiative arrow of time, manifested in waves (e.g. light and sound) travelling only expanding (rather than focusing) in time (see light cone); 2. Entropic arrow of time: according to the second law of thermodynamics an isolated system evolves toward a larger disorder rather than orders spontaneously; 3. Quantum arrow time, which is related to irreversibility of measurement in quantum mechanics according to the Copenhagen interpretation of quantum mechanics; 4. Weak arrow of time: preference for a certain time direction of weak force in particle physics (see violation of CP symmetry); 5.Cosmological arrow of time, which follows the accelerated expansion of the Universe after the Big Bang. The relationship(s) between these different Arrows of Time is a hotly debated topic in theoretical physics.[86] |

時間の矢 詳細は「時間の矢」を参照 物体が逆方向に移動できる空間(3次元)とは異なり、時間は1つの方向性しか持たないように見える。過去は後ろにあり、固定され、不変である。一方、未来 は前にあるが、必ずしも固定されているわけではない。しかし、物理法則のほとんどは、あらゆるプロセスが前進と後退の両方で進行することを許容している。 時間の可逆性を破る物理現象はわずかしかない。この時間方向性は「時間の矢」として知られている。時間の矢として認められている例は以下の通りである: [78][79][80][81][82][83][84][85] 1. 放射状の時間軸:波(例:光や音)が時間の中で拡大するのみ(収束しない)で進行することに現れる(光円錐を参照)。 2. エントロピーの時間軸:熱力学第二法則によると、孤立したシステムは自然に秩序化するよりもむしろ大きな無秩序に向かって進化する。 3. 量子の時間軸:これは、コペンハーゲン解釈による量子力学における測定の不可逆性に関連している。 4. 弱い時間の矢:素粒子物理学における弱い力の特定の時間方向への偏り(CP対称性の破れを参照)。 5. ビッグバン後の宇宙の加速的膨張に起因する宇宙の時間の矢。 これらの異なる時間の矢の関係は、理論物理学における活発な議論の対象となっている。[86] |

| Classical mechanics In non-relativistic classical mechanics, Newton's concept of "relative, apparent, and common time" can be used in the formulation of a prescription for the synchronization of clocks. Events seen by two different observers in motion relative to each other produce a mathematical concept of time that works sufficiently well for describing the everyday phenomena of most people's experience. In the late nineteenth century, physicists encountered problems with the classical understanding of time, in connection with the behavior of electricity and magnetism. Einstein resolved these problems by invoking a method of synchronizing clocks using the constant, finite speed of light as the maximum signal velocity. This led directly to the conclusion that observers in motion relative to one another measure different elapsed times for the same event. |

古典力学 非相対論的な古典力学では、ニュートンの「相対的、仮想的、一般的な時間」という概念を、時計の同期化のための処方の策定に利用することができる。互いに 相対的に運動している2人の異なる観察者が目にする事象は、ほとんどの人々が経験する日常的な現象を説明するのに十分なほど、数学的な時間の概念を生み出 す。19世紀後半、物理学者たちは電気や磁気の挙動に関連して、古典的な時間の理解に問題があることに気づいた。アインシュタインは、信号の最大速度とし て光の一定かつ有限の速度を使用して時計を同期させる方法を採用することで、これらの問題を解決した。これにより、互いに相対運動している観測者は、同じ 出来事に対して異なる経過時間を測定するという結論に直接つながった。 |

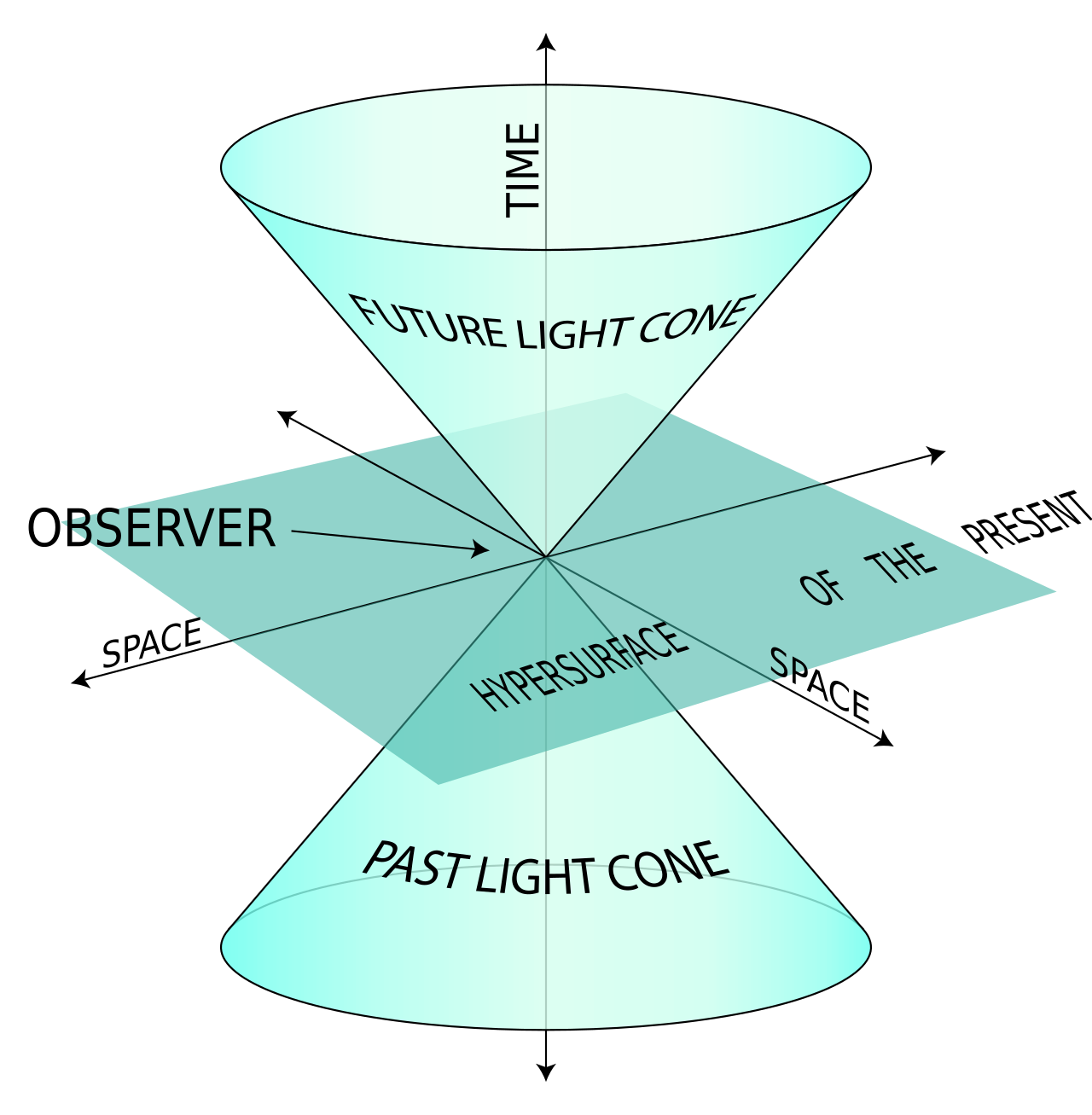

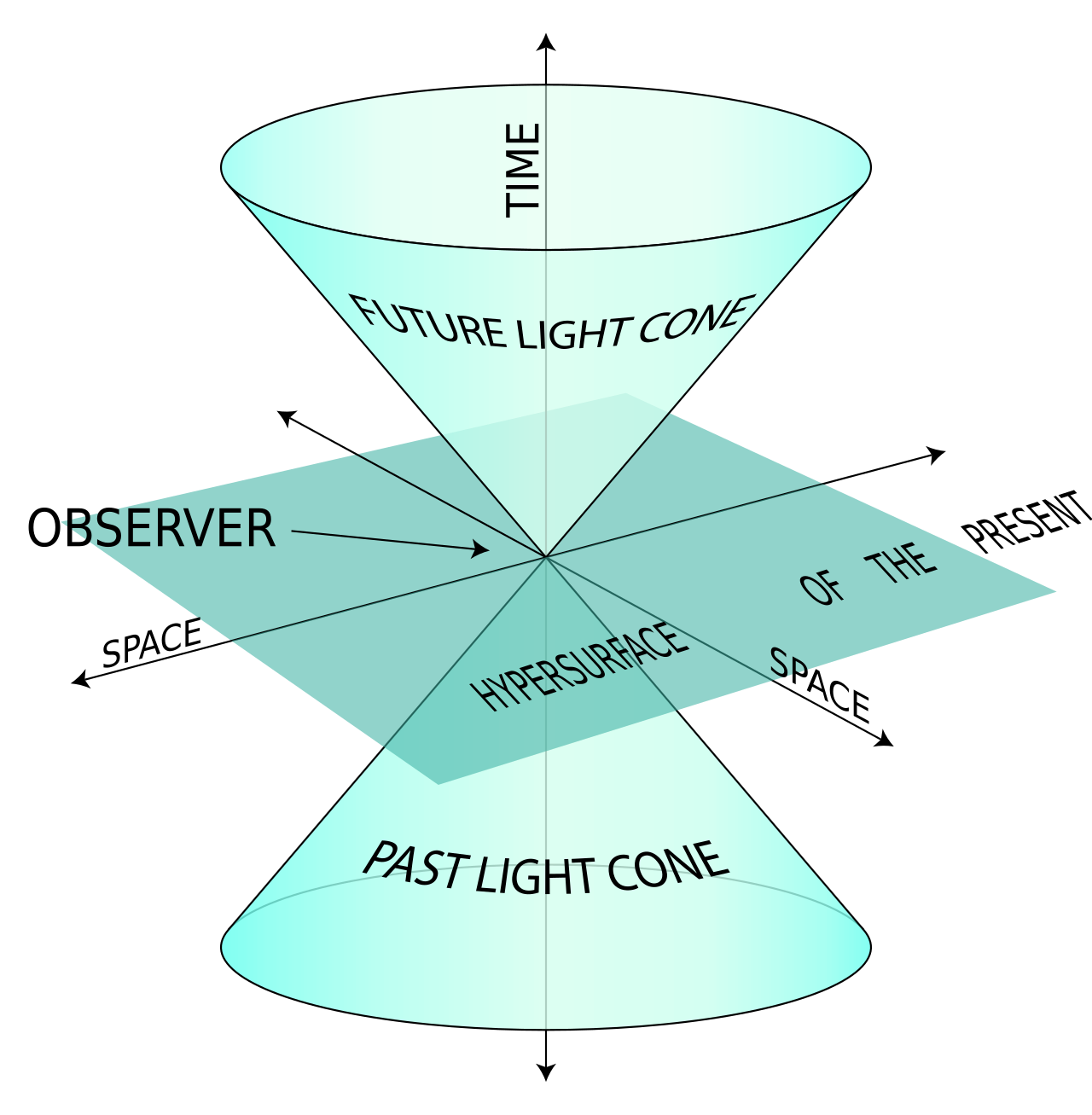

| Spacetime Main article: Spacetime Time has historically been closely related with space, the two together merging into spacetime in Einstein's special relativity and general relativity. According to these theories, the concept of time depends on the spatial reference frame of the observer, and the human perception, as well as the measurement by instruments such as clocks, are different for observers in relative motion. For example, if a spaceship carrying a clock flies through space at (very nearly) the speed of light, its crew does not notice a change in the speed of time on board their vessel because everything traveling at the same speed slows down at the same rate (including the clock, the crew's thought processes, and the functions of their bodies). However, to a stationary observer watching the spaceship fly by, the spaceship appears flattened in the direction it is traveling and the clock on board the spaceship appears to move very slowly. On the other hand, the crew on board the spaceship also perceives the observer as slowed down and flattened along the spaceship's direction of travel, because both are moving at very nearly the speed of light relative to each other. Because the outside universe appears flattened to the spaceship, the crew perceives themselves as quickly traveling between regions of space that (to the stationary observer) are many light years apart. This is reconciled by the fact that the crew's perception of time is different from the stationary observer's; what seems like seconds to the crew might be hundreds of years to the stationary observer. In either case, however, causality remains unchanged: the past is the set of events that can send light signals to an entity and the future is the set of events to which an entity can send light signals.[87][88] |

時空 詳細は「時空」を参照 時間と空間は歴史的に密接に関連しており、アインシュタインの特殊相対性理論および一般相対性理論では、この2つは時空へと融合する。これらの理論による と、時間の概念は観察者の空間的参照枠に依存し、人間による知覚や時計などの機器による測定は、相対運動中の観察者にとっては異なるものとなる。例えば、 時計を搭載した宇宙船が光速に近い速度で宇宙空間を飛行している場合、宇宙船内の乗組員は時間の速度の変化に気づかない。なぜなら、同じ速度で移動するも のはすべて同じ速度で減速するからだ(時計、乗組員の思考プロセス、身体機能を含む)。しかし、宇宙船が飛ぶのを静止した状態で観察している観察者にとっ ては、宇宙船は進行方向に平らに伸びて見え、宇宙船内の時計は非常にゆっくりと動いているように見える。 一方、宇宙船の乗組員も、互いに光速に近い速度で移動しているため、観察者を宇宙船の進行方向に沿って遅く平らに動いているように知覚する。宇宙船の外側 の宇宙が平らに見えるため、乗組員は静止している観察者から見ると何光年も離れている宇宙の領域間を素早く移動しているように知覚する。これは、乗組員の 時間の認識が静止している観察者のそれとは異なるという事実によって説明される。乗組員にとっては数秒にしか感じられないことが、静止している観察者に とっては何百年にも感じられるかもしれない。しかし、いずれの場合でも因果関係は不変である。過去とは、ある存在に光信号を送ることができる一連の出来事 であり、未来とは、ある存在が光信号を送ることができる一連の出来事である。[87][88] |

Two-dimensional space depicted in three-dimensional spacetime. The past and future light cones are absolute, the "present" is a relative concept different for observers in relative motion. |

三次元時空に描かれた二次元空間。過去と未来の光の円錐は絶対的であり、「現在」は相対運動中の観察者にとっては異なる相対的な概念である。 |

| Dilation Main article: Time dilation  Relativity of simultaneity: Event B is simultaneous with A in the green reference frame, but it occurred before in the blue frame, and occurs later in the red frame. Einstein showed in his thought experiments that people travelling at different speeds, while agreeing on cause and effect, measure different time separations between events, and can even observe different chronological orderings between non-causally related events. Though these effects are typically minute in the human experience, the effect becomes much more pronounced for objects moving at speeds approaching the speed of light. Subatomic particles exist for a well-known average fraction of a second in a lab relatively at rest, but when travelling close to the speed of light they are measured to travel farther and exist for much longer than when at rest. According to the special theory of relativity, in the high-speed particle's frame of reference, it exists, on the average, for a standard amount of time known as its mean lifetime, and the distance it travels in that time is zero, because its velocity is zero. Relative to a frame of reference at rest, time seems to "slow down" for the particle. Relative to the high-speed particle, distances seem to shorten. Einstein showed how both temporal and spatial dimensions can be altered (or "warped") by high-speed motion. Einstein (The Meaning of Relativity): "Two events taking place at the points A and B of a system K are simultaneous if they appear at the same instant when observed from the middle point, M, of the interval AB. Time is then defined as the ensemble of the indications of similar clocks, at rest relative to K, which register the same simultaneously." Einstein wrote in his book, Relativity, that simultaneity is also relative, i.e., two events that appear simultaneous to an observer in a particular inertial reference frame need not be judged as simultaneous by a second observer in a different inertial frame of reference. |

膨張 詳細は「時間の遅れ」を参照  同時性の相対性:イベントBは緑色の参照フレームではイベントAと同時であるが、青色のフレームではイベントBが先に発生しており、赤色のフレームではイベントBが後に発生している。 アインシュタインは思考実験により、異なる速度で移動する人々は、因果関係には同意するものの、イベント間の時間の経過を異なるように測定し、因果関係の ないイベント間では異なる時間順序を観察することさえあり得ることを示した。これらの効果は通常、人間の経験ではごくわずかであるが、光速に近い速度で移 動する物体では、その影響ははるかに顕著になる。 素粒子は、実験室では比較的静止した状態で、周知の平均的な分数秒間だけ存在するが、光速に近い速度で移動すると、静止している時よりもはるかに長い距離 を移動し、より長い時間存在することが測定される。特殊相対性理論によると、高速で移動する粒子の基準では、平均寿命として知られる標準的な時間だけ存在 し、その時間内に移動する距離はゼロである。なぜなら、その速度はゼロだからだ。静止している基準と比較すると、粒子にとっては時間が「遅く」感じられ る。高速で移動する粒子と比較すると、距離が短く感じられる。アインシュタインは、高速運動によって時間的および空間的次元がどのように変化(または「歪 曲」)するかを示した。 アインシュタイン(『相対性理論の意味』):「システムKのA点とB点で起こる2つの事象は、AB間の中央点Mから観察したときに同じ瞬間に見えた場合、 同時である。 したがって、時間は、Kに対して静止している同様の時計の指示値の集合体として定義され、それらの時計は同じ瞬間を同時に記録する。」 アインシュタインは著書『相対性理論』の中で、同時性も相対的であると述べている。すなわち、ある慣性参照系における観察者にとっては同時に起こっている ように見える2つの事象も、異なる慣性参照系における2人目の観察者にとっては同時に起こっていると判断する必要はない。 |

Relativistic versus Newtonian Views of spacetime along the world line of a rapidly accelerating observer in a relativistic universe. The events ("dots") that pass the two diagonal lines in the bottom half of the image (the past light cone of the observer in the origin) are the events visible to the observer. The animations visualise the different treatments of time in the Newtonian and the relativistic descriptions. At the heart of these differences are the Galilean and Lorentz transformations applicable in the Newtonian and relativistic theories, respectively. In the figures, the vertical direction indicates time. The horizontal direction indicates distance (only one spatial dimension is taken into account), and the thick dashed curve is the spacetime trajectory ("world line") of the observer. The small dots indicate specific (past and future) events in spacetime. The slope of the world line (deviation from being vertical) gives the relative velocity to the observer. In both pictures the view of spacetime changes when the observer accelerates. In the Newtonian description these changes are such that time is absolute:[89] the movements of the observer do not influence whether an event occurs in the 'now' (i.e., whether an event passes the horizontal line through the observer). However, in the relativistic description the observability of events is absolute: the movements of the observer do not influence whether an event passes the "light cone" of the observer. Notice that with the change from a Newtonian to a relativistic description, the concept of absolute time is no longer applicable: events move up and down in the figure depending on the acceleration of the observer. |

相対論的視点とニュートン力学的な視点 相対論的な宇宙空間における、急速に加速する観測者の世界線に沿った時空の相対論的視点とニュートン力学的な視点。 画像下半分の2本の対角線(原点における観測者の過去光円錐)を通過する事象(「点」)は、観測者が目にする事象である。 アニメーションは、ニュートン力学と相対論の時間に対する異なる取り扱いを視覚化している。これらの相違の核心にあるのは、ニュートン力学と相対性理論のそれぞれに適用されるガリレイ変換とローレンツ変換である。 図では、縦方向が時間を示している。横方向は距離(考慮されるのは1つの空間次元のみ)を示し、太い破線は観察者の時空軌道(「世界線」)である。小さな点は時空における特定の(過去と未来の)出来事を示している。 世界線の傾き(垂直からのずれ)は、観察者に対する相対速度を表している。どちらの図でも、観察者が加速すると時空の見え方が変わる。 ニュートン力学の記述では、これらの変化は時間が絶対的であることを意味する。すなわち、観察者の動きは、ある事象が「今」に起こるかどうか(すなわち、ある事象が観察者の通る水平線を通過するかどうか)に影響を与えない。 しかし、相対論的な記述では、事象の観測可能性は絶対的である。すなわち、観測者の動きは、事象が観測者の「光円錐」を通過するかどうかには影響しない。 ニュートン力学的な記述から相対論的な記述への変更に伴い、絶対時間の概念はもはや適用できないことに注意。事象は観測者の加速度に応じて図の中で上下に 動く。 |

| Quantization See also: Chronon Time quantization is a hypothetical concept. In the modern established physical theories (the Standard Model of Particles and Interactions and General Relativity) time is not quantized. Planck time (~ 5.4 × 10−44 seconds) is the unit of time in the system of natural units known as Planck units. Current established physical theories are believed to fail at this time scale, and many physicists expect that the Planck time might be the smallest unit of time that could ever be measured, even in principle. Tentative physical theories that describe this time scale exist; see for instance loop quantum gravity. Thermodynamics The second law of thermodynamics states that entropy must increase over time (see Entropy). This can be in either direction – Brian Greene theorizes that, according to the equations, the change in entropy occurs symmetrically whether going forward or backward in time. So entropy tends to increase in either direction, and our current low-entropy universe is a statistical aberration, in a similar manner as tossing a coin often enough that eventually heads will result ten times in a row. However, this theory is not supported empirically in local experiment.[90] |

量子化 関連情報:クロノン 時間の量子化は仮説上の概念である。現代の確立された物理理論(素粒子と相互作用の標準模型および一般相対性理論)では、時間は量子化されていない。 プランク時間(約5.4×10−44秒)は、プランク単位として知られる自然単位の体系における時間の単位である。現在の確立された物理理論は、この時間 スケールでは失敗すると考えられており、多くの物理学者は、プランク時間が原理的に測定可能な最小の時間単位である可能性があると期待している。この時間 スケールを説明する暫定的な物理理論は存在しており、例えばループ量子重力を参照のこと。 熱力学 熱力学の第二法則は、エントロピーは時間とともに増加しなければならないと述べている(エントロピーを参照)。これはどちらの方向にも起こりうる。ブライ アン・グリーンは、方程式によれば、エントロピーの変化は時間軸の順方向でも逆方向でも対称的に起こると理論づけている。つまり、エントロピーはどちらの 方向にも増加する傾向があり、現在の低エントロピー宇宙は、コインを何度も投げているうちに、最終的に10回連続で表が出るような統計的な異常である。し かし、この理論は局所的な実験では経験的に裏付けられていない。[90] |

| Travel Main article: Time travel See also: Time travel in fiction, Wormhole, and Twin paradox Time travel is the concept of moving backwards or forwards to different points in time, in a manner analogous to moving through space, and different from the normal "flow" of time to an earthbound observer. In this view, all points in time (including future times) "persist" in some way. Time travel has been a plot device in fiction since the 19th century. Travelling backwards or forwards in time has never been verified as a process, and doing so presents many theoretical problems and contradictive logic which to date have not been overcome. Any technological device, whether fictional or hypothetical, that is used to achieve time travel is known as a time machine. A central problem with time travel to the past is the violation of causality; should an effect precede its cause, it would give rise to the possibility of a temporal paradox. Some interpretations of time travel resolve this by accepting the possibility of travel between branch points, parallel realities, or universes. Another solution to the problem of causality-based temporal paradoxes is that such paradoxes cannot arise simply because they have not arisen. As illustrated in numerous works of fiction, free will either ceases to exist in the past or the outcomes of such decisions are predetermined. As such, it would not be possible to enact the grandfather paradox because it is a historical fact that one's grandfather was not killed before his child (one's parent) was conceived. This view does not simply hold that history is an unchangeable constant, but that any change made by a hypothetical future time traveller would already have happened in his or her past, resulting in the reality that the traveller moves from. More elaboration on this view can be found in the Novikov self-consistency principle. |

旅行 詳細は「時間旅行」を参照 関連項目:フィクションにおける時間旅行、ワームホール、ツインパラドックス 時間旅行とは、空間を移動することに類似した方法で、異なる時点へと前後に移動するという概念である。地球上の観察者にとっては、通常の時間の「流れ」と は異なる。この観点では、すべての時点(未来の時間を含む)は、何らかの形で「持続」している。タイムトラベルは19世紀以来、フィクションの筋立ての手 法として使われてきた。時間を遡ったり進んだりすることは、プロセスとして一度も証明されたことはなく、そうすることは多くの理論的な問題や矛盾した論理 を提起するが、今日まで克服されていない。フィクションであろうと仮説であろうと、タイムトラベルを達成するために使用されるあらゆる技術的装置はタイム マシンとして知られている。 過去へのタイムトラベルにおける中心的な問題は因果律の違反であり、結果が原因に先行する場合には時間的パラドックスの可能性が生じる。タイムトラベルに 関するいくつかの解釈では、分岐点、並行現実、あるいは宇宙間の移動の可能性を受け入れることで、この問題を解決している。 因果律に基づく時間的パラドックスの問題に対する別の解決策は、そのようなパラドックスがこれまで発生しなかったという理由だけで、今後も発生しないとい うものである。数多くのフィクション作品で描かれているように、自由意志は過去においては存在しなくなるか、あるいはそのような決定の結果はあらかじめ定 められている。そのため、祖父が子供(自分の親)が生まれる前に殺されることはなかったという歴史的事実があるため、祖父のパラドックスは発生しない。こ の見解は、単に歴史は不変の定数であるというものではなく、仮説上の未来からの旅行者によるいかなる変化も、すでに彼または彼女の過去に起こったことであ り、その結果として旅行者が移動する現実が生まれるというものである。この見解に関するより詳細な説明は、ノヴィコフの一貫性原理を参照のこと。 |

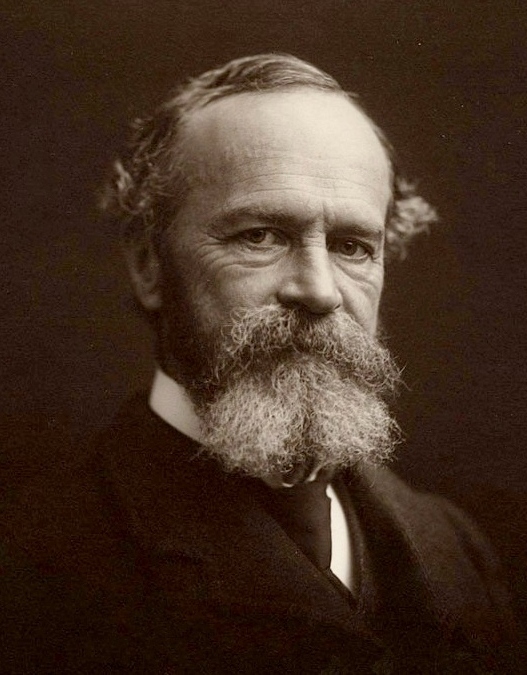

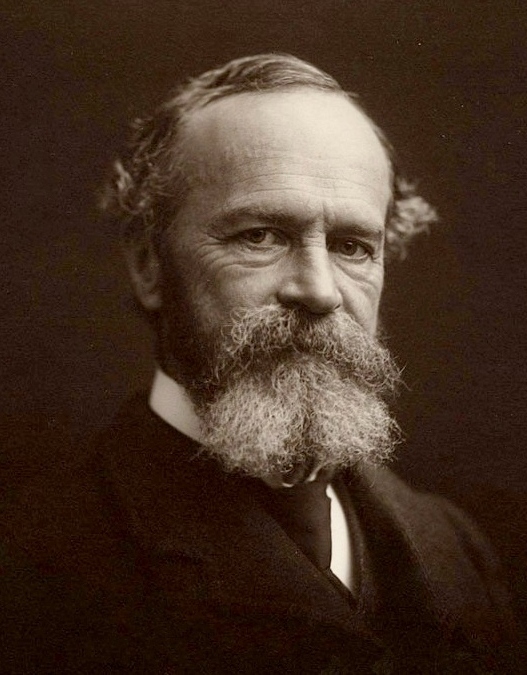

Perception Philosopher and psychologist William James Main article: Time perception The specious present refers to the time duration wherein one's perceptions are considered to be in the present. The experienced present is said to be 'specious' in that, unlike the objective present, it is an interval and not a durationless instant. The term specious present was first introduced by the psychologist E. R. Clay, and later developed by William James.[91] Biopsychology The brain's judgment of time is known to be a highly distributed system, including at least the cerebral cortex, cerebellum and basal ganglia as its components. One particular component, the suprachiasmatic nuclei, is responsible for the circadian (or daily) rhythm, while other cell clusters appear capable of shorter-range (ultradian) timekeeping. Psychoactive drugs can impair the judgment of time. Stimulants can lead both humans and rats to overestimate time intervals,[92][93] while depressants can have the opposite effect.[94] The level of activity in the brain of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and norepinephrine may be the reason for this.[95] Such chemicals will either excite or inhibit the firing of neurons in the brain, with a greater firing rate allowing the brain to register the occurrence of more events within a given interval (speed up time) and a decreased firing rate reducing the brain's capacity to distinguish events occurring within a given interval (slow down time).[96] Mental chronometry is the use of response time in perceptual-motor tasks to infer the content, duration, and temporal sequencing of cognitive operations. |

知覚 哲学者であり心理学者でもあるウィリアム・ジェームズ 詳細は「時間の知覚」を参照 スペイシャス・プレゼント(スペイシャス・プレゼント)とは、知覚が現在にあるとみなされる時間的持続を指す。経験された現在とは、客観的な現在とは異な り、持続のない瞬間ではなく間隔であるという点で「スペイシャス(見せかけの)」である。この用語は心理学者E. R. クレイによって初めて導入され、後にウィリアム・ジェームズによって発展した。 生物心理学 脳の時間に関する判断は、高度に分散されたシステムであり、少なくとも大脳皮質、小脳、線状体を含むことが知られている。 視交叉上核と呼ばれる特定の構成要素は、概日(または毎日の)リズムを司っているが、他の細胞群はより短い範囲(ウルトラディアン)の時間管理が可能であ る。 向精神薬は時間の判断を損なう可能性がある。覚醒剤は人間にもラットにも時間間隔を過大評価させる可能性があるが[92][93]、一方で鎮静剤は逆の効 果をもたらす可能性がある[94]。この理由として、ドーパミンやノルエピネフリンなどの神経伝達物質の脳内活動レベルが関係している可能性がある [95]。このような化学物質は 脳内のニューロンの発火を促進または抑制するが、発火率が高ければ、脳は一定時間内に起こる事象をより多く認識することができ(時間の高速化)、発火率が 低ければ、脳は一定時間内に起こる事象を区別する能力が低下する(時間の低速化)。[96] 精神クロノメーターとは、知覚運動課題における反応時間を利用して、認知操作の内容、持続時間、時間的順序を推測することである。 |

| Early childhood education Children's expanding cognitive abilities allow them to understand time more clearly. Two- and three-year-olds' understanding of time is mainly limited to "now and not now". Five- and six-year-olds can grasp the ideas of past, present, and future. Seven- to ten-year-olds can use clocks and calendars.[97] Alterations In addition to psychoactive drugs, judgments of time can be altered by temporal illusions (like the kappa effect),[98] age,[99] and hypnosis.[100] The sense of time is impaired in some people with neurological diseases such as Parkinson's disease and attention deficit disorder. Psychologists assert that time seems to go faster with age, but the literature on this age-related perception of time remains controversial.[101] Those who support this notion argue that young people, having more excitatory neurotransmitters, are able to cope with faster external events.[96] Spatial conceptualization Although time is regarded as an abstract concept, there is increasing evidence that time is conceptualized in the mind in terms of space.[102] That is, instead of thinking about time in a general, abstract way, humans think about time in a spatial way and mentally organize it as such. Using space to think about time allows humans to mentally organize temporal events in a specific way. This spatial representation of time is often represented in the mind as a Mental Time Line (MTL).[103] Using space to think about time allows humans to mentally organize temporal order. These origins are shaped by many environmental factors[102]––for example, literacy appears to play a large role in the different types of MTLs, as reading/writing direction provides an everyday temporal orientation that differs from culture to culture.[103] In western cultures, the MTL may unfold rightward (with the past on the left and the future on the right) since people read and write from left to right.[103] Western calendars also continue this trend by placing the past on the left with the future progressing toward the right. Conversely, Arabic, Farsi, Urdu and Israeli-Hebrew speakers read from right to left, and their MTLs unfold leftward (past on the right with future on the left), and evidence suggests these speakers organize time events in their minds like this as well.[103] This linguistic evidence that abstract concepts are based in spatial concepts also reveals that the way humans mentally organize time events varies across cultures––that is, a certain specific mental organization system is not universal. So, although Western cultures typically associate past events with the left and future events with the right according to a certain MTL, this kind of horizontal, egocentric MTL is not the spatial organization of all cultures. Although most developed nations use an egocentric spatial system, there is recent evidence that some cultures use an allocentric spatialization, often based on environmental features.[102] A study of the indigenous Yupno people of Papua New Guinea focused on the directional gestures used when individuals used time-related words.[102] When speaking of the past (such as "last year" or "past times"), individuals gestured downhill, where the river of the valley flowed into the ocean. When speaking of the future, they gestured uphill, toward the source of the river. This was common regardless of which direction the person faced, revealing that the Yupno people may use an allocentric MTL, in which time flows uphill.[102] A similar study of the Pormpuraawans, an aboriginal group in Australia, revealed a similar distinction in which when asked to organize photos of a man aging "in order," individuals consistently placed the youngest photos to the east and the oldest photos to the west, regardless of which direction they faced.[104] This directly clashed with an American group that consistently organized the photos from left to right. Therefore, this group also appears to have an allocentric MTL, but based on the cardinal directions instead of geographical features.[104] The wide array of distinctions in the way different groups think about time leads to the broader question that different groups may also think about other abstract concepts in different ways as well, such as causality and number.[102] |

幼児教育 子どもの認知能力が発達するにつれ、時間をより明確に理解できるようになる。2歳児と3歳児の時間に対する理解は主に「今と今ではない」というものに限ら れる。5歳児と6歳児は過去、現在、未来という概念を把握できる。7歳児から10歳児は時計やカレンダーを使用できる。[97] 変化 向精神薬の他に、時間に関する判断は時間的錯覚(カッパ効果のような)[98]、年齢[99]、催眠[100]によっても変化する。パーキンソン病や注意欠陥障害などの神経疾患を持つ一部の人々においては、時間の感覚が損なわれる。 心理学者は、年齢とともに時間が早く過ぎるように感じられると主張しているが、この加齢に伴う時間の知覚に関する文献は依然として議論の的となっている。 [101] この考えを支持する人々は、興奮性神経伝達物質を多く持つ若者は、より速い外部の出来事に対処できると主張している。[96] 空間的思考 時間は抽象的な概念とみなされているが、時間というものは心の中で空間として概念化されているという証拠が増えている。[102] すなわち、人間は時間を一般的な抽象的な方法で考えるのではなく、空間的な方法で考え、それを空間として精神的に整理する。時間を考えるのに空間を使うこ とで、人間は時間的な出来事を特定の方法で精神的に整理することができる。 この空間的な時間の表現は、メンタルタイムライン(MTL)として心の中に表されることが多い。[103] 空間を使って時間を考えることで、人間は時間的な順序を心の中で整理することができる。 これらの起源は、多くの環境要因によって形作られる。[102] 例えば、読み書きの方向は文化によって異なる日常的な時間的志向を提供するため、読み書きの方向は、異なるタイプのMTLにおいて大きな役割を果たしてい るようだ。[103] 西洋文化では、 人々は左から右に読み書きするため、MTLは右方向に展開する(左に過去、右に未来)。[103] 西洋のカレンダーもこの傾向を踏襲しており、過去は左側に、未来は右側に向かって進む。逆に、アラビア語、ペルシア語、ウルドゥー語、イスラエル・ヘブラ イ語話者は右から左に読み、彼らのMTLは左方向に展開する(右に過去、左に未来)。また、証拠によると、これらの話者は時間的な出来事も同様に頭の中で 整理しているようだ。 抽象的な概念が空間的な概念に基づいているというこの言語学的証拠は、人間が時間的な出来事を頭の中で整理する方法は文化によって異なる、つまり、特定の 精神的な整理システムは普遍的ではないことを示している。つまり、西洋文化では通常、ある種のMTLに従って過去の出来事を左に、未来の出来事を右に関連 付けるが、この種の水平方向の自己中心的なMTLは、すべての文化の空間的構成ではない。ほとんどの先進国では自己中心的な空間システムが使用されている が、一部の文化では環境の特徴に基づくことが多い他者中心的な空間化を使用しているという最近の証拠がある。 パプアニューギニアの先住民ユプノ族の研究では、個人が時間に関する言葉を使う際に使用する方向を示すジェスチャーに焦点が当てられた。[102] 過去(「昨年」や「昔」など)について話す際には、個人は谷の川が海に流れ込む下流の方向を指さす。未来について話す際には、川の源流である上流の方向を 指さす。これは、その人物がどちらの方向を向いているかに関係なく共通しており、ユプノ族の人々は、時間が上に向かって流れる「allocentric MTL」を使用している可能性があることを示している。 オーストラリアの先住民グループであるポーンプルアワ族の同様の研究では、ある男性の「年齢を重ねる」様子を写真に撮り、その写真を整理するように依頼し たところ、個人は常に、どの方向を向いているかに関わらず、最も若い写真を東に、最も古い写真を西に配置したという、同様の区別が明らかになった。 [104] これは、常に写真を左から右に整理するアメリカ人グループと真っ向から対立する。したがって、このグループも、地理的特徴ではなく、基本方位に基づく、自 己中心的なMTLを持っているように見える。 異なるグループが時間について考える方法における幅広い相違は、因果関係や数といった、他の抽象的概念についても異なる方法で考える可能性があるという、より幅広い疑問につながる。[102] |

| Use See also: Time management In sociology and anthropology, time discipline is the general name given to social and economic rules, conventions, customs, and expectations governing the measurement of time, the social currency and awareness of time measurements, and people's expectations concerning the observance of these customs by others. Arlie Russell Hochschild[105][106] and Norbert Elias[107] have written on the use of time from a sociological perspective. The use of time is an important issue in understanding human behavior, education, and travel behavior. Time-use research is a developing field of study. The question concerns how time is allocated across a number of activities (such as time spent at home, at work, shopping, etc.). Time use changes with technology, as the television or the Internet created new opportunities to use time in different ways. However, some aspects of time use are relatively stable over long periods of time, such as the amount of time spent traveling to work, which despite major changes in transport, has been observed to be about 20–30 minutes one-way for a large number of cities over a long period. Time management is the organization of tasks or events by first estimating how much time a task requires and when it must be completed, and adjusting events that would interfere with its completion so it is done in the appropriate amount of time. Calendars and day planners are common examples of time management tools. |

使用 関連項目:時間管理 社会学や人類学では、時間規律とは、時間の測定、社会的通貨、時間測定の認識、および他者によるこれらの慣習の順守に関する人々の期待を管理する社会的・ 経済的規則、慣習、習慣、および期待の総称である。Arlie Russell Hochschild[105][106]とNorbert Elias[107]は、社会学的な視点から時間の使い方について書いている。 時間の使い方というものは、人間の行動、教育、旅行行動を理解する上で重要な問題である。時間利用の研究は発展途上の学問分野である。問題は、時間という ものが、いくつかの活動(例えば、家庭で過ごす時間、仕事をする時間、買い物をする時間など)にどのように割り当てられているかということである。テレビ やインターネットの登場により、時間を異なる方法で使う新たな機会が生まれたため、時間の使い方はテクノロジーの進歩とともに変化している。しかし、通 勤・通学に費やす時間のように、長期間にわたって比較的安定している時間の使い方の側面もある。交通手段が大きく変化したにもかかわらず、多くの都市では 長期間にわたって片道20~30分程度であることが観察されている。 時間管理とは、まず最初に、ある作業にどれだけの時間が必要か、いつまでに完了しなければならないかを予測し、その完了を妨げるような出来事は調整して、適切な時間内に完了できるようにすることである。カレンダーや手帳は、時間管理ツールの一般的な例である。 |

| Sequence of events A sequence of events, or series of events, is a sequence of items, facts, events, actions, changes, or procedural steps, arranged in time order (chronological order), often with causality relationships among the items.[108][109][110] Because of causality, cause precedes effect, or cause and effect may appear together in a single item, but effect never precedes cause. A sequence of events can be presented in text, tables, charts, or timelines. The description of the items or events may include a timestamp. A sequence of events that includes the time along with place or location information to describe a sequential path may be referred to as a world line. Uses of a sequence of events include stories,[111] historical events (chronology), directions and steps in procedures,[112] and timetables for scheduling activities. A sequence of events may also be used to help describe processes in science, technology, and medicine. A sequence of events may be focused on past events (e.g., stories, history, chronology), on future events that must be in a predetermined order (e.g., plans, schedules, procedures, timetables), or focused on the observation of past events with the expectation that the events will occur in the future (e.g., processes, projections). The use of a sequence of events occurs in fields as diverse as machines (cam timer), documentaries (Seconds From Disaster), law (choice of law), finance (directional-change intrinsic time), computer simulation (discrete event simulation), and electric power transmission[113] (sequence of events recorder). A specific example of a sequence of events is the timeline of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster. |

出来事の順序 出来事の順序または出来事の系列とは、項目、事実、出来事、行動、変更、または手続きの順序を時間順(年代順)に配列したものであり、多くの場合、項目間 に因果関係がある。[108][109][110] 因果関係があるため、原因は結果に先行する、または原因と結果が単一の項目に一緒に表示される場合があるが、結果が原因に先行することはない。一連の出来 事は、テキスト、表、チャート、またはタイムラインで提示することができる。項目または出来事の説明にはタイムスタンプを含めることができる。時間ととも に場所または位置情報を含めて順序的な経路を説明する一連の出来事は、世界線と呼ばれることがある。 一連の出来事の用途には、物語[111]、歴史的な出来事(年代順)、手順の方向や手順[112]、スケジュール活動のタイムテーブルなどがある。出来事 の連続は、科学、技術、医学におけるプロセスの説明にも役立つ。出来事の連続は、過去の出来事(例えば、物語、歴史、年代順)に焦点を当てたり、あらかじ め定められた順序でなければならない未来の出来事(例えば、計画、スケジュール、手順、タイムテーブル)に焦点を当てたり、あるいは、将来起こるであろう 出来事を想定して過去の出来事を観察することに焦点を当てたり(例えば、プロセス、予測)することができる。一連の出来事の使用は、機械(カムタイ マー)、ドキュメンタリー(「Seconds From Disaster」)、法律(法の選択)、金融(方向変化固有時間)、コンピュータシミュレーション(離散事象シミュレーション)、電力送電[113] (一連の出来事記録)など、多様な分野で使用されている。一連の出来事の具体例としては、福島第一原子力発電所事故のタイムラインがある。 |

| List of UTC timing centers Loschmidt's paradox Time metrology Organizations Antiquarian Horological Society – AHS (United Kingdom) Chronometrophilia (Switzerland) Deutsche Gesellschaft für Chronometrie – DGC (Germany) National Association of Watch and Clock Collectors – NAWCC (United States) Miscellaneous arts and sciences Date and time representation by country List of cycles Nonlinear narrative Philosophy of physics Rate (mathematics) Miscellaneous units Fiscal year Half-life Hexadecimal time Tithi Unix epoch |

協定世界時(UTC)のタイムゾーンセンター一覧 ロシュミットのパラドックス 時間計測 組織 英国時計古書協会(AHS) クロノメトリー愛好家協会(スイス ドイツ時計協会(DGC)(ドイツ 全米時計・時計収集家協会(NAWCC)(米国 その他の学問 国別日時表記 周期一覧 非線形物語 物理学の哲学 レート(数学) その他の単位 会計年度 半減期 16進法による時間 ティティ UNIXエポック |

| Barbour, Julian (1999). The End

of Time: The Next Revolution in Our Understanding of the Universe.

Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-514592-2. Craig Callendar, Introducing Time, Icon Books, 2010, ISBN 978-1-84831-120-6 Das, Tushar Kanti (1990). The Time Dimension: An Interdisciplinary Guide. New York: Praeger. ISBN 978-0-275-92681-6. – Research bibliography Davies, Paul (1996). About Time: Einstein's Unfinished Revolution. New York: Simon & Schuster Paperbacks. ISBN 978-0-684-81822-1. Feynman, Richard (1994) [1965]. The Character of Physical Law. Cambridge (Mass): The MIT Press. pp. 108–126. ISBN 978-0-262-56003-0. Galison, Peter (1992). Einstein's Clocks and Poincaré's Maps: Empires of Time. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-02001-4. Benjamin Gal-Or, Cosmology, Physics and Philosophy, Springer Verlag, 1981, 1983, 1987, ISBN 0-387-90581-2, 0-387-96526-2. Charlie Gere, (2005) Art, Time and Technology: Histories of the Disappearing Body, Berg Highfield, Roger (1992). Arrow of Time: A Voyage through Science to Solve Time's Greatest Mystery. Random House. ISBN 978-0-449-90723-8. Landes, David (2000). Revolution in Time. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00282-1. Lebowitz, Joel L. (2008). "Time's arrow and Boltzmann's entropy". Scholarpedia. 3 (4): 3448. Bibcode:2008SchpJ...3.3448L. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.3448. Mermin, N. David (2005). It's About Time: Understanding Einstein's Relativity. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12201-4. Morris, Richard (1985). Time's Arrows: Scientific Attitudes Toward Time. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-61766-0. Penrose, Roger (1999) [1989]. The Emperor's New Mind: Concerning Computers, Minds, and the Laws of Physics. New York: Oxford University Press. pp. 391–417. ISBN 978-0-19-286198-6. Archived from the original on 26 December 2010. Retrieved 9 April 2011. Price, Huw (1996). Time's Arrow and Archimedes' Point. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-511798-1. Retrieved 9 April 2011. Reichenbach, Hans (1999) [1956]. The Direction of Time. New York: Dover. ISBN 978-0-486-40926-9. Rovelli, Carlo (2006). What is time? What is space?. Rome: Di Renzo Editore. ISBN 978-88-8323-146-9. Archived from the original on 27 January 2007. Rovelli, Carlo (2018). The Order of Time. New York: Riverhead. ISBN 978-0735216105. Stiegler, Bernard, Technics and Time, 1: The Fault of Epimetheus Roberto Mangabeira Unger and Lee Smolin, The Singular Universe and the Reality of Time, Cambridge University Press, 2014, ISBN 978-1-107-07406-4. Whitrow, Gerald J. (1973). The Nature of Time. Holt, Rinehart and Wilson (New York). Whitrow, Gerald J. (1980). The Natural Philosophy of Time. Clarendon Press (Oxford). Whitrow, Gerald J. (1988). Time in History. The evolution of our general awareness of time and temporal perspective. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-285211-3. |

バーバー、ジュリアン(1999年)。『時の終わり:宇宙に対する我々の理解における次の革命』オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-514592-2。 クレイグ・カレンダー著『Introducing Time』Icon Books、2010年、ISBN 978-1-84831-120-6 タス・カンティ・ダス著『The Time Dimension: An Interdisciplinary Guide』ニューヨーク:プラガー、1990年、ISBN 978-0-275-92681-6。研究文献目録 デイヴィス、ポール(1996年)。『アバウト・タイム:アインシュタインの未完の革命』。ニューヨーク:サイモン・アンド・シュスター・ペーパーバックス。ISBN 978-0-684-81822-1。 ファインマン、リチャード(1994年)[1965年]。『物理法則の性格』。マサチューセッツ州ケンブリッジ: The MIT Press. pp. 108–126. ISBN 978-0-262-56003-0. Galison, Peter (1992). Einstein's Clocks and Poincaré's Maps: Empires of Time. New York: W.W. Norton. ISBN 978-0-393-02001-4. ベンジャミン・ガル=オー著、『宇宙論、物理学、哲学』、シュプリンガー・フェアラーク、1981年、1983年、1987年、ISBN 0-387-90581-2、0-387-96526-2。 チャーリー・ゲア著、『アート、時間、テクノロジー:消えゆく身体の歴史』、Berg Highfield, Roger (1992). Arrow of Time: A Voyage through Science to Solve Time's Greatest Mystery. Random House. ISBN 978-0-449-90723-8. Landes, David (2000). Revolution in Time. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-00282-1. Lebowitz, Joel L. (2008). 「Time's arrow and Boltzmann's entropy」. Scholarpedia. 3 (4): 3448. Bibcode:2008SchpJ...3.3448L. doi:10.4249/scholarpedia.3448. Mermin, N. David (2005). It's About Time: Understanding Einstein's Relativity. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-12201-4. Morris, Richard (1985). Time's Arrows: Scientific Attitudes Toward Time. New York: Simon and Schuster. ISBN 978-0-671-61766-0. ペンローズ、ロジャー (1999) [1989]. 『皇帝の新しい心:コンピュータ、心、物理法則について』. ニューヨーク: オックスフォード大学出版局. pp. 391–417. ISBN 978-0-19-286198-6. 2010年12月26日オリジナルよりアーカイブ。2011年4月9日取得。 プライス、ヒュー(1996年)。『時の矢とアルキメデスの点』。オックスフォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-511798-1。2011年4月9日取得。 ライヘンバッハ、ハンス(1999年)[1956年]。『時間の方向』。ニューヨーク:ドーヴァー。ISBN 978-0-486-40926-9。 ロヴェッリ、カルロ(2006年)。『時間とは何か?空間とは何か?』。ローマ:ディ・レンツォ・エディトーレ。ISBN 978-88-8323-146-9. 2007年1月27日オリジナルよりアーカイブ。 ロヴェッリ、カルロ(2018年)。『時間の秩序』。ニューヨーク:リヴァーヘッド。ISBN 978-0735216105。 スティグレール、ベルナール、『技術と時間』第1巻:エピメテウスの過ち ロベルト・マンガベイラ・ウンジェルとリー・スモリン著、『特異宇宙と時間の現実』ケンブリッジ大学出版、2014年、ISBN 978-1-107-07406-4。 ウィットロー著、『時間の性質』ホルト、ラインハート、ウィルソン(ニューヨーク)。 ウィットロー、ジェラルド J. (1980年). 『時間の自然哲学』. Clarendon Press (オックスフォード). ウィットロー、ジェラルド J. (1988年). 『歴史における時間』. 時間に対する一般的な認識と時間的視点の進化. オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-285211-3. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Time | |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆