批判的医療人類学

Critical Medical Anthropology

解説:池田光穂(医療人類学プロジェクト)

| Critical

medical anthropology (CMA) is a branch of medical anthropology that

blends critical theory and ground-level ethnographic approaches in the

consideration of the political economy of health, and the effect of

social inequality on people's health. It puts emphasis on the structure

of social relationships, rather than purely biomedical factors in

analyzing health and accounting for its determinants. CMA starts with the idea that human health is a biosocial and political ecological product. Consequently, CMA is critical of the tendency to naturalize the process of health and illness in the health and social sciences. CMA dates to the 1980s, but has deeper roots in critical theory concerning the social determinants of health. CMA adds an anthropological dimension to traditional critical approaches, thereby avoiding a top-down perspective. In other words, CMA recognizes that there is interaction between the macro-level of social structure, the meso-level of social organization and agentive action, and the micro-level of individual experience and health. During the early years of medical anthropology's formation, explanations within the discipline tended to be narrowly focused on explaining health-related beliefs and behaviors at the local level in terms of specific ecological conditions, cultural configurations, or psychological factors. While providing needed insight about the nature and function of traditional and folk medical models, the initial perspectives in medical anthropology tended to ignore the wider causes and determinants of human decision making and behavior. Explanations that are limited to accounting for health-related issues in terms of the influence of human personalities, culturally constituted motivations and understandings, or even local ecological relationships, emergent critical medical anthropologists began to argue, are inadequate because they tend not to include examination of the structures of social relationship that unite (commonly in an unequal fashion) and influence far-flung individuals, communities, and even whole nations. A critical understanding, by contrast, involves paying close attention to what has been called the “vertical links” that connect the social group of interest to the larger regional, national, and global human society and to the configuration of social relationships that contribute to the patterning of human behavior, belief, attitude, and emotion. Consequently, what came to be called critical medical anthropology focused attention on understanding the origins of dominant cultural constructions in health, including which social class, gender, or ethnic group's interests particular health concepts express and under what set of historic conditions they arise. Further, CMA emphasizes structures of power and inequality in health care systems and the contributions of health ideas and practices in reinforcing inequalities in the wider society. Moreover, CMA addresses the social origins of illness, such as the way in which poverty, discrimination, industrial pollution of the environment, social violence, and fear of violence contribute to poor health. Critical medical anthropologists argue that experience and “agency,” that is, individual and group decision-making and action, are constructed and reconstructed in the action arena between socially constituted categories of meaning and the political-economic forces that shape the context [and texture] of daily life. In other words, people develop their own individual and collective understandings and responses to illness and to other threats to their well-being, but they do so in a world that is not of their own making, a world in which inequality of access to health care, the media, productive resources (e.g., land, potable water, clean air), and valued social statuses play a significant role in their daily options. Additionally, while recognizing the fundamental importance of physical (including biological) reality in health, such as the nature of particular pathogens or the release of toxins into the environment, CMA emphasizes the fact that it is not merely the idea of “nature”—the way external reality is conceived and related to by humans—but also the very physical shape of nature, including human biology, that has been deeply influenced by an evolutionary history of social inequality, overt and covert social conflict, and the operation of both physical power and the power to shape dominant ideas and conceptions in society and internationally through processes of globalization, control of production and reproduction, and control of labor. |

批判的医療人類学(CMA)は医療人類学の一

分野であり、健康の政治経

済や社会的不平等が人々の健康に及ぼす影響を考察する上で、批判的理論と地に足のついたエスノグラフィ的アプローチを融合させたものである。健康を分析

し、その決定要因を説明する上で、純粋に生物医学的な要因よりも、むしろ社会的関係の構造に重きを置く。 CMAは、人間の健康は生物社会的・政治生態学的な産物であるという考えから出発している。その結果、CMAは健康科学や社会科学において、健康と病気の プロセスを自然化する傾向に批判的である。CMAは1980年代に始まったが、健康の社会的決定要因に関する批判的理論に深く根ざしている。CMAは、伝 統的な批判的アプローチに人間学的な側面を加えることで、トップダウンの視点を回避している。言い換えれば、CMAは、社会構造のマクロレベル、社会組織 と主体的行動のメゾレベル、そして個人の経験と健康のミクロレベルの間に相互作用があることを認識している。 医療人類学が形成された初期には、この学問分野での説明は、特定の生態学的条件、文化的構成、または心理学的要因の観点から、ローカルレベルでの健康に関 する信念や行動を説明することに焦点が絞られる傾向があった。伝統的・民間的な医療モデルの性質や機能については必要な洞察が得られるものの、医療人類学 の初期の視点は、人間の意思決定や行動のより広い原因や決定要因を無視する傾向があった。人間の個性や、文化的に構成された動機や理解、あるいは局所的な 生態学的関係の影響という観点から、健康に関連する問題を説明することに限定された説明では不十分であると、新興の批判的医療人類学者たちは主張し始め た。なぜなら、遠く離れた個人、地域社会、さらには国家全体を結びつけ(一般的には不平等な形で)、影響を及ぼす社会的関係の構造を検討しない傾向がある からである。これとは対照的に、批判的理解とは、関心のある社会集団をより大きな地域的、国家的、世界的な人間社会へとつなぐ「縦のつながり」と呼ばれる ものや、人間の行動、信念、態度、感情のパターン化に寄与する社会的関係の構成に細心の注意を払うことである。 その結果、批判的医療人類学と呼ばれるようになったものでは、健康における支配的な文化的構築の起源を理解することに焦点が当てられるようになった。さら にCMAは、医療システムにおける権力と不平等の構造、そしてより広い社会における不平等を強化する上での健康思想と実践の貢献を強調している。さらに CMAは、貧困、差別、産業による環境汚染、社会的暴力、暴力への恐怖がどのように不健康に寄与しているかなど、病気の社会的起源を取り上げる。批判的医 療人類学者は、経験や「主体性」、つまり個人や集団の意思決定や行動は、社会的に構成された意味のカテゴリーと、日常生活の文脈[と質感]を形成する政治 経済的な力との間の行動場で構築され、再構築されると主張する。言い換えれば、人々は病気や自分たちの幸福を脅かすその他の脅威に対して、個人的・集団的 な理解と対応を自分たちで作り上げていくが、それは自分たちで作り上げたものではない世界、つまり医療、メディア、生産的資源(例えば、土地、飲料水、き れいな空気)、価値ある社会的地位へのアクセスにおける不平等が、日々の選択肢において重要な役割を果たしている世界で行われるのである。 さらにCMAは、特定の病原体の性質や環境への毒素の放出など、健康における物理的(生物学的なものを含む)現実の基本的な重要性を認識しながらも、単に 「自然」という観念、つまり外的現実が人間によって観念され、関連づけられる方法だけでなく、自然の物理的な形そのものであるという事実を強調している、 それは、社会的不平等、公然・非公然の社会的対立、物理的権力と、グローバリゼーション、生産と再生の支配、労働の支配の過程を通じて、社会や国際社会に おける支配的な考え方や概念を形成する権力の両方が作用してきた進化の歴史によって、深く影響を受けてきたという事実である。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Critical_medical_anthropology April 7,2024 | |

| More than a laboratory

physician, Rudolf Virchow

was an impassioned advocate for social and political reform. His

ideology involved social inequality as the cause of diseases that

requires political actions,[111] stating: Medicine is a social science, and politics is nothing else but medicine on a large scale. Medicine, as a social science, as the science of human beings, has the obligation to point out problems and to attempt their theoretical solution: the politician, the practical anthropologist, must find the means for their actual solution... Science for its own sake usually means nothing more than science for the sake of the people who happen to be pursuing it. Knowledge which is unable to support action is not genuine – and how unsure is activity without understanding... If medicine is to fulfill her great task, then she must enter the political and social life... The physicians are the natural attorneys of the poor, and the social problems should largely be solved by them.[112][113][114] Virchow actively worked for social change to fight poverty and diseases. His methods involved pathological observations and statistical analyses. He called this new field of social medicine a "social science". His most important influences could be noted in Latin America, where his disciples introduced his social medicine.[115] For example, his student Max Westenhöfer became Director of Pathology at the medical school of the University of Chile, becoming the most influential advocate. One of Westenhöfer's students, Salvador Allende, through social and political activities based on Virchow's doctrine, became the 29th President of Chile (1970–1973).[116] Virchow made himself known as a pronounced pro-democracy progressive in the year of revolutions in Germany (1848). His political views are evident in his Report on the Typhus Outbreak of Upper Silesia, where he states that the outbreak could not be solved by treating individual patients with drugs or with minor changes in food, housing, or clothing laws, but only through radical action to promote the advancement of an entire population, which could be achieved only by "full and unlimited democracy" and "education, freedom and prosperity".[24] These radical statements and his minor part in the revolution caused the government to remove him from his position in 1849, although within a year he was reinstated as prosector "on probation". Prosector was a secondary position in the hospital. This secondary position in Berlin convinced him to accept the chair of pathological anatomy at the medical school in the provincial town of Würzburg, where he continued his scientific research. Six years later, he had attained fame in scientific and medical circles, and was reinstated at Charité Hospital.[20] In 1859, he became a member of the Municipal Council of Berlin and began his career as a civic reformer. Elected to the Prussian Diet in 1862, he became leader of the Radical or Progressive party; and from 1880 to 1893, he was a member of the Reichstag.[21] He worked to improve healthcare conditions for Berlin citizens, especially by working towards modern water and sewer systems. Virchow is credited as a founder of anthropology[117] and of social medicine, frequently focusing on the fact that disease is never purely biological, but often socially derived or spread.[118] |

ルドルフ・

ウィルヒョー(ウィルヒョウ、フィルヒョウあるいはヴィルヒョー)は実験室医師である以上に、社会的・政治的改革の熱烈な提唱者であった。彼のイ

デオロギーは、政治的行動を必要とする病気の原因として社会的不平等を取り上げ、次のように述べている: 医学は社会科学であり、政治とは大規模な医学以外の何ものでもない。医 学は社会科学であり、人間の科学として、問題を指摘し、その理論的解決を試みる義務がある。それ自身のための科学は、通常、それを追い求める人々のための 科学以上の意味を持たない。行動を支えることのできない知識は本物ではない。もし医学がその偉大な使命を果たそうとするならば、政治や社会生活に参入しな ければならない...。医師は貧しい人々の自然な相談相手であり、社会問題の大部分は医師によって解決されるべきである。 ヴィルヒョーは貧困と病気と闘うための社会変革に積極的に取り組んだ。彼の方法は病理学的観察と統計的分析であった。彼はこの新しい社会医学の分野を「社 会科学」と呼んだ。彼の最も重要な影響はラテンアメリカに見られ、彼の弟子たちが彼の社会医学を導入した。例えば、弟子のマックス・ウェステンヘーファー はチリ大学医学部の病理学部長となり、最も影響力のある提唱者となった。ヴェステンヘーファーの教え子の一人であるサルバドール・アジェンデは、ヴィル ヒョーの教義に基づく社会的・政治的活動を通じて、第29代チリ大統領に就任した(1970-1973年)。 ヴィルヒョーは、ドイツにおける革命の年(1848年)に、顕著な民主主義推進派としてその名を知らしめた。彼の政治的見解は、『上シレジアのチフス流行 に関する報告書』に顕著であり、そこでは、個々の患者を薬物で治療したり、食物、住居、衣服に関する法律を少し変えるだけでは、この流行は解決できないと 述べている。 こうした急進的な発言と革命における彼の軽微な役割によって、政府は1849年に彼をその地位から解任したが、1年以内に彼は「保護観察付き」でプロセク ターとして復職した。監察医は病院の副次的な地位であった。ベルリンでのこの二次的な地位によって、彼は地方都市ヴュルツブルクの医学部で病理解剖学の講 座を受け持つことになり、そこで科学的研究を続けた。6年後、彼は科学界と医学界で名声を得、シャリテ病院に復職した。 1859年、ベルリン市議会議員となり、市民改革者としてのキャリアをスタートさせる。1862年にプロイセン国会議員に選出され、急進党の党首となり、 1880年から1893年まで帝国議会議員を務めた。1880年から1893年まで帝国議会議員を務め、特に近代的な上下水道システムの整備に取り組むな ど、ベルリン市民の医療環境の改善に努めた。ヴィルヒョーは、人類学と社会医学の創始者として知られ、病気は決して純粋に生物学的なものではなく、しばし ば社会的に派生したり、広まったりするものであるという事実にしばしば焦点を当てた。 |

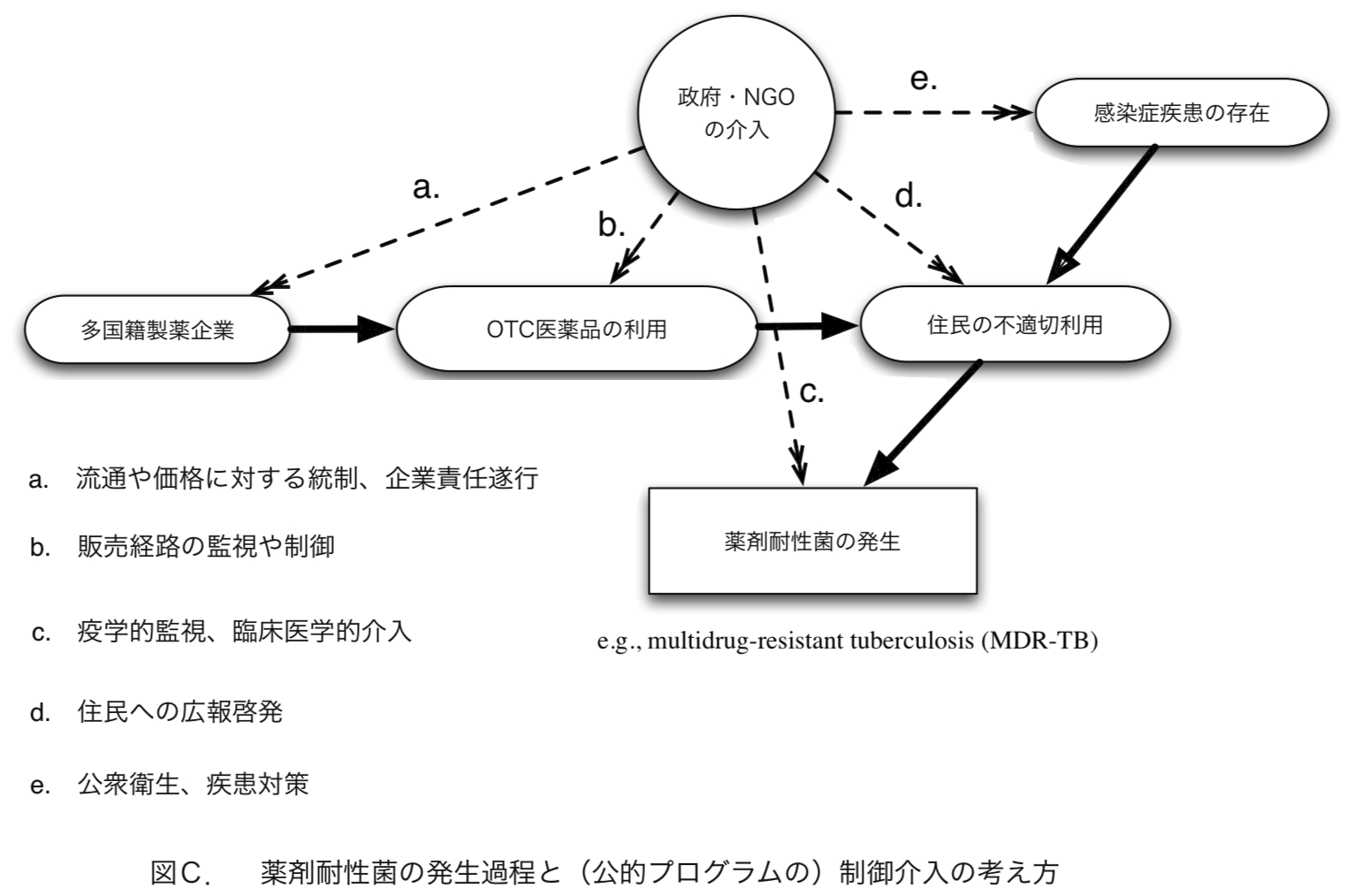

薬剤耐性菌の例として多剤耐性結核菌(Multi- Drug

Resistant Tuberculosis,

MDR-TB)をあげる。途上国における結核対策は、担菌の可能性をもつ患者を発見し、その喀痰を採取し、その患者に投薬しながら、患者を監視(サーベイ

ランス)するというシステムで通常おこなわれている。この単純なシステムでは多剤耐性が生じることは考えにくい。したがって、多剤耐性の発生には複数の医

薬品の機会的濫用が考えられる。[監視下におかれる患者にとって]長期の投薬とそこから生まれる多剤耐性菌の発生には、主に2つの系列の要因の問題が絡む

ように思われる。ひとつは製薬企業が長期にわたる薬品の売り上げを確保しようとする市場の原理である。これにより濫用が生まれる素地ができる。ただし、こ

れだけでは薬剤が同一の種類で販売されている場合には問題が起こらない。多剤耐性を生む潜在力をもつ複数の薬品が「医薬品選択の自由」という市場原理のも

とで濫用されないと、事態が生じないからだ。図C.では水平に左から右へ移行する実線の矢印の系列がその最初のものである。他方、患者にとって医薬品の調

達を公的なサービスだけで受け入れることができない以上、患者はOTC(Over The Counter,

店頭で直接購入できる)医薬品に依存せざるをえない。長期にわたる投薬は、病状管理に医学的に適切な知識をもたなかったり、定期的な医薬品購入が経済的理

由で阻害された時、医薬品の不適切利用という事態が引き起こされる。こういう事態は、原疾患の疫学的存在がなければ起こりえない。右上から左下に移行する

もうひとつの系列が交錯してはじめて薬剤耐性菌が生じる。このように多剤耐性菌の発生には2つの系列の要因が重なって生じるとひとまず解釈することができ

る(つづきは「持続可能性の意味と医療人類学」で)。

★批判的医療人類学の思考とは?

・マルクス主義から受け継いだ健康の政治経済的因子の重視:「健康の政治経済学(political economy of health)」

・

社会全体をシステムとしてみる考え方:「マルクス主義と経済人類学」——社会審級の概念

●批判的医療人類学ないしは社会医学のダークサイドは「全体主義的誘惑」である

リンク

文献(テキスト)

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1997-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆