A collection of tips for thinking about

cultural representations of the Vietnam War

ベトナム戦争の文化表象を考えるためのヒント集

A collection of tips for thinking about

cultural representations of the Vietnam War

かいせつ:池田光穂

ザ・ニューヨーク・タイムズが推薦する「ベトナム戦 争に関する」フィクション・ノンフィクションの必読書20冊(20 Must-Read Books on the Vietnam War, By SUSAN ELLINGWOODSEPT. 15, 2017)ゆきゆきてベトコン!読書カタログ

https://www.nytimes.com/2017/09/15/books/20-must-read-books-on-the-vietnam-war.html

フィクション

ノンフィクション

リンク

文献

その他の情報

◆ 授業資料: (2003年 5月8日)まで の宿題:

図書館に行って「ベトナム戦争」に関連するさまざまな書籍(歴史 書のような事実の記録の他に、小説や戯曲、映画などを題材にした著作でもかまわない)を最低1冊借りてこよう。あるいは図書館のOPAC検索や国立情報学 研究所のWebcatなどで、ベトナム戦争に関する書籍のリストを作成しよう。

| 回数、 日程 | テーマ | 内容・ とりあげる作品 |

| 1 | ベトナムの表象とはなにか? | トリン・ミン・ハ『姓はヴェト、名はナム』

大友克洋『気分はもう戦争』 樹村みのり「星に住む人びと」『星に住む人びと』 秋田書店 ボニータコミックス > 1982年10月10日発行 澤田教一・酒井淑夫『戦場——二人のピュリツァー賞カメラマン』共同通信社、 2002年 |

| 2 | ベトナム戦争クロニクル | 生井英考『ジャングルクルーズにうってつけの日』ちく

ま文庫、1993年[★原著は1987年を増補したもの。この本は私のベトナム戦争への関心を確固としたも

のとし、{医療人類学を専攻する}私の研究そのものにもさまざまな影響を与えた本でした]

朴根好「ヴェトナム戦争と「東アジアの奇跡」」山之内靖・酒井直樹編『総力戦体 制からグローバリゼーションへ』所収、Pp.80-120、東京:平凡社、2003年。 虐殺の事実とアメリカ陸軍による「歴史の否認」 タース,ニック『動くものはすべて殺せ:アメリカ兵はベトナムで何をしたか』布

施由紀子訳、みすず書房,2015年(Kill anything that moves : the real American war in

Vietnam / Nick Turse, Metropolitan Books : Henry Holt (2013)) |

| 3 | 国民解放の思想 | ファノン『地に呪われた者』

チャールズ・フェン『ホー・チ・ミン伝(上・下)』(岩波新書) 陸井三郎訳、岩波書店 |

| 4 | 植民地暴力 | コンラッド『闇の奥』

コッポラ、F.F.監督『地獄の黙示録』 ◆『地獄の黙示録』 (仮想授業用シラバス) キャサリン・ベステマン編『暴力論集(Violence, A Reader)』[リンク] |

| 5 | 「残虐な『日本』兵」の表象 | ヴァン・デル・ポスト『影の獄にて』

思索社(→大島渚監督『戦場のメリークリスマス』)[影の獄他のヴァン・デル・ポスト評は、山口昌男(「本の神話学」?)にある]

J・G・バラード(Ballard, James. Graham., 1930-)『太陽の帝国』高橋和久訳、東京:国書刊行会。(→スピルバーグ監督『太陽の帝国』)[→Guardian Unlimited によるバラードの紹介はこち ら] |

| 6 | 戦争の記憶 | 原一男『ゆきゆきて神軍』

山田洋次監督 『馬鹿がタンクでやってくる』 |

| 7 | 天皇のポートレイト、あるいは御真影の威光 | 若桑みどり『皇后の肖像』筑摩書房

原武史『可視化された帝国』みすず書房 田中丸勝彦『さまよえる英霊たち』柏書房 |

| 8 | 核戦争の脅威 | ディビッド・ハルバースタム(Halberstam,

David)『ベスト&ブライテスト(上・中・下)』浅野輔訳、朝日文庫、東京:朝日新聞社、1999年[原著は定冠詞がついてThe

Best and the Brightest で、1972年に出版されています]

マクナマラ、R.S.『マクナマラ回顧録 : ベトナムの悲劇と教訓』仲晃訳、 東京 共同通信社、1997年 |

| 9 | べ平連 | ヘイブ

ンズ、トーマス R.H.『海の向こうの火事 : ベトナム戦争と日本1965-1975』 吉川勇一訳、

東京:筑摩書房、1990年

鶴見良行『べ平連』(鶴見良行著作集2)東京 : みすず書房、2002年 小熊英二「第16章 死者の越境」(鶴 見俊輔と小田実、と吉川勇一[少しだけ]についての記述があります)『<民主>と<愛 国>』Pp.717-792、東京:新曜社 |

| 10 | 全共闘 | 全共闘白書編集委員会編『全共闘』東京 : 新潮社、1994年 |

| 11 | 「優しい侵略」:右翼の修辞学 | 小林よしのり『新・ゴーマニズム宣言SPECIAL台

湾論』小学館、2000年

東アジア文史哲ネットワーク編『<小林よしのり『台湾論』>を超えて』作品社、 2001年 矢内原忠雄『帝国主義下の台湾』岩波書店、1988年(オリジナルは1929 年) |

| 12 | 兵士の実践共同体 | チェ・ゲバラ『ゲリラ戦争』

毛沢東『実践論』 『マッシュ:M*A*S*H』(朝鮮戦争時代の野戦病院を描いたコメディ映画)

[Mash_1970_screenplay.pdf] with

password 『フルメタル・ジャケット』『ブラック・ホーク・ダウン』 ◆ マクドナルド化する社会 |

| 13 | 水俣からみるベトナム戦争 | 環境汚

染:枯葉剤(→残留DDT、ダイオキシン)

人災・過失:カネミ油症 レイチェル・カーソン『沈黙の春』青樹簗一訳、新潮文庫、東京:新潮社、 2001年 岡村昭彦,1972「ベトナム戦争と水俣病——「新」植民地主義者の二つの顔」 『国労文化』7号、ページ不詳。(→この文章は岡村昭彦集(筑摩書房)には収載されていません) 社会問題をどのように表象する か? 石牟礼道子、森崎和江、姜信 子 |

| 14 | 総合討論 | 総合討論 |

| 15 | 試験 | 筆記試験 |

Evidence

of the Massacre at My Lai, American Experience

|

Haeberle photographed the bodies

of this man and boy on the road back towards the village. In 2009,

Haeberle admitted he had destroyed more graphic photos of My Lai. |

|

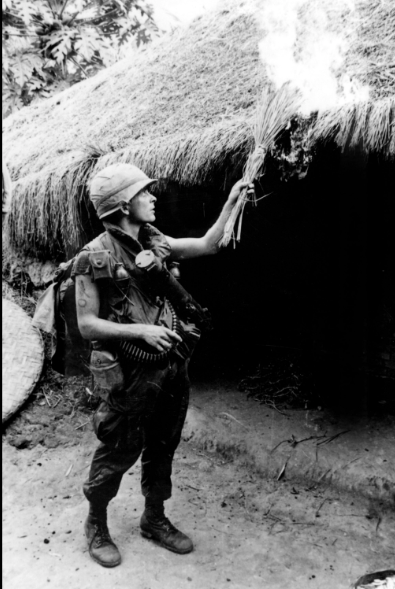

Many of the villagers lived in

small thatched huts that solders called hooches. Here, Private First

Class Delpone sets fire to one. |

|

Haeberle carried two cameras

with him on March 16. Using black and white film in an Army camera, he

was to take pictures of "newsworthy events" that might be published in

hometown newspapers. He also had his personal camera, which carried

color film. |

|

After leaving the village,

Haeberle testified he came across this group of bodies in the road. "A

small child came out ... like he was kneeling down to find his mother,

and some GI just finished him." |

|

Haeberle left My Lai on the

Medevac helicopter with Carter. The rest of Charlie Company went on to

another nearby village. |

|

Franklin and Private Wyatt

search through belongings for evidence of the Viet Cong. Credit: My Lai

Massacre Museum |

|

Haeberle testified that a GI

standing next to him shot this boy immediately after this photograph

was taken. 妹のトゥ・ハ・チャンを守るドゥック・チャン・ヴァン |

|

The Peers report found that

Captain Medina (not pictured) instructed his men to "burn the houses,

kill the livestock, and destroy the crops and foodstuffs." |

| The My Lai

massacre (/miː laɪ/ mee ly; Vietnamese: Thảm sát Mỹ Lai [tʰâːm ʂǎːt

mǐˀ lāːj] ⓘ) was a war crime committed by the United States Army on 16

March 1968, involving the mass murder of unarmed civilians in Sơn Mỹ

village, Quảng Ngãi province, South Vietnam, during the Vietnam War.[1]

At least 347 and up to 504 civilians, almost all women, children, and

elderly men, were murdered by U.S. soldiers from C Company, 1st

Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade and B Company, 4th

Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade of the 23rd (Americal)

Division (organized as part of Task Force Barker). Some of the women

were gang-raped and their bodies mutilated, and some soldiers mutilated

and raped children as young as 12.[2][3] The incident was the largest

massacre of civilians by U.S. forces in the 20th century.[4] On the morning of the massacre, C Company, commanded by Captain Ernest Medina, was sent into one of the village's hamlets (marked on maps as My Lai 4) expecting to engage the Viet Cong's Local Force 48th Battalion, which was not present. The killing began while the troops were searching the village for guerillas, and continued after they realized that no guerillas seemed to be present. Villagers were gathered together, held in the open, then murdered with automatic weapons, bayonets, and hand grenades; one large group of villagers was shot in an irrigation ditch. Soldiers also burned down homes and killed livestock. Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson Jr. and his helicopter crew are credited with attempting to stop the massacre. On the same day, B Company massacred an additional 60 to 155 people in the nearby hamlet of My Khe 4. The massacre was originally reported as a battle against Viet Cong troops, and was covered up in initial investigations by the U.S. Army. The efforts of veteran Ronald Ridenhour and journalist Seymour Hersh broke the news of the massacre to the American public in November 1969, prompting global outrage and contributing to domestic opposition to U.S. involvement in the Vietnam War.[5] Twenty-six soldiers were charged with criminal offenses, but only Lieutenant William Calley Jr., the leader of 1st Platoon in C Company, was convicted. He was found guilty of murdering 22 villagers and originally given a life sentence, but served three-and-a-half years under house arrest after U.S. president Richard Nixon commuted his sentence. |

ミライ虐殺(英語発音: /miː laɪ/ mee

ly、ベトナム語: Thảm sát Mỹ Lai [tʰâːm ʂǎːt mǐˀ lāːj] ⓘ)は、1968年3月16日に

1968年3月16日、ベトナム戦争中の南ベトナムクァンガイ省ソンミ村で、武装していない民間人を大量に殺害した事件である。[1]

少なくとも347人、最大で504人の民間人(ほぼ全員が女性、子供、老人)が、第23歩兵師団(バーカー特戦部隊の一部として編成)の第11旅団第20

歩兵連隊第1大隊C中隊および第3歩兵連隊第4大隊B中隊の米兵によって殺害された。女性の中には集団レイプされ、身体を損壊された者もおり、また12歳

ほどの子供をレイプしたり、身体を損壊する兵士もいた。[2][3]

この事件は20世紀における米軍による民間人虐殺事件としては最大規模のものである。[4] 虐殺の朝、エルネスト・メディナ大尉が指揮するC中隊は、ベトコンの現地部隊第48大隊と交戦するものと期待して、村の集落のひとつ(地図上では「マイ・ ライ4」と表記)に派遣されたが、現地部隊はそこにいなかった。部隊がゲリラを捜索している間に殺戮が始まり、ゲリラがいないことが判明した後も殺害は続 いた。村民たちは集められ、屋外に留置された後、自動小銃、銃剣、手榴弾で殺害された。灌漑用水路では、村民の大きな集団が銃撃された。兵士たちは家屋を 焼き払い、家畜を殺した。准尉ヒュー・トンプソン・ジュニアと彼のヘリコプター乗組員は、虐殺を止めようとしたことで称賛されている。同じ日、B中隊は近 くの村、マイケ4でさらに60人から155人を虐殺した。 この虐殺は当初、ベトコン部隊との戦闘として報告され、米軍による初期の調査では隠蔽された。退役軍人ロナルド・ライデンアワーとジャーナリストのシーモ ア・ハーシュの努力により、1969年11月にこの虐殺のニュースがアメリカ国民に伝えられ、世界中で怒りが巻き起こり、ベトナム戦争へのアメリカの関与 に対する国内の反対運動に貢献した。[5] 26人の兵士が刑事犯罪で起訴されたが、有罪判決を受けたのはC中隊第1小隊のリーダー、ウィリアム・カリー・ジュニア中尉のみであった。彼は22人の村 民殺害の罪で有罪となり、当初は終身刑を言い渡されたが、リチャード・ニクソン米大統領が減刑したため、3年半の自宅軟禁で服役した。 |

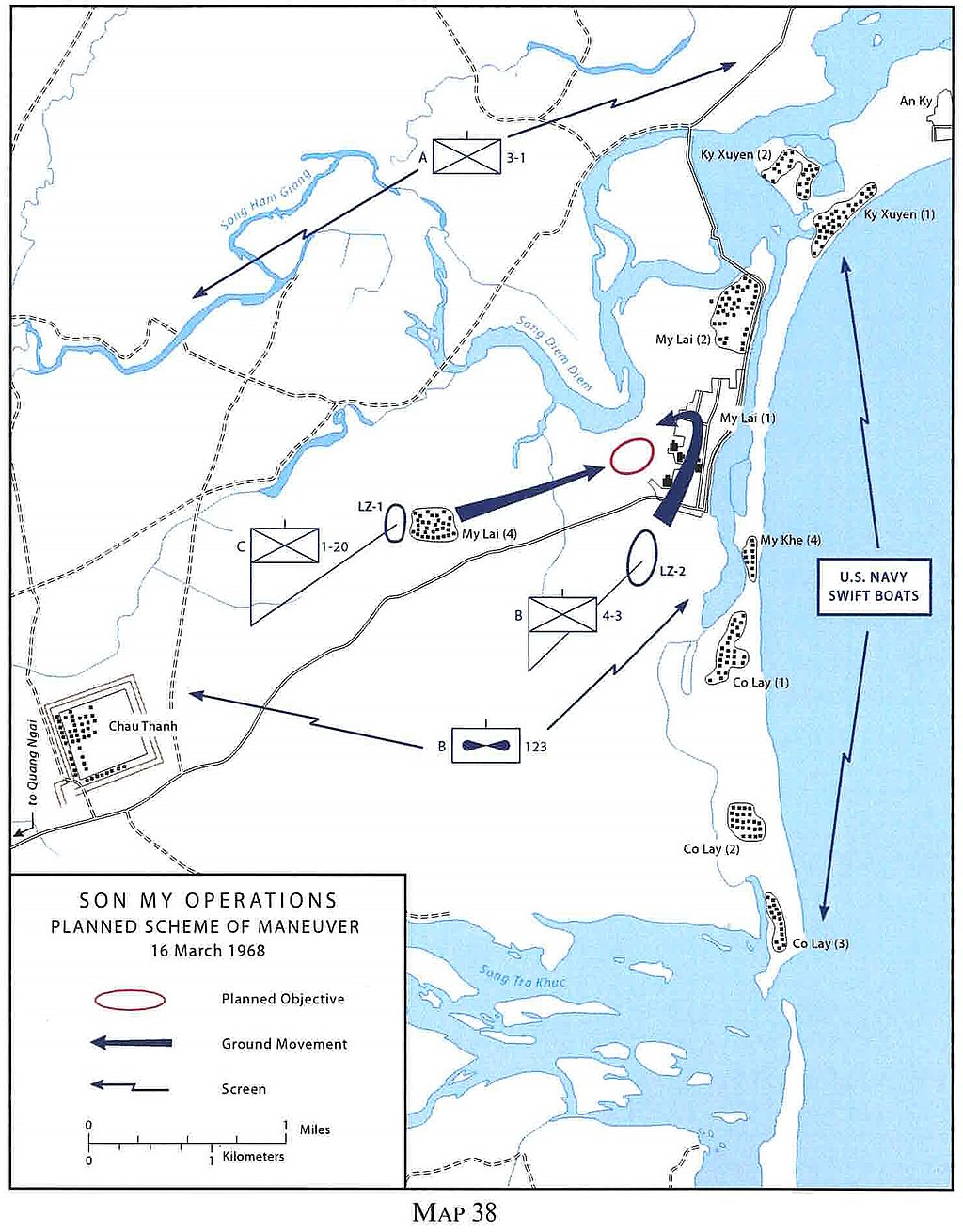

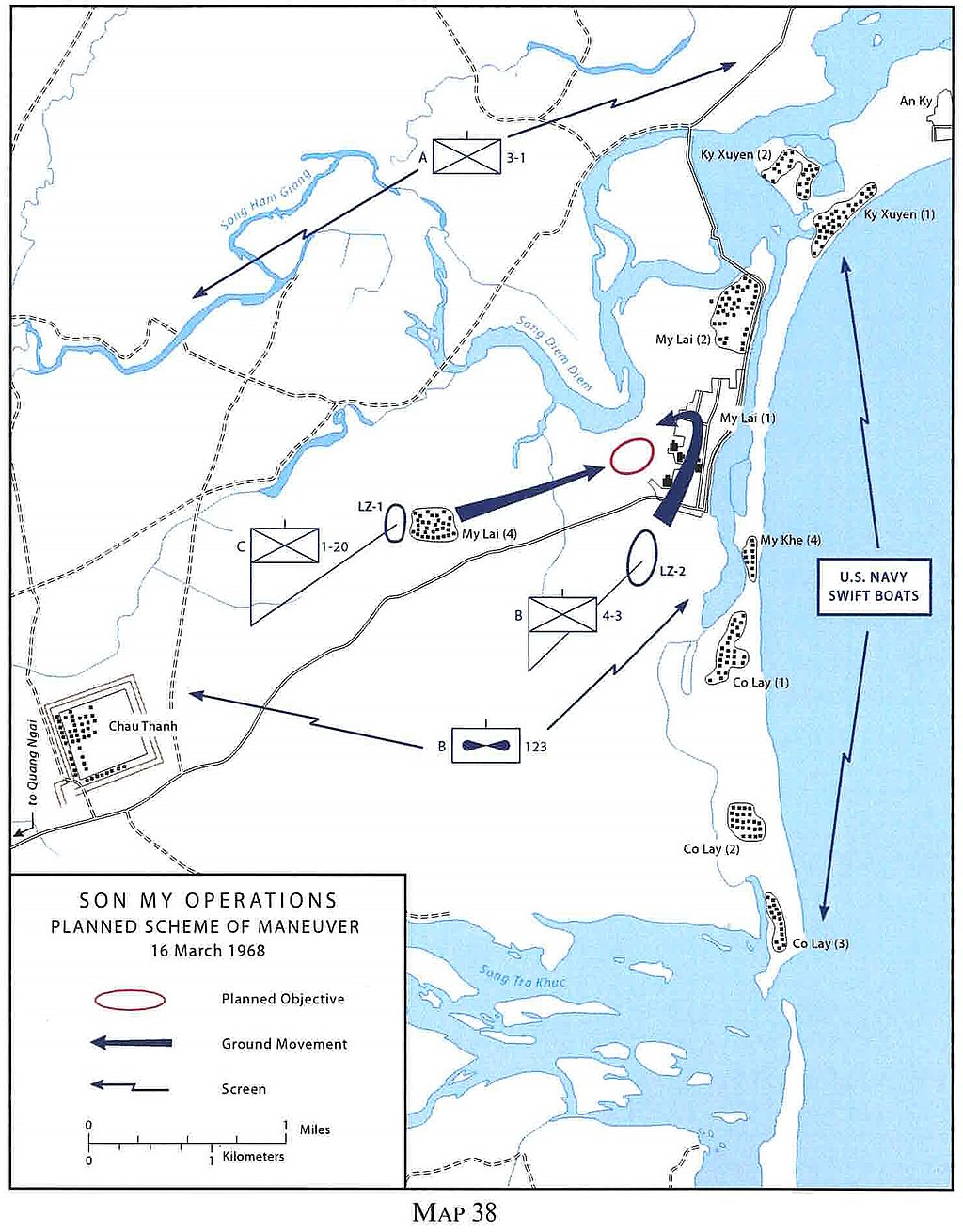

Operation Sơn Mỹ operations, 16 March 1968 Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 11th Brigade, 23rd Infantry Division, arrived in South Vietnam in December 1967. Though their first three months in Vietnam passed without any direct contact with People's Army of Vietnam or Viet Cong (VC) forces, by mid-March the company had suffered 28 casualties involving mines or booby-traps.[6] During the Tet Offensive in January 1968, attacks were carried out in Quảng Ngãi by the VC 48th Local Force Battalion. U.S. military intelligence assumed that the 48th Battalion, having retreated and dispersed, was taking refuge in the village of Sơn Mỹ, in Quảng Ngãi province. A number of specific hamlets within that village – designated Mỹ Lai (1) through Mỹ Lai (6) – were suspected of harboring the 48th.[7] Sơn Mỹ was located southwest of the Batangan Peninsula, a VC stronghold throughout the war. In February and March 1968, the U.S. Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) was aggressively trying to regain the strategic initiative in South Vietnam after the Tet Offensive, and the search-and-destroy operation against the 48th Battalion thought to be located in Sơn Mỹ became a small part of the U.S. military's overall strategy. Task Force Barker (TF Barker), a battalion-sized ad hoc unit of 11th Brigade, was to be deployed for the operation. It was formed in January 1968, composed of three rifle companies of the 11th Brigade, including Charlie Company, led by Lieutenant Colonel (LTC) Frank A. Barker. Sơn Mỹ village was included in the area of operations of TF Barker. The area of operations (AO) was codenamed Muscatine AO,[8] after Muscatine County, Iowa, the home county of the 23rd Division's commander, Major General Samuel W. Koster. In February 1968, TF Barker had already tried to secure Sơn Mỹ, with limited success.[9] After that, the village area began to be referred to as Pinkville by TF Barker troops.[10] The U.S. Army slang name for the hamlets and sub-hamlets in that area was Pinkville,[11] due to the reddish-pink color used on military maps to denote a more densely populated area, and the carnage was initially referred to as the Pinkville Massacre.[12][13] On 16–18 March, TF Barker planned to engage and destroy the remnants of the 48th Battalion, allegedly hiding in the Sơn Mỹ village area. Before the engagement, Colonel Oran K. Henderson, the 11th Brigade commander, urged his officers to "go in there aggressively, close with the enemy and wipe them out for good".[14] In turn, LTC Barker reportedly ordered the 1st Battalion commanders to burn the houses, kill the livestock, destroy food supplies, and destroy and/or poison the wells.[15] On the eve of the attack, at the Charlie Company briefing, Captain Ernest Medina told his men that nearly all the civilian residents of the hamlets in Sơn Mỹ village would have left for the market by 07:00, and that any who remained would most likely be VC or VC sympathizers.[16] He was asked whether the order included the killing of women and children. Those present later gave differing accounts of Medina's response. Some, including platoon leaders, testified that the orders, as they understood them, were to kill all VC and North Vietnamese combatants and "suspects" (including women and children, as well as all animals), to burn the village, and pollute the wells.[17] He was quoted as saying, "They're all VC, now go and get them", and was heard to reply to the question "Who is my enemy?", by saying, "Anybody that was running from us, hiding from us, or appeared to be the enemy. If a man was running, shoot him, sometimes even if a woman with a rifle was running, shoot her."[18] At Calley's trial, one defense witness testified that he remembered Medina instructing to destroy everything in the village that was "walking, crawling or growling".[19] Charlie Company was to enter the village of Sơn Mỹ spearheaded by 1st Platoon, engage the enemy, and flush them out. The other two companies from TF Barker were ordered to secure the area and provide support if needed. The area was designated a free fire zone, where American forces were allowed to deploy artillery and air strikes in populated areas, without consideration of risk to civilian or non-combatant lives.[20] Varnado Simpson, a rifleman in Charlie Company, said, "We were told to leave nothing standing. We did what we were told, regardless of whether they were civilians."[21][22] Killings  Photograph taken by Ronald L. Haeberle of South Vietnamese women and children in Mỹ Lai before being killed in the massacre.[23] According to Haeberle, soldiers had attempted to rip the blouse off the woman in the back while her mother, in the front of the photo, tried to protect her.[24] On the morning of 16 March at 07:30, around 100 soldiers from Charlie Company led by Medina, following a short artillery and helicopter gunship barrage, landed in helicopters at Sơn Mỹ, a patchwork of individual homesteads, grouped settlements, rice paddies, irrigation ditches, dikes, and dirt roads, connecting an assortment of hamlets and sub-hamlets. The largest among them were the hamlets Mỹ Lai, Cổ Lũy, Mỹ Khê, and Tu Cung.[25]: 1–2 The GIs expected to engage the Vietcong Local Force 48th Battalion, which was one of the Vietcong's most successful units.[26] Although the GIs were not fired upon after landing, they still suspected there were VC guerrillas hiding underground or in the huts. Confirming their suspicions, the gunships engaged several armed enemies in the vicinity of Mỹ Lai, killing four; later, one weapon was retrieved from the site.[27] According to the operational plan, 1st Platoon, led by Second Lieutenant (2LT) William Calley, and 2nd Platoon, led by 2LT Stephen Brooks, entered the hamlet of Tu Cung in line formation at 08:00, while the 3rd Platoon, commanded by 2LT Jeffrey U. Lacross,[28][29] and Captain Medina's command post remained outside. On approach, both platoons fired at people they saw in the rice fields and in the brush.[30] Instead of the expected enemy, the GIs found women, children and old men, many of whom were cooking breakfast over outdoor fires.[26] The villagers were getting ready for a market day and at first did not panic or run away as they were herded into the hamlet's common spaces and homestead yards. Harry Stanley, a machine gunner from Charlie Company, said during the U.S. Army Criminal Investigation Division inquiry that the killings started without warning. He first observed a member of 1st Platoon strike a Vietnamese man with a bayonet. Then the same trooper pushed another villager into a well and threw a grenade in the well. Next, he saw fifteen or twenty people, mainly women and children, kneeling around a temple with burning incense. They were praying and crying. They were all killed by shots to the head.[31] Most of the killings occurred in the southern part of Tu Cung, a sub-hamlet of Xom Lang, which was a home to 700 residents.[32] Xom Lang was erroneously marked on the U.S. military operational maps of Quảng Ngãi Province as Mỹ Lai. A large group of approximately 70–80 villagers was rounded up by 1st Platoon in Xom Lang and led to an irrigation ditch east of the settlement. They were then pushed into the ditch and shot dead by soldiers after repeated orders issued by Calley, who was also shooting. PFC Paul Meadlo testified that he expended several M16 rifle magazines. He recollected that women were saying "No VC" and were trying to shield their children.[31] He remembered that he was shooting old men and women, ranging in ages from grandmothers to teenagers, many with babies or small children in their arms, since he was convinced at that time that they were all booby-trapped with grenades and poised to attack.[33] On another occasion during the security sweep of My Lai, Meadlo again fired into civilians side by side with Lieutenant Calley.[34] PFC Dennis Konti, a witness for the prosecution,[35] told of one especially gruesome episode during the shooting, "A lot of women had thrown themselves on top of the children to protect them, and the children were alive at first. Then, the children who were old enough to walk got up and Calley began to shoot the children".[36] Other 1st Platoon members testified that many of the deaths of individual Vietnamese men, women and children occurred inside Mỹ Lai during the security sweep. To ensure the hamlets could no longer offer support to the enemy, the livestock was shot as well.[37] When PFC Michael Bernhardt entered the subhamlet of Xom Lang, the massacre was underway: I walked up and saw these guys doing strange things ... Setting fire to the hootches and huts and waiting for people to come out and then shooting them ... going into the hootches and shooting them up ... gathering people in groups and shooting them ... As I walked in you could see piles of people all through the village ... all over. They were gathered up into large groups. I saw them shoot an M79 grenade launcher into a group of people who were still alive. But it was mostly done with a machine gun. They were shooting women and children just like anybody else. We met no resistance and I only saw three captured weapons. We had no casualties. It was just like any other Vietnamese village – old papa-sans, women and kids. As a matter of fact, I don't remember seeing one military-age male in the entire place, dead or alive.[38] One group of 20–50 villagers was herded south of Xom Lang and killed on a dirt road. According to U.S. Army photographer Sgt. Ronald Haeberle's eyewitness account of the massacre, in one instance, There were some South Vietnamese people, maybe fifteen of them, women and children included, walking on a dirt road maybe 100 yards [90 m] away. All of a sudden the GIs just opened up with M16s. Beside the M16 fire, they were shooting at the people with M79 grenade launchers ... I couldn't believe what I was seeing.[39] Calley testified that he heard the shooting and arrived on the scene. He observed his men firing into a ditch with Vietnamese people inside, then began to take part in the shooting himself, using an M16 from a distance of no more than 5 feet (1.5 m). During the massacre, a helicopter landed on the other side of the ditch and the pilot asked Calley if they could provide any medical assistance to the wounded civilians in Mỹ Lai; Calley admitted replying that "a hand grenade was the only available means he had for their evacuation". At 11:00 Medina radioed an order to cease fire, and 1st Platoon took a break, during which they ate lunch.[40]  An unidentified man and child who were killed on a road Members of 2nd Platoon killed at least 60–70 Vietnamese, as they swept through the northern half of Mỹ Lai and through Binh Tay, a small sub-hamlet about 400 metres (1,300 ft) north of Mỹ Lai.[41] After the initial sweeps by 1st and 2nd Platoons, 3rd Platoon was dispatched to deal with any "remaining resistance". 3rd Platoon, which stayed in reserve, reportedly rounded up and killed a group of seven to twelve women and children.[41] Since Charlie Company had not met any enemy opposition at Mỹ Lai and did not request back-up, Bravo Company, 4th Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment of TF Barker was transported by air between 08:15 and 08:30 3 km (2 mi) away. It attacked the subhamlet My Hoi of the hamlet known as Cổ Lũy, which was mapped by the Army as Mỹ Khê. During this operation, between 60 and 155 people, including women and children, were killed.[42] Over the remaining day, both companies were involved in the further burning and destruction of dwellings, as well as continued mistreatment of Vietnamese detainees. While it was noted in the Courts Martial proceedings that some soldiers of Charlie Company did not participate in any killings, it was noted they neither openly protested against them nor filed complaints later to their superiors.[43] William Thomas Allison, a professor of Military History at Georgia Southern University, wrote, "By midmorning, members of Charlie Company had killed hundreds of civilians and raped or assaulted countless women and young girls. They encountered no enemy fire and found no weapons in My Lai itself".[44] By the time the killings stopped, Charlie Company had suffered one casualty – a soldier who had intentionally shot himself in the foot to avoid participating in the massacre – and just three enemy weapons were confiscated.[45] Rapes See also: Rape during the Vietnam War According to the Peers Commission Investigation, the U.S. government allocated commission for inquiry into the incident, concluded at least 20 Vietnamese women and girls were raped during the Mỹ Lai massacre. Since there had been little research over the case other than that of the Peers Commission, which solely accounts the cases with explicit rape signs like torn cloth and nudity, the actual number of rapes is not easy to estimate. According to the reports, the rape victims ranged between the ages of 10 and 45, with nine being under 18. The sexual assaults included gang rapes and sexual torture.[46] No U.S. serviceman was charged with rape. According to an eyewitness, as reported by Seymour Hersh in his book on the massacre, a woman was raped after her children were killed by the U.S. soldiers. Another Vietnamese villager also noticed soldiers rape a 13-year-old girl.[46] Helicopter crew intervention Warrant Officer Hugh Thompson Jr., a helicopter pilot from Company B (Aero-Scouts), 123rd Aviation Battalion, Americal Division, saw dead and wounded civilians as he was flying over the village of Sơn Mỹ, providing close-air support for ground forces.[47] The crew made several attempts to radio for help for the wounded. They landed their helicopter by a ditch, which they noted was full of bodies and in which they could discern movement by survivors.[47] Thompson asked a sergeant he encountered there (David Mitchell of 1st Platoon) if he could help get the people out of the ditch; the sergeant replied that he would "help them out of their misery". Thompson, shocked and confused, then spoke with 2LT Calley, who claimed to be "just following orders". As the helicopter took off, Thompson saw Mitchell firing into the ditch.[47] Thompson and his crew witnessed an unarmed woman being kicked and shot at point-blank range by Medina, who later claimed that he thought she had a hand grenade.[48] Thompson then saw a group of civilians at a bunker being approached by ground personnel. Thompson landed, and told his crew that if the soldiers shot at the villagers while he was trying to get them out of the bunker, then they were to open fire on the soldiers.[47] Thompson later testified that he spoke with a lieutenant (identified as Stephen Brooks of 2nd Platoon) and told him there were women and children in the bunker, and asked if the lieutenant would help get them out. According to Thompson, "he [the lieutenant] said the only way to get them out was with a hand grenade". Thompson testified that he then told Brooks to "just hold your men right where they are, and I'll get the kids out." He found 12–16 people in the bunker, coaxed them out and led them to the helicopter, standing with them while they were flown out in two groups.[47] Returning to Mỹ Lai, Thompson and other air crew members noticed several large groups of bodies.[49] Spotting some survivors in the ditch, Thompson landed again. A crew member, Specialist 4 Glenn Andreotta, entered the ditch and returned with a bloodied but apparently unharmed four-year-old girl, who was then flown to safety.[47] Upon returning to the LZ Dottie base in his OH-23, Thompson reported to his section leader, Captain Barry Lloyd, that the American infantry were no different from Nazis in their slaughter of innocent civilians: It's mass murder out there. They're rounding them up and herding them in ditches and then just shooting them.[50] Thompson then reported what he had seen to his company commander, Major Frederic W. Watke, using terms such as "murder" and "needless and unnecessary killings". Thompson's statements were confirmed by other helicopter pilots and air crew members.[51] For his actions at Mỹ Lai, Thompson was awarded the Distinguished Flying Cross, while his crew members Glenn Andreotta and Lawrence Colburn were awarded the Bronze Star. Glenn Andreotta was awarded his medal posthumously, as he was killed in Vietnam on April 8, 1968.[52] As the DFC citation included a fabricated account of rescuing a young girl from Mỹ Lai from "intense crossfire",[53] Thompson threw his medal away.[54][55] He later received a Purple Heart for other services in Vietnam.[56] In March 1998, the helicopter crew's medals were replaced by the Soldier's Medal, the highest the U.S. Army can award for bravery not involving direct conflict with the enemy. The medal citations state they were "for heroism above and beyond the call of duty while saving the lives of at least 10 Vietnamese civilians during the unlawful massacre of non-combatants by American forces at My Lai".[57] Thompson initially refused to accept the medal when the U.S. Army wanted to award it quietly. He demanded it be done publicly and that his crew be honored in the same way.[58][59][60] |

作戦 ソンミ作戦、1968年3月16日 第1大隊第20歩兵連隊第11旅団第23歩兵師団チャーリー中隊は、1967年12月に南ベトナムに到着した。ベトナムでの最初の3か月間は、ベトナム人 民軍やベトコン(VC)部隊との直接的な接触はなかったが、3月中旬までに、地雷や仕掛け爆弾による死傷者が28人に達した。 1968年1月のテト攻勢の際には、ベトコン第48地方部隊大隊によるクァンガイへの攻撃が行われた。米軍情報部は、撤退して散開した第48大隊がクァン ガイ省のソンミ村に避難していると推定した。その村の中にある特定の村落、ミライ(1)からミライ(6)までの村落が、第48大隊をかくまっている疑いが あった。ソンミはバタンガン半島の南西に位置し、終戦までベトコンの拠点であった。 1968年2月と3月、米軍ベトナム軍事援助司令部(MACV)は、テト攻勢後の南ベトナムにおける戦略的イニシアチブの回復を積極的に試みており、ソン ミに所在すると考えられていた第48大隊に対する捜索・掃討作戦は、米軍の全体戦略の一部となった。この作戦には、第11旅団の臨時編成による大隊規模の 部隊であるタスクフォース・バーカー(TF Barker)が投入されることになった。TF Barkerは1968年1月に編成され、フランク・A・バーカー中佐(LTC)が指揮するチャーリー中隊を含む第11旅団の3つのライフル中隊で構成さ れた。ソンミ村はTF Barkerの作戦地域に含まれていた。作戦地域(AO)は、第23師団の司令官であるサミュエル・W・コスター少将の出身地であるアイオワ州マスカ ティーン郡にちなんで「マスカティーンAO」というコードネームが付けられた。 1968年2月、TFバーカーはすでにソンミ村の確保を試みており、限定的な成功を収めていた。[9]その後、TFバーカー部隊は村の地域をピンクビルと 呼び始めた。[10]米軍の俗語で その地域にある村落や小村落に対する米軍の俗語での呼称はピンクヴィル(Pinkville)であったが、これは軍用地図で人口密集地域を示すのに赤みが かったピンク色が使われていたためであり、この大虐殺は当初ピンクヴィル虐殺(Pinkville Massacre)と呼ばれた。 3月16日から18日にかけて、TFバーカーはソンミ村一帯に潜伏しているとされる第48大隊の残党と交戦し、これを壊滅させる計画を立てた。交戦に先立 ち、第11旅団司令官オーラン・K・ヘンダーソン大佐は、部下たちに「積極的にそこに入り込み、敵と接近して、敵を完全に殲滅する」よう促した。[14] 一方、バーカー大佐は第1大隊指揮官たちに、家屋を焼き払い、家畜を殺し、食料を破壊し、井戸を破壊または毒殺するよう命じたと伝えられている。[15] 攻撃前夜、チャーリー中隊のブリーフィングで、アーネスト・メディナ大尉は部下たちに、ソンミ村の村落のほぼ全ての民間人居住者は午前7時までに市場に出 かけているはずであり、残っている者はほとんどがベトコンまたはベトコンのシンパであるだろうと告げた。[16] 彼は、その命令には女性や子供の殺害も含まれているのかと尋ねられた。その場に居合わせた者たちは、その後、メディナの返答について異なる証言をしてい る。小隊長を含む一部の者は、彼らが理解した命令は、ベトコンおよび北ベトナムの戦闘員と「容疑者」(女性や子供、そしてすべての動物を含む)をすべて殺 害し、村を焼き払い、井戸を汚染することだったと証言した。 「彼らは全員ベトコンだ。さあ、捕まえに行け」と発言したと伝えられ、「私の敵は誰か?」という質問に対しては、「我々から逃げたり、隠れたり、敵のよう に見える者は誰でもだ。男が逃げているのを見たら撃て。時にはライフルを持った女が逃げているのを見ても撃て」と答えたと伝えられている。 カリーの裁判では、弁護側の証人のひとりが、メディナが「歩いている、這っている、唸っている」村のものはすべて破壊するよう指示していたのを覚えている と証言した。[19] チャーリー中隊は、第1小隊を先陣にソンミ村に入り、敵と交戦し、敵を追い出すことになっていた。TFバーカーの他の2つの部隊は、その地域を確保し、必 要に応じて支援を行うよう命令されていた。この地域は「自由砲撃地域」に指定され、アメリカ軍は民間人や非戦闘員の命を顧みることなく、人口密集地域に砲 撃や空爆を行うことが許されていた。[20] チャーリー中隊のライフル兵であったヴァーナード・シンプソンは、「我々は何も残さないよう言われていた。民間人であろうと、言われた通りにした」と語っ ている。[21][22] 殺害  虐殺で殺害される前にミライ村で撮影された南ベトナムの女性と子供たち。ヘーベルレによると、兵士たちは後ろの女性のブラウスを引き裂こうとし、写真の前 の女性は娘を守ろうとしていたという。 3月16日の朝7時30分、メディナ率いるチャーリー中隊の兵士約100名が、砲撃とヘリコプターからの攻撃の後に、ソンミにヘリコプターで降り立った。 ソンミは、個人の家屋、集落、水田、灌漑用水路、堤防、未舗装の道路などが入り混じった場所であり、いくつかの村落やその下位村落を結んでいた。その中で も最大のものは、ミライ、コルーイ、ミケ、トゥクンの村落であった。[25]:1-2 GIたちはベトコンの最も成功した部隊のひとつであるベトコンのローカルフォース第48大隊と交戦するものと予想されていた。[26] GIたちは上陸後発砲を受けなかったが、それでも地下や小屋に隠れているベトコンのゲリラがいるのではないかと疑っていた。彼らの疑いを裏付けるように、 Mỹ Laiの近辺で武装した敵数名と交戦し、4名を殺害した。その後、現場から1丁の武器が回収された。[27] 作戦計画に従い、ウィリアム・カリー少尉(2LT)率いる第1小隊とスティーブン・ブルックス少尉(2LT)率いる第2小隊は、8時00分に整列した隊列 を組んでトゥクン村に入った。一方、ジェフリー・U・ラクロス少尉(2LT)が指揮する第3小隊とメディナ大尉の指揮所は村の外に残った。接近する際に、 両小隊は水田や藪の中に人影を見つけて発砲した。 予想していた敵ではなく、GIたちは女性や子供、老人を見つけた。その多くは屋外の火で朝食を作っていた。[26] 村人たちは市場の日の準備をしており、最初はパニックを起こしたり逃げ出したりせず、集落の共有スペースや民家の庭に追い立てられていた。チャーリー中隊 の機関銃手ハリー・スタンリーは、米陸軍犯罪捜査部の調査で、殺害は警告なしに始まったと述べた。彼はまず、第1小隊の隊員がベトナム人男性に銃剣で攻撃 を加えるのを目撃した。次に、同じ隊員が別の村民を井戸に突き落とし、手榴弾を投げ込んだ。次に、主に女性と子供からなる15人か20人の人々が、燃える 線香の周りに跪いているのを目撃した。彼らは祈り、泣いていた。彼らは全員、頭部を銃撃されて死亡した。[31] 殺害のほとんどは、チュン村の南部、ソム・ラン村の小村落で発生した。この地域には700人の住民が住んでいた。[32] ソム・ラン村は、クァンガイ省の米軍作戦地図に誤って「ミライ」と記載されていた。 ソム・ランの第1小隊によって、約70~80人の村民からなる大集団が捕らえられ、集落の東にある灌漑用水路に連行された。彼らは用水路に突き落とされ、 発砲しながら何度も命令を下したキャリー軍曹の後に続いて、兵士たちに射殺された。ポール・ミードロ一等兵は、M16ライフルの弾倉を数個使い切ったと証 言した。彼は、女性たちが「ノー・ベトコン(VCはいない)」と言いながら、子供たちをかばおうとしていたことを思い出した。[31] 彼は、祖母からティーンエイジャーまで、多くの赤ん坊や小さな子供を抱えた老女や老人を撃ったことを覚えている。その当時、彼は彼ら全員が手榴弾で待ち伏 せし、攻撃態勢にあると確信していたからだ。[33] また、ミライの治安維持活動中、ミードロはキャリー中尉とともに再び民間人に向けて発砲した。[34] 検察側の証人であるデニス・コンティ一等兵は、この銃撃戦中の特に凄惨なエピソードについて、「多くの女性が子供たちを庇って自分たちの体の上に子供たち を投げ出した。子供たちは最初は生きていた。しかし、歩ける年齢の子供たちが立ち上がると、カリーは子供たちを撃ち始めた」と証言した。[36] 他の第1小隊の隊員たちは、ベトナム人男性、女性、子供の死体の多くは、ミライ村内の掃討作戦中に発生したと証言した。 村が敵に支援を提供できなくなるよう、家畜も撃ち殺された。[37] マイケル・バーンハード一等兵がソム・ランの小村落に入ったとき、虐殺は進行中であった。 私はそこまで歩いていき、男たちが奇妙なことをしているのを目にした。酒や小屋に火を放ち、人々が出てくるのを待ってから彼らを撃った。酒場に入って彼ら を撃ち、人々をグループごとに集めて撃った。私が歩いていると、村の至る所に人々の山が見えた。彼らは大きなグループにまとめられていた。私は、まだ生き ている人々のグループに向かってM79グレネードランチャーが撃ち込まれるのを見た。しかし、ほとんどは機関銃でなされた。彼らは他の人々と同じように、 女性や子供たちを撃っていた。我々は抵抗に遭うことはなく、捕獲した武器は3つしか目にしていない。我々には死傷者は出なかった。そこは他のベトナムの村 と変わらず、年老いた男性や女性、子供たちがいた。実際、私はその場所で、生死を問わず、軍事年齢の男性を一人も目にした覚えがない。 20~50人の村民の一団がソム・ラングの南に追い立てられ、未舗装の道路で殺された。米軍の写真家、ロナルド・ヘーベルレ軍曹による虐殺の目撃証言によ ると、ある事例では、 100ヤード(約90メートル)ほど離れた未舗装の道路を、南ベトナム人(女性や子供を含む)が15人ほど歩いていた。突然、GIたちがM16で銃撃を開 始した。M16の銃撃に加えて、彼らはM79グレネードランチャーで人々を撃っていた。私は自分の目で信じられないものを見ていた。 カリーは、銃声を聞いて現場に駆けつけたと証言した。彼は、ベトナム人がいる溝に向かって部下たちが発砲しているのを目撃し、その後、自らもM16を5 フィート(1.5m)以内の距離から使用して発砲に参加した。虐殺の最中、溝の反対側にヘリコプターが着陸し、パイロットがメイ・ライの負傷した民間人に 対して医療支援を提供できるかどうかキャリーに尋ねた。キャリーは「彼らの避難には手榴弾が唯一の手段だ」と答えたことを認めた。11:00にメディナが 停戦命令を無線で伝え、第1小隊は休憩に入り、その間、昼食をとった。  道路で死亡した身元不明の男と子供 第2小隊の隊員は、ミライの北半分と、ミライの北400メートル(1,300フィート)にあるビンタイという小さな村落を掃討し、少なくとも60~70人 のベトナム人を殺害した。[41] 第1小隊と第2小隊による最初の掃討の後、第3小隊が「残存する抵抗」に対処するために派遣された。予備部隊として待機していた第3小隊は、7人から12 人の女性と子供からなる集団を捕らえて殺害したと伝えられている。 チャーリー中隊はミ・ライで敵の抵抗に遭うことはなく、支援を要請しなかったため、TFバーカーの第3歩兵連隊第4大隊ブラボー中隊は、8時15分から8 時30分の間に3キロメートル(2マイル)離れた地点まで空輸された。それは、ミ・ホイ(My Hoi)と呼ばれる村落の小村落、コ・ルイ(Cổ Lũy)を攻撃した。この作戦中、女性や子供を含む60人から155人が死亡した。 残りの1日、両中隊はさらに住居の焼き討ちや破壊を行い、ベトナム人捕虜への虐待も続けた。チャーリー中隊の一部の兵士は殺害行為に参加しなかったことが 軍法会議で指摘されたが、彼らは公然と殺害に抗議することもなく、後になって上官に苦情を申し立てることもなかったとされている。 ジョージア・サザン大学の軍事史教授であるウィリアム・トーマス・アリソンは、「午前中には、チャーリー中隊の隊員たちは数百人の民間人を殺害し、数えき れないほどの女性や少女をレイプしたり暴行を加えたりしていた。彼らはミライで敵の攻撃に遭うこともなく、武器も発見できなかった」と書いている。 [44] 虐殺が止んだ時点で、チャーリー中隊は1人の犠牲者(虐殺に加わることを避けるために故意に自分の足を撃った兵士)を出し、敵の武器はわずか3丁しか押収 できなかった。 強姦 関連項目:ベトナム戦争中の強姦 ピアーズ委員会の調査によると、米国政府は事件の調査委員会を設置し、ミライ虐殺では少なくとも20人のベトナム人女性と少女が強姦されたと結論付けた。 ピアーズ委員会による調査以外には、この事件に関する研究はほとんど行われておらず、ピアーズ委員会は、衣服が破れていたり裸であったりするなど、明白な レイプの兆候がある事件のみを扱っているため、実際のレイプの件数を推定するのは容易ではない。報告書によると、レイプ被害者の年齢は10歳から45歳 で、18歳未満が9人であった。性的暴行には集団レイプや性的拷問も含まれていた。 米軍兵士がレイプ容疑で起訴されたケースはなかった。虐殺に関するシーモア・ハーシュの著書で報告されているように、ある目撃者の証言によると、米兵に子 供を殺された後、女性がレイプされた。また、別のベトナム人村民は、米兵が13歳の少女をレイプするのを目撃した。 ヘリコプター乗組員の介入 アメリカ陸軍第123航空大隊B中隊(エアロ・スカウト)のヘリコプターパイロット、ヒュー・トンプソン・ジュニア准尉は、ソンミ村の上空を飛行中に地上 部隊への近接航空支援を行っていた際、死傷した民間人を目撃した。[47] 乗組員は負傷者救助の支援を要請するため、無線で連絡を試みた。彼らはヘリコプターを溝のそばに着陸させたが、そこは死体でいっぱいで、生存者の動きが確 認できた。トンプソンはそこで出会った軍曹(第1小隊のデビッド・ミッチェル)に、溝から人々を助け出せるかどうか尋ねた。軍曹は「彼らを苦しみから救っ てやろう」と答えた。ショックを受け混乱したトンプソンは、2等陸尉のカリーと話し、カリーは「ただ命令に従っただけだ」と主張した。ヘリコプターが離陸 する際に、トンプソンはミッチェルが溝に向かって発砲しているのを目撃した。 トンプソンと彼の乗組員は、メディナが非武装の女性を蹴り、至近距離から銃撃するのを目撃した。メディナは後に、その女性が手榴弾を持っていると思ったと 主張した。[48] トンプソンはその後、バンカーにいる民間人の集団が地上部隊に近づいているのを目撃した。トンプソンは着陸し、乗組員に、もし兵士たちが村人をバンカーか ら救い出そうとしている間に村人を撃つようなことがあれば、兵士たちに銃撃を加えるよう伝えた。[47] トンプソンは後に、中尉(第2小隊のスティーブン・ブルックスと特定されている)と話し、その際に、そのバンカーに女性や子供たちがいることを伝え、中尉 が彼らを外に出すのを手伝ってくれるかどうか尋ねた、と証言した。トンプソンによると、「中尉は、彼らを外に出す唯一の方法は手榴弾を使うことだと言っ た」という。トンプソンは、ブルックスに「部下たちをそのままの位置に待機させておいてくれ。私が子供たちを外に出す」と伝えたと証言した。彼は掩蔽壕に 12~16人の人々がいるのを見つけ、彼らを外に連れ出し、ヘリコプターまで誘導した。そして、彼らが2つのグループに分かれてヘリコプターで脱出する 間、彼らと共に立っていた。[47] ミ・ライに戻ったトンプソンと他の航空クルーは、いくつかの大きな死体群に気づいた。[49] 溝の中に生存者数名を見つけたトンプソンは、再び着陸した。クルーのグレン・アンドレオッタ特技兵は溝に入り、血まみれではあったが、どうやら無傷の4歳 の少女を連れ戻し、その少女はその後、安全な場所にヘリで搬送された。[47] OH-23でドロシー基地のLZに戻ったトンプソンは、セクションリーダーのバリー・ロイド大尉に、米軍歩兵部隊は罪のない民間人の虐殺においてナチスと 何ら変わらないと報告した。 あそこでは大量殺人が行われている。彼らは民間人を一か所に集め、溝に追い込んで、ただ撃っているだけだ。 トンプソンは、自分の目にしたことを「殺人」や「不必要かつ不必要な殺害」などの表現を用いて、自分の部隊の指揮官であるフレデリック・W・ワトケ少佐に 報告した。トンプソンの供述は、他のヘリコプターパイロットや航空部隊の乗組員によっても確認された。 ミ・ライでの行動により、トンプソンはディスティングイッシュト・フライング・クロス勲章を授与され、乗組員のグレン・アンドレオッタとローレンス・コル バーンはブロンズスター勲章を授与された。グレン・アンドレオッタは1968年4月8日にベトナムで戦死したため、死後に勲章を授与された。[52] DFCの表彰文には、ミィライ村から少女を「激しい十字砲火」から救出したというでっちあげの記述が含まれていたため、トンプソンは勲章を投げ捨てた。 [54][55] その後、ベトナムでのその他の功績により、トンプソンはパープルハート勲章を授与された。[56] 1998年3月、ヘリコプター乗組員の勲章は、敵との直接的な戦闘に関与しない勇敢さに対して米陸軍が授与できる最高位の勲章であるソルジャー・メダルに 置き換えられた。勲章の叙勲理由は「ミライ村における米軍による非戦闘員の違法な虐殺の際に、少なくとも10人のベトナム民間人の命を救った際の義務を超 越した英雄的行為」である。 トンプソンは当初、米軍がひっそりと勲章を授与しようとした際には、その受領を拒否した。彼は公の場で勲章を授与し、彼の乗組員も同様に称えるよう要求し た。[58][59][60] |

Aftermath Dead bodies outside a burning home. After returning to base at about 11:00, Thompson reported the massacre to his superiors.[61]: 176–179 His allegations of civilian killings quickly reached LTC Barker, the operation's overall commander. Barker radioed his executive officer to find out from Medina what was happening on the ground. Medina then gave the cease-fire order to Charlie Company to "cut [the killing] out – knock it off".[62] Since Thompson made an official report of the civilian killings, he was interviewed by Colonel Oran Henderson, the commander of the 11th Infantry Brigade.[63] Concerned, senior American officers canceled similar planned operations by Task Force Barker against other villages (My Lai 5, My Lai 1, etc.) in Quảng Ngãi Province.[64] Despite Thompson's revealing information, Henderson issued a Letter of Commendation to Medina on 27 March 1968. The following day, 28 March, the commander of Task Force Barker submitted a combat action report for the 16 March operation, in which he stated that the operation in Mỹ Lai was a success, with 128 VC combatants killed. The Americal Division commander, General Koster, sent a congratulatory message to Charlie Company. General William C. Westmoreland, the head of MACV, also congratulated Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry for "outstanding action", saying that they had "dealt [the] enemy [a] heavy blow".[65]: 196 Later, he changed his stance, writing in his memoir that it was "the conscious massacre of defenseless babies, children, mothers, and old men in a kind of diabolical slow-motion nightmare that went on for the better part of a day, with a cold-blooded break for lunch".[66] Owing to the chaotic circumstances of the war and the U.S. Army's decision not to undertake a definitive body count of noncombatants in Vietnam, the number of civilians killed at Mỹ Lai cannot be stated with certainty. Estimates vary from source to source, with 347 and 504 being the most commonly cited figures. The memorial at the site of the massacre lists 504 names, with ages ranging from one to 82. A later investigation by the U.S. Army arrived at a lower figure of 347 deaths,[citation needed] the official U.S. estimate. The official estimate by the local government remains 504.[67] Investigation and cover-up Initial reports claimed "128 Viet Cong and 22 civilians" had been killed in the village during a "fierce fire fight". Westmoreland congratulated the unit on the "outstanding job". As relayed at the time by Stars and Stripes magazine, "U.S. infantrymen had killed 128 Communists in a bloody day-long battle."[68] On 16 March 1968, in the official press briefing known as the "Five O'Clock Follies", a mimeographed release included this passage: "In an action today, Americal Division forces killed 128 enemy near Quang Ngai City. Helicopter gunships and artillery missions supported the ground elements throughout the day."[69] Initial investigations of the Mỹ Lai operation were undertaken by Colonel Henderson, under orders from the Americal Division's executive officer, Brigadier General George H. Young. Henderson interviewed several soldiers involved in the incident, then issued a written report in late-April claiming that some 20 civilians were inadvertently killed during the operation. According to Henderson's report, the civilian casualties that occurred were accidental and mainly attributed to long-range artillery fire.[70] The Army at this time was still describing the event as a military victory that had resulted in the deaths of 128 enemy combatants.[26] Six months later, Tom Glen, a 21-year-old soldier of the 11th Light Infantry Brigade, wrote a letter to General Creighton Abrams, the new MACV commander.[71] He described an ongoing and routine brutality against Vietnamese civilians on the part of American forces in Vietnam that he had personally witnessed, and then concluded, It would indeed be terrible to find it necessary to believe that an American soldier that harbors such racial intolerance and disregard for justice and human feeling is a prototype of all American national character; yet the frequency of such soldiers lends credulity to such beliefs. ... What has been outlined here I have seen not only in my own unit, but also in others we have worked with, and I fear it is universal. If this is indeed the case, it is a problem which cannot be overlooked, but can through a more firm implementation of the codes of MACV (Military Assistance Command Vietnam) and the Geneva Conventions, perhaps be eradicated.[72] Colin Powell, then a 31-year-old Army major serving as an assistant chief of staff of operations for the Americal Division, was charged with investigating the letter, which did not specifically refer to Mỹ Lai, as Glen had limited knowledge of the events there. In his report, Powell wrote, "In direct refutation of this portrayal is the fact that relations between Americal Division soldiers and the Vietnamese people are excellent." A 2018 U.S. Army case study of the massacre noted that Powell "investigated the allegations described in the [Glen] letter. He proved unable to uncover either wide-spread unnecessary killings, war crimes, or any facts related to My Lai ..."[73] Powell's handling of the assignment was later characterized by some observers as "whitewashing" the atrocities of Mỹ Lai.[72] In May 2004, Powell, then United States Secretary of State, told CNN's Larry King, "I mean, I was in a unit that was responsible for Mỹ Lai. I got there after Mỹ Lai happened. So, in war, these sorts of horrible things happen every now and again, but they are still to be deplored."[74] Seven months prior to the massacre at Mỹ Lai, on Robert McNamara's orders, the Inspector General of the U.S. Defense Department investigated press coverage of alleged atrocities committed in South Vietnam. In August 1967, the 200-page report "Alleged Atrocities by U.S. Military Forces in South Vietnam" was completed.[42] Independently of Glen, Specialist 5 Ronald L. Ridenhour, a former door gunner from the Aviation Section, Headquarters Company, 11th Infantry Brigade, sent a letter in March 1969 to thirty members of Congress imploring them to investigate the circumstances surrounding the "Pinkville" incident.[75][76] He and his pilot, Warrant Officer Gilbert Honda, flew over Mỹ Lai several days after the operation and observed a scene of complete destruction. At one point, they hovered over a dead Vietnamese woman with a patch of the 11th Brigade on her body.[77] Ridenhour himself had not been present when the massacre occurred, but his account was compiled from detailed conversations with soldiers of Charlie Company who had witnessed and, in some cases, participated in the killing.[78] He became convinced that something "rather dark and bloody did indeed occur" at Mỹ Lai, and was so disturbed by the tales he heard that within three months of being discharged from the Army he penned his concerns to Congress[75] as well as the Chairman of the Joint Chiefs of Staff, and the President.[70] He included the name of Michael Bernhardt, an eyewitness who agreed to testify, in the letter.[79] Most recipients of Ridenhour's letter ignored it, with the exception of Congressman Mo Udall[80] and Senators Barry Goldwater and Edward Brooke.[81] Udall urged the House Armed Services Committee to call on Pentagon officials to conduct an investigation.[76] Public revelation and reaction Under mounting pressure caused by Ridenhour's letter, on 9 September 1969, the Army quietly charged Calley with six specifications of premeditated murder for the deaths of 109 South Vietnamese civilians near the village of Sơn Mỹ, at a hamlet called simply "My Lai".[82][83] Calley's court martial was not released to the press and did not commence until over a year later in November 1970. However, word of Calley's prosecution found its way to American investigative reporter and freelance journalist Seymour Hersh.[84] My Lai was first revealed to the public on November 13, 1969—more than a year and a half after the incident—when Hersh published a story through the Dispatch News Service. After extensive interviews with Calley, Hersh broke the Mỹ Lai story in 35 newspapers; additionally, the Alabama Journal in Montgomery and the New York Times ran separate stories on the allegations against Calley on 12 and 13 November, respectively.[85] On 20 November, explicit color photographs and eye-witness testimony of the massacre taken by U.S. Army combat photographer Ronald L. Haeberle were published in The Cleveland Plain Dealer. The same day, Time, Life and Newsweek all covered the story, and CBS televised an interview with Paul Meadlo, a soldier in Calley's unit during the massacre.[86] From the U.S. Government and Army's point of view, Haeberle's photos transformed the massacre from potentially manageable to a very serious problem. The day after their publication, Melvin Laird the Secretary of Defense discussed them with Henry Kissinger who was at the time National Security Advisor to President Richard Nixon. Laird was recorded as saying that while he would like "to sweep it under the rug", the photographs prevented it. "They're pretty terrible", he said. "There are so many kids just laying there; these pictures are authentic".[87] Within the Army, the reaction was similar. Chief Warrant Officer André Feher, with the U.S. Army's Criminal Investigation Division (CID), was assigned the case in early August 1969. After he interviewed Haeberle, and was shown the photographs which he described as "evidence that something real bad had happened", he and the Pentagon officials he reported to realized "that news of the massacre could not be contained".[88] The story threatened to undermine the U.S. war effort and severely damage the Nixon presidency. Inside the White House, officials privately discussed how to contain the scandal. On November 21, National Security Advisor Henry Kissinger emphasized that the White House needed to develop a "game plan", to establish a "press policy", and maintain a "unified line" in its public response. The White House established a "My Lai Task Force" whose mission was to "figure out how best to control the problem", to make sure administration officials "all don't go in different directions" when discussing the incident, and to "engage in dirty tricks". These included discrediting key witnesses and questioning Hersh's motives for releasing the story. What soon followed was a public relations offensive by the administration designed to shape how My Lai would be portrayed in the press and understood among the American public.[89] As members of Congress called for an inquiry and news correspondents abroad expressed their horror at the massacre, the General Counsel of the Army Robert Jordan was tasked with speaking to the press. He refused to confirm allegations against Calley. Noting the significance that the statement was given at all, Bill Downs of ABC News said it amounted to the first public expression of concern by a "high defense official" that American troops "might have committed genocide".[90] On 24 November 1969, Lieutenant General William R. Peers was appointed by the Secretary of the Army and the Army Chief of Staff to conduct a thorough review of the My Lai incident, 16–19 March 1968, and its investigation by the Army.[91] Peers's final report,[41] presented to higher-ups on 17 March 1970, was highly critical of top officers at brigade and divisional levels for participating in the cover-up, and the Charlie Company officers for their actions at Mỹ Lai.[92] According to Peers' findings: [The 1st Battalion] members had killed at least 175–200 Vietnamese men, women, and children. The evidence indicates that only 3 or 4 were confirmed as Viet Cong although there were undoubtedly several unarmed VC (men, women, and children) among them and many more active supporters and sympathizers. One man from the company was reported as wounded from the accidental discharge of his weapon. ... a tragedy of major proportions had occurred at Son My.[41] In 2003 Hugh Thompson, the pilot who had intervened during the massacre, said of the Peers report: The Army had Lieutenant General William R. Peers conduct the investigation. He conducted a very thorough investigation. Congress did not like his investigation at all, because he pulled no punches, and he recommended court-martial for I think 34 people, not necessarily for the murder but for the cover-up. Really the cover-up phase was probably as bad as the massacre itself, because he recommended court-martial for some very high-ranking individuals.[93]: 28 In 1968, an American journalist, Jonathan Schell, wrote that in the Vietnamese province of Quang Ngai, where the Mỹ Lai massacre occurred, up to 70% of all villages were destroyed by the air strikes and artillery bombardments, including the use of napalm; 40 percent of the population were refugees, and the overall civilian casualties were close to 50,000 a year.[94] Regarding the massacre at Mỹ Lai, he stated, "There can be no doubt that such an atrocity was possible only because a number of other methods of killing civilians and destroying their villages had come to be the rule, and not the exception, in our conduct of the war".[95] In May 1970, a sergeant who participated in Operation Speedy Express wrote a confidential letter to then Army Chief of Staff Westmoreland describing civilian killings he said were on the scale of the massacre occurring as "a My Lai each month for over a year" during 1968–69. Two other letters to this effect from enlisted soldiers to military leaders in 1971, all signed "Concerned Sergeant", were uncovered within declassified National Archive documents. The letters describe common occurrences of civilian killings during population pacification operations. Army policy also stressed very high body counts and this resulted in dead civilians being marked down as combatants. Alluding to indiscriminate killings described as unavoidable, the commander of the 9th Infantry Division, then Major General Julian Ewell, in September 1969, submitted a confidential report to Westmoreland and other generals describing the countryside in some areas of Vietnam as resembling the battlefields of Verdun.[96][97] In July 1969, the Office of Provost Marshal General of the Army began to examine the evidence regarding possible criminal charges. Eventually, Calley was charged with several counts of premeditated murder in September 1969, and 25 other officers and enlisted men were later charged with related crimes.[98] In April 1972, Congressman Les Aspin sued the Department of Defense in District Court to reveal the Peers Commission. [99] Following the massacre a Pentagon task force called the Vietnam War Crimes Working Group (VWCWG) investigated alleged atrocities which were committed against South Vietnamese civilians by U.S. troops and created a secret archive of some 9,000 pages which documents 320 alleged incidents from 1967 to 1971 including 7 massacres in which at least 137 civilians died; 78 additional attacks targeting noncombatants in which at least 57 were killed, 56 were wounded and 15 were sexually assaulted; and 141 incidents of U.S. soldiers torturing civilian detainees or prisoners of war. 203 U.S. personnel were charged with crimes, 57 of them were court-martialed and 23 of them were convicted. The VWCWG also investigated over 500 additional alleged atrocities but it could not verify them.[100][101] Court martial On 17 November 1970, a court-martial in the United States charged 14 officers, including Major General Koster, the Americal Division's commanding officer, with suppressing information related to the incident. Most of the charges were later dropped. Brigade commander Colonel Henderson was the only high ranking commanding officer who stood trial on charges relating to the cover-up of the Mỹ Lai massacre; he was acquitted on 17 December 1971.[102] During the four-month-long trial, Calley consistently claimed that he was following orders from his commanding officer, Captain Medina. Despite that, he was convicted and sentenced to life in prison on 29 March 1971, after being found guilty of premeditated murder of not fewer than 20 people. Two days later, President Richard Nixon made the controversial decision to have Calley released from armed custody at Fort Benning, Georgia, and put under house arrest pending appeal of his sentence. Calley's conviction was upheld by the Army Court of Military Review in 1973 and by the U.S. Court of Military Appeals in 1974.[103] In August 1971, Calley's sentence was reduced by the convening authority from life to twenty years. Calley would eventually serve three and one-half years under house arrest at Fort Benning including three months in the disciplinary barracks at Fort Leavenworth, Kansas. In September 1974, he was paroled by the Secretary of the Army, Howard Callaway.[103][104] In a separate trial, Medina denied giving the orders that led to the massacre, and was acquitted of all charges, effectively negating the prosecution's theory of "command responsibility", now referred to as the "Medina standard". Several months after his acquittal, however, Medina admitted he had suppressed evidence and had lied to Henderson about the number of civilian deaths.[105] Captain Kotouc, an intelligence officer from 11th Brigade, was also court-martialed and found not guilty. Koster was demoted to brigadier general and lost his position as the Superintendent of West Point. His deputy, Brigadier General Young, received a letter of censure. Both were stripped of Distinguished Service Medals which had been awarded for service in Vietnam.[106] Of the 26 men initially charged, Calley was the only one convicted.[107] Some have argued that the outcome of the Mỹ Lai courts-martial failed to uphold the laws of war established in the Nuremberg and Tokyo War Crimes Tribunals.[108] Classification as a war crime Telford Taylor, a senior American prosecutor at Nuremberg, wrote that legal principles established at the war crimes trials could have been used to prosecute senior American military commanders for failing to prevent atrocities such as the one at Mỹ Lai.[109] Howard Callaway, Secretary of the Army, was quoted in The New York Times in 1976 as stating that Calley's sentence was reduced because Calley honestly believed that what he did was a part of his orders—a rationale that contradicts the standards set at Nuremberg and Tokyo, where following orders was not a defense for committing war crimes.[108] On the whole, aside from the Mỹ Lai courts-martial, there were 36 military trials held by the U.S. Army from January 1965 to August 1973 for crimes against civilians in Vietnam.[65]: 196 Some authors[110] have argued that the light punishments of the low-level personnel present at Mỹ Lai and unwillingness to hold higher officials responsible was part of a pattern in which the body-count strategy and the so-called "Mere Gook Rule" encouraged U.S. soldiers to err on the side of killing suspected Vietnamese enemies even if there was a very good chance that they were civilians. This in turn, Nick Turse argues, made lesser known massacres similar to Mỹ Lai and a pattern of war crimes common in Vietnam.[110] |

その後 燃える家屋の外に並ぶ死体。 11時頃に基地に戻った後、トンプソンは上官に虐殺の事実を報告した。[61]:176-179 民間人殺害の申し立てはすぐに、作戦全体の指揮官であるバーカー大佐の耳に入った。バーカーは副官に無線で連絡し、メディナから現地で何が起こっているの かを確かめた。メディナはチャーリー中隊に停戦命令を下し、「(殺害を)やめろ、やめさせろ」と命じた。[62] トンプソンが民間人殺害の公式報告を行ったため、第11歩兵旅団の司令官オラン・ヘンダーソン大佐による事情聴取が行われた。[63] 懸念を抱いた米国の上級将校たちは、タスクフォース・バーカーによる他の村々(マイ・ライ5、マイ・ライ1など)に対する同様の作戦を中止させた。ライ 5、ライ1など)に対する作戦を中止した。[64] トンプソンの暴露にもかかわらず、ヘンダーソン大佐は1968年3月27日にメディナに表彰状を送っている。 翌日、3月28日、タスクフォース・バーカーの司令官は、3月16日の作戦に関する戦闘行動報告書を提出し、その中でミライでの作戦は成功であり、128 人のベトコン戦闘員が死亡したと述べた。アメリカ陸軍師団の司令官であるコスター将軍はチャーリー中隊に祝辞を送った。 MACVの司令官であるウィリアム・C・ウェストモアランド大将も、第1大隊第20歩兵連隊チャーリー中隊の「卓越した行動」を称賛し、「敵に大きな打撃 を与えた」と述べた。[65]:196 その後、 彼はその後、姿勢を変更し、回顧録に「丸一日近くにわたって、悪魔的なスローモーションの悪夢のような光景の中で、無防備な赤ん坊、子供、母親、老人たち が意識的に虐殺された。 戦争の混沌とした状況と、米軍がベトナムにおける非戦闘員の正確な死者数を確認する作業を行わなかったため、ミーライで殺害された民間人の正確な数は不明 である。 推定値は情報源によって異なり、347人と504人が最もよく引用される数字である。虐殺現場にある記念碑には、1歳から82歳までの504人の名前が記 載されている。その後、米軍による調査では、米軍による公式な推定値である347人というより低い数字が導き出された。[要出典] 地元政府による公式な推定値は依然として504人のままである。[67] 調査と隠蔽 初期の報告では、「激しい銃撃戦」で「ベトコン128名と民間人22名」が死亡したと主張された。ウェストモアランドは部隊の「素晴らしい働き」を称賛し た。当時『星条旗』誌が伝えたところによると、「米陸軍歩兵部隊は1日をかけた激戦で128名の共産主義者を殺害した」という。 1968年3月16日、「5時の茶番」として知られる公式の記者会見で、謄写版刷りのリリースに次の一節が含まれていた。「本日、アメリカ陸軍師団の部隊 はクァンガイ市近郊で128名の敵を殺害した。ヘリコプターによる攻撃と砲撃は、終日、地上部隊を支援した」[69] アメリカ師団の副官ジョージ・H・ヤング准将の命令により、ヘンダーソン大佐がミーライ作戦の初期調査を行った。ヘンダーソンは事件に関与した数人の兵士 に事情聴取を行い、4月下旬に書面による報告書を提出し、作戦中に20人ほどの民間人が誤って死亡したと主張した。ヘンダーソンの報告書によると、民間人 の死傷は偶発的なものであり、主に長距離砲撃によるものだったとされている。[70] この時点でも、陸軍は依然としてこの出来事を、128人の敵戦闘員の死を伴う軍事的勝利として説明していた。[26] それから6ヶ月後、第11軽歩兵旅団の21歳の兵士トム・グレンは、新任のMACV司令官クレイトン・エイブラムス大将に手紙を書いた。[71] 彼は、ベトナム駐留米軍によるベトナム民間人に対する現在進行中の日常的な残虐行為について、自身が目撃したことを説明し、次のように結論づけた。 このような人種的不寛容や正義や人情を顧みない考えを抱く米兵が、全米国民の典型であると信じなければならないとしたら、それは本当に恐ろしいことだ。し かし、そのような兵士が頻繁に現れることで、そのような考えが信憑性を帯びてくる。... ここで概説したことは、私の部隊だけでなく、共に任務にあたった他の部隊でも目にしたことであり、それが一般的であることを懸念している。もしこれが事実 であるならば、見過ごすことのできない問題であるが、MACV(ベトナム軍事援助司令部)およびジュネーブ条約の規定をより厳格に実施することで、おそら く根絶できるだろう。 当時31歳の陸軍少佐でアメリカ師団の作戦部副部長を務めていたコリン・パウエルは、グレンが現地での出来事について限られた知識しかもっていなかったた め、この手紙の調査を命じられた。パウエルは報告書の中で、「この描写を真っ向から否定する事実として、アメリカ師団の兵士とベトナムの人々との関係が良 好であることが挙げられる」と記した。2018年の米陸軍による虐殺のケーススタディでは、パウエルが「グレンの手紙に記された申し立てを調査した」と指 摘している。彼は、広範囲にわたる不必要な殺害、戦争犯罪、あるいはミライに関連する事実を明らかにすることはできなかった...」[73] パウエルの任務への対応は、後に一部の観察者によってミライの残虐行為を「隠蔽」したと評された。[72] 2004年5月、当時の国務長官であったパウエルは、CNNのラリー・キングに対し、「私はミライの部隊に所属していた。ミライの事件が起こった後、私は そこに着任した。戦争では、このような恐ろしいことが時折起こるが、それでもなお、非難されるべきことである」と述べた。 ミイラ虐殺の7ヶ月前、ロバート・マクナマラの命令により、米国防総省の監察総監が南ベトナムにおける残虐行為疑惑の報道を調査した。1967年8月、 200ページに及ぶ報告書「南ベトナムにおける米軍による残虐行為疑惑」が完成した。 グレンとは別に、第11歩兵師団本部中隊航空部隊の元機銃手である専門部員5ロナルド・L・ライデンアワーは、1969年3月に30人の連邦議会議員に手 紙を送り、 「ピンクヴィル」事件の状況を調査するよう強く求めた。[75][76] 彼とパイロットのギルバート・ホンダ准尉は、作戦の数日後にミライ上空を飛行し、完全な破壊の現場を目撃した。ある時、彼らは11旅団のワッペンを付けた 死んだベトナム人女性の遺体の上空にホバリングした。[77] リデンアワー自身は虐殺の現場には居合わせなかったが、虐殺を目撃し、場合によっては加担したチャーリー中隊の兵士たちと詳細にわたって会話を交わし、そ の内容を記録した。彼はミィライで「かなり陰惨で血なまぐさい出来事が実際に起こった」と確信し、 そこで聞いた話に心を乱され、軍を除隊してから3か月も経たないうちに、彼は懸念を議会[75]および統合参謀本部議長、大統領に宛てて手紙を書いた [70]。手紙には、証言に同意した目撃者マイケル・バーンハートの名前も記載されていた[79]。 ライデンアワーの手紙を受け取ったほとんどの者はそれを無視したが、モ・ユダ下院議員[80]とバリー・ゴールドウォーター上院議員およびエドワード・ブ ルック上院議員[81]は例外であった。ユダは下院軍事委員会に国防総省高官に調査を行うよう要請した。 公にされた事実と反応 リデンアワーの手紙による圧力の高まりを受け、1969年9月9日、陸軍はひっそりと、単に「ミライ」と呼ばれる村落の近くにあるソーン・ミ村で、109 人の南ベトナム民間人が死亡した事件について、故意殺人罪の6つの容疑でカリーを起訴した 単に「ミライ」と呼ばれる集落で、109人の南ベトナム民間人が死亡した事件について、カーリーを計画殺人罪の6つの容疑で起訴した。[82][83] カーリーの軍法会議は報道陣に公開されず、1年以上後の1970年11月まで開始されなかった。しかし、カーリーの起訴のニュースは、アメリカの調査報道 記者でフリーランスのジャーナリストであるシーモア・ハーシュの耳に入った。[84] M 事件から1年半以上が経過した1969年11月13日、ハーシュがディスパッチ・ニュース・サービスを通じて記事を公表し、マイ・ライ事件が初めて公に なった。 ハーシュは、キャリーに対する広範な取材を行った後、35の新聞に「ミィ・ライ事件」の記事を掲載した。さらに、アラバマ州モンゴメリーの「アラバマ・ ジャーナル」紙と「ニューヨーク・タイムズ」紙は、それぞれ11月12日と13日に、キャリーに対する告発に関する別々の記事を掲載した。[85] 11月20日には、米陸軍の戦場カメラマン、ロナルド・L・ヘーベルレが撮影した虐殺の生々しいカラー写真と目撃者の証言が、「クリーブランド・プレー ン・ディーラー」紙に掲載された。 同日、タイム、ライフ、ニューズウィークの各誌がこの事件を取り上げ、CBSは、虐殺の際にカリー伍長の部隊に所属していた兵士ポール・ミードロのインタ ビューを放映した。[86] 米国政府および軍の観点では、ヘーベルの写真により、虐殺は対処可能な問題から非常に深刻な問題へと変貌した。 公開の翌日、国防長官メルヴィン・レアードは、当時リチャード・ニクソン大統領の国家安全保障顧問であったヘンリー・キッシンジャーとこの件について話し 合った。レアードは「この件をうやむやにしたい」が、写真がそれを妨げていると述べたと記録されている。「ひどい写真だ。あそこに横たわっている子供たち がたくさんいる。この写真は本物だ」と彼は言った。[87] 陸軍内でも反応は同様であった。 米国陸軍犯罪捜査部(CID)の首席准尉アンドレ・フェーハーは、1969年8月初旬にこの事件を担当することになった。 ヘーベルレの事情聴取を行い、「本当にひどいことが起こった証拠」と表現した写真を見せられた後、フェーハーと彼の上司である国防総省高官は「虐殺の ニュースを隠し通すことはできない」と悟った。[88] T このニュースは米国の戦争努力を損ない、ニクソン大統領の地位を大きく傷つける可能性があった。ホワイトハウス内部では、当局者たちが非難を封じ込める方 法を非公式に話し合った。11月21日、ヘンリー・キッシンジャー国家安全保障顧問は、ホワイトハウスは「ゲームプラン」を練り、「報道方針」を確立し、 公式対応において「統一した方針」を維持する必要があると強調した。ホワイトハウスは「マイ・ライ対策本部」を設置し、その任務は「問題をいかにして最も 効果的にコントロールするか」を把握すること、事件について政府高官が「全員が別々の方向に向かわない」ようにすること、そして「汚い手を使う」ことだっ た。これには、主要な証人の信用を失墜させたり、ハーシュが記事を公表した動機を問いただしたりすることが含まれていた。その後すぐに、政府による広報攻 勢が始まり、ミライ事件が報道でどのように取り上げられ、アメリカ国民にどう理解されるかを形作ろうとした。[89] 米議会議員が調査を要求し、海外特派員が虐殺に対する恐怖を表明する中、陸軍のロバート・ジョーダン法務官が報道陣に説明を行うこととなった。 ジョーダンは、カリーに対する告発を認めることを拒否した。 ABCニュースのビル・ダウンズは、この声明が発表されたことの重要性を指摘し、米軍が「大量虐殺を行った可能性がある」という懸念を「国防高官」が初め て公に表明したことになると述べた。[90] 1969年11月24日、陸軍長官と陸軍参謀総長は、ウィリアム・R・ピアース中将を、1968年3月16日から19日にかけてのミライ事件と陸軍による その調査を徹底的に検証するよう任命した。 ピアーズの最終報告書[41]は、1970年3月17日に上層部に提出され、隠蔽工作に加担した旅団および師団レベルの最高幹部、およびミ・ライでの行動 についてチャーリー中隊の士官たちを厳しく批判した。 ピアーズの調査結果によると、 第1大隊の隊員たちは少なくとも175人から200人のベトナム人男性、女性、子供を殺害した。証拠によると、ベトコンとして確認されたのは3人か4人だ けだったが、その中には間違いなく非武装のベトコン(男性、女性、子供)が数人おり、さらに多くの活動的な支持者や同情者がいた。小隊の一人が誤って自分 の銃を発射したために負傷したと報告された。... ソンミでは大規模な悲劇が起こった。[41] 2003年、虐殺の現場に介入したパイロットのヒュー・トンプソンはピアーズ報告について次のように述べた。 陸軍はウィリアム・R・ピアース中将に調査を行わせた。彼は非常に徹底的な調査を行った。議会は彼の調査をまったく好まなかった。なぜなら、彼は遠慮する ことなく、34人(必ずしも殺人ではなく、隠蔽工作の容疑者)に軍法会議を勧告したからだ。実際、隠蔽工作の段階は、おそらく虐殺そのものと同じくらいひ どいものだった。なぜなら、彼は非常に高位の人物数名に軍法会議を勧告したからだ。[93]: 28 1968年、米国人ジャーナリストのジョナサン・シェルは、ミライ虐殺の舞台となったベトナムのクァンガイ省では、ナパーム弾を含む空爆や砲撃により、最 大で全村の70%が破壊され、人口の40%が難民となり、 年間5万人近くに上った。[94] 彼は、ミ・ライ虐殺について、「このような残虐行為が可能だったのは、民間人を殺害し、彼らの村を破壊する他の多くの方法が、戦争遂行における例外ではな く、常態化していたからに他ならない」と述べた。[95] 1970年5月、スピードエクスプレス作戦に参加した軍曹が、1968年から69年にかけて「毎月のように、1年以上にわたって起こった」虐殺の規模で民 間人が殺害されたと述べ、当時の陸軍参謀総長ウェストモアランドに宛てて機密文書を書いた。1971年に下士官兵が軍の指導者たちに宛てた、同じ趣旨の2 通の手紙も、すべて「Concerned Sergeant(懸念する軍曹)」の署名入りで、機密解除された米国国立公文書記録管理局の文書から発見された。これらの手紙は、住民の平和化作戦中に 一般市民が殺害されることが日常茶飯事であることを伝えている。また、陸軍の方針も、非常に高い死者数を強調しており、その結果、死亡した一般市民が戦闘 員として記録されることになった。1969年9月、第9歩兵師団の司令官(当時ジュリアン・ユーウェル少将)は、やむを得ない無差別殺戮について言及し、 ヴェルダン(ベルダン)の戦場に似たベトナムのいくつかの地域の様子をウェストモアランドや他の将軍たちに報告した。 1969年7月、陸軍法務総監室は刑事責任の可能性に関する証拠の調査を開始した。最終的に、キャリーは1969年9月に計画殺人罪で起訴され、後に25 人の士官と下士官兵が関連犯罪で起訴された。 1972年4月、レス・アスピン下院議員は、ピアーズ委員会の報告書を公開するために国防総省を連邦地方裁判所に提訴した。 [99] 虐殺の後、国防総省のタスクフォースであるベトナム戦争犯罪作業部会(VWCWG)が、米軍による南ベトナム民間人に対する残虐行為の疑惑を調査し、 1967年から1971年までの320件の疑惑事件を記録した約9,000ページの秘密文書を作成した。その中には、少なくとも137人の民間人が死亡し た7件の虐殺、少なくとも57人が死亡、56人が負傷、15人が性的暴行を受けた非戦闘員を標的とした78件の追加攻撃が含まれている。 。その中には、少なくとも137人の民間人が死亡した7件の虐殺、少なくとも57人が死亡、56人が負傷、15人が性的暴行を受けた非戦闘員を標的とした 78件の追加攻撃、米兵による民間人拘留者や捕虜への拷問141件が含まれている。203人の米軍関係者が罪に問われ、そのうち57人が軍法会議にかけら れ、23人が有罪判決を受けた。VWCWGはさらに500件以上の残虐行為疑惑を調査したが、立証することはできなかった。[100][101] 軍法会議 1970年11月17日、アメリカ合衆国軍法会議は、アメリカ陸軍アメリカ師団指揮官のコスター少将を含む14人の将校を、この事件に関する情報の隠蔽容 疑で起訴した。 ほとんどの容疑は後に取り下げられた。ミライ虐殺の隠蔽に関する罪状で裁判にかけられた高級指揮官は、師団長のヘンダーソン大佐ただ一人であった。彼は 1971年12月17日に無罪となった。 4ヶ月にわたる裁判の間、キャリーは一貫して、上官であるメディナ大尉の命令に従っただけだと主張した。にもかかわらず、1971年3月29日、20人以 上の計画殺人罪で有罪となり、終身刑を言い渡された。その2日後、リチャード・ニクソン大統領は物議を醸す決定を下し、ジョージア州フォートベニングの武 装警備からキャリーを解放し、判決の控訴審まで自宅軟禁とすることを決定した。キャリーの有罪判決は、1973年に軍事再審査裁判所、1974年に米軍控 訴裁判所によって支持された。 1971年8月、召集権限者により、カリーの刑期は終身刑から20年に減刑された。カリーは最終的に、カンザス州フォート・レブンワースの懲戒営舎での3 か月間を含め、フォート・ベニングでの自宅軟禁で3年半服役した。1974年9月、彼はハワード・キャロウェイ陸軍長官により仮釈放された。 別の裁判で、メディナは虐殺につながる命令を下したことを否定し、すべての罪状について無罪となった。これにより、検察側の「指揮官責任」という理論は事 実上否定され、現在では「メディナ基準」と呼ばれている。しかし、無罪判決から数か月後、メディナは証拠を隠蔽し、民間人の死者数についてヘンダーソンに 嘘をついていたことを認めた。 第11旅団の情報将校であったコトゥー大尉も軍法会議にかけられ、無罪となった。コスターは准将に降格となり、ウェストポイントの校長の職も失った。彼の 副官であったヤング准将は、非難の書簡を受け取った。両者ともベトナムでの功績により授与されていた殊勲章をはく奪された。 当初起訴された26人のうち、有罪判決を受けたのはカリーだけだった。[107] マイ・ライの軍事裁判の結果は、ニュルンベルク裁判や東京裁判で確立された戦争法を遵守していないという意見もある。[108] 戦争犯罪としての分類 ニュルンベルク裁判のアメリカ側主任検事であったテルフォード・テイラーは、戦争犯罪裁判で確立された法原則は、ミィライ事件のような残虐行為を防止でき なかったとして、アメリカ軍の上級司令官を起訴するのに使用できたはずだと書いている。 ハワード・キャロウェイ陸軍長官は、1976年のニューヨーク・タイムズ紙で、キャリーが減刑されたのは、キャリーが自分のしたことは命令の一部だと正直 に信じていたからだと述べたと引用された。これは、ニュルンベルクや東京で定められた基準とは矛盾する論理であり、そこでは命令に従ったことは戦争犯罪の 弁明にはならない 。全体として、ミィライの軍事法廷を除いて、1965年1月から1973年8月までの間に、ベトナム民間人に対する戦争犯罪に関して米陸軍が実施した軍事 裁判は36件であった。[65]:196 一部の著者は[110]、ミ・ライに居合わせた下級兵士の軽い処罰と、高官の責任追及を避けようとする姿勢は、死体数戦略と「単なるゴーク人(Mere Gook)ルール」と呼ばれるものが、米兵に、ベトナム人の敵と疑われる人物が民間人である可能性が極めて高い場合でも、殺害する側に傾くよう促したとい うパターンの一環であったと主張している。このことが、ミライのようなあまり知られていない虐殺や、ベトナムでよく見られた戦争犯罪のパターンを生み出し たと、ニック・ターセは主張している。[110] |

| Survivors In early 1972, the camp at Mỹ Lai (2) where the survivors of the Mỹ Lai massacre had been relocated was largely destroyed by Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) artillery and aerial bombardment, and remaining eyewitnesses were dispersed. The destruction was officially attributed to "Viet Cong terrorists". Quaker service workers in the area gave testimony in May 1972 by Martin Teitel at hearings before the Congressional Subcommittee to Investigate Problems Connected with Refugees and Escapees in South Vietnam. In June 1972, Teitel's account was published in The New York Times.[111] Many American soldiers who had been in Mỹ Lai during the massacre accepted personal responsibility for the loss of civilian lives. Some of them expressed regrets without acknowledging any personal guilt, as, for example, Ernest Medina, who said, "I have regrets for it, but I have no guilt over it because I didn't cause it. That's not what the military, particularly the United States Army, is trained for."[112] Lawrence La Croix, a squad leader in Charlie Company in Mỹ Lai, stated in 2010: "A lot of people talk about My Lai, and they say, 'Well, you know, yeah, but you can't follow an illegal order.' Trust me. There is no such thing. Not in the military. If I go into a combat situation and I tell them, 'No, I'm not going. I'm not going to do that. I'm not going to follow that order', well, they'd put me up against the wall and shoot me."[113] On 16 March 1998, a gathering of local people and former American and Vietnamese soldiers stood together at the place of the Mỹ Lai massacre in Vietnam to commemorate its 30th anniversary. American veterans Hugh Thompson and Lawrence Colburn, who were shielding civilians during the massacre, addressed the crowd. Among the listeners was Phan Thi Nhanh, a 14-year-old girl at the time of the massacre. She was saved by Thompson and vividly remembered that tragic day, "We don't say we forget. We just try not to think about the past, but in our hearts we keep a place to think about that".[114] Colburn challenged Lieutenant Calley "to face the women we faced today who asked the questions they asked, and look at the tears in their eyes and tell them why it happened".[114] No American diplomats or any other officials attended the meeting. More than a thousand people turned out on 16 March 2008, forty years after the massacre. The Sơn Mỹ Memorial drew survivors and families of victims and some returning U.S. veterans. One woman (an 8-year-old at the time) said, "Everyone in my family was killed in the Mỹ Lai massacre—my mother, my father, my brother and three sisters. They threw me into a ditch full of dead bodies. I was covered with blood and brains."[115] The U.S. was unofficially represented by a volunteer group from Wisconsin called Madison Quakers, who in 10 years built three schools in Mỹ Lai and planted a peace garden.[116] On 19 August 2009, Calley made his first public apology for the massacre in a speech to the Kiwanis club of Greater Columbus, Georgia:[117][118] "There is not a day that goes by that I do not feel remorse for what happened that day in My Lai", he told members of the club. "I feel remorse for the Vietnamese who were killed, for their families, for the American soldiers involved and their families. I am very sorry. ... If you are asking why I did not stand up to them when I was given the orders, I will have to say that I was a 2nd lieutenant getting orders from my commander and I followed them—foolishly, I guess."[119][120] Trần Văn Đức, who was seven years old at the time of the Mỹ Lai massacre and now resides in Remscheid, Germany, called the apology "terse". He wrote a public letter to Calley describing the plight of his and many other families to remind him that time did not ease the pain, and that grief and sorrow over lost lives will forever stay in Mỹ Lai.[121] |

生存者 1972年初頭、ミライ虐殺の生存者が移住していたミライ(2)のキャンプは、ベトナム共和国軍(ARVN)の砲撃と空爆によりほぼ全壊し、残っていた目 撃者も散り散りになった。この破壊行為は公式には「ベトコンのテロ」によるものとされた。1972年5月、この地域のクエーカー教徒の奉仕活動家たちが、 マーティン・タイテルによる証言を、南ベトナムにおける難民と逃亡兵に関連する問題を調査する連邦議会の小委員会の公聴会で行った。1972年6月、タイ テルの証言はニューヨーク・タイムズ紙に掲載された。 虐殺の際にミ・ライにいた多くのアメリカ兵は、民間人の死に対して個人的な責任を感じていた。 罪の意識を認めないまでも、後悔の念を表明した兵士もいた。例えば、アーネスト・メディナは「私は後悔しているが、私はそれを引き起こしたわけではないの で罪の意識はない。軍隊、特にアメリカ陸軍はそういう訓練を受けていない」と述べた。 ミイラのチャーリー中隊の分隊長であったローレンス・ラ・クロワは2010年に「多くの人がミイラについて語っているが、彼らは『まあ、そうだな、でも違 法な命令には従えない』と言う。信じてくれ。そんなことはありえない。軍隊ではありえない。もし戦闘状況に陥り、私が『いや、私は行かない。そんなことは しない。そんな命令には従わない』と彼らに言ったら、彼らは私を壁際に立たせて銃撃するだろう」[113] 1998年3月16日、ベトナムのミーライ虐殺の現場で、地元住民と元米兵およびベトナム兵士たちが、虐殺30周年を記念して肩を並べた。虐殺の際に民間 人を庇い、命を落とした米軍退役軍人のヒュー・トンプソンとローレンス・コルバーンが、集まった人々に語りかけた。 その場に居合わせた聴衆の中には、虐殺当時14歳だったファン・ティ・ニャンもいた。 彼女はトンプソンに救われたが、その悲惨な日を鮮明に覚えていた。「私たちは忘れたとは言いません。ただ、過去について考えないようにしているだけだ。し かし、心の中には、そのことを考える場所を確保している」と語った。[114] コルバーンは、キャリー中尉に「今日、私たちが直面した女性たちに、彼女たちが投げかけた質問を投げかけ、彼女たちの目から涙が流れるのを見て、なぜこの ようなことが起こったのかを伝えてほしい」と訴えた。[114] この会合には、米国の外交官やその他の政府関係者は出席しなかった。 虐殺から40年後の2008年3月16日には、1000人以上の人々がソンミ記念館を訪れた。生存者や被害者の遺族、そして帰還した米国人退役軍人たちが 訪れた。ある女性(当時8歳)は、「私の家族は皆、ミィライ虐殺で殺されました。母も、父も、兄も、そして3人の姉妹も。彼らは私を死体でいっぱいの溝に 投げ込んだ。私は血と脳みそだらけだった」[115] 米国は非公式に、ウィスコンシン州のボランティアグループ「マディソン・クエーカー」によって代表された。このグループは10年間にミライに3つの学校を 建設し、平和の庭を造った。[116] 2009年8月19日、キャリーはジョージア州コロンバス大都市圏のキワニスクラブでのスピーチで、虐殺について初めて公に謝罪した。 「ミライで起こったことについて、後悔の念を抱かない日は一日たりともありません」と、彼はクラブのメンバーに語った。「殺されたベトナム人、彼らの家 族、関与したアメリカ兵とその家族に対して、私は後悔の念を抱いている。本当に申し訳なく思っている。... 命令を受けた時に、なぜ彼らに立ち向かわなかったのかと問うのであれば、私は司令官から命令を受ける2等陸尉であり、愚かにもその命令に従ったと答えざる を得ないだろう」[119][120] ミライ虐殺当時7歳で、現在はドイツのレムシャイト在住のチャン・ヴァン・ドゥック氏は、謝罪を「簡潔」と表現した。彼は、自分や多くの家族が経験した苦 境をカルーに伝える公開書簡を書き、年月が経っても苦痛が和らぐことはなく、命を落とした人々への悲しみと喪失感はミライで永遠に続くことをカルーに思い 出させた。[121] |

| Participants Officers LTC Frank A. Barker – commander of the Task Force Barker, a battalion-sized unit, assembled to attack the VC 48th Battalion supposedly based in and around Mỹ Lai. He allegedly ordered the destruction of the village and supervised the artillery barrage and combat assault from his helicopter. Reported the operation as a success; was killed in Vietnam on 13 June 1968, in a mid-air collision before the investigation had begun.[41][122] CPT Kenneth W. Boatman – an artillery forward observer; was accused by the Army of failure to report possible misconduct, but the charge was dropped.[123] MAJ Charles C. Calhoun – operations officer of Task Force Barker; charges against him of failure to report possible misconduct were dropped.[123] 2LT William Calley – platoon leader, 1st Platoon, Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry Regiment, 11th Infantry Brigade, 23rd Infantry Division. Was charged in premeditating the murder of 102 civilians,[124] found guilty and sentenced to life. Was paroled in September 1974 by the Secretary of the Army Howard Callaway. LTC William D. Guinn Jr. – Deputy Province Senior Advisor/Senior Sector Advisor for Quangngai Province. Charges against him of dereliction of duty and false swearing brought by the Army were dropped.[123] COL Oran K. Henderson – 11th Infantry Brigade commander, who ordered the attack and flew in a helicopter over Mỹ Lai during it. After Hugh Thompson immediately reported multiple killings of civilians, Henderson started the cover-up by dismissing the allegation about the massacre and reporting to the superiors that indeed 20 people from Mỹ Lai died by accident. Accused of cover-up and perjury by the Army; charges dropped.[41] MG Samuel W. Koster – commander of the 23rd Infantry Division, was not involved with planning the Mỹ Lai search-and-destroy mission. However, during the operation he flew over Mỹ Lai and monitored the radio communications.[125] Afterward, Koster did not follow up with the 11th Brigade commander COL Henderson on the initial investigation, and later was involved in the cover-up. Was charged by the Army with failure to obey lawful regulations, dereliction of duty, and alleged cover-up; charges dropped. Later was demoted to brigadier general and stripped of a Distinguished Service Medal.[123] CPT Eugene M. Kotouc – military intelligence officer assigned to Task Force Barker;[126] he partially provided information, on which the Mỹ Lai combat assault was approved; together with Medina and a South Vietnamese officer, he interrogated, tortured and allegedly executed VC and NVA suspects later that day. Was charged with maiming and assault, tried by the jury and acquitted.[43] CPT Dennis H. Johnson – 52d Military Intelligence Detachment, assigned to Task Force Barker, was accused of failure to obey lawful regulations; however, charges were later dropped.[123] 2LT Jeffrey U. Lacross – platoon leader, 3rd Platoon, Charlie Company; testified that his platoon did not meet any armed resistance in Mỹ Lai, and that his men did not kill anybody; however, since, in his words, both Calley and Brooks reported a body count of 60 for their platoons, he then submitted a body count of 6.[127] MAJ Robert W. McKnight – operations officer of the 11th Brigade; was accused of false swearing by the Army, but charges were subsequently dropped.[123] CPT Ernest Medina – commander of Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry; nicknamed Mad Dog by subordinates. He planned, ordered, and supervised the execution of the operation in Sơn Mỹ village. Was accused of failure to report a felony and of murder; went to trial and was acquitted.[128] CPT Earl Michles[129] – officer during My Lai operation; he died in a helicopter crash three months later. BG George H. Young Jr. – assistant division commander, 23rd Infantry Division; charged with alleged cover-up, failure to obey lawful regulations and dereliction of duty by the Army; charges were dismissed.[123] MAJ Frederic W. Watke – commander of Company B, 123rd Aviation Battalion, 23rd Infantry Division, providing helicopter support on 16 March 1968. Testified that he informed COL Henderson about killings of civilians in My Lai as reported by helicopter pilots.[130] Accused of failure to obey lawful regulations and dereliction of duty; charges dropped.[123] CPT Thomas K. Willingham – Company B, 4th Battalion, 3rd Infantry Regiment, assigned to Task Force Barker; charged with making false official statements and failure to report a felony; charges dropped.[123] Altogether, 14 officers directly and indirectly involved with the operation, including two generals, were investigated in connection with the Mỹ Lai massacre, except for LTC Frank A. Barker, CPT Earl Michaels, and 2LT Stephen Brooks, who all died before the beginning of the investigation.[123][106][131] 1st Platoon, Charlie Company, 1st Battalion, 20th Infantry PFC James Bergthold, Sr. – Assistant gunner and ammo bearer on a machine gun team with Maples. Was never charged with a crime. Admitted that he killed a wounded woman he came upon in a hut, to put her out of her misery. PFC Michael Bernhardt – Rifleman; he dropped out of the University of Miami to volunteer for the Army.[132] Bernhardt refused to kill civilians at Mỹ Lai. Captain Medina reportedly later threatened Bernhardt to deter him from exposing the massacre. As a result, Bernhardt was given more dangerous assignments such as point duty on patrol and would later be afflicted with a form of trench foot as a direct result. Bernhardt told Ridenhour, who was not present at Mỹ Lai during the massacre, about the events, pushing him to continue his investigation.[133] Later he would help expose and detail the massacre in numerous interviews with the press, and he served as a prosecution witness in the trial of Medina, where he was subjected to intense cross examination by defense counsel F. Lee Bailey backed by a team of attorneys including Gary Myers. Bernhardt is a recipient of the New York Society for Ethical Culture's 1970 Ethical Humanist Award.[134] PFC Herbert L. Carter – "tunnel rat"; shot himself in the foot while reloading his pistol and claimed that he shot himself in the foot to be MEDEVACed out of the village when the massacre started.[135] PFC Dennis L. Conti – Grenadier/Minesweeper; testified that he initially refused to shoot but later fired some M79 rounds at a group of fleeing people with unknown effect. SP4 Lawrence C. La Croix – Squad Leader; testified favorably for Captain Medina during his trial. In 1993, he sent a letter to the Los Angeles Times, saying, "Now, 25 years later, I have only recently stopped having flashbacks of that morning. I still cannot touch a weapon without vomiting. I am unable to interact with any of the large Vietnamese population in Los Angeles for fear that they might find out who I am; and, because I cannot stand the pain of remembering or wondering if maybe they had relatives or loved ones who were victims at Mỹ Lai ... some of us will walk in the jungles and hear the cries of anguish for all eternity".[136] PFC James Joseph Dursi – Rifleman; followed orders to round up civilians, but refused to open fire, even when ordered to do so by Lieutenant Calley. Earlier that day, he had shot a fleeing villager who was apparently carrying a weapon but turned out to be a woman carrying her baby. Afterwards, Dursi had vowed to not kill again.[137] PFC Ronald Grzesik – a team leader. He claimed he followed orders to round up civilians but refused to kill them.[citation needed] SP4 Robert E. Maples – Machine gunner attached to SSG Bacon's squad; stated that he refused an order to kill civilians hiding in a ditch and claimed his commanding officer threatened to shoot him.[138] PFC Paul D. Meadlo – Rifleman; said he was afraid of being shot if he did not participate. Lost his foot to a land mine the next day; later, he publicly admitted his part in the massacre. SSG David Mitchell – Squad Leader; accused by witnesses of shooting people at the ditch site; pleaded not guilty. Mitchell was acquitted.[139] SP4 Charles Sledge – Radiotelephone Operator; later a prosecution witness. PV2 Harry Stanley – Grenadier; claimed to have refused an order from Lieutenant Calley to kill civilians that were rounded-up in a bomb-crater but refused to testify against Calley. After he was featured in a documentary and several newspapers, the city of Berkeley, California, designated 17 October as "Harry Stanley Day".[140] SGT Esequiel Torres – previously had tortured and hanged an old man because Torres found his bandaged leg suspicious. He and Roschevitz (described below) were involved in the shooting of a group of ten women and five children in a hut. Calley ordered Torres to man the machine gun and open fire on the villagers that had been grouped together. Before everyone in the group was down, Torres ceased fire and refused to fire again. Calley took over the M60 and finished shooting the remaining villagers in that group himself.[141] Torres was charged with murder but acquitted. SP4 Frederick J. Widmer – Assistant Radiotelephone Operator; Widmer, who has been the subject of pointed blame, is quoted as saying, "The most disturbing thing I saw was one boy—and this was something that, you know, this is what haunts me from the whole, the whole ordeal down there. And there was a boy with his arm shot off, shot up half, half hanging on and he just had this bewildered look in his face and like, 'What did I do, what's wrong?' He was just, you know, it's, it's hard to describe, couldn't comprehend. I, I shot the boy, killed him and it's—I'd like to think of it more or less as a mercy killing because somebody else would have killed him in the end, but it wasn't right."[142] Widmer died on 11 August 2016, aged 68.[143] Before being shipped to South Vietnam, all of Charlie Company's soldiers went through an advanced infantry training and basic unit training at Pohakuloa Training Area in Hawaii.[144][145] At Schofield Barracks they were taught how to treat POWs and how to distinguish VC guerrillas from civilians by a Judge Advocate.[135] Other soldiers Nicholas Capezza – Chief Medic; HHQ Company;[146] insisted he saw nothing unusual. William Doherty and Michael Terry – 3rd Platoon soldiers who participated in the killing of the wounded in a ditch.[75] SGT Ronald L. Haeberle – Photographer; Information Office, 11th Brigade; was attached to Charlie Company. Then SGT Haeberle carried two Army issued black and white cameras for official photos and his own personal camera containing color slide film.[147] He submitted the black and white photos as part of the report on the operation to brigade authorities. By his own testimony at the Courts Martial, he admitted that official photographs generally did not include soldiers committing the killings and generally avoided identifying the individual perpetrators, while his personal color camera contained a few images of soldiers killing elderly men, women of various ages and children. Haeberle also testified that he destroyed most of the color slides which incriminated individual soldiers on the basis that he believed it was unfair to place the blame only on these individuals when many more were equally guilty. He gave his color images to his hometown newspaper, The Plain Dealer, and then sold them to Life magazine. Criticism was initially levelled at Haeberle for not reporting what he witnessed or turning in his color photographs to the Army. He responded that "he had never considered" turning in his personal color photos and explained, "If a general is smiling wrong in a photograph, I have learned to destroy it. ... My experience as a G.I. over there is that if something doesn't look right, a general smiling the wrong way ... I stopped and destroyed the negative." He felt his photographs would never have seen the light of day if he had turned them in.[148] It was confirmed in the U.S. Army's own investigation that Haeberle had, in fact, been reprimanded for taking pictures which "were detrimental to the United States Army".[149] Sergeant Minh, Duong – ARVN interpreter, 52nd Military intelligence Detachment, attached to Task Force Barker; confronted Captain Medina about the number of civilians that were killed. Medina reportedly replied, "Sergeant Minh, don't ask anything – those were the orders."[150] SGT Gary D. Roschevitz – Grenadier; 2nd platoon;[151] according to the testimony of James M. McBreen, Roschevitz killed five or six people standing together with a canister shot from his M79 grenade launcher, which had a shotgun effect after exploding;[152] also grabbed an M16 rifle from Varnado Simpson to kill five Vietnamese prisoners. According to various witnesses, he later forced several women to undress with the intention of raping them. When the women refused, he reportedly shot at them.[153]: 19–20 PFC Varnado Simpson – Rifleman; 2nd Platoon; admitted that he slew around 10 people in My Lai on CPT Medina's orders to kill not only people, but even cats and dogs.[154][155] He fired at a group of people where he allegedly saw a man with a weapon, but instead killed a woman with a baby.[31] He committed suicide in 1997, after repeatedly acknowledging remorse for several murders in Mỹ Lai.[citation needed] SGT Kenneth Hodges, squad leader, was charged with rape and murder during the My Lai Massacre. In every interview given he strictly claimed that he was following orders.[156] Rescue helicopter crew WO1 Hugh Thompson Jr. SP4 Glenn Andreotta SP4 Lawrence Colburn |