ヒト免疫不全ウィルス感染症/エイズ

HIV/AIDS

ヒト免疫不全ウィルス感染症/エイズ

解説:池田光穂

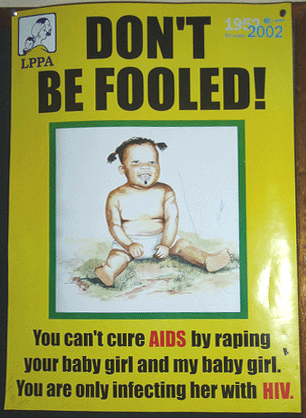

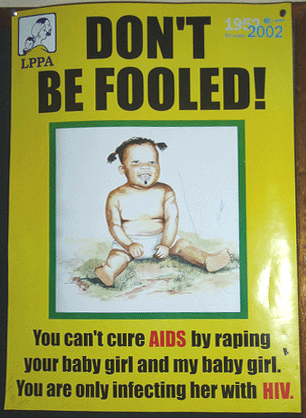

後天性免疫不全症候群(こうてんせいめん えきふぜんしょうこうぐん Acquired immune deficiency syndrome, AIDS(エイズ))は、ヒト免疫不全ウイルス(HIV)が免疫細胞に感染し、免疫細胞を破壊して後天的に免疫不全を起こす疾患である(ウィキペディ ア;https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/HIV/AIDS)。 ここまでは正しい。しかしながら、ウィキペディア(日本語)がその直後に指摘するような「性感染症の一つ」という表現は根本的に誤りで ある。とりわけ我が国には「薬害エイズ」という傷害事件がおこったことを忘れてはならない。また、医療現場で、ヒト免疫不全ウイルス(HIV)への血液あ るいは粘液から直接、注射針等による誤針差しなどから感染することもある。また、母子感染——つまり出産時における母子の間の垂直感染もあり、これらも性 行為を媒介する疾患(STD)ではない。

” a disease of the human immune system that is characterized cytologically especially by reduction in the numbers of CD4-bearing helper T cells (ヘルパー/インデューサーT細胞)to 20 percent or less of normal rendering the subject highly vulnerable to life-threatening conditions (as Pneumocystis carinii pneumonia) and to some that become life-threatening (as Kaposi's sarcoma) and that is caused by infection with HIV commonly transmitted in infected blood and bodily secretions (as semen) especially during illicit intravenous drug use and sexual intercourse” - (Merriam-Webster Online Dictionary, http://www.m-w.com/)

HIV研究(略史)——ウィキペディア日本語など

1983年に、パスツール研究所のリュック・モンタニエとフランソワーズ・バレシヌシらによって

エイズ患者より発見され「LAV (Lymphadenopathy-associated

virus)」と命名された。1984年に、アメリカ国立衛生研究所(NIH)のロバート・ギャロらも分離に成功しており、「HTLV-III

(Human T-lymphotropic virus type

III)」と命名した。続いて、カリフォルニア大学サンフランシスコ校のレヴィらも分離に成功し、「ARV (AIDS-associated

retrovirus)」と命名した。LAV、HTLV-IIIおよびARVは、のちにいずれも同じウイルスであることが明らかとなりHIV-1と改称さ

れ、1985年には、モンタニエらが、エイズ患者から新たな原因ウイルスを分離し、「LAV-2

(Lymphadenopathy-associated virus-2)」と命名し、LAV-2はその後HIV-2と改称された。

最初の発見者をめぐって、モンタニエとギャロの仏米の研究チームが長年にわたって対立し、1994年に両者がともに最初であるとして決着したが、長期の対

立はエイズ治療薬の特許が絡むもので、治療薬の発売を遅らせないための政治的決着であった。2008年10月6日、フランスのモンタニエとバレシヌシの2

人がウイルスの発見者として、2008年のノーベル生理学・医学賞を授与された。

●デュースバーグの異端説

カリフォルニア大学バークレー校教授のピーター・デュースバーグ (Peter Duesberg) などのように、AIDSの原因がHIVであると認めないエイズ否認主義は科学界で明確に否定されている[2]。ピーター・H・デュースバーグ(Peter H. Duesberg)は、ドイツ系アメリカ人の分子生物学者で、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の分子・細胞生物学教授である。癌の遺伝的側面に関する初期 の研究で知られる。HIVはエイズを引き起こさないとするエイズ否定論(debunked claim)の提唱者である。デュースバーグは癌遺伝子と癌の研究で早くから高い評価を受けていた。1970年、ピーター・K・ボグトとともに、鳥類のが んを引き起こすウイルスが、がんを引き起こさないウイルスに比べて余分な遺伝物質を持っていることを報告し、この物質ががんに貢献しているという仮説を立 てた[1][2]。 36歳のとき、カリフォルニア大学バークレー校の終身教授に就任し、49歳で全米科学アカデミー会員に選出された。1986年には米国国立衛生研究所から 優秀研究者賞を受賞し、1986年から1987年までメリーランド州ベセスダのNIH研究所でフォガティ奨学生として滞在した。

| Long considered a

contrarian by his scientific colleagues,[3] Duesberg began to gain

public notoriety with a March 1987 article in Cancer Research entitled

"Retroviruses as Carcinogens and Pathogens: Expectations and

Reality".[4] In this and subsequent writings, Duesberg proposed his

hypothesis that AIDS is caused by long-term consumption of recreational

drugs or antiretroviral drugs, and that the retrovirus known as 'HIV'

is a harmless passenger virus. In contrast, the scientific consensus is

that HIV infection causes AIDS;[5] Duesberg's HIV/AIDS claims have been

addressed and rejected as erroneous by the scientific

community.[6][7][8] Reviews of his opinions in Nature[9] and

Science[10] asserted that they were unpersuasive and based on selective

reading of the literature, and that although Duesberg had a right to a

dissenting opinion, his failure to fairly review evidence that HIV

causes AIDS meant that his opinion lacked credibility.[10][11] |

科学者仲間からは長い間、異端児とみなされていたデュース

バーグは、1987年3月に『Cancer Research』に発表した「Retroviruses as Carcinogens and

Pathogens」という論文で世間に知られるようになった[3]。この論文とその後の著作で、デュースバーグは、エイズは娯楽用麻薬や抗レトロウイル

ス薬の長期摂取によって引き起こされ、「HIV」として知られるレトロウイルスは無害なパッセンジャーウイルスであるという仮説を提示した[4]。これに

対し、HIV感染がエイズを引き起こすというのが一般的な科学的合意事項である[5]

。デュースバーグのHIV/AIDSに関する主張は科学界で取り上げられ、誤りとして否定されている[6][7][8] 。

Nature[9]やScience[10]で発表した見解のレビューでは、説得力がなく文献を選択的に読んだことに基づいており、反対意見を述べる権利

はあるがHIVがエイズを引き起こすという証拠について公正な評価をしなかったことから彼の意見は信頼性が欠けていると主張する[10][11]。 |

| Duesberg's views are cited as

major influences on South African HIV/AIDS policy under the

administration of Thabo Mbeki, which embraced AIDS denialism. Duesberg

served on an advisory panel to Mbeki convened in 2000. The Mbeki

administration's failure to provide antiretroviral drugs in a timely

manner, due in part to the influence of AIDS denialism, is thought to

be responsible for hundreds of thousands of preventable AIDS deaths and

HIV infections in South Africa.[12][13] Duesberg disputed these

findings in an article in the journal Medical Hypotheses,[14] but the

journal's publisher, Elsevier, later retracted Duesberg's article over

accuracy and ethics concerns as well as its rejection during peer

review.[15][16] The incident prompted several complaints to Duesberg's

institution, the University of California, Berkeley, which began a

misconduct investigation of Duesberg in 2009.[17][18] The investigation

was dropped in 2010, with university officials finding "insufficient

evidence ... to support a recommendation for disciplinary

action."[19][20] |

エイズ否定論を掲げたタボ・ムベキ政権下の南アフリカ共和国の

HIV/AIDS政策に大きな影響を与えたとされるデュースバーグの見解。2000年に開催されたムベキの諮問委員会にも参加している。エイズ否定論の影

響もあり、ムベキ政権が抗レトロウイルス薬をタイムリーに提供できなかったことが、南アフリカにおける予防可能な数十万人のエイズ死亡とHIV感染の原因

と考えられている[12][13]。 デュースバーグはこれらの発見に対して雑誌『Medical

Hypotheses』の論文で反論したが、同誌の発行元エルゼビアは後に正確さと倫理的問題、さらにピアレビュー時の拒否によりデュースバーグの論文を

撤回している[14]。 15][16]

この事件はデュースバーグの所属するカリフォルニア大学バークレー校に複数の苦情をもたらし、同大学は2009年にデュースバーグの不正行為の調査を開始

した[17][18]。大学当局は「懲戒処分の勧告を支持するには...

証拠不十分」と判断し、調査は2010年に取り下げられた[19][20][21]。 |

| https://bit.ly/3w6NC7f |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

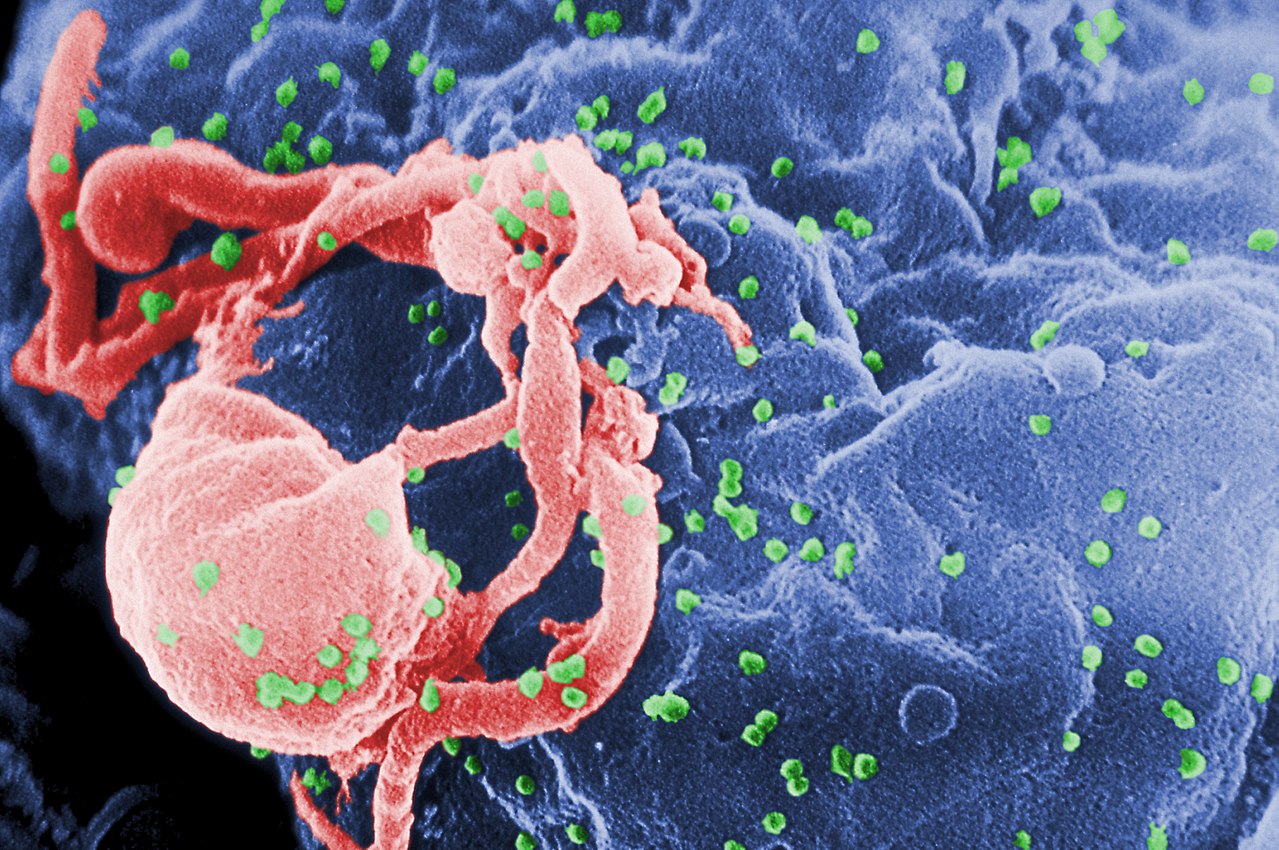

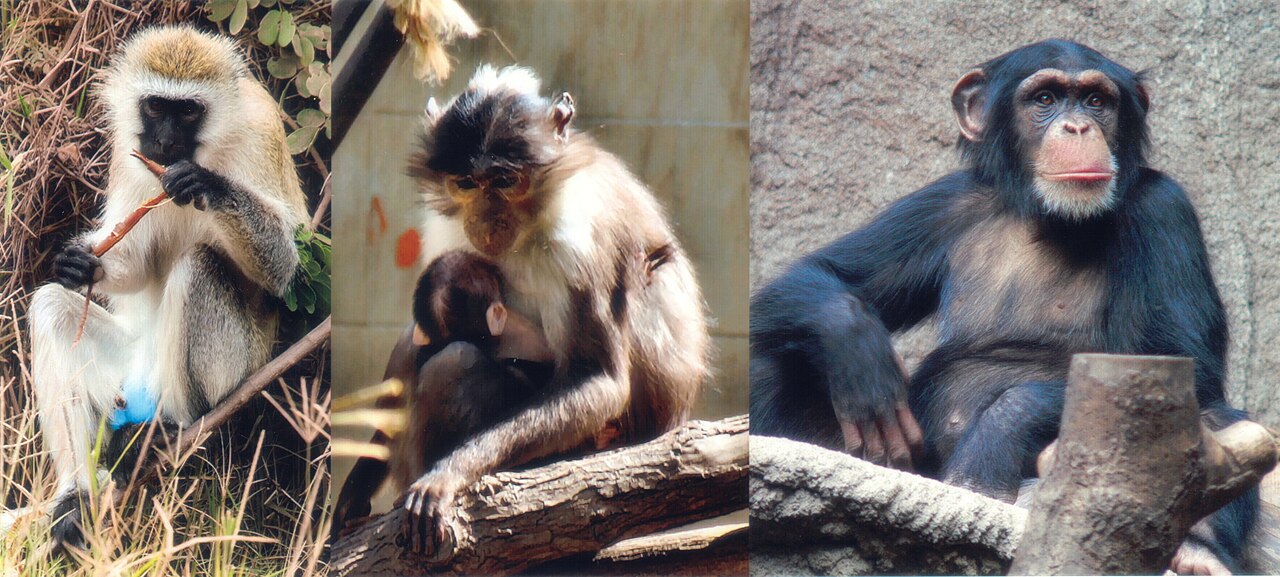

| AIDS is caused by a

human immunodeficiency virus (HIV), which originated in non-human

primates in Central and West Africa. While various sub-groups of the

virus acquired human infectivity at different times, the present

pandemic had its origins in the emergence of one specific strain –

HIV-1 subgroup M – in Léopoldville in the Belgian Congo (now Kinshasa

in the Democratic Republic of the Congo) in the 1920s.[1] There are two types of HIV: HIV-1 and HIV-2. HIV-1 is more virulent, more easily transmitted, and the cause of the vast majority of HIV infections globally.[2] The pandemic strain of HIV-1 is closely related to a virus found in chimpanzees of the subspecies Pan troglodytes troglodytes, which live in the forests of the Central African nations of Cameroon, Equatorial Guinea, Gabon, the Republic of the Congo, and the Central African Republic. HIV-2 is less transmissible and is largely confined to West Africa, along with its closest relative, a virus of the sooty mangabey (Cercocebus atys atys), an Old World monkey inhabiting southern Senegal, Guinea-Bissau, Guinea, Sierra Leone, Liberia, and western Ivory Coast.[2][3] |

エイズは、中央および西アフリカの非ヒト霊長類を起源とするヒト免疫不

全ウイルス(HIV)によって引き起こされる。ウイルスのさまざまな亜グループが異なる時期にヒトへの感染能力を獲得したが、現在のパンデミックは、

1920年代にベルギー領コンゴ(現コンゴ民主共和国キンシャサ)のレオポルドヴィルで特定のHIV-1サブグループM株が出現したことに端を発してい

る。[1] HIVにはHIV-1とHIV-2の2種類がある。HIV-1はより感染力が強く、感染しやすく、世界的に見るとHIV感染症の大半の原因となっている。 [2] HIV-1のパンデミック株は、カメルーン、赤道ギニア、ガボン、コンゴ共和国、中央アフリカ共和国といった中央アフリカ諸国の森林に生息するチンパン ジーの一種、Pan troglodytes troglodytesに存在するウイルスと密接な関係がある。HIV-2は感染力が弱く、その近縁種であるスーティ・マンガベイ(Cercocebus atys atys)のウイルスとともに、主に西アフリカに限定されている。スーティ・マンガベイは、セネガル南部、ギニアビサウ、ギニア、シエラレオネ、リベリ ア、コートジボワール西部に生息する旧世界ザルである。[2][3] |

Transmission from non-humans to humans Left to right: the African green monkey, source of SIV; the sooty mangabey, source of HIV-2; and the chimpanzee, source of HIV-1 Research in this area is conducted using molecular phylogenetics, comparing viral genomic sequences to determine relatedness. HIV-1 from chimpanzees and gorillas to humans Scientists generally accept that the known strains (or groups) of HIV-1 are most closely related to the simian immunodeficiency viruses (SIVs) endemic in wild ape populations of West Central African forests.[4][5] In particular, each of the known HIV-1 strains is either closely related to the SIV that infects the chimpanzee subspecies Pan troglodytes troglodytes (SIVcpz) or closely related to the SIV that infects western lowland gorillas, called SIVgor.[6][7][8][9][10][11] The pandemic HIV-1 strain (group M or Main) and a rare strain found only in a few Cameroonian people (group N) are clearly derived from SIVcpz strains endemic in Pan troglodytes troglodytes chimpanzee populations living in Cameroon.[6] Another very rare HIV-1 strain (group P) is clearly derived from SIVgor strains of Cameroon.[9] Finally, the primate ancestor of HIV-1 group O, a strain infecting 100,000 people mostly from Cameroon but also from neighbouring countries, was confirmed in 2006 to be SIVgor.[8] The pandemic HIV-1 group M is most closely related to the SIVcpz collected from the southeastern rain forests of Cameroon (modern East Province) near the Sangha River.[6] Thus, this region is presumably where the virus was first transmitted from chimpanzees to humans. However, reviews of the epidemiological evidence of early HIV-1 infection in stored blood samples, and of old cases of AIDS in Central Africa, have led many scientists to believe that HIV-1 group M early human centre was probably not in Cameroon, but rather further south in the Democratic Republic of the Congo (then the Belgian Congo), more probably in its capital city, Kinshasa (formerly Léopoldville).[6][12][13] Using HIV-1 sequences preserved in human biological samples along with estimates of viral mutation rates, scientists calculate that the jump from chimpanzee to human probably happened during the late 19th or early 20th century, a time of rapid urbanisation and colonisation in equatorial Africa. Exactly when the zoonosis occurred is not known. Some molecular dating studies suggest that HIV-1 group M had its most recent common ancestor (MRCA) (that is, started to spread in the human population) in the early 20th century, probably between 1915 and 1941.[14][15][16] A study published in 2008, analyzing viral sequences recovered from a biopsy made in Kinshasa, in 1960, along with previously known sequences, suggested a common ancestor between 1873 and 1933 (with central estimates varying between 1902 and 1921).[17] Genetic recombination had earlier been thought to "seriously confound" such phylogenetic analysis, but later "work has suggested that recombination is not likely to systematically bias [results]", although recombination is "expected to increase variance".[17] The results of a 2008 phylogenetics study support the later work and indicate that HIV evolves "fairly reliably".[17][18] Further research was hindered due to the primates being critically endangered. Sample analyses resulted in little data due to the rarity of experimental material. The researchers, however, were able to hypothesize a phylogeny from the gathered data. They were also able to use the molecular clock of a specific strain of HIV to determine the initial date of transmission, which is estimated to be around 1915–1931.[19] |

非ヒトからヒトへの感染 左から右へ:SIVの感染源であるアフリカミドリザル、HIV-2の感染源であるススイロマンガベイ、HIV-1の感染源であるチンパンジー この分野の研究は、分子系統学を用いてウイルスのゲノム配列を比較し、関連性を特定する形で実施されている。 チンパンジーとゴリラからヒトへのHIV-1 科学者たちは一般的に、HIV-1の既知の株(またはグループ)は、西中央アフリカの森林地帯に生息する野生類人猿の集団に蔓延しているサル免疫不全ウイ ルス(SIV)と最も密接な関係にあると認めている。[4][5] 特に、既知のHIV-1株はそれぞれ、チンパンジー亜種であるPan troglodytes troglodytes(SIVcpz)に感染するSIVと密接な関係にあるか、 (SIVcpz)または西部低地ゴリラに感染するSIV(SIVgor)と密接に関連している。[6][7][8][9][10][11] パンデミックHIV-1株(グループMまたはMain)と、カメルーンの一部の人々だけに発見されたまれな株(グループN)は、明らかに カメルーンに生息するチンパンジー集団に蔓延しているSIVcpz株に由来していることが明らかになっている。[6] また、非常にまれなHIV-1株(グループP)は、カメルーンのSIVgor株に由来していることが明らかになっている。[9] さらに、HIV-1グループOの霊長類の祖先である株は、主にカメルーンから、また 近隣諸国からも10万人が感染していることが確認されたが、2006年にSIVgorであることが確認された。[8] パンデミックHIV-1グループMは、カメルーン南東部の熱帯雨林(現東州)のサンガ川付近で採取されたSIVcpzと最も近縁である。[6] したがって、この地域が、おそらくウイルスがチンパンジーからヒトに初めて感染した場所であると考えられる。しかし、保存されていた血液サンプルにおける 初期のHIV-1感染の疫学的証拠や、中央アフリカにおける初期のAIDS症例の調査結果を検証した結果、多くの科学者は、HIV-1グループMの初期の ヒト中心は、おそらくカメルーンではなく、さらに南のコンゴ民主共和国(当時はベルギー領コンゴ)に存在していた可能性が高いと考えるようになった。 ヒトの生物学的サンプルに保存されているHIV-1の配列とウイルスの変異率の推定値を基に、科学者たちは、チンパンジーからヒトへの感染は、おそらく 19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけて、赤道アフリカで都市化と植民地化が急速に進んだ時期に起こったと推定している。人獣共通感染症がいつ発生したのか は正確には分かっていない。分子年代測定法を用いた研究では、HIV-1グループMの最も近い共通祖先(MRCA)(すなわち、ヒト集団内で感染が広がり 始めた時期)は20世紀初頭、おそらく1915年から1941年の間であったと示唆されている。[14][15][16] 2008年に発表された研究では、 1960年にキンシャサで行われた生検から回収されたウイルス配列を、既知の配列とともに分析したところ、1873年から1933年の間に共通の祖先が存 在したことが示唆された(中央値は1902年から1921年の間)。[17] 遺伝子組み換えは、以前はこのような系統発生分析を「深刻に混乱させる」と考えられていたが、 その後、「組み換えは系統解析の結果を系統的に歪める可能性は低い」という研究結果が示されたが、組み換えは「分散を増加させることが予想される」という 結果が出ている。[17] 2008年の系統発生学の研究結果は、この後の研究を裏付けるものであり、HIVは「かなり確実に」進化していることを示している。[17][18] 霊長類が絶滅の危機に瀕しているため、さらなる研究は妨げられている。サンプル分析では、実験材料が非常に希少であったため、得られるデータはわずかで あった。しかし、研究者は収集したデータから系統発生の仮説を立てることができた。また、特定のHIV株の分子時計を使用して、感染の初期の日付を特定す ることができ、それは1915年から1931年頃と推定されている。[19] |

| HIV-2 from sooty mangabeys to humans See also: HIV subtypes Similar research has been undertaken with SIV strains collected from several wild sooty mangabey (Cercocebus atys atys) (SIVsmm) populations of the West African nations of Sierra Leone, Liberia, and Ivory Coast. The resulting phylogenetic analyses show that the viruses most closely related to the two strains of HIV-2 that spread considerably in humans (HIV-2 groups A and B) are the SIVsmm found in the sooty mangabeys of the Tai forest, in western Ivory Coast.[3] There are six additional known HIV-2 groups, each having been found in just one person. They all seem to derive from independent transmissions from sooty mangabeys to humans. Groups C and D have been found in two people from Liberia, groups E and F have been discovered in two people from Sierra Leone, and groups G and H have been detected in two people from the Ivory Coast. These HIV-2 strains are probably dead-end infections, and each of them is most closely related to SIVsmm strains from sooty mangabeys living in the same country where the human infection was found.[3][20] Molecular dating studies suggest that both the epidemic groups (A and B) started to spread among humans between 1905 and 1961 (with the central estimates varying between 1932 and 1945).[21] [22] |

ススマンガベイからヒトへのHIV-2 参照:HIVのサブタイプ 同様の研究が、西アフリカのシエラレオネ、リベリア、コートジボワールといった国民から採取された野生のススマンガベイ(Cercocebus atys atys)の複数の個体群から収集されたSIV株(SIVsmm)でも実施されている。その結果、系統発生学的な分析により、ヒトの間で広範囲に広がった 2つのHIV-2株(HIV-2グループAおよびB)に最も近縁なウイルスは、コートジボワール西部のタイ森林に生息するスーティ・マンガベイから発見さ れたSIVsmmであることが示された。[3] HIV-2グループは他に6つ知られており、それぞれ1人の人格で発見されている。これらはすべて、スーティ・マンガベイからヒトへの独立した感染に由来 しているようだ。CおよびDグループはリベリアの2人から、EおよびFグループはシエラレオネの2人から、GおよびHグループはコートジボワールの2人か ら発見されている。これらのHIV-2株は、おそらく行き止まりの感染であり、それぞれが、ヒトへの感染が発見されたのと同じ国に生息するスーティ・マン ガベイのSIVsm株と最も密接に関連している。[3][20] 分子年代学的研究によると、両方の流行グループ(AとB)は、1905年から1961年の間にヒトの間で感染が広がり始めた(中央値は1932年から1945年の間)ことが示唆されている。[21][22] |

| Bushmeat practice According to the natural transfer theory (also called "hunter theory" or "bushmeat theory"), in the "simplest and most plausible explanation for the cross-species transmission"[10] of SIV or HIV (post mutation), the virus was transmitted from an ape or monkey to a human when a hunter was cut or otherwise injured while hunting or butchering an infected animal. The resulting exposure to blood or other bodily fluids of the animal can result in SIV infection.[23] Rural Africans who were not keen to pursue agricultural practices in the jungle turned to non-domesticated animals as their primary source of meat. This over-exposure to bushmeat and malpractice of butchery increased blood-to-blood contact, which then increased the probability of transmission.[24] A recent serological survey showed that human infections by SIV are not rare in Central Africa: the percentage of people showing seroreactivity to antigens—evidence of current or past SIV infection—was 2.3% among the general population of Cameroon, 7.8% in villages where bushmeat is hunted or used, and 17.1% in the most exposed people of these villages.[25] How the SIV virus would have transformed into HIV after infection of the hunter or bushmeat handler from the ape/monkey is still a matter of debate, although natural selection would favour any viruses capable of adjusting so that they could infect and reproduce in the T cells of a human host. |

ブッシュミートによる感染 自然伝播説(「ハンター説」または「ブッシュミート説」とも呼ばれる)によると、SIVまたはHIV(変異後)の「種を越えた感染の最も単純かつもっとも らしい説明」[10]では、感染した動物を狩猟または解体中にハンターが傷を負うなどして、ウイルスがサルからヒトに感染したとされている。その結果、動 物から血液や体液にさらされることで、SIVに感染する可能性がある。[23] ジャングルでの農業を好まず、肉の主な供給源として家畜以外の動物を利用していたアフリカの農村地域の人々。このブッシュミートへの過剰な接触と不適切な 食肉処理により、血液と血液が接触する機会が増え、感染の確率が高まったのである。[24] 最近の血清学調査では、中央アフリカではSIVによるヒトへの感染は珍しくないことが示されている。現在または過去にSIVに感染した証拠である抗原に対 する血清反応陽性者の割合は、カメルーンの一般人口では2.3%、 狩猟や食用にブッシュミートを捕獲する村では7.8%、そしてその村の中でも最も感染の危険性が高い人々では17.1%であった。[25] 猿やサルからハンターやブッシュミートの処理者に感染した後、SIVウイルスがどのようにHIVへと変化したのかについては、現在も議論が続いている。し かし、自然淘汰の観点では、人間の宿主のT細胞に感染し、増殖できるような変化を遂げたウイルスが有利になるだろう。 |

| Emergence Unresolved questions about HIV origins and emergence The discovery of the main HIV/SIV phylogenetic relationships permits explaining broad HIV biogeography: the early centres of the HIV-1 groups were in Central Africa, where the primate reservoirs of the related SIVcpz and SIVgor viruses (chimpanzees and gorillas) exist; similarly, the HIV-2 groups had their centres in West Africa, where sooty mangabeys, which harbour the related SIVsmm virus, exist. However, these relationships do not explain more detailed patterns of biogeography, such as why epidemic HIV-2 groups (A and B) only evolved in the Ivory Coast, which is one of only six countries harbouring the sooty mangabey.[citation needed] It is also unclear why the SIVcpz endemic in the chimpanzee subspecies Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii (inhabiting the Democratic Republic of Congo, Central African Republic, Rwanda, Burundi, Uganda, and Tanzania) did not spawn an epidemic HIV-1 strain to humans, while the Democratic Republic of Congo was the main centre of HIV-1 group M, a virus descended from SIVcpz strains of a subspecies (Pan troglodytes troglodytes) that does not exist in this country. It is clear that the several HIV-1 and HIV-2 strains descend from SIVcpz, SIVgor, and SIVsmm viruses,[3][8][9][10][12][20] and that bushmeat practice provides the most plausible cause of cross-species transfer to humans.[10][12][25] However, some loose ends remain. It is not yet explained why only four HIV groups (HIV-1 groups M and O, and HIV-2 groups A and B) spread considerably in human populations, despite bushmeat practices being widespread in Central and West Africa,[13] and the resulting human SIV infections being common.[25] It also remains unexplained why all epidemic HIV groups emerged in humans nearly simultaneously, and only in the 20th century, despite very old human exposure to SIV (a 2010 phylogenetic study demonstrated that SIV is at least tens of thousands of years old).[26] |

出現 HIVの起源と出現に関する未解決の問題 HIV/SIVの系統発生上の主な関係性が明らかになったことで、HIVの広範な生物地理学を説明することが可能となった。HIV-1グループの初期の中 心地は中央アフリカであり、関連するSIVcpzおよびSIVgorウイルス(チンパンジーおよびゴリラ)の霊長類貯蔵宿主が存在する。同様に、HIV- 2グループの中心地は西アフリカであり、関連するSIVsmmウイルスを保有するスーティ・マンガベイが存在する。しかし、これらの関係性は、例えば、流 行しているHIV-2グループ(AとB)が、ススマンガベイを保有する6か国のうちの1つであるコートジボワールでしか進化していない理由など、生物地理 学のより詳細なパターンを説明していない。また、チンパンジー亜種であるPan troglodytes schweinfurthii( (コンゴ民主共和国、中央アフリカ共和国、ルワンダ、ブルンジ、ウガンダ、タンザニアに生息)が、ヒトにHIV-1の流行株を生み出さなかった理由につい ては不明である。一方、コンゴ民主共和国はHIV-1グループMの主な中心地であり、この国には存在しない亜種(Pan troglodytes troglodytes)のSIVcpz株から派生したウイルスである。HIV-1およびHIV-2のいくつかの系統がSIVcpz、SIVgor、 SIVsmmウイルスに由来することは明らかである。[3][8][9][10][12][20] また、ブッシュミートがヒトへの種間感染の最も有力な原因であることも明らかである。[10][12][25] しかし、いくつかの疑問が残っている。 中央および西アフリカでブッシュミートが広く食されているにもかかわらず、HIVの4つのグループ(HIV-1グループMおよびO、HIV-2グループAおよびB)のみがヒト集団で大幅に広がっている理由については、まだ説明されていない。 また、SIVに人類が曝露されたのは非常に古い時代であったにもかかわらず(2010年の系統発生学的研究では、SIVは少なくとも数万年は古いことが証 明されている)、すべての流行HIVグループがほぼ同時に、しかも20世紀になって初めて人類に発生した理由も説明されていない。[26] |

| Origin and epidemic emergence Several of the theories of HIV origin accept the established knowledge of the HIV/SIV phylogenetic relationships, and also accept that bushmeat practice was the most likely cause of the initial transfer to humans. All of them propose that the simultaneous epidemic emergences of four HIV groups in the late 19th-early 20th century, and the lack of previous known emergences, are explained by new factor(s) that appeared in the relevant African regions in that timeframe. These new factor(s) would have acted either to increase human exposures to SIV, to help it to adapt to the human organism by mutation (thus enhancing its between-humans transmissibility), or to cause an initial burst of transmissions crossing an epidemiological threshold, and therefore increasing the probability of continued spread. Genetic studies of the virus suggested in 2008 that the most recent common ancestor of the HIV-1 M group dates back to the Belgian Congo city of Léopoldville (modern Kinshasa), circa 1910.[17] Proponents of this dating link the HIV epidemic with the emergence of colonialism and growth of large colonial African cities, leading to social changes, including a higher degree of non-monogamous sexual activity, the spread of prostitution, and the concomitant high frequency of genital ulcer diseases (such as syphilis) in nascent colonial cities.[13] In 2014, a study conducted by scientists from the University of Oxford and the University of Leuven, in Belgium, revealed that because approximately one million people every year would flow through the prominent city of Kinshasa,[1] it might have served as the origin of the first suspected HIV cases in the 1920s.[1] Kinshasa also experienced the earliest retroactive diagnosis of HIV, in the LEO70 sample, which was isolated from a preserved plasma sample of "an adult Bantu male" who also had a Sickle cell trait and G6PDD taken in 1959.[27] It is also believed that passengers riding on the region's Belgian railway trains were able to spread the virus to larger areas, combining with the active sex trade, rapid population growth and unsterilized needles used in health clinics to create what became the African AIDS crisis.[1] |

起源と流行の発生 HIVの起源に関するいくつかの説は、HIV/SIVの系統発生学上の関係に関する確立された知識を認め、また、ブッシュミートが人間への最初の感染の原 因となった可能性が最も高いことを認めている。それらの説はすべて、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけての4つのHIVグループの同時発生と、それ以前 に知られていた発生例の欠如は、その時期にアフリカの関連地域に現れた新たな要因によって説明できると提案している。これらの新たな因子は、SIVへのヒ トの曝露を増やすか、突然変異によってヒトの体内に適応しやすくするか(そのためヒトからヒトへの感染力を高める)、あるいは疫学的な閾値を超える最初の 感染の急増を引き起こし、その結果、継続的な感染拡大の可能性を高めるかのいずれかの作用をしたと考えられる。 2008年のウイルスの遺伝子研究では、HIV-1 Mグループの最も近い共通祖先は、1910年頃のベルギー領コンゴの都市レオポルドヴィル(現在のキンシャサ)にまで遡ると推定されている。[17] この年代を根拠とする説では、HIV 流行を植民地主義の台頭と大規模な植民地アフリカ都市の成長に結びつけ、非一夫一婦制の性行為の増加、売春の蔓延、それに伴う性器潰瘍疾患(梅毒など)の 発生頻度の高まりといった社会変化を招いたと主張している。 2014年、オックスフォード大学とベルギーのルーヴェン大学の科学者による研究で、キンシャサという著名な都市には毎年約100万人が流入しているた め、[1] 1920年代に疑わしいHIV感染症の最初の症例が発生した場所である可能性が明らかになった。[1] キンシャサでは、LEO70サンプルでHIVの最も早い遡及的診断も行われた。1959年に採取された「バントゥー族の成人男性」の保存血漿サンプルから 分離されたもので、鎌状赤血球とG6PDDの形質も持っていた。[27] また、この地域のベルギー国鉄の列車に乗っていた乗客が、活発な性産業、急速な人口増加、保健クリニックで使用される未滅菌の注射針と結びついて、ウイル スをより広い地域に広げ、アフリカにおけるエイズ危機を引き起こしたと考えられている。[1] |

| Social changes and urbanization Beatrice Hahn, Paul M. Sharp, and their colleagues proposed that "[the epidemic emergence of HIV] most likely reflects changes in population structure and behaviour in Africa during the 20th century and perhaps medical interventions that provided the opportunity for rapid human-to-human spread of the virus".[10] After the Scramble for Africa started in the 1880s, European colonial powers established cities, towns, and other colonial stations. A largely masculine labor force was hastily recruited to work in fluvial and sea ports, railways, other infrastructures, and in plantations. This disrupted traditional tribal values and favored casual sexual activity with an increased number of partners. In the nascent cities women felt relatively liberated from rural tribal rules[28] and many remained unmarried or divorced during long periods,[13][29] this being rare in African traditional societies.[30] This was accompanied by unprecedented increase in people's movements. Michael Worobey and colleagues observed that the growth of cities probably played a role in the epidemic emergence of HIV, since the phylogenetic dating of the two older strains of HIV-1 (groups M and O), suggest that these viruses started to spread soon after the main Central African colonial cities were founded.[17] |

社会の変化と都市化 ベアトリス・ハーン、ポール・M・シャープ、および彼らの同僚は、「(HIVの急激な発生は)おそらく20世紀のアフリカにおける人口構造と行動の変化、 およびウイルスの急速な人から人への感染機会をもたらした医療介入を反映している」と提案した。[10] 1880年代にアフリカの争奪戦が始まってから、ヨーロッパの植民地勢力は都市や町、その他の植民地拠点を建設した。河川や海の港、鉄道、その他のインフ ラ、プランテーションなどで働く労働力として、主に男性が急遽募集された。これにより、伝統的な部族の価値観が崩壊し、パートナーの数が増え、カジュアル な性行為が好まれるようになった。都市では、女性たちは農村の部族の規則から比較的解放されたと感じており[28]、多くの女性が長い間未婚のままか離婚 した状態だった[13][29]。これはアフリカの伝統的社会では珍しいことである[30]。これに伴い、人々の移動がかつてないほど増加した。 マイケル・ウォロベイ(Michael Worobey)とその同僚は、HIV-1の2つの古い系統(グループMとO)の系統発生年代を推定したところ、中央アフリカの主要な植民都市が建設され た直後にこれらのウイルスが蔓延し始めたことが示唆されたため、都市の成長がHIVの流行発生に何らかの役割を果たした可能性があると指摘している。 [17] |

| Colonialism in Africa Amit Chitnis, Diana Rawls, and Jim Moore proposed that HIV may have emerged epidemically as a result of harsh conditions, forced labor, displacement, and unsafe injection and vaccination practices associated with colonialism, particularly in French Equatorial Africa.[31] The workers in plantations, construction projects, and other colonial enterprises were supplied with bushmeat, which would have contributed to an increase in hunting and, it follows, a higher incidence of human exposure to SIV. Several historical sources support the view that bushmeat hunting indeed increased, both because of the necessity to supply workers and because firearms became more widely available.[31][32][33] The colonial authorities also gave many vaccinations against smallpox, and injections, of which many would be made without sterilising the equipment between uses. Chitnis et al. proposed that both these parenteral risks and the prostitution associated with forced labor camps could have caused serial transmission (or serial passage) of SIV between humans (see discussion of this in the next section).[31] In addition, they proposed that the conditions of extreme stress associated with forced labor could depress the immune system of workers, therefore prolonging the primary acute infection period of someone newly infected by SIV, thus increasing the odds of both adaptation of the virus to humans, and of further transmissions.[34] The authors proposed that HIV-1 originated in the area of French Equatorial Africa in the early 20th century (when the colonial abuses and forced labor were at their peak). Later research established that these theories were mostly correct: HIV-1 groups M and O started to spread in humans in late 19th–early 20th century.[14][15][16][17] In addition, all groups of HIV-1 descend from either SIVcpz or SIVgor from apes living to the west of the Ubangi River, either in countries that belonged to the French Equatorial Africa federation of colonies, in Equatorial Guinea (then a Spanish colony), or in Cameroon (which was a German colony between 1884 and 1916, and then fell to Allied forces in World War I, and had most of its area administered by France, in close association with French Equatorial Africa). This theory was later dubbed "Heart of Darkness" by Jim Moore,[35] alluding to the book of the same title written by Joseph Conrad, the main focus of which is colonial abuses in equatorial Africa. |

アフリカにおける植民地主義 アミット・チトニス、ダイアナ・ロウズ、ジム・ムーアは、HIVは特にフランス領赤道アフリカにおいて、植民地主義に伴う過酷な環境、強制労働、移住、安 全でない注射や予防接種などの結果として、流行病として発生した可能性があると提言した。[31] プランテーション、建設プロジェクト、その他の植民地事業に従事する労働者にはブッシュミートが供給されていたため、狩猟の増加につながり、その結果、 SIVにさらされる人間の割合が高まったと考えられる。複数の歴史的資料が、労働者への供給の必要性と銃器がより広く入手可能になったという両方の理由か ら、ブッシュミート狩りが実際に増加したという見解を裏付けている。[31][32][33] 植民地当局はまた、天然痘の予防接種や注射を数多く実施したが、その多くは器具を消毒せずに使用していた。Chitnisらは、これらの非経口的なリスク と強制労働収容所に関連する売春が、SIVのヒト間での連続感染(または連続伝播)を引き起こした可能性があると提案している(この点については次項で議 論する)[31]。さらに、彼らは 強制労働に伴う極度のストレス状態が労働者の免疫システムを低下させ、その結果、新たにSIVに感染した人の急性感染期間が長引き、ウイルスがヒトに適応 する可能性と、さらに感染が拡大する可能性が高まる、と彼らは提案した。 著者は、HIV-1は20世紀初頭(植民地支配による虐待と強制労働がピークに達した時期)にフランス領赤道アフリカ地域で発生したと提案した。その後の 研究により、これらの理論はほぼ正しいことが証明された。HIV-1グループMとOは、19世紀後半から20世紀初頭にかけてヒトの間で感染を広げ始め た。[14][15][16][17] さらに、HIV-1のすべてのグループは、ウバンギ川の西側に生息するサルから派生したSIVcpzまたはSIVgorのいずれかに由来する 、フランス領赤道アフリカ連邦に属する植民地であった国々、赤道ギニア(当時はスペイン領)、またはカメルーン(1884年から1916年まではドイツ 領、その後第一次世界大戦で連合国軍に降伏し、その領土のほとんどがフランスによって統治された。 この説は後に、赤道アフリカにおける植民地支配の横暴を主題としたジョゼフ・コンラッドの同名の小説を引用して、ジム・ムーアによって「闇の奥」と名付けられた。 |

| Unsterile injections In several articles published since 2001, Preston Marx, Philip Alcabes, and Ernest Drucker proposed that HIV emerged because of rapid serial human-to-human transmission of SIV (after a bushmeat hunter or handler became SIV-infected) through unsafe or unsterile injections.[20][36][37] Although both Chitnis et al.[31] and Sharp et al.[10] also suggested that this may have been one of the major risk factors at play in HIV emergence (see above), Marx et al. enunciated the underlying mechanisms in greater detail, and wrote the first review of the injection campaigns made in colonial Africa.[20][36] Central to the Marx et al. argument is the concept of adaptation by serial passage (or serial transmission): an adventitious virus (or other pathogen) can increase its biological adaptation to a new host species if it is rapidly transmitted between hosts, while each host is still in the acute infection period. This process favors the accumulation of adaptive mutations more rapidly, therefore increasing the odds that a better adapted viral variant will appear in the host before the immune system suppresses the virus.[20] Such better adapted variants could then survive in the human host for longer than the short acute infection period, in high numbers (high viral load), which would grant it more possibilities of epidemic spread. Marx et al. reported experiments of cross-species transfer of SIV in captive monkeys (some of which made by themselves), in which the use of serial passage helped to adapt SIV to the new monkey species after passage by three or four animals.[20] In agreement with this model is also the fact that, while both HIV-1 and HIV-2 attain substantial viral loads in the human organism, adventitious SIV infecting humans seldom does so: people with SIV antibodies often have very low or even undetectable SIV viral load.[25] This suggests that both HIV-1 and HIV-2 are adapted to humans, and serial passage could have been the process responsible for it. Marx et al. proposed that unsterile injections (that is, injections where the needle or syringe is reused without sterilization or cleaning between uses), which were likely very prevalent in Africa, during both the colonial period and afterwards, provided the mechanism of serial passage that permitted HIV to adapt to humans, therefore explaining why it emerged epidemically only in the 20th century.[20][36] |

不衛生な注射 2001年以降に発表された複数の論文で、プレストン・マークス、フィリップ・アルカベス、アーネスト・ドラッカーは、SIV(ブッシュミートハンターま たは取扱者がSIVに感染した後)が、安全でない、または不衛生な注射によって急速に連続してヒトからヒトへと感染したためにHIVが出現したと提唱し た。[20][36][37] Chitnisら[31]とシャープら[10]の両者も、HIV出現の主要な危険因子のひとつである可能性を示唆しているが(前述)、マルクスらはその根 底にあるメカニズムをより詳細に説明し、植民地時代のアフリカで行われた注射キャンペーンに関する最初のレビューを執筆した[20][36]。 マルクスらの主張の中心は、連続感染(または連続伝播)による適応という概念である。すなわち、偶発的なウイルス(または他の病原体)が、各宿主が急性感 染期にある間に、宿主間で急速に伝播される場合、そのウイルスは新たな宿主種に対する生物学的適応力を高めることができる。このプロセスにより、適応変異 の蓄積がより急速に進むため、免疫系がウイルスを抑制する前に、より適応したウイルス変異体が宿主に出現する可能性が高くなる。[20] このようなより適応した変異体は、急性感染期間よりも長い期間、多数(高ウイルス量)でヒトの宿主の中で生き延びることができ、その結果、より広範囲に流 行する可能性が高くなる。 Marxらは、飼育下のサルにおけるSIVの種間伝播の実験(一部はサル自身によるもの)を報告している。その実験では、3~4匹のサルを経由した後、連続継代法を用いることでSIVを新たなサル種に適応させることができた。 このモデルと一致する事実として、HIV-1とHIV-2の両方がヒトの体内でかなりのウイルス量に達する一方で、ヒトに感染した外来のSIVがそうなる ことはまれである。SIV抗体を持つ人々は、SIVウイルス量が非常に低いか、あるいは検出できない場合が多い。[25] このことは、HIV-1とHIV-2の両方がヒトに適応しており、連続継代がその原因となった可能性があることを示唆している。 マルクスらは、植民地時代およびその後の時代を通じて、アフリカでは非滅菌注射(すなわち、注射針や注射器を滅菌や洗浄をせずに再使用する注射)が広く行 われていた可能性が高いことを指摘し、これがHIVがヒトに適応する連続感染のメカニズムを提供し、20世紀になって初めてHIVが大流行した理由を説明 できると提唱した。[20][36] |

| Massive injections of the antibiotic era Marx et al. emphasize the massive number of injections administered in Africa after antibiotics were introduced (around 1950) as being the most likely implicated in the origin of HIV because, by these times (roughly in the period 1950 to 1970), injection intensity in Africa was maximal. They argued that a serial passage chain of 3 or 4 transmissions between humans is an unlikely event (the probability of transmission after a needle reuse is something between 0.3% and 2%, and only a few people have an acute SIV infection at any time), and so HIV emergence may have required the very high frequency of injections of the antibiotic era.[20] The molecular dating studies place the initial spread of the epidemic HIV groups before that time (see above).[14][15][16][17][21][22] According to Marx et al., these studies could have overestimated the age of the HIV groups, because they depend on a molecular clock assumption, may not have accounted for the effects of natural selection in the viruses, and the serial passage process alone would be associated with strong natural selection.[38][20] |

抗生物質時代の大量注射 マルクスらは、抗生物質が導入された後(1950年頃)のアフリカで大量に行なわれた注射が、HIVの起源に最も関連している可能性が高いと強調してい る。なぜなら、この頃(1950年から1970年頃)のアフリカでは注射の使用が最大規模であったからだ。彼らは、3~4人の人間の間で連続的に感染が起 こることはありそうもないと主張した(針の再使用後の感染確率は0.3~2%の間であり、急性SIV感染症にかかる人はいつでもごくわずかである)。した がって、HIVの出現には抗生物質時代の非常に高い注射頻度が必要だった可能性がある。[20] 分子年代測定法による研究では、HIVグループの最初の流行はそれ以前(上記参照)とされている。[14][15][16][17][21][22] Marx らによると、これらの研究では 分子時計の仮定に依存しているため、ウイルスにおける自然淘汰の影響を考慮していない可能性があり、連続継代プロセスだけでも強い自然淘汰と関連している ためである。[38][20] |

| Injection campaigns against sleeping sickness David Gisselquist proposed that the mass injection campaigns to treat trypanosomiasis (sleeping sickness) in Central Africa were responsible for the emergence of HIV-1.[39] Unlike Marx et al.,[20] Gisselquist argued that the millions of unsafe injections administered during these campaigns were sufficient to spread rare HIV infections into an epidemic, and that evolution of HIV through serial passage was not essential to the emergence of the HIV epidemic in the 20th century.[39] This theory focuses on injection campaigns that peaked in the period 1910–40, that is, around the time the HIV-1 groups started to spread.[14][15][16][17] It also focuses on the fact that many of the injections in these campaigns were intravenous (which are more likely to transmit SIV/HIV than subcutaneous or intramuscular injections), and many of the patients received many (often more than 10) injections per year, therefore increasing the odds of SIV serial passage.[39] |

睡眠病に対する予防接種キャンペーン デビッド・ギセルクイストは、中央アフリカにおけるトリパノソーマ症(睡眠病)の治療を目的とした集団予防接種キャンペーンがHIV-1の出現の原因であ ると提唱した。[39] ギセルクイストは、 ギセルクイストは、これらのキャンペーン中に実施された何百万もの安全でない注射が、まれなHIV感染症を流行へと広げるのに十分であったと主張し、 HIVの進化は、20世紀におけるHIVの流行の出現に不可欠なものではないと主張した。[39] この理論は、1910年から1940年の間にピークに達した注射撲滅キャンペーン、すなわちHIV-1グループが蔓延し始めた時期に焦点を当てている。 [14][15][16][17] また、この理論は、 これらのキャンペーンにおける注射の多くが静脈注射であったこと(皮下注射や筋肉注射よりもSIV/HIV感染の可能性が高い)、また、多くの患者が年間 で多数(10回以上ということも多い)の注射を受けていたため、SIVの連続感染の可能性が高まったという事実にも焦点を当てている。[39] |

| Other early injection campaigns Jacques Pépin and Annie-Claude Labbé reviewed the colonial health reports of Cameroon and French Equatorial Africa for the period 1921–59, calculating the incidences of the diseases requiring intravenous injections. They concluded that trypanosomiasis, leprosy, yaws, and syphilis were responsible for most intravenous injections. Schistosomiasis, tuberculosis, and vaccinations against smallpox represented lower parenteral risks: schistosomiasis cases were relatively few; tuberculosis patients only became numerous after mid-century; and there were few smallpox vaccinations in the lifetime of each person.[40] The authors suggested that the very high prevalence of the Hepatitis C virus in southern Cameroon and forested areas of French Equatorial Africa (around 40–50%) can be better explained by the unsterile injections used to treat yaws, because this disease was much more prevalent than syphilis, trypanosomiasis, and leprosy in these areas. They suggested that all these parenteral risks caused not only the massive spread of Hepatitis C but also the spread of other pathogens, and the emergence of HIV-1: "the same procedures could have exponentially amplified HIV-1, from a single hunter/cook occupationally infected with SIVcpz to several thousand patients treated with arsenicals or other drugs, a threshold beyond which sexual transmission could prosper."[40] They do not suggest specifically serial passage as the mechanism of adaptation. According to Pépin's 2011 book, The Origins of AIDS,[41] the virus can be traced to a central African bush hunter in 1921, with colonial medical campaigns using improperly sterilized syringe and needles playing a key role in enabling a future epidemic. Pépin concludes that AIDS spread silently in Africa for decades, fueled by urbanization and prostitution since the initial cross-species infection. Pépin also claims that the virus was brought to the Americas by a Haitian teacher returning home from Zaire in the 1960s.[42] Sex tourism and contaminated blood transfusion centers ultimately propelled AIDS to public consciousness in the 1980s and a worldwide pandemic.[41] |

その他の初期の予防接種キャンペーン ジャック・ペパンとアニー・クロード・ラブは、1921年から1959年のカメルーンとフランス領赤道アフリカの植民地保健報告書を調査し、静脈注射を必 要とする病気の発生率を算出した。彼らは、トリパノソーマ症、ハンセン病、瘡、梅毒が静脈注射の主な原因であると結論付けた。一方、下痢アメーバ症、結 核、天然痘の予防接種は非経口投与のリスクが低いとされた。下痢アメーバ症の症例は比較的少なく、結核患者が急増したのは20世紀半ば以降であり、天然痘 の予防接種は各人の人格が形成される間に実施されることはほとんどなかったからである。[40] 著者は、カメルーン南部およびフランス領赤道アフリカの森林地帯におけるC型肝炎ウイルスの非常に高い感染率(40~50%前後)は、梅毒、トリパノソー マ症、ハンセン病よりもはるかに高い有病率を示していることから、この地域のイボの治療に用いられていた非無菌注射によってよりよく説明できると示唆し た。彼らは、非経口投与によるこうしたリスクが、C型肝炎の蔓延だけでなく、他の病原体の蔓延、そしてHIV-1の出現をも引き起こした可能性があると示 唆している。「同じ手順によってHIV-1は指数関数的に増幅され、SIVcpzに感染した単独のハンター兼料理人が、ヒ素やその他の薬剤で治療を受けた 数千人の患者へと増殖した可能性がある。 ペピンの2011年の著書『エイズの起源』によると、[41] ウイルスは1921年の中央アフリカのブッシュハンターにまで遡ることができるが、不適切に消毒された注射器と針を使用した植民地時代の医療キャンペーン が、将来の流行を可能にする上で重要な役割を果たした。ペピンは、エイズは最初の種を超えた感染以来、都市化と売春によって煽られながら、アフリカで数十 年間静かに広がったと結論づけている。また、ペパンは、1960年代にザイールから帰国したハイチの教師がウイルスをアメリカ大陸に持ち込んだと主張して いる。[42] 1980年代には、セックス・ツーリズムと汚染された輸血がエイズを一般の人々の意識に浸透させ、世界的な流行を引き起こした。[41] |

| Genital ulcer diseases and evolution of sexual activity João Dinis de Sousa, Viktor Müller, Philippe Lemey, and Anne-Mieke Vandamme proposed that HIV became epidemic through sexual serial transmission, in nascent colonial cities, helped by a high frequency of genital ulcers, caused by genital ulcer diseases (GUD).[13] GUD are simply sexually transmitted diseases that cause genital ulcers; examples are syphilis, chancroid, lymphogranuloma venereum, and genital herpes. These diseases increase the probability of HIV transmission dramatically, from around 0.01–0.1% to 4–43% per heterosexual act, because the genital ulcers provide a portal of viral entry, and contain many activated T cells expressing the CCR5 co-receptor, the main cell targets of HIV.[13][43] |

性器潰瘍疾患と性行為の進化 ジョアン・ディニス・デ・ソウザ、ビクター・ミュラー、フィリップ・レメイ、アン・ミーク・ヴァンダムは、性器潰瘍症(GUD)による性器潰瘍の多発が原 因で、初期の植民都市において、HIVが性行為による連続感染によって流行したと提唱した。[13] GUDは、性器潰瘍を引き起こす単純な性感染症であり、梅毒、鼠径リンパ肉腫症、鼡径リンパ肉腫症、性器ヘルペスなどがその例である。これらの疾患は、性 器潰瘍がウイルスの侵入経路となり、HIVの主な標的細胞であるCCR5共受容体を発現する活性化T細胞が多数存在するため、異性間性交渉1回あたりの HIV感染確率を0.01~0.1%から4~43%へと劇的に増加させる。[13][43] |

| Probable time interval of cross-species transfer Sousa et al. use molecular dating techniques to estimate the time when each HIV group split from its closest SIV lineage. Each HIV group necessarily crossed to humans between this time and the time when it started to spread (the time of the MRCA), because after the MRCA certainly all lineages were already in humans, and before the split with the closest simian strain, the lineage was in a simian. HIV-1 groups M and O split from their closest SIVs around 1931 and 1915, respectively. This information, together with the datations of the HIV groups' MRCAs, mean that all HIV groups likely crossed to humans in the early 20th century.[13] |

種間伝播の起こったおおよその時間間隔 Sousa らは、分子年代測定法を用いて、各HIVグループが最も近いSIV系統から分岐した時期を推定した。MRCA以降、すべての系統が確実にヒトに存在してい たため、各HIVグループは、その拡散が始まった時期(MRCAの時期)と、最も近い類人猿株との分岐時期との間のいずれかの時期に、ヒトに伝播したはず である。HIV-1グループMとOは、それぞれ1931年と1915年頃に最も近いSIVから分岐した。この情報とHIVグループのMRCAsの年代測定 を併せて考えると、すべてのHIVグループが20世紀初頭にヒトに感染した可能性が高いことを意味する。[13] |

| Strong genital ulcer disease incidence in nascent colonial cities The authors reviewed colonial medical articles and archived medical reports of the countries at or near the ranges of chimpanzees, gorillas and sooty mangabeys, and found that genital ulcer diseases (GUDs) peaked in the colonial cities during their early growth period (up to 1935). The colonial authorities recruited men to work in railways, fluvial and sea ports, and other infrastructure projects, and most of these men did not bring their wives with them. Then, the highly male-biased sex ratio favoured prostitution, which in its turn caused an explosion of GUD (especially syphilis and chancroid). After the mid-1930s, people's movements were more tightly controlled, and mass surveys and treatments (of arsenicals and other drugs) were organized, and so the GUD incidences started to decline. They declined even further after World War II, because of the heavy use of antibiotics, so that, by the late 1950s, Léopoldville (which is the probable center of HIV-1 group M) had a very low GUD incidence. Similar processes happened in the cities of Cameroon and Ivory Coast, where HIV-1 group O and HIV-2 respectively evolved.[13] Therefore, the peak GUD incidences in cities have a good temporal coincidence with the period when all main HIV groups crossed to humans and started to spread.[13][14][15][16][17][21][22] In addition, the authors gathered evidence that syphilis and the other GUDs were, like injections, absent from the densely forested areas of Central and West Africa before organized colonialism socially disrupted these areas (starting in the 1880s).[13] Thus, this theory also potentially explains why HIV emerged only after the late 19th century. |

植民都市における性器潰瘍の罹患率が高い 著者は、チンパンジー、ゴリラ、スーティ・マンガベイの生息域内またはその近辺にある植民地時代の医学記事や医療報告書を調査し、性器潰瘍疾患(GUD) が植民地都市で初期成長期(1935年まで)にピークに達していることを発見した。植民地当局は、鉄道、河川、港湾、その他のインフラプロジェクトに従事 する労働者を募集し、これらの労働者の大半は妻を連れていなかった。そのため、男性に偏った性比は売春を助長し、それがGUD(特に梅毒や陰部皮膚炎)の 爆発的な増加を招いた。1930年代半ば以降、人々の移動はより厳しく管理されるようになり、大規模な調査と治療(ヒ素やその他の薬剤による)が組織され たため、GUDの発生率は低下し始めた。第二次世界大戦後は抗生物質が大量に使用されたため、さらに減少した。その結果、1950年代後半には、レオポル ドヴィル(HIV-1グループMの中心地である可能性が高い)では、GUDの発生率は非常に低くなった。カメルーンとコートジボワールの都市でも同様の現 象が起こり、それぞれHIV-1グループOとHIV-2が進化した。[13] したがって、都市部におけるGUDのピーク発生率は、すべての主要なHIVグループがヒトに感染し、蔓延し始めた時期と時期的に一致している。[13] [14][15][16][17][21][22] さらに、著者は、梅毒やその他の GUDs(性感染症)は、植民地化が組織的に進行し、社会が混乱する以前(1880年代以降)には、中央および西アフリカの森林地帯には存在していなかっ たという証拠を収集した。[13] したがって、この理論もHIVが19世紀後半になって初めて出現した理由を説明できる可能性がある。 |

| Female genital mutilation Uli Linke has argued that the practice of female genital mutilation (either or both of clitoridectomy and infibulation) is responsible for the high incidence of AIDS in Africa, since intercourse with a female who has undergone clitoridectomy is conducive to exchange of blood.[44] |

女性器切除 ウリ・リンケは、女性器切除(クリトリス切除または陰核切除と処女膜切除の両方またはいずれか一方)の慣行が、クリトリス切除を受けた女性との性交渉が血液の交換を促すため、アフリカにおけるエイズの高発生率の原因であると主張している。[44] |

| Male circumcision distribution and HIV origins Male circumcision may reduce the probability of HIV acquisition by men[citation needed]. Leaving aside blood transfusions, the highest HIV-1 transmissibility ever measured was from female prostitutes with 85% prevalence of HIV to uncircumcised men with GUD—"A cumulative 43% ... seroconverted to HIV-1 after a single sexual exposure." There was no seroconversion in the absence of male GUD.[43] Sousa et al. reasoned that the adaptation and epidemic emergence of each HIV group may have required such extreme conditions, and thus reviewed the existing ethnographic literature for patterns of male circumcision and hunting of apes and monkeys for bushmeat, focusing on the period 1880–1960, and on most of the 318 ethnic groups living in Central and West Africa.[13] They also collected censuses and other literature showing the ethnic composition of colonial cities in this period. Then, they estimated the circumcision frequencies of the Central African cities over time. Sousa et al. charts reveal that male circumcision frequencies were much lower in several cities of western and central Africa in the early 20th century than they are currently. The reason is that many ethnic groups not performing circumcision by that time gradually adopted it, to imitate other ethnic groups and enhance the social acceptance of their boys (colonialism produced massive intermixing between African ethnic groups).[13][30] About 15–30% of men in Léopoldville and Douala in the early 20th century should be uncircumcised, and these cities were the probable centers of HIV-1 groups M and O, respectively.[13] The authors studied early circumcision frequencies in 12 cities of Central and West Africa, to test if this variable correlated with HIV emergence. This correlation was strong for HIV-2: among 6 West African cities that could have received immigrants infected with SIVsmm, the two cities from the Ivory Coast studied (Abidjan and Bouaké) had much higher frequency of uncircumcised men (60–85%) than the others, and epidemic HIV-2 groups emerged initially in this country only. This correlation was less clear for HIV-1 in Central Africa.[13] |

男性の割礼の分布とHIVの起源 男性の割礼は、男性がHIVに感染する確率を減少させる可能性がある[要出典]。輸血はさておき、これまで測定されたHIV-1の感染力は、GUDを持つ 包茎でない男性にHIVの感染率が85%の女性売春婦からが最も高かった。「累積43%...単回の性的接触でHIV-1に感染した。」 男性にGUDがなければ、抗体陽転は起こらなかった。[43] Sousaらは、各HIVグループの適応と流行の発生にはこのような極端な条件が必要だったのではないかと推論し、 1880年から1960年の期間と、中央および西アフリカに居住する318の民族集団のほとんどに焦点を当てて、彼らはまた、この時代の植民地都市の民族 構成を示す国勢調査やその他の文献も収集した。そして、彼らは中央アフリカの都市における割礼の頻度を時代ごとに推定した。 Sousa らの図表は、20世紀初頭の西および中央アフリカのいくつかの都市では、男性の割礼率が現在よりもはるかに低かったことを明らかにしている。その理由は、 それまで割礼を行なっていなかった多くの民族が、他の民族の真似をして、自分たちの少年に対する社会的な受容性を高めるために、徐々に割礼を取り入れるよ うになったためである(植民地主義により、アフリカの民族の間で大規模な交流が生まれた)。20世紀初頭のレオポルドヴィルとドゥアラでは、男性の 15~30%が割礼を受けていなかったはずであり、これらの都市はそれぞれHIV-1グループMとOの中心地であった可能性が高い。 著者は、この変数がHIVの出現と相関関係にあるかどうかを検証するために、中央および西アフリカの12都市における初期の割礼の頻度を調査した。この相 関関係はHIV-2では顕著であった。SIVsmmsに感染した移民を受け入れている可能性のある西アフリカの6都市のうち、研究対象となったコートジボ ワール(アビジャンとブアケ)の2都市では、割礼を受けていない男性の割合が60~85%と、他の都市よりもはるかに高かった。また、HIV-2の流行グ ループは、この国のみで最初に発生した。この相関関係は、中央アフリカのHIV-1ではそれほど明確ではなかった。[13] |

| Computer simulations of HIV emergence Sousa et al. then built computer simulations to test if an 'ill-adapted SIV' (meaning a simian immunodeficiency virus already infecting a human but incapable of transmission beyond the short acute infection period) could spread in colonial cities. The simulations used parameters of sexual transmission obtained from the current HIV literature. They modelled people's 'sexual links', with different levels of sexual partner change among different categories of people (prostitutes, single women with several partners a year, married women, and men), according to data obtained from modern studies of sexual activity in African cities. The simulations let the parameters (city size, proportion of people married, GUD frequency, male circumcision frequency, and transmission parameters) vary, and explored several scenarios. Each scenario was run 1,000 times, to test the probability of SIV generating long chains of sexual transmission. The authors postulated that such long chains of sexual transmission were necessary for the SIV strain to adapt better to humans, becoming an HIV capable of further epidemic emergence. The main result was that genital ulcer frequency was by far the most decisive factor. For the GUD levels prevailing in Léopoldville in the early 20th century, long chains of SIV transmission had a high probability. For the lower GUD levels existing in the same city in the late 1950s (see above), they were much less likely. And without GUD (a situation typical of villages in forested equatorial Africa before colonialism) SIV could not spread at all. City size was not an important factor. The authors propose that these findings explain the temporal patterns of HIV emergence: no HIV emerging in tens of thousands of years of human slaughtering of apes and monkeys, several HIV groups emerging in the nascent, GUD-riddled, colonial cities, and no epidemically successful HIV group emerging in mid-20th century, when GUD was more controlled, and cities were much bigger. Male circumcision had little to moderate effect in their simulations, but, given the geographical correlation found, the authors propose that it could have had an indirect role, either by increasing genital ulcer disease itself (it is known that syphilis, chancroid, and several other GUDs have higher incidences in uncircumcised men), or by permitting further spread of the HIV strain, after the first chains of sexual transmission permitted adaptation to the human organism. One of the main advantages of this theory is stressed by the authors: "It [the theory] also offers a conceptual simplicity because it proposes as causal factors for SIV adaptation to humans and initial spread the very same factors that most promote the continued spread of HIV nowadays: promiscuous [sic] sex, particularly involving sex workers, GUD, and possibly lack of circumcision."[13] |

HIV出現のコンピュータシミュレーション Sousaらは次に、コンピュータシミュレーションを構築し、「不適応SIV」(ヒトに感染しているが、急性感染期を過ぎると感染能力を失うサル免疫不全 ウイルスを意味する)が植民都市で蔓延するかどうかを検証した。シミュレーションでは、現在のHIV研究文献から得られた性感染のパラメータを使用した。 また、アフリカの都市における最近の性行動研究から得られたデータに基づき、人々の「性的つながり」をモデル化し、異なるカテゴリーの人々(売春婦、年に 複数のパートナーを持つ独身女性、既婚女性、男性)の間で異なるレベルの性的パートナーの変更を想定した。シミュレーションでは、パラメータ(都市の規 模、既婚者の割合、GUDの頻度、男性の割礼の頻度、および感染パラメータ)を変化させ、複数のシナリオを検討した。各シナリオは、SIVが長い連鎖の性 感染を引き起こす確率をテストするために1,000回実行された。著者は、SIV株がヒトにより適応し、さらなる流行を引き起こすHIVとなるためには、 このような長い連鎖の性感染が必要であると仮定した。 主な結果は、性器潰瘍の発生率が最も決定的な要因であるということだった。20世紀初頭のレオポルドヴィルで蔓延していたGUDレベルでは、SIVの長い 感染連鎖が起こる可能性は高かった。しかし、1950年代後半の同市で存在していたより低いGUDレベル(上記参照)では、その可能性ははるかに低かっ た。そして、GUDがなければ(植民地化以前の赤道アフリカの森林地帯の村々で典型的に見られた状況)、SIVはまったく広がらなかっただろう。都市の規 模は重要な要因ではなかった。著者らは、これらの発見がHIV出現の時間的パターンを説明すると提案している。すなわち、人類が何万年もの間、類人猿や猿 を殺戮してきた間にはHIVは出現せず、GUDが蔓延した植民地都市の初期には複数のHIVグループが出現し、GUDがより抑制され、都市がはるかに大き くなった20世紀半ばには、大流行に成功したHIVグループは出現しなかった。 男性の割礼は、彼らのシミュレーションではほとんど影響を与えないか、あるいは中程度の影響しか与えないが、地理的な相関関係が認められることから、著者 は、間接的な役割を果たした可能性があると提案している。すなわち、性器潰瘍自体の増加(梅毒、鼠径リンパ肉腫、およびその他のいくつかのGUDは、割礼 を受けていない男性に高い発生率が見られることが知られている)によるものか、あるいは、最初の性的感染の連鎖がヒトの生体への適応を可能にした後、 HIV株のさらなる拡大を許容したことによるもの、である。 この理論の主な利点のひとつとして、著者は次のように強調している。「この理論は、SIVがヒトに適応し、初期に広がった原因として、現在HIVの継続的 な拡大を最も促進している要因とまったく同じ要因を提案しているため、概念的に単純である。その要因とは、特に性労働者が関わる乱交セックス、GUD、そ して場合によっては割礼の欠如である」[13] |

| Iatrogenic and other theories Iatrogenic theories propose that medical interventions were responsible for HIV origins. By proposing factors that only appeared in Central and West Africa after the late 19th century, they seek to explain why all HIV groups also started after that. The theories centred on the role of parenteral risks, such as unsterile injections, transfusions,[20][31][39][40] or smallpox vaccinations[31] are accepted as plausible by most scientists of the field. Discredited HIV/AIDS origins theories include several iatrogenic theories, such as the polio vaccine hypothesis which argues that the early oral polio vaccines were contaminated with a chimpanzee virus, leading to the Central African outbreak.[45] |

医原説とその他の説 医原説は、HIVの起源は医療行為によるものだとする説である。19世紀後半以降に中央および西アフリカで出現した要因を提案することで、すべてのHIVグループもその後に出現した理由を説明しようとしている。 非経口的なリスク、例えば不衛生な注射、輸血、天然痘ワクチン[31]などが中心となった理論は、その分野の科学者の大半が妥当であると認めている。 否定されたHIV/AIDS起源説には、いくつかの医原説が含まれている。例えば、初期の経口ポリオワクチンがチンパンジーウイルスに汚染されていたため、中央アフリカで発生したというポリオワクチン仮説などである。[45] |

| Pathogenicity of SIV in non-human primates In most non-human primate species, natural SIV infection does not cause a fatal disease (but see below). Comparison of the gene sequence of SIV with HIV should, therefore, provide information about the factors necessary to cause disease in humans. The factors that determine the virulence of HIV as compared to most SIVs are only now being elucidated. Non-human SIVs contain a nef gene that down-regulates CD3, CD4, and MHC class I expression; most non-human SIVs, therefore, do not induce immunodeficiency; the HIV-1 nef gene, however, has lost its ability to down-regulate CD3, which results in the immune activation and apoptosis that is characteristic of chronic HIV infection.[46] In addition, a long-term survey of chimpanzees naturally infected with SIVcpz in Gombe National Park, Tanzania found that, contrary to the previous paradigm, chimpanzees with SIVcpz infection do experience an increased mortality, and also suffer from a human AIDS-like illness.[47] SIV pathogenicity in wild animals could exist in other chimpanzee subspecies and other primate species as well, and stay unrecognized by lack of relevant long term studies. |

非ヒト霊長類におけるSIVの病原性 ほとんどの非ヒト霊長類の種では、自然感染によるSIVは致死的な疾患を引き起こさない(ただし下記参照)。 したがって、SIVとHIVの遺伝子配列を比較すれば、ヒトに疾患を引き起こすのに必要な因子に関する情報が得られるはずである。 ほとんどのSIVと比較してHIVの病原性を決定する因子は、現在ようやく解明されつつある。非ヒトSIVにはCD3、CD4、MHCクラスIの発現を抑 制するネフ遺伝子が含まれているが、ほとんどの非ヒトSIVは免疫不全を引き起こさない。しかし、HIV-1のネフ遺伝子はCD3を抑制する能力を失って おり、これが慢性HIV感染に特徴的な免疫活性化とアポトーシスを引き起こしている。 さらに、タンザニアのゴンベ国立公園でSIVcpzに自然感染したチンパンジーの長期的な調査では、これまでのパラダイムとは逆に、SIVcpzに感染し たチンパンジーは死亡率が上昇し、 また、ヒトのエイズに似た病気を患うことも分かっている。[47] 野生動物におけるSIVの病原性は、他のチンパンジー亜種や他の霊長類にも存在する可能性があり、長期にわたる研究が不足しているため、認識されていない 可能性がある。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_HIV/AIDS |

**

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆