補完代替医療

Complementary and Alternative Medicine, CAM

解説:池田光穂

補完代替医療 (Complementary and Alternative Medicine, CAM)、補完代替医療には、代替補完医療(Alternative and Complimentary medicine)、補完医療(Complimentary medicine)、代替医療(aternative medicine)などの同義語がある。

| 代替医療(aternative medicine) | 文字通り近代医療あるいはコスモポリタン医療が十分に普及していない部分で、その医療の代わりにおこなわれる医療。あるいは、近代医療あるいはコスモポリタン医療は普及する「以前の」医療で、現時点では近代医療あるいはコスモポリタン医療の代わりに(aternative)に動員されている医療。 |

| 補完医療(Complimentary medicine) | 近代医療あるいはコスモポリタン医療が十分に普及しても、近代医療あるいはコスモポリタン医療から得られない利得(ベネフィット)を追求するために、使われている医療。 |

★補完代替医療の定義

米国の国立がん研究所 (National Cancer Intsitute)では、(がん患者のニーズの高い)補完代替医療は、「『標準的な医療ケア』の部分ではない、医療的産物と諸実践である(the term for medical products and practices that are not part of standard medical care)」と解説している。つまり、米国では、医師(M.D., medical doctor)と整骨治療医師(D.O., doctor of osteopathy)の学位をもつ専門家、ならびに「理学療法士、医療助手、臨床心理学者、そして看護師」がおこなう実践のみが「標準的な医療ケア」の範囲に含まれているのであり、それ以外は、実質的に全 部、補完代替医療 と呼ばれるのである。「標準的な医療ケア」 とは、生物医療、アロパシー、西洋起源の、主流をなしている、正統的な、あるいは通常の医療(biomedicine or allopathic, Western, mainstream, orthodox, or regular medicine)のことである。ここでアロパシー医療とは日本では馴染みのない言葉であるが、いわゆる西洋医学の主流の方法であり、それはホメオパシー 医療(同毒療法などといわれ一般に医学的根拠がないと証明された医療)ではないものを指している(→Complementary and Alternative Medicine, by NCI)。もっとも、北米大陸やヨーロッパ大陸では、ホメオパシー医療はとても人気があり、それは東アジアにお ける中国伝統医療と同じくらいであるということを忘れてはならない。

つまり、補完代替医療とは、主流派ではない非正統的医療のことであ る。米国の補完代替医療(CAM)と重なる部分があるにも関わらず(先に述べた)日本の統合医療は、日本の医学界にきちんと した地歩を持っているために、日本では正当性が与えられている違いがある(→Complementary and Alternative Medicine, by NCI)。

Complementary and Alternative Medicine, CAM =

Complementary medicine + Alternative medicine

Integrative medicine = (main) Integrative

medicine + effective CAM

ジョンズホプキンス大学のサイト では「伝統的代替医療」につぎの5つの療法を列挙している。つまり、(i)鍼[Acupuncture]、(ii)アーユルベーダー [Ayurveda]、(iii)ホメオパシー[Homeopathy]、(iv)ナチュロパシー[Naturopathy]、(v)中国あるいは東洋医療[Chinese or Oriental medicine]、である。これは日本の伝統的施術者にとっては噴飯物かもしれないが、米国の通常の人たちにはこのような理 解が一般的である、ということを日本の伝統的施術者はきちんと理解しておかねばならない(→Types of Complementary and Alternative Medicine, by Johns Hopkins Medicine)。

※以下に代替医療の一例を紹介する。

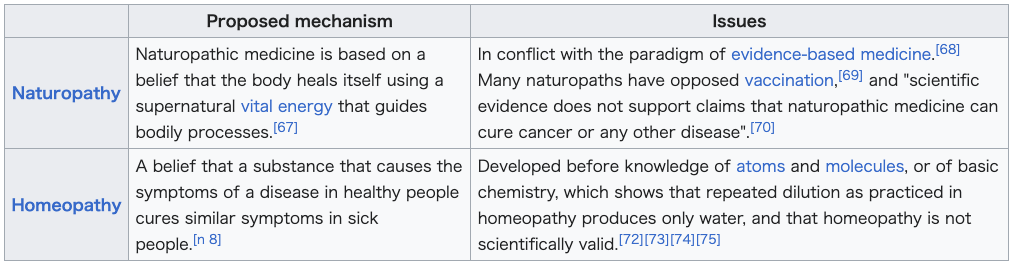

★非科学的信条体系(Unscientific belief systems)

| 提唱されたメカニズム |

問題点(イシュー) | |

| ナチュロパシー(Naturopathy) |

自然療法(ナチュロパシー)は、身体が超自然的な生命エネルギーによって自らを癒し、身体のプロセスを導くという信念に基づいている。[67] |

エビデンスに基づく医療のパラダイムと矛盾している。[68]多くの自然療法医は予防接種に反対してきた。[69]そして「自然療法が癌やその他の病気を治せるとの主張を科学的な証拠は支持していない」。[70] |

| ホメオパシー(Homeopathy) |

同属療法(ホメオパシー)とは、ある物質が健康な人に病気の症状を引き起こす場合、その物質が病気の人の同様の症状を治すという考え。[n 8] |

原子や分子の知識、あるいは基礎化学の知識が確立される前に開発されたもので、ホメオパシーで実践されるような反復希釈は単なる水を生むだけであり、ホメオパシーは科学的に有効ではないことを示している。[72][73][74][75] |

☆

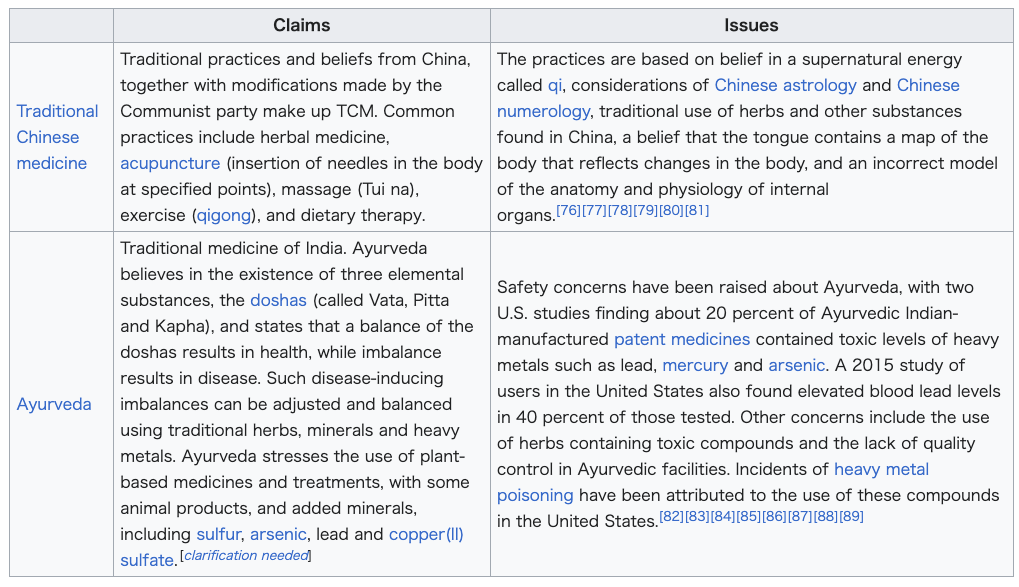

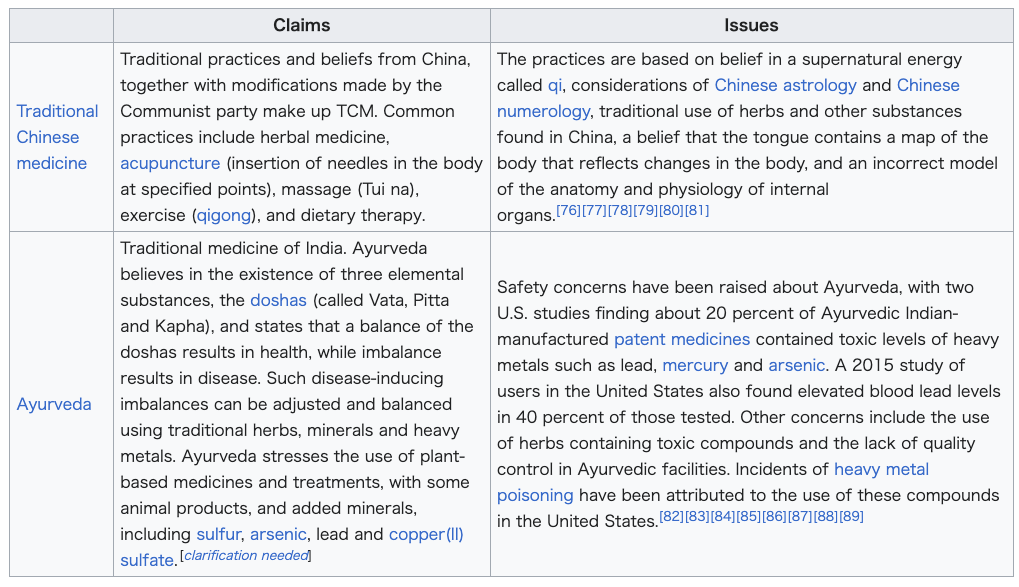

★伝統的民族体系(Traditional ethnic systems)

| その医学の内容(クレイム) |

問題点(イシュー) | |

| 伝統的中国医学, TCM (Traditional Chinese medicine) |

中国の伝統的な医療行為と信仰、それに共産党による修正を加えたものが中医学である。一般的な治療法には、漢方薬、鍼治療(体の特定のポイントに針を刺す)、マッサージ(推拿)、運動療法(気功)、食事療法が含まれる。 |

これらの実践は、気と呼ばれる超自然的なエネルギーへの信

仰、中国占星術と中国数秘術の考察、中国で発見されたハーブやその他の物質の伝統的な使用、舌が身体の変化を反映する身体の地図を含んでいるという信念、

そして内臓の解剖学と生理学に関する誤ったモデルに基づいている。[76][77][78][79][80][81] |

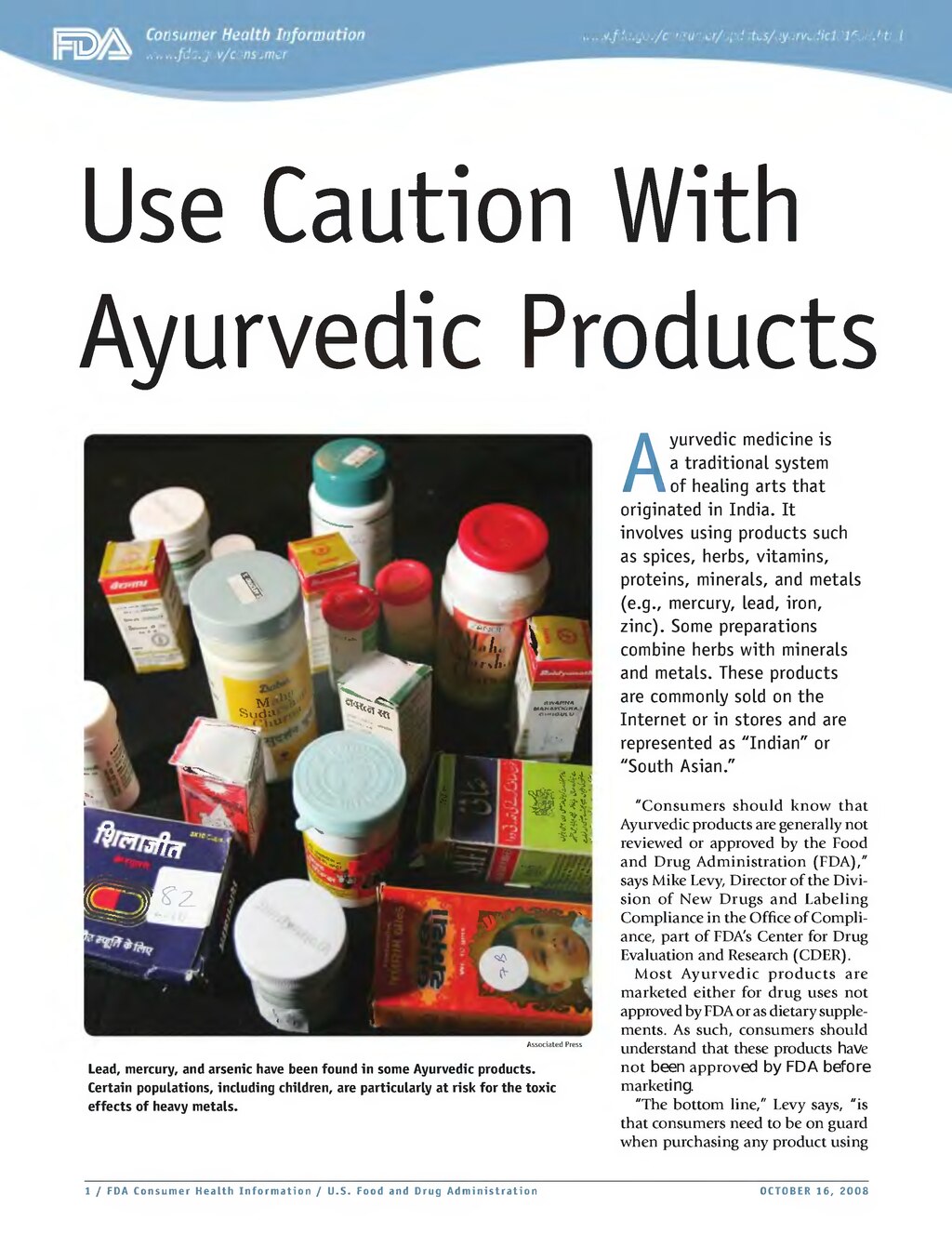

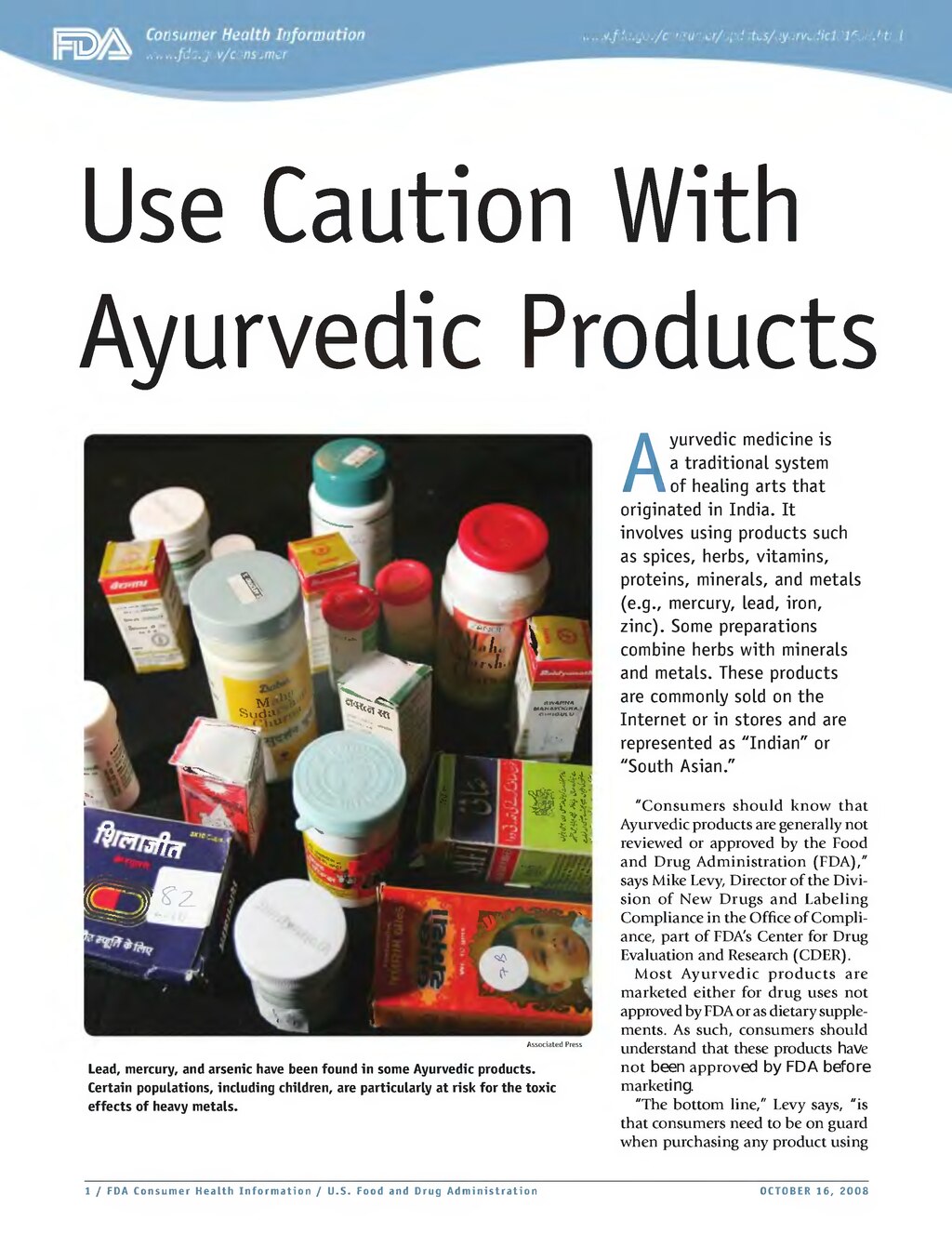

| アーユルベーダ(Ayurveda) |

インドの伝統医学。アーユルヴェーダは三つの元素物質、

ドーシャ(ヴァータ、ピッタ、カパと呼ばれる)の存在を信じ、ドーシャの均衡が健康をもたらし、不均衡が病気を引き起こすと説く。こうした病気を誘発する

不均衡は、伝統的なハーブ、鉱物、重金属を用いて調整し均衡させることができる。アーユルヴェーダは植物由来の薬や治療法を重視し、一部の動物性製品や硫

黄、ヒ素、鉛、硫酸銅(II)などの鉱物を添加する。[くわしい説明が必要] |

アーユルヴェーダには安全性の懸念が指摘されている。米国

の2つの研究では、インド製アーユルヴェーダ特許医薬品の約20%に鉛、水銀、ヒ素などの有害なレベルの重金属が含まれていた。2015年の米国利用者調

査でも、検査対象者の40%で血中鉛濃度の上昇が確認された。その他の懸念事項には、有毒化合物を含むハーブの使用や、アーユルヴェーダ施設における品質

管理の欠如が含まれる。米国では、これらの化合物使用による重金属中毒事例が報告されている。[82][83][84][85][86][87][88]

[89] |

☆

☆

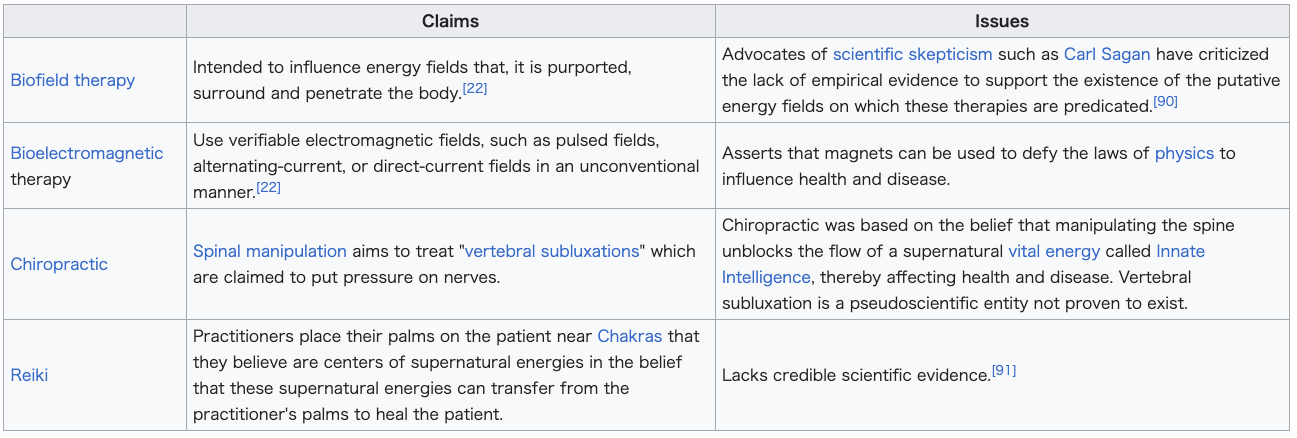

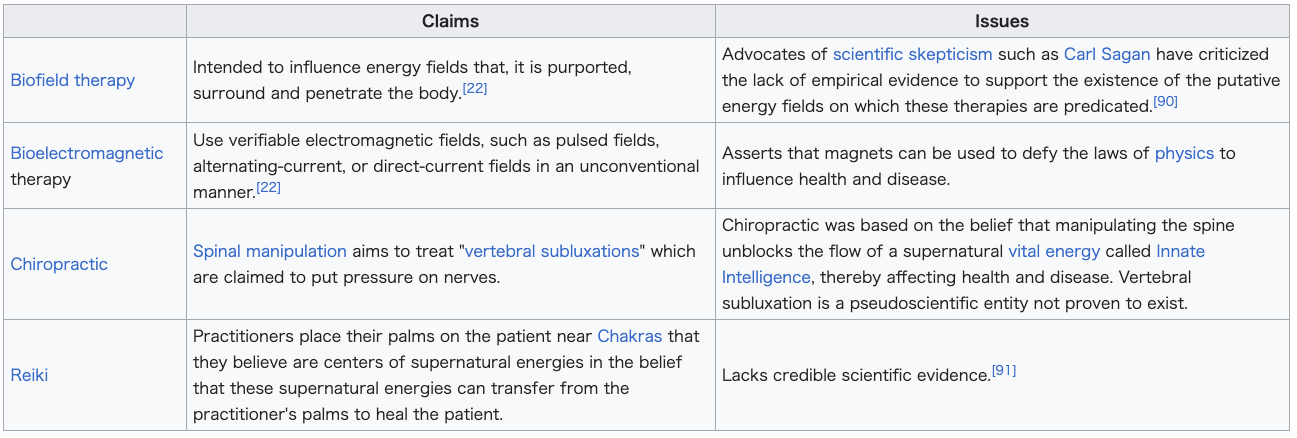

★超自然的エネルギー(Supernatural energies)

| その医学/療法の内容(クレイム) | 問題点(イシュー) | |

| バイオフィールド治療(Biofield therapy) |

身体を取り囲み、貫通していると言われるエネルギー場に影響を与えることを目的としている。[22] |

カール・セーガンのような科学的懐疑論の提唱者たちは、これらの療法の根拠となっているとされるエネルギー場の存在を裏付ける実証的証拠の欠如を批判している。[90] |

| 生体電磁気療法(Bioelectromagnetic therapy) |

パルス電磁場、交流電磁場、直流電磁場など、検証可能な電磁場を従来とは異なる方法で用いる。[22] |

磁石を使えば物理法則に逆らって健康や病気に影響を与えられると主張する。 |

| カイロプラクティック(Chiropractic) |

脊椎マニピュレーションは、神経に圧迫を与えるとされる「椎骨の亜脱臼」を治療することを目的としている。 |

カイロプラクティックは、脊椎を操作することで「生来の知性」と呼ばれる超自然的な生命エネルギーの流れが妨げられ、それによって健康や病気に影響を与えるという信念に基づいていた。椎骨の亜脱臼は、存在が証明されていない疑似科学的な概念である。 |

| 霊氣・レイキ(Reiki) |

施術者は、超自然的なエネルギーの中心点と信じているチャクラ付近に患者の体に掌を当てる。この超自然的なエネルギーが施術者の掌から患者に移り、治癒をもたらすと信じているからだ。 |

信頼できる科学的根拠が欠けている。[91] |

☆

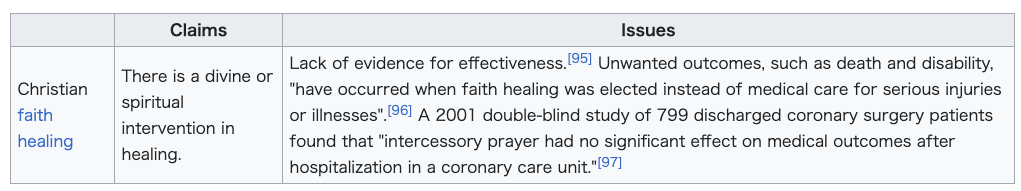

★

| その医学/療法の内容(クレイム) | 問題点(イシュー) |

|

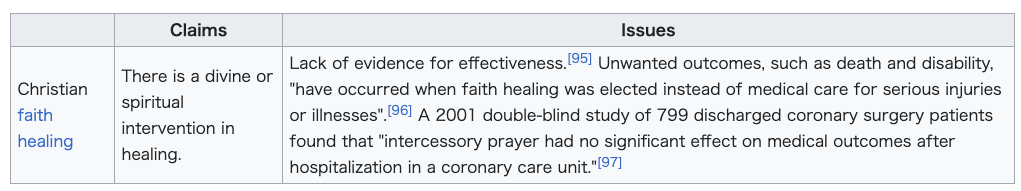

| クリスチャン信仰治療(Christian faith healing) |

癒しには神聖な、あるいは霊的な介入がある。 |

有効性を示す証拠がない。[95]

死亡や障害といった望ましくない結果が、「重傷や重病に対して医療ケアの代わりに信仰治療が選択された場合に発生した」。[96]

2001年の二重盲検試験(冠動脈手術後退院患者799名対象)では、「冠動脈ケアユニットでの入院後、執り成しの祈りが医療的転帰に有意な影響を与えな

かった」と報告されている。[97] |

☆

★

☆代替医療(Alternative

medicine)

| Alternative

medicine refers to practices that aim to achieve the healing

effects of conventional medicine, but that typically lack biological

plausibility, testability, repeatability, or supporting evidence of

effectiveness. Such practices are generally not part of evidence-based

medicine. Unlike modern medicine, which employs the scientific method

to test plausible therapies by way of responsible and ethical clinical

trials, producing repeatable evidence of either effect or of no effect,

alternative therapies reside outside of mainstream medicine[n 1][n 2]

and do not originate from using the scientific method, but instead rely

on testimonials, anecdotes, religion, tradition, superstition, belief

in supernatural "energies", pseudoscience, errors in reasoning,

propaganda, fraud, or other unscientific sources. Frequently used terms

for relevant practices are New Age medicine, pseudo-medicine,

unorthodox medicine, holistic medicine, fringe medicine, and

unconventional medicine, with little distinction from quackery. Some alternative practices are based on theories that contradict the established science of how the human body works; others appeal to the supernatural or superstitions to explain their effect or lack thereof. In others, the practice has plausibility but lacks a positive risk–benefit outcome probability. Research into alternative therapies often fails to follow proper research protocols (such as placebo-controlled trials, blind experiments and calculation of prior probability), providing invalid results. History has shown that if a method is proven to work, it eventually ceases to be alternative and becomes mainstream medicine. Much of the perceived effect of an alternative practice arises from a belief that it will be effective, the placebo effect, or from the treated condition resolving on its own (the natural course of disease). This is further exacerbated by the tendency to turn to alternative therapies upon the failure of medicine, at which point the condition will be at its worst and most likely to spontaneously improve. In the absence of this bias, especially for diseases that are not expected to get better by themselves such as cancer or HIV infection, multiple studies have shown significantly worse outcomes if patients turn to alternative therapies. While this may be because these patients avoid effective treatment, some alternative therapies are actively harmful (e.g. cyanide poisoning from amygdalin, or the intentional ingestion of hydrogen peroxide) or actively interfere with effective treatments. The alternative medicine sector is a highly profitable industry with a strong lobby,[1] and faces far less regulation over the use and marketing of unproven treatments. Complementary medicine (CM), complementary and alternative medicine (CAM), integrated medicine or integrative medicine (IM), and holistic medicine attempt to combine alternative practices with those of mainstream medicine. Traditional medicine practices become "alternative" when used outside their original settings and without proper scientific explanation and evidence. Alternative methods are often marketed as more "natural" or "holistic" than methods offered by medical science, that is sometimes derogatorily called "Big Pharma" by supporters of alternative medicine. Billions of dollars have been spent studying alternative medicine, with few or no positive results and many methods thoroughly disproven. |

代替医療とは、従来の医療と同等の治療効果を目的とするが、生物学的妥

当性、検証可能性、再現性、あるいは有効性を裏付ける証拠を通常欠いている実践を指す。こうした実践は一般的にエビデンスに基づく医療の一部ではない。現

代医学が科学的メソッドを用いて、責任ある倫理的な臨床試験によって妥当な治療法を検証し、効果の有無を再現可能な証拠として示すのとは異なり、代替療法

は主流の医学の外側に位置する[n 1][n

2]。科学的メソッドに基づくものではなく、体験談、逸話、宗教、伝統、迷信、超自然的な「エネルギー」への信仰、

疑似科学、推論の誤り、プロパガンダ、詐欺、その他の非科学的根拠に依拠している。関連する実践に対して頻繁に使用される用語には、ニューエイジ医療、疑

似医療、非正統医療、ホリスティック医療、フリンジ医療、非従来型医療などがあり、これらはペテン師的行為との区別がほとんどない。 一部の代替療法は、人体の働きに関する確立された科学と矛盾する理論に基づいている。また、その効果や無効性を説明するために超自然現象や迷信に訴えるも のもある。また、その実践には妥当性があるものの、リスクと利益のバランスがプラスとなる結果の確率が欠けている場合もある。代替療法の研究は、適切な研 究プロトコル(プラセボ対照試験、盲検化実験、事前確率の計算など)に従わないことが多く、無効な結果をもたらす。歴史が示すように、ある方法が有効であ ると証明されれば、それはやがて代替療法ではなくなり、主流の医療となる。 代替療法の効果の多くは、その有効性を信じるプラセボ効果、あるいは治療対象の病状が自然治癒する(自然経過)ことに起因している。この傾向は、医学的治 療が失敗した時点で代替療法に頼る傾向によってさらに悪化する。その時点では病状が最も深刻であり、自然治癒の可能性が最も高いのだ。このバイアスを除け ば、特にがんやHIV感染のように自然治癒が期待できない疾患において、代替療法を選択した患者は複数の研究で明らかに予後が悪化することが示されてい る。これは患者が有効な治療を回避するためかもしれないが、一部の代替療法は積極的に有害である(例:アミグダリンによるシアン化物中毒、過酸化水素の意 図的摂取)か、有効な治療を妨害する。 代替医療分野は強力なロビー活動[1]を持つ高収益産業であり、未検証治療の使用や販売に対する規制がはるかに緩い。補完医療(CM)、補完代替医療 (CAM)、統合医療(IM)、ホリスティック医療は、代替療法と主流医療を組み合わせようとするものだ。伝統医療の実践は、本来の環境外で使用され、適 切な科学的説明や証拠を伴わない場合、「代替」となる。代替療法は、医療科学が提供する手法よりも「自然」または「ホリスティック」であると宣伝されるこ とが多く、代替医療支持者からは時に「ビッグファーマ」と蔑称される。代替医療の研究には数十億ドルが費やされてきたが、肯定的な結果はほとんどなく、多 くの手法は完全に否定されている。 |

| Definitions and terminology See also: Terminology of alternative medicine  Marcia Angell: "There cannot be two kinds of medicine – conventional and alternative."[2] The terms alternative medicine, complementary medicine, integrative medicine, holistic medicine, natural medicine, unorthodox medicine, fringe medicine, unconventional medicine, and new age medicine are used interchangeably as having the same meaning and are almost synonymous in most contexts.[3][4][5][6] Terminology has shifted over time, reflecting the preferred branding of practitioners.[7] For example, the United States National Institutes of Health department studying alternative medicine, currently named the National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH), was established as the Office of Alternative Medicine (OAM) and was renamed the National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine (NCCAM) before obtaining its current name. Therapies are often framed as "natural" or "holistic", implicitly and intentionally suggesting that conventional medicine is "artificial" and "narrow in scope".[1][8] The meaning of the term "alternative" in the expression "alternative medicine", is not that it is an effective alternative to medical science (though some alternative medicine promoters may use the loose terminology to give the appearance of effectiveness).[9][10] Loose terminology may also be used to suggest meaning that a dichotomy exists when it does not (e.g., the use of the expressions "Western medicine" and "Eastern medicine" to suggest that the difference is a cultural difference between the Asian east and the European west, rather than that the difference is between evidence-based medicine and treatments that do not work).[9] |

定義と用語 関連項目:代替医療の用語  マーシア・アンジェル: 「医療に二種類——従来型と代替型——など存在しえない」[2] 代替医療、補完医療、統合医療、ホリスティック医療、自然療法、非正統医療、周辺医療、非従来型医療、ニューエイジ医療といった用語は、同じ意味を持つも のとして互換的に用いられ、ほとんどの文脈でほぼ同義である[3] [4][5][6] 用語は時代とともに変化し、施術者の好むブランディングを反映している。[7] 例えば、米国国立衛生研究所(NIH)の代替医療研究部門は、現在は国立補完統合医療センター(NCCIH)と命名されているが、設立当初は代替医療局 (OAM)と呼ばれ、その後国立補完代替医療センター(NCCAM)と改称され、現在の名称に至った。療法はしばしば「自然」または「ホリスティック」と 位置付けられ、暗黙的かつ意図的に、従来の医学が「人工的」で「視野が狭い」ことを示唆している。[1] [8] 「代替医療」という表現における「代替」の意味は、それが医学科学に代わる有効な選択肢であるということではない(ただし、一部の代替医療推進者は、効果 があるように見せかけるためにこの曖昧な用語を使うことがある)。[9][10] 曖昧な用語は、実際には存在しない二分法が存在するかのように示唆するためにも用いられる(例:「西洋医学」と「東洋医学」という表現を用いて、その差異 がアジアの東とヨーロッパの西という文化的差異であるかのように示唆し、実証に基づく医学と効果のない治療法との差異であることを隠す)。[9] |

| Alternative medicine Alternative medicine is defined loosely as a set of products, practices, and theories that are believed or perceived by their users to have the healing effects of medicine,[n 3][n 4] but whose effectiveness has not been established using scientific methods,[n 3][n 5][13][14][15][9] or whose theory and practice is not part of biomedicine,[n 4][n 1][n 2][n 6] or whose theories or practices are directly contradicted by scientific evidence or scientific principles used in biomedicine.[9][13][19] "Biomedicine" or "medicine" is that part of medical science that applies principles of biology, physiology, molecular biology, biophysics, and other natural sciences to clinical practice, using scientific methods to establish the effectiveness of that practice. Unlike medicine,[n 1] an alternative product or practice does not originate from using scientific methods, but may instead be based on hearsay, religion, tradition, superstition, belief in supernatural energies, pseudoscience, errors in reasoning, propaganda, fraud, or other unscientific sources.[n 5][9][11][13][19] Some other definitions seek to specify alternative medicine in terms of its social and political marginality to mainstream healthcare.[20] This can refer to the lack of support that alternative therapies receive from medical scientists regarding access to research funding, sympathetic coverage in the medical press, or inclusion in the standard medical curriculum.[20] For example, a widely used[21] definition devised by the US NCCIH calls it "a group of diverse medical and health care systems, practices, and products that are not generally considered part of conventional medicine".[22] However, these descriptive definitions are inadequate in the present-day when some conventional doctors offer alternative medical treatments and introductory courses or modules can be offered as part of standard undergraduate medical training;[23] alternative medicine is taught in more than half of US medical schools and US health insurers are increasingly willing to provide reimbursement for alternative therapies.[24] |

代替医療 代替医療とは、大まかに言えば、利用者が医療と同等の治療効果を持つと信じたり認識したりしている製品、施術、理論の集合体である[n 3][n 4]。しかしその有効性は科学的手法によって確立されていない[n 3][n 5][13]。[14][15][9] あるいはその理論や実践が生物医学の一部ではないもの[n 4][n 1][n 2][n 6]、あるいはその理論や実践が生物医学で使用される科学的証拠や科学的原理と直接矛盾するもの。[9][13][19] 「生物医学」または「医学」とは、生物学、生理学、分子生物学、生物物理学、その他の自然科学の原理を臨床実践に応用し、その実践の有効性を科学的方法を 用いて確立する医学科学の一分野である。医学とは異なり、代替製品や実践は科学的方法の使用に由来せず、代わりに伝聞、宗教、伝統、迷信、超自然的エネル ギーへの信仰、疑似科学、推論の誤り、プロパガンダ、詐欺、その他の非科学的根拠に基づいている場合がある。 他の定義では、代替医療を主流医療に対する社会的・政治的周縁性という観点から特定しようとする[20]。これは、代替療法が研究資金へのアクセス、医学 メディアにおける好意的な報道、標準的な医学カリキュラムへの組み込みに関して、医学研究者から十分な支援を得られていない状況を指す場合がある。 [20] 例えば、米国国立補完統合医療センター(NCCIH)が考案した広く用いられる[21]定義では、代替医療を「一般に従来型医療の一部とは見なされない多 様な医療・健康システム、実践、製品群」と位置付けている。[22] しかし、現代においてはこうした記述的定義は不十分である。なぜなら、一部の従来型医師が代替医療的治療を提供し、標準的な学部医学教育の一環として入門 コースやモジュールが提供される場合があるからだ[23]。米国の医学部の半数以上で代替医療が教えられており、米国の健康保険会社は代替療法に対する償 還を提供する意向を強めている[24]。 |

| Complementary or integrative

medicine Complementary medicine (CM) or integrative medicine (IM) is when alternative medicine is used together with mainstream medical treatment in a belief that it improves the effect of treatments.[n 7][11][26][27][28] For example, acupuncture (piercing the body with needles to influence the flow of a supernatural energy) might be believed to increase the effectiveness or "complement" science-based medicine when used at the same time.[29][30][31] Significant drug interactions caused by alternative therapies may make treatments less effective, notably in cancer therapy.[32][33][34] Several medical organizations differentiate between complementary and alternative medicine including the UK National Health Service (NHS),[35] Cancer Research UK,[36] and the US Center for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), the latter of which states that "Complementary medicine is used in addition to standard treatments" whereas "Alternative medicine is used instead of standard treatments."[37] Complementary and integrative interventions are used to improve fatigue in adult cancer patients.[38][39] David Gorski has described integrative medicine as an attempt to bring pseudoscience into academic science-based medicine[40] with skeptics such as Gorski and David Colquhoun referring to this with the pejorative term "quackademia".[41] Robert Todd Carroll described Integrative medicine as "a synonym for 'alternative' medicine that, at its worst, integrates sense with nonsense. At its best, integrative medicine supports both consensus treatments of science-based medicine and treatments that the science, while promising perhaps, does not justify"[42] Rose Shapiro has criticized the field of alternative medicine for rebranding the same practices as integrative medicine.[3] CAM is an abbreviation of the phrase complementary and alternative medicine.[43][44][45] The 2019 World Health Organization (WHO) Global Report on Traditional and Complementary Medicine states that the terms complementary and alternative medicine "refer to a broad set of health care practices that are not part of that country's own traditional or conventional medicine and are not fully integrated into the dominant health care system. They are used interchangeably with traditional medicine in some countries."[46] In the 1990s, integrative medicine started to be marketed by a new term, "functional medicine".[47] The Integrative Medicine Exam by the American Board of Physician Specialties[48] includes the following subjects: Manual Therapies, Biofield Therapies, Acupuncture, Movement Therapies, Expressive Arts, Traditional Chinese Medicine, Ayurveda, Indigenous Medical Systems, Homeopathic Medicine, Naturopathic Medicine, Osteopathic Medicine, Chiropractic, and Functional Medicine.[48] |

補完医療または統合医療 補完医療(CM)または統合医療(IM)とは、代替医療を主流の医療治療と併用し、治療効果を高めるとの考えに基づくものである。[n 7][11][26][27] [28] 例えば、鍼治療(超自然的なエネルギーの流れに影響を与えるために体に針を刺すこと)は、同時に使用することで科学に基づく医療の効果を高めたり「補完」 したりすると信じられている場合がある。[29][30][31] 代替療法による重大な薬物相互作用は、特にがん治療において、治療の効果を低下させる可能性がある。[32][33][34] 英国国民保健サービス(NHS)[35]、英国がん研究機構[36]、米国疾病予防管理センター(CDC)など、複数の医療機関が補完医療と代替医療を区 別している。後者は「補完医療は標準治療に加えて使用される」のに対し、「代替医療は標準治療の代わりに用いられる」と定義している[37]。 補完・統合的介入は、成人がん患者の疲労改善に用いられる。[38][39] デイヴィッド・ゴースキは、統合医療を疑似科学を学術的科学に基づく医療に取り込もうとする試みと説明している。[40]ゴースキやデイヴィッド・コル クーンといった懐疑論者は、これを蔑称「クワッカデミア」と呼んでいる。[41] ロバート・トッド・キャロルは統合医療を「最悪の場合、理性を非理性と統合する『代替』医療の同義語。最良の場合でも、科学に基づく医療の合意治療と、科 学的には有望かもしれないが正当化されない治療の両方を支持するもの」と評した[42]。ローズ・シャピロは代替医療分野が同じ実践を統合医療と再ブラン ド化した点を批判している。[3] CAMは補完代替医療(complementary and alternative medicine)の略語である。[43][44][45] 2019年の世界保健機関(WHO)伝統的・補完医療グローバル報告書は、補完代替医療という用語が「当該国の伝統的・標準医療の一部ではなく、主流医療 システムに完全に統合されていない広範な健康実践を指す」と述べている。一部の国では伝統医療と交替的に使用される」。[46] 1990年代、統合医療は新たな用語「機能性医療」として市場展開され始めた。[47] 米国医師専門委員会による統合医療試験[48]では、以下の科目が含まれる:手技療法、バイオフィールド療法、鍼治療、運動療法、表現芸術療法、伝統中国 医学、アーユルヴェーダ、先住民医療体系、ホメオパシー医学、自然療法医学、オステオパシー医学、カイロプラクティック、機能医学。[48] |

| Other terms See also: Traditional medicine Traditional medicine (TM) refers to certain practices within a culture which have existed since before the advent of medical science,[49][50] Many TM practices are based on "holistic" approaches to disease and health, versus the scientific evidence-based methods in conventional medicine.[51][52] The 2019 WHO report defines traditional medicine as "the sum total of the knowledge, skill and practices based on the theories, beliefs and experiences indigenous to different cultures, whether explicable or not, used in the maintenance of health as well as in the prevention, diagnosis, improvement or treatment of physical and mental illness."[46] When used outside the original setting and in the absence of scientific evidence, TM practices are typically referred to as "alternative medicine".[53][54][55] Holistic medicine is another rebranding of alternative medicine. In this case, the words balance and holism are often used alongside complementary or integrative, claiming to take into fuller account the "whole" person, in contrast to the supposed reductionism of medicine.[56][57] |

その他の用語 関連項目: 伝統医療 伝統医療(TM)とは、医学が生まれる以前から文化の中で存在してきた特定の医療行為を指す[49][50]。多くの伝統医療は、従来の医学における科学 的根拠に基づく方法とは対照的に、病気と健康に対する「全体論的」アプローチに基づいている[51][52]。2019年のWHO報告書は伝統医学を「健 康維持ならびに身体的・精神的疾患の予防、診断、改善、治療に用いられる、異なる文化に固有の理論、信念、経験に基づく知識、技術、実践の総体。その説明 可能性の有無を問わない」と定義している[46]。本来の環境外で使用され、科学的根拠を欠く場合、伝統医学の実践は通常「代替医療」と呼ばれる。 [53][54][55] ホリスティック医療は代替医療の別名である。この場合、「バランス」や「ホリスティック」という言葉が「補完的」や「統合的」と併せて用いられ、医学の還 元主義的傾向に対抗し、人格を「全体」としてより包括的に捉えると主張される。[56][57] |

| Challenges in defining

alternative medicine Prominent members of the science[58][59] and biomedical science community[2] say that it is not meaningful to define an alternative medicine that is separate from a conventional medicine because the expressions "conventional medicine", "alternative medicine", "complementary medicine", "integrative medicine", and "holistic medicine" do not refer to any medicine at all.[2][58][59][55] Others say that alternative medicine cannot be precisely defined because of the diversity of theories and practices it includes, and because the boundaries between alternative and conventional medicine overlap, are porous, and change.[16][60] Healthcare practices categorized as alternative may differ in their historical origin, theoretical basis, diagnostic technique, therapeutic practice and in their relationship to the medical mainstream.[61] Under a definition of alternative medicine as "non-mainstream", treatments considered alternative in one location may be considered conventional in another.[62] Critics say the expression is deceptive because it implies there is an effective alternative to science-based medicine, and that complementary is deceptive because it implies that the treatment increases the effectiveness of (complements) science-based medicine, while alternative medicines that have been tested nearly always have no measurable positive effect compared to a placebo.[9][40][63][64] Journalist John Diamond wrote that "there is really no such thing as alternative medicine, just medicine that works and medicine that doesn't",[59][65] a notion later echoed by Paul Offit: "The truth is there's no such thing as conventional or alternative or complementary or integrative or holistic medicine. There's only medicine that works and medicine that doesn't. And the best way to sort it out is by carefully evaluating scientific studies—not by visiting Internet chat rooms, reading magazine articles, or talking to friends."[58] |

代替医療の定義における課題 科学界[58][59]および生物医学界[2]の著名な研究者らは、代替医療を従来の医療とは別個のものとして定義することは意味がないと述べている。な ぜなら「従来の医療」「代替医療」「補完医療」「統合医療」「ホリスティック医療」といった表現は、いずれも特定の医療を指すものではないからだ。[2] [58][59][55] 他には、代替医療は包含する理論や実践が多様であること、また代替医療と従来型医療の境界が重なり合い、浸透しやすく、変化するため、正確に定義できない と主張する者もいる。代替医療に分類される医療行為は、歴史的起源、理論的根拠、診断技術、治療実践、そして主流医療との関係において異なる場合がある。 代替医療を「非主流」と定義すると、ある地域では代替療法と見なされる治療法が、別の地域では従来療法と見なされる可能性がある。[62] 批判者は、この表現が科学に基づく医療に効果的な代替手段があるかのように誤解を招くと指摘する。また「補完」という表現も、その治療法が科学に基づく医 療の効果を高める(補完する)かのように誤解を招くとされる。実際、検証された代替医療のほとんどは、プラセボと比較して測定可能な効果を示さない。 [9][40][63][64] ジャーナリストのジョン・ダイアモンドは「代替医療など実際には存在せず、効果のある医療と効果のない医療があるだけだ」と記した[59][65]。この 考えは後にポール・オフィットも「真実は、従来型医療や代替医療、補完医療、統合医療、ホリスティック医療などというものは存在しないということだ。効果 のある医療と効果のない医療だけがある。そしてそれを区別する最善の方法は、インターネットの掲示板を見たり雑誌記事を読んだり友人と話したりすることで はなく、科学的研究を慎重に評価することだ」と述べている。[58] |

| Types See also: List of forms of alternative medicine Alternative medicine consists of a wide range of health care practices, products, and therapies. The shared feature is a claim to heal that is not based on the scientific method. Alternative medicine practices are diverse in their foundations and methodologies.[22] Alternative medicine practices may be classified by their cultural origins or by the types of beliefs upon which they are based.[11][9][19][22] Methods may incorporate or be based on traditional medicinal practices of a particular culture, folk knowledge, superstition,[66] spiritual beliefs, belief in supernatural energies (antiscience), pseudoscience, errors in reasoning, propaganda, fraud, new or different concepts of health and disease, and any bases other than being proven by scientific methods.[11][9][13][19] Different cultures may have their own unique traditional or belief based practices developed recently or over thousands of years, and specific practices or entire systems of practices. Unscientific belief systems  "They told me if I took 1000 pills at night I should be quite another thing in the morning", an early 19th-century satire on Morison's Vegetable Pills, an alternative medicine supplement Alternative medicine, such as using naturopathy or homeopathy in place of conventional medicine, is based on belief systems not grounded in science.[22]  |

代替医療の種類 関連項目: 代替医療の形態一覧 代替医療は、幅広い健康に関する行為、製品、療法から成る。共通点は、科学的根拠に基づかない治療効果を主張することだ。代替医療の実践は、その基盤や方 法論において多様である。[22] 代替医療の実践は、文化的起源や、その基盤となる信念の種類によって分類されることがある。[11][9][19][22] その手法は、特定の文化における伝統的な医療行為、民間知識、迷信[66]、精神的信念、超自然的なエネルギーへの信仰(反科学)、疑似科学、推論の誤 り、プロパガンダ、詐欺、健康と疾病に関する新たな概念や異なる概念、そして科学的方法によって証明されたもの以外のあらゆる根拠を取り入れたり、それら に基づいたりすることがある。[11][9][13][19] 異なる文化圏には、近年または数千年にわたり発展した独自の伝統的・信念に基づく実践、特定の施術法、あるいは施術体系全体が存在する。 非科学的な信念体系  「夜に1000錠飲めば朝にはすっかり別人のようになる」と彼らは言った──19世紀初頭の風刺文。モリソンの野菜錠剤(代替医療サプリメント)を揶揄し たもの 代替医療(例:自然療法やホメオパシーを従来の医療に代えて使用すること)は、科学に根ざさない信念体系に基づいている。[22]  |

Traditional ethnic systems Ready-to-drink traditional Chinese medicine mixture  Acupuncture involves insertion of needles in the body. Alternative medical systems may be based on traditional medicine practices, such as traditional Chinese medicine (TCM), Ayurveda in India, or practices of other cultures around the world.[22] Some useful applications of traditional medicines have been researched and accepted within ordinary medicine, however the underlying belief systems are seldom scientific and are not accepted. Traditional medicine is considered alternative when it is used outside its home region; or when it is used together with or instead of known functional treatment; or when it can be reasonably expected that the patient or practitioner knows or should know that it will not work – such as knowing that the practice is based on superstition.  |

伝統的な民族医療体系 飲用可能な漢方薬調合液  鍼治療は体に針を刺す行為である。 代替医療体系は、漢方医学(TCM)、インドのアーユルヴェーダ、あるいは世界各国の伝統医療実践に基づく場合がある[22]。伝統医療の有用な応用例は 一般医学内で研究・採用されているが、その根底にある信念体系は科学的根拠が乏しく、医学界で認められることは稀である。 伝統医療は、以下の場合に代替医療と見なされる:1. 発祥地域外で使用される場合2. 既知の有効な治療法と併用される、またはそれに代わる場合3. 患者や施術者がその効果が期待できないと知り、あるいは知るべき状況にある場合(例:その実践が迷信に基づいていると認識している場合)  |

| Supernatural energies Bases of belief may include belief in existence of supernatural energies undetected by the science of physics, as in biofields, or in belief in properties of the energies of physics that are inconsistent with the laws of physics, as in energy medicine.[22]  |

超自然的なエネルギー 信仰の基盤には、物理学の科学では検出されない超自然的なエネルギーの存在を信じるもの(例:生体エネルギー)や、物理学の法則と矛盾する物理エネルギーの性質を信じるもの(例:エネルギー医学)が含まれることがある。[22]  |

| Herbal remedies and other substances Main article: Herbal medicine Substance based practices use substances found in nature such as herbs, foods, non-vitamin supplements and megavitamins, animal and fungal products, and minerals, including use of these products in traditional medical practices that may also incorporate other methods.[22][92][93] Examples include healing claims for non-vitamin supplements, fish oil, Omega-3 fatty acid, glucosamine, echinacea, flaxseed oil, and ginseng.[94] Herbal medicine, or phytotherapy, includes not just the use of plant products, but may also include the use of animal and mineral products.[92] It is among the most commercially successful branches of alternative medicine, and includes the tablets, powders and elixirs that are sold as "nutritional supplements".[92] Only a very small percentage of these have been shown to have any efficacy, and there is little regulation as to standards and safety of their contents.[92] |

ハーブ療法およびその他の物質 主な記事: ハーブ療法 物質に基づく療法は、ハーブ、食品、非ビタミン系サプリメントやメガビタミン、動物性・菌類由来製品、鉱物など自然界に存在する物質を用いる。これらは伝 統医療において他の手法と組み合わせて使用される場合もある。[22][92][93] 例としては、非ビタミン系サプリメント、魚油、オメガ3脂肪酸、グルコサミン、エキナセア、亜麻仁油、高麗人参に対する治療効果の主張がある。[94] ハーブ療法(フィトセラピー)は、植物製品の使用だけでなく、動物性・鉱物性製品の使用も含む場合がある。[92] これは代替医療の中でも商業的に最も成功している分野の一つであり、「栄養補助食品」として販売される錠剤、粉末、エリキシル剤などを含む。[92] これらの中で有効性が実証されているものはごく一部であり、内容物の基準や安全性に関する規制はほとんど存在しない。[92] |

| Religion, faith healing, and prayer See also: Shamanism  |

宗教、信仰による癒し、そして祈り 関連項目:シャーマニズム  |

A chiropractor "adjusting" the spine |

カイロプラクターが背骨を「調整」している |

| NCCIH classification The United States agency National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health (NCCIH) has created a classification system for branches of complementary and alternative medicine that divides them into five major groups. These groups have some overlap, and distinguish two types of energy medicine: veritable which involves scientifically observable energy (including magnet therapy, colorpuncture and light therapy) and putative, which invokes physically undetectable or unverifiable energy.[98] None of these energies have any evidence to support that they affect the body in any positive or health promoting way.[1] 1. Whole medical systems: Cut across more than one of the other groups; examples include traditional Chinese medicine, naturopathy, homeopathy, and ayurveda. 2. Mind-body interventions: Explore the interconnection between the mind, body, and spirit, under the premise that they affect "bodily functions and symptoms". A connection between mind and body is conventional medical fact, and this classification does not include therapies with proven function such as cognitive behavioral therapy. 3. "Biology"-based practices: Use substances found in nature such as herbs, foods, vitamins, and other natural substances. (As used here, "biology" does not refer to the science of biology, but is a usage newly coined by NCCIH in the primary source used for this article. "Biology-based" as coined by NCCIH may refer to chemicals from a nonbiological source, such as use of the poison lead in traditional Chinese medicine, and to other nonbiological substances.) 4. Manipulative and body-based practices: feature manipulation or movement of body parts, such as is done in bodywork, chiropractic, and osteopathic manipulation. 5. Energy medicine: is a domain that deals with putative and verifiable energy fields: ・Biofield therapies are intended to influence energy fields that are purported to surround and penetrate the body. The existence of such energy fields have been disproven. ・Bioelectromagnetic-based therapies use verifiable electromagnetic fields, such as pulsed fields, alternating-current, or direct-current fields in a non-scientific manner. |

NCCIH分類 米国政府機関である国立補完統合医療センター(NCCIH)は、補完代替医療の分野を5つの主要グループに分類する体系を構築した。これらのグループには 一部重複があり、エネルギー医学を2種類に区別している。一つは科学的に観測可能なエネルギー(磁気療法、カラーパンクチャー、光療法を含む)を扱う「実 在型」、もう一つは物理的に検出不能または検証不能なエネルギーを扱う「仮説型」である[98]。いずれのエネルギーも、身体に何らかの有益な影響や健康 増進効果をもたらすことを裏付ける証拠は存在しない[1]。 1. 総合医療体系:他の複数のグループにまたがる。例として、伝統中国医学、自然療法、ホメオパシー、アーユルヴェーダがある。 2. 心身介入療法:心、身体、精神の相互関係を探求し、「身体機能や症状」に影響を与えるという前提のもとで行われる。心と身体の関連性は従来の医学的事実であり、認知行動療法など効果が証明されている療法はこの分類に含まれない。 3. 「生物学」に基づく実践:ハーブ、食品、ビタミン、その他の天然物質など、自然界に存在する物質を用いる。(ここでいう「生物学」は生物学の科学を指すの ではなく、本記事の主要情報源であるNCCIHが新たに造語した用法である。NCCIHが提唱する「生物学ベース」は、中国伝統医学における鉛毒の使用な ど非生物学的起源の化学物質や、その他の非生物学的物質を指す場合もある。) 4. 操作・身体ベース療法:身体部位の操作や移動を特徴とする。ボディワーク、カイロプラクティック、オステオパシー操作などが該当する。 5. エネルギー医療:実在が主張され検証可能なエネルギー場を扱う領域である: ・バイオフィールド療法は、身体を取り囲み浸透するとされるエネルギー場に影響を与えることを目的とする。このようなエネルギー場の存在は否定されている。 ・生体電磁気ベース療法は、パルス電磁場、交流電磁場、直流電磁場など検証可能な電磁場を非科学的な方法で使用する。 |

| History Main article: History of alternative medicine The history of alternative medicine may refer to the history of a group of diverse medical practices that were collectively promoted as "alternative medicine" beginning in the 1970s, to the collection of individual histories of members of that group, or to the history of western medical practices that were labeled "irregular practices" by the western medical establishment.[9][99][100][101][102] It includes the histories of complementary medicine and of integrative medicine. Before the 1970s, western practitioners that were not part of the increasingly science-based medical establishment were referred to "irregular practitioners", and were dismissed by the medical establishment as unscientific and as practicing quackery.[99][100] Until the 1970s, irregular practice became increasingly marginalized as quackery and fraud, as western medicine increasingly incorporated scientific methods and discoveries, and had a corresponding increase in success of its treatments.[102] In the 1970s, irregular practices were grouped with traditional practices of nonwestern cultures and with other unproven or disproven practices that were not part of biomedicine, with the entire group collectively marketed and promoted under the single expression "alternative medicine".[9][99][100][102][103] Use of alternative medicine in the west began to rise following the counterculture movement of the 1960s, as part of the rising new age movement of the 1970s.[9][104][105] This was due to misleading mass marketing of "alternative medicine" being an effective "alternative" to biomedicine, changing social attitudes about not using chemicals and challenging the establishment and authority of any kind, sensitivity to giving equal measure to beliefs and practices of other cultures (cultural relativism), and growing frustration and desperation by patients about limitations and side effects of science-based medicine.[9][100][102][101][103][105][106] At the same time, in 1975, the American Medical Association, which played the central role in fighting quackery in the United States, abolished its quackery committee and closed down its Department of Investigation.[99]: xxi [106] By the early to mid 1970s the expression "alternative medicine" came into widespread use, and the expression became mass marketed as a collection of "natural" and effective treatment "alternatives" to science-based biomedicine.[9][106][107][108] By 1983, mass marketing of "alternative medicine" was so pervasive that the British Medical Journal (BMJ) pointed to "an apparently endless stream of books, articles, and radio and television programmes urge on the public the virtues of (alternative medicine) treatments ranging from meditation to drilling a hole in the skull to let in more oxygen".[106] An analysis of trends in the criticism of complementary and alternative medicine (CAM) in five prestigious American medical journals during the period of reorganization within medicine (1965–1999) was reported as showing that the medical profession had responded to the growth of CAM in three phases, and that in each phase, changes in the medical marketplace had influenced the type of response in the journals.[109] Changes included relaxed medical licensing, the development of managed care, rising consumerism, and the establishment of the USA Office of Alternative Medicine (later National Center for Complementary and Alternative Medicine, currently National Center for Complementary and Integrative Health).[n 9] |

歴史 主な記事: 代替医療の歴史 代替医療の歴史とは、1970年代から「代替医療」として一括りに推進されてきた多様な医療行為群の歴史を指す場合もあれば、その構成要素となる個々の医 療行為の歴史を指す場合もある。あるいは西洋医学の権威によって「非正規医療」とレッテルを貼られた西洋医療行為の歴史を指す場合もある。[9][99] [100][101][102] これには補完医療と統合医療の歴史も含まれる。1970年代以前、科学に基づく医療体制に属さない西洋医療従事者は「非正規医療従事者」と呼ばれ、医療体 制から非科学的であり、偽医療を実践していると軽蔑されていた。[99][100] 1970年代まで、西洋医学が科学的技法や発見を次第に取り入れ、治療の成功率が相応に高まるにつれ、非正規医療は偽医療や詐欺としてますます周縁化され ていった。[102] 1970年代には、非正規医療は非西洋文化の伝統的医療や、生物医学に属さない他の未検証・反証された医療と一括りにされ、これら全体が「代替医療」とい う単一の表現で総称され、マーケティングや宣伝が行われるようになった。[9][99][100][102][103] 西洋における代替医療の利用は、1960年代のカウンターカルチャー運動に続き、1970年代に台頭したニューエイジ運動の一環として増加し始めた。 [9][104] [105] これは主に以下の要因による:- 「代替医療」が生物医学に代わる有効な選択肢であるという誤解を招く大衆向けマーケティング- 化学物質を使用しないという社会的態度の変化とあらゆる権威への挑戦- 他文化の信念や実践を平等に扱うべきだという感覚(文化的相対主義)- 科学に基づく医療の限界や副作用に対する患者の不満と絶望感の高まり[9] [100][102][101][103][105][106] 同時に1975年、米国における偽医療対策の中核的役割を担ってきた米国医師会(AMA)は、偽医療対策委員会を廃止し調査部門を閉鎖した。[99]: xxi [106] 1970年代前半から中盤にかけて、「代替医療」という表現が広く使われるようになり、科学に基づく生物医学への「自然」で効果的な治療法の「代替」とし て大衆向けに売り出されるようになった。[9] [106][107][108] 1983年までに「代替医療」の大衆向けマーケティングは極めて広範となり、英国医学雑誌(BMJ)は「瞑想から頭蓋骨に穴を開けて酸素を取り込む治療法 に至るまで、(代替医療の)効能を一般に推奨する書籍、記事、ラジオ・テレビ番組が絶え間なく流れ続けている」と指摘した。[106] 医学界の再編期(1965-1999年)における5つの権威ある米国医学雑誌での補完代替医療(CAM)批判の傾向分析は、医療専門職がCAMの成長に三 段階で対応したことを示した。各段階において、医療市場の変化が雑誌上の対応の性質に影響を与えていた。[109] 変化には、医師免許の緩和、マネージドケアの発展、消費者主義の高まり、米国代替医療局(後に国立補完代替医療センター、現在は国立補完統合医療セン ター)の設立が含まれた。[n 9] |

| Medical education Mainly as a result of reforms following the Flexner Report of 1910[111] medical education in established medical schools in the US has generally not included alternative medicine as a teaching topic.[n 10] Typically, their teaching is based on current practice and scientific knowledge about: anatomy, physiology, histology, embryology, neuroanatomy, pathology, pharmacology, microbiology and immunology.[113] Medical schools' teaching includes such topics as doctor-patient communication, ethics, the art of medicine,[114] and engaging in complex clinical reasoning (medical decision-making).[115] Writing in 2002, Snyderman and Weil remarked that by the early twentieth century the Flexner model had helped to create the 20th-century academic health center, in which education, research, and practice were inseparable. While this had much improved medical practice by defining with increasing certainty the pathophysiological basis of disease, a single-minded focus on the pathophysiological had diverted much of mainstream American medicine from clinical conditions that were not well understood in mechanistic terms, and were not effectively treated by conventional therapies.[116] By 2001 some form of CAM training was being offered by at least 75 out of 125 medical schools in the US.[117] Exceptionally, the School of Medicine of the University of Maryland, Baltimore, includes a research institute for integrative medicine (a member entity of the Cochrane Collaboration).[118][119] Medical schools are responsible for conferring medical degrees, but a physician typically may not legally practice medicine until licensed by the local government authority. Licensed physicians in the US who have attended one of the established medical schools there have usually graduated Doctor of Medicine (MD).[120] All states require that applicants for MD licensure be graduates of an approved medical school and complete the United States Medical Licensing Examination (USMLE).[120] |

医学教育 主に1910年のフレックスナー報告書[111]に続く改革の結果として、米国の既存医学部における医学教育は、代替医療を教育テーマとして含めてこな かった。通常、その教育内容は解剖学、生理学、組織学、発生学、神経解剖学、病理学、薬理学、微生物学、免疫学といった、現行の診療と科学的知見に基づい ている。[113] 医学部の教育には、医師と患者のコミュニケーション、倫理、医療の技術[114]、複雑な臨床推論(医療意思決定)の遂行[115]といった主題も含まれ る。2002年に執筆したスナイダーマンとウェイルは、20世紀初頭までにフレックスナー・モデルが教育、研究、実践が不可分な20世紀の学術医療セン ター創出に寄与したと指摘した。これは疾患の病態生理学的基盤を確固たるものとして定義することで医療実践を大きく改善したが、病態生理学への偏重は、メ カニズム的に十分に理解されておらず、従来の治療法では効果的に対処できなかった臨床症状から、主流のアメリカ医学の多くを遠ざける結果となった [116]。 2001年までに、米国の125の医学部のうち少なくとも75校が何らかの形で補完代替医療(CAM)の研修を提供していた[117]。特筆すべきは、メ リーランド大学ボルチモア校医学部が統合医療研究所(コクラン・コラボレーションの加盟機関)を設置している点である[118][119]。医学部は医学 学位を授与する責任を負うが、医師は通常、地方政府当局から免許を取得するまで合法的に医療行為を行えない。米国の認可医学校を卒業した免許取得医師は、 通常医学博士(MD)の学位を取得している。[120] 全州において、MD免許申請者は認可医学校の卒業生であり、米国医師免許試験(USMLE)を修了していることが要求される。[120] |

| Efficacy Edzard Ernst, an authority on scientific study of alternative therapies and diagnoses and the first university professor of CAM, in 2012 There is a general scientific consensus that alternative therapies lack the requisite scientific validation, and their effectiveness is either unproved or disproved.[11][9][121][122] Many of the claims regarding the efficacy of alternative medicines are controversial, since research on them is frequently of low quality and methodologically flawed.[123] Selective publication bias, marked differences in product quality and standardisation, and some companies making unsubstantiated claims call into question the claims of efficacy of isolated examples where there is evidence for alternative therapies.[124] The Scientific Review of Alternative Medicine points to confusions in the general population – a person may attribute symptomatic relief to an otherwise-ineffective therapy just because they are taking something (the placebo effect); the natural recovery from or the cyclical nature of an illness (the regression fallacy) gets misattributed to an alternative medicine being taken; a person not diagnosed with science-based medicine may never originally have had a true illness diagnosed as an alternative disease category.[125] Edzard Ernst, the first university professor of Complementary and Alternative Medicine, characterized the evidence for many alternative techniques as weak, nonexistent, or negative[126] and in 2011 published his estimate that about 7.4% were based on "sound evidence", although he believes that may be an overestimate.[127] Ernst has concluded that 95% of the alternative therapies he and his team studied, including acupuncture, herbal medicine, homeopathy, and reflexology, are "statistically indistinguishable from placebo treatments", but he also believes there is something that conventional doctors can usefully learn from the chiropractors and homeopath: this is the therapeutic value of the placebo effect, one of the strangest phenomena in medicine.[128][129] In 2003, a project funded by the CDC identified 208 condition-treatment pairs, of which 58% had been studied by at least one randomized controlled trial (RCT), and 23% had been assessed with a meta-analysis.[130] According to a 2005 book by a US Institute of Medicine panel, the number of RCTs focused on CAM has risen dramatically. As of 2005, the Cochrane Library had 145 CAM-related Cochrane systematic reviews and 340 non-Cochrane systematic reviews. An analysis of the conclusions of only the 145 Cochrane reviews was done by two readers. In 83% of the cases, the readers agreed. In the 17% in which they disagreed, a third reader agreed with one of the initial readers to set a rating. These studies found that, for CAM, 38.4% concluded positive effect or possibly positive (12.4%), 4.8% concluded no effect, 0.7% concluded harmful effect, and 56.6% concluded insufficient evidence. An assessment of conventional treatments found that 41.3% concluded positive or possibly positive effect, 20% concluded no effect, 8.1% concluded net harmful effects, and 21.3% concluded insufficient evidence. However, the CAM review used the more developed 2004 Cochrane database, while the conventional review used the initial 1998 Cochrane database.[131] Alternative therapies do not "complement" (improve the effect of, or mitigate the side effects of) functional medical treatment.[n 7][11][26][27][28] Significant drug interactions caused by alternative therapies may instead negatively impact functional treatment by making prescription drugs less effective, such as interference by herbal preparations with warfarin.[132][33] In the same way as for conventional therapies, drugs, and interventions, it can be difficult to test the efficacy of alternative medicine in clinical trials. In instances where an established, effective, treatment for a condition is already available, the Helsinki Declaration states that withholding such treatment is unethical in most circumstances. Use of standard-of-care treatment in addition to an alternative technique being tested may produce confounded or difficult-to-interpret results.[133] Cancer researcher Andrew J. Vickers has stated: Contrary to much popular and scientific writing, many alternative cancer treatments have been investigated in good-quality clinical trials, and they have been shown to be ineffective. The label "unproven" is inappropriate for such therapies; it is time to assert that many alternative cancer therapies have been "disproven".[134] |

有効性 代替療法と診断の科学的研究における権威であり、CAM(補完代替医療)の最初の大学教授であるエドザード・エルンストは、2012年に次のように述べている 代替療法には必要な科学的検証が欠けており、その有効性は証明されていないか、あるいは反証されているというのが、科学界の一般的な合意である。代替医療 の有効性に関する主張の多くは論争の的となっている。なぜなら、それらに関する研究は質が低く方法論的に欠陥がある場合が多いからだ。選択的出版バイア ス、製品品質と標準化における顕著な差異、根拠のない主張を行う企業などにより、代替療法に証拠がある孤立した事例の有効性主張は疑問視されている。 代替医療の科学的レビューは、一般市民における混乱を指摘している。例えば、症状の緩和を、単に何かを服用しているという理由だけで(プラセボ効果)、本 来は効果のない療法に帰属させることがある。病気の自然治癒や周期的な性質(回帰の誤謬)が、代替医療の服用によるものと誤って帰属されることもある。科 学に基づく医療で診断されていない人は、そもそも代替医療の疾患カテゴリーとして診断されるような真の病気を持っていなかった可能性がある。[125] 補完代替医療の初代大学教授であるエザード・エルンストは、多くの代替療法の証拠を「弱い」「存在しない」「否定的なもの」と特徴づけ[126]、 2011年には約7.4%が「確かな証拠」に基づくと推定したが、これは過大評価かもしれないとも述べている[127]。エルンストは、自身と研究チーム が調査した代替療法(鍼治療、漢方薬、ホメオパシー、リフレクソロジーを含む)の95%が「プラセボ治療と統計的に区別できない」と結論づけた。しかし同 時に、カイロプラクターやホメオパスから現代医師が学ぶべき点があると指摘している。それはプラセボ効果の治療的価値であり、医学上最も奇妙な現象の一つ である[128][129]。 2003年、CDCが資金提供したプロジェクトでは208の疾患-治療ペアを特定し、そのうち58%が少なくとも1つのランダム化比較試験(RCT)で研 究され、23%がメタ分析で評価されていた。[130] 米国医学研究所パネルによる2005年の書籍によれば、CAMに焦点を当てたRCTの数は劇的に増加している。 2005年時点で、コクラン・ライブラリーには145件のCAM関連コクラン系統的レビューと340件の非コクラン系統的レビューが収録されていた。2名 の読者が、この145件のコクランレビューの結論のみを分析した。83%のケースで読者の見解は一致した。17%の意見不一致事例では、第三の読者が当初 の読者のいずれか一方の見解に同意し評価を確定した。これらの研究では、CAMについて38.4%が「肯定的効果」または「おそらく肯定的効果」と結論付 け、4.8%が「効果なし」、0.7%が「有害効果」、56.6%が「証拠不十分」と結論付けた。従来療法の評価では、41.3%が肯定的またはおそらく 肯定的効果、20%が効果なし、8.1%が純粋な有害効果、21.3%が証拠不十分と結論づけた。ただし代替医療のレビューではより発展した2004年版 コクラン・データベースを使用し、従来療法のレビューでは初期の1998年版コクラン・データベースを使用した。[131] 代替療法は機能的医療治療を「補完」(効果を高めたり副作用を軽減したり)しない。[n 7][11][26][27][28] むしろ代替療法による重大な薬物相互作用は、処方薬の効果を低下させることで機能的治療に悪影響を及ぼす可能性がある。例えばハーブ製剤がワルファリンに 干渉する事例が挙げられる。[132][33] 従来の治療法、薬物、介入と同様に、代替医療の有効性を臨床試験で検証することは難しい場合がある。ある疾患に対して確立された効果的な治療法がすでに利 用可能な場合、ヘルシンキ宣言は、そのような治療を差し控えることは、ほとんどの場合、非倫理的であると述べている。検証中の代替療法に加えて標準治療を 使用すると、結果が混乱したり、解釈が困難になったりする可能性がある。[133] がん研究者のアンドルー・J・ヴィッカースは次のように述べている。 多くの大衆向けや科学的な文献とは対照的に、多くの代替がん治療は質の高い臨床試験で調査されており、その効果がないことが証明されている。「未証明」と いうレッテルは、こうした治療法には不適切である。多くの代替がん治療は「反証された」と断言すべき時が来ている。[134] |

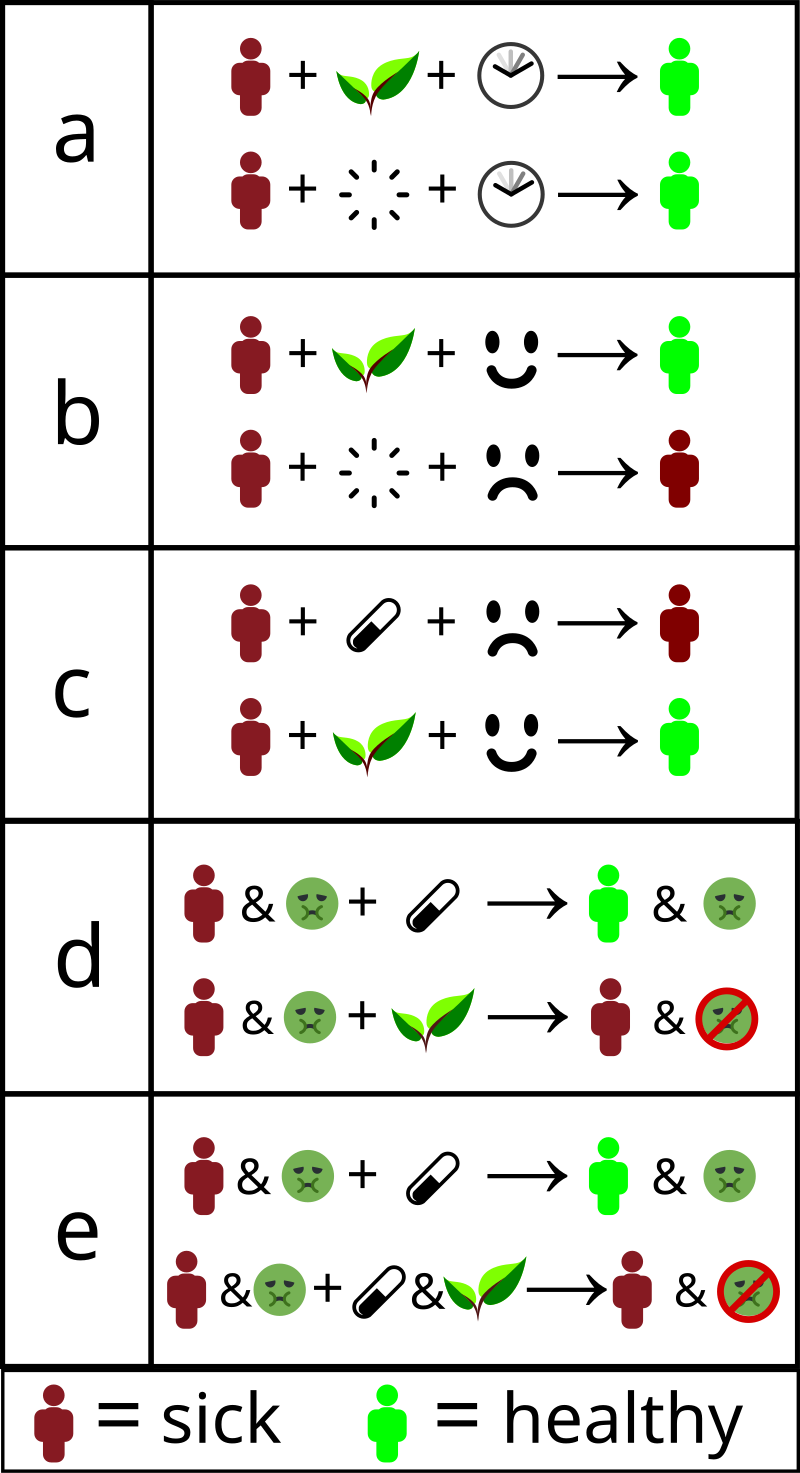

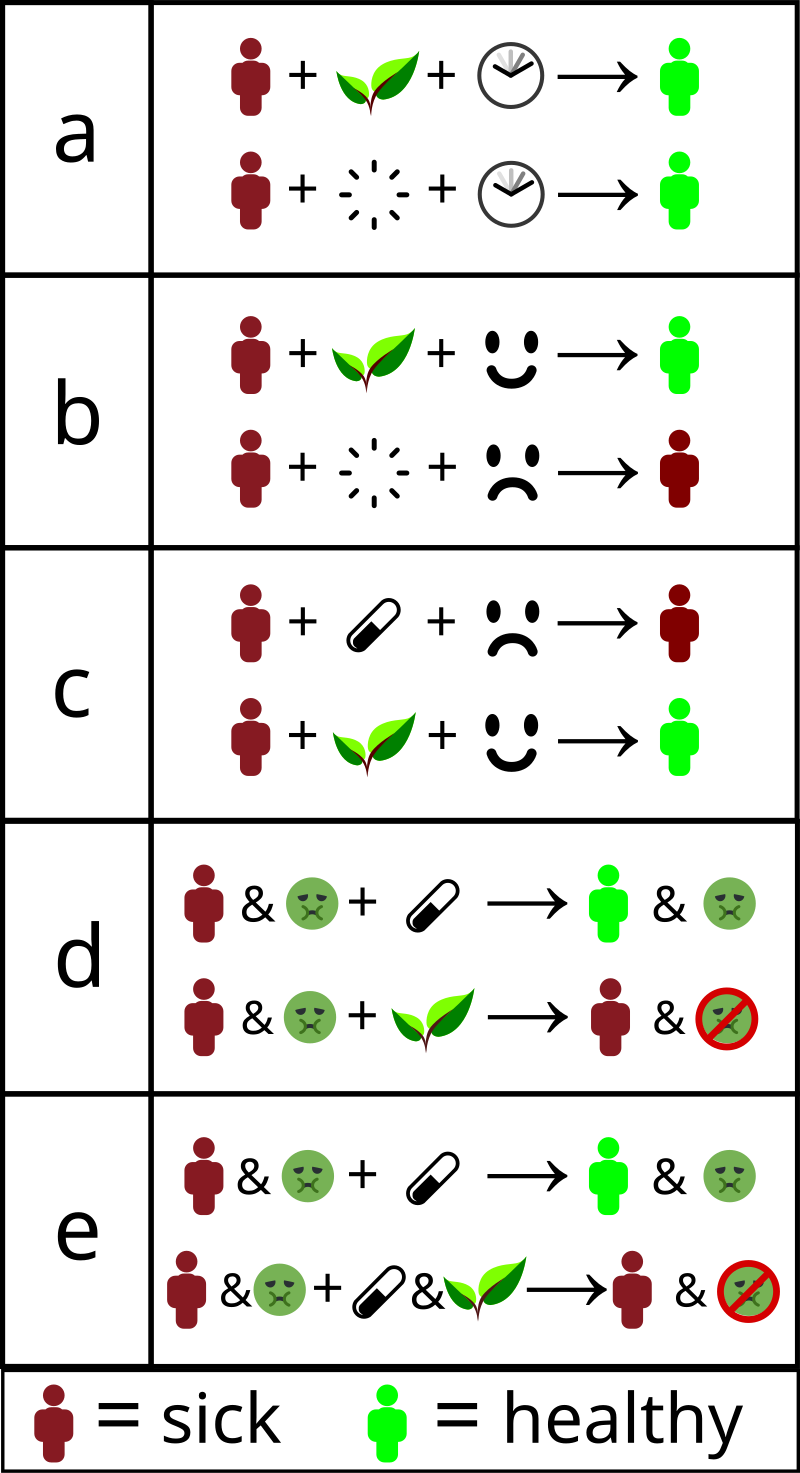

| Perceived mechanism of effect Anything classified as alternative medicine by definition does not have a proven healing or medical effect.[2][9][13][14][15] However, there are different mechanisms through which it can be perceived to "work". The common denominator of these mechanisms is that effects are mis-attributed to the alternative treatment.  How alternative therapies "work": a) Misinterpreted natural course – the individual gets better without treatment. b) Placebo effect or false treatment effect – an individual receives "alternative therapy" and is convinced it will help. The conviction makes them more likely to get better. c) Nocebo effect – an individual is convinced that standard treatment will not work, and that alternative therapies will work. This decreases the likelihood standard treatment will work, while the placebo effect of the "alternative" remains. d) No adverse effects – Standard treatment is replaced with "alternative" treatment, getting rid of adverse effects, but also of improvement. e) Interference – Standard treatment is "complemented" with something that interferes with its effect. This can both cause worse effect, but also decreased (or even increased) side effects, which may be interpreted as "helping". Researchers, such as epidemiologists, clinical statisticians and pharmacologists, use clinical trials to reveal such effects, allowing physicians to offer a therapeutic solution best known to work. "Alternative treatments" often refuse to use trials or make it deliberately hard to do so. Placebo effect A placebo is a treatment with no intended therapeutic value. An example of a placebo is an inert pill, but it can include more dramatic interventions like sham surgery. The placebo effect is the concept that patients will perceive an improvement after being treated with an inert treatment. The opposite of the placebo effect is the nocebo effect, when patients who expect a treatment to be harmful will perceive harmful effects after taking it. Placebos do not have a physical effect on diseases or improve overall outcomes, but patients may report improvements in subjective outcomes such as pain and nausea.[135] A 1955 study suggested that a substantial part of a medicine's impact was due to the placebo effect.[136][135] However, reassessments found the study to have flawed methodology.[136][137] This and other modern reviews suggest that other factors like natural recovery and reporting bias should also be considered.[135][137] All of these are reasons why alternative therapies may be credited for improving a patient's condition even though the objective effect is non-existent, or even harmful.[132][40][64] David Gorski argues that alternative treatments should be treated as a placebo, rather than as medicine.[40] Almost none have performed significantly better than a placebo in clinical trials.[76][63][138][92] Furthermore, distrust of conventional medicine may lead to patients experiencing the nocebo effect when taking effective medication.[132] |

効果の認識されるメカニズム 代替医療と定義されるものは、その定義上、証明された治療効果や医学的効果を持たない。[2][9][13][14][15] しかし、それらが「効く」と認識されるメカニズムは様々である。これらのメカニズムに共通するのは、効果が代替療法に誤って帰属される点だ。  代替療法が「効く」とされる仕組み: a) 自然経過の誤解 – 治療を受けなくても個人が回復する。 b) プラセボ効果または偽治療効果 – 個人が「代替療法」を受け、それが効くと確信する。その確信が回復の可能性を高める。 c) ノセボ効果 – 標準治療は効かず代替療法が効くと個人が確信する。これにより標準治療の効果が低下する一方、「代替」療法のプラセボ効果は持続する。 d) 副作用の排除 – 標準治療を「代替」療法に置き換えることで副作用はなくなるが、同時に改善効果も失われる。 e) 干渉効果 – 標準治療にその効果を妨げるものが「補完」される。これにより効果が悪化する一方、副作用が減る(あるいは増える)こともあり、これが「効果がある」と解 釈されることがある。疫学者、臨床統計学者、薬理学者などの研究者は、臨床試験を通じてこうした効果を明らかにし、医師が最も効果があると知られている治 療法を提供できるようにしている。「代替療法」はしばしば試験の実施を拒否するか、意図的に困難にする。 プラセボ効果 プラセボとは、治療的価値を持たない治療法である。無効な錠剤がその例だが、偽手術のような劇的な介入も含む。プラセボ効果とは、無効な治療を受けた患者 が改善を実感するという概念である。プラセボ効果の反対はノセボ効果であり、治療が有害であると予期する患者が、治療後に有害な効果を実感する現象を指 す。 プラセボは疾患に物理的な効果をもたらさず、全体的な治療成績を改善しない。しかし患者は痛みや吐き気といった主観的症状の改善を報告することがある [135]。1955年の研究では、薬効の相当部分がプラセボ効果によるものだと示唆された。[136][135] しかし再評価により、この研究には方法論上の欠陥があったことが判明した。[136][137] この研究や他の現代的なレビューは、自然回復や報告バイアスなどの他の要因も考慮すべきだと示唆している。[135][137] これら全てが、代替療法が客観的な効果が存在しない、あるいは有害であるにもかかわらず、患者の状態改善に寄与していると評価される理由である。 [132][40][64] デイビッド・ゴーシキは、代替療法は医療ではなくプラセボとして扱うべきだと主張している。[40] 臨床試験においてプラセボより有意に優れた効果を示したものはほとんどない。[76][63][138][92] さらに、従来の医療への不信感は、有効な薬を服用する患者にノセボ効果を引き起こす可能性がある。[132] |

| Regression to the mean A patient who receives an inert treatment may report improvements afterwards that it did not cause.[135][137] Assuming it was the cause without evidence is an example of the regression fallacy. This may be due to a natural recovery from the illness, or a fluctuation in the symptoms of a long-term condition.[137] The concept of regression toward the mean implies that an extreme result is more likely to be followed by a less extreme result. |

平均への回帰 無効な治療を受けた患者は、その治療が原因ではないにもかかわらず、後に改善を報告することがある。[135][137] 証拠なしにそれが原因だと仮定するのは回帰の誤謬の一例である。これは病気からの自然回復、あるいは慢性疾患の症状の変動による可能性がある。[137] 平均への回帰という概念は、極端な結果の後に、より極端でない結果が続く可能性が高いことを示唆している。 |

| Other factors There are also reasons why a placebo treatment group may outperform a "no-treatment" group in a test which are not related to a patient's experience. These include patients reporting more favourable results than they really felt due to politeness or "experimental subordination", observer bias, and misleading wording of questions.[137] In their 2010 systematic review of studies into placebos, Asbjørn Hróbjartsson and Peter C. Gøtzsche write that "even if there were no true effect of placebo, one would expect to record differences between placebo and no-treatment groups due to bias associated with lack of blinding."[135] Alternative therapies may also be credited for perceived improvement through decreased use or effect of medical treatment, and therefore either decreased side effects or nocebo effects towards standard treatment.[132] |

その他の要因 試験においてプラセボ治療群が「無治療」群を上回る結果を示す理由は、患者の体験とは無関係なものもある。これには、礼儀や「実験的従属」による実際の感 覚よりも良好な結果を報告する患者、観察者バイアス、誤解を招く質問の表現などが含まれる。[137] 2010年のプラセボ研究の系統的レビューにおいて、アスビョルン・フロビャルトソンとピーター・C・ゲッツェは「仮にプラセボに真の効果がない場合で も、盲検化不足に伴うバイアスにより、プラセボ群と無治療群の間に差異が記録されることが予想される」と記している。[135] 代替療法は、医療処置の使用量や効果の減少を通じて知覚された改善の要因とみなされることもあり、その結果、標準治療に対する副作用の減少またはノセボ効 果が生じる可能性がある。[132] |

| Use and regulation Appeal Practitioners of complementary medicine usually discuss and advise patients as to available alternative therapies. Patients often express interest in mind-body complementary therapies because they offer a non-drug approach to treating some health conditions.[139] In addition to the social-cultural underpinnings of the popularity of alternative medicine, there are several psychological issues that are critical to its growth, notably psychological effects, such as the will to believe,[140] cognitive biases that help maintain self-esteem and promote harmonious social functioning,[140] and the post hoc, ergo propter hoc fallacy.[140] In a 2018 interview with The BMJ, Edzard Ernst stated: "The present popularity of complementary and alternative medicine is also inviting criticism of what we are doing in mainstream medicine. It shows that we aren't fulfilling a certain need-we are not giving patients enough time, compassion, or empathy. These are things that complementary practitioners are very good at. Mainstream medicine could learn something from complementary medicine."[141] Marketing Alternative medicine is a profitable industry with large media advertising expenditures. Accordingly, alternative practices are often portrayed positively and compared favorably to "big pharma".[1] The popularity of complementary & alternative medicine (CAM) may be related to other factors that Ernst mentioned in a 2008 interview in The Independent: Why is it so popular, then? Ernst blames the providers, customers and the doctors whose neglect, he says, has created the opening into which alternative therapists have stepped. "People are told lies. There are 40 million websites and 39.9 million tell lies, sometimes outrageous lies. They mislead cancer patients, who are encouraged not only to pay their last penny but to be treated with something that shortens their lives." At the same time, people are gullible. It needs gullibility for the industry to succeed. It doesn't make me popular with the public, but it's the truth.[142] Paul Offit proposed that "alternative medicine becomes quackery" in four ways: by recommending against conventional therapies that are helpful, promoting potentially harmful therapies without adequate warning, draining patients' bank accounts, or by promoting "magical thinking".[58] Promoting alternative medicine has been called dangerous and unethical.[n 11][144]  Friendly and colorful images of herbal treatments may look less threatening or dangerous when compared to conventional medicine. This is an intentional marketing strategy.[145][146] Social factors Authors have speculated on the socio-cultural and psychological reasons for the appeal of alternative medicines among the minority using them in lieu of conventional medicine. There are several socio-cultural reasons for the interest in these treatments centered on the low level of scientific literacy among the public at large and a concomitant increase in antiscientific attitudes and new age mysticism.[140] Related to this are vigorous marketing[147] of extravagant claims by the alternative medical community combined with inadequate media scrutiny and attacks on critics.[140][148] Alternative medicine is criticized for taking advantage of the least fortunate members of society.[1] There is also an increase in conspiracy theories toward conventional medicine and pharmaceutical companies,[34] mistrust of traditional authority figures, such as the physician, and a dislike of the current delivery methods of scientific biomedicine, all of which have led patients to seek out alternative medicine to treat a variety of ailments.[148] Many patients lack access to contemporary medicine, due to a lack of private or public health insurance, which leads them to seek out lower-cost alternative medicine.[149] Medical doctors are also aggressively marketing alternative medicine to profit from this market.[147] Patients can be averse to the painful, unpleasant, and sometimes-dangerous side effects of biomedical treatments. Treatments for severe diseases such as cancer and HIV infection have well-known, significant side-effects. Even low-risk medications such as antibiotics can have potential to cause life-threatening anaphylactic reactions in a very few individuals. Many medications may cause minor but bothersome symptoms such as cough or upset stomach. In all of these cases, patients may be seeking out alternative therapies to avoid the adverse effects of conventional treatments.[140][148] |

使用と規制 訴求力 補完医療の施術者は通常、利用可能な代替療法について患者と話し合い、助言する。患者はしばしば心身療法への関心を示す。なぜならそれらは特定の健康状態を治療する非薬物療法を提供するためだ。[139] 代替医療の普及には社会文化的背景に加え、その成長に重要な心理的要因がいくつか存在する。特に「信じたいという意志」[140]、自尊心の維持や調和的 な社会機能を促進する認知バイアス[140]、事後性誤謬(post hoc, ergo propter hoc)[140]といった心理的効果が挙げられる。 2018年のBMJ誌インタビューでエドザード・エルンストは次のように述べている:「補完代替医療の現在の人気は、主流医療の在り方への批判も招いてい る。これは我々が特定のニーズを満たせていないことを示している——患者に十分な時間、思いやり、共感を注いでいないのだ。これらは補完医療実践者が非常 に得意とする分野である。主流医療は補完医療から学ぶべき点がある」[141] マーケティング 代替医療は収益性の高い産業であり、メディア広告費も多額である。したがって、代替医療の実践はしばしば肯定的に描かれ、「大手製薬会社」と比べて好意的に比較される。[1] 補完代替医療(CAM)の人気は、アーンストが2008年のインディペンデント紙インタビューで言及した他の要因とも関連している可能性がある: ではなぜこれほど人気があるのか?アーンストは提供者、顧客、そして医師の怠慢が原因だと指摘する。その怠慢が隙間を生み、代替療法師が入り込む余地を 作ったのだと彼は言う。「人々は嘘を吹き込まれている。4000万のウェブサイトのうち3990万が嘘を流布し、時にはとんでもない嘘だ。癌患者を誤導 し、最後の1円まで払わせると同時に、寿命を縮める治療を受けさせるよう促している」。同時に人々は騙されやすい。この産業が成功するには騙されやすさが 必要だ。大衆に好かれる発言ではないが、これが真実だ。[142] ポール・オフィットは「代替医療がペテン師的行為となる」四つのパターンを提唱した:有益な従来療法を否定すること、十分な警告なしに有害な可能性のある 療法を推奨すること、患者の銀行口座を枯渇させること、あるいは「魔法的思考」を助長することである。[58] 代替医療の推進は危険かつ非倫理的と評されてきた。[n 11] [144]  ハーブ療法の親しみやすくカラフルなイメージは、従来の医療と比較すると脅威や危険性が少なく見える。これは意図的なマーケティング戦略だ。[145][146] 社会的要因 著者らは、従来の医療の代わりに代替医療を利用する少数派におけるその魅力の背景にある社会文化的・心理的要因について推測している。こうした治療法への 関心には、一般大衆の科学的リテラシーの低さと、それに伴う反科学的態度やニューエイジ神秘主義の台頭を中心とした、いくつかの社会文化的理由がある。 [140] これに関連して、代替医療コミュニティによる誇大広告の積極的な展開[147]、不十分なメディアの検証、批判者への攻撃が挙げられる。[140] [148] 代替医療は社会の恵まれない層を搾取していると批判されている。[1] さらに、従来の医療や製薬企業に対する陰謀論の増加[34]、医師などの伝統的権威者への不信感、科学的バイオメディシンの現行提供方法への嫌悪感などが あり、これら全てが患者を様々な疾患の治療に代替医療を求めるように導いている。[148] 多くの患者は、民間・公的医療保険の不足により現代医療へのアクセスが制限され、低コストの代替医療を求めるようになる。[149] 医師もまた、この市場から利益を得るため、代替医療を積極的に販売している。[147] 患者は、生物医学的治療の痛みを伴う、不快で、時に危険な副作用を嫌うことがある。がんやHIV感染症などの重篤な疾患に対する治療法には、よく知られた 重大な副作用がある。抗生物質のような低リスクの薬剤でさえ、ごく少数の個人において生命を脅かすアナフィラキシー反応を引き起こす可能性がある。多くの 薬剤は、咳や胃の不快感といった軽度だが煩わしい症状を引き起こすことがある。こうした全てのケースにおいて、患者は従来の治療法の有害な副作用を避ける ために代替療法を求めることがある。[140][148] |

| Prevalence of use According to research published in 2015, the increasing popularity of CAM needs to be explained by moral convictions or lifestyle choices rather than by economic reasoning.[150] In developing nations, access to essential medicines is severely restricted by lack of resources and poverty. Traditional remedies, often closely resembling or forming the basis for alternative remedies, may comprise primary healthcare or be integrated into the healthcare system. In Africa, traditional medicine is used for 80% of primary healthcare, and in developing nations as a whole over one-third of the population lack access to essential medicines.[151] In Latin America, inequities against BIPOC communities keep them tied to their traditional practices and therefore, it is often these communities that constitute the majority of users of alternative medicine. Racist attitudes towards certain communities disable them from accessing more urbanized modes of care. In a study that assessed access to care in rural communities of Latin America, it was found that discrimination is a huge barrier to the ability of citizens to access care; more specifically, women of Indigenous and African descent, and lower-income families were especially hurt.[152] Such exclusion exacerbates the inequities that minorities in Latin America already face. Consistently excluded from many systems of westernized care for socioeconomic and other reasons, low-income communities of color often turn to traditional medicine for care as it has proved reliable to them across generations. Commentators including David Horrobin have proposed adopting a prize system to reward medical research.[153] This stands in opposition to the current mechanism for funding research proposals in most countries around the world. In the US, the NCCIH provides public research funding for alternative medicine. The NCCIH has spent more than US$2.5 billion on such research since 1992 and this research has not demonstrated the efficacy of alternative therapies.[138][154][155][156][157][158] As of 2011, the NCCIH's sister organization in the NIC Office of Cancer Complementary and Alternative Medicine had given out grants of around $105 million each year for several years.[159] Testing alternative medicine that has no scientific basis (as in the aforementioned grants) has been called a waste of scarce research resources.[160][161] That alternative medicine has been on the rise "in countries where Western science and scientific method generally are accepted as the major foundations for healthcare, and 'evidence-based' practice is the dominant paradigm" was described as an "enigma" in the Medical Journal of Australia.[162] A 15-year systematic review published in 2022 on the global acceptance and use of CAM among medical specialists found the overall acceptance of CAM at 52% and the overall use at 45%.[163] In the United States In the United States, the 1974 Child Abuse Prevention and Treatment Act (CAPTA) required that for states to receive federal money, they had to grant religious exemptions to child neglect and abuse laws regarding religion-based healing practices.[164] Thirty-one states have child-abuse religious exemptions.[165] The use of alternative medicine in the US has increased,[11][166] with a 50 percent increase in expenditures and a 25 percent increase in the use of alternative therapies between 1990 and 1997 in America.[166] According to a national survey conducted in 2002, "36 percent of U.S. adults aged 18 years and over use some form of complementary and alternative medicine."[167] Americans spend many billions on the therapies annually.[166] Most Americans used CAM to treat and/or prevent musculoskeletal conditions or other conditions associated with chronic or recurring pain.[149] In America, women were more likely than men to use CAM, with the biggest difference in use of mind-body therapies including prayer specifically for health reasons".[149] In 2008, more than 37% of American hospitals offered alternative therapies, up from 27 percent in 2005, and 25% in 2004.[168] More than 70% of the hospitals offering CAM were in urban areas.[citation needed] A survey of Americans found that 88 percent thought that "there are some good ways of treating sickness that medical science does not recognize".[11] Use of magnets was the most common tool in energy medicine in America, and among users of it, 58 percent described it as at least "sort of scientific", when it is not at all scientific.[11] In 2002, at least 60 percent of US medical schools have at least some class time spent teaching alternative therapies.[11] "Therapeutic touch" was taught at more than 100 colleges and universities in 75 countries before the practice was debunked by a nine-year-old child for a school science project.[11][91] Prevalence of use of specific therapies The most common CAM therapies used in the US in 2002 were prayer (45%), herbalism (19%), breathing meditation (12%), meditation (8%), chiropractic medicine (8%), yoga (5–6%), body work (5%), diet-based therapy (4%), progressive relaxation (3%), mega-vitamin therapy (3%) and visualization (2%).[149][169] In Britain, the most often used alternative therapies were Alexander technique, aromatherapy, Bach and other flower remedies, body work therapies including massage, Counseling stress therapies, hypnotherapy, meditation, reflexology, Shiatsu, Ayurvedic medicine, nutritional medicine, and yoga.[170] Ayurvedic medicine remedies are mainly plant based with some use of animal materials.[171] Safety concerns include the use of herbs containing toxic compounds and the lack of quality control in Ayurvedic facilities.[85][87] According to the National Health Service (England), the most commonly used complementary and alternative medicines (CAM) supported by the NHS in the UK are: acupuncture, aromatherapy, chiropractic, homeopathy, massage, osteopathy and clinical hypnotherapy.[172] In palliative care Complementary therapies are often used in palliative care or by practitioners attempting to manage chronic pain in patients. Integrative medicine is considered more acceptable in the interdisciplinary approach used in palliative care than in other areas of medicine. "From its early experiences of care for the dying, palliative care took for granted the necessity of placing patient values and lifestyle habits at the core of any design and delivery of quality care at the end of life. If the patient desired complementary therapies, and as long as such treatments provided additional support and did not endanger the patient, they were considered acceptable."[173] The non-pharmacologic interventions of complementary medicine can employ mind-body interventions designed to "reduce pain and concomitant mood disturbance and increase quality of life."[174] |

使用の普及率 2015年に発表された研究によれば、代替医療(CAM)の普及拡大は、経済的理由ではなく、道徳的信念や生活様式の選択によって説明される必要がある。[150] 発展途上国では、資源不足と貧困により必須医薬品へのアクセスが著しく制限されている。伝統療法は、しばしば代替療法と酷似しているか、その基礎を形成し ており、一次医療を構成したり、医療システムに統合されたりする可能性がある。アフリカでは一次医療の80%が伝統医療に依存し、発展途上国全体では人口 の3分の1以上が必須医薬品を利用できない状況にある。[151] ラテンアメリカでは、BIPOCコミュニティに対する不平等が彼らを伝統的慣行に縛り付け、結果として代替医療利用者の大半をこれらのコミュニティが占め ることが多い。特定のコミュニティに対する人種差別的な態度は、彼らがより都市化された医療形態を利用することを妨げている。ラテンアメリカの農村地域に おける医療アクセスを評価した研究では、差別が市民の医療アクセス能力に対する巨大な障壁であることが判明した。具体的には、先住民やアフリカ系女性、低 所得世帯が特に深刻な影響を受けている。[152] このような排除は、ラテンアメリカの少数派が既に直面している不平等をさらに悪化させる。低所得の有色人種コミュニティは、社会経済的理由などから西洋化 された医療システムの多くから一貫して排除されているため、世代を超えて信頼性が証明されている伝統医療に頼ることが多い。 デイヴィッド・ホロビンら論者は、医学研究を奨励する賞金制度の導入を提案している[153]。これは世界中のほとんどの国で研究提案に資金を提供する現 行の仕組みとは対立する。米国では、NCCIHが代替医療への公的研究資金を提供している。NCCIHは1992年以降、この種の研究に25億米ドル以上 を費やしたが、代替療法の有効性は実証されていない。[138][154][155][156][157] [158] 2011年時点で、NCCIHの姉妹組織である国立がん研究所(NIC)傘下の補完代替医療部門は、数年にわたり年間約1億500万ドルの助成金を交付し ていた。[159] 科学的根拠のない代替医療(前述の助成金対象のような)を検証することは、限られた研究資源の浪費と指摘されている。[160] [161] 代替医療が「西洋科学と科学的メソッドが医療の主要基盤として広く受け入れられ、『エビデンスに基づく』実践が主流のパラダイムである国々」で増加してい る現象は、オーストラリア医学雑誌において「謎」と評された。[162] 2022年に発表された15年間の系統的レビューでは、医療専門家におけるCAM(補完代替医療)の世界的な受容度と使用率が調査され、CAMの全体的な 受容度は52%、使用率は45%と判明した。[163] アメリカ合衆国 アメリカ合衆国では、1974年の児童虐待防止・治療法(CAPTA)により、州が連邦資金を受け取るためには、宗教に基づく治療行為に関する児童虐待・ ネグレクト法の宗教的免除を認めることが義務付けられた。[164] 31州が児童虐待に関する宗教的免除を認めている。[165] アメリカにおける代替医療の利用は増加しており、 [11][166]。1990年から1997年の間に代替療法の支出は50%、利用率は25%増加した[166]。2002年の全国調査によれば、「18 歳以上の米国成人の36%が何らかの補完代替医療を利用している」という。[167] アメリカ人は年間数十億ドルをこれらの療法に費やしている。[166] ほとんどのアメリカ人は、筋骨格系の疾患や慢性・反復性疼痛に関連する他の症状の治療や予防にCAMを利用していた。[149] アメリカでは、女性が男性よりもCAMを利用する傾向が強く、特に健康目的での祈りを含む心身療法の利用に最も大きな差が見られた。[149] 2008年には、米国の病院の37%以上が代替療法を提供しており、2005年の27%、2004年の25%から増加した。[168] CAMを提供する病院の70%以上は都市部にあった。[出典必要] アメリカ人を対象とした調査では、88%が「医学が認めない病気の治療法にも有効なものがある」と考えていた。[11] エネルギー医療において磁石の使用が最も一般的であり、その利用者の中で58%が「少なくともある程度科学的」と評価していたが、実際には全く科学的根拠 がない。[11] 2002年時点で、米国の医学部の少なくとも60%が代替療法を教える授業時間を設けていた。[11] 「セラピューティック・タッチ」は75カ国100以上の大学で教えられていたが、9歳の児童が学校の科学プロジェクトでその非科学性を暴いたことで廃れ た。[11][91] 特定療法の利用頻度 2002年に米国で最も一般的に使用されていた代替医療は、祈り(45%)、ハーブ療法(19%)、呼吸瞑想(12%)、瞑想(8%)、カイロプラク ティック(8%)、ヨガ(5~6%)、ボディワーク(5%)、食事療法(4%)、漸進的リラクゼーション(3%)、 メガビタミン療法(3%)、視覚化(2%)であった。[149][169] 英国では、最もよく利用される代替療法は、アレクサンダー・テクニック、アロマセラピー、バッハおよびその他のフラワーレメディ、マッサージを含むボディ ワーク療法、カウンセリングストレス療法、催眠療法、瞑想、リフレクソロジー、指圧、アーユルヴェーダ医学、栄養医学、ヨガであった。[170] アーユルヴェーダ医学の治療法は、主に植物ベースで、動物性材料も一部使用されている。[171] 安全上の懸念事項としては、有毒化合物を含むハーブの使用や、アーユルヴェーダ施設における品質管理の欠如などが挙げられる。[85] [87] 英国国民保健サービス(NHS)によると、英国でNHSが支援する最も一般的に使用されている補完代替医療(CAM)は、鍼治療、アロマセラピー、カイロプラクティック、ホメオパシー、マッサージ、整骨療法、臨床催眠療法である。[172] 緩和ケアにおける補完療法 補完療法は緩和ケアや、患者の慢性疼痛管理を試みる医療従事者によって頻繁に用いられる。統合医療は、他の医療分野よりも緩和ケアの学際的アプローチにお いてより受け入れられやすいと考えられている。「緩和ケアは、終末期ケアの初期経験から、質の高い終末期ケアの設計と提供において、患者の価値観と生活習 慣を中核に据える必要性を当然のこととしてきた。患者が補完療法を希望し、かつそのような治療が追加的な支援を提供し、患者の生命を危険にさらさない限 り、それらは容認可能とみなされた。」[173] 補完医療の非薬物療法は、「痛みを軽減し、それに伴う気分障害を緩和し、生活の質を高める」ことを目的とした心身療法を活用することができる。[174] |

| Regulation Further information: Regulation of alternative medicine and Regulation and prevalence of homeopathy [icon] This section needs expansion. You can help by making an edit request. (May 2018)  Health campaign flyers, as in this example from the Food and Drug Administration, warn the public about unsafe products. The alternative medicine lobby has successfully pushed for alternative therapies to be subject to far less regulation than conventional medicine.[1] Some professions of complementary/traditional/alternative medicine, such as chiropractic, have achieved full regulation in North America and other parts of the world[175] and are regulated in a manner similar to that governing science-based medicine. In contrast, other approaches may be partially recognized and others have no regulation at all.[175] In some cases, promotion of alternative therapies is allowed when there is demonstrably no effect, only a tradition of use. Despite laws making it illegal to market or promote alternative therapies for use in cancer treatment, many practitioners promote them.[176] Regulation and licensing of alternative medicine ranges widely from country to country, and state to state.[175] In Austria and Germany complementary and alternative medicine is mainly in the hands of doctors with MDs,[43] and half or more of the American alternative practitioners are licensed MDs.[177] In Germany herbs are tightly regulated: half are prescribed by doctors and covered by health insurance.[178] Government bodies in the US and elsewhere have published information or guidance about alternative medicine. The U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA), has issued online warnings for consumers about medication health fraud.[179] This includes a section on Alternative Medicine Fraud, such as a warning that Ayurvedic products generally have not been approved by the FDA before marketing.[180] |

規制 詳細情報:代替医療の規制およびホメオパシーの規制と普及状況 [icon] この節は拡充が必要です。編集依頼を行うことで貢献できます。(2018年5月)  食品医薬品局(FDA)のこの例のように、健康キャンペーンのチラシは一般市民に安全でない製品について警告している。 代替医療ロビーは、代替療法が従来の医療よりもはるかに少ない規制しか受けないよう成功裏に働きかけてきた。[1] カイロプラクティックなど、補完・伝統・代替医療のいくつかの専門職は、北米や世界の他の地域で完全な規制を達成しており[175]、科学に基づく医療を 統治するものと同様の方法で規制されている。一方、他の手法は部分的に認められる場合もあれば、全く規制されていないものもある[175]。効果がないこ とが証明されているにもかかわらず、使用の伝統があるという理由だけで代替療法の宣伝が許可されるケースもある。がん治療への代替療法の使用を宣伝・販売 することを違法とする法律があるにもかかわらず、多くの施術者がそれらを推奨している[176]。 代替医療の規制と免許制度は国や州によって大きく異なる[175]。オーストリアとドイツでは補完代替医療は主に医学博士(MD)を持つ医師が担っており [43]、米国の代替医療従事者の半数以上は免許を持つ医師である[177]。ドイツではハーブ療法は厳しく規制されており、その半数は医師が処方し健康 保険の対象となる[178]。 米国をはじめとする各国政府機関は、代替医療に関する情報や指針を公表している。米国食品医薬品局(FDA)は、医薬品関連の健康詐欺について消費者向け オンライン警告を発出している[179]。これには「代替医療詐欺」の項目が含まれ、例えばアーユルヴェーダ製品は一般的に販売前にFDAの承認を得てい ないとの警告が掲載されている[180]。 |

| Risks and problems The National Science Foundation has studied the problematic side of the public's attitudes and understandings of science fiction, pseudoscience, and belief in alternative medicine. They use a quote from Robert L. Park to describe some issues with alternative medicine: Alternative medicine is another concern. As used here, alternative medicine refers to all treatments that have not been proven effective using scientific methods. A scientist's view of the situation appeared in a recent book (Park 2000b)": Between homeopathy and herbal therapy lies a bewildering array of untested and unregulated treatments, all labeled alternative by their proponents. Alternative seems to define a culture rather than a field of medicine—a culture that is not scientifically demanding. It is a culture in which ancient traditions are given more weight than biological science, and anecdotes are preferred over clinical trials. Alternative therapies steadfastly resist change, often for centuries or even millennia, unaffected by scientific advances in the understanding of physiology or disease. Incredible explanations invoking modern physics are sometimes offered for how alternative therapies might work, but there seems to be little interest in testing these speculations scientifically.[11] |

リスクと問題点 米国国立科学財団は、一般市民のSFや疑似科学に対する態度や理解、代替医療への信仰といった問題点を研究している。代替医療に関する問題点を説明する際、ロバート・L・パークの言葉を引用している: 代替医療もまた懸念材料だ。ここでいう代替医療とは、科学的方法で有効性が証明されていない全ての治療法を指す。科学者の見解は近著(Park 2000b)にこう記されている: ホメオパシーとハーブ療法の間には、検証も規制もされていない治療法が驚くほど多様にある。これら全てが支持者によって「代替」と称される。代替医療は医 療分野というより文化を定義するようだ——科学的な厳密さを求めない文化である。この文化では、生物学的な科学よりも古代の伝統が重視され、臨床試験より も逸話が優先される。代替療法は変化を頑なに拒み、生理学や疾病に関する科学的進歩の影響を受けずに、しばしば数世紀、あるいは数千年にわたって存続す る。代替療法の作用機序について現代物理学を引用した信じがたい説明が提示されることもあるが、こうした推測を科学的に検証する意欲はほとんど見られな い。[11] |

| Negative outcomes See also: List of herbs with known adverse effects According to the Institute of Medicine, use of alternative medical techniques may result in several types of harm: "Direct harm, which results in adverse patient outcome."[181] "Economic harm, which results in monetary loss but presents no health hazard;" "Indirect harm, which results in a delay of appropriate treatment, or in unreasonable expectations that discourage patients and their families from accepting and dealing effectively with their medical conditions;" Interactions with conventional pharmaceuticals Forms of alternative medicine that are biologically active can be dangerous even when used in conjunction with conventional medicine. Examples include immuno-augmentation therapy, shark cartilage, bioresonance therapy, oxygen and ozone therapies, and insulin potentiation therapy. Some herbal remedies can cause dangerous interactions with chemotherapy drugs, radiation therapy, or anesthetics during surgery, among other problems.[44][132][33] An example of these dangers was reported by Associate Professor Alastair MacLennan of Adelaide University, Australia regarding a patient who almost bled to death on the operating table after neglecting to mention that she had been taking "natural" potions to "build up her strength" before the operation, including a powerful anticoagulant that nearly caused her death.[182] To ABC Online, MacLennan also gives another possible mechanism: And lastly there's the cynicism and disappointment and depression that some patients get from going on from one alternative medicine to the next, and they find after three months the placebo effect wears off, and they're disappointed and they move on to the next one, and they're disappointed and disillusioned, and that can create depression and make the eventual treatment of the patient with anything effective difficult, because you may not get compliance, because they've seen the failure so often in the past.[183] |

有害な結果 関連項目:有害作用が確認されているハーブの一覧 米国医学研究所によれば、代替医療技術の使用は以下のような複数の種類の害をもたらす可能性がある: 「直接的な害:患者の有害な結果をもたらすもの」[181] 「経済的損害:金銭的損失をもたらすが健康被害を伴わないもの」 「間接的損害:適切な治療の遅延、あるいは患者や家族が自身の病状を受け入れ効果的に対処することを妨げる不合理な期待を生むもの」 従来の医薬品との相互作用 生物学的に活性な代替医療は、従来の医療と併用しても危険な場合がある。例としては、免疫増強療法、サメ軟骨、バイオレゾナンス療法、酸素・オゾン療法、 インスリン増強療法などが挙げられる。一部のハーブ療法は、化学療法薬、放射線療法、手術中の麻酔薬などとの危険な相互作用を引き起こす可能性がある。 [44][132] [33] こうした危険性の事例として、オーストラリア・アデレード大学のアラステア・マクレナン准教授が報告した。ある患者は手術前に「体力増強」を目的とした 「自然派」薬液を服用していたことを伝えなかったため、強力な抗凝固剤の影響で手術台上で出血死寸前となった。[182] マクレナンはABCオンラインに対し、別の可能性として次のようなメカニズムも示している: 最後に、代替医療を次々と試す患者が陥る冷笑、失望、抑うつがある。3ヶ月もすればプラセボ効果が薄れ、 失望して次へ移り、また失望と幻滅を味わう。これが鬱状態を生み、最終的に効果的な治療を施すことを困難にする。なぜなら、過去に何度も失敗を経験してい るため、患者の治療への協力が得られない可能性があるからだ。[183] |

| Side-effects Conventional treatments are subjected to testing for undesired side-effects, whereas alternative therapies, in general, are not subjected to such testing at all. Any treatment – whether conventional or alternative – that has a biological or psychological effect on a patient may also have potential to possess dangerous biological or psychological side-effects. Attempts to refute this fact with regard to alternative therapies sometimes use the appeal to nature fallacy, i.e., "That which is natural cannot be harmful." Specific groups of patients such as patients with impaired hepatic or renal function are more susceptible to side effects of alternative remedies.[184][185] An exception to the normal thinking regarding side-effects is homeopathy. Since 1938, the FDA has regulated homeopathic products in "several significantly different ways from other drugs."[186] Homeopathic preparations, termed "remedies", are extremely dilute, often far beyond the point where a single molecule of the original active (and possibly toxic) ingredient is likely to remain. They are, thus, considered safe on that count, but "their products are exempt from good manufacturing practice requirements related to expiration dating and from finished product testing for identity and strength", and their alcohol concentration may be much higher than allowed in conventional drugs.[186] |

副作用 従来の治療法は望ましくない副作用について試験を受けるが、代替療法は一般的にそのような試験を全く受けていない。患者に生物学的または心理的影響を与え る治療法は、それが従来のものであれ代替のものであれ、危険な生物学的または心理的副作用を伴う可能性がある。代替療法に関してこの事実を否定しようとす る試みでは、時に「自然なものに害はない」という自然の訴求という誤謬が用いられる。肝機能や腎機能が低下している患者などの特定の患者群は、代替療法の 副作用の影響を受けやすい。[184][185] 副作用に関する通常の考え方に対する例外がホメオパシーである。1938年以来、FDAはホメオパシー製品を「他の医薬品とは大きく異なる複数の方法で」 規制している[186]。「レメディ」と呼ばれるホメオパシー製剤は極めて希釈されており、元の有効成分(そしておそらく毒性のある成分)の分子が単一で 残存する可能性のある濃度をはるかに超えていることが多い。したがって、この点では安全と見なされるが、「有効期限に関する適正製造規範(GMP)の要件 や、完成品の同一性・強度試験から免除されている」。また、アルコール濃度が従来の医薬品で許容される値を大幅に上回る場合もある。[186] |

| Treatment delay Alternative medicine may discourage people from getting the best possible treatment.[187] Those having experienced or perceived success with one alternative therapy for a minor ailment may be convinced of its efficacy and persuaded to extrapolate that success to some other alternative therapy for a more serious, possibly life-threatening illness.[188] For this reason, critics argue that therapies that rely on the placebo effect to define success are very dangerous. According to mental health journalist Scott Lilienfeld in 2002, "unvalidated or scientifically unsupported mental health practices can lead individuals to forgo effective treatments" and refers to this as opportunity cost. Individuals who spend large amounts of time and money on ineffective treatments may be left with precious little of either, and may forfeit the opportunity to obtain treatments that could be more helpful. In short, even innocuous treatments can indirectly produce negative outcomes.[189] Between 2001 and 2003, four children died in Australia because their parents chose ineffective naturopathic, homeopathic, or other alternative medicines and diets rather than conventional therapies.[190] |

治療の遅れ 代替医療は、人々が最善の治療を受けることを妨げる可能性がある。[187] 軽度の病気に対してある代替療法で成功を経験した、あるいは成功したと感じた人々は、その有効性を確信し、より深刻で命に関わる可能性のある病気に対する 他の代替療法にもその成功を当てはめようとするかもしれない。[188] このため、批判者は、プラセボ効果に依存して成功を定義する療法は非常に危険だと主張する。2002年に精神保健ジャーナリストのスコット・リリエンフェ ルドは「検証されていない、あるいは科学的に裏付けのない精神保健実践は、個人が効果的な治療を放棄する原因となり得る」と述べ、これを機会費用と呼ん だ。効果のない治療に多大な時間と金銭を費やす個人は、その貴重な資源をほとんど残さず、より有益な治療を得る機会を放棄する可能性がある。要するに、無 害な治療法でさえ間接的に悪影響を及ぼし得るのだ[189]。2001年から2003年にかけて、オーストラリアでは4人の子供が死亡した。原因は、親が 従来の治療法ではなく、効果のない自然療法、ホメオパシー、その他の代替医療や食事療法を選択したことにある[190]。 |

| Unconventional cancer "cures" There have always been "many therapies offered outside of conventional cancer treatment centers and based on theories not found in biomedicine. These alternative cancer cures have often been described as 'unproven,' suggesting that appropriate clinical trials have not been conducted and that the therapeutic value of the treatment is unknown." However, "many alternative cancer treatments have been investigated in good-quality clinical trials, and they have been shown to be ineffective.... The label 'unproven' is inappropriate for such therapies; it is time to assert that many alternative cancer therapies have been 'disproven'."[134] Edzard Ernst has stated: any alternative cancer cure is bogus by definition. There will never be an alternative cancer cure. Why? Because if something looked halfway promising, then mainstream oncology would scrutinize it, and if there is anything to it, it would become mainstream almost automatically and very quickly. All curative "alternative cancer cures" are based on false claims, are bogus, and, I would say, even criminal.[191] |