悪魔

Devil

ミ ケランジェロ作「聖アントニウスの苦悩」。様々な誘惑をする悪魔達にもがき苦しむ大アントニオスを描いている。

☆

悪魔(devil)

とは、様々な文化や宗教的伝統において考えられているように、悪の神話的な擬人化である[1] 敵対的で破壊的な力の対象化と見なされている[2]

ジェフリー・バートン・ラッセルは、悪魔の異なる概念は、1)神から独立した悪の原理、2)神の一側面、3)悪に転じた被造物(堕天使)、4)人間の悪の

象徴[3]: 23としてまとめることができると述べている。

悪魔を神話に持つそれぞれの伝統、文化、宗教は、悪の顕現について異なるレンズを提供している[4]。これらの視点の歴史は、神学、神話、精神医学、芸

術、文学と絡み合い、それぞれの伝統の中で独自に発展している。[サタン(ユダヤ教)、ルシファー(キリスト教)、ベルゼブブ(ユダヤ教・キリスト教)、

メフィストフェレス(ドイツ語)、イブリス(イスラム教)などである。

| A devil is the

mythical personification of evil as it is conceived in various cultures

and religious traditions.[1] It is seen as the objectification of a

hostile and destructive force.[2] Jeffrey Burton Russell states that

the different conceptions of the devil can be summed up as 1) a

principle of evil independent from God, 2) an aspect of God, 3) a

created being turning evil (a fallen angel) or 4) a symbol of human

evil.[3]: 23 Each tradition, culture, and religion with a devil in its mythos offers a different lens on manifestations of evil.[4] The history of these perspectives intertwines with theology, mythology, psychiatry, art, and literature, developing independently within each of the traditions.[5] It occurs historically in many contexts and cultures, and is given many different names—Satan (Judaism), Lucifer (Christianity), Beelzebub (Judeo-Christian), Mephistopheles (German), Iblis (Islam)—and attributes: it is portrayed as blue, black, or red; it is portrayed as having horns on its head, and without horns, and so on.[6][7] |

悪魔とは、様々な文化や宗教的伝統において考えられているように、悪の

神話的な擬人化である[1] 敵対的で破壊的な力の対象化と見なされている[2]

ジェフリー・バートン・ラッセルは、悪魔の異なる概念は、1)神から独立した悪の原理、2)神の一側面、3)悪に転じた被造物(堕天使)、4)人間の悪の

象徴[3]: 23としてまとめることができると述べている。 悪魔を神話に持つそれぞれの伝統、文化、宗教は、悪の顕現について異なるレンズを提供している[4]。これらの視点の歴史は、神学、神話、精神医学、芸 術、文学と絡み合い、それぞれの伝統の中で独自に発展している。[サタン(ユダヤ教)、ルシファー(キリスト教)、ベルゼブブ(ユダヤ教・キリスト教)、 メフィストフェレス(ドイツ語)、イブリス(イスラム教)などである。 |

| Etymology The Modern English word devil derives from the Middle English devel, from the Old English dēofol, that in turn represents an early Germanic borrowing of the Latin diabolus. This in turn was borrowed from the Greek διάβολος diábolos, "slanderer",[8] from διαβάλλειν diabállein, "to slander" from διά diá, "across, through" and βάλλειν bállein, "to hurl", probably akin to the Sanskrit gurate, "he lifts up".[9] |

語源 現代英語のdevilは中英語のdevelに由来し、古英語のdēofolから派生した。これはギリシア語のδιάβολος diábolos「中傷する者」[8]から借用されたもので、διαβάλειν diabállein「中傷する」のδιά diá「横切る、貫く」とβάλλειν bállein「投げつける」に由来する。 |

| Definitions In his book The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity, Jeffrey Burton Russell discusses various meanings and difficulties that are encountered when using the term devil. He does not claim to define the word in a general sense, but he describes the limited use that he intends for the word in his book—limited in order to "minimize this difficulty" and "for the sake of clarity". In this book Russell uses the word devil as "the personification of evil found in a variety of cultures", as opposed to the word Satan, which he reserves specifically for the figure in the Abrahamic religions.[10] Yvonne Bonnetain describes the Devil as a mythic explanation model, in form of a personified supernatural power, for death, disease, and everything hostile to humanity.[11] In the Introduction to his book Satan: A Biography, Henry Ansgar Kelly discusses various considerations and meanings that he has encountered in using terms such as devil and Satan, etc. While not offering a general definition, he describes that in his book "whenever diabolos is used as the proper name of Satan", he signals it by using "small caps".[12] The Oxford English Dictionary has a variety of definitions for the meaning of "devil", supported by a range of citations: "Devil" may refer to Satan, the supreme spirit of evil, or one of Satan's emissaries or demons that populate Hell, or to one of the spirits that possess a demoniac person; "devil" may refer to one of the "malignant deities" feared and worshiped by "heathen people", a demon, a malignant being of superhuman powers; figuratively "devil" may be applied to a wicked person, or playfully to a rogue or rascal, or in empathy often accompanied by the word "poor" to a person—"poor devil".[13] |

定義 ジェフリー・バートン・ラッセルはその著書『悪魔』の中で、悪魔という言葉を使う際に遭遇する様々な意味や困難について論じている: ジェフリー・バートン・ラッセルは、『悪魔:古代から原始キリスト教までの悪の認識』という本の中で、悪魔という言葉を使う際に遭遇する様々な意味や困難 について論じている。彼はこの言葉を一般的な意味で定義するとは主張していないが、「この困難を最小化するため」と「明瞭にするため」に、この言葉を限定 的に使用することを意図している。ラッセルはこの本の中で、悪魔という言葉を「様々な文化に見られる悪の擬人化」として使っており、サタンという言葉とは 対照的に、アブラハムの宗教に登場する人物のために特別に留保している[10]。 イヴォンヌ・ボネタンは悪魔を、死や病気、人類に敵対するあらゆるものに対する、擬人化された超自然的な力という形をとった神話的な説明モデルとして説明 している[11]。 彼の著書『Satan: ヘンリー・アンスガー・ケリーは、その著書『Satan: A Biography』の序文で、悪魔やサタンなどの用語を使用する際に遭遇した様々な考察や意味について論じている。一般的な定義を提供するわけではない が、彼は自身の著書の中で「サタンの固有名詞としてディアボロスが使われる時はいつでも」、「小さな大文字」を使うことでそれを示していると記述している [12]。 オックスフォード英語辞典には、「悪魔」の意味について様々な定義があり、様々な引用によって裏付けられている: 「悪魔」は、悪の最高霊魂であるサタン、あるいは地獄に跋扈するサタンの使者や悪魔の一人、あるいは悪魔に取り憑かれた人格に取り憑かれた霊魂の一人を指 すことがある; 「悪魔」は、「異教の人々」が恐れ崇拝する「悪神」の一人、悪魔、超人的な力を持つ悪意のある存在を指すこともある。比喩的に「悪魔」は、邪悪な人格、あ るいは悪党やいたずら者に戯れに適用されることもあるし、共感においてはしばしば「かわいそうな」という言葉を伴って、ある人物-「かわいそうな悪魔」に 適用されることもある。[13] |

| History Pre-Historic period to Archaic period Most early belief-systems had no unifying concept of evil.R[14] In the oldest available records, evil is part of nature. In Mesopotamia, evil is sometimes said to derive from primordial chaos, but there are no inherently evil demons or devils. Various spirits and deities could do both good and evil depending on whim.[15] The oldest known Egyptian beliefs had no evil deities; the gods were morally ambivalent and required to submit to the divine order of the cosmos, evil being an action violating said harmony.[16] In old Hindu beliefs, deities, reflecting the supreme reality, are both benevolent and fierce.[17] Even in the Old Testament, the evil, and hence devilish characteristics, are an expression of Yahweh's wrath.[11] Among ancient Middle Eastern beliefs, Zorastrianism was the first institutionized belief-system which developed a clear demonology headed by a supreme spirit of Evil (Angra Mainyu), i.e. Devil.[18][15] Around 600 BC, Zarathustra urged his followers to turn away from the devas, in favor of dedicating worship to Ahura Mazda alone.[19] Unique to Zarathustra's revelation was that he claimed that evil is not part of the Godhead (or ultimate reality), but a separate principle independent from God.[19] For the formulation of Good and Evil as entirely separate principles, Zarathustra argued that God (Ahura Mazda) freely chooses goodness, while Angra Mainyu freely chooses evil.[20][11] By doing so, he established the first known dualistic cosmological system, which would later influence other religions, including Judaism, Christianity, Manichaeism, and Islam.[21] Alienated from the new sole deity, spirits of previous belief-systems thus became associated with the forces of evil and hence demons.[22] As servants of the destructive spirit, the demons were believed to follow only evil; inflicting pain and causing destruction. Unfortunate souls, who find themselves in the domain of the evil spirits after death (i.e. in hell), are also tortured by the demons.[23] Spirits found to align with the new sole deity then became the Godhead's servants (i.e. angels).[22][24] Thus, the originally monistic Canaanite form of Judaism absorbs parts of Persian dualistic tendencies during the Post-exilic period.[25][26] However, Second-Temple Judaism, and later Christianity, differ from Persian dualism in some regards: the proposed omnipotence of God of the former does not allow for a radical dualism as proposed by Zorastrianism and later Manichaeism. Judeo-Christian tradition differs from earlier monistic beliefs by limiting the power of their Godhead through an evil principle or force, introduced by Zorastrianism.[25] Christianity in particular, struggled with reconciling God's omnipresence with God's benevolence.[27] While Zorastrianism sacrificed God's omnipotence for God's benevolence, thus giving rise to a principle Devil as independent from God, Christianity mostly insisted on the Devil being created and mildly dependent on God.[27] |

歴史 有史以前~アルカイック時代 最古の記録では、悪は自然の一部である。メソポタミアでは、悪は原初の混沌に由来すると言われることもあるが、本質的に悪である悪魔やデビルは存在しな い。最古のエジプト信仰には邪悪な神々は存在せず、神々は道徳的に両義的であり、宇宙の神聖な秩序に服従する必要があった。[17]旧約聖書においても、 邪悪なもの、つまり悪魔的な性質はヤハウェの怒りの表れである[11]。古代中東の信仰の中で、ゾラストリア教は、邪悪の至高の精霊(アングラ・マイ ニュ)、すなわち悪魔を頂点とする明確な悪魔論を発展させた最初の制度化された信仰体系であった[18][15]。 紀元前600年頃、ツァラトゥストラは信奉者たちにデーヴァたちからの離反を促し、アフラ・マズダのみに崇拝を捧げることを支持した[19]。ツァラトゥ ストラの啓示の特徴は、悪が神格(あるいは究極的な現実)の一部ではなく、神から独立した別の原理であると主張したことであった[19]。 善と悪を完全に別の原理として定式化するために、ツァラトゥストラは神(アフラ・マズダ)は善を自由に選択し、アングラ・マイニュは悪を自由に選択すると 主張した。[20][11]そうすることによって彼は、後にユダヤ教、キリスト教、マニ教、イスラム教を含む他の宗教に影響を与えることになる、知られて いる最初の二元論的な宇宙論的体系を確立した[21]。新しい唯一の神から疎外された、以前の信仰体系の霊魂は、こうして悪の力、したがって悪魔と関連付 けられるようになった[22]。破壊的な霊魂の手下として、悪魔は悪にのみ従い、苦痛を与え、破壊を引き起こすと信じられていた。死後(すなわち地獄で) 悪霊の領域に身を置くことになった不幸な魂もまた悪魔によって拷問される[23]。その後、新たな唯一神と一致することが判明した霊たちは、神格のしもべ (すなわち天使)となった[22][24]。 しかし、第二神殿のユダヤ教、そして後のキリスト教は、ペルシアの二元論とはいくつかの点で異なっている。ユダヤ教・キリスト教の伝統は、ゾラストリア主 義によって導入された悪の原理や力によって神格の力を制限することで、それ以前の一元論的な信仰とは異なっている[25]。個別主義は特に、神の全存在と 神の博愛との調和に苦心した。[27]ゾラストリア主義が神の博愛のために神の全能を犠牲にし、その結果、神から独立した原理としての悪魔を生み出したの に対して、キリスト教は悪魔が創造されたものであり、神にわずかに依存していることを主に主張していた[27]。 |

Platonism and early Christianity

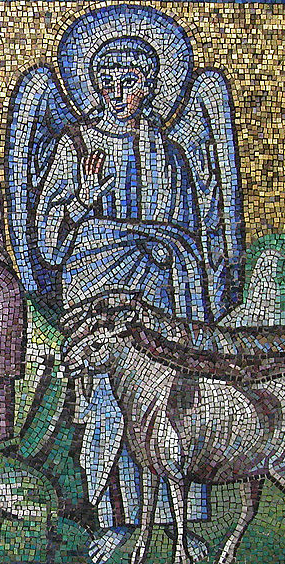

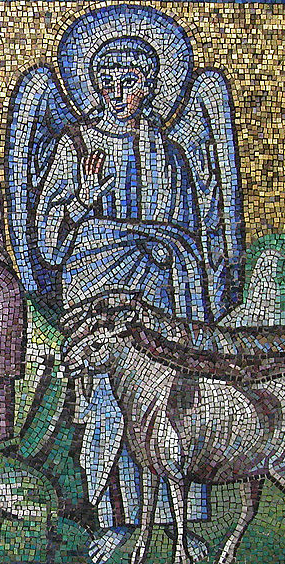

in Antiquity Excerpt of a Byzantine-Mosaic-Image. A blue angel, probably representing the Devil, standing before goats. Early 6th century. One way Christianity addressed the problem of evil was by distinguishing between mind and body, an idea inherited from Greek Platonism. Similar to Zorastrianism, Platonism was dualistic. However, Platonism and Christianity differ from Persian dualism insofar as that they associated goodness only with spirit and evil with matter, proposing a form of mind–body dualism.[28] According to Plato, God is like a craftsman (Demiurge) who builds the best possible world. However, God has to abide by the laws of nature and can only work with the material presented. Matter, thus, becomes the refractionary element in Plato's and later Neoplatonic models of the cosmos, resisting the perfection God originally intended.[29][30] In religious beliefs, applying such theories of evil, matter (Greek: hyle Ὕλη) becomes a sphere of lack of goodness and transforms matter into the devilish principle par excellence.[29][31] According to Neoplatonic cosmology, evil (or matter) results from a lack of goodness. The good spirit at the centre gives rise to several emanations, each decreasing in goodness and increasing in deficiency. Thus, in Christianity, following the privation theory of the Neo-Platonists, the Devil became the principle for the thing most remote from God.[32] Details were worked out by Christian scholars, such as Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite[32] and John of Damascus[33] who argued that evil is merely a lack (or removal) of goodness. As such, the Devil was conceptualized as a fallen angel; a being brought forth as good first, but then turned evil by abandoning goodness.[34] John of Damascus used the privation theory to combat dualistic approaches to evil.[35] Similar rebuttals were written by Augustine of Hippo.[36] The possibly strongest form of body-mind dualism, and a radical step back towards absolute dualism as conceptualized earlier in Zorastrianism, was reestablished by Manichaeism. Manichaeism was a major religion[37] founded in the third century AD by the Parthian[38] prophet Mani (c. 216–274 AD), in the Sasanian Empire.[39] One of its key concepts is the doctrine of Two Principles and Three Moments: the world could be described as resulting from a past moment, in which two principles (good and evil) were separate, a contemporary moment in which both principles are mixed due to an assault of the world of darkness on the realm of light, and a future moment when both principles are distinct forever.[40] |

古代におけるプラトン主義と初期キリスト教 ビザンチン・モザイク画の抜粋。悪魔を表すと思われる青い天使がヤギの前に立っている。6世紀初頭。 キリスト教が悪の問題に対処する一つの方法は、ギリシャのプラトン主義から受け継いだ考え方である心と体を区別することだった。ゾラストリア主義と同様 に、プラトン主義も二元論的だった。しかし、プラトン主義とキリスト教は、善を精神にのみ関連づけ、悪を物質に関連づけるという点で、ペルシアの二元論と は異なっており、心身二元論の一形態を提唱していた[28]。プラトンによれば、神は可能な限り最良の世界を構築する職人(デミウルゲ)のような存在であ る。しかし、神は自然の法則に従わなければならず、提示された物質でしか働くことができない。したがって物質は、プラトンや後の新プラトン主義の宇宙モデ ルでは屈折した要素となり、神が本来意図した完全性に抵抗する。宗教的信仰では、このような悪の理論を適用することで、物質(ギリシア語: hyle Ὕλη)は善の欠如の球体となり、物質を卓越した悪魔的原理へと変容させる。 新プラトン主義の宇宙論によれば、悪(あるいは物質)は善の欠如から生じる。中心にある善の精神はいくつかの発露を生み、それぞれが善を減少させ、欠乏を 増加させる。したがって、キリスト教では、新プラトン主義者の欠乏論に従って、悪魔は神から最も遠いものの原理となった[32]。詳細は、悪は善の欠如 (または除去)に過ぎないと主張したアレオパギテ人シュード=ディオニュシオス[32]やダマスカスのヨハネ[33]などのキリスト教の学者によって研究 された。そのため、悪魔は堕天使として概念化され、最初は善として生み出された存在であったが、善を放棄することによって悪に転じたのである[34]。ダ マスコのヨハネは、悪に対する二元論的なアプローチと闘うために欠乏説を用いた[35]。 おそらく最も強力な形の身心二元論であり、ゾラストリア主義において以前に概念化されたような絶対的二元論への根本的な後退は、マニ教によって再確立され た。マニ教は、ササン朝においてパルティア人[38]の預言者マニ(紀元216年頃~274年)によって紀元3世紀に創始された主要な宗教[37]であっ た。[39]その重要な概念のひとつは、二つの原理と三つの瞬間の教義である。世界は、二つの原理(善と悪)が別々であった過去の瞬間、光の領域に対する 闇の世界の攻撃によって両方の原理が混血の状態にある現代の瞬間、そして両方の原理が永遠に別々である未来の瞬間の結果として表現される[40]。 |

Spread through Europe in late

Antiquity and early Medieval Age The Devil on horseback. Nuremberg Chronicle (1493). Due to Christian dualistic monotheism, non-Christian deities became associated with demons. Ephesians 6:12, stating " our struggle is not against flesh and blood, but against the rulers, against the authorities, against the powers of this dark world and against the spiritual forces of evil in the heavenly realms" inspired early Christians to think of themselves on a mission to "drive out demons".[41] By the fourth century, most Christians took it for granted that the Greek pagans worshipped demons and thus belong to the realm of the spiritually impure.[42] In the 2nd century, Justin Martyr already conceptualized the pagan deities as demons, responsible for persecution of Christians.[43] By the end of the sixth century, Mediterranean society widely identified themselves as unequivocally Christian, with an exception to Jews.[44] The last recorded worship of another non-Christian deity is dated to the 570s.[44] Tatian considered the pagan gods to be under the power of fate.[45] The daimons (spirits) of the Greeks thus became the demons of the Christian's belief-system under the leadership of Zeus, whom they equated with he Devil, i.e. the leader of the foreign spirits.[45] The Christians, however, would have broken free from the influence of the gods of the Greek pantheon and thus also free from the fetters of fate and the law.[46] Abstract notions of the Devil, such as regarding evil as the mere absence of good, were far too subtle to be embraced by most theologians during the Early Middle Ages. Instead, they sought a more concrete image of the Devil to represent spiritual struggle and pain. Thus, the Devil became more of a concrete entity. From the 4th through the 12th centuries, Christian ideas combined with European pagan beliefs, created a vivid folklore about the Devil. In many German folktales, the deceived giants of pagan tales, are substituted by a devil.[47] For example, the devil builds a bridge in exchange for the first passing being's soul, then people let a dog pass the bridge first and the devil is cheated.[48] At the same time, magical rites calling upon pagan deities were replaced by references to Jesus Christ.[49][50] |

古代におけるプラトン主義と初期キリスト教 ビザンチン・モザイク画の抜粋。悪魔を表すと思われる青い天使がヤギの前に立っている。6世紀初頭。 キリスト教が悪の問題に対処する一つの方法は、ギリシャのプラトン主義から受け継いだ考え方である心と体を区別することだった。ゾラストリア主義と同様 に、プラトン主義も二元論的だった。しかし、プラトン主義とキリスト教は、善を精神にのみ関連づけ、悪を物質に関連づけるという点で、ペルシアの二元論と は異なっており、心身二元論の一形態を提唱していた[28]。プラトンによれば、神は可能な限り最良の世界を構築する職人(デミウルゲ)のような存在であ る。しかし、神は自然の法則に従わなければならず、提示された物質でしか働くことができない。したがって物質は、プラトンや後の新プラトン主義の宇宙モデ ルでは屈折した要素となり、神が本来意図した完全性に抵抗する。宗教的信仰では、このような悪の理論を適用することで、物質(ギリシア語: hyle Ὕλη)は善の欠如の球体となり、物質を卓越した悪魔的原理へと変容させる。 新プラトン主義の宇宙論によれば、悪(あるいは物質)は善の欠如から生じる。中心にある善の精神はいくつかの発露を生み、それぞれが善を減少させ、欠乏を 増加させる。したがって、キリスト教では、新プラトン主義者の欠乏論に従って、悪魔は神から最も遠いものの原理となった[32]。詳細は、悪は善の欠如 (または除去)に過ぎないと主張したアレオパギテ人シュード=ディオニュシオス[32]やダマスカスのヨハネ[33]などのキリスト教の学者によって研究 された。そのため、悪魔は堕天使として概念化され、最初は善として生み出された存在であったが、善を放棄することによって悪に転じたのである[34]。ダ マスコのヨハネは、悪に対する二元論的なアプローチと闘うために欠乏説を用いた[35]。 おそらく最も強力な形の身心二元論であり、ゾラストリア主義(=ゾロアスター教)において以前に概念化されたような絶対的二元論への根本的な後退は、マニ 教によって再確立された。マニ教は、ササン朝においてパルティア人[38]の預言者マニ(紀元216年頃~274年)によって紀元3世紀に創始された主要 な宗教[37]であった。[39]その重要な概念のひとつは、二つの原理と三つの瞬間の教義である。世界は、二つの原理(善と悪)が別々であった過去の瞬 間、光の領域に対する闇の世界の攻撃によって両方の原理が混血の状態にある現代の瞬間、そして両方の原理が永遠に別々である未来の瞬間の結果として表現さ れる[40]。 |

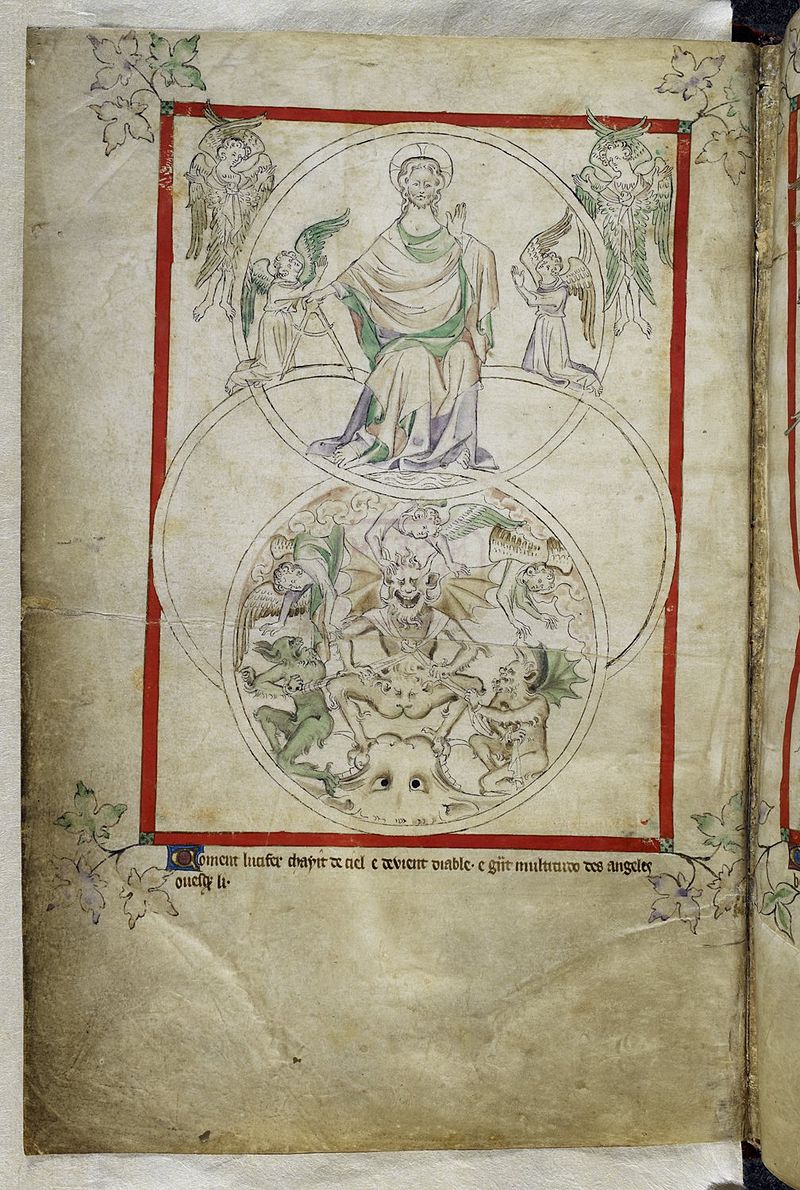

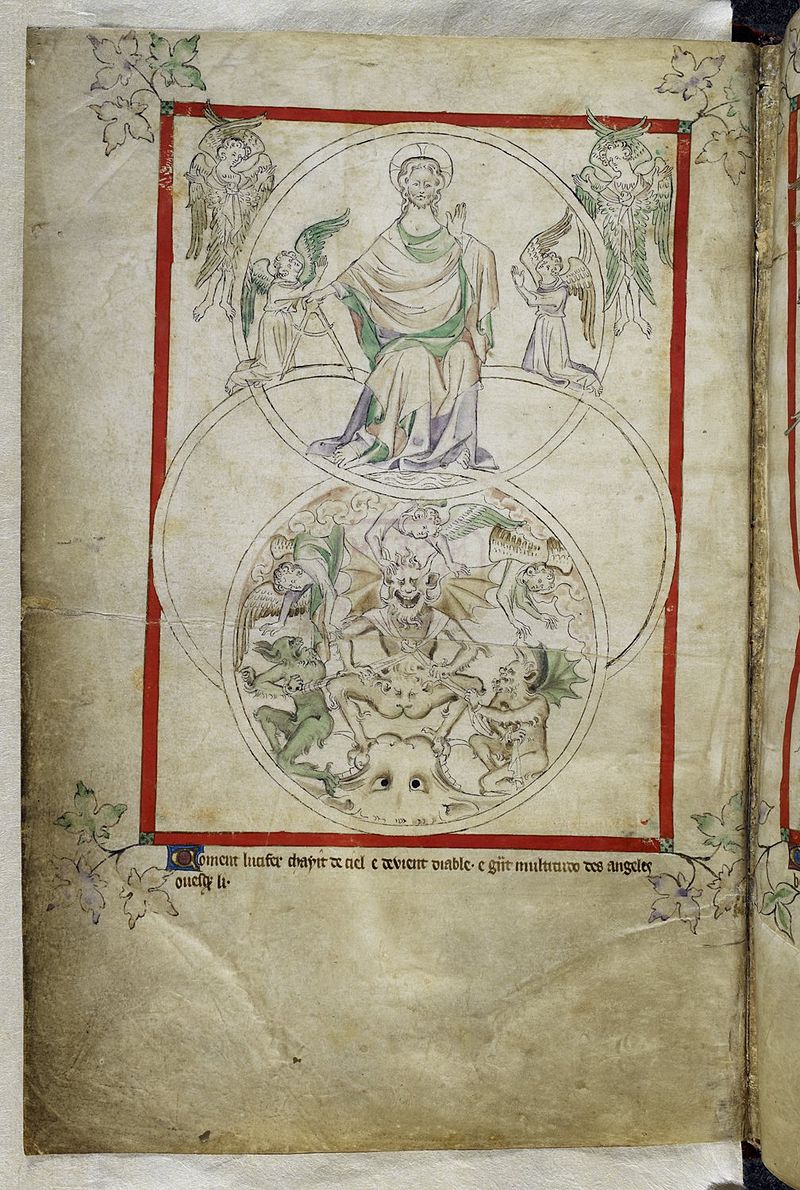

Revival of Dualism in the

Medieval Age God and Lucifer – The Queen Mary Psalter (1310–1320), f.1v – BL Royal MS 2 B VII  Satan (the dragon; on the left) gives to the beast of the sea (on the right) power represented by a sceptre in a detail of panel III.40 of the medieval French Apocalypse Tapestry, produced between 1377 and 1382. Cosmological dualism underwent a revival in the 12th century by through Catharism, probably influenced by Bogomilism in the 10th century.[51] What is known of the Cathars largely comes in what is preserved by the critics in the Catholic Church which later destroyed them in the Albigensian Crusade. Alain de Lille, c. 1195, accused the Cathars of believing in two gods, one of light and one of darkness.[52] Durand de Huesca, responding to a Cathar tract c. 1220 indicates that they regarded the physical world as the creation of Satan.[53] In the Gospel of the Secret Supper, Lucifer, just as in prior Gnostic systems, appears as an evil demiurge, who created the material world and traps souls inside.[54] Bogomilism owed many ideas to the earlier Paulicians in Armenia and the Near East and had strong impact on the history of the Balkans. Their true origin probably lies within earlier sects such as Nestorianism, Marcionism and Borboritism, who all share the notion of a docetic Jesus. Like these earlier movements, Bogomilites agree upon a dualism between body and soul, matter and spirit, and a struggle between good and evil.[55] The Catholic church sanctioned dualistic teachings in the Fourth Council of the Lateran (1215), by affirming that God created everything from nothing; that the devil and his demons were created good, but turned evil by their own will; that humans yielded to the devil's temptations, thus falling into sin; and that, after Resurrection, the damned will suffer along with the devil, while the saved enjoy eternity with Christ.[56] Only a few theologians from the University of Paris, in 1241, proposed the contrary assertion, that God created the devil evil and without his own decision.[57] After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, parts of Bogomil Dualism remained in Balkan folklore concerning creation: according to a story, dated back to the eleventh to thirteenth century, before God created the world, he meets a goose on the eternal ocean. The name of the Goose is reportedly Satanael and it claims to be a god. When God asks Satanael who he is, the devil answers "the god of gods". God requests that the devil then dive to the bottom of the sea to carry some mud, and from this mud, they fashioned the world. God created his fiery angels from the right part of a flint rock, and the Devil created his demons from the left part of the flint. Later, the devil tries to assault God but is thrown into the abyss. He remains lurking on the creation of God and planning another attack on heaven.[58] This myth shares some resemblance with Pre-Islamic Turkic creation myths as well as Bogomilite thoughts.[59] The story bears resemblance to other Turko-Mongolian cosmogonies. According to one myth found among the Siberian Tatars, God and his first creation are envisaged in the form of ducks. God asks his creature and companion to dive into the ocean to retrieve some earth. However, the second duck, identified with Erlik Khan, turns against God and becomes his rival.[59] A similar legend is recorded among the Altai Turks. Erlik and God swam together over the primordial waters. When God was about to create the Earth, he sent Erlik to dive into the waters and collect some mud. Erlik hid some inside his mouth to later create his own world. But when God commanded the Earth to expand, Erlik got troubled by the mud in his mouth. God aided Erlik to spit it out. The mud carried by Erlik gave place to the unpleasant areas of the world. Because of his sin, he was assigned to evil. Since he claimed equality with God by creating his own world, God punishes Erlik Khan, by granting him his own kingdom in the Underworld.[59][60][61] In one variant, recorded by Verbitsky Vasily, not only Erlik Khan, but also the spirits he created, were banished form the heavens and cast down to the lower realms.[62] |

中世における二元論の復活 神とルシファー - クイーン・メアリー詩篇(1310-1320年)、f.1v - BL Royal MS 2 B VII  1377年から1382年にかけて制作された中世フランスの黙示録タペストリーのパネルIII.40の細部に描かれている。 宇宙論的二元論は、おそらく10世紀のボゴミリズムの影響を受けたと思われるカタリ派によって、12世紀に復活を遂げた[51]。カタリ派について知られ ているのは、後にアルビゲンス十字軍で滅ぼされたカトリック教会の批判者たちによって保存されているものが大部分である。アラン・ド・リールは1195年 頃、カタールは光と闇の2つの神を信じていると非難している[52]。[53]『秘密の晩餐』の福音書の中で、ルシファーは、それ以前のグノーシス主義に おけるのと同様に、物質世界を創造し、その中に魂を閉じ込める邪悪なデミウルゲとして登場する[54]。ボゴミリズムは、アルメニアと近東のパウロ派に多 くの思想を負っており、バルカン半島の歴史に強い影響を与えた。ボゴミリズムの本当の起源は、おそらくネストリウス派、マルキオン派、ボルボル派などの初 期の宗派の中にあり、これらの宗派はすべてドクティックなイエスという概念を共有していた。これらの初期の運動と同様に、ボゴミール派も肉体と魂、物質と 精神の二元論、善と悪の闘争に同意している。[55] カトリック教会はラテラノ第四公会議(1215年)において、神が無からすべてを創造したこと、悪魔とその悪魔は善いものとして創造されたが、自らの意志 によって悪に転じたこと、人間は悪魔の誘惑に屈し、その結果罪に陥ったこと、復活後、呪われた者は悪魔とともに苦しみ、救われた者はキリストとともに永遠 を享受することを肯定し、二元論的な教えを承認した。[56]1241年にパリ大学の数人の神学者だけが、神は悪魔を邪悪に創造し、悪魔自身の決断なしに 創造したという、反対の主張を提唱した[57]。 オスマン帝国が崩壊した後も、ボゴミル二元論の一部はバルカン半島の創造に関する民間伝承に残っていた。11世紀から13世紀まで遡る話によれば、神が世 界を創造する前に、神は永遠の海でガチョウと出会う。ガチョウの名はサタナエルといい、神であると主張したと伝えられている。神がサタナエルに何者かと尋 ねると、悪魔は「神々の中の神」と答える。神は悪魔に、海の底に潜って泥を運ぶように頼み、この泥から世界を造った。神は火打石の右の部分から炎の天使を 創造し、悪魔は火打石の左の部分から悪魔を創造した。その後、悪魔は神を襲おうとしたが、奈落の底に投げ込まれた。悪魔は神の創造に潜み続け、天国への再 攻撃を計画している[58]。この神話は、ボゴミライトの思想だけでなく、イスラム以前のテュルク人の創造神話とも類似点がある[59]。 この物語は他のテュルコ=モンゴル人の宇宙起源説とも類似している。シベリアのタタール人に見られる神話によると、神とその最初の創造物はアヒルの姿で描 かれている。神はその被造物と仲間に、海に潜って土を取ってくるように頼む。しかし、2羽目のアヒルはエルリク・ハーンと同一視され、神に反旗を翻して彼 のライバルとなった[59]。同様の伝説がアルタイ・トルコ人の間にも記録されている。エルリクと神は原初の水の上を一緒に泳いでいた。神が地球を創造し ようとしたとき、神はエルリクに水に潜って泥を集めるように命じた。エルリクは、後に自分の世界を創造するために、その一部を口の中に隠した。しかし、神 が地球を拡大するように命じたとき、エルリクは泥を口に含んで困った。神は泥を吐き出すようエルリクを助けた。エルリクが運んだ泥は、世界の不快な場所を 作り出した。その罪のために、彼は悪に配属された。彼は自分の世界を創造することで神との平等を主張したため、神はエルリク・ハーンに冥界に自分の王国を 与えることで罰した[59][60][61]。 ヴェルビツキー・ヴァシリーによって記録されたある異説では、エルリク・ハーンだけでなく、彼が創造した精霊たちも天界から追放され、下界に落とされた [62]。 |

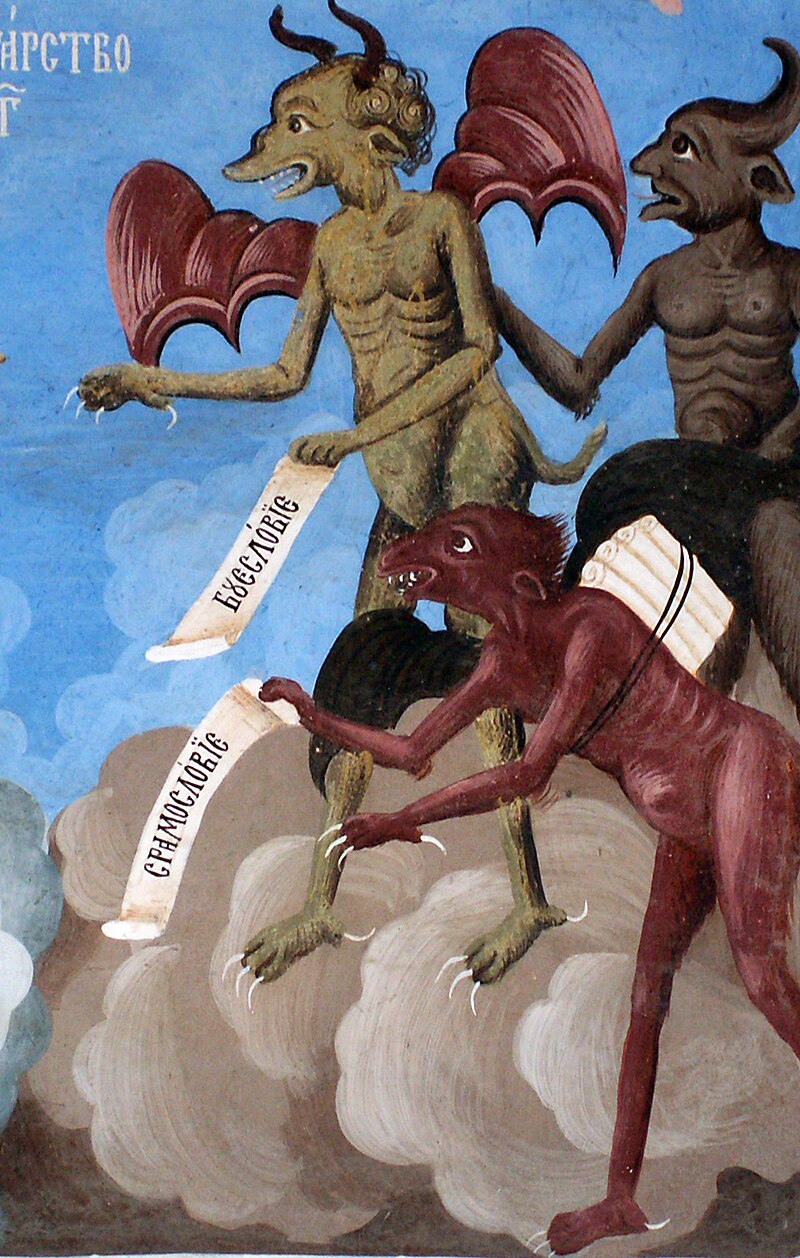

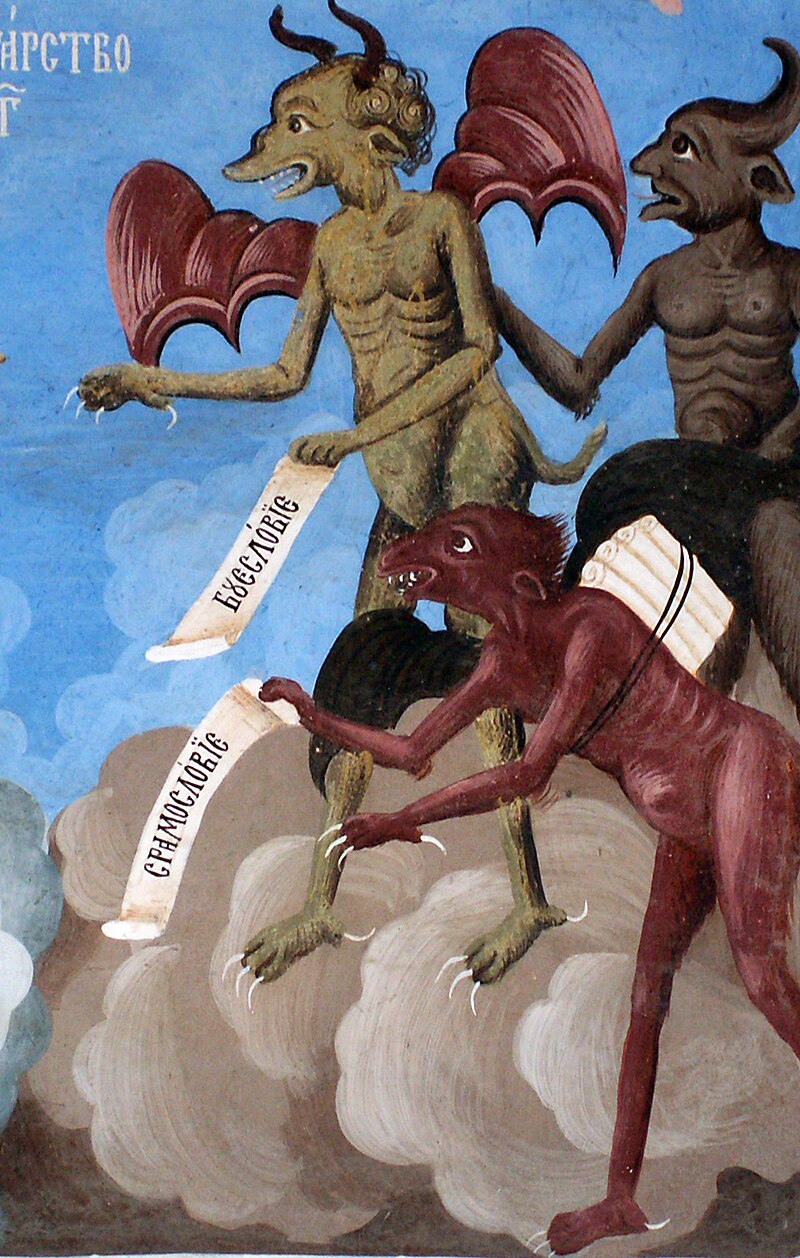

| Christianity Main article: Devil in Christianity See also: Satan § Christianity, and War in Heaven  The Fallen Angel (1847) by Alexandre Cabanel  A fresco detail from the Rila Monastery, in which demons are depicted as having grotesque faces and bodies In Christianity, the devil or Satan is a fallen angel who is the primary opponent of God.[63][64] Some Christians also considered the Roman and Greek deities to be devils.[6][7] Christianity describes Satan as a fallen angel who terrorizes the world through evil,[63] is opposed to truth,[65] and shall be condemned, together with the fallen angels who follow him, to eternal fire at the Last Judgment.[63] Christian Bible  Horns of a goat and a ram, goat's fur and ears, nose and canines of a pig; a typical depiction of the devil in Christian art. The goat, ram and pig are consistently associated with the devil.[66] Detail of a 16th-century painting by Jacob de Backer in the National Museum in Warsaw. Old Testament The Devil is identified with several figures in the Bible including the serpent in the Garden of Eden, Lucifer, Satan, the tempter of the Gospels, Leviathan, and the dragon in the Book of Revelation. Some parts of the Bible, which do not refer to an evil spirit or Satan at the time of the composition of the texts, are interpreted as references to the Devil in Christian tradition.[67] Genesis 3 mentions the serpent in the Garden of Eden, which tempts Adam and Eve into eating the forbidden fruit from the tree of the knowledge of good and evil, thus causing their expulsion from the Garden. The Babylonian myth of a rising star, as the embodiment of a heavenly being who is thrown down for his attempt to ascend into the higher planes of the gods, is also found in the Bible and interpreted as a fallen angel (Isaiah 14:12–15).[68][69] Ezekiel's cherub in Eden is thought to be a description of the major characteristic of the Devil, that he was created good, as a high ranking angel and lived in Eden, later turning evil on his own accord:[70] You were in Eden, the garden of God; every precious stone adorned you: ruby, topaz, emerald, chrysolite, onyx, jasper, sapphire, turquoise, and beryl. Gold work of tambourines and of pipes was in you. In the day that you were created they were prepared. You were the anointed cherub who covers: and I set you, so that you were on the holy mountain of God; you have walked up and down in the midst of the stones of fire. You were perfect in your ways from the day that you were created, until unrighteousness was found in you. — Ezekiel 28:13–15[71] The Hebrew term śāṭān (Hebrew: שָּׂטָן) was originally a common noun meaning "accuser" or "adversary" and derived from a verb meaning primarily "to obstruct, oppose".[72][73] Satan is conceptualized as a heavenly being hostile to humans and a personification of evil 18 times in Job 1–2 and Zechariah 3.[74] In the Book of Job, Job is a righteous man favored by God.[75] Job 1:6–8[76] describes the "sons of God" (bənê hā'ĕlōhîm) presenting themselves before God.[75] Satan thinks Job only loves God because he has been blessed, so he requests that God tests the sincerity of Job's love for God through suffering, expecting Job to abandon his faith.[77] God consents; Satan destroys Job's family, health, servants and flocks, yet Job refuses to condemn God.[77] New Testament The Devil figures much more prominently in the New Testament and in Christian theology than in the Old Testament.[78] The Devil is a unique entity throughout the New Testament, neither identical to the demons nor the fallen angels,[79][80] the tempter and perhaps rules over the kingdoms of earth.[81] In the temptation of Christ (Matthew 4:8–9 and Luke 4:6–7),[82] the devil offers all kingdoms of the earth to Jesus, implying they belong to him.[83] Since Jesus does not dispute this offer, it may indicate that the authors of those gospels believed this to be true.[83] This event is described in all three synoptic gospels, (Matthew 4:1–11,[84] Mark 1:12–13[85] and Luke 4:1–13).[86] Some Church Fathers, such as Irenaeus, reject that the Devil holds such power, arguing that, since the devil was a liar since the beginning, he also lied here and that all kingdoms belong to God, referring to Proverbs 21.[87][88] Adversaries of Jesus are suggested to be under the influence of the Devil. John 8:40 speaks about the Pharisees as the "offspring of the devil". John 13:2[89] states that the Devil entered Judas Iscariot before Judas's betrayal (Luke 22:3).[90][91] In all three synoptic gospels (Matthew 9:22–29,[92] Mark 3:22–30[93] and Luke 11:14–20),[94] Jesus himself is also accused of serving the Devil. Jesus's adversaries claim that he receives the power to cast out demons from Beelzebub, the Devil. In response, Jesus says that a house divided against itself will fall, and that there would be no reason for the devil to allow one to defeat the devil's works with his own power.[95] According to the First Epistle of Peter, "Like a roaring lion your adversary the devil prowls around, looking for someone to devour" (1 Peter 5:8).[96] The authors of the Second Epistle of Peter and the Epistle of Jude believe that God prepares judgment for the devil and his fellow fallen angels, who are bound in darkness until the Divine retribution.[97] In the Epistle to the Romans, the inspirer of sin is also implied to be the author of death.[97] The Epistle to the Hebrews speaks of the devil as the one who has the power of death but is defeated through the death of Jesus (Hebrews 2:14).[98][99] In the Second Epistle to the Corinthians, Paul the Apostle warns that Satan is often disguised as an angel of light.[97] In the Book of Revelation, a dragon/serpent "called the devil, or Satan" wages war against the archangel Michael resulting in the dragon's fall. The devil is described with features similar to primordial chaos monsters, like the Leviathan in the Old Testament.[79] The identification of this serpent as Satan supports identification of the serpent in Genesis with the devil.[100] |

キリスト教 主な記事 キリスト教における悪魔 も参照のこと: 悪魔 § キリスト教、天国での戦争  アレクサンドル・カバネル作『堕天使』(1847年  リラ修道院のフレスコ画で、悪魔はグロテスクな顔と体を持つものとして描かれている。 キリスト教では、悪魔またはサタンは神の主な敵対者である堕天使である[63][64]。一部のキリスト教徒はローマ神話やギリシャ神話の神々も悪魔であ ると考えていた[6][7]。 キリスト教では、サタンは悪によって世界を恐怖に陥れ[63]、真理に敵対し[65]、彼に従う堕天使と共に最後の審判で永遠の火に堕とされる堕天使であ ると説明している[63]。 キリスト教聖書  山羊と雄羊の角、山羊の毛皮と耳、豚の鼻と犬歯、キリスト教美術における悪魔の典型的な描写。ヤギ、雄羊、豚は一貫して悪魔と関連付けられている [66]。ワルシャワの国民博物館にあるヤコブ・デ・バッカーによる16世紀の絵画の詳細。 旧約聖書 悪魔は、エデンの園の蛇、ルシファー、サタン、福音書の誘惑者、リヴァイアサン、ヨハネの黙示録の竜など、聖書の中のいくつかの人物と同一視されている。 創世記3章には、アダムとイヴを誘惑して善悪を知る木から禁断の果実を食べさせ、園から追放する原因となったエデンの園の蛇が登場する。バビロニア神話に 登場する昇る星は、神々のより高い次元に昇ろうとしたために投げ落とされた天の存在の体現であるが、聖書にも登場し、堕天使と解釈されている(イザヤ 14:12-15)[68][69]。 エゼキエル書のエデンの園のケルブは、悪魔の主要な特徴である、悪魔が高位の天使として善良に創造され、エデンに住んでいたが、後に自らの意思で悪に転じ たという描写であると考えられている[70]。 ルビー、トパーズ、エメラルド、クリソライト、オニキス、ジャスパー、サファイア、トルコ石、ベリル。タンバリンとパイプの金細工があなたの中にあった。 あなたが造られた日、彼らは備えられた。わたしはあなたを据え、神の聖なる山の上に置かせ、火の石の中を上り下りさせた。あなたは造られた日から、あなた のうちに不義が見いだされるまで、その道において完全であった。 - エゼキエル28:13-15[71]。 ヘブライ語のśāṭān(ヘブライ語: שָן)はもともと「告発者」や「敵対者」を意味する普通名詞であり、主に「妨害する、反対する」を意味する動詞に由来する。[72][73]サタンは人 間に敵対する天の存在として概念化され、ヨブ記1-2章とゼカリヤ書3章に18回登場する悪の擬人化である[74]。ヨブ記では、ヨブは神に寵愛された義 人である。[75] ヨブ記1:6-8[76]には、「神の子ら」(bənê hā'ĕlōhîm)が神の前に姿を現す様子が描かれている[75]。サタンはヨブが神を愛しているのは自分が祝福されているからだけだと考え、ヨブが信 仰を捨てることを期待して、苦悩を通してヨブの神への愛の真摯さを神に試すよう要求する。[サタンはヨブの家族、健康、しもべ、群れを滅ぼすが、ヨブは神 を非難することを拒む[77]。 新約聖書 悪魔は新約聖書とキリスト教神学において、旧約聖書よりもはるかに顕著に登場する[78]。悪魔は新約聖書全体を通してユニークな存在であり、悪魔とも堕 天使とも同一ではなく[79][80]、誘惑者であり、おそらく地上の王国を支配している[81]。キリストの誘惑(マタイ4:8-9とルカ4:6-7) [82]において、悪魔は地上のすべての王国をイエスに差し出し、それらがイエスのものであることをほのめかす。[83] イエスはこの申し出に異議を唱えなかったので、これらの福音書の著者はこれが真実であると信じていたのかもしれない。[86] イレナイオスのような一部の教父は、悪魔がそのような力を持つことを否定し、悪魔は初めから嘘つきであったので、ここでも嘘をつき、箴言21章を参照しな がら、すべての王国は神のものであると主張している[87][88]。 イエスの敵対者は悪魔の影響下にあることが示唆されている。ヨハネ8:40はパリサイ人について「悪魔の子孫」と語っている。ヨハネ13:2[89]は、 ユダの裏切り(ルカ22:3)の前に悪魔がイスカリオテのユダに入り込んだと述べている[90][91]。 3つの共観福音書すべて(マタイ9:22-29、[92] マルコ3:22-30[93]、ルカ11:14-20)[94]において、イエス自身も悪魔に仕えていると非難されている。イエスの敵対者たちは、イエス は悪魔ベルゼブブから悪霊を追い出す力を受けていると主張する。それに対してイエスは、それ自身に対して分裂した家は倒れると言い、悪魔が自分の力で悪魔 の業を打ち負かすことを許す理由はないと言う[95]。 ペテロ第一の手紙によれば、「悪魔は、ほえたける獅子のように、あなたがたの敵であり、食い尽くす者を捜し求めてうろついています」(ペテロ第一の手紙 5:8)[96]。ペテロ第二の手紙とユダの手紙の著者は、神は悪魔とその仲間の堕天使たちのために裁きを準備し、彼らは神の報復があるまで暗闇の中に拘 束されていると信じている。[97]ローマ人への手紙では、罪の霊感者が死の創造者であることも暗示されている[97]。ヘブル人への手紙では、悪魔は死 の力を持っているが、イエスの死によって打ち負かされた者として語られている(ヘブル2:14)[98][99]。コリント人への第二の手紙では、使徒パ ウロは、サタンはしばしば光の天使に変装していると警告している[97]。 ヨハネの黙示録(番街)では、「悪魔、あるいはサタンと呼ばれる」竜/蛇が大天使ミカエルに戦いを挑み、その結果、竜は倒れる。悪魔は、旧約聖書のリヴァ イアサンのような原初のカオスの怪物に似た特徴を持って描写されている[79]。この蛇がサタンであるという同定は、創世記の蛇が悪魔であるという同定を 裏付けるものである[100]。 |

| Theology In Christian theology the Devil is the personification of evil, traditionally held to have rebelled against God in an attempt to become equal to God himself.[a] He is said to be a fallen angel, who was expelled from Heaven at the beginning of time, before God created the material world, and is in constant opposition to God.[102][103] Many scholars explain the Devil's fall from God's grace in Neoplatonic fashion. According to Origen, God created rational creatures first then the material world. The rational creatures are divided into angels and humans, both endowed with free will,[104] and the material world is a result of their evil choices.[105][106] Therefore, the Devil is considered most remote from the presence of God, and those who adhere to the Devil's will follow the Devil's removal from God's presence.[107] Similar, Pseudo-Dionysius the Areopagite considers evil as a deficiency having no real ontological existence. Thus the Devil is conceptualized as the entity most remote from God.[108] Dante Alighieri's Inferno follows a similar portrayal of the Devil by placing him at the bottom of hell where he becomes the center of the material and sinful world to which all sinfulness is drawn.[109] From the beginning of the early modern period (around the 1400s), Christians started to imagine the Devil as an increasingly powerful entity, actively leading people into falsehood. For Martin Luther the Devil was not a deficit of good, but a real, personal and powerful entity, with a presumptuous will against God, his word and his creation.[110][111] Luther lists several hosts of greater and lesser devils. Greater devils would incite to greater sins, like unbelief and heresy, while lesser devils to minor sins like greed and fornication. Among these devils also appears Asmodeus known from the Book of Tobit.[b] These anthropomorphic devils are used as stylistic devices for his audience, although Luther regards them as different manifestations of one spirit (i.e. the Devil).[c] Others rejected that the Devil has any independent reality on his own. David Joris was the first of the Anabaptists to suggest the Devil was only an allegory (c. 1540); this view found a small but persistent following in the Netherlands.[114] The Devil as a fallen angel symbolized Adam's fall from God's grace and Satan represented a power within man.[114] Rudolf Bultmann taught that Christians need to reject belief in a literal devil as part of formulating an authentic faith in today's world.[115] |

神学 キリスト教神学において悪魔は悪の擬人化であり、伝統的に神と同等になろうとして神に反逆したとされている[a]。神が物質世界を創造する前の太古の昔に 天国から追放された堕天使であり、常に神と対立していると言われている[102][103]。 多くの学者は悪魔が神の恩寵から堕落したことを新プラトン主義的に説明している。オリゲンによれば、神はまず理性的な被造物を創造し、次に物質世界を創造 した。理性的な被造物は天使と人間に分けられ、両者には自由意志が与えられており[104]、物質世界は彼らの邪悪な選択の結果である[105] [106]。したがって、悪魔は神の臨在から最も遠い存在であり、悪魔の意志に従う者は悪魔が神の臨在から排除されることに従うと考えられている [107]。同様に、アレオパギテ人シュード=ディオニュシオスは、悪を実在論的な存在を持たない欠陥とみなしている。ダンテ・アリギエーリの『地獄篇』 は悪魔を地獄の底に置くことによって、悪魔を同様の描写に従っており、そこでは悪魔はすべての罪深さが引き寄せられる物質的で罪深い世界の中心となる [109]。 近世の初め(1400年代頃)から、キリスト教徒は悪魔をますます強力な存在として想像するようになり、人々を積極的に偽りに導くようになった。マルティ ン・ルターにとって悪魔とは、善の欠落ではなく、実在する人格的で強力な存在であり、神やその言葉や被造物に対して僭越な意志を持つものであった [110][111]。大いなる悪魔は不信仰や異端のような大罪を煽動し、小さき悪魔は貪欲や姦淫のような小罪を煽動する。これらの悪魔の中には、『トビ ト書』で知られるアスモデウスも登場する[b]。これらの擬人化された悪魔は、ルターが聴衆のために文体上の工夫として用いたものであるが、ルターはそれ らを一つの霊(すなわち悪魔)の異なる現れとみなしている[c]。 また、悪魔がそれ自体で独立した実在を持つことを否定する者もいた。堕天使としての悪魔はアダムの神の恩寵からの堕落を象徴しており、サタンは人間の内な る力を象徴していた[114]。ルドルフ・ブルルトマンは、今日の世界において本物の信仰を形成する一環として、クリスチャンは文字通りの悪魔への信仰を 拒否する必要があると説いていた[115]。 |

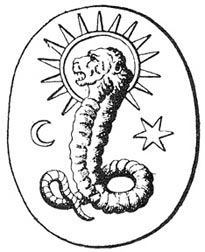

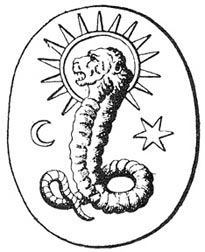

| Gnostic religions See also: Demiurge § Gnosticism  A lion-faced deity found on a Gnostic gem in Bernard de Montfaucon's L'antiquité expliquée et représentée en figures, a depiction of Yaldabaoth. Gnostic and Gnostic-influenced religions postulate the idea that the material world is inherently evil. The One true God is remote, beyond the material universe; therefore, this universe must be governed by an inferior imposter deity. This deity was identified with the deity of the Old Testament by some sects, such as the Sethians and the Marcions. Tertullian accuses Marcion of Sinope, that he [held that] the Old Testament was a scandal to the faithful … and … accounted for it by postulating [that Jehovah was] a secondary deity, a demiurgus, who was god, in a sense, but not the supreme God; he was just, rigidly just, he had his good qualities, but he was not the good god, who was Father of Our Lord Jesus Christ.[116] John Arendzen (1909) in the Catholic Encyclopedia (1913) mentions that Eusebius accused Apelles, the 2nd-century AD Gnostic, of considering the Inspirer of Old Testament prophecies to be not a god, but an evil angel.[117] These writings commonly refer to the Creator of the material world as "a demiurgus"[116] to distinguish him from the One true God. Some texts, such as the Apocryphon of John and On the Origin of the World, not only demonized the Creator God but also called him by the name of the devil in some Jewish writings, Samael.[118] |

グノーシス主義宗教 も参照のこと: デミウルゲ§グノーシス主義  Bernard de MontfauconのL'antiquitée expliquée et représentée en figuresに描かれたグノーシスの宝石に見られるライオンの顔をした神で、ヤルダバオトの描写である。 グノーシス主義やグノーシス主義の影響を受けた宗教は、物質世界は本質的に邪悪であるという考えを前提としている。それゆえ、この宇宙は劣った偽者の神に よって支配されなければならない。この神は、セティウス派やマルキオン派などの一部の宗派によって旧約聖書の神と同一視された。テルトゥリアヌスは、シノ ペのマルキオンを次のように非難している。 [エホバは二次的な神、デミウルゴスであり、ある意味では神であったが、至高の神ではなかった。エホバは公正であり、厳格であり、良い性質を持っていた が、われわれの主イエス・キリストの父である良い神ではなかった」[116]。 カトリック百科事典』(1913)のジョン・アレンゼン(1909)は、エウセビオスが紀元後2世紀のグノーシス主義者であるアペレスを、旧約聖書の預言 の霊感者を神ではなく邪悪な天使であると考えていると非難したことに触れている[117]。これらの著作は、物質世界の創造主を唯一の真の神から区別する ために、一般的に「デミウルゴス」[116]と呼んでいる。ヨハネの黙示録』や『世界の起源』のようないくつかの書物は、創造主である神を悪魔化しただけ でなく、ユダヤ教のいくつかの書物では悪魔の名前であるサマエルと呼んでいた[118]。 |

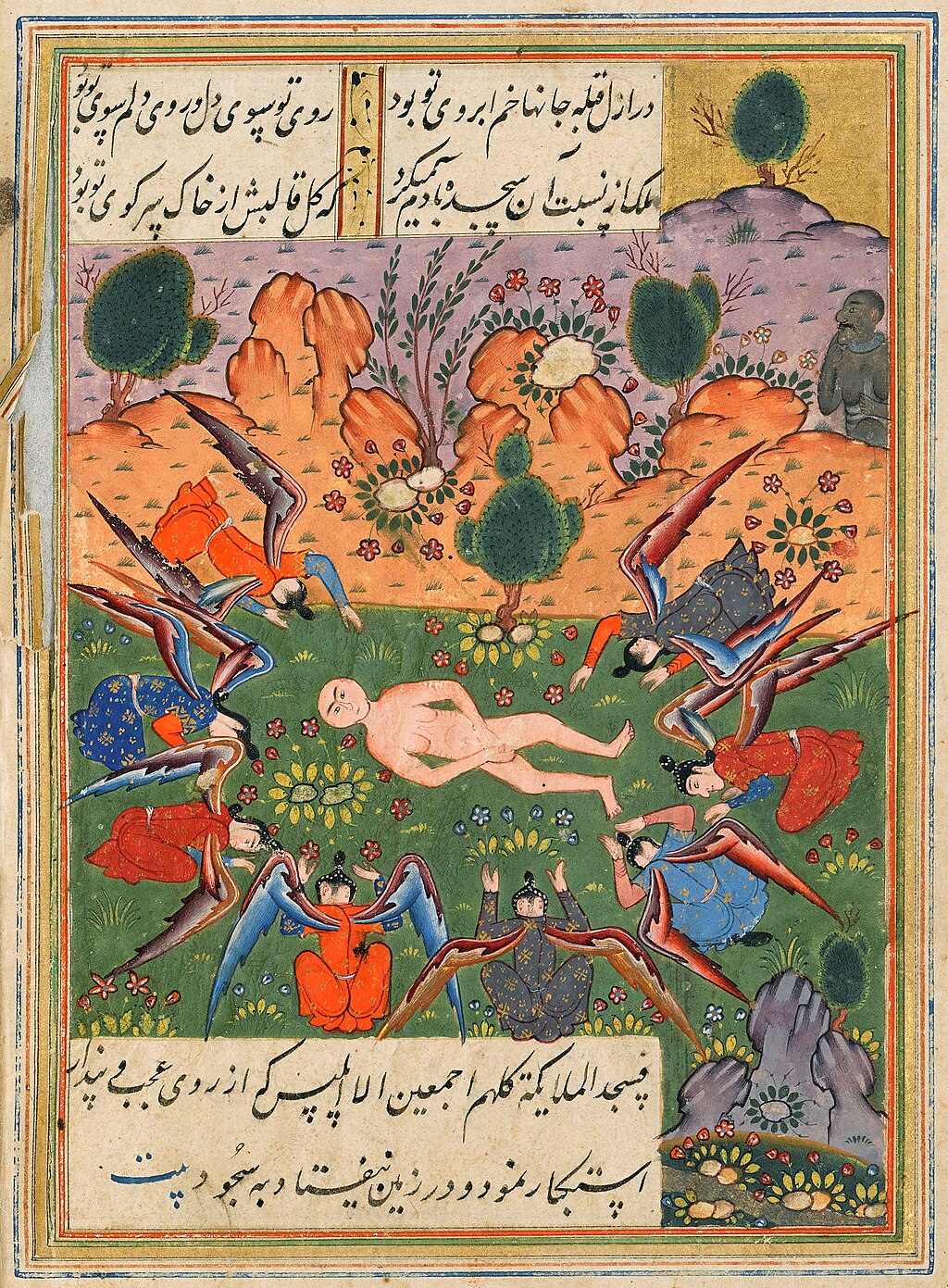

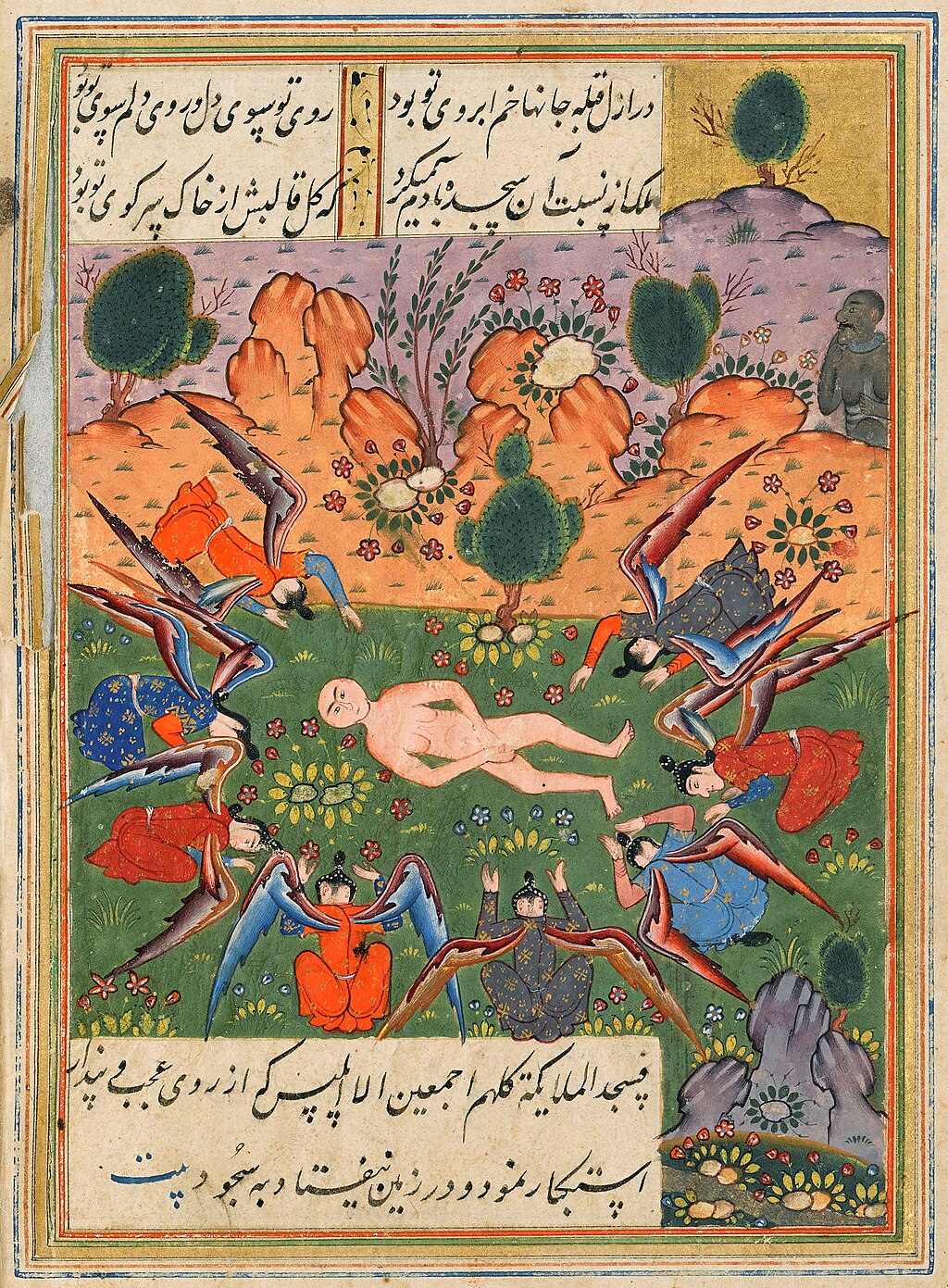

| Islam Main articles: Azazil and Iblis See also: Satan § Islam  Iblis (top right on the picture) refuses to prostrate before the newly created Adam from a Persian miniature. In Islam, the principle of evil is expressed by two terms referring to the same entity:[119][120][121] Shaitan (meaning astray, distant or devil) and Iblis. Iblis is the proper name of the devil representing the characteristics of evil.[122] Iblis is mentioned in the Quranic narrative about the creation of humanity. When God created Adam, he ordered the angels to prostrate themselves before him. Out of pride, Iblis refused and claimed to be superior to Adam.[Quran 7:12] Therefore, pride but also envy became a sign of "unbelief" in Islam.[122] Thereafter, Iblis was condemned to Hell, but God granted him a request to lead humanity astray,[123] knowing the righteous would resist Iblis's attempts to misguide them. In Islam, both good and evil are ultimately created by God. But since God's will is good, the evil in the world must be part of God's plan.[124] Actually, God allowed the devil to seduce humanity. Evil and suffering are regarded as a test or a chance to prove confidence in God.[124] Some philosophers and mystics emphasized Iblis himself as a role model of confidence in God. Because God ordered the angels to prostrate themselves, Iblis was forced to choose between God's command and God's will (not to praise someone other than God). He successfully passed the test, yet his disobedience caused his punishment and therefore suffering. However, he stays patient and is rewarded in the end.[125] Muslims hold that the pre-Islamic jinn, tutelary deities, became subject under Islam to the judgment of God, and that those who did not submit to the law of God are devils.[126] Although Iblis is often compared to the devil in Christian theology, Islam rejects the idea that Satan is an opponent of God and the implied struggle between God and the devil.[clarification needed] Iblis might either be regarded as the most monotheistic or the greatest sinner, but remains only a creature of God. Iblis did not become an unbeliever due to his disobedience, but because of attributing injustice to God; that is, by asserting that the command to prostrate himself before Adam was inappropriate.[127] There is no reference to angelic revolt in the Quran and no mention of Iblis trying to take God's throne,[128][129] and Iblis's sin could be forgiven at any time by God.[130] According to the Quran, Iblis's disobedience was due to his disdain for humanity, a narrative already occurring in early New Testament apocrypha.[131] As in Christianity, Iblis was once a pious creature of God but later cast out of Heaven due to his pride. However, to maintain God's absolute sovereignty,[132] Islam matches the line taken by Irenaeus instead of the later Christian consensus that the devil did not rebel against God but against humanity.[17][120] Further, although Iblis is generally regarded as a real bodily entity,[133] he plays a less significant role as the personification of evil than in Christianity. Iblis is merely a tempter, notable for inciting humans into sin by whispering into humans minds (waswās), akin to the Jewish idea of the devil as yetzer hara.[134][135] On the other hand, Shaitan refers unilaterally to forces of evil, including the devil Iblis who causes mischief.[136] Shaitan is also linked to humans' psychological nature, appearing in dreams, causing anger, or interrupting the mental preparation for prayer.[133] Furthermore, the term Shaitan also refers to beings who follow the evil suggestions of Iblis. Also, the principle of shaitan is in many ways a symbol of spiritual impurity, representing humans' own deficits, in contrast to a "true Muslim", who is free from anger, lust and other devilish desires.[137] In Muslim culture, devils are believed to be hermaphrodite creatures created from hell-fire, with one male and one female thigh, and able to procreate without a mate. It is generally believed that devils can harm the souls of humans through their whisperings. While whisperings tempt humans to sin, the devils might enter the hearth (qalb) of an individual. If the devils take over the soul of a person, this would render them aggressive or insane.[138] In extreme cases, the alterings of the soul are believed to have effect on the body, matching its spiritual qualities.[139] |

イスラム教 主な記事 アザジルとイブリス も参照のこと: サタン§イスラム教  イブリス(写真右上)は、ペルシャの細密画から、新しく創造されたアダムの前にひれ伏すことを拒否している。 イスラム教では、悪の原理は同じ存在を指す2つの用語によって表現される:[119][120][121]シャイターン(迷い、遠い、悪魔の意)とイブリ ス。イブリスは悪の特徴を表す悪魔の固有名詞である[122]。イブリスはクルアーンにおける人類の創造に関する物語の中で言及されている。神がアダムを 創造した時、神は天使たちに彼の前にひれ伏すように命じた。プライドから、イブリスはそれを拒否し、アダムよりも優れていると主張した[クルアーン7: 12]。それゆえ、プライドだけでなく、妬みもイスラム教では「不信心」の印となった[122]。その後、イブリスは地獄に堕とされたが、神は人類を迷わ せるためにイブリスの要求を認めた[123]。イスラームでは、善も悪も最終的には神が創造したものである。しかし、神の善い意志は善であるため、この世 の悪は神の計画の一部でなければならない[124]。哲学者や神秘主義者の中には、イブリス自身を神への信頼の模範として強調する者もいた[124]。神 が天使たちにひれ伏すように命じたため、イブリスは神の命令と神の意志(神以外の者を賛美してはならない)のどちらかを選ぶことを余儀なくされた。イブリ スはそのテストに合格したが、不従順であったために罰を受け、苦悩した。しかし、彼は忍耐を続け、最後には報われる[125]。 イスラム教徒は、イスラム教以前の主神であるジンはイスラム教の下で神の裁きを受けるようになり、神の掟に従わなかった者は悪魔であるとする[126]。 キリスト教神学ではイブリスはしばしば悪魔と比較されるが、イスラームではサタンが神の敵対者であるという考えや、神と悪魔の暗黙の闘争を否定している [要出典]。イブリスは不従順のために不信心になったのではなく、神に不義を帰したために、つまりアダムの前にひれ伏すようにという命令は不適切であった と主張したために、不信心になったのである。[127]。コーランには天使の反乱についての言及はなく、イブリスが神の王座を奪おうとしたことについての 言及もない[128][129]。イブリスの罪は神によっていつでも赦される可能性がある[130]。コーランによれば、イブリスの不従順は人間性を軽蔑 したことによるものであり、この物語は新約聖書の初期のアポクリファにすでに登場している[131]。 キリスト教におけるように、イブリスはかつて敬虔な神の被造物であったが、後に高慢のために天国から追放された。しかし、神の絶対的な主権を維持するため に[132]、イスラム教は悪魔が神に反抗したのではなく、人類に反抗したという後のキリスト教のコンセンサスではなく、イレナイオスのとった路線と一致 している[17][120]。 さらに、イブリスは一般的に実在の肉体的存在と見なされているが[133]、キリスト教におけるよりも悪の擬人化としての役割は小さい。イブリスは単なる 誘惑者であり、人間の心にささやく(waswās)ことによって人間を罪に煽動することで注目されており、ユダヤ教における悪魔の思想(yetzer hara)に似ている[134][135]。 一方、シャイタンは、災いを引き起こす悪魔イブリスを含む悪の力を一方的に指している[136]。シャイタンはまた、夢の中に現れたり、怒りを引き起こし たり、祈りのための精神的な準備を邪魔したりするなど、人間の心理的な性質とも関連している[133]。さらに、シャイタンという用語は、イブリスの邪悪 な暗示に従う存在も指している。また、シャイタンの原理は多くの意味で精神的な不純さの象徴であり、怒りや欲望、その他の悪魔的な欲望から自由である「真 のムスリム」とは対照的に、人間自身の欠陥を表している[137]。 イスラム文化では、悪魔は地獄の業火から生み出された両性具有の生き物であり、片方の太ももは男性、片方の太ももは女性であり、伴侶がいなくても子孫を残 すことができると信じられている。一般的に、悪魔はそのささやきによって人間の魂を傷つけることができると信じられている。悪魔のささやきは人間を罪に誘 惑するが、悪魔は個人の囲炉裏(カルブ)に入り込むかもしれない。悪魔が人格を乗っ取ると、その人格は攻撃的になったり正気を失ったりする[138]。極 端な場合、魂の変質は肉体に影響を及ぼし、その霊的な性質と一致すると信じられている[139]。 |

| Sunni theology Islamic theology (kalam) does not discuss the role of Iblis in as much as related to angels and demons (jinn and shayāṭīn), but rather in his role as the principle of evil. One major concern of Muslim theologians was to disprove cosmological dualism, the idea that the Devil partakes in the creation of the world, i.e. that God creates goodness and the Devil creates evil.[140][141][142] According to Sunni creed, God is the originator of both good and evil. Thus, the Devil, as embodiment of evil, is an example on the fate of the disbelievers (kuffār), rather than an independent principle. Like Iblis, disbelievers are also held to be misguided by God, for, as it has been demonstrated in the case of Iblis, belief and unbelief depend on God's will not on the individual.[143][144] It further shows that the blessed can become damned and the damned become blessed, as Iblis, when he was the leader of the angels, was happy, but miserable after his fall.[145] Abu-Sufyani is the opposite example, someone who was miserable but then became blessed once he became a Muslim.[145] The principle Devil also demonstrates that disobedience does not equal unbelief because Iblis became an unbeliever due to his arrogance and will to follow his own desires rather than loving God.[146][147] In Sufism and mysticism See also: Nafs In contrast to Occidental philosophy, the Sufi idea of seeing "Many as One" and considering the creation in its essence as the Absolute, leads to the idea of the dissolution of any dualism between the ego substance and the "external" substantial objects. The rebellion against God, mentioned in the Quran, takes place on the level of the psyche that must be trained and disciplined for its union with the spirit that is pure. Since psyche drives the body, flesh is not the obstacle to humans but rather an unawareness that allows the impulsive forces to cause rebellion against God on the level of the psyche. Yet it is not a dualism between body, psyche and spirit, since the spirit embraces both psyche and corporeal aspects of humanity.[148] Since the world is held to be the mirror in which God's attributes are reflected, participation in worldly affairs is not necessarily seen as opposed to God.[134] The devil activates the selfish desires of the psyche, leading the human astray from the Divine.[149] Thus, it is the I that is regarded as evil, and both Iblis and Pharao are present as symbols for uttering "I" in ones own behavior. Therefore, it is recommended to use the term I as little as possible. It is only God who has the right to say "I", since it is only God who is self-subsistent. Uttering "I" is therefore a way to compare oneself to God, regarded as shirk.[150] Islamist movements See also: Taghut Many Salafi strands emphasize a dualistic worldview between believers and unbelievers,[151] The unbelievers are considered to be under the domain of the Devil and are the enemies of the faithful. The former are credited with tempting the latter to sin and away from God's path. The Devil will ultimately be defeated by the power of God, but remains until then a serious threat for the believer.[152] The notion of a substantial reality of evil (or a form of dualism between God and the Devil) has no precedence in the Quran or earlier Muslim traditions.[153] The writings of ibn Sina, Ghazali, and ibn Taimiyya, all describe evil as the absence of good, rather than having any positive existence. Accordingly, infidelity among humans, civilizations, and empires are not described as evil or devilish in Classical Islamic sources.[153] This is in stark contrast to Islamists, such as Osama bin Laden, who justifies his violence against the infidels by contrary assertions.[153] While in classical hadiths, devils (shayāṭīn) and jinn are responsible for ritual impurity, many Salafis substitute local demons by an omnipresent threat through the Devil himself.[154] Only through remembrance of God and ritual purity, can the devil be kept away.[155] As such, the Devil becomes an increasingly powerful entity who is believed to interfer with both personal and political life.[156] For example, many Salafis blame the Devil for Western emancipation.[157] |

スンニ派神学 イスラム神学(カラーム)では、イブリスの役割を天使や悪魔(ジンやシャヤーン)に関連するものとしてではなく、むしろ悪の原理としての役割として論じて いる。ムスリム神学者たちの主要な関心事の一つは、悪魔が世界の創造に関与しているという考え、すなわち神が善を創造し悪魔が悪を創造するという宇宙論的 二元論を反証することであった[140][141][142]。スンニ派の信条によれば、神は善と悪の両方の起源である。したがって、悪の体現者としての 悪魔は、独立した原理というよりも、不信心者(クッファール)の運命の一例である。イブリスのケースで示されたように、信仰と不信仰は個人ではなく神の意 志に依存するからである[143][144]。 また、イブリスが天使の指導者であったときは幸福であったが、堕落した後は悲惨であったように、祝福された者が呪われるようになり、呪われた者が祝福され るようになることもある[145]。 スーフィズムと神秘主義において も参照のこと: ナフス 西洋哲学とは対照的に、「多を一と見なし」、被造物をその本質において絶対的なものと見なすスーフィズムの考えは、自我物質と「外的な」実質的対象との間 のあらゆる二元論の解消という考えにつながる。コーランで言及されている神への反抗は、純粋な精神との結合のために訓練され、鍛錬されなければならない精 神のレベルで起こる。精神が肉体を動かしているのだから、肉体は人間にとって障害ではなく、むしろ精神のレベルで神への反抗を引き起こす衝動的な力を許し ている無自覚なものなのだ。しかし、精神は人間の精神と肉体の両方の側面を包含しているので、肉体、精神、精神の間の二元論ではない。[悪魔は精神の利己 的な欲望を活性化させ、人間を神から迷わせる[149]。したがって、悪とみなされるのは「私」であり、イブリスとファラオの両方が、自らの行動において 「私」を口にすることの象徴として存在する。したがって、「私」という言葉をできるだけ使わないことが推奨される。私」と言う権利があるのは神だけであ り、神だけが自存しているからである。したがって、「私」を口にすることは、自分を神と比較することであり、シルクとみなされる[150]。 イスラム主義運動 以下も参照のこと: タフート 多くのサラフィー派は信者と未信者の二元論的世界観を強調する[151]。未信者は悪魔の支配下にあり、信者の敵であると考えられている。前者は後者を誘 惑して罪を犯させ、神の道から遠ざけると信じられている。悪魔は最終的には神の力によって倒されるが、それまでは信者にとって深刻な脅威であり続ける [152]。 イブン・シーナ、ガザーリー、イブン・タイミヤの著作では、悪は積極的な存在ではなく、善の不在として記述されている[153]。従って、人間、文明、帝 国における不忠実は、古典的イスラーム典拠では悪や悪魔として記述されていない[153]。これは、オサマ・ビンラディンのようなイスラーム主義者が、異 教徒に対する暴力を逆の主張によって正当化しているのとは対照的である[153]。 古典的ハディースでは、悪魔(シャヤーン)やジンは儀礼の不浄に責任があるが、多くのサラフィー教徒は悪魔自身を通して遍在する脅威によって地元の悪魔を 代用する[154]。 そのため、悪魔はますます強力な存在となり、個人生活と政治生活の両方に干渉すると信じられている[156]。例えば、多くのサラフィー教徒は西洋解放を 悪魔のせいにしている[157]。 |

| Judaism Further information: Satan § Judaism Yahweh, the god in pre-exilic Judaism, created both good and evil, as stated in Isaiah 45:7: "I form the light, and create darkness: I make peace, and create evil: I the Lord do all these things." The Devil does not exist in Jewish scriptures. Satan, who will later become a representative for the Devil in Christian tradition, is not yet the Devil. The Hebrew term śāṭān (Hebrew: שָּׂטָן), meaning "accuser" or "adversary", was applied to both human and heavenly adversaries.[158][159] However, even when the term is referring to a supernatural adversary, such as in Numbers 22:22 and in Job 1–2, Satan is merely one "of the Sons of God", a manifestation of God's will.[160] Under influence of Zoroastrianism during the Achaemenid Empire, which introduced the idea of Evil as a separate principle into the Jewish belief system, Satan gradually developed into an independent principle, abolishing the Godhead from evil actions.[126] In the Book of Jubilees, the evil angel Mastema substitutes deprecated actions of Yahweh.[161][162] Nonetheless, Mastema can only act with God's permission[163] and only succeeds then attacking non-Jewish nations.[164] In the Book of Enoch, there is an entire class of angels called satans.[165] According to Jeffrey Burton Russell, Satan is yet another name for Azazel, the leader of the rebel angel of the story.[165] Derek R. Brown argues that here, the Devil and the satans are still distinct: while Azazel and his angels rebel against God, the satans act on God's behalf as God's executioners of Divine Judgement.[166] The fallen angels are blamed for introducing the forbidden arts of war into the world and sire demonic offspring with human women.[167] By ascribing the origin of evil to angels acting from God independently, evil is attributed to something supernatural from without; external to the prevailing belief-system.[168] Due to resemblance of the fallen angels with creatures of Greek mythology, the fallen angels might be a reaction invading Hellenistic culture, resulting in perceived oppression of the Jews.[169] The story of fallen angels, proposing a second independent power in heaven, was at odds with later Rabbinic Judaism.[170] Therefore, the Book of Enoch, which depicted the evil as an independent force besides God were rejected.[171] After the apocalyptic period, references to Satan in the Tanakh are thought to be allegorical.[172] |

ユダヤ教 さらに詳しい情報 サタン§ユダヤ教 イザヤ書45:7にあるように、滅亡前のユダヤ教における神ヤハウェは善と悪の両方を創造した: 「わたしは光を形づくり、闇を創造する: わたしは光を造り、闇を造り、平和を造り、悪を造る: わたしは平和をつくり、悪をつくる。悪魔はユダヤ教の聖典には存在しない。後にキリスト教の伝統における悪魔の代表となるサタンは、まだ悪魔ではない。ヘ ブライ語で「告発者」または「敵対者」を意味するśāṭān(ヘブライ語: ש↪Mn_5An↩Ø↪Mn_5An↩)は、人間と天の敵対者の両方に適用された。[158][159]しかし、民数記22:22やヨブ記1-2のよう に、この言葉が超自然的な敵対者を指している場合でも、サタンは「神の子たち」の一人であり、神の意志の現れでしかない[160]。 アケメネス朝時代のゾロアスター教の影響を受け、悪を独立した原理としてユダヤ教の信仰体系に導入したサタンは、次第に独立した原理へと発展し、悪の行動 から神格を廃した[126]。 ジェフリー・バートン・ラッセルによれば、サタンとはこの物語の反逆天使のリーダーであるアザゼルの別名である[165]。[166]堕天使は禁じられた 戦争の術をこの世に持ち込んだり、人間の女性と悪魔の子孫を作ったりしたことで非難されている[167]。悪の起源を神から独立して行動する天使に帰する ことで、悪は一般的な信仰体系から外れた、外部から来た超自然的なものに帰せられる[168]。堕天使がギリシア神話の生き物に似ていることから、堕天使 はヘレニズム文化に侵入した反動であり、ユダヤ人に対する抑圧をもたらしたと考えられている[169]。 堕天使の物語は、天における第二の独立した力を提案しており、後のラビ派ユダヤ教と対立していた[170]。 そのため、神以外の独立した力として悪を描いたエノク書は否定された[171]。 終末論的な時代以降、タナフにおけるサタンへの言及は寓意的なものであると考えられている[172]。 |

| Mandaeism Main article: World of Darkness (Mandaeism) See also: Mandaeism and Ruha In Mandaean mythology, Ruha fell apart from the World of Light and became the queen of the World of Darkness, also referred to as Sheol.[173][174][175] She is considered evil and a liar, sorcerer and seductress.[176]: 541 She gives birth to Ur, also referred to as Leviathan. He is portrayed as a large, ferocious dragon or snake and is considered the king of the World of Darkness.[174] Together they rule the underworld and create the seven planets and twelve zodiac constellations.[174] Also found in the underworld is Krun, the greatest of the five Mandaean Lords of the underworld. He dwells in the lowest depths of creation and his epithet is the 'mountain of flesh'.[177]: 251 Prominent infernal beings found in the World of Darkness include lilith, nalai (vampire), niuli (hobgoblin), latabi (devil), gadalta (ghost), satani (Satan) and various other demons and evil spirits.[174][173] Manichaeism Main article: Prince of Darkness (Manichaeism) In Manichaeism, God and the devil are two unrelated principles. God created good and inhabits the realm of light, while the devil (also called the prince of darkness[178][179]) created evil and inhabits the kingdom of darkness. The contemporary world came into existence, when the kingdom of darkness assaulted the kingdom of light and mingled with the spiritual world.[180] At the end, the devil and his followers will be sealed forever and the kingdom of light and the kingdom of darkness will continue to co-exist eternally, never to commingle again.[181] Hegemonius (4th century CE) accuses that the Persian prophet Mani, founder of the Manichaean sect in the 3rd century CE, identified Jehovah as "the devil god which created the world"[182] and said that "he who spoke with Moses, the Jews, and the priests … is the [Prince] of Darkness, … not the god of truth."[178][179] Yazidism Dualism is rejected by Yazidis;[183] according to Yazidism, evil is nonexistent[184] and there is no entity that represents evil in opposition to God. Yazidis adhere to strict monism and are prohibited from uttering the word "devil" and from speaking of anything related to Hell.[185] |

マンデイズム 主な記事 闇の世界(マンダイ教) 以下も参照のこと: マンダイ教とルハ マンダイの神話では、ルーハは光の世界から堕落し、シェオールとも呼ばれる闇の世界の女王となった[173][174][175]: 541 彼女はリヴァイアサンとも呼ばれるウルを産む。彼は大きく獰猛な竜または蛇として描かれ、闇の世界の王と考えられている[174]。彼らは共に冥界を支配 し、7つの惑星と12の星座を創造する[174]。彼は創造の最下層に棲み、彼の諡号は「肉の山」である[177]: 251 暗黒の世界で見られる顕著な地獄の存在には、リリス、ナライ(吸血鬼)、ニウリ(ホブゴブリン)、ラタビ(悪魔)、ガダルタ(幽霊)、サタニ(サタン)、 その他様々な悪魔や悪霊が含まれる[174][173]。 マニ教 主な記事 闇の王子(マニ教) マニ教では、神と悪魔は無関係な二つの原理である。神は善を創造し、光の領域に住むが、悪魔(闇の王子とも呼ばれる[178][179])は悪を創造し、 闇の王国に住む。現代の世界は、闇の王国が光の王国を襲い、霊的な世界と交わることで誕生した[180]。最後には、悪魔とその従者たちは永遠に封印さ れ、光の王国と闇の王国は永遠に共存し続け、二度と交わることはない[181]。 ヘゲモニウス(紀元4世紀)は、紀元3世紀にマニ教派の創始者であるペルシアの預言者マニがエホバを「世界を創造した悪魔の神」[182]と見なし、 「モーセ、ユダヤ人、祭司たちと話した者は......闇の[王子]であり、......真理の神ではない」と述べたと非難している[178] [179]。 ヤズィード主義 ヤズィディ教では二元論は否定されている[183]。ヤズィディ教によれば、悪は存在せず[184]、神に対立する悪を象徴する存在は存在しない。ヤズィ ディ教徒は厳格な一元論を信奉しており、「悪魔」という言葉を口にすることや地獄に関することを口にすることを禁じられている[185]。 |

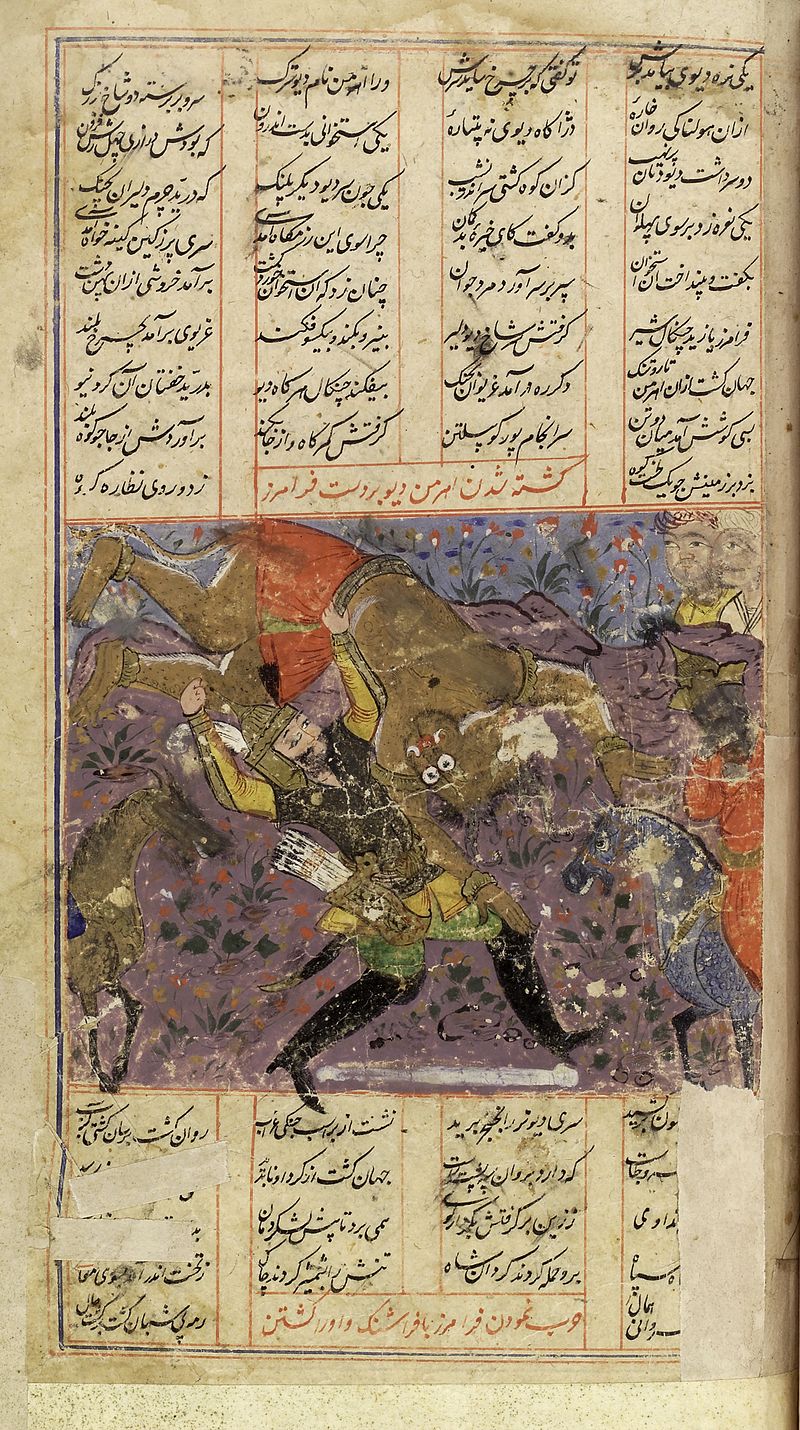

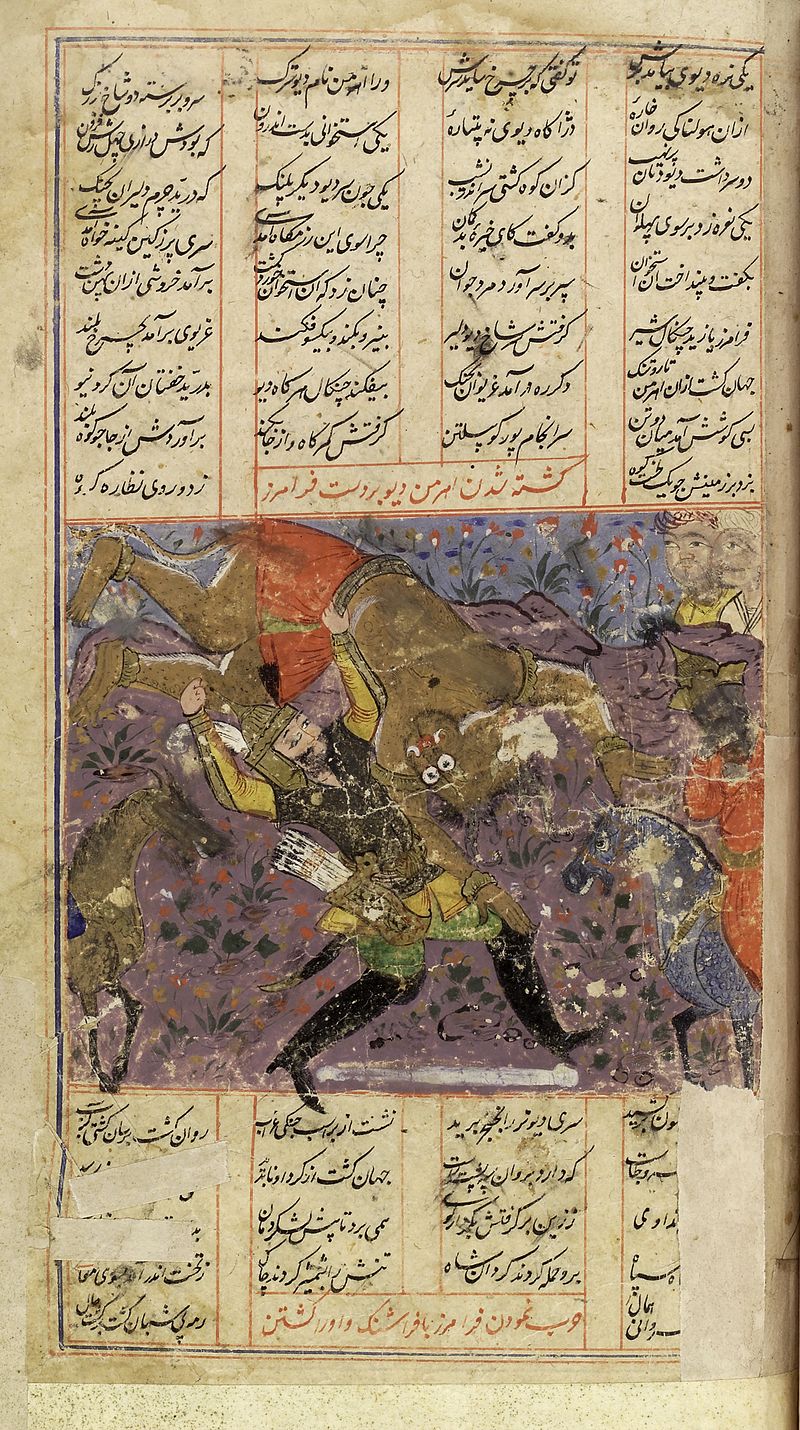

| Zoroastrianism Main articles: Angra Mainyu and Dualistic cosmology  Ahriman Div being slain during a scene from the Shahnameh Zoroastrianism probably introduced the first idea of the devil; a principle of evil independently existing apart from God.[25] In Zoroastrianism, good and evil derive from two ultimately opposed forces.[186] The force of good is called Ahura Mazda and the "destructive spirit" in the Avestan language is called Angra Mainyu. The Middle Persian equivalent is Ahriman. They are in eternal struggle and neither is all-powerful, especially Angra Mainyu is limited to space and time: in the end of time, he will be finally defeated. While Ahura Mazda creates what is good, Angra Mainyu is responsible for every evil and suffering in the world, such as toads and scorpions.[25] Iranian Zoroastrians also considered the Daeva as devil creature, because of this in the Shahnameh, it is mentioned as both Ahriman Div (Persian: اهریمن دیو, romanized: Ahriman Div) as a devil. |

ゾロアスター教 主な記事 アングラ・マイニュと二元論的宇宙論  シャーフマーネ』の一場面で殺されるアーリマン神 ゾロアスター教では、善と悪は究極的に対立する2つの力に由来する[186]。善の力はアフラ・マズダ(Ahura Mazda)と呼ばれ、アヴェスター語では「破壊的な霊」はアングラ・マインユ(Angra Mainyu)と呼ばれる。中世ペルシア語ではアーリマンと呼ばれる。両者は永遠の闘争を続けており、どちらも万能ではなく、特にアングラ・マイニュは空 間と時間に限定されている。アフラ・マズダが善を創造するのに対して、アングラ・マイニュはヒキガエルやサソリのようなこの世のあらゆる悪と苦悩の責任者 である[25]。イランのゾロアスター教徒もダエーヴァを悪魔の創造物とみなし、そのため『シャーフマーネ』ではアーリマン・ディヴ(ペルシア語: اهریمن دیو, ローマ字表記: Ahriman Div)と悪魔の両方で言及されている。 |

| Devil in moral philosophy Spinoza A non-published manuscript of Spinoza's Ethics contained a chapter (Chapter XXI) on the devil, where Spinoza examined whether the devil may exist or not. He defines the devil as an entity which is contrary to God.[187]: 46 [188]: 150 However, if the devil is the opposite of God, the devil would consist of Nothingness, which does not exist.[187]: 145 In a paper called On Devils, he writes that we can a priori find out that such a thing cannot exist. Because the duration of a thing results in its degree of perfection, and the more essence a thing possess the more lasting it is, and since the devil has no perfection at all, it is impossible for the devil to be an existing thing.[189]: 72 Evil or immoral behaviour in humans, such as anger, hate, envy, and all things for which the devil is blamed for could be explained without the proposal of a devil.[187]: 145 Thus, the devil does not have any explanatory power and should be dismissed (Occam's razor). Regarding evil through free choice, Spinoza asks how it can be that Adam would have chosen sin over his own well-being. Theology traditionally responds to this by asserting it is the devil who tempts humans into sin, but who would have tempted the devil? According to Spinoza, a rational being, such as the devil must have been, could not choose his own damnation.[190] The devil must have known his sin would lead to doom, thus the devil was not knowing, or the devil did not know his sin will lead to doom, thus the devil would not have been a rational being. Spinoza concluded a strict determinism in which moral agency as a free choice, cannot exist.[187]: 150 |

道徳哲学における悪魔 スピノザ スピノザの『倫理学(エチカ)』の未発表の写本には悪魔に関する章(第二十一章)があり、そこでスピノザは悪魔が存在するかどうかを検討した。彼は悪魔を 神に反する存在として定義している[187]: 46 [188]: 150 しかしながら、悪魔が神の反対であるとすれば、悪魔は存在しない無から成ることになる[187]: 145 『悪魔について』という論文の中で、彼は、そのようなものが存在しえないことをア・プリオリに見出すことができると書いている。なぜなら、事物の存続期間 はその完全性の程度に帰結し、事物がより多くの本質を持つほど、それはより永続的であり、悪魔は完全性を全く持たないので、悪魔が存在する事物であること は不可能だからである[189]: 145 したがって、悪魔には説明力がなく、退けられるべきである(オッカムの剃刀)。 自由選択による悪について、スピノザは、アダムが自分の幸福よりも罪を選んだということがどうしてありうるのか、と問うている。神学は伝統的に、人間を罪 に誘惑するのは悪魔であると主張することでこれに答えてきたが、誰が悪魔を誘惑したのだろうか?スピノザによれば、悪魔がそうであったに違いないような理 性的な存在は、自ら破滅を選ぶことはできなかった。スピノザは、自由な選択としての道徳的主体性が存在しえない厳密な決定論を結論づけた[187]: 150 |

Kant Engraving of Immanuel Kant The Devil found a way into rational discourse through Immanuel Kant's personification of the "idea of absolute egoism".[34] In Religion Within the Limits of Reason Alone, Immanuel Kant uses the devil as the personification of maximum moral reprehensibility. Deviating from the common Christian idea, Kant does not locate the morally reprehensible in sensual urges. Since evil has to be intelligible, only when the sensual is consciously placed above the moral obligation can something be regarded as morally evil. Thus, to be evil, the devil must be able to comprehend morality but consciously reject it, and, as a spiritual being (Geistwesen), having no relation to any form of sensual pleasure. It is necessarily required for the devil to be a spiritual being because if the devil were also a sensual being, it would be possible that the devil does evil to satisfy lower sensual desires, and does not act from the mind alone. The devil acts against morals, not to satisfy sensual lust, but solely for the sake of evil. As such, the devil is unselfish, for he does not benefit from his evil deeds. However, Kant denies that a human being could ever be completely devilish, since a human does not act evil for the sake of evil itself, but for is perceived as good, such as a law or self-love.[191] Kant argues that despite that there are devilish vices (ingratitude, envy, and malicious joy), i.e., vices that do not bring any personal advantage, however, the person cannot act for the sake of evil itself and thus, not be considered a devil. In his Lecture on Moral Philosophy (1774/75) Kant gives an example of a tulip seller who was in possession of a rare tulip, but when he learned that another seller had the same tulip, he bought it from him and then destroyed it instead of keeping it for himself. If he had acted according to his sensual urges, the seller would have kept the tulip for himself to make a profit, but not have destroyed it. Nevertheless, the destruction of the tulip cannot be completely absolved from sensual impulses, since a sensual joy or relief still accompanies the destruction of the tulip and therefore cannot be thought of solely as a violation of morality.[192]: 156–173 Kant further argues that a (spiritual) devil would be a self-contradiction. If the devil would be defined by doing evil, the devil had no free choice in the first place. But if the devil had no free-choice, the devil could not have been held accountable for his actions, since he had no free will but was only following his nature.[193] |

カント イマヌエル・カント 悪魔は、イマヌエル・カントが「絶対的エゴイズムの思想」を擬人化することによって、合理的言説に登場するようになった。一般的なキリスト教の考え方から 逸脱して、カントは道徳的に非難されるべきものを感覚的衝動に位置づけない。悪は理解可能なものでなければならないので、感覚的なものが道徳的義務よりも 意識的に上位に置かれて初めて、何かが道徳的に悪であるとみなされるのである。したがって、悪魔が悪であるためには、道徳を理解することができなくてはな らないが、意識的にそれを拒否し、精神的存在(Geistwesen)として、いかなる形の官能的快楽とも無関係でなければならない。悪魔が霊的存在であ ることが必然的に要求されるのは、もし悪魔が官能的存在でもあれば、悪魔が低次の官能的欲望を満たすために悪を行う可能性があり、心だけで行動しないから である。悪魔は道徳に反して行動するが、それは官能的な欲望を満たすためではなく、もっぱら悪のためである。悪魔は私利私欲がなく、悪行によって利益を得 ることはない。 しかしカントは、人間は悪そのもののために悪を行うのではなく、法や自己愛のような善として認識されるもののために悪を行うので、人間が完全に悪魔的であ ることはあり得ないと否定している[191]。カントは『道徳哲学講義』(1774/75)の中で、あるチューリップ売りの例を挙げている。彼は珍しい チューリップを持っていたが、他の売り手が同じチューリップを持っていることを知ると、その売り手からチューリップを買い取り、自分のものにせずに処分し た。もし彼が官能的な衝動に従って行動していたなら、その売り手はチューリップを自分のものにして利益を得ただろう。とはいえ、チューリップの破壊には依 然として官能的な喜びや安堵が伴うため、チューリップの破壊を官能的な衝動から完全に免れることはできず、したがって、道徳の違反としてのみ考えることは できない[192]: 156-173 カントはさらに、(精神的な)悪魔は自己矛盾であると主張する。もし悪魔が悪を行うことによって定義されるのであれば、悪魔にはそもそも自由選択がなかっ たことになる。しかし悪魔に自由選択がなかったとすれば、悪魔には自由意志がなく、ただ自分の本性に従っていただけであるから、悪魔は自分の行為について 責任を問われることはなかったことになる[193]。 |

| Titles Honorifics or styles of address used to indicate devil-figures. Ash-Shaytan "Satan", the attributive Arabic term referring to the devil Angra Mainyu, Ahriman: "malign spirit", "unholy spirit" Dark lord Der Leibhaftige [Teufel] (German): "[the devil] in the flesh, corporeal"[194] Diabolus, Diabolos (Greek: Διάβολος) The Evil One The Father of Lies (John 8:44), in contrast to Jesus ("I am the truth"). Iblis, name of the devil in Islam The Lord of the Underworld / Lord of Hell / Lord of this world Lucifer / the Morning Star (Greek and Roman): the bringer of light, illuminator; the planet Venus, often portrayed as Satan's name in Christianity Kölski (Iceland)[195] Mephistopheles Old Scratch, the Stranger, Old Nick: a colloquialism for the devil, as indicated by the name of the character in the short story "The Devil and Tom Walker" Prince of darkness, the devil in Manichaeism Ruprecht (German form of Robert), a common name for the Devil in Germany (see Knecht Ruprecht (Knight Robert)) Satan / the Adversary, Accuser, Prosecutor; in Christianity, the devil (The ancient/old/crooked/coiling) Serpent Voland (fictional character in The Master and Margarita) |

称号 悪魔を示すために使われる敬称や呼び方。 Ash-Shaytan 「Satan」、悪魔を指すアラビア語の帰納的な用語。 アングラ・マイニュ、アーリマン: 「悪霊」、「穢れた霊」 暗黒卿 Der Leibhaftige [Teufel](ドイツ語): 「[悪魔が]肉体を持つ、肉体的な」[194]。 ディアボルス、ディアボロス(ギリシア語: Διάβολος) 邪悪な者 嘘の父(ヨハネ8:44)、イエスとは対照的である(「わたしは真理である」)。 イブリス、イスラム教における悪魔の名前 冥界の主/地獄の主/この世の主 ルシファー/モーニングスター(ギリシア・ローマ):光をもたらす者、照明者;金星、キリスト教ではしばしばサタンの名として描かれる ケルスキ(アイスランド)[195] メフィスト オールド・スクラッチ、ストレンジャー、オールド・ニック:悪魔の口語表現で、短編 「The Devil and Tom Walker」 の登場人物の名前に示されている。 暗闇の王子、マニ教における悪魔 ルプレヒト(ロベルトのドイツ語形):ドイツにおける悪魔の通称(クネヒト・ルプレヒト(騎士ロベルト)を参照)。 サタン/敵対者、告発者、検察官;キリスト教では悪魔 (古代/古い/曲がった/巻き付いた)蛇 ヴォランド(『巨匠とマルガリータ』に登場する架空の人物) |

| Contemporary belief |

Contemporary belief(省略) |

| Deal with the

Devil Devil in popular culture Hades Krampus,[199][200] in the Tyrolean area also Tuifl[201][202] Non-physical entity Theistic Satanism Underworld |

悪魔との取引(契約) ポピュラー・カルチャーにおける悪魔 黄泉 クランプス、[199][200]チロル地方ではトゥイフル[201][202]とも呼ばれる。 非物理的存在 神霊的悪魔崇拝 冥界 |

| Sources Boureau, Alain (2006). Satan the Heretic: The Birth of Demonology in the Medieval West. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-06748-3. Brüggemann, Romy (2010). Die Angst vor dem Bösen: Codierungen des malum in der spätmittelalterlichen und frühneuzeitlichen Narren-, Teufel- und Teufelsbündnerliteratur [The fear of evil: Coding of the malum in the late medieval and early modern literature of fools, devils and allies of the devil] (in German). Königshausen & Neumann. ISBN 978-3-8260-4245-4. Costen, Michael (1997). The Cathars and the Albigensian Crusade. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4332-1. Farrar, Thomas J. (2014). "Satan in early Gentile Christian communities: An exegetical study in Mark and 2 Corinthians" (PDF). dianoigo. Retrieved 15 April 2022. Geisenhanslüke, Achim; Mein, Georg; Overthun, Rasmus (2015) [2009]. Geisenhanslüke, Achim; Mein, Georg (eds.). Monströse Ordnungen: Zur Typologie und Ästhetik des Anormalen [Monstrous Orders: On the Typology and Aesthetics of the Abnormal]. Literalität und Liminalität (in German). Vol. 12. Bielefeld: Transcript Verlag. doi:10.1515/9783839412572. ISBN 978-3-8394-1257-2. Goetz, Hans-Werner (2016). Gott und die Welt. Religiöse Vorstellungen des frühen und hohen Mittelalters. Teil I, Band 3: IV. Die Geschöpfe: Engel, Teufel, Menschen [God and the world. Religious Concepts of the Early and High Middle Ages. Part I, Volume 3: IV. The Creatures: Angels, Devils, Humans] (in German). Vandenhoeck & Ruprecht. ISBN 978-3-8470-0581-0. Grant, Robert M. (2006). Irenaeus of Lyons. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-81518-0. Kelly, Henry Ansgar (2004). The Devil, demonology, and witchcraft: the development of Christian beliefs in evil spirits. Wipf and Stock Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59244-531-8. OCLC 56727898. Kolb, Robert; Dingel, Irene; Batka, Lubomir, eds. (2014). The Oxford Handbook of Martin Luther's Theology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960470-8. Koskenniemi, Erkki; Fröhlich, Ida (2013). Evil and the Devil. A&C Black. ISBN 978-0-567-60738-6. Lambert, Malcolm (1998). The Cathars. Wiley-Blackwell. ISBN 978-0-631-20959-1. Oberman, Heiko Augustinus (2006). Luther: Man Between God and the Devil. Yale University Press. ISBN 978-0-300-10313-7. Orlov, Andrei A. (2011). Dark Mirrors: Azazel and Satanael in Early Jewish Demonology. SUNY Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-3953-2. Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1986). Lucifer: The Devil in the Middle Ages. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9429-1. Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1987a). Satan: The Early Christian Tradition. Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9413-0. Russell, Jeffrey Burton (1987b). The Devil: Perceptions of Evil from Antiquity to Primitive Christianity. Ithaca, N.Y: Cornell University Press. ISBN 978-0-8014-9409-3. Theißen, Gerd (2009). Erleben und Verhalten der ersten Christen: Eine Psychologie des Urchristentums [Experience and Behavior of the First Christians: A Psychology of Early Christianity] (in German). Gütersloher Verlagshaus. ISBN 978-3-641-02817-6. Tyneh, Carl S. (2003). Orthodox Christianity: Overview and Bibliography. Nova Publishers. ISBN 978-1-59033-466-9. Tzamalikos, Panayiotis (2007). Origen: Philosophy of History & Eschatology. BRILL. ISBN 978-90-474-2869-5. |

出典 Boureau, Alain (2006). Satan the Heretic: The Birth of Demonology in the Medieval West. University of Chicago Press. ISBN 978-0-226-06748-3. ブリュッゲマン、ロミー(2010)。悪への恐怖:中世後期および近世初期の道化師、悪魔、悪魔の同盟者に関する文学における悪のコード化(ドイツ語)。 Königshausen & Neumann。ISBN 978-3-8260-4245-4。 Costen, Michael (1997). The Cathars and the Albigensian Crusade. Manchester University Press. ISBN 978-0-7190-4332-1. Farrar, Thomas J. (2014). 「初期の異邦人キリスト教コミュニティにおけるサタン:マルコによる福音書とコリントの信徒への手紙二における解釈学的研究」 (PDF). dianoigo. 2022年4月15日取得。 Geisenhanslüke, Achim; Mein, Georg; Overthun, Rasmus (2015) [2009]. ガイゼンハンスリュケ、アキム;マイン、ゲオルク(編)。『怪物の秩序:異常の類型学と美学について』 [Monstrous Orders: On the Typology and Aesthetics of the Abnormal]。リテラシーとリミナル性(ドイツ語)。第 12 巻。ビーレフェルト:Transcript Verlag。doi:10.1515/9783839412572。ISBN 978-3-8394-1257-2。 ゲッツ、ハンス・ヴェルナー (2016)。神と世界。中世初期および中世盛期の宗教観。第 I 部、第 3 巻:IV. 生き物たち:天使、悪魔、人間 [神と世界。中世初期および中世盛期の宗教的概念。第 I 部、第 3 巻:IV. 生き物たち:天使、悪魔、人間](ドイツ語)。ヴァンデンフック&ルプレヒト。ISBN 978-3-8470-0581-0。 グラント、ロバート M. (2006)。リヨンのイレネウス。ラウトリッジ。ISBN 978-1-134-81518-0。 ケリー、ヘンリー・アンスガー(2004)。悪魔、悪魔学、魔術:悪霊に関するキリスト教の信仰の発展。ウィップ・アンド・ストック出版社。ISBN 978-1-59244-531-8。OCLC 56727898。 コルブ、ロバート、ディンゲル、アイリーン、バトカ、ルボミール編(2014)。『オックスフォード・ハンドブック:マルティン・ルターの神学』オックス フォード大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-19-960470-8。 コスケニエミ、エルッキ、フレーリック、アイダ(2013)。『悪と悪魔』A&C Black。ISBN 978-0-567-60738-6。 ランバート、マルコム(1998)。カタリ派。ワイリー・ブラックウェル。ISBN 978-0-631-20959-1。 オーバーマン、ハイコ・アウグスティヌス(2006)。ルター:神と悪魔の間に立つ男。イェール大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-300-10313-7。 オルロフ、アンドレイ A. (2011)。『闇の鏡:初期ユダヤ教の悪魔学におけるアザゼルとサタナエル』。SUNY Press。ISBN 978-1-4384-3953-2。 ラッセル、ジェフリー・バートン(1986)。『ルシファー:中世の悪魔』。コーネル大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8014-9429-1。 ラッセル、ジェフリー・バートン(1987a)。『サタン:初期キリスト教の伝統』。コーネル大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8014-9413-0。 ラッセル、ジェフリー・バートン (1987b)。『悪魔:古代から原始キリスト教における悪の認識』。ニューヨーク州イサカ:コーネル大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8014-9409-3。 タイセン、ゲルト(2009)。『初期キリスト教徒の経験と行動:初期キリスト教の心理学』(ドイツ語)。ギュタースロー出版社。ISBN 978-3-641-02817-6。 タイネ、カール・S(2003)。正教キリスト教:概要と参考文献。ノヴァ出版社。ISBN 978-1-59033-466-9。 ツァマリコス、パナヨティス(2007)。オリゲネス:歴史哲学と終末論。ブリル。ISBN 978-90-474-2869-5。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Devil |

★悪

魔の文化史 / ジョルジュ・ミノワ著 ; 平野隆文訳、東京 : 白水社 , 2004.7. - (文庫クセジュ ; 876)

変 幻自在で、軽やかな肉体をもつ、空中に住むサタン—悪魔は、今も存在している!聖書が誕生するよりはるか昔のバビロニアに起源をもつ「彼ら」が、神や権力 に対する抵抗のシンボルとなってゆく四千年の歴史を、詳しく解説する。文学・映画・音楽などの、親しみやすい切り口からも語る、悪魔史入門の決定版。

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099