歴史主義のジレンマからの克服法

How to escape from your mental condition that has been caught by so called, "Historicism’s Dilemmas"

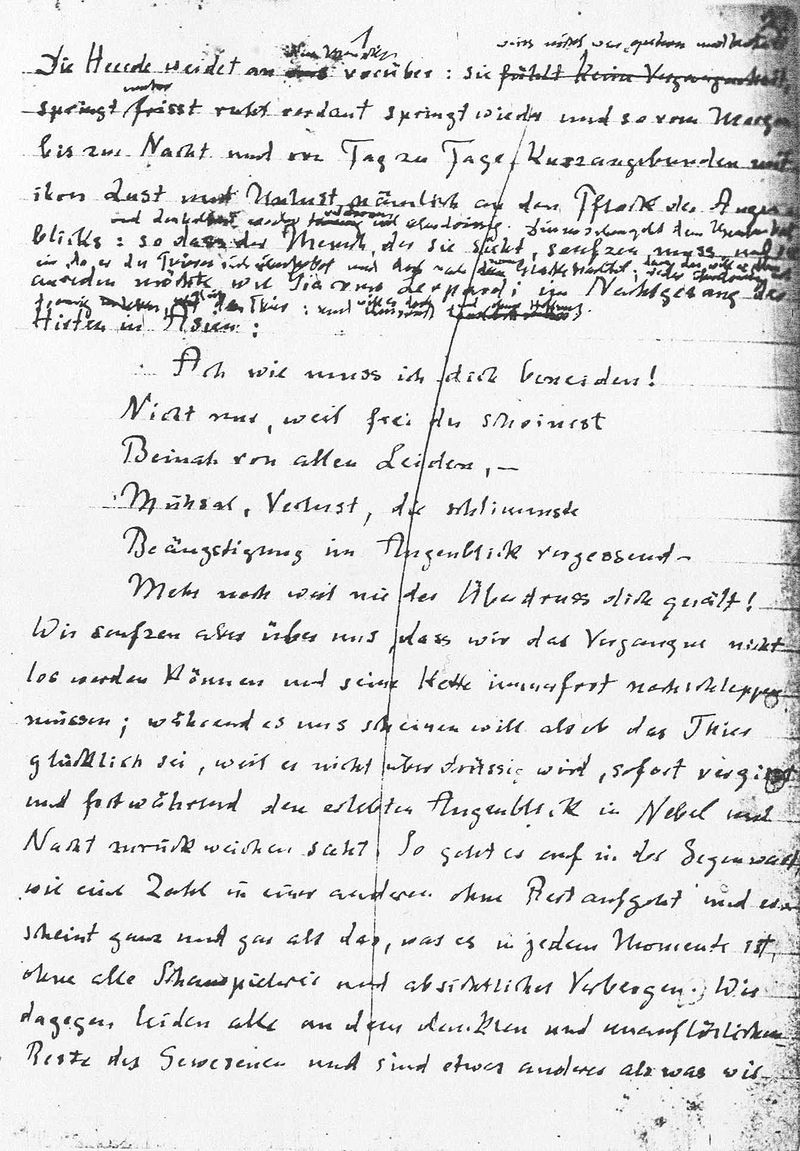

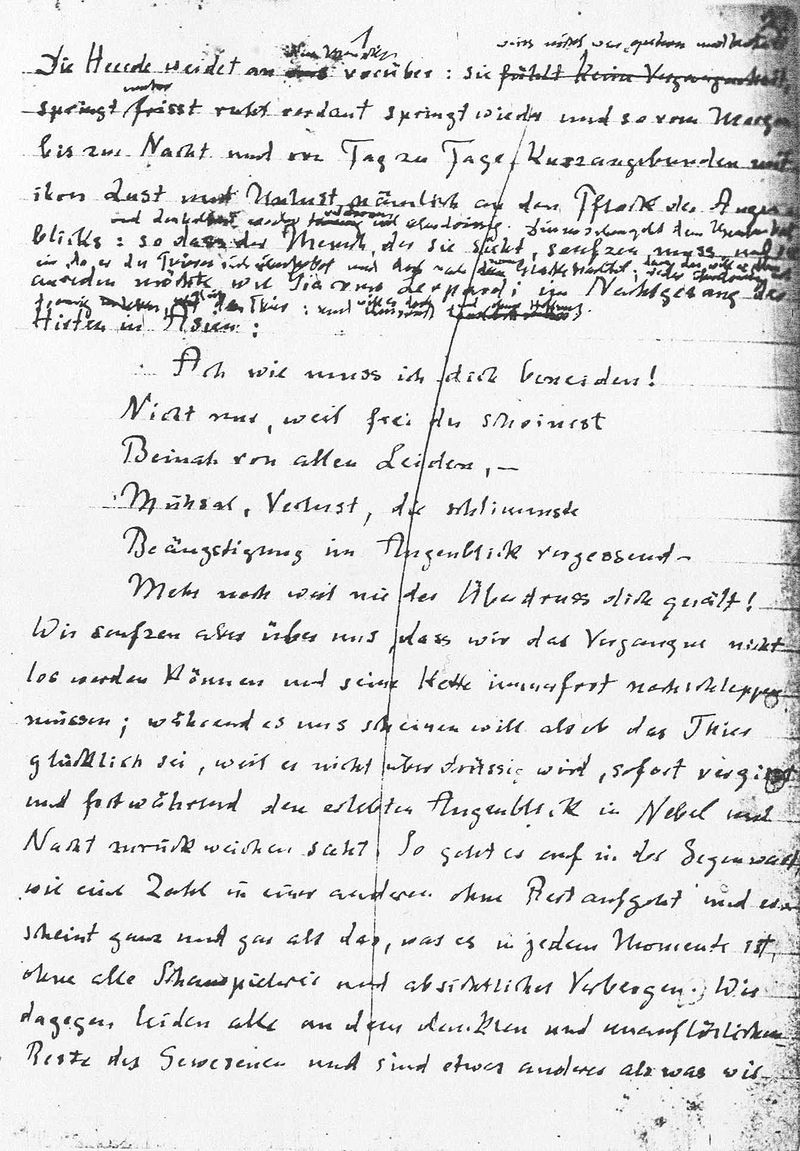

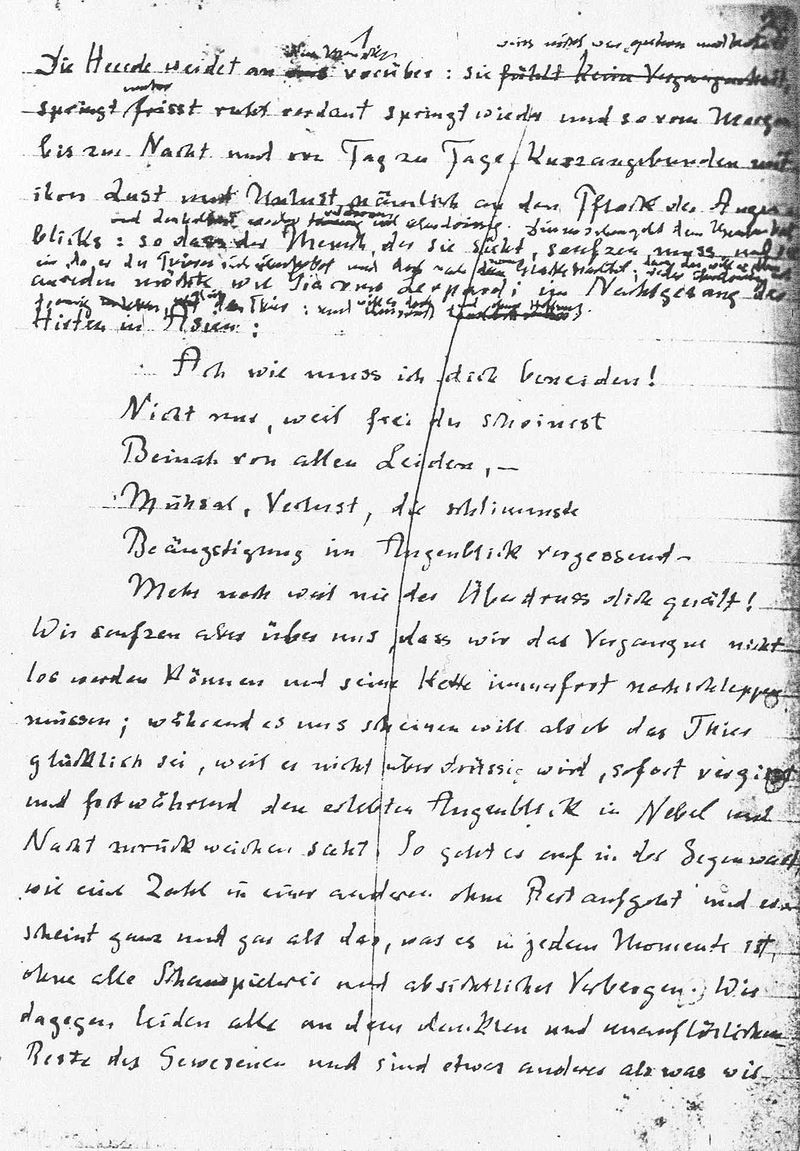

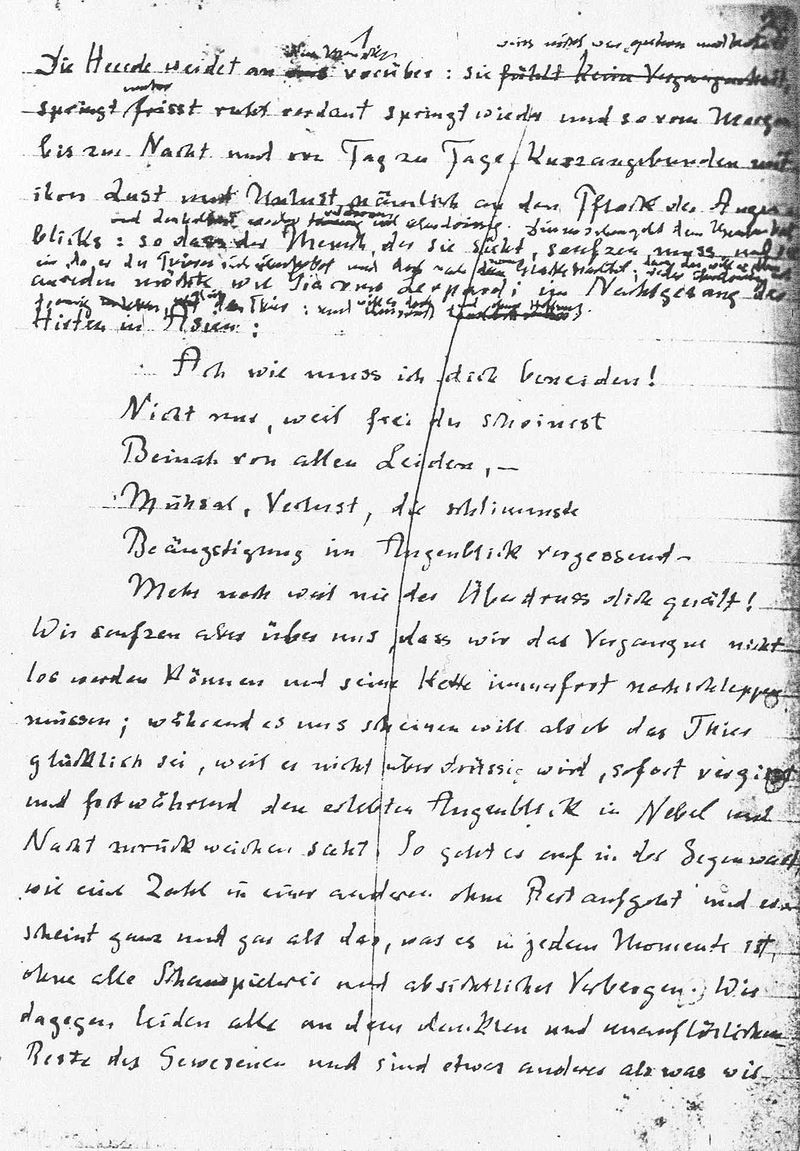

Draft for the first chapter of the second Unzeitgemässe Betrachtung

歴史主義(historicism)のジレンマとは、歴史家は 「歴史の外に立って歴史を俯瞰できる」という主張と、歴史家もまた歴史の中に存在するわけだから「歴史の外に立って歴史を俯瞰できることなどできない」と いう2つの異なる主張に挟まれることをいう。これは、歴史家が歴史分析をする過程のなかで、歴史の外側から俯瞰できるような心の状態——詳細な歴史事象に 精通した歴史家はその歴史を生きた人と同様あるいはそれ以上にものをよく知る——は経験から来るものであり、また、そのような歴史の物知りにこのようなこ とに納得するような人々の合意がまずある。そして、後者の「歴史の外に立って歴史を俯瞰できることなどできない」というのは、我々は時間的空間的存在だか ら、歴史を知るというものものまた、歴史家の固有な視座や立場から逃れて存在するわけがないという認識論あるいは理論的な立場からの反省意識である。

ポストモダンの思想家フレデリック・ジェイムソン(Fredric Jameson, 1934- )は、これまで、人々が、このような歴史主義のジレンマから逃れてきた方法には4つほどあると指摘した。それぞれ、1)尚古主義(好古主義ともいう)、 2)実存主義的歴史主義、3)構造的類型学、4)ニーチェ的な反歴史主義(counter-historicism)である。

"James

Clifford has recently written of the imperative of

counter-historical work, “reaching into the past for alternative

futures.” Thinking counter-historically, he goes on to say, “is not

about claiming that it could — or should — have been different. It’s a

process of thinking historically in the present, breaking the spell of

inevitability” (Clifford 329)."(Flint, 1999:511)

ジェームズ・クリフォードは最近、カウンターヒスト

リーの必要性を説いている。反歴史的に考えるということは、「違ったかもしれない、

あるいは違ったはずだと主張することではない。必然性の呪縛を解き放ち、現在において歴史的に考えるプロセスなのである」。

ニーチェの反歴史(=反時代的)というアイディアは「歴史の効用と害悪」のなかで指摘されて いる。反歴史は、好古趣味的歴史記述も、記念碑的歴史記述を放棄して、批判的アプローチをとる立場である。

反歴史の立場は、デイヴィッド・ビアールによれば、ヴァルター・ベンヤミンが「歴史哲学テー ゼVII」において「歴史を逆なでする」アプローチに酷似する。

"Think of the darkness and the great cold / In this valley, which resounds with misery. – Brecht, Threepenny Opera/ Fustel de Coulanges recommended to the historian, that if he wished to reexperience an epoch, he should remove everything he knows about the later course of history from his head. There is no better way of characterizing the method with which historical materialism has broken. It is a procedure of empathy. Its origin is the heaviness at heart, the acedia, which despairs of mastering the genuine historical picture, which so fleetingly flashes by. The theologians of the Middle Ages considered it the primary cause of melancholy. Flaubert, who was acquainted with it, wrote: “Peu de gens devineront combien il a fallu être triste pour ressusciter Carthage.” [Few people can guess how despondent one has to be in order to resuscitate Carthage.] The nature of this melancholy becomes clearer, once one asks the question, with whom does the historical writer of historicism actually empathize. The answer is irrefutably with the victor. Those who currently rule are however the heirs of all those who have ever been victorious. Empathy with the victors thus comes to benefit the current rulers every time. This says quite enough to the historical materialist. Whoever until this day emerges victorious, marches in the triumphal procession in which today’s rulers tread over those who are sprawled underfoot. The spoils are, as was ever the case, carried along in the triumphal procession. They are known as the cultural heritage. In the historical materialist they have to reckon with a distanced observer. For what he surveys as the cultural heritage is part and parcel of a lineage [Abkunft: descent] which he cannot contemplate without horror. It owes its existence not only to the toil of the great geniuses, who created it, but also to the nameless drudgery of its contemporaries. There has never been a document of culture, which is not simultaneously one of barbarism. And just as it is itself not free from barbarism, neither is it free from the process of transmission, in which it falls from one set of hands into another. The historical materialist thus moves as far away from this as measurably possible. He regards it as his task to brush history against the grain." - On the Concept of History, VII

「不幸が響き渡るこの谷の闇と寒さを思え。-

ブレヒト『三文オペラ』/フステル・ド・クーランジュは歴史家に、ある時代を再び体験したければ、その後の歴史の流れについて知っていることをすべて頭か

ら取り除くべきだと勧めた。史的唯物論が破たんした方法を特徴づけるのに、これ以上の方法はない。それは共感の手続きである。その起源は、あっという間に

過ぎ去ってしまう真の歴史像を理解することに絶望する心の重苦しさ、アケディアにある。中世の神学者たちは、これを憂鬱の第一の原因と考えた。中世の神学

者たちは、これを憂鬱の第一の原因とみなし、これを知っていたフローベールはこう書いている。[カルタゴを蘇生させるためには、人はどれほど落胆しなけれ

ばならないかを想像できる人はほとんどいない。]

この憂鬱の正体は、歴史主義の歴史作家が実際に誰と共感しているのかという問いを立てれば、明らかになる。その答えはまぎれもなく勝者である。しかし、現

在支配している人々は、過去に勝利したすべての人々の後継者である。したがって、勝者への共感は常に現在の支配者を利することになる。このことは、歴史的

唯物論者には十分なことである。今日まで勝利を収めてきた者が誰であれ、今日の支配者たちが足元で倒れている者たちの上を歩く凱旋行進をする。戦利品は、

かつてそうであったように、凱旋行進とともに運ばれる。それらは文化遺産として知られている。史的唯物論者にとっては、文化遺産は距離を置いた観察者のも

のである。というのも、彼が文化遺産として調査しているものは、彼が恐怖なくしては思い描くことのできない系譜[Abkunft:子孫]の一部分であり一

部分だからである。その存在は、それを創造した偉大な天才たちの労苦に負うだけでなく、同時代の人々の名もなき苦役にも負っている。文化の文書が、同時に

野蛮の文書でなかったことはない。そして、それ自体が野蛮と無縁でないように、文化もまた、ある人の手から別の人の手へと受け継がれる過程と無縁ではな

い。このように、歴史的唯物論者は、可能な限りこのことから遠ざかる。歴史を逆さまにすることが、彼の仕事なのである。」

◎今村仁司『ベ ンヤミンの〈問い〉』講談社、1995:︎▶︎benjamins_inquiry_imamura1995_Part1.pdf▶benjamins_inquiry_imamura1995_Part2.pdf︎︎▶︎benjamins_inquiry_imamura1995_Part3.pdf▶︎︎

序論:ベンヤミンのアクチュアリティ

1.認識の方法

2.歴史と歴史家の形象

3.暴力と崇高

4.倦怠論

5.根源史の概念

★ニーチェ『反時代的考察』1876年

| Untimely Meditations

(German: Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen), also translated as Unfashionable

Observations[1] and Thoughts Out of Season,[2] consists of four works

by the philosopher Friedrich Nietzsche, started in 1873 and completed

in 1876. The work comprises a collection of four (out of a projected 13) essays concerning the contemporary condition of European, especially German, culture. A fifth essay, published posthumously, had the title "We Philologists", and gave as a "Task for philology: disappearance".[3] Nietzsche here began to discuss the limitations of empirical knowledge, and presented what would appear compressed in later aphorisms. It combines the naivete of The Birth of Tragedy with the beginnings of his more mature polemical style. It was Nietzsche's most humorous work, especially for the essay "David Strauss: the confessor and the writer." ++++++++++++++ Die Unzeitgemäßen Betrachtungen bestehen aus vier Abhandlungen von Friedrich Nietzsche, die zwischen 1873 und 1876 erschienen: Erstes Stück: David Strauss, der Bekenner und der Schriftsteller, 1873; Zweites Stück: Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben, 1874; Drittes Stück: Schopenhauer als Erzieher, 1874; Viertes Stück: Richard Wagner in Bayreuth, 1876. Nietzsche hatte zunächst vor, den Unzeitgemäßen Betrachtungen die ganzen 30er Jahre seines Lebens zu widmen. In seinen Plänen tauchen bis zu 13 Arbeitstitel auf mit Themen wie „Staat“, „Religion“, „Naturwissenschaft“, „Arbeit und Eigentum“ und „Wir Philologen“. Realisiert wurden nur vier der Betrachtungen.[1] |

Untimely

Meditations』(ドイツ語:Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen)は、『Unfashionable

Observations』[1]、『Thoughts Out of

Season』[2]とも訳され、哲学者フリードリヒ・ニーチェが1873年に書き始め、1876年に完成させた4つの作品から成る。 この作品は、ヨーロッパ、特にドイツ文化の現代的状況に関する4つのエッセイ(予定されていた13編のうち)から成る。ニーチェはここで、経験的知識の限 界について論じ始め、後の格言に圧縮されて現れるものを提示した。悲劇の誕生』の素朴さと、より成熟した極論的文体の始まりが組み合わされている。ニー チェの最もユーモラスな作品であり、特に「ダヴィッド・シュトラウス:告白者と作家」というエッセイが有名である。 ++++++++++++++ 1873年から1876年にかけて発表されたフリードリヒ・ニーチェの4つのエッセイから成る: 第一篇:ダヴィッド・シュトラウス、告白者と作家(1873年)、第二篇:人生における歴史の利用と不利益について(1874年)、第三篇:教育者として のショーペンハウアー(1874年)、第四篇:バイロイトにおけるリヒャルト・ワーグナー(1876年)である。 ニーチェは当初、人生の30年代すべてを『未時の省察』に捧げるつもりだった。国家」、「宗教」、「自然科学」、「労働と財産」、「われわれ言語学者」と いったテーマで、最大13の著作が計画されていた。このうち、実現したのはわずか4つだった[1]。 |

| Publication Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen has been one of the more difficult of Nietzsche's titles to be translated into English, with each subsequent translation offering a new variation. Thus: Untimely Meditations (Hollingdale, 1983), Thoughts Out of Season (Ludovici, 1909), Untimely Reflections (Ronald Hayman, 1980), Unmodern Observations (Arrowsmith, 2011) and Inopportune Speculations, Unfashionable Observations or Essays in Sham Smashing (H. L. Mencken, 1908). Many different plans for the series are found in Nietzsche's notebooks, most of them showing a total of thirteen essays. The titles and subjects vary with each entry, the project conceived to last six years (one essay every six months). A typical outline dated "Autumn 1873" reads as follows: The Cultural Philistine History The Philosopher The Scholar Art The Teacher Religion State War Nation The Press Natural Science Folk Society Commerce Language Nietzsche abandoned the project after completing only four essays, seeming to lose interest after the publication of the third.[4] |

出版 Unzeitgemässe Betrachtungen』は、ニーチェのタイトルの中でも英訳が困難なもののひとつであり、翻訳が進むごとに新たなバリエーションが生まれている。こ のように Untimely Meditations』(Hollingdale, 1983)、『Thoughts Out of Season』(Ludovici, 1909)、『Untimely Reflections』(Ronald Hayman, 1980)、『Unmodern Observations』(Arrowsmith, 2011)、『Inopportune Speculations, Unfashionable Observations or Essays in Sham Smashing』(H. L. Mencken, 1908)など。 ニーチェのノートには、このシリーズのさまざまな企画が多数残されており、そのほとんどが合計13のエッセイを紹介している。タイトルと主題は項目ごとに 異なり、プロジェクトは6年間(半年ごとに1本のエッセイ)続く予定だった。1873年秋」の典型的なアウトラインは次のようなものである: 文化の俗人 歴史 哲学者 学者 芸術 教師 宗教 国家 戦争 国家 報道 自然科学 民間社会 商業 言語 ニーチェは4つのエッセイを書き上げただけでこのプロジェクトを放棄し、3番目のエッセイの出版後に興味を失ったようだった[4]。 |

| "David Strauss: the Confessor

and the Writer" "David Strauss: the Confessor and the Writer", 1873 ("David Strauss: der Bekenner und der Schriftsteller") attacks David Strauss's "The Old and the New Faith: A Confession" (1871), which Nietzsche holds up as an example of the German thought of the time. He paints Strauss's "New Faith"—scientifically-determined universal mechanism based on the progression of history—as a vulgar reading of history in the service of a degenerate culture, polemically attacking not only the book but also Strauss as a Philistine of pseudo-culture. |

「ダヴィッド・シュトラウス:告白者と作家 ダヴィッド・シュトラウス:告白者と作家』1873年("David Strauss: der Bekenner und der Schriftsteller")は、ダヴィッド・シュトラウスの『旧教と新教』を攻撃している: ニーチェが当時のドイツ思想の一例として取り上げた『告白』(1871年)を攻撃している。彼はシュトラウスの「新信仰」--歴史の進行に基づく科学的に 決定された普遍的メカニズム--を、退廃した文化に奉仕する低俗な歴史の読み方として描き、この本だけでなくシュトラウスをも偽文化のペリシテ人として極 論的に攻撃する。 |

"On the Use and Abuse of

History for Life" "On the Use and Abuse of

History for Life"Draft for the first chapter of the second Unzeitgemässe Betrachtung "On the Use and Abuse of History for Life", 1874 ("Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben") offers—instead of the prevailing view of "knowledge as an end in itself"—an alternative way of reading history, one where living life becomes the primary concern, along with a description of how this might improve the health of a society. It also introduces an attack against the basic precepts of classic humanism. In this essay, Nietzsche attacks both the historicism of man (the idea that man is created through history) and the idea that one can possibly have an objective concept of man, since a major aspect of man resides in his subjectivity. Nietzsche expands the idea that the essence of man dwells not inside of him, but rather above him, in the following essay, "Schopenhauer als Erzieher" ("Schopenhauer as Educator"). Glenn Most argues for the possible translation of the essay as "The Use and Abuse of History Departments for Life", as Nietzsche used the term Historie and not Geschichte. Furthermore, he alleges that this title may have its origins via Jacob Burckhardt, who would have referred to Leon Battista Alberti's treatise, De commodis litterarum atque incommodis (On the Advantages and Disadvantages of Literary Studies, 1428). Glenn Most argues that the untimeliness of Nietzsche here resides in calling for a return, beyond historicism, to Humboldt's humanism, and, maybe even beyond, to the first humanism of the Renaissance.[3] This particular essay is notable for showcasing the increasingly strident elitism Nietzsche was developing inside his mind. Nietzsche's "untimely" thesis flies directly into the face of demotic modernity in aggressively asserting the dispensability of the majoritarian mass of humanity and history's only meaning residing solely in "great individuals": To me, the masses seem to be worth a glance only in three respects: first as blurred copies of great men, presented on bad paper with worn out printing plates, then as the resistance against the great men, and finally as working implements of the great. For the rest, let the devil and statistics carry them off.[5] |

"人生のための歴史の利用と濫用について" "人生のための歴史の利用と濫用について"第2回『Unzeitgemässe Betrachtung』第1章草稿 1874年の "On the Use and Abuse of History for Life"("生活のための歴史の利用と濫用について")は、「知識それ自体が目的である」という一般的な見解の代わりに、「生活を営むことが第一の関心 事である」という歴史の読み方を提示し、それがどのように社会の健全性を向上させるかを説明している。また、古典的人文主義の基本的教訓に対する攻撃も紹 介している。 このエッセイでニーチェは、人間の歴史主義(人間は歴史を通して創造されるという考え方)と、人間の主要な側面は主観性にあるのだから、客観的な人間概念 を持ちうるという考え方の両方を攻撃している。ニーチェは、人間の本質は人間の内部にあるのではなく、むしろ人間の上位にあるという考えを、次のエッセイ 『教育者としてのショーペンハウアー』("Schopenhauer als Erzieher")で展開している。グレン・モストは、ニーチェがGeschichteではなくHistorieという用語を使っていることから、この 小論を「人生における歴史部の利用と濫用」と訳す可能性を主張している。さらに、このタイトルの起源はヤコブ・ブルクハルトにあり、彼はレオン・バッティ スタ・アルベルティの論文『De commodis litterarum atque incommodis』(文学研究の利点と欠点について、1428年)を参照したのではないかと主張している。グレン・モストは、ここでのニーチェの非時 代性は、歴史主義を超えて、フンボルトの人文主義への回帰を求めるところにあり、さらにその先には、ルネサンスの最初の人文主義への回帰があるかもしれな いと論じている[3]。 この特別なエッセイは、ニーチェが心の中でますますエリート主義を強めていたことを示すものとして注目される。ニーチェの「時期尚早」なテーゼは、デモ ティックな近代の面目躍如たるものであり、人類の多数主義的な大衆の無用の長物と、「偉大な個人」のみに存在する歴史の唯一の意味を積極的に主張してい る: 私にとっては、大衆は3つの点でしか一見の価値がないように思える。第一に、印刷版が擦り切れた粗悪な紙に印刷された偉大な人物の不鮮明なコピーとして、 次に、偉大な人物に対する抵抗勢力として、最後に、偉大な人物の作業道具として。それ以外は、悪魔と統計に任せておけばいい[5]。 |

| Schopenhauer as Educator Schopenhauer as Educator ("Schopenhauer als Erzieher"), 1874, describes how the philosophic genius of Schopenhauer might bring on a resurgence of German culture. Nietzsche gives special attention to Schopenhauer's individualism, honesty and steadfastness as well as his cheerfulness, despite Schopenhauer's noted pessimism. |

教育者としてのショーペンハウアー 1874年の『教育者としてのショーペンハウアー』("Schopenhauer als Erzieher")は、天才的な哲学者ショーペンハウアーがいかにしてドイツ文化の復活をもたらすかを描いている。ニーチェは、ショーペンハウアーの個 人主義、正直さ、堅実さ、そして、ショーペンハウアーが悲観主義者であると指摘されているにもかかわらず、彼の明るさに特別な注意を払っている。 |

| Richard Wagner in Bayreuth Richard Wagner in Bayreuth, 1876 (that is, after a gap of two years from the previous essay), investigates the music, drama and personality of Richard Wagner—less flatteringly than Nietzsche's friendship with his subject might suggest. The original draft was in fact more critical than the final version. Nietzsche considered not publishing it because of his changing attitudes to Wagner and his art. He was persuaded to redraft the article by his friend, the enthusiastic Wagnerian Peter Gast who helped him prepare a less contentious version.[6] |

バイロイトのリヒャルト・ワーグナー バイロイトのリヒャルト・ワーグナー』(1876年)は、ニーチェとその対象との親交から想像されるよりも、お世辞抜きで、リヒャルト・ワーグナーの音 楽、演劇、人格を調査している。原案は最終版よりも批判的だった。ニーチェは、ワーグナーとその芸術に対する態度の変化から、出版を見送ることも考えた。 ニーチェは、友人の熱心なワグネリアンであるペーター・ガストに説得され、より批判的でない原稿を書き直すことにした[6]。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Untimely_Meditations |

|

| Inhalt der vier Unzeitgemäßen

Betrachtungen Erstes Stück: David Strauß, der Bekenner und der Schriftsteller Die Schrift ist eine Polemik gegen den „Bildungsphilister“ David Friedrich Strauß, den Nietzsche mit derben Worten zu verhöhnen sucht. Nietzsche lehnt die sich gegen Schopenhauer wendende säkularisierte Frömmigkeit von Strauß ab und unterstellt ihm ein parasitäres Verhältnis zu den deutschen Klassikern. Strauß bediene sich einer korrupten deutschen Sprache, und so übt Nietzsche denn auch Sprachkritik im Stile Schopenhauers.[1] Das Gelegenheitswerk, das 1873 erschien, war ein gesellschaftlicher Skandal, nicht zuletzt wegen des Gebrauchs des Kampfbegriffes „Bildungsphilister“. Der so bezeichnete David Strauß hatte mit seiner bibelkritischen Untersuchung Das Leben Jesu um 1835 einen gesellschaftlichen Skandal ausgelöst und wurde in späteren Jahren zunehmend zu einem angesehenen Vertreter einer materialistisch beeinflussten Geistesrichtung. Zweites Stück: Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben → Hauptartikel: Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben Das Zweite Stück ist eine Kritik an der Geschichtswissenschaft seiner Zeit, oder besser an dem falschen Verhältnis, das man zu ihr aufgebaut und tradiert habe. Nietzsche ist durchaus der Meinung, dass von der historischen Betrachtung etwas Heilsames ausgehen könnte, wenn das Verhältnis denn ein richtiges wäre, aber er bescheinigt seiner Zeit eine kolossale Überbewertung alles Historischen und der historischen Bildung überhaupt. Nietzsche ist also nicht nur der Meinung, dass man die Historie völlig falsch versteht, sondern auch, dass sie bei Weitem überbewertet wird.[1] Der Text, den Nietzsche 1874 veröffentlichte, hatte eine sehr große Wirkungsgeschichte, die über die Philosophie weit hinausreicht; bis heute spielt er eine wesentliche Rolle in kontroversen Diskursen von Philosophen, Historikern und Kulturwissenschaftlern.[2] Daher gilt die Schrift Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben als die mit Abstand wirkmächtigste der vier Unzeitgemäßen Betrachtungen. Drittes Stück: Schopenhauer als Erzieher Diese dritte, 1874 erschienene Unzeitgemäße Betrachtung ist eine Hommage an Nietzsches philosophischen Lehrer Arthur Schopenhauer, in dem Nietzsche einen Erzieher erkennt und anerkennt. Einen Erzieher nennt Nietzsche jene großen Menschen und Genies, die helfen, die Menschen von äußeren und äußerlichen Nebensächlichkeiten und Identitäten zu befreien und zu sich selbst zu finden. Was Nietzsche an Schopenhauer besonders schätzt, ist dessen Wahrhaftigkeit – auch im Leiden – und dessen Liebe zur Wahrheit. Im Spiegel dieser Wahrheitsliebe findet Nietzsche zu sich selbst.[1] Viertes Stück: Richard Wagner in Bayreuth Wagners Pläne zu den Festspielen in Bayreuth schienen 1874 zu scheitern und die erste Fassung von Richard Wagner in Bayreuth geht auf Gründe für Wagners mögliches Scheitern ein. Es sind überraschend kritische Befunde über Wagners moralische und künstlerische Eigenschaften, in denen Nietzsche zunächst den Grund für Wagners drohendes Scheitern erblickt. Als der Text 1875 fertig ist, verwirft Nietzsche ihn aber. Inzwischen waren die Bayreuther Festspiele für 1876 angesetzt und Nietzsche griff den Plan für die Unzeitgemäße Betrachtung wieder auf, jetzt aber als Würdigung von Wagners Lebensleistung im Moment des größten Erfolges. Und trotzdem offenbart der Text ernüchternde Einblicke in Wagners Natur: von Wagners Dilettantismus ist die Rede, aber auch von dessen schauspielerischem Unvermögen. Der Text ist über weite Strecken eine geschickte Collage von Wagnerzitaten, die versuchen, den alten revolutionären Geist von Wagner zu beschwören.[1] Wirkungsgeschichtlich blieb der Text, der 1876 erschien, hinter den beiden späteren Wagnerkritiken Der Fall Wagner und Nietzsche contra Wagner zurück. |

時機を逸した4つの反省の内容 第一篇:ダヴィッド・シュトラウス、告白者と作家 この作品は、ニーチェが粗野な言葉で嘲笑しようとしている「教育の哲学者」ダヴィド・フリードリヒ・シュトラウスに対する極論である。ニーチェは、ショー ペンハウアーに向けられたシュトラウスの世俗化された敬虔主義を否定し、ドイツ古典に寄生していると非難する。シュトラウスは堕落したドイツ語を使ってい たので、ニーチェもショーペンハウアー風の言語を批判した[1]。 1873年に時折発表されたこの著作は、「ビルドゥングスフィリスター」という闘争用語が使われていたこともあって、社会的なスキャンダルとなった。その ようなレッテルを貼られたダヴィッド・シュトラウスは、1835年頃に『イエスの生涯』という聖書批判的な研究書を発表して社会的なスキャンダルを引き起 こし、後年には唯物論の影響を受けた知的運動の代表者としてますます尊敬を集めるようになった。 枚目:人生における歴史の利点と欠点について → 主な記事 人生にとっての歴史の利点と欠点について 第二の戯曲は、同時代の歴史科学というか、築き上げられ伝えられてきた誤った関係に対する批判である。ニーチェは確かに、関係が正しければ歴史観察から有 益なものが生まれるという意見を持っているが、彼は同時代のあらゆる歴史的なもの、歴史教育一般がとんでもなく過大評価されていたことを証言している。そ れゆえニーチェは、歴史は完全に誤解されているという意見だけでなく、歴史は非常に過大評価されているという意見も持っている[1]。 ニーチェが1874年に発表したこのテキストは、哲学の枠をはるかに超えた大きな影響力を持ち、今日に至るまで、哲学者、歴史学者、文化科学者の間で論争 を呼ぶ言説の中で重要な役割を担っている[2]。 このため、『Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben』は、4つの『Unzeitgemäßen Betrachtungen』の中で最も影響力のあるものと考えられている。 第三篇:教育者としてのショーペンハウアー 1874年に出版されたこの3番目の『未時の省察』は、ニーチェの哲学の師であるアルトゥール・ショーペンハウアーへのオマージュであり、ニーチェは ショーペンハウアーを教育者として認め、その存在を認めている。ニーチェは、人々を外面的・外在的な些細なことやアイデンティティから解放し、自分自身を 見出す手助けをする偉大な人々や天才を教育者と呼んでいる。ニーチェがショーペンハウアーについて特に高く評価しているのは、彼の真実性である。この真実 の愛の鏡の中に、ニーチェは自分自身を見出す[1]。 第4曲:バイロイトのリヒャルト・ワーグナー ワーグナーのバイロイト音楽祭計画は1874年に失敗に終わったようで、『バイロイトにおけるリヒャルト・ワーグナー』の第1版は、ワーグナーの失敗の可 能性の理由を取り上げている。これは、ワーグナーの道徳的・芸術的資質に関する驚くべき批判的所見であり、ニーチェは当初、そこにワーグナーの目前に迫っ た失敗の理由を見出していた。しかし、1875年にテキストが完成したとき、ニーチェはそれを却下した。その間にバイロイト音楽祭が1876年に予定さ れ、ニーチェは再び『Unzeitgemäße Betrachtung』の構想を練る。ワーグナーのディレッタンティズムが語られる一方で、彼の行動力のなさについても語られている。長い文章は、ワー グナーの引用を巧みにコラージュしたもので、ワーグナーの古い革命精神を呼び起こそうとしている[1]。 歴史的なインパクトという点では、1876年に発表されたこのテキストは、後に発表された2つのワーグナー批評『ワーグナーの没落』と『ワーグナーに対抗 するニーチェ』に遅れをとった。 |

| Ausgaben Siehe Nietzsche-Ausgabe für allgemeine Informationen. Den vollständigen Text liefert die Kritische Studienausgabe (KSA) in Band 1. Der Band KSA 1 erscheint auch als Einzelband unter der ISBN 3-423-30151-1. Der zugehörige Apparat befindet sich im Kommentarband (KSA 14), S. 64–74. Es gibt (der KSA textkritisch unterlegene) Ausgaben aller Unzeitgemäßen Betrachtungen im Goldmann Verlag mit Anmerkungen von Peter Pütz, ISBN 3-442-07638-2, im Insel Verlag mit einem Nachwort von Ralph-Rainer Wuthenow, ISBN 3-458-32209-4. Kommentare Barbara Neymeyr: Kommentar zu Nietzsches Unzeitgemässen Betrachtungen. I. David Strauss der Bekenner und der Schriftsteller. II. Vom Nutzen und Nachtheil der Historie für das Leben (= Historischer und kritischer Kommentar zu Friedrich Nietzsches Werken. Band 1/2). De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2020, ISBN 978-3-11-028682-3. – XXV + 652 S. Barbara Neymeyr: Kommentar zu Nietzsches Unzeitgemässen Betrachtungen. III. Schopenhauer als Erzieher. IV. Richard Wagner in Bayreuth (= Historis |

エディション 一般的な情報はニーチェ版を参照。 全テキストはKritische Studienausgabe(KSA)第1巻で提供されている。 KSA第1巻は単行本としてISBN 3-423-30151-1でも出版されている。対応する注釈は注釈巻(KSA 14)の64-74頁にある。 すべてのUnzeitgemäße Betrachtungenの版(KSAよりテキスト批評的に劣る)がGoldmann Verlagから出版されている。 ゴールドマン出版、ペーター・ピュッツによる注釈付き、ISBN 3-442-07638-2、 ラルフ=ライナー・ヴューテノフによる後書き付きでインゼル出版(ISBN 3-458-32209-4)。 解説書 バーバラ・ネイマイヤー:『ニーチェの不時の反省』解説。I. 告白者ダヴィッド・シュトラウスと作家。II Vom Nutzen und Nachtheil der Historie für das Leben(=フリードリヒ・ニーチェ著作の歴史的・批評的解説。第1/2巻)。De Gruyter, Berlin / Boston 2020, ISBN 978-3-11-028682-3. バーバラ・ネイマイヤー:ニーチェ『未時の省察』の解説。III 教育者としてのショーペンハウアー。IV.バイロイトにおけるリヒャルト・ワーグナー バイロイトにおけるリヒャルト・ワーグナー(=ヒストリス |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Unzeitgem%C3%A4%C3%9Fe_Betrachtungen |

リンク

文献

その他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆