Ewig Wiederkehren

(Eternal Recurrence)

アンナ・カレーニナ/Sisyphus by Titian (1548–49) /Giotto di Bondoneによるキリストの磔刑

Ewig Wiederkehren

(Eternal Recurrence)

アンナ・カレーニナ/Sisyphus by Titian (1548–49) /Giotto di Bondoneによるキリストの磔刑

★永劫回帰はフリードリヒ・ニーチェの哲学の中心的な考え方であり、それによれば、あらゆる 出来事が無限に繰り返される。フリードリヒ・ニーチェにとって、この循環的な時間の理解は、生命に対する最高の肯定の基礎である。

★しばしば、現代人にとって永劫回帰は、シジフォスの神話に似て、人間経験が全く同じように 繰り返されるという意味で、[懲罰としての]恐怖の対象のように思えるが、フリードリヒ・ニーチェは、このことを良きものとして捉えており、「生命に対す る最高の肯定の基礎」あるいは、ツァラトゥストラの超人の思想として考えられている。

★また、毎年繰り返される「聖週 間」のキリストの受難劇は、生きている人間(とりわけカソリック教徒)にとって、毎年毎年、キリストの復活が再演されるが、これも、一種の生きている限り、あるいはキリスト教が存続しつづけるか ぎりの永劫回帰の神話を再演(=表象)しているともいえるのである。

☆レフ・トルストイの小説『アンナ・カレーニナ』の小説を読む人類にとって、小説のなかの主人公であるエージェントにとっては、物語のなかで、永遠に鉄道自殺を繰り返すシジフォス的な《実存的理性》を体現する存在になる。

| Die Ewige

Wiederkunft

des Gleichen ist ein zentraler Gedanke in Friedrich Nietzsches

Philosophie, dem zufolge sich alle Ereignisse unendlich oft

wiederholen. Dieses zyklische Zeitverständnis ist für Nietzsche die

Grundlage höchster Lebensbejahung. |

永劫回帰はフリードリヒ・ニーチェの哲学の中心的な考え方であり、それ

によれば、あらゆる出来事が無限に繰り返される。ニーチェにとって、この循環的な時間の理解は、生命に対する最高の肯定の基礎である。 |

| Inhaltsverzeichnis 1 Der Gedanke Nietzsches 1.1 In Also sprach Zarathustra 1.2 Die kosmologische Hypothese 1.3 Deutungen 2 Diskutierte Parallelen 3 Literatur 4 Weblinks 5 Einzelnachweise |

目次 1 ニーチェの思想 1.1 『ツァラトゥストラはこう言った』 1.2 宇宙論的仮説 1.3 解釈 2 類似点について考察する 3 参考文献 4 ウェブリンク 5 参考文献 |

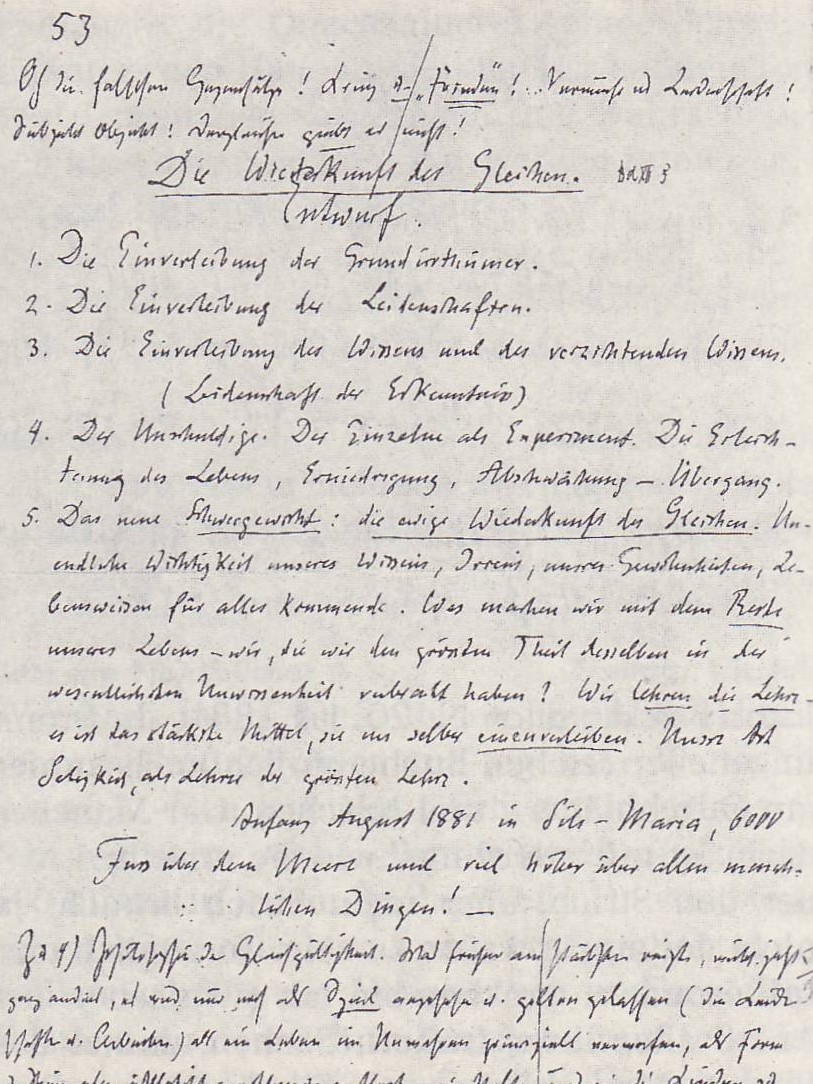

Der Gedanke Nietzsches Ort von Nietzsches Inspiration: „bei einem mächtigen pyramidal aufgethürmten Block unweit Surlei“.  Niederschrift nach Nietzsches mystischem Erlebnis, „6000 Fuss über dem Meere und viel höher über allen menschlichen Dingen“. Nietzsche selbst beschrieb in seiner Autobiographie Ecce homo, wie ihn dieser Gedanke in einem Augenblick der Inspiration überfiel:[1] „Die Grundconception des Werks [Also sprach Zarathustra], der Ewige-Wiederkunfts-Gedanke, diese höchste Formel der Bejahung, die überhaupt erreicht werden kann –, gehört in den August des Jahres 1881: er ist auf ein Blatt hingeworfen, mit der Unterschrift: ‚6000 Fuss jenseits von Mensch und Zeit.‘ Ich ging an jenem Tage am See von Silvaplana durch die Wälder; bei einem mächtigen pyramidal aufgethürmten Block unweit Surlei machte ich Halt. Da kam mir dieser Gedanke.“[2] Diese Schilderung wird durch ein entsprechendes Fragment in Nietzsches Nachlass bestätigt,[3] das dort weitere Betrachtungen nach sich zieht, in denen bald die Figur Zarathustra auftaucht. Zum ersten Mal vorgestellt hat Nietzsche den Gedanken dann im Vierten Buch, Aphorismus 341, von Die fröhliche Wissenschaft und damit direkt vor dem Anfang von Also sprach Zarathustra. Dies ist die ausführlichste Beschreibung des Gedankens außerhalb des Nachlasses und enthält, abgesehen vom Namen, bereits alle Elemente der Lehre: „Das grösste Schwergewicht. – Wie, wenn dir eines Tages oder Nachts, ein Dämon in deine einsamste Einsamkeit nachschliche und dir sagte: ‚Dieses Leben, wie du es jetzt lebst und gelebt hast, wirst du noch einmal und noch unzählige Male leben müssen; und es wird nichts Neues daran sein, sondern jeder Schmerz und jede Lust und jeder Gedanke und Seufzer und alles unsäglich Kleine und Grosse deines Lebens muss dir wiederkommen, und Alles in der selben Reihe und Folge – und ebenso diese Spinne und dieses Mondlicht zwischen den Bäumen, und ebenso dieser Augenblick und ich selber. Die ewige Sanduhr des Daseins wird immer wieder umgedreht – und du mit ihr, Stäubchen vom Staube!‘ – Würdest du dich nicht niederwerfen und mit den Zähnen knirschen und den Dämon verfluchen, der so redete? Oder hast du einmal einen ungeheuren Augenblick erlebt, wo du ihm antworten würdest: ‚du bist ein Gott und nie hörte ich Göttlicheres!‘ Wenn jener Gedanke über dich Gewalt bekäme, er würde dich, wie du bist, verwandeln und vielleicht zermalmen; die Frage bei Allem und Jedem ‚willst du diess noch einmal und noch unzählige Male?‘ würde als das grösste Schwergewicht auf deinem Handeln liegen! Oder wie müsstest du dir selber und dem Leben gut werden, um nach Nichts mehr zu verlangen, als nach dieser letzten ewigen Bestätigung und Besiegelung?“[4] Bezeichnungen wie „der ungeheure Augenblick“ und „das größte Schwergewicht“ haben in der Literatur ebenso Anklang gefunden wie etwa „der große Mittag“, „Ring der Ringe“, „Rad des Seins“ und ähnliche Wendungen Nietzsches. Der von vielen Interpreten gebrauchte Begriff „ewige Wiederkehr“ (statt Wiederkunft) findet sich dagegen bei Nietzsche nur sehr selten und an abgelegenen Stellen. Darauf ist erst in neuester Zeit aufmerksam gemacht worden, ebenso wie darauf, dass der Begriff „Wiederkunft“ (Parusie) schon vor Nietzsche in der christlichen Theologie gebräuchlich war.[5] Freilich findet sich in Apg 3,21 EU gerade der von der Stoa für die Wiederkehr (im nicht christlichen Sinn, siehe unten) gebräuchliche Begriff apokatastasis. |

ニーチェの思想 ニーチェの霊感の源となった場所:「シュルレイから遠くない、巨大なピラミッド型の岩の近く」。  ニーチェの神秘体験の後、書き留められた「海抜6000フィート、そして人間が作り出した物自体よりもはるかに高い場所」。 ニーチェ自身、自伝『 Ecce homo 』の中で、この考えがどのようにしてひらめきとして彼に訪れたかを次のように説明している。 「作品『ツァラトゥストラはこう語った』の基本構想、永劫回帰の思想、そして、達成し得る肯定の最高の公式は、すべて1881年8月に属する。それは紙の 1枚に書き留められ、見出しとして『人間と時間を超えた6000フィート』と記されている。その日、私はシルヴァプラーナの湖の近くの森を歩いていた。ス ルレイからそう遠くない場所にある巨大なピラミッド型の岩の近くで立ち止まった。その時、その考えが浮かんだのだ。」[2] この記述は、ニーチェの遺品の中から見つかった対応する断片によって裏付けられている。[3] それに続いて、ツァラトゥストラの姿がすぐに現れるさらなる考察が続いている。ニーチェは『悦ばしき科学』の第4巻、格言341で初めてこの考えを示し、 こうして『ツァラトゥストラはこう語った』の冒頭の直前に位置づけた。これは遺稿以外でこの考えについて最も詳細に述べたものであり、名称を除いてはすで に教義のすべての要素を含んでいる。 「最大の重み。もし、ある日、あるいはある夜、悪魔があなたの最も孤独な孤独に入り込み、あなたにこう言ったとしたらどうだろうか。「君が今生きているよ うに、そして生きてきたように、この人生を君は何度も何度も生きなければならない。そして、そこには何も新しいものはない。しかし、あらゆる痛みやあらゆ る喜び、あらゆる思考やため息、そして君の人生におけるあらゆる言葉にできない小さなことや大きなことが君のもとに帰ってくる。そして、すべてが同じ順序 と順番で繰り返されるのだ。この蜘蛛も、木々の間から差し込む月光も、この瞬間も、そして私自身も。永遠に続く砂時計は何度も何度もひっくり返される。そ して、あなたも一緒にひっくり返されるのだ、ちりの粒よ!あなたは倒れ、歯を食いしばり、そう言った悪魔を呪うことはないだろうか?あるいは、あなたはか つて、彼にこう答えるような途方もない瞬間を経験したことがあるだろうか。「あなたは神であり、私はこれほど神聖なものを聞いたことがない!」もしその考 えがあなたを支配するようになったら、それはありのままのあなたを変容させ、おそらくあなたを打ちのめすだろう。すべての人や物事において、「あなたはこ れを何度も何度も何度も繰り返したいですか?」という問いが、あなたの行動に最も重くのしかかるだろう!あるいは、この最後の永遠の確認と封印をこれ以上 望むものがないほど、自分自身と人生に対してどれほど良くあらねばならないだろうか?」[4] 「途方もない瞬間」や「最大の強調」といった表現は、文学においても「偉大なる正午」、「指環」、「存在の輪」といったニーチェの表現と同様に広く好まれ ている。多くの解釈者が用いている「永劫回帰」(returnではなく)という用語は、ニーチェの著作ではごくまれにしか見られない。この指摘は最近に なってなされたものであり、ニーチェ以前のキリスト教神学において「回帰」という用語(パルーシア)がすでに使用されていたという事実も指摘されている。 [5] もちろん、ストア哲学で「回帰」(キリスト教的な意味ではない。以下を参照)に使用されていた「アポカタスタシス」という用語は、使徒行伝3:21 EUにも見られる。 |

| In Also sprach Zarathustra Es herrscht inzwischen weitgehend Einigkeit, dass die Ewige Wiederkunft tatsächlich ein überaus wichtiger, wenn nicht der zentrale Gedanke von Also sprach Zarathustra ist. Die „ewige Wiederkunft“ ist die „große bejahende mystische Erfahrung“, die in diesem Werk in unterschiedlichen Variationen auftritt.[6] Die Figur Zarathustra ist von Nietzsche als der Lehrer der ewigen Wiederkunft gedacht. Die Lehre wird dabei „weniger bewiesen, als vielmehr in Form von Symbolen verkündet“.[7] Es werden aber auch die Möglichkeit des exoterischen (nicht mystischen, nicht esoterischen) Lehrens überhaupt und seine Folgen für den Lehrer problematisiert.[8] So bricht im Buch Zarathustra eine Rede ab, als sie zu dem Gedanken hinführt[9]; und er ringt mit sich selbst bei der Aussicht, zum „Verkünder“ des Gedankens zu werden.[10] Als er ihn schließlich zum ersten Mal darstellt, geschieht dies ausdrücklich in Form eines Rätsels oder Gleichnisses.[11] Die ausführlichste Behandlung der „ewigen Wiederkunft“ in Also sprach Zarathustra findet sich im Kapitel „Der Genesende“[12], das auf den zentralen Abschnitt „Von alten und neuen Tafeln“ folgt. Wiederum wird ausführlich geschildert, wie der „abgründigste Gedanke“ Zarathustra mit Ekel erfüllt. Nur seine Tiere sind bei ihm, und sie sind es, die die „ewige Wiederkunft“ schließlich beschreiben: „Alles geht, Alles kommt zurück; ewig rollt das Rad des Seins. Alles stirbt, Alles blüht wieder auf, ewig läuft das Jahr des Seins. Alles bricht, Alles wird neu gefügt; ewig baut sich das gleiche Haus des Seins. Alles scheidet, Alles grüsst sich wieder; ewig bleibt sich treu der Ring des Seins. In jedem Nu beginnt das Sein; um jedes Hier rollt sich die Kugel Dort. Die Mitte ist überall. Krumm ist der Pfad der Ewigkeit.“ Worauf Zarathustra antwortet: „[…] wie gut wisst ihr, was sich in sieben Tagen erfüllen musste: – – und wie jenes Unthier mir in den Schlund kroch und mich würgte! Aber ich biss ihm den Kopf ab und spie ihn weg von mir. Und ihr, – ihr machtet schon ein Leier-Lied daraus?“ Auch dieser ganze Abschnitt steht im Zusammenhang mit den genannten sprachphilosophischen Reflexionen.[8] Zarathustra klärt aber auf, warum ihm der Gedanke einen solchen Ekel hervorruft. Dem Gedanken zufolge kehrt auch der kleinste Mensch ewig wieder: „Alles ist gleich, es lohnt sich nichts, Wissen würgt.“ Und: „Nackt hatte ich einst Beide gesehn, den grössten Menschen und den kleinsten Menschen: allzuähnlich einander, – allzumenschlich auch den Grössten noch! Allzuklein der Grösste! – Das war mein Überdruss am Menschen! Und ewige Wiederkunft auch des Kleinsten! – Das war mein Überdruss an allem Dasein!“ Zum Schluss des Kapitels sprechen wieder die Tiere aus, sie wüssten, was Zarathustra bei seinem Tod sagen würde: „Nun sterbe und schwinde ich, würdest du sprechen, und im Nu bin ich ein Nichts. Die Seelen sind so sterblich wie die Leiber. Aber der Knoten von Ursachen kehrt wieder, in den ich verschlungen bin, – der wird mich wieder schaffen! Ich selber gehöre zu den Ursachen der ewigen Wiederkunft. Ich komme wieder, mit dieser Sonne, mit dieser Erde, mit diesem Adler, mit dieser Schlange – nicht zu einem neuen Leben oder besseren Leben oder ähnlichen Leben: – ich komme ewig wieder zu diesem gleichen und selbigen Leben, im Grössten und auch im Kleinsten, dass ich wieder aller Dinge ewige Wiederkunft lehre, – – dass ich wieder das Wort spreche vom grossen Erden- und Menschen-Mittage, dass ich wieder den Menschen den Übermenschen künde. Ich sprach mein Wort, ich zerbreche an meinem Wort: so will es mein ewiges Loos –, als Verkündiger gehe ich zu Grunde!“ |

『ツァラトゥストラはこう語った』 永劫回帰は、この作品の中心的な考え方ではないにしても、実際にはきわめて重要な考え方であるという点については、現在では広く同意が得られている。「永 劫回帰」は、この作品の中でさまざまなバリエーションで描かれている「偉大な肯定的な神秘体験」である。6] ツァラトゥストラの人物像は、永劫回帰の教師としてニーチェによって構想された。この教義は「象徴の形で宣言されるよりも証明されていない」。7] しかし、通俗的な(神秘主義的でも秘教的でもない)可能性は 一般的に、その教えと教師に及ぼす影響が問題視されている。8] したがって、ツァラトゥストラという本では、思考に導くスピーチが途切れる。9] そして、彼はその思考の「宣言者」になるという見通しに、自分自身と葛藤する。10] 彼が最終的に初めてそれを提示するとき、それは明らかに謎やたとえ話の形をとっている。11] ツァラトゥストラにおける「永劫回帰」の最も広範な説明は、「病み上がり」の章に見られる。この章は、「古い石版と新しい石版」という中心的な部分に続く ものである。ここでも、ツァラトゥストラが「最も深淵な思考」に嫌悪感を抱く様子が詳細に描写されている。彼には動物たちだけがついており、動物たちが最 後に「永劫回帰」について説明する。 「すべては去り、すべては戻る。存在の輪は永遠に回転する。すべては死に、すべては再び花開く。存在の年は永遠に続く。 すべては壊れ、すべては再編成される。同じ存在の家は永遠に建てられ続ける。すべては分離し、すべては再び自らを迎える。存在の環は永遠に真実であり続け る。 存在はあらゆる瞬間に始まる。そこにある玉はあらゆる場所を転がる。真ん中はどこにでもある。永遠の道は曲がりくねっている。 ツァラトゥストラは答える。 「... 7日間で成し遂げなければならないことを、君はよく知っている。 そして、あの怪物が私の喉に忍び込み、私を絞め殺そうとした!しかし私はその頭を噛みちぎり、それを吐き捨てた。 そして君は、すでにそれを竪琴の歌にしているのか?」 このセクション全体も、前述の言語哲学に関する考察と関連している。8] しかし、ツァラトゥストラは、その考えが彼に嫌悪感を抱かせる理由を説明している。その考えによれば、どんなに小さな人間でも永遠に生き続けるという。 「すべては同じであり、価値のあるものは何もない。知識は息苦しい」そして、 「裸の私はかつて、最も偉大な人間と最も小さな人間の両方を見た。彼らはあまりにも似通っており、最も偉大な人間でさえもあまりにも人間的だった! 最も偉大な人間はあまりにも小さかった!それが私が人間に対して抱いた嫌悪感だった!そして最も小さな人間も永劫回帰する!それが私が存在に対して抱いた 嫌悪感だった!」 章の終わりで、動物たちは再び、ツァラトゥストラが死の際に何を言うかを知っていると言う。 「今、私は死に、消え去る。そして一瞬にして私は無になる。魂は肉体と同じように死すべきものだ。 しかし、私が巻き込まれた原因の結び目が再び戻ってくる。それが私を再び作り出すのだ!私自身が永劫回帰の原因の一部なのだ。 私は再びやって来る。この太陽とともに、この地球とともに、この鷲とともに、この蛇とともに。新しい人生でも、より良い人生でも、似たような人生でもな い。 永遠に、この同じ同じ人生に、最も偉大で、また最も小さなものとして、私は再び永劫回帰の物自体を教えるのだ。 地球と人間の大いなる正午の言葉を再び語り、人間に超人について告げる。 私は言葉を語り、言葉を破る。それが私の永遠の運命だ。告げ人として滅びるのだ!」 |

| Die kosmologische Hypothese Nietzsche war nicht der erste, der die Hypothese von der Ewigkeit der Welt aufstellte – siehe Parallelen. Der auch in Notizen Nietzsches vielfach variierte Versuch eines naturwissenschaftlichen Beweises für die ewige Wiederkunft verläuft ungefähr folgendermaßen: Angenommen wird, dass die Zeit sich sowohl in die Vergangenheit als auch in die Zukunft unendlich ausdehnt, die gesamte „Kraft“, Materie oder Energie, und folglich die Anzahl der möglichen „Kombinationen“ oder Zustände der Welt, aber endlich ist. Daraus wird geschlossen, es müsse jeder mögliche Zustand der Welt bereits unendlich oft eingetreten sein und noch unendlich oft eintreten. Nietzsche selbst hat diese Beweisversuche niemals publiziert, sie wurden erst im Rahmen der Veröffentlichung seines Nachlasses bekannt. Es lässt sich nicht eindeutig sagen, ob er selbst an diese nachträglichen Begründungsversuche seines intuitiv gewonnenen Gedankens geglaubt hat: in seinen Notizbüchern wechseln Zweifel und Gewissheit ab, „ohne aber je zu einer Formulierung zu gelangen, die an Überzeugungskraft derjenigen gleichkommt, mit der er die Konsequenzen jenes ‚mächtigsten Gedankens‘ beschreibt.“[13] Bereits in der frühesten Nietzsche-Deutung zu Beginn des 20. Jahrhunderts wurde darüber gestritten, ob das physikalisch-kosmologische Konzept der Wiederkunft selbst oder der Gedanke als mystisches Erlebnis und seine ethischen Folgen bedeutender sind. Im Rahmen dieses etwas unübersichtlichen Streits hat der Mathematiker, Astronom und Nietzsche-Kenner Felix Hausdorff unter dem Pseudonym Paul Mongré die erste Widerlegung von Nietzsches kosmologischen Beweisversuchen gegeben.[14] Hausdorff zweifelte insbesondere Nietzsches Prämissen an. Rein logisch hielt Hausdorff die Wiederkunft zwar auch für nicht widerlegbar, merkte aber an, dass die Physik mit dem heute als Zweiten Hauptsatz der Thermodynamik bekannten Prinzip ihr widerspricht. Diese Argumentation ist aber nicht stichhaltig, wie schon Ludwig Boltzmann 1896[15] in der Auseinandersetzung mit Ernst Zermelo über die physikalische Interpretation des Wiederkehrsatzes von Henri Poincaré festgestellt hat. Georg Simmel gab 1907 ein Beispiel, um zu zeigen, dass die Hypothese selbst unter Nietzsches Annahmen nicht notwendig folgt.[16] Auch andere Elemente von Nietzsches unterschiedlichen Beweisskizzen sind in der Literatur mehrfach in Frage gestellt worden. Das Konzept der Wiederkunft hat in der modernen Naturwissenschaft zunächst kaum Vertreter gefunden. In der modernen Kosmologie kehrt der Wiederkunft-Gedanke nun jedoch selbst wieder, wenn auch unter anderen Prämissen als bei Nietzsche; zahlreiche – allerdings spekulative – kosmologische Szenarien und Hypothesen implizieren eine zeitliche, räumliche oder raumzeitliche Wiederkehr von allem in allen Variationen.[17] |

宇宙論的仮説 ニーチェは世界の永遠性を仮説として初めて提唱した人物ではない。類似点を参照。ニーチェのノートにもさまざまな形で記されている永劫回帰の科学的証明の 試みは、次のようなものである。時間は過去にも未来にも無限に広がっていると仮定し、総体としての「力」、すなわち物質またはエネルギー、そしてその結果 として起こりうる「組み合わせ」または世界の状態の数は有限であると仮定する。このことから、世界のあり得る状態はすべて無限に何度も起こっており、今後 も無限に何度も起こるだろうという結論が導かれる。 ニーチェ自身は、これらの証明の試みを公表することはなかった。それらは、彼の文学的遺稿の出版という文脈においてのみ知られるようになった。彼自身が直 観的に得た考えを正当化するためのこれらの回顧的な試みを信じていたかどうかを断言することはできない。彼のノートでは、疑いと確信が交互に現れるが、 「『最も強力な思考』の結果を説明するものと同等の説得力を持つ定式に到達することなく」[13] 20世紀初頭におけるニーチェの初期の解釈においても、再臨に関する物理的宇宙論的概念それ自体か、神秘体験としての考えとその倫理的帰結のどちらがより 重要であるかについて論争があった。このやや混乱した論争の文脈において、数学者であり天文学者であり、またニーチェの専門家でもあったフェリックス・ハ ウズドルフは、ポール・モングレというペンネームで、ニーチェの宇宙論的証明の試みに対する最初の反論を提示した。14] ハウズドルフは特にニーチェの前提条件に疑義を呈した。純粋に論理的な観点から、ハウスドルフは再臨説も反論の余地がないと考えていたが、熱力学第二法則 として現在知られている原理によって物理学がそれに矛盾していることを指摘した。しかし、この論拠は有効ではない。なぜなら、ルートヴィヒ・ボルツマンは 1896年にすでに[15]、エルンスト・ツェルメロとの間でアンリ・ポアンカレの帰還定理の物理学的解釈をめぐって論争した際に、そのことを述べている からである。1907年には、ゲオルク・ジンメルがニーチェの仮定から必ずしもその仮説が導かれるわけではないことを示す例を提示している。ニーチェのさ まざまな証明の他の要素についても、文献では繰り返し疑問が呈されている。回帰の概念は当初、現代科学ではほとんど支持者がいなかった。しかし、現代の宇 宙論では、ニーチェとは異なる前提条件ではあるものの、回帰の概念自体が再び登場している。多数の(ただし推測の域を出ない)宇宙論のシナリオや仮説で は、あらゆるものの時間的、空間的、あるいは時空的な回帰が、そのすべてのバリエーションにおいて暗示されている。 |

| Deutungen Die Ewige Wiederkunft des Gleichen hängt nach Ansicht vieler Interpreten mit einigen anderen Gedanken Nietzsches zusammen. Vor allem die Verbindung zum Konzept des „Übermenschen“ ist in der neueren Nietzsche-Deutung herausgestellt und untersucht worden. Salomé Lou Andreas-Salomé deutete in ihrem Nietzschebuch[18] die „ewige Wiederkunft“ als eine Umkehrung Schopenhauerscher Philosophie. In buddhistischer Sprache habe Nietzsche die Bejahung des Samsara, des ewigen Kreislaufs des Leidens, als höchstes Ziel gesehen, während Schopenhauer wie der Buddhismus das Nirwana als Ende des Samsara anstrebte. Diese Deutung verweist auf einen Aphorismus Nietzsches aus Jenseits von Gut und Böse: „Wer, gleich mir, mit irgend einer räthselhaften Begierde sich lange darum bemüht hat, den Pessimismus in die Tiefe zu denken und aus der halb christlichen, halb deutschen Enge und Einfalt zu erlösen, mit der er sich diesem Jahrhundert zuletzt dargestellt hat, nämlich in Gestalt der Schopenhauerischen Philosophie; wer wirklich einmal mit einem asiatischen und überasiatischen Auge in die weltverneinendste aller möglichen Denkweisen hinein und hinunter geblickt hat – jenseits von Gut und Böse, und nicht mehr, wie Buddha und Schopenhauer, im Bann und Wahne der Moral –, der hat vielleicht ebendamit, ohne dass er es eigentlich wollte, sich die Augen für das umgekehrte Ideal aufgemacht: für das Ideal des übermüthigsten lebendigsten und weltbejahendsten Menschen, der sich nicht nur mit dem, was war und ist, abgefunden und vertragen gelernt hat, sondern es, so wie es war und ist, wieder haben will, in alle Ewigkeit hinaus, unersättlich da capo rufend, nicht nur zu sich, sondern zum ganzen Stücke und Schauspiele, und nicht nur zu einem Schauspiele, sondern im Grunde zu Dem, der gerade dies Schauspiel nöthig hat – und nöthig macht: weil er immer wieder sich nöthig hat – und nöthig macht – – Wie? Und dies wäre nicht – circulus vitiosus deus?“[19] Simmel Georg Simmel zweifelte, wie oben beschrieben, die kosmologische Hypothese an und betonte dagegen den ethischen Aspekt des Gedankens, den er in die Nähe des kategorischen Imperativs Kants rückte. Nietzsche habe den Gedanken als „regulative Idee“ konzipiert, dabei aber in mehrerlei Hinsicht nicht hinreichend durchdacht.[20] Heidegger Bekannt geworden ist die eigenwillige und systematisch komplexe Interpretation Martin Heideggers. Dieser hat u. a. in seiner Vorlesung aus dem Sommersemester 1937[21] diesen Gedanken neu interpretiert und auf seinen Begriff des „Grundes“ bezogen. Dabei kritisierte er seiner Meinung nach verfälschende Interpretationen insbesondere von Ernst Bertram und Alfred Baeumler. |

解釈 多くの解釈者によれば、「同じものの永遠回帰」は他の多くのニーチェ的思想と結びついている。特に、最近のニーチェ解釈では、「超人」の概念との関連が強 調され、検討されている。 サロメ ルー・アンドレアス=サロメはニーチェの著書[18]の中で、「永遠の回帰」をショーペンハウアーの哲学の逆転として解釈している。ニーチェは、仏教の言 葉で言えば、輪廻(苦悩の永遠のサイクル)の肯定を最高のゴールとみなし、ショーペンハウアーは仏教と同様に輪廻の終わりとしての涅槃を目指した。この解 釈は、『善悪の彼岸』にあるニーチェの格言を指している: 「私のように、長い間、悲観主義をその深みまで考え、半キリスト教的、半ドイツ的な狭量さと単純さ、すなわちショーペンハウアー哲学の形をとって、この世 紀に最後に姿を現したものから贖い出そうと、不可解な願望をもって努力してきた者がいる; 善悪を超え、もはやブッダやショーペンハウアーのように道徳の呪縛や錯覚にとらわれてはいない: 最も高揚し、生き生きとし、世界を肯定する人間の理想は、過去にあったもの、現在にあるものと折り合いをつけ、それを容認することを学んだだけでなく、未 来永劫、過去にあったもの、現在にあるものを再び手に入れたいと願い、自分自身だけでなく、芝居や見世物全体に対して、そして見世物だけでなく、基本的に は、この見世物を必要とし、それを必要とされる方に対して、飽くことなくダ・カーポと呼びかけることである: なぜなら、彼は自分自身を何度も何度も必要としているからである。そして、これは - circulus vitiosus deus - ではないだろうか」[19]。 ジンメル 上述のように、ゲオルク・ジンメルは宇宙論的仮説を疑い、カントの定言命法に近い思想の倫理的側面を強調した。ニーチェはこの思想を「調整的思想」として 考えていたが、いくつかの点で十分に考えていなかった[20]。 ハイデガー マルティン・ハイデガーの特異で体系的に複雑な解釈はよく知られている。1937年の夏学期の講義[21]において、ハイデガーはこの思想を再解釈し、 「理性」の概念と関連づけた。そうすることで、彼は、特にエルンスト・ベルトラムとアルフレッド・ボイムラーによる偽りの解釈を批判した。 |

| Zurückweisung der „Wiederkunft“ Baeumler hatte in seiner – für die nationalsozialistische Nietzsche-Deutung entscheidenden – Konstruktion eines „Systems Nietzsche“ die „ewige Wiederkunft“ einerseits mit dem „Willen zur Macht“ und dem germanisch-heroischen „Übermenschen“ (in Baeumlers Deutung) andererseits für unvereinbar erklärt und daher die Wiederkunft als „erratische[n] Block“ ausgeschieden.[22] Eine bei einigen Interpreten anklingende Kritik an Nietzsche ist vielleicht am konsequentesten von Josef Hofmiller dargelegt worden.[23] Demnach fällt Nietzsches Gedanke der ewigen Wiederkunft unter die von ihm selbst andernorts heftig kritisierten metaphysischen Gedanken. Nietzsche selbst habe den auch von ihm kritisierten Fehlschluss begangen: „Der Gedanke, der mich so erhebt, hinreißt […] – der Gedanke muß wahr sein!“ Hofmiller spekuliert, häufige oder eindringliche Déjà-vu-Erlebnisse bei Nietzsche seien die Grundlage für dessen Eingebung; und die Tatsache, dass er nicht fähig war, sich rational gegen den zur fixen Idee werdenden Gedanken zu wehren, sei das erste Anzeichen von Nietzsches Geisteskrankheit. Zudem diene das Konzept ihm als Ersatz für metaphysische und religiöse, auch christliche Ideen, von denen er sich nie habe lösen können. Letztlich sei die „Wiederkunft“ aber ein nebensächlicher und mangelhafter Teil von Nietzsches Lehren: „Diese Theorie, so wichtig sie Nietzsche selbst erschien, so tiefe Erschütterungen, so grandiose Schauder sie ihm schenkte, ist sie nicht dennoch in seiner Philosophie etwas Nebensächliches? Könnte sie nicht ebenso gut nicht da sein? Fällt ein Stein von Nietzsches Gedankenbau, wenn wir sie wegnehmen? Für Nietzsche allerdings fällt etwas anderes mit seiner Lehre: die Jenseits-Beleuchtung, der metaphysische Hintergrund, der Ewigkeitsakzent des Zarathustra […] Uns erscheint dieser Gedanke fremd, unheimlich, abstrus. […] Sehen wir jedoch vom Biographischen ab, so können wir nicht umhin, gerade seine beiden Hauptideen, die vom Übermenschen und die von der Wiederkunft, als Fremdkörper auszuscheiden.“ Als Beleg für die These, der Ewige-Wiederkunfts-Gedanke sei ein Zeichen von Nietzsches Geisteskrankheit, sind auch übereinstimmende Zeugnisse Franz Overbecks, Lou Andreas-Salomés und Resa von Schirnhofers zitiert worden, nach denen Nietzsche sie in unheimlicher Weise, leise sprechend und tief erschüttert in dieses Geheimnis „eingeweiht“ hat.[24] Gegen die Ausscheidung der „ewigen Wiederkunft“ aus Nietzsches Werk, wie sie von Interpreten wie Baeumler und Hofmiller – die im Übrigen sehr gegensätzliche Nietzsche-Deutungen gaben – gefordert worden ist, hat sich nach Heidegger am deutlichsten Karl Löwith ausgesprochen. Mazzino Montinari erkannte später trotz Kritik an Löwiths Versuch einer Systematisierung die „zentrale Position dieser Lehre im ganzen Denken Nietzsches“ an.[25] Löwith Löwith deutete Also sprach Zarathustra als eine „antichristliche Bergpredigt“. Die „ewige Wiederkehr“ sei der einheitsstiftende Gedanke in Nietzsches ganzem Werk. Nietzsche habe den absurd scheinenden Versuch gewagt, eine antike Kosmologie auf der Spitze der Modernität zu wiederholen: damit sollte der Nihilismus, der „Tod Gottes“ überwunden werden. Löwith sieht darin einen Gegenentwurf zur christlichen Teleologie, einen „Ersatz für den Unsterblichkeitsglauben“ und eine „physikalische Metaphysik“. Nietzsches Versuch sei schließlich gescheitert, weil er mit der ewigen Wiederkunft Unvereinbares vereinen wollte, nämlich eine heidnische Kosmologie mit einem auch von Nietzsche nicht völlig überwundenen, aus dem säkularisierten Christentum stammenden Fortschrittsglauben sowie einen Versuch der höchsten Sinngebung für das menschliche Dasein mit einem absolut sinnlosen Kreislauf der Welt. Es bleibe fragwürdig, wie die Fatalität gewollt, der amor fati erreicht werden kann.[26] |

「二度来るもの」の拒絶 ボイムラーは、国家社会主義によるニーチェ解釈にとって重要な「ニーチェ体系」を構築する中で、「永劫回帰」は「力への意志」やゲルマン的・英雄的な「超 人」(ボイムラーの解釈)とは両立しないと宣言し、したがって「永劫回帰」を「不規則な障害物」として排除した。[22] おそらくニーチェに対する最も一貫した批判は、一部の解釈者によって繰り返されているが、ヨゼフ・ホフミラーによって展開されている。23] これによると、ニーチェの永劫回帰の考えは、彼自身が他の場所で激しく批判した形而上学的な考えに該当する。ホフミラーは、ニーチェ自身も批判した誤りを 犯していると主張している。「自分をそこまで高めてくれる思考、自分をそこまで運んでくれる思考……その思考は真実でなければならない!」 ホフミラーは、ニーチェにおける頻繁または強烈な既視体験が、彼のインスピレーションの基盤となったのではないかと推測している。また、強迫観念となった 考えに対して合理的に自己弁護できなかったという事実は、ニーチェの精神疾患の最初の兆候である。さらに、この概念は、ニーチェが決して自分自身から切り 離すことのできなかった形而上学的、宗教的、さらにはキリスト教的な考えの代用として役立った。しかし結局のところ、「第二の到来」はニーチェの教えの取 るに足らない不完全な部分である。 「この理論は、ニーチェ自身にとってどれほど重要に見え、どれほど衝撃的で壮大な戦慄を与えたとしても、彼の哲学においては二次的なものではないだろう か? それがないとしてもいいのではないか? ニーチェの思想構造から石が落ちるようなものではないだろうか?しかし、ニーチェにとって、彼の教えとともに何かが失われる。それは、超悟り、形而上学的 な背景、ツァラトゥストラの永遠のアクセントである。この考えは、私たちには奇妙で、不気味で、難解に思える。しかし、伝記的なものを無視するならば、彼 の2つの主要な考え、すなわち超人と再臨の考えを異物として除外することは避けられない。 永劫回帰の思想がニーチェの精神の病の兆候であるという説の証拠として、フランツ・オーバーベック、ル・アンドレアス=サロメ、レザ・フォン・シルンホー ファーの一致した証言も引用されている。それによると、ニーチェは「不可解な方法で」彼らにこの秘密を「伝授」し、静かに話し、深く震えながら語ったとい う。 ハイデガーに続いて、レーヴィットは、ボイムラーやホフミラーといった解釈者たちが求めたように、ニーチェの著作から「永劫回帰」を排除することに最も明 確に反対を唱えた人物であった。ちなみに、ボイムラーとホフミラーは、ニーチェについて非常に対照的な解釈を行っていた。マッツィーノ・モンティナーリ は、レーヴィットの体系化の試みを批判したにもかかわらず、後に「ニーチェの思想におけるこの教義の中心的な位置」を認めた。 レーヴィット レーヴィットは『ツァラトゥストラはこう語った』を「反キリスト教の山上の垂訓」と解釈した。「永劫回帰」は、ニーチェの作品のすべてに共通する統一的な 考えである。ニーチェは、一見すると無意味にも思える試みとして、古代の宇宙論を近代の頂点で繰り返そうとした。これは、ニヒリズム、すなわち「神の死」 を克服することを意図したものだった。レーヴィットは、これをキリスト教の目的論に対する代替案であり、「不死の信念の代替案」であり、「物理的形而上 学」であると見なしている。ニーチェの試みは最終的に失敗に終わった。なぜなら、彼は永劫回帰と相容れないもの、すなわち、世俗化したキリスト教に由来す る進歩への信仰と異教の宇宙論を調和させようとしたからであり、また、世界における全く意味のないサイクルに人間の存在に最高の意義を与える試みも、ニー チェは完全に克服できなかったからである。宿命を意図し、運命に身を委ねることをいかに達成できるのか、依然として疑問が残る。 |

| Klossowski Die Wendung „circulus vitiosus deus“, also etwa „der Teufelskreis als Gott“, ist von Pierre Klossowski als Titel seiner Nietzsche-Interpretation gewählt worden, in deren Zentrum die Ewige Wiederkunft steht; so wie diese in der ganzen französischen Nietzsche-Rezeption, die in den 1960er und 1970er Jahren ihren Höhepunkt hatte, starke Beachtung fand. Klossowski, der auch Nietzsches Pathologie in die philosophische Deutung einbezog, legte ein besonderes Augenmerk auf die politischen Ausführungen, die sich im Nachlass Nietzsches finden. Hierin dient der Gedanke der Wiederkunft als „selektive Lehre“, die zur Schaffung einer Herrenkaste dient. Klossowski verband dies mit einer Betrachtung der realen industrialisierten Welt und der Mechanismen des Kapitalismus, die wiederum Bezüge zu Georges Batailles „Aufhebung der Ökonomie“ hat.[27] Sehr ungewöhnlich ist Klossowskis Deutung der Wiederkunft als eine Lehre, die die Ich-Identität aufhebt, indem sie gewissermaßen das Subjekt unendlich viele unterschiedliche Identitäten durchlaufen lässt. Skirl gibt den Gehalt des Gedankens prägnant so wieder: „daß alles schon einmal da gewesen ist, aber in jedem Moment trotzdem Neues entsteht, daß jeder Moment neu und unverbraucht ist, unschuldig ist. Damit will N[ietzsche] eine Synthese aus antiken (kreisenden) herakliteisch-pythagoreischen Lehren und dem neuzeitlichen Zeitpfeil der modernen Physik […] erreichen – auf daß diese Versöhnung von Antike und Neuzeit in die Welt- und Wertvorstellung der Menschen gelange“[28]. Römpp Georg Römpp zufolge gibt es bei Nietzsche überhaupt keine Lehre der ewigen Wiederkunft. Er begründet dies zunächst mit dem Hinweis auf Nietzsches erkenntnis- und wissenschaftskritische Philosophie, die eine kosmologische These ausschließt, sowie mit Nietzsches Moralkritik, die eine ethische Interpretation nicht zulässt. Darüber hinaus zeigt eine philologisch genaue und kontextbezogene Interpretation der entsprechenden Stellen in ‚Also sprach Zarathustra‘ (Dritter Teil, Vom Gesicht und Rätsel 1–3, sowie Der Genesende 2), dass Nietzsche gerade die Auffassung als eine ‚Lehre‘ scharf kritisiert. Zu einer ‚Lehre‘ wird Nietzsches Gedanke nur von seinen Tieren umgeformt, die er als ‚Schalks-Narren‘ und ‚Drehorgeln‘ bezeichnet, weil sie ein ‚Leier-Lied‘ aus seinen Gedanken machen. Bei der Interpretation des Gedankens selbst muss der Kontext des Sprechens berücksichtigt werden. Zarathustra spricht über die ewige Wiederkunft mit einem ‚Zwerg‘, den er auch als ‚Geist der Schwere‘ bezeichnet, was nichts Gutes ist für einen Philosophen, der den ‚Tanz‘ als Metapher für sein Denken auffasste. Unmittelbar danach verwandelt sich aber die Szene in das Bild von einem Hirten, dem eine Schlange in den Mund gekrochen war, von der er sich auf Zarathustras Rat durch einen kräftigen Biss befreien kann. Römpp zufolge kommentiert Nietzsche damit den Gedanken von der ewigen Wiederkunft als eine Sprachfigur, die der Philosoph in der kontextuellen Abhängigkeit von einer spezifischen Denkweise (dem ‚Geist der Schwere‘) gebraucht. Er kann sich von ihr aber befreien durch die radikale Abwendung von eben solchen Sprachfiguren. In ihrer Gesamtheit entsprechen sie der Struktur der ‚Metaphysik‘, die Nietzsche zufolge in die Sprache ‚gekrochen‘ ist wie die Schlange, von der sich der Philosoph nur durch einen ‚guten Biss‘ lösen kann. Erst damit wird das ‚Lachen‘ erreicht’, das jenen ‚Geist der Schwere‘ und die von ihm abhängigen Sprachfiguren endgültig zum Verschwinden bringt.[29] |

クロソウスキー Circulus vitiosus deus、すなわち「神としての悪循環」というフレーズは、ピエール・クロソウスキーがニーチェ解釈のタイトルに選んだものであり、その中心は「永遠の帰 還(=永劫回帰)」である。ニーチェの病理学も哲学的解釈に含めたクロソウスキーは、ニーチェの遺品に見られる政治的発言に特に注目した。ここでは、再臨 の思想は、支配者カーストを作り出すための「選択的教義」として機能している。クロソウスキーはこれを、現実の工業化された世界と資本主義のメカニズムに ついての考察と結びつけ、ジョルジュ・バタイユの「経済の廃絶」[27]を参照している。 スカールはこの思想の内容を次のように簡潔に要約している:「すべてはすでに一度そこにあったが、それにもかかわらず、すべての瞬間に新しい何かが生じ、 すべての瞬間が新しく、使い尽くされていない、無垢なものである」。これによってニエチェは、古代の(円環的な)ヘラクレイト派・ピタゴラス派の教えと、 現代物理学の時間の矢という現代的な教えの統合を達成しようとしている[......]-この古代と現代の和解が、人々の世界観や価値観の中に入り込むよ うに」[28]。 レムップ ゲオルク・レムップによれば、ニーチェには永遠回帰の教義はまったくない。彼はまず、宇宙論的テーゼを排除するニーチェの認識論的・科学批判的哲学と、倫 理的解釈を許さないニーチェの道徳批判を参照して、これを正当化する。 さらに、『ツァラトゥストラはかく語りき』の関連箇所(第3部、『顔と謎について』1~3、『療養者』2)を文献学的に正確に、文脈に沿って解釈すると、 ニーチェがまさに「教義」の概念を鋭く批判していることがわかる。ニーチェの思考は、彼の動物たちによってのみ「教義」に変換される。動物たちは、彼の思 考から「竪琴の歌」を作るので、彼は「シャルクス・ナレン」や「ドレホルゲルン」と呼んでいる。 思想そのものを解釈する際には、話の文脈を考慮に入れなければならない。ツァラトゥストラは「小人」と永遠の帰還について語るが、その「小人」は「重苦し さの精神」とも言っており、「舞踏」を思考の比喩とした哲学者としては好ましいことではない。しかしその直後、この場面は、蛇を口に這わされた羊飼いが、 ツァラトゥストラの忠告を強く噛み締めることで解放されるというイメージに変貌する。 レムプによれば、ニーチェはこのように、哲学者が特定の思考法(「重力の精神」)に文脈上依存して用いる言葉の形象としての永遠回帰の思想についてコメン トしている。しかし、彼は、まさにそのような言葉の形象から根本的に目を背けることによって、そこから自らを解放することができる。ニーチェによれば、形 而上学は蛇のように言語の中に「這入」っており、哲学者はそこから「よく噛む」ことによってのみ自由になれるのである。そのとき初めて、「笑い」は達成さ れ、その「重苦しさの精神」とそれに依存する言葉の形象は、最終的に消滅するのである。 |

Diskutierte Parallelen „Allem Zukünftigen beißt das Vergangene in den Schwanz“ notierte Nietzsche. Mit dem Ouroboros und ähnlichen Symbolen ist die Ewige Wiederkunft illustriert worden. Nietzsche war nicht der erste, der die kosmologische Lehre von der Wiederkehr vertreten hat. Der Religionswissenschaftler Mircea Eliade hat 1949 in seiner vergleichenden Untersuchung „Kosmos und Geschichte: Der Mythos der ewigen Wiederkehr“ gezeigt, dass sich zyklische Kosmologien weltweit in fast allen mythologischen Traditionen finden.[30] Jorge Luis Borges – der, offenbar ohne Hausdorffs Schrift zu kennen, Nietzsches Beweis mit ganz ähnlichen Argumenten aus der Mengenlehre Georg Cantors zu widerlegen versuchte – hat eine Reihe von Parallelstellen von der Antike bis in die Gegenwart zusammengestellt, in denen gleiche oder ähnliche Gedanken besprochen werden.[31] Die ältesten europäischen Belege für den Gedanken sind nur indirekt überlieferte Angaben zweier Schüler des Aristoteles, Dikaiarchos und Eudemos von Rhodos, aus denen hervorgeht, dass spätestens im 4. Jahrhundert v. Chr. die Vorstellung der ewigen Wiederkunft unter Pythagoreern verbreitet war. Zu nennen ist zudem Heraklit: „Und es ist immer ein und dasselbe, was in uns wohnt: Lebendes und Totes und Waches und Schlafendes und Junges und Altes. Denn dieses ist umschlagend jenes und jenes zurück und umschlagend dieses.“[32] Nemesius von Emesa (4. Jahrhundert n. Chr.) berichtet in seinem Werk Über die Natur des Menschen (Kapitel 38), dass Stoiker diese Ansicht vertraten und sie mit einem astrologischen Fatalismus verbanden: Sie meinten, dass nach einer bestimmten Zeit („Großes Jahr“) alle Planeten wieder ihre Ausgangsstellungen am Himmel erreichen und dann ebenso wie die Kreisläufe der Gestirne auch die menschlichen Schicksale wieder von vorn beginnen müssen: Es wird dann wieder einen Sokrates und einen Platon geben. Nietzsche wies in Ecce homo auf diese „Spuren davon“ in der Stoa hin und bezeichnete Heraklit als möglichen Urheber der stoischen Lehre.[33] In seiner zweiten Unzeitgemäßen Betrachtung (Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben) von 1874 hatte er bereits die einschlägige Tradition der Pythagoreer erwähnt, doch ohne ihr eine Berechtigung zuzugestehen.[34] Auch in den Aufzeichnungen zu einer seiner philologischen Vorlesungen an der Universität Basel Anfang der 1870er Jahre findet sich der Gedanke bei der Besprechung der Pythagoreer. Augustinus bekämpfte die Lehre in Buch 12 seines De civitate Dei (Kapitel 11 (manche Ausgaben: 12) und 13 (14)). Lucilio Vanini schrieb sie Platon zu (wobei wohl an dessen „Großes Jahr“ im Timaios gedacht ist, das aber der hier gemeinten Hypothese nur ähnlich ist, möglicherweise auch an die Folge der vier Elemente von Feuer, Luft, Wasser, Erde, Tim. 49 bf), verwarf sie aber. David Hume stellte in seinen Dialogues Concerning Natural Religion genau den vermeintlichen Beweis Nietzsches vor, hielt die Idee aber offenbar für absurd. John Stuart Mill erwähnte die Möglichkeit eines periodischen Weltablaufs in seinem A System of Logic (III. Buch, Kapitel V, §. 8), verneinte sie aber beiläufig ohne Angabe von Gründen. „Nietzsche wußte, daß die Ewige Wiederkehr jenen Fabeln, Befürchtungen oder Zerstreuungen zugehört, die immer wieder auftauchen […] Seine Offenbarung von einem Sammeltext herzuleiten oder von der Historia philosophiae graeco-romana der außerordentlichen Professoren Ritter und Preller, kam für Zarathustra nicht in Betracht […] Der prophetische Stil erlaubt nicht die Verwendung von Anführungszeichen und ebensowenig das gelehrsame Zitieren von Büchern und Autoren […].“ – Jorge Luis Borges[35] Es gibt noch eine weitere mögliche Quelle für Nietzsches Inspiration: gerade zu der Zeit, als Nietzsche seine Idee formulierte, diskutierten naturwissenschaftliche und philosophische Autoren unter anderem diese Hypothese. Die Diskussion hatte sich bereits Jahre zuvor gerade an den von Lord Kelvin und Rudolf Clausius vertretenen Grundsätzen der Thermodynamik entzündet. Mit großer Sicherheit gelesen hat Nietzsche Eugen Dührings Cursus der Philosophie als streng wissenschaftlicher Weltanschauung und Lebensgestaltung (1875) sowie Otto Casparis Der Zusammenhang der Dinge (1881). Die letztgenannte Schrift, in der der Gedanke am Rande mit einem unwissenschaftlichen Argument abgelehnt wird, dürfte zu Nietzsches „Inspiration“ erheblich beigetragen haben. Von diesem Buch ausgehend wollte Nietzsche sich in der folgenden Zeit einen Überblick über die aktuelle Diskussion verschaffen; er erwog sogar ein naturwissenschaftliches Studium. Unter den von ihm gelesenen Schriften sind J. G. Vogts Die Kraft. Eine real-monistische Weltanschauung (1878) und Schriften Otto Liebmanns zu erwähnen. Dührings Schrift enthält ebenso wie ein Vortrag Carl von Nägelis, den Nietzsche 1884 las, Einwände gegen die Hypothese. Mit Nägelis Vortrag wiederum hat sich später Friedrich Engels befasst. Auf Auguste Blanquis L'éternité par les astres (1872), das fast dieselbe Hypothese enthält, hat wahrscheinlich ein Bekannter Nietzsche nach der Lektüre der Fröhlichen Wissenschaft hingewiesen. Schließlich gibt es ähnliche Gedanken in Gustave Le Bons L'Homme et les societés (1881). Nietzsches Theorie basierte also auf einer gerade damals aktuellen wissenschaftlichen Hypothese.[36] Die Anklänge an buddhistische Symbolik, die Nietzsche durch die Vermittlung Arthur Schopenhauers aufnahm, sind oben bereits dargestellt worden. Schließlich gibt es bei Nietzsche in den nachgelassenen Zarathustra-Notizen Stellen, die an das alte Symbol des Ouroboros denken lassen.[37] Bei der Diskussion zur kosmologischen Hypothese ist allerdings nicht zu vergessen, dass Nietzsche seine Beweisversuche nicht publizierte, sich der Naturwissenschaft nicht zuwandte und mit Also sprach Zarathustra eine ganz andere Darstellungsform wählte. So hat Giorgio Colli den tieferen Wert der Suche nach Quellen und Parallelen bestritten, indem er Also sprach Zarathustra als einen Versuch deutete, das „unmittelbare“, vorsprachliche Erlebnis zu fassen: „Als Wurzel der Vision von der ewigen Wiederkunft suche man weniger das Nachklingen doxographischer Berichte über eine alte pythagoreische Lehre oder wissenschaftliche Hypothesen des 19. Jahrhunderts als vielmehr das Wiederauftauchen kulminierender Momente der vorsokratischen Spekulation, die auf eine Unmittelbarkeit hingewiesen haben, die in der Zeit wieder auffindbar ist, jedoch aus ihr hinausführt und so ihre nicht umkehrbare Eingleisigkeit aufhebt. Wenn man zurückgeht bis zu diesem nicht mehr Darstellbaren, so läßt sich nur sagen, daß das Unmittelbare außerhalb der Zeit – die ‚Gegenwart‘ des Parmenides und das ‚Aion‘ des Heraklit – in das Gewebe der Zeit eingeflochten sind, so daß in dem, was vorher oder nachher wirklich erscheint, jedes Vorher ein Nachher und jedes Nachher ein Vorher ist und jeder Augenblick ein Anfang.“[38] Der Bergsonianer Milič Čapek verwies darauf, dass entsprechende Überlegungen auch in den Zeitvorstellungen bei Charles Sanders Peirce und dem französischen Wissenschaftshistoriker Abel Rey zu finden sind.[39] |

類似性を論じる ニーチェは「過去は来るべきすべてのものの尻尾を噛む」と述べている。永遠の回帰は、ウロボロスや類似のシンボルで説明されてきた。 再臨の宇宙論的教義を唱えたのはニーチェが最初ではない。1949年、宗教学者ミルチェア・エリアーデは、その比較研究『宇宙と歴史:永遠回帰の神話』の 中で、循環する宇宙論が世界中のほとんどすべての神話の伝統に見られることを示した[30]。 ホルヘ・ルイス・ボルヘスは、明らかにハウスドルフの著作を知らず、ゲオルク・カントールの集合論から非常によく似た論証でニーチェの証明に反論しようと したが、古代から現在に至るまで、同じ、あるいは類似の考え方が議論されている一連の並列的な文章を編集している。 ヨーロッパで最も古い証拠は、アリストテレスの二人の弟子、ディカイアルコスとロードス島のエウデモスから間接的に伝わった情報のみで、そこから、遅くと も紀元前4世紀には、ピタゴラス派の間に永遠回帰の思想が広まっていたことが浮かび上がってくる。ヘラクレイトスもまた言及されるべきである: 「生きているものと死んでいるもの、起きているものと眠っているもの、若いものと老いているもの。これがあれを変え、あれが戻ってこれを変えているからで ある」[32]。 エメーサのネメシウス(紀元4世紀)は、その著作『人間の本質について』(第38章)の中で、ストア派がこのような見解を持ち、占星術的運命論と組み合わ せていたと報告している: 彼らは、ある時期(「大いなる年」)が過ぎると、すべての惑星が天空の元の位置に戻り、天体の周期と同じように、人間の運命もまた最初からやり直さなけれ ばならないと信じていた: ソクラテスとプラトンが再び誕生するのだ。ニーチェは『Ecce homo』において、ストアにおけるこうした「この痕跡」に言及し、ストア派の教義の起源となりうる人物としてヘラクレイトスを挙げている。1874年の 2回目の時期尚早な考察(Vom Nutzen und Nachteil der Historie für das Leben)において、彼はすでにピタゴラス人の関連する伝統に言及していたが、それを正当化することはなかった。 [34] この考え方は、1870年代初頭にバーゼル大学でピュタゴラス派について講義した際のメモにも見られる。 聖アウグスティヌスは『De civitate Dei』第12巻(第11章(一部の版では第12章)と第13章(第14章))でこの教義と闘っている。ルキリオ・ヴァニーニは、この説をプラトンのもの としたが(おそらく『ティマイオス』の「大いなる年」を考えてのことであろうが、しかし、この仮説はここで意味する仮説に似ているだけであり、おそらく 火、空気、水、土の四大元素の順序(Tim.49 bf)にも似ている)、否定した。デイヴィッド・ヒュームは『自然宗教に関する対話』の中で、まさにニーチェの証明と思われるものを提示したが、どうやら その考えは不合理だと考えたようだ。ジョン・スチュアート・ミルは『論理学体系』(第三巻第五章第八節)の中で、世界の周期的経過の可能性に言及したが、 理由を述べることなくさりげなく否定した。 ニーチェは、永劫回帰が、繰り返し現れる寓話、恐怖、気晴らしに属することを知っていた[...]彼の啓示を、集合的なテキストや、リッターやプレラー助 教授の『Historia philosophiae graeco-romana』から導くことは、ツァラトゥストラにとっては問題外だった[...]予言的な文体は、逆カンマの使用を許さず、書物や著者の 博学な引用もほとんど許さない[...]」。 - ホルヘ・ルイス・ボルヘス[35] ニーチェの着想にはもう一つ可能性がある。ニーチェが自分の考えを練っていたまさにその頃、科学者や哲学者の間でこの仮説が議論されていた。その数年前、 ケルヴィン卿とルドルフ・クラウジウスが提唱した熱力学の原理によって、議論はすでに盛り上がっていた。ニーチェはオイゲン・デューリングの 『Cursus der Philosophie als streng wissenschaftlicher Weltanschauung und Lebensgestaltung』(1875年)やオットー・カスパーリの『Der Zusammenhang der Dinge』(1881年)をほぼ確実に読んでいた。後者の著作は、余白に非科学的な論証を加えて思想を否定しており、ニーチェの「ひらめき」に大きく貢 献したと思われる。この本をもとに、ニーチェは次の時代の議論を俯瞰しようと考え、自然科学を学ぼうとさえ考えた。彼が読んだ著作のなかには、J. G. フォクトの『Die Kraft』がある。Eine real-monistische Weltanschauung』(1878年)やオットー・リープマンの著作である。デューリングの著作には仮説に対する異論が含まれており、ニーチェが 1884年に読んだカール・フォン・ネーゲリの講義にも異論が含まれている。ネゲリの講義は、後にフリードリヒ・エンゲルスによって論じられた。オーギュ スト・ブランキのL'éternité par les astres (1872)もほぼ同じ仮説を含んでおり、おそらくニーチェの知人が『フレーリヒ・ヴィッセンシャフト』を読んだ後に参照したのだろう。最後に、ギュス ターヴ・ル・ボンの『人間と社会』(1881年)にも同様の考えがある。したがってニーチェの理論は、当時流行していた科学的仮説に基づいていた [36]。 ニーチェがアルトゥール・ショーペンハウアーを媒介として吸収した仏教的象徴主義の反響については、すでに述べたとおりである。最後に、ニーチェの遺稿 『ツァラトゥストラ』には、古代の象徴であるウロボロス[37]を想起させる箇所がある。 しかし、宇宙論的仮説を論じる際に忘れてはならないのは、ニーチェは証明の試みを公表せず、自然科学に目を向けず、『ツァラトゥストラはかく語りき』では まったく異なる表現形式を選んだということである。例えば、ジョルジョ・コッリは、『ツァラトゥストラはかく語りき』を「即時的」な、言語以前の経験を把 握しようとする試みと解釈することで、典拠や類似の探求のより深い価値に異議を唱えている: 「永遠の帰還のヴィジョンの根源として、人が求めるのは、古代のピュタゴラスの教義や19世紀の科学的仮説のドクソグラフィ的説明の響きよりも、時間の中 で回収可能でありながら時間の外につながり、その結果、不可逆的な単一性を打ち消す即時性を指し示す、ソクラテス以前の思索のクライマックスの瞬間の再現 である。このもはや表象不可能な即物性に立ち戻るならば、パルメニデスの『現在』やヘラクレイトスの『アイオン』といった時間の外側の即物性が時間の織物 の中に織り込まれており、その結果、実際に前や後に現れるものにおいては、あらゆる前が後であり、あらゆる後が前であり、あらゆる瞬間が始まりなのであ る」[38]。 ベルクソン派のミリチュ・チャペックは、チャールズ・サンダース・パイスやフランスの科学史家アベル・レイの時間概念にも対応する考察が見られると指摘し ている[39]。 |

| Literatur Oskar Becker: Nietzsches Beweise für seine Lehre von der ewigen Wiederkunft. In: Oskar Becker: Dasein und Dawesen, Pfullingen 1963. Mircea Eliade (1949): Kosmos und Geschichte. Der Mythos der ewigen Wiederkehr, v. a. Kap. III 2: Die kosmischen Zyklen und die Geschichte, Insel, Frankfurt 2007. Volker Gerhardt: Gipfel der Internität. Zu Günter Abels Rekonstruktion der Wiederkehr, in: Nietzsche Studien 16 (1987), 444–466. Gerd Harders: Der gerade Kreis – Nietzsche und die Geschichte der Ewigen Wiederkehr. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-428-12499-2. Joachim Harst: „Alle Jahrtausende ein Ende machen“. Typologie, Eschatologie und Ewige Wiederkunft bei Nietzsche. Nietzscheforschung, Band 24, Heft 1, 2017. S. 341–352. Paolo D'Iorio: Cosmologie d'éternel retour in: Nietzsche-Studien 24 (1995), S. 62–123. (Überblick über die Diskussionen des kosmologischen Lehrsatzes, besonders unter philosophischen und wissenschaftlichen Autoren in Deutschland in der zweiten Hälfte des 19. Jahrhunderts. Belegt das Interesse Nietzsches an diesen Diskussionen.); engl. Übersetzung "The Eternal Return: Genesis and Interpretation", in The Agonist, vol. III, issue I, spring 2011. Pierre Klossowski: Nietzsche und der Circulus vitiosus deus. Mit einem Nachwort von Gerd Bergfleth. Matthes und Seitz, München 1986, ISBN 3-88221-231-4. (Französische Erstausgabe 1969) Karl Löwith: Anhang zu Nietzsches Philosophie der ewigen Wiederkehr des Gleichen. Zur Geschichte der Nietzsche-Deutungen, in: Sämtliche Schriften, Bd. 6. Stuttgart 1987 (1955). Rudolf Paulsen: Ewige Wiederkunft des Gleichen oder Aufwärts-Entwickelung? (1921). Texte zur Nietzsche-Rezeption (1873–1963), hrsg. von Bruno Hillebrand, Berlin, Boston, Max Niemeyer Verlag. 1978, S. 206. Georg Römpp: Nietzsche leicht gemacht. Eine Einführung in sein Denken. UTB 3718, Böhlau, Köln u. a. 2013, ISBN 978-3-8252-3718-9. Miguel Skirl: Ewige Wiederkunft. In: Ottmann, Henning: Nietzsche-Handbuch. Metzler, Stuttgart-Weimar 2000, S. 222–230. |

文学 オスカー・ベッカー:ニーチェの永遠回帰の教義の証明。Oskar Becker: Dasein und Dawesen, Pfullingen 1963. ミルチャ・エリアーデ (1949): 宇宙と歴史。Der Mythos der ewigen Wiederkehr, esp. chap. III 2: Die kosmischen Zyklen und die Geschichte, Insel, Frankfurt 2007. Volker Gerhardt: Gipfel der Internität. Günter Abelの再帰の再構築について, Nietzsche Studien 16 (1987), 444-466. Gerd Harders: Der gerade Kreis - Nietzsche und die Geschichte der Ewigen Wiederkehr. Duncker & Humblot, Berlin 2007, ISBN 978-3-428-12499-2. Joachim Harst: 「Making an end to all millennia」. ニーチェにおける類型論、終末論、永遠回帰。ニーチェ研究』第24巻第1号、2017年、341-352頁。 Paolo D'Iorio: Cosmologie d'éternel retour in: Nietzsche-Studien 24 (1995), pp.62-123.(19世紀後半のドイツの哲学者・科学者を中心とした宇宙論的定理の議論を概観する。ニーチェがこれらの議論に関心を持っていた証拠 である);英訳「The Eternal Return: Genesis and Interpretation」(『アゴニスト』第III巻第1号、2011年春号)。III, issue I, spring 2011. Pierre Klossowski: Nietzsche and the Circulus vitiosus deus. Gerd Bergflethによるあとがき付き。Matthes and Seitz, Munich 1986, ISBN 3-88221-231-4. (フランス語初版1969年) カール・レーヴィット: ニーチェの『永劫回帰の哲学』への補遺。ニーチェの解釈の歴史について, Sämtliche Schriften, vol. 6. Stuttgart 1987 (1955). ルドルフ・ポールセン:同じことの永遠回帰か、それとも上昇発展か?(1921). Texte zur Nietzsche-Rezeption (1873-1963), ed. by Bruno Hillebrand, Berlin, Boston, Max Niemeyer Verlag. 1978, S. 206. Georg Römpp: Nietzsche made easy. 彼の思想入門。UTB 3718, Böhlau, Cologne et al., 2013, ISBN 978-3-8252-3718-9. Miguel Skirl: Eternal return. In: Ottmann, Henning: Nietzsche Handbook. Metzler, Stuttgart-Weimar 2000, pp. |

| https://de.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ewige_Wiederkunft |

リンク

文献

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099