Arthur

Szyk (June 3, 1894 – September 13,

1951)

情報論

Information theory

Arthur

Szyk (June 3, 1894 – September 13,

1951)

解説と評論:池田光 穂

★情報(Information)は、知らせる力を持つ何かを指す抽象的な概念である。最も根本的なレベルでは、それは感知可能なもの、あるいはそれらの抽象化に対する解釈(おそらく形式 的なもの)に関わる。完全にランダムではない自然過程や、あらゆる媒体における観察可能なパターンは、ある程度の情報を伝達していると言える。デジタル信 号やその他のデータが離散的な記号を用いて情報を伝達するのに対し、アナログ信号、詩、絵画、音楽やその他の音、電流といった他の現象や人工物は、より連 続的な形で情報を伝達する。情報は知識そのものではなく、解釈を通じて表現から導き出される意味である(→「情報人類学」)。

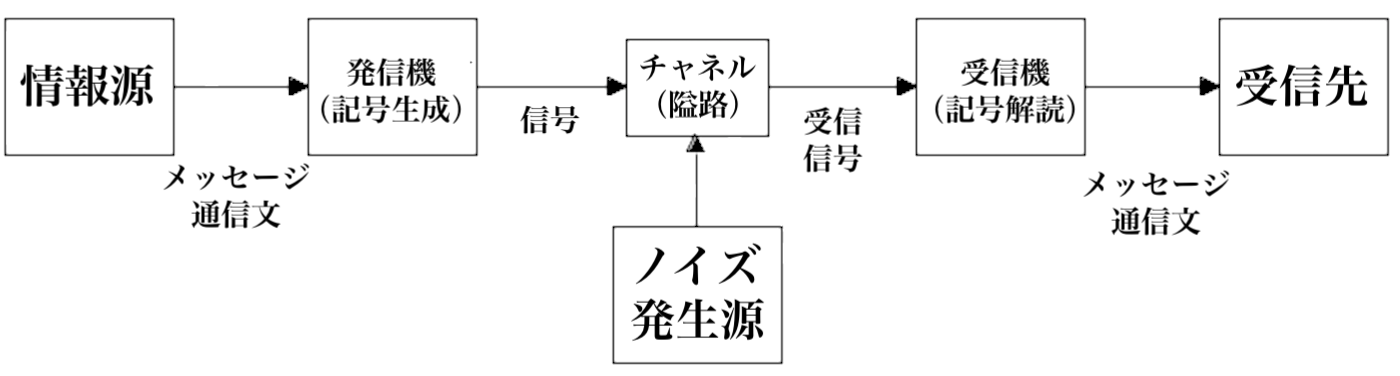

★情報理論:「20世紀半ば、「情報」という言葉は、エントロピーと いう概念に関連した新しい意味を獲得しました。1948年、ノーバート・ウィナーの著書 『サイバネティクス、あるいは動物と機械における制御と通信』が刊行され、情報について、物質やエネルギーと並ぶ自然の第三の基礎概念として論じられた。 同時に、クロード・シャノンは、 ハリー・ナイキストとラルフ・ハートリーの考えを発展させ、ビットという概念を情報量の測定単位として導入した。通信チャネルにおける信号伝送の最適化の 問題を検討し、彼は「意味論的側面は技術的な問題とは無関係である」と確信し、独自の通信モデルを提案しました。[9]。ウォーレン・ウィーバー[英語] は、彼らの理論では「情報」という言葉は一般的な意味ではなく、意味の存在を意味しない伝達信号の特性として使用されていることを明確にしている[21] [20] [22]。この用語の理解は、情報処理や情報技術[17]などの概念の基礎となっている。ラース・クォートラップ[デンマーク語] は、シャノンとウィーバーの理論における情報は、客観的な定量的価値として、またメッセージ送信者の主観的な選択として、矛盾して記述されていると指摘し ている[23] [24]。記号論の観点からは、数学的情報理論は構文(記号間の相互関係)のみを記述し、意味論 (記号と意味の関係)や語用論(記号と人間との関係)には触れていない[22]。哲学者ペーター・ヤニヒ[独語] は、このことに記号論者 チャールズ・モリス の思想の影響を見出しており、彼は、構文の問題を解決することが、意味論と語用論の問題を解決するための前提条件となるだろうと考えていました[25] 。1952年、意味論的情報理論はイェホシュア・バー・ヒレルとルドルフ・カーナップ[26]によって発表された。1980年代、シャノンの理論は、フ レッド・ドレッツキーによって認識論の観点から、またジョン・バーワイズ[英語] 、そしてジョン・ペリー[英語] 言語哲学[15][12] 。意味情報理論は、データ(一連の音や記号)とその意味内容[27]を区別している。」(出典:ロシア語ウィキ「情報理論」)

シャノン&ウィーバーのコミュニケーションモデル

★以下は情報の説明

| Information

is an abstract concept that refers to something which has the power to

inform. At the most fundamental level, it pertains to the

interpretation (perhaps formally) of that which may be sensed, or their

abstractions. Any natural process that is not completely random and any

observable pattern in any medium can be said to convey some amount of

information. Whereas digital signals and other data use discrete signs

to convey information, other phenomena and artifacts such as analogue

signals, poems, pictures, music or other sounds, and currents convey

information in a more continuous form.[1] Information is not knowledge

itself, but the meaning that may be derived from a representation

through interpretation.[2] The concept of information is relevant or connected to various concepts,[3] including constraint, communication, control, data, form, education, knowledge, meaning, understanding, mental stimuli, pattern, perception, proposition, representation, and entropy. Information is often processed iteratively: Data available at one step are processed into information to be interpreted and processed at the next step. For example, in written text each symbol or letter conveys information relevant to the word it is part of, each word conveys information relevant to the phrase it is part of, each phrase conveys information relevant to the sentence it is part of, and so on until at the final step information is interpreted and becomes knowledge in a given domain. In a digital signal, bits may be interpreted into the symbols, letters, numbers, or structures that convey the information available at the next level up. The key characteristic of information is that it is subject to interpretation and processing. The derivation of information from a signal or message may be thought of as the resolution of ambiguity or uncertainty that arises during the interpretation of patterns within the signal or message.[4] Information may be structured as data. Redundant data can be compressed up to an optimal size, which is the theoretical limit of compression. The information available through a collection of data may be derived by analysis. For example, a restaurant collects data from every customer order. That information may be analyzed to produce knowledge that is put to use when the business subsequently wants to identify the most popular or least popular dish.[citation needed] Information can be transmitted in time, via data storage, and space, via communication and telecommunication.[5] Information is expressed either as the content of a message or through direct or indirect observation. That which is perceived can be construed as a message in its own right, and in that sense, all information is always conveyed as the content of a message. Information can be encoded into various forms for transmission and interpretation (for example, information may be encoded into a sequence of signs, or transmitted via a signal). It can also be encrypted for safe storage and communication. The uncertainty of an event is measured by its probability of occurrence. Uncertainty is proportional to the negative logarithm of the probability of occurrence. Information theory takes advantage of this by concluding that more uncertain events require more information to resolve their uncertainty. The bit is a typical unit of information. It is 'that which reduces uncertainty by half'.[6] Other units such as the nat may be used. For example, the information encoded in one "fair" coin flip is log2(2/1) = 1 bit, and in two fair coin flips is log2(4/1) = 2 bits. A 2011 Science article estimates that 97% of technologically stored information was already in digital bits in 2007 and that the year 2002 was the beginning of the digital age for information storage (with digital storage capacity bypassing analogue for the first time).[7] |

情報は、知らせる力を持つ何かを指す抽象的な概念だ。最も根本的なレベ

ルでは、それは感知可能なもの、あるいはそれらの抽象化に対する解釈(おそらく形式的なもの)に関わる。完全にランダムではない自然過程や、あらゆる媒体

における観察可能なパターンは、ある程度の情報を伝達していると言える。デジタル信号やその他のデータが離散的な記号を用いて情報を伝達するのに対し、ア

ナログ信号、詩、絵画、音楽やその他の音、電流といった他の現象や人工物は、より連続的な形で情報を伝達する。情報は知識そのものではなく、解釈を通じて

表現から導き出される意味である。[2] 情報の概念は、制約、コミュニケーション、制御、データ、形式、教育、知識、意味、理解、精神的刺激、パターン、知覚、命題、表現、エントロピーなど、様々な概念に関連あるいは結びついている。[3] 情報はしばしば反復的に処理される。ある段階で入手可能なデータは、次の段階で解釈・処理される情報へと変換される。例えば、書かれたテキストでは、各記 号や文字はそれが属する単語に関連する情報を伝え、各単語はそれが属する句に関連する情報を伝え、各句はそれが属する文に関連する情報を伝える。この過程 が最終段階まで続き、情報が解釈されて特定の領域における知識となる。デジタル信号においては、ビットが次の階層で利用可能な情報を伝達する記号、文字、 数字、または構造へと解釈される。情報の核心的特性は、解釈と処理の対象となる点にある。 信号やメッセージからの情報の導出は、信号やメッセージ内のパターン解釈過程で生じる曖昧さや不確実性の解消と捉えられる。[4] 情報はデータとして構造化される。冗長なデータは圧縮により最適サイズまで縮小可能であり、これが圧縮の理論的限界である。 データ集合から得られる情報は分析によって導出される。例えば飲食店は顧客注文データを収集する。この情報を分析し、後に人気料理や不人気料理を特定する際に活用される知識を生成する。[出典必要] 情報は時間軸(データ保存による)と空間軸(通信・電気通信による)で伝達される。[5] 情報はメッセージの内容として、あるいは直接的・間接的観察を通じて表現される。知覚されたものはそれ自体がメッセージと解釈され得る。この意味で、あら ゆる情報は常にメッセージの内容として伝達される。 情報は伝達と解釈のために様々な形式に符号化される(例えば、記号列に符号化される、あるいは信号を介して伝達される)。安全な保存と通信のために暗号化されることもある。 事象の不確実性は発生確率によって測定される。不確実性は発生確率の負の対数に比例する。情報理論はこの性質を利用し、不確実な事象ほどその不確実性を解 消するために多くの情報が必要だと結論づける。ビットは典型的な情報の単位である。これは「不確実性を半分に減らすもの」である[6]。ナットなどの他の 単位も使用される。例えば、1回の「公正な」コイン投げに符号化された情報はlog2(2/1) = 1ビットであり、2回の公正なコイン投げではlog2(4/1) = 2ビットとなる。2011年の『サイエンス』誌の論文によれば、2007年時点で技術的に保存された情報の97%は既にデジタルビットで存在しており、 2002年が情報保存におけるデジタル時代の始まりであった(デジタル保存容量が初めてアナログを凌駕した年である)。[7] |

| Etymology and history of the concept This section has multiple issues. Please help improve it or discuss these issues on the talk page. (Learn how and when to remove these messages) This article contains too many or overly lengthy quotations. (August 2025) You can help expand this section with text translated from the corresponding article in Russian. (August 2025) Click [show] for important translation instructions. The English word "information" comes from Middle French enformacion/informacion/information 'a criminal investigation' and its etymon, Latin informatiō(n) 'conception, teaching, creation'.[8] In English, "information" is an uncountable mass noun. References on "formation or molding of the mind or character, training, instruction, teaching" date from the 14th century in both English (according to Oxford English Dictionary) and other European languages. In the transition from Middle Ages to Modernity the use of the concept of information reflected a fundamental turn in epistemological basis – from "giving a (substantial) form to matter" to "communicating something to someone". Peters (1988, pp. 12–13) concludes: Information was readily deployed in empiricist psychology (though it played a less important role than other words such as impression or idea) because it seemed to describe the mechanics of sensation: objects in the world inform the senses. But sensation is entirely different from "form" – the one is sensual, the other intellectual; the one is subjective, the other objective. My sensation of things is fleeting, elusive, and idiosyncratic. For Hume, especially, sensory experience is a swirl of impressions cut off from any sure link to the real world... In any case, the empiricist problematic was how the mind is informed by sensations of the world. At first informed meant shaped by; later it came to mean received reports from. As its site of action drifted from cosmos to consciousness, the term's sense shifted from unities (Aristotle's forms) to units (of sensation). Information came less and less to refer to internal ordering or formation, since empiricism allowed for no preexisting intellectual forms outside of sensation itself. Instead, information came to refer to the fragmentary, fluctuating, haphazard stuff of sense. Information, like the early modern worldview in general, shifted from a divinely ordered cosmos to a system governed by the motion of corpuscles. Under the tutelage of empiricism, information gradually moved from structure to stuff, from form to substance, from intellectual order to sensory impulses.[9] In the modern era, the most important influence on the concept of information is derived from the Information theory developed by Claude Shannon and others. This theory, however, reflects a fundamental contradiction. Northrup (1993)[10] wrote: Thus, actually two conflicting metaphors are being used: The well-known metaphor of information as a quantity, like water in the water-pipe, is at work, but so is a second metaphor, that of information as a choice, a choice made by :an information provider, and a forced choice made by an :information receiver. Actually, the second metaphor implies that the information sent isn't necessarily equal to the information received, because any choice implies a comparison with a list of possibilities, i.e., a list of possible meanings. Here, meaning is involved, thus spoiling the idea of information as a pure "Ding an sich." Thus, much of the confusion regarding the concept of information seems to be related to the basic confusion of metaphors in Shannon's theory: is information an autonomous quantity, or is information always per SE information to an observer? Actually, I don't think that Shannon himself chose one of the two definitions. Logically speaking, his theory implied information as a subjective phenomenon. But this had so wide-ranging epistemological impacts that Shannon didn't seem to fully realize this logical fact. Consequently, he continued to use metaphors about information as if it were an objective substance. This is the basic, inherent contradiction in Shannon's information theory." (Northrup, 1993, p. 5) In their seminal book The Study of Information: Interdisciplinary Messages,[11] Almach and Mansfield (1983) collected key views on the interdisciplinary controversy in computer science, artificial intelligence, library and information science, linguistics, psychology, and physics, as well as in the social sciences. Almach (1983,[12] p. 660) himself disagrees with the use of the concept of information in the context of signal transmission, the basic senses of information in his view all referring "to telling something or to the something that is being told. Information is addressed to human minds and is received by human minds." All other senses, including its use with regard to nonhuman organisms as well to society as a whole, are, according to Machlup, metaphoric and, as in the case of cybernetics, anthropomorphic. Hjørland (2007) [13] describes the fundamental difference between objective and subjective views of information and argues that the subjective view has been supported by, among others, Bateson,[14] Yovits,[15][16] Span-Hansen,[17] Brier,[18] Buckland,[19] Goguen,[20] and Hjørland.[21] Hjørland provided the following example: A stone on a field could contain different information for different people (or from one situation to another). It is not possible for information systems to map all the stone's possible information for every individual. Nor is any one mapping the one "true" mapping. But people have different educational backgrounds and play different roles in the division of labor in society. A stone in a field represents typical one kind of information for the geologist, another for the archaeologist. The information from the stone can be mapped into different collective knowledge structures produced by e.g. geology and archaeology. Information can be identified, described, represented in information systems for different domains of knowledge. Of course, there are much uncertainty and many and difficult problems in determining whether a thing is informative or not for a domain. Some domains have high degree of consensus and rather explicit criteria of relevance. Other domains have different, conflicting paradigms, each containing its own more or less implicate view of the informativeness of different kinds of information sources. (Hjørland, 1997, p. 111, emphasis in original). |

語源と概念の歴史 この節には複数の問題点がある。改善に協力するか、トークページで議論してほしい。(これらのメッセージを削除する方法とタイミングについて学ぶ) この記事には引用が多すぎるか、引用が長すぎる。(2025年8月) 対応するロシア語記事から翻訳したテキストでこの節を拡張できる。(2025年8月)重要な翻訳指示については[表示]をクリックせよ。 英語の「information」は中世フランス語のenformacion/informacion/information(刑事捜査)およびその語源であるラテン語informatiō(n)(構想、教育、創造)に由来する。[8] 英語において「information」は不可算名詞である。 「精神や性格の形成・育成、訓練、指導、教育」に関する言及は、英語(オックスフォード英語辞典による)および他のヨーロッパ言語において14世紀に遡 る。中世から近代への移行期において、情報の概念の使用は認識論的基盤における根本的な転換を反映していた——「物質に(実質的な)形を与える」ことから 「誰かに何かを伝える」ことへの転換である。ピーターズ(1988年、12-13頁)は次のように結論づけている: 経験主義心理学において「情報」は容易に採用された(ただし「印象」や「観念」といった他の用語ほど重要な役割は果たさなかった)。なぜならそれは感覚の メカニズムを説明しているように見えたからだ:世界にある物体が感覚に情報を与える。しかし感覚は「形式」とは全く異なる——前者は感覚的、後者は知的で ある。前者は主観的、後者は客観的である。物事に対する私の感覚は儚く、捉えどころがなく、個人差が大きい。特にヒュームにとって感覚的経験とは、現実世 界との確かな繋がりを断たれた印象の渦である...いずれにせよ、経験論者の課題は、心が世界の感覚によっていかに形成されるかだった。当初「形成され る」は「形作られる」を意味したが、後に「報告を受ける」という意味に変化した。その作用の場が宇宙から意識へと移るにつれ、この用語の意味は「統一性」 (アリストテレスのイデア)から「単位」(感覚の)へと移行した。経験主義は感覚そのもの以外に先在する知的形態を認めなかったため、情報はますます内的 な秩序や形成を指すものではなくなった。代わりに、情報は断片的で変動し、偶然的な感覚の素材を指すようになった。情報という概念は、近世世界観全般と同 様に、神によって秩序づけられた宇宙から、微粒子の運動によって支配される体系へと移行した。経験主義の指導のもと、情報は次第に構造から物質へ、形式か ら実体へ、知的秩序から感覚的衝動へと移行していった。[9] 近代において、情報概念に最も重要な影響を与えたのは、クロード・シャノンらが発展させた情報理論である。しかしこの理論は根本的な矛盾を反映している。ノースラップ(1993)[10]はこう記した: つまり実際には二つの矛盾する隠喩が使われているのだ: 水管内の水のような量としての情報のよく知られた隠喩が機能しているが、同時に第二の隠喩、すなわち情報提供者による選択、そして情報受領者による強制的 な選択としての情報という隠喩も機能している。実際、第二の隠喩は、送信された情報が必ずしも受信された情報と等しくないことを示唆している。なぜなら、 いかなる選択も可能性のリスト、すなわち可能な意味のリストとの比較を意味するからだ。ここで意味が関与するため、情報は純粋な「物自体」という概念が損 なわれる。したがって、情報概念に関する混乱の多くは、シャノンの理論における隠喩の基本的な混同に関連しているようだ。すなわち、情報は自律的な量なの か、それとも常に観察者にとっての「情報そのもの」なのか?実際、シャノン自身がこの二つの定義のいずれかを選択したとは思えない。論理的に言えば、彼の 理論は情報を主観的現象として示唆していた。しかしこの論理的事実は、認識論的にあまりにも広範な影響を及ぼしたため、シャノン自身はその本質を完全に理 解していなかったようだ。結果として彼は、情報を客観的実体であるかのように隠喩を使い続けた。これがシャノン情報理論に内在する根本的矛盾である。」 (Northrup, 1993, p. 5) アルマックとマンスフィールド(1983)は、画期的な著作『情報研究:学際的メッセージ』[11]において、コンピュータ科学、人工知能、図書館情報 学、言語学、心理学、物理学、そして社会科学における学際的論争に関する主要な見解を集めた。アルマック自身(1983年[12]、p. 660)は、信号伝達の文脈における情報概念の使用に異議を唱えている。彼の見解では、情報の基本的な意味はすべて「何かを伝えること、あるいは伝えられ る何か」を指す。情報は人間の精神に向けられ、人間の精神によって受け取られるのだ。マクループによれば、非人間的有機体や社会全体に関する使用を含む他 の全ての意味は隠喩的であり、サイバネティクスの場合のように擬人化されている。 ヒョールランド(2007)[13]は、情報の客観的見解と主観的見解の根本的な差異を説明し、主観的見解がベイトソン[14]、ヨヴィッツ、 [15][16]、スパン=ハンセン[17]、ブライアー[18]、バックランド[19]、ゴグエン[20]、ヨールランド[21]らによって支持されて きたと論じている。ヨールランドは以下の例を挙げている: 野原にある石は、人によって(あるいは状況によって)異なる情報を含む可能性がある。情報システムが、あらゆる個人に対してその石の持つ可能性のある全て の情報をマッピングすることは不可能だ。また、いずれのマッピングも唯一の「真の」マッピングではない。しかし人々は異なる教育背景を持ち、社会の分業に おいて異なる役割を担っている。野原の石は地質学者にとっては典型的なある種の情報であり、考古学者にとっては別の情報である。石からの情報は、例えば地 質学や考古学によって生み出される異なる集合的知識構造へマッピングされうる。情報は、異なる知識領域の情報システムにおいて識別され、記述され、表現さ れうる。もちろん、ある事象が特定の領域にとって有益かどうかを判断するには、多くの不確実性と困難な問題が存在する。合意が高度に形成され、関連性の基 準が比較的明示的な領域もあれば、異なる対立するパラダイムが存在する領域もある。それぞれのパラダイムは、異なる種類の情報源の有益性について、多かれ 少なかれ暗黙的な独自の視点を内包しているのだ(Hjørland, 1997, p. 111, 原文強調)。 |

| Information theory Main article: Information theory Information theory is the scientific study of the quantification, storage, and communication of information. The field itself was fundamentally established by the work of Claude Shannon in the 1940s, with earlier contributions by Harry Nyquist and Ralph Hartley in the 1920s.[22][23] The field is at the intersection of probability theory, statistics, computer science, statistical mechanics, information engineering, and electrical engineering. A key measure in information theory is entropy. Entropy quantifies the amount of uncertainty involved in the value of a random variable or the outcome of a random process. For example, identifying the outcome of a fair coin flip (with two equally likely outcomes) provides less information (lower entropy) than specifying the outcome from a roll of a die (with six equally likely outcomes). Some other important measures in information theory are mutual information, channel capacity, error exponents, and relative entropy. Important sub-fields of information theory include source coding, algorithmic complexity theory, algorithmic information theory, and information-theoretic security.[citation needed] Applications of fundamental topics of information theory include source coding/data compression (e.g. for ZIP files), and channel coding/error detection and correction (e.g. for DSL). Its impact has been crucial to the success of the Voyager missions to deep space, the invention of the compact disc, the feasibility of mobile phones and the development of the Internet. The theory has also found applications in other areas, including statistical inference,[24] cryptography, neurobiology,[25] perception,[26] linguistics, the evolution[27] and function[28] of molecular codes (bioinformatics), thermal physics,[29] quantum computing, black holes, information retrieval, intelligence gathering, plagiarism detection,[30] pattern recognition, anomaly detection[31] and even art creation. |

情報理論 主な記事: 情報理論 情報理論とは、情報の定量化、保存、伝達に関する科学的研究である。この分野自体は、1940年代のクロード・シャノンの研究によって根本的に確立された が、1920年代のハリー・ナイキストとラルフ・ハートリーの先行研究があった。[22][23] この分野は、確率論、統計学、計算機科学、統計力学、情報工学、電気工学の交差点に位置する。 情報理論における重要な指標はエントロピーである。エントロピーは、確率変数の値や確率過程の結果に伴う不確実性の量を定量化する。例えば、公平なコイン 投げの結果(2つの等確率の結果)を特定することは、サイコロの目の結果(6つの等確率の結果)を特定するよりも少ない情報(低いエントロピー)を提供す る。情報理論におけるその他の重要な指標には、相互情報量、チャネル容量、誤り指数、相対エントロピーがある。情報理論の重要なサブ分野には、情報源符号 化、アルゴリズム的複雑性理論、アルゴリズム情報理論、情報理論的セキュリティが含まれる。[出典が必要] 情報理論の基本的なトピックの応用には、ソース符号化/データ圧縮(例:ZIPファイル)やチャネル符号化/誤り検出・訂正(例:DSL)が含まれる。そ の影響は、深宇宙へのボイジャー探査機の成功、コンパクトディスクの発明、携帯電話の実現可能性、インターネットの発展に決定的であった。この理論は他の 分野でも応用されている。統計的推論[24]、暗号学、神経生物学[25]、知覚[26]、言語学、分子コードの進化[27]と機能[28](バイオイン フォマティクス)、 熱物理学[29]、量子コンピューティング、ブラックホール、情報検索、情報収集、剽窃検出[30]、パターン認識、異常検出[31]、さらには芸術創作 に至るまで幅広い分野で応用されている。 |

| As sensory input Often information can be viewed as a type of input to an organism or system. Inputs are of two kinds. Some inputs are important to the function of the organism (for example, food) or system (energy) by themselves. In his book Sensory Ecology[32] biophysicist David B. Dusenbery called these causal inputs. Other inputs (information) are important only because they are associated with causal inputs and can be used to predict the occurrence of a causal input at a later time (and perhaps another place). Some information is important because of association with other information but eventually there must be a connection to a causal input. In practice, information is usually carried by weak stimuli that must be detected by specialized sensory systems and amplified by energy inputs before they can be functional to the organism or system. For example, light is mainly (but not only, e.g. plants can grow in the direction of the light source) a causal input to plants but for animals it only provides information. The colored light reflected from a flower is too weak for photosynthesis but the visual system of the bee detects it and the bee's nervous system uses the information to guide the bee to the flower, where the bee often finds nectar or pollen, which are causal inputs, a nutritional function. |

感覚入力として 情報は往々にして、生物やシステムへの一種の入力と見なせる。入力には二種類ある。ある入力は、それ自体が生物(例えば食物)やシステム(エネルギー)の 機能にとって重要だ。生物物理学者デイビッド・B・デュゼンベリーは著書『感覚生態学』[32]で、これらを因果入力と呼んだ。他の入力(情報)は、因果 入力と関連付けられ、後時(場合によっては別の場所)における因果入力の発生を予測するために利用可能であるという点でのみ重要である。一部の情報は他の 情報との関連性ゆえに重要だが、最終的には因果入力との接続が必須となる。 実際には、情報は通常、弱い刺激によって運ばれる。それらは特殊な感覚システムによって検出され、エネルギー入力によって増幅されて初めて、生物やシステ ムにとって機能的となる。例えば、光は主に(ただし唯一ではない。例えば植物は光源の方向へ成長する)植物にとって因果的入力だが、動物にとっては情報し か提供しない。花から反射される色付き光は光合成には弱すぎるが、蜂の視覚系はそれを感知し、蜂の神経系はその情報を利用して蜂を花へと導く。そこで蜂は しばしば蜜や花粉(これらは栄養機能という因果的入力)を見つけるのである。 |

| As an influence that leads to transformation Information is any type of pattern that influences the formation or transformation of other patterns.[33][34] In this sense, there is no need for a conscious mind to perceive, much less appreciate, the pattern. Consider, for example, DNA. The sequence of nucleotides is a pattern that influences the formation and development of an organism without any need for a conscious mind. One might argue though that for a human to consciously define a pattern, for example a nucleotide, naturally involves conscious information processing. However, the existence of unicellular and multicellular organisms, with the complex biochemistry that leads, among other events, to the existence of enzymes and polynucleotides that interact maintaining the biological order and participating in the development of multicellular organisms, precedes by millions of years the emergence of human consciousness and the creation of the scientific culture that produced the chemical nomenclature. Systems theory at times seems to refer to information in this sense, assuming information does not necessarily involve any conscious mind, and patterns circulating (due to feedback) in the system can be called information. In other words, it can be said that information in this sense is something potentially perceived as representation, though not created or presented for that purpose. For example, Gregory Bateson defines "information" as a "difference that makes a difference".[35] If, however, the premise of "influence" implies that information has been perceived by a conscious mind and also interpreted by it, the specific context associated with this interpretation may cause the transformation of the information into knowledge. Complex definitions of both "information" and "knowledge" make such semantic and logical analysis difficult, but the condition of "transformation" is an important point in the study of information as it relates to knowledge, especially in the business discipline of knowledge management. In this practice, tools and processes are used to assist a knowledge worker in performing research and making decisions, including steps such as: Review information to effectively derive value and meaning Reference metadata if available Establish relevant context, often from many possible contexts Derive new knowledge from the information Make decisions or recommendations from the resulting knowledge Stewart (2001) argues that transformation of information into knowledge is critical, lying at the core of value creation and competitive advantage for the modern enterprise. In a biological framework, Mizraji [36] has described information as an entity emerging from the interaction of patterns with receptor systems (eg: in molecular or neural receptors capable of interacting with specific patterns, information emerges from those interactions). In addition, he has incorporated the idea of "information catalysts", structures where emerging information promotes the transition from pattern recognition to goal-directed action (for example, the specific transformation of a substrate into a product by an enzyme, or auditory reception of words and the production of an oral response) The Danish Dictionary of Information Terms[37] argues that information only provides an answer to a posed question. Whether the answer provides knowledge depends on the informed person. So a generalized definition of the concept should be: "Information" = An answer to a specific question". When Marshall McLuhan speaks of media and their effects on human cultures, he refers to the structure of artifacts that in turn shape our behaviors and mindsets. Also, pheromones are often said to be "information" in this sense. |

変容をもたらす影響として 情報は、他のパターンの形成や変容に影響を与えるあらゆる種類のパターンである[33][34]。この意味において、そのパターンを認識する意識的な心は 不要であり、ましてや評価する必要などない。例えばDNAを考えてみよう。ヌクレオチドの配列は、意識的な心など必要とせずに生物の形成と発達に影響を与 えるパターンである。とはいえ、人間が意識的にパターン(例えばヌクレオチド)を定義するには、当然ながら意識的な情報処理が伴うと反論する者もいるだろ う。しかし、単細胞生物や多細胞生物の存在、そして酵素やポリヌクレオチドといった生物学的秩序を維持し多細胞生物の発達に寄与する相互作用をもたらす複 雑な生化学は、人間の意識の出現や化学命名法を生み出した科学文化の創出よりも数百万年も前に存在していた。 システム理論は時に、この意味での情報を指すように見える。情報には必ずしも意識的な心は関与せず、システム内で(フィードバックにより)循環するパター ンは情報と呼べるという前提だ。言い換えれば、この意味での情報は、その目的で創造されたり提示されたりしたものではないが、潜在的に表象として知覚され 得るものと言える。例えばグレゴリー・ベイトソンは「情報」を「差異を生む差異」と定義している[35]。 しかし「影響」という前提が、情報が意識的な精神によって知覚され、かつ解釈されたことを意味する場合、この解釈に関連する特定の文脈が、情報を知識へと 変容させる原因となり得る。「情報」と「知識」の複雑な定義は、こうした意味論的・論理的分析を困難にするが、「変容」という条件は、特に知識管理という ビジネス分野において、知識に関連する情報研究における重要な点である。この実践では、知識労働者が調査や意思決定を行うのを支援するツールやプロセスが 用いられ、以下のようなステップを含む: 情報を精査し、効果的に価値と意味を導出する 利用可能な場合はメタデータを参照する 多くの可能な文脈の中から関連する文脈を確立する 情報から新たな知識を導出する 得られた知識から意思決定や提言を行う スチュワート(2001)は、情報を知識へ変換することが現代企業における価値創造と競争優位性の核心であり、極めて重要だと論じている。 生物学的枠組みにおいて、ミズラジ[36]は情報を「パターンと受容体システムの相互作用から生じる実体」と定義している(例:特定のパターンと相互作用 可能な分子受容体や神経受容体において、情報はその相互作用から生じる)。さらに彼は「情報触媒」の概念を取り入れている。これは出現する情報が、パター ン認識から目的指向行動への移行を促進する構造を指す(例:酵素による基質の特定変換、言葉の聴覚的受容と口頭応答の生成)。 デンマーク情報用語辞典[37]は、情報は提示された質問への回答のみを提供すると論じている。その答えが知識をもたらすかどうかは、情報を与えられた人格に依存する。したがって、この概念の一般化された定義は「情報」=「特定の質問に対する答え」となる。 マーシャル・マクルーハンがメディアとそれが人間文化に及ぼす影響について語る際、彼は私たちの行動や思考様式を形成する人工物の構造を指している。また、フェロモンもこの意味において「情報」であると言われることが多い。 |

| Accuracy and precision Complex adaptive system Complex system Data storage Engram Free Information Infrastructure Freedom of information Informatics Information and communication technologies Information architecture Information broker Information continuum Information ecology Information engineering Information geometry Information inequity Information infrastructure Information management Information metabolism Information overload Information quality (InfoQ) Information science Information sensitivity Information technology Information theory Information warfare Infosphere Lexicographic information cost Library science Meme Philosophy of information Quantum information Receiver operating characteristic Satisficing |

正確性と精密性 複雑適応システム 複雑システム データ保存 エングラム 自由情報インフラ 情報の自由 情報学 情報通信技術 情報アーキテクチャ 情報ブローカー 情報連続体 情報生態学 情報工学 情報幾何学 情報不平等 情報インフラ 情報管理 情報代謝 情報過多 情報品質(InfoQ) 情報科学 情報感受性 情報技術 情報理論 情報戦争 情報圏 辞書順情報コスト 図書館学 ミーム 情報哲学 量子情報 受信者動作特性 満足化 |

| 1. John B. Anderson; Rolf Johnnesson (1996). Understanding Information Transmission. Ieee Press. ISBN 978-0-471-71120-9. 2. Hubert P. Yockey (2005). Information Theory, Evolution, and the Origin of Life. Cambridge University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-511-54643-3. 3. Luciano Floridi (2010). Information – A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-160954-1. 4. Webler, Forrest (25 February 2022). "Measurement in the Age of Information". Information. 13 (3): 111. doi:10.3390/info13030111. 5. "World_info_capacity_animation". YouTube. 11 June 2011. Archived from the original on 21 December 2021. Retrieved 1 May 2017. 6. "DT&SC 4-5: Information Theory Primer, Online Course". YouTube. University of California. 2015. 7. Hilbert, Martin; López, Priscila (2011). "The World's Technological Capacity to Store, Communicate, and Compute Information". Science. 332 (6025): 60–65. Bibcode:2011Sci...332...60H. doi:10.1126/science.1200970. PMID 21310967. S2CID 206531385. Free access to the article at martinhilbert.net/WorldInfoCapacity.html 8. Oxford English Dictionary, Third Edition, 2009, full text 9. Peters, J. D. (1988). Information: Notes Toward a Critical History. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 12, 10-24. 10. Qvortrup, L. (1993). The controversy over the concept of information. An overview and a selected and annotated bibliography. Cybernetics & Human Knowing 1(4), 3-24. 11. Machlup, Fritz & Una Mansfield (eds.). 1983. The Study of Information: Interdisciplinary Messages. New York: Wiley. 12. Machlup, Fritz. 1983. "Semantic Quirks in Studies of Information," pp. 641-71 in Fritz Machlup & Una Mansfield, The Study of Information: Interdisciplinary Messages. New York: Wiley. 13. Hjørland, B. (2007). Information: Objective or Subjective/Situational?. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(10), 1448-1456. 14. Bateson, G. (1972). Steps to an ecology of mind. New York: Ballantine. 15. Yovits, M.C. (1969). Information science: Toward the development of a true scientific discipline. American Documentation (Vol. 20, pp. 369–376). 16. Yovits, M. C. (1975). A theoretical framework for the development of information science. In International Federation for Documentation. Study Committee Research on the Theoretical Basis of Information. Meeting (1974: Moscow) Information science, its scope, objects of research and problems: Collection of papers [presented at the meeting of the FID Study Committee "Research on the Theoretical Basis of Information"] 24–26 April 1974, Moscow (pp. 90–114). FID 530. Moscow: VINITI 17. Spang-Hanssen, H. (2001). How to teach about information as related to documentation. Human IT, (1), 125–143. Retrieved May 14, 2007, from http://www.hb.se/bhs/ith/1-01/hsh.htm Archived 2008-02-19 at the Wayback Machine 18. Brier, S. (1996). Cybersemiotics: A new interdisciplinary development applied to the problems of knowledge organisation and document retrieval in information science. Journal of Documentation, 52(3), 296–344. 19. Buckland, M. (1991). Information and information systems. New York: Greenwood Press. 20. Goguen, J. A. (1997). Towards a social, ethical theory of information. In G. Bowker, L. Gasser, L. Star, & W. Turner, Erlbaum (Eds.), Social science research, technical systems and cooperative work: Beyond the great divide (pp. 27–56). Hillsdale, NJ: Erlbaum. Retrieved May 14, 2007, from http://cseweb.ucsd.edu/~goguen/ps/sti.pdf 21. Hjørland, B. (1997). Information seeking and subject representation. An activity-theoretical approach to information science. Westport: Greenwood Press. 22. Pérez-Montoro Gutiérrez, Mario; Edelstein, Dick (2007). The Phenomenon of Information: A Conceptual Approach to Information Flow. Lanham (Md.): Scarecrow Press. pp. 21–22. ISBN 978-0-8108-5942-5. 23. Wesołowski, Krzysztof (2009). Introduction to Digital Communication Systems (PDF) (1. publ ed.). Chichester: Wiley. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-470-98629-5. 24. Burnham, K. P. and Anderson D. R. (2002) Model Selection and Multimodel Inference: A Practical Information-Theoretic Approach, Second Edition (Springer Science, New York) ISBN 978-0-387-95364-9. 25. F. Rieke; D. Warland; R Ruyter van Steveninck; W Bialek (1997). Spikes: Exploring the Neural Code. The MIT press. ISBN 978-0-262-68108-7. 26. Delgado-Bonal, Alfonso; Martín-Torres, Javier (3 November 2016). "Human vision is determined based on information theory". Scientific Reports. 6 (1) 36038. Bibcode:2016NatSR...636038D. doi:10.1038/srep36038. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5093619. PMID 27808236. 27. cf; Huelsenbeck, J. P.; Ronquist, F.; Nielsen, R.; Bollback, J. P. (2001). "Bayesian inference of phylogeny and its impact on evolutionary biology". Science. 294 (5550): 2310–2314. Bibcode:2001Sci...294.2310H. doi:10.1126/science.1065889. PMID 11743192. S2CID 2138288. 28. Allikmets, Rando; Wasserman, Wyeth W.; Hutchinson, Amy; Smallwood, Philip; Nathans, Jeremy; Rogan, Peter K. (1998). "Thomas D. Schneider], Michael Dean (1998) Organization of the ABCR gene: analysis of promoter and splice junction sequences". Gene. 215 (1): 111–122. doi:10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00269-8. PMID 9666097. 29. Jaynes, E. T. (1957). "Information Theory and Statistical Mechanics". Phys. Rev. 106 (4): 620. Bibcode:1957PhRv..106..620J. doi:10.1103/physrev.106.620. S2CID 17870175. 30. Bennett, Charles H.; Li, Ming; Ma, Bin (2003). "Chain Letters and Evolutionary Histories". Scientific American. 288 (6): 76–81. Bibcode:2003SciAm.288f..76B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0603-76. PMID 12764940. Archived from the original on 7 October 2007. Retrieved 11 March 2008. 31. David R. Anderson (1 November 2003). "Some background on why people in the empirical sciences may want to better understand the information-theoretic methods" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 23 July 2011. Retrieved 23 June 2010. 32. Dusenbery, David B. (1992). Sensory Ecology. New York: W.H. Freeman. ISBN 978-0-7167-2333-2. 33. Shannon, Claude E. (1949). The Mathematical Theory of Communication. Bibcode:1949mtc..book.....S. 34. Casagrande, David (1999). "Information as verb: Re-conceptualizing information for cognitive and ecological models" (PDF). Journal of Ecological Anthropology. 3 (1): 4–13. doi:10.5038/2162-4593.3.1.1. 35. Bateson, Gregory (1972). Form, Substance, and Difference, in Steps to an Ecology of Mind. University of Chicago Press. pp. 448–466. 36. Mizraji, E. (2021). "The biological Maxwell's demons: exploring ideas about the information processing in biological systems". Theory in Biosciences. 140 (3): 307–318. doi:10.1007/s12064-021-00354-6. PMC 8568868. PMID 34449033. 37. Simonsen, Bo Krantz. "Informationsordbogen – vis begreb". Informationsordbogen.dk. Retrieved 1 May 2017. |

1. ジョン・B・アンダーソン、ロルフ・ヨネソン (1996). 『情報伝達を理解する』. Ieee Press. ISBN 978-0-471-71120-9. 2. ヒューバート・P・ヨッキー (2005). 『情報理論、進化、そして生命の起源』. ケンブリッジ大学出版局. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-511-54643-3。 3. ルチアーノ・フロリディ (2010). 『情報 - 非常に短い入門書』. オックスフォード大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-19-160954-1. 4. フォレスト・ウェブラー (2022年2月25日). 「情報化時代における測定」. 情報。13 (3): 111. doi:10.3390/info13030111. 5. 「World_info_capacity_animation」。YouTube。2011年6月11日。2021年12月21日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2017年5月1日取得。 6. 「DT&SC 4-5: 情報理論入門、オンラインコース」。YouTube。カリフォルニア大学。2015年。 7. Hilbert, Martin; López, Priscila (2011). 「情報を保存、伝達、計算する世界の技術的能力」。Science. 332 (6025): 60–65. Bibcode:2011Sci...332...60H. doi:10.1126/science.1200970. PMID 21310967. S2CID 206531385. この記事は martinhilbert.net/WorldInfoCapacity.html で無料で閲覧できる。 8. 『オックスフォード英語辞典』第3版、2009年、全文 9. Peters, J. D. (1988). 情報:批判的歴史に向けた覚書. Journal of Communication Inquiry, 12, 10-24. 10. クヴォルトルップ, L. (1993). 情報概念をめぐる論争. 概観と選書・注釈付き書誌. 『サイバネティクスと人間の知』1(4), 3-24. 11. マクループ, フリッツ & ウナ・マンスフィールド (編). 1983. 『情報研究: 学際的メッセージ』. ニューヨーク: ワイリー. 12. マクループ, フリッツ. 1983. 「情報研究における意味論的癖」, pp. 641-71, フリッツ・マクループ & ウナ・マンスフィールド編, 『情報研究:学際的メッセージ』. ニューヨーク: ワイリー. 13. ヒョールランド, B. (2007). 情報:客観的か主観的/状況的か?. Journal of the American Society for Information Science and Technology, 58(10), 1448-1456. 14. ベイトソン, G. (1972). 心の生態学への道. ニューヨーク: バレティン. 15. ヨヴィッツ, M.C. (1969). 情報科学:真の科学分野としての発展に向けて。アメリカン・ドキュメンテーション(第20巻、369–376頁)。 16. ヨヴィッツ、M. C. (1975). 情報科学発展のための理論的枠組み。国際文書連盟。情報理論的基盤研究委員会。会議(1974年モスクワ)『情報科学、その範囲、研究対象及び問題点:論 文集[FID研究委員会「情報の理論的基礎に関する研究」会議にて発表]1974年4月24–26日、モスクワ』(pp. 90–114)。FID 530。モスクワ:VINITI 17. Spang-Hanssen, H. (2001). 文献情報に関連する情報教育の方法論. Human IT, (1), 125–143. 2007年5月14日取得, http://www.hb.se/bhs/ith/1-01/hsh.htm Archived 2008-02-19 at the Wayback Machine 18. Brier, S. (1996). サイバー記号論:情報科学における知識の組織化と文書検索の問題に適用される新しい学際的発展。Journal of Documentation, 52(3), 296–344. 19. Buckland, M. (1991). 情報と情報システム。ニューヨーク:グリーンウッド・プレス。 20. Goguen, J. A. (1997). 情報の社会的・倫理的理論に向けて。G. Bowker、L. Gasser、L. Star、W. Turner、Erlbaum (編)、社会科学研究、技術システム、共同作業:大きな隔たりを超えて (pp. 27–56)。ニュージャージー州ヒルズデール:Erlbaum。2007年5月14日、http: //cseweb.ucsd.edu/~goguen/ps/sti.pdf から取得。 21. Hjørland, B. (1997). 情報探索と主題表現。情報科学への活動理論的アプローチ。ウェストポート:グリーンウッド・プレス。 22. Pérez-Montoro Gutiérrez, Mario; Edelstein, Dick (2007). 情報の現象:情報フローへの概念的アプローチ。ラナム(メリーランド州):スケアクロウ・プレス。21-22 ページ。ISBN 978-0-8108-5942-5。 23. Wesołowski, Krzysztof (2009). デジタル通信システム入門 (PDF) (第 1 版). チチェスター: ワイリー. p. 2. ISBN 978-0-470-98629-5. 24. バーナム、K. P.、アンダーソン D. R. (2002) 『モデル選択とマルチモデル推論:実用的な情報理論的アプローチ』第 2 版 (Springer Science、ニューヨーク) ISBN 978-0-387-95364-9。 25. F. Rieke; D. Warland; R Ruyter van Steveninck; W Bialek (1997). 『スパイク:神経コードの探求』 MITプレス。ISBN 978-0-262-68108-7。 26. Delgado-Bonal, Alfonso; Martín-Torres, Javier (2016年11月3日)。「人間の視覚は情報理論に基づいて決定される」. Scientific Reports. 6 (1) 36038. Bibcode:2016NatSR...636038D. doi:10.1038/srep36038. ISSN 2045-2322. PMC 5093619. PMID 27808236. 27. 参照; Huelsenbeck, J. P.; Ronquist, F.; Nielsen, R.; Bollback, J. P. (2001). 「系統樹のベイズ推定とその進化生物学への影響」. Science. 294 (5550): 2310–2314. Bibcode:2001Sci...294.2310H. doi:10.1126/science.1065889. PMID 11743192. S2CID 2138288. 28. アリクメッツ, ランド; ワッサーマン, ワイエス・W.; ハッチンソン, エイミー; スモールウッド, フィリップ; ネイサンズ, ジェレミー; ローガン, ピーター・K. (1998). 「トーマス・D・シュナイダー, マイケル・ディーン (1998) ABCR遺伝子の構成: プロモーターおよびスプライス接合部配列の解析」. 遺伝子. 215 (1): 111–122. doi:10.1016/s0378-1119(98)00269-8. PMID 9666097. 29. Jaynes, E. T. (1957). 「情報理論と統計力学」. Phys. Rev. 106 (4): 620. Bibcode:1957PhRv..106..620J. doi:10.1103/physrev.106.620. S2CID 17870175. 30. Bennett, Charles H.; Li, Ming; Ma, Bin (2003). 「チェーンレターと進化史」. サイエンティフィック・アメリカン。288 (6): 76–81. Bibcode:2003SciAm.288f..76B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0603-76. PMID 12764940. 2007年10月7日にオリジナルからアーカイブ。2008年3月11日に取得。 31. David R. Anderson (2003年11月1日). 「経験科学に携わる人々が行う情報理論的手法のより深い理解という行為に関する背景情報」 (PDF). 2011年7月23日にオリジナル (PDF) からアーカイブ。2010年6月23日に取得。 32. デイヴィッド・B・デュゼンベリー (1992). 『感覚生態学』. ニューヨーク: W.H. フリーマン. ISBN 978-0-7167-2333-2. 33. クロード・E・シャノン (1949). 『通信の数学的理論』. Bibcode:1949mtc..book.....S. 34. カサグランデ、デイヴィッド(1999)。「動詞としての情報:認知モデルと生態学的モデルのための情報の再概念化」(PDF)。生態人類学ジャーナル。3 (1): 4–13。doi:10.5038/2162-4593.3.1.1。 35. ベイトソン、グレゴリー(1972)。『形態、実体、差異』、『心の生態学への歩み』所収。シカゴ大学出版局。pp. 448–466. 36. Mizraji, E. (2021). 「生物学的なマクスウェルの悪魔:生物学的システムにおける情報処理に関する考察」. Theory in Biosciences. 140 (3): 307–318. doi:10.1007/s12064-021-00354-6. PMC 8568868. PMID 34449033. 37. シモンセン、ボー・クランツ。「情報用語辞典 – 概念解説」。Informationsordbogen.dk。2017年5月1日取得。 |

| Further reading Liu, Alan (2004). The Laws of Cool: Knowledge Work and the Culture of Information. University of Chicago Press. Bekenstein, Jacob D. (August 2003). "Information in the holographic universe". Scientific American. 289 (2): 58–65. Bibcode:2003SciAm.289b..58B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0803-58. PMID 12884539. Gleick, James (2011). The Information: A History, a Theory, a Flood. New York, NY: Pantheon. Lin, Shu-Kun (2008). "Gibbs Paradox and the Concepts of Information, Symmetry, Similarity and Their Relationship". Entropy. 10 (1): 1–5. arXiv:0803.2571. Bibcode:2008Entrp..10....1L. doi:10.3390/entropy-e10010001. S2CID 41159530. Floridi, Luciano (2005). "Is Information Meaningful Data?" (PDF). Philosophy and Phenomenological Research. 70 (2): 351–370. doi:10.1111/j.1933-1592.2005.tb00531.x. hdl:2299/1825. S2CID 5593220. Floridi, Luciano (2005). "Semantic Conceptions of Information". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). The Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy (Winter 2005 ed.). Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Floridi, Luciano (2010). Information: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford: Oxford University Press. Logan, Robert K. What is Information? – Propagating Organization in the Biosphere, the Symbolosphere, the Technosphere and the Econosphere. Toronto: DEMO Publishing. Machlup, F. and U. Mansfield, The Study of information : interdisciplinary messages. 1983, New York: Wiley. xxii, 743 p. ISBN 978-0471887171 Nielsen, Sandro (2008). "The Effect of Lexicographical Information Costs on Dictionary Making and Use". Lexikos. 18: 170–189. Stewart, Thomas (2001). Wealth of Knowledge. New York, NY: Doubleday. Young, Paul (1987). The Nature of Information. Westport, Ct: Greenwood Publishing Group. ISBN 978-0-275-92698-4. Kenett, Ron S.; Shmueli, Galit (2016). Information Quality: The Potential of Data and Analytics to Generate Knowledge. Chichester, United Kingdom: John Wiley and Sons. doi:10.1002/9781118890622. ISBN 978-1-118-87444-8. |

追加文献(さらに読む) 劉、アラン(2004)。『クールな法則:知識労働と情報文化』。シカゴ大学出版局。 ベッケンシュタイン、ジェイコブ・D.(2003年8月)。「ホログラフィック宇宙における情報」。『サイエンティフィック・アメリカン』。289巻2 号:58–65頁。Bibcode:2003SciAm.289b..58B. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0803-58. PMID 12884539. グレイク、ジェームズ(2011)。『情報:その歴史、理論、そして洪水』。ニューヨーク州ニューヨーク:パンテオン。 林樹坤(2008)。「ギブスの逆説と情報・対称性・類似性の概念及びそれらの関係」。『エントロピー』10巻1号:1–5頁。arXiv: 0803.2571。Bibcode:2008Entrp..10....1L。doi:10.3390/entropy-e10010001. S2CID 41159530. フロリディ、ルチアーノ(2005)。「情報は意味のあるデータか?」(PDF)。『哲学と現象学研究』70巻2号:351–370頁。doi: 10.1111/j.1933-1592.2005.tb00531.x. hdl:2299/1825. S2CID 5593220. フロリディ、ルチアーノ (2005). 「情報の意味論的概念」. ザルタ、エドワード N. (編). スタンフォード哲学百科事典(2005年冬版). スタンフォード大学形而上学研究所. フロリディ, ルチアーノ (2010). 『情報:超短編入門』. オックスフォード: オックスフォード大学出版局. ローガン, ロバート・K. 『情報とは何か? – 生物圏、記号圏、技術圏、経済圏における組織の伝播』. トロント: DEMO出版. マクループ, F. と U. マンスフィールド, 『情報研究:学際的メッセージ』. 1983年, ニューヨーク: ワイリー. xxii, 743 p. ISBN 978-0471887171 ニールセン, サンドロ (2008). 「辞書作成と使用における語彙学的情報コストの影響」. Lexikos. 18: 170–189. スチュワート、トーマス (2001). 知識の富. ニューヨーク、NY: ダブルデイ. ヤング、ポール (1987). 情報の性質. ウェストポート、コネチカット州: グリーンウッド出版グループ. ISBN 978-0-275-92698-4. ケネット、ロン S.、シュムエリ、ガリット (2016)。『情報品質:知識を生み出すデータと分析の可能性』。英国チチェスター:ジョン・ワイリー・アンド・サンズ。doi: 10.1002/9781118890622。ISBN 978-1-118-87444-8。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Information |

情 報論拾遺

■Information

theory is the mathematical study of the quantification, storage, and

communication of information. The field was originally established by

the works of Harry Nyquist and Ralph Hartley, in the 1920s, and Claude

Shannon in the 1940s. The field, in applied mathematics, is at the

intersection of probability theory, statistics, computer science,

statistical mechanics, information engineering, and electrical

engineering.

■A

key measure in information theory is entropy. Entropy quantifies the

amount of uncertainty involved in the value of a random variable or the

outcome of a random process. For example, identifying the outcome of a

fair coin flip (with two equally likely outcomes) provides less

information (lower entropy, less uncertainty) than specifying the

outcome from a roll of a die (with six equally likely outcomes). Some

other important measures in information theory are mutual information,

channel capacity, error exponents, and relative entropy. Important

sub-fields of information theory include source coding, algorithmic

complexity theory, algorithmic information theory and

information-theoretic security.

■Applications of fundamental topics of information theory include source coding/data compression (e.g. for ZIP files), and channel coding/error detection and correction (e.g. for DSL). Its impact has been crucial to the success of the Voyager missions to deep space, the invention of the compact disc, the feasibility of mobile phones and the development of the Internet. The theory has also found applications in other areas, including statistical inference, cryptography, neurobiology, perception, linguistics, the evolution and function of molecular codes (bioinformatics), thermal physics, molecular dynamics,quantum computing, black holes, information retrieval, intelligence gathering, plagiarism detection, pattern recognition, anomaly detection and even art creation.

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Information_theory

■

情報理論とは、情報の定量化、保存、伝達に関する数学的研究である。1920年代にハリー・ナイキストとラルフ・ハートリーが、1940年代にクロード・

シャノンがこの分野を確立した。応用数学におけるこの分野は、確率論、統計学、コンピュータサイエンス、統計力学、情報工学、電気工学の交差点に位置す

る。

■

情報理論における重要な尺度はエントロピーである。エントロピーとは、確率変数の値やランダムプロセスの結果に含まれる不確定性の量を定量化したものであ

る。例えば、公平なコインフリップ(2つの可能性が等しい)の結果を特定することは、サイコロの目(6つの可能性が等しい)の結果を特定することよりも少

ない情報(より低いエントロピー、より少ない不確実性)を提供します。情報理論における他の重要な尺度には、相互情報量、チャンネル容量、誤差指数、相対

エントロピーなどがある。情報理論の重要な下位分野には、情報源符号化、アルゴリズム複雑性理論、アルゴリズム情報理論、情報理論的セキュリティなどがあ

る。

■ 情報理論の基本的なトピックの応用には、ソース符号化/データ圧縮(ZIPファイルなど)、チャネル符号化/エラー検出・訂正(DSLなど)などがある。 その影響は、深宇宙へのボイジャー・ミッションの成功、コンパクト・ディスクの発明、携帯電話の実現可能性、インターネットの発展に極めて重要であった。 この理論はまた、統計的推論、暗号学、神経生物学、知覚、言語学、分子コードの進化と機能(バイオインフォマティクス)、熱物理学、分子動力学、量子コン ピューティング、ブラックホール、情報検索、情報収集、盗作検出、パターン認識、異常検出、さらには芸術の創造など、他の分野にも応用されている。

■

情報理論は、情報の伝達、処理、抽出、利用を研究する。抽象的には、情報は不確実性の解消と考えることができる。ノイズの多いチャネル上での情報通信の場

合、この抽象的概念は1948年にクロード・シャノンによって「通信の数学的理論」と題された論文で公式化された。この論文では、情報は可能なメッセージ

の集合として考えられ、目標はノイズの多いチャネル上でこれらのメッセージを送信し、チャネルノイズにもかかわらず、受信者が低いエラー確率でメッセージ

を再構成することである。シャノンの主要な結果であるノイズ・チャネル符号化定理は、多くのチャネルが使用される限界において、漸近的に達成可能な情報率

は、単にメッセージが送信されるチャネルの統計量に依存するチャネル容量に等しいことを示した。

■

符号理論とは、ノイズの多いチャネル上でのデータ通信の効率を高め、誤り率をチャネル容量近くまで低減するための、符号と呼ばれる明示的な方法を見つける

ことに関係している。これらの符号は、データ圧縮(ソース符号化)と誤り訂正(チャネル符号化)技術に大別できる。後者の場合、シャノンの研究が可能であ

ることを証明した方法を見つけるのに何年もかかった。

■

情報理論符号の第3のクラスは、暗号アルゴリズム(符号と暗号の両方)である。符号理論や情報理論からの概念、方法、結果は、単位禁止などの暗号や暗号解

読に広く使われている。

++++

※これらの論考は、野村一夫『インフォアーツ論』として洋泉社 より2003年初頭に発売されました。下記の書評は論文刊行時に論文に対しておこなわれたものです。

野村一夫氏(以下、野村)のインターネットの歴史観は、幸福なインターネット大公開時代(= 池田がパラフレイズす ると 「よいハッカーが公共圏を形成していた時代」)から、情報工学的転回を経て、情報教育が工学化さ れてゆく、不幸な時代へと転落してゆくことである。これが、野村のいうインフォテックの時代の招 来である。このような不幸な〈転回〉がおこった背景には、ネットのガバナンス原理が変化して、大公開時 代が〈転回〉市民主義的転回を生みださなかったことだ。このような不幸な歴史を、もういちどやり直そうとして構築されたのが、インフォアーツ構想で あ る。インフォアーツにおいて育成される諸能力は、野村(『教育と医学』論文)によると以下の5点 である。

|

(1)情報調査能力 Information research skills (2)情報を批判的に吟味する能力 Ability to critically examine

information (3)コミュニカビリティ communicability (4)シティズンシップ citizenship (5)ユニバーサルデザインの理解 Understanding Universal Design |

(再掲)

人文研究において、インターネットを利用して日々教育に従事する研究者にとっては、まさにそ の通 り!ととも言える主張であるが、野村はそのようなインフォアーツにもとづく基礎の要請を<苗床集 団の育成>という言葉で表現する。そのような意味では、すでに死に体になっている大学の教養教育 の古い体質そのものを懐かしむ原理主義者どもに、顔を洗ってこれらの論文の精神をきちんと学べと つよく薦めたい論文となっている。

■野

村一夫氏のその後の展開について......

2017年における野村氏は、「学びの認知科学的転回」がおこっていると指摘する。そして、そのような転回後には、 「社会知」に関する基礎教養(リアル・リベラルアーツ)が必要だと主張する。

社会知の主体的学習のためには、その教育のためのコミュニケーション・デザインが必要だとも主張している。それを野村 氏は、レイヤーのメタファーで説明する。

「高 等教育において主体的に学習されるべき内容は「研究成果の薄められたヴァージョン」ではなく、社会の中に埋め込まれた共有知識の特定のレイヤーである。そ のレイヤーを「社会知」と総称することにすると、社会知は教科書の中にあるのではなく、人びとによって絶えず参照され、再演され、発話され、行動評価の基 準となるものである。この循環過程を「知識過程」と呼ぶ。流言のように無規制状態の知識過程から、人文学や近代科学や世界宗教のように高度に整備された知 識体系に至るまで多彩なレイヤーがありうる」『平成30年度特別推進研究助成金申請書(國學院大學)』より。

【参考】池田光穂「コミュニケーション」 より

【考察】

インフォテックとインフォアーツをあまりにも対比的に描いている。インフォテックはインフォ アー ツの確かに仮想敵ではあるが、インフォテックの中にも、野村が育成されなければならない諸能力の 課題があり、それらは共通していると言えないだろうか?もし、そうであるなら、どのようにして、このような対比が可能になるのか?

それは、仮想敵を立てる前から存在する野村のネット倫理の精神に由来する。つまり、それは <常識 ある市民>の育成というソキウスの指導的原理そのものにほかならない。野村が歴史をもう一度やりなおしたい気持ちはよくわかる。しかし、もしそうだとした ら、なぜ ネッ トのガバンナンス原理がインフォテック主導のように変節した理由を明らかにするほうが先決ではな いのか?

敵の論理を分析することは敵の論理に巻き込まれるという警句を忘れるわけにはいかない。しか し、 ガバナンスの原理の変容のより重要視しなければならない理由は、私はネットの外部からきた経済の グローバリゼーションの影響であると考えている(経済原理はネットによって加速推進されたのであ って、大公開時代は経済原理がネット化を押し進めた主要な要因ではないと考えているのだ)。

ネットを貨幣の隠喩で語る思想が、ネット上における貨幣(=情報価値)の流通のメタファーと して とらえられているからである。私は大学の一部の同僚とともに、ネットを生命系の隠喩としてとらえ るほうが、(変容する現在の)ガバナンス原理の動態をよく把握できるものであると信じて研究を開 始している。この方面からの研究もまた、野村のいうインフォアーツの苗床集団の育成に、べつのか たちで必ず役立つはずだ。だから、これは、さまざまなクリーシェのパロディを使いながら、インターネットにおける市民 化の 問題を真剣に考えている、すばらしい論文なのである。ネットにおけるさまざまな社会問題を眉をひ そめた後になんとかしなくちゃ、と感じた全ての人が読まなくてはならない論文である。

【結論】

ここでの野村用語における、イ ンフォテックとインフォアーツは、20年が経っても人口に膾炙しなかった。だが、野村のいうインフォテックとは、従来の情報工学的な発想から抜けきれてい ない情報論ないしは情報学である。そして、インフォアーツは、哲学や人文学、さらには社会学や人類学などのフィールドサイエンスの影響を受けて、「転回」 を遂げた、新しい情報論、新しい情報学のことである。このような情報論的転回 (Informatic Turn)が、21世紀初頭に起こったことは確かである。

その野村の慧眼を記して、野村一夫は「情報論的

転回」の提唱者であり、名実ともに彼をその命名者と名付けてもよいのである。

クレジット:池田光穂「インフォテックとインフォアーツの戦争:野村一夫さん(2003)の思想

を論評する」2003年

| Richard Saul Wurman

(born March 26, 1935) is an American architect and graphic designer.

Wurman has written, designed, and published 90 books and created the

TED conferences,[1] the EG Conference,[further explanation needed] and

TEDMED. |

リチャード・ソール・ワーマン(1935年3月26日生まれ)はアメリ

カの建築家、グラフィックデザイナー。これまでに90冊の本を執筆、デザイン、出版し、TEDカンファレンス、[1]EGカンファレンス、[2]

TEDMEDを創設した。 |

| Career Wurman chaired the IDCA Conference in 1972, the First Federal Design assembly in 1973, and the annual American Institute of Architects (AIA) conference in 1976. He created and chaired several conferences, including the TED conferences from 1984 through 2003, TEDMED from 1995 through 2010, and the WWW conference. He works with Esri and RadicalMedia on comparative cartographic initiatives for mapping urban settings, which is planned to culminate in the creation of a network of live urban observatories around the world. Wurman supports SENS Research Foundation, a nonprofit biotechnology organization that seeks to repair the damages of aging and extend healthy lifespan.[3] |

経歴 1972年のIDCA会議、1973年の第1回連邦デザイン会議、1976年のアメリカ建築家協会(AIA)年次会議の議長を務める。1984年から 2003年までのTED会議、1995年から2010年までのTEDMED、WWW会議など、いくつかの会議を創設し、議長を務めた。 Esri社およびRadicalMedia社と共同で、都市環境をマッピングするための比較地図作成に取り組んでいる。 ワーマンは、老化によるダメージを修復し、健康寿命を延ばすことを目指す非営利バイオテクノロジー団体、SENS Research Foundationを支援している[3]。 |

| Publications Wurman has written, designed, and published nearly a hundred books on varying topics, including Notebooks and Drawings of Louis I. Kahn (1963) and What Will Be Has Always Been (1986), a collection of words bt Louis Kahn. Wurman's map-oriented and infographic guidebooks include the Access travel series (starting with Access/LA in 1980), several books on healthcare, Understanding USA (1999). Information Anxiety (1989) and its second edition (2000). His books about information architecture and information design include Information Architects (1996) and UnderstandingUnderstanding (2017). |

出版物 Louis I. KahnのNotebooks and Drawings of Louis I. Kahn(1963年)、ルイス・カーンの言葉を集めたWhat Will Be Has Always Been(1986年)など、さまざまなテーマで100冊近くの本を執筆、デザイン、出版。地図指向のインフォグラフィック・ガイドブックには、 『Access travel』シリーズ(1980年の『Access/LA』からスタート)、ヘルスケアに関する数冊の本、『Understanding USA』(1999年)などがある。Information Anxiety』(1989年)とその第2版(2000年)。情報アーキテクチャと情報デザインに関する著書には、『Information Architects』(1996年)、『UnderstandingUnderstanding』(2017年)などがある。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Richard_Saul_Wurman |

リンク(サイト外)

リンク(サイト内)

参考文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆