メキシコの壁画運動あるいは壁画主義

Mexican muralism, Muralismo mexicano

Mural by Diego

Rivera of the Aztec city of Tenochtitlan and life in Aztec times.

☆

メキシコ壁画(Mexican

muralism)とは、メキシコ革命直後(1910-1920年)にメキシコ政府が資金を提供し、メキシコの過去、現在、未来のヴィジョンを描

き、多くの公共施設の壁を、メキシコ人の国の歴史に対する理解を再構築するための教訓的なシーンに変えたアートプロジェクトを指す。壁に描かれた大きな壁

画は、社会的、政治的、歴史的なメッセージを含んでいた。1920年代から始まった壁画プロジェクトは、「ビッグ3」または「三大巨頭」として知られる芸

術家グループによって率いられた。このグループは、ディエゴ・リベラ、ホセ・クレメンテ・オロスコ、ダビド・アルファロ・シケイロスで構成されていた。

ビッグ3ほど著名ではないが、メキシコでは女性も壁画を制作した。1920年代から1970年代にかけて、礼拝堂、学校、政府庁舎など多くの公共の場で、

民族主義的、社会的、政治的なメッセージを込めた壁画が数多く制作された。この伝統は、アメリカを含むアメリカ大陸の他の地域にも大きな影響を与え、チ

カーノ・アート運動のインスピレーションとなった。

| Mexican muralism

refers to the art project initially funded by the Mexican government in

the immediate wake of the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920) to depict

visions of Mexico's past, present, and future, transforming the walls

of many public buildings into didactic scenes designed to reshape

Mexicans' understanding of the nation's history. The murals, large

artworks painted onto the walls themselves had social, political, and

historical messages. Beginning in the 1920s, the muralist project was

headed by a group of artists known as "The Big Three" or "The Three

Greats".[1] This group was composed of Diego Rivera, José Clemente

Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros. Although not as prominent as the Big

Three, women also created murals in Mexico. From the 1920s to the

1970s, many murals with nationalistic, social and political messages

were created in many public settings such as chapels, schools,

government buildings, and much more. The popularity of the Mexican

muralist project started a tradition which continues to this day in

Mexico; a tradition that has had a significant impact in other parts of

the Americas, including the United States, where it served as

inspiration for the Chicano art movement. |

メキシコ壁画(Mexican muralism)

とは、メキシコ革命直後(1910-1920年)にメキシコ政府が資金を提供し、メキシコの過去、現在、未来のヴィジョンを描き、多くの公共施設の壁を、

メキシコ人の国の歴史に対する理解を再構築するための教訓的なシーンに変えたアートプロジェクトを指す。壁に描かれた大きな壁画は、社会的、政治的、歴史

的なメッセージを含んでいた。1920年代から始まった壁画プロジェクトは、「ビッグ3」または「三大巨頭」として知られる芸術家グループによって率いら

れた[1]。このグループは、ディエゴ・リベラ、ホセ・クレメンテ・オロスコ、ダビド・アルファロ・シケイロスで構成されていた。ビッグ3ほど著名ではな

いが、メキシコでは女性も壁画を制作した。1920年代から1970年代にかけて、礼拝堂、学校、政府庁舎など多くの公共の場で、民族主義的、社会的、政

治的なメッセージを込めた壁画が数多く制作された。この伝統は、アメリカを含むアメリカ大陸の他の地域にも大きな影響を与え、チカーノ・アート運動のイン

スピレーションとなった。 |

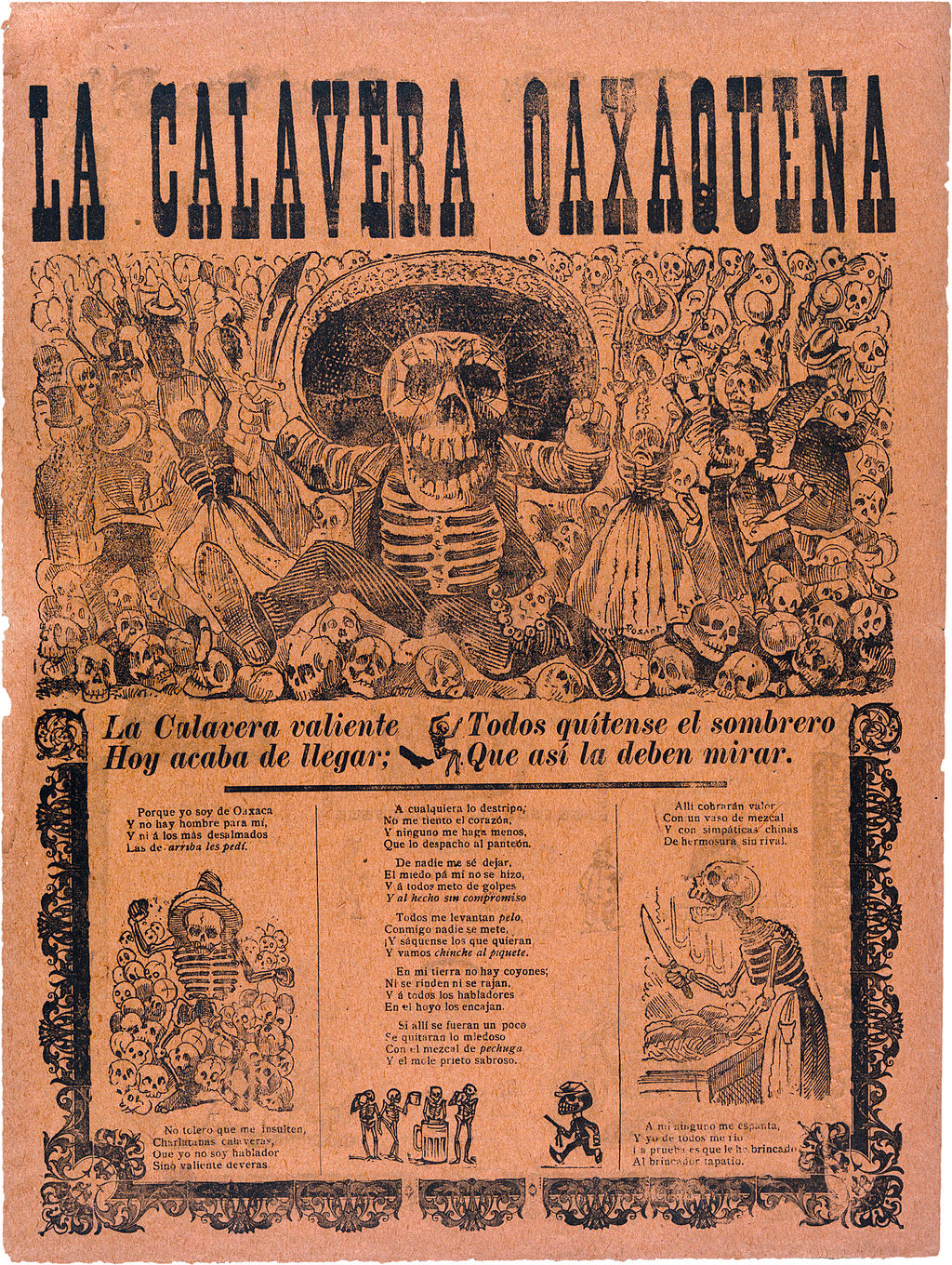

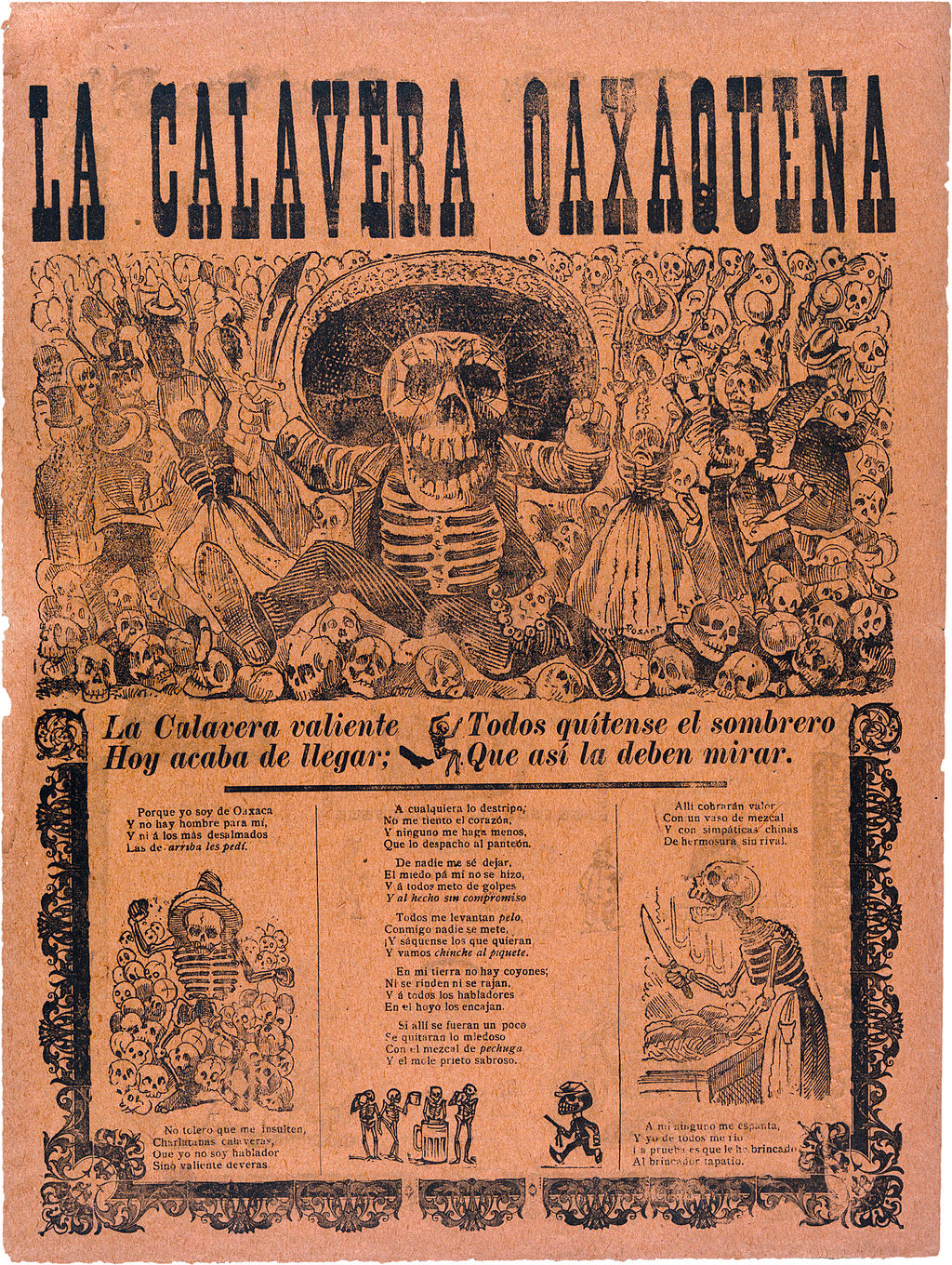

Background Mural from Bonampak Mexico has had a tradition of painting murals, starting with the Olmec civilization in the pre Hispanic period and into the colonial period, with murals mostly painted to evangelize and reinforce Christian doctrine.[2] The modern mural tradition has its roots in the 19th century, with this use of political and social themes. The first Mexican mural painter to use philosophical themes in his work was Juan Cordero in the mid-19th century. Although he did mostly work with religious themes such as the cupola of the Santa Teresa Church and other churches, he painted a secular mural at the request of Gabino Barreda at the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria (since disappeared).[3]  1903 broadsheet by José Guadalupe Posada The latter 19th century was dominated politically by the Porfirio Díaz regime. This government was the first to push for the cultural development of the country, supporting the Academy of San Carlos and sending promising artists abroad to study. However, this effort left out indigenous culture and people, with the aim of making Mexico like Europe.[2] Gerardo Murillo, also known as Dr. Atl, is considered to be the first modern Mexican muralist with the idea that Mexican art should reflect Mexican life.[4] Academy training and the government had only promoted imitations of European art. Atl and other early muralists pressured the Diaz government to allow them to paint on building walls to escape this formalism.[5] Atl also organized an independent exhibition of native Mexican artists promoting many indigenous and national themes along with color schemes that would later appear in mural painting.[6] The first modern Mexican mural, painted by Atl, was a series of female nudes using "Atlcolor", a substance Atl invented himself, very shortly before the beginning of the Mexican Revolution.[7] Another influence on the young artists of the late Porfirian period was the graphic work of José Guadalupe Posada, who mocked European styles and created cartoons with social and political criticism.[6] Critiquing the political policies of the Díaz dictatorship through art was popularized by Posada. Posada influenced muralists to embrace and continue criticizing the Díaz dictatorship in their works. The muralists also embraced the characters and satire present in Posada's works.[8] The Mexican Revolution itself was the culmination of political and social opposition to Porfirio Díaz policies. One important oppositional group was a small intellectual community that included Antonio Curo, Alfonso Reyes and José Vasconcelos. They promoted a populist philosophy that coincided with the social and political criticism of Atl and Posada and influenced the next generation of painters such as Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco and David Alfaro Siqueiros.[9] These ideas gained power as a result of the Mexican Revolution, which overthrew the Díaz regime in less than a year.[9] However, there was nearly a decade of fighting among the various factions vying for power. Governments changed frequently with a number of assassinations, including that of Francisco I. Madero who initiated the struggle. It ended in the early 1920s with one-party rule in the hands of the Álvaro Obregón faction, which became the Partido Revolucionario Institucional (PRI).[2] During the Revolution, Atl supported the Carranza faction and promoted the work of Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros, who would later be the founders of the muralism movement. Through the war and until 1921, Atl continued to paint murals among other activities including teaching the Mexico's next generation of artists and muralists.[7] |

背景 ボナンパクの壁画 メキシコには、ヒスパニック以前のオルメカ文明に始まり、植民地時代まで壁画を描く伝統があり、壁画は主にキリスト教の教義を伝道し強化するために描かれ ていた[2]。現代の壁画の伝統は19世紀にルーツを持ち、政治的、社会的なテーマが用いられている。メキシコの壁画画家で初めて哲学的なテーマを作品に 用いたのは、19世紀半ばのフアン・コルデロである。彼はサンタ・テレサ教会やその他の教会のクーポラなど宗教的なテーマの作品を主に手がけていたが、ガ ビノ・バレダの依頼で国立準備学校(現在は消滅)に世俗的な壁画を描いた[3]。  ホセ・グアダルーペ・ポサダによる1903年の壁新聞 19世紀後半は、ポルフィリオ・ディアス政権が政治的に支配していた。この政権は、サン・カルロス・アカデミーを支援し、有望な芸術家を海外に留学させる など、国の文化発展を推し進めた最初の政権であった。しかしこの努力は、メキシコをヨーロッパのようにすることを目的とし、土着の文化や人々を置き去りに した[2]。Dr.Atlとしても知られるジェラルド・ムリーリョは、メキシコ美術はメキシコの生活を反映すべきだという考えを持った最初の近代メキシコ の壁画家であると考えられている[4]。アトルをはじめとする初期の壁画家たちは、このような形式主義から逃れるために、建物の壁に絵を描くことを許可す るようディアス政権に圧力をかけた[5]。アトルはまた、後に壁画に登場することになる配色とともに、多くの土着的、国家的テーマを推進するメキシコ出身 の芸術家たちの独立した展覧会を組織した。 [6] アトルによって描かれたメキシコ初の近代壁画は、メキシコ革命が始まるごく直前にアトルが自ら発明した物質「アトルカラー」を使用した一連の女性のヌード であった[7] 。ポルフィリア時代後期の若い芸術家たちに影響を与えたもう一つの作品は、ホセ・グアダルーペ・ポサダのグラフィック作品であり、彼はヨーロッパの様式を 嘲笑し、社会的・政治的批判を込めた漫画を制作した[6] 。ポサダは壁画家たちに影響を与え、彼らの作品の中でディアス独裁政権を受け入れ、批判し続けた。壁画家たちはまた、ポサダの作品に登場する人物や風刺を 受け入れた[8]。 メキシコ革命そのものが、ポルフィリオ・ディアスの政策に対する政治的・社会的反対の集大成であった。重要な反対グループのひとつは、アントニオ・クー ロ、アルフォンソ・レイエス、ホセ・バスコンセロスらを含む小さな知識人コミュニティであった。彼らは、アトルやポサダの社会的・政治的批判と一致するポ ピュリスト哲学を推進し、ディエゴ・リベラ、ホセ・クレメンテ・オロスコ、ダビド・アルファロ・シケイロスといった次世代の画家たちに影響を与えた [9]。 これらの思想は、1年足らずでディアス政権を打倒したメキシコ革命の結果として力を得た[9]が、権力を争う様々な派閥の間で10年近く戦いが続いた。闘 争の発端となったフランシスコ1世マデロの暗殺を含め、政権は頻繁に交代した。1920年代初頭、アルバロ・オブレゴン派による一党支配で終結し、PRI (Partido Revolucionario Institucional)となった[2]。革命期、アトラスはカランサ派を支持し、後に壁画運動の創始者となるリベラ、オロスコ、シケイロスの作品を 奨励した。戦争を経て1921年まで、アトルはメキシコの次世代の芸術家や壁画家を指導するなどの活動の中で壁画を描き続けた[7]。 |

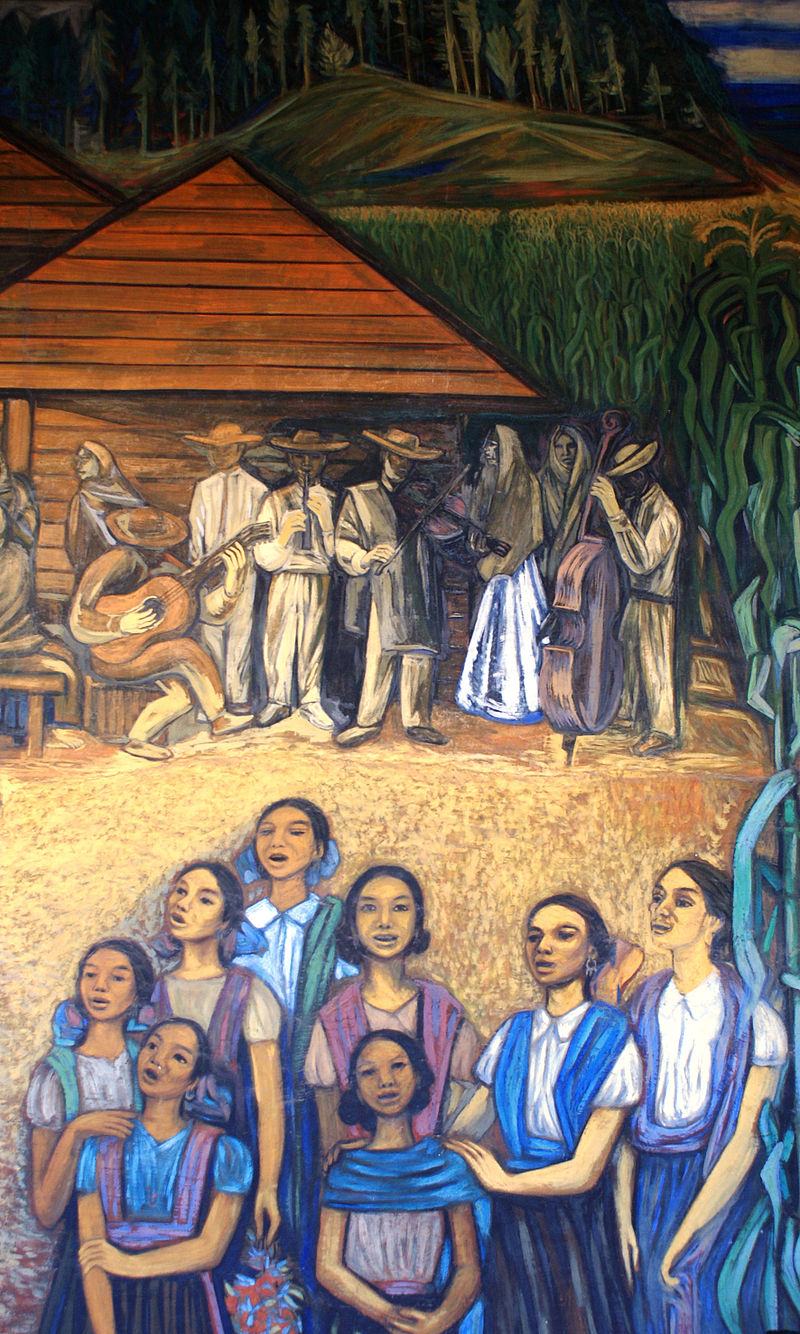

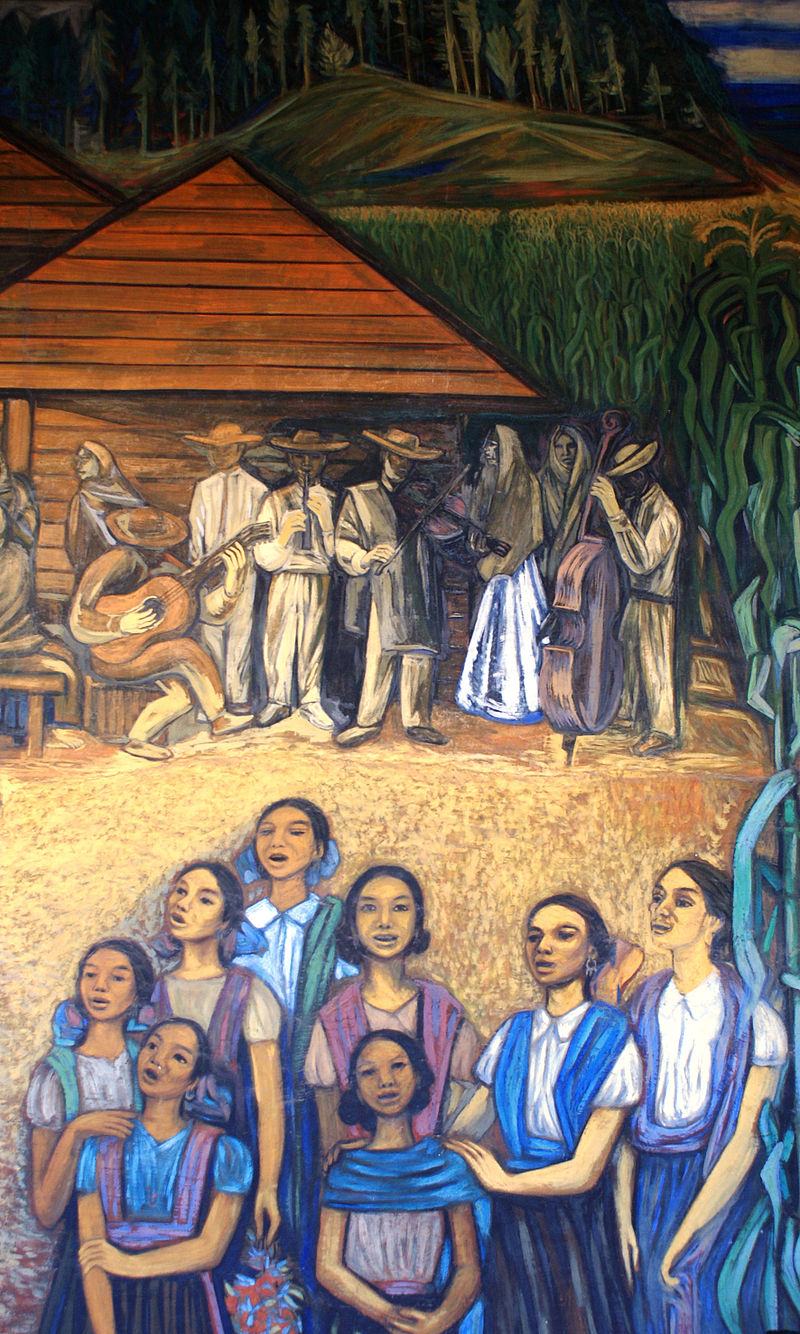

Mural movement Eagle and snake image from the Colegio San Ildefonso project by Jean Charlot. In 1921, after the end of the military phase of the Revolution, General Alvaro Obregón rose to power.[10] In the aftermath of the Revolution, Mexico had entered a transition from an "oligarchic" state to a "modernizing" state, one that favored urbanization and the bourgeoisie citizens of society. As the country underwent this reformation, General Obregón realized that the reconstruction of a post-revolution Mexico would require a comprehensive alteration of symbols associated with Mexican identity on both cultural and political grounds. Shortly after the wars end, Obregón appointed José Vasconcelos to act as the Secretaría de Educación Pública, or Minister of Public Education. In his efforts to help raise a sense of nationalism and promote the inclusion of the masses in political and social ideologies, it was Vasconcelos' idea to have a government-backed mural project.[2] His time as secretary was short but it set how muralism would develop. His image was painted on a tempera mural in 1921 by Roberto Montenegro, but this was short lived. His successor at the Secretaría de Educación Pública ordered it painted out.[2] Parallel to the utilization of murals during the pre-Hispanic and the colonial period, the murals were not to simply satisfy aesthetic purposes, but to promote certain social ideals in the Mexican people.[10][2][5] These ideals or principles were to glorify the Mexican Revolution and the identity of Mexico as a mestizo nation.[2] This placed great emphasis on the pride associated with the indigenous culture of Mexico. The government began to hire the country's best artists to paint murals, calling some of them home from their time in Europe, including Diego Rivera.[9] These initial muralists included Dr. Atl, Ramón Alva de la Canal, Federico Cantú and others but the main three artists that spearheaded the muralist project were David Alfaro Siqueiros, José Clemente Orozco and Diego Rivera. These three artists, commonly known as "Los Tres Grandes", claimed to act as both the "'voice and vote' of the Mexican national consciousness," calling themselves "guardians of the national soul".[10] The muralists differed in style and temperament, but all believed that art was for the education and betterment of the people. This was behind their acceptance of these commissions as well as their creation of the Syndicate of Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors.[9]  Mural in the Palacio de Bellas Artes by Rufino Tamayo. The first government sponsored mural project was on the three levels of interior walls of the old Jesuit institution Colegio San Ildefonso, at that time used for the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria.[5][6] Most of the murals in the Escuela National Preparatoria, or National Preparatory School, were done by José Clemente Orozco with themes of a mestizo Mexico, the ideas of renovation, and the reality of the Revolution's violence.[5] Also at the National Preparatory School, Fernando Leal painted Los Danzantes de Chalma (Dancers of Chalma) no earlier than 1922. Opposite that mural, Jean Charlot painted La conquista de Tenochtitlán (Conquest of Tenochtitlan) by Jean Charlot—invited by Leal.[11] Rivera also contributed his first-ever government-backed mural to the National Preparatory School in 1922 called Creation, functioning as an allegorical depiction of the holy trinity representing love, hope, and faith.[12]  Ramón Alva de la Canal, Mural at Colegio San Ildefonso The movement was strongest from the 1920s to the 1950s, which corresponded to the country's transformation from a mostly rural and mostly illiterate society to an industrialized one. While today, Murals are seen as symbols of Mexican identity, at the time they were controversial, especially those with socialist messages plastered on centuries-old colonial buildings.[5] One of the basic underpinnings of the nascence of a post revolutionary Mexican art was that it should be public, available to the citizenry and above all not the province of a few wealthy collectors. The great societal upheaval made the concept possible as well as a lack of relatively wealthy middle class to support the arts.[2] On this, the painters and the government agreed. One other point of agreement was that artists should have complete freedom of expression. This would lead to another element added to the murals over their development. In addition to the original ideas of a reconstructed Mexico and the elevation of Mexico's indigenous and rural identity, many of the muralists, including the three main painters, also included elements of Marxism, especially in trying to frame the struggle of the working class against oppression.[2][5] This struggle, which had been going on since the sixteenth century, along with class, culture, and race conflicts were interpreted by muralists.[13] The inception and early years of Mexico's muralist movement are often considered the most ideologically pure and untainted by contradictions between socialist ideals and government manipulation. This initial phase is referred to as the "heroic" phase while the period after 1930 is the "statist" phase with the transition to the latter phase caused by José Vasconcelos's resignation in 1924.[14] Scholar Mary Coffey describes those who "acknowledge a change but refrain from judgment about its consequences" as taking the soft line and those who see all murals after 1930 as "propaganda for a corrupt state" as taking a hard line.[14] Another stance is that the evolution of Mexican muralism as having an uncomplicated relationship with the government and as an accurate reflection of avant-garde and proletariat sentiments. However, hard liners see the movement as complicit in the corrupt government's power consolidation under the guise of a socialist regime.[14] Art historian Leonard Folgarait has a slightly different view. He marks 1940 as the end of the post-revolutionary period in Mexico as well as the renaissance era of the muralist movement.[15] The conclusion of the Lázaro Cárdenas administration (1934 – 1940) and the beginning of the Manuel Avila Camacho (1940 – 1946) administration saw the rise of an ultraconservative Mexico.[15] The country's policy was aimed at maintaining and strengthening a capitalist society.[15] Mural artists like the Big Three spent the post-revolutionary period developing their work based on the promises of a better future, and with the advent of conservatism they lost their subject and their voice. The Mexican government began to distance itself from mural projects and mural production became relatively privatized. This privatization was a result of patronage from the growing national bourgeoisie. Murals were increasingly contracted for theaters, banks, and hotels.[16] |

壁画の動き ジャン・シャルロによるコレヒオ・サン・イルデフォンソ・プロジェクトからの鷲と蛇のイメージ。 1921年、革命の軍事段階が終わった後、アルバロ・オブレゴン将軍が権力を握った[10]。革命後のメキシコは、「寡頭政治」国家から「近代化」国家へ の移行期を迎え、都市化とブルジョアジー市民社会を支持する国家となった。このような改革が進む中、オブレゴン将軍は、革命後のメキシコの再建には、メキ シコのアイデンティティに関連するシンボルを文化的、政治的に包括的に改変する必要があることを悟った。 戦争終結後まもなく、オブレゴンはホセ・ヴァスコンセロスを公共教育省(Secretary de Educación Pública)に任命した。ナショナリズムの意識を高め、大衆を政治的・社会的イデオロギーに取り込むことを促進するために、バスコンセロスは政府が支 援する壁画プロジェクトを発案した[2]。彼のイメージは1921年にロベルト・モンテネグロによってテンペラ壁画に描かれたが、これは短命に終わった。 彼の後任の公共教育省長官がこの壁画を描き消すよう命じたのである[2]。 前ヒスパニック時代や植民地時代の壁画の活用と平行して、壁画は単に美的目的を満たすためではなく、メキシコ国民の特定の社会的理想を促進するためであっ た[10][2][5]。これらの理想または原則は、メキシコ革命とメスティーソ国家としてのメキシコのアイデンティティを賛美するものであった[2]。 政府は、ディエゴ・リベラを含むヨーロッパ滞在から帰国した何人かを呼び寄せ、壁画を描くために国内最高の芸術家を雇い始めた[9]。これらの初期の壁画 家には、アトル博士、ラモン・アルバ・デ・ラ・カナル、フェデリコ・カントゥなどがいたが、壁画家プロジェクトの先頭に立った主な3人の芸術家は、ダビ ド・アルファロ・シケイロス、ホセ・クレメンテ・オロスコ、ディエゴ・リベラであった。通称「ロス・トレス・グランデス」として知られるこの3人の芸術家 は、「メキシコの国民意識の『代弁者』であると同時に『投票者』」であると主張し、自らを「国民の魂の守護者」と呼んだ[10]。壁画家たちのスタイルや 気質はそれぞれ異なっていたが、全員が芸術は国民の教育と向上のためにあると信じていた。これが、彼らがこれらの依頼を受けた背景であり、また技術労働 者、画家、彫刻家のシンジケートを設立した背景でもあった[9]。  ルフィノ・タマヨによるパラシオ・デ・ベラス・アルテスの壁画。 政府がスポンサーとなった最初の壁画プロジェクトは、旧イエズス会施設のコレヒオ・サン・イルデフォンソの3層の内壁で、当時は国立準備学校として使用さ れていた。 [5][6]国立準備学校の壁画のほとんどは、ホセ・クレメンテ・オロスコによるもので、メスティーソ・メヒコ、改築の思想、革命の暴力の現実をテーマに している[5]。その壁画の反対側には、ジャン・シャルロが描いた『テノチティトランの征服』(La conquista de Tenochtitlán)がある[11]。リベラはまた、1922年に、愛、希望、信仰を表す聖なる三位一体を寓意的に描いた『天地創造』 (Creation)と呼ばれる、政府が支援した初めての壁画を国立準備学校に寄せた[12]。  ラモン・アルバ・デ・ラ・カナル、コレヒオ・サン・イルデフォンソの壁画 この運動が最も盛んだったのは1920年代から1950年代にかけてで、この時期は、ほとんどが農村で、ほとんど読み書きのできない社会から工業化された 社会への変貌に対応していた。今日では、壁画はメキシコのアイデンティティの象徴とみなされているが、当時は、特に何世紀も前の植民地時代の建物に社会主 義的なメッセージを貼り付けた壁画は物議を醸した[5]。革命後のメキシコ芸術の誕生の基本的な基盤のひとつは、芸術は公共のものであり、市民が利用でき るものであるべきであり、何よりも一部の裕福なコレクターのものであってはならないということだった。社会の大変動は、芸術を支える比較的裕福な中産階級 が不足していたことと同様に、このコンセプトを可能にした[2]。もうひとつの合意点は、芸術家は完全な表現の自由を持つべきだということだった。このこ とは、壁画が発展していく過程で、別の要素を加えることにつながっていく。 再建されたメキシコとメキシコの先住民や農村のアイデンティティの高揚という当初の考えに加え、3人の主要な画家を含む多くの壁画家たちはマルクス主義の 要素も取り入れ、特に抑圧に対する労働者階級の闘争の枠組みを作ろうとした。 メキシコの壁画運動の創始期と初期は、しばしば最もイデオロギー的に純粋で、社会主義の理想と政府の操作との間の矛盾に汚染されていないと考えられてい る。この初期段階は「英雄的」段階と呼ばれ、1930年以降の期間は「国家主義的」段階であり、後期段階への移行は1924年のホセ・ヴァスコンセロスの 辞任によって引き起こされた。 [14] 学者メアリー・コフィーは、「変化は認めるが、その結果についての判断は控える」人々をソフト路線、1930年以降のすべての壁画を「腐敗した国家のプロ パガンダ」と見なす人々をハード路線と表現している[14]。もう一つのスタンスは、メキシコ壁画の進化は政府との単純な関係ではなく、アヴァンギャルド とプロレタリアートの感情を正確に反映したものであるというものである。しかし、強硬派はこの運動を、社会主義体制を装った腐敗した政府の権力強化に加担 したものと見ている[14]。 美術史家のレナード・フォルガレは、少し違った見方をしている。ラサロ・カルデナス政権(1934年 - 1940年)が終わり、マヌエル・アビラ・カマチョ政権(1940年 - 1946年)が始まると、超保守的なメキシコが台頭した。 [ビッグスリーのような壁画芸術家たちは、革命後、より良い未来の約束に基づいて作品を発展させることに費やしたが、保守主義の出現により、彼らはその主 題と発言力を失った。 メキシコ政府は壁画プロジェクトから距離を置くようになり、壁画制作は相対的に民営化された。この民営化は増大する国家ブルジョワジーの庇護の結果であっ た。壁画はますます劇場、銀行、ホテルのために請け負われるようになった[16]。 |

Mexican School of Painting and

Sculpture Mural by Jorge González Camarena at the Palacio de Bellas Artes Mexican populist art production from the 1920s to the 1950s is often grouped under the name of Escuela Mexicana de Pintura y Escultura,[17] coined in the 1930s by art historians and critics. The term is not well-defined as it does not distinguish among some important stylistic and thematic difference, there is no firm agreement which artists belong to it nor if muralism should be considered part of it or if these artworks should be left separate from the more well-known murals of the movement.[18][19] It is not a school in the classic sense of the word as it includes work by more than one generation and with different styles that sometimes clash. However, it does involve a number of important characteristics. Mexican School mural painting was a combination of public ideals and artistic aesthetics "positioned as a constituent of the official public sphere."[20] Three formal components of official Mexican muralism are defined as: 1) Direct participation in official publicity and discourse[21] 2) Reciprocal integration of the visual discourse of the mural to an array of communicative practices participant in defining official publicity (including a variety of scriptural genres, but also public speech, debate and provocative public "event")[21] 3) The development and public thematizing of a social-realist aesthetic (albeit multiform in character) as the visual register for the public sense of the mural work and as the doxic, or unquestioned, limits for public dispute over the representational space of the mural image[21] Most painters in this school worked in Mexico City or other cities in Mexico, working almost uninterrupted on projects and/or as teachers, generally with support of the government. Most were concerned with the history and identity of Mexico and politically active. Most art from this school was not created for direct sale but rather for diffusion in both Mexico and abroad. Most were formally trained, often studying in Europe and/or in the Academy of San Carlos.[19]  Mural by Alfredo Zalce at the state government palace in Morelia. A large quantity of murals were produced in most of the country from the 1920s to 1970, generally with themes related to politics and nationalism focused often on the Mexican Revolution, mestizo identity and Mesoamerican cultural history.[2] Scholar, Teresa Meade also states that "indigenismo; the glorification of rural and urban labor and the working man, woman, and child; social criticism to the point of ridicule and mockery; and denunciation of the national, and especially, international ruling classes" were also themes present in the murals at this time.[22] These served as a form of cohesion among members of the movement.[5] The political and nationalistic aspects had little directly to do with the Mexican Revolution, especially in the later decades of the movement. The goal was more to glorify the revolution itself, highlighting its results as a means to legitimatize the post Revolution government.[2] The other political orientation was that of Marxism, especially class struggle. This political group grew strongest in the early movement with Rivera, Orozco and Siqueiros all of which being openly avowed communists. The political messages became less radical but they remained firmly to the left.[2] Much of the mural production glorified indigenismo, or the indigenous aspect of Mexican culture as artists of the movement collectively considered it to be an important factor in the reconstruction of a more modern Mexico. These themes were added with the idea of reexamining the country's history from a different perspective. One other aspect that most of the muralists shared was a rejection of the idea that art was only for the elite, but rather as a benefit for the masses.[5] The various reasons for the focus on ancient Mesoamerica may be divided into three basic categories: the desire to glorify the accomplishments of the perceived original cultures of the Mexican nation; the attempt to locate residual pre-Hispanic forms, practices, and beliefs among contemporaneous indigenous peoples; and the study of parallels between the past and present. Within this last context, the torture of Cuauhtémoc was painted by Siqueiros in 1950 in the Palacio Nacional, one of his few depictions of indigenous cultures of any period.[23] Many of the murals from the muralist project took on monumental status because of where they were situated, mostly on the walls of colonial era government buildings and the themes that were painted.[5] The mural painters of Mexico freely shared ideas and techniques in public spaces in order to capture the attention of the masses. While many of the themes are shared between artists, the work of each artist was distinctive as the government did not impose a set style. These artists were so distinctive that they can generally be deduced without needing to look at the artist's signatures.[9] Techniques used in the production of these murals also included the revival of old techniques such as the fresco, painting on freshly plastered walls and encaustic or hot wax painting.[5][6] Others used mosaics and high fire ceramics, as well as metal parts, and layers of cement.[5] The most innovative of the artists was Siqueiros, who worked with pyroxene, a commercial enamel, and Duco (used to paint cars), resins, asbestos and old machinery, and was one of the first to use airbrush for artistic purposes. He pored, sprayed, dripped and splattered paint for the effects they created haphazardly.[9] |

メキシコ絵画・彫刻学校 パラシオ・デ・ベージャス・アルテスにあるホルヘ・ゴンサレス・カマレーナの壁画 1920年代から1950年代にかけてのメキシコの大衆主義的な美術作品は、1930年代に美術史家や批評家によって作られた「メキシコ絵画・彫刻学校」 [17]という名称でまとめられることが多い。この用語は、いくつかの重要な様式やテーマの違いを区別していないため、明確には定義されておらず、どの アーティストが所属しているのか、壁画はその一部とみなされるべきか、またはこれらの芸術作品は、よりよく知られている運動の壁画とは別に残されるべきか どうか、確固たる合意はありません[18][19]。しかし、いくつかの重要な特徴を含んでいる。 メキシコ派の壁画は「公的な公共圏の構成要素として位置づけられた」公共的理念と芸術的美学の組み合わせであった[20]: 1) 公的な宣伝と言説への直接的な参加[21] 2) 公的な宣伝の定義付けに参加するコミュニケーション実践の数々(様々な聖典ジャンルを含むが、公の演説、討論、挑発的な公的「出来事」も含まれる)への壁 画の視覚的言説の相互的統合[21] 3) 壁画作品の公的な感覚の視覚的登録として、また公序良俗として、社会的リアリズムの美学(多義的な性格を持つが)の発展と公的な主題化、 この一派の画家たちのほとんどは、メキシコシティやメキシコの他の都市で、ほとんど中断されることなく、プロジェクトや教師として、一般的には政府の支援 を受けながら活動していた。ほとんどの画家はメキシコの歴史とアイデンティティに関心を持ち、政治的に積極的であった。この一派の芸術のほとんどは、直接 販売するためではなく、メキシコ国内外に広めるために制作された。ほとんどが正式な訓練を受けており、しばしばヨーロッパおよび/またはサン・カルロス・ アカデミーで学んだ[19]。  モレリアの州政府宮殿にあるアルフレド・ザルセによる壁画。 1920年代から1970年にかけて、メキシコのほとんどの地域で、政治やナショナリズムに関連するテーマで、メキシコ革命、メスティーソのアイデンティ ティ、メソアメリカの文化史に焦点を当てた壁画が大量に制作された。 [2]学者のテレサ・ミードも、「土着主義、農村や都市での労働、働く男、女、子供の賛美、嘲笑や嘲笑に近い社会批判、国内、特に国際的な支配階級への非 難」もこの時期の壁画に存在したテーマであったと述べている[22]。もうひとつの政治的方向性はマルクス主義、特に階級闘争であった。この政治的グルー プは、リベラ、オロスコ、シケイロスなど、公然と共産主義者を公言していた初期の運動で最も強くなった。政治的メッセージは急進的なものではなくなった が、左派であることに変わりはない[2]。 壁画制作の多くはインディヘニスモ、つまりメキシコ文化の土着的側面を賛美した。これらのテーマは、異なる視点からメキシコの歴史を見直すという考えのも とに加えられた。古代メソアメリカに焦点を当てた様々な理由は、3つの基本的なカテゴリーに分けられるかもしれない:メキシコ民族の原初の文化であると認 識されるものの功績を称揚したいという願望、同時代の先住民の中に残存する先ヒスパニック時代の形式、慣習、信仰を探し出そうとする試み、過去と現在の類 似性の研究。この最後の文脈の中で、クアウテモックの拷問は1950年にシケイロスがパラシオ・ナシオナルに描いたものであり、あらゆる時代の先住民文化 を描いた彼の数少ない作品の一つである[23]。 メキシコの壁画画家たちは、大衆の注目を集めるために、公共の場でアイデアや技法を自由に共有した。テーマの多くは画家間で共有されているが、政府が決 まったスタイルを押し付けなかったため、それぞれの画家の作品は特徴的であった。これらの壁画の制作に用いられた技法には、フレスコ画、漆喰を塗ったばか りの壁へのペインティング、エンカウスティックやホット・ワックス・ペインティングといった古い技法の復活も含まれる[9]。 [5][6]また、モザイクや高火度セラミック、金属部品、セメントの層を使ったものもあった。最も革新的だったのはシケイロスで、市販のエナメルである 輝石やデュコ(自動車の塗装に使われる)、樹脂、アスベスト、古い機械などを使って作品を制作し、エアブラシを芸術目的で最初に使った一人だった。彼は絵 の具を注ぎ、吹き付け、垂らし、飛び散らせ、無造作に作り出す効果を狙った[9]。 |

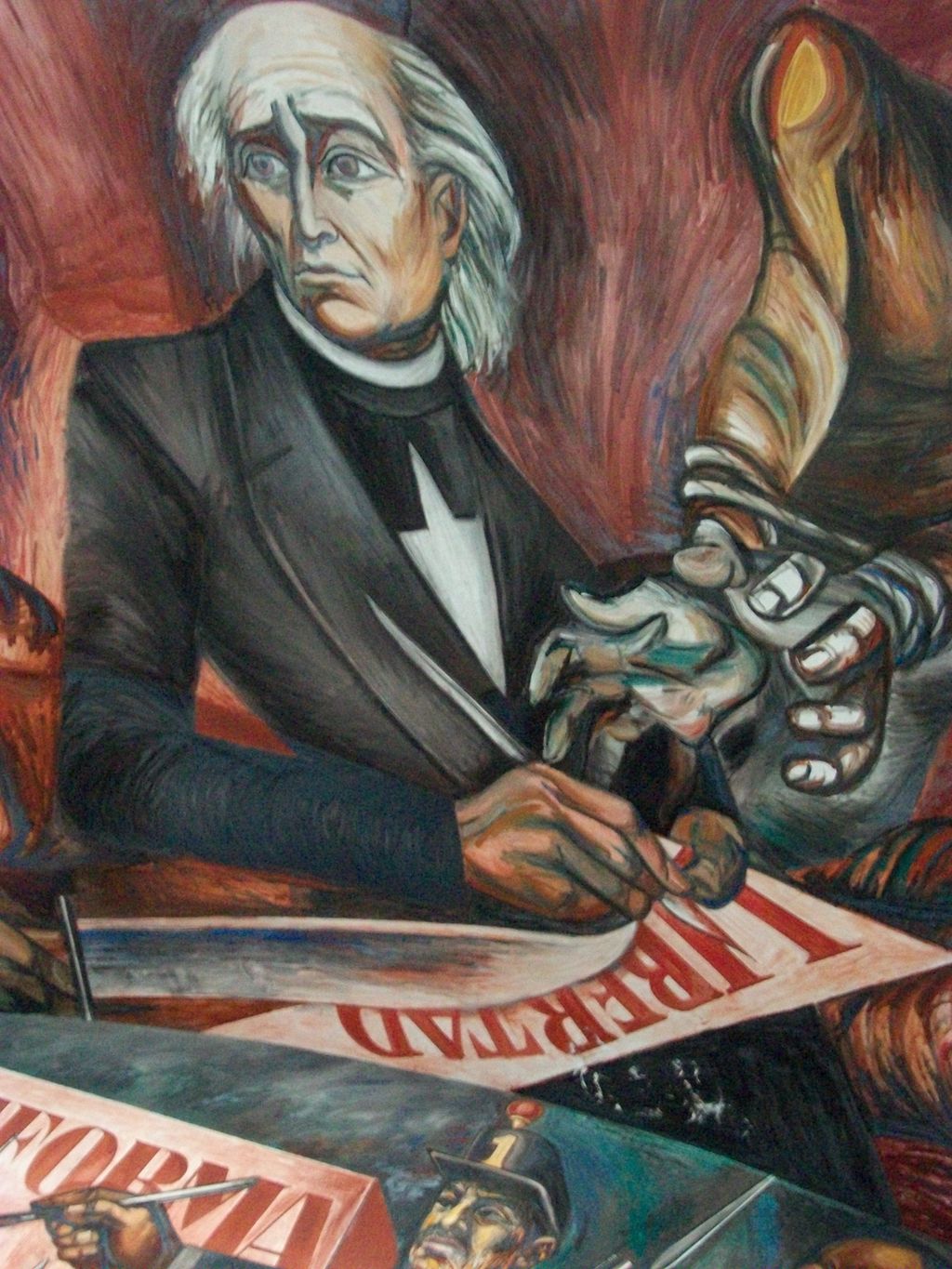

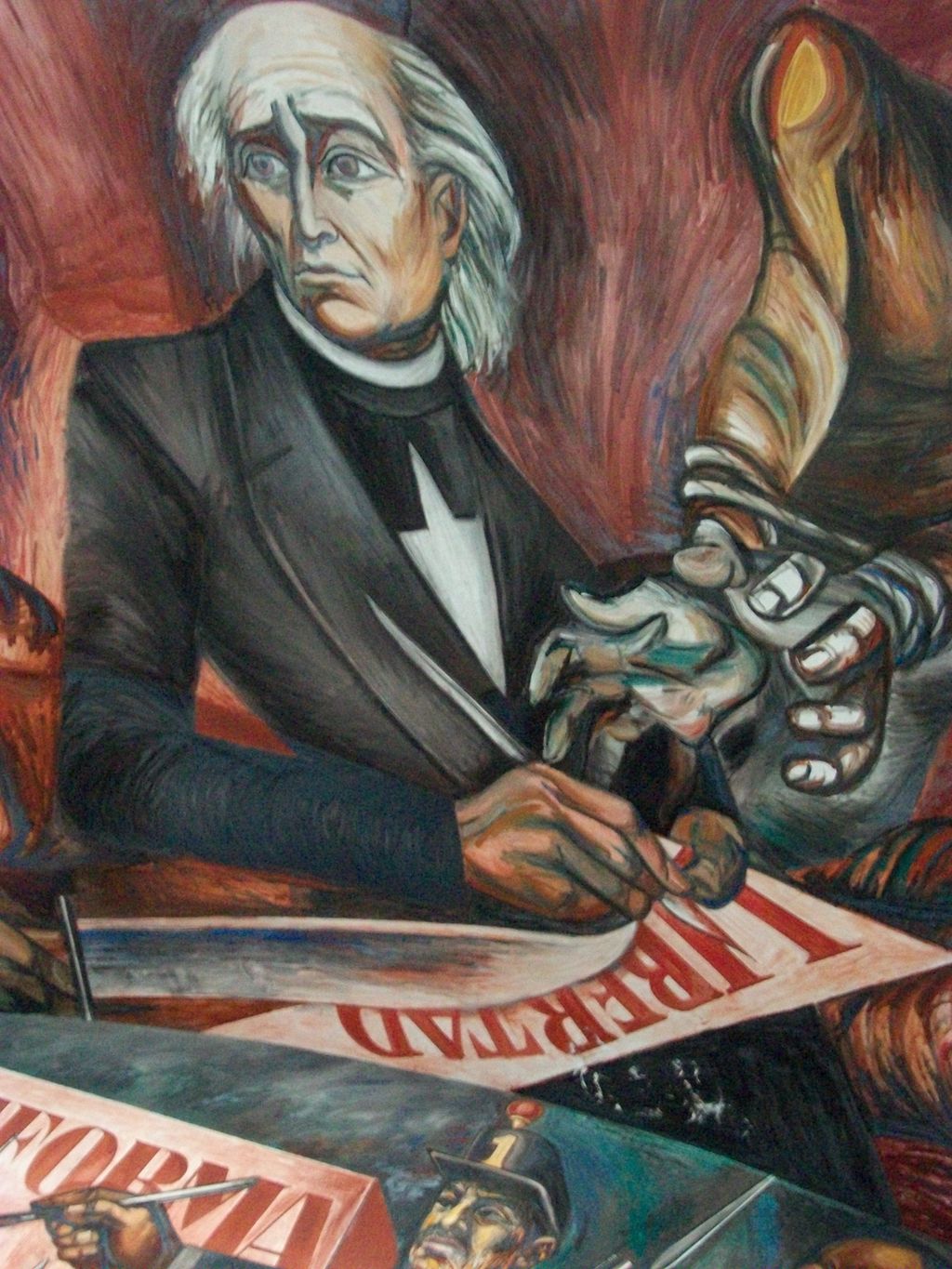

| Artists Los Tres Grandes (The Three Greats)  The History of Mexico mural in the main stairwell of the National Palace, by Diego Rivera (1929-1935) By far, the three most influential muralists from the 20th century are Diego Rivera, José Clemente Orozco, and David Siqueiros, called "los tres grandes" (the three great ones).[4][5] All believed that art was the highest form of human expression and a key force in social revolution.[4] Their work was the driving force that defined the movement originally set into motion by Vasconcelos. It created a mythology around the Mexican Revolution and the Mexican people which is still influential to this day, as well as promote Marxist ideals. At the time the works were painted, they also served as a form of catharsis over what the country had endured during the war.[5] However, the three were different in their artistic expression. To summarize the general types of contributions the Three Greats made, Rivera's works were utopian and idealist, Orozco's were critical and pessimistic, while the most radical of the three was Siqueiros, who heavily focused on a scientific future.[5][9] These three different points of views on the war was shaped by their own personal experiences with Mexican Revolution. In Rivera case, he was in Europe during the revolution and had never experienced the horrors of the war. While never experiencing the war first hand, his art primarily focused on what he perceived to be the social benefits from the revolution.[5] Orozco and Siqueiros, on the other hand, both fought in the war, which subsequently resulted in a more pessimistic approach to their artwork when depicting the revolution; with Siqueros' artwork being notably more radical and focused on portraying a scientific future.[2][5]  Miguel Hidalgo abolishing slavery by José Clemente Orozco Of the three, Diego Rivera was the most traditional in terms of painting styles, drawing heavily from European modernism. In his narrative mural images, Rivera incorporated elements of cubism[20] His themes were Mexican, often scenes of everyday life and images of ancient Mexico.[12] He originally painted this in bright colors in the European style but modified it to more earthy tones to imitate indigenous murals. His greatest contribution is the promotion of Mexico's indigenous past into how many people both inside and outside of the country view it.[6][9] One of the most prominent examples of this is Rivera's contribution to the Mexican National Palace, translated as The History of Mexico, which he worked on from1929-1935.[12] José Clemente Orozco's art also began with a European style of expression; however, his art developed into an angry denunciation of oppression especially by those he considered to be of the evil and brutal higher economic class.[6] His work was somber and dire, with emphasis on human suffering and fear of the technology of the future, intent on displaying the reality of the war.[9] His work shows an "expressionist use of color, slashing lines, and parodic distortions of the human figure."[24] Like most other muralists, Orozco condemned the Spanish as destroyers of indigenous culture, but he did have kinder depictions such as that of a Franciscan friar tending to an emaciated indigenous period.[6] Unlike other artists, Orozco never glorified the Mexican Revolution, having fought in it, but rather depicted the horrors of this war. It caused many of his murals to be heavily criticized and even defaced.[9]  View of the Polyforum Cultural Siqueiros in Mexico City David Alfaro Siqueiros was the youngest and most radical of the three. He joined the Venustiano Carranza army when he was eighteen and experienced the Revolution from the front lines.[5][6] Although all three muralists were communists, Siqueiros was the most dedicated, as evidenced by his portrayals of the proletarian masses. His work is also characterized with rapid, sweeping, bold lines and the use of modern enamels, machinery and other elements related to technology. His style showed a "futurist blurring of form and technique." His fascination with technology as it relates to art was exemplified when he emphasized the mass communications visual technology of photograph and motion picture in his eventual movement toward neorealism.[24] His radical politics made him unwelcome in Mexico and the United States, so he did much of his work in South America.[6][9] However, his masterpiece is considered to be the Polyforum Cultural Siqueiros, located in Mexico City.[2] El Cuarto Grande (The Fourth Great One)[25]  "Nacimiento de Nuestra Nacionalidad" (1952) was one of Rufino Tamayo's abstract pieces that is now in the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City. While Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros are usually regarded as the most influential mural artists of the period, Rufino Tamayo also contributed to the movement of the 1920s.[25][26] Tamayo was younger than the Big Three and he often argued against their attitudes. He argued against their isolationist work after his art studies in Europe where he became heavily influenced by post World War II abstractions. He believed that the Mexican Revolution would ultimately harm Mexico due to the progressive attitudes that were arising. When he returned to Mexico after staying in Europe, he wanted his artwork to express pre-Conquest art but in his own abstract style.[27] Tamayo was heavily influenced by the early pre-Columbian history of Mexico and it is evident in his piece titled "Nacimiento de Nuestra Nacionalidad".[25] He expresses the violence that was used during the Spanish conquest of native Mexicans. The center shows a human figure holding a mechanical weapon, sitting atop a horse and surrounded by a glowing light which depicted a 'godlike' Spanish conquistador. The horse is shaped like a majestic creature because it was a creature that the native Mexicans had never seen before.[25] Overall, this piece offers an immense amount of imagery and is a reflection of the initial defeat of Mexican nationalism and shows the traumatic and oppressive history. Tamayo was proud of his Mexican roots and expressed his nationalism in a more traditional way than Rivera or Siqueiros. His focus was on accepting both his Spanish and native background and ultimately expressing the way he felt through the colors, shapes and culture in a modern abstract way.[26] Ultimately, Tamayo wanted the Mexican people to not forget their roots; it shows why he was so persistent in using inspiration from the pre-Columbian period as well as incorporating his own perspective of the Mexican Revolution.[28] |

アーティスト ロス・トレス・グランデス(三大巨頭)  ディエゴ・リベラ作、国立宮殿大階段の壁画「メキシコの歴史」(1929-1935年) 20世紀において最も影響力のある3人の壁画家は、ディエゴ・リベラ、ホセ・クレメンテ・オロスコ、ダビド・シケイロスであり、「ロス・トレス・グランデ ス(三大巨頭)」と呼ばれる[4][5]。この作品は、メキシコ革命とメキシコの人々にまつわる神話を作り上げ、マルクス主義の理想を推進するだけでな く、今日に至るまで影響力を持ち続けている。作品が描かれた当時は、戦争中に国が耐えたものに対するカタルシスの形としても機能していた[5]。しかし、 3人の芸術表現は異なっていた。三人の偉大な芸術家たちが行った貢献の一般的なタイプを要約すると、リベラの作品はユートピア的で理想主義的であり、オロ スコの作品は批判的で悲観的であった。リベラの場合、革命時にヨーロッパにいたため、戦争の恐怖を体験したことがなかった。一方、オロスコとシケイロスは ともに戦争を体験しており、その結果、革命を描く際に、より悲観的なアプローチをとるようになった。  ホセ・クレメンテ・オロスコによる奴隷制廃止のミゲル・イダルゴ 3人のうち、ディエゴ・リベラは最も伝統的な画風で、ヨーロッパのモダニズムから多大な影響を受けた。彼の物語的な壁画のイメージにおいて、リベラはキュ ビスムの要素を取り入れた[20]。彼のテーマはメキシコ的であり、日常生活のシーンや古代メキシコのイメージであることが多かった[12]。彼は当初、 これをヨーロッパ風の明るい色彩で描いていたが、土着の壁画を模倣するため、より土っぽい色調に修正した。彼の最も大きな貢献は、メキシコの先住民の過去 を国の内外の多くの人々がどのように見るかを広めたことである[6][9]。その最も顕著な例のひとつが、彼が1929年から1935年にかけて手がけた 『メキシコの歴史』と訳されるメキシコ国立宮殿へのリベラの貢献である[12]。 ホセ・クレメンテ・オロスコの芸術もまた、ヨーロッパ風の表現から始まったが、彼の芸術は、特に邪悪で残忍な上級経済階級とみなされる人々による抑圧に対 する怒りの告発へと発展した[6]。 [他の多くの壁画家同様、オロスコはスペイン人を先住民文化の破壊者として非難したが、フランシスコ会の修道士がやせ衰えた先住民の世話をしているような 優しい描写もあった[6]。そのため、彼の壁画の多くは激しく批判され、汚されることさえあった[9]。  メキシコ・シティのシケイロス文化ポリフォラムの眺め ダビッド・アルファロ・シケイロスは3人の中で最も若く、最も過激だった。18歳でヴェヌスティアーノ・カランサ軍に入隊し、最前線から革命を体験した [5][6]。3人の壁画家全員が共産主義者であったが、シケイロスが最も熱心であったことは、プロレタリア大衆を描いた作品からも明らかである。彼の作 品はまた、急速で、一掃された、大胆な線と、近代的なエナメル、機械、その他の技術に関連する要素の使用が特徴である。彼の作風は "未来派的な形態と技法の曖昧さ "を示している。彼の急進的な政治性はメキシコやアメリカでは歓迎されなかったため、南米で多くの作品を制作した[6][9]。しかし、彼の最高傑作はメ キシコシティにあるポリフォラム・カルチュラル・シケイロスと考えられている[2]。 エル・クアルト・グランデ(第四の偉大なるもの)[25]。  「Nacimiento de Nuestra Nacionalidad" (1952)はルフィノ・タマヨの抽象作品のひとつで、現在はメキシコシティのパラシオ・デ・ベージャス・アルテス(国立芸術宮殿/劇場)にある。 リベラ、オロスコ、シケイロスは通常、この時代の最も影響力のある壁画作家と見なされているが、ルフィノ・タマヨもまた1920年代のムーブメントに貢献 した[25][26]。彼はヨーロッパで美術を学び、第二次世界大戦後の抽象画に大きな影響を受けた後、彼らの孤立主義的な作品に異議を唱えた。彼は、メ キシコ革命が先進的な態度を生んだため、最終的にメキシコに害を及ぼすと考えていた。ヨーロッパでの滞在を終えてメキシコに戻った彼は、征服以前の芸術を 表現しつつも、彼独自の抽象的なスタイルで作品を制作することを望んだ[27]。 タマヨはコロンブス以前のメキシコの歴史に大きな影響を受けており、それは「Nacimiento de Nuestra Nacionalidad」というタイトルの作品に表れている[25]。中央には、機械的な武器を持ち、馬の上に座り、「神のような」スペインの征服者を 描いた輝く光に包まれた人間の姿が描かれている。全体として、この作品は膨大な量のイメージを提供し、メキシコのナショナリズムの最初の敗北の反映であ り、トラウマ的で抑圧的な歴史を示している。タマヨはメキシコ人のルーツに誇りを持ち、リベラやシケイロスよりも伝統的な方法でナショナリズムを表現し た。最終的に、タマヨはメキシコの人々が自分たちのルーツを忘れないことを望んでいた。それは、彼がなぜコロンブス以前の時代からインスピレーションを得 ることに固執し、またメキシコ革命の独自の視点を取り入れていたかを示している[28]。 |

| Revolutionary themes and ideas One of the best examples of Rivera's perspective on the revolution can be seen in his mural at the chapel of the Chapingo Autonomous University (murals)[6] The most dominant artwork in this mural is The Liberated Earth 1926-27 Fresco which depicts Rivera's second wife, Guadalupe Marín, Voluptuous and recumbent, hand held aloft, she symbolizes the fertility of the land, and exudes a dominant, life-affirming energy which triumphs artistically against the injustices depicted elsewhere.[29] This artwork sits as the final site to be seen, representing Rivera's view of what the Mexican revolution would bring – a free and productive earth in which natural forces being able to be harnessed for the benefit of man. To say Liberated Earth acts as a fictional finalism of a social Mexico would be supported by the preceding artworks in Chapingo Chapel. These prior artworks showcase the evolution of the agrarian movement paralleled with the evolution of Earth, both timelines of events being heavily reflective of Rivera's own positive views.[12] Orozco's view point on the Mexican Revolution can be seen in his mural The Trench (1922-1924), Mexico that can be found at the Escuela Nacional Preparatoria. The dynamic lines and diluted color palette exemplify the dismal tone Orozco sets to exemplify his negative attitude towards the revolution. Contrary to many other revolutionary artists, one can also note how Orozco leaves the faces of the soldiers hidden, further displaying his own ideologies about the war. This form of anonymity functions as commentary towards the war and the soldiers that fought for the revolution – that they will be forgotten, despite their courageous sacrifice in hopes of a brighter future. From this more violent and realistic representation of the revolution, Orozco's aim is to get viewers to question if the revolutionary war was worth the sacrifices made.[16] These artworks sparked massive controversy, even leading to the defacing of this mural, but was then later repainted in 1926.[30] Siqueiros brought a nuance to the idea of the Mexican Revolution. Although he held a radically negative opinion towards the revolution, he also depicted images of the scientific future while the other two artists' primary focus was on their experience and view on the revolution. In 1939 Siqueros, in collaboration with a group of other revolutionary artists, constructed a mural at the Electrical Workers Union Building titled Portrait of the Bourgeoise (1939), Mexico City Mexico. Together, these artists aimed to present their belief that the violence of the revolutionary war stemmed from the utilization of the flaw economic system they knew as capitalism, used as a tool of perpetuating the control of fascist leaders.[16] This piece of art demonstrates the horrors of war, the artists' own negative views toward the role of capitalism during the Revolution, and how the proletariat Mexican citizens were being overlooked and taken advantage of by the Bourgeoise. The emotional toll of war is also highlighted by the reaction of a frightened, on-looking mother and child pair, further reflecting the artist's own reactions toward capitalism. Among all of the pessimistic imagery is also a symbol of hope manifested by a lone man dressed in the clothing of a guerrilla fighter. He's seen grasping a rifle pointed towards Bourgeoise leaders present during the revolution. This symbolizes a promising future in which Mexico overcomes the obstacles faced in the revolution and embraces technology, as seen in the depictions of electrical towers at the top of the mural.[31] Political expression The Big Three struggled to express their leftist leanings after the initial years painting murals under government supervision. These struggles with the post-revolution government lead the muralists to create a union of artists and produce a radical manifesto. José Vasconcelos, the Secretary of Public Education under President Álvaro Obregón (1920–24) contracted Rivera, Siqueiros, and Orozco to pursue painting with the moral and financial support of the new post-revolutionary government.[32] Vasconcelos, while seeking to promote nationalism and "la raza cósmica," seemed to contradict this sentiment as he guided the muralists to create works in a classic, European style. The murals became a target of Vasconcelos's criticism when the Big Three departed from classical proportion and figure. Siqueiros was dissatisfied with the incongruity between the murals and the revolutionary concerns of the muralists, and he advocated discussion among the artists of their future works. In 1922 the muralists founded the Union of Revolutionary Technical Workers, Painters, and Sculptors of Mexico. The Union then released a manifesto listing education, art of public utility, and beauty for all as the social goals of their future artistic endeavors.[33] |

革命のテーマと思想 この壁画の中で最も支配的な作品は、リベラの2番目の妻、グアダルーペ・マリンを描いた『解放された大地』1926-27年フレスコ画である。 [29] この作品は、メキシコ革命がもたらすもの、すなわち、自然の力が人間の利益のために利用される自由で生産的な大地についてのリベラの見解を表す、最終的な 場所として置かれている。解放された大地』は、社会的なメキシコの架空の最終論として機能していると言えば、チャピンゴ礼拝堂の先行作品からも裏付けられ るだろう。これらの先行作品は、地球の進化と並行して農民運動の進化を示し、両方の出来事のタイムラインは、リベラ自身の肯定的な見解を色濃く反映してい る[12]。 メキシコ革命に対するオロスコの視点は、エスクエラ ナショナル プレパラトリアにある彼の壁画『The Trench』(1922-1924)、メキシコに見ることができる。ダイナミックな線と薄められた色調は、オロスコが革命に対する否定的な態度を例証す るために設定した悲惨なトーンを示している。他の多くの革命家たちとは対照的に、オロスコは兵士たちの顔を隠したままにしている。この匿名性は、戦争と革 命のために戦った兵士たちに対するコメントとして機能している。この革命のより暴力的で現実的な表現から、オロスコの狙いは、革命戦争が犠牲を払うに値す るものであったのかどうか、見る者に疑問を抱かせることにある[16]。これらの作品は大論争を巻き起こし、この壁画の汚損にまで至ったが、その後 1926年に塗り直された[30]。 シケイロスはメキシコ革命の思想にニュアンスをもたらした。彼は革命に対して根本的に否定的な意見を持っていたが、他の2人の画家が革命に対する経験や見 解に主眼を置いていたのに対し、彼は科学的な未来のイメージも描いていた。1939年、シケロスは他の革命芸術家グループと共同で、メキシコ・シティの電 気労働組合ビルに『ブルジョワーズの肖像』(1939年)というタイトルの壁画を制作した。これらの芸術家たちは共に、革命戦争の暴力は、ファシスト指導 者の支配を永続させる道具として使用された、資本主義として彼らが知っている欠陥のある経済システムの利用から生じているという信念を提示することを目指 した[16]。この芸術作品は、戦争の恐怖、革命中の資本主義の役割に対する芸術家たち自身の否定的な見解、そしてプロレタリアートであるメキシコ市民が いかにブルジョワーズによって見過ごされ、利用されていたかを示している。戦争の感情的な犠牲は、怯え、監視する母子ペアの反応によっても強調され、資本 主義に対する画家自身の反応をさらに反映している。悲観的なイメージのなかには、ゲリラ戦士の服装をした一人の男による希望の象徴もある。彼は、革命に立 ち会ったブルジョワーズの指導者たちに向けられたライフルを握っている。これは、壁画上部の電気塔の描写に見られるように、メキシコが革命で直面した障害 を克服し、テクノロジーを受け入れる有望な未来を象徴している[31]。 政治的表現 ビッグスリーは、政府の監視下で壁画を描いていた初期の数年間を経て、左翼的傾向を表現することに苦心した。革命後の政府とのこうした闘争は、壁画家たち に芸術家組合を作らせ、急進的なマニフェストを作成させた。アルバロ・オブレゴン大統領(1920-24)の下で公教育長官を務めていたホセ・バスコンセ ロスは、革命後の新政府の道徳的・財政的支援を受けて絵画を追求するよう、リベラ、シケイロス、オロスコと契約した[32]。バスコンセロスは、ナショナ リズムと「ラ・ラサ・コスミカ」を推進しようとしながらも、壁画家たちに古典的なヨーロッパ風の作品を制作するよう指導したため、この感情とは矛盾するよ うに思われた。ビッグスリーが古典的なプロポーションや人物像から逸脱したことで、壁画はバスコンセロスの批判の的となった。シケイロスは壁画と壁画家た ちの革命的関心との間の不調和に不満を抱き、将来の作品について芸術家たちの間で議論することを提唱した。 1922年、壁画家たちはメキシコ革命的技術労働者、画家、彫刻家組合を設立した。そして同組合は、彼らの将来の芸術活動の社会的目標として、教育、公益 的芸術、万人のための美を挙げたマニフェストを発表した[33]。 |

Influence La Ciencia in Atlixco, Puebla by Jorge Figueroa Acosta After nearly a century since the beginning of the movement, Mexican artists still produce murals and other forms of art with the same "mestizo" message. Murals can be found in government buildings, former churches and schools in nearly every part of the country.[2][34] One recent example is a cross cultural project in 2009 to paint a mural in the municipal market of Teotitlán del Valle, a small town in the state of Oaxaca. High school and college students from Georgia, United States, collaborated with town authorities to design and paint a mural to promote nutrition, environmental protection, education and the preservation of Zapotec language and customs.[34]  Mural of Salvador Alvarado, former governor of Yucatan, displayed at the governor's palace, Merida (Yucatan), Mexico. Painted by Fernando Castro Pacheco. Mexican muralism brought mural painting back to the forefront of Western art in the 20th century with its influence spreading abroad, especially promoting the idea of mural painting as a form of promoting social and political ideas.[5] It offered an alternative to non-representational abstraction after World War I with figurative works that reflect society and its immediate concerns. While most Mexican muralists had little desire to be part of the international art scene, their influence spread to other parts of the Americas. Muralists influenced by Mexican muralism include Carlos Mérida of Guatemala, Oswaldo Guayasamín of Ecuador and Candido Portinari of Brazil.[6]  View of the mural in the Palacio de Gobierno Rivera, Orozco, and Siqueiros all spent time in the United States. Orozco was the first to paint murals in the late 1920s at Pomona College in Claremont, California, staying until 1934 and becoming popular with academic institutions.[2][4] During the Great Depression, the Works Progress Administration employed artists to paint murals, which paved the way for Mexican muralists to find commissions in the country.[4] Rivera lived in the United States from 1930 to 1934. During this time, he put on an influential show of his easel work at the Museum of Modern Art.[2][4] The success of Orozco and Rivera prompted U.S. artists to study in Mexico and opened doors for many other Mexican artists to find work in the country.[2] Siqueiros did not fare as well. He was exiled to the US from Mexico in 1932, moving to Los Angeles. During this time, he painted three murals, but they were painted over.[2][4] The only one of the three to survive, América Tropical (full name: América Tropical: Oprimida y Destrozada por los Imperialismos, or Tropical America: Oppressed and Destroyed by Imperialism[35]), was restored by the Getty Conservation Institute and the América Tropical Interpretive Center opened to provide public access.[36] The concept of mural as political message was transplanted to the United States, especially in the former Mexican territory of the Southwest. It served as inspiration to the later Chicano muralism but the political messages are different.[2] Revolutionary Nicaragua developed a tradition of muralism during the Sandinista period.[37] |

影響力 ホルヘ・フィゲロア・アコスタ作「プエブラ州アトリックスコのラ・シエンシア(科学)」 この運動が始まってから1世紀近く経った今でも、メキシコの芸術家たちは、同じ「メスティーソ」のメッセージを込めた壁画やその他の芸術作品を制作してい る。最近の例としては、2009年にオアハカ州の小さな町、テオティトラン・デル・バジェの市営市場に壁画を描くという異文化プロジェクトがある[2] [34]。アメリカ・ジョージア州の高校生と大学生が町当局と協力して、栄養、環境保護、教育、サポテカ族の言語と習慣の保護を促進するための壁画をデザ インし、描いた[34]。  メキシコ、メリダ(ユカタン州)の知事公邸に展示されている、元ユカタン州知事サルバドール・アルバラードの壁画。フェルナンド・カストロ・パチェコが描 いた。 メキシコ壁画は、20世紀に西洋美術の最前線に壁画を復活させ、その影響は海外にも広がり、特に社会的、政治的思想を広める形としての壁画の考えを広めた [5]。第一次世界大戦後、社会とその身近な関心事を反映した具象的な作品によって、非具象的な抽象表現に代わるものを提供した。ほとんどのメキシコの壁 画家は国際的なアートシーンに参加することをほとんど望んでいなかったが、彼らの影響はアメリカ大陸の他の地域にも広がった。メキシコ壁画の影響を受けた 壁画家には、グアテマラのカルロス・メリダ、エクアドルのオズワルド・グアヤサミン、ブラジルのカンディド・ポルティナリなどがいる[6]。  パラシオ・デ・ゴビエルノ(国家宮殿)の壁画の眺め リベラ、オロスコ、シケイロスはいずれもアメリカで過ごした。オロスコは1920年代後半、カリフォルニア州クレアモントにあるポモナ・カレッジで壁画を 描いたのが最初で、1934年まで滞在し、学術機関で人気を博した[2][4]。大恐慌の最中、労働進歩局は壁画を描く芸術家を雇用し、メキシコ人壁画家 が国内で仕事を見つける道を開いた[4]。オロスコとリベラの成功は、アメリカの芸術家たちにメキシコへの留学を促し、他の多くのメキシコ人芸術家たちに メキシコで仕事を見つける道を開いた。彼は1932年にメキシコからアメリカに追放され、ロサンゼルスに移り住んだ。この間、彼は3つの壁画を描いたが、 塗りつぶされてしまった[2][4]: 正式名称:América Tropical: Oprimida y Destrozada por los Imperialismos、熱帯アメリカ: 帝国主義によって抑圧され、破壊された[35])がゲッティ保存修復研究所によって修復され、一般公開のためにアメリカ・トロピカル解説センターがオープ ンした[36]。 政治的メッセージとしての壁画のコンセプトはアメリカ、特に旧メキシコ領の南西部に移植された。革命期のニカラグアはサンディニスタ時代に壁画の伝統を発 展させた[37]。 |

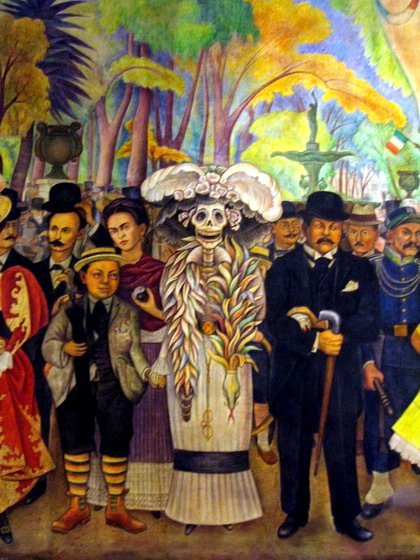

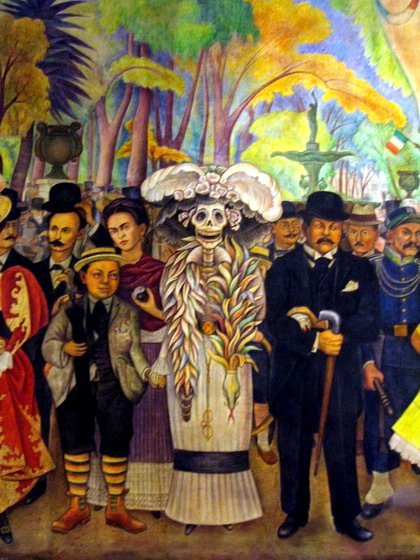

| Women of Mexican muralism Aurora Reyes Flores, the first woman muralist Aurora Reyes Flores was a political activist, teacher, and the first recognized female Mexican muralist. She focused on highlighting problems of those that she considered unprotected.[38][39] Her first mural, "Atentado a Las Maestras Rurales" (Attack on Rural Teachers), depicts a woman who is being dragged by the hair by a man who is also tearing up a book with his other hand. Another man, whose face is covered by the large sombrero on his head, also begins beating the woman with the butt of his rifle. Behind a door stand three children witnessing the violence take place as they look on in utter shock and disbelief. The mural reflected Reyes' concerns with the education system and the struggle to improve social conditions for working women.[38] Elena Huerta Muzquiz, created the largest mural in Mexico by a woman Elena Huerta's 450 square meter work is the largest mural created by a woman in Mexico, taking her two years to complete.[40] Located in Saltillo, Mexico, the mural shows two different scenes. One scene depicts the independence of Mexico in 1810 with Miguel Hidalgo y Costilla, while the other scene shows Hidalgo alongside contemporary independence leaders who contributed to the independence movements of Mexico.[41] Huerta was not only known for her artwork, but also for her literary works, as she was a writer and feminist. In her lifetime, she was able to create only three murals. She captured the true essence of the Mexican Muralist movement through her passion and ability to keep Mexican culture viable.[38]  "Sueño de una tarde dominical el la Alameda Central" by Diego Rivera (1947).[42] Rina Lazo, Rivera's "Right Hand" woman As Rina Lazo worked alongside Rivera, she became heavily influenced by his artwork and even helped him on one of the most outstanding murals of the Mexican Revolution: "Sueno de Una Tarde Dominical en la Alameda Central" (Dream of a Sunday Afternoon in Alameda Central Park).[38] She became Rivera's assistant for a total of ten years, right up until his death in 1957. However, she also worked on her own pieces and ultimately had to navigate through her own personal struggles on how to fully depict Mexican nationalism in her own way. Moreover, painting alongside Rivera helped her understand the concepts of Mexican muralism which captured social and political awareness but also showed the indigenous roots that have shaped Latin Americans and Mexicans.[43] At the time, it was rare for a woman to have such popularity and independence, but despite working in a heavily male dominated field, Lazo successfully managed to become a muralist.[43] While she was originally from Guatemala, Huerta began to grow fond of Mexico during her collaboration with Rivera despite originally being from Guatemala, ultimately showing the influence that the Mexican Revolution had through her artwork. Fanny Rabel Considered one of the first female artists of the Mexican muralism movement,[44] she painted several murals, the most important one being located at the National Museum of Anthropology in Mexico City.  Cortés y Malinche por José Clemente Orozco https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Mexican_muralism |

メキシコ壁画の女性たち アウロラ・レイエス・フローレス、最初の女性壁画家 アウロラ・レイエス・フローレスは政治活動家、教師であり、メキシコ初の女性壁画家として知られる。彼女の最初の壁画である "Atentado a Las Maestras Rurales"(農村の教師への攻撃)は、髪を引っ張られている女性を描いている。頭にかぶった大きなソンブレロで顔を隠したもう一人の男も、ライフル の尻で女性を殴り始める。ドアの向こうには、暴力を目撃している3人の子供たちが立っており、彼らはまったくの衝撃と不信の中でその様子を見つめている。 この壁画は、レイエスの教育制度に対する懸念と、働く女性の社会的条件を改善するための闘いを反映していた[38]。 エレナ・ウエルタ・ムスキズ、女性によるメキシコ最大の壁画を制作 エレナ・ウエルタの450平方メートルの作品は、メキシコ最大の女性による壁画で、完成までに2年を要した[40]。ひとつはミゲル・イダルゴ・イ・コス ティージャと1810年のメキシコ独立を描いた場面で、もうひとつはメキシコの独立運動に貢献した同時代の独立指導者たちとイダルゴを並べた場面である [41]。 ウエルタは芸術作品だけでなく、作家でありフェミニストであったため、文学作品でも知られている。彼女が生涯に制作できた壁画はわずか3点。彼女はメキシ コ文化を存続させるための情熱と能力を通して、メキシコ壁画運動の真髄を捉えた[38]。  ディエゴ・リベラによる「Sueño de una tarde dominical el la Alameda Central」(1947年)[42]。 リナ・ラソ、リベラの「右腕」 リナ・ラソはリベラのそばで働くうちに、彼の作品に大きな影響を受けるようになり、メキシコ革命の最も傑出した壁画のひとつを手掛けた: 「アラメダ中央公園の日曜日の午後の夢』[38]。彼女は1957年にリベラが亡くなるまで、合計10年間リベラのアシスタントを務めた。しかし、彼女は 自分の作品にも取り組み、最終的には、メキシコのナショナリズムを自分なりに完全に描くにはどうしたらいいかという個人的な葛藤を乗り越えなければならな かった。さらに、リベラと一緒に絵を描くことで、社会的、政治的意識を捉えつつ、ラテンアメリカ人とメキシコ人を形成してきた土着のルーツを示すメキシコ 壁画のコンセプトを理解するのに役立った[43]。当時、女性がこのような人気と独立性を持つことは稀だったが、男性優位の激しい分野で働いていたにもか かわらず、ラゾは壁画家になることに成功した。 [43]グアテマラ出身でありながら、リベラとの共同制作の中でメキシコが好きになり、最終的にはメキシコ革命の影響を作品を通して示すことになった。 ファニー・ラベル メキシコ壁画運動の最初の女性アーティストの一人とされ[44]、いくつかの壁画を描いたが、最も重要なものはメキシコシティの国立人類学博物館にある。  コルテスとマリンチェ(ホセ・クレメンテ・オロスコ) |

| Additional prominent artworks Diego Rivera, Creation, National Preparatory School, 1922 Diego Rivera, History of Mexico, National Palace, 1929–35 Diego Rivera, The Sleeping Earth, Chapingo Chapel, 1926-1928 Diego Rivera, Fecund Earth, Chapingo Chapel, 1926-1928 Diego Rivera, Underground Organization of the Agrarian Movement, Chapingo Chapel, 1926-1928 Orozco, The Revolutionary Trinity, National Preparatory School, 1923-1924 Orozco, The Rich People, National Preparatory School, 1924 Orozco, The Trench, National Preparatory School, 1926 Orozco, Catharsis, Palacio de Bellas Artes, 1934-1935 Siqueiros & Renau, Portrait of the Bourgeoisie, Electrical Workers Union,1939-1940 |

|

| Mexican art Category:Mexican muralists Murals of Los Angeles |

|

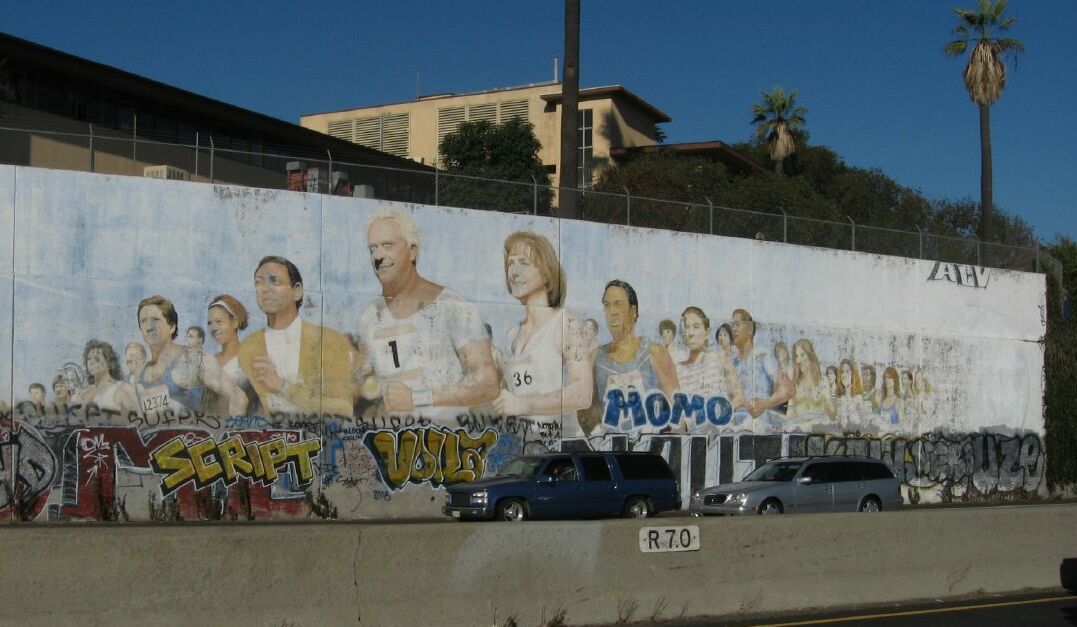

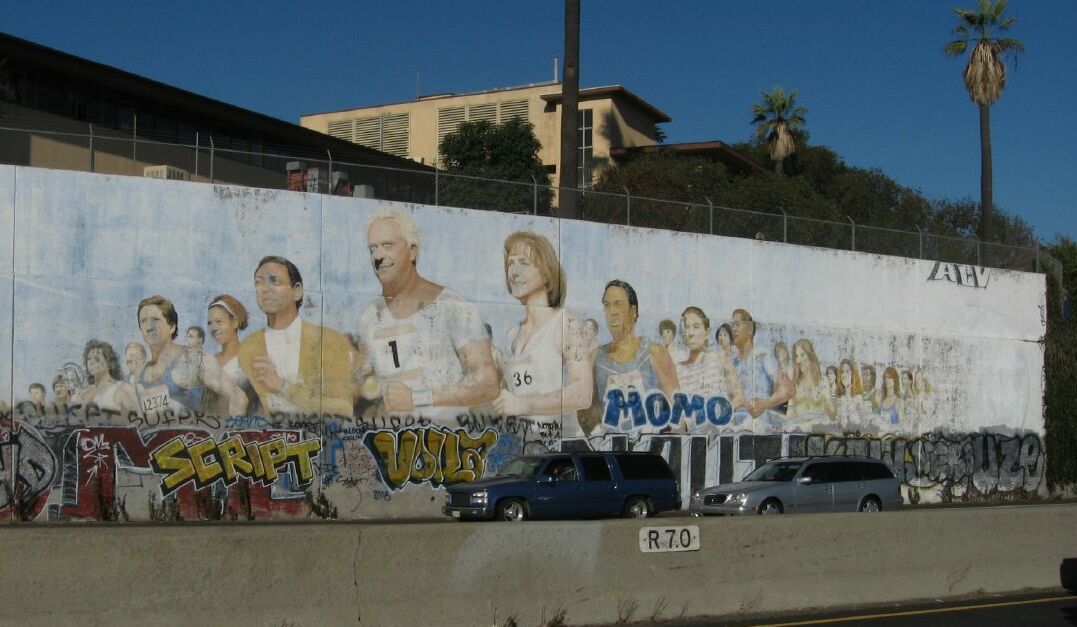

| Murals of

Los Angeles Greater Los Angeles, California, is home to thousands of murals, earning it the nickname "the mural capital of the world" or "the mural capital of America."[a][7][8][9][10][11] The city's mural culture began and proliferated throughout the 20th century.[12] Murals in Los Angeles often reflect the social and political movements of their time and highlight cultural symbols representative of Southern California.[13] In particular, murals in Los Angeles have been influenced by the Chicano art movement and the culture of Los Angeles.[7][13] Murals are considered a distinctive form of public art in Los Angeles, often associated with street art, billboards, and contemporary graffiti.[14][15] From 2002 to 2013, Los Angeles had a moratorium on the creation of new murals in the city, stemming from legal conflicts regarding large-scale commercial out-of-home advertising, primarily billboards.[16][17]: 237 The ban was lifted with the passing of LA Ordinance No. 182706, known as the mural ordinance.[18][19] Mural registration is administered through the City of Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs.[20] Because of the large number of murals throughout the city, numerous programs exist for their preservation and documentation, including the Mural Conservancy of Los Angeles, the Getty Conservation Institute, and others.[21][22] |

ロサンゼルスの壁画 ロサンゼルスの壁画は、当時の社会運動や政治運動を反映し、南カリフォルニアを代表する文化的シンボルを強調することが多い[12]。 [13]特に、ロサンゼルスの壁画はチカーノ芸術運動やロサンゼルスの文化に影響を受けている[7][13]。壁画はロサンゼルスのパブリックアートの特 徴的な形態と考えられており、しばしばストリートアート、ビルボード、現代的なグラフィティと関連付けられている[14][15]。 2002年から2013年まで、ロサンゼルスでは大規模な商業施設外広告(主にビルボード)に関する法的対立に起因する、市内での新たな壁画の作成に対す るモラトリアムがあった[16][17]: 237 この禁止令は壁画条例として知られるLA条例第182706号の可決によって解除された。 [18][19]壁画の登録はロサンゼルス市文化局によって管理されている[20]。市内に多数の壁画があるため、ロサンゼルスの壁画保存協会、ゲッティ 保存協会など、壁画の保存と記録のための数多くのプログラムが存在する[21][22]。 |

History Murals by Dean Cornwell in the Grand Rotunda of the Los Angeles Central Library depicting California history (1933) Many of the city's oldest murals have been lost, usually from weathering or the process of urban development. Among the earliest known murals from Los Angeles were featured in the central business district, including those of Einar Petersen in 1912 and a ceramic tile panel for a cafeteria, created in 1913.[12][13] The New Deal Main article: New Deal artwork Abbot Kinney and the Story of Venice (1941) by Edward Biberman, originally commissioned for a post office in Venice, Los Angeles, depicts developer Abbot Kinney and scenes from the history of Venice, including the Venice of America canal district and the Venice oil boom.[23][24][25]  In the early 1930s, most prominent Los Angeles murals were on commercial rather than civic buildings.[26] Notable exceptions to this trend include the political works of muralists David Alfaro Siqueiros and Myer Shaffer, often supported by artistic and cultural institutions in the city.[27] Between 1933 and 1943, the United States government, as part of the New Deal, funded "federal art projects", a series of murals, paintings, and sculptures in and around public institutions.[28][29]: 40 These funds supported the creation of hundreds of murals around Los Angeles. Many of the resultant works feature rural landscapes, scenes from regional history, and portrayals of immigration, especially influenced by Mexican muralism after the Mexican Revolution (1910-1920).[28][30][31] Certain murals funded by the project were subsequently painted over, often because of their political overtones.[27][32] For example, Myer Shaffer's The Social Aspects of Tuberculosis (1936) at the Los Angeles Tuberculosis Sanitarium, originally supported by the Federal Art Project, was covered completely by 1938 because of its Communist themes.[27][33] Shaffer went on to document the growing number of murals blanketed by local authorities in the Jewish Community Press.[27] 2002 mural moratorium Through the 1980s, commercial advertising on signage and billboards in Los Angeles was regulated by multiple government institutions, including the California Department of Transportation (Caltrans),[34] often without clear distinctions between murals and other types of signs.[16] Numerous efforts to ban billboards in the city had been proposed and in 1984 Los Angeles City Council passed a law preventing the development of billboards within 600 feet of each other.[35] Some advertisers sought to present commercials works as murals, in order to take advantage of a rule exempting murals from restrictions on sign posting.[16][36] In the 1990s, the Los Angeles city council faced lawsuits from advertisers, based on the claim that restrictions on commercial speech were an unfair exception to the First Amendment.[16][36][37][38] In 1999, the Los Angeles Department of Cultural Affairs was in the process of developing guidelines for the regulation of supergraphic signage, including advertising billboards. In June of the same year, Jackie Goldberg, city councilmember for Los Angeles City Council District 13, filed a motion to temporarily halt the placement of new billboards after an influx of new signs were erected to pre-empt forthcoming regulations.[39]: 130 An interim control ordinance (ICO 173562) prohibiting the issuance of building permits for any off-site signs was passed to combat the accelerated pace of sign development in Hollywood, signed in 2000 by Los Angeles mayor Richard Riordan.[40][41] An extension to ICO 173562 was instituted in 2001, initially presented by city councilmember Eric Garcetti, also of the 13th district.[39]: 75–77 In April 2002, LA Ordinance No. 174547 was passed, banning new "off-site signs" across the city.[42][43] "(I) Off-site signs. No off-site sign shall be allowed in any zone, except when off-site signs are specifically permitted pursuant to a legally adopted specific plan, supplemental use district or an approved development agreement. Further, that legally permitted existing signs shall not be altered or enlarged." — LA Ordinance No. 174547[42] The definition of an off-site sign structure had recently been added to the municipal code after the implementation of a periodic sign inspection program.[b][45]: 2 Later, in May 2002, City Council adopted LA Ordinance No. 174552, approved by mayor James Hahn, creating the supplemental use district designation "SN" for sign districts.[46][47] The establishment of sign districts would allow certain districts to have more flexible regulations regarding sign posting, with the intent of minimizing public advertising, the expansion of which being seen as a blight on the city.[46][48][49] A March 2003 amendment to the municipal code updated the definition of an off-site sign to: Off-Site Sign. A sign which displays any message directing attention to a business, product, service, profession, commodity, activity, event, person, institution or any other commercial message, which is generally conducted, sold, manufactured, produced, offered or occurs elsewhere than on the premises where the sign is located. — LA Ordinance No. 175151 (2003)[50]: 16 Previously, in autumn 2002, three advertising companies had filed a lawsuit against the city of Los Angeles on the grounds that the restrictions on off-site signs limited their freedom of expression.[51][52] The companies were initially granted a preliminary injunction against the city, although it was vacated shortly thereafter by the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals, in part based on the subsequent 2003 amendment.[51][52]  Fading mural in Hollywood  Restored mural in Hollywood Hollywood Jazz — 1945-1972 (1990), a tile mural by Richard Wyatt Jr. at Capitol Records depicting significant jazz musicians, was restored in 2013.[53][54][55] In 2013, City Council and mayor Eric Garcetti passed LA Ordinance No. 182706, amending the city municipal code to allow for the creation and preservation of existing and new non-commercial murals.[18][56] LA Ordinance No. 182825 the same year amended the Los Angeles administrative code, maintaining the general prohibition of murals on single family residences and accessory structures but excepting residences in city council districts 1, 9, and 14.[57][58][59] In 2017, Ordinance No. 185059 extended the exemption to Los Angeles City Council District 15 after being proposed by councilmember Joe Buscaino.[60][61] El Monte city council instituted a similar ban in the adjacent city in 1977.[62][63]: 89 [64] The ban was later lifted and numerous mural projects have since been organized in the city.[65][66][67] |

歴史 ロサンゼルス中央図書館のグランド・ロタンダにあるディーン・コーンウェルによるカリフォルニアの歴史を描いた壁画(1933年) ロサンゼルス最古の壁画の多くは、風化や都市開発の過程で失われてしまった。ロサンゼルスで最も古い壁画として知られているのは、1912年に描かれたア イナー・ピーターセンのものや、1913年に描かれたカフェテリアのセラミックタイルパネルなど、ビジネス街の中心部に描かれたものである[12] [13]。 ニューディール 主な記事 ニューディールのアートワーク  エドワード・ビバーマンによる『アボット・キニーとヴェニスの物語』(1941年)は、元々はロサンゼルスのヴェニスの郵便局のために依頼されたもので、 開発者のアボット・キニーと、ヴェニス・オブ・アメリカ運河地区やヴェニスの石油ブームなど、ヴェニスの歴史の一場面を描いている[23][24] [25]。 1930年代初頭、ロサンゼルスの著名な壁画のほとんどは、市民的な建物よりもむしろ商業的な建物に描かれていた[26]。 この傾向の注目すべき例外として、壁画家デイヴィッド・アルファロ・シケイロスとマイヤー・シェイファーの政治的な作品があり、しばしば市内の芸術的・文 化的施設によって支援された[27]。 1933年から1943年にかけて、アメリカ政府はニューディールの一環として、公共施設やその周辺に壁画、絵画、彫刻を制作する「連邦アートプロジェク ト」に資金を提供した[28][29]: 40 これらの資金により、ロサンゼルス周辺に何百もの壁画が制作された。出来上がった作品の多くは、田園風景、地域の歴史の一場面、移民の描写を特徴としてお り、特にメキシコ革命(1910年~1920年)後のメキシコ壁画の影響を受けている[28][30][31]。このプロジェクトによって資金が提供され た一部の壁画は、政治的な含みを持つことが多いため、その後塗り替えられた。 [27][32]例えば、マイヤー・シェイファーがロサンゼルスの結核療養所に描いた『結核の社会的側面』(1936年)は、元々連邦アートプロジェクト によって支援されていたが、共産主義をテーマにしていたため、1938年までに完全に覆われてしまった。 2002年壁画モラトリアム 1980年代まで、ロサンゼルスの看板やビルボードにおける商業広告は、カリフォルニア州運輸局(Caltrans)を含む複数の政府機関によって規制さ れており[34]、壁画と他の種類の看板との明確な区別がないことが多かった[16]。市内でのビルボードを禁止する数々の取り組みが提案され、1984 年にロサンゼルス市議会は、互いに600フィート(約9.5メートル)以内のビルボードの開発を防止する法律を可決した[35]。 [35]一部の広告主は、壁画を看板掲示の制限から免除する規則を利用するため、CM作品を壁画として提示しようとした[16][36]。 1990年代、ロサンゼルス市議会は、商業的言論の制限は憲法修正第1条の不当な例外であるという主張に基づき、広告主からの訴訟に直面した[16] [36][37][38]。 1999年、ロサンゼルス市文化局は広告看板を含むスーパーグラフィック看板の規制のためのガイドラインを作成中であった。同年6月、ロサンゼルス市議会 第13区の市議会議員であるジャッキー・ゴールドバーグは、近々予定されている規制を先取りするように新たな看板が次々と建てられたため、新たな看板の設 置を一時的に停止する動議を提出した[39]: 130 ハリウッドで加速する看板開発に対抗するため、敷地外看板の建築許可発行を禁止する暫定管理条例(ICO 173562)が可決され、2000年にリチャード・リオーダン市長が署名した[40][41] ICO 173562の延長が2001年に制定され、当初は同じく13区のエリック・ガルセッティ市議会議員が提出した[39]: 75-77 2002年4月、LA条例第174547号が可決され、市全域で新たな「オフサイトサイン」が禁止された[42][43]。 「(I)オフサイトサイン。オフサイトサインが法的に採択された特定の計画、補完的な使用地区または承認された開発契約に従って特別に許可されている場合 を除き、オフサイトサインは、任意のゾーンで許可されてはならない。さらに、法的に許可された既存の看板を変更または拡大してはならない。 - LA条例第174547号[42]。 その後、2002年5月、市議会はジェームズ・ハーン市長によって承認されたLA条例第174552号を採択し、標識地区の補足使用地区指定「SN」を創 設した[46][47]。 [46][47]標識地区の設立は、特定の地区が標識掲示に関してより柔軟な規制を持つことを可能にするものであり、公共広告の拡大を最小限に抑えること を意図しており、市の害悪とみなされている[46][48][49]。2003年3月の市法の改正により、敷地外標識の定義が更新された: 敷地外標識。事業、製品、サービス、職業、商品、活動、イベント、人物、機関、またはその他の商業的メッセージに注意を向けるメッセージを表示する標識 で、一般的に実施、販売、製造、生産、提供、または標識が設置されている敷地内とは別の場所で発生するもの。 - LA条例第175151号(2003年)[50]: 16 以前、2002年秋に3つの広告会社が、敷地外の看板に対する規制が表現の自由を制限しているとして、ロサンゼルス市を提訴していた[51][52]。こ の会社は当初、市に対する仮差し止め命令を認められたが、その後すぐに第9巡回控訴裁判所により、その後の2003年の改正に基づく部分もあり、取り消さ れた[51][52]。  ハリウッドの色あせた壁画  ハリウッドの修復された壁画 キャピトル・レコードのリチャード・ワイアット・ジュニアによる重要なジャズ・ミュージシャンを描いたタイル壁画「ハリウッド・ジャズ-1945- 1972」(1990年)が2013年に修復された[53][54][55]。 2013年、市議会とエリック・ガルセッティ市長はLA条例第182706号を可決し、既存および新規の非商業的な壁画の制作と保存を認めるよう市条例を 改正した[18][56]。182825は同年にロサンゼルス市行政法を改正し、一戸建て住宅と付属構造物への壁画の一般的な禁止を維持したが、市議会第 1、9、14選挙区の住宅は例外とした[57][58][59]。2017年、ジョー・ブスカイノ議員の提案により、条例第185059号はロサンゼルス 市議会第15選挙区まで例外を拡大した[60][61]。 エルモンテ市議会は1977年に隣接する市で同様の禁止令を制定した[62][63]: 89 [64] 後に禁止令は解除され、その後市内で数多くの壁画プロジェクトが組織されている[65][66][67]。 |

| Major themes Chicano art movement Main article: Chicano art movement Since the original settlement of Los Angeles by the pobladores from New Spain (modern Mexico), the art and culture of the city have been heavily influenced by that of Mexico.[13] Multiple major waves of immigration have brought migrants to the region, including the Mexican–American War (1846-1848), the California Gold Rush (1848-1855), and the growth of agriculture in California in the early 20th century.[68][69][70] Some of the earliest known murals in Los Angeles come from Mexican refugees, including David Alfaro Siqueiros, known as one of the "Big Three" of Mexican muralism.[c][71][72] Siqueiros's fresco mural América Tropical (1932), at El Pueblo de Los Ángeles Historical Monument, is the only of his American murals found in its original location, although it was once painted over due to its controversial anti-imperialist message.[27][73][74][75] The Chicano movement and California labor movement, especially in the 1960s, were sources of inspiration for many murals in the region.[10] Labor leaders Cesar Chavez and Dolores Huerta often appear prominently in murals, as does the Aztec eagle, a symbol featured in the logo of the United Farm Workers, an agricultural labor union.[76]: 40 Religious identity, predominantly Catholicism, has also been a major theme.[77] In the second half of the century, the Chicano street art movement spread throughout barrios and other neighborhoods in East Los Angeles.[78][79][80] In 1974, muralist and activist Judy Baca organized a citywide mural program in Los Angeles.[80][81][82] The program resulted in the production of hundreds of murals across the city, including Baca's Great Wall of Los Angeles (1978) along the Tujunga Wash.[d][83][84][85] In 1976, with painter Christina Schlesinger and filmmaker Donna Deitch, Baca founded the Social and Public Art Resource Center, a community art center that sponsors the development and restoration of murals throughout the city.[10] Sports and athletics  Year 2026 (1994), a graffiti tagged roadside mural along the Santa Monica Freeway, was painted by Ramiro Fauve for the Los Angeles Marathon.[86][87] See also: Sports in Los Angeles Many Los Angeles sports icons and teams are commemorated in murals, especially near their respective stadiums. Roadside murals have been commissioned for the Los Angeles Marathon multiple times, dating back to the original race in 1986.[86] Other major sports events represented in murals include the 1994 FIFA World Cup,[88] the Los Angeles Rams' 2022 victory in Super Bowl LVI at SoFi Stadium,[89][90] the Los Angeles Lakers' multiple NBA championships,[91][92] the Los Angeles Dodgers' 2020 World Series win,[93][94] the Los Angeles Kings' two Stanley Cup wins in 2012 and 2014,[95] and the MLS Cups of the LA Galaxy.[96][97] A number of murals also exist honoring significant Los Angeles baseball players, such as Jackie Robinson,[e][99] Sandy Koufax,[100][101] Fernando Valenzuela,[102] and others.[103][104] Olympics Los Angeles has hosted the Summer Olympics twice, in 1932 and 1984.[f][105][107] Prior to the 1932 Summer Olympics, Los Angeles Times art critic Arthur Millier recommended taking visiting attendees on a tour of the city's murals.[26] For the 1984 Summer Olympics, a series of ten murals were painted along the 110 and 101 freeways as part of the Olympic Arts Festival.[108][109][110] Beginning in 2007 after years of disrepair and tagging, Caltrans "hibernated" the murals, applying a coating and layer of gray paint to be removed later for restoration.[110][111][112] Efforts to restore many of the Olympic Festival freeway murals began in commemoration of the 30th anniversary of the Games.[111][113][114] Kobe Bryant Main article: Murals of Kobe Bryant  Los Angeles Culture (2016), a mural located near the Lakers' home venue of Crypto.com Arena, depicts a celebratory Kobe Bryant and is one of numerous basketball-inspired murals in the city painted by sports muralist Jonas Never.[115][116][117] Kobe Bryant was a highly-decorated basketball player for the Los Angeles Lakers, winning five championships with the team. Throughout his career, murals were created acknowledging his accomplishments, including his career-high 81 point game in 2006 and retirement in 2016.[118][119] Following his 2020 death in a helicopter crash, many tributes to Bryant were created around the city, frequently featuring his daughter Gianna, who was also killed in the crash.[120][121] The prominence of these murals has led to their becoming a notable tourist attraction, resulting in maps and city guides documenting the collection of Kobe artwork.[122][123][124] In media The documentary film Mur Murs (1981) by French filmmaker Agnès Varda explores murals across the city and shares imagery of Los Angeles murals with Varda's feature film from the same year, Documenteur.[125][126][127] The documentary Exit Through the Gift Shop (2010) directed by street artist Banksy tells the story of Thierry Guetta, a French street artist in Los Angeles.[128][129] |

主なテーマ チカーノ芸術運動 主な記事 チカーノ芸術運動 ニュー・スペイン(現在のメキシコ)からのポブラドールによるロサンゼルスの入植以来、ロサンゼルスの芸術と文化はメキシコの影響を強く受けてきた [13]。メキシコ・アメリカ戦争(1846年-1848年)、カリフォルニア・ゴールドラッシュ(1848年-1855年)、20世紀初頭のカリフォル ニアにおける農業の発展など、複数の大きな移民の波がこの地域に移民をもたらした。 [68][69][70]ロサンゼルスで最も古くから知られている壁画のいくつかは、メキシコ壁画の「ビッグスリー」の一人として知られるダビッド・アル ファロ・シケイロスを含むメキシコ難民によるものである。 [c][71][72]エル・プエブロ・デ・ロサンゼルス歴史モニュメントにあるシケイロスのフレスコ壁画『América Tropical』(1932年)は、彼のアメリカ壁画の中で唯一、元の場所で発見されているが、その反帝国主義的メッセージが物議を醸したため、一度は 塗り替えられた[27][73][74][75]。 チカーノ運動とカリフォルニアの労働運動、特に1960年代は、この地域の多くの壁画のインスピレーションの源であった[10]。労働者のリーダーである シーザー・チャベスやドロレス・ウエルタは、農業労働組合であるユナイテッド・ファーム・ワーカーズのロゴに描かれているシンボルであるアステカの鷲と同 様に、しばしば壁画に大きく登場する[76]: 40 宗教的アイデンティティ(主にカトリック)も主要なテーマであった[77]。今世紀後半には、チカーノのストリートアート運動がイースト・ロサンゼルスの バリオやその他の地域に広がった[78][79][80]。 1974年、壁画家であり活動家であったジュディ・バッカは、ロサンゼルス市全体の壁画プログラムを組織した[80][81][82]。 このプログラムによって、トゥハンガ・ウォッシュ沿いのバッカの「ロサンゼルスの長城」(1978年)を含む、数百の壁画が市全体で制作された[d] [83][84][85]。 1976年、バッカは画家のクリスティーナ・シュレシンジャー、映画監督のドナ・ダイチと共に、ソーシャル・アンド・パブリック・アート・リソース・セン ターを設立した。 スポーツと陸上競技  サンタモニカ・フリーウェイ沿いの落書きされた道路沿いの壁画『2026年』(1994年)は、ロサンゼルス・マラソンのためにラミロ・フォーブによって 描かれた[86][87]。 こちらも参照: ロサンゼルスのスポーツ ロサンゼルスのスポーツアイコンやチームの多くは、特にそれぞれのスタジアムの近くに壁画で記念されている。ロサンゼルス・マラソンでは、1986年の初 開催以来、何度も沿道の壁画が依頼されている[86]。 [86]その他にも、1994年のFIFAワールドカップ、[88]2022年のスーパーボウルLVIでのロサンゼルス・ラムズの優勝(SoFiスタジア ム)、[89][90]ロサンゼルス・レイカーズの複数のNBA優勝、[91][92]ロサンゼルス・ドジャースの2020年ワールドシリーズ優勝、 [93][94]ロサンゼルス・キングスの2012年と2014年の2度のスタンレーカップ優勝、[95]LAギャラクシーのMLSカップなどがある。 [96][97]ジャッキー・ロビンソン[e][99]サンディ・クーファックス[100][101]フェルナンド・バレンズエラ[102]など、ロサン ゼルスの重要な野球選手を称える壁画も数多く存在する[103][104]。 オリンピック ロサンゼルスは1932年と1984年の2度、夏季オリンピックを開催している[f][105][107] 1932年の夏季オリンピックに先立ち、ロサンゼルス・タイムズの美術評論家アーサー・ミリエは、訪れた参加者に街の壁画を見学することを勧めている [26] 1984年の夏季オリンピックでは、オリンピック・アート・フェスティバルの一環として、フリーウェイ110号線と101号線沿いに10枚の壁画が描かれ た。 [108][109][110]何年にもわたって荒廃し、タグが付けられた後、2007年からカルトランスは壁画を「冬眠」させ、コーティングとグレーの ペンキの層を塗り、後で修復のために取り除いた[110][111][112]。 オリンピック・フェスティバルのフリーウェイの壁画の多くを修復する努力は、大会の30周年を記念して始まった[111][113][114]。 コービー・ブライアント 主な記事 コービー・ブライアントの壁画  レイカーズの本拠地であるクリプト・ドットコム・アリーナの近くにある壁画「ロサンゼルス・カルチャー」(2016年)は、祝福するコービー・ブライアン トを描いており、スポーツ壁画家ジョナス・ネヴァーによって描かれた市内にあるバスケットボールにインスパイアされた数多くの壁画のひとつである [115][116][117]。 コービー・ブライアントは、ロサンゼルス・レイカーズで5度の優勝を果たし、非常に栄誉あるバスケットボール選手だった。彼のキャリアを通して、2006 年のキャリアハイとなる81得点ゲームや2016年の引退など、彼の功績を称える壁画が制作された[118][119]。 2020年にヘリコプター事故で亡くなった後、ブライアントへのオマージュが街のあちこちに制作され、同じく事故で亡くなった娘のジアナが描かれることが 多くなった[120][121]。これらの壁画が目立つようになったことで、コービーのアートワークのコレクションを記録した地図やシティガイドが作られ るようになり、注目される観光名所となった[122][123][124]。 メディア フランスの映画監督アニエス・ヴァルダによるドキュメンタリー映画『Mur Murs』(1981年)は、街中の壁画を探求し、ヴァルダが同年に監督した長編映画『Documenteur』とロサンゼルスの壁画のイメージを共有し ている[125][126][127] ストリートアーティストのバンクシーが監督したドキュメンタリー映画『Exit Through the Gift Shop』(2010年)は、ロサンゼルスのフランス人ストリートアーティスト、ティエリー・ゲッタの物語を描いている[128][129]。 |

★21世紀のメキシコ革命 : オアハカのストリートアーティストがつむぐ物語歌 (コリード) / 山越英嗣著, 春風社 , 2020.

内容説明

ガスマスクの聖母、モヒカンの英雄サパタ…州政府への抗議運動に際して現れたストリートアートは日本人画家・竹田鎮三郎の影響を受けた先住民アーティストたちによるものだった。グローバルな力関係のなかでアートと政治、歴史意識、アイデンティティはいかに絡み合うのか?

目次

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆ ☆

☆