ロボット

Robot

ロボット

Robot

ここにイエス己を信じたるユダヤ人に言ひたまふ『汝等もし常に我が言に居らば、眞にわが弟子なり。また眞理を知らん、而して眞理は汝らに自由を得さすべし』(ヨハネ福音 8:31-32)。

bot - 1. an autonomous

program on the internet or another network that can interact with

systems or users. "you can program your bot to store data in the

database of your choice." 2. (chiefly in science fiction) a robot. "we have maintenance bots in there."

「ロボットとは、複雑な一連の動作を自動的に行うことができる機械 (a machine capable of carrying out a complex series of actions automatically)、特にコンピュータによってプログラム可能な機械のことである。ロボットは、外部の制御装置によって導かれることもあれば、 内部に制御が組み込まれていることもある。ロボットは人間の形に沿って作られることもあるが、ほとんどのロボットは美観を気にせずにタスクを実行するため に設計された機械である」ウィキペディア英語をDeepLに て翻訳)。

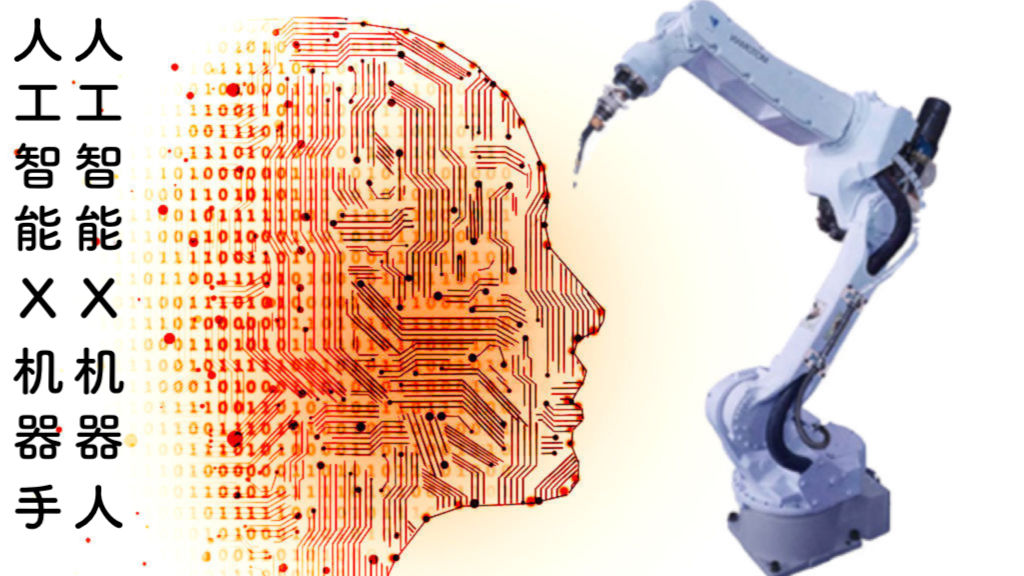

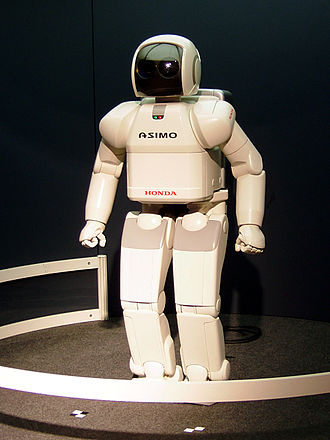

ウィキペディア英語 のRobot には、冒頭に3葉の写真がリンクされているが、この2枚は現代世界がロボットをどのような表象を通して理解しているのか参考になるので掲げる。また真ん中の写真はもともと「工業用ロボット」の写真であったが、火星で働くキュリオシティのロボットドリルの写真に入れ替えた。

|

|

|

| ASIMO (Advanced Step in

Innovative Mobility) is a humanoid robot created by Honda in 2000. |

View of Curiosity’s robotic arm showing drill in place, with Yellowknife Bay and Mount Sharp in the background. Click for larger version. Credit: NASA / JPL-Caltech / Olivier de Goursac | The quadrupedal military robot

Cheetah, an evolution of BigDog (pictured), was clocked as the world's

fastest legged robot in 2012, beating the record set by an MIT bipedal

robot in 1989 |

以上のロボットのうち、インターネットを「徘徊す る」コンピュータープログラムを「ロボット」と呼称することもある。この場合の類語は「クローラ、クローラー、ボット、スパイダー」などと言い換えられ る。他方、「複雑な一連の動作を自動的に行うことができる機械 (a machine capable of carrying out a complex series of actions automatically)」については、「ゴーレム、自動人形、オートマトン、人造人間」などが、その類語としてあげられる。

1 概要

2 歴史

3 今後の展開と傾向

3.1 新機能とプロトタイプ

4 語源

5 現代のロボット

5.1 移動型ロボット

5.2 産業用ロボット(マニピュレーティング)

5.3 サービスロボット

5.4 教育用(対話型)ロボット

5.5 モジュール型ロボット

5.6 協調型ロボット

6 社会におけるロボット

6.1 自律性と倫理的問題

6.2 軍事用ロボット

6.3 失業との関係

7 現代の利用

7.1 汎用自律型ロボット

7.2 工場用ロボット

7.3 汚れる作業、危険な作業、退屈な作業、立ち入りが困難な作業

7.4 軍事用ロボット

7.5 採掘ロボット

7.6 ヘルスケア

7.7 研究用ロボット

7.8 現代アートと彫刻

8 大衆文化におけるロボット

8.1 文学

8.2 映画

8.3 セックスロボット

8.4 大衆文化に描かれた問題点

9 関連項目

9.1 特定のロボット工学の概念

9.2 ロボット工学の手法と分類

9.3 特定のロボットとデバイス

| Concept The idea of automata originates in the mythologies of many cultures around the world. Engineers and inventors from ancient civilizations, including Ancient China,[14] Ancient Greece, and Ptolemaic Egypt,[15] attempted to build self-operating machines, some resembling animals and humans. Early descriptions of automata include the artificial doves of Archytas,[16] the artificial birds of Mozi and Lu Ban,[17] a "speaking" automaton by Hero of Alexandria, a washstand automaton by Philo of Byzantium, and a human automaton described in the Lie Zi.[14] |

コンセプト オー トマタ(自律機械)という概念は、世界中の多くの文化圏の神話に由来している。古代中国[14]、古代ギリシャ、天動説エジプト[15]などの古代文明の 技術者や発明家たちは、動物や人間に似た自己作動する機械を作ろうと試みた。オートマタの初期の記述には、アルキタスの人工鳩[16]、モジと魯班の人工 鳥、アレクサンドリアの英雄による「話す」オートマトン、ビザンチウムのフィロによる洗面台のオートマトン、『列子』に書かれた人間のオートマトン [14]が含まれている。 |

| Early beginnings Many ancient mythologies, and most modern religions include artificial people, such as the mechanical servants built by the Greek god Hephaestus[18] (Vulcan to the Romans), the clay golems of Jewish legend and clay giants of Norse legend, and Galatea, the mythical statue of Pygmalion that came to life. Since circa 400 BC, myths of Crete include Talos, a man of bronze who guarded the island from pirates. In ancient Greece, the Greek engineer Ctesibius (c. 270 BC) "applied a knowledge of pneumatics and hydraulics to produce the first organ and water clocks with moving figures."[19][20] In the 4th century BC, the Greek mathematician Archytas of Tarentum postulated a mechanical steam-operated bird he called "The Pigeon". Hero of Alexandria (10–70 AD), a Greek mathematician and inventor, created numerous user-configurable automated devices, and described machines powered by air pressure, steam and water.[21] The 11th century Lokapannatti tells of how the Buddha's relics were protected by mechanical robots (bhuta vahana yanta), from the kingdom of Roma visaya (Rome); until they were disarmed by King Ashoka.[22] In ancient China, the 3rd-century text of the Lie Zi describes an account of humanoid automata, involving a much earlier encounter between Chinese emperor King Mu of Zhou and a mechanical engineer known as Yan Shi, an 'artificer'. Yan Shi proudly presented the king with a life-size, human-shaped figure of his mechanical 'handiwork' made of leather, wood, and artificial organs.[14] There are also accounts of flying automata in the Han Fei Zi and other texts, which attributes the 5th century BC Mohist philosopher Mozi and his contemporary Lu Ban with the invention of artificial wooden birds (ma yuan) that could successfully fly.[17] |

初期の始まり 多くの古代神話や現代の宗教には、ギリシャ神話のヘパイストス[18](ローマ神話ではヴァルカン)が作った機械の召使い、ユダヤ伝説の粘土ゴーレムや北 欧伝説の粘土巨人、命を得たピグマリオンの神話像ガラテアなど、人造人間が登場している。紀元前400年頃からクレタ島の神話には、海賊から島を守った青 銅の男タロスなどが登場する。 古代ギリシャでは、ギリシャ人技師クテシビウス(紀元前270年頃)が「空気力学と水力学の知識を応用して、数字が動く最初のオルガン時計と水時計を作っ た」[19][20]。紀元前4世紀には、ギリシャ数学者のタレントムのアルキタスが「ピジョン」と呼ぶ機械式の蒸気作動の鳥を提唱している。ギリシャの 数学者であり発明家であるアレクサンドリアの英雄(AD10-70)は、ユーザーが設定可能な自動装置を数多く作成し、空気圧、蒸気、水によって動く機械 について説明した[21]。 11世紀のLokapannattiは、仏陀の遺物がRoma visaya(ローマ)の王国から機械ロボット(bhuta vahana yanta)によって保護されていたことを伝えている; それらはアショカ王によって武装解除されるまで...[22]。 古代中国では、3世紀の「Lie Zi」のテキストに、人型オートマタについての記述があり、中国の周の皇帝MuとYan Shiとして知られる機械技師、「artificer」との出会いがもっと前にあった。燕石は皮、木、人工臓器で作られた等身大の人型の機械「手工品」を 誇らしげに王に贈った[14]。また『韓非子』などにも空を飛ぶオートマタの記述があり、紀元前5世紀のモヒスト教徒の哲学者・茂吉とその同世代の魯班 が、飛ぶことに成功した人工の木製の鳥(馬遠)の発明を行ったとされている[17]。 |

| In

1066, the Chinese inventor Su Song built a water clock in the form of a

tower which featured mechanical figurines which chimed the

hours.[23][24][25] His mechanism had a programmable drum machine with

pegs (cams) that bumped into little levers that operated percussion

instruments. The drummer could be made to play different rhythms and

different drum patterns by moving the pegs to different locations.[25] Samarangana Sutradhara, a Sanskrit treatise by Bhoja (11th century), includes a chapter about the construction of mechanical contrivances (automata), including mechanical bees and birds, fountains shaped like humans and animals, and male and female dolls that refilled oil lamps, danced, played instruments, and re-enacted scenes from Hindu mythology.[26][27][28] 13th century Muslim Scientist Ismail al-Jazari created several automated devices. He built automated moving peacocks driven by hydropower.[29] He also invented the earliest known automatic gates, which were driven by hydropower,[30] created automatic doors as part of one of his elaborate water clocks.[31] One of al-Jazari's humanoid automata was a waitress that could serve water, tea or drinks. The drink was stored in a tank with a reservoir from where the drink drips into a bucket and, after seven minutes, into a cup, after which the waitress appears out of an automatic door serving the drink.[32] Al-Jazari invented a hand washing automaton incorporating a flush mechanism now used in modern flush toilets. It features a female humanoid automaton standing by a basin filled with water. When the user pulls the lever, the water drains and the female automaton refills the basin.[33] Mark E. Rosheim summarizes the advances in robotics made by Muslim engineers, especially al-Jazari, as follows: Unlike the Greek designs, these Arab examples reveal an interest, not only in dramatic illusion, but in manipulating the environment for human comfort. Thus, the greatest contribution the Arabs made, besides preserving, disseminating and building on the work of the Greeks, was the concept of practical application. This was the key element that was missing in Greek robotic science.[34] |

1066

年、中国の発明家である蘇頌は、時を告げる機械的なフィギュアを備えた塔の形をした水時計を作った[23][24][25]

彼の機構には、打楽器を操作する小さなレバーにぶつかるペグ(カム)のあるプログラム可能なドラムマシンがあった。ドラマーはペグを異なる場所に移動させ

ることで、異なるリズムや異なるドラムパターンを演奏させることができた[25]。 Bhoja(11世紀)によるサンスクリット語の論文『Samarangana Sutradhara』には、機械仕掛け(オートマタ)の製作についての章があり、機械仕掛けの蜂や鳥、人間や動物の形をした噴水、石油ランプを補充し、 踊り、楽器を演奏し、ヒンドゥー神話の場面を再現する男女の人形などがある[26][27][28]。 13世紀のイスラム科学者イスマイル・アルジャザリは、いくつかの自動化装置を作った。彼は水力発電によって駆動する自動で動く孔雀を作った[29]。 彼はまた、水力発電によって駆動する最古の知られた自動ゲートを発明し[30]、彼の精巧な水時計の1つとして自動ドアを作った[31]。 アル・ジャザーリの人型自動機械の1つは、水、お茶、飲み物を提供できるウェイトレスであった。飲み物はリザーバー付きのタンクに貯蔵され、そこからバケ ツに滴り落ち、7分後にカップに入り、その後、自動ドアからウェイトレスが現れ、飲み物を提供する[32] アル・ジャザーリは、現在の水洗トイレに使われている洗浄機構を組み込んだ手洗いオートマトンを発明した。これは,女性のヒューマノイド・オートマトン が,水を張った洗面器のそばに立っているのが特徴である.ユーザーがレバーを引くと、水が排出され、女性のオートマトンが洗面器に水を補給する[33]。 マーク・E・ロズハイムは、イスラム教徒の技術者、特にアル・ジャザーリによるロボット工学の進歩を次のように要約している。 ギリシャのデザインとは異なり、これらのアラブの例は、劇的なイリュージョンだけでなく、人間の快適さのために環境を操作することへの関心を明らかにして いる。このように、アラブ人の最大の貢献は、ギリシア人の仕事を保存し、普及させ、基礎としたことに加えて、実用化という概念であった。これはギリシャの ロボット科学に欠けていた重要な要素であった[34]。 |

| In

Renaissance Italy, Leonardo da Vinci (1452–1519) sketched plans for a

humanoid robot around 1495. Da Vinci's notebooks, rediscovered in the

1950s, contained detailed drawings of a mechanical knight now known as

Leonardo's robot, able to sit up, wave its arms and move its head and

jaw.[36] The design was probably based on anatomical research recorded

in his Vitruvian Man. It is not known whether he attempted to build it.

According to Encyclopædia Britannica, Leonardo da Vinci may have been

influenced by the classic automata of al-Jazari.[29] In Japan, complex animal and human automata were built between the 17th to 19th centuries, with many described in the 18th century Karakuri zui (Illustrated Machinery, 1796). One such automaton was the karakuri ningyō, a mechanized puppet.[37] Different variations of the karakuri existed: the Butai karakuri, which were used in theatre, the Zashiki karakuri, which were small and used in homes, and the Dashi karakuri which were used in religious festivals, where the puppets were used to perform reenactments of traditional myths and legends. In France, between 1738 and 1739, Jacques de Vaucanson exhibited several life-sized automatons: a flute player, a pipe player and a duck. The mechanical duck could flap its wings, crane its neck, and swallow food from the exhibitor's hand, and it gave the illusion of digesting its food by excreting matter stored in a hidden compartment.[38] |

ル

ネサンス期のイタリアでは、1495年頃、レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチ(1452-1519)が人型ロボットの設計図を描いている。1950年代に再発見さ

れたダ・ヴィンチのノートには、現在レオナルドのロボットとして知られている、座ったり、腕を振ったり、頭と顎を動かすことができる機械騎士の詳細な図面

があった[36]。このデザインはおそらく、『ヴィトルヴィアン・マン』に記録された解剖学的研究に基づいていると思われる。彼がそれを作ろうとしたかど

うかは定かではない。ブリタニカ百科事典によれば、レオナルド・ダ・ヴィンチはアル・ジャザーリの古典的なオートマタに影響を受けていた可能性がある

[29]。 日本では17世紀から19世紀にかけて動物や人間の複雑なオートマタが作られ、18世紀の『からくり随筆』(1796年)には多くの記述がある。からくり 人形には、演劇用の「舞台からくり」、家庭用の「座敷からくり」、宗教祭で神話や伝説を再現する「出しからくり」などがあった[37]。 フランスでは、1738年から1739年にかけて、ジャック・ド・ヴォーカンソンがフルート奏者、パイプ奏者、アヒルという実物大のからくり人形を数点出 品した。機械仕掛けのアヒルは羽ばたき、首をかしげ、展示者の手から食べ物を飲み込むことができ、隠された区画に蓄えられた物質を排泄することで食べ物を 消化するように見せかけた[38]。 |

| Remote-controlled systems Remotely operated vehicles were demonstrated in the late 19th century in the form of several types of remotely controlled torpedoes. The early 1870s saw remotely controlled torpedoes by John Ericsson (pneumatic), John Louis Lay (electric wire guided), and Victor von Scheliha (electric wire guided).[39] The Brennan torpedo, invented by Louis Brennan in 1877, was powered by two contra-rotating propellers that were spun by rapidly pulling out wires from drums wound inside the torpedo. Differential speed on the wires connected to the shore station allowed the torpedo to be guided to its target, making it "the world's first practical guided missile".[40] In 1897 the British inventor Ernest Wilson was granted a patent for a torpedo remotely controlled by "Hertzian" (radio) waves[41][42] and in 1898 Nikola Tesla publicly demonstrated a wireless-controlled torpedo that he hoped to sell to the US Navy.[43][44] In 1903, the Spanish engineer Leonardo Torres y Quevedo demonstrated a radio control system called "Telekino", which he wanted to use to control an airship of his own design. Unlike the previous systems, which carried out actions of the 'on/off' type, Torres device was able to memorize the signals received to execute the operations on its own and could carry out to 19 different orders.[45][46] Archibald Low, known as the "father of radio guidance systems" for his pioneering work on guided rockets and planes during the First World War. In 1917, he demonstrated a remote controlled aircraft to the Royal Flying Corps and in the same year built the first wire-guided rocket. |

遠隔操作システム 遠隔操作される乗り物は、19世紀後半に数種類の遠隔操作魚雷という形で実証された。1870年代初頭には、John Ericsson(空気圧式)、John Louis Lay(電線誘導式)、Victor von Scheliha(電線誘導式)による遠隔操作式魚雷が登場した[39]。 1877 年にルイス・ブレナンによって発明されたブレナン魚雷は、魚雷の内部に巻かれたドラムから ワイヤを急速に引き出すことによって回転する 2 つの逆回転プロペラによって動力を与えられた。1897年にイギリスの発明家アーネスト・ウィルソンが「ヘルツ波」(電波)によって遠隔制御される魚雷の 特許を取得し[41][42]、1898年にニコラ・テスラがアメリカ海軍に売り込もうとした無線制御の魚雷を公開デモンストレーションしている[43] [44]。 1903年にスペインのエンジニアであるLeonardo Torres y Quevedoは、彼自身の設計による飛行船を制御するために使いたかった「Telekino」と呼ばれる無線制御システムを実演している。それまでの 「オン/オフ」式の動作を行うシステムとは異なり、トーレスの装置は受信した信号を記憶して自力で動作を実行することができ、19種類もの命令を実行する ことができた[45][46]。 アーチボルド・ロウは、第一次世界大戦中に誘導ロケットと誘導飛行機の先駆的な仕事をしたことから「無線誘導装置の父」として知られている。1917年、王立飛行隊に遠隔操作の飛行機を実演し、同じ年に最初のワイヤーガイド付きロケットを作った。 |

| Origin of the term 'robot' 'Robot' was first applied as a term for artificial automata in the 1920 play R.U.R. by the Czech writer, Karel Čapek. However, Josef Čapek was named by his brother Karel as the true inventor of the term robot.[6][7] The word 'robot' itself was not new, having been in the Slavic language as robota (forced labor), a term applied to peasants obligated to compulsory service under the feudal system (see: Robot Patent).[47][48] Čapek's fictional story postulated the technological creation of artificial human bodies without souls, and the old theme of the feudal robota class eloquently fit the imagination of a new class of manufactured, artificial workers. English pronunciation of the word has evolved relatively quickly since its introduction. In the U.S. during the late '30s to early '40s the second syllable was pronounced with a long "O" like "row-boat."[49][better source needed] By the late '50s to early '60s, some were pronouncing it with a short "U" like "row-but" while others used a softer "O" like "row-bought."[50] By the '70s, its current pronunciation "row-bot" had become predominant. |

ロボット」の語源 ロボット」は、チェコの作家カレル・チャペックが1920年に発表した戯曲「R.U.R.」において、人工オートマトンに対する用語として初めて適用され た。しかし、ロボットという言葉の真の発明者として、ヨゼフ・チャペックは弟のカレルによって名指しされている[6][7]。 ロボット」という言葉自体は新しいものではなく、スラブ語では封建制度下で強制労働を義務付けられた農民に対する言葉としてロボタ(強制労働)として存在 していた(「ロボット特許」の項を参照)。 チャペックのフィクションは、魂のない人工的な人体を技術的に作り出すことを想定しており、封建的なロボタ階級という古いテーマが、製造された人工労働者 という新しい階級の想像に雄弁に物語っていたのである [47][48] 。 英語の発音は、この言葉の登場以来、比較的早く変化してきた。30年代後半から40年代前半のアメリカでは、第2音節は「ロウボート」のように長い 「オー」で発音されていた[49][better source needed] 50年代後半から60年代前半には、「ロウバット」のように短い「ウ」で発音するものもあれば、「ロウボート」のように柔らかい「オー」で発音するものも あった[50] 70年代までに現在の「ロウボット」の発音が一般的になっていた。 |

| Early robots In 1928, one of the first humanoid robots, Eric, was exhibited at the annual exhibition of the Model Engineers Society in London, where it delivered a speech. Invented by W. H. Richards, the robot's frame consisted of an aluminium body of armour with eleven electromagnets and one motor powered by a twelve-volt power source. The robot could move its hands and head and could be controlled through remote control or voice control.[51] Both Eric and his "brother" George toured the world.[52] Westinghouse Electric Corporation built Televox in 1926; it was a cardboard cutout connected to various devices which users could turn on and off. In 1939, the humanoid robot known as Elektro was debuted at the 1939 New York World's Fair.[53][54] Seven feet tall (2.1 m) and weighing 265 pounds (120.2 kg), it could walk by voice command, speak about 700 words (using a 78-rpm record player), smoke cigarettes, blow up balloons, and move its head and arms. The body consisted of a steel gear, cam and motor skeleton covered by an aluminum skin. In 1928, Japan's first robot, Gakutensoku, was designed and constructed by biologist Makoto Nishimura. |

初期のロボット 1928年、最初の人型ロボットの1つであるEricが、ロンドンで開催されたModel Engineers Societyの年次展示会に出展され、スピーチを行った。W. H. Richardsが発明したこのロボットのフレームは、アルミニウムの装甲体に11個の電磁石と12ボルトの電源で動くモーター1個で構成されていた。ロ ボットは手と頭を動かすことができ、リモコンや音声で操作することができた[51]。 エリックと「弟」のジョージは共に世界ツアーを行った[52]。 ウェスティングハウス・エレクトリック社は1926年にTelevoxを製作した。それはユーザーがオン・オフできる様々な機器に接続された厚紙の切り抜 きであった。1939年のニューヨーク万国博覧会で、エレクトロとして知られる人型ロボットがデビューした[53][54] 身長7フィート(2.1m)、体重265ポンド(120.2kg)、音声コマンドによる歩行、約700語の会話(78回転レコードプレイヤー使用)、タバ コ、風船の爆破、頭部と腕の動きが可能である。ボディは鋼鉄製のギア、カム、モーターの骨格をアルミの皮で覆ったものであった。1928年、生物学者の西 村真琴によって日本初のロボット「学天則」が設計・製作された。 |

| Modern autonomous robots The first electronic autonomous robots with complex behaviour were created by William Grey Walter of the Burden Neurological Institute at Bristol, England in 1948 and 1949. He wanted to prove that rich connections between a small number of brain cells could give rise to very complex behaviors – essentially that the secret of how the brain worked lay in how it was wired up. His first robots, named Elmer and Elsie, were constructed between 1948 and 1949 and were often described as tortoises due to their shape and slow rate of movement. The three-wheeled tortoise robots were capable of phototaxis, by which they could find their way to a recharging station when they ran low on battery power. Walter stressed the importance of using purely analogue electronics to simulate brain processes at a time when his contemporaries such as Alan Turing and John von Neumann were all turning towards a view of mental processes in terms of digital computation. His work inspired subsequent generations of robotics researchers such as Rodney Brooks, Hans Moravec and Mark Tilden. Modern incarnations of Walter's turtles may be found in the form of BEAM robotics.[55] |

現代の自律型ロボット 複雑な動作をする最初の電子自律型ロボットは、1948年と1949年にイギリスのブリストルにあるバーデン神経学研究所のウィリアム・グレイ・ウォル ターによって作られた。彼は、少数の脳細胞間の豊かなつながりが非常に複雑な行動を生み出すことを証明したかったのだ。つまり、脳の働きの秘密は、脳の配 線にあるということだ。エルマーとエルシーと名付けられた最初のロボットは、1948年から1949年にかけて製作され、その形と動作の遅さからしばしば カメと形容された。この3輪のカメ型ロボットは光軸を持ち、電池が少なくなると充電ステーションに向かうことができた。 ウォルターは、アラン・チューリングやジョン・フォン・ノイマンといった同時代の研究者たちが、精神活動をデジタル計算の観点から捉えようとしていた時代 に、純粋にアナログの電子回路を使って脳のプロセスをシミュレートすることの重要性を説いた。彼の研究は、ロドニー・ブルックス、ハンス・モラヴェック、 マーク・ティルデンといった次世代のロボット研究者にインスピレーションを与えた。ウォルターのカメの現代的な化身は、ビームロボット工学の形で見られる かもしれない[55]。 |

| The

first digitally operated and programmable robot was invented by George

Devol in 1954 and was ultimately called the Unimate. This ultimately

laid the foundations of the modern robotics industry.[56] Devol sold

the first Unimate to General Motors in 1960, and it was installed in

1961 in a plant in Trenton, New Jersey to lift hot pieces of metal from

a die casting machine and stack them.[57] Devol's patent for the first

digitally operated programmable robotic arm represents the foundation

of the modern robotics industry.[58] The first palletizing robot was introduced in 1963 by the Fuji Yusoki Kogyo Company.[59] In 1973, a robot with six electromechanically driven axes was patented[60][61][62] by KUKA robotics in Germany, and the programmable universal manipulation arm was invented by Victor Scheinman in 1976, and the design was sold to Unimation. Commercial and industrial robots are now in widespread use performing jobs more cheaply or with greater accuracy and reliability than humans. They are also employed for jobs which are too dirty, dangerous or dull to be suitable for humans. Robots are widely used in manufacturing, assembly and packing, transport, earth and space exploration, surgery, weaponry, laboratory research, and mass production of consumer and industrial goods.[63] |

最

初のデジタル操作およびプログラム可能なロボットは、1954年にGeorge

Devolによって発明され、最終的にUnimateと呼ばれることになった。Devolは1960年に最初のUnimateをGeneral

Motorsに売り、それは1961年にニュージャージー州トレントンの工場に設置され、ダイカストマシンから熱い金属片を持ち上げて積み重ねた[57]

Devolの最初のデジタルで動作するプログラマブルなロボットアームの特許が、現代のロボット産業の基盤を代表するものとなった[58]。 1973年にはドイツのKUKAロボティクス社によって6つの電気機械駆動軸を持つロボットの特許[60][61][62]が取られ、1976年にはビク ター・シャインマンによってプログラマブルユニバーサルマニピュレーションアームが発明され、その設計はユニメーションに売却された。 現在、商業用・産業用ロボットは、人間よりも安価に、あるいは高い精度と信頼性で仕事を行うために広く使用されている。また、汚れたり、危険であったり、 退屈であったりするため、人間には適さないような仕事にも使用されている。ロボットは、製造、組立・梱包、輸送、地球・宇宙探査、外科手術、兵器、実験室 研究、消費財・工業製品の大量生産などに広く利用されている[63]。 |

| Various

techniques have emerged to develop the science of robotics and robots.

One method is evolutionary robotics, in which a number of differing

robots are submitted to tests. Those which perform best are used as a

model to create a subsequent "generation" of robots. Another method is

developmental robotics, which tracks changes and development within a

single robot in the areas of problem-solving and other functions.

Another new type of robot is just recently introduced which acts both

as a smartphone and robot and is named RoboHon.[64] As robots become more advanced, eventually there may be a standard computer operating system designed mainly for robots. Robot Operating System is an open-source set of programs being developed at Stanford University, the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the Technical University of Munich, Germany, among others. ROS provides ways to program a robot's navigation and limbs regardless of the specific hardware involved. It also provides high-level commands for items like image recognition and even opening doors. When ROS boots up on a robot's computer, it would obtain data on attributes such as the length and movement of robots' limbs. It would relay this data to higher-level algorithms. Microsoft is also developing a "Windows for robots" system with its Robotics Developer Studio, which has been available since 2007.[65] Japan hopes to have full-scale commercialization of service robots by 2025. Much technological research in Japan is led by Japanese government agencies, particularly the Trade Ministry.[66] Many future applications of robotics seem obvious to people, even though they are well beyond the capabilities of robots available at the time of the prediction.[67][68] As early as 1982 people were confident that someday robots would:[69] 1. Clean parts by removing molding flash 2. Spray paint automobiles with absolutely no human presence 3. Pack things in boxes—for example, orient and nest chocolate candies in candy boxes 4. Make electrical cable harness 5. Load trucks with boxes—a packing problem 6. Handle soft goods, such as garments and shoes 7. Shear sheep 8. prosthesis 9. Cook fast food and work in other service industries 10. Household robot. Generally such predictions are overly optimistic in timescale. |

ロ

ボット工学やロボットの科学を発展させるために、さまざまな手法が登場している。そのひとつが進化型ロボティクスで、さまざまなロボットがテストにかけら

れます。その中で最も優れたロボットをモデルとして、次の世代のロボットを作っていく。また、一つのロボットの中で、問題解決などの機能の変化や発達を追

跡する「発達型ロボティクス」もあります。また、つい最近、スマートフォンとしてもロボットとしても機能する新しいタイプのロボットが登場し、「ロボホ

ン」と名付けられている[64]。 ロボットがより高度になれば、最終的には、主にロボットのために設計された標準的なコンピューターオペレーティングシステムが存在することになるかもしれ ない。ロボットオペレーティングシステムは、スタンフォード大学、マサチューセッツ工科大学、ドイツのミュンヘン工科大学などで開発されているオープン ソースのプログラムセットである。ROSは、特定のハードウェアに関係なく、ロボットのナビゲーションや手足をプログラムする方法を提供します。また、画 像認識やドアを開けるなどの高度なコマンドも提供します。ROSは、ロボットのコンピュータで起動すると、ロボットの手足の長さや動きなどの属性データを 取得します。このデータをより高度なアルゴリズムに中継する。マイクロソフトも、2007年から提供しているRobotics Developer Studioで、「ロボットのためのWindows」システムを開発している[65]。 日本では、2025年までにサービスロボットの本格的な商業化を目指している。日本における多くの技術研究は、日本の政府機関、特に通産省が主導している[66]。 ロボット工学の多くの将来の応用は、それが予測の時点で利用可能なロボットの能力をはるかに超えているにもかかわらず、人々にとって明白であると思われ る。 67][68] 1982年の時点で、人々はいつの日かロボットが以下のことを行うようになると確信していた[69] 1. 成形フラッシュを除去することによる部品の洗浄 2. 人間が全く介在しない自動車のスプレー塗装 3. 例えば、チョコレート・キャンディをキャンディ・ボックスの中で向きを変えて入れ子にする。電気ケーブルのハーネスを作る 5.トラックへの箱の積み込み-荷造り問題 6. 衣料品や靴などの軟包装品の取り扱い 7. 羊の毛を刈る 8. 義足 9. ファーストフードの調理やその他のサービス産業で働く 10. 家庭用ロボット 一般に、このような予測は時間軸において過度に楽観的である。 |

| In

2008, Caterpillar Inc. developed a dump truck which can drive itself

without any human operator.[70] Many analysts believe that self-driving

trucks may eventually revolutionize logistics.[71] By 2014, Caterpillar

had a self-driving dump truck which is expected to greatly change the

process of mining. In 2015, these Caterpillar trucks were actively used

in mining operations in Australia by the mining company Rio Tinto Coal

Australia.[72][73][74][75] Some analysts believe that within the next

few decades, most trucks will be self-driving.[76] A literate or 'reading robot' named Marge has intelligence that comes from software. She can read newspapers, find and correct misspelled words, learn about banks like Barclays, and understand that some restaurants are better places to eat than others.[77] Baxter is a new robot introduced in 2012 which learns by guidance. A worker could teach Baxter how to perform a task by moving its hands in the desired motion and having Baxter memorize them. Extra dials, buttons, and controls are available on Baxter's arm for more precision and features. Any regular worker could program Baxter and it only takes a matter of minutes, unlike usual industrial robots that take extensive programs and coding to be used. This means Baxter needs no programming to operate. No software engineers are needed. This also means Baxter can be taught to perform multiple, more complicated tasks. Sawyer was added in 2015 for smaller, more precise tasks.[78] Prototype cooking robots have been developed and could be programmed for autonomous, dynamic and adjustable preparation of discrete meals.[79][80] |

2008

年、キャタピラー社は人間が操作しなくても自動運転できるダンプトラックを開発した[70]。

多くのアナリストは、自動運転トラックは最終的に物流に革命をもたらすかもしれないと考えている[71]。

2014年までに、キャタピラー社は鉱業のプロセスを大きく変えることが期待されている自動運転ダンプトラックを有していた。2015年、これらのキャタ

ピラー社のトラックは、鉱山会社のリオ・ティント・コール・オーストラリアによって、オーストラリアの採掘作業で活発に使用された[72][73]

[74][75]。 今後数十年の間に、ほとんどのトラックが自動運転になると考えるアナリストもいる[76]。 Margeという名の識字ロボットあるいは「読書ロボット」は、ソフトウェアに由来する知能を有している。彼女は新聞を読み、スペルミスの単語を見つけて 訂正し、バークレイズのような銀行について学び、あるレストランが他のレストランよりも良い場所であることを理解することができる[77]。 バクスターは、2012年に発表された新しいロボットで、ガイダンスによって学習する。作業者は、バクスターの手を望ましい動作で動かし、それをバクス ターに記憶させることによって、バクスターに作業の実行方法を教えることができる。バクスターの腕には、より精密で高機能なダイヤル、ボタン、コントロー ルが用意されています。Baxterのプログラミングは、通常の産業用ロボットのように大規模なプログラムやコーディングを必要とせず、一般の作業者でも 数分程度で行うことができます。つまり、バクスターはプログラミング不要で動作します。ソフトウェア技術者も必要ありません。これはまた、バクスターが複 数の、より複雑な作業を行うように教えられることを意味します。ソーヤーは、より小さく、より精密なタスクのために2015年に追加された[78]。 プロトタイプの調理ロボットが開発されており、自律的、動的、かつ調整可能な離散的な食事の準備のためにプログラムすることができた[79][80]。 |

| Robots in society Roughly half of all the robots in the world are in Asia, 32% in Europe, and 16% in North America, 1% in Australasia and 1% in Africa.[107] 40% of all the robots in the world are in Japan,[108] making Japan the country with the highest number of robots. |

社会におけるロボット 世界のロボットのおよそ半分がアジアに、32%がヨーロッパに、16%が北米に、1%がオーストラレーシアに、1%がアフリカにある[107]。世界のロボットの40%は日本にあり[108]、日本は最もロボットが多い国になっている。 |

| Autonomy and ethical questions As robots have become more advanced and sophisticated, experts and academics have increasingly explored the questions of what ethics might govern robots' behavior,[110][111] and whether robots might be able to claim any kind of social, cultural, ethical or legal rights.[112] One scientific team has said that it was possible that a robot brain would exist by 2019.[113] Others predict robot intelligence breakthroughs by 2050.[114] Recent advances have made robotic behavior more sophisticated.[115] The social impact of intelligent robots is subject of a 2010 documentary film called Plug & Pray.[116] Vernor Vinge has suggested that a moment may come when computers and robots are smarter than humans. He calls this "the Singularity".[117] He suggests that it may be somewhat or possibly very dangerous for humans.[118] This is discussed by a philosophy called Singularitarianism. In 2009, experts attended a conference hosted by the Association for the Advancement of Artificial Intelligence (AAAI) to discuss whether computers and robots might be able to acquire any autonomy, and how much these abilities might pose a threat or hazard. They noted that some robots have acquired various forms of semi-autonomy, including being able to find power sources on their own and being able to independently choose targets to attack with weapons. They also noted that some computer viruses can evade elimination and have achieved "cockroach intelligence." They noted that self-awareness as depicted in science-fiction is probably unlikely, but that there were other potential hazards and pitfalls.[117] Various media sources and scientific groups have noted separate trends in differing areas which might together result in greater robotic functionalities and autonomy, and which pose some inherent concerns.[119][120][121] |

自律性と倫理的問題 ロボットがより高度化し洗練されるにつれて、専門家や学者はロボットの行動をどのような倫理が支配しうるか[110][111]、ロボットが何らかの社会 的、文化的、倫理的あるいは法的権利を主張しうるかといった問題をますます探求している。 [112] ある科学者チームは2019年までにロボットの脳が存在する可能性があると述べている[113] 他の人々は2050年までにロボットの知能が飛躍的に向上すると予測している[114] 最近の進歩によってロボットの行動はより高度になっている[115] 知的ロボットの社会への影響は2010年のドキュメンタリー映画『プラグ&プレイ』の主題となっている[116]。 ヴァーナー・ヴィンジはコンピュータとロボットが人間よりも賢くなる瞬間が来るかもしれないことを示唆している。彼はこれを「特異点」と呼んでいる [117]。 彼はそれが人間にとって多少、あるいは非常に危険かもしれないと示唆している[118]。 これは特異点主義という哲学によって論じられている。 2009年、人工知能学会(AAAI)主催の会議に専門家が出席し、コンピュータやロボットが何らかの自律性を獲得することができるかどうか、またこれら の能力がどの程度脅威や危険をもたらす可能性があるかについて議論された。AAAIでは、ロボットの中には、自分で電源を探したり、自分で攻撃対象を選ん だりする半自律性を獲得しているものがあることを紹介した。また、コンピュータウイルスの中には、駆除を回避できるものがあり、「ゴキブリ知能」を獲得し ていると指摘した。彼らはSFで描かれるような自己認識はおそらくあり得ないが、他の潜在的な危険や落とし穴があることを指摘した[117]。様々なメ ディアや科学グループは、より大きなロボットの機能性と自律性を一緒にもたらすかもしれない異なる領域における別々の傾向を指摘しており、それらはいくつ かの固有の懸念をもたらしている[119][120][121]。 |

| Military robots Some experts and academics have questioned the use of robots for military combat, especially when such robots are given some degree of autonomous functions.[122] There are also concerns about technology which might allow some armed robots to be controlled mainly by other robots.[123] The US Navy has funded a report which indicates that, as military robots become more complex, there should be greater attention to implications of their ability to make autonomous decisions.[124][125] One researcher states that autonomous robots might be more humane, as they could make decisions more effectively. However, other experts question this.[126] One robot in particular, the EATR, has generated public concerns[127] over its fuel source, as it can continually refuel itself using organic substances.[128] Although the engine for the EATR is designed to run on biomass and vegetation[129] specifically selected by its sensors, which it can find on battlefields or other local environments, the project has stated that chicken fat can also be used.[130] Manuel De Landa has noted that "smart missiles" and autonomous bombs equipped with artificial perception can be considered robots, as they make some of their decisions autonomously. He believes this represents an important and dangerous trend in which humans are handing over important decisions to machines.[131] |

軍事用ロボット 一部の専門家や学者は、軍事戦闘のためのロボットの使用、特にそのようなロボットがある程度の自律的な機能を与えられている場合に疑問を呈している [122]。 また、一部の武装ロボットを他のロボットによって主に制御することを可能にするかもしれない技術についての懸念もある[123] アメリカ海軍は、軍事ロボットがより複雑になるにつれ、その自律的判断能力の意味合いにもっと注意を向けるべきであることを示した報告書に資金提供してい る。 124][125] ある研究者は自律ロボットはより効率的に判断を下すことができてより人間的かもしれないと述べている。しかし、他の専門家はこれに疑問を呈している [126]。 特にロボットの1つであるEATRは、有機物質を用いて継続的に燃料を補給することができるため、その燃料源に関して公共の懸念を生み出している [127]。 EATRのエンジンは、戦場やその他の地域環境で見つけることができるセンサによって特に選択されたバイオマスや植物[129]で走るように設計されてい るものの、プロジェクトは鶏脂も用いることができると表明している[130]。 Manuel De Landaは、人工的な知覚を備えた「スマートミサイル」や自律型爆弾が、その決定の一部を自律的に行うため、ロボットとみなすことができると指摘してい る。彼はこれが、人間が重要な決定を機械に委ねるという重要かつ危険な傾向を代表することができると考えている[131]。 |

| Relationship to unemployment For centuries, people have predicted that machines would make workers obsolete and increase unemployment, although the causes of unemployment are usually thought to be due to social policy.[132] A recent example of human replacement involves Taiwanese technology company Foxconn who, in July 2011, announced a three-year plan to replace workers with more robots. At present the company uses ten thousand robots but will increase them to a million robots over a three-year period.[133] Lawyers have speculated that an increased prevalence of robots in the workplace could lead to the need to improve redundancy laws.[134] Kevin J. Delaney said "Robots are taking human jobs. But Bill Gates believes that governments should tax companies’ use of them, as a way to at least temporarily slow the spread of automation and to fund other types of employment."[135] The robot tax would also help pay a guaranteed living wage to the displaced workers. The World Bank's World Development Report 2019 puts forth evidence showing that while automation displaces workers, technological innovation creates more new industries and jobs on balance.[136] |

失業との関係 何世紀にもわたって、人々は機械が労働者を時代遅れにし、失業を増加させると予測してきたが、失業の原因は通常、社会政策によるものだと考えられている[132]。 人間の代替に関する最近の例としては、台湾のテクノロジー企業であるFoxconnが2011年7月に、労働者をより多くのロボットで置き換える3年計画 を発表したことが挙げられる。現在同社は1万台のロボットを使用しているが、3年間で100万台まで増加させる予定である[133]。 弁護士は、職場におけるロボットの普及が進むことで、余剰人員削減法を改善する必要性が生じる可能性があると推測している[134]。 ケビン・J・ディレイニーは、「ロボットは人間の仕事を奪っている。しかし、ビル・ゲイツは、少なくとも一時的に自動化の普及を遅らせ、他の種類の雇用に 資金を供給する方法として、政府が企業のロボット使用に課税すべきと考えている」[135] ロボット税は、離職した労働者に生活賃金を保証することにも役立つだろう。 世界銀行の世界開発報告書2019は、自動化が労働者を追い出す一方で、技術革新はバランスよくより多くの新しい産業と雇用を生み出すことを示す証拠を示している[136]。 |

| At present, there are two main types of robots, based on their use: general-purpose autonomous robots and dedicated robots. Robots can be classified by their specificity of purpose. A robot might be designed to perform one particular task extremely well, or a range of tasks less well. All robots by their nature can be re-programmed to behave differently, but some are limited by their physical form. For example, a factory robot arm can perform jobs such as cutting, welding, gluing, or acting as a fairground ride, while a pick-and-place robot can only populate printed circuit boards. |

現在、ロボットはその用途から、汎用自律型ロボットと専用ロボットの2種類に大別される。 ロボットは、その目的の特異性によって分類することができます。ある特定の作業を非常にうまくこなすように設計されたロボットもあれば、それほどでもない 作業を幅広くこなすように設計されたロボットもある。すべてのロボットは、その性質上、異なる動作をするように再プログラムすることができますが、物理的 な形状によって制限されるものもあります。例えば、工場のロボットアームは、切断、溶接、接着、縁日の乗り物のような役割を果たすことができますが、ピッ クアンドプレースロボットはプリント回路基板を入れることだけができます。 現在、ロボットはその用途から、汎用自律型ロボットと専用ロボットの2種類に大別される。 ロボットは、その目的の特異性によって分類することができます。ある特定の作業を非常にうまくこなすように設計されたロボットもあれば、それほどでもない 作業を幅広くこなすように設計されたロボットもある。すべてのロボットは、その性質上、異なる動作をするように再プログラムすることができますが、物理的 な形状によって制限されるものもあります。例えば、工場のロボットアームは、切断、溶接、接着、縁日の乗り物のような役割を果たすことができますが、ピッ クアンドプレースロボットはプリント回路基板を入れることだけができます。 |

| General-purpose

autonomous robots can perform a variety of functions independently.

General-purpose autonomous robots typically can navigate independently

in known spaces, handle their own re-charging needs, interface with

electronic doors and elevators and perform other basic tasks. Like

computers, general-purpose robots can link with networks, software and

accessories that increase their usefulness. They may recognize people

or objects, talk, provide companionship, monitor environmental quality,

respond to alarms, pick up supplies and perform other useful tasks.

General-purpose robots may perform a variety of functions

simultaneously or they may take on different roles at different times

of day. Some such robots try to mimic human beings and may even

resemble people in appearance; this type of robot is called a humanoid

robot. Humanoid robots are still in a very limited stage, as no

humanoid robot can, as of yet, actually navigate around a room that it

has never been in.[citation needed] Thus, humanoid robots are really

quite limited, despite their intelligent behaviors in their well-known

environments. |

汎用自

律型ロボットは、様々な機能を独立して実行することができます。汎用自律型ロボットは通常、既知の空間を単独で航行し、充電の必要性を自ら処理し、電子ド

アやエレベーターと連動し、その他の基本的な作業を行うことができます。汎用ロボットはコンピュータと同様に、ネットワークやソフトウェア、アクセサリー

と連携して、その利便性を高めることができます。人や物を認識し、会話し、仲間を提供し、環境の質を監視し、アラームに応答し、物資を拾い上げ、その他の

有用な作業を行うことができる。汎用ロボットは、さまざまな機能を同時に実行することもあれば、時間帯によって異なる役割を担うこともある。このようなロ

ボットの中には、人間を模倣しようとするものもあり、外見が人間に似ている場合もあります。このようなロボットは、ヒューマノイドロボットと呼ばれていま

す。このようなロボットはヒューマノイドロボットと呼ばれる。ヒューマノイドロボットはまだ非常に限定的な段階にあり、今のところ一度も入ったことのない

部屋の中を実際に移動できるロボットはない[citation needed] 。 |

| Fears

and concerns about robots have been repeatedly expressed in a wide

range of books and films. A common theme is the development of a master

race of conscious and highly intelligent robots, motivated to take over

or destroy the human race. Frankenstein (1818), often called the first

science fiction novel, has become synonymous with the theme of a robot

or android advancing beyond its creator. Other works with similar themes include The Mechanical Man, The Terminator, Runaway, RoboCop, the Replicators in Stargate, the Cylons in Battlestar Galactica, the Cybermen and Daleks in Doctor Who, The Matrix, Enthiran and I, Robot. Some fictional robots are programmed to kill and destroy; others gain superhuman intelligence and abilities by upgrading their own software and hardware. Examples of popular media where the robot becomes evil are 2001: A Space Odyssey, Red Planet and Enthiran. The 2017 game Horizon Zero Dawn explores themes of robotics in warfare, robot ethics, and the AI control problem, as well as the positive or negative impact such technologies could have on the environment. Another common theme is the reaction, sometimes called the "uncanny valley", of unease and even revulsion at the sight of robots that mimic humans too closely.[109] More recently, fictional representations of artificially intelligent robots in films such as A.I. Artificial Intelligence and Ex Machina and the 2016 TV adaptation of Westworld have engaged audience sympathy for the robots themselves. |

ロ

ボットに対する恐怖や懸念は、さまざまな書籍や映画で繰り返し表現されてきました。共通するテーマは、意識と高度な知能を持つロボットのマスターレースが

開発され、人類を乗っ取るか破壊することを動機とすることである。最初のSF小説と呼ばれる『フランケンシュタイン』(1818年)は、ロボットやアンド

ロイドが創造主を超えて進化するというテーマの代名詞となっている。 同様のテーマを持つ他の作品には、『機械人間』、『ターミネーター』、『ランナウェイ』、『ロボコップ』、『スターゲイト』のレプリカント、『ギャラク ティカ』のサイロン、『ドクター・フー』のサイバーマンやデレク、『マトリックス』、『エンシラン』、『アイ、ロボット』などがある。フィクションのロ ボットの中には、殺戮と破壊のためにプログラムされたものもあれば、自らのソフトウェアとハードウェアをアップグレードすることで超人的な知性と能力を獲 得するものもある。ロボットが悪になる人気メディアの例としては、『2001年宇宙の旅』、『レッド・プラネット』、『エンシラン』などがある。 2017年のゲーム『Horizon Zero Dawn』では、戦争におけるロボット工学、ロボット倫理、AI制御問題、さらにはそうした技術が環境に与え得るプラスまたはマイナスの影響といったテーマが探求されています。 もう一つの共通のテーマは、時に「不気味の谷」と呼ばれる、あまりに人間を模倣したロボットを見たときの不安や反発さえも感じる反応である[109]。 より最近では、『A.I.人工知能』や『エクス・マキナ』などの映画や2016年にテレビ放映された『ウエストワールド』における人工知能ロボットのフィクション表現は、ロボット自身に対する観客の同情を誘うものとなっている。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robot |

https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator |

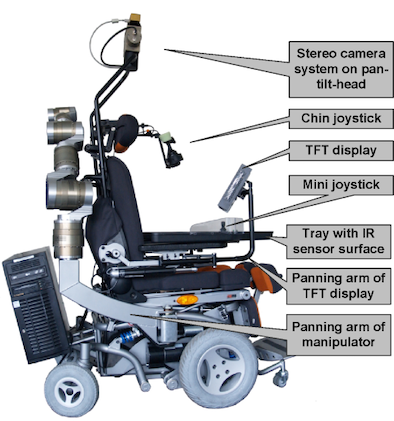

Toy robots on display

at the Museo del Objeto del Objeto in Mexico City./ The Care-Providing

Robot FRIEND/ A U.S. Marine Corps technician prepares to use a

telerobot to detonate a buried improvised explosive device near Camp

Fallujah, Iraq. and

Al-Jazari – A Musical Toy.

+++

Links

リンク

文献

その他の情報