主権

Sovereignty

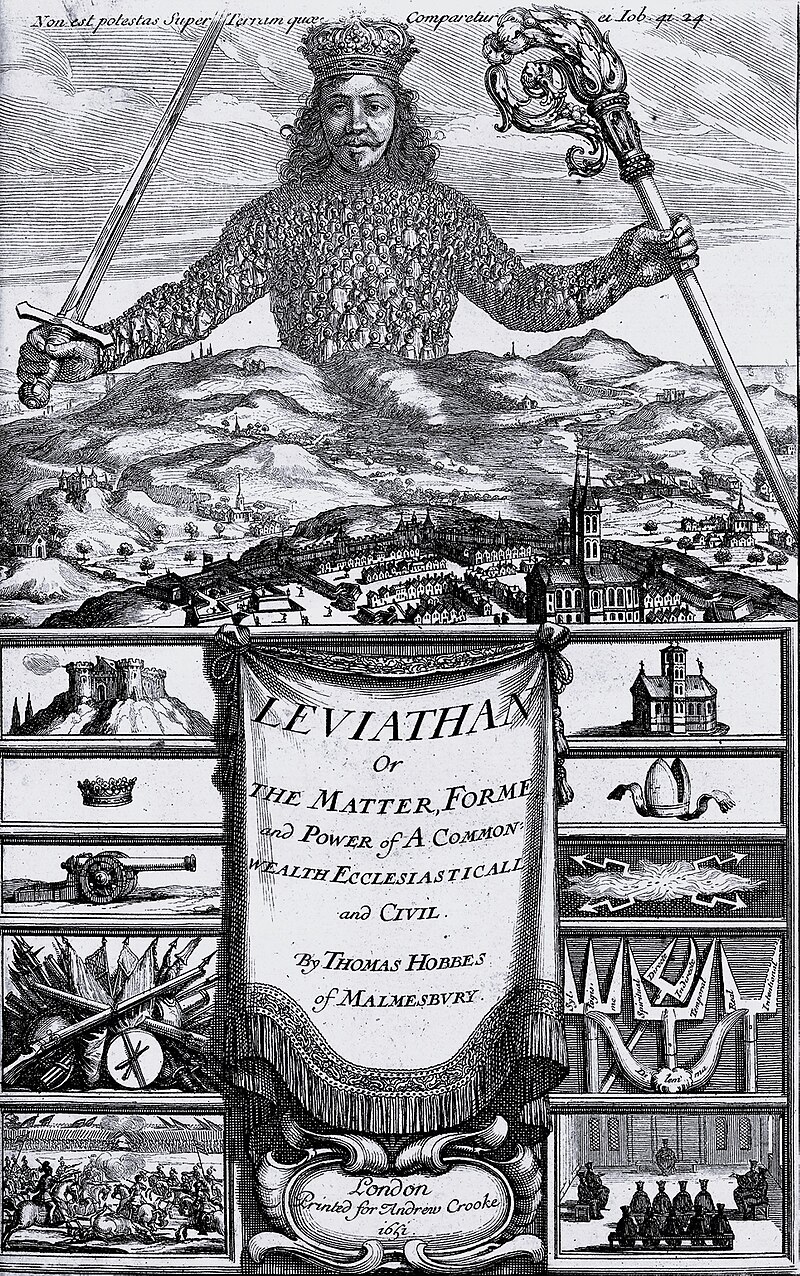

The

frontispiece of Thomas Hobbes' Leviathan (1651), depicting the

Sovereign as a massive body wielding a sword and crosier and composed

of many individual people

☆ 主権(Sovereignty) は一般的に、最高の権威として定義される。[1][2][3] 主権は国家内の階層構造を必然的に伴うものであり、国家の外部にも自律性を必要とする。[4] どのような国家においても、主権は他の人々に対して最終的な権限を持ち、既存の法律を変更する人格、機関、組織に与えられる。[5] 政治理論において、主権とは、ある政治体制に対して最高の合法的な権限を意味する実質的な用語である。 [6] 国際法においては、主権とは国家による権力の行使を指す。 デ・ジュリ(de jure)主権とは、そのための法的権利を指し、デ・ファクト(de facto)主権とは、そのための事実上の能力を指す。 デ・ジュリおよびデ・ファクト主権が問題の場所および時間において存在し、同一の組織内に存在するという通常の期待が裏切られた場合、これは特別な懸念事 項となる可能性がある。

| Sovereignty

can generally be defined as supreme authority.[1][2][3] Sovereignty

entails hierarchy within a state as well as external autonomy for

states.[4] In any state, sovereignty is assigned to the person, body or

institution that has the ultimate authority over other people and to

change existing laws.[5] In political theory, sovereignty is a

substantive term designating supreme legitimate authority over some

polity.[6] In international law, sovereignty is the exercise of power

by a state. De jure sovereignty refers to the legal right to do so; de

facto sovereignty refers to the factual ability to do so. This can

become an issue of special concern upon the failure of the usual

expectation that de jure and de facto sovereignty exist at the place

and time of concern, and reside within the same organization. |

主

権は一般的に、最高の権威として定義される。[1][2][3]

主権は国家内の階層構造を必然的に伴うものであり、国家の外部にも自律性を必要とする。[4]

どのような国家においても、主権は他の人々に対して最終的な権限を持ち、既存の法律を変更する人格、機関、組織に与えられる。[5]

政治理論において、主権とは、ある政治体制に対して最高の合法的な権限を意味する実質的な用語である。 [6]

国際法においては、主権とは国家による権力の行使を指す。 デ・ジュリ(de jure)主権とは、そのための法的権利を指し、デ・ファクト(de

facto)主権とは、そのための事実上の能力を指す。

デ・ジュリおよびデ・ファクト主権が問題の場所および時間において存在し、同一の組織内に存在するという通常の期待が裏切られた場合、これは特別な懸念事

項となる可能性がある。 |

| Etymology The term arises from the unattested Vulgar Latin *superanus (itself a derived form of Latin super – "over") meaning "chief", "ruler".[7] Its spelling, which has varied since the word's first appearance in English in the 14th century, was influenced by the English word "reign".[8][9] |

語源 この用語は、証明されていない俗ラテン語の*superanus(ラテン語のsuper(「~の上に」)に由来する派生形)に由来し、「最高位」、「支配 者」を意味する。[7] 14世紀に英語に初めて登場して以来、表記は変化しているが、これは英語の「reign」という語の影響を受けている。[8][9] |

| Concepts The concept of sovereignty has had multiple conflicting components, varying definitions, and diverse and inconsistent applications throughout history.[10][11][12][13] The current notion of state sovereignty contains four aspects: territory, population, authority and recognition.[12] According to Stephen D. Krasner, the term could also be understood in four different ways: Domestic sovereignty – actual control over a state exercised by an authority organized within this state Interdependence sovereignty – actual control of movement across the state's borders International legal sovereignty – formal recognition by other sovereign states Westphalian sovereignty – there is no other authority in the state aside from the domestic sovereign (such other authorities might be e.g. a political organization or any other external agent).[10] Often, these four aspects all appear together, but this is not necessarily the case – they are not affected by one another, and there are historical examples of states that were non-sovereign in one aspect while at the same time being sovereign in another of these aspects.[10] According to Immanuel Wallerstein, another fundamental feature of sovereignty is that it is a claim that must be recognized if it is to have any meaning: Sovereignty is a hypothetical trade, in which two potentially (or really) conflicting sides, respecting de facto realities of power, exchange such recognitions as their least costly strategy.[14] There are two additional components of sovereignty that should be discussed, empirical sovereignty and juridical sovereignty.[15] Empirical sovereignty deals with the legitimacy of who is in control of a state and the legitimacy of how they exercise their power.[15] Tilly references an example where nobles in parts of Europe were allowed to engage in private rights and Ustages, a constitution by Catalonia recognized that right which demonstrates empirical sovereignty.[16] As David Samuel points out, this is an important aspect of a state because there has to be a designated individual or group of individuals that are acting on behalf of the people of the state.[17] Juridical sovereignty emphasizes the importance of other states recognizing the rights of a state to exercise their control freely with little interference.[15] For example, Jackson, Rosberg and Jones explain how the sovereignty and survival of African states were more largely influenced by legal recognition rather than material aid.[18] Douglass North identifies that institutions want structure and these two forms of sovereignty can be a method for developing structure.[19] For a while, the United Nations highly valued juridical sovereignty and attempted to reinforce its principle often.[15] More recently, the United Nations is shifting away and focusing on establishing empirical sovereignty.[15] Michael Barnett notes that this is largely due to the effects of the post Cold War era because the United Nations believed that to have peaceful relations states should establish peace within their territory.[15] As a matter of fact, theorists found that during the post Cold War era many people focused on how stronger internal structures promote inter-state peace.[20] For instance, Zaum argues that many weak and impoverished countries that were affected by the Cold War were given assistance to develop their lacking sovereignty through this sub-concept of "empirical statehood".[21] |

概念 主権の概念は、歴史を通じて、相反する複数の要素、定義の相違、多様かつ一貫性のない適用が存在してきた。[10][11][12][13] 現在の国家主権の概念には、領土、人口、権限、承認という4つの側面がある。[12] スティーブン・D・クラズナーによると、この用語は4つの異なる方法で理解できる。 国内主権 - 国内で組織された権限によって行使される国家に対する実際の支配 相互依存主権 – 国家の国境を越えた移動に対する実際の支配 国際法的主権 – 他の主権国家による正式な承認 ウェストファリア的主権 – 国内の主権国家以外に国家内に他の権限は存在しない(そのような他の権限は、例えば政治組織やその他の外部機関である可能性がある)[10] この4つの側面はしばしば同時に存在するが、必ずしもそうとは限らない。相互に影響し合うものではなく、ある側面では主権を持たないが、他の側面では主権 を持つ国家の歴史的例もある。[10] イマニュエル・ウォーラーステインによると、主権のもう一つの基本的な特徴は、意味を持つためには承認されなければならない主張であるということである。 主権とは、潜在的に(あるいは実際に)対立する2つの勢力が、権力の事実上の現実を尊重し、最もコストのかからない戦略として、そのような承認を交換する仮想的な取引である。 主権には、さらに2つの要素、経験的な主権と法的な主権がある。経験的な主権は、国家を統制する者の正当性と、その権力の行使の正当性を取り扱う。 [15] ティリーは、ヨーロッパの一部の貴族が私権やウステージ(土地の権利)に関与することを許されていた例を挙げている。カタルーニャの憲法は、この権利を認 めており、これは経験的統治権を示している。[16] デビッド・サミュエルが指摘しているように、これは国家の重要な側面である。なぜなら、国家の国民を代表して行動する個人または個人グループが存在しなけ ればならないからだ。 [17] 法的主体性は、他国が国家の権利を尊重し、干渉を最小限に抑えながら自由に統制を行うことを重視する。[15] 例えば、ジャクソン、ロスバーグ、ジョーンズは、アフリカ諸国の主権と存続は、物質的な支援よりもむしろ法的承認によってより大きな影響を受けると説明し ている。[18] ダグラス・ノースは、制度には構造が必要であり、この2つの主権の形態は構造を開発する方法となり得ることを指摘している。[19] しばらくの間、国連は法的主権を非常に重視し、その原則を強化しようと試みていた。[15] 最近では、国連は方針を転換し、実証的主権の確立に重点を置いている。[15] マイケル・バーネットは、これは主に冷戦後の影響によるものであると指摘している。国連は、国家間の平和的な関係を築くためには、それぞれの領土内で平和 を確立すべきだと考えていたからだ。 [15] 実際、理論家たちは、冷戦後の時代において、多くの人々が国内の構造を強化することが国家間の平和を促進する方法に注目していたことを発見した。[20] 例えば、ザウムは、冷戦の影響を受けた多くの弱小国や貧困国が、この「経験的な国家」という概念の下位概念を通じて、欠如していた主権を発展させるための 支援を受けた、と主張している。[21] |

| History Classical The Roman jurist Ulpian observed that:[22] The people transferred all their imperium and power to the Emperor. Cum lege regia, quae de imperio eius lata est, populus ei et in eum omne suum imperium et potestatem conferat (Digest I.4.1) The laws do not bind the emperor. Princeps legibus solutus est (Digest I.3.31) A decision by the emperor has the force of law. Quod principi placuit legis habet vigorem. (Digest I.4.1) Ulpian was expressing the idea that the emperor exercised a rather absolute form of sovereignty that originated in the people, although he did not use the term expressly. |

歴史 古典 ローマの法学者ウルピアヌスは次のように述べている。 人民は皇帝にすべてのインペリウムと権力を委譲した。 Cum lege regia, quae de imperio eius lata est, populus ei et in eum omne suum imperium et potestatem conferat (Digest I.4.1) 法律は皇帝を拘束しない。プリンケプス・レギブス・ソルタス(Digest I.3.31) 皇帝の決定は法律としての効力を有する。クオド・プリンケ・プラウィト・レギス・ハベト・ヴィゴレン(Digest I.4.1) ウルピアヌスは、皇帝が国民に由来するかなり絶対的な主権を行使するという考えを表現していたが、その考えを明確に表現したわけではなかった。 |

| Medieval Ulpian's statements were known in medieval Europe, but sovereignty was an important concept in medieval times. Medieval monarchs were not sovereign, at least not strongly so, because they were constrained by, and shared power with, their feudal aristocracy. Furthermore, both were strongly constrained by custom.[6] Sovereignty existed during the Medieval period as the de jure rights of nobility and royalty.[23] |

中世 ウルピアヌスの主張は中世ヨーロッパで知られていたが、中世では主権は重要な概念であった。中世の君主は、少なくとも強くは主権者ではなかった。なぜな ら、封建的な貴族階級に制約され、彼らと権力を共有していたからである。さらに、両者は慣習によって強く制約されていた。[6] 中世には、主権は貴族と王族のデ・ジュリ権利として存在していた。[23] |

| Reformation Sovereignty reemerged as a concept in the late 16th century, a time when civil wars had created a craving for a stronger central authority when monarchs had begun to gather power onto their own hands at the expense of the nobility, and the modern nation state was emerging. Jean Bodin, partly in reaction to the chaos of the French wars of religion, presented theories of sovereignty calling for a strong central authority in the form of absolute monarchy. In his 1576 treatise Les Six Livres de la République ("Six Books of the Republic") Bodin argued that it is inherent in the nature of the state that sovereignty must be:[6] Absolute: On this point, he said that the sovereign must be hedged in with obligations and conditions, must be able to legislate without his (or its) subjects' consent, must not be bound by the laws of his predecessors, and could not, because it is illogical, be bound by his own laws. Perpetual: Not temporarily delegated as to a strong leader in an emergency or a state employee such as a magistrate. He held that sovereignty must be perpetual because anyone with the power to enforce a time limit on the governing power must be above the governing power, which would be impossible if the governing power is absolute. The treatise is frequently viewed as the first European text theorizing state sovereignty.[24] Bodin rejected the notion of transference of sovereignty from people to the ruler (also known as the sovereign); natural law and divine law confer upon the sovereign the right to rule. And the sovereign is not above divine law or natural law. He is above (i.e. not bound by) only positive law, that is, laws made by humans. He emphasized that a sovereign is bound to observe certain basic rules derived from the divine law, the law of nature or reason, and the law that is common to all nations (jus gentium), as well as the fundamental laws of the state that determine who is the sovereign, who succeeds to sovereignty, and what limits the sovereign power. Thus, Bodin's sovereign was restricted by the constitutional law of the state and by the higher law that was considered as binding upon every human being.[6] The fact that the sovereign must obey divine and natural law imposes ethical constraints on him. Bodin also held that the lois royales, the fundamental laws of the French monarchy which regulated matters such as succession, are natural laws and are binding on the French sovereign. Despite his commitment to absolutism, Bodin held some moderate opinions on how government should in practice be carried out. He held that although the sovereign is not obliged to, it is advisable for him, as a practical expedient, to convene a senate from whom he can obtain advice, to delegate some power to magistrates for the practical administration of the law, and to use the Estates as a means of communicating with the people.[citation needed] Bodin believed that "the most divine, most excellent, and the state form most proper to royalty is governed partly aristocratically and partly democratically".[25] |

改革 主権という概念が再び登場したのは16世紀後半のことである。この時代には、君主が貴族を犠牲にして権力を一手に集め始め、市民戦争によってより強力な中央権力への渇望が生じ、近代国民国家が誕生しつつあった。ジャン・ボダンは、 フランス宗教戦争の混乱への反発もあり、絶対王政という強力な中央権力を求める主権論を提示した。1576年の論文『Les Six Livres de la République(共和国の6冊の本)』において、ボダンは主権は国家の本質に内在するものであり、以下の条件を満たさなければならないと主張した。 絶対的:この点について、彼は、主権者は義務や条件によって制限され、被治者の同意なしに立法でき、前任者の法律に縛られることなく、また、非論理的であるため、自らの法律に縛られることもできないはずであると述べた。 永続的:緊急時に強力な指導者として一時的に権限を委譲されたり、裁判官のような国家公務員として権限を委譲されたりすることはない。彼は、統治権力に期 限を課す権限を持つ者は、統治権力よりも上位にいなければならないため、主権は永続的でなければならないと主張した。しかし、統治権力が絶対的なものであ る場合、これは不可能である。 この論文は、国家主権を理論化した最初のヨーロッパの文章であると見なされることが多い。 ボダンは、人民から統治者(君主とも呼ばれる)への主権の移譲という概念を否定した。自然法と神聖法は、統治者に統治する権利を与える。そして、統治者は 神聖法や自然法の上位に立つものではない。主権者は、人間が制定した法律である実定法のみに服従する(すなわち、実定法に縛られる)のであって、神法や自 然法には服従しない。彼は、主権者は神法、自然法、理性法、およびすべての国民に共通する法(国際法)から導き出される特定の基本的な規則を遵守する義務 があることを強調した。また、主権者は誰か、誰が主権を継承するか、主権の力を制限するものは何かを決定する国家の基本法にも従う義務がある。したがっ て、ボダンの主権者は、国家の憲法法および人間すべてに拘束力を持つと考えられていた上位法によって制限されていたのである。[6] 主権者が神聖法および自然法に従わなければならないという事実は、彼に倫理的な制約を課す。ボダンはまた、王位継承などを規定するフランス王政の基本法で あるロワ・ロワイヤル(lois royales)は自然法であり、フランス君主を拘束するものであると主張した。 絶対主義に傾倒していたにもかかわらず、ボダンは政府が実際にはどのように運営されるべきかについて、いくつかの穏健な意見を持っていた。彼は、君主には その義務はないが、実際的な便宜を図るために、助言を得られる元老院を召集し、法律の実際的な運用を裁判官に委任し、国民との意思疎通の手段として三部会 を利用することが望ましいと主張した。 [要出典] ボダンは、「王族にとって最も神聖で、最も優れ、最もふさわしい国家形態は、部分的に貴族主義的に、部分的に民主主義的に統治されることである」と考えて いた。[25] |

| Age of Enlightenment During the Age of Enlightenment, the idea of sovereignty gained both legal and moral force as the main Western description of the meaning and power of a State. In particular, the "Social contract" as a mechanism for establishing sovereignty was suggested and, by 1800, widely accepted, especially in the new United States and France, though also in Great Britain to a lesser extent. Thomas Hobbes, in Leviathan (1651) put forward a conception of sovereignty similar to Bodin's, which had just achieved legal status in the "Peace of Westphalia", but for different reasons. He created the first modern version of the social contract (or contractarian) theory, arguing that to overcome the "nasty, brutish and short" quality of life without the cooperation of other human beings, people must join in a "commonwealth" and submit to a "Soveraigne [sic] Power" that can compel them to act in the common good. Hobbes was thus the first to write that relations between the people and the sovereign were based on negotiation rather than natural submission.[26]: 10 His expediency argument attracted many of the early proponents of sovereignty. Hobbes strengthened the definition of sovereignty beyond either Westphalian or Bodin's, by saying that it must be:[citation needed][27] Absolute: because conditions could only be imposed on a sovereign if there were some outside arbitrator to determine when he had violated them, in which case the sovereign would not be the final authority. Indivisible: The sovereign is the only final authority in his territory; he does not share final authority with any other entity. Hobbes held this to be true because otherwise there would be no way of resolving a disagreement between the multiple authorities. Hobbes' hypothesis—that the ruler's sovereignty is contracted to him by the people in return for his maintaining their physical safety—led him to conclude that if and when the ruler fails, the people recover their ability to protect themselves by forming a new contract. Hobbes's theories decisively shape the concept of sovereignty through the medium of social contract theories. Jean-Jacques Rousseau's (1712–1778) definition of popular sovereignty (with early antecedents in Francisco Suárez's theory of the origin of power), provides that the people are the legitimate sovereign. Rousseau considered sovereignty to be inalienable; he condemned the distinction between the origin and the exercise of sovereignty, a distinction upon which constitutional monarchy or representative democracy is founded. John Locke, and Montesquieu are also key figures in the unfolding of the concept of sovereignty; their views differ with Rousseau and with Hobbes on this issue of alienability. The second book of Jean-Jacques Rousseau's Du Contrat Social, ou Principes du droit politique (1762) deals with sovereignty and its rights. Sovereignty, or the general will, is inalienable, for the will cannot be transmitted; it is indivisible since it is essentially general; it is infallible and always right, determined and limited in its power by the common interest; it acts through laws. Law is the decision of the general will regarding some object of common interest, but though the general will is always right and desires only good, its judgment is not always enlightened, and consequently does not always see wherein the common good lies; hence the necessity of the legislator. But the legislator has, of himself, no authority; he is only a guide who drafts and proposes laws, but the people alone (that is, the sovereign or general will) has authority to make and impose them.[28][29] Rousseau, in the Social Contract[30] argued, "the growth of the State giving the trustees of public authority more and means to abuse their power, the more the Government has to have force to contain the people, the more force the Sovereign should have in turn to contain the Government," with the understanding that the Sovereign is "a collective being of wonder" (Book II, Chapter I) resulting from "the general will" of the people, and that "what any man, whoever he may be, orders on his own, is not a law" (Book II, Chapter VI) – and predicated on the assumption that the people have an unbiased means by which to ascertain the general will. Thus the legal maxim, "there is no law without a sovereign."[31] According to Hendrik Spruyt, the sovereign state emerged as a response to changes in international trade (forming coalitions that wanted sovereign states)[4] so that the sovereign state's emergence was not inevitable; "it arose because of a particular conjuncture of social and political interests in Europe."[32] Once states are recognized as sovereign, they are rarely recolonized, merged, or dissolved.[33] |

啓蒙時代 啓蒙時代には、主権という概念が、国家の意義と権力を説明する西洋の主要な概念として、法的にも道徳的にも力を得た。特に、主権を確立する仕組みとしての 「社会契約」が提唱され、1800年までに、特に新生アメリカ合衆国とフランスで広く受け入れられた。ただし、イギリスでも、より限定的ながら受け入れら れた。 トマス・ホッブズは著書『リヴァイアサン』(1651年)の中で、ボダンと類似した主権の概念を提唱したが、その理由は異なっていた。彼は社会契約(また は契約論)理論の最初の近代版を創り出し、他の人間との協力なしに「不快で、粗野で、短絡的」な生活の質を克服するには、人々は「連邦」に参加し、公益の ために行動することを強制できる「主権者(sic)の権力」に従う必要があると主張した。ホッブズは、人民と君主の関係は自然な服従ではなく交渉に基づく ものであると初めて書いた人物である。[26]:10 彼の便宜主義的な主張は、君主制の初期の提唱者の多くを惹きつけた。ホッブズは、君主制の定義をウェストファリアやボダンの定義を超えて強化し、次のよう に述べた。 絶対的:主権者に条件を課すことができるのは、主権者がその条件に違反したかどうかを判断する外部の仲裁者が存在する場合のみであり、その場合、主権者は最終的な権威者ではない。 分割不可能:主権者は自らの領土における唯一の最終的な権威者であり、他のいかなる存在とも最終的な権威を共有しない。ホッブズは、そうでないと複数の権威者間の意見の相違を解決する方法がないため、これを真実であるとした。 ホッブズの仮説、すなわち統治者の主権は、統治者が人民の身体的安全を維持することを条件に、人民から委任されたものであるという仮説から、統治者が失敗した場合、人民は新たな契約を結ぶことで、自分自身を守る能力を回復するという結論に達した。 ホッブズの理論は、社会契約説の媒介を通じて、主権の概念を明確に形作っている。ジャン=ジャック・ルソー(1712年~1778年)の人民主権の定義 (フランシスコ・スアレスの権力起源論に初期の先行例がある)では、人民こそが正当な主権者であるとしている。ルソーは主権は譲渡不可能であると考え、主 権の起源と行使を区別することを非難した。この区別は立憲君主制や代表制民主主義の基盤となっている。ジョン・ロックやモンテスキューも主権概念の展開に おいて重要な人物である。彼らの見解は、主権の譲渡可能性という問題について、ルソーやホッブズの見解とは異なる。 ジャン=ジャック・ルソーの著書『社会契約論、または政治的権利の原理』(1762年)の第2巻では、主権とその権利について論じられている。主権、すな わち一般意志は譲渡不可能であり、意志は伝達できないため、不可分である。また、本質的に一般であるため、絶対的であり、常に正しい。法とは、共通の利益 に関する何らかの対象について、一般意志が下す決定である。一般意志は常に正しく、善のみを望むが、その判断は常に賢明であるとは限らず、したがって、共 通善がどこにあるのかを常に認識しているわけではない。したがって、立法者の必要性がある。しかし、立法者はそれ自体として何の権限も持たない。立法者 は、法律を起草し提案するガイドにすぎず、それらを制定し強制する権限を持つのは人民(すなわち、主権者または一般意志)だけである。[28][29] ルソーは『社会契約書』[30]の中で、「国家が成長し、公的権威の受託者が権力を乱用する手段と機会が増えるにつれ、政府は国民を抑制する力を強め、君 主は政府を抑制する力を強めるべきである」と主張した。ルソーは、君主とは「驚異的な集合体」であり (第2巻、第1章)であり、また「いかなる者であれ、その者が独自に命じたことは、法ではない」(第2巻、第6章)と理解されている。そして、人民が一般 意志を公平に確認できる手段を持っているという前提に基づいている。したがって、「主権者なしに法はない」という法格律が導かれる。[31] ヘンドリック・スプルイトによると、主権国家は国際貿易の変化(主権国家を求める連合の形成)への対応として出現したものであり[4]、主権国家の出現は 必然的なものではなかった。「それはヨーロッパにおける社会と政治の特定の利害関係が重なった結果として生じた」のである[32]。 国家が主権国家として認められた後は、再植民地化、合併、消滅されることはほとんどない[33]。 |

| Post World War II world order Today, no state is sovereign in the sense they were prior to the Second World War.[34] Transnational governance agreements and institutions, the globalized economy,[35] and pooled sovereignty unions such as the European union have eroded the sovereignty of traditional states. The centuries long movement which developed a global system of sovereign states came to an end when the excesses of World War II made it clear to nations that some curtailment of the rights of sovereign states was necessary if future cruelties and injustices were to be prevented.[36][37] In the years immediately prior to the war, political theorist Carl Schmitt argued that sovereignty had supremacy over constitutional and international constraints arguing that states as sovereigns could not be judged and punished.[38] After the Holocaust, the vast majority of states rejected the prior Westphalian permissiveness towards such supremacist power based sovereignty formulations and signed the Universal Declaration of Human Rights in 1948. It was the first step towards circumscription of the powers of sovereign nations, soon followed by the Genocide Convention which legally required nations to punish genocide. Based on these and similar human rights agreements, beginning in 1990 there was a practical expression of this circumscription when the Westphalian principle of non-intervention was no longer observed for cases where the United Nations or another international organization endorsed a political or military action. Previously, actions in Yugoslavia, Bosnia, Kosovo, Somalia, Rwanda, Haiti, Cambodia or Liberia would have been regarded as illegitimate interference in internal affairs. In 2005, the revision of the concept of sovereignty was made explicit with the Responsibility to Protect agreement endorsed by all member states of the United Nations. If a state fails this responsibility either by perpetrating massive injustice or being incapable of protecting its citizens, then outsiders may assume that responsibility despite prior norms forbidding such interference in a nation's sovereignty.[39] European integration is the second form of post-world war change in the norms of sovereignty, representing a significant shift since member nations are no longer absolutely sovereign. Some theorists, such as Jacques Maritain and Bertrand de Jouvenel have attacked the legitimacy of the earlier concepts of sovereignty, with Maritain advocating that the concept be discarded entirely since it:[36] stands in the way of international law and a world state, internally results in centralism, not pluralism obstructs the democratic notion of accountability Efforts to curtail absolute sovereignty have met with substantial resistance by sovereigntist movements in multiple countries who seek to "take back control" from such transnational governance groups and agreements, restoring the world to pre World War II norms of sovereignty.[40] |

第二次世界大戦後の世界秩序 今日、第二次世界大戦以前の感覚で主権国家である国家は存在しない。[34] 国際的な統治協定や機関、グローバル化した経済、[35] そして欧州連合のような主権を共有する連合は、伝統的な国家の主権を浸食してきた。主権国家によるグローバルなシステムを構築する数世紀にわたる動きは、 第二次世界大戦の行き過ぎによって、将来の残虐行為や不正を防ぐためには主権国家の権利をある程度制限する必要があることが国民に明らかになったことで、 終焉を迎えた。[36][37] 戦争直前の数年間、政治理論家のカール・シュミットは、主権は憲法や国際的な制約よりも優位にあると主張し、主権国家である国家は裁かれるべきではなく、 罰せられるべきではないと論じた。 [38] ホロコーストの後、大多数の国家は、このような覇権主義的な権力に基づく主権の概念に対するそれまでのウェストファリア的寛容さを拒絶し、1948年に世 界人権宣言に署名した。これは主権国家の権限を制限する第一歩であり、間もなく、ジェノサイドを処罰することを各国に法的に義務付ける「ジェノサイド条 約」が締結された。これらおよび同様の人権協定に基づき、1990年以降、国際連合やその他の国際機関が政治的または軍事行動を承認した場合には、ウェス トファリア原則の不干渉が適用されなくなった。それ以前であれば、ユーゴスラビア、ボスニア、コソボ、ソマリア、ルワンダ、ハイチ、カンボジア、リベリア での行動は、内政への不当な干渉と見なされていたであろう。2005年には、国連の全加盟国が承認した「保護責任」の合意により、主権の概念の修正が明確 に示された。国家が大規模な不正を犯したり、自国民を守ることができないなどして、この責任を果たせなかった場合、それまでは国家の主権への干渉を禁じる 規範があったにもかかわらず、外部の者がその責任を引き受ける可能性がある。 欧州統合は、主権の規範における第二次世界大戦後の変化の形であり、加盟国がもはや絶対的な主権を有していないという点で、大きな転換点となっている。 ジャック・マリテーヌやベルトラン・ド・ジュヴェネルなどの一部の理論家は、主権の概念の正当性を攻撃しており、マリテーヌは、主権の概念は完全に破棄さ れるべきだと主張している。なぜなら、それは 国際法や世界国家の実現を妨げるものであり、 内部的には中央集権主義を招き、多元主義にはつながらない 民主主義の説明責任の概念を妨げる 絶対的主権を制限しようとする試みは、このような超国家的な統治グループや協定から「主権を取り戻す」ことを求める複数の国々における主権主義運動による実質的な抵抗に直面しており、世界を第二次世界大戦前の主権の規範に戻そうとしている。[40] |

| Definition and types There exists perhaps no conception the meaning of which is more controversial than that of sovereignty. It is an indisputable fact that this conception, from the moment when it was introduced into political science until the present day, has never had a meaning which was universally agreed upon. Lassa Oppenheim (30-03-1858 – 07-10-1919), an authority on international law[41] Absoluteness An important factor of sovereignty is its degree of absoluteness.[42][43] A sovereign power has absolute sovereignty when it is not restricted by a constitution, by the laws of its predecessors, or by custom, and no areas of law or policy are reserved as being outside its control. International law; policies and actions of neighboring states; cooperation and respect of the populace; means of enforcement; and resources to enact policy are factors that might limit sovereignty. For example, parents are not guaranteed the right to decide some matters in the upbringing of their children independent of societal regulation, and municipalities do not have unlimited jurisdiction in local matters, thus neither parents nor municipalities have absolute sovereignty. Theorists have diverged over the desirability of increased absoluteness. |

定義と種類 主権という概念ほど、その意味について論争の的となるものはないかもしれない。この概念が政治学に導入された瞬間から今日に至るまで、普遍的に合意された意味を持ったことは一度もないという事実は疑いようのない事実である。 ラッサ・オッペンハイム(1858年3月30日 - 1919年10月7日)は国際法の権威である。[41] 絶対性 主権の重要な要素は、その絶対性である。[42][43] 主権は、憲法、先例となる法律、または慣習によって制限されない場合、絶対的な主権を有する。また、法律や政策の分野が、その支配外として留保されること もない。国際法、近隣諸国の政策や行動、国民の協力や尊重、強制手段、政策実施のための資源などは、主権を制限する要因となり得る。例えば、親は社会的な 規制とは無関係に、子供の養育に関する事項を決定する権利を保証されているわけではない。また、地方自治体は地域の問題について無制限の管轄権を持ってい るわけではない。したがって、親も自治体も絶対的な主権を持っているわけではない。絶対性を高めることの是非については、理論家たちの意見は分かれてい る。 |

| Exclusivity A key element of sovereignty in a legalistic sense is that of exclusivity of jurisdiction also described as the ultimate arbiter in all disputes on the territory. Specifically, the degree to which decisions made by a sovereign entity might be contradicted by another authority. Along these lines, the German sociologist Max Weber proposed that sovereignty is a community's monopoly on the legitimate use of force; and thus any group claiming the right to violence must either be brought under the yoke of the sovereign, proven illegitimate or otherwise contested and defeated for sovereignty to be genuine.[44] International law, competing branches of government, and authorities reserved for subordinate entities (such as federated states or republics) represent legal infringements on exclusivity. Social institutions such as religious bodies, corporations, and competing political parties might represent de facto infringements on exclusivity. |

排他性 法的な意味での主権の重要な要素は、その領土におけるあらゆる紛争の最終的な裁定者とも表現される、管轄権の排他性である。具体的には、主権を有する主体 が下した決定が、他の権限によってどの程度まで覆される可能性があるかということである。この観点から、ドイツの社会学者マックス・ウェーバーは、主権と は、合法的な武力行使を独占する共同体であると提唱した。したがって、暴力の権利を主張するいかなる集団も、主権者の支配下に置かれるか、非合法であるこ とが証明されるか、あるいは主権が真正であるために異議が唱えられ、敗北しなければならない。[44] 国際法、競合する政府機関、従属する団体(連邦国家や共和国など)に留保された権限は、独占に対する法的な侵害を意味する。宗教団体、企業、競合する政党 などの社会制度は、独占権に対する事実上の侵害を意味する可能性がある。 |

| De jure and de facto De jure, or legal, sovereignty concerns the expressed and institutionally recognised right to exercise control over a territory. De facto sovereignty means sovereignty exists in practice, irrespective of anything legally accepted as such, usually in writing. Cooperation and respect of the populace; control of resources in, or moved into, an area; means of enforcement and security; and ability to carry out various functions of state all represent measures of de facto sovereignty. When control is practiced predominantly by the military or police force it is considered coercive sovereignty. |

デ・ジュリおよびデ・ファクト デ・ジュリ(法的)な主権とは、領土に対する支配権を行使する明示された、かつ制度的に認められた権利を意味する。事実上の主権とは、通常、書面による法 的承認の有無に関わらず、主権が実際に存在することを意味する。住民との協力と尊重、地域内の資源または地域に移動する資源の管理、強制手段と安全保障、 国家のさまざまな機能を遂行する能力は、すべて事実上の主権の尺度である。主権が主に軍または警察によって行使される場合、それは強制的な主権であると考 えられる。 |

| Sovereignty and independence This section needs additional citations for verification. Please help improve this article by adding citations to reliable sources in this section. Unsourced material may be challenged and removed. (July 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) State sovereignty is sometimes viewed synonymously with independence, however, sovereignty can be transferred as a legal right whereas independence cannot.[45] A state can achieve de facto independence long after acquiring sovereignty, such as in the case of Cambodia, Laos and Vietnam.[45] Additionally, independence can also be suspended when an entire region becomes subject to an occupation. For example, when Iraq was overrun by foreign forces in the Iraq War of 2003, Iraq had not been annexed by any country, so sovereignty over it had not been claimed by any foreign state (despite the facts on the ground). Alternatively, independence can be lost completely when sovereignty itself becomes the subject of dispute. The pre-World War II administrations of Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia maintained an exile existence (and considerable international recognition) whilst their territories were annexed by the Soviet Union and governed locally by their pro-Soviet functionaries. When in 1991 Latvia, Lithuania and Estonia re-enacted independence, it was done so on the basis of continuity directly from the pre-Soviet republics.[45][46] Another complicated sovereignty scenario can arise when regime itself is the subject of dispute. In the case of Poland, the People's Republic of Poland which governed Poland from 1945 to 1989 is now seen to have been an illegal entity by the modern Polish administration. The post-1989 Polish state claims direct continuity from the Second Polish Republic which ended in 1939. For other reasons, however, Poland maintains its communist-era outline as opposed to its pre-World War II shape which included areas now in Belarus, Czech Republic, Lithuania, Slovakia and Ukraine but did not include some of its western regions that were then in Germany. Additionally sovereignty can be achieved without independence, such as how the Declaration of State Sovereignty of the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic made the Russian Soviet Federative Socialist Republic a sovereign entity within but not independent from the USSR. At the opposite end of the scale, there is no dispute regarding the self-governance of certain self-proclaimed states such as the Republic of Kosovo or Somaliland (see List of states with limited recognition, but most of them are puppet states) since their governments neither answer to a bigger state nor is their governance subjected to supervision. The sovereignty (i.e. legal right to govern) however, is disputed in both cases as the first entity is claimed by Serbia and the second by Somalia. |

主権と独立 この節には検証可能な参考文献や出典が全く示されていないか、不十分である。出典を追加して記事の信頼性向上にご協力ください。 出典の記載がない内容は、異議申し立ておよび削除の対象となる可能性がある。 (July 2015) (Learn how and when to remove this message) 国家の主権は独立と同義語として捉えられることもあるが、主権は法的な権利として移転できるのに対し、独立はできない。国家は主権を獲得してから長い年月 を経て、事実上の独立を達成することがある。例えばカンボジア、ラオス、ベトナムの場合がそうである。例えば、2003年のイラク戦争で外国軍がイラクを 制圧した際、イラクはどの国にも併合されていなかったため、その主権はどの外国にも主張されていなかった(現地の状況とは裏腹に)。また、主権そのものが 紛争の対象となった場合、完全に独立を失うこともある。第二次世界大戦前のラトビア、リトアニア、エストニアの政府は亡命政府として存続し(国際社会から も一定の承認を得ていた)、その領土はソビエト連邦に併合され、親ソビエト派の役人によって現地で統治されていた。1991年にラトビア、リトアニア、エ ストニアが再び独立を宣言した際には、ソビエト連邦崩壊前の共和国から直接の連続性を基礎としていた。 体制自体が論争の対象となっている場合にも、主権に関する複雑な状況が生じることがある。ポーランドの場合、1945年から1989年までポーランドを統 治したポーランド人民共和国は、現在のポーランド政府によって違法な存在と見なされている。1989年以降のポーランド国家は、1939年に終結した第二 次ポーランド共和国から直接の連続性があるとしている。しかし、その他の理由により、ポーランドは第二次世界大戦前の形とは対照的に、共産主義時代の概略 を維持している。第二次世界大戦前の形には、現在のベラルーシ、チェコ共和国、リトアニア、スロバキア、ウクライナの地域が含まれていたが、当時ドイツ領 であった西部の一部地域は含まれていなかった。 さらに、ロシア・ソビエト連邦社会主義共和国が国家主権宣言によってソビエト連邦内の主権国家となったように、独立を伴わない主権の獲得もあり得る。 その反対の極端な例としては、コソボ共和国やソマリランド(国家承認が限定的な国家の一覧を参照)などの、自称国家の自治権については論争の余地がない。 なぜなら、これらの政府はより大きな国家に従属しておらず、その統治は監督下に置かれていないからである。しかし、主権(すなわち統治する法的権利)は、 どちらの場合も、セルビアとソマリアがそれぞれ領有権を主張しているため、係争中である。 |

| Internal Further information: Free state (polity) Internal sovereignty is the relationship between sovereign power and the political community. A central concern is legitimacy: by what right does a government exercise authority? Claims of legitimacy might refer to the divine right of kings, or to a social contract (i.e. popular sovereignty).[citation needed] Max Weber offered a first categorization of political authority and legitimacy with the categories of traditional, charismatic and legal-rational. With "sovereignty" meaning holding supreme, independent authority over a region or state, "internal sovereignty" refers to the internal affairs of the state and the location of supreme power within it.[47] A state that has internal sovereignty is one with a government that has been elected by the people and has the popular legitimacy. Internal sovereignty examines the internal affairs of a state and how it operates. It is important to have strong internal sovereignty to keeping order and peace. When you have weak internal sovereignty, organisations such as rebel groups will undermine the authority and disrupt the peace. The presence of a strong authority allows you to keep the agreement and enforce sanctions for the violation of laws. The ability for leadership to prevent these violations is a key variable in determining internal sovereignty.[48] The lack of internal sovereignty can cause war in one of two ways: first, undermining the value of agreement by allowing costly violations; and second, requiring such large subsidies for implementation that they render war cheaper than peace.[49] Leadership needs to be able to promise members, especially those like armies, police forces, or paramilitaries will abide by agreements. The presence of strong internal sovereignty allows a state to deter opposition groups in exchange for bargaining. While the operations and affairs within a state are relative to the level of sovereignty within that state, there is still an argument over who should hold the authority in a sovereign state. This argument between who should hold the authority within a sovereign state is called the traditional doctrine of public sovereignty. This discussion is between an internal sovereign or an authority of public sovereignty. An internal sovereign is a political body that possesses ultimate, final and independent authority; one whose decisions are binding upon all citizens, groups and institutions in society. Early thinkers believed sovereignty should be vested in the hands of a single person, a monarch. They believed the overriding merit of vesting sovereignty in a single individual was that sovereignty would therefore be indivisible; it would be expressed in a single voice that could claim final authority. An example of an internal sovereign is Louis XIV of France during the seventeenth century; Louis XIV claimed that he was the state. Jean-Jacques Rousseau rejected monarchical rule in favor of the other type of authority within a sovereign state, public sovereignty. Public Sovereignty is the belief that ultimate authority is vested in the people themselves, expressed in the idea of the general will. This means that the power is elected and supported by its members, the authority has a central goal of the good of the people in mind. The idea of public sovereignty has often been the basis for modern democratic theory.[50] Modern internal sovereignty Further information: Tribal sovereignty Within the modern governmental system, internal sovereignty is usually found in states that have public sovereignty and is rarely found within a state controlled by an internal sovereign. A form of government that is a little different from both is the UK parliament system. John Austin argued that sovereignty in the UK was vested neither in the Crown nor in the people but in the "Queen-in-Parliament".[6] This is the origin of the doctrine of parliamentary sovereignty and is usually seen as the fundamental principle of the British constitution. With these principles of parliamentary sovereignty, majority control can gain access to unlimited constitutional authority, creating what has been called "elective dictatorship" or "modern autocracy". Public sovereignty in modern governments is a lot more common with examples like the US, Canada, Australia and India where the government is divided into different levels.[51] |

内部主権 詳細情報:自由国家(政体) 内部主権とは、主権と政治共同体との関係である。 中心となる関心事は正当性であり、政府はどのような権利に基づいて権限を行使するのかという問題である。 正当性の主張は、王の神聖な権利、あるいは社会契約(すなわち人民主権)を指す場合がある。[要出典] マックス・ウェーバーは、政治的権限と正当性の最初の分類として、伝統的、カリスマ的、法的・合理的なカテゴリーを提示した。 「主権」とは、地域や国家に対して最高かつ独立した権限を持つことを意味し、「内政主権」とは、国家の内部問題と、その内部における最高権力の所在を指 す。[47] 内政主権を持つ国家とは、国民によって選出された政府を持ち、国民の支持に基づく正統性を有する国家である。内政主権は、国家の内部問題と、その運営方法 を検証する。秩序と平和を維持するためには、強力な内政主権が重要である。内部主権が弱い場合、反政府組織などの組織が権威を弱体化させ、平和を乱すこと になる。強力な権威があれば、合意を維持し、法律違反に対する制裁を課すことができる。リーダーシップがこうした違反を防止する能力は、内部主権を決定す る上で重要な変数である。[48] 内部主権の欠如は、次の2つのいずれかの方法で戦争を引き起こす可能性がある。まず、高額な違反を許すことで合意の価値を損なうこと、そして、実施に多大 な補助金を必要とするため、戦争が平和よりも安価になることである。[49] リーダーシップは、特に軍隊、警察、準軍事組織などのメンバーが合意を遵守することを約束できなければならない。強力な内部主権の存在は、国家が交渉と引 き換えに反対派グループを抑止することを可能にする。国家内の活動や事柄はその国家内の主権のレベルに相対するものであるが、主権国家において権限を誰が 保有すべきかについては依然として議論がある。 主権国家において権限を誰が保有すべきかというこの議論は、伝統的な公主権の教義と呼ばれる。この議論は、内部主権または公主権の権限の間で行われる。内 部主権者は、究極的、最終的、かつ独立した権限を有する政治的機関であり、その決定は社会のすべての市民、グループ、機関に対して拘束力を有する。初期の 思想家たちは、主権は単一の個人、君主の手に委ねられるべきだと考えていた。彼らは、単一の個人に主権を委ねる最大の利点は、主権が不可分であること、つ まり、最終的な権限を主張できる単一の声として表現されることだと考えていた。17世紀のフランス王ルイ14世は、自らが国家であると主張した。ジャン= ジャック・ルソーは君主制を否定し、主権国家における別の権威形態である人民主権を支持した。人民主権とは、究極の権限は人民自身に帰属するという信念で あり、一般意思の概念に表現されている。これは、権力は構成員によって選出され、支持されるものであり、権力は人民の幸福という中心的な目標を念頭に置い ていることを意味する。公共主権の考え方は、しばしば近代民主主義理論の基礎となっている。[50] 近代の内部主権 詳細は「部族主権」を参照 近代の政府システムにおいては、内部主権は通常、公共主権を有する国家に存在し、内部主権によって統制される国家に存在することはまれである。両者ともと はやや異なる形態の政府が、英国議会制である。ジョン・オースティンは、英国における主権は王冠にも国民にも帰属せず、「議会における女王」にあると主張 した。[6] これが議会の主権の教義の起源であり、通常、英国憲法の基本原則と見なされている。この議会の主権の原則により、多数派支配は無制限の憲法上の権限を手に 入れることができ、いわゆる「選挙による独裁」または「現代の専制政治」が生まれる。現代の政府における国民の主権は、米国、カナダ、オーストラリア、イ ンドなど、政府が異なるレベルに分かれている国々でより一般的である。[51] |

| External See also: Sovereign state § Recognition External sovereignty concerns the relationship between sovereign power and other states. For example, the United Kingdom uses the following criterion when deciding under what conditions other states recognise a political entity as having sovereignty over some territory; "Sovereignty." A government which exercises de facto administrative control over a country and is not subordinate to any other government in that country or a foreign sovereign state. (The Arantzazu Mendi, [1939] A.C. 256), Stroud's Judicial Dictionary External sovereignty is connected with questions of international law – such as when, if ever, is intervention by one country into another's territory permissible? Following the Thirty Years' War, a European religious conflict that embroiled much of the continent, the Peace of Westphalia in 1648 established the notion of territorial sovereignty as a norm of noninterference in the affairs of other states, so-called Westphalian sovereignty, even though the treaty itself reaffirmed the multiple levels of the sovereignty of the Holy Roman Empire. This resulted as a natural extension of the older principle of cuius regio, eius religio (Whose realm, his religion), leaving the Roman Catholic Church with little ability to interfere with the internal affairs of many European states. It is a myth, however, that the Treaties of Westphalia created a new European order of equal sovereign states.[52][53] In international law, sovereignty means that a government possesses full control over affairs within a territorial or geographical area or limit. Determining whether a specific entity is sovereign is not an exact science, but often a matter of diplomatic dispute. There is usually an expectation that both de jure and de facto sovereignty rest in the same organisation at the place and time of concern. Foreign governments use varied criteria and political considerations when deciding whether or not to recognise the sovereignty of a state over a territory.[citation needed] Membership in the United Nations requires that "[t]he admission of any such state to membership in the United Nations will be affected by a decision of the General Assembly upon the recommendation of the Security Council."[54] Sovereignty may be recognized even when the sovereign body possesses no territory or its territory is under partial or total occupation by another power. The Holy See was in this position between the annexation in 1870 of the Papal States by Italy and the signing of the Lateran Treaties in 1929, a 59-year period during which it was recognised as sovereign by many (mostly Roman Catholic) states despite possessing no territory – a situation resolved when the Lateran Treaties granted the Holy See sovereignty over the Vatican City. Another case, sui generis is the Sovereign Military Order of Malta, the third sovereign entity inside Italian territory (after San Marino and the Vatican City State) and the second inside the Italian capital (since in 1869 the Palazzo di Malta and the Villa Malta receive extraterritorial rights, in this way becoming the only "sovereign" territorial possessions of the modern Order), which is the last existing heir to one of several once militarily significant, crusader states of sovereign military orders. In 1607 its Grand masters were also made Reichsfürst (princes of the Holy Roman Empire) by the Holy Roman Emperor, granting them seats in the Reichstag, at the time the closest permanent equivalent to an UN-type general assembly; confirmed 1620. These sovereign rights were never deposed, only the territories were lost. Over 100 modern states maintain full diplomatic relations with the order,[55] and the UN awarded it observer status.[56] The governments-in-exile of many European states (for instance, Norway, Netherlands or Czechoslovakia) during the Second World War were regarded as sovereign despite their territories being under foreign occupation; their governance resumed as soon as the occupation had ended. The government of Kuwait was in a similar situation vis-à-vis the Iraqi occupation of its country during 1990–1991.[57] The government of Republic of China (ROC) was generally recognized as sovereign over China from 1911 to 1971 despite the 1949 victory of the Communists in the Chinese civil war and the retreat of the ROC to Taiwan. The ROC represented China at the United Nations until 1971, when the People's Republic of China obtained the UN seat.[58]: 228 The ROC political status as a state became increasingly disputed; it became commonly known as Taiwan. The International Committee of the Red Cross is commonly mistaken to be sovereign. It has been granted various degrees of special privileges and legal immunities in many countries, including Belgium, France, Switzerland,[59] Australia, Russia, South Korea, South Africa and the US, and soon in Ireland. The Committee is a private organisation governed by Swiss law.[60] |

外部 関連情報:主権国家 § 承認 外部主権とは、主権と他の国家との関係を指す。例えば、英国は、ある政治的実体がどの領土に対して主権を有していると他の国家が承認するかを決定する際に、以下の基準を用いている。 「主権」 ある国に対して事実上の行政権を行使し、その国の政府または外国の主権国家に従属しない政府。 (The Arantzazu Mendi, [1939] A.C. 256)、ストロードの司法辞典 外部主権は、国際法上の問題と関連している。例えば、ある国が他国の領土に介入することが許されるのはどのような場合か、という問題である。 ヨーロッパの大部分を巻き込んだ宗教戦争である30年戦争の後、1648年のウェストファリア条約では、いわゆるウェストファリア主権として、他国の内政 に干渉しないという原則として領土主権の概念が確立された。ただし、この条約自体は神聖ローマ帝国の複数のレベルにおける主権を再確認するものであった。 これは、クィウス・レギオ・エイウス・レリギオ(「その領域、その宗教」)という古い原則の自然な延長として生じたものであり、ローマ・カトリック教会が 多くのヨーロッパ諸国の内政に干渉する能力をほとんど持たないまま残された。しかし、ウェストファリア条約が対等な主権国家からなる新たなヨーロッパ秩序 を創出したというのは神話である。 国際法において、主権とは、政府が領土または地理的領域内における事柄を完全に管理できることを意味する。特定の主体が主権を有するかどうかを決定するこ とは、厳密な科学ではなく、しばしば外交上の論争となる。通常、問題となっている場所や時間において、デ・ユリス(法的な)主権とデ・ファクト(事実上 の)主権が同じ組織に属することが期待されている。外国政府は、領土に対する国家の主権を承認するかどうかを決定する際に、さまざまな基準と政治的考慮を 用いる。[要出典] 国連への加盟には、「『そのような国家の国連への加盟は、安全保障理事会の勧告に基づく総会の決定により決定される』」ことが必要である。[54] 主権は、主権を有する機関が領土を保有していない場合や、その領土が他国によって部分的にまたは完全に占領されている場合でも、認められることがある。 1870年の教皇領のイタリア併合から1929年のラテラノ条約締結までの間、バチカン市国はこのような立場にあった。59年間にわたって、領土を持たな いにもかかわらず、多くの(主にローマ・カトリックの)国家から主権を認められていた。この状況は、ラテラノ条約によってバチカン市国に対する主権がバチ カンに認められたことで解消された。また、イタリア領内にある3番目の主権国家(サンマリノ、バチカン市国に次ぐ)であり、イタリア首都内にある2番目の 主権国家(1869年にマルタ宮殿とマルタ荘園が治外法権を獲得して以来、この2つは近代の騎士団にとって唯一の「主権」 領土は、かつて軍事的にも重要な十字軍騎士団国家のひとつであったが、現存する最後の継承者である。1607年には、大管長は神聖ローマ皇帝からライヒス フュルスト(神聖ローマ帝国の諸侯)の称号も与えられ、帝国議会での議席が認められた。これは当時、国連総会に最も近い恒久的な機関であった。1620年 に確認された。これらの主権は一度も剥奪されることなく、失われたのは領土のみであった。100以上の現代国家が、この教団と完全な外交関係を維持してお り[55]、国連はオブザーバー資格を与えている[56]。 第二次世界大戦中の多くのヨーロッパ諸国(例えば、ノルウェー、オランダ、チェコスロバキア)の亡命政府は、領土が外国の占領下にあったにもかかわらず、 主権を有するとみなされていた。占領が終了すると、これらの政府による統治が再開された。1990年から1991年にかけてのイラクによる占領下にあった クウェート政府も同様の状況にあった。[57] 中華民国政府は、1911年から1971年にかけて、中国における主権者として一般的に認められていた。これは、1949年の中国内戦における共産党の勝 利と中華民国の台湾への撤退にもかかわらずである。中華民国は1971年まで国連において中国を代表していたが、この年、中華人民共和国が国連の席を得 た。[58]: 228 中華民国の国家としての政治的地位は次第に論争の的となり、一般的に「台湾」と呼ばれるようになった。 赤十字国際委員会は、しばしば主権を有していると誤解されている。ベルギー、フランス、スイス、オーストラリア、ロシア、韓国、南アフリカ、アメリカ合衆 国など多くの国で、さまざまな程度の特別権限と法的特権が認められており、まもなくアイルランドでも認められる。赤十字国際委員会はスイス法に基づく民間 団体である。 |

| Shared and pooled Just as the office of head of state can be vested jointly in several persons within a state, the sovereign jurisdiction over a single political territory can be shared jointly by two or more consenting powers, notably in the form of a condominium.[61] Likewise the member states of international organizations may voluntarily bind themselves by treaty to a supranational organization, such as a continental union. In the case of the European Union member-states, this is called "pooled sovereignty".[62][63] Another example of shared and pooled sovereignty is the Acts of Union 1707 which created the unitary state now known as the United Kingdom.[64][65][66] It was a full economic union, meaning the Scottish and English systems of currency, taxation and laws regulating trade were aligned.[67] Nonetheless, Scotland and England never fully surrendered or pooled all of their governance sovereignty; they retained many of their previous national institutional features and characteristics, particularly relating to their legal, religious and educational systems.[68] In 2012, the Scottish Government, created in 1998 through devolution in the United Kingdom, negotiated terms with the Government of the United Kingdom for the 2014 Scottish independence referendum which resulted in the people of Scotland deciding to continue the pooling of its sovereignty with the rest of the United Kingdom. |

共有および共同 国家元首の職務が国家内の複数の人格に共同で帰属しうるのと同様に、単一の政治的領域に対する主権的管轄権は、特に共同統治の形態で、同意した2つ以上の権力によって共同で共有されうる。 同様に、国際組織の加盟国は、条約によって自発的に超国家組織、例えば大陸同盟などに自らを拘束することがある。欧州連合加盟国の場合、これを「共有主権」と呼ぶ。[62][63] 主権の共有とプール(共有)のもう一つの例は、現在のイギリスとして知られる単一国家を創設した1707年の連合法である。 [64][65][66] これは完全な経済同盟であり、スコットランドとイングランドの通貨、課税、貿易を規制する法律のシステムが統一されたことを意味する。[67] しかし、スコットランドとイングランドは、統治の主権を完全に放棄したり、すべてを共有したわけではない。両国は、特に法律、宗教、教育システムに関連し て、以前の国民制度の特徴や特性の多くを維持している。 [68] 1998年に英国の地方分権により設立されたスコットランド政府は、2014年のスコットランド独立の是非を問う住民投票について英国政府と交渉し、その 結果、スコットランドの人々は英国の他の地域との主権の共有を継続することを決定した。 |

| Nation-states A community of people who claim the right of self-determination based on a common ethnicity, history and culture might seek to establish sovereignty over a region, thus creating a nation-state. Such nations are sometimes recognised as autonomous areas rather than as fully sovereign, independent states. |

国民国家 共通の民族性、歴史、文化に基づいて自決権を主張する人々の共同体は、地域に対する主権を確立しようとするかもしれない。その結果、国民国家が誕生する。このような国家は、完全な主権を有する独立国家ではなく、自治地域として認められることもある。 |

| Federations In a federal system of government, sovereignty also refers to powers which a constituent state or republic possesses independently of the national government. In a confederation, constituent entities retain the right to withdraw from the national body and the union is often more temporary than a federation.[69] Different interpretations of state sovereignty in the United States of America, as it related to the expansion of slavery and fugitive slave laws, led to the outbreak of the American Civil War. Depending on the particular issue, sometimes both northern and southern states justified their political positions by appealing to state sovereignty. Fearing that slavery would be threatened by results of the 1860 presidential election, eleven slave states declared their independence from the federal Union and formed a new confederation.[70] The United States government rejected the secessions as rebellion, declaring that secession from the Union by an individual state was unconstitutional, as the states were part of an indissoluble federation in Perpetual Union.[71] |

連邦 政府の連邦制においては、主権とはまた、構成州や共和国が中央政府とは独立して有する権限を指す。連合においては、構成単位は国家機構からの離脱権を保持しており、連合は連邦よりも一時的なものであることが多い。 奴隷制の拡大と逃亡奴隷法に関連して、アメリカ合衆国における国家主権の解釈が異なることが、南北戦争の勃発につながった。特定の問題によっては、北部と 南部の両方の州が、自らの政治的立場を国家主権に訴えることで正当化した。1860年の大統領選挙の結果によって奴隷制が脅かされることを恐れた11の奴 隷州は、連邦からの独立を宣言し、新たな連合を結成した。[70] 米国政府は、この離脱を反逆行為として拒絶し、個々の州による連邦からの離脱は違憲であると宣言した。なぜなら、各州は不可分の永久連合の一部であるから だ。[71] |

| Sovereignty versus military occupation In situations related to war, or which have arisen as the result of war, most modern scholars still commonly fail to distinguish between holding sovereignty and exercising military occupation. In regard to military occupation, international law prescribes the limits of the occupant's power. Occupation does not displace the sovereignty of the occupied state, though for the time being the occupant may exercise supreme governing authority. Nor does occupation effect any annexation or incorporation of the occupied territory into the territory or political structure of the occupant, and the occupant's constitution and laws do not extend of their own force to the occupied territory.[72] To a large extent, the original academic foundation for the concept of "military occupation" arose from On the Law of War and Peace (1625) by Hugo Grotius and The Law of Nations (1758) by Emmerich de Vattel. Binding international rules regarding the conduct of military occupation were more carefully codified in the 1907 Hague Convention (and accompanying Hague Regulations). In 1946, the Nuremberg International Military Tribunal stated with regard to the Hague Convention on Land Warfare of 1907: "The rules of land warfare expressed in the Convention undoubtedly represented an advance over existing International Law at the time of their adoption ... but by 1939 these rules ... were recognized by all civilized nations and were regarded as being declaratory of the laws and customs of war." |

主権と軍事占領 戦争に関連する状況、または戦争の結果として生じた状況において、ほとんどの現代の学者は依然として、主権の保有と軍事占領の実行を区別できていない。 軍事占領に関しては、国際法は占領者の権限の限界を規定している。占領は占領国の主権を奪うものではないが、占領者は当面の間、最高統治権を行使できる。 また、占領は占領地域の併合や占領者の領土や政治体制への編入を意味するものではなく、占領者の憲法や法律は占領地域に自動的に適用されるものではない。 「軍事占領」という概念の学術的な基礎は、ほぼ全面的に、フーゴー・グローティウスの『戦争と平和の法』(1625年)とエメリク・デ・ヴァッテルの『国 家法』(1758年)に由来している。軍事占領の遂行に関する拘束力のある国際規則は、1907年のハーグ条約(および同条約に付随するハーグ規則)にお いてより慎重に成文化された。 1946年、ニュルンベルク国際軍事法廷は、1907年の陸戦のハーグ条約について、「条約に示された陸戦の規則は、その採択時の既存の国際法を間違いな く前進させたものであったが、1939年までにこれらの規則は...すべての文明国によって認められ、戦争の法と慣習を明示するものとしてみなされるよう になった」と述べた。 |

| Acquisition Main article: Acquisition of sovereignty A number of modes for acquisition of sovereignty are presently or have historically been recognized in international law as lawful methods by which a state may acquire sovereignty over external territory. The classification of these modes originally derived from Roman property law and from the 15th and 16th century with the development of international law. The modes are:[73] Cession is the transfer of territory from one state to another usually by means of treaty; Occupation is the acquisition of territory that belongs to no state (or terra nullius); Prescription is the effective control of territory of another acquiescing state; Operations of nature is the acquisition of territory through natural processes like river accretion or volcanism; Creation is the process by which new land is (re)claimed from the sea such as in the Netherlands. Adjudication and Conquest  |

獲得 主権の取得 詳細は主権の取得を参照 主権の取得には、現在または歴史的に国際法で合法的な方法として認められているいくつかの形態がある。これらの形態の分類は、もともとローマの財産法に由来し、15世紀から16世紀にかけて国際法が発展する中で生まれた。その形態は以下の通りである。 割譲とは、通常は条約によって、ある国家から別の国家へ領土が移転することである。 占領とは、どの国家にも属さない領土(terra nullius)の獲得を指す。 時効とは、他国の領有を認める国家による領土の実効支配を指す。 自然作用とは、河川の堆積や火山作用などの自然現象による領土の獲得を指す。 創造とは、オランダのように、海から新たな土地を(再)獲得するプロセスを指す。 裁定と 征服  |

| Justifications There exist vastly differing views on the moral basis of sovereignty. A fundamental polarity is between theories which assert that sovereignty is vested directly in the sovereigns by divine or natural right, and theories which assert it originates from the people. In the latter case there is a further division into those which assert that the people effectively transfer their sovereignty to the sovereign (Hobbes), and those which assert that the people retain their sovereignty (Rousseau).[74] During the brief period of absolute monarchies in Europe, the divine right of kings was an important competing justification for the exercise of sovereignty. The Mandate of Heaven had similar implications in China for the justification of the Emperor's rule, though it was largely replaced with discussions of Western-style sovereignty by the late 19th century.[75] A republic is a form of government in which the people, or some significant portion of them, retain sovereignty over the government and where offices of state are not granted through heritage.[76][77] A common modern definition of a republic is a government having a head of state who is not a monarch.[78][79] Democracy is based on the concept of popular sovereignty. In a direct democracy the public plays an active role in shaping and deciding policy. Representative democracy permits a transfer of the exercise of sovereignty from the people to a legislative body or an executive (or to some combination of the legislature, executive and Judiciary). Many representative democracies provide limited direct democracy through referendum, initiative, and recall. Parliamentary sovereignty refers to a representative democracy where the parliament is ultimately sovereign, rather than the executive power or the judiciary. |

正当化 主権の道徳的根拠については、大きく異なる見解が存在する。根本的な対立は、主権が神権または自然権によって君主たちに直接付与されると主張する理論と、 主権が人民に由来すると主張する理論との間にある。後者の場合、人民が実質的に主権を君主たちに譲渡すると主張するもの(ホッブズ)と、人民が主権を保持 すると主張するもの(ルソー)とにさらに分かれる。[74] ヨーロッパにおける絶対王政の短い期間においては、王の神聖な権利は主権の行使を正当化する重要な対抗概念であった。天命は中国において皇帝の支配を正当化する同様の含みを持ち、19世紀末までには西洋式の主権に関する議論にほぼ取って代わられたが、[75] 共和国とは、国民またはそのかなりの部分が政府に対する主権を保持し、国家の役職が世襲によって与えられることがない政治形態である。[76][77] 現代における一般的な共和国の定義は、君主ではない国家元首を持つ政府である。[78][79] 民主主義は人民主権の概念に基づいている。直接民主主義では、国民が政策の形成と決定に積極的に関与する。代表制民主主義では、主権の行使を国民から立法 機関や行政機関(あるいは立法、行政、司法の組み合わせ)に移譲することが認められている。多くの代表制民主主義では、国民投票、発議、リコールを通じて 限定的な直接民主主義が認められている。 議会主権とは、行政権や司法権ではなく議会が最終的な主権を持つ代表制民主主義を指す。 |

| Views Classical liberals such as John Stuart Mill consider every individual as sovereign. Realists view sovereignty as being untouchable and as guaranteed to legitimate nation-states.[citation needed] Rationalists see sovereignty similarly to realists. However, rationalism states that the sovereignty of a nation-state may be violated in extreme circumstances, such as human rights abuses.[citation needed] Internationalists believe that sovereignty is outdated and an unnecessary obstacle to achieving peace, in line with their belief in a global community. In the light of the abuse of power by sovereign states such as Hitler's Germany or Stalin's Soviet Union, they argue that human beings are not necessarily protected by the state whose citizens they are and that the respect for state sovereignty on which the UN Charter is founded is an obstacle to humanitarian intervention.[80] Anarchists and some libertarians deny the sovereignty of states and governments. Anarchists often argue for a specific individual kind of sovereignty, such as the Anarch as a sovereign individual. Salvador Dalí, for instance, talked of "anarcho-monarchist" (as usual for him, tongue in cheek); Antonin Artaud of Heliogabalus: Or, The Crowned Anarchist; Max Stirner of The Ego and Its Own; Georges Bataille and Jacques Derrida talked of a kind of "antisovereignty". Therefore, anarchists join a classical conception of the individual as sovereign of himself, which forms the basis of political consciousness. The unified consciousness is sovereignty over one's own body, as Nietzsche demonstrated (see also Pierre Klossowski's book on Nietzsche and the Vicious Circle). See also sovereignty of the individual and self-ownership. Imperialists hold a view of sovereignty where power rightfully exists with those states that hold the greatest ability to impose the will of said state, by force or threat of force, over the populace of other states with weaker military or political will. They effectively deny the sovereignty of the individual in deference to either the good of the whole or to divine right.[citation needed] According to Matteo Laruffa "sovereignty resides in every public action and policy as the exercise of executive powers by institutions open to the participation of citizens to the decision-making processes"[81] |

見解 ジョン・スチュアート・ミルなどの古典的自由主義者は、すべての個人は主権者であると考える。 現実主義者は、主権は不可侵であり、合法的な国民国家に保証されていると考える。 合理主義者は、現実主義者と同様に主権を捉える。しかし、合理主義は、人権侵害などの極端な状況下では、国民国家の主権が侵害される可能性があるとしている。 国際主義者は、主権は時代遅れであり、平和の達成にとって不必要な障害であると信じている。これは、グローバルコミュニティの信念に沿ったものである。ヒ トラーのドイツやスターリンのソビエト連邦のような主権国家による権力の乱用を踏まえ、彼らは、人間は必ずしも自国民である国家によって守られているわけ ではないと主張し、国連憲章の基礎となっている国家主権の尊重は、人道的介入の障害であると主張している。 アナーキストや一部のリバタリアンは、国家や政府の主権を否定する。アナーキストは、しばしば「アナーキストを主権者たる個人」とするような、特定の個人 による主権を主張する。例えば、サルバドール・ダリは「アナルコ君主制」(彼らしく皮肉を込めて)について語り、アントナン・アルトーは『ヘリオガバル ス、あるいは王冠を戴いたアナーキスト』を、マックス・シュティルナーは『自我と自己』を、ジョルジュ・バタイユとジャック・デリダは「反主権」について 語っている。したがって、アナーキストは、政治的意識の基礎をなす、自己の主権者としての古典的な個人の概念に合流する。統一された意識とは、ニーチェが 示したように、自己の身体に対する主権である(ニーチェと悪循環に関するピエール・クロソフスキの著書も参照)。個人の主権と自己所有権も参照。 帝国主義者は、自国の意思を他国の国民に対して、武力または武力の威嚇によって、軍事力や政治的意思が弱い他国に強制する能力が最も高い国家に正当な権力 が存在するという主権観を持っている。彼らは、全体的な利益や神聖な権利を尊重する立場から、個人の主権を事実上否定している。 マッテオ・ラルファによると、「主権は、意思決定プロセスへの市民参加を可能にする機関による行政権の行使として、あらゆる公共の行動や政策に存在する」[81]。 |

| Air sovereignty Autonomous area Basileus Mandate of Heaven National sovereignty Plenary authority Self-ownership Self-sovereign identity Souverainism Suzerainty |

領空主権 自治地域 君主 天命 国民主権 完全な権限 自己所有 自己主権的アイデンティティ 宗主権論 宗主権 |

| Benton, Lauren (2010). A Search

for Sovereignty: Law and Geography in European Empires, 1400–1900.

Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-88105-0. Grimm, Dieter (2015). Howard, Dick (ed.). Sovereignty: The Origin and Future of a Political and Legal Concept. Columbia Studies in Political Thought / Political History. Translated by Cooper, Belinda (e-book ed.). Columbia University Press. ISBN 9780231539302. Paris, R. (2020). "The Right to Dominate: How Old Ideas About Sovereignty Pose New Challenges for World Order." International Organization Philpott, Dan (2016). "Sovereignty". Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Prokhovnik, Raia (2007). Sovereignties: contemporary theory and practice. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire New York, N.Y: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403913234. Prokhovnik, Raia (2008). Sovereignty: history and theory. Exeter, UK Charlottesville, VA: Imprint Academic. ISBN 9781845401412. Thomson, Janice E. (1996). Mercenaries, pirates, and sovereigns: state-building and extraterritorial violence in early modern Europe. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-0-691-02571-1. |

ベントン、ローレン(2010年)。『主権の探求:1400年から1900年のヨーロッパ帝国における法と地理』ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-521-88105-0。 グリム、ディーター(2015年)。ハワード、ディック(編)。『主権:政治的・法的概念の起源と未来』 コロンビア大学出版局。ISBN 9780231539302。 パリ、R. (2020年)。「支配する権利:主権に関する古い考え方が世界秩序に新たな課題をもたらす方法」『インターナショナル・オーガニゼーション』 Philpott, Dan (2016). 「Sovereignty」. Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Metaphysics Research Lab, Stanford University. Prokhovnik, Raia (2007). Sovereignties: contemporary theory and practice. Houndmills, Basingstoke, Hampshire New York, N.Y: Palgrave Macmillan. ISBN 9781403913234. Prokhovnik, Raia (2008). 主権:歴史と理論。英国エクセター、バージニア州シャーロッツビル:Imprint Academic. ISBN 9781845401412. トムソン、ジャニス・E. (1996年). 傭兵、海賊、そして君主:初期近代ヨーロッパにおける国家形成と域外暴力. プリンストン大学出版. ISBN 978-0-691-02571-1. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sovereignty |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆