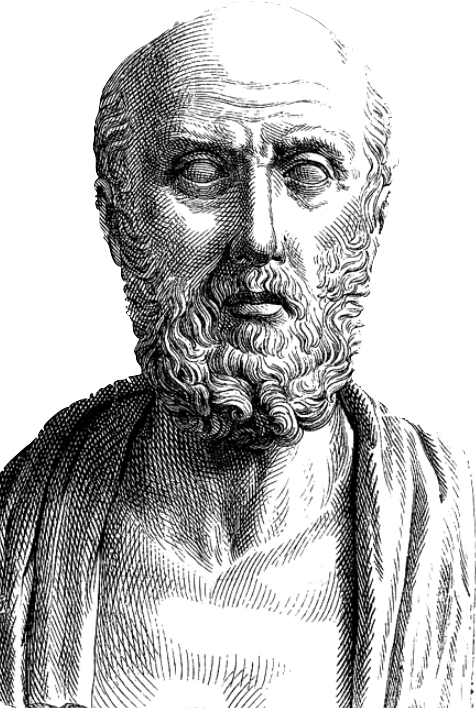

ヒポクラテス

Hippocrates, ca. 460 BC-370 BC

☆ コスのヒポクラテス(ギリシア語: DZποκράτης ΚǷος, Hippokrátēs ho Kôios; c. 460 - c. 370 BC)は、ヒポクラテス2世としても知られる古典期のギリシアの医師で、医学史上最も傑出した人物の一人と考えられている。ヒポクラテスは伝統的に「医学 の父」と呼ばれ、予後診断や臨床観察、系統的な疾病分類、体液学説の確立など、医学界に多大な貢献をした。ヒポクラテス派の医学は古代ギリシアの医学に革 命をもたらし、伝統的に医学が関連していた他の分野(神学や哲学)とは異なる学問分野として確立させ、医学を職業として確立させた。

| Hippocrates

of Kos (/hɪˈpɒkrətiːz/; Greek: Ἱπποκράτης ὁ Κῷος, translit. Hippokrátēs

ho Kôios; c. 460 – c. 370 BC), also known as Hippocrates II, was a

Greek physician of the classical period who is considered one of the

most outstanding figures in the history of medicine. He is

traditionally referred to as the "Father of Medicine" in recognition of

his lasting contributions to the field, such as the use of prognosis

and clinical observation, the systematic categorization of diseases, or

the formulation of humoral theory. The Hippocratic school of medicine

revolutionized ancient Greek medicine, establishing it as a discipline

distinct from other fields with which it had traditionally been

associated (theurgy and philosophy), thus establishing medicine as a

profession.[1][2] However, the achievements of the writers of the Hippocratic Corpus, the practitioners of Hippocratic medicine, and the actions of Hippocrates himself were often conflated; thus very little is known about what Hippocrates actually thought, wrote, and did. Hippocrates is commonly portrayed as the paragon of the ancient physician and credited with coining the Hippocratic Oath, which is still relevant and in use today. He is also credited with greatly advancing the systematic study of clinical medicine, summing up the medical knowledge of previous schools, and prescribing practices for physicians through the Hippocratic Corpus and other works.[1][3] |

コ

スのヒポクラテス(/hɪˈpɒkrətiː/; ギリシア語: DZποκράτης ΚǷος, translated. Hippokrátēs

ho Kôios; c. 460 - c. 370

BC)は、ヒポクラテス2世としても知られる古典期のギリシアの医師で、医学史上最も傑出した人物の一人と考えられている。ヒポクラテスは伝統的に「医学

の父」と呼ばれ、予後診断や臨床観察、系統的な疾病分類、体液学説の確立など、医学界に多大な貢献をした。ヒポクラテス派の医学は古代ギリシアの医学に革

命をもたらし、伝統的に医学が関連していた他の分野(神学や哲学)とは異なる学問分野として確立させ、医学を職業として確立させた[1][2]。 しかし、ヒポクラテス語録の執筆者、ヒポクラテス医学の実践者、ヒポクラテス自身の行動はしばしば混同され、ヒポクラテスが実際に何を考え、何を書き、何 をしたのかについてはほとんど知られていない。ヒポクラテスは一般に古代の医師の模範として描かれ、ヒポクラテスの誓いを作ったとされている。ヒポクラテ スはまた、臨床医学の体系的な研究を大きく前進させ、それまでの学派の医学知識を総括し、『ヒポクラテス語録』やその他の著作を通じて医師のための実践法 を処方したことでも知られている[1][3]。 |

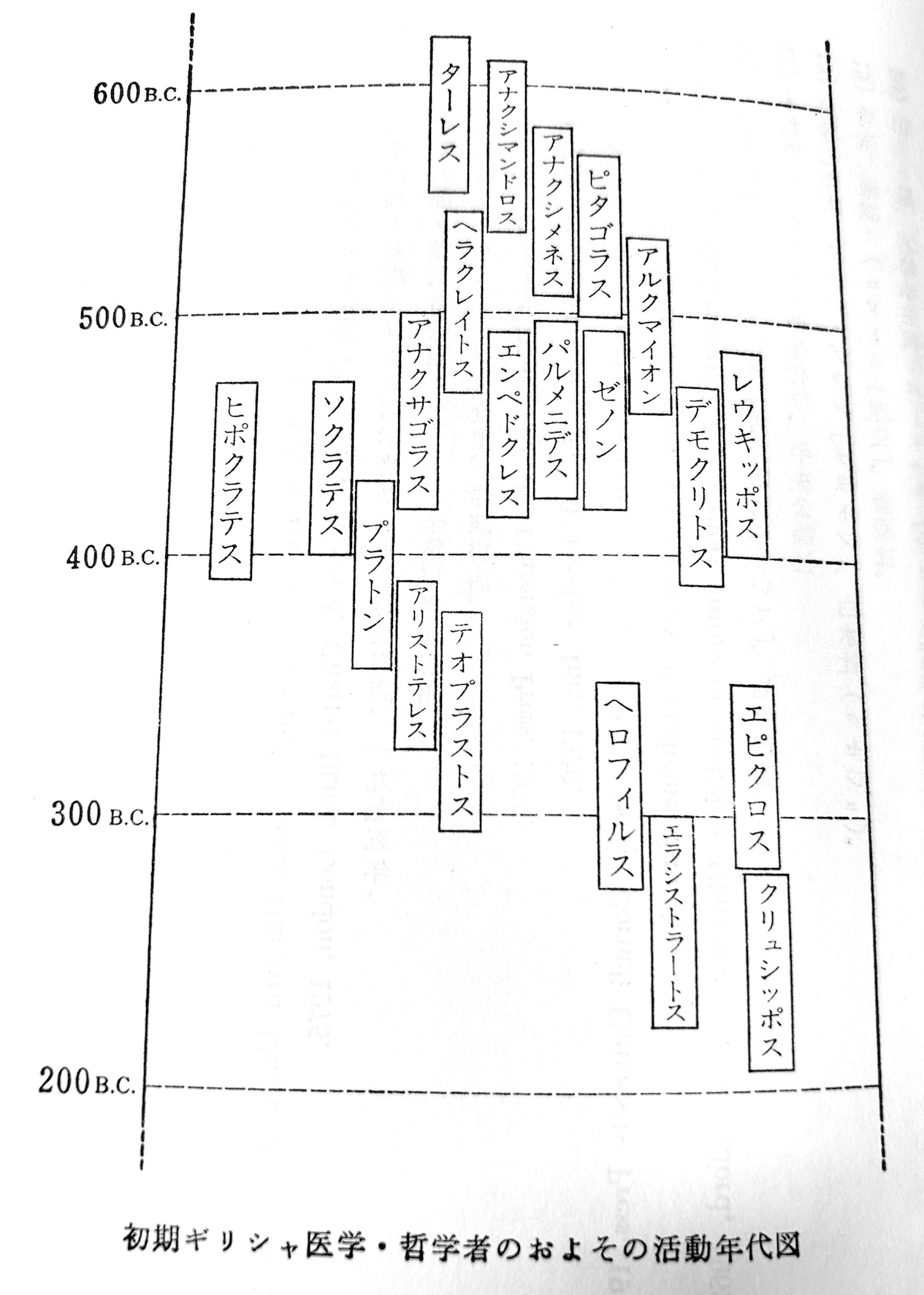

Biography Illustration of the story of Hippocrates refusing the presents of the Achaemenid Emperor Artaxerxes, who was asking for his services. Painted by Girodet, 1792.[4] Historians agree that Hippocrates was born around the year 460 BC on the Greek island of Kos; other biographical information, however, is likely to be untrue.[5] Soranus of Ephesus, a 2nd-century Greek physician,[6] was Hippocrates' first biographer and is the source of most personal information about him. Later biographies are in the Suda of the 10th century AD, and in the works of John Tzetzes, which date from the 12th century AD.[1][7] Hippocrates is mentioned in passing in the writings of two contemporaries: in Plato's dialogues Protagoras and Phaedrus,[8] and in Aristotle's Politics, all of which date from the 4th century BC.[9] Soranus wrote that Hippocrates' father was Heraclides, a physician, and his mother was Praxitela, daughter of Tizane. The two sons of Hippocrates, Thessalus and Draco, and his son-in-law, Polybus, were his students. According to Galen, a later physician, Polybus, was Hippocrates' true successor, while Thessalus and Draco each had a son named Hippocrates (Hippocrates III and IV).[10][11] Soranus said that Hippocrates learned medicine from his father and grandfather (Hippocrates I), and studied other subjects with Democritus and Gorgias. Hippocrates was probably trained at the asklepieion of Kos, and took lessons from the Thracian physician Herodicus of Selymbria. Plato mentions Hippocrates in two of his dialogues: in Protagoras, Plato describes Hippocrates as "Hippocrates of Kos, the Asclepiad";[12][13] while in Phaedrus, Plato suggests that "Hippocrates the Asclepiad" thought that a complete knowledge of the nature of the body was necessary for medicine.[14] Hippocrates taught and practiced medicine throughout his life, traveling at least as far as Thessaly, Thrace, and the Sea of Marmara. Several different accounts of his death exist. He died, probably in Larissa, at the age of 83, 85 or 90, though some say he lived to be well over 100.[11]  Hipopocrates and other Greek thinkers |

伝記 ヒポクラテスがアケメネス朝皇帝アルタクセルクセスからの贈り物を断った挿絵。1792年、ジロデによって描かれた[4]。 歴史家たちは、ヒポクラテスが紀元前460年頃にギリシャのコス島で生まれたことに同意している。しかし、その他の伝記的情報は真実ではない可能性が高い[5]。 2世紀のギリシャの医師であるエフェソスのソラヌス[6]は、ヒポクラテスの最初の伝記作者であり、ヒポクラテスに関するほとんどの個人的な情報の源と なっている。ヒポクラテスは、紀元前4世紀に書かれたプラトンの対話篇『プロタゴラス』と『パイドロス』[8]、およびアリストテレスの『政治学』[9] という、同時代の2人の著書の中で言及されている。 ソラヌスは、ヒポクラテスの父は医師ヘラクリデス、母はティザネの娘プラクシテラであったと記している。ヒポクラテスの2人の息子テッサロスとドラコ、そ して義理の息子ポリブスは、ヒポクラテスの弟子であった。ガレノスによれば、後の医師ポリブスがヒポクラテスの真の後継者であり、テッサロスとドラコには それぞれヒポクラテスという名の息子(ヒポクラテス3世と4世)がいた[10][11]。 ソラヌスは、ヒポクラテスは父と祖父(ヒポクラテス1世)から医学を学び、デモクリトスとゴルギアスから他の学問を学んだと述べている。ヒポクラテスはお そらくコスのアスクレピオンで訓練を受け、セリンブリアのトラキア人医師ヘロディクスの教えを受けたのであろう。プラトンは『プロタゴラス』においてヒポ クラテスを「アスクレピオスであるコス島のヒポクラテス」と表現し[12][13]、『パイドロス』においてプラトンは「アスクレピオスであるヒポクラテ ス」が医学には身体の性質についての完全な知識が必要であると考えていたことを示唆している[14]。ヒポクラテスの死については、いくつかの異なる説が ある。彼はおそらくラリッサで83歳、85歳、90歳で亡くなったが、100歳以上生きたという説もある[11]。  ヒポクラテスの時代:彼と古代ギリシア時代の哲学者・思想家たち |

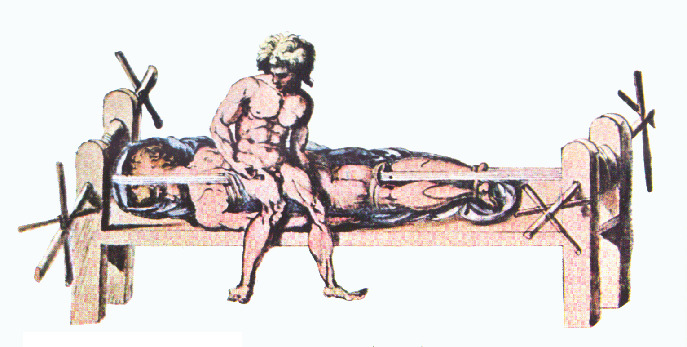

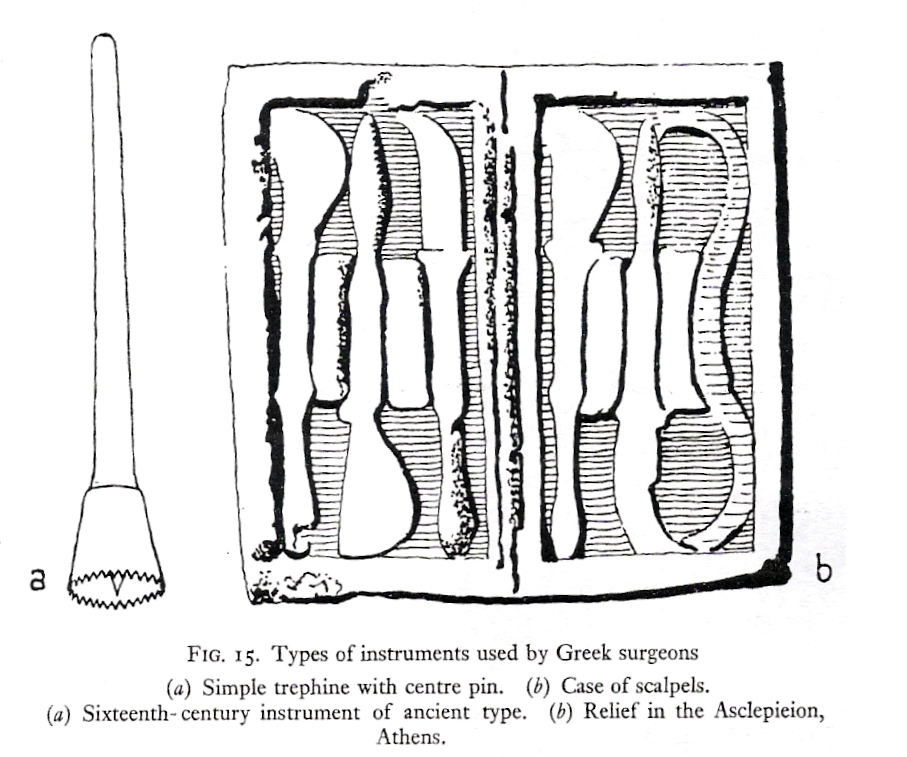

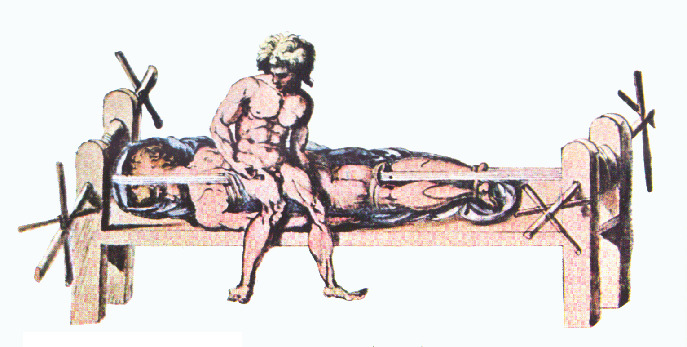

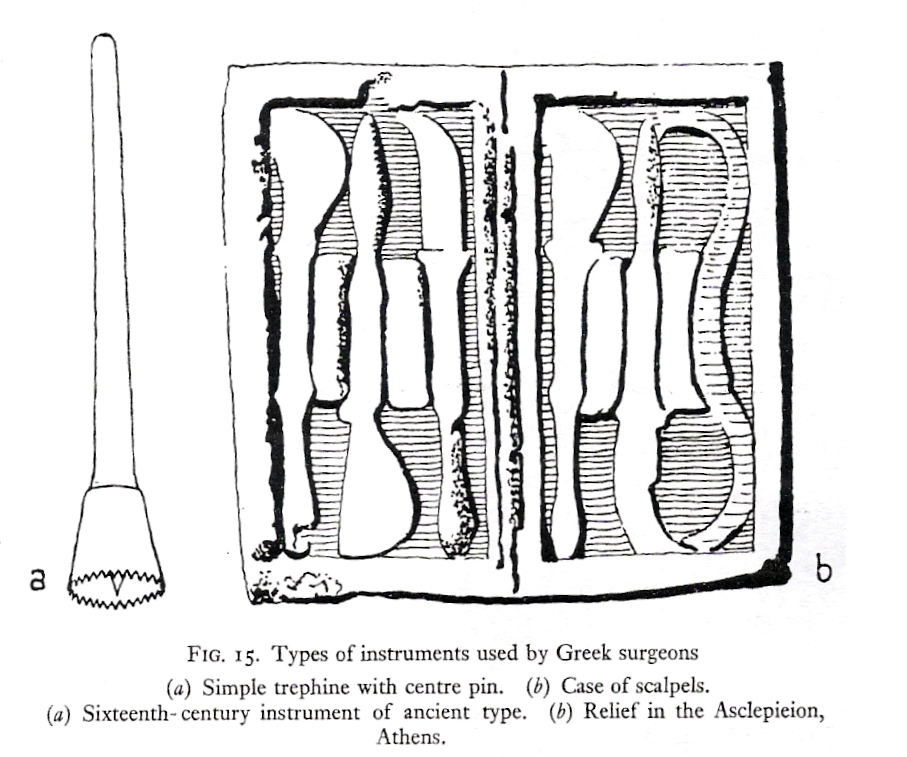

| Hippocratic theory It is thus with regard to the disease called Sacred: it appears to me to be nowise more divine nor more sacred than other diseases, but has a natural cause from the originates like other affections. Men regard its nature and cause as divine from ignorance and wonder.... — Hippocrates, On the Sacred Disease Hippocrates is credited as the first person to believe that diseases were caused naturally, not because of superstition and gods.[15][16][17][18] He was acknowledged by the disciples of Pythagoras for allying philosophy and medicine.[15] He separated the discipline of medicine from religion, believing and arguing that disease was not a punishment inflicted by the gods but rather the product of environmental factors, diet, and living habits. There is not a single mention of a mystical illness in the entirety of the Hippocratic Corpus. However, Hippocrates did hold many convictions that were based on incorrect anatomy and physiology, such as Humorism.[16][17][18] Ancient Greek schools of medicine were split into the Knidian and Koan on how to deal with disease. The Knidian school of medicine focused on diagnosis. Medicine at the time of Hippocrates knew almost nothing of human anatomy and physiology because of the Greek taboo forbidding the dissection of humans. The Knidian school consequently failed to distinguish when one disease caused many possible series of symptoms.[19] The Hippocratic school or Koan school achieved greater success by applying general diagnoses and passive treatments. Its focus was on patient care and prognosis, not diagnosis. It could effectively treat diseases and allowed for a great development in clinical practice.[20][21] Hippocratic medicine and its philosophy are far removed from modern medicine, in which the physician focuses on specific diagnosis and specialized treatment, both of which were espoused by the Knidian school. This shift in medical thought since Hippocrates' day has generated serious criticism of their denunciations; for example, the French doctor M. S. Houdart called the Hippocratic treatment a "meditation upon death".[22] If you want to learn about the health of a population, look at the air they breathe, the water they drink, and the places where they live.[23][24] — Hippocrates, 5th century BC Analogies have been drawn between Thucydides' historical method and the Hippocratic method, in particular the notion of "human nature" as a way of explaining foreseeable repetitions for future usefulness, for other times or for other cases.[25] Crisis  Asklepieion on Kos An important concept in Hippocratic medicine was that of a crisis, a point in the progression of disease at which either the illness would begin to triumph and the patient would succumb to death, or the opposite would occur and natural processes would make the patient recover. After a crisis, a relapse might follow, and then another deciding crisis. According to this doctrine, crises tend to occur on critical days, which were supposed to be a fixed time after the contraction of a disease. If a crisis occurred on a day far from a critical day, a relapse might be expected. Galen believed that this idea originated with Hippocrates, though it is possible that it predated him.[26]  Illustration of a Hippocratic bench, date unknown Hippocratic medicine was humble and passive. The therapeutic approach was based on "the healing power of nature" ("vis medicatrix naturae" in Latin). According to this doctrine, the body contains within itself the power to re-balance the four humours and heal itself (physis).[27] Hippocratic therapy focused on simply easing this natural process. To this end, Hippocrates believed "rest and immobilization [were] of capital importance".[28] In general, the Hippocratic medicine was very kind to the patient; treatment was gentle, and emphasized keeping the patient clean and sterile. For example, only clean water or wine were ever used on wounds, though "dry" treatment was preferable. Soothing balms were sometimes employed.[29] Hippocrates was reluctant to administer drugs and engage in specialized treatment that might prove to be wrongly chosen; generalized therapy followed a generalized diagnosis.[29][30] Some of the generalized treatments he prescribed are fasting and the consumption of a mix of honey and vinegar. Hippocrates once said that "to eat when you are sick, is to feed your sickness". However, potent drugs were used on certain occasions.[31] This passive approach was very successful in treating relatively simple ailments such as broken bones, which required traction to stretch the skeletal system and relieve pressure on the injured area. The Hippocratic bench and other devices were used to this end.[32] In Hippocrates' time it was thought that fever was a disease in and of itself.[33] Hippocrates treated patients with fever by starving them out,[34] believing that 'starving' the fever was a way to neutralize the disease.[35] He may therefore have been the originator of the idea "Feed a cold, starve a fever".[36] One of the strengths of Hippocratic medicine was its emphasis on prognosis. At Hippocrates' time, medicinal therapy was quite immature, and often the best thing that physicians could do was to evaluate an illness and predict its likely progression based upon data collected in detailed case histories.[18][37] Professionalism  A number of ancient Greek surgical tools. On the left is a trephine; on the right, a set of scalpels. Hippocratic medicine made good use of these tools.[38] Hippocratic medicine was notable for its strict professionalism, discipline, and rigorous practice.[39] The Hippocratic work On the Physician recommends that physicians always be well-kempt, honest, calm, understanding, and serious. The Hippocratic physician paid careful attention to all aspects of his practice: he followed detailed specifications for, "lighting, personnel, instruments, positioning of the patient, and techniques of bandaging and splinting" in the ancient operating room.[40] He even kept his fingernails to a precise length.[41] The Hippocratic School gave importance to the clinical doctrines of observation and documentation. These doctrines dictate that physicians record their findings and their medicinal methods in a very clear and objective manner, so that these records may be passed down and employed by other physicians.[11] Hippocrates made careful, regular note of many symptoms including complexion, pulse, fever, pains, movement, and excretions.[37] He is said to have measured a patient's pulse when taking a case history to discover whether the patient was lying.[42] Hippocrates extended clinical observations into family history and environment.[43] "To him medicine owes the art of clinical inspection and observation."[18] |

ヒポクラテスの理論 聖なる病と呼ばれる病気は、他の病気よりも神々しくも神聖でもない。人々は無知と驚きから、その性質と原因を神聖なものと見なしている......。 - ヒポクラテス『聖なる病について ヒポクラテスは、病気は迷信や神々のせいではなく、自然に引き起こされると信じた最初の人物として知られている[15][16][17][18]。彼は哲 学と医学を結びつけたことで、ピタゴラスの弟子たちから認められていた[15]。ヒポクラテス全集には、神秘的な病気についての記述はひとつもない。しか し、ヒポクラテスはユーモリズムのような間違った解剖学や生理学に基づく多くの信念を持っていた[16][17][18]。 古代ギリシアの医学の学派は、病気への対処法についてクニディアンとコアンに分かれていた。クニディア派の医学は診断に重点を置いていた。ヒポクラテスの 時代の医学は、ギリシャのタブーによって人間の解剖が禁じられていたため、人間の解剖学や生理学についてほとんど何も知らなかった。ヒポクラテス学派は、 一般的な診断と受動的な治療によって大きな成功を収めた。その焦点は診断ではなく、患者のケアと予後にあった。それは効果的に病気を治療することができ、 臨床における大きな発展を可能にした[20][21]。 ヒポクラテスの医学とその哲学は、医師が特定の診断と専門的な治療に重点を置く現代医学とはかけ離れており、クニディウス学派はその両方を信奉していた。 このようなヒポクラテスの時代からの医学思想の変化は、彼らの糾弾に対する深刻な批判を生んでいる。例えば、フランスの医師M・S・ウダールは、ヒポクラ テスの治療を「死の瞑想」と呼んだ[22]。 ある集団の健康状態について知りたければ、彼らが呼吸する空気、飲む水、そして彼らが住む場所を見ればよい[23][24]。 - ヒポクラテス、紀元前5世紀 トゥキュディデスの歴史的手法とヒポクラテスの手法の間には類似性があり、特に「人間の本性」という概念は、他の時代や他の事例に対して、将来の有用性のために予測可能な繰り返しを説明する方法として描かれている[25]。 危機  コス島におけるアスクレピオン ヒポクラテス医学における重要な概念は危機であり、病気の進行の中で、病気が勝利を収め始め、患者が死に至るか、あるいはその逆が起こり、自然のプロセス が患者を回復させるかのいずれかである。危機の後には再発が起こり、さらに危機が訪れる。この教義によれば、危機は重要な日に発生する傾向があり、それは 病気に罹患してから一定の時間が経過した後とされていた。もし危機が臨界日から離れた日に起これば、再発が予想される。ガレノスは、この考え方はヒポクラ テスに由来すると考えていたが、ヒポクラテス以前からあった可能性もある[26]。  ヒポクラテスのベンチのイラスト、年代不明 ヒポクラテスの医学は謙虚で受動的であった。治療のアプローチは、「自然の治癒力」(ラテン語で「vis medicatrix naturae」)に基づいていた。この教義によれば、身体には4つの体液のバランスを整え、自己治癒力(フィジス)を高める力が備わっているとされる [27]。この目的のために、ヒポクラテスは「安静と固定が極めて重要である」と考えた[28]。一般的に、ヒポクラテスの医学は患者に非常に優しく、治 療は穏やかで、患者を清潔で無菌状態に保つことを重視した。例えば、傷口には清潔な水かワインしか使われなかったが、「乾いた」治療が好まれた。鎮静効果 のあるバームが使われることもあった[29]。 ヒポクラテスは、薬剤を投与したり、間違った選択であることが判明するかもしれない専門的な治療に従事することに消極的であった;一般的な治療は、一般的 な診断に従った[29][30]。ヒポクラテスはかつて、「病気のときに食べることは、病気を養うことである」と言った。この受動的なアプローチは、骨折 のような比較的単純な病気の治療には非常に効果的で、骨格系を伸ばして負傷部位の圧力を和らげる牽引が必要だった。この目的のためにヒポクラテスのベンチ やその他の器具が用いられた[32]。 ヒポクラテスの時代には、発熱はそれ自体が病気であると考えられていた[33]。ヒポクラテスは、発熱を「飢えさせる」ことが病気を中和する方法であると考え、飢えさせることによって発熱患者を治療した[34]。 ヒポクラテス医学の長所のひとつは、予後を重視することであった。ヒポクラテスの時代には、薬物療法は非常に未熟であり、医師ができる最善のことは、病気を評価し、詳細な病歴で収集されたデータに基づいてその進行の可能性を予測することであった[18][37]。 プロフェッショナリズム  古代ギリシャの手術器具の数々。左はトレフィン、右はメス。ヒポクラテス医学はこれらの道具をうまく活用していた[38]。 ヒポクラテスの著作『医師について』では、医師は常に身だしなみを整え、誠実で、冷静で、理解力があり、真面目であることが推奨されている[39]。ヒポ クラテスの医師は、診療のあらゆる面に細心の注意を払っていた。古代の手術室では、「照明、人員、器具、患者の位置、包帯やスプリントの技術」についての 詳細な仕様に従った[40]。 爪の長ささえも正確に保った[41]。 ヒポクラテス学派は、観察と記録という臨床の教義を重要視していた。ヒポクラテスは、顔色、脈拍、発熱、痛み、運動、排泄物など、多くの症状を注意深く定期的に記録していた。 [ヒポクラテスは臨床的な観察を家族歴や環境にも広げていた[43]。 |

Direct contributions to medicine Clubbing of fingers in a patient with Eisenmenger's syndrome; first described by Hippocrates, clubbing is also known as "Hippocratic fingers".  A woodcut of the reduction of a dislocated shoulder with a Hippocratic device Hippocrates and his followers were first to describe many diseases and medical conditions.[44] He is given credit for the first description of clubbing of the fingers, an important diagnostic sign in chronic lung disease, lung cancer and cyanotic heart disease. For this reason, clubbed fingers are sometimes referred to as "Hippocratic fingers".[45] Hippocrates was also the first physician to describe Hippocratic face in Prognosis. Shakespeare famously alludes to this description when writing of Falstaff's death in Act II, Scene iii. of Henry V.[46][47] Hippocrates began to categorize illnesses as acute, chronic, endemic and epidemic, and use terms such as, "exacerbation, relapse, resolution, crisis, paroxysm, peak, and convalescence."[37][48] Another of Hippocrates' major contributions may be found in his descriptions of the symptomatology, physical findings, surgical treatment and prognosis of thoracic empyema, i.e. suppuration of the lining of the chest cavity. His teachings remain relevant to present-day students of pulmonary medicine and surgery.[49] Hippocrates was the first documented chest surgeon and his findings and techniques, while crude, such as the use of lead pipes to drain chest wall abscess, are still valid.[49] The Hippocratic school of medicine described well the ailments of the human rectum and the treatment thereof, despite the school's poor theory of medicine. Hemorrhoids, for instance, though believed to be caused by an excess of bile and phlegm, were treated by Hippocratic physicians in relatively advanced ways.[50][51] Cautery and excision are described in the Hippocratic Corpus, in addition to the preferred methods: ligating the hemorrhoids and drying them with a hot iron. Other treatments such as applying various salves are suggested as well.[52][53] Today, "treatment [for hemorrhoids] still includes burning, strangling, and excising."[50] Also, some of the fundamental concepts of proctoscopy outlined in the Corpus are still in use.[50][51] For example, the uses of the rectal speculum, a common medical device, are discussed in the Hippocratic Corpus.[51] This constitutes the earliest recorded reference to endoscopy.[54][55] Hippocrates often used lifestyle modifications such as diet and exercise to treat diseases such as diabetes, what is today called lifestyle medicine. Two popular but likely misquoted attributions to Hippocrates are "Let food be your medicine, and medicine be your food" and "Walking is man's best medicine".[56] Both appear to be misquotations, and their exact origins remain unknown.[57][58] In 2017, researchers claimed that, while conducting restorations on the Saint Catherine's Monastery in South Sinai, they found a manuscript which contains a medical recipe of Hippocrates. The manuscript also contains three recipes with pictures of herbs that were created by an anonymous scribe.[59] |

医学への直接的貢献 アイゼンメンジャー症候群の患者における指の棍棒形成。ヒポクラテスによって初めて記述され、棍棒形成は「ヒポクラテスの指」とも呼ばれる。  ヒポクラテスの器具による肩の脱臼の軽減の木版画 ヒポクラテスとその信奉者たちは、多くの疾患や病状を最初に記述した。 慢性肺疾患、肺がん、チアノーゼ性心疾患の重要な診断徴候である指の内反を最初に記述したのは、ヒポクラテスである[44]。このため、指の内反は「ヒポ クラテスの指」と呼ばれることもある[45]。ヒポクラテスはまた、予後診断においてヒポクラテスの顔を記述した最初の医師でもある。シェイクスピアは、 『ヘンリー五世』の第二幕第三場でファルスタッフの死を書く際に、この記述を引用していることで有名である[46][47]。 ヒポクラテスは、病気を急性、慢性、風土病、流行病に分類し、「増悪、再燃、解消、危機、発作、ピーク、回復」といった用語を用いるようになった。ヒポク ラテスは、記録に残る最初の胸部外科医であり、胸壁膿瘍のドレナージに鉛管を使用するなど、粗雑ではあるが、彼の知見と技術は今でも有効である[49]。 ヒポクラテス学派の医学は、その貧弱な医学理論にもかかわらず、人間の直腸の病気とその治療法についてよく記述していた。例えば、痔は胆汁と痰の過剰に よって引き起こされると信じられていたが、ヒポクラテスの医師たちは比較的先進的な方法で治療していた[50][51]。今日でも、「(痔核の)治療に は、焼灼、絞扼、切除が含まれる」[50]。 [50][51] 例えば、一般的な医療器具である直腸鏡の使用法が『ヒポクラテス語録』で論じられている[51] 。 ヒポクラテスの2つの有名な、しかし誤引用である可能性が高い帰結は、「食を薬とし、薬を食とせよ」と「歩くことは人間の最良の薬である」である[56]。 2017年、研究者たちは、南シナイにある聖カタリナ修道院の修復を行っているときに、ヒポクラテスの医学レシピを含む写本を発見したと主張した。この写本には、匿名の書記によって作成された薬草の絵が描かれた3つのレシピも含まれている[59]。 |

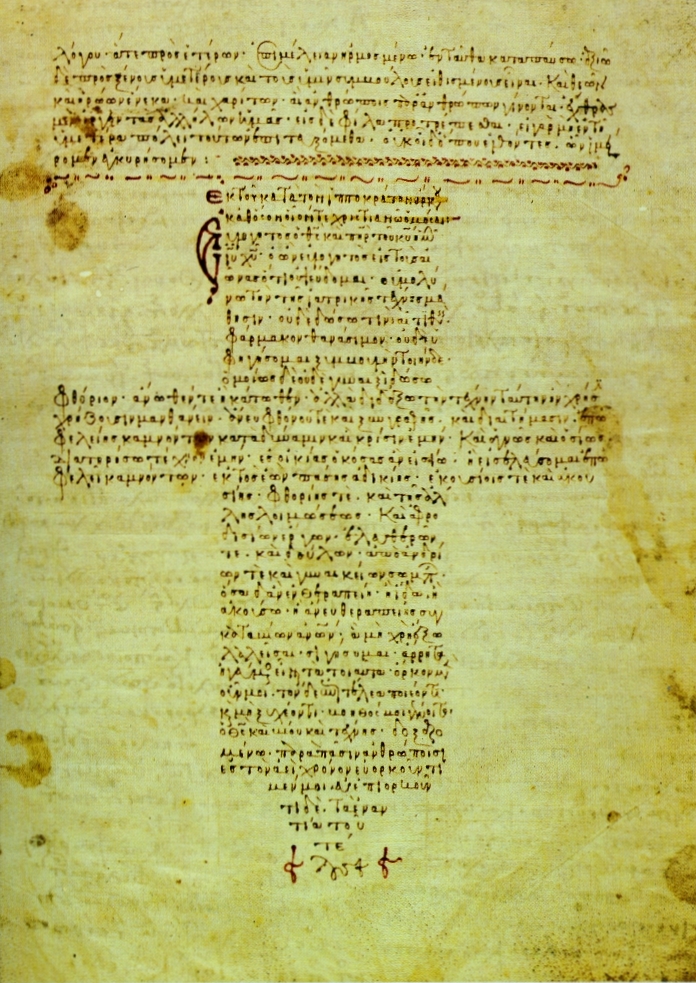

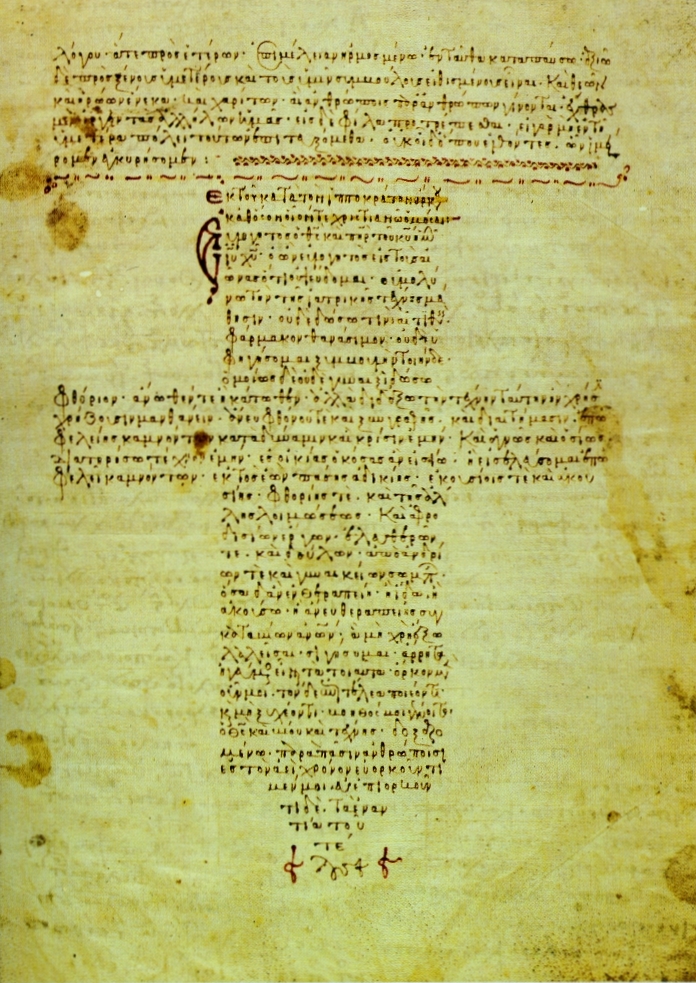

| Hippocratic Corpus Main article: Hippocratic Corpus  A 12th-century Byzantine manuscript of the Oath in the form of a cross The Hippocratic Corpus (Latin: Corpus Hippocraticum) is a collection of around seventy early medical works collected in Alexandrian Greece.[60] It is written in Ionic Greek. The question of whether Hippocrates himself was the author of any of the treatises in the corpus has not been conclusively answered,[61] but modern debate revolves around only a few of the treatises seen as potentially authored by him. Because of the variety of subjects, writing styles and apparent date of construction, the Hippocratic Corpus could not have been written by one person (Ermerins numbers the authors at nineteen).[31] The corpus came to be known by his name because of his fame, possibly all medical works were classified under 'Hippocrates' by a librarian in Alexandria.[12][40][62] The volumes were probably produced by his students and followers.[63] The Hippocratic Corpus contains textbooks, lectures, research, notes and philosophical essays on various subjects in medicine, in no particular order.[61][64] These works were written for different audiences, both specialists and laymen, and were sometimes written from opposing viewpoints; significant contradictions can be found between works in the Corpus.[65] Among the treatises of the Corpus are The Hippocratic Oath; The Book of Prognostics; On Regimen in Acute Diseases; Aphorisms; On Airs, Waters and Places; Instruments of Reduction; On The Sacred Disease; etc.[31] Hippocratic Oath Main article: Hippocratic Oath The Hippocratic Oath, a seminal document on the ethics of medical practice, was attributed to Hippocrates in antiquity although new information shows it may have been written after his death. This is probably the most famous document of the Hippocratic Corpus. Recently, the authenticity of the document's author has come under scrutiny. While the Oath is rarely used in its original form today, it serves as a foundation for other, similar oaths and laws that define good medical practice and morals.[66] Such derivatives are regularly taken by modern medical graduates about to enter medical practice.[12][67][68] |

ヒポクラテス聖典 主な記事 ヒポクラテス聖典  十字架の形をした誓いの12世紀のビザンチン写本 ヒポクラテス・コルプス』(ラテン語:Corpus Hippocraticum)は、アレクサンドリア・ギリシャで収集された約70の初期の医学書を集めたものである[60]。ヒポクラテス自身がこのコー パスに収録されている論文の著者であるかどうかについては、決定的な答えが得られていない[61]が、現代の議論は、ヒポクラテスが執筆した可能性のある いくつかの論文を中心に展開されている。ヒポクラテスの名で知られるようになったのは、彼の名声のためであり、おそらくアレクサンドリアの司書によってす べての医学書が「ヒポクラテス」の下に分類されたのであろう[12][40][62]。 ヒポクラテス語録』には、医学における様々な主題に関する教科書、講義、研究、ノート、哲学的エッセイが順不同で収められている[61][64]。これら の著作は、専門家と素人という異なる読者に向けて書かれ、時には相反する視点から書かれることもあった。 [ヒポクラテスの誓い』、『予言の書』、『急性疾患における養生法』、『格言』、『空気、水、場所について』、『還元器具』、『聖なる病について』などが ある[31]。 ヒポクラテスの誓い 主な記事 ヒポクラテスの誓い ヒポクラテスの誓いは、医術の倫理に関する代表的な文書であり、ヒポクラテスの死後に書かれたものである可能性が新しい情報によって示されているが、古代 にはヒポクラテスのものとされていた。ヒポクラテス語録の中で最も有名な文書であろう。最近、この文書の著者の真偽が問われている。今日、この誓いがその ままの形で使用されることはほとんどないが、良い医療行為とモラルを定義する他の類似した誓いや法律の基礎として役立っている[66]。このような派生物 は、医療行為に入ろうとする現代の医学卒業生が定期的に受けている[12][67][68]。 |

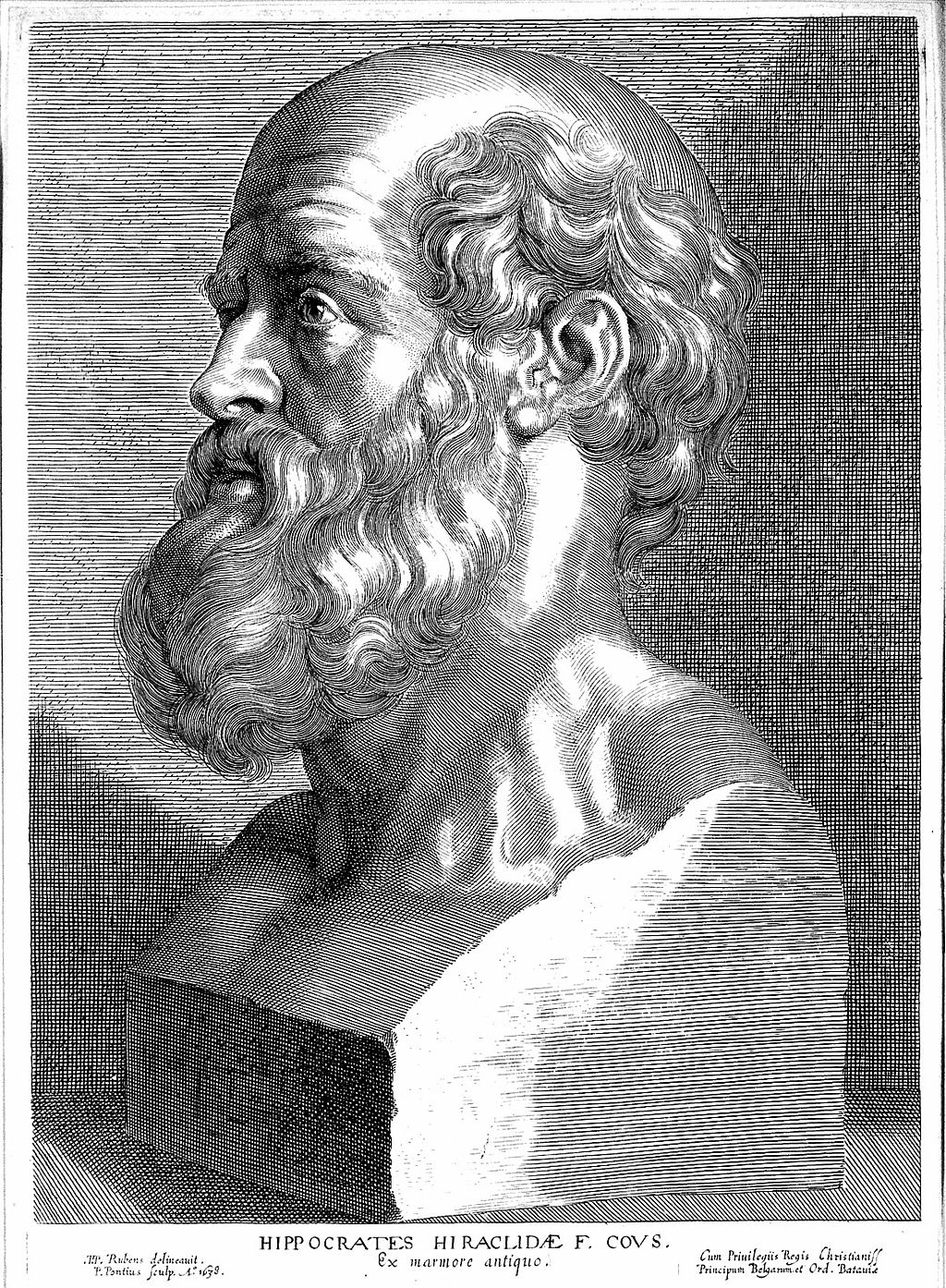

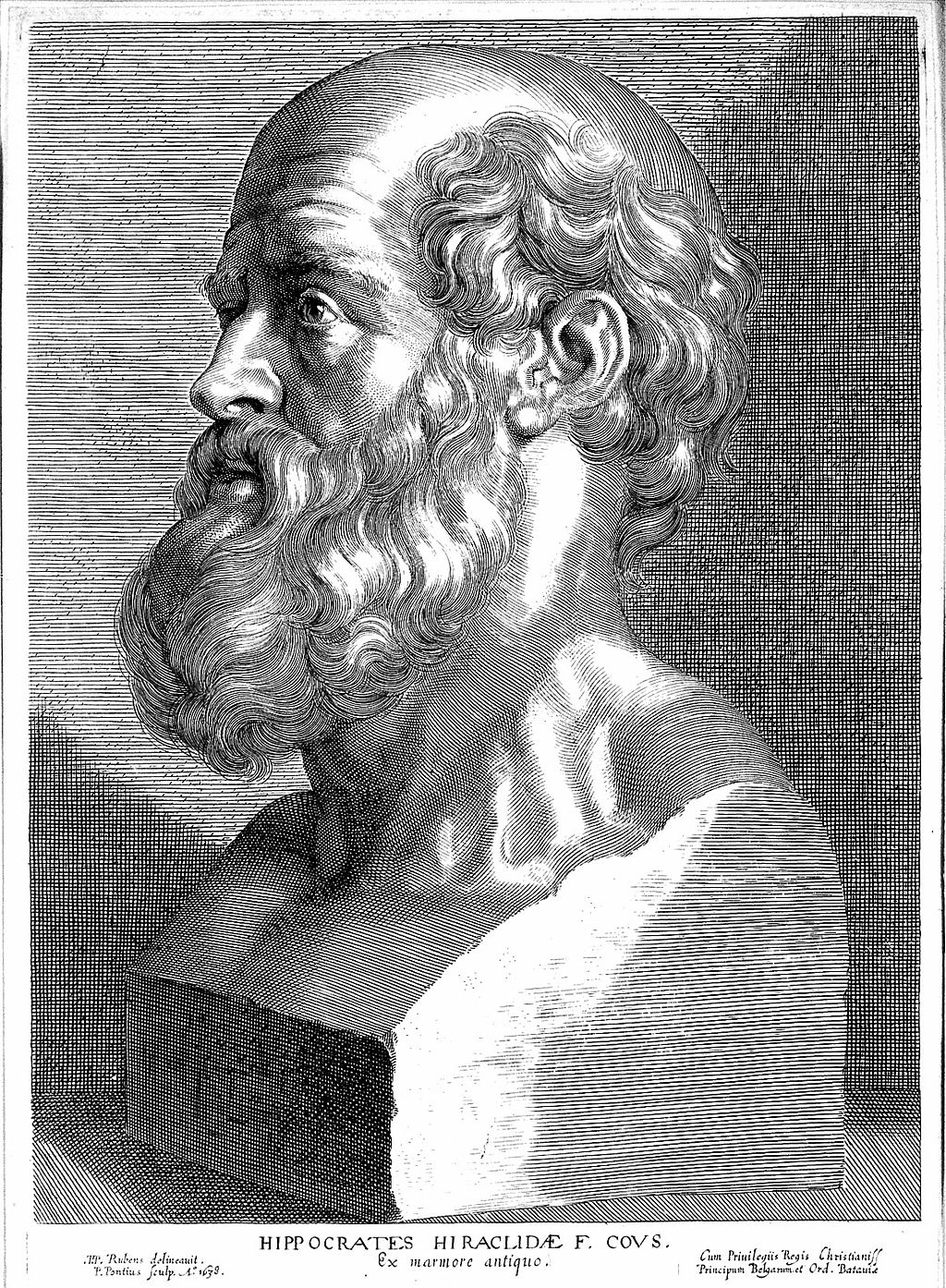

Legacy Mural painting showing Galen and Hippocrates. 12th century; Anagni, Italy Although Hippocrates neither founded the school of medicine named after him, nor wrote most of the treatises attributed to him, he is traditionally regarded as the "Father of Medicine".[69] His contributions revolutionized the practice of medicine; but after his death the advancement stalled.[70] So revered was Hippocrates that his teachings were largely taken as too great to be improved upon and no significant advancements of his methods were made for a long time.[12][28] The centuries after Hippocrates' death were marked as much by retrograde movement as by further advancement. For instance, "after the Hippocratic period, the practice of taking clinical case-histories died out," according to Fielding Garrison.[71] After Hippocrates, another significant physician was Galen, a Greek who lived from AD 129 to AD 200. Galen perpetuated the tradition of Hippocratic medicine, making some advancements, but also some regressions.[72][73] In the Middle Ages, the Islamic world adopted Hippocratic methods and developed new medical technologies.[74] After the European Renaissance, Hippocratic methods were revived in western Europe and even further expanded in the 19th century. Notable among those who employed Hippocrates' rigorous clinical techniques were Thomas Sydenham, William Heberden, Jean-Martin Charcot and William Osler. Henri Huchard, a French physician, said that these revivals make up "the whole history of internal medicine."[75] Image  Engraving: bust of Hippocrates by Paulus Pontius after Peter Paul Rubens, 1638 According to Aristotle's testimony, Hippocrates was known as "The Great Hippocrates".[76] Concerning his disposition, Hippocrates was first portrayed as a "kind, dignified, old country doctor" and later as "stern and forbidding".[12] He is certainly considered wise, of very great intellect and especially as very practical. Francis Adams describes him as "strictly the physician of experience and common sense."[19] His image as the wise, old doctor is reinforced by busts of him, which wear large beards on a wrinkled face. Many physicians of the time wore their hair in the style of Jove and Asklepius. Accordingly, the busts of Hippocrates that have been found could be only altered versions of portraits of these deities.[70] Hippocrates and the beliefs that he embodied are considered medical ideals. Fielding Garrison, an authority on medical history, stated, "He is, above all, the exemplar of that flexible, critical, well-poised attitude of mind, ever on the lookout for sources of error, which is the very essence of the scientific spirit."[75] "His figure... stands for all time as that of the ideal physician," according to A Short History of Medicine, inspiring the medical profession since his death.[77] Legends The Travels of Sir John Mandeville reports (incorrectly) that Hippocrates was the ruler of the islands of "Kos and Lango" [sic], and recounts a legend about Hippocrates' daughter. She was transformed into a hundred-foot long dragon by the goddess Diana, and is the "lady of the manor" of an old castle. She emerges three times a year, and will be turned back into a woman if a knight kisses her, making the knight into her consort and ruler of the islands. Various knights try, but flee when they see the hideous dragon; they die soon thereafter. This is a version of the legend of Melusine.[78] |

遺産 ガレノスとヒポクラテスを描いた壁画。12世紀、イタリア、アナニ ヒポクラテスは、彼の名を冠した医学部を創設したわけでもなく、彼によるとされる論文のほとんどを書いたわけでもないが、伝統的に「医学の父」とみなされ ている[69]。彼の貢献は医学の実践に革命をもたらしたが、彼の死後、進歩は停滞した。 [ヒポクラテスの死後数世紀は、さらなる進歩よりも逆行が目立った。例えば、フィールディング・ギャリソンによれば、「ヒポクラテスの時代以降、臨床の症 例記録をとる習慣は廃れた」[71]。 ヒポクラテスの後のもう一人の重要な医師は、AD129年からAD200年まで生きたギリシャ人のガレンであった。ガレノスはヒポクラテスの医学の伝統を 永続させ、いくつかの進歩を遂げたが、後退もした[72][73]。 中世では、イスラム世界がヒポクラテスの方法を採用し、新しい医療技術を開発した[74]。 ヨーロッパのルネサンス以降、ヒポクラテスの方法は西ヨーロッパで復活し、19世紀にはさらに拡大した。ヒポクラテスの厳格な臨床技術を採用した人物とし て、トーマス・シデナム、ウィリアム・ヘバーデン、ジャン=マルタン・シャルコー、ウィリアム・オスラーなどが有名である。フランスの医師アンリ・ユ シャールは、これらの復興が「内科学の全歴史」を構成していると述べている[75]。 画像  エングレーヴィング:ヒポクラテスの胸像、パウルス・ポンティウス作、ピーター・パウル・ルーベンス後、1638年 アリストテレスの証言によれば、ヒポクラテスは「偉大なるヒポクラテス」として知られていた[76]。ヒポクラテスの性格については、最初は「親切で威厳 のある、田舎の老医師」として描かれ、後には「厳格で禁欲的」な人物として描かれた[12]。フランシス・アダムスは彼を「経験と常識に厳格な医師」と評 している[19]。 賢明な老医師としての彼のイメージは、皺だらけの顔に大きな髭を蓄えた彼の胸像によって補強されている。当時の多くの医師は、ヨーヴェやアスクレピオスの スタイルで髪を結っていた。従って、発見されたヒポクラテスの胸像は、これらの神々の肖像画を変化させたものにすぎない可能性がある[70]。医学史の権 威であるフィールディング・ギャリソン(Fielding Garrison)は、「彼は何よりも、科学的精神の真髄である、誤りの原因を常に探し求める、柔軟で批判的な、よく構えた心の態度の模範である」と述べ ている[75]。 伝説 ジョン・マンデヴィル卿の旅行記』は、ヒポクラテスが「コス島とランゴ島」[中略]の支配者であったと(誤って)報告しており、ヒポクラテスの娘について の伝説を語っている。ヒポクラテスの娘は、女神ディアナによって100フィートもあるドラゴンに姿を変えられ、古城の "荘園の女主人 "となっている。彼女は年に3回現れ、騎士がキスをすれば女に戻り、その騎士を彼女の妃にして島々の支配者とする。様々な騎士が試すが、恐ろしいドラゴン を見て逃げ出し、その後すぐに死んでしまう。これはメリュジーヌ伝説の一バージョンである[78]。 |

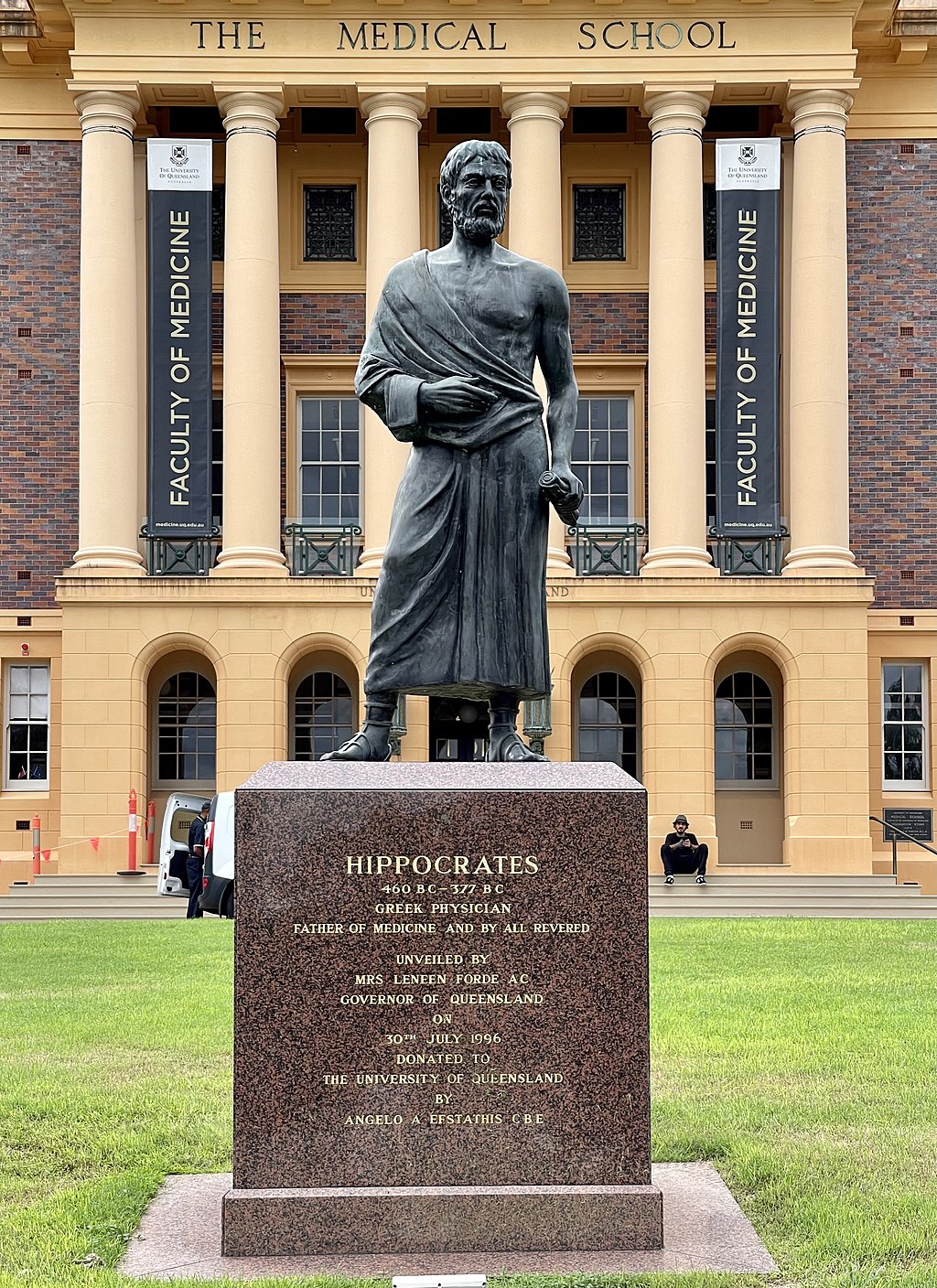

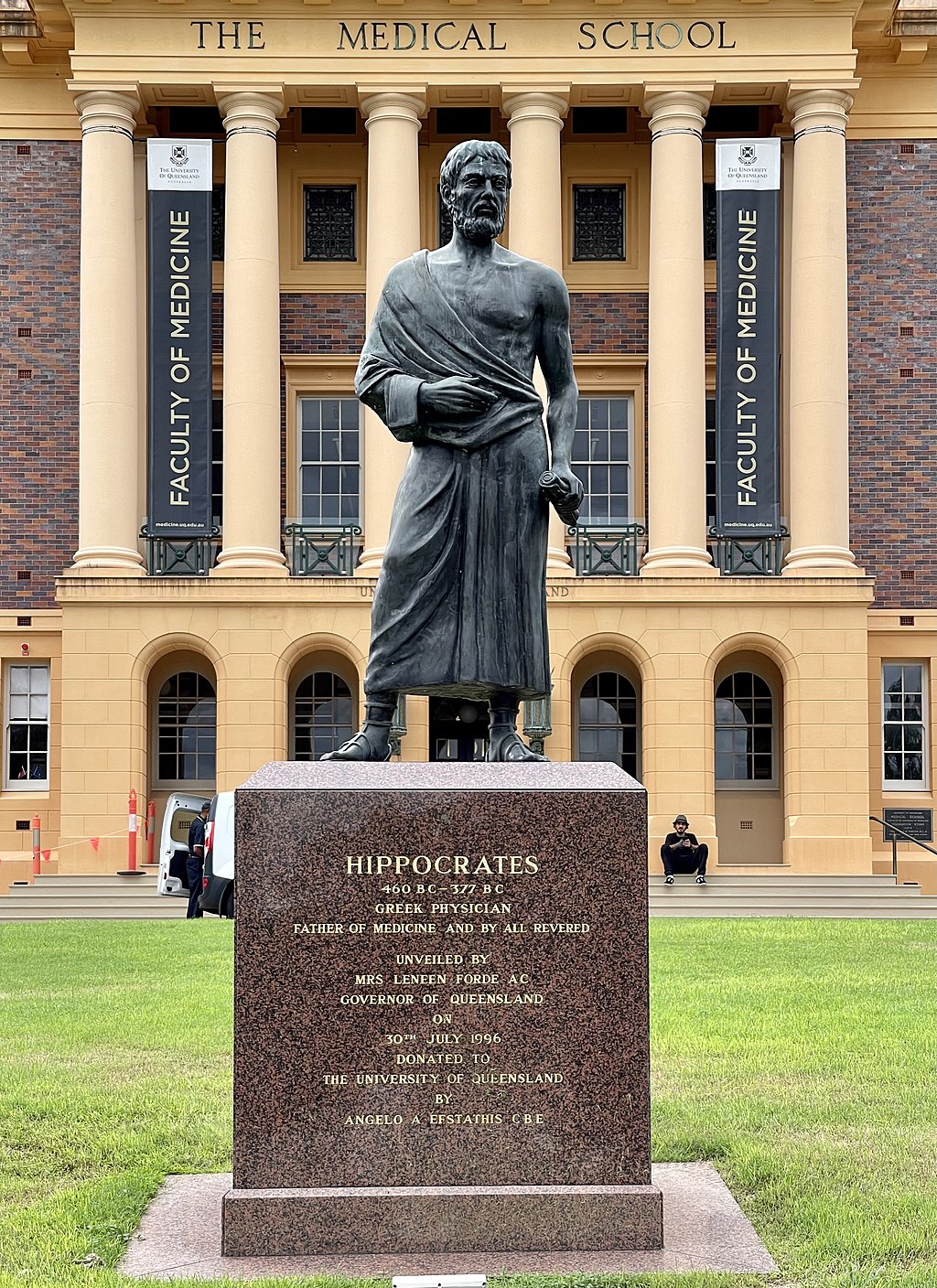

Namesakes Statue of Hippocrates in front of the Mayne Medical School in Brisbane Some clinical symptoms and signs have been named after Hippocrates as he is believed to be the first person to describe them. Hippocratic face is the change produced in the countenance by death, or long sickness, excessive evacuations, excessive hunger, and the like. Clubbing, a deformity of the fingers and fingernails, is also known as Hippocratic fingers. Hippocratic succussion is the internal splashing noise of hydropneumothorax or pyopneumothorax. Hippocratic bench (a device which uses tension to aid in setting bones) and Hippocratic cap-shaped bandage are two devices named after Hippocrates.[79] Hippocratic Corpus and Hippocratic Oath are also his namesakes. Risus sardonicus, a sustained spasming of the face muscles may also be termed the Hippocratic Smile. The most severe form of hair loss and baldness is called the Hippocratic form.[80] In the modern age, a lunar crater has been named Hippocrates. The Hippocratic Museum, a museum on the Greek island of Kos is dedicated to him. The Hippocrates Project is a program of the New York University Medical Center to enhance education through use of technology. Project Hippocrates (an acronym of "HIgh PerfOrmance Computing for Robot-AssisTEd Surgery") is an effort of the Carnegie Mellon School of Computer Science and Shadyside Medical Center, "to develop advanced planning, simulation, and execution technologies for the next generation of computer-assisted surgical robots."[81] Both the Canadian Hippocratic Registry and American Hippocratic Registry are organizations of physicians who uphold the principles of the original Hippocratic Oath as inviolable through changing social times. |

名前の由来 ブリスベンのメーン医科大学前のヒポクラテス像 いくつかの臨床症状や徴候は、ヒポクラテスが最初に記述したと考えられているため、ヒポクラテスにちなんで命名されている。ヒポクラテス顔とは、死や長患 い、過度の排泄、過度の空腹などによって生じる表情の変化のことである。指や爪の変形である棍棒指は、ヒポクラテスの指とも呼ばれる。ヒポクラテスのサッ カッションとは、水気胸や膿気胸の際の体内飛沫音のこと。ヒポクラテスの名を冠した器具として、ヒポクラテス・ベンチ(張力を利用して骨を固定する器具) とヒポクラテス・キャップ型包帯がある[79]。顔の筋肉が持続的に痙攣するサルドニカス症は、ヒポクラテスの微笑と呼ばれることもある。抜け毛やハゲの 最も深刻な形態はヒポクラテス型と呼ばれる[80]。 現代では、月のクレーターがヒポクラテスと名付けられた。ギリシャのコス島にあるヒポクラテス博物館はヒポクラテスに捧げられている。ヒポクラテスプロ ジェクトは、ニューヨーク大学医療センターのプログラムで、テクノロジーを利用して教育を強化するもの。プロジェクト・ヒポクラテス("HIgh PerfOrmance Computing for Robot-AssisTEd Surgery "の頭文字)は、カーネギーメロン大学コンピューターサイエンス学部とシェイディサイド・メディカルセンターの取り組みであり、「次世代コンピューター支 援手術ロボットのための高度な計画、シミュレーション、実行技術を開発する」[81]。カナダ・ヒポクラテス登録とアメリカ・ヒポクラテス登録はともに、 社会的な時代の変化の中でも侵すことのできない、オリジナルのヒポクラテスの誓いの原則を支持する医師の組織である。 |

| Genealogy Hippocrates' legendary genealogy traces his paternal heritage directly to Asklepius and his maternal ancestry to Heracles.[31] According to Tzetzes's Chiliades, the ahnentafel of Hippocrates II is:[82]  A mosaic of Hippocrates on the floor of the Asclepieion of Kos, with Asklepius in the middle, 2nd–3rd century 1. Hippocrates II. 2. Heraclides 4. Hippocrates I. 8. Gnosidicus 16. Nebrus 32. Sostratus III. 64. Theodorus II. 128. Sostratus, II. 256. Thedorus 512. Cleomyttades 1024. Crisamis 2048. Dardanus 4096. Sostratus 8192. Hippolochus 16384. Podalirius 32768. Asklepius |

系図 ヒポクラテスの伝説的な系図では、父方の先祖はアスクレピオスに、母方の先祖はヘラクレスに直接つながっている[31]。 ツェツェスの『キリアデス』によれば、ヒポクラテス2世のアーネンタフェルは以下の通りである[82]。  コスのアスクレピオンの床に描かれたヒポクラテスのモザイク画、中央にアスクレピオス、2~3世紀 1. ヒポクラテス2世。 2. ヘラクレイデス 4. ヒポクラテス1世 8. グノシディクス 16. ネブルス 32. ソストラトゥスIII. 64. テオドロス II. 128. ソストラトゥス II. 256. テドロス 512. クレオミタデス 1024. クリサミス 2048. ダルダヌス 4096. ソストラトゥス 8192. ヒッポロクス 16384. ポダリリウス 32768. アスクレピオス |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hippocrates |

|

ヒポクラテスの時代:彼と古代ギリシア時代の哲学者・思想家たち(二宮 1983:179)

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆