ラテンアメリカという概念

Concepts on Latin America

Narrative of a five years' expedition against the revolted Negroes of Surinam, by Blake, William, 1757-1827[白人種は自らの足で自立できない] / América Invertida (1943)

ラテンアメリカという概念

Concepts on Latin America

Narrative of a five years' expedition against the revolted Negroes of Surinam, by Blake, William, 1757-1827[白人種は自らの足で自立できない] / América Invertida (1943)

池田光穂

このページは、ラテンアメリカという用語と概念が、イスパノアメリカ(や対概念とされるアン

グロアメリカ)と並んで、政治的あるいは地政学的概念であり、文化的中立性などを担保することができないことを証明(ないしは主張)するために作

られたも

のである(→「クロノトポスとしてのラテンアメリカ」

「ラテンアメリカ1825年」「イスパノアメリカ」「アン

グロアメリカ」)。

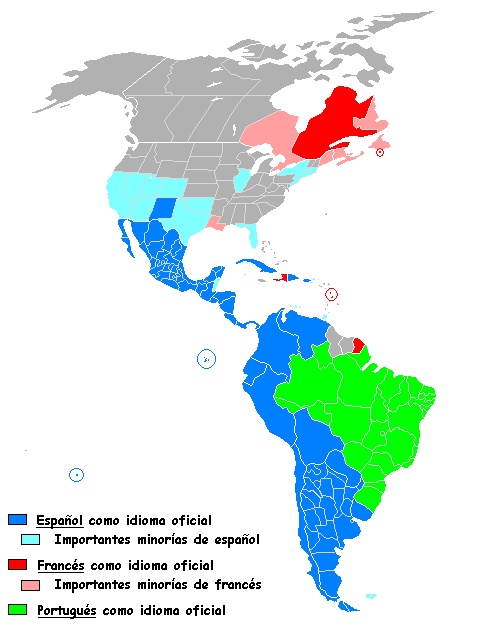

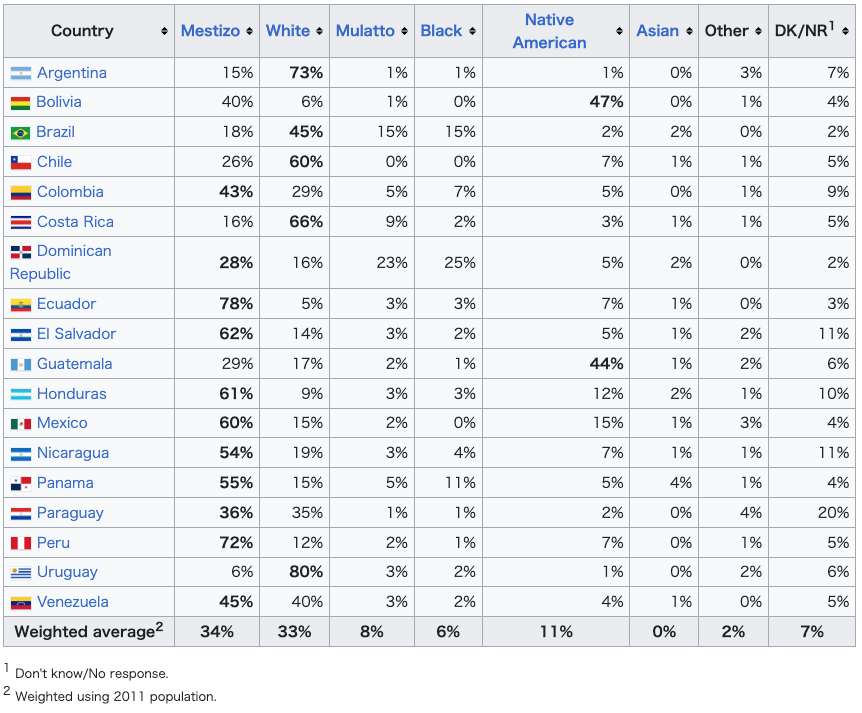

さて、ウィキペディア(日本語)でラテンアメリカを引くと およそ次のような記述に出会う(2021年3月27日現在):「ラテンアメリカ(西: Latinoamérica, América Latina, 葡: América Latina, 英: Latin America, 仏: Amérique latine)は、アングロアメリカに対す る概念で、アメリカ大陸の北半球中緯度から南半球にかけて存在する独立 国及び非独立地域を指す総称である[田中高, 1997『ラテンアメリカ研究への招待』新評論]。 ここでの「ラテン」という接頭語は「イベリア(系)の」という意味であり、これらの 地を支配していた旧宗主国が、ほぼスペインとポルトガルであったことに由来している。 多くの地域がスペイン語、ポルトガル語、フランス語などのラテン系言語を公用語として用いており、社会文化もそれに沿ったものであったことから名付けられ た。 図(上掲の地球儀の緑■の領域をさす)にあるようにラテンア メリカは北アメリカ大陸のメキシコをふくみ、南米大陸のガイアナ・スリナムをふくまない。ラテンアメリカは中南米と呼称される場合もあるが、図に合う正確 な表現ではない[1987『ラテン・アメリカを知る事典』平凡社]。」

では、アングロアメリカと

はなにか?「アングロアメリカ(Anglo-America)は、アメリカ州(米州)のうち、イギリスあるいはイングランドと歴史的・民族的・文化的・言

語的なつながりが深い地域の名称。大まかに言えば、アメリカ合衆国とカナダからなる。これらの国々は、イギリスの旧領で、英語を公用語とし、イギリス系住

民が(比較的)多く、プロテスタント系キリスト教徒が(比較的)多い[要出典]。アングロアメリカはラテン系のスペインとポルトガルの旧領だったラテンア

メリカとの対義語で使われる」(→日本語ウィキペディア「アングロアメリカ」)

この解説から次のようなこととその「問題点」がわか る。

1)アングロアメリカと対立する概念である。すなわ ちアング ロアメリカという概念が存在しないと、ラテンアメリカという概念すらその存 在が怪しくなる。 しかし、アングロアメリカはしばしば、先住民の土地だといわれるが、アングロアメリカという概念抜きにラテンアメリカの存在を多くの人は自明視している。 また、歴史的には、北米大陸の西沿岸から少なく見積もって2、300キロぐらいの範囲は、スペイン(後のメキシコ)やロシアの植民ポストが多く存在してお り北米にも「かつてのラテンアメリカ」が多く存在する。この問題は、実は1860年代にまで遡り、ナポレオン3世が、新大陸での覇権を主張するために、 1861年のメキシコ出兵以降アングロアメリカに対抗するために政治的概念として使い、ミシェル・シュヴァリエを使い、パンラテン主義を主張した。

2)「ラテン」という接頭語は「イベリア(系)の」 という意味であるが、ラテン諸語=ロマンス語の範疇から考えると、このラテン=イベリア半島という概念はあまりにも大雑把すぎる。むしろ、歴史家がいう 「スペインとポルトガルの植民地由来」と表明するほうが正確であり、スペインとポルトガルはラテン世界の構成メンバーだからである。

3)スペインとポルトガルという言挙げの舌の根も乾 かないうちに、「スペイン語、ポルトガル語、フランス語などのラテン系言語を公用語」と言い、次の文章では「南米大陸のガイアナ・スリナムをふくまない」 と恣意的な排除をしている。ガイアナでは先住民の存在の他に、「1834年に奴隷制度が廃止されると、砂糖工場の労働力としてまず年季奉公人としてイング ランド人、アイルランド人、マルタ人、ドイツ人、マデイラ諸島からのポルトガル人などが導入されたが、やがてインド人が導入され、約34万人のインド・パ キスタン系移民が1838年 - 1917年までに流入した。彼らは主に黒人奴隷廃止後の農園労働者となった」。スリナムで は「ギアナ地方がヨーロッパ(スペイン)人に「発見」されたのは1499年である。16世紀にオランダ、イギリス、フランス、スペインの探検家によって探 検され、17世紀に入るとイギリス人とオランダ人が入植し、黒人奴隷を使用してタバコ栽培を行った。両国は領有権を巡り争ったが1667年のブレダ条約で オランダはニューアムステルダム(現ニューヨーク)とスリナムを交換し、その後幾度かイギリスによる占領があったものの、以降オランダの領有権が確定し た」ために、公用語はオランダ語である。

ラテ

ンアメリカの名称

ラテ

ンアメリカの名称

「ホセ・マリア・トーレス・カイセード(José María Torres Caicedo, 1830-1889)とフラン シスコ・ビルバオ(Francisco Bilbao, 1823-1865)によって1856年初めて用いられたと言われるが、その後、ナポレオン 3世(在位1852-1870)による介入は、 新大陸でのフランスの覇権を主張するために、1861年のメキシコ出兵以降、マクシミリアーノ皇帝(1864-1867)を即位させ、アングロアメリカに 対抗するために政治的概念として使い、ミシェル・シュヴァリエを使い、パン・ラテン主義を主張した。他方で、スペイン系の植民者や知識人はイスパノアメリ カという名称を選好するのは、当然である。ラテンアメリカもイスパノアメリカも政治的な言語によるカテゴリー区分なのである。

典拠:"L'expression « Amérique latine » a été utilisée pour la première fois par le poète colombien José María Torres Caicedo en 1856 et par le socialiste chilien Francisco Bilbao, tous deux proches de Lamennais. Le concept d'une Amérique catholique et latine s’opposant à une Amérique anglo-saxonne et protestante a été repris par l’entourage de Napoléon III. En 1861, c’est au nom de la défense de ces pays « latins », considérés comme culturellement proches de la France, que l'empereur envoie une expédition du Mexique6 dans un contexte de panlatinisme7. Le développement de l'expression « Amérique latine » est donc lié aux visées coloniales de Napoléon III dans cette région, aux alentours de 1860, lors de l'aventure mexicaine. C'est le Français Michel Chevalier qui mit alors en avant un concept de « panlatinité » destiné à promouvoir les ambitions françaises en opposant les régions de langue romane (espagnol, portugais, et français) dans les Amériques, aux régions de langue anglaise8. Cette sorte d'« ingérence » est toujours combattue, au nom des droits de la mère patrie, par Madrid, où le concept d'Amérique latine n'a toujours pas droit de cité, mais où prévaut au contraire le concept d'hispanité9. Les Espagnols ont toujours préféré les expressions Hispanoamérica ou encore Iberoamérica pour la désigner4. Plus récemment, les géographes utilisent l'expression « Extrême-Occident » pour parler de l'Amérique latine10,11. L'Académie française définit l’Amérique latine comme « l'ensemble des pays d'Amérique anciennement colonisés par l'Espagne et par le Portugal »12." - Étymologie et apparition de l’idée d’Amérique latine.

「ラテンアメリカ "という表現は、1856年にコロンビアの詩人ホセ・マリア・トーレス・カイセードとチリの社会主義者フラン シスコ・ビルバオによって初めて使われた。アン グロサクソンとプロテスタントのアメリカと対立するカトリックとラテンアメリカというコンセプトは、ナポレオン3世の側近たちに よって取り上げられた。 1861年、フランスに文化的に近いと考えられていたこれらの「ラテン」諸国を防衛するという名目で、皇帝は汎ラテン主義を背景にメキシコに遠征隊を派遣 した6。したがって、「ラテンアメリカ」という用語の発展は、1860年頃、メキシコの冒険の最中に、ナポレオン3世がこの地域で抱いた植民地的野心と結 びついている。アメリカ大陸のロマンス語圏(スペイン語、ポルトガル語、フランス語)と英語圏を対比させることで、フランスの野心を促進させるために「汎 ラテン」という概念を提唱したのは、フランス人のミシェル・シュヴァリエだった。このような 「干渉 」は、ラテンアメリカという概念がいまだに存在しないマドリードでは、祖国の権利の名の下に、いまだに反対されている。スペイン人は常に、ラテンアメリカ の呼称としてイスパノアメリカーやイベロアメリカーという表現を好んできた。最近では、地理学者がラテンアメリカを指すのに、「ファーウェスト」という表 現を使っている。アカデミー・フランセーズは、ラテンアメリカを「かつてスペインとポルトガルが植民地としたすべてのアメリカ諸国」と定義している」

++

| América Latina

o Latinoamérica es una región formada por el conjunto de países de

América donde predominan las lenguas romances (lenguas derivadas del

latín), sobre todo la española y la portuguesa y, en menor medida, la

francesa.156789 Geográficamente incluye la mayor parte del

continente americano, desde el archipiélago de Tierra del Fuego, en

América del Sur, hasta el río Bravo en la frontera entre México y

Estados Unidos, en América del Norte, abarcando las islas caribeñas e

incluyendo la parte central del continente,10 con excepción de los

países de la región donde no se hablan lenguas romances.11 De los tres

idiomas que definen a América Latina, el español y el portugués son los

predominantes, quedando el francés como idioma de solo un 3 % de la

población de la región. El gentilicio es latinoamericano11213 desde que en junio de 1856 la usaron los intelectuales Francisco Bilbao y José María Torres Caicedo.1415 Aunque el término «latino» se origina del gentilicio de Lacio y por herencia se refiere a los pueblos latinos que fueron romanizados y que conservaron las lenguas romances,1617 se ha popularizado su uso como abreviatura de la palabra «latinoamericano», aceptada por el Diccionario de la lengua española de la ASALE y la RAE.18 En América, se le denominan países latinos a aquellos que tuvieron origen en la colonización de España, Portugal y Francia; aquellos en los cuales se instaló esta cultura neolatina, resultado del mestizaje con los pueblos originarios de América y en menor medida del África subsahariana.19 Tras las guerras de independencia en el siglo xix, las corrientes migratorias de los siglos xix y xx aportaron millones de inmigrantes españoles, portugueses e italianos que sumaron más elementos de carácter latino (en especial a Argentina, Brasil, Uruguay y Venezuela). No obstante, hubo también un importante movimiento migratorio de individuos portadores de otras culturas europeas (germánica y eslava), asiáticas, africanas o incluso árabes.202122 |

ラテンアメリカ(スペイン語:América

Latina)は、アメリカ州に属する国々で構成される地域であり、ロマンス諸語(ラテン語に由来する言語)が主に話されている地域である。特にスペイン

語とポルトガル語が話されており、また、フランス語も若干話されている。 156789

地理的には、南米のティエラ・デル・フエゴ諸島から北米のメキシコと米国の国境にあるリオ・グランデまで、アメリカ大陸の大部分を含み、カリブ海諸島も含

まれ、大陸の中央部も含まれるが、ロマンス諸語が話されていない地域の国々は例外である。

ラテンアメリカを定義する3つの言語のうち、スペイン語とポルトガル語が優勢であり、フランス語は地域の人口のわずか3%の人々にしか話されていない。 ラテンアメリカという呼称は、1856年6月に知識人のフランシスコ・ビルバオとホセ・マリア・トーレス・カイセドによって使用されて以来、ラテンアメリ カ11213と呼ばれている。 1415 「ラテン系」という用語はラツィオ州の住民呼称に由来し、継承により、ローマ化されロマンス諸語を保持したラテン民族を指すようになったが、1617 その使用は「ラテンアメリカ」の略語として一般化し、ASALEとRAEのスペイン語辞典にも採用されている。18 アメリカでは、スペイン、ポルトガル、フランスの植民地化に起源を持つ国々はラテン諸国と呼ばれている。この新ラテン文化は、アメリカ大陸の先住民との混 血、そしてより少ない程度ではあるがサハラ以南のアフリカとの混血の結果として確立されたものである。 19 19世紀の独立戦争の後、19世紀から20世紀にかけての移民の流れにより、スペイン、ポルトガル、イタリアから数百万人の移民が流入し、ラテン的な要素 がさらに加わった(特にアルゼンチン、ブラジル、ウルグアイ、ベネズエラ)。しかし、他のヨーロッパ(ゲルマン系およびスラブ系)、アジア、アフリカ、さ らにはアラブ文化圏からの個人による大規模な移住もあった。20 21 22 |

| Concepto El concepto de una América culturalmente «latina» por oposición a otra América «anglosajona» fue introducido por el político y economista francés Michel Chevalier23 en Cartas sobre América del Norte,24 un libro que publicó en 1836 tras viajar por los Estados Unidos, México y Cuba, aunque sin usar la expresión «América Latina». En este libro suscita la idea de que al igual que en Europa existía una diferencia cultural entre anglosajones al norte y latinos al sur. Bajo esta idea Francia se siente como la dueña y protectora de toda la latinidad. No se sabe cuál fue el primer autor que combinó las palabras «América» y «Latina»,25 según Ardao (Nuestra América Latina, 1986, p. 40), Caicedo afirma que «desde 1851 empezamos a dar a la América española el calificativo de latina» (Mis ideas y mis principios, 1875, p. 151). Aunque muchos le atribuyen el término al filósofo y político chileno Francisco Bilbao, por una conferencia que realizó en París el 22 de junio de 1856 titulado «Iniciativa de la América: Idea de un Congreso Federal de las Repúblicas» o «El Congreso Normal Americano», publicado posteriormente en el tomo I de sus Obras Completas editadas por su hermano, Manuel Bilbao, en Buenos Aires, 1866.26 En el texto propone la creación de una confederación de repúblicas de la región como alternativa para buscar un modelo de desarrollo que tenga en cuenta las características propias de su población y su geografía, además de poder hacer frente a proyectos imperialistas foráneos.27 Un año más tarde, el escritor colombiano José María Torres Caicedo también usó el término en el poema «Las dos Américas», publicado en la revista El Correo de Ultramar, de París, el 15 de febrero de 1857, donde afirma que los países de la región debían unirse en un frente común para preservar su territorio y de su modelo democrático.28  Memorial da América Latina, São Paulo. Nótese la representación que de América Latina hace el arquitecto brasileño Oscar Niemeyer: de México hacia el Sur incluyendo las Antillas. Las dos Américas (frag.) La raza de la América Latina, al frente tiene la sajona raza, enemiga mortal que ya amenaza su libertad destruir y su pendón. José María Torres Caicedo En la década de 1860, el término fue usado por los franceses para reivindicar un mayor protagonismo en la región:29 el emperador Napoleón III impulsó una campaña para destacar el parentesco cultural de los países de herencia hispana y lusitana con Francia dado el común origen latino de sus culturas, pero también de las regiones con herencia francesa, como Quebec, la Acadia, la Luisiana y las islas del Caribe. De esta manera, el Segundo Imperio Francés pretendía ser un líder cultural y político en América.30 Este movimiento se evidenció en el plano político al instalar a su protegido Maximiliano como Emperador de México, devenido en una suerte de protectorado francés.31 Así, debido parcialmente al esfuerzo de Napoleón III, la expresión «América Latina» fue aceptada a partir de 1870 de manera casi universal.32 Es importante destacar a los historiadores Arturo Ardao y Miguel Rojas Mix que fueron los primeros en abordar el término "América Latina" desde un punto de vista más allá que simplemente definir su significado y comprender su empleo, casi generalizado temas como: explorar el origen, desarrollo y adaptación del concepto de América Latina. Ellos afirmaron que desde su origen mismo la expresión «Latinoamérica» ha tenido connotaciones antiimperialistas y anticolonialistas, 3334 por tanto se usó de manera opuesta a cualquier proyecto imperialista, especialmente para contrarrestar el expansionismo estadounidense bajo la idea del «Destino Manifiesto», pero también contra el imperialismo europeo, caracterizado como despótico. De hecho, el propio Bilbao, durante la invasión francesa de México, escribió «Emancipación del Espíritu en América», donde pedía a todos los países latinoamericanos que apoyaran la causa mexicana contra Francia, alegando que Francia era «hipócrita, porque ella se llama a sí misma protectora de la raza latina sólo para someterla a su régimen de explotación; traidora, porque habla de libertad y nacionalidad, cuando, incapaz de conquistar la libertad por sí misma, ¡esclaviza a los demás!».3536 Entre otros eventos históricos contemporáneos a los autores que tanto Bilbao como Torres Caicedo mencionan como argumento central de sus propuestas, el más evidente y recurrente en ambas obras es la intervención estadounidense en México, donde a raíz del Tratado de Guadalupe Hidalgo, este último país cedería más de la mitad de su territorio. Ambos autores también hablan del peligro de perder el istmo de Panamá. Torres Caicedo también hace mención expresa de la invasión de Nicaragua, donde el filibustero estadounidense William Walker trató de crear una colonia de habla inglesa y restaurar la esclavitud, abolida hacía ya tres décadas en ese país. Seis años después de «Iniciativa de la América», Bilbao continuaría además con su proyecto anticolonialista al escribir La América en peligro (1862),37 donde se opuso tajantemente a la invasión francesa de México. En ese sentido, Miguel Rojas Mix afirma que «Bilbao no solo antecede a otros pensadores en la utilización de la expresión América latina, también es precursor en la significación que este concepto va a adquirir más tarde en el lenguaje de las izquierdas latinoamericanas. En él, el concepto se acuña en un pensamiento anticolonialista, antiimperialista y de un proyecto de sociedad socialista».38 |

概念 文化的に「ラテン系」のアメリカという概念は、「アングロサクソン系」のアメリカに対する概念であり、フランス人政治家であり経済学者でもあるミシェル・ シュヴァリエ(Michel Chevalier)が1836年に米国、メキシコ、キューバを旅行した後、著書『北米に関する書簡(Letters on North America)』で紹介したものである。ただし、「ラテンアメリカ」という表現は使用されていない。この著書の中で、彼はヨーロッパと同様に、北部のア ングロサクソン人と南部のラテン系住民の間には文化的な違いがあるという考えを提示している。この考え方に基づき、フランスはラテンアメリカ全体を所有し 保護する立場にあると感じている。 アルダオによると、「アメリカ」と「ラテン」という言葉を組み合わせた最初の著者は誰かは不明であるが(『我らがラテンアメリカ』、1986年、40ペー ジ)、カイセドは「1851年から、我々はスペイン語圏アメリカをラテンアメリカと呼ぶようになった」(『私の考えと原則』、1875年、151ページ) と述べている。この用語は、チリの哲学者であり政治家であったフランシスコ・ビルバオに由来するものとする見解が多いが、これは1856年6月22日にパ リで行われた彼の講演「アメリカのイニシアティブ:共和国連邦議会構想」または「標準的なアメリカ議会」に由来するものである。この講演は後に、彼の弟マ ヌエル・ビルバオがブエノスアイレスで編集した全集第1巻(1866年)に掲載された。 26 その文章の中で、彼は、その地域の人口や地理的特性を考慮した発展モデルを見出すための代替案として、また、外国の帝国主義的プロジェクトに対抗できるも のとして、その地域における共和国連合の創設を提案している。 27 その1年後、コロンビア人作家ホセ・マリア・トーレス・カイセドも、1857年2月15日にパリで発行された雑誌『エル・コレオ・デ・ウルトラマル』に掲 載された詩「ラス・ドス・アメリカス(Las dos Américas)」の中で、この用語を使用している。同氏は、この地域の国々は領土と民主主義モデルを守るために団結すべきであると主張している。28  サンパウロの『Memorial da América Latina』。ブラジルの建築家オスカー・ニーマイヤーによるラテンアメリカの表現に注目:メキシコから南のアンティル諸島までを含む。 Las dos Américas(断片) ラ・ラサ・デ・ラ・アメリカ・ラティーナ(ラテンアメリカの人種)の 見出しには、サクソン人種が掲げられている。 このサクソン人種は、 ラテンアメリカの自由と国旗を脅かす死の敵である。 ホセ・マリア・トーレス・カイセド 1860年代、フランス人はこの地域でより大きな役割を主張するためにこの用語を使用した。 29 皇帝ナポレオン3世は、ラテン語を起源とする文化という共通点から、スペイン語圏やポルトガル語圏の国々、そしてケベック、アカディア、ルイジアナ、カリ ブ海諸島といったフランス語圏の地域との文化的親和性を強調するキャンペーンを開始した。このようにして、第二帝政フランスはアメリカにおける文化面およ び政治面でのリーダーとなることを目指した。30 この動きは政治レベルでも明らかであり、皇帝の寵愛を受けるマクシミリアンをメキシコ皇帝に即位させ、事実上のフランス保護領とした。31 このように、ナポレオン3世の努力もあって、「ラテンアメリカ」という表現は1870年以降ほぼ世界的に受け入れられるようになった。32 ここで強調すべきは、アルトゥーロ・アルダオとミゲル・ロハス・ミックスという二人の歴史家が、単に「ラテンアメリカ」という用語の意味を定義し、その用 法を理解する以上の視点から、この用語にアプローチした最初の人物であったということである。彼らは、この概念の起源、発展、適応を探求するなど、ほぼ一 般化されたトピックにまで踏み込んでいる。彼らは、「ラテンアメリカ」という表現は、その起源から反帝国主義、反植民地主義的な含みを帯びており、 3334 したがって、あらゆる帝国主義的プロジェクト、特に「明白な運命」という考えに基づく米国の拡張主義に対抗するために、また専制的なものとして特徴づけら れるヨーロッパの帝国主義に対しても用いられていたと述べている。事実、ビルバオ自身、フランスによるメキシコ侵攻のさなか、「アメリカにおける精神の解 放」を著し、フランスに対するメキシコの闘争を支援するようラテンアメリカ諸国に呼びかけた。ビルバオは、フランスは「偽善的である。なぜなら、人種を搾 取する体制に服従させるために、自らを人種の保護者と称しているからだ。また、フランスは「裏切り的である。なぜなら、自由や国家について語る一方で、 自分自身で自由を勝ち取ることができないのに、他者を奴隷化しているからだ!」と主張した。35 36 ビルバオとトーレス・カイセドの両氏が提案の中心的な論点として挙げている作家と同時代の歴史的事件の中で、両氏の作品に最も明白に繰り返し登場するの は、グアダルーペ・イダルゴ条約の結果、メキシコが国土の半分以上を割譲することになった米国のメキシコ介入である。両著者はまた、パナマ地峡が失われる 危険性についても言及している。トーレス・カイセドは、ニカラグアへの侵攻についても明確に言及している。アメリカ人フィリーズターのウィリアム・ウォー カーが、英語を話す植民地を建設し、30年前に同国で廃止された奴隷制を復活させようとした事件である。ビルバオは『アメリカにおける危機』(1862 年)37でも、フランスによるメキシコ侵略に強く反対するなど、著書『アメリカのイニシアティブ』から6年後も、反植民地主義プロジェクトを継続してい た。この点について、ミゲル・ロハス・ミックスは「ビルバオはラテンアメリカという表現を最初に用いた思想家の一人であるだけでなく、この概念が後にラテ ンアメリカ左派の言語で獲得する意味においても先駆者である。彼において、この概念は反植民地主義、反帝国主義思想と社会主義社会の構想の中で生み出され た」と述べている。38 |

| Etimología El término latinoamericano deriva de las palabras (latino) persona natural del Lacio y (América) palabra derivada de Américo Vespucio que participó en al menos dos viajes39 de exploración al Nuevo Mundo. |

語源 ラテンアメリカという用語は、ラツィオ州出身の人物を意味するラテン語(ラティウム)と、少なくとも2回の新大陸探検航海に参加したアメリゴ・ヴェスプッチに由来するアメリカ(アメリカ)という言葉から派生している。 |

| Definición La expresión América Latina o Latinoamérica tiene varios usos y connotaciones divergentes:40 En su acepción más simple, «América Latina» suele referirse exclusivamente a los países de habla española y portuguesa del continente americano, incluyendo a Puerto Rico, aunque sea un Estado Libre Asociado de los Estados Unidos de América. Esta acepción sería sinónimo de Iberoamérica, pero suele considerarse incompleta al excluir territorios que sin ser específicamente de habla hispana o portuguesa, culturalmente pueden considerarse latinos. En su acepción más generalmente aceptada, englobaría también a los países de habla francesa, es decir, Haití, los territorios franceses de ultramar en América y la Isla Clipperton. Según la definición de la Real Academia Española, «América Latina» es el conjunto de los países americanos que fueron colonizados por naciones latinas, es decir, España, Portugal o Francia.41 De acuerdo al Diccionario Panhispánico de Dudas, para referirse exclusivamente a los países de lengua española es más propio usar el término específico Hispanoamérica o, si se incluye Brasil, país de habla portuguesa, el término Iberoamérica.1 Otra acepción menos aceptada englobaría también aquellos territorios de Norteamérica en los que las lenguas latinas tienen carácter oficial o predominante, esto es, los estados de California, Arizona, Nevada, Nuevo México, Texas y Florida en EE. UU., donde hay una presencia importante del español, y los territorios francófonos de Quebec, Nuevo Brunswick, Manitoba y Ontario en Canadá y Luisiana en EE. UU. Una variante de la anterior es la de incluir aquellos territorios que pueden considerarse como culturalmente latinos o con una presencia importante de la cultura latina, pero excluyendo los territorios que culturalmente serían más próximos a la cultura angloamericana. Así, se incluirían los anteriores territorios de Norteamérica con presencia importante del español, pero se excluirían los territorios francófonos de Norteamérica por ser culturalmente más próximos a la cultura angloamericana que a la latina, a pesar del idioma. En este caso, algunos incluyen a Belice y a las Islas Vírgenes de los Estados Unidos, ya que aunque tienen el inglés como lengua oficial, tienen una fuerte presencia del español y de la cultura latina. En ninguna acepción se incluye a los países de lengua no latina, salvo lo indicado para Belice y las Islas Vírgenes de los Estados Unidos. Estos países no incluidos son Surinam, Guyana y diversos países del Caribe de habla inglesa y neerlandesa. En la jerga internacional geopolítica es común usar el término compuesto América Latina y el Caribe para designar a todos los territorios del Hemisferio Occidental que se extienden al sur de los Estados Unidos, incluyendo a los países anteriores.40 |

定義 ラテンアメリカまたはラテンアメリカという表現は、さまざまな用途があり、多様な含みを持つ。 最も単純な意味では、「ラテンアメリカ」という用語は通常、アメリカ大陸のスペイン語およびポルトガル語圏の国々を指す。これにはプエルトリコも含まれる が、プエルトリコはアメリカ合衆国の自治領である。この定義はイベロアメリカと同義であるが、スペイン語やポルトガル語を話すわけではないが文化的にラテ ン系と見なされる地域を除外しているため、不完全であると見なされることが多い。 最も一般的に受け入れられている意味では、フランス語圏の国々、すなわちハイチ、アメリカにあるフランスの海外領土、クリッパートン島も含まれる。スペイ ン王立アカデミーの定義によると、「ラテンアメリカ」とは、ラテン諸国、すなわちスペイン、ポルトガル、フランスによって植民地化されたアメリカ諸国のグ ループを指す。41 汎スペイン語辞典によると、スペイン語圏の国々を指す場合は、ヒスパノアメリカという特定の用語を使用するのがより適切であり、ポルトガル語圏の国である ブラジルを含める場合は、イベロアメリカという用語を使用するのが適切である。1 あまり一般的ではないもう一つの意味としては、ラテン語が公用語または主流言語となっている北米の地域、すなわち、スペイン語が広く使用されている米国の カリフォルニア州、アリゾナ州、ネバダ州、ニューメキシコ州、テキサス州、フロリダ州、およびカナダのケベック州、ニューブランズウィック州、マニトバ 州、オンタリオ州、米国ルイジアナ州などのフランス語話者の地域も含まれる。 上記とは異なる方法として、文化的にラテン系と見なされる、あるいはラテン文化が広く浸透している地域を含めるが、文化的にアングロ・アメリカ文化に近い 地域は除外するという方法もある。したがって、前述のスペイン語が広く浸透している北米の地域は含まれるが、北米のフランス語圏は、言語はスペイン語でも ラテン文化よりもアングロ・アメリカ文化に近いことから除外される。この場合、公用語は英語であるものの、スペイン語とラテン文化が強く浸透していること から、ベリーズと米領バージン諸島を含める場合もある。 ラテン語圏以外の国は、ベリーズと米領バージン諸島を除いて、一切含まれない。これらの国々には、スリナム、ガイアナ、および英語やオランダ語を話すカリ ブ海諸国が含まれる。国際的な地政学用語では、米国より南に広がる西半球の全領土を指す場合、ラテンアメリカおよびカリブ海という複合語が一般的に使用さ れる。40 |

| Controversia terminológica Existen desacuerdos sobre la neutralidad en el punto de vista de la versión actual de este artículo o sección. En la página de discusión puedes consultar el debate al respecto. Véase también: Uso de la palabra americano (a)  Lenguas romances en América. Las expresiones Latinoamérica y América Latina, son términos que en la actualidad son comúnmente aceptados por la población de los países a los que se refiere, sin embargo, tienen sus detractores, en especial entre los grupos hispanistas, indigenistas y antirracistas. Los primeros, hispanistas, por dar prioridad a la influencia española sobre la portuguesa o francesa. De hecho, incluso autores brasileños como Nélida Piñón dudan de que el nombre abarque a su país, por no ser hispano.42 El término latinoamericano también es criticado en cuanto a que, según muchos estudiosos, parece integrar de manera forzada a las colonias francesas que en poco se parecen histórica y culturalmente al resto de las regiones hispanoamericanas. El escritor mexicano Carlos Fuentes, por su parte, acuñó la variante "Indo-Afro-Ibero América" en su libro Valiente mundo nuevo (1990). Los grupos indigenistas y antirracistas por considerar que se trata de un término eurocentrista impuesto por los colonizadores, ya que jamás podrían considerarse de origen latino ni los indígenas, ni los afroamericanos, decisivos cuantitativa y cualitativamente en la composición de la población.43 Incluso en muchos casos los indígenas no hablan idiomas europeos. El uso mismo del nombre «América» ha sido históricamente controvertido. A principios del siglo xix, el líder independentista Simón Bolívar quiso llamar a toda la región «Colombia», en honor a Cristóbal Colón. Según el parecer del Libertador, Colón tenía más mérito que Américo Vespucio para dar nombre al continente («América» se hizo popular en Europa por las cartas geográficas de Mercator, primeros planos de América que salían de España hacia el resto de Europa). Antiguamente, se utilizaba el término «Indias Occidentales» para nombrar al continente. El subcontinente sur también era llamado «América Meridional» o «América del Mediodía». En cuanto al subcontinente norte, la Nueva España era también conocida como la «América Septentrional», México se declaró independiente con ese nombre durante el Congreso de Anáhuac en 1813. Respecto a las denominaciones latino o Latinoamérica, el filólogo e historiador español Ramón Menéndez Pidal, el 4 de enero de 1918, comentó, en una extensa carta dirigida al director del diario madrileño El Sol, que fue publicada por este mismo, entre otras cosas, lo siguiente:44 Desde que hacia 1910 empezó a generalizarse, principalmente por Francia y los Estados Unidos, la denominación de América latina. La propiedad de tal nombre me parece muy dudosa. El adjetivo latino, aplicado a las naciones que heredaron la lengua del Lacio está perfectamente en su puesto; pero como en este sentido no envuelve ningún concepto de raza, sino sólo de idioma, me parece del todo desmesurado el extender su significado hasta aplicarlo a naciones que recibieron su lengua, no del Lacio, sino de la Península hispánica, de Castilla y de Portugal. Esas naciones americanas no heredaron la lengua latina, como la heredaron España, Francia e Italia de su colonización romana, sino que recibieron lenguas hispánicas, lengua castellana y portuguesa, y éstas, para adjetivarlas aludiendo a sus orígenes, se llaman comúnmente neolatinas y no latinas. Ramón Menéndez Pidal44 Una de las nuevas posturas teóricas sobre la «América Latina», que se vincula más a aspectos antropológicos y sociológicos que al lingüístico, y parte del concepto «horizonte cultural».45 Se entiende por este último al espacio geográfico y temporal en el que prevalecen pautas culturales comunes, las cuales pueden incluir la utilización de una lengua determinada. En este sentido, los partidarios de esta postura entienden que países del Caribe, Centro y Sudamérica como Jamaica, Surinam, Barbados o Belice son parte de América Latina, ya que las pautas culturales de la población de los mismos poseen similitudes con otros países iberoamericanos, diferenciándose de las prácticas de las naciones de América Anglosajona, a la que ven como otro horizonte cultural. Asimismo, las regiones francófonas de Canadá (pese a que el francés es una lengua latina) la incluirían en la América Anglosajona, por los mismos motivos anteriormente expuestos. Entre los partidarios de esta postura encontramos a reconocidos estudiosos, como Miguel Rojas Mix, Ricardo Méndez, Pedro Cunill Grau, John Cole, Rodolfo Bertoncello, Diego M. Ríos y Andrea Salleras. |

用語をめぐる論争 この記事または節の現在のバージョンの観点において、中立性に関する意見の相違がある。 議論のページでは、この主題に関する議論を参照することができる。 参照:  アメリカにおけるアメリカン・ロマンス語という用語の使用。 ラテンアメリカ(Latinoamérica)およびラテンアメリカ(América Latina)という表現は、現在では一般的にそれらの国々の住民に受け入れられている用語であるが、特にヒスパニック学者、土着主義者、反人種差別主義 者グループの間では反対意見もある。 前者は、ポルトガル語やフランス語よりもスペイン語の影響を優先させるという理由による。実際、ブラジルの作家であるネリダ・ピニョン(Nélida Piñón)でさえ、ブラジルはイスパノアメリカ諸国ではないとして、その国名が含まれていることに疑問を呈している。42 また、多くの学者が指摘するように、ラテンアメリカという用語は、歴史的にも文化的にもスペイン語圏の他の地域とほとんど類似点のないフランス植民地を無 理やり含めているように見えるとして批判されている。メキシコ人作家のカルロス・フエンテスは、著書『Valiente mundo nuevo(Brave New World)』(1990年)の中で、「インド・アフリカ・イベロ・アメリカ」という別の呼称を考案した。 先住民主義者や反人種差別主義者グループは、この名称を植民地主義者によって押し付けられたヨーロッパ中心主義的な用語であるとみなしている。なぜなら、 先住民やアフリカ系アメリカ人が人口構成において量的にも質的にも決定的なラテン語起源であるとは考えられないからである。43 多くの場合、先住民はヨーロッパの言語を話さない。 「アメリカ」という名称の使用自体が、歴史的に論争の的となってきた。19世紀初頭、独立運動の指導者シモン・ボリバルは、クリストファー・コロンブスに 敬意を表して、この地域全体を「コロンビア」と呼ぼうとした。解放者」の意見では、コロンブスはアメリゴ・ヴェスプッチよりも、この大陸にその名をつけた 功績が大きいというのだ(「アメリカ」という名称は、メルカトルの地理地図によってヨーロッパで普及した。この地図は、スペインを離れヨーロッパの他の地 域に渡ったアメリカ大陸初の地図であった)。かつては「西インド諸島」という名称が大陸の名称として使われていた。南半球の亜大陸は「南アメリカ」または 「南のアメリカ」とも呼ばれていた。北半球の亜大陸については、ヌエバ・エスパーニャは「北アメリカ」とも呼ばれており、1813年のアナワク会議におい てメキシコは「北アメリカ」という名称で独立を宣言した。 ラテンまたはラテンアメリカという名称について、スペインの文献学者であり歴史家でもあるラモン・メネンデス・ピダルは、1918年1月4日、マドリードの新聞『エル・ソル』の編集長宛てに送った長文の手紙の中で、次のようにコメントしている。44 1910年頃から、ラテンアメリカという名称は主にフランスと米国で広まり始めた。このような名称の所有権は、私には非常に疑わしく思える。ラツィオの言 語を受け継いだ国々に対して「ラテン」という形容詞を適用することは、まったく妥当である。しかし、この意味では人種に関する概念は一切含まれず、言語の みが対象となるため、ラツィオではなくスペイン半島やカスティーリャ、ポルトガルから言語を受け継いだ国々に対して、その意味を拡大して適用するのは、 まったく行き過ぎであるように思える。これらのアメリカ諸国は、スペイン、フランス、イタリアがローマの植民地化から継承したラテン語ではなく、むしろ、 カスティーリャ語やポルトガル語といったヒスパニック言語を受け継いだ。これらの言語は、その起源を暗示するものとして、一般的にネオラテン語と呼ばれ、 ラテン語とは呼ばれない。 ラモン・メネンデス・ピダル44 「ラテンアメリカ」に関する新しい理論的立場の一つであり、言語学よりもむしろ人類学や社会学の側面と関連しており、「文化的地平」という概念に基づいて いる。45 後者は、共通の文化的パターンが優勢な地理的・時間的空間と理解されており、特定の言語の使用も含まれる可能性がある。この意味において、この立場を支持 する人々は、ジャマイカ、スリナム、バルバドス、ベリーズなどのカリブ海諸国、中南米諸国はラテンアメリカの一部であると理解している。これらの国の住民 の文化パターンは、他のイベロアメリカ諸国と類似しており、アングロサクソン系アメリカ諸国の慣習とは異なっている。彼らは、アングロサクソン系アメリカ 諸国を別の文化圏と見なしている。同様に、カナダのフランス語圏(フランス語はラテン語系言語であるにもかかわらず)も、上記の理由からアングロサクソン 系アメリカに含めることになるだろう。この立場を支持する著名な学者には、ミゲル・ロハス・ミックス、リカルド・メンデス、ペドロ・クニル・グラウ、ジョ ン・コール、ロドルフォ・ベルトンチェロ、ディエゴ・M・リオス、アンドレア・サレラスなどがいる。 |

| https://es.wikipedia.org/wiki/Am%C3%A9rica_Latina |

☆英語版ウィキペディアの項目

| Latin Americans (Spanish: Latinoamericanos;

Portuguese: Latino-americanos; French:

Latino-américains) are the citizens of Latin American countries (or

people with cultural, ancestral or national origins in Latin America). Latin American countries and their diasporas are multi-ethnic and multi-racial. Latin Americans are a pan-ethnicity consisting of people of different ethnic and national backgrounds. As a result, some Latin Americans do not take their nationality as an ethnicity, but identify themselves with a combination of their nationality, ethnicity and their ancestral origins.[18] In addition to the indigenous population, Latin Americans include people with Old World ancestors who arrived since 1492. Latin America has the largest diasporas of Spaniards, Portuguese, Africans, Italians, Lebanese and Japanese in the world.[19][20][21] The region also has large German (second largest after the United States),[22] French, Palestinian (largest outside the Arab states),[23] Chinese and Jewish diasporas. The specific ethnic and/or racial composition varies from country to country and diaspora community to diaspora community: many have a predominance of mixed indigenous and European descent or mestizo, population; in others, native Americans are a majority; some are mostly inhabited by people of European ancestry; others are primarily mulatto.[18][24] The largest single group are white Latin Americans.[18] Together with the people of part European ancestry, they combine for almost the totality of the population.[18] Latin Americans and their descendants can be found almost everywhere in the world, particularly in densely populated urban areas. The most important migratory destinations for Latin Americans are found in the United States, Spain, France, Canada, Italy and Japan. |

ラテンアメリカ人(スペイン語:ラテンアメリカ人、ポルトガル語:ラテ

ンアメリカ人、フランス語:ラテンアメリカ人)とは、ラテンアメリカ諸国の国民(またはラテンアメリカに文化的、先祖的、あるいは民族的起源を持つ人々)

を指す。 ラテンアメリカ諸国とそのディアスポラは多民族・多人種である。ラテンアメリカ人は、さまざまな民族・国家背景を持つ人々からなる汎民族である。そのた め、ラテンアメリカ人の中には、民族性として自国の国籍を認識せず、国籍、民族性、先祖の出身地を組み合わせたものとして自己を認識する者もいる。先住民 に加え、ラテンアメリカ人には1492年以降に到来した旧世界出身の祖先を持つ人々も含まれる。ラテンアメリカには、世界最大のスペイン人、ポルトガル 人、アフリカ人、イタリア人、レバノン人、そして日本人のディアスポラが存在する。[19][20][21] この地域には、ドイツ人(米国に次いで2番目に多い)[22]、フランス人、パレスチナ人(アラブ諸国以外では最大)[23]、中国人、ユダヤ人のディア スポラも存在する。 特定の民族および/または人種構成は国によって、またディアスポラのコミュニティによって異なる。多くの国では、先住民とヨーロッパ人の混血またはメスチ ゾが人口の大半を占めている。また、アメリカ先住民が多数派を占める国もある。ヨーロッパ系の人々が多く住んでいる地域もある。また、混血が大半を占める 地域もある。[18][24] 最大の単一グループは、白人ラテンアメリカ人である。[18] ヨーロッパ系の人々と併せると、人口のほぼ全体を占めることになる。[18] ラテンアメリカ人とその子孫は、世界のほぼあらゆる場所で見られ、特に人口密度の高い都市部に集中している。ラテンアメリカ人の主な移住先は、アメリカ合 衆国、スペイン、フランス、カナダ、イタリア、日本である。 |

| Definition Main article: Latin America  Latin American countries (green) in the Americas Latin America (Spanish: América Latina or Latinoamérica; Portuguese: América Latina; French: Amérique latine) is the region of the Americas where Romance languages (i.e., those derived from Latin)—particularly Spanish and Portuguese, as well as French—are primarily spoken.[25][26] It includes 21 countries or territories: Mexico in North America; Guatemala, Honduras, El Salvador, Nicaragua, Costa Rica and Panama in Central America; Colombia, Venezuela, Ecuador, Peru, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, Chile, Argentina and Uruguay in South America; and Cuba, Haiti, the Dominican Republic and Puerto Rico in the Caribbean—in summary, Hispanic America, plus Brazil and Haiti. Canada and the United States, despite having sizeable Romance-speaking communities, are almost never included in the definition, primarily for being predominantly English-speaking Anglosphere countries. Latin America, therefore, can be defined as all those parts of the Americas that were once part of the Spanish, Portuguese or French colonial empires,[27] namely Spanish America, Colonial Brazil and New France. |

定義 詳細は「ラテンアメリカ」を参照  南北アメリカにおけるラテンアメリカ諸国(緑色) ラテンアメリカ(スペイン語: América Latina または Latinoamérica、ポルトガル語: América Latina、フランス語: Amérique latine)は、アメリカ州の地域であり、ロマンス諸語(すなわちラテン語に由来する言語)が主に話されている地域である。特にスペイン語とポルトガル 語、そしてフランス語が話されている。 北米のメキシコ、中米のグアテマラ、ホンジュラス、エルサルバドル、ニカラグア、コスタリカ、パナマ、南米のコロンビア、ベネズエラ、エクアドル、ペ ルー、ボリビア、ブラジル、パラグアイ、チリ、アルゼンチン、ウルグアイ、カリブ海のキューバ、ハイチ、ドミニカ共和国、プエルトリコの21の国と地域を 含み、要約すると、ヒスパニック・アメリカとブラジル、ハイチである。カナダと米国は、ロマンス語話者のコミュニティがかなりの規模で存在しているにもか かわらず、主に英語話者のアングロサミア諸国であるという理由で、この定義にはほとんど含まれない。 したがって、ラテンアメリカとは、かつてスペイン、ポルトガル、またはフランスの植民地帝国の一部であったアメリカ大陸のすべての地域、すなわちスペイン 語圏アメリカ、植民地ブラジル、ヌーベルフランスを指す。 |

| Demographics Ethnic and Racial groups Main article: Race and ethnicity in Latin America  Wititi dancers from Colca Canyon, Peru. Indigenous people make up most of the population in Bolivia and Guatemala, and a quarter in Peru .  Mexican musicians from the Jalisco Philharmonic Orchestra. Mestizos comprise the majority of Mexicans  Italian Argentine youths in Oberá. Over 60% of Argentina's population has some degree of Italian ancestry.[28][29]  Afro-Colombian fruit sellers in Cartagena.  Woman from Curitiba, one of over a million Japanese Brazilians.  Rapa Nui dancers from Easter Island, Chile. The Rapa Nui are a Polynesian people. The population of Latin America comprises a variety of ancestries, ethnic groups and races, making the region one of the most diverse in the world. The specific composition varies from country to country: many have a predominance of mixed European and native American, or mestizo, population; in others, native Americans are a majority; some are dominated by inhabitants of European ancestry; and some countries' populations are primarily mulatto. Black, Asian, and zambo (mixed black and native American) minorities are also identified regularly. White Latin Americans are the largest single group, accounting for more than one-third of the population.[18][30] Asians. People of Asian descent number several million in Latin America. The majority of Asian descendants in the country are either of West Asian (such as Lebanese or Syrian) or East Asian (like Chinese or Japanese) descent.[31] The first Asians to settle in the region were Filipino, as a result of Spain's trade involving Asia and the Americas. The Brazilian Institute of Geography and Statistics states that the country's largest Asian communities are from West Asia and East Asia.[32] It is estimated that 7 to 10 million Brazilians are of Lebanese descent.[33][34] Around 2 million Brazilians self-identify as being "Yellow" (amarela or of East Asian descent) according to the 2010 census.[35] The country is home to the largest ethnic Japanese community outside Japan itself, estimated as high as 1.5 million, and circa 200,000 ethnic Chinese and 100,000 ethnic Koreans.[36][37] Ethnic Koreans also number tens of thousands of individuals in Argentina and Mexico.[38] The 2017 census stated that under 40,000 Peruvians self-identified as having Chinese or Japanese ancestry.[39] Though other estimates claim as much as 1.47 million people of East Asian descent reside in the country.[40][41] Lebanese and Syrian descendants have also formed notable communities in countries like Mexico and Argentina.[42] The Martiniquais population includes a mixed African, European and native American descent, and an East Indian (Asian Indian) population is also present in Martinique.[43] In Guadeloupe, an estimated 14% of the population is of East Asian descent. Blacks. Millions of African slaves were brought to Latin America from the 16th century onward, most of whom were sent to the Caribbean region and Brazil. Today, people identified as "black" are most numerous in Brazil (more than 10 million) and in Haiti (more than 7 million).[44] Significant populations are also found in Cuba, Dominican Republic, Puerto Rico, Panama and Colombia. Latin Americans of mixed black and white ancestry, called mulattoes, are far more numerous than blacks. Native Americans. The indigenous population of Latin America arrived during the Lithic stage. In post-Columbian times, they experienced tremendous population decline, particularly in the early decades of colonization. They have since recovered in numbers, surpassing sixty million (by some estimates[30]), though, with the growth of the other groups, they now comprise a majority only in Bolivia. In Guatemala, native Americans are a large minority that comprises 41% of the population.[45] Mexico's 21% (9.8% in the official 2005 census) is the next largest ratio, and one of the largest indigenous population in the Americas in absolute numbers. Most of the remaining countries have native American minorities, in every case making up less than one-tenth of the respective country's population. In many countries, people of mixed indigenous and European ancestry, known as mestizos, make up the majority of the population. Mestizos. Intermixing between Europeans and native Americans began early in the colonial period and was extensive. The resulting people, known as mestizos, make up the majority of the population in half of the countries of Latin America. Additionally, mestizos comprise large minorities in nearly all the other mainland countries. Mulattoes. Mulattoes are people of mixed European and African ancestry, mostly descended from Spanish, French, or Portuguese settlers on one side and African slaves on the other, during the colonial period. Brazil is home to Latin America's largest mulatto population. Mulattoes form a majority in the Dominican Republic and are also numerous in Cuba, Puerto Rico, Nicaragua, Panama, Peru, Colombia, and Ecuador. Smaller populations of mulattoes are found in other Latin American countries.[30] Whites. Beginning in the late 15th century, large numbers[18] of Iberian colonists settled in what became Latin America (Portuguese in Brazil and Spaniards elsewhere in the region), and at present most white Latin Americans are of Spanish, Portuguese or Italian ancestry. Iberians brought the Spanish and Portuguese languages, the Catholic faith, and many Iberian traditions. Brazil, Argentina, Mexico and Venezuela contain the largest numbers of Europeans in Latin America in pure numbers.[18] They make up the majority of the population of Argentina, Costa Rica, Cuba and Uruguay and roughly half of Brazil's and Venezuela's population.[18][46] Of the millions of immigrants since most of Latin America gained independence in the 1810s–1820s, Italians formed the largest group, and next were Spaniards and Portuguese.[47] Many others arrived, such as French, Germans, Greeks, Poles, Ukrainians, Russians, Croats, Serbs, Latvians, Lithuanians, English, Jews, Irish and Welsh. Most Latin Americans have some degree of European ancestry, when talking into account those of either mixed or full European descent.[48] Zambos: Intermixing between blacks and native Americans was especially prevalent in Colombia and Brazil, often due to slaves running away (becoming cimarrones: maroons) and being taken in by indigenous villagers. In Spanish-speaking nations, people of this mixed ancestry are known as zambos,[49] and they are also known as cafuzos in Brazil. Multi-ethnic/Multi-racials: In addition to the foregoing groups, Latin America also has millions of peoples who belong to multiracial backgrounds.[citation needed]  |

人口統計 民族および人種グループ 詳細は「ラテンアメリカにおける人種と民族(→人種概念をめぐるノート)」を参照  ペルーのクスコ渓谷のウィティティの踊り手。ボリビアとグアテマラでは先住民が人口の大半を占め、ペルーでは4分の1を占める。  メキシコのハリスコ・フィルハーモニー管弦楽団の音楽家。メキシコ人の大半は混血である  アルゼンチンのオベラに住むイタリア系アルゼンチン人の若者。アルゼンチンの人口の60%以上がイタリア系である。  カルタヘナのアフリカ系コロンビア人の果物売り。  100万人以上の日系ブラジル人の一人であるクリチバの女性。  チリのイースター島に住むラパ・ヌイ族のダンサー。ラパ・ヌイ族はポリネシア人である。 ラテンアメリカは、さまざまな祖先を持つ人々、民族、人種から構成されており、世界で最も多様な地域のひとつとなっている。その構成は国によって異なり、 ヨーロッパ人とアメリカ先住民の混血、すなわちメスチゾが人口の大部分を占める国が多い。また、アメリカ先住民が多数派を占める国もある。ヨーロッパ系住 民が人口の大半を占める国や、混血が主となっている国もある。黒人、アジア人、そして黒人と先住民の混血であるサンボ(zambo)の少数民族も定期的に 確認されている。 白人のラテンアメリカ人は最大の単一グループであり、人口の3分の1以上を占めている。 アジア系。ラテンアメリカにおけるアジア系住民は数百万に上る。ブラジル国内のアジア系住民の大半は西アジア(レバノン人やシリア人など)または東アジア (中国人や日本人など)の血を引いている。ブラジル地理統計院は、同国最大の東アジア系および西アジア系コミュニティはレバノン系であると述べている。 [32] 推定700万人から1,000万人のブラジル人がレバノン系であるとされている。[33][34] 2010年の国勢調査によると、約200万人のブラジル人が「黄色人種」(amarelaまたは東アジア系)であると自己申告している。[35] 同国には、日本国外では最大の日本人コミュニティがあり、 150万人と推定される最大の日本人コミュニティ、およそ20万人の中国人、10万人の韓国人が暮らしている。[36][37] 韓国人もアルゼンチンとメキシコに数万人いる。[38] 2017年の国勢調査では、4万人未満のペルー人が中国または日本の祖先であると自己申告していると述べている。[39] 他の推定では、 東アジア系の人々が147万人も居住しているという推計もあるが[40][41]、レバノン人とシリア人の子孫もメキシコやアルゼンチンなどの国々で顕著 なコミュニティを形成している[42]。マルティニーク島には、アフリカ、ヨーロッパ、先住民のアメリカ人の混血の人々や、東インド人(アジア系インド 人)も居住している[43]。グアドループ島では、人口の14%が東アジア系である。 黒人。16世紀以降、数百万人のアフリカ人奴隷がラテンアメリカに連れてこられ、そのほとんどがカリブ海地域とブラジルに送られた。今日、「黒人」とされ る人々はブラジル(1,000万人以上)とハイチ(700万人以上)に最も多く存在している。[44] また、キューバ、ドミニカ共和国、プエルトリコ、パナマ、コロンビアにもかなりの人口が存在している。黒人と白人の混血であるラテンアメリカ人は、ムラー トと呼ばれ、黒人よりもはるかに多い。 ネイティブアメリカン。ラテンアメリカの土着民族は、石器時代に到来した。コロンブス以降の時代には、特に植民地化の初期の数十年間に、人口が大幅に減少 した。その後、人口は回復し、6,000万人を超えた(推定値による[30])が、他のグループの増加に伴い、現在はボリビアのみで多数派を占めている。 グアテマラでは、先住民は人口の41%を占める大きな少数派である。[45] メキシコの21%(2005年の公式国勢調査では9.8%)は、次に大きな割合であり、絶対数ではアメリカ大陸で最大の先住民人口のひとつである。 残りのほとんどの国々では、先住民は少数派であり、いずれもそれぞれの国の人口の10分の1以下である。多くの国々では、先住民とヨーロッパ人の混血であ るメスチーソと呼ばれる人々が人口の多数を占めている。 メスチーソ。ヨーロッパ人と先住民の混血は、植民地時代初期から始まり、広範囲にわたって行われた。その結果生まれたメスチーソと呼ばれる人々は、ラテン アメリカ諸国の半数で人口の多数を占めている。さらに、メスチーソは、他のほとんどの本土諸国でも大きな少数派を構成している。 ムラート。ムラートはヨーロッパ人とアフリカ人の混血であり、そのほとんどが植民地時代にスペイン人、フランス人、ポルトガル人の入植者の一方とアフリカ 人奴隷の一方の血筋を受け継いでいる。ブラジルはラテンアメリカ最大のムラート人口を抱える国である。ムラートはドミニカ共和国では多数派であり、キュー バ、プエルトリコ、ニカラグア、パナマ、ペルー、コロンビア、エクアドルでも多数を占めている。ラテンアメリカ諸国には、より少数の混血が存在する。 [30] 白人。15世紀後半から、イベリア半島からの多数の入植者(ブラジルではポルトガル人、その他の地域ではスペイン人)がラテンアメリカに移住し、現在で は、ラテンアメリカ人の白人の大半はスペイン人、ポルトガル人、イタリア人の子孫である。イベリア人はスペイン語やポルトガル語、カトリック信仰、そして 多くのイベリアの伝統をもたらした。ブラジル、アルゼンチン、メキシコ、ベネズエラにはラテンアメリカで最も多くのヨーロッパ人が純粋な数で存在してい る。[18] 彼らはアルゼンチン、コスタリカ、キューバ、ウルグアイの人口の大多数を占め、ブラジルとベネズエラの人口の約半数を占めている。[18][46] 1810年代から1820年代にかけてラテンアメリカ諸国のほとんどが独立を達成して以来、数百万人の移民のうち、イタリア人が最大のグループを形成し、 次いでスペイン人とポルトガル人が続いている。[47] その他にも、フランス人、ドイツ人、ギリシャ人、ポーランド人、ウクライナ人、ロシア人、クロアチア人、 イタリア人が最も多く、次いでスペイン人、ポルトガル人が多い。[47] その他にも、フランス人、ドイツ人、ギリシャ人、ポーランド人、ウクライナ人、ロシア人、クロアチア人、セルビア人、ラトビア人、リトアニア人、イギリス 人、ユダヤ人、アイルランド人、ウェールズ人などが多く移住している。ラテンアメリカ人のほとんどは、ヨーロッパ人の血を引く者、またはヨーロッパ人の血 を引く混血である。 ザンボス:黒人とアメリカ先住民の混血は、特にコロンビアとブラジルで多く見られ、その原因は奴隷の逃亡(シマロン:マローン)や先住民の村に受け入れら れたことによる場合が多い。スペイン語圏では、この混血の人々はザンボスと呼ばれ、ブラジルではカフゾスとも呼ばれる。 多民族・多人種:前述のグループに加え、ラテンアメリカには多民族背景を持つ何百万人もの人々がいる。[要出典]  |

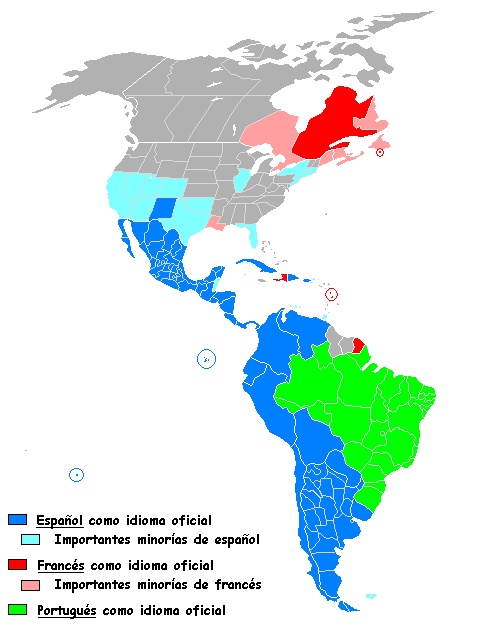

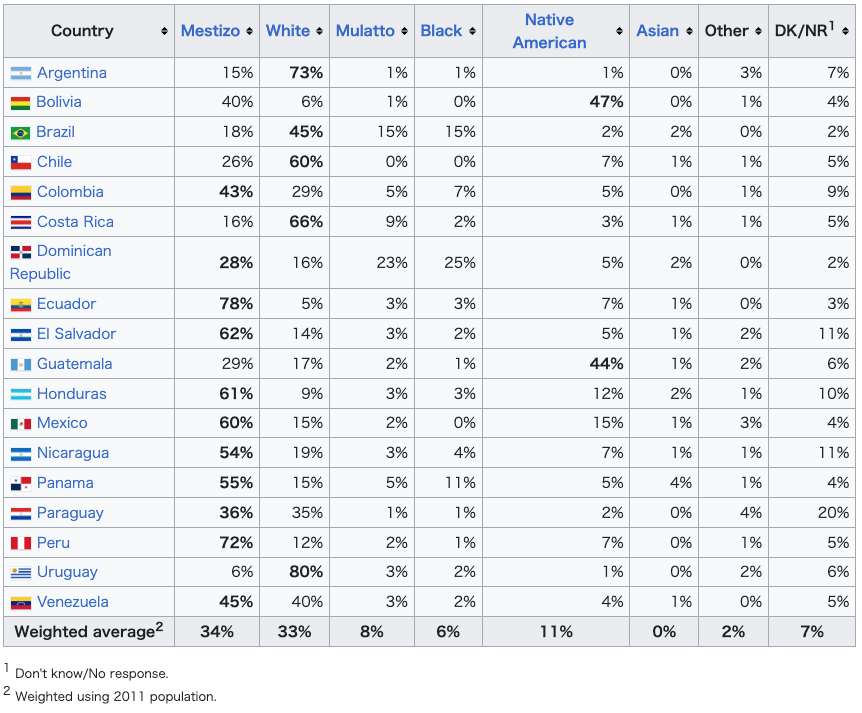

| Racial groups according to

self-identification The Latinobarómetro surveys have asked respondents in 18 Latin American countries what race they considered themselves to belong to. The figures shown below are averages for 2007 through 2011.[53]  |

自己認識による人種グループ ラテン・オロメーターの調査では、18カ国のラテンアメリカ諸国に住む回答者に、自分自身がどの人種に属すると考えているかを尋ねている。以下に示す数値 は、2007年から2011年までの平均値である。[53]  |

Language Linguistic map of Latin America. Spanish in green, Portuguese in orange, and French in blue. Spanish and Portuguese are the predominant languages of Latin America. Spanish is the official language of most of the countries on the Latin American mainland, as well as in Puerto Rico (where it is co-official with English), Cuba and the Dominican Republic. Portuguese is spoken only in Brazil, the biggest and most populous country in the region. French is spoken in Haiti, as well as in the French overseas departments of French Guiana in South America and Guadeloupe and Martinique in the Caribbean. Dutch is the official language of some Caribbean islands and in Suriname on the continent; however, as Dutch is a Germanic language, these territories are not considered part of Latin America. Indigenous languages are widely spoken in Peru, Guatemala, Bolivia and Paraguay, and, to a lesser degree, in Mexico, Chile and Ecuador. In Latin American countries not named above, the population of speakers of indigenous languages is small or non-existent. In Peru, Quechua is an official language, alongside Spanish and any other indigenous language in the areas where they predominate. In Ecuador, while holding no official status, the closely related Quichua is a recognized language of the indigenous people under the country's constitution; however, it is only spoken by a few groups in the country's highlands. In Bolivia, Aymara, Quechua and Guaraní hold official status alongside Spanish. Guarani is, along with Spanish, an official language of Paraguay, and is spoken by a majority of the population (who are, for the most part, bilingual), and it is co-official with Spanish in the Argentine province of Corrientes. In Nicaragua, Spanish is the official language, but, on the country's Caribbean coast English and indigenous languages such as Miskito, Sumo, and Rama also hold official status. Colombia recognizes all indigenous languages spoken within its territory as official, though fewer than 1% of its population are native speakers of these. Nahuatl is one of the 62 native languages spoken by indigenous people in Mexico that are officially recognized by the government as "national languages" along with Spanish. Other European languages spoken in Latin America include: English, by some groups in Argentina, Chile, Costa Rica, Nicaragua, Panama and Puerto Rico, as well as in nearby countries that may or may not be considered Latin American, such as Belize and Guyana; English is also used as a major foreign language in Latin American commerce and education. Other languages spoken in parts of Latin America include German in southern Brazil, southern Chile, Argentina, portions of northern Venezuela and Paraguay; Italian in Brazil, Argentina, Uruguay and Venezuela; Polish, Ukrainian and Russian in southern Brazil; and Welsh[54][55][56][57][58][59] in southern Argentina. Hebrew and Yiddish are used by Jewish diasporas in Argentina and Brazil. In several nations, especially in the Caribbean region, creole languages are spoken. The most widely spoken creole language in the Caribbean and Latin America in general is Haitian Creole, the predominant language of Haiti; it is derived primarily from French and certain West African tongues with indigenous, English, Portuguese and Spanish influences as well. The other most spoken Creole is Antillean Creole French that is primarily spoken in the Lesser Antilles. It is a French-based creole, that is the local language spoken among the natives of the Caribbean islands of Saint Lucia and Dominica and also in Martinique and Guadeloupe. Creole languages of mainland Latin America, similarly, are derived from European languages and various African tongues. Religion Main article: Religion in Latin America  Procession of Our Lord and the Virgin of the Miracle in Salta city. The vast majority of Latin Americans are Christians (90%),[60] mostly Roman Catholics.[61] About 71% of the Latin American population consider themselves Catholic.[62] Membership in Protestant denominations is increasing, particularly in Brazil, Guatemala and Puerto Rico. Argentina hosts the largest communities of both Jews[63][64][65] and Muslims[66][67][68] in Latin America. Indigenous religions and rituals are practiced in countries with large indigenous populations, especially Bolivia, Guatemala, Mexico and Peru, and Afro-Latin American religions such as Santería, Candomblé, Umbanda, Macumba and Vodou are practiced in countries with large Afro-Latin American populations, especially Cuba, Brazil, Dominican Republic and Haiti. Latin America constitutes, in absolute terms, the world's second largest Christian population, after Europe.[69] Migration See also: Latino Americans, Latin American Canadians, Latin Americans in the United Kingdom, Latin American Australians, and Latin American Asian According to the 2005 Colombian census or DANE, about 3,331,107 Colombians currently live abroad.[70] The number of Brazilians living overseas is estimated at 2 million people.[71] An estimated 1.5 to two million Salvadorians reside in the United States.[72] At least 1.5 million Ecuadorians have gone abroad, mainly to the United States and Spain.[73] Approximately 1.5 million Dominicans live abroad, mostly in the United States.[74] More than 1.3 million Cubans live abroad, most of them in the United States.[75] It is estimated that over 800,000 Chileans live abroad, mainly in Argentina, Canada, United States and Spain. Other Chilean nationals may be located in countries like Costa Rica, Mexico and Sweden.[76] An estimated 700,000 Bolivians were living in Argentina as of 2006 and another 33,000 in the United States.[77] Central Americans living abroad in 2005 were 3,314,300,[78] of which 1,128,701 were Salvadorans,[79] 685,713 were Guatemalans,[80] 683,520 were Nicaraguans,[81] 414,955 were Hondurans,[82] 215,240 were Panamanians[83] and 127,061 were Costa Rica.[84] As of 2006, Costa Rica and Chile were the only two countries with global positive migration rates.[85] Notable Latin Americans For a more comprehensive list, see List of Latin Americans. |

言語 中南米の言語地図。緑色がスペイン語、オレンジ色がポルトガル語、青色がフランス語。 スペイン語とポルトガル語は中南米で最も広く使用されている言語である。スペイン語は中南米本土のほとんどの国々、プエルトリコ(英語と並んで公用語)、 キューバ、ドミニカ共和国で公用語として使用されている。ポルトガル語は、この地域最大の人口を擁するブラジルでしか話されていない。フランス語はハイ チ、および南米のフランス領ギアナ、カリブ海のグアドループ島とマルティニーク島で話されている。オランダ語はカリブ海のいくつかの島々、および大陸のス リナムで公用語となっているが、オランダ語はゲルマン語派に属するため、これらの地域はラテンアメリカの一部とは見なされていない。 先住民の言語は、ペルー、グアテマラ、ボリビア、パラグアイで広く話されており、また、程度は低いがメキシコ、チリ、エクアドルでも話されている。上記以 外のラテンアメリカ諸国では、先住民の言語を話す人口は少ないか、あるいは皆無である。 ペルーでは、ケチュア語はスペイン語やその他の先住民言語が優勢な地域で、それらと共に公用語として使用されている。エクアドルでは、公式な地位は持たな いものの、ケチュア語と密接な関係にあるキチュア語は、同国の憲法の下で先住民の言語として認められている。しかし、この言語は同国高地の少数のグループ によってのみ話されている。ボリビアでは、アイマラ語、ケチュア語、グアラニー語がスペイン語と共に公用語として使用されている。グアラニー語はスペイン 語とともにパラグアイの公用語であり、人口の大多数(ほとんどがバイリンガル)が使用している。また、アルゼンチンのコリエンテス州ではスペイン語と並ん で公用語となっている。ニカラグアではスペイン語が公用語であるが、カリブ海沿岸部では英語や先住民の言語であるミスキート語、スモ語、ラマ語なども公用 語として認められている。コロンビアでは、国内で話されている先住民の言語はすべて公用語として認められているが、これらの言語を母語とする人口は国民の 1%にも満たない。 ナワトル語は、メキシコの先住民が話す62の先住民言語のひとつであり、スペイン語とともに「国語」として政府に公式に認められている。 ラテンアメリカで話されているその他のヨーロッパ言語には、アルゼンチン、チリ、コスタリカ、ニカラグア、パナマ、プエルトリコの一部のグループ、および ラテンアメリカと見なされる場合も見なされない場合もある近隣諸国(ベリーズ、ガイアナなど)で話されている英語がある。英語はラテンアメリカの商業およ び教育の主要な外国語としても使用されている。ラテンアメリカの一部で話されているその他の言語には、ブラジル南部、チリ南部、アルゼンチン、ベネズエラ 北部の一部、パラグアイで話されているドイツ語、ブラジル、アルゼンチン、ウルグアイ、ベネズエラで話されているイタリア語、ブラジル南部で話されている ポーランド語、ウクライナ語、ロシア語、アルゼンチン南部で話されているウェールズ語がある。 カリブ海地域を中心に、いくつかの国々ではクレオール語が話されている。カリブ海地域および中南米全体で最も広く話されているクレオール語はハイチ・クレ オール語で、ハイチの主要言語である。これは主にフランス語と西アフリカの言語を基にしており、先住民、英語、ポルトガル語、スペイン語の影響も受けてい る。他に広く話されているクレオール語はアンティル・クレオール語で、主に小アンティル諸島で話されている。これはフランス語をベースにしたクレオール語 で、カリブ海のセントルシアやドミニカ、マルティニーク、グアドループの原住民の間で話されている現地語である。ラテンアメリカ本土のクレオール語も同様 に、ヨーロッパの言語とアフリカのさまざまな言語に由来している。 宗教 詳細は「ラテンアメリカの宗教」を参照  サルタ市で行われた「我らが主と奇跡の聖母」の行列。 ラテンアメリカ人の大半はキリスト教徒(90%)であり、そのほとんどがローマ・カトリック教徒である。ラテンアメリカ人口の約71%が自らをカトリック 教徒であると考えている。プロテスタントの宗派への加入は増加しており、特にブラジル、グアテマラ、プエルトリコで顕著である。アルゼンチンにはラテンア メリカ最大のユダヤ人[63][64][65]およびイスラム教徒[66][67][68]のコミュニティがある。先住民の宗教や儀式は、特にボリビア、 グアテマラ、メキシコ、ペルーといった先住民の人口が多い国々で信仰されている。また、サンテリア、カンドンブレ、ウンバンダ、マクンバ、ブードゥーと いったアフリカ系ラテンアメリカ人の宗教は、特にキューバ、ブラジル、ドミニカ共和国、ハイチといったアフリカ系ラテンアメリカ人の人口が多い国々で信仰 されている。ラテンアメリカは、絶対数で世界第2位のキリスト教徒人口を抱える地域である。 移民 関連項目:ラテンアメリカ系カナダ人、イギリス在住ラテンアメリカ系住民、オーストラリア在住ラテンアメリカ系住民、アジア系ラテンアメリカ系住民 2005年のコロンビア国勢調査またはDANEによると、現在、約3,331,107人のコロンビア人が海外に居住している。[70] 海外在住のブラジル人の数は200万人と推定されている。[71] 推定150万から200万人のエルサルバドル人が米国に居住している。[72] 少なくとも150万人のエクアドル人が海外に居住している 、主にアメリカ合衆国とスペインに在住している。[73] およそ150万人のドミニカ人が海外に在住しており、そのほとんどがアメリカ合衆国在住である。[74] 130万人以上のキューバ人が海外に在住しており、そのほとんどがアメリカ合衆国在住である。[75] 80万人以上のチリ人が海外に在住しており、そのほとんどがアルゼンチン、カナダ、アメリカ合衆国、スペイン在住であると推定されている。その他のチリ国 民は、コスタリカ、メキシコ、スウェーデンなどの国々にいる可能性がある。[76] 2006年の時点で、推定70万人のボリビア人がアルゼンチンに、さらに3万3000人がアメリカ合衆国に住んでいる。[77] 2005年に海外に住んでいた中米人は331万4300人で、そのうち112万8701人が 1,128,701人がエルサルバドル人[79]、685,713人がグアテマラ人[80]、683,520人がニカラグア人[81]、414,955人 がホンジュラス人[82]、215,240人がパナマ人[83]、127,061人がコスタリカ人であった[84]。 2006年の時点で、コスタリカとチリは世界的に見て移民の純増率がプラスとなっている唯一の2か国である。[85] 著名なラテンアメリカ人 より包括的なリストについては、ラテンアメリカ人の一覧を参照のこと。 |

| Argentines Bolivians Brazilians Californios Chileans Colombians Costa Ricans Cubans Dekasegi Dominicans Ecuadorians Filipinos Guatemalans Haitians Hondurans History of Latin America Italians Japanese Mexicans Latin American culture Latinos Los Angeles, California Mexicans Miami Neomexicanos Nicaraguans Nuyoricans Panamanians Paraguayans Peruvians Portuguese people Puerto Ricans Québécois people Salvadorans Spaniards Tejanos Uruguayans Venezuelans |

アルゼンチン人 ボリビア人 ブラジル人 カリフォルニア人 チリ人 コロンビア人 コスタリカ人 キューバ人 出稼ぎ労働者 ドミニカ人 エクアドル人 フィリピン人 グアテマラ人 ハイチ人 ホンジュラス人 ラテンアメリカ史 イタリア人 日本人メキシコ人 ラテンアメリカ文化 ラテン系住民 ロサンゼルス(カリフォルニア州) メキシコ人 マイアミ 新メキシコ人 ニカラグア人 ニューヨーク市在住のニカラグア人 パナマ人 パラグアイ人 ペルー人 ポルトガル人 プエルトリコ人 ケベック人 エルサルバドル人 スペイン人 テキサス人 ウルグアイ人 ベネズエラ人 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Latin_Americans |

|

Robert Farris Thompson (December 30, 1932 – November 29, 2021) was an American art historian and writer who specialized in Africa and the Afro-Atlantic world. He was a member of the faculty at Yale University from 1965 to his retirement more than fifty years later and served as the Colonel John Trumbull Professor of the History of Art.[1] Thompson coined the term "black Atlantic" in his 1983 book Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy – the expanded subject of Paul Gilroy's book The Black Atlantic.[2] He lived in the Yoruba region of southwest Nigeria while he conducted his research of Yoruba arts history. He was affiliated with the University of Ibadan and frequented Yoruba village communities. Thompson studied the African arts of the diaspora in the United States, Mexico, Argentina, Brazil, Cuba, Haiti, Puerto Rico, Surinam and several Caribbean islands. Career at Yale In 1955, Thompson received his B.A. from Yale University. After receiving his bachelor's degree and serving in the 7th Army in Stuttgart, he continued his studies at Yale, where he received his Master's degree in 1961 and his Ph.D. in 1965.[3] He was the first Yale professor and second person in the United States (the first being Roy Sieber at the University of Iowa in 1956) to receive a professorship in African Art history.[4] Having served as Master of Timothy Dwight College from 1978 until 2010, he was the longest serving master of a residential college at Yale. Thompson was one of America's most prominent scholars of African art,[5] and presided over exhibitions of African art at the National Gallery of Art in Washington D.C. He was one of the longest-serving alumni of Yale. Publications and areas of study Beginning with an article on Afro-Cuban dance and music (published in 1958), Thompson dedicated his life to the study of art history of the Afro-Atlantic world.[3] His first book was Black Gods and Kings, which was a close reading of the art history of the Yoruba people of southwestern Nigeria (population of approximately 40 million).[3] Other published works include African Art in Motion, Flash of the Spirit (1983), Face of the Gods, and Tango: The Art History of Love.[3] Thompson also published an introduction to the diaries of Keith Haring. Some of his works have even been translated into German, Portuguese, French and Flemish.[3] Additionally, Thompson also studied the art of Guillermo Kuitca and José Bedia, and was anthologized 15 times.[3] Awards The College Art Association presented its inaugural Distinguished Lifetime Achievement Award for Art Writing to Thompson in 2003,[6] and was named CAA's Distinguished Scholar in 2015.[7] In 2007, Thompson was given the "Outstanding Contribution to Dance Research" award, by the Congress on Research in Dance.[1] Personal life and death Thompson was born in El Paso, Texas.[8] He spoke French, Italian, Portuguese, and Spanish fluently and could speak Yoruba, Ki-Kongo[9] and German, Flemish, and Kreyol[which?][10] at an intermediate level. He has been to nearly all 47 countries of Africa and is survived by a sister, two children, four grandchildren and a great granddaughter.[9] Thompson died from COVID-19-complicated Parkinson's disease on November 29, 2021, at a nursing home in New Haven, Connecticut. He was 88.[11][12] |

ロバート・ファリス・トンプソン(Robert Farris Thompson、1932年12月30日 - 2021年11月29日)は、アフリカとアフロ・アトランティック世界を専門とするアメリカの美術史家、作家である。1965年から50年以上後に引退す るまでイェール大学の教授を務め、美術史のジョン・トランブル大佐講座の教授を務めた[1]。トンプソンは1983年の著書『Flash of the Spirit』で「ブラック・アトランティック」という言葉を生み出し た: これはポール・ギルロイの著書『The Black Atlantic』(邦題『ブラック・アトランティック』)の拡大版である[2]。 彼はナイジェリア南西部のヨルバ地方に住み、ヨルバ芸術史の研究を行った。彼はイバダン大学に所属し、ヨルバの村落共同体に頻繁に出入りしていた。アメリ カ、メキシコ、アルゼンチン、ブラジル、キューバ、ハイチ、プエルトリコ、スリナム、カリブ海の島々で、ディアスポラのアフリカ芸術を研究した。 エール大学でのキャリア 1955年、トンプソンはイェール大学で学士号を取得した。学士号取得後、シュトゥットガルトの第7軍に従軍した後、イェール大学で研究を続け、1961 年に修士号、1965年に博士号を取得した[3]。アフリカ美術史の教授職を得た最初のイェール大学教授であり、アメリカでは2人目(1人目は1956年 にアイオワ大学のロイ・シーバー)である[4]。 1978年から2010年までティモシー・ドワイト・カレッジの校長を務め、イェール大学の全寮制カレッジの校長としては最も長く在任した。アメリカで最 も著名なアフリカ美術研究者の一人であり[5]、ワシントンD.C.の国民美術館でアフリカ美術展を主宰した。 出版物と研究分野 1958年に出版されたアフロ・キューバのダンスと音楽に関する論文に始まり、アフロ・アトランティック世界の美術史の研究に生涯を捧げた[3]: トンプソンはまた、キース・ヘリングの日記を紹介する本も出版している。さらに、ギレ ルモ・クイトカとホセ・ベディアの芸術も研究し、15回のアンソロジーを受けている[3]。 受賞歴 2003年、カレッジ・アート・アソシエーションはトンプソンに第1回アート・ライティング特別生涯功労賞を授与し[6]、2015年にはCAAの特別奨 学生に選出された[7]。2007年、トンプソンはダンス研究会議から「ダンス研究への顕著な貢献」賞を授与された[1]。 私生活と死 フランス語、イタリア語、ポルトガル語、スペイン語を流暢に話し[8]、ヨルバ語、キ・コンゴ語[9]、ドイツ語、フラマン語、クレヨール語[どの] [10]を中級レベルで話すことができた。彼はアフリカのほぼ47カ国すべてに行ったことがあり、妹、2人の子供、4人の孫、ひ孫がいる[9]。 トンプソンは2021年11月29日、コネチカット州ニューヘイブンの老人ホームでCOVID-19合併パーキンソン病により死去した。88歳だった [11][12]。 |

| Bibliography 1971 Black Gods and Kings: Yoruba Art at UCLA 1974 African Art in Motion: Icon and Act in the Collection of Katharine Coryton White 1981 The Four Moments of the Sun: Kongo Art in Two Worlds 1983 Flash of the Spirit: African and Afro-American Art and Philosophy 1993 Face of the Gods: Art and Altars of Africa and the African Americas 1999 The Art of William Edmondon 2005 Tango: The Art History of Love 2011 Aesthetic of the Cool: Afro-Atlantic Art and Music |

書誌 1971年 黒い神々と王たち UCLAのヨルバ美術 1974年 動くアフリカ美術: キャサリン・コリントン・ホワイトのコレクションにおけるアイコンと行為 1981年 太陽の4つの瞬間: 二つの世界におけるコンゴ美術 1983 精神の閃光 アフリカとアフロ・アメリカンの芸術と哲学 1993年 神々の顔:アフリカとアフリカ系アメリカ人の芸術と祭壇 1999年 ウィリアム・エドモンドンの芸術 2005 タンゴ 愛の美術史 2011年 クールの美学 アフリカ系アメリカ人の芸術と音楽 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Robert_Farris_Thompson |

ラテ

ンアメリカ域内における文化の「均質性の神話」

ラテ

ンアメリカ域内における文化の「均質性の神話」

ラテンアメリカの歴史と文化を注意深く調べると、ラ

テンアメリカは文化的に均質な全体を構成していないことがわかる。また言語による共通性で、しばしば国際会議などが行いやすい、CNN、ABC、BBCな

どの国際的なパンアメリカ的放送局もスペイン語での報道をおこない、またソープオペラやコメディーショーを配信することができるが、地域的な固有性はつね

に保たれており、文化的なものが節合されるプロセスはきわめて複雑である。また「ラテンアメリカ」という表現は、コロンブス以前の地域の過去(の記憶)を

消去し去るという意味でも、先住民の側からはスペイン・ポルトガルによるヨーロッパ白人による支配状況は依然として続いているという指摘もある(→)。

独立戦争後1825年の新大陸とりわけラテンアメリ カとよばれる政治的領域の区分についてのべてみよう。

|

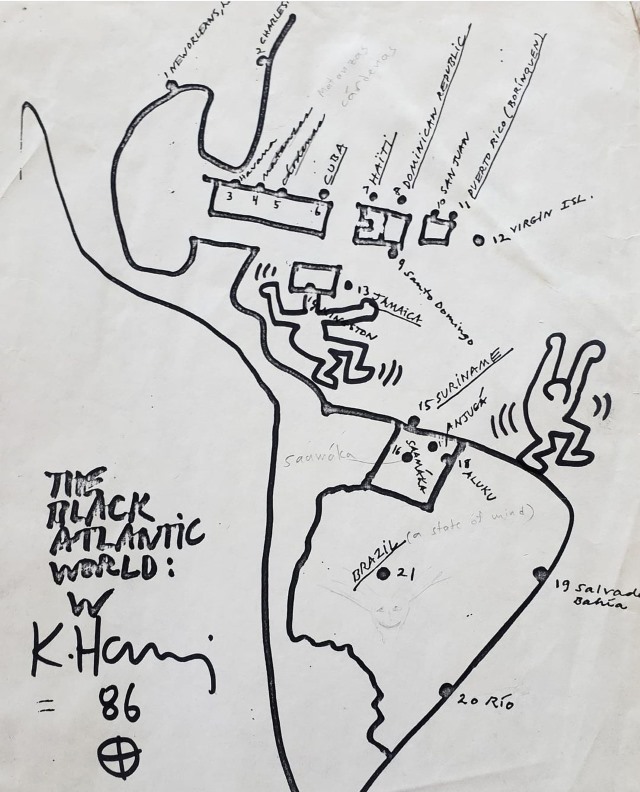

After many years

of thinking I had mistakenly thrown this out, I found my Keith Haring

today! Haring came to a class being taught by Robert

Ferris Thompson, 1932-2021

(Master T) in 1986, and he came with a sharpie. If you gave him a sheet

of paper he would give you a little drawing. I handed him the xerox map

that we were given in class (showing the path of African culture

through the Americas), and he added the figures to make the map dance.

Time to get it framed! By @blakeatphillips 「長年、間違って捨ててしまったと思っていたが、今日、ついにキース・ヘリングの作品を見つけた! 1986年、キース・ヘリングはロバート・フェリス・トンプソン[Robert Ferris Thompson](マスターT)[このページの上掲]の授業に出席し、マジックペンを持ってやって来た。彼に紙を渡すと、小さな 絵を描いてくれた。私は彼に、授業で渡されたコピーの地図(アメリカ大陸におけるアフリカ文化の伝播経路を示す)を手渡した。すると、彼はその地図に踊っ ているような人物を描き加えた。額縁に入れて飾る時が来た!」 |

|

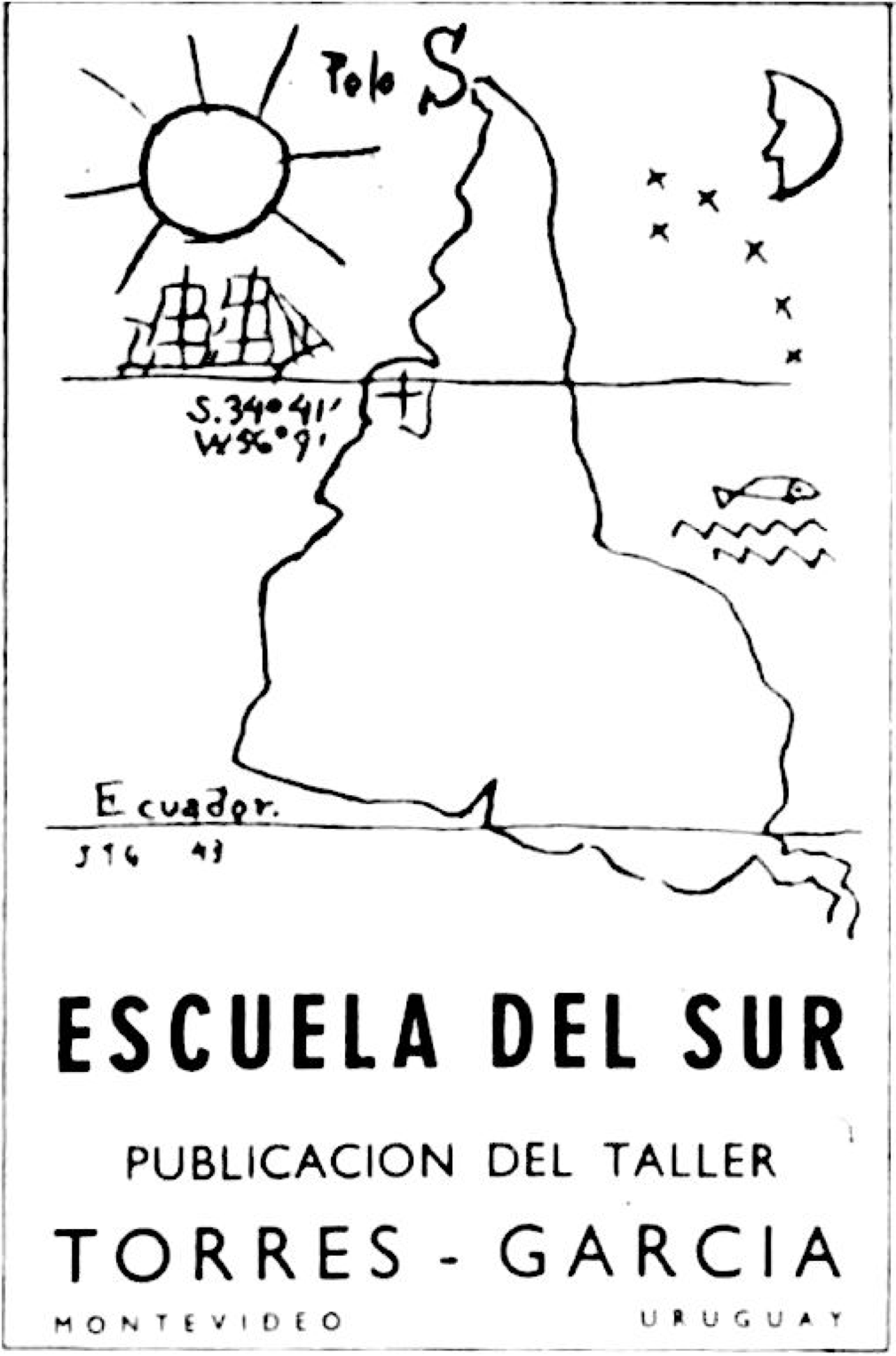

Joaquín

Torres-García

(28 July 1874 – 8 August 1949) was a Uruguayan-Spanish artist[1] who

was born in Montevideo, Uruguay. Torres-García emigrated to Catalunya,

Spain as an adolescent, where he began his career as an artist in 1891.

For the next three decades, Torres-García embraced the Catalan identity

and led the cultural scene in Barcelona and Europe. As a painter,

sculptor, muralist, novelist, writer, teacher, and theorist,

Torres-García was considered a "renaissance" or "universal man." He

used a simple metaphor to deal with eternal struggles he faced between

the old and the new, between classical and avant-garde, between reason

and feeling, and between figuration and abstraction: there is no

contradiction or incompatibility. Like Goethe, Torres-García sought to

integrate classicism and modernity.[2] Although he lived and worked

primarily in Spain, Torres-García was also active in the United States,

Italy, France, and Uruguay; he influenced European and North American

and South American modern art. - América

Invertida (1943) ホアキン・トーレス・ガルシア(1874年7月28日 - 1949年8月8日)は、ウルグアイのモンテビデオ生まれのウルグアイ系スペイン人芸術家である。トーレス・ガルシアは青年期にスペインのカタルーニャに 移住し、1891年にアーティストとしてのキャリアをスタートさせた。その後30年にわたり、トーレス・ガルシアはカタルーニャのアイデンティティを受け 入れ、バルセロナやヨーロッパの文化シーンを牽引した。画家、彫刻家、壁画画家、小説家、作家、教師、理論家として、トーレス・ガルシアは「ルネサンス」 または「万能の人」とみなされていた。彼は、新旧、古典と前衛、理性と感情、具象と抽象の間で直面した永遠の葛藤を、シンプルな比喩を用いて表現した。す なわち、矛盾や不調和はないというのだ。トーレス・ガルシアはゲーテと同様に、古典主義と現代性を統合しようとした。[2] スペインを主な活動拠点としていたが、アメリカ、イタリア、フランス、ウルグアイでも活躍し、ヨーロッパや北米、南米の現代美術に影響を与えた。 |

| "Traditional"

Latin American's Territory |

|

|

緑の広大な領域がメキシ

コである。出典は:Territorial

evolution of North America since 1763(Wikipedia) アメリカ大陸の脱植民地化は、数世紀にわたって行われ、アメリカ大陸のほとんどの国がヨーロッパの支配から独立を勝ち取った。アメリカ大陸で最初に行われ たのはアメリカ独立革命であり、アメリカ独立革命戦争(1775年~1783年)におけるイギリスの敗北は、イギリスの敵国であったフランスとスペインの 支援を受けた大国に対する勝利であった。その後、ヨーロッパではフランス革命が起こり、これらの出来事はアメリカ大陸のスペイン、ポルトガル、フランスの 植民地に大きな影響を与えた(→「南北アメリカ大陸の脱 植民地化」)。 |

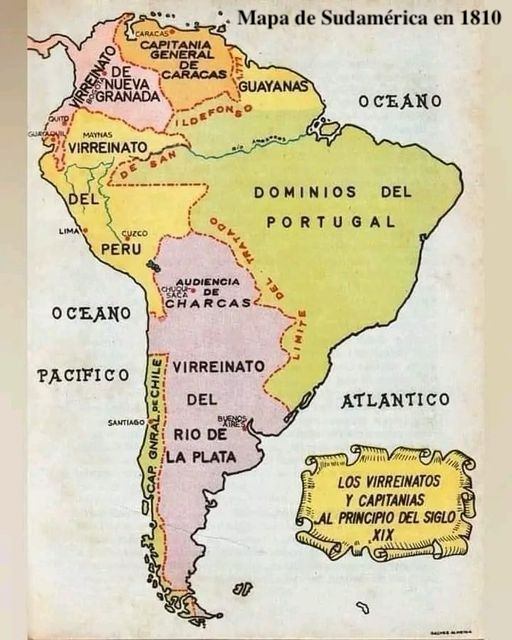

|

1810年当時の南アメリカ アメリカ大陸の脱植民地化は、数世紀にわたって行われ、アメリカ大陸のほとんどの国がヨーロッパの支配から独立を勝ち取った。アメリカ大陸で最初に行われ たのはアメリカ独立革命であり、アメリカ独立革命戦争(1775年~1783年)におけるイギリスの敗北は、イギリスの敵国であったフランスとスペインの 支援を受けた大国に対する勝利であった。その後、ヨーロッパではフランス革命が起こり、これらの出来事はアメリカ大陸のスペイン、ポルトガル、フランスの 植民地に大きな影響を与えた。革命の波は続き、ラテンアメリカではいくつかの独立国が誕生した。ハイチ革命は1791年から1804年まで続き、フランス 領の奴隷植民地が独立した。ナポレオンによるスペイン占領に端を発したフランスとの半島戦争により、スペイン領アメリカにおけるスペイン系クリオール人た ちはスペインへの忠誠を疑うようになり、独立運動が活発化し、最終的にスペイン領アメリカ独立戦争(1808年~1833年)へと発展した。この戦争は主 に植民地出身者たちの対立グループ間で戦われ、スペイン軍との戦いは二次的なものに過ぎなかった。同時に、ポルトガル王政はフランスによるポルトガル侵攻 の際にブラジルに逃亡した。王宮がリスボンに戻った後、摂政ペドロ王子はブラジルに残り、1822年にブラジル帝国の皇帝として即位した。 スペインは1800年代の終わりまでに、カリブ海に残っていた3つの植民地をすべて失うことになる。サント・ドミンゴは1821年にスペイン領ハイチ共和 国として独立を宣言した。旧フランス領ハイチとの統合と分裂を経て、ドミニカ共和国の大統領は1861年にスペインの植民地に戻す協定に署名した。これが ドミニカ回復戦争の引き金となり、1865年にドミニカ共和国はスペインから2度目の独立を果たした。キューバは10年戦争(1868年~1878年)、 小戦争(1879年~1880年)、そして最終的にキューバ独立戦争(1895年~1898年)でスペインからの独立を求めて戦った。1898年のアメリ カの介入は米西戦争となり、アメリカはプエルトリコ、グアム(現在もアメリカの領土)、太平洋上のフィリピン諸島を獲得した。軍事占領下にあったキューバ は、1902年に独立するまでアメリカの保護領となった。 植民地大国の自主的な撤退による平和的な独立は、20世紀後半には一般的となった。しかし、北米には現在でもイギリスとオランダの植民地(ほとんどがカリ ブ海諸島)が存在する。フランスは、かつての植民地の大半(フランス領ギアナ、グアドループ島、マルティニーク)を、フランスの完全な構成省として完全に 統合している(→「南北アメリカ大陸の脱植民地化」)。 |

|

スペイン独立戦争(1825)後の政治

区分 出典は、South America, 1825, 出典はブログによる投稿者によるものである。 |

|

1875年のブラジル内戦に先立つ時点での南アメリカの政治区分 http: //www.alternatehistory.com/discussion/showthread.php?t=222529 |

| 【清水透のテーゼ】 ラテンアメリカ五〇〇年 : 歴史のトルソー / 清水透著, 東京 : 岩波書店 , 2017.12. - (岩波現代文庫 ; 学術 ; 372) |

1)先住民社会への寄生性と差別性(p.39) 2)野蛮への恐怖(p.41) 3)世界的な人種混交の場(p.43) |

|

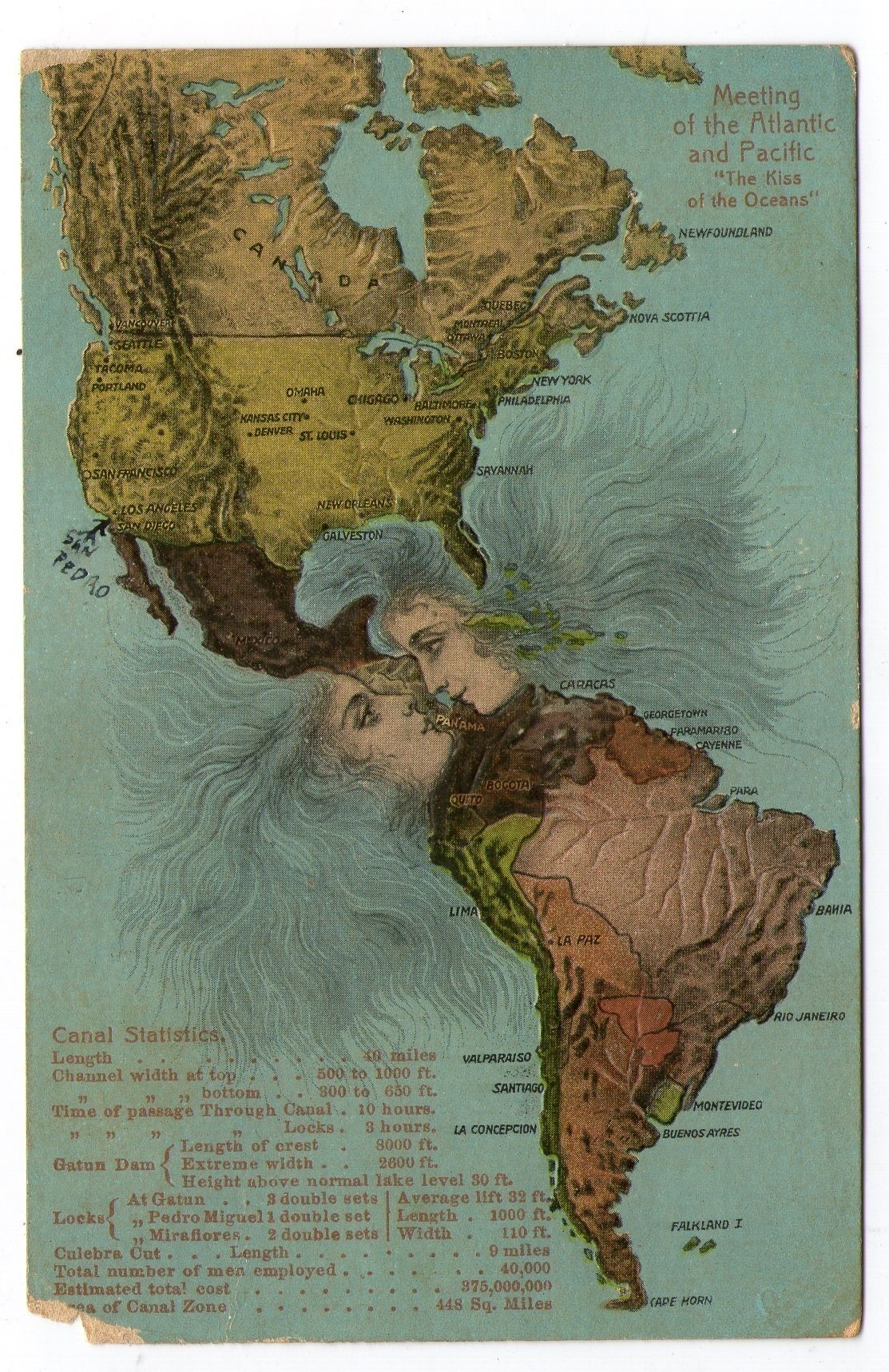

The Kiss of the oceans - postcard from 1923. パナマ運河は1914年8月15日に開通(→「パナマ運河の歴史」)。 |

それが50年後の1875年には、そのいくつかの領 域が再度、ヨーロッパ列強に再占領さたり、独立国内部で分裂をしていることがわかる。

●ラテンアメリカという概念を「所有」しようとする意思

自分たちが根無し草だという意識には、2つの感覚が

ある。ひとつには、世界と自分たちが断絶しているという意識、もうひとつは、世界を創造しようといする意思である。

★ラテンアメリカの代替物としての「ヒスパニック(Hispanic)」→「イスパノアメリカ」を見よ!!

ヒスパニック(スペイン語:hispano)という用語は、スペイン、スペイン語、またはヒ スパニアに関連する人々、文化、国々を広く指す。特に米国では、文脈によっては「ヒスパニック」が民族または超民族的な用語として使用されることもある。 この用語は一般的に、スペイン人およびスペイン語話者(ヒスパニック語話者)の人口と、ヒスパニックアメリカ(大陸)およびヒスパニックアフリカ(赤道ギ ニアおよび係争中の西サハラ地域)の国々を指す。これらの国々は、主に16世紀から20世紀にかけての植民地化により、かつてスペイン帝国の一部であっ た。スペイン以外のヒスパニック語話者の国の文化は、先住のヒスパニック文化やその他の外国の影響も受けている。フィリピン、マリアナ諸島、その他の国々 を含む旧スペイン領東インドにもスペインの影響が見られる。しかし、これらの地域ではスペイン語は主要言語ではなく、その結果、これらの地域の住民は通 常、ヒスパニックとは見なされない。ヒスパニック文化とは、音楽、文学、服装、建築、料理など、ヒスパニック地域の人々が一般的に共有している習慣、伝 統、信念、芸術形態の集合体であるが、国や地域によって大きく異なる場合もある。スペイン語は、ヒスパニックの人々が共有する主な文化要素である。

リンク

文献

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆