ハーレム・ルネサンス

Harlem Renaissance

☆ ハーレム・ルネサンスは、1920年代から1930年代にかけて、ニューヨーク市マンハッタン区ハーレムを中心に、アフリカ系アメリカ人の音楽、ダンス、 アート、ファッション、文学、演劇、政治、学問の分野における知的・文化的な復興運動であった。当時、この運動は「ニュー・ニグロ・ムーブメント」として 知られていた。これは、1925年にアラン・ロックが編集したアンソロジー『ザ・ニュー・ニグロ』にちなんで名付けられたものである。この運動には、公民 権獲得のための闘争が再び活発化した影響を受けたアメリカ北東部および中西部の都市部における、アフリカ系アメリカ人の新しい文化表現も含まれていた。ま た、南部のジム・クロウ法による人種差別的な状況から逃れるために、アフリカ系アメ リカ人の労働者が大規模に移住したことも影響している。 この運動はハーレムを中心に起こったが、フランス・パリに住んでいたアフリカやカリブ海の植民地出身のフランス語話者黒人作家たちにも影響を与えた。 [3][4][5][6][7] その思想の多くは、その後も長く生き続けた。 ジェームズ・ウェルドン・ジョンソンが好んで呼んだ「ハーレム・ルネサンス」の「ニグロ文学の開花」の絶頂期は、1924年から1929年の間に起こっ た。黒人作家たちのパーティーが開催され、多くの白人出版社関係者が出席した。1929年、株式市場が大暴落し、世界大恐慌が始まった年である。ハーレ ム・ルネサンスは、アフリカ系アメリカ人の芸術の再生であったと考えられている。[8]

| The Harlem

Renaissance was an intellectual and cultural revival of

African-American music, dance, art, fashion, literature, theater,

politics and scholarship centered in Harlem, Manhattan, New York City,

spanning the 1920s and 1930s.[1] At the time, it was known as the "New

Negro Movement", named after The New Negro, a 1925 anthology edited by

Alain Locke. The movement also included the new African-American

cultural expressions across the urban areas in the Northeast and

Midwest United States affected by a renewed militancy in the general

struggle for civil rights, combined with the Great Migration of

African-American workers fleeing the racist conditions of the Jim Crow

Deep South,[2] as Harlem was the final destination of the largest

number of those who migrated north. Though it was centered in the Harlem neighborhood, many francophone black writers from African and Caribbean colonies who lived in Paris, France, were also influenced by the movement.[3][4][5][6][7] Many of its ideas lived on much longer. The zenith of this "flowering of Negro literature", as James Weldon Johnson preferred to call the Harlem Renaissance, took place between 1924—when Opportunity: A Journal of Negro Life hosted a party for black writers where many white publishers were in attendance—and 1929, the year of the stock-market crash and the beginning of the Great Depression. The Harlem Renaissance is considered to have been a rebirth of the African-American arts.[8] |

ハーレム・ルネサンスは、1920年代から1930年代にかけて、

ニューヨーク市マンハッタン区ハーレムを中心に、アフリカ系アメリカ人の音楽、ダンス、アート、ファッション、文学、演劇、政治、学問の分野における知

的・文化的な復興運動であった。当時、この運動は「ニュー・ニグロ・ムーブメント」として知られていた。これは、1925年にアラン・ロックが編集したア

ンソロジー『ザ・ニュー・ニグロ』にちなんで名付けられたものである。この運動には、公民権獲得のための闘争が再び活発化した影響を受けたアメリカ北東部

および中西部の都市部における、アフリカ系アメリカ人の新しい文化表現も含まれていた。また、南部のジム・クロウ法による人種差別的な状況から逃れるため

に、アフリカ系アメリカ人の労働者が大規模に移住したことも影響している。 この運動はハーレムを中心に起こったが、フランス・パリに住んでいたアフリカやカリブ海の植民地出身のフランス語話者黒人作家たちにも影響を与えた。 [3][4][5][6][7] その思想の多くは、その後も長く生き続けた。 ジェームズ・ウェルドン・ジョンソンが好んで呼んだ「ハーレム・ルネサンス」の「ニグロ文学の開花」の絶頂期は、1924年から1929年の間に起こっ た。黒人作家たちのパーティーが開催され、多くの白人出版社関係者が出席した。1929年、株式市場が大暴落し、世界大恐慌が始まった年である。ハーレ ム・ルネサンスは、アフリカ系アメリカ人の芸術の再生であったと考えられている。[8] |

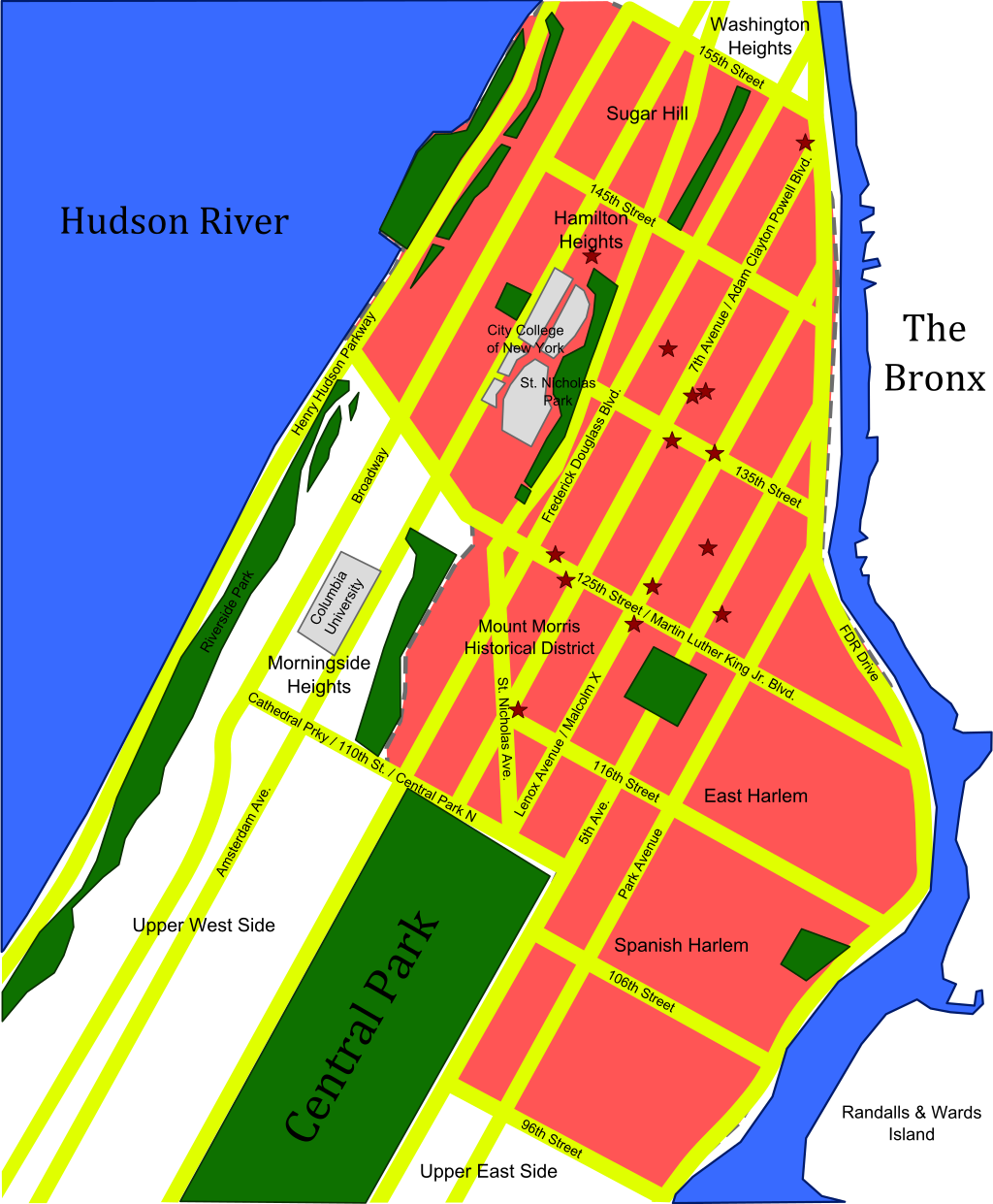

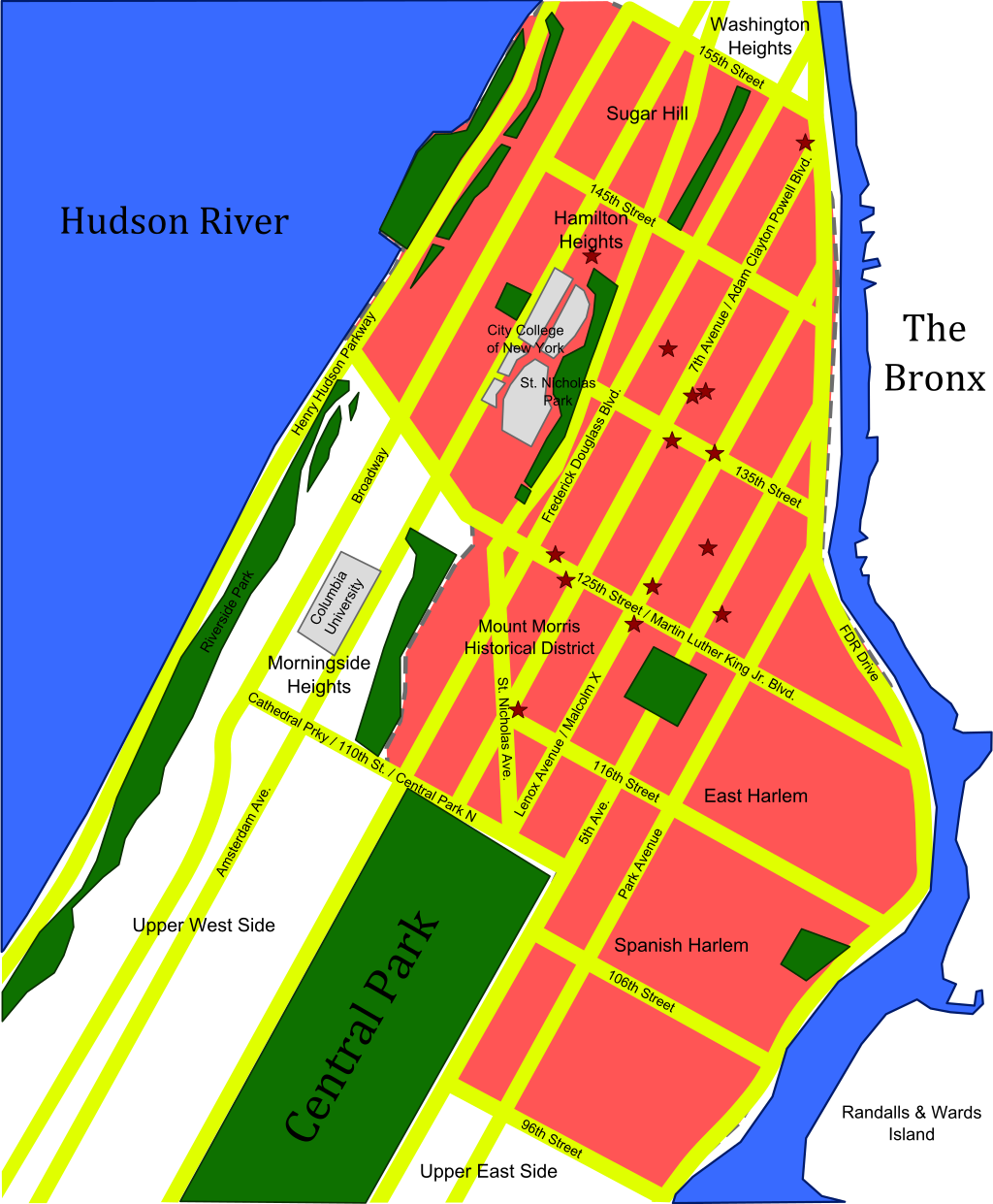

Background A map of Upper Manhattan with pink sections for Harlem Harlem in Upper Manhattan Until the end of the Civil War, the majority of African Americans had been enslaved and lived in the South. During the Reconstruction Era, the emancipated African Americans began to strive for civic participation, political equality, and economic and cultural self-determination. Soon after the end of the Civil War, the Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 gave rise to speeches by African-American congressmen addressing this bill.[9] By 1875, sixteen African Americans had been elected and served in Congress and gave numerous speeches with their newfound civil empowerment.[10] The Ku Klux Klan Act of 1871 was followed by the passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1875, part of Reconstruction legislation by Republicans. During the mid-to-late 1870s, racist whites organized in the Democratic Party launched a murderous campaign of racist terrorism to regain political power throughout the South. From 1890 to 1908, they proceeded to pass legislation that disenfranchised most African Americans and many poor whites, trapping them without representation. They established white supremacist regimes of Jim Crow segregation in the South and one-party block voting behind Southern Democrats.  Philip A. Payton Jr. founded the Afro-American Realty Company in 1903, which sought to fight housing discrimination and encourage Black migration into Harlem.[11] Democratic Party politicians (many having been former slaveowners and political and military leaders of the Confederacy) conspired to deny African Americans their exercise of civil and political rights by terrorizing black communities with lynch mobs and other forms of vigilante violence[12] as well as by instituting a convict labor system that forced many thousands of African Americans back into unpaid labor in mines, plantations and on public works projects such as roads and levees. Convict laborers were typically subject to brutal forms of corporal punishment, overwork and disease from unsanitary conditions. Death rates were extraordinarily high.[13] While a small number of African Americans were able to acquire land shortly after the Civil War, most were exploited as sharecroppers.[14] Whether sharecropping or on their own acreage, most of the black population was closely financially dependent on agriculture. This added another impetus for the Migration: the arrival of the boll weevil. The beetle eventually came to waste 8% of the country's cotton yield annually and thus disproportionately impacted this part of America's citizenry.[15] As life in the South became increasingly difficult, African Americans began to migrate north in great numbers. Most of the future leading lights of what was to become known as the "Harlem Renaissance" movement arose from a generation that had memories of the gains and losses of Reconstruction after the Civil War. Sometimes their parents, grandparents – or they themselves – had been slaves. Their ancestors had sometimes benefited by paternal investment in cultural capital, including better-than-average education. Many in the Harlem Renaissance were part of the early 20th century Great Migration out of the South into the African-American neighborhoods of the Northeast and Midwest. African Americans sought a better standard of living and relief from the institutionalized racism in the South. Others were people of African descent from racially stratified communities in the Caribbean who came to the United States hoping for a better life. Uniting most of them was their convergence in Harlem. |

背景 アッパー・マンハッタンの地図。ピンク色の部分がハーレム アッパー・マンハッタンのハーレム 南北戦争が終結するまで、アフリカ系アメリカ人の大半は奴隷として南部に住んでいた。再建時代には、解放されたアフリカ系アメリカ人は市民権の獲得、政治 的平等、経済的・文化的な自己決定を目指して努力を始めた。南北戦争の終結直後、1871年のクークラックスクラン法により、この法案について演説するア フリカ系アメリカ人の下院議員が現れた。[9] 1875年までに、16人のアフリカ系アメリカ人が下院議員に選出され、議会で務め、市民権の獲得によって得た新たな力を背景に、数多くの演説を行った。 [10] 1871年のクー・クラックス・クラン法に続き、共和党による再建法の一部として、1875年の公民権法が可決された。1870年代の中頃から後半にかけ て、南部全域で政治的権力を取り戻すため、民主党に組織された人種差別主義者の白人が、人種差別テロの殺人キャンペーンを開始した。1890年から 1908年にかけて、彼らはほとんどのアフリカ系アメリカ人と多くの貧しい白人から選挙権を奪う法律を次々と可決し、彼らを代表者不在の状況に追い込ん だ。南部ではジム・クロウ法による白人至上主義体制を確立し、南部民主党による一党 支配体制を敷いた。  フィリップ・A・ペイトン・ジュニアは1903年にアフリカ系アメリカ人不動産会社を設立し、住宅差別と戦い、黒人のハーレムへの移住を促進しようとし た。 民主党の政治家(その多くは元奴隷所有者であり、南部連合の政治・軍事指導者であった)は、リンチ暴徒やその他の自警団による暴力によって黒人社会を恐怖 に陥れることで[12]、また、何千人ものアフリカ系アメリカ人を鉱山や農園、道路や堤防などの公共事業プロジェクトでの無給労働に強制的に従事させる囚 人労働制度を導入することで、アフリカ系アメリカ人の市民的・政治的権利の行使を否定しようと共謀した。囚人労働者は、通常、残虐な体罰、過酷な労働、不 衛生な環境による病気などに苦しめられた。死亡率は極めて高かった。[13] 南北戦争直後に土地を手に入れたアフリカ系アメリカ人は少数であったが、ほとんどの者は小作人として搾取されていた。[14] 小作人であろうと、自分の土地であろうと、黒人の大半は農業に経済的に大きく依存していた。これが、移住のさらなる推進要因となった。アメリカシロヒトリ の到来である。この甲虫は最終的に、毎年アメリカ国内の綿花生産量の8%を無駄にするまでに至り、アメリカ国民のこの一部に不均衡な影響を与えた。 [15]南部での生活がますます困難になるにつれ、アフリカ系アメリカ人の北部への移住が急増した。 後に「ハーレム・ルネサンス」として知られるようになる運動の将来の指導者の多くは、南北戦争後の再建期における利益と損失を記憶する世代から生まれた。 彼らの両親や祖父母、あるいは彼ら自身が奴隷であったこともある。彼らの祖先は、平均以上の教育など、父親が文化資本に投資した恩恵を受けていたこともあ る。 ハーレム・ルネサンスの多くは、20世紀初頭に南部から北東部および中西部のアフリカ系アメリカ人居住区へと移住した大移動の一部であった。アフリカ系ア メリカ人は、南部の制度化された人種主義からの解放とより良い生活水準を求めていた。その他には、カリブ海地域の人種的階層社会から、より良い生活を求め て米国に移住したアフリカ系の人々もいた。彼らのほとんどがハーレムに集まった。 |

| Development https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CC66Ma4dmc8 A silent short documentary on the Negro Artist. Richmond Barthé working on Kalombwan (1934) During the early portion of the 20th century, Harlem was the destination for migrants from around the country, attracting both people from the South seeking work and an educated class who made the area a center of culture, as well as a growing "Negro" middle class. These people were looking for a fresh start in life and this was a good place to go. The district had originally been developed in the 19th century as an exclusive suburb for the white middle and upper middle classes; its affluent beginnings led to the development of stately houses, grand avenues, and world-class amenities such as the Polo Grounds and the Harlem Opera House. During the enormous influx of European immigrants in the late 19th century, the once exclusive district was abandoned by the white middle class, who moved farther north. Harlem became an African-American neighborhood in the early 1900s. In 1910, a large block along 135th Street and Fifth Avenue was bought by various African-American realtors and a church group.[16] Many more African Americans arrived during the First World War. Due to the war, the migration of laborers from Europe virtually ceased, while the war effort resulted in a massive demand for unskilled industrial labor. The Great Migration brought hundreds of thousands of African Americans to cities such as Chicago, Philadelphia, Detroit, Washington, D.C., and New York. Despite the increasing popularity of Negro culture, virulent white racism, often by more recent ethnic immigrants, continued to affect African-American communities, even in the North.[17] After the end of World War I, many African-American soldiers—who fought in segregated units such as the Harlem Hellfighters—came home to a nation whose citizens often did not respect their accomplishments.[18] Race riots and other civil uprisings occurred throughout the United States during the Red Summer of 1919, reflecting economic competition over jobs and housing in many cities, as well as tensions over social territories. |

発展 https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=CC66Ma4dmc8 ニグロの芸術家についての無声短編ドキュメンタリー。リッチモンド・バルテが『カラバン』(1934年)に取り組む 20世紀の初期、ハーレムは全米各地からの移住者の目的地であり、南部から仕事を探してやって来る人々や、この地域を文化の中心地とする教育を受けた階 級、そして成長しつつあった「ニグロ」の中流階級を惹きつけた。 これらの人々は人生の再出発を求めており、ハーレムはまさにうってつけの場所であった。この地区はもともと19世紀に、白人の中流階級および上流階級のた めの高級住宅街として開発された。その裕福な始まりは、立派な邸宅や大通り、ポロ競技場やハーレム・オペラハウスといった世界クラスのアメニティの開発に つながった。19世紀後半にヨーロッパからの移民が大量に流入した際、かつての高級住宅街は白人の中流階級に捨てられ、彼らはさらに北へと移り住んだ。 ハーレムは1900年代初頭にアフリカ系アメリカ人の居住区となった。1910年、135丁目と5番街沿いの広大な区画が、さまざまなアフリカ系アメリカ 人の不動産業者と教会グループによって買収された。[16]第一次世界大戦中には、さらに多くのアフリカ系アメリカ人がやって来た。戦争により、ヨーロッ パからの労働者の移住は事実上停止したが、一方で戦争への取り組みにより、熟練していない工業労働者に対する需要が大幅に高まった。大移動により、何十万 人ものアフリカ系アメリカ人がシカゴ、フィラデルフィア、デトロイト、ワシントンD.C.、ニューヨークなどの都市に移住した。 ニグロ文化の人気が高まっていたにもかかわらず、しばしば最近移住してきた民族による激しい白人至上主義が、北部でもアフリカ系アメリカ人社会に影響を与 え続けた。[17] 第1次世界大戦が終結すると、ハーレム・ヘルファイターズなどの隔離された部隊で戦った多くのアフリカ系アメリカ人兵士が 帰国した彼らに対して、国民の多くは彼らの功績を尊重していなかった。[18] 1919年の「レッド・サマー」には、人種暴動やその他の市民蜂起が全米で発生し、多くの都市における仕事や住宅をめぐる経済競争や、社会的領域をめぐる 緊張を反映していた。 |

| Mainstream recognition of Harlem culture The first stage of the Harlem Renaissance started in the late 1910s. In 1917, the premiere of Granny Maumee, The Rider of Dreams, and Simon the Cyrenian: Plays for a Negro Theater took place. These plays, written by white playwright Ridgely Torrence, featured African-American actors conveying complex human emotions and yearnings. They rejected the stereotypes of the blackface and minstrel show traditions. In 1917, James Weldon Johnson called the premieres of these plays "the most important single event in the entire history of the Negro in the American Theater".[19] Another landmark came in 1919, when the communist poet Claude McKay published his militant sonnet "If We Must Die", which introduced a dramatically political dimension to the themes of African cultural inheritance and modern urban experience featured in his 1917 poems "Invocation" and "Harlem Dancer". Published under the pseudonym Eli Edwards, these were his first appearance in print in the United States after immigrating from Jamaica.[20] Although "If We Must Die" never alluded to race, African-American readers heard its note of defiance in the face of racism and the nationwide race riots and lynchings then taking place. By the end of the First World War, the fiction of James Weldon Johnson and the poetry of Claude McKay were describing the reality of contemporary African-American life in America. The Harlem Renaissance grew out of the changes that had taken place in the African-American community since the abolition of slavery, as the expansion of communities in the North. These accelerated as a consequence of World War I and the great social and cultural changes in the early 20th-century United States. Industrialization attracted people from rural areas to cities and gave rise to a new mass culture. Contributing factors leading to the Harlem Renaissance were the Great Migration of African Americans to Northern cities, which concentrated ambitious people in places where they could encourage each other, and the First World War, which had created new industrial work opportunities for tens of thousands of people. Factors leading to the decline of this era include the Great Depression. |

ハーレム文化の主流としての認知 ハーレム・ルネサンスの第一段階は1910年代後半に始まった。1917年には『夢の騎手マミーおばあさん』と『シリアのシモン:ニグロ劇場のための劇』 が初演された。これらの劇は、白人劇作家リッジリー・トーレンスによって書かれたもので、アフリカ系アメリカ人の俳優たちが複雑な人間感情や憧れを表現し た。彼らは、ブラックフェイスやミンストレル・ショーの伝統にみられるステレオタイプを否定した。1917年、ジェームズ・ウェルドン・ジョンソンは、こ れらの演劇の初演を「アメリカ演劇におけるニグロの歴史全体において最も重要な出来事」と呼んだ。[19] 1919年には、共産主義者の詩人クロード・マッケイが、1917年の詩「祈り」と「ハーレムのダンサー」で取り上げたアフリカ文化の継承と近代都市の経 験というテーマに劇的な政治的側面を導入した、戦闘的なソネット「死なねばならないのなら」を発表した。イーライ・エドワーズという偽名で発表されたこの 作品は、ジャマイカから移住した後のマッケイが米国で初めて出版した作品であった。[20] 「If We Must Die」は人種について言及したものではなかったが、当時全米で起こっていた人種主義や暴動、リンチに直面していたアフリカ系アメリカ人の読者たちは、こ の作品に抵抗の響きを聞き取った。第一次世界大戦が終結する頃には、ジェームズ・ウェルドン・ジョンソンの小説やクロード・マッケイの詩が、当時のアメリ カにおけるアフリカ系アメリカ人の生活の実態を描写していた。 ハーレム・ルネサンスは、奴隷制度廃止以降、北部で拡大したアフリカ系アメリカ人コミュニティの変化から生まれた。第一次世界大戦と20世紀初頭の米国に おける社会と文化の大きな変化により、この動きは加速した。工業化により、農村部から都市部へと人々が流入し、新たな大衆文化が誕生した。ハーレム・ル ネッサンスの要因となったのは、北部の都市部へのアフリカ系アメリカ人の大移動であり、これにより、野心ある人々が互いに刺激を与え合える場所に集中した こと、そして第一次世界大戦により、何万人もの人々に新たな工業労働の機会が生まれたことである。この時代の衰退の要因となったのは、世界大恐慌である。 |

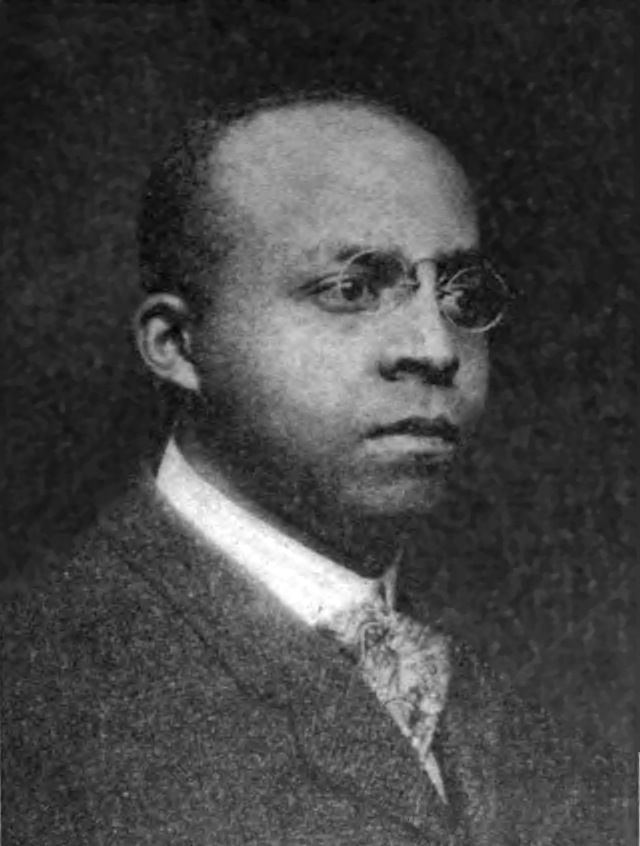

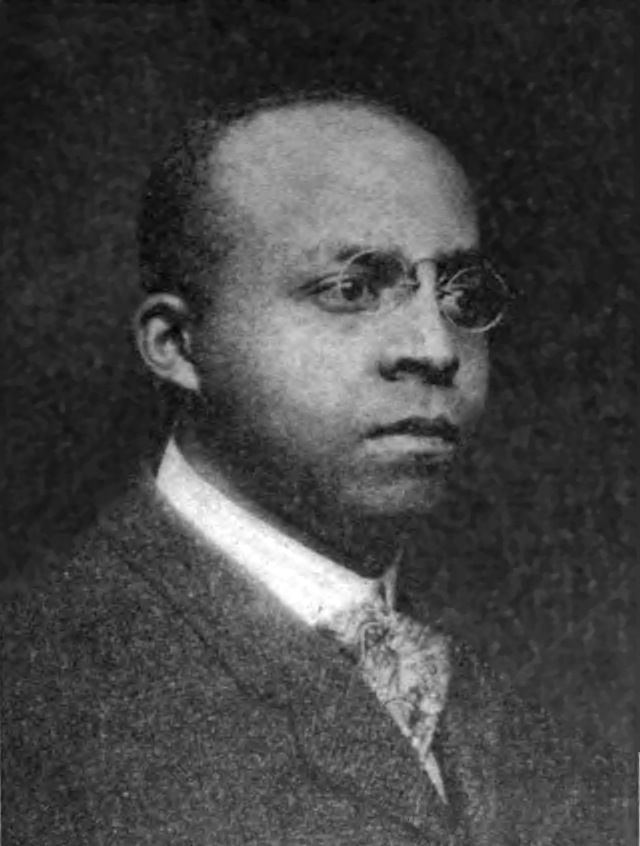

| Literature In 1917, Hubert Harrison, "The Father of Harlem Radicalism", founded the Liberty League and The Voice, the first organization and the first newspaper, respectively, of the "New Negro Movement". Harrison's organization and newspaper were political but also emphasized the arts (his newspaper had "Poetry for the People" and book review sections). In 1927, in the Pittsburgh Courier, Harrison challenged the notion of the Renaissance. He argued that the "Negro Literary Renaissance" notion overlooked "the stream of literary and artistic products which had flowed uninterruptedly from Negro writers from 1850 to the present," and said the so-called "Renaissance" was largely a white invention.[21][22] Alternatively, a writer like the Chicago-based author, Fenton Johnson, who began publishing in the early 1900s, is called a "forerunner" of the Harlem Renaissance,[23][24] "one of the first negro revolutionary poets".[25] Nevertheless, with the Harlem Renaissance came a sense of acceptance for African-American writers; as Langston Hughes put it, with Harlem came the courage "to express our individual dark-skinned selves without fear or shame".[26] Alain Locke's anthology The New Negro was considered the cornerstone of this cultural revolution.[27] The anthology featured several African-American writers and poets, from the well-known, such as Zora Neale Hurston and communists Langston Hughes and Claude McKay, to the lesser known, like the poet Anne Spencer.[28] Many poets of the Harlem Renaissance were inspired to tie threads of African-American culture into their poems; as a result, jazz poetry was heavily developed during this time. "The Weary Blues" was a notable jazz poem written by Langston Hughes.[29] Through their works of literature, black authors were able to give a voice to the African-American identity, and strived for a community of support and acceptance. |

文学 1917年、「ハーレム急進主義の父」と呼ばれるヒューバート・ハリソンが、リバティ・リーグとニュー・ニグロ・ムーブメントの最初の組織および新聞であ る『ザ・ヴォイス』をそれぞれ創設した。ハリソンの組織と新聞は政治的なものであったが、芸術も重視していた(彼の新聞には「人々のための詩」と書評のセ クションがあった)。1927年、ハリソンはピッツバーグ・クーリエ紙でルネサンスの概念に異議を唱えた。彼は、「ニグロ文学ルネサンス」という概念は、 「1850年から現在に至るまで、途切れることなくニグロ作家から生み出されてきた文学的・芸術的作品の流れ」を見落としていると主張し、いわゆる「ルネ サンス」は主に白人の発明であると述べた。[21][22 。一方、シカゴ在住の作家フェントン・ジョンソン(Fenton Johnson)のように、1900年代初頭から出版活動を開始した作家は、ハーレム・ルネサンスの「先駆者」[23][24]、「ニグロ革命詩人の第一 人者」[25]と呼ばれている。 しかし、ハーレム・ルネサンスはアフリカ系アメリカ人作家たちに受け入れられたという感覚をもたらした。ラングストン・ヒューズは、ハーレムは「恐れや恥 じらいなく、私たち個々の黒人としての自己を表現する」勇気をもたらしたと表現した。[26] アラン・ロックのアンソロジー『ザ・ニュー・ニグロ』は、 この文化革命の礎石と見なされていた。このアンソロジーには、ゾラ・ニール・ハーストンや共産主義者のラングストン・ヒューズ、クロード・マッケイといっ た著名な作家や詩人から、詩人のアン・スペンサーのようなあまり知られていない作家まで、数名の黒人作家や詩人が参加していた。 ハーレム・ルネサンスの多くの詩人たちは、アフリカ系アメリカ文化の糸を詩に織り込むことにインスピレーションを受けた。その結果、この時代にはジャズ詩 が盛んに作られた。「The Weary Blues」は、ラングストン・ヒューズが書いた有名なジャズ詩である。[29] 黒人作家たちは文学作品を通じて、アフリカ系アメリカ人のアイデンティティに声を吹き込み、支援と受容のコミュニティを築くことに尽力した。 |

| Religion Christianity played a major role in the Harlem Renaissance. Many of the writers and social critics discussed the role of Christianity in African-American lives. For example, a famous poem by Langston Hughes, "Madam and the Minister", reflects the temperature and mood towards religion in the Harlem Renaissance.[30] The cover story for The Crisis magazine's publication in May 1936 explains how important Christianity was regarding the proposed union of the three largest Methodist churches of 1936. This article shows the controversial question of unification for these churches.[31] The article "The Catholic Church and the Negro Priest", also published in The Crisis, January 1920, demonstrates the obstacles that African-American priests faced in the Catholic Church. The article confronts what it saw as policies based on race that excluded African Americans from higher positions in the Church.[32] |

宗教 キリスト教はハーレム・ルネサンスにおいて大きな役割を果たした。多くの作家や社会評論家が、アフリカ系アメリカ人の生活におけるキリスト教の役割につい て論じた。例えば、ラングストン・ヒューズの有名な詩「マダム・アンド・ザ・ミニスター」は、ハーレム・ルネサンスにおける宗教に対する温度や雰囲気を反 映している。[30] 1936年5月に発行された雑誌『ザ・クライシス』の表紙記事では、1936年に提案された3つの最大のメソジスト教会の合併に関して、キリスト教がどれ ほど重要であったかを説明している。この記事は、これらの教会の統一に関する物議を醸す問題を示している。[31] 同じく『クライシス』誌に掲載された「カトリック教会とニグロ司祭」という記事(1920年1月)は、アフリカ系アメリカ人の司祭がカトリック教会で直面 した障害を明らかにしている。この記事は、人種に基づく政策がアフリカ系アメリカ人の教会での昇進を妨げていると見なしている。[32] |

Discourse Religion and Evolution Ad Various forms of religious worship existed during this time of African-American intellectual reawakening. Although there were racist attitudes within the current Abrahamic religious arenas, many African Americans continued to push towards the practice of a more inclusive doctrine. For example, George Joseph MacWilliam presents various experiences of rejection on the basis of his color and race during his pursuit towards priesthood, yet he shares his frustration in attempts to incite action on the part of The Crisis magazine community.[32] There were other forms of spiritualism practiced among African Americans during the Harlem Renaissance. Some of these religions and philosophies were inherited from African ancestry. For example, the religion of Islam was present in Africa as early as the 8th century through the Trans-Saharan trade. Islam came to Harlem likely through the migration of members of the Moorish Science Temple of America, which was established in 1913 in New Jersey.[citation needed] Various forms of Judaism were practiced, including Orthodox, Conservative and Reform Judaism, but it was Black Hebrew Israelites that founded their religious belief system during the early 20th century in the Harlem Renaissance.[citation needed] Traditional forms of religion acquired from various parts of Africa were inherited and practiced during this era. Some common examples were Voodoo and Santeria.[citation needed] |

談話 宗教と進化広告 アフリカ系アメリカ人の知的覚醒のこの時代には、さまざまな形態の宗教的崇拝が存在していた。 現行のアブラハムの宗教の分野では人種差別的な態度も見られたが、多くのアフリカ系アメリカ人はより包括的な教義の実践に向けて努力を続けた。例えば、 ジョージ・ジョセフ・マクウィリアムは、神職者になるための追求の過程で、肌の色や人種を理由に拒絶された様々な経験を提示しているが、一方で『クライシ ス』誌のコミュニティに何らかの行動を起こさせようとした際のフラストレーションも述べている。 ハーレム・ルネサンス期のアフリカ系アメリカ人社会では、他にもさまざまな形のスピリチュアリズムが実践されていた。これらの宗教や哲学の中には、アフリ カに起源を持つものもあった。例えば、イスラム教は8世紀には早くもサハラ交易を通じてアフリカに存在していた。イスラム教は、1913年にニュージャー ジー州で設立されたムーア人サイエンス・テンプル・オブ・アメリカの信者たちの移住によってハーレムにもたらされたと考えられている。[要出典] ユダヤ教のさまざまな形態が実践されていたが、正統派、保守派、改革派ユダヤ教などである。しかし、20世紀初頭のハーレム・ルネサンス期に独自の信仰体 系を確立したのはブラック・ヘブライ・イスラエル人であった。[要出典] この時代には、アフリカのさまざまな地域から伝わった伝統的な宗教形態が受け継がれ、実践されていた。よく知られている例としては、ブードゥー教やサンテ リア教などがある。[要出典] |

| Criticism Religious critique during this era was found in music, literature, art, theater and poetry. The Harlem Renaissance encouraged analytic dialogue that included the open critique and the adjustment of current religious ideas. One of the major contributors to the discussion of African-American renaissance culture was Aaron Douglas, who, with his artwork, also reflected the revisions African Americans were making to the Christian dogma. Douglas uses biblical imagery as inspiration to various pieces of artwork, but with the rebellious twist of an African influence.[33] Countee Cullen's poem "Heritage" expresses the inner struggle of an African American between his past African heritage and the new Christian culture.[34] A more severe criticism of the Christian religion can be found in Langston Hughes's poem "Merry Christmas", where he exposes the irony of religion as a symbol for good and yet a force for oppression and injustice.[35] |

批判 この時代の宗教批判は、音楽、文学、芸術、演劇、詩に見られた。ハーレム・ルネサンスは、オープンな批判や現行の宗教的観念の調整を含む分析的対話を奨励した。 アフリカ系アメリカ人のルネサンス文化に関する議論に大きく貢献した人物の一人にアーロン・ダグラスがおり、彼は作品を通じて、アフリカ系アメリカ人がキ リスト教の教義に対して行っている修正を反映させた。ダグラスは聖書のイメージをさまざまな作品のインスピレーションとして用いているが、アフリカの影響 による反抗的なひねりを加えている。 カウンティー・カレンの詩「遺産」は、アフリカの過去とキリスト教の新しい文化との間で葛藤するアフリカ系アメリカ人の内面の苦悩を表現している。 [34] キリスト教に対するより厳しい批判は、ラングストン・ヒューズの詩「メリー・クリスマス」に見られる。この詩では、宗教が善の象徴であると同時に抑圧と不 正の力であるという皮肉が暴かれている。[35] |

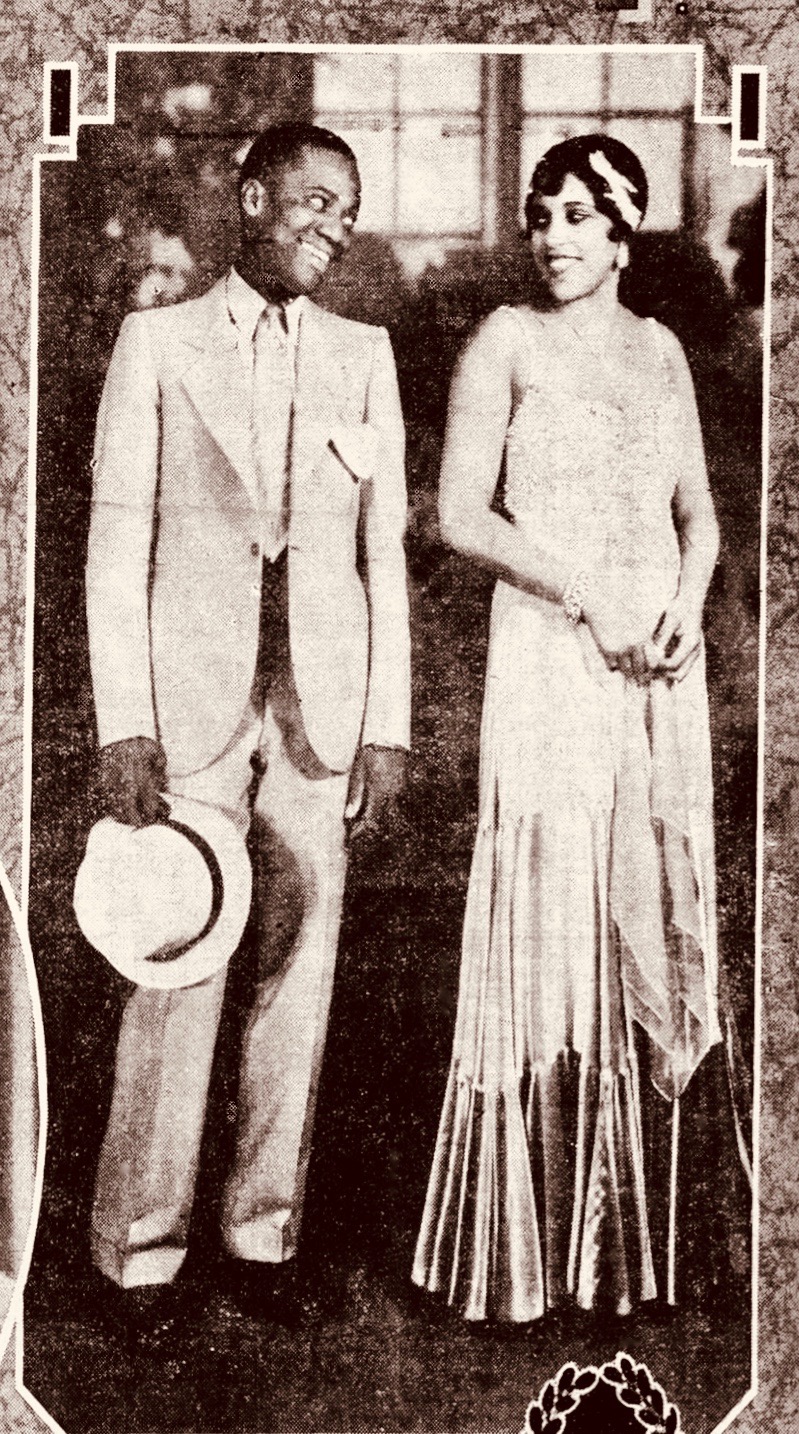

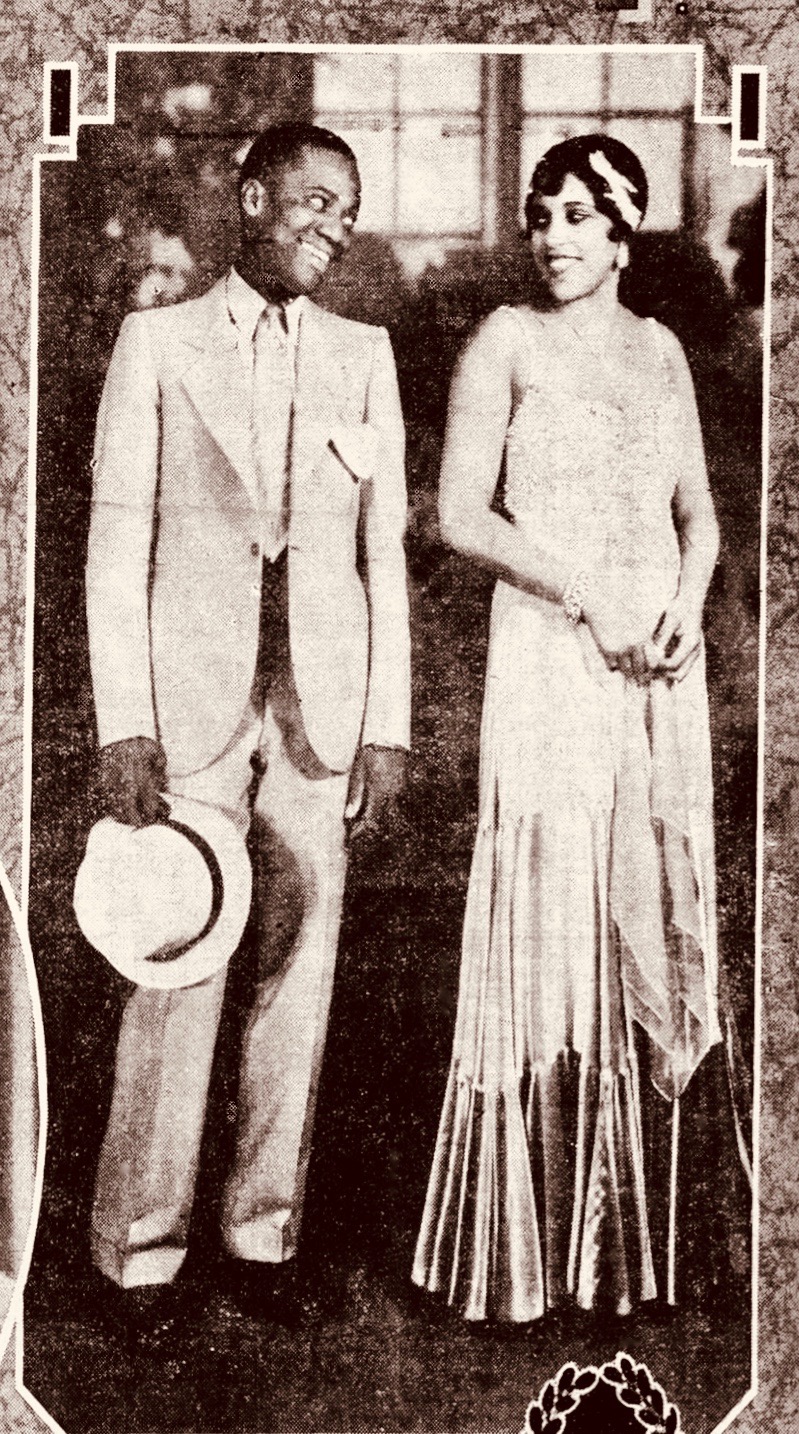

Music The multi-talented Adelaide Hall and Bill 'Bojangles' Robinson in the musical comedy Brown Buddies on Broadway, 1930 A new way of playing the piano called the Harlem Stride style was created during the Harlem Renaissance helping to blur the lines between the poor African Americans and socially elite African Americans. The traditional jazz band was composed primarily of brass instruments and was considered a symbol of the South, but the piano was considered an instrument of the wealthy. With this instrumental modification to the existing genre, the wealthy African Americans now had more access to jazz music. Its popularity soon spread throughout the country and was consequently at an all-time high. Innovation and liveliness were important characteristics of performers in the beginnings of jazz. Jazz performers and composers at the time such as Eubie Blake, Noble Sissle, Jelly Roll Morton, Luckey Roberts, James P. Johnson, Willie "The Lion" Smith, Andy Razaf, Fats Waller, Ethel Waters, Adelaide Hall,[36] Florence Mills and bandleaders Duke Ellington, Louis Armstrong and Fletcher Henderson were extremely talented, skillful, competitive and inspirational. They laid great parts of the foundations for future musicians of their genre.[37][38][39] Duke Ellington gained popularity during the Harlem Renaissance. According to Charles Garrett, "The resulting portrait of Ellington reveals him to be not only the gifted composer, bandleader, and musician we have come to know, but also an earthly person with basic desires, weaknesses, and eccentricities."[8] Ellington did not let his popularity get to him. He remained calm and focused on his music. During this period, the musical style of blacks was becoming more and more attractive to whites. White novelists, dramatists and composers started to exploit the musical tendencies and themes of African Americans in their works. Composers (including William Grant Still, William L. Dawson and Florence Price) used poems written by African-American poets in their songs, and would implement the rhythms, harmonies and melodies of African-American music—such as blues, spirituals and jazz—into their concert pieces. African Americans began to merge with whites into the classical world of musical composition. The first African-American male to gain wide recognition as a concert artist in both his region and internationally was Roland Hayes. He trained with Arthur Calhoun in Chattanooga, and at Fisk University in Nashville. Later, he studied with Arthur Hubbard in Boston and with George Henschel and Amanda Ira Aldridge in London, England. Hayes began singing in public as a student, and he toured with the Fisk Jubilee Singers in 1911.[40] |

音楽 多才なアデレード・ホールとビル・ボージャングルズ・ロビンソンによるミュージカルコメディ『ブラウン・バディーズ』のブロードウェイ公演(1930年) ハーレム・ルネサンスの時代に生まれたハーレム・ストライド・スタイルと呼ばれるピアノの新しい演奏法は、貧しいアフリカ系アメリカ人と社会的エリートの アフリカ系アメリカ人の間の境界線を曖昧にするのに役立った。 伝統的なジャズバンドは主に金管楽器で構成され、南部の象徴とみなされていたが、ピアノは富裕層の楽器と考えられていた。この既存のジャンルへの楽器の変 更により、裕福なアフリカ系アメリカ人にもジャズ音楽がより身近なものとなった。 ジャズの人気はすぐに全米に広がり、その結果、ジャズはかつてないほどの人気を博した。 革新性と活気は、ジャズの初期における演奏家の重要な特徴であった。当時のジャズの演奏家や作曲家であるユービー・ブレイク、ノーブル・シスル、ジェ リー・ロール・モートン、ラッキー・ロバーツ、ジェイムズ・P・ジョンソン、ウィリー・ザ・ライオン・スミス、アンディ・ラザフ、ファッツ・ウォーラー、 エセル・ウォーターズ、アデレード・ホール、フローレンス・ミルズ、そしてバンドリーダーのデューク・エリントン、ルイ・アームストロング、フレッ チャー・ヘンダーソンらは、非常に才能豊かで、熟練しており、競争心に富み、インスピレーションに満ちていた。彼らは、そのジャンルの将来のミュージシャ ンたちの基礎の大部分を築いた。[37][38][39] デューク・エリントンはハーレム・ルネサンスの時代に人気を博した。チャールズ・ギャレットによると、「エリントンに関するこの結果の肖像画は、我々が知 るようになった才能ある作曲家、バンドリーダー、音楽家であるだけでなく、基本的欲求、弱点、奇癖を持つ人間味のある人物であることを明らかにしている」 [8]。エリントンは人気に浮かれることはなかった。彼は冷静さを保ち、音楽に集中し続けた。 この時期、黒人の音楽スタイルはますます白人の心を引きつけるようになっていた。白人の小説家、劇作家、作曲家たちが、アフリカ系アメリカ人の音楽の傾向 やテーマを作品に取り入れるようになったのだ。作曲家(ウィリアム・グラント・スティル、ウィリアム・L・ドーソン、フローレンス・プライスなど)は、ア フリカ系アメリカ人の詩人の詩を曲に使用し、ブルース、スピリチュアル、ジャズなどのアフリカ系アメリカ人の音楽のリズム、ハーモニー、メロディを自身の コンサート曲に取り入れた。アフリカ系アメリカ人は、作曲というクラシックの世界に白人とともに溶け込んでいった。地域および国際的に広く認知された初の コンサートアーティストとなったアフリカ系アメリカ人男性は、ローランド・ヘイズであった。彼はチャタヌーガでアーサー・カルフーンに、ナッシュビルの フィスク大学で学んだ。その後、ボストンでアーサー・ハバードに、ロンドンでジョージ・ヘンシェルとアマンダ・アイラ・オルドリッジに師事した。ヘイズは 学生時代から人前で歌い始め、1911年にはフィスク・ジュビリー・シンガーズの一員としてツアーを行った。[40] |

Musical theatre Poster for Run, Little Chillun According to James Vernon Hatch and Leo Hamalian, all-black review, Run, Little Chillun, is considered one of the most successful musical dramas of the Harlem Renaissance.[41] |

ミュージカル 『走れ、チルン』のポスター ジェームズ・ヴァーノン・ハッチとレオ・ハマリアンによるオールブラックのレビュー『走れ、チルン』は、ハーレム・ルネサンスにおける最も成功したミュージカルドラマのひとつと考えられている。[41] |

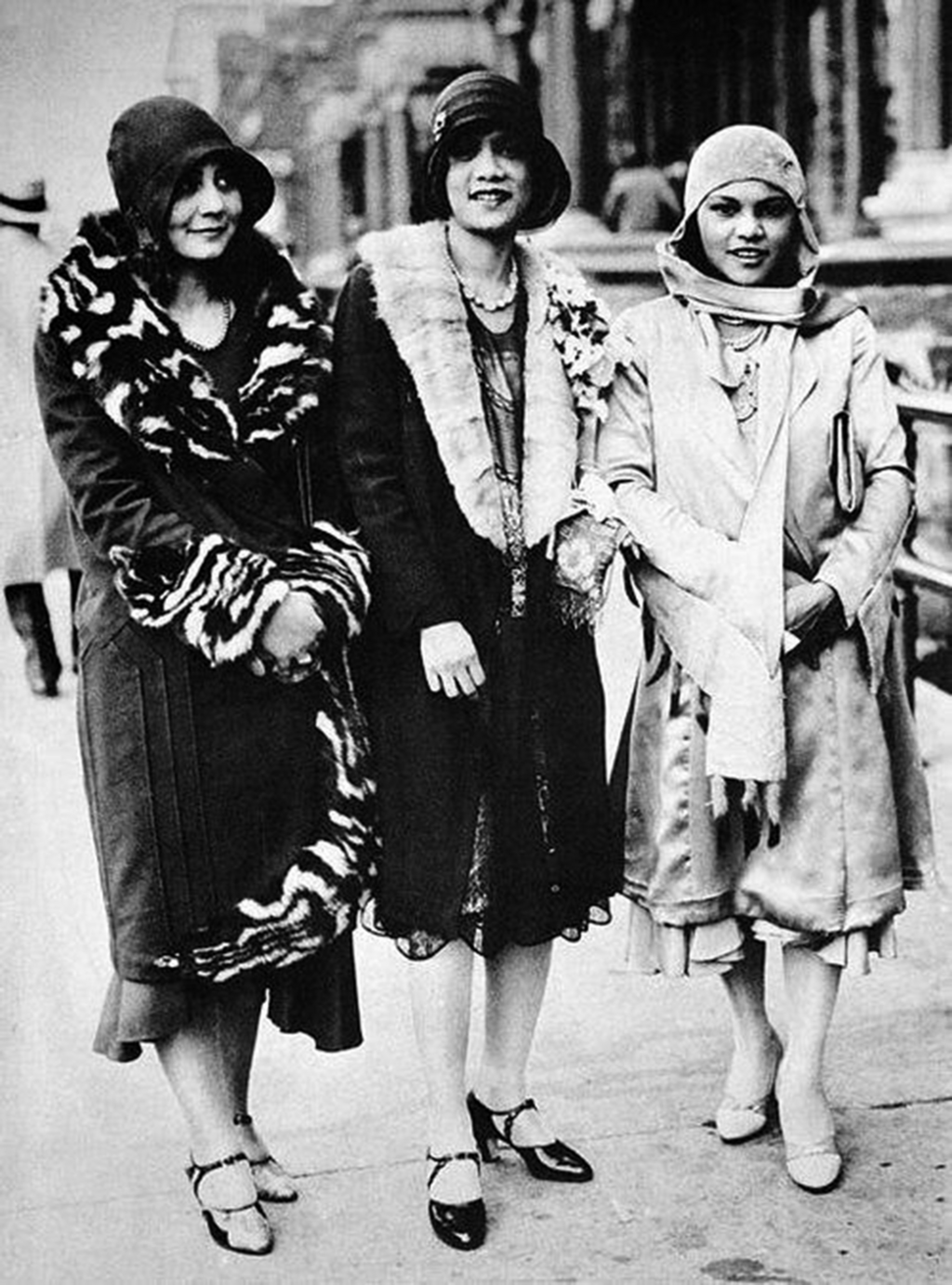

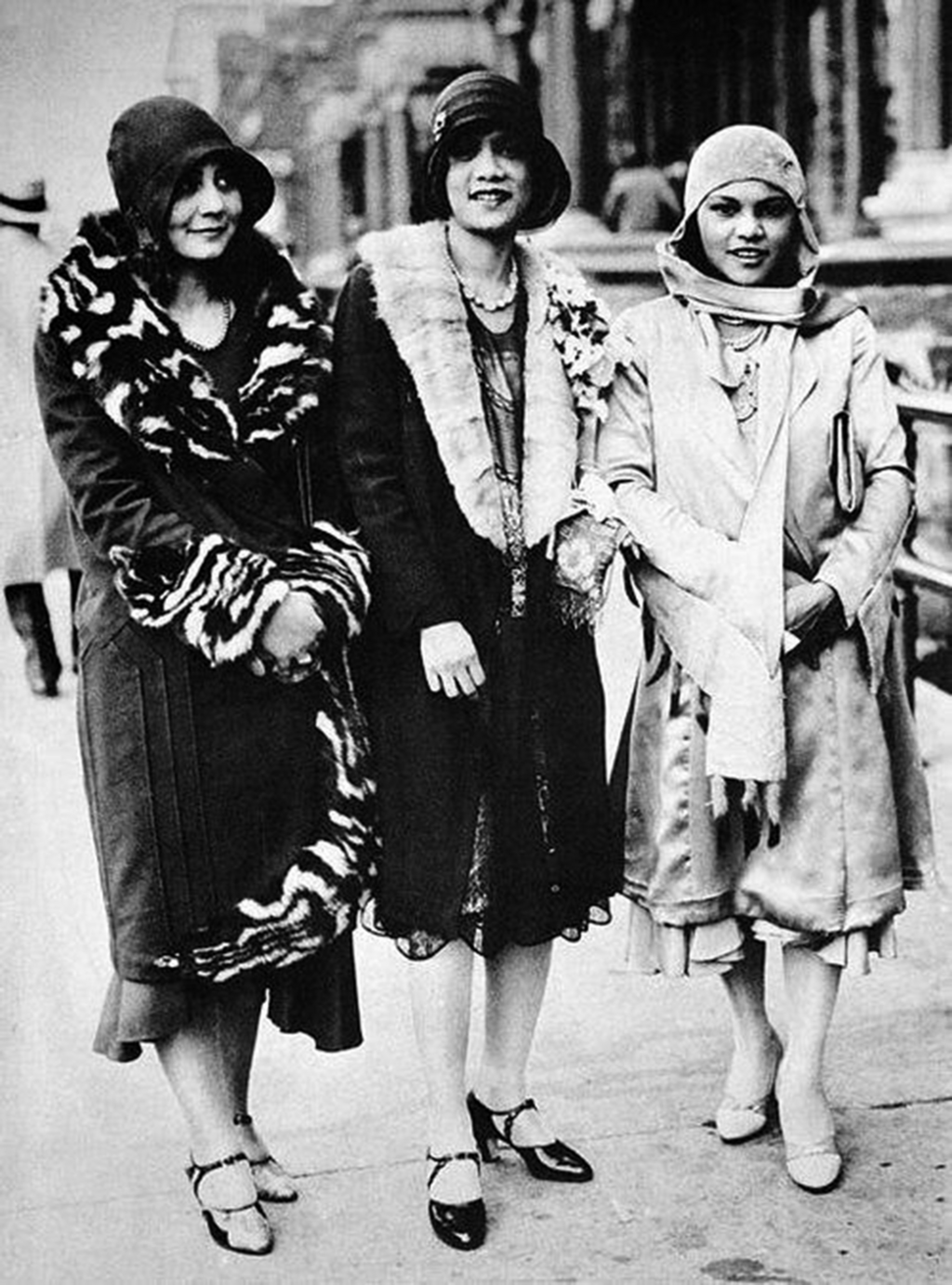

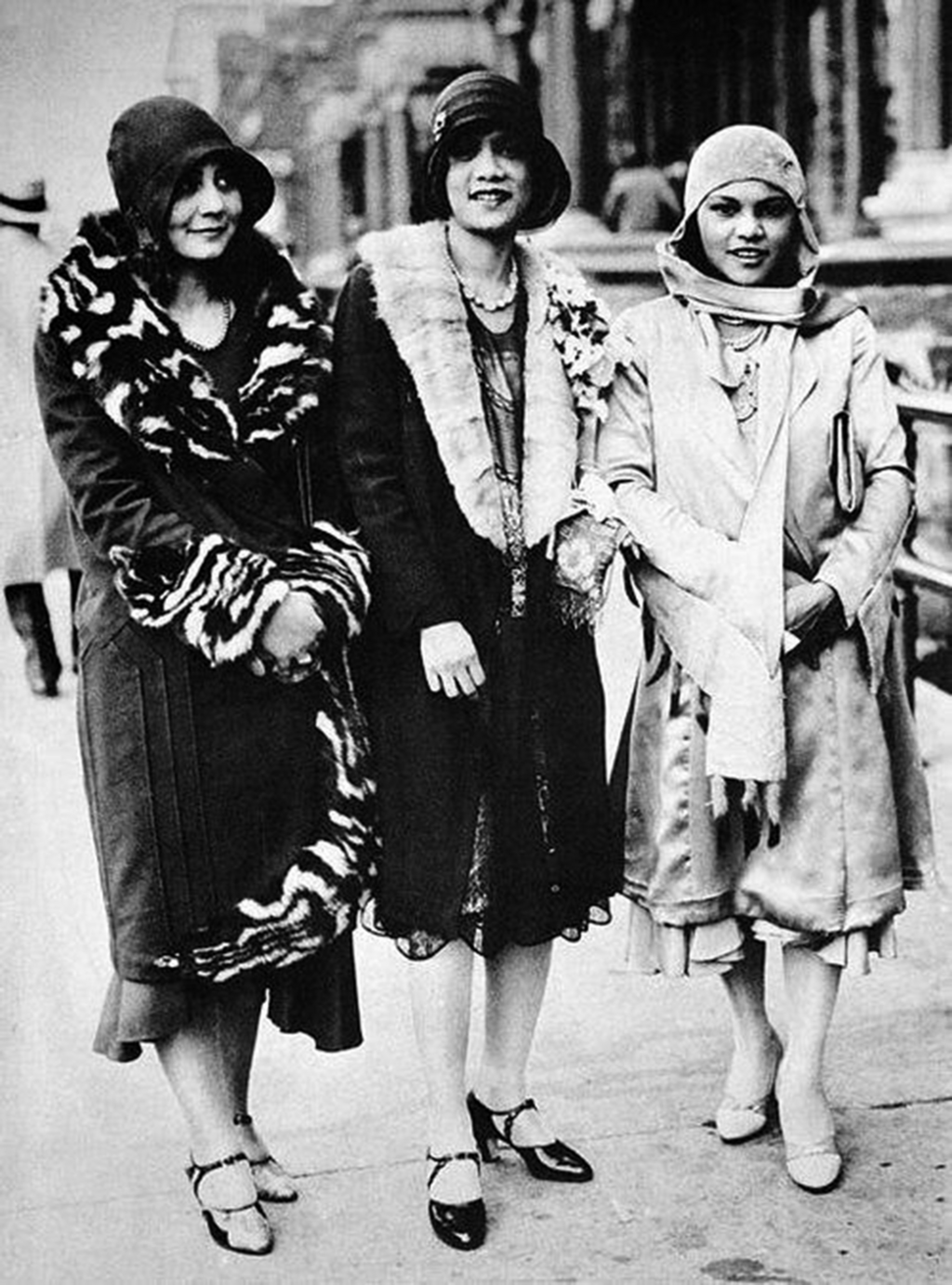

Fashion Three African-American women in Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance in 1925 During the Harlem Renaissance, the African-American clothing scene took a dramatic turn from the prim and proper many young women preferred, from short skirts and silk stockings to drop-waisted dresses and cloche hats.[42] Women wore loose-fitted garments and accessorized with long strand pearl bead necklaces, feather boas, and cigarette holders. The fashion of the Harlem Renaissance was used to convey elegance and flamboyancy and needed to be created with the vibrant dance style of the 1920s in mind.[43] Popular by the 1930s was a trendy, egret-trimmed beret. Men wore loose suits that led to the later style known as the "Zoot", which consisted of wide-legged, high-waisted, peg-top trousers, and a long coat with padded shoulders and wide lapels. Men also wore wide-brimmed hats, colored socks,[44] white gloves and velvet-collared Chesterfield coats. During this period, African Americans expressed respect for their heritage through a fad for leopard-skin coats, indicating the power of the African animal. While performing in Paris during the height of the Renaissance, the extraordinarily successful black dancer Josephine Baker was a major fashion trendsetter for black and white women alike. Her gowns from the couturier Jean Patou were copied, especially her stage costumes, which Vogue magazine called "startling". Josephine Baker is also credited for highlighting the "art deco" fashion era after she performed the "Danse Sauvage". During this Paris performance, she adorned a skirt made of string and artificial bananas. Ethel Moses was another popular black performer. Moses starred in silent films in the 1920s and 1930s and was recognizable by her signature bob hairstyle. |

ファッション Three African-American women in Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance in 1925 ハーレムルネサンス期には、アフリカ系アメリカ人の服装は劇的に変化し、多くの若い女性たちが好んだ清楚で上品なスタイルから、短いスカートとシルクス トッキングからウエストが落ちたドレスとクローシュ帽へと変化した。[42] 女性たちはゆったりとした衣服を身にまとい、長い真珠のネックレス、羽根のボアズ、シガレットホルダーをアクセサリーとして身につけた。ハーレム・ルネサ ンスのファッションは、優雅さと華やかさを表現するために用いられ、1920年代の活気あるダンススタイルを念頭に置いて創作する必要があった。[43] 1930年代に流行したのは、白鷺の羽飾りがついた流行のベレー帽であった。 男性はゆったりとしたスーツを着用し、これが後に「ズート」と呼ばれるスタイルにつながった。ズートは、ワイドレッグでハイウエスト、ペグトップのズボン と、肩パッドと幅広のラペルが付いたロングコートで構成されていた。男性はつばの広い帽子、色付きの靴下[44]、白い手袋、ビロードの襟のチェスター フィールドコートも着用していた。この時代、アフリカ系アメリカ人は、ヒョウ柄のコートが流行したことによって、自分たちの伝統に対する敬意を示し、アフ リカの動物の持つ力を示した。 ルネサンスの最盛期にパリで活躍した、非常に成功した黒人ダンサー、ジョセフィン・ベイカーは、黒人女性、白人女性を問わず、ファッションのトレンドセッ ターとして大きな影響力を持っていた。 彼女がデザイナーのジャン・パトゥから仕立てたドレスは、特にステージ衣装としてコピーされ、ヴォーグ誌は「衝撃的」と評した。また、ジョセフィン・ベイ カーは「ダン・ソバージュ」を披露した後、「アール・デコ」ファッションの時代を強調したことでも知られている。このパリのパフォーマンスでは、彼女は紐 と人工バナナでできたスカートを身にまとった。エセル・モーゼスもまた人気の黒人パフォーマーであった。モーゼスは1920年代と1930年代にサイレン ト映画で主演を務め、彼女のトレードマークであるボブヘアスタイルで知られていた。 |

| Photography James Van Der Zee's photography played an important role in shaping and documenting the cultural and social life of Harlem during the Harlem Renaissance. His photographs were instrumental in shaping the image and identity of the African-American community during the Harlem Renaissance. His work documented the achievements of cultural figures and helped to challenge stereotypes and racist attitudes,[45] which in turn promoted pride and dignity among African Americans in Harlem and beyond. Van Der Zee's studio was not just a place for taking photographs; it was also a social and cultural hub for Harlem residents.[46] People would come to his studio not only to have their portraits taken, but also to socialize and to participate in the community events that he hosted. Van Der Zee's studio played an important role in the cultural life of Harlem during the early 20th century, and helped to foster a sense of community and pride among its residents. Some notable persons photographed are Marcus Garvey, the leader of the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA), a black nationalist organization that promoted Pan-Africanism and economic independence for African Americans. Other notable black persons he photographed are Countee Cullen, a poet and writer who was associated with the Harlem Renaissance; Josephine Baker, a dancer and entertainer who became famous in France and was known for her provocative performances; W. E. B. Du Bois, a sociologist, historian and civil rights activist who was a leading figure in the African-American community in the early 20th century; Langston Hughes, a poet, novelist and playwright who was one of the most important writers of the Harlem Renaissance; and Madam C.J. Walker, an entrepreneur and philanthropist who was one of the first African-American women to become a self-made millionaire, as well as her daughter, Dorthy Waring, an artist and author of 12 novels. Van Der Zee's work gained renewed attention in the 1960s and 1970s, when interest in the Harlem Renaissance was revived. Van Der Zee's photographs have been featured in numerous exhibitions over the years. One notable exhibition was "Harlem on My Mind: Cultural Capital of Black America, 1900–1968,"[47] which was organized by the Metropolitan Museum of Art in 1969. The exhibit included over 300 photographs, many of which were by Van Der Zee, and was one of the first major exhibitions to focus on the cultural achievements of African Americans in Harlem. Van Der Zee's work was the eyes of Harlem. His photographs are recognized as important documents of African-American life and culture during the early 20th century. They serve as a visual record of the achievements of the Harlem Renaissance.[48] Kelli Jones called him "the official chronicler of the Harlem Renaissance."[49] His portraits of writers, musicians, artists and other cultural figures helped to promote their work and bring attention to the vibrant creative scene known as Harlem. |

写真 ジェームズ・ヴァン・ダー・ジーの写真は、ハーレム・ルネサンス期のハーレムの文化と社会生活の形成と記録において重要な役割を果たした。彼の写真は、 ハーレム・ルネサンス期におけるアフリカ系アメリカ人社会のイメージとアイデンティティの形成に役立った。彼の作品は文化人の功績を記録し、固定観念や人 種差別的な態度に異議を唱えるのに役立ち、[45] それによってハーレムやその他の地域のアフリカ系アメリカ人の誇りと尊厳を促進した。 ヴァン・ダー・ゼーのスタジオは、単に写真を撮影する場所ではなく、ハーレム住民の社交と文化の中心でもあった。[46] 人々は、ポートレートを撮影してもらうだけでなく、交流を深めたり、彼が主催するコミュニティのイベントに参加するためにスタジオを訪れた。ヴァン・ ダー・ゼーのスタジオは、20世紀初頭のハーレムの文化的生活において重要な役割を果たし、住民たちの間にコミュニティ意識と誇りを育むのに貢献した。 著名な人物としては、アフリカ系アメリカ人の汎アフリカ主義と経済的自立を推進した黒人民族主義団体、全米黒人改善協会(UNIA)の指導者、マーカス・ ガーベイが挙げられる。その他、彼が撮影した著名な黒人には、ハーレム・ルネサンスに関わった詩人であり作家のカウンティー・カレン、フランスで有名にな り、挑発的なパフォーマンスで知られたダンサーでありエンターテイナーのジョセフィン・ベイカー、20世紀初頭のアフリカ系アメリカ人社会の指導的人物で あり、社会学者、歴史家、公民権運動家であったW. E. B. デュボイス 世紀の黒人社会の指導的人物であった社会学者、歴史家、公民権運動活動家、W. E. B. デュボイス、ハーレム・ルネッサンスの最も重要な作家の一人である詩人、小説家、劇作家のラングストン・ヒューズ、そして、一代で億万長者となった最初の 黒人女性実業家であり慈善家であるマダム・C.J.ウォーカー、そして彼女の娘で12の小説の著者であるアーティストのドロシー・ウェアリングである。 ヴァン・ダー・ジーの作品は、ハーレム・ルネサンスへの関心が再び高まった1960年代と1970年代に再び注目を集めるようになった。ヴァン・ダー・ ジーの写真は、長年にわたって数多くの展覧会で展示されてきた。注目すべき展覧会としては、1969年にメトロポリタン美術館が企画した「ハーレム・オ ン・マイ・マインド: 1969年にメトロポリタン美術館が企画した「ハーレム・オン・マイ・マインド:1900年~1968年の黒人文化の首都」[47]である。この展示会に は300点を超える写真が展示され、その多くはヴァン・ダー・ゼーによるもので、ハーレムにおけるアフリカ系アメリカ人の文化的な功績に焦点を当てた最初 の主要な展示会のひとつとなった。 ヴァン・ダー・ゼーの作品はハーレムの目であった。彼の写真は、20世紀初頭のアフリカ系アメリカ人の生活と文化を伝える重要な資料として認められてい る。 また、ハーレム・ルネサンスの業績を視覚的に記録したものともなっている。[48] ケリー・ジョーンズは、彼を「ハーレム・ルネサンスの公式記録者」と呼んだ。[49] 作家、音楽家、芸術家、その他の文化的人物の肖像写真は、彼らの作品の宣伝に役立ち、ハーレムとして知られる活気のある創造的なシーンに注目を集めること にもなった。 |

| Painting Aaron Douglas, born in Kansas in 1899 and often referred to as the "Father of African-American Art", is one of the most affluential painters of the Harlem Renaissance.[50] Through his paintings that utilize color, shape, and line, Douglas creates a collapsing of time as he merges the past, present, and future of American-American history. Fragmentation of the picture plane, geometry, and hard-edge abstraction are present in most of his paintings during the Harlem Renaissance. Douglas drew inspiration from both ancient Egyptian and Native American motifs.[50] |

絵画 アーロン・ダグラスは1899年にカンザスで生まれ、「アフリカ系アメリカ人芸術の父」と呼ばれることも多いが、ハーレム・ルネサンス期の最も影響力のあ る画家の一人である。[50] 色彩、形、線を用いた絵画を通じて、ダグラスはアメリカ黒人の歴史における過去、現在、未来を融合させ、時間の崩壊を作り出している。ハーレム・ルネサン ス期の彼の絵画作品のほとんどには、画面の断片化、幾何学、ハードエッジ抽象がみられる。ダグラスは古代エジプトとネイティブ・アメリカンのモチーフの両 方からインスピレーションを得ていた。[50] |

| Sculpting Augusta Savage, born in Florida in 1892, was a culture, advocate, and teacher during the Harlem Renaissance who put black everyday people at the forefront of her works. In 1932, Savage founded the Savage Studio of Arts and Crafts, providing free art classes in painting, printmaking, and sculpting. She secured government funding for the school to train youths and adults. Known as a leading light within the Harlem community, Savage encouraged artists to seek financial compensation for their works, which led to the start of the Harlem Artist Guild in 1935. Augusta Savage was the only African American commissioned to create an exhibit for the 1939 World Fair in New York, where she showcased her piece Lift Every Voice and Sing, which quickly became one of the most popular pieces within the fair.[51] |

彫刻 オーガスタ・サヴェージは1892年にフロリダで生まれ、ハーレム・ルネサンス期に文化の擁護者、推進者、教師として活躍し、黒人の日常の人々を作品の前 面に押し出した。1932年、サヴェージはサヴェージ美術工芸スタジオを設立し、絵画、版画、彫刻の無料美術クラスを提供した。彼女は若者や大人を訓練す るための学校に政府からの資金援助を確保した。ハーレムのコミュニティにおける指導者的存在として知られたサヴェッジは、アーティストたちに作品の対価を 求めるよう奨励し、1935年にはハーレム・アーティスト・ギルドの設立につながった。オーガスタ・サヴェッジは、1939年のニューヨーク万国博覧会で 展示を依頼された唯一の黒人アーティストであり、彼女の作品「Lift Every Voice and Sing」は、万国博覧会で最も人気のある作品のひとつとなった。 |

Characteristics and themes A jazz combo playing Trumpeter Dizzy Gillespie is emblematic of the mixture of high class society, popular art, and virtuosity of jazz. Characterizing the Harlem Renaissance was an overt racial pride that came to be represented in the idea of the New Negro, who through intellect and production of literature, art and music could challenge the pervading racism and stereotypes to promote progressive or socialist politics, and racial and social integration. The creation of art and literature would serve to "uplift" the race. There would be no uniting form singularly characterizing the art that emerged from the Harlem Renaissance. Rather, it encompassed a wide variety of cultural elements and styles, including a Pan-African perspective, "high-culture" and "low-culture" or "low-life", from the traditional form of music to the blues and jazz, traditional and new experimental forms in literature such as modernism and the new form of jazz poetry. This duality meant that numerous African-American artists came into conflict with conservatives in the black intelligentsia, who took issue with certain depictions of black life. Some common themes represented during the Harlem Renaissance were the influence of the experience of slavery and emerging African-American folk traditions on black identity, the effects of institutional racism, the dilemmas inherent in performing and writing for elite white audiences, and the question of how to convey the experience of modern black life in the urban North. The Harlem Renaissance was one of primarily African-American involvement. It rested on a support system of black patrons and black-owned businesses and publications. However, it also depended on the patronage of white Americans, such as Carl Van Vechten and Charlotte Osgood Mason, who provided various forms of assistance, opening doors which otherwise might have remained closed to the publication of work outside the black American community. This support often took the form of patronage or publication. Carl Van Vechten was one of the most noteworthy white Americans involved with the Harlem Renaissance. He allowed for assistance to the black American community because he wanted racial sameness. There were other whites interested in so-called "primitive" cultures, as many whites viewed black American culture at that time, and wanted to see such "primitivism" in the work coming out of the Harlem Renaissance. As with most fads, some people may have been exploited in the rush for publicity. Interest in African-American lives also generated experimental but lasting collaborative work, such as the all-black productions of George Gershwin's opera Porgy and Bess, and Virgil Thomson and Gertrude Stein's Four Saints in Three Acts. In both productions the choral conductor Eva Jessye was part of the creative team. Her choir was featured in Four Saints.[52] The music world also found white band leaders defying racist attitudes to include the best and the brightest African-American stars of music and song in their productions. The African Americans used art to prove their humanity and demand for equality. The Harlem Renaissance led to more opportunities for blacks to be published by mainstream houses. Many authors began to publish novels, magazines and newspapers during this time. The new fiction attracted a great amount of attention from the nation at large. Among authors who became nationally known were Jean Toomer, Jessie Fauset, Claude McKay, Zora Neale Hurston, James Weldon Johnson, Alain Locke, Omar Al Amiri, Eric D. Walrond and Langston Hughes. Richard Bruce Nugent (1906–1987), who wrote "Smoke, Lilies, and Jade", made an important contribution, especially in relation to experimental form and LGBT themes in the period.[53] The Harlem Renaissance helped lay the foundation for the post-World War II protest movement of the Civil Rights movement. Moreover, many black artists who rose to creative maturity afterward were inspired by this literary movement. The Renaissance was more than a literary or artistic movement, as it possessed a certain sociological development—particularly through a new racial consciousness—through ethnic pride, as seen in the Back to Africa movement led by Jamaican Marcus Garvey. At the same time, a different expression of ethnic pride, promoted by W. E. B. Du Bois, introduced the notion of the "talented tenth". Du Bois wrote of the Talented Tenth: The Negro race, like all races, is going to be saved by its exceptional men. The problem of education, then, among Negroes must first of all deal with the Talented Tenth; it is the problem of developing the best of this race that they may guide the mass away from the contamination and death of the worst.[54] These "talented tenth" were considered the finest examples of the worth of black Americans as a response to the rampant racism of the period. No particular leadership was assigned to the talented tenth, but they were to be emulated. In both literature and popular discussion, complex ideas such as Du Bois's concept of "twoness" (dualism) were introduced (see The Souls of Black Folk; 1903).[55] Du Bois explored a divided awareness of one's identity that was a unique critique of the social ramifications of racial consciousness. This exploration was later revived during the Black Pride movement of the early 1970s. |

特徴とテーマ ジャズ・コンボの演奏 トランペット奏者のディジー・ガレスピーは、上流社会、大衆芸術、そしてジャズの卓越性を象徴している。 ハーレム・ルネサンスの特徴は、あからさまな人種的誇りであり、それは「ニュー・ニグロ」という概念に表れていた。ニュー・ニグロは、知性と文学、芸術、 音楽の創作活動を通じて、蔓延する人種主義や固定観念に異議を唱え、進歩主義や社会主義の政治、人種的・社会的統合を推進することができた。芸術や文学の 創作は、人種を「高揚」させるのに役立つと考えられていた。 ハーレム・ルネサンスから生まれた芸術を特徴づける統一的な様式は存在しなかった。むしろ、それは幅広い文化要素や様式を包含しており、汎アフリカ的な視 点、ハイカルチャー、ローカルチャーまたはローカルライフ、伝統的な音楽からブルースやジャズ、モダニズムなどの文学における伝統的および新しい実験的な 形式、ジャズ詩の新しい形式などがあった。この二面性により、黒人インテリ層の一部の保守派は、黒人生活の描写に問題があると主張し、多数の黒人アーティ ストと対立した。 ハーレム・ルネサンスで表現された共通のテーマには、奴隷制の経験や台頭しつつあったアフリカ系アメリカ人の民間伝承が黒人のアイデンティティに与えた影 響、制度的人種主義の影響、エリート白人読者向けの執筆やパフォーマンスに内在するジレンマ、そして北部都市における現代の黒人生活の経験をいかに伝える かという問題などがあった。 ハーレム・ルネサンスは、主にアフリカ系アメリカ人が関与した運動であった。黒人パトロンや黒人経営の企業や出版物の支援システムに支えられていた。しか し、カール・ヴァン・ヴェクテンやシャーロット・オズグッド・メイソンといった白人アメリカ人の支援にも依存していた。彼らはさまざまな形で支援を行い、 黒人アメリカ人コミュニティ以外からの作品出版が閉ざされたままになっていたかもしれない扉を開いた。この支援は、後援や出版という形をとることが多かっ た。カール・ヴァン・ヴェクテンは、ハーレム・ルネサンスに関わった最も注目すべき白人アメリカ人の一人である。彼は黒人アメリカ人コミュニティへの支援 を可能にしたが、それは人種的な同一性を求めていたからである。 当時、多くの白人が黒人文化をそう見ていたように、いわゆる「プリミティブ」文化に関心を寄せる白人もいた。ハーレム・ルネサンスの作品にそうした「プリ ミティヴィズム」を見出そうとしたのだ。ほとんどの流行と同様に、一部の人々は、注目を浴びるために利用された可能性もある。 アフリカ系アメリカ人の生活への関心は、ジョージ・ガーシュウィンのオペラ『ポーギーとベス』の黒人キャストによる上演や、ヴァージル・トムソンとガート ルード・スタインによる『四聖人』のような、実験的でありながらも長続きした共同作業を生み出した。どちらの作品でも、合唱指揮者のエヴァ・ジェシーが制 作チームの一員であった。彼女の合唱団は『Four Saints』でフィーチャーされた。[52] 音楽界では、人種差別的な態度に抵抗する白人バンドリーダーたちが、音楽と歌の分野で最も優秀で才能あるアフリカ系アメリカ人のスターたちを自身の作品に 起用するようになった。 アフリカ系アメリカ人は芸術を用いて、自分たちの人間性を証明し、平等を要求した。ハーレム・ルネサンスは、主流派の出版社から出版される機会を黒人に与 えることにつながった。この時代には、多くの作家が小説や雑誌、新聞の出版を手がけるようになった。新しいフィクションは、国民全体から大きな注目を集め た。全国的に知られるようになった作家には、ジーン・トゥーマー、ジェシー・フォセット、クロード・マッケイ、ゾラ・ニール・ハーストン、ジェームズ・ ウェルドン・ジョンソン、アラン・ロック、オマール・アル・アミリ、エリック・D・ウォルロンド、ラングストン・ヒューズなどがいる。 特に、この時代の実験的な形式やLGBTのテーマに関連して、重要な貢献をした。 ハーレム・ルネサンスは、第二次世界大戦後の公民権運動という抗議運動の基礎を築くのに役立った。さらに、その後創作の成熟期を迎えた多くの黒人アーティストたちは、この文学運動からインスピレーションを得た。 ルネサンスは文学や芸術の運動にとどまらず、特にジャマイカ出身のマーカス・ガーベイが主導した「アフリカ回帰」運動に見られるように、民族の誇りや新た な人種意識を通じて、ある種の社会学的発展をもたらした。同時に、W. E. B. デュボイスが推進した異なる民族の誇りの表現は、「才能ある10分の1」という概念を導入した。デュボイスは「才能ある10分の1」について次のように述 べている。 ニグロ人種は、他のあらゆる人種と同様に、その優れた人物によって救われるだろう。したがって、ニグロ人種における教育の問題は、まず何よりも「才能の 10分の1」の問題に対処しなければならない。それは、この人種から最も優れた人材を育成し、彼らに最悪の汚染や死から大衆を導いてもらうという問題であ る。 この「才能の10分の1」は、当時蔓延していた人種主義への対応として、黒人アメリカ人の価値の最も優れた例であると考えられていた。才能の10分の1」 には特別な指導者は割り当てられなかったが、彼らを手本とすべきであるとされた。文学や一般論においても、デュ・ボワの「トゥーネス(二元論)」のような 複雑な概念が紹介された(『黒人の魂』、1903年を参照)。[55] デュ・ボワは、人種意識の社会的影響に関する独自の批判として、アイデンティティの分裂した意識について探求した。この探求は、1970年代初頭のブラッ ク・プライド運動で再び注目されるようになった。 |

| Influence A new black identity  Langston Hughes, communist novelist and poet, photographed by Carl Van Vechten, 1936 The Harlem Renaissance was successful in that it brought the black experience clearly within the corpus of American cultural history. Not only through an explosion of culture, but on a sociological level, the legacy of the Harlem Renaissance redefined how America, and the world, viewed African Americans. The migration of Southern blacks to the North changed the image of the African American from rural, undereducated peasants to one of urban, cosmopolitan sophistication. This new identity led to a greater social consciousness, and African Americans became players on the world stage, expanding intellectual and social contacts internationally. The progress—both symbolic and real—during this period became a point of reference from which the African-American community gained a spirit of self-determination that provided a growing sense of both black urbanity and black militancy, as well as a foundation for the community to build upon for the Civil Rights struggles in the 1950s and 1960s. The urban setting of rapidly developing Harlem provided a venue for African Americans of all backgrounds to appreciate the variety of black life and culture. Through this expression, the Harlem Renaissance encouraged the new appreciation of folk roots and culture. For instance, folk materials and spirituals provided a rich source for the artistic and intellectual imagination, which freed blacks from the establishment of past condition. Through sharing in these cultural experiences, a consciousness sprung forth in the form of a united racial identity. However, there was some pressure within certain groups of the Harlem Renaissance to adopt sentiments of conservative white America in order to be taken seriously by the mainstream. The result being that queer culture, while far-more accepted in Harlem than most places in the country at the time, was most fully lived out in the smoky dark lights of bars, nightclubs and cabarets in the city.[56] It was within these venues that the blues music scene boomed, and, since it had not yet gained recognition within popular culture, queer artists used it as a way to express themselves honestly.[56] Even though there were factions within the Renaissance that were accepting of queer culture/lifestyles, one could still be arrested for engaging in homosexual acts. Many people, including author Alice Dunbar Nelson and "The Mother of Blues" Gertrude "Ma" Rainey,[57] had husbands but were romantically linked to other women as well.[58] |

影響力 新しい黒人のアイデンティティ  ラングストン・ヒューズ、共産主義小説家・詩人、カール・ヴァン・ヴェヒテン撮影、1936年 ハーレム・ルネッサンスは、黒人の経験をアメリカ文化史の中に明確に位置づけたという点で成功した。文化の爆発的な広がりだけでなく、社会学的なレベルで も、ハーレム・ルネッサンスの遺産は、アメリカ、そして世界がアフリカ系アメリカ人をどのように見ていたかを再定義した。南部の黒人たちが北部へ移住した ことで、アフリカ系アメリカ人のイメージは、農村の低学歴の農民から、都会的でコスモポリタンな洗練されたものへと変化した。この新しいアイデンティティ のおかげで社会意識が高まり、アフリカ系アメリカ人は世界の舞台で活躍するようになり、知的・社会的交流を国際的に広げた。 この時期の進歩は象徴的なものであると同時に現実のものでもあり、アフリカ系アメリカ人コミュニティが自己決定の精神を獲得する際の参照点となった。この精神は、黒人の都会性と黒人の過激さの両方の感覚を高め、1950年代と1960年代の公民権闘争の土台となった。 急速に発展するハーレムという都市環境は、あらゆる背景を持つアフリカ系アメリカ人に、黒人の多様な生活と文化を理解する場を提供した。このような表現を 通じて、ハーレム・ルネッサンスは民俗のルーツや文化を新たに評価することを促した。例えば、民俗資料や霊歌は、芸術的・知的想像力の豊かな源泉となり、 黒人を過去の条件の定着から解放した。こうした文化的経験を共有することで、人種的アイデンティティの統一という意識が芽生えた。 しかし、ハーレム・ルネッサンスの特定のグループの中には、主流派に真剣に受け入れてもらうために、保守的な白人アメリカの感情を取り入れるべきだという 圧力があった。その結果、クィア文化は、ハーレムでは当時の国内のほとんどの場所よりもはるかに受け入れられていたものの、街のバー、ナイトクラブ、キャ バレーの煙のような暗い灯りの中で最も完全に生き抜かれることになった[56]。ブルース・ミュージック・シーンが活況を呈したのはこうした場であり、大 衆文化の中ではまだ認知されていなかったため、クィアのアーティストたちは自分たちを正直に表現する方法としてブルースを利用した[56]。 ルネサンス内部には、クィア文化/ライフスタイルを受け入れる派閥があったとはいえ、同性愛行為に関与することで逮捕されることもあった。作家のアリス・ ダンバー・ネルソンや「ブルースの母」ガートルード・「マー」・レイニーを含む多くの人々[57]は、夫を持ちながらも他の女性とも恋愛関係にあった [58]。 |

| Women and the LGBTQ community During the Harlem Renaissance, various well-known figures, including Claude Mckay, Langston Hughes, and Ethel Waters, are believed to have had private same-gender relationships, although this aspect of their lives remained undisclosed to the public during that era.[59][60] In the Harlem music scene, places such as the Cotton Club and Rockland Palace routinely held gay drag shows in addition to straight performances. Lesbian or bisexual women performers, such as blues singers Gladys Bentley and Bessie Smith, were a part of this cultural movement, which contributed to a renewed interest in African-American culture among the black community and introduced it to a wider audience.[61] Although women's contributions to culture were often overlooked at the time, contemporary black feminist critics have endeavored to re-evaluate and recognize the cultural production of women during the Harlem Renaissance. Authors such as Nella Larsen and Jessie Fauset have gained renewed critical acclaim for their work from modern perspectives.[62] Blues singer Gertrude "Ma" Rainey was known to dress in traditionally male clothing, and her blues lyrics often reflected her sexual proclivities for women, which was extremely radical at the time. Ma Rainey was also the first person to introduce blues music into vaudeville.[63] Rainey's protégé, Bessie Smith, was another artist who used the blues as a way to express unapologetic views on same-gender relations, with such lines as "When you see two women walking hand in hand, just look em' over and try to understand: They'll go to those parties – have the lights down low – only those parties where women can go."[56] Rainey, Smith, and artist Lucille Bogan were collectively known as "The Big Three of the Blues."[64]  Blues singer Gladys Bentley Another prominent blues singer was Gladys Bentley, who was known to cross-dress. Bentley was the club owner of Clam House on 133rd Street in Harlem, which was a hub for queer patrons. The Hamilton Lodge in Harlem hosted an annual drag ball, drawing thousands of people to watch young men dance in drag. Though there were safe spaces within Harlem, there were prominent voices, such as that of Abyssinian Baptist Church's minister Adam Clayton Powell Sr., who actively opposed homosexuality.[58] The Harlem Renaissance was instrumental in fostering the "New Negro" movement, an endeavor by African Americans to redefine their identity free from degrading stereotypes. The Neo-New Negro movement further challenged racial definitions, stereotypes, and gender norms and roles, seeking to address normative sexuality and sexism in American society.[65] These ideas received some pushback, particularly regarding sexual freedom for women,[57] which was seen as confirming the stereotype that black women were sexually uninhibited. Some members of the black bourgeoisie saw this as hindering the overall progress of the black community and fueling racist sentiments. Yet queer culture and artists defined major portions of the Harlem Renaissance; Henry Louis Gates Jr., in a 1993 essay titled "The Black Man's Burden", wrote that the Harlem Renaissance "was surely as gay as it was black".[58][65] |

女性とLGBTQコミュニティ ハーレム・ルネッサンス期には、クロード・マッケイ、ラングストン・ヒューズ、エセル・ウォーターズなど、さまざまな著名人がプライベートで同性との関係を持っていたと考えられているが、このような側面はその時代には一般には公表されていなかった[59][60]。 ハーレムの音楽シーンでは、コットン・クラブやロックランド・パレスといった場所では、ストレートのパフォーマンスに加えて、ゲイのドラッグ・ショーが日 常的に行われていた。ブルース・シンガーのグラディス・ベントレーやベッシー・スミスといったレズビアンやバイセクシュアルの女性パフォーマティは、この 文化的な動きの一部であり、黒人コミュニティの間でアフリカ系アメリカ人文化への関心を新たにし、より多くの聴衆に紹介することに貢献した[61]。 当時、女性の文化への貢献は見過ごされがちであったが、現代の黒人フェミニスト批評家たちは、ハーレム・ルネッサンスにおける女性の文化的生産を再評価 し、認識しようと努めている。ネラ・ラーセンやジェシー・フォーセットのような作家は、現代的な視点からその作品を再評価している[62]。 ブルース・シンガーのガートルード・「マー」・レイニーは、伝統的に男性の服装をすることで知られており、彼女のブルースの歌詞はしばしば女性に対する性 癖を反映したもので、当時としては極めて過激なものであった。レイニーの弟子であるベッシー・スミスもまた、ブルースを同性間関係に対する率直な見解を表 明する手段として使ったアーティストであった: 二人の女性が手をつないで歩いているのを見かけたら、彼女たちをよく見て、理解しようとするんだ。女性が行けるのは、照明を落としたパーティーだけなん だ」[56]。レイニー、スミス、そしてアーティストのルシル・ボーガンは、まとめて「ブルースのビッグ・スリー」と呼ばれた[64]。  ブルース・シンガー、グラディス・ベントレー もう一人の著名なブルース・シンガーはグラディス・ベントレーで、彼女は女装することで知られていた。ベントレーはハーレムの133丁目にあるクラムハウ スのクラブオーナーで、そこはクィアの常連客たちの拠点だった。ハーレムのハミルトン・ロッジでは毎年ドラッグ・ボールが開催され、若い男たちが女装して 踊るのを見るために何千人もの人々が集まった。ハーレム内にも安全な空間はあったが、アビシニアン・バプティスト教会の牧師アダム・クレイトン・パウエ ル・シニアのように、同性愛に積極的に反対する著名な声もあった[58]。 ハーレム・ルネッサンスは、アフリカ系アメリカ人による「ニュー・ニグロ」運動、つまり品位を落とすようなステレオタイプから解放された自分たちのアイデ ンティティを再定義しようとする試みの育成に役立った。ネオ・ニュー・ニグロ運動はさらに、人種的定義、ステレオタイプ、ジェンダー規範と役割に異議を唱 え、アメリカ社会における規範的なセクシュアリティと性差別に取り組もうとした[65]。 こうした考えには反発もあり、特に女性の性的自由[57]に関しては、黒人女性は性的に奔放であるという固定観念を裏付けるものと見なされていた。黒人ブ ルジョワジーのなかには、これが黒人社会の全体的な進歩を妨げ、人種差別感情を煽るものだと考える者もいた。ヘンリー・ルイス・ゲイツ・ジュニアは、「黒 人の重荷」と題された1993年のエッセイの中で、ハーレム・ルネッサンスは「黒人であったのと同様にゲイであったことは確かである」と書いている [58][65]。 |

| Criticism of the movement Many critics point out that the Harlem Renaissance could not escape its history and culture in its attempt to create a new one, or sufficiently separate from the foundational elements of white, European culture. Often Harlem intellectuals, while proclaiming a new racial consciousness, resorted to mimicry of their white counterparts by adopting their clothing, sophisticated manners and etiquette. This "mimicry" may also be called assimilation, as that is typically what minority members of any social construct must do in order to fit social norms created by that construct's majority.[66] This could be seen as a reason that the artistic and cultural products of the Harlem Renaissance did not overcome the presence of white-American values and did not reject these values.[citation needed] In this regard, the creation of the "New Negro", as the Harlem intellectuals sought, was considered a success.[by whom?] The Harlem Renaissance appealed to a mixed audience. The literature appealed to the African-American middle class and to whites. Magazines such as The Crisis, a monthly journal of the NAACP, and Opportunity, an official publication of the National Urban League, employed Harlem Renaissance writers on their editorial staffs, published poetry and short stories by black writers, and promoted African-American literature through articles, reviews and annual literary prizes. However, as important as these literary outlets were, the Renaissance relied heavily on white publishing houses and white-owned magazines.[67] A major accomplishment of the Renaissance was to open the door to mainstream white periodicals and publishing houses, although the relationship between the Renaissance writers and white publishers and audiences created some controversy. W. E. B. Du Bois did not oppose the relationship between black writers and white publishers, but he was critical of works such as Claude McKay's bestselling novel Home to Harlem (1928) for appealing to the "prurient demand[s]" of white readers and publishers for portrayals of black "licentiousness".[67] Langston Hughes spoke for most of the writers and artists when he wrote in his essay "The Negro Artist and the Racial Mountain" (1926) that black artists intended to express themselves freely, no matter what the black public or white public thought.[68] Hughes in his writings also returned to the theme of racial passing, but, during the Harlem Renaissance, he began to explore the topic of homosexuality and homophobia. He began to use disruptive language in his writings. He explored this topic because it was a theme that during this time period was not discussed.[69] African-American musicians and writers were among mixed audiences as well, having experienced positive and negative outcomes throughout the New Negro Movement. For musicians, Harlem, New York's cabarets and nightclubs shined a light on black performers and allowed for black residents to enjoy music and dancing. However, some of the most popular clubs (that showcased black musicians) were exclusively for white audiences; one of the most famous white-only nightclubs in Harlem was the Cotton Club, where popular black musicians like Duke Ellington frequently performed.[70] Ultimately, the black musicians who appeared at these white-only clubs became far more successful and became a part of the mainstream music scene.[citation needed] Similarly, black writers were given the opportunity to shine once the New Negro Movement gained traction as short stories, novels and poems by black authors began taking form and getting into various print publications in the 1910s and 1920s.[71] Although a seemingly good way to establish their identities and culture, many authors note how hard it was for any of their work to actually go anywhere. Writer Charles Chesnutt in 1877, for example, notes that there was no indication of his race alongside his publication in Atlantic Monthly (at the publisher's request).[72] A prominent factor in the New Negro's struggle was that their work had been made out to be "different" or "exotic" to white audiences, making a necessity for black writers to appeal to them and compete with each other to get their work out.[71] Famous black author and poet Langston Hughes explained that black-authored works were placed in a similar fashion to those of oriental or foreign origin, only being used occasionally in comparison to their white-made counterparts: Once a spot for a black work was "taken", black authors had to look elsewhere to publish.[72] Certain aspects of the Harlem Renaissance were accepted without debate, and without scrutiny. One of these was the future of the "New Negro". Artists and intellectuals of the Harlem Renaissance echoed American progressivism in its faith in democratic reform, in its belief in art and literature as agents of change, and in its almost uncritical belief in itself and its future. This progressivist worldview rendered black intellectuals—just like their white counterparts—unprepared for the rude shock of the Great Depression, and the Harlem Renaissance ended abruptly because of naïve assumptions about the centrality of culture, unrelated to economic and social realities.[73] |

運動に対する批判 多くの批評家は、ハーレム・ルネッサンスが新しいものを創造しようとする試みの中で、その歴史と文化から逃れることができなかった、あるいは白人、ヨー ロッパ文化の基礎的要素から十分に分離することができなかったと指摘している。ハーレムの知識人たちはしばしば、新しい人種意識を宣言する一方で、彼らの 服装や洗練されたマナーやエチケットを採用することで、白人相手の模倣に頼った。この「模倣」は同化とも呼ばれるかもしれないが、それは一般的に、どのよ うな社会構成の少数派メンバーも、その社会構成の多数派が作り上げた社会規範に適合するために行わなければならないことだからである[66]。このこと は、ハーレム・ルネッサンスの芸術的・文化的産物が白人系アメリカ人の価値観の存在を克服せず、これらの価値観を拒絶しなかった理由とみなすことができる [要出典]。この点で、ハーレムの知識人たちが求めた「新しいニグロ」の創造は成功とみなされた[by whom?]。 ハーレム・ルネサンスはさまざまな読者にアピールした。文学はアフリカ系アメリカ人の中産階級と白人にアピールした。NAACPの月刊誌『The Crisis』やナショナリズムの機関誌『Opportunity』などの雑誌は、ハーレム・ルネッサンスの作家を編集スタッフに起用し、黒人作家の詩や 短編小説を掲載し、記事、批評、毎年の文学賞を通じてアフリカ系アメリカ人文学を宣伝した。しかし、こうした文学の発信源が重要であったのと同様に、ルネ サンスは白人の出版社や白人が所有する雑誌に大きく依存していた[67]。 ルネサンスの大きな功績は、主流の白人の定期刊行物や出版社に門戸を開いたことであったが、ルネサンスの作家と白人の出版社や読者との関係はいくつかの論 争を引き起こした。W・E・B・デュボワは黒人作家と白人出版社との関係に反対はしなかったが、クロード・マッケイのベストセラー小説『ハーレムへの家 路』(1928年)のような作品が、黒人の「淫らな」描写を求める白人読者や出版社の「prurient demand[s]」に訴えているとして批判的であった[67]。 ラングストン・ヒューズはエッセイ「ニグロの芸術家と人種の山」(1926年)の中で、黒人の芸術家たちは黒人の大衆や白人の大衆がどう思おうと、自分た ちを自由に表現することを意図していると書いたとき、ほとんどの作家や芸術家たちの代弁者となった[68]。 ヒューズは著作の中でも人種のすれ違いというテーマに立ち戻ったが、ハーレム・ルネッサンスの時期には同性愛や同性愛嫌悪というテーマを探求し始めた。彼 は著作の中で破壊的な言葉を使い始めた。彼がこのテーマを探求したのは、この時代には議論されていなかったテーマだったからである[69]。 アフリカ系アメリカ人のミュージシャンや作家もまた、ニュー・ニグロ・ムーブメントを通じて肯定的な結果も否定的な結果も経験し、様々な聴衆の中にいた。 ミュージシャンにとっては、ニューヨークのハーレムのキャバレーやナイトクラブが黒人パフォーマーに光を当て、黒人住民が音楽やダンスを楽しむことを可能 にしていた。ハーレムで最も有名な白人専用ナイトクラブのひとつがコットン・クラブで、デューク・エリントンなどの人気黒人ミュージシャンが頻繁に演奏し ていた[70]。最終的に、こうした白人専用クラブに出演した黒人ミュージシャンははるかに成功し、メインストリームの音楽シーンの一部となった[要出 典]。 同様に、黒人作家は、ニュー・ニグロ・ムーブメントが支持を集めると、1910年代から1920年代にかけて、黒人作家による短編小説や詩が形となり、さ まざまな印刷出版物に掲載されるようになり、輝く機会を与えられた[71]。一見、彼らのアイデンティティや文化を確立するための良い方法であるように見 えるが、多くの作家は、彼らの作品が実際にどこにも出回ることがいかに困難であったかを指摘している。例えば、1877年の作家チャールズ・チェスナット は、『アトランティック・マンスリー』誌に掲載された彼の作品には、(出版社の要請で)自分の人種について何も書かれていなかったと記している[72]。 新ニグロの闘争の顕著な要因は、彼らの作品が白人の聴衆にとって「異なる」または「エキゾチック」であるとされてきたことであり、黒人作家が彼らにアピー ルし、彼らの作品を世に出すために互いに競争する必要性を作っていた[71]。 有名な黒人作家であり詩人であるラングストン・ヒューズは、黒人が執筆した作品は、東洋または外国由来の作品と同じようなやり方で配置され、白人が制作し た作品と比較してたまに使われるだけであったと説明している: 黒人作品のための場所が「取られて」しまうと、黒人作家は出版するために他の場所を探さなければならなかった[72]。 ハーレム・ルネッサンスのある側面は、議論することなく、精査することなく受け入れられた。そのひとつが「新しいニグロ」の未来だった。ハーレム・ルネッ サンスの芸術家や知識人たちは、民主的改革への信頼、変革の担い手としての芸術と文学への信念、そして自分自身とその未来に対するほとんど無批判な信念に おいて、アメリカの進歩主義と呼応していた。この進歩主義的な世界観は、白人知識人と同様に黒人知識人を大恐慌の無礼な衝撃に備えることができないものと し、ハーレム・ルネッサンスは、経済的・社会的現実とは無関係な文化の中心性についてのナイーブな思い込みのために、唐突に終わった[73]。 |

| Works associated with the Harlem Renaissance Blackbirds of 1928 Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance (book) The New Negro: The Life of Alain Locke Shuffle Along, musical Untitled (The Birth), painting Voodoo (opera) When Washington Was in Vogue The Negro in Art Taboo (1922 play) There'll Be Some Changes Made |

ハーレム・ルネッサンス関連作品 1928年のブラックバード ハーレム・ルネッサンス百科事典(書籍) 新しいニグロ アラン・ロックの生涯 シャッフル・アロング(ミュージカル 無題(誕生)、絵画 ブードゥー(オペラ) ワシントンが流行っていた頃 芸術の中のニグロ タブー(1922年の戯曲) いくつかの変更が加えられる |

| Black Arts Movement, 1960s and 1970s Black Renaissance in D.C. Chicago Black Renaissance List of female entertainers of the Harlem Renaissance List of figures from the Harlem Renaissance New Negro Niggerati William E. Harmon Foundation award Cotton Club, nightclub General: Roaring Twenties African-American art African-American culture African-American literature List of African-American visual artists |

黒人芸術運動、1960年代と1970年代 D.C.におけるブラック・ルネッサンス シカゴのブラック・ルネッサンス ハーレム・ルネッサンスの女性エンターテイナー一覧 ハーレム・ルネッサンスの人物リスト ニュー・ニグロ ニゲラティ ウィリアム・E・ハーモン財団賞 コットンクラブ(ナイトクラブ 一般的な ロアリング・トゥエンティーズ アフリカ系アメリカ人の芸術 アフリカ系アメリカ人文化 アフリカ系アメリカ人文学 アフリカ系アメリカ人視覚芸術家リスト |

| Amos, Shawn, compiler.

Rhapsodies in Black: Words and Music of the Harlem Renaissance. Los

Angeles: Rhino Records, 2000. 4 Compact Discs. Andrews, William L.; Frances S. Foster; Trudier Harris, eds. The Concise Oxford Companion To African American Literature. New York: Oxford Press, 2001. ISBN 1-4028-9296-9 Bean, Annemarie. A Sourcebook on African-American Performance: Plays, People, Movements. London: Routledge, 1999; pp. vii + 360. Greaves, William documentary From These Roots. Hicklin, Fannie Ella Frazier. "The American Negro Playwright, 1920–1964". PhD Dissertation, Department of Speech, University of Wisconsin, 1965. Ann Arbor: University Microfilms 65–6217. Huggins, Nathan. Harlem Renaissance. New York: Oxford University Press, 1973. ISBN 0-19-501665-3 Hughes, Langston. The Big Sea. New York: Knopf, 1940. Hutchinson, George. The Harlem Renaissance in Black and White. New York: Belknap Press, 1997. ISBN 0-674-37263-8 Lewis, David Levering, ed. The Portable Harlem Renaissance Reader. New York: Viking Penguin, 1995. ISBN 0-14-017036-7 Lewis, David Levering. When Harlem Was in Vogue. New York: Penguin, 1997. ISBN 0-14-026334-9 Ostrom, Hans. A Langston Hughes Encyclopedia. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2002. Ostrom, Hans and J. David Macey, eds. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of African American Literature. 5 volumes. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2005. Patton, Venetria K., and Maureen Honey, eds. Double-Take: A Revisionist Harlem Renaissance Anthology. New Jersey: Rutgers University Press, 2006. Perry, Jeffrey B. A Hubert Harrison Reader. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001. Perry, Jeffrey B. Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883–1918. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008. Powell, Richard, and David A. Bailey, eds. Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997. Rampersad, Arnold. The Life of Langston Hughes. 2 volumes. New York: Oxford University Press, 1986 and 1988. Robertson, Stephen, et al., "Disorderly Houses: Residences, Privacy, and the Surveillance of Sexuality in 1920s Harlem", Journal of the History of Sexuality, 21 (September 2012), 443–66. Soto, Michael, ed. Teaching The Harlem Renaissance. New York: Peter Lang, 2008. Tracy, Steven C. Langston Hughes and the Blues. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988. Watson, Steven. The Harlem Renaissance: Hub of African-American Culture, 1920–1930. New York: Pantheon Books, 1995. ISBN 0-679-75889-5 Williams, Iain Cameron. "Underneath a Harlem Moon ... The Harlem to Paris Years of Adelaide Hall". Continuum Int. Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0826458939 Wintz, Cary D. Black Culture and the Harlem Renaissance. Houston: Rice University Press, 1988. Wintz, Cary D. Harlem Speaks: A Living History of the Harlem Renaissance. Naperville, Illinois: Sourcebooks, Inc., 2007 |

エイモス、ショーン、コンパイラー ラプソディーズ・イン・ブラック: ハーレム・ルネッサンスの言葉と音楽。ロサンゼルス: Rhino Records, 2000. 4 Compact Discs. Andrews, William L.; Frances S. Foster; Trudier Harris, eds. The Concise Oxford Companion To African American Literature. ニューヨーク: Oxford Press, 2001. ISBN 1-4028-9296-9 Bean, Annemarie. A Sourcebook on African-American Performance: 演劇、人々、運動。London: Routledge, 1999; pp. Greaves, William documentary From These Roots. Hicklin, Fannie Ella Frazier. 「The American Negro Playwright, 1920-1964」. Hannie Ella Frazier. 「The American Negro Playwright, 1920-1964」. ウィスコンシン大学言語学部博士論文、1965年。アナーバー: University Microfilms 65-6217. Huggins, Nathan. ハーレム・ルネッサンス. New York: オックスフォード大学出版局, 1973. ISBN 0-19-501665-3 ヒューズ、ラングストン. The Big Sea. ニューヨーク: Knopf, 1940. Hutchinson, George. The Harlem Renaissance in Black and White. New York: Belknap Press, 1997. ISBN 0-674-37263-8 Lewis, David Levering, ed. The Portable Harlem Renaissance Reader. ニューヨーク: Viking Penguin, 1995. ISBN 0-14-017036-7 Lewis, David Levering. When Harlem Was in Vogue. ニューヨーク: Penguin, 1997. ISBN 0-14-026334-9 Ostrom, Hans. ラングストン・ヒューズ百科事典. Westport: Greenwood Press, 2002. Ostrom, Hans and J. David Macey, eds. The Greenwood Encyclopedia of African American Literature. 全 5 巻。Westport: Greenwood Press, 2005. Patton, Venetria K., and Maureen Honey, eds. Double-Take: A Revisionist Harlem Renaissance Anthology. ニュージャージー州: Rutgers University Press, 2006. A Hubert Harrison Reader. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001. Perry, Jeffrey B. Hubert Harrison: The Voice of Harlem Radicalism, 1883-1918. New York: Columbia University Press, 2008. Powell, Richard, and David A. Bailey, eds. Rhapsodies in Black: Rhapsodies in Black: Art of the Harlem Renaissance. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1997. Rampersad, Arnold. ラングストン・ヒューズの生涯. 全2巻。ニューヨーク: Oxford University Press, 1986 and 1988. Robertson, Stephen, et al., "Disorderly Houses: 1920年代ハーレムにおける住居、プライバシー、セクシュアリティの監視」『セクシュアリティ史ジャーナル』21号(2012年9月)、443-66。 ソト、マイケル編 Teaching The Harlem Renaissance. ニューヨーク: Peter Lang, 2008. Tracy, Steven C. Langston Hughes and the Blues. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 1988. Watson, Steven. The Harlem Renaissance: The Harlem Renaissance: Hub of African-American Culture, 1920-1930. ニューヨーク: Pantheon Books, 1995. ISBN 0-679-75889-5 ウィリアムズ、アイアン・キャメロン 「ハーレムの月の下で.... The Harlem to Paris Years of Adelaide Hall」. Continuum Int. Publishing, 2003. ISBN 0826458939 Wintz, Cary D. Black Culture and the Harlem Renaissance. ヒューストン: Rice University Press, 1988. Wintz, Cary D. Harlem Speaks: A Living History of the Harlem Renaissance. イリノイ州ネーパービル: ソースブックス社、2007年 |

| Further reading Brown, Linda Rae (1990). "William Grant Still, Florence Price, and William Dawson: Echoes of the Harlem Renaissance". In Samuel A. Floyd, Jr (ed.), Black Music in the Harlem Renaissance, Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, pp. 71–86. Buck, Christopher (2013). Harlem Renaissance in: The American Mosaic: The African American Experience. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. Evans, Curtis J. (2008), The Burden of Black Religion, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-532931-5 Johnson, Michael K. (2019), Can't Stand Still: Taylor Gordon and the Harlem Renaissance. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 9781496821966 (online) King, Shannon (2015). Whose Harlem Is This, Anyway? Community Politics and Grassroots Activism during the New Negro Era. New York University Press. Lassieur, Alison. (2013). The Harlem Renaissance: An Interactive History Adventure, North Mankato, Minnesota: Capstone Press, ISBN 9781476536095 Murrell, Denise (2018). Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Murrell, Denise, ed. (2024). The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism. Exh. cat. Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 9781588397737 Padva, Gilad (2014). "Black Nostalgia: Poetry, Ethnicity, and Homoeroticism in Looking for Langston and Brother to Brother". In Padva, Gilad, Queer Nostalgia in Cinema and Pop Culture, pp. 199–226. Basingstoke, UK, and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Wall, Cheryl A. (2016). The Harlem Renaissance: A Very Short Introduction. Oxford University Press. Wintz, Cary D., and Paul Finkelman (2012). Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance. London: Routledge. |

さらに詳しく読む Brown, Linda Rae (1990). 「ウィリアム・グラント・スティル、フローレンス・プライス、ウィリアム・ドーソン: ハーレム・ルネッサンスの響き」. Samuel A. Floyd, Jr (ed.), Black Music in the Harlem Renaissance, Knoxville: University of Tennessee Press, pp.71-86. Buck, Christopher (2013). ハーレム・ルネッサンス The American Mosaic: The African American Experience. Santa Barbara, California: ABC-CLIO. Evans, Curtis J. (2008), The Burden of Black Religion, Oxford University Press, ISBN 978-0-19-532931-5. Johnson, Michael K. (2019), Can't Stand Still: Taylor Gordon and the Harlem Renaissance. Jackson: University Press of Mississippi, ISBN 9781496821966(オンライン) キング・シャノン(2015) ハーレムはいったい誰のものなのか?新ニグロ時代のコミュニティ政治と草の根活動。New York University Press. Lassieur, Alison. (2013). The Harlem Renaissance: An Interactive History Adventure, North Mankato, Minnesota: キャップストーン出版、ISBN 9781476536095 Murrell, Denise (2018). Posing Modernity: The Black Model from Manet and Matisse to Today. New Haven and London: Yale University Press. Murrell, Denise, ed. (2024). The Harlem Renaissance and Transatlantic Modernism. Exh. cat. メトロポリタン美術館。ISBN 9781588397737 Padva, Gilad (2014). 「Black Nostalgia: ラングストンを探して』と『ブラザー・トゥ・ブラザー』における詩、エスニシティ、ホモエロティシズム」. In Padva, Gilad, Queer Nostalgia in Cinema and Pop Culture, pp. Basingstoke, UK, and New York: Palgrave Macmillan. Wall, Cheryl A. (2016). ハーレム・ルネッサンス: A Very Short Introduction. オックスフォード大学出版局。 Wintz, Cary D., and Paul Finkelman (2012). Encyclopedia of the Harlem Renaissance. London: Routledge. |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Harlem_Renaissance |

|

#FallenThroughTheCracks:

Black Artists in History - #RichmondBarthe

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆