嗅覚論

On Smellosophy : what the nose

tells the mind by A-S. Barwich

嗅覚論

On Smellosophy : what the nose

tells the mind by A-S. Barwich

☆「ある匂いを知覚することは決して完了することのない 認知の始まりだ。そしてそれは始まりだけにとどまる感覚なのである」(ポール・ヴァレリー)

☆「苦いアーモンドを思わせる匂いがすると、ああ、この恋も報われなかったのだなとつい思って しまうが、こればかりはどうしようもなかった」ガブリエル・ガルシア=マルケス『コレラの時代 の愛』

☆「マドレーヌを少し柔らかくした紅茶をスプーン一杯口に運んだ。しかし、ケーキのくずが混じった紅茶が口に触れたまさにその瞬間、私は身震いした。」マルセル・プルースト『失われた時を求めて』

★『においが心を動かす : ヒトは嗅覚の動物である』 /

A・S・バーウィッチ著 ; 大田直子訳、河出書房新社 , 2021年(Smellosophy : what the nose tells

the mind / Ann-Sophie

Barwich, Harvard University Press , 2020)★匂いが命を決める : ヒト・昆虫・動植物を誘う嗅覚 / ビル・S・ハンソン著 ; 大沢章子訳, 亜紀書房 , 2023年

書籍解説「脳が感覚情報を変換する方法についての既成概念を覆す、嗅覚の先駆的な探求。数十 年にわたる認知研究の結果、外部からの刺激が脳の特定の領域に神経パターンを「閃かせる」ことが明らかになっている。このため、脳を空間としてとらえ、 「ここでは顔に反応する」「ここでは左手の感覚を認識する」というようにマッピングすることが可能である。しかし、最近になって神経科学で注目されるよう になった嗅覚は、このような仕組みにはなっていないことが判明した。A. S. バーウィッチは、一見単純な疑問を投げかける。鼻は脳に何を伝え、脳はそれをどのように理解するのだろうか?バーウィッチは、神経科学、心理学、化学、香 水の専門家にインタビューし、匂いの生物学的メカニズムと無数の意味を理解しようと努めている。彼女は、嗅覚システムに対する視覚のパラダイムに基づくア イデアのリサイクルを止める時が来たと主張している。香りは、視覚的なイメージと比較して、しばしば気まぐれで無限であり、明確に定義された神経領域とは 一致しない。嗅覚は依然として謎であるが、バーウィッチは、我々が知っていることは、脳が地図のように機能するだけでなく、単純な臭いや複雑な臭いを感知 し処理する測定器として機能していることを示唆していると提案する。嗅覚について説明すると、哲学者が構築してきた知覚の理論が崩れてしまう。(本書の) 嗅覚論は、脳がどのように感覚情報を表現しているかを理解するための新しいモデルを提示する」。

★アン=ソフィー・バーウィッチ(Ann-Sophie Barwich)へのサイト内リンクはこちら.

★スメルスケープ(匂い景観:smellscape)はこちらからリンク.

Olfactory system

(smell) Olfactory system

(smell)Like the sense of taste, the sense of smell, or the olfactiory system, is also responsive to chemical stimuli.[17] Unlike taste, there are hundreds of olfactory receptors (388 functional ones according to one 2003 study[41]), each binding to a particular molecular feature. Odor molecules possess a variety of features and, thus, excite specific receptors more or less strongly. This combination of excitatory signals from different receptors makes up what humans perceive as the molecule's smell.[42] The olfactory receptor neurons are located in a small region within the superior nasal cavity. This region is referred to as the olfactory epithelium and contains bipolar sensory neurons. Each olfactory sensory neuron has dendrites that extend from the apical surface of the epithelium into the mucus lining the cavity. As airborne molecules are inhaled through the nose, they pass over the olfactory epithelial region and dissolve into the mucus. These odorant molecules bind to proteins that keep them dissolved in the mucus and help transport them to the olfactory dendrites. The odorant–protein complex binds to a receptor protein within the cell membrane of an olfactory dendrite. These receptors are G protein–coupled, and will produce a graded membrane potential in the olfactory neurons.[17] In the brain, olfaction is processed by the olfactory cortex. Olfactory receptor neurons in the nose differ from most other neurons in that they die and regenerate on a regular basis. The inability to smell is called anosmia. Some neurons in the nose are specialized to detect pheromones.[43] Loss of the sense of smell can result in food tasting bland. A person with an impaired sense of smell may require additional spice and seasoning levels for food to be tasted. Anosmia may also be related to some presentations of mild depression, because the loss of enjoyment of food may lead to a general sense of despair. The ability of olfactory neurons to replace themselves decreases with age, leading to age-related anosmia. This explains why some elderly people salt their food more than younger people do.[17] Causes of Olfactory dysfunction can be caused by age, exposure to toxic chemicals, viral infections, epilepsy, some sort of neurodegenerative disease, head trauma, or as a result of another disorder. [5] As studies in olfaction have continued, there has been a positive correlation to its dysfunction or degeneration and early signs of Alzheimers and sporadic Parkinson's disease. Many patients don't notice the decline in smell before being tested. In Parkinson's Disease and Alzheimers, an olfactory deficit is present in 85 to 90% of the early onset cases. [5]There is evidence that the decline of this sense can precede the Alzheimers or Parkinson's Disease by a couple years. Although the deficit is present in these two diseases, as well as others, it is important to make note that the severity or magnitude vary with every disease. This has brought to light some suggestions that olfactory testing could be used in some cases to aid in differentiating many of the neurodegenerative diseases. [5] Those who were born without a sense of smell or have a damaged sense of smell usually complain about 1, or more, of 3 things. Our olfactory sense is also used as a warning against bad food. If the sense of smell is damaged or not there, it can lead to a person contracting food poisoning more often. Not having a sense of smell can also lead to damaged relationships or insecurities within the relationships because of the inability for the person to not smell body odor. Lastly, smell influences how food and drink taste. When the olfactory sense is damaged, the satisfaction from eating and drinking is not as prominent. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Sense +++++++++++++++++++++++++ |

嗅覚系(におい) 嗅覚系(におい)味覚と同様に嗅覚、または嗅覚系も化学的刺激に反応する[17]。味覚とは異なり、何百もの嗅覚受容体(2003年のある研究によると388の機能的なも の[41])があり、それぞれが特定の分子特徴に結合している。匂い分子は様々な特徴を持っているため、特定の受容体を多かれ少なかれ強く興奮させる。異 なる受容体からのこの興奮性シグナルの組み合わせは、人間が分子の匂いとして認識するものを構成している[42]。 嗅覚受容体ニューロンは、上鼻腔内の小さな領域に位置している。この領 域は嗅上皮と呼ばれ、双極性の感覚ニューロンを含んでいる。各嗅覚神経細胞は、上皮 の頂膜表面から腔内を覆う粘液に伸びる樹状突起を持つ。空気中の分子が鼻から吸い込まれると、嗅覚上皮領域の上を通過し、粘液に溶け込む。これらのにおい 分子は、粘液に溶け込んだ状態を維持するタンパク質と結合し、嗅覚の樹状突起に運ぶのを助ける。匂い物質とタンパク質の複合体は、嗅覚樹状突起の細胞膜に ある受容体タンパク質と結合する。これらの受容体はGタンパク質結合型であり、嗅覚ニューロンにおいて段階的な膜電位を発生させることになる[17]。 脳内では、嗅覚は嗅覚皮質で処理される。鼻の嗅覚受容体ニューロンは、 他のほとんどのニューロンとは異なり、定期的に死滅し再生する。匂いを嗅ぐことがで きない状態は、無嗅覚症と呼ばれる。鼻の神経細胞の中には、フェロモンを感知することに特化したものがある。嗅覚が損なわれた人は、食物を味わうために追 加のスパイスおよび調味料のレベルを必要とする場合がある。食物の楽しみの喪失は一般的な絶望感につながるため、無嗅覚症は軽度のうつ病のいくつかの症状 とも関連することがある。嗅覚ニューロンの交換能力は、加齢とともに低下し、加齢性無臭症を引き起こす。これは、一部の高齢者が若い人よりも食べ物に塩を かける理由を説明するものである[17]。 嗅覚障害の原因は、加齢、有毒化学物質への曝露、ウイルス感染、てんかん、ある種の神経変性疾患、頭部外傷、または他の疾患の結果として引き起こされるこ とがある。[5] 嗅覚の研究が進むにつれ、嗅覚の機能不全や変性とアルツハイマー病や散 発性パーキンソン病の初期症状との間に正の相関関係があることが分かってきた。多く の患者は、検査を受ける前に嗅覚の衰えに気づかない。パーキンソン病とアルツハイマー病では、早期発症例の85~90%に嗅覚障害が認められる。[5]こ の感覚の低下は、アルツハイマー病やパーキンソン病に2、3年先行することがあるという証拠がある。これらの2つの病気や他の病気でも欠損は存在するが、 その重症度や大きさはすべての病気によって異なることに注意することが重要である。このことから、神経変性疾患の鑑別に嗅覚検査が使われるケースがあるこ とが示唆されている。[5] 生まれつき嗅覚がない、または嗅覚が損なわれている人は、通常3つのうちの1つ、またはそれ以上について訴える。私たちの嗅覚は、悪い食べ物に対する警告 としても使われている。嗅覚が損なわれていたり、なかったりすると、食中毒にかかりやすくなる。また、嗅覚がないと、体臭を感じないため、人間関係が悪く なったり、人間関係が不安定になったりする。最後に、嗅覚は食べ物や飲み物の味に影響を与える。嗅覚が損なわれると、食べたり飲んだりしたときの満足感が 得られなくなるのだ。 https://www.deepl.com/ja/translator 1)嗅覚はどう進化してきたか : 生き物たちの匂い世界 / 新村芳人著、東京 : 岩波書店 , 2018.10. - (岩波科学ライブラリー ; 278) 2)に おいが心を動かす : ヒトは嗅覚の動物である / A・S・バーウィッチ著 ; 大田直子訳, 河出書房新社 , 2021 +++++++++++++++++ |

| Ann-Sophie Barwich Ann-Sophie Barwich is a cognitive scientist, an empirical philosopher, and a historian of science. She is an Assistant Professor with joint positions in the Cognitive Science Program[1] and the Department of History and Philosophy of Science[2] at Indiana University Bloomington. Barwich is best known for her interdisciplinary[3] work on the history, philosophy, and neuroscience of olfaction. Her book, Smellosophy: What the Nose tells the Mind,[4] highlights the importance of thinking about the sense of smell as a model for neuroscience and the senses.[5][6][7][8][9] She is also noted for her analyses on methodological issues in molecular biology[10] and neuroscience.[11] |

アン=ソフィー・バーウィッチ アン=ソフィー・バーウィッチは、認知科学者であり、経験的哲学者であ り、科学史家である。インディアナ大学ブルーミントン校の認知科学プログラム[1]と科学史・科学哲学科[2]で共同研究を行う助教である。バーウィッチ 氏は、嗅覚の歴史、哲学、神経科学に関する学際的な研究[3]で最もよく知られています。彼女の著書『Smellosophy: 鼻が心に語ること』[4]は、神経科学と感覚のモデルとして嗅覚について考えることの重要性を強調している[5][6][7][8][9]。また分子生物 学[10]と神経科学の方法論問題に対する彼女の分析でも注目されている[11]。 |

| Biography Ann-Sophie Barwich, originally from Weimar, East Germany,[12] received her Magister Artium (M.A.) in German Literature Studies and Philosophy in 2009 at the Humboldt University of Berlin with her thesis on causality in Leibniz and its relevance for theories of biological classification.[13] She received her Ph.D. in Philosophy in 2013 at the Centre for the Study of the Life Sciences at University of Exeter with advisors John Dupré and Michael Hauskeller, taking a philosophy of science approach to olfaction theory in her dissertation.[14] Barwich held a postdoctoral fellowship at the Konrad Lorenz Institute for Evolution and Cognition Research[15] before receiving the prestigious Presidential Scholar in Society and Neuroscience fellowship at the Center for Science and Society at Columbia University.[16] At the center, she worked in the neuroscience lab of Stuart Firestein on the project “From the Air to the Brain: Laboratory Routines in Olfaction”. |

略歴 東ドイツのワイマール出身のアン=ソフィー・バーウィッチは[12]、2009年にライプニッツにおける因果関係と生物分類の理論との関連についての論文 でベルリンフンボルト大学のドイツ文学研究および哲学のマジスター・アーティウム(修士号)を取得した[13]。2013年にエクセター大学の生命科学研 究センターでジョン・デュプレおよびマイケル・ハウスケラーのアドバイザーと共に哲学の博士号を取得、論文では嗅覚理論に対する科学哲学のアプローチを 行っている[14]。 [14] バーウィッチは、コンラート・ローレンツ進化認知研究所[15]で博士研究員を務めた後、コロンビア大学の科学と社会センターで社会と神経科学における名 誉ある大統領奨学生となった[16]。同センターでは、スチュアート・ファイアスタインの神経科学研究室で「空気から脳へ:嗅覚における研究室のルーティン」プロジェクトに従事。 |

| Research Barwich's research focuses on the chemical senses, with olfaction as the main target of study. Her approach applies philosophical ideas to empirical research to inform theories and methods on how perception and cognition should be modeled in the brain. This combines historical and philosophical analyses with sociological, qualitative methods that include interviews with experts in neuroscience, psychology, chemistry, and the industry of perfumery. A prime example is the research that went into the book Smellosophy,[4] in which she interviewed numerous neuroscientists such as Linda Buck, Stuart Firestein, philosophers including Barry C. Smith, winemaker Allison Tauziet, perfumers Harry Fremont and Christophe Laudamiel, sensory chemists such as Ann C. Noble, Avery Gilbert, as well as zoologists and biophysicists.[17] Her publications[18] are clustered around two areas: (1) the perceptual and cultural dimensions of smell and its link to cognition, which brings theoretical analyses to the empirical exploration of three aspects of odor: its affective nature, its phenomenological structure, and its cross-modal influences with the other senses, and (2) the role of scientific expertise in laboratory-based neuroscience, focusing on how current advances in olfaction can contribute to the conceptual foundations of neuroscience. By tracking the emergence, success, and decline of standard laboratory routines, her research investigates the cognitive and behavioral patterns that influence scientific decision-making. Barwich is also notable in philosophy of neuroscience[11] and philosophy of molecular biology [10] for her work on the historical and philosophical study of G-protein coupled receptors (GPCRs).[19] |

研究内容 バーウィッチの研究は、嗅覚を中心とした化学感覚に焦点を当てています。彼女のアプローチは、哲学的思想を実証的研究に適用し、知覚と認知が脳内でどのよ うにモデル化されるべきかに関する理論と方法に情報を提供するものである。これは、歴史的、哲学的な分析と、神経科学、心理学、化学、香水産業の専門家へ のインタビューを含む社会学的、定性的な方法を組み合わせたものだ。その代表例が書籍『Smellosophy』[4]で、リンダ・バック、スチュアー ト・ファイアスタイン、バリー・C・スミスなどの哲学者、ワインメーカーのアリソン・タウジエット、調香師のハリー・フレモント、クリストフ・ラウドミエ ル、感覚化学者のアン・C・ノーブル、アベリー・ギルバート、動物学者、生物物理学者などに多数のインタビューを行った研究[17]である。 1)匂いの知覚的・文化的側面とその認知への関連性、すなわち匂いの感情的性質、現象学的構造、他の感覚とのクロスモーダルな影響という3つの側面の経験 的探求に理論分析をもたらすもの、(2)実験室ベースの神経科学における科学の専門性の役割、嗅覚における現在の進歩が神経科学の概念的基礎にどのように 貢献できるかに焦点を当てるもの、に分類されます[18]。標準的な実験ルーチンの出現、成功、衰退を追跡することで、科学的意思決定に影響を与える認 知・行動パターンを研究している。また、Gタンパク質共役型受容体(GPCR)の歴史的・哲学的研究により、神経科学の哲学[11]や分子生物学の哲学 [10]でも注目される存在である[19]。 |

| Media appearances Her work, especially her book,[4] has been covered by Science[6] and national outlets including The New York Times,[20] The Wall Street Journal,[5] Harpers,[7] The Spectator,[9] and The Times Literary Supplement.[8] Smellosophy has also been selected by The Daily Telegraph as one of the "best wine books to buy for Christmas."[21] The parenting magazine Fatherly covered her work in articles on children's sense of smell,[22] pre-teens' body odor,[23] and debunking the myth that humans have a poor sense of smell.[24] She has been interviewed by the Italian newspaper la Repubblica,[25] Lynne Malcolm's All in the Mind program at ABC Radio National,[26] and the Radio New Zealand Nine to Noon with Kathryn Ryan program.[27] Barwich was also invited to appear on the game show Tell Me Something I Don't Know on Freakonomics Radio.[28] |

メディアへの登場 彼女の仕事、特に著書[4]は、サイエンス[6]や、ニューヨークタイムズ[20]、ウォールストリートジャーナル[5]、ハーパーズ[7]、スペクタク ル、タイムズリテラリーサプリメントなどの全国紙で取り上げられている。 また、スメロソフィーがデイリーテレグラフの「クリスマスに買いたいワイン本ベスト」に選出されている[8][21]。 育児雑誌『Fatherly』では、子どもの嗅覚[22]、プレティーンの体臭[23]、「人間の嗅覚は低い」という俗説の否定に関する記事で彼女の仕事 を取り上げた[24]。 [24] イタリアの新聞 la Repubblica、[25] ABC Radio National の Lynne Malcolm の All in the Mind プログラム、[26] Radio New Zealand Nine to Noon with Kathryn Ryan プログラムからインタビューを受けた。 27] Barwich は Freakonomics Radio のゲームショー Tell Me Something I Don't Know にも招待された[28]。 |

| Public writings Barwich is currently a writer for the column Molecules to Mind: The sense of smell as a window into mind and brain in Psychology Today.[35] She has also written on smell training[36] and wine tasting[37] for the NEO.LIFE magazine, on the philosophy and science of olfaction for Aeon[38] and Nautilus Quarterly,[39][40] and the importance of olfaction for philosophy in The Philosophers' Magazine.[41] During the COVID-19 pandemic, she wrote about COVID-19-related loss of smell and what it means for our understanding of the mind for StatNews.[42] De Standaard[43] picked up Barwich's work to address one of the core symptoms of COVID-19: the loss of smell and taste. Focusing on the case of Mary Hesse, she has also written for Aeon on the erasure of women philosophers from collective memory.[44] |

一般向け著作物 バーウィッチは現在、『Psychology Today』のコラム「Molecules to Mind」の執筆者である[35]。また、NEO.LIFE誌では嗅覚トレーニング[36]やワインテイスティング[37]について、Aeon[38]や Nautilus Quarterlyでは嗅覚の哲学・科学について、The Philosophers' Magazineでは哲学における嗅覚の重要性について執筆している [39] [40]。 [41] COVID-19が流行した際、彼女はCOVID-19に関連する嗅覚の喪失とそれが心の理解にとって何を意味するかについて『スタットニュース』に寄稿 しています[42] 。 デ・スタンダード』[43]はバーウィッチの仕事を取り上げ、COVID-19の中核症状の一つ、嗅覚と味覚の喪失について取り上げています。メアリー・ ヘッセのケースに焦点を当て、集合的記憶から女性哲学者が消去されることについて『イオン』にも寄稿している[44]。 |

| Selected bibliography Barwich, Ann-Sophie (2020). Smellosophy: What the Nose tells the Mind. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674983694. Barwich, Ann-Sophie (2020). "What makes a discovery successful? The story of Linda Buck and the olfactory receptors" (PDF). Cell. 181 (4): 749–753. doi:10.1016/j.cell.2020.04.040. PMID 32413294. S2CID 218627484. Barwich, Ann-Sophie (2019). "The value of failure in science: The story of grandmother cells in neuroscience". Frontiers in Neuroscience. 13 (1121): 1121. doi:10.3389/fnins.2019.01121. PMC 6822296. PMID 31708726. Barwich, Ann-Sophie (2018). "Measuring the World: Olfaction as a Process Model of Perception". Everything flows: Towards a processual philosophy of biology. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780198779636. Barwich, Ann-Sophie; Karim, Baschir (2017). "The Manipulability of What? The History of G–Protein Coupled Receptors". Biology and Philosophy. 32 (6): 1317–1339. doi:10.1007/s10539-017-9608-9. hdl:2022/26207. S2CID 148645746. Barwich, Ann-Sophie (2016). "What is so special about smell? Olfaction as a model system in neurobiology". Postgraduate Medical Journal. 92 (1083): 27–33. doi:10.1136/postgradmedj-2015-133249. PMID 26534994. S2CID 31525667. Barwich, Ann-Sophie; Chang, Hasok (2015). "Sensory measurements: coordination and standardization". Biological Theory. 10 (3): 200–211. doi:10.1007/s13752-015-0222-2. S2CID 82111463. Barwich, Ann-Sophie (2014). "A sense so rare: Measuring olfactory experiences and making a case for a process perspective on sensory perception". Biological Theory. 9 (3): 258–268. doi:10.1007/s13752-014-0165-z. S2CID 84039814. |

|

https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Ann-Sophie_Barwich |

|

| Patricia

Smith Churchland

(born 16 July 1943)[3] is a Canadian-American analytic

philosopher[1][2] noted for her contributions to neurophilosophy and

the philosophy of mind. She is UC President's Professor of Philosophy

Emerita at the University of California, San Diego (UCSD), where she

has taught since 1984. She has also held an adjunct professorship at

the Salk Institute for Biological Studies since 1989.[4] She is a

member of the Board of Trustees Moscow Center for Consciousness Studies

of Philosophy Department, Moscow State University.[5] In 2015, she was

elected a Fellow of the American Academy of Arts & Sciences.[6]

Educated at the University of British Columbia, the University of

Pittsburgh, and Somerville College, Oxford, she taught philosophy at

the University of Manitoba from 1969 to 1984 and is married to the

philosopher Paul Churchland.[7] Larissa MacFarquhar, writing for The

New Yorker, observed of the philosophical couple that: "Their work is

so similar that they are sometimes discussed, in journals and books, as

one person."[8] |

パトリシア・スミス・チャーチランド(Patricia

Smith

Churchland、1943年7月16日生まれ)[3]は、神経哲学と心の哲学への貢献で知られるカナダ系アメリカ人の分析哲学者[1][2]であ

る。カリフォルニア大学サンディエゴ校(UCSD)の哲学名誉教授であり、1984年から同校で教鞭をとっている。彼女はまた、1989年からソーク生物

学研究所の非常勤教授を務めている[4]。 彼女は、モスクワ大学哲学科の意識研究のための評議員モスクワセンターのメンバーである[5]

2015年に、彼女はアメリカ芸術科学アカデミーのフェローに選出された。 [6]

ブリティッシュ・コロンビア大学、ピッツバーグ大学、オックスフォードのサマーヴィル・カレッジで教育を受け、1969年から1984年までマニトバ大学

で哲学を教え、哲学者のポール・チャーチランドと結婚した[7]

ラリッサ・マクファーカーはニューヨーカーのために書いて、この哲学的カップルについてこう観察している。「彼らの仕事は非常によく似ているため、雑誌や

本では一人の人間として論じられることもある」[8]。 |

| Biography Early life and education Churchland was born Patricia Smith in Oliver, British Columbia,[3] and raised on a farm in the South Okanagan valley.[9][10] Both of her parents lacked a high-school education; her father and mother left school after grades 6 and 8 respectively. Her mother was a nurse and her father worked in newspaper publishing in addition to running the family farm. In spite of their limited education, Churchland has described her parents as interested in the sciences, and the worldview they instilled in her as a secular one. She has also described her parents as eager for her to attend college, and though many farmers in their community thought this "hilarious and a grotesque waste of money", they saw to it that she did so.[10] She took her undergraduate degree at the University of British Columbia, graduating with honors in 1965.[7] She received a Woodrow Wilson Fellowship to study at the University of Pittsburgh, where she took an M.A. in 1966.[7][11] Thereafter she studied at Somerville College, Oxford as a British Council and Canada Council Fellow, obtaining a B. Phil in 1969.[7] Academic career Churchland's first academic appointment was at the University of Manitoba, where she was an assistant professor from 1969 to 1977, an associate professor from 1977 to 1982, and promoted to a full professorship in 1983.[7] It was here that she began to make a formal study of neuroscience with the help and encouragement of Larry Jordan, a professor with a lab in the Department of Physiology there.[9][10][12] From 1982 to 1983 she was a Visiting Member in Social Science at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton.[13] In 1984, she was invited to take up a professorship in the department of philosophy at UCSD, and relocated there with her husband Paul, where both have remained since.[14] Since 1989, she has also held an adjunct professorship at the Salk Institute adjacent to UCSD's campus, where she became acquainted with Jonas Salk[4][9] whose name the Institute bears. Describing Salk, Churchland has said that he "liked the idea of neurophilosophy, and he gave me a tremendous amount of encouragement at a time when many other people thought that we were, frankly, out to lunch."[10] Another important supporter Churchland found at the Salk Institute was Francis Crick.[9][10] At the Salk Institute, Churchland has worked with Terrence Sejnowski's lab as a research collaborator.[15] Her collaboration with Sejnowski culminated in a book, The Computational Brain (MIT Press, 1993), co-authored with Sejnowski. Churchland was named the UC President's Professor of Philosophy in 1999, and served as Chair of the Philosophy Department at UCSD from 2000-2007.[7] She attended and was a speaker at the secularist Beyond Belief symposia in 2006, 2007, and 2008.[16][17][18] Personal life Churchland first met her husband, the philosopher Paul Churchland, while they were both enrolled in a class on Plato at the University of Pittsburgh,[10] and they were married after she completed her B.Phil at Somerville College, Oxford.[9] Their children are Mark M. Churchland (born 1972) and Anne K. Churchland (born 1974), both of whom are neuroscientists.[19][20] Churchland is considered an atheist,[21] however she identified herself as pantheist in a 2012 interview.[22][23] |

略歴 幼少期と教育 チャーチランドはブリティッシュ・コロンビア州のオリバーでパトリシア・スミスに生まれ[3]、南オカナガン渓谷の農場で育った[9][10]。 両親は共に高校教育を受けず、父親は6年生、母親は8年生で学校を去った。母親は看護師、父親は農場を経営する傍ら、新聞社で働いていた。しかし、両親は 科学に興味があり、その世界観は世俗的なものであったと語っている。また、両親は彼女が大学に行くことを熱望しており、地域の多くの農家が「滑稽で、お金 の無駄遣いだ」と思ったが、彼女が大学に行くように仕向けたと述べている[10]。 [7] その後、ウッドロウ・ウィルソン奨学金を得てピッツバーグ大学に留学し、1966年に修士号を取得[7][11] その後、ブリティッシュ評議会およびカナダ評議会のフェローとしてオックスフォードのサマーヴィル・カレッジで学び、1969年に理学士を取得[7] 。 研究者としての経歴 チャーチランドは、マニトバ大学で1969年から1977年まで助教授、1977年から1982年まで准教授を務め、1983年に正教授に昇任した [7]。このとき、生理学教室に研究室を持つラリー・ジョーダン教授の援助と奨励を受けて神経科学を正式に研究するようになった[9][10][12]。 [1982年から1983年までプリンストン高等研究所で社会科学の客員研究員[13]。1984年にカリフォルニア大学の哲学科の教授に招かれ、夫の ポールとともに移り住み、現在に至る[14]。チャーチランドはソークについて、「神経哲学の考え方が好きで、他の多くの人が私たちは正直言って昼食抜き だと考えていたときに、彼は私に多大な励ましを与えてくれた」と述べている[10]。チャーチランドがソーク研究所で見つけたもう一人の重要な支援者はフ ランシス・クリックである[9]。 [ソーク研究所では、テレンス・セジュノフスキーの研究室と共同研究を行っていた[15]。セジュノフスキーとの共同研究は、『計算脳』(MIT Press, 1993)という書籍に結実した。チャーチランドは1999年にカリフォルニア大学大統領哲学教授に任命され、2000年から2007年までカリフォルニ ア大学大学院哲学科の学科長を務めた[7]。 2006年、2007年、2008年に開催された世俗主義者のシンポジウム「ビヨンド・ビリーフ」に参加し、講演を行った[16][17][18]。 私生活 チャーチランドは、ピッツバーグ大学でプラトンに関する授業を受けていた時に、夫である哲学者のポール・チャーチランドと初めて出会い[10]、オックス フォードのサマーヴィル・カレッジで博士号を取得した後に結婚した[9]。 彼らの子供はマーク・M・チャーチランド(1972年生)とアン・K・チャーチランド(1974年生)で、2人とも神経科学者である[19][20] チャーチランドは無神論者として知られているが、2012年にインタビューに応じた際は汎神主義者として自らを認めた[21][22][23] 。 |

| Philosophical work Churchland is broadly allied to a view of philosophy as a kind of 'proto-science' - asking challenging but largely empirical questions. She advocates the scientific endeavour, and has dismissed significant swathes of professional philosophy as obsessed with what she regards as unnecessary.[24] Churchland's own work has focused on the interface between neuroscience and philosophy. According to her, philosophers are increasingly realizing that to understand the mind one must understand the brain. She applies findings from neuroscience to address traditional philosophical questions about knowledge, free will, consciousness and ethics. She is associated with a school of thought called eliminative materialism, which argues that common sense, immediately intuitive, or "folk psychological" concepts such as thought, free will, and consciousness will likely need to be revised in a physically reductionistic way as neuroscientists discover more about the nature of brain function.[25] 2014 saw a brief exchange of views on these topics with Colin McGinn in the pages of the New York Review Of Books.[26] https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Patricia_Churchland Neurophilosophy: Toward a Unified Science of the Mind-Brain. (1986) Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. "The Hornswoggle Problem". (1996) San Diego, La Jolla, CA. Journal of Consciousness Studies. Brain-Wise: Studies in Neurophilosophy. (2002) Cambridge, Massachusetts: The MIT Press. Braintrust: What Neuroscience Tells Us about Morality. (2011) Princeton University Press. eBook ISBN 9781400838080[31] Touching A Nerve: The Self As Brain. (2013) W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-0393058321 Conscience: The Origins of Moral Intuition. (2019) W. W. Norton & Company. ISBN 978-1324000891 American philosophy Eliminative materialism Neurophilosophy List of American philosophers Materialism Monism Philosophy of mind Reductionism Scientism |

哲学的な仕事 チャーチランドは、哲学を一種の「原始科学」として捉え、挑戦的でありながら実証的な問いを投げかけるという考え方に広く賛同している[24]。科学的な 試みを提唱しており、専門家である哲学者のかなりの部分が不要と考えるものに取り憑かれているとして退けている[24]。 チャーチランドは、神経科学と哲学の接点に焦点を当てた研究を行っています。チャーチランドによれば、哲学者は、心を理解するためには脳を理解しなければならない(Neurophilosophy)ことを次第に認識するようになっている。 チャーチランドは、神経科学の知見を応用し、知識、自由意志、意識、倫理に関する従来の哲学的な問いに取り組んでいる。彼女は消去的唯物論と呼ばれる学派 と関連しており、思考、自由意志、意識といった常識的、直ちに直感的、あるいは「民間心理学的」な概念は、神経科学者が脳機能の本質についてより多くを発 見するにつれ、おそらく物理的に還元的な方法で修正する必要があると論じている[25] 2014年にはニューヨークレビューオブブックスのページでコリン・マギンとこれらのテーマについて短い意見の交換が行われている[26]。 |

|

|

|

| 序章 鼻から突っ込む |

|

| 第1章 鼻の歴史 |

|

| 第2章 現代の嗅覚研究——岐路にたつ |

|

| 第3章 鼻を意識する——匂いの認知 |

|

| 第4章 行動はどうして化学を感じるのか——においの感情的性質 |

|

| 第5章 空間で——鼻から脳へ |

|

| 第6章 分子から知覚へ |

|

| 第7章 嗅球につく指紋 |

|

| 第8章 におい地図から、におい測定へ |

|

| 第9章 スキルとしての知覚 |

|

| 第10章 要点——心と脳をのぞく窓としての鼻 |

|

The olfactory system,

or sense of smell, is the sensory system used for smelling (olfaction).

Olfaction is one of the special senses, that have directly associated

specific organs. Most mammals and reptiles have a main olfactory system

and an accessory olfactory system. The main olfactory system detects

airborne substances, while the accessory system senses fluid-phase

stimuli. The olfactory system,

or sense of smell, is the sensory system used for smelling (olfaction).

Olfaction is one of the special senses, that have directly associated

specific organs. Most mammals and reptiles have a main olfactory system

and an accessory olfactory system. The main olfactory system detects

airborne substances, while the accessory system senses fluid-phase

stimuli.The senses of smell and taste (gustatory system) are often referred to together as the chemosensory system, because they both give the brain information about the chemical composition of objects through a process called transduction. |

嗅覚系(嗅覚)は、匂いを嗅ぐ(嗅ぐ)ための感覚器官である。嗅覚は特

殊な感覚のひとつで、特定の器官と直接関連する。ほとんどの哺乳類と爬虫類には、主嗅覚系と副嗅覚系がある。主嗅覚系は空気中の物質を感知し、副嗅覚系は

液相の刺激を感知する。 嗅覚と味覚(味覚系)は化学感覚系と呼ばれることが多いが、これは両者が伝達と呼ばれる過程を経て、物体の化学組成に関する情報を脳に与えるからである。 |

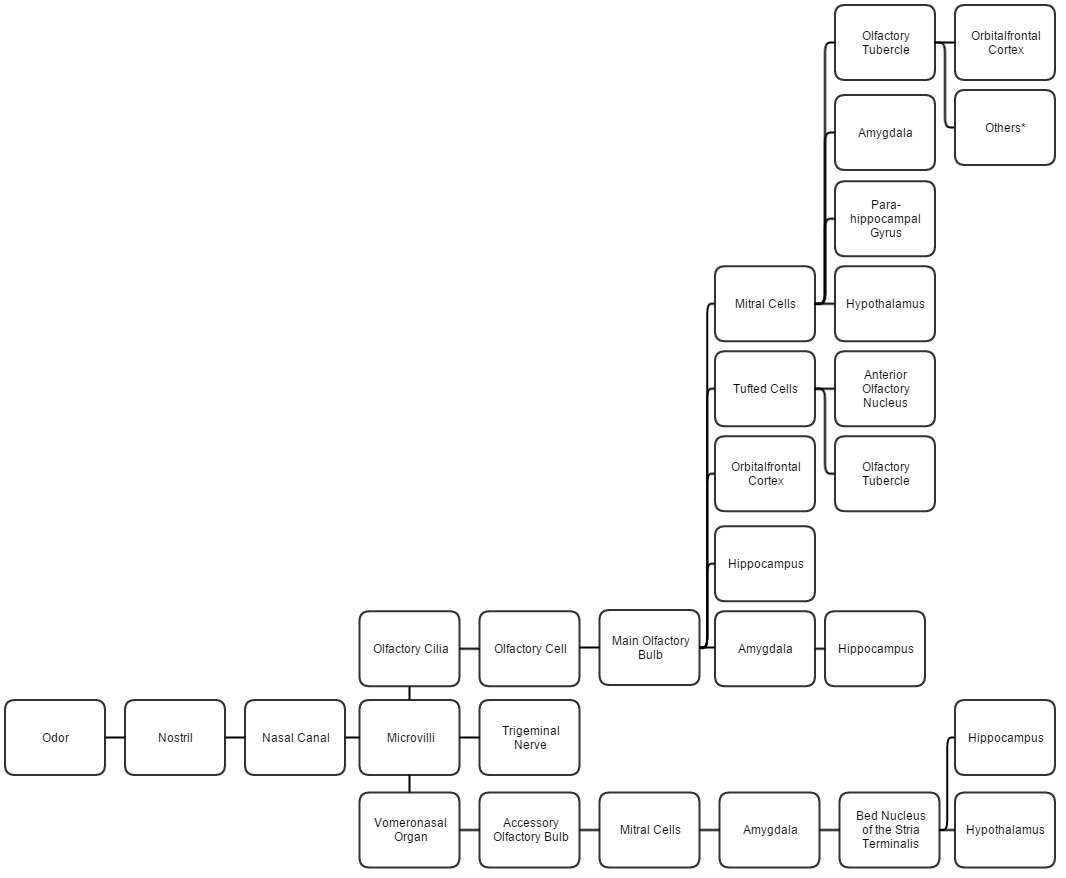

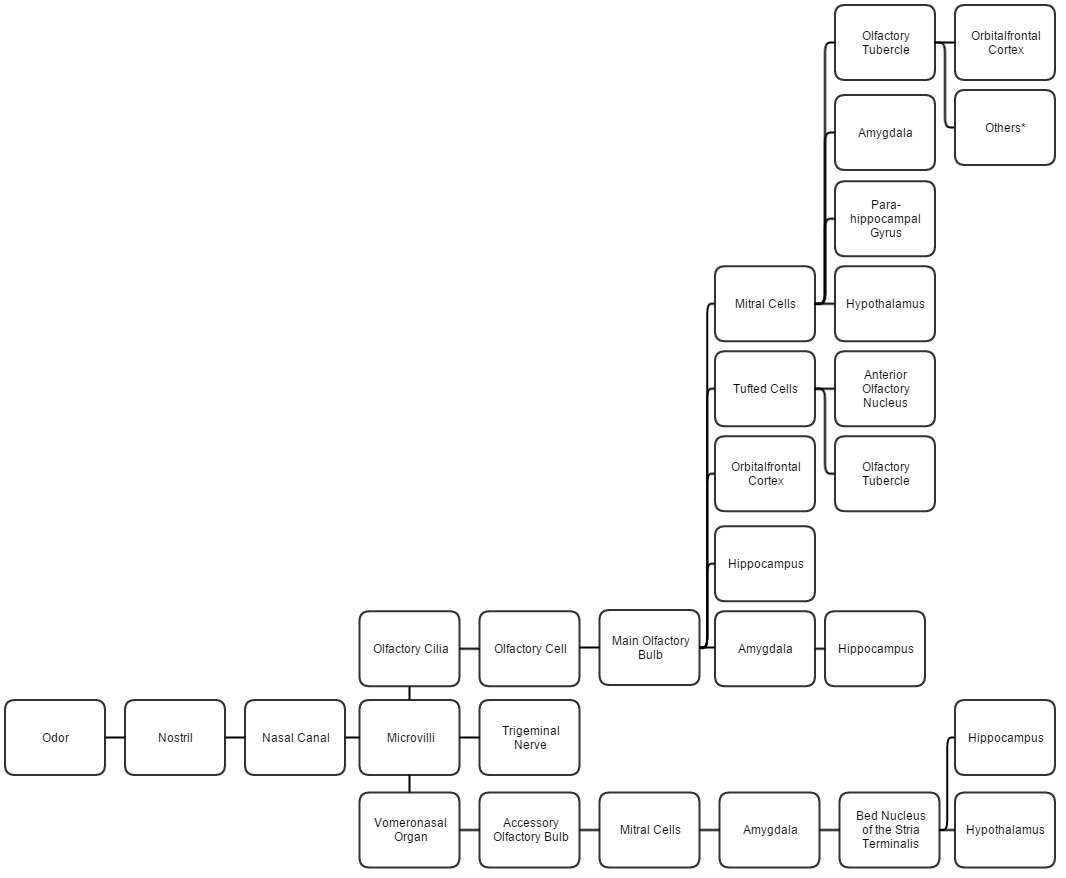

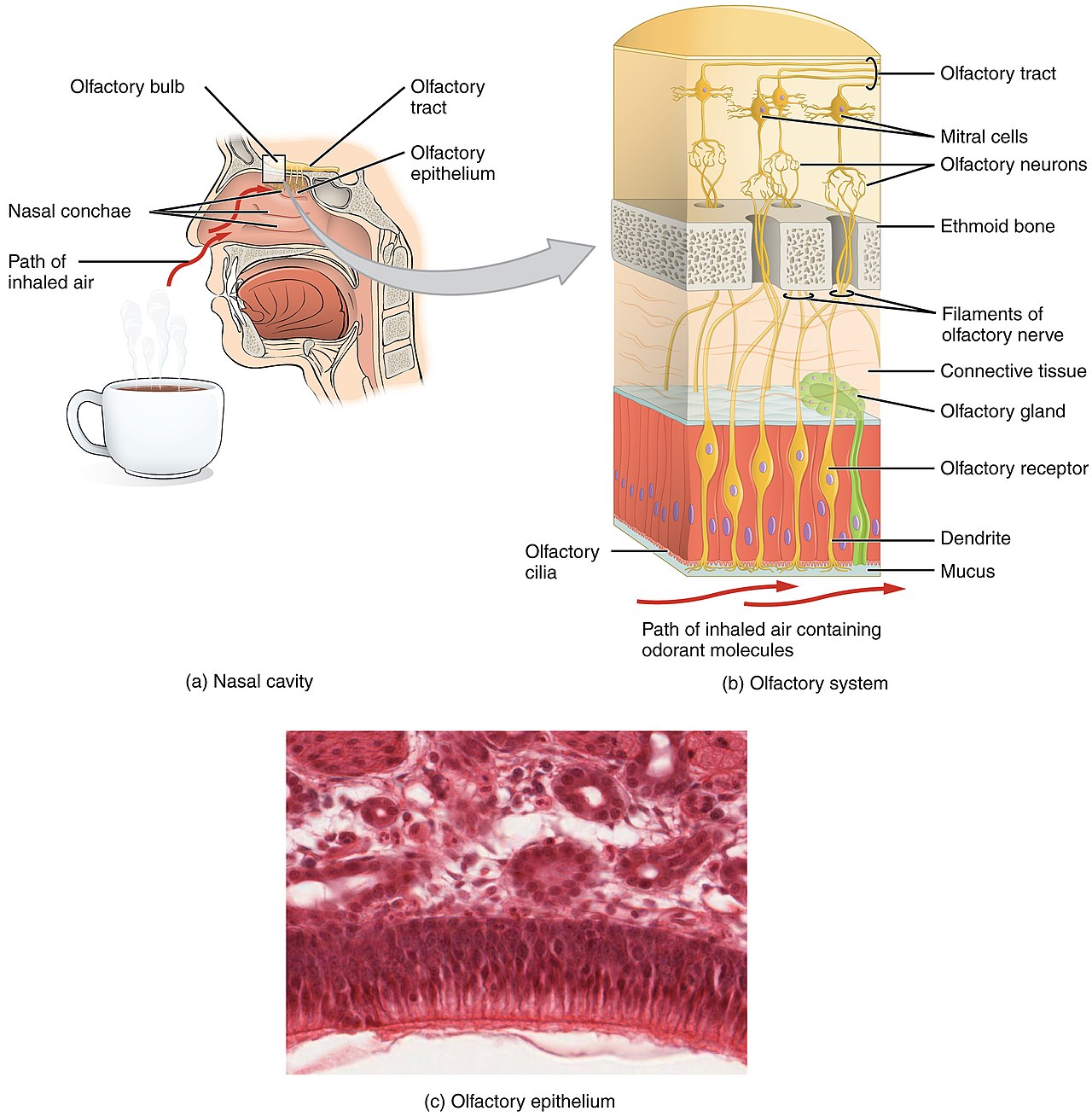

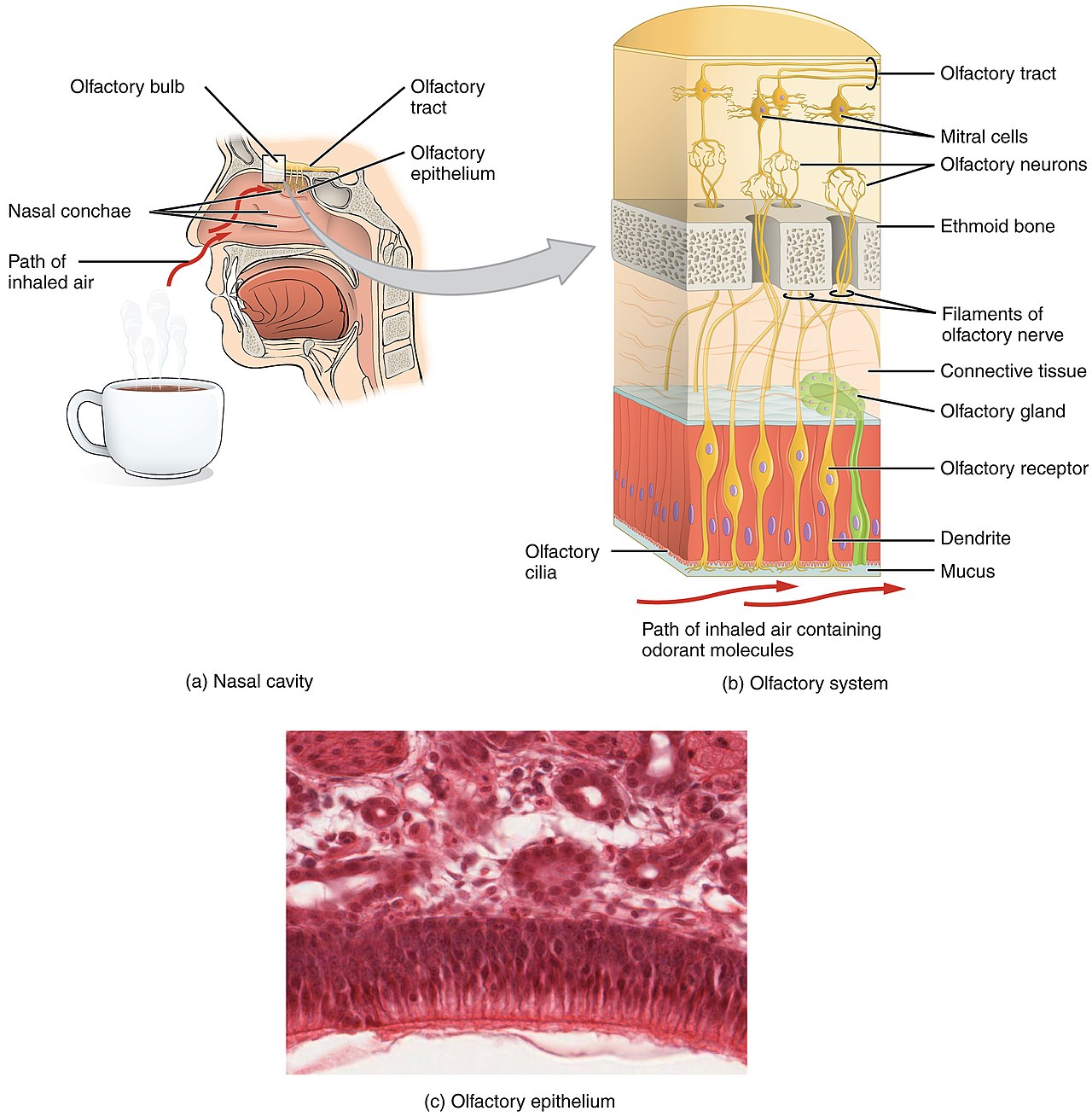

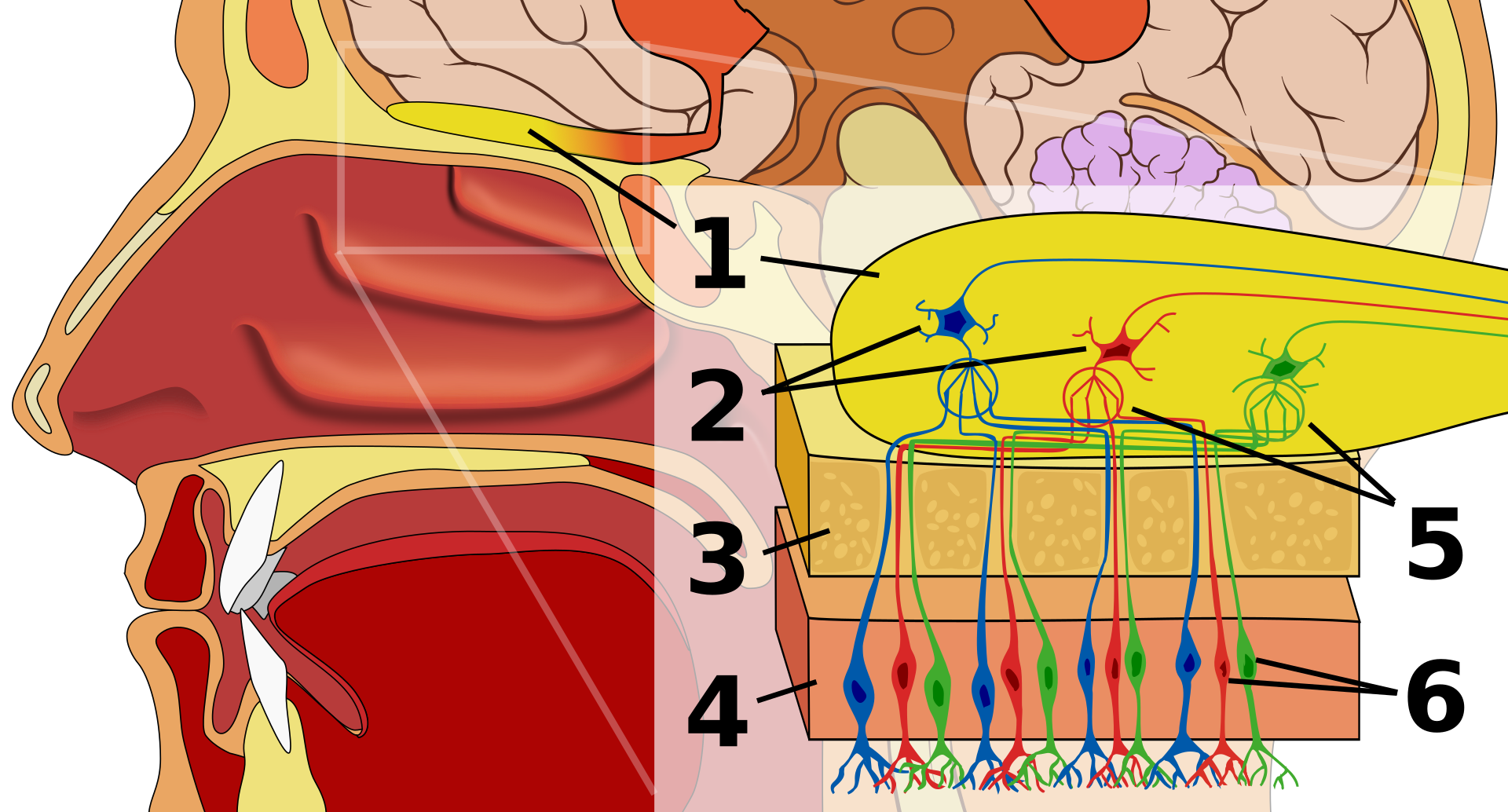

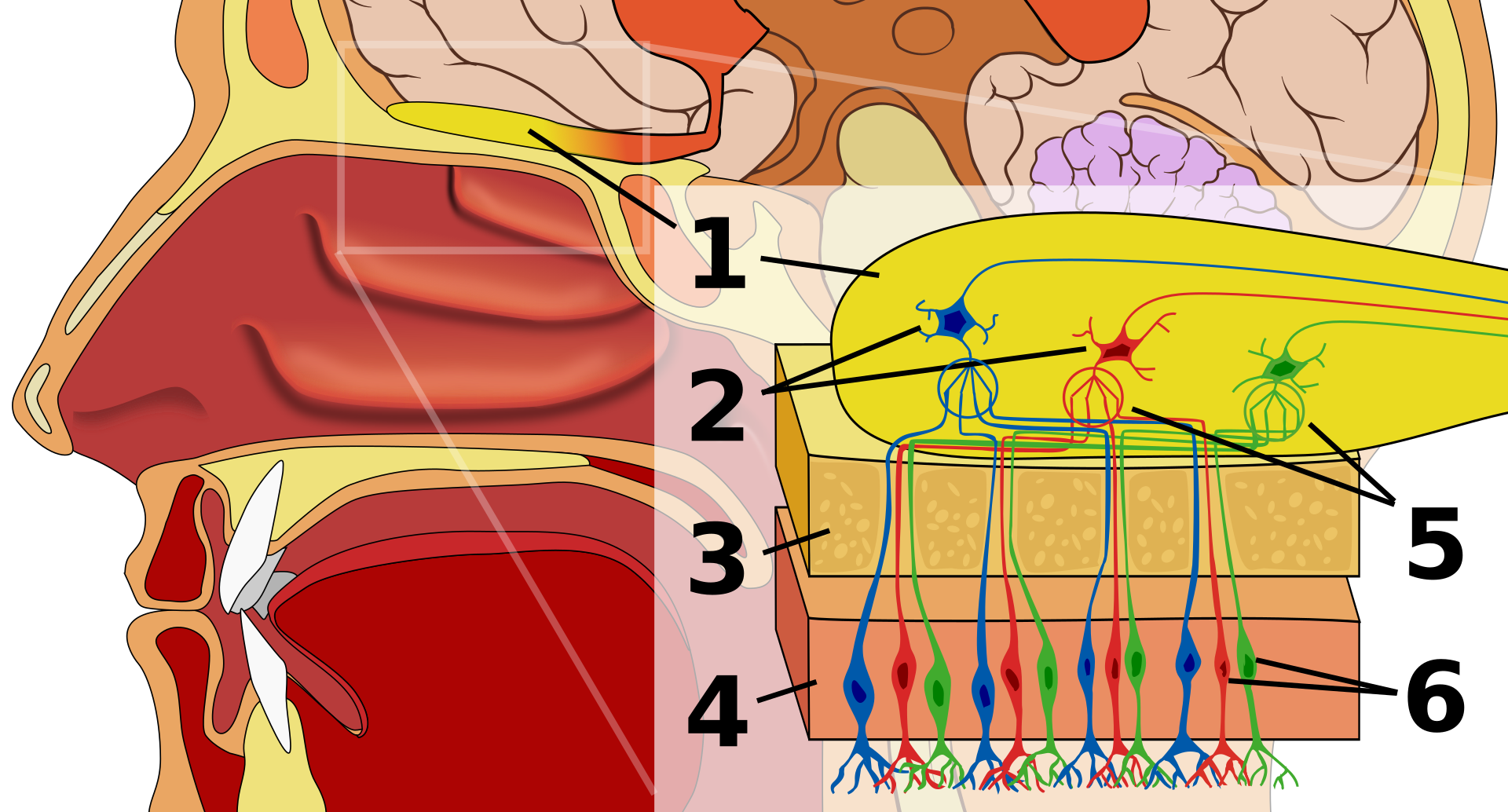

Structure This diagram linearly (unless otherwise mentioned) tracks the projections of all known structures that allow for olfaction to their relevant endpoints in the human brain. Peripheral The peripheral olfactory system consists mainly of the nostrils, ethmoid bone, nasal cavity, and the olfactory epithelium (layers of thin tissue covered in mucus that line the nasal cavity). The primary components of the layers of epithelial tissue are the mucous membranes, olfactory glands, olfactory neurons, and nerve fibers of the olfactory nerves.[1] Odor molecules can enter the peripheral pathway and reach the nasal cavity either through the nostrils when inhaling (olfaction) or through the throat when the tongue pushes air to the back of the nasal cavity while chewing or swallowing (retro-nasal olfaction).[2] Inside the nasal cavity, mucus lining the walls of the cavity dissolves odor molecules. Mucus also covers the olfactory epithelium, which contains mucous membranes that produce and store mucus, and olfactory glands that secrete metabolic enzymes found in the mucus.[3] Transduction  Action potential propagated by olfactory stimuli in an axon. Olfactory sensory neurons in the epithelium detect odor molecules dissolved in the mucus and transmit information about the odor to the brain in a process called sensory transduction.[4][5] Olfactory neurons have cilia (tiny hairs) containing olfactory receptors that bind to odor molecules, causing an electrical response that spreads through the sensory neuron to the olfactory nerve fibers at the back of the nasal cavity.[2] Olfactory nerves and fibers transmit information about odors from the peripheral olfactory system to the central olfactory system of the brain, which is separated from the epithelium by the cribriform plate of the ethmoid bone. Olfactory nerve fibers, which originate in the epithelium, pass through the cribriform plate, connecting the epithelium to the brain's limbic system at the olfactory bulbs.[6] |

構造 この図は、(特に断りのない限り)嗅覚を可能にするすべての既知の構造の、ヒトの脳における関連する終点への投影を直線的に追跡したものである。 末梢 末梢嗅覚系は主に、鼻孔、篩骨、鼻腔、嗅上皮(鼻腔を覆う粘液で覆われた薄い組織の層)から構成される。上皮組織の層の主な構成要素は、粘膜、嗅腺、嗅神 経細胞、嗅神経の神経線維である[1]。 臭気分子は末梢経路から侵入し、吸入時に鼻孔から(嗅覚)、または咀嚼や嚥下時に舌が空気を鼻腔の奥に押し出す際に喉から(後鼻腔嗅覚)、鼻腔に到達す る。粘液はまた嗅上皮も覆っている。嗅上皮には、粘液を産生・貯蔵する粘膜と、粘液に含まれる代謝酵素を分泌する嗅腺がある[3]。 伝達  嗅覚刺激によって軸索に伝搬される活動電位。 上皮にある嗅覚ニューロンは、粘液に溶けている匂い分子を感知し、感覚伝達と呼ばれるプロセスで、匂いに関する情報を脳に伝達する[4][5]。嗅覚 ニューロンには、匂い分子と結合する嗅覚受容体を含む繊毛(小さな毛)があり、電気的な反応を引き起こして、感覚ニューロンを通じて鼻腔の奥にある嗅神経 線維に広がる[2]。 嗅覚神経と嗅覚線維は、末梢嗅覚系から脳の中枢嗅覚系に匂いの情報を伝達する。嗅覚神経は篩骨篩板によって上皮から隔てられている。嗅覚神経線維は上皮か ら発生し、篩骨板を通り、嗅球で上皮と脳の大脳辺縁系をつなぐ[6]。 |

Central Details of olfaction system The main olfactory bulb transmits pulses to both mitral and tufted cells, which help determine odor concentration based on the time certain neuron clusters fire (called 'timing code'). These cells also note differences between highly similar odors and use that data to aid in later recognition. The cells are different with mitral having low firing-rates and being easily inhibited by neighboring cells, while tufted have high rates of firing and are more difficult to inhibit.[7][8][9][10] How the bulbar neural circuit transforms odor inputs to the bulb to the bulbar responses that are sent to the olfactory cortex can be partly understood by a mathematical model.[11] The uncus houses the olfactory cortex which includes the piriform cortex (posterior orbitofrontal cortex), amygdala, olfactory tubercle, and parahippocampal gyrus. The olfactory tubercle connects to numerous areas of the amygdala, thalamus, hypothalamus, hippocampus, brain stem, retina, auditory cortex, and olfactory system. *In total it has 27 inputs and 20 outputs. An oversimplification of its role is to state that it: checks to ensure odor signals arose from actual odors rather than villi irritation, regulates motor behavior (primarily social and stereotypical) brought on by odors, integrates auditory and olfactory sensory info to complete the aforementioned tasks, and plays a role in transmitting positive signals to reward sensors (and is thus involved in addiction).[12][13][14] The amygdala (in olfaction) processes pheromone, allomone, and kairomone (same-species, cross-species, and cross-species where the emitter is harmed and the sensor is benefited, respectively) signals. Due to cerebrum evolution this processing is secondary and therefore is largely unnoticed in human interactions.[15] Allomones include flower scents, natural herbicides, and natural toxic plant chemicals. The info for these processes comes from the vomeronasal organ indirectly via the olfactory bulb.[16] The main olfactory bulb's pulses in the amygdala are used to pair odors to names and recognize odor to odor differences.[17][18] Stria terminalis, specifically bed nuclei (BNST), act as the information pathway between the amygdala and hypothalamus, as well as the hypothalamus and pituitary gland. BNST abnormalities often lead to sexual confusion and immaturity. BNST also connects to the septal area, rewarding sexual behavior.[19][20] Mitral pulses to the hypothalamus promote/discourage feeding, whereas accessory olfactory bulb pulses regulate reproductive and odor-related-reflex processes. The hippocampus (although minimally connected to the main olfactory bulb) receives almost all of its olfactory information via the amygdala (either directly or via the BNST). The hippocampus forms new and reinforces existing memories. Similarly, the parahippocampus encodes, recognizes and contextualizes scenes.[21] The parahippocampal gyrus houses the topographical map for olfaction. The orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) is heavily correlated with the cingulate gyrus and septal area to act out positive/negative reinforcement. The OFC is the expectation of reward/punishment in response to stimuli. The OFC represents the emotion and reward in decision making.[22] The anterior olfactory nucleus distributes reciprocal signals between the olfactory bulb and piriform cortex.[23] The anterior olfactory nucleus is the memory hub for smell.[24] When different odor objects or components are mixed, humans and other mammals sniffing the mixture (presented by, e.g., a sniff bottle) are often unable to identify the components in the mixture even though they can recognize each individual component presented alone.[25] This is largely because each odor sensory neuron can be excited by multiple odor components. It has been proposed that, in an olfactory environment typically composed of multiple odor components (e.g., odor of a dog entering a kitchen that contains a background coffee odor), feedback from the olfactory cortex to the olfactory bulb[26] suppresses the pre-existing odor background (e.g., coffee) via olfactory adaptation,[27] so that the newly arrived foreground odor (e.g., dog) can be singled out from the mixture for recognition.[28] 1: Olfactory bulb 2: Mitral cells 3: Bone 4: Nasal epithelium 5: Glomerulus 6: Olfactory receptor cells |

中枢 嗅覚システムの詳細 主嗅球は分裂細胞と房状細胞の両方にパルスを伝達し、特定のニューロン群が発火する時間(「タイミングコード」と呼ばれる)に基づいて臭いの濃度を決定す るのに役立つ。これらの細胞はまた、類似性の高い匂い同士の違いを記録し、そのデータを後の認識に役立てる。この細胞は、マイトラルは発火率が低く、隣接 する細胞によって抑制されやすいのに対し、タフテッドは発火率が高く、抑制されにくいという違いがある[7][8][9][10]。嗅球神経回路がどのよ うにして嗅皮質に送られる嗅球反応に変化するかは、数学的モデルによって部分的に理解することができる[11]。 嗅球には、梨状皮質(後部眼窩前頭皮質)、扁桃体、嗅結帯、海馬傍回を含む嗅覚皮質がある。 嗅覚結節は、扁桃体、視床、視床下部、海馬、脳幹、網膜、聴覚野、嗅覚系の多くの部位とつながっている。*全部で27の入力と20の出力がある。その役割 を単純化し過ぎると、臭気信号が絨毛の刺激ではなく実際の臭気から生じたことを確認する、臭気によって引き起こされる運動行動(主に社会的、定型的)を制 御する、前述のタスクを完了するために聴覚と嗅覚の感覚情報を統合する、報酬センサーに肯定的な信号を伝達する役割を果たす(したがって中毒に関与する) [12][13][14]となる。 嗅覚における)扁桃体は、フェロモン、アロモン、ケイロモン(それぞれ、同種、異種、および放出者が害を受け、センサーが利益を受ける異種)のシグナルを 処理する。大脳の進化により、この処理は二次的なものであるため、人間の相互作用ではほとんど気づかれない。アロモンには、花の香り、天然の除草剤、天然 の有毒植物化学物質が含まれる。これらのプロセスの情報は、嗅球を介して間接的に鋤鼻器官からもたらされる[16]。扁桃体にある嗅球の主なパルスは、匂 いと名前のペアリングや、匂いと匂いの違いを認識するために使用される[17][18]。 終末線、特にベッド核(BNST)は、扁桃体と視床下部、および視床下部と下垂体の間の情報経路として働く。BNSTの異常はしばしば性的混乱や未成熟に つながる。BNSTは中隔領域にもつながっており、性的行動に報酬を与える [19][20] 。 視床下部への僧帽筋パルスは摂食を促進/抑制し、副嗅球パルスは生殖および臭覚関連反射過程を調節する。 海馬は(主嗅球とは最小限のつながりしかないが)嗅覚情報のほとんどすべてを扁桃体を介して(直接またはBNSTを介して)受け取る。海馬は新しい記憶を 形成し、既存の記憶を強化する。 同様に、海馬傍は情景を符号化し、認識し、文脈化する[21]。海馬傍回には嗅覚の地形図がある。 眼窩前頭皮質(OFC)は、帯状回および中隔領域と大きく相関しており、正の強化/負の強化を作用させる。OFCは刺激に対する報酬/罰の期待である。 OFCは意思決定における情動と報酬を表す[22]。 前嗅核は嗅球と梨状皮質の間で相互信号を分配する[23]。前嗅核は嗅覚の記憶ハブである[24]。 異なる匂いの対象物や成分が混在している場合、ヒトや他の哺乳類は、(例えば嗅覚瓶によって提示された)混合物を嗅ぐと、単独で提示された個々の成分を認 識できても、混合物中の成分を識別できないことが多い[25]。これは主に、各嗅覚ニューロンが複数の匂い成分によって興奮することができるためである。 一般的に複数のにおい成分から構成される嗅覚環境(例えば、背景のコーヒーのにおいを含むキッチンに犬が入るにおい)では、嗅覚皮質から嗅球へのフィード バック[26]により、嗅覚順応を介して背景の既存のにおい(例えば、コーヒー)が抑制され[27]、新たに到着した前景のにおい(例えば、犬)を混合物 から抽出して認識することができると提唱されている[28]。 1: 嗅球 2: 僧帽細胞 3: 骨 4: 鼻上皮 5: 糸球体 6: 嗅覚受容細胞 |

|

|

| Clinical significance Loss of smell is known as anosmia. Anosmia can occur on both sides or a single side. Olfactory problems can be divided into different types based on their malfunction. The olfactory dysfunction can be total (anosmia), incomplete (partial anosmia, hyposmia, or microsmia), distorted (dysosmia), or can be characterized by spontaneous sensations like phantosmia. An inability to recognize odors despite a normally functioning olfactory system is termed olfactory agnosia. Hyperosmia is a rare condition typified by an abnormally heightened sense of smell. Like vision and hearing, the olfactory problems can be bilateral or unilateral meaning if a person has anosmia on the right side of the nose but not the left, it is a unilateral right anosmia. On the other hand, if it is on both sides of the nose it is called bilateral anosmia or total anosmia.[29] Destruction to olfactory bulb, tract, and primary cortex (brodmann area 34) results in anosmia on the same side as the destruction. Also, irritative lesion of the uncus results in olfactory hallucinations. Damage to the olfactory system can occur by traumatic brain injury, cancer, infection, inhalation of toxic fumes, or neurodegenerative diseases such as Parkinson's disease and Alzheimer's disease. These conditions can cause anosmia. In contrast, recent finding suggested the molecular aspects of olfactory dysfunction can be recognized as a hallmark of amyloidogenesis-related diseases and there may even be a causal link through the disruption of multivalent metal ion transport and storage.[30] Doctors can detect damage to the olfactory system by presenting the patient with odors via a scratch and sniff card or by having the patient close their eyes and try to identify commonly available odors like coffee or peppermint candy. Doctors must exclude other diseases that inhibit or eliminate 'the sense of smell' such as chronic colds or sinusitus before making the diagnosis that there is permanent damage to the olfactory system. Prevalence of olfactory dysfunction in the general US population was assessed by questionnaire and examination in a national health survey in 2012-2014.[31] Among over a thousand persons aged 40 years and older, 12.0% reported a problem with smell in the past 12 months and 12.4% had olfactory dysfunction on examination. Prevalence rose from 4.2% at age 40-49 to 39.4% at 80 years and older and was higher in men than women, in blacks and Mexican Americans than in whites and in less than more educated. Of concern for safety, 20% of persons aged 70 and older were unable to identify smoke and 31%, natural gas. |

臨床的意義 嗅覚消失は無嗅覚症として知られる。無嗅覚症は両側に起こることもあれば、片側に起こることもある。 嗅覚障害は、その機能不全によって異なるタイプに分けられる。嗅覚機能障害は、完全なもの(無嗅覚症)、不完全なもの(部分的無嗅覚症、低嗅覚症、微嗅覚 症)、歪んだもの(異嗅覚症)、または幻臭症のような自発的な感覚を特徴とするものがある。嗅覚系が正常に機能しているにもかかわらず、においを認識でき ない状態を嗅覚無嗅覚という。嗅覚過敏症は、嗅覚が異常に亢進する稀な疾患である。視覚や聴覚と同様に、嗅覚障害も両側性または片側性の場合がある。つま り、右側の鼻に無嗅覚があり、左側の鼻に無嗅覚がない場合は、片側性の右側無嗅覚症である。一方、鼻の両側にある場合は、両側性無嗅覚症または完全無嗅覚 症と呼ばれる[29]。 嗅球、嗅路、一次皮質(ブロドマン野34)の破壊は、破壊と同じ側に無嗅覚症をもたらす。また、嗅球の刺激性病変は嗅覚幻覚を引き起こす。 嗅覚系の損傷は、外傷性脳損傷、がん、感染症、有毒ガスの吸入、またはパーキンソン病やアルツハイマー病などの神経変性疾患によって起こりうる。これらの 疾患は無嗅覚症を引き起こす可能性がある。対照的に、最近の発見は、嗅覚機能障害の分子的側面がアミロイド形成関連疾患の特徴として認識されることを示唆 し、多価金属イオンの輸送と貯蔵の障害を通じて因果関係がある可能性さえある。医師は、スクラッチ・アンド・スニッフ・カードを介して患者に匂いを提示す るか、患者に目を閉じてもらい、コーヒーやペパーミント・キャンディーのような一般的に入手可能な匂いを識別しようとすることで、嗅覚系の損傷を検出する ことができる。医師は、嗅覚系に永続的な障害があると診断する前に、慢性的な風邪や副鼻腔炎など、「嗅覚」を阻害または除去する他の疾患を除外しなければ ならない。 米国の一般人口における嗅覚障害の有病率は、2012年から2014年にかけて実施された国民健康調査において、質問票と検査によって評価された [31]。40歳以上の1,000人以上のうち、12.0%が過去12ヵ月間に嗅覚に問題があったと報告し、12.4%が検査で嗅覚障害を指摘された。有 病率は40~49歳の4.2%から80歳以上の39.4%に上昇し、女性よりも男性、白人よりも黒人やメキシコ系アメリカ人、高学歴よりも低学歴で高かっ た。70歳以上の20%が煙を、31%が天然ガスを識別できなかった。 |

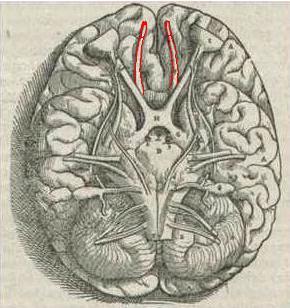

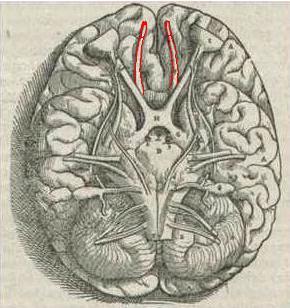

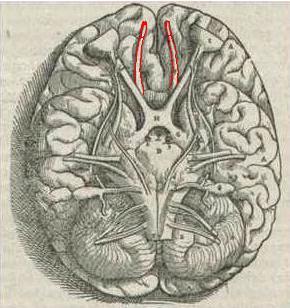

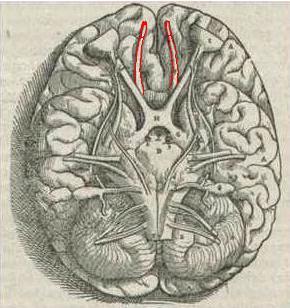

Causes of olfactory dysfunction Vesalius' Fabrica, 1543. Human Olfactory bulbs and Olfactory tracts outlined in red The common causes of olfactory dysfunction: advanced age, viral infections, exposure to toxic chemicals, head trauma, and neurodegenerative diseases.[29] Age Age is the strongest reason for olfactory decline in healthy adults, having even greater impact than does cigarette smoking. Age-related changes in smell function often go unnoticed and smell ability is rarely tested clinically unlike hearing and vision. 2% of people under 65 years of age have chronic smelling problems. This increases greatly between people of ages 65 and 80 with about half experiencing significant problems smelling. Then for adults over 80, the numbers rise to almost 75%.[32] The basis for age-related changes in smell function include closure of the cribriform plate,[29] and cumulative damage to the olfactory receptors from repeated viral and other insults throughout life. Viral infections The most common cause of permanent hyposmia and anosmia are upper respiratory infections. Such dysfunctions show no change over time and can sometimes reflect damage not only to the olfactory epithelium, but also to the central olfactory structures as a result of viral invasions into the brain. Among these virus-related disorders are the common cold, hepatitis, influenza and influenza-like illness, as well as herpes. Notably, COVID-19 is associated with olfactory disturbance.[33] Most viral infections are unrecognizable because they are so mild or entirely asymptomatic.[29] Exposure to toxic chemicals Chronic exposure to some airborne toxins such as herbicides, pesticides, solvents, and heavy metals (cadmium, chromium, nickel, and manganese), can alter the ability to smell.[34] These agents not only damage the olfactory epithelium, but they are likely to enter the brain via the olfactory mucosa.[35] Head trauma Trauma-related olfactory dysfunction depends on the severity of the trauma and whether strong acceleration/deceleration of the head occurred. Occipital and side impact causes more damage to the olfactory system than frontal impact.[36] However, recent evidence from individuals with traumatic brain injury suggests that smell loss can occur with changes in brain function outside of olfactory cortex. [37] Neurodegenerative diseases Neurologists have observed that olfactory dysfunction is a cardinal feature of several neurodegenerative diseases such as Alzheimer's disease and Parkinson's disease. Most of these patients are unaware of an olfactory deficit until after testing where 85% to 90% of early-stage patients showed decreased activity in central odor processing structures.[38] Other neurodegenerative diseases that affect olfactory dysfunction include Huntington's disease, multi-infarct dementia, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and schizophrenia. These diseases have more moderate effects on the olfactory system than Alzheimer's or Parkinson's diseases.[39] Furthermore, progressive supranuclear palsy and parkinsonism are associated with only minor olfactory problems. These findings have led to the suggestion that olfactory testing may help in the diagnosis of several different neurodegenerative diseases.[40] Neurodegenerative diseases with well-established genetic determinants are also associated with olfactory dysfunction. Such dysfunction, for example, is found in patients with familial Parkinson's disease and those with Down syndrome.[41] Further studies have concluded that the olfactory loss may be associated with intellectual disability, rather than any Alzheimer's disease-like pathology.[42] Huntington's disease is also associated with problems in odor identification, detection, discrimination, and memory. The problem is prevalent once the phenotypic elements of the disorder appear, although it is unknown how far in advance the olfactory loss precedes the phenotypic expression.[29] |

嗅覚機能障害の原因 ヴェサリウスのファブリカ、1543年。ヒトの嗅球と嗅路の赤い輪郭。 嗅覚機能障害の一般的な原因:高齢、ウイルス感染、有毒化学物質への暴露、頭部外傷、神経変性疾患[29]。 加齢 加齢は、健康な成人における嗅覚機能低下の最も強い原因であり、喫煙よりも大きな影響を及ぼす。加齢に伴う嗅覚機能の変化は気づかれないことが多く、聴覚 や視覚とは異なり、嗅覚能力が臨床的に検査されることはほとんどない。65歳未満の人の2%が慢性的な嗅覚障害を持っている。これが65歳から80歳にな ると大幅に増加し、約半数が嗅覚に重大な問題を抱えている。加齢に伴う嗅覚機能の変化の基礎には、篩状板の閉鎖[29]、および生涯を通じて繰り返される ウイルスやその他の障害による嗅覚受容体への累積的な損傷がある。 ウイルス感染 永続的な低嗅覚症や無嗅覚症の最も一般的な原因は、上気道感染症である。このような機能障害は経時的な変化を示さず、時に嗅覚上皮だけでなく、脳内へのウ イルス侵入の結果としての中枢嗅覚構造の損傷を反映することがある。これらのウイルス関連疾患には、感冒、肝炎、インフルエンザおよびインフルエンザ様疾 患、ヘルペスなどがある。特に、COVID-19は嗅覚障害と関連している[33]。ほとんどのウイルス感染は、非常に軽度であるか、まったく無症状であ るため、認識できない[29]。 有毒化学物質への暴露 除草剤、殺虫剤、溶剤、重金属(カドミウム、クロム、ニッケル、マンガン)などの空気中の有害物質に慢性的に暴露されると、嗅覚が変化することがある [34]。 頭部外傷 外傷に関連した嗅覚機能障害は、外傷の重症度や頭部の強い加速/減速が起こったかどうかによって異なる。後頭部や側頭部の衝撃は、前頭部の衝撃よりも嗅覚 系により大きな損傷を与える[36]。しかしながら、外傷性脳損傷者から得られた最近の証拠は、嗅覚皮質以外の脳機能の変化によって嗅覚障害が起こりうる ことを示唆している。[37] 神経変性疾患 神経学者は、嗅覚機能障害がアルツハイマー病やパーキンソン病などの神経変性疾患の主な特徴であることを観察している。これらの患者のほとんどは、検査後 まで嗅覚障害に気づかないが、初期段階の患者の85%~90%では、中枢嗅覚処理構造の活動低下が認められた[38]。 嗅覚機能障害に影響を及ぼす他の神経変性疾患には、ハンチントン病、多発性脳梗塞性認知症、筋萎縮性側索硬化症、統合失調症などがある。これらの疾患は、 アルツハイマー病やパーキンソン病よりも嗅覚系への影響が穏やかである。これらの所見から、嗅覚検査がいくつかの異なる神経変性疾患の診断に役立つ可能性 が示唆されている[40]。 遺伝的決定因子が確立している神経変性疾患も嗅覚障害と関連している。例えば、このような機能障害は、家族性パーキンソン病やダウン症の患者に見られる [41]。さらなる研究では、嗅覚の喪失は、アルツハイマー病のような病態ではなく、知的障害と関連している可能性があると結論づけられている[42]。 ハンチントン病はまた、匂いの識別、検出、弁別、記憶における問題と関連している。この問題は、障害の表現型要素が現れると蔓延するが、嗅覚消失が表現型 発現にどの程度先行するかは不明である[29]。 |

| History Linda B. Buck and Richard Axel won the 2004 Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine for their work on the olfactory system. |

歴史 リンダ・B・バックとリチャード・アクセルは、嗅覚系の研究で2004年ノーベル生理学・医学賞を受賞。 |

| Olfactic communication Sinusitis https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Olfactory_system |

|

|

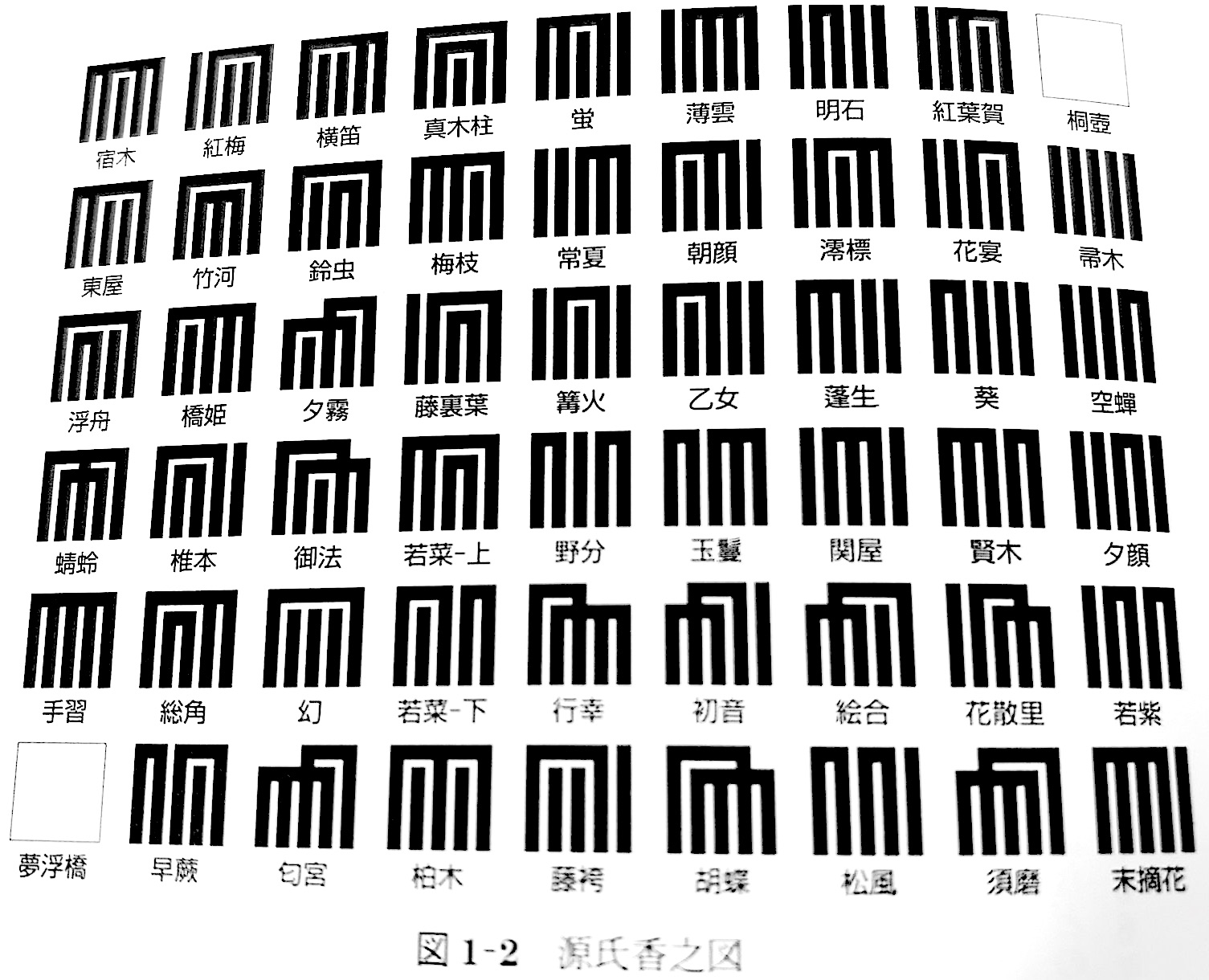

「源氏香」——ウィキペディア「香道」より 香 道、源氏香遊び 源氏香(げんじこう)は、香道の楽しみ方の一つである。源氏香の成立は享保の頃と考えられ、『源氏物語』を利用した組香である。 「源氏香」では、5種の香木を各5包ずつ(計25包)用意する。 香元はこの25包を切り交ぜ、中から任意の5包をとってひとつを焚き、客に香炉を順にまわし、香を聞く。これを5回繰り返す。 香炉が5回まわり、すべての香が終了したあと、客は5つの香りの異同を紙に記す。この書き方こそが源氏香の特徴である。まず5本の縦線を書き、右から、同 じ香りであったと思うものを横線でつないでいく(たとえば、右図の2段目 から3番目の「澪標」は、1、2、4番目に聞いた香が同じ香りで、3番目、5番目に聞いた香はそれぞれ独立した香りであるという意味)。この5本の線を組 み合わせてできる型は52通りあり、この52通りの図を『源氏物語』五十四帖のうち「桐壷」「夢浮橋」を除いた五十二帖にあてはめる[1]。この対応関係 を記したものが「源氏香の図」である。客はこの「源氏香の図」を見ながら自分の書いた図と照合し、源氏物語の該当する巻名を書いて答とする。 完全に正解すると、記録紙に「玉(ぎょく)」と書かれる。 |

★

| What the nose knows, by Colleen Walsh, February 27, 2020 |

|

| “… I carried to my lips a

spoonful of the tea in which I had let soften a bit of madeleine. But

at the very instant when the mouthful of tea mixed with cake crumbs

touched my palate, I quivered, attentive to the extraordinary thing

that was happening inside me.” It’s a seminal passage in literature, so famous in fact, that it has its own name: the Proustian moment — a sensory experience that triggers a rush of memories often long past, or even seemingly forgotten. For French author Marcel Proust, who penned the legendary lines in his 1913 novel, “À la recherche du temps perdu,” it was the soupçon of cake in tea that sent his mind reeling. But according to a biologist and an olfactory branding specialist Wednesday, it was the nose that was really at work. This should not be surprising, as neuroscience makes clear. Smell and memory seem to be so closely linked because of the brain’s anatomy, said Harvard’s Venkatesh Murthy, Raymond Leo Erikson Life Sciences Professor and chair of the Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology. Murthy walked the audience through the science early in the panel discussion “Olfaction in Science and Society,” sponsored by the Harvard Museum of Natural History in collaboration with the Harvard Brain Science Initiative. Smells are handled by the olfactory bulb, the structure in the front of the brain that sends information to the other areas of the body’s central command for further processing. Odors take a direct route to the limbic system, including the amygdala and the hippocampus, the regions related to emotion and memory. “The olfactory signals very quickly get to the limbic system,” Murthy said. But, as with Proust, taste plays a role, too, said Murthy, whose lab explores the neural and algorithmic basis of odor-guided behaviors in terrestrial animals. |

「マドレーヌを少し柔らかくした紅茶をスプーン一杯口に運んだ。しかし、ケーキのくずが混じった紅茶が口に触れたまさにその瞬間、私は身震いした。 プルースト的瞬間とは、長い間忘れていた、あるいは忘れていたかのような記憶を呼び起こす感覚的な体験のことである。1913年の小説『À la recherche du temps perdu(失われた時を求めて)』でこの伝説的な台詞を書いたフランスの作家マルセル・プルーストにとって、彼の心を揺り動かしたのは紅茶に入れたケー キのひと口だった。 しかし、生物学者と嗅覚ブランディングの専門家によれば、本当に働いていたのは鼻であったという。 神経科学が明らかにしているように、これは驚くべきことではない。嗅覚と記憶は、脳の解剖学的構造から密接に結びついているようだ、とハーバード大学の ヴェンカテッシュ・マーシー教授(レイモンド・レオ・エリクソン生命科学教授、分子細胞生物学科長)は言う。ハーバード自然史博物館がハーバード脳科学イ ニシアティブと共同で主催したパネルディスカッション「科学と社会における嗅覚」の序盤で、マーシーは聴衆に科学について説明した。 匂いは嗅球で処理される。嗅球は脳の前部にある構造で、情報を体の中枢にある他の部位に送り、さらに処理する。匂いは、扁桃体や海馬を含む大脳辺縁系(感情や記憶に関連する領域)に直接届く。「嗅覚シグナルは非常に素早く大脳辺縁系に到達します」とマーシーは言う。 しかし、プルーストと同じように、味覚もその役割を果たしている、とマーシーは言う。彼の研究室では、陸上動物における匂いによる行動の神経的・アルゴリズム的基盤を探求している。 |

| https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/02/how-scent-emotion-and-memory-are-intertwined-and-exploited/ |

咀嚼すると、食べ物に含まれる分子が「鼻上皮まで後鼻腔から戻ってく

る」と彼は言う。美しく複雑な味を食べるとき、それらはすべて匂いなのです」。マーシーは、バニラやチョコレートのアイスクリームなどを食べるときに鼻を

つまむと、その理論を試すことができるという。味を感じる代わりに、"甘い味しかしない "と彼は言う。 何十年もの間、個人や企業は匂いの喚起力を利用する方法を模索してきた。かつての恋人がつけていたコロンや香水を思い浮かべてほしい。そして、1950年 代の映画産業が考案したアロマラマやスメル・オー・ビジョンは、映画館に適切な匂いを吹き込み、観客を物語により深く引き込もうとした。数年前、ハーバー ド大学の科学者デビッド・エドワーズは、iPhoneで写真やテキストだけでなく香りも共有できる新技術に取り組んだ。 今日、家やオフィスの香りはビッグビジネスだ。香りのブランディングは様々な業界で流行しており、ホテルでは客室やロビーにその特徴的な香りを漂わせることが多いと、2018年のハーバード・ビジネス・レビューの記事の著者は指摘している。 「混雑した市場で目立つことがますます難しくなっている現代では、ブランドを感情的かつ印象的に差別化する必要があります。「顧客により強い印象を与えるために、香りがどのような役割を果たせるかを考えることで、新しい方法でブランドについて考えてみよう。 その教訓をよく知っているのが、彼女が「嗅覚的ブランディング会社」と呼ぶ12.29の共同設立者兼鼻(香り)ディレクターのドーン・ゴールドワームである。 |

| https://news.harvard.edu/gazette/story/2020/02/how-scent-emotion-and-memory-are-intertwined-and-exploited/ |

ゴールドワームの有名な顧客の中には、スポーツウェア大手のナイキもい

る。ナイキの特徴的な香りは、バスケットボールのラバースニーカーがコートを擦るときの匂いや、サッカーのクリートが芝生や土の中で放つ匂いにインスパイ

アされたものだと、彼女は自社サイトのビデオで説明している。彼女のゴールは、"ブランドと消費者の間に即時的で記憶に残るつながり

"を生み出すことだという。 自分の会社を立ち上げる前、10年以上にわたってセレブリティのためにシグネチャー・フレグランスをデザインしてきたゴールドワームは、科学にも精通している。彼女は5年間香水学校で学び、その後ニューヨーク大学で修士号を取得した。 講演の中で彼女は、嗅覚は胎児が子宮の中で唯一完全に発達した感覚であり、視覚が引き継がれる10歳頃までの子供で最も発達する感覚だと説明した。そして「匂いと感情はひとつの記憶として保存される」ため、幼少期は "一生好きな匂いと嫌いな匂いの基礎 "を作る時期になりがちだとゴールドワームは言う。 彼女はまた、人は色で匂いを感じる傾向があると説明し、聴衆に手渡した香りに浸した紙片でその関連性を示した。ほとんどの人がそうであるように、彼女の聴衆も柑橘系の香りのマンダリンをオレンジ、黄色、緑の色と連想した。草の香りのベチバーを嗅ぐと、聴衆は緑と茶色を思い浮かべた。 鼻に気をつけて、と両氏は聴衆に注意を促した。鼻にある骨板は嗅球とつながっており、嗅球から脳に信号が送られるのだが、この骨板は特に傷つきやすい。つ まり、頭部外傷は「骨板を切り離し」、嗅覚を完全に失わせ、無嗅覚症にしてしまう可能性があるのだ、とマーシー氏は言う。(2月27日は無嗅覚症啓発デー である)。 「自転車に乗ったり、過激なスポーツをするときはヘルメットをかぶりましょう。 人は加齢とともに嗅覚が鈍くなる傾向があります。でも心配は要りません。鼻は体の筋肉のようなもので、毎日、重りを使うのではなく、鼻をかむことで鍛えることができると彼女は言う。 「鼻に注意を払うだけです。「鼻を使えば使うほど、強くなるのです」。 |

| Published online 2013 Oct 10. doi: 10.3389/fnsys.2013.00066 PMCID: PMC3794443 PMID: 24124415 Effects of odor on emotion, with implications Mikiko Kadohisa* Author information Article notes Copyright and License information PMC Disclaimer Go to: Abstract The sense of smell is found widely in the animal kingdom. Human and animal studies show that odor perception is modulated by experience and/or physiological state (such as hunger), and that some odors can arouse emotion, and can lead to the recall of emotional memories. Further, odors can influence psychological and physiological states. Individual odorants are mapped via gene-specified receptors to corresponding glomeruli in the olfactory bulb, which directly projects to the piriform cortex and the amygdala without a thalamic relay. The odors to which a glomerulus responds reflect the chemical structure of the odorant. The piriform cortex and the amygdala both project to the orbitofrontal cortex (OFC) which with the amygdala is involved in emotion and associative learning, and to the entorhinal/hippocampal system which is involved in long-term memory including episodic memory. Evidence that some odors can modulate emotion and cognition is described, and the possible implications for the treatment of psychological problems, for example in reducing the effects of stress, are considered. Keywords: odor, emotion, amygdala, hippocampus, prefrontal cortex |

においが感情に及ぼす影響とその意味 Mikiko Kadohisa 著者情報 論文ノート 著作権およびライセンス情報 PMC免責事項 戻る 要旨 嗅覚は動物界に広く存在する。ヒトや動物の研究から、匂いの知覚は経験や生理的状態(空腹など)によって調節されること、匂いの中には情動を喚起し、情動的記憶を想起させるものがあることが示されている。さらに、匂いは心理的・生理的状態に影響を与えることもある。嗅 球は視床を介さずに梨状皮質と扁桃体に直接投射される。糸球体が反応するにおいは、におい物質の化学構造を反映している。梨状皮質と扁桃体はともに眼窩前 頭皮質(OFC)に投射しており、OFCは扁桃体とともに情動と連合学習に関与しており、内嗅/海馬系はエピソード記憶を含む長期記憶に関与している。いくつかの匂いが感情や認知を調節することができるという証拠について述べ、ストレスの影響を軽減するなど、心理的問題の治療への可能な影響について考察する。 キーワード:匂い、情動、扁桃体、海馬、前頭前皮質 |

| Front. Behav. Neurosci., 10 March 2020 Sec. Emotion Regulation and Processing Volume 14 - 2020 | https://doi.org/10.3389/fnbeh.2020.00035 Behavioral and Neurobiological Convergence of Odor, Mood and Emotion: A Review Ioannis Kontaris1* Brett S. East2,3 Donald A. Wilson2,3* **** https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fnbeh.2020.00035/full |

嗅覚は進化の過程で接近行動や回避行動を促し、情動と同義であるという

仮説さえ立てられてきた(Herz, 2000; Yeshurun and Sobel,

2010)。上記のように、嗅覚系の神経解剖学的構造と気分や感情の基盤となる回路は、ヒトとヒト以外の動物モデルの両方において密接に関連しており、匂

いが快楽的反応を喚起し、気分や感情に影響を与えるという強力な証拠が増えつつある。しかしながら、様々な未解決の疑問があり、このトピックに関する研究

をより厳密に行う必要がある。10年前にHerzが行ったアロマセラピーに関する優れた総説(Herz,

2009)には、気分に対する匂いの影響も含まれており、この分野の研究の長所と短所の両方が概説されている。弱点の多くは、以下の必要性を含め、依然と

して残っている:

(1)より大きなサンプリングサイズと統計的検出力、(2)より大きな刺激制御、(3)香りの効果を形成する文脈や個人差の影響(年齢、性別、遺伝、文化

的背景、香りの経験、嗜好など)の認識。 このリストに、感情と気分への影響を区別する必要性を加える。例えば、実験的に誘発された一過性の不安(すなわち、短時間の情動状態)が、長引く不安性気 分障害をモデル化することは明らかではない。一過性の不安と不安気分障害の神経生物学が異なることを考えると、匂い操作の有効性も異なるかもしれない。う つ病やその他の気分障害についても同様である。したがって、これらの現象に対するにおいの効果を調べるには、感情や気分の違いに注意を払う必要がある。 また、ヒトはげっ歯類ではなく、その逆もまた然りである。感情や気分は内的状態の意識的な解釈であり、ヒト以外の動物モデルには真の相同性があるかもしれ ないし、ないかもしれない。例えば、げっ歯類モデルにおける「恐怖」の神経生物学については、嫌悪刺激を示す合図に反応して「凍りつく」ようにげっ歯類を 訓練することで、何十年にもわたって研究されてきたにもかかわらず、「脅威を検知して反応するメカニズムは、意識的な恐怖を生じさせるメカニズムと同じで はない」(LeDoux, 2014; 2871ページ)。さらに、げっ歯類が抗うつ薬で治療可能なうつ病様の行動を示すことがあるが、そのげっ歯類が人間が経験するようなうつ病であるかどうか は不明である。同様に、ヒトとヒト以外の動物の嗅覚処理の基礎となる回路には多くの強い類似性があるが、ヒトでは嗅覚回路と感情・気分回路の間の正確な解 剖学的結合の多くはわかっていない。例えば、PCXの前部と後部の機能と接続は、ヒト(Howard et al., 2009)とげっ歯類(Kadohisa and Wilson, 2006)の間で密接に一致しているように見えるが、ヒトの嗅球の正確な位置と大きさの定義はまだ大きく異なっている(Wesson and Wilson, 2011)。ここで重要なのは、動物モデルとヒトとの比較研究を否定することではない。知覚、認知、行動の神経生物学的メカニズムの解明は、動物モデルを 通じて目覚ましい進歩を遂げてきた。むしろ、特に感情や気分の意識的な経験が測定結果にとって非常に重要な分野では、こうしたモデルの潜在的な限界を常に 意識しておくことが重要である。 最後に、嗅覚障害は、統合失調症、うつ病、多くの認知症など、多くの病態と関連している。この関連は、嗅覚と感情・気分ネットワークとの強い結びつきを反 映しており、嗅覚機能の喪失が多くの疾患の初期バイオマーカーとして機能する可能性、および/または少なくともいくつかの症状の治療のための潜在的な手段 となる可能性を提起している。しかし、においで治療したいと考える同じ集団において、におい知覚の低下や変化が起こることは明らかな問題である。1つの選 択肢として、嗅覚曝露やトレーニングによって嗅覚能力や感度が向上する可能性があり(Wysockiら、1989;Hummelら、2009;Al Aïnら、2019;Flemingら、2019)、気分や感情の匂い調節の窓口が再び開かれる可能性がある。 |

| Smellscape The smellscape concept was introduced by Porteous (1985), who suggested that perceptions of smell, while comparable to spatially ordered visual impressions, differ in their episodic nature, and academic interest in the concept and its analysis and design approaches has grown over the past 30 years. Henshaw (2014, p. 5) supplemented Porteous's definition of smellscape, describing it as “referring to the overall smell environment, but with the acknowledgment that as human beings, we are only capable of detecting this partially at any one point of time, although we may carry a mental image or memory of the smellscape in its totality.” The word smell in this concept differs from odour—the combined substances in the air that cause olfactory sensations—as it emphasizes the human experience as a perceptual construct (Xiao et al., 2018a). https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.700514/full - Porteous, J. D. (1985). Smellscape. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 9, 356–378. doi: 10.1177/030913338500900303 - Henshaw, V. (2014). Urban Smellscapes: Understanding and Designing City Smell Environments. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203072776 - Xiao, J., Tait, M., and Kang, J. (2018a). A perceptual model of smellscape pleasantness. Cities 76, 105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2018.01.013 |

スメルスケープ スメルスケープの概念はPorteous(1985)によって導入され、彼はニオイの知覚は空間的に秩序化された視覚的印象に匹敵するものの、そのエピソード的な性質において異なるこ とを示唆した。Henshaw (2014, p. 5)はPorteousのsmellscapeの定義を補足し、「全体的な匂いの環境を指すが、人間として、ある時点では部分的にしか匂いを感知すること ができないが、全体的な匂いのイメージや記憶を持っている可能性がある」と述べている。この概念における匂いという言葉は、知覚構成要素としての人間の経 験を強調するため、匂い(嗅覚感覚を引き起こす空気中の複合物質)とは異なる(Xiao et al.2018a). https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fpsyg.2021.700514/full - Porteous, J. D. (1985). Smellscape. Prog. Phys. Geogr. 9, 356–378. doi: 10.1177/030913338500900303 - Henshaw, V. (2014). Urban Smellscapes: Understanding and Designing City Smell Environments. New York, NY: Routledge. doi: 10.4324/9780203072776 - Xiao, J., Tait, M., and Kang, J. (2018a). A perceptual model of smellscape pleasantness. Cities 76, 105–115. doi: 10.1016/j.cities.2018.01.013 |

+++

リンク

文献

その他の情報