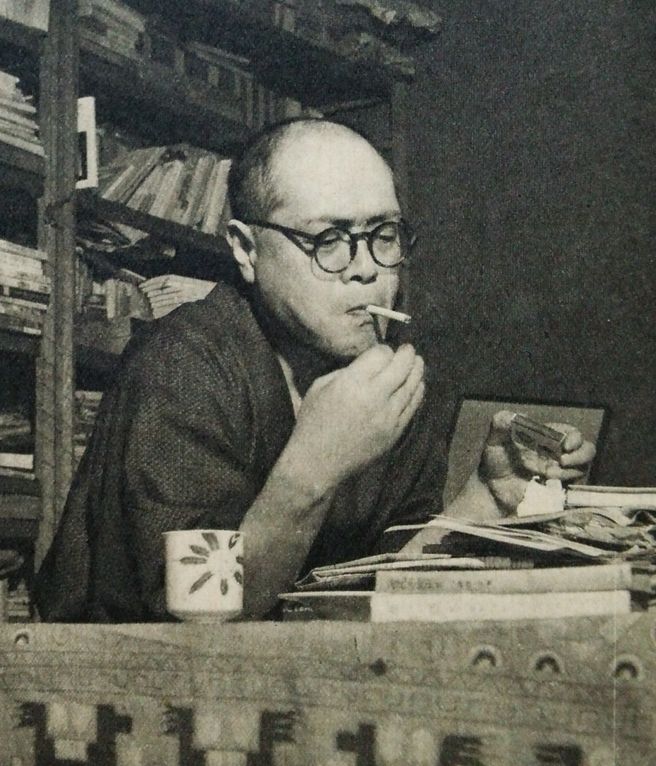

竹内 好

Yoshimi TAKEUCHI, 1910-1977

☆ 竹内 好(たけうち よしみ、1910年10月 - 1977年3月3日)は、日本の中国学者(シノノジスト, 支那学者)である。

| Yoshimi Takeuchi (竹内 好, Takeuchi Yoshimi, born October 1910 — 3 March 1977) was a Japanese Sinologist. |

竹内 好(たけうち よしみ、1910年10月 - 1977年3月3日)は、日本の中国学者である。 |

| Biography Yoshimi Takeuchi was a Sinologist, a cultural critic and translator. He studied Chinese author Lu Xun and translated Lu's works into Japanese. His book-length study, Lu Xun (1944) ignited a significant reaction in the world of Japanese thought during and after the Pacific War. Takeuchi formed a highly successful Chinese literature study group with Taijun Takeda in 1934 and this is regarded as the beginning of modern Sinology in Japan. He was a professor at Tokyo Metropolitan University from 1953 to 1960 when he resigned in protest. He was known as a distinguished critic of Sino-Japanese issues and his complete works (vols. 17) were published by Chikuma Shobo during 1980–82. In 1931, Takeuchi graduated from high school and entered the faculty of letters at Tokyo Imperial University, where he met his lifelong friend, Taijun Takeda. Together they formed the Chinese Literature Research Society (Chugoku Bungaku Kenkyukai) and in 1935, they published an official organ for the group, Chugoku Bungaku Geppo in order to open up the study of contemporary Chinese literature as opposed to the "old-style" Japanese Sinology. During 1937 to 1939 he studied abroad in Beijing where he became depressed due to the geo-political situation and drank heavily. In 1940, he changed the title of the official organ from Chugoku Bungaku Geppo to Chugoku Bungaku in which he published a controversial article, "The Greater East Asia War and our resolve" in January 1942. In January 1943, he broke up the Chinese Literature Research Society and decided to discontinue the publication of Chugoku Bungaku despite the group becoming quite successful. In December, he was called up for the Chinese front and stayed there until 1946. This encounter with what he saw as the real living China and Chinese people, as opposed to the abstract China of his studies, made a deep impression on him. He threw himself into a study of the modern colloquial language[1] and during this time, his maiden work was published, the book-length study Lu Xun (1944). After repatriation, his essays On leader consciousness and What is modernity? became the focus of public attention in 1948 during the Japanese occupation. It is from such essays that his status as an important postwar critic was gradually acknowledged. After 1949, he was greatly moved by the foundation of the People's Republic of China (PRC) and he continued to refer to the PRC in his articles and books. In 1953, he became a full professor at Tokyo Metropolitan University, a post he eventually resigned from in protest after Prime Minister Kishi Nobusuke rammed the revised U.S.-Japan Security Treaty through the National Diet with only members of his own party present in May 1960 despite the massive Anpo Protests expressing popular opposition to the new treaty.[2] During the anti-treaty struggle, Takeuchi played a leading role as one of the foremost intellectuals in postwar Japan under the slogan he coined: "democracy or dictatorship?"[2] From 1963, he argued in favor of Mao Zedong and the Chinese Cultural Revolution in his magazine Chugoku published by Chugoku no Kai until the diplomatic normalization between Japan and the PRC (1972). He was particularly interested in Mao's "Philosophy of base/ground" (konkyochi tetsugaku) which involves the principle of making one's enemy one's own. For Takeuchi, this was similar to Lu Xun's notion of cheng-cha, or endurance/resistance. In his later years, Takeuchi devoted himself to doing a new translation of Lu Xun's works. |

略歴 中国学者、文化評論家、翻訳家。中国の作家魯迅を研究し、魯迅の作品を日本語に翻訳した。著書『魯迅』(1944年)は、太平洋戦争中から戦後にかけての 日本の思想界に大きな反響を呼んだ。竹内は1934年に武田泰淳と中国文学研究会を結成し、大きな成功を収めたが、これが日本における近代中国学の始まり とされている。1953年から1960年まで東京都立大学の教授を務め、1960年に抗議のため辞任した。著名な日中問題評論家として知られ、1980年 から82年にかけて全集(全17巻)が筑摩書房から刊行された。 1931年、竹内は高校を卒業し、東京帝国大学文学部に入学、そこで生涯の友である武田泰淳と出会う。中国文学研究会」を結成し、1935年には機関紙 『中国文学月報』を刊行した。1937年から1939年にかけて北京に留学し、地政学的な情勢から鬱状態に陥り、大酒を飲んだ。1940年、機関紙の題名 を『中国文学月報』から『中国文学』に改め、1942年1月には「大東亜戦争とわれわれの決意」という論評を発表した。1943年1月、中国文学研究会を 解散し、『中国文学』の廃刊を決定する。12月には中国戦線に召集され、1946年まで駐留した。抽象的な中国ではなく、生身の中国、中国人の姿との出会 いは、彼に深い感銘を与えた。彼は現代口語の研究に没頭し[1]、その間に処女作となる長編研究書『魯迅』(1944年)を出版した。 帰国後の1948年、日本占領下で彼のエッセイ『指導者意識について』『近代とは何か』が世間の注目を集めた。戦後重要な批評家としての彼の地位が徐々に 認められるようになったのは、こうしたエッセイからである。1949年以降、彼は中華人民共和国の成立に大きな感動を覚え、論文や著書で中華人民共和国に ついて言及し続けた。1953年には首都大学東京の正教授となったが、1960年5月に岸信介首相が日米安全保障条約改定案を自民党議員のみで強行採決し たことに抗議し、同条約反対の民意を示す大規模な安保反対運動が起きたにもかかわらず国会を通過させたことに抗議して辞任した[2]。 反条約闘争の間、竹内は自身の造語である「民主主義か独裁主義か」をスローガンに掲げ、戦後日本の有数の知識人として主導的な役割を果たした: 1963年から日中国交正常化(1972年)までの間、中国の会発行の雑誌『中国』で毛沢東と中国文化大革命を支持する論陣を張った。竹内は、毛沢東の 「基地の哲学」に個別主義的な関心を寄せていた。竹内にとって、これは魯迅の「成敗」、つまり我慢と抵抗の概念に似ていた。晩年、竹内は魯迅の作品の新訳 に力を注いだ。 |

| Yu Dafu In his graduation thesis, Takeuchi discussed Yu Dafu. He concluded: Yu Dafu—he was an agonal poet. He pursued self-agony with a sincere manner and brought abnormal influence in the Chinese literary world by coming to light in bold expression. Because his agony sums up his young contemporaries' agony.[3] "Not <politics> (accommodating oneself to external authority) but <literature> (digging down self-agony). Yu Dafu did not reign over the people but was connected with others' agony. Takeuchi described his style as 'art of the strength that devoting oneself solely to weakness'."[4] |

郁文 竹内は卒業論文の中で、郁達夫(郁达夫, 郁文)について論じている。彼はこう結論づけた: 郁文は激情詩人である。彼は真摯な態度で自己の苦悩を追求し、大胆な表現で明るみに出ることで、中国文学界に異常な影響をもたらした。なぜなら、彼の苦悩は同時代の若い詩人たちの苦悩を集約しているからである[3]。 「<政治>(外部の権威に自分を合わせること)ではなく、<文学>(自己の苦悩を掘り下げること)である。郁文は民衆の上に君臨 したのではなく、他者の苦悩に寄り添ったのである。竹内は彼の作風を『ひたすら弱さに徹する強さの芸術』と表現した」[4]。 |

| Japan as a humiliation Shina and Chugoku Takeuchi felt guilty about the Second Sino-Japanese War in 1937. At that time, Tokyo called China as not "Shina" but "Chugoku" for directing friendship between Japan and the Wang Jingwei regime. In Japanese, "Shina" is a discriminatory word for China. Takeuchi attempted to culturally resist such a manner in a period of a total war. However, as he knew the Greater East Asia War was also to some extent intended and characterized as a war to liberate East and Southeast Asian nations, Takeuchi pathetically declared his resolve (1942) for what he saw as a war of justice, which is generally interpreted as his cooperation with the war effort. After defeat in 1945, however, he knew that the declared aims of the war were deceptive and he tried to explain its aporias of both the liberation of colonies and anti-imperialism. |

屈辱としての日本 支那と中国 竹内は1937年の日中戦争に後ろめたさを感じていた。当時、東京は日本と汪精衞政権との友好を演出するために、中国を「支那」ではなく「中国」と呼ん だ。日本語では「支那」は中国に対する差別語である。竹内は、総力戦の時代にあって、そのような態度に文化的に抵抗しようとした。 しかし、大東亜戦争が東アジアや東南アジアの国民を解放するための戦争であることを知っていたため、竹内は情けなくも正義の戦争への決意を表明した (1942年)。しかし、1945年の敗戦後、彼は宣言された戦争の目的が欺瞞に満ちたものであることを知り、植民地解放と反帝国主義の両面における戦争 のアポリアについて説明しようとした。 |

| Overcoming modernity "Overcoming modernity" was one of the catchwords that took hold of Japanese intellectuals during the war. Or perhaps it was one of the magic words. "Overcoming modernity" served as a symbol that was associated with the "Greater East Asian War".[5] In denouncing the intelligentsia for their wartime collaboration, it is common to lump these two symposiums[6] together.[7] Rather my task is to distinguish among the symbolization of the symposiums, its ideas, and those who exploited these ideas.[8] It is difficult if not virtually impossible to strip the ideology from ideas, or to extract the ideas from ideology. But we must recognize the relative independence of ideas from the systems or institutions that exploit them, we must risk the difficulty of distinguishing the actual ideas. Otherwise it would be impossible to draw forth the energy buried within them. In other words, it would be impossible to form tradition.[9] After the defeat of 1945, Japanese journalism was full of discussion surrounding the issue of war responsibility, particularly that intellectuals and a famous wartime symposium entitled "Overcoming Modernity" which involved literary critic, Kobayashi Hideo and Kyoto-school philosopher, Nishida Kitaro. Wartime intellectuals were classified into three groups: Literary World, the "Japanese Romantics" (such as Yasuda Yojiro) and the Kyoto School. The "Overcoming Modernity" symposium was held in wartime Japan in (1942) and sought to interpret Japanese imperialism’s Asian mission in a positive historical light, as not any kind of simple fawning on Fascism, but rather ultimately, a step in the proper direction of Japan's destiny as an integral part of Asia. This was only a step, however, as, according to Takeuchi, while highlighting the aporias of modernity, the "Overcoming Modernity" debates failed to make those aporias themselves the subject of thought. Critic Odagiri Hideo criticized the symposium as an "ideological campaign consisting in the defense and theorization of the militaristic tennō state and the submission to its war system". His view was accepted widely in post-war Japan. However, Takeuchi strongly opposed this easy pseudo-leftist formula. The Pacific War's dual aspects of colonial invasion and anti-imperialism were united, and it was by this time impossible to separate these aspects.[10] For the Kyoto School, it was dogma that was important; they were indifferent to reality. I don't even think that they represented a "defense of the fait accompli that might makes right." These philosophers disregarded the facts.[11] Yasuda was at one and the same time a "born demagogue" and a "spiritual treasure"; he could not have been a spiritual treasure were he not also a demagogue. This is the Japanese spirit itself. Yasuda represents something illimitable, he is an extreme type of Japanese universalist from which there is no escape. ... The intellectual role played by Yasuda was that of eradicating thought through the destruction of all categories. ... This[12] may be the voice of heaven or earth, but it is not human language. It must be a revelation of the "souls of our Imperial ancestors." There is not even any usage of the "imperial we." This is a medium. And the role that everyone had "eagerly anticipated" was that of the medium itself, who appears at the end as the "lead actor in a great farce." Yasuda played this role brilliantly. By destroying all values and categories of thought, he relieved the thinking subject of all responsibility.[13] Kobayashi Hideo was able to divest all meaning from facts, but he could not go beyond this. Literary World could only wait for the "medium" that was Yasuda to come and announce the disarmament of ideas.[14] In sum, the "Overcoming Modernity" symposium marked the final attempt at forming thought, an attempt that, however, failed. Such formation of thought would at least take as its point of departure the aim of transforming the logic of total war. It failed in that it ended in the destruction of thought.[15] In wartime 1942, Takeuchi declared a resolve on the war without fanatical chauvinism. In the postwar, Takeuchi's discussion was centred on the dual aspects of the Greater East Asia War. He attempted to resist war characteristics by using his own logic. However, for him, the wartime symposiums failed in the end. "Overcoming Modernity" resulted in scholastic chaos. Kobayashi Hideo of Literary World, who beat "World-Historical Standpoint" of the Kyoto School, was unworthy at this time. On behalf of such Kobayashi, Yasuda Yojuro of the Japanese Romantics showed only contempt. |

近代性の克服(あるいは近代の超克) 「近代性の克服」は、戦時中に日本の知識人の間で定着したキャッチフレーズのひとつである。あるいは呪術的な言葉の一つであったかもしれない。「近代性の克服」は、「大東亜戦争」を連想させるシンボルとして機能した[5]。 知識人の戦時協力関係を糾弾する際、この2つのシンポジウム[6]をひとくくりにするのが一般的である[7]。 むしろ私の課題は、シンポジウムの象徴化、その思想、そしてこれらの思想を利用した人々を区別することである[8]。 イデオロギーからイデオロギーを取り除いたり、イデオロギーからイデオロギーを抽出したりすることは、事実上不可能ではないにしても難しい。しかし私たち は、イデオロギーとそれを利用するシステムや制度との相対的な独立性を認識しなければならない。そうでなければ、その中に埋もれているエネルギーを引き出 すことは不可能である。言い換えれば、伝統を形成することは不可能なのである[9]。 1945年の敗戦後、日本のジャーナリズムは戦争責任の問題をめぐる議論に明け暮れ、特に知識人たちや、文芸評論家の小林秀雄や京都学派の哲学者である西 田幾多郎が参加した「近代の克服」と題された有名な戦時シンポジウムが行われた。戦時中の知識人は3つのグループに分類された: 文学界、「日本ロマン派」(安田洋次郎など)、京都学派である。近代性の克服」シンポジウムは1942年に戦時中の日本で開催され、日本帝国主義のアジア における使命を、ファシズムへの単純な媚びではなく、むしろ最終的にはアジアの不可欠な一部としての日本の運命の適切な方向への一歩として、歴史的に肯定 的に解釈しようとした。しかし、これは一歩にすぎなかった。竹内によれば、「近代の克服」論議は近代のアポリアに焦点を当てながらも、そのアポリアそのも のを思想の主題にすることはできなかったのである。 評論家の小田切秀雄は、このシンポジウムを「軍国主義的な天皇制国家の擁護と理論化、そしてその戦争体制への服従からなるイデオロギーキャンペーン」だと批判した。彼の見解は戦後の日本で広く受け入れられた。しかし、竹内はこの安易な似非左翼の定式に強く反対した。 太平洋戦争の植民地侵略と反帝国主義という二面性は一体であり、この時点でこれらの側面を切り離すことは不可能であった[10]。 京都学派にとって重要なのはドグマであり、彼らは現実には無関心だった。彼らが 「力が正義を作るという既成事実の擁護 」を代表していたとも思えない。これらの哲学者たちは事実を軽視していた[11]。 安田は「生まれながらのデマゴーグ」であると同時に「精神の宝」であった。これは日本精神そのものである。安田は救いようのないものの象徴であり、そこか ら逃れることのできない極端な日本万能主義者なのである。... 安田が果たした知的役割は、あらゆるカテゴリーの破壊を通じて思想を根絶することだった。... これは[12]天の声かもしれないし地の声かもしれないが、人間の言葉ではない。それは 「皇祖の魂 」の啓示に違いない。「皇室の我々 "という用法すらない。これは媒体なのだ。そして、誰もが 「熱望していた 」役柄は、最後に 「大茶番の主役 」として登場する霊媒そのものであった。安田はこの役割を見事に演じた。あらゆる価値観や思考のカテゴリーを破壊することによって、彼は思考する主体をあ らゆる責任から解放した[13]。 小林秀雄は事実からあらゆる意味を切り離すことはできたが、それを超えることはできなかった。文学界は、安田という「媒体」がやってきて思想の武装解除を宣言するのを待つしかなかった[14]。 まとめると、「近代の克服」シンポジウムは、思想形成の最後の試みであり、しかしその試みは失敗に終わった。このような思想形成は、少なくとも総力戦の論理を変革するという目的を出発点とするものであった。それは思想の破壊に終わったという点で失敗したのである[15]。 戦時中の1942年、竹内は狂信的な排外主義を排して戦争への決意を表明した。戦後、竹内の議論の中心は大東亜戦争の二面性にあった。彼は独自の論理で戦 争の特質に抵抗しようとした。しかし、彼にとって戦時中のシンポジウムは結局失敗に終わった。「近代の克服 "は学問的混乱を招いた。京都学派の「世界史的立場」を打ち破った文壇の小林秀雄は、このとき不甲斐なかった。そんな小林に代わって、日本ロマン派の安田 洋次郎は侮蔑の眼差ししか示さなかった。 |

| National literature criticism During 1951 to 1953, Takeuchi argued with literary critic, Sei Itō over the nature of a national literature (cf. Treaty of San Francisco). In 1954, Takeuchi published Kokumin Bungaku-ron [Theory of a national literature]. He criticized Japanese modernism for avoiding the problem of the "nation". Takeuchi envisaged national literature as needing to address the aporia of the nation as a cultural practice. |

国民文学批判 1951年から1953年にかけて、竹内は文芸評論家の伊藤整とナショナリズムをめぐって論争を繰り広げた(サンフランシスコ条約を参照)。1954年、 竹内は『国民文学論』を発表した。彼は日本のモダニズムが「国民」の問題を避けていると批判した。竹内はナショナリズムが文化的実践として国民のアポリア に取り組む必要があると考えたのである。 |

| Foresight and mistakes In 1960, the Japanese government rammed a revised version of the Treaty of Mutual Cooperation and Security through the House of Representatives. Takeuchi saw it undemocratic and he decided to resign as professor of Tokyo Metropolitan University. Takeuchi attempted to generalize war experiences of the Japanese people to establish Japanese democratic subjectivity. As a result, he failed to accomplish his goal. Takeuchi said, "Now, I think the Japanese nation will die out. Maybe, there is a possibility to be restored to life in the future. However, Japan is stateless in the present." |

先見の明と過ち 1960年、日本政府は日米安保条約の改定案を衆議院で強行採決した。竹内はこれを非民主的とみなし、首都大学東京の教授を辞任することを決意した。竹内 は日本人の戦争体験を一般化し、日本人の民主的主体性を確立しようとした。その結果、彼は目的を達成することができなかった。竹内は「今、日本国民は滅び ると思う。もしかしたら、将来、復活する可能性はあるかもしれない。しかし、現在の日本は無国籍である。」 |

| "Asia as method" Lu Xun "According to Takeuchi, the core part of Lu Xun 'is awareness of the literature which was acquired through a confrontation with politics'. Literature in itself is directly powerless. However, as a result, literature could be involved in politics by devoting literature to literature. A writer could be powerful if he would dig down mental "darkness" and realize self-denial and self-innovation without dependence. Lu Xun was aware of this, so Takeuchi calls it "reform" ('eshin').[16] |

「方法としてのアジア 魯迅 竹内によれば、魯迅の核心部分は「政治との対決を通して獲得された文学への認識」である。文学それ自体は直接的には無力である。しかし、文学を文学に捧げ ることで、文学は政治に関わることができる。精神的な「闇」を掘り下げ、依存することなく自己否定と自己革新を実現すれば、作家は力を発揮できる。魯迅は このことを自覚していたので、竹内はそれを「改革」(「エシン」)と呼んでいる[16]。 |

| Chinese modernity and Japanese modernity For Takeuchi, Japanese society was authoritarian and discriminatory. Takeuchi criticized Japanese modernists and modernization theorists who adopted a stopgap measure and recognized Japan as superior to Asia aiming at though revolutions. Takeuchi argued that Chinese modernity qualitatively surpassed the Japanese model. However, those modernists looked down on Asia and concluded Japan was not Asian. Generally speaking, the Japanese Meiji modernists had a tendency to interpret Asia as backward. For Takeuchi, Japan and his greatest "darkness" were nothing but the issue of war responsibility. In What is modernity? (1948), Takeuchi stated: "Ultranationalism and Japanism were once fashionable. These were to have banished Europe; they were not to have banished the slave structure that accommodates Europe. Now modernism is fashionable as a reaction against these ideologies, but the structure that accommodates modernity is still not problematized. Japan, in other words, attempts to replace the master; it does not seek independence. This is equivalent to treating Tojo Hideki as a backward student, so that other honor students remain in power in order to preserve the honor student culture itself. It is impossible to negate Tojo by opposing him: one must go beyond him. To accomplish this, however, one must even utilize him."[17] "<Class-A war criminals> and <Non-class-A war criminals> are supplement relations.[18] It is meaningless to declare 'Japanism' to oppose with the West. Likewise, it is meaningless to declare Western modernism to oppose with 'Japanism'. In order to deny <Tojo>, you must not oppose with <Tojo> and must surpass <Tojo> by facing up to your image of <Tojo>. And it was equal to war-time Takeuchi himself who adopted <December 8> and criticized the Greater East Asia Writers' Congress.[19][20] |

中国の近代と日本の近代 竹内にとって日本社会は権威主義的で差別的であった。竹内は、日本近代主義者や近代化論者たちが、その場しのぎの対応策を採用し、日本が革命を目指すアジ アよりも優れていると認識していることを批判した。竹内は、中国の近代は日本の近代を質的に凌駕していると主張した。しかし、それらの近代主義者はアジア を見下し、日本はアジアではないと結論づけた。一般的に言って、日本の明治近代主義者はアジアを後進国として解釈する傾向があった。 竹内にとって、日本とその最大の「闇」は戦争責任の問題に他ならなかった。竹内は『近代とは何か?(1948年)の中で、竹内はこう述べている: 「かつてウルトラナショナリズムとジャパニズムが流行した。これらはヨーロッパを追放するものであったが、ヨーロッパを収容する奴隷構造を追放するもので はなかった。今、モダニズムはこれらのイデオロギーに対する反動として流行しているが、近代を収容する構造はまだ問題化されていない。つまり、日本は主人 に取って代わろうとするのであって、自立を求めるのではない。これは東条英機を後進扱いすることと等価であり、優等生文化そのものを維持するために、他の 優等生が権力を維持する。東条に対抗して東条を否定することは不可能である。しかし、そのためには、東條を利用することさえ必要なのである」[17]。 「A級戦犯>と<非A級戦犯>は補完関係である。 欧米と対立するために<日本主義>を宣言することは無意味である。同様に、「日本主義」と対立する西洋近代主義を宣言することも無意味である。東條>を否 定するためには、<東條>と対立してはならず、<東條>のイメージと向き合うことによって、<東條>を超えなければならない。そして、<12月8日>を採 択し、大東亜作家会議を批判したのは、戦時中の竹内自身であったに等しい[19][20]。 |

| Japanese Asianism Takeuchi admitted modern Japanese Asianism ended with an empty official slogan "Greater East Asia Co-Prosperity Sphere" and Japanese defeat of 1945 after all. In post-war Japan, the Greater East Asia War thoroughly denied at all. Takeuchi questioned Japanese pacifism which led to lose the attitudes and responsibilities towards Asia as an Asian nation. Takeuchi depressed such a situation. He set to reviewing Japanese modern history through Asianism. Takeuchi edited an anthology of Asianism in which he commented that Asianism is not an ideology but a trend and that it is impossible to distinguish between "invasion" and "solidarity" in Japanese Asianism. He explained that "Asianism" originated from Tokichi Tarui and Yukichi Fukuzawa in the 1880s. The former Tarui argued for unionizing Japan and Korea equally to strengthen Greater East Asian security. Takeuchi appreciated Tarui's work as an unprecedented masterpiece. The latter Fukuzawa argued for Japan casting off Asia who was barbarian and vulgar company.[21] Takeuchi appreciated Fukuzawa's article as a stronger appeal to the public than Tarui's. The victories of the First Sino-Japanese War and the Russo-Japanese War made Japanese solidarity with Asia further and further. After the victories of the above wars, Japan inclined to build a "new order" in East Asia. Japan could not be a hope of Asia. Takeuchi indicated Japanese structural defect derived from wrong honours. He interpreted Japanese Asianism as Ko-A (raising Asia) taken over Datsu-A (casting off Asia). For Takeuchi, Asia is not a geographical concept but a concept against "modern Europe", and so, Japan is non-Asian. When the Japanese accomplish to overcome modernity, they can be Asian. By "modern Europe", it is feudal class society full of discrimination and authoritarianism. "Asia" could be liberation from imperialism, which cut off a relationship between dominant and subject. Perhaps, his views were non-realist and progressive in a sense. Takeuchi wished Japan to be Asianized. The concept of Asia is nothing but an ideal for him. He said: "In a political dimension, post-war Bandung conference made an idea of Asianness in history". Referring to Rabindranath Tagore and Lu Xun, Takeuchi addressed: Rather the Orient must re-embrace the West, it must change the West itself in order to realize the latter's outstanding cultural values on a greater scale. Such a rollback of culture or values would create universality. The Orient must change the West in order to further elevate those universal values that the West itself produced. This is the main problem facing East-West relations today, and it is at once a political and cultural issue.[22] |

日本のアジア主義 竹内氏は、近代日本のアジア主義が「大東亜共栄圏」という空疎な公式スローガンと1945年の日本の敗戦で終わったことを認めた。戦後の日本では、大東亜 戦争は徹底的に否定された。竹内は日本の平和主義に疑問を投げかけ、アジア国民としてのアジアに対する態度や責任を失わせた。竹内はそのような状況を憂鬱 にした。彼はアジア主義を通して日本の近代史を見直そうとした。 竹内はアジア主義に関するアンソロジーを編集し、その中で、アジア主義はイデオロギーではなく一つの傾向であり、日本のアジア主義において「侵略」と「連 帯」を区別することは不可能であると論じた。彼は、「アジア主義」の起源は1880年代の樽井藤吉と福沢諭吉であると説明した。前者の樽井は、大東亜の安 全保障を強化するために、日本と韓国を等しく統合することを主張した。竹内は樽井の仕事を空前の傑作と評価した。後者の福沢は、日本が野蛮で低俗なアジア を切り捨てることを主張した[21]。竹内は、福沢の論文が樽井の論文よりも大衆に強くアピールしていると評価した。日清戦争と日露戦争の勝利は、日本人 のアジアに対する連帯をますます強めた。上記の戦争の勝利の後、日本は東アジアに「新しい秩序」を築くことに傾いた。日本はアジアの希望にはなれなかっ た。竹内は、間違った名誉に由来する日本の構造的欠陥を指摘した。彼は、日本のアジア主義を、「耕A」(アジアを高める)が「達A」(アジアを捨てる)に 取って代わられたと解釈した。 竹内にとってアジアとは地理的な概念ではなく、「近代ヨーロッパ」に対する概念であり、日本は非アジアである。日本人が近代を乗り越えたとき、アジア人に なれるのである。近代ヨーロッパ」とは、差別と権威主義に満ちた封建的階級社会である。「アジア」とは、支配者と被支配者の関係を断ち切る帝国主義からの 解放かもしれない。おそらく、彼の考えはある意味で非現実主義的であり、進歩的だったのだろう。 竹内は日本がアジア化することを願っていた。彼にとってアジアという概念は理想に過ぎない。彼は言った: 「政治的な次元では、戦後のバンドン会議がアジアという概念を歴史に定着させた」。ラビンドラナート・タゴールと魯迅を引き合いに出し、竹内はこう語った: 東洋は西洋を再認識しなければならないのではなく、西洋の優れた文化的価値をより大きなスケールで実現するために、西洋そのものを変えなければならない。 そのような文化や価値の後退は、普遍性を生み出すだろう。西洋が生み出した普遍的価値をさらに高めるために、東洋は西洋を変えなければならない。これは今 日の東西関係が直面している主要な問題であり、同時に政治的・文化的な問題でもある[22]。 |

| The origin of peace After 1945, Takeuchi has called upon the normalization between China and Japan. In 1972, the Joint Communiqué of the Government of Japan and the Government of the People's Republic of China was concluded. Takeuchi criticized the Japanese attitudes towards the past. The issues of history have been a big concern in the Sino-Japanese relations. |

平和の原点 1945年以降、竹内は日中国交正常化を呼びかけてきた。1972年、日本政府と中華人民共和国政府の共同コミュニケが締結された。竹内は過去に対する日本の態度を批判した。歴史問題は日中関係における大きな関心事である。 |

| Major works What Is Modernity?: Writings of Takeuchi Yoshimi, Columbia University Press (2005) edited, translated, and with an introduction by Richard F. Calichman Ways of introducing culture: focusing upon Lu Xun (1948) What is modernity? (1948) The question of politics and literature (1948) Hu Shih and Dewey (1952) Overcoming modernity (1959) Asia as method (1960) |

主な作品 近代とは何か?竹内好著、コロンビア大学出版局、2005年、リチャード・カリッチマン編・訳・序文付き 文化紹介の方法:魯迅を中心に(1948年) 近代とは何か?(1948) 政治と文学の問題(1948年) 胡詩とデューイ(1952年) 近代性の克服(1959年) 方法としてのアジア(1960年) |

| Lu Xun Masao Maruyama Nationalism Orientalism Pan-Asianism Postcolonialism Shuichi Kato Shunsuke Tsurumi Walter Benjamin |

魯迅 丸山眞男 ナショナリズム オリエンタリズム 汎アジア主義 ポストコロニアリズム 加藤秀一 鶴見俊輔 ウォルター・ベンヤミン |

| Bibliography Beasley, William G. (1987) "Japan and Pan-Asianism: Problems of Definition" in Hunter (1987) Calichman, Richard F. (2004) Takeuchi Yoshimi: displacing the west, Cornell University East Asia Program Calichman, Richard F. [ed. and trans.] (2005) What Is Modernity?: Writings of Takeuchi Yoshimi, Columbia University Press Calichman, Richard F. [ed. and trans.] (2008) Overcoming Modernity: Cultural Identity in Wartime Japan, Columbia University Press Chen, Kuan-Hsing & Chua Beng Huat [eds.] (2007) The Inter-Asia cultural studies reader, Routledge Duus, Peter [ed.] (1988) The Cambridge history of Japan: The twentieth century, vol. 6, Cambridge University Press Gordon, Andrew [ed.] (1993) Postwar Japan as history, University of California Press Hunter, Janet [ed.] (1987) Aspects of Pan-Asianism, Suntory Toyota International Centre for Economics and Related Disciplines, London School of Economics and Political Science Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674988484. Katzenstein, Peter J. & Takashi Shiraishi [eds.] (1997) Network Power: Japan and Asia, Cornell University Press Koschmann, J. Victor (1993) "Intellectuals and Politics" in Gordon (1993), pp. 395–423 Koschmann, J. Victor (1997) "Asianism's Ambivalent Legacy" in Katzenstein et al. (1997), pp. 83–110 McCormack, Gavan (1996/2001) The Emptiness of Japanese Affluence, M.E. Sharp Oguma, Eiji (2002) "Minshu" to "Aikoku": Sengo-Nihon no Nashonarizumu to Kokyosei, Shinyosha, pp. 394–446, pp. 883–94 Olson, Lawrence (1992) Ambivalent moderns: portraits of Japanese cultural identity, Rowman & Littlefield Saaler, Sven & J. Victor Koschmann [eds.] (2007) Pan-Asianism in Modern Japanese History: Colonialism, regionalism and borders, Routledge Sun, Ge (2001) "How does Asia mean?" in Chen et al. (2007) Takeuchi, Yoshimi (1980–82) Takeuchi Yoshimi zenshu, vols.1-17, Chikuma Shobo Takeuchi, Yoshimi; Marukawa, Tetsushi & Masahisa Suzuki [eds.] (2006) Takeuchi Yoshimi Serekushon: "Sengo Shiso" wo Yomi-naosu, vols.1-2, Nihon Keizai Hyoron-sha Tanaka, Stefan (1993) Japan's Orient: rendering pasts into history, University of California Press |

参考文献 Beasley, William G. (1987) "Japan and Pan-Asianism: 定義の問題」Hunter (1987) 所収 Calichman, Richard F. (2004) Takeuchi Yoshimi: displacing the west, Cornell University East Asia Program. Calichman, Richard F. [ed. and trans.] (2005) What Is Modernity? Writings of Takeuchi Yoshimi, Columbia University Press. Calichman, Richard F. [ed. and trans.] (2008) Overcoming Modernity: 戦時下の日本における文化的アイデンティティ, コロンビア大学出版局. Chen, Kuan-Hsing & Chua Beng Huat [eds.] (2007) The Inter-Asia cultural studies reader, Routledge. Duus, Peter [ed.] (1988) The Cambridge history of Japan: The twentieth century, vol.6, Cambridge University Press. Gordon, Andrew [ed.] (1993) 歴史としての戦後日本, University of California Press. Hunter, Janet [ed.] (1987) Aspects of Pan-Asianism, Suntory Toyota International Centre for Economics and Related Disciplines, London School of Economics and Political Science. Kapur, Nick (2018). Japan at the Crossroads: Conflict and Compromise after Anpo. Harvard University Press. ISBN 9780674988484. Katzenstein, Peter J. & Takashi Shiraishi [eds.] (1997) Network Power: コーネル大学出版局 Koschmann, J. Victor (1993) 「Intellectuals and Politics」 in Gordon (1993), pp. Koschmann, J. Victor (1997) 「Asianism's Ambivalent Legacy」 in Katzenstein et al. (1997), pp. McCormack, Gavan (1996/2001) The Emptiness of Japanese Affluence, M.E. Sharp. 小熊英二 (2002) 『民衆』と『愛国』: 小熊英二 (2002) 『「民衆」と「愛国」-センゴク・ニホンの梨園と共生』新曜社、394-446頁、883-94頁 Olson, Lawrence (1992) Ambivalent moderns: portraits of Japanese cultural identity, Rowman & Littlefield. Saaler, Sven & J. Victor Koschmann [eds.] (2007) Pan-Asianism in Modern Japanese History: Colonialism, regionalism and borders, Routledge. Sun, Ge (2001) 「How does Asia mean?」 in Chen et al. 竹内好 (1980-82) 『竹内好全集』1-17巻 筑摩書房 竹内好; 丸川哲史・鈴木正久編 (2006) 『竹内好先生「戦後思想」を読む』1-2巻, 日本経済評論社. 田中ステファン(1993)『日本の東洋:過去を歴史にする』カリフォルニア大学出版会 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Yoshimi_Takeuchi |

★日本語ウィキペディア「竹内 好」

| 竹内 好(た

けうち よしみ、1910年(明治43年)10月2日 -

1977年(昭和52年)3月3日)は、日本の中国文学者、文芸評論家、思想家。魯迅の研究・翻訳や、日中関係論、日本文化などの問題をめぐり言論界で、

多くの評論発言を行った。著書に『魯迅』(1944年)、『現代中国論』(1951年)、『日本イデオロギイ』(1952年)など。 |

|

| 経歴 出生から学生時代 1910年、長野県南佐久郡臼田町(現・佐久市)で生まれた[1]。東京市麹町区富士見小学校、東京府立第一中学校(現・東京都立日比谷高等学校)を経 て、1931年、旧制大阪高等学校[2] から東京帝国大学文学部支那文学科に入学[3]。1934年に支那哲学支那文学科を卒業[4]。  1953年、中国文学研究会での竹内(奥の右から2番目)。奥右端は武田泰淳。 大学在学中に武田泰淳らと「中国文学研究会」を結成し、卒業後もそこを中心に活動した。メンバーには他に、増田渉、松枝茂夫、岡崎俊夫、松井武男、一戸務 [5]、小野忍、実藤恵秀、千田九一、飯塚朗[6] らがいた。雑誌『中国文学月報』を発行し、1940年からは『中国文学』と雑誌名を変更して刊行[7]。 ただ竹内は一貫して編集した雑誌には不満であった。例えば昭和14年秋の月報後記にこうある。 「何といふつまらない月報であらう。我々は何を好んで齷齪するか。我々は今日すでに月報を砦にする孤高の精神を失つてゐるのだ。月報を見ることは形骸を見 るやうに傷ましい。我らはひらめきのない人生を潔しとしない。既に存立の根拠を失ひ、また消滅の理由さへ見出し得ないならば、それは明かに嗤笑さるべき瞳 濁れる凡愚の怯惰の行為ではないか。」 --竹内好 『中国文学月報』「二年間」、高島俊男『本と中国と日本人と』ちくま文庫P47より ところは雑誌は潰れず、中国文学研究会は活動し続けた。高島俊男は、「かように自分の作った雑誌をクソミソに言い、同人にも寄稿者にも読者にも悪態をつき ながら、会も雑誌もつぶれなかったのだから、竹内にはそれだけの魅力、ないしカリスマ性があったのだろう。」と言っている。[8] |

|

| 大学卒業から終戦まで 1937年から2年間、北京に留学。1942年、第一回大東亜文学者大会が東京でひらかれたが、会として参加を拒否[9]。1943年、中国文学研究会は解散[6]。1943年に陸軍に召集。1945年8月、湖南省岳州で敗戦を迎え、1946年7月に復員した[10]。 戦後 1949年に慶應義塾大学講師となり、1955年までつとめた[11]。『展望』1950年4月号に「日本共産党に与う」を発表し、日本共産党を批判した[12]。1952年から1年間、東京大学非常勤講師を兼任[11]。 1953年、思想の科学研究会会長となった[11]。雑誌『思想の科学』編集長もつとめた[13]。1953年、東京都立大学人文学部教授に着任[11]。 1960年5月20日、新安保条約の承認が衆議院本会議で強行採決される。翌5月21日、竹内は強行採決に抗議して東京都立大学に辞表を提出[14]。 「憲法の眼目の一つである議会主義が失われた」「内閣総理大臣による憲法無視の状態の下で、東京都立大学教授の職に止まることは、公務員として憲法を尊重 し擁護する旨の就職の際の誓約にそむき、かつ教育者としての良心にそむく」と述べた。竹内に翻意を求めた人文学部教授会は最終的に6月27日に辞表を受理 した[15]。その後、雑誌『中国』を刊行。1961年から当時は珍しかったスキーを51歳で始め「老人スキー」を称した。 1964年からは自身が監修し、門下生に翻訳させた『中国の思想』を徳間書店から刊行。当初は諸子百家だけであったが、一般知識人からの好評を受けてロン グセラーになると『史記』『三国志 (歴史書)』『十八史略』といった史書類も翻訳した。「漢文ぎらい」を標榜する竹内の思想により、訳文のみで意味が取れるような文章にしていた。これらの 仕事は仕事がなく経済的に困窮していた門下生を経済的に助けた。[16] 『魯迅文集』刊行中の1977年3月3日、食道癌により、東京都武蔵野市の病院で死去した[17]。66歳没。葬儀委員長は埴谷雄高がつとめた。墓所は多磨霊園(10-1-14)。 |

|

| 受賞 1970年:「中国を知るために」により、毎日出版文化賞を受賞[18]。 |

|

| 研究内容・業績 伊藤整や野間宏らと国民文学論争を展開し、「近代主義と民族の問題」(1951)「国民文学の問題点」(1952)「文学における独立とはなにか」 (1954)などの関係諸論文を『国民文学論』(1954)にまとめた[19]。 また門下生と多数の中国文学の翻訳を行った。 雑誌『中国』 雑誌『中国』の母体となった「中国の会」は、尾崎秀樹が普通社主宰で1960年ごろに立ち上げ、野原四郎、竹内、橋川文三、安藤彦太郎、新島淳良、今井清 一らをメンバーとした[20]。「中国の会」は、雑誌『中国』を1963年から、普通社のシリーズ「中国新書」の挟み込み雑誌として刊行[21]。しか し、同1963年に普通社が倒産したため、雑誌『中国』は、「中国の会」編集で勁草書房から1964年から1967年まで刊行[22]。さらに雑誌『中 国』は、「中国の会」編集、徳間書店発行で、1967年から1974年まで刊行された[22]。 魯迅研究 同時代の中国文学作品を翻訳紹介、ならびに研究し、晩年には魯迅研究に没頭した。 魯迅は、近代文学を建設した人である。魯迅を、近代文学以前であると見ることはできない。[省略] 魯迅には、前近代的なものが多く含まれているが、それにもかかわらず、前近代を含むという形で、やはりそれは近代というほかないようなものである。(「近 代とは何か(日本と中国の場合)」1948年)[23] |

|

| 主張・思想 戦後、明治以後の日本の近代史がどこで間違ったのかという問題意識を持って出発し、反戦の頑強なシンボルと目されていた日本の共産主義の行く末を厳しく見 守る態度をとった。戦時中から取り組んでいた魯迅の研究は、必然的に中国の近代化の問題へと関心をひきつける結果となった。日本のマルクス主義史学への懐 疑心が生まれ、開発途上国の近代化の過程は明治維新に代表される日本型が唯一のモデルではなく、もっと多様なのではないかと考えた。その点で戦後に読んだ デューイの日中文化比較論に感銘を受けている[24]。また、日本の文化構造が奴隷的で主体性の欠いていることを指摘し、日本のインテリ層の進歩主義を批 判した。 マルクス主義者を含めての近代主義者たちは、血塗られた民族主義をよけて通った。自分を被害者と規定し、ナショナリズムのウルトラ化を自己の責任外の出来 事とした。「日本ロマン派」を黙殺することが正しいとされた。しかし、「日本ロマン派」を倒したものは、彼らではなくて外の力なのである。外の力によって 倒されたものを、自分が倒したように、自分の力を過信したことはなかっただろうか。それによって、悪夢は忘れられたかもしれないが、血は洗い清められな かったのではないか。(「近代主義と民族の問題」1951年)[25] 日本人の中国大陸などアジア地域に対する道義性を問いただし、アジア主義の観点を再発掘して「太平洋戦争(大東亜戦争)」の再評価を促した。「侵略はよく ないことだが、しかし侵略には、連帯感のゆがめられた表現という側面もある。無関心で他人まかせでいるよりは、ある意味では健全でさえある[26]」と、 ある種の評価もしている。 大東亜戦争は、植民地侵略戦争であると同時に、対帝国主義の戦争でもあった。この二つの側面は、事実上一本化されていたが、論理上は区別されなければなら ない。[中略] 太平洋戦争において両側面は癒着していたのであって、この癒着をはがすことはこの段階ではもう不可能だったからである。というよりも、癒着をはがす論理が ありうることを、われわれは戦後に東京裁判でのパール判事の少数意見からはじめて教わったくらいであり・・・(「近代の超克」1959年)[27] 戦後になって読み始めた毛沢東の著作で、抗日戦争に対する見通しが正確だったことに驚き、毛沢東の土着的発想を学ぶことで太平天国の乱を源流とする中国の人民革命の特質がつかめることを期待した。その毛沢東思想の原型を井崗山時代に求め、根拠地理論へ到達した。 純粋毛沢東とはなにか。それは、敵は強大であって我は弱小であるという認識と、しかも我は不敗であるという確信の矛盾の組み合わせからなる。これこそ、毛 沢東思想の根本であり、原動力であって、かつ、今日の中共の一切の理論と実践の源をなすものである。それは半封建、半植民地の中国の現実の革命の中から引 き出された最も高い、最も包括的な原理であり、したがって普遍的真理である。それは物心両面の一切の事象と、個人から国家に至る一切の関係を規定する根本 法則であって、実践による内容付けによってそれ自体が生成発展する。(「評伝 毛沢東」1951年)[28] また、雑誌『世界』1965年1月号の特集「転機にたつ日本の選択」に掲載された論文「周作人から核実験まで」の中で「けれども、理性をはなれて、感情の 点では、言いにくいことですが、内心ひそかに、よくやった、よくぞアングロサクソンとその手下ども(日本人を含む)の鼻をあかしてくれた、という一種の感 動の念のあることを隠すことができません[29]」と毛沢東による一方的核実験と核保有宣言に際してポストコロニアルの視点から意見を表明した。 |

|

| 著作 著書 『魯迅』日本評論社 1944 創元文庫 1952 未来社 1961、新版1983・2002 講談社文芸文庫 1994 『魯迅雑記』世界評論社 1949、勁草書房 1976 『現代中国論』旧河出文庫 1951 新編・勁草書房 1975 『日本イデオロギイ』筑摩書房 1952 こぶし文庫 1999 『魯迅入門』東洋書館 1953 講談社文芸文庫 1996 『国民文学論』 東京大学出版会 1954 『知識人の課題』大日本雄弁会講談社 1954 『不服従の遺産』筑摩書房 1961 『竹内好評論集』全3巻 筑摩書房 1966 新編 現代中国論 新編 日本イデオロギイ 日本とアジア 『中国を知るために』全3巻 勁草書房 1967-1973 『予見と錯誤』筑摩書房 1970 『日本と中国のあいだ』文藝春秋(人と思想) 1973 『転形期 戦後日記抄』創樹社 1974 『続 魯迅雑記』勁草書房 1978 『方法としてのアジア わが戦前・戦中・戦後 1935-1976』創樹社 1978 『近代の超克』筑摩叢書、1983 (解説松本健一) 『竹内好談論集1 国民文学論の行方』 蘭花堂 1985 『内なる中国』筑摩叢書、1987(編・解説松本健一) 『日本とアジア』ちくま学芸文庫 1993 (新編解説加藤祐三) 『竹内好セレクション』全2巻 日本経済評論社 2006 (丸川哲史・鈴木将久編) 日本への/からのまなざし アジアへの/からのまなざし 竹内好全集 『竹内好全集』(全17巻) 筑摩書房、1980-1982 魯迅 魯迅入門 現代中国の文学 現代中国論 中国の人民革命 中国革命と日本 方法としてのアジア 中国・インド・朝鮮 毛沢東 日本イデオロギイ 民衆・知識人・官僚主義 国の独立と理想 国民文学論 近代日本の文学 表現について 近代日本の思想 人間の解放と教育 不服従の遺産 1960年代 中国を知るために 1 中国を知るために 2 作家について・書物について 自画像 わが著作 魯迅友の会・中国の会 戦前戦中集 日記 上 日記 下 補遺 初期習作 著作目録・年譜・人名索引 編著 『現代中国の作家たち』岡崎俊夫共編 和光社 1954 『国民文学と言語』河出新書 1954 『戦後の民衆運動』青木新書 1956 『現代日本思想大系9 アジア主義』筑摩書房 1963 『状況的 対談集』合同出版 1970 『近代日本と中国』橋川文三共編 朝日選書 1974 『アジア学の展開のために』創樹社 1975 翻訳 賽金花 劉半農 中国文学叢書5 生活社 1942 小学教師 倪煥之、葉紹鈞 大阪屋号書店 1943 嵐の中の木の葉 林語堂 三笠書房 1951 魯迅作品集 筑摩書房 1953 魯迅評論集 岩波新書 1953、岩波文庫 1981 続魯迅作品集 筑摩書房 1955 魯迅作品集 筑摩叢書(全3巻)、1966 野草 魯迅 岩波文庫、1955 のち改版 阿Q正伝・狂人日記 魯迅 岩波文庫、1955 のち改版 林商店・春蚕 茅盾 現代世界文学全集 新潮社、1956 両地書 魯迅・許広平、松枝茂夫共訳 岩波書店(選集) 1956、筑摩叢書 1978 文芸講話 毛沢東、岩波文庫、1956 夜明け前-子夜 茅盾 中国現代文学全集 平凡社、1963 山峡中、山中送客記(艾蕪)/夜哨線(葉紫)現代中国文学・河出書房新社、1971 故事新編 魯迅 岩波文庫 1979 魯迅文集(全6巻)筑摩書房 1983、ちくま文庫 1991 この他監修の書として 中国の思想(全13巻)、徳間書店、1964がある。 |

|

| 参考文献 大澤真幸編 『ナショナリズム論の名著50』平凡社 2002 大塚健洋編 『近代日本政治思想史入門:原典で学ぶ19の思想』ミネルヴァ書房 1999 岡本幸治編 『近代日本のアジア観』ミネルヴァ書房 1998 岡山麻子 『竹内好の文学精神』論創社 2002 小熊英二 『〈民主〉と〈愛国〉 戦後日本のナショナリズムと公共性』新曜社 2002 ローレンス・オルソン/黒川創、北沢恒彦、中尾ハジメ共訳 『アンビヴァレント・モダーンズ-江藤淳・竹内好・吉本隆明・鶴見俊輔』新宿書房 1997 加々美光行 『鏡の中の日本と中国:中国学とコ・ビヘイビオリズムの視座』日本評論社 2007 菅孝行 『竹内好論:亜細亜への反歌』 三一書房 1976 粕谷一希 『対比列伝』 新潮社 1982。「ロマン主義について―保田與重郎と竹内好」 アンドルー・ゴードン編『歴史としての戦後日本』 中村政則監訳、みすず書房 2001 子安宣邦 『「近代の超克」とは何か』 青土社 2008 孫歌 『アジアを語ることのジレンマ』 岩波書店 2002 孫歌 『竹内好という問い』 岩波書店 2005 都築勉 『戦後日本の知識人 丸山眞男とその時代』 世織書房 1995 鶴見俊輔 『竹内好 ある方法の伝記』 リブロポート〈シリーズ民間日本学者〉 1995/岩波現代文庫 2010 鶴見俊輔、加々美光行共編 『無根のナショナリズムを超えて 竹内好を再考する』日本評論社 2007 中川幾郎 『竹内好の文学と思想』 オリジン出版センター 1985 松本健一 『竹内好論』 第三文明社 1975/岩波現代文庫(改訂版) 2005 松本健一 『竹内好「日本のアジア主義」精読』 岩波現代文庫 2000 丸川哲史 『竹内好 人と思考の軌跡 アジアとの出会い』 河出書房新社 2010 米原謙 『日本政治思想』 ミネルヴァ書房 2007 渡辺一民 『武田泰淳と竹内好』 みすず書房 2010 |

|

| アイデンティティー ドイツ観念論 モダニズム 市民派 戦後民主主義 進歩的文化人 |

|

| https://x.gd/WJS5Z |

リ ンク

文 献

そ の他の情報

CC

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

☆

☆

☆