Empedocles of Akragas,

c.494-c.434 BC

エンペドクレス

Empedocles of Akragas,

c.494-c.434 BC

解説:池田光穂

エンペドクレス(/ɛmˈpɛdəkliːz/; 古代ギリシャ語:

Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; 紀元前494年頃 -

紀元前434年頃、紀元前444年から443年頃が活動期)は、ギリシャのソクラテス以前の哲学者であり、シチリア島のギリシャ都市アクラガス出身の市民

であった。エンペドクレスの哲学は、四元素説という宇宙生成論を生み出したことで最もよく知られている。彼はまた、元素をミヘさせる「愛」と分離させる

「争い」という二つの力を提唱した。

エンペドクレスは動物犠牲や食用のための動物殺害の慣行に異議を唱えた。彼は独特の輪廻転生の教義を発展させた。一般的に、詩で思想を記録した最後のギリ

シャ哲学者と見なされている。彼の著作の一部は現存しており、他のどの前ソクラテス派哲学者よりも多い。エンペドクレスの死は古代の作家たちによって神話

化され、数多くの文学作品の題材となってきた。

というのも、私はかつては少年だったし少女でもあった。 樹木でもあり鳥でもある。大海のなかで迷子だった魚でもある(自然について、断片1117)

For I have been ere now a boy and a girl, a bush and a bird and a dumb fish in the sea. R. P. 182.

★エンペドクレス

| Empedocles

(/ɛmˈpɛdəkliːz/; Ancient Greek: Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; c. 494 – c. 434 BC, fl.

444–443 BC) was a Greek pre-Socratic philosopher and a native citizen

of Akragas, a Greek city in Sicily. Empedocles' philosophy is known

best for originating the cosmogonic theory of the four classical

elements. He also proposed forces he called Love and Strife which would

mix and separate the elements, respectively. Empedocles challenged the practice of animal sacrifice and killing animals for food. He developed a distinctive doctrine of reincarnation. He is generally considered the last Greek philosopher to have recorded his ideas in verse. Some of his work survives, more than is the case for any other pre-Socratic philosopher. Empedocles' death was mythologized by ancient writers, and has been the subject of a number of literary treatments. |

エンペドクレス(/ɛmˈpɛdəkliːz/; 古代ギリシャ語:

Ἐμπεδοκλῆς; 紀元前494年頃 -

紀元前434年頃、紀元前444年から443年頃が活動期)は、ギリシャのソクラテス以前の哲学者であり、シチリア島のギリシャ都市アクラガス出身の市民

であった。エンペドクレスの哲学は、四元素説という宇宙生成論を生み出したことで最もよく知られている。彼はまた、元素をミヘさせる「愛」と分離させる

「争い」という二つの力を提唱した。 エンペドクレスは動物犠牲や食用のための動物殺害の慣行に異議を唱えた。彼は独特の輪廻転生の教義を発展させた。一般的に、詩で思想を記録した最後のギリ シャ哲学者と見なされている。彼の著作の一部は現存しており、他のどの前ソクラテス派哲学者よりも多い。エンペドクレスの死は古代の作家たちによって神話 化され、数多くの文学作品の題材となってきた。 |

Life Empedocles, 17th-century engraving The exact dates of Empedocles' birth and death are unknown, and ancient accounts of his life conflict on the exact details. However, they agree that he was born in the early 5th century BC in the Greek city of Akragas in Magna Graecia, present-day Sicily.[1] Modern scholars believe the accuracy of the accounts that he came from a rich and noble family and that his grandfather, also named Empedocles, had won a victory in the horse race at Olympia in the 71st Olympiad (496–495 BC).[a] Little else can be determined with accuracy.[1] Primary sources of information on the life of Empedocles come from the Hellenistic period, several centuries after his own death and long after any reliable evidence about his life would have perished.[2] Modern scholarship generally believes that these biographical details, including Aristotle's assertion that he was the "father of rhetoric",[b] his chronologically impossible tutelage under Pythagoras, and his employment as a doctor and miracle worker, were fabricated from interpretations of Empedocles' poetry, as was common practice for the biographies written during this time.[2] |

エンペドクレス 17世紀の版画 エンペドクレスの生没年は正確には知られていない。古代の記録も詳細については矛盾している。しかし、彼が紀元前5世紀初頭にマグナ・グラエキア(現在の シチリア島)のギリシャ都市アクラガスで生まれたという点では一致している。[1] 現代の学者は、彼が裕福で高貴な家系の出身であり、祖父(同じくエンペドクレスという名)が第71回オリンピア競技大会(紀元前496-495年)の競馬 で勝利を収めたという記述の正確性を認めている。[a] それ以外の事実は正確に特定できない。[1] エンペドクレスの生涯に関する一次資料は、彼の死後数世紀を経たヘレニズム時代のものであり、彼の人生に関する信頼できる証拠が失われて久しい時期のもの だ。[2] 現代の研究では、これらの伝記的詳細——アリストテレスが主張した「修辞学の父」[b]という称号、年代的に不可能なピタゴラスへの師事、医師兼奇跡行者 としての活動——は、当時の伝記作法に則りエンペドクレスの詩の解釈から捏造されたものと広く考えられている。[2] |

Death and legacy The Death of Empedocles by Salvator Rosa (1615–1673), depicting the legendary alleged suicide of Empedocles jumping into Mount Etna in Sicily According to Aristotle, Empedocles died at the age of 60 (c. 430 BC), but other writers have him living as long as 109 years.[c] Likewise, myths survive about his death: a tradition traced to Heraclides Ponticus posits that some force removed him from Earth somehow, while another tradition had him die in the flames of Sicily’s Mount Etna.[d] Diogenes Laërtius records the legend that Empedocles threw himself into Mount Etna so people would believe his body had vanished and he had turned into an immortal god;[e] the volcano, however, threw back one of his bronze sandals, revealing the deceit. Another legend maintains that he jumped into the volcano to prove to his disciples that he was immortal: he believed he would come back as a god after being consumed by the fire. In Icaro-Menippus [it], a comedic dialogue written by the second-century satirist Lucian of Samosata, Empedocles's final fate is re-imagined. Rather than being incinerated in Mount Etna, one of its eruptions carries him up into the heavens. Although singed by the ordeal, Empedocles survives and continues his life on the Moon, surviving on dew. Burnet states that, although Empedocles likely did not die in Sicily, both general versions of the story (one in which he kills himself, the other in which he discovers he’s the first man to survive leaving Earth) could be easily accepted by ancient writers, as there was no local tradition to contradict them.[3] Empedocles's death is the subject of Friedrich Hölderlin's play Tod des Empedokles (The Death of Empedocles) as well as Matthew Arnold's poem Empedocles on Etna. Lucretius speaks of him enthusiastically, evidently viewing him as his model.[f] Horace also refers to the death of Empedocles in his work Ars Poetica and admits poets have the right to destroy themselves.[g] |

死と遺産 サルヴァトーレ・ローザ(1615–1673)作『エンペドクレスの死』。伝説によると、エンペドクレスはシチリア島のエトナ山に身を投げて自殺したとさ れる アリストテレスによれば、エンペドクレスは60歳で死去した(紀元前430年頃)。しかし他の著述家たちは、彼が109歳まで生きたと記している[c]。 同様に、彼の死に関する伝説も残っている。ヘラクレイデス・ポンティコスに由来する伝承では、何らかの力が彼を地球から連れ去ったとされ、別の伝承ではシ チリアのエトナ山の炎の中で死んだとされる。[d] ディオゲネス・ラエルティオスは、エンペドクレスが自らの肉体が消滅し不死の神となったと人々に信じさせるため、自らエトナ山に飛び込んだという伝説を記 録している[e]。しかし火山は彼の青銅のサンダル片方を吐き出し、その偽りを暴いた。別の伝説では、弟子たちに自らの不死を証明するため火山に飛び込ん だとされている。彼は炎に飲み込まれた後、神として復活すると信じていたのだ。サモサタのルキアノスによる2世紀の風刺詩『イカロス・メニッポス』では、 エンペドクレスの最期が再解釈されている。エトナ山で焼かれる代わりに、噴火によって天界へ運ばれるのだ。焼け焦げたものの、エンペドクレスは生き延び、 月面で露を糧に生き続ける。 バーネットは、エンペドクレスがシチリアで死んだ可能性は低いと述べつつも、二つの一般的な物語(自殺説と地球を離れて生存した初の男として発見される 説)は、古代の作家たちにとって容易に受け入れられたと指摘する。なぜなら、それらを否定する現地の伝承が存在しなかったからだ。[3] エンペドクレスの死は、フリードリヒ・ヘルダーリンの戯曲『エンペドクレスの死』や、マシュー・アーノルドの詩『エトナ山のエンペドクレス』の主題となっ ている。 ルクレティウスは彼を熱狂的に称賛し、明らかに自らの模範と見なしている。[f] ホラティウスもまた『詩技論』においてエンペドクレスの死に言及し、詩人には自らを滅ぼす権利があると認めている。[g] |

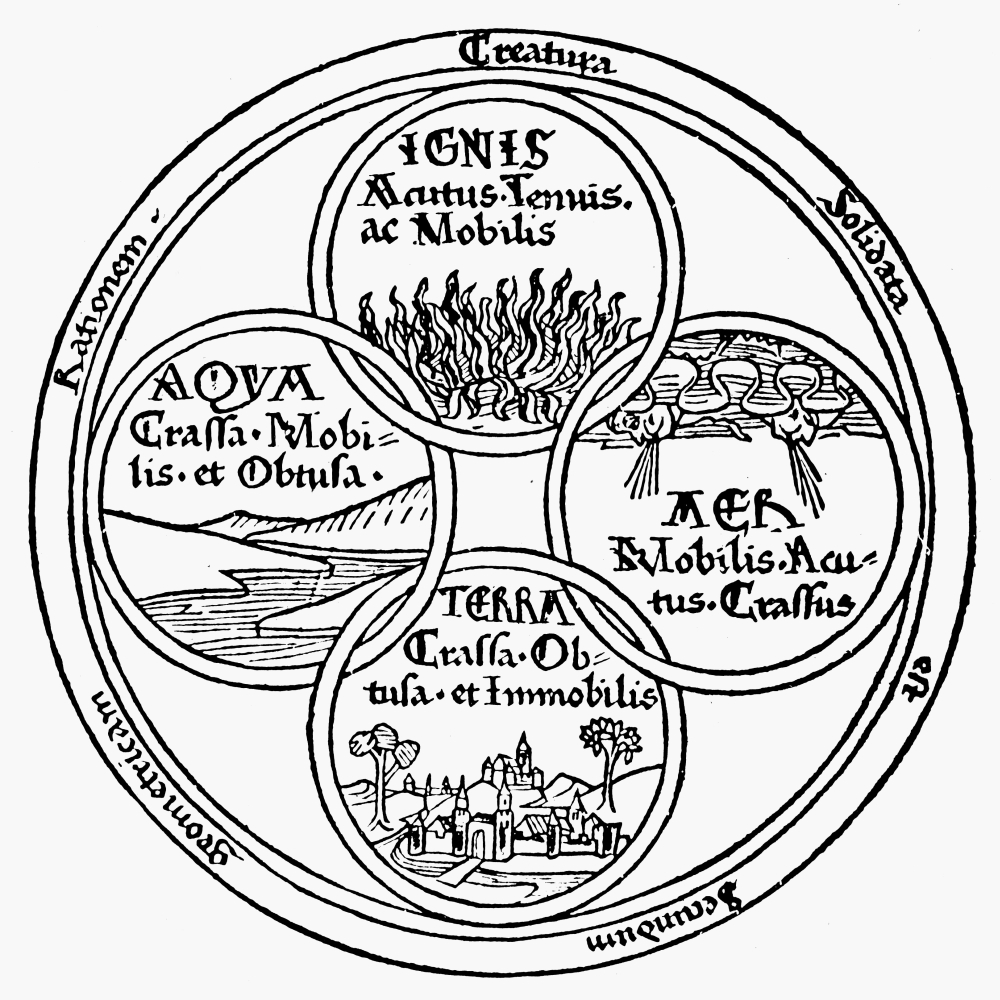

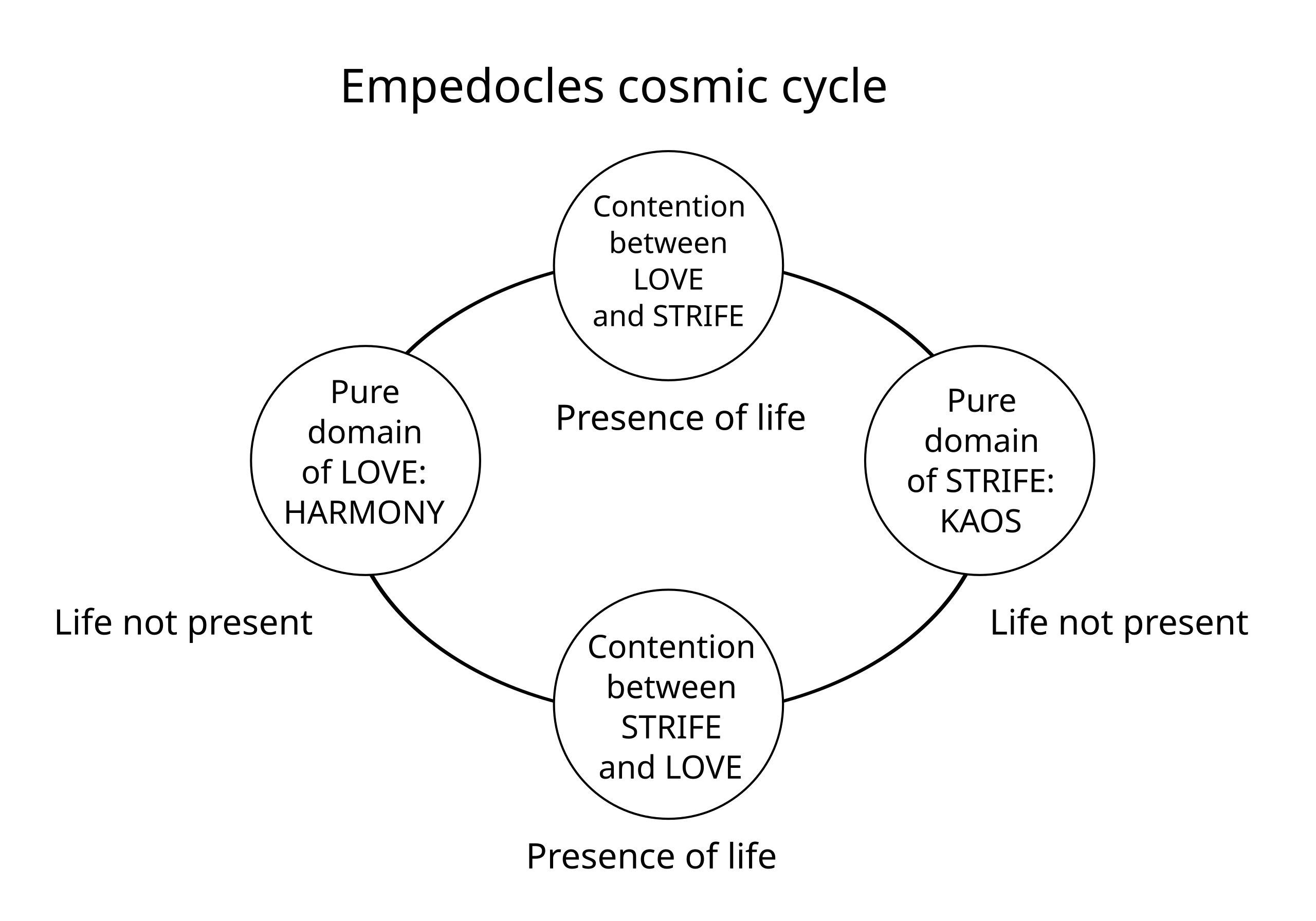

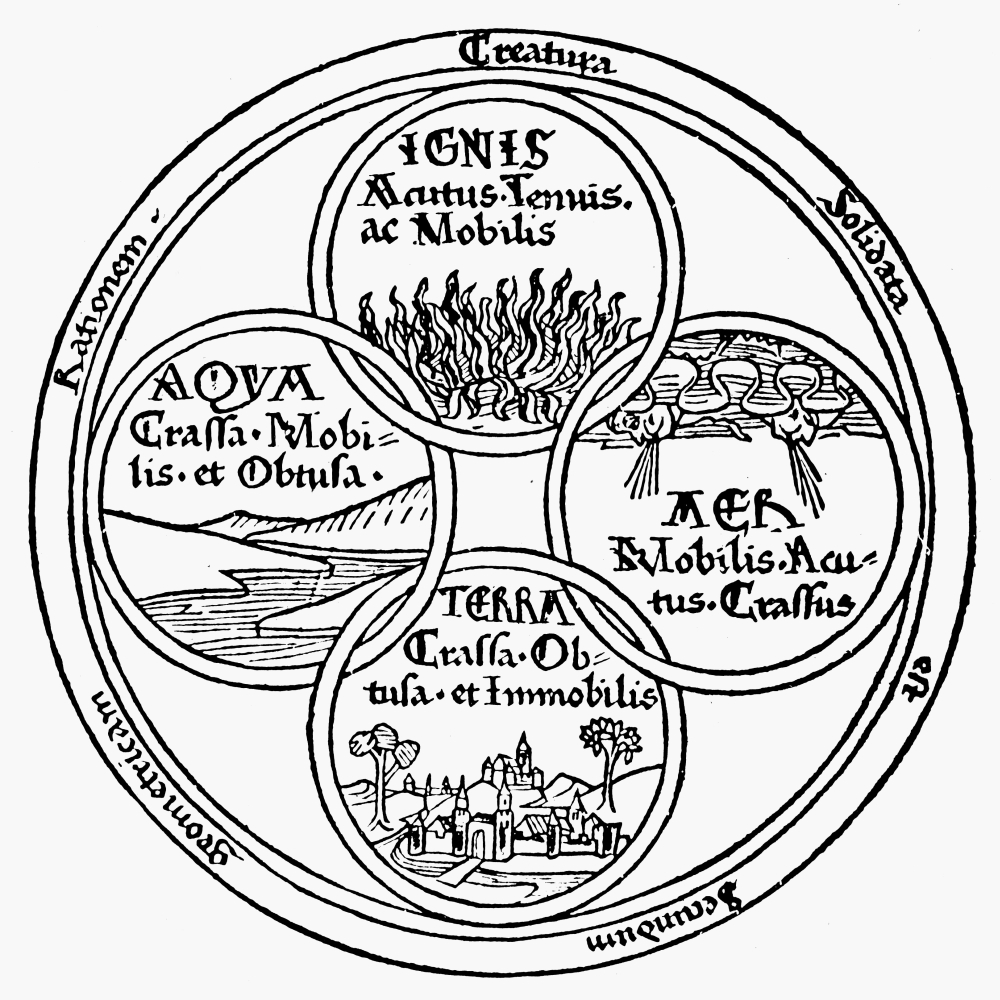

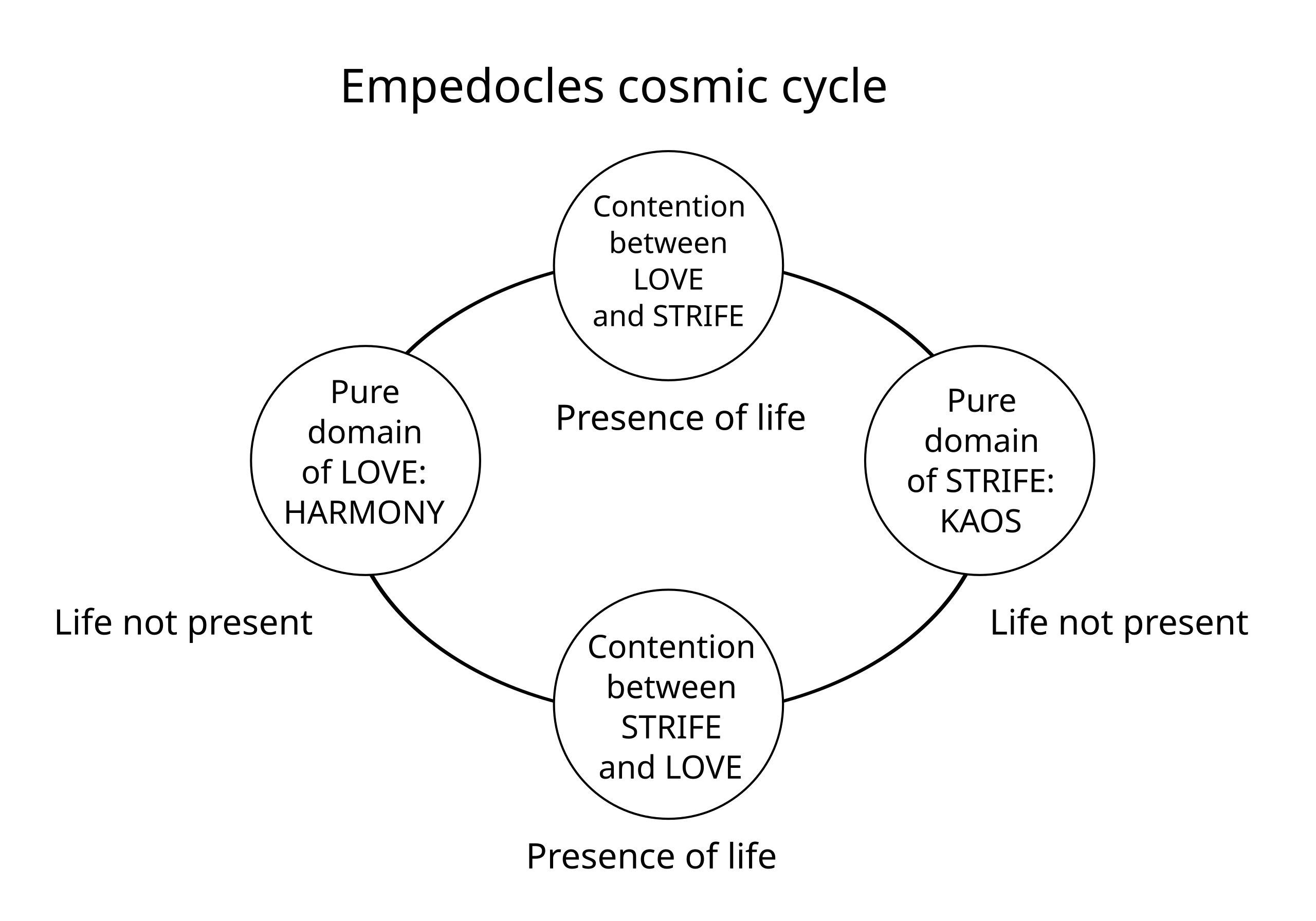

| Philosophy See also: Classical element § Hellenistic philosophy Based on the surviving fragments of his work, modern scholars generally believe that Empedocles was directly responding to Parmenides' doctrine of monism and was likely acquainted with the work of Anaxagoras, although it is unlikely he was aware of either the later Eleatics or the doctrines of the Atomists.[5] Many later accounts of his life claim that Empedocles studied with the Pythagoreans on the basis of his doctrine of reincarnation, although he may have instead learned this from a local tradition rather than directly from the Pythagoreans.[5] However, as the Modern Greek philosopher Helle Lambridis has argued, while Empedocles seems to have borrowed from the Eleatic tradition (with Parmenides at its centre) as well as from the Heraclitean and Pythagorean schools of thought, his own philosophy is very different from all these three influences. The work of Empedocles, Lambridis suggests, must be seen in relation to the work of the Greeks as a whole that borrowed elements from Egypt, Babylon and other Eastern cultures to produce a totally different philosophy.[6] Cosmogony  Empedocles' theory four elements (fire, air, water and earth), woodcut from a 1472 edition of Lucretius' De rerum natura Empedocles established four ultimate elements which make all the structures in the world—fire, air, water, earth.[7][h] Empedocles called these four elements "roots",[8] which he also identified with the mythical names of Zeus, Hera, Nestis, and Aidoneus[i] (e.g., "Now hear the fourfold roots of everything: enlivening Hera, Hades, shining Zeus. And Nestis, moistening mortal springs with tears").[9] Empedocles never used the term "element" (στοιχεῖον, stoicheion), which seems to have been first used by Plato.[j][better source needed] According to the different proportions in which these four indestructible and unchangeable elements are combined with each other the difference of the structure is produced.[7] It is in the aggregation and segregation of elements thus arising, that Empedocles, like the atomists, found the real process which corresponds to what is popularly termed growth, increase or decrease. One interpreter describes his philosophy as asserting that "Nothing new comes or can come into being; the only change that can occur is a change in the juxtaposition of element with element."[7] This theory of the four elements became the standard dogma for the next two thousand years. The four elements, however, are simple, eternal, and unalterable, and as change is the consequence of their mixture and separation, it was also necessary to suppose the existence of moving powers that bring about mixture and separation. The four elements are both eternally brought into union and parted from one another by two divine powers, Love and Strife (Philotes and Neikos).[7] Love (φιλότης) is responsible for the attraction of different forms of what we now call matter, and Strife (νεῖκος) is the cause of their separation.[k] If the four elements make up the universe, then Love and Strife explain their variation and harmony. Love and Strife are attractive and repulsive forces, respectively, which are plainly observable in human behavior, but also pervade the universe. The two forces wax and wane in their dominance, but neither force ever wholly escapes the imposition of the other.  Empedocles' cosmic cycle is based on the conflict between love and strife. As the best and original state, there was a time when the pure elements and the two powers co-existed in a condition of rest and inertness in the form of a sphere.[7] The elements existed together in their purity, without mixture and separation, and the uniting power of Love predominated in the sphere: the separating power of Strife guarded the extreme edges of the sphere.[l] Since that time, strife gained more sway[7] and the bond which kept the pure elementary substances together in the sphere was dissolved. The elements became the world of phenomena we see today, full of contrasts and oppositions, operated on by both Love and Strife.[7] Empedocles assumed a cyclical universe whereby the elements return and prepare the formation of the sphere for the next period of the universe. Empedocles attempted to explain the separation of elements, the formation of earth and sea, of Sun and Moon, of atmosphere.[7] He also dealt with the first origin of plants and animals, and with the physiology of humans.[7] As the elements entered into combinations, there appeared strange results—heads without necks, arms without shoulders.[7][m] Then as these fragmentary structures met, there were seen horned heads on human bodies, bodies of oxen with human heads, and figures of double sex.[7][n] But most of these products of natural forces disappeared as suddenly as they arose; only in those rare cases where the parts were found to be adapted to each other did the complex structures last.[7] Thus the organic universe sprang from spontaneous aggregations that suited each other as if this had been intended.[7] Soon various influences reduced creatures of double sex to a male and a female, and the world was replenished with organic life.[7] |

哲学 関連項目: 古代ギリシャの五元素説 § ヘレニズム哲学 現存する断片から判断すると、現代の学者は一般的にエンペドクレスがパルメニデスの単一論に直接応答しており、アナクサゴラスの著作にも精通していたと考 える。ただし、後のエレア学派や原子論者の学説については知らなかった可能性が高い。[5] 彼の転生説に基づき、多くの後世の伝記はエンペドクレスがピタゴラス派に学んだと主張するが、実際にはピタゴラス派から直接ではなく、地元の伝統から学ん だ可能性もある。[5] しかし現代ギリシャの哲学者ヘレ・ランブリディスが論じたように、エンペドクレスはエレア学派(中心にパルメニデスを置く)やヘラクレイトス学派、ピタゴ ラス学派の思想から借用したようだが、彼自身の哲学はこれら三つの影響とは大きく異なる。ランブリディスによれば、エンペドクレスの著作は、エジプトやバ ビロン、その他の東方文化から要素を借用しつつ全く異なる哲学を生み出した、ギリシャ人全体の業績と関連付けて捉える必要がある。[6] 宇宙生成論  エンペドクレスの四元素説(火、空気、水、地)。ルクレティウスの『物性論』1472年版の木版画 エンペドクレスは世界を構成する四つの究極的元素——火、空気、水、地——を確立した。[7][h]エンペドクレスはこの四元素を「根源」と呼び[8]、 神話上のゼウス、ヘラ、ネスティス、アイドネウス[i]の名と同一視した(例:「今こそ万物の四つの根源を聞け:生命を与えるヘラ、冥界のゼウス、輝くゼ ウス。そして涙で死すべき泉を潤すネスティス」)。エンペドクレスは「元素」(στοιχεῖον, stoicheion)という用語を一度も使わなかった。この用語はプラトンが初めて使ったと思われる。[j][より良い出典が必要] この四つの不滅で不変の元素が互いに組み合わさる比率の違いによって、構造の違いが生み出されるのだ。[7] このように生じる元素の集合と分離の中に、エンペドクレスは原子論者たちと同様に、一般に成長・増加・減少と呼ばれる現象に対応する真の過程を見出した。 ある解釈者は彼の哲学を「新たなものは何一つ生じず、生じ得ない。起こり得る唯一の変化とは、元素と元素の並置関係の変化である」と主張するものだと説明 している。[7] この四元素説は、その後二千年にわたり標準的な教義となった。 しかし四元素は単純で永遠かつ不変であり、変化はその混合と分離の結果であるため、混合と分離をもたらす運動力を仮定する必要があった。四元素は、愛 (φιλότης)と争い(νεῖκος)という二つの神聖な力によって、永遠に結合され、また分離される。[7] 愛は、現代で物質と呼ぶ異なる形態の吸引を担い、争いはそれらの分離の原因である。[k] もし四元素が宇宙を構成するなら、愛と争いはその多様性と調和を説明する。愛と争いはそれぞれ引力と斥力であり、人間の行動に明瞭に観察されるだけでな く、宇宙全体に遍在する。二つの力は支配力を増減させるが、いずれの力も他方の影響から完全に逃れることはない。  エンペドクレスの宇宙循環は、愛と争いの対立に基づいている。 最良かつ原初の状態として、純粋な元素と二つの力が球体の形で静止と無活動の状態に共存していた時代があった[7]。元素は混ざり合いも分離もなく純粋な 状態で共存し、球体内では結合する力である愛が優勢だった。分離する力である争いは球体の端を守っていた。[l] その後、争いが勢力を増し[7]、球体内で純粋な元素物質を結びつけていた絆は解けた。元素は今日我々が目にする現象の世界となり、対照と対立に満ち、愛 と争いの両方に作用されるようになった[7]。エンペドクレスは循環する宇宙を想定し、元素が戻ってきて球体の形成を準備し、次の宇宙の周期を迎えるとい う。 エンペドクレスは元素の分離、大地と海、太陽と月、大気の形成を説明しようとした[7]。また植物と動物の最初の起源、そして人間の生理学についても論じ た。[7] 元素が結合する過程で、奇妙な結果が現れた――首のない頭、肩のない腕である。[7][m] こうした断片的な構造が結合すると、人間の体に角の生えた頭、牛の体に人間の頭、両性具有の姿が見られた。[7][n] しかし自然の力が生み出したこれらの産物の大半は、現れたのと同じように突然消え去った。稀に、各部分が互いに適合していると判明した場合のみ、複雑な構 造体が存続したのである。[7] このようにして有機的な宇宙は、あたかも意図されたかのように互いに適合する自発的な集合体から生まれたのだ。[7] 間もなく様々な影響により両性具有の生物は雄と雌に分化され、世界は有機的生命で満たされたのである。[7] |

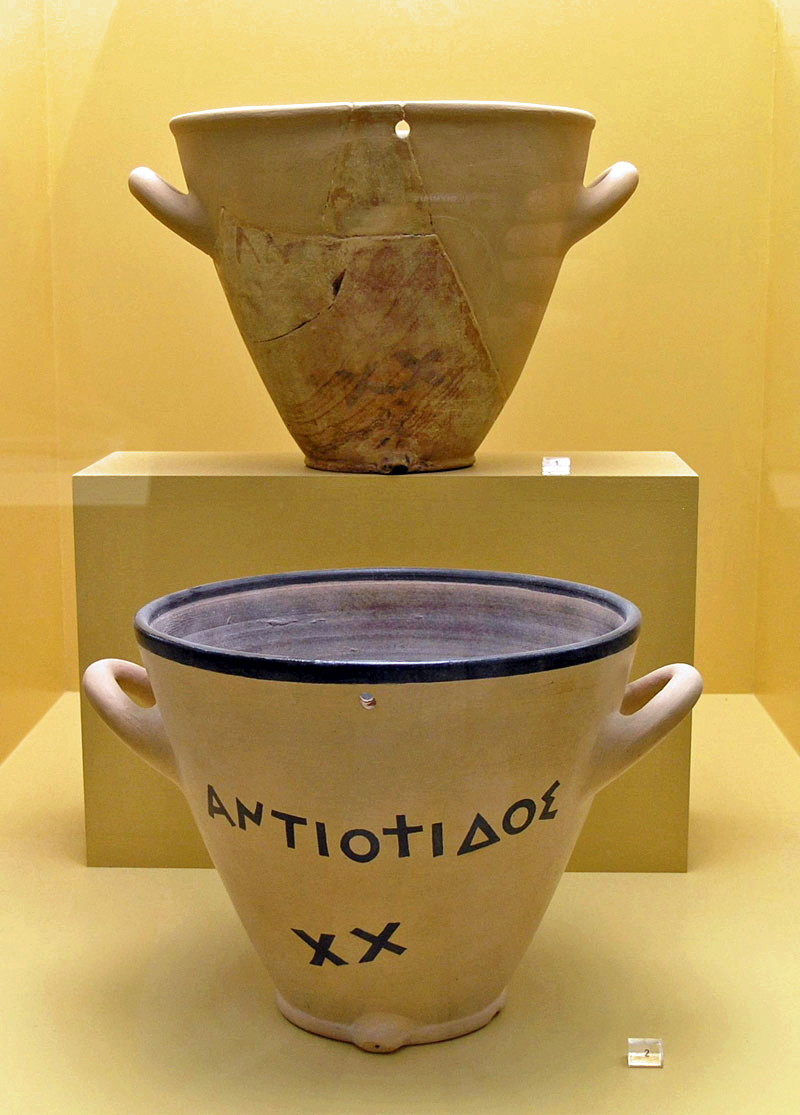

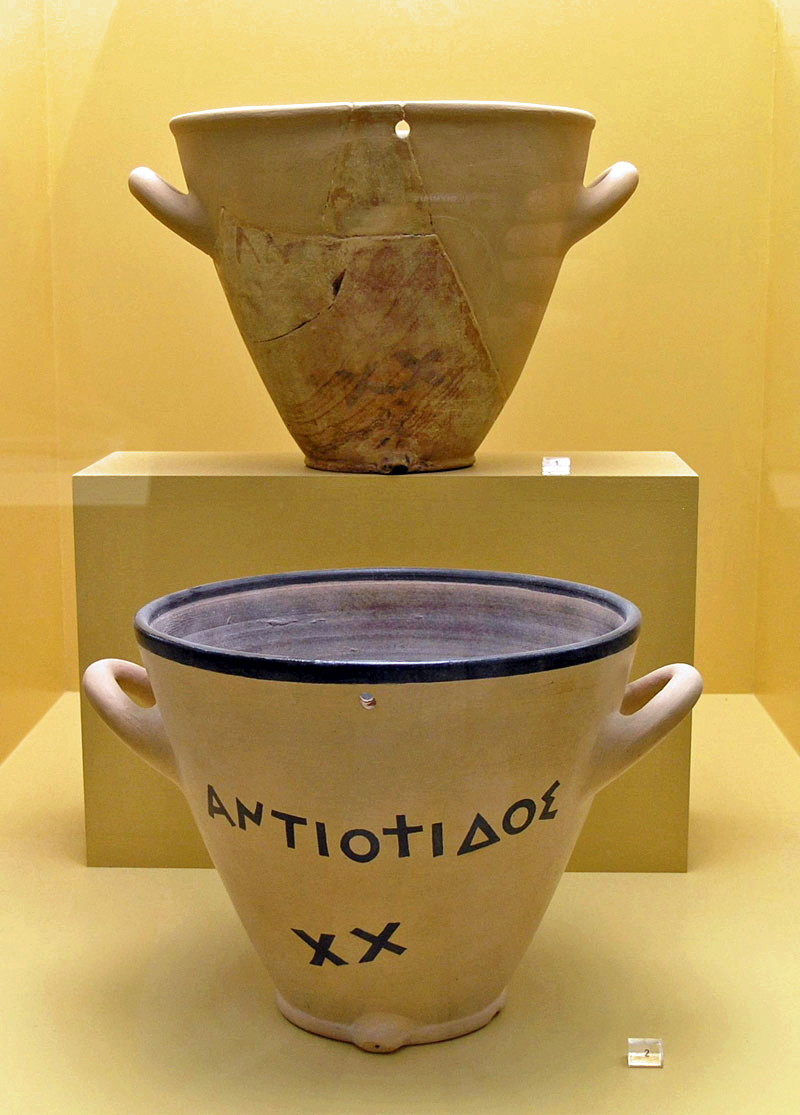

| Psychology Like Pythagoras, Empedocles believed in the transmigration of the soul or metempsychosis, that souls can be reincarnated between humans, animals and even plants.[o] According to him, all humans, or maybe only a selected few among them,[10] were originally long-lived daimons who dwelt in a state of bliss until committing an unspecified crime, possibly bloodshed or perjury.[10][11] As a consequence, they fell to Earth, where they would be forced to spend 30,000 cycles of metempsychosis through different bodies before being able to return to the sphere of divinity.[10][11] One's behavior during his lifetime would also determine his next incarnation.[10] Wise people, who have learned the secret of life, are closer to the divine,[7][p] while their souls similarly are closer to the freedom from the cycle of reincarnations, after which they are able to rest in happiness for eternity.[q] This cycle of mortal incarnation seems to have been inspired by the god Apollo's punishment as a servant to Admetus.[11]  A display of two 5th century BCE clepsydras, or "water clocks" from the Ancient Agora Museum in Athens Empedocles was a vegetarian[r][12] and advocated vegetarianism, since the bodies of animals are also dwelling places of punished souls.[s] For Empedocles, all living things were on the same spiritual plane; plants and animals are links in a chain where humans are a link too.[7] Empedocles is credited with the first comprehensive theory of light and vision. Historian Will Durant noted that "Empedocles suggested that light takes time to pass from one point to another."[13][14] He put forward the idea that we see objects because light streams out of our eyes and touches them. While flawed, this became the fundamental basis on which later Greek philosophers and mathematicians like Euclid would construct some of the most important theories of light, vision, and optics.[15][better source needed] Knowledge is explained by the principle that elements in the things outside us are perceived by the corresponding elements in ourselves.[t] Like is known by like. The whole body is full of pores and hence respiration takes place over the whole frame. In the organs of sense these pores are specially adapted to receive the effluences which are continually rising from bodies around us; thus perception occurs.[u] In vision, certain particles go forth from the eye to meet similar particles given forth from the object, and the resultant contact constitutes vision.[v] Perception is not merely a passive reflection of external objects.[16][better source needed] Empedocles also attempted to explain the phenomenon of respiration by means of an elaborate analogy with the clepsydra, an ancient device for conveying liquids from one vessel to another.[w][17] This fragment has sometimes been connected to a passage[x] in Aristotle's Physics where Aristotle refers to people who twisted wineskins and captured air in clepsydras to demonstrate that void does not exist. The fragment certainly implies that Empedocles knew about the corporeality of air, but he says nothing whatever about the void, and there is no evidence that Empedocles performed any experiment with clepsydras.[17] |

心理学 ピタゴラスと同様に、エンペドクレスは魂の輪廻転生、すなわち魂が人間、動物、さらには植物の間で生まれ変わることを信じていた。[o] 彼によれば、全ての人間、あるいは選ばれた少数のみ[10]は、もともと長寿の精霊(ダイモン)であり、特定の罪(おそらく流血や偽証)を犯すまでは至福 の状態に暮らしていた。その結果、彼らは地上に堕ち、神性の領域へ戻れるようになるまで、異なる肉体を通じて3万回の輪廻転生を強いられることになる。 [10][11] 人の生前の行いは、次の転生先も決定する。[10] 生命の秘義を悟った賢者は神性に近く[7][p]、その魂も同様に輪廻の束縛から解放されやすく、その後永遠の幸福に安らぐことができる[q]。この死す べき者の転生サイクルは、アポロン神がアドメトスの僕として罰せられた神話に由来するようだ[11]。  アテネ古代アゴラ博物館所蔵の紀元前5世紀の水時計(クレプシドラ)二点展示 エンペドクレスは菜食主義者であり[r][12]、動物の身体も罰せられた魂の住処であるとして菜食を提唱した[s]。彼にとって全ての生き物は同じ精神 的次元にあり、植物や動物は人間も含まれる連鎖の一環であった。[7] エンペドクレスは光と視覚に関する最初の包括的理論を提唱したとされる。歴史家ウィル・デュラントは「エンペドクレスは光が一点から他点へ到達するには時 間を要すると示唆した」と記している[13][14]。彼は、我々が物体を見るのは光が我々の目から流れ出てそれらに触れるからだという考えを提示した。 この理論には欠陥があったものの、後にユークリッドのようなギリシャの哲学者や数学者が、光・視覚・光学に関する最も重要な理論を構築する基礎となった。 [15][より良い出典が必要] 知識は、外界の事物にある要素が、我々自身の中にある対応する要素によって知覚されるという原理で説明される。[t] 似たものは似たものによって知られる。全身は毛穴で満たされており、したがって呼吸は全身を通じて行われる。感覚器官においては、これらの孔は周囲の物体 から絶えず発せられる気流を受け取るよう特別に適応している。こうして知覚が生じるのだ。[u] 視覚においては、特定の粒子が眼から発せられ、対象物から放出される類似の粒子と出会い、その結果生じる接触が視覚を構成する。[v] 知覚は単に外部対象の受動的な反映ではないのだ。[16][より良い出典が必要] エンペドクレスはまた、呼吸の現象を、液体を一つの容器から別の容器へ移す古代の装置である漏斗(クレプシドラ)との精巧な類推によって説明しようとし た。[w][17] この断片は、アリストテレスの『物理学』にある一節[x]と関連づけられることがある。そこではアリストテレスが、空袋を捻って漏斗に空気を閉じ込める人 々を例に挙げて、虚空は存在しないと論じている。この断片は確かにエンペドクレスが空気の物質性を認識していたことを示唆しているが、虚空については一切 言及しておらず、エンペドクレスが水時計を用いた実験を行った証拠は存在しない。[17] |

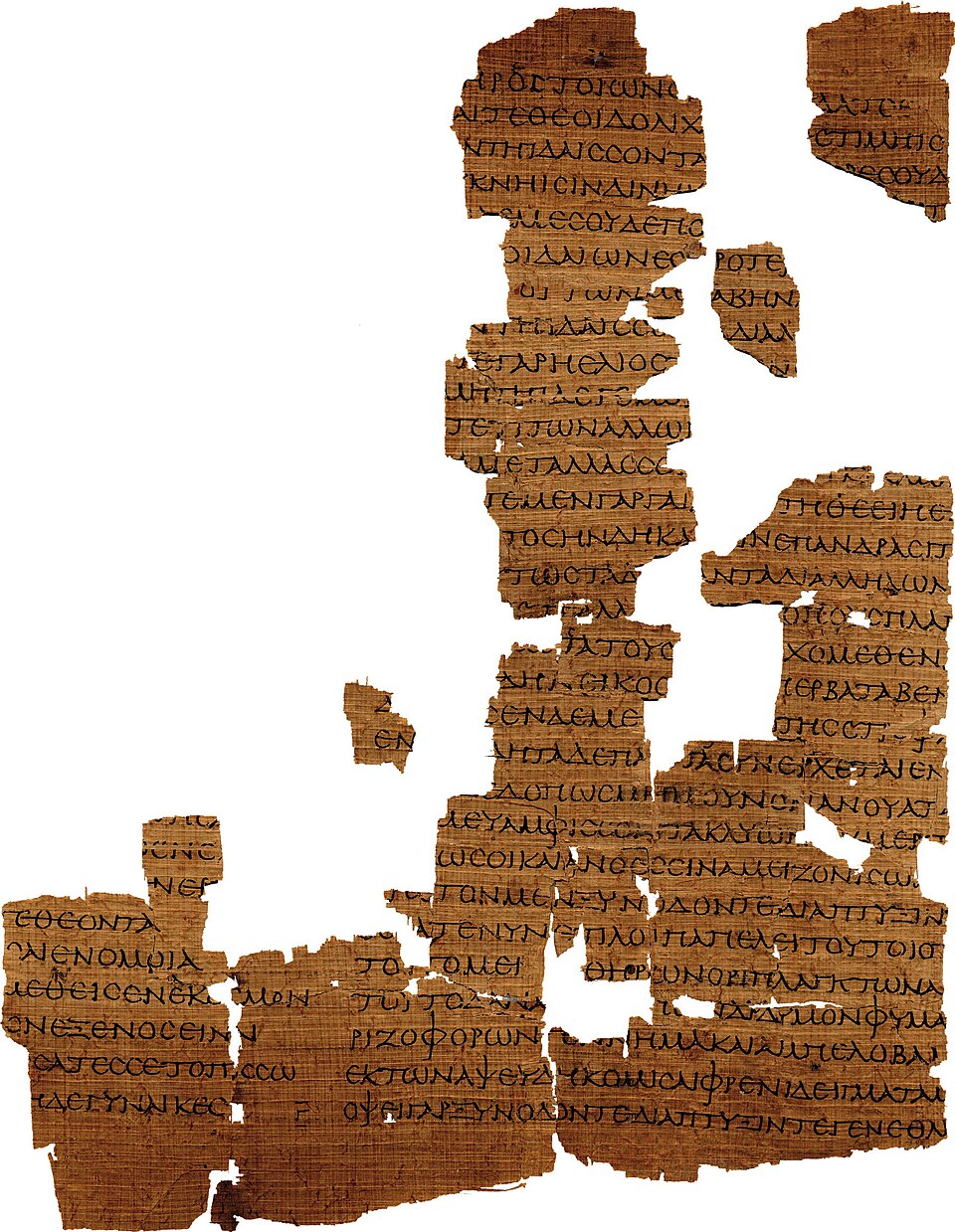

Writings The Strasbourg Empedocles papyrus contained over 50 lines from Empedocles' work On Nature that were not published until 1999.[18] According to Diogenes Laertius,[y] Empedocles wrote two poems, "On Nature" and "On Purifications", which together comprised 5000 lines. However, only some 550 lines of his poetry survive, quoted in fragments by later ancient sources. In old editions of Empedocles, about 450 lines were ascribed to "On Nature" which outlined his philosophical system, and explains not only the nature and history of the universe, including his theory of the four classical elements, but also theories on causation, perception, and thought, as well as explanations of terrestrial phenomena and biological processes. The other 100 lines were typically ascribed to his "Purifications", which was taken to be a poem about ritual purification, or the poem that contained all his religious and ethical thought, which early editors supposed that it was a poem that offered a mythical account of the world which may, nevertheless, have been part of Empedocles' philosophical system. A late 20th century discovery has changed this situation. The Strasbourg papyrus[18][z] contains a large section of "On Nature", including many lines formerly attributed to "On Purifications".[19] This has raised considerable debate[20][21] about whether the surviving fragments of his teaching should be attributed to two separate poems, with different subject matter; whether they may all derive from one poem with two titles;[22] or whether one title refers to part of the whole poem. |

著作 ストラスブール・エンペドクレス・パピルスには、エンペドクレスの著作『自然について』から50行以上が含まれていたが、これらは1999年まで公表され なかった。[18] ディオゲネス・ラエルティオスによれば、エンペドクレスは『自然について』と『浄化について』という二つの詩を書き、これらは合わせて5000行を構成し ていた。しかし現存するのは約550行のみで、後代の古代文献に断片的に引用されている。 エンペドクレスの古版では、約450行が『自然について』に帰属されていた。この著作は彼の哲学体系を概説し、四元素説を含む宇宙の性質と歴史だけでな く、因果関係・知覚・思考に関する理論、さらに地上の現象や生物学的過程の説明も扱っている。残りの100行は通常『浄化論』に帰属され、儀礼浄化に関す る詩、あるいは彼の宗教的・倫理的思考を全て含む詩と解釈されてきた。初期の編集者たちは、この詩が世界の神話的説明を提供するものと推測したが、それは エンペドクレスの哲学体系の一部であった可能性もある。 20世紀後半の発見がこの状況を変えた。ストラスブール・パピルス[18][z]には『自然について』の大部分が収められており、かつて『浄化について』 に帰属していた多くの行も含まれている。[19] これにより、現存する断片を主題の異なる二つの別々の詩に帰すべきか、あるいは二つの題名を持つ一つの詩に由来するものか、あるいは一つの題名が全体の断 片を指すものかについて、大きな議論[20][21]が巻き起こった。 |

| Notes Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 51 Aristotle, Poetics, 1, ap. Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 57. Apollonius, ap. Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 52, comp. 74, 73 Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 67, 69, 70, 71; Horace, ad Pison. 464, etc. Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 69 See especially Lucretius, i. 716, etc.[4] Horace Ars Poetica Frag. B17 (Simplicius, Physics, 157–159) Frag. B6 (Sextus Empiricus, Against the Mathematicians, x, 315) Plato, Timaeus, 48b–c Frag. B35, B26 (Simplicius, Physics, 31–34) Frag. B35 (Simplicius, Physics, 31–34; On the Heavens, 528–530) Frag. B57 (Simplicius, On the Heavens, 586) Frag. B61 (Aelian, On Animals, xvi 29) Frag. B127 (Aelian, On Animals, xii. 7); Frag. B117 (Hippolytus, i. 3.2) Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies, iv. 23.150 Clement of Alexandria, Miscellanies, v. 14.122 Plato, Meno Sextus Empiricus, Against the Mathematicians, ix. 127; Hippolytus, vii. 21 Frag. B109 (Aristotle, On the Soul, 404b11–15) Frag. B100 (Aristotle, On Respiration, 473b1–474a6) Frag. B84 (Aristotle, On the Senses and their Objects, 437b23–438a5) Aristotle, On Respiration 13 Aristotle, Physics, 213a24–7 Diogenes Laërtius, viii. 77 Not to be confused with the Strasbourg papyrus containing Christian prayers |

注 ディオゲネス・ラエルティオス、第八巻51 アリストテレス、『詩学』第一巻、ディオゲネス・ラエルティオスによる引用、第八巻57 アポロニオス、ディオゲネス・ラエルティオスによる引用、第八巻52、比較74、73 ディオゲネス・ラエルティオス、第八巻67、69、70、71;ホラティウス、ピソへの手紙464など ディオゲネス・ラエルティオス、第八巻69 特にルクレティウス、第一巻716など参照[4] ホラティウス『詩技論』 断片B17(シンプリキオス『物理学』157–159) 断片B6(セクストス・エンピリコス『数学者に対する論駁』x, 315) プラトン『ティマイオス』48b–c 断片B35, B26(シンプリキオス『物理学』31–34) 断片B35(シンプリキオス『物理学』31–34;『天界論』528–530) 断片B57(シンプリキオス『天界論』586) 断片B61(アエリウス『動物誌』xvi 29) 断片 B127(アエリアヌス『動物論』xii. 7);断片 B117(ヒッポリュトス i. 3.2) アレクサンドリアのクレメンス『雑録』iv. 23.150 アレクサンドリアのクレメンス『雑録』v. 14.122 プラトン『メノン』 セクストス・エンピリコス『数学者に対する反論』9.127;ヒッポリュトス7.21 断片B109(アリストテレス『魂について』404b11–15) 断片B100(アリストテレス『呼吸について』473b1–474a6) 断片B84(アリストテレス『感覚とその対象について』437b23–438a5) アリストテレス『呼吸論』13 アリストテレス『物理学』213a24–7 ディオゲネス・ラエルティオス、viii. 77 キリスト教の祈りを収めたストラスブール・パピルスと混同してはならない |

| References 1. Kingsley & Parry 2020, §1. 2. Inwood 2001, pp. 6–8. 3. Burnet 1892, pp. 202–203. 4. Sedley 2003. 5. Inwood 2001, p. 6-8. 6. Lambridis, Helle (1976). Empedocles: A Philosophical Investigation. Tuscaloosa: University of Alabama Press. pp. 38–39. 7. Wallace 1911. 8. Ströker, E. (September 1968). "Element and Compound. On the Scientific History of Two Fundamental Chemical Concepts". Angewandte Chemie International Edition in English. 7 (9): 718–724. doi:10.1002/anie.196807181. ISSN 0570-0833. 9. Kingsley 1995. 10. Inwood 2001, pp. 55–68. 11. Primavesi 2008, pp. 261–268. 12. Fragments of Empedocles 136 - 139 13. Durant, Will. The Story of Civilization, Volume 2: The Life of Greece (New York; Simon & Schuster) 1939, p. 339. 14. Empedocles (and with him all others who used the same forms of expression) was wrong in speaking of light as 'travelling' or being at a given moment between the earth and its envelope, its movement being unobservable by us; that view is contrary both to the clear evidence of argument and to the observed facts; if the distance traversed were short, the movement might have been unobservable, but where the distance is from extreme East to extreme West, the draught upon our powers of belief is too great. Aristotle, On the soul 418b 15. Let There be Light 7 August 2006 01:50 BBC Four 16. "Empedocles – Encyclopedia". 17. Barnes 2002, p. 313. 18. Martin & Primavesi 1999. 19. Kingsley & Parry 2020. 20. Inwood 2001, pp. 8–21. 21. Trépanier 2004. 22. Osborne 1987, pp. 24–31, 108. |

参考文献 1. キングズリー&パリー 2020, §1. 2. インウッド 2001, pp. 6–8. 3. バーネット 1892, pp. 202–203. 4. セドリー 2003. 5. インウッド 2001, p. 6-8. 6. ランブリディス, ヘレ (1976). 『エンペドクレス: 哲学探究』. タスカルーサ: アラバマ大学出版局. pp. 38–39. 7. ウォレス 1911. 8. シュトローカー, E. (1968年9月). 「元素と化合物. 二つの基礎的な化学概念の科学的歴史について」. 応用化学国際版英語版。7巻9号:718–724頁。doi:10.1002/anie.196807181。ISSN 0570-0833。 9. キングズリー 1995年。 10. インウッド 2001年、55–68頁。 11. プリマヴェージ 2008, pp. 261–268. 12. エンペドクレス断片 136 - 139 13. デュラント, ウィル. 『文明の物語』第2巻: ギリシャの生涯 (ニューヨーク; サイモン・アンド・シュスター) 1939, p. 339. 14. エンペドクレス(および彼と同じ表現形式を用いた他の者たち)は、光が「移動する」とか、ある瞬間には地球とその外殻の間に存在すると述べた点で誤ってい た。その動きは我々には観測不可能である。この見解は、論証の明らかな証拠にも、観測された事実にも反する。移動距離が短ければ、その動きは観察不可能 だったかもしれないが、移動距離が極東から極西までであるならば、我々の信じる力を引き出すには大きすぎる。アリストテレス、『魂について』 418b 15. 『光あれ』 2006年8月7日 01:50 BBC Four 16. 「エンペドクレス – 百科事典」。 17. バーンズ 2002、313 ページ。 18. マーティン&プリマヴェシ 1999。 19. キングスリー&パリー 2020。 20. インウッド 2001、8-21 ページ。 21. トレパニエ 2004。 22. オスボーン 1987、24-31 ページ、108 ページ。 |

| Bibliography Ancient Testimony Laërtius, Diogenes. "Pythagoreans: Empedocles" . Lives of the Eminent Philosophers. Vol. 2:8. Translated by Hicks, Robert Drew (Two volume ed.). Loeb Classical Library. References Barnes, Jonathan (11 September 2002). The Presocratic Philosophers. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-96512-0. Burnet, John (1892). Early Greek Philosophy. Adam and Charles Black. Inwood, Brad (2001). The Poem of Empedocles: A Text and Translation with an Introduction (Revised ed.). University of Toronto Press. ISBN 978-0-8020-8353-1. Guthrie, W. K. C. (1962). A History of Greek Philosophy: Volume 2, The Presocratic Tradition from Parmenides to Democritus. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29421-8. Kingsley, K. Scarlett; Parry, Richard (2020). "Empedocles". In Zalta, Edward N. (ed.). Stanford Encyclopedia of Philosophy. Kingsley, Peter (1995). Ancient Philosophy, Mystery, and Magic: Empedocles and Pythagorean Tradition. Oxford: Clarendon Press. ISBN 0-19-814988-3. Martin, Alain; Primavesi, Oliver (1999). L'Empédocle de Strasbourg: (P. Strasb. gr. Inv. 1665-1666) (in French). Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-015129-9. Primavesi, Oliver (27 October 2008). "Empedocles: Physical and Mythical Divinity". In Curd, Patricia; Graham, Daniel W. (eds.). The Oxford Handbook of Presocratic Philosophy. Oxford University Press, US. ISBN 978-0-19-514687-5. Osborne, Catherine (1987). Rethinking early Greek philosophy : Hippolytus of Rome and the Presocratics. London: Duckworth. ISBN 0-7156-1975-6. Sedley, D. N. (2003). Lucretius and the Transformation of Greek Wisdom. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-54214-2. Trépanier, Simon (2004). Empedocles: An Interpretation. Routledge. ISBN 978-0-415-96700-6. Wallace, William (1911). "Empedocles" . Encyclopædia Britannica. Vol. 9 (11th ed.). pp. 344–345. Wright, M. R. (1995). Empedocles: The Extant Fragments (new ed.). London: Bristol Classical Press. ISBN 1-85399-482-0. Further reading Chitwood, Ava (2004). Death by philosophy : the biographical tradition in the life and death of the archaic philosophers Empedocles, Heraclitus, and Democritus. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 9780472113880. Campbell, Gordon. "Empedocles". In Fieser, James; Dowden, Bradley (eds.). Internet Encyclopedia of Philosophy. ISSN 2161-0002. OCLC 37741658. Freeman, Kathleen (1948). Ancilla to the Pre-Socratic Philosophers: A Complete Translation of the Fragments in Diels Fragmente Der Vorsokratiker. Forgotten Books. ISBN 978-1-60680-256-4. Gottlieb, Anthony (2000). The Dream of Reason: A History of Western Philosophy from the Greeks to the Renaissance. London: Allen Lane. ISBN 0-7139-9143-7. Kirk, G. S.; Raven, J.E.; Schofield, M. (1983). The Presocratic Philosophers: A Critical History (2nd ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-25444-2. Lambridis, Helle (1976). Empedocles : a philosophical investigation. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press. ISBN 0-8173-6615-6. Long, A. A. (1999). The Cambridge Companion to Early Greek Philosophy. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-44122-6. Saetta Cottone, Rossella (2023). Soleil et connaissance. Empédocle avant Platon. Paris: Les Belles Lettres. ISBN 9782350882031. Stamatellos, Giannis (2007). Plotinus and the Presocratics: A Philosophical Study of Presocratic Influences in Plotinus' Enneads. Albany: SUNY Press. Stamatellos, Giannis (2012). Introduction to Presocratics: A Thematic Approach to Early Greek Philosophy with Key Readings. Wiley-Blackwell. Wellmann, Tom (2020). Die Entstehung der Welt. Studien zum Straßburger Empedokles-Papyrus. Berlin/Boston: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-063372-6. |

参考文献 古代の証言 ディオゲネス・ラエルティオス『著名な哲学者列伝』第2巻8章「ピタゴラス学派:エンペドクレス」ロバート・ドリュー・ヒックス訳(全2巻)。ローブ古典 叢書。 参考文献 ジョナサン・バーンズ(2002年9月11日)『前ソクラテス派哲学者』ラウトリッジ。ISBN 978-1-134-96512-0。 バーネット、ジョン(1892)。『初期ギリシャ哲学』。アダム・アンド・チャールズ・ブラック社。 インウッド、ブラッド(2001)。『エンペドクレスの詩:序文付きテキストと翻訳』(改訂版)。トロント大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-8020-8353-1。 ガスリー、W. K. C.(1962)。『ギリシャ哲学史:第2巻、パルメニデスからデモクリトスまでの前ソクラテス派の伝統』。ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 978-0-521-29421-8。 キングスリー、K. スカーレット、パリー、リチャード (2020). 「エンペドクレス」. ザルタ、エドワード N. (編). スタンフォード哲学百科事典. キングスリー、ピーター (1995). 古代哲学、神秘、そして呪術:エンペドクレスとピタゴラス学派の伝統. オックスフォード:クラレンドン・プレス. ISBN 0-19-814988-3。 マーティン、アラン;プリマヴェシ、オリバー(1999)。『ストラスブールのエンペドクレス:(P. Strasb. gr. Inv. 1665-1666)』(フランス語)。ウォルター・デ・グルイター。ISBN 978-3-11-015129-9。 プリマヴェージ、オリバー (2008年10月27日). 「エンペドクレス:物理的かつ神話的な神性」. パトリシア・カード、ダニエル・W・グラハム (編). 『オックスフォード・プレソクラテス哲学ハンドブック』. オックスフォード大学出版局、米国. ISBN 978-0-19-514687-5. オズボーン、キャサリン (1987). 『初期ギリシャ哲学の再考:ローマのヒッポリュトスと前ソクラテス派』. ロンドン:ダックワース. ISBN 0-7156-1975-6. セドリー、D. N. (2003). 『ルクレティウスとギリシャの知恵の変容』. ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ISBN 978-0-521-54214-2. トレパニエ、サイモン(2004)。『エンペドクレス:解釈』ラウトリッジ。ISBN 978-0-415-96700-6。 ウォレス、ウィリアム(1911)。「エンペドクレス」『ブリタニカ百科事典』第9巻(第11版)。344–345頁。 ライト、M. R.(1995)。『エンペドクレス:現存する断片』(新版)。ロンドン:ブリストル古典出版社。ISBN 1-85399-482-0。 追加文献(さらに読む) チットウッド、アヴァ(2004)。哲学による死:古代哲学者エンペドクレス、ヘラクレイトス、デモクリトスの生と死における伝記的伝統。アナーバー:ミ シガン大学出版局。ISBN 9780472113880。 キャンベル、ゴードン。「エンペドクレス」。フィザー、ジェームズ、ダウデン、ブラッドリー(編)。インターネット哲学百科事典。ISSN 2161-0002。OCLC 37741658。 フリーマン、キャスリーン(1948)。『ソクラテス以前の哲学者たちへのアンシラ:ディールス『Fragmente Der Vorsokratiker』の断片の完全翻訳』。Forgotten Books。ISBN 978-1-60680-256-4。 ゴットリーブ、アンソニー (2000)。『理性の夢:ギリシャからルネサンスまでの西洋哲学史』。ロンドン:アレン・レーン。ISBN 0-7139-9143-7。 カーク、G. S.、レイヴン、J.E.、スコフィールド、M. (1983)。『ソクラテス以前の哲学者たち:批判的歴史(第 2 版)』。ケンブリッジ:ケンブリッジ大学出版局。ISBN 0-521-25444-2。 ランブリディス、ヘレ(1976)。『エンペドクレス:哲学探究』。タスカルーサ、アラバマ州:アラバマ大学出版局。ISBN 0-8173-6615-6。 ロング、A. A. (1999). 『ケンブリッジ初期ギリシャ哲学事典』. ケンブリッジ: ケンブリッジ大学出版局. ISBN 0-521-44122-6. サエッタ・コットーネ、ロッセラ (2023). 『太陽と認識:プラトン以前のエンペドクレス』. パリ: レ・ベル・レター. ISBN 9782350882031. スタマテロス、ヤニス(2007)。『プロティノスと前ソクラテス派:プロティノスの『エンネアデス』における前ソクラテス派の影響に関する哲学的研 究』。オールバニ:SUNYプレス。 スタマテロス、ヤニス(2012)。『前ソクラテス派入門:主要文献による初期ギリシャ哲学のテーマ別アプローチ』。ワイリー・ブラックウェル。 ウェルマン、トム(2020年)。『世界の生成。ストラスブール・エンペドクレス・パピルス研究』。ベルリン/ボストン:ウォルター・デ・グリュイター。 ISBN 978-3-11-063372-6。 |

| https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Empedocles |

★クレジット:エンペドクレス, このページは「西洋哲学における自然」よりスピンオフ/オンしたものです

リンク

文献

Copyleft, CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099

Thomas

Aquinas, by Carlo Crivelli (1430-1495)

++

Copyleft,

CC, Mitzub'ixi Quq Chi'j, 1996-2099